DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02736-9

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-21

مقالة

إعادة التفكير في فرضية منحنى كوزنتس البيئي عبر 214 دولة: تأثير 12 عاملاً اقتصادياً ومؤسسياً وتكنولوجياً ومواردياً واجتماعياً

الملخص

قدمت الأبحاث على مدى العقود الثلاثة الماضية أدلة تجريبية غنية لنظرية منحنى كوزنتس البيئي المعكوس على شكل حرف U، ولكن المشاكل الحالية التي تواجه إجراءات التخفيف من تغير المناخ تتطلب منا إعادة فحص شكل منحنى كوزنتس البيئي العالمي بدقة. تناولت هذه الورقة منحنى كوزنتس البيئي على شكل حرف N في مجموعة من 214 دولة مع 12 متغيراً تقليدياً وناشئاً، بما في ذلك المؤسسات والمخاطر، وتكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات، والذكاء الاصطناعي، واستخدام الموارد والطاقة، وبعض العوامل الاجتماعية المختارة. تم تطوير نموذج فك الارتباط ثنائي الأبعاد المستند إلى منحنى كوزنتس البيئي على شكل حرف N لتجميع الدول المتجانسة لاستكشاف تأثيرات انبعاثات الكربون غير المتجانسة بين المجموعات لكل متغير. تظهر نتائج البحث العالمية أن الحدود الخطية والتكعيبية للناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد إيجابية بشكل ملحوظ، بينما الحد التربيعي سلبي بشكل ملحوظ، بغض النظر عما إذا كانت متغيرات إضافية قد أضيفت. وهذا يعني الوجود القوي لمنحنى كوزنتس البيئي على شكل حرف N. تم التأكيد على أن المخاطر الجيوسياسية، وتكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات، والأمن الغذائي تؤثر بشكل إيجابي على انبعاثات الكربون للفرد، بينما تأثير المخاطر المركبة، وجودة المؤسسات، والاقتصاد الرقمي، وانتقال الطاقة، وشيخوخة السكان سلبي بشكل ملحوظ. تأثير الذكاء الاصطناعي، وإيجارات الموارد الطبيعية، والانفتاح التجاري، وعدم المساواة في الدخل غير مهم. نقاط الانعطاف لمنحنى كوزنتس البيئي على شكل حرف N مع الأخذ في الاعتبار جميع المتغيرات الإضافية هي 45.08 و73.44 ألف دولار أمريكي، على التوالي. من خلال دمج نقاط التحول ومعاملات فك الارتباط المحسوبة، يتم تصنيف جميع الدول إلى ست مجموعات بناءً على نموذج فك الارتباط ثنائي الأبعاد. تظهر نتائج الانحدار الجماعي اللاحقة عدم التجانس في الاتجاه والحجم لتأثيرات انبعاثات الكربون لمعظم المتغيرات. أخيراً، تم اقتراح استراتيجيات تخفيض انبعاثات الكربون المتمايزة للدول في ست مراحل من فك الارتباط ثنائي الأبعاد.

المقدمة

مراجعة الأدبيات والخلفية النظرية

مراجعة الأدبيات

وتدهور البيئة، من قبل (غروس مان وكروجر، 1991) في دراستهم الرائدة حول الآثار البيئية لاتفاقية التجارة الحرة لأمريكا الشمالية. قام الباحثون الأوائل في منحنى كوزنتس البيئي بتحليل العلاقة بين النمو الاقتصادي ومؤشرات تدهور البيئة المختلفة دون أي متغيرات تفسيرية أخرى وحصلوا على الكثير من الأدلة على وجود علاقة على شكل U مقلوب من الارتباطات الإيجابية ثم السلبية بين الاثنين (غروس مان وكروجر، 1991؛ بيكرمان، 1992؛ غروس مان وكروجر، 1995؛ هيرينك وآخرون، 2001).

تتعلق القضية الأولى التي تم انتقادها على نطاق واسع بالتباين المزعوم الموجود في دراسة عينة منحنى كوزنتس البيئي. لتوفير تقييم ومرجع أوسع، تختار عدد كبير من دراسات منحنى كوزنتس البيئي استخدام بيانات مقطعية أو بيانات عينة تشمل مجموعة من الدول (كاكا وزيرفاس، 2013ب). على الرغم من أن هذه الدراسات غالباً ما تجادل بأن اختيار مجموعات الدول يعتمد على الروابط الوثيقة بينها (مثل الروابط الإقليمية، وروابط التجارة، والاتفاقيات الدولية، إلخ)، إلا أن منحنيات منحنى كوزنتس البيئي التي تم الحصول عليها من مجموعات الدول غالباً ما تثبت أنها غير مناسبة لكل منها (ليال وماركيس، 2022). انتقاد ثانٍ معقد يتساءل عن الصلة العملية لإطار مفهوم منحنى كوزنتس البيئي ونموذج التنمية (غيل وآخرون، 2018). حتى إذا تم تقييم منحنى كوزنتس البيئي لكل دولة بدقة، فإنه سيصور فقط مسار تطوير أساسي للمستقبل. ومع ذلك، فإن القضية الأكثر أهمية في الوقت الحاضر هي كيفية تقليل التلوث البيئي وإصلاح الأضرار البيئية وفقاً لرؤية منحنى كوزنتس البيئي بدلاً من مجرد “النمو الآن والتنظيف لاحقاً” (غيل وآخرون، 2018). القضية الثالثة مقترحة في (ستيرن، 2017). بعد مراجعة 25 عاماً من تطور أبحاث منحنى كوزنتس البيئي، أعرب عن قلقه من أن نموذج منحنى كوزنتس البيئي يتجاهل تأثيرات أخرى باستثناء النمو وأكد أن “هم القوة المعاكسة لتأثير الحجم.” بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم الإشارة أيضاً إلى قضايا اقتصادية قياسية أخرى، بما في ذلك اختيار متغيرات التلوث، وحساسية النتائج لطرق القياس، وعقلانية نقاط الانعطاف (ليال وماركيس، 2022).

H2: يبقى EKC على شكل N قويًا مع المتغيرات الإضافية.

بين المتغيرات الإضافية الـ 12 المعنية وانبعاثات الكربون استنادًا إلى الأدبيات السابقة. تغطي هذه العوامل أربعة جوانب: المؤسسات والمخاطر، التكنولوجيا الرقمية، استخدام الموارد والطاقة، وعوامل اجتماعية أخرى.

تخضع الانبعاثات لنقاش مكثف. وجدت الدراسات التجريبية التي أجراها رونغ رونغ لي وآخرون (2023) أن استكشاف الموارد الطبيعية يحفز مباشرة النمو الاقتصادي ومن ثم يزيد من البصمة البيئية. بالمقابل، يعتقد بعض العلماء (شيومين وآخرون، 2021؛ رونغ رونغ لي وآخرون، 2024) أنه مع دمج الطاقة النظيفة وتقنيات حماية البيئة، يمكن أن يؤدي استخراج الموارد الطبيعية أيضًا إلى تحسين البيئة المحلية. من ناحية أخرى، تمثل انتقال الطاقة نتيجة مبادرة البشر للتخلص من الوقود الأحفوري التقليدي والتحول إلى الطاقة النظيفة. تدعم النتائج التجريبية أن هذا التحول النظامي في نظام الطاقة يمكن أن يقلل بشكل فعال من انبعاثات الكربون في معظم البلدان (دوغان وسكير، 2016؛ إنغليسي-لوتز ودوغان، 2018) على الرغم من أن التباين بين البلدان في مجموعات الدخل المختلفة غالبًا ما يكون كبيرًا (نجوين وكاكيناكا، 2019).

الطريقة والبيانات المنهجية

طريقة اختبار التعدد الخطي: عامل تضخم التباين (VIF): يحدث التعدد الخطي عندما يمكن التنبؤ بدقة بخطية من متغير مستقل واحد بواسطة متغيرات مستقلة أخرى.

الذي يقلل من استقرار تقدير المعلمات للمتغيرات المتأثرة. يهدف هذا المقال إلى تحليل شكل منحنى EKC العالمي تحت تأثير 12 متغيرًا إضافيًا. على الرغم من أننا بذلنا قصارى جهدنا لاختيار المحددات من زوايا مختلفة للاقتراب من منحنى انبعاث الكربون، قد تتداخل البيانات الأصلية المستخدمة في حساب المتغيرات البديلة جزئيًا. لذلك، نقوم بفحص درجة التعدد الخطي في النموذج لضمان التوازن بين الشمولية وعدم تكرار تركيبات المتغيرات.

كمثال، في معادلة الانحدار التالية:

| الجدول 1 معايير تحديد أشكال EKC الشائعة. | |||

|

|

|

شكل EKC | |

|

|

|

|

ن |

|

|

|

|

إنفيرتد إن |

|

|

|

|

أنت |

|

|

|

|

U مقلوب |

|

|

|

خطية | |

|

|

|||

| رقم الدولة | حالة مفصولة |

|

|

نطاق الفصل المرن (E) |

| الدولة 1 | فصل مطلق |

|

|

(

|

| الدولة 2 | فصل نسبي |

|

[0,0.8) | |

| الدولة 3 | التوصيل التوسعي |

|

[0.8,1.2) | |

| الدولة 4 | توسيع الفصل السلبي |

|

[1.2،

|

|

| الدولة 5 | فصل سلبي قوي |

|

|

|

| الدولة 6 | فصل سلبي ضعيف |

|

[0,0.8) | |

| الدولة 7 | الاقتران المتنحي |

|

[0.8,1.2) | |

| الدولة 8 | فصل الركود |

|

[1.2،

|

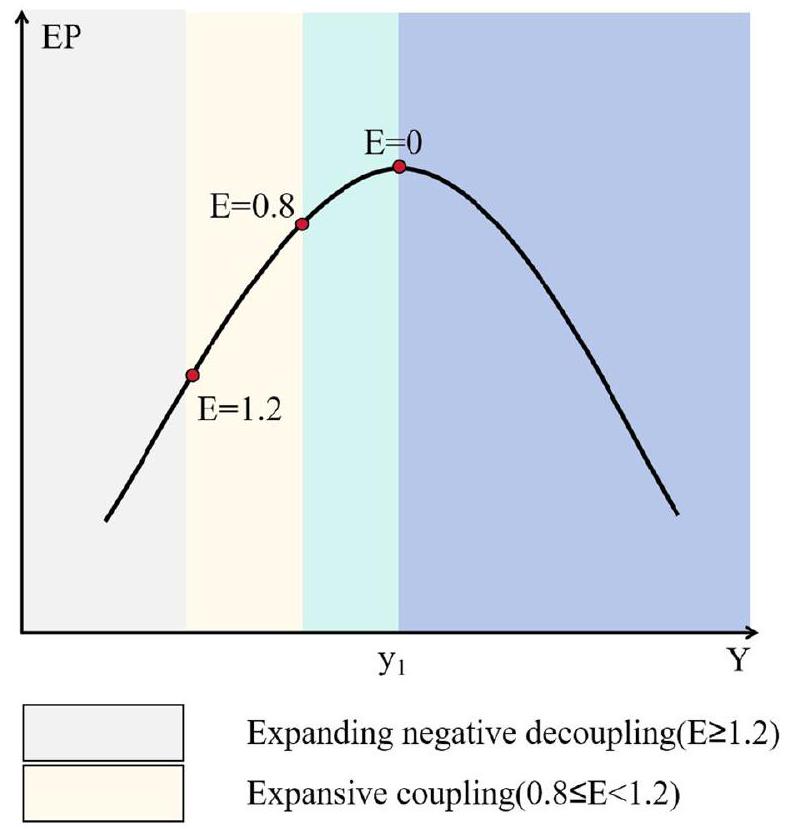

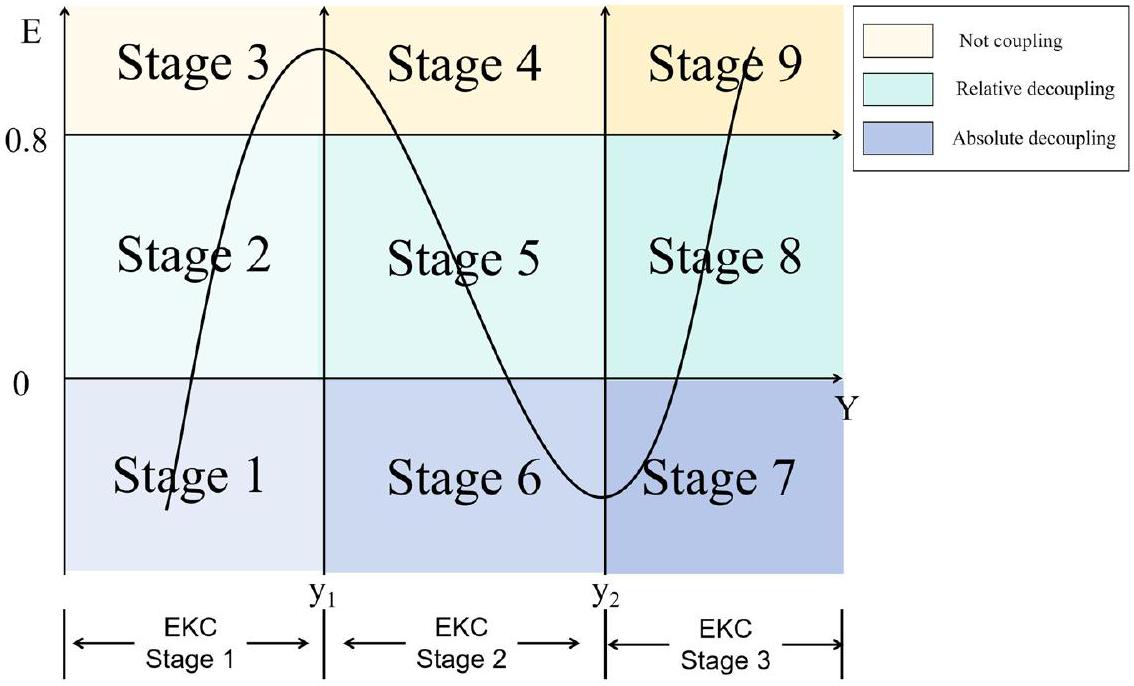

فصل الانفصال (الحالات 5-8)، والتي، مع ذلك، تتجاوز نطاق نظرية EKC.

