DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202311970

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38198824

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

طبقات أحادية مُعدلة ذاتية التجميع المشتركة

الملخص

حمض الفوسفونيك [4-(3,6-ثنائي الميثيل-9H-كاربازول-9-يل)بيوتيل] (Me-4PACz) ذات الجزيئات المجمعة ذاتياً (SAM) هي طريقة فعالة لحل مشكلة الواجهة المدفونة.

1. المقدمة

2. النتائج والمناقشة

تشكل طبقة أحادية كثيفة بسبب تأثير الحواجز الستيرية، بينما يمكن لـ Co-SAM بسهولة تشكيل طبقة أحادية كثيفة وموحدة لأن PC يمكنه ملء الفراغات داخل هيكل SAM، مما يضمن تغطية أكثر اكتمالاً. مجموعات الفوسفات، أيونات الأمونيوم الرباعية، و

الفيلم، وهذه النتيجة تم إثباتها أيضًا بواسطة مطيافية الإلكترونات فوق البنفسجية (UPS).

نصف القطر الأكبر لأيون الأمونيوم الرباعي (

الجهاز المعالج بواسطة SAM الوحيد. هذه الزيادة في المجال الكهربائي مفيدة لتسهيل نقل الشحنات وتحسين

تم تقليل النموذج الحركي في الوقت نفسه، مما يؤكد مرة أخرى أن Co-SAM يمكن أن يعزز نقل الحامل (الشكل 5f).

تم تقييم الاستقرار التشغيلي للأجهزة المغلفة تحت تتبع نقطة القدرة القصوى (MPP) والتعرض لمصباح ثنائي باعث للضوء (LED) بنفس شدة ضوء الشمس (بدون فلتر للأشعة فوق البنفسجية) في الهواء المحيط عند درجة حرارة

3. الخاتمة

المعلومات الداعمة

شكر وتقدير

تعارض المصالح

بيان توفر البيانات

الكلمات المفتاحية

تاريخ الاستلام: 11 نوفمبر 2023

تمت المراجعة: 15 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2024

[3] ف. ما، ي. تشاو، ج. لي، إكس. تشانغ، هـ. غو، ج. يو، مجلة الكيمياء الطاقية 2021، 52، 393.

[4] ز.-و. قاو، ي. وانغ، و. س. هـ. تشوي، مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 2022، 12، 2104030.

[5] سي. سي. بوايد، آر. سي. شالكروس، تي. موت، آر. كيرنر، إل. بيرتولوزي، آ. أونو، إس. كافاديا، سي. تشوسي، إي. ج. وولف، جي. ويرنر، جي. آ. ريفورد، سي. دي باولا، آ. ف. بالمستروم، زي. ج. يو، جي. جي. بيري، إس. ف. بينت، زي. سي. هولمان، جي. إم. لوثر، إي. إل. راتكليف، إن. آر. أرمسترونغ، إم. دي. مكغيهي، جول 2020، 4، 1759.

[6] و. تشين، ي. زو، ج. تشين، ي. وو، ب. تو، ف.-ز. ليو، ل. هوانغ، أ. م. سي. نج، أ. ب. دجوريسيك، ز. هي، مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 2019، 9، 1803872.

[7] X. Zhu، C. F. J. Lau، K. Mo، S. Cheng، Y. Xu، R. Li، C. Wang، Q. Zheng، Y. Liu، T. Wang، Q. Lin، Z. Wang، Nano Energy 2022، 103، 107849.

[8] C. Li, X. Wang, E. Bi, F. Jiang, S. M. Park, Y. Li, L. Chen, Z. Wang, L. Zeng, H. Chen, Y. Liu, C. R. Grice, A. Abudulimu, J. Chung, Y. Xian, T. Zhu, H. Lai, B. Chen, R. J. Ellingson, F. Fu, D. S. Ginger, Z. Song, E. H. Sargent, Y. Yan, Science 2023, 379, 690.

[9] ت. وانغ، ف. تشنغ، ج. تانغ، ج. كاو، ب. يو، ج. تشاو، ف. يان، أدف. ساي. 2021، 8، 2004315.

[10] ل. لي، ي. وانغ، إكس. وانغ، ر. لين، إكس. لو، ز. ليو، ك. تشو، س. شيونغ، ق. باو، ج. تشين، ي. تيان، ي. دينغ، ك. شياو، ج. وو، م. إ. سعيدامينوف، هـ. لين، س.-ك. ما، ز. تشاو، ي. وو، ل. تشانغ، هـ. تان، نات. إنرجي 2022، 7، 708.

[11] ي. هوانغ، ب. وانغ، ت. ليو، د. لي، ي. تشانغ، ت. تشانغ، إكس. ياو، ي. وانغ، أ. أميني، ي. كاي، ب. شو، ز. تانغ، ج. شينغ، س. تشينغ، مواد متقدمة وظيفية 2023، 33، 2302375.

[12] ر. هي، و. وانغ، ز. يي، ف. لانغ، ج. تشين، ج. لو، ج. تشو، ج. ثيسبروميل، س. شاه، ك. وي، ي. لو، ج. وانغ، هـ. لاي، هـ. هوانغ، ج. تشو، ب. زو، إكس. يين، س. رين، إكس. هاو، ل. وو، ج. تشانغ، ج. تشانغ، م. ستولترفوهت، ف. فو، و. تانغ، د. تشاو، ناتشر 2023، 618، 80.

[13] س. تشانغ، ف. يي، إكس. وانغ، ر. تشين، هـ. تشانغ، ل. زهان، إكس. جيانغ، ي. لي، إكس. جي، س. ليو، م. يو، ف. يو، ي. تشانغ، ر. وو، ز. ليو، ز. نينغ، د. نهر، ل. هان، ي. لين، هـ. تيان، و. تشين، م. ستولترفوهت، ل. تشانغ، و.-هـ. تشو، ي. وو، ساينس 2023، 380، 404.

[14] ل. ماو، ت. يانغ، هـ. تشانغ، ج. شي، ي. هو، ب. زينغ، ف. لي، ج. قونغ، إكس. فانغ، ي. صن، إكس. ليو، ج. دو، أ. هان، ل. تشانغ، و. ليو، ف. منغ، إكس. كوي، ز. ليو، م. ليو، مواد متقدمة 2022، 34، 2206193.

[15] ق. جيانغ، ر. تيروات، ر. أ. كيرنر، إ. أ. غولدينغ، ي. شيان، إكس. وانغ، ج. م. نيوكيرك، ي. يان، ج. ج. بيري، ك. زو، ناتشر 2023، 623، 313.

[16] ب. نيو، هـ. ليو، ي. هوانغ، إ. غو، م. يان، ز. شين، ك. يان، ب. يان، ج. ياو، ي. فانغ، هـ. تشين، س.-ز. لي، مواد متقدمة 2023، 35، 2212258.

[17] I. كافيدجيسكا، I. ليفين، A. موسيينكو، N. ماتيتشوك، T. بيرترام، A. العشوري، C. A. كاوفمان، S. ألبريخت، R. شلاتمان، I. لاورمان، Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023، 33، 2302924.

[18] ج. تاو، إكس. ليو، ج. شين، س. هان، ل. جوان، ج. فو، د.-ب. كوانغ، س. يانغ، ACS نانو 2022، 16، 10798.

