DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-22

أدلة على إنتاج الأكسجين المظلم في قاع البحر العميق

تم القبول: 6 يونيو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 يوليو 2024

(W) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تستهلك الكائنات الحية في قاع البحر العميق الأكسجين، والذي يمكن قياسه من خلال تجارب غرف القاع في الموقع. هنا نبلغ عن مثل هذه التجارب في قاع البحر العميق المغطى بالعقدة المتعددة المعادن في المحيط الهادئ، حيث زاد الأكسجين على مدى يومين ليصل إلى أكثر من ثلاثة أضعاف التركيز الخلفي، والذي نُعزيه من خلال الحضانة خارج الموقع إلى العقدة المتعددة المعادن. نظرًا للجهود العالية المحتملة (حتى 0.95 فولت) على أسطح العقد، نفترض أن التحليل الكهربائي لمياه البحر قد يساهم في إنتاج هذا الأكسجين المظلم.

معدلات

لتطهير الهواء من الغرف بينما يغوص المسبار. حتى لو كان من الممكن احتجاز فقاعة هواء لفترة كافية للوصول إلى قاع البحر، فإن الانتشار الغازي لـ

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Jorgensen, B. B. et al. Sediment oxygen consumption: role in the global marine carbon cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 228, 103987 (2022).

- Smith, K. L. Jr et al. Climate, carbon cycling and deep-ocean ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19211-19218 (2009).

- Smith, Jr. K. L. et al. Large salp bloom export from the upper ocean and benthic community response in the abyssal northeast Pacific: day to week resolution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 745-757 (2014).

- Sweetman, A. K. et al. Key role of bacteria in the short-term cycling of carbon at the abyssal seafloor in a low particulate organic carbon flux region of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 694-713 (2019).

- Mewes, K. et al. Diffusive transfer of oxygen from seamount basaltic crust into overlying sediments: an example from the ClarionClipperton Fracture Zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 433, 215-225 (2016).

- Kuhn, T. et al. Widespread seawater circulation in

oceanic crust: impact on heat flow and sediment geochemistry. Geology 45, 799-802 (2017). - Zhang, D. et al. Microbe-driven elemental cycling enables microbial adaptation to deep-sea ferromanganese nodule sediment fields. Microbiome 11, 160 (2023).

- Kraft, B. et al. Oxygen and nitrogen production by an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon. Science 375, 97-100 (2022).

- Ershov, B. G. Radiation-chemical decomposition of seawater: the appearance and accumulation of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 168, 108530 (2020).

- Dresp, S. et al. Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: opportunities and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933-942 (2019).

- He, Y. et al. Recent progress of manganese dioxide based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Ind. Chem. Mater. 1, 312 (2023).

- Kuhn, T. et al. in Deep-Sea Mining (ed. Sharma, R.) 23-63 (Springer, 2017).

- Tian, L. Advances in manganese-based oxides for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 14400 (2020).

- Teng, Y. et al. Atomically thin defect-rich Fe-Mn-O hybrid nanosheets as highly efficient electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802463 (2018).

- Wegorzewski, A. V. & Kuhn, T. The influence of suboxic diagenesis on the formation of manganese nodules in the Clarion Clipperton nodule belt of the Pacific Ocean. Mar. Geol. 357, 123-138 (2014).

- Robins, L. J. et al. Manganese oxides, Earth surface oxygenation, and the rise of oxygenic photosynthesis. Earth Sci. Rev. 239, 104368 (2023).

- Chyba, C. F. & Had, K. P. Life without photosynthesis. Science 292, 2026-2027 (2001).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

طرق

تم إصلاحه على الفور لعملية المعايرة باستخدام microWinkler. ثم تم خلط العينة جيدًا باستخدام كرة زجاجية وضعت في الحاوية وتم وضعها في الظلام في

قاع البحر

أخذ عينات من الميكروبيولوجيا

وتم تجميع ASVs إلى

قياسات مساحة سطح العقدة متعددة المعادن

تحلل الإشعاع

قياسات الكيمياء الكهربائية

تم وضع الأطباق والمجسات البلاتينية على العقد في مواقع عشوائية، مع ضمان الاتصال بإحدى طريقتين. إما أننا قمنا بحفر ثقب بعناية في بعض العقد بحيث يمكن تثبيت سلك بلاتيني داخلها بينما يتم الضغط على سلك بلاتيني ثانٍ بقوة ضد سطح العقد باستخدام مشبك. بدلاً من ذلك، تم الضغط على الأسلاك البلاتينية بقوة ضد نقطتين مختلفتين على سطح العقد وتم تثبيتها في مكانها باستخدام مشبك. ثم تم تسجيل الفولتية لـ

نمذجة الجيوكيمياء

حضانات النواة خارج الموقع

سدادة مطاطية، مما يسمح بـ

حسابات لتحديد حجم التداخل

توفر البيانات

References

- Bittig, H. C. et al. Oxygen optode sensors: principle, characterization, calibration, and application in the ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 429 (2018).

- Caporaso J. G. et al. EMP 16 S Illumina amplicon protocol V.1. protocols.io. https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nuudeww (2018).

- Parada, A. E. et al. Every base matters. Assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1403-1414 (2016).

- Apprill, A. et al. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806 R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 75, 129-137 (2015).

- Choppin, G. et al. Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry (Elsevier, 2002).

- Katz, J. J. et al. The Chemistry of the Actinide Elements 2nd edn (Springer, 1986).

- Lide, D. R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics Vol. 85 (CRC Press, 2004).

- Nier, A. O. A redetermination of the relative abundances of the isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, argon, and potassium. Phys. Rev. 77, 789 (1950).

- Stumm, W. and Morgan, J. J. Aquatic Chemistry: An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters 2nd edn (John Wiley & Sons, 1981).

- Cheng, H. et al. Improvements in

Th dating, 230 Th and 234 U half-life values, and U-Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371, 82-91 (2013). - Edwards, R. L. et al.

systematics and the precise measurement of time over the past 500,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 81, 175-192 (1987). - Shen, C. C. et al. Uranium and thorium isotopic and concentration measurements by magnetic sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Chem. Geol. 185, 165-178 (2002).

- Ershov, B. G. & Gordeev, A. V. A model for radiolysis of water and aqueous solutions of

and . Radiat. Phys. Chem. 77, 928-935 (2008). - DeWitt, J. et al. The effect of grain size on porewater radiolysis.Earth Space Sci. 9, e2021EA002024 (2021).

- Blair, C. C. et al. Radiolytic hydrogen and microbial respiration in subsurface sediments. Astrobiology 7, 951-970 (2007).

- Shriwastav, A. et al. A modified Winkler’s method for determination of dissolved oxygen concentration in water: dependence of method accuracy on sample volume. Measurement 106, 190-195 (2017).

- Stevens, E. D. Use of plastic materials in oxygen-measuring systems. J. Appl. Physiol. 72, 801-804 (1992).

- Sweetman, A. K. Data collected from replicate benthic chamber experiments conducted at abyssal depths across the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), Pacific Ocean. Dryad https://doi.org/ 10.5061/dryad.tdz08kq6w (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

يعمل S.F. و T.K. أيضًا في المعهد الفيدرالي لعلوم الأرض والموارد الطبيعية، الذي يمتلك حقوق الاستكشاف في منطقة CCZ.

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8.

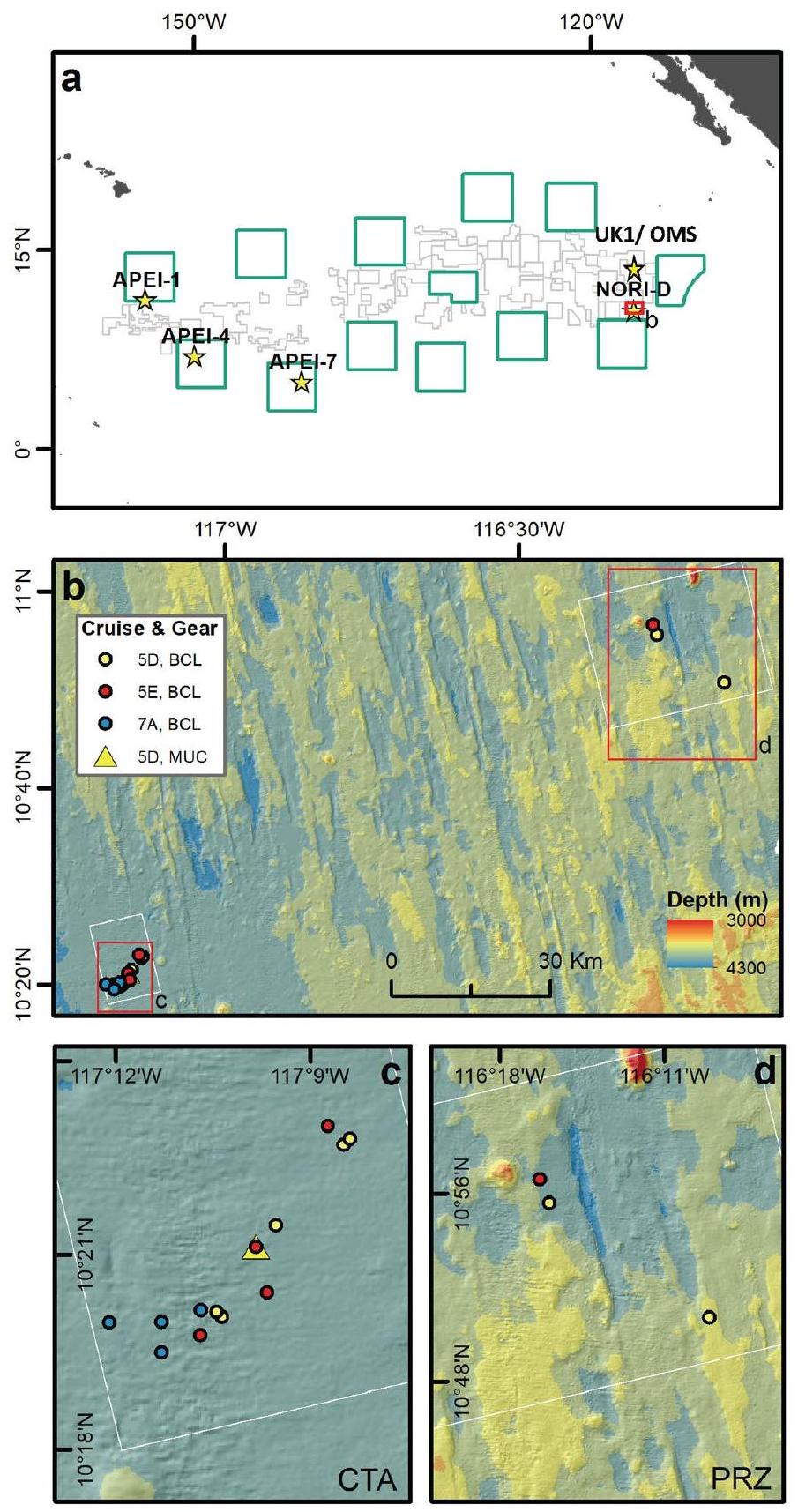

(ب-د) من NORI-D في المحيط الهادئ العميق المركزي. يتم أيضًا عرض موقع نشر جهاز جمع العينات المتعدد (MUC) الذي أخذ عينات من الرواسب للتجارب الخارجية التي أجريت خلال رحلة 5D (ج).

