DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01398-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38743205

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-14

استشهد بـ

تم القبول: 15 مارس 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 مايو 2024

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

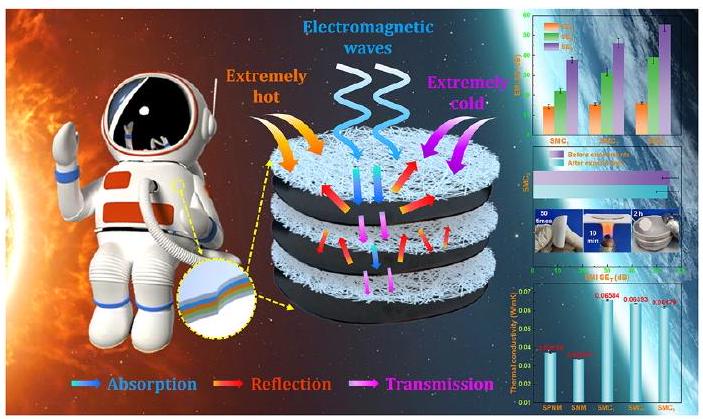

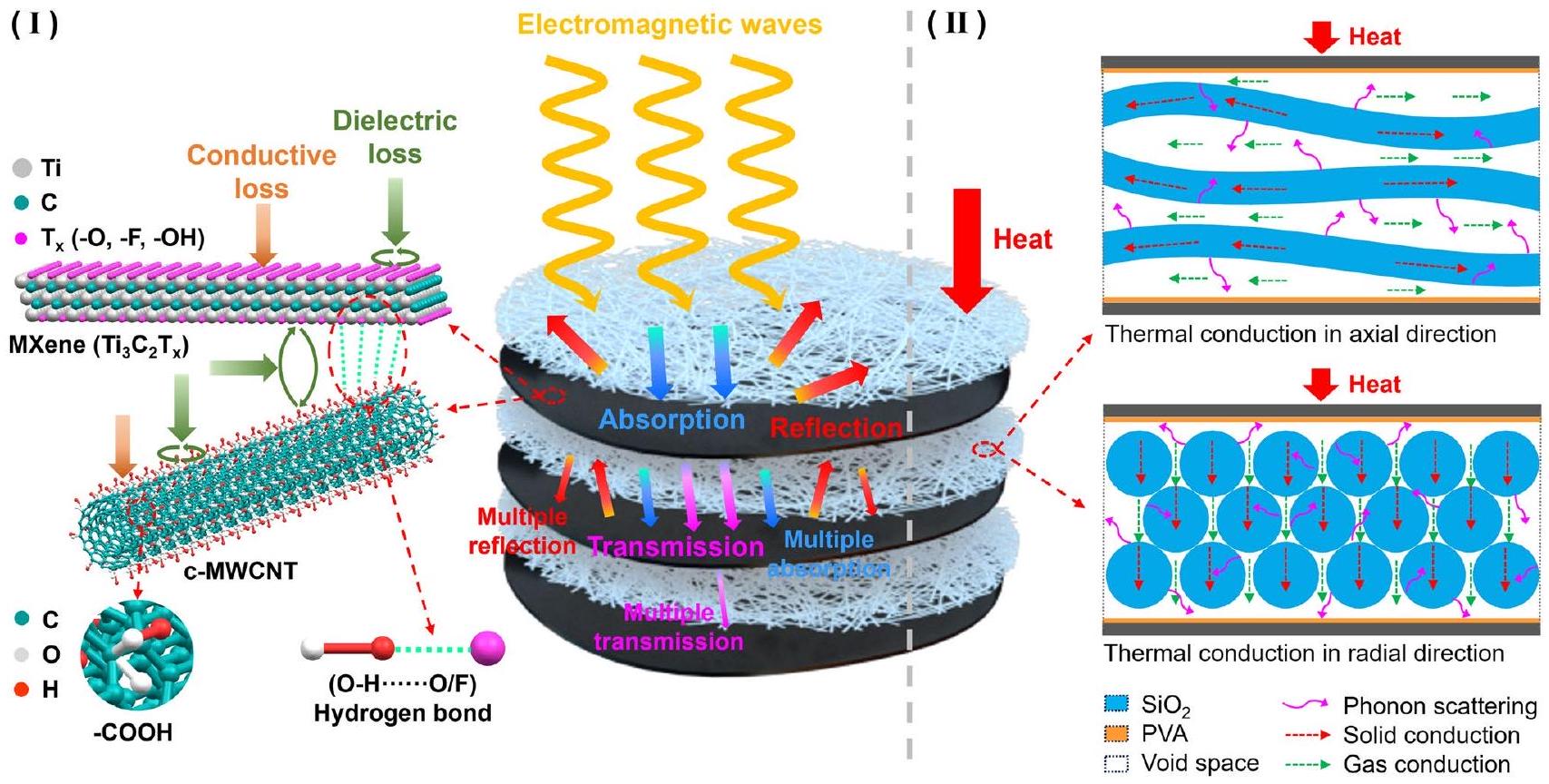

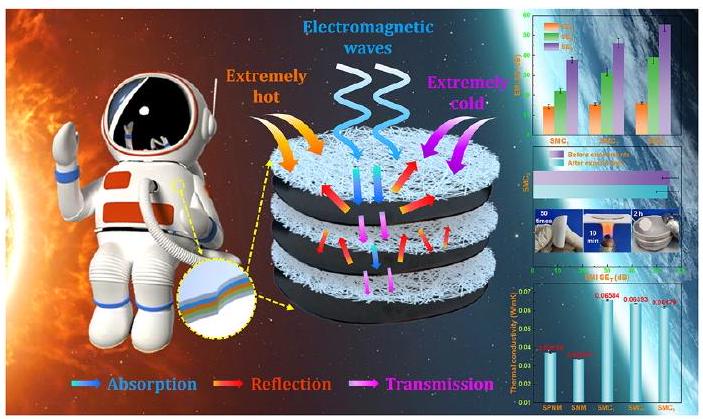

أغشية نانوية من السيليكا اللاصقة MXene@c-MWCNT تعزز من أداء درع التداخل الكهرومغناطيسي والعزل الحراري في البيئات القاسية

النقاط البارزة

- ال

أغشية الألياف النانوية و MXene@c-MWCNT كطبقة واحدة تم ربطهم معًا بـ محلول PVA. - عندما يتم زيادة الوحدة الهيكلية إلى ثلاث طبقات، فإن الناتج

لديه تداخل كهرومغناطيسي متوسط بمعدل 55.4 ديسيبل وموصلية حرارية منخفضة . -

تظهر درعًا مستقرًا ضد التداخل الكهرومغناطيسي وعزلًا حراريًا ممتازًا حتى في بيئات الحرارة والبرودة الشديدة.

الملخص

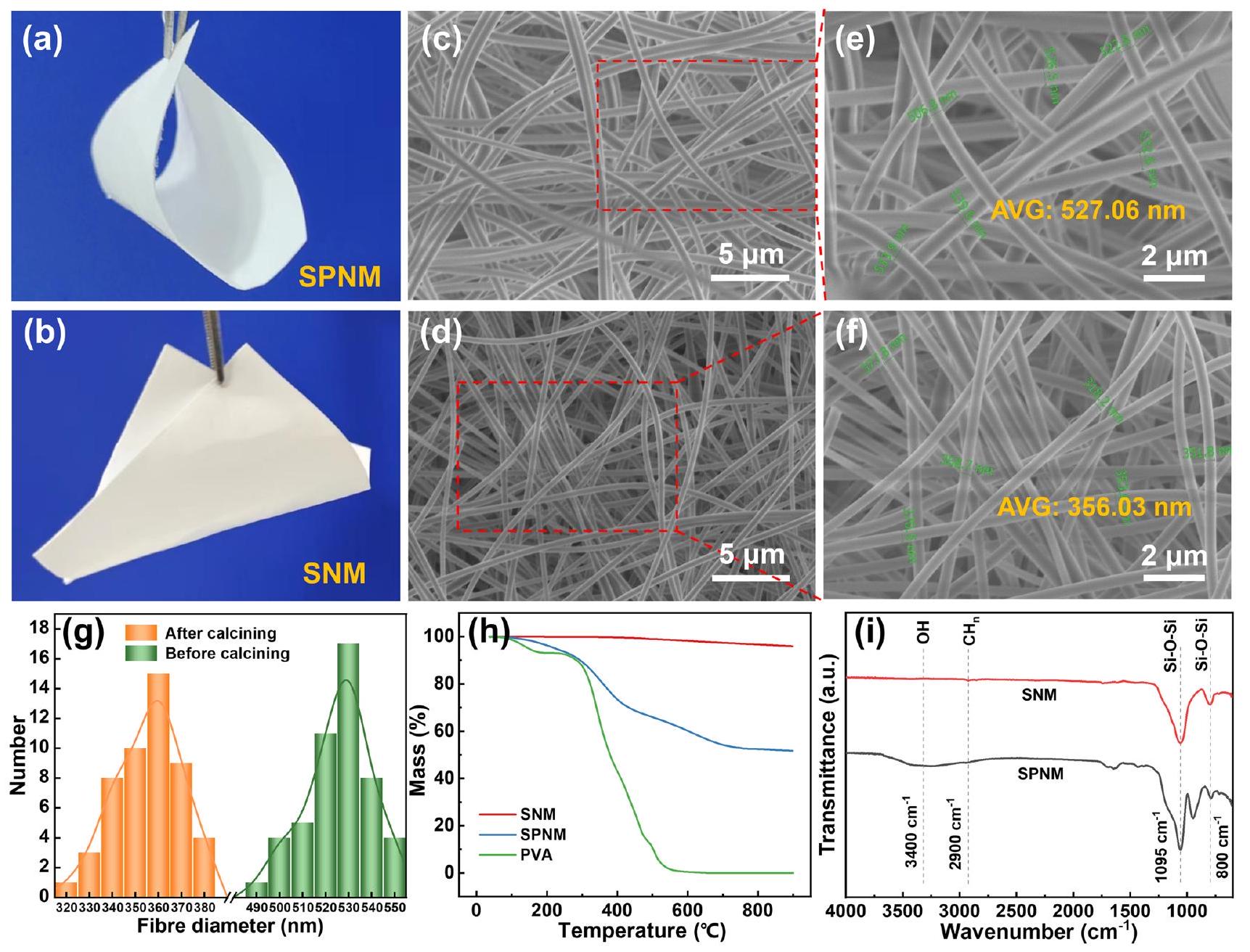

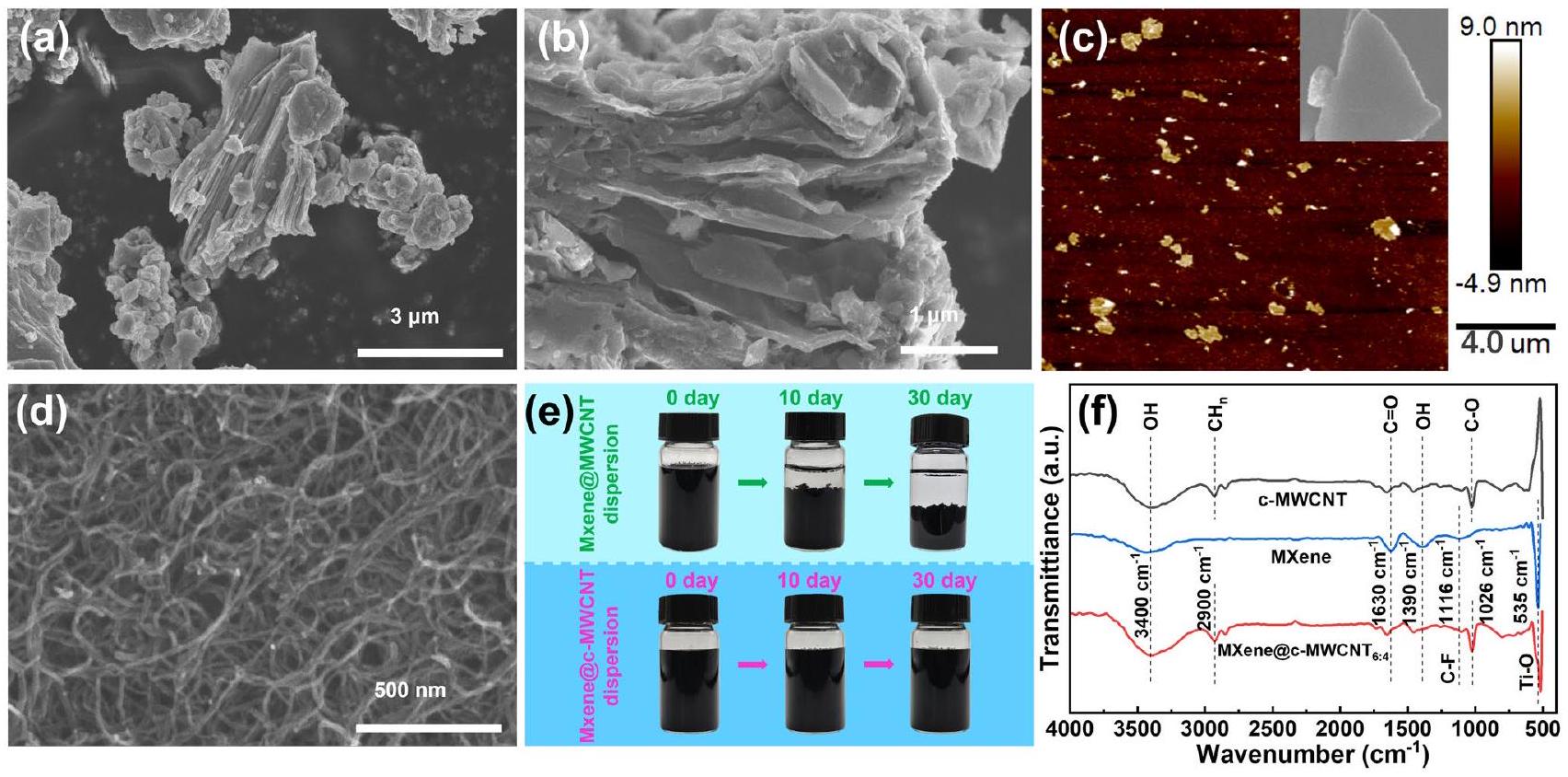

تم تصنيع مركب خفيف الوزن ومرن ومستقر حرارياً من خلال دمج أغشية الألياف النانوية السيليكا (SNM) مع فيلم هجين MXene@c-MWCNT. تم تحضير SNM المرنة ذات العزل الحراري الممتاز من خلال التحلل المائي والتكثيف للتترايثيل أورثوسيليكات بواسطة تقنية النانو الكهربائية والتكلس عند درجات حرارة عالية؛ الـ MXene@c-MWCNT

