DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58026-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40140373

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-26

أنماط التنقل العالمية والإقليمية للمعادن (المعدنية) في التربة والمخاطر المرتبطة بها

تم القبول: 10 مارس 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 26 مارس 2025

الملخص

لتقييم المخاطر المرتبطة بتلوث التربة بالمعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) بدقة وإبلاغ عمليات الترميم وصنع السياسات الفعالة

الحصول على بيانات شاملة ودقيقة لتحديد الأنواع المعدنية (أو المعادن) في التربة على نطاق قاري أو عالمي لا يزال يمثل تحديًا كبيرًا، مما يعيق الجهود المبذولة لتقييم وفهم الحركة العالمية لمثل هذه الملوثات. على الرغم من أن التقنيات التحليلية المتقدمة، مثل مطيافية الامتصاص بالأشعة السينية عالية الطاقة وتقنية تخفيف النظائر، يمكن أن تحدد بدقة تحديد الأنواع المعدنية (أو المعادن).

النتائج

أنماط عالمية ومحركات رئيسية لتحرك المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) في التربة

كان

زيادة خطر تحرك المعادن (أو المعادن الثقيلة) تحت مبادرة الأربعة بالألف

خطر تعبئة مرتفع لستة معادن (أو عناصر شبيهة بالمعادن) شائعة على الأقل في عام 2024؛ كانت هذه النسبة

