DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00552-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200272

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

أطلس خلية واحدة لمبيض الفأر المتقدم في السن

تاريخ القبول: 1 ديسمبر 2023

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 10 يناير 2024

(4) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

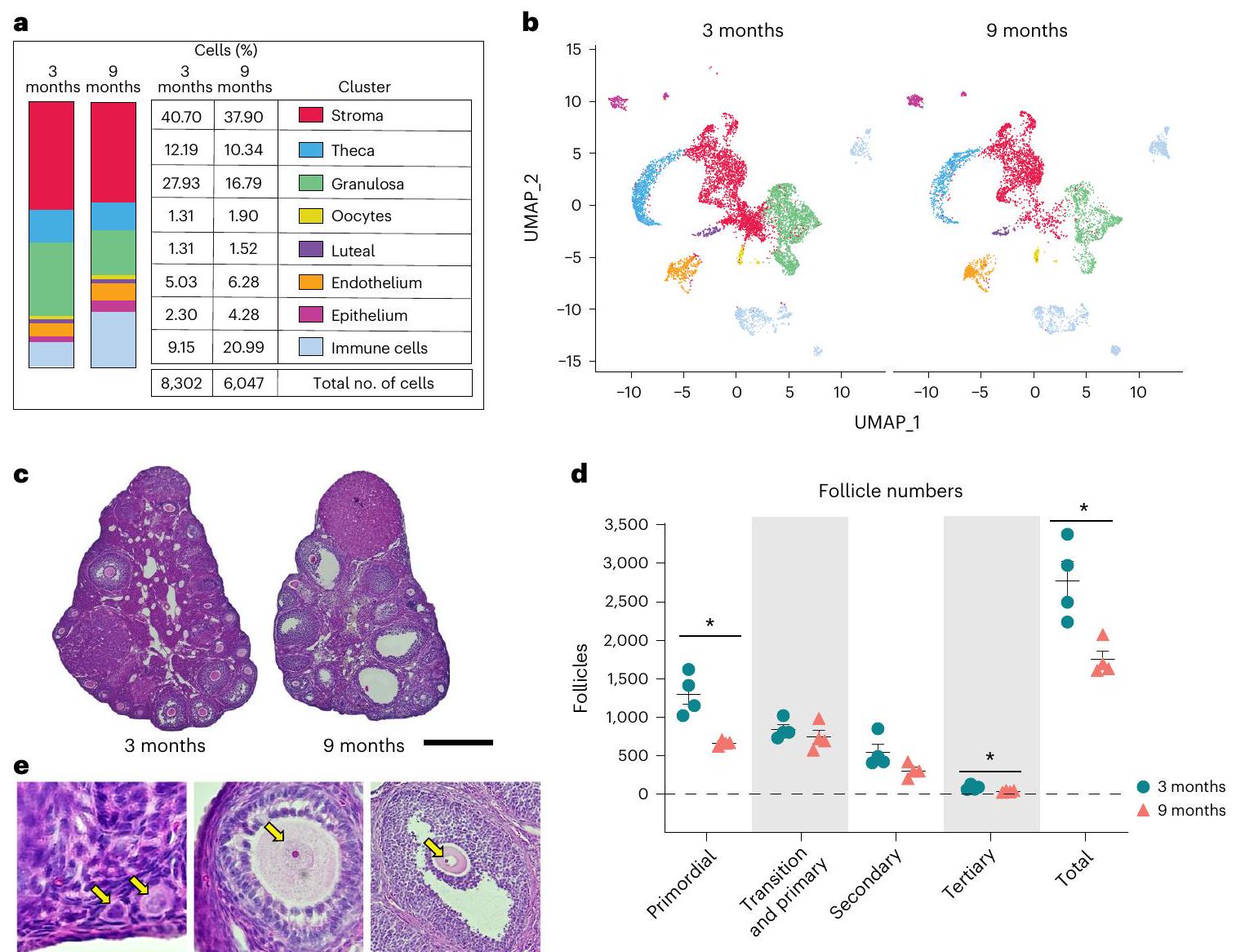

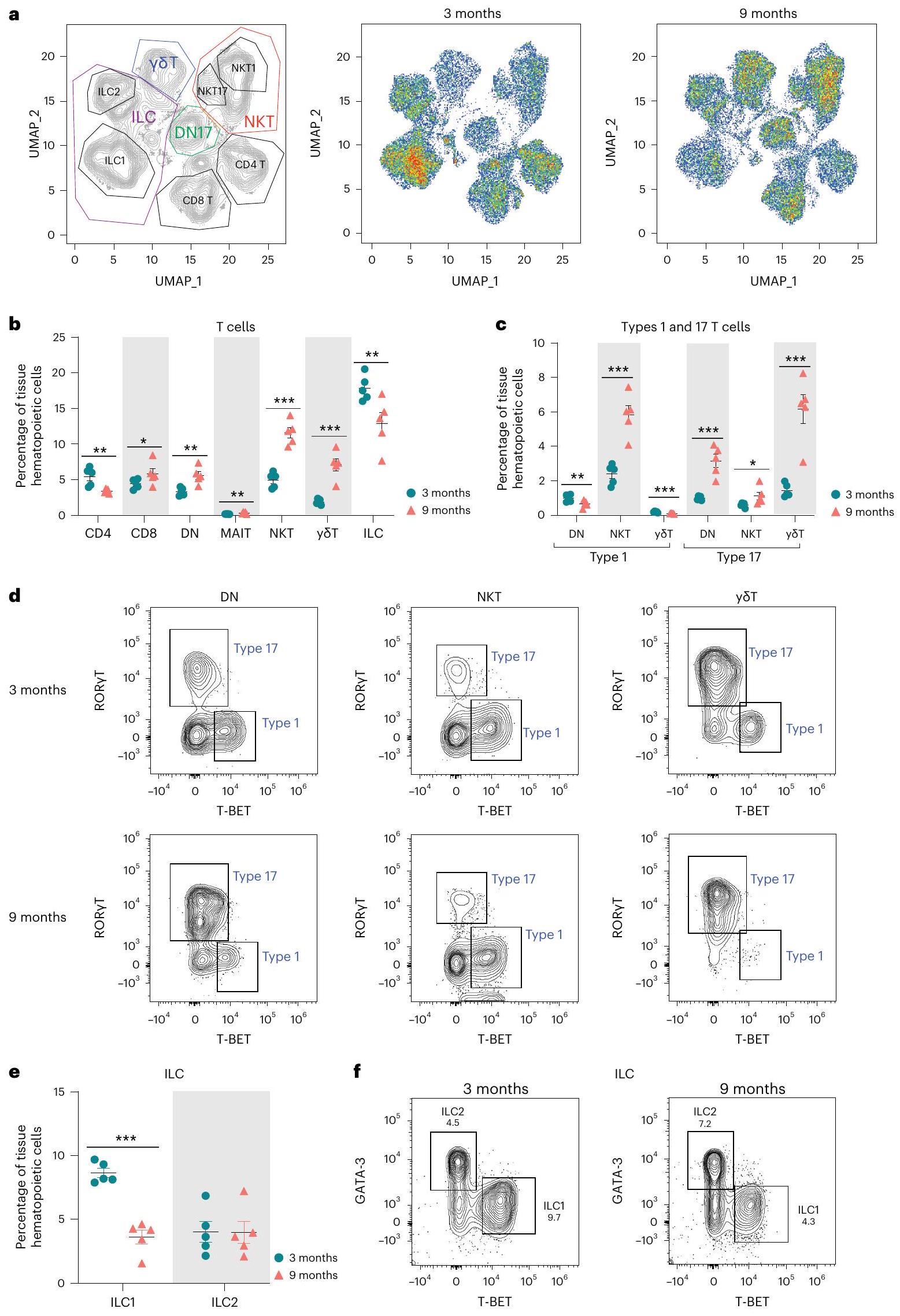

يؤدي تقدم المبيض في السن إلى انخفاض الخصوبة، واضطراب الإشارات الهرمونية وزيادة عبء الأمراض المزمنة. تبدأ هذه التأثيرات في الظهور قبل فترة طويلة من استنفاد الجريبات. تعاني النساء من انخفاض حاد في الخصوبة حوالي 35 عامًا، وهو ما يتوافق مع انخفاض جودة البويضات. على الرغم من وجود مجموعة متزايدة من الأعمال، إلا أن هذا المجال يفتقر إلى خريطة خلوية شاملة للتغيرات النسخية في مبيض الفأر المتقدم في السن لتحديد المحركات المبكرة لانخفاض المبيض. لسد هذه الفجوة، قمنا بإجراء تسلسل RNA على مستوى الخلية الواحدة على أنسجة المبيض من الفئران الشابة (3 أشهر) والفئران المتقدمة في السن (9 أشهر). كشفت تحليلاتنا عن تضاعف عدد الخلايا المناعية في المبيض المتقدم في السن، مع زيادة أكبر في نسب اللمفاويات، وهو ما تم تأكيده بواسطة قياس التدفق. كما وجدنا أيضًا انخفاضًا مرتبطًا بالعمر في مسارات الكولاجيناز في الخلايا الليفية السدوية، وهو ما يتوافق مع زيادة تليف المبيض. أظهرت خلايا الجريبات استجابة للضغط، وإشارات مناعية وإشارات تليفية مع تقدم العمر. يوفر هذا التقرير رؤى حاسمة حول الآليات المسؤولة عن أنماط تقدم المبيض في السن. يمكن استكشاف البيانات بشكل تفاعلي عبر تطبيق ويب قائم على Shiny.

من المعروف عن أنواع الخلايا التي تطور هذه الأنماط أولاً و/أو تساهم بشكل رئيسي في تغيير البيئة المحلية. علاوة على ذلك، لا يزال غير واضح ما إذا كانت الخلايا في الجريبات، أو السدى أو كليهما تلعب أدوارًا آلية في تعزيز استنفاد الجريبات وفشل المبيض. سعت الأعمال الأخيرة إلى فك رموز الدور المحتمل الذي تلعبه خلايا السدى المبيضية في صحة المبيض والمرض