تم تنفيذها في NORI-D. الـ

تم تنفيذها في NORI-D. الـ

العلاج

في نوى MUC، وأدنى

البيانات الموسعة الجدول 1 | مواقع وأعماق نشر حجرة قاع البحر في NORI-D

| رحلة بحرية | تاريخ | إطلاق المركبة الهبوطية | منطقة | محطة | العمق (م) |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS268 | CTA | STM-001 | ٤٢٨٥ |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS271 | CTA | STM-001 | 4284 |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS273 | CTA | STM-014 | ٤٣٠٦ |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS276 | CTA | STM-014 | ٤٣٠٦ |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS279 | CTA | STM-007 | 4280 |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS282 | PRZ | SPR-033 | 4245 |

| 5D | مايو-يونيو 2021 | AKS286 | PRZ | SPR-041 | ٤١٢٧ |

| 5E | نوفمبر-ديسمبر 2021 | AKS313 | CTA | STM-014 | 4304 |

| 5E | نوفمبر-ديسمبر 2021 | AKS316 | CTA | STM-001 | ٤٢٨٥ |

| 5E | نوفمبر-ديسمبر 2021 | AKS318 | CTA | STM-007 | 4277 |

| 5E | نوفمبر-ديسمبر 2021 | AKS321 | CTA | STM-001 | ٤٢٨٥ |

| 5E | نوفمبر-ديسمبر 2021 | AKS328 | PRZ | SPR-033 | 4243 |

| 7أ | أغسطس-سبتمبر 2022 | AKS329 | CTA | تي إف-021 | ٤٢٨٩ |

| 7أ | أغسطس-سبتمبر 2022 | AKS331 | CTA | STM-001 | 4286 |

| 7أ | أغسطس-سبتمبر 2022 | AKS334 | CTA | TF-028 | 4278 |

| 7A | أغسطس-سبتمبر 2022 | AKS336 | CTA | تي إف-021 | 4271 |

البيانات الموسعة الجدول 2 | التغير الصافي الكلي في الأكسجين المقاس بواسطة

| إطلاق المركبة الهبوطية | غرفة | مستشعر أوبتود | علاج | حجم مرحلة الماء (لتر) | وقت البدء – الانتهاء (ساعة) تم تسجيل أجهزة الاستشعار

|

الإجمالي

|

وزن (غ) العقيدات (أفق الرواسب) | تدفق DOP (

|

هيمنة الإنتاج الصافي/ التنفس |

| AKS268 | 2 | ب | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS268 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٣.٨١٢ | 0-47 | 1008 |

|

10.5 | إنتاج |

| AKS271 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS273 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٤.٥٩٨ | 0-47 | 1545 |

|

16.1 | إنتاج |

| AKS276 | 2 | ب |

|

غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS276 | ٣ | أ |

|

3.933 | 0-47 | 671 |

|

6.1 | إنتاج |

| AKS279 | ٣ | أ | مياه البحر المفلترة | ٤.٦٥٩ | 0-47 | ١٦٣٩ |

|

16.5 | إنتاج |

| AKS282 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٤.٥٩٨ | 0-47 | 246 | – | 1.7 | إنتاج |

| AKS286 | 2 | ب |

|

غير متوفر | 0-45.48 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS286 | ٣ | أ |

|

6.050 | 0-47 | ٣٢٩ |

|

٢.٤ | إنتاج |

| AKS313 | 1 | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS313 | ٢ | أ | تحكم (بدون حقن) | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | إنتاج |

| AKS316 | 1 | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | 2.118 | 0-47 | 639 |

|

٥.٩ | إنتاج |

| AKS316 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٢.٤٢٠ | 0-47 | ١٥٢٦ |

|

15.6 | إنتاج |

| AKS318 | 1 | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | التنفس |

| AKS318* | ٣ | أ | تحكم (بدون حقن) | 2.783 | 0.23-47 | – | 596 (0-2 سم) | – | إنتاج |

| AKS321 | 1 | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | غير متوفر | 0-47 | – | – | – | التنفس |

| AKS321* | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٢.٧٨٣ | 1.33-47 | – |

|

– | إنتاج |

| AKS328 | 2 | ب | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٣.٦٩١ | 0-47 | 257 |

|

2.0 | إنتاج |

| AKS328 | ٣ | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | 3.812 | 0-47 | 683 | 556 (0-5 سم) | 6.4 | إنتاج |

| AKS329 | 1 | أ | تحكم (بدون حقن) | 3.872 | 0-47 | 904 |

|

9.5 | إنتاج |

| AKS329 | 2 | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | 3.872 | 0-47 | 774 |

|

8.1 | إنتاج |

| AKS331* | 2 | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٢.٧٢٣ | 0.06-46.45 | – |

|

– | إنتاج |

| AKS331* | ٣ | ب | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٣.٢٠٧ | 0.07-47 | – |

|

– | إنتاج |

| AKS334 | 2 | أ | كتلة الطحالب الميتة | ٤.١٧٥ | 0-47 | 1710 |

|

18.0 | إنتاج |

| AKS334 | ٣ | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | 5.143 | 0-47 | ٦٥٢ |

|

5.7 | إنتاج |

| AKS336 | ٣ | ب | تحكم (بدون حقن) | ٤.٤٧٧ | 0-47 | 1408 | 622 (

|

14.4 | إنتاج |

| متوسط

|

|

|

البيانات الموسعة الجدول 3 | أوقات الانتشار النظرية للفقاعات ذات الجدران الرقيقة مقابل الفقاعات ذات الجدران السميكة في قاع البحر

| الحضانة | الوقت (ثانية) المطلوب للانتشار بافتراض جدار رقيق (

|

الوقت (ثانية) المطلوب للانتشار بافتراض وجود فقاعة ذات جدران سميكة (10000 نانومتر) |

| AKS268-الفصل3 | 0.012 | 1.226 |

| AKS273-الفصل3 | 0.014 | 1.411 |

| AKS276-الفصل 3 | 0.011 | 1.068 |

| AKS279-الفصل3 | 0.014 | 1.442 |

| AKS282-الفصل3 | 0.008 | 0.768 |

| AKS286-الفصل3 | 0.009 | 0.854 |

| AKS316-Ch1 | 0.011 | 1.053 |

| AKS316-الفصل 3 | 0.014 | 1.407 |

| AKS328-الفصل2 | 0.008 | 0.780 |

| AKS328-الفصل3 | 0.011 | 1.080 |

| AKS329-الفصل1 | 0.012 | 1.182 |

| AKS329-الفصل2 | 0.011 | 1.122 |

| AKS334-Ch2 | 0.015 | 1.463 |

| AKS334-الفصل3 | 0.011 | 1.061 |

| AKS336-الفصل 3 | 0.014 | 1.372 |

| يعني

|

|

|

البيانات الموسعة الجدول 4 | الحد الأدنى والحد الأقصى من إمكانيات الجهد (ملي فولت) المقاسة على سطح العقيدات متعددة المعادن

| الجهد الأدنى (ملي فولت) | إيماءة. 1 | إيماءة. 2 | عقد. 3 | العقد. 4 | العقد. 5 | العقد. 6 | عقد. 6 (بارد) | نود. 7 | نود. 7 (بارد) | العقد. 8 | نود. 9 | عقد. 10 | العقد. 11 | العقد. 12 | مستمر |

| السجل 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ٥٨.٥٥ | ٧٧.٨٣ | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 78.81 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| السجل 2 | 8.97 | ١٨.٤٥ | 15.48 | 3.03 | 0.00 | ٩٧.٣٠ | ٤٠.٩٠ | 79.56 | 21.65 | 25.34 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 53.68 | 0.01 | ٤.٤٨ |

| السجل 3 | 12.00 | 0.00 | ٢٦.٤٨ | 1.78 | ٣.١٤ | 100.26 | ٥٧.٦٩ | 81.87 | ٢٢.١٣ | ٥.٥٧ | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 22.30 | 0.97 |

| السجل 4 | 8.67 | 1.01 | ٢٩.٢١ | 21.06 | ٢٤.٨٧ | ٨٨.٦٩ | ٥٤.١٤ | 44.84 | ٣٧.٣١ | ٣٦.٨٩ | 15.42 | ٢٣.٢٦ | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| سجل 5 | ٧.٧٧ | 0.64 | 18.68 | 21.91 | 14.89 | ٥٢.٦٨ | 60.72 | ٢٢.٣٦ | 30.80 | 50.57 | 0.00 | 9.28 | 1.83 | 3.34 | |

| السجل 6 | 0.00 | 6.28 | 8.45 | 13.81 | 17.71 | ٤٩.٤٧ | ٨٥.٩٨ | ٥٥.١٧ | ٧١.٥٧ | ٣٨.٢٠ | 0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| سجل 7 | 0.00 | ٢.٩٥ | 3.98 | 14.25 | 0.90 | 69.44 | ٧٥.٥٧ | 75.75 | 72.06 | 44.82 | 1.10 | ||||

| سجل 8 | 14.17 | 0.00 | ١٦.٩٧ | 14.62 | 15.03 | 66.93 | 0.07 | 78.40 | ٥٧.٦٤ | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||

| السجل 9 | ٥.٥٧ | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.35 | ٣٣.٦٩ | 81.75 | ٥٩.٨٣ | 8.03 | 1.66 | |||||

| سجل 10 | ٥.٠٠ | 3.52 | ٣.٢٩ | ١٨.١٥ | ٢٤.٧٩ | 0.04 | ٢٠.٦٩ | 65.61 | ٢٧.٩٦ | 3.53 | |||||

| سجل 11 | 6.14 | ٣.٣٩ | ٣٢.٣٩ | 13.09 | ٢٥.٨٤ | ٣٦.٤٦ | |||||||||

| سجل 12 | 1.52 | 5.21 | ٢٥.٤٢ | ١٦.٨٤ | 25.45 | ٣٦.٤٦ | |||||||||

| سجل 13 | 0.48 | 0.16 | ٢٧.٨٥ | ٢٦.٢٣ | 0.01 | 61.34 | |||||||||

| سجل 14 | 7.12 | ٤.٠٩ | ٢٨.٦١ | ٢٤.٩٢ | 12.71 | 60.85 | |||||||||

| سجل 15 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 16.31 | 0.00 | ٥١.٧٢ | ||||||||||

