DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00850-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39774609

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-08

إبر ميكرونية حلزونية مزدوجة الطبقة مدعومة بالاهتزازات الدقيقة لاستخراج سائل الأنسجة الجلدية بسرعة للكشف عن الجلوكوز بطريقة minimally invasive

الملخص

تم استكشاف هيدروجيلات متنوعة لإنشاء إبر دقيقة (MNs) minimally invasive لاستخراج السائل بين الأنسجة (ISF). ومع ذلك، فإن الطرق الحالية تستغرق وقتًا طويلاً وعادة ما تتطلب

مقدمة

اضطراب أو تغيير كبير في سلامة وهيكل الطبقة الخارجية من الجلد، المعروفة باسم الطبقة القرنية (SC) وتسبب صدمة موضعية للجلد

لمعالجة هذه المشكلة، ظهرت الجسيمات النانوية كأداة بارزة لاستغلال مجال الإشعاع الداخلي للكشف عن المؤشرات الحيوية بسبب خصائصها الفريدة ومزاياها.

لقد أظهرت الهلاميات المتشابكة مثل PVA/PVP و GelMA نسبة انتفاخ جيدة، وهي عامل حاسم لاستخراج السائل بين الخلايا بكفاءة.

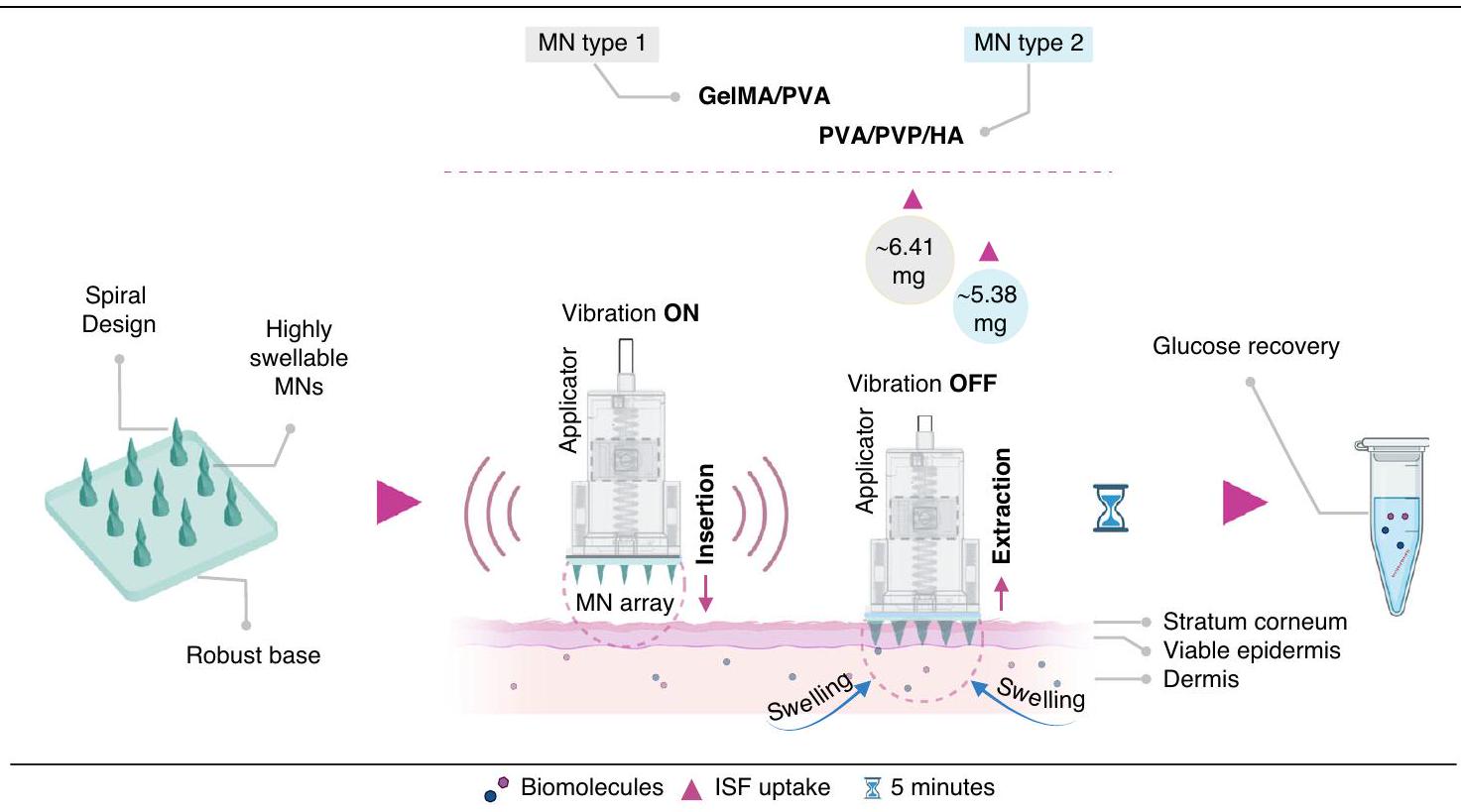

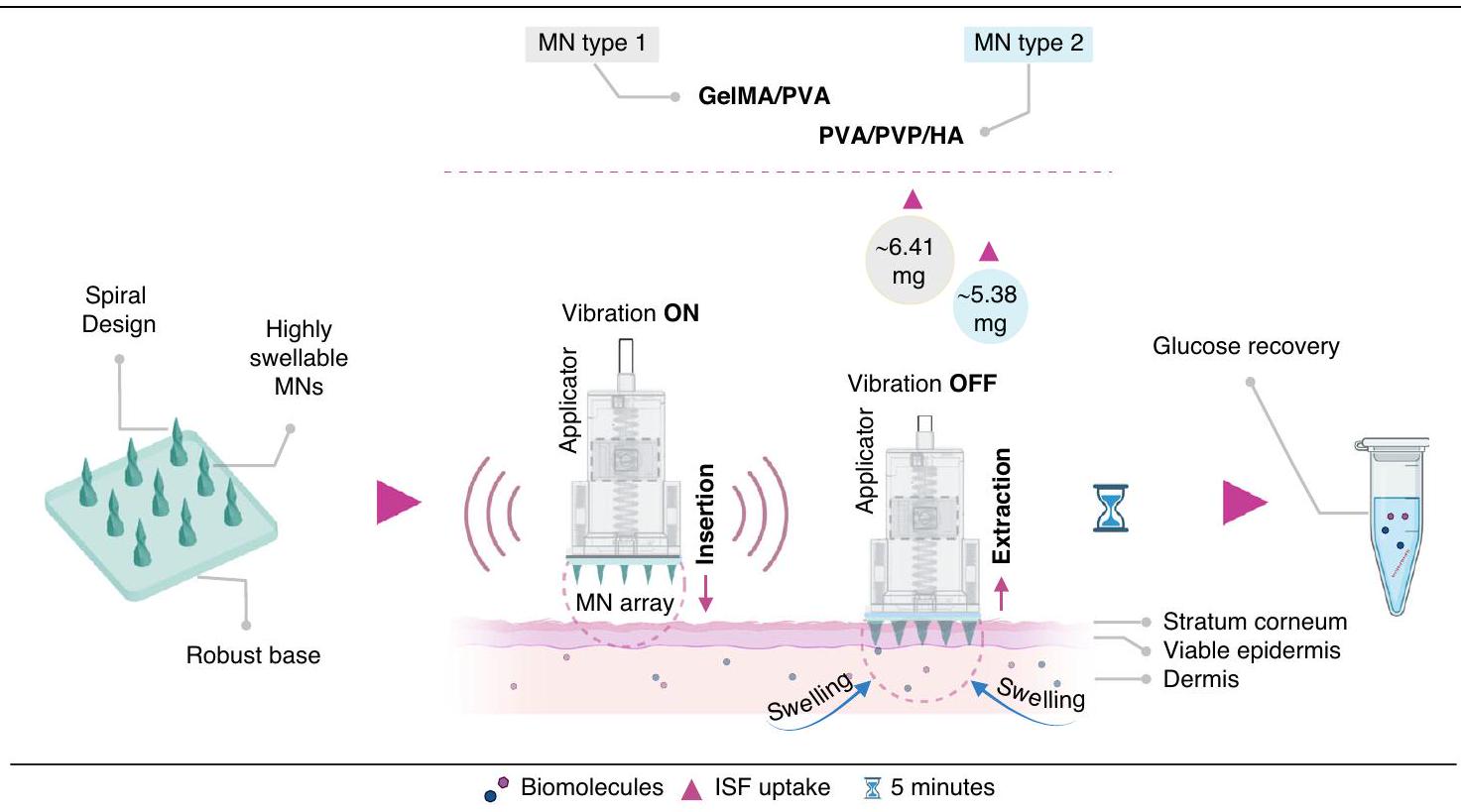

لذلك، هناك حاجة لاستخراج السائل بين الأنسجة (ISF) بسرعة وتحليل العلامات الحيوية. تقدم هذه الدراسة نوعين متميزين من الإبر الدقيقة ذات الطبقات المزدوجة المرتبطة ببعضها البعض، المصنوعة من هلام الجيلاتين/البولي فينيل الكحول وهلام البولي فينيل الكحول/البولي فينيل بيروليدون/حمض الهيالورونيك لاستخراج السائل بين الأنسجة بسرعة. وفقًا لمعرفتي، فإن تكوين الإبر الدقيقة على شكل لولب يمثل تصميمًا جديدًا لم يتم استكشافه سابقًا. وقد عززت تركيبات الهلام المختارة (هلام الجيلاتين/البولي فينيل الكحول وهلام البولي فينيل الكحول/البولي فينيل بيروليدون/حمض الهيالورونيك) بشكل كبير سلوك الانتفاخ للإبر الدقيقة مقارنة بالدراسات السابقة.

تحلل أهمية طبقة قاعدة موحدة لاختراق فعال للإبر الدقيقة (MN) في الجلد. نظرًا لمرونته، تم اختيار بولي إيثيلين جلايكول دايكريلات (PEGDA) كقاعدة لمصفوفة الإبر الدقيقة GelMA/PVA، بينما تم اختيار PVP كقاعدة لمصفوفة الإبر الدقيقة PVA/PVP/HA. تم تحديد أوقات التجفيف المثلى لقاعدة PVP من خلال نهج من خطوتين، حيث تتطلب الإبر الدقيقة GelMA وقت تجفيف أقصر. تدرس هذه الدراسة أيضًا خصائص الانتفاخ والميكانيكية للإبر الدقيقة لتقييم قدراتها على الإدخال في الجلد واستخراج السائل بين الخلايا (ISF). تم إجراء اختبارات الانتفاخ في كل من PBS وISF الاصطناعي، بينما تم استخدام اختبارات الضغط لتقييم الخصائص الميكانيكية للإبر الدقيقة.