تقوم خطان عموديان

تعريف المتغيرات ووصف البيانات. وفقًا لمتطلبات الطرق والنماذج التي تم مناقشتها سابقًا، يستخدم هذا المقال انبعاثات الكربون لكل فرد كمتغير مفسر، والناتج المحلي الإجمالي لكل فرد كمتغير مفسر، و12 متغيرًا تغطي المخاطر المؤسسية، والتكنولوجيا الرقمية، واستخدام الموارد، والقضايا الاجتماعية كمتغيرات ضابطة. بناءً على توفر البيانات، يتم تحديد نطاق البحث في هذا المقال ليكون 214 دولة من 1960 إلى 2020. يتم تلخيص التعريفات، ووحدات القياس، ومصادر البيانات لجميع المتغيرات في الجدول S1. يمكن ملاحظة أن المتغيرات المفسرة والمتغيرات المفسرة كلها مستمدة من قاعدة بيانات WDI التي طورتها البنك الدولي (Worldbank، 2023a).

النتائج التجريبية

اختبار أولي

| الطريقة | FE | استبدال PCE بـ CE | FE ثنائية الاتجاه | RE | نظام GMM |

| النموذج | النموذج 1 | النموذج R1 | النموذج R2 | النموذج R3 | النموذج R4 |

| PGDP | 0.5408*** (0.0165) | 40.6234*** (2.3427) | 0.6086*** (0.0189) | 0.4444*** (0.0139) | 0.5377*** (0.0000) |

| PGDP2 | -0.0113*** (0.0004) | -0.7826*** (0.0591) | -0.0124*** (0.0004) | -0.0079*** (0.0003) | -0.0093*** (0.0000) |

| PGDP3 | 0.0001*** (0.0000) | 0.0044*** (0.0004) | 0.0001*** (0.0000) | 0.0000*** (0.0000) | 0.0001*** (0.0000) |

| ثابت | 1.1640*** (0.0854) | -95.5816*** (12.0906) | 0.3822 * (0.2273) | 1.5389*** (0.2768) | -0.1154*** (0.0002) |

| بلد FE | نعم | نعم | نعم | لا | – |

| سنة FE | لا | لا | نعم | لا | – |

| اختبار سارجان

|

1.0000 | ||||

| AR(2) | 0.1736 | ||||

| y1 | ٣٣.٤٤ | ٣٨.٦٦ | ٣٥.٩٢ | ٤٠.٧١ | ٤٩.٤٨ |

| y2 | ٧٧.٥٤ | ٧٨.٩٦ | ٧٧.٣٦ | 91.42 | 70.06 |

| نطاق عينة pgdp | [0.124,183.2] | ||||

| بلد | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 |

| ن | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 | 8356 |

النتائج التجريبية للبانل العالمي

موضح في الجدول 3. أولاً، معامل الحد التكعيبي للناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد (PGDP3) في النموذج 1 أكبر بكثير من 0 عند

| طريقة | الانحدار التدريجي مع نماذج التأثير الثابت | |||||

| نموذج | النموذج 1 | النموذج 2 | موديل 3 | النموذج 4 | النموذج 5 | النموذج 6 |

| بي جي دي بي | 0.5408*** | 0.6059*** | 0.5066*** | 0.4708*** | 0.6231*** | 0.9117*** |

| PGDP2 | -0.0113*** | -0.0110*** | -0.0071*** | -0.0077*** | -0.0113*** | -0.0163*** |

| PGDP3 | .00007*** | 0.0001*** | 0.0000*** | 0.0000*** | 0.0001*** | 0.0001*** |

| تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات | 0.0025** | 0.0033*** | 0.0023*** | 0.0011 | -0.0004 | |

| دي | -0.1066*** | -0.0745*** | -0.0371*** | -0.0452*** | -0.0656*** | |

| با | -0.0906*** | -0.1616*** | -0.1940*** | -0.2646*** | -0.1777*** | |

| FS | 0.0071*** | 0.0027*** | 0.0035*** | 0.0083*** | -0.0130*** | |

| NRR | 0.0001*** | 0.0002*** | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| مفتوح | -0.0022*** | 0.0002 | -0.0032** | -0.0011 | ||

