DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02372-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833970

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-20

إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، جودة النوم، الاكتئاب وصعوبة المراهقين في وصف المشاعر: نموذج وساطة معتدلة

الملخص

الخلفية والأهداف: يرتبط إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية ارتباطًا وثيقًا بجودة النوم بين المراهقين. ومع ذلك، تتطلب الآليات الأساسية التي تحرك هذه العلاقات مزيدًا من الاستكشاف. تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى تعزيز فهم الآليات النفسية التي تربط بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم من خلال التحقيق في الاكتئاب كعامل وساطة وصعوبة وصف المشاعر كعامل معتدل.

الطرق: تم إجراء استبيان ذاتي مع 1,670 مراهقًا في الصين، يقيم إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، جودة النوم، الاكتئاب، وصعوبة وصف المشاعر. تم إجراء تحليلات وصفية وارتباطية على هذه المتغيرات، تلتها بناء نموذج وساطة معتدلة. النتائج: كان إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية مرتبطًا بشكل إيجابي كبير بجودة النوم، الاكتئاب، وصعوبة وصف المشاعر بين المراهقين. كانت صعوبة وصف المشاعر مرتبطة أيضًا بشكل إيجابي كبير بالاكتئاب. كان الاكتئاب وسيطًا جزئيًا في العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم، بينما زادت صعوبة وصف المشاعر من العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب. الاستنتاج: توضح هذه الدراسة المزيد من الآليات النفسية التي تربط بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين. يعمل الاكتئاب كعامل وساطة، بينما تعزز صعوبة وصف المشاعر العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب. تسلط هذه النتائج الضوء على دور صعوبة وصف المشاعر في التفاعل بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم، مما يوفر رؤى قيمة لفهم أكثر شمولاً وتدخلات مستهدفة تهدف إلى تحسين جودة النوم لدى المراهقين.

المقدمة

تتعدد العوامل المساهمة في جودة النوم السيئة وتعقيدها. من بين هذه العوامل، وُجد أن إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية مرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بجودة النوم لدى المراهقين [12]. مع التطور السريع للأجهزة الإلكترونية الذكية ومواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، أصبحت مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية تدريجيًا جزءًا لا يتجزأ من الحياة اليومية للناس ومنصة مهمة للحصول على المعلومات والانخراط في التفاعلات الاجتماعية [13]. تظهر الأبحاث أن

ارتفاع انتشار إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية مرتبط بالعمر الأصغر والعيش في دول جماعية [18]. على الرغم من أن إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية لم يتم تصنيفه كتشخيص رسمي أو حالة صحية في الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (DSM-5-TR) أو التصنيف الدولي للأمراض، الإصدار الحادي عشر (ICD-11)، ولا يوجد توافق على تصنيفه، مع وجود اختلافات كبيرة في طرق التصنيف، إلا أن الاستخدام المفرط والإجباري لمواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية يمكن أن يتداخل بشكل كبير مع الحياة اليومية للمراهقين، مما يؤثر سلبًا على صحتهم البدنية، ووظائفهم الاجتماعية، ورفاهيتهم النفسية [19]. نظرًا لانتشار إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية في فئات المراهقين السكانية وتأثيراته السلبية المحتملة، تزايدت الانتباه المجتمعي لهذه الظاهرة. يشير إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية إلى انشغال الفرد المفرط بمواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، والذي يتميز بدافع قوي لاستخدام هذه المنصات وكمية كبيرة من الوقت والطاقة المستثمرة فيها، مما يمكن أن يؤثر سلبًا على الصحة البدنية والنفسية [13]. تعتبر السلوكيات الاجتماعية المفرطة والإدمانية شكلًا من أشكال السلوكيات الخطرة عبر الإنترنت، المرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بتقليل مدة النوم، وانخفاض جودة النوم، والأرق [20]. يميل المراهقون الذين لديهم مستويات أعلى من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وأوقات استخدام أطول، خاصة أولئك الذين يشاركون في استخدام الشبكات الاجتماعية بشكل سلبي، إلى إظهار جودة نوم أسوأ [21]. يميل المراهقون الذين يعانون من جودة نوم سيئة إلى قضاء وقت أطول على الشبكات الاجتماعية مقارنة بأولئك الذين لديهم جودة نوم أفضل [22]. أظهرت الأبحاث أنه في الأفراد الذين يعانون من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، يمكن أن يؤدي التعرض المطول للضوء الأزرق إلى تثبيط إفراز الميلاتونين، وتعطيل النوم وإيقاعات الساعة البيولوجية، وبالتالي تقليل جودة النوم [23]. تم التحقق من الدور التنبؤي لإدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية على جودة النوم الذاتية السيئة في عينات المراهقين، حيث كان المراهقون الذين يعانون من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية أكثر عرضة بـ 3.25 مرة للإبلاغ عن جودة نوم ذاتية سيئة مقارنة بأولئك الذين يستخدمون الشبكات الاجتماعية بشكل طبيعي [24]. بناءً على المراجعة أعلاه، تفترض هذه الدراسة أن هناك ارتباطًا إيجابيًا كبيرًا بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين.

في العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين، قد يعمل الاكتئاب كعامل وساطة مهم. الاكتئاب هو مصدر قلق كبير للصحة العامة بين المراهقين. أفادت دراسة تحليلية شاملة حديثة بمعدلات انتشار للاكتئاب الخفيف إلى الشديد، المعتدل إلى الشديد، والشديد عند

مع الشبكات الاجتماعية [27]. أظهرت العديد من الدراسات وجود علاقة إيجابية بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب [27، 28]. وفقًا لعلاج القبول والالتزام (ACT)، قد يؤدي إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية إلى اعتماد الأفراد لاستراتيجيات تنظيم عاطفي تجنبية متنوعة (مثل التفكير المفرط وكبت الأفكار) لتقليل تكرار أو شدة أو مدة هذه التجارب الداخلية غير السارة [29]. يمكن أن تكون هذه الاستجابة الصارمة للعواطف الداخلية ضارة، مما يؤدي إلى تحفيز المزيد من المشاعر والأفكار السلبية، وفي النهاية تؤدي إلى الاكتئاب. يتماشى هذا الرأي مع الأبحاث التي وجدت أن الأفراد الذين يعانون من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية هم أكثر عرضة لتجربة الاكتئاب، خاصة عندما يشاركون في كبت الأفكار. يعتبر إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية عامل ضعف أساسي للضيق العاطفي [30]. وفقًا لفرضية الاضطراب الإدماني الثانوي، يمكن أن تحفز السلوكيات الإدمانية اضطرابات الصحة النفسية الأخرى، وخاصة الاكتئاب [31]. قد يقضي المستخدمون المدمنون أوقاتًا وطاقة متزايدة في العالم الافتراضي، وعندما يغادرون البيئة عبر الإنترنت لمواجهة الواقع، غالبًا ما يشعرون بالإحباط أو الاكتئاب [32]. علاوة على ذلك، يعتبر الاكتئاب محددًا رئيسيًا لجودة النوم السيئة لدى المراهقين. وجدت الدراسات أن أكثر من

ومع ذلك، قد تتفاقم العلاقة بين المتغيرات المذكورة أعلاه لدى الأفراد الذين لديهم خصائص معينة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة السلوكيات السلبية أو النتائج النفسية السلبية. إحدى هذه الخصائص هي مستوى صعوبة وصف المشاعر، وهو بُعد رئيسي من أليكسيثيميا [39]. يُعرّف مصطلح أليكسيثيميا، الذي قدمه بيتر سيفنيوس، المرضى الذين يواجهون صعوبة في العلاج النفسي الموجه نحو البصيرة [40]. يُعرّف الآن بأنه عدم القدرة على تحديد ووصف مشاعر المرء أو مشاعر الآخرين [41]. تعتبر صعوبة وصف المشاعر تجسيدًا لضعف الإدراك العاطفي، والمعالجة، والتنظيم [42]، وهي عامل خطر لتطور مشكلات نفسية متنوعة وسلوكيات غير تكيفية [43]. تشير الأبحاث إلى أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالمشكلات العاطفية مثل الاكتئاب [44]. يمكن أن تؤدي أليكسيثيميا إلى تفاقم المشاعر السلبية مثل الاكتئاب بسبب تأثيرها على الوعي العاطفي والتعبير [45]. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تؤدي إلى علاقات بين شخصية سيئة، مما يزيد من الأعباء النفسية. ترتبط صعوبة وصف المشاعر بكفاءة اجتماعية أقل وشعبية أقل بين الأقران [46]. من خلال التأثير على التفاعل الاجتماعي، وتنظيم العواطف، والوعي الذاتي، والدعم الاجتماعي، تزيد صعوبة وصف المشاعر بشكل كبير من خطر الاكتئاب [47]. وفقًا لنموذج “الأغنياء يزدادون غنى”، قد يكون المراهقون الذين يعانون من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وصعوبة وصف المشاعر أكثر عرضة للاكتئاب [48]. يقترح بعض المؤلفين حتى أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر والاكتئاب قد تكون مفاهيم غير قابلة للتمييز [49]. لذلك، بناءً على المراجعة أعلاه، من الواضح أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر يمكن أن تعزز العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب التي تم مناقشتها في هذه الدراسة، مما يزيد من مدى النتائج النفسية والسلوكية السلبية. وبالتالي، نفترض أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر تعزز قوة العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين.