تقدم الدراسة أيضًا نسخة متقدمة من جهاز تطبيق MN الحاصل على براءة اختراع لدينا، القادر على إدخال MNs بسرعة

النتائج والمناقشة تصميم الحلزوني

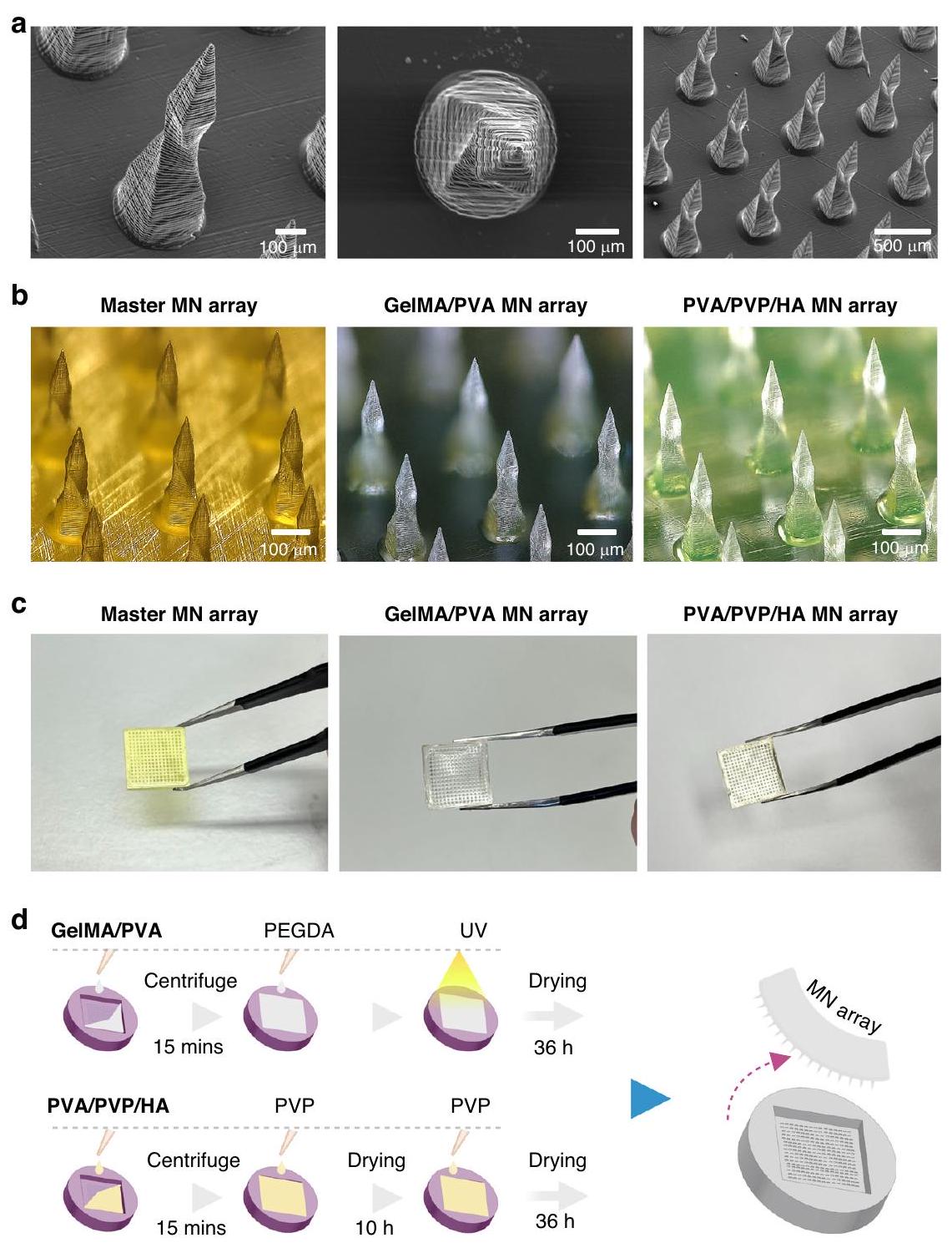

تصنيع MNs الحلزونية وتحسين الطبقات الأساسية

يتم استخدامه كمدخل ثم يتم تقطيعه إلى سلسلة من الصور ثنائية الأبعاد تُسمى الأقنعة الرقمية التي تُظهر أو تُخفي مناطق محددة من طبقة معينة. كل طبقة لها قناع، ويتم إضافة كل طبقة حتى تكتمل الهيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد بالكامل. تم إرسال بيانات التقطيع إلى نظام الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد لتصنيع الطبقات الفردية. يمكن لتقنية PuSL تحقيق دقة تصل إلى عدة ميكرومترات أو مئات النانومترات من خلال التحكم في عدسة الإسقاط. تم طباعة مصفوفة MN الرئيسية باستخدام مادة مقاومة لدرجات الحرارة العالية (HTL) باستخدام هذه التقنية المتقدمة.

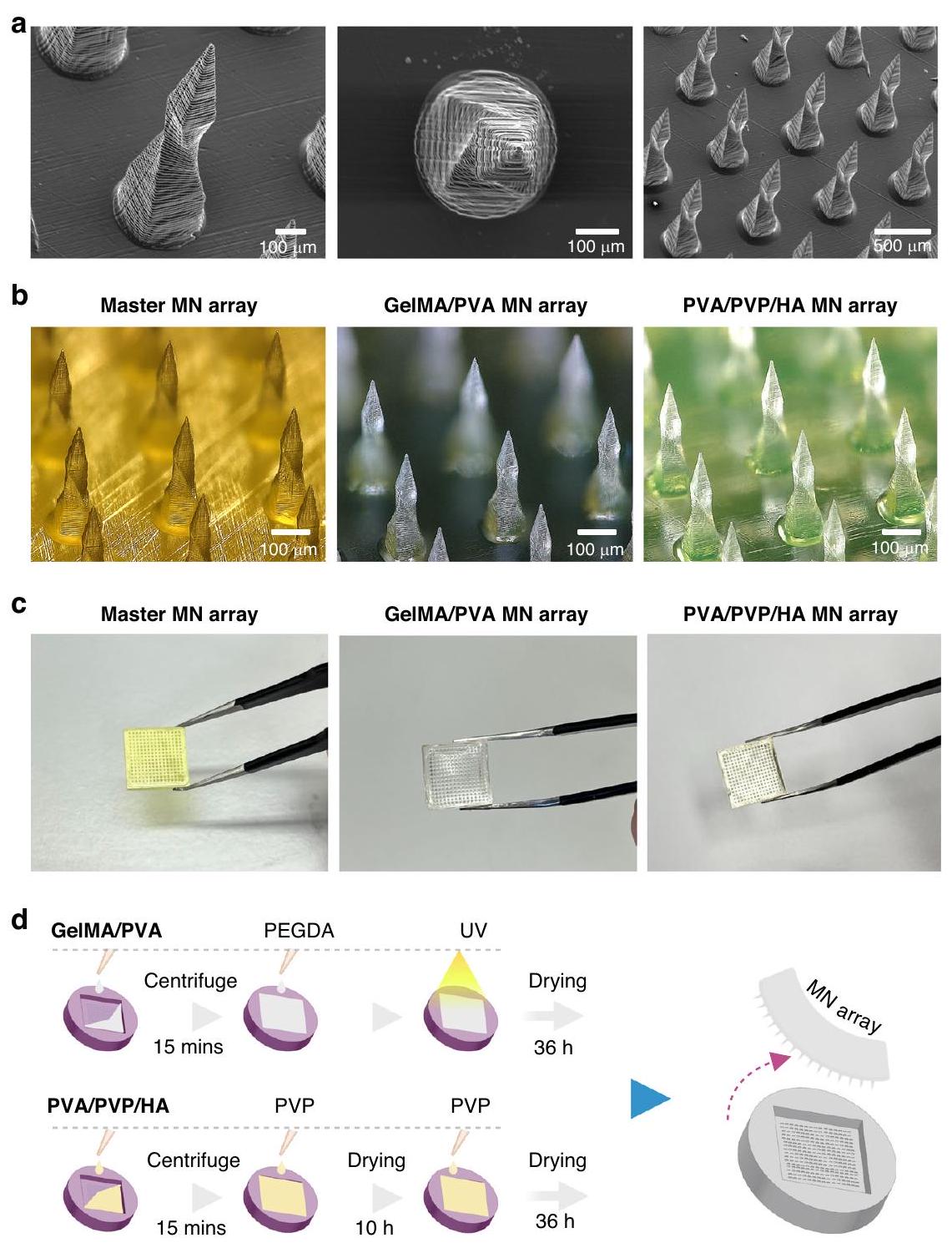

بعد إنشاء القالب الرئيسي للإبر الدقيقة، تم استخدامه لإنشاء قوالب سلبية من PDMS (الشكل التكميلي S1) لتكرار مصفوفات الإبر الدقيقة GelMA/PVA وPVA/PVP/HA. تم تشكيل جميع النسخ من الإبر الدقيقة دون أي عيب، مما يشبه الشكل الحلزوني للمصفوفة الرئيسية، كما هو موضح في الشكل 2a؛ ومع ذلك، لوحظ انكماش طولي عبر جميع أنواع الإبر الدقيقة (الرئيسية والنسخ) مقارنةً بأبعادها الأولية في CAD.

رابطة، تشكل هيكلًا متماسكًا من طبقة واحدة في مصفوفة MN النهائية. ومع ذلك، لم تنجح المحاولة لإدماج PEGDA في حلول PVA/PVP/HA كقاعدة كما هو متوقع. على سبيل المثال، لم يتشكل PEGDA كطبقة موحدة مع محلول PVA/PVP/HA. بسبب محتواه من المحفز الضوئي، تصلب قاعدة PEGDA بشكل أسرع عند تعرضها للأشعة فوق البنفسجية مقارنةً بمحلول PVA/PVP/HA، مما أدى إلى عدم كفاية الربط بين الطبقتين. لمعالجة ذلك، تم إجراء ثلاثة اختبارات: واحد مع مزيج من PVA/PVP (

