DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111196

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

آثار تدخلات التصميم البيوفيلي على الأداء المعرفي لطلاب الجامعات: دراسة تجريبية سمعية بصرية في بيئة مكتب افتراضية غامرة

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

البيئة الداخلية

كفاءة العمل

التصميم البيوفيلي

المشهد الصوتي الداخلي

متعدد المجالات

الملخص

يجب أن تكون العلاقة بين الإنسان والطبيعة عنصرًا رئيسيًا في تصميم البيئات الداخلية الداعمة والمريحة. وقد ظهر اهتمام مؤخرًا بإدخال حلول قائمة على الطبيعة داخل البيئات عبر تدخلات التصميم البيوفيلي (BD). وقد تم تحديد الفوائد المتعلقة بكفاءة العمل في الدراسات المخبرية دون إمكانية إجراء تقييمات تصميم أولية. مؤخرًا، تم اعتماد الواقع الافتراضي بفضل مزاياه في جمع البيانات في بيئات واقعية للغاية. حتى الآن، كان معظم البحث حول BD يركز على الاتصال البصري مع الطبيعة على الرغم من أن الناس يختبرون حواسًا متعددة في وقت واحد. في هذه الورقة، يتم تقديم نهج تصميم جديد لتقييم أولي لتدخل BD في الواقع الافتراضي.

1. المقدمة

الهندسة البشرية. مؤخرًا، تحولت بشكل متزايد إلى قضايا الصحة والرفاهية (مثل WELL)، مما أدى إلى تحفيز اهتمام عالمي واهتمام علمي بقطاع البناء المستدام والصحي. على وجه الخصوص، كان تعزيز كفاءة العمل في مكان العمل دافعًا رئيسيًا حيث اعترفت القطاعات الخاصة والعامة بأهمية بيئة داخلية تركز على شاغليها. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، زادت جائحة COVID-19 من قلق الموظفين بشأن فعالية مساحات عملهم، متسائلين عما إذا كانت تلبي احتياجاتهم وتعزز الرفاهية بالإضافة إلى أماكن عملهم المنزلية خلال فترات العمل الذكي.

1.1. التصميم البيوفيلي لبيئات المكاتب

[9-11] أكدت مجموعة من النظريات النفسية على فوائد التعرض لـ NBS، والتي يمكن أن تعزز تأثيرًا إيجابيًا على راحة الإنسان (الظروف الهيدروحرارية) [12]، والصحة والرفاهية (مثل تقليل القلق والتوتر) [13،14] والعواطف (مثل السعادة، والرضا، والتفضيل البصري) [13،15].

1.2. الفوائد التي توفرها العلاقة البصرية والصوتية مع الطبيعة على الأداء المعرفي

الإنتاجية المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا. وفقًا لـ Lohr [27] و Khan [28]، أفاد المشاركون في الغرفة التي تحتوي على نباتات بأنهم يشعرون بمزيد من الانتباه مقارنةً بالأشخاص في الغرفة التي لا تحتوي على نباتات.

1.3. استخدام الواقع الافتراضي لتقييم فوائد تدخلات التصميم البيوفيلي

جمع البيانات المعقدة في بيئات واقعية للغاية [50]. يعد الواقع الافتراضي والبيئات الافتراضية الغامرة (IVE) وسائل صالحة لمحاكاة تكوينات تصميم بديلة، دون قيود الدراسات المعملية [51]. يتم دعم الباحثين والمهنيين لتحسين دمج «البعد البشري» من مراحل التصميم المبكرة، على سبيل المثال، لقياس سلوك المستخدم النهائي، وجمع التعليقات في الوقت الحقيقي، وتحسين التواصل لفهم أفضل للمشروع عبر بيئات ثلاثية الأبعاد متعددة الحواس [52]. ميزة أخرى حاسمة هي إمكانية التلاعب بشكل صحيح بالمتغيرات المرغوبة (مثل، الأبعاد البصرية والصوتية). وهذا يؤدي إلى تقصير كبير في إجراءات التصميم [53].

1.4. أسئلة البحث

تحت سيناريوهات سمعية بصرية مشتركة تتضمن NBS.

على وجه الخصوص، كان المؤلفون مهتمين بالأسئلة البحثية التالية:

- RQ1. هل الواقع الافتراضي فعال في دراسة تدخلات تصميم البيوفيلية من حيث الشعور العالي بالوجود والانغماس وانخفاض مرض الفضاء الإلكتروني؟

- RQ2. هل توفر العلاقة البصرية والصوتية مع الطبيعة فوائد من حيث ذاكرة العمل لدى الشاغلين، وكبح النفس، وأداء التبديل بين المهام؟

2. المواد والطرق

2.1. معدات غرفة الاختبار

2.2. المواد الصوتية

مواصفات المستشعرات.

| حساس | نموذج | نطاق القياس | دقة |

| درجة حرارة الهواء | دلتا أوه إم – | -40 إلى |

|

| HP3217R |

|

قياس | |

| متألق | دلتا أوه إم – | -10 إلى | فئة 1/3 DIN (

|

| درجة الحرارة | TP3275 |

|

من 15 إلى

|

| سرعة الهواء | دلتا أوه إم – |

|

|

| AP3203 |

|

||

| مستشعر SCL | إمبريس بلس – | 0.01 إلى 100 | – |

| إمباتيكا |

|

||

| حساس HR | إمبريس بلس – | 24 إلى 240 | 3 نبضة في الدقيقة (بدون حركة)/5 نبضات في الدقيقة |

