DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19580

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38382573

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-21

أصل وتنوع الأوركيديات

الملخص

ملخص

المؤلفون للتواصل: أوسكار أ. بيريز-إسكوبار البريد الإلكتروني:o.perez-escobar@kew.org

ويليام ج. بيكر البريد الإلكتروني:w.baker@kew.org

ألكسندر أنتونيللي البريد الإلكتروني:a.antonelli@kew.org

تاريخ الاستلام: 4 سبتمبر 2023 تاريخ القبول: 4 ديسمبر 2023

نباتات جديدة (2024) 242: 700-716 doi: 10.1111/nph.19580 – تشكل الأوركيد واحدة من أكثر الإشعاعات روعة بين النباتات المزهرة. ومع ذلك، فإن أصلها وانتشارها عبر العالم ونقاط التركيز في التنوع لا تزال غير مؤكدة بسبب نقص تحليل فيلوغرافي محدث. – نقدم شجرة عائلة الأوركيدية جديدة تعتمد على بيانات تسلسل عالية الإنتاجية وبيانات سونجر، تغطي جميع الفصائل الخمس، 17/22 قبيلة، 40/49 تحت قبيلة، 285/736 جنس، وحوالي 7% (1921) من 29524 نوع مقبول، ونستخدمها لاستنتاج تطور النطاق الجغرافي، والتنوع، وأنماط التنوع من خلال إضافة توزيعات جغرافية منظمة من قائمة النباتات الوعائية العالمية. – يُستنتج أن السلف المشترك الأكثر حداثة للأوركيد عاش في لوراسيا في أواخر العصر الطباشيري. يُفسر النطاق الحديث لفصيلة أوبستازيويد، التي تتكون من جنسين مع 16 نوعًا من الهند إلى شمال أستراليا، على أنه متبقي، مشابه للعديد من المجموعات الأخرى التي انقرضت في خطوط العرض العليا بعد التبريد المناخي العالمي خلال العصر الأيوسيني. على الرغم من أصلها القديم، فإن تنوع أنواع الأوركيد الحديثة نشأ بشكل رئيسي على مدى الـ 5 ملايين سنة الماضية، مع أعلى معدلات التنوع في بنما وكوستاريكا.

- تغير هذه النتائج فهمنا للأصل الجغرافي للأوركيديات، الذي تم اقتراحه سابقًا كأسترالي، وتحدد أمريكا الوسطى كمنطقة للتنوع البيولوجي السريع والحديث.

مقدمة

المواد والطرق

جمع العينات الضريبية، إعداد مكتبة الحمض النووي والتسلسل

إزالة السائل العلوي، أولاً لإزالة الإيزوبروبانول وثانياً لغسل راسب الحمض النووي

تم التقدير باستخدام مقياس الفلورية Quantus (Promega)، وتم تقدير توزيع حجم الشظايا باستخدام إما نظام TapeStation 4200 أو محلل البيولوجيا Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies، سانتا كلارا، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). أخيرًا، استخدمنا مجموعة مجسات Angiosperms353 لتغني هذه المكتبات الجينومية لـ 353 جين نووي منخفض النسخ (Johnson et al.، 2019)، مع تعديل التجميع المتساوي للمكتبات إلى مجموعات من

تحليل بيانات التسلسل عالي الإنتاجية وسلسلة سانجر

eye باستخدام Geneious v.8.0 (المتاحة على https://www.geneious.com/). المحاذاة النوكليوتيدية Sanger/Angiosperms353 متاحة على doi:

استنتاجات النشوء والتطور القائمة على المسافة، والاحتمالية القصوى، والبايزي، والتجمع المتعدد الأنواع

تحليلات تأريخ الساعة الجزيئية وتجميع النشوء والتطور على مستوى الأنواع

(1) تم استنتاج العمود الفقري عن طريق أخذ عينات فرعية من محاذاة الجينات النووية ذات النسخ المنخفضة Angiosperms353 باستخدام SortaDate v.1.0 (Smith et al., 2018). هنا، اخترنا أفضل 25 محاذاة جينات نووية ذات نسخ منخفضة مع أدنى معامل تباين من الجذر إلى الطرف (أي أعلى تشابه مع الساعة). ضمنت هذه الاختيار تمثيل التنوع الجنسي الكامل كما تم أخذ عينات من

مجموعة البيانات عالية الإنتاجية ML (أي 285 جنسًا؛ انظر الطرق S1؛ الجداول S3، S4). تم استيراد هذه المجموعة الفرعية من البيانات في Beauti v.2.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019) كأقسام غير مرتبطة، مع نفس الأولويات المستخدمة من قبل Pérez-Escobar et al. (2021a)، كما يلي: (1) نموذج استبدال النوكليوتيدات GTR ونموذج تباين المعدل بين المواقع تم نمذجته بواسطة توزيع

(2) تم إنتاج نشوء وتطور فوقي على مستوى الأنواع من Orchidaceae من خلال إدخال محاذاة ITS وmatK كأقسام غير مرتبطة في Beauti v.2.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019)، باستخدام نفس الأولويات كما في (1). علاوة على ذلك، تم استخدام شجرة توافق ML الناتجة في RAxML v.8.0 من مصفوفة ITS-matK الفائقة كشجرة بداية.

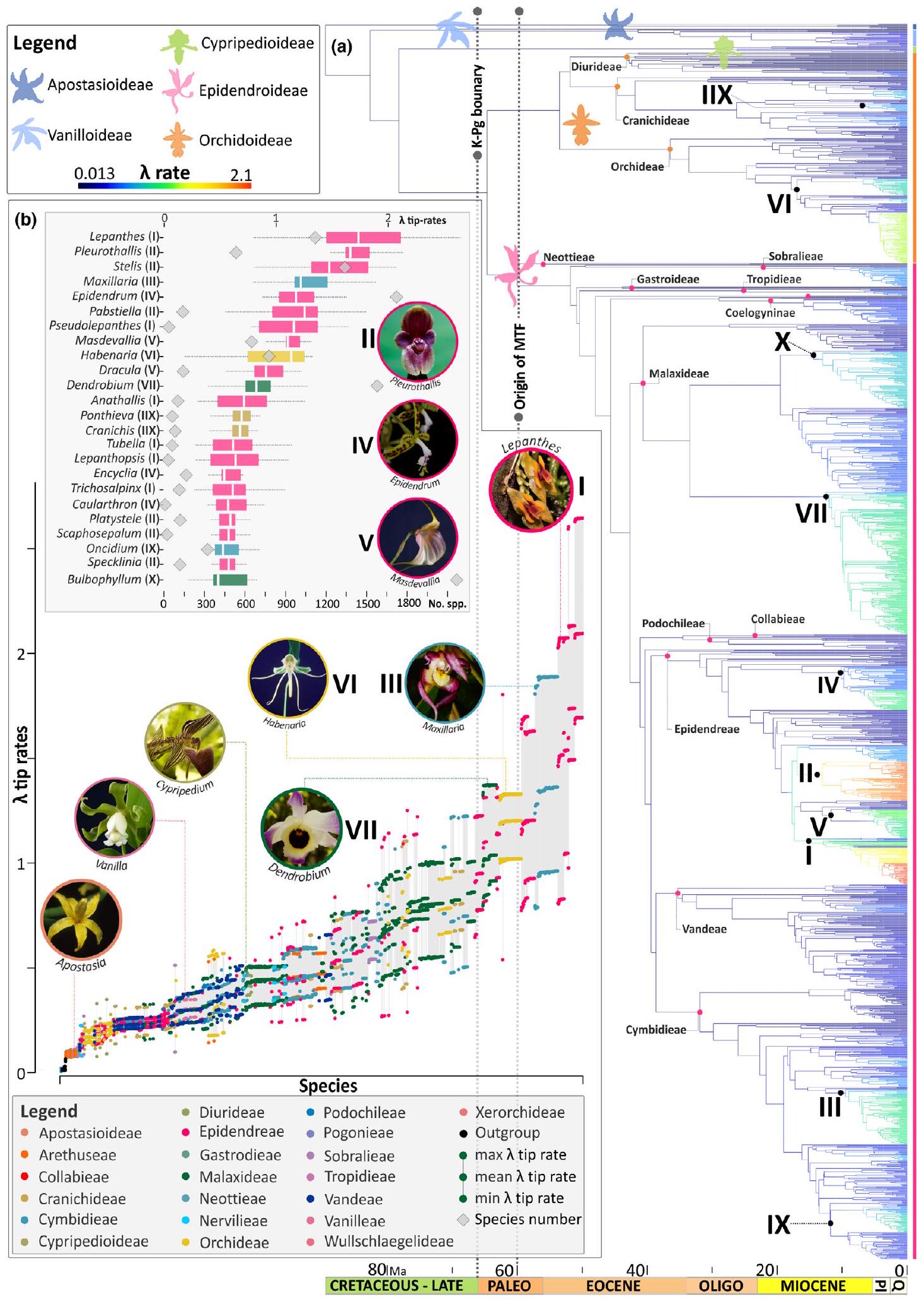

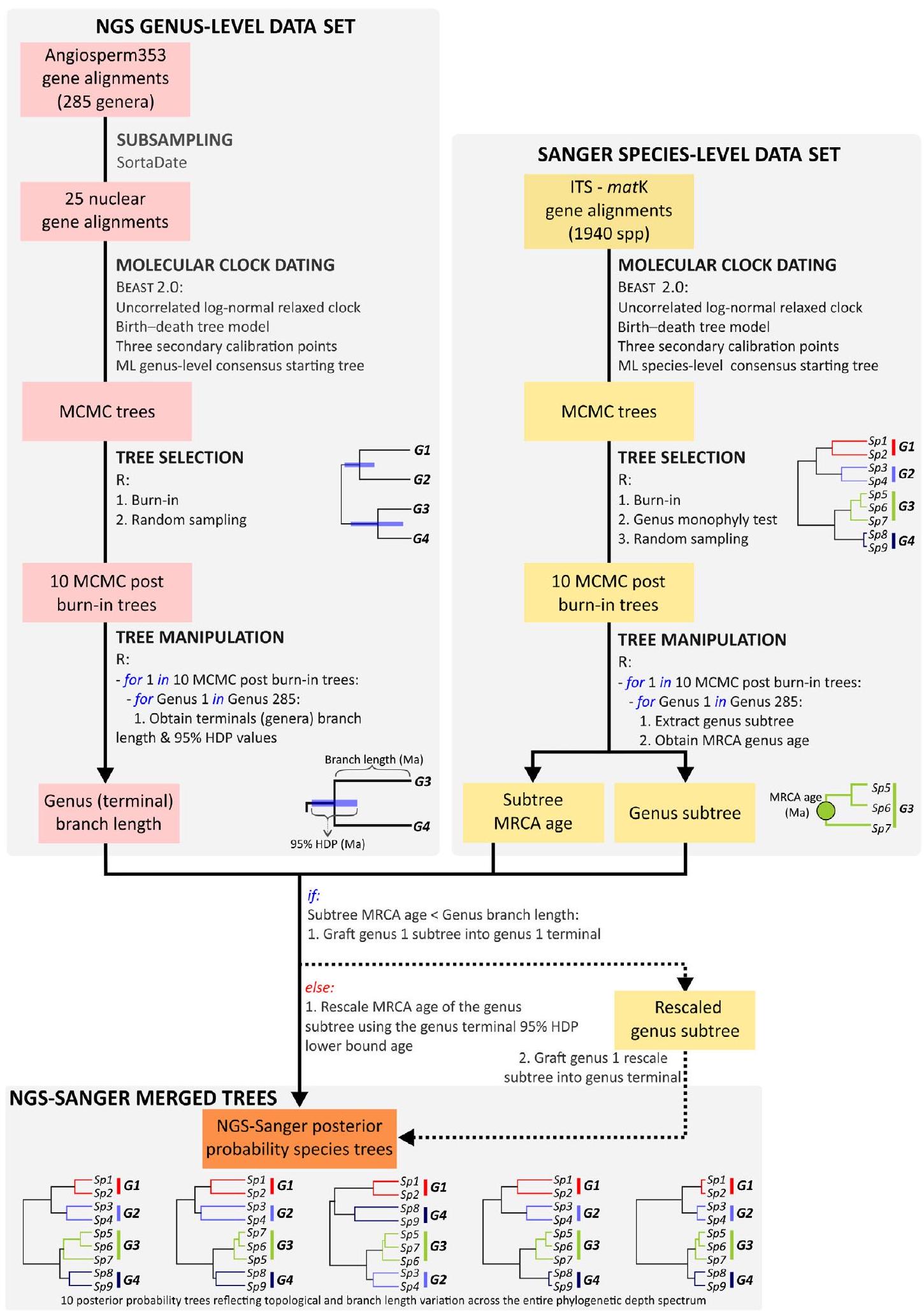

(3) لمحاولة استيعاب عدم اليقين النشوي، قمنا بإنشاء 10 أشجار أنواع فوقية من خلال خط أنابيب جديد (الشكل 2) بدلاً من استخدام شجرة توافق واحدة ذات مصداقية قصوى. أولاً، أخذنا عينات عشوائية من 10 أشجار لاحقة مستمدة من تحليلات BEAST التي أجريت على مجموعة بيانات Angiosperms353 على مستوى الجنس ومجموعة بيانات Sanger على مستوى الأنواع ITS-matK. ثم، لكل جنس ممثل في كرونوجرام Angiosperms353، قمنا بتقليم فرع نظيره المأخوذ من كرونوجرام Sanger على مستوى الأنواع و proceeded to graft it onto the corresponding stem of the Angiosperms353 chronogram. تم إجراء هذه العملية على كل زوج من الأشجار اللاحقة المأخوذة عشوائيًا (لذا تُسمى أشجار الأنواع باحتمالية لاحقة (PP)). يتم تقديم وصف تفصيلي لخط الأنابيب في الطرق S1.

