DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38555664

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-24

SDU-

جامعة جنوب الدنمارك

أداة لتقييم خطر التحيز في الدراسات غير العشوائية لمتابعة آثار التعرض (ROBINS-E)

نُشر في:

البيئة الدولية

10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

2024

النسخة النهائية المنشورة

CC BY-NC

هيغينز، ج. ب. ت.، مورغان، ر. ل.، روني، أ. أ.، تايلور، ك. و.، ثاير، ك. أ.، سيلفا، ر. أ.، ليميريس، س.، أكل، إ. أ.، بيتيسون، ت. ف.، بيركمان، ن. د.، غلين، ب. س.، هروبجارتسون، أ.، لاكيند، ج. س.، مكالينان، أ.، ميربول، ج. ج.، ناتشمان، ر. م.، أوباغي، ج. إ.، أوكونور، أ.، رادكي، إ. ج.، … ستيرن، ج. أ. س. (2024). أداة لتقييم خطر التحيز في الدراسات غير العشوائية لمتابعة آثار التعرض (ROBINS-E). البيئة الدولية، 186، المقال 108602.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

هذا العمل مقدم لكم من جامعة جنوب الدنمارك.

ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك، فقد تم مشاركته وفقًا للشروط الخاصة بالأرشفة الذاتية.

إذا لم يتم ذكر أي ترخيص آخر، تنطبق هذه الشروط:

- يمكنك تنزيل هذا العمل للاستخدام الشخصي فقط.

- لا يجوز لك توزيع المادة بشكل إضافي أو استخدامها لأي نشاط يهدف إلى الربح أو لتحقيق مكاسب تجارية.

- يمكنك توزيع عنوان URL الذي يحدد هذه النسخة المفتوحة الوصول بحرية

أداة لتقييم خطر التحيز في الدراسات غير العشوائية لمتابعة آثار التعرض (ROBINS-E)

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

خطر التحيز

مربك

تحيز الاختيار

تحيز التصنيف/تحيز القياس

تعرض

علم الأوبئة

البيئية

الملخص

الخلفية: توفر الدراسات الوبائية الملاحظة بيانات حيوية لتقييم الآثار المحتملة للتعرضات البيئية والمهنية والسلوكية على صحة الإنسان. تلعب المراجعات المنهجية لهذه الدراسات دورًا رئيسيًا في إبلاغ السياسات والممارسات. يجب أن تتضمن المراجعات المنهجية تقييمات لمخاطر التحيز في نتائج الدراسات المشمولة. الهدف: تطوير أداة جديدة، مخاطر التحيز في الدراسات غير العشوائية – للتعرضات (ROBINS-E) لتقييم مخاطر التحيز في التقديرات من دراسات المجموعات حول التأثير السببي للتعرض على نتيجة. الطرق والنتائج: تم تطوير ROBINS-E من قبل مجموعة كبيرة من الباحثين من تخصصات بحثية وصحية عامة متنوعة من خلال سلسلة من مجموعات العمل، والاجتماعات الشخصية، ومرحلة الاختبار التجريبي. تهدف الأداة إلى تقييم مخاطر التحيز في نتيجة محددة (تقدير تأثير التعرض) من دراسة ملاحظة فردية تفحص تأثير تعرض ما على نتيجة. تُعلم سلسلة من الاعتبارات الأولية التقييم الأساسي لـ ROBINS-E، بما في ذلك تفاصيل النتيجة التي يتم تقييمها والتأثير السببي الذي يتم تقديره.

1. المقدمة

2. تطوير ROBINS-E

3. نظرة عامة على ROBINS-E

تشير الأسئلة إلى ذلك. على سبيل المثال، السؤال 4.2 (“هل من المحتمل أن التحليل تم تصحيحه لتأثير التدخلات بعد التعرض التي تأثرت بالتعرض السابق؟”) غير قابل للتطبيق إذا كانت الإجابة على السؤال 4.1 (“هل كانت هناك تدخلات بعد التعرض تأثرت بالتعرض السابق خلال فترة المتابعة؟”) هي “لا” أو “ربما لا” أو “لا توجد معلومات”.

