DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.05.013

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38735395

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-22

إبر دقيقة مجوفة لتوصيل الأدوية العينية

تم النشر في:

نسخة الوثيقة:

بوابة أبحاث جامعة كوينز بلفاست:

حقوق الناشر

هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول تم نشرها بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام العادل (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)، والذي يسمح بالاستخدام غير المقيد، والتوزيع، وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط ذكر المؤلف والمصدر.

الحقوق العامة

سياسة الإزالة

الوصول المفتوح

إبر مجهرية مجوفة لتوصيل الأدوية للعين

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

قليلة التوغل

فوق المشيمية

التصوير البصري التوافقي

التهاب القزحية

الأوعية الدموية

جزيئات نانوية

جزيئات دقيقة

حول العين

عبر الصلبة

الملخص

الإبر الدقيقة (MNs) هي إبر بحجم ميكرون، عادةً

1. المقدمة

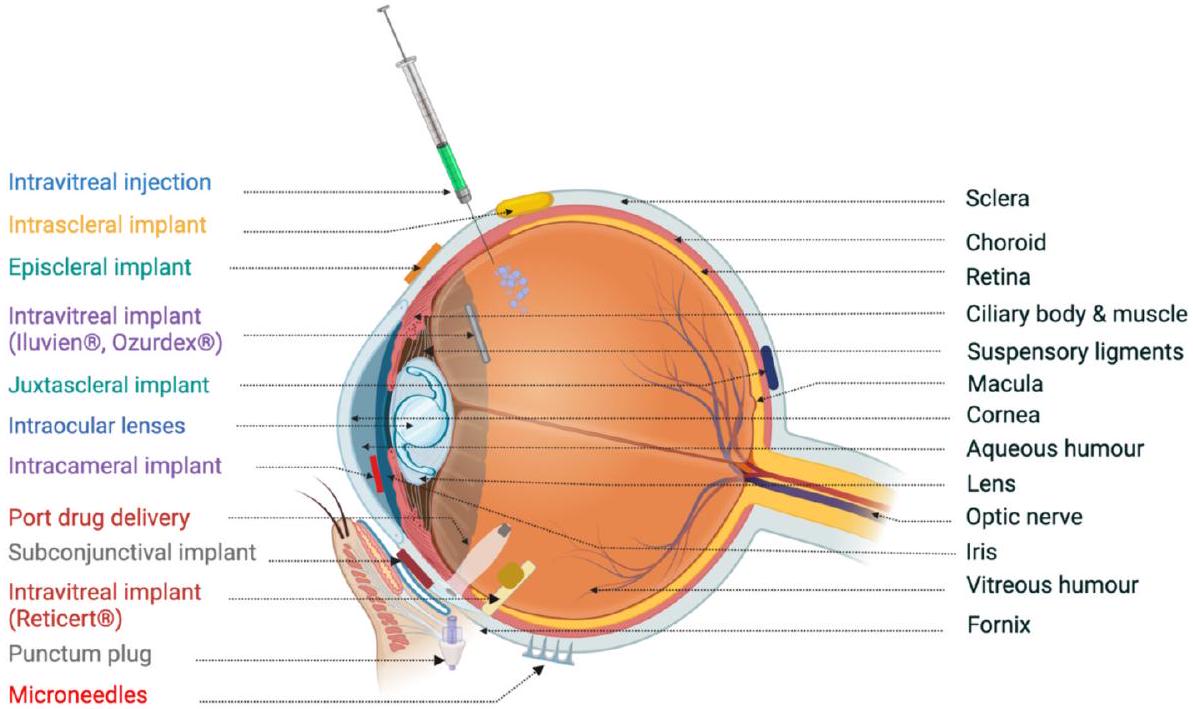

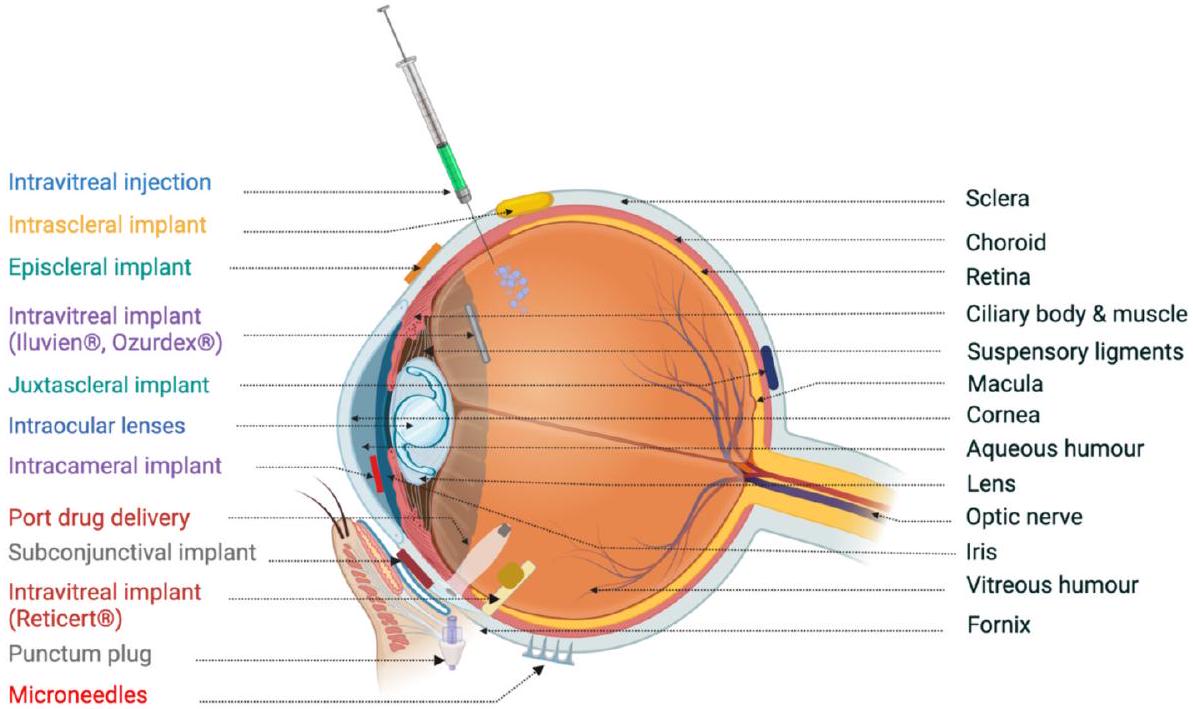

قد تؤدي إدارة مثل هذه الأدوية إلى آثار جانبية نظامية. دواء آخر موصوف على نطاق واسع لعلاج الأمراض العينية الخلفية هو الحقن داخل الجسم الزجاجي. على الرغم من أنها شديدة التوغل وتحمل مخاطر، إلا أن هذه الحقن داخل الجسم الزجاجي للعلاجات المحتملة تُوصف بسبب الفوائد المحتملة. حاليًا، يتم اختبار الحقن داخل الجسم الزجاجي للأجسام المضادة وحيدة النسيلة، وهي بيفاسيزوماب ورانبيزوماب، لقدرتها على علاج الأمراض الوعائية الجديدة التي تسبب العمى، بما في ذلك اعتلال الشبكية الناتج عن الخداج. ترتبط هذه الحقن المتكررة داخل الجسم الزجاجي بعدة أحداث سلبية قصيرة المدى، مثل التهاب باطن العين، انفصال الشبكية، نزيف داخل الجسم الزجاجي، وارتفاع خطر الإصابة بالمياه البيضاء. مؤخرًا، تم التحقيق في الحقن المحيطة بالعين كطرق أقل توغلاً لتحقيق نتائج علاجية في تجويف الجسم الزجاجي. تشمل الطرق تحت البطينية، تحت الملتحمة، وحول الكرة العينية الحقن المحيطة بالعين. هذه الطرق في الإدارة أقل توغلاً ولكنها تتطلب التغلب على حاجز الصلبة أو المشيمية أو الخلايا الصبغية الشبكية للوصول إلى موقع الإدارة.

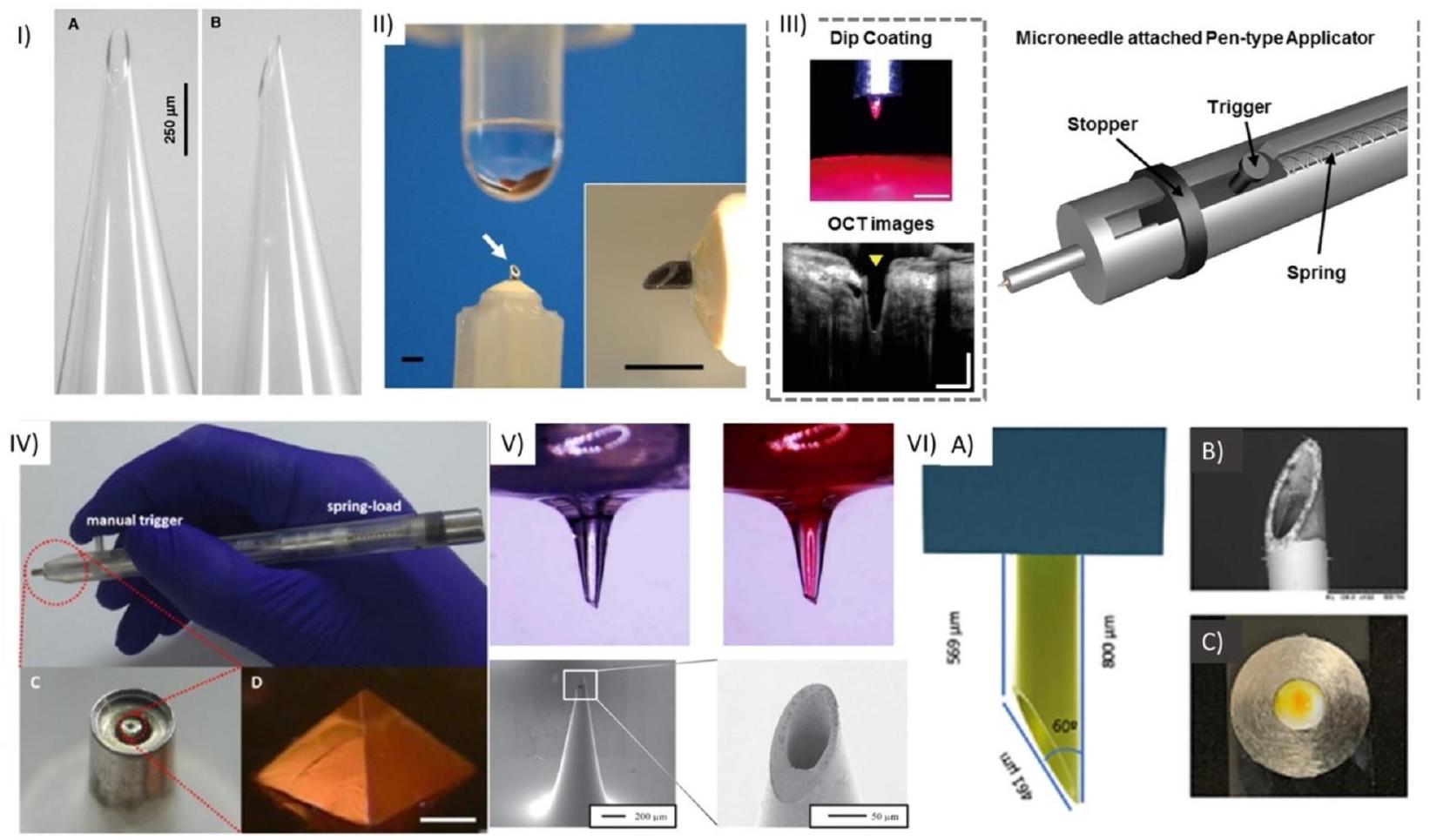

2. MNs المجوفة

توصيل، يهدف إلى تحسين نتائج العلاج لأمراض العين. توفر هذه الإبر الدقيقة توصيلًا دقيقًا وموجهًا للأدوية إلى أنسجة العين المحددة، مثل القرنية أو الغرفة الأمامية. من خلال تجاوز الحواجز العينية، تعزز توافر الأدوية البيولوجي، مما يضمن تركيزات أعلى من الأدوية في الموقع المطلوب مع تقليل الآثار الجانبية النظامية. تجعل الأبعاد الدقيقة للغاية وانخفاض التدخل للإبر الدقيقة أقل إزعاجًا للمرضى. تمكن قدراتها على الجرعات المتحكم بها من إدارة دقيقة للأدوية، وقد يكون لها أيضًا إمكانيات لأخذ عينات من السوائل العينية أو التشخيصات. تم تصنيع الإبر الدقيقة باستخدام مواد متنوعة، بما في ذلك زجاج البوروسيليكات، والمعادن، والبوليمر، والتيتانيوم، والسيراميك، والسيليكون، والتي تتضمن ثقبًا عبر هيكل الإبرة الدقيقة.

2.1. تصنيع HMNs

طرق التصنيع قد تم استخدامها للإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام، اعتمادًا على خصائص المادة التي سيتم إنشاء الإبر المجهرية منها [44]. تركز هذه القسم على الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام، وتصنيعها، وتطبيقها العيني (الجدول 1).

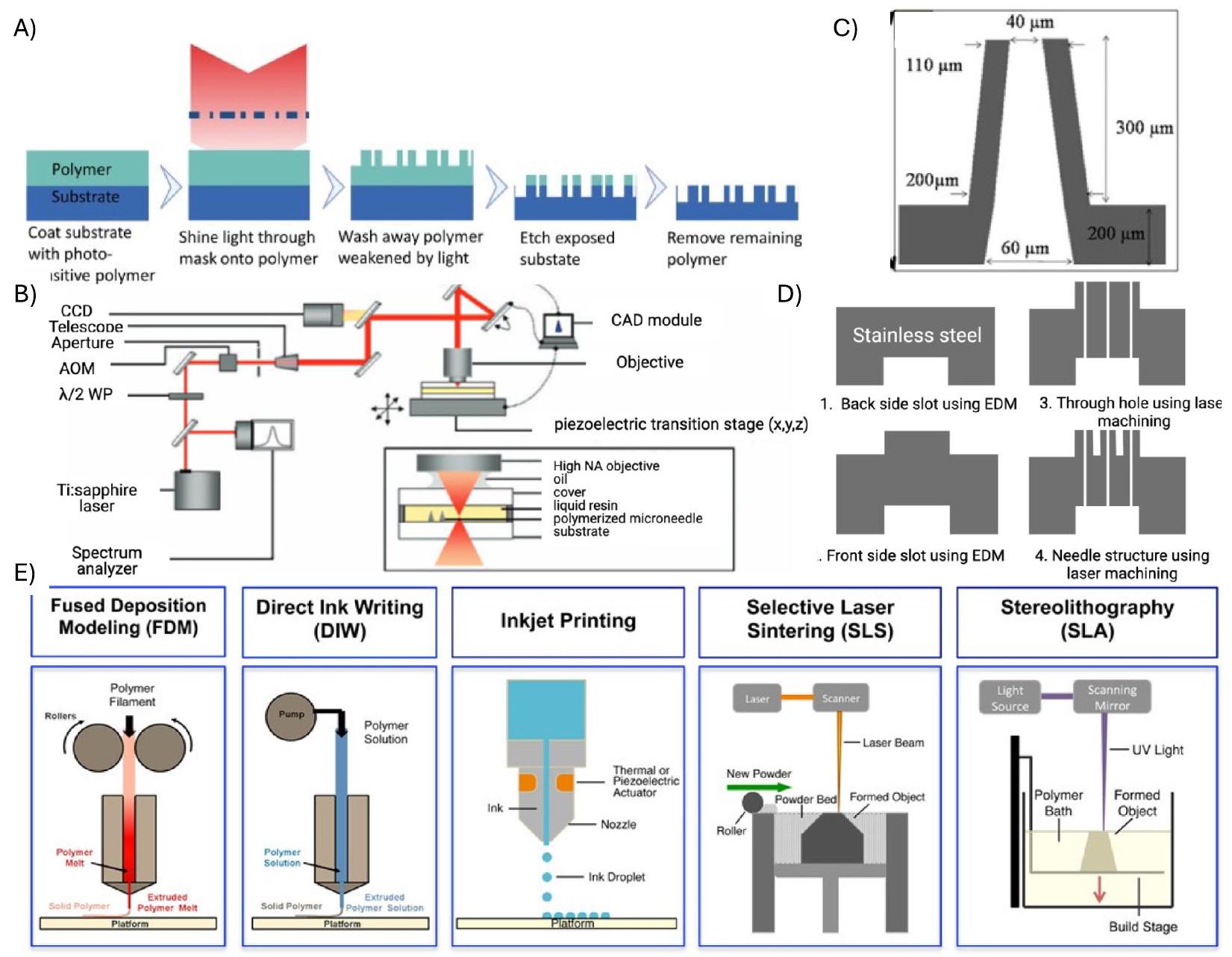

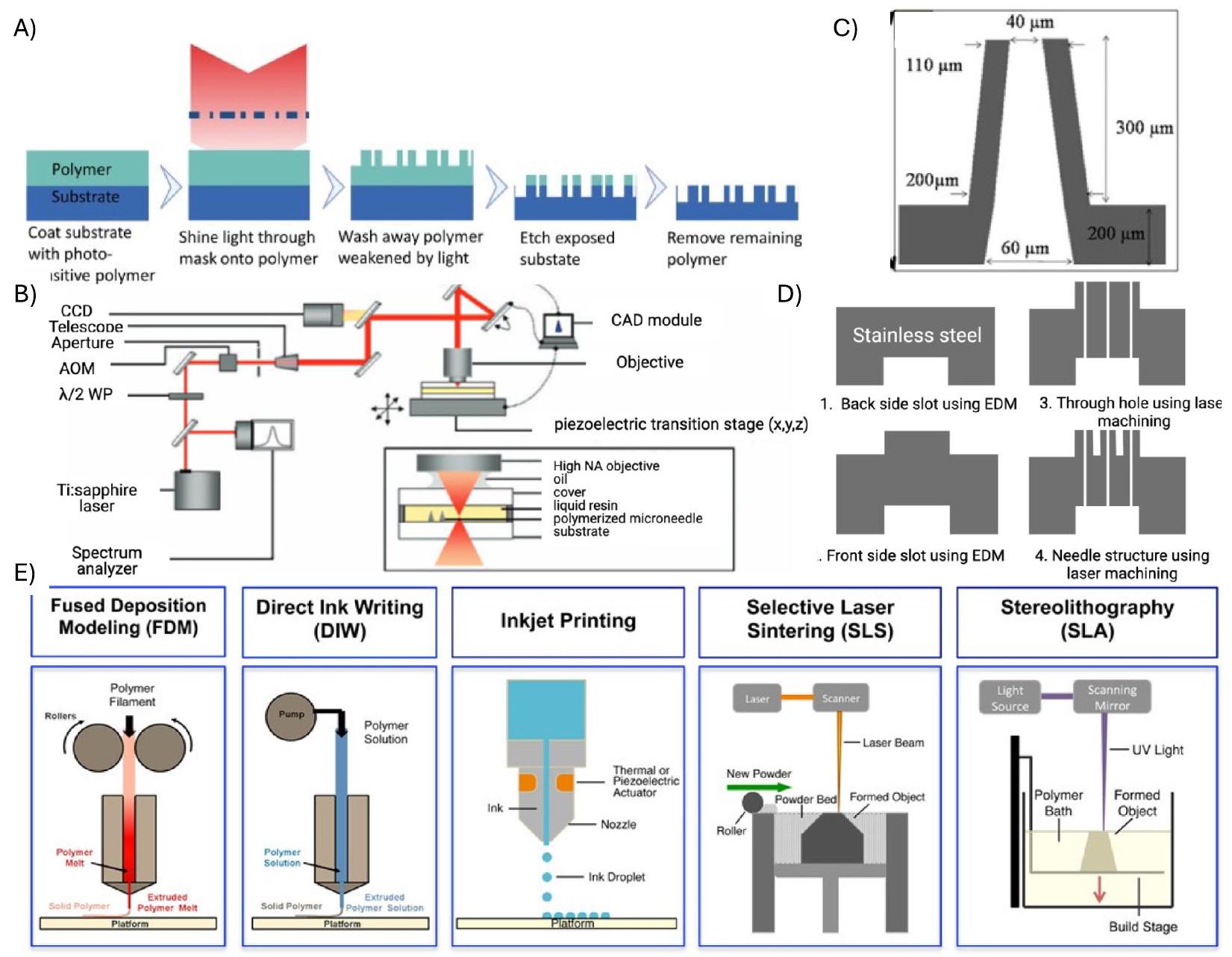

2.1.1. التصنيع التنازلي

2.1.1.1. الفوتوليثوغرافي. الطريقة الأكثر شيوعًا لتصنيع الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام هي الفوتوليثوغرافي بالتزامن مع إما الحفر الأيوني التفاعلي العميق (DRIE) أو الحفر الرطب. الفوتوليثوغرافي هو تقنية تستخدم لنقل نمط من قناع إلى شريحة في ثلاث خطوات. يتم تغليف شرائح السيليكون بطبقة رقيقة من مادة مقاومة للضوء إما عن طريق الطلاء الدوراني أو الرش. ثم يتم تعريض هذه الشرائح المطلية لأشعة UV من خلال قناع فوتوغرافي وأخيرًا يتم تطويرها لإزالة المقاومة المتبقية، مما يكشف عن ميزات القناع [44]. يتم الحصول على الهياكل النهائية باستخدام إما طرق الحفر الرطب أو الجاف (الشكل 2A). يستخدم الحفر الرطب محلول قلوي أو حمضي يعرف باسم المحلول الحفري لحفر المناطق غير المحمية من الشريحة. هذه الطريقة لحفر السيليكون مفيدة بسبب بساطتها وسهولة تنفيذها ومعدل الحفر العالي، مما يمنع بدوره تدمير الطبقة الواقية [52]. على الرغم من هذه المزايا، هناك العديد من العيوب الكبيرة، مثل التكاليف العالية وعدم القدرة على الحفاظ على نفس معدل الحفر الأولي طوال العملية [45]. بسبب انتشار العيوب، يتم استخدام حفر DRIE بشكل أكثر تكرارًا من عمليات الحفر الرطب. DRIE، المعروف أيضًا بعملية بوش، هو تقنية شديدة التوجه لإنشاء هياكل السيليكون [53]. تستخدم عملية بوش ثلاث خطوات: إيداع طبقة بوليمر، إزالة الطبقة المودعة ثم السيليكون

ملخص لتقنيات التصنيع المستخدمة للإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام المصنوعة من مواد مختلفة.