| إي تي | -0.0298*** | -0.0409*** | -0.0795*** | -0.1157*** | ||

| سي آر | -0.0120*** | -0.0098*** | -0.0055 | |||

| الذكاء الاصطناعي | -0.0006 | 0.0001 | ||||

| IIE | -0.0179* | -0.0202* | ||||

| جي بي آر | 0.0020** | |||||

| معدل الذكاء | -0.1206*** | |||||

| R-squared | 0.122 | 0.136 | 0.231 | 0.225 | 0.573 | 0.718 |

| ملاحظة | 8460 | 6838 | 4791 | ٣٦٥٢ | 1280 | 725 |

| بلد | 191 | 181 | ١٧٧ | ١٣٣ | 60 | 40 |

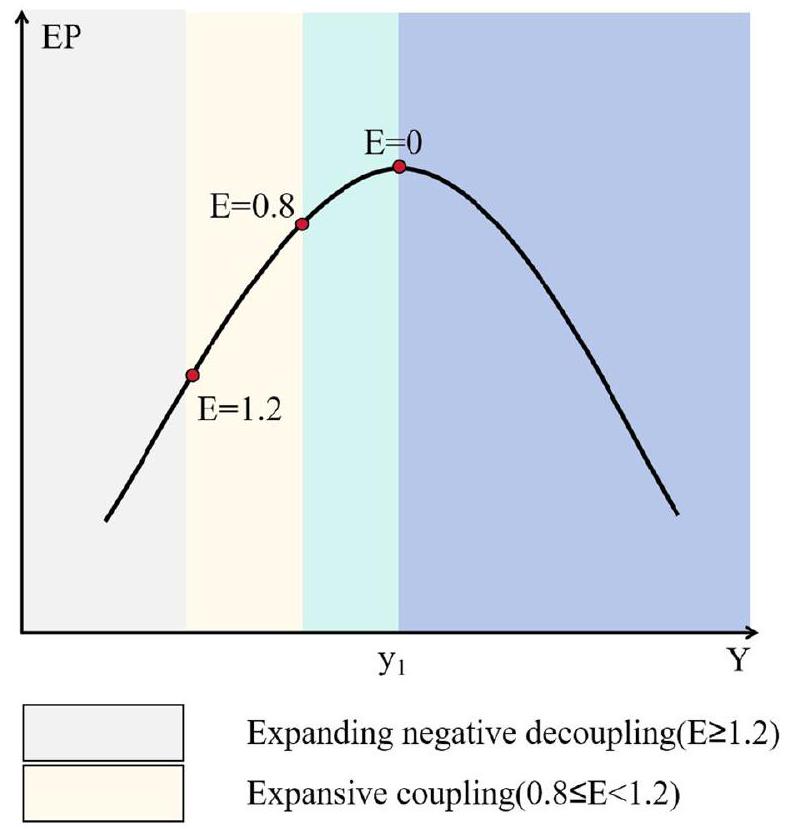

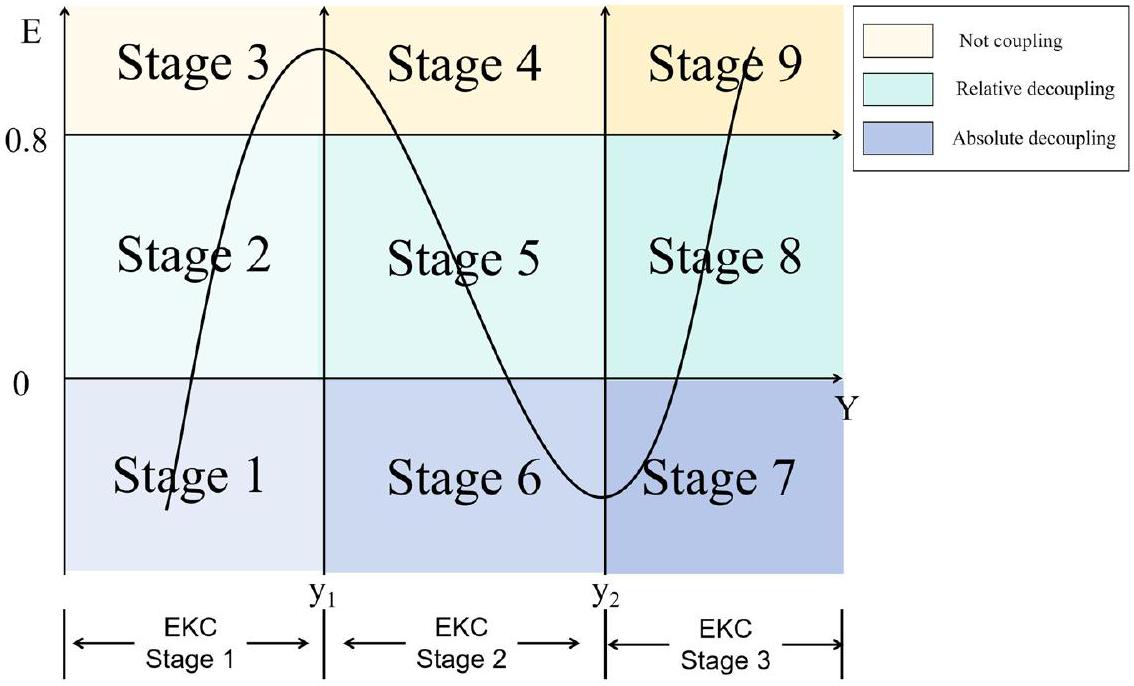

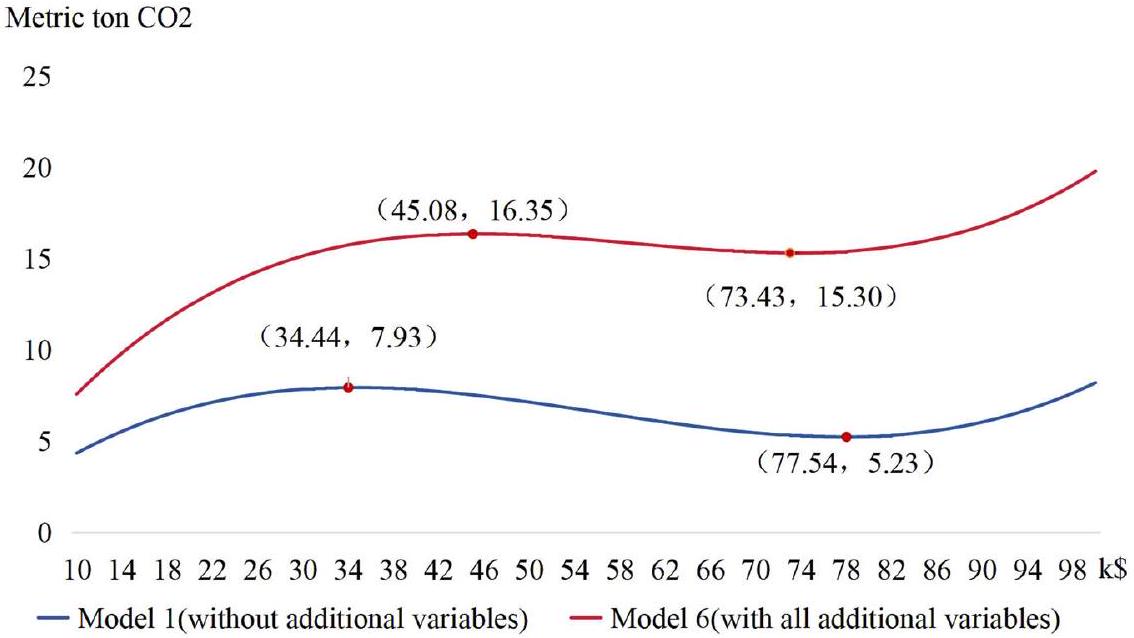

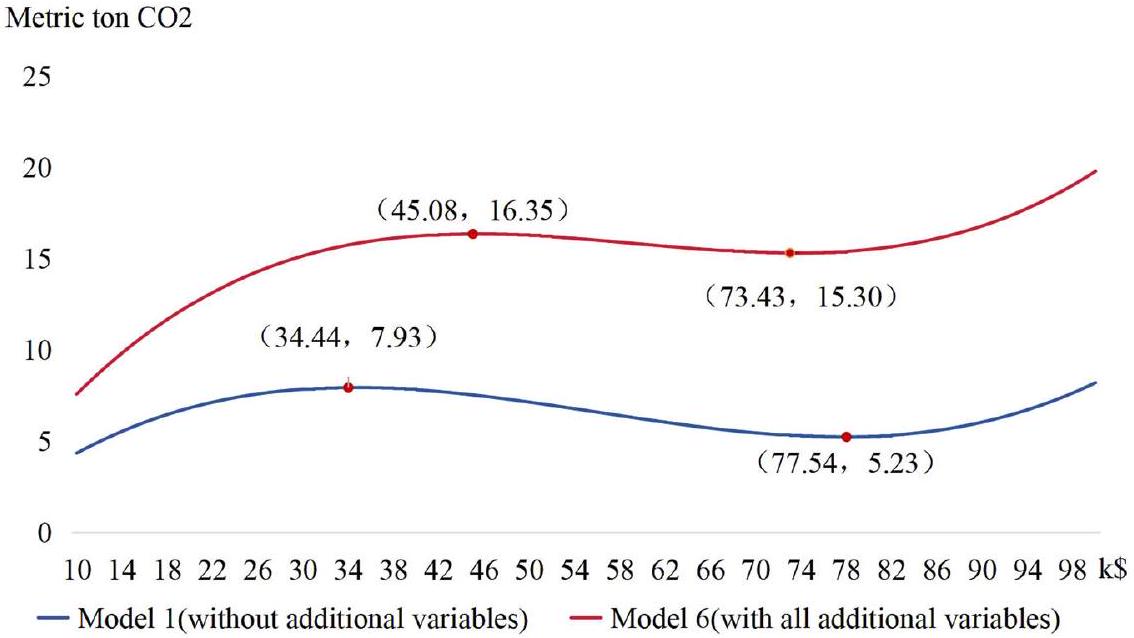

الشخص)، على التوالي. هذه النتيجة تختلف عن نقطة الانعطاف في EKC في النموذج 1. نحن نقارن بين منحنيات المعادلة التكعيبية التي تتوافق مع المعاملات المقدرة في الشكل 3 لمناقشة تأثير المتغيرات الضابطة على شكل EKC. يظهر الشكل 3 أنه بعد أخذ المتغيرات الضابطة في الاعتبار، لم يتقلص فقط الفضاء الاقتصادي بين نقطتي الانعطاف من 43.10 ألف دولار أمريكي إلى 28.35 ألف دولار أمريكي، ولكن أيضًا انخفضت انبعاثات الكربون للفرد بين نقطتي الانعطاف من حوالي 2.70 طن متري إلى حوالي 1.05 طن متري. وهذا يشير إلى أن EKC يبدو أنه ينحني لأعلى عند محاولة حساب متغيرات تفسيرية أخرى. ونتيجة لذلك، فإن الجزء الوحيد المتناقص من منحنى انبعاثات الكربون على شكل N قد تقلص في كل من “المدة” و”الفضاء المتناقص”، مما يكشف عن وضع أكثر حدة في التخفيف من تغير المناخ العالمي.

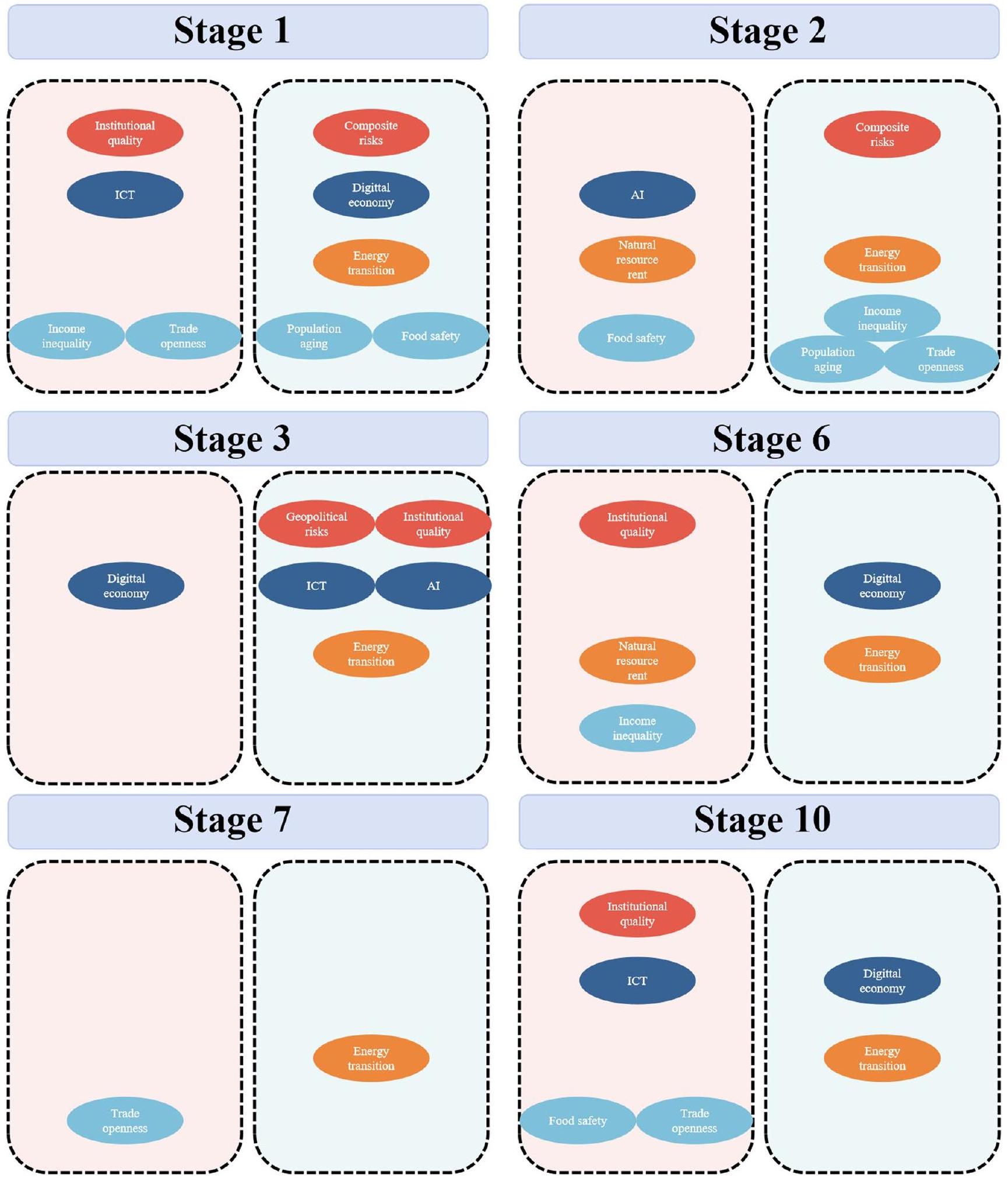

انبعاثات الكربون. وهذا يؤدي إلى مناقشة H3. يضيف النموذج 2 أربعة متغيرات ضابطة بناءً على النموذج 1. مع اعتبار مستوى الدلالة 5% كمعيار، فإن معاملات تأثير تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات والأمن الغذائي إيجابية، بينما معاملات تأثير الاقتصاد الرقمي وشيخوخة السكان سلبية. نحن نفحص قوة تأثير هذه المتغيرات بالتزامن مع نتائج أخرى من الانحدارات التدريجية. مقارنة نتائج تقدير النموذج 2 مع النماذج الأربعة اللاحقة (النموذج

| التصنيف | العامل | اختصار | قرار التأثير |

| المؤسسة | المخاطر الجيوسياسية | GPR | + |

| المخاطر الشاملة | CR | – | |

| جودة المؤسسات | IQ | – | |

| التكنولوجيا | الاقتصاد الرقمي | DE | – |

| الذكاء الاصطناعي | AI | ||

| تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات | ICT | + | |

| الموارد | انتقال الطاقة | ET | – |

| الموارد الطبيعية | NRR | ||

| المجتمع | شيخوخة السكان | PA | – |

| الأمن الغذائي | FS | + | |

| انفتاح التجارة | OPEN | ||

| عدم المساواة في الدخل | IIE |

تسبب الحكومات والمستثمرون، والتي غالبًا ما ترتبط بنماذج الإنتاج غير المسؤولة وسوء استخدام الوقود الأحفوري (فاكولتشوك وآخرون، 2020؛ زوكسينغ تشاو وآخرون، 2023). التأثير المخفض لجودة المؤسسات على انبعاثات الكربون العالمية يتماشى مع فرضية التأثير التنظيمي ويتماشى مع الأبحاث السابقة لـ 3 دول آسيوية (سلمان وآخرون، 2019) و30 دولة في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء (كريم وآخرون، 2022). لذلك، يلعب بيئة التنمية الدولية والمحلية المستقرة والأنظمة الفعالة دورًا لا يمكن تعويضه في تقليل انبعاثات الكربون وتحقيق التخفيف من تغير المناخ العالمي.