تم تحسين وقت التجفيف لقاعدة PVP باستخدام استراتيجية من خطوتين. في البداية،

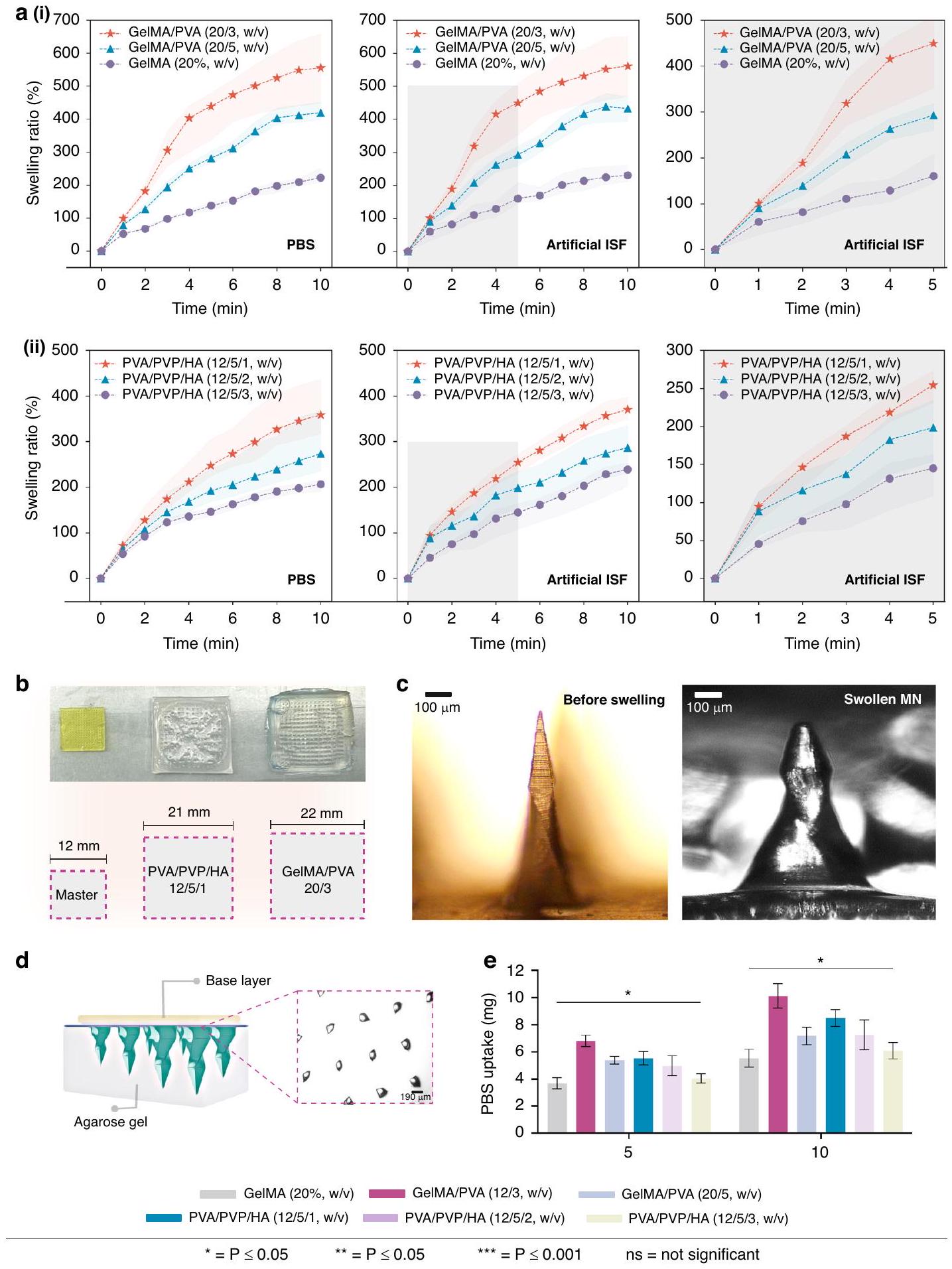

ديناميكية التورم وامتصاص PBS في المختبر

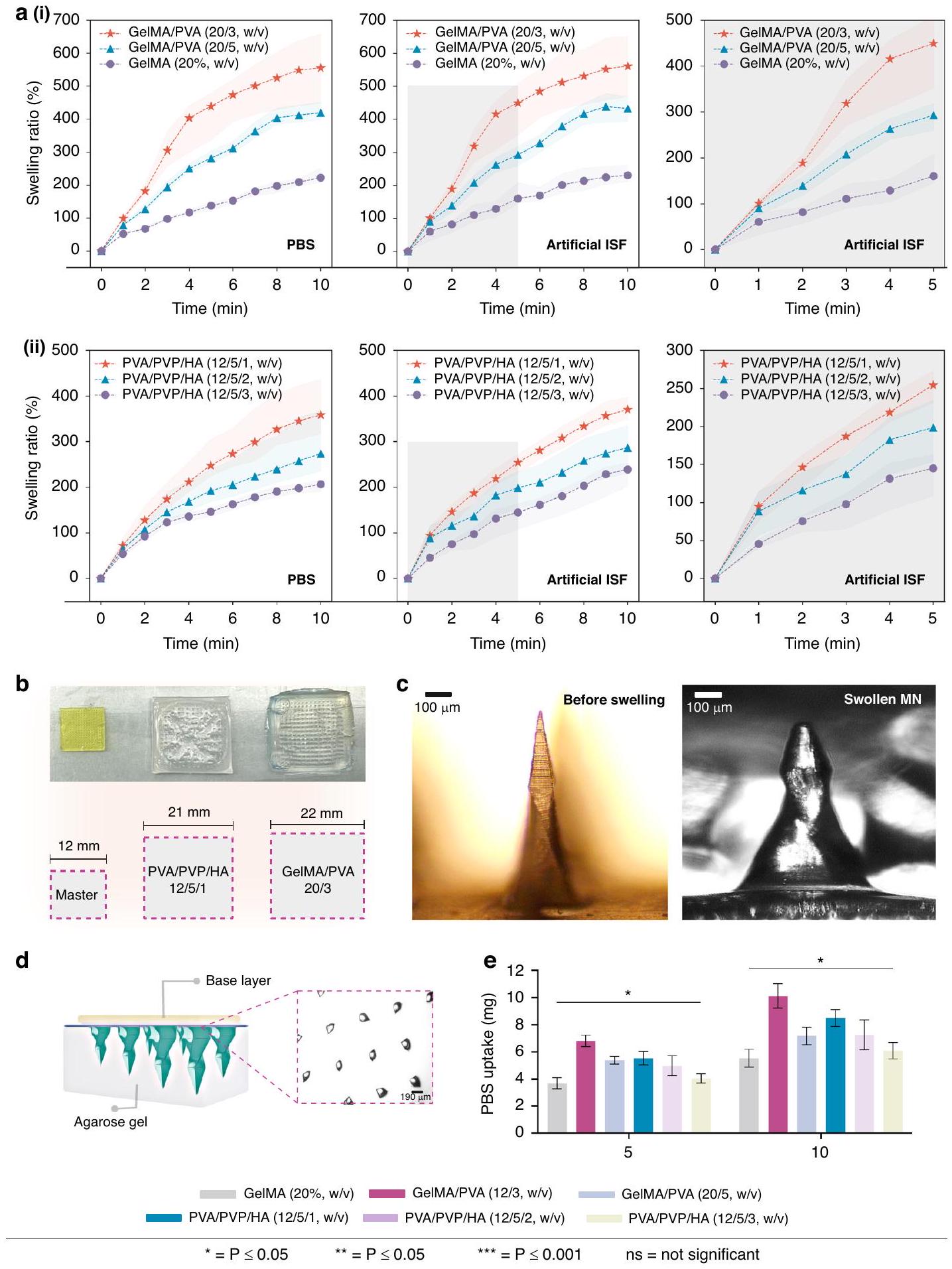

تم إجراء اختبارات نسبة التورم لـ MNs في ISF الاصطناعي و PBS (محلول ملحي معزول بالفوسفات) لمدة تصل إلى 10 دقائق. أظهرت النتائج في الشكل 3a(i-ii) أن قدرة التورم لـ MNs تزداد مع مرور الوقت بعد الغمر. في ISF الاصطناعي، كان لـ GelMA (

على التوالي، وهي أعلى من الدراسات المماثلة المبلغ عنها

تم إجراء تجارب إضافية مع تركيزات متغيرة من PVA و PVP فقط. ومع ذلك، لم تكن قدرة التورم التي تم الحصول عليها لـ MNs مثالية (الشكل التكميلي S3). لذلك، تم إدخال HA، وتم إعداد ثلاثة تركيزات مختلفة من HA (

تم إجراء تجارب مماثلة في PBS لاختبار التورم. أظهرت MNs اختلافات طفيفة في PBS مقارنةً بـ ISF الاصطناعي. على سبيل المثال، أظهرت تركيبات GelMA/PVA ميلًا أعلى قليلاً للتورم عند الغمر في ISF الاصطناعي،

كان التمدد والتورم لمصفوفات MN ملحوظًا بصريًا أيضًا. مع تورم MNs، زادت بشكل كبير في الحجم، مما يؤكد قدرتها على امتصاص PBS بشكل فعال. أشارت النتائج إلى أن مصفوفة MN GelMA/PVA (20/3، w/v) أظهرت زيادة كبيرة في

تم إجراء تجارب أيضًا على نموذج الجلد الذي تم بناؤه باستخدام هيدروجيل الأجاروز لتقييم قدرة امتصاص PBS لـ MNs، كما هو موضح في الشكل 3d. لوحظ نمط متسق من زيادة امتصاص PBS عبر تركيبات GelMA/PVA و PVA/PVP/HA المختلفة، كما هو موضح في الشكل 3e. من بينها، أظهرت GelMA/PVA