| حساس ST | إمبريس بلس – | 0 إلى

|

|

| إمباتيكا |

|

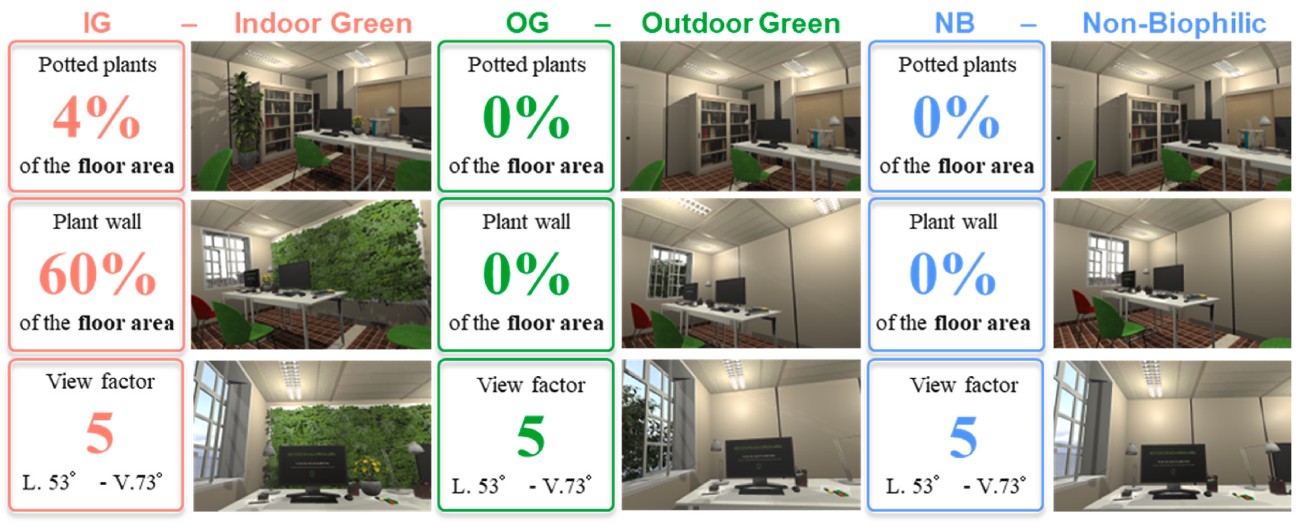

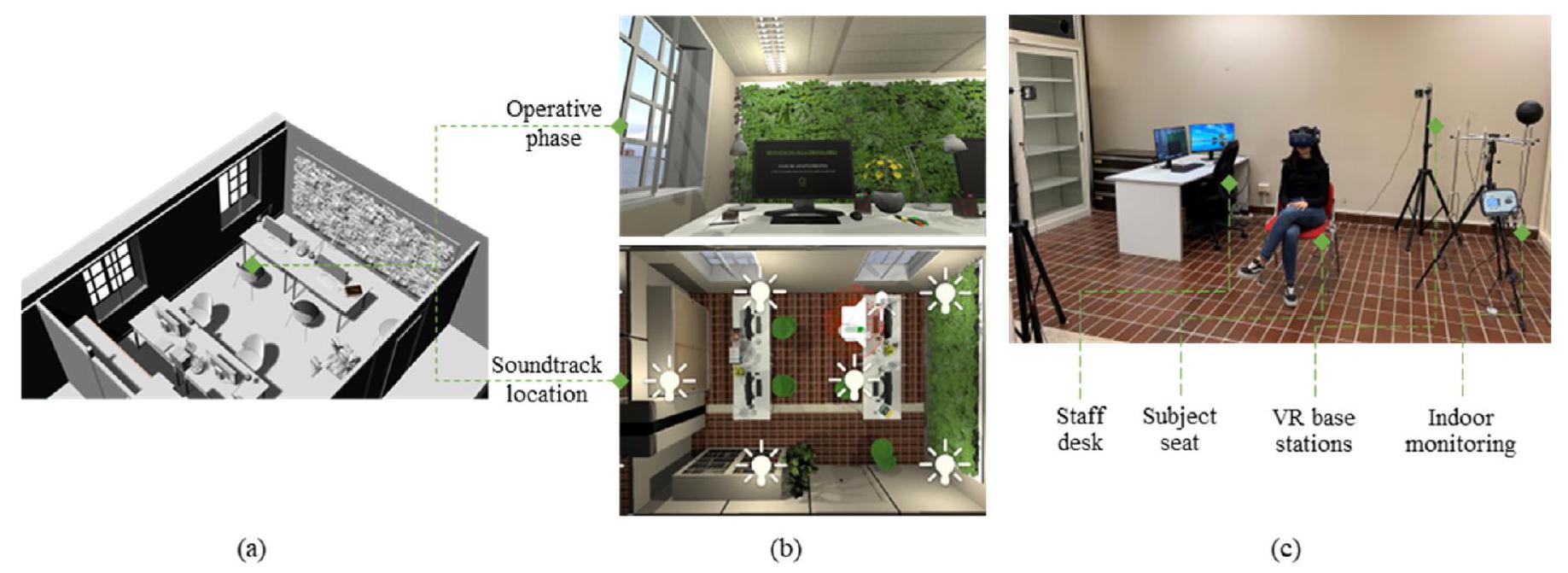

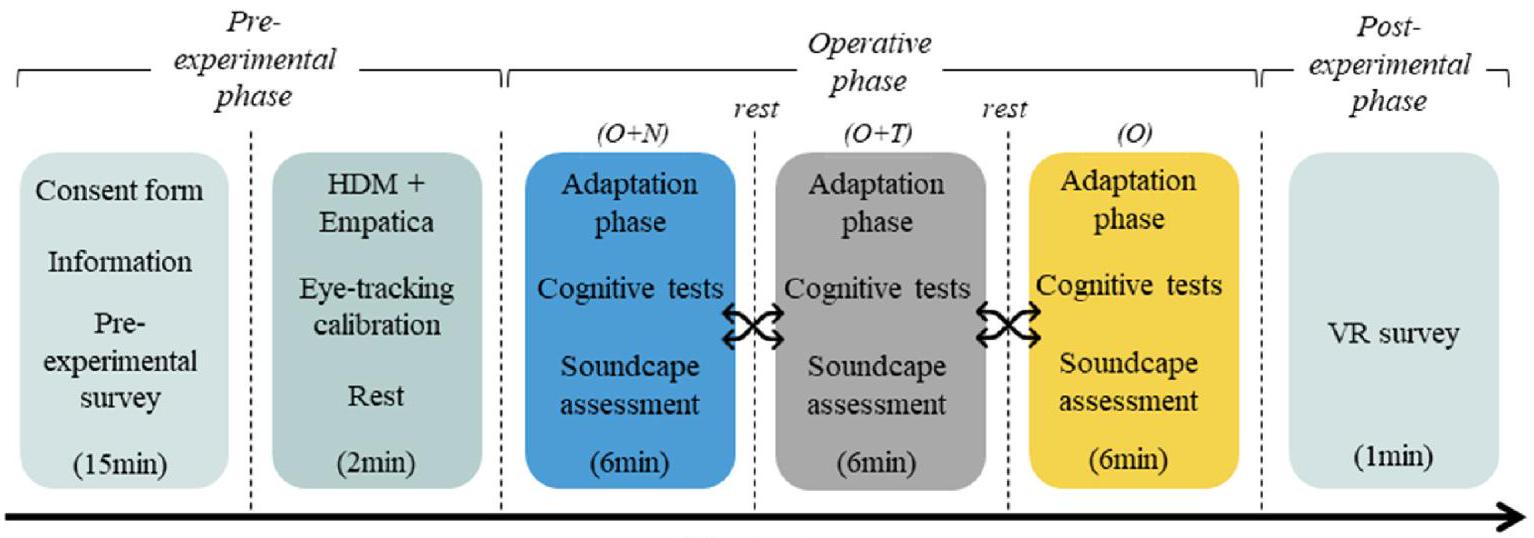

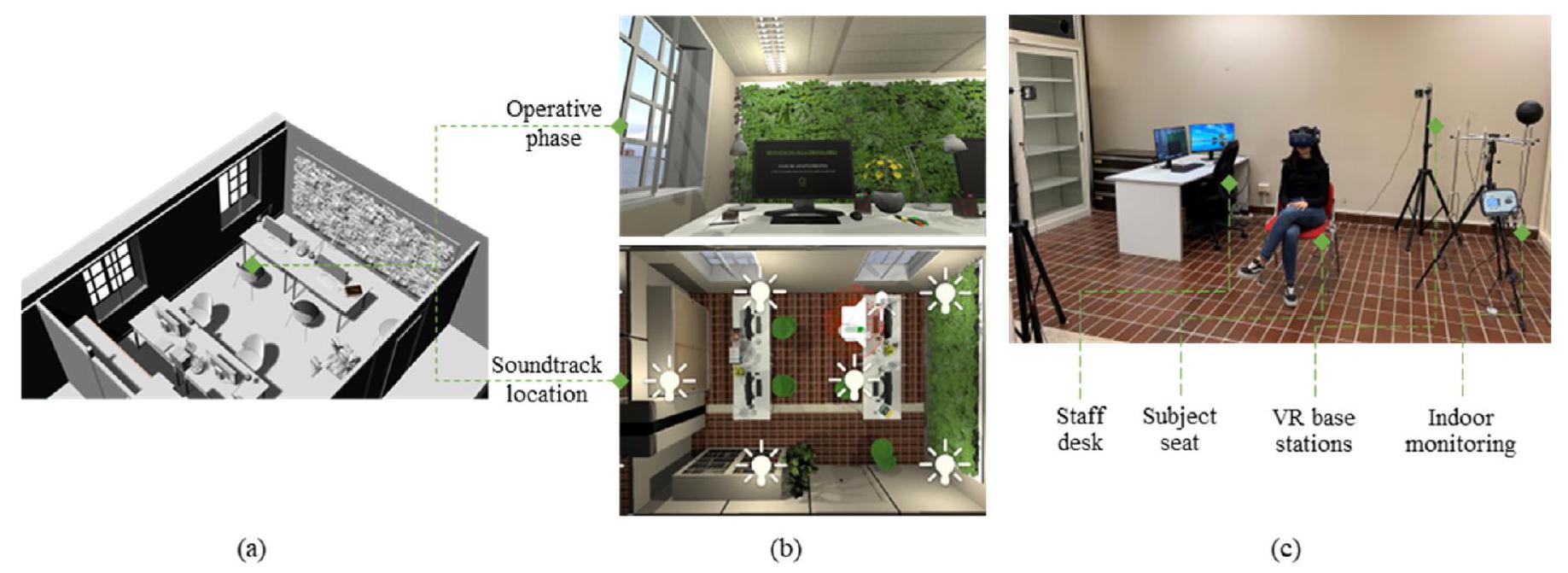

2.3. البيئة الافتراضية

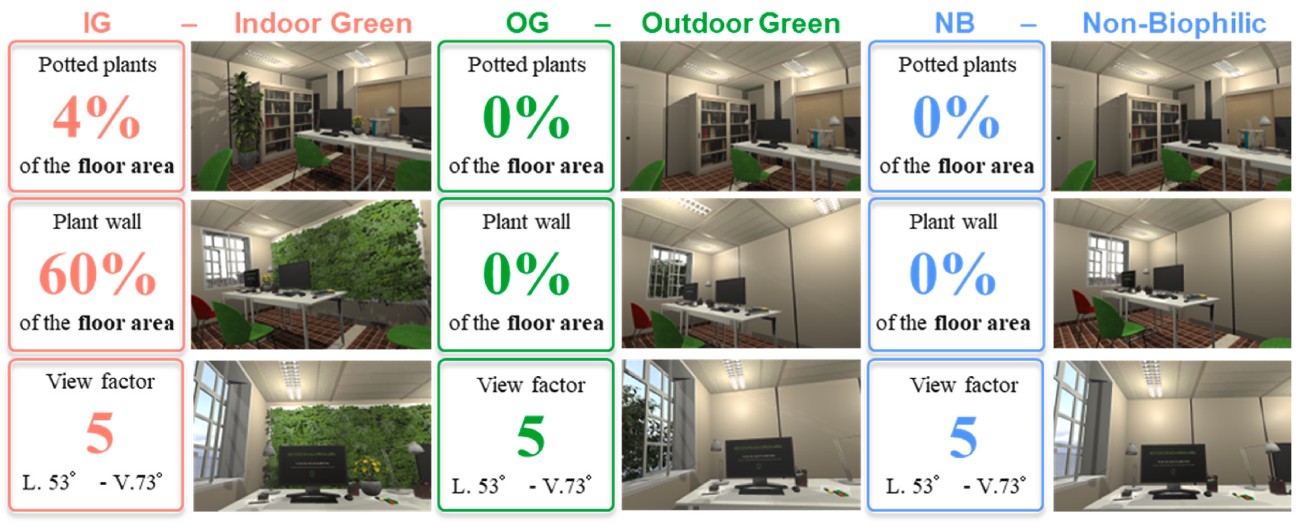

النوافذ). بشكل محدد، في حالة الأخضر الداخلي (IG) تم إضافة جدار نباتي ونباتات في أصص داخل غرفة المكتب، والتي تُستخدم بشكل متكرر في ممارسات التصميم البيوفيلي الداخلي؛ تمثل حالة الأخضر الخارجي (OG) المنظر الطبيعي للأشجار من النوافذ. من وجهة نظر كمية، تم إضافة المساحات الخضراء بما يتجاوز الحد الأدنى المطلوب من معيار WELL [74] لدعم رفاهية الشاغلين والمساحات الاستعادة من خلال توفير اتصال بالطبيعة. وبالتالي، غطى جدار النباتات مساحة جدار تعادل

2.4. تصميم الاستطلاع

تم قياس الجودة العاطفية المدركة للصوتيات من قبل المشاركين من خلال ثمانية سمات إدراكية تم تقييمها على مقياس ليكرت من خمسة مستويات (من «موافق بشدة» إلى «غير موافق بشدة»)، وفقًا للنموذج الذي قدمه أكسلسون وآخرون [42] والمواصفة الفنية ISO/TS 12913-2 [80] للبيئات الحضرية (الخارجية): ممتعة، مثيرة، مليئة بالأحداث، فوضوية، غير ممتعة، رتيبة، خالية من الأحداث، وهادئة.

2.5. مقياس كفاءة العمل

سؤال ومقياس تقييم حول الإحساس بالوجود والانغماس واستبيان مرض السيبرانية.

| عامل | سؤال | مقياس التقييم | |||

| الرضا الرسومي (GP) | أقدر الرسوم البيانية والصور للنموذج الافتراضي | أختلف تمامًا / أوافق تمامًا | |||

| الوجود المكاني (SP) | أختلف تمامًا / أوافق تمامًا | ||||

|

|||||

| المشاركة (INV) | خلال التجربة، لم أكن مدركًا للعالم الحقيقي من حولي | أختلف تمامًا / أوافق تمامًا | |||

| الواقعية المتمرسة (REAL) | لقد أدركت الأشياء داخل المكتب الافتراضي على أنها صحيحة من حيث النسب (أي، كانت بحجم ومسافة تقريبية صحيحة بالنسبة لي وبالنسبة للأشياء الأخرى). | أختلف تمامًا / أوافق تمامًا | |||

| كان لدي شعور بالقدرة على التفاعل مع مساحة المكتب (مثل التقاط الأشياء) | |||||

| دوار الفضاء الإلكتروني |

|

ليس على الإطلاق/الكثير |

وصف مقاييس اختبارات الوظائف المعرفية.

| اختبار الوظائف المعرفية | مقاييس الأداء | مدة الاختبار | ||

| مقدار التماثل | عدد الأخطاء في تصنيف الأرقام إلى زوجية/ فردية وأكبر/ أقل من “5” | 63 ثانية | ||

| أوسبان |

|

69 ثانية | ||

| درجة OSPAN (مجموع عدد الإجابات الصحيحة/الخاطئة وعدد الحروف المبلغ عنها بشكل صحيح) عدد الأخطاء في اللون المسترجع وسرعة المعالجة | ||||