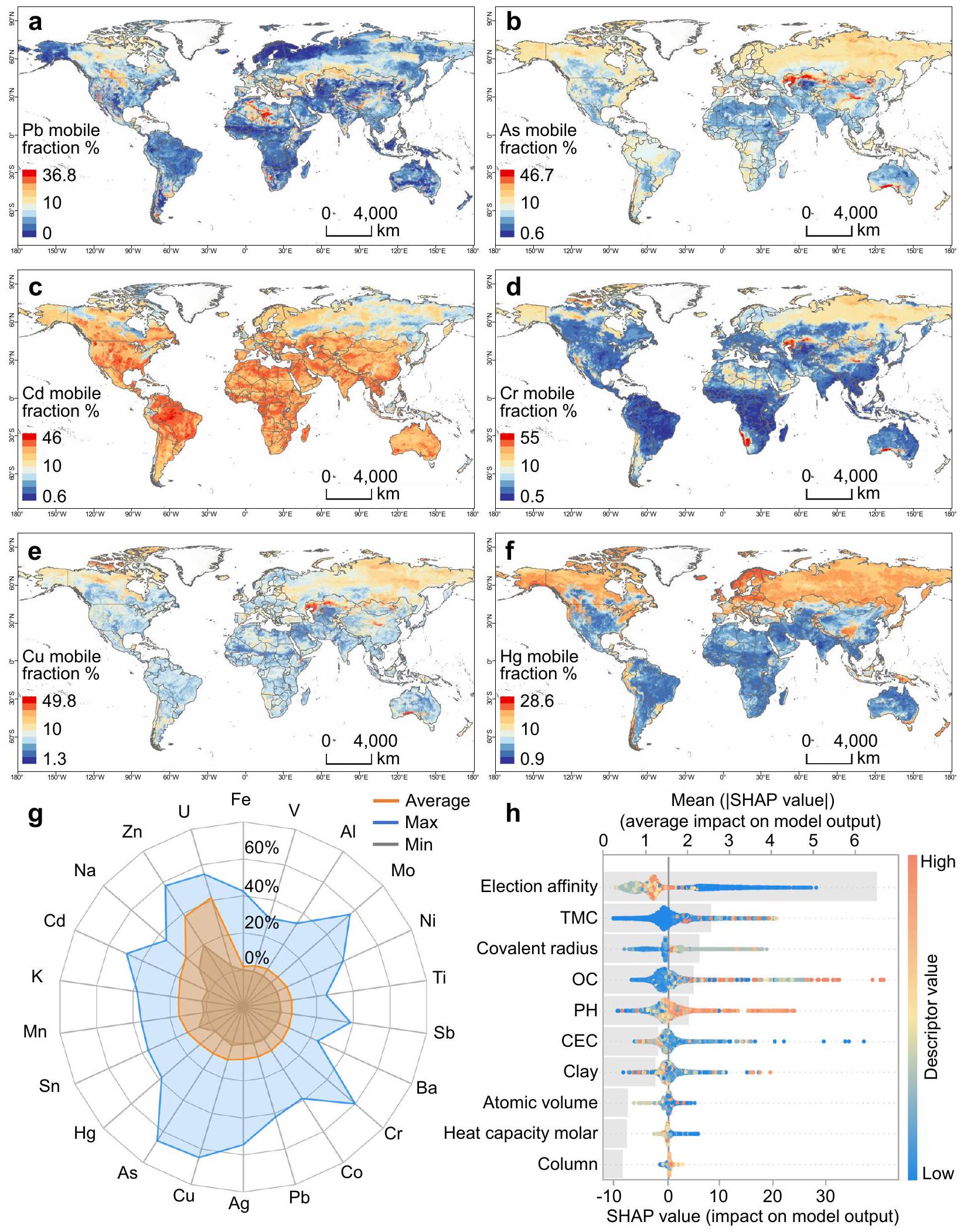

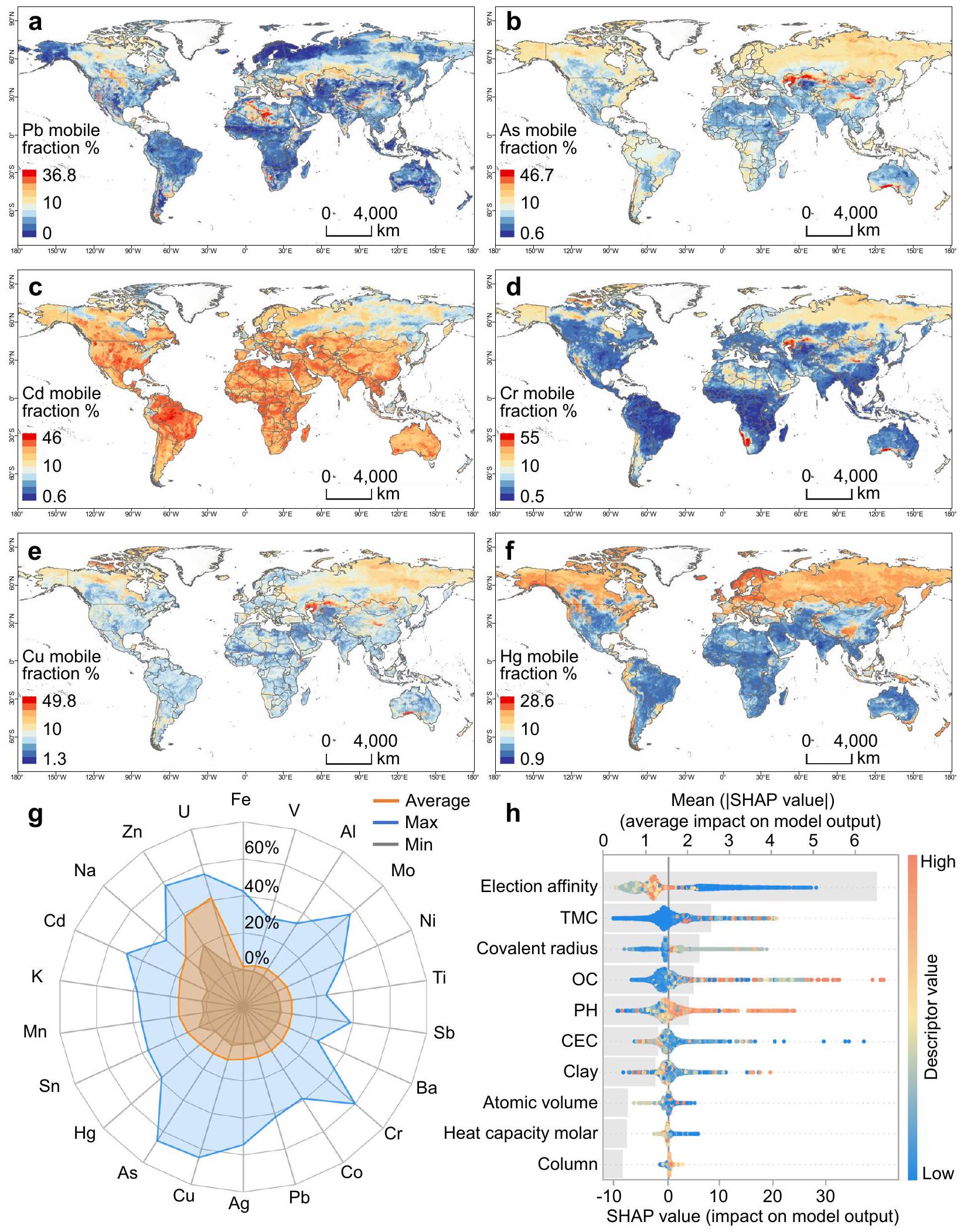

نموذج توزيع عالمي للجزء المتنقل لـ

من خلال رسم سحابة لقيم SHAP المقابلة لها. يمثل لون النقطة القيمة النسبية للوصف في مجموعة البيانات (من العالي إلى المنخفض موضحًا بالألوان البرتقالية إلى الزرقاء). تُظهر الموقع الأفقي للنقاط ما إذا كان تأثير ذلك الوصف يساهم بشكل إيجابي أو سلبي في تلك الحالة التنبؤية.