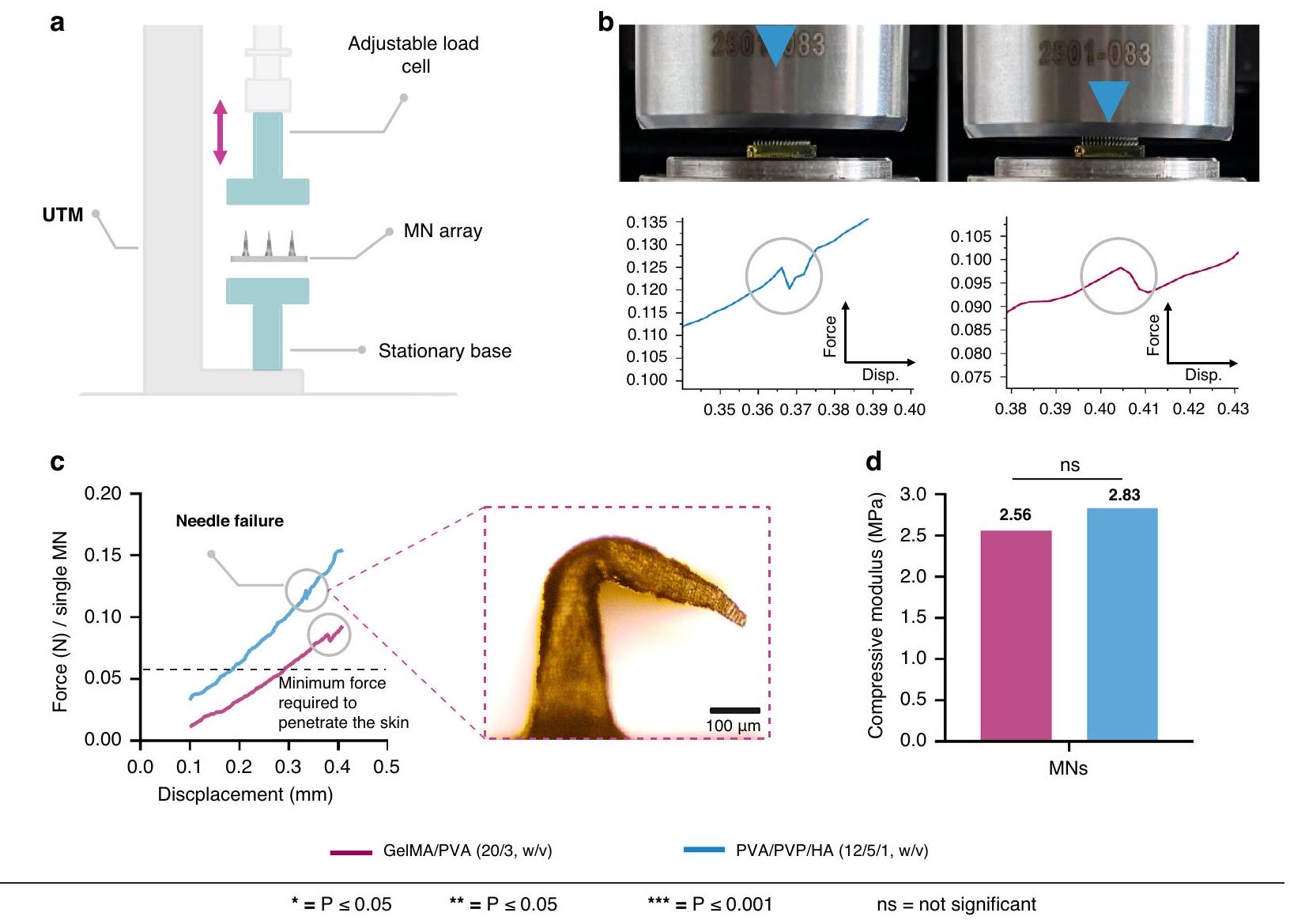

الخصائص الميكانيكية لـ MNs الحلزونية

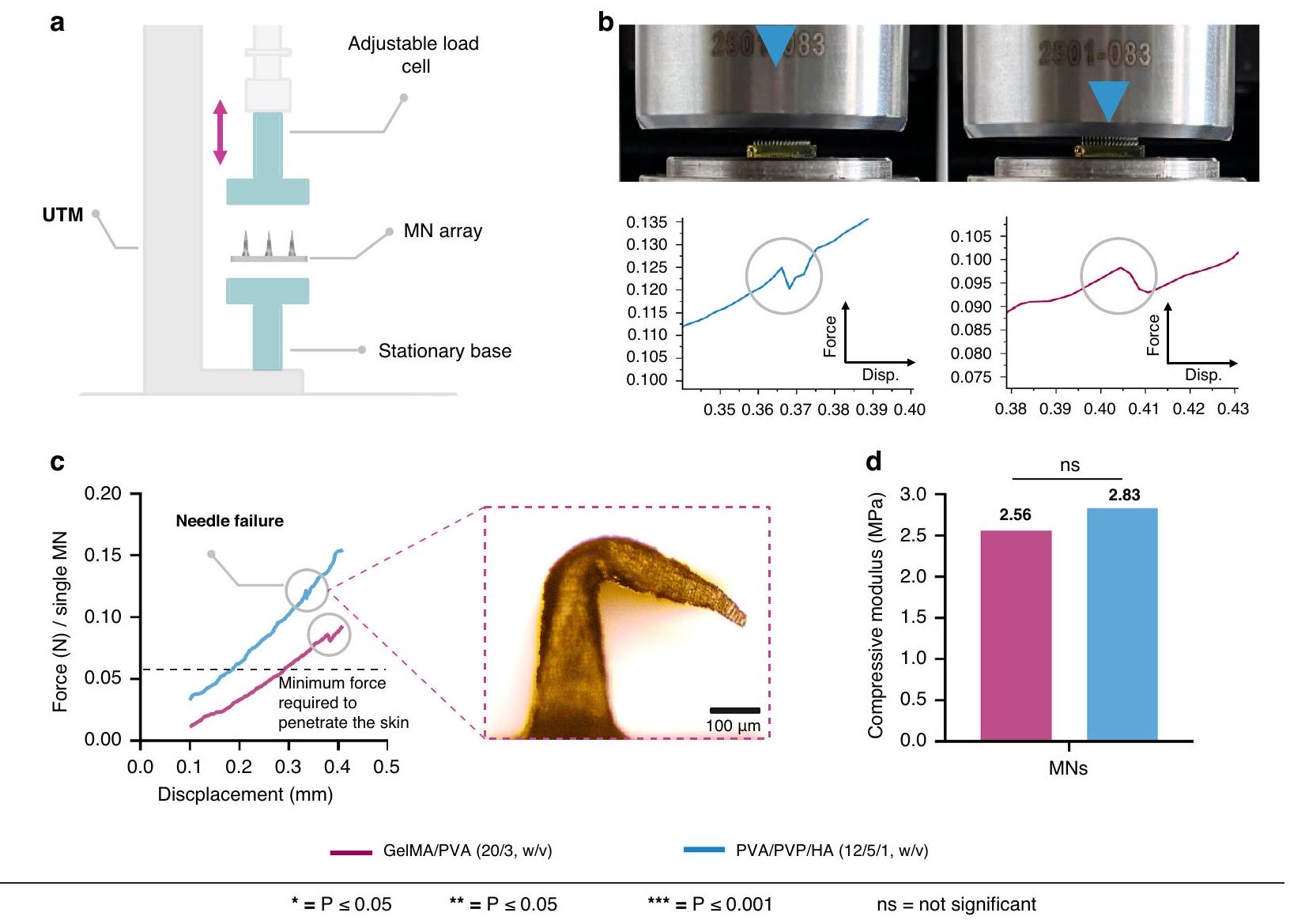

الإزاحة، كما هو موضح في الشكل 4a. على الرغم من أن كل مصفوفة في الاختبار كانت تحتوي على 225 MNs، تم حساب قياس القوة لتمثيل إبرة واحدة في منحنيات القوة-الإزاحة التي توفر رؤى حاسمة حول السلوك الميكانيكي لـ MNs. عندما يتصل طرف MN لأول مرة باللوحة العليا لـ UTM، تزداد القوة إلى ذروتها، ثم تنخفض إلى نقطة منخفضة قبل أن ترتفع إلى ذروة ثانية. تشير الذروة الأولية إلى حمل الفشل، مما يؤدي إلى تشوه دائم في هيكل MN. يظهر الشكل 4b تأثير الضغط

بالنسبة لـ GelMA/PVA (

لقد أظهرت العديد من الدراسات حول MNs خصائص ميكانيكية جيدة باستخدام مواد مشابهة مثل PVA/PVA و GelMA و HA. على سبيل المثال، أفاد زو وآخرون أن معامل الانضغاط زاد من