| ستروب | تعتمد على سرعة معالجة الموضوعات |

2.6. الإجراء التجريبي

2.7. المشاركون

خصائص المشاركين في الدراسة (

| بشكل عام | إنستغرام | أو جي | ملاحظة | |

| جنس | ||||

| أنثى | ٣٦ ٪ | ٤٤ ٪ | ٣٥ ٪ | ٢٩ ٪ |

| ذكر | 64 % | 57 % | 65 % | 71 % |

| عمر | ||||

| ٢٠-٢٥ | 79 % | 68 % | 79 % | 92 % |

| ٢٦-٣٠ | 17 % | 25 % | 17 % | ٨ ٪ |

| 31-39 | ٤ % | ٨ ٪ | 3 % | – |

| ٤٠-٤٥ | – | – | ٢ ٪ | – |

| 50-60 | – | – | – | – |

| المستوى التعليمي | ||||

| غير متخرج | ٣٤ ٪ | ٤٣ ٪ | ٣٥ ٪ | ٢٦ ٪ |

| تخرج | 60 % | ٤٩ ٪ | ٥٩ ٪ | 74 % |

| دكتوراه، مدرسة دراسات عليا | ٥ ٪ | ٨ ٪ | 6 % | |

| مشاكل الرؤية | ||||

| لا شيء | ٤٤ ٪ | ٤٤ ٪ | 52 % | ٣٨ ٪ |

| قصر النظر | ٣٣ ٪ | ٢٩ ٪ | ٢٦ ٪ | ٤٤ ٪ |

| قصر النظر + الاستجماتيزم | 15 % | 17 % | ١٨ ٪ | 9 % |

| استجماتيزم | ٧ ٪ | 9 % | ٥ ٪ | ٨ ٪ |

| مد البصر |

|

1 % | – | ٢ ٪ |

| خبرة سابقة مع الواقع الافتراضي | ||||

| أبداً | 54 % | 53 % | ٥٥ ٪ | 53 % |

| مرة واحدة | ٢٦ ٪ | 25 % | 27 % | 27 % |

| أكثر من مرة | 20 % | 22 % | ١٨ ٪ | 20 % |

| استخدام ألعاب الفيديو | ||||

| أبداً | ٣٢ ٪ | 42 % | ٣٣ ٪ | 20 % |

| نادراً | 42 % | ٤٩ % | ٣٩ ٪ | ٣٦ ٪ |

| بشكل متكرر | 19 % | ٨ ٪ | 20 % | 30 % |

| كل يوم | ٧ ٪ | 1 % | ٨ ٪ | 14 % |

2.8. التحليل الإحصائي

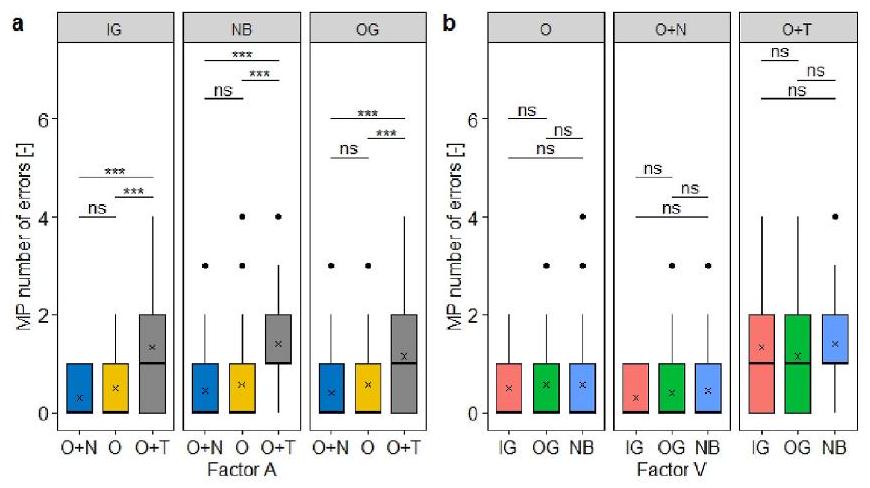

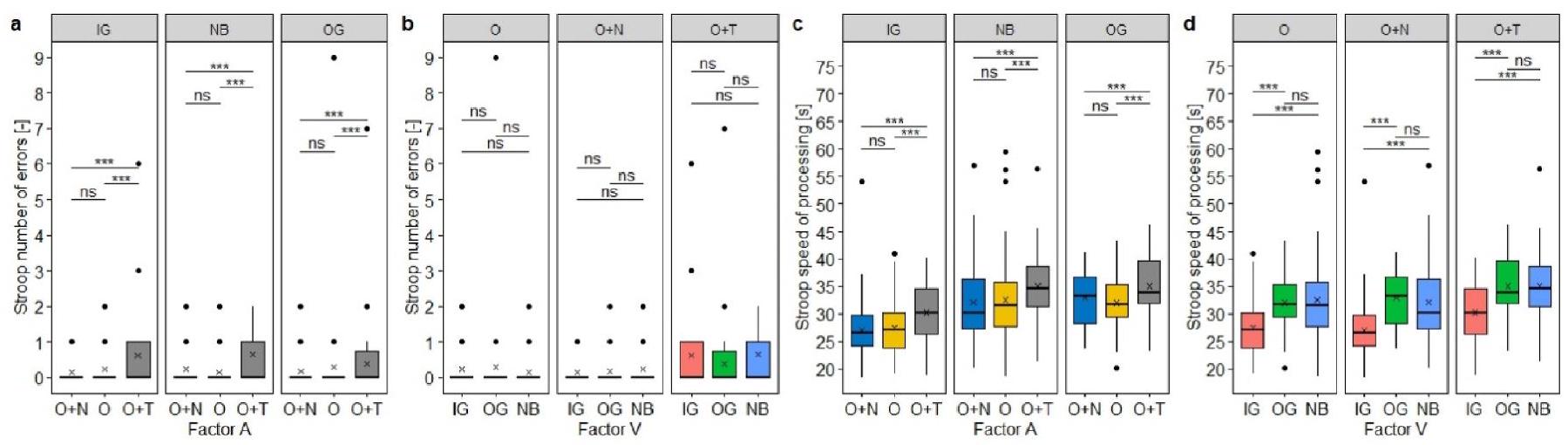

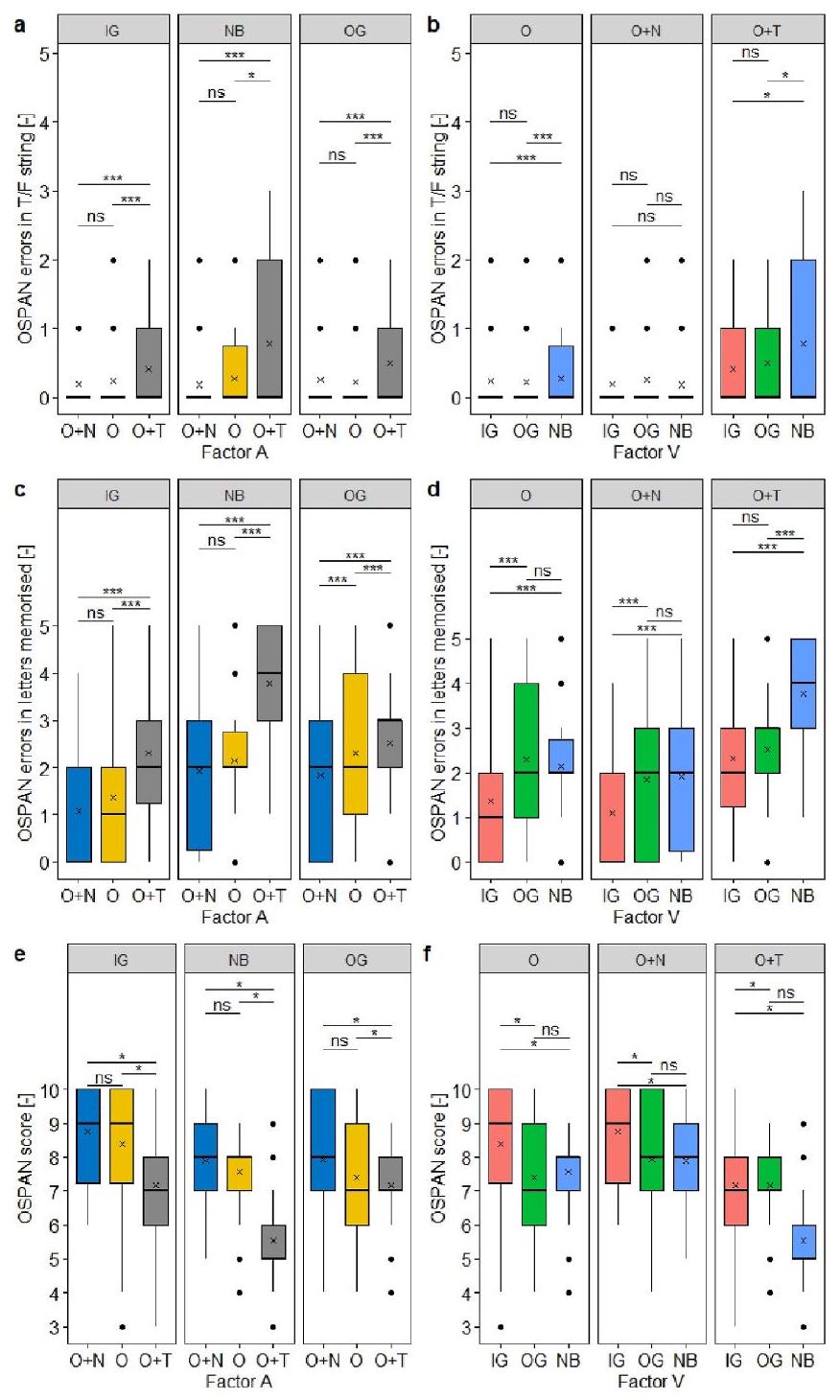

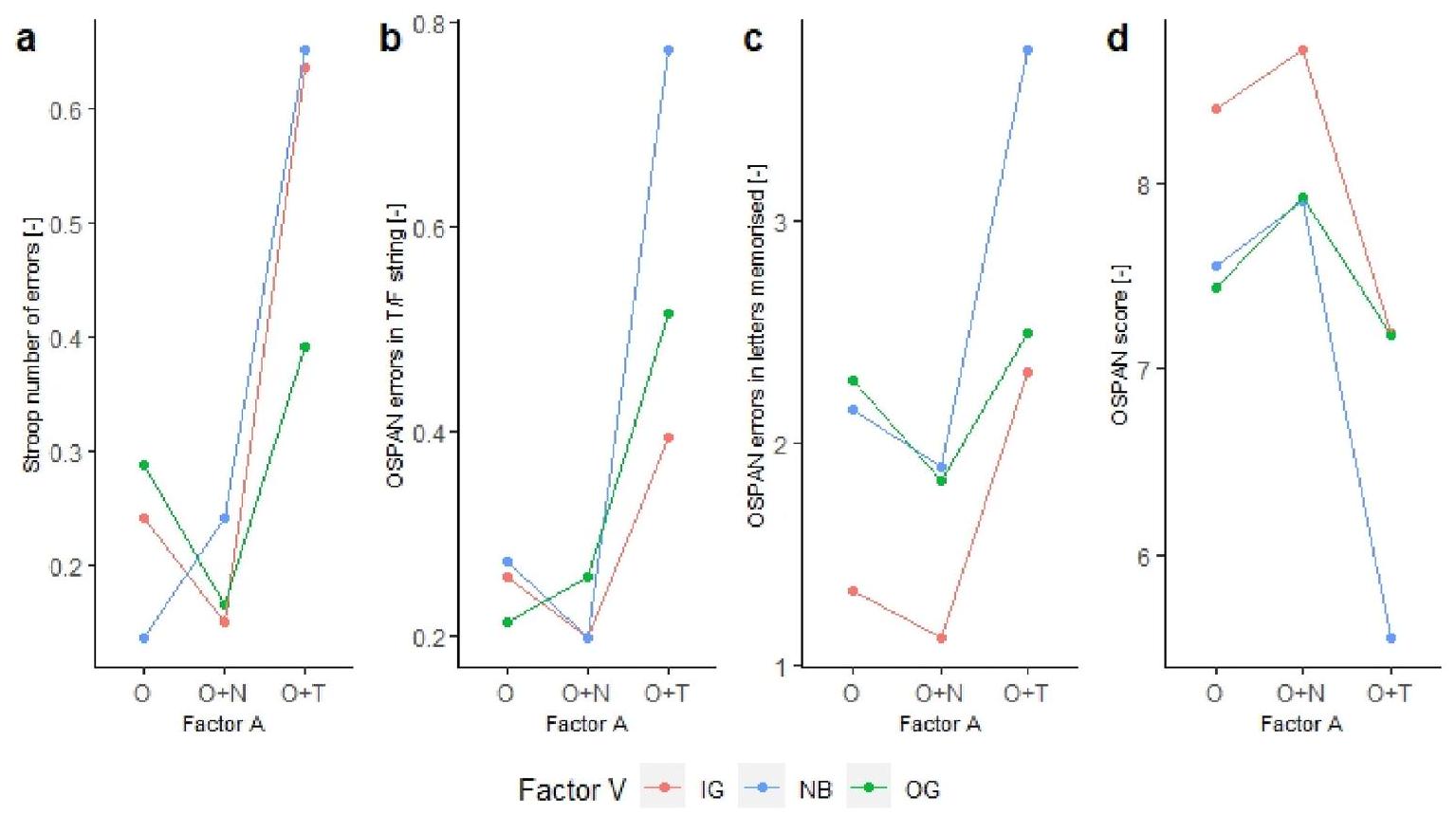

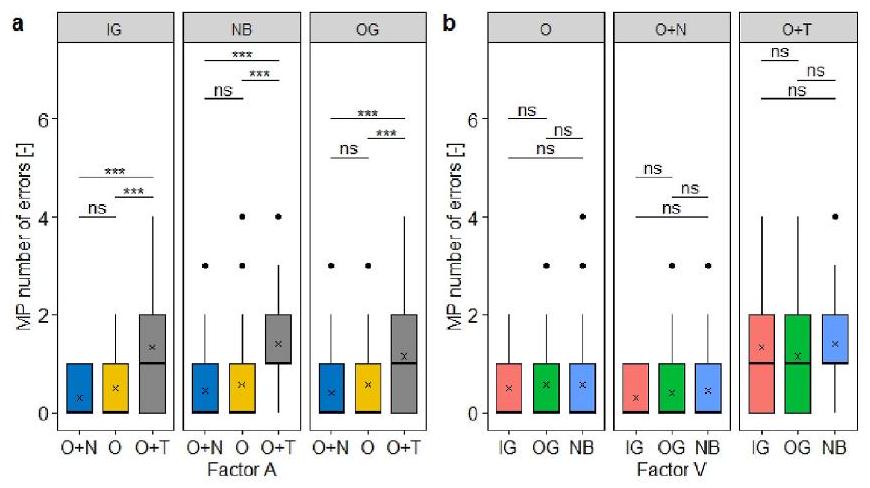

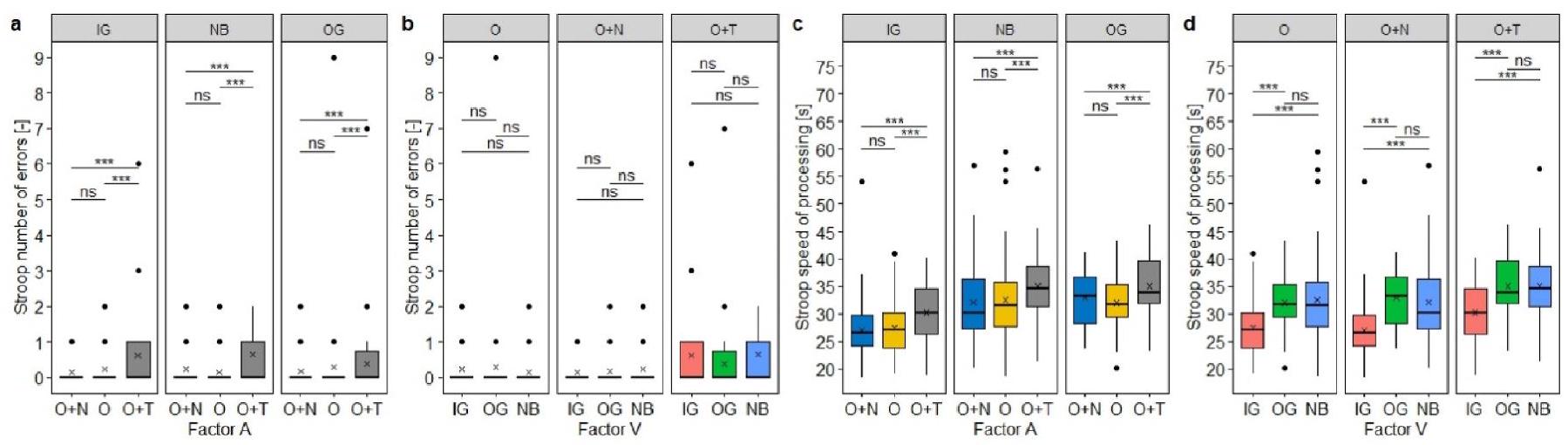

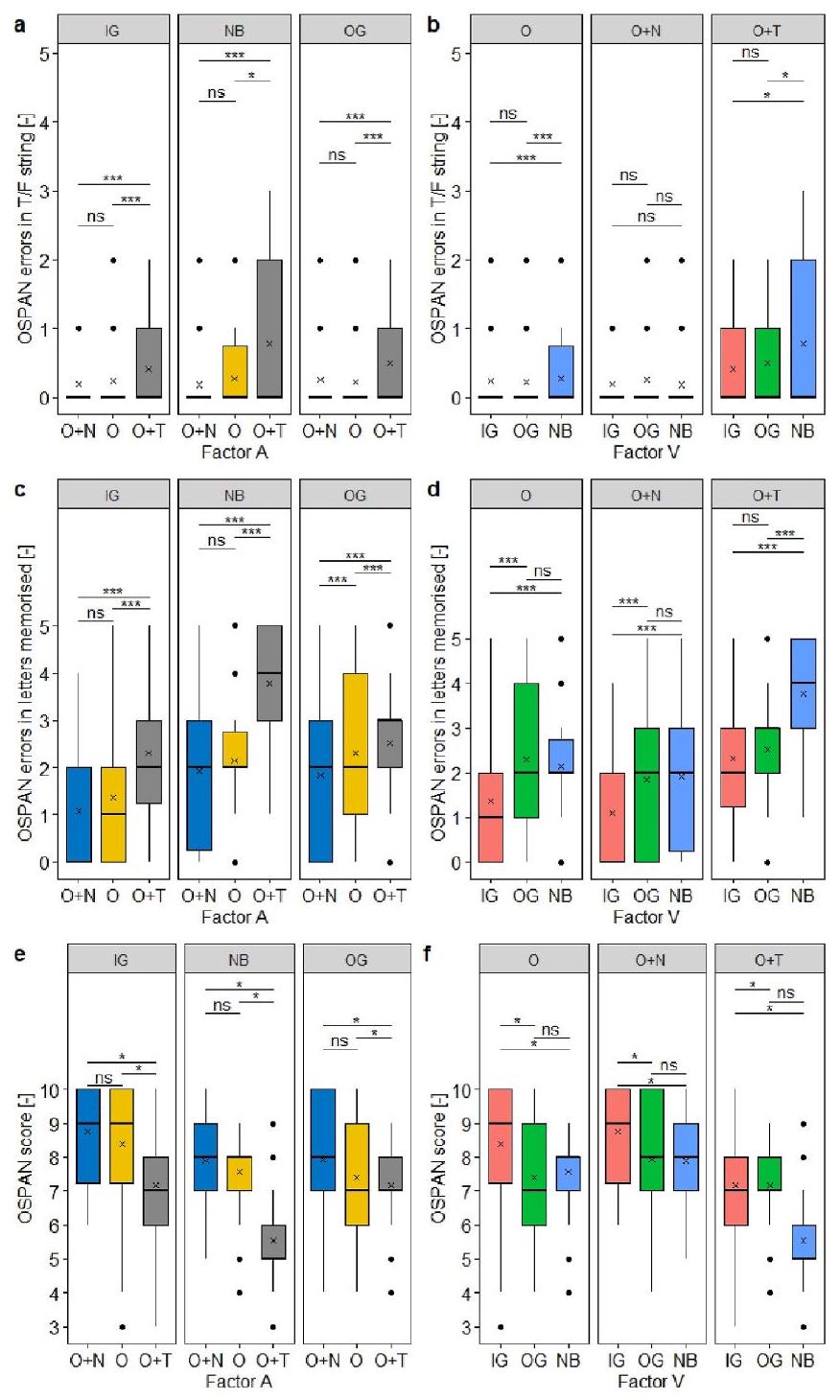

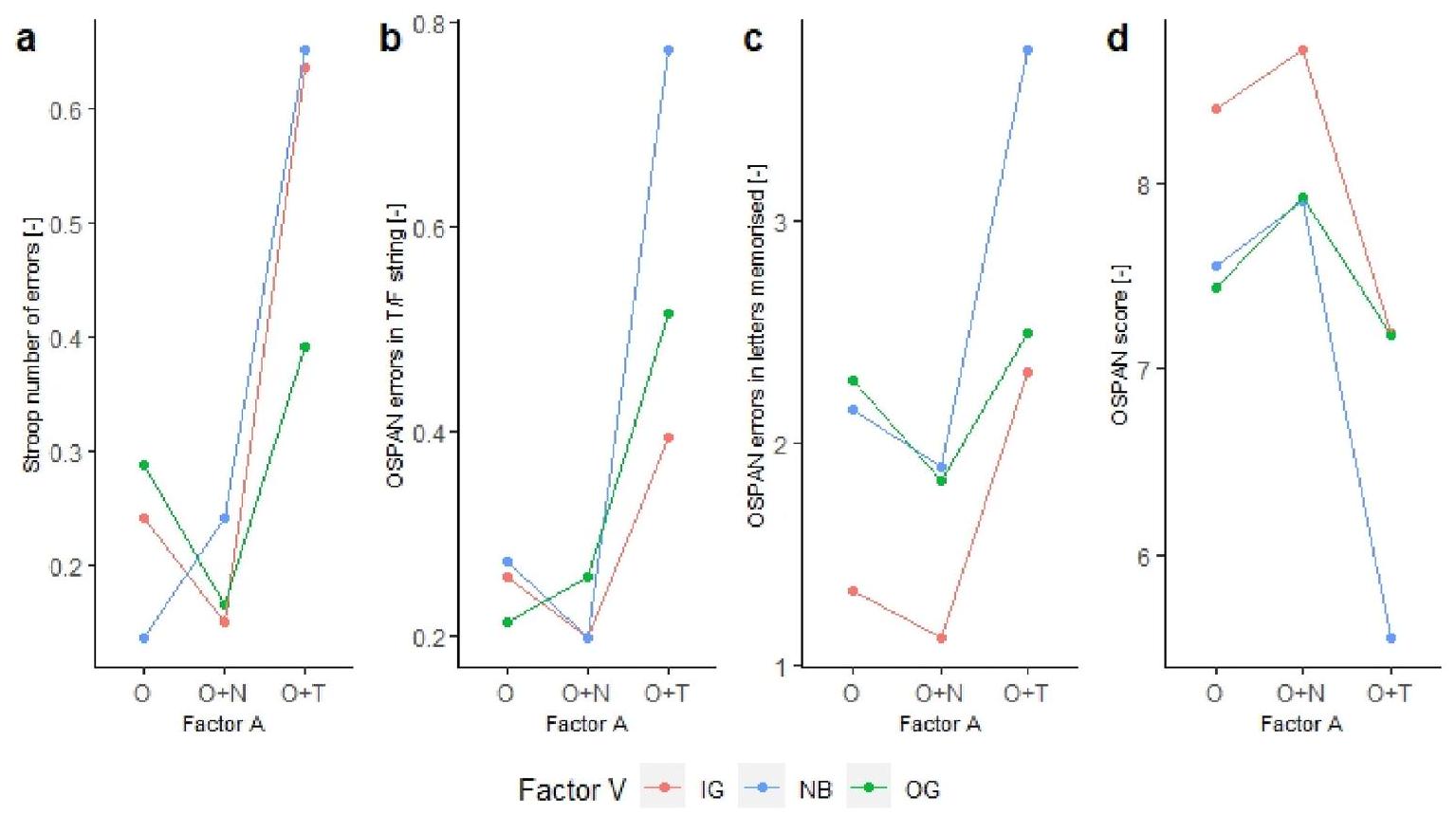

للبحث في الفرق بين المجموعات باستخدام حزمة R emmeans وتطبيق تصحيح بونفيروني لأخذ المقارنات المتعددة المخطط لها في الاعتبار. كما تم طباعة مخططات التفاعل لتفسير أي تأثيرات تفاعلية محتملة بين العامل V والعامل A.