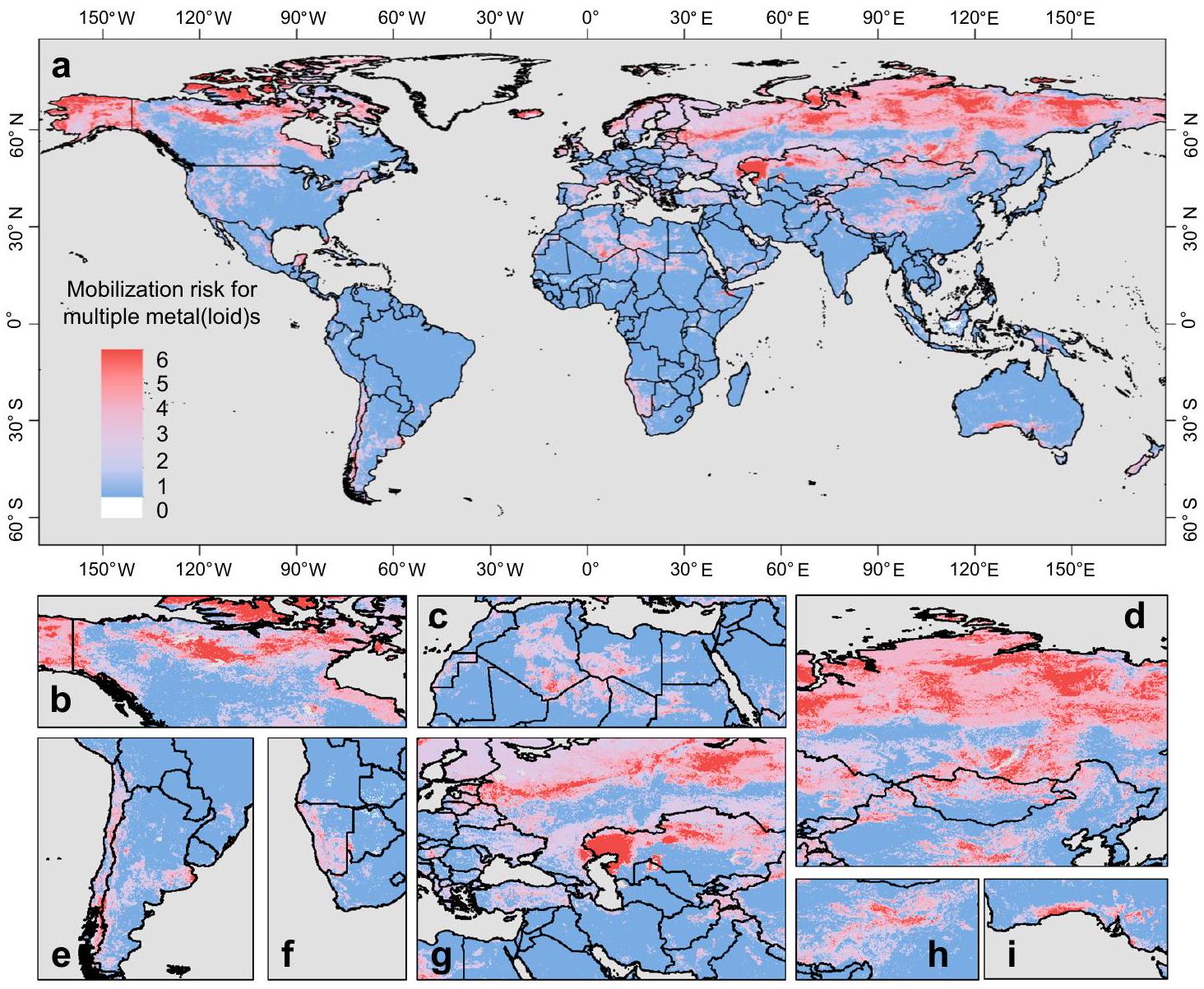

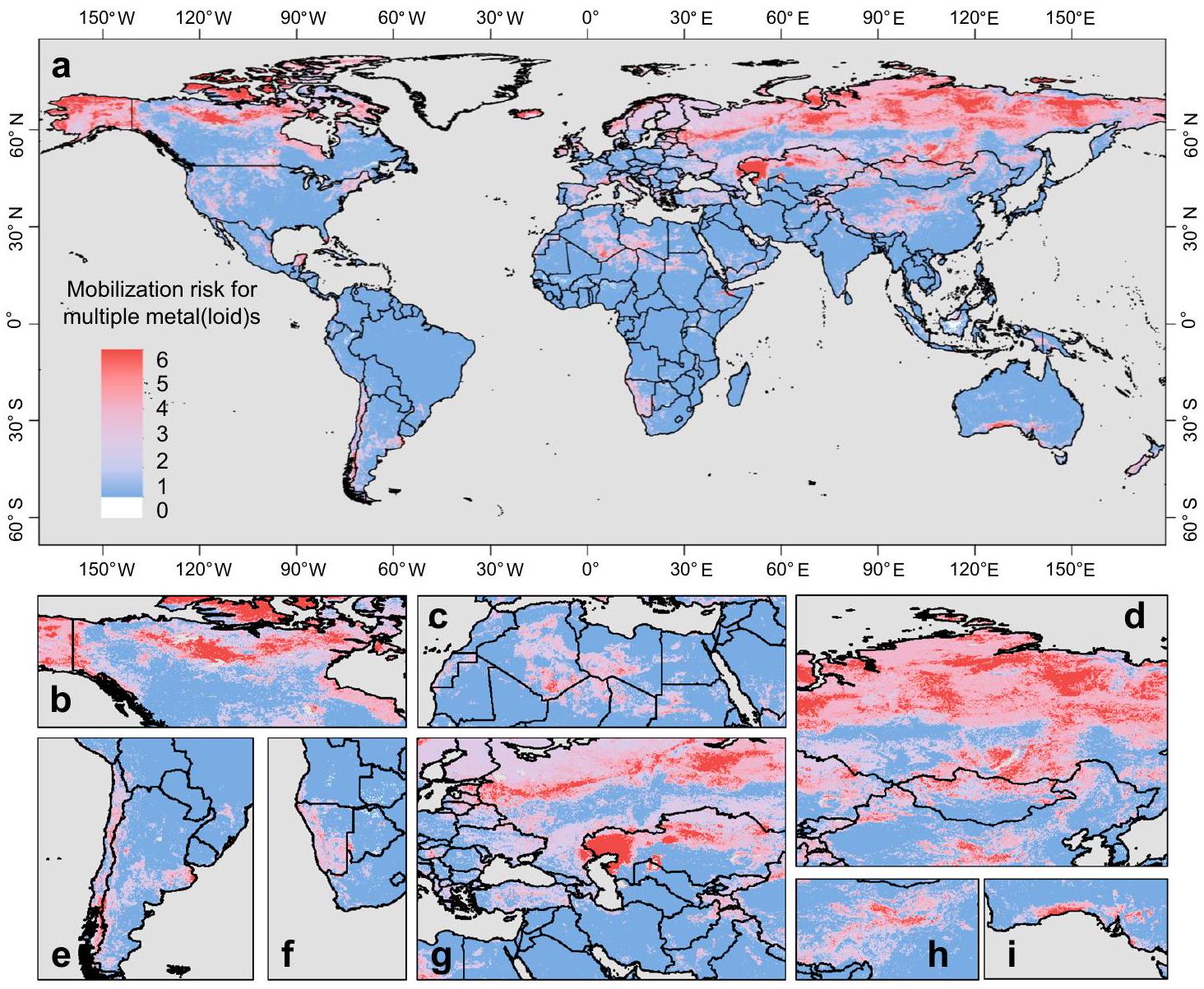

المعادن (أو المعادن غير المعدنية) التي تم تحديدها بمخاطر تحرك متوسطة إلى عالية في السيناريوهات الأساسية لموقع معين؛ ب-1 مقاطع مكبرة من النقاط الساخنة المعتادة لمخاطر التحرك. تم توفير بيانات المصدر كملف بيانات مصدر.

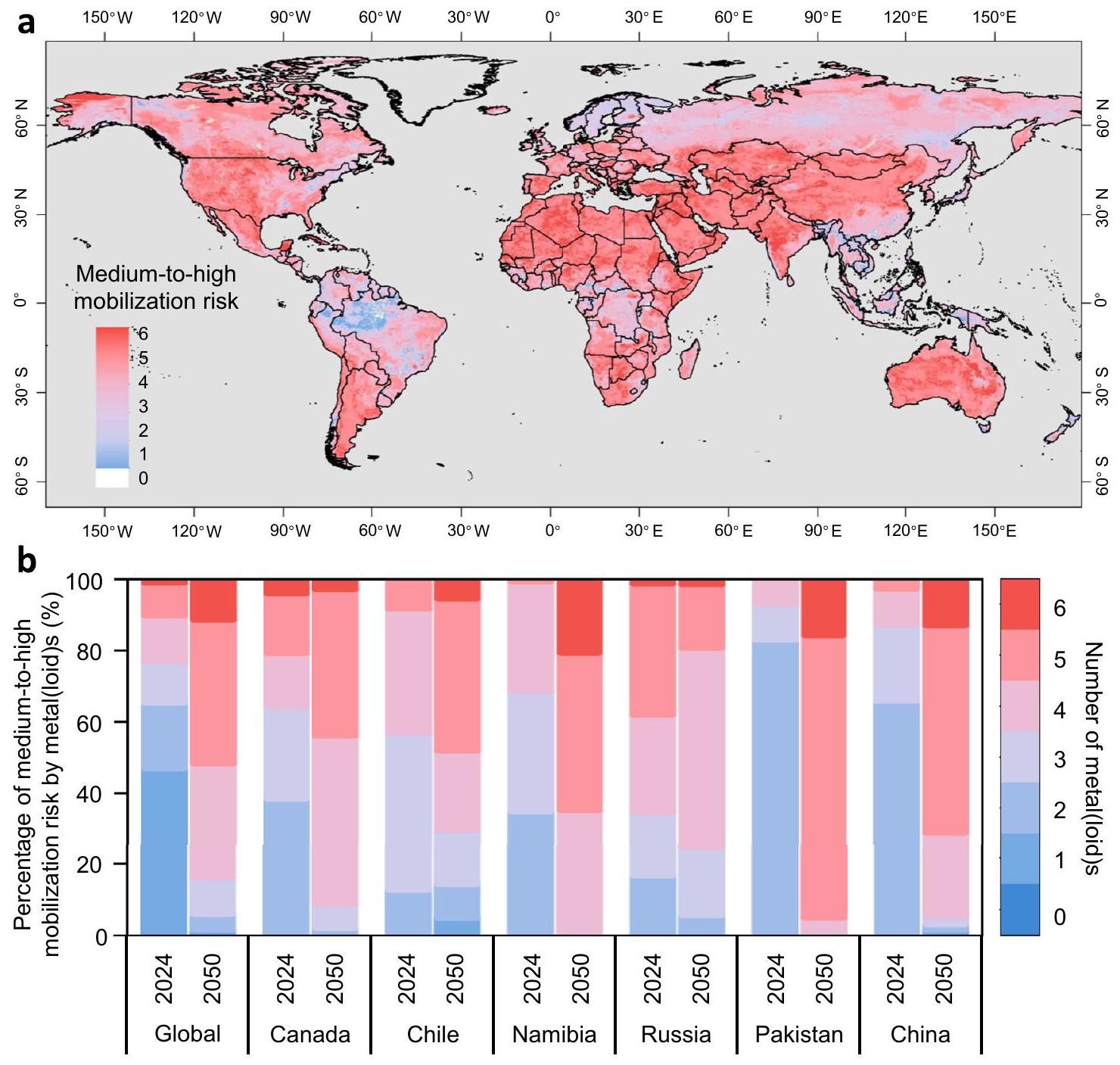

زيادة واضحة في خطر التعبئة عندما تم اعتماد مبادرة الأربعة بالألف.