تحليلات الجغرافيا الحيوية

التحليل المكاني لتنوع الأنواع ومعدلات التخصص

و

برنامج QGIS v.3.0 (متوفر فيhttps://www.qgis.org/ en/site/forusers/download.html) و الـ

النتائج

إطار فيلوجيني جديد لعائلة الأوركيد

تشير تقديرات الساعة الجزيئية وإعادة بناء الجغرافيا الحيوية إلى أصل عائلة الأوركيد من لوراسيا خلال العصر الطباشيري المتأخر

مشتقة من الكرونوجرامات الزهرية و أعمار العقد التاجية للكرونوجرامات سانجر، أشارت إلى أن عدم التوافق في الأعمار بين كلا المجموعتين كان ضئيلاً (الطرق S1؛ الأشكال S10، S11)، مما يوحي بأن الأعمار المطلقة المستخلصة من الأشجار العشر ذات الاحتمالية اللاحقة كانت موثوقة. سبعة من أصل 10 من إعادة بناء الجغرافيا الحيوية (التي أجريت على 10 أشجار الأنواع ذات الاحتمالية اللاحقة) دعمت لوراسيا (نيركتك + بالياركتك) كمكان نشأة السلف المشترك الأكثر حداثة للأوركيديات (احتمالية نسبية

تخصص الأوركيد في الفضاء والزمن

كان هناك تنوع بمعدل واحد أو حتى اثنين في معدلات تكوين الأنواع (الشكل 5c، الإطار). كشفت تحليلات معدلات تكوين الأنواع لدينا عن تسارعات متعددة داخل كل تحت عائلة، مع أسرع معدلات في Orchidoideae وEpidendroideae، بدءًا من الفترة المبكرة

نقاش

توافق إطارنا العالمي لعلم الوراثة الجزيئية للأوركيد مع الدراسات الحديثة لعلم الوراثة الجزيئية للأوركيد

أصل الأوركيديات من العصر الطباشيري في لوراسيا

مثال آخر في عائلة الأوركيد (Orchidaceae) على نطاق قديم متبقي هو تحت العائلة Cypripedioideae (أوركيدات الصندل)، التي تحتوي على خمسة أجناس و169 نوعًا حاليًا (136 من العالم القديم و33 من العالم الجديد). من المحتمل أن يكون سلف أوركيدات الصندل قد كان له توزيع مستمر في المناطق الاستوائية الشمالية، حيث هاجرت أوركيدات الصندل نحو الجنوب إلى كلا جانبي المحيط الهادئ بسبب برودة المناخ في أواخر العصر الحديث (Guo et al., 2012؛ الشكل 4).

نقطة ساخنة لتنوع أنواع الأوركيد في أمريكا الوسطى

كوستاريكا وبنما تعمل كمعبر بيولوجي بين نقطتي التنوع البيولوجي في شمال ميسوأمريكا وشمال الأنديز، مما يؤدي إلى التعايش الحالي بين المجموعات الشمالية والجنوبية (برجر، 1980؛ كابيل، 2016). تدعم هذه النتائج وتوسع فرضية تطور الغابات الاستوائية في أمريكا الوسطى بسرعة ومؤخراً (كانو وآخرون، 2022). ومع ذلك، على الرغم من أن تحليلاتنا لمعدلات التخصص الجغرافي تقدم وجهات نظر جديدة حول تطور تنوع الأوركيد، فإننا نحث على الحذر في تفسير العلاقة بين

الاستنتاجات

شكر وتقدير

المصالح المتنافسة

مساهمات المؤلفين

أوركيد

ويليام ج. بيكر (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-6727-1831

سيدوني بيلوت (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-6355-237X

دييغو بوغارين (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8408-8841

مارثا تشاريتونيدو (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-96578362

غيوم شوميكي (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-45476195

فابيان ل. كوندامين (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-16739910

نيكولا إس. فلاناغان (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-4909-8710

باربرا غرافنديل (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6508-0895

كارلوس هاراميلو (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-2616-5079

إيليا ج. ليتش (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3837-8186

روبرت مونسhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-9635-2884

أوليفييه مورن (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4151-6164

كاثارينا نارجار (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0459-5991

أوسكار أ. بيريز-إسكوبار (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-91662410

شارلوت فيليبس (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2200-9677

ناتاليا أ. س. برزيلومسكا (دhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-92074565

سوزان س. رينر (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3704-0703

إريك سميبت (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1177-1682

أليخاندرو زولواغا (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5874-6353

توفر البيانات

References

Ali JR, Heaney LR. 2021. Wallace’s line, Wallacea, and associated divides and areas: history of a tortuous tangle of ideas and labels. Biological Reviews 96: 922-942.

Baker WJ, Bailey P, Barber V, Barker A, Bellot S, Bishop D, Botigué LR, Brewer G, Carruthers T, Clarkson JJ et al. 2022. A comprehensive phylogenetic platform for exploring the angiosperm tree of life. Systematic Biology 71: 301-319.

Baker WJ, Couvreur TLP. 2012. Global biogeography and diversification of palms sheds light on the evolution of tropical lineages. II. Diversification history and origin of regional assemblages. Journal of Biogeography 40: 286-298.

Balbuena JA, Miguez-Lozano R, Blasco-Costa I. 2013. PACo: a novel Procustres application to cophylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 8: e61408.

Batista J, de Bem BL, Gonzalez-Tamayo R, Figueroa XM, Cribb P. 2011. A synopsis of the New World Habenaria (Orchidaceae) I. Harvard Papers in Botany 16: 1-47.

Beeravolu R, Condamine F. 2016. An extended maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction and cladogenesis. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/038695.

Benzing DH. 2000. Bromeliaceae: profile of an adaptive radiation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchene S, Fourment M, Gavryushina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kuhnert D, De Maio N et al. 2019. Beast 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Computational Biology 15: e1006650.

Bouetard A, Lefeuvre P, Gigant R, Séverine Bory S, Pignal M, Besse P, Grisoni M. 2010. Evidence of transoceanic dispersion of the genus Vanilla based on plastid DNA phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55: 621-630.

Brummitt K. 2001. World geographical scheme for recording plant distributions,

Burgener L, Hyland E, Reich RJ, Scotese C. 2023. Cretaceous climates: mapping paleo-Köppen climatic zones using a Bayesian statistical analysis of lithologic,

paleontologic and geochemical proxies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 613: 111373.

Burger WC. 1980. Why are there so many kinds of flowering plants in Costa Rica? Brenesia 17: 371-388.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. Blast+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421.

Camara-Leret R, Frodin DG, Adema F, Anderson C, Appelhans M, George A, Guerrero SA, Ashton P, Baker WJ, Barfod AS et al. 2020. New Guinea has the world’s richest Island flora. Nature 584: 579-583.

Cano A, Stauffer FW, Andermann T, Liberal IM, Zizka A, Bacon CD, Lorenzi H, Christe C, Töpel M, Perret M et al. 2022. Recent and local diversification of Central American understorey palms. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31: 1513-1525.

Chase M. 2001. The origin and biogeography of Orchidaceae. In: Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN, eds. Genera Orchidacearum: vol. 2. Orchidoideae (part one). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chase MW, Cameron KM, Freudenstein JV, Pridgeon AM, Salazar G, van den Berg C, Schuiteman A. 2015. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 177: 151-174.

Chomicki G, Bidel LPR, Ming F, Coiro M, Zhang X, Wang Y, Jay-Allemand C, Renner SS. 2015. The velamen protects photosynthetic orchid roots against UV-B damage, and a large dated phylogeny implies multiple gains and losses of this function during the Cenozoic. New Phytologist 205: 1330-1341.

Christenhusz MJ, Byng JW. 2016. The number of known plant species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 261: 201-217.

Collinson ME, Hooker JJ. 2003. Paleogene vegetation of Eurasia: framework for mammalian faunas. Deinsea 10: 41-83.

Collobert G, Perez-Lamarque B, Dubuisson J-Y, Martos F. 2022. Gains and losses of the epiphytic lifestyle in epidendroid orchids: review and new analyses with succulent traits. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2022.09.30.510324.

Condamine F, Rolland J, Morlon H. 2013. Macroevolutionary perspectives to environmental change. Ecology Letters 16: 72-85.

Conran JG, Bannister JM, Lee DE. 2009. Earliest orchid macrofossils: early Miocene Dendrobium and Earina (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae) from New Zealand. American Journal of Botany 96: 466-474.

Couvreur TLP, Forest F, Baker WJ. 2011. Origin and global diversification patterns of tropical rain forests: inferences from a complete genus-level phylogeny of palms. BMC Biology 9: 44.

Crain BJ, Fernández M. 2020. Biogeographical analyses to facilitate targeted conservation of orchid diversity in Costa Rica. Diversity and Distributions 26: 853-866.

Cribb P, Pridgeon A. 2009. Claderia: phylogenetics. In: Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN, eds. Genera Orchidacearum: vol. 5. Epidendroideae (part two). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dauby G, Zaiss R, Blach-Overgaard A, Catarino L, Damen T, Deblauwe V, Dessin S, Dransfield J, Droissart V, Duarte MC et al. 2016. Rainbio: a megadatabase of tropical African vascular plants distributions. PhytoKeys 74: 1-18.

De Lamotte DF, Fourdan B, Leleu S, Francois L, Clarens P. 2015. Style of rifting and the stages of Pangea break-up. Tectonics 34: 1009-1029.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. 1990. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13-15.

Dressler RL. 1990. The orchids: natural history and classification. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Driese GS, Kenneth HO, Sally PH, Zheng-Hua L, Debra SJ. 2007. Paleosol evidence for Quaternary uplift and for climate and ecosystem changes in the Cordillera de Talamanca, Costa Rica. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 248: 1-23.

Eiserhardt WL, Couvreur TLP, Baker WJ. 2017. Plant phylogeny as a window on the evolution of hyperdiversity in the tropical rainforest biome. New Phytologist 214: 1408-1422.

Freudenstein JV, Chase MW. 2015. Phylogenetic relationships in Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae), one of the great flowering plant radiations: progressive specialization and diversification. Annals of Botany 115: 665-681.

Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Doucette A, Giraldo G, McDaniel J, Clements MA et al. 2016. Orchid historical

biogeography, diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal. Journal of Biogeography 43: 1905-1916.

Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Iles WJD, Clements MA, Arroyo MTK, Leebens-Mack J et al. 2015. Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20151553.

Górniak M, Paun O, Chase MW. 2010. Phylogenetic relationships within Orchidaceae based on a low-copy nuclear coding gene,

Govaerts R, Lughadha EN, Black N, Turner R, Paton A. 2021. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for exploring global plant diversity. Scientific Data 8: 215.

Grace OM, Pérez-Escobar OA, Lucas EJ, Vorontsova MS, Lewis GP, Walker BE, Lohmann LG, Knapp S, Wilkie P, Sarkinen T et al. 2021. Botanical monograph in the Anthropocene. Trends in Plant Science 26: 433-441.

Grafe KW, Frisch IM, Villa MM. 2002. Geodynamic evolution of southern Costa Rica related to low-angle subduction of the Cocos Ridge: constraints from thermochronology. Tectonophysics 348: 187-204.

