DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06794-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200299

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

أدلة على تأثير الإنسان على فقدان الثلوج في نصف الكرة الشمالي

تاريخ الاستلام: 2 مارس 2023

تم القبول: 24 أكتوبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 10 يناير 2024

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

توثيق معدل وحجم وأسباب فقدان الثلوج أمر ضروري لتحديد وتيرة تغير المناخ ولإدارة المخاطر المختلفة لأمن المياه الناتجة عن انخفاض غطاء الثلوج.

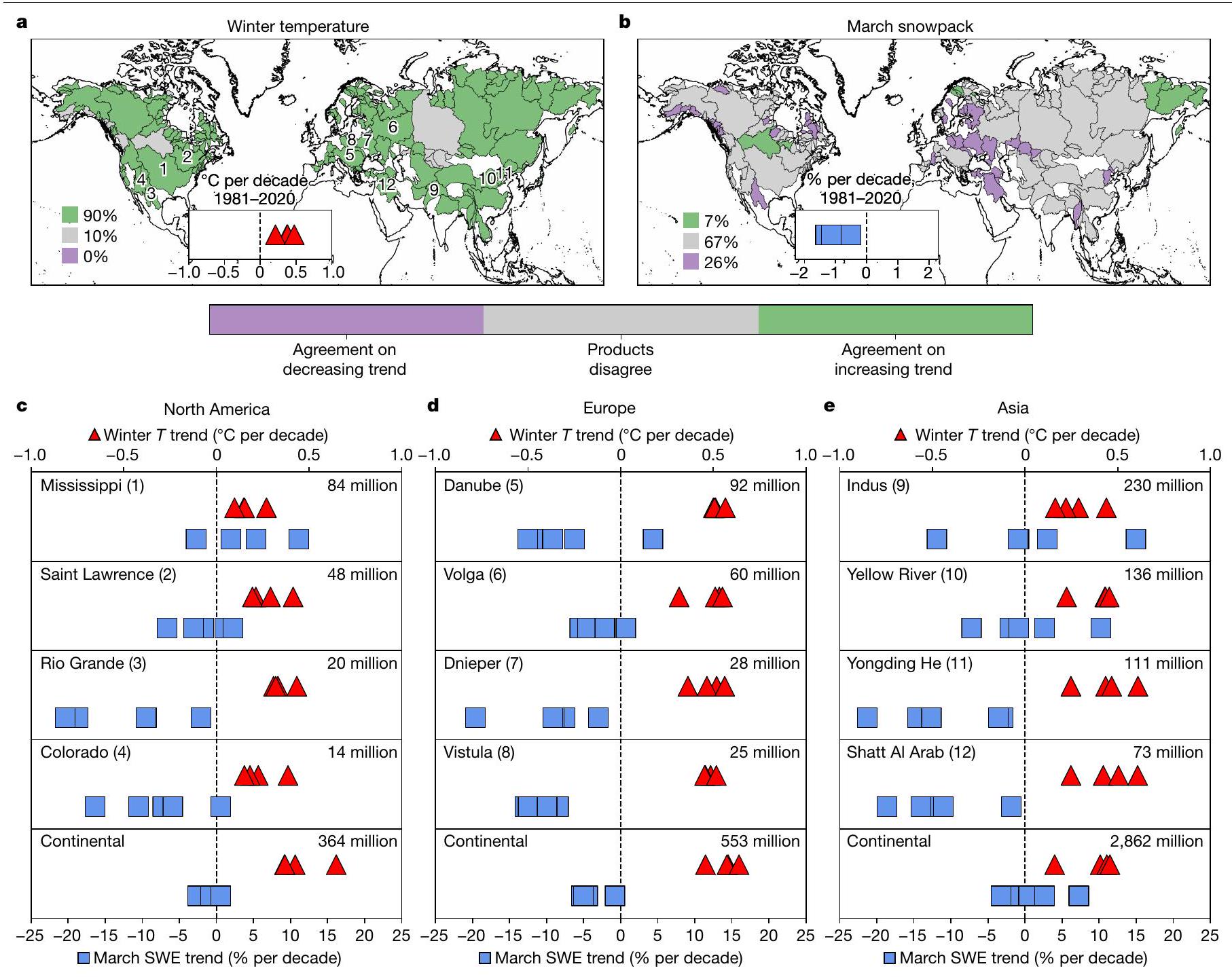

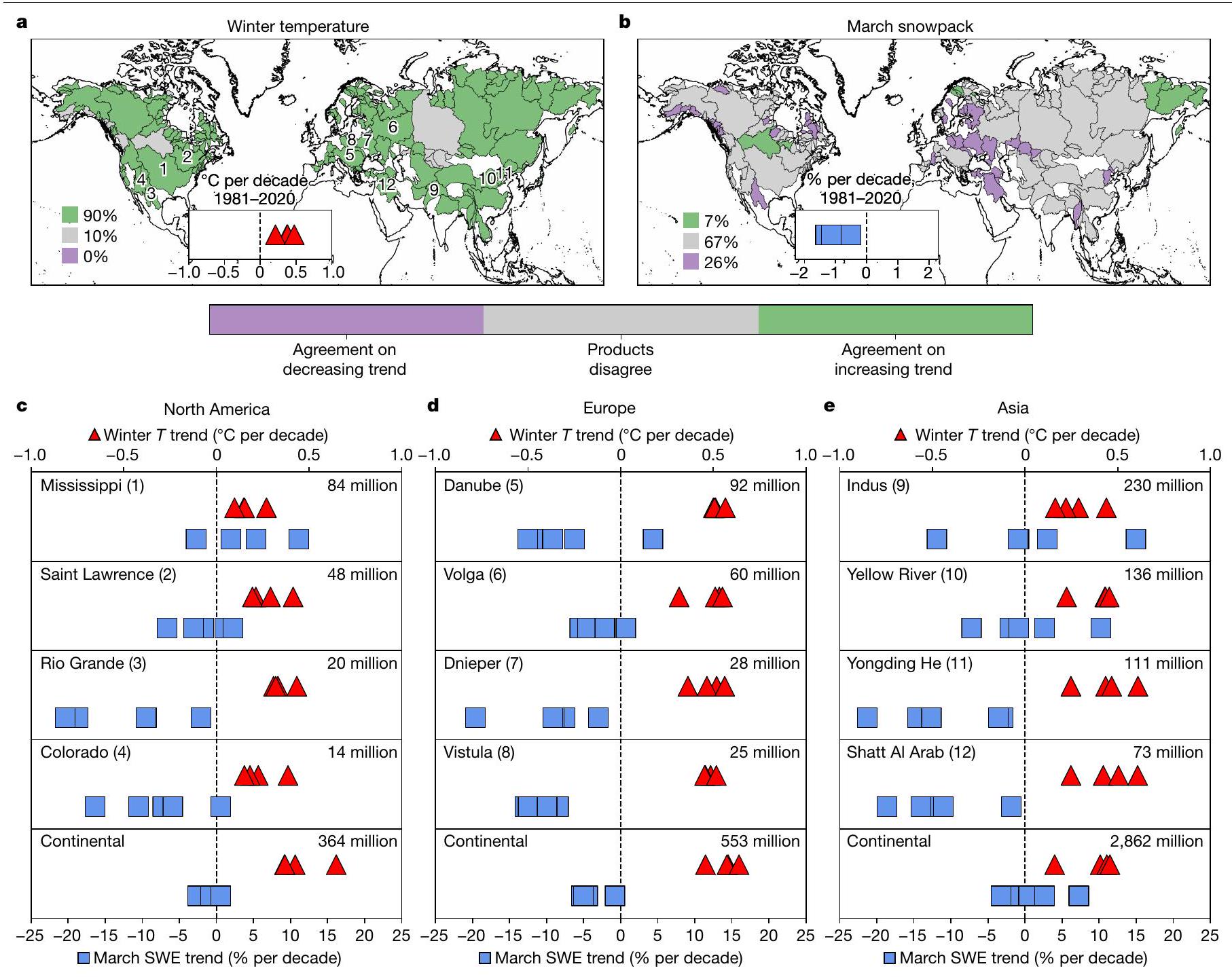

نصف الكرة الشمالي، لكن اتجاهات تراكم الثلوج ليست كذلك. أ، ب، توافق عبر المنتجات الملاحظة (الجدول التكميلي 1) على اتجاهات متوسط درجة الحرارة من نوفمبر إلى مارس (الشتاء

ستستجيب طبقة الثلج ومياه الجريان الناتجة عنها للاحتباس الحراري الإضافي. معًا، توفر نتائجنا توثيقًا شاملاً للتأثيرات التاريخية والمستقبلية لتغير المناخ على تخزين مياه الثلوج.