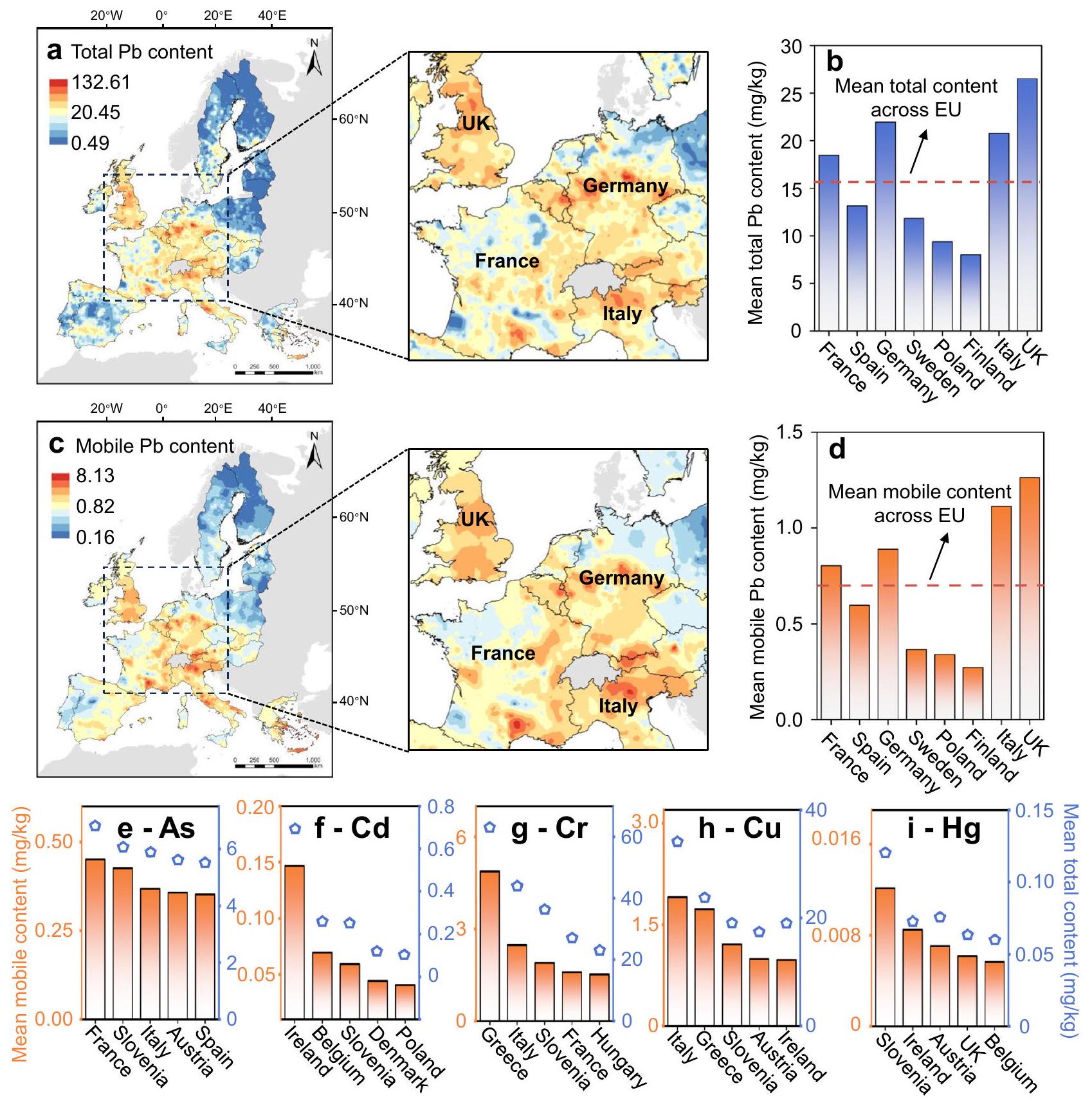

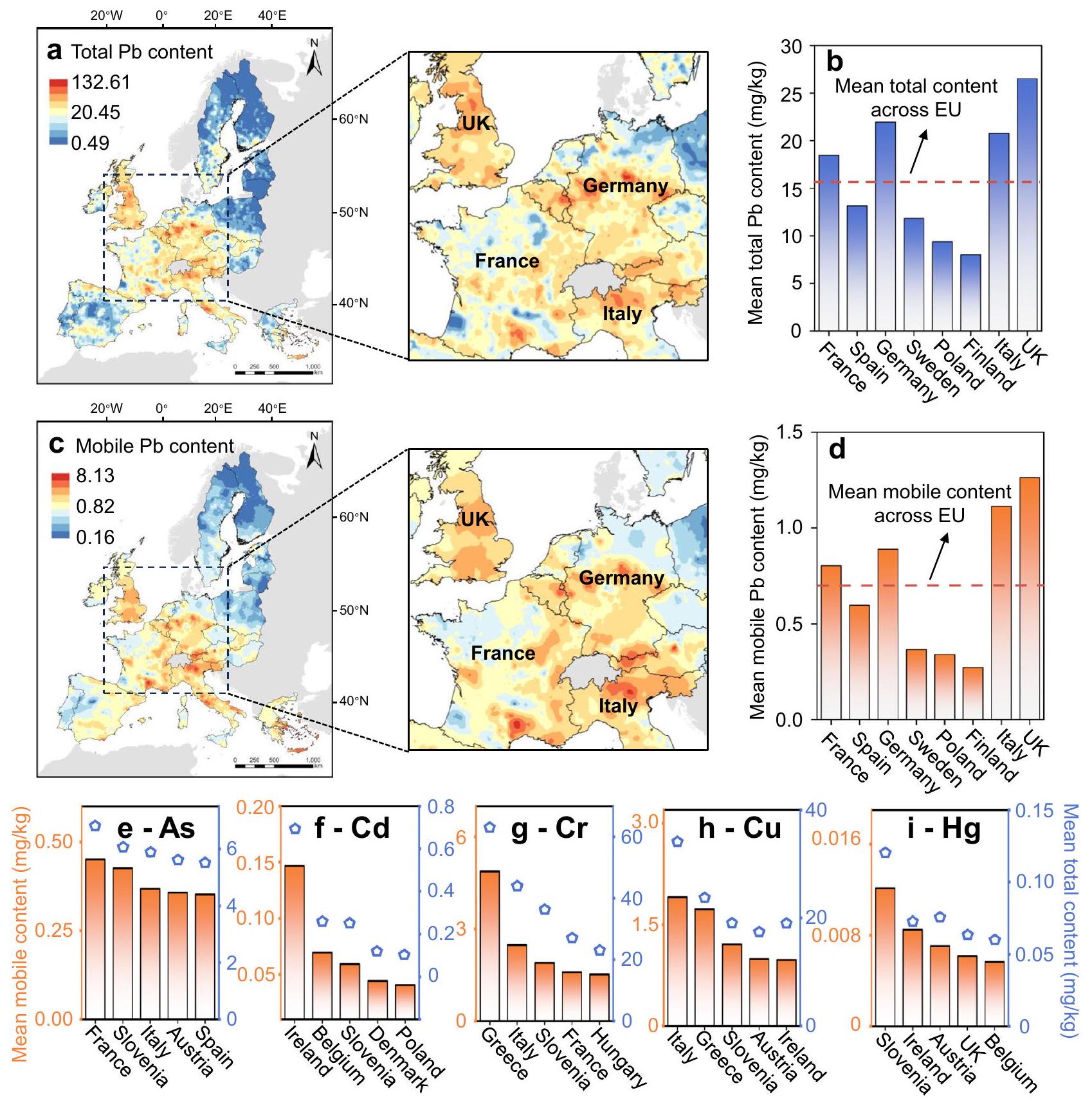

الفروق المكانية في محتويات المعادن (المعدنية) الكلية والمتنقلة في تربة الاتحاد الأوروبي

