DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06435-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38218942

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-13

أيض الأحماض الأمينية في بيولوجيا الأورام والعلاج

الملخص

يلعب استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية أدوارًا مهمة في بيولوجيا الأورام وعلاج الأورام. لقد أظهرت الأدلة المتزايدة أن الأحماض الأمينية تساهم في تكوين الأورام ومناعة الأورام من خلال العمل كمواد مغذية وجزيئات إشارة، ويمكن أن تنظم أيضًا نسخ الجينات والتعديل الوراثي. لذلك، فإن استهداف استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية سيوفر أفكارًا جديدة لعلاج الأورام ويصبح نهجًا علاجيًا مهمًا بعد الجراحة والعلاج الإشعاعي والعلاج الكيميائي. في هذه المراجعة، نقوم بتلخيص التقدم الأخير في استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية في الأورام الخبيثة وتفاعلها مع مسارات الإشارة بالإضافة إلى تأثيرها على الميكروبيئة الورمية والتعديل الوراثي. بشكل جماعي، نبرز أيضًا التطبيق العلاجي المحتمل والتوقعات المستقبلية.

حقائق

- تحدي استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية المتغيرة في الأورام التصنيف التقليدي للأحماض الأمينية الأساسية وغير الأساسية.

- ظهرت الأحماض الأمينية كمنظمات محورية في الأورام، وشاركت في مجموعة متنوعة من التفاعلات ثنائية الاتجاه بما في ذلك مسارات الإشارة، والبيئة الدقيقة للورم، والتعديلات الوراثية.

- تتوافق التجارب السريرية مع فكرة أن تقليل تناول الأحماض الأمينية قد يحسن من توقعات مرض السرطان.

أسئلة مفتوحة

- من بين التأثيرات العديدة التي يتم تنظيمها في الوقت نفسه بواسطة بعض الأحماض الأمينية، هل هناك تأثير رئيسي يحدد تقدم أو كبح الورم؟

- ما هي الاستراتيجيات المثلى والتحديات العاجلة لترجمة العلاجات المعتمدة على الأحماض الأمينية في المستقبل القريب؟

- هل يرتبط استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية المتغيرة، الموصوف في أورام مختلفة، ارتباطًا سببيًا بأسبابها وعلم الأمراض الخاص بها؟

مقدمة

تتكاثر خلايا السرطان، كمانحين للكربون والنيتروجين للتخلص من قيود التغذية. وبالتالي، تم دراسة استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية بشكل موسع بعد استقلاب الجلوكوز في الورم.

إعادة برمجة استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية في السرطان

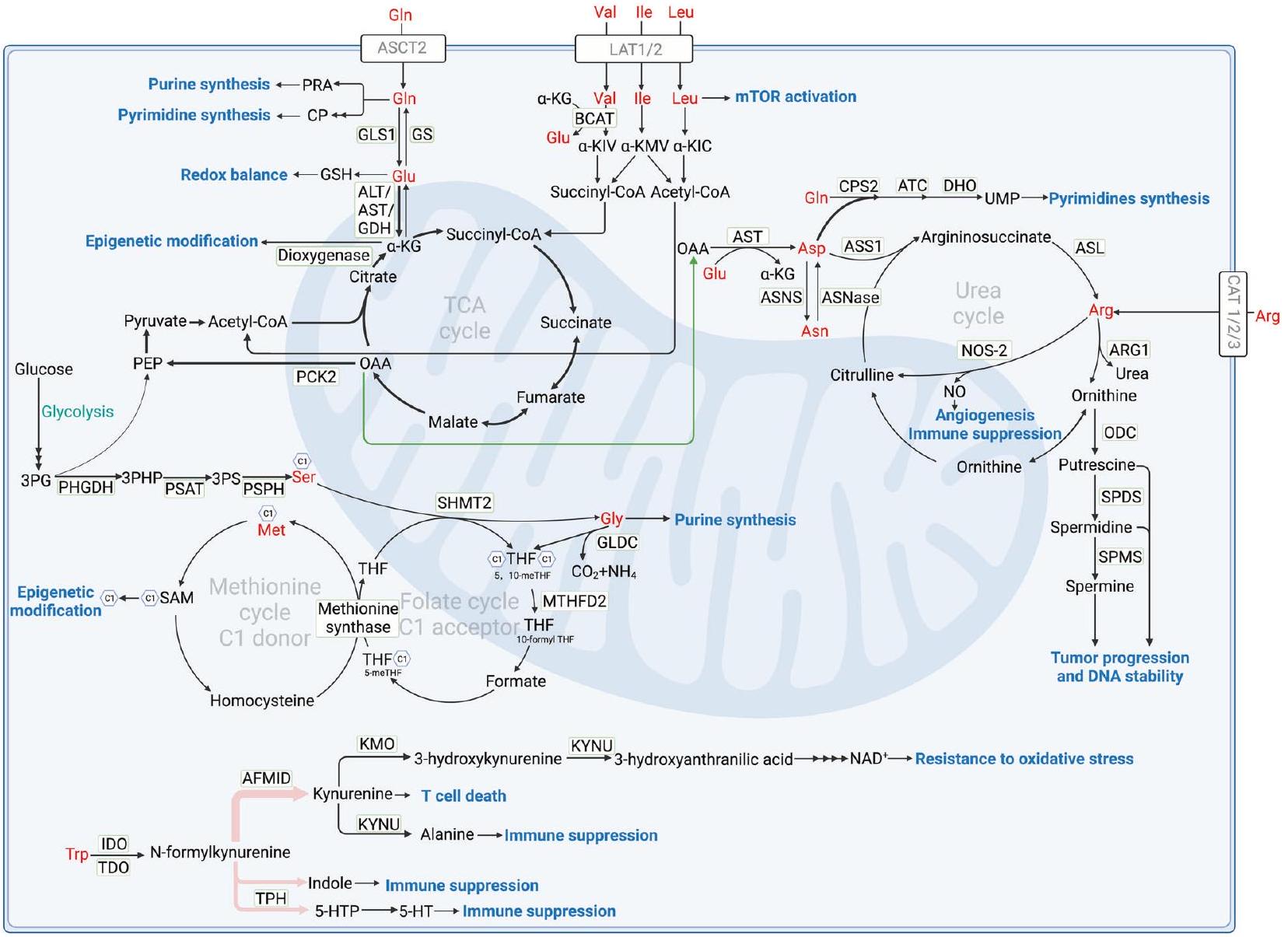

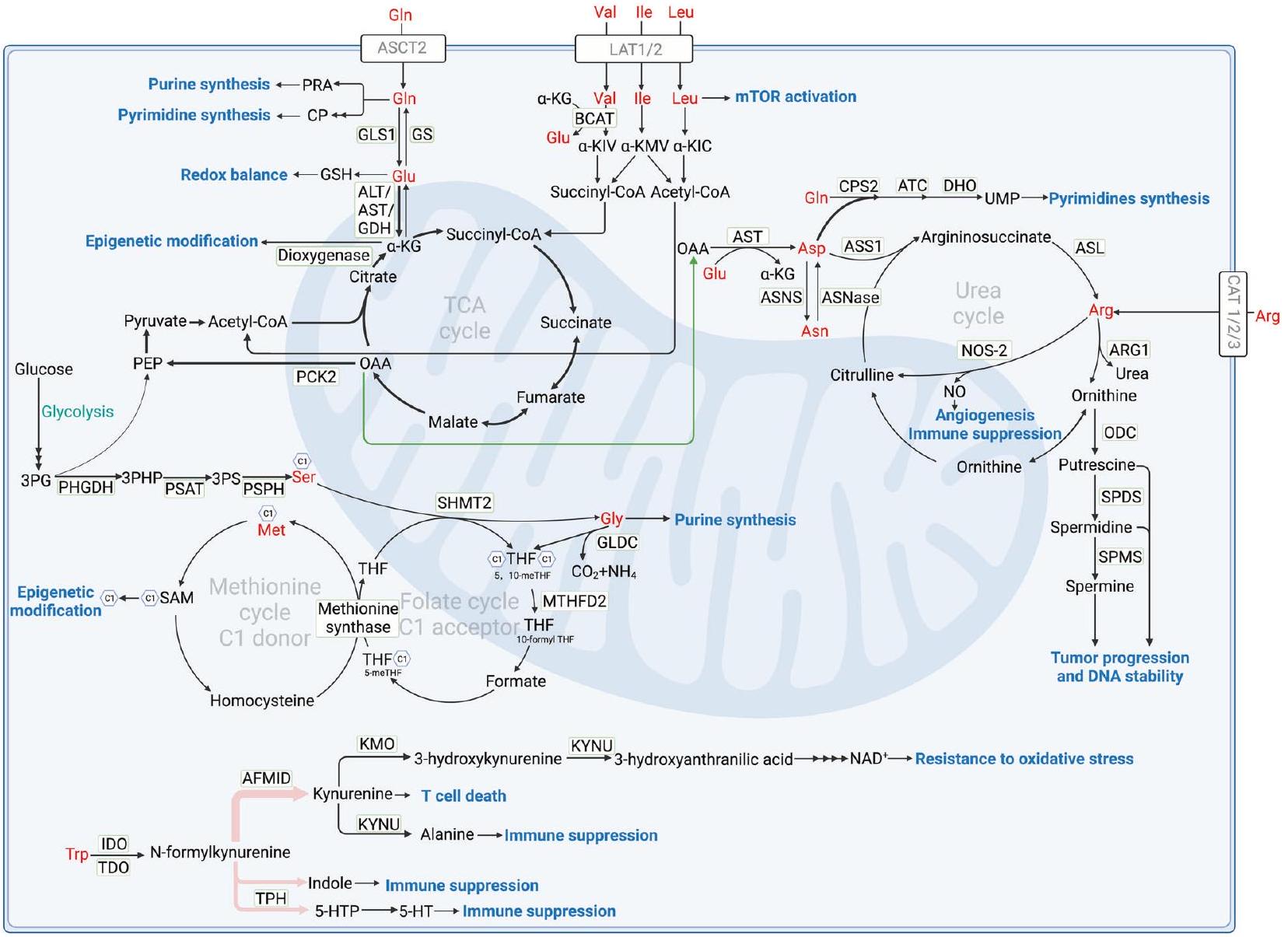

أيض الجلوتامين

وبذلك تحفيز الفيروبتوز [25]. بالإضافة إلى التحلل الجلوتاميني، يمكن أن يتم استقلاب الجلوتامين إلى وسائط مثل فوسفات الكاربامويل (CP) والأمين الفوسفوريبوزي (PRA) من أجل تخليق البيورينات والبيريميدينات، التي تعد مكونات أساسية لتخليق وإصلاح الحمض النووي خلال تكاثر الورم السريع [31، 32].

أيض الأرجينين

أيض الأحماض الأمينية ذات السلسلة المتفرعة (BCAA)

الورم الدبقي متعدد الأشكال وسرطان الخلايا الكلوية الصافية [49، 50]. تم استخدام أدوية تستهدف LATs (BAY-8002، JPH203، OKY034، إلخ) بالفعل في العلاج ما قبل السريري للسرطان [51، 52].

بروتين ربط عامل البدء 4E 1 (4EBP-1)، كيناز الريبوسوم S6 1 (S6K1)، وبروتين ربط عنصر تنظيم الستيرول (SREBP)، لتنظيم البلعمة الذاتية وتخليق الدهون، النوكليوتيدات والبروتينات [55] (سيتم توضيحه لاحقًا في مسارات الإشارة في استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية). من ناحية أخرى، تعتبر الأحماض الأمينية المتفرعة السلسلة، وخاصة الليوسين، ضرورية لتخليق البروتين حيث أنها مطلوبة بشدة في ترجمة البروتينات الجديدة [56].

أيض التريبتوفان

تم الحفاظ عليه من خلال الإشارات الورمية الذاتية [71، 72]. أظهرت الدراسات أن تعبير IDO1 داخل الورم يرتبط بتكرار النقائل الكبدية في سرطان القولون والمستقيم [73]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الإفراط في التعبير عن IDO1 يعزز حركة خلايا سرطان الرئة، بينما أدى تقليل تعبيره إلى تقليل حركة السرطان [74]. يرتبط TDO، وهو إنزيم يحفز نفس التفاعل مثل IDO1، أيضًا بتوقعات سيئة عند الإفراط في التعبير عنه [66]. في نموذج فأر لسرطان الرئة، أدى تثبيط TDO إلى تقليل عدد العقيدات الورمية في الرئتين [75].

أسپاراجين وأسبارتات

استقلاب السيرين/الجلايسين والكربون الواحد

مسارات الإشارة في استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية

J. Chen et al.

مستويات الأحماض الأمينية تؤثر على مسارات الإشارة، ولكن التغيرات في مسارات الإشارة يمكن أن تؤثر أيضًا على استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية.