أداء العزل للفيلم المركب بالكامل (SMC)

أداء العزل للفيلم المركب بالكامل (SMC)

1 المقدمة

لقد تم دراستها على نطاق واسع [21-23]. ومع ذلك، فإن الاستقرار الميكانيكي والكيميائي والحراري الضعيف يحد بشكل كبير من نطاق تطبيقها [24]. تحتوي أنابيب الكربون النانوية (CNT) على نسبة أبعاد عالية، وكثافة منخفضة، وخصائص ميكانيكية بارزة، وموصلية كهربائية عالية، واستقرار كيميائي جيد [25-27]؛ لذلك، فهي مادة حشو موصلة مثالية أخرى للحماية من EMI؛ وللأسف، كانت مشكلة التشتت الضعيف دائمًا قائمة [28]. وقد وُجد أن الجمع بين MXene وCNT بوسائل خاصة يمكن أن يتغلب ليس فقط على عيوب كل منهما، ولكن أيضًا يجعل الحشوات الهجينة تتمتع بخصائص شاملة جيدة [29]. على سبيل المثال، قام Zhou وزملاؤه [30] بدمج MXene وCNT بشكل موحد من خلال الترشيح المعزز بالفراغ وأظهروا أداءً جيدًا في الحماية من EMI وقوة شد عالية ومرونة في الأفلام الناتجة من MXene/CNT. في الواقع، تحتوي الحشوات الموصلة مثل MXene وCNT على موصلية حرارية كبيرة [31-33]، لذا فإن كيفية دمجها مع مواد العزل الحراري وتنسيق أداء الحماية من EMI والعزل الحراري تظل دائمًا تحديًا في تصميم بدلات الحماية الفضائية.

الفيلم الوظيفي المركب الذي تم الحصول عليه في هذا العمل له آفاق تطبيق واسعة في مجالات متطرفة مثل الفضاء.

2 المواد والأساليب

2.1 المواد

2.2 إعداد المواد النووية الخاصة

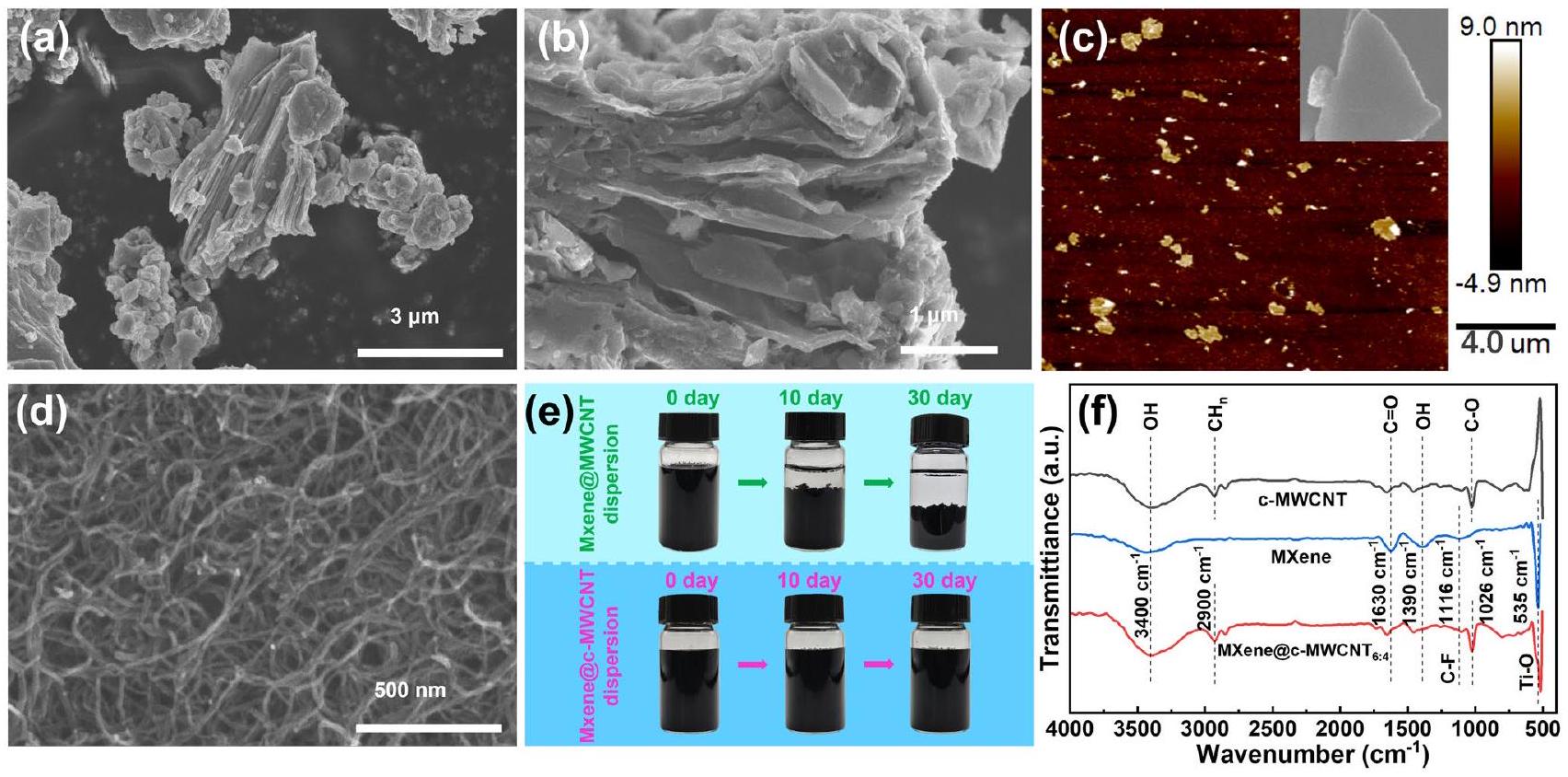

2.3 تحضير MXene@c-MWCNT

محلول (12 م) يتم تحريكه في

2.4 إعداد

2.5 توصيف

(

2.6 اختبار درع EMI

أين

2.7 اختبار العزل الحراري

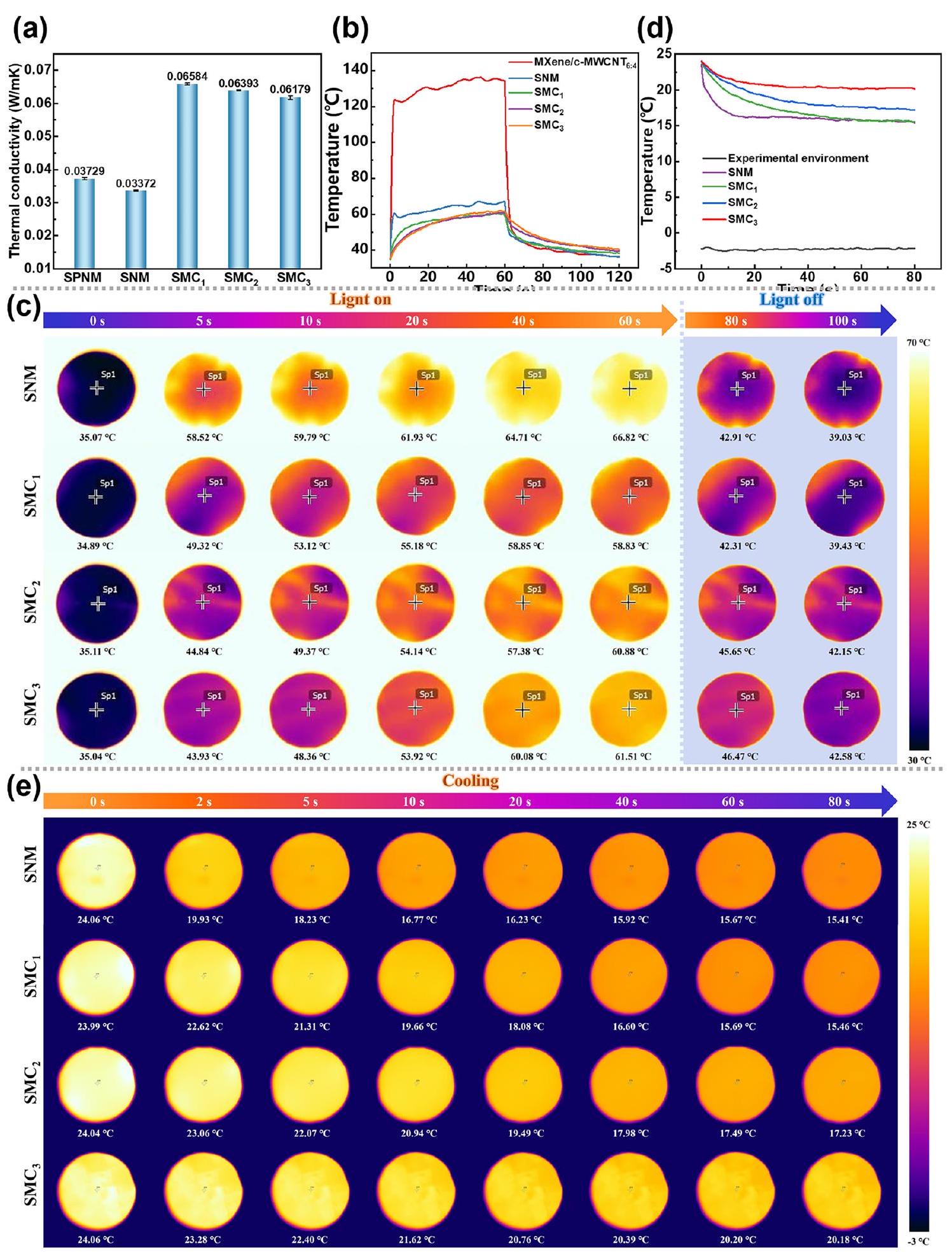

تغيرات درجة حرارة السطح لعينات مختلفة على مر الزمن. لضمان موثوقية البيانات، يجب أن تكون درجة الحرارة الأولية للعينات تحت تجارب مشابهة (بيئة عالية الحرارة أو باردة) متسقة.