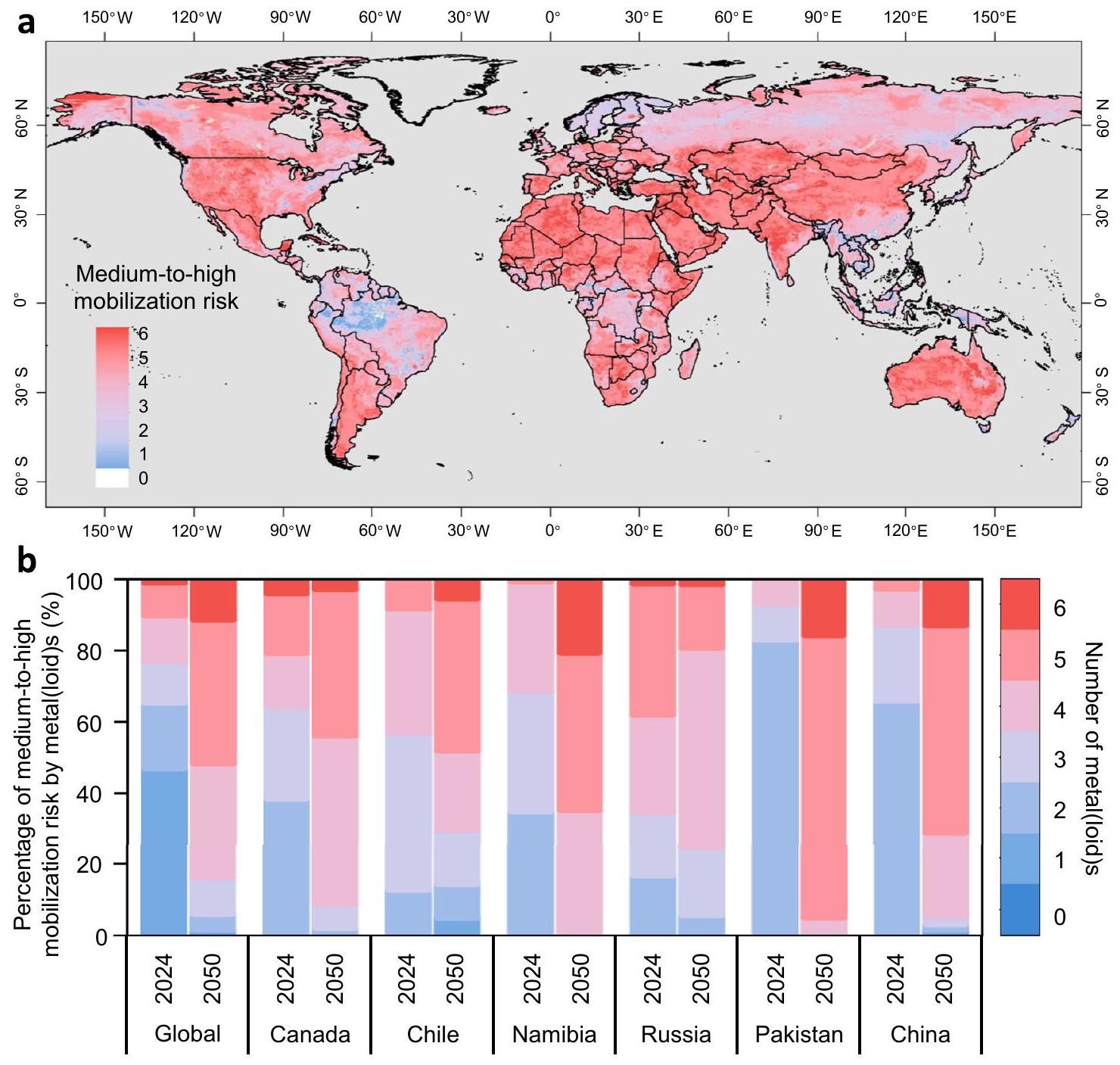

تم تحديد المعادن (الفلزات) الشائعة التي تُعتبر ذات مخاطر تحرك متوسطة إلى عالية في السيناريوهات الأساسية لموقع معين. تُظهر الرسوم البيانية الشريطية النسبة المئوية للأراضي التي تم تحديدها على أنها محفوفة بالمخاطر بواسطة المعادن (الفلزات) الشائعة، مما يبرز الدول التي تواجه مخاطر تحرك كبيرة. تم توفير بيانات المصدر كملف بيانات مصدر.

أظهرت أعلى محتوى من الرصاص المتنقل؛ ومع ذلك، تجاوزت إيطاليا ألمانيا من حيث الرصاص المتنقل (الشكل 4ب، د).

نقاش

نموذج تفرقة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) الذي يمكّن من التنبؤ بتفرقة 49 معدنًا (أو معدنًا شبيهًا) في أنواع التربة المتنوعة، من المتوقع أن يقلل بشكل كبير من الموارد والوقت المطلوبين للمسوحات الجيولوجية. لذلك، يمكّن نموذج حركة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) في التربة من إنشاء وتحديث خرائط حركة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) العالمية بشكل دوري.

طريقة الفاصل الهندسي في طيف الألوان. e-i متوسط المحتويات الكلية والمتنقلة للزرنيخ،

تجارب الاستخراج المتسلسل. وبالتالي، فإن اعتماد نموذجنا في دراسات نطاق الموقع يمكن أن يوفر للممارسين القدرة الفريدة على تقييم حركة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) في التربة بسرعة وموثوقية.

يمكن تقييم خرائط توزيع التنقل مع البيانات المتعلقة بمصادر المعادن الرئيسية، مما يوجه اختبارات التنقل التفصيلية، ويساعد في التخطيط الصناعي، ويدعم إدارة المحاصيل (الملاحظة التكميلية 2). على سبيل المثال، تم العثور على جنوب تشيلي وناميبيا وكازاخستان كمناطق ذات مخاطر عالية في التحرك مع احتمال كبير لتراكم المعادن في التربة بسبب المصادر الطبيعية والبشرية، والتي يجب أن تخضع لاختبارات ومراقبة تفصيلية لتحرك المعادن.

(ملاحظة إضافية 3). إن فحص التأثير الجماعي لخصائص التربة على حركة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) يسهل تصنيف جميع المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) التي تم التحقيق فيها إلى ثلاث مجموعات بناءً على تأثير خصائص التربة (ملاحظة إضافية 3). يمكن أن يكون هذا النوع من تصنيف المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) بمثابة معيار لتوجيه جهود معالجة التربة عندما تكون البيانات المحددة عن معدن (أو معدن شبيه) معين غير متوفرة ولكنها وفيرة بالنسبة لمعادين (أو معادن شبيهة) في نفس المجموعة. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يعزز نموذج حركة المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) استراتيجيات المعالجة لدينا من خلال توفير استجابات حركة أكثر تخصيصًا لخصائص التربة المتنوعة (مثل درجة حموضة التربة)، مما يقترح بالتالي المسار الأكثر كفاءة لتثبيت المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) في التربة. على سبيل المثال، قد يوجد نطاق آمن متنوع لدرجة الحموضة، حيث

طرق

تجميع قاعدة بيانات عالمية لتفكيك المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) في التربة

نمذجة تنقل المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) باستخدام التعلم الآلي الموجه بواسطة النظرية

موثوقية النمذجة، وعدم اليقين في التنبؤ، وأهمية الوصف

نموذج XGBoost الأمثل

توزيع تنقل المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) العالمية والمحركات الرئيسية

حققنا في التغير في تنقل المعادن (أو المعادن الشبيهة) المتأثر بجهد بشري نموذجي لمواجهة تغير المناخ العالمي، وهو احتجاز الكربون في التربة. تم تحليل احتجاز الكربون في التربة لأنه تم التعرف عليه كطريقة واعدة لإزالة CO2 من الغلاف الجوي عن طريق احتجاز C كـ OC في التربة. بعبارة أخرى، يخفف احتجاز الكربون في التربة من الزيادة السريعة في انبعاثات

تطبيق نماذج تنقل التعلم الآلي عبر تربة الاتحاد الأوروبي

تصوير البيانات والتحليلات الإحصائية

توفر البيانات

يمكن العثور على بيانات المعادن (المعدنية) عبر الاتحاد الأوروبي في قاعدة بيانات مسح إطار منطقة استخدام الأراضي/غطاء الأرض (LUCAS) لعام 2009

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Hou, D. et al. Metal contamination and bioremediation of agricultural soils for food safety and sustainability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 366-381 (2020).

- O’Connor, D., Hou, D., Ok, Y. S. & Lanphear, B. P. The effects of iniquitous lead exposure on health. Nat. Sustain. 3, 77-79 (2020).

- Thornton, I. & Abrahams, P. Soil ingestion-a major pathway of heavy metals into livestock grazing contaminated land. Sci. Total Environ. 28, 287-294 (1983).

- Bull, K. R., Murton, R. K., Osborn, D., Ward, P. & Cheng, L. High levels of cadmium in Atlantic seabirds and sea-skaters. Nature 269, 507-509 (1977).

- Rodríguez-Eugenio, N., McLaughlin, M. & Pennock, D. Soil Pollution: A Hidden Reality. (FAO, Rome, 2018).

- Pérez, A. P. & Eugenio, N. R. Status of Local Soil Contamination in Europe. https://doi.org/10.2760/093804, JRC107508 (EUR 29124 EN, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018).

- Zhao, F.-J., Ma, Y., Zhu, Y.-G., Tang, Z. & McGrath, S. P. Soil contamination in China: current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 750-759 (2015).

- Nardi, F., Annis, A., Di Baldassarre, G., Vivoni, E. R. & Grimaldi, S. GFPLAIN250m, a global high-resolution dataset of Earth’s floodplains. Sci. Data 6, 180309 (2019).

- Macklin, M. G. et al. Impacts of metal mining on river systems: a global assessment. Science 381, 1345-1350 (2023).

- Foley, J. A. et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478, 337-342 (2011).

- Tilman, D., Balzer, C., Hill, J. & Befort, B. L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 20260-20264 (2011).

- Hou, D. & Ok, Y. S. Soil pollution-speed up global mapping. Nature 566, 455-456 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Climate and vegetation as primary drivers for global mercury storage in surface soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10665-10675 (2019).