إشارة مفروضة في ملاحظات غلاف الثلج

تظهر حزم الثلوج في الربيع، مع ملاحظات في الموقع تشير إلى زيادة تزيد عن 20% في العقد في السهول الكبرى الشمالية وأجزاء من سيبيريا، في حين تشير المنتجات الموزعة إلى زيادات أكثر تواضعًا تتراوح بين 5% إلى 10% في العقد. المناطق التي تهيمن عليها الثلوج والتي تفتقر إلى ملاحظات في الموقع، مثل آسيا الجبلية العالية وهضبة التبت، تظهر اتجاهات ضعيفة في متوسط الملاحظات الموزعة (الشكل 2ب)، مما يتعارض مع الاتجاهات غير المتسقة في المنتجات البيانية الفردية (الشكل 1ب، هـ والشكل الممتد 1).

المحاكاة وكل منتج SWE ملاحظ (OBS) (انظر الأسطورة). يشير المدرج التكراري الرمادي إلى دالة كثافة الاحتمال التجريبية للارتباطات المكانية بين الاتجاهات من المحاكاة التاريخية وجميع الاتجاهات الممكنة لمدة 40 عامًا من المحاكاة غير المدفوعة (PIC) (

تستبعد الانبعاثات البشرية تفشل في التقاط نمط التغير المرصود للثلوج (الشكل 2d).

الاتجاهات في كل مجموعة بيانات ملاحظات مع تلك من المتوسط الجماعي لتجربتين مناخيتين مختلفتين: محاكاة HIST (الرموز الحمراء في الشكل 2e)، التي تمثل الضغط البشري التاريخي ومحاكاة التاريخ الطبيعي، أو HIST-NAT، (الرموز الزرقاء في الشكل 2e)، التي تمثل مناخًا تاريخيًا بدون انبعاثات غازات دفيئة ناجمة عن الإنسان. أخيرًا، نقارن الارتباطات المرصودة بالتوزيع الصفري لحساب احتمال أن درجة التشابه بين الملاحظات ومحاكاة HIST وHIST-NAT قد نشأت من التغير الطبيعي.

المقالة

تغيرات أكوام الثلوج على مستوى حوض النهر

جنوب غرب الولايات المتحدة وأوروبا، بما يتماشى مع الاتجاهات طويلة الأجل من قياسات SWE المباشرة هناك

الاتجاه والاتجاه المعاد بناؤه مع إزالة التغييرات القسرية في درجة الحرارة.

استجابة قسرية – حول الاختلافات الهيكلية لنموذج المناخ وعدم اليقين في الملاحظات في SWE ودرجة الحرارة وهطول الأمطار في حوالي واحد من كل ثمانية أحواض (الشكل البياني الموسع 7).

كلا من عدم اليقين الأكبر في هطول الأمطار والمساهمة الأكبر للتقلبات الداخلية في عدم اليقين الهيدرولوجي

الحساسية غير الخطية للثلج تجاه الاحترار

السكان في

تحديد العلاقة بين درجات الحرارة المناخية وحساسية الثلوج (الشكل 4 أ).

التخزين عبر نصف الكرة الشمالي (على سبيل المثال، الشكل 1). كما يوضح لماذا يجب أن نتوقع تسارع فقدان الثلوج بسرعة، مع عواقب واسعة النطاق على أمن المياه (الشكل 4 ب).

فحص شكل العلاقة بين متوسط درجات حرارة الشتاء وحساسية الثلوج الهامشية لتغير درجة الحرارة يوضح لماذا كان اكتشاف الثلوج صعبًا حتى الآن ولماذا تشير حتى مستويات الاحترار المعتدلة إلى انخفاضات أكثر حدة في الثلوج في المستقبل (الشكل 4 أ). تعتمد استجابة الثلوج لـ

إدارة واستغلال عدم اليقين في الثلوج

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- بارنيت، تي. بي.، آدام، جي. سي. وليتنامير، دي. بي. التأثيرات المحتملة لمناخ دافئ على توفر المياه في المناطق التي تهيمن عليها الثلوج. ناتشر 438، 303-309 (2005).

- إيميرزيل، و. و. وآخرون. أهمية وهشاشة أبراج المياه في العالم. ناتشر 577، 364-369 (2020).

- مانكين، ج. س.، فيفيرولي، د.، سينغ، د.، هوكسترا، أ. ي. وديفنباخ، ن. س. الإمكانية التي توفرها الثلوج لتلبية الطلب البشري على المياه في الحاضر والمستقبل. رسائل البحث البيئي 10، 114016 (2015).

- تشين، ي. وآخرون. المخاطر الزراعية الناتجة عن تغير ذوبان الثلوج. نات. تغير المناخ 10، 459-465 (2020).

- غوتليب، أ. ر. ومانكين، ج. س. مراقبة وقياس وتقييم عواقب جفاف الثلوج. نشرة الجمعية الأمريكية للأرصاد الجوية 103، E1041-E1060 (2022).

- مورتيمر، سي. وآخرون. تقييم منتجات مكافئ مياه الثلج طويلة الأمد في نصف الكرة الشمالي. كريوسفير 14، 1579-1594 (2020).

- فوكس-كيمبر ب. وآخرون في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي (تحرير ماسون-ديلموتي، ف. وآخرون) 1211-1362 (الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ، مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

- ويليامز، أ. ب. وآخرون. مساهمة كبيرة من الاحترار الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية في جفاف كبير ناشئ في أمريكا الشمالية. ساينس 368، 314-318 (2020).

- مانكين، ج. س. وآخرون. تقرير فريق عمل الجفاف التابع للإدارة الوطنية للمحيطات والغلاف الجوي عن جفاف جنوب غرب الولايات المتحدة 2020-2021 (فريق عمل الجفاف NOAA، MAPP وNIDIS، 2021).

- ماكابي، ج. ج. وديتينجر، م. د. الأنماط الأساسية وقابلية التنبؤ بتغيرات تراكم الثلوج من سنة إلى أخرى في غرب الولايات المتحدة من خلال الروابط البعيدة مع مناخ المحيط الهادئ. مجلة الأرصاد الهيدرولوجية 3، 13-25 (2002).

- زامبييري، م.، سكوكيمارّو، إ. وغوالدي، س. التأثير الأطلسي على تساقط الثلوج في الربيع فوق جبال الألب في الـ 150 سنة الماضية. رسائل البحث البيئي 8، 034026 (2013).

