DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21957

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

إشراك المستهلكين من خلال تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي: مراجعة منهجية، نموذج مفاهيمي، وأبحاث إضافية

المراسلات

البريد الإلكتروني: lindah@sunway.edu.my

الملخص

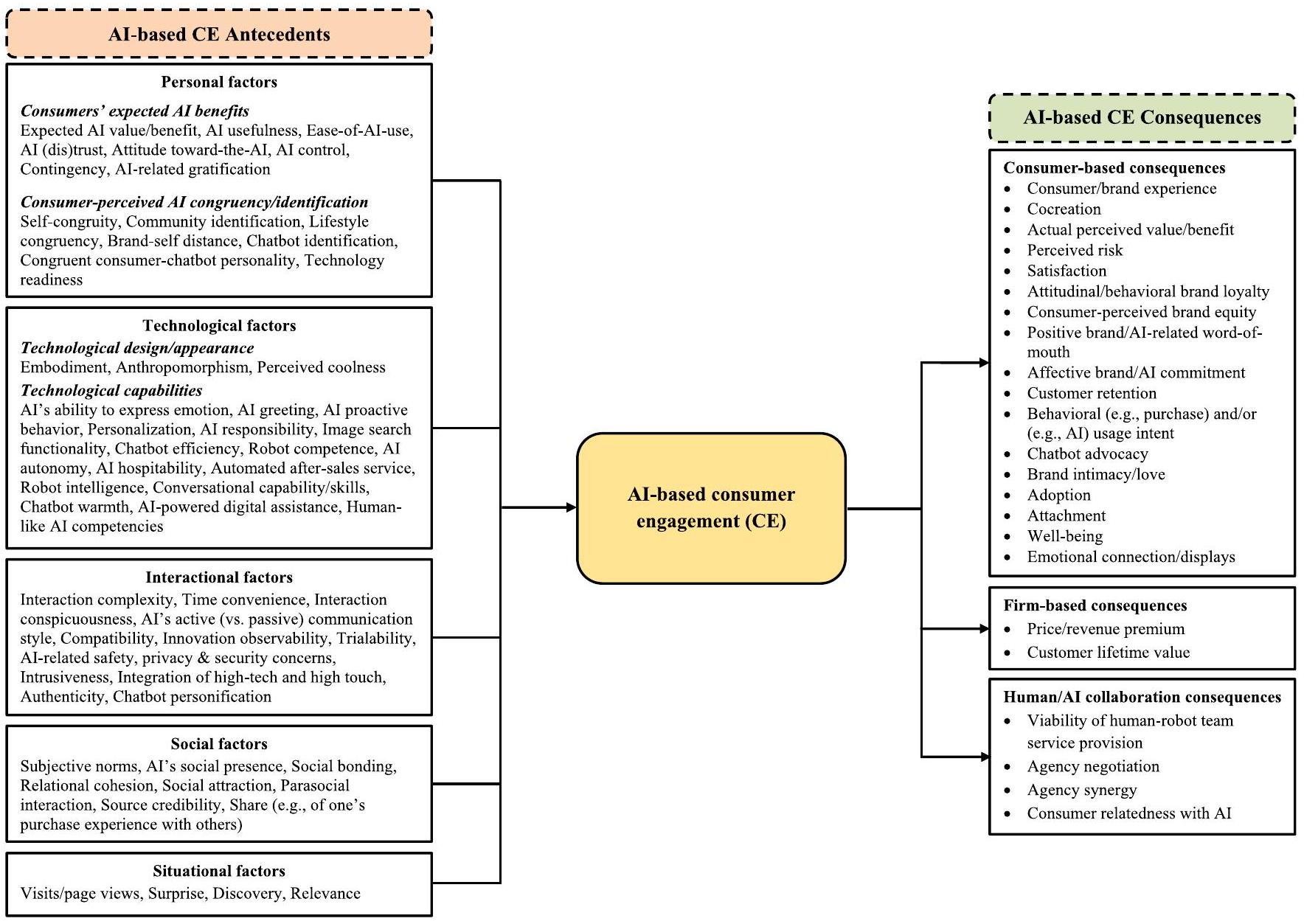

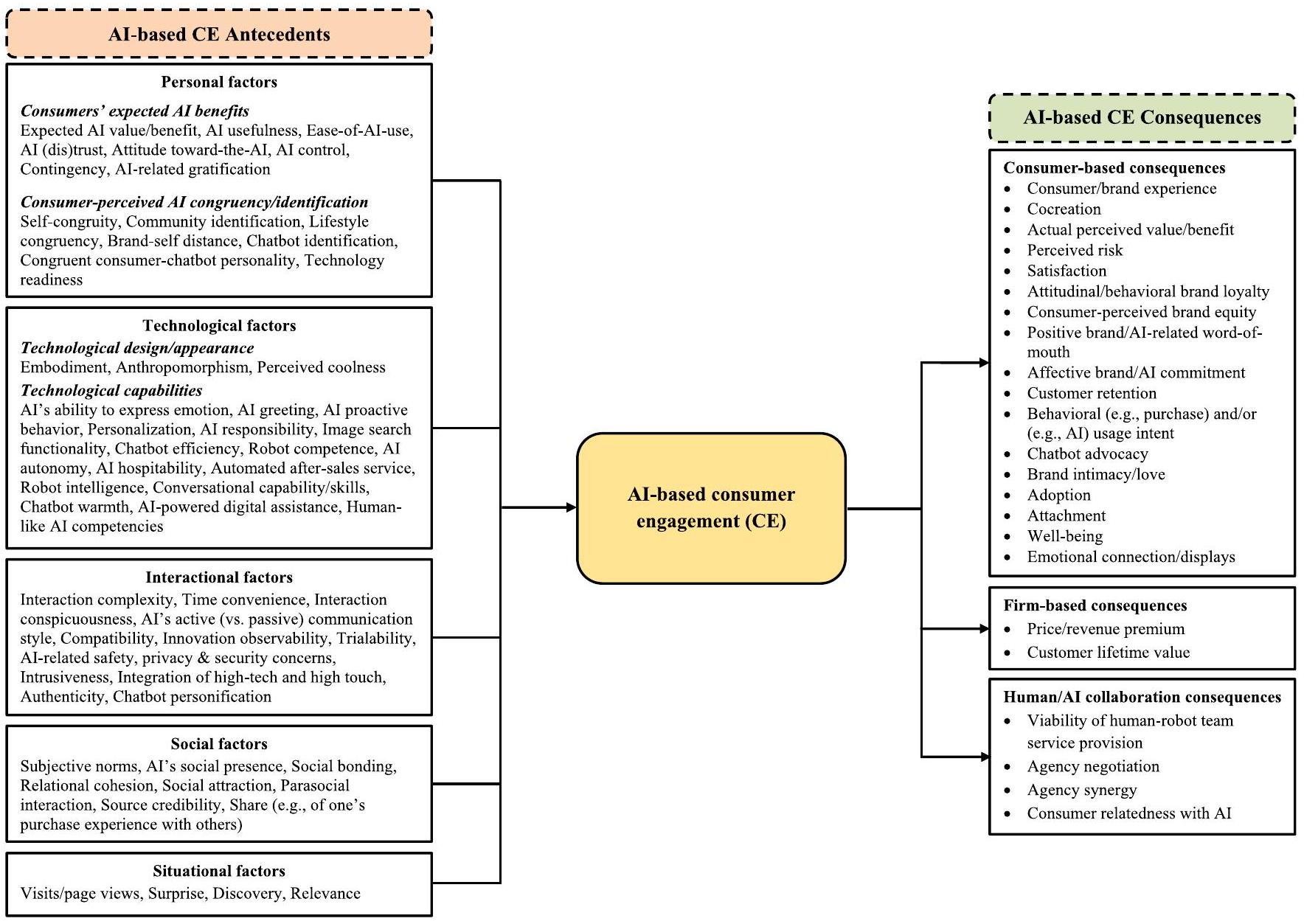

بينما يكتسب تفاعل المستهلكين (CE) في سياق التقنيات المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) (مثل، الدردشة الآلية، المنتجات الذكية، المساعدات الصوتية، أو السيارات المستقلة) زخمًا، تظل الموضوعات التي تميز هذا العمل الناشئ والمتعدد التخصصات غير محددة، مما يكشف عن فجوة مهمة في الأدبيات. لمعالجة هذه الفجوة، نقوم بإجراء مراجعة منهجية لـ 89 دراسة باستخدام نهج العناصر المفضلة للإبلاغ عن المراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية (PRISMA) لتلخيص أدبيات CE المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي. تسفر مراجعتنا عن ثلاثة موضوعات رئيسية لـ CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي، بما في ذلك (1) تقديم خدمات أكثر دقة من خلال CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي؛ (2) قدرة CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي على (المشاركة في) خلق قيمة مدركة من قبل المستهلك، و(3) تقليل جهد المستهلك في تنفيذ مهامهم من خلال CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي. كما نطور نموذجًا مفاهيميًا يقترح العوامل السابقة لـ CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي من عوامل شخصية، تكنولوجية، تفاعلية، اجتماعية، وظرفية، ونتائج CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي من نتائج قائمة على المستهلك، قائمة على الشركة، ونتائج التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي. نختتم بتقديم تداعيات ذات صلة لتطوير النظرية (مثل، من خلال تقديم أسئلة بحث مستقبلية مستمدة من الموضوعات المقترحة لـ CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي) والممارسة (مثل، من خلال تقليل التكاليف المدركة من قبل المستهلك لتفاعلاتهم مع علامتهم التجارية/شركتهم).

الكلمات الرئيسية

1 | المقدمة

زيادة الولاء أو سلوك التوصية؛ برودي وآخرون، 2011)، مما يعزز الميزة التنافسية القائمة على الشركات. بينما كانت الأدبيات، تقليديًا، تركز على تفاعل المستهلكين مع العلامات التجارية، يتم منح اهتمام متزايد لتفاعلهم مع تقنيات معينة وتأثير ذلك على تفاعلهم مع العلامة التجارية، والذي تم تسميته بالتفاعل مع العلامة التجارية المدعوم بالتكنولوجيا (هوليبيك وبلك، 2021).

“والمهام من خلال التكيف المرن” (هاينلاين وكابلان، 2019، ص. 5)، والمشاركة كمورد استثماري للمستهلك في تفاعلاتهم المتعلقة بالعلامة التجارية (مثل، الذكاء الاصطناعي) (مثل، هوليبيك وآخرون، 2019؛ كومار وآخرون، 2019). بشكل عام، من خلال تجميع وتقييم مجموعة أبحاث تجربة العملاء المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي، تمهد تحليلاتنا الطريق لمزيد من تطوير هذا المجال بين التخصصات (بيج وآخرون، 2021؛ بولك وبيرج، 2018).