- Almendras, M.-L., Carballa, M., Diels, L., Vanbroekhoven, K. & Chamy, R. Prediction of heavy metals mobility and bioavailability in contaminated soil using sequential extraction and biosensors. J. Environ. Eng. 135, 839-844 (2009).

- Wang, J., Man, Y., Yin, R. & Feng, X. Isotopic and spectroscopic investigation of mercury accumulation in Houttuynia cordata colonizing historically contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7997-8007 (2022).

- Li, Q. et al. Speciation of heavy metals in soils and their immobilization at micro-scale interfaces among diverse soil components. Sci. Total Environ. 825, 153862 (2022).

- Liang, Y. et al. Geochemical controls on the distribution and bioavailability of heavy metals in sediments from Yangtze River to the East China Sea: assessed by sequential extraction versus diffusive gradients in thin-films (DGT) technique. J. Hazard. Mater. 452, 131253 (2023).

- Bagherifam, S., Brown, T. C., Bagherifam, S. & Baglieri, A. Sequential extraction of labile and recalcitrant fractions of soil organic matter: a case study focusing on antimony (Sb) in humic acids, fulvic acids and humin fractions of long-term aged contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 327, 121610 (2023).

- Mbodji, M. et al. Speciation of metals by sequential extractions of agricultural soils located near a dumpsite for prediction of element availability to vegetables. Talanta 244, 123411 (2022).

- Blumenstock, J., Cadamuro, G. & On, R. Predicting poverty and wealth from mobile phone metadata. Science 350, 1073-1076 (2015).

- Toetzke, M., Banholzer, N. & Feuerriegel, S. Monitoring global development aid with machine learning. Nat. Sustain. 5, 533-541 (2022).

-

. et al. Fertilizer management for global ammonia emission reduction. Nature 626, 792-798 (2024). - Jin, J. et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 320, 417-426 (2016).

- Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 718 (2019).

- Benhachem, F. Z. & Harrache, D. Chemical speciation and potential mobility of heavy metals in forest soil near road traffic in Hafir, Algeria. J. Health Pollut. 11, 210614 (2021).

- Wang, X. S. & Qin, Y. Leaching characteristics of heavy metals and As from two urban roadside soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 132, 83-92 (2007).

-

. et al. Cr migration potential and species properties in the soil profile from a chromate production site in the groundwater depression cone area. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 109, 600-608 (2022). - Zeng, X., Jin, Q., Wang, P. & Huang, C. Distribution and speciation of heavy metal(loid)s in soils under multiple preservative-treated wooden trestles. Toxics 11, 249 (2023).

- Bradford, M. A. A leaky sink. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 475-476 (2017).

- Minasny, B. et al. Soil carbon 4 per mille. Geoderma 292, 59-86 (2017).

- Ballabio, C. et al. Mapping LUCAS topsoil chemical properties at European scale using Gaussian process regression. Geoderma 355, 113912 (2019).

- Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil 7, 217-240 (2021).

- Zhang, S. et al. Escalating arsenic contamination throughout Chinese soils. Nat. Sustain. 7, 766-775 (2024).

- Hlavay, J., Prohaska, T., Weisz, M., Wenzel, W. W. & Stingeder, G. J. Determination of trace elements bound to soil and sediment fractions (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 76, 415-442 (2004).

- Tessier, A. & Campbell, P. G. C. Comment on “Pitfalls of sequential extractions” by P. M. V. Nirel and F. M. M. Morel. Water Res. 25, 115-117 (1991).

- Sutherland, R. A. BCR

-701: a review of 10-years of sequential extraction analyses. Anal. Chim. Acta 680, 10-20 (2010). - Tack, F. M. G. & Verloo, M. G. Chemical speciation and fractionation in soil and sediment heavy metal analysis: a review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 59, 225-238 (1995).

- Shober, A. L., Stehouwer, R. C. & MacNeal, K. E. Chemical fractionation of trace elements in biosolid-amended soils and correlation with trace elements in crop tissue. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 38, 1029-1046 (2007).

- Kim, R.-Y. et al. Bioavailability of heavy metals in soils: definitions and practical implementation-a critical review. Environ. Geochem. Health 37, 1041-1061 (2015).

- Hernández-Moreno, J. M., Rodríguez-González, J. I. & Espino-Mesa, M. Evaluation of the BCR sequential extraction for trace elements in European reference volcanic soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 58, 419-430 (2007).

- Rohatgi, A. et al. WebPlotDigitizer user manual version 3.4. 1-18 https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer (2014).

- Bogusz, A. & Oleszczuk, P. Sequential extraction of nickel and zinc in sewage sludge- or biochar/sewage sludge-amended soil. Sci. Total Environ. 636, 927-935 (2018).

- Huang, Y. et al. Size, distribution, and vulnerability of the global soil inorganic carbon. Science 384, 233-239 (2024).

- Shaheen, S. M. & Rinklebe, J. Geochemical fractions of chromium, copper, and zinc and their vertical distribution in floodplain soil profiles along the Central Elbe River, Germany. Geoderma 228-229, 142-159 (2014).

- Jiang, Y. et al. Topological representations of crystalline compounds for the machine-learning prediction of materials properties. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 28 (2021).

- Podgorski, J. & Berg, M. Global threat of arsenic in groundwater. Science 368, 845-850 (2020).

- Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 65, 386-408 (1958).

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436-444 (2015).

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5-32 (2001).

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189-1232 (2001).

- Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785-794 (ACM, 2016).

- Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 3146-3154 (2017).

- Aiken, E., Bellue, S., Karlan, D., Udry, C. & Blumenstock, J. E. Machine learning and phone data can improve targeting of humanitarian aid. Nature 603, 864-870 (2022).

- Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273-297 (1995).

- Kleinbaum, D. G., Dietz, K., Gail, M., Klein, M. & Klein, M. Logistic Regression. (Springer, New York, 2002).

- Ketkar, N. Introduction to Keras. In Deep Learning with Python, 97-111 (Springer, 2017).

- Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825-2830 (2011).

- Cook-Patton, S. C. et al. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 585, 545-550 (2020).

- Barber, R. F., Candès, E. J., Ramdas, A. & Tibshirani, R. J. Predictive inference with the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 49, 486-507 (2021).

- Nemani, V. et al. Uncertainty quantification in machine learning for engineering design and health prognostics: a tutorial. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 205, 110796 (2023).

- Altmann, A., Toloşi, L., Sander, O. & Lengauer, T. Permutation importance: a corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 26, 1340-1347 (2010).

- van den Hoogen, J. et al. Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature 572, 194-198 (2019).

- Jennings, A. A. Analysis of worldwide regulatory guidance values for the most commonly regulated elemental surface soil contamination. J. Environ. Manag. 118, 72-95 (2013).

- Muckley, E. S., Saal, J. E., Meredig, B., Roper, C. S. & Martin, J. H. Interpretable models for extrapolation in scientific machine learning. Digit. Discov. 2, 1425-1435 (2023).

- Zhan, J. et al. Evaluating interpolation and extrapolation performance of neural retrieval models. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2486-2496 (ACM, New York, 2022).

- Haaf, D., Six, J. & Doetterl, S. Global patterns of geo-ecological controls on the response of soil respiration to warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 623-627 (2021).

- Liu, J., Zhang, X.-H., Tran, H., Wang, D.-Q. & Zhu, Y.-N. Heavy metal contamination and risk assessment in water, paddy soil, and rice

around an electroplating plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 18, 1623-1632 (2011). - Tóth, G., Hermann, T., Szatmári, G. & Pásztor, L. Maps of heavy metals in the soils of the European Union and proposed priority areas for detailed assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 565, 1054-1062 (2016).

- Orgiazzi, A., Ballabio, C., Panagos, P., Jones, A. & Fernández-Ugalde, O. LUCAS soil, the largest expandable soil dataset for Europe: a review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69, 140-153 (2018).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261-272 (2020).