[19] ل. يانغ، هـ. زو، ي. دوآن، م. وو، ك. هي، ي. لي، د. شو، هـ. زو، س. يانغ، ز. فانغ، س. ليو، ز. ليو، مواد متقدمة 2023، 35، 2211545.

[20] د. تشانغ، إكس. وانغ، تي. تيان، إكس. شيا، ج. دوآن، ز. فان، ف. لي، مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 2023، 469، 143789.

[21] م. ليو، ل. بي، و. جيانغ، ز. زينغ، س.-و. تسونغ، ف. ر. لين، أ. ك.-ي. جين، مواد متقدمة 2023، 2304415.

[22] س. م. بارك، م. وي، ن. لمبسي، و. يو، ت. حسيني، ل. أغوستا، ف. كارنيفالي، هـ. ر. أتاباتو، ب. سيرلز، ف. ت. إيكيماير، هـ. شين، م. فافاي، د. تشوي، ك. دارابي، إ. د. جونغ، ي. يانغ، د. ب. كيم، س. م. زاكير الدين، ب. تشين، أ. أماسسيان، ت. فيليتر، م. ج. كاناتزيديس، ك. ر. غراهام، ل. شياو، أ. روثليسبيرغر، م. غراتزل، إ. هـ. سارجنت، ناتشر 2023، 624، 289.

[23] س. يانغ، ي. وانغ، ب. ليو، ي.-ب. تشينغ، هـ. ج. تشاو، هـ. ج. يانغ، نات. إنرجي 2016، 1، 15016.

[24] ق. تشو، ج. تشيو، ر. زوانغ، م. يو، ج. ليو، ي. هوا، ل. دينغ، إكس. تشانغ، مواد واجهات ACS التطبيقية 2023، 15، 40676.

[25] سي. ليو، ل. هوانغ، إكس. تشو، إكس. وانغ، ج. ياو، ز. ليو، س. ف. ليو، و. ما، ب. شو، مجلة العلوم 2021، 66، 1419.

[26] ق. تشاو، ي. لي، ي. تشانغ، ج. تشاو، ت. وانغ، ب. يانغ، إكس. بو، ج. يانغ، هـ. تشين، إكس. تشين، إكس. لي، س. غاسمي، هـ. سالاري، أ. هاغفيلدت، إكس. لي، مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 2022، 12، 2201435.

[27] ق. ليانغ، ك. ليو، م. صن، ز. رين، ب. و. ك. فونغ، ج. هوانغ، م. كوين، ز. وو، د. شين، ج.-س. لي، ج. هاو، إكس. لو، ب. هوانغ، ج. لي، مواد متقدمة 2022، 34، 2200276.

[28] C. بي، Q. وانغ، Y. شاو، Y. يوان، Z. شياو، J. هوانغ، نات. كوميونيك. 2015، 6، 7747.

[29] ن. وو، ت. يانغ، ز. وانغ، ي. وو، ي. وانغ، ج. ما، هـ. لي، ي. دو، د. تشاو، س. وانغ، ب. ليو، و. هوانغ، إكس. رين، س. ف. ليو، ك. تشاو، مواد متقدمة 2023، 35، 2304809.

[30] هـ. زانغ، ن.-ج. بارك، أنجيو. كيم.، إنت. إد. 2022، 61، 202212268.

[31] ب. يانغ، د. بوجاتشوك، ج. سُو، ل. فاغنر، هـ. كيم، ج. ليم، أ. هينش، ج. بوشلو، م. ك. نازير الدين، أ. هاجفيلدت، مراجعات الجمعية الكيميائية 2022، 51، 7509.

[32] ن. رولستون، ك. أ. بوش، أ. د. برينتس، أ. غولد-باركر، ي. دينغ، م. ف. توني، م. د. مكغي، ر. هـ. داوسكاردت، مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 2018، 8، 1802139.

[33] هـ. زانغ، ز. تشين، م. كوين، ز. رين، ك. ليو، ج. هوانغ، د. شين، ز. وو، ي. زانغ، ج. هاو، س.-ش. لي، إكس. لو، ز. تشنغ، و. يو، ج. لي، مواد متقدمة 2021، 33، 2008487.

[34] إكس. تشانغ، ج.-إكس. تشونغ، س. لي، ك. ياو، ي. فانغ، ج. يانغ، ي. تان، ك. شيو، ل. كيو، ك. وانغ، ي. بينغ، و.-كيو. وو، أنجيو. كيم.، إنت. إد. 2023، 62، 202309292.

[35] هـ. وي، ي. يانغ، س. تشين، هـ. ج. شيانغ، نات. كوميونيك. 2021، 12، 637.

[36] م. سليب، ت. ماتسوي، ك. دومانسكي، ج.-ي. سيو، أ. أوماديسينغو، س. م. زاكير الدين، ج.-ب. كوريا-باينا، و. ر. تريس، أ. أباتي، أ. هاجفيلدت، م. غراتزل، ساينس 2016، 354، 206.

[37] C.-C. Zhang، S. Yuan، Y.-H. Lou، Q.-W. Liu، M. Li، H. Okada، Z.-K. Wang، Adv. Mater. 2020، 32، 2001479.

[38] ج. يانغ، ت. وانغ، ي. لي، إكس. بو، هـ. تشين، ي. لي، ب. يانغ، ي. تشانغ، ج. تشاو، ق. كاو، إكس. تشين، س. غاسمي، أ. هاغفيلدت، إكس. لي، سول. آر. آر. إل 2022، 6، 2200422.

[39] ت. وانغ، ي. لي، ق. قاو، ج. يانغ، ب. يانغ، إكس. بو، ي. تشانغ، ج. تشاو، ي. تشانغ، هـ. تشين، أ. هاجفيلدت، إكس. لي، علوم الطاقة والبيئة 2022، 15، 4414.

[40] ز. لي، ب. لي، إكس. وو، س. أ. شيفارد، س. زانغ، د. قاو، ن. ج. لونغ، ز. زو، ساينس 2022، 376، 416.

[41] ق. جيانغ، ي. تشاو، إكس. تشانغ، إكس. يانغ، ي. تشين، ز. تشو، ق. يي، إكس. لي، ز. يين، ج. يو، نات. فوتونيكس 2019، 13، 460.

[42] ق. كاو، ي. تشانغ، إكس. بو، ج. تشاو، ت. وانغ، ك. تشانغ، هـ. تشن، إكس. هي، ج. يانغ، س. تشانغ، إكس. لي، ج. كيمياء الطاقة 2023، 86، 9.

[43] هـ. تشينغ، س. ليو، ج. زوانغ، ج. كاو، ت. وانغ، و.-ي. وونغ، ف. يان، مواد متقدمة وظيفية 2022، 32، 2204880.

[44] هـ. تشين، ج. يانغ، ق. كاو، ت. وانغ، إكس. بو، إكس. هي، إكس. تشين، إكس. لي، طاقة نانو 2023، 117، 108883.

[45] ق. تشاو، ج. يانغ، ت. وانغ، ي. لي، إكس. بو، ج. تشاو، ي. تشانغ، هـ. تشو، إكس. لي، إكس. لي، علوم الطاقة والبيئة 2021، 14، 5406.