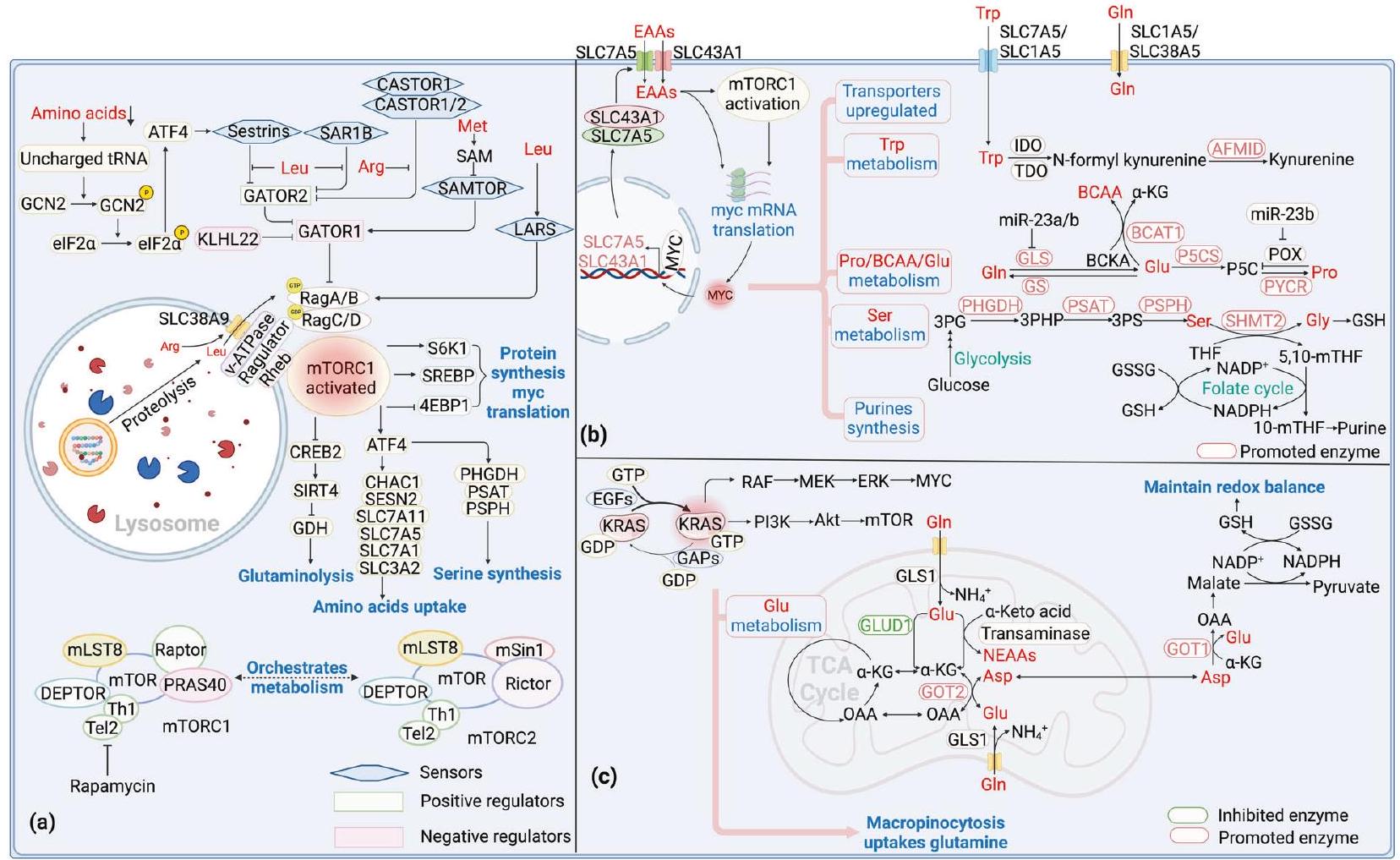

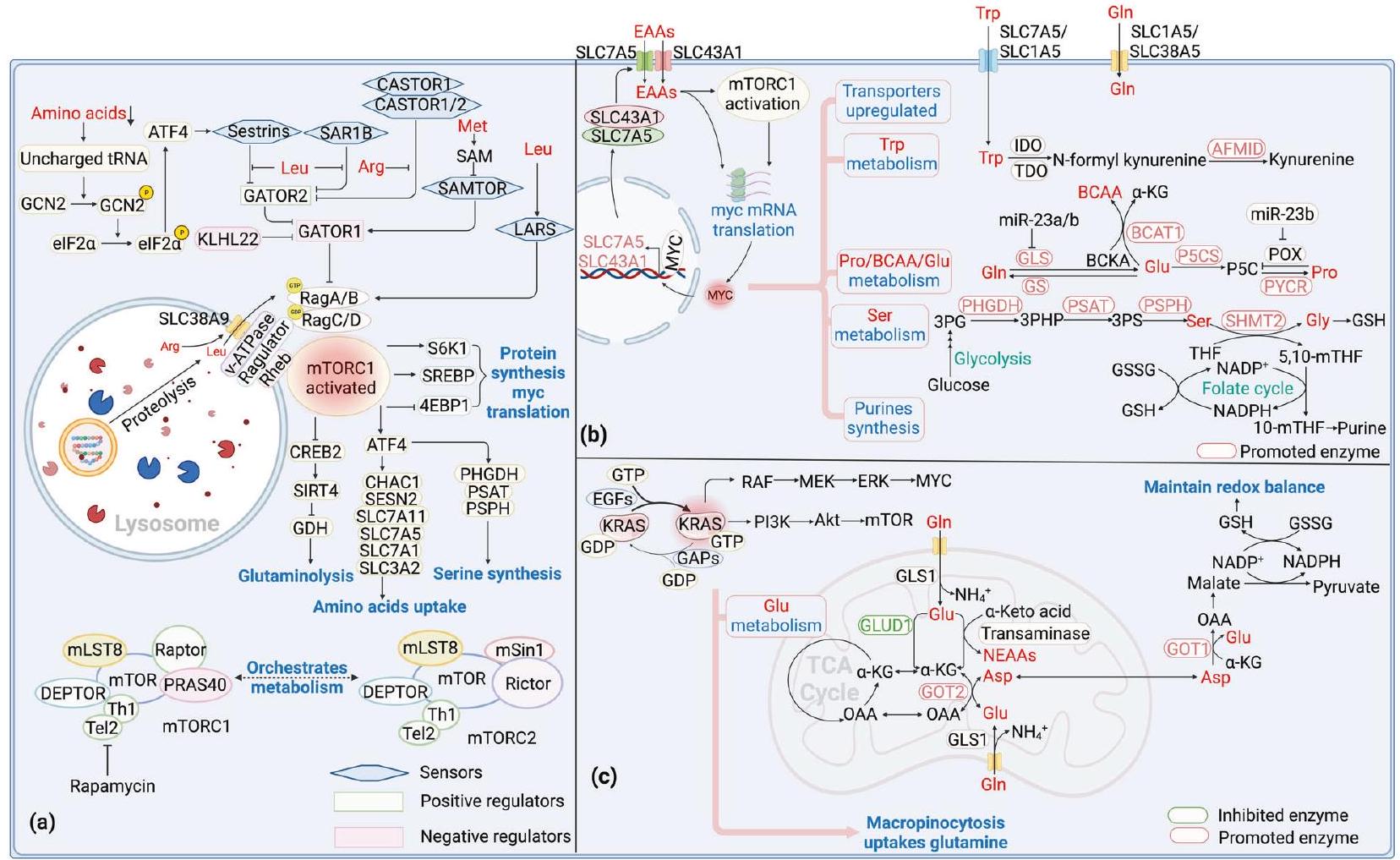

mTOR يستشعر وينظم استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية

mTOR هو كيناز بروتين غير نمطي من نوع السيرين/الثريونين، يعمل كنقطة تقارب بين الأيض البنائي والهدم. نظرًا للاختلافات في الهيكل والوظيفة، يتم تصنيف مجمعات mTOR إلى mTORC1 وmTORC2. يتكون mTORC1، الذي يتأثر بتثبيط الراباميسين، من mTOR وRaptor وmLST8 وTti/Tel2 ووحدات مثبطة PRAS40 وDeptor. إن فسفرة PRAS40 وDeptor تخفف من تثبيطها وتفعّل mTORC1. 4EBP-1 وS6K1 وSREBP هي عوامل فعالة في مجرى mTORC1، والتي ترتبط بزيادة في التخليق وكذلك بتوقعات سيئة في السرطان. يتم تنظيم mTORC1 سلبًا بواسطة ظروف الطاقة المنخفضة، ونقص الأكسجين، وتلف الحمض النووي. كما يتم تنظيمه إيجابيًا بواسطة عوامل النمو مثل مسار الأنسولين/عامل النمو الشبيه بالأنسولين-1 (IGF-1) وإشارات Ras المعتمدة على كيناز التيروزين. بشكل خاص، عندما تكون الأحماض الأمينية وفيرة، يتم تنظيم مسار إشارة mTORC1 إيجابيًا لنقل الإشارات لتسهيل تخليق البروتين. على العكس، في حالة نقص الأحماض الأمينية، يتم تثبيط ترجمة البروتينات لتلبية احتياجات الطاقة. نظرًا لأن خلايا السرطان غالبًا ما توجد في بيئة فقيرة بالمغذيات، يتم تنظيم mTORC1 سلبًا باستمرار للتكيف مع التغيرات الأيضية. يتكون mTORC2، الذي لا يتأثر بالراباميسين، من mTOR وmSIN1 وmLST8 وTti/Tel2 ووحدات مثبطة Rictor وDeptor. التوازن بين mTORC1 وmTORC2 ينظم عمليات أيضية متنوعة، على الرغم من أن فهمنا لـ mTORC2 لا يزال محدودًا. نحن نركز بشكل أساسي على وظيفة mTORC1 أدناه.

تنشيط mTORC1 من خلال مستشعرات السيتوبلازم [108]. وبالتالي، تسمح مستشعرات الليزوزوم بدمج معلومات المغذيات الليزوزومية في تنظيم نشاط mTORC1. بشكل جماعي، الأحماض الأمينية ليست فقط مصادر للطاقة وتخليق البروتين في تكوين الأورام، ولكنها تعمل أيضاً على mTORC1 كجزيئات إشارة.

السيرين [110]. بذكاء، يمكن أن ينظم ATF4 أيضاً تعبير ناقلات الأحماض الأمينية الأخرى مثل CHAC1، SESN2، SLC7A11، SLC7A5، SLC7A1، و SLC3A2، ويزيد من امتصاص الأحماض الأمينية [111]. عند تراكم الجلوتامين، يقوم mTORC1 بتقليل miR-23a و miR-23b ومن ثم يعزز تعبير GLS لتسريع تحلل الجلوتامين. عندما يكون الجلوتامين ناقصاً، يقوم mTORC1 بكبح نسخ مثبط GDH SIRT4، مما يحفز إعادة بناء الجلوتامين [112]. كما ينشط mTORC1 أيض الأرجينين من خلال تعزيز تعبير ODC في خلايا RAS المحولة لتعزيز إنتاج البوليمين وتقدم الورم. ميكانيكياً، يعزز mTORC1 الارتباط بين mRNA ODC وبروتين ربط mRNA، مما يعزز استقرار mRNA ODC وتعبيره [113]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يؤدي تنظيم mTORC1 بشكل إيجابي إلى استقرار MYC، الذي بدوره يحفز تعبير ASS1 من خلال التنافس مع HIF1a على مواقع ربط المحفز ASS1 وبالتالي يعزز تعبير الأرجينين [114]. بشكل جماعي، ينظم mTORC1 أيض الأحماض الأمينية من خلال مؤثرات إشارية متعددة، بما في ذلك ناقلات الأحماض الأمينية، والإنزيمات التخليقية والكاتابولية. كما يلعب جزيء الإشارة السفلي mTORC1 MYC أدواراً تنظيمية واسعة في أيض الأحماض الأمينية.