- Cordier, T. et al. Flexible and Systematic Uncertainty Estimation with Conformal Prediction via the MAPIE library, In Proceedings of the Twelfth Symposium on Conformal and Probabilistic Prediction with Applications 204, 549-581 (PMLR, Limassol, 2023).

- Qi, C. C. et al. Figshare https://figshare.com/s/fa76e3cb3e0e070 9df8d (2025).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2025

مدرسة المعادن والبيئة، جامعة جنوب الوسط، تشانغشا 410083، الصين. مدرسة هندسة الموارد والسلامة، جامعة جنوب الوسط، تشانغشا 410083، الصين. مدرسة علوم البيئة والهندسة، جامعة العلوم والتكنولوجيا الجنوبية، شنتشن 518000، الصين. قسم الهندسة المدنية، جامعة موناش، كلايتون 3800 فيكتوريا، أستراليا. مدرسة الفيزياء والإلكترونيات، جامعة جنوب الوسط، تشانغشا 410083 هونان، الصين. قسم الهندسة المدنية والمواد والبيئة، جامعة إلينوي في شيكاغو (UIC)، إلينوي 60607، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

كلية الهندسة الكيميائية، جامعة هuaqiao، شيامن 361021، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني:zhang_lin@csu.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58026-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40140373

Publication Date: 2025-03-26

Global and regional patterns of soil metal(loid) mobility and associated risks

Accepted: 10 March 2025

Published online: 26 March 2025

Abstract

To assess the risks associated with soil metal(loid) contamination accurately and inform effective remediation and policymaking

Obtaining comprehensive, fine-resolution soil metal(loid) speciation data at continental or global scales remains a significant challenge, hindering efforts to assess and understand the global mobility of such pollutants. Although advanced analytical techniques, such as highenergy resolution X-ray absorption spectroscopy and isotope dilution, can accurately determine metal(loid) speciation

Results

Global patterns and key drivers of soil metal(loid) mobility

was

Escalated metal(loid) mobilization risk under the four per mille initiative

high mobilization risk for at least six prevalent metal(loid)s in 2024; this proportion was

a-f Modeled global distribution of the mobile fraction for

through a swarm plot of their corresponding SHAP values. The color of the dot represents the relative value of the descriptor in the dataset (high-to-low depicted as orange-to-blue). The horizontal location of the dots shows whether the effect of that descriptor contributes positively or negatively in that prediction instance (

metal(loid)s identified with medium-to-high mobilization risk in baseline scenarios for a specific site; b-i Zoomed-in sections of the typical mobilization risk hotspots. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

evident increase in the mobilization risk when the Four Per Mille Initiative was adopted.

Spatial disparities in total and mobile metal(loid) contents in EU soils

of prevalent metal(loid)s identified as medium-to-high mobilization risk in baseline scenarios for a specific site. The bar charts depict the percentage of land identified to be risky by various prevalent metal(loid)s, highlighting the countries that face significant mobilization risks. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

exhibited the highest mobile Pb content; however, Italy exceeded Germany in terms of mobile Pb (Fig. 4b, d).

Discussion

metal(loid) fractionation model, which enables the fractionation prediction of 49 metal(loid)s in diverse soil types, is expected to significantly reduce the resources and time required for geological surveys. Therefore, our soil metal(loid) mobility model enables the creation and routine updating of global metal(loid) mobility maps.

geometric interval method in the color spectrum. e-i Mean total and mobile contents of As,

sequential extraction experiments. Thus, embracing our model in sitescale studies can provide practitioners with a unique ability to assess soil metal(loid) mobility rapidly and reliably.

the mobility distribution maps can be evaluated together with data on the major metal(loid) sources, guiding detailed mobility testing, aiding in industrial planning, and supporting crop management (Supplementary Note 2). For example, south Chile, Namibia, and Kazakhstan were found to be the mobilization risk hotspots with a high probability of soil metal(loid) accumulation due to natural and anthropogenic sources, which should undergo detailed metal(loid) mobility testing and monitoring.

(Supplementary Note 3). Examining the collective effect of soil attributes on the mobility of metal(loid)s facilitates the classification of all investigated metal(loid)s into three groups on the basis of the influence of soil attributes (Supplementary Note 3). This type of metal(loid) grouping can serve as a benchmark for guiding soil remediation efforts when specific data is lacking for a particular metal(loid) but is abundant for similar metal(loid)s in the same group. Moreover, the metal(loid) mobility model can advance our remediation strategies by providing more tailored mobility responses to varying soil attributes (i.e., soil pH), thus suggesting the most efficient pathway to stabilize metal(loid)s in soils. For example, there might exist a varied safe pH range, where

Methods

Assembling a global database for metal(loid) fractionation in soil

Metal(loid) mobility modeling using theory-guided ML

Modeling reliability, prediction uncertainty, and descriptor importance

optimal XGBoost model

Global metal(loid) mobility distribution and key drivers

investigated the variation in metal(loid) mobility influenced by a typical human endeavor to tackle global climate change, that is, soil carbon sequestration. Soil carbon sequestration was analyzed as it has been recognized as a promising technique to remove atmospheric CO2 by sequestering C as soil OC. In other words, soil carbon sequestration mitigates the rapid increase in global

Applying ML mobility models across the EU soils

Data visualization and statistical analyzes

Data availability

metal(loid) data across EU can be found in the Land Use/Land Cover Area Frame Survey (LUCAS) 2009 database

Code availability

References

- Hou, D. et al. Metal contamination and bioremediation of agricultural soils for food safety and sustainability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 366-381 (2020).

- O’Connor, D., Hou, D., Ok, Y. S. & Lanphear, B. P. The effects of iniquitous lead exposure on health. Nat. Sustain. 3, 77-79 (2020).

- Thornton, I. & Abrahams, P. Soil ingestion-a major pathway of heavy metals into livestock grazing contaminated land. Sci. Total Environ. 28, 287-294 (1983).

- Bull, K. R., Murton, R. K., Osborn, D., Ward, P. & Cheng, L. High levels of cadmium in Atlantic seabirds and sea-skaters. Nature 269, 507-509 (1977).

- Rodríguez-Eugenio, N., McLaughlin, M. & Pennock, D. Soil Pollution: A Hidden Reality. (FAO, Rome, 2018).

- Pérez, A. P. & Eugenio, N. R. Status of Local Soil Contamination in Europe. https://doi.org/10.2760/093804, JRC107508 (EUR 29124 EN, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018).

- Zhao, F.-J., Ma, Y., Zhu, Y.-G., Tang, Z. & McGrath, S. P. Soil contamination in China: current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 750-759 (2015).

- Nardi, F., Annis, A., Di Baldassarre, G., Vivoni, E. R. & Grimaldi, S. GFPLAIN250m, a global high-resolution dataset of Earth’s floodplains. Sci. Data 6, 180309 (2019).

- Macklin, M. G. et al. Impacts of metal mining on river systems: a global assessment. Science 381, 1345-1350 (2023).

- Foley, J. A. et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478, 337-342 (2011).

- Tilman, D., Balzer, C., Hill, J. & Befort, B. L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 20260-20264 (2011).

- Hou, D. & Ok, Y. S. Soil pollution-speed up global mapping. Nature 566, 455-456 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Climate and vegetation as primary drivers for global mercury storage in surface soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10665-10675 (2019).

- Almendras, M.-L., Carballa, M., Diels, L., Vanbroekhoven, K. & Chamy, R. Prediction of heavy metals mobility and bioavailability in contaminated soil using sequential extraction and biosensors. J. Environ. Eng. 135, 839-844 (2009).

- Wang, J., Man, Y., Yin, R. & Feng, X. Isotopic and spectroscopic investigation of mercury accumulation in Houttuynia cordata colonizing historically contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7997-8007 (2022).

- Li, Q. et al. Speciation of heavy metals in soils and their immobilization at micro-scale interfaces among diverse soil components. Sci. Total Environ. 825, 153862 (2022).

- Liang, Y. et al. Geochemical controls on the distribution and bioavailability of heavy metals in sediments from Yangtze River to the East China Sea: assessed by sequential extraction versus diffusive gradients in thin-films (DGT) technique. J. Hazard. Mater. 452, 131253 (2023).