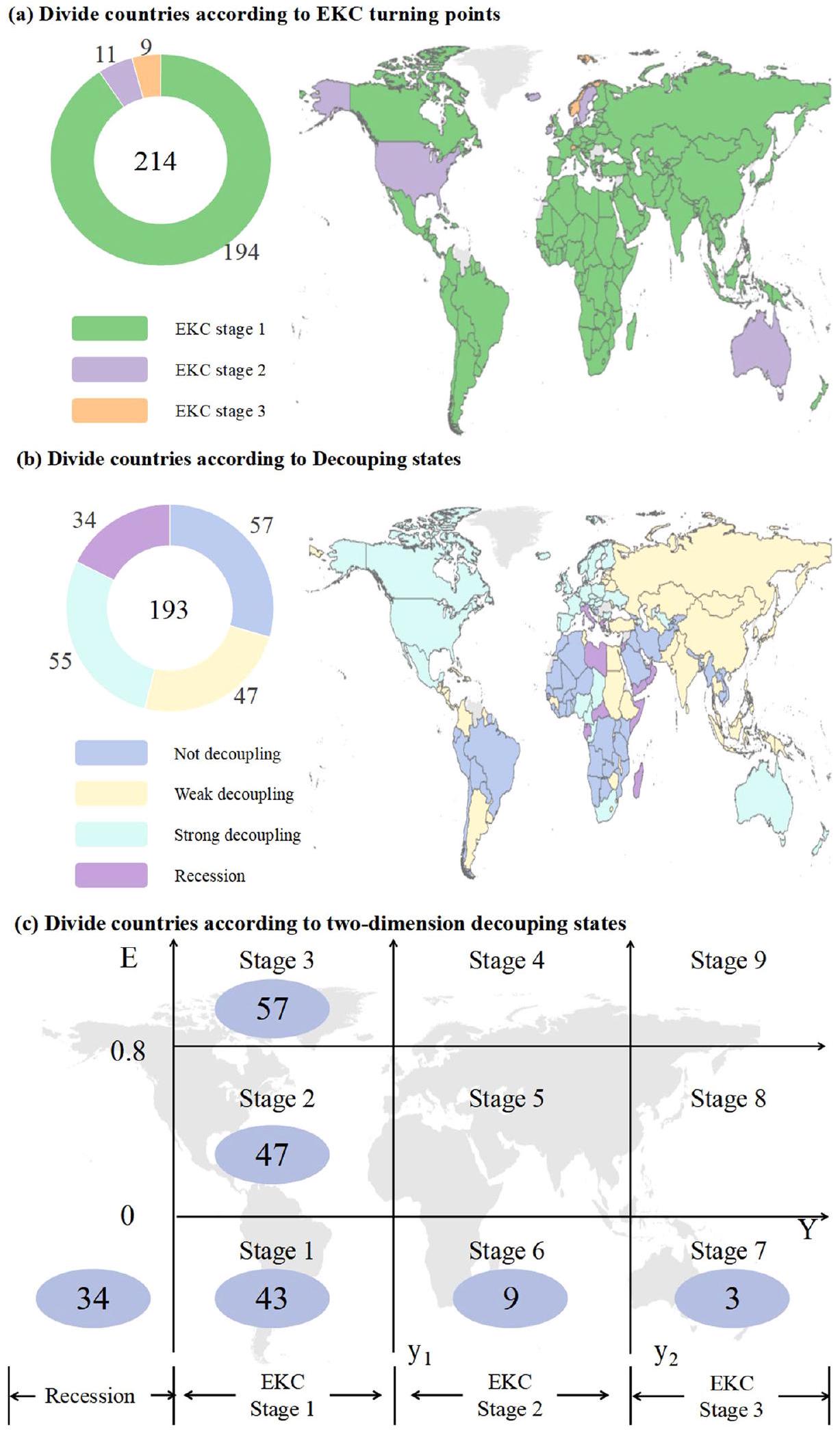

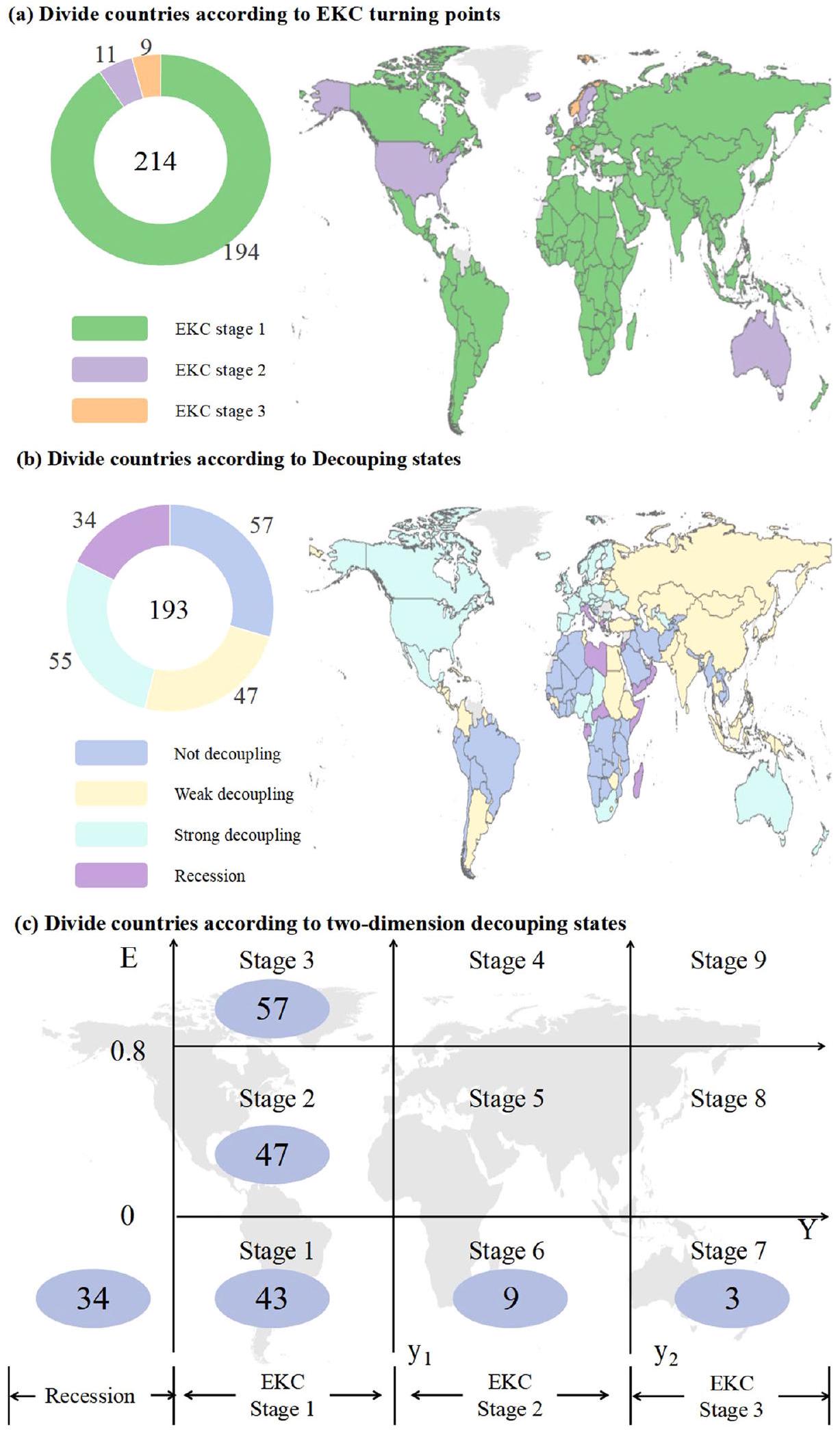

مجموعة 214 دولة من خلال نموذج فك الارتباط ثنائي الأبعاد.

| مرحلة EKC | EKC1 | EKC1 | EKC1 | EKC 2 | EKC 3 | ركود اقتصادي |

| فصل الدولة | عدم الفصل | فصل ضعيف | فصل قوي | فصل قوي | فصل قوي | |

| مرحلة فك الارتباط ثنائية الأبعاد | المرحلة 3 | المرحلة 2 | المرحلة 1 | المرحلة 6 | المرحلة 7 | المرحلة 10 |

| نموذج | النموذج 7 | النموذج 8 | النموذج 9 | النموذج 10 | النموذج 11 | النموذج 12 |

| بي جي دي بي | 0.2658*** | 0.3806*** | 0.0855*** | 0.1721*** | 0.3591*** | |

| تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات | -0.0027*** | 0.0090*** | 0.0083*** | |||

| دي | 0.0927*** | -0.0825*** | -0.1865*** | -0.0842*** | ||

| با | -0.1906*** | -0.1774*** | ||||

| FS | 0.0057*** | -0.0033*** | 0.0143*** | |||

| NRR | 0.0001*** | 0.0024*** | ||||

| مفتوح | -0.0032*** | 0.0021** | 0.0780*** | 0.0098** | ||

| إي تي | -0.0033** | -0.0267*** | -0.0515*** | -0.1096*** | -0.4661*** | -0.0389*** |

| سي آر | -0.0123*** | -0.0067** | ||||

| IIE | -0.0042*** | 0.0067*** | 0.0299** | |||

| الذكاء الاصطناعي | -0.0619*** | 0.0020*** | ||||

| جي بي آر | -0.0044*** | |||||

| معدل الذكاء | -0.0142** | 0.0674*** | 0.0884*** | 0.0567** | ||

| ملاحظات | 1469 | 1324 | 1005 | ٢٧٥ | 77 | 635 |

| R-squared | 0.556 | 0.585 | 0.٣٣٧ | 0.551 | 0.882 | 0.461 |

| رقم الهوية | ٥٦ | ٤٧ | 37 | 10 | ٣ | 23 |

العينة التي يكون فيها الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد أعلى من نقطة الانعطاف الأولى في منحنى كوزنتس البيئي قد حققت انفصالاً قوياً. بعبارة أخرى، من بين المراحل الستة ثنائية الأبعاد للانفصال التي تتوافق مع المرحلتين الثانية والثالثة من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي (المرحلة 4-9)، يوجد 9 دول في المرحلة 6، و3 دول في المرحلة.

على التوالي. قد يكون من المحير في البداية أن معامل تأثير التنمية الاقتصادية على انبعاثات الكربون أكثر وضوحًا في الدول ذات الفصل الضعيف مقارنة بالدول غير المفصولة. يمكن أن يكون السبب في ذلك أن نماذج التنمية الاقتصادية لهذه الدول، بما في ذلك معظم الدول النامية في آسيا، قد تم تحسينها إلى حد ما في العقدين الماضيين، لكن تكاليفها البيئية المتوسطة طوال عملية التنمية لا تزال مرتفعة (رونغ رونغ لي وآخرون، 2021). تحتاج هذه الدول إلى الاستفادة الكاملة من نتائج التنمية الاقتصادية السابقة والسعي للتحول من الفصل الضعيف إلى الفصل القوي (هانيف وآخرون، 2019). يظهر النموذج 9 أنه في عينة الفصل القوي في المرحلة الأولى من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي، فإن تأثير الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد على انبعاثات الكربون للفرد ليس له دلالة إحصائية. وهذا يتماشى مع نظرية الفصل، مما يشير إلى أنهم لا يتطورون مباشرة بتكلفة بيئية عالية. يظهر النموذج 10 أنه في الدول التي دخلت فيها التنمية الاقتصادية المرحلة الثانية من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي، فإن كل زيادة بمقدار 1 دولار أمريكي في الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد تؤدي إلى زيادة انبعاثات الكربون للفرد بمقدار 0.0855 طن متري. بالنظر إلى الحجم النسبي الصغير للمعامل، يمكن اعتبار أن منحنى كوزنتس البيئي على شكل N مدعوم، أي أن التنمية الاقتصادية مصحوبة بتلوث بيئي أقل في المرحلة الثانية من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي. ومع ذلك، يظهر النموذج 11 أنه عندما تدخل التنمية الاقتصادية المرحلة الثالثة من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي، يتم إعادة الاتصال بين النمو الاقتصادي وانبعاثات الكربون. مقارنة بالمرحلة الثانية من منحنى كوزنتس البيئي، فإن انبعاثات الكربون للفرد لكل