- ديزر، سي.، فيليبس، أ.، بوردت، ف. وتينغ، هـ. عدم اليقين في توقعات تغير المناخ: دور التباين الداخلي. ديناميات المناخ 38، 527-546 (2012).

- بارنيت، ت. ب. وآخرون. التغيرات التي تسببها الأنشطة البشرية في هيدرولوجيا غرب الولايات المتحدة. ساينس 319، 1080-1083 (2008).

- بيرس، د. و. وآخرون. نسب تأثيرات الإنسان على انخفاض غطاء الثلج في غرب الولايات المتحدة. مجلة المناخ 21، 6425-6444 (2008).

- نجفي، م. ر.، زويرس، ف. وجيليت، ن. نسبة انخفاض غطاء الثلج الربيعي الملحوظ في كولومبيا البريطانية إلى التغير المناخي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية. مجلة المناخ 30، 4113-4130 (2017).

- جونغ، د. آي.، سوشاما، ل. ونفيد خاليق، م. نسب تغييرات مكافئ مياه الثلج الربيعي (SWE) في نصف الكرة الشمالي إلى التأثيرات البشرية. ديناميكا المناخ 48، 3645-3658 (2017).

- مانكين، ج. س. وديفنباخ، ن. س. تأثير تقلبات درجة الحرارة وهطول الأمطار على اتجاهات الثلوج على المدى القريب. ديناميات المناخ 45، 1099-1116 (2015).

- مانكين، ج. س.، لينهار، ف.، كواتس، س. ومككينون، ك. أ. قيمة مجموعات الظروف الأولية الكبيرة في اتخاذ قرارات التكيف القوية. مستقبل الأرض 8، e2012EF001610 (2020).

- لينر، ف. وآخرون. تقسيم عدم اليقين في توقعات المناخ باستخدام مجموعات كبيرة متعددة وCMIP5/6. ديناميات نظام الأرض 11، 491-508 (2020).

- مودريك، ل. وآخرون. اتجاهات تغطية الثلوج التاريخية في نصف الكرة الشمالي والتغيرات المتوقعة في مجموعة النماذج المتعددة CMIP6. الغلاف الجليدي 14، 2495-2514 (2020).

- ديفنباخ، ن. س.، شيرر، م. وآشفاق، م. استجابة الظواهر الهيدرولوجية المعتمدة على الثلوج للاحتباس الحراري المستمر. نات. مناخ. تغيير 3، 379-384 (2013).

- كوكي، ك.، رايسانين، ب.، لوجيوس، ك.، لوومارانت، أ. & ريهلا، أ. تقييم مكافئ مياه الثلج في نصف الكرة الشمالي في نماذج CMIP6 خلال 1982-2014. كرايو سفير 16، 1007-1030 (2022).

- Guo، R.، Deser، C.، Terray، L. & Lehner، F. التأثير البشري على اتجاهات هطول الأمطار الشتوية (1921-2015) في أمريكا الشمالية وأوراسيا كما يكشف عنه التعديل الديناميكي. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 46، 3426-3434 (2019).

مقالة

- أو’غورمان، ب. أ. استجابات متباينة للثلوج المتوسطة والقصوى لتغير المناخ. ناتشر 512، 416-418 (2014).

- براون، ر. د. وموت، ب. و. استجابة غطاء الثلج في نصف الكرة الشمالي لتغير المناخ. مجلة المناخ 22، 2124-2145 (2009).

- تشين، سي. وزانغ، إكس. التأثيرات البشرية على التغيرات في موسم درجة الحرارة في المناطق الأرضية ذات العرض الجغرافي المتوسط إلى العالي. مجلة المناخ 28، 5908-5921 (2015).

- غودموندسون، ل.، سيني فيراتني، س. إ. وزانغ، إكس. تم الكشف عن تغير المناخ الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية في موارد المياه العذبة المتجددة في أوروبا. نات. مناخ. تغيير 7، 813-816 (2017).

- بادرو، ر. س. وآخرون. التغيرات الملحوظة في توفر المياه خلال موسم الجفاف المنسوبة إلى تغير المناخ الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية. نات. جيوسي. 13، 477-481 (2020).

- جرانت، ل. وآخرون. نسب تغير أنظمة البحيرات العالمية إلى التأثيرات البشرية. نات. جيوسي. 14، 849-854 (2021).

- أباتزوجلو، ج. ت. وويليامز، أ. ب. تأثير التغير المناخي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية على حرائق الغابات في غابات غرب الولايات المتحدة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 113، 11770-11775 (2016).

- ويليامز، أ. ب.، كوك، ب. آي. وسمر دون، ج. إي. التعزيز السريع للجفاف الكبير الناشئ في جنوب غرب أمريكا الشمالية في 2020-2021. نات. مناخ. تغيير 12، 232-234 (2022).

- ياو، ف. وآخرون. الأقمار الصناعية تكشف عن تراجع واسع النطاق في تخزين مياه البحيرات العالمية. ساينس 380، 743-749 (2023).

- ديفنباخ، ن. س.، دافنبورت، ف. ف. وبورك، م. الاحترار التاريخي زاد من خسائر تأمين المحاصيل في الولايات المتحدة. رسائل البحث البيئي 16، 084025 (2021).

- كالاهان، سي. دبليو. ومانكين، جي. إس. النسبة الوطنية للأضرار المناخية التاريخية. تغير المناخ 172، 40 (2022).

- موت، ب. و.، لي، س.، ليتنماير، د. ب.، شياو، م. و إنجل، ر. انخفاضات دراماتيكية في غطاء الثلج في غرب الولايات المتحدة. npj علوم المناخ والغلاف الجوي 1، 2 (2018).

- مارتي، سي.، تيلغ، أ.-م. وجوناس، تي. أدلة حديثة على تراجع كبير في مكافئات مياه الثلوج في جبال الألب الأوروبية. مجلة الأرصاد الهيدرولوجية 18، 1021-1031 (2017).

- بوليغينا، أ. ن.، غروسمان، ب. ي.، رازوفاييف، ف. ن. وكورشونوفا، ن. ن. التغيرات في خصائص غطاء الثلج في شمال أوراسيا منذ عام 1966. رسائل البحث البيئي 6، 045204 (2011).

- جاين، س. وآخرون. أهمية التباين الداخلي لتقييم نماذج المناخ. npj علوم المناخ والغلاف الجوي 6، 68 (2023).

- مانكين، ج. س. وآخرون. تأثير التباين الداخلي على تعرض السكان للتغيرات الهيدرولوجية المناخية. رسائل البحث البيئي 12، 044007 (2017).

- بنتنجا، ر. وسيلتن، ف. م. الزيادات المستقبلية في هطول الأمطار في القطب الشمالي مرتبطة بالتبخر المحلي وتراجع الجليد البحري. ناتشر 509، 479-482 (2014).

- هوكينز، إ. وسوتون، ر. الإمكانية لتقليل عدم اليقين في توقعات تغير هطول الأمطار الإقليمية. ديناميات المناخ 37، 407-418 (2011).

- جينينغز، ك. س.، وينشيل، ت. س.، ليفنيه، ب. ومولوتش، ن. ب. التباين المكاني لعتبة درجة حرارة المطر-الثلج عبر نصف الكرة الشمالي. نات. كوم. 9، 1148 (2018).

- سيريز، م. س. وبارى، ر. ج. عمليات وتأثيرات تعزيز القطب الشمالي: تجميع بحثي. تغييرات كوكب الأرض 77، 85-96 (2011).

- أحواض الأنهار الكبرى في العالم (المعهد الفيدرالي للهيدرولوجيا، 2020).