- Bagherifam, S., Brown, T. C., Bagherifam, S. & Baglieri, A. Sequential extraction of labile and recalcitrant fractions of soil organic matter: a case study focusing on antimony (Sb) in humic acids, fulvic acids and humin fractions of long-term aged contaminated soils. Environ. Pollut. 327, 121610 (2023).

- Mbodji, M. et al. Speciation of metals by sequential extractions of agricultural soils located near a dumpsite for prediction of element availability to vegetables. Talanta 244, 123411 (2022).

- Blumenstock, J., Cadamuro, G. & On, R. Predicting poverty and wealth from mobile phone metadata. Science 350, 1073-1076 (2015).

- Toetzke, M., Banholzer, N. & Feuerriegel, S. Monitoring global development aid with machine learning. Nat. Sustain. 5, 533-541 (2022).

-

. et al. Fertilizer management for global ammonia emission reduction. Nature 626, 792-798 (2024). - Jin, J. et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 320, 417-426 (2016).

- Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 718 (2019).

- Benhachem, F. Z. & Harrache, D. Chemical speciation and potential mobility of heavy metals in forest soil near road traffic in Hafir, Algeria. J. Health Pollut. 11, 210614 (2021).

- Wang, X. S. & Qin, Y. Leaching characteristics of heavy metals and As from two urban roadside soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 132, 83-92 (2007).

-

. et al. Cr migration potential and species properties in the soil profile from a chromate production site in the groundwater depression cone area. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 109, 600-608 (2022). - Zeng, X., Jin, Q., Wang, P. & Huang, C. Distribution and speciation of heavy metal(loid)s in soils under multiple preservative-treated wooden trestles. Toxics 11, 249 (2023).

- Bradford, M. A. A leaky sink. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 475-476 (2017).

- Minasny, B. et al. Soil carbon 4 per mille. Geoderma 292, 59-86 (2017).

- Ballabio, C. et al. Mapping LUCAS topsoil chemical properties at European scale using Gaussian process regression. Geoderma 355, 113912 (2019).

- Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil 7, 217-240 (2021).

- Zhang, S. et al. Escalating arsenic contamination throughout Chinese soils. Nat. Sustain. 7, 766-775 (2024).

- Hlavay, J., Prohaska, T., Weisz, M., Wenzel, W. W. & Stingeder, G. J. Determination of trace elements bound to soil and sediment fractions (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 76, 415-442 (2004).

- Tessier, A. & Campbell, P. G. C. Comment on “Pitfalls of sequential extractions” by P. M. V. Nirel and F. M. M. Morel. Water Res. 25, 115-117 (1991).

- Sutherland, R. A. BCR

-701: a review of 10-years of sequential extraction analyses. Anal. Chim. Acta 680, 10-20 (2010). - Tack, F. M. G. & Verloo, M. G. Chemical speciation and fractionation in soil and sediment heavy metal analysis: a review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 59, 225-238 (1995).

- Shober, A. L., Stehouwer, R. C. & MacNeal, K. E. Chemical fractionation of trace elements in biosolid-amended soils and correlation with trace elements in crop tissue. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 38, 1029-1046 (2007).

- Kim, R.-Y. et al. Bioavailability of heavy metals in soils: definitions and practical implementation-a critical review. Environ. Geochem. Health 37, 1041-1061 (2015).

- Hernández-Moreno, J. M., Rodríguez-González, J. I. & Espino-Mesa, M. Evaluation of the BCR sequential extraction for trace elements in European reference volcanic soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 58, 419-430 (2007).

- Rohatgi, A. et al. WebPlotDigitizer user manual version 3.4. 1-18 https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer (2014).

- Bogusz, A. & Oleszczuk, P. Sequential extraction of nickel and zinc in sewage sludge- or biochar/sewage sludge-amended soil. Sci. Total Environ. 636, 927-935 (2018).

- Huang, Y. et al. Size, distribution, and vulnerability of the global soil inorganic carbon. Science 384, 233-239 (2024).

- Shaheen, S. M. & Rinklebe, J. Geochemical fractions of chromium, copper, and zinc and their vertical distribution in floodplain soil profiles along the Central Elbe River, Germany. Geoderma 228-229, 142-159 (2014).

- Jiang, Y. et al. Topological representations of crystalline compounds for the machine-learning prediction of materials properties. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 28 (2021).

- Podgorski, J. & Berg, M. Global threat of arsenic in groundwater. Science 368, 845-850 (2020).

- Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 65, 386-408 (1958).

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436-444 (2015).

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5-32 (2001).

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189-1232 (2001).

- Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785-794 (ACM, 2016).

- Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 3146-3154 (2017).

- Aiken, E., Bellue, S., Karlan, D., Udry, C. & Blumenstock, J. E. Machine learning and phone data can improve targeting of humanitarian aid. Nature 603, 864-870 (2022).

- Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273-297 (1995).

- Kleinbaum, D. G., Dietz, K., Gail, M., Klein, M. & Klein, M. Logistic Regression. (Springer, New York, 2002).

- Ketkar, N. Introduction to Keras. In Deep Learning with Python, 97-111 (Springer, 2017).

- Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825-2830 (2011).

- Cook-Patton, S. C. et al. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 585, 545-550 (2020).

- Barber, R. F., Candès, E. J., Ramdas, A. & Tibshirani, R. J. Predictive inference with the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 49, 486-507 (2021).

- Nemani, V. et al. Uncertainty quantification in machine learning for engineering design and health prognostics: a tutorial. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 205, 110796 (2023).

- Altmann, A., Toloşi, L., Sander, O. & Lengauer, T. Permutation importance: a corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 26, 1340-1347 (2010).

- van den Hoogen, J. et al. Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature 572, 194-198 (2019).

- Jennings, A. A. Analysis of worldwide regulatory guidance values for the most commonly regulated elemental surface soil contamination. J. Environ. Manag. 118, 72-95 (2013).

- Muckley, E. S., Saal, J. E., Meredig, B., Roper, C. S. & Martin, J. H. Interpretable models for extrapolation in scientific machine learning. Digit. Discov. 2, 1425-1435 (2023).

- Zhan, J. et al. Evaluating interpolation and extrapolation performance of neural retrieval models. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2486-2496 (ACM, New York, 2022).

- Haaf, D., Six, J. & Doetterl, S. Global patterns of geo-ecological controls on the response of soil respiration to warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 623-627 (2021).

- Liu, J., Zhang, X.-H., Tran, H., Wang, D.-Q. & Zhu, Y.-N. Heavy metal contamination and risk assessment in water, paddy soil, and rice

around an electroplating plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 18, 1623-1632 (2011). - Tóth, G., Hermann, T., Szatmári, G. & Pásztor, L. Maps of heavy metals in the soils of the European Union and proposed priority areas for detailed assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 565, 1054-1062 (2016).

- Orgiazzi, A., Ballabio, C., Panagos, P., Jones, A. & Fernández-Ugalde, O. LUCAS soil, the largest expandable soil dataset for Europe: a review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69, 140-153 (2018).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261-272 (2020).

- Cordier, T. et al. Flexible and Systematic Uncertainty Estimation with Conformal Prediction via the MAPIE library, In Proceedings of the Twelfth Symposium on Conformal and Probabilistic Prediction with Applications 204, 549-581 (PMLR, Limassol, 2023).

- Qi, C. C. et al. Figshare https://figshare.com/s/fa76e3cb3e0e070 9df8d (2025).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

(c) The Author(s) 2025

School of Metallurgy and Environment, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China. School of Resources and Safety Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China. School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518000, China. Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, Clayton 3800 Victoria, Australia. School of Physics and Electronics, Central South University, Changsha 410083 Hunan, China. Department of Civil, Materials, and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), Illinois 60607, USA.

College of Chemical Engineering, Huaqiao University, Xiamen 361021, China. e-mail: zhang_lin@csu.edu.cn