MYC يقود أيض الأحماض الأمينية

J. تشين وآخرون.

KRAS المتغير وأيض الأحماض الأمينية

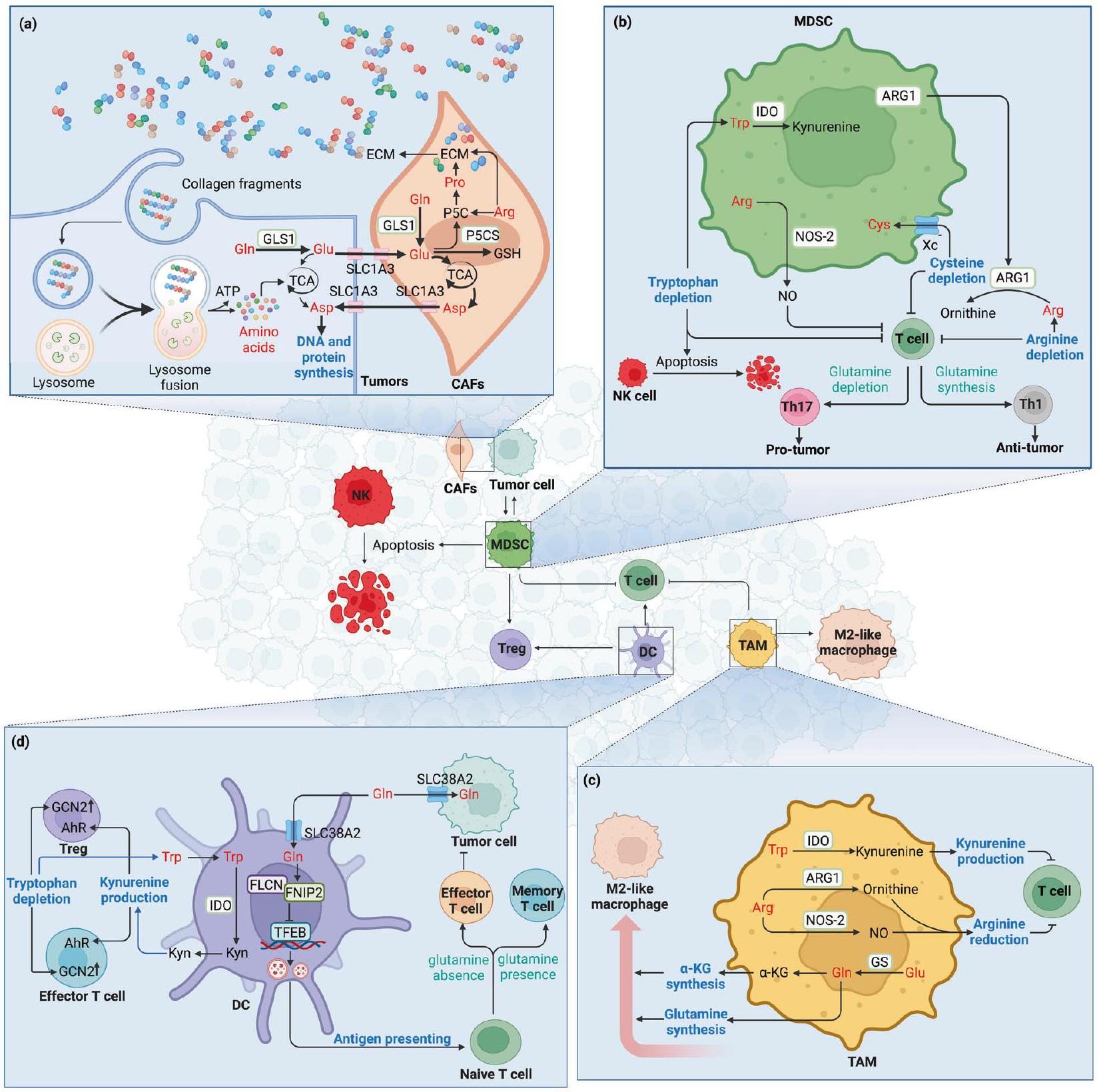

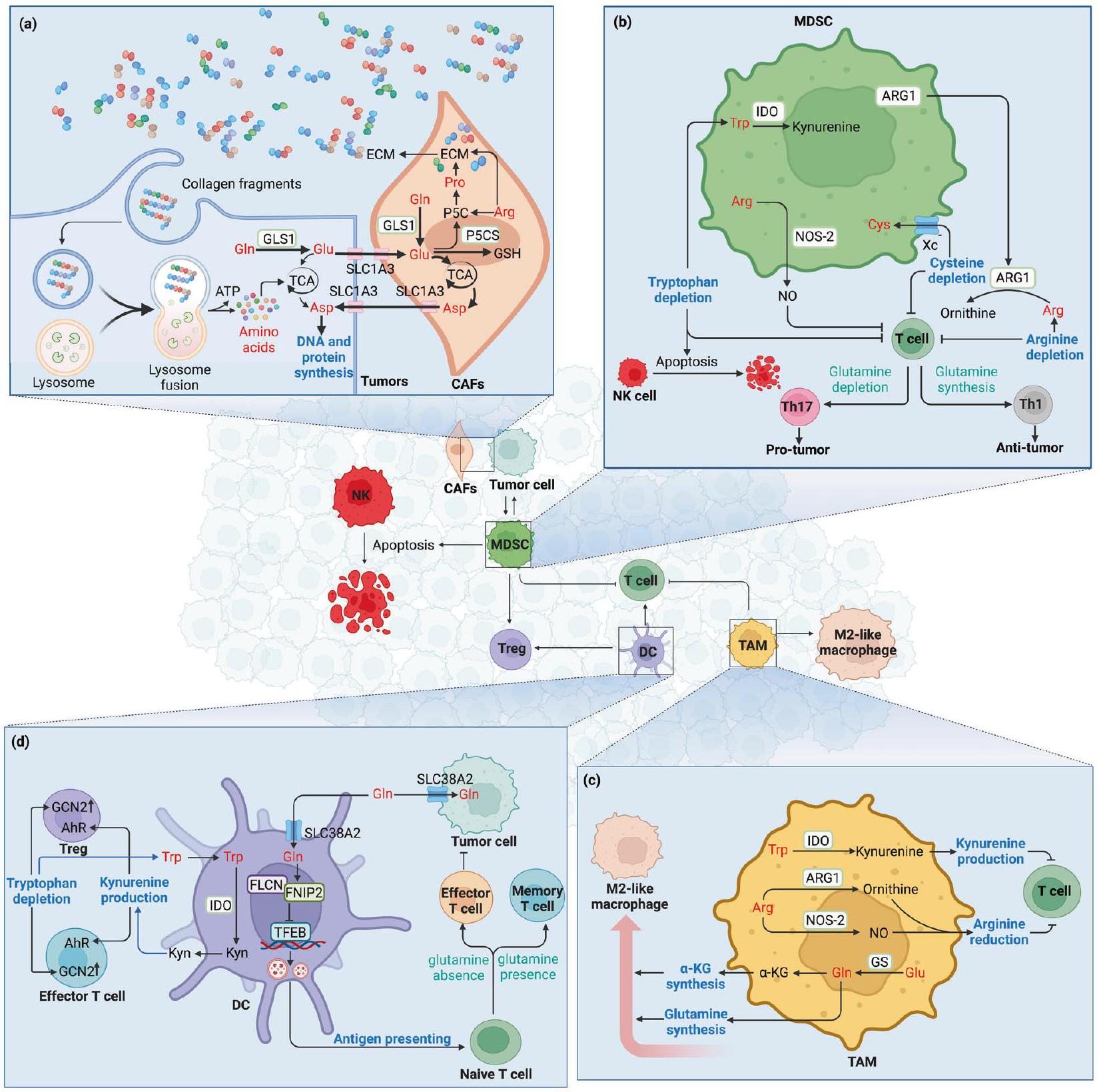

الأحماض الأمينية في بيئة الورم الدقيقة

الماكروبينوسيتوز في TME يأخذ الأحماض الأمينية

استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية وCAFs

. وبالتالي، فإن حذف P5CS يقلل من إنتاج الكولاجين وبالتالي إنتاج ECM، والذي يمكن إنقاذه من خلال مكملات البروتين [145].

استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية وخلايا المناعة

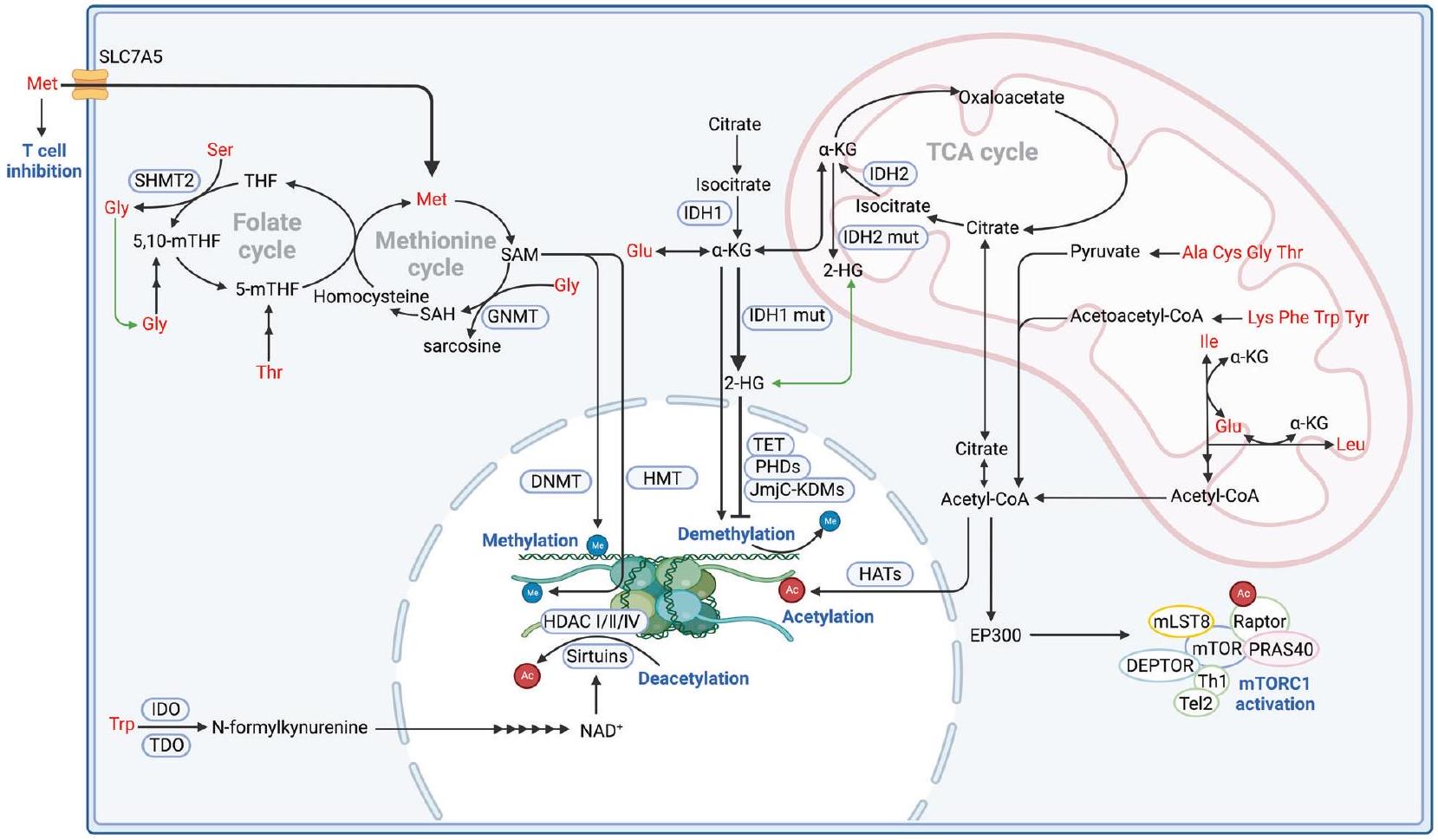

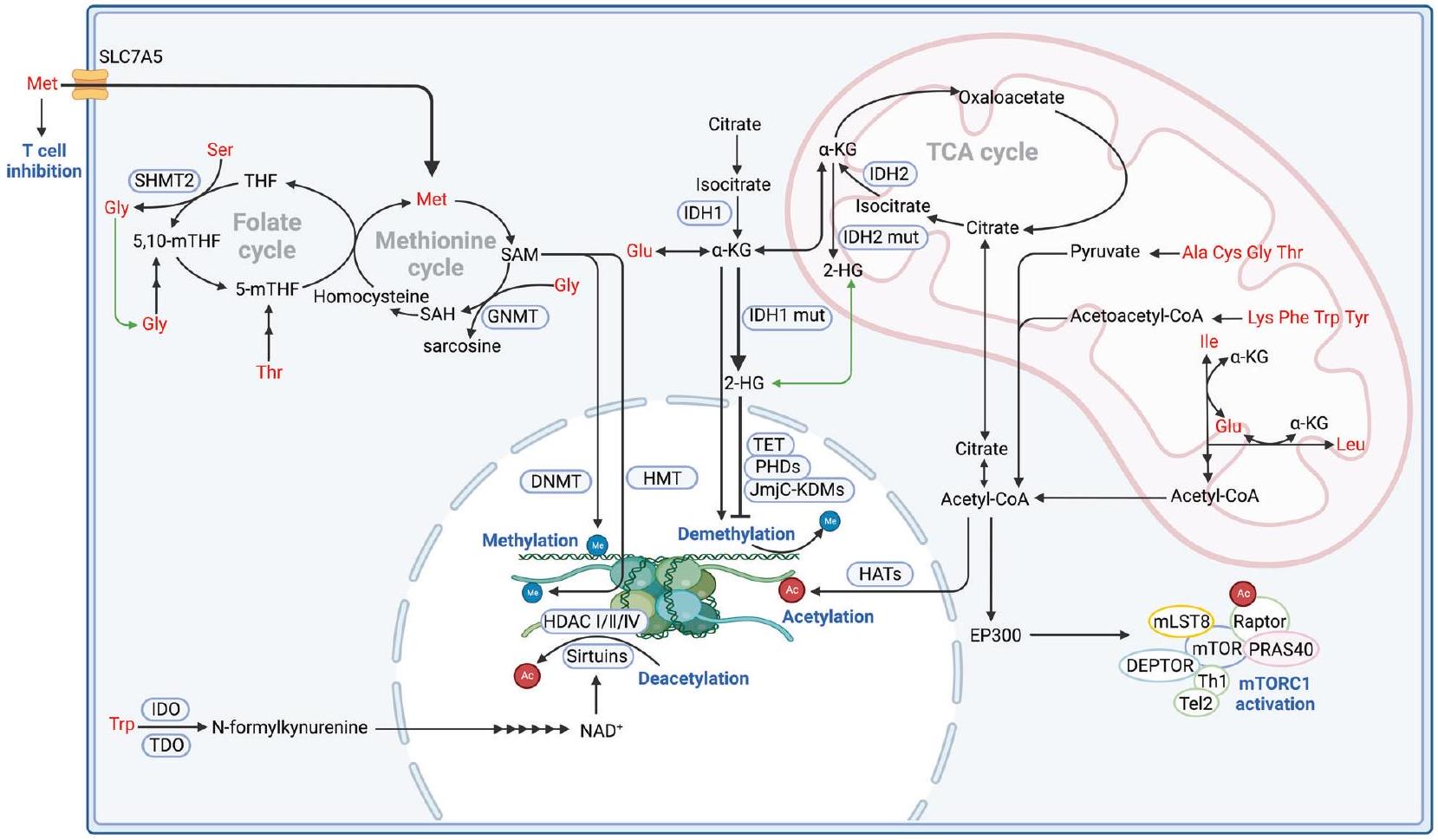

أيض الأحماض الأمينية والتعديل الوراثي

تعتبر المستقلبات الحمضية مثل SAM و acetyl-CoA ركائز أساسية للتعديل الجيني، بينما يتطلب أيض الأحماض الأمينية أيضًا تعديلًا جينيًا للإنزيمات الأيضية المرتبطة [166]. تؤثر هذه العلاقة التنظيمية المتبادلة بشكل عميق على تقدم الورم.