Guo Y-Y, Luo Y-B, Liu Z-J, Wang X-Q. 2012. Evolution and biogeography of the slipper orchids: eocene vicariance of the conduplicate genera in the Old and New World Tropics. PLoS ONE7: e38788.

Gustafsson ALS, Verola CF, Antonelli A. 2010. Reassessing the temporal evolution of orchids with new fossils and a Bayesian relaxed clock, with implications for the diversification of the rare South American genus Hoffmannseggella (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae). BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 1-13.

Huson DH, Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23: 254-267.

Johnson MG, Gardner EM, Liu Y, Medina R, Goffinet B, Shaw AJ, Zerega NJ, Wicket NJ. 2016. HybPiper: extracting coding sequence and introns for phylogenetics from high-throughput sequencing reads using target enrichment. Applications in Plant Sciences 4: 1600016.

Johnson MG, Pokorny LP, Dodsworth SD, Botigué LR, Cowan RS, Devault A, Eiserhardt WL, Epitawalage N, Forest F, Kim JT et al. 2019. A universal probe set for targeted sequencing of 353 nuclear genes from any flowering plant designed using k-medoids clustering. Systematic Biology 68: 594-606.

Jones DL. 1997. Cooktownia robertsii, a remarkable new genus and species of Orchidaceae from Australia. Austrobaileya 5: 71-78.

Kapelle M. 2016. The montane cloud forests of the Cordillera de Talamanca. In: Kapelle M, ed. Costa Rican ecosystems. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Karremans A, Watteyn C, Scaccabarozzi D, Pérez-Escobar OA, Bogarín D. 2023. Evolution of seed dispersal modes in the Orchidaceae: has the Vanilla mystery been solved? Horticulturae 9: 1270.

Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. Maff: multiple sequence alignment software v.7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772-780.

Kirby SH. 2011. Active mountain building and the distribution of “core” Maxillariinae species in tropical Mexico and Central America. Lankesteriana 11: 275-291.

Korasidis VA, Wing SL, Shields CA, Kiehl JT. 2022. Global changes in terrestrial vegetation and continental climate during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 37: e2021PA004325.

Li Y, Ma L, Liu D-K, Zhao X-WZD, Ke S, Chen G-Z, Zheng Q, Liu Z-J, Lan S. 2023. Apostasia fujianica (Apostasioideae, Orchidaceae), a new Chinese species: evidence from morphological, genome size and molecular analyses. Phytotaxa 583: 277-284.

Louca S, Pennell MW. 2021. Why extinction estimates from extant phylogenies are so often zero. Current Biology 31: 3168-3173.

Magallón S, Sánchez-Reyes LL, Gómez-Acevedo SL. 2019. Thirty clues to the exceptional diversification of flowering plants. Annals of Botany 123: 491-503.

Maldonado C, Molina CI, Zizka A, Persson C, Taylor CM, Alban J, Chilquillo E, Ronsted N, Antonelli A. 2015. Estimating species diversity and distribution in the era of Big Data: to what extent can we trust public databases? Global Ecology and Biogeography 24: 973-984.

Matzke NJ. 2013. Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founderevent speciation, imperfect detection, and fossil allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Frontiers of Biogeography 5: 243-248.

Meseguer AS, Condamine FL. 2020. Ancient tropical extinctions at high latitudes contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient. Evolution 74: 19661987.

Morell KD, Fisher DM, Gardner TW, La Femina P, Davidson D, Teletzke A. 2011. Quaternary outer fore-arc deformation and uplift inboard of the Panama Triple Junction, Burica Peninsula. Journal of Geophysical Research 116: B05402.

Mosquera-Mosquera HR, Valencia-Barrera RM, Acedo C. 2019. Variation and evolutionary transformation of some characters of the pollinarium and pistil in Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 305: 353-374.

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853-858.

Nauheimer L, Schley RJ, Clements MA, Micheneau C, Nargar K. 2018. Australian orchid biogeography at continental scale: molecular phylogenetic insights from the sun orchids (Thelymitra, Orchidaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 127: 304-319.

Niissalo MA, Leong PKF, Tay FEL, Choo LM, Kurzweil H, Khew GS. 2023. A new species of Claderia (Orchidaceae). Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 75: 21-41.

Parra-Sánchez E, Pérez-Escobar OA, Edwards DP. 2023. Neutral-based processes overrule niche-based processes in shaping tropical montane orchid communities across spatial scales. Journal of Ecology 111: 1614-1628.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Balbuena JA, Gottschling M. 2016. Rumbling orchids: how to assess divergent evolution between chloroplast endosymbionts and the nuclear host. Systematic Biology 65: 51-65.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Bellot S, Przelomska NAS, Flowers JM, Nesbitt M, Ryan P, Gutaker RM, Gros-Balthazard M, Wells T, Kuhnhäuser BG et al. 2021a. Molecular clocks and archaeogenomics of a late period Egyptian date palm leaf reveal introgression from wild relatives and add timestamps on the domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 4475-4492.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Chomicki G, Condamine FL, Karremans AP, Bogarín D, Matzke NJ, Silvestro D, Antonelli A. 2017. Recent origin and rapid speciation of Neotropical orchids in the world’s richest plant biodiversity hotspot. New Phytologist 215: 891-905.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Dodsworth S, Bogarín D, Balbuena JA, Schley RJ, Kikuchi IZ, Morris SK, Epitawalage N, Cowan R, Maurin O et al. 2021b. Hundreds of nuclear and plastid loci yield novel insights into orchid relationships. American Journal of Botany 108: 1166-1180.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Zizka A, Bermúdez MA, Meseguer AS, Condamine FL, Hoorn C, Hooghiemstra H, Pu Y, Bogarín D, Boschman LM et al. 2022. The Andes through time: evolution and distribution of Andean floras. Trends in Plant Science 27: 1-12.

Poinar G, Rasmussen FN. 2017. Orchids from the past, with a new species in Baltic amber. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 183: 327-333.

Poinar G Jr. 2016a. Orchid pollinaria (Orchidaceae) attached to stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Dominican amber. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie Und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen 279: 287-293.

Poinar G Jr. 2016b. Beetles with orchid pollinaria in Dominican and Mexican amber. American Entomologist 62: 172-177.

Portik DM, Wiens JJ. 2020. SuperCRUNCH: a bioinformatics toolkit for creating and manipulating supermatrices and other large phylogenetic datasets. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11: 7763-7772.

Rabosky DL, Grundler M, Anderson C, Title P, Shi JF, Brown JW, Huang H, Larson JG. 2014. BAMMTools: an R package for the analysis of evolutionary dynamics on phylogenetic trees. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5: 701-707.

Rabosky DL, Santini F, Eastman J, Smith SA, Sidlauskas B, Chang J, Alfaro ME. 2013. Rates of speciation and morphological evolution are correlated across the largest vertebrate radiation. Nature Communications 4: 1958.

Rangel TF, Colwell RK, Graves GR, Fucikova K, Rahbek C, Diniz-Filho JF. 2015. Phylogenetic uncertainty revisited: implications for ecological analyses. Evolution 69: 1301-1312.

Ree RH, Smith SA. 2008. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Systematic Biology 57: 4-14.

Selosse M-A, Petrolli R, Mujica MI, Laurent L, Perez-Lamarque B, Figura T, Bourceret A, Jacquemyn H, Li T, Gao J et al. 2022. The waiting room hypothesis revisited by orchids: were orchid mycorrhizal fungi recruited among root endophytes? Annals of Botany 129: 259-270.

Serna-Sánchez M, Pérez-Escobar OA, Bogarín D, Torres-Jimenez MF, AlvarezYela AC, Arcila-Galvis JE, Hall C, de Barros D, Pinheiro F, Dodsworth S et al. 2021. Plastid phylogenomics resolves ambiguous relationships within the orchid family and provides a solid timeframe for biogeography and macroevolution. Scientific Reports 11: 6858.

Simpson L, Clements MA, Orel HK, Crayn DM, Nargar K. 2022. Plastid phylogenomics clarifies broad-level relationships in Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) and provides insights into range evolution of Australasian section Adelopetalum. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2022.07.24.500920.

Smith SA, Brown JW, Walker JF. 2018. So many genes, so little time: a practical approach to divergence-time estimation in the genomic era. PLoS ONE 13: e0197433.

Smith SA, Moore MJ, Brown JW, Ya Y. 2015. Analysis of phylogenomic datasets reveal conflict, concordance, and gene duplications with examples from animals and plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 150.

Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML v.8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and postanalysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312-1313.

Thompson JB, Davis KE, Dodd HO, Priest NK. 2023. Speciation across the Earth driven by global cooling in terrestrial orchids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 120: e2102408120.

Tietje M, Antonelli A, Baker WJ, Govaerts R, Smith SA, Eiserhardt WL. 2022. Global variation in diversification rate and species richness are unlinked in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 119: e2120662119.

Title PO, Rabosky DL. 2019. Tip rates, phylogenies and diversification: what are we estimating, and how good are the estimates? Methods in Ecology and Evolution 10: 821-834.

Töpel M, Zizka A, Maria Fernanda Calió MF, Scharn R, Silvestro D, Antonelli A. 2017. SpeciesGeoCoder: fast categorization of species occurrences for analyses of biodiversity, biogeography, ecology, and evolution. Systematic Biology 66: 145-151.

Van den Berg C, Goldman DH, Freudenstein JV, Pridgeon AM, Cameron KM, Chase MW. 2005. AN overview of the phylogenetic relationships within Epidendroideae inferred from multiple DNA regions and re-circumscription of Epidendreae and Arethuseae (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany 92: 613-624.

Velasco JA, Pinto-Ledezma JN. 2022. Mapping species diversification metrics in macroecology: prospects and challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10: 1-18.

Viruel J, Segarra-Moragues JG, Raz L, Forest F, Wilkin P, Sanmartín I, Catalán P. 2015. Late Cretaceous – Early Eocene origin of yams (Dioscorea, Dioscoreaceae) in the Laurasian Palaeartic and their subsequent OligoceneMiocene diversification. Journal of Biogeography 43: 672-750.

Vitt P, Taylor A, Rakosy D, Kreft H, Meyer A, Wigelt P, Knight TM. 2023. Global conservation prioritization of the Orchidaceae. Scientific Reports 13: 6718.

Wing SL, Boucher LD. 1998. Ecological aspects of the Cretaceous flowering plant radiation. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Science 26: 379-421.

Wing SL, Strömberg C, Hickey LJ, Tiver F, Willis B, Burnham RJ, Behrensmeyer AK. 2012. Floral and environmental gradients on a Late Cretaceous landscape. Ecological Monographs 82: 23-457.

Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S. 2018. Astral-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19: 153.

Zhang C, Zhao Y, Braun EL, Mirarab S. 2021. Taper: pinpointing errors in multiple sequence alignments despite varying rates of evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 20: 1-14.

Zhang G, Hu Y, Huang M-Z, Huang W-C, Liu D-K, Zhang D, Hu H, Downing JL, Liu Z-J, Ma H. 2023. Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of Orchidaceae using nuclear genes and evolutionary insights into epiphytism. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 65: 1204-1225.

المعلومات الداعمة

التي تم الحصول عليها، على التوالي، من 10 أشجار الأجناس على مستوى NGS التي تم أخذ عينات عشوائية منها وأشجار الأنواع على مستوى Sanger.

- *المؤلفون الرئيسيون.