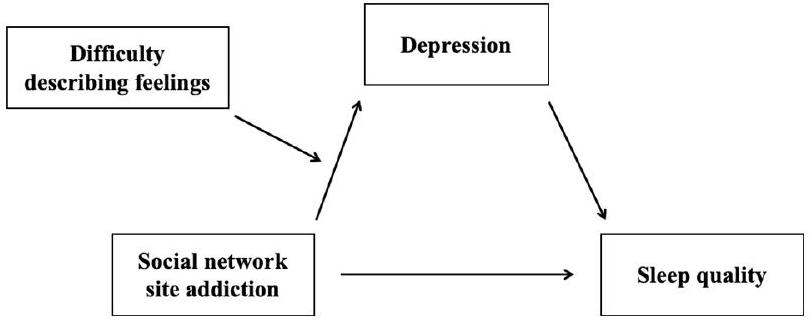

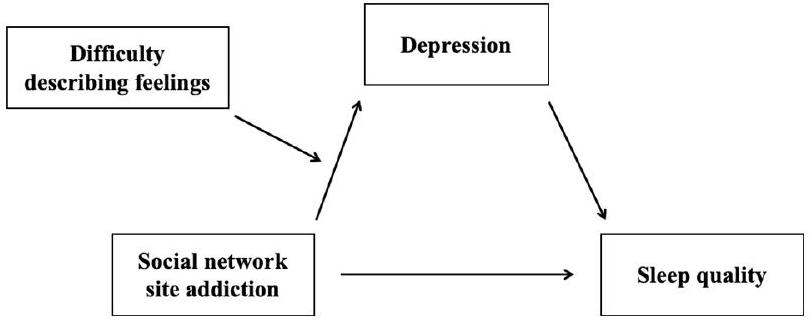

استكشفت الأبحاث السابقة العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين، بالإضافة إلى الدور التنبؤي لهذه العلاقة. ومع ذلك، فإن الأبحاث حول هذه العلاقة لدى المراهقين الصينيين محدودة. لتكملة الأبحاث في هذا المجال واستكشاف الآليات النفسية الأساسية، تقدم هذه الدراسة الاكتئاب كمتغير وسيط وصعوبة وصف المشاعر كمتغير معدل. وبالتالي، تبني هذه الدراسة نموذج مسار مفترض (الشكل 1).

طرق البحث

المشاركون

حصلت الدراسة على موافقة لجنة الأخلاقيات الطبية التابعة للمؤسسة التي ينتمي إليها المؤلف قبل تنفيذها، مما يضمن أن تصميم الدراسة وعملية جمع البيانات تتوافق مع المتطلبات الأخلاقية والقانونية. التزمت جميع الإجراءات بالمعايير والإرشادات التي وضعتها لجنة الأخلاقيات، مما زاد من موثوقية الدراسة وثقة المشاركين. شملت الاستبيانات غير الصالحة تلك التي تحتوي على ردود نمطية أو تلك التي كانت أوقات ردودها قصيرة جدًا أو طويلة جدًا. شارك ما مجموعه 1,915 مراهقًا في الاستطلاع، وبعد استبعاد الردود غير الصالحة، تم الحصول على 1,670 استبيانًا صالحًا (693 صبيًا، 997 فتاة؛ 767 في الصف الأول، 803 في الصف الثاني، 100 في الصف الثالث؛ 110 مع دخل عائلي شهري أقل من

إجراءات

إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية

جودة النوم

الاكتئاب

الاكتئاب. معامل كرونباخ

صعوبة في وصف المشاعر

معالجة البيانات وتحليلها

| المتغيرات | 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ |

| 1 الجنس | – | ||||

| 2 عمر | 0.010 | – | |||

| 3 إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية | 0.076** | 0.092*** | – | ||

| 4 اكتئاب | 0.067** | 0.038 | 0.465*** | – | |

| 5 جودة النوم | 0.085** | 0.063* | 0.467*** | 0.637*** | – |

| 6 صعوبة في وصف المشاعر | 0.005 | 0.057* | 0.375*** | 0.575*** | 0.341*** |

تم التحكم في المتغيرات الديموغرافية مثل الجنس والعمر والحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية كمتغيرات مصاحبة. تم تحديد مستوى دلالة قدره 0.05 لجميع الاختبارات.