3. النتائج

3.1. RQ1. هل VR أداة واعدة للتحقيق في تدخلات بحث التصميم البيوفيلي من حيث إحساس عالٍ بالوجود والانغماس وانخفاض مرض الفضاء الإلكتروني؟

غير ملحوظة حيث أن بين

- المكتب:

من المشاركين أفادوا بأنهم سمعوا بعض الضوضاء النموذجية في مكان العمل مثل، «لوحة المفاتيح»، و«الكمبيوتر المحمول»، و«الفأرة»، و«نشاط الكتابة» (69 %)، و«تنبيه الهاتف» (13 %)، بينما وصفوا البيئة الداخلية بأنها تتميز بضوضاء «مكتب» عامة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم تحديد الأصوات الناتجة عن «الأشخاص» مثل «الكلام» غير المفهوم ( ) و«الخطوات» ( ). بشكل عام، 82 من المشاركين وصفوا الأصوات بأنها تأتي من الجانب الداخلي للغرفة الافتراضية. - المكتب + الطبيعة: حددت العينة الكاملة (100 %) أصوات «الطبيعة» من «الطيور» القادمة من «النافذة» المفتوحة على الجانب الأيسر من المكتب. بالإضافة إلى ذلك،

من المشاركين أفادوا بأنهم سمعوا أيضًا أصوات المكتب الداخلية. - المكتب + المرور:

من المشاركين وصفوا البيئة الصوتية بأنها تشمل أصوات «المرور»، و«الطريق»، و«السيارات»، و«الحافلات»، وأصوات «الزمام» القادمة من «النافذة» المفتوحة على الجانب الأيسر من المكتب. في هذا السيناريو الصوتي، فقط من العينة وصفوا بوضوح وجود أصوات المكتب الداخلية، حيث بدت أصوات المرور أكثر هيمنة.

3.2. RQ2. هل توفر الروابط البصرية والصوتية مع الطبيعة فوائد من حيث ذاكرة العمل للمقيمين، والقدرة على التثبيط، وأداء التبديل المعرفي في المهام؟

3.2.1. اختبار الحجم-التساوي

3.2.2. اختبار ستروب

مقارنة الدرجات على مقياس من خمسة نقاط لأربعة مؤشرات (* تبرز المؤشرات الأعلى من الدراسة الحالية).

| المؤشر | هذه الدراسة | [52] | [90] | [91] | [92] | [93] | [94] | [95] |

| GS | 4.40 | 4.58* | 4.64* | 3.93 | – | 3.65 | – | – |

| SP | 4.29 | 4.21 | 4.18 | 3.44 | 4.24 | 3.39 | 3.68 | 3.74 |

| INV | 4.05 | 4.15* | 4.29* | 3.27 | 4.11* | 3.23 | – | – |

| REAL | 4.45 | 4.47* | 4.51* | 2.68 | ٣.٥٤ | 2.73 | 3.75 | 3.21 |

ملخص للتأثيرات الرئيسية والتفاعلية لنوع السيناريو البصري (المتغير المستقل 1) ونوع السيناريو الصوتي (المتغير المستقل 2) على معلمة الاختبارات المعرفية الثلاثة من اختبار GLMM Anova. تقدم الجدول إحصائية كاي المربعة، وقيم p، وقيم إيتا المربعة العامة.

| معامل الوظيفة الإدراكية | عامل | مستوى | المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | أنوفا، النوع “III” (GLMM) |

|

المقارنة الزوجية | نتيجة المقارنة الثنائية |

| أخطاء أرقام النواب | ف | ملاحظة | 0.81(0.97) |

|

|||

| إنستغرام | 0.71(0.79) | ||||||

| أو جي | 0.70(0.87) | ||||||

| أ | أو | 0.55(0.85) |

|

0.96 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.38(0.59) |

|

|

||||

|

|

1.30(1.19) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| أخطاء رقم ستروب | ف | ملاحظة | 0.34(0.60) |

|

|||

| إنستغرام | 0.33(0.61) | ||||||

| أو جي | 0.28(0.87) | ||||||

| أ | أو | 0.22(0.69) |

|

0.77 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.18(0.45) |

|

|

||||

|

|

0.55(0.94) |

|

|

||||

| سرعة تنفيذ ستروب | VxA |

|

|||||

| V | ملاحظة | ٣٣٫٢٤(٦٫٦٧) |

|

0.81 | ملاحظة – إنستغرام |

|

|

| إنستغرام | ٢٨.٤٧(٦.١٩) | إنستغرام – أوريجينال غانغستر |

|

||||

| أو جي | ٣٤.٢١(٦.٨٩) | أو جي – إن بي | ص

|

||||

| أ | أو | ٣١.٧١(٥.٩٣) |

|

0.17 |

|

ص

|

|

|

|

31.02(6.39) |

|

|

||||

|

|

٣٣٫٩٩(٦٫٥٠) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| أخطاء OSPAN صحيح/خطأ | ف | ملاحظة | 0.41(0.61) |

|

0.10 | ملاحظة – إنستغرام |

|

| إنستغرام | 0.28(0.52) | إنستغرام – أوريجينال غانغستر |

|

||||

| أو جي | 0.33(0.52) | أو جي – إن بي |

|

||||

| أ | أو | 0.25(0.49) |

|

0.90 |

|

ص

|

|

|

|

0.21(0.43) |

|

|

||||

|

|

0.56(0.72) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| أخطاء OSPAN في الرسائل | ف | ملاحظة | ٢.٦٢(١.٣٤) |

|

0.36 | ملاحظة – إنستغرام |

|

| إنستغرام | 1.59(1.36) | إنستغرام – أو جي |

|

||||

| أو جي | 2.22(1.57) | أو جي – إن بي |

|

||||

| أ | أو | 1.94(1.48) |

|

0.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.62(1.50) |

|

|

||||

|

|

2.87(1.29) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| درجة OSPAN | ف | ملاحظة | 7.00(1.35) |

|

0.25 | ملاحظة – إنستغرام |

|

| إنستغرام | 8.11(1.57) | إنستغرام – أصلي | بادج

|

||||

| أو جي | 7.51(1.60) | أو جي – إن بي |

|

||||

| أ | أو | ٧.٧٩(١.٥٩) |

|

0.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

8.19(1.57) |

|

|

||||

|

|

6.64(1.37) |

|

بادج

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

الأصوات في حالة IG (

3.2.3. اختبار OSPAN

متوسط البيانات والانحراف المعياري للمهام المعرفية عبر سيناريوهات العامل V والعامل A.

| العامل الخامس | العامل أ | اختبار MP | اختبار ستروب | اختبار OSPAN | |||

| عدد الأخطاء | عدد الأخطاء في استرجاع الألوان | سرعة التنفيذ | عدد الأخطاء في T/F | عدد الأخطاء في الرسائل المسترجعة | درجة OSPAN | ||

| [-] | [-] | [s] | [-] | [-] | [-] | ||

| إنستغرام |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إنستغرام | أو |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إنستغرام |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| أو جي |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| أو جي | أو |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| أو جي |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ملاحظة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ملاحظة | أو |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ملاحظة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حدث مع Indoor Green في حالة N (

الشكل 8 ج يظهر تأثير التفاعل، الذي تم تأكيده من خلال نتائج GLMM (قيمة p

4. المناقشة

4.1. RQ1. هل تعتبر الواقع الافتراضي أداة واعدة للتحقيق في تدخلات تصميم البيوفيلية من حيث الشعور العالي بالوجود والانغماس وانخفاض مرض الفضاء الإلكتروني؟

4.2. RQ2. هل توفر العلاقة البصرية والصوتية مع الطبيعة فوائد من حيث ذاكرة العمل لدى الشاغلين، والقدرة على التثبيط، وأداء التبديل بين المهام؟

سجلت درجات OSPAN انخفاضًا بنسبة % مقارنة بحالة الصوت الطبيعي. فيما يتعلق بالعامل البصري، تم تسليط الضوء على التأثير الإيجابي لوجود العناصر الطبيعية. حصل المشاركون على درجات أعلى في سيناريو الأخضر الداخلي مقارنة بالبيئات غير البيوفيلية والأخضر الخارجي.

مع الحاجة إلى التفاوض مع الشاغلين. تُظهر الدراسة تأثيرًا إيجابيًا محتملاً مثيرًا للاهتمام يمكن أن تجلبه المحفزات الصوتية من حيث الأداء المعرفي، فيما يتعلق ليس بمستوى الصوت ولكن بنوع الصوت نفسه والمعنى الدلالي الذي يحمله. يجب ملاحظة، على سبيل المثال، أنه عند نفس مستوى الصوت، فإن تأثيرات السيناريوهين الصوتيين (حركة المرور والطبيعة) مختلفة تمامًا ومع ظواهر تفاعلية مثيرة للاهتمام مع البيئة البصرية. يتماشى هذا مع الأدبيات الحديثة حول تصميم الصوت الداخلي، التي تهدف إلى توصيف إدراكي للمحفزات الصوتية من أجل استخدام الصوت كموارد لتصميم مساحات معيشة وعمل داعمة وصحية. علاوة على ذلك، يؤكد هذا على أهمية دراسة العلاقة بين الشاغل والمبنى من خلال نهج متعدد المجالات، والذي يأخذ في الاعتبار تعقيد الإدراك الحسي المتعدد للمستخدم في البيئة المبنية.

5. الاستنتاجات

- تم تحديد الواقع الافتراضي كوسيلة واعدة لإجراء تقييمات قبل الإشغال لإمكانات الحلول المستندة إلى الطبيعة وتدخلات تصميم البيوفيلية خلال المرحلة المبكرة من تصميم الأماكن الداخلية (الصلاحية البيئية). في الواقع، تم توفير مستوى ممتاز من الإحساس بالوجود والانغماس للمشاركين مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الأبعاد البصرية والصوتية، ولم يتم تجربة مستويات مرض السيبرانية ذات الصلة.

- يمكن أن تساهم الروابط البصرية وغير البصرية مع الطبيعة بشكل إيجابي في تشكيل بيئة مكتبية أكثر دعمًا من خلال الواقع الافتراضي. كان هناك تغيير إيجابي في تبديل المهام، وكبح الوظائف، وذاكرة العمل لدى المستخدمين في سيناريوهات الأخضر الداخلي والأخضر الخارجي مقارنةً بالسيناريو غير البيوفيلي. تم الكشف عن دقة أعلى في سيناريو الصوت الطبيعي بينما كان سيناريو صوت المرور هو البيئة الصوتية الأكثر إزعاجًا. وفقًا للنتائج، كانت أفضل حالة بصرية*صوتية لتحسين كفاءة عمل المشاركين تحدث مع الأصوات الطبيعية في حالة الأخضر الداخلي.

تم تجنيدهم للتحقيق في التأثير المفيد المحتمل للطبيعة وفقًا للجنس والعمر والتعليم. ثانيًا، حتى إذا تم الكشف عن اختلافات ذات صلة بين مستويات العامل الخامس، يجب إجراء اختبار تمهيدي لـ “القدرات المعرفية الأساسية” للمشاركين كخط أساس لتقليل أي تحيز متعلق بتصميم بين الموضوعات. ثالثًا، نظرًا للقيود الزمنية على التعرض للواقع الافتراضي وتصميم الأساليب التجريبية كتصميم مختلط بين/داخل الموضوعات، تم اختبار كل سيناريو صوتي لمدة حوالي 7 دقائق. حتى إذا تم تسليط الضوء على نتائج واعدة بشأن الوظائف المعرفية، يُوصى بمزيد من الفحص للفوائد الإيجابية للتعرض المطول للاتصال البصري وغير البصري بالطبيعة، على سبيل المثال من خلال تقييد الإجراء التجريبي إلى سيناريو واحد في كل مرة (لتقليل التعرض العام للواقع الافتراضي). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن تمتد الأنشطة البحثية المستقبلية إلى توسيع الاستبيان المطبق للتحقيق في مزاج المشاركين وتفضيلاتهم ورضاهم المتعلق بالمحفزات السمعية البصرية المجمعة.

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

الملحق

توزيعات بيانات البقايا [100-102]. النظرية الأساسية لـ GLMM هي أن استجابات الموضوعات هي مجموع العوامل الثابتة، وهي المتغيرات ذات الاهتمام التي تم التحكم فيها خلال الدراسة، والعوامل العشوائية التي يمكن أن تؤثر على التغاير في البيانات.

ملخص التأثيرات الرئيسية لاختلافات الجنس وأنواع الترتيب على معلمات الاختبارات الإدراكية الثلاثة من اختبار GLMM Anova. يقدم الجدول إحصائية كاي المربعة والقيم p.

| معلمة الوظيفة الإدراكية | Anova، النوع “III” (GLMM) – الجنس | Anova، النوع “III” (GLMM) – الترتيب |

| أخطاء عدد MP |

|

|

| أخطاء عدد ستروب |

|

|

| سرعة تنفيذ ستروب |

|

|

| أخطاء OSPAN T/F |

|

|

| أخطاء OSPAN في الحروف |

|

|

| درجة OSPAN |

|

|

تم إنشاء معيار أكايكي للمعلومات (AIC)، والمعاملات الهامشية (

AIC، الهامشية والشرطية

| متغير المجموعة | المتغير التابع | AIC |

|

|

| اختبار إدراكي | أخطاء عدد MP | 1322.3 | 0.19 | 0.29 |

| أخطاء عدد ستروب | 845.8 | 0.09 | 0.19 | |

| سرعة معالجة ستروب | 3684.7 | 0.19 | 0.33 | |

| أخطاء OSPAN T/F | 869.6 | 0.07 | 0.11 | |

| أخطاء OSPAN في الحروف | 2100.9 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| درجة OSPAN | 2507.9 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

References

[2] B. Sowińska-Swierkosz, J. García, What are Nature-based solutions (NBS)? Setting core ideas for concept clarification, Nature-Based Solut. 2 (2022) 100009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2022.100009.