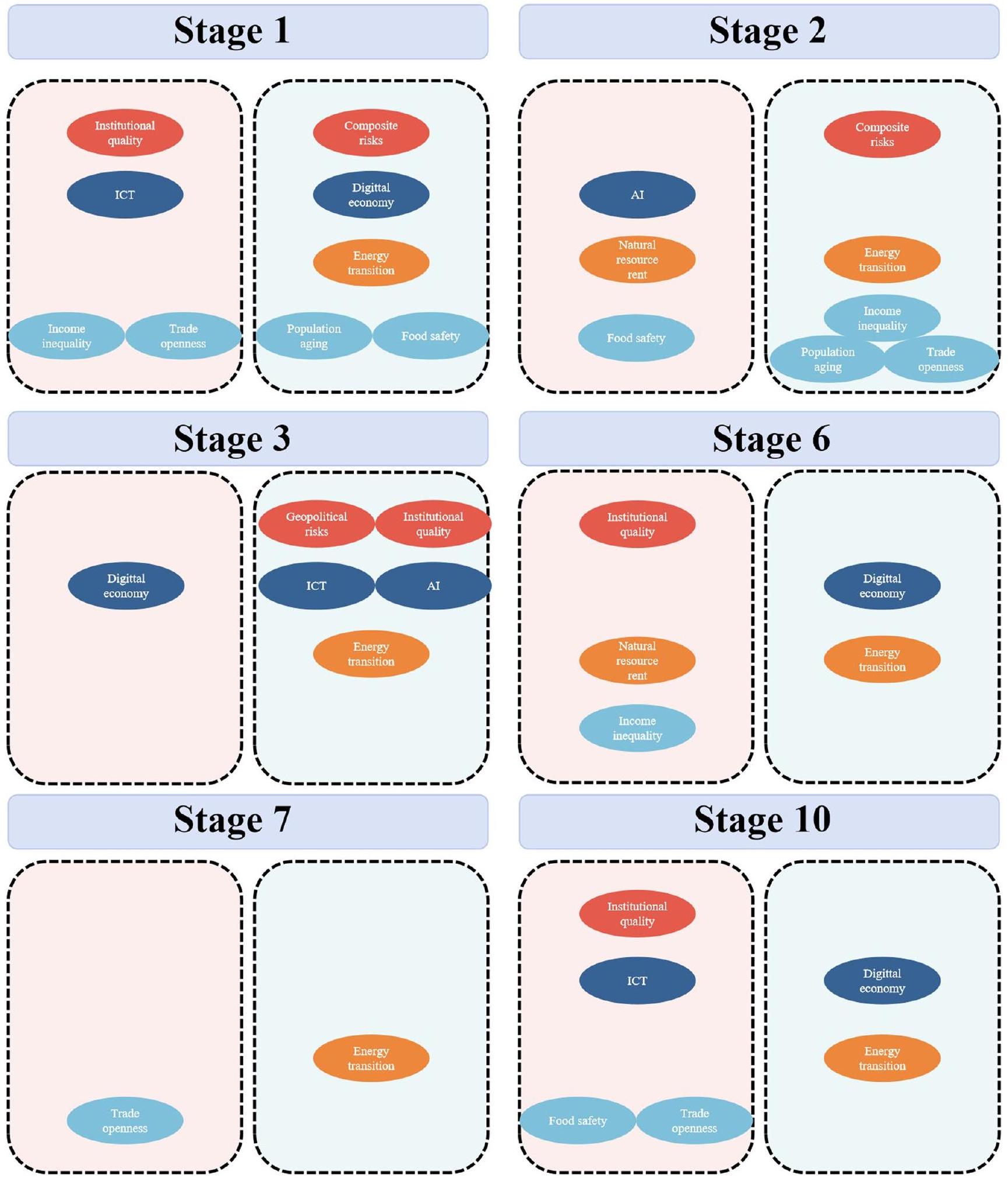

قد تؤدي النماذج والتكنولوجيا الرقمية إلى انبعاثات كربونية مفرطة (Feng Dong et al., 2022a). لذلك، تحتاج هذه الدول إلى التركيز على بصمة الكربون لنموذج التنمية الاقتصادية الرقمية أثناء تطوير تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات. تقلل الذكاء الاصطناعي من الانبعاثات في الدول من المرحلة الثالثة بينما تزيد من الانبعاثات في الدول من المرحلة الثانية، وهو ما ليس له دلالة كبيرة في المجموعات الأخرى، مما يشير إلى أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يحتاج إلى استخدامه في الاقتصاد والمجتمع بحذر أكبر.

يقلل من انبعاثات الكربون. الدلالة السياسية هي أن هذه الدول يجب أن تحسن من بناء وتنفيذ اللوائح البيئية بينما تسعى إلى استقرار البيئة الاقتصادية والسياسية والمالية المحلية (كريم وآخرون، 2022). من حيث التكنولوجيا الرقمية، تعزز تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات الكربون

تقلل التكنولوجيا الرقمية من انبعاثات الكربون. يُظهر ذلك أن هذه الدول يجب أن تولي اهتمامًا لقضية بصمة الكربون في صناعة تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات وتشجع على اختراق تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات في القطاعات الاقتصادية الأخرى لتشكيل صناعة اقتصادية رقمية أوسع وأعمق. من حيث استخدام الموارد، فإن تأثير تقليل الانبعاثات الناتج عن انتقال الطاقة كبير. بالنظر إلى أن حجم التأثير ليس مثاليًا، يجب على الدول التي لا تزال في المرحلة الأولى أن تعطي الأولوية للتنمية الاقتصادية وتقوم تدريجيًا بنشر إنتاج واستخدام الطاقة النظيفة بالتزامن مع التنمية الاقتصادية. من حيث الإدارة الاجتماعية، فإن عدم المساواة في الدخل والانفتاح التجاري يجلبان المزيد من انبعاثات الكربون، بينما يقلل شيخوخة السكان والأمن الغذائي من انبعاثات الكربون. يبدو أنه من ناحية، يجب على هذه الدول أن تقدم سياسات مالية وزراعية لتعزيز التوزيع العادل للثروة وتحسين أمن إنتاج الغذاء (أكبر وآخرون، 2019). من ناحية أخرى، تحتاج إلى تقديم المزيد من المنتجات والتقنيات الخضراء في عملية التجارة الدولية أو تعزيز الاستثمار (كيانغ وانغ وآخرون، 2023ب).

الركود، التنمية الاقتصادية لها معامل تأثير عالٍ على انبعاثات الكربون. هذه الدول تحتاج ليس فقط إلى استقرار اقتصادها ولكن من المفترض أيضًا أن تجد طرقًا لتقليل التكاليف البيئية. تشير النتائج إلى أنها بحاجة إلى وضع لوائح بيئية أكثر صرامة ومعالجة قضايا انبعاثات الكربون في تكنولوجيا المعلومات والاتصالات، وإنتاج الغذاء، والانفتاح التجاري. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن اعتبار الاقتصاد الرقمي وانتقال الطاقة كخطوات إضافية في تطوير الصناعات الخضراء.

الملاحظات الختامية

فصل قوي، وركود، على التوالي. بناءً على ذلك، قمنا بإنشاء إحداثيات فصل ثنائية الأبعاد ودمجنا الحالات الثلاث لكل من البعدين المذكورين مع بعضها للحصول على تسع حالات فصل ثنائية الأبعاد. نقسم العينة إلى خمس مجموعات من خلال مطابقة نتائج العينة غير الركودية مع تسع حالات الفصل. من بينها، هناك 43 و47 و57 و9 و3 دول في المراحل 1 و2 و3 و6 و7، على التوالي. بإضافة الدول المتراجعة (المرحلة 10) نحصل على 6 لوحات. نقوم أيضًا بإجراء انحدارات خطية متعددة في هذه اللوحات ونناقش التأثيرات المتباينة للتنمية الاقتصادية و12 متغيرًا إضافيًا على انبعاثات الكربون. النتائج تؤكد تمامًا الفرضية H4 وتظهر أن تأثيرات معظم المتغيرات تختلف وفقًا لظروف الدول. المتغير الأكثر قوة هو انتقال الطاقة، الذي يظهر تأثيرًا كبيرًا في تقليل الكربون في جميع المجموعات. ومع ذلك، فإن حجم تأثير انتقال الطاقة أيضًا متباين. في الدول ذات مستويات التنمية الاقتصادية الأعلى والفصل، تكون تأثيرات انتقال الطاقة أقوى. أخيرًا، نناقش خطط تقليل الانبعاثات المختلفة للدول في مراحل الفصل الثنائية الأبعاد المختلفة بناءً على اتجاه تأثير المتغيرات.

توفر البيانات

نُشر على الإنترنت: 21 فبراير 2024

ملاحظات

2 عدد الدول التي تنتمي إلى المرحلتين الثانية والثالثة من EKC في فك الارتباط ثنائي الأبعاد في الشكل 4c أقل من تلك الموجودة في الشكل 4a. وذلك لأن بعض الدول لديها فقط بيانات الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد ولكن لا تملك بيانات كافية عن انبعاثات الكربون في العقدين الماضيين.

References

Allard A, Takman J, Uddin GS, Ahmed A (2018) The N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve: an empirical evaluation using a panel quantile regression approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:5848-5861

Álvarez-Herránz A, Balsalobre D, Cantos JM, Shahbaz M (2017) Energy innovations-GHG emissions nexus: fresh empirical evidence from OECD countries. Energy Policy 101:90-100

Andreoni J, Levinson A (2001) The simple analytics of the environmental Kuznets curve. J Public Econ 80(2):269-286

Ang JB (2008) Economic development, pollutant emissions and energy consumption in Malaysia. J Policy Model 30(2):271-278

Anser MK, Syed QR, Apergis N (2021) Does geopolitical risk escalate

Apergis N, Ozturk I (2015) Testing environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Asian countries. Ecol Indic 52:16-22

Asiedu E (2006) Foreign direct investment in Africa: The role of natural resources, market size, government policy, institutions and political instability. World Econ 29(1):63-77

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Shahbaz M, Roubaud D, Farhani S (2018) How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Sinha A, Driha OM, Mubarik MS (2021) Assessing the impacts of ageing and natural resource extraction on carbon emissions: a proposed policy framework for European economies. J Clean Prod 296:126470

Bashir MF (2022) Discovering the evolution of Pollution Haven Hypothesis: a literature review and future research agenda. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(32):48210-48232

Beckerman W (1992) Economic growth and the environment: Whose growth? Whose environment? World Dev 20(4):481-496

Berkeley (2024) Press Release: 2023 was warmest year since 1850. Berkeley Earth. https://berkeleyearth.org/press-release-2023-was-the-warmest-year-on-recordpress-release/

Brown PT, Hanley H, Mahesh A, Reed C, Strenfel SJ, Davis SJ et al. (2023) Climate warming increases extreme daily wildfire growth risk in California. Nature 621(7980):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06444-3

Caldara D, Iacoviello M (2022) Measuring geopolitical risk. Am Econ Rev 112(4):1194-1225

Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, Trisos CH, Zipfel CM, Eskew EA et al. (2022) Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 607(7919):555-562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

Cavicchioli R, Ripple WJ, Timmis KN, Azam F, Bakken LR, Baylis M et al. (2019) Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(9):569-586

Charfeddine L, Umlai M (2023) ICT sector, digitization and environmental sustainability: a systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2022. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 184:113482

Cheng P, Tang H, Lin F, Kong X (2023) Bibliometrics of the nexus between food security and carbon emissions: hotspots and trends. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(10):25981-25998

Cole MA (2004) Trade, the pollution haven hypothesis and the environmental Kuznets curve: examining the linkages. Ecol Econ 48(1):71-81

Dai M, Sun M, Chen B, Shi L, Jin M, Man Y et al. (2023) Country-specific net-zero strategies of the pulp and paper industry. Nature 626:327-334. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-023-06962-0

Diaz D, Moore F (2017) Quantifying the economic risks of climate change. Nat Clim Change 7(11):774-782

Dinda S (2004) Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: a survey. Ecol Econ 49(4):431-455

Do TK (2021) Resource curse or rentier peace? The impact of natural resource rents on military expenditure. Resour Policy 71:101989

Dogan E, Seker F (2016) Determinants of

Dong F, Hu M, Gao Y, Liu Y, Zhu J, Pan Y (2022a) How does digital economy affect carbon emissions? Evidence from global 60 countries. Sci Total Environ 852:158401

Dong F, Li Y, Gao Y, Zhu J, Qin C, Zhang X (2022b) Energy transition and carbon neutrality: exploring the non-linear impact of renewable energy development on carbon emission efficiency in developed countries. Resour Conserv Recycl 177:106002

Dong M, Wang G, Han X (2023) Artificial intelligence, industrial structure optimization, and

Duan H, Zhou S, Jiang K, Bertram C, Harmsen M, Kriegler E et al. (2021) Assessing China’s efforts to pursue the 1.5 C warming limit. Science 372(6540):378-385

Fakher HA, Ahmed Z, Acheampong AO, Nathaniel SP (2023) Renewable energy, nonrenewable energy, and environmental quality nexus: an investigation of the N-shaped Environmental Kuznets Curve based on six environmental indicators. Energy 263:125660

Fan J, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Shao S, Ma M (2021) How does population aging affect household carbon emissions? Evidence from Chinese urban and rural areas. Energy Econ 100:105356

Fankhauser S, Smith SM, Allen M, Axelsson K, Hale T, Hepburn C et al. (2022) The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nat Clim Change 12(1):15-21

Farooq S, Ozturk I, Majeed MT, Akram R (2022) Globalization and

Fawzy S, Osman AI, Doran J, Rooney DW (2020) Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ Chem Lett 18:2069-2094

Gill AR, Viswanathan KK, Hassan S (2018) The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) and the environmental problem of the day. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 81:1636-1642

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1991) Environmental impacts of a North American free trade agreement. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, MA, USA

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1995) Economic growth and the environment. Q J Econ 110(2):353-377

Guan Y, Yan J, Shan Y, Zhou Y, Hang Y, Li R et al. (2023) Burden of the global energy price crisis on households. Nat Energy 8(3):304-316

Hanif I, Raza SMF, Gago-de-Santos P, Abbas Q (2019) Fossil fuels, foreign direct investment, and economic growth have triggered

Hassan T, Khan Y, He C, Chen J, Alsagr N, Song H (2022) Environmental regulations, political risk and consumption-based carbon emissions: evidence from OECD economies. J Environ Manag 320:115893

Heerink N, Mulatu A, Bulte E (2001) Income inequality and the environment: aggregation bias in environmental Kuznets curves. Ecol Econ 38(3):359-367

Higón DA, Gholami R, Shirazi F (2017) ICT and environmental sustainability: a global perspective. Telemat Inform 34(4):85-95

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jacob D, Taylor M, Guillén Bolaños T, Bindi M, Brown S et al. (2019) The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 C . Science 365(6459):eaaw6974

Hossain MR, Rej S, Awan A, Bandyopadhyay A, Islam MS, Das N et al. (2023) Natural resource dependency and environmental sustainability under N-shaped EKC: the curious case of India. Resour Policy 80:103150