2 | الخلفية النظرية

2.1 | تفاعل المستهلك

يُعرّف هوليبيك وآخرون (2019، ص. 166) ذلك على أنه “استثمار المستهلك في … الموارد الفعالة [مثل المعرفة/ المهارات السلوكية]، والموارد القابلة للتشغيل [مثل المعدات] في تفاعلاتهم مع العلامة التجارية.” على الرغم من هذه الاختلافات، نستخلص السمات العامة التالية لتجربة العميل.

2.2 | الذكاء الاصطناعي

القدرة على أداء مهام محددة بدقة متزايدة مع مرور الوقت، قد تساعد تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تتضمن تقنيات التعلم الآلي أو التعلم العميق، أو الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، المستهلكين في إكمال مهامهم بشكل أكثر كفاءة أو فعالية (هوانغ وراست، 2021؛ شياي وآخرون، 2022). على سبيل المثال، تميل روبوتات الدردشة إلى تقديم توصيات أو حلول للمنتجات أكثر دقة وشمولية أو تخصيصًا للمستهلكين مع مرور الوقت (دويفيدي وآخرون، 2023).

3 | المنهجية

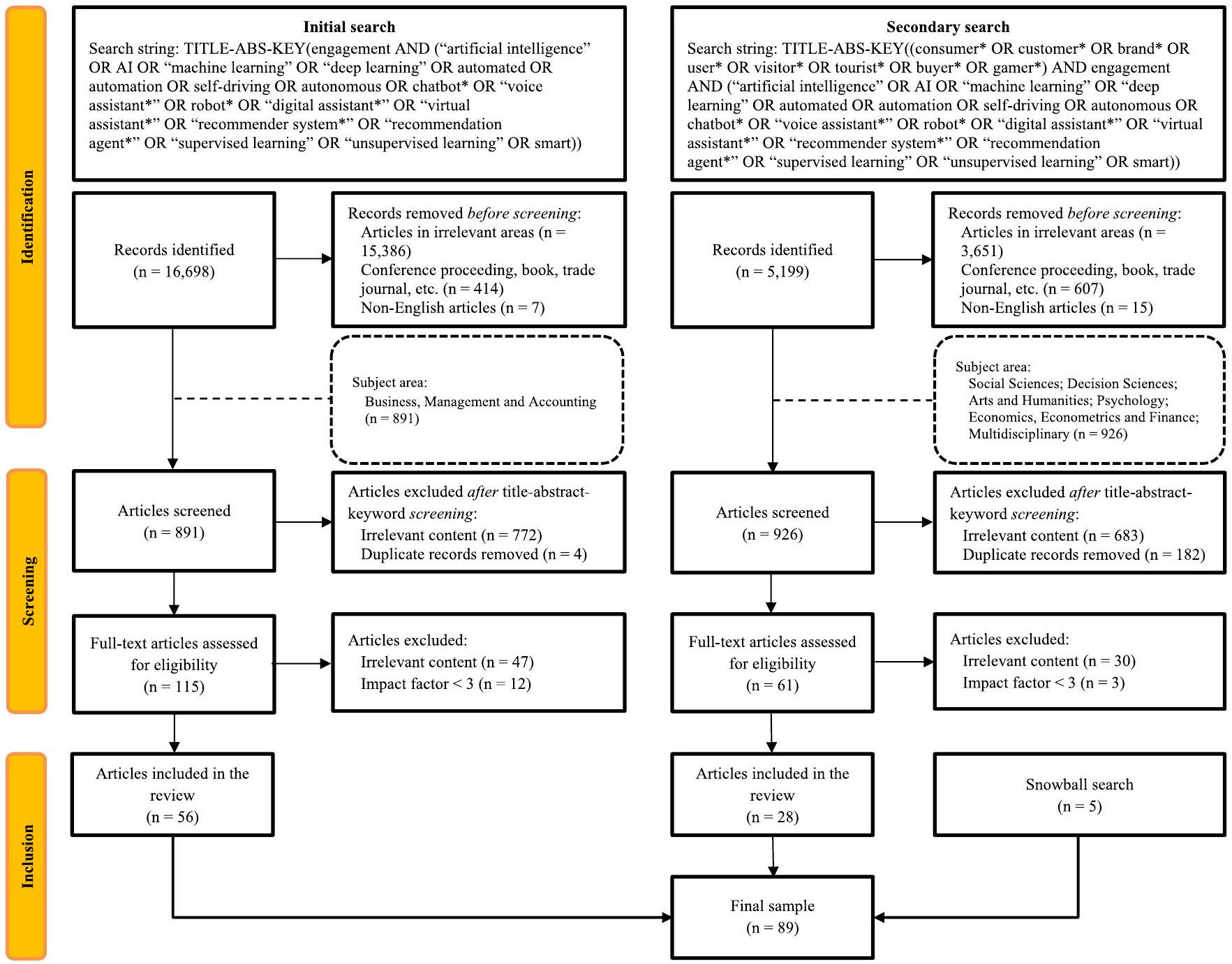

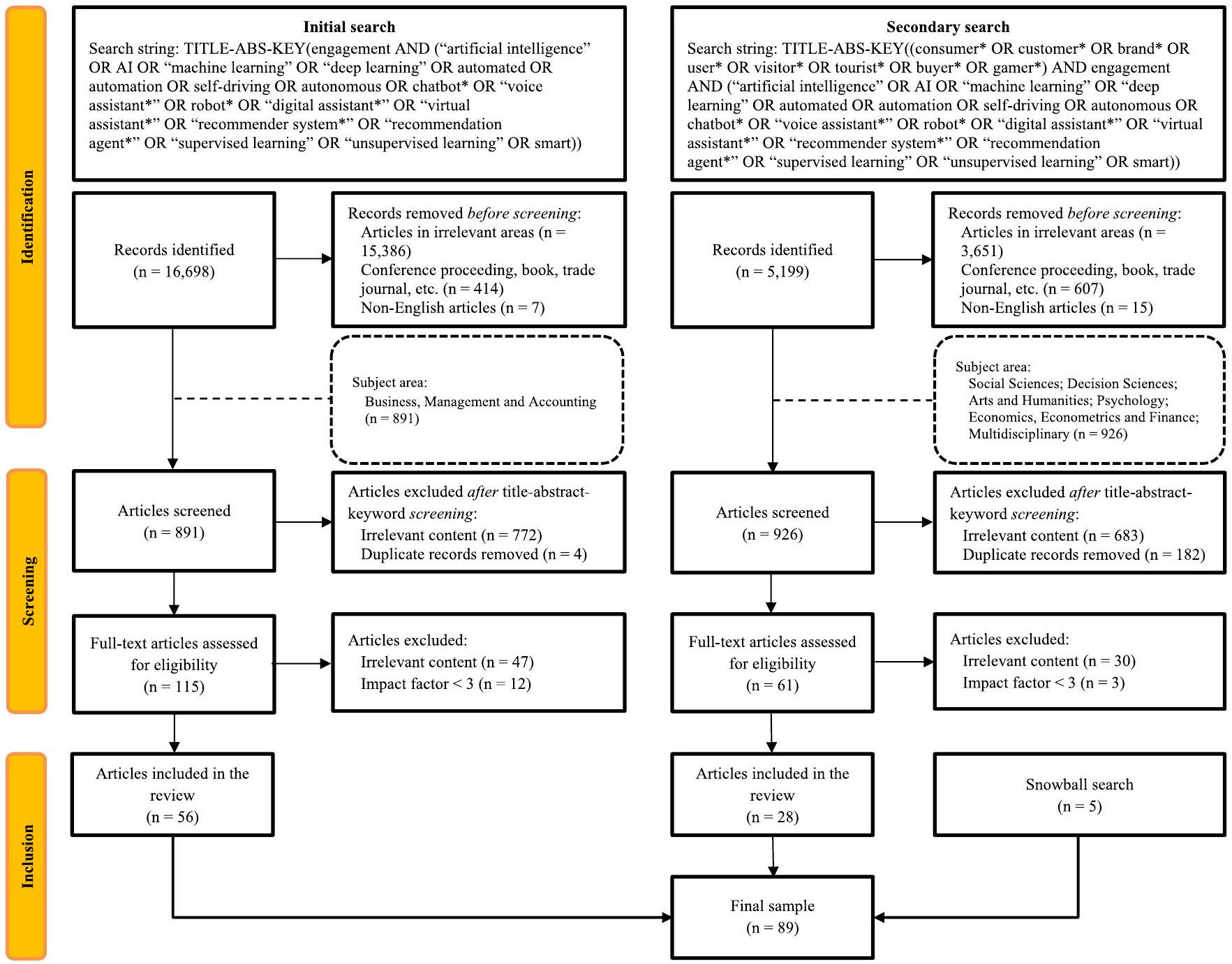

تركزت على الذكاء الاصطناعي وسلوك الشراء الاندفاعي (مقابل تجربة العملاء المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي). لذلك، في مرحلة الإدراج، احتفظنا بإجمالي 56 مقالة من بحثنا الأدبي الأولي (انظر الشكل 1).

4 | النتائج

4.1 | التحليل الوصفي

(أي، 141) في علم النفس والتسويق، وزياو وكومار (2021) (أي، 113). تم الحصول على عينة مقالاتنا من 54 مجلة، بما في ذلك مجلة أبحاث الأعمال (5 مقالات)، مجلة أبحاث الخدمة (4)، الحواسيب في سلوك الإنسان (4)، المجلة الدولية للتفاعل بين الإنسان والحاسوب (4)، مجلة الأبحاث في التسويق التفاعلي (4)، مجلة البيع بالتجزئة وخدمات المستهلك (4)، وحدود علم النفس (3). تم تضمين متوسط الاقتباسات لكل من مقالاتنا المدروسة أيضًا في المعلومات الداعمة: الملحق 2.