النتائج

اختبار انحياز الطريقة الشائعة

تحليل الارتباط

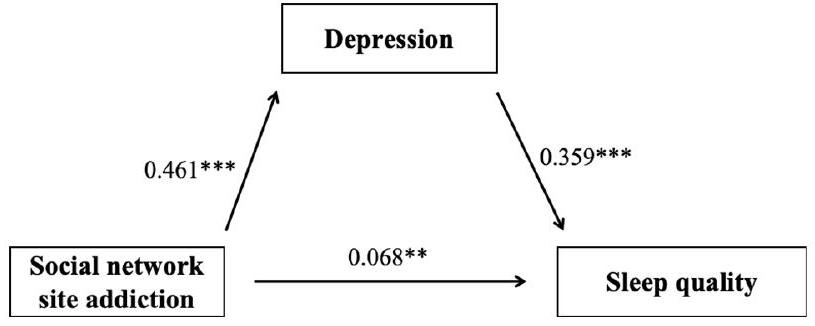

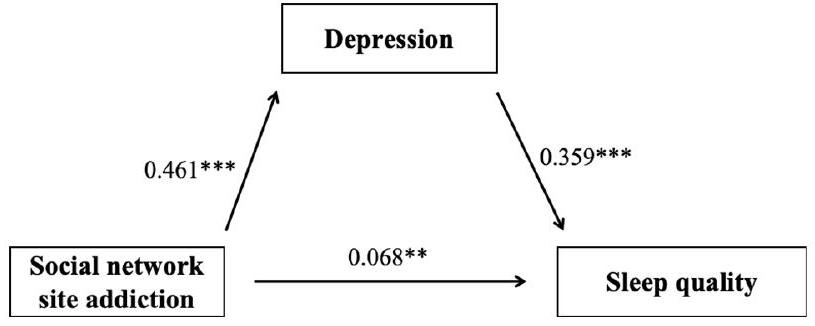

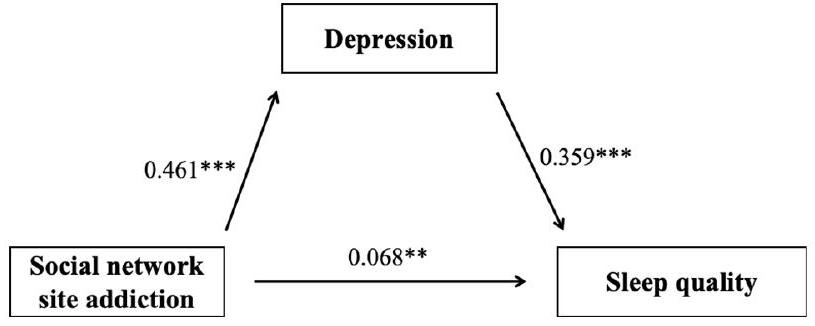

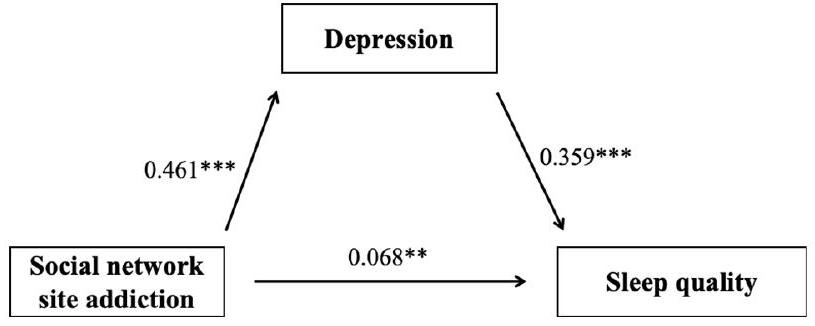

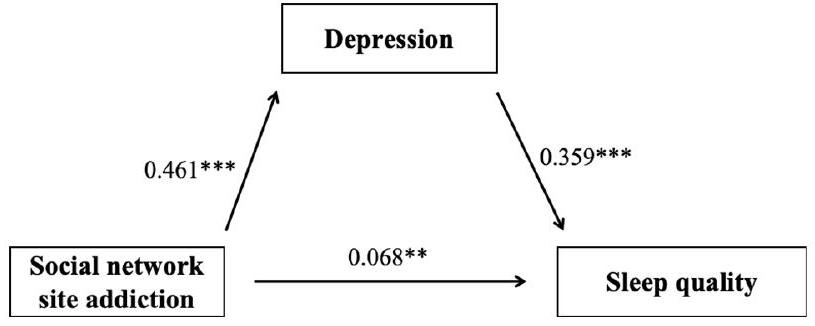

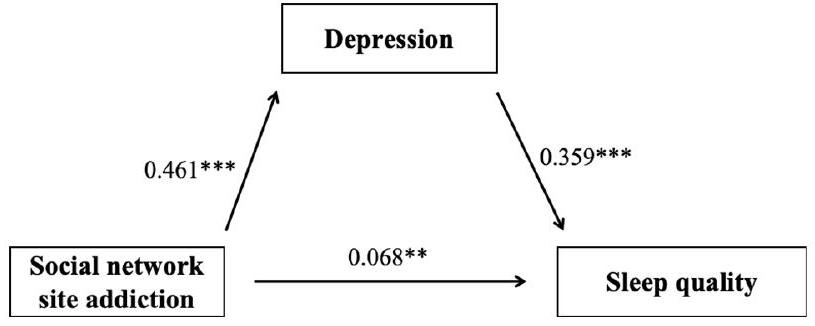

اختبار نموذج الوساطة

| متغير النتيجة | المتغيرات التنبؤية |

|

SE | ت |

|

ف |

| جودة النوم | إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية | 0.233 | 0.024 | 9.765*** | 0.068 | 30.416*** |

| جنس | 0.104 | 0.024 | 4.372*** | |||

| عمر | -0.026 | 0.024 | -1.066 | |||

| الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.391 | |||

| الاكتئاب | إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية | 0.461 | 0.022 | 21.080*** | 0.218 | 116.175*** |

| جنس | 0.032 | 0.022 | 1.480 | |||

| عمر | -0.009 | 0.022 | -0.411 | |||

| الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية | -0.037 | 0.022 | -1.672 | |||

| جودة النوم | إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية | 0.068 | 0.025 | 2.663** | 0.169 | 67.641*** |

| الاكتئاب | 0.359 | 0.025 | 14.208*** | |||

| جنس | 0.092 | 0.022 | 4.110*** | |||

| عمر | -0.022 | 0.023 | -0.985 | |||

| الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.995 |

| الطريق الوسيط |

|

SE |

|

|

|||||||

| التأثير الكلي | 0.233 | 0.024 |

|

||||||||

| الأثر المباشر | 0.068 | 0.025 |

|

||||||||

| التأثيرات غير المباشرة | 0.165 | 0.015 |

|

|

اختبار الوساطة المعتدلة

| المتغيرات | الاكتئاب | جودة النوم | ||||

|

|

SE | ت |

|

SE | ت | |

| إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية (أ) | 0.285 | 0.020 | 14.013*** | 0.068 | 0.025 | 2.663** |

| صعوبة في وصف المشاعر (ب) | 0.500 | 0.021 | 23.983*** | |||

|

|

0.109 | 0.018 | 6.171*** | |||

| الاكتئاب | 0.359 | 0.025 | 14.208*** | |||

| جنس | 0.043 | 0.019 | 2.303* | 0.092 | 0.022 | 4.110*** |

| عمر | -0.020 | 0.019 | -1.048 | -0.022 | 0.023 | -0.985 |

| الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية | -0.034 | 0.019 | -1.812 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.995 |

|

|

0.419 | 0.169 | ||||

| ف | 199.986*** | 67.641*** | ||||

| مستويات DDF |

|

SE |

|

|

|

||||||||

| منخفض | 0.175 | 0.027 |

|

0.122 | 0.228 | ||||||||

| وسيط | 0.285 | 0.020 |

|

0.245 | 0.324 | ||||||||

| عالي | 0.394 | 0.027 |

|

0.341 | 0.447 |

نقاش

تظهر الدراسة وجود علاقة إيجابية بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم بين المراهقين، وهو ما يتماشى مع أبحاث مماثلة. على سبيل المثال، أبرزت مراجعة منهجية وجود ارتباط كبير بين الألعاب متعددة اللاعبين عبر الإنترنت وسوء جودة النوم. أبلغت دراسة مقطعية واسعة النطاق عن الطلاب الكنديين عن احتمال أعلى لتقليل مدة النوم المرتبطة باستخدام الشبكات الاجتماعية، ولاحظت علاقة جرعة-استجابة بين استخدام الشبكات الاجتماعية وتقليل مدة النوم. تشمل الآليات المحتملة التي يؤثر بها إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية على جودة النوم التحفيز النفسي (أي زيادة الإثارة بسبب استخدام وسائل الإعلام عبر الإنترنت مما يؤدي إلى صعوبة في النوم)، وتأثير الشاشات المضيئة (أي تعرض الضوء الذي يقمع الهرمونات المعززة للنوم مثل الميلاتونين)، والانزعاج الجسدي (مثل السلوك المستقر المفرط المرتبط باستخدام الشبكات الاجتماعية المرضي مما يؤدي إلى انزعاج في الرقبة، مما قد يؤثر على جودة النوم). تدعم دراستنا أيضًا نظرية إزاحة النوم، التي تفترض أن استخدام الشبكات الاجتماعية، كنشاط ترفيهي غير منظم يفتقر إلى أوقات بداية ونهاية واضحة، يمكن أن يزيح بسهولة وقت النوم، مما يؤثر على مدة النوم وجودته. باختصار، تشير نتائجنا إلى وجود علاقة كبيرة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم بين المراهقين، مدعومة بأدلة بيولوجية.

تدعم هذه الدراسة الفرضية القائلة بأن الاكتئاب يتوسط العلاقة بين مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية

الإدمان وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين، بما يتماشى مع الأبحاث السابقة [63، 64]. وقد أثبتت الدراسات السابقة وجود ارتباط قوي بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب [80]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إثبات العلاقة بين الاكتئاب وجودة النوم بشكل قوي [81]. وفقًا لنموذج ACT (العلاج بالقبول والالتزام) [29]، فإن إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية، كعملية أساسية من عدم المرونة النفسية، يقلل من مرونة الأفراد النفسية ويؤدي إلى مشاكل نفسية خطيرة. عندما يتم تقييد المشاعر السلبية بواسطة التفكير الجامد أو عندما يتجنب الأفراد بوعي التجارب أو المواقف التي قد تثير مشاعر سلبية، فمن المحتمل أن تتفاقم هذه المشكلات [82]. قد يجد الأفراد الذين يعانون من إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية أن جهودهم لتجنب مشاعر وأفكار معينة تعززها فقط، مما يؤدي إلى عدم القدرة على قبول ومعالجة الأفكار والمشاعر السلبية بشكل فعال، وبالتالي يؤدي إلى مشاكل نفسية مثل الاكتئاب والقلق. الاكتئاب، كعاطفة سلبية، غالبًا ما يصاحب مجموعة من المشكلات لدى المراهقين، مثل الانطواء، reluctance to communicate with peers, reduced physical activity, and increased sedentary behavior, all of which contribute to poorer sleep quality [83]. تقريبًا