3 النتائج والمناقشة

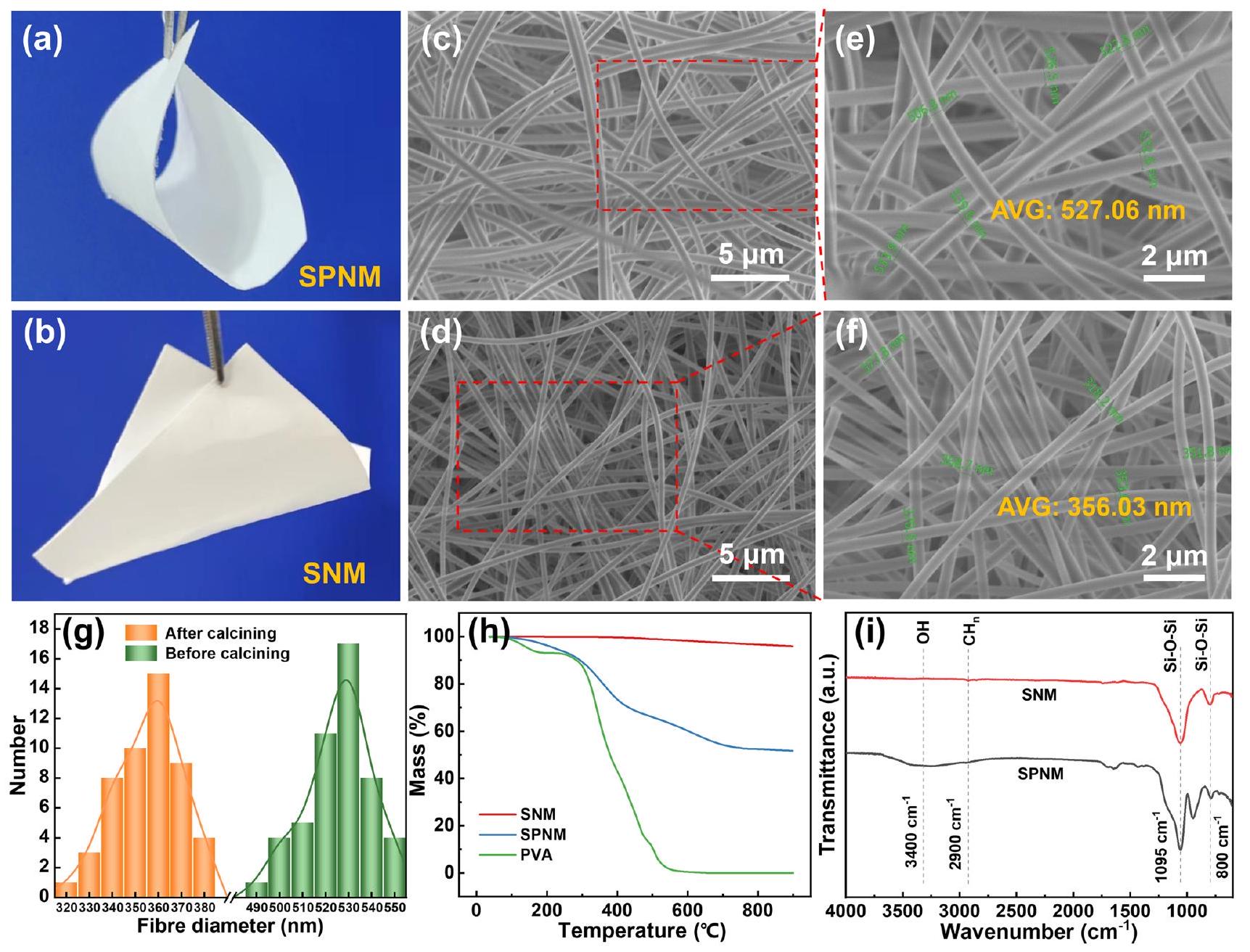

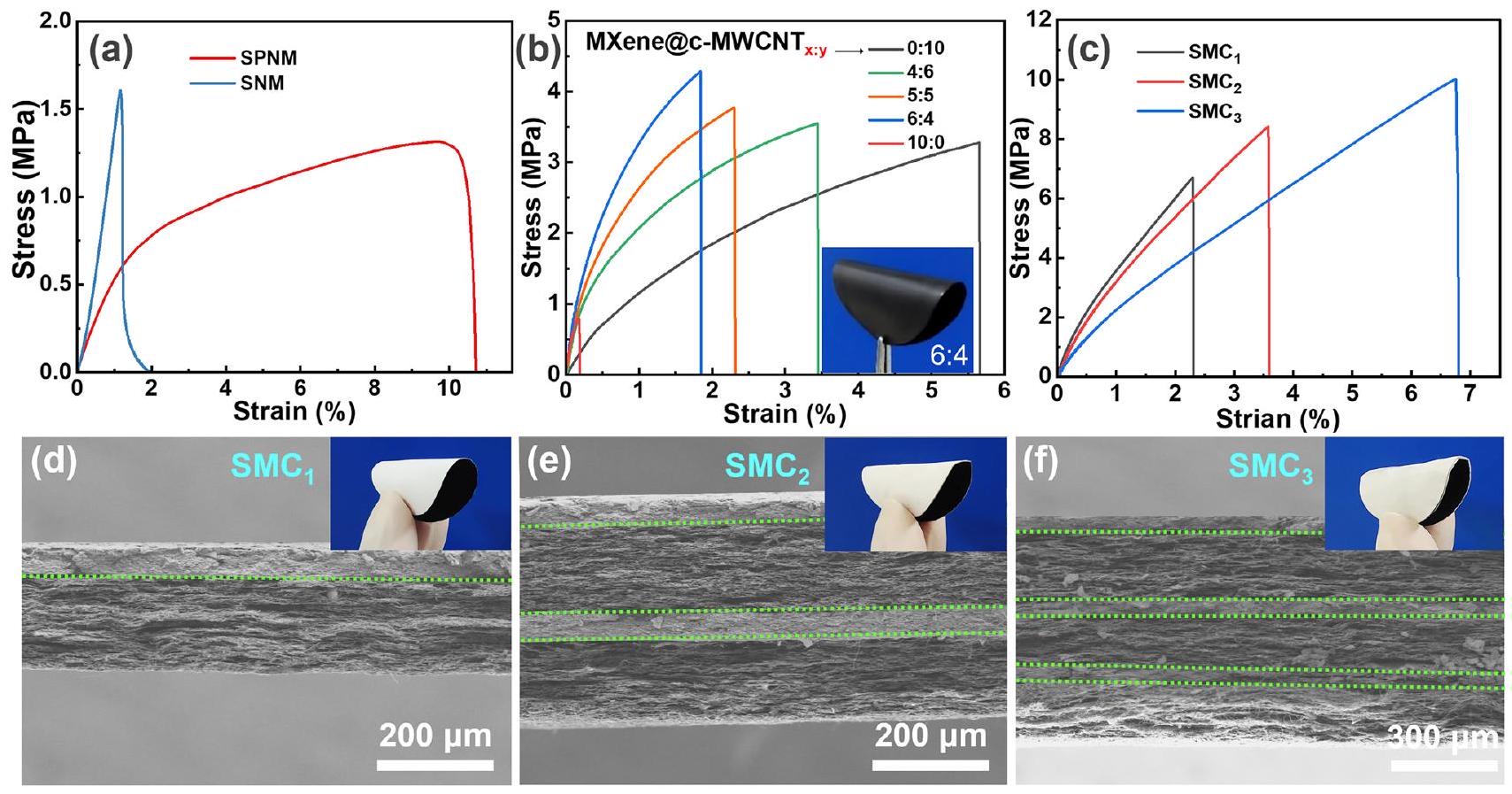

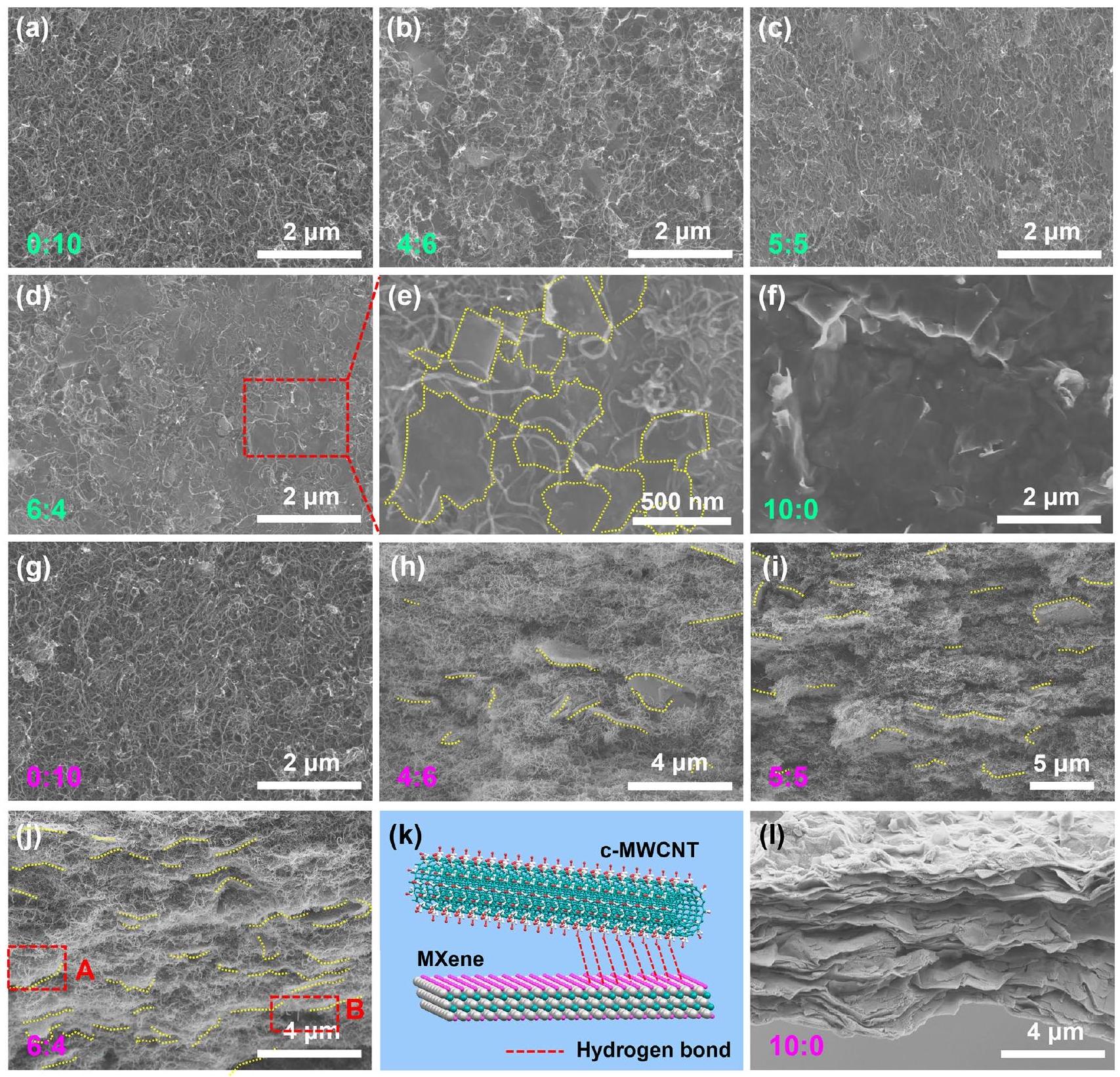

3.1 توصيف

في مرحلتين: نطاق

و

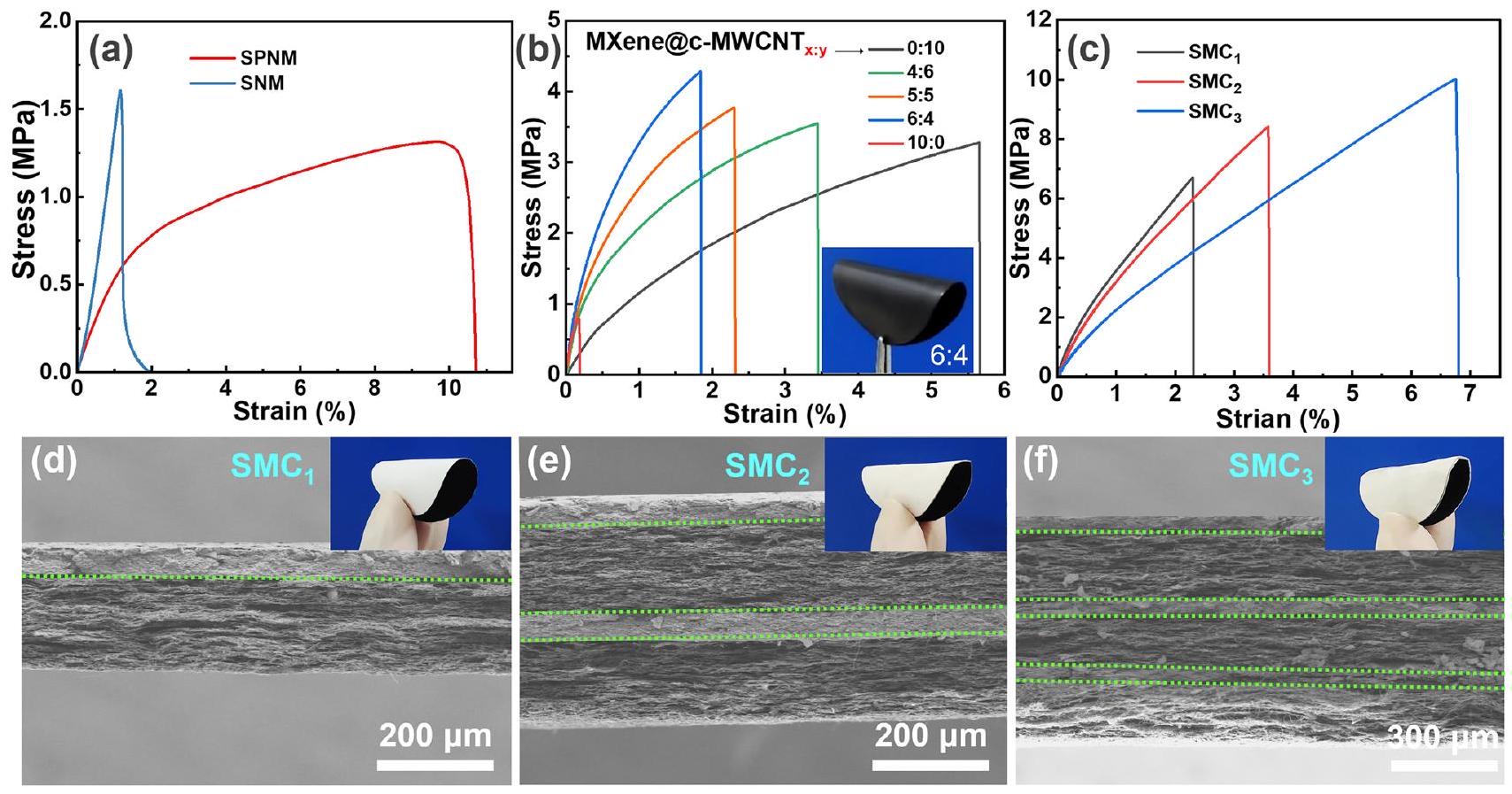

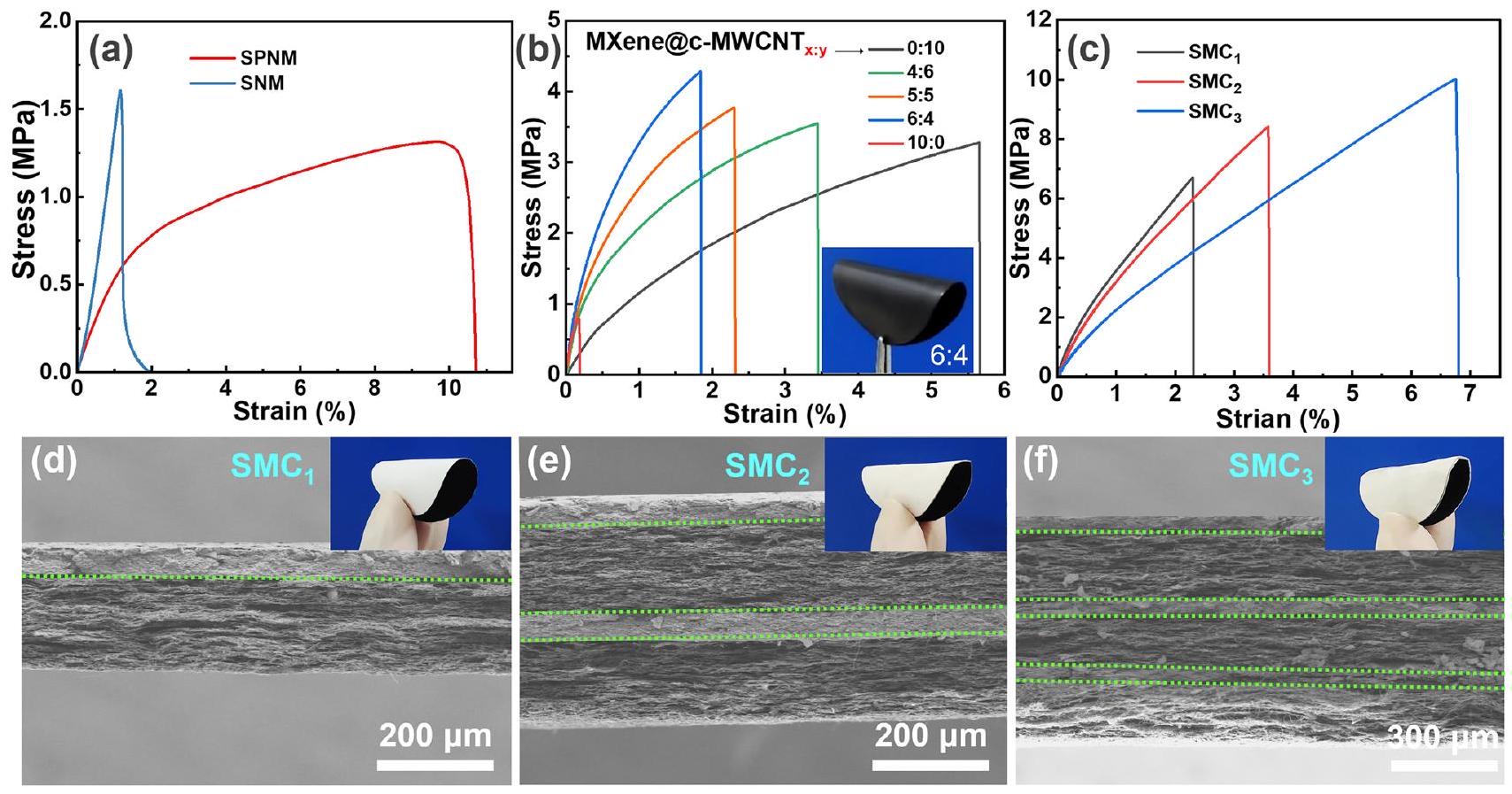

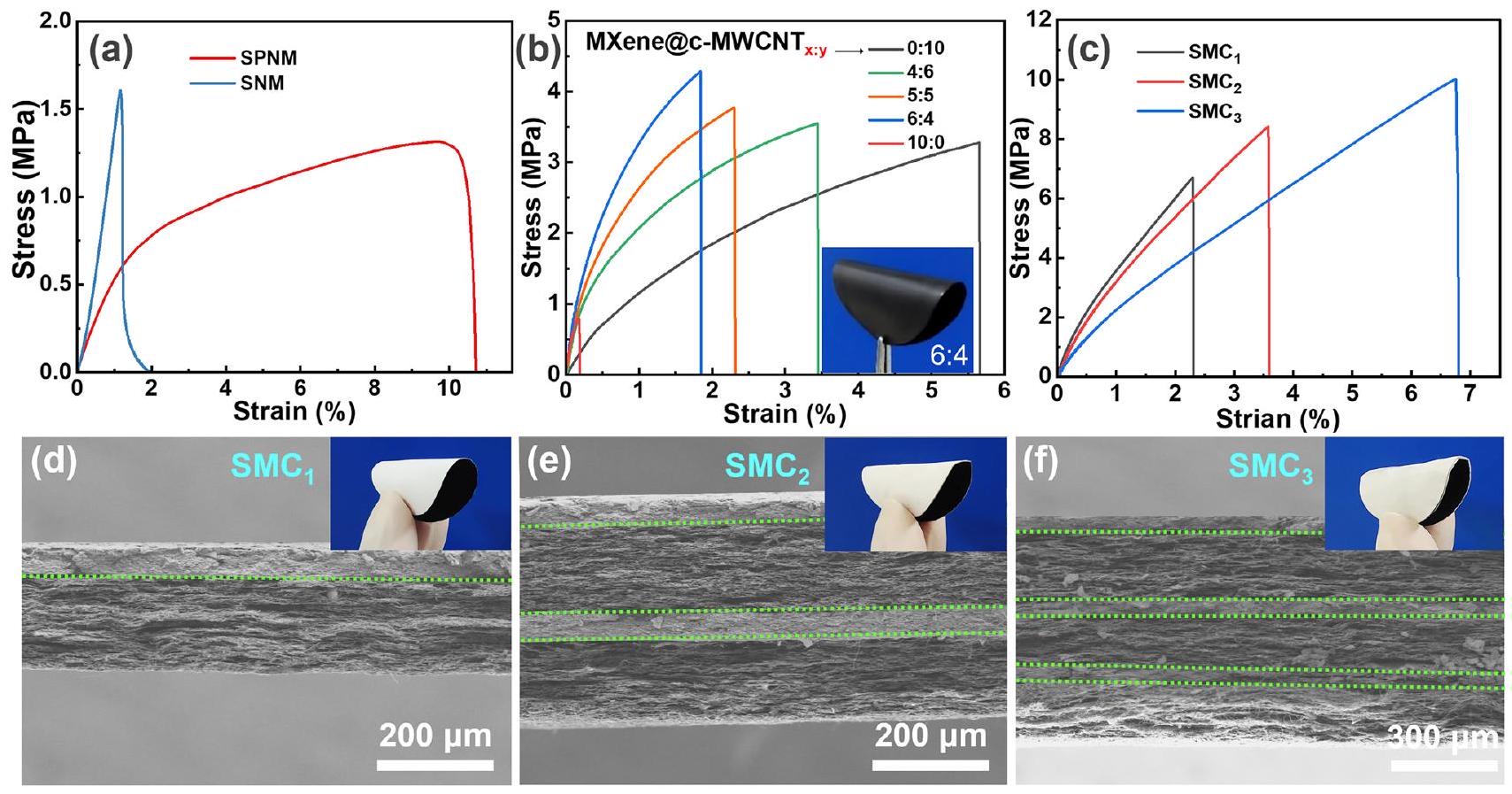

3.2 الأداء الميكانيكي للشد

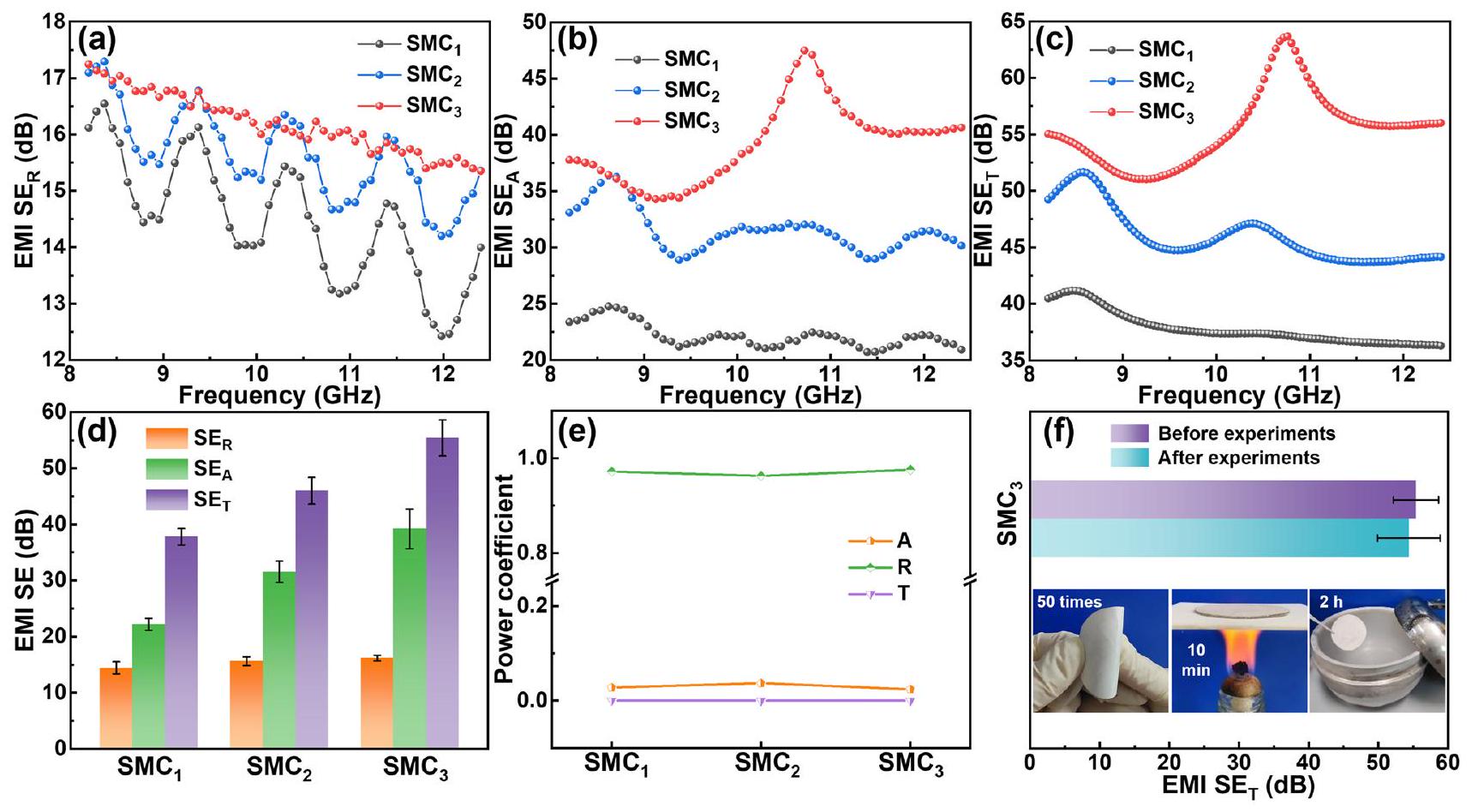

3.3 أداء درع التداخل الكهرومغناطيسي

محدد بسماكة الدرع (

و

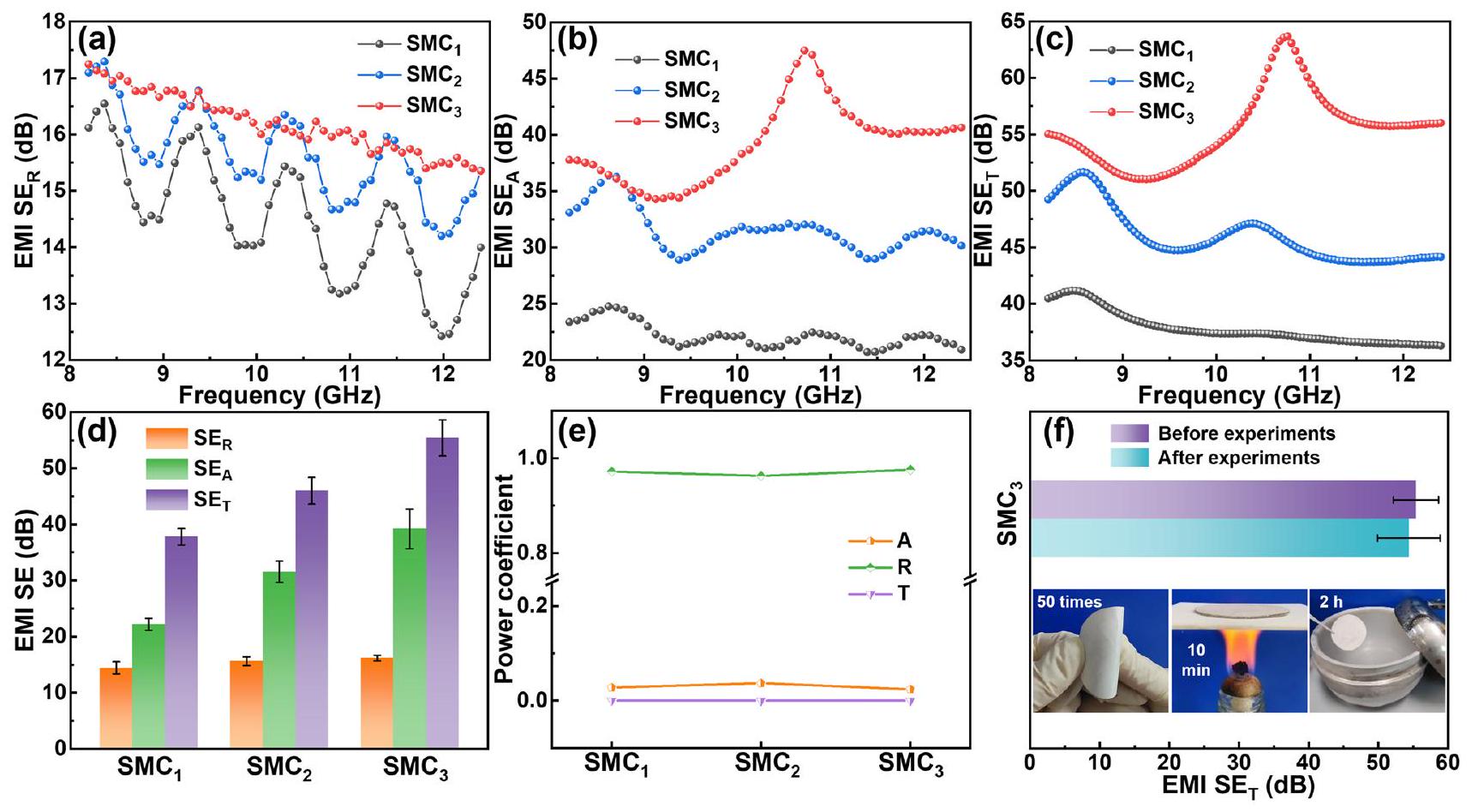

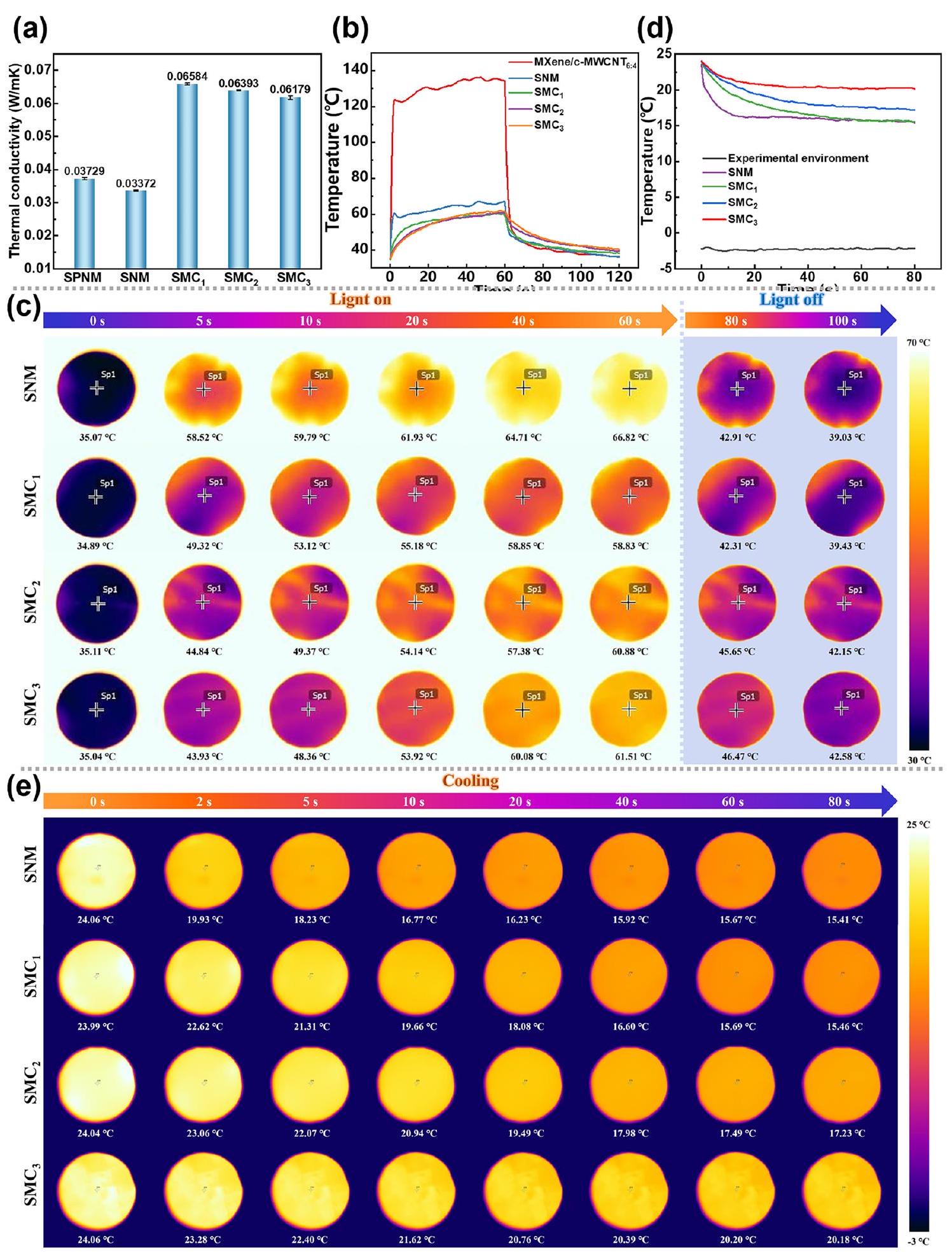

3.4 أداء العزل الحراري

يتوافق مع

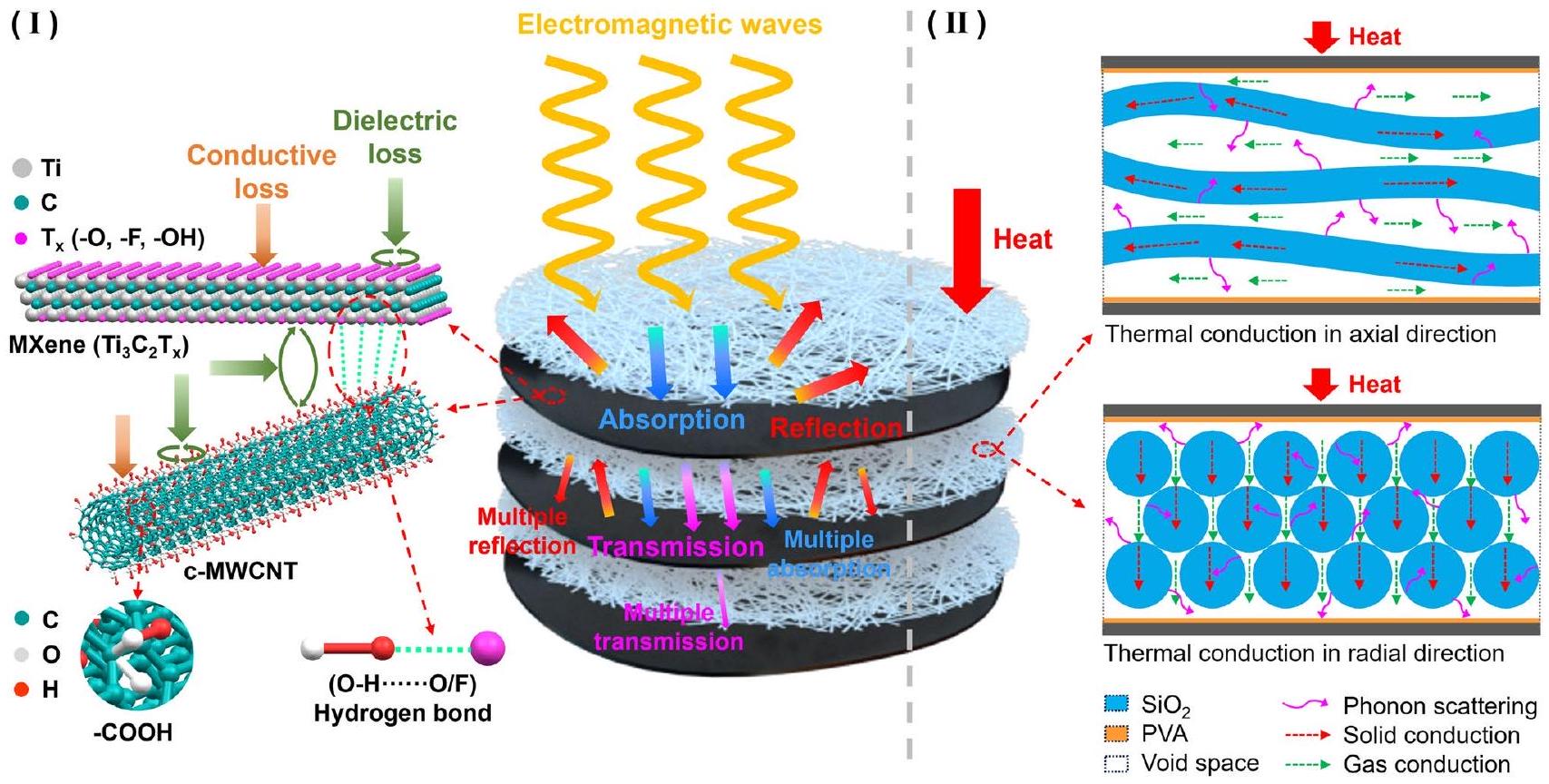

3.5 آلية التأثير المزدوج لحماية EMI وعزل الحرارة

يجعل الإشعاع تحت الأحمر ينعكس ويمتص عدة مرات، مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض

4 الاستنتاج

عدد طبقات الوحدات الهيكلية. من المهم أن يقدم

الإعلانات

References

- P. Weiss, M.P. Mohamed, T. Gobert, Y. Chouard, N. Singh et al., Advanced materials for future lunar extravehicular activity space suit. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000028 (2020). https:// doi.org/10.1002/admt. 202000028

- Z. Han, Y. Song, J. Wang, S. Li, D. Pan et al., Research progress of thermal insulation materials used in spacesuits. ES Energy Environ. 21, 947 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esee947

- J. Yang, H. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, J. Gu, Layered structural PBAT composite foams for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 31 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01246-8