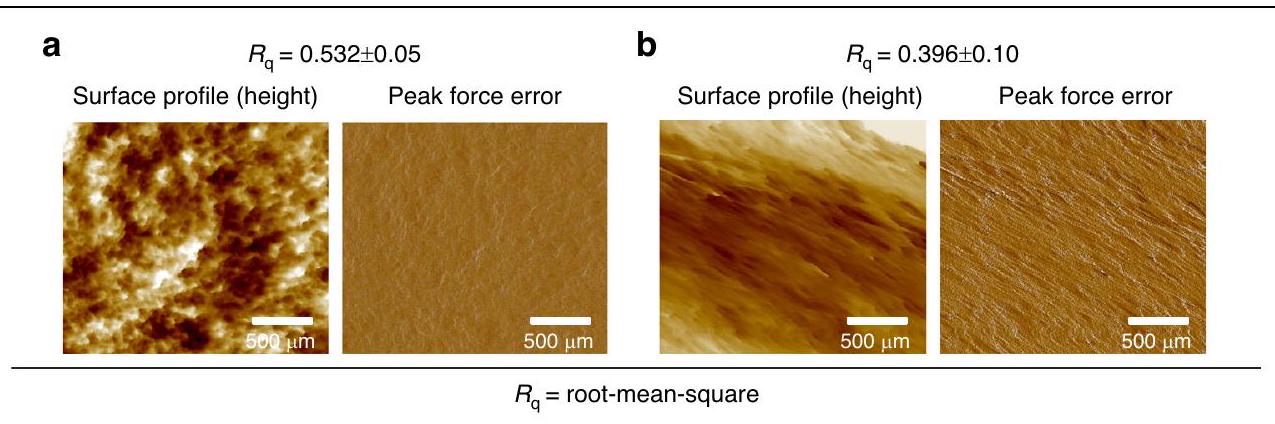

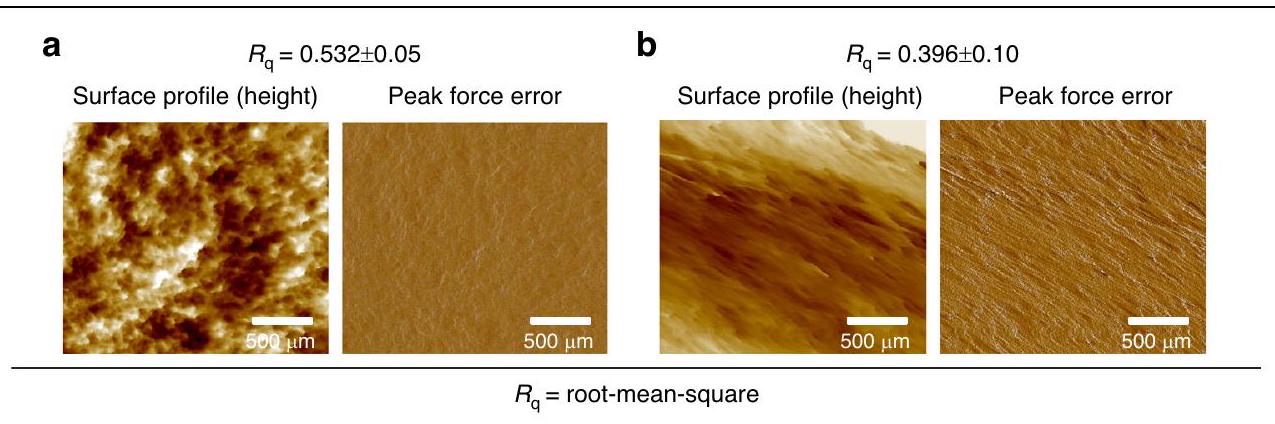

توصيف السطح

يمكن أن تؤثر التغيرات الدقيقة في الارتفاع عبر السطح على التفاعلات مع الجلد

تم تقييم MNs لخصائص خشونة السطح باستخدام المجهر الذري (AFM). GelMA/ PVA (

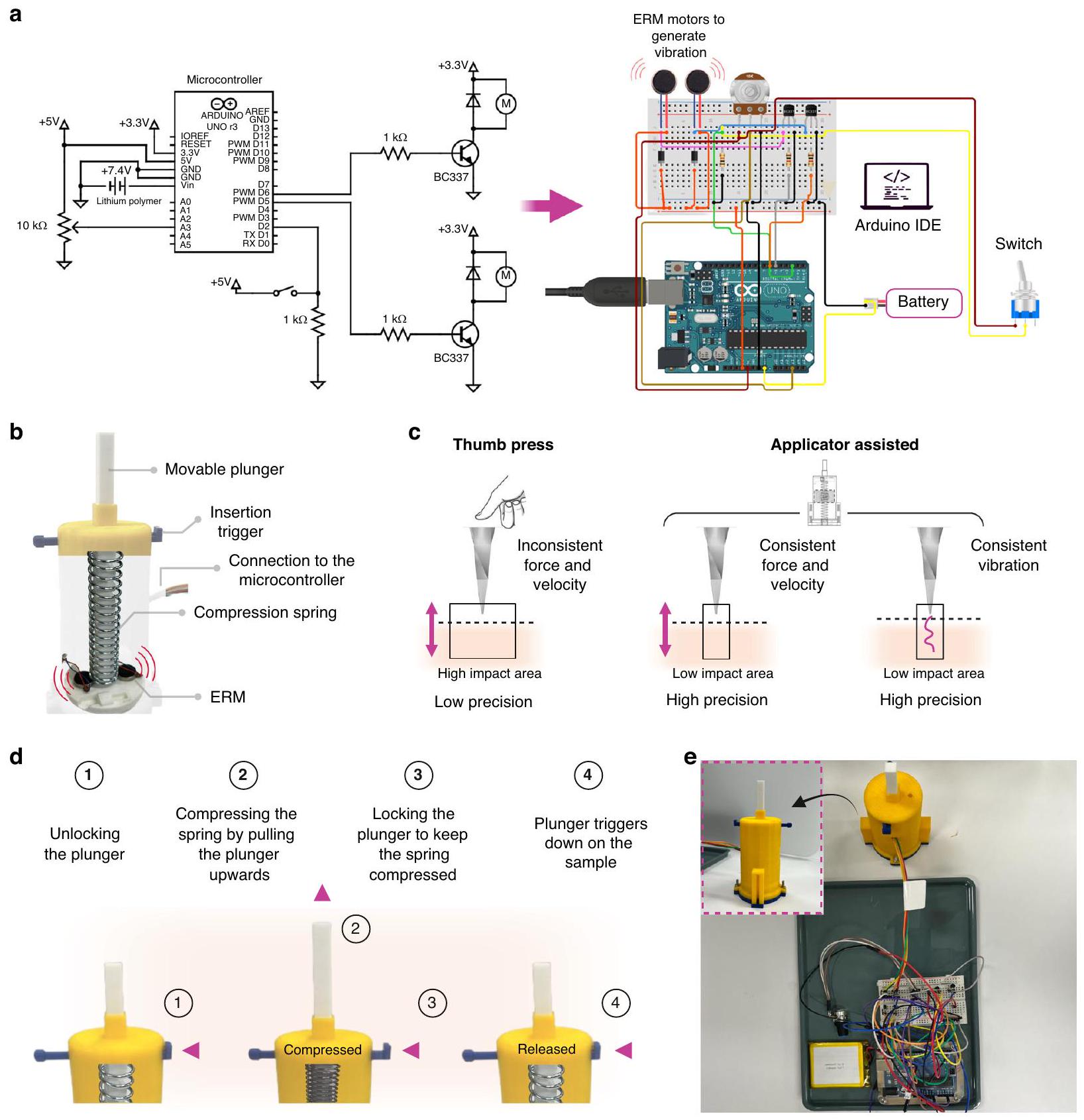

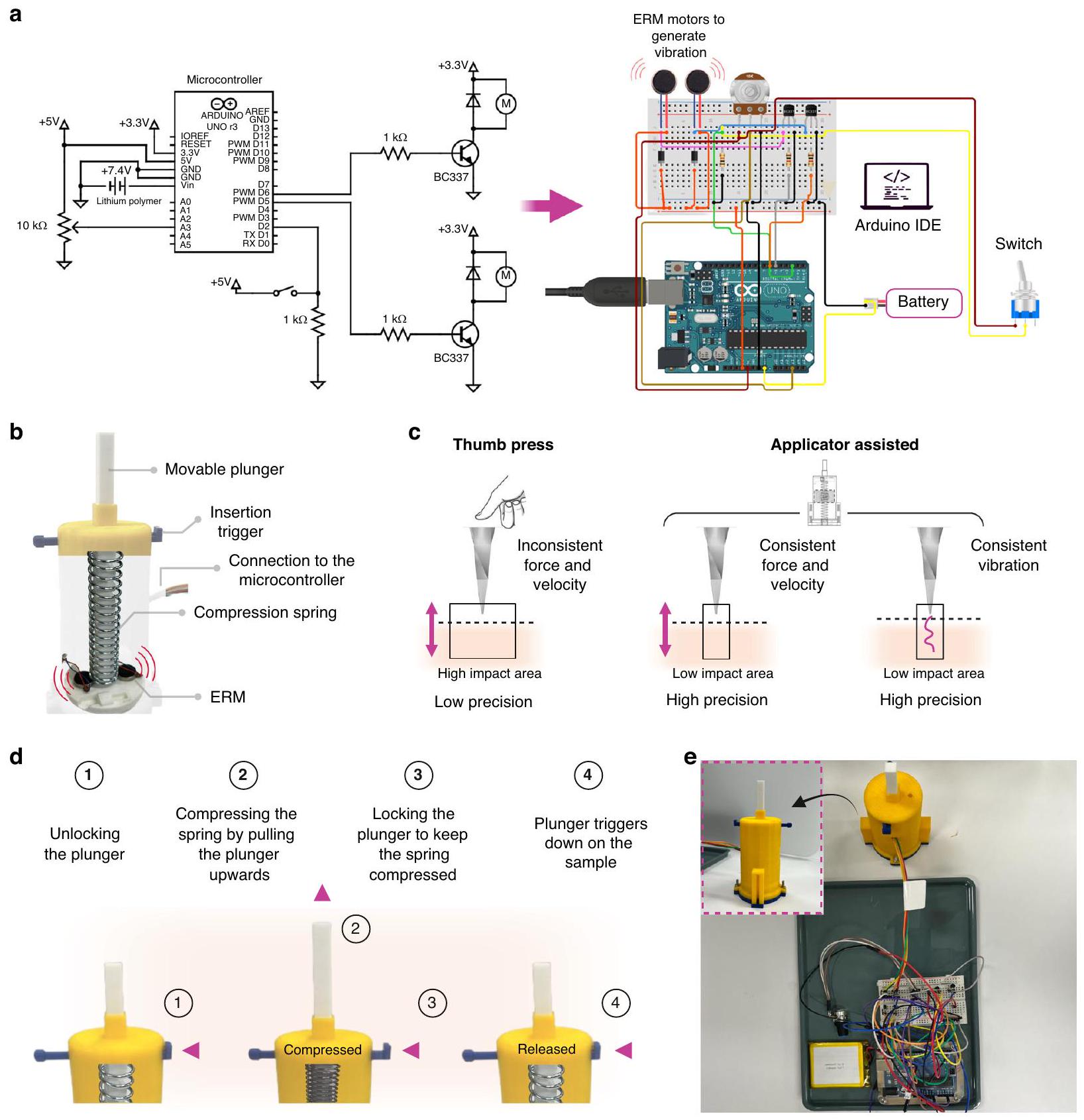

جهاز إدخال MNs واستخراج ISF بمساعدة الاهتزازات الدقيقة مع متحكم دقيق من نوع أردوينو

برمجة من خلال بيئة تطوير أوردوينو (Arduino IDE) مكنت من تحكم أدق من التعديلات اليدوية (المقاوم المتغير).

تعزيز الوظائف العامة للنظام. على الرغم من ذلك، تم دمج مقاوم متغير كطريقة تحكم احتياطية، مما يسمح بإجراء تعديلات يدوية على الجهد المطبق على محركات ERM عند الضرورة. هذا يضمن أن التحكم اليدوي لا يزال متاحًا إذا لم يكن IDE الخاص بـ Arduino متاحًا. لذلك، تم إدخال ترانزستورات لتكبير الإشارة إلى مستوى الجهد المطلوب. كما تمت إضافة ثنائيات لحماية الترانزستورات من ارتفاعات الجهد العكسي والحفاظ على استقرار الدائرة. علاوة على ذلك، تم استخدام مقاومات لتحديد التيار المتدفق عبر الترانزستورات والمحركات، مما يضمن تشغيلًا آمنًا وفعالًا. عندما يقرأ Arduino الإشارات من المقاوم المتغير، فإنه يحولها إلى جهد، والذي يتحكم بعد ذلك في اهتزاز محركي ERM، مترجمًا الإشارات الكهربائية إلى اهتزاز مادي. الشكل 6ب يوضح التصميم الميكانيكي والتكوين الداخلي لجهاز MN. يقوم زناد الإدخال ببدء العملية، بينما يوفر نابض الضغط القوة اللازمة لدفع MNs إلى الجلد.

تعتبر القدرة على اختراق الجلد بشكل متسق ودقيق واحدة من التحديات الأساسية للإبر القابلة للتورم، والتي تتأثر بعوامل مختلفة مثل القوة المطبقة، وسرعة الإدخال، والخصائص الميكانيكية لـ

النابض وتخزين الطاقة الكامنة. ثم يتم قفل المكبس للحفاظ على هذا الضغط. عند التفعيل، يتم تحرير الطاقة المخزنة في النابض، مما يدفع MNs إلى عينة الجلد بقوة ودقة محكومة. الشكل 6هـ يظهر الإعداد الفعلي لجهاز التطبيق المتصل بالمكون الإلكتروني لاختبار إدخال MN.

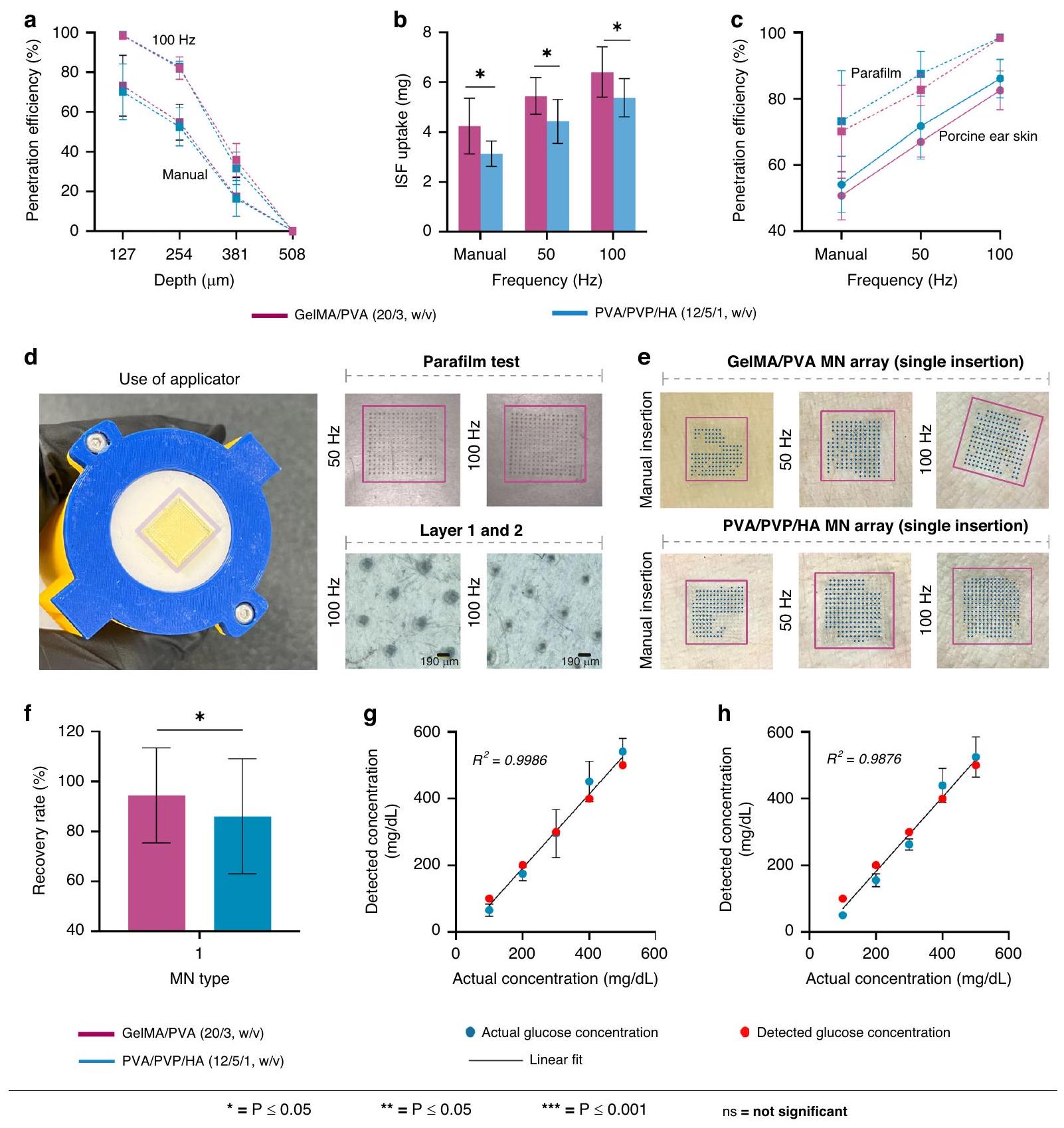

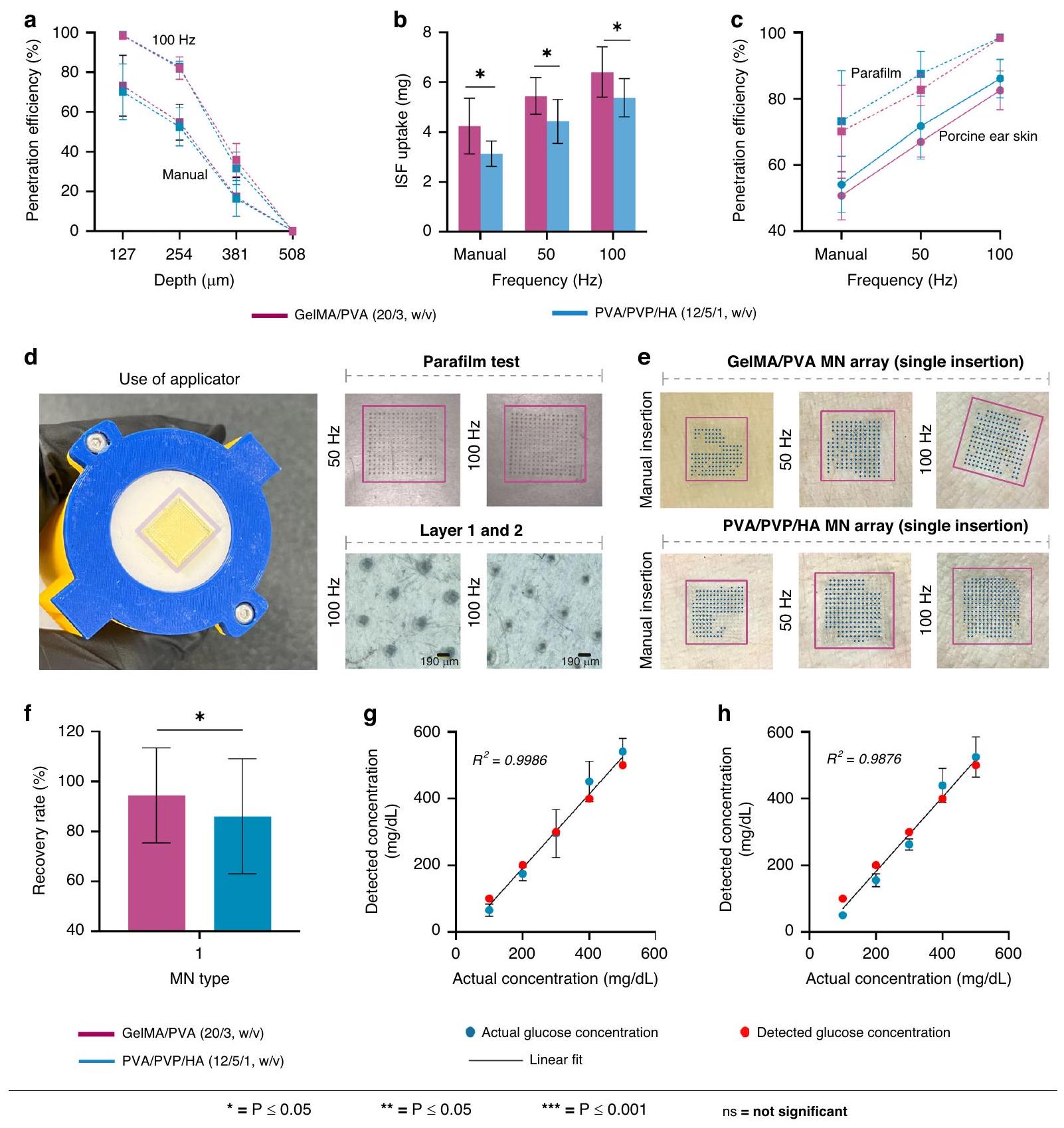

إدخال MNs، استخراج ISF، واستعادة الجلوكوز

نسبة MNs الحلزونية في مجموعة التي اخترقت نموذج الجلد بدون اهتزاز للطبقة الأولى كانت