النتائج

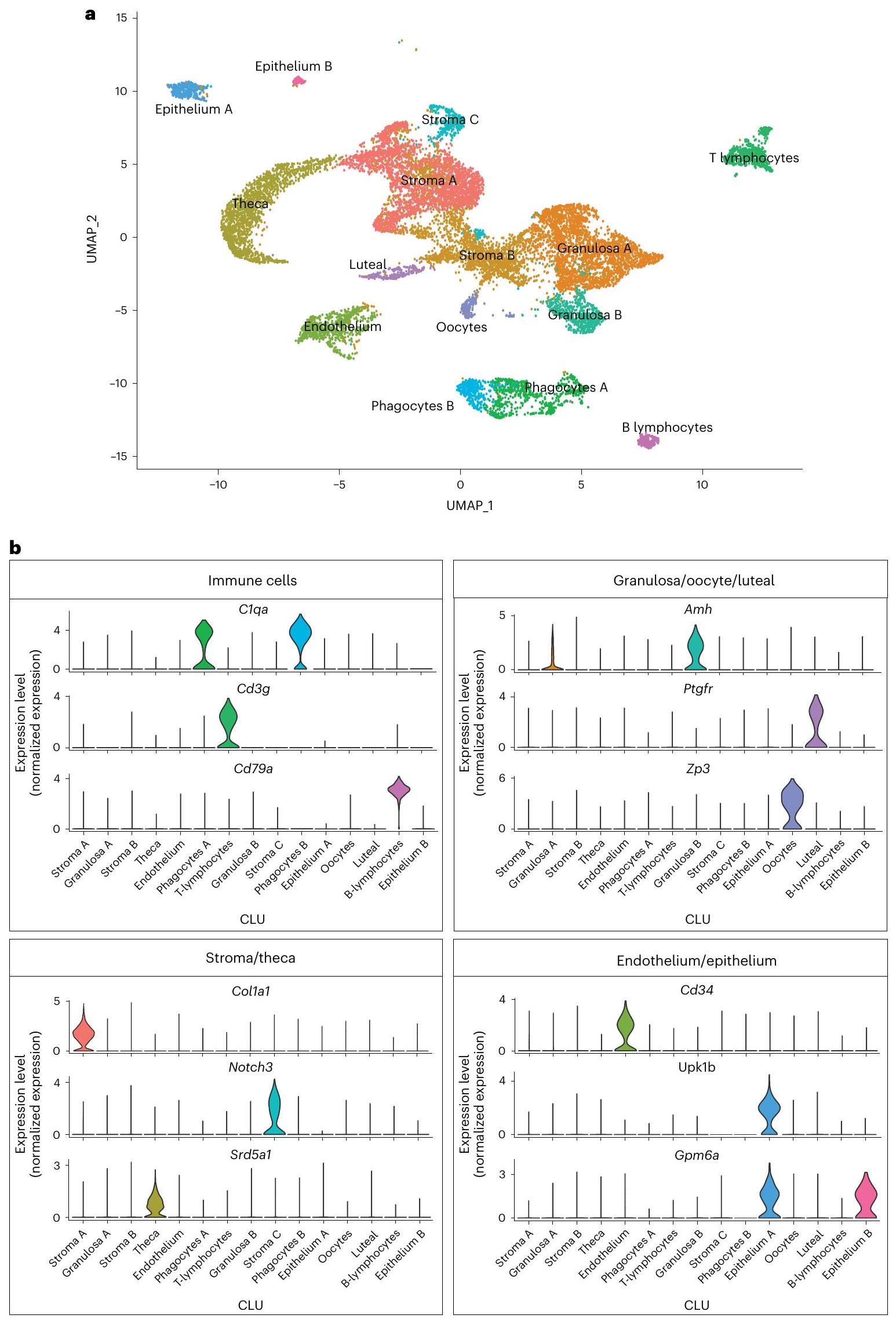

scRNA-seq لمبيض الفأر البالغ عبر الأعمار الإنجابية

, الخلايا البطانية (

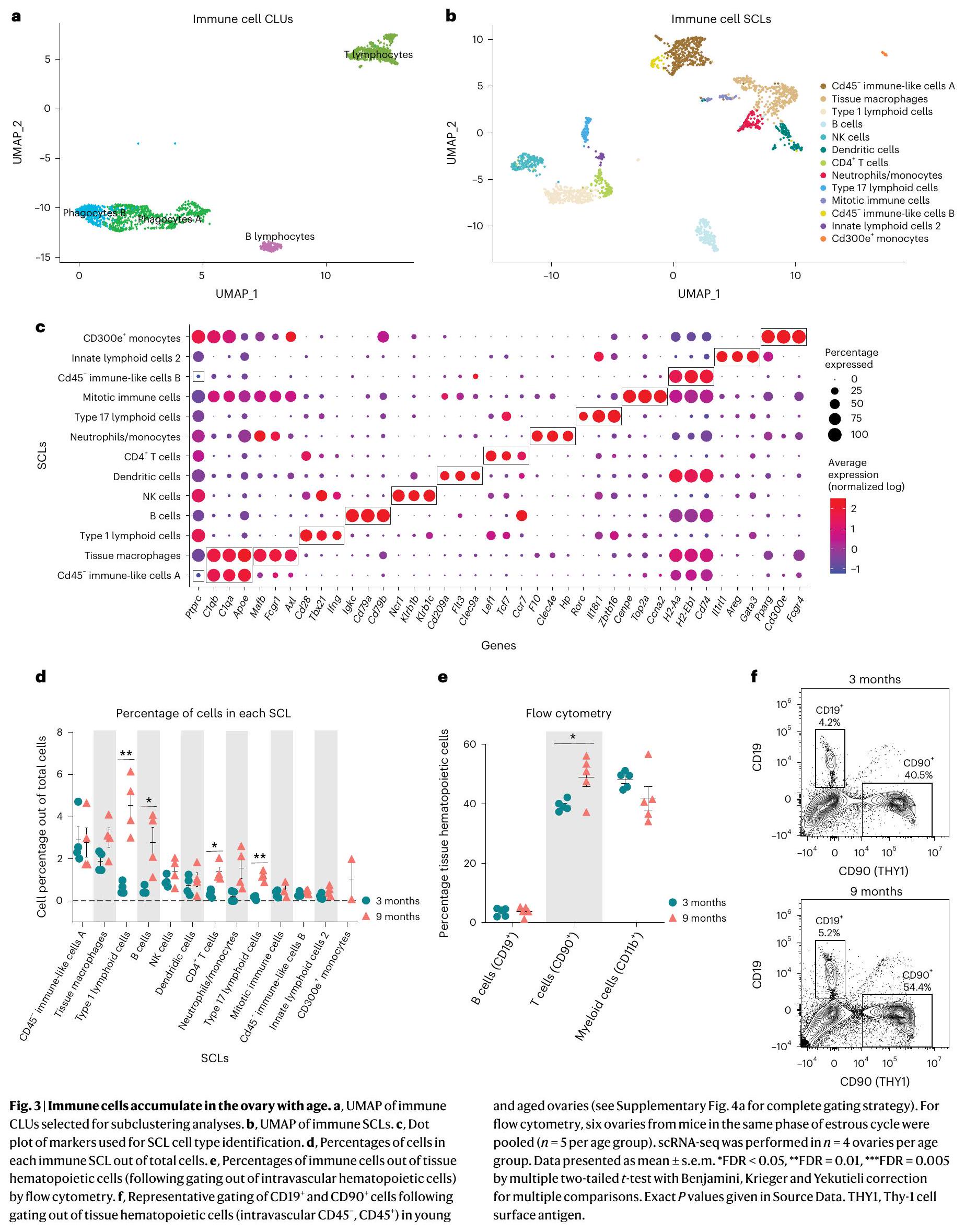

تغيرات خلايا المناعة المبيضية مع التقدم في العمر

علامة خلوية مناعية راسخة. تم تحديد هذين SCLs على أنهما

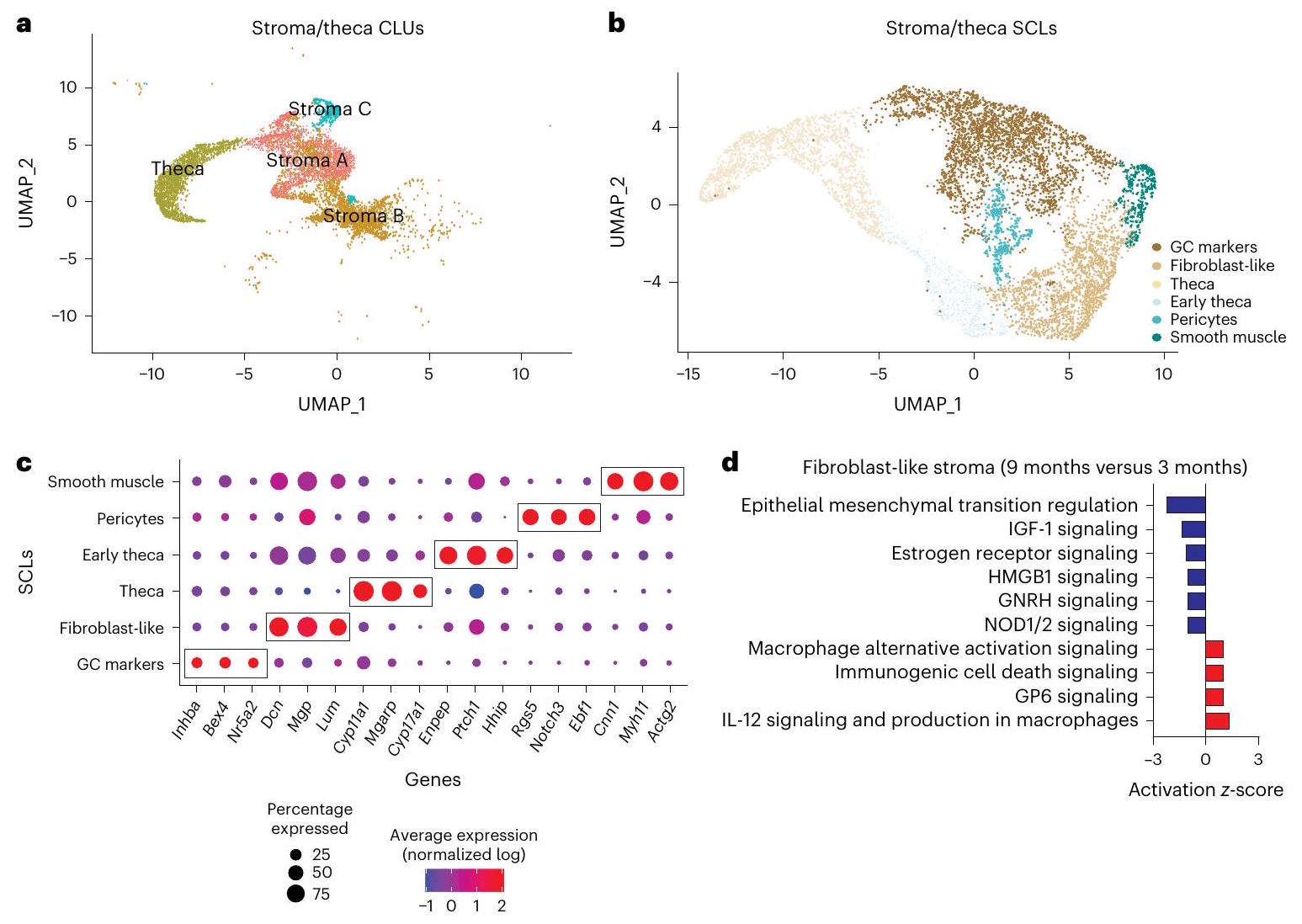

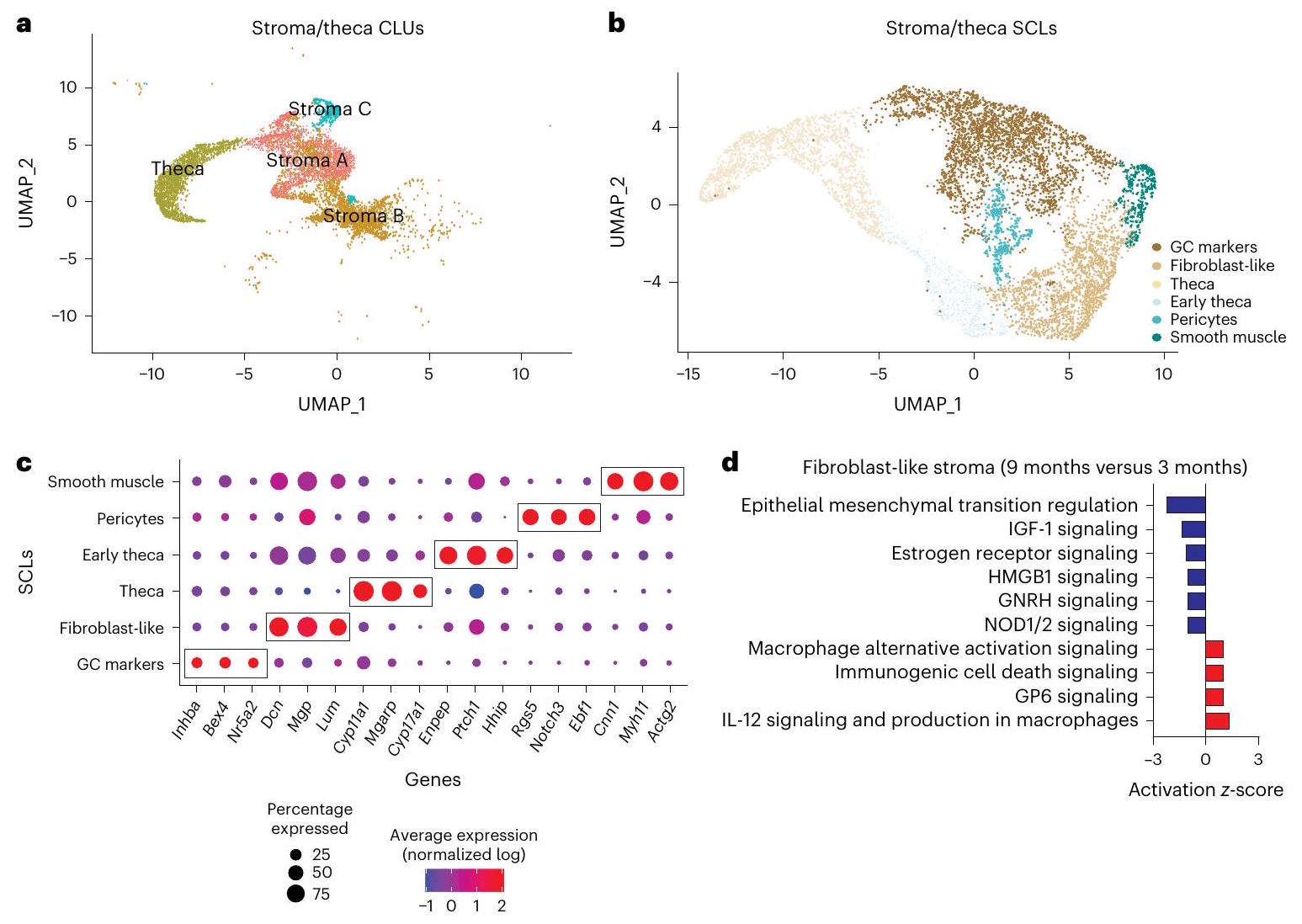

يكشف التجميع الفرعي للستروما وTCs عن تغييرات مرتبطة بالعمر

من الجينات الستيرويدية بما في ذلك Ptch1 وHhip

خلايا الدم الجذعية.