- D. An, Y. Chen, R. He, H. Yu, Z. Sun et al., The polymerbased thermal interface materials with improved thermal conductivity, compression resilience, and electromagnetic interference shielding performance by introducing uniformly melamine foam. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 136 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00709-1

- M. Clausi, M. Zahid, A. Shayganpour, I.S. Bayer, Polyimide foam composites with nano-boron nitride (BN) and silicon carbide ( SiC ) for latent heat storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 798-812 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00426-1

- A. Riahi, M.B. Shafii, Experimental evaluation of a vapor compression cycle integrated with a phase change material storage tank for peak load shaving. Eng. Sci. 23, 870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d870

- X. Zhao, K. Ruan, H. Qiu, X. Zhong, J. Gu, Fatigue-resistant polyimide aerogels with hierarchical cellular structure for broadband frequency sound absorption and thermal insulation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 171 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00747-9

- Z. Li, D. Pan, Z. Han, D.J.P. Kumar, J. Ren et al., Boron nitride whiskers and nano alumina synergistically enhancing the vertical thermal conductivity of epoxy-cellulose aerogel nanocomposites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00804-3

- L. Yin, J. Xu, B. Zhang, L. Wang, W. Tao et al., A facile fabrication of highly dispersed

aerogel composites with high adsorption desulfurization performance. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 132581 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132581 - S. Karamikamkar, H.E. Naguib, C.B. Park, Advances in precursor system for silica-based aerogel production toward improved mechanical properties, customized morphology, and multifunctionality: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 276, 102101 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2020.102101

- M. Liu, H. Wu, Y. Wang, J. Ren, D.A. Alshammari et al., Flexible cementite/ferroferric oxide/silicon dioxide/carbon nanofibers composite membrane with low-frequency dispersion weakly negative permittivity. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 217 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00799-x

- C. Liu, S. Wang, N. Wang, J. Yu, Y.-T. Liu et al., From 1D nanofibers to 3D nanofibrous aerogels: a marvellous evolution of electrospun

nanofibers for emerging applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 194 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00937-y - Y. Si, X. Mao, H. Zheng, J. Yu, B. Ding, Silica nanofibrous membranes with ultra-softness and enhanced tensile strength for thermal insulation. RSC Adv. 5, 6027-6032 (2015). https:// doi.org/10.1039/C4RA12271B