| المادة | تقنية التصنيع | المزايا | العيوب | المراجع |

| سيليكون | الفوتوليثوغرافي متبوعًا بالحفر الرطب | بسيط، سهل التنفيذ، | مكلف، عدم القدرة على الحفاظ على معدل الحفر الأولي | [45] |

| الفوتوليثوغرافي متبوعًا بـ DRIE | الحفر الأيوني عالي الاتجاه يؤدي إلى دقة أعلى، نسبة عالية من الأبعاد | مكلف، عمليات تصنيع معقدة | [46] | |

| بوليمر | التشكيل الدقيق | بسيط ومنخفض التكلفة | قوة ميكانيكية ضعيفة | [47] |

| الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد باستخدام نمذجة الإيداع المنصهر | متعددة الاستخدامات، فعالة من حيث التكلفة ويمكنها طباعة مواد قابلة للتجديد | طباعة بدقة أقل وبالتالي غير قادرة على طباعة هياكل أدق | [48] | |

| الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد باستخدام SLA بالليزر | قابلة للتعقيم مما يعني أنه يمكن تعقيم الإبر المجهرية، بوليمر متوافق حيويًا مستخدم، فعالة من حيث التكلفة، موحدة، وقابلة للتكرار | فتح الثقب العلوي يمثل تحديًا مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض الحدة وقدرات اختراق أقل | [49] | |

| معدن | تشغيل الميكرو بالليزر بالأشعة تحت الحمراء | إنتاج سريع ويمكن توسيع نطاق المواد | حدود في ارتفاع الإبر المجهرية المنتجة وجدرانها الجانبية خشنة | [49] |

| أنظمة بلمرة الفوتونين مع الكتابة المباشرة بالليزر والتشكيل | دقة عالية، قابلة للتكرار، دقة عالية وتحكم، دقة ميزات عالية | تكلفة عالية للمعدات، بطيء (عادة ما يستغرق

|

[50] | |

| زجاج بوروسيليكات | سحب الماصة | خامل | طريقة تصنيع طويلة، حساسة/هشة | [51] |

2.1.1.2. تشغيل التفريغ الإلكتروني (EDM). تم استخدام تشغيل التفريغ الإلكتروني (EDM)، وهو تقنية تصنيع تنازلي،

لتخليق الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام بدقة ملحوظة. يعمل EDM على مبدأ التفريغ الكهربائي لتشكيل المواد الموصلة. يوفر EDM تحكمًا استثنائيًا في عملية التشغيل، خاصة في سياق تخليق الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام، والتي تتطلب التحكم في الأشكال لإنتاج أشكال (إبر) ذات نسبة أبعاد عالية. يعمل EDM عن طريق إنشاء تفريغ شرارة محكوم بين قطب كهربائي و

المعدن (المسمى قطعة العمل)، عادةً من الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ أو التيتانيوم. يعمل السائل العازل المحيط بالتفريغ الكهربائي كوسيلة تبريد ويزيل الحطام الناتج أثناء العملية. يعمل هذا السائل العازل أيضًا كعازل كهربائي، مما يمنع حدوث قوس مستمر بين القطب الكهربائي وقطعة العمل. لتخليق الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام، يتم عادةً صنع القطب الكهربائي من مادة موصلة، مثل النحاس أو الجرافيت، ويتم تشكيله بعناية ليتناسب مع الهندسة المطلوبة للإبر المجهرية. أعد فينايكومار وآخرون الإبر المجهرية القابلة للاستخدام بارتفاع

2.1.2. تقنية التصنيع الإضافي

2.1.2.1. نمذجة الإيداع المنصهر. يمكن تصنيع HMNs البوليمرية عبر الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد باستخدام نمذجة الإيداع المنصهر (FDM). تم تطوير التقنية في عام 1989 بواسطة سكوت كرومب. FDM هي تقنية تذوب المادة إلى حالة سائلة في رأس سائل، ثم يتم إيداع هذه السائلة بشكل انتقائي من خلال الفوهة لإنتاج هيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد مباشرة من نموذج التصميم المدعوم بالحاسوب (CAD) بطريقة طبقة تلو الأخرى [67]. يمكن استخدام أنواع مختلفة من المواد، مثل حمض البولي لاكتيك (PLA)، والبولي إيثيلين عالي الكثافة (HDPE)، والبولي إيثيلين تيريفثاليت PETT (t-glase)، وخيوط الخشب والمعادن [68-71]. هذه

الطريقة متعددة الاستخدامات وفعالة من حيث التكلفة ويمكن استخدامها لطباعة المواد القابلة للتجديد، ولكن هناك قيود كبيرة. عملية الطباعة لها دقة أقل وبالتالي غير قادرة على صنع هياكل أدق [72]. أحد التغييرات في طباعة FDM هو طريقة تصنيع الألياف المستمرة (CFF)، التي تعزز قوة الأجزاء المطبوعة باستخدام الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد [73]. استخدم ناميكي وآخرون طريقة CFF لتصنيع مركبات ألياف الكربون PLA، وكانت قوة الشد للألياف

2.1.3. تعدد الفوتونات

2.2. خصائص HMN لتوصيل الأدوية العينية

قوة HMNs. يعتبر قطر الثقب وزاوية التحدب وتصميم المحول عوامل حاسمة تؤثر بشكل كبير على نجاح اختراق HMNs للأنسجة العينية مع تقليل التدخل. علاوة على ذلك، فإن القوة المطبقة أثناء الحقن هي معيار أساسي لضمان الحد الأدنى من تلف الأنسجة. تتناول هذه الفقرة الخصائص الأساسية لـ HMNs لتوصيل الأدوية العينية بشكل minimally invasive.