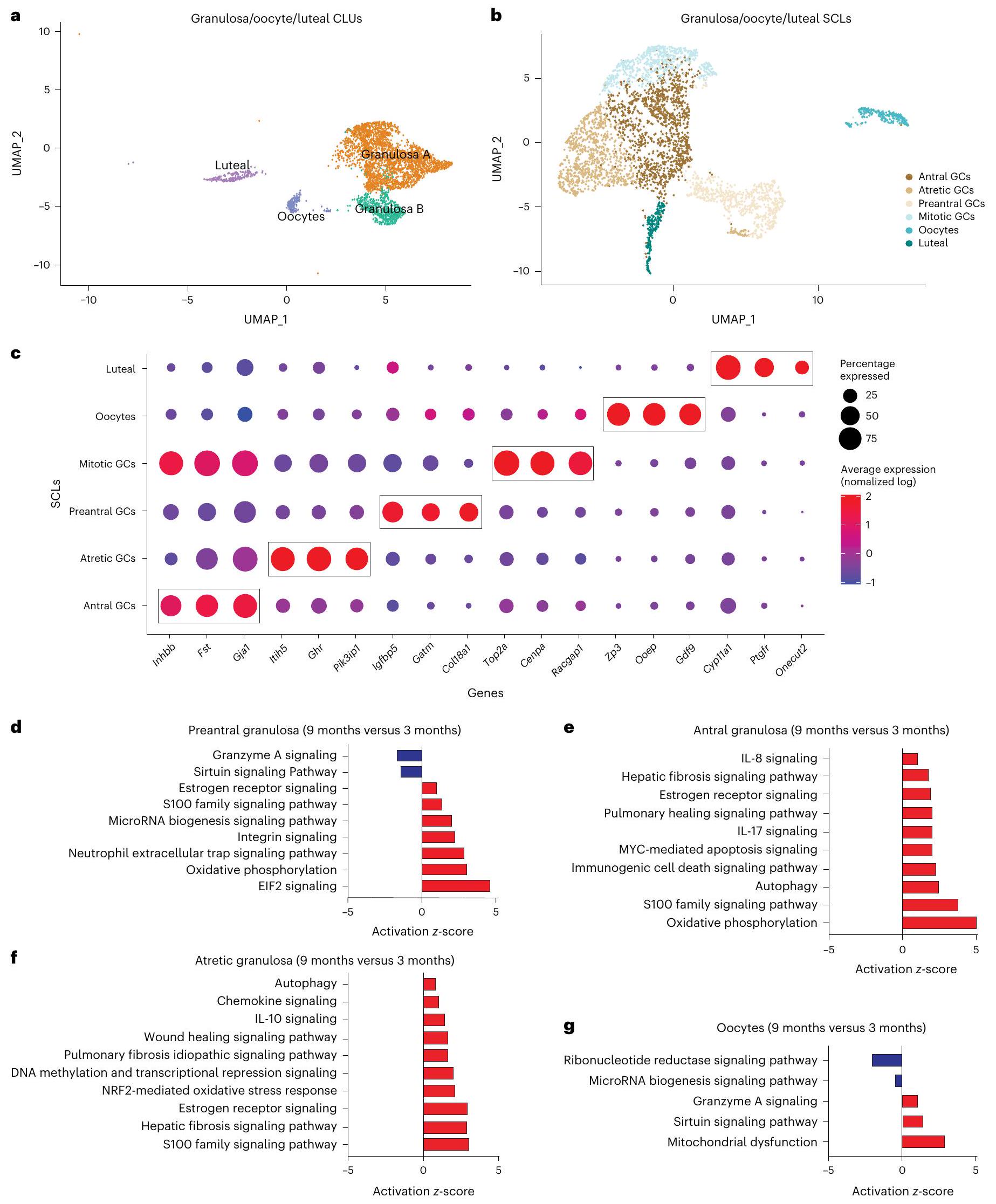

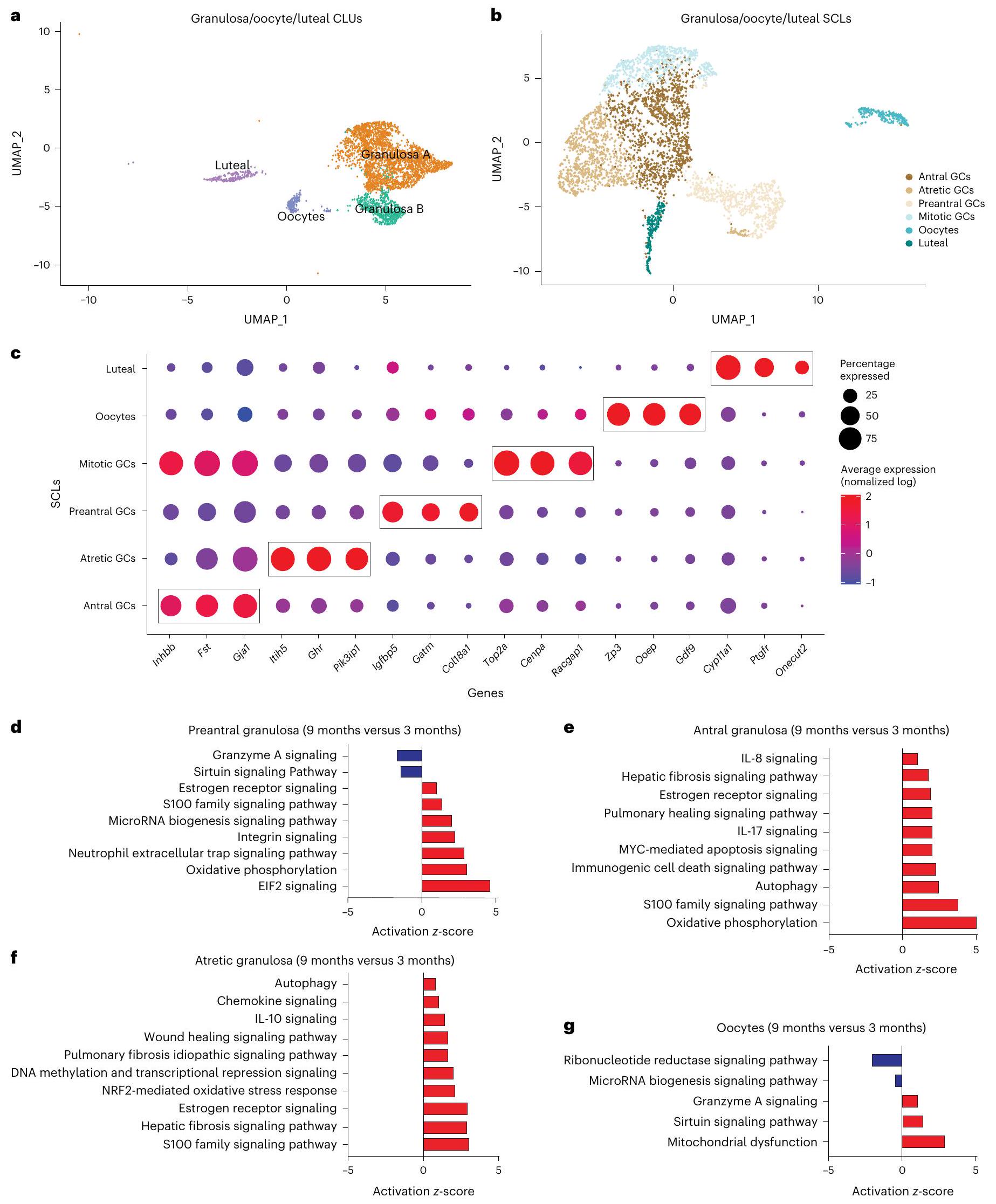

يؤثر الشيخوخة على خلايا SCL في الخلايا الحبيبية، البويضات، والخلايا اللوتينية

أربعة أنواع متميزة من خلايا سكل (SCLs) تم تحديدها كجزء من الجريبات في مراحل مختلفة من التطور. شملت هذه الخلايا سكل ما قبل الأنيترال، الأنيترال، الانقسام، والجريبات المتراجعة. تقوم خلايا الجريبات بإرسال إشارات إلى البويضات لتوفير إشارات.