الميثيلation

التنافس مع خلايا T على الميثيونين. يؤدي نقص الميثيونين في خلايا T إلى تقليل تعبير H 3 K 79 me 2، مما يعزز

إزالة الميثيل

الأسيتيلation وإزالة الأسيتيل

J. Chen et al.

تحفيز الترانساميناز. تساهم أحماض أمينية أخرى مثل الليسين، والفينيل ألانين، والتريبتوفان، والتيروزين أيضًا في إنتاج الأسيتيل-CoA من خلال تشكيل الأسيتوأسيتيل-CoA. بالمثل، يقوم الألانين، والسيرين، والتريبتوفان، والسيستين، والجلايسين، والثريونين بتخليق الأسيتيل-CoA من خلال تكوين البيروفات. يوفر أيض الليوسين الأسيتيل-CoA لإنزيم الأسيتيل ترانسفيراز EP300، مما يؤدي إلى أسيتيل تنظيم Raptor لـ mTORC1. تؤدي هذه الأسيتيلation في النهاية إلى تنشيط mTORC1 وتغيير أيض الأحماض الأمينية [187]. ينتج أيض الإيزوليوسين والليوسين الأسيتيل-CoA داخل الميتوكوندريا. بعد ذلك، يجب نقل الأسيتيل-CoA الميتوكوندري إلى السيتوبلازم والنواة لتنظيم تعبير الجينات من خلال آليات جينية [188].

الفوسفوريلation، والسكسينيلation، واللاكتيلation

| هدف | دواء | نوع السرطان | المراحل السريرية | |

| ناقلات الأحماض الأمينية | ASCT2 | تاموكسيفين ورالوكسيفين | سرطان الثدي | موافق |

| ASCT2 | PGS-siRNA | سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا | ما قبل السريرية | |

| ASCT2 | V-9302 | HCC | ما قبل السريرية | |

| القطط | فيراباميل | سرطان القولون والمستقيم | ما قبل السريرية | |

| SLC6A14 | ليبوبوليمرات خفية محملة بالدوستكسل المعدل بالأسبارتات | سرطان الرئة | ما قبل السريرية | |

| أيض الأسباراجين | ASNS | ميتفورمين | سرطانات متعددة | ما قبل السريرية |

| أسبارلاس | لوكيميا اللمفاويات الحادة | موافق | ||

| أيض الأرجينين | أدي | ADI-PEG20 | سرطان المبيض | المرحلة الثالثة |

| INCB001158 | الأورام الصلبة المتقدمة أو النقيليّة | المرحلة الثانية | ||

| أيض الجلوتامين | جي إل إس | تيلاجلينستات | سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا، اللمفوما، الورم الدبقي، سرطان الثدي، سرطان البنكرياس، وسرطان الكلى [234] | المرحلة الثانية |

| جي إل إس 1 | 968 | سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا [235] | ما قبل السريرية | |

| أيض الكربون الواحد | دي إتش إف آر | ميثوتريكسات | سرطانات متعددة | موافق |

| ثيميديلات سينثاز | 5-فلورويوراسيل | سرطانات متعددة | موافق |

استهداف استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية في علاج الأورام

مثبطات ناقلات الأحماض الأمينية

الأورام. يتم تنظيم ناقلات الأحماض الأمينية الكاتيونية مثل CAT-1 وCAT-2 وCAT-3 لليسين والأرجينين والهستيدين بشكل غير طبيعي في الأورام وترتبط بمقاومة الأدوية. على وجه التحديد، يظهر تعبير CAT-1 ارتباطًا مع درجة الورم في سرطان البروستاتا. كما يلعب دورًا محوريًا في تعزيز النمو والتكاثر والانتشار في سرطان القولون وسرطان الثدي. زيادة تعبير CAT-3 تعزز امتصاص الأرجينين وبالتالي تحفز الأورام على التكيف مع نقص الجلوتامين. تقليل تعبير CATs (CAT-1 وCAT-3) من خلال النقل الفيروسي باستخدام shRNAs أو مواد كيميائية مثل الفيراباميل يوقف تكاثر الأورام ويحفز الموت. على العكس، فإن فقدان CAT2 يزيد من تفاقم تكوين الأورام القولونية المرتبطة بالالتهابات.

تثبيط إنزيمي لتمثيل الأحماض الأمينية

تثبيط ASNS أو تثبيط الميتفورمين للـ ETC يحد من تخليق الأسباراجين في الورم، مما يعيق نمو الورم في نماذج الفئران المتعددة [219]. طفرة Kras تنشط مسار إشارة ATF4 من خلال AKT وNRF2 في سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا. عندما يتم تثبيط ASNS بواسطة AKT ويتم استنفاد الأسباراجين الخارجي في نفس الوقت، يمكن تقليل نمو الورم [220]. لذلك، فإن ASNS هو هدف علاجي واعد أيضًا لسرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا المتحور Kras.

حمض أميني معدّل غذائي

J. تشين وآخرون.

الملخص

REFERENCES

- Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27-47.

- Sivanand S, Vander Heiden MG. Emerging roles for branched-chain amino acid metabolism in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:147-56.

- Zhang Y, Morar M, Ealick SE. Structural biology of the purine biosynthetic pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3699-724.

- Morita M, Kudo K, Shima H, Tanuma N. Dietary intervention as a therapeutic for cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:498-504.

- Wei Z, Liu X, Cheng C, Yu W, Yi P. Metabolism of amino acids in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:603837.

- Taniguchi S, Elhance A, Van Duzer A, Kumar S, Leitenberger JJ, Oshimori N. Tumor-initiating cells establish an IL-33-TGF-

niche signaling loop to promote cancer progression. Science. 2020;369:eaay1813. - Butler M, van der Meer LT, van Leeuwen FN. Amino acid depletion therapies: starving cancer cells to death. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32:367-81.

- Ji Y, Wu Z, Dai Z, Sun K, Wang J, Wu G. Nutritional epigenetics with a focus on amino acids: implications for the development and treatment of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;27:1-8.

- Vettore L, Westbrook RL, Tennant DA. New aspects of amino acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:150-6.

- Lieu EL, Nguyen T, Rhyne S, Kim J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:15-30.

- Lukey MJ, Katt WP, Cerione RA. Targeting amino acid metabolism for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:796-804.

- Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang X-Y, Pfeiffer HK, et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18782-7.

- Patel D, Menon D, Bernfeld E, Mroz V, Kalan S, Loayza D, et al. Aspartate rescues s-phase arrest caused by suppression of glutamine utilization in KRas-driven cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9322-9.

- Luengo A, Gui DY, Vander Heiden MG. Targeting metabolism for cancer therapy. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:1161-80.

- Reynolds MR, Lane AN, Robertson B, Kemp S, Liu Y, Hill BG, et al. Control of glutamine metabolism by the tumor suppressor Rb. Oncogene. 2014;33:556-66.

- Wang Q, Tiffen J, Bailey CG, Lehman ML, Ritchie W, Fazli L, et al. Targeting amino acid transport in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: effects on cell cycle, cell growth, and tumor development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1463-73.

- Ren P, Yue M, Xiao D, Xiu R, Gan L, Liu H, et al. ATF4 and N-Myc coordinate glutamine metabolism in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells through ASCT2 activation. J Pathol. 2015;235:90-100.

- Willems L, Jacque N, Jacquel A, Neveux N, Maciel TT, Lambert M, et al. Inhibiting glutamine uptake represents an attractive new strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:3521-32.

- Lu J, Chen M, Tao Z, Gao S, Li Y, Cao Y, et al. Effects of targeting SLC1A5 on inhibiting gastric cancer growth and tumor development in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8:76458-67.

- Wang Q, Hardie RA, Hoy AJ, van Geldermalsen M, Gao D, Fazli L, et al. Targeting ASCT2-mediated glutamine uptake blocks prostate cancer growth and tumour development. J Pathol. 2015;236:278-89.

- van Geldermalsen M, Wang Q, Nagarajah R, Marshall AD, Thoeng A, Gao D, et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple-negative basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:3201-8.

- Zhao J-S, Shi S, Qu H-Y, Keckesova Z, Cao Z-J, Yang L-X, et al. Glutamine synthetase licenses APC/C-mediated mitotic progression to drive cell growth. Nat Metab. 2022;4:239-53.

- Wang Z, Liu F, Fan N, Zhou C, Li D, Macvicar T, et al. Targeting glutaminolysis: new perspectives to understand cancer development and novel strategies for potential target therapies. Front Oncol. 2020;10:589508.

- Ramirez-Peña E, Arnold J, Shivakumar V, Joseph R, Vidhya Vijay G, den Hollander

, et al. The epithelial to mesenchymal transition promotes glutamine independence by suppressing expression. Cancers. 2019;11:1610. - Suzuki S, Venkatesh D, Kanda H, Nakayama A, Hosokawa H, Lee E, et al. GLS2 is a tumor suppressor and a regulator of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2022;82:3209-22.

- Xiang L, Mou J, Shao B, Wei Y, Liang H, Takano N, et al. Glutaminase 1 expression in colorectal cancer cells is induced by hypoxia and required for tumor growth, invasion, and metastatic colonization. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:40.

- Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762-5.

- Wang JB, Erickson JW, Fuji R, Ramachandran S, Gao P, Dinavahi R, et al. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:207-19.

- Kahlert UD, Cheng M, Koch K, Marchionni L, Fan X, Raabe EH, et al. Alterations in cellular metabolome after pharmacological inhibition of Notch in glioblastoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1246-55.

- Matés JM, Pérez-Gómez C, Núñez de Castro I, Asenjo M, Márquez J. Glutamine and its relationship with intracellular redox status, oxidative stress and cell proliferation/death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:439-58.

- Bott AJ, Maimouni S, Zong W-X. The Pleiotropic effects of glutamine metabolism in cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:770.

- Fu S, Li Z, Xiao L, Hu W, Zhang L, Xie B, et al. Glutamine synthetase promotes radiation resistance via facilitating nucleotide metabolism and subsequent DNA damage repair. Cell Rep. 2019;28:1136-1143.e4.

- Vincent EE, Sergushichev A, Griss T, Gingras M-C, Samborska B, Ntimbane T, et al. Mitochondrial Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase regulates metabolic adaptation and enables glucose-independent tumor growth. Mol Cell. 2015;60:195-207.

- Lio C-WJ, Yuita H, Rao A. Dysregulation of the TET family of epigenetic regulators in lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2019;134:1487-97.

- Ji JX, Cochrane DR, Tessier-Cloutier B, Chen SY, Ho G, Pathak KV, et al. Arginine depletion therapy with ADI-PEG20 limits tumor growth in argininosuccinate synthase-deficient ovarian cancer, including small-cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4402-13.

- Lee JS, Adler L, Karathia H, Carmel N, Rabinovich S, Auslander N, et al. Urea cycle dysregulation generates clinically relevant genomic and biochemical signatures. Cell. 2018;174:1559-1570.e22.

- Scalise M, Console L, Rovella F, Galluccio M, Pochini L, Indiveri C. Membrane transporters for amino acids as players of cancer metabolic rewiring. Cells 2020;9:2028.

- Abdelmagid SA, Rickard JA, McDonald WJ, Thomas LN, Too CKL. CAT-1mediated arginine uptake and regulation of nitric oxide synthases for the survival of human breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1084-92.

- Bachmann AS, Geerts D. Polyamine synthesis as a target of MYC oncogenes. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:18757-69.

- Grzywa TM, Sosnowska A, Matryba P, Rydzynska Z, Jasinski M, Nowis D, et al. Myeloid cell-derived arginase in cancer immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:938.

- Kryczek I, Zou L, Rodriguez P, Zhu G, Wei S, Mottram P, et al. B7-H4 expression identifies a novel suppressive macrophage population in human ovarian carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:871-81.

- Novita Sari I, Setiawan T, Seock Kim K, Toni Wijaya Y, Won Cho K, Young Kwon H. Metabolism and function of polyamines in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:91-104.

- Ha HC, Sirisoma NS, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL, Woster PM, Casero RA Jr. The natural polyamine spermine functions directly as a free radical scavenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11140-5.

- Ha HC, Yager JD, Woster PA, Casero RA Jr. Structural specificity of polyamines and polyamine analogues in the protection of DNA from strand breaks induced by reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:298-303.

- Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664-6.

- Brito C, Naviliat M, Tiscornia AC, Vuillier F, Gualco G, Dighiero G, et al. Peroxynitrite inhibits T lymphocyte activation and proliferation by promoting impairment of tyrosine phosphorylation and peroxynitrite-driven apoptotic death. J Immunol. 1999;162:3356-66.

- Singh N, Ecker GF. Insights into the structure, function, and ligand discovery of the large neutral amino acid Transporter 1, LAT1. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1278.

- Wang Q, Holst J. L-type amino acid transport and cancer: targeting the mTORC1 pathway to inhibit neoplasia. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1281-94.

- Zhang B, Chen Y, Shi X, Zhou M, Bao L, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. Regulation of branched-chain amino acid metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor in glioblastoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:195-206.

- Elorza A, Soro-Arnáiz I, Meléndez-Rodríguez F, Rodríguez-Vaello V, Marsboom G, de Cárcer G, et al. HIF2a acts as an mTORC1 activator through the amino acid carrier SLC7A5. Mol Cell. 2012;48:681-91.

- Quanz M, Bender E, Kopitz C, Grünewald S, Schlicker A, Schwede W, et al. Preclinical efficacy of the novel monocarboxylate Transporter 1 inhibitor BAY8002 and associated markers of resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:2285-96.

- Zhao X, Sakamoto S, Wei J, Pae S, Saito S, Sazuka T, et al. Contribution of the L-Type amino acid transporter family in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6178.