| سجل 16 | 1.59 | 3.09 | 15.70 | 0.00 | ٧٦.٥١ | ||||||||||

| سجل 17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.12 | ٤.٧٠ | 78.77 | ||||||||||

| سجل 18 | 7.83 | 0.00 | ١٣.٦٤ | 17.90 | ٦٥.١٧ | ||||||||||

| سجل 19 | 6.33 | 0.75 | ٢٠.٦٧ | ٢٤.٦٨ | ٤٩.٤٥ | ||||||||||

| سجل 20 | 10.06 | 12.24 | ٢٩.٩٤ | ٢٠.٤٩ | ٤٩.٤٥ | ||||||||||

| الجهد الأقصى (ملي فولت) | |||||||||||||||

| السجل 1 | 10.93 | ٥٢.٧٣ | ٢٦٦.٨٠ | ٥٢.٩٩ | ٤٥.٦٩ | ١٠٢.٨٧ | 70.85 | 80.11 | ١١٦.٢٣ | ٣٩.٢٧ | ٢١٩.٦٧ | 19.36 | ٩٨.٤١ | 128.40 | ٥٢.٩١ |

| السجل 2 | 9.81 | 21.46 | ٢٢.٩٥ | ٤.٨٩ | 0.47 | 99.85 | 42.24 | 82.60 | 30.74 | ٢٨.٩٤ | ٧٢٢٫٠٠ | ١١٢.٦٣ | 70.40 | ٤٠٧.٥٦ | 7.72 |

| السجل 3 | 13.84 | 12.00 | ٢٨.٣٦ | 3.01 | 8.44 | ١٠٣.٤٨ | ٥٩.١٢ | 82.80 | ٢٧.٦١ | ٦.٦١ | ٤٨٥.٥٢ | 178.04 | 952.61 | ٥٩.٥٠ | 11.15 |

| السجل 4 | 12.28 | ٣.٥١ | 31.39 | ٢٤.٨٨ | ٢٨.٩٨ | ٩٦.٨٢ | ٥٨.٣٣ | ٥٧.٦٤ | ٣٨.٥٨ | ٣٩.٤٧ | ٣٥٠.٧٨ | 65.84 | 600.43 | ٢.٩٦ | |

| سجل 5 | 8.99 | ٤.٨٧ | 75.42 | ٢٣.١٥ | 21.01 | ٧٧.١٦ | 65.41 | 31.91 | ٣٤.٢٢ | 53.26 | ٣٦١.٧١ | 25.45 | ١١٨.٧١ | 7.56 | |

| سجل 6 | 3.17 | ٧.٢٧ | 12.12 | 14.86 | ٢٥.٧٧ | ٧٤.٥٥ | ٢٦٦.٧٦ | ٨٠.٥٠ | 91.66 | 42.18 | 128.61 | 8.71 | |||

| سجل 7 | ٤.٢٩ | 5.08 | 9.94 | 14.86 | 1.11 | ٧٧.٧٣ | ١٠٢.٤٥ | 78.95 | 73.12 | ٧٧.١٤ | 2.85 | ||||

| سجل 8 | ٢٥.٢٢ | 2.63 | ٢٠.١٥ | 18.49 | 16.85 | 69.20 | 71.41 | 84.31 | ٥٧.٩١ | 11.12 | 0.88 | ||||

| السجل 9 | 7.45 | 1.34 | 9.36 | 8.69 | 10.91 | ٣٧.٨١ | 82.78 | 65.62 | 11.87 | 2.45 | |||||

| سجل 10 | 8.38 | 14.61 | 3.81 | ٢٨.٧٣ | ٢٦.٧٣ | ١١٣.٦٢ | ٢٨.٣٤ | 65.91 | ٣٣.٣٥ | 8.70 | |||||

| سجل 11 | 7.73 | 9.19 | ٣٥.٠٠ | 14.85 | 28.08 | ٣٩.٤٦ | |||||||||

| سجل 12 | 3.17 | 7.02 | ٣٢.٩٩ | 18.21 | ٣٣.٠٥ | ٣٩.٤٦ | |||||||||

| سجل 13 | 2.94 | 5.52 | ٣٢.٢١ | 31.65 | 12.76 | 63.50 | |||||||||

| سجل 14 | 9.83 | 6.43 | ٣١.٨٦ | ٢٦.٥٩ | ٢١.٧١ | ٦١.٧٤ | |||||||||

| سجل 15 | 2.45 | 7.04 | ٢٢.٤٥ | 3.49 | ٥٢.٣٨ | ||||||||||

| سجل 16 | 6.76 | ٦.٤٥ | 21.56 | 11.27 | 79.14 | ||||||||||

| سجل 17 | ٥.٥٤ | ٤.٣٧ | ٢٤.٩٧ | 9.10 | 81.13 | ||||||||||

| سجل 18 | 10.19 | 0.95 | ٢٠:٣٠ | ٢٠.٣٨ | 68.18 | ||||||||||

| سجل 19 | 7.91 | 2.13 | ٢٤.١٦ | ٢٧.٨٩ | ٥٢.٥٨ | ||||||||||

| سجل 20 | 14.32 | ١٣.٥٧ | ٣٤.٤٠ | ٢٧.٧٤ | ٥٢.٥٨ |

الرابطة الاسكتلندية لعلوم البحار (SAMS)، أوبان، المملكة المتحدة. جامعة هيريوت وات، إدنبرة، المملكة المتحدة. مركز جيومار هيلمهولتز لأبحاث المحيطات كيل، كيل، ألمانيا. قسم البيولوجيا، جامعة بوسطن، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. برنامج المعلوماتية الحيوية، جامعة بوسطن، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الأرض والبيئة، جامعة مينيسوتا، مينيابوليس، مينيسوتا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. كلية البيئة، جامعة ليدز، ليدز، المملكة المتحدة. مدرسة العلوم، الفيزياء وعلوم الأرض، جامعة كونستراكتور بريمن، بريمن، ألمانيا. المعهد الفيدرالي لعلوم الأرض والموارد الطبيعية (BGR)، هانوفر، ألمانيا. المعهد التكنولوجي، جامعة نورث وسترن، إيفانستون، إلينوي، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: Andrew.Sweetman@sams.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8