4. اعتبارات أولية

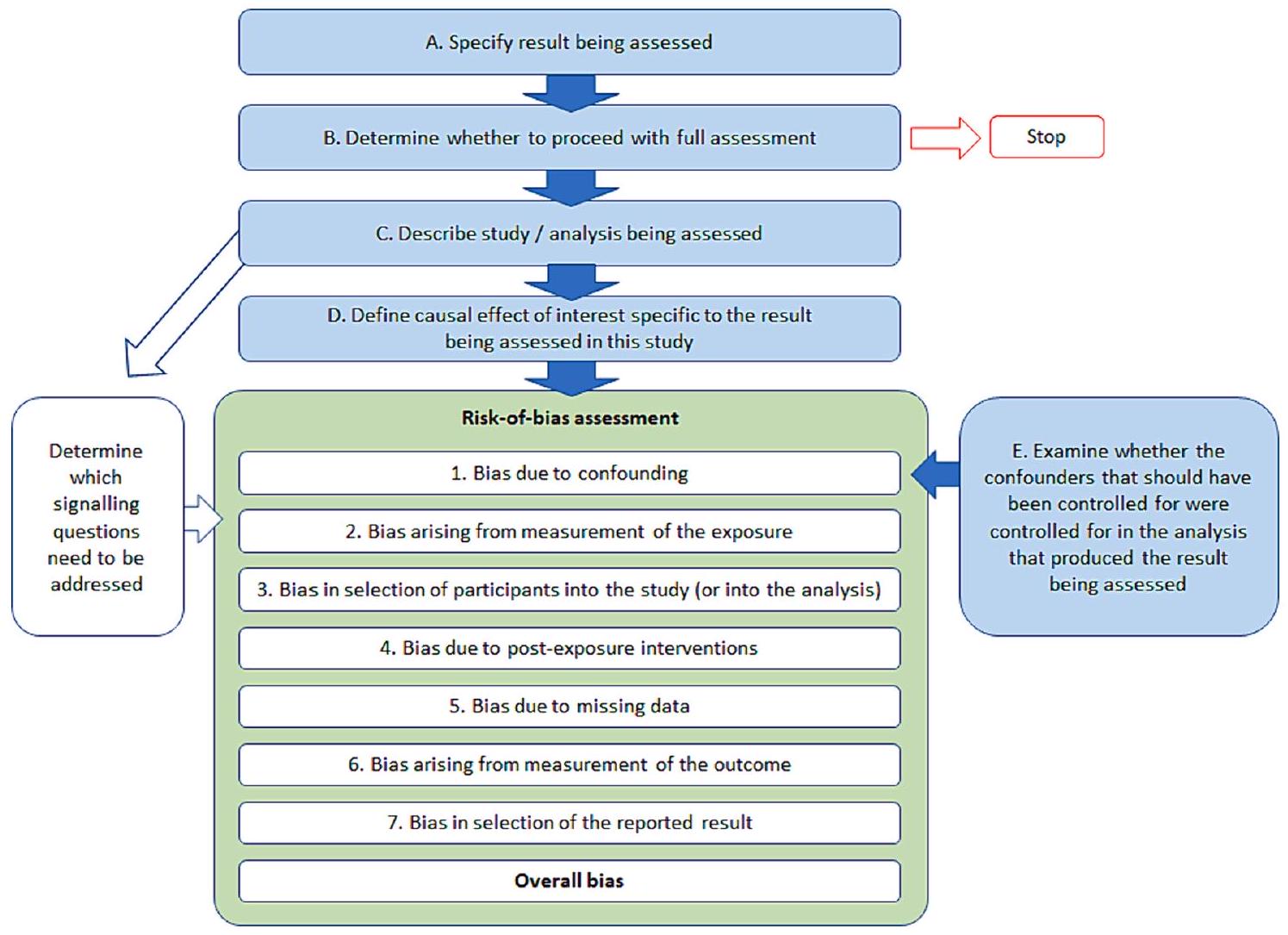

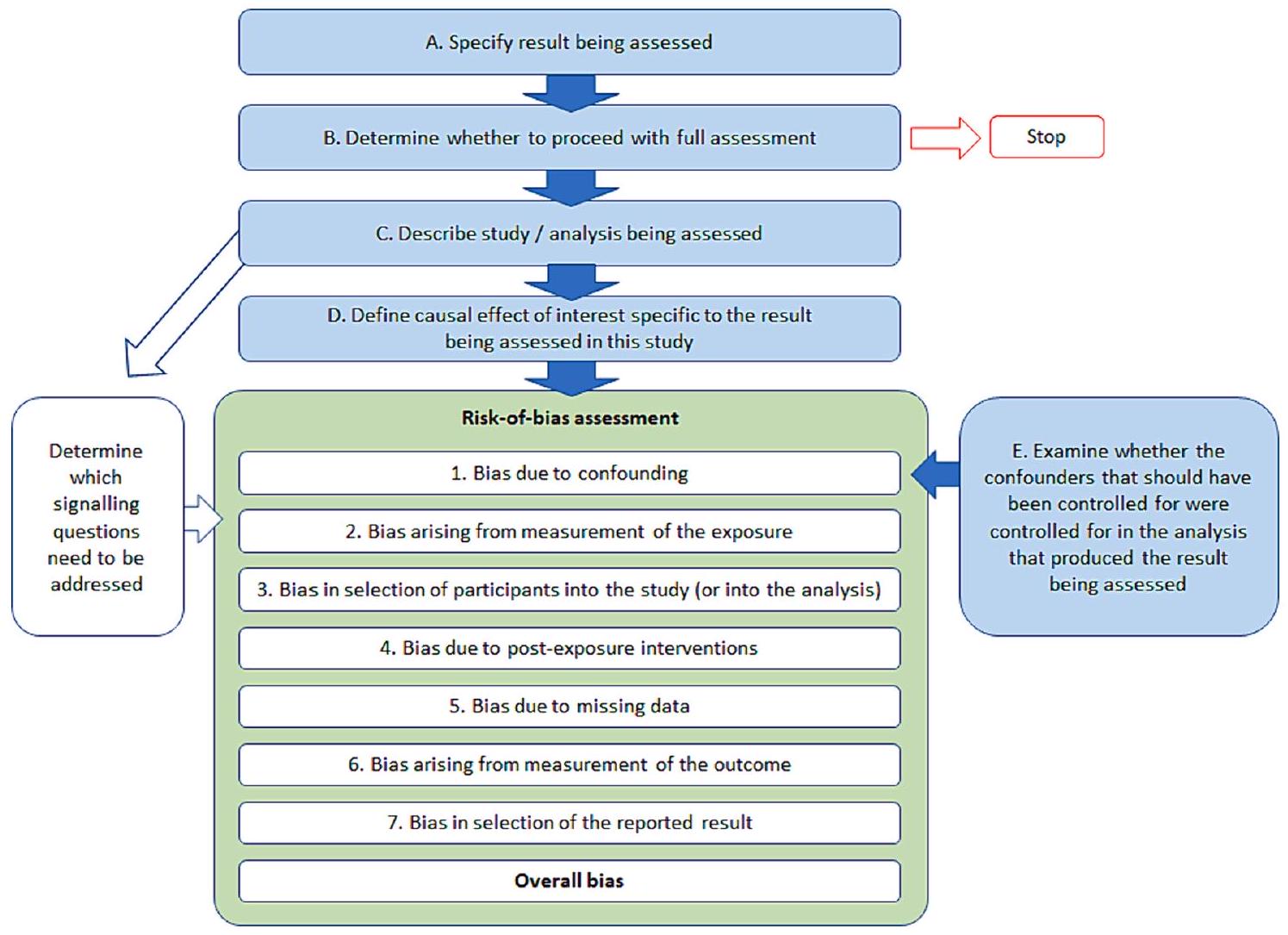

يسهل هذا القسم تحديد النتائج التي تكون في خطر كبير من التحيز، مما يسمح للمستخدم بتجنب تقييم مفصل لخطر التحيز (الشكل 1، الجزء ب). قد يكون هذا هو الحال، على سبيل المثال، إذا كانت أسئلة الفحص تحدد أن هناك تداخلاً كبيراً وأن الدراسة لم تحاول السيطرة عليه. كانت هذه الأسئلة قد أدرجت في الأصل ضمن مجالات التحيز ذات الصلة، وكانت الإجابات عليها قد تؤدي إلى حكم بـ ‘خطر كبير جداً من التحيز’ لذلك المجال. كانت الدوافع لإدراجها في الخطوة ب هي أن التقييمات الكاملة لخطر التحيز قد لا تكون مطلوبة إذا كان من المقرر في أي حال الحكم عليها بأنها في خطر كبير جداً من التحيز.

5. مجالات التحيز

- مقياس التعرض المستخدم في الدراسة يصف بشكل جيد مقياس التعرض المعني;

- من المحتمل أن يكون هناك خطأ في، أو تصنيف خاطئ، لقياسات التعرض في الدراسة;

- كان هناك خطأ في القياس (أو تصنيف خاطئ) مختلف؛ و

- كان من الممكن أن يؤدي خطأ القياس غير المختلف (أو التصنيف الخاطئ) إلى تحيز تقدير التأثير.

- بداية المتابعة وبداية نافذة التعرض كانت هي نفسها؛

- اختيار المشاركين في الدراسة (أو في التحليل) كان يعتمد على خصائص المشاركين التي لوحظت بعد بداية نافذة التعرض؛

- (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) كانت هذه الخصائص متأثرة بالتعرض (أو سبب التعرض) ومتأثرة بالنتيجة (أو سبب النتيجة)؛ و

- (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) تم استخدام تقنيات التعديل لتصحيح وجود تحيزات الاختيار. كان خطأ التصنيف) سيؤدي إلى تحيز

تقدير التأثير. تقدير التأثير.

سواء كان:

بداية المتابعة وبداية نافذة التعرض كانت هي نفسها؛

(التحليل) لوحظت بعد بداية نافذة التعرض؛ (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) كانت هذه الخصائص متأثرة بالتعرض (أو سبب التعرض) ومتأثرة بالنتيجة (أو سبب النتيجة)؛ و لتصحيح وجود تحيزات الاختيار.

لي؛ و

لتصحيح.

- كانت هناك تدخلات بعد التعرض تأثرت بالتعرض السابق؛ و

- (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) تم تصحيح التحليل لتأثير هذه التدخلات بعد التعرض.