4.2 | مواضيع CE المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي

4.2.1 | تحسين دقة تقديم الخدمة من خلال CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي

| المؤلف(ون) | المقدمات | عواقب |

| بريتان وآخرون (2015) | قدرة الروبوت على التعبير عن المشاعر | – |

| رودريغيز-ليزونديا وآخرون (2015) | تجسيد، تحية الروبوت، والروبوت ذو المظهر النشط | – |

| ألوري وآخرون (2019) | – | خلق القيمة المشتركة |

| مولينيو وآخرون (2019) | – | – |

| موريؤشي (2019) | المعايير الذاتية والفائدة المدركة | ولاء العملاء |

| مالكاهي وآخرون (2019) | جاهزية التكنولوجيا (التفاؤل، الابتكار، عدم الراحة، وانعدام الأمان)، المخاطر المدركة، والثقة | نية التبني |

| Bindewald وآخرون (2020) | الأتمتة | – |

| تشنغ وجيانغ (2020) | فعل تواصلي نشط | – |

| فان وآخرون (2020) | جودة تجربة العميل الذكية (تفاعل الإنسان، جودة النظام الذكي، جودة الخدمة الذاتية، وجودة محتوى المنتج) | شراء الولاء والكلام الإيجابي |

| برينتس و نغوين (2020) | تجربة الخدمة مع الموظفين وتجربة الخدمة مع الذكاء الاصطناعي | ولاء العملاء |

| برينتس وآخرون (2020) | رضا العملاء عن الذكاء الاصطناعي | – |

| شوتزلر وآخرون (2020) | مهارة المحادثة في الدردشة والوجود الاجتماعي | – |

| عبد الله وآخرون (2021) | قبول ممارسات الذكاء الاصطناعي | – |

| برترانديا وآخرون (2021) | – | الفوائد المدركة (تحرير الوقت، التغلب على نقاط الضعف البشرية، وتجاوز القدرات البشرية) والمخاطر المدركة (خطر فقدان الكفاءات، خطر الأداء، وخطر الأمان والخصوصية) |

| تشاكر وأيكول (2021) | – | – |

| تشونغ وآخرون (2021) | خلق القيمة المشتركة | القيمة المدركة للعلامة التجارية |

| غرايمز وآخرون (2021) | قدرة الذكاء الاصطناعي المحادثي | – |

| هينكنز وآخرون (2021) | الشخصية المدركة والتطفل المدرك | رفاهية العميل (الكفاءة الذاتية وقلق التكنولوجيا) |

| هولبيك وآخرون (2021) | – | – |

| هوانغ وراست (2021) | – | – |

| كُل وآخرون (2021) | رسالة الدردشة الآلية الدافئة (مقابل الكفء) والمسافة بين العلامة التجارية والذات | – |

| كومار وآخرون (2021) | الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤول | القيمة المدركة (القيمة الأداتية والقيمة النهائية) |

| ماكلين وآخرون (2021) | خصائص الأفراد (الحضور الاجتماعي، الذكاء المدرك، والجاذبية الاجتماعية)، خصائص التكنولوجيا (الفائدة المدركة وسهولة الاستخدام)، وخصائص الموقف (الفوائد النفعية، الفوائد الترفيهية، وانعدام الثقة) | نية استخدام العلامة التجارية ونية الشراء |

| موريؤشي (2021) | التجسيد | نية إعادة الاستخدام |

| ناصر وآخرون (2021) | – | – |

| أوه وكانغ (2021) | – | – |

| بيريز-فيغا وآخرون (2021) | – | – |

| ريفا وماوري (2021) | – | – |

| شومانوف وجونسون (2021) | شخصية متوافقة بين المستهلك والدردشة الآلية | – |

| سينغ وآخرون (2021) | – | – |

| المؤلف(ون) | المقدمات | عواقب |

| تساي وآخرون (2021) | التواصل الاجتماعي لروبوتات الدردشة، التفاعل شبه الاجتماعي، والحوار المدرك | – |

| فيرنوتشيو وآخرون (2021) | مساعدات صوتية من علامات تجارية معروفة تعتمد على تجربة العلامة التجارية داخل السيارة | – |

| شياو وكومار (2021) | رضا العملاء والعواطف | – |

| بلاسي وآخرون (2022) | – | – |

| تشاندرا وآخرون (2022) | كفاءات الذكاء الاصطناعي الشبيهة بالبشر (كفاءة الذكاء الاصطناعي المعرفية، كفاءة الذكاء الاصطناعي العلائقية، وكفاءة الذكاء الاصطناعي العاطفية) وثقة المستخدم في الذكاء الاصطناعي | – |

| تشين، كينغ، وآخرون. (2022) | الثقة في المنصة والثقة في المضيف | ولاء العملاء |

| تشين، برينتس، وآخرون. (2022) | تجربة التفاعل | – |

| فانغ وآخرون (2022) | احتياج الرضا، عاطفة السياح، والرابطة الاجتماعية مع الروبوتات | – |

| فوينتس-مورايدا وآخرون (2022) | – | قبول الروبوتات الاجتماعية |

| غاو وآخرون (2022) | التفاعل المدرك والتخصيص | خلق القيمة المشتركة |

| غوري وآخرون (2022) | – | – |

| هاري وآخرون (2022) | راحة الوقت، التفاعلية، التوافق، التعقيد، القابلية للملاحظة، وقابلية التجربة | الرضا ونية استخدام العلامة التجارية |

| هيرنانديز-أورتيغا وآخرون (2022) | التماسك العلاقي | – |

| هلي وآخرون (2022) | الموقف تجاه استخدام روبوتات الخدمة | – |

| هولبيك، منيدجل، وآخرون. (2022) | التحكم السلوكي المدرك | نية الشراء |

| هيون وآخرون (2022) | العناصر الاجتماعية الوظيفية (الضيافة المدركة، البرودة، سلامة الروبوت، وكفاءة أداء الروبوت) | جدوى خدمة فرق الإنسان والروبوت ونية استخدام روبوتات الخدمة |

| جيانغ وآخرون (2022) | رضا العملاء عن خدمات الدردشة الآلية | نية الشراء والزيادة السعرية |

| كانغ ولو (2022) | التعاون بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي (تفاوض الوكالة وتآزر الوكالة) | – |

| لي وآخرون (2022) | سلوك الروبوتات الاستباقي والثقة في روبوتات الخدمة | – |

| ليم وزانغ (2022) | الاعتماد المدرك والموقف تجاه الأخبار المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي | اعتماد الأخبار المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي |

| لوريرو وآخرون (2022) | توافق نمط الحياة وتحديد الدردشة الآلية | الدعوة لروبوتات الدردشة |

| ماسلو وآخرون (2022) | استخدام نظام التوصية من قبل المستهلكين ووجهات نظرهم (‘الزيارات، مشاهدات الصفحات’، الصلة، الاكتشاف/التنسيق، المفاجأة، ‘الخصوصية، الأمان’، و’الثقة، الوكالة’) | النتائج طويلة الأجل للعلامة التجارية (قيمة الحياة، (الكلمة) الشفهية، قيمة العلامة التجارية، واحتفاظ المزود) |

| ميلي وروسو-سبينا (2022) | – | – |

| ميلي وآخرون (2022) | دمج التكنولوجيا العالية واللمسة الإنسانية | الرفاهية |

| مصطفى وكاساماني (2022) | ثقة المستخدم الأولية في الدردشة الآلية | – |

| وي و برينتس (2022) | جودة الخدمة | ولاء العملاء |

| وين وآخرون (2022) | تصور العملاء للذكاء الاصطناعي (الشخصنة المدركة والاستقلالية)، عامل الموضوع (الثقة في الذكاء الاصطناعي والكفاءة الذاتية)، وعامل البيئة (الهوية المجتمعية) | سلوكيات خلق القيمة المشتركة |

| يانغ ولين (2022) | – | – |

| يو وآخرون (2022) | الحضور الاجتماعي | نية الشراء |

| المؤلف(ون) | المقدمات | عواقب |

| زو وآخرون (2022) | تجارب التدفق | – |

| أجيكغوز وآخرون (2023) | المواقف تجاه استخدام المساعدات الصوتية والاستعداد لتقديم معلومات الخصوصية | – |

| أقديم وكاسالو (2023) | القيمة المدركة | – |

| أسانتي وآخرون (2023) | عناصر (كفاءة الدردشة الآلية، وظيفة البحث عن الصور، كفاءة نظام التوصيات، وخدمة ما بعد البيع الآلية) | – |

| أسلم (2023) | – | – |

| تشانغ وآخرون (2023) | تجربة تقنيات السفر الذكية المدركة | النيات السلوكية |

| دونغ وآخرون (2023) | موثوقية المصدر والتحكم في المحتوى | الإزعاج المدرك للإعلانات |

| غاور وآخرون (2023) | – | – |

| قو وجيانغ (2023) | نسخة إعلانات مخصصة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي | – |

| هوبرت وآخرون (2023) | أنماط ICAP (أي: السلبية، النشطة، البناءة، والتفاعلية) | – |

| كومار، شارما، وآخرون (2023) | – | – |

| كومار، فرونتيس، وآخرون. (2023) | – | فائدة العميل |

| لي وآخرون (2023) | الكفاءة المدركة، -الدفء، و -الفائدة | – |

| لين وو (2023) | إشباعات المستهلكين (البحث عن المعلومات، التفاعل الاجتماعي، وإشباع الترفيه) | حميمية العلامة التجارية، الالتزام العاطفي، نية السلوك المتعلقة بالدردشة الآلية، ونية الشراء |

| نازير وآخرون (2023) | التكنولوجيا | تجربة المستهلك المرضية |

| نجوين وآخرون (2023) | اللغة البشرية المدركة والأصالة المتصورة | – |

| بول وآخرون (2023) | – | – |

| برينتس وآخرون (2023) | الاستقلالية، الكفاءة، والترابط | رفاهية المستهلك والارتباط |

| رحمن وآخرون (2023) | مساعدة رقمية مدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي | تجربة تسوق العلامة التجارية الفاخرة للعميل |

| ساتارابو وآخرون (2023) | – | – |

| شاه وآخرون (2023) | جودة خدمة الروبوت | قبول العميل |

| شارما وآخرون (2023) | شارك | – |

| سوان وآخرون (2023) | الكفاءة الذاتية الرقمية وجودة الخدمة العلائقية | خلق قيمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الاستباقي ونية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي |

| أوبادياي وكامبل (2023) | التجسيد والتجربة الذكية | حب العلامة التجارية |

| شيا وآخرون (2023) | الوحدة، الثقة، وتجسيد الدردشة الآلية | تطوير العلاقات |

| شيا-كارسون وآخرون (2023) | قيمة الترفيه، الاتصال العاطفي، والمحتوى التعليمي | – |

| شيونغ وآخرون (2023) | تكنولوجيا السياحة الذكية | تجارب سياحية لا تُنسى |

| شيوي وآخرون (2023) | تفاعلات المساعد الصوتي، إدراك الكفاءة، وإدراك الدفء | – |

| ين وآخرون (2023) | بيئة الذكاء الاصطناعي الملحوظة، التوافق الذاتي المثالي، والثقة | – |

| يو وآخرون (2024) | العروض العاطفية (السعادة، الحزن، الاشمئزاز، والدهشة) | – |

4.2.2 | قدرة الذكاء الاصطناعي القائم على تجربة العملاء (CE) على (المشاركة في) خلق قيمة مدركة من قبل العملاء

“أنشطة مرتبطة بالعلامة التجارية” (Hollebeek et al., 2019, ص. 167). عندما يدرك المستهلكون أن تفاعلاتهم مع الذكاء الاصطناعي ذات قيمة، فإنهم يميلون إلى الحصول على قيمة إيجابية مدركة (مشاركة في إنشائها) من تفاعلاتهم مع هذه، والعكس صحيح (Fang et al., 2022; Prentice et al., 2020)، مما يغذي عادةً رغبتهم في الاستمرار في التفاعل مع هذه (Lalicic & Weismayer, 2021).