Publication Date: 2024-07-22

Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor

Accepted: 6 June 2024

Published online: 22 July 2024

(W) Check for updates

Abstract

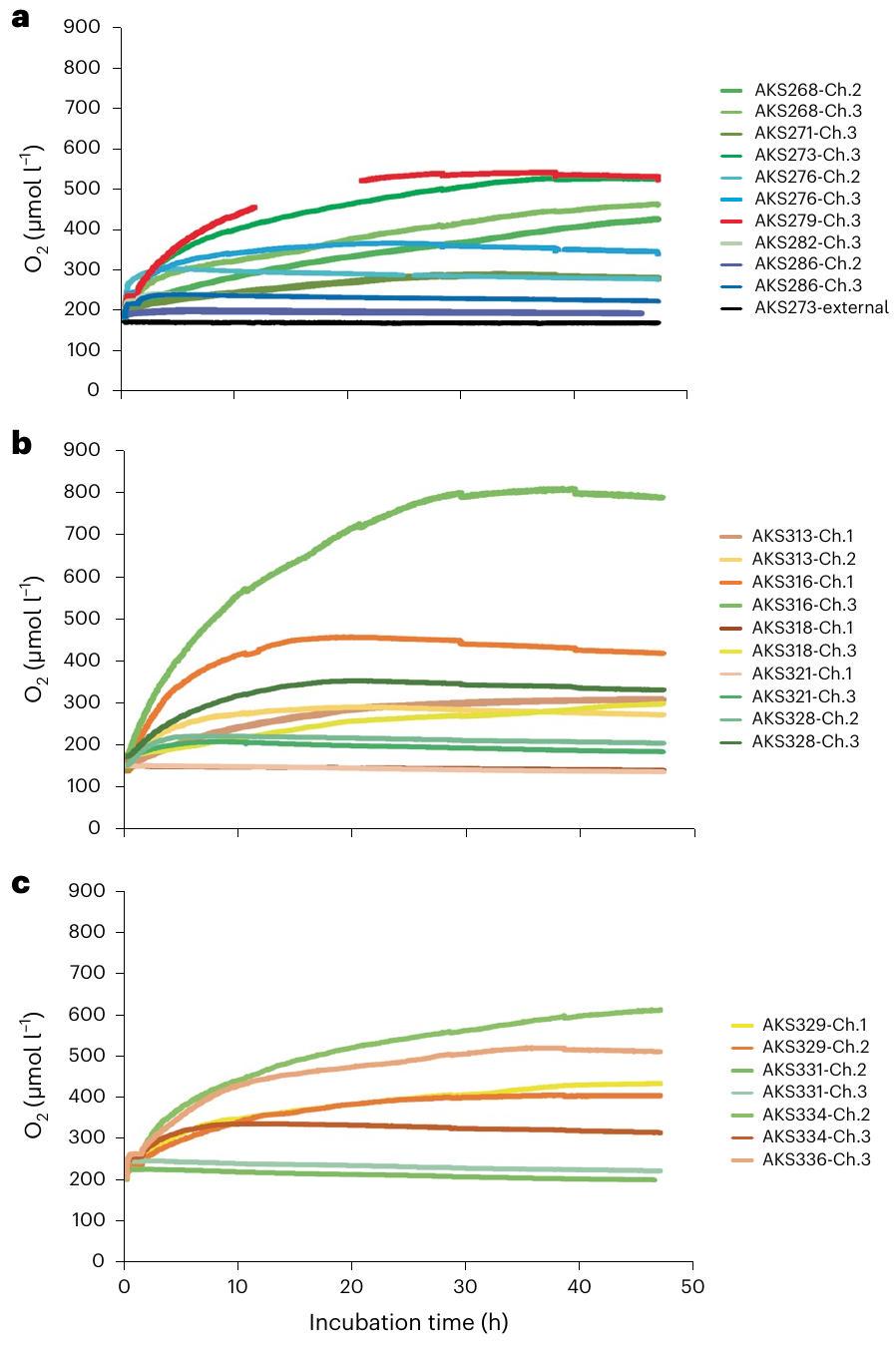

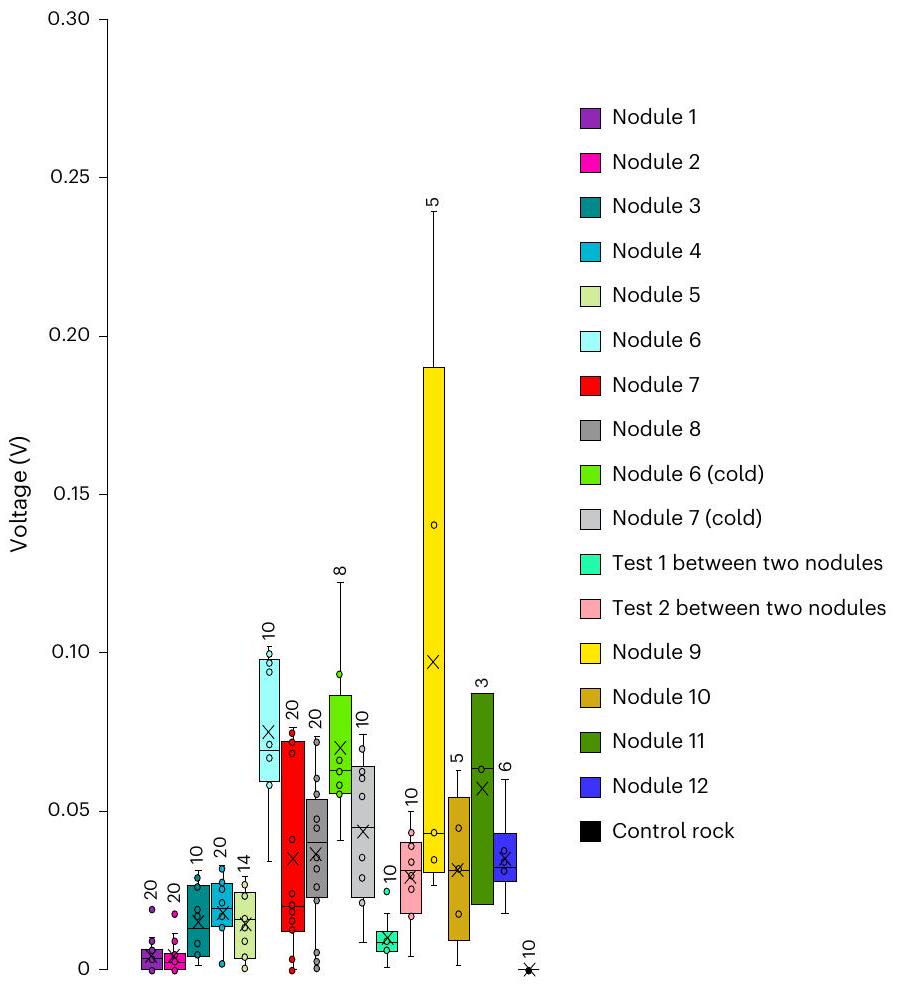

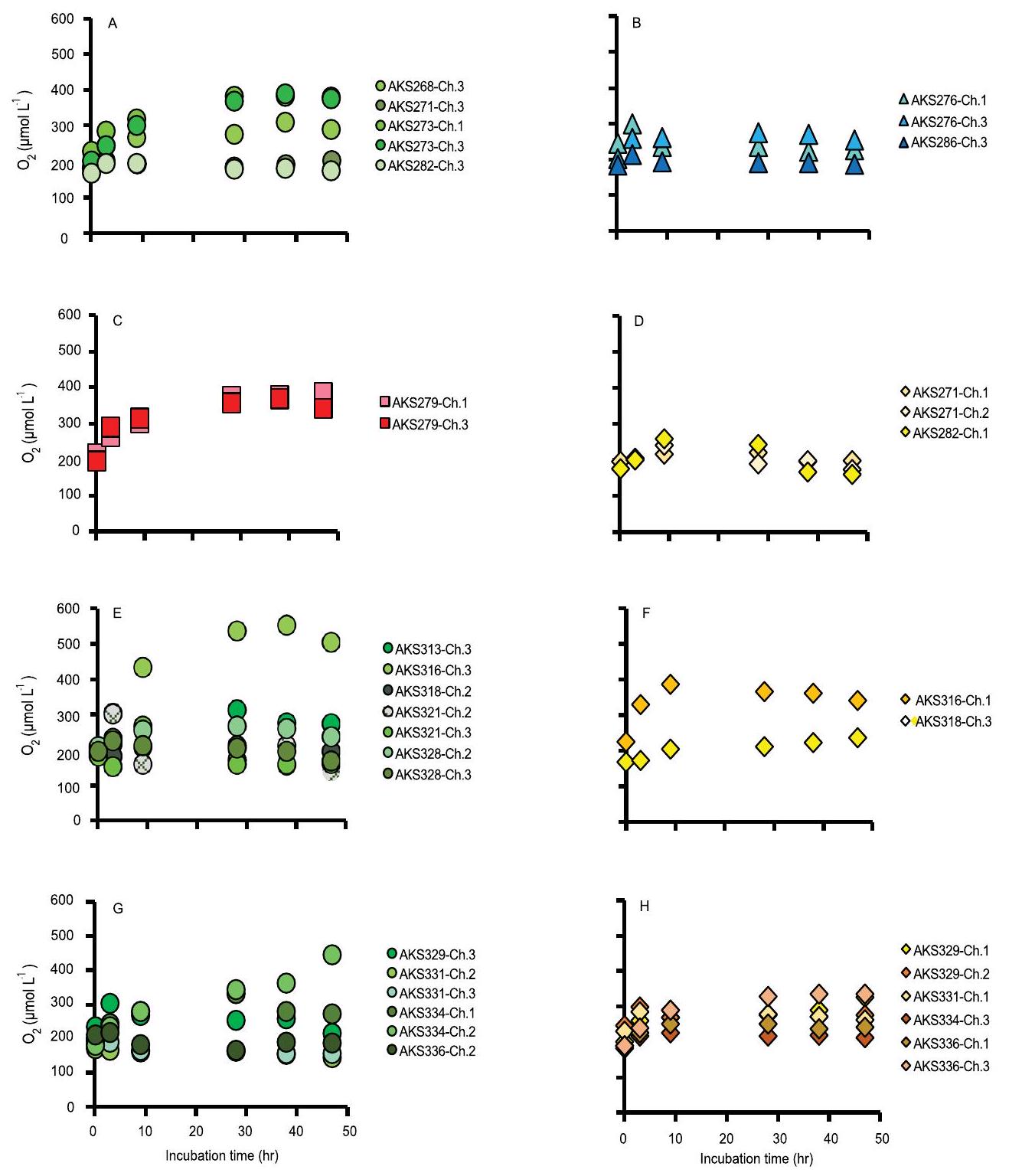

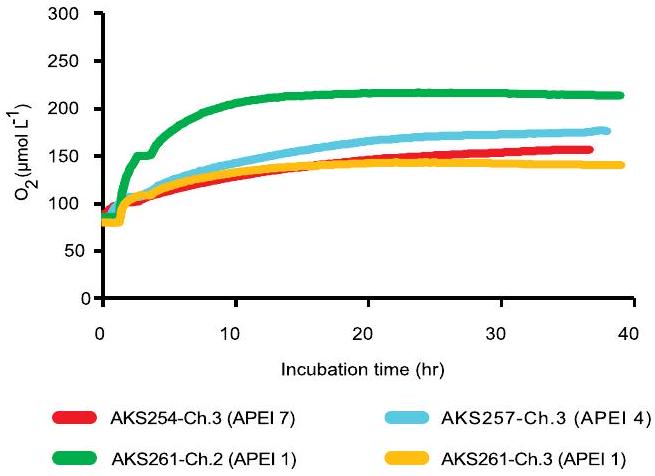

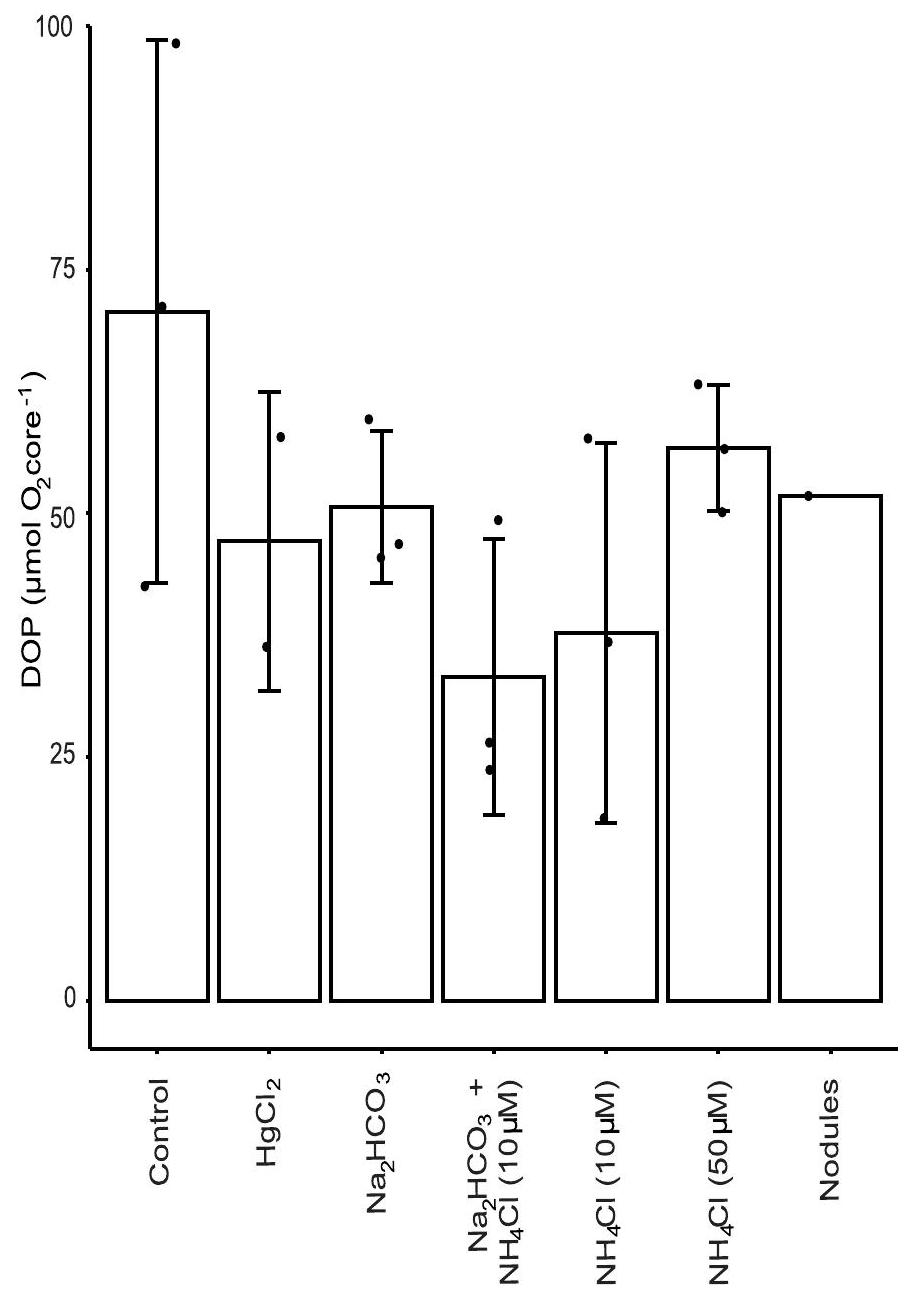

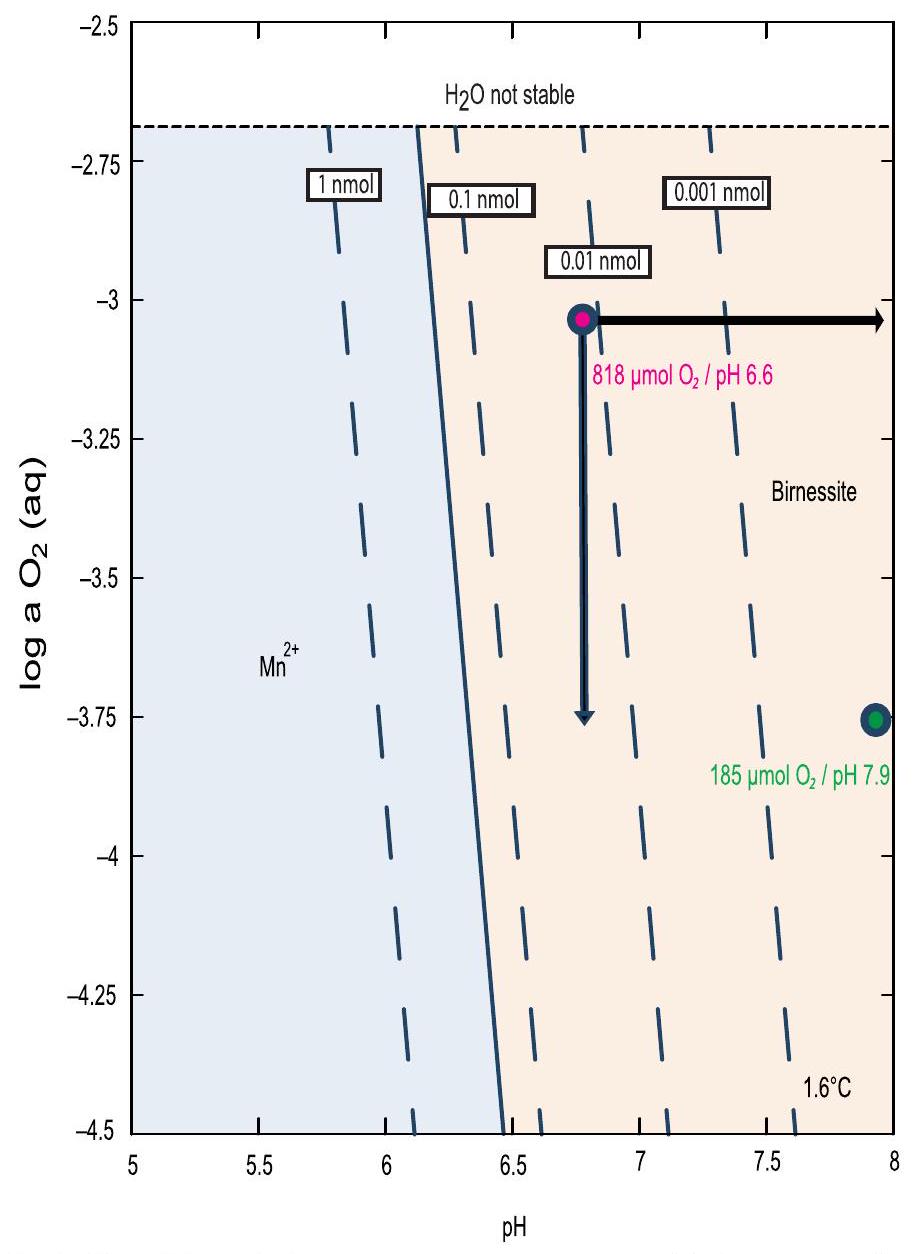

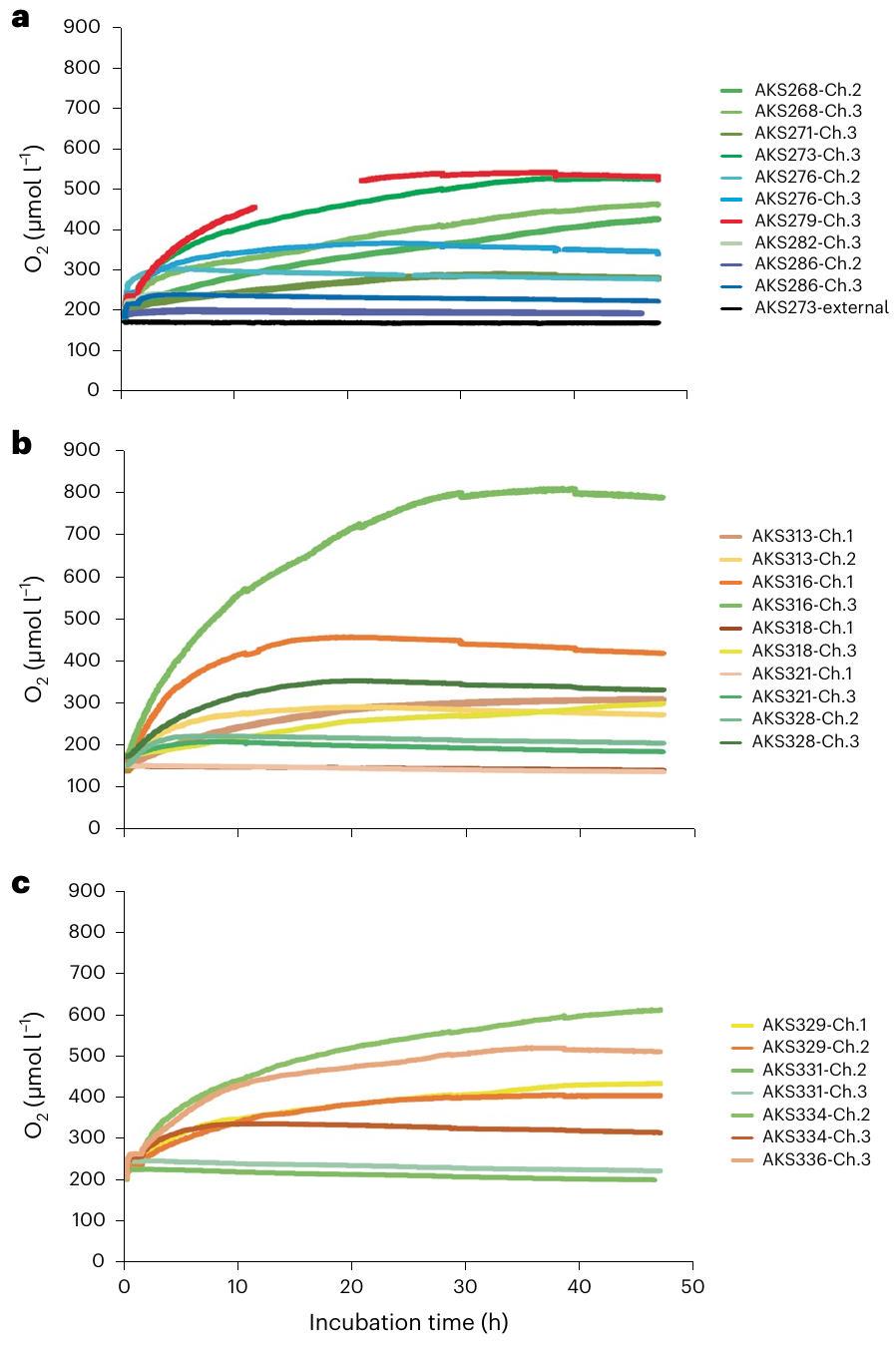

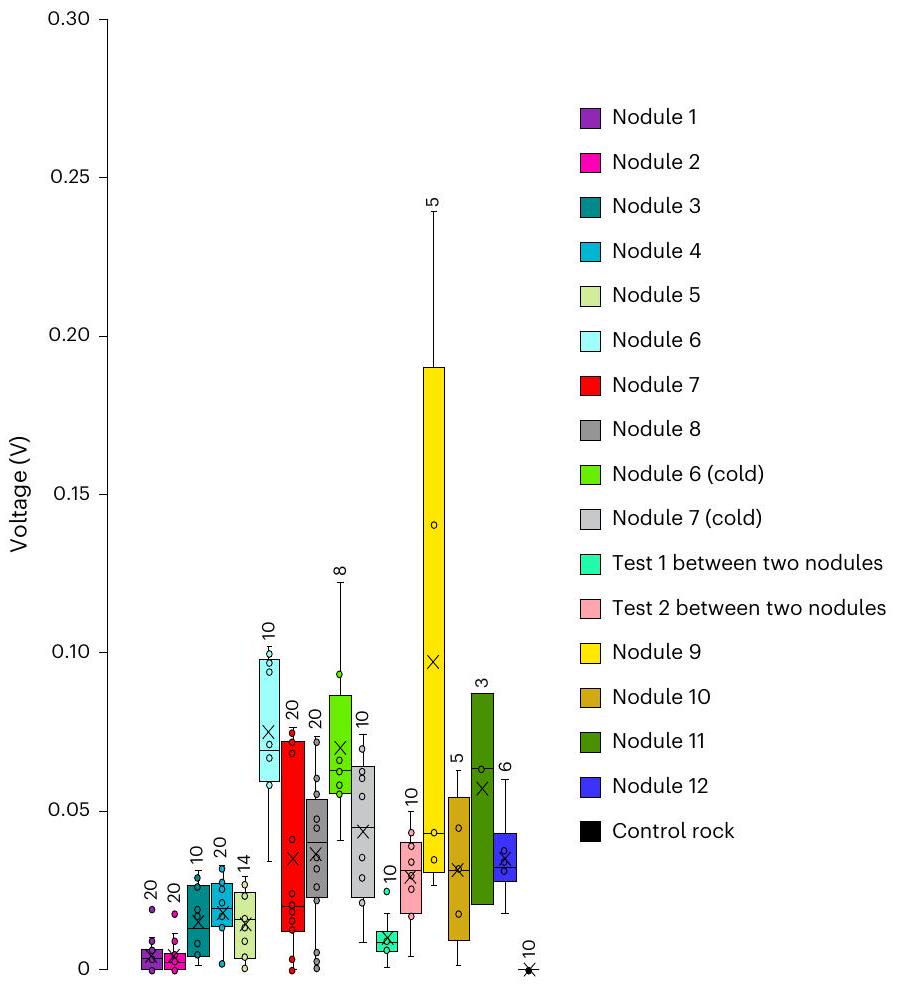

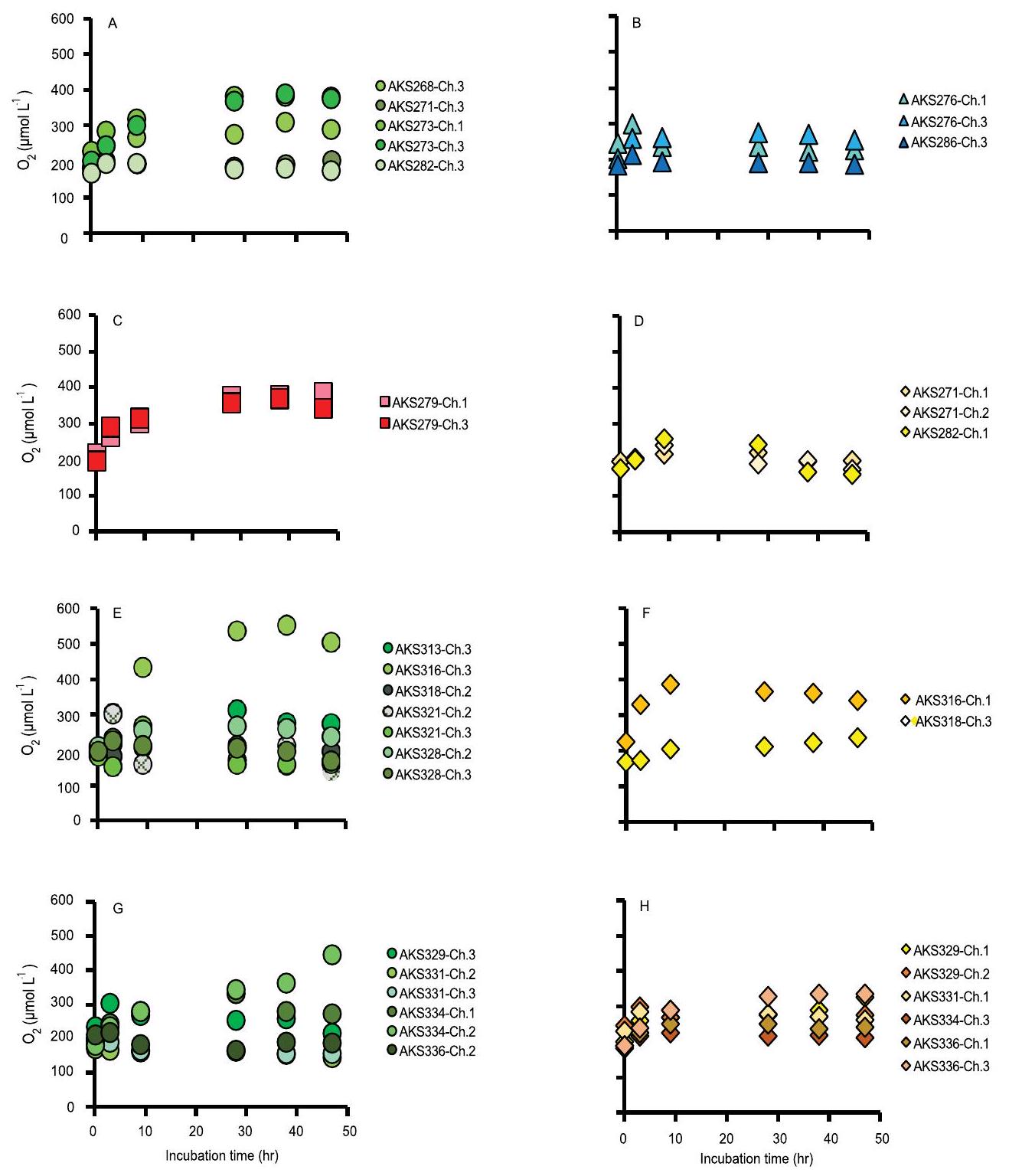

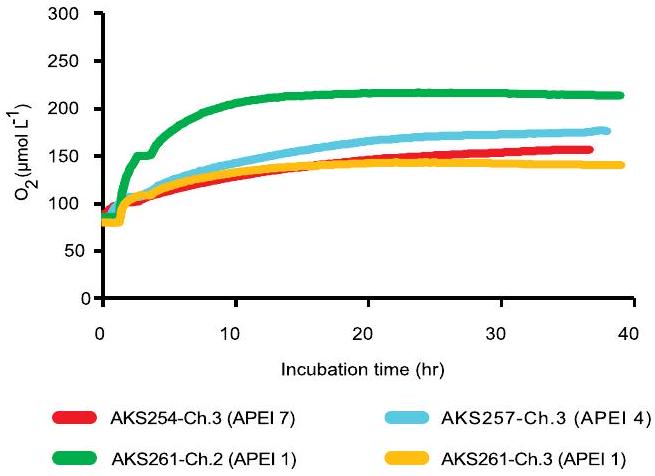

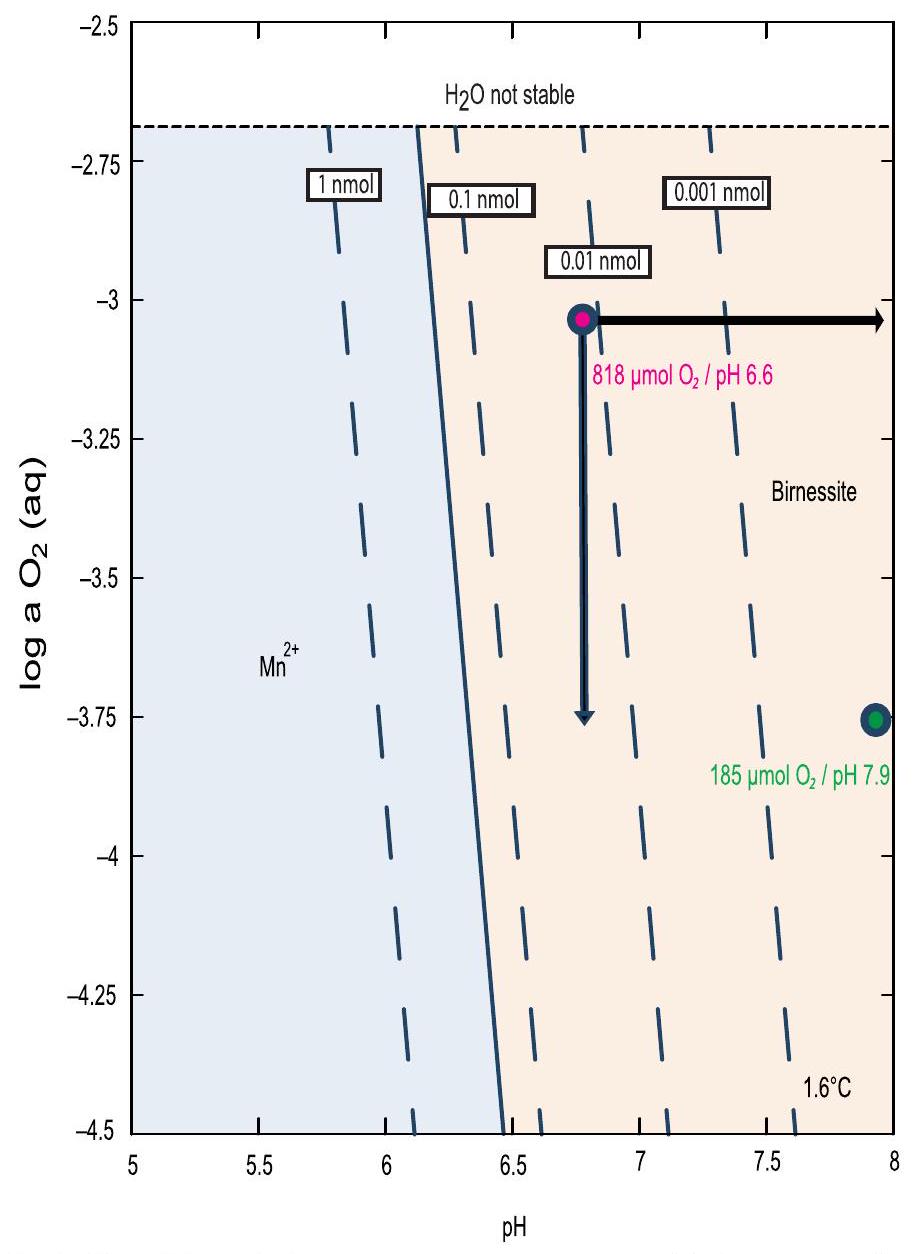

Deep-seafloor organisms consume oxygen, which can be measured by in situ benthic chamber experiments. Here we report such experiments at the polymetallic nodule-covered abyssal seafloor in the Pacific Ocean in which oxygen increased over two days to more than three times the background concentration, which from ex situ incubations we attribute to the polymetallic nodules. Given high voltage potentials (up to 0.95 V ) on nodule surfaces, we hypothesize that seawater electrolysis may contribute to this dark oxygen production.

rates of

to purge air from the chambers as the lander sinks. Even if an air bubble could be trapped long enough to reach the seafloor, gaseous diffusion of