[46] X. Pu، J. Zhao، Y. Li، Y. Zhang، H.-L. Loi، T. Wang، H. Chen، X. He، J. Yang، X. Ma، X. Li، Q. Cao، Nano Energy 2023، 112، 108506.

[47] ر. تشين، ج. وانغ، ز. ليو، ف. رين، س. ليو، ج. تشو، هـ. وانغ، إكس. مينغ، ز. تشانغ، إكس. جوان، و. ليانغ، ب. أ. تروشن، ي. تشي، ل. هان، و. تشين، نات. إنرجي 2023، 8، 839.

[48] X. Deng, F. Qi, F. Li, S. Wu, F. R. Lin, Z. Zhang, Z. Guan, Z. Yang, C.-S. Lee, A. K.-Y. Jen, أنجيو. كيم., إنت. إد. 2022, 61, 202203088.

[49] ج. زوانغ، ج. وانغ، ف. يان، رسائل نانو-ميكرو. 2023، 15، 84.

[50] ب. شي، ي. دينغ، ب. دينغ، ق. شينغ، ت. كودالي، ج. م. سوتير-فيلا، إ. يافوز، ج. ياو، و. فان، ج. شيو، ي. تيان، د. غو، ك. تشاو، س. تان، إكس. تشانغ، ل. ياو، ب. ج. دايسون، ج. ل. سلاك، د. يانغ، ج. شيو، م. ك. نازير الدين، ي. يانغ، ر. وانغ، ناتشر 2023، 620، 323.

- ق. كاو، ت. وانغ، م. شياو، ل. زوانغ، ق. وي، هـ.-ل. لوئي، ب. كانغ، ج. زوانغ، ج. فنغ، ف. يانقسم الفيزياء التطبيقية

جامعة بوليتكنك هونغ كونغ

هونغ هوم، كولون، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة 999077، جمهورية الصين الشعبية

البريد الإلكتروني: apafyan@polyu.edu.hkيمكن العثور على رقم التعريف ORCID للمؤلفين في هذه المقالة تحتhttps://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202311970© 2024 المؤلف(ون). المواد المتقدمة نشرتها وايلي-فيتش GmbH. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب شروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للنسب، الذي يسمح بالاستخدام والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح.

ق. تشاو، إكس. بو، إكس. هي، إتش. تشين، بي. قوه، جي. فنغ، إكس. ليالمختبر الوطني الرئيسي لمعالجة التصلب

مركز مواد الطاقة النانوية

كلية علوم المواد والهندسة

جامعة شمال غرب بوليتكنيك

شيان 710072، جمهورية الصين الشعبية

البريد الإلكتروني: lixh32@nwpu.edu.cn - [1] هـ. زانغ، ج. تشاو، ج. ياو، و. س. هـ. تشوي، أنجيو. كيم.، إنت. إد. 2023، 62، 202219307.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202311970