IFR (2023) World Robotics 2023 Report. International Federation of Robotics. https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/world-robotics-2023-report-asia-ahead-of-europe-and-the-americas

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2023) Reflections on “Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels”. J Econ 234:111-114

Inglesi-Lotz R, Dogan E (2018) The role of renewable versus non-renewable energy to the level of

IPCC (2023) AR 6. intergovernmental panel on climate change. https://www.ipcc. ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

ITU (2023) ICT statistics. International Telecommunication Union. https://www. itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

Jahanger A, Hossain MR, Onwe JC, Ogwu SO, Awan A, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2023) Analyzing the N-shaped EKC among top nuclear energy generating nations: a novel dynamic common correlated effects approach. Gondwana Res 116:73-88

Kaika D, Zervas E (2013a) The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) theory-Part A: concept, causes and the

Kaika D, Zervas E (2013b) The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) theory. Part B: critical issues. Energy Policy 62:1403-1411

Karim S, Appiah M, Naeem MA, Lucey BM, Li M (2022) Modelling the role of institutional quality on carbon emissions in Sub-Saharan African countries. Renew Energy 198:213-221

Koondhar MA, Shahbaz M, Memon KA, Ozturk I, Kong R (2021) A visualization review analysis of the last two decades for environmental Kuznets curve “EKC” based on co-citation analysis theory and pathfinder network scaling algorithms. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:16690-16706

Kuznets

Lantz V, Feng Q (2006) Assessing income, population, and technology impacts on

Lark TJ, Spawn SA, Bougie M, Gibbs HK (2020) Cropland expansion in the United States produces marginal yields at high costs to wildlife. Nat Commun 11(1):4295

Le HP, Ozturk I (2020) The impacts of globalization, financial development, government expenditures, and institutional quality on

Leal PH, Marques AC (2022) The evolution of the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis assessment: a literature review under a critical analysis perspective. Heliyon

Li R, Wang Q, Guo J (2024) Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis of carbon emissions: exploring the impact of geopolitical risks, natural resource rents, corrupt governance, and energy intensity. J Environ Manag 351:119663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119663

Li R, Wang Q, Li L, Hu S (2023) Do natural resource rent and corruption governance reshape the environmental Kuznets curve for ecological footprint? Evidence from 158 countries. Resour Policy 85:103890

Li R, Wang Q, Liu Y, Jiang R (2021) Per-capita carbon emissions in 147 countries: the effect of economic, energy, social, and trade structural changes. Sustain Prod Consum 27:1149-1164

Li Y, Zhang Y, Pan A, Han M, Veglianti E (2022) Carbon emission reduction effects of industrial robot applications: Heterogeneity characteristics and influencing mechanisms. Technol Soc 70:102034

Liu B, Yang X, Zhang J (2024) Nonlinear effect of industrial robot applications on carbon emissions: evidence from China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 104:107297

Lorente DB, Álvarez-Herranz A (2016) Economic growth and energy regulation in the environmental Kuznets curve. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:16478-16494

Luan F, Yang X, Chen Y, Regis PJ (2022) Industrial robots and air environment: a moderated mediation model of population density and energy consumption. Sustain Prod Consum 30:870-888

Mao F, Miller JD, Young SL, Krause S, Hannah DM (2022) Inequality of household water security follows a Development Kuznets Curve. Nat Commun 13(1):4525

Naeem MA, Appiah M, Taden J, Amoasi R, Gyamfi BA (2023) Transitioning to clean energy: assessing the impact of renewable energy, bio-capacity and access to clean fuel on carbon emissions in OECD economies. Energy Econ 127:107091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107091

Naseem S, Guang Ji T, Kashif U (2020) Asymmetrical ARDL correlation between fossil fuel energy, food security, and carbon emission: providing fresh information from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:31369-31382

Nguyen KH, Kakinaka M (2019) Renewable energy consumption, carbon emissions, and development stages: some evidence from panel cointegration analysis. Renew Energy 132:1049-1057

Numan U, Ma B, Meo MS, Bedru HD (2022) Revisiting the N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve for economic complexity and ecological footprint. J Clean Prod 365:132642

PRS (2023) ICRG. The International Country Risk Guide. https://www.prsgroup. com/explore-our-products/icrg/

Rashdan MOJ, Faisal F, Tursoy T, Pervaiz R (2021) Investigating the N-shape EKC using capture fisheries as a biodiversity indicator: empirical evidence from selected 14 emerging countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:36344-36353

Ray DK, Gerber JS, MacDonald GK, West PC (2015) Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat Commun 6(1):5989

Roelfsema M, van Soest HL, Harmsen M, van Vuuren DP, Bertram C, den Elzen M et al. (2020) Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat Commun 11(1):2096

Rojas-Vallejos J, Lastuka A (2020) The income inequality and carbon emissions trade-off revisited. Energy Policy 139:111302

Salman M, Long X, Dauda L, Mensah CN (2019) The impact of institutional quality on economic growth and carbon emissions: Evidence from Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand. J Clean Prod 241:118331

Schiermeier Q (2020) The US has left the Paris climate deal-what’s next? Nature 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03066-x

Tapio P (2005) Towards a theory of decoupling: degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp Policy 12(2):137-151

Tollefson J (2022) What the war in Ukraine means for energy, climate and food. Nature 604(7905):232-233

Ullah A, Khan S, Khamjalas K, Ahmad M, Hassan A, Uddin I (2023) Environmental regulation, renewable electricity, industrialization, economic complexity, technological innovation, and sustainable environment: testing the N-shaped EKC hypothesis for the G-10 economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(44):99713-99734

Usman O, Alola AA, Sarkodie SA (2020) Assessment of the role of renewable energy consumption and trade policy on environmental degradation using innovation accounting: evidence from the US. Renew Energy 150:266-277

Vakulchuk R, Overland I, Scholten D (2020) Renewable energy and geopolitics: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 122:109547

Wang K, Zhu Y, Zhang J (2021) Decoupling economic development from municipal solid waste generation in China’s cities: Assessment and prediction based on Tapio method and EKC models. Waste Manag 133:37-48

Wang Q, Ge Y, Li R (2024a) Does improving economic efficiency reduce ecological footprint? The role of financial development, renewable energy, and industrialization. Energy Environ 0958305X231183914. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0958305X231183914

Wang Q, Hu S, Li R (2024b) Could information and communication technology (ICT) reduce carbon emissions? The role of trade openness and financial development. Telecommunications Policy, 102699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. telpol.2023.102699

Wang Q, Ren F, Li R (2023a) Exploring the impact of geopolitics on the environmental Kuznets curve research. Sustain Dev 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd. 2743

Wang Q, Wang L, Li R (2023b) Trade openness helps move towards carbon neutrality-insight from 114 countries. Sustain Dev 2023. https://doi.org/10. 1002/sd. 2720

Worldbank (2023a) WDI. World Development Index. https://datatopics. worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

Worldbank (2023b) WGI. World Governance Index. https://www.govindicators.org/

Xiaoman W, Majeed A, Vasbieva DG, Yameogo CEW, Hussain N (2021) Natural resources abundance, economic globalization, and carbon emissions: advancing sustainable development agenda. Sustain Dev 29(5):1037-1048

Yi M, Liu Y, Sheng MS, Wen L (2022) Effects of digital economy on carbon emission reduction: new evidence from China. Energy Policy 171:113271

Zhang J, Lyu Y, Li Y, Geng Y (2022a) Digital economy: an innovation driving factor for low-carbon development. Environ Impact Assess Rev 96:106821

Zhang L, Mu R, Zhan Y, Yu J, Liu L, Yu Y et al. (2022b) Digital economy, energy efficiency, and carbon emissions: evidence from provincial panel data in China. Sci Total Environ 852:158403

Zhao J, Shahbaz M, Dong X, Dong K (2021a) How does financial risk affect global

Zhao S, Hafeez M, Faisal CMN (2022) Does ICT diffusion lead to energy efficiency and environmental sustainability in emerging Asian economies? Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:12198-12207

Zhao W, Zhong R, Sohail S, Majeed MT, Ullah S (2021b) Geopolitical risks, energy consumption, and

Zhao Z, Gozgor G, Lau MCK, Mahalik MK, Patel G, Khalfaoui R (2023) The impact of geopolitical risks on renewable energy demand in OECD countries. Energy Econ 122:106700

Zhengxia T, Haseeb M, Usman M, Shuaib M, Kamal M, Khan MF (2023) The role of monetary and fiscal policies in determining environmental pollution: revisiting the N-shaped EKC hypothesis for China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(38):89756-89769

Zou T, Zhang X, Davidson E (2022) Global trends of cropland phosphorus use and sustainability challenges. Nature 611(7934):81-87

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

الموافقة الأخلاقية

الموافقة المستنيرة

معلومات إضافية

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

© المؤلفون 2024

كلية الاقتصاد والإدارة، جامعة الصين للبترول (شرق الصين)، تشينغداو 266580، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. كلية الاقتصاد والإدارة، جامعة شينجيانغ، وولوموتشي 830046، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. البريد الإلكتروني: wangqiang7@upc.edu.cn; lirr@upc.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02736-9

Publication Date: 2024-02-21

ARTICLE

Rethinking the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis across 214 countries: the impacts of 12 economic, institutional, technological, resource, and social factors