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

بيانات

لأغراض النسبة المستندة إلى نماذج المناخ وإعادة البناء المستندة إلى الملاحظات، نقوم بإعادة توزيع جميع البيانات إلى

منطقة خلية الشبكة (بالـ

نسبة اتجاهات SWE إلى التأثيرات البشرية

إعادة بناء الثلوج المعتمدة على الملاحظات

افتراضات حول عتبات درجة الحرارة لتقسيم الأمطار والثلوج أو ذوبان الثلوج، والتي يمكن أن تختلف بشكل كبير في المكان وتساهم هي نفسها في عدم اليقين في التقديرات النموذجية للثلج المائي.

إعادة بناء غطاء الثلج الافتراضي

التاريخية. ثم يتم تجميع هذه الإعادات الافتراضية بشكل مشابه إلى مستوى الحوض ويتم حساب الاتجاهات الخطية في SWE لهذه السيناريوهات الافتراضية باستخدام مقدر Theil-Sen. يتم حساب تأثير التغيرات القسرية في درجة الحرارة والهطول بشكل فردي (الشكل 3c، d) ومجتمعة (الشكل 3e) كفرق بين كل اتجاه تاريخي والاتجاهات الافتراضية بناءً على نفس مجموعة بيانات SWE-درجة الحرارة-الهطول. لكل من 120 عضوًا في مجموعة إعادة البناء، لدينا 101 تقدير للتأثير الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية (واحد من كل تحقيق لنموذج المناخ؛ الجدول التوضيحي 2)، بإجمالي 12,120 تقدير لكل حوض. باستخدام فقط أول تحقيق من كل نموذج مناخ، بدلاً من جميع الجولات المتاحة، ينتج نتائج متطابقة تقريبًا (الشكل التوضيحي 6).

لاختبار صحة هذا النهج بشكل أكبر باستخدام التغيرات القسرية في درجة الحرارة والهطول لتقدير SWE الافتراضي، نكرر هذا البروتوكول باستخدام مخرجات نموذج المناخ فقط في إطار ‘نموذج مثالي’. لكل نموذج، نقوم بتناسب النموذج التجريبي الموصوف في المعادلة (1) باستخدام بيانات SWE ودرجة الحرارة والهطول من محاكاة CMIP6 HIST على مدى فترة 1981-2020، بدلاً من الملاحظات. ثم، نستخدم الغابة العشوائية المدربة على هذه البيانات HIST للتنبؤ بـ SWE الافتراضي باستخدام درجة الحرارة والهطول من محاكاة HIST-NAT. أخيرًا، نقارن الاتجاهات القسرية (HIST ناقص HIST-NAT) المحسوبة من نهج إعادة البناء مع الاتجاهات القسرية ‘الحقيقية’ المحسوبة باستخدام المخرجات المباشرة لـ SWE من تجارب نموذج المناخ HIST و HIST-NAT (الشكل التوضيحي 9 والشكل التوضيحي 7). تشير الشبه القوي في أنماط الاستجابات القسرية ‘الحقيقية’ والمعاد بناؤها إلى أن استخدام الملاحظات مع إزالة التغيرات القسرية في درجة الحرارة والهطول ينتج تقديرات معقولة لتغير SWE القسري.

تقدير عدم اليقين

لقياس حجم عدم اليقين الذي تسببه كل مصدر، نقوم بحساب الانحراف المعياري لاتجاهات SWE المفروضة عبر بعد واحد، مع الاحتفاظ بجميع الأبعاد الأخرى عند متوسطها. على سبيل المثال، يتم إعطاء عدم اليقين الناتج عن الاختلافات في هيكل النموذج من خلال الانحراف المعياري لاتجاهات SWE المفروضة عبر 12 نموذج مناخي (مع الأخذ في الاعتبار فقط التجربة الأولى من كل منها)، مع أخذ المتوسط عبر جميع مجموعات بيانات SWE-درجة الحرارة-الهطول.

لعزل عدم اليقين عن التباين الداخلي في درجة الحرارة وهطول الأمطار، نستخدم 50 زوجًا من محاكاة HIST وHIST-NAT من نموذج MIROC6.

متسق مع الأعمال السابقة في تقسيم عدم اليقين

في كل حوض، نأخذ في الاعتبار عدم اليقين النسبي لكل واحد (على سبيل المثال،

حساسية الثلج لدرجة الحرارة

تغيرات جريان المياه الناتجة عن تراكم الثلوج

تغيرات الثلوج المستقبلية وتدفق المياه

الفرق بين مناخ نهاية القرن والمناخ التاريخي (1981-2020) من نماذج المناخ. نقوم بتعديل درجة الحرارة بشكل إضافي ونعدل هطول الأمطار بناءً على النسبة المئوية للتغير بين المناخ التاريخي والمناخ المستقبلي. ثم نقوم بعمل توقعات لغطاء الثلوج المناخي المستقبلي باستخدام البيانات المعدلة والنموذج الموصوف في المعادلة (1) المدرب على البيانات التاريخية.

هيمنة الثلج

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

45. مونييز-ساباتر، ج. وآخرون. ERA5-Land: مجموعة بيانات إعادة تحليل عالمية متطورة لتطبيقات الأراضي. بيانات علوم الأرض 13، 4349-4383 (2021).

46. كوباياشي، س. وآخرون. إعادة تحليل JRA-55: المواصفات العامة والخصائص الأساسية. مجلة جمعية الأرصاد الجوية اليابانية السلسلة الثانية 93، 5-48 (2015).

47. جيلارو، ر. وآخرون. التحليل الرجعي لعصر الحديث للأبحاث والتطبيقات، النسخة 2 (MERRA-2). مجلة المناخ 30، 5419-5454 (2017).

48. لوجوس، ك. وآخرون. مبادرة تغير المناخ الثلجي ESA (Snow_cci): حزمة بيانات البحث المناخي العالمية اليومية لمستوى 3 من مكافئ المياه الثلجية (SWE) (1979-2020)، الإصدار 2.0. مركز تحليل بيانات البيئة NERC EDS.https://doi.org/10.5285/4647cc9a d3c044439d6c643208d3c494 (2022).

49. أباتزوجلو، ج. ت.، دوبروفسكي، س. ز.، باركس، س. أ. وهيغويش، ك. س. تيرا كلمايت، مجموعة بيانات عالمية عالية الدقة عن المناخ الشهري وتوازن المياه المناخي من 1958-2015. بيانات علمية 5، 170191 (2018).

50. شبكة قياس الثلوج (SNOTEL) (خدمة الحفاظ على الموارد الطبيعية التابعة لوزارة الزراعة الأمريكية، 2022).

51. فيونيت، ف.، مورتيمر، س.، برادي، م.، أرنال، ل. وبراون، ر. مجموعة بيانات مكافئ المياه الثلجية التاريخية الكندية (CanSWE، 1928-2020). بيانات علوم الأرض 13، 4603-4619 (2021).

52. فونترودونا-باخ، أ.، شيفلي، ب.، وودز، ر.، تويلينغ، أ. ج. ولارسون، ج. ر. NH-SWE: مجموعة بيانات مكافئ مياه الثلج في نصف الكرة الشمالي استنادًا إلى سلسلة زمنية لعمق الثلج في الموقع. بيانات علوم الأرض 15، 2577-2599 (2023).

53. هيرسباخ، هـ. وآخرون. إعادة التحليل العالمية ERA5. مجلة الجمعية الملكية للأرصاد الجوية 146، 1999-2049 (2020).