- كانت البيانات الكاملة حول حالة التعرض، والنتيجة، والخلط متاحة لجميع المشاركين أو تقريبًا جميعهم؛

- (لتحليلات الحالات الكاملة) من المحتمل أن يكون الاستبعاد من التحليل مرتبطًا بالقيمة الحقيقية للنتيجة وتم تضمين المتنبئين بالافتقار في نموذج التحليل؛ و

- (لتحليلات البيانات المملوءة) تم إجراء التعبئة بشكل مناسب.

مجالات التحيز المدرجة في أداة ROBINS-E، مع ملخص للقضايا المعالجة لدراسات المجموعة.

| مجال التحيز | القضايا المعالجة | ||||

| التحيز بسبب الخلط |

|

| التحيز في اختيار المشاركين في الدراسة |

- من المحتمل أن يختلف قياس أو تحديد النتيجة بين مجموعات التعرض أو مستويات التعرض؛

- كان مقدمو تقييم النتائج على علم بتاريخ تعرض المشاركين في الدراسة؛ و

- (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) من المحتمل أن يكون تقييم النتيجة قد تأثر بمعرفة تاريخ تعرض المشاركين.

التحيز في اختيار النتيجة المبلغ عنها

- من المحتمل أن تكون النتيجة العددية التي يتم تقييمها قد تم اختيارها، بناءً على النتائج، من قياسات تعرض متعددة ضمن مجال النتيجة؛

- من المحتمل أن تكون النتيجة العددية التي يتم تقييمها قد تم اختيارها، بناءً على النتائج، من قياسات نتائج متعددة ضمن مجال النتيجة؛

(مستمر في الصفحة التالية)

| مجال التحيز | القضايا المعالجة | ||

|

6. الخطر العام للتحيز

قد يكون من الصعب التنبؤ باتجاه التحيز بشكل عام. يمكن استخدام أحكام خطر التحيز للمجالات الفردية لإبلاغ الأحكام حول تأثير ذلك المجال على الاتجاه المحتمل للتحيز بشكل عام. يتم اشتقاق الحكم الافتراضي للتهديد للاستنتاجات بطريقة مشابهة للحكم العام لخطر التحيز؛ على سبيل المثال، يكون الحكم العام ‘نعم’ إذا كان يُعتبر أن هناك تهديدًا للاستنتاجات في أي من مجالات التحيز السبعة.

7. حساسية الدراسة وملاءمة تصميمها

8. المناقشة

فهم ما يعنيه التداخل وكذلك ما هي العوامل المربكة (الأسباب الشائعة لكل من التعرض والنتيجة) التي من المحتمل أن تكون موجودة في السياق المحدد لكل دراسة. ثانيًا، ستعتمد دقة تقييم خطر التحيز على جودة المعلومات المتاحة حول الدراسة التي يتم تقييمها. نشجع على الرجوع إلى أكبر قدر ممكن من المعلومات المتاحة. بالإضافة إلى الأوراق المنشورة التي تصف طرق الدراسة ونتائجها، يمكن أن تُستمد هذه المعلومات من تقارير غير منشورة أو من خلال المراسلة مع الباحثين في الدراسة. ثالثًا، تتطلب تقييمات ROBINS-E أحكامًا تستند إلى المعلومات المتاحة. لذلك، من المستحيل تجنب الذاتية وتباين التقييم بين المقيمين. ومع ذلك، يجب أن تجعل نشر الإجابات على الأسئلة الإشارية والتبرير لهذه الإجابات أحكام خطر التحيز شفافة. سيكون من المهم بشكل خاص تبرير الإجابات على الأسئلة الإشارية التي تؤدي إلى حكم “خطر تحيز مرتفع جدًا” ضمن الخطوة B من الاعتبارات الأولية، حيث إن هذه تشير إلى أنه لن يتم إجراء تقييم كامل لخطر التحيز.

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين في CRediT

الحصول على التمويل، التصور.

إعلان عن المصالح المتنافسة

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

الملحق أ. البيانات التكميلية

References

Eick, S.M., Goin, D.E., Lam, J., Woodruff, T.J., Chartres, N., 2022. Authors’ rebuttal to integrated risk information system (IRIS) response to “assessing risk of bias in human environmental epidemiology studies using three tools: different conclusions from different tools”. Syst Rev. 11 (1), 53.

Guyatt, G.H., Oxman, A.D., Vist, G.E., Zunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., et al., 2008. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336 (7650), 924-926.

Guyatt, G., Oxman, A.D., Akl, E.A., Kunz, R., Vist, G., Brozek, J., et al., 2011. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 (4), 383-394.

Hernán, M.A., Robins, J.M., 2020. Causal inference: what if. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton.

Hoffmann, S., Aiassa, E., Angrish, M., Beausoleil, C., Bois, F.Y., Ciccolallo, L., et al., 2022. Application of evidence-based methods to construct mechanism-driven chemical assessment frameworks. ALTEX 39 (3), 499-518.