Online content

References

- Jorgensen, B. B. et al. Sediment oxygen consumption: role in the global marine carbon cycle. Earth Sci. Rev. 228, 103987 (2022).

- Smith, K. L. Jr et al. Climate, carbon cycling and deep-ocean ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19211-19218 (2009).

- Smith, Jr. K. L. et al. Large salp bloom export from the upper ocean and benthic community response in the abyssal northeast Pacific: day to week resolution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 745-757 (2014).

- Sweetman, A. K. et al. Key role of bacteria in the short-term cycling of carbon at the abyssal seafloor in a low particulate organic carbon flux region of the eastern Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 694-713 (2019).

- Mewes, K. et al. Diffusive transfer of oxygen from seamount basaltic crust into overlying sediments: an example from the ClarionClipperton Fracture Zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 433, 215-225 (2016).

- Kuhn, T. et al. Widespread seawater circulation in

oceanic crust: impact on heat flow and sediment geochemistry. Geology 45, 799-802 (2017). - Zhang, D. et al. Microbe-driven elemental cycling enables microbial adaptation to deep-sea ferromanganese nodule sediment fields. Microbiome 11, 160 (2023).

- Kraft, B. et al. Oxygen and nitrogen production by an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon. Science 375, 97-100 (2022).

- Ershov, B. G. Radiation-chemical decomposition of seawater: the appearance and accumulation of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 168, 108530 (2020).

- Dresp, S. et al. Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: opportunities and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933-942 (2019).

- He, Y. et al. Recent progress of manganese dioxide based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Ind. Chem. Mater. 1, 312 (2023).

- Kuhn, T. et al. in Deep-Sea Mining (ed. Sharma, R.) 23-63 (Springer, 2017).

- Tian, L. Advances in manganese-based oxides for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 14400 (2020).

- Teng, Y. et al. Atomically thin defect-rich Fe-Mn-O hybrid nanosheets as highly efficient electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802463 (2018).

- Wegorzewski, A. V. & Kuhn, T. The influence of suboxic diagenesis on the formation of manganese nodules in the Clarion Clipperton nodule belt of the Pacific Ocean. Mar. Geol. 357, 123-138 (2014).

- Robins, L. J. et al. Manganese oxides, Earth surface oxygenation, and the rise of oxygenic photosynthesis. Earth Sci. Rev. 239, 104368 (2023).