2.2.1. أهمية قطر الثقب وقوة الحقن

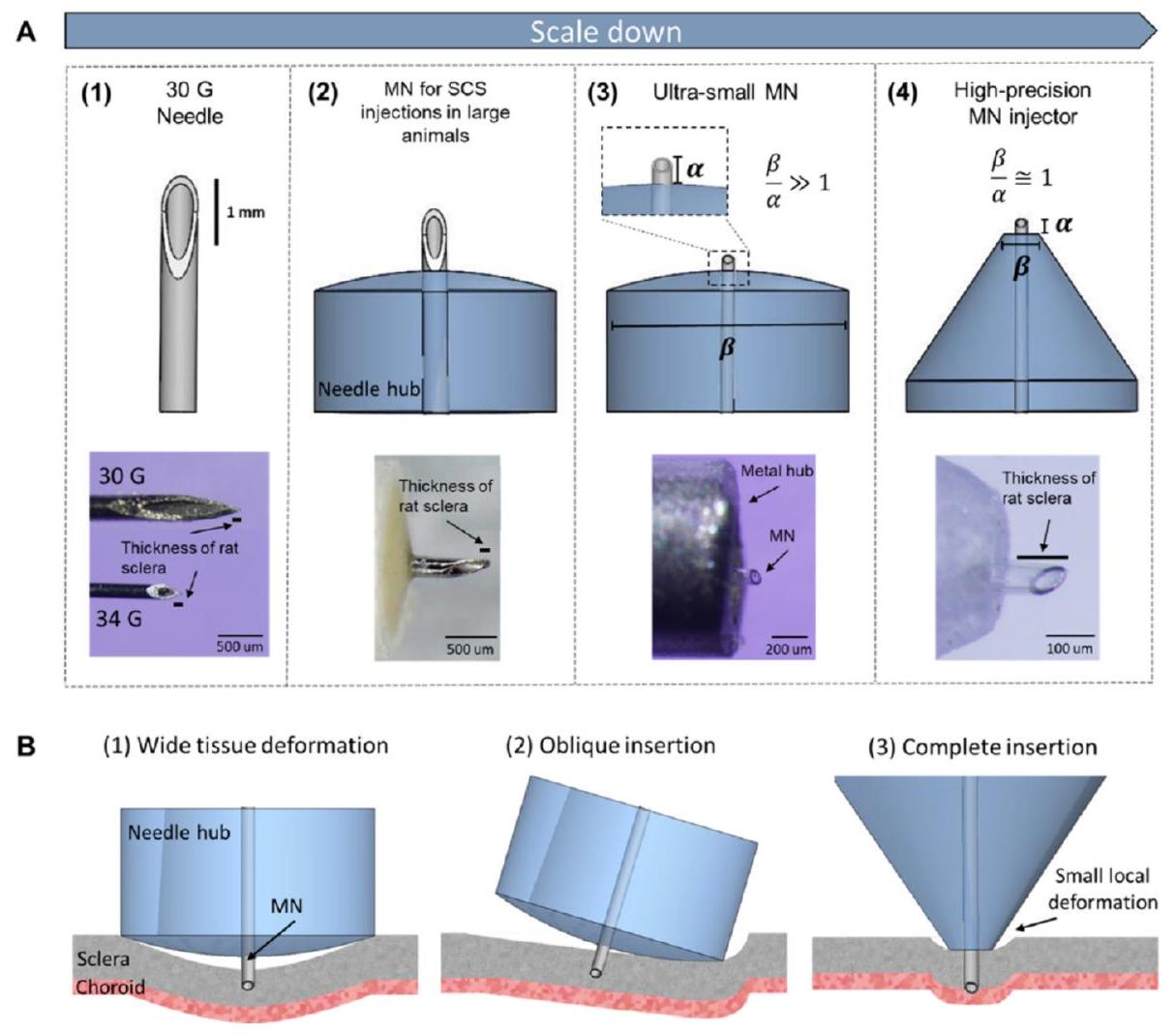

2.2.2. تأثير تصميم المحول على الإدخال

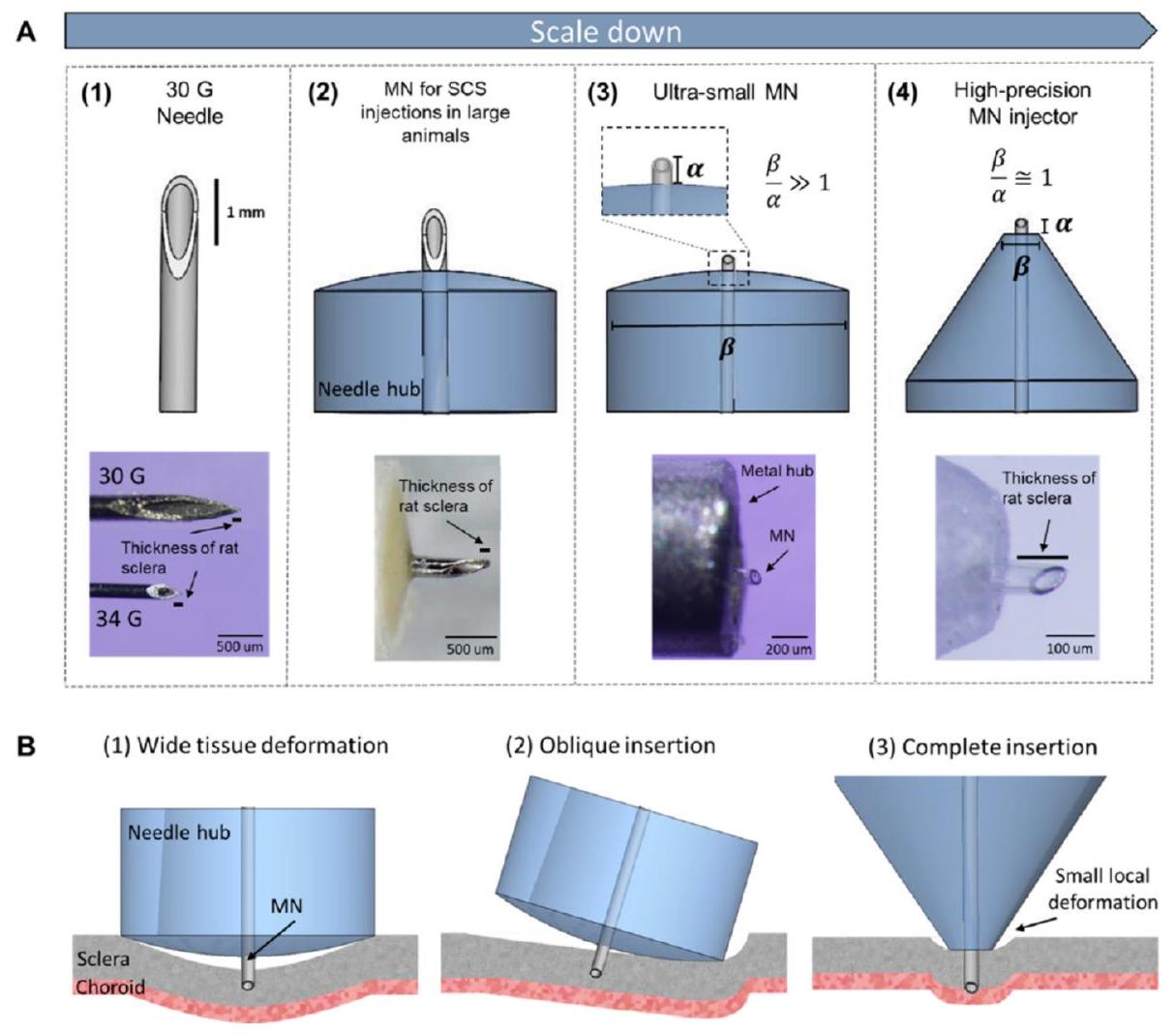

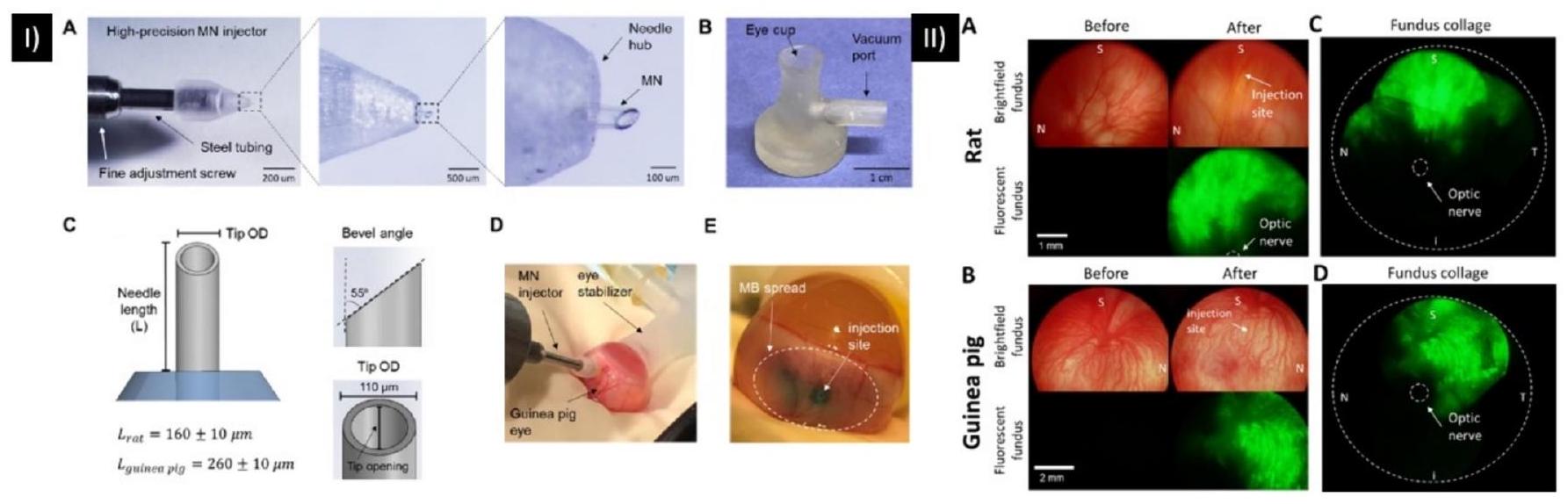

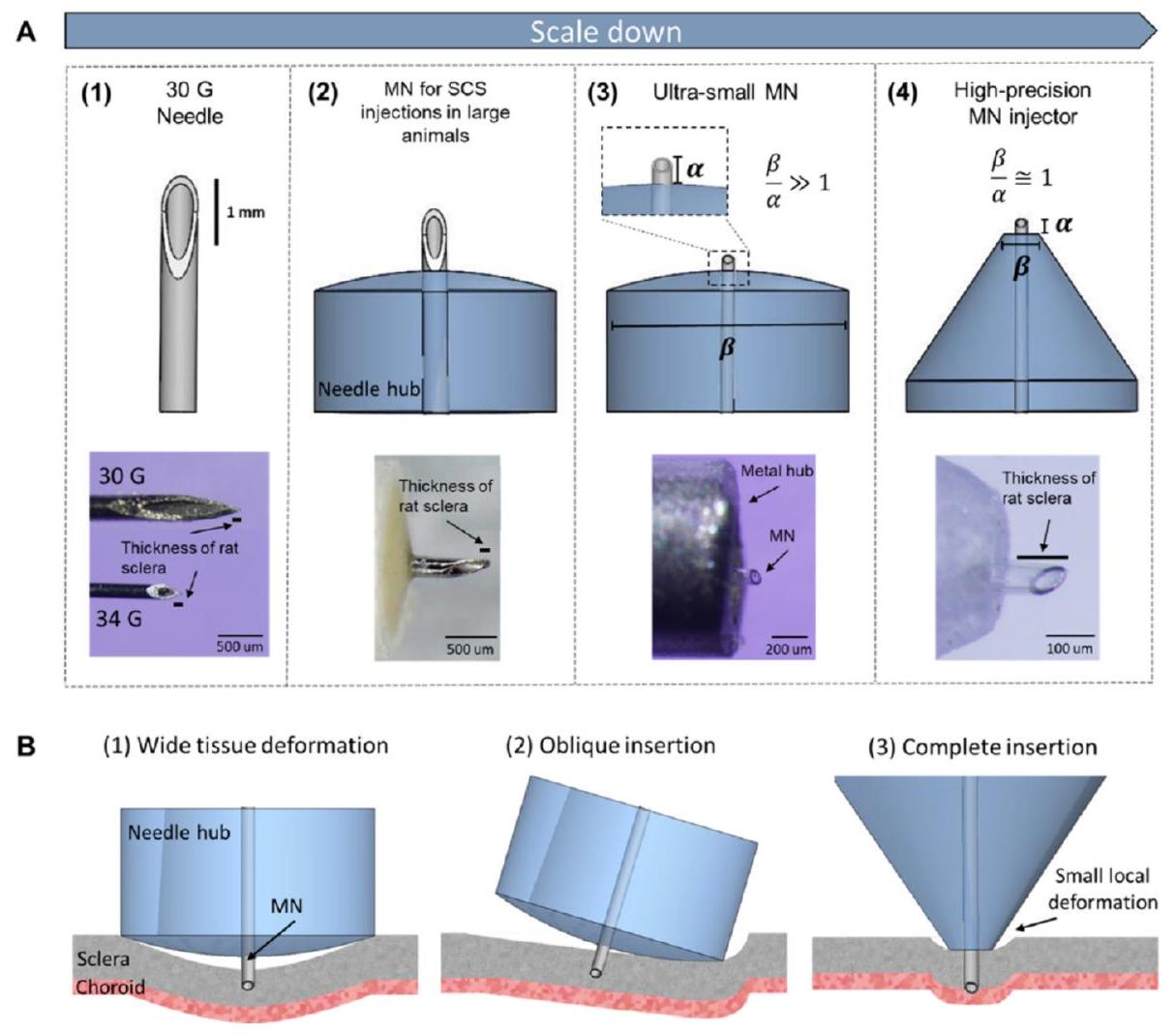

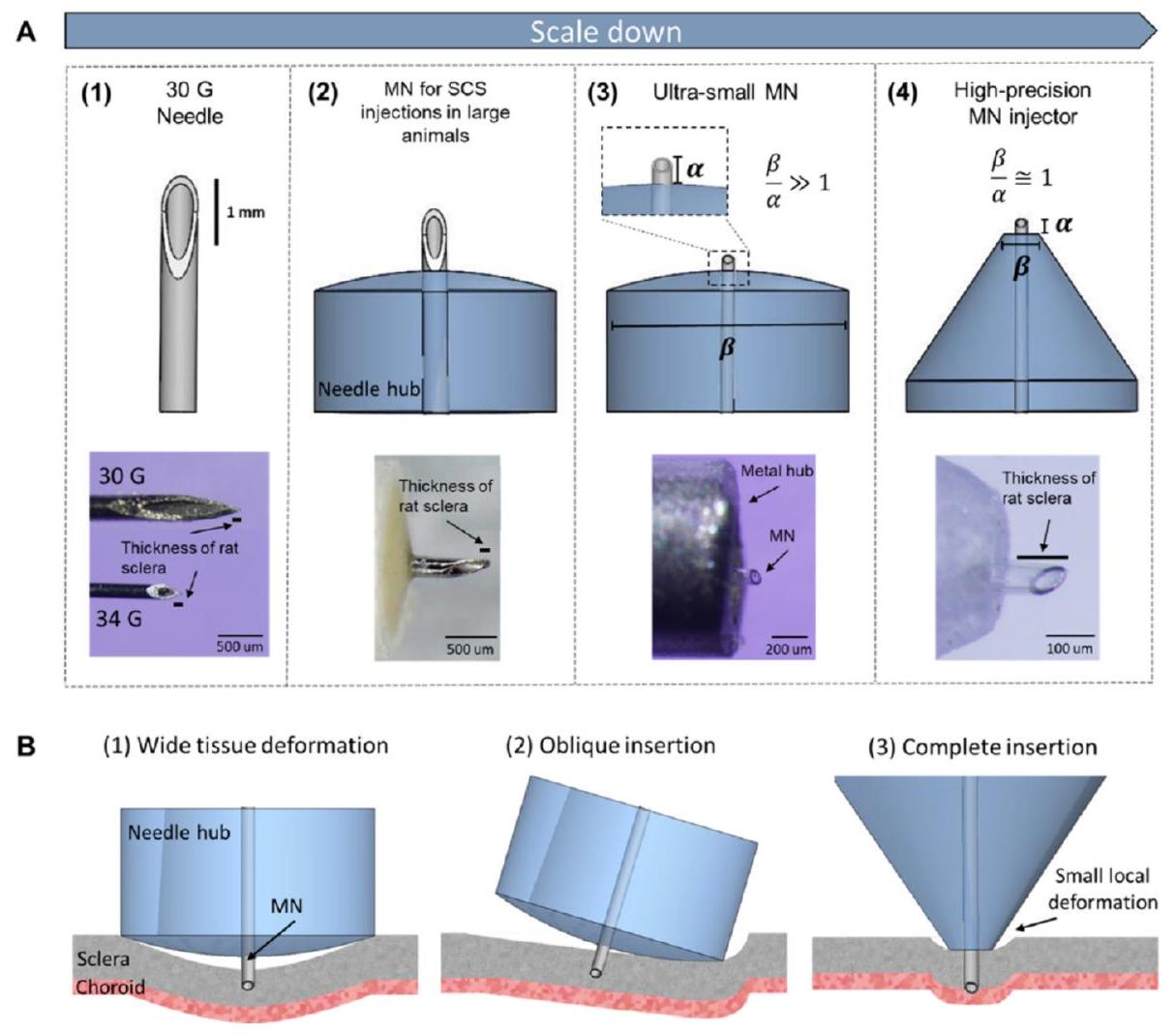

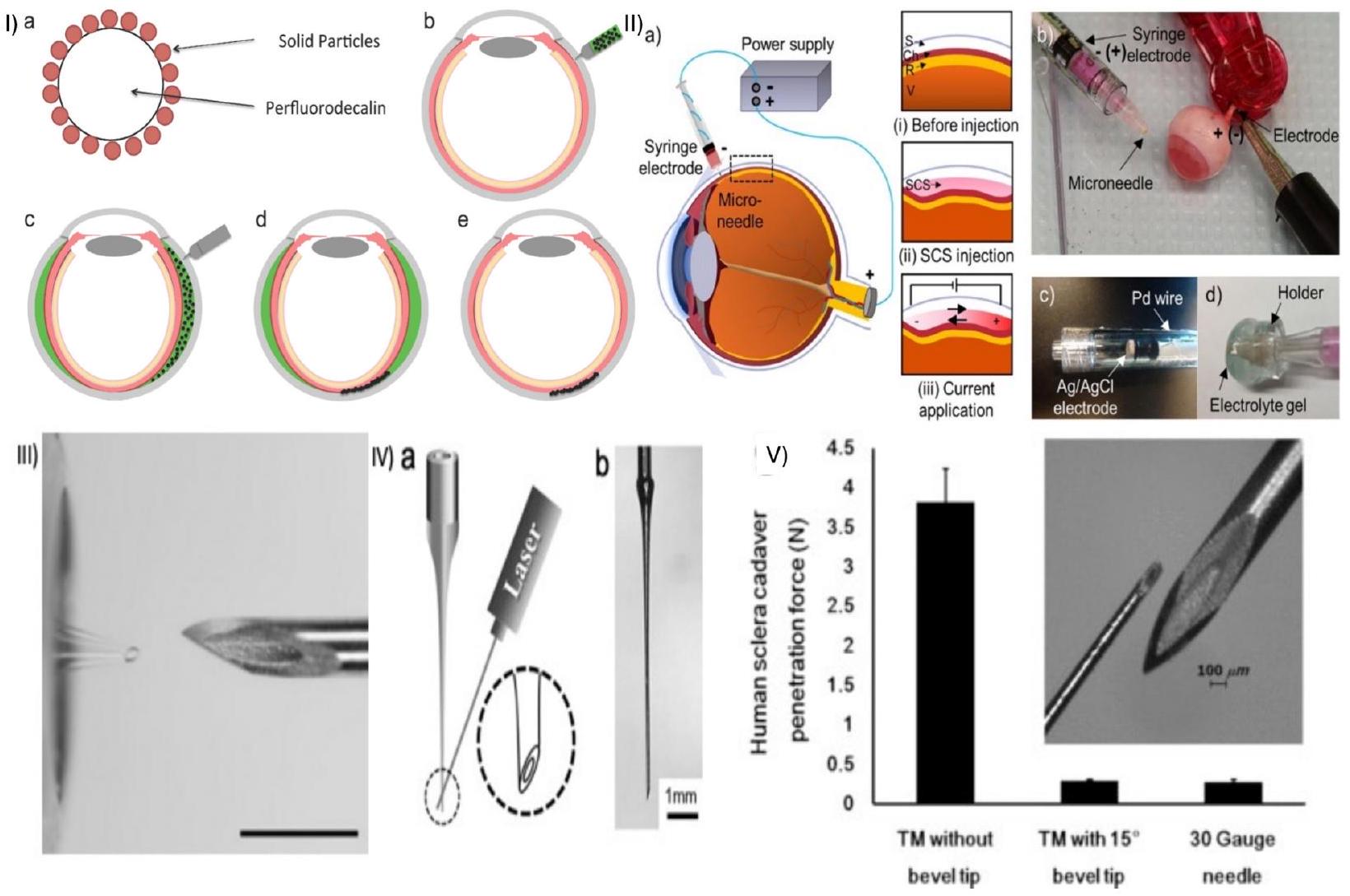

قطر المحور و a هو طول الإبرة، كما هو موضح في الشكل 4. طورت هذه الدراسة تقنية توصيل MN قوية لحقن SCS في الجرذان وخنازير غينيا من خلال التحكم في أبعاد MN وتحسينها، وتفاعلات الأنسجة مع المحور، وثبات العين أثناء الحقن. تم تحقيق التوصيل المستهدف بمعدل نجاح مرتفع في الجرذان وخنازير غينيا باستخدام طريقة حقن بسيطة من خطوة واحدة [88].

2.2.3. تأثير زاوية الحافة على توصيل الدواء

3. توزيع الأدوية وموقع الإعطاء

سيتم أيضًا استخدام طرق أكثر تقليدية وغير محلية، مثل التسليم داخل الجسم الزجاجي والتسليم الموضعي.

3.1. توزيع الدواء بعد الإعطاء الموضعي

كما هو الحال مع الجسم الهدبي والعدسة. بسبب تدفق السائل المائي من مقدمة العين، فإن التوزيع إلى الغرفة الخلفية غير محتمل جداً. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تتخلل الأدوية إلى الملتحمة بدلاً من القرنية. يتم اعتماد هذا المسار عادةً بواسطة الجزيئات الكبيرة المحبة للماء، التي تتجاوز القرنية بالتحرك عبر الملتحمة والصلبة قبل الانتقال إلى هياكل الأنسجة مثل الجسم الهدبي. نظراً لزيادة نفاذية هذا النسيج مقارنةً بالقرنية، فإن ذلك يشكل تحدياً كبيراً لتوصيل الأدوية موضعياً ويبرز نقص خصوصية الأنسجة مقارنةً بمسار إدارة الأدوية عبر SCS، على سبيل المثال. بمجرد امتصاصه في الملتحمة، يتم التخلص من الدواء تماماً من العين عبر الدورة الدموية الجهازية. يمكن أن يسبب هذا في حد ذاته مشاكل، حيث أظهرت الأدوية الشائعة مثل حاصرات بيتا مثل التيمولول أن لها آثاراً غير مستهدفة مثل مشاكل القلب مثل بطء القلب.

3.2. توزيع الدواء بعد حقن IVT

تم تثبيت الخرز (المشحون إيجابياً) بشكل كامل. قد تؤثر التغيرات في خصائص الزجاج بسبب الاختلافات في الموقع التشريحي، والعمر، والمرض على نقل الجسيمات النانوية [105].

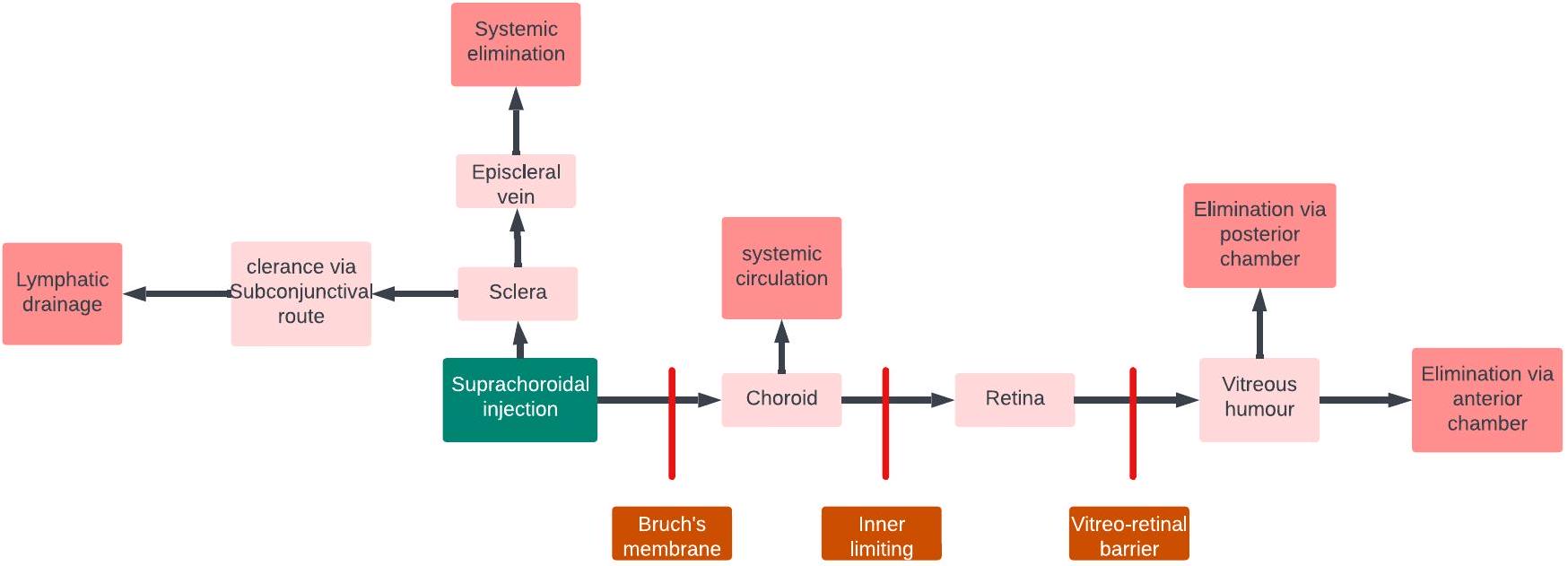

3.3. توزيع الدواء بعد الحقن فوق المشيمية

خيارًا جذابًا لتوصيل الأدوية المستهدفة إلى الشبكية. باختصار، بينما يمكن أن تشكل الحواجز مثل المشيمية، وحاجز BRB، و RPE تحديات لتوصيل الأدوية إلى الشبكية عبر طريق SCS، فإن الخصائص الفريدة لهذا الطريق، بما في ذلك تقليل فقدان الدواء في الدورة الدموية الجهازية وزيادة مستويات الدواء في موقع الهدف، تجعلها نهجًا واعدًا لتوصيل الأدوية بكفاءة إلى الشبكية (الشكل 10).

3.4. توزيع الدواء بعد الإدارة المحيطة بالعين

تقليل تصريف الدموع الأنفية [130] الشكل 11 يوضح مصير دواء بعد الإدارة المحيطة بالعين. درس كاجي وآخرون الحركية الدوائية لليبوبروتينات من الأمفوتيريسين ب (amp B) في الحقن تحت الملتحمة. كشفت الدراسة أن السمية العينية كانت أقل بكثير بالنسبة لحقن الأمفوتيريسين ب الليبوزومي مقارنة بحقن amp B أو ديكسيكولات. مقارنةً بقطرات العين الموضعية، تم الكشف عن تركيزات أكبر بكثير من amp

4. أنواع التركيبات القابلة للتسليم عبر الشبكات الصحية المنزلية

4.1. تسليم الحلول باستخدام الشبكات المتنقلة عالية السرعة

تم صياغتها كحلول قابلة للذوبان لتوصيل فعال وامتصاص سريع. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن إعادة تكوين الحلول من الأشكال المسحوقة، مما يوفر الراحة وسهولة التعامل والتغليف. بشكل عام، تجعل مزايا هذه الحلول منها خيارات قيمة وعملية لتوصيل الأدوية.

4.1.1. حول العين

4.1.2. داخل العين

4.2. توصيل المحاليل اللزجة باستخدام HMs

مع لزوجة المحلول. أبلغ أولمنديجر وآخرون عن تغييرات في ضغط العين الداخلي وقوة الحقن عند حقن محاليل ذات لزوجات مختلفة في عيون خنازير مذبوحة. لوحظ أن معدل الحقن لعب دورًا مهمًا في تحديد قوة الحقن، أي أن قوة الحقن عند معدلات الحقن المنخفضة كانت أقل بكثير من تلك عند معدلات الحقن الأعلى. كما لوحظ أنه حتى

4.2.1. حول العين

4.2.2. داخل العين

4.3. توصيل الجسيمات الدقيقة والنانوية باستخدام HMNs

. تم العثور على أنظمة توصيل الأدوية الجسيمية النانوية ذات الالتصاق المخاطي المحسن والاختراق المخاطي تعزز وقت الإقامة للأدوية في تجويف العين؛ ومع ذلك، فإن حجم الجسيمات في التعليق النانوي أمر حيوي لتقليل التهيج داخل سطح العين وتصريف الدموع. تشمل تقنيات توصيل الأدوية الأخرى المستخدمة لإدارة أمراض العين في الجزء الخلفي قيد البحث الجسيمات الدقيقة ذات التجميع الذاتي وزرعات طويلة المفعول للأدوية المضادة للالتهابات (مثل ديكساميثازون) [156]. ومع ذلك، فإن الإفراج المفاجئ عن الأدوية من مثل هذه الزرعات يثبط استخدامها في علاج أمراض العين على المدى الطويل. تركز هذه القسم على توزيع الجسيمات النانوية/المتناهية في HMNs.

4.3.1. حول العين

الحجم (20 أو 200 نانومتر). أظهرت الدراسة أن اتجاه الحافة (زمنيًا أو أنفيًا) يؤثر على توزيع الجسيمات داخل SCS، حيث يحدث توزيع أكبر في الاتجاه المعاكس للحافة. في عيون البشر، أظهرت حقن MN على بعد 2 و 8 مم من العصب البصري أن الشرايين الخلفية القصيرة عملت كحاجز أمام انتشار الدواء الفعال نحو العصب البصري والبقعة. مما يبرز أهمية موقع الإدارة،

4.3.2. داخل العين

5. ملخص التحديات والفرص في توصيل الأدوية العينية

6. الخاتمة

ملخص استخدام الإبر المجهرية في توصيل الأدوية العينية.

| مادة التصنيع | الأبعاد | حجم الحقن | موقع الهدف | التطبيق | المرجع. |

| زجاج |

|

|

الصلبة | توزيع المحلول والجزيئات النانوية في الصلبة | [36] |

| زجاج |

|

|

الصلبة | توصيل صبغة الورد البنفسجي في الصلبة الخنزيرية | [171] |

| زجاج |

|

|

SCS | توصيل الجزيئات النانوية (20 و200 نانومتر) والجزيئات الدقيقة (2 و

|

[123] |

| معدن | 400 و500 و

|

|

الصلبة | توصيل هيدروجيل Cs-g-PNIPAAm المحمل بالسونيتيب | [172] |

| معدن |

|

|

SCS | تحقيق جدوى استهداف الجاذبية في توصيل الجزيئات المحملة بكثافة عالية المحاطة بطبقة خارجية من الجزيئات النانوية الموصومة بالفلووريسئين إلى SCS | [143] |

| معدن |

|

|

SCS | توزيع الجزيئات النانوية (200 نانومتر) في SCS | [161] |

| معدن |

|

|

SCS | توصيل الفيروسات المرتبطة بالأدينوفيروس (AAV8) عبر الصلبة/تحت الشبكية | [129] |

| معدن |

|

|

SCS | توزيع المحاليل اللزجة غير النيوتونية في SCS | [119] |

| معدن |

|

30 و50 و

|

الصلبة | توصيل الهيدروجيل القابل للاستجابة الحرارية | [120] |

| معدن |

|

|

SCS | تحقيق تأثير زاوية الحافة على التوصيل إلى SCS | [76] |

| معدن |

|

|

الطريق فوق الجفني | توزيع الجزيئات المجهرية المحملة بالبريمودين (20-45

|

[173] |

| معدن |

|

|

|

تعليق التريامسينولون القابل للحقن

|

[113] |

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود تضارب في المصالح.

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

References

[2] A. Malhotra, F.J. Minja, A. Crum, D. Burrowes, Ocular anatomy and crosssectional imaging of the eye, Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 32 (2011) 2-13, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2010.10.009.

[3] C.A. Curcio, M. Johnson, Structure, Function, and Pathology of Bruch’s Membrane, Retina Fifth Edition, Elsevier Inc., in, 2012, pp. 465-481, https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-1-4557-0737-9.00020-5.

[4] J.W. Kiel, The ocular circulation, Colloquium Series on Integrated Systems Physiology: From Molecule to Function 3 (2011) 1-81, https://doi.org/10.4199/ c00024ed1v01y201012isp012.

[5] A. Michalinos, S. Zogana, E. Kotsiomitis, A. Mazarakis, T. Troupis, Anatomy of the ophthalmic artery: a review concerning its modern surgical and clinical applications, Anat Res Int 2015 (2015) 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/ 591961.

[6] S. Mishima, Clinical pharmacokinetics of the eye, Proctor lecture, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 21 (1981) 504.

[7] T. Yasukawa, Y. Ogura, Y. Tabata, H. Kimura, P. Wiedemann, Y. Honda, Drug delivery systems for vitreoretinal diseases, Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 23 (2004) 253-281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.02.003.

[8] R.C. Nagarwal, S. Kant, P.N. Singh, P. Maiti, J.K. Pandit, Polymeric nanoparticulate system: a potential approach for ocular drug delivery, J. Control. Release 136 (2009) 2-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.12.018.

[9] B.C. Harder, S. von Baltz, J.B. Jonas, F.C. Schlichtenbrede, Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 27 (2011) 623-627, https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2011.0060.

[10] V.-P. Ranta, E. Mannermaa, K. Lummepuro, A. Subrizi, A. Laukkanen, M. Antopolsky, L. Murtomäki, M. Hornof, A. Urtti, Barrier analysis of periocular drug delivery to the posterior segment, J. Control. Release 148 (2010) 42-48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.028.

[11] H. Nomoto, F. Shiraga, N. Kuno, E. Kimura, S. Fujii, K. Shinomiya, A.K. Nugent, K. Hirooka, T. Baba, Pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab after topical, subconjunctival, and intravitreal Administration in Rabbits, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50 (2009) 4807-4813, https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.08-3148.

[12] Y. Wang, D. Fei, M. Vanderlaan, A. Song, Biological activity of bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF antibody in vitro, Angiogenesis 7 (2004) 335-345, https:// doi.org/10.1007/S10456-004-8272-2/METRICS.

[13] R.K. Balachandran, V.H. Barocas, Computer modeling of drug delivery to the posterior eye: effect of active transport and loss to choroidal blood flow, Pharm. Res. 25 (2008) 2685-2696, https://doi.org/10.1007/S11095-008-9691-3/ FIGURES/6.

[14] P. Causin, F. Malgaroli, Mathematical assessment of drug build-up in the posterior eye following transscleral delivery, J. Math. Ind. 6 (2016) 1-19, https://doi.org/ 10.1186/S13362-016-0031-7/FIGURES/9.

[15] S. Molokhia, K. Papangkorn, C. Butler, J.W. Higuchi, B. Brar, B. Ambati, S.K. Li, W.I. Higuchi, Transscleral iontophoresis for noninvasive ocular drug delivery of macromolecules, Https://Home.Liebertpub.Com/Jop 36 (2020) 247-256, https://doi.org/10.1089/JOP.2019.0081.

[16] J.L. Paris, L.K. Vora, M.J. Torres, C. Mayorga, R.F. Donnelly, Microneedle array patches for allergen-specific immunotherapy, Drug Discov. Today 28 (2023) 103556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103556.

[17] L.K. Vora, K. Moffatt, R.F. Donnelly, 9 – Long-Lasting Drug Delivery Systems Based on Microneedles, in: E. Larrañeta, T.R.R. Singh, R.F.B.T.-L.-A.D.D. S. Donnelly (Eds.), Woodhead Publ Ser Biomater, Woodhead Publishing, 2022, pp. 249-287, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821749-8.00010-0.

[18] E. McAlister, M. Kirkby, J. Domínguez-Robles, A.J. Paredes, Q.K. Anjani, K. Moffatt, L.K. Vora, A.R.J. Hutton, P.E. McKenna, E. Larrañeta, R.F. Donnelly, The role of microneedle arrays in drug delivery and patient monitoring to prevent diabetes induced fibrosis, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 175 (2021) 113825, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.06.002.

[19] M.I. Nasiri, L.K. Vora, J.A. Ershaid, K. Peng, I.A. Tekko, R.F. Donnelly, A. Juhaina, Ershaid, I.A. Ke Peng, Tekko, R.F. Donnelly, Nanoemulsion-based dissolving microneedle arrays for enhanced intradermal and transdermal delivery, drug Deliv, Transl. Res. 1 (2021) 3, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-021-01107-0.

[20] L.K. Vora, A.H. Sabri, P.E. McKenna, A. Himawan, A.R.J. Hutton, U. Detamornrat, A.J. Paredes, E. Larrañeta, R.F. Donnelly, Microneedle-based biosensing, nature reviews, Bioengineering 2 (2024) 64-81, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44222-023-00108-7.

[21] A. Himawan, L.K. Vora, A.D. Permana, S. Sudir, A.R. Nurdin, R. Nislawati, R. Hasyim, C.J. Scott, R.F. Donnelly, Where microneedle meets biomarkers: futuristic application for diagnosing and monitoring localized external organ diseases, Adv Healthc Mater n/a 2202066 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1002/ adhm. 202202066.

[22] L.K. Vora, K. Moffatt, I.A. Tekko, A.J. Paredes, F. Volpe-Zanutto, D. Mishra, K. Peng, R.R.S. Thakur, R.F. Donnelly, Microneedle array systems for long-acting drug delivery, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 159 (2021) 44-76.

[23] Y. Wu, L.K. Vora, Y. Wang, M.F. Adrianto, I.A. Tekko, D. Waite, R.F. Donnelly, R. R.S. Thakur, Long-acting nanoparticle-loaded bilayer microneedles for protein delivery to the posterior segment of the eye, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 165 (2021) 306-318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.05.022.

[24] Y. Wu, L.K. Vora, R.F. Donnelly, T.R.R. Singh, Rapidly dissolving bilayer microneedles enabling minimally invasive and efficient protein delivery to the posterior segment of the eye, Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. (2022), https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s13346-022-01190-x.

[25] Y. Wu, L.K. Vora, D. Mishra, M.F. Adrianto, S. Gade, A.J. Paredes, R.F. Donnelly, T.R.R. Singh, Nanosuspension-loaded dissolving bilayer microneedles for hydrophobic drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye, Biomaterials Advances 137 (2022) 212767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.212767.

[26] A.A. Albadr, I.A. Tekko, L.K. Vora, A.A. Ali, G. Laverty, R.F. Donnelly, R.R. S. Thakur, Rapidly dissolving microneedle patch of amphotericin B for intracorneal fungal infections, Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. (2021), https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s13346-021-01032-2.

[27] F. Volpe-Zanutto, L.K. Vora, I.A. Tekko, P.E. McKenna, A.D. Permana, A.H. Sabri, Q.K. Anjani, H.O. McCarthy, A.J. Paredes, R.F. Donnelly, Hydrogel-forming microarray patches with cyclodextrin drug reservoirs for long-acting delivery of poorly soluble cabotegravir sodium for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, J. Control. Release 348 (2022) 771-785, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCONREL.2022.06.028.