- Ananieva EA, Wilkinson AC. Branched-chain amino acid metabolism in cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:64-70.

- Ericksen RE, Lim SL, McDonnell E, Shuen WH, Vadiveloo M, White PJ, et al. Loss of BCAA catabolism during carcinogenesis enhances mTORC1 activity and promotes tumor development and progression. Cell Metab. 2019;29:1151-1165.e6.

- Tian T, Li X, Zhang J. mTOR signaling in cancer and mTOR inhibitors in solid tumor targeting therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:755.

- Kamphorst JJ, Nofal M, Commisso C, Hackett SR, Lu W, Grabocka E, et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. 2015;75:544-53.

- Cano-Crespo S, Chillarón J, Junza A, Fernández-Miranda G, García J, Polte C, et al. CD98hc (SLC3A2) sustains amino acid and nucleotide availability for cell cycle progression. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14065.

- Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681-706.

- Mayers JR, Wu C, Clish CB, Kraft P, Torrence ME, Fiske BP, et al. Elevation of circulating branched-chain amino acids is an early event in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma development. Nat Med. 2014;20:1193-8.

- Liu X-H, Zhai X-Y. Role of tryptophan metabolism in cancers and therapeutic implications. Biochimie. 2021;182:131-9.

- Della Chiesa M, Carlomagno S, Frumento G, Balsamo M, Cantoni C, et al. The tryptophan catabolite L-kynurenine inhibits the surface expression of NKp46and NKG2D-activating receptors and regulates NK-cell function. Blood. 2006;108:4118-25.

- Abd El-Fattah EE. IDO/kynurenine pathway in cancer: possible therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med. 2022;20:347.

- Xue C, Li G, Zheng Q, Gu X, Shi Q, Su Y, et al. Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2023;35:1304-26.

- Tummala KS, Gomes AL, Yilmaz M, Graña O, Bakiri L, Ruppen I, et al. Inhibition of de novo NAD(+) synthesis by oncogenic URI causes liver tumorigenesis through DNA damage. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:826-39.

- Muthusamy T, Cordes T, Handzlik MK, You L, Lim EW, Gengatharan J, et al. Serine restriction alters sphingolipid diversity to constrain tumour growth. Nature. 2020;586:790-5.

- Platten M, Nollen EAA, Röhrig UF, Fallarino F, Opitz CA. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:379-401.

- Sarrouilhe D, Mesnil M. Serotonin and human cancer: a critical view. Biochimie. 2019;161:46-50.

- Schneider MA, Heeb L, Beffinger MM, Pantelyushin S, Linecker M, Roth L, et al. Attenuation of peripheral serotonin inhibits tumor growth and enhances immune checkpoint blockade therapy in murine tumor models. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabc8188.

- Hezaveh K, Shinde RS, Klötgen A, Halaby MJ, Lamorte S, Ciudad MT, et al. Tryptophan-derived microbial metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in tumor-associated macrophages to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity. 2022;55:324-340.e8.

- Jia Y, Wang H, Wang Y, Wang T, Wang M, Ma M, et al. Low expression of Bin1, along with high expression of IDO in tumor tissue and draining lymph nodes, are predictors of poor prognosis for esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1095-106.

- Mellor AL, Lemos H, Huang L. Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and tolerance: where are we now? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1360.

- Kindler J, Lim CK, Weickert CS, Boerrigter D, Galletly C, Liu D, et al. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2860-72.

- Brandacher G, Perathoner A, Ladurner R, Schneeberger S, Obrist P, Winkler C, et al. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in colorectal cancer: effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1144-51.

- Tang D, Yue L, Yao R, Zhou L, Yang Y, Lu L, et al. P53 prevent tumor invasion and metastasis by down-regulating IDO in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:54548-57.

- Hsu YL, Hung JY, Chiang SY, Jian SF, Wu CY, Lin YS, et al. Lung cancer-derived galectin-1 contributes to cancer associated fibroblast-mediated cancer progression and immune suppression through TDO2/kynurenine axis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27584-98.

- Garcia-Bermudez J, Baudrier L, La K, Zhu XG, Fidelin J, Sviderskiy VO, et al. Aspartate is a limiting metabolite for cancer cell proliferation under hypoxia and in tumours. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:775-81.

- Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini DM. An essential role of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in cell proliferation is to enable aspartate synthesis. Cell. 2015;162:540-51.

- Sullivan LB, Luengo A, Danai LV, Bush LN, Diehl FF, Hosios AM, et al. Aspartate is an endogenous metabolic limitation for tumour growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:782-8.

- Krall AS, Xu S, Graeber TG, Braas D, Christofk HR. Asparagine promotes cancer cell proliferation through use as an amino acid exchange factor. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11457.

- Knott SRV, Wagenblast E, Khan S, Kim SY, Soto M, Wagner M, et al. Asparagine bioavailability governs metastasis in a model of breast cancer. Nature. 2018;554:378-81.

- Luo M, Brooks M, Wicha MS. Asparagine and glutamine: co-conspirators fueling metastasis. Cell Metab. 2018;27:947-9.

- Pavlova NN, Hui S, Ghergurovich JM, Fan J, Intlekofer AM, White RM, et al. As extracellular glutamine levels decline, asparagine becomes an essential amino acid. Cell Metab. 2018;27:428-38.e5.

- Lee GY, Haverty PM, Li L, Kljavin NM, Bourgon R, Lee J, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies PSMB4 and SHMT2 as potential cancer driver genes. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3114-26.

- Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science. 2012;336:1040-4.

- Nilsson R, Jain M, Madhusudhan N, Sheppard NG, Strittmatter L, Kampf C, et al. Metabolic enzyme expression highlights a key role for MTHFD2 and the mitochondrial folate pathway in cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3128.

- Maddocks ODK, Labuschagne CF, Adams PD, Vousden KH. Serine metabolism supports the methionine cycle and DNA/RNA Methylation through De Novo ATP synthesis in cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2016;61:210-21.

- Wei Z, Song J, Wang G, Cui X, Zheng J, Tang Y, et al. Deacetylation of serine hydroxymethyl-transferase 2 by SIRT3 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4468.

- Wan X, Wang C, Huang Z, Zhou D, Xiang S, Qi Q, et al. Cisplatin inhibits SIRT3deacetylation MTHFD2 to disturb cellular redox balance in colorectal cancer cell. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:649.

- Wang C, Wan X, Yu T, Huang Z, Shen C, Qi Q, et al. Acetylation stabilizes phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase by disrupting the interaction of E3 ligase RNF5 to promote breast tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108021.

- Tajan M, Hennequart M, Cheung EC, Zani F, Hock AK, Legrave N, et al. Serine synthesis pathway inhibition cooperates with dietary serine and glycine limitation for cancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2021;12:366.

- Parsa S, Ortega-Molina A, Ying HY, Jiang M, Teater M, Wang J, et al. The serine hydroxymethyltransferase-2 (SHMT2) initiates lymphoma development through epigenetic tumor suppressor silencing. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:653-64.

- Xia J, Zhang J, Wu X, Du W, Zhu Y, Liu X, et al. Blocking glycine utilization inhibits multiple myeloma progression by disrupting glutathione balance. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4007.

- Liu C, Zou W, Nie D, Li S, Duan C, Zhou M, et al. Loss of PRMT7 reprograms glycine metabolism to selectively eradicate leukemia stem cells in CML. Cell Metab. 2022;34:818-835.e7.

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;169:361-71.

- Karlsson E, Pérez-Tenorio G, Amin R, Bostner J, Skoog L, Fornander T, et al. The mTOR effectors 4EBP1 and S6K2 are frequently coexpressed, and associated with a poor prognosis and endocrine resistance in breast cancer: a retrospective study including patients from the randomised Stockholm tamoxifen trials. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R96.

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274-93.

- Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan K-L. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:133-9.

- He X-D, Gong W, Zhang J-N, Nie J, Yao C-F, Guo F-S, et al. Sensing and transmitting intracellular amino acid signals through reversible lysine aminoacylations. Cell Metab. 2018;27:151-166.e6.

- Chen J, Ou Y, Luo R, Wang J, Wang D, Guan J, et al. SAR1B senses leucine levels to regulate mTORC1 signalling. Nature. 2021;596:281-4.

- Durán RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, Heiserich L, Skendaj R, Gottlieb E, et al. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell. 2012;47:349-58.

- Gu X, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Condon KJ, Liu GY, Krawczyk PA, et al. SAMTOR is an -adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2017;358:813-8.

- Chen J, Ou Y, Yang Y, Li W, Xu Y, Xie Y, et al. KLHL22 activates amino-aciddependent mTORC1 signalling to promote tumorigenesis and ageing. Nature. 2018;557:585-9.

- Han JM, Jeong SJ, Park MC, Kim G, Kwon NH, Kim HK, et al. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase is an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1-signaling pathway. Cell. 2012;149:410-24.

- Mossmann D, Park S, Hall MN. mTOR signalling and cellular metabolism are mutual determinants in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:744-57.

- Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell. 2012;150:1196-208.

- Wyant GA, Abu-Remaileh M, Wolfson RL, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Danai LV, et al. mTORC1 activator SLC38A9 is required to efflux essential amino acids from lysosomes and use protein as a nutrient. Cell. 2017;171:642-654.e12.

- Shen K, Sabatini DM. Ragulator and SLC38A9 activate the Rag GTPases through noncanonical GEF mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:9545-50.

- Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, et al. Metabolism. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2015;347:188-94.

- Ben-Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult SJH, Asara JM, Manning BD. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science. 2016;351:728-33.

- Zhu J, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:436-50.

- Simcox J, Lamming DW. The central moTOR of metabolism. Dev Cell. 2022;57:691-706.

- Csibi A, Fendt S-M, Li C, Poulogiannis G, Choo AY, Chapski DJ, et al. The mTORC1 pathway stimulates glutamine metabolism and cell proliferation by repressing SIRT4. Cell. 2013;153:840-54.

- Origanti S, Nowotarski SL, Carr TD, Sass-Kuhn S, Xiao L, Wang JY, et al. Ornithine decarboxylase mRNA is stabilized in an mTORC1-dependent manner in Rastransformed cells. Biochem J. 2012;442:199-207.

- Tsai WB, Aiba I, Long Y, Lin HK, Feun L, Savaraj N, et al. Activation of Ras/PI3K/ ERK pathway induces c-Myc stabilization to upregulate argininosuccinate synthetase, leading to arginine deiminase resistance in melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2622-33.

- Wahlström T, Henriksson MA. Impact of MYC in regulation of tumor cell metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:563-9.

- Huang H, Weng H, Zhou H, Qu L. Attacking c-Myc: targeted and combined therapies for cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:6543-54.

- Babu E, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Iribe Y, Tangtrongsup S, et al. Identification of a novel system

amino acid transporter structurally distinct from heterodimeric amino acid transporters. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43838-45. - Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98). J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23629-32.

- Yue M, Jiang J, Gao P, Liu H, Qing G. Oncogenic MYC activates a feedforward regulatory loop promoting essential amino acid metabolism and tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3819-32.

- Venkateswaran N, Lafita-Navarro MC, Hao YH, Kilgore JA, Perez-Castro L, Braverman J, et al. MYC promotes tryptophan uptake and metabolism by the kynurenine pathway in colon cancer. Genes Dev. 2019;33:1236-51.

- Dong Y, Tu R, Liu H, Qing G. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism: oncogenic MYC in the driver’s seat. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:124.

- Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ, Ruas JL. Kynurenines: tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science. 2017;357:eaaf9794.

- El Ansari R, McIntyre A, Craze ML, Ellis IO, Rakha EA, Green AR. Altered glutamine metabolism in breast cancer; subtype dependencies and alternative adaptations. Histopathology. 2018;72:183-90.

- Bott AJ, Peng IC, Fan Y, Faubert B, Zhao L, Li J, et al. Oncogenic Myc induces expression of glutamine synthetase through promoter demethylation. Cell Metab. 2015;22:1068-77.

- Geng P, Qin W, Xu G. Proline metabolism in cancer. Amino Acids. 2021;53:1769-77.

- Liu W, Zabirnyk O, Wang H, Shiao YH, Nickerson ML, Khalil S, et al. miR-23b targets proline oxidase, a novel tumor suppressor protein in renal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4914-24.

- Liu W, Le A, Hancock C, Lane AN, Dang CV, Fan TWM, et al. Reprogramming of proline and glutamine metabolism contributes to the proliferative and metabolic responses regulated by oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8983-8.

- Xie M, Pei D-S. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2: a novel target for human cancer therapy. Investig N. Drugs. 2021;39:1671-81.

- Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The frequency of ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2969-74.

- Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:605-35.

- Spiegel J, Cromm PM, Zimmermann G, Grossmann TN, Waldmann H. Smallmolecule modulation of Ras signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:613-22.

- Chakrabarti G, Gerber DE, Boothman DA. Expanding antitumor therapeutic windows by targeting cancer-specific nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-biogenesis pathways. Clin Pharm. 2015;7:57-68.

- Guo JY, Chen H-Y, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:460-70.

- Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4557-66.

- Swanson JA, Watts C. Macropinocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:424-8.

- Palm W, Araki J, King B, DeMatteo RG, Thompson CB. Critical role for PI3-kinase in regulating the use of proteins as an amino acid source. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8628-E8636.

- Recouvreux MV, Commisso C. Macropinocytosis: a metabolic adaptation to nutrient stress in cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:261.

- Zhang YF, Li Q, Huang PQ, Su T, Jiang SH, Hu LP, et al. A low amino acid environment promotes cell macropinocytosis through the YY1-FGD6 axis in Rasmutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2022;41:1203-15.

- Corbet C, Draoui N, Polet F, Pinto A, Drozak X, Riant O, et al. The SIRT1/HIF2a axis drives reductive glutamine metabolism under chronic acidosis and alters tumor response to therapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5507-19.