- Chyba, C. F. & Had, K. P. Life without photosynthesis. Science 292, 2026-2027 (2001).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

immediately fixed for microWinkler titration. The sample was then mixed thoroughly using a glass bead placed in the exetainer and placed in the dark in a

Benthic

Microbiology sampling

and ASVs were clustered to

Polymetallic nodule surface area measurements

Radiolysis

Electrochemistry measurements

dish and the platinum probes placed on the nodule at random locations, ensuring contact in one of two ways. We either carefully drilled a hole into some nodules so one platinum wire could be fixed inside it while the second platinum wire was firmly pressed against the nodule surface using a clamp. Alternatively, the platinum wires were pressed firmly against two different spots on the nodule surface and held in place using a clamp. Voltages were then recorded for

Geochemistry modelling

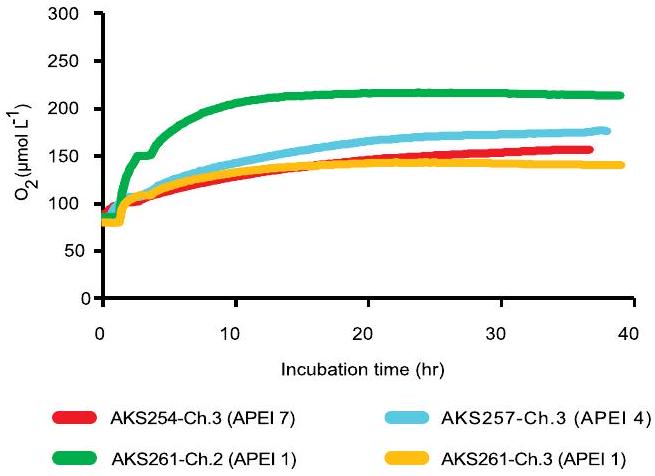

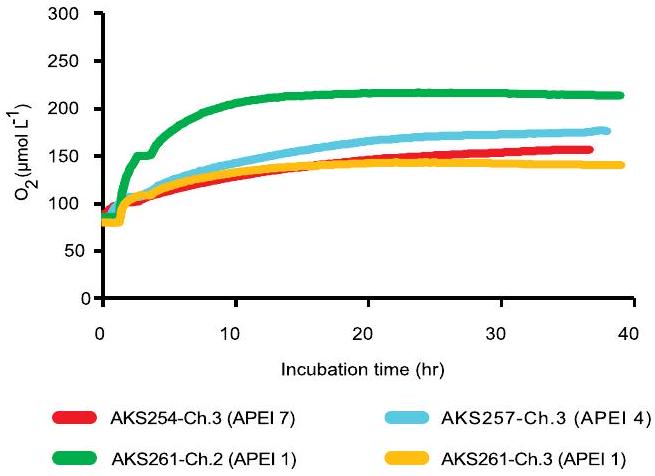

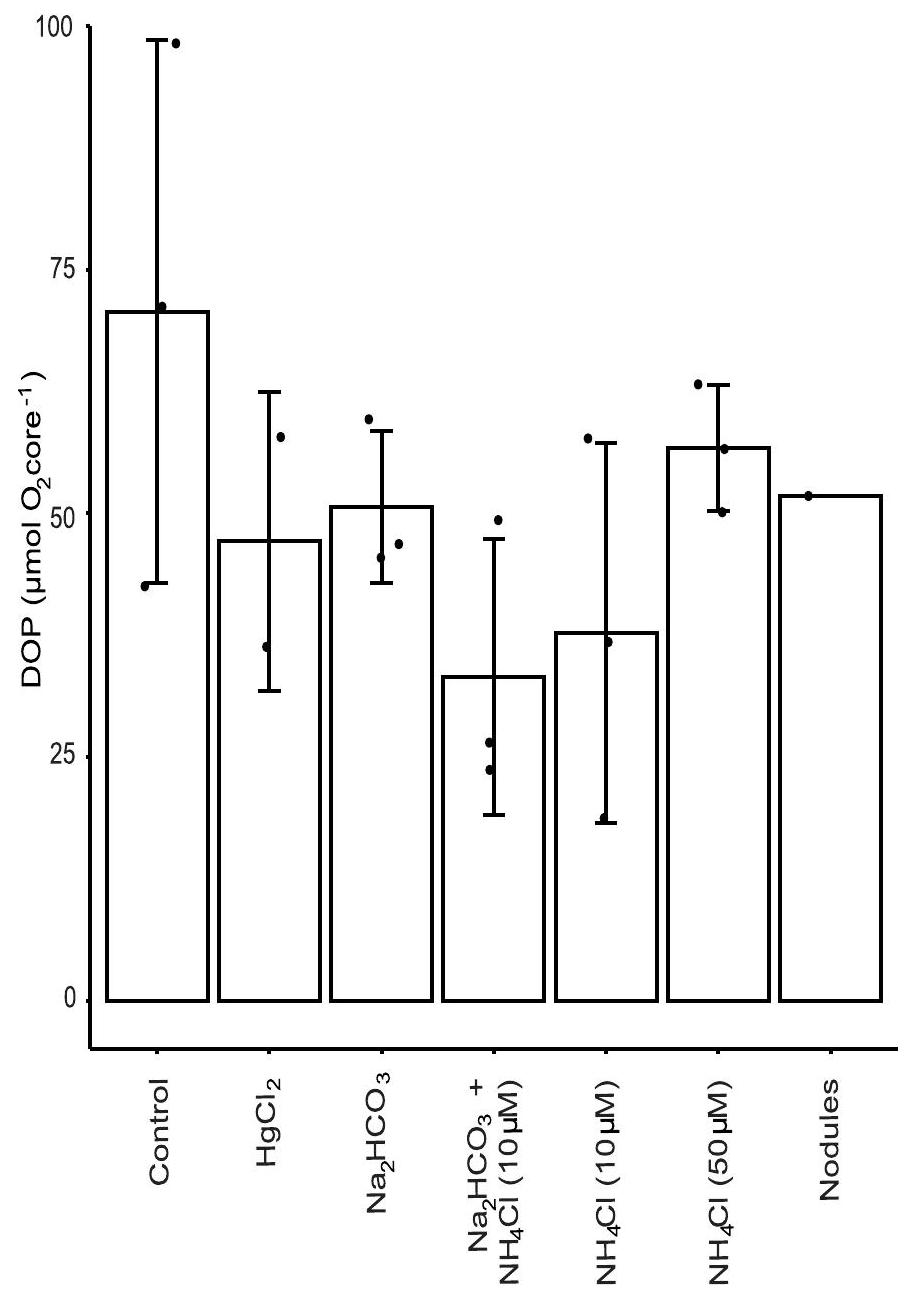

Ex situ core incubations

rubber stopper, allowing for

Calculations to quantify intrusion of

Data availability

References

- Bittig, H. C. et al. Oxygen optode sensors: principle, characterization, calibration, and application in the ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 429 (2018).

- Caporaso J. G. et al. EMP 16 S Illumina amplicon protocol V.1. protocols.io. https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nuudeww (2018).

- Parada, A. E. et al. Every base matters. Assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1403-1414 (2016).

- Apprill, A. et al. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806 R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 75, 129-137 (2015).

- Choppin, G. et al. Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry (Elsevier, 2002).

- Katz, J. J. et al. The Chemistry of the Actinide Elements 2nd edn (Springer, 1986).

- Lide, D. R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics Vol. 85 (CRC Press, 2004).

- Nier, A. O. A redetermination of the relative abundances of the isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, argon, and potassium. Phys. Rev. 77, 789 (1950).

- Stumm, W. and Morgan, J. J. Aquatic Chemistry: An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters 2nd edn (John Wiley & Sons, 1981).

- Cheng, H. et al. Improvements in

Th dating, 230 Th and 234 U half-life values, and U-Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371, 82-91 (2013). - Edwards, R. L. et al.

systematics and the precise measurement of time over the past 500,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 81, 175-192 (1987). - Shen, C. C. et al. Uranium and thorium isotopic and concentration measurements by magnetic sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Chem. Geol. 185, 165-178 (2002).

- Ershov, B. G. & Gordeev, A. V. A model for radiolysis of water and aqueous solutions of

and . Radiat. Phys. Chem. 77, 928-935 (2008). - DeWitt, J. et al. The effect of grain size on porewater radiolysis.Earth Space Sci. 9, e2021EA002024 (2021).

- Blair, C. C. et al. Radiolytic hydrogen and microbial respiration in subsurface sediments. Astrobiology 7, 951-970 (2007).

- Shriwastav, A. et al. A modified Winkler’s method for determination of dissolved oxygen concentration in water: dependence of method accuracy on sample volume. Measurement 106, 190-195 (2017).

- Stevens, E. D. Use of plastic materials in oxygen-measuring systems. J. Appl. Physiol. 72, 801-804 (1992).

- Sweetman, A. K. Data collected from replicate benthic chamber experiments conducted at abyssal depths across the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), Pacific Ocean. Dryad https://doi.org/ 10.5061/dryad.tdz08kq6w (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

S.F. and T.K. also work for the Federal Institute for Geoscience and Natural Resources, which holds exploration rights in the CCZ.

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8.

(b-d) of NORI-D in the central abyssal Pacific. The deployment location for the multi-corer (MUC) that sampled sediments for the ex situ experiments conducted during the 5D cruise is also shown (c).