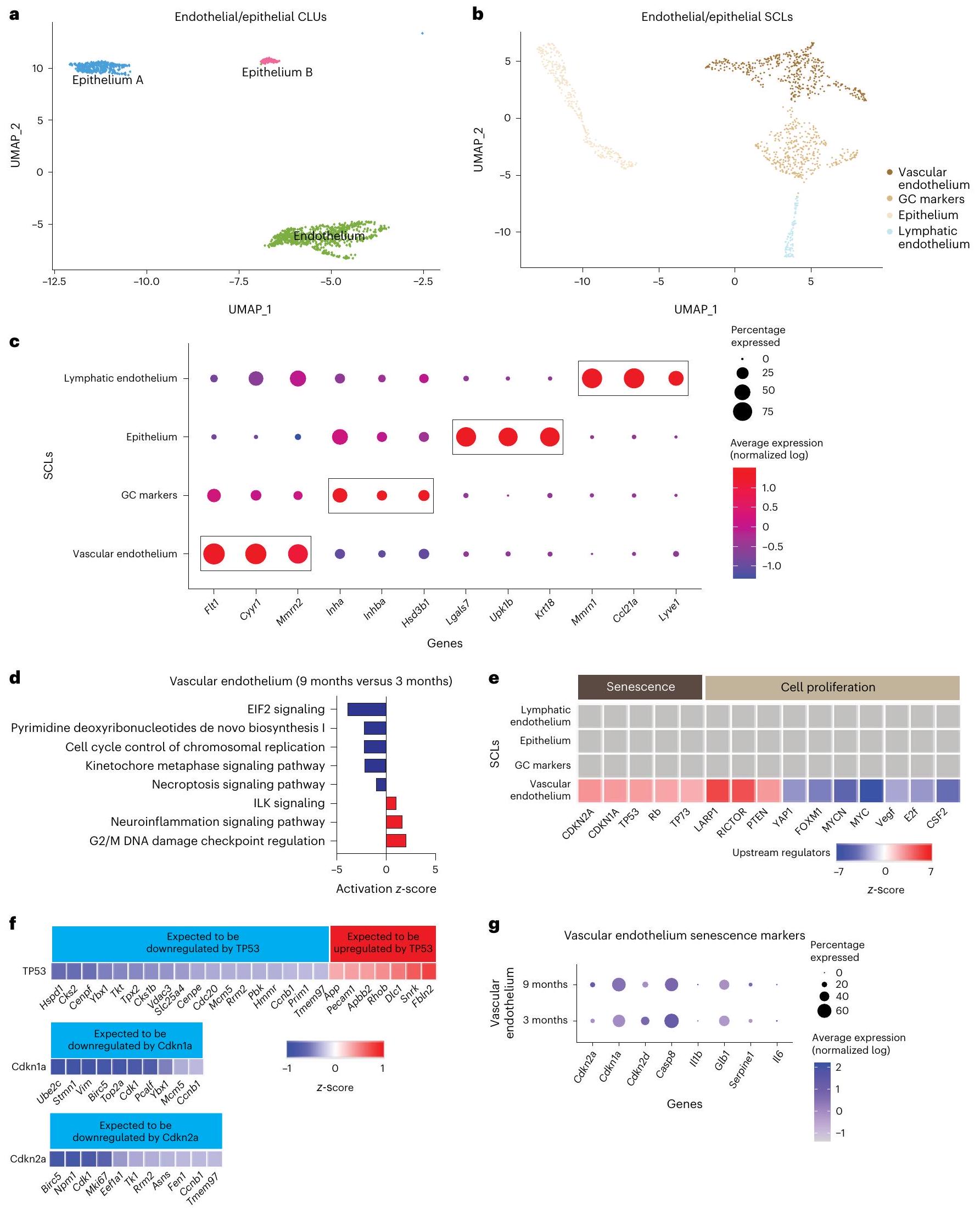

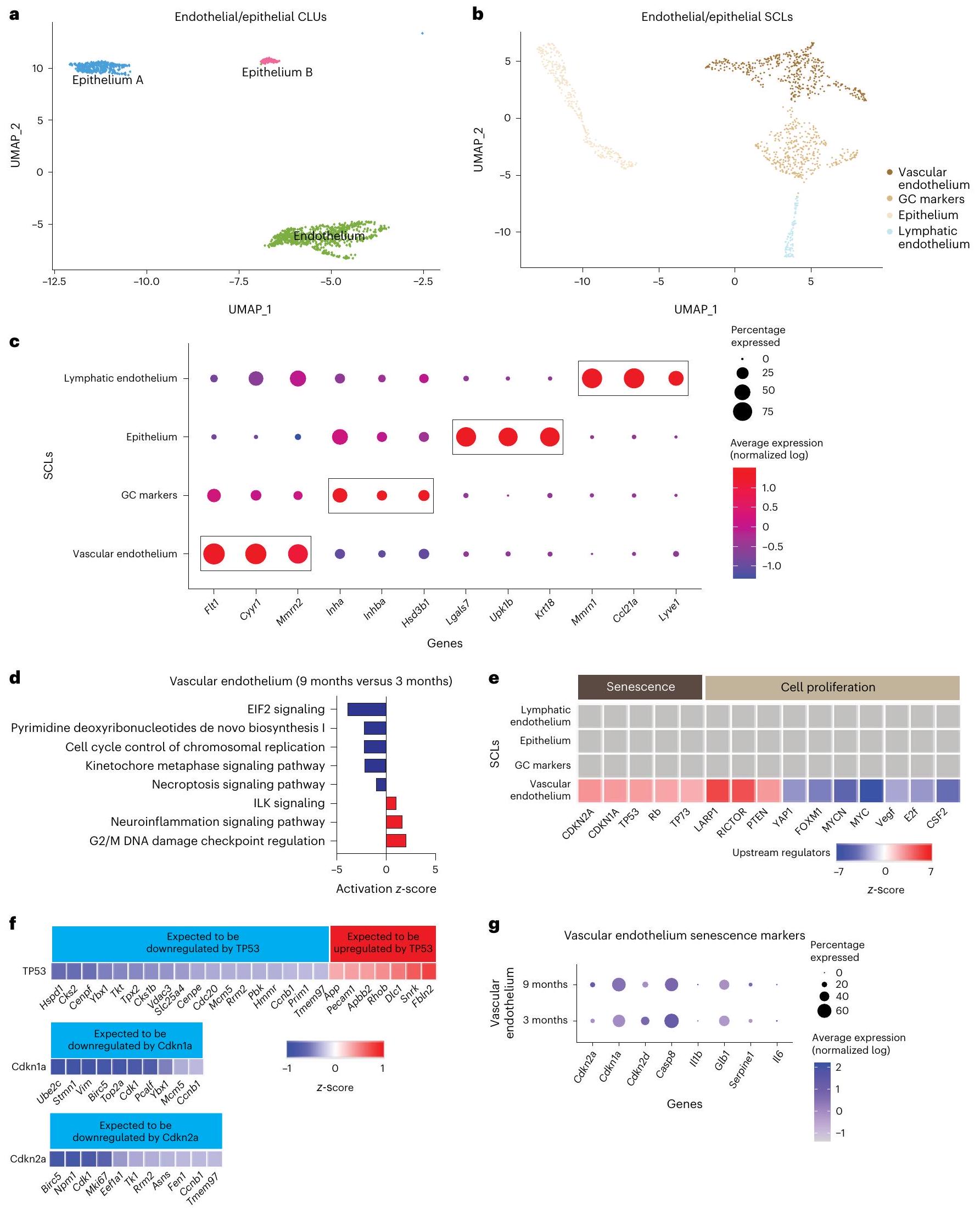

تتأثر خلايا البطانية والظهارية بشكل طفيف بالعمر

الاتجار وإزالة النفايات

نقاش

الخلايا T التكيفية التي يتم تجنيدها عمومًا من الدورة الدموية

يمكن تجنيد اللمفاويات المتداولة إلى الأنسجة استجابةً لإشارات التهابية مشابهة

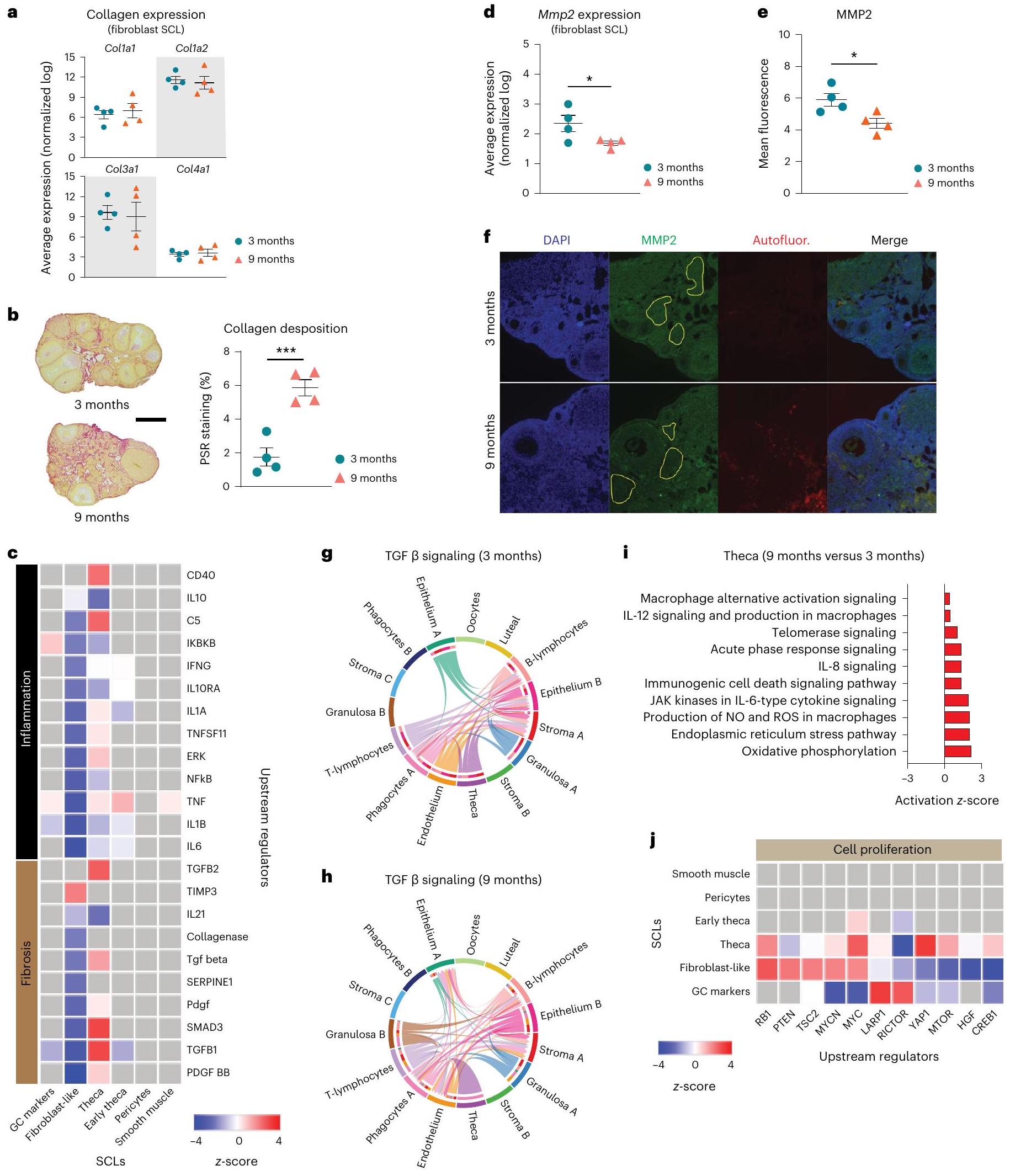

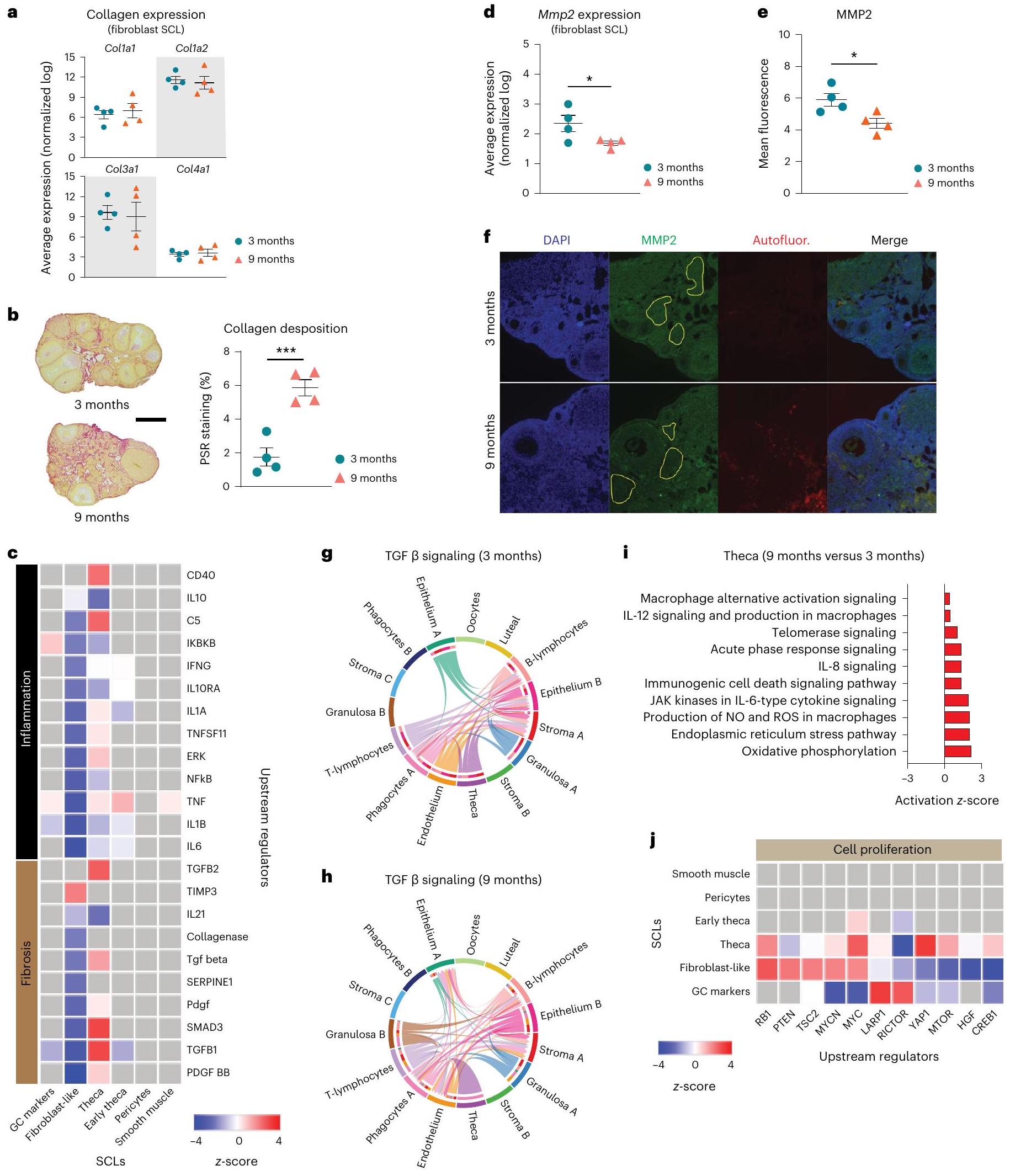

تم جمع مبايض الرئيسيات غير البشرية خلال فترة ما حول انقطاع الطمث، بينما تم جمع مبايض الفئران قبل فترة ما حول انقطاع الطمث. بالإضافة إلى الاستجابات المناعية، وجدنا أيضًا أن GCs وTCs تظهر تحفيزًا مرتبطًا بالعمر للاستجابات الليفية كما يتضح من زيادة تنشيط مسار TGF

طرق

الحيوانات وجمع الأنسجة والتفكيك لـ scRNA-seq

ثقب. تم إجراء التروية باستخدام

بناء مكتبة scRNA-seq

مراقبة جودة scRNA-seq وتحليل البيانات

علم الأنسجة

المناعية الفلورية

قياس التدفق الخلوي

الإحصائيات وإعادة الإنتاج

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Johnson, J. A. & Tough, S. No-271-delayed child-bearing. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 39, e500-e515 (2017).

- Broekmans, F. J., Soules, M. R. & Fauser, B. C. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr. Rev. 30, 465-493 (2009).

- Levine, M. E. et al. Menopause accelerates biological aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9327-9332 (2016).

- Wellons, M., Ouyang, P., Schreiner, P. J., Herrington, D. M. & Vaidya, D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause 19, 1081-1087 (2012).

- Tchernof, A., Calles-Escandon, J., Sites, C. K. & Poehlman, E. T. Menopause, central body fatness, and insulin resistance: effects of hormone-replacement therapy. Coron. Artery Dis. 9, 503-511 (1998).

- Muka, T. et al. Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 767-776 (2016).

- Ossewaarde, M. E. et al. Age at menopause, cause-specific mortality and total life expectancy. Epidemiology 16, 556-562 (2005).

- May-Panloup, P. et al. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update 22, 725-743 (2016).

- Lim, J. & Luderer, U. Oxidative damage increases and antioxidant gene expression decreases with aging in the mouse ovary. Biol. Reprod. 84, 775-782 (2011).

- Yang, L. et al. The role of oxidative stress and natural antioxidants in ovarian aging. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 617843 (2020).

- Ansere, V. A. et al. Cellular hallmarks of aging emerge in the ovary prior to primordial follicle depletion. Mech. Ageing Dev. 194, 111425 (2021).

- Briley, S. M. et al. Reproductive age-associated fibrosis in the stroma of the mammalian ovary. Reproduction 152, 245-260 (2016).

- Lliberos, C. et al. Evaluation of inflammation and follicle depletion during ovarian ageing in mice. Sci. Rep. 11, 278 (2021).

- Amargant, F. et al. Ovarian stiffness increases with age in the mammalian ovary and depends on collagen and hyaluronan matrices. Aging Cell 19, e13259 (2020).

- Umehara, T. et al. Female reproductive life span is extended by targeted removal of fibrotic collagen from the mouse ovary. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn4564 (2022).

- Mara, J. N. et al. Ovulation and ovarian wound healing are impaired with advanced reproductive age. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 9686-9713 (2020).

- Foley, K. G., Pritchard, M. T. & Duncan, F. E. Macrophage-derived multinucleated giant cells: hallmarks of the aging ovary. Reproduction 161, V5-V9 (2021).

- Wang, S. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of primate ovarian aging. Cell 180, 585-600 (2020).

- Wang, S. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of human ovarian aging at single-cell resolution. Preprint at Research Square https://doi. org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1624864/v1 (2022).

- Lu, H. et al. Current animal model systems for ovarian aging research. Aging Dis. 13, 1183-1195 (2022).

- Russ, J. E., Haywood, M. E., Lane, S. L., Schoolcraft, W. B. & KatzJaffe, M. G. Spatially resolved transcriptomic profiling of ovarian aging in mice. iScience 25, 104819 (2022).

- Ankel-Simons, F. & Cummins, J. M. Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: implications for theories on human evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13859-13863 (1996).

- Zhang, D., Keilty, D., Zhang, Z. F. & Chian, R. C. Mitochondria in oocyte aging: current understanding. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 9, 29-38 (2017).

- Zhang, G. et al. Expression of mitochondria-associated genes (PPARGC1A, NRF-1, BCL-2 and BAX) in follicular development and atresia of goat ovaries. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 50, 465-473 (2015).

- Muhl, L. et al. Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination. Nat. Commun. 11, 3953 (2020).

- Morris, M. E. et al. A single-cell atlas of the cycling murine ovary. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife. 77239 (2022).

- Baek, S. H. et al. Single cell transcriptomic analysis reveals organ specific pericyte markers and identities. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 876591 (2022).

- Wagner, M. et al. Single-cell analysis of human ovarian cortex identifies distinct cell populations but no oogonial stem cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 1147 (2020).

- Marti, N. et al. Genes and proteins of the alternative steroid backdoor pathway for dihydrotestosterone synthesis are expressed in the human ovary and seem enhanced in the polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 441, 116-123 (2017).

- Sontheimer, R. D., Racila, E. & Racila, D. M. C1q: its functions within the innate and adaptive immune responses and its role in lupus autoimmunity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 14-23 (2005).

- Lin, G., Finger, E. & Gutierrez-Ramos, J. C. Expression of CD34 in endothelial cells, hematopoietic progenitors and nervous cells in fetal and adult mouse tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1508-1516 (1995).

- Garcillan, B. et al. CD3G or CD3D knockdown in mature, but not immature, T lymphocytes similarly cripples the human TCRalphabeta complex. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 608490 (2021).

- Carpenter, A. R. et al. Uroplakin 1b is critical in urinary tract development and urothelial differentiation and homeostasis. Kidney Int. 89, 612-624 (2016).

- Berisha, B., Rodler, D., Schams, D., Sinowatz, F. & Pfaffl, M. W. Prostaglandins in superovulation induced bovine follicles during the preovulatory period and early corpus luteum. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 467 (2019).

- Chu, P. G. & Arber, D. A. CD79: a review. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 9, 97-106 (2001).

- Hu, C. et al. CellMarker 2.0: an updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D870-D876 (2023).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. & Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1091-1094 (2008).

- Szabo, S. J. et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell 100, 655-669 (2000).

- Ivanov, I. I. et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17

helper cells. Cell 126, 1121-1133 (2006). - Savage, A. K. et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity 29, 391-403 (2008).

- Kovalovsky, D. et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1055-1064 (2008).

- Coletta, S. et al. The immune receptor CD300e negatively regulates T cell activation by impairing the STAT1-dependent antigen presentation. Sci. Rep. 10, 16501 (2020).

- Asano, Y. Age-related accumulation of non-heme ferric and ferrous iron in mouse ovarian stroma visualized by sensitive nonheme iron histochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 60, 229-242 (2012).

- Urzua, U., Chacon, C., Espinoza, R., Martinez, S. & Hernandez, N. Parity-dependent hemosiderin and lipofuscin accumulation in the reproductively aged mouse ovary. Anal. Cell Pathol. (Amst.) 2018, 1289103 (2018).

- Evangelou, K. & Gorgoulis, V. G. Sudan Black B, the specific histochemical stain for lipofuscin: a novel method to detect senescent cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1534, 111-119 (2017).