تكشف دراستنا أيضًا أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر تؤثر على العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب، بما يتماشى مع فرضيتنا الأولية. وفقًا للنموذج المعرفي-العاطفي، فإن الأفراد الذين يواجهون صعوبة في إدراك وفهم وقبول ووصف مشاعرهم، أو الذين يفشلون في استخدام استراتيجيات إدارة عاطفية مناسبة، يكونون أكثر عرضة لتجربة مشاعر سلبية وتطوير الاكتئاب. أولئك الذين يواجهون صعوبة في وصف المشاعر قد يشعرون بالعجز عن تغيير وضعهم ويختبرون معلومات عاطفية ساحقة ومربكة. من الناحية المفاهيمية، لأن صعوبة وصف المشاعر

صعوبة التعرف على المشاعر هي مكونات أساسية للاكسيثيميا، وقد تعيق هذه التحديات الأفراد الذين يعانون من مستويات عالية من الاكسيثيميا عن البحث عن الآخرين ومحاولة التعبير عن مشاعرهم (أي أنهم غير متأكدين من مشاعرهم الخاصة وكيفية التواصل بدقة مع الآخرين). تؤثر صعوبة وصف المشاعر على فهمهم وإدراكهم لحالاتهم العاطفية، مما يجعل من الصعب أن يصبحوا واعين أو يعبروا بدقة عن مشاعرهم. كما أن هذه الصعوبة تعيق قدرتهم على فهم مشاعر الآخرين بدقة في الحياة اليومية وتعيق التواصل بمشاعرهم للآخرين. يمكن أن تؤدي هذه القيود إلى تراكم المشاعر السلبية التي لا يتم الإفراج عنها أو معالجتها في الوقت المناسب. وفقًا لنموذج الشلال العاطفي، فإن المشاعر السلبية الشديدة تحفز عملية تفكير مفرطة، مما يزيد من حدة المشاعر السلبية الأولية، مما يخلق حلقة مفرغة قد تؤدي إلى ردود فعل عاطفية متسلسلة تتفاقم تدريجيًا، مما قد يؤدي إلى الاكتئاب. كما تفسر نظرية الضغط العام أن الأفراد الذين يعانون من صعوبة في وصف المشاعر قد يواجهون صعوبة في التعبير عن مشاعرهم والتواصل بها، مما يؤدي إلى سوء الفهم والعلاقات المتوترة، وبالتالي زيادة الضغط في إدارة العلاقات الشخصية. هذا يزيد من مشاعر العزلة والوحدة الموجودة مسبقًا، مما يساهم بشكل أكبر في الاكتئاب. الأفراد الذين يعانون من صعوبة في التعرف على المشاعر، عند مواجهة انفصال عاطفي شامل، قد يختبرون أيضًا مستويات عالية من القلق والاكتئاب. قد تتفاقم هذه الحالة بسبب الإحباط الناتج عن عدم القدرة على الاتصال بمشاعرهم ومشاعر الآخرين. أظهرت الأبحاث السابقة أن صعوبة وصف المشاعر مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالاكتئاب، وأن الأفراد الذين يعانون من هذه الصعوبة هم أكثر عرضة لتطوير الاكتئاب في المستقبل، وهو ما تؤكده دراسات أخرى. باختصار، تؤكد نتائجنا الفرضية الأولية بأن صعوبة وصف المشاعر يمكن أن تعزز العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية والاكتئاب.

في الختام، تستكشف دراستنا العلاقة بين إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية وجودة النوم لدى المراهقين، وتناقش الدور الوسيط للاكتئاب والدور المعدل لصعوبة وصف المشاعر. تحتوي هذه الدراسة على عدة قيود. أولاً، اعتمدت الأبحاث على بيانات استبيانات ذاتية، مما قد يؤدي إلى عدم الدقة، خاصة بسبب التحيزات المحتملة مثل الآراء الذاتية، أخطاء استرجاع الذاكرة، أو المعلومات المفقودة، مما يؤثر على موضوعية وصلاحية البيانات. على الرغم من أن استخدام البيانات الذاتية شائع في الأبحاث النفسية، يمكن أن تعزز الدراسات المستقبلية موثوقية البيانات من خلال دمج طرق قياس موضوعية أخرى، مثل الملاحظات السلوكية أو التقييمات الفسيولوجية، لتقليل تأثير هذه التحيزات. ثانياً، بينما كانت المقاييس المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة، بما في ذلك إدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية

الخاتمة

عامل معتدل. تؤكد النتائج على أهمية أن يقوم الأفراد والعائلات والمدارس والمجتمع بمعالجة الآثار السلبية المرتبطة بإدمان مواقع الشبكات الاجتماعية. بشكل خاص، بالنسبة للأفراد الذين يعانون من صعوبة عالية في وصف المشاعر، من الضروري إجراء تقييمات مصنفة ومحددة القيمة بناءً على نتائج قياسهم، لتقديم تدخلات علاجية مستهدفة وشخصية.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 20 يناير 2025

References

- Harrington J, Lee-Chiong T. Basic biology of sleep. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56(2):319-30.

- Bruce ES, Lunt L, McDonagh JE. Sleep in adolescents and young adults. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(5):424-8.

- Kopasz M, et al. Sleep and memory in healthy children and adolescents – a critical review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):167-77.

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):561-9.

- Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescence: physiology, cognition and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:182-8.

- Burnell K, et al. Associations between adolescents’ Daily Digital Technology Use and Sleep. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):450-6.

- Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):637-47.

- Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and Depression. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1059-68.

- GREGORY AM, O’CONNOR TG. Sleep problems in Childhood: a Longitudinal Study of Developmental Change and Association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):964-71.

- Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: a meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:586-604.

- Peach HD, Gaultney JF. Sleep, impulse control, and sensation-seeking predict delinquent behavior in adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):293-9.

- Alimoradi Z, et al. Internet addiction and sleep problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;47:51-61.

- Andreassen CS, Pallesen S. Social network site addiction – an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4053-61.

- Vannucci A, et al. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: a meta-analysis. Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2020. pp. 258-74.

- Caner N, Efe YS, Başdaş Ö. The contribution of social media addiction to adolescent LIFE: social appearance anxiety. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(12):8424-33.

- Montag C, et al. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict Behav. 2024;153:107980.

- Armstrong-Carter E, et al. Momentary links between adolescents’ social media use and social experiences and motivations: individual differences by peer susceptibility. Dev Psychol. 2023;59(4):707-19.

- Cheng C, et al. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Metaanalysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict Behav. 2021;117:106845.

- Akhtar N et al. Unveiling mechanism of SNSs addiction on wellbeing: the moderating role of loneliness and social anxiety. Behav Inform Technol, 2024: pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2417390.

- Wang W, et al. Cyberbullying and depression among Chinese college students: a moderated mediation model of social anxiety and neuroticism. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:54-61.

- Hussain Z, Griffiths MD. The associations between problematic social networking site use and sleep quality, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, anxiety and stress. Germany: Springer; 2021. pp. 686-700.

- Alonzo R, et al. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Elsevier Science: Netherlands; 2021.

- Touitou Y, Touitou D, Reinberg A. Disruption of adolescents’ circadian clock: the vicious circle of media use, exposure to light at night, sleep loss and risk behaviors. J Physiol Paris. 2016;110(4 Pt B):467-79.

- Chen YL, Gau SS. Sleep problems and internet addiction among children and adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(4):458-65.

- Lu B, Lin L, Su X. Global burden of depression or depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;354:553-62.

- Clark MS, Jansen KL, Cloy JA. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(5):442-8.

- Carli V, et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology. 2013;46(1):1-13.

- Steffen A, et al. Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):142.

- Na E et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for destructive experiential avoidance (ACT-DEA): a feasibility study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(24).

- Liu C, Liu Z, Yuan G. Cyberbullying victimization and problematic internet use among Chinese adolescents: longitudinal mediation through mindfulness and depression. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(14):2822-31.

- Yang

, et al. A bidirectional association between internet addiction and depression: a large-sample longitudinal study among Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:416-24. - Wartberg L, et al. A longitudinal study on psychosocial causes and consequences of internet gaming disorder in adolescence. Psychol Med. 2019;49(2):287-94.

- Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Lemoine P. Comorbidity of mental and insomnia disorders in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):185-97.

- Goodyer IM, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy versus brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depression (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observerblind, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(12):1-94.

- Morphy H, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30(3):274-80.

- Patten CA, et al. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):E23.

- Riemann D, et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):19-31.

- Moulton CD, Pickup JC, Ismail K. The link between depression and diabetes: the search for shared mechanisms. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(6):461-71.