4.2.3 | قلل الذكاء الاصطناعي في تجربة العميل من جهد المستهلك في تنفيذ مهامهم

الاستثمار (على سبيل المثال، في تحديد العلامات المناسبة) وزيادة سهولة استخدام التكنولوجيا المتصورة، كما اقترح في نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (ديفيس، 1989)، مع تقليل توقعاتهم للجهد التكنولوجي، كما تم الإعراب عنه في النظرية الموحدة لقبول واستخدام التكنولوجيا (فينكاتيش وآخرون، 2003). وبالمثل، فإن شركات مثل أمازون أو ماكدونالدز تقوم بشكل متزايد بتوصيل طلباتها من خلال الروبوتات الأرضية أو الطائرات بدون طيار (مثل الطائرات المسيرة)، مما يزيل حاجة المستهلكين لجمع طلباتهم ويسمح بتوصيل أسرع. ونتيجة لذلك، من المتوقع أن يرتفع اعتماد المستهلكين للتكنولوجيا واستخدامها المستمر.

4.3 | النموذج المفاهيمي

4.3.1 | العوامل السابقة المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي

حدد المؤلفون العوامل التفاعلية الرئيسية التالية التي تشكل تجربة العملاء المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي: وضوح التفاعل، قابلية الابتكار (مثل، الدردشة الآلية) للملاحظة، أسلوب الاتصال، التوافق/قابلية التجربة، تعقيد التفاعل، ومخاوف الخصوصية والأمان والسلامة (مثل، جاو وآخرون، 2022؛ ماسلوفسكا وآخرون، 2022؛ يين وآخرون، 2023).

4.3.2 | عواقب الاقتصاد الدائري القائم على الذكاء الاصطناعي

5 | الآثار، القيود، والبحوث المستقبلية

5.1 | الآثار النظرية

توحيد الرؤى السابقة، مما يؤدي إلى الآثار النظرية التالية.

| موضوع CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي | أسئلة بحثية نموذجية | ||||

| توفير خدمات دقيقة بشكل متزايد من خلال CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي |

|

||||

| قدرة الذكاء الاصطناعي القائم على الاقتصاد الدائري على (المشاركة في) خلق قيمة مدركة من قبل المستهلك |

|

||||

| قلل الذكاء الاصطناعي القائم على البيانات من جهد المستهلك في تنفيذ مهامهم |

|

5.2 | الآثار الإدارية

5.3 | القيود والبحوث المستقبلية

يمكن للباحثين المستقبليين، لذلك، استشارة قواعد بيانات أخرى أو ذات صلة (مثل Web of Science/Google Scholar) للحصول على بياناتهم وضم الأعمال غير الإنجليزية في مراجعاتهم المستقبلية حول CE المعتمد على الذكاء الاصطناعي.

شكر وتقدير

بيان تضارب المصالح

بيان توافر البيانات

أوركيد

شكري منيدجل (د)http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8510-800X

ماركو سارستيدت (D)http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5424-4268

يوهان يانسون (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2593-9439

سيغيتاس أوربونافيتشيوس (د)http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4176-2573

REFERENCES

Acikgoz, F., Perez-Vega, R., Okumus, F., & Stylos, N. (2023). Consumer engagement with AI-powered voice assistants: A behavioral reasoning perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 40(11), 2226-2243.

Akdim, K., & Casaló, L. V. (2023). Perceived value of Al-based recommendations service: the case of voice assistants. Service Business, 17(1), 81-112.

Aluri, A., Price, B., & McIntyre, N. (2019). Using machine learning to cocreate value through dynamic customer engagement in a brand loyalty program. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(1), 78-100.

Ameen, N., Sharma, G., Tarba, S., Rao, A., & Chopra, R. (2022). Toward advancing theory on creativity in marketing and artificial intelligence. Psychology & Marketing, 39(9), 1802-1825.

Asante, I., Jiang, Y., Hossin, A., & Luo, X. (2023). Optimization of consumer engagement with artificial intelligence elements on electronic commerce platforms. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 24(1), 7-28.

Ashfaq, M., Yun, J., & Yu, S. (2021). My smart speaker is cool! Perceived coolness, perceived values, and users’ attitude toward smart speakers. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 37(6), 560-573.

Aslam, U. (2023). Understanding the usability of retail fashion brand chatbots: Evidence from customer expectations and experiences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103377.

Baabdullah, A. M., Alalwan, A. A., Slade, E. L., Raman, R., & Khatatneh, K. F. (2021). SMEs and artificial intelligence (AI): Antecedents and consequences of AI-based B2B practices. Industrial Marketing Management, 98, 255-270.

Barnes, S., & de Ruyter, K. (2022). Guest editorial: Artificial intelligence as a market-facing technology: Getting closer to the consumer through innovation and insight. European Journal of Marketing, 56(6), 1585-1589.

Beckers, S. F. M., Van Doorn, J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2018). Good, better, engaged? The effect of company-initiated customer engagement behavior on shareholder value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46, 366-383.

Belanche, D., Casaló, L., Schepers, J., & Flavián, C. (2021). Examining the effects of robots’ physical appearance, warmth, and competence in frontline services: The Humanness-Value-Loyalty model. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2357-2376.

Bertrandias, L., LOWE, B., Sadik-Rozsnyai, O., & Carricano, M. (2021). Delegating decision-making to autonomous products: A value model emphasizing the role of well-being. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 169, 120846.

Bilro, R. G., & Loureiro, S. M. C. (2020). A consumer engagement systematic review: Synthesis and research agenda. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 24(3), 283-307.

Bindewald, J. M., Miller, M. E., & Peterson, G. L. (2020). Creating effective automation to maintain explicit user engagement. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(4), 341-354.

Blasi, S., Gobbo, E., & Sedita, S. R. (2022). Smart cities and citizen engagement: Evidence from Twitter data analysis on Italian municipalities. Journal of Urban Management, 11(2), 153-165.

Bretan, M., Hoffman, G., & Weinberg, G. (2015). Emotionally expressive dynamic physical behaviors in robots. International Journal of HumanComputer Studies, 78, 1-16.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252-271.

Brown, R., Coventry, L., Sillence, E., Blythe, J., Stumpf, S., Bird, J., & Durrant, A. C. (2022). Collecting and sharing self-generated health and lifestyle data: Understanding barriers for people living with long-term health conditions-A survey study. Digital Health, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221084458

Çakar, K., & Aykol, Ş. (2021). Understanding travellers’ reactions to robotic services: A multiple case study approach of robotic hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(1), 155-174.

Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17, 79-89.

Celsi, R. L., & Olson, J. C. (1988). The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 210-224.

Chandra, S., Shirish, A., & Srivastava, S. C. (2022). To be or not to be human? Theorizing the role of human-like competencies in conversational artificial intelligence agents. Journal of Management Information Systems, 39(4), 969-1005.

Chang, J. Y. S., Konar, R., Cheah, J. H., & Lim, X. J. (2023). Does privacy still matter in smart technology experience? A conditional mediation analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics. https://doi.org/10.1057/ s41270-023-00240-8

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81-93.

Chen, Q., Gong, Y., Lu, Y., & Tang, J. (2022). Classifying and measuring the service quality of AI chatbot in frontline service. Journal of Business Research, 145, 552-568.

Chen, X., Cheah, S., & Shen, A. (2019). Empirical study on behavioral intentions of short-term rental tenants-The moderating role of past experience. Sustainability, 11(12), 3404.

Chen, Y., Keng, C., & Chen, Y. (2022). How interaction experience enhances customer engagement in smart speaker devices? The moderation of gendered voice and product smartness. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(3), 403-419.

Chen, Y., Prentice, C., Weaven, S., & Hsiao, A. (2022). The influence of customer trust and AI on customer engagement and loyalty-The case of the home-sharing industry. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 912339.

Cheung, M. L., Pires, G., Rosenberger III, P. J., Leung, W. K. S., & Chang, M. K. (2021). The role of social media elements in driving cocreation and engagement. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(10), 1994-2018.

Clarke, J. (2011). What is a systematic review? Evidence-based Nursing, 14(3):64.

Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

Dong, B., Zhuang, M., Fang, E., & Huang, M. (2023). Tales of two channels: Digital advertising performance between AI recommendation and

user subscription channels. Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10. 1177/00222429231190021

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253-266.

Van Doorn, J., Mende, M., Noble, S. M., Hulland, J., Ostrom, A. L., Grewal, D., & Petersen, J. A. (2017). Domo arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 43-58.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H., Albashrawi, M. A., Al-Busaidi, A. S., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette, Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., … Wright, R. (2023). Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642.

Dzieza, J. (2023). AI is a lot of work. https://www.theverge.com/features/ 23764584/ai-artificial-intelligence-data-notation-labor-scale-surge-remotasks-openai-chatbots

Fan, X., Ning, N., & Deng, N. (2020). The impact of the quality of intelligent experience on smart retail engagement. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(7), 877-891.

Fang, S., Han, X., & Chen, S. (2022). The impact of tourist-robot interaction on tourist engagement in the hospitality industry:

Fuentes-Moraleda, L., Lafuente-lbañez, C., Fernandez Alvarez, N., & Villace-Molinero, T. (2022). Willingness to accept social robots in museums: An exploratory factor analysis according to visitor profile. Library Hi Tech, 40(4), 894-913.

Gao, L., Li, G., Tsai, F., Gao, C., Zhu, M., & Qu, X. (2022). The impact of artificial intelligence stimuli on customer engagement and value cocreation: The moderating role of customer ability readiness. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(2), 317-333.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Gauer, V., Axsen, J., Dütschke, E., Long, Z., & Kelber, A. (2023). Who is more attached to their car? Comparing automobility engagement and response to shared, automated and electric mobility in Canada and Germany. Energy Research & Social Science, 99, 103048.

Ghouri, A. M., Mani, V., Haq, M. A., & Kamble, S. S. (2022). The micro foundations of social media use: Artificial intelligence integrated routine model. Journal of Business Research, 144, 80-92.

Giang Barrera, K., & Shah, D. (2023). Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113420.

Grimes, G. M., Schuetzler, R. M., & Giboney, J. S. (2021). Mental models and expectation violations in conversational AI interactions. Decision Support Systems, 144, 113515.

Grundner, L., & Neuhofer, B. (2021). The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: A futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100511.

Guo, B., & Jiang, Z. (2023). Influence of personalised advertising copy on consumer engagement: A field experiment approach. Electronic Commerce Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-023-09721-5

Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2019). A brief history of artificial intelligence: On the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. California Management Review, 61(4), 5-14.

Hair, J., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). Data, measurement, and causal inferences in machine learning: Opportunities and challenges for marketing. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 29(1), 65-77.

Hand, C., Dall’Olmo Riley, F., Harris, P., Singh, J., & Rettie, R. (2009). Online grocery shopping: The influence of situational factors. European Journal of Marketing, 43(9/10), 1205-1219.

Hari, H., lyer, R., & Sampat, B. (2022). Customer brand engagement through chatbots on bank websites-Examining the antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 38(13), 1212-1227.

Harmeling, C. M., Moffett, J. W., Arnold, M. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2017). Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 312-335.

Heller, J., Chylinski, M., De Ruyter, K., Keeling, D. I., Hilken, T., & Mahr, D. (2021). Tangible service automation: Decomposing the technologyenabled engagement process (TEEP) for augmented reality. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 84-103.