[28] Y.A. Naser, I.A. Tekko, L.K. Vora, K. Peng, Q.K. Anjani, B. Greer, C. Elliott, H. O. McCarthy, R.F. Donnelly, Hydrogel-forming microarray patches with solid dispersion reservoirs for transdermal long-acting microdepot delivery of a hydrophobic drug, J. Control. Release 356 (2023) 416-433, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.03.003.

[29] M. Li, L.K. Vora, K. Peng, R.F. Donnelly, Trilayer microneedle array assisted transdermal and intradermal delivery of dexamethasone, Int. J. Pharm. 612 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121295.

[30] K. Peng, L.K. Vora, J. Domínguez-Robles, Y.A. Naser, M. Li, E. Larrañeta, R. F. Donnelly, Hydrogel-forming microneedles for rapid and efficient skin deposition of controlled release tip-implants, Mater. Sci. Eng. C 127 (2021) 112226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2021.112226.

[31] K. Glover, D. Mishra, S. Gade, L.K. Vora, Y. Wu, A.J. Paredes, R.F. Donnelly, T.R. R. Singh, Microneedles for advanced ocular drug delivery, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 201 (2023) 115082, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2023.115082.

[32] L.K. Vora, A.H. Sabri, Y. Naser, A. Himawan, A.R.J. Hutton, Q.K. Anjani, F. VolpeZanutto, D. Mishra, M. Li, A.M. Rodgers, A.J. Paredes, E. Larrañeta, R.R. S. Thakur, R.F. Donnelly, Long-acting microneedle formulations, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 201 (2023) 115055, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2023.115055.

[33] H. Abd-El-Azim, I.A. Tekko, A. Ali, A. Ramadan, N. Nafee, N. Khalafallah, T. Rahman, W. Mcdaid, R.G. Aly, L.K. Vora, S.J. Bell, F. Furlong, H.O. McCarthy, R. F. Donnelly, Hollow microneedle assisted intradermal delivery of hypericin lipid nanocapsules with light enabled photodynamic therapy against skin cancer, J. Control. Release (2022) S0168-3659(22)00365-0. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2022.06.027.

[34] S.R. Patel, A.S.P. Lin, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Suprachoroidal drug delivery to the back of the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 28 (2011) 166-176, https://doi.org/10.1007/S11095-010-0271-Y/FIGURES/7.

[35] J. Jiang, J.S. Moore, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 26 (2009) 395-403, https://doi. org/10.1007/S11095-008-9756-3/FIGURES/7.

[36] J. Jiang, J.S. Moore, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 26 (2009) 395-403, https://doi. org/10.1007/s11095-008-9756-3.

[37] S.S. Gade, S. Pentlavalli, D. Mishra, L.K. Vora, D. Waite, C.I. Alvarez-Lorenzo, M. R. Herrero Vanrell, G. Laverty, E. Larraneta, R.F. Donnelly, R.R.S. Thakur, Injectable depot forming Thermoresponsive hydrogel for sustained Intrascleral delivery of Sunitinib using hollow microneedles, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 38 (2022) 433-448, https://doi.org/10.1089/JOP.2022.0016.

[38] P. Dardano, S. De Martino, M. Battisti, B. Miranda, I. Rea, L. De Stefano, One-Shot Fabrication of Polymeric Hollow Microneedles by Standard Photolithography, Polymers 13 (2021) 520, https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM13040520.

[39] O. Khandan, M.Y. Kahook, M.P. Rao, Fenestrated microneedles for ocular drug delivery, Sensors Actuators B Chem. 223 (2016) 15-23, https://doi.org/10.1016/ J.SNB.2015.09.071.

[40] K. Ita, Ceramic microneedles and hollow microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: two decades of research, J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 44 (2018) 314-322, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JDDST.2018.01.004.

[41] J. Jiang, J.S. Moore, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 26 (2009) 395-403, https://doi. org/10.1007/S11095-008-9756-3/FIGURES/7.

[42] J.H. Kim, H.B. Song, K.J. Lee, I.H. Seo, J.Y. Lee, S.M. Lee, J.H. Kim, W. Ryu, Impact insertion of transfer-molded microneedle for localized and minimally invasive ocular drug delivery, J. Control. Release 209 (2015) 272-279, https:// doi.org/10.1016/J.JCONREL.2015.04.041.

[43] H. Kai, L. Liu, K. Nagamine, al -, C. Barrett, K. Dawson, S. Terashima, C. Tatsukawa, T. Takahashi, M. Suzuki, S. Aoyagi, Fabrication of hyaluronic acid hollow microneedle array, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59 (2020) SIIJ03, https://doi.org/ 10.35848/1347-4065/AB7312.

[44] M. Layani, X. Wang, S. Magdassi, Novel materials for 3D printing by Photopolymerization, Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1706344, https://doi.org/10.1002/ ADMA. 201706344.

[45] E. Neu, L. Render, M. Radtke, R. Nelz, Plasma treatments and photonic nanostructures for shallow nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond, Optical Materials Express, Vol. 9, Issue 12, Pp. 4716-4733. doi:https://doi.org/10.1364/ OME.9.004716.

[46] Y. Li, H. Zhang, R. Yang, Y. Laffitte, U. Schmill, W. Hu, M. Kaddoura, E.J. M. Blondeel, B. Cui, Fabrication of sharp silicon hollow microneedles by deepreactive ion etching towards minimally invasive diagnostics, Microsystems & Nanoengineering 5 (2019) 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-019-0077-y.

[47] E. Larrañeta, R.E.M. Lutton, A.D. Woolfson, R.F. Donnelly, Microneedle arrays as transdermal and intradermal drug delivery systems: materials science, manufacture and commercial development, Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 104 (2016) 1-32, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MSER.2016.03.001.

[48] M.A. Luzuriaga, D.R. Berry, J.C. Reagan, R.A. Smaldone, J.J. Gassensmith, Lab on a Chip Biodegradable 3D printed polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery

[49] S.N. Economidou, M.J. Uddin, M.J. Marques, D. Douroumis, W.T. Sow, H. Li, A. Reid, J.F.C. Windmill, A. Podoleanu, A novel 3D printed hollow microneedle microelectromechanical system for controlled, personalized transdermal drug delivery, Addit. Manuf. 38 (2021) 101815, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. ADDMA.2020.101815.

[50] P.R. Miller, M. Moorman, R.D. Boehm, S. Wolfley, V. Chavez, J.T. Baca, C. Ashley, I. Brener, R.J. Narayan, R. Polsky, Fabrication of hollow metal microneedle arrays using a molding and electroplating method, MRS Adv 4 (2019) 1417-1426, https://doi.org/10.1557/ADV.2019.147/METRICS.

[51] J. Jiang, J.S. Moore, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 26 (2009) 395-403, https://doi. org/10.1007/s11095-008-9756-3.

[52] M.A. Gosálvez, I. Zubel, E. Viinikka, Wet etching of silicon, handbook of silicon based MEMS, Mater. Technol. (2010) 447-480, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817786-0.00017-7.

[53] Y. Liu, P.F. Eng, O.J. Guy, K. Roberts, H. Ashraf, N. Knight, Advanced deep reactive-ion etching technology for hollow microneedles for transdermal blood sampling and drug delivery, IET Nanobiotechnol. 7 (2013) 59-62, https://doi. org/10.1049/IET-NBT.2012.0018.

[54] C.J.W. Bolton, O. Howells, G.J. Blayney, P.F. Eng, J.C. Birchall, B. Gualeni, K. Roberts, H. Ashraf, O.J. Guy, Hollow silicon microneedle fabrication using advanced plasma etch technologies for applications in transdermal drug delivery, Lab Chip 20 (2020) 2788-2795, https://doi.org/10.1039/D0LC00567C.

[55] Á. Cárcamo-Martínez, B. Mallon, J. Domínguez-Robles, L.K. Vora, Q.K. Anjani, R. F. Donnelly, Hollow microneedles: a perspective in biomedical applications, Int. J. Pharm. 599 (2021) 120455, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120455.

[56] A. Doraiswamy, A. Ovsianikov, S.D. Gittard, N.A. Monteiro-Riviere, R. Crombez, E. Montalvo, W. Shen, B.N. Chichkov, R.J. Narayan, Fabrication of microneedles using two photon polymerization for transdermal delivery of nanomaterials, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 10 (2010) 6305-6312, https://doi.org/10.1166/ JNN.2010.2636.

[57] K.B. Vinayakumar, P.G. Kulkarni, M.M. Nayak, N.S. Dinesh, G.M. Hegde, S. G. Ramachandra, K. Rajanna, A hollow stainless steel microneedle array to deliver insulin to a diabetic rat, J. Micromech. Microeng. 26 (2016) 065013, https://doi.org/10.1088/0960-1317/26/6/065013.

[58] M. Guvendiren, J. Molde, R.M.D. Soares, J. Kohn, Designing biomaterials for 3D printing, ACS Biomater Sci. Eng. 2 (2016) 1679-1693, https://doi.org/10.1021/ ACSBIOMATERIALS.6B00121/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AB-2016-00121K_0002. JPEG.

[59] V. Linares, M. Casas, I. Caraballo, Printfills: 3D printed systems combining fused deposition modeling and injection volume filling, Application to colon-specific drug delivery, European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 134 (2019) 138-143, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJPB.2018.11.021.

[60] S. Sarker, A. Colton, Z. Wen, X. Xu, M. Erdi, A. Jones, P. Kofinas, E. Tubaldi, P. Walczak, M. Janowski, Y. Liang, R.D. Sochol, 3D-printed microinjection needle arrays via a hybrid DLP-direct laser writing strategy, Adv Mater Technol 8 (2023) 2201641, https://doi.org/10.1002/ADMT. 202201641.

[61] S.D. Gittard, R.J. Narayan, Laser direct writing of micro- and nano-scale medical devices, Expert Rev. Med. Devices 7 (2010) 343-356, https://doi.org/10.1586/ ERD.10.14.

[62] M.A.S.R. Saadi, A. Maguire, N.T. Pottackal, M.S.H. Thakur, M.M. Ikram, A. J. Hart, P.M. Ajayan, M.M. Rahman, Direct ink writing: a 3D printing Technology for Diverse Materials, Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2108855, https://doi.org/10.1002/ ADMA. 202108855.

[63] W. Zapka, Pros and cons of inkjet Technology in Industrial Inkjet Printing, Handbook of Industrial Inkjet Printing: A Full System Approach 1-2 (2017) 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527687169.CH1.

[64] G. Huebner, I. Reinhold, W. Voit, O. Buergy, R. Askeland, J. Corrall, W. Zapka, Comparing inkjet with other printing processes, mainly screen printing, Inkjet Printing in Industry (2022) 57-92, https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527828074. CH4.

[65] W. Zapka, Handbook of Industrial Inkjet Printing: A Full System Approach 1-2, 2017, pp. 1-908, https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527687169.

[66] E. Mathew, G. Pitzanti, A.L. Gomes Dos Santos, D.A. Lamprou, Optimization of printing parameters for digital light processing 3d printing of hollow microneedle arrays, Pharmaceutics 13 (2021) 1837, https://doi.org/10.3390/ PHARMACEUTICS13111837/S1.

[67] O.A. Mohamed, S.H. Masood, J.L. Bhowmik, Optimization of fused deposition modeling process parameters: a review of current research and future prospects, Adv. Manuf. 3 (2015) 42-53, https://doi.org/10.1007/S40436-014-0097-7/ TABLES/2.

[68] M. Bhayana, J. Singh, A. Sharma, M. Gupta, A review on optimized FDM 3D printed wood/PLA bio composite material characteristics, Mater Today Proc (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATPR.2023.03.029.

[69] Z. Liu, Q. Lei, S. Xing, Mechanical characteristics of wood, ceramic, metal and carbon fiber-based PLA composites fabricated by FDM, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8 (2019) 3741-3751, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMRT.2019.06.034.

[70] M. Kariz, M. Sernek, M. Obućina, M.K. Kuzman, Effect of wood content in FDM filament on properties of 3D printed parts, Mater Today Commun 14 (2018) 135-140, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MTCOMM.2017.12.016.

[71] A.A. Bakır, R. Atik, S. Özerinç, Effect of fused deposition modeling process parameters on the mechanical properties of recycled polyethylene terephthalate parts, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138 (2021) 49709, https://doi.org/10.1002/ APP. 49709.

[72] M.A. Luzuriaga, D.R. Berry, J.C. Reagan, R.A. Smaldone, J.J. Gassensmith, Biodegradable 3D printed polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery, Lab Chip 18 (2018) 1223-1230, https://doi.org/10.1039/C8LC00098K.

[73] H. Brooks, D. Tyas, S. Molony, Tensile and fatigue failure of 3D printed parts with continuous fibre reinforcement, Int. J. Rapid Manuf. 6 (2017) 97, https://doi.org/ 10.1504/IJRAPIDM.2017.082152.

[74] S. Sarker, A. Colton, Z. Wen, X. Xu, M. Erdi, A. Jones, P. Kofinas, E. Tubaldi, P. Walczak, M. Janowski, Y. Liang, R.D. Sochol, 3D-printed microinjection needle arrays via a hybrid DLP-direct laser writing strategy, Adv Mater Technol 8 (2023) 2201641, https://doi.org/10.1002/ADMT. 202201641.

[75] A.S. Cordeiro, I.A. Tekko, M.H. Jomaa, L. Vora, E. McAlister, F. Volpe-Zanutto, M. Nethery, P.T. Baine, N. Mitchell, D.W. McNeill, Two-photon polymerisation 3D printing of microneedle array templates with versatile designs: application in the development of polymeric drug delivery systems, Pharm. Res. 37 (2020) 1-15.

[76] L.K. Vora, I.A. Tekko, F.V. Zanutto, A. Sabri, R.K.M. Choy, J. Mistilis, P. Kwarteng, C. Jarrahian, H.O. McCarthy, R.F. Donnelly, A bilayer microarray patch (MAP) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: the role of MAP designs and formulation composition in enhancing long-acting drug delivery, Pharmaceutics 16 (2024), https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16010142.

[77] S.P. Davis, M.R. Prausnitz, M.G. Allen, Fabrication and characterization of laser micromachined hollow microneedles, TRANSDUCERS 2003-12th international conference on solid-state sensors, Actuators and Microsystems, Digest of Technical Papers 2 (2003) 1435-1438, https://doi.org/10.1109/ SENSOR.2003.1217045.

[78] Z. Faraji Rad, R.E. Nordon, C.J. Anthony, L. Bilston, P.D. Prewett, J.-Y. Arns, C. H. Arns, L. Zhang, G.J. Davies, High-Fidelity Replication of Thermoplastic Microneedles With Open Microfluidic Channels 3, 2017, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/micronano.2017.34.

[79] Z. Faraji Rad, P.D. Prewett, G.J. Davies, High-resolution two-photon polymerization: the most versatile technique for the fabrication of microneedle arrays, Microsystems & Nanoengineering 7 (2021) 1-17, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41378-021-00298-3.

[80] A.C. Parenky, S. Wadhwa, H.H. Chen, A.S. Bhalla, K.S. Graham, M. Shameem, Container closure and delivery considerations for intravitreal drug administration, AAPS PharmSciTech 22 (2021) 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1208/ s12249-021-01949-4.

[81] A. Allmendinger, Y.L. Butt, C. Mueller, Intraocular pressure and injection forces during intravitreal injection into enucleated porcine eyes, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 166 (2021) 87-93, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJPB.2021.06.001.

[82] B. Wahlberg, H. Ghuman, J.R. Liu, M. Modo, Ex vivo biomechanical characterization of syringe-needle ejections for intracerebral cell delivery, Sci. Rep. 8 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-27568-X.

[83] M.S. Lhernould, Optimizing hollow microneedles arrays aimed at transdermal drug delivery, Microsyst. Technol. 19 (2013) 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1007/ S00542-012-1663-1/FIGURES/2.

[84] F. Akhter, G.N.W. Bascos, M. Canelas, B. Griffin, R.L. Hood, Mechanical characterization of a fiberoptic microneedle device for controlled delivery of fluids and photothermal excitation, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 112 (2020) 104042, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMBBM.2020.104042.

[85] R. Lyle Hood, M.A. Kosoglu, M. Parker, C.G. Rylander, Effects of microneedle design parameters on hydraulic resistance, Journal of Medical Devices, Transactions of the ASME 5 (2011) 1-5, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4004833/ 475592.

[86] N. Roxhed, B. Samel, L. Nordquist, P. Griss, G. Stemme, Painless drug delivery through microneedle-based transdermal patches featuring active infusion, IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 55 (2008) 1063-1071, https://doi.org/10.1109/ TBME.2007.906492.

[87] A. Rodríguez, D. Molinero, E. Valera, T. Trifonov, L.F. Marsal, J. Pallarès, R. Alcubilla, Fabrication of silicon oxide microneedles from macroporous silicon, Sensors Actuators B Chem. 109 (2005) 135-140, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. SNB.2005.03.015.

[88] A. Hejri, I.I. Bowland, J.M. Nickerson, M.R. Prausnitz, Suprachoroidal delivery in rats and Guinea pigs using a high-precision microneedle injector, Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 12 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1167/TVST.12.3.31.

[89] A. Hejri, I.I. Bowland, J.M. Nickerson, M.R. Prausnitz, Suprachoroidal delivery in rats and Guinea pigs using a high-precision microneedle injector, Transl Vis, Sci. Technol. 12 (2023) 31, https://doi.org/10.1167/TVST.12.3.31.

[90] G.E. Marshall, Human scleral elastic system: an immunoelectron microscopic study, Br. J. Ophthalmol. 79 (1995) 57-64, https://doi.org/10.1136/ BJO.79.1.57.

[91] E. Cone-Kimball, C. Nguyen, E.N. Oglesby, M.E. Pease, M.R. Steinhart, H. A. Quigley, Scleral structural alterations associated with chronic experimental intraocular pressure elevation in mice, Mol. Vis. 19 (2013) 2023. /pmc/articles/ PMC3783364/ (accessed July 1, 2023).

[92] C. Cunanan, Ophthalmologic applications: Glaucoma drains and implants, in: Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials, Third Edition, Elsevier Inc., 2013, pp. 940-946, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-087780-8.00080-2.

[93] T. Irimia, M.V. Ghica, L. Popa, V. Anuţa, A.L. Arsene, C.E. Dinu-Pîrvu, Strategies for improving ocular drug bioavailability and corneal wound healing with chitosan-based delivery systems, Polymers (Basel) 10 (2018), https://doi.org/ 10.3390/POLYM10111221.

[94] A. Mandal, R. Bisht, I.D. Rupenthal, A.K. Mitra, Polymeric micelles for ocular drug delivery: from structural frameworks to recent preclinical studies, J. Control. Release 248 (2017) 96, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCONREL.2017.01.012.

[95] S. Lin, C. Ge, D. Wang, Q. Xie, B. Wu, J. Wang, K. Nan, Q. Zheng, W. Chen, Overcoming the anatomical and physiological barriers in topical eye surface medication using a peptide-decorated polymeric micelle, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (2019) 39603-39612, https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSAMI.9B13851/ ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/AM9B13851_0009.JPEG.

[96] E.A. Mun, P.W.J. Morrison, A.C. Williams, V.V. Khutoryanskiy, On the barrier properties of the cornea: a microscopy study of the penetration of fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, polymers, and sodium fluorescein, Mol. Pharm. 11 (2014) 3556-3564, https://doi.org/10.1021/MP500332M/SUPPL_FILE/MP500332M_ SI_001.PDF.

[97] M.R. Prausnitz, Permeability of cornea, sclera, and conjunctiva: a literature analysis for drug delivery to the eye, J. Pharm. Sci. 87 (1998) 1479-1488, https://doi.org/10.1021/JS9802594.

[98] J. Mäenpää, O. Pelkonen, Cardiac safety of ophthalmic timolol, Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 15 (2016) 1549-1561, https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2016.1225718.

[99] N.D.A. S-, 1. 1 Retinal Vein Occlusion OZURDEX ® (dexamethasone intravitreal implant) is indicated for the treatment of macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) or central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). 1. 2 Posterior Segment Uveitis OZUR, 2014, pp. 4-17.

[100] E. Magill, S. Demartis, E. Gavini, A.D. Permana, R.R.S. Thakur, M.F. Adrianto, D. Waite, K. Glover, C.J. Picco, A. Korelidou, U. Detamornrat, L.K. Vora, L. Li, Q. K. Anjani, R.F. Donnelly, J. Domínguez-Robles, E. Larrañeta, Solid implantable devices for sustained drug delivery, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 199 (2023) 114950, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2023.114950.

[101] K. Peynshaert, J. Devoldere, A.-K. Minnaert, S.C. De Smedt, K. Remaut, Morphology and composition of the inner limiting membrane: species-specific variations and relevance toward drug delivery research, Curr. Eye Res. 44 (2019) 465-475, https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2019.1565890.

[102] E.A. Mun, P.W.J. Morrison, A.C. Williams, V.V. Khutoryanskiy, On the barrier properties of the cornea: a microscopy study of the penetration of fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, polymers, and sodium fluorescein, Mol. Pharm. 11 (2014) 3556-3564, https://doi.org/10.1021/MP500332M/SUPPL_FILE/MP500332M_ SI_001.PDF.

[103] R.G. Brewton, R. Mayne, Mammalian vitreous humor contains networks of hyaluronan molecules: electron microscopic analysis using the hyaluronanbinding region (G1) of aggrecan and link protein, Exp. Cell Res. 198 (1992) 237-249, https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4827(92)90376-J.

[104] Z.X. Ren, R.G. Brewton, R. Mayne, An analysis by rotary shadowing of the structure of the mammalian vitreous humor and zonular apparatus, J. Struct. Biol. 106 (1991) 57-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/1047-8477(91)90062-2.

[105] Q. Xu, N.J. Boylan, J.S. Suk, Y.Y. Wang, E.A. Nance, J.C. Yang, P.J. McDonnell, R. A. Cone, E.J. Duh, J. Hanes, Nanoparticle diffusion in, and microrheology of, the bovine vitreous ex vivo, J. Control. Release 167 (2013) 76-84, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/J.JCONREL.2013.01.018.

[106] K. Lee, S. Park, D.H. Jo, C.S. Cho, H.Y. Jang, J. Yi, M. Kang, J. Kim, H.Y. Jung, J. H. Kim, W. Ryu, A. Khademhosseini, Self-plugging microneedle (SPM) for intravitreal drug delivery, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 11 (2022) 2102599, https://doi. org/10.1002/adhm. 202102599 CO – AHMDBJ.