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38198824

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

Co-Self-Assembled Monolayers Modified

Abstract

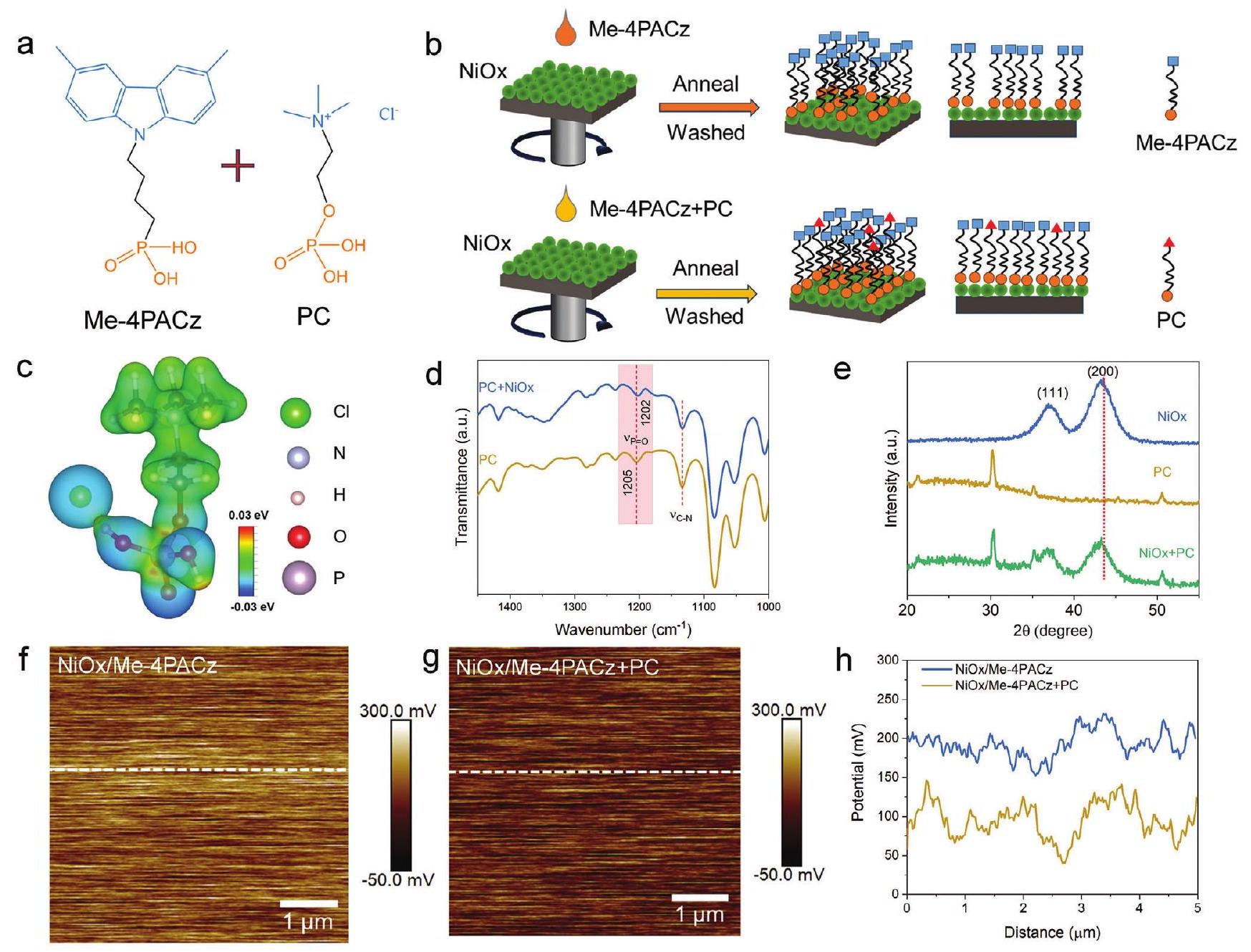

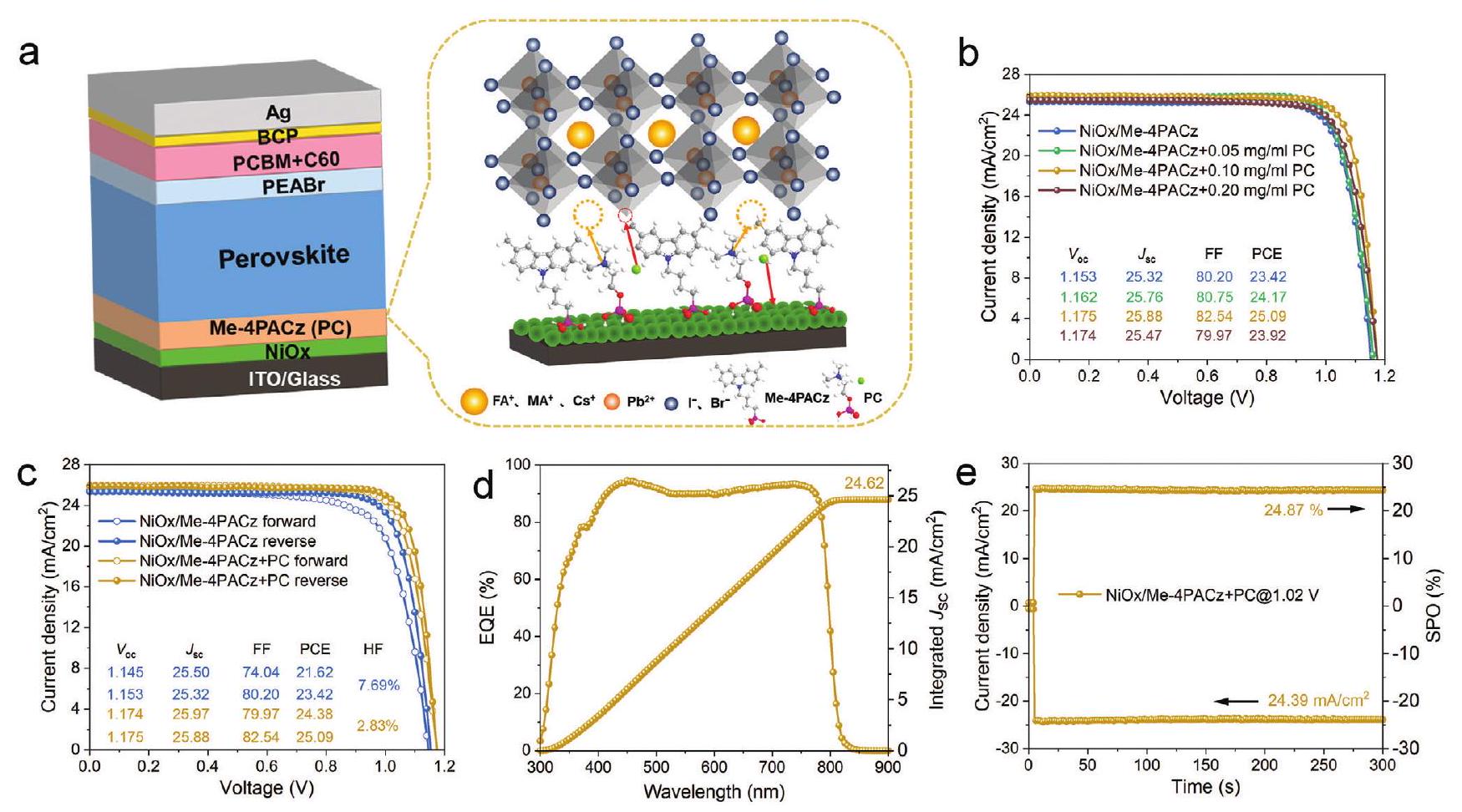

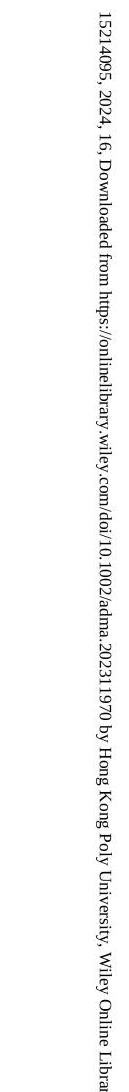

[4-(3,6-dimethyl-9H-carbazol-9yl)butyl]phosphonic acid (Me-4PACz) self-assembled molecules (SAM) are an effective method to solve the problem of the buried interface of