Henkens, B., Verleye, K., & Larivière, B. (2021). The smarter, the better?! Customer well-being, engagement, and perceptions in smart service systems. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38(2), 425-447.

Hepziba, E., & John, F. (2020). Role of chat-bots in customer engagement valence. Psychology & Education, 57(9), 2181-2186.

Hernández-Ortega, B., Aldas-Manzano, J., & Ferreira, I. (2022). Relational cohesion between users and smart voice assistants. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(5), 725-740.

Herrando, C., Jiménez-Martínez, J., & Martín-De Hoyos, M. J. (2017). Passion at first sight: How to engage users in social commerce contexts. Electronic Commerce Research, 17, 701-720.

Hlee, S., Park, J., Park, H., Koo, C., & Chang, Y. (2022). Understanding customer’s meaningful engagement with AI-powered service robots. Information Technology & People, 36(3), 1020-1047.

Hobert, S., Følstad, A., & Law, E. L. C. (2023). Chatbots for active learning: A case of phishing email identification. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 179, 103108.

Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (2018). Consumer and object experience in the internet of things: An assemblage theory approach. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(6), 1178-1204.

Hollebeek, L., Kumar, V., & Srivastava, R. K. (2022). From customer-, to actor-, to stakeholder engagement: Taking stock, conceptualization, and future directions. Journal of Service Research, 25(2), 328-343.

Hollebeek, L., Menidjel, C., Itani, O., Clark, M., & Sigurdsson, V. (2022). Consumer engagement with self-driving cars: A theory of planned behavior-informed perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing & Logistics, 35(2), 2029-2046.

Hollebeek, L., Sarstedt, M., Menidjel, C., Sprott, D., & Urbonavicius, S. (2023). Hallmarks and potential pitfalls of customer- and consumer engagement scales: A systematic review. Psychology & Marketing, 40(6), 1074-1088.

Hollebeek, L., Sharma, T., Pandey, R., Sanjal, P., & Clark, M. (2022). Fifteen years of customer engagement research: A bibliometric- and network Analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(2), 293-309.

Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(7-8), 785-807.

Hollebeek, L. D., & Belk, R. (2021). Consumers’ technology-facilitated brand engagement and wellbeing: Positivist TAM/PERMA- vs. consumer culture theory perspectives. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38(2), 387-401.

Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149-165.

Hollebeek, L. D., Kumar, V., Srivastava, R. K., & Clark, M. K. (2023). Moving the stakeholder journey forward. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51, 23-49.

Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). SD logic-informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47, 161-185.

Hu, Q., & Pan, Z. (2023). Can AI benefit individual resilience? The mediation roles of AI routinization and infusion. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103339.

Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research, 21(2), 155-172.

Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2021). Engaged to a robot? The role of AI in service. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 30-41.

Huang, T. L., Tsiotsou, R. H., & Liu, B. S. (2023). Delineating the role of mood maintenance in augmenting reality (AR) service experiences: An application in tourism. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, 122385.

Hyun, Y., Hlee, S., Park, J., & Chang, Y. (2022). Discovering meaningful engagement through interaction between customers and service robots. The Service Industries Journal, 42(13-14), 973-1000.

Islam, J. U., Rahman, Z., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A solicitation of congruity theory. Internet Research, 28(1), 23-45.

Jain, S., & Gandhi, A. V. (2021). Impact of artificial intelligence on impulse buying behaviour of Indian shoppers in fashion retail outlets. International Journal of Innovation Science, 13(2), 193-204.

Jia, J., & Wang, J. (2016). Do customer participation and cognitive ability influence satisfaction? The Service Industries Journal, 36(9-10), 416-437.

Jiang, H., Cheng, Y., Yang, J., & Gao, S. (2022). Al-powered chatbot communication with customers: Dialogic interactions, satisfaction, engagement, and customer behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 134, 107329.

Kang, H., & Lou, C. (2022). Al agency vs. human agency: Understanding human-AI interactions on TikTok and their implications for user engagement. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 27(5), 1-13.

Karaosmanoglu, E., Altinigne, N., & Isiksal, D. G. (2016). CSR motivation and customer extra-role behavior: Moderation of ethical corporate identity. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4161-4167.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customerbased brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1-22.

de Kervenoael, R., Hasan, R., Schwob, A., & Goh, E. (2020). Leveraging human-robot interaction in hospitality services: Incorporating the role of perceived value, empathy, and information sharing into visitors’ intentions to use social robots. Tourism Management, 78, 104042.

Kumar, P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Anand, A. (2021). Responsible artificial intelligence (AI) for value formation and market performance in healthcare: The mediating role of patient’s cognitive engagement. Information Systems Frontiers, 25, 2197-2220.

Kumar, P., Sharma, S., & Dutot, V. (2023). Artificial intelligence (AI)enabled CRM capability in healthcare: The impact on service innovation. International Journal of Information Management, 69, 102598.

Kumar, V., Dixit, A., Javalgi, R. G., & Dass, M. (2016). Research framework, strategies, and applications of intelligent agent technologies (IATs) in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 24-45.

Kumar, V., Rajan, B., Gupta, S., & Pozza, I. D. (2019). Customer engagement in service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 138-160.

Lalicic, L., & Weismayer, C. (2021). Consumers’ reasons and perceived value co-creation of using artificial intelligence-enabled travel service agents. Journal of Business Research, 129, 891-901.

Le, Q., Tan, L. P., & Hoang, T. (2022). Customer brand co-creation on social media: A systematic review. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 40(8), 1038-1053.

Lee, Y., Ha, M., Kwon, S., Shim, Y., & Kim, J. (2019). Egoistic and altruistic motivation: How to induce users’ willingness to help for imperfect Al. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 180-196.

Leffrang, D., & Mueller, O. (2023). Al washing: The framing effect of labels on algorithmic advice utilization. ICIS 2023, Hyderabad, India.

Leung, E., Paolacci, G., & Puntoni, S. (2018). Man versus machine: Resisting automation in identity-based consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(6), 818-831.

Li, B., Yao, R., & Nan, Y. (2023). How do friendship artificial intelligence chatbots (FAIC) benefit the continuance using intention and customer engagement? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(6), 1376-1398.

Li, D., Liu, C., & Xie, L. (2022). How do consumers engage with proactive service robots? The roles of interaction orientation and corporate reputation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11), 3962-3981.

Li, Q., Guo, X., & Bai, X. (2017). Weekdays or weekends: Exploring the impacts of microblog posting patterns on gratification and addiction. Information & Management, 54(5), 613-624.

Lim, J. S., & Zhang, J. (2022). Adoption of AI-driven personalization in digital news platforms: An integrative model of technology acceptance and perceived contingency. Technology in Society, 69, 101965.

Lim, W. M., Rasul, T., Kumar, S., & Ala, M. (2022). Past, present, and future of customer engagement. Journal of Business Research, 140, 439-458.

Lin, J. S., & Wu, L. (2023). Examining the psychological process of developing consumer-brand relationships through strategic use of social media brand chatbots. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, 107488.

Liu, F., Li, J., Mizerski, D., & Soh, H. (2012). Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8), 922-937.

Liu-Thompkins, Y., Okazaki, S., & Li, H. (2022). Artificial empathy in marketing interactions: Bridging the human-AI gap in affective and social customer experience. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50, 1198-1218.

Longoni, C., & Cian, L. (2022). Artificial intelligence in utilitarian vs. hedonic contexts: The “word-of-machine” effect. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 91-108.

Loureiro, S. M. C., Ali, F., & Ali, M. (2022). Symmetric and asymmetric modeling to understand drivers and consequences of hotel chatbot engagement. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2124346

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 136-154.

Marriott, H., & Pitardi, V. (2023). One is the loneliest number… Two can be as bad as one. The influence of AI friendship apps on users’ wellbeing and addiction. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10. 1002/mar. 21899

Maslowska, E., Malthouse, E. C., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2022). The role of recommender systems in fostering consumers’ long-term platform engagement. Journal of Service Management, 33(4/5), 721-732.

McLean, G., Osei-Frimpong, K., & Barhorst, J. (2021). Alexa, do voice assistants influence consumer brand engagement? Examining the role of AI powered voice assistants in influencing consumer brand engagement. Journal of Business Research, 124, 312-328.

Mehta, J., Jarenwattananon, P., & Shapiro, A. (2023). Behind the secretive work of the many, many humans helping to train AI. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/26/ 1184392406/behind-the-secretive-work-of-the-many-many-humans-helping-to-train-ai

Mehta, P., Jebarajakirthy, C., Maseeh, H., Anubha, A., Raiswa, S., & Dhanda, K. (2022). Artificial intelligence in marketing: A metaanalytic review. Psychology & Marketing, 39(11), 2013-2038.

Mele, C., Marzullo, M., Di Bernardo, I., Russo-Spena, T., Massi, R., La Salandra, A., & Cialabrini, S. (2022). A smart tech lever to augment caregivers’ touch and foster vulnerable patient engagement and well-being. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 32(1), 52-74.

Mele, C., & Russo-Spena, T. (2022). The architecture of the phygital customer journey: A dynamic interplay between systems of insights and systems of engagement. European Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 72-91.

Menidjel, C., Hollebeek, L., Leppiman, A., & Riivits-Arkonsuo, I. (2022). Role of AI in enhancing customer engagement, loyalty, and loyalty program performance. In K. De Ruyter, D. Keeling, & D. Cox (Eds.), The handbook of research on customer loyalty. Edward-Elgar.

Menidjel, C., Hollebeek, L. D., Urbonavicius, S., & Sigurdsson, V. (2023). Why switch? The role of customer variety-seeking and engagement in driving service switching intention. Journal of Services Marketing, 37(5), 592-605.

Mills, N. (2021). Will self-driving cars disrupt the insurance industry? https:// www.forbes.com/sites/columbiabusinessschool/2021/03/25/will-self-driving-cars-disrupt-the-insurance-industry/?sh=3f28d8801dbf

Mishra, S., Ewing, M. T., & Cooper, H. B. (2022). Artificial intelligence focus and firm performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(6), 1176-1197.

Moher, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2019). Smart city communication via social media: Analysing residents’ and visitors’ engagement. Cities, 94, 247-255.

Moriuchi, E. (2019). Okay, Google! An empirical study on voice assistants on consumer engagement and loyalty. Psychology & Marketing, 36(5), 489-501.

Moriuchi, E. (2021). An empirical study on anthropomorphism and engagement with disembodied Als and consumers’ re-use behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 38(1), 21-42.

Mostafa, R. B., & Kasamani, T. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of chatbot initial trust. European Journal of Marketing, 56(6), 1748-1771.

Mulcahy, R., Letheren, K., McAndrew, R., Glavas, C., & Russell-Bennett, R. (2019). Are households ready to engage with smart home technology? Journal of Marketing Management, 35(15-16), 1370-1400.

Nasir, J., Bruno, B., Chetouani, M., & Dillenbourg, P. (2021). What if social robots look for productive engagement? Automated assessment of goal-centric engagement in learning applications. International Journal of Social Robotics, 14, 55-71.