المؤلفون الكبار.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19580

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38382573

Publication Date: 2024-02-21

The origin and speciation of orchids

Abstract

Summary

Authors for correspondence: Oscar A. Pérez-Escobar Email: o.perez-escobar@kew.org

William J. Baker Email: w.baker@kew.org

Alexandre Antonelli Email: a.antonelli@kew.org

Received: 4 September 2023 Accepted: 4 December 2023

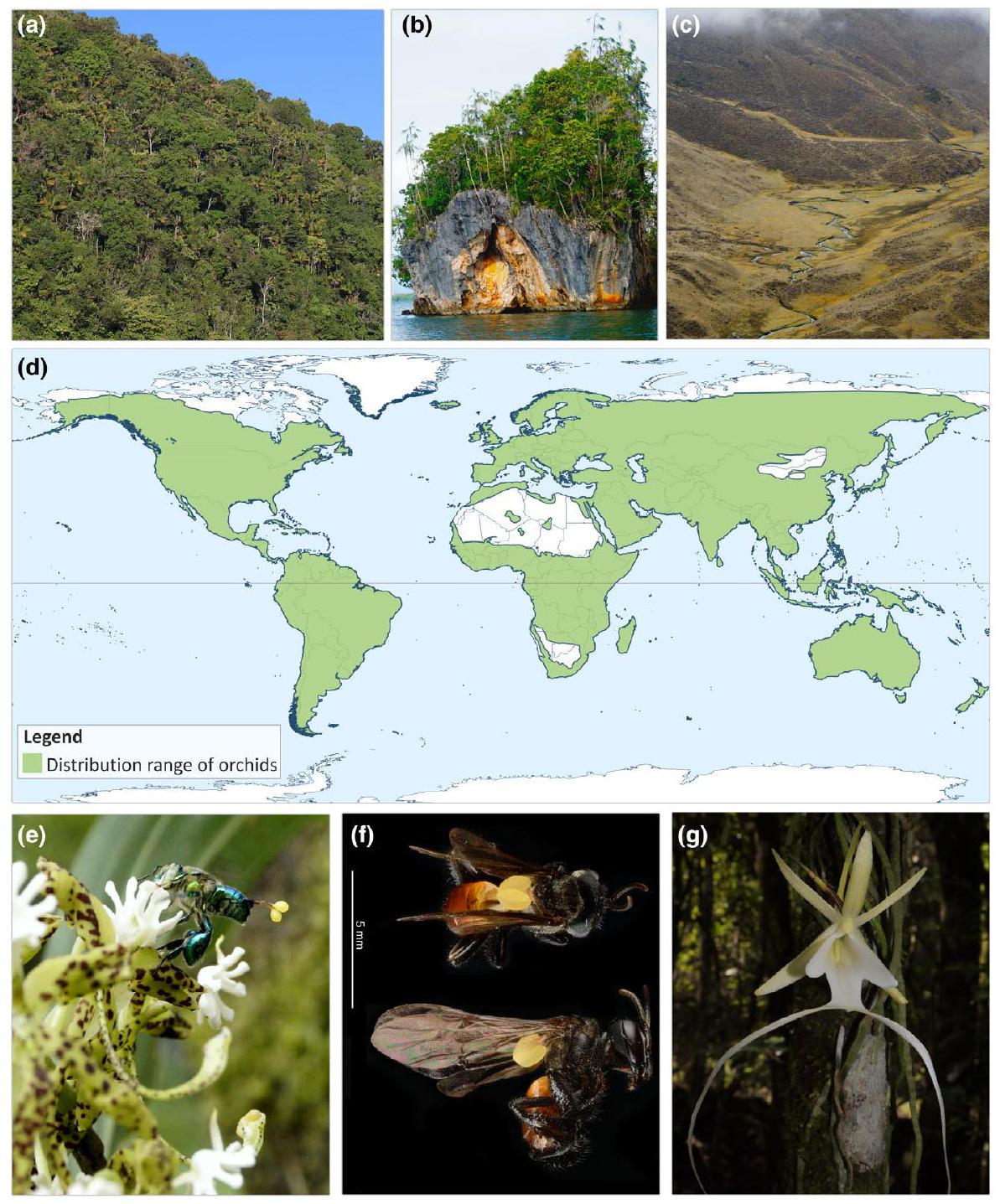

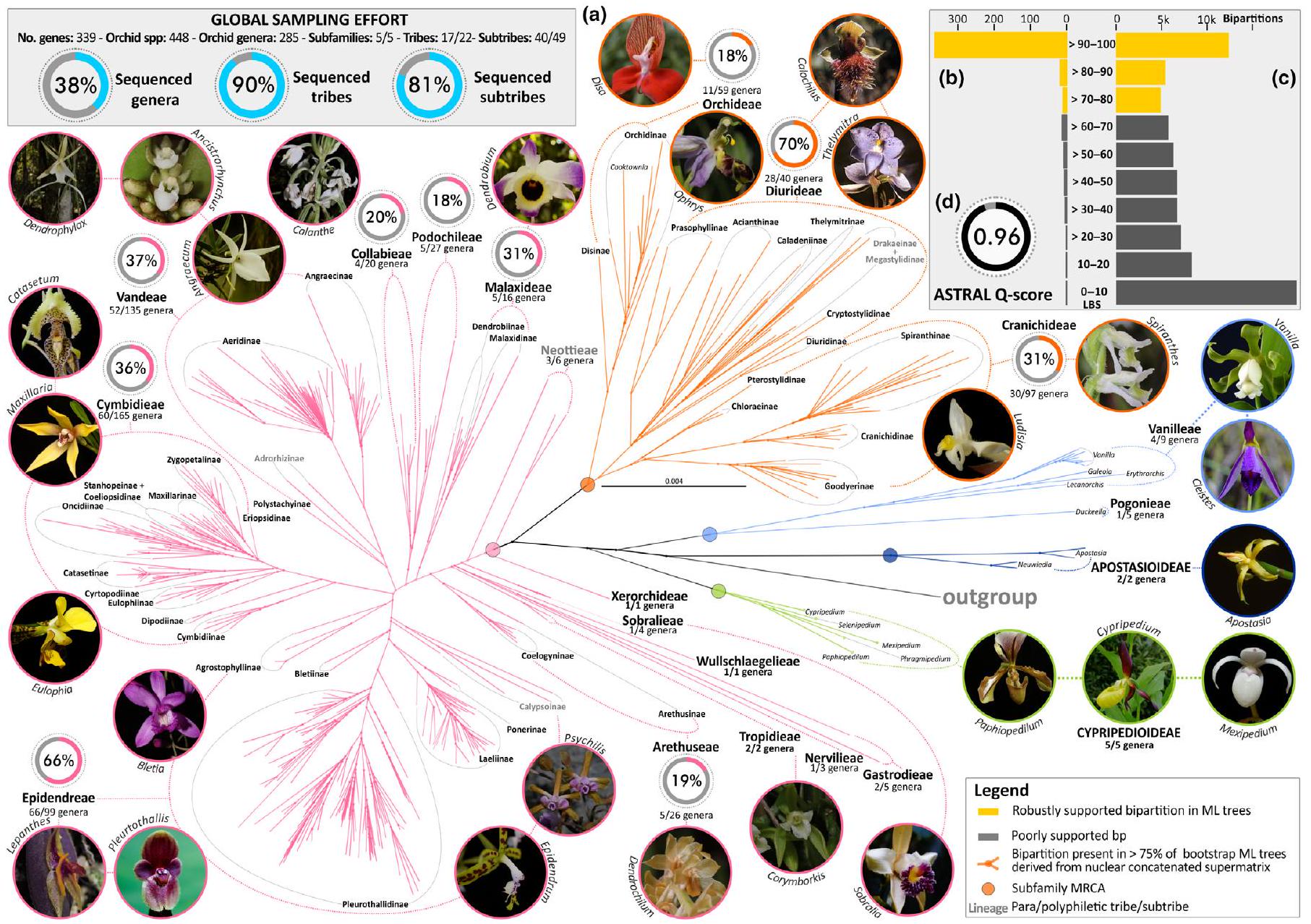

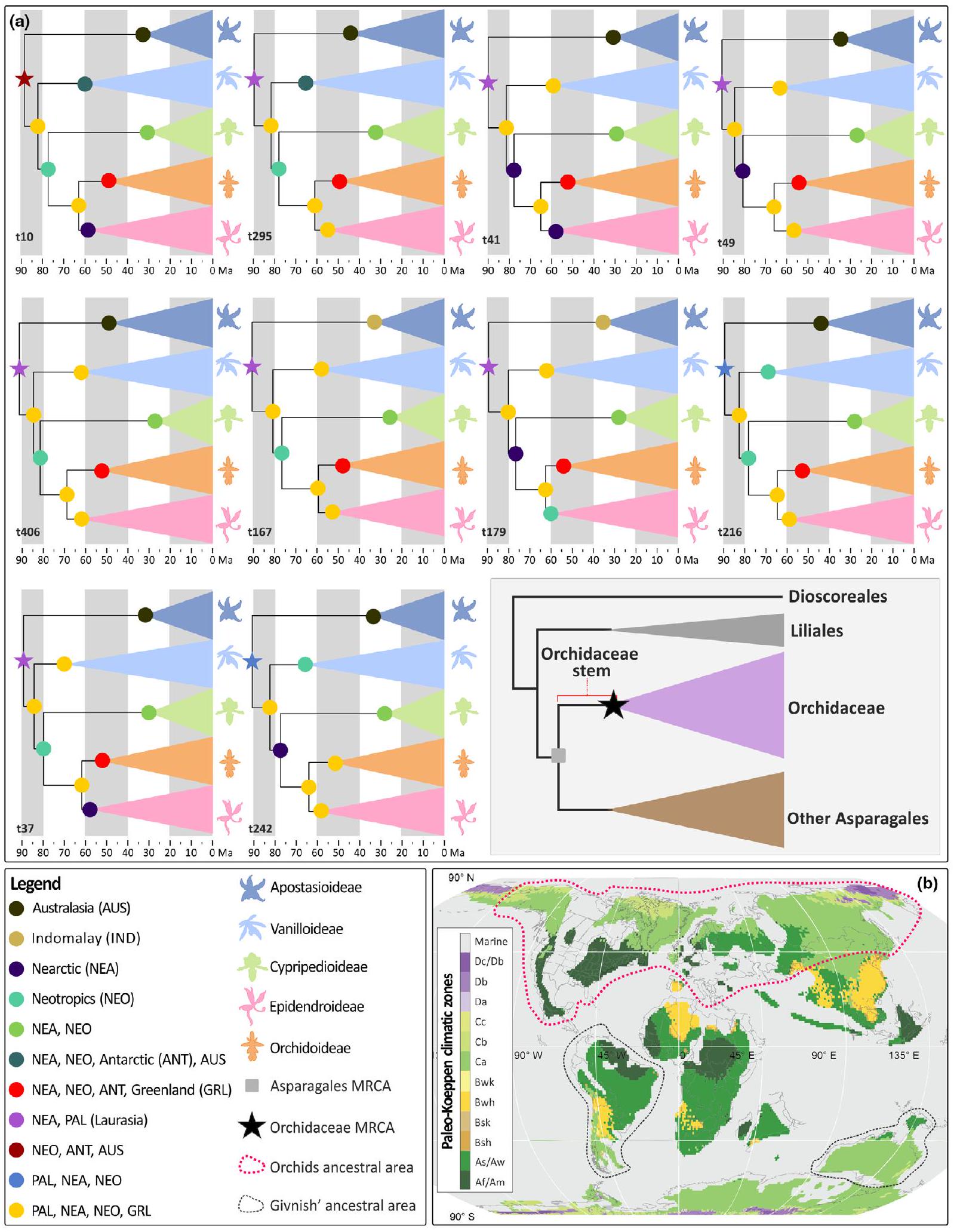

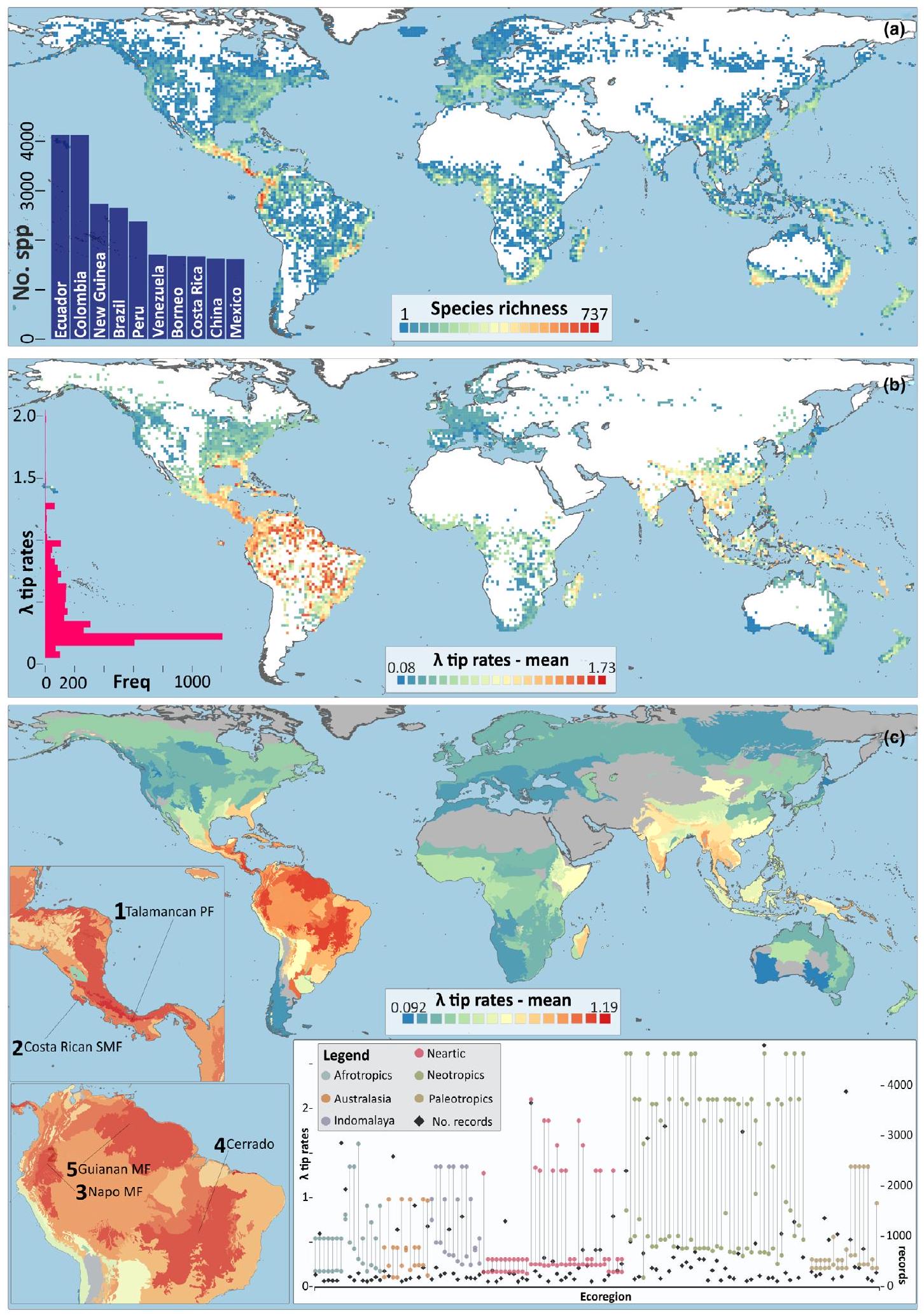

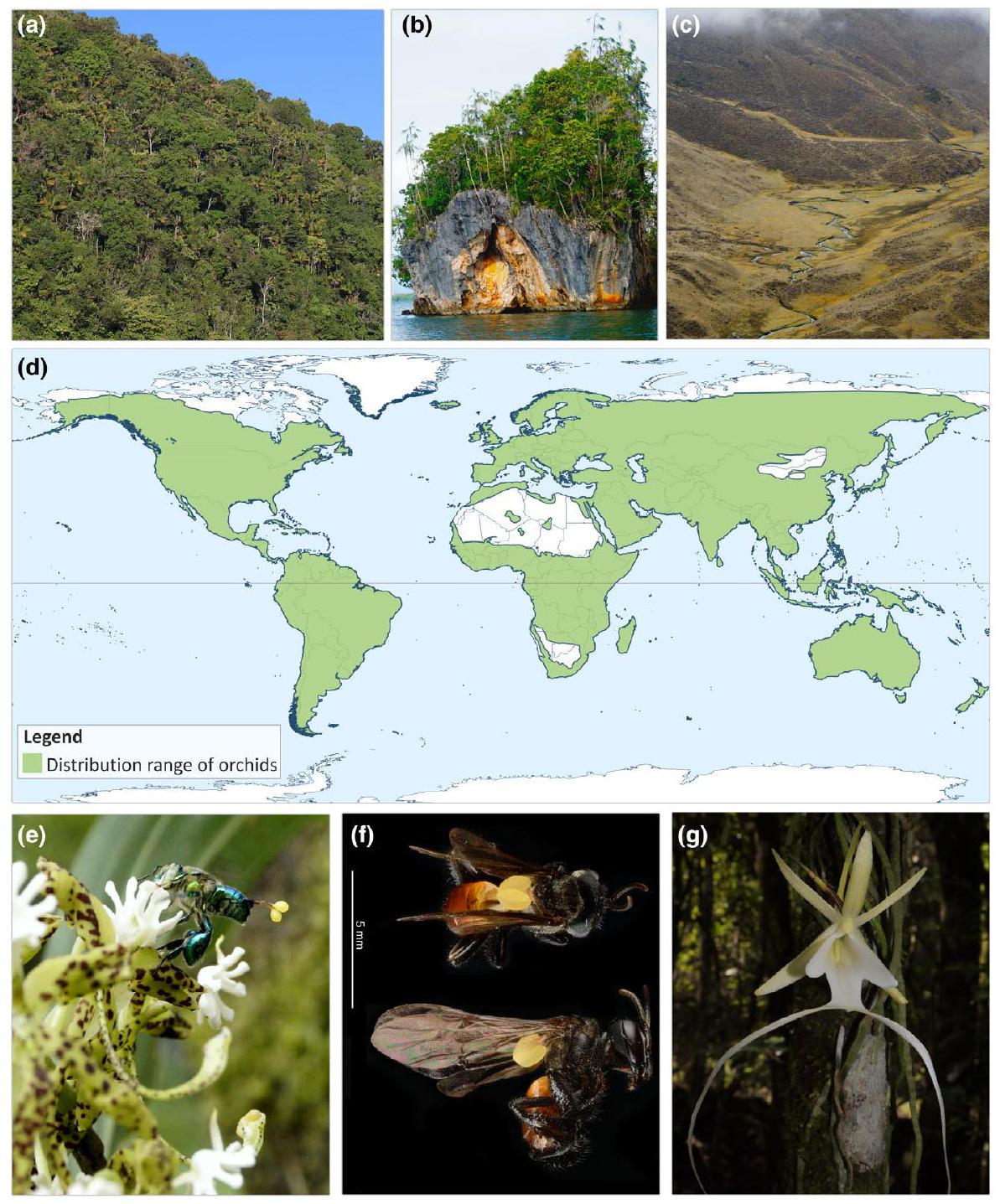

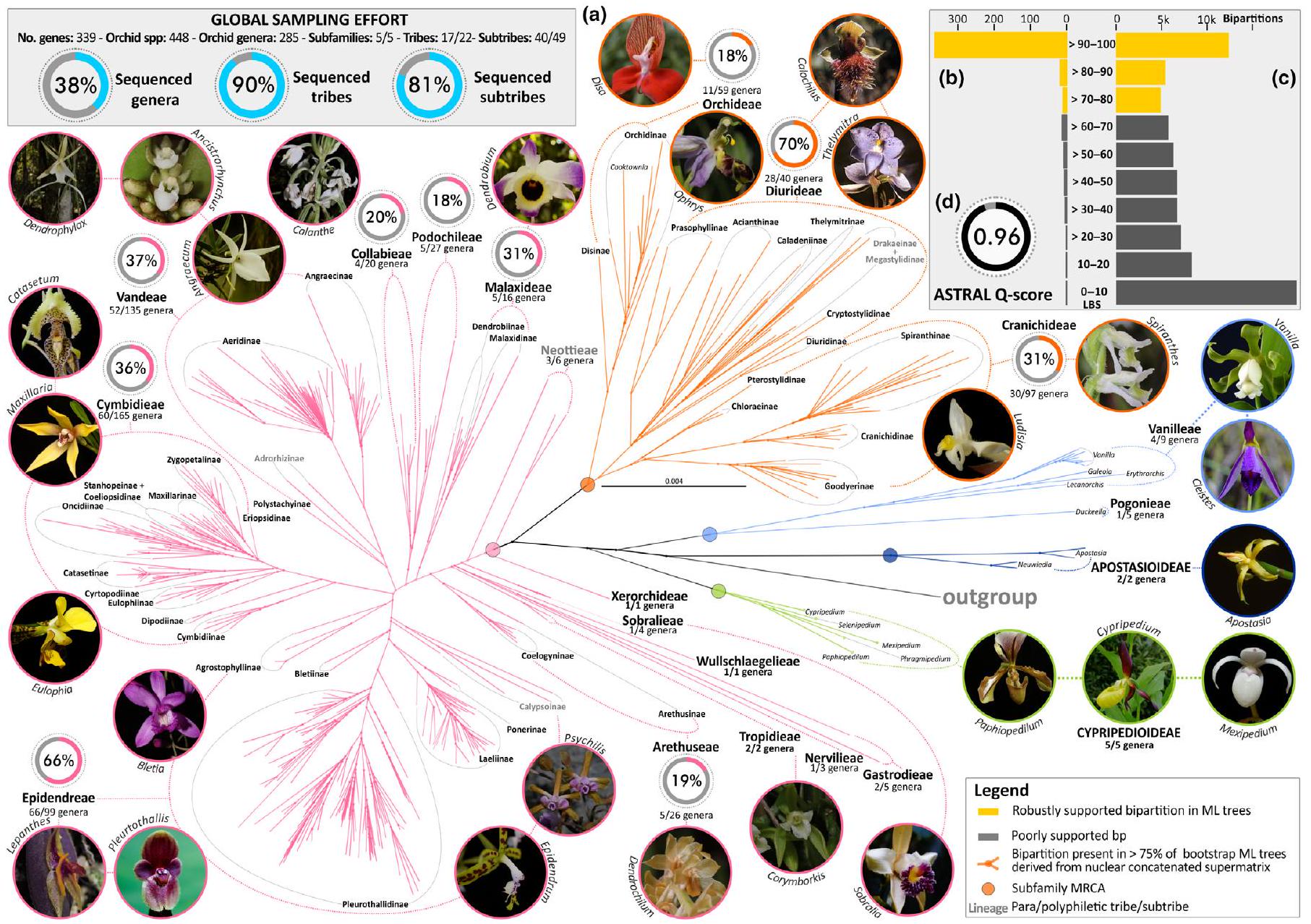

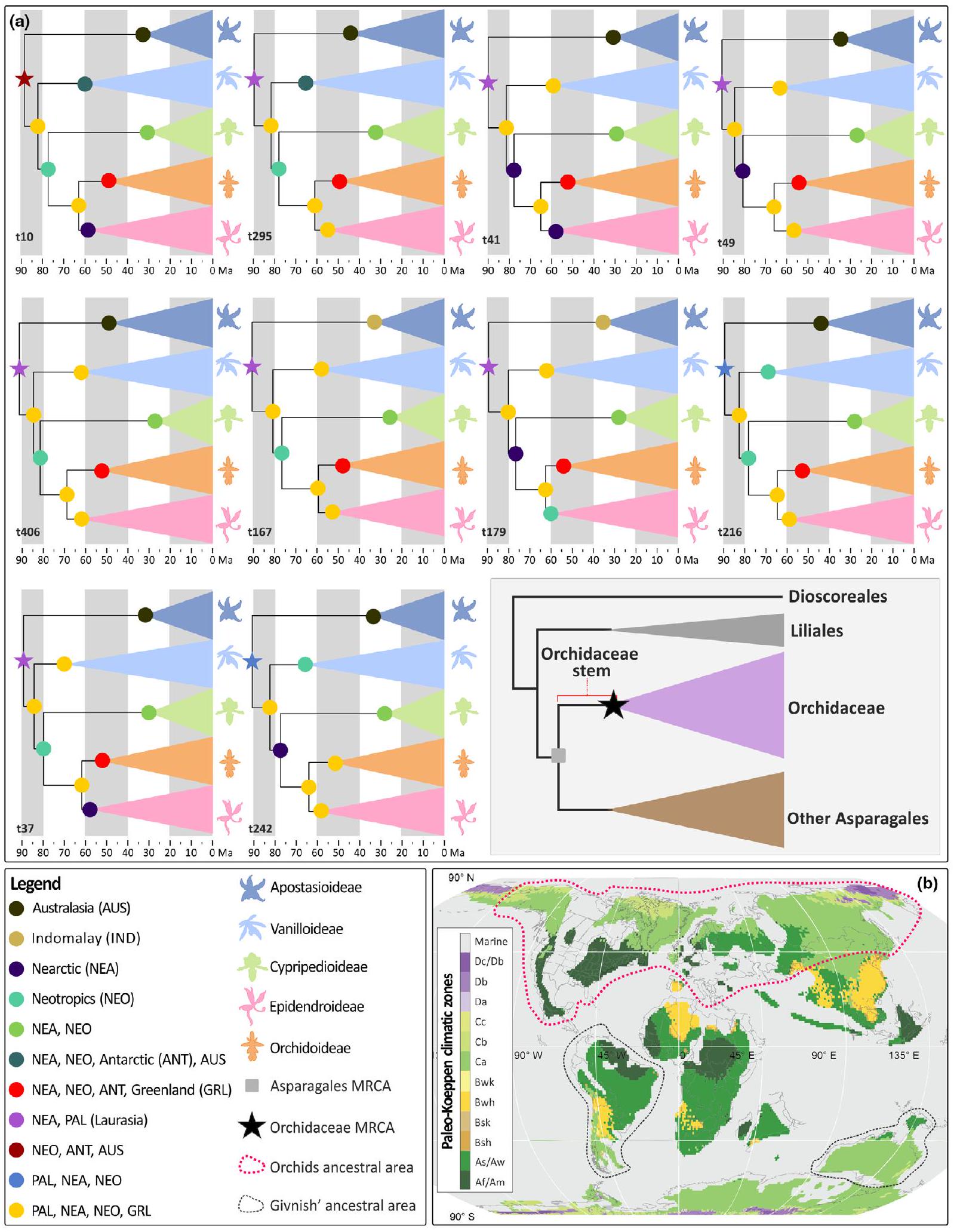

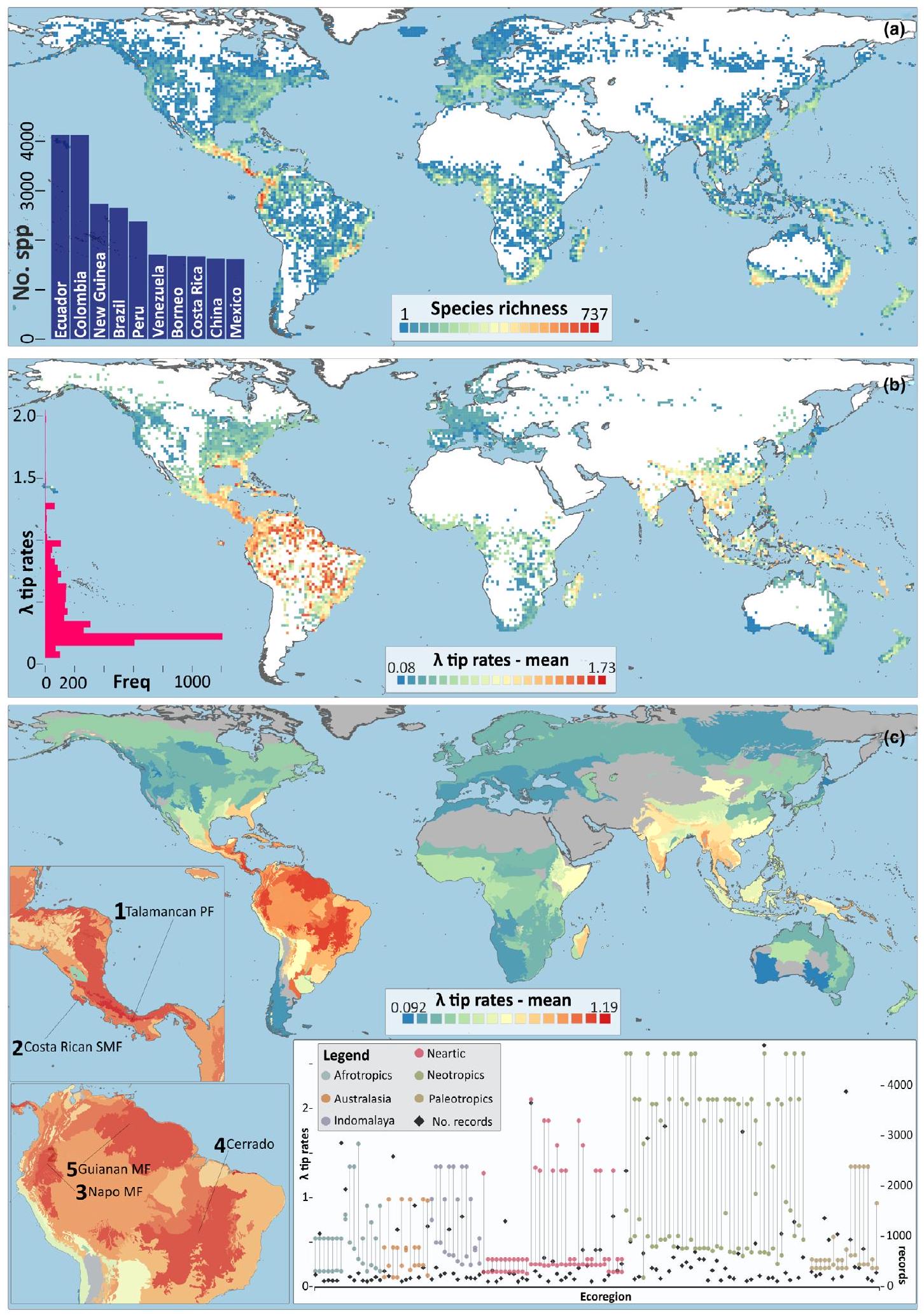

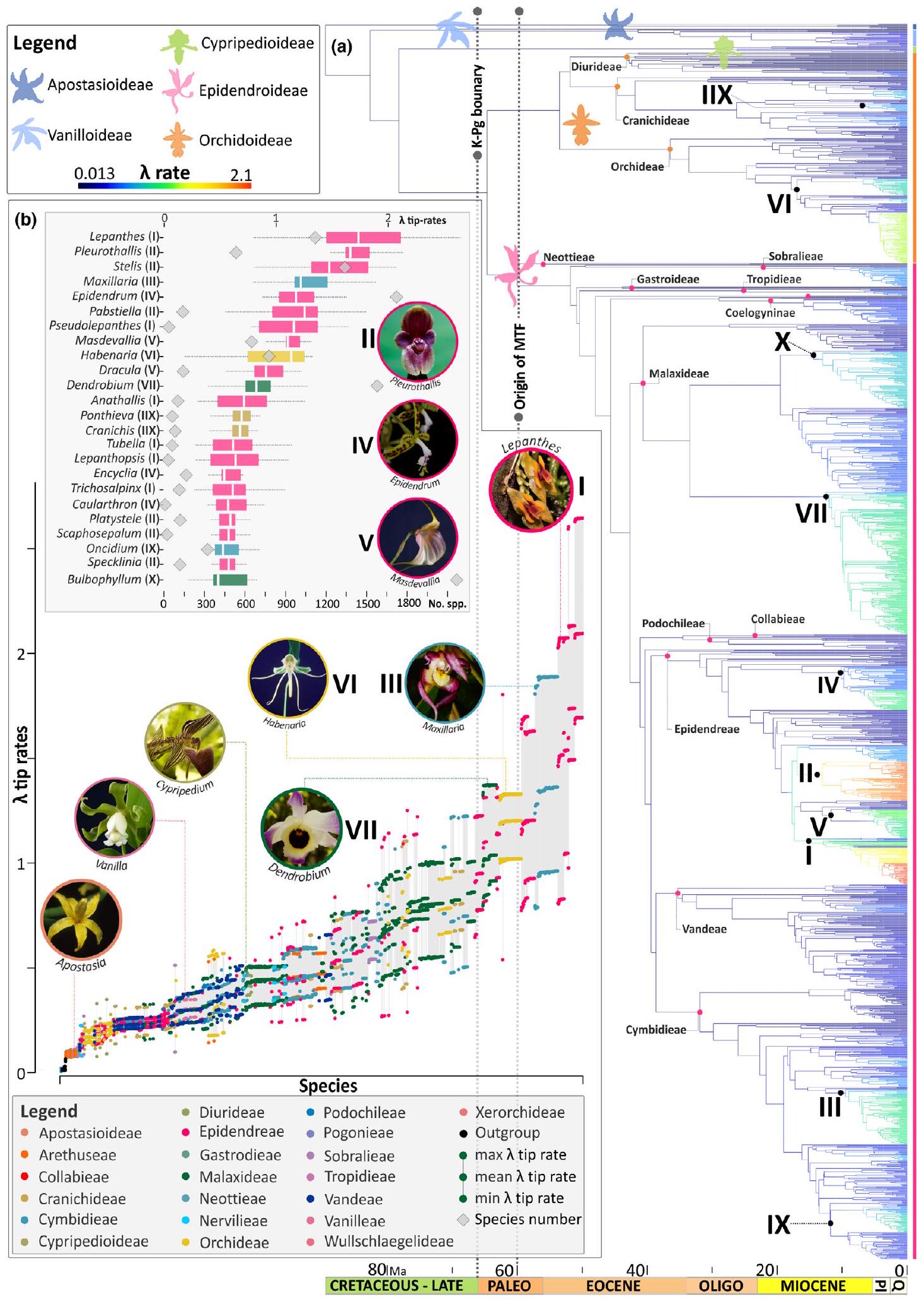

New Phytologist (2024) 242: 700-716 doi: 10.1111/nph. 19580 – Orchids constitute one of the most spectacular radiations of flowering plants. However, their origin, spread across the globe, and hotspots of speciation remain uncertain due to