54. شنايدر، يو. وآخرون. إعادة تحليل بيانات GPCC الكاملة النسخة 6.0 في

55. بيك، هـ. إ. وآخرون. MSWEP V2 العالمية كل 3 ساعات

56. روهدي، ر. أ. وهاوسفاذر، ز. سجل درجات حرارة الأرض/المحيط في بيركلي. بيانات علوم الأرض 12، 3469-3479 (2020).

57. درجة الحرارة الموحدة العالمية من CPC. مركز التنبؤ بالمناخ NOAA (2023).

58. هاريغان، س. وآخرون. إعادة تحليل تصريف الأنهار العالمية التشغيلية GloFAS-ERA5 من 1979 حتى الآن. بيانات علوم الأرض 12، 2043-2060 (2020).

59. جيلت، ن. ب. وآخرون. مشروع المقارنة بين نماذج الكشف والنسب (DAMIP v1.0) كإسهام في CMIP6. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 9، 3685-3697 (2016).

60. الكثافة السكانية الموزعة للعالم، الإصدار 4 (GPWv4): عدد السكان (مركز بيانات وتطبيقات العلوم الاجتماعية التابع لناسا، 2016);https://doi.org/10.7927/H4X63JVC.

61. غيغي، ج.، همفري، ف.، سيني فيراتني، س. إ. وغودموندسون، ل. GRUN: مجموعة بيانات تصريف عالمية مبنية على الملاحظات من 1902 إلى 2014. بيانات علوم الأرض 11، 1655-1674 (2019).

62. فوجل، إ. وآخرون. آثار الظروف المناخية المتطرفة على غلات الزراعة العالمية. رسائل البحث البيئي 14، 054010 (2019).

63. لويلر، ج. ج.، وايت، د.، نيلسون، ر. ب. وبلستين، أ. ر. التنبؤ بالتحولات في النطاق الناتجة عن المناخ: اختلافات النماذج وموثوقية النماذج. التغير العالمي في البيولوجيا 12، 1568-1584 (2006).

64. كيم، ر. س. وآخرون. مشروع عدم اليقين في تجميع الثلوج (SEUP): قياس عدم اليقين في مكافئ مياه الثلوج عبر أمريكا الشمالية من خلال نمذجة سطح الأرض الجماعية. كريوسفير 15، 771-791 (2021).

65. كومي، د.، روبنسون، أ. ورامشتورف، س. زيادة عالمية في درجات الحرارة الشهرية القياسية. تغير المناخ 118، 771-782 (2013).

66. رحمتسورف، س. وكومو، د. زيادة الأحداث المتطرفة في عالم دافئ. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 108، 17905-17909 (2011).

67. زوموالد، م. وآخرون. فهم وتقييم عدم اليقين في مجموعات بيانات المناخ الملاحظة لتقييم النماذج باستخدام التجميعات. وايلي إنتر ديسبلين. ريف. مناخ. تغيير 11، e654 (2020).

68. تاتيب، هـ. وآخرون. وصف وتقييم أساسي للحالة المتوسطة المحاكية، والتنوع الداخلي، وحساسية المناخ في MIROC6. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 12، 2727-2765 (2019).

69. هوكينز، إ. وسوتون، ر. الإمكانية لتقليل عدم اليقين في توقعات المناخ الإقليمي. نشرة الجمعية الأمريكية للأرصاد الجوية 90، 1095-1108 (2009).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى ألكسندر ر. غوتليب. تشكر مجلة نيتشر جونى بوليائين، وريان ويب، والمراجعين الآخرين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة الأقران لهذا العمل. تقارير مراجعي الأقران متاحة.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

متوسط الاتجاه عبر جميع المنتجات الخمسة. تم تظليل خلايا الشبكة حيث تتفق أقل من 4 منتجات على اتجاه العلامة. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام cartopy v0.18.0.

شمال أوراسيا. أ-ك، الاتجاه في مارس SWE من 1981 إلى 2020 من محاكاة نماذج المناخ التاريخية. يمكن العثور على تفاصيل النماذج في البيانات الموسعة.

النقطة تمثل حوض نهر. الخط المتقطع يدل على إعادة البناء المثالية. يتم عرض معامل ارتباط بيرسون في الزاوية السفلى اليمنى. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام cartopy v0.18.0. تأتي حدود أحواض الأنهار من قاعدة بيانات مراكز بيانات الجريان العالمي للأحواض الكبرى في العالم.

مقالة

القيم المستمدة من ذلك المنتج. تُظهر الإضافات توزيع المهارات عبر الأحواض، مع وجود الخط الأحمر والقيمة التي تشير إلى الوسيط. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام cartopy v0.18.0. تأتي حدود أحواض الأنهار من قاعدة بيانات المراكز العالمية لتدفق المياه حول الأنهار الكبرى في العالم.

رسم بياني متفرق للاتجاهات المعاد بناؤها مقابل الاتجاهات المرصودة، حيث يمثل كل نقطة موقعًا في الموقع. يتم تلوين النقاط حسب كثافتها. الخط المنقط يدل على التوافق التام بين الاتجاهات المعاد بناؤها والاتجاهات المرصودة. يتم عرض معامل ارتباط بيرسون في الزاوية السفلى اليمنى. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام cartopy v0.18.0.

اتجاهات متوسط مجموعة CMIP6 المفروضة (HIST ناقص HIST-NAT) في SWE لشهر مارس من 1981-2020 بناءً على (أ) مخرجات نموذج المناخ لـ SWE و (ب) SWE المقدرة باستخدام درجة حرارة وهطول الأمطار من نموذج المناخ ونموذج الغابة العشوائية.

c، مخطط تشتت للاتجاهات المعاد بناؤها مقابل الاتجاهات الأصلية، حيث يمثل كل نقطة خلية شبكية. يتم تلوين النقاط حسب كثافتها. الخط المنقط يدل على التوافق التام بين الاتجاهات المعاد بناؤها والاتجاهات الأصلية. يتم عرض الارتباط المكاني في الزاوية السفلى اليمنى.

مقالة

الاتجاهات، حيث يمثل كل نقطة حوضًا. الخط المتقطع يدل على التوافق التام بين الاتجاهات المعاد بناؤها والملاحظة. يتم عرض الارتباط المكاني في الجهة اليسرى الوسطى. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام cartopy v0.18.0. تأتي حدود أحواض الأنهار من قاعدة بيانات المراكز العالمية لتدفق المياه حول العالم.