- D.P. Yu, Q.L. Hang, Y. Ding, H.Z. Zhang, Z.G. Bai et al., Amorphous silica nanowires: intensive blue light emitters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 3076-3078 (1998). https://doi.org/10. 1063/1.122677

- L. Wang, S. Tomura, F. Ohashi, M. Maeda, M. Suzuki et al., Synthesis of single silica nanotubes in the presence of citric

acid. J. Mater. Chem. 11, 1465-1468 (2001). https://doi.org/ - J. Niu, J. Sha, Z. Liu, Z. Su, J. Yu et al., Silicon nano-wires fabricated by thermal evaporation of silicon wafer. Phys. E Low Dimension. Syst. Nanostruct. 24, 268-271 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2004.04.040

- Z. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Z. Li, L. Zhang, Z. Liu et al., Synthesis of carbon

core-sheath nanofibers with nanoparticles embedded in via electrospinning for high-performance microwave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 513-524 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-021-00350-w - S. Chanthee, C. Asavatesanupap, D. Sertphon, T. Nakkhong, N. Subjalearndee et al., Electrospinning with natural rubber and Ni doping for carbon dioxide adsorption and supercapacitor applications. Eng. Sci. 27, 975 (2024). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es975

- H. Mhetre, Y. Kanse, Y. Chendake, Influence of Electrospinning voltage on the diameter and properties of 1-dimensional zinc oxide nanofiber. ES Mater. Manuf. 20, 838 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esmm5f838

- T. Sirimekanont, P. Supaphol, K. Sombatmankhong, Titanium (IV) oxide composite hollow nanofibres with silver oxide outgrowth by combined sol-gel and electrospinning techniques and their potential applications in energy and environment. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 115 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00690-9

- J. Cheng, C. Li, Y. Xiong, H. Zhang, H. Raza et al., Recent advances in design strategies and multifunctionality of flexible electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 80 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00823-7

- A. Udayakumar, P. Dhandapani, S. Ramasamy, S. Angaiah, Layered double hydroxide (LDH)-MXene nanocomposite for electrocatalytic water splitting: current status and perspective. ES Energy Environ. 24, 901 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.30919/esee901

- S. Zheng, N. Wu, Y. Liu, Q. Wu, Y. Yang et al., Multifunctional flexible, crosslinked composites composed of trashed MXene sediment with high electromagnetic interference shielding performance. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00741-1

- B. Li, N. Wu, Q. Wu, Y. Yang, F. Pan et al., From “100%” utilization of MAX/MXene to direct engineering of wearable, multifunctional E-textiles in extreme environments. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2307301 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1002/adfm. 202307301

- N.M. Soudagar, V.K. Pandit, V.M. Nikale, S.G. Thube, S.S. Joshi et al., Influence of surfactant on the supercapacitive behavior of polyaniline-carbon nanotube composite thin films. ES Gen. 2, 1018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esg1018

- S.S. Wagh, D.B. Salunkhe, S.P. Patole, S. Jadkar, R.S. Patil et al., Zinc oxide decorated carbon nanotubes composites for photocatalysis and antifungal application. ES Energy Environ. 21, 945 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee945

- A. Huang, Y. Guo, Y. Zhu, T. Chen, Z. Yang et al., Durable washable wearable antibacterial thermoplastic polyurethane/ carbon nanotube@silver nanoparticles electrospun membrane strain sensors by multi-conductive network. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00684-7

- C. Pramanik, J.R. Gissinger, S. Kumar, H. Heinz, Carbon nanotube dispersion in solvents and polymer solutions: mechanisms, assembly, and preferences. ACS Nano 11, 1280512816 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b07684

- T. Xu, Y. Wang, K. Liu, Q. Zhao, Q. Liang et al., Ultralight MXene/carbon nanotube composite aerogel for high-performance flexible supercapacitor. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00675-8

- B. Zhou, Y. Li, Z. Li, J. Ma, K. Zhou et al., Fire/heat-resistant, anti-corrosion and folding

MXene/single-walled carbon nanotube films for extreme-environmental EMI shielding and solar-thermal conversion applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 9, 10425-10434 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/d1tc00289a - Q. Gao, Y. Pan, G. Zheng, C. Liu, C. Shen et al., Flexible multilayered MXene/thermoplastic polyurethane films with excellent electromagnetic interference shielding, thermal conductivity, and management performances. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 4, 274-285 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-021-00221-4

- H. Zhan, Y.W. Chen, Q.Q. Shi, Y. Zhang, R.W. Mo et al., Highly aligned and densified carbon nanotube films with superior thermal conductivity and mechanical strength. Carbon 186, 205-214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021. 09.069

- D. Kong, Z.M. El-Bahy, H. Algadi, T. Li, S.M. El-Bahy et al., Highly sensitive strain sensors with wide operation range from strong MXene-composited polyvinyl alcohol/sodium carboxymethylcellulose double network hydrogel. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1976-1987 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00531-1

- X. Guan, Q. Zhang, C. Dong, R. Zhang, M. Peng et al., A firstprinciples study of Janus monolayer MXY (

, W; X, Y van der Waals heterojunctions for integrated optical fibers. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 3232-3244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00557-5 - Y. Yu, Y. Huang, L. Li, L. Huang, S. Zhang, Silica ceramic nanofiber membrane with ultra-softness and high temperature insulation. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 4080-4091 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1007/s10853-022-06913-6

- S. Zhang, B. Cheng, Z. Jia, Z. Zhao, X. Jin et al., The art of framework construction: hollow-structured materials toward high-efficiency electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1658-1698 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s42114-022-00514-2

- D.-Q. Zhang, T.-T. Liu, J.-C. Shu, S. Liang, X.-X. Wang et al., Self-assembly construction of

architecture with green EMI shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 26807-26816 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b06509 - R.B.J. Chandra, B. Shivamurthy, S.B.B. Gowda, M.S. Kumar, Flexible linear low-density polyethylene laminated aluminum

and nickel foil composite tapes for electromagnetic interference shielding. Eng. Sci. 21, 777 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es8d777 - Z. Zeng, F. Jiang, Y. Yue, D. Han, L. Lin et al., Flexible and ultrathin waterproof cellular membranes based on high-conjunction metal-wrapped polymer nanofibers for electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 32, e1908496 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 201908496

- T. Gao, Y. Ma, L. Ji, Y. Zheng, S. Yan et al., Nickel-coated wood-derived porous carbon (Ni/WPC) for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 2328-2338 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00420-7

- J.-L. Shie, Y.-H. Chen, C.-Y. Chang, J.-P. Lin, D.-J. Lee et al., Thermal pyrolysis of poly(vinyl alcohol) and its major products. Energy Fuels 16, 109-118 (2002). https://doi.org/10. 1021/ef010082s

- Z. Zhang, J. Liu, F. Wang, J. Kong, X. Wang, Fabrication of bulk macroporous zirconia by combining sol-gel with calcination processes. Ceram. Int. 37(7), 2549-2553 (2011). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.03.054

- Z. Wu, X. Wang, S.H.K. Annamareddy, S. Gao, Q. Xu et al., Dielectric properties and thermal conductivity of polyvinylidene fluoride synergistically enhanced with silica@multiwalled carbon nanotubes and boron nitride. ES Mater. Manuf. 22, 847 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esmm5f847

- C. Lin, Y. Zhang, S. Zhang, X.X. Wang, J. Yang et al., Facile fabrication of a novel

composites catalysts with enhanced photocatalytic performances. ES Energy Environ. 20, 860 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8c860 - H. Algadi, T. Das, J. Ren, H. Li, High-performance and stable hybrid photodetector based on a monolayer molybdenum disulfide

nitrogen doped graphene quantum dots GQDs)/all-inorganic perovskite nanocrystals triple junction. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 56 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00634-3 - Q. Hu, H. Suzuki, H. Gao, H. Araki, W. Yang et al., Highfrequency FTIR absorption of

nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 378, 299-304 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett. 2003.07.015 - V.S. Sivasankarapillai, T.S.K. Sharma, K.-Y. Hwa, S.M. Wabaidur, S. Angaiah et al., MXene based sensing materials: current status and future perspectives. ES Energy Environ. 15, 4-14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8c618

- N. Wu, Y. Yang, C. Wang, Q. Wu, F. Pan et al., Ultrathin cellulose nanofiber assisted ambient-pressure-dried, ultralight, mechanically robust, multifunctional MXene aerogels. Adv. Mater. 35, e2207969 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202207969

- J. Wang, H. Kang, H. Ma, Y. Liu, Z. Xie et al., Super-fast fabrication of MXene film through a combination of ion induced gelation and vacuum-assisted filtration. Eng. Sci. 15, 57-66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d446

- Y. Cao, M. Weng, M.H.H. Mahmoud, A.Y. Elnaggar, L. Zhang et al., Flame-retardant and leakage-proof phase change composites based on MXene/polyimide aerogels toward

solar thermal energy harvesting. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1253-1267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00504-4 - Y. Wei, W. Luo, Z. Zhuang, B. Dai, J. Ding et al., Fabrication of ternary MXene/

polyaniline nanostructure with good electrochemical performances. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 4, 1082-1091 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-021-00323-z - F. Jia, Z. Lu, S. Li, J. Zhang, Y. Liu et al., Asymmetric c-MWCNT/AgNWs/PANFs hybrid film constructed by tailoring conductive-blocks strategy for efficient EMI shielding. Carbon 217, 118600 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon. 2023.118600

- B. Dai, Y. Ma, F. Dong, J. Yu, M. Ma et al., Overview of MXene and conducting polymer matrix composites for electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 704-754 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00510-6

- S. Kowshik, U.S. Rao, S. Sharma, P. Hiremath, R. Prasad K.S., et al., Mechanical properties of eggshell filled non-post-cured and post-cured GFRP composites: a comparative study. ES Mater. Manuf. 22, 1043 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 30919/esmm1043

- W. Zou, X. Zheng, X. Hu, J. Huang, G. Wang et al., Recent Advances in Injection Molding of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Polymer Composites: A Review. ES. Gen. 1, 938 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esg938

- V. Managuli, Y.S. Bothra, S. Sujith Kumar, P. Gaur, P.L. Chandracharya et al., Overview of mechanical characterization of bone using nanoindentation technique and its applications. Eng. Sci. 22, 820 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ es8d820

- B. Li, N. Wu, Y. Yang, F. Pan, C. Wang et al., Graphene oxideassisted multiple cross-linking of MXene for large-area, highstrength, oxidation-resistant, and multifunctional films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213357 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adfm. 202213357

- H. Cheng, Z. Lu, Q. Gao, Y. Zuo, X. Liu et al., PVDF-Ni/PECNTs composite foams with co-continuous structure for electromagnetic interference shielding and photo-electro-thermal properties. Eng. Sci. 16, 331-340 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es8d518

- D. Zhang, S. Liang, J. Chai, T. Liu, X. Yang et al., Highly effective shielding of electromagnetic waves in

nanosheets synthesized by a hydrothermal method. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 134, 77-82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jpcs.2019.05.041 - P. Wang, L. Yang, J. Ling, J. Song, T. Song et al., Frontal ring-opening metathesis polymerized polydicyclopentadiene carbon nanotube/graphene aerogel composites with enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 2066-2077 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s42114-022-00543-x

- J. Cheng, H. Zhang, M. Ning, H. Raza, D. Zhang et al., Emerging materials and designs for low- and multi-band electromagnetic wave absorbers: the search for dielectric and magnetic

synergy? Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200123 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202200123 - D. Zhang, H. Wang, J. Cheng, C. Han, X. Yang et al., Conductive

-NS/CNTs hybrids based 3D ultra-thin mesh electromagnetic wave absorbers with excellent absorption performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 528, 147052 (2020). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147052 - C. Xiong, Q. Xiong, M. Zhao, B. Wang, L. Dai et al., Recent advances in non-biomass and biomass-based electromagnetic shielding materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00774-6

- H. Lee, S.H. Ryu, S.J. Kwon, J.R. Choi, S.B. Lee et al., Absorption-Dominant mmWave EMI shielding films with ultralow reflection using ferromagnetic resonance frequency tunable M-type ferrites. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 76 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01058-w

- H. Zhang, T. Liu, Z. Huang, J. Cheng, H. Wang et al., Engineering flexible and green electromagnetic interference shielding materials with high performance through modulating

nanosheets on carbon fibers. J. Materiomics 8, 327-334 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2021.09.003 - M. Seol, U. Hwang, J. Kim, D. Eom, I.-K. Park et al., Solution printable multifunctional polymer-based composites for smart electromagnetic interference shielding with tunable frequency and on-off selectivities. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00609-w

- K. Ruan, X. Shi, Y. Zhang, Y. Guo, X. Zhong et al., Electric-field-induced alignment of functionalized carbon nanotubes inside thermally conductive liquid crystalline polyimide composite films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309010 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie. 202309010

- T. Zhang, J. Xu, T. Luo, Extremely high thermal conductivity of aligned polyacetylene predicted using

first-principles-informed united-atom force field. ES Energy Environ. 16, 67-73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8 c719 - Q. Xu, Z. Wu, W. Zhao, M. He, N. Guo et al., Strategies in the preparation of conductive polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels for applications in flexible strain sensors, flexible supercapacitors, and triboelectric nanogenerator sensors: an overview. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s42114-023-00783-5