[107] P.A. Campochiaro, D.M. Marcus, C.C. Awh, C. Regillo, A.P. Adamis, V. Bantseev, Y. Chiang, J.S. Ehrlich, S. Erickson, W.D. Hanley, J. Horvath, K.F. Maass, N. Singh, F. Tang, G. Barteselli, The port delivery system with Ranibizumab for Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results from the randomized phase 2 ladder clinical trial, Ophthalmology 126 (2019) 1141-1154, https://doi. org/10.1016/J.OPHTHA.2019.03.036.

[108] E.R. Chen, P.K. Kaiser,

therapeutic potential of the Ranibizumab port delivery system in the treatment of AMD: evidence to date

, Clin. Ophthalmol. 14 (2020) 1349-1355, https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S194234.[109] B. Chiang, K. Wang, C. Ross Ethier, M.R. Prausnitz, Clearance kinetics and clearance routes of molecules from the Suprachoroidal space after microneedle injection, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58 (2017) 545, https://doi.org/10.1167/ IOVS.16-20679.

[110] S. Einmahl, M. Savoldelli, F. D’Hermies, C. Tabatabay, R. Gurny, F. Behar-Cohen, Evaluation of a novel biomaterial in the suprachoroidal space of the rabbit eye, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43 (2002) 1533-1539.

[111] E.M. Abarca, J.H. Salmon, B.C. Gilger, Effect of choroidal perfusion on ocular tissue distribution after intravitreal or Suprachoroidal injection in an arterially perfused ex vivo pig eye model, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 29 (2013) 715-722, https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2013.0063.

[112] T.W. Olsen, X. Feng, K. Wabner, K. Csaky, S. Pambuccian, J. Douglas Cameron, Pharmacokinetics of pars plana intravitreal injections versus microcannula suprachoroidal injections of bevacizumab in a porcine model, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52 (2011) 4749-4756, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6291.

[113] XIPERE® (triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension), SCS Microinjector® HCP Website (2024). https://www.xipere.com/hcp/scs-microinjector/ (accessed April 18, 2024).

[114] https://fyra.io, Achieving Drug Delivery Via the Suprachoroidal Space – Retina Today. https://retinatoday.com/articles/2014-july-aug/achieving-drug-delivery -via-the-suprachoroidal-space, 2024 (accessed April 18, 2024).

[115] J. Thomas, L. Kim, T. Albini, S. Yeh, Triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension for suprachoroidal use in the treatment of macular edema associated with uveitis, Expert Rev Ophthalmol 17 (2022) 165-173, https://doi.org/ 10.1080/17469899.2022.2114456.

[116] B. Gonenc, J. Chae, P. Gehlbach, R.H. Taylor, I. Iordachita, Towards RobotAssisted Retinal Vein Cannulation: A Motorized Force-Sensing Microneedle Integrated with a Handheld Micromanipulator †, Sensors 17 (2017) 2195, https:// doi.org/10.3390/S17102195.

[117] S. Lampen, R. Khurana, D.B.-… & V. Science, undefined 2018, Suprachoroidal Space Alterations after Delivery of Triamcinolone Acetonide: Post-Hoc Analysis of the Phase 1/2 HULK Study of Patients with Diabetic, Iovs.Arvojournals.OrgSIR Lampen, RN Khurana, DM Brown, CC WykoffInvestigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2018•iovs.Arvojournals.Org. https://iovs.arvojournals.org/articl e.aspx?articleid=2693633, 2024. (Accessed 18 April 2024).

[118] S. Lampen, R. Khurana, D.B.-… & V. Science, undefined 2018, Suprachoroidal Space Alterations after Delivery of Triamcinolone Acetonide: Post-Hoc Analysis of the Phase

[119] B. Gu, J. Liu, X. Li, Q.K. Ma, M. Shen, L. Cheng, Real-time monitoring of Suprachoroidal space (SCS) following SCS injection using ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography in Guinea pig eyes, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56 (2015) 3623-3634, https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.15-16597.

[120] K. Cholkar, S.R. Dasari, D. Pal, A.K. Mitra, Eye: anatomy, physiology and barriers to drug delivery, Ocular Transporters and Receptors: Their Role in Drug Delivery (2013) 1-36, https://doi.org/10.1533/9781908818317.1.

[121] D.A. Goldstein, D. Do, G. Noronha, J.M. Kissner, S.K. Srivastava, Q.D. Nguyen, Suprachoroidal corticosteroid administration: a novel route for local treatment of noninfectious uveitis, Transl Vis, Sci. Technol. 5 (2016) 4-11, https://doi.org/ 10.1167/tvst.5.6.14.

[122] Z. Habot-Wilner, G. Noronha, C.C. Wykoff, Suprachoroidally injected pharmacological agents for the treatment of chorio-retinal diseases: a targeted approach, Acta Ophthalmol. 97 (2019) 460-472, https://doi.org/10.1111/ AOS. 14042.

[123] H.F. Edelhauser, R.S. Verhoeven, B. Burke, C.B. Struble, S.R. Patel, Intraocular distribution and targeting of triamcinolone Acetonide suspension administered into the Suprachoroidal space, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55 (2014) 5259.

[124] B. Chiang, Y.C. Kim, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Circumferential flow of particles in the suprachoroidal space is impeded by the posterior ciliary arteries, Exp. Eye Res. 145 (2016) 424-431, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2016.03.008.

[125] L. Muya, V. Kansara, M.E. Cavet, T. Ciulla, Suprachoroidal injection of triamcinolone Acetonide suspension: ocular pharmacokinetics and distribution in rabbits demonstrates high and durable levels in the Chorioretina, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 38 (2022) 459, https://doi.org/10.1089/JOP.2021.0090.

[126] M. Figus, C. Posarelli, A. Passani, T.G. Albert, F. Oddone, A.T. Sframeli, M. Nardi, The supraciliary space as a suitable pathway for glaucoma surgery: ho-hum or

home run? Surv. Ophthalmol. 62 (2017) 828-837, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. SURVOPHTHAL.2017.05.002.

[127] M. Figus, C. Posarelli, A. Passani, T.G. Albert, F. Oddone, A.T. Sframeli, M. Nardi, The supraciliary space as a suitable pathway for glaucoma surgery: ho-hum or home run? Surv. Ophthalmol. 62 (2017) 828-837, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. SURVOPHTHAL.2017.05.002.

[128] S. Raghava, M. Hammond, U.B. Kompella, Periocular routes for retinal drug delivery, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 1 (2004) 99-114, https://doi.org/10.1517/ 17425247.1.1.99.

[129] K. Hosoya, M. Tachikawa, The inner blood-retinal barrier, in: C.Y. Cheng (Ed.), Biology and Regulation of Blood-Tissue Barriers, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Springer, New York, 2013.

[130] J. Barar, A.R. Javadzadeh, Y. Omidi, Ocular novel drug delivery: impacts of membranes and barriers, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 5 (2008) 567-581, https://doi. org/10.1517/17425247.5.5.567.

[131] Z. Shi, S.K. Li, P. Charoenputtakun, C.Y. Liu, D. Jasinski, P. Guo, RNA nanoparticle distribution and clearance in the eye after subconjunctival injection with and without thermosensitive hydrogels, J. Control. Release 270 (2018) 14-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCONREL.2017.11.028.

[132] Y.C. Kim, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Targeted delivery of antiglaucoma drugs to the supraciliary space using microneedles, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55 (2014) 7387-7397, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14651.

[133] J.H. Jung, B. Chiang, H.E. Grossniklaus, M.R. Prausnitz, Ocular drug delivery targeted by iontophoresis in the suprachoroidal space using a microneedle, J. Control. Release 277 (2018) 14-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2018.03.001.

[134] S.R. Patel, A.S.P. Lin, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Suprachoroidal drug delivery to the back of the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 28 (2011) 166-176, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-010-0271-y.

[135] C.Y. Lee, K. Lee, Y.S. You, S.H. Lee, H. Jung, Tower microneedle via reverse drawing lithography for innocuous intravitreal drug delivery, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2 (2013) 812-816, https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 201200239.

[136] A.P. Nesterov, S.N. Basinsky, A. Isaev, A new method for posterior sub-Tenon’s drug administration, Ophthalmic Surg. 24 (1993) 59-61.

[137] K.G. Falavarjani, J. Khadamy, A. Karimi Moghaddam, N. Karimi, M. Modarres, Posterior sub-tenon’s bevacizumab injection in diabetic macular edema; a pilot study, Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology 29 (2015) 270-273, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sjopt.2015.06.002.

[138] Y.C. Kim, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Targeted delivery of Antiglaucoma drugs to the Supraciliary space using microneedles, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55 (2014) 7387-7397, https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.14-14651.

[139] Y.C. Kim, H.E. Grossniklaus, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrastromal delivery of bevacizumab using microneedles to treat corneal neovascularization, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55 (2014) 7376-7386, https://doi.org/10.1167/ IOVS.14-15257.

[140] R. Gaudana, H.K. Ananthula, A. Parenky, A.K. Mitra, Ocular drug delivery, AAPS J. 12 (2010) 348, https://doi.org/10.1208/S12248-010-9183-3.

[141] C.M. Kumar, H. Eid, C. Dodds, Sub-Tenon’s anaesthesia: complications and their prevention, Eye (Lond.) 25 (2011) 694-703, https://doi.org/10.1038/ EYE.2011.69.

[142] B. Chiang, Y.C. Kim, A.C. Doty, H.E. Grossniklaus, S.P. Schwendeman, M. R. Prausnitz, Sustained reduction of intraocular pressure by supraciliary delivery of brimonidine-loaded poly(lactic acid) microspheres for the treatment of glaucoma, J. Control. Release 228 (2016) 48-57, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. JCONREL. 2016.02.041.

[143] S.R. Patel, A.S.P. Lin, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Suprachoroidal drug delivery to the back of the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 28 (2011) 166-176, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-010-0271-y.

[144] C.Y. Lee, K. Lee, Y.S. You, S.H. Lee, H. Jung, Tower microneedle via reverse drawing lithography for innocuous intravitreal drug delivery, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2 (2013) 812-816, https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 201200239.

[145] J. Jiang, J.S. Moore, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Intrascleral drug delivery to the eye using hollow microneedles, Pharm. Res. 26 (2009) 395-403, https://doi. org/10.1007/s11095-008-9756-3.

[146] C.Y. Lee, Y.S. You, S.H. Lee, H. Jung, Tower microneedle minimizes vitreal reflux in intravitreal injection, Biomed. Microdevices 15 (2013) 841-848, https://doi. org/10.1007/s10544-013-9771-y.

[147] M. Moster, A. Azuara-Blanco, Keep an eye out for bleb-related infections, Rev. Ophthalmol. (2003). https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/keep -an-eye-out-for-bleb-related-infections.

[148] S. Thoongsuwan, H.H.D. Lam, R.B. Bhisitkul, Bleb-associated infections after intravitreal injection, Retin Cases Brief Rep 5 (2011) 315-317, https://doi.org/ 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181f66bba.

[149] M.E. Verdugo, J. Alling, E.S. Lazar, M. Del Cerro, J. Ray, G. Aguirre, Posterior segment approach for subretinal transplantation or injection in the canine model, Cell Transplant. 10 (2001) 317-327, https://doi.org/10.3727/ 000000001783986710.

[150] E. Toropainen, S.J. Fraser-Miller, D. Novakovic, E.M. Del Amo, K.-S. Vellonen, M. Ruponen, T. Viitala, O. Korhonen, S. Auriola, L. Hellinen, M. Reinisalo, U. Tengvall, S. Choi, M. Absar, C. Strachan, A. Urtti, Biopharmaceutics of topical ophthalmic suspensions: importance of viscosity and particle size in ocular absorption of indomethacin, Pharmaceutics 13 (2021) 452, https://doi.org/ 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040452.

[151] A. Allmendinger, Y.L. Butt, C. Mueller, Intraocular pressure and injection forces during intravitreal injection into enucleated porcine eyes, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 166 (2021) 87-93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.06.001.

[152] Y.C. Kim, K.H. Oh, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Formulation to target delivery to the ciliary body and choroid via the suprachoroidal space of the eye using microneedles, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 95 (2015) 398-406, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.020.

[153] R.R.S. Thakur, S.J. Fallows, H.L. McMillan, R.F. Donnelly, D.S. Jones, Microneedle-mediated intrascleral delivery of in situ forming thermoresponsive implants for sustained ocular drug delivery, J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 66 (2014) 584-595, https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp. 12152.

[154] S.S. Gade, S. Pentlavalli, D. Mishra, L.K. Vora, D. Waite, C.I. Alvarez-Lorenzo, M. R. Herrero Vanrell, G. Laverty, E. Larraneta, R.F. Donnelly, R.R.S. Thakur, Injectable depot forming Thermoresponsive hydrogel for sustained Intrascleral delivery of Sunitinib using hollow microneedles, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 38 (2022) 433-448, https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2022.0016.

[155] W. Su, C. Liu, X. Jiang, Y. Lv, Q. Chen, J. Shi, H. Zhang, Q. Ma, C. Ge, F. Kong, X. Li, Y. Liu, Y. Chen, D. Qu, An intravitreal-injectable hydrogel depot doped borneol-decorated dual-drug-coloaded microemulsions for long-lasting retina delivery and synergistic therapy of wAMD, J Nanobiotechnology 21 (2023) 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1186/S12951-023-01829-Y/FIGURES/8.

[156] Allergan, Ozurdex (dexamethasone intravitreal implant) 0.7 mg , (2023). https ://hcp.ozurdex.com/ (accessed April 15, 2024).

[157] Y.C. Kim, K.H. Oha, H.F. Edelhauserb, M.R. Prausnitza, Formulation to target delivery to the ciliary body and choroid via the suprachoroidal space of the eye using microneedles, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 95 (2015) 398-406, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.020.

[158] Y.C. Kim, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Particle-stabilized emulsion droplets for gravity-mediated targeting in the posterior segment of the eye, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 3 (2014) 1272-1282, https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 201300696.

[159] B. Chiang, Y.C. Kim, A.C. Doty, H.E. Grossniklaus, S.P. Schwendeman, M. R. Prausnitz, Sustained reduction of intraocular pressure by supraciliary delivery of brimonidine-loaded poly(lactic acid) microspheres for the treatment of glaucoma, J. Control. Release 228 (2016) 48-57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2016.02.041.

[160] S.R. Patel, D.E. Berezovsky, B.E. McCarey, V. Zarnitsyn, H.F. Edelhauser, M. R. Prausnitz, Targeted administration into the Suprachoroidal space using a microneedle for drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53 (2012) 4433-4441, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.129872.

[161] B. Chiang, Y.C. Kim, H.F. Edelhauser, M.R. Prausnitz, Circumferential flow of particles in the suprachoroidal space is impeded by the posterior ciliary arteries, Exp. Eye Res. 145 (2016) 424-431, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2016.03.008.

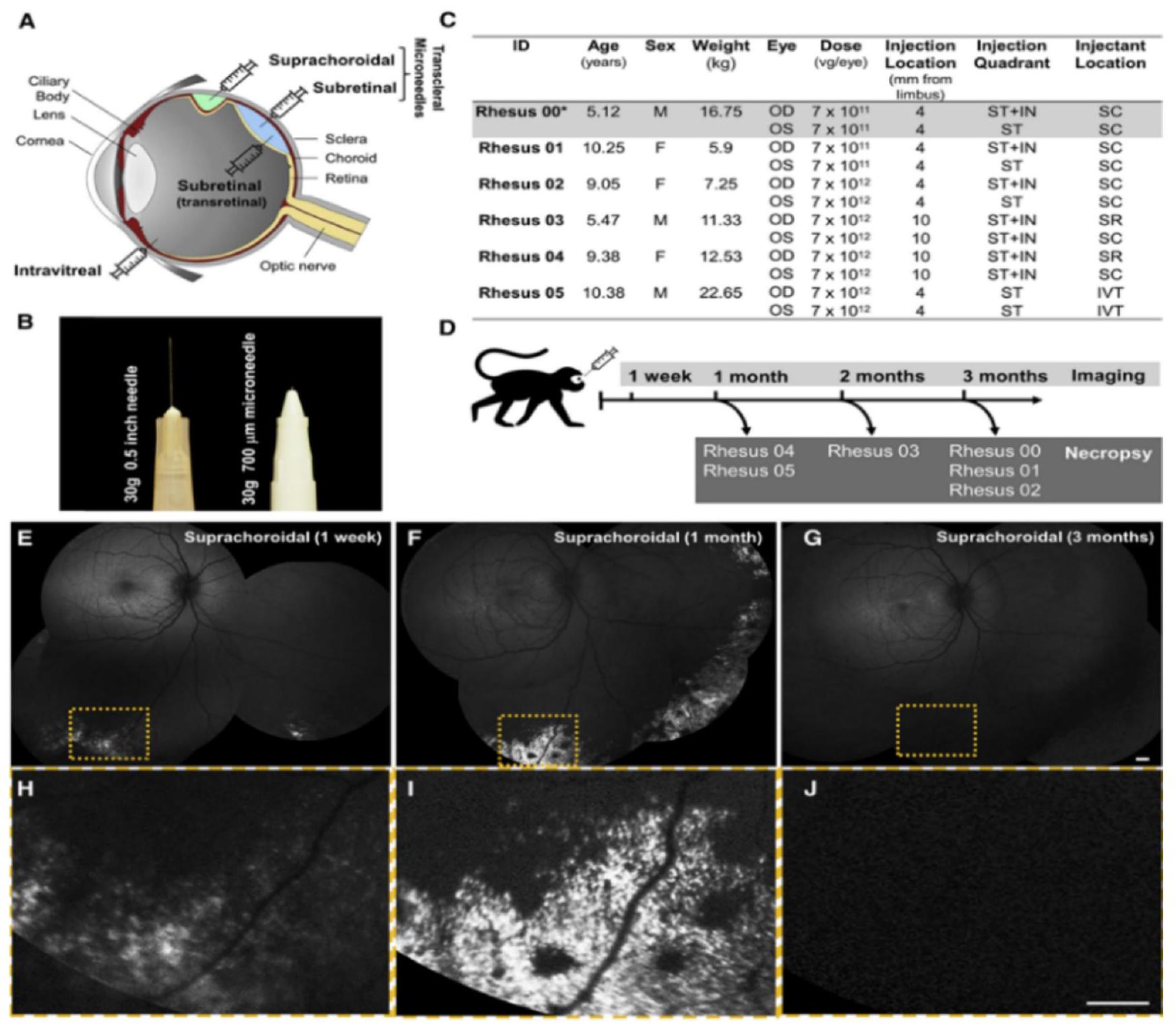

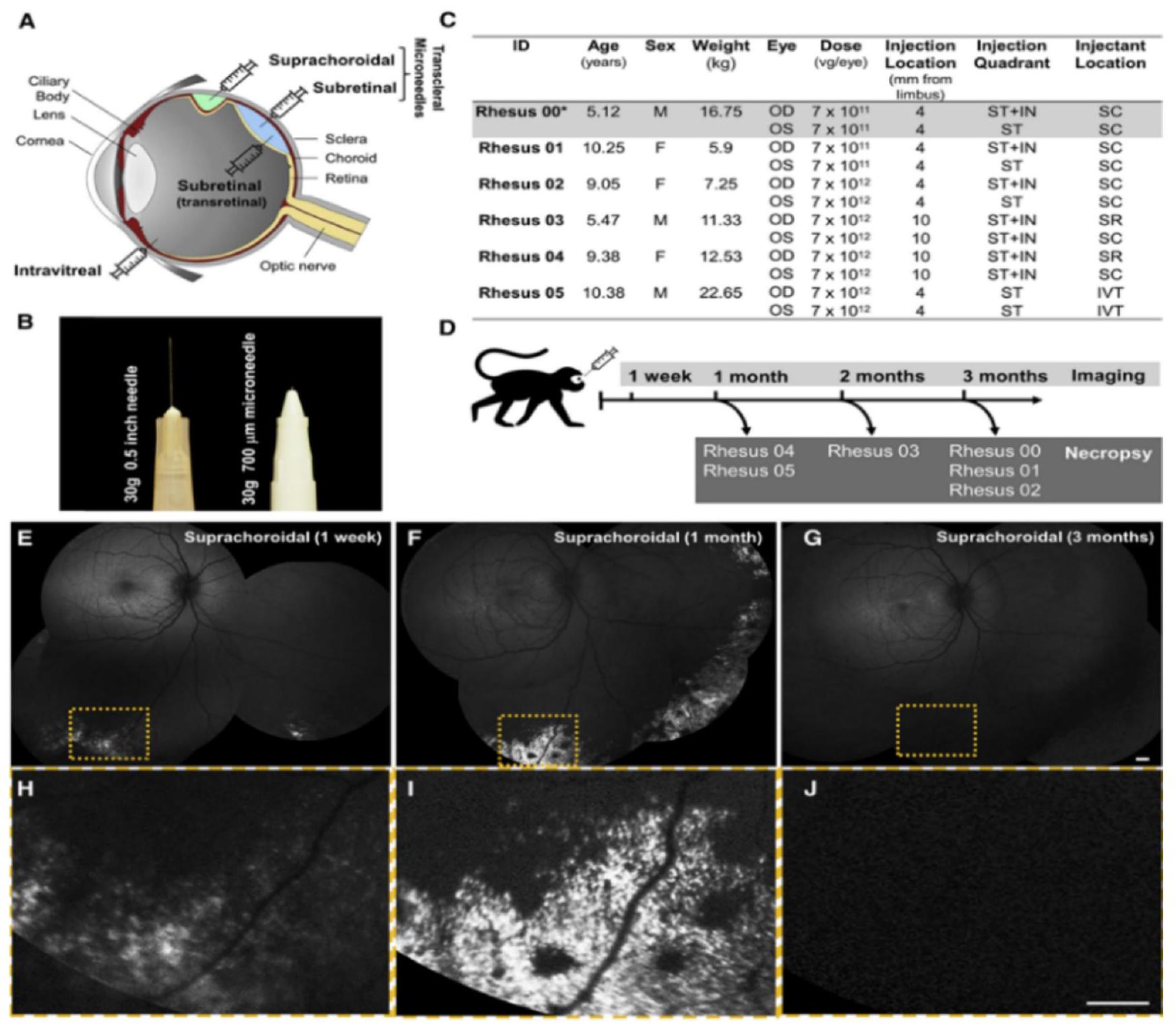

[162] G. Yiu, S.H. Chung, I.N. Mollhoff, U.T. Nguyen, S.M. Thomasy, J. Yoo, D. Taraborelli, G. Noronha, Suprachoroidal and subretinal injections of AAV using Transscleral microneedles for retinal gene delivery in nonhuman Primates, Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 16 (2020) 179-191, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. OMTM.2020.01.002.