Hoffmann, S., Whaley, P., Tsaioun, K., 2022. How evidence-based methodologies can help identify and reduce uncertainty in chemical risk assessment. ALTEX 39 (2), 175-182.

Lawlor, D.A., Tilling, K., Davey, S.G., 2016. Triangulation in aetiological epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45 (6), 1866-1886.

Mansournia, M.A., Etminan, M., Danaei, G., Kaufman, J.S., Collins, G., 2017. Handling time varying confounding in observational research. BMJ 359, j4587.

Morgan, R.L., Thayer, K.A., Santesso, N., Holloway, A.C., Blain, R., Eftim, S.E., et al., 2018. Evaluation of the risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) and the ‘target experiment’ concept in studies of exposures: rationale and preliminary instrument development. Environ. Int. 120, 382-387.

Morgan, R.L., Thayer, K.A., Santesso, N., Holloway, A.C., Blain, R., Eftim, S.E., et al., 2019. A risk of bias instrument for non-randomized studies of exposures: a users’ guide to its application in the context of GRADE. Environ. Int. 122, 168-184.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2022. A Review of U.S. EPA’s ORD Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments: 2020 Version. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

National Toxicology Program, 2015. Handbook for Preparing Report on Carcinogens Monographs 2015. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/rochandbook.

National Toxicology Program, 2015. OHAT Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies 2015. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/riskbias.

Pufulete, M., Mahadevan, K., Johnson, T.W., Pithara, C., Redwood, S., Benedetto, U., et al., 2022. Confounders and co-interventions identified in non-randomized studies of interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 148, 115-123.

Radke, E.G., Glenn, B.S., Kraft, A.D., 2021. Integrated risk information system (IRIS) response to “assessing risk of bias in human environmental epidemiology studies using three tools: different conclusions from different tools”. Syst Rev. 10 (1), 235.

Schunemann, H.J., Cuello, C., Akl, E.A., Mustafa, R.A., Meerpohl, J.J., Thayer, K., et al., 2018. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol.

Sterne, J.A.C., 2013. Why the Cochrane risk of bias tool should not include funding source as a standard item (Editorial). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12, ED000076.

Sterne, J.A.C., Hernán, M.A., Reeves, B.C., Savović, J., Berkman, N.D., Viswanathan, M., et al., 2016. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 355, 14919.

Sterne, J.A., Jüni, P., Schulz, K.F., Altman, D.G., Bartlett, C., Egger, M., 2002. Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in ‘meta-epidemiological’ research. Stat. Med. 21 (11), 1513-1524.

Sterne, J.A.C., Savovic, J., Page, M.J., Elbers, R.G., Blencowe, N.S., Boutron, I., et al., 2019. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366, 14898.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2022. ORD staff handbook for developing IRIS assessments (EPA/600/R-22/268). U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC.

Woodruff, T.J., Sutton, P., 2014. The navigation guide systematic review methodology: a rigorous and transparent method for translating environmental health science into better health outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 122 (10), 1007-1014.

- Corresponding author at: Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, 39 Whatley Road, Bristol BS8 2PS, UK.

E-mail address: julian.higgins@bristol.ac.uk (J.P.T. Higgins).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38555664

Publication Date: 2024-03-24

SDU-

University of Southern Denmark

A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E)

Published in:

Environment International

10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

2024

Final published version

CC BY-NC

Higgins, J. P. T., Morgan, R. L., Rooney, A. A., Taylor, K. W., Thayer, K. A., Silva, R. A., Lemeris, C., Akl, E. A., Bateson, T. F., Berkman, N. D., Glenn, B. S., Hróbjartsson, A., LaKind, J. S., McAleenan, A., Meerpohl, J. J., Nachman, R. M., Obbagy, J. E., O’Connor, A., Radke, E. G., … Sterne, J. A. C. (2024). A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environment International, 186, Article 108602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602

This work is brought to you by the University of Southern Denmark.

Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving.

If no other license is stated, these terms apply:

- You may download this work for personal use only.

- You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain

- You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version

A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E)