- Preece DA, et al. What is alexithymia? Using factor analysis to establish its latent structure and relationship with fantasizing and emotional reactivity. J Pers. 2020;88(6):1162-76.

- Sifneos PE. The prevalence of’alexithymic’ characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22(2):255-62.

- Ricciardi L, et al. Alexithymia in Neurological Disease: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(3):179-87.

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness., in Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. 1997, Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, US. p. xxii, 359-xxii, 359.

- De Gucht V, Heiser W. Alexithymia and somatisation: a quantitative review of the literature. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(5):425-34.

- Celikel FC, et al. Alexithymia and temperament and character model of personality in patients with major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):64-70.

- Kyranides MN, Christofides D, Çetin M. Difficulties in facial emotion recognition: taking psychopathic and alexithymic traits into account. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):239.

- Philippot P, Feldman RS. Age and social competence in preschoolers’ decoding of facial expression. Br J Soc Psychol. 1990;29(Pt 1):43-54.

- Martini

, et al. Association of emotion recognition ability and interpersonal emotional competence in anorexia nervosa: a study with a multimodal dynamic task. Int J Eat Disord. 2023;56(2):407-17. - Kraut R, et al. Internet paradox revisited. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing; 2002. pp. 49-74.

- Marchesi C, et al. The TAS-20 more likely measures negative affects rather than alexithymia itself in patients with major depression, panic disorder, eating disorders and substance use disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):972-8.

- Elphinston RA, Noller P. Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(11):631-5.

- Wei Q, Negative Emotions and Problematic Social Network Sites Usage.: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of gender, 2018, Central China Normal University.

- Liu Y, et al. The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23350.

- Liu Y et al. The relationship between physical activity and internet addiction among adolescents in western China: a chain mediating model of anxiety and inhibitory control. Psychol Health Med. 2024;29(9):1-17. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/13548506.2024.2357694.

- Murphy KR, Davidshofer CO. Psychological testing: Principles and applications., in Psychological testing: Principles and applications. 1994, PrenticeHall, Inc: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US. p. xi, 548-xi, 548.

- Hosseinkhani Z, et al. Academic stress and adolescents Mental Health: a Multilevel Structural equation modeling (MSEM) Study in Northwest of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20(4):e00496.

- Zimmerman M, et al. Developing brief scales for use in clinical practice: the reliability and validity of single-item self-report measures of depression symptom severity, psychosocial impairment due to depression, and quality of life. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1536-41.

- Gogol K, et al. My questionnaire is too long! The assessments of motivationalaffective constructs with three-item and single-item measures. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2014;39(3):188-205.

- Postmes T, Haslam SA, Jans L. A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br J Soc Psychol. 2013;52(4):597-617.

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2000). Inadequate Sleep Optional Module. National Health Interview Survey 2000. Retrieved from https://www. cdc.gov/sleep/surveillance.html

- Snyder E, et al. A new single-item Sleep Quality Scale: results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(11):1849-57.

- Waasdorp TE, et al. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among Middle and High School Youth. J Child Fam stud. 2019;28(9):2606-17.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335-43.

- Gong X et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol, 2010;18(4):443-446. https://doi. org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.020.

- Liu Y, et al. Anxiety, inhibitory control, physical activity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):663.

- Shen Q, et al. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24348.

- Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(1):23-32.

- Zhu X, et al. Cross-cultural validation of a Chinese translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):489-96.

- Liu Y, et al. The mediating effect of internet addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9781.

- Gong Xu, Xie Xiyao, Xu Rui, et al. The Chinese Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in Chinese university students: a test report [J]. Chinese J Clin Psyc. 2010;18(04):443-446. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki. 100 5-3611.2010.04.020.

- Podsakoff PM, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879-903.

- Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Routledge, 2018(1).

- Berkovits I, Hancock GR, Nevitt J. Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations. Sage Publications: US; 2000. pp. 877-92.

- Lam LT. Internet gaming addiction, problematic use of the internet, and sleep problems: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(4):444.

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, Chaput JP. Use of social media is associated with short sleep duration in a dose-response manner in students aged 11 to 20 years. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(4):694-700.

- Hale L, et al. Youth screen Media habits and Sleep: sleep-friendly screen behavior recommendations for clinicians, educators, and parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(2):229-45.

- van der Lely S, et al. Blue blocker glasses as a countermeasure for alerting effects of evening light-emitting diode screen exposure in male teenagers. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):113-9.

- Fossum IN, et al. The association between use of electronic media in bed before going to sleep and insomnia symptoms, daytime sleepiness, morningness, and chronotype. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12(5):343-57.

- Van den Bulck J. Is television bad for your health? Behavior and body image of the adolescent couch potato. Germany: Springer; 2000. pp. 273-88.

- Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017;39:47-53.

- Wong HY et al. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(6).

- Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(6):521-9.

- Ford BQ , et al. The psychological health benefits of accepting negative emotions and thoughts: Laboratory, diary, and longitudinal evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018;115(6):1075-92.

- Asarnow LD. Depression and sleep: what has the treatment research revealed and could the HPA axis be a potential mechanism? Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;34:112-6.

- Reynolds CR, Kupfer DJ. Sleep research in affective illness: state of the art circa 1987. Sleep. 1987;10(3):199-215.

- Yasugaki S et al. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and depression. Neurosci Res, 2023;S0168-0102(23):00087-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures. 2023.04.006.

- Perez-Caballero L, et al. Monoaminergic system and depression. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;377(1):107-13.

- Takahashi K, et al. Locus coeruleus neuronal activity during the sleep-waking cycle in mice. Neuroscience. 2010;169(3):1115-26.

- Sakurai T. The neural circuit of orexin (hypocretin): maintaining sleep and wakefulness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(3):171-81.

- Shariq AS, et al. Evaluating the role of orexins in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:1-7.

- Hasking P, et al. A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cogn Emot. 2017;31(8):1543-56.

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. The role of relationships in understanding the alexi-thymia-depression link. John Wiley & Sons: US; 2013. pp. 470-80.

- Kieraité M , et al. Our similarities are different the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2024;340:116099.

- Spitzer C, et al. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(4):240-6.

- Morie KP, et al. The process of emotion identification: considerations for psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;148:264-74.

- Luminet O, Nielson KA, Ridout N. Cognitive-emotional processing in alexithymia: an integrative review. Cogn Emot. 2021;35(3):449-87.

- Selby EA, Joiner TJ. Cascades of emotion: the emergence of Borderline personality disorder from emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2009;13(3):219.

- Morie KP, Alexithymia E-R, et al. Strategies, and traumatic experiences in prenatally Cocaine-exposed young adults. Am J Addict. 2020;29(6):492-9.

- AGNEW R. FOUNDATION FOR A GENERAL STRAIN THEORY, OF CRIME AND DELINQUENCY. Criminology. 1992;30(1):47-88.

- Xiao W, et al. Why are individuals with alexithymia symptoms more likely to have Mobile phone addiction? The multiple mediating roles of Social Interaction Anxiousness and Boredom Proneness. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1631-41.

- Bamonti PM, et al. Association of alexithymia and depression symptom severity in adults aged 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):51-6.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

بينغفان ليو

714421675@qq.com

يانغ ليو

Idyedu@foxmail.com

كلية علوم الرياضة، جامعة جيشوه، جيشوه، الصين

كلية التربية البدنية وعلوم الصحة، جامعة قوانغشي مينزو، ناننينغ، الصين

كلية التربية البدنية، جامعة شيشانغ، شيشانغ، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02372-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39833970

Publication Date: 2025-01-20

Social network site addiction, sleep quality, depression and adolescent difficulty describing feelings: a moderated mediation model

Abstract

Background and objectives Social network site addiction is strongly correlated with sleep quality among adolescents. However, the underlying mechanisms driving these relationships require further exploration. This study aims to supplement the understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking social network site addiction and sleep quality by investigating depression as a mediating factor and difficulty describing feelings as a moderating factor.