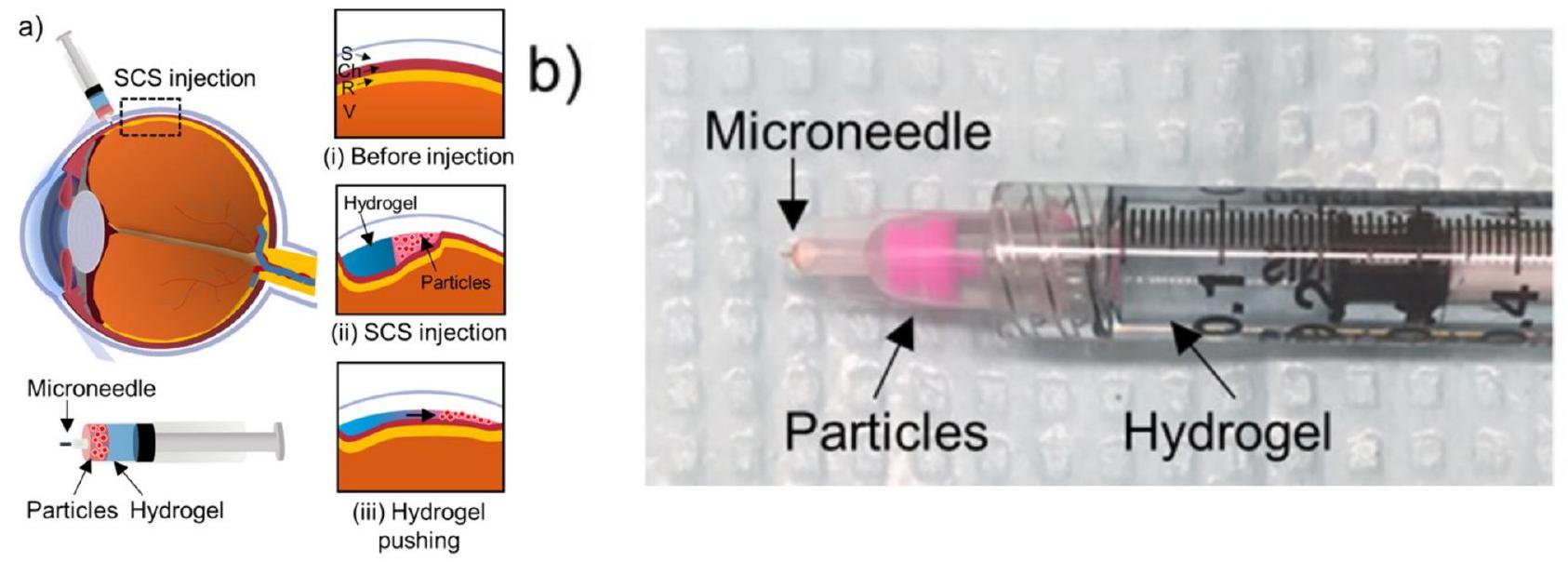

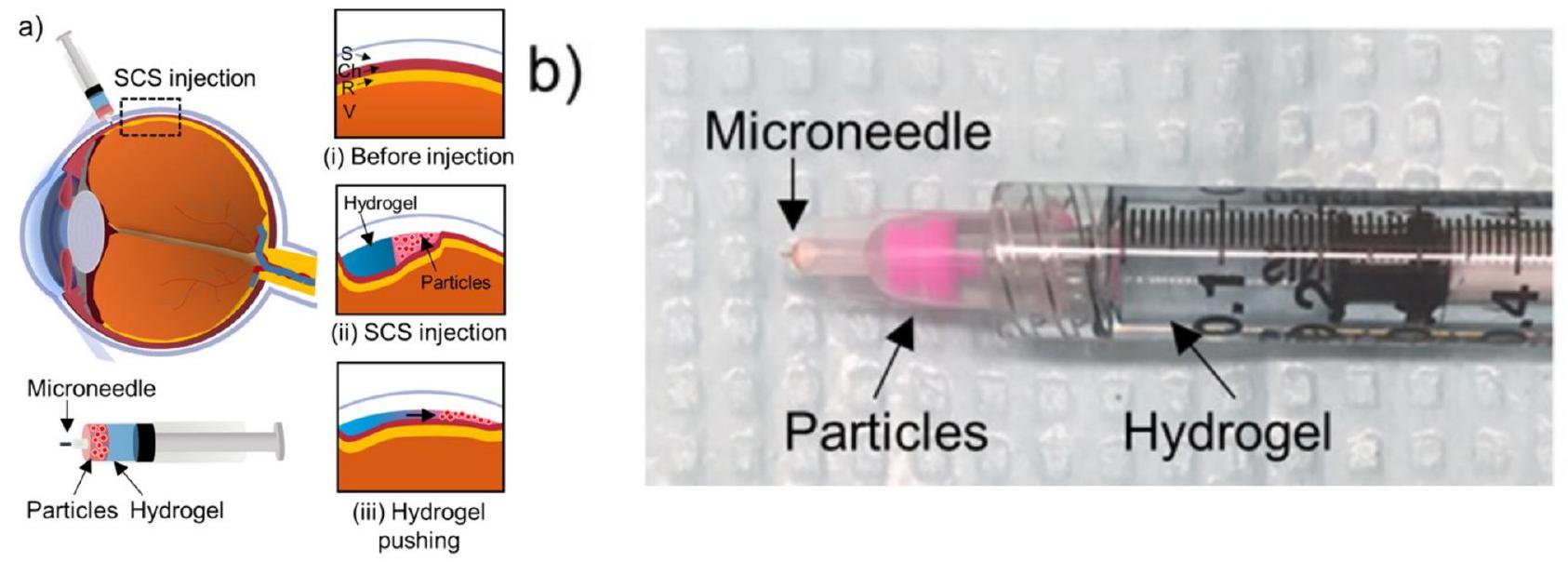

[163] J.H. Jung, P. Desit, M.R. Prausnitz, Targeted drug delivery in the Suprachoroidal space by swollen hydrogel pushing, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59 (2018) 2069-2079, https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.17-23758.

[164] G. Yiu, S.H. Chung, I.N. Mollhoff, U.T. Nguyen, S.M. Thomasy, J. Yoo, D. Taraborelli, G. Noronha, Suprachoroidal and subretinal injections of AAV using Transscleral microneedles for retinal gene delivery in nonhuman Primates, Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 16 (2020) 179-191, https://doi.org/10.1016/J. OMTM.2020.01.002.

[165] J.H. Jung, S. Park, J.J. Chae, M.R. Prausnitz, Collagenase injection into the suprachoroidal space of the eye to expand drug delivery coverage and increase posterior drug targeting, Exp. Eye Res. 189 (2019) 107824, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107824.

[166] O. Galvin, A. Srivastava, O. Carroll, R. Kulkarni, S. Dykes, S. Vickers, K. Dickinson, A.L. Reynolds, C. Kilty, G. Redmond, R. Jones, S. Cheetham, A. Pandit, B.N. Kennedy, A sustained release formulation of novel quininibhyaluronan microneedles inhibits angiogenesis and retinal vascular permeability in viv, J. Control. Release 223 (2016) 198-207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2016.04.004.

[167] D. Mitry, D.G. Charteris, B.W. Fleck, H. Campbell, J. Singh, The epidemiology of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: geographical variation and clinical associations, Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94 (2010) 678-684, https://doi.org/10.1136/ bjo.2009.157727.

[168] P.P. Storey, M. Pancholy, T.D. Wibbelsman, A. Obeid, D. Su, D. Borkar, S. Garg, O. Gupta, Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment after Intravitreal Injection of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, in: Ophthalmology, Elsevier Inc, in, 2019, pp. 1424-1431, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.04.037.

[169] S. Wu, K.C. Tang, Advanced subconjunctival anesthesia for cataract surgery, AsiaPacific, J. Ophthalmol. 7 (2018) 296-300, https://doi.org/10.22608/ APO. 2018231.

[170] J.H. Jung, B. Chiang, H.E. Grossniklaus, M.R. Prausnitz, Ocular drug delivery targeted by iontophoresis in the suprachoroidal space using a microneedle, J. Control. Release 277 (2018) 14-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2018.03.001.

[171] G. Mahadevan, H. Sheardown, P. Selvaganapathy, PDMS embedded microneedles as a controlled release system for the eye, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0885328211433778.

[172] R.R. Thakur Singh, I. Tekko, K. McAvoy, H. McMillan, D. Jones, R.F. Donnelly, Minimally invasive microneedles for ocular drug delivery, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 14 (2017) 525-537, https://doi.org/10.1080/17425247.2016.1218460 CO – EODDAW.

[173] B. Chiang, Y.C. Kim, A.C. Doty, H.E. Grossniklaus, S.P. Schwendeman, M. R. Prausnitz, Sustained reduction of intraocular pressure by supraciliary delivery of brimonidine-loaded poly(lactic acid) microspheres for the treatment of glaucoma, J. Control. Release 228 (2016) 48-57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jconrel.2016.02.041.

- Abbreviations: AMD, Age-related macular degeneration; amp B, Amphotericin B; AS, Anterior segment; BCVA, Best corrected visual acuity; CMC, Carboxymethylcellulose; DR, Diabetic retinopathy; DRIE, Deep reactive ion etching; FDM, Fused deposition modeling; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GAGs, Glycosaminoglycans; HMN, Hollow microneedle; IOP, Intraocular pressure; IVT, Intravitreal injections; LDW, Laser direct writing; LPCA, Long posterior ciliary artery; MC, Methylcellulose; MN, Microneedle; NEI, National Eye Institute; OCT, Optical coherence tomography; PDS, Port delivery system; PS, Posterior segment; Re, Reynolds number; RPE, Retinal pigment epithelium; SCS, Suprachoroidal space; SPCA, Short posterior ciliary artery; TNF-alpha, Tumor necrosis factor alpha; TTR, Tear turnover rate; VAS, Visual analog scale; VH, Vitreous humor.

- Corresponding authors.

E-mail addresses: L.vora@qub.ac.uk (L.K. Vora), r.thakur@qub.ac.uk (R.R.S. Thakur).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.05.013

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38735395

Publication Date: 2024-05-22

Hollow microneedles for ocular drug delivery

Published in:

Document Version:

Queen’s University Belfast – Research Portal:

Publisher rights

This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited.

General rights

Take down policy

Open Access

Hollow microneedles for ocular drug delivery

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Minimally invasive

Suprachoroidal

Optical coherence tomography

Uveitis

Vasculature

Nanoparticles

Microparticles

Periocular

Transscleral

Abstract

Microneedles (MNs) are micron-sized needles, typically

1. Introduction

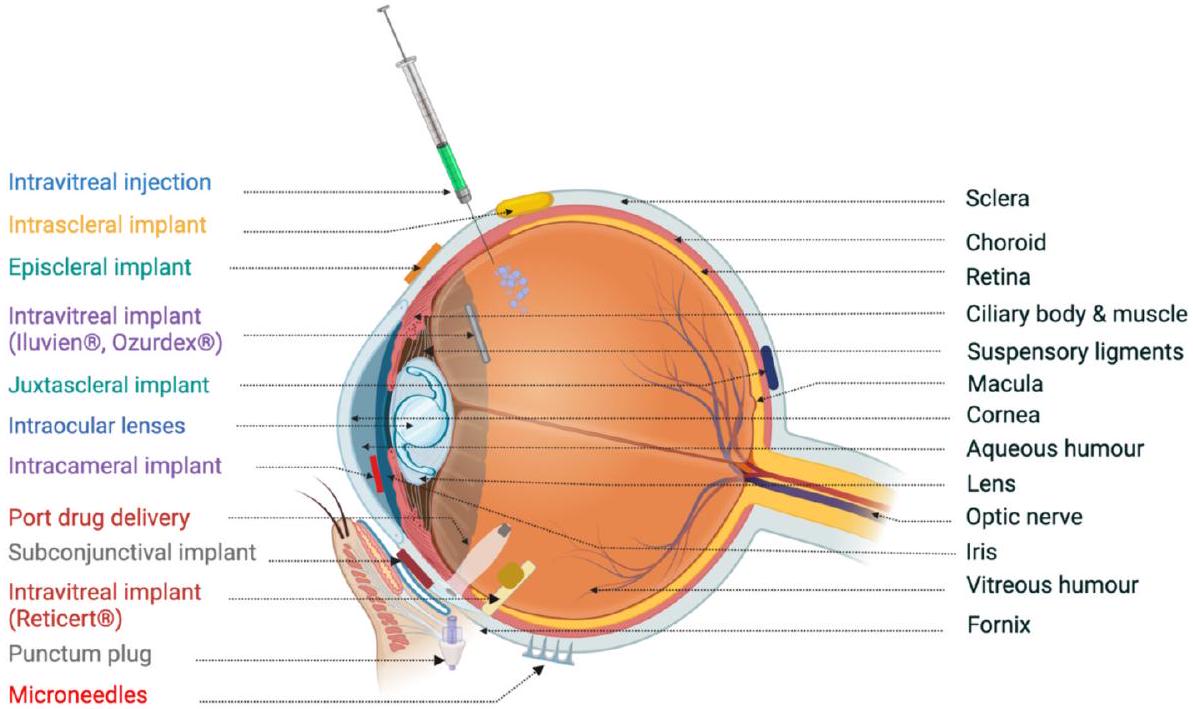

administration of such drugs may lead to systemic side effects. Another widely prescribed medication for treating posterior ocular diseases is intravitreal injections. Although they are highly invasive and risk bearing, these intravitreal injections of potential therapeutics are prescribed due to potential advantages [8]. Currently, intravitreal injections of monoclonal antibodies, namely, bevacizumab and ranibizumab, are being tested for their ability to treat blindness-causing neovascular diseases, including retinopathy of prematurity [9]. These frequent intravitreal injections are associated with several short-term adverse events, such as endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, intravitreal hemorrhage, and a high risk of cataracts. More recently, periocular injections have been investigated as less invasive methods to achieve therapeutic results in the vitreous cavity. The subventricular, subconjunctival, and peribulbar routes involve periocular injections. These routes of administration are less invasive but are required to overcome the scleral, choroidal or RPE barrier to reach the site of administration [10].