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Risk of bias

Confounding

Selection bias

Misclassification/measurement bias

Exposure

Epidemiology

Environmental

Abstract

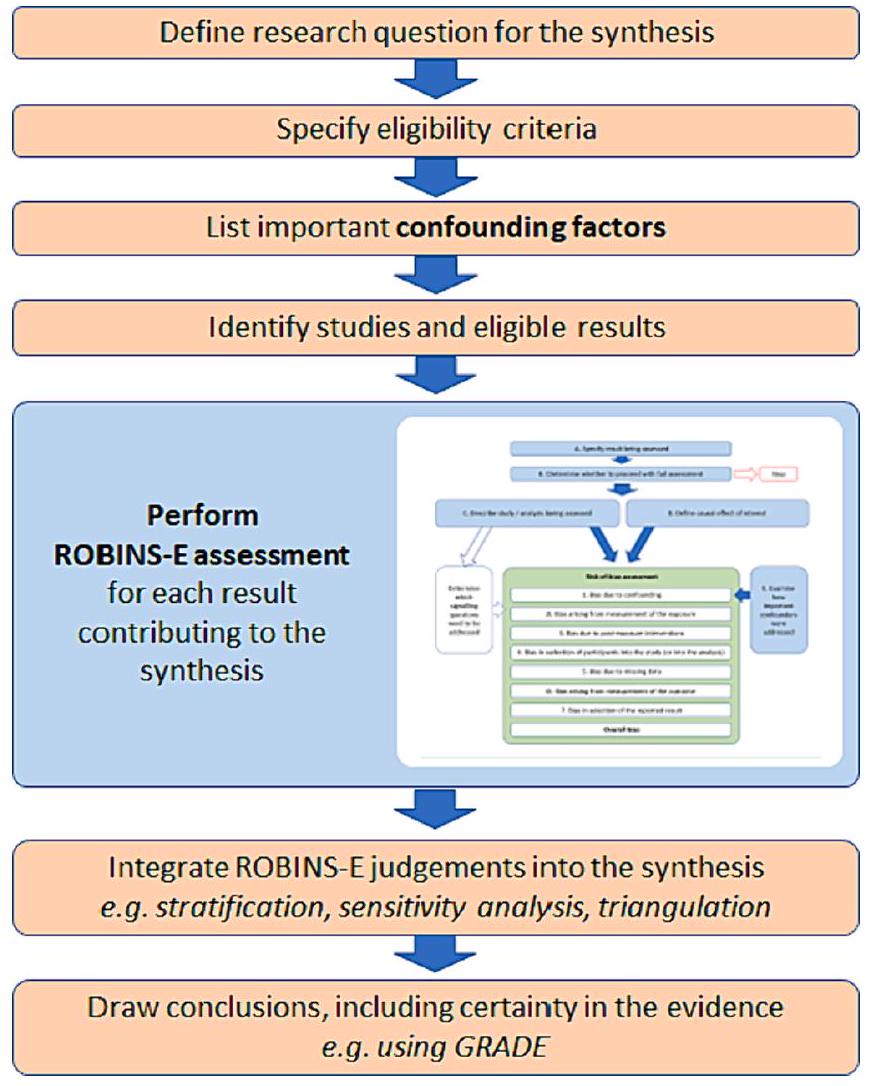

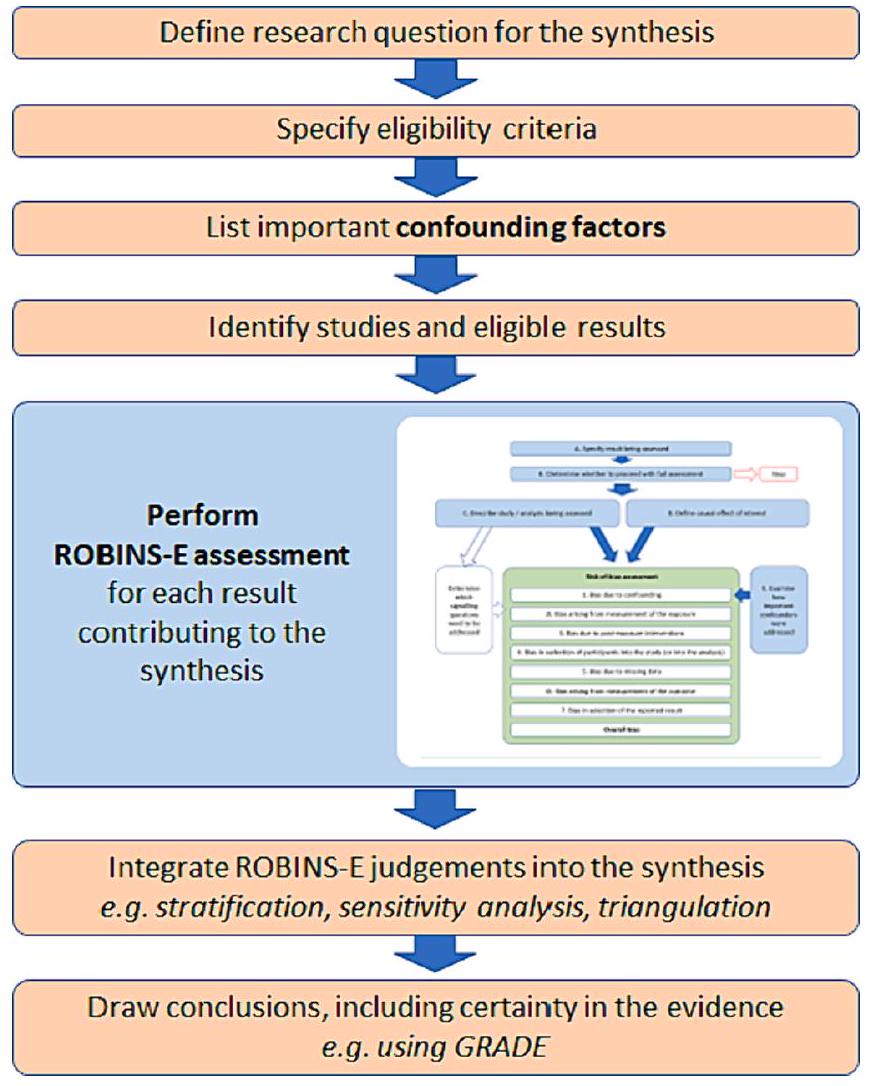

Background: Observational epidemiologic studies provide critical data for the evaluation of the potential effects of environmental, occupational and behavioural exposures on human health. Systematic reviews of these studies play a key role in informing policy and practice. Systematic reviews should incorporate assessments of the risk of bias in results of the included studies. Objective: To develop a new tool, Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Exposures (ROBINS-E) to assess risk of bias in estimates from cohort studies of the causal effect of an exposure on an outcome. Methods and results: ROBINS-E was developed by a large group of researchers from diverse research and public health disciplines through a series of working groups, in-person meetings and pilot testing phases. The tool aims to assess the risk of bias in a specific result (exposure effect estimate) from an individual observational study that examines the effect of an exposure on an outcome. A series of preliminary considerations informs the core ROBINS-E assessment, including details of the result being assessed and the causal effect being estimated. The

1. Introduction

2. Development of ROBINS-E

3. Overview of ROBINS-E

questions indicate this. For example, question 4.2 (“Is it likely that the analysis corrected for the effect of post-exposure interventions that were influenced by prior exposure?”) is not applicable if the answer to question 4.1 (“Were there post-exposure interventions that were influenced by prior exposure during the follow-up period?”) is “No”, Probably no” or “No information”.

4. Preliminary considerations

section then facilitates identification of results that are at very high risk of bias, allowing the user to avoid a detailed risk of bias assessment (Fig. 1, part B). This might be the case, for example, if the screening questions identify that there is substantial confounding and the study has made no attempt to control for it. These screening questions were originally included within the relevant bias domains, and answers to these had the potential to lead to a judgement of ‘Very high risk of bias’ for the domain. The motivation for their inclusion in Step B was that full risk-of-bias assessments may not required if the result will in any case be judged as at very high risk of bias.

5. Bias domains

- the measure of exposure used in the study well characterizes the exposure metric of interest;

- there was likely to be error in, or misclassification of, the exposure measurements in the study;

- there was differential measurement (or misclassification) error; and

- non-differential measurement (or misclassification) error would have biased the effect estimate.