[3] IUCN, Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions, First Edit, Gland, Switzerland, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN•CH.2020.08.en.

[4] B.A. Johnson, P. Kumar, N. Okano, R. Dasgupta, B.R. Shivakoti, Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation: a systematic review of systematic reviews, Nature-Based Solut. 2 (2022) 100042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nbsj.2022.100042.

[5] Y. Xing, P. Jones, I. Donnison, Characterisation of nature-based solutions for the built environment, Sustain. Times 9 (2017) 1-20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ su9010149.

[6] S.R. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, M. Mador, Biophilic Design : the Theory, Science, and Practiceof Bringing Buildings to Life, 2008.

[7] R. Stephen, Kellert, Nature by Design: the Practice of Biophilic Design, Yale University Press, 2018.

[8] N. Wijesooriya, A. Brambilla, Bridging biophilic design and environmentally sustainable design: a critical review, J. Clean. Prod. 283 (2021) 124591, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124591.

[9] European Ventilation Industry Association, Evia’s Eu Manifesto: Good Indoor Air Quality Is a Basic Human Right, 2019.

[10] Y. Al Horr, M. Arif, A. Kaushik, A. Mazroei, M. Katafygiotou, E. Elsarrag, Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: a review of the literature, Build. Environ. 105 (2016) 369-389, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2016.06.001.

[11] ASHRAE standard, Journal – June 2019 (2019), Vol. 61, No. 6, pp. 1-85.

[12] Y. Jiang, N. Li, A. Yongga, W. Yan, Short-term effects of natural view and daylight from windows on thermal perception, health, and energy-saving potential, Build. Environ. 208 (2022) 108575, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108575.

[13] R.S. Ulrich, R.F. Simonst, B.D. Lositot, E. Fioritot, M.A. Milest, M. Zelsont, Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments, 1991.

[14] S. Kaplan, The restorative environment: nature and human experience, in: D. Relf (Ed.), Role Hortic. Hum. Well Being Soc. Dev., Timber Press, 1992, pp. 134-142.

[15] B. Browning, C. Cooper, The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace, 2015. http://humanspaces.com/resources/reports/.

[16] S. Kaplan, The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework, J. Environ. Psychol. 15 (1995) 169-182, https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944 (95)90001-2.

[17] W.D. Browning, C.O. Ryan, J.O. Clancy, 14 Patterns ofBiophilic Design: improving health & wellbeing in the built environment, Terrapin Bright Green 1 (2014) 1-64.

[18] W.H. Ko, S. Schiavon, H. Zhang, L.T. Graham, G. Brager, I. Mauss, Y.W. Lin, The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance, Build. Environ. 175 (2020) 106779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2020.106779.

[19] C.Y. Chang, P.K. Chen, Human response to window views and indoor plants in the workplace, Hortscience 40 (2005) 1354-1359, https://doi.org/10.21273/ hortsci.40.5.1354.

[20] E. Largo-Wight, W. William Chen, V. Dodd, R. Weiler, Healthy workplaces: the effects of nature contact at work on employee stress and health, Publ. Health Rep. 126 (2011) 124-126, https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549111260s116.

[21] J.J. Alvarsson, S. Wiens, M.E. Nilsson, Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 7 (2010) 1036-1046, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7031036.

[22] E. Ratcliffe, B. Gatersleben, P.T. Sowden, Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery, J. Environ. Psychol. 36 (2013) 221-228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.08.004.

[23] E. Ratcliffe, B. Gatersleben, P.T. Sowden, Associations with bird sounds: how do they relate to perceived restorative potential? J. Environ. Psychol. 47 (2016) 136-144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.009.

[24] M.R. Marselle, K.N. Irvine, A. Lorenzo-Arribas, S.L. Warber, Does perceived restorativeness mediate the effects of perceived biodiversity and perceived naturalness on emotional well-being following group walks in nature? J. Environ Psychol. 46 (2016) 217-232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.008.

[25] R.K. Raanaas, K.H. Evensen, D. Rich, G. Sjøstrøm, G. Patil, Benefits of indoor plants on attention capacity in an office setting, J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (2011) 99-105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.11.005.

[26] L. Gao, S. Wang, J. Li, H. Li, Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces, Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 127 (2017) 107-113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. resconrec.2017.08.030.

[27] V.I. Lohr, C.H. Pearson-Mims, G.K. Goodwin, Interior plants may improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a windowless environment, J. Environ. Hortic. 14 (1996) 97-100, https://doi.org/10.24266/0738-2898-14.2.97.

[28] A.R. Khan, A. Younis, A. Riaz, M.M. Abbas, Effect of interior plantscaping on indoor academic environment, J. Agric. Res. 43 (2005) 235-242.

[29] M. Nieuwenhuis, C. Knight, T. Postmes, S.A. Haslam, The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: three field experiments, J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 20 (2014) 199-214, https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000024.

[30] S. Shibata, N. Suzuki, Effects of an indoor plant on creative task performance and mood, Scand. J. Psychol. 45 (2004) 373-381, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14679450.2004.00419.x.

[31] S. Shibata, N. Suzuki, Effects of the foliage plant on creative task performance and mood, J. Environ. Psychol. 22 (2002) 265-272, https://doi.org/10.1006/ jevp. 232.

[32] N. Hähn, E. Essah, T. Blanusa, Biophilic design and office planting: a case study of effects on perceived health, well-being and performance metrics in the workplace, Intell. Build. Int. 13 (2021) 241-260, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17508975.2020.1732859.

[33] L. E.Larsen, J. Adams, B. Deal, B.S. Kweon, Tyler, Plants in the workplace the effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions, Environ. Behav. 30 (1999) 261-281, papers2://publication/uuid/BD10AA79-D958-43EF-A03B-013230F826C7.

[34] J. Ayuso Sanchez, T. Ikaga, S. Vega Sanchez, Quantitative improvement in workplace performance through biophilic design: a pilot experiment case study, Energy Build. 177 (2018) 316-328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enbuild.2018.07.065.

[35] H. Jahncke, S. Hygge, N. Halin, A.M. Green, K. Dimberg, Open-plan office noise: cognitive performance and restoration, J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (2011) 373-382, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.07.002.

[36] H. Jahncke, P. Björkeholm, J.E. Marsh, J. Odelius, P. Sörqvist, Office noise: can headphones and masking sound attenuate distraction by background speech? Work 55 (2016) 505-513, https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162421.

[37] S.C. Van Hedger, H.C. Nusbaum, L. Clohisy, S.M. Jaeggi, M. Buschkuehl, M. G. Berman, Of cricket chirps and car horns: the effect of nature sounds on cognitive performance, Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26 (2019) 522-530, https://doi.org/ 10.3758/s13423-018-1539-1.

[38] E. Stobbe, R. Lorenz, S. Kühn, On how natural and urban soundscapes alter brain activity during cognitive performance, J. Environ. Psychol. 91 (2023) 102141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102141.

[39] S. Aristizabal, K. Byun, P. Porter, N. Clements, C. Campanella, L. Li, A. Mullan, S. Ly, A. Senerat, I.Z. Nenadic, W.D. Browning, V. Loftness, B. Bauer, Biophilic

office design: exploring the impact of a multisensory approach on human wellbeing, J. Environ. Psychol. 77 (2021) 101682, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jenvp.2021.101682.

[40] ISO – International Organization for Standardization, ISO/TS 12913: 2014 Acoustics – Soundscape Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework, 2014.

[41] S. Torresin, E. Ratcliffe, F. Aletta, R. Albatici, F. Babich, T. Oberman, J. Kang, The actual and ideal indoor soundscape for work, relaxation, physical and sexual activity at home: a case study during the COVID-19 lockdown in London, Front. Psychol. 13 (2022) 1-24, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1038303.

[42] O. Axelsson, M.E. Nilsson, B. Berglund, A principal components model of soundscape perception, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128 (2010) 2836-2846, https://doi. org/10.1121/1.3493436.

[43] E. Ratcliffe, Sound and soundscape in restorative natural environments: a narrative literature review, Front. Psychol. 12 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2021.570563.

[44] K. Hume, M. Ahtamad, Physiological responses to and subjective estimates of soundscape elements, Appl. Acoust. 74 (2013) 275-281, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.10.009.

[45] K. Uebel, M. Marselle, A.J. Dean, J.R. Rhodes, A. Bonn, Urban green space soundscapes and their perceived restorativeness, People Nat 3 (2021) 756-769, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10215.

[46] D. Francomano, M.I. Rodríguez González, A.E.J. Valenzuela, Z. Ma, A.N. Raya Rey, C.B. Anderson, B.C. Pijanowski, Human-nature connection and soundscape perception: insights from Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, J. Nat. Conserv. 65 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2021.126110.

[47] Y. Suko, K. Saito, N. Takayama, S. Warisawa, Effect of Faint Road Traffic Noise Mixed in Birdsong on the Perceived Restorativeness and Listeners ‘ Physiological Response: an Exploratory Study, (n.d.).

[48] J.Y. Choi, S.A. Park, S.J. Jung, J.Y. Lee, K.C. Son, Y.J. An, S.W. Lee, Physiological and psychological responses of humans to the index of greenness of an interior space, Complement, Ther. Med. 28 (2016) 37-43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ctim.2016.08.002.

[49] E. Tsekeri, A. Lilli, M. Katsiokalis, K. Gobakis, A. Mania, D. Kolokotsa, On the integration of nature-based solutions with digital innovation for health and wellbeing in cities, in: 2022 7th Int. Conf. Smart Sustain. Technol. Split. 2022, 2022, pp. 1-6, https://doi.org/10.23919/SpliTech55088.2022.9854269.

[50] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M.D. Orazio, Development and application of an experimental framework for the use of virtual reality to assess building users productivity, J. Build. Eng. 70 (2023) 106280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2023.106280.

[51] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M. D’Orazio, C. Di Perna, Exploring the use of immersive virtual reality to assess occupants’ productivity and comfort in workplaces: an experimental study on the role of walls colour, Energy Build. 253 (2021) 111508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111508.

[52] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M. D’Orazio, Immersive virtual vs real office environments: a validation study for productivity, comfort and behavioural research, Build. Environ. (2023) 109996, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. BUILDENV.2023.109996.

[53] Y. Zhang, H. Liu, S.C. Kang, M. Al-Hussein, Virtual reality applications for the built environment: research trends and opportunities, Autom. ConStruct. 118 (2020) 103311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103311.

[54] S. Yeom, H. Kim, T. Hong, Psychological and physiological effects of a green wall on occupants: a cross-over study in virtual reality, Build. Environ. 204 (2021) 108134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108134.

[55] J. Yin, N. Arfaei, P. MacNaughton, P.J. Catalano, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Effects of biophilic interventions in office on stress reaction and cognitive function: a randomized crossover study in virtual reality, Indoor Air 29 (2019) 1028-1039, https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12593.

[56] A. Sedghikhanshir, Y. Zhu, Y. Chen, B. Harmon, Exploring the impact of green walls on occupant thermal state in immersive virtual environment, Sustain. Times 14 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031840.

[57] J. Yin, J. Yuan, N. Arfaei, P.J. Catalano, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: a between-subjects experiment in virtual reality, Environ. Int. 136 (2020) 105427, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105427.

[58] A. Emamjomeh, Y. Zhu, M. Beck, The potential of applying immersive virtual environment to biophilic building design: a pilot study, J. Build. Eng. 32 (2020) 101481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101481.

[59] S. Yeom, H. Kim, T. Hong, H.S. Park, D.E. Lee, An integrated psychological score for occupants based on their perception and emotional response according to the windows’ outdoor view size, Build. Environ. 180 (2020), https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107019.

[60] D. Haryndia, T. Ayu, Effects of Biophilic Virtual Reality Interior Design on Positive Emotion of University Students Responses, 2020.

[61] N. Kim, J. Gero, Neurophysiological responses to biophilic design: a pilot experiment using VR and eeg biomimetic inspired architectural design view project design neurocognition view project, Des. Comput. Cogn. (2022) 1-21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359892380.

[62] J. Yin, S. Zhu, P. MacNaughton, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment, Build. Environ. 132 (2018) 255-262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.006.

[63] Z. Li, Y. Wang, H. Liu, H. Liu, Physiological and psychological effects of exposure to different types and numbers of biophilic vegetable walls in small spaces, Build. Environ. 225 (2022) 109645, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109645.

[64] Q. Lei, C. Yuan, S.S.Y. Lau, A quantitative study for indoor workplace biophilic design to improve health and productivity performance, J. Clean. Prod. 324 (2021) 129168, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129168.

[65] G. Ozcelik, B. Becerik-Gerber, Benchmarking thermoception in virtual environments to physical environments for understanding human-building interactions, Adv. Eng. Inf. 36 (2018) 254-263, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aei.2018.04.008.

[66] K. Lyu, A. Brambilla, A. Globa, R. De Dear, An immersive multisensory virtual reality approach to the study of human-built environment interactions, Autom. ConStruct. 150 (2023) 104836, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104836.

[67] S. Torresin, G. Pernigotto, F. Cappelletti, A. Gasparella, Combined effects of environmental factors on human perception and objective performance: a review of experimental laboratory works, Indoor Air 28 (2018) 525-538, https://doi. org/10.1111/ina.12457.

[68] M. Schweiker, E. Ampatzi, M.S. Andargie, R.K. Andersen, E. Azar, V. M. Barthelmes, C. Berger, L. Bourikas, S. Carlucci, G. Chinazzo, L.P. Edappilly, M. Favero, S. Gauthier, A. Jamrozik, M. Kane, A. Mahdavi, C. Piselli, A.L. Pisello, A. Roetzel, A. Rysanek, K. Sharma, S. Zhang, Review of multi-domain approaches to indoor environmental perception and behaviour, Build. Environ. 176 (2020) 106804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106804.

[69] K. Lyu, R. de Dear, A. Brambilla, A. Globa, Restorative benefits of semi-outdoor environments at the workplace: does the thermal realm matter? Build. Environ. 222 (2022) 109355 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109355.

[70] S. Shin, M.H.E.M. Browning, A.M. Dzhambov, Window access to nature restores: a virtual reality experiment with greenspace views, sounds, and smells, Ecopsychology 14 (2022) 253-265, https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0032.

[71] DeltaOHM, HD32.1 thermal microclimate. https://www.deltaohm.com/it/prod otto/hd32-1-datalogger-per-la-misura-del-microclima/, 2022. (Accessed 1 November 2022).

[72] DeltaOHM, DeltaLog10. https://www.deltaohm.com/it/support/software/del talog-10/, 2022. (Accessed 1 February 2022).

[73] Empatica, EmbracePlus. https://www.empatica.com/en-eu/embraceplus/, 2022. (Accessed 1 November 2022).

[74] International WELL Building Instituite, WELL v2, 2020. https://v2.wellcertified. com/en/wellv2/overview.

[75] C.E. Commission, Windows and Offices: a Study of Office Worker Performance and the Indoor Environment, 2003.

[76] Unity. https://unity.com, 2021. (Accessed 7 May 2021).