| مجموعة بيانات | نوع مجموعة البيانات | قرار | سنوات |

| مكافئ مياه الثلج | |||

| سنو تيل | في الموقع | نقطة (

|

1977-حتى الآن |

| CanSWE | في الموقع | نقطة (

|

1928-2020 |

| NH-SWE | في الموقع (عمق الثلج المحول إلى SWE) | نقطة (

|

1950-2020 |

| ERA5-Land* | إعادة تحليل |

|

1950-الحاضر |

| JRA-55* | إعادة تحليل |

|

1958-حتى الآن |

| ميرا-2* | إعادة تحليل |

|

1981-حتى الآن |

| ثلج-CCI | الاستشعار عن بُعد السلبي + في الموقع |

|

1981-الحاضر |

| تيرا كلمايت* | نموذج توازن المياه الملاحظ T&P + |

|

1958-حتى الآن |

| هطول | |||

| ERA5 | إعادة تحليل |

|

1980-الحاضر |

| GPCC | مقياس متداخل |

|

1891-حتى الآن |

| ميرا-2 | إعادة تحليل |

|

1981-حتى الآن |

| MSWEP | الدمج بين الأقمار الصناعية/المقياس |

|

1979-حتى الآن |

| تيرا كلمايت | مقياس/إعادة تحليل مدمج |

|

1958-حتى الآن |

| درجة الحرارة | |||

| بيركلي إيرث (بيست) | مُتداخل في الموقع |

|

1753-الحاضر |

| مركز توقعات المناخ (CPC) | مُتداخِل في الموقع |

|

1979-حتى الآن |

| ERA5 | إعادة تحليل |

|

1979-حتى الآن |

| ميرا-2 | إعادة تحليل |

|

1981-حتى الآن |

مقالة

البيانات الموسعة الجدول 2 | ملخص نماذج CMIP6 المستخدمة في التحليل

| اسم الطراز | مركز النمذجة | قرار | الإنجازات (#) | ||

| ACCESS-CM2 | منظمة الكومنولث للبحوث العلمية والصناعية |

|

ر[1-3]ي1ب1ف1 (3) | ||

| ACCESS-ESM1-5 | منظمة الكومنولث للبحوث العلمية والصناعية |

|

ر[1-3]ي1ب1ف1 (3) | ||

| بي سي سي – سي إس إم 2 – إم آر | مركز بكين للمناخ |

|

ر1ي1ب1ف1 (1) | ||

| CNRM-CM6-1 |

|

|

ر1ي1ب1ف2 (1) | ||

| CanESM5 | المركز الكندي لنمذجة المناخ والتحليل |

|

ر[1-25]ي1ب1ف1 (25) | ||

| FGOALS-g3* | المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للنمذجة العددية لعلوم الغلاف الجوي والديناميكا المائية الجيولوجية |

|

ر1ي1ب1ف1 (1) | ||

| جي إف دي إل – سي إم 4 | مختبر ديناميات السوائل الجيوفيزيائية |

|

r1[i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| جي إف دي إل – إي إس إم 4 | مختبر ديناميات السوائل الجيوفيزيائية |

|

r[1-3]i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | معهد بيير-سيمون لابلاس |

|

ر[1-2، 4-6]ي1ب1ف1 (5) | ||

| MIROC6 | المركز الدولي لمحاكاة الأرض |

|

r[1-50]i1p1f1 (50) | ||

| إم آر آي – إي إس إم 2 – 0 | معهد الأبحاث الجوية |

|

ر[1-5]ي1ب1ف1 (5) | ||

| نورESM2-LM | المركز النرويجي للمناخ |

|

ر[1-3]ي1ب1ف1 (3) |

برنامج الدراسات العليا في علم البيئة، التطور، البيئة والمجتمع، كلية دارتموث، هانوفر، نيوهامبشير، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الجغرافيا، كلية دارتموث، هانوفر، نيوهامبشير، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الأرض، كلية دارتموث، هانوفر، نيوهامبشير، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم فيزياء المحيطات والمناخ، مرصد لامونت-دوهرتي للأرض، جامعة كولومبيا، نيويورك، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: alexander.r.gottlieb.gr@dartmouth.edu - *تشير إلى منتج SWE المستخدم في الشكل 1.

- *لا توجد بيانات مكافئة لمياه الثلوج الشهرية من تشغيل التحكم ما قبل الصناعية المؤرشفة.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06794-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200299

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

Evidence of human influence on Northern Hemisphere snow loss

Received: 2 March 2023

Accepted: 24 October 2023

Published online: 10 January 2024

Open access

Abstract

Documenting the rate, magnitude and causes of snow loss is essential to benchmark the pace of climate change and to manage the differential water security risks of snowpack declines

Northern Hemisphere, but snowpack trends are not. a,b, Agreement across observational products (Supplementary Table 1) on the sign of trends in November-March average temperature (winter

snowpack and the runoff it generates will respond to additional warming. Together, our results provide a thorough documentation of the historical and future effects of climate change on snow water storage.

A forced signal in snowpack observations

spring snowpacks, with in situ observations indicating a deepening of over 20% per decade in the Northern Great Plains and parts of Siberia, whereas gridded products indicate more modest increases of 5% to 10% per decade. Snow-dominated regions that lack in situ observations, such High Mountain Asia and the Tibetan Plateau, show weak trends in the gridded observational ensemble mean (Fig. 2b), which belie directionally inconsistent trends in individual data products (Fig.1b,e and Extended Data Fig. 1).

simulations and each observational (OBS) SWE product (see legend). The grey histogram indicates the empirical probability density function of spatial correlations between trends from the historical simulations and all possible 40-year trends from unforced pre-industrial control (PIC) simulations (

exclude anthropogenic emissions fail to capture the observed pattern of snow change (Fig. 2d).

trends in each observational dataset with those from the ensemble mean of two different climate experiments: the HIST simulations (red symbols in Fig. 2e), representing historical anthropogenic forcing and the historical-nat, or HIST-NAT, simulations (blue symbols in Fig. 2e), representing a historical climate without human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, we compare the observed correlations to the null distribution to calculate the probability that the degree of similarity between the observations and HIST and HIST-NAT simulations could have arisen from natural variability.

Article

River-basin-scale snowpack changes

the southwestern USA and Europe, in agreement with the long-term trends from in situ SWE measurements there

trend and the reconstructed trend with forced changes to temperature removed.

of forced response-over climate model structural differences and observational uncertainty in SWE, temperature and precipitationin roughly one in eight basins (Extended Data Fig. 7).

both the greater model uncertainty in precipitation and the larger contribution of internal variability to hydroclimate uncertainty

Nonlinear sensitivity of snow to warming

population in

defining the relationshipbetween climatological temperatures and snow sensitivity (Fig. 4a).

storage across the Northern Hemisphere (for example, Fig. 1). It also makes clear why we should expect snow losses to rapidly accelerate, with widespread water security consequences (Fig. 4b).

Examining the shape of the relationship between average winter temperatures and the marginal sensitivity of snow change to temperature change clarifies why snow detection has been elusive so far and why even modest levels of warming suggest much sharper snow declines to come (Fig. 4a). The responsiveness of snow to

Managing and leveraging snow uncertainty

Online content

- Barnett, T. P., Adam, J. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature 438, 303-309 (2005).

- Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature 577, 364-369 (2020).

- Mankin, J. S., Viviroli, D., Singh, D., Hoekstra, A. Y. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. The potential for snow to supply human water demand in the present and future. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 114016 (2015).

- Qin, Y. et al. Agricultural risks from changing snowmelt. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 459-465 (2020).

- Gottlieb, A. R. & Mankin, J. S. Observing, measuring, and assessing the consequences of snow drought. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, E1041-E1060 (2022).

- Mortimer, C. et al. Evaluation of long-term Northern Hemisphere snow water equivalent products. Cryosphere 14, 1579-1594 (2020).

- Fox-Kemper B. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1211-1362 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Williams, A. P. et al. Large contribution from anthropogenic warming to an emerging North American megadrought. Science 368, 314-318 (2020).

- Mankin, J. S. et al. NOAA Drought Task Force Report on the 2020-2021 Douthwestern US Drought (NOAA Drought Task Force, MAPP and NIDIS, 2021).

- McCabe, G. J. & Dettinger, M. D. Primary modes and predictability of year-to-year snowpack variations in the western United States from teleconnections with Pacific Ocean climate. J. Hydrometeorol. 3, 13-25 (2002).

- Zampieri, M., Scoccimarro, E. & Gualdi, S. Atlantic influence on spring snowfall over the Alps in the past 150 years. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034026 (2013).

- Deser, C., Phillips, A., Bourdette, V. & Teng, H. Uncertainty in climate change projections: the role of internal variability. Clim. Dyn. 38, 527-546 (2012).

- Barnett, T. P. et al. Human-induced changes in the hydrology of the western United States. Science 319, 1080-1083 (2008).