1. Introduction

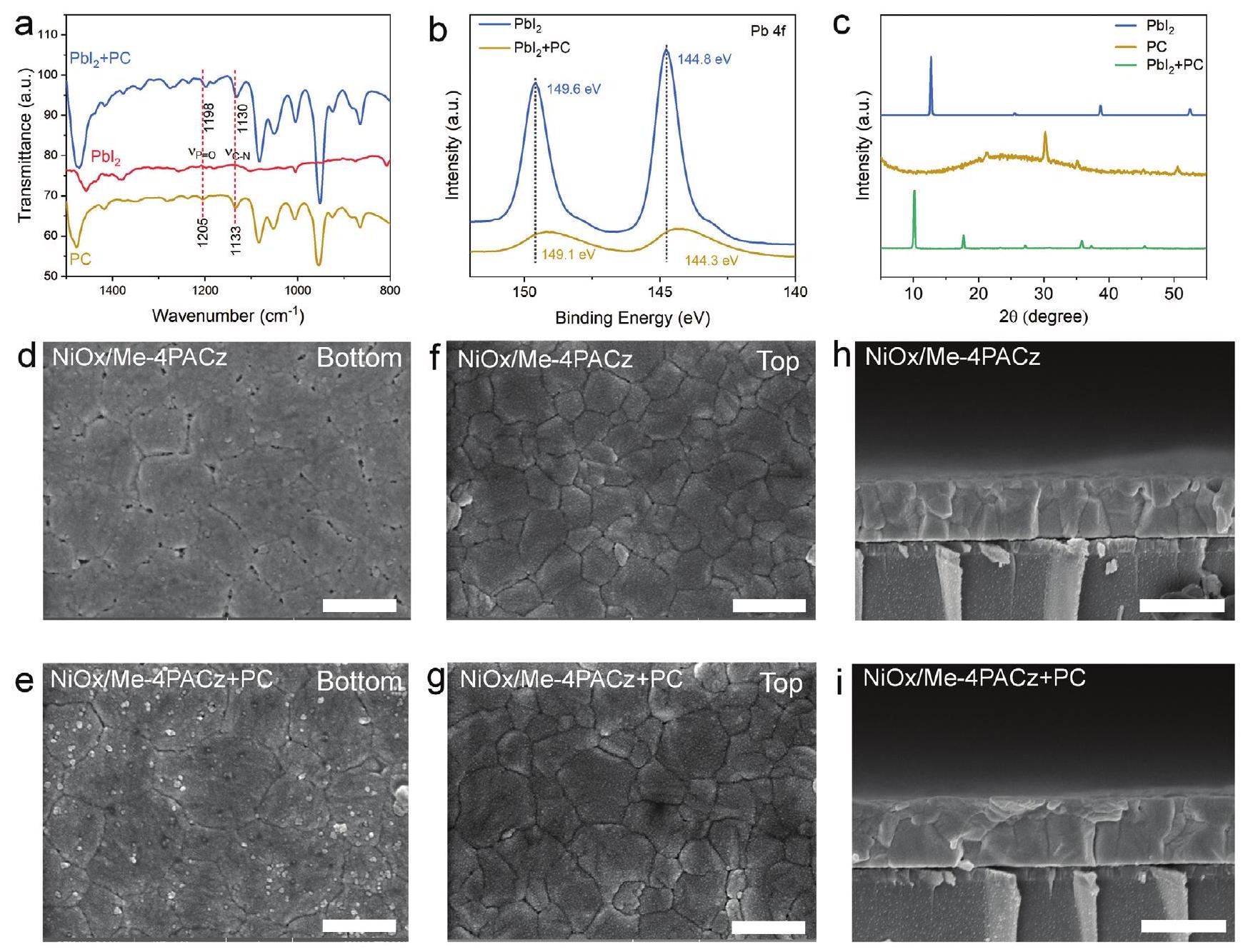

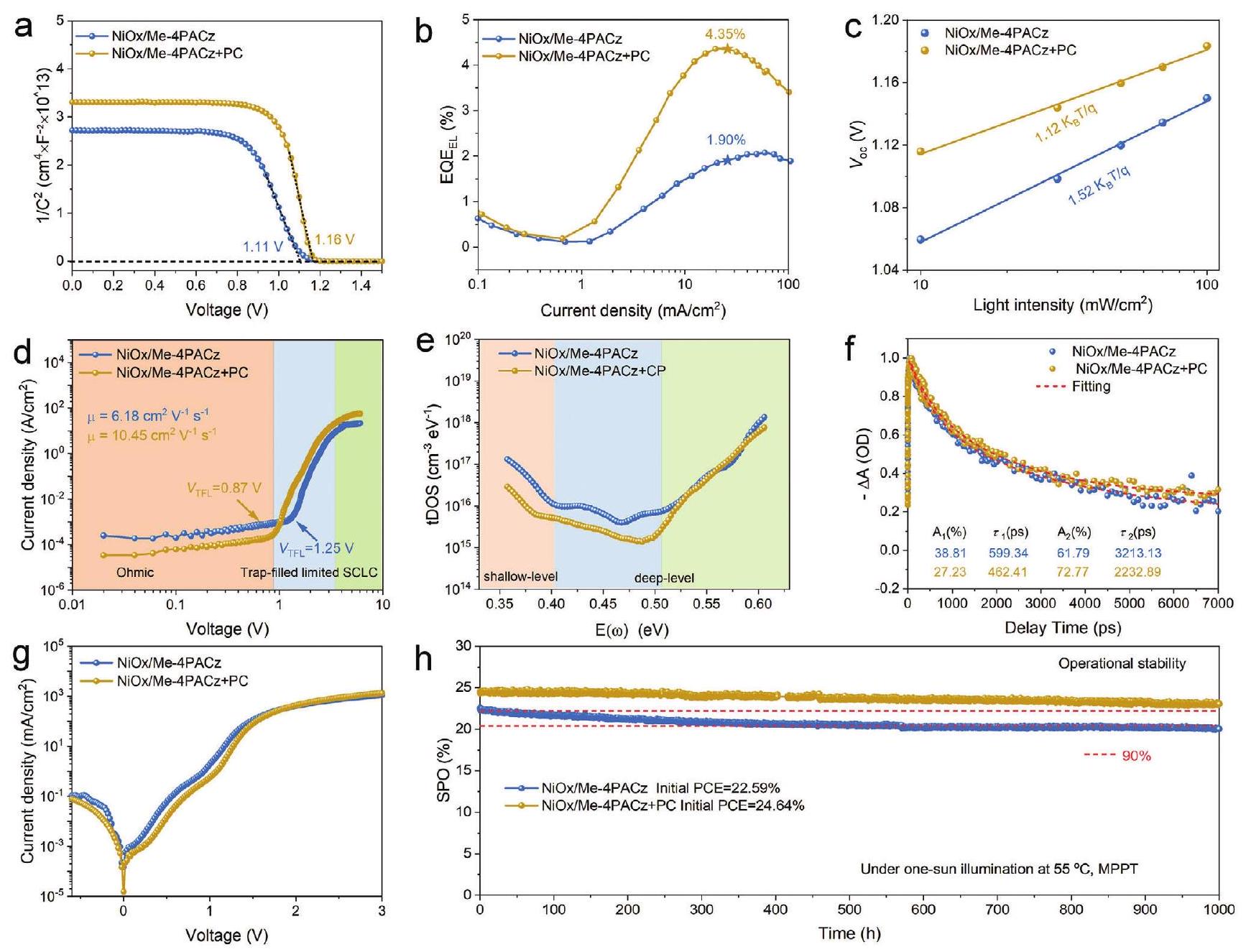

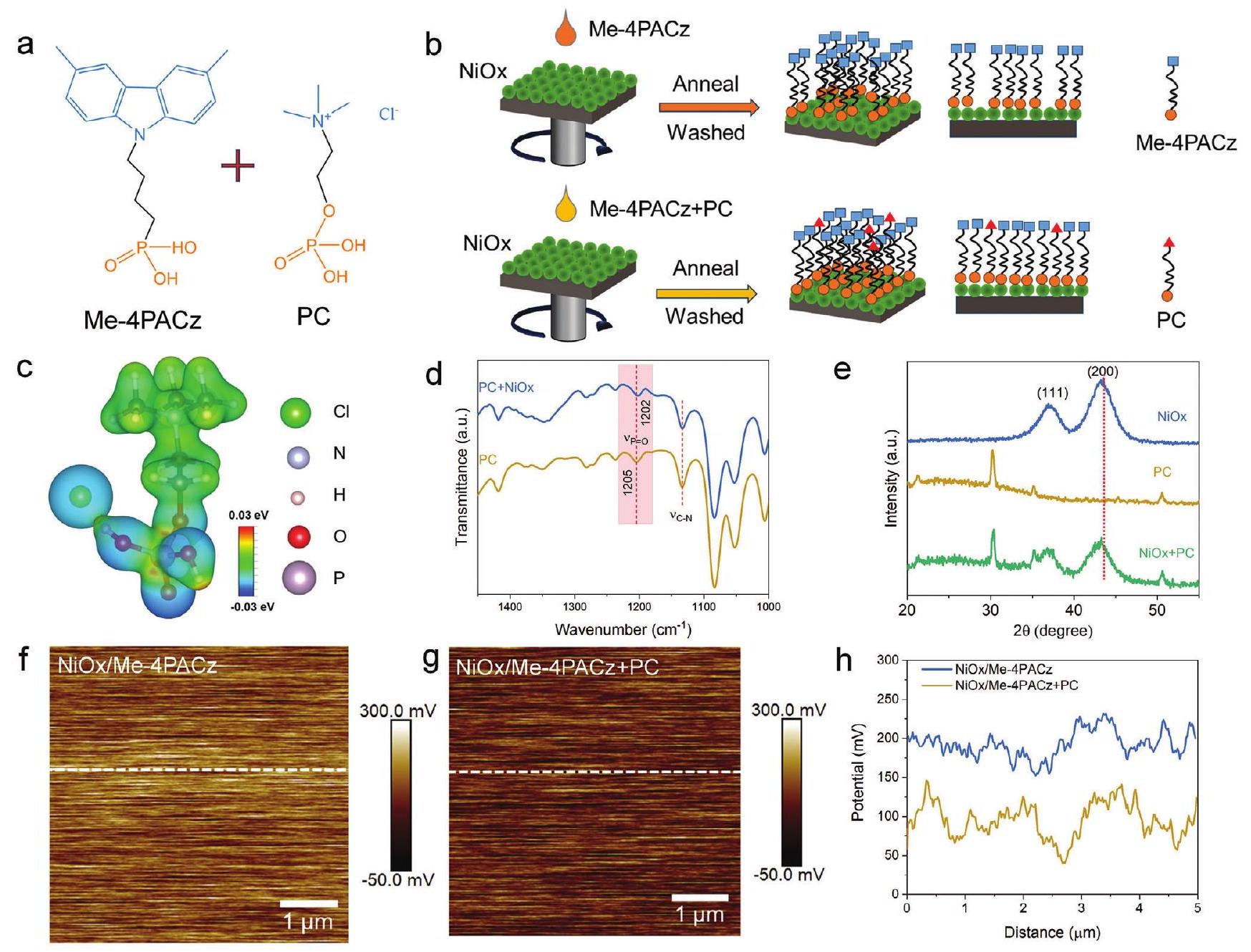

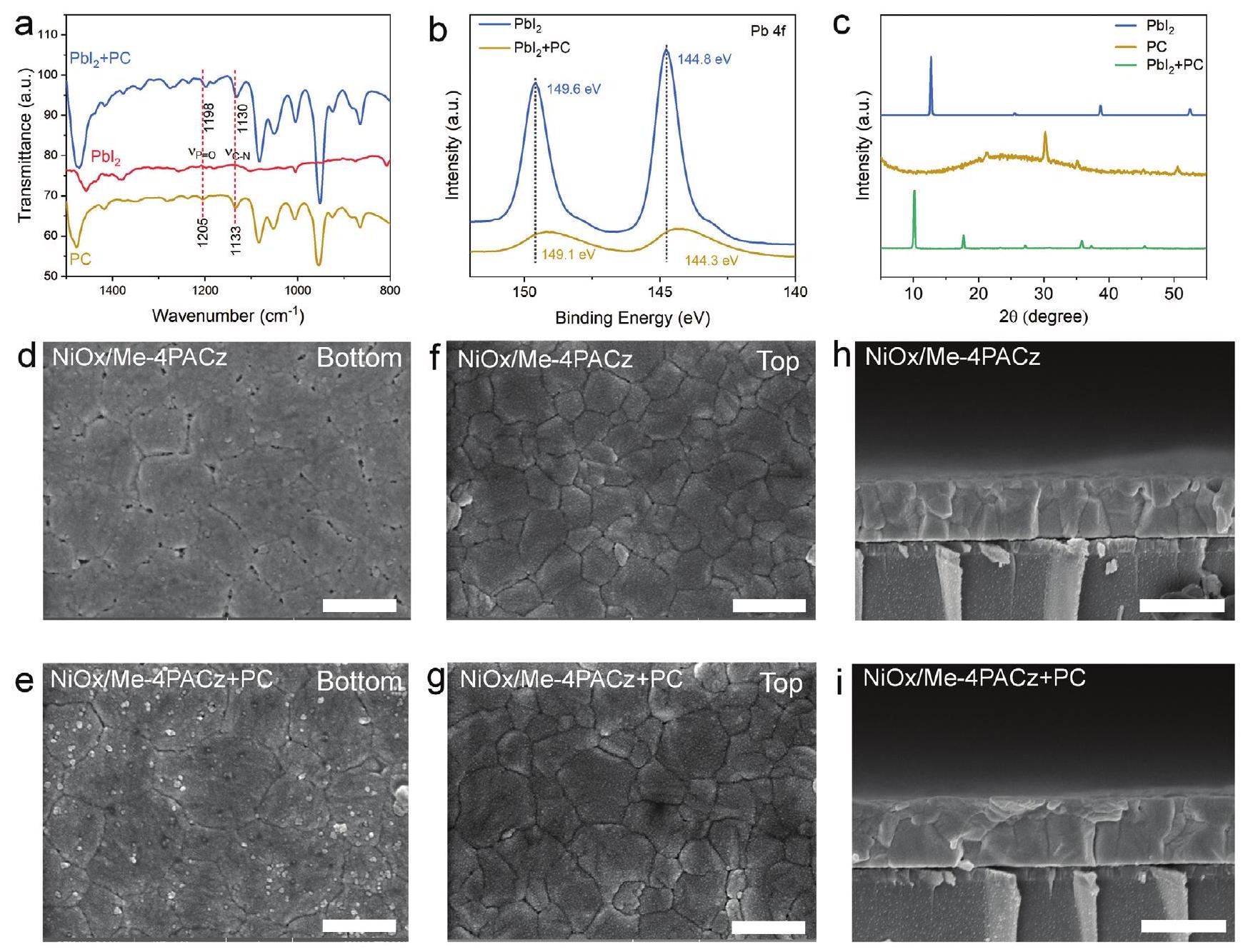

2. Results and Discussion

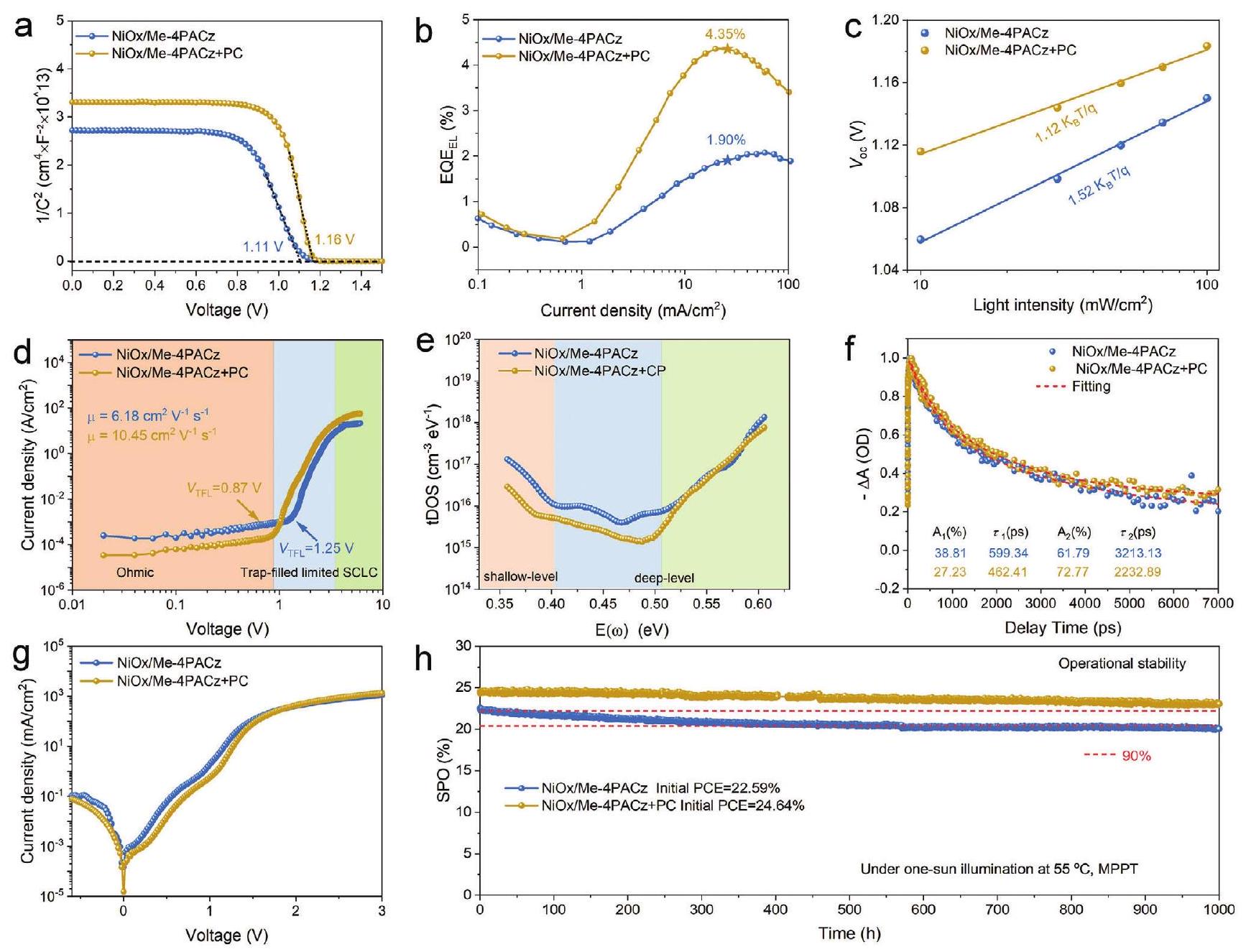

form a dense monolayer due to the steric hindrance effect, while Co-SAM easily forms a dense and uniform single monolayer because PC can fill the vacancies within the SAM structure, ensuring more complete coverage. The phosphate groups, quaternary ammonium ions, and

film, and this result is also proved by Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS).

the larger radius of the quaternary ammonium ion (

the single SAM-treated device. This enhancement in the electric field is advantageous for facilitating charge transport and improving the

kinetic model is simultaneously reduced, which once again verifies that Co-SAM can promote carrier transport (Figure 5f).

The operational stability of the encapsulated devices was evaluated under maximum power point (MPP) tracking and exposure to a white light-emitting diode (LED) lamp with the same intensity as one-sunlight (without UV filter) in ambient air at a temperature of

3. Conclusion

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

Data Availability Statement

Keywords

Received: November 11, 2023

Revised: December 15, 2023

Published online: January 15, 2024

[3] F. Ma, Y. Zhao, J. Li, X. Zhang, H. Gu, J. You, J. Energy Chem. 2021, 52, 393.