[77] IMotions A/S, iMotions (9.3), Copenhagen, Denmark. https://imotions.com/, 2022.

[78] SteamVR plugin. https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/tools/integration/st eamvr-plugin-32647, 2021.

[79] S. Torresin, R. Albatici, F. Aletta, F. Babich, T. Oberman, S. Siboni, J. Kang, Indoor soundscape assessment: a principal components model of acoustic perception in residential buildings, Build. Environ. 182 (2020) 107152, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107152.

[80] ISO – International Organization for Standardization, ISO/TS 12913-3:2019 Acoustics – Soundscape – Part 3: Data Analysis, 2019, p. 22.

[81] J.R. Stroop, Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions, J. Exp. Psychol. 18 (1935) 643-662, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054651.

[82] N. Unsworth, R.P. Heitz, J.C. Schrock, R.W. Engle, An automated version of the operation span task, Behav. Res. Methods 37 (2005) 498-505, https://doi.org/ 10.3758/BF03192720.

[83] M. Wendt, S. Klein, T. Strobach, More than attentional tuning – investigating the mechanisms underlying practice gains and preparation in task switching, Front. Psychol. 8 (2017) 1-9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00682.

[84] ASHRAE standard, ANSI/ASHRAE standard 55-2004: thermal environmental conditions for human occupancy, in: Am. Soc. Heating, Refrig. Air-Conditioning Eng. Inc. 2004, 2004, pp. 1-34.

[85] J. Munafo, M. Diedrick, T.A. Stoffregen, The virtual reality head-mounted display Oculus Rift induces motion sickness and is sexist in its effects, Exp. Brain Res. 235 (2017) 889-901, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-016-4846-7.

[86] Y. Zhu, S. Saeidi, T. Rizzuto, A. Roetzel, R. Kooima, Potential and challenges of immersive virtual environments for occupant energy behavior modeling and validation: a literature review, J. Build. Eng. 19 (2018) 302-319, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jobe.2018.05.017.

[87] A. Heydarian, B. Becerik-Gerber, Use of immersive virtual environments for occupant behaviour monitoring and data collection, J. Build. Perform. Simul. 10 (2017) 484-498, https://doi.org/10.1080/19401493.2016.1267801.

[88] F. A.Faul, E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, Buchner, G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences, Behav. Res. Methods 35 (2007) 175-191. https://www.psychologie.hhu. de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower.

[89] R. Studio. https://www.rstudio.com, 2021. (Accessed 31 May 2021).

[90] A. Latini, S. Di Loreto, E. Di Giuseppe, M. D’Orazio, C. Di Perna, Crossed effect of acoustics on thermal comfort and productivity in workplaces: a case study in virtual reality, J. Architect. Eng. 29 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1061/JAEIED. AEENG-1533, 04023009-1/10.

[91] N. Tawil, I.M. Sztuka, K. Pohlmann, S. Sudimac, S. Kühn, The living space: psychological well-being and mental health in response to interiors presented in virtual reality, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 18 (2021), https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijerph182312510.

[92] S. Yeom, H. Kim, T. Hong, M. Lee, Determining the optimal window size of office buildings considering the workers’ task performance and the building’s energy consumption, Build. Environ. 177 (2020) 106872, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2020.106872.

[93] T. Hong, M. Lee, S. Yeom, K. Jeong, Occupant responses on satisfaction with window size in physical and virtual built environments, Build. Environ. 166 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106409.

[94] K. Chamilothori, J. Wienold, M. Andersen, Adequacy of immersive virtual reality for the perception of daylit spaces: comparison of real and virtual environments, LEUKOS – J. Illum. Eng. Soc. North Am. 15 (2019) 203-226, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15502724.2017.1404918.

[95] F. Abd-Alhamid, M. Kent, C. Bennett, J. Calautit, Y. Wu, Developing an innovative method for visual perception evaluation in a physical-based virtual environment, Build. Environ. 162 (2019) 106278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2019.106278.

[96] M. Pellegatti, S. Torresin, C. Visentin, F. Babich, N. Prodi, Indoor soundscape, speech perception, and cognition in classrooms: a systematic review on the effects of ventilation-related sounds on students, Build. Environ. 236 (2023) 110194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110194.

[97] S. Torresin, R. Albatici, F. Aletta, F. Babich, T. Oberman, J. Kang, Acoustic design criteria in naturally ventilated residential buildings: new research perspectives by applying the indoor soundscape approach, Appl. Sci. 9 (2019), https://doi.org/ 10.3390/app9245401.

[98] S. Torresin, F. Aletta, F. Babich, E. Bourdeau, J. Harvie-Clark, J. Kang, L. Lavia, A. Radicchi, R. Albatici, Acoustics for supportive and healthy buildings: emerging themes on indoor soundscape research, Sustain. Times 12 (2020) 1-27, https:// doi.org/10.3390/su12156054.

[99] U.B. Erçakmak, P.N. Dökmeci Yörükoğlu, Comparing Turkish and European noise management and soundscape policies: a proposal of indoor soundscape integration to architectural design and application, Acoustics 1 (2019) 847-865, https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1040051.

[100] B.M. Bolker, M.E. Brooks, C.J. Clark, S.W. Geange, J.R. Poulsen, M.H.H. Stevens, J.S. White, Generalized Linear Mixed Models : a Practical Guide for Ecology and Evolution, 2008, pp. 127-135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008.

[101] B. Winter, Statistics for Linguists: an Introduction Using R, 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.4324/9781315165547.

[102] A. West, Brady, Kathleen Welch, Galecki, Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2008.s216.

[103] D. Barr, R. Levy, C. Scheepers, H.J. Tily, Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: keep it maximal, J. Mem. Lang. 68 (2014) 1-43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001. Random.

[104] C.J. Ferguson, An Effect Size Primer : A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers 40 (2009) 532-538, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808.

- Corresponding author. Department of Construction, Civil Engineering and Architecture, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Via Brecce Bianche, Ancona, 60131, Italy.

E-mail address: e.digiuseppe@staff.univpm.it (E. Di Giuseppe).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111196

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

Effects of Biophilic Design interventions on university students’ cognitive performance: An audio-visual experimental study in an Immersive Virtual office Environment

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Indoor environment

Work efficiency

Biophilic design

Indoor soundscape

Multi-domain

Abstract

The human-nature connection should be a key component in the design of supportive and comfortable indoor environments. An interest in introducing Nature Based Solutions indoor via Biophilic Design (BD) intervention recently emerged. Related benefits for work efficiency have been identified in lab-studies without the possibility to perform preliminary design assessments. Recently, VR has been adopted thanks to its advantages for data collection in highly realistic environments. To date, most of the research on BD has been focused on the visual connection with nature even if people experience multiple senses simultaneously. In this paper, a new design approach for preliminary assessment of BD intervention in VR is presented. A

1. Introduction

ergonomics. More recently, they have increasingly shifted to health and wellbeing issues (e.g., WELL), thus catalysing a global concern and scientific attention to a sustainable and healthy building sector. In particular, enhancing work efficiency in the workplace has been a primary driver with private and public sectors recognising the importance of an occupant-focused indoor environment. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic heightened employee concern about the effectiveness of their working spaces, wondering if they correctly answer their needs and foster well-being as well as their home workplaces during smart-working periods.

1.1. Biophilic design for office environments

[9-11]A multitude of psychological-oriented theories emphasized the benefits of NBS exposure, which can promote a positive impact on human comfort (hygrothermal conditions) [12], health and well-being (e.g., anxiety and stress reduction) [13,14] and emotions (e.g., happiness, satisfaction, visual preference) [13,15].

1.2. Benefits provided by visual and acoustical connection to nature on cognitive performance

self-reported productivity. According to Lohr [27] and Khan [28] participants in the room with plants reported feeling more attentive than people in the room with no greenery.

1.3. Using virtual reality to assess the benefits of biophilic design interventions

collection of complex data in highly realistic one-to-one environments [50]. VR and Immersive Virtual Environments (IVE) are valid means to simulate alternative design configurations, without the limitation of laboratory-based studies [51]. Researchers and professionals are then supported to improve the integration of the «human dimension» from the early design stages, for example, to measure end-user behaviour, collect feedback in real-time, and improve communication for a better understanding of the project via multisensory 3D environments [52]. Another crucial advantage is the possibility to properly manipulate the desired variables (e.g., visual and acoustic dimensions). This results in a greatly shortened design procedure [53].

1.4. Research questions

under combined audio-visual scenarios involving NBS.

In particular, the authors were interested in the following research questions:

- RQ1. Is VR effective in investigating Biophilic Design research interventions in terms of a high sense of presence and immersivity and low cybersickness?

- RQ2. Does visual and acoustic connection with nature confer benefits in terms of occupants’ working memory, inhibition, and taskswitching cognitive performance?

2. Material and methods

2.1. Test room equipment

2.2. Sound material

Sensors specifications.

| Sensor | Model | Measure Range | Accuracy |

| Air Temperature | DeltaOHM – | -40 to |

|

| HP3217R |

|

measurement | |

| Radiant | DeltaOHM – | -10 to | Class 1/3 DIN (

|

| Temperature | TP3275 |

|

from 15 to

|

| Air velocity | DeltaOHM – |

|

|

| AP3203 |

|

||

| SCL sensor | Embrace Plus – | 0.01 to 100 | – |

| Empatica |

|

||

| HR sensor | Embrace Plus – | 24 to 240 | 3 bpm (no motion)/5 bpm |

| ST sensor | Embrace Plus – | 0 to

|

|

| Empatica |

|

2.3. Virtual environment

windows). Specifically, in the Indoor Green condition (IG) a living wall and potted plants were added within the office room, which is frequently used in indoor biophilic design practices; the Outdoor Green (OG) condition represents the natural view of trees to the windows. From a quantitative point of view, the greenery was added exceeding the minimum requirement of the WELL Standard [74] to support occupant well-being and restorative spaces by providing a connection to nature. Thus, the plant wall covered a wall area equal to

2.4. Survey design

buildings (such as present for residential buildings [79]), participants’ perceived affective quality of soundscapes was measured through eight perceptual attributes rated on a five-level Likert scales (from «strongly agree » to «strongly disagree»), following the model by Axelsson et al. [42] and ISO/TS 12913-2 technical specification [80] for (outdoor) urban environments: pleasant, exciting, eventful, chaotic, unpleasant, monotonous, uneventful, and calm.

2.5. Work efficiency measure

Question and rating scale about sense of presence and immersivity and cybersickness questionnaire.

| Factor | Question | Rating scale | |||

| Graphical satisfaction (GP) | I appreciate the graphics and images of the virtual model | totally disagree/ totally agree | |||

| Spatial presence (SP) | totally disagree/ totally agree | ||||

|

|||||

| Involvement (INV) | During the experience, I was not aware of the real world around me | totally disagree/ totally agree | |||

| Experienced realism (REAL) | I perceived the objects inside the virtual office as proportionally correct (i.e., they had about the right size and distance from me and other objects) | totally disagree/ totally agree | |||

| I had the feeling of being able to interact with the office space (e.g. grab objects) | |||||

| Cybersickness |

|

not at all/a lot |

The description of the cognitive functions tests metrics.

| Cognitive function test | Performance metrics | Test duration | ||

| MagnitudeParity | number of errors in the classification of the digits even/odd and greater/lower than ” 5 “ | 63 s | ||

| OSPAN |

|

69 s | ||

| OSPAN score (the sum of the number of the right true/false and the letters correctly reported) number of errors in the colour recalled speed of processing | ||||

| Stroop | dependent on subjects’ speed of processing |

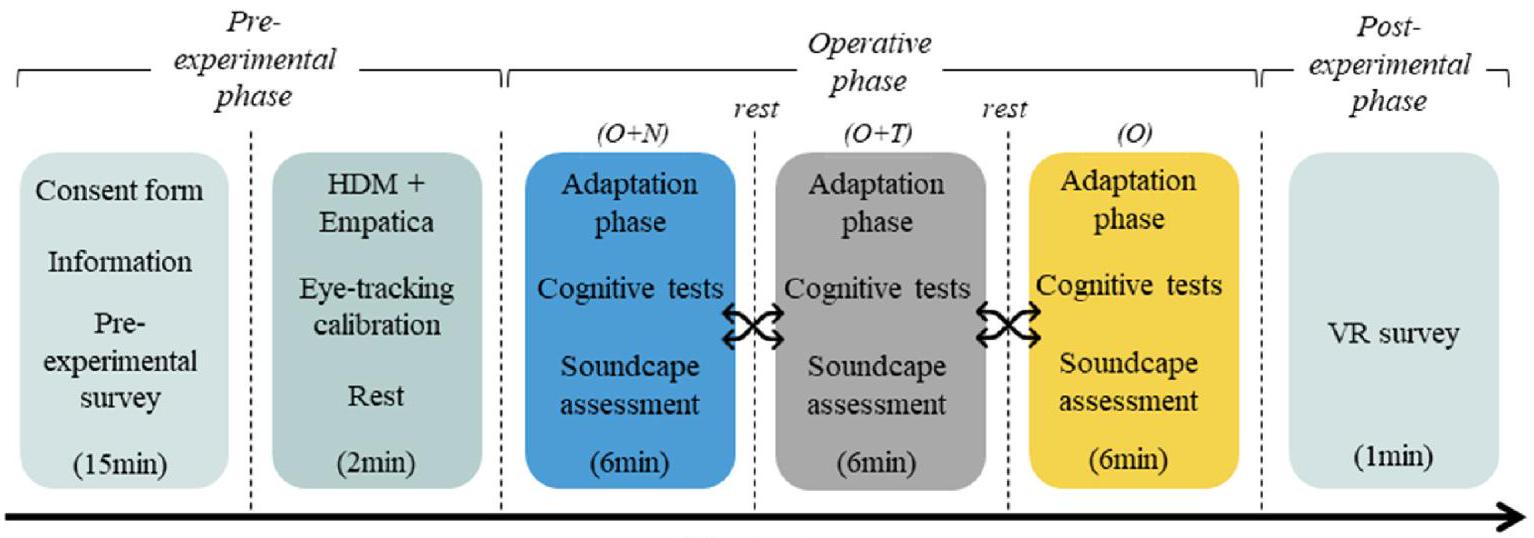

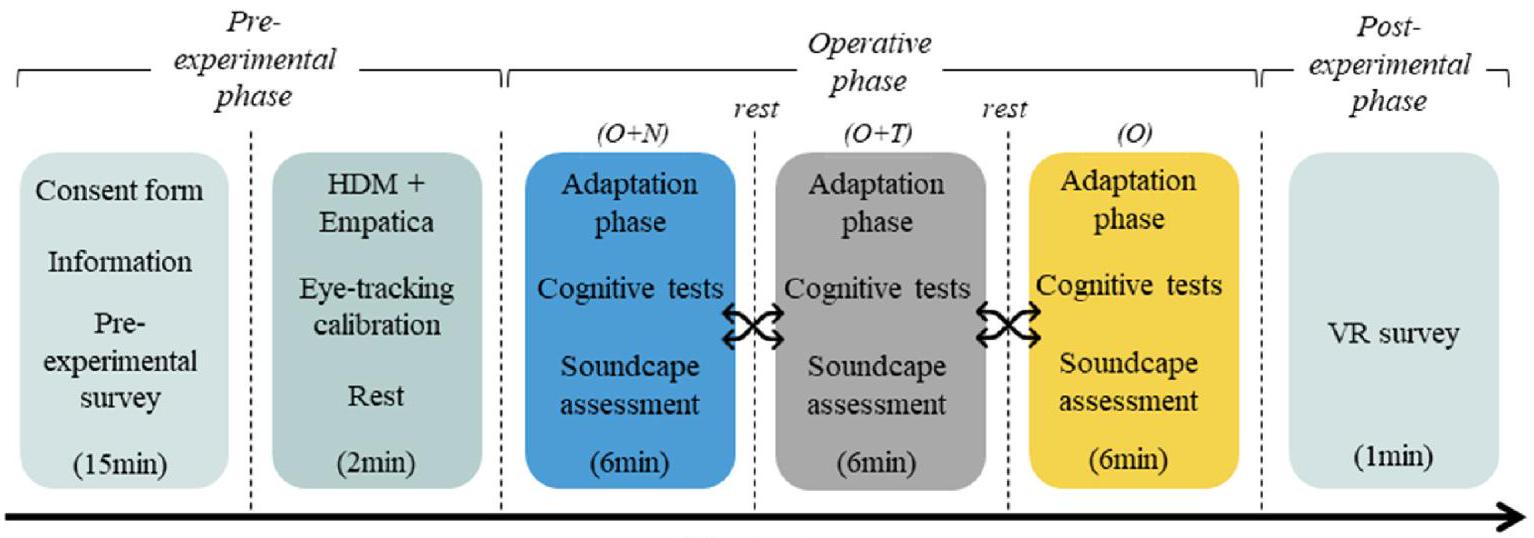

2.6. Experimental procedure

2.7. Participants

Characteristics of study participants (

| Overall | IG | OG | NB | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 36 % | 44 % | 35 % | 29 % |