- J. Cheng, H. Zhang, H. Wang, Z. Huang, H. Raza et al., Tailoring self-polarization of bimetallic organic frameworks with multiple polar units toward high-performance consecutive multi-band electromagnetic wave absorption at gigahertz. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201129 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1002/adfm. 202201129

- D. Skoda, J. Vilcakova, R.S. Yadav, B. Hanulikova, T. Capkova et al., Nickel nanoparticle-decorated reduced graphene oxide via one-step microwave-assisted synthesis and its lightweight and flexible composite with Polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene-ran-butylene)-block-polystyrene polymer for electromagnetic wave shielding application. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00692-7

- X. Zhang, Q. Tian, B. Wang, N. Wu, C. Han et al., Flexible porous SiZrOC ultrafine fibers for high-temperature thermal insulation. Mater. Lett. 299, 130131 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.matlet.2021.130131

- X. Zhong, M. He, C. Zhang, Y. Guo, J. Hu et al., Heterostructured BN@Co-C@C endowing polyester composites excellent thermal conductivity and microwave absorption at C band. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adfm. 202313544

Duo Pan, panduonerc@zzu.edu.cn; Hu Liu, liuhu@zzu.edu.cn

Key Laboratory of Materials Processing and Mold (Zhengzhou University), Ministry of Education, National Engineering Research Center for Advanced Polymer Processing Technology, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450002, People’s Republic of China

School of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, People’s Republic of China

Key Laboratory of Multifunctional Nanomaterials and Smart Systems, Advanced Materials Division, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, People’s Republic of China

Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Macromolecular Science and Technology, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an 710072, People’s Republic of China

College of Chemistry & Green Catalysis Center, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, People’s Republic of China

Mechanical and Construction Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Environment, Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne NE1 8, UK

Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Nasr City 11884, Cairo, Egypt

Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia

Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01398-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38743205

Publication Date: 2024-05-14

Cite as

Accepted: 15 March 2024

Published online: 14 May 2024

© The Author(s) 2024

MXene@c-MWCNT Adhesive Silica Nanofiber Membranes Enhancing Electromagnetic Interference Shielding and Thermal Insulation Performance in Extreme Environments

HIGHLIGHTS

- The

nanofiber membranes and MXene@c-MWCNT as one unit layer were bonded together with PVA solution. - When the structural unit is increased to three layers, the resulting

has an average electromagnetic interference of 55.4 dB and a low thermal conductivity of . -

exhibit stable electromagnetic interference shielding and excellent thermal insulation even in extreme heat and cold environment.

Abstract

A lightweight flexible thermally stable composite is fabricated by combining silica nanofiber membranes (SNM) with MXene@c-MWCNT hybrid film. The flexible SNM with outstanding thermal insulation are prepared from tetraethyl orthosilicate hydrolysis and condensation by electrospinning and high-temperature calcination; the MXene@c-MWCNT

insulation performance of the whole composite film (SMC

insulation performance of the whole composite film (SMC

1 Introduction

been widely studied [21-23]. However, poor mechanical, chemical and thermal stability greatly limits its application range [24]. Carbon nanotube (CNT) has high aspect ratio, low density, outstanding mechanical properties, high electrical conductivity, and good chemical stability [25-27]; therefore, it is another ideal EMI shielding conductive filler; unfortunately, weak dispersion has always been a problem [28]. It has been found that the combination of MXene and CNT by special means can not only overcome the defects of each other, but also make the hybrid fillers have good comprehensive properties [29]. For example, Zhou et al. [30] combined MXene and CNT uniformly through vacuumassisted filtration and demonstrated good EMI shielding performance and high tensile strength and toughness in the obtained MXene/CNT films. In fact, conductive fillers such as MXene and CNT have considerable thermal conductivity [31-33], so how to combine them with thermal insulation materials and coordinate EMI shielding and thermal insulation performance is always a challenge in the design of aerospace protective suits.

composite functional film obtained in this work has broad application prospects in extreme fields like aerospace.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

2.2 Preparation of SNM

2.3 Preparation of MXene@c-MWCNT

solution ( 12 M ) being stirred at

2.4 Preparation of

2.5 Characterization

(

2.6 EMI Shielding Testing

where

2.7 Thermal Insulation Testing

surface temperature changes of different samples over time. In order to ensure the reliability of the data, the initial temperature of the samples under similar experiment (hightemperature or cold environment) needs to be consistent.

3 Results and Discussion

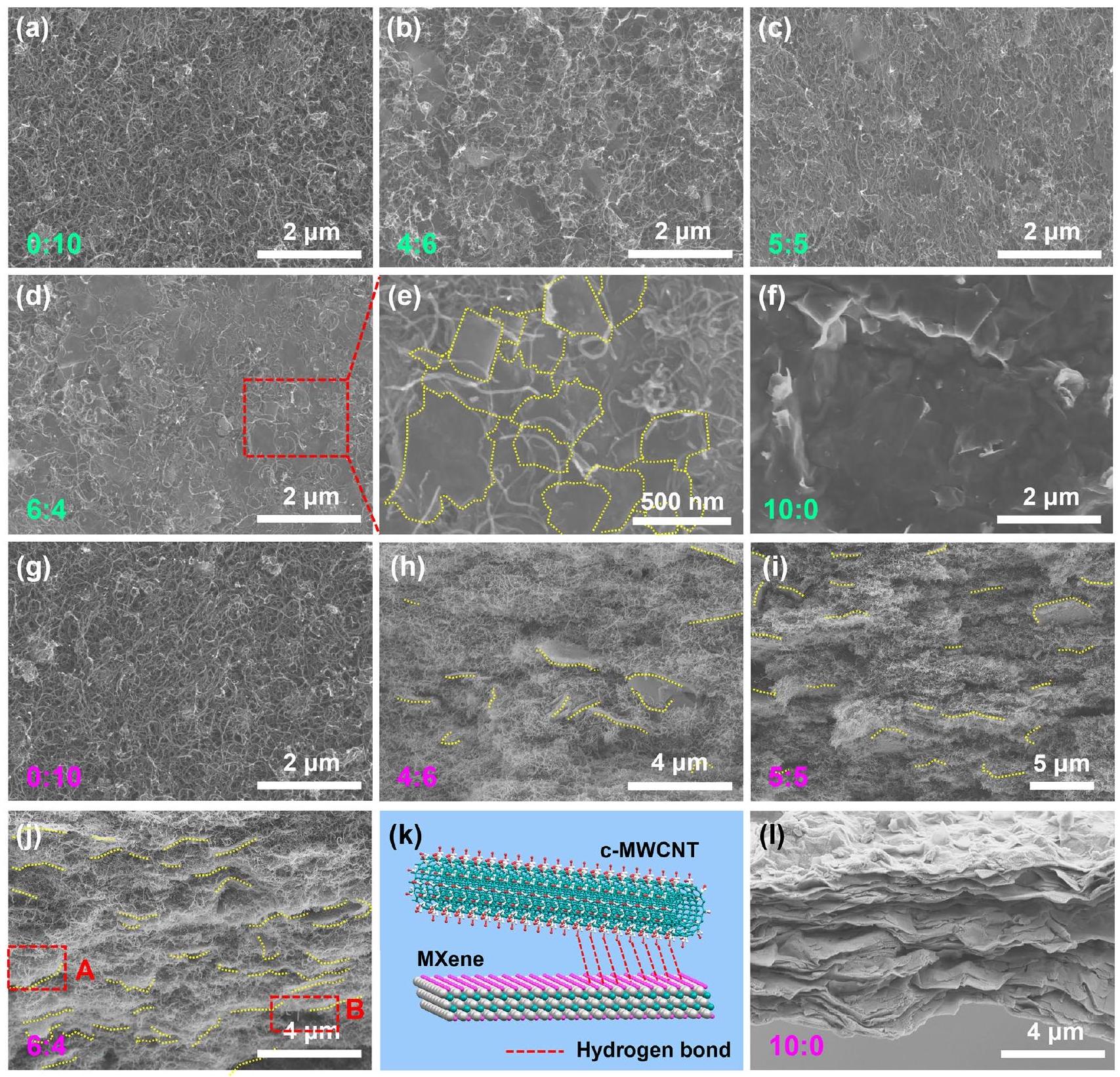

3.1 Characterization

in two stages: the range of

and

3.2 Mechanical Tensile Performance

3.3 Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Performance

determined by the shielding thickness (

and

3.4 Thermal Insulation Performance

corresponding to

3.5 Dual-Effect Mechanism of EMI Shielding and Heat Insulation

makes the infrared radiation multiple reflect and absorb, resulting in lowering of

4 Conclusion

number of structural unit layers. Importantly,

Declarations

References

- P. Weiss, M.P. Mohamed, T. Gobert, Y. Chouard, N. Singh et al., Advanced materials for future lunar extravehicular activity space suit. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000028 (2020). https:// doi.org/10.1002/admt. 202000028

- Z. Han, Y. Song, J. Wang, S. Li, D. Pan et al., Research progress of thermal insulation materials used in spacesuits. ES Energy Environ. 21, 947 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esee947

- J. Yang, H. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, J. Gu, Layered structural PBAT composite foams for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 31 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01246-8

- D. An, Y. Chen, R. He, H. Yu, Z. Sun et al., The polymerbased thermal interface materials with improved thermal conductivity, compression resilience, and electromagnetic interference shielding performance by introducing uniformly melamine foam. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 136 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00709-1

- M. Clausi, M. Zahid, A. Shayganpour, I.S. Bayer, Polyimide foam composites with nano-boron nitride (BN) and silicon carbide ( SiC ) for latent heat storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 798-812 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00426-1

- A. Riahi, M.B. Shafii, Experimental evaluation of a vapor compression cycle integrated with a phase change material storage tank for peak load shaving. Eng. Sci. 23, 870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d870

- X. Zhao, K. Ruan, H. Qiu, X. Zhong, J. Gu, Fatigue-resistant polyimide aerogels with hierarchical cellular structure for broadband frequency sound absorption and thermal insulation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 171 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s42114-023-00747-9

- Z. Li, D. Pan, Z. Han, D.J.P. Kumar, J. Ren et al., Boron nitride whiskers and nano alumina synergistically enhancing the vertical thermal conductivity of epoxy-cellulose aerogel nanocomposites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00804-3

- L. Yin, J. Xu, B. Zhang, L. Wang, W. Tao et al., A facile fabrication of highly dispersed

aerogel composites with high adsorption desulfurization performance. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 132581 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132581 - S. Karamikamkar, H.E. Naguib, C.B. Park, Advances in precursor system for silica-based aerogel production toward improved mechanical properties, customized morphology, and multifunctionality: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 276, 102101 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2020.102101

- M. Liu, H. Wu, Y. Wang, J. Ren, D.A. Alshammari et al., Flexible cementite/ferroferric oxide/silicon dioxide/carbon nanofibers composite membrane with low-frequency dispersion weakly negative permittivity. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 217 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00799-x

- C. Liu, S. Wang, N. Wang, J. Yu, Y.-T. Liu et al., From 1D nanofibers to 3D nanofibrous aerogels: a marvellous evolution of electrospun

nanofibers for emerging applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 194 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00937-y - Y. Si, X. Mao, H. Zheng, J. Yu, B. Ding, Silica nanofibrous membranes with ultra-softness and enhanced tensile strength for thermal insulation. RSC Adv. 5, 6027-6032 (2015). https:// doi.org/10.1039/C4RA12271B

- D.P. Yu, Q.L. Hang, Y. Ding, H.Z. Zhang, Z.G. Bai et al., Amorphous silica nanowires: intensive blue light emitters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 3076-3078 (1998). https://doi.org/10. 1063/1.122677

- L. Wang, S. Tomura, F. Ohashi, M. Maeda, M. Suzuki et al., Synthesis of single silica nanotubes in the presence of citric

acid. J. Mater. Chem. 11, 1465-1468 (2001). https://doi.org/ - J. Niu, J. Sha, Z. Liu, Z. Su, J. Yu et al., Silicon nano-wires fabricated by thermal evaporation of silicon wafer. Phys. E Low Dimension. Syst. Nanostruct. 24, 268-271 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2004.04.040

- Z. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Z. Li, L. Zhang, Z. Liu et al., Synthesis of carbon

core-sheath nanofibers with nanoparticles embedded in via electrospinning for high-performance microwave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 513-524 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-021-00350-w - S. Chanthee, C. Asavatesanupap, D. Sertphon, T. Nakkhong, N. Subjalearndee et al., Electrospinning with natural rubber and Ni doping for carbon dioxide adsorption and supercapacitor applications. Eng. Sci. 27, 975 (2024). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es975

- H. Mhetre, Y. Kanse, Y. Chendake, Influence of Electrospinning voltage on the diameter and properties of 1-dimensional zinc oxide nanofiber. ES Mater. Manuf. 20, 838 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esmm5f838

- T. Sirimekanont, P. Supaphol, K. Sombatmankhong, Titanium (IV) oxide composite hollow nanofibres with silver oxide outgrowth by combined sol-gel and electrospinning techniques and their potential applications in energy and environment. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 115 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00690-9

- J. Cheng, C. Li, Y. Xiong, H. Zhang, H. Raza et al., Recent advances in design strategies and multifunctionality of flexible electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 80 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00823-7

- A. Udayakumar, P. Dhandapani, S. Ramasamy, S. Angaiah, Layered double hydroxide (LDH)-MXene nanocomposite for electrocatalytic water splitting: current status and perspective. ES Energy Environ. 24, 901 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.30919/esee901