- Ruan, J. et al. Novel Myh11 dual reporter mouse model provides definitive labeling and identification of smooth muscle cellsbrief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 41, 815-821 (2021).

- Deaton, R. A. et al. A new autosomal Myh11-CreER(T2) smooth muscle cell lineage tracing and gene knockout mouse modelbrief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 203-211 (2023).

- Rosas-Canyelles, E., Dai, T., Li, S. & Herr, A. E. Mouse-to-mouse variation in maturation heterogeneity of smooth muscle cells. Lab Chip 18, 1875-1883 (2018).

- Martinez, F. O., Helming, L. & Gordon, S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 451-483 (2009).

- Steiger, S. et al. Immunomodulatory molecule IRAK-M balances macrophage polarization and determines macrophage responses during renal fibrosis. J. Immunol. 199, 1440-1452 (2017).

- Li, Y. L., Sato, M., Kojima, N., Miura, M. & Senoo, H. Regulatory role of extracellular matrix components in expression of matrix metalloproteinases in cultured hepatic stellate cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 24, 255-261 (1999).

- Nelson, J. F., Felicio, L. S., Randall, P. K., Sims, C. & Finch, C. E. A longitudinal study of estrous cyclicity in aging C57BL/6J mice: I. Cycle frequency, length and vaginal cytology. Biol. Reprod. 27, 327-339 (1982).

- Davidson, S. et al. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 704-717 (2021).

- Knight, P. G. & Glister, C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development. Reproduction 132, 191-206 (2006).

- McCloskey, C. W. et al. Metformin abrogates age-associated ovarian fibrosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 632-642 (2020).

- Li, M. O., Wan, Y. Y., Sanjabi, S., Robertson, A. K. & Flavell, R. A. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 99-146 (2006).

- Dompe, C. et al. Human granulosa cells-stemness properties, molecular cross-talk and follicular angiogenesis. Cells https://doi. org/10.3390/cells10061396 (2021).

- Meinsohn, M. C. et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals suppressive transcriptional programs regulated by MIS/AMH in neonatal ovaries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2100920118 (2021).

- Fan, X. et al. Single-cell reconstruction of follicular remodeling in the human adult ovary. Nat. Commun. 10, 3164 (2019).

- Chen, A. Q., Wang, Z. G., Xu, Z. R., Yu, S. D. & Yang, Z. G. Analysis of gene expression in granulosa cells of ovine antral growing follicles using suppressive subtractive hybridization. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 115, 39-48 (2009).

- Wigglesworth, K., Lee, K. B., Emori, C., Sugiura, K. & Eppig, J. J. Transcriptomic diversification of developing cumulus and mural granulosa cells in mouse ovarian follicles. Biol. Reprod. 92, 23 (2015).

- Lee, J. H. & Berger, J. M. Cell cycle-dependent control and roles of DNA topoisomerase II. Genes (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ genes10110859 (2019).

- Blanchard, J. M. Cyclin A2 transcriptional regulation: modulation of cell cycle control at the G1/S transition by peripheral cues. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60, 1179-1184 (2000).

- Piersanti, R. L., Santos, J. E. P., Sheldon, I. M. & Bromfield, J. J. Lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha alter gene expression of oocytes and cumulus cells during bovine in vitro maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 86, 1909-1920 (2019).

- Stocco, C., Telleria, C. & Gibori, G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 28, 117-149 (2007).

- Salmon, N. A., Handyside, A. H. & Joyce, I. M. Oocyte regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone expression in granulosa cells during ovarian follicle development in mice. Dev. Biol. 266, 201-208 (2004).

- Shrikhande, L., Shrikhande, B. & Shrikhande, A. AMH and its clinical implications. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 70, 337-341 (2020).

- Brown, H. M. & Russell, D. L. Blood and lymphatic vasculature in the ovary: development, function and disease. Hum. Reprod. Update 20, 29-39 (2014).

- Brown, H. M., Robker, R. L. & Russell, D. L. Development and hormonal regulation of the ovarian lymphatic vasculature. Endocrinology 151, 5446-5455 (2010).

- Hartanti, M. D. et al. Formation of the bovine ovarian surface epithelium during fetal development. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 68, 113-126 (2020).

- Hummitzsch, K. et al. A new model of development of the mammalian ovary and follicles. PLoS ONE 8, e55578 (2013).

- Schulz, A. et al. The soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 contributes to structural and functional changes in endothelial cells in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms232416059 (2022).

- Galvagni, F. et al. Dissecting the CD93-Multimerin 2 interaction involved in cell adhesion and migration of the activated endothelium. Matrix Biol. 64, 112-127 (2017).

- Fujimoto, N. et al. Single-cell mapping reveals new markers and functions of lymphatic endothelial cells in lymph nodes. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000704 (2020).

- Bloom, S. I., Islam, M. T., Lesniewski, L. A. & Donato, A. J. Mechanisms and consequences of endothelial cell senescence. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 38-51 (2023).

- Wang, J. J. et al. Single-cell transcriptome landscape of ovarian cells during primordial follicle assembly in mice. PLoS Biol. 18, e3001025 (2020).

- Pei, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics analysis reveals a cell atlas and cell communication in yak ovary. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms24031839 (2023).

- Gilardi, K. V., Shideler, S. E., Valverde, C. R., Roberts, J. A. & Lasley, B. L. Characterization of the onset of menopause in the rhesus macaque. Biol. Reprod. 57, 335-340 (1997).

- Isola, J. V. V. et al. Mild calorie restriction, but not 17alphaestradiol, extends ovarian reserve and fertility in female mice. Exp. Gerontol. 159, 111669 (2022).

- Franasiak, J. M. et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil. Steril. 101, 656-663 e651 (2014).

- Ben Yaakov, T., Wasserman, T., Aknin, E. & Savir, Y. Single-cell analysis of the aged ovarian immune system reveals a shift towards adaptive immunity and attenuated cell function. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife. 74915 (2023).

- Masopust, D. & Soerens, A. G. Tissue-resident T cells and other resident leukocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 37, 521-546 (2019).

- Yuzen, D., Arck, P. C. & Thiele, K. Tissue-resident immunity in the female and male reproductive tract. Semin. Immunopathol. 44, 785-799 (2022).

- Wang, X. & Tian, Z. Gammadelta T cells in liver diseases. Front. Med. 12, 262-268 (2018).

- Hammerich, L. et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6-dependent accumulation of gammadelta

cells in injured liver restricts hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59, 630-642 (2014). - Peng, X. et al. IL-17A produced by both gammadelta T and Th17 cells promotes renal fibrosis via RANTES-mediated leukocyte infiltration after renal obstruction. J. Pathol. 235, 79-89 (2015).

- Simonian, P. L. et al. Gammadelta T cells protect against lung fibrosis via IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2239-2253 (2010).

- Yan, X. et al. Deleterious effect of the IL-23/IL-17A axis and gammadeltaT cells on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1, e004408 (2012).

- Bank, I. The role of

cells in fibrotic diseases. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. https://doi.org/10.5041/RMMJ. 10256 (2016). - Zhang, M. & Zhang, S. T cells in fibrosis and fibrotic diseases. Front. Immunol. 11, 1142 (2020).

- Bruno, M. E. C. et al. Accumulation of gammadelta T cells in visceral fat with aging promotes chronic inflammation. Geroscience 44, 1761-1778 (2022).

- Moutuou, M. M., Gauthier, S. D., Chen, N., Leboeuf, D. & Guimond, M. Studying peripheral T cell homeostasis in mice: a concise technical review. Methods Mol. Biol. 2111, 267-283 (2020).

- Nguyen, Q. P., Deng, T. Z., Witherden, D. A. & Goldrath, A. W. Origins of CD4

circulating and tissue-resident memory T-cells. Immunology 157, 3-12 (2019). - Wilkinson, P. C., Komai-Koma, M. & Newman, I. Locomotion and chemotaxis of lymphocytes. Autoimmunity 26, 55-72 (1997).

- Dong, Y. et al. The role of regulatory T cells in thymectomyinduced autoimmune ovarian disease. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji. 12683 (2017).

- Sharif, K. et al. Insights into the autoimmune aspect of premature ovarian insufficiency. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 101323 (2019).

- Zhang, Z., Schlamp, F., Huang, L., Clark, H. & Brayboy, L. Inflammaging is associated with shifted macrophage ontogeny and polarization in the aging mouse ovary. Reproduction 159, 325-337 (2020).

- Ahmadzadeh, K., Vanoppen, M., Rose, C. D., Matthys, P. & Wouters, C. H. Multinucleated giant cells: current insights in phenotype, biological activities, and mechanism of formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 873226 (2022).

- Weivoda, M. M. & Bradley, E. W. Macrophages and bone remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 38, 359-369 (2023).

- Kameda, T. et al. Estrogen inhibits bone resorption by directly inducing apoptosis of the bone-resorbing osteoclasts. J. Exp. Med. 186, 489-495 (1997).

- Goretzlehner, G., Krause, B., Nehmzow, M. & Ulrich, U. [Endocrine diseases in pregnancy]. Z. Arztl. Fortbild. (Jena) 84, 135-141 (1990).

- Adamopoulos, I. E. et al. IL-17A gene transfer induces bone loss and epidermal hyperplasia associated with psoriatic arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1284-1292 (2015).

- Anderson, J. M. Multinucleated giant cells. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7, 40-47 (2000).

- Fais, S. et al. Multinucleated giant cells generation induced by interferon-gamma. Changes in the expression and distribution of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 during macrophages fusion and multinucleated giant cell formation. Lab. Invest. 71, 737-744 (1994).

- Lind, A. K. et al. Collagens in the human ovary and their changes in the perifollicular stroma during ovulation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85, 1476-1484 (2006).

- Liu, G. Y. & Sabatini, D. M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 183-203 (2020).

- Schneider, A. et al. The interconnections between somatic and ovarian aging in murine models. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 1579-1586 (2021).

- Young, M. D. & Behjati, S. SoupX removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Gigascience https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa151 (2020).

- Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495-502 (2015).

- Liu, Y. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals divergent, globally patterned immune responses in murine skin inflammation. iScience 23, 101582 (2020).

- Nguyen, H. T. T., Guevarra, R. B., Magez, S. & Radwanska, M. Single-cell transcriptome profiling and the use of AID deficient mice reveal that B cell activation combined with antibody class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation do not benefit the control of experimental trypanosomosis. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1010026 (2021).

- McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329-337 (2019).

- Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

- Isola, J. V. V. et al. 17Alpha-estradiol promotes ovarian aging in growth hormone receptor knockout mice, but not wild-type littermates. Exp. Gerontol. 129, 110769 (2020).

- Saccon, T. D. et al. Primordial follicle reserve, DNA damage and macrophage infiltration in the ovaries of the long-living Ames dwarf mice. Exp. Gerontol. 132, 110851 (2020).

- Anderson, K. G. et al. Intravascular staining for discrimination of vascular and tissue leukocytes. Nat. Protoc. 9, 209-222 (2014).

- Ruxton, G. D. & Neuhäuser, M. When should we use one-tailed hypothesis testing? Methods Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.2041-210X.2010.00014.x (2010).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلفون 2024

natureportfolio

آخر تحديث من قبل المؤلفين: 31/10/2023

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات تتناول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والشيفرة

معلومات السياسة حول توفر كود الكمبيوتر

تحليل البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

البحث الذي يتضمن مشاركين بشريين، بياناتهم، أو مواد بيولوجية

| التقارير عن الجنس والنوع الاجتماعي | غير متوفر |

| التقارير عن العرق أو الإثنية أو غيرها من التجمعات الاجتماعية ذات الصلة | غير متوفر |

| خصائص السكان | غير متوفر |

| التوظيف | غير متوفر |

| رقابة الأخلاقيات | غير متوفر |

التقارير الخاصة بالمجال

علوم الحياة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة بجميع الأقسام، انظرnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم الحياتية

| حجم العينة | لـ scRNA-Seq،

|

| استثناءات البيانات | لم يتم إزالة أي عينات من التحليل. تم تحديد جميع المعايير لاستبعاد البيانات مسبقًا. الخلايا التي تحتوي على أقل من 400 عدد UMI، أقل من 200 جين، أو أكثر من

|

| التكرار | تم تضمين أربع نسخ بيولوجية لكل مجموعة. كانت جميع النسخ البيولوجية ناجحة وتم تضمينها في التحليل. تم التحقق من النتائج على مستوى الخلية الواحدة بواسطة طرق متوازية حيثما كان ذلك ممكنًا، بما في ذلك تحليل تدفق الخلايا والتقييمات النسيجية. تم مقارنة النتائج ودمجها مع مجموعات البيانات المنشورة سابقًا. |

| العشوائية | نظرًا لأن المجموعات التجريبية المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة كانت مفصولة حسب العمر، لم يكن من الممكن عشوائية العينات. تم شراء الفئران من مختبر جاكسون في الأعمار المستهدفة. |

| عمى | تم إجراء التقييمات النسيجية بطريقة عمياء. بالنسبة لتحضير مكتبة الخلايا المفردة، تم عشوائية ترتيب العينات وكان الشخص الذي يحضر العينات غير مدرك لتجميع العينات. بالنسبة لتحليل بيانات الخلايا المفردة، لم يكن من الممكن تطبيق العمى بسبب الأساليب الإحصائية المختارة للمقارنة حسب المجموعة. تم إعطاء كل عينة بيانات وصفية تحدد المجموعة المعينة. يجب استدعاء الهويات أثناء الترميز من أجل تقييم التعبير التفاضلي بين المجموعات. لا يمكن إجراء التحليل الصحيح دون معرفة من أي مجموعة تأتي كل هوية. تم التعامل مع جميع العينات بشكل متساوٍ خلال خطوات مراقبة الجودة. |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | ||

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| إكس |  |

||

| البحث ذو الاستخدام المزدوج الذي يثير القلق | |||

|

|

||

الأجسام المضادة

| الأجسام المضادة المستخدمة |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التحقق |

|

الحيوانات وغيرها من الكائنات البحثية

فئران إناث من سلالة C57Bl/6J بعمر 3 و 9 أشهر. تم الاحتفاظ بالفئران في

لم يتم استخدام حيوانات برية في الدراسة.