Abstract

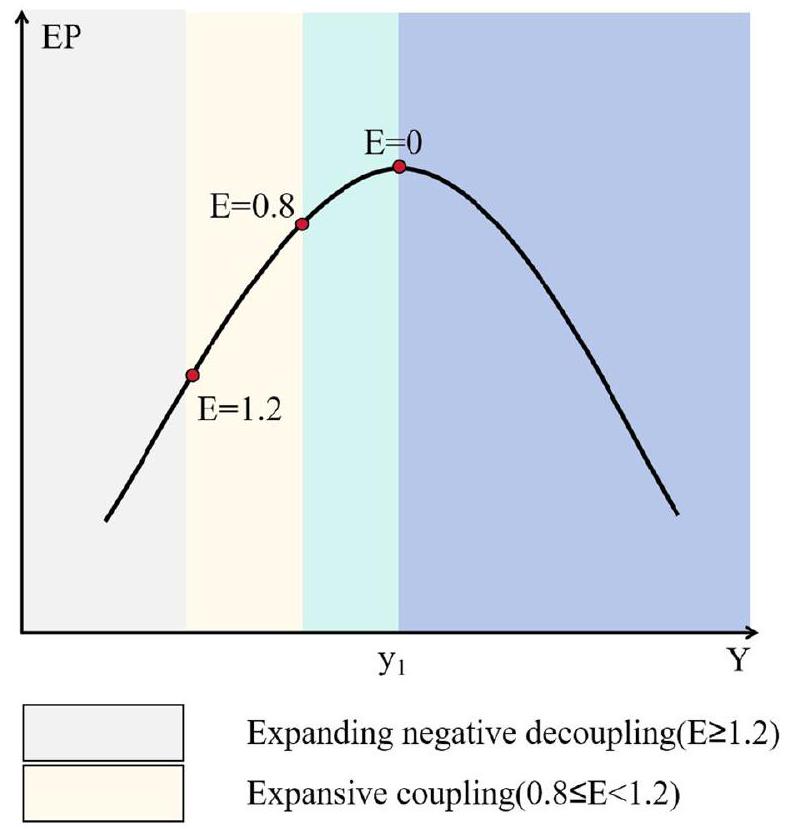

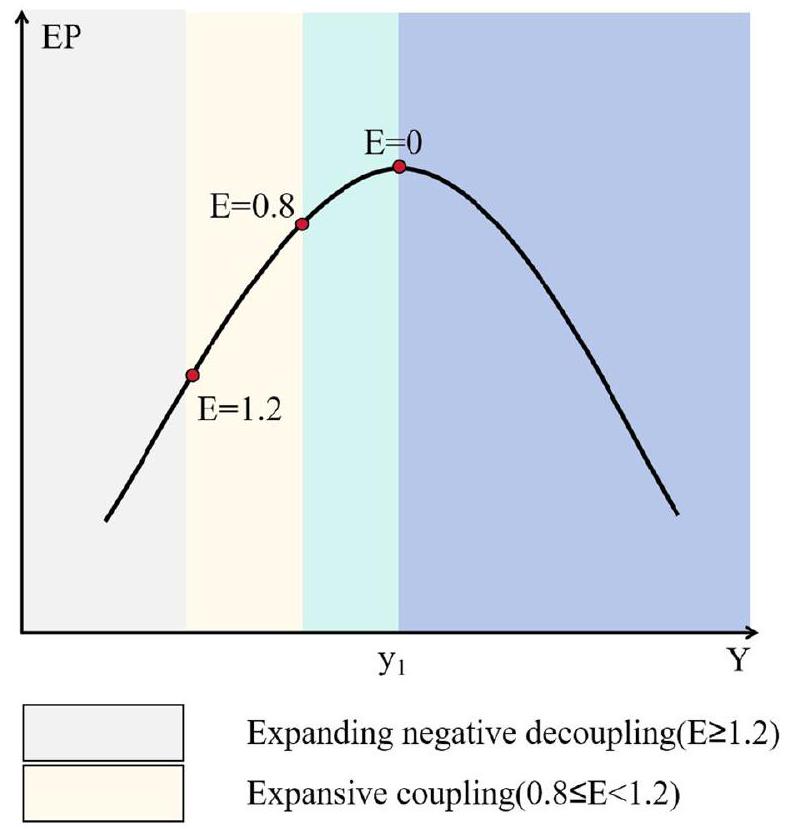

Research over the past three decades has provided rich empirical evidence for the inverted U-shaped EKC theory, but current problems facing advancing climate mitigation actions require us to re-examine the shape of global EKC rigorously. This paper examined the N -shaped EKC in a panel of 214 countries with 12 traditional and emerging variables, including institutions and risks, information and communication technology (ICT), artificial intelligence(AI), resource and energy use, and selected social factors. The two-dimensional Tapio decoupling model based on N-shaped EKC to group homogeneous countries is developed to explore the inter-group heterogeneous carbon emission effects of each variable. Global research results show that the linear and cubic terms of GDP per capita are significantly positive, while the quadratic term is significantly negative, regardless of whether additional variables are added. This means the robust existence of an N-shaped EKC. Geopolitical risk, ICT, and food security are confirmed to positively impact per capita carbon emissions, while the impact of composite risk, institutional quality, digital economy, energy transition, and population aging are significantly negative. The impact of AI, natural resource rents, trade openness, and income inequality are insignificant. The inflection points of the N -shaped EKC considering all additional variables are 45.08 and 73.44 thousand US dollars, respectively. Combining the turning points and the calculated decoupling coefficients, all countries are categorized into six groups based on the two-dimensional decoupling model. The subsequent group regression results show heterogeneity in the direction and magnitude of the carbon emission impacts of most variables. Finally, differentiated carbon emission reduction strategies for countries in six two-dimensional decoupling stages are proposed.

Introduction

Literature review and theoretical background

Literature review

growth and environmental degradation, was proposed by (Grossman and Krueger, 1991) in their landmark study of the environmental impacts of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Early EKC researchers analyzed the relationship between economic growth and various environmental degradation indicators without any other explanatory variables and obtained much evidence for an inverted U-shaped of first positive and then negative linkages between the two (Grossman and Krueger, 1991; Beckerman, 1992; Grossman and Krueger, 1995; Heerink et al., 2001).

first issue that has been widely criticized relates to the alleged heterogeneity present in the EKC panel study. To provide a broader assessment and reference, a considerable number of EKC studies choose to use cross-sectional or panel data including a group of countries (Kaika and Zervas, 2013b). Although these studies often argue that the selection of country groups is based on the close links between them (such as regional links, trade links, international agreements, etc.), however, the EKC curves obtained from country groups often prove to be unsuitable for each of them (Leal and Marques, 2022). A second thorny criticism questions the practical relevance of the EKC conceptual framework and development model (Gill et al., 2018). Even if each country’s EKC curve were accurately assessed, it would only depict a baseline development trajectory for the future. However, the more important issue at present is how to reduce environmental pollution and repair environmental damage according to the EKC insight rather than just “grow now and clean later”(Gill et al., 2018). The third issue is proposed in (Stern, 2017). After reviewing the 25 years of evolution of EKC research, he worried that the EKC model ignores the impact of other effects except growth and underscored that “they are the opposite force of the scale effect.” In addition, other econometrics issues, including the selection of pollution variables, the sensitivity of results to measurement methods, and the rationality of inflection points, were also pointed out (Leal and Marques, 2022).

H2: The N-shaped EKC remains robust with additional variables.

between the involved 12 additional variables and carbon emissions based on previous literature. These factors cover four perspectives: institutions and risks, digital technology, resource and energy utilization, and other social factors.

emissions is subject to intense debate. Empirically Rongrong Li et al. (2023) found that the exploration of natural resources directly triggers economic growth and subsequently stimulates an increase in ecological footprint. In contrast, combined with clean energy and environmental protection technology, some scholars (Xiaoman et al., 2021; Rongrong Li et al., 2024) believe that natural resource extraction can also improve the local environment. On the other hand, energy transition represents the result of human beings taking the initiative to eliminate traditional fossil fuels and shift to clean energy. Empirical results support that this systemic transformation of the energy system can effectively reduce carbon emissions in most countries (Dogan and Seker, 2016; Inglesi-Lotz and Dogan, 2018) though the heterogeneity among country in different income groups is often significant (Nguyen and Kakinaka, 2019).

Method and data Methodology

Multicollinearity test method: variance inflation factor (VIF): Multicollinearity results from one independent variable being accurately linearly predicted by other independent variables,

which reduces the stability of parameter estimation for the affected variables. This article aims to analyze the shape of the global EKC curve under the influence of 12 additional variables. Even though we have made the best efforts to select determinants from different lenses to approach the carbon emission curve, the original data used in the calculation of different proxy variables may partially overlap. Therefore, we examine the degree of multicollinearity in the model to ensure balance between comprehensiveness and non-replication of variable combinations.

as an example, in the following regression equation:

| Table 1 Determination criteria for common EKC shapes. | |||

|

|

|

EKC shape | |

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

Inverted N |

|

|

|

|

U |

|

|

|

|

Inverted U |

|

|

|

Linearity | |

|

|

|||

| State number | Decoupled state |

|

|

Decoupling elastic (E) range |

| State 1 | Absolute decoupling |

|

|

(

|

| State 2 | Relative decoupling |

|

[0,0.8) | |

| State 3 | Expansive coupling |

|

[0.8,1.2) | |

| State 4 | Expanding negative decoupling |

|

[1.2,

|

|

| State 5 | Strong negative decoupling |

|

|

|

| State 6 | Weak negative decoupling |

|

[0,0.8) | |

| State 7 | Recessive coupling |

|

[0.8,1.2) | |

| State 8 | Recession decoupling |

|

[1.2,

|

of decoupling (States 5-8), which, however, are beyond the scope of the EKC theory.

shape) or two inflection points ( N -shape, inverted N -shape). Taking the 2D decoupling model based on N-shaped EKC as an example, two vertical lines

Variable definition and data description. According to the requirements of the methods and models discussed previously, this article uses per capita carbon emissions as the explained variable, per capita GDP as the explanatory variable, and 12 variables covering institutional risks, digital technology, resource utilization, and social issues as control variables. Based on data availability, the research scope of this article is determined to be 214 countries from 1960 to 2020 . The definitions, measurement units, and data sources of all variables are summarized in Table S 1 . It can be seen that the explanatory variables and the explained variables are all derived from the WDI database developed by the World Bank (Worldbank, 2023a).

Empirical results

Preliminary test

| Method | FE | Replacing PCE with CE | Two-way FEs | RE | System GMM |

| Model | Model 1 | Model R1 | Model R2 | Model R3 | Model R4 |

| PGDP | 0.5408*** (0.0165) | 40.6234*** (2.3427) | 0.6086*** (0.0189) | 0.4444*** (0.0139) | 0.5377*** (0.0000) |

| PGDP2 | -0.0113*** (0.0004) | -0.7826*** (0.0591) | -0.0124*** (0.0004) | -0.0079*** (0.0003) | -0.0093*** (0.0000) |

| PGDP3 | 0.0001*** (0.0000) | 0.0044*** (0.0004) | 0.0001*** (0.0000) | 0.0000*** (0.0000) | 0.0001*** (0.0000) |

| Constant | 1.1640*** (0.0854) | -95.5816*** (12.0906) | 0.3822* (0.2273) | 1.5389*** (0.2768) | -0.1154*** (0.0002) |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | – |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | No | – |

| Sargan test

|

1.0000 | ||||

| AR(2) | 0.1736 | ||||

| y1 | 33.44 | 38.66 | 35.92 | 40.71 | 49.48 |

| y2 | 77.54 | 78.96 | 77.36 | 91.42 | 70.06 |

| Sample range of pgdp | [0.124,183.2] | ||||

| Country | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 | 191 |

| N | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 | 8356 |

Empirical results of global panel

shown in Table 3. First, the coefficient of the cubic term of per capita GDP (PGDP3) in Model 1 is significantly greater than 0 at the

| Method | Stepwise regression with FE models | |||||

| Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| PGDP | 0.5408*** | 0.6059*** | 0.5066*** | 0.4708*** | 0.6231*** | 0.9117*** |

| PGDP2 | -0.0113*** | -0.0110*** | -0.0071*** | -0.0077*** | -0.0113*** | -0.0163*** |

| PGDP3 | .00007*** | 0.0001*** | 0.0000*** | 0.0000*** | 0.0001*** | 0.0001*** |

| ICT | 0.0025** | 0.0033*** | 0.0023*** | 0.0011 | -0.0004 | |

| DE | -0.1066*** | -0.0745*** | -0.0371*** | -0.0452*** | -0.0656*** | |

| PA | -0.0906*** | -0.1616*** | -0.1940*** | -0.2646*** | -0.1777*** | |

| FS | 0.0071*** | 0.0027*** | 0.0035*** | 0.0083*** | -0.0130*** | |

| NRR | 0.0001*** | 0.0002*** | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| OPEN | -0.0022*** | 0.0002 | -0.0032** | -0.0011 | ||

| ET | -0.0298*** | -0.0409*** | -0.0795*** | -0.1157*** | ||

| CR | -0.0120*** | -0.0098*** | -0.0055 | |||

| AI | -0.0006 | 0.0001 | ||||

| IIE | -0.0179* | -0.0202* | ||||

| GPR | 0.0020** | |||||

| IQ | -0.1206*** | |||||

| R-squared | 0.122 | 0.136 | 0.231 | 0.225 | 0.573 | 0.718 |

| Observation | 8460 | 6838 | 4791 | 3652 | 1280 | 725 |

| Country | 191 | 181 | 177 | 133 | 60 | 40 |

person), respectively. This result is different from the EKC inflection point in Model 1. We juxtapose the cubic equation curves corresponding to the estimated coefficients in Fig. 3 to discuss the influence of the control variables on the shape of the EKC. Figure 3 shows that after taking control variables into account, not only did the economic growth space between the two inflection points shrink from 43.10 thousand US dollars to 28.35 thousand US dollars, but also the reduction of per capita carbon emissions between the inflection points is compressed from about 2.70 metric tons to about 1.05 metric tons. This suggests that the EKC appears to be bent upwards when trying to account for other explanatory variables. As a result, the only declining part of the N -shaped carbon emissions curve has shrunk in both “duration” and “descending space,” revealing a more severe global climate mitigation situation.

carbon emissions. This leads to the discussion of H3. Model 2 adds four control variables based on Model 1. Taking the 5% significance level as the standard, the impact coefficients of ICT and food security are positive, and the impact coefficients of digital economy and population aging are negative. We examine the robustness of the effects of these variables in conjunction with other results of the stepwise regressions. Comparing the estimation results of Model 2 with the subsequent four models (Model

| Classification | Factor | Abbr. | Decision of effect |

| Institution | Geopolitical Risks | GPR | + |

| Composite Risk | CR | – | |

| Institutional Quality | IQ | – | |

| Technology | Digital Economy | DE | – |

| Artificial | AI | ||

| ICT | ICT | + | |

| Resources | Energy Transition | ET | – |

| Natural Resource | NRR | ||

| Society | Population Aging | PA | – |

| Food Safety | FS | + | |

| Trade Openness | OPEN | ||

| Income Inequality | IIE |

governments and investors, which are often linked to irresponsible production models and misuse of fossil fuels (Vakulchuk et al., 2020; Zuoxiang Zhao et al., 2023). The reducing effect of institutional quality on global carbon emissions is consistent with the regulatory effect hypothesis and consistent with previous research for 3 Asian countries (Salman et al., 2019) and 30 Sub-Saharan African countries (Karim et al., 2022). Therefore, a stable international and domestic development environment and effective systems play an irreplaceable role in reducing carbon emissions and achieving global climate mitigation.