على الرغم من أن اختبار بارافيلم يوفر رؤى قيمة لتحليل قدرات اختراق الجلد لـ MNs

قبل الاختبار على عينات بيولوجية (جلد أذن خنزير)، تم الإبلاغ عن أنه يظهر أعماق اختراق أعلى من تلك التي لوحظت في جلد الخنزير

بعد تطبيق مجموعات MN يدويًا لمدة 5 دقائق على جلد أذن الخنزير، كان امتصاص ISF لـ جلما/بفا (20/3، w/v) فقط

سرعة إدخال MN أيضًا عامل حاسم يؤثر على مقاومة الجلد أثناء الاختراق. الدراسات

حيث تسبب السرعات الأعلى تشوهًا أكبر، مما يؤدي إلى خفض قوة كسر الجلد وزيادة اختراق الجلد

MN القابلة للتورم، التي عادة ما تكون لديها قوة ميكانيكية أقل من الأنواع الأخرى بسبب قدرتها على التورم. علاوة على ذلك، فإن الطبيعة الديناميكية للاهتزاز تسمح لـ MNs بتجاوز المقاومة اللزجة الطبيعية للجلد بشكل أكثر فعالية من تطبيق القوة الثابتة. إن الجمع بين السرعة (

ومع ذلك، بسبب الطبيعة المتورمة للميكروإبر الهيدروجيل، تضعف بنيتها عند اختراقها للطبقة السطحية، مما يجعلها أقل قدرة على تحمل الاهتزاز المستمر. كما أن قدرة الميكروإبر على تحمل اختراق الطبقة السطحية المعزز بالاهتزاز مرتبطة أيضًا بالقوة الميكانيكية للميكروإبر. الترددات الأعلى (

لتقييم قدرة الإبر الدقيقة على استعادة المؤشرات الحيوية، تم اختيار الجلوكوز كالجزيء الحيوي المستهدف داخل مصفوفة الجل الأجاروز. تم تطبيق مصفوفات الإبر الدقيقة على مصفوفة الأجاروز لمدة 5 دقائق، بعد ذلك تم إزالتها وذوبانها في

قد تنخفض دون عتبة الحساسية لمجموعة اختبار الكشف عن الجلوكوز. تدعم دقة نتائجنا حقيقة أن مجموعة اختبار الكشف عن الجلوكوز المستخدمة حساسة للغاية، مما يسمح بالكشف بسهولة عن تركيزات الجلوكوز المستحثة من

الخاتمة

تتأثر أداء الإبر الدقيقة (MNs) في استخراج السائل بين الأنسجة (ISF) بعدة عوامل، بما في ذلك تصميمها، وموادها، وقدرتها على الانتفاخ، وخصائصها الميكانيكية، وتقنية الإدخال. لذلك، كان أحد أهداف هذه الدراسة هو التحقيق في استخدام مادة GelMA فقط كمواد للإبر الدقيقة وتقييم قدرتها على استخراج حجم أكبر من السائل بين الأنسجة في فترة زمنية قصيرة.

عائد قدره 5.8 جرام من 10 جرام الأولية. تم تخزين البوليمر المسبق في

درجة الاستبدال لجيلما

تصنيع MNs من GeIMA و GeIMA/PVA

تصنيع MNs من PVA/PVP/HA

تم تجفيفها عند

جهاز تطبيق مخصص يعتمد على أردوينو

تم ضبط المقبض الذي يتحكم في سرعة مكبس الأخدود على

نسب انتفاخ MNs في PBS و ISF الاصطناعي

تحديد الخصائص الميكانيكية

المعادلات التالية:

توصيف الشكل

تم تقييم الشكل الحلزوني للإبر الدقيقة باستخدام مجهر إلكتروني مس扫描 (SEM، JSM-7001F، JEOL، اليابان). تم طلاء الإبر الدقيقة بطبقة رقيقة بسماكة 12 نانومتر من البلاتين لمنع الشحن. ثم تم تصوير العينة في مجهر SEM ذو الانبعاث الميداني عند جهد تسريع قدره 10 كيلو فولت في وضع الفراغ العالي (HighVac) مع مستوى تكبير من

خصائص السطح

اختبار الإدخال واستخراج ISF خارج الجسم

تم تطبيق المصفوفات على إعداد الجلد المحاكى يدويًا وباستخدام جهاز التطبيق المصنوع خصيصًا بترددات 50 هرتز و100 هرتز. بعد الإدخال، تم إيقاف عملية الاهتزاز المجهري بعد بضع ثوانٍ حدثت خلالها توسيع الميكروثقوب، وبعد ذلك تم ترك مصفوفات الإبر الدقيقة في مكانها لمدة 30 ثانية قبل إزالتها. ثم تم فحص الثقوب في طبقات البارافيلم تحت المجهر (كارل زيس أكسيو، يينا، ألمانيا) لتقييم كفاءة الإدخال.

تم الحصول على جلد أذن الخنزير المذبوح حديثًا من جزار محلي (بريسبان، أستراليا) وتم تخزينه في ورق الألمنيوم في

كشف تركيز الجلوكوز في المختبر

التحليل الإحصائي

شكر وتقدير

تفاصيل المؤلف

مساهمات المؤلفين

تضارب المصالح

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 يناير 2025

References

- Lee, B. H., Shirahama, H., Cho, N. J. & Tan, L. P. Efficient and controllable synthesis of highly substituted gelatin methacrylamide for mechanically stiff hydrogels. RSC Adv. 5, 106094-106097 (2015).

- Heikenfeld, J. et al. Accessing analytes in biofluids for peripheral biochemical monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 407-419 (2019).

- Sriram, S. Study of needle stick injuries among healthcare providers: evidence from a teaching hospital in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 8, 599-603 (2019).

- Serafin, A., Malinowski, M. & Prażmowska-Wilanowska, A. Blood volume and pain perception during finger prick capillary blood sampling: are all safety lancets equal? Postgrad. Med. 132, 288-295 (2020).

- Biswas, J. et al. Effect of Hypodermic Needle Versus Safety Lancet on the Fear and Anxiety of Needle Prick Among Undergraduate Medical Students During

6. McMurtry, C. M. et al. Far from “Just a Poke”: common painful needle procedures and the development of needle fear. Clin. J. Pain. 31, S3-S11 (2015).

7. Raju, K. S. R., Taneja, I., Singh, S. P. & Wahajuddin Utility of noninvasive biomatrices in pharmacokinetic studies. Biomed. Chromatogr. 27, 1354-1366 (2013).

8. Brinkman, J. E., Dorius, B. & Sharma, S. Physiology, Body Fluids. [Updated 2023 Jan 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482447/.

9. Elhassan E. A. & Schrier R. W. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology: Fourth Edition, 85-99 (2010).

10. Wiig, H. & Swartz, M. A. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1005-1060 (2012).

11. Mathew, J., Sankar, P. & Varacallo, M. Physiology, Blood Plasma. 2023 Apr 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

12. Sagedal, S. et al. Intermittent saline flushes during haemodialysis do not alleviate coagulation and clot formation in stable patients receiving reduced doses of dalteparin. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 21, 444-449 (2006).

13. Müller, A. C. et al. A comparative proteomic study of human skin suction blister fluid from healthy individuals using immunodepletion and ITRAQ labeling. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3715-3727 (2012).

14. Reusch, M. K., Mansbridge, J. N., Nickoloff, B. J. & Morhenn, V. B. Immunophenotyping of skin cells during healing of suction blister injury. Dermatology 183, 179-183 (1991).

15. Bruschi, M. L. Strategies to modify the drug release from pharmaceutical systems. 1-199 (Woodhead Publishing, Elsevier, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/ C2014-0-02342-8.

16. Saifullah, K. M. & Faraji Rad, Z. Sampling dermal interstitial fluid using microneedles: A review of recent developments in sampling methods and microneedle-based biosensors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2201763 (2023).

17. Ma, S., Li, J., Pei, L., Feng, N. & Zhang, Y. Microneedle-based interstitial fluid extraction for drug analysis: advances, challenges, and prospects. J. Pharm. Anal. 13, 111-126 (2023).

18. Gill, H. S., Denson, D. D., Burris, B. A. & Prausnitz, M. R. Effect of microneedle design on pain in human volunteers. Clin. J. Pain. 24, 585-594 (2008).

19. Rad, Z. F., Prewett, P. D. & Davies, G. J. An overview of microneedle applications, materials, and fabrication methods. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 1034-1046 (2021).

20. Zhang, X., Zhang, W., Wu, W. & Chen, J. Programmable SARS-CoV-2 mutation detection platform based on ligation-triggered isothermal exponential amplification coupled with self-priming amplification. Microchem. J. 195, 109477 (2023).

21. Yoon, H. J. et al. Cold water fish gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for tissue engineering application. PLoS ONE 11, e0163902 (2016).

22. Doğan, E. E. et al. Synthesis, characterization and some biological properties of PVA/PVP/PN hydrogel nanocomposites: antibacterial and biocompatibility. Adv. Mater. Sci. 19, 32-45 (2019).

23. Shi, Y., Xiong, D., Liu, Y., Wang, N. & Zhao, X. Swelling, mechanical and friction properties of PVA/PVP hydrogels after swelling in osmotic pressure solution. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 65, 172-180 (2016).

24. Sun, M. et al. Synthesis and properties of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels and their recent applications in load-bearing tissue. Polymers 10, 1290 (2018).

25. Teodorescu, M., Bercea, M. & Morariu, S. Biomaterials of PVA and PVP in medical and pharmaceutical applications: perspectives and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 37, 109-131 (2019).

26. Zhu, J. et al. Phase segregated Pt-SnO2/C nanohybrids for highly efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Small 16, 1905910 (2020).

27.

28. Fonseca, D. F. S. et al. Swellable gelatin methacryloyl microneedles for extraction of interstitial skin fluid toward minimally invasive monitoring of urea. Macromol. Biosci. 20, 2000195 (2020).

29. Chang, H. et al. A swellable microneedle patch to rapidly extract skin interstitial fluid for timely metabolic analysis. Adv. Mater 29, 1702243 (2017).