نظرًا لأن هذه دراسة عن شيخوخة المبايض، فقد قمنا بتقييم إناث الفئران فقط.

تدفق الخلايا

المؤامرات

توضح تسميات المحاور العلامة والفلوركروم المستخدم (مثل CD4-FITC).

المقاييس على المحاور واضحة تمامًا. قم بتضمين الأرقام على المحاور فقط للرسم البياني في أسفل اليسار من المجموعة (المجموعة هي تحليل للعلامات المتطابقة).

جميع الرسوم البيانية هي رسوم بيانية متساوية الارتفاع مع نقاط شاذة أو رسوم بيانية بالألوان الزائفة.

المنهجية

للحصول على عدد كافٍ من الخلايا لاستراتيجية التصفية المقترحة، تم تجميع ست مبايض من ثلاثة فئران.

5-ليزر سايتك أورا

فلو جو 10.9 (بيكتون ديكنسون)

لم يتم إجراء أي فرز. لضمان عدد كافٍ من الخلايا في مجموعات الخلايا المتميزة بعد التصفية، تم تجميع 6 مبايض لكل عينة.

لتحليل بيانات تدفق السيتومتر، قمنا أولاً باستبعاد الثنائيات باستخدام هيستوجرام FSH-A/FSH-C. ثم تم استبعاد الخلايا الميتة بناءً على صبغة Zombie NIR. بعد ذلك، قمنا بتحديد خلايا الدم النخاعية في الأنسجة كـ CD45+ i.v. CD45-. ثم تم تحديد خلايا الدم النخاعية في الأنسجة بشكل متسلسل كما هو موضح في الشكل التوضيحي 4.

برنامج أبحاث الشيخوخة والتمثيل الغذائي، مؤسسة أبحاث الطب في أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. برنامج أبحاث الجينات والأمراض البشرية، مؤسسة أبحاث الطب في أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الأعصاب، مركز علوم الصحة بجامعة أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الفسيولوجيا، مركز علوم الصحة بجامعة أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز شؤون المحاربين القدامى الطبي في مدينة أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. كلية التغذية، الجامعة الفيدرالية في بيلوتاس، بيلوتاس، البرازيل. برنامج أبحاث التهاب المفاصل وعلم المناعة السريرية، مؤسسة أبحاث الطب في أوكلاهوما، مدينة أوكلاهوما، أوكلاهوما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: خوسيه في. في. إيسولا، سارة ر. أوكاناس. -البريد الإلكتروني: مايكل-ستوت@أومرف.أورغ - الجريبات والمناطق ذات الفلورية الذاتية. تم تكرار هذا الاختبار بشكل مستقل لكل تكرار بيولوجي. ج، ح، مخططات وترية لـ CellChat لـ TGF

تفاعلات مسارات الإشارة في وحدات الجسم الأصفر المبيضي (CLUs) في 3 أشهر (g) و9 أشهر (h). i، مسارات IPA الكلاسيكية التي تشير إلى تنشيط مسارات محددة بسبب الشيخوخة في خلايا TC. j، تحليلات المنظمين العلويين في IPA للتغيرات المرتبطة بالعمر في السدى وSCLs في خلايا TC (9 مقابل 3 أشهر). -النتيجة) المتعلقة بتكاثر الخلايا ( حسب الفئة العمرية). تم إجراء تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية في المبايض حسب الفئة العمرية. البيانات مقدمة كمتوسط س.م. بجانب واحد -اختبار أو ذو ذيلين -اختبار (د، هـ). ROS، أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية. دقيق القيم المعروضة في بيانات المصدر.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00552-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200272

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

A single-cell atlas of the aging mouse ovary

Accepted: 1 December 2023

Published online: 10 January 2024

(4) Check for updates

Abstract

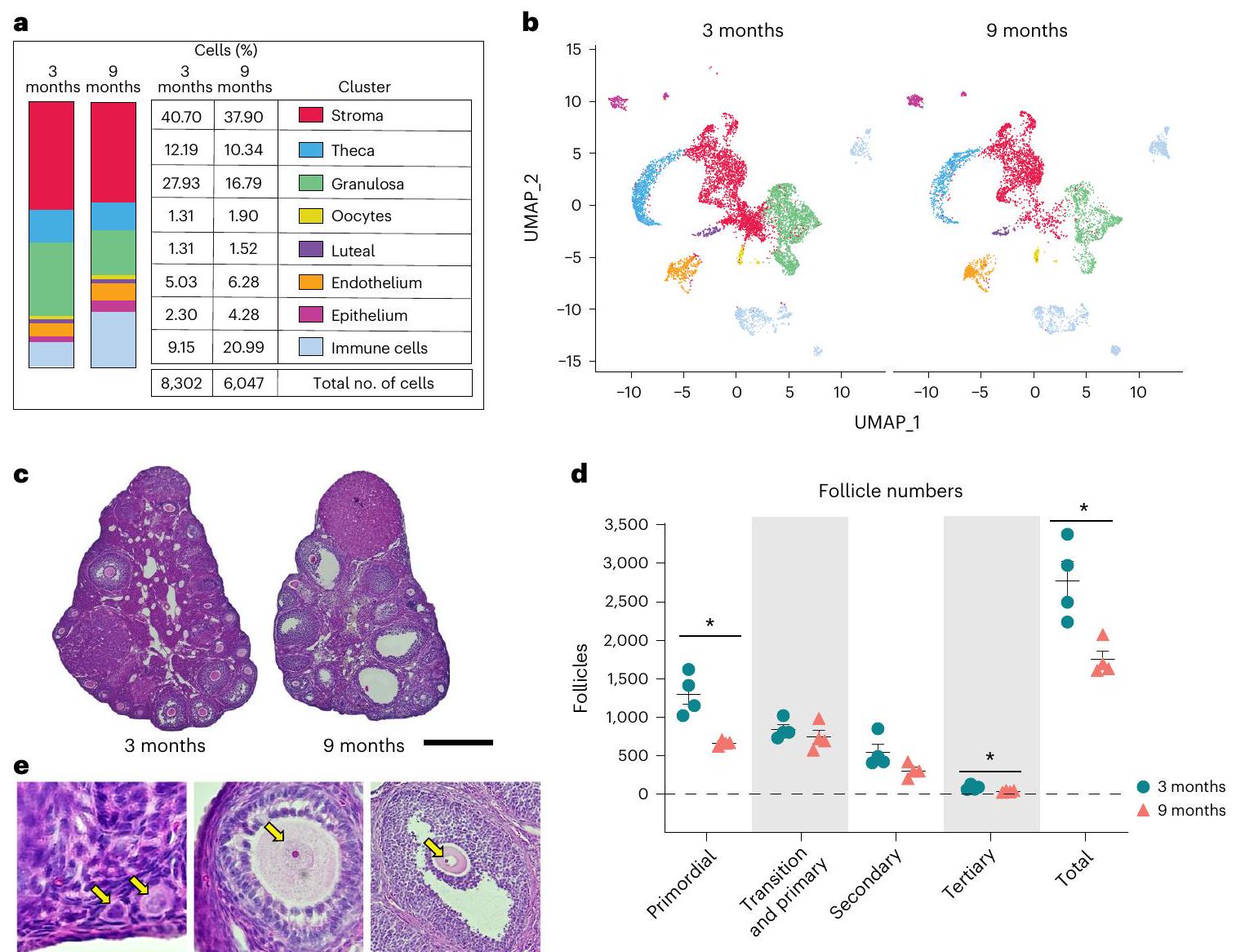

Ovarian aging leads to diminished fertility, dysregulated endocrine signaling and increased chronic disease burden. These effects begin to emerge long before follicular exhaustion. Female humans experience a sharp decline in fertility around 35 years of age, which corresponds to declines in oocyte quality. Despite a growing body of work, the field lacks a comprehensive cellular map of the transcriptomic changes in the aging mouse ovary to identify early drivers of ovarian decline. To fill this gap we performed single-cell RNA sequencing on ovarian tissue from young (3-month-old) and reproductively aged (9-month-old) mice. Our analysis revealed a doubling of immune cells in the aged ovary, with lymphocyte proportions increasing the most, which was confirmed by flow cytometry. We also found an age-related downregulation of collagenase pathways in stromal fibroblasts, which corresponds to rises in ovarian fibrosis. Follicular cells displayed stress-response, immunogenic and fibrotic signaling pathway inductions with aging. This report provides critical insights into mechanisms responsible for ovarian aging phenotypes. The data can be explored interactively via a Shiny-based web application.

little is known about which cell types develop these phenotypes first and/or dominantly contribute to the changing local microenvironment. Moreover, it remains unclear whether cells in the follicle, stroma or both play mechanistic roles in the promotion of follicular depletion and ovarian failure. Recent work has sought to unravel the potential role played by ovarian stromal cells in ovarian health and disease