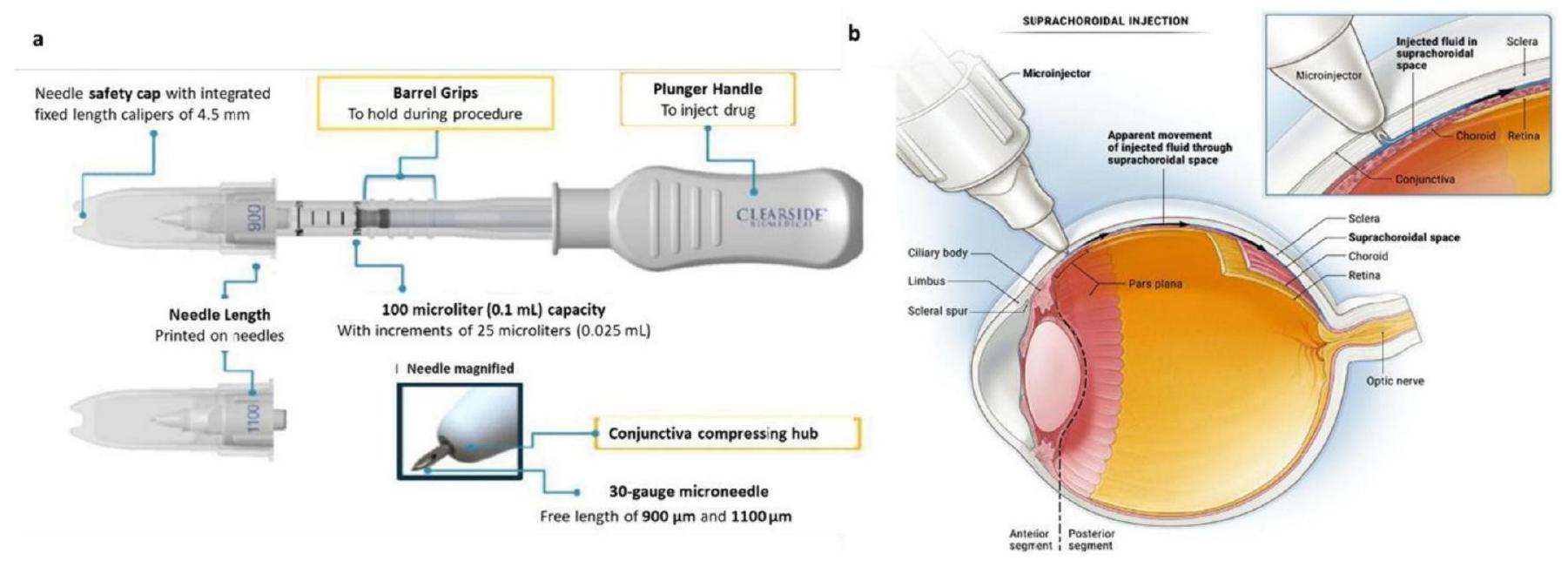

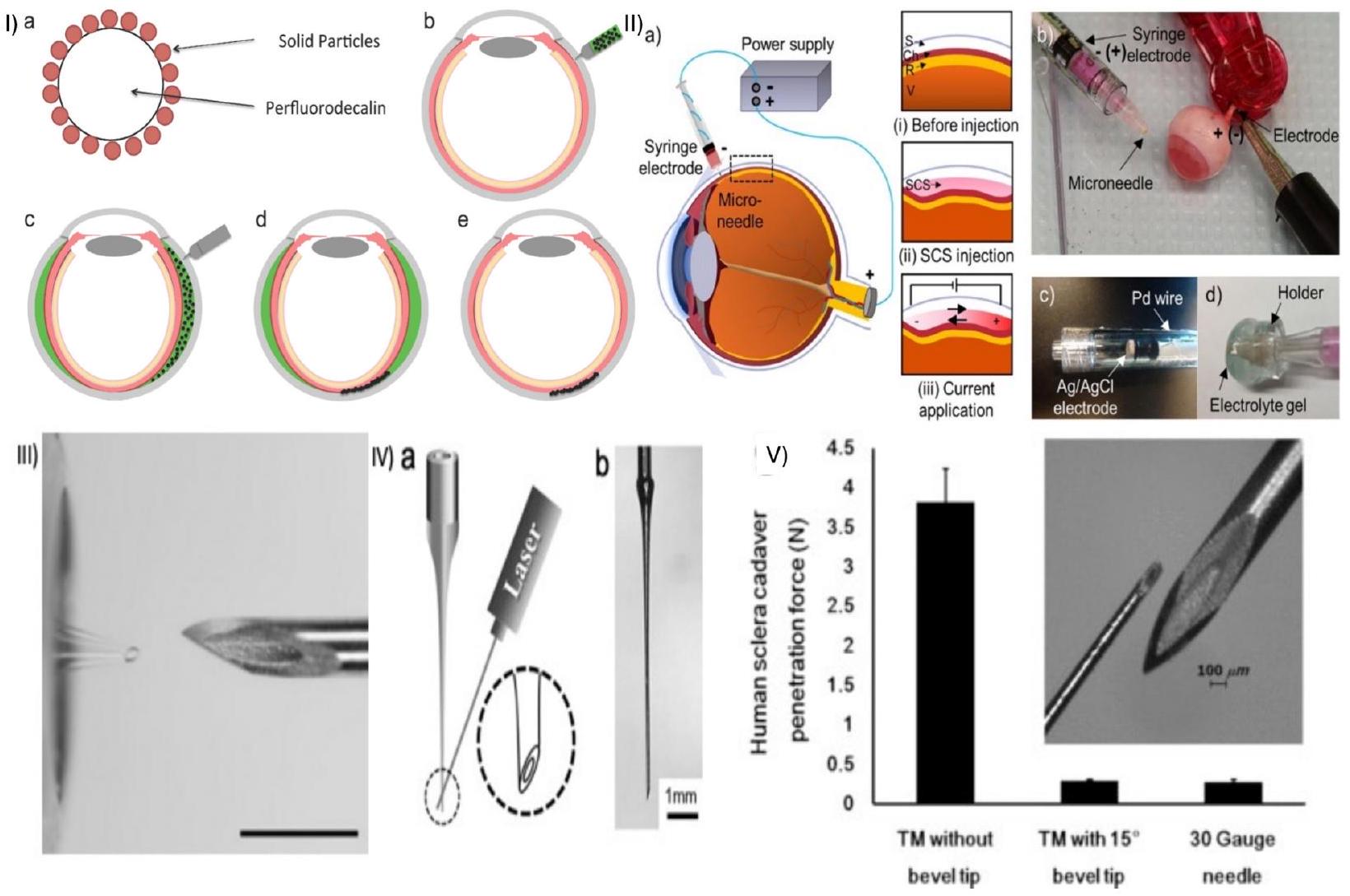

2. Hollow MNs

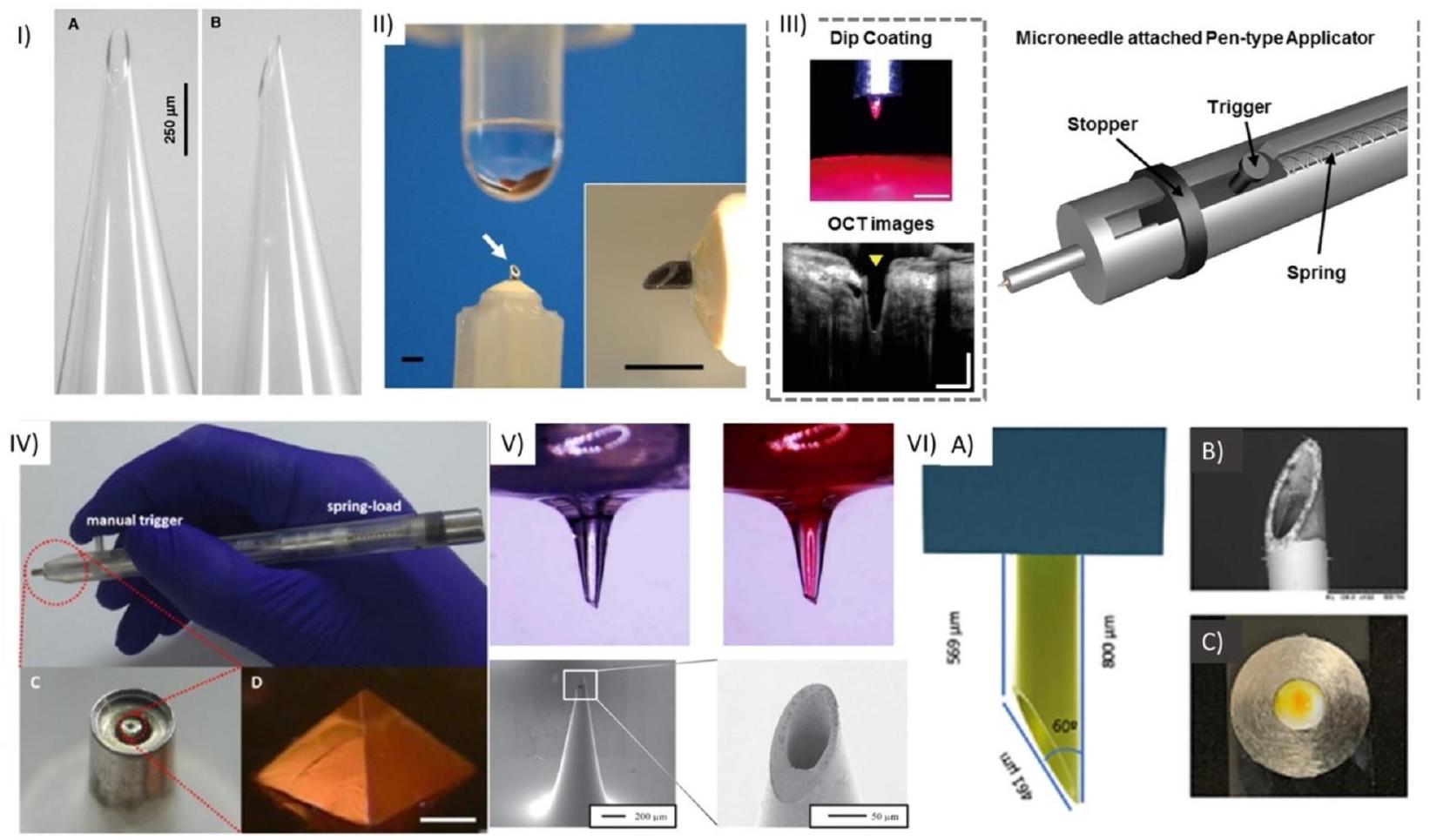

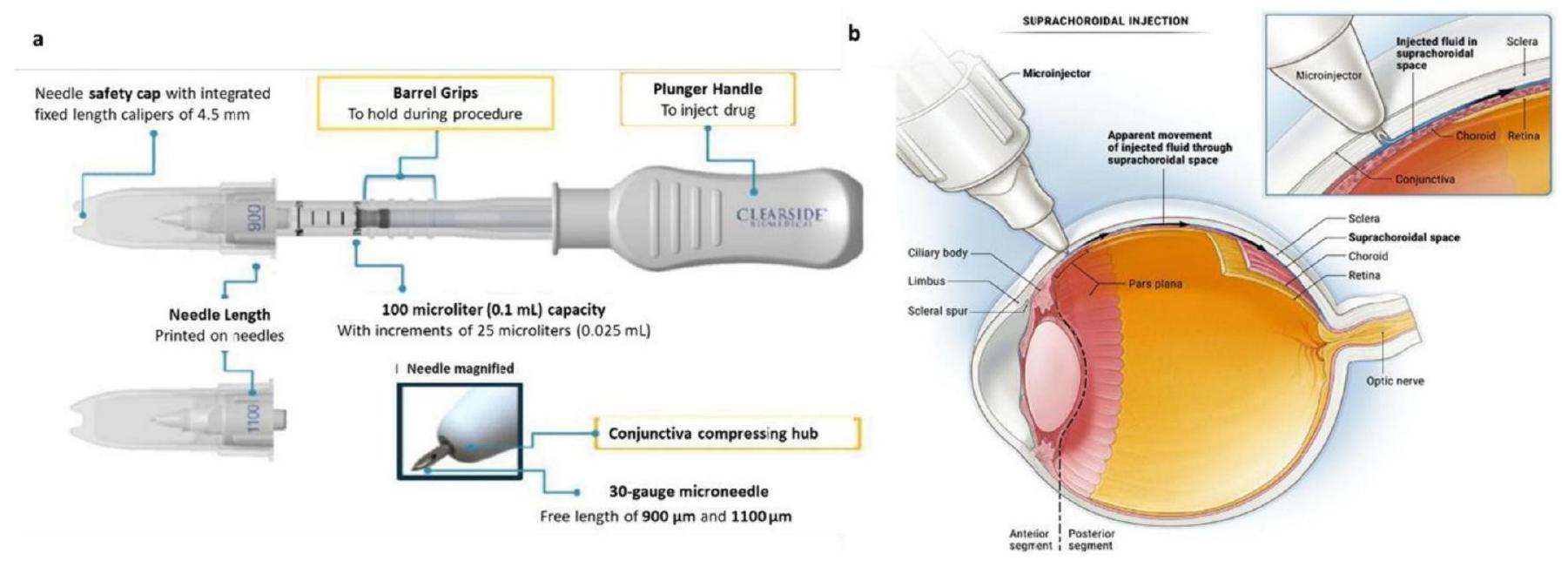

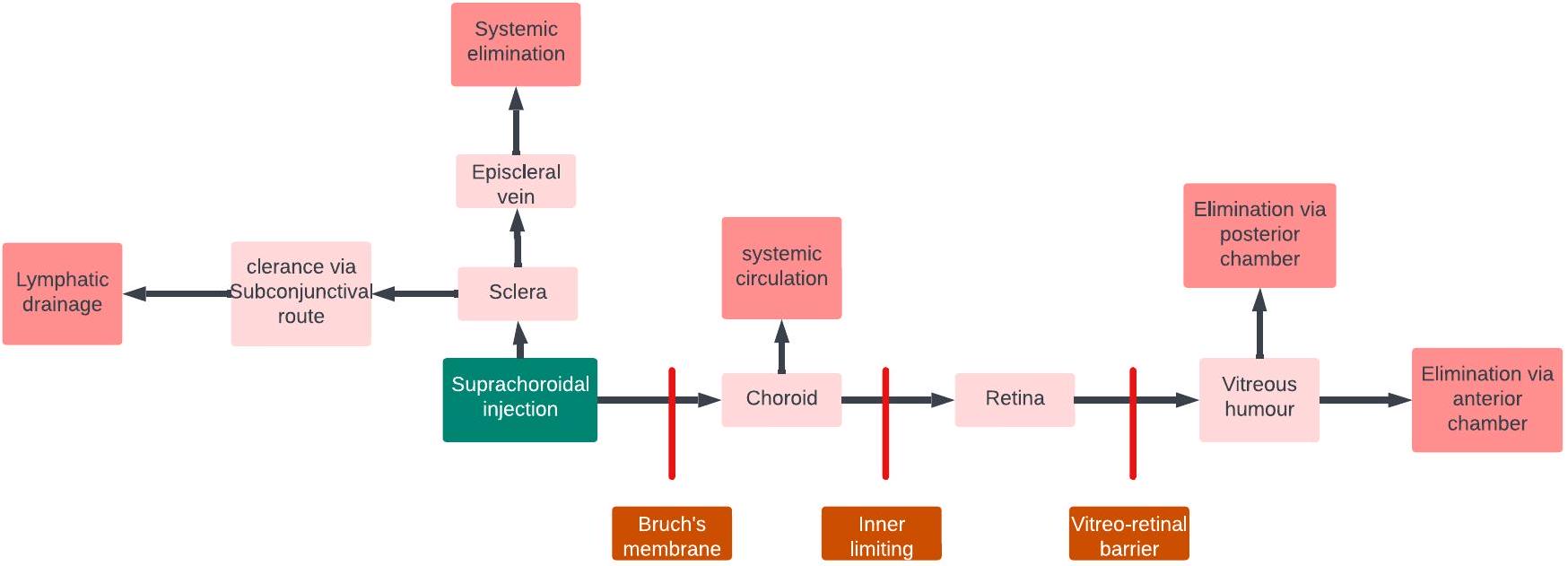

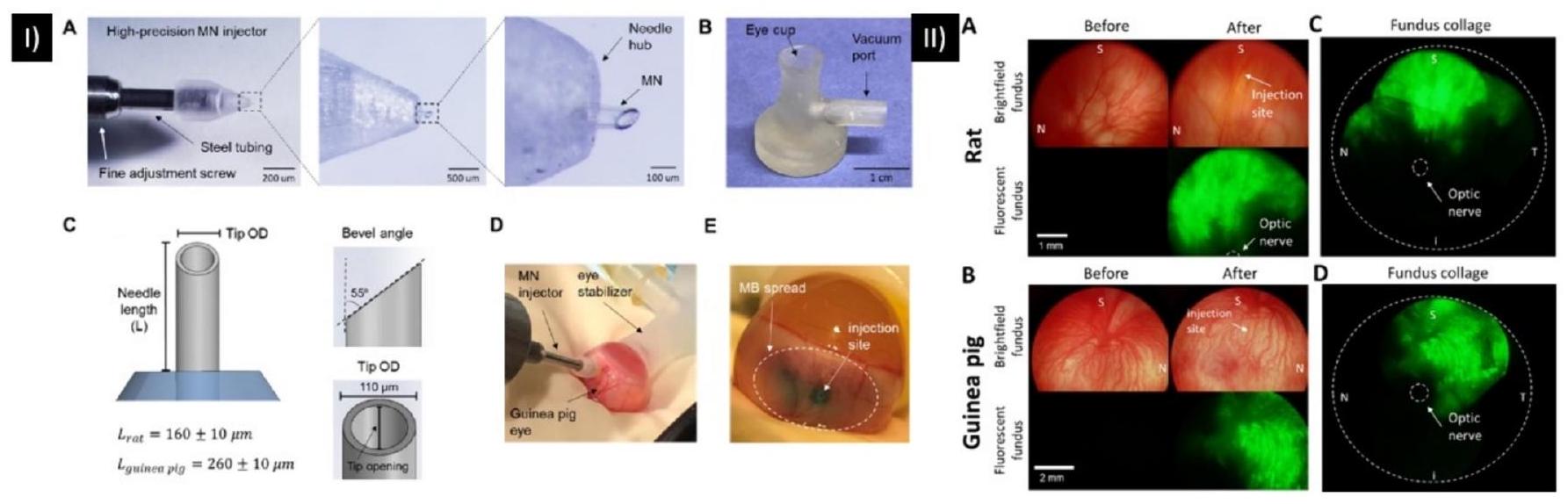

delivery, aiming to improve treatment outcomes for eye diseases. These microneedles offer precise and targeted delivery of medications to specific ocular tissues, such as the cornea or anterior chamber. By bypassing ocular barriers, they enhance drug bioavailability, ensuring higher drug concentrations at the desired site while minimizing systemic side effects. The ultrafine dimensions and reduced invasiveness of HMNs make them less uncomfortable for patients. Their controlled dosage capabilities enable accurate drug administration, and they may also have potential for ocular fluid sampling or diagnostics [34,35]. HMNs have been fabricated using various materials, including borosilicate glass [36] (Fig. 1 I), metal [37] (Fig. 1 II, III, V, VI), polymer [38] (Fig. 1 VI), titanium [39], ceramic [40], and silicon (Fig. 1 VII), which incorporate a bore through the MN structure (Fig. 1).

2.1. Manufacturing of HMNs

fabrication methods have been employed for HMNs, depending on the properties of the material from which the MN will be created [44]. This section focuses on HMNs, their fabrication, and their ocular application (Table 1).

2.1.1. Subtractive manufacturing

2.1.1.1. Photolithography. The most common method for HMN fabrication is photolithography in conjunction with either deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) or wet etching. Photolithography is a technique used to transfer a pattern from a mask to a wafer in three steps. Silicon wafers are coated with a thin layer of photoresist either by spin or spray coating. These coated wafers are then exposed to UV light through a photomask and finally developed to remove residual resist, revealing the features of the mask [44]. The final structures are obtained using either wet or dry etching methods (Fig. 2A). Wet etching uses an alkaline or acidic solution known as an etchant to etch unprotected regions of the wafer. This method for silicon etching is advantageous due to its simplicity, easy implementation and high etching rate, which in turn prevents destruction of the protective layer [52]. Despite these advantages, there are many significant disadvantages, such as high costs and the inability to maintain the same initial etch rate throughout the process [45]. Due to the prevalence of disadvantages, DRIE etching is used more frequently than wet etching processes. DRIE, also known as the Bosch process, is a highly anisotropic technique for creating silicon structures [53]. The Bosch process utilizes three steps: the deposition of a polymer layer, the removal of the deposited layer and then a silicon

Summary of manufacturing techniques used for HMNs made from different materials.

| Material | Fabrication Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| Silicon | Photolithography followed by wet etching | Simple, easy implementation, | Expensive, incapability in maintaining initial etch rate | [45] |

| Photolithography followed by DRIE | High anisotropic etching leads to finer resolution, high aspect ratio | Expensive, Complicated fabrication processes | [46] | |

| Polymer | Micromoulding | Simple and low cost | Poor mechanical strength | [47] |

| 3D printing using fused deposition modeling | Versatile, cost effective and can print renewable materials | Lower resolution printing and therefore is incapable of printing finer structures | [48] | |

| 3D printing using laser SLA | Autoclavable meaning the MNs can be sterilized, Biocompatible polymer used, cost effective, uniform, and reproducible | Top bore opening is challenging that leading to decreased sharpness and inferior piercing capabilities | [49] | |

| Metal | Infrared laser micromachining | Rapid production and the range of materials can be expanded | Limitation in the height of the MNs produced and the sidewalls are rough | [49] |

| Two photon polymerization systems with Laser direct write and molding | High precision, reproducible, high accuracy and control, high feature resolution | High cost of equipment, slow (usually takes

|

[50] | |

| Borosilicate glass | Pipette pulling | Inert | Long fabrication method, Delicate/fragile | [51] |

2.1.1.2. Electron discharge machining (EDM). Electron discharge machining (EDM), a subtractive manufacturing technique, has been

utilized for synthesizing HMNs with remarkable precision. EDM works on the principle of electrical discharge to shape conductive materials. EDM offers exceptional control over the machining process, especially in the context of HMN synthesis, which requires control over geometries to produce shapes (needles) with a high aspect ratio. EDM operates by creating a controlled spark discharge between an electrode and the

metal (called the workpiece), typically stainless steel or titanium. The dielectric fluid surrounding the electrical discharge acts as a coolant and removes the debris generated during the process. This dielectric fluid also serves as an electrical insulator, preventing a continuous arc between the electrode and the workpiece. For HMN synthesis, the electrode is typically made from a conductive material, such as copper or graphite, and is carefully shaped to match the desired MN geometry. Vinaykumar et al. prepared HMNs with a height of

2.1.2. Additive manufacturing technique

2.1.2.1. Fused deposition modeling. Polymeric HMNs can be fabricated via 3D printing using fused deposition modeling (FDM). The technique was developed in 1989 by Scott Crump. FDM is a technique that melts material into a liquid state in a liquefier head, and this liquid is then selectively deposited through the nozzle to produce a 3D structure directly from a computer aided design (CAD) model in a layer-by-layer manner [67]. Various types of materials can be used, such as poly-lactic acid (PLA), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polyethylene terephthalate PETT (t-glase), wood and metal filaments [68-71]. This

method is versatile and cost effective and can be used to print renewable materials, but there are major limitations. The printing process has lower resolution and therefore is unable to make finer structures [72]. Another variation of FDM printing is the continuous fiber fabrication method (CFF), which enhances the strength of parts printed using 3D printing [73]. Namiki et al. utilized the CFF method for the fabrication of carbon fiber PLA composites, and the tensile strength of fibers was

2.1.3. Two-photon polymerizations

2.2. HMN properties for ocular drug delivery

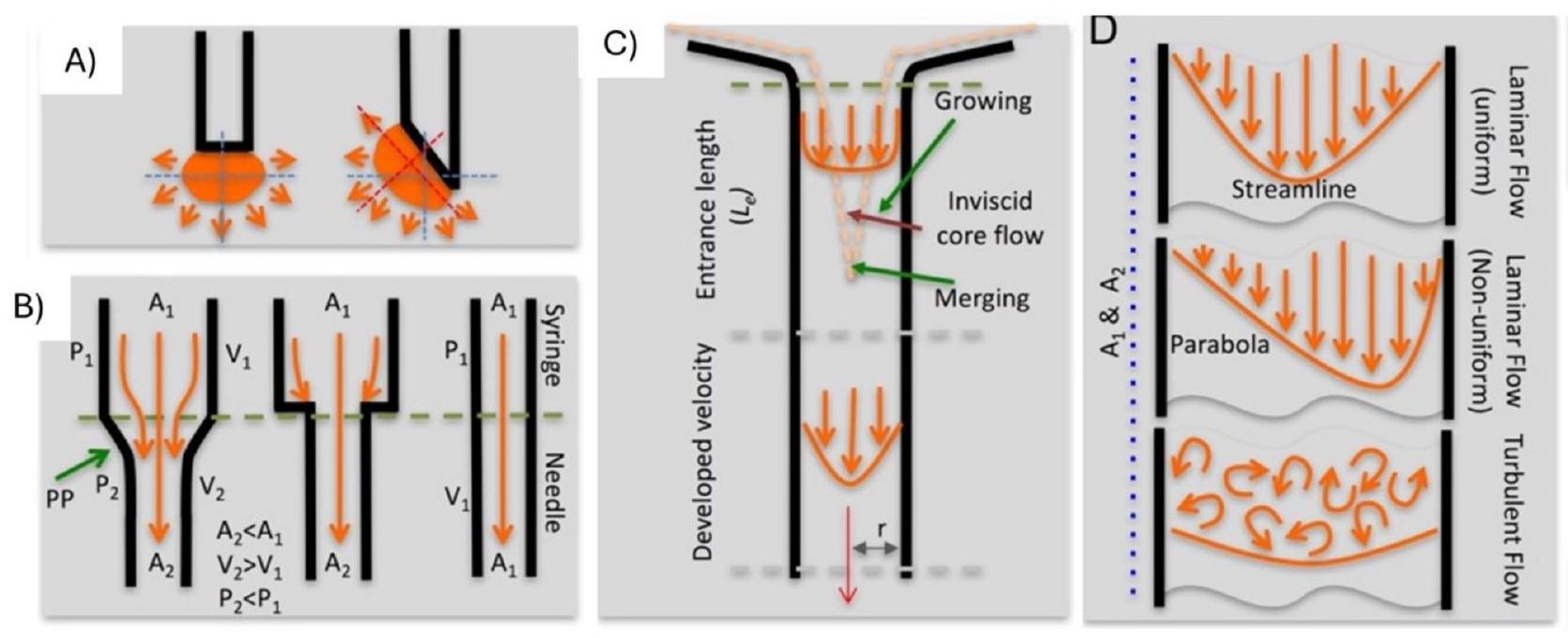

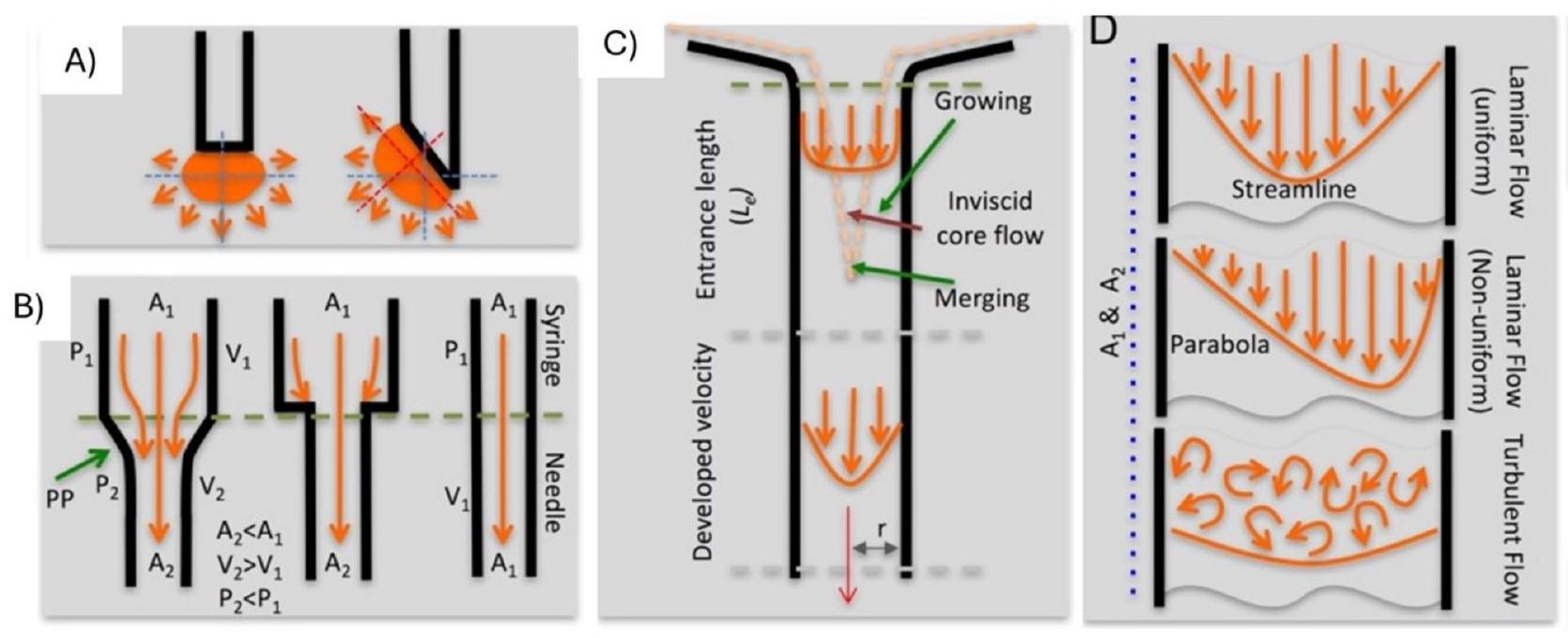

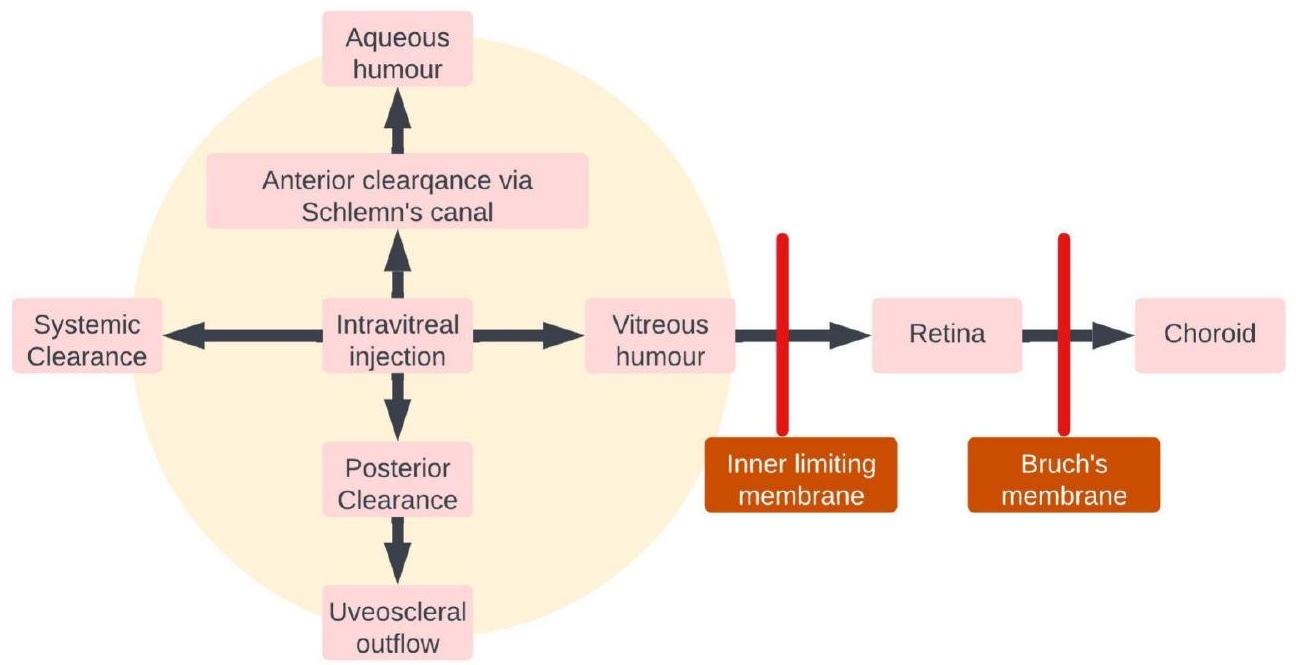

strength of HMNs. The bore diameter, bevel angle, and adapter design are critical factors that significantly influence the successful penetration of HMNs into ocular tissues while minimizing invasiveness. Moreover, the force exerted during injection is an essential criterion to ensure minimal tissue damage. This section details the essential properties of HMNs for minimally invasive ocular drug delivery.