Nazir, S., Khadim, S., Ali Asadullah, M., & Syed, N. (2023). Exploring the influence of artificial intelligence technology on consumer repurchase intention: The mediation and moderation approach. Technology in Society, 72, 102190.

Nima, A. A., Cloninger, K. M., Persson, B. N., Sikström, S., & Garcia, D. (2020). Validation of subjective well-being measures using item response theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3036.

Oh, J., & Kang, H. (2021). User engagement with smart wearables: Four defining factors and a process model. Mobile Media & Communication, 9(2), 314-335.

De Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Pinto, D. C., Herter, M. M., Sampaio, C. H., & Babin, B. J. (2020). Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48, 1211-1228.

Ornelas Sánchez, S. A., & Vera Martínez, J. (2021). The more I know, the more I engage: Consumer education’s role in consumer engagement in the coffee shop context. British Food Journal, 123(2), 551-562.

Ozuem, W., Willis, M., Howell, K., Lanaster, G., & Ng, R. (2021). Determinants of online brand communities’ and millennials’ characteristics: A social influence perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 38(5), 794-818.

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S…. Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Parasuraman, A. (2000). Technology Readiness Index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research, 2(4), 307-320.

Paul, J., Ueno, A., & Dennis, C. (2023). ChatGPT and consumers: Benefits, pitfalls and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(4), 1213-1225.

Peng, C., van Doorn, J., Eggers, F., & Wieringa, J. E. (2022). The effect of required warmth on consumer acceptance of artificial intelligence in service: The moderating role of AI-human collaboration. International Journal of Information Management, 66, 102533.

Perez-Vega, R., Kaartemo, V., Lages, C. R., Borghei Razavi, N., & Männistö, J. (2021). Reshaping the contexts of online customer engagement behavior via artificial intelligence: A conceptual framework. Journal of Business Research, 129, 902-910.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences-A practical guide. Blackwell.

Piercy, N. F. (2006). Driving organizational citizenship behaviors and salesperson in-role behavior performance: The role of management control and perceived organizational support. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 244-262.

Pitardi, V., Bartikowski, B., Osburg, V. S., & Yoganathan, V. (2023). Effects of gender congruity in human-robot service interactions: The moderating role of masculinity. International Journal of Information Management, 70, 102489.

Pollock, A., & Berge, E. (2018). How to do a systematic review. International Journal of Stroke, 13(2), 138-156.

Pradeep, A., Appel, A., & Sthanunathan, S. (2019). Al for marketing and product innovation. Wiley.

Prajogo, D. I., & McDermott, P. (2011). Examining competitive priorities and competitive advantage in service organisations using Importance-Performance Analysis matrix. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(5), 465-483.

Prentice, C., Loureiro, S. M. C., & Guerreiro, J. (2023). Engaging with intelligent voice assistants for wellbeing and brand attachment. Journal of Brand Management, 30, 449-460.

Prentice, C., Weaven, S., & Wong, I. A. (2020). Linking AI quality performance and customer engagement: The moderating effect of Al preference. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102629.

Rafaeli, S. (1988). From new media to communication. SAGE Annual Review of Communication Research: Advancing Communication Science, 16, 110-134.

Rahman, M. S., Bag, S., Hossain, M. A., Abdel Fattah, F. A. M., Gani, M. O., & Rana, N. P. (2023). The new wave of Al-powered luxury brands online shopping experience: The role of digital multisensory cues and customers’ engagement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 72, 103273.

Rana, J., Gaur, L., Singh, G., Awan, U., & Rasheed, M. I. (2021). Reinforcing customer journey through artificial intelligence: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(7), 1738-1758.

Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., Loureiro, S. M. C., Khan, I., & Hasan, R. (2023). Exploring tourists’ virtual reality-based brand engagement: A uses-andgratifications perspective. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi.org/10. 1177/00472875231166598

Rehman, Z., Baharun, R., & Salleh, N. (2020). Antecedents, consequences, and reducers of perceived risk in social media: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. Psychology & Marketing, 37(1), 74-86.

Richards, K. A., & Jones, E. (2008). Customer relationship management: Finding value drivers. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(2), 120-130.

Riva, G., & Mauri, M. (2021). MuMMER: How robotics can reboot social interaction and customer engagement in shops and malls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 24(3), 210-211.

Rodriguez-Lizundia, E., Marcos, S., Zalama, E., Gómez-García-Bermejo, J., & Gordaliza, A. (2015). A bellboy robot: Study of the effects of robot behaviour on user engagement and comfort. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 82, 83-95.

Saldanha, N., Mulye, R., & Rahman, K. (2020). A strategic view of celebrity endorsements through the attachment lens. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 28(5), 434-454.

Sampson, S. E. (2021). A strategic framework for task automation in professional services. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 122-140.

Sattarapu, P. K., Wadera, D., Nguyen, N. P., Kaur, J., Kaur, S., & Mogaji, E. (2023). Tomeito or Tomahto: Exploring consumer’s accent and their engagement with artificially intelligent interactive voice assistants. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb. 2195

Saxena, S. (2022). Evolving uncertainty in healthcare service interactions during COVID-19: Artificial intelligence-a threat or support to value cocreation? Cyber-Physical Systems, 93-116.

Schaarschmidt, M., & Dose, D. (2023). Customer engagement in idea contests: Emotional and behavioral consequences of idea rejection. Psychology & Marketing, 40(5), 988-909.

Schamari, J., & Schaefers, T. (2015). Leaving the home turf: How brands can use webcare on consumer-generated platforms to increase positive consumer engagement. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 30(1), 20-33.

Schneble, C. O., & Shaw, D. M. (2021). Driver’s views on driverless vehicles: Public perspectives on defining and using autonomous cars. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, 100446.

Seckler, M., Heinz, S., Forde, S., Tuch, A. N., & Opwis, K. (2015). Trust and distrust on the web: User experiences and website characteristics. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 39-50.

Shah, T. R., Kautish, P., & Mehmood, K. (2023). Influence of robots service quality on customers’ acceptance in restaurants. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(12), 3117-3137.

Sharma, P., Ueno, A., Dennis, C., & Turan, C. P. (2023). Emerging digital technologies and consumer decision-making in retail sector: Towards an integrative conceptual framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107913.

Shobhit, K., Bigné, E., Catrambone, V., & Valenza, G. (2023). Heart rate variability in marketing research: A systematic review and methodological perspectives. Psychology & Marketing, 40(1), 190-208.

Shumanov, M., & Johnson, L. (2021). Making conversations with chatbots more personalized. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106627.

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747-770.

Singh, J., Nambisan, S., Bridge, R. G., & Brock, J. K. U. (2021). One-voice strategy for customer engagement. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 42-65.

So, K., King, C., & Sparks, B. (2014). Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), 304-329.

Storbacka, K., Brodie, R. J., Böhmann, T., Maglio, P. P., & Nenonen, S. (2016). Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value cocreation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3008-3017.

Sundar, S. S., Bellur, S., Oh, J., Jia, H., & Kim, H. S. (2016). Theoretical importance of contingency in human-computer interaction: Effects of message interactivity on user engagement. Communication Research, 43(5), 595-625.

Sung, E., Bae, S., Han, D. I. D., & Kwon, O. (2021). Consumer engagement via interactive artificial intelligence and mixed reality. International Journal of Information Management, 60, 102382.

Swaminathan, K., & Venkitasubramony, R. (2024). Demand forecasting for fashion products: A systematic review. International Journal of Forecasting, 40(1), 247-267.

Swan, E. L., Peltier, J. W., & Dahl, A. J. (2023). Artificial intelligence in healthcare: the value co-creation process and influence of other digital health transformations. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-09-2022-0293

Sweeney, J. C., Danaher, T. S., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2015). Customer effort in value cocreation activities: Improving quality of life and behavioral intentions of health care customers. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 318-335.

Thaichon, P., Ngo, L., Quach, S., & Wirtz, J. (2023). The dark side of AI in marketing management: Ethics and biases. Australasian Marketing Journal. (Special Issue Cal I). https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/Call-for-Papers – AMJ Special Issue -% 20The%20dark%20side%20of%20AI%20in%20marketing% 20management-1645185260787.pdf

Tsai, W. H. S., Liu, Y., & Chuan, C. H. (2021). How chatbots’ social presence communication enhances consumer engagement: The mediating role of parasocial interaction and dialogue. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(3), 460-482.

Upadhyay, N., & Kamble, A. (2023). Why can’t we help but love mobile banking chatbots? Perspective of stimulus-organism-response. Journal of Financial Services Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1057/ s41264-023-00237-5

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G., & Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Verma, S., Sharma, R., Deb, S., & Maitra, D. (2021). Artificial intelligence in marketing: Systematic review and future research direction. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 1(1):100002.

Vernuccio, M., Patrizi, M., & Pastore, A. (2021). Developing voice-based branding: Insights from the Mercedes case. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(5), 726-739.

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., Dalela, V., & Morgan, R. M. (2014). A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 22(4), 401-420.

Wei, H., & Prentice, C. (2022). Addressing service profit chain with artificial and emotional intelligence. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(6), 730-756.

Wen, H., Zhang, L., Sheng, A., Li, M., & Guo, B. (2022). From “human-tohuman” to “human-to-non-human”-Influence factors of artificial intelligence-enabled consumer value co-creation behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 863313.

Wirtz, J., Patterson, P. G., Kunz, W. H., Gruber, T., Lu, V. N., Paluch, S., & Martins, A. (2018). Brave new world: Service robots in the frontline. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 907-931.

Wu, C., & Monfort, A. (2023). Role of artificial intelligence in marketing strategies and performance. Psychology & Marketing, 40(3), 484-496.

Xiao, L., & Kumar, V. (2021). Robotics for customer service: A useful complement or an ultimate substitute? Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 9-29.

Xie, T., Pentina, I., & Hancock, T. (2023). Friend, mentor, lover: Does chatbot engagement lead to psychological dependence? Journal of Service Management, 34(4), 806-828.

Xie, Z., Yu, Y., & Jing, C. (2022). The searching artificial intelligence: Consumers show less aversion to algorithm-recommended search product. Psychology & Marketing, 39(10), 1902-1919.

Xie-Carson, L., Benckendorff, P., & Hughes, K. (2023). Not so different after all? A netnographic exploration of user engagement with nonhuman influencers on social media. Journal of Business Research, 167, 114149.

Xue, J., Niu, Y., Liang, X., & Yin, S. (2023). Unraveling the effects of voice assistant interactions on digital engagement: The moderating role of

adult playfulness. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023. 2227834

Yang, Z., & Lin, Z. (2022). Interpretable video tag recommendation with multimedia deep learning framework. Internet Research, 32(2), 518-535.

Yin, D., Li, M., & Qiu, H. (2023). Do customers exhibit engagement behaviors in AI environments? The role of psychological benefits and technology readiness. Tourism Management, 97, 104745.

Yu, J., Dickinger, A., So, K. K. F., & Egger, R. (2024). Artificial intelligencegenerated virtual influencer: Examining the effects of emotional display on user engagement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 76, 103560.