Results

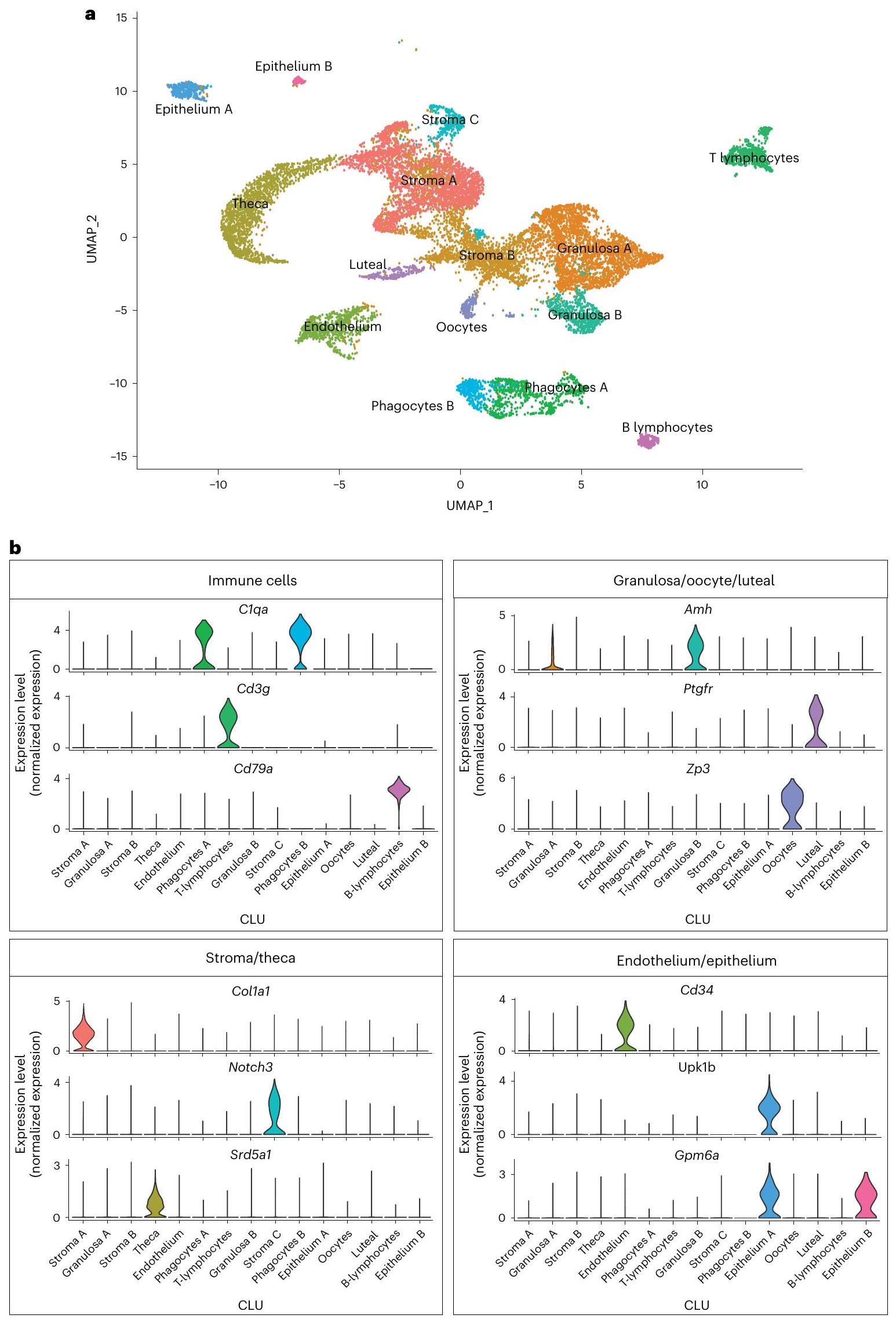

scRNA-seq of the adult mouse ovary across reproductive ages

endothelial cells (

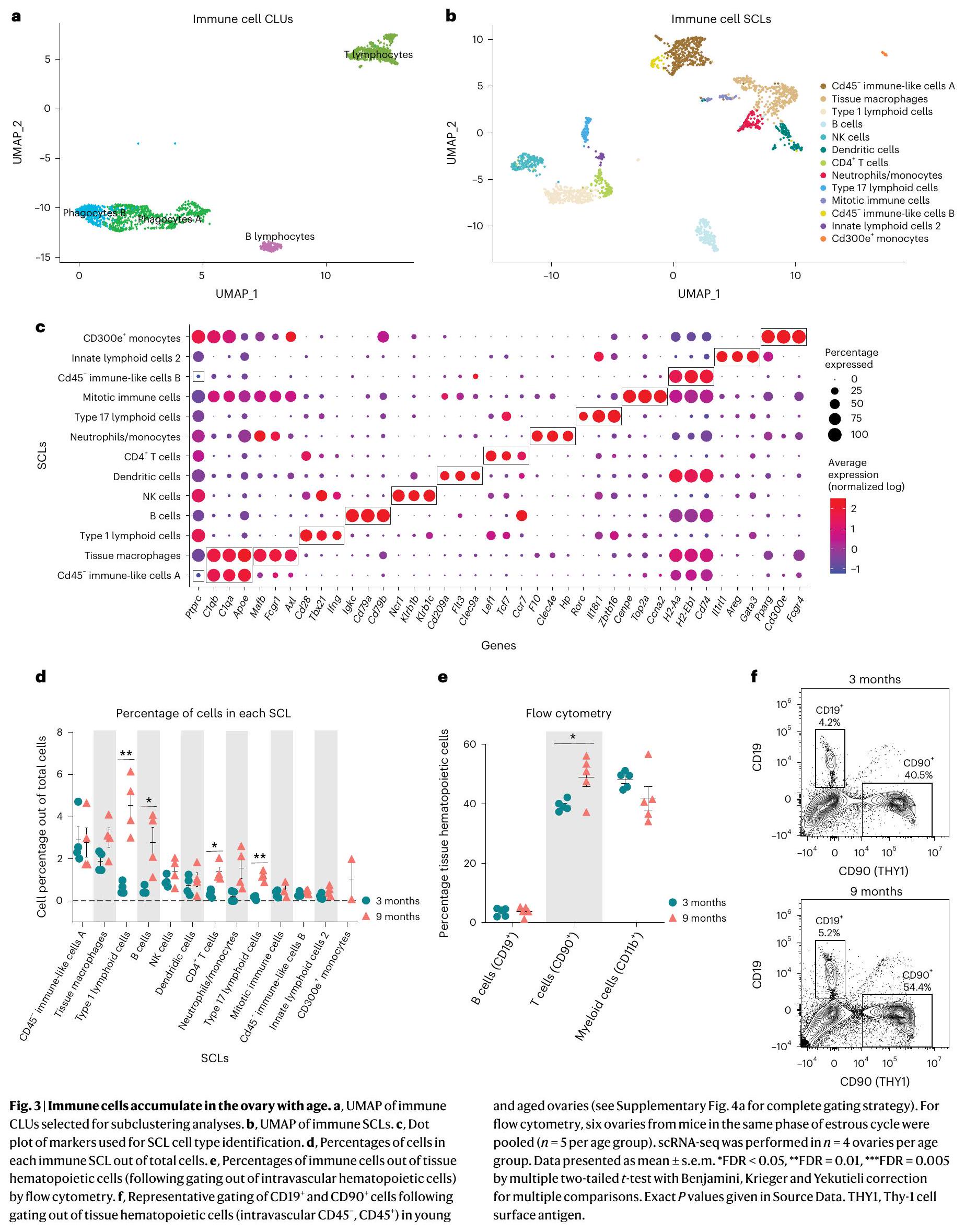

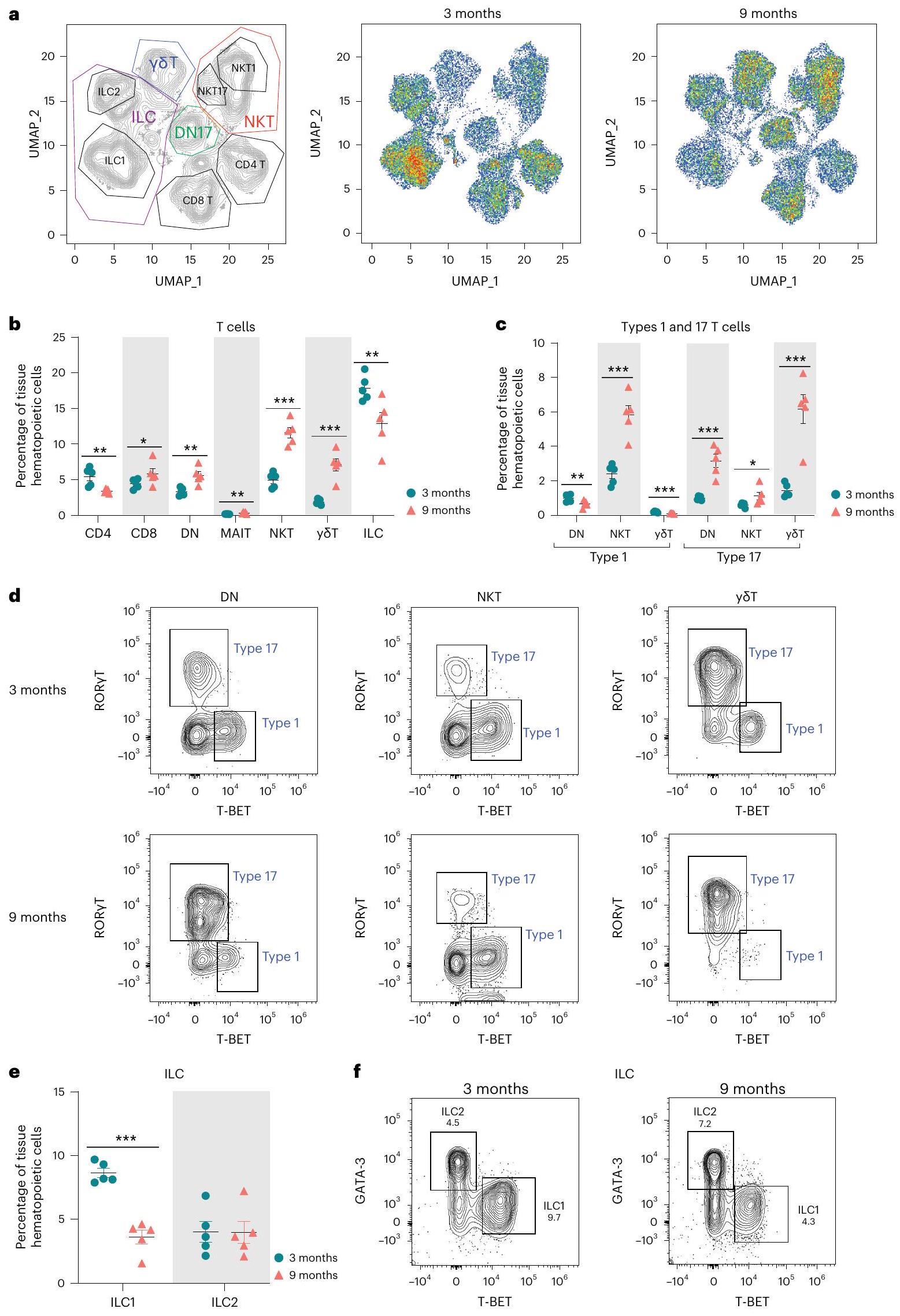

Ovarian immune cell changes with aging

well-established immune cell marker. These two SCLs were identified as

Subclustering of stroma and TCs reveals age-related changes

of steroidogenic genes including Ptch1 and Hhip

hematopoietic cells.

Aging affects granulosa, oocyte and luteal cell SCLs

four distinct SCLs that were identified as being part of follicles at different stages of development. These SCLs included preantral, antral, mitotic and atretic GCs. GCs signal to oocytes to provide cues

Endothelial and epithelial SCLs are mildly affected by age

trafficking and waste removal

Discussion

to adaptive T cells that are generally recruited from the circulation

circulating lymphocytes could be recruited into tissue in response to similar proinflammatory signals

nonhuman primate ovaries being collected during the perimenopausal period, whereas the mouse ovaries were collected before the periestropausal period. In addition to immunogenic responses, we also found that GCs and TCs display age-related induction of fibrotic responses as evidenced by increased TGF

Methods

Animals and tissue collection and dissociation for scRNA-seq

puncture. Perfusion was performed with

scRNA-seq library construction

scRNA-seq quality control and data analysis

Histology

Immunofluorescence

Flow cytometry

Statistics and reproducibility

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Johnson, J. A. & Tough, S. No-271-delayed child-bearing. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 39, e500-e515 (2017).

- Broekmans, F. J., Soules, M. R. & Fauser, B. C. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr. Rev. 30, 465-493 (2009).

- Levine, M. E. et al. Menopause accelerates biological aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9327-9332 (2016).

- Wellons, M., Ouyang, P., Schreiner, P. J., Herrington, D. M. & Vaidya, D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause 19, 1081-1087 (2012).

- Tchernof, A., Calles-Escandon, J., Sites, C. K. & Poehlman, E. T. Menopause, central body fatness, and insulin resistance: effects of hormone-replacement therapy. Coron. Artery Dis. 9, 503-511 (1998).

- Muka, T. et al. Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 767-776 (2016).

- Ossewaarde, M. E. et al. Age at menopause, cause-specific mortality and total life expectancy. Epidemiology 16, 556-562 (2005).

- May-Panloup, P. et al. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update 22, 725-743 (2016).

- Lim, J. & Luderer, U. Oxidative damage increases and antioxidant gene expression decreases with aging in the mouse ovary. Biol. Reprod. 84, 775-782 (2011).

- Yang, L. et al. The role of oxidative stress and natural antioxidants in ovarian aging. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 617843 (2020).

- Ansere, V. A. et al. Cellular hallmarks of aging emerge in the ovary prior to primordial follicle depletion. Mech. Ageing Dev. 194, 111425 (2021).

- Briley, S. M. et al. Reproductive age-associated fibrosis in the stroma of the mammalian ovary. Reproduction 152, 245-260 (2016).

- Lliberos, C. et al. Evaluation of inflammation and follicle depletion during ovarian ageing in mice. Sci. Rep. 11, 278 (2021).

- Amargant, F. et al. Ovarian stiffness increases with age in the mammalian ovary and depends on collagen and hyaluronan matrices. Aging Cell 19, e13259 (2020).

- Umehara, T. et al. Female reproductive life span is extended by targeted removal of fibrotic collagen from the mouse ovary. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn4564 (2022).

- Mara, J. N. et al. Ovulation and ovarian wound healing are impaired with advanced reproductive age. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 9686-9713 (2020).

- Foley, K. G., Pritchard, M. T. & Duncan, F. E. Macrophage-derived multinucleated giant cells: hallmarks of the aging ovary. Reproduction 161, V5-V9 (2021).

- Wang, S. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of primate ovarian aging. Cell 180, 585-600 (2020).

- Wang, S. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of human ovarian aging at single-cell resolution. Preprint at Research Square https://doi. org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1624864/v1 (2022).

- Lu, H. et al. Current animal model systems for ovarian aging research. Aging Dis. 13, 1183-1195 (2022).

- Russ, J. E., Haywood, M. E., Lane, S. L., Schoolcraft, W. B. & KatzJaffe, M. G. Spatially resolved transcriptomic profiling of ovarian aging in mice. iScience 25, 104819 (2022).

- Ankel-Simons, F. & Cummins, J. M. Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: implications for theories on human evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13859-13863 (1996).

- Zhang, D., Keilty, D., Zhang, Z. F. & Chian, R. C. Mitochondria in oocyte aging: current understanding. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 9, 29-38 (2017).

- Zhang, G. et al. Expression of mitochondria-associated genes (PPARGC1A, NRF-1, BCL-2 and BAX) in follicular development and atresia of goat ovaries. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 50, 465-473 (2015).

- Muhl, L. et al. Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination. Nat. Commun. 11, 3953 (2020).

- Morris, M. E. et al. A single-cell atlas of the cycling murine ovary. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife. 77239 (2022).

- Baek, S. H. et al. Single cell transcriptomic analysis reveals organ specific pericyte markers and identities. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 876591 (2022).

- Wagner, M. et al. Single-cell analysis of human ovarian cortex identifies distinct cell populations but no oogonial stem cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 1147 (2020).

- Marti, N. et al. Genes and proteins of the alternative steroid backdoor pathway for dihydrotestosterone synthesis are expressed in the human ovary and seem enhanced in the polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 441, 116-123 (2017).

- Sontheimer, R. D., Racila, E. & Racila, D. M. C1q: its functions within the innate and adaptive immune responses and its role in lupus autoimmunity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 14-23 (2005).

- Lin, G., Finger, E. & Gutierrez-Ramos, J. C. Expression of CD34 in endothelial cells, hematopoietic progenitors and nervous cells in fetal and adult mouse tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1508-1516 (1995).

- Garcillan, B. et al. CD3G or CD3D knockdown in mature, but not immature, T lymphocytes similarly cripples the human TCRalphabeta complex. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 608490 (2021).

- Carpenter, A. R. et al. Uroplakin 1b is critical in urinary tract development and urothelial differentiation and homeostasis. Kidney Int. 89, 612-624 (2016).

- Berisha, B., Rodler, D., Schams, D., Sinowatz, F. & Pfaffl, M. W. Prostaglandins in superovulation induced bovine follicles during the preovulatory period and early corpus luteum. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 467 (2019).

- Chu, P. G. & Arber, D. A. CD79: a review. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 9, 97-106 (2001).

- Hu, C. et al. CellMarker 2.0: an updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D870-D876 (2023).

- Heng, T. S., Painter, M. W. & Immunological Genome Project, C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1091-1094 (2008).

- Szabo, S. J. et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell 100, 655-669 (2000).

- Ivanov, I. I. et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17

helper cells. Cell 126, 1121-1133 (2006). - Savage, A. K. et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity 29, 391-403 (2008).

- Kovalovsky, D. et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1055-1064 (2008).

- Coletta, S. et al. The immune receptor CD300e negatively regulates T cell activation by impairing the STAT1-dependent antigen presentation. Sci. Rep. 10, 16501 (2020).

- Asano, Y. Age-related accumulation of non-heme ferric and ferrous iron in mouse ovarian stroma visualized by sensitive nonheme iron histochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 60, 229-242 (2012).

- Urzua, U., Chacon, C., Espinoza, R., Martinez, S. & Hernandez, N. Parity-dependent hemosiderin and lipofuscin accumulation in the reproductively aged mouse ovary. Anal. Cell Pathol. (Amst.) 2018, 1289103 (2018).

- Evangelou, K. & Gorgoulis, V. G. Sudan Black B, the specific histochemical stain for lipofuscin: a novel method to detect senescent cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1534, 111-119 (2017).

- Ruan, J. et al. Novel Myh11 dual reporter mouse model provides definitive labeling and identification of smooth muscle cellsbrief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 41, 815-821 (2021).

- Deaton, R. A. et al. A new autosomal Myh11-CreER(T2) smooth muscle cell lineage tracing and gene knockout mouse modelbrief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 203-211 (2023).

- Rosas-Canyelles, E., Dai, T., Li, S. & Herr, A. E. Mouse-to-mouse variation in maturation heterogeneity of smooth muscle cells. Lab Chip 18, 1875-1883 (2018).