- start of follow-up and start of the exposure window were the same;

- selection of participants into the study (or into the analysis) was based on participant characteristics observed after the start of the exposure window;

- (if applicable) these characteristics were influenced by exposure (or a cause of exposure) and influenced by outcome (or a cause of the outcome); and

- (if applicable) adjustment techniques were used to correct for the presence of selection biases. misclassification) error would have biased the

effect estimate. effect estimate.

hether:

start of follow-up and start of the exposure window were the same;

analysis) observed after the start of the exposure window; (if applicable) these characteristics were influenced by exposure (or a cause of exposure) and influenced by outcome (or a cause of the outcome); and to correct for the presence of selection biases.

me); and

to corse.

- there were post-exposure interventions influenced by prior exposure; and

- (if applicable) the analysis corrected for the effect of these post-exposure interventions.

- complete data on exposure status, the outcome, and confounders were available for all or nearly all participants;

- (for complete case analyses) omission from the analysis is likely to be related to the true value of the outcome and predictors of missingness were included in the analysis model; and

- (for analyses with imputed data) imputation was performed appropriately.

Bias domains included in the ROBINS-E tool, with a summary of the issues addressed for cohort studies.

| Bias domain | Issues addressed | ||||

| Bias due to confounding |

|

| Bias in selection of participants into the study |

- measurement or ascertainment of the outcome is likely to have differed between exposure groups or levels of exposure;

- outcome assessors were aware of study participants’ exposure history; and

- (if applicable) assessment of the outcome were likely to have been influenced by knowledge of participants’ exposure history.

Bias in selection of the reported result

- the numerical result being assessed is likely to have been selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple exposure measurements within the outcome domain;

- the numerical result being assessed is likely to have been selected, on the basis of the results, from multiple outcome measurements within the outcome domain;

(continued on next page)

| Bias domain | Issues addressed | ||

|

6. Overall risk of bias

of bias. Predicting the direction of bias overall may be difficult. Risk-ofbias judgements for the individual domains might be used to inform judgements about the influence of that domain on the likely direction of bias overall. The default judgement for the threat to conclusions is derived in a similar way to the overall risk-of-bias judgement; for example, the overall judgement is ‘Yes’ if there is considered to be a threat to conclusions in any of the seven bias domains.