- Powell DW, Mifflin RC, Valentich JD, Crowe SE, Saada JI, West AB. Myofibroblasts. I. Paracrine cells important in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1-9.

- Chen X, Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:99-115.

- Tajan M, Hock AK, Blagih J, Robertson NA, Labuschagne CF, Kruiswijk F, et al. A role for p53 in the adaptation to glutamine starvation through the expression of SLC1A3. Cell Metab. 2018;28:721-736.e6.

- Bertero T, Oldham WM, Grasset EM, Bourget I, Boulter E, Pisano S, et al. Tumorstroma mechanics coordinate amino acid availability to sustain tumor growth and malignancy. Cell Metab. 2019;29:124-140.e10.

- Liu T, Han C, Fang P, Ma Z, Wang X, Chen H, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblastspecific IncRNA LINC01614 enhances glutamine uptake in lung adenocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:141.

- Schwörer S, Berisa M, Violante S, Qin W, Zhu J, Hendrickson RC, et al. Proline biosynthesis is a vent for TGF

-induced mitochondrial redox stress. Embo j. 2020;39:e103334. - Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C, Feng Y, Fuhrer T, et al. L-Arginine modulates

cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell. 2016;167:829-842.e13. - Consonni FM, Porta C, Marino A, Pandolfo C, Mola S, Bleve A, et al. Myeloidderived suppressor cells: ductile targets in disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:949.

- Srivastava MK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Rodriguez P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine and cysteine. Cancer Res. 2010;70:68-77.

- Baumjohann D, Kageyama R, Clingan JM, Morar MM, Patel S, de Kouchkovsky D, et al. The microRNA cluster miR-17~92 promotes TFH cell differentiation and represses subset-inappropriate gene expression. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:840-8.

- Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:399-416.

- Palmieri EM, Menga A, Martín-Pérez R, Quinto A, Riera-Domingo C, De Tullio G, et al. Pharmacologic or genetic targeting of glutamine synthetase skews macrophages toward an M1-like phenotype and inhibits tumor metastasis. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1654-66.

- Ma G, Zhang Z, Li P, Zhang Z, Zeng M, Liang Z, et al. Reprogramming of glutamine metabolism and its impact on immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20:114.

- Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49-61.

- Wang W, Zou W. Amino acids and their transporters in T cell immunity and cancer therapy. Mol Cell. 2020;80:384-95.

- Verbist KC, Guy CS, Milasta S, Liedmann S, Kamiński MM, Wang R, et al. Metabolic maintenance of cell asymmetry following division in activated T lymphocytes. Nature. 2016;532:389-93.

- Stepka P, Vsiansky V, Raudenska M, Gumulec J, Adam V, Masarik M. Metabolic and amino acid alterations of the tumor microenvironment. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28:1270-89.

- Klysz D, Tai X, Robert PA, Craveiro M, Cretenet G, Oburoglu L, et al. Glutaminedependent

-ketoglutarate production regulates the balance between helper 1 cell and regulatory T cell generation. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra97. - Munn DH, Sharma MD, Baban B, Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D, et al. GCN2 kinase in T cells mediates proliferative arrest and anergy induction in response to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Immunity. 2005;22:633-42.

- Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and metabolic control of immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:137-43.

- Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, Bradfield CA. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:3190-8.

- Guo C, You Z, Shi H, Sun Y, Du X, Palacios G, et al. SLC38A2 and glutamine signalling in cDC1s dictate anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2023;620:200-8.

- Corsale AM, Di Simone M, Lo Presti E, Picone C, Dieli F, Meraviglia S. Metabolic changes in tumor microenvironment: how could they affect

T cells functions? Cells. 2021;10:2896. - Douguet L, Bod L, Lengagne R, Labarthe L, Kato M, Avril MF, et al. Nitric oxide synthase 2 is involved in the pro-tumorigenic potential of

cells in melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1208878. - Wu J, Li G, Li L, Li D, Dong Z, Jiang P. Asparagine enhances LCK signalling to potentiate CD8 T-cell activation and anti-tumour responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23:75-86.

- Cavalli G , Heard E . Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature. 2019;571:489-99.

- Su X, Wellen KE, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolic control of methylation and acetylation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;30:52-60.

- Mentch SJ, Locasale JW. One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics: understanding the specificity. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2016;1363:91-8.

- Michalak EM, Burr ML, Bannister AJ, Dawson MA. The roles of DNA, RNA and histone methylation in ageing and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:573-89.

- Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343-57.

- Bian Y, Li W, Kremer DM, Sajjakulnukit P, Li S, Crespo J, et al. Cancer SLC43A2 alters T cell methionine metabolism and histone methylation. Nature. 2020;585:277-82.

- Cheng H, Qiu Y, Xu Y, Chen L, Ma K, Tao M, et al. Extracellular acidosis restricts one-carbon metabolism and preserves

cell stemness. Nat Metab. 2023;5:314-30. - Dai Z, Mentch SJ, Gao X, Nichenametla SN, Locasale JW. Methionine metabolism influences genomic architecture and gene expression through H3K4me3 peak width. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1955.

- Shyh-Chang N, Locasale JW, Lyssiotis CA, Zheng Y, Teo RY, Ratanasirintrawoot S, et al. Influence of threonine metabolism on S -adenosylmethionine and histone methylation. Science. 2013;339:222-6.

- Obata F, Kuranaga E, Tomioka K, Ming M, Takeishi A, Chen C-H, et al. Necrosisdriven systemic immune response alters SAM metabolism through the FOXOGNMT axis. Cell Rep. 2014;7:821-33.

- Melnyk S, Pogribna M, Pogribny IP, Yi P, James SJ. Measurement of plasma and intracellular S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine utilizing coulometric electrochemical detection: alterations with plasma homocysteine and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate concentrations. Clin Chem. 2000;46:265-72.

- Martínez-Chantar ML, Vázquez-Chantada M, Ariz U, Martínez N, Varela M, Luka Z, et al. Loss of the glycine N -methyltransferase gene leads to steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology. 2008;47:1191-9.

- Liao Y-J, Liu S-P, Lee C-M, Yen C-H, Chuang P-C, Chen C-Y, et al. Characterization of a glycine N -methyltransferase gene knockout mouse model for hepatocelIular carcinoma: Implications of the gender disparity in liver cancer susceptibility. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:816-26.

- An J, Rao A, Ko M. TET family dioxygenases and DNA demethylation in stem cells and cancers. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e323.

- Baksh SC, Finley LWS. Metabolic coordination of cell fate by a-KetoglutarateDependent Dioxygenases. Trends Cell Biol. 2021;31:24-36.

- Huang J, Yu J, Tu L, Huang N, Li H, Luo Y. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations In Glioma: From Basic Discovery To Therapeutics Development. Front Oncol. 2019;9:506.

- Tommasini-Ghelfi S, Murnan K, Kouri FM, Mahajan AS, May JL, Stegh AH. Cancerassociated mutation and beyond: the emerging biology of isocitrate dehydrogenases in human disease. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaaw4543.

- Tönjes M, Barbus S, Park YJ, Wang W, Schlotter M, Lindroth AM, et al. BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism in gliomas carrying wild-type IDH1. Nat Med. 2013;19:901-8.

- Raffel S, Falcone M, Kneisel N, Hansson J, Wang W, Lutz C, et al. BCAT1 restricts aKG levels in AML stem cells leading to IDHmut-like DNA hypermethylation. Nature. 2017;551:384-8.

- Mahlknecht U, Hoelzer D. Histone acetylation modifiers in the pathogenesis of malignant disease. Mol Med. 2000;6:623-44.

- Lee JV, Carrer A, Shah S, Snyder NW, Wei S, Venneti S, et al. Akt-dependent metabolic reprogramming regulates tumor cell histone acetylation. Cell Metab. 2014;20:306-19.

- Park SY, Kim JS. A short guide to histone deacetylases including recent progress on class II enzymes. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:204-12.

- Son SM, Park SJ, Lee H, Siddiqi F, Lee JE, Menzies FM, et al. Leucine signals to mTORC1 via its metabolite acetyl-coenzyme A. Cell Metab. 2019;29:192-201.e7.

- White PJ, McGarrah RW, Grimsrud PA, Tso S-C, Yang W-H, Haldeman JM, et al. The BCKDH kinase and phosphatase integrate BCAA and lipid metabolism via regulation of ATP-Citrate Lyase. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1281-1293.e7.

- Kouzarides T. Histone acetylases and deacetylases in cell proliferation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:40-8.

- Kebede AF, Schneider R, Daujat S. Novel types and sites of histone modifications emerge as players in the transcriptional regulation contest. Febs

. 2015;282:1658-74. - Sun L, Zhang H, Gao P. Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer. Protein Cell. 2022;13:877-919.

- Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:121-35.

- Adachi Y, De Sousa-Coelho AL, Harata I, Aoun C, Weimer S, Shi X, et al. I-Alanine activates hepatic AMP-activated protein kinase and modulates systemic glucose metabolism. Mol Metab. 2018;17:61-70.

- Deng L, Yao P, Li L, Ji F, Zhao S, Xu C, et al. p53-mediated control of aspartateasparagine homeostasis dictates LKB1 activity and modulates cell survival. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1755.

- Cohen I, Poręba E, Kamieniarz K, Schneider R. Histone modifiers in cancer: friends or foes? Genes Cancer. 2011;2:631-47.

- Tian Q, Yuan P, Quan C, Li M, Xiao J, Zhang L, et al. Phosphorylation of BCKDK of BCAA catabolism at Y246 by Src promotes metastasis of colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39:3980-96.

- Han T, Zhan W, Gan M, Liu F, Yu B, Chin YE, et al. Phosphorylation of glutaminase by PKCɛ is essential for its enzymatic activity and critically contributes to tumorigenesis. Cell Res. 2018;28:655-69.

- Smestad J, Erber L, Chen Y, Maher LJ 3rd. Chromatin succinylation correlates with active gene expression and is perturbed by defective TCA cycle metabolism. iScience. 2018;2:63-75.

- Piñeiro M, González PJ, Hernández F, Palacián E. Interaction of RNA polymerase II with acetylated nucleosomal core particles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:370-6.

- Eniafe J, Jiang S. The functional roles of TCA cycle metabolites in cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40:3351-63.

- Tong Y, Guo D, Lin SH, Liang J, Yang D, Ma C, et al. SUCLA2-coupled regulation of GLS succinylation and activity counteracts oxidative stress in tumor cells. Mol Cell. 2021;81:2303-16.e8.

- Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C, Weng Y, et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature. 2019;574:575-80.

- Su J, Zheng Z, Bian C, Chang S, Bao J, Yu H, et al. Functions and mechanisms of lactylation in carcinogenesis and immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1253064.

- Xiong J, He J, Zhu J, Pan J, Liao W, Ye H, et al. Lactylation-driven METTL3mediated RNA m(6)A modification promotes immunosuppression of tumorinfiltrating myeloid cells. Mol Cell. 2022;82:1660-1677.e10.

- Fung MKL, Chan GC-F. Drug-induced amino acid deprivation as strategy for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:144.

- Bhutia YD, Babu E, Ramachandran S, Ganapathy V. Amino acid transporters in cancer and their relevance to “glutamine addiction”: novel targets for the design of a new class of anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1782-8.

- Schulte ML, Fu A, Zhao P, Li J, Geng L, Smith ST, et al. Pharmacological blockade of ASCT2-dependent glutamine transport leads to antitumor efficacy in preclinical models. Nat Med. 2018;24:194-202.

- Cha YJ, Kim E-S, Koo JS. Amino acid transporters and glutamine metabolism in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:907.

- Peng JB, Zhuang L, Berger UV, Adam RM, Williams BJ, Brown EM, et al. CaT1 expression correlates with tumor grade in prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:729-34.

- Lowman XH, Hanse EA, Yang Y, Ishak Gabra MB, Tran TQ, Li H, et al. p53 promotes cancer cell adaptation to glutamine deprivation by upregulating Slc7a3 to increase arginine uptake. Cell Rep. 2019;26:3051-3060.e4.

- Werner A, Pieh D, Echchannaoui H, Rupp J, Rajalingam K, Theobald M, et al. Cationic amino acid Transporter-1-Mediated Arginine uptake is essential for chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell proliferation and viability. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1268.

- Banjarnahor S, König J, Maas R. Screening of commonly prescribed drugs for effects on the CAT1-mediated transport of L-arginine and arginine derivatives. Amino Acids. 2022;54:1101-8.

- Coburn LA, Singh K, Asim M, Barry DP, Allaman MM, Al-Greene NT, et al. Loss of solute carrier family 7 member 2 exacerbates inflammation-associated colon tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2019;38:1067-79.

- Wang C, Wu J, Wang Z, Yang Z, Li Z, Deng H, et al. Glutamine addiction activates polyglutamine-based nanocarriers delivering therapeutic siRNAs to orthotopic lung tumor mediated by glutamine transporter SLC1A5. Biomaterials. 2018;183:77-92.

- Rogala-Koziarska K, Samluk Ł, Nałęcz KA. Amino acid transporter SLC6A14 depends on heat shock protein HSP90 in trafficking to the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:1544-55.

- Luo Q, Yang B, Tao W, Li J, Kou L, Lian H, et al. ATB(

) transporter-mediated targeting delivery to human lung cancer cells via aspartate-modified docetaxelloading stealth liposomes. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:295-304. - Avramis VI, Tiwari PN. Asparaginase (native ASNase or pegylated ASNase) in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1:241-54.