2.2.1. Significance of the bore diameter and force of injection

2.2.2. Effect of adapter design on insertion

hub diameter and a is the length of the needle, as described in Fig. 4. This study developed a robust MN delivery technique for SCS injection in rats and guinea pigs by controlling and optimizing MN dimensions, tissue-hub interactions, and eye stabilization during injection. Targeted delivery was accomplished with a high success rate in rats and guinea pigs using a simple, one-step injection method [88].

2.2.3. Effect of the bevel angle on drug delivery

3. Drug distribution and site of administration

more conventional, nonlocalized approaches, such as intravitreal delivery and topical delivery, will also be made.

3.1. Drug distribution following topical administration

as the ciliary body and lens. Due to the flow of aqueous humor from the front of the eye, distribution into the posterior chamber is very unlikely. Moreover, drugs can permeate into the conjunctiva as opposed to the cornea. This route is typically adopted by large hydrophilic molecules, which then bypass the cornea by moving through the conjunctiva and sclera before moving into tissue structures such as the ciliary body. Given the greater permeability of this tissue in comparison to the cornea [98], this poses a significant challenge for topical delivery and highlights its lack of tissue specificity in comparison to the SCS administration route, for example. Once absorbed into the conjunctiva, the drug is completely cleared from the eye via systemic circulation. This in itself can cause issues, with commonly applied drugs such as beta blockers such as timolol being shown to have off-target effects such as cardiac issues such as bradycardia [98].

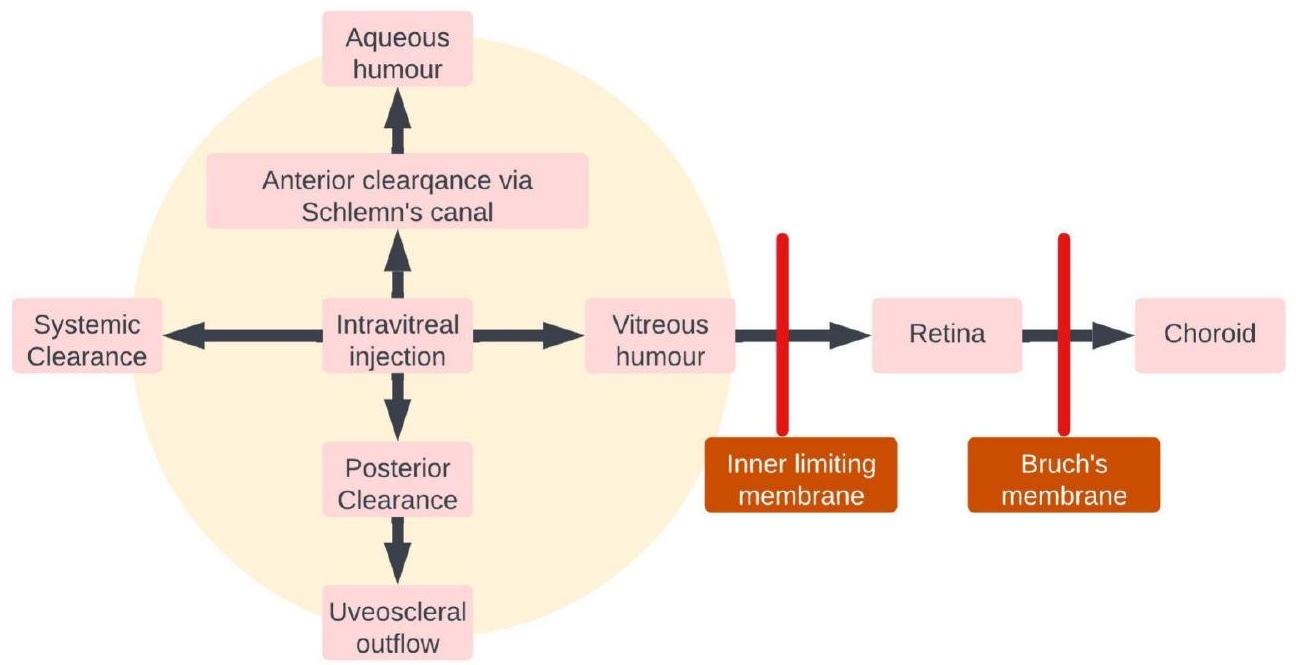

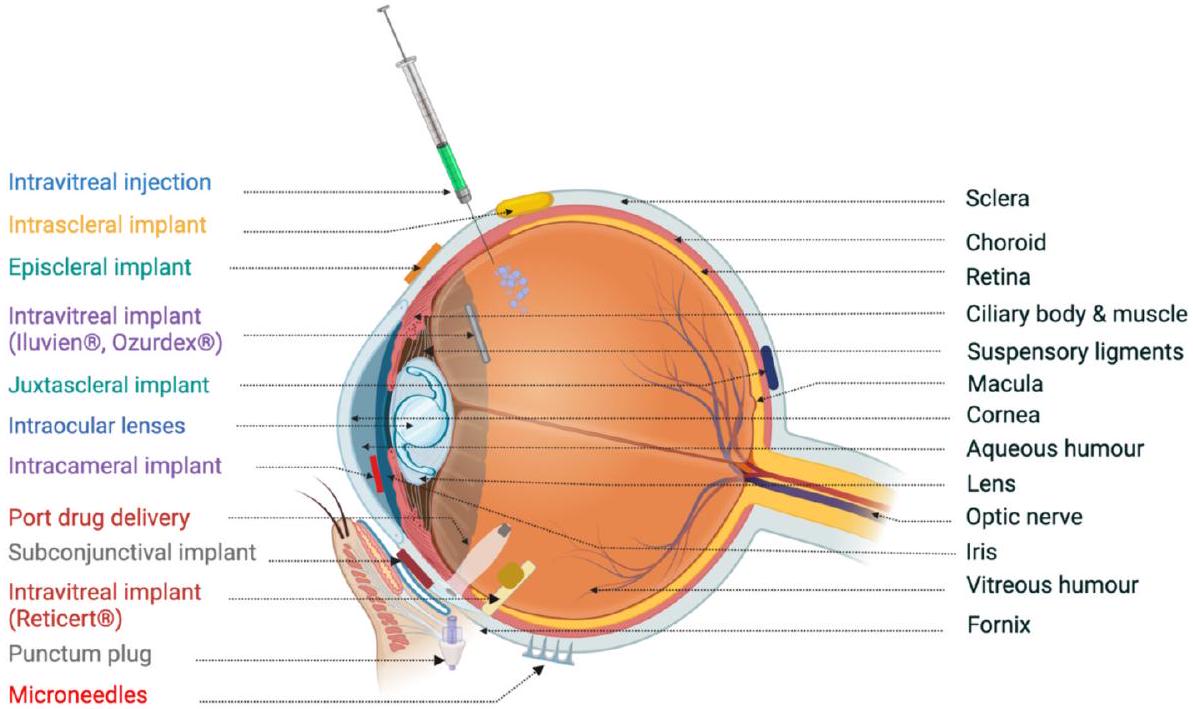

3.2. Drug distribution following IVT injection

beads (positively charged) were completely immobilized. Variations in vitreous properties due to differences in anatomical site, age, and disease may affect nanoparticle transport [105].

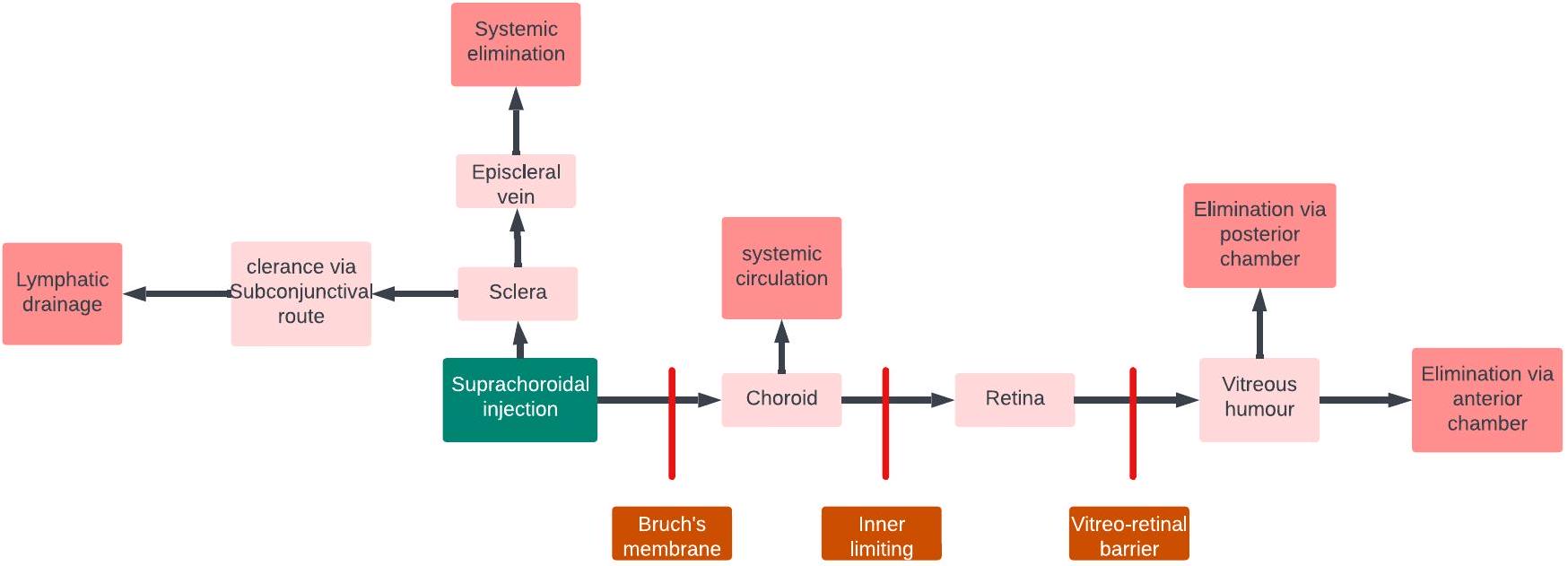

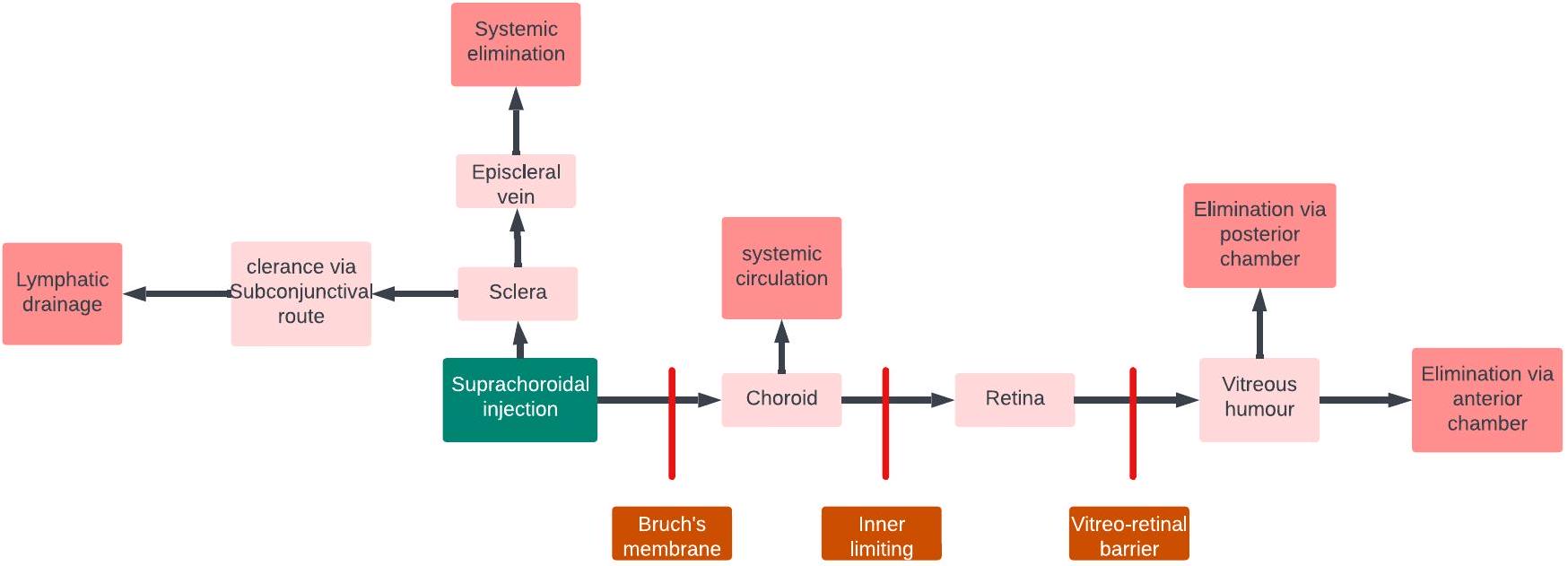

3.3. Drug distribution following suprachoroidal injection

an attractive option for targeted drug delivery to the retina. In summary, while barriers such as the choroid, BRB, and RPE can pose challenges for drug delivery to the retina through the SCS route, the unique characteristics of this route, including reduced drug loss into the systemic circulation and increased drug levels at the target site, make it a promising approach for efficient drug delivery to the retina (Fig. 10).

3.4. Drug distribution following periocular administration

reducing nasolacrimal drainage [130] Fig. 11 illustrates the fate of a drug following periocular administration. Kaji et al. studied the pharmacokinetics of amphotericin B (amp B) liposomes on subconjunctival injections. The study revealed that ocular toxicity was significantly lower for subconjunctival injections of liposomal B than for amp B or deoxycholate injection. Compared with those of topical eye drops, significantly greater concentrations of amp

4. Types of formulations deliverable via HMNs

4.1. Delivery of solutions using HMNs

formulated as soluble solutions for effective delivery and rapid absorption. Additionally, solutions can be reconstituted from powdered forms, providing convenience and ease of handling and packaging. Overall, the advantages of these solutions make them valuable and practical choices for drug delivery.

4.1.1. Periocular

4.1.2. Intraocular

4.2. Delivery of viscous solutions using HMs

proportional to the viscosity of the solution. Allmendinger et al. reported changes in the IOP and force of injection upon injection of solutions with various viscosities in enucleated porcine eyes. It was observed that the rate of injection played an important role in deciding the force of injection, i.e., the force of injection at lower injection rates was considerably lower than that at higher injection rates. It was also observed that up to

4.2.1. Periocular

4.2.2. Intraocular

4.3. Delivery of Micro- and nanoparticles using HMNs

drainage. Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems with enhanced mucoadhesion and mucopenetration have been found to enhance the residence time of drugs in the ocular cavity; however, the particle size of the nanosuspension is imperative for minimizing irritation inside the ocular surface and tear drainage. Other drug delivery technologies used to manage posterior segment ocular diseases under research include selfaggregating microparticles and long-acting implants for antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., dexamethasone) [156]. However, the burst release of drugs from such implants discourages their use in long-term ocular disease treatment. This section focuses on the distribution of nano/microparticles in HMNs.

4.3.1. Periocular

size ( 20 or 200 nm ). The study revealed that the bevel direction (temporally or nasally) affects the particle distribution within the SCS, with a greater distribution occurring in the opposite direction to the bevel. In human eyes, MN injections at 2 and 8 mm from the optic nerve revealed that the short posterior arteries acted as a barrier to effective drug diffusion toward the optic nerve and macula. Further highlighting the importance of the administration site, a

4.3.2. Intraocular

5. Summary of challenges and opportunities in ocular drug delivery

6. Conclusion

Summary of the use of MNs in ocular drug delivery.

| Fabrication material | Dimensions | Injection volume | Target location | Application | Ref. |

| Glass |

|

|

Sclera | Distribution of solution and nanoparticles in sclera | [36] |

| Glass |

|

|

Sclera | Delivery of rose Bengal dye in porcine sclera | [171] |

| Glass |

|

|

SCS | Delivery of nano- (20 and 200 nm ) and microparticles ( 2 and

|

[123] |

| Metal | 400, 500 and

|

|

Sclera | Delivery of sunitinib loaded Cs-g-PNIPAAm hydrogel | [172] |

| Metal |

|

|

SCS | Investigate viability of gravity-mediated targeting in the delivery of high-density perfluorodecalin encapsulated within an outer layer of fluorescein-tagged polystyrene nanoparticles to the SCS | [143] |

| Metal |

|

|

SCS | Distribution of nanoparticles ( 200 nm ) in SCS | [161] |

| Metal |

|

|

SCS | Transscleral/subretinal delivery of adeno-associated virus (AAV8) vectors | [129] |

| Metal |

|

|

SCS | Distribution of viscous non-Newtonian solutions in SCS | [119] |

| Metal |

|

30, 50 and

|

Sclera | Delivery of thermoresponsive depot-forming hydrogels | [120] |

| Metal |

|

|

SCS | Investigate the influence of bevel angle on delivery into SCS | [76] |

| Metal |

|

|

Supraciliary route | Distribution of brimodine-loaded microspheres (20-45

|

[173] |

| Metal |

|

|

|

triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension

|

[113] |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Data availability

Acknowledgments

References

[2] A. Malhotra, F.J. Minja, A. Crum, D. Burrowes, Ocular anatomy and crosssectional imaging of the eye, Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 32 (2011) 2-13, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2010.10.009.

[3] C.A. Curcio, M. Johnson, Structure, Function, and Pathology of Bruch’s Membrane, Retina Fifth Edition, Elsevier Inc., in, 2012, pp. 465-481, https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-1-4557-0737-9.00020-5.

[4] J.W. Kiel, The ocular circulation, Colloquium Series on Integrated Systems Physiology: From Molecule to Function 3 (2011) 1-81, https://doi.org/10.4199/ c00024ed1v01y201012isp012.

[5] A. Michalinos, S. Zogana, E. Kotsiomitis, A. Mazarakis, T. Troupis, Anatomy of the ophthalmic artery: a review concerning its modern surgical and clinical applications, Anat Res Int 2015 (2015) 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/ 591961.

[6] S. Mishima, Clinical pharmacokinetics of the eye, Proctor lecture, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 21 (1981) 504.

[7] T. Yasukawa, Y. Ogura, Y. Tabata, H. Kimura, P. Wiedemann, Y. Honda, Drug delivery systems for vitreoretinal diseases, Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 23 (2004) 253-281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.02.003.

[8] R.C. Nagarwal, S. Kant, P.N. Singh, P. Maiti, J.K. Pandit, Polymeric nanoparticulate system: a potential approach for ocular drug delivery, J. Control. Release 136 (2009) 2-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.12.018.

[9] B.C. Harder, S. von Baltz, J.B. Jonas, F.C. Schlichtenbrede, Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 27 (2011) 623-627, https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2011.0060.

[10] V.-P. Ranta, E. Mannermaa, K. Lummepuro, A. Subrizi, A. Laukkanen, M. Antopolsky, L. Murtomäki, M. Hornof, A. Urtti, Barrier analysis of periocular drug delivery to the posterior segment, J. Control. Release 148 (2010) 42-48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.028.

[11] H. Nomoto, F. Shiraga, N. Kuno, E. Kimura, S. Fujii, K. Shinomiya, A.K. Nugent, K. Hirooka, T. Baba, Pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab after topical, subconjunctival, and intravitreal Administration in Rabbits, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50 (2009) 4807-4813, https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.08-3148.

[12] Y. Wang, D. Fei, M. Vanderlaan, A. Song, Biological activity of bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF antibody in vitro, Angiogenesis 7 (2004) 335-345, https:// doi.org/10.1007/S10456-004-8272-2/METRICS.

[13] R.K. Balachandran, V.H. Barocas, Computer modeling of drug delivery to the posterior eye: effect of active transport and loss to choroidal blood flow, Pharm. Res. 25 (2008) 2685-2696, https://doi.org/10.1007/S11095-008-9691-3/ FIGURES/6.

[14] P. Causin, F. Malgaroli, Mathematical assessment of drug build-up in the posterior eye following transscleral delivery, J. Math. Ind. 6 (2016) 1-19, https://doi.org/ 10.1186/S13362-016-0031-7/FIGURES/9.

[15] S. Molokhia, K. Papangkorn, C. Butler, J.W. Higuchi, B. Brar, B. Ambati, S.K. Li, W.I. Higuchi, Transscleral iontophoresis for noninvasive ocular drug delivery of macromolecules, Https://Home.Liebertpub.Com/Jop 36 (2020) 247-256, https://doi.org/10.1089/JOP.2019.0081.

[16] J.L. Paris, L.K. Vora, M.J. Torres, C. Mayorga, R.F. Donnelly, Microneedle array patches for allergen-specific immunotherapy, Drug Discov. Today 28 (2023) 103556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103556.

[17] L.K. Vora, K. Moffatt, R.F. Donnelly, 9 – Long-Lasting Drug Delivery Systems Based on Microneedles, in: E. Larrañeta, T.R.R. Singh, R.F.B.T.-L.-A.D.D. S. Donnelly (Eds.), Woodhead Publ Ser Biomater, Woodhead Publishing, 2022, pp. 249-287, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821749-8.00010-0.