[4] Z.-W. Gao, Y. Wang, W. C. H. Choy, Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2104030.

[5] C. C. Boyd, R. C. Shallcross, T. Moot, R. Kerner, L. Bertoluzzi, A. Onno, S. Kavadiya, C. Chosy, E. J. Wolf, J. Werner, J. A. Raiford, C. De Paula, A. F. Palmstrom, Z. J. Yu, J. J. Berry, S. F. Bent, Z. C. Holman, J. M. Luther, E. L. Ratcliff, N. R. Armstrong, M. D. Mcgehee, Joule 2020, 4, 1759.

[6] W. Chen, Y. Zhou, G. Chen, Y. Wu, B. Tu, F.-Z. Liu, L. Huang, A. M. C. Ng, A. B. Djurisic, Z. He, Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803872.

[7] X. Zhu, C. F. J. Lau, K. Mo, S. Cheng, Y. Xu, R. Li, C. Wang, Q. Zheng, Y. Liu, T. Wang, Q. Lin, Z. Wang, Nano Energy 2022, 103, 107849.

[8] C. Li, X. Wang, E. Bi, F. Jiang, S. M. Park, Y. Li, L. Chen, Z. Wang, L. Zeng, H. Chen, Y. Liu, C. R. Grice, A. Abudulimu, J. Chung, Y. Xian, T. Zhu, H. Lai, B. Chen, R. J. Ellingson, F. Fu, D. S. Ginger, Z. Song, E. H. Sargent, Y. Yan, Science 2023, 379, 690.

[9] T. Wang, F. Zheng, G. Tang, J. Cao, P. You, J. Zhao, F. Yan, Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004315.

[10] L. Li, Y. Wang, X. Wang, R. Lin, X. Luo, Z. Liu, K. Zhou, S. Xiong, Q. Bao, G. Chen, Y. Tian, Y. Deng, K. Xiao, J. Wu, M. I. Saidaminov, H. Lin, C.-Q. Ma, Z. Zhao, Y. Wu, L. Zhang, H. Tan, Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 708.

[11] Y. Huang, B. Wang, T. Liu, D. Li, Y. Zhang, T. Zhang, X. Yao, Y. Wang, A. Amini, Y. Cai, B. Xu, Z. Tang, G. Xing, C. Cheng, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2302375.