Group 214 countries through two-dimensional decoupling model.

| EKC stage | EKC1 | EKC1 | EKC1 | EKC 2 | EKC 3 | Economic recession |

| Decoupling state | Not decoupling | Weak decoupling | Strong decoupling | Strong decoupling | Strong decoupling | |

| 2D decoupling stage | Stage 3 | Stage 2 | Stage 1 | Stage 6 | Stage 7 | Stage 10 |

| Model | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 |

| PGDP | 0.2658*** | 0.3806*** | 0.0855*** | 0.1721*** | 0.3591*** | |

| ICT | -0.0027*** | 0.0090*** | 0.0083*** | |||

| DE | 0.0927*** | -0.0825*** | -0.1865*** | -0.0842*** | ||

| PA | -0.1906*** | -0.1774*** | ||||

| FS | 0.0057*** | -0.0033*** | 0.0143*** | |||

| NRR | 0.0001*** | 0.0024*** | ||||

| OPEN | -0.0032*** | 0.0021** | 0.0780*** | 0.0098** | ||

| ET | -0.0033** | -0.0267*** | -0.0515*** | -0.1096*** | -0.4661*** | -0.0389*** |

| CR | -0.0123*** | -0.0067** | ||||

| IIE | -0.0042*** | 0.0067*** | 0.0299** | |||

| AI | -0.0619*** | 0.0020*** | ||||

| GPR | -0.0044*** | |||||

| IQ | -0.0142** | 0.0674*** | 0.0884*** | 0.0567** | ||

| Observations | 1469 | 1324 | 1005 | 275 | 77 | 635 |

| R-squared | 0.556 | 0.585 | 0.337 | 0.551 | 0.882 | 0.461 |

| Number of id | 56 | 47 | 37 | 10 | 3 | 23 |

sample whose GDP per capita is higher than the first inflection point of the EKC have achieved strong decoupling. In other words, among the six two-dimensional decoupling stages corresponding to the second and third stages of EKC (Stage 4-9), 9 countries are in Stage 6, and 3 countries are in Stage

respectively. It may be puzzling at first that the impact coefficient of economic development on carbon emissions is more pronounced in weak decoupling countries than in nondecoupling countries. The reason can be that the economic development models of these countries, including most Asian developing countries, have been optimized to a certain extent in the past two decades, but their average environmental costs throughout the development process are still high (Rongrong Li et al., 2021). These countries need to make full use of the results of past economic development and strive to transform from weak decoupling to strong decoupling (Hanif et al., 2019). Model 9 shows that in the sample of strong decoupling in the first stage of EKC, the impact of per capita GDP on per capita carbon emissions is not significant. This is consistent with the decoupling theory, suggesting that they are not developing directly at a high ecological cost. Model 10 shows that in countries whose economic development has entered the second stage of EKC, for every US$1 increase in GDP per capita, carbon emissions per capita increase by 0.0855 metric tons. Considering the relatively small size of the coefficient, it can be considered that N-shaped EKC is supported, that is, economic development accompanied by less environmental pollution in the second phase of EKC. However, Model 11 shows that when economic development enters the third stage of EKC, economic growth and carbon emissions are reconnected. Compared to the second phase of EKC, carbon emissions per capita for every

model and digital technology may lead to excessive carbon emissions (Feng Dong et al., 2022a). Therefore, these countries need to focus on the carbon footprint of the digital economic development model in the process of developing ICT. AI reduces emissions in Stage 3 countries while increasing emissions in Stage 2 countries, which is not significant in other groups, indicating that AI needs to be used in the economy and society with more caution.

reduces carbon emissions. The policy implication is that these countries should improve the construction and implementation of environmental regulations while striving to stabilize the domestic economic, political, and financial environment (Karim et al., 2022). In terms of digital technology, ICT promotes carbon

emissions, while digital technology reduces carbon emissions. It shows that these countries should pay attention to the carbon footprint issue of the ICT industry and encourage the penetration of ICT into other economic sectors to form a broader and deeper digital economic industry. In terms of resource utilization, the emission reduction effect of the energy transition is significant. Considering that the magnitude of the effect is not ideal, countries currently in Stage 1 should prioritize economic development and gradually deploy the production and utilization of clean energy in conjunction with economic development. In terms of social management, income inequality, and trade openness bring more carbon emissions, while population aging and food security reduce carbon emissions. It seems that, on the one hand, these countries should introduce fiscal and agricultural production policies to promote fair distribution of wealth and improve food production security (Akbar et al., 2019). On the other hand, they need to introduce more green products and technologies in the process of international trade or investment promotion (Qiang Wang et al., 2023b).

recession, economic development has a high coefficient of impact on carbon emissions. These countries not only need to stabilize their economy but are also supposed to find ways to reduce environmental costs. The results indicate that they need to establish more robust environmental regulations and address carbon emissions issues in ICT, food production, and trade openness. In addition, the digital economy and energy transition can be seen as further developments in green industries.

Concluding remarks

strong decoupling, and recession, respectively. Based on this, we established two-dimensional decoupling coordinates and combined the three states of each of the above two dimensions with each other to obtain nine two-dimensional decoupling states. We divide the sample into five groups by matching the non-recession sample results to the nine decoupling conditions. Among them, there are 43, 47, 57, 9, and 3 countries in Stages 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7, respectively. Adding the declining countries (Stage 10) we get 6 panels. We also conduct multiple linear regressions in these panels and discuss the heterogeneous effects of economic development and 12 additional variables on carbon emissions. The results completely validate H4 and show that the effects of most variables vary according to country conditions. The most robust variable is the energy transition, which shows a significant carbon reduction effect in all groupings. However, the magnitude of the impact of energy transition is also heterogeneous. In countries with higher levels of economic development and decoupling, the effects of energy transition are stronger. Finally, we discuss the differential emission reduction plans of countries in different two-dimensional decoupling stages based on the direction of influence of variables.

Data availability

Published online: 21 February 2024

Notes

2 The number of countries belonging to the second and third stages of EKC in twodimensional decoupling in Fig. 4c is smaller than that in Fig. 4a. This is because some countries only have per capita GDP data but do not have enough carbon emission data in the past two decades.

References

Allard A, Takman J, Uddin GS, Ahmed A (2018) The N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve: an empirical evaluation using a panel quantile regression approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:5848-5861

Álvarez-Herránz A, Balsalobre D, Cantos JM, Shahbaz M (2017) Energy innovations-GHG emissions nexus: fresh empirical evidence from OECD countries. Energy Policy 101:90-100

Andreoni J, Levinson A (2001) The simple analytics of the environmental Kuznets curve. J Public Econ 80(2):269-286

Ang JB (2008) Economic development, pollutant emissions and energy consumption in Malaysia. J Policy Model 30(2):271-278

Anser MK, Syed QR, Apergis N (2021) Does geopolitical risk escalate

Apergis N, Ozturk I (2015) Testing environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Asian countries. Ecol Indic 52:16-22

Asiedu E (2006) Foreign direct investment in Africa: The role of natural resources, market size, government policy, institutions and political instability. World Econ 29(1):63-77

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Shahbaz M, Roubaud D, Farhani S (2018) How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Sinha A, Driha OM, Mubarik MS (2021) Assessing the impacts of ageing and natural resource extraction on carbon emissions: a proposed policy framework for European economies. J Clean Prod 296:126470

Bashir MF (2022) Discovering the evolution of Pollution Haven Hypothesis: a literature review and future research agenda. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(32):48210-48232

Beckerman W (1992) Economic growth and the environment: Whose growth? Whose environment? World Dev 20(4):481-496

Berkeley (2024) Press Release: 2023 was warmest year since 1850. Berkeley Earth. https://berkeleyearth.org/press-release-2023-was-the-warmest-year-on-recordpress-release/

Brown PT, Hanley H, Mahesh A, Reed C, Strenfel SJ, Davis SJ et al. (2023) Climate warming increases extreme daily wildfire growth risk in California. Nature 621(7980):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06444-3

Caldara D, Iacoviello M (2022) Measuring geopolitical risk. Am Econ Rev 112(4):1194-1225

Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, Trisos CH, Zipfel CM, Eskew EA et al. (2022) Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 607(7919):555-562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

Cavicchioli R, Ripple WJ, Timmis KN, Azam F, Bakken LR, Baylis M et al. (2019) Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(9):569-586

Charfeddine L, Umlai M (2023) ICT sector, digitization and environmental sustainability: a systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2022. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 184:113482

Cheng P, Tang H, Lin F, Kong X (2023) Bibliometrics of the nexus between food security and carbon emissions: hotspots and trends. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(10):25981-25998

Cole MA (2004) Trade, the pollution haven hypothesis and the environmental Kuznets curve: examining the linkages. Ecol Econ 48(1):71-81

Dai M, Sun M, Chen B, Shi L, Jin M, Man Y et al. (2023) Country-specific net-zero strategies of the pulp and paper industry. Nature 626:327-334. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-023-06962-0

Diaz D, Moore F (2017) Quantifying the economic risks of climate change. Nat Clim Change 7(11):774-782

Dinda S (2004) Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: a survey. Ecol Econ 49(4):431-455

Do TK (2021) Resource curse or rentier peace? The impact of natural resource rents on military expenditure. Resour Policy 71:101989

Dogan E, Seker F (2016) Determinants of

Dong F, Hu M, Gao Y, Liu Y, Zhu J, Pan Y (2022a) How does digital economy affect carbon emissions? Evidence from global 60 countries. Sci Total Environ 852:158401

Dong F, Li Y, Gao Y, Zhu J, Qin C, Zhang X (2022b) Energy transition and carbon neutrality: exploring the non-linear impact of renewable energy development on carbon emission efficiency in developed countries. Resour Conserv Recycl 177:106002

Dong M, Wang G, Han X (2023) Artificial intelligence, industrial structure optimization, and

Duan H, Zhou S, Jiang K, Bertram C, Harmsen M, Kriegler E et al. (2021) Assessing China’s efforts to pursue the 1.5 C warming limit. Science 372(6540):378-385

Fakher HA, Ahmed Z, Acheampong AO, Nathaniel SP (2023) Renewable energy, nonrenewable energy, and environmental quality nexus: an investigation of the N-shaped Environmental Kuznets Curve based on six environmental indicators. Energy 263:125660

Fan J, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Shao S, Ma M (2021) How does population aging affect household carbon emissions? Evidence from Chinese urban and rural areas. Energy Econ 100:105356

Fankhauser S, Smith SM, Allen M, Axelsson K, Hale T, Hepburn C et al. (2022) The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nat Clim Change 12(1):15-21

Farooq S, Ozturk I, Majeed MT, Akram R (2022) Globalization and

Fawzy S, Osman AI, Doran J, Rooney DW (2020) Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ Chem Lett 18:2069-2094

Gill AR, Viswanathan KK, Hassan S (2018) The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) and the environmental problem of the day. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 81:1636-1642

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1991) Environmental impacts of a North American free trade agreement. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, MA, USA

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1995) Economic growth and the environment. Q J Econ 110(2):353-377

Guan Y, Yan J, Shan Y, Zhou Y, Hang Y, Li R et al. (2023) Burden of the global energy price crisis on households. Nat Energy 8(3):304-316

Hanif I, Raza SMF, Gago-de-Santos P, Abbas Q (2019) Fossil fuels, foreign direct investment, and economic growth have triggered

Hassan T, Khan Y, He C, Chen J, Alsagr N, Song H (2022) Environmental regulations, political risk and consumption-based carbon emissions: evidence from OECD economies. J Environ Manag 320:115893

Heerink N, Mulatu A, Bulte E (2001) Income inequality and the environment: aggregation bias in environmental Kuznets curves. Ecol Econ 38(3):359-367

Higón DA, Gholami R, Shirazi F (2017) ICT and environmental sustainability: a global perspective. Telemat Inform 34(4):85-95

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jacob D, Taylor M, Guillén Bolaños T, Bindi M, Brown S et al. (2019) The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 C . Science 365(6459):eaaw6974

Hossain MR, Rej S, Awan A, Bandyopadhyay A, Islam MS, Das N et al. (2023) Natural resource dependency and environmental sustainability under N-shaped EKC: the curious case of India. Resour Policy 80:103150

IFR (2023) World Robotics 2023 Report. International Federation of Robotics. https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/world-robotics-2023-report-asia-ahead-of-europe-and-the-americas

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2023) Reflections on “Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels”. J Econ 234:111-114

Inglesi-Lotz R, Dogan E (2018) The role of renewable versus non-renewable energy to the level of

IPCC (2023) AR 6. intergovernmental panel on climate change. https://www.ipcc. ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

ITU (2023) ICT statistics. International Telecommunication Union. https://www. itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

Jahanger A, Hossain MR, Onwe JC, Ogwu SO, Awan A, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2023) Analyzing the N-shaped EKC among top nuclear energy generating nations: a novel dynamic common correlated