- Pierce, D. W. et al. Attribution of declining western U.S. snowpack to human effects. J. Clim. 21, 6425-6444 (2008).

- Najafi, M. R., Zwiers, F. & Gillett, N. Attribution of the observed spring snowpack decline in British Columbia to anthropogenic climate change. J. Clim. 30, 4113-4130 (2017).

- Jeong, D. I., Sushama, L. & Naveed Khaliq, M. Attribution of spring snow water equivalent (SWE) changes over the Northern Hemisphere to anthropogenic effects. Clim. Dyn. 48, 3645-3658 (2017).

- Mankin, J. S. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Influence of temperature and precipitation variability on near-term snow trends. Clim. Dyn. 45, 1099-1116 (2015).

- Mankin, J. S., Lehner, F., Coats, S. & McKinnon, K. A. The value of initial condition large ensembles to robust adaptation decision-making. Earths Future 8, e2012EF001610 (2020).

- Lehner, F. et al. Partitioning climate projection uncertainty with multiple large ensembles and CMIP5/6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 491-508 (2020).

- Mudryk, L. et al. Historical Northern Hemisphere snow cover trends and projected changes in the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble. Cryosphere 14, 2495-2514 (2020).

- Diffenbaugh, N. S., Scherer, M. & Ashfaq, M. Response of snow-dependent hydrologic extremes to continued global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 379-384 (2013).

- Kouki, K., Räisänen, P., Luojus, K., Luomaranta, A. & Riihelä, A. Evaluation of Northern Hemisphere snow water equivalent in CMIP6 models during 1982-2014. Cryosphere 16, 1007-1030 (2022).

- Guo, R., Deser, C., Terray, L. & Lehner, F. Human influence on winter precipitation trends (1921-2015) over North America and Eurasia revealed by dynamical adjustment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 3426-3434 (2019).

Article

- O’Gorman, P. A. Contrasting responses of mean and extreme snowfall to climate change. Nature 512, 416-418 (2014).

- Brown, R. D. & Mote, P. W. The response of Northern Hemisphere snow cover to a changing climate. J. Clim. 22, 2124-2145 (2009).

- Qian, C. & Zhang, X. Human influences on changes in the temperature seasonality in midto high-latitude land areas. J. Clim. 28, 5908-5921 (2015).

- Gudmundsson, L., Seneviratne, S. I. & Zhang, X. Anthropogenic climate change detected in European renewable freshwater resources. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 813-816 (2017).

- Padrón, R. S. et al. Observed changes in dry-season water availability attributed to humaninduced climate change. Nat. Geosci. 13, 477-481 (2020).

- Grant, L. et al. Attribution of global lake systems change to anthropogenic forcing. Nat. Geosci. 14, 849-854 (2021).

- Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11770-11775 (2016).

- Williams, A. P., Cook, B. I. & Smerdon, J. E. Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020-2021. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 232-234 (2022).

- Yao, F. et al. Satellites reveal widespread decline in global lake water storage. Science 380, 743-749 (2023).

- Diffenbaugh, N. S., Davenport, F. V. & Burke, M. Historical warming has increased U.S. crop insurance losses. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 084025 (2021).

- Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. National attribution of historical climate damages. Climatic Change 172, 40 (2022).

- Mote, P. W., Li, S., Lettenmaier, D. P., Xiao, M. & Engel, R. Dramatic declines in snowpack in the western US. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 2 (2018).

- Marty, C., Tilg, A.-M. & Jonas, T. Recent evidence of large-scale receding snow water equivalents in the European Alps. J. Hydrometeorol. 18, 1021-1031 (2017).

- Bulygina, O. N., Groisman, P. Y., Razuvaev, V. N. & Korshunova, N. N. Changes in snow cover characteristics over northern Eurasia since 1966. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 045204 (2011).

- Jain, S. et al. Importance of internal variability for climate model assessment. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 68 (2023).

- Mankin, J. S. et al. Influence of internal variability on population exposure to hydroclimatic changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 044007 (2017).

- Bintanja, R. & Selten, F. M. Future increases in Arctic precipitation linked to local evaporation and sea-ice retreat. Nature 509, 479-482 (2014).

- Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. The potential to narrow uncertainty in projections of regional precipitation change. Clim. Dyn. 37, 407-418 (2011).

- Jennings, K. S., Winchell, T. S., Livneh, B. & Molotch, N. P. Spatial variation of the rain-snow temperature threshold across the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 9, 1148 (2018).

- Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: a research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85-96 (2011).

- GRDC Major River Basins of the World (Federal Institute of Hydrology, 2020).

© The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Data

For the climate-model-based attribution and observation-based reconstructions, we regrid all data to

by the grid cell area (in

Attributing SWE trends to anthropogenic forcing

Observation-based snow reconstructions

assumptions about temperature thresholds for rain-snow partitioning or snowmelt, which can vary substantially in space and are themselves a contributor to uncertainty in modelled estimates of SWE

Counterfactual snowpack reconstructions

historical values. These gridded counterfactual reconstructions are then similarly aggregated to the basin scale and linear trends in SWE for these counterfactual scenarios are calculated using the Theil-Sen estimator. The effect of forced changes to temperature and precipitation individually (Fig. 3c,d) and in combination (Fig. 3e) is calculated as the difference between each historical trend and the counterfactual trends based on the same SWE-temperature-precipitation dataset combination. For each of the 120 reconstruction ensemble members, we have 101 estimates of the anthropogenic effect (one from each climate model realization; Extended Data Table 2), for a total of 12,120 estimates for each basin. Using only the first realization from each climate model, rather than all available runs, produces nearly identical results (Supplementary Fig. 6).

To further test the validity of this approach of using forced changes in temperature and precipitation to estimate counterfactual SWE, we repeat this protocol using exclusively climate model output in a ‘perfect model’ framework. For each model, we fit the empirical model described in equation (1) using SWE, temperature and precipitation data from the CMIP6 HIST simulations over the 1981-2020 period, rather than observations. Then, we use the random forest trained on these HIST data to predict counterfactual SWE using temperature and precipitation from the HIST-NAT simulations. Finally, we compare the forced (HIST minus HIST-NAT) trends calculated from the reconstruction approach to the ‘true’ forced trends calculated by using the direct SWE output from the HIST and HIST-NAT climate model experiments (Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 7). The strong similarity in the patterns of the ‘true’ and reconstructed forced responses indicates that using observations with forced changes in temperature and precipitation removed produces reasonable estimates of a forced SWE change.

Uncertainty quantification

To quantify the magnitude of uncertainty introduced by each source, we calculate the standard deviation of forced SWE trends across a single dimension, holding all others at their mean. For instance, the uncertainty due to differences in model structure is given by the standard deviation of forced SWE trends across the 12 climate models (considering only the first realization from each), taking the mean across all SWE-temperature-precipitation dataset combinations.

To isolate the uncertainty from internal variability in temperature and precipitation, we use 50 pairs of HIST and HIST-NAT simulations from the MIROC6 model

Consistent with previous work in uncertainty partitioning

in each basin, we consider the fractional uncertainty of each (for example,

Temperature sensitivity of snowpack

Snowpack-driven runoff changes

Future snowpack and runoff changes

difference between the end-of-century and historical (1981-2020) climate from the climate models. We additively adjust temperature and adjust precipitation by the percentage change between historical and future climate. We then make predictions of future climatological snowpack using the adjusted data and the model described in equation (1) trained on historical data.

Snow dominance

Data availability

Code availability

45. Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349-4383 (2021).

46. Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn Ser. II 93, 5-48 (2015).

47. Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419-5454 (2017).