- Van Trimpont M, Peeters E, De Visser Y, Schalk AM, Mondelaers V, De Moerloose B, et al. Novel Insights on the Use of L-Asparaginase as an efficient and safe anticancer therapy. Cancers. 2022;14:902.

- Krall AS, Mullen PJ, Surjono F, Momcilovic M, Schmid EW, Halbrook CJ, et al. Asparagine couples mitochondrial respiration to ATF4 activity and tumor growth. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1013-1026.e6.

- Gwinn DM, Lee AG, Briones-Martin-Del-Campo M, Conn CS, Simpson DR, Scott AI, et al. Oncogenic KRAS regulates amino acid homeostasis and asparagine biosynthesis via ATF4 and alters sensitivity to L-Asparaginase. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:91-107.e6.

- Qiu F, Huang J, Sui M. Targeting arginine metabolism pathway to treat argininedependent cancers. Cancer Lett. 2015;364:1-7.

- Holtsberg FW, Ensor CM, Steiner MR, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) conjugated arginine deiminase: effects of PEG formulations on its pharmacological properties. J Controlled Release. 2002;80:259-71.

- Steggerda SM, Bennett MK, Chen J, Emberley E, Huang T, Janes JR, et al. Inhibition of arginase by CB-1158 blocks myeloid cell-mediated immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:101.

- Yao S, Janku F, Subbiah V, Stewart J, Patel SP, Kaseb A, et al. Phase 1 trial of ADIPEG20 plus cisplatin in patients with pretreated metastatic melanoma or other advanced solid malignancies. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1533-9.

- Jeon H, Kim JH, Lee E, Jang YJ, Son JE, Kwon JY, et al. Methionine deprivation suppresses triple-negative breast cancer metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67223-34.

- Durando X, Farges M-C, Buc E, Abrial C, Petorin-Lesens C, Gillet B, et al. Dietary methionine restriction with FOLFOX regimen as first line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer: a feasibility study. Oncology. 2010;78:205-9.

- Sanderson SM, Gao X, Dai Z, Locasale JW. Methionine metabolism in health and cancer: a nexus of diet and precision medicine. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:625-37.

- Maddocks ODK, Athineos D, Cheung EC, Lee P, Zhang T, van den Broek NJF, et al. Modulating the therapeutic response of tumours to dietary serine and glycine starvation. Nature. 2017;544:372-6.

- Viana LR, Tobar N, Busanello ENB, Marques AC, de Oliveira AG, Lima TI, et al. Leucine-rich diet induces a shift in tumour metabolism from glycolytic towards oxidative phosphorylation, reducing glucose consumption and metastasis in Walker-256 tumour-bearing rats. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15529.

- Ishak Gabra MB, Yang Y, Li H, Senapati P, Hanse EA, Lowman XH, et al. Dietary glutamine supplementation suppresses epigenetically-activated oncogenic pathways to inhibit melanoma tumour growth. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3326.

- Yue T, Li J, Zhu J, Zuo S, Wang X, Liu Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide creates a favorable immune microenvironment for colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83:595-612.

- Fang L, Hao Y, Yu H, Gu X, Peng Q, Zhuo H, et al. Methionine restriction promotes cGAS activation and chromatin untethering through demethylation to enhance antitumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1118-1133.e12.

- Kim J, DeBerardinis RJ. Mechanisms and implications of metabolic heterogeneity in cancer. Cell Metab. 2019;30:434-46.

- Varghese S, Pramanik S, Williams L, Hodges HR, Hudgens CW, Fischer GM, et al. The Glutaminase Inhibitor CB-839 (Telaglenastat) enhances the antimelanoma activity of T-Cell-Mediated immunotherapies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021;20:500-11.

- Han T, Guo M, Zhang T, Gan M, Xie C, Wang JB. A novel glutaminase inhibitor968 inhibits the migration and proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting EGFR/ERK signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:28063-73.

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والإذن متاحة على http://www.nature.com/ إعادة الطبع

© المؤلفون 2024

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للمناعة والالتهابات ومعهد المناعة، جامعة الطب البحري/الجامعة الطبية العسكرية الثانية، شنغهاي 200433، الصين. معهد شنغهاي لأبحاث الخلايا الجذعية والترجمة السريرية، شنغهاي 200120، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: جي تشين، ليكون كوي. البريد الإلكتروني: xusheng@immunol.orgتم التحرير بواسطة البروفيسور أنستاسيس ستيفانو

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06435-w

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38218942

Publication Date: 2024-01-13

Amino acid metabolism in tumor biology and therapy

Abstract

Amino acid metabolism plays important roles in tumor biology and tumor therapy. Accumulating evidence has shown that amino acids contribute to tumorigenesis and tumor immunity by acting as nutrients, signaling molecules, and could also regulate gene transcription and epigenetic modification. Therefore, targeting amino acid metabolism will provide new ideas for tumor treatment and become an important therapeutic approach after surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. In this review, we systematically summarize the recent progress of amino acid metabolism in malignancy and their interaction with signal pathways as well as their effect on tumor microenvironment and epigenetic modification. Collectively, we also highlight the potential therapeutic application and future expectation.

FACTS

- Altered amino acid metabolism in tumors challenges the traditional classification of essential and nonessential amino acids.

- Amino acids have emerged as pivotal regulators in tumors, participated in a myriad of bidirectional interactions including signal pathways, tumor microenvironment, and epigenetic modifications.

- Clinical trials align with the idea that limiting amino acid intake may improve cancer prognoses.

OPEN QUESTIONS

- Among the several effects that are simultaneously regulated by certain amino acid, is there a chief effect that determines the progression or repression of tumor?

- What are the optimal strategies and urgent challenges for the clinical translation of amino acids-based therapies in the near future?

- Is the altered amino acids metabolism, described in different tumors, causally linked to their tumor etiology and pathogenesis?

INTRODUCTION

proliferating cancer cells, as carbon and nitrogen donors to get rid of the nutrition limitation [3]. Thus, amino acid metabolism has been extensively studied following glucose metabolism in tumor.

REPROGRAMMED AMINO ACID METABOLISM IN CANCER

Glutamine metabolism

and thereby inducing ferroptosis [25]. In addition to glutaminolysis, glutamine can be metabolized into intermediates like carbamoyl phosphate (CP) and phosphoribosyl amine (PRA) for the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, which are essential components for DNA synthesis and repair during rapidly tumor proliferation [31, 32].

Arginine metabolism

Branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism

glioblastoma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma [49, 50]. Drugs targeting LATs (BAY-8002, JPH203, OKY034 etc.) have already been used in preclinical treatment of cancer [51, 52].

initiation factor 4E binding protein 1(4EBP-1), p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), to regulate autophagy and synthesize lipids, nucleotides and proteins [55] (Detailed later in signal pathways in amino acid metabolism). For another, BCAAs, especially leucine, are essential for protein synthesis as they are in great demand in new protein translation [56].

Tryptophan metabolism

maintained through tumor-intrinsic oncogenic signaling [71, 72]. Studies found that intratumoural IDO1 expression has been shown to correlate with the frequency of liver metastases in colorectal cancer [73]. Besides, overexpression of IDO1 augmentes the motility of lung cancer cells, whereas its knockdown reduced cancer motility [74]. TDO, an enzyme that catalyzes the same reaction as IDO1, is also linked to a poor prognosis when overexpressed [66]. In a mouse model of lung cancer, inhibited TDO resulted in a reduction in the number of tumor nodules in the lungs [75].

Asparagine and aspartate

Serine/glycine and one-carbon metabolism

SIGNAL PATHWAYS IN AMINO ACID METABOLISM

J. Chen et al.

amino acid levels impact signal pathways, but alterations in signaling pathways can also affect amino acid metabolism.

mTOR senses and regulates amino acid metabolism

mTOR is an atypical serine/threonine protein kinase, acting as a convergence point for anabolism and catabolism. Due to differences in structure and function, mTOR complexes are categorized as mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1, which is sensitive to rapamycin inhibition, comprises mTOR, Raptor, mLST8, Tti/Tel2 and suppressive subunits PRAS40 and Deptor. The phosphorylation of PRAS40 and Deptor relieves its inhibition and activates mTORC1 [94]. 4EBP-1, S6K1 and SREBP are downstream effectors of mTORC1, which are associated with upregulated synthesis as well as poor prognosis in cancer [95]. mTORC1 is negatively regulated by low energy conditions, hypoxia, and DNA damage. It is also positively regulated by growth factors like insulin/insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1) pathway and receptor tyrosine kinasedependent Ras signaling. Particularly, when amino acids are abundant, the mTORC1 signaling pathway is positively regulated to transmit signals to facilitate protein synthesis. Conversely, under condition of amino acid insufficiency, the translation of proteins is inhibited to meet energy demand. Considering that cancer cells often exist in a nutrient-deficient environment, mTORC1 is consistently negatively regulated to adapt to metabolic alterations. mTORC2, which is insensitive to rapamycin, consists of mTOR, mSIN1, mLST8, Tti/Tel2 and suppressive subunit Rictor and Deptor. The balance between mTORC1 and mTORC2 orchestrates various metabolic processes, although our understanding of mTORC2 remains limited [96]. We mainly focus on the function of mTORC1 below.

activate mTORC1 through cytoplasmic sensors [108]. Thus, lysosomal sensors allow for the integration of lysosomal nutrient information into the regulation of mTORC1 activity. Collectively, amino acids are not only sources for energy and protein synthesis in tumorigenesis, but also act on mTORC1 as signaling molecules.

serine [110]. Astutely, ATF4 can also regulate the expression of other amino acid transporters such as CHAC1, SESN2, SLC7A11, SLC7A5, SLC7A1, and SLC3A2, and increase amino acid uptake [111]. Upon the accumulation of glutamine, mTORC1 downregulates miR-23a and miR-23b and subsequently promotes GLS expression to accelerate glutamine catabolism. When glutamine is deficient, mTORC1 represses the transcription of GDH inhibitor SIRT4, prompting glutamine anaplerosis [112]. mTORC1 also activates arginine catabolism by promoting ODC expression in RAS transformed cells to promote polyamine production and tumor progression. Mechanically, mTORC1 promotes the association between ODC mRNA and mRNA-binding protein, promoting ODC mRNA stabilization and expression [113]. Besides, positively regulated mTORC1 leads to the stabilization of MYC, which in turn induces ASS1 expression by competing with HIF1a for ASS1 promoter binding sites and therefore promotes arginine expression [114]. Collectively, mTORC1 regulates amino acid metabolism through multiple signaling effectors, including amino acid transporters, synthetic and catabolic enzymes. mTORC1 downstream signaling molecule MYC also plays extensive regulatory roles in amino acid metabolism.

Myc drives amino acid metabolism

J. Chen et al.

Altered KRAS and amino acid metabolism

AMINO ACIDS IN TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

Macropinocytosis in TME takes up amino acids

Amino acid metabolism and CAFs

production. Thus, P5CS deletion decreases collagen and therefore ECM production, which could be rescued with proline supplementation [145].

Amino acid metabolism and immune cells

AMINO ACID METABOLISM AND EPIGENETIC MODIFICATION

acid metabolites like SAM and acetyl-CoA are essential substrates for epigenetic modification, while amino acid metabolism also requires epigentic modification of associated metabolic enzymes [166]. This reciprocal regulatory relationship has a profound impact on tumor progression.

Methylation

outcompete T cells for methionine. Methionine deficiency in T cells leads to downregulation of H 3 K 79 me 2 , promoting

Demethylation

Acetylation and deacetylation

J. Chen et al.

catalyze of transaminase. Other amino acids such as lysine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine also contribute to acetylCoA production by forming acetoacetyl-CoA. Similarly, alanine, serine, tryptophan, cysteine, glycine, and threonine synthesize acetyl-CoA through pyruvate formation. Leucine metabolism provides acetyl-CoA to the EP300 acetyltransferase, leading to acetylation of mTORC1 regulator Raptor. This acetylation ultimately results in mTORC1 activation and altered amino acid metabolism [187]. Isoleucine and leucine catabolism generates acetyl-CoA within the mitochondria. Subsequently, mitochondrial acetyl-CoA must be transported to the cytoplasm and nucleus to regulate gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms [188].

Phosphorylation, succinylation, and lactylation

| Target | Drug | Cancer type | Clinical phases | |

| Amino acid transporters | ASCT2 | Tamoxifen and Raloxifene | Breast cancer | Approved |

| ASCT2 | PGS-siRNA | NSCLC | Preclinical | |

| ASCT2 | V-9302 | HCC | Preclinical | |

| CATs | verapamil | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical | |

| SLC6A14 | Aspartate-modified docetaxel-loading stealth liposomes | Lung cancer | Preclinical | |

| Asparagine metabolism | ASNS | metformin | Multiple cancers | Preclinical |

| Asparlas | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Approved | ||

| Arginine metabolism | ADI | ADI-PEG20 | Ovarian cancer | Phase III |

| INCB001158 | Advanced or metastatic solid tumors | Phase II | ||

| Glutamine metabolism | GLS | Telaglenastat | NSCLC, lymphoma, glioma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and kidney cancer [234] | Phase II |

| GLS1 | 968 | NSCLC [235] | Preclinical | |

| One-carbon metabolism | DHFR | Methotrexate | Multiple cancers | Approved |

| Thymidylate synthase | 5-fluorouracil | Multiple cancers | Approved |

TARGETING AMINO ACID METABOLISM IN TUMOR THERAPY

Amino acid transporters inhibition

tumors. Cationic amino acid transporters like CAT-1, CAT-2 and CAT-3 for lysine, arginine, and histidine are also dysregulated in tumors and associated with drug resistance. Specifically, CAT-1 expression exhibits a correlation with tumor grade in prostate cancer [208]. It also plays a pivotal role in promoting growth, proliferation, and metastasis of colorectal cancer and breast cancer [210]. Upregulated CAT-3 increases arginine uptake and thereby induces tumors to adapt glutamine deprivation [39]. Downregulation of CATs (CAT-1, CAT-3) through lentiviral transduction with shRNAs or chemical like verapamil shuts down tumor proliferation and induces death [211,212]. Conversely, loss of CAT2 exacerbates inflammation-associated colon tumorigenesis [213].