| Male | 64 % | 57 % | 65 % | 71 % |

| Age | ||||

| 20-25 | 79 % | 68 % | 79 % | 92 % |

| 26-30 | 17 % | 25 % | 17 % | 8 % |

| 31-39 | 4 % | 8 % | 3 % | – |

| 40-45 | – | – | 2 % | – |

| 50-60 | – | – | – | – |

| Educational level | ||||

| Non-graduated | 34 % | 43 % | 35 % | 26 % |

| Graduated | 60 % | 49 % | 59 % | 74 % |

| PhD, post-graduate school | 5 % | 8 % | 6 % | |

| Eyesight problems | ||||

| None | 44 % | 44 % | 52 % | 38 % |

| Myopia | 33 % | 29 % | 26 % | 44 % |

| Myopia + Astigmatism | 15 % | 17 % | 18 % | 9 % |

| Astigmatism | 7 % | 9 % | 5 % | 8 % |

| Hyperopia |

|

1 % | – | 2 % |

| Previous experience with VR | ||||

| Never | 54 % | 53 % | 55 % | 53 % |

| Once | 26 % | 25 % | 27 % | 27 % |

| More than once | 20 % | 22 % | 18 % | 20 % |

| Videogames usage | ||||

| Never | 32 % | 42 % | 33 % | 20 % |

| Rarely | 42 % | 49 % | 39 % | 36 % |

| Frequently | 19 % | 8 % | 20 % | 30 % |

| Everyday | 7 % | 1 % | 8 % | 14 % |

2.8. Statistical analysis

were undertaken to investigate the difference between groups using the R package emmeans and applying the Bonferroni correction to account for planned multiple comparisons. Interaction plots were also printed to interpret any possible interaction effects between Factor V and Factor A .

3. Results

3.1. RQ1. Is VR a promising tool to investigate Biophilic Design research interventions in terms of a high sense of presence and immersivity and low cybersickness?

were negligible since between

- Office:

of participants reported having heard some typical workplace noises such as, «keyboard», «laptop», «mouse», «typing activity» (69 %), and «telephone alert» (13 %), while described the indoor environment as characterized by general «office» noise. In addition, sounds generated by «people» like unintelligible « speech» ( ) and «steps» ( ) were also identified. In general, 82 of participants describe the sounds as coming from the inner side of the virtual room. - Office + Nature: the whole sample (100 %) identified the «natural sounds» of «birds » coming from the open «window » on the lefthand side of the office. In addition,

of participants reported having heard also indoor office sounds. - Office + Traffic:

of participants described the acoustic environment as including «traffic», «road», «cars», «buses», and «horn » noises coming from the open «window» on the left-hand side of the office. In this acoustic scenario, only of the sample clearly described the presence of indoor office sounds, as traffic sounds seemed more predominant.

3.2. RQ2. Does visual and acoustic connection with nature confer benefits in terms of occupants’ working memory, inhibition, and task-switching cognitive performance?

3.2.1. The Magnitude-Parity test

3.2.2. The Stroop test

Comparison of scores on a five-point scale of the four indicators (* highlight the indicators higher than the present study).

| Indicator | This study | [52] | [90] | [91] | [92] | [93] | [94] | [95] |

| GS | 4.40 | 4.58* | 4.64* | 3.93 | – | 3.65 | – | – |

| SP | 4.29 | 4.21 | 4.18 | 3.44 | 4.24 | 3.39 | 3.68 | 3.74 |

| INV | 4.05 | 4.15* | 4.29* | 3.27 | 4.11* | 3.23 | – | – |

| REAL | 4.45 | 4.47* | 4.51* | 2.68 | 3.54 | 2.73 | 3.75 | 3.21 |

Summary of the main and interaction effects of the type of visual scenario (independent variable 1) and the type of acoustic scenario (independent variable 2) on the parameter of the three cognitive tests from the GLMM Anova test. The table presents the Chi-squared statistic, the p-values, the generalized eta squared values (

| Cognitive function parameter | Factor | Level | Mean(sd) | Anova, type “III” (GLMM) |

|

Pairwise comparison | Pairwise comparison result |

| MP number errors | V | NB | 0.81(0.97) |

|

|||

| IG | 0.71(0.79) | ||||||

| OG | 0.70(0.87) | ||||||

| A | O | 0.55(0.85) |

|

0.96 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.38(0.59) |

|

|

||||

|

|

1.30(1.19) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| Stroop number errors | V | NB | 0.34(0.60) |

|

|||

| IG | 0.33(0.61) | ||||||

| OG | 0.28(0.87) | ||||||

| A | O | 0.22(0.69) |

|

0.77 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.18(0.45) |

|

|

||||

|

|

0.55(0.94) |

|

|

||||

| Stroop speed of execution | VxA |

|

|||||

| V | NB | 33.24(6.67) |

|

0.81 | NB – IG |

|

|

| IG | 28.47(6.19) | IG – OG |

|

||||

| OG | 34.21(6.89) | OG – NB | p

|

||||

| A | O | 31.71(5.93) |

|

0.17 |

|

p

|

|

|

|

31.02(6.39) |

|

|

||||

|

|

33.99(6.50) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| OSPAN errors T/F | V | NB | 0.41(0.61) |

|

0.10 | NB – IG |

|

| IG | 0.28(0.52) | IG – OG |

|

||||

| OG | 0.33(0.52) | OG – NB |

|

||||

| A | O | 0.25(0.49) |

|

0.90 |

|

p

|

|

|

|

0.21(0.43) |

|

|

||||

|

|

0.56(0.72) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| OSPAN errors in letters | V | NB | 2.62(1.34) |

|

0.36 | NB – IG |

|

| IG | 1.59(1.36) | IG – OG |

|

||||

| OG | 2.22(1.57) | OG – NB |

|

||||

| A | O | 1.94(1.48) |

|

0.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

1.62(1.50) |

|

|

||||

|

|

2.87(1.29) |

|

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

| OSPAN score | V | NB | 7.00(1.35) |

|

0.25 | NB – IG |

|

| IG | 8.11(1.57) | IG – OG | padj

|

||||

| OG | 7.51(1.60) | OG – NB |

|

||||

| A | O | 7.79(1.59) |

|

0.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

8.19(1.57) |

|

|

||||

|

|

6.64(1.37) |

|

padj

|

||||

| VxA |

|

||||||

sounds in the IG condition (

3.2.3. The OSPAN test

Data mean and standard deviation of the cognitive tasks across Factor V and Factor A scenarios.

| Factor V | Factor A | MP test | Stroop test | OSPAN test | |||

| number of errors | number of errors in the colour recall | speed of execution | number of errors in the T/F | number of errors in letters recalled | OSPAN score | ||

| [-] | [-] | [s] | [-] | [-] | [-] | ||

| IG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IG | O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OG | O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NB | O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

occurred with Indoor Green in the N condition (

Fig. 8 c shows an interaction effect, confirmed by GLMM results ( p value

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1. Is VR a promising tool to investigate Biophilic Design research interventions in terms of a high sense of presence and immersivity and low cybersickness?

4.2. RQ2. Does visual and acoustic connection with nature confer benefits in terms of occupants’ working memory, inhibition, and task-switching cognitive performance?

% lower OSPAN scores occurred compared to Natural sound condition. Regarding the visual factor, a positive influence of the presence of natural elements was highlighted. Participants scored higher when in the Indoor Green scenario than in the Non-Biophilic and Outdoor Green environments (

with the need for negotiation with the occupants [98]. The study shows a potentially interesting positive impact that sound stimuli can bring in terms of cognitive performance, in relation not to the sound level but to the type of sound per se and the semantic meaning it carries. It should be noted, for example, that at the same sound level, the impacts of the two acoustic scenarios (Traffic and Natural) are completely different and with interesting phenomena of interaction with the visual environment. This is in line with the recent literature on indoor soundscaping [79,99], which aims at a perceptive characterisation of sound stimuli in order to use sound as a resource for the design of supportive and healthy living and working spaces. Furthermore, this stresses the importance of investigating the relationship between the occupant and the building with a multi-domain approach, which considers the complexity of the user’s multi-sensory perception in the built environment.

5. Conclusions

- Virtual Reality has been identified as an promising way to conduct pre-occupancy evaluations of the potential of Nature-Based Solutions and Biophilic Design research interventions during the early indoor design stage (ecological validity). Indeed, an excellent level of sense of presence and immersivity was provided to participants considering the visual and acoustical dimension and no relevant cybersickness disorder levels were experienced.

- Visual and non-visual connections with nature can positively contribute to shaping a more supportive office environment through VR. There was a positive change in the users’ task switching, inhibition and working memory functions in the Indoor Green and Outdoor Green scenarios in comparison with the non-biophilic scenario. Higher accuracy was detected in the Natural sound scenario while the Traffic sound scenario was the most disruptive acoustic environment. According to the results, the best visual*acoustic condition for improving participants’ work efficiency occurred with Natural sounds in the Indoor Green condition.

recruited to investigate the potential beneficial effect of nature according to gender, age, and education. Secondly, even if relevant differences were detected between Factor V levels, an introductory test of “basic cognitive abilities” should be administered to participants as a baseline to reduce any bias related to the between-subject design. Thirdly, due to time limitations to VR exposure and the design of the experimental methods as a mixed-between/within-subject design, each acoustic scenario was tested for about 7 min . Even if promising results on cognitive functions were highlighted, it is recommended to further examine the positive benefits of prologued exposure to visual and non-visual connection with nature, for instance by limiting the experimental procedure to a single scenario at a time (in order to limit the general exposure to the IVE). In addition, future research activity could extend the administered survey to investigate participants’ mood, preferences and satisfaction related to the combined audio-visual stimuli.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Appendix

residual data distributions [100-102]. The basic theory of the GLMM is that subjects’ responses are the sum of fixed factors, which are the variables of interest controlled during the study, and random factors that can influence the covariance of the data.

Summary of the main effects of gender differences and order types on the parameters of the three cognitive tests from the GLMM Anova test. The table presents the Chi-squared statistic and the p-values.

| Cognitive function parameter | Anova, type “III” (GLMM) – gender | Anova, type “III” (GLMM) – order |

| MP number errors |

|

|

| Stroop number errors |

|

|

| Stroop speed of execution |

|

|

| OSPAN errors T/F |

|

|

| OSPAN errors in letters |

|

|

| OSPAN score |

|

|

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the marginal (

AIC, marginal and conditional

| Group variable | Dependent variable | AIC |

|

|

| Cognitive test | MP number errors | 1322.3 | 0.19 | 0.29 |

| Stroop number errors | 845.8 | 0.09 | 0.19 | |

| Stroop speed of processing | 3684.7 | 0.19 | 0.33 | |

| OSPAN errors T/F | 869.6 | 0.07 | 0.11 | |

| OSPAN errors in letters | 2100.9 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| OSPAN score | 2507.9 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

References

[2] B. Sowińska-Swierkosz, J. García, What are Nature-based solutions (NBS)? Setting core ideas for concept clarification, Nature-Based Solut. 2 (2022) 100009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2022.100009.

[3] IUCN, Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions, First Edit, Gland, Switzerland, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN•CH.2020.08.en.

[4] B.A. Johnson, P. Kumar, N. Okano, R. Dasgupta, B.R. Shivakoti, Nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation: a systematic review of systematic reviews, Nature-Based Solut. 2 (2022) 100042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nbsj.2022.100042.

[5] Y. Xing, P. Jones, I. Donnison, Characterisation of nature-based solutions for the built environment, Sustain. Times 9 (2017) 1-20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ su9010149.

[6] S.R. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, M. Mador, Biophilic Design : the Theory, Science, and Practiceof Bringing Buildings to Life, 2008.

[7] R. Stephen, Kellert, Nature by Design: the Practice of Biophilic Design, Yale University Press, 2018.

[8] N. Wijesooriya, A. Brambilla, Bridging biophilic design and environmentally sustainable design: a critical review, J. Clean. Prod. 283 (2021) 124591, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124591.

[9] European Ventilation Industry Association, Evia’s Eu Manifesto: Good Indoor Air Quality Is a Basic Human Right, 2019.

[10] Y. Al Horr, M. Arif, A. Kaushik, A. Mazroei, M. Katafygiotou, E. Elsarrag, Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: a review of the literature, Build. Environ. 105 (2016) 369-389, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2016.06.001.

[11] ASHRAE standard, Journal – June 2019 (2019), Vol. 61, No. 6, pp. 1-85.

[12] Y. Jiang, N. Li, A. Yongga, W. Yan, Short-term effects of natural view and daylight from windows on thermal perception, health, and energy-saving potential, Build. Environ. 208 (2022) 108575, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108575.

[13] R.S. Ulrich, R.F. Simonst, B.D. Lositot, E. Fioritot, M.A. Milest, M. Zelsont, Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments, 1991.

[14] S. Kaplan, The restorative environment: nature and human experience, in: D. Relf (Ed.), Role Hortic. Hum. Well Being Soc. Dev., Timber Press, 1992, pp. 134-142.

[15] B. Browning, C. Cooper, The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace, 2015. http://humanspaces.com/resources/reports/.

[16] S. Kaplan, The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework, J. Environ. Psychol. 15 (1995) 169-182, https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944 (95)90001-2.