the lack of an up-to-date phylogeographic analysis. – We present a new Orchidaceae phylogeny based on combined high-throughput and Sanger sequencing data, covering all five subfamilies, 17/22 tribes, 40/49 subtribes, 285/736 genera, and c. 7% (1921) of the 29524 accepted species, and use it to infer geographic range evolution, diversity, and speciation patterns by adding curated geographical distributions from the World Checklist of Vascular Plants. – The orchids’ most recent common ancestor is inferred to have lived in Late Cretaceous Laurasia. The modern range of Apostasioideae, which comprises two genera with 16 species from India to northern Australia, is interpreted as relictual, similar to that of numerous other groups that went extinct at higher latitudes following the global climate cooling during the Oligocene. Despite their ancient origin, modern orchid species diversity mainly originated over the last 5 Ma , with the highest speciation rates in Panama and Costa Rica.

- These results alter our understanding of the geographic origin of orchids, previously proposed as Australian, and pinpoint Central America as a region of recent, explosive speciation.

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Taxon sampling, DNA library preparation and sequencing

supernatant removal, first to remove the isopropanol and second to wash the DNA pellet with

estimated using a Quantus fluorometer (Promega), and fragment size distribution was estimated using either a 4200 TapeStation system or an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyser (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, we used the Angiosperms353 probe set to enrich these genomic libraries for 353 low-copy nuclear genes (Johnson et al., 2019), modifying the equimolar pooling of libraries into groups of

High-throughput and Sanger sequencing data analyses

eye with Geneious v.8.0 (available at https://www.geneious.com/). The Sanger/Angiosperms353 nucleotide alignments are accessible at doi:

Distance-based, maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and multispecies coalescence phylogenomic inferences