Methods A self-report survey was conducted with 1,670 adolescents in China, assessing social network site addiction, sleep quality, depression, and difficulty describing feelings. Descriptive and correlational analyses were performed on these variables, followed by the construction of a moderated mediation model. Results Social network site addiction was significantly positively correlated with sleep quality, depression, and difficulty describing feelings among adolescents. Difficulty describing feelings was also significantly positively correlated with depression. Depression partially mediated the relationship between social network site addiction and sleep quality, while difficulty describing feelings intensified the relationship between social network site addiction and depression. Conclusion This study further elucidates the psychological mechanisms linking social network site addiction and sleep quality in adolescents. Depression acts as a mediating factor, while difficulty describing feelings strengthens the relationship between social network site addiction and depression. These findings highlight the role of difficulty describing feelings in the interplay between social network site addiction and sleep quality, offering valuable insights for a more comprehensive understanding and targeted interventions aimed at improving sleep quality in adolescents.

Introduction

The factors contributing to poor sleep quality are diverse and complex. Among these, social network site addiction has been found to be closely related to sleep quality in adolescents [12]. With the rapid development of smart electronic devices and social network sites, social network sites have gradually become an indispensable part of people’s daily lives and an important platform for obtaining information and engaging in social interactions [13]. Research shows that

higher prevalence of social network site addiction is associated with younger age and living in collectivist countries [18]. Although social network site addiction has not been classified as an official diagnosis or health condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) or the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11), and there is no consensus on its classification, with significant differences in the methods of categorization, excessive and compulsive use of social network sites can still significantly interfere with adolescents’ daily lives, negatively affecting their physical health, social functioning, and mental well-being [19]. Given the prevalence of social network site addiction in adolescent populations and its potential negative impacts, societal attention to this phenomenon has been increasing. Social network site addiction refers to an individual’s excessive preoccupation with social networks, characterized by a strong motivation to use these platforms and a significant amount of time and energy spent on them, which can negatively impact both physical and mental health [13]. Problematic and addictive social network behaviors are considered a form of online risk behavior, closely associated with reduced sleep duration, decreased sleep quality, and insomnia [20]. Adolescents with higher levels of social network site addiction and longer usage times, especially those who engage in passive social network use, typically exhibit poorer sleep quality [21]. Adolescents with poor sleep quality tend to spend more time on social networks than those with better sleep quality [22]. Research has shown that in individuals with social network site addiction, prolonged exposure to blue light can inhibit melatonin secretion, disrupt sleep and circadian rhythms, and subsequently lower sleep quality [23]. The predictive role of social network site addiction on poor subjective sleep quality has been validated in adolescent samples, with adolescents suffering from social network site addiction being 3.25 times more likely to report poor subjective sleep quality than those with normal social network use [24]. Based on the above review, this study hypothesizes that there is a significant positive correlation between social network site addiction and sleep quality in adolescents.

In the relationship between social network site addiction and sleep quality in adolescents, depression may serve as an important mediating factor. Depression is a significant public health concern among adolescents. A recent meta-analysis reported prevalence rates of mild to severe, moderate to severe, and severe depression at

with social networks [27]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between social network site addiction and depression [27, 28]. According to acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), social network site addiction may lead individuals to adopt various avoidant emotional regulation strategies (such as rumination and thought suppression) to reduce the frequency, intensity, or duration of these unpleasant internal experiences [29]. This rigid response to internal emotions can be harmful, triggering more negative emotions and thoughts, and eventually leading to depression. Consistent with this view, research has found that individuals with social network site addiction are more likely to experience depression, especially when they engage in thought suppression. Social network site addiction is considered a core vulnerability factor for emotional distress [30]. According to the secondary addictive disorder hypothesis, addictive behaviors can trigger other mental health disorders, especially depression [31]. Addicted users may spend increasing amounts of time and energy in the virtual world, and when they leave the online environment to face reality, they often feel frustrated or depressed [32]. Moreover, depression is a key determinant of poor sleep quality in adolescents. Studies have found that over

However, the relationship between the aforementioned variables may be exacerbated in individuals with certain characteristics, leading to increased adverse behaviors or negative psychological outcomes. One such characteristic is the level of difficulty describing feelings, a key dimension of alexithymia [39]. The term alexithymia, introduced by Peter Sifneos, describes patients who have difficulty with insight-oriented psychotherapy [40]. It is now defined as the inability to identify and describe one’s own or others’ emotions [41]. Difficulty describing feelings is considered a manifestation of impaired emotional cognition, processing, and regulation [42], and it is a risk factor for the development of various psychological issues and maladaptive behaviors [43]. Research indicates that difficulty describing feelings is highly correlated with emotional problems such as depression [44]. Alexithymia can exacerbate negative emotions like depression due to its impact on emotional awareness and expression [45]. Moreover, it can lead to poor interpersonal relationships, thereby increasing psychological burdens. Difficulty describing feelings is associated with lower social competence and reduced peer popularity [46]. By affecting social interaction, emotional regulation, self-awareness, and social support, difficulty describing feelings significantly increases the risk of depression [47]. According to the “rich get richer” model, adolescents with social network site addiction and difficulty describing feelings may be more prone to depression [48]. Some authors even suggest that difficulty describing feelings and depression may be indistinguishable constructs [49]. Therefore, based on the above review, it is evident that difficulty describing feelings can enhance the relationship between social network site addiction and depression discussed in this study, further exacerbating the extent of negative psychological and behavioral outcomes. Consequently, we hypothesize that difficulty describing feelings amplifies the strength of the relationship between social network site addiction, depression, and sleep quality in adolescents.

Previous research has explored the relationship between social network site addiction and sleep quality in adolescents, as well as the predictive role of this relationship. However, research on this relationship in Chinese adolescents is limited. To further supplement research in this area and explore the underlying psychological mechanisms, this study introduces depression as a mediating variable and difficulty describing feelings as a moderating variable. Thus, this study constructs a hypothesized pathway model (Fig. 1).

Methods

Participants

The study received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the author’s affiliated institution before its implementation, ensuring that the study design and data collection process complied with ethical and legal requirements. All procedures adhered to the standards and guidelines set by the ethics committee, which further enhanced the reliability of the study and the trust of the participants. Invalid questionnaires included those with patterned responses or those with response times that were either too short or too long. A total of 1,915 adolescents participated in the survey, and after excluding invalid responses, 1,670 valid questionnaires were obtained ( 693 boys, 997 girls; 767 in Grade 1, 803 in Grade 2, 100 in Grade 3; 110 with family monthly income below

Measures

Social network site addiction

Sleep quality

Depression

of depression. The Cronbach’s

Difficulty describing feelings

Data processing and analysis

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 Gender | – | ||||

| 2 Age | 0.010 | – | |||

| 3 Social network site addiction | 0.076** | 0.092*** | – | ||

| 4 Depression | 0.067** | 0.038 | 0.465*** | – | |

| 5 Sleep quality | 0.085** | 0.063* | 0.467*** | 0.637*** | – |

| 6 Difficulty describing feelings | 0.005 | 0.057* | 0.375*** | 0.575*** | 0.341*** |

demographic variables such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status were controlled as covariates. A significance level of 0.05 was set for all tests.

Results

Common method bias test

Correlation analysis

Mediation model test

| Outcome variable | Predictor variables |

|

SE | t |

|

F |

| Sleep quality | Social network site addiction | 0.233 | 0.024 | 9.765*** | 0.068 | 30.416*** |

| Gender | 0.104 | 0.024 | 4.372*** | |||

| Age | -0.026 | 0.024 | -1.066 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.391 | |||

| Depression | Social network site addiction | 0.461 | 0.022 | 21.080*** | 0.218 | 116.175*** |

| Gender | 0.032 | 0.022 | 1.480 | |||

| Age | -0.009 | 0.022 | -0.411 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | -0.037 | 0.022 | -1.672 | |||

| Sleep quality | Social network site addiction | 0.068 | 0.025 | 2.663** | 0.169 | 67.641*** |

| Depression | 0.359 | 0.025 | 14.208*** | |||

| Gender | 0.092 | 0.022 | 4.110*** | |||

| Age | -0.022 | 0.023 | -0.985 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.995 |

| Intermediary Path |

|

SE |

|

|

|||||||

| Total Effect | 0.233 | 0.024 |

|

||||||||

| Direct Effect | 0.068 | 0.025 |

|

||||||||

| Indirect effects | 0.165 | 0.015 |

|

|

Moderated mediation test

| Variables | Depression | Sleep quality | ||||

|

|

SE | t |

|

SE | t | |

| Social network site addiction (A) | 0.285 | 0.020 | 14.013*** | 0.068 | 0.025 | 2.663** |