Yu, X., Xu, Z., Song, Y., & Liu, X. (2022). The cuter, the better? The impact of cuteness on intention to purchase AI voice assistants: A moderated serial-mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1036848.

Zhou, X., Kim, S., & Wang, L. (2019). Money helps when money feels: Money anthropomorphism increases charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(5), 953-972.

Zhu, W., Yan, R., & Song, Y. (2022). Analysing the impact of smart city service quality on citizen engagement in a public emergency. Cities, 120, 103439.

Zorzela, L., Loke, Y. K., loannidis, J. P., Golder, S., Santaguida, P., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & Vohra, S. (2016). PRISMA harms checklist: Improving harms reporting in systematic reviews. BMJ, 352, i157.

معلومات داعمة

- هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب شروط رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام، والتوزيع، وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح.

© 2024 المؤلفون. علم النفس والتسويق منشور من قبل وايلي بيريوديكالز LLC. - الاختصارات: الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI)؛ تفاعل المستهلك (CE).

- الاختصارات: الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI)؛ تفاعل المستهلك (CE).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21957

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Engaging consumers through artificially intelligent technologies: Systematic review, conceptual model, and further research

Correspondence

Email: lindah@sunway.edu.my

Abstract

While consumer engagement (CE) in the context of artificially intelligent (AI-based) technologies (e.g., chatbots, smart products, voice assistants, or autonomous cars) is gaining traction, the themes characterizing this emerging, interdisciplinary corpus of work remain indeterminate, exposing an important literature-based gap. Addressing this gap, we conduct a systematic review of 89 studies using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach to synthesize the AI-based CE literature. Our review yields three major themes of AI-based CE, including (i) Increasingly accurate service provision through AI-based CE; (ii) Capacity of AI-based CE to (co)create consumer-perceived value, and (iii) AI-based CE’s reduced consumer effort in their task execution. We also develop a conceptual model that proposes the AI-based CE antecedents of personal, technological, interactional, social, and situational factors, and the AI-based CE consequences of consumerbased, firm-based, and human-AI collaboration outcomes. We conclude by offering pertinent implications for theory development (e.g., by offering future research questions derived from the proposed themes of AI-based CE) and practice (e.g., by reducing consumer-perceived costs of their brand/firm interactions).

KEYWORDS

1 | INTRODUCTION

enhanced loyalty or recommendation behavior; Brodie et al., 2011), lifting firm-based competitive advantage. While the literature has, traditionally, centered on consumers’ engagement with brands, growing attention is being afforded to their engagement with specific technologies and its effect on their brand engagement, which has been designated technology-facilitated brand engagement (Hollebeek & Belk, 2021).

and tasks through flexible adaptation” (Haenlein & Kaplan, 2019, p. 5), and engagement as a consumer’s resource investment in their brand-related (e.g., AI) interactions (e.g., Hollebeek et al., 2019; Kumar et al., 2019). Overall, by collating and assessing the corpus of Al-based CE research, our analyses pave the way for this crossdisciplinary area’s further development (Page et al., 2021; Pollock & Berge, 2018).

2 | THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 | Consumer engagement

agent/object,” Hollebeek et al. (2019, p. 166) conceptualize it as a consumer’s “investment of …operant resources [e.g., cognitive/ behavioral knowledge/skills], and operand resources [e.g., equipment] in [their] brand interactions.” Notwithstanding these differences, we distil the following generic CE traits.

2.2 | Artificial intelligence

ability to perform specific tasks increasingly accurately over time, AI applications that incorporate machine- or deep learning, or generative AI, technology may help consumers complete their tasks more efficiently or effectively (Huang & Rust, 2021; Xie et al., 2022). For example, chatbots tend to offer consumers more accurate, comprehensive, or personalized product recommendations or solutions over time (Dwivedi et al., 2023).

3 | METHODOLOGY

focused on AI and impulse buying behavior (vs. AI-based CE). Therefore, in the Inclusion phase, we retained a total of 56 articles from our initial literature search (see Figure 1).

4 | FINDINGS

4.1 | Descriptive analysis

(i.e., 141) in Psychology & Marketing, and Xiao and Kumar (2021) (i.e., 113). Our article sample was sourced from 54 journals, including the Journal of Business Research (5 articles), Journal of Service Research (4), Computers in Human Behavior (4), International Journal of HumanComputer Interaction (4), Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing (4), Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services (4), and Frontiers in Psychology (3). Average citations for each of our studied articles are also included in Supporting Information: Appendix 2.

4.2 | Al-based CE themes

4.2.1 | Increasingly accurate service provision through AI-based CE

| Author(s) | Antecedents | Consequences |

| Bretan et al. (2015) | Robot’s ability to express emotion | – |

| Rodriguez-Lizundia et al. (2015) | Embodiment, robot’s greeting, and active-looking robot | – |

| Aluri et al. (2019) | – | Value co-creation |

| Molinillo et al. (2019) | – | – |

| Moriuchi (2019) | Subjective norms and perceived usefulness | Customer loyalty |

| Mulcahy et al. (2019) | Technology readiness (optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity), perceived risk, and trust | Intention to adopt |

| Bindewald et al. (2020) | Automation | – |

| Cheng and Jiang (2020) | Active communicative action | – |

| Fan et al. (2020) | Customer smart experience quality (human-interaction, smart system quality, self-service quality, and product content quality) | Purchase loyalty and positive word-of-mouth |

| Prentice and Nguyen (2020) | Service experience with employees and service experience with Al | Customer loyalty |

| Prentice et al. (2020) | Customer satisfaction with AI | – |

| Schuetzler et al. (2020) | Chatbot conversational skill and social presence | – |

| Baabdullah et al. (2021) | Acceptance of AI practices | – |

| Bertrandias et al. (2021) | – | Perceived benefits (freeing time, overcoming human weaknesses, and outperforming human capacities) and perceived risks (risk of loss of competencies, performance risk, and security and privacy risk) |

| Çakar and Aykol (2021) | – | – |

| Cheung et al. (2021) | Value cocreation | Perceived brand value |

| Grimes et al. (2021) | Conversational AI capability | – |

| Henkens et al. (2021) | Perceived personalization and perceived intrusiveness | Customer well-being (self-efficacy and technology anxiety) |

| Hollebeek et al. (2021) | – | – |

| Huang and Rust (2021) | – | – |

| Kull et al. (2021) | Warm (vs. competent) chatbot message and brand-self distance | – |

| Kumar et al. (2021) | Responsible AI | Perceived value (instrumental value and terminal value) |

| McLean et al. (2021) | Al attributes (social presence, perceived intelligence, and social attraction), technology attributes (perceived usefulness and -ease of use), and situation attributes (utilitarian benefits, hedonic benefits, and distrust) | Brand usage intention and purchase intention |

| Moriuchi (2021) | Anthropomorphism | Intention to re-use |

| Nasir et al. (2021) | – | – |

| Oh and Kang (2021) | – | – |

| Perez-Vega et al. (2021) | – | – |

| Riva and Mauri (2021) | – | – |

| Shumanov and Johnson (2021) | Congruent consumer-chatbot personality | – |

| Singh et al. (2021) | – | – |

| Author(s) | Antecedents | Consequences |

| Tsai et al. (2021) | Chatbots’ social presence communication, parasocial interaction, and perceived dialogue | – |

| Vernuccio et al. (2021) | Brand experience-based in-car name-brand voice assistants | – |

| Xiao and Kumar (2021) | Customer satisfaction and -emotions | – |

| Blasi et al. (2022) | – | – |

| Chandra et al. (2022) | Human-like AI competencies (AI cognitive-, AI relational-, and AI emotional competency) and user trust in Al | – |

| Chen, Keng, et al. (2022) | Trust in the platform and trust in the host | Customer loyalty |

| Chen, Prentice, et al. (2022) | Interaction experience | – |

| Fang et al. (2022) | Need satisfaction, tourist emotion, and social bond with robots | – |

| Fuentes-Moraleda et al. (2022) | – | Acceptance of social robots |

| Gao et al. (2022) | Perceived interactivity and -personalization | Value co-creation |

| Ghouri et al. (2022) | – | – |

| Hari et al. (2022) | Time convenience, interactivity, compatibility, complexity, observability, and trialability | Satisfaction and brand usage intent |

| Hernández-Ortega et al. (2022) | Relational cohesion | – |

| Hlee et al. (2022) | Attitude toward using service robots | – |

| Hollebeek, Menidjel, et al. (2022) | Perceived behavioral control | Purchase intent |

| Hyun et al. (2022) | Socio-functional elements (perceived hospitability, coolness, -robot safety, and robot performance competence) | Viability of human-robot team service and intention to use service robots |

| Jiang et al. (2022) | Customers’ satisfaction with chatbot services | Purchase intention and price premium |

| Kang and Lou (2022) | Human-AI collaboration (agency negotiation and agency synergy) | – |

| Li et al. (2022) | Robots’ proactive behavior and trust in service robots | – |

| Lim and Zhang (2022) | Perceived contingency and attitude toward AIpowered news | Adoption of AI-powered news |

| Loureiro et al. (2022) | Lifestyle congruency and chatbot identification | Chatbot advocacy |

| Maslowska et al. (2022) | Consumers’ recommender system use and perceptions (‘visits, page views,’ relevance, discovery/curation, surprise, ‘privacy, security,’ and ‘trust, agency’) | Brand’s long-term outcomes (lifetime value, (e)word-of-mouth, brand equity, and provider retention) |

| Mele and Russo-Spena (2022) | – | – |

| Mele et al. (2022) | Integration of high-tech and high-touch | Well-being |

| Mostafa and Kasamani (2022) | Chatbot initial trust | – |

| Wei and Prentice (2022) | Al service quality | Customer loyalty |

| Wen et al. (2022) | Customers’ perception of AI (perceived personalization and -autonomy), subject factor (trust in AI and selfefficacy), and environment factor (community identification) | Value co-creation behaviors |

| Yang and Lin (2022) | – | – |

| Yu et al. (2022) | Social presence | Intention to purchase |

| Author(s) | Antecedents | Consequences |

| Zhu et al. (2022) | Flow experiences | – |

| Acikgoz et al. (2023) | Attitudes towards using voice assistants and willingness to provide privacy information | – |

| Akdim and Casaló (2023) | Perceived value | – |

| Asante et al. (2023) | Al elements (chatbot efficiency, image search functionality, recommendation system efficiency, and automated after-sales service) | – |

| Aslam (2023) | – | – |

| Chang et al. (2023) | Perceived smart travel technologies experience | Behavioral intentions |

| Dong et al. (2023) | Source credibility and content control | Perceived ad intrusiveness |

| Gauer et al. (2023) | – | – |

| Guo and Jiang (2023) | Al-generated personalized advertising copy | – |

| Hobert et al. (2023) | ICAP modes (i.e., passive, active, constructive, and interactive) | – |