30. Ebrahiminejad, V., Rad, Z. F., Prewett, P. D. & Davies, G. J. Fabrication and testing of polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 13, 629-640 (2022). 13:55.

31. Römgens, A. M., Bader, D. L., Bouwstra, J. A., Baaijens, F. P. T. & Oomens, C. W. J. Monitoring the penetration process of single microneedles with varying tip diameters. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 40, 397-405 (2014).

32. Han, W. T. et al. Improved cell viability for large-scale biofabrication with photo-crosslinkable hydrogel systems through a dual-photoinitiator approach. Biomater. Sci. 8, 450-461 (2019).

33. He, R. et al. Carbon nanotubes: construction of aptamer-siRNA chimera/PEI/5FU/Carbon nanotube/collagen membranes for the treatment of peritoneal dissemination of drug-resistant gastric cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 1901201 (2020).

34. Luo, Z. et al. Organ-on-a-Chip: organ-on-a-chip for cancer and immune organs modeling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1801054 (2019).

35. Himawan, A. et al. Multifunctional low temperature-cured PVA/PVP/citric acidbased hydrogel forming microarray patches: Physicochemical characteristics and hydrophilic drug interaction. Eur. Polym. J. 186, 111836 (2023).

36. Makvandi, P. et al. Engineering microneedle patches for improved penetration: analysis, skin models and factors affecting needle insertion. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 1 (2021).

37. Davis, S. P., Landis, B. J., Adams, Z. H., Allen, M. G. & Prausnitz, M. R. Insertion of microneedles into skin: measurement and prediction of insertion force and needle fracture force. J. Biomech. 37, 1155-1163 (2004).

38. Malek-Khatabi, A., Faraji Rad, Z., Rad-Malekshahi, M. & Akbarijavar, H. Development of dissolvable microneedle patches by CNC machining and micromolding for drug delivery. Mater. Lett. 330, 133328 (2023).

39. Nair, K. et al. Investigation of plasma treatment on micro-injection moulded microneedle for drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 7, 471-485 (2015).

40. Ebrahiminejad, V., Malek-khatabi, A. & Faraji Rad, Z. Influence of low-frequency vibration and skin strain on insertion mechanics and drug diffusion of PVA/ PVP dissolving microneedles. Adv. Mater. Technol. 9, 2301272 (2024).

41. Ling, J. et al. Critical roles of CX3CR1(+) mononuclear phagocytes in maintaining gut-liver axis health. J. Bionic Eng. 13, 303-304 (2016).

42. Aoyagi, S., Izumi, H. & Fukuda, M. Biodegradable polymer needle with various tip angles and consideration on insertion mechanism of mosquito’s proboscis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 143, 20-28 (2008).

43. Kundan, K. K., Laha, S. & Ghatak, A. Vibration assisted puncturing of a soft brittle solid. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 26, 26-34 (2019).

44. Larrañeta, E. et al. A proposed model membrane and test method for microneedle insertion studies. Int. J. Pharm. 472, 65-73 (2014).

45. Czekalla, C., Schönborn, K. H., Lademann, J. & Meinke, M. C. Noninvasive determination of epidermal and stratum corneum thickness in vivo using two-photon microscopy and optical coherence tomography: impact of body area, age, and gender. Ski. Pharm. Physiol. 32, 142-150 (2019).

46. Alrimawi, B. H., Lee, J. Y., Ng, K. W. & Goh, C. F. In vitroevaluation of microneedle strength: a comparison of test configurations and experimental insights. RSC Pharm. 1, 227-233 (2024).

47. Leone, M. et al. Universal Applicator for Digitally-Controlled Pressing Force and Impact Velocity Insertion of Microneedles into Skin. Pharmaceutics 10, 211 (2018).

48. Kim, J. et al. Bioinspired microneedle insertion for deep and precise skin penetration with low force: why the application of mechanophysical stimuli should be considered. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 78, 480-490 (2018).

49. Mahvash, M. & Dupont, P. E. Mechanics of dynamic needle insertion into a biological material. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 934-943 (2010).

50. Mahvash, M. & Dupont, P. E. Fast needle insertion to minimize tissue deformation and damage. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 2009, 3097-3102 (2009).

51. Steil, G. M. et al. Interstitial fluid glucose dynamics during insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Diabetologia 48, 1833-1840 (2005).

- Correspondence: Zahra Faraji Rad (Zahra.FarajiRad@usq.edu.au)

School of Engineering, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD 4300, Australia

Centre for Future Materials, Institute for Advanced Engineering and Space Sciences, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD, Australia Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00850-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39774609

Publication Date: 2025-01-08

Micro-vibration assisted dual-layer spiral microneedles to rapidly extract dermal interstitial fluid for minimally invasive detection of glucose

Abstract

Various hydrogels have been explored to create minimally invasive microneedles (MNs) to extract interstitial fluid (ISF). However, current methods are time-consuming and typically require

Introduction

significant disruption or alteration in the integrity and structure of the outermost layer of the skin, known as the stratum corneum (SC) and cause local trauma to the skin

To address this issue, MNs have emerged as a prominent tool to harness the ISF for biomarker detection due to their unique properties and advantages

Cross-linked hydrogels such as PVA/PVP and GelMA have demonstrated a good swelling ratio, a crucial factor for efficient ISF extraction

Therefore, there is a need for rapid ISF extraction and biomarker analysis. This study introduces two distinct types of cross-linked, dual-layer spiral structured MNs made of GelMA/PVA and PVA/PVP/HA hydrogels for rapid ISF extraction. To the author’s knowledge, the spiral-shaped MN configuration represents a novel design that has not been explored previously. The chosen hydrogel combinations (GelMA/PVA and PVA/PVP/HA) significantly enhanced the swelling behavior of the MNs compared to previous studies

analyzes the importance of a uniform base layer for effective MN penetration into the skin. Due to its flexibility, Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate (PEGDA) is selected for the GelMA/PVA MN array base, while PVP is chosen for the PVA/PVP/HA MN array base. Optimal drying times for the PVP base are determined through a two-step approach, with GelMA MNs requiring a shorter drying time. This study further investigates the swelling and mechanical properties of the MNs to assess their capabilities in insertion into the skin and ISF extraction. Swelling tests are conducted in both PBS and artificial ISF, while compression tests are utilized to assess the mechanical characteristics of the MNs.

The study also introduces an advanced version of our patented MN applicator capable of inserting MNs at a velocity of

Results and discussion Spiral design

Fabrication of spiral MNs and optimization of base layers

as an input and is then sliced into a series of 2D images called digital masks that show or hide specific areas of a layer. Each layer has a mask, and each layer is added until the entire 3D structure is complete. Slicing data was sent to the 3D printing system to fabricate individual layers. PuSL technology can achieve resolutions of several micrometers or hundreds of nanometers by controlling the projection lens. The master MN array was printed in high temperature resistance (HTL) material using this advanced technology.

After creating the master MN , it was used to create PDMS negative molds (Supplementary Fig. S1) to replicate GelMA/PVA and PVA/PVP/HA MN arrays. All MN replicas were formed without any defect, resembling the spiral shape of the master array, as shown in Fig. 2a; however, longitudinal shrinkage was observed across all MN types (master and replica) compared to their initial CAD dimension

bond, forming a cohesive, single-layer structure in the final MN array. However, the attempt to incorporate PEGDA into PVA/PVP/HA solutions as a base did not work as expected. For instance, PEGDA did not form a uniform layer with the PVA/PVP/HA solution. Due to its photoinitiator content, the PEGDA base hardened more rapidly when exposed to UV light than the PVA/PVP/HA solution, leading to inadequate bonding between the two layers. To address this, three tests were conducted: one with the combination of PVA/PVP (

The drying time for the PVP base was optimized using a two-step strategy. Initially,

Swelling kinetics and PBS uptake in vitro

The swelling ratios of the MNs were conducted in artificial ISF and PBS (Phosphate-buffered Saline) for up to 10 min . The results in Fig. 3a(i-ii) demonstrated that the swelling ability of the MNs increases over time after immersion. In artificial ISF, GelMA (

respectively, which are higher than similar reported studies

Further experiments were conducted with varying concentrations of PVA and PVP only. However, the obtained swelling ability of the MNs was not optimal (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, HA was introduced, and three different concentrations of HA (

Similar experiments were carried out in PBS for the swelling test. The MNs exhibited subtle differences in PBS compared to artificial ISF. For example, GelMA/PVA compositions showed a slightly higher swelling tendency when immersed in artificial ISF,

Expansion and swelling of the MN arrays were also very noticeable visually. As the MNs swelled, they significantly increased in size, confirming their ability to effectively absorb PBS. The results indicated that the GelMA/PVA (20/3, w/v) MN array exhibited a substantial increase in

Experiments were also conducted on the skin model constructed using agarose hydrogel to assess the PBS uptake capacity of MNs, as illustrated in Fig. 3d. A consistent pattern of increased PBS uptake was observed across various GelMA/PVA and PVA/PVP/HA compositions, as shown in Fig. 3e. Among them, GelMA/PVA

Mechanical properties of the spiral MNs

displacement curve, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. Although each array in the test had 225 MNs , the force measurement was calculated to represent a single needle in the force-displacement curves which provides critical insights into the mechanical behavior of the MNs. When the tip of the MN first contacts the upper plate of the UTM, the force increases to a peak, then drops to a low point before rising to a second peak. The initial peak indicates the failure load, resulting in permanent deformation of the MN structure. Figure 4b shows the impact of compression

For GelMA/PVA (

Many studies of MNs have demonstrated good mechanical properties using similar materials such as PVA/PVA, GelMA, and HA. For example, Zhu et al., reported that compressive modulus increased from

Surface characterization

the micro-scale variations in height across the surface, can influence interactions with the skin

MNs were assessed for surface roughness properties using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). The GelMA/ PVA (

Micro-vibration assisted MNs insertion and ISF extraction MN applicator with arduino microcontroller

The programming through the Arduino IDE enabled finer control than manual adjustments (potentiometer),

enhancing the system’s overall functionality. Despite this, a potentiometer was still incorporated as a backup control method, allowing for manual adjustments of the voltage applied to the ERM motors when necessary. This ensures that manual control can still be available if the Arduino IDE is not accessible. Therefore, two transistors were introduced to amplify the signal to the required voltage level. Diodes were also added to protect the transistors from reverse voltage spikes and maintain circuit stability. Furthermore, resistors were used to limit the current flowing through the transistors and motors, ensuring safe and efficient operation. When the Arduino reads signals from the potentiometer, it converts them to voltage, which then controls the vibration of the two ERMs, translating electrical signals into physical vibration. Figure 6b shows the mechanical design and internal configuration of the MN applicator. The insertion trigger initiates the action, while the compression spring provides the necessary force for the plunger to push the MNs into the skin.

One of the fundamental challenges for swellable MNs is the consistent and precise skin penetration, which is influenced by various factors such as the applied force, the velocity of insertion, and the mechanical properties of the

spring and storing potential energy. The plunger is then locked to maintain this compression. When triggered, the stored energy in the spring is released, driving the MNs into the skin sample with controlled force and precision. Figure 6e shows the actual physical setup of the applicator device connected to the electronic component for the MN insertion test.