- Martinez, F. O., Helming, L. & Gordon, S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 451-483 (2009).

- Steiger, S. et al. Immunomodulatory molecule IRAK-M balances macrophage polarization and determines macrophage responses during renal fibrosis. J. Immunol. 199, 1440-1452 (2017).

- Li, Y. L., Sato, M., Kojima, N., Miura, M. & Senoo, H. Regulatory role of extracellular matrix components in expression of matrix metalloproteinases in cultured hepatic stellate cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 24, 255-261 (1999).

- Nelson, J. F., Felicio, L. S., Randall, P. K., Sims, C. & Finch, C. E. A longitudinal study of estrous cyclicity in aging C57BL/6J mice: I. Cycle frequency, length and vaginal cytology. Biol. Reprod. 27, 327-339 (1982).

- Davidson, S. et al. Fibroblasts as immune regulators in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 704-717 (2021).

- Knight, P. G. & Glister, C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development. Reproduction 132, 191-206 (2006).

- McCloskey, C. W. et al. Metformin abrogates age-associated ovarian fibrosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 632-642 (2020).

- Li, M. O., Wan, Y. Y., Sanjabi, S., Robertson, A. K. & Flavell, R. A. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 99-146 (2006).

- Dompe, C. et al. Human granulosa cells-stemness properties, molecular cross-talk and follicular angiogenesis. Cells https://doi. org/10.3390/cells10061396 (2021).

- Meinsohn, M. C. et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals suppressive transcriptional programs regulated by MIS/AMH in neonatal ovaries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2100920118 (2021).

- Fan, X. et al. Single-cell reconstruction of follicular remodeling in the human adult ovary. Nat. Commun. 10, 3164 (2019).

- Chen, A. Q., Wang, Z. G., Xu, Z. R., Yu, S. D. & Yang, Z. G. Analysis of gene expression in granulosa cells of ovine antral growing follicles using suppressive subtractive hybridization. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 115, 39-48 (2009).

- Wigglesworth, K., Lee, K. B., Emori, C., Sugiura, K. & Eppig, J. J. Transcriptomic diversification of developing cumulus and mural granulosa cells in mouse ovarian follicles. Biol. Reprod. 92, 23 (2015).

- Lee, J. H. & Berger, J. M. Cell cycle-dependent control and roles of DNA topoisomerase II. Genes (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/ genes10110859 (2019).

- Blanchard, J. M. Cyclin A2 transcriptional regulation: modulation of cell cycle control at the G1/S transition by peripheral cues. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60, 1179-1184 (2000).

- Piersanti, R. L., Santos, J. E. P., Sheldon, I. M. & Bromfield, J. J. Lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha alter gene expression of oocytes and cumulus cells during bovine in vitro maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 86, 1909-1920 (2019).

- Stocco, C., Telleria, C. & Gibori, G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 28, 117-149 (2007).

- Salmon, N. A., Handyside, A. H. & Joyce, I. M. Oocyte regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone expression in granulosa cells during ovarian follicle development in mice. Dev. Biol. 266, 201-208 (2004).

- Shrikhande, L., Shrikhande, B. & Shrikhande, A. AMH and its clinical implications. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 70, 337-341 (2020).

- Brown, H. M. & Russell, D. L. Blood and lymphatic vasculature in the ovary: development, function and disease. Hum. Reprod. Update 20, 29-39 (2014).

- Brown, H. M., Robker, R. L. & Russell, D. L. Development and hormonal regulation of the ovarian lymphatic vasculature. Endocrinology 151, 5446-5455 (2010).

- Hartanti, M. D. et al. Formation of the bovine ovarian surface epithelium during fetal development. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 68, 113-126 (2020).

- Hummitzsch, K. et al. A new model of development of the mammalian ovary and follicles. PLoS ONE 8, e55578 (2013).

- Schulz, A. et al. The soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 contributes to structural and functional changes in endothelial cells in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms232416059 (2022).

- Galvagni, F. et al. Dissecting the CD93-Multimerin 2 interaction involved in cell adhesion and migration of the activated endothelium. Matrix Biol. 64, 112-127 (2017).

- Fujimoto, N. et al. Single-cell mapping reveals new markers and functions of lymphatic endothelial cells in lymph nodes. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000704 (2020).

- Bloom, S. I., Islam, M. T., Lesniewski, L. A. & Donato, A. J. Mechanisms and consequences of endothelial cell senescence. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 38-51 (2023).

- Wang, J. J. et al. Single-cell transcriptome landscape of ovarian cells during primordial follicle assembly in mice. PLoS Biol. 18, e3001025 (2020).

- Pei, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics analysis reveals a cell atlas and cell communication in yak ovary. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms24031839 (2023).

- Gilardi, K. V., Shideler, S. E., Valverde, C. R., Roberts, J. A. & Lasley, B. L. Characterization of the onset of menopause in the rhesus macaque. Biol. Reprod. 57, 335-340 (1997).

- Isola, J. V. V. et al. Mild calorie restriction, but not 17alphaestradiol, extends ovarian reserve and fertility in female mice. Exp. Gerontol. 159, 111669 (2022).

- Franasiak, J. M. et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil. Steril. 101, 656-663 e651 (2014).

- Ben Yaakov, T., Wasserman, T., Aknin, E. & Savir, Y. Single-cell analysis of the aged ovarian immune system reveals a shift towards adaptive immunity and attenuated cell function. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife. 74915 (2023).

- Masopust, D. & Soerens, A. G. Tissue-resident T cells and other resident leukocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 37, 521-546 (2019).

- Yuzen, D., Arck, P. C. & Thiele, K. Tissue-resident immunity in the female and male reproductive tract. Semin. Immunopathol. 44, 785-799 (2022).

- Wang, X. & Tian, Z. Gammadelta T cells in liver diseases. Front. Med. 12, 262-268 (2018).

- Hammerich, L. et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6-dependent accumulation of gammadelta

cells in injured liver restricts hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59, 630-642 (2014). - Peng, X. et al. IL-17A produced by both gammadelta T and Th17 cells promotes renal fibrosis via RANTES-mediated leukocyte infiltration after renal obstruction. J. Pathol. 235, 79-89 (2015).

- Simonian, P. L. et al. Gammadelta T cells protect against lung fibrosis via IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2239-2253 (2010).

- Yan, X. et al. Deleterious effect of the IL-23/IL-17A axis and gammadeltaT cells on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1, e004408 (2012).

- Bank, I. The role of

cells in fibrotic diseases. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. https://doi.org/10.5041/RMMJ. 10256 (2016). - Zhang, M. & Zhang, S. T cells in fibrosis and fibrotic diseases. Front. Immunol. 11, 1142 (2020).

- Bruno, M. E. C. et al. Accumulation of gammadelta T cells in visceral fat with aging promotes chronic inflammation. Geroscience 44, 1761-1778 (2022).

- Moutuou, M. M., Gauthier, S. D., Chen, N., Leboeuf, D. & Guimond, M. Studying peripheral T cell homeostasis in mice: a concise technical review. Methods Mol. Biol. 2111, 267-283 (2020).

- Nguyen, Q. P., Deng, T. Z., Witherden, D. A. & Goldrath, A. W. Origins of CD4

circulating and tissue-resident memory T-cells. Immunology 157, 3-12 (2019). - Wilkinson, P. C., Komai-Koma, M. & Newman, I. Locomotion and chemotaxis of lymphocytes. Autoimmunity 26, 55-72 (1997).

- Dong, Y. et al. The role of regulatory T cells in thymectomyinduced autoimmune ovarian disease. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji. 12683 (2017).

- Sharif, K. et al. Insights into the autoimmune aspect of premature ovarian insufficiency. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 101323 (2019).

- Zhang, Z., Schlamp, F., Huang, L., Clark, H. & Brayboy, L. Inflammaging is associated with shifted macrophage ontogeny and polarization in the aging mouse ovary. Reproduction 159, 325-337 (2020).

- Ahmadzadeh, K., Vanoppen, M., Rose, C. D., Matthys, P. & Wouters, C. H. Multinucleated giant cells: current insights in phenotype, biological activities, and mechanism of formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 873226 (2022).

- Weivoda, M. M. & Bradley, E. W. Macrophages and bone remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 38, 359-369 (2023).

- Kameda, T. et al. Estrogen inhibits bone resorption by directly inducing apoptosis of the bone-resorbing osteoclasts. J. Exp. Med. 186, 489-495 (1997).

- Goretzlehner, G., Krause, B., Nehmzow, M. & Ulrich, U. [Endocrine diseases in pregnancy]. Z. Arztl. Fortbild. (Jena) 84, 135-141 (1990).

- Adamopoulos, I. E. et al. IL-17A gene transfer induces bone loss and epidermal hyperplasia associated with psoriatic arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1284-1292 (2015).

- Anderson, J. M. Multinucleated giant cells. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7, 40-47 (2000).

- Fais, S. et al. Multinucleated giant cells generation induced by interferon-gamma. Changes in the expression and distribution of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 during macrophages fusion and multinucleated giant cell formation. Lab. Invest. 71, 737-744 (1994).

- Lind, A. K. et al. Collagens in the human ovary and their changes in the perifollicular stroma during ovulation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85, 1476-1484 (2006).

- Liu, G. Y. & Sabatini, D. M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 183-203 (2020).

- Schneider, A. et al. The interconnections between somatic and ovarian aging in murine models. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 1579-1586 (2021).

- Young, M. D. & Behjati, S. SoupX removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Gigascience https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa151 (2020).

- Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495-502 (2015).

- Liu, Y. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals divergent, globally patterned immune responses in murine skin inflammation. iScience 23, 101582 (2020).

- Nguyen, H. T. T., Guevarra, R. B., Magez, S. & Radwanska, M. Single-cell transcriptome profiling and the use of AID deficient mice reveal that B cell activation combined with antibody class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation do not benefit the control of experimental trypanosomosis. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1010026 (2021).

- McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329-337 (2019).

- Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

- Isola, J. V. V. et al. 17Alpha-estradiol promotes ovarian aging in growth hormone receptor knockout mice, but not wild-type littermates. Exp. Gerontol. 129, 110769 (2020).

- Saccon, T. D. et al. Primordial follicle reserve, DNA damage and macrophage infiltration in the ovaries of the long-living Ames dwarf mice. Exp. Gerontol. 132, 110851 (2020).

- Anderson, K. G. et al. Intravascular staining for discrimination of vascular and tissue leukocytes. Nat. Protoc. 9, 209-222 (2014).

- Ruxton, G. D. & Neuhäuser, M. When should we use one-tailed hypothesis testing? Methods Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.2041-210X.2010.00014.x (2010).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): 10/31/2023

Reporting Summary

Statistics

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Policy information about availability of computer code

Data analysis

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

| Reporting on sex and gender | NA |

| Reporting on race, ethnicity, or other socially relevant groupings | NA |

| Population characteristics | NA |

| Recruitment | NA |

| Ethics oversight | NA |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences Behavioural & social sciences Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | For scRNA-Seq,

|

| Data exclusions | No samples were removed from analysis. All criteria for data exclusion were pre-established. Cells with less than 400 UMI counts, less than 200 genes, or greater than

|

| Replication | Four biological replicates were included for each group. All biological replicates were successful and included in analysis. Single-cell findings were verified by orthogonal methods where possible, including flow cytometry and histological assessments. Findings were compared and integrated with previously published datasets. |

| Randomization | Since the experimental groups used in this study were separated by age, it was not possible to randomize samples. Mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory at the intended ages. |

| Blinding | Histological assessments were performed in a blinded manner. For single-cell library preparation, the sample order was randomized and the person preparing the samples were blinded to the sample grouping. For single-cell data analysis, blinding was not possible due to the statistical methods chosen to compare by group. Each sample was given assigned group-identifying meta-data. The identities have to be called during coding in order to assess differential expression between groups. It is not possible to perform the correct analysis without knowing from which group each identity is from. All samples were treated equivalently during quality control steps. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| X |  |

||

| Dual use research of concern | |||

|

|

||

Antibodies

| Antibodies used |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Validation |

|

Animals and other research organisms

3- and 9-month-old C57Bl/6J female mice. Mice were kept at

No wild animals were used in the study.

Since this is an ovarian aging study we only evaluated female mice.

Flow Cytometry

Plots

The axis labels state the marker and fluorochrome used (e.g. CD4-FITC).

The axis scales are clearly visible. Include numbers along axes only for bottom left plot of group (a ‘group’ is an analysis of identical markers).

All plots are contour plots with outliers or pseudocolor plots.

Methodology

To obtain enough cells for the gating strategy proposed, six ovaries from three mice were pooled (

5-laser Cytek Aurora

FlowJo 10.9 (Becton Dickinson)

No sorting was performed. To assure sufficient number of cells in the distinct cell populations after gating, 6 ovaries were pooled for each sample.

For the analysis of the flow cytoemtry data we first excluded doublets using a FSH-A/FSH-C histogram. Dead cells were then excluded based on Zombie NIR staining. We then gated on tissue hematopoietic cells as CD45+ i.v. CD45-. The resulting tissue hematopoietic were then sequentially gated as shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Aging & Metabolism Research Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. Genes & Human Disease Research Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. Neuroscience Department, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. Physiology Department, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. Oklahoma City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. Nutrition College, Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil. Arthritis & Clinical Immunology Research Program, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK, USA. These authors contributed equally: José V. V. Isola, Sarah R. Ocañas. -mail: michael-stout@omrf.org - follicles and autofluorescent regions. This assay was repeated independently for each biological replicate.g,h, CellChat chord diagrams of TGF

signaling pathway interactions in 3-month (g) and 9-month ovarian CLUs (h). i, IPA canonical pathways indicating activation of specific pathways by aging in TCs. j, IPA upstream regulator analyses of age-related changes in stroma and TC SCLs ( 9 versus 3 months old, -score) related to cell proliferation ( per age group). scRNA-seq was performed in ovaries per age group. Data presented as mean s.e.m. by one-tailed -test or two-tailed -test (d,e). ROS, reactive oxygen species. Exact values shown in Source Data.