carried out at NORI-D. The

carried out at NORI-D. The

Treatment

in MUC cores, and the lowest

Extended Data Table 1 | In-situ benthic chamber lander deployment locations and depths in NORI-D

| Cruise | Date | Lander deployment | Area | Station | Depth (m) |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS268 | CTA | STM-001 | 4285 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS271 | CTA | STM-001 | 4284 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS273 | CTA | STM-014 | 4306 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS276 | CTA | STM-014 | 4306 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS279 | CTA | STM-007 | 4280 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS282 | PRZ | SPR-033 | 4245 |

| 5D | May-June 2021 | AKS286 | PRZ | SPR-041 | 4127 |

| 5E | November-December 2021 | AKS313 | CTA | STM-014 | 4304 |

| 5E | November-December 2021 | AKS316 | CTA | STM-001 | 4285 |

| 5E | November-December 2021 | AKS318 | CTA | STM-007 | 4277 |

| 5E | November-December 2021 | AKS321 | CTA | STM-001 | 4285 |

| 5E | November-December 2021 | AKS328 | PRZ | SPR-033 | 4243 |

| 7A | August-September 2022 | AKS329 | CTA | TF-021 | 4289 |

| 7A | August-September 2022 | AKS331 | CTA | STM-001 | 4286 |

| 7A | August-September 2022 | AKS334 | CTA | TF-028 | 4278 |

| 7A | August-September 2022 | AKS336 | CTA | TF-021 | 4271 |

Extended Data Table 2 | Total net oxygen change measured by

| Lander deployment | Chamber | Optode sensor | Treatment | Volume of water phase (L) | Start-End time (hr) optodes logged

|

Total

|

Weight (g) of nodules (sediment horizon) | DOP flux (

|

Net production/ respiration dominated |

| AKS268 | 2 | B | Dead-algal biomass | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS268 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 3.812 | 0-47 | 1008 |

|

10.5 | Production |

| AKS271 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS273 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 4.598 | 0-47 | 1545 |

|

16.1 | Production |

| AKS276 | 2 | B |

|

NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS276 | 3 | A |

|

3.933 | 0-47 | 671 |

|

6.1 | Production |

| AKS279 | 3 | A | Filtered seawater | 4.659 | 0-47 | 1639 |

|

16.5 | Production |

| AKS282 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 4.598 | 0-47 | 246 | – | 1.7 | Production |

| AKS286 | 2 | B |

|

NA | 0-45.48 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS286 | 3 | A |

|

6.050 | 0-47 | 329 |

|

2.4 | Production |

| AKS313 | 1 | B | Control (no injection) | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS313 | 2 | A | Control (no injection) | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Production |

| AKS316 | 1 | B | Control (no injection) | 2.118 | 0-47 | 639 |

|

5.9 | Production |

| AKS316 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 2.420 | 0-47 | 1526 |

|

15.6 | Production |

| AKS318 | 1 | B | Control (no injection) | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Respiration |

| AKS318* | 3 | A | Control (no injection) | 2.783 | 0.23-47 | – | 596 (0-2cm) | – | Production |

| AKS321 | 1 | B | Control (no injection) | NA | 0-47 | – | – | – | Respiration |

| AKS321* | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 2.783 | 1.33-47 | – |

|

– | Production |

| AKS328 | 2 | B | Dead-algal biomass | 3.691 | 0-47 | 257 |

|

2.0 | Production |

| AKS328 | 3 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 3.812 | 0-47 | 683 | 556 (0-5cm) | 6.4 | Production |

| AKS329 | 1 | A | Control (no injection) | 3.872 | 0-47 | 904 |

|

9.5 | Production |

| AKS329 | 2 | B | Control (no injection) | 3.872 | 0-47 | 774 |

|

8.1 | Production |

| AKS331* | 2 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 2.723 | 0.06-46.45 | – |

|

– | Production |

| AKS331* | 3 | B | Dead-algal biomass | 3.207 | 0.07-47 | – |

|

– | Production |

| AKS334 | 2 | A | Dead-algal biomass | 4.175 | 0-47 | 1710 |

|

18.0 | Production |

| AKS334 | 3 | B | Control (no injection) | 5.143 | 0-47 | 652 |

|

5.7 | Production |

| AKS336 | 3 | B | Control (no injection) | 4.477 | 0-47 | 1408 | 622 (

|

14.4 | Production |

| Mean

|

|

|

Extended Data Table 3 | Theoretical diffusion times for thin versus thick-walled bubbles at the seafloor

| Incubation | Time (sec) required for diffusion assuming a thin-walled (

|

Time (sec) required for diffusion assuming a thick-walled (10000 nm) bubble |

| AKS268-Ch3 | 0.012 | 1.226 |

| AKS273-Ch3 | 0.014 | 1.411 |

| AKS276-Ch3 | 0.011 | 1.068 |

| AKS279-Ch3 | 0.014 | 1.442 |

| AKS282-Ch3 | 0.008 | 0.768 |

| AKS286-Ch3 | 0.009 | 0.854 |

| AKS316-Ch1 | 0.011 | 1.053 |

| AKS316-Ch3 | 0.014 | 1.407 |

| AKS328-Ch2 | 0.008 | 0.780 |

| AKS328-Ch3 | 0.011 | 1.080 |

| AKS329-Ch1 | 0.012 | 1.182 |

| AKS329-Ch2 | 0.011 | 1.122 |

| AKS334-Ch2 | 0.015 | 1.463 |

| AKS334-Ch3 | 0.011 | 1.061 |

| AKS336-Ch3 | 0.014 | 1.372 |

| Mean

|

|

|

Extended Data Table 4 | Minimum and maximum voltage potentials (mV) measured on the surface of polymetallic nodules

| Min. voltage (mV) | Nod. 1 | Nod. 2 | Nod. 3 | Nod. 4 | Nod. 5 | Nod. 6 | Nod. 6 (cold) | Nod. 7 | Nod. 7 (cold) | Nod. 8 | Nod. 9 | Nod. 10 | Nod. 11 | Nod. 12 | Cont. |

| Record 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 58.55 | 77.83 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 78.81 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Record 2 | 8.97 | 18.45 | 15.48 | 3.03 | 0.00 | 97.30 | 40.90 | 79.56 | 21.65 | 25.34 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 53.68 | 0.01 | 4.48 |

| Record 3 | 12.00 | 0.00 | 26.48 | 1.78 | 3.14 | 100.26 | 57.69 | 81.87 | 22.13 | 5.57 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 22.30 | 0.97 |

| Record 4 | 8.67 | 1.01 | 29.21 | 21.06 | 24.87 | 88.69 | 54.14 | 44.84 | 37.31 | 36.89 | 15.42 | 23.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Record 5 | 7.77 | 0.64 | 18.68 | 21.91 | 14.89 | 52.68 | 60.72 | 22.36 | 30.80 | 50.57 | 0.00 | 9.28 | 1.83 | 3.34 | |

| Record 6 | 0.00 | 6.28 | 8.45 | 13.81 | 17.71 | 49.47 | 85.98 | 55.17 | 71.57 | 38.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |||

| Record 7 | 0.00 | 2.95 | 3.98 | 14.25 | 0.90 | 69.44 | 75.57 | 75.75 | 72.06 | 44.82 | 1.10 | ||||

| Record 8 | 14.17 | 0.00 | 16.97 | 14.62 | 15.03 | 66.93 | 0.07 | 78.40 | 57.64 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||

| Record 9 | 5.57 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.35 | 33.69 | 81.75 | 59.83 | 8.03 | 1.66 | |||||

| Record 10 | 5.00 | 3.52 | 3.29 | 18.15 | 24.79 | 0.04 | 20.69 | 65.61 | 27.96 | 3.53 | |||||

| Record 11 | 6.14 | 3.39 | 32.39 | 13.09 | 25.84 | 36.46 | |||||||||

| Record 12 | 1.52 | 5.21 | 25.42 | 16.84 | 25.45 | 36.46 | |||||||||

| Record 13 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 27.85 | 26.23 | 0.01 | 61.34 | |||||||||

| Record 14 | 7.12 | 4.09 | 28.61 | 24.92 | 12.71 | 60.85 | |||||||||

| Record 15 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 16.31 | 0.00 | 51.72 | ||||||||||

| Record 16 | 1.59 | 3.09 | 15.70 | 0.00 | 76.51 | ||||||||||

| Record 17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.12 | 4.70 | 78.77 | ||||||||||

| Record 18 | 7.83 | 0.00 | 13.64 | 17.90 | 65.17 | ||||||||||

| Record 19 | 6.33 | 0.75 | 20.67 | 24.68 | 49.45 | ||||||||||

| Record 20 | 10.06 | 12.24 | 29.94 | 20.49 | 49.45 | ||||||||||

| Max. voltage (mV) | |||||||||||||||

| Record 1 | 10.93 | 52.73 | 266.80 | 52.99 | 45.69 | 102.87 | 70.85 | 80.11 | 116.23 | 39.27 | 219.67 | 19.36 | 98.41 | 128.40 | 52.91 |

| Record 2 | 9.81 | 21.46 | 22.95 | 4.89 | 0.47 | 99.85 | 42.24 | 82.60 | 30.74 | 28.94 | 722.00 | 112.63 | 70.40 | 407.56 | 7.72 |

| Record 3 | 13.84 | 12.00 | 28.36 | 3.01 | 8.44 | 103.48 | 59.12 | 82.80 | 27.61 | 6.61 | 485.52 | 178.04 | 952.61 | 59.50 | 11.15 |

| Record 4 | 12.28 | 3.51 | 31.39 | 24.88 | 28.98 | 96.82 | 58.33 | 57.64 | 38.58 | 39.47 | 350.78 | 65.84 | 600.43 | 2.96 | |

| Record 5 | 8.99 | 4.87 | 75.42 | 23.15 | 21.01 | 77.16 | 65.41 | 31.91 | 34.22 | 53.26 | 361.71 | 25.45 | 118.71 | 7.56 | |

| Record 6 | 3.17 | 7.27 | 12.12 | 14.86 | 25.77 | 74.55 | 266.76 | 80.50 | 91.66 | 42.18 | 128.61 | 8.71 | |||

| Record 7 | 4.29 | 5.08 | 9.94 | 14.86 | 1.11 | 77.73 | 102.45 | 78.95 | 73.12 | 77.14 | 2.85 | ||||

| Record 8 | 25.22 | 2.63 | 20.15 | 18.49 | 16.85 | 69.20 | 71.41 | 84.31 | 57.91 | 11.12 | 0.88 | ||||

| Record 9 | 7.45 | 1.34 | 9.36 | 8.69 | 10.91 | 37.81 | 82.78 | 65.62 | 11.87 | 2.45 | |||||

| Record 10 | 8.38 | 14.61 | 3.81 | 28.73 | 26.73 | 113.62 | 28.34 | 65.91 | 33.35 | 8.70 | |||||

| Record 11 | 7.73 | 9.19 | 35.00 | 14.85 | 28.08 | 39.46 | |||||||||

| Record 12 | 3.17 | 7.02 | 32.99 | 18.21 | 33.05 | 39.46 | |||||||||

| Record 13 | 2.94 | 5.52 | 32.21 | 31.65 | 12.76 | 63.50 | |||||||||

| Record 14 | 9.83 | 6.43 | 31.86 | 26.59 | 21.71 | 61.74 | |||||||||

| Record 15 | 2.45 | 7.04 | 22.45 | 3.49 | 52.38 | ||||||||||

| Record 16 | 6.76 | 6.45 | 21.56 | 11.27 | 79.14 | ||||||||||

| Record 17 | 5.54 | 4.37 | 24.97 | 9.10 | 81.13 | ||||||||||

| Record 18 | 10.19 | 0.95 | 20.30 | 20.38 | 68.18 | ||||||||||

| Record 19 | 7.91 | 2.13 | 24.16 | 27.89 | 52.58 | ||||||||||

| Record 20 | 14.32 | 13.57 | 34.40 | 27.74 | 52.58 |

The Scottish Association for Marine Science, (SAMS), Oban, UK. Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK. GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Kiel, Germany. Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. Bioinformatics Program, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Faculty of Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. School of Science, Physics and Earth Sciences, Constructor University Bremen, Bremen, Germany. Federal Institute for Geoscience and Natural Resources (BGR), Hannover, Germany. Technological Institute, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. e-mail: Andrew.Sweetman@sams.ac.uk