MNs insertion, ISF extraction, and glucose recovery

The percentage of spiral MNs in an array which penetrated the skin model without vibration for the first layer was

Although the parafilm test provides valuable insights for analyzing the skin penetration capabilities of the MNs

before testing on biological samples (porcine ear skin), It has been reported to demonstrate higher penetration depths than those observed in porcine skin

After MN arrays were manually applied for 5 min on the porcine ear skin, ISF uptake for GelMA/PVA (20/3, w/v) was only

The velocity of MN insertion is also a critical factor influencing skin resistance during penetration. Studies

where higher velocities cause greater deformation, thereby lowering the skin’s fracture strength and enhancing skin penetration

swellable MNs, which typically have lower mechanical strength than other types due to their swellability. Moreover, the dynamic nature of vibration allows MNs to overcome the skin’s natural viscoelastic resistance more effectively than a static application of force. The combination of velocity (

Nonetheless, due to the swelling nature of the hydrogel MNs, their structure weakens upon penetrating the SC, making them less capable of enduring continuous vibration. The ability of MNs to withstand vibration-enhanced penetration of the SC is also related to mechanical strength of the MNs. Higher frequencies (

To assess the ability of MNs to recover biomarkers, glucose was chosen as the target biomolecule within the agarose gel matrix. The MN arrays were applied to the agarose matrix for 5 min , after which they were removed and dissolved at

may fall below the sensitivity threshold of the glucose detection assay kit. The accuracy of our results is supported by the fact that the glucose detection kit used is highly sensitive, which comfortably detects the induced glucose concentrations of

Conclusion

The performance of MNs in extracting ISF is influenced by several factors, including their design, material, swelling ability, mechanical characteristics, and insertion technique. Therefore, one of the objectives of this study was to investigate using only GelMA as the MN material and assess its ability to extract a higher volume of ISF within a short timeframe (

yield of 5.8 g from the initial 10 g . The prepolymer was stored at

Degree of substitution of GelMA

Fabrication of GeIMA and GeIMA/PVA MNs

Fabrication of PVA/PVP/HA MNs

were dried at

Arduino-based custom-made applicator

The knob controlling the speed of the groove plunger was set to

Swelling ratios of the MNs in PBS and artificial ISF

Determination of mechanical properties

the following equations:

Morphology characterization

The spiral morphology of the MNs was assessed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-7001F, JEOL, Japan). The MNs were sputter-coated with a 12 nm thick layer of platinum to prevent charging. The sample was then imaged in the field emission SEM at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV in high vacuum mode (HighVac) with a magnification level of

Surface characterizations

Insertion test and extraction of ISF ex vivo

arrays were applied to the simulated skin setup both manually and using the custom-made applicator at frequencies of 50 Hz and 100 Hz . After insertion, the microvibration process was stopped after a few seconds during which micropore widening occurred, after which the MN arrays were left in place for 30 s before being removed. The holes in the Parafilm layers were then examined under a microscope (Carl Zeiss Axio, Jena, Germany) to assess the efficiency of insertion.

Freshly slaughtered porcine ear skin was sourced from a local butcher (Brisbane, Australia) and stored in aluminum foil at

Detection of glucose concentration in vitro

Statistical analysis

Acknowledgements

Author details

Author contributions

Conflict of interest

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Published online: 08 January 2025

References

- Lee, B. H., Shirahama, H., Cho, N. J. & Tan, L. P. Efficient and controllable synthesis of highly substituted gelatin methacrylamide for mechanically stiff hydrogels. RSC Adv. 5, 106094-106097 (2015).

- Heikenfeld, J. et al. Accessing analytes in biofluids for peripheral biochemical monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 407-419 (2019).

- Sriram, S. Study of needle stick injuries among healthcare providers: evidence from a teaching hospital in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 8, 599-603 (2019).

- Serafin, A., Malinowski, M. & Prażmowska-Wilanowska, A. Blood volume and pain perception during finger prick capillary blood sampling: are all safety lancets equal? Postgrad. Med. 132, 288-295 (2020).

- Biswas, J. et al. Effect of Hypodermic Needle Versus Safety Lancet on the Fear and Anxiety of Needle Prick Among Undergraduate Medical Students During

6. McMurtry, C. M. et al. Far from “Just a Poke”: common painful needle procedures and the development of needle fear. Clin. J. Pain. 31, S3-S11 (2015).

7. Raju, K. S. R., Taneja, I., Singh, S. P. & Wahajuddin Utility of noninvasive biomatrices in pharmacokinetic studies. Biomed. Chromatogr. 27, 1354-1366 (2013).

8. Brinkman, J. E., Dorius, B. & Sharma, S. Physiology, Body Fluids. [Updated 2023 Jan 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482447/.

9. Elhassan E. A. & Schrier R. W. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology: Fourth Edition, 85-99 (2010).

10. Wiig, H. & Swartz, M. A. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1005-1060 (2012).

11. Mathew, J., Sankar, P. & Varacallo, M. Physiology, Blood Plasma. 2023 Apr 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

12. Sagedal, S. et al. Intermittent saline flushes during haemodialysis do not alleviate coagulation and clot formation in stable patients receiving reduced doses of dalteparin. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 21, 444-449 (2006).

13. Müller, A. C. et al. A comparative proteomic study of human skin suction blister fluid from healthy individuals using immunodepletion and ITRAQ labeling. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3715-3727 (2012).

14. Reusch, M. K., Mansbridge, J. N., Nickoloff, B. J. & Morhenn, V. B. Immunophenotyping of skin cells during healing of suction blister injury. Dermatology 183, 179-183 (1991).

15. Bruschi, M. L. Strategies to modify the drug release from pharmaceutical systems. 1-199 (Woodhead Publishing, Elsevier, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/ C2014-0-02342-8.

16. Saifullah, K. M. & Faraji Rad, Z. Sampling dermal interstitial fluid using microneedles: A review of recent developments in sampling methods and microneedle-based biosensors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2201763 (2023).

17. Ma, S., Li, J., Pei, L., Feng, N. & Zhang, Y. Microneedle-based interstitial fluid extraction for drug analysis: advances, challenges, and prospects. J. Pharm. Anal. 13, 111-126 (2023).

18. Gill, H. S., Denson, D. D., Burris, B. A. & Prausnitz, M. R. Effect of microneedle design on pain in human volunteers. Clin. J. Pain. 24, 585-594 (2008).

19. Rad, Z. F., Prewett, P. D. & Davies, G. J. An overview of microneedle applications, materials, and fabrication methods. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 1034-1046 (2021).

20. Zhang, X., Zhang, W., Wu, W. & Chen, J. Programmable SARS-CoV-2 mutation detection platform based on ligation-triggered isothermal exponential amplification coupled with self-priming amplification. Microchem. J. 195, 109477 (2023).

21. Yoon, H. J. et al. Cold water fish gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for tissue engineering application. PLoS ONE 11, e0163902 (2016).

22. Doğan, E. E. et al. Synthesis, characterization and some biological properties of PVA/PVP/PN hydrogel nanocomposites: antibacterial and biocompatibility. Adv. Mater. Sci. 19, 32-45 (2019).

23. Shi, Y., Xiong, D., Liu, Y., Wang, N. & Zhao, X. Swelling, mechanical and friction properties of PVA/PVP hydrogels after swelling in osmotic pressure solution. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 65, 172-180 (2016).

24. Sun, M. et al. Synthesis and properties of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels and their recent applications in load-bearing tissue. Polymers 10, 1290 (2018).

25. Teodorescu, M., Bercea, M. & Morariu, S. Biomaterials of PVA and PVP in medical and pharmaceutical applications: perspectives and challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 37, 109-131 (2019).

26. Zhu, J. et al. Phase segregated Pt-SnO2/C nanohybrids for highly efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. Small 16, 1905910 (2020).

27.

28. Fonseca, D. F. S. et al. Swellable gelatin methacryloyl microneedles for extraction of interstitial skin fluid toward minimally invasive monitoring of urea. Macromol. Biosci. 20, 2000195 (2020).

29. Chang, H. et al. A swellable microneedle patch to rapidly extract skin interstitial fluid for timely metabolic analysis. Adv. Mater 29, 1702243 (2017).

30. Ebrahiminejad, V., Rad, Z. F., Prewett, P. D. & Davies, G. J. Fabrication and testing of polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 13, 629-640 (2022). 13:55.

31. Römgens, A. M., Bader, D. L., Bouwstra, J. A., Baaijens, F. P. T. & Oomens, C. W. J. Monitoring the penetration process of single microneedles with varying tip diameters. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 40, 397-405 (2014).

32. Han, W. T. et al. Improved cell viability for large-scale biofabrication with photo-crosslinkable hydrogel systems through a dual-photoinitiator approach. Biomater. Sci. 8, 450-461 (2019).

33. He, R. et al. Carbon nanotubes: construction of aptamer-siRNA chimera/PEI/5FU/Carbon nanotube/collagen membranes for the treatment of peritoneal dissemination of drug-resistant gastric cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 1901201 (2020).

34. Luo, Z. et al. Organ-on-a-Chip: organ-on-a-chip for cancer and immune organs modeling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1801054 (2019).

35. Himawan, A. et al. Multifunctional low temperature-cured PVA/PVP/citric acidbased hydrogel forming microarray patches: Physicochemical characteristics and hydrophilic drug interaction. Eur. Polym. J. 186, 111836 (2023).

36. Makvandi, P. et al. Engineering microneedle patches for improved penetration: analysis, skin models and factors affecting needle insertion. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 1 (2021).

37. Davis, S. P., Landis, B. J., Adams, Z. H., Allen, M. G. & Prausnitz, M. R. Insertion of microneedles into skin: measurement and prediction of insertion force and needle fracture force. J. Biomech. 37, 1155-1163 (2004).

38. Malek-Khatabi, A., Faraji Rad, Z., Rad-Malekshahi, M. & Akbarijavar, H. Development of dissolvable microneedle patches by CNC machining and micromolding for drug delivery. Mater. Lett. 330, 133328 (2023).

39. Nair, K. et al. Investigation of plasma treatment on micro-injection moulded microneedle for drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 7, 471-485 (2015).

40. Ebrahiminejad, V., Malek-khatabi, A. & Faraji Rad, Z. Influence of low-frequency vibration and skin strain on insertion mechanics and drug diffusion of PVA/ PVP dissolving microneedles. Adv. Mater. Technol. 9, 2301272 (2024).

41. Ling, J. et al. Critical roles of CX3CR1(+) mononuclear phagocytes in maintaining gut-liver axis health. J. Bionic Eng. 13, 303-304 (2016).

42. Aoyagi, S., Izumi, H. & Fukuda, M. Biodegradable polymer needle with various tip angles and consideration on insertion mechanism of mosquito’s proboscis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 143, 20-28 (2008).

43. Kundan, K. K., Laha, S. & Ghatak, A. Vibration assisted puncturing of a soft brittle solid. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 26, 26-34 (2019).

44. Larrañeta, E. et al. A proposed model membrane and test method for microneedle insertion studies. Int. J. Pharm. 472, 65-73 (2014).

45. Czekalla, C., Schönborn, K. H., Lademann, J. & Meinke, M. C. Noninvasive determination of epidermal and stratum corneum thickness in vivo using two-photon microscopy and optical coherence tomography: impact of body area, age, and gender. Ski. Pharm. Physiol. 32, 142-150 (2019).

46. Alrimawi, B. H., Lee, J. Y., Ng, K. W. & Goh, C. F. In vitroevaluation of microneedle strength: a comparison of test configurations and experimental insights. RSC Pharm. 1, 227-233 (2024).

47. Leone, M. et al. Universal Applicator for Digitally-Controlled Pressing Force and Impact Velocity Insertion of Microneedles into Skin. Pharmaceutics 10, 211 (2018).

48. Kim, J. et al. Bioinspired microneedle insertion for deep and precise skin penetration with low force: why the application of mechanophysical stimuli should be considered. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 78, 480-490 (2018).

49. Mahvash, M. & Dupont, P. E. Mechanics of dynamic needle insertion into a biological material. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 57, 934-943 (2010).

50. Mahvash, M. & Dupont, P. E. Fast needle insertion to minimize tissue deformation and damage. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 2009, 3097-3102 (2009).

51. Steil, G. M. et al. Interstitial fluid glucose dynamics during insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Diabetologia 48, 1833-1840 (2005).

- Correspondence: Zahra Faraji Rad (Zahra.FarajiRad@usq.edu.au)

School of Engineering, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD 4300, Australia

Centre for Future Materials, Institute for Advanced Engineering and Space Sciences, University of Southern Queensland, Springfield, QLD, Australia Full list of author information is available at the end of the article