[12] R. He, W. Wang, Z. Yi, F. Lang, C. Chen, J. Luo, J. Zhu, J. Thiesbrummel, S. Shah, K. Wei, Y. Luo, C. Wang, H. Lai, H. Huang, J. Zhou, B. Zou, X. Yin, S. Ren, X. Hao, L. Wu, J. Zhang, J. Zhang, M. Stolterfoht, F. Fu, W. Tang, D. Zhao, Nature 2023, 618, 80.

[13] S. Zhang, F. Ye, X. Wang, R. Chen, H. Zhang, L. Zhan, X. Jiang, Y. Li, X. Ji, S. Liu, M. Yu, F. Yu, Y. Zhang, R. Wu, Z. Liu, Z. Ning, D. Neher, L. Han, Y. Lin, H. Tian, W. Chen, M. Stolterfoht, L. Zhang, W.-H. Zhu, Y. Wu, Science 2023, 380, 404.

[14] L. Mao, T. Yang, H. Zhang, J. Shi, Y. Hu, P. Zeng, F. Li, J. Gong, X. Fang, Y. Sun, X. Liu, J. Du, A. Han, L. Zhang, W. Liu, F. Meng, X. Cui, Z. Liu, M. Liu, Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2206193.

[15] Q. Jiang, R. Tirawat, R. A. Kerner, E. A. Gaulding, Y. Xian, X. Wang, J. M. Newkirk, Y. Yan, J. J. Berry, K. Zhu, Nature 2023, 623, 313.

[16] B. Niu, H. Liu, Y. Huang, E. Gu, M. Yan, Z. Shen, K. Yan, B. Yan, J. Yao, Y. Fang, H. Chen, C.-Z. Li, Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2212258.

[17] I. Kafedjiska, I. Levine, A. Musiienko, N. Maticiuc, T. Bertram, A. AlAshouri, C. A. Kaufmann, S. Albrecht, R. Schlatmann, I. Lauermann, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2302924.

[18] J. Tao, X. Liu, J. Shen, S. Han, L. Guan, G. Fu, D.-B. Kuang, S. Yang, ACS Nano 2022, 16, 10798.

[19] L. Yang, H. Zhou, Y. Duan, M. Wu, K. He, Y. Li, D. Xu, H. Zou, S. Yang, Z. Fang, S. Liu, Z. Liu, Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2211545.