Molecular-clock-dating analyses and species-level phylogeny assembly

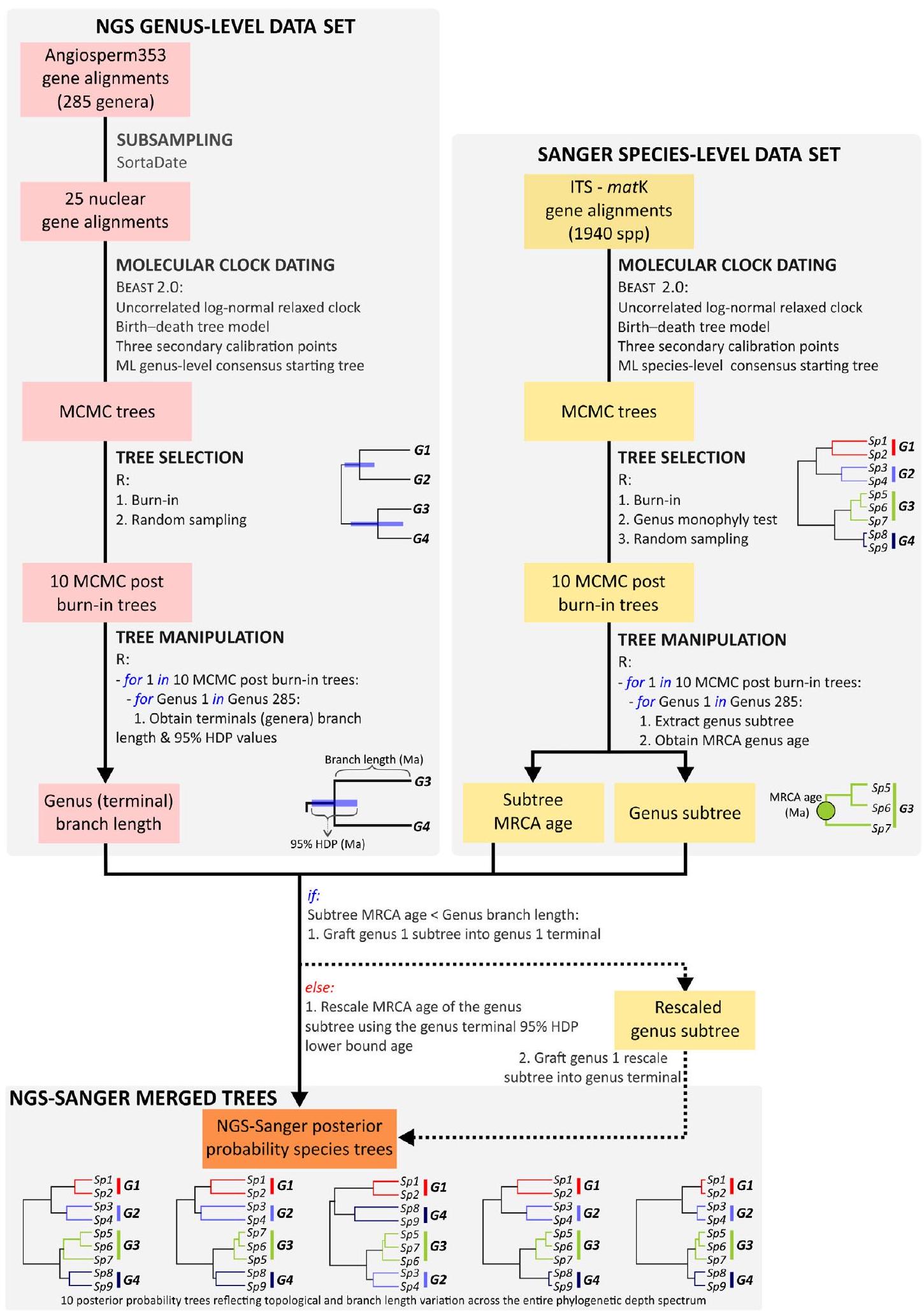

(1) The backbone was inferred by subsampling the Angiosperms353 low-copy nuclear gene alignments using SortaDate v.1.0 (Smith et al., 2018). Here, we selected the top 25 low-copy nuclear gene alignments with the lowest root-to-tip variance coefficient (i.e. highest clock-likeness). This selection ensured the representation of the entire generic diversity as sampled by

the ML high-throughput dataset (i.e. 285 genera; see Methods S1; Tables S3, S4). This data subset was imported in Beauti v.2.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019) as unlinked partitions, with the same priors employed by Pérez-Escobar et al. (2021a), as follows: (1) the GTR nucleotide substitution model and a rate heterogeneity among sites modelled by a

(2) A species-level-ultrametric phylogeny of Orchidaceae was produced by inputting the ITS and matK alignments as unlinked partitions in Beauti v.2.6 (Bouckaert et al., 2019), using the same priors as in (1). Furthermore, the ML consensus phylogram produced in RAxML v.8.0 from the ITS-matK supermatrix was used as a starting tree.

(3) To try to accommodate phylogenetic uncertainty, we constructed 10 ultrametric species trees through a novel pipeline (Fig. 2) instead of using a single consensus maximum clade credibility tree. We first randomly sampled 10 posterior trees derived from the BEAST analyses conducted on the genus-level Angiosperms353 and the ITS-matK Sanger species-level datasets. Then, for each genus represented in the Angiosperms353 chronograms, we pruned its counterpart clade sampled on the species-level Sanger chronogram and proceeded to graft it onto the corresponding stem of the Angiosperms353 chronogram. This operation was conducted on each pair of randomly sampled posterior trees (hence called posterior probability (PP) species trees). A detailed description of the pipeline is provided in the Methods S1.

Biogeographic analyses

Spatial analysis of species diversity and speciation rates

and

software QGIS v.3.0 (available at https://www.qgis.org/ en/site/forusers/download.html) and the

Results

A new phylogenomic framework for the orchid family

Molecular clock dating and biogeographic reconstructions point to a Laurasian origin of Orchidaceae during the Late Cretaceous

derived from the Angiosperm 353 chronograms and crown node ages of the Sanger chronograms indicated that age discordance between both datasets was minimal (Methods S1; Figs S10, S11), thus suggesting that absolute ages obtained from the 10 posterior probability trees were reliable. Seven of the 10 biogeographical reconstructions (conducted on the 10 PP species trees) supported Laurasia (Nearctic + Palearctic) as the place of origin for the most recent common ancestor of orchids (relative probability

Orchid speciation in space and time

here had one- or even two-fold variation in their speciation rates (Fig. 5c, inset). Our speciation rate analyses unveiled multiple accelerations within each subfamily with the fastest tip rates in Orchidoideae and Epidendroideae, starting from the early

Discussion

Congruence of our global orchid phylogenomic framework with recent orchid phylogenomic studies

A Laurasian, Cretaceous origin of Orchidaceae

et al., 2009). Another example in the Orchidaceae of an ancient relictual range is the subfamily Cypripedioideae (slipper orchids), with five genera and 169 extant species (136 Old World and 33 New World). The ancestor of the slipper orchids likely had a continuous distribution in the boreotropics from where slipper orchids migrated southwards to both sides of the Pacific Ocean due to the climate cooling in the late Cenozoic (Guo et al., 2012; Fig. 4).

A Central American hotspot of orchid speciation

of Costa Rica and Panama acts as a biological crossroads between the two biodiversity hotspots of northern Mesoamerica and the northern Andes, resulting in the current coexistence of northern and southern groups (Burger, 1980; Kapelle, 2016). These findings support and expand the hypothesis of Central American tropical forests having evolved rapidly and recently (Cano et al., 2022). Nevertheless, although our analyses of geographical speciation rates offer new perspectives on the evolution of orchid diversity, we urge caution in interpreting the relationship between

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

Author contributions

ORCID

William J. Baker (D https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6727-1831

Sidonie Bellot (D https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6355-237X

Diego Bogarín (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8408-8841

Martha Charitonidou (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-96578362

Guillaume Chomicki (D https://orcid.org/0000-0003-45476195

Fabien L. Condamine (D https://orcid.org/0000-0003-16739910

Nicola S. Flanagan (D https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4909-8710

Barbara Gravendeel (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6508-0895

Carlos Jaramillo (D https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2616-5079

Ilia J. Leitch (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3837-8186

Robert Müntz (D https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9635-2884

Olivier Maurin (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4151-6164

Katharina Nargar (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0459-5991

Oscar A. Pérez-Escobar (D https://orcid.org/0000-0001-91662410

Charlotte Phillips (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2200-9677

Natalia A. S. Przelomska (D https://orcid.org/0000-0001-92074565

Susanne S. Renner (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3704-0703

Eric Smidt (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1177-1682

Alejandro Zuluaga (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5874-6353

Data availability

References

Ali JR, Heaney LR. 2021. Wallace’s line, Wallacea, and associated divides and areas: history of a tortuous tangle of ideas and labels. Biological Reviews 96: 922-942.

Baker WJ, Bailey P, Barber V, Barker A, Bellot S, Bishop D, Botigué LR, Brewer G, Carruthers T, Clarkson JJ et al. 2022. A comprehensive phylogenetic platform for exploring the angiosperm tree of life. Systematic Biology 71: 301-319.

Baker WJ, Couvreur TLP. 2012. Global biogeography and diversification of palms sheds light on the evolution of tropical lineages. II. Diversification history and origin of regional assemblages. Journal of Biogeography 40: 286-298.

Balbuena JA, Miguez-Lozano R, Blasco-Costa I. 2013. PACo: a novel Procustres application to cophylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 8: e61408.

Batista J, de Bem BL, Gonzalez-Tamayo R, Figueroa XM, Cribb P. 2011. A synopsis of the New World Habenaria (Orchidaceae) I. Harvard Papers in Botany 16: 1-47.

Beeravolu R, Condamine F. 2016. An extended maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction and cladogenesis. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/038695.

Benzing DH. 2000. Bromeliaceae: profile of an adaptive radiation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchene S, Fourment M, Gavryushina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kuhnert D, De Maio N et al. 2019. Beast 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Computational Biology 15: e1006650.

Bouetard A, Lefeuvre P, Gigant R, Séverine Bory S, Pignal M, Besse P, Grisoni M. 2010. Evidence of transoceanic dispersion of the genus Vanilla based on plastid DNA phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55: 621-630.

Brummitt K. 2001. World geographical scheme for recording plant distributions,

Burgener L, Hyland E, Reich RJ, Scotese C. 2023. Cretaceous climates: mapping paleo-Köppen climatic zones using a Bayesian statistical analysis of lithologic,

paleontologic and geochemical proxies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 613: 111373.

Burger WC. 1980. Why are there so many kinds of flowering plants in Costa Rica? Brenesia 17: 371-388.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. Blast+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421.

Camara-Leret R, Frodin DG, Adema F, Anderson C, Appelhans M, George A, Guerrero SA, Ashton P, Baker WJ, Barfod AS et al. 2020. New Guinea has the world’s richest Island flora. Nature 584: 579-583.

Cano A, Stauffer FW, Andermann T, Liberal IM, Zizka A, Bacon CD, Lorenzi H, Christe C, Töpel M, Perret M et al. 2022. Recent and local diversification of Central American understorey palms. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31: 1513-1525.

Chase M. 2001. The origin and biogeography of Orchidaceae. In: Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN, eds. Genera Orchidacearum: vol. 2. Orchidoideae (part one). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chase MW, Cameron KM, Freudenstein JV, Pridgeon AM, Salazar G, van den Berg C, Schuiteman A. 2015. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 177: 151-174.

Chomicki G, Bidel LPR, Ming F, Coiro M, Zhang X, Wang Y, Jay-Allemand C, Renner SS. 2015. The velamen protects photosynthetic orchid roots against UV-B damage, and a large dated phylogeny implies multiple gains and losses of this function during the Cenozoic. New Phytologist 205: 1330-1341.

Christenhusz MJ, Byng JW. 2016. The number of known plant species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 261: 201-217.

Collinson ME, Hooker JJ. 2003. Paleogene vegetation of Eurasia: framework for mammalian faunas. Deinsea 10: 41-83.

Collobert G, Perez-Lamarque B, Dubuisson J-Y, Martos F. 2022. Gains and losses of the epiphytic lifestyle in epidendroid orchids: review and new analyses with succulent traits. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2022.09.30.510324.

Condamine F, Rolland J, Morlon H. 2013. Macroevolutionary perspectives to environmental change. Ecology Letters 16: 72-85.

Conran JG, Bannister JM, Lee DE. 2009. Earliest orchid macrofossils: early Miocene Dendrobium and Earina (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae) from New Zealand. American Journal of Botany 96: 466-474.

Couvreur TLP, Forest F, Baker WJ. 2011. Origin and global diversification patterns of tropical rain forests: inferences from a complete genus-level phylogeny of palms. BMC Biology 9: 44.

Crain BJ, Fernández M. 2020. Biogeographical analyses to facilitate targeted conservation of orchid diversity in Costa Rica. Diversity and Distributions 26: 853-866.

Cribb P, Pridgeon A. 2009. Claderia: phylogenetics. In: Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN, eds. Genera Orchidacearum: vol. 5. Epidendroideae (part two). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dauby G, Zaiss R, Blach-Overgaard A, Catarino L, Damen T, Deblauwe V, Dessin S, Dransfield J, Droissart V, Duarte MC et al. 2016. Rainbio: a megadatabase of tropical African vascular plants distributions. PhytoKeys 74: 1-18.

De Lamotte DF, Fourdan B, Leleu S, Francois L, Clarens P. 2015. Style of rifting and the stages of Pangea break-up. Tectonics 34: 1009-1029.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. 1990. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13-15.

Dressler RL. 1990. The orchids: natural history and classification. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

Driese GS, Kenneth HO, Sally PH, Zheng-Hua L, Debra SJ. 2007. Paleosol evidence for Quaternary uplift and for climate and ecosystem changes in the Cordillera de Talamanca, Costa Rica. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 248: 1-23.

Eiserhardt WL, Couvreur TLP, Baker WJ. 2017. Plant phylogeny as a window on the evolution of hyperdiversity in the tropical rainforest biome. New Phytologist 214: 1408-1422.

Freudenstein JV, Chase MW. 2015. Phylogenetic relationships in Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae), one of the great flowering plant radiations: progressive specialization and diversification. Annals of Botany 115: 665-681.

Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Doucette A, Giraldo G, McDaniel J, Clements MA et al. 2016. Orchid historical

biogeography, diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal. Journal of Biogeography 43: 1905-1916.

Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Iles WJD, Clements MA, Arroyo MTK, Leebens-Mack J et al. 2015. Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20151553.

Górniak M, Paun O, Chase MW. 2010. Phylogenetic relationships within Orchidaceae based on a low-copy nuclear coding gene,

Govaerts R, Lughadha EN, Black N, Turner R, Paton A. 2021. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for exploring global plant diversity. Scientific Data 8: 215.

Grace OM, Pérez-Escobar OA, Lucas EJ, Vorontsova MS, Lewis GP, Walker BE, Lohmann LG, Knapp S, Wilkie P, Sarkinen T et al. 2021. Botanical monograph in the Anthropocene. Trends in Plant Science 26: 433-441.

Grafe KW, Frisch IM, Villa MM. 2002. Geodynamic evolution of southern Costa Rica related to low-angle subduction of the Cocos Ridge: constraints from thermochronology. Tectonophysics 348: 187-204.

Guo Y-Y, Luo Y-B, Liu Z-J, Wang X-Q. 2012. Evolution and biogeography of the slipper orchids: eocene vicariance of the conduplicate genera in the Old and New World Tropics. PLoS ONE7: e38788.

Gustafsson ALS, Verola CF, Antonelli A. 2010. Reassessing the temporal evolution of orchids with new fossils and a Bayesian relaxed clock, with implications for the diversification of the rare South American genus Hoffmannseggella (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae). BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 1-13.

Huson DH, Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23: 254-267.

Johnson MG, Gardner EM, Liu Y, Medina R, Goffinet B, Shaw AJ, Zerega NJ, Wicket NJ. 2016. HybPiper: extracting coding sequence and introns for phylogenetics from high-throughput sequencing reads using target enrichment. Applications in Plant Sciences 4: 1600016.

Johnson MG, Pokorny LP, Dodsworth SD, Botigué LR, Cowan RS, Devault A, Eiserhardt WL, Epitawalage N, Forest F, Kim JT et al. 2019. A universal probe set for targeted sequencing of 353 nuclear genes from any flowering plant designed using k-medoids clustering. Systematic Biology 68: 594-606.

Jones DL. 1997. Cooktownia robertsii, a remarkable new genus and species of Orchidaceae from Australia. Austrobaileya 5: 71-78.

Kapelle M. 2016. The montane cloud forests of the Cordillera de Talamanca. In: Kapelle M, ed. Costa Rican ecosystems. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Karremans A, Watteyn C, Scaccabarozzi D, Pérez-Escobar OA, Bogarín D. 2023. Evolution of seed dispersal modes in the Orchidaceae: has the Vanilla mystery been solved? Horticulturae 9: 1270.

Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. Maff: multiple sequence alignment software v.7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772-780.

Kirby SH. 2011. Active mountain building and the distribution of “core” Maxillariinae species in tropical Mexico and Central America. Lankesteriana 11: 275-291.

Korasidis VA, Wing SL, Shields CA, Kiehl JT. 2022. Global changes in terrestrial vegetation and continental climate during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 37: e2021PA004325.

Li Y, Ma L, Liu D-K, Zhao X-WZD, Ke S, Chen G-Z, Zheng Q, Liu Z-J, Lan S. 2023. Apostasia fujianica (Apostasioideae, Orchidaceae), a new Chinese species: evidence from morphological, genome size and molecular analyses. Phytotaxa 583: 277-284.

Louca S, Pennell MW. 2021. Why extinction estimates from extant phylogenies are so often zero. Current Biology 31: 3168-3173.

Magallón S, Sánchez-Reyes LL, Gómez-Acevedo SL. 2019. Thirty clues to the exceptional diversification of flowering plants. Annals of Botany 123: 491-503.

Maldonado C, Molina CI, Zizka A, Persson C, Taylor CM, Alban J, Chilquillo E, Ronsted N, Antonelli A. 2015. Estimating species diversity and distribution in the era of Big Data: to what extent can we trust public databases? Global Ecology and Biogeography 24: 973-984.

Matzke NJ. 2013. Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founderevent speciation, imperfect detection, and fossil allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Frontiers of Biogeography 5: 243-248.

Meseguer AS, Condamine FL. 2020. Ancient tropical extinctions at high latitudes contributed to the latitudinal diversity gradient. Evolution 74: 19661987.

Morell KD, Fisher DM, Gardner TW, La Femina P, Davidson D, Teletzke A. 2011. Quaternary outer fore-arc deformation and uplift inboard of the Panama Triple Junction, Burica Peninsula. Journal of Geophysical Research 116: B05402.

Mosquera-Mosquera HR, Valencia-Barrera RM, Acedo C. 2019. Variation and evolutionary transformation of some characters of the pollinarium and pistil in Epidendroideae (Orchidaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 305: 353-374.

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853-858.

Nauheimer L, Schley RJ, Clements MA, Micheneau C, Nargar K. 2018. Australian orchid biogeography at continental scale: molecular phylogenetic insights from the sun orchids (Thelymitra, Orchidaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 127: 304-319.

Niissalo MA, Leong PKF, Tay FEL, Choo LM, Kurzweil H, Khew GS. 2023. A new species of Claderia (Orchidaceae). Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 75: 21-41.

Parra-Sánchez E, Pérez-Escobar OA, Edwards DP. 2023. Neutral-based processes overrule niche-based processes in shaping tropical montane orchid communities across spatial scales. Journal of Ecology 111: 1614-1628.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Balbuena JA, Gottschling M. 2016. Rumbling orchids: how to assess divergent evolution between chloroplast endosymbionts and the nuclear host. Systematic Biology 65: 51-65.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Bellot S, Przelomska NAS, Flowers JM, Nesbitt M, Ryan P, Gutaker RM, Gros-Balthazard M, Wells T, Kuhnhäuser BG et al. 2021a. Molecular clocks and archaeogenomics of a late period Egyptian date palm leaf reveal introgression from wild relatives and add timestamps on the domestication. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38: 4475-4492.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Chomicki G, Condamine FL, Karremans AP, Bogarín D, Matzke NJ, Silvestro D, Antonelli A. 2017. Recent origin and rapid speciation of Neotropical orchids in the world’s richest plant biodiversity hotspot. New Phytologist 215: 891-905.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Dodsworth S, Bogarín D, Balbuena JA, Schley RJ, Kikuchi IZ, Morris SK, Epitawalage N, Cowan R, Maurin O et al. 2021b. Hundreds of nuclear and plastid loci yield novel insights into orchid relationships. American Journal of Botany 108: 1166-1180.

Pérez-Escobar OA, Zizka A, Bermúdez MA, Meseguer AS, Condamine FL, Hoorn C, Hooghiemstra H, Pu Y, Bogarín D, Boschman LM et al. 2022. The Andes through time: evolution and distribution of Andean floras. Trends in Plant Science 27: 1-12.

Poinar G, Rasmussen FN. 2017. Orchids from the past, with a new species in Baltic amber. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 183: 327-333.

Poinar G Jr. 2016a. Orchid pollinaria (Orchidaceae) attached to stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Dominican amber. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie Und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen 279: 287-293.

Poinar G Jr. 2016b. Beetles with orchid pollinaria in Dominican and Mexican amber. American Entomologist 62: 172-177.

Portik DM, Wiens JJ. 2020. SuperCRUNCH: a bioinformatics toolkit for creating and manipulating supermatrices and other large phylogenetic datasets. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11: 7763-7772.

Rabosky DL, Grundler M, Anderson C, Title P, Shi JF, Brown JW, Huang H, Larson JG. 2014. BAMMTools: an R package for the analysis of evolutionary dynamics on phylogenetic trees. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5: 701-707.

Rabosky DL, Santini F, Eastman J, Smith SA, Sidlauskas B, Chang J, Alfaro ME. 2013. Rates of speciation and morphological evolution are correlated across the largest vertebrate radiation. Nature Communications 4: 1958.

Rangel TF, Colwell RK, Graves GR, Fucikova K, Rahbek C, Diniz-Filho JF. 2015. Phylogenetic uncertainty revisited: implications for ecological analyses. Evolution 69: 1301-1312.

Ree RH, Smith SA. 2008. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Systematic Biology 57: 4-14.

Selosse M-A, Petrolli R, Mujica MI, Laurent L, Perez-Lamarque B, Figura T, Bourceret A, Jacquemyn H, Li T, Gao J et al. 2022. The waiting room hypothesis revisited by orchids: were orchid mycorrhizal fungi recruited among root endophytes? Annals of Botany 129: 259-270.

Serna-Sánchez M, Pérez-Escobar OA, Bogarín D, Torres-Jimenez MF, AlvarezYela AC, Arcila-Galvis JE, Hall C, de Barros D, Pinheiro F, Dodsworth S et al. 2021. Plastid phylogenomics resolves ambiguous relationships within the orchid family and provides a solid timeframe for biogeography and macroevolution. Scientific Reports 11: 6858.

Simpson L, Clements MA, Orel HK, Crayn DM, Nargar K. 2022. Plastid phylogenomics clarifies broad-level relationships in Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae) and provides insights into range evolution of Australasian section Adelopetalum. BioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2022.07.24.500920.

Smith SA, Brown JW, Walker JF. 2018. So many genes, so little time: a practical approach to divergence-time estimation in the genomic era. PLoS ONE 13: e0197433.

Smith SA, Moore MJ, Brown JW, Ya Y. 2015. Analysis of phylogenomic datasets reveal conflict, concordance, and gene duplications with examples from animals and plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 150.

Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML v.8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and postanalysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312-1313.

Thompson JB, Davis KE, Dodd HO, Priest NK. 2023. Speciation across the Earth driven by global cooling in terrestrial orchids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 120: e2102408120.

Tietje M, Antonelli A, Baker WJ, Govaerts R, Smith SA, Eiserhardt WL. 2022. Global variation in diversification rate and species richness are unlinked in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 119: e2120662119.

Title PO, Rabosky DL. 2019. Tip rates, phylogenies and diversification: what are we estimating, and how good are the estimates? Methods in Ecology and Evolution 10: 821-834.

Töpel M, Zizka A, Maria Fernanda Calió MF, Scharn R, Silvestro D, Antonelli A. 2017. SpeciesGeoCoder: fast categorization of species occurrences for analyses of biodiversity, biogeography, ecology, and evolution. Systematic Biology 66: 145-151.

Van den Berg C, Goldman DH, Freudenstein JV, Pridgeon AM, Cameron KM, Chase MW. 2005. AN overview of the phylogenetic relationships within Epidendroideae inferred from multiple DNA regions and re-circumscription of Epidendreae and Arethuseae (Orchidaceae). American Journal of Botany 92: 613-624.

Velasco JA, Pinto-Ledezma JN. 2022. Mapping species diversification metrics in macroecology: prospects and challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 10: 1-18.

Viruel J, Segarra-Moragues JG, Raz L, Forest F, Wilkin P, Sanmartín I, Catalán P. 2015. Late Cretaceous – Early Eocene origin of yams (Dioscorea, Dioscoreaceae) in the Laurasian Palaeartic and their subsequent OligoceneMiocene diversification. Journal of Biogeography 43: 672-750.

Vitt P, Taylor A, Rakosy D, Kreft H, Meyer A, Wigelt P, Knight TM. 2023. Global conservation prioritization of the Orchidaceae. Scientific Reports 13: 6718.

Wing SL, Boucher LD. 1998. Ecological aspects of the Cretaceous flowering plant radiation. Annual Reviews of Earth and Planetary Science 26: 379-421.

Wing SL, Strömberg C, Hickey LJ, Tiver F, Willis B, Burnham RJ, Behrensmeyer AK. 2012. Floral and environmental gradients on a Late Cretaceous landscape. Ecological Monographs 82: 23-457.

Zhang C, Rabiee M, Sayyari E, Mirarab S. 2018. Astral-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19: 153.

Zhang C, Zhao Y, Braun EL, Mirarab S. 2021. Taper: pinpointing errors in multiple sequence alignments despite varying rates of evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 20: 1-14.

Zhang G, Hu Y, Huang M-Z, Huang W-C, Liu D-K, Zhang D, Hu H, Downing JL, Liu Z-J, Ma H. 2023. Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of Orchidaceae using nuclear genes and evolutionary insights into epiphytism. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 65: 1204-1225.

Supporting Information

node ages obtained, respectively, from the 10 randomly sampled NGS genus-level and Sanger species-level posterior probability trees.

- *Lead authors.

Senior authors.