- S. Zheng, N. Wu, Y. Liu, Q. Wu, Y. Yang et al., Multifunctional flexible, crosslinked composites composed of trashed MXene sediment with high electromagnetic interference shielding performance. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 161 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00741-1

- B. Li, N. Wu, Q. Wu, Y. Yang, F. Pan et al., From “100%” utilization of MAX/MXene to direct engineering of wearable, multifunctional E-textiles in extreme environments. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2307301 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1002/adfm. 202307301

- N.M. Soudagar, V.K. Pandit, V.M. Nikale, S.G. Thube, S.S. Joshi et al., Influence of surfactant on the supercapacitive behavior of polyaniline-carbon nanotube composite thin films. ES Gen. 2, 1018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ esg1018

- S.S. Wagh, D.B. Salunkhe, S.P. Patole, S. Jadkar, R.S. Patil et al., Zinc oxide decorated carbon nanotubes composites for photocatalysis and antifungal application. ES Energy Environ. 21, 945 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee945

- A. Huang, Y. Guo, Y. Zhu, T. Chen, Z. Yang et al., Durable washable wearable antibacterial thermoplastic polyurethane/ carbon nanotube@silver nanoparticles electrospun membrane strain sensors by multi-conductive network. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 101 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-023-00684-7

- C. Pramanik, J.R. Gissinger, S. Kumar, H. Heinz, Carbon nanotube dispersion in solvents and polymer solutions: mechanisms, assembly, and preferences. ACS Nano 11, 1280512816 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b07684

- T. Xu, Y. Wang, K. Liu, Q. Zhao, Q. Liang et al., Ultralight MXene/carbon nanotube composite aerogel for high-performance flexible supercapacitor. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00675-8

- B. Zhou, Y. Li, Z. Li, J. Ma, K. Zhou et al., Fire/heat-resistant, anti-corrosion and folding

MXene/single-walled carbon nanotube films for extreme-environmental EMI shielding and solar-thermal conversion applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 9, 10425-10434 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/d1tc00289a - Q. Gao, Y. Pan, G. Zheng, C. Liu, C. Shen et al., Flexible multilayered MXene/thermoplastic polyurethane films with excellent electromagnetic interference shielding, thermal conductivity, and management performances. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 4, 274-285 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-021-00221-4

- H. Zhan, Y.W. Chen, Q.Q. Shi, Y. Zhang, R.W. Mo et al., Highly aligned and densified carbon nanotube films with superior thermal conductivity and mechanical strength. Carbon 186, 205-214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2021. 09.069

- D. Kong, Z.M. El-Bahy, H. Algadi, T. Li, S.M. El-Bahy et al., Highly sensitive strain sensors with wide operation range from strong MXene-composited polyvinyl alcohol/sodium carboxymethylcellulose double network hydrogel. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1976-1987 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00531-1

- X. Guan, Q. Zhang, C. Dong, R. Zhang, M. Peng et al., A firstprinciples study of Janus monolayer MXY (

, W; X, Y van der Waals heterojunctions for integrated optical fibers. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 3232-3244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00557-5 - Y. Yu, Y. Huang, L. Li, L. Huang, S. Zhang, Silica ceramic nanofiber membrane with ultra-softness and high temperature insulation. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 4080-4091 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1007/s10853-022-06913-6

- S. Zhang, B. Cheng, Z. Jia, Z. Zhao, X. Jin et al., The art of framework construction: hollow-structured materials toward high-efficiency electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1658-1698 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s42114-022-00514-2

- D.-Q. Zhang, T.-T. Liu, J.-C. Shu, S. Liang, X.-X. Wang et al., Self-assembly construction of

architecture with green EMI shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 26807-26816 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b06509 - R.B.J. Chandra, B. Shivamurthy, S.B.B. Gowda, M.S. Kumar, Flexible linear low-density polyethylene laminated aluminum

and nickel foil composite tapes for electromagnetic interference shielding. Eng. Sci. 21, 777 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es8d777 - Z. Zeng, F. Jiang, Y. Yue, D. Han, L. Lin et al., Flexible and ultrathin waterproof cellular membranes based on high-conjunction metal-wrapped polymer nanofibers for electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 32, e1908496 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 201908496

- T. Gao, Y. Ma, L. Ji, Y. Zheng, S. Yan et al., Nickel-coated wood-derived porous carbon (Ni/WPC) for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 2328-2338 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00420-7

- J.-L. Shie, Y.-H. Chen, C.-Y. Chang, J.-P. Lin, D.-J. Lee et al., Thermal pyrolysis of poly(vinyl alcohol) and its major products. Energy Fuels 16, 109-118 (2002). https://doi.org/10. 1021/ef010082s

- Z. Zhang, J. Liu, F. Wang, J. Kong, X. Wang, Fabrication of bulk macroporous zirconia by combining sol-gel with calcination processes. Ceram. Int. 37(7), 2549-2553 (2011). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.03.054

- Z. Wu, X. Wang, S.H.K. Annamareddy, S. Gao, Q. Xu et al., Dielectric properties and thermal conductivity of polyvinylidene fluoride synergistically enhanced with silica@multiwalled carbon nanotubes and boron nitride. ES Mater. Manuf. 22, 847 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esmm5f847

- C. Lin, Y. Zhang, S. Zhang, X.X. Wang, J. Yang et al., Facile fabrication of a novel

composites catalysts with enhanced photocatalytic performances. ES Energy Environ. 20, 860 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8c860 - H. Algadi, T. Das, J. Ren, H. Li, High-performance and stable hybrid photodetector based on a monolayer molybdenum disulfide

nitrogen doped graphene quantum dots GQDs)/all-inorganic perovskite nanocrystals triple junction. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 56 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00634-3 - Q. Hu, H. Suzuki, H. Gao, H. Araki, W. Yang et al., Highfrequency FTIR absorption of

nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 378, 299-304 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett. 2003.07.015 - V.S. Sivasankarapillai, T.S.K. Sharma, K.-Y. Hwa, S.M. Wabaidur, S. Angaiah et al., MXene based sensing materials: current status and future perspectives. ES Energy Environ. 15, 4-14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8c618

- N. Wu, Y. Yang, C. Wang, Q. Wu, F. Pan et al., Ultrathin cellulose nanofiber assisted ambient-pressure-dried, ultralight, mechanically robust, multifunctional MXene aerogels. Adv. Mater. 35, e2207969 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202207969

- J. Wang, H. Kang, H. Ma, Y. Liu, Z. Xie et al., Super-fast fabrication of MXene film through a combination of ion induced gelation and vacuum-assisted filtration. Eng. Sci. 15, 57-66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.30919/es8d446

- Y. Cao, M. Weng, M.H.H. Mahmoud, A.Y. Elnaggar, L. Zhang et al., Flame-retardant and leakage-proof phase change composites based on MXene/polyimide aerogels toward

solar thermal energy harvesting. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 1253-1267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-022-00504-4 - Y. Wei, W. Luo, Z. Zhuang, B. Dai, J. Ding et al., Fabrication of ternary MXene/

polyaniline nanostructure with good electrochemical performances. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 4, 1082-1091 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s42114-021-00323-z - F. Jia, Z. Lu, S. Li, J. Zhang, Y. Liu et al., Asymmetric c-MWCNT/AgNWs/PANFs hybrid film constructed by tailoring conductive-blocks strategy for efficient EMI shielding. Carbon 217, 118600 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon. 2023.118600

- B. Dai, Y. Ma, F. Dong, J. Yu, M. Ma et al., Overview of MXene and conducting polymer matrix composites for electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 704-754 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00510-6

- S. Kowshik, U.S. Rao, S. Sharma, P. Hiremath, R. Prasad K.S., et al., Mechanical properties of eggshell filled non-post-cured and post-cured GFRP composites: a comparative study. ES Mater. Manuf. 22, 1043 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 30919/esmm1043

- W. Zou, X. Zheng, X. Hu, J. Huang, G. Wang et al., Recent Advances in Injection Molding of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Polymer Composites: A Review. ES. Gen. 1, 938 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/esg938

- V. Managuli, Y.S. Bothra, S. Sujith Kumar, P. Gaur, P.L. Chandracharya et al., Overview of mechanical characterization of bone using nanoindentation technique and its applications. Eng. Sci. 22, 820 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30919/ es8d820

- B. Li, N. Wu, Y. Yang, F. Pan, C. Wang et al., Graphene oxideassisted multiple cross-linking of MXene for large-area, highstrength, oxidation-resistant, and multifunctional films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213357 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adfm. 202213357

- H. Cheng, Z. Lu, Q. Gao, Y. Zuo, X. Liu et al., PVDF-Ni/PECNTs composite foams with co-continuous structure for electromagnetic interference shielding and photo-electro-thermal properties. Eng. Sci. 16, 331-340 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 30919/es8d518

- D. Zhang, S. Liang, J. Chai, T. Liu, X. Yang et al., Highly effective shielding of electromagnetic waves in

nanosheets synthesized by a hydrothermal method. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 134, 77-82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jpcs.2019.05.041 - P. Wang, L. Yang, J. Ling, J. Song, T. Song et al., Frontal ring-opening metathesis polymerized polydicyclopentadiene carbon nanotube/graphene aerogel composites with enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 2066-2077 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s42114-022-00543-x

- J. Cheng, H. Zhang, M. Ning, H. Raza, D. Zhang et al., Emerging materials and designs for low- and multi-band electromagnetic wave absorbers: the search for dielectric and magnetic

synergy? Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200123 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202200123 - D. Zhang, H. Wang, J. Cheng, C. Han, X. Yang et al., Conductive

-NS/CNTs hybrids based 3D ultra-thin mesh electromagnetic wave absorbers with excellent absorption performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 528, 147052 (2020). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147052 - C. Xiong, Q. Xiong, M. Zhao, B. Wang, L. Dai et al., Recent advances in non-biomass and biomass-based electromagnetic shielding materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00774-6

- H. Lee, S.H. Ryu, S.J. Kwon, J.R. Choi, S.B. Lee et al., Absorption-Dominant mmWave EMI shielding films with ultralow reflection using ferromagnetic resonance frequency tunable M-type ferrites. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 76 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01058-w

- H. Zhang, T. Liu, Z. Huang, J. Cheng, H. Wang et al., Engineering flexible and green electromagnetic interference shielding materials with high performance through modulating

nanosheets on carbon fibers. J. Materiomics 8, 327-334 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2021.09.003 - M. Seol, U. Hwang, J. Kim, D. Eom, I.-K. Park et al., Solution printable multifunctional polymer-based composites for smart electromagnetic interference shielding with tunable frequency and on-off selectivities. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00609-w

- K. Ruan, X. Shi, Y. Zhang, Y. Guo, X. Zhong et al., Electric-field-induced alignment of functionalized carbon nanotubes inside thermally conductive liquid crystalline polyimide composite films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309010 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie. 202309010

- T. Zhang, J. Xu, T. Luo, Extremely high thermal conductivity of aligned polyacetylene predicted using

first-principles-informed united-atom force field. ES Energy Environ. 16, 67-73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.30919/esee8 c719 - Q. Xu, Z. Wu, W. Zhao, M. He, N. Guo et al., Strategies in the preparation of conductive polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels for applications in flexible strain sensors, flexible supercapacitors, and triboelectric nanogenerator sensors: an overview. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s42114-023-00783-5

- J. Cheng, H. Zhang, H. Wang, Z. Huang, H. Raza et al., Tailoring self-polarization of bimetallic organic frameworks with multiple polar units toward high-performance consecutive multi-band electromagnetic wave absorption at gigahertz. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201129 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1002/adfm. 202201129

- D. Skoda, J. Vilcakova, R.S. Yadav, B. Hanulikova, T. Capkova et al., Nickel nanoparticle-decorated reduced graphene oxide via one-step microwave-assisted synthesis and its lightweight and flexible composite with Polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene-ran-butylene)-block-polystyrene polymer for electromagnetic wave shielding application. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00692-7

- X. Zhang, Q. Tian, B. Wang, N. Wu, C. Han et al., Flexible porous SiZrOC ultrafine fibers for high-temperature thermal insulation. Mater. Lett. 299, 130131 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.matlet.2021.130131

- X. Zhong, M. He, C. Zhang, Y. Guo, J. Hu et al., Heterostructured BN@Co-C@C endowing polyester composites excellent thermal conductivity and microwave absorption at C band. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adfm. 202313544

Duo Pan, panduonerc@zzu.edu.cn; Hu Liu, liuhu@zzu.edu.cn

Key Laboratory of Materials Processing and Mold (Zhengzhou University), Ministry of Education, National Engineering Research Center for Advanced Polymer Processing Technology, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450002, People’s Republic of China

School of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, People’s Republic of China

Key Laboratory of Multifunctional Nanomaterials and Smart Systems, Advanced Materials Division, Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Suzhou 215123, People’s Republic of China

Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Macromolecular Science and Technology, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an 710072, People’s Republic of China

College of Chemistry & Green Catalysis Center, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, People’s Republic of China

Mechanical and Construction Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Environment, Northumbria University, Newcastle Upon Tyne NE1 8, UK

Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Nasr City 11884, Cairo, Egypt

Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia

Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, 21944 Taif, Saudi Arabia