48. Luojus, K. et al. ESA Snow Climate Change Initiative (Snow_cci): snow water equivalent (SWE) level 3 C daily global climate research data package (CRDP)(1979-2020), version 2.0. NERC EDS Centre for Environmental Data Analysis. https://doi.org/10.5285/4647cc9a d3c044439d6c643208d3c494 (2022).

49. Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a highresolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958-2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

50. Snowpack Telemetry Network (SNOTEL) (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2022).

51. Vionnet, V., Mortimer, C., Brady, M., Arnal, L. & Brown, R. Canadian historical Snow Water Equivalent dataset (CanSWE, 1928-2020). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4603-4619 (2021).

52. Fontrodona-Bach, A., Schaefli, B., Woods, R., Teuling, A. J. & Larsen, J. R. NH-SWE: Northern Hemisphere Snow Water Equivalent dataset based on in situ snow depth time series. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 2577-2599 (2023).

53. Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999-2049 (2020).

54. Schneider, U. et al. GPCC full data reanalysis version 6.0 at

55. Beck, H. E. et al. MSWEP V2 global 3-hourly

56. Rohde, R. A. & Hausfather, Z. The Berkeley Earth land/ocean temperature record. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3469-3479 (2020).

57. CPC Global Unified Temperature. NOAA Climate Prediction Center (2023).

58. Harrigan, S. et al. GloFAS-ERA5 operational global river discharge reanalysis 1979-present. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2043-2060 (2020).

59. Gillett, N. P. et al. The Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP v1.0) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3685-3697 (2016).

60. Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Count (NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center, 2016); https://doi.org/10.7927/H4X63JVC.

61. Ghiggi, G., Humphrey, V., Seneviratne, S. I. & Gudmundsson, L. GRUN: an observationbased global gridded runoff dataset from 1902 to 2014. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1655-1674 (2019).

62. Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054010 (2019).

63. Lawler, J. J., White, D., Neilson, R. P. & Blaustein, A. R. Predicting climate-induced range shifts: model differences and model reliability. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1568-1584 (2006).

64. Kim, R. S. et al. Snow Ensemble Uncertainty Project (SEUP): quantification of snow water equivalent uncertainty across North America via ensemble land surface modeling. Cryosphere 15, 771-791 (2021).

65. Coumou, D., Robinson, A. & Rahmstorf, S. Global increase in record-breaking monthlymean temperatures. Climatic Change 118, 771-782 (2013).

66. Rahmstorf, S. & Coumou, D. Increase of extreme events in a warming world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17905-17909 (2011).

67. Zumwald, M. et al. Understanding and assessing uncertainty of observational climate datasets for model evaluation using ensembles. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11, e654 (2020).

68. Tatebe, H. et al. Description and basic evaluation of simulated mean state, internal variability, and climate sensitivity in MIROC6. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 2727-2765 (2019).

69. Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. The potential to narrow uncertainty in regional climate predictions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 90, 1095-1108 (2009).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Alexander R. Gottlieb. Peer review information Nature thanks Jouni Pulliainen, Ryan Webb and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

f, Average trend across all 5 products. Grid cells where fewer than 4 products agree on the sign of the trend are hatched. Maps were generated using cartopy v0.18.0.

Northern Eurasia. a-k, Trend in March SWE from 1981 to 2020 from historical climate model simulations. Details of models can be found in Extended Data

dot represents a river basin. Dashed line denotes perfect reconstruction. Pearson’s correlation is shown in bottom right corner. Maps were generated using cartopy v0.18.0. River basin boundaries come from the Global Runoff Data Centre’s Major River Basins of the World database

Article

values from that product. Insets show the distribution of skill across basins, with the red line and value indicating the median. Maps were generated using cartopy v0.18.0. River basin boundaries come from the Global Runoff Data Centre’s Major River Basins of the World database

c, Scatterplot of reconstructed versus observed trends, where each dot represents an in situ location. Points are colored by their density. Dashed line denotes perfect agreement between reconstructed and observed trends. Pearson’s correlation is shown in bottom right corner. Maps were generated using cartopy v0.18.0.

CMIP6 ensemble mean forced (HIST minus HIST-NAT) trends in March SWE from 1981-2020 based on (a) climate model SWE output and (b) SWE estimated using climate model temperature and precipitation and Random Forest model.

c, Scatterplot of reconstructed versus original trends, where each dot represents a grid cell. Points are colored by their density. Dashed line denotes perfect agreement between reconstructed and original trends. Spatial correlation is shown in the bottom right corner.

Article

trends, where each dot represents a basin. Dashed line denotes perfect agreement between reconstructed and observed trends. Spatial correlation is shown in center left. Maps were generated using cartopy v0.18.0. River basin boundaries come from the Global Runoff Data Centre’s Major River Basins of the World database

| Dataset | Dataset Type | Resolution | Years |

| Snow Water Equivalent | |||

| SNOTEL | In situ | Point (

|

1977-present |

| CanSWE | In situ | Point (

|

1928-2020 |

| NH-SWE | In situ (snow depth converted to SWE) | Point (

|

1950-2020 |

| ERA5-Land* | Reanalysis |

|

1950-present |

| JRA-55* | Reanalysis |

|

1958-present |

| MERRA-2* | Reanalysis |

|

1981-present |

| Snow-CCI | Passive remote sensing + in situ |

|

1981-present |

| TerraClimate* | Observed T&P + water balance model |

|

1958-present |

| Precipitation | |||

| ERA5 | Reanalysis |

|

1980-present |

| GPCC | Interpolated gauge |

|

1891-present |

| MERRA-2 | Reanalysis |

|

1981-present |

| MSWEP | Merged satellite/gauge |

|

1979-present |

| TerraClimate | Merged gauge/reanalysis |

|

1958-present |

| Temperature | |||

| Berkeley Earth (BEST) | Interpolated in situ |

|

1753-present |

| Climate Prediction Center (CPC) | Interpolated in situ |

|

1979-present |

| ERA5 | Reanalysis |

|

1979-present |

| MERRA-2 | Reanalysis |

|

1981-present |

Article

Extended Data Table 2 | Summary of CMIP6 models used in the analysis

| Model Name | Modeling Center | Resolution | Realizations (#) | ||

| ACCESS-CM2 | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

|

r[1-3]i1p1f1 (3) | ||

| ACCESS-ESM1-5 | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

|

r[1-3]i1p1f1 (3) | ||

| BCC-CSM2-MR | Beijing Climate Center |

|

r1i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| CNRM-CM6-1 |

|

|

r1i1p1f2 (1) | ||

| CanESM5 | Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis |

|

r[1-25]i1p1f1 (25) | ||

| FGOALS-g3* | State Key Laboratory for Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Science and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics |

|

r1i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| GFDL-CM4 | Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory |

|

r1[i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| GFDL-ESM4 | Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory |

|

r[1-3]i1p1f1 (1) | ||

| IPSL-CM6A-LR | Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace |

|

r[1-2,4-6]i1p1f1 (5) | ||

| MIROC6 | International Centre for Earth Simulation |

|

r[1-50]i1p1f1 (50) | ||

| MRI-ESM2-0 | Meteorological Research Institute |

|

r[1-5]i1p1f1 (5) | ||

| NorESM2-LM | Norwegian Climate Center |

|

r[1-3]i1p1f1 (3) |

Graduate Program in Ecology, Evolution, Environment and Society, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA. Department of Geography, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA. Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA. Division of Ocean and Climate Physics, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. e-mail: alexander.r.gottlieb.gr@dartmouth.edu - *indicates SWE product used in Fig. 1.

- *No monthly snow water equivalent from the pre-industrial control run archived.