| Difficulty describing feelings (B) | 0.500 | 0.021 | 23.983*** | |||

|

|

0.109 | 0.018 | 6.171*** | |||

| Depression | 0.359 | 0.025 | 14.208*** | |||

| Gender | 0.043 | 0.019 | 2.303* | 0.092 | 0.022 | 4.110*** |

| Age | -0.020 | 0.019 | -1.048 | -0.022 | 0.023 | -0.985 |

| Socioeconomic status | -0.034 | 0.019 | -1.812 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.995 |

|

|

0.419 | 0.169 | ||||

| F | 199.986*** | 67.641*** | ||||

| DDF Levels |

|

SE |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Low | 0.175 | 0.027 |

|

0.122 | 0.228 | ||||||||

| Medium | 0.285 | 0.020 |

|

0.245 | 0.324 | ||||||||

| High | 0.394 | 0.027 |

|

0.341 | 0.447 |

Discussion

The study demonstrates a positive correlation between social network site addiction and sleep quality among adolescents, a finding consistent with similar research [12]. For instance, a systematic review highlighted a significant association between multiplayer online gaming and poor sleep quality [73]. A large-scale cross-sectional study of Canadian students reported a higher likelihood of reduced sleep duration associated with social network use and observed a dose-response relationship between social network use and reduced sleep duration [74]. The potential mechanisms by which social network site addiction affects sleep quality include psychological stimulation (i.e., increased arousal due to internet media use leading to difficulty falling asleep) [75], the impact of illuminated screens (i.e., light exposure suppressing sleep-promoting hormones such as melatonin) [76], and physical discomfort (e.g., excessive sedentary behavior associated with pathological social network use leading to cervical discomfort, which may affect sleep quality) [77]. Our study also supports the sleep displacement theory [78], which posits that social network use, as an unstructured leisure activity lacking clear start and end times, can easily displace sleep time, thereby affecting sleep duration and quality [79]. In summary, our findings indicate a significant correlation between social network site addiction and sleep quality among adolescents, supported by biological evidence.

This study supports the hypothesis that depression mediates the relationship between social network site

addiction and sleep quality in adolescents, aligning with previous research [63, 64]. Prior studies have established a strong association between social network site addiction and depression [80]. Additionally, the relationship between depression and sleep quality has been robustly demonstrated [81]. According to the ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) model [29], social network site addiction, as a primary process of psychological inflexibility, reduces individuals’ psychological flexibility and leads to severe psychological issues. When negative emotions are constrained by rigid thinking or when individuals consciously avoid experiences or situations that may elicit negative feelings, these issues are likely to intensify [82]. Individuals with social network site addiction may find that their efforts to avoid certain emotions and thoughts only amplify them, leading to an inability to effectively accept and process negative thoughts and emotions, thereby resulting in psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. Depression, as a negative emotion, often accompanies a range of issues in adolescents, such as introversion, reluctance to communicate with peers, reduced physical activity, and increased sedentary behavior, all of which contribute to poorer sleep quality [83]. Approximately

Our study also reveals that difficulty describing feelings moderates the relationship between social network site addiction and depression, consistent with our initial hypothesis. According to the cognitive-emotional model, individuals who struggle to perceive, understand, accept, and describe their emotions, or who fail to employ appropriate emotional management strategies, are at higher risk of experiencing negative emotions and developing depression [90]. Those with difficulty describing feelings may feel powerless to change their situation and experience overwhelming and confusing emotional information [91]. Conceptually, because difficulty describing feelings

and difficulty recognizing emotions are core components of alexithymia [92], these challenges may hinder or limit individuals with high levels of alexithymia from seeking out others and attempting to express their emotions (i.e., they are uncertain of their own feelings and how to accurately communicate with others) [93]. Difficulty describing feelings affects their insight into and understanding of their emotional states, making it hard to become aware of or correctly express their emotions [94]. This difficulty also impairs their ability to accurately understand others’ emotions in daily life and hinders the communication of their feelings to others [95]. This limitation can lead to the accumulation of negative emotions that are not released or processed in a timely manner. According to the emotional cascade model [96], intense negative emotions trigger a ruminative process, which further amplifies the initial negative emotions, creating a vicious cycle that may result in progressively severe emotional chain reactions, potentially leading to depression [97]. General strain theory also explains that individuals with difficulty describing feelings may struggle to articulate and communicate their emotions [98]leading to misunderstandings and strained relationships, thereby increasing their stress in managing interpersonal relationships [99]. This exacerbates pre-existing feelings of isolation and loneliness, further contributing to depression. Individuals with difficulty recognizing emotions, when battling pervasive emotional detachment, may also experience high levels of anxiety and depression [94]. This situation may worsen due to the frustration of being unable to connect with their own and others’ emotions. Previous research [92] has shown that difficulty describing feelings is closely related to depression, and individuals with this difficulty are more likely to develop depression in the future, a finding corroborated by other studies [100]. In summary, our results confirm the initial hypothesis that difficulty describing feelings can intensify the relationship between social network site addiction and depression.

In conclusion, our study further explores the relationship between social network site addiction and sleep quality in adolescents, and discusses the mediating role of depression and the moderating role of difficulty describing feelings. This study has several limitations. First, the research relied on self-reported survey data, which may lead to inaccuracies, especially due to potential biases such as subjective opinions, memory recall errors, or missing information, thereby affecting the objectivity and validity of the data. Although the use of self-reported data is common in psychological research, future studies could enhance data reliability by incorporating other objective measurement methods, such as behavioral observations or physiological assessments, to reduce the impact of these biases. Second, while the scales used in this study, including the Social Network Site Addiction

Conclusion

a moderating factor. The findings underscore the importance for individuals, families, schools, and society to address the negative impacts associated with social network site addiction. Specifically, for individuals with high levels of difficulty describing feelings, it is crucial to conduct stratified and valence-specific assessments based on their measurement results, to provide targeted and personalized treatment interventions.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 20 January 2025

References

- Harrington J, Lee-Chiong T. Basic biology of sleep. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56(2):319-30.

- Bruce ES, Lunt L, McDonagh JE. Sleep in adolescents and young adults. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(5):424-8.

- Kopasz M, et al. Sleep and memory in healthy children and adolescents – a critical review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(3):167-77.

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):561-9.

- Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescence: physiology, cognition and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:182-8.

- Burnell K, et al. Associations between adolescents’ Daily Digital Technology Use and Sleep. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(3):450-6.

- Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):637-47.

- Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and Depression. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1059-68.

- GREGORY AM, O’CONNOR TG. Sleep problems in Childhood: a Longitudinal Study of Developmental Change and Association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):964-71.

- Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: a meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:586-604.

- Peach HD, Gaultney JF. Sleep, impulse control, and sensation-seeking predict delinquent behavior in adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):293-9.

- Alimoradi Z, et al. Internet addiction and sleep problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;47:51-61.

- Andreassen CS, Pallesen S. Social network site addiction – an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4053-61.

- Vannucci A, et al. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: a meta-analysis. Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2020. pp. 258-74.

- Caner N, Efe YS, Başdaş Ö. The contribution of social media addiction to adolescent LIFE: social appearance anxiety. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(12):8424-33.

- Montag C, et al. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict Behav. 2024;153:107980.

- Armstrong-Carter E, et al. Momentary links between adolescents’ social media use and social experiences and motivations: individual differences by peer susceptibility. Dev Psychol. 2023;59(4):707-19.

- Cheng C, et al. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Metaanalysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict Behav. 2021;117:106845.

- Akhtar N et al. Unveiling mechanism of SNSs addiction on wellbeing: the moderating role of loneliness and social anxiety. Behav Inform Technol, 2024: pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2417390.

- Wang W, et al. Cyberbullying and depression among Chinese college students: a moderated mediation model of social anxiety and neuroticism. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:54-61.

- Hussain Z, Griffiths MD. The associations between problematic social networking site use and sleep quality, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, anxiety and stress. Germany: Springer; 2021. pp. 686-700.

- Alonzo R, et al. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Elsevier Science: Netherlands; 2021.

- Touitou Y, Touitou D, Reinberg A. Disruption of adolescents’ circadian clock: the vicious circle of media use, exposure to light at night, sleep loss and risk behaviors. J Physiol Paris. 2016;110(4 Pt B):467-79.

- Chen YL, Gau SS. Sleep problems and internet addiction among children and adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Sleep Res. 2016;25(4):458-65.

- Lu B, Lin L, Su X. Global burden of depression or depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;354:553-62.

- Clark MS, Jansen KL, Cloy JA. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(5):442-8.

- Carli V, et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology. 2013;46(1):1-13.