Amino acid metabolism enzymatic inhibition

inhibited ASNS or metformin inhibited ETC limits tumor asparagine synthesis, impairing tumor growth in multiple mouse models [219]. Kras mutation activates the ATF4 signaling pathway through its downstream AKT and NRF2 in NSCLC. When ASNS is inhibited by AKT and the extracellular asparagine is depleted simultaneously, tumor growth can be reduced [220]. Therefore, ASNS is also a promising therapeutic target for Krasmutated NSCLC.

Amino acids modified dietary

J. Chen et al.

SUMMARY

REFERENCES

- Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27-47.

- Sivanand S, Vander Heiden MG. Emerging roles for branched-chain amino acid metabolism in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:147-56.

- Zhang Y, Morar M, Ealick SE. Structural biology of the purine biosynthetic pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3699-724.

- Morita M, Kudo K, Shima H, Tanuma N. Dietary intervention as a therapeutic for cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:498-504.

- Wei Z, Liu X, Cheng C, Yu W, Yi P. Metabolism of amino acids in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:603837.

- Taniguchi S, Elhance A, Van Duzer A, Kumar S, Leitenberger JJ, Oshimori N. Tumor-initiating cells establish an IL-33-TGF-

niche signaling loop to promote cancer progression. Science. 2020;369:eaay1813. - Butler M, van der Meer LT, van Leeuwen FN. Amino acid depletion therapies: starving cancer cells to death. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32:367-81.

- Ji Y, Wu Z, Dai Z, Sun K, Wang J, Wu G. Nutritional epigenetics with a focus on amino acids: implications for the development and treatment of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;27:1-8.

- Vettore L, Westbrook RL, Tennant DA. New aspects of amino acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:150-6.

- Lieu EL, Nguyen T, Rhyne S, Kim J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:15-30.

- Lukey MJ, Katt WP, Cerione RA. Targeting amino acid metabolism for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:796-804.

- Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Sayed N, Zhang X-Y, Pfeiffer HK, et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18782-7.

- Patel D, Menon D, Bernfeld E, Mroz V, Kalan S, Loayza D, et al. Aspartate rescues s-phase arrest caused by suppression of glutamine utilization in KRas-driven cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9322-9.

- Luengo A, Gui DY, Vander Heiden MG. Targeting metabolism for cancer therapy. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:1161-80.

- Reynolds MR, Lane AN, Robertson B, Kemp S, Liu Y, Hill BG, et al. Control of glutamine metabolism by the tumor suppressor Rb. Oncogene. 2014;33:556-66.

- Wang Q, Tiffen J, Bailey CG, Lehman ML, Ritchie W, Fazli L, et al. Targeting amino acid transport in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: effects on cell cycle, cell growth, and tumor development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1463-73.

- Ren P, Yue M, Xiao D, Xiu R, Gan L, Liu H, et al. ATF4 and N-Myc coordinate glutamine metabolism in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells through ASCT2 activation. J Pathol. 2015;235:90-100.

- Willems L, Jacque N, Jacquel A, Neveux N, Maciel TT, Lambert M, et al. Inhibiting glutamine uptake represents an attractive new strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:3521-32.

- Lu J, Chen M, Tao Z, Gao S, Li Y, Cao Y, et al. Effects of targeting SLC1A5 on inhibiting gastric cancer growth and tumor development in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8:76458-67.

- Wang Q, Hardie RA, Hoy AJ, van Geldermalsen M, Gao D, Fazli L, et al. Targeting ASCT2-mediated glutamine uptake blocks prostate cancer growth and tumour development. J Pathol. 2015;236:278-89.

- van Geldermalsen M, Wang Q, Nagarajah R, Marshall AD, Thoeng A, Gao D, et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple-negative basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:3201-8.

- Zhao J-S, Shi S, Qu H-Y, Keckesova Z, Cao Z-J, Yang L-X, et al. Glutamine synthetase licenses APC/C-mediated mitotic progression to drive cell growth. Nat Metab. 2022;4:239-53.

- Wang Z, Liu F, Fan N, Zhou C, Li D, Macvicar T, et al. Targeting glutaminolysis: new perspectives to understand cancer development and novel strategies for potential target therapies. Front Oncol. 2020;10:589508.

- Ramirez-Peña E, Arnold J, Shivakumar V, Joseph R, Vidhya Vijay G, den Hollander

, et al. The epithelial to mesenchymal transition promotes glutamine independence by suppressing expression. Cancers. 2019;11:1610. - Suzuki S, Venkatesh D, Kanda H, Nakayama A, Hosokawa H, Lee E, et al. GLS2 is a tumor suppressor and a regulator of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2022;82:3209-22.

- Xiang L, Mou J, Shao B, Wei Y, Liang H, Takano N, et al. Glutaminase 1 expression in colorectal cancer cells is induced by hypoxia and required for tumor growth, invasion, and metastatic colonization. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:40.

- Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762-5.

- Wang JB, Erickson JW, Fuji R, Ramachandran S, Gao P, Dinavahi R, et al. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:207-19.

- Kahlert UD, Cheng M, Koch K, Marchionni L, Fan X, Raabe EH, et al. Alterations in cellular metabolome after pharmacological inhibition of Notch in glioblastoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1246-55.

- Matés JM, Pérez-Gómez C, Núñez de Castro I, Asenjo M, Márquez J. Glutamine and its relationship with intracellular redox status, oxidative stress and cell proliferation/death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:439-58.

- Bott AJ, Maimouni S, Zong W-X. The Pleiotropic effects of glutamine metabolism in cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:770.

- Fu S, Li Z, Xiao L, Hu W, Zhang L, Xie B, et al. Glutamine synthetase promotes radiation resistance via facilitating nucleotide metabolism and subsequent DNA damage repair. Cell Rep. 2019;28:1136-1143.e4.

- Vincent EE, Sergushichev A, Griss T, Gingras M-C, Samborska B, Ntimbane T, et al. Mitochondrial Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase regulates metabolic adaptation and enables glucose-independent tumor growth. Mol Cell. 2015;60:195-207.

- Lio C-WJ, Yuita H, Rao A. Dysregulation of the TET family of epigenetic regulators in lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2019;134:1487-97.

- Ji JX, Cochrane DR, Tessier-Cloutier B, Chen SY, Ho G, Pathak KV, et al. Arginine depletion therapy with ADI-PEG20 limits tumor growth in argininosuccinate synthase-deficient ovarian cancer, including small-cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4402-13.

- Lee JS, Adler L, Karathia H, Carmel N, Rabinovich S, Auslander N, et al. Urea cycle dysregulation generates clinically relevant genomic and biochemical signatures. Cell. 2018;174:1559-1570.e22.

- Scalise M, Console L, Rovella F, Galluccio M, Pochini L, Indiveri C. Membrane transporters for amino acids as players of cancer metabolic rewiring. Cells 2020;9:2028.

- Abdelmagid SA, Rickard JA, McDonald WJ, Thomas LN, Too CKL. CAT-1mediated arginine uptake and regulation of nitric oxide synthases for the survival of human breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1084-92.

- Bachmann AS, Geerts D. Polyamine synthesis as a target of MYC oncogenes. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:18757-69.

- Grzywa TM, Sosnowska A, Matryba P, Rydzynska Z, Jasinski M, Nowis D, et al. Myeloid cell-derived arginase in cancer immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:938.

- Kryczek I, Zou L, Rodriguez P, Zhu G, Wei S, Mottram P, et al. B7-H4 expression identifies a novel suppressive macrophage population in human ovarian carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2006;203:871-81.

- Novita Sari I, Setiawan T, Seock Kim K, Toni Wijaya Y, Won Cho K, Young Kwon H. Metabolism and function of polyamines in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:91-104.

- Ha HC, Sirisoma NS, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL, Woster PM, Casero RA Jr. The natural polyamine spermine functions directly as a free radical scavenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11140-5.

- Ha HC, Yager JD, Woster PA, Casero RA Jr. Structural specificity of polyamines and polyamine analogues in the protection of DNA from strand breaks induced by reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:298-303.

- Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664-6.

- Brito C, Naviliat M, Tiscornia AC, Vuillier F, Gualco G, Dighiero G, et al. Peroxynitrite inhibits T lymphocyte activation and proliferation by promoting impairment of tyrosine phosphorylation and peroxynitrite-driven apoptotic death. J Immunol. 1999;162:3356-66.

- Singh N, Ecker GF. Insights into the structure, function, and ligand discovery of the large neutral amino acid Transporter 1, LAT1. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1278.

- Wang Q, Holst J. L-type amino acid transport and cancer: targeting the mTORC1 pathway to inhibit neoplasia. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1281-94.

- Zhang B, Chen Y, Shi X, Zhou M, Bao L, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. Regulation of branched-chain amino acid metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor in glioblastoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:195-206.

- Elorza A, Soro-Arnáiz I, Meléndez-Rodríguez F, Rodríguez-Vaello V, Marsboom G, de Cárcer G, et al. HIF2a acts as an mTORC1 activator through the amino acid carrier SLC7A5. Mol Cell. 2012;48:681-91.

- Quanz M, Bender E, Kopitz C, Grünewald S, Schlicker A, Schwede W, et al. Preclinical efficacy of the novel monocarboxylate Transporter 1 inhibitor BAY8002 and associated markers of resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:2285-96.

- Zhao X, Sakamoto S, Wei J, Pae S, Saito S, Sazuka T, et al. Contribution of the L-Type amino acid transporter family in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6178.

- Ananieva EA, Wilkinson AC. Branched-chain amino acid metabolism in cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:64-70.

- Ericksen RE, Lim SL, McDonnell E, Shuen WH, Vadiveloo M, White PJ, et al. Loss of BCAA catabolism during carcinogenesis enhances mTORC1 activity and promotes tumor development and progression. Cell Metab. 2019;29:1151-1165.e6.

- Tian T, Li X, Zhang J. mTOR signaling in cancer and mTOR inhibitors in solid tumor targeting therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:755.

- Kamphorst JJ, Nofal M, Commisso C, Hackett SR, Lu W, Grabocka E, et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. 2015;75:544-53.

- Cano-Crespo S, Chillarón J, Junza A, Fernández-Miranda G, García J, Polte C, et al. CD98hc (SLC3A2) sustains amino acid and nucleotide availability for cell cycle progression. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14065.

- Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681-706.

- Mayers JR, Wu C, Clish CB, Kraft P, Torrence ME, Fiske BP, et al. Elevation of circulating branched-chain amino acids is an early event in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma development. Nat Med. 2014;20:1193-8.

- Liu X-H, Zhai X-Y. Role of tryptophan metabolism in cancers and therapeutic implications. Biochimie. 2021;182:131-9.

- Della Chiesa M, Carlomagno S, Frumento G, Balsamo M, Cantoni C, et al. The tryptophan catabolite L-kynurenine inhibits the surface expression of NKp46and NKG2D-activating receptors and regulates NK-cell function. Blood. 2006;108:4118-25.

- Abd El-Fattah EE. IDO/kynurenine pathway in cancer: possible therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med. 2022;20:347.

- Xue C, Li G, Zheng Q, Gu X, Shi Q, Su Y, et al. Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2023;35:1304-26.

- Tummala KS, Gomes AL, Yilmaz M, Graña O, Bakiri L, Ruppen I, et al. Inhibition of de novo NAD(+) synthesis by oncogenic URI causes liver tumorigenesis through DNA damage. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:826-39.

- Muthusamy T, Cordes T, Handzlik MK, You L, Lim EW, Gengatharan J, et al. Serine restriction alters sphingolipid diversity to constrain tumour growth. Nature. 2020;586:790-5.

- Platten M, Nollen EAA, Röhrig UF, Fallarino F, Opitz CA. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:379-401.

- Sarrouilhe D, Mesnil M. Serotonin and human cancer: a critical view. Biochimie. 2019;161:46-50.

- Schneider MA, Heeb L, Beffinger MM, Pantelyushin S, Linecker M, Roth L, et al. Attenuation of peripheral serotonin inhibits tumor growth and enhances immune checkpoint blockade therapy in murine tumor models. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabc8188.

- Hezaveh K, Shinde RS, Klötgen A, Halaby MJ, Lamorte S, Ciudad MT, et al. Tryptophan-derived microbial metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in tumor-associated macrophages to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity. 2022;55:324-340.e8.

- Jia Y, Wang H, Wang Y, Wang T, Wang M, Ma M, et al. Low expression of Bin1, along with high expression of IDO in tumor tissue and draining lymph nodes, are predictors of poor prognosis for esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1095-106.

- Mellor AL, Lemos H, Huang L. Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and tolerance: where are we now? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1360.

- Kindler J, Lim CK, Weickert CS, Boerrigter D, Galletly C, Liu D, et al. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2860-72.

- Brandacher G, Perathoner A, Ladurner R, Schneeberger S, Obrist P, Winkler C, et al. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in colorectal cancer: effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1144-51.

- Tang D, Yue L, Yao R, Zhou L, Yang Y, Lu L, et al. P53 prevent tumor invasion and metastasis by down-regulating IDO in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:54548-57.

- Hsu YL, Hung JY, Chiang SY, Jian SF, Wu CY, Lin YS, et al. Lung cancer-derived galectin-1 contributes to cancer associated fibroblast-mediated cancer progression and immune suppression through TDO2/kynurenine axis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27584-98.