[20] D. Zhang, X. Wang, T. Tian, X. Xia, J. Duan, Z. Fan, F. Li, Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143789.

[21] M. Liu, L. Bi, W. Jiang, Z. Zeng, S.-W. Tsang, F. R. Lin, A. K.-Y. Jen, Adv. Mater. 2023, 2304415.

[22] S. M. Park, M. Wei, N. Lempesis, W. Yu, T. Hossain, L. Agosta, V. Carnevali, H. R. Atapattu, P. Serles, F. T. Eickemeyer, H. Shin, M. Vafaie, D. Choi, K. Darabi, E. D. Jung, Y. Yang, D. B. Kim, S. M. Zakeeruddin, B. Chen, A. Amassian, T. Filleter, M. G. Kanatzidis, K. R. Graham, L. Xiao, U. Rothlisberger, M. Grätzel, E. H. Sargent, Nature 2023, 624, 289.

[23] S. Yang, Y. Wang, P. Liu, Y.-B. Cheng, H. J. Zhao, H. G. Yang, Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 15016.

[24] Q. Zhou, J. Qiu, R. Zhuang, M. Yu, J. Liu, Y. Hua, L. Ding, X. Zhang, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 40676.

[25] C. Liu, L. Huang, X. Zhou, X. Wang, J. Yao, Z. Liu, S. F. Liu, W. Ma, B. Xu, Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 1419.

[26] Q. Cao, Y. Li, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, T. Wang, B. Yang, X. Pu, J. Yang, H. Chen, X. Chen, X. Li, S. Ghasemi, H. Salari, A. Hagfeldt, X. Li, Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201435.

[27] Q. Liang, K. Liu, M. Sun, Z. Ren, P. W. K. Fong, J. Huang, M. Qin, Z. Wu, D. Shen, C.-S. Lee, J. Hao, X. Lu, B. Huang, G. Li, Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200276.

[28] C. Bi, Q. Wang, Y. Shao, Y. Yuan, Z. Xiao, J. Huang, Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7747.

[29] N. Wu, T. Yang, Z. Wang, Y. Wu, Y. Wang, C. Ma, H. Li, Y. Du, D. Zhao, S. Wang, P. Liu, W. Huang, X. Ren, S. F. Liu, K. Zhao, Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2304809.

[30] H. Zhang, N.-G. Park, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 202212268.

[31] B. Yang, D. Bogachuk, J. Suo, L. Wagner, H. Kim, J. Lim, A. Hinsch, G. Boschloo, M. K. Nazeeruddin, A. Hagfeldt, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 7509.

[32] N. Rolston, K. A. Bush, A. D. Printz, A. Gold-Parker, Y. Ding, M. F. Toney, M. D. Mcgehee, R. H. Dauskardt, Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802139.

[33] H. Zhang, Z. Chen, M. Qin, Z. Ren, K. Liu, J. Huang, D. Shen, Z. Wu, Y. Zhang, J. Hao, C.-S. Lee, X. Lu, Z. Zheng, W. Yu, G. Li, Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2008487.

[34] X. Chang, J.-X. Zhong, S. Li, Q. Yao, Y. Fang, G. Yang, Y. Tan, Q. Xue, L. Qiu, Q. Wang, Y. Peng, W.-Q. Wu, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202309292.

[35] H. Wei, Y. Yang, S. Chen, H. J. Xiang, Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 637.

[36] M. Saliba, T. Matsui, K. Domanski, J.-Y. Seo, A. Ummadisingu, S. M. Zakeeruddin, J.-P. Correa-Baena, W. R. Tress, A. Abate, A. Hagfeldt, M. Grätzel, Science 2016, 354, 206.

[37] C.-C. Zhang, S. Yuan, Y.-H. Lou, Q.-W. Liu, M. Li, H. Okada, Z.-K. Wang, Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001479.

[38] J. Yang, T. Wang, Y. Li, X. Pu, H. Chen, Y. Li, B. Yang, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, Q. Cao, X. Chen, S. Ghasemi, A. Hagfeldt, X. Li, Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2200422.

[39] T. Wang, Y. Li, Q. Cao, J. Yang, B. Yang, X. Pu, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, Y. Zhang, H. Chen, A. Hagfeldt, X. Li, Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4414.

[40] Z. Li, B. Li, X. Wu, S. A. Sheppard, S. Zhang, D. Gao, N. J. Long, Z. Zhu, Science 2022, 376, 416.

[41] Q. Jiang, Y. Zhao, X. Zhang, X. Yang, Y. Chen, Z. Chu, Q. Ye, X. Li, Z. Yin, J. You, Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 460.

[42] Q. Cao, Y. Zhang, X. Pu, J. Zhao, T. Wang, K. Zhang, H. Chen, X. He, J. Yang, C. Zhang, X. Li, J. Energy Chem. 2023, 86, 9.

[43] H. Cheng, C. Liu, J. Zhuang, J. Cao, T. Wang, W.-Y. Wong, F. Yan, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204880.

[44] H. Chen, J. Yang, Q. Cao, T. Wang, X. Pu, X. He, X. Chen, X. Li, Nano Energy 2023, 117, 108883.

[45] Q. Cao, J. Yang, T. Wang, Y. Li, X. Pu, J. Zhao, Y. Zhang, H. Zhou, X. Li, X. Li, Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 5406.

[46] X. Pu, J. Zhao, Y. Li, Y. Zhang, H.-L. Loi, T. Wang, H. Chen, X. He, J. Yang, X. Ma, X. Li, Q. Cao, Nano Energy 2023, 112, 108506.

[47] R. Chen, J. Wang, Z. Liu, F. Ren, S. Liu, J. Zhou, H. Wang, X. Meng, Z. Zhang, X. Guan, W. Liang, P. A. Troshin, Y. Qi, L. Han, W. Chen, Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 839.

[48] X. Deng, F. Qi, F. Li, S. Wu, F. R. Lin, Z. Zhang, Z. Guan, Z. Yang, C.-S. Lee, A. K.-Y. Jen, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 202203088.

[49] J. Zhuang, J. Wang, F. Yan, Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 84.

[50] P. Shi, Y. Ding, B. Ding, Q. Xing, T. Kodalle, C. M. Sutter-Fella, I. Yavuz, C. Yao, W. Fan, J. Xu, Y. Tian, D. Gu, K. Zhao, S. Tan, X. Zhang, L. Yao, P. J. Dyson, J. L. Slack, D. Yang, J. Xue, M. K. Nazeeruddin, Y. Yang, R. Wang, Nature 2023, 620, 323.

- Q. Cao, T. Wang, M. Xiao, L. Zhuang, Q. Wei, H.-L. Loi, B. Kang, J. Zhuang, G. Feng, F. YanDepartment of Applied Physics

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR 999077, P. R. China

E-mail: apafyan@polyu.edu.hkThe ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202311970© 2024 The Author(s). Advanced Materials published by Wiley-VCH GmbH. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Q. Cao, X. Pu, X. He, H. Chen, P. Guo, G. Feng, X. LiState Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing

Center for Nano Energy Materials

School of Materials Science and Engineering

Northwestern Polytechnical University

Xi’an 710072, P. R. China

E-mail: lixh32@nwpu.edu.cn - [1] H. Zhang, C. Zhao, J. Yao, W. C. H. Choy, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202219307.