- Steffen A, et al. Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):142.

- Na E et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for destructive experiential avoidance (ACT-DEA): a feasibility study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(24).

- Liu C, Liu Z, Yuan G. Cyberbullying victimization and problematic internet use among Chinese adolescents: longitudinal mediation through mindfulness and depression. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(14):2822-31.

- Yang

, et al. A bidirectional association between internet addiction and depression: a large-sample longitudinal study among Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:416-24. - Wartberg L, et al. A longitudinal study on psychosocial causes and consequences of internet gaming disorder in adolescence. Psychol Med. 2019;49(2):287-94.

- Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Lemoine P. Comorbidity of mental and insomnia disorders in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):185-97.

- Goodyer IM, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy versus brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depression (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observerblind, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(12):1-94.

- Morphy H, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30(3):274-80.

- Patten CA, et al. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):E23.

- Riemann D, et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):19-31.

- Moulton CD, Pickup JC, Ismail K. The link between depression and diabetes: the search for shared mechanisms. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(6):461-71.

- Preece DA, et al. What is alexithymia? Using factor analysis to establish its latent structure and relationship with fantasizing and emotional reactivity. J Pers. 2020;88(6):1162-76.

- Sifneos PE. The prevalence of’alexithymic’ characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22(2):255-62.

- Ricciardi L, et al. Alexithymia in Neurological Disease: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(3):179-87.

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness., in Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. 1997, Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, US. p. xxii, 359-xxii, 359.

- De Gucht V, Heiser W. Alexithymia and somatisation: a quantitative review of the literature. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(5):425-34.

- Celikel FC, et al. Alexithymia and temperament and character model of personality in patients with major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):64-70.

- Kyranides MN, Christofides D, Çetin M. Difficulties in facial emotion recognition: taking psychopathic and alexithymic traits into account. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):239.

- Philippot P, Feldman RS. Age and social competence in preschoolers’ decoding of facial expression. Br J Soc Psychol. 1990;29(Pt 1):43-54.

- Martini

, et al. Association of emotion recognition ability and interpersonal emotional competence in anorexia nervosa: a study with a multimodal dynamic task. Int J Eat Disord. 2023;56(2):407-17. - Kraut R, et al. Internet paradox revisited. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing; 2002. pp. 49-74.

- Marchesi C, et al. The TAS-20 more likely measures negative affects rather than alexithymia itself in patients with major depression, panic disorder, eating disorders and substance use disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):972-8.

- Elphinston RA, Noller P. Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(11):631-5.

- Wei Q, Negative Emotions and Problematic Social Network Sites Usage.: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of gender, 2018, Central China Normal University.

- Liu Y, et al. The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):23350.

- Liu Y et al. The relationship between physical activity and internet addiction among adolescents in western China: a chain mediating model of anxiety and inhibitory control. Psychol Health Med. 2024;29(9):1-17. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/13548506.2024.2357694.

- Murphy KR, Davidshofer CO. Psychological testing: Principles and applications., in Psychological testing: Principles and applications. 1994, PrenticeHall, Inc: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US. p. xi, 548-xi, 548.

- Hosseinkhani Z, et al. Academic stress and adolescents Mental Health: a Multilevel Structural equation modeling (MSEM) Study in Northwest of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20(4):e00496.

- Zimmerman M, et al. Developing brief scales for use in clinical practice: the reliability and validity of single-item self-report measures of depression symptom severity, psychosocial impairment due to depression, and quality of life. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1536-41.

- Gogol K, et al. My questionnaire is too long! The assessments of motivationalaffective constructs with three-item and single-item measures. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2014;39(3):188-205.

- Postmes T, Haslam SA, Jans L. A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br J Soc Psychol. 2013;52(4):597-617.

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2000). Inadequate Sleep Optional Module. National Health Interview Survey 2000. Retrieved from https://www. cdc.gov/sleep/surveillance.html

- Snyder E, et al. A new single-item Sleep Quality Scale: results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(11):1849-57.

- Waasdorp TE, et al. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among Middle and High School Youth. J Child Fam stud. 2019;28(9):2606-17.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335-43.

- Gong X et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol, 2010;18(4):443-446. https://doi. org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.020.

- Liu Y, et al. Anxiety, inhibitory control, physical activity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):663.

- Shen Q, et al. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24348.

- Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(1):23-32.

- Zhu X, et al. Cross-cultural validation of a Chinese translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):489-96.

- Liu Y, et al. The mediating effect of internet addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9781.

- Gong Xu, Xie Xiyao, Xu Rui, et al. The Chinese Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in Chinese university students: a test report [J]. Chinese J Clin Psyc. 2010;18(04):443-446. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki. 100 5-3611.2010.04.020.

- Podsakoff PM, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879-903.

- Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Routledge, 2018(1).

- Berkovits I, Hancock GR, Nevitt J. Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations. Sage Publications: US; 2000. pp. 877-92.

- Lam LT. Internet gaming addiction, problematic use of the internet, and sleep problems: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(4):444.

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, Chaput JP. Use of social media is associated with short sleep duration in a dose-response manner in students aged 11 to 20 years. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(4):694-700.

- Hale L, et al. Youth screen Media habits and Sleep: sleep-friendly screen behavior recommendations for clinicians, educators, and parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(2):229-45.

- van der Lely S, et al. Blue blocker glasses as a countermeasure for alerting effects of evening light-emitting diode screen exposure in male teenagers. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):113-9.

- Fossum IN, et al. The association between use of electronic media in bed before going to sleep and insomnia symptoms, daytime sleepiness, morningness, and chronotype. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12(5):343-57.

- Van den Bulck J. Is television bad for your health? Behavior and body image of the adolescent couch potato. Germany: Springer; 2000. pp. 273-88.

- Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017;39:47-53.

- Wong HY et al. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(6).

- Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(6):521-9.

- Ford BQ , et al. The psychological health benefits of accepting negative emotions and thoughts: Laboratory, diary, and longitudinal evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018;115(6):1075-92.

- Asarnow LD. Depression and sleep: what has the treatment research revealed and could the HPA axis be a potential mechanism? Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;34:112-6.

- Reynolds CR, Kupfer DJ. Sleep research in affective illness: state of the art circa 1987. Sleep. 1987;10(3):199-215.

- Yasugaki S et al. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and depression. Neurosci Res, 2023;S0168-0102(23):00087-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures. 2023.04.006.

- Perez-Caballero L, et al. Monoaminergic system and depression. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;377(1):107-13.

- Takahashi K, et al. Locus coeruleus neuronal activity during the sleep-waking cycle in mice. Neuroscience. 2010;169(3):1115-26.

- Sakurai T. The neural circuit of orexin (hypocretin): maintaining sleep and wakefulness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(3):171-81.

- Shariq AS, et al. Evaluating the role of orexins in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:1-7.

- Hasking P, et al. A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cogn Emot. 2017;31(8):1543-56.

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. The role of relationships in understanding the alexi-thymia-depression link. John Wiley & Sons: US; 2013. pp. 470-80.

- Kieraité M , et al. Our similarities are different the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2024;340:116099.

- Spitzer C, et al. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(4):240-6.

- Morie KP, et al. The process of emotion identification: considerations for psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;148:264-74.

- Luminet O, Nielson KA, Ridout N. Cognitive-emotional processing in alexithymia: an integrative review. Cogn Emot. 2021;35(3):449-87.

- Selby EA, Joiner TJ. Cascades of emotion: the emergence of Borderline personality disorder from emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2009;13(3):219.

- Morie KP, Alexithymia E-R, et al. Strategies, and traumatic experiences in prenatally Cocaine-exposed young adults. Am J Addict. 2020;29(6):492-9.

- AGNEW R. FOUNDATION FOR A GENERAL STRAIN THEORY, OF CRIME AND DELINQUENCY. Criminology. 1992;30(1):47-88.

- Xiao W, et al. Why are individuals with alexithymia symptoms more likely to have Mobile phone addiction? The multiple mediating roles of Social Interaction Anxiousness and Boredom Proneness. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1631-41.

- Bamonti PM, et al. Association of alexithymia and depression symptom severity in adults aged 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):51-6.

Publisher’s note

- *Correspondence:

Pingfan Liu

714421675@qq.com

Yang Liu

Idyedu@foxmail.com

School of Sports Science, Jishou University, Jishou, China

School of Physical Education and Health Science, Guangxi Minzu University, Nanning, China

School of Physical Education, Xichang University, Xichang, China