7. Study sensitivity and appropriateness of its design

8. Discussion

understanding of what confounding means as well as what confounders (common causes of both exposure and outcome) are likely to be present in the specific context of each study. Second, the accuracy of a risk-ofbias assessment will depend on the quality of information available about the study being assessed. We encourage reference to the maximum possible amount of available information. In addition to published papers describing the study’s methods and results, such information may be derived from unpublished reports or through correspondence with the study investigators. Third, ROBINS-E assessments require judgements based on the available information. It is therefore impossible to avoid subjectivity and between-assessor variability. However, publication of answers to signalling questions and justification for these should make risk of bias judgements transparent. It will be particularly important to justify answers to signalling questions that lead to a judgement of ‘Very high risk of bias’ within Step B of the preliminary considerations, since these imply that a full risk-of-bias assessment will not be conducted.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

Eick, S.M., Goin, D.E., Lam, J., Woodruff, T.J., Chartres, N., 2022. Authors’ rebuttal to integrated risk information system (IRIS) response to “assessing risk of bias in human environmental epidemiology studies using three tools: different conclusions from different tools”. Syst Rev. 11 (1), 53.

Guyatt, G.H., Oxman, A.D., Vist, G.E., Zunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., et al., 2008. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336 (7650), 924-926.

Guyatt, G., Oxman, A.D., Akl, E.A., Kunz, R., Vist, G., Brozek, J., et al., 2011. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 (4), 383-394.

Hernán, M.A., Robins, J.M., 2020. Causal inference: what if. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton.

Hoffmann, S., Aiassa, E., Angrish, M., Beausoleil, C., Bois, F.Y., Ciccolallo, L., et al., 2022. Application of evidence-based methods to construct mechanism-driven chemical assessment frameworks. ALTEX 39 (3), 499-518.

Hoffmann, S., Whaley, P., Tsaioun, K., 2022. How evidence-based methodologies can help identify and reduce uncertainty in chemical risk assessment. ALTEX 39 (2), 175-182.

Lawlor, D.A., Tilling, K., Davey, S.G., 2016. Triangulation in aetiological epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45 (6), 1866-1886.

Mansournia, M.A., Etminan, M., Danaei, G., Kaufman, J.S., Collins, G., 2017. Handling time varying confounding in observational research. BMJ 359, j4587.

Morgan, R.L., Thayer, K.A., Santesso, N., Holloway, A.C., Blain, R., Eftim, S.E., et al., 2018. Evaluation of the risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) and the ‘target experiment’ concept in studies of exposures: rationale and preliminary instrument development. Environ. Int. 120, 382-387.

Morgan, R.L., Thayer, K.A., Santesso, N., Holloway, A.C., Blain, R., Eftim, S.E., et al., 2019. A risk of bias instrument for non-randomized studies of exposures: a users’ guide to its application in the context of GRADE. Environ. Int. 122, 168-184.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2022. A Review of U.S. EPA’s ORD Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments: 2020 Version. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

National Toxicology Program, 2015. Handbook for Preparing Report on Carcinogens Monographs 2015. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/rochandbook.

National Toxicology Program, 2015. OHAT Risk of Bias Rating Tool for Human and Animal Studies 2015. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/riskbias.

Pufulete, M., Mahadevan, K., Johnson, T.W., Pithara, C., Redwood, S., Benedetto, U., et al., 2022. Confounders and co-interventions identified in non-randomized studies of interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 148, 115-123.

Radke, E.G., Glenn, B.S., Kraft, A.D., 2021. Integrated risk information system (IRIS) response to “assessing risk of bias in human environmental epidemiology studies using three tools: different conclusions from different tools”. Syst Rev. 10 (1), 235.

Schunemann, H.J., Cuello, C., Akl, E.A., Mustafa, R.A., Meerpohl, J.J., Thayer, K., et al., 2018. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol.

Sterne, J.A.C., 2013. Why the Cochrane risk of bias tool should not include funding source as a standard item (Editorial). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12, ED000076.

Sterne, J.A.C., Hernán, M.A., Reeves, B.C., Savović, J., Berkman, N.D., Viswanathan, M., et al., 2016. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 355, 14919.

Sterne, J.A., Jüni, P., Schulz, K.F., Altman, D.G., Bartlett, C., Egger, M., 2002. Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in ‘meta-epidemiological’ research. Stat. Med. 21 (11), 1513-1524.

Sterne, J.A.C., Savovic, J., Page, M.J., Elbers, R.G., Blencowe, N.S., Boutron, I., et al., 2019. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366, 14898.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2022. ORD staff handbook for developing IRIS assessments (EPA/600/R-22/268). U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC.

Woodruff, T.J., Sutton, P., 2014. The navigation guide systematic review methodology: a rigorous and transparent method for translating environmental health science into better health outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 122 (10), 1007-1014.

- Corresponding author at: Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, 39 Whatley Road, Bristol BS8 2PS, UK.

E-mail address: julian.higgins@bristol.ac.uk (J.P.T. Higgins).