| Kumar, Sharma, et al. (2023) | – | – |

| Kumar, Vrontis, et al. (2023) | – | Customer benefit |

| Li et al. (2023) | Perceived competence, -warmth, and -usefulness | – |

| Lin and Wu (2023) | Consumer gratifications (information seeking-, social interaction-, and entertainment gratification) | Brand intimacy, affective commitment, chatbotrelated behavioral intention, and purchase intention |

| Nazir et al. (2023) | Al technology | Satisfying consumer experience |

| Nguyen et al. (2023) | Anthropomorphic language and perceived authenticity | – |

| Paul et al. (2023) | – | – |

| Prentice et al. (2023) | Autonomy, competence, and relatedness | Consumer well-being and attachment |

| Rahman et al. (2023) | Al-powered digital assistance | Customer’s luxury brand shopping experience |

| Sattarapu et al. (2023) | – | – |

| Shah et al. (2023) | Robot service quality | Customer acceptance |

| Sharma et al. (2023) | Share | – |

| Swan et al. (2023) | Digital self-efficacy and relational service quality | Anticipatory AI value cocreation and intention to adopt AI |

| Upadhyay and Kamble (2023) | Anthropomorphism and smart experience | Brand love |

| Xie et al. (2023) | Loneliness, trust, and chatbot personification | Relationship development |

| Xie-Carson et al. (2023) | Entertainment value, emotional connection, and educational content | – |

| Xiong et al. (2023) | Smart tourism technologies | Memorable tourism experiences |

| Xue et al. (2023) | Voice assistant interactions, competence perception, and warmth perception | – |

| Yin et al. (2023) | Conspicuous AI environment, ideal self-congruity, and trust | – |

| Yu et al. (2024) | Emotional displays (happiness, sadness, disgust, and surprise) | – |

4.2.2 | Capacity of AI-based CE to (co)create customer-perceived value

brand-related activities” (Hollebeek et al., 2019, p. 167). When consumers perceive their AI interactions to be of value, they will tend to derive positive perceived (cocreated) value from their interactions with these, and vice versa (Fang et al., 2022; Prentice et al., 2020), typically fueling their desire to continue engaging with these (Lalicic & Weismayer, 2021).

4.2.3 | AI-based CE’s reduced consumer effort in their task execution

investment (e.g., in determining suitable tags) and boosting the technology’s perceived ease of use, as proposed in the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), while lowering their technological effort expectancy, as professed in the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Likewise, companies like Amazon or McDonald’s are increasingly delivering their orders through land-based or airborne robots (e.g., drones), removing consumers’ need to collect their order and enabling faster delivery. In turn, consumers’ technology adoption and continued usage are expected to rise.

4.3 | Conceptual model

4.3.1 | AI-based CE antecedents

authors have identified the following main interactional factors that shape AI-based CE: Interaction conspicuousness, innovation (e.g., chatbot) observability, communication style, compatibility/trialability, interaction complexity, and privacy, security, and safety concerns (e.g., Gao et al., 2022; Maslowska et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2023).

4.3.2 | Consequences of AI-based CE

5 | IMPLICATIONS, LIMITATIONS, AND FURTHER RESEARCH

5.1 | Theoretical implications

consolidate prior insight, yielding the following theoretical implications.

| Al-based CE theme | Sample research questions | ||||

| Increasingly accurate service provision through AI-based CE |

|

||||

| Capacity of AI-based CE to (co)create consumer-perceived value |

|

||||

| Al-based CE’s reduced consumer effort in their task execution |

|

5.2 | Managerial implications

5.3 | Limitations and further research

journals. Future researchers could, therefore, consult other or related databases (e.g., Web of Science/Google Scholar) to source their data and include non-English works in their further reviews of Al-based CE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

ORCID

Choukri Menidjel (D) http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8510-800X

Marko Sarstedt (D) http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5424-4268

Johan Jansson (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2593-9439

Sigitas Urbonavicius (D) http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4176-2573

REFERENCES

Acikgoz, F., Perez-Vega, R., Okumus, F., & Stylos, N. (2023). Consumer engagement with AI-powered voice assistants: A behavioral reasoning perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 40(11), 2226-2243.

Akdim, K., & Casaló, L. V. (2023). Perceived value of Al-based recommendations service: the case of voice assistants. Service Business, 17(1), 81-112.

Aluri, A., Price, B., & McIntyre, N. (2019). Using machine learning to cocreate value through dynamic customer engagement in a brand loyalty program. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(1), 78-100.

Ameen, N., Sharma, G., Tarba, S., Rao, A., & Chopra, R. (2022). Toward advancing theory on creativity in marketing and artificial intelligence. Psychology & Marketing, 39(9), 1802-1825.

Asante, I., Jiang, Y., Hossin, A., & Luo, X. (2023). Optimization of consumer engagement with artificial intelligence elements on electronic commerce platforms. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 24(1), 7-28.

Ashfaq, M., Yun, J., & Yu, S. (2021). My smart speaker is cool! Perceived coolness, perceived values, and users’ attitude toward smart speakers. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 37(6), 560-573.

Aslam, U. (2023). Understanding the usability of retail fashion brand chatbots: Evidence from customer expectations and experiences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 74, 103377.

Baabdullah, A. M., Alalwan, A. A., Slade, E. L., Raman, R., & Khatatneh, K. F. (2021). SMEs and artificial intelligence (AI): Antecedents and consequences of AI-based B2B practices. Industrial Marketing Management, 98, 255-270.

Barnes, S., & de Ruyter, K. (2022). Guest editorial: Artificial intelligence as a market-facing technology: Getting closer to the consumer through innovation and insight. European Journal of Marketing, 56(6), 1585-1589.

Beckers, S. F. M., Van Doorn, J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2018). Good, better, engaged? The effect of company-initiated customer engagement behavior on shareholder value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46, 366-383.

Belanche, D., Casaló, L., Schepers, J., & Flavián, C. (2021). Examining the effects of robots’ physical appearance, warmth, and competence in frontline services: The Humanness-Value-Loyalty model. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2357-2376.

Bertrandias, L., LOWE, B., Sadik-Rozsnyai, O., & Carricano, M. (2021). Delegating decision-making to autonomous products: A value model emphasizing the role of well-being. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 169, 120846.

Bilro, R. G., & Loureiro, S. M. C. (2020). A consumer engagement systematic review: Synthesis and research agenda. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 24(3), 283-307.

Bindewald, J. M., Miller, M. E., & Peterson, G. L. (2020). Creating effective automation to maintain explicit user engagement. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(4), 341-354.

Blasi, S., Gobbo, E., & Sedita, S. R. (2022). Smart cities and citizen engagement: Evidence from Twitter data analysis on Italian municipalities. Journal of Urban Management, 11(2), 153-165.

Bretan, M., Hoffman, G., & Weinberg, G. (2015). Emotionally expressive dynamic physical behaviors in robots. International Journal of HumanComputer Studies, 78, 1-16.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252-271.

Brown, R., Coventry, L., Sillence, E., Blythe, J., Stumpf, S., Bird, J., & Durrant, A. C. (2022). Collecting and sharing self-generated health and lifestyle data: Understanding barriers for people living with long-term health conditions-A survey study. Digital Health, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221084458

Çakar, K., & Aykol, Ş. (2021). Understanding travellers’ reactions to robotic services: A multiple case study approach of robotic hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(1), 155-174.

Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17, 79-89.

Celsi, R. L., & Olson, J. C. (1988). The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 210-224.

Chandra, S., Shirish, A., & Srivastava, S. C. (2022). To be or not to be human? Theorizing the role of human-like competencies in conversational artificial intelligence agents. Journal of Management Information Systems, 39(4), 969-1005.

Chang, J. Y. S., Konar, R., Cheah, J. H., & Lim, X. J. (2023). Does privacy still matter in smart technology experience? A conditional mediation analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics. https://doi.org/10.1057/ s41270-023-00240-8

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81-93.

Chen, Q., Gong, Y., Lu, Y., & Tang, J. (2022). Classifying and measuring the service quality of AI chatbot in frontline service. Journal of Business Research, 145, 552-568.

Chen, X., Cheah, S., & Shen, A. (2019). Empirical study on behavioral intentions of short-term rental tenants-The moderating role of past experience. Sustainability, 11(12), 3404.

Chen, Y., Keng, C., & Chen, Y. (2022). How interaction experience enhances customer engagement in smart speaker devices? The moderation of gendered voice and product smartness. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(3), 403-419.

Chen, Y., Prentice, C., Weaven, S., & Hsiao, A. (2022). The influence of customer trust and AI on customer engagement and loyalty-The case of the home-sharing industry. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 912339.

Cheung, M. L., Pires, G., Rosenberger III, P. J., Leung, W. K. S., & Chang, M. K. (2021). The role of social media elements in driving cocreation and engagement. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(10), 1994-2018.

Clarke, J. (2011). What is a systematic review? Evidence-based Nursing, 14(3):64.

Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

Dong, B., Zhuang, M., Fang, E., & Huang, M. (2023). Tales of two channels: Digital advertising performance between AI recommendation and

user subscription channels. Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10. 1177/00222429231190021

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253-266.

Van Doorn, J., Mende, M., Noble, S. M., Hulland, J., Ostrom, A. L., Grewal, D., & Petersen, J. A. (2017). Domo arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 43-58.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H., Albashrawi, M. A., Al-Busaidi, A. S., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette, Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., … Wright, R. (2023). Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642.

Dzieza, J. (2023). AI is a lot of work. https://www.theverge.com/features/ 23764584/ai-artificial-intelligence-data-notation-labor-scale-surge-remotasks-openai-chatbots

Fan, X., Ning, N., & Deng, N. (2020). The impact of the quality of intelligent experience on smart retail engagement. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(7), 877-891.

Fang, S., Han, X., & Chen, S. (2022). The impact of tourist-robot interaction on tourist engagement in the hospitality industry:

Fuentes-Moraleda, L., Lafuente-lbañez, C., Fernandez Alvarez, N., & Villace-Molinero, T. (2022). Willingness to accept social robots in museums: An exploratory factor analysis according to visitor profile. Library Hi Tech, 40(4), 894-913.

Gao, L., Li, G., Tsai, F., Gao, C., Zhu, M., & Qu, X. (2022). The impact of artificial intelligence stimuli on customer engagement and value cocreation: The moderating role of customer ability readiness. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(2), 317-333.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Gauer, V., Axsen, J., Dütschke, E., Long, Z., & Kelber, A. (2023). Who is more attached to their car? Comparing automobility engagement and response to shared, automated and electric mobility in Canada and Germany. Energy Research & Social Science, 99, 103048.

Ghouri, A. M., Mani, V., Haq, M. A., & Kamble, S. S. (2022). The micro foundations of social media use: Artificial intelligence integrated routine model. Journal of Business Research, 144, 80-92.

Giang Barrera, K., & Shah, D. (2023). Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113420.

Grimes, G. M., Schuetzler, R. M., & Giboney, J. S. (2021). Mental models and expectation violations in conversational AI interactions. Decision Support Systems, 144, 113515.