[17] W.D. Browning, C.O. Ryan, J.O. Clancy, 14 Patterns ofBiophilic Design: improving health & wellbeing in the built environment, Terrapin Bright Green 1 (2014) 1-64.

[18] W.H. Ko, S. Schiavon, H. Zhang, L.T. Graham, G. Brager, I. Mauss, Y.W. Lin, The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance, Build. Environ. 175 (2020) 106779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2020.106779.

[19] C.Y. Chang, P.K. Chen, Human response to window views and indoor plants in the workplace, Hortscience 40 (2005) 1354-1359, https://doi.org/10.21273/ hortsci.40.5.1354.

[20] E. Largo-Wight, W. William Chen, V. Dodd, R. Weiler, Healthy workplaces: the effects of nature contact at work on employee stress and health, Publ. Health Rep. 126 (2011) 124-126, https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549111260s116.

[21] J.J. Alvarsson, S. Wiens, M.E. Nilsson, Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 7 (2010) 1036-1046, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7031036.

[22] E. Ratcliffe, B. Gatersleben, P.T. Sowden, Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery, J. Environ. Psychol. 36 (2013) 221-228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.08.004.

[23] E. Ratcliffe, B. Gatersleben, P.T. Sowden, Associations with bird sounds: how do they relate to perceived restorative potential? J. Environ. Psychol. 47 (2016) 136-144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.009.

[24] M.R. Marselle, K.N. Irvine, A. Lorenzo-Arribas, S.L. Warber, Does perceived restorativeness mediate the effects of perceived biodiversity and perceived naturalness on emotional well-being following group walks in nature? J. Environ Psychol. 46 (2016) 217-232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.008.

[25] R.K. Raanaas, K.H. Evensen, D. Rich, G. Sjøstrøm, G. Patil, Benefits of indoor plants on attention capacity in an office setting, J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (2011) 99-105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.11.005.

[26] L. Gao, S. Wang, J. Li, H. Li, Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces, Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 127 (2017) 107-113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. resconrec.2017.08.030.

[27] V.I. Lohr, C.H. Pearson-Mims, G.K. Goodwin, Interior plants may improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a windowless environment, J. Environ. Hortic. 14 (1996) 97-100, https://doi.org/10.24266/0738-2898-14.2.97.

[28] A.R. Khan, A. Younis, A. Riaz, M.M. Abbas, Effect of interior plantscaping on indoor academic environment, J. Agric. Res. 43 (2005) 235-242.

[29] M. Nieuwenhuis, C. Knight, T. Postmes, S.A. Haslam, The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: three field experiments, J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 20 (2014) 199-214, https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000024.

[30] S. Shibata, N. Suzuki, Effects of an indoor plant on creative task performance and mood, Scand. J. Psychol. 45 (2004) 373-381, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14679450.2004.00419.x.

[31] S. Shibata, N. Suzuki, Effects of the foliage plant on creative task performance and mood, J. Environ. Psychol. 22 (2002) 265-272, https://doi.org/10.1006/ jevp. 232.

[32] N. Hähn, E. Essah, T. Blanusa, Biophilic design and office planting: a case study of effects on perceived health, well-being and performance metrics in the workplace, Intell. Build. Int. 13 (2021) 241-260, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17508975.2020.1732859.

[33] L. E.Larsen, J. Adams, B. Deal, B.S. Kweon, Tyler, Plants in the workplace the effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions, Environ. Behav. 30 (1999) 261-281, papers2://publication/uuid/BD10AA79-D958-43EF-A03B-013230F826C7.

[34] J. Ayuso Sanchez, T. Ikaga, S. Vega Sanchez, Quantitative improvement in workplace performance through biophilic design: a pilot experiment case study, Energy Build. 177 (2018) 316-328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enbuild.2018.07.065.

[35] H. Jahncke, S. Hygge, N. Halin, A.M. Green, K. Dimberg, Open-plan office noise: cognitive performance and restoration, J. Environ. Psychol. 31 (2011) 373-382, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.07.002.

[36] H. Jahncke, P. Björkeholm, J.E. Marsh, J. Odelius, P. Sörqvist, Office noise: can headphones and masking sound attenuate distraction by background speech? Work 55 (2016) 505-513, https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162421.

[37] S.C. Van Hedger, H.C. Nusbaum, L. Clohisy, S.M. Jaeggi, M. Buschkuehl, M. G. Berman, Of cricket chirps and car horns: the effect of nature sounds on cognitive performance, Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26 (2019) 522-530, https://doi.org/ 10.3758/s13423-018-1539-1.

[38] E. Stobbe, R. Lorenz, S. Kühn, On how natural and urban soundscapes alter brain activity during cognitive performance, J. Environ. Psychol. 91 (2023) 102141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102141.

[39] S. Aristizabal, K. Byun, P. Porter, N. Clements, C. Campanella, L. Li, A. Mullan, S. Ly, A. Senerat, I.Z. Nenadic, W.D. Browning, V. Loftness, B. Bauer, Biophilic

office design: exploring the impact of a multisensory approach on human wellbeing, J. Environ. Psychol. 77 (2021) 101682, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jenvp.2021.101682.

[40] ISO – International Organization for Standardization, ISO/TS 12913: 2014 Acoustics – Soundscape Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework, 2014.

[41] S. Torresin, E. Ratcliffe, F. Aletta, R. Albatici, F. Babich, T. Oberman, J. Kang, The actual and ideal indoor soundscape for work, relaxation, physical and sexual activity at home: a case study during the COVID-19 lockdown in London, Front. Psychol. 13 (2022) 1-24, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1038303.

[42] O. Axelsson, M.E. Nilsson, B. Berglund, A principal components model of soundscape perception, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128 (2010) 2836-2846, https://doi. org/10.1121/1.3493436.

[43] E. Ratcliffe, Sound and soundscape in restorative natural environments: a narrative literature review, Front. Psychol. 12 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2021.570563.

[44] K. Hume, M. Ahtamad, Physiological responses to and subjective estimates of soundscape elements, Appl. Acoust. 74 (2013) 275-281, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.10.009.

[45] K. Uebel, M. Marselle, A.J. Dean, J.R. Rhodes, A. Bonn, Urban green space soundscapes and their perceived restorativeness, People Nat 3 (2021) 756-769, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10215.

[46] D. Francomano, M.I. Rodríguez González, A.E.J. Valenzuela, Z. Ma, A.N. Raya Rey, C.B. Anderson, B.C. Pijanowski, Human-nature connection and soundscape perception: insights from Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, J. Nat. Conserv. 65 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2021.126110.

[47] Y. Suko, K. Saito, N. Takayama, S. Warisawa, Effect of Faint Road Traffic Noise Mixed in Birdsong on the Perceived Restorativeness and Listeners ‘ Physiological Response: an Exploratory Study, (n.d.).

[48] J.Y. Choi, S.A. Park, S.J. Jung, J.Y. Lee, K.C. Son, Y.J. An, S.W. Lee, Physiological and psychological responses of humans to the index of greenness of an interior space, Complement, Ther. Med. 28 (2016) 37-43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ctim.2016.08.002.

[49] E. Tsekeri, A. Lilli, M. Katsiokalis, K. Gobakis, A. Mania, D. Kolokotsa, On the integration of nature-based solutions with digital innovation for health and wellbeing in cities, in: 2022 7th Int. Conf. Smart Sustain. Technol. Split. 2022, 2022, pp. 1-6, https://doi.org/10.23919/SpliTech55088.2022.9854269.

[50] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M.D. Orazio, Development and application of an experimental framework for the use of virtual reality to assess building users productivity, J. Build. Eng. 70 (2023) 106280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2023.106280.

[51] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M. D’Orazio, C. Di Perna, Exploring the use of immersive virtual reality to assess occupants’ productivity and comfort in workplaces: an experimental study on the role of walls colour, Energy Build. 253 (2021) 111508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111508.

[52] A. Latini, E. Di Giuseppe, M. D’Orazio, Immersive virtual vs real office environments: a validation study for productivity, comfort and behavioural research, Build. Environ. (2023) 109996, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. BUILDENV.2023.109996.

[53] Y. Zhang, H. Liu, S.C. Kang, M. Al-Hussein, Virtual reality applications for the built environment: research trends and opportunities, Autom. ConStruct. 118 (2020) 103311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103311.

[54] S. Yeom, H. Kim, T. Hong, Psychological and physiological effects of a green wall on occupants: a cross-over study in virtual reality, Build. Environ. 204 (2021) 108134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108134.

[55] J. Yin, N. Arfaei, P. MacNaughton, P.J. Catalano, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Effects of biophilic interventions in office on stress reaction and cognitive function: a randomized crossover study in virtual reality, Indoor Air 29 (2019) 1028-1039, https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12593.

[56] A. Sedghikhanshir, Y. Zhu, Y. Chen, B. Harmon, Exploring the impact of green walls on occupant thermal state in immersive virtual environment, Sustain. Times 14 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031840.

[57] J. Yin, J. Yuan, N. Arfaei, P.J. Catalano, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: a between-subjects experiment in virtual reality, Environ. Int. 136 (2020) 105427, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105427.

[58] A. Emamjomeh, Y. Zhu, M. Beck, The potential of applying immersive virtual environment to biophilic building design: a pilot study, J. Build. Eng. 32 (2020) 101481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101481.

[59] S. Yeom, H. Kim, T. Hong, H.S. Park, D.E. Lee, An integrated psychological score for occupants based on their perception and emotional response according to the windows’ outdoor view size, Build. Environ. 180 (2020), https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107019.

[60] D. Haryndia, T. Ayu, Effects of Biophilic Virtual Reality Interior Design on Positive Emotion of University Students Responses, 2020.

[61] N. Kim, J. Gero, Neurophysiological responses to biophilic design: a pilot experiment using VR and eeg biomimetic inspired architectural design view project design neurocognition view project, Des. Comput. Cogn. (2022) 1-21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359892380.

[62] J. Yin, S. Zhu, P. MacNaughton, J.G. Allen, J.D. Spengler, Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment, Build. Environ. 132 (2018) 255-262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.006.

[63] Z. Li, Y. Wang, H. Liu, H. Liu, Physiological and psychological effects of exposure to different types and numbers of biophilic vegetable walls in small spaces, Build. Environ. 225 (2022) 109645, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109645.

[64] Q. Lei, C. Yuan, S.S.Y. Lau, A quantitative study for indoor workplace biophilic design to improve health and productivity performance, J. Clean. Prod. 324 (2021) 129168, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129168.

[65] G. Ozcelik, B. Becerik-Gerber, Benchmarking thermoception in virtual environments to physical environments for understanding human-building interactions, Adv. Eng. Inf. 36 (2018) 254-263, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aei.2018.04.008.

[66] K. Lyu, A. Brambilla, A. Globa, R. De Dear, An immersive multisensory virtual reality approach to the study of human-built environment interactions, Autom. ConStruct. 150 (2023) 104836, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104836.

[67] S. Torresin, G. Pernigotto, F. Cappelletti, A. Gasparella, Combined effects of environmental factors on human perception and objective performance: a review of experimental laboratory works, Indoor Air 28 (2018) 525-538, https://doi. org/10.1111/ina.12457.

[68] M. Schweiker, E. Ampatzi, M.S. Andargie, R.K. Andersen, E. Azar, V. M. Barthelmes, C. Berger, L. Bourikas, S. Carlucci, G. Chinazzo, L.P. Edappilly, M. Favero, S. Gauthier, A. Jamrozik, M. Kane, A. Mahdavi, C. Piselli, A.L. Pisello, A. Roetzel, A. Rysanek, K. Sharma, S. Zhang, Review of multi-domain approaches to indoor environmental perception and behaviour, Build. Environ. 176 (2020) 106804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106804.

[69] K. Lyu, R. de Dear, A. Brambilla, A. Globa, Restorative benefits of semi-outdoor environments at the workplace: does the thermal realm matter? Build. Environ. 222 (2022) 109355 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109355.

[70] S. Shin, M.H.E.M. Browning, A.M. Dzhambov, Window access to nature restores: a virtual reality experiment with greenspace views, sounds, and smells, Ecopsychology 14 (2022) 253-265, https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2021.0032.

[71] DeltaOHM, HD32.1 thermal microclimate. https://www.deltaohm.com/it/prod otto/hd32-1-datalogger-per-la-misura-del-microclima/, 2022. (Accessed 1 November 2022).

[72] DeltaOHM, DeltaLog10. https://www.deltaohm.com/it/support/software/del talog-10/, 2022. (Accessed 1 February 2022).

[73] Empatica, EmbracePlus. https://www.empatica.com/en-eu/embraceplus/, 2022. (Accessed 1 November 2022).

[74] International WELL Building Instituite, WELL v2, 2020. https://v2.wellcertified. com/en/wellv2/overview.

[75] C.E. Commission, Windows and Offices: a Study of Office Worker Performance and the Indoor Environment, 2003.

[76] Unity. https://unity.com, 2021. (Accessed 7 May 2021).

[77] IMotions A/S, iMotions (9.3), Copenhagen, Denmark. https://imotions.com/, 2022.

[78] SteamVR plugin. https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/tools/integration/st eamvr-plugin-32647, 2021.

[79] S. Torresin, R. Albatici, F. Aletta, F. Babich, T. Oberman, S. Siboni, J. Kang, Indoor soundscape assessment: a principal components model of acoustic perception in residential buildings, Build. Environ. 182 (2020) 107152, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107152.

[80] ISO – International Organization for Standardization, ISO/TS 12913-3:2019 Acoustics – Soundscape – Part 3: Data Analysis, 2019, p. 22.

[81] J.R. Stroop, Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions, J. Exp. Psychol. 18 (1935) 643-662, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054651.

[82] N. Unsworth, R.P. Heitz, J.C. Schrock, R.W. Engle, An automated version of the operation span task, Behav. Res. Methods 37 (2005) 498-505, https://doi.org/ 10.3758/BF03192720.

[83] M. Wendt, S. Klein, T. Strobach, More than attentional tuning – investigating the mechanisms underlying practice gains and preparation in task switching, Front. Psychol. 8 (2017) 1-9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00682.

[84] ASHRAE standard, ANSI/ASHRAE standard 55-2004: thermal environmental conditions for human occupancy, in: Am. Soc. Heating, Refrig. Air-Conditioning Eng. Inc. 2004, 2004, pp. 1-34.

[85] J. Munafo, M. Diedrick, T.A. Stoffregen, The virtual reality head-mounted display Oculus Rift induces motion sickness and is sexist in its effects, Exp. Brain Res. 235 (2017) 889-901, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-016-4846-7.

[86] Y. Zhu, S. Saeidi, T. Rizzuto, A. Roetzel, R. Kooima, Potential and challenges of immersive virtual environments for occupant energy behavior modeling and validation: a literature review, J. Build. Eng. 19 (2018) 302-319, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jobe.2018.05.017.

[87] A. Heydarian, B. Becerik-Gerber, Use of immersive virtual environments for occupant behaviour monitoring and data collection, J. Build. Perform. Simul. 10 (2017) 484-498, https://doi.org/10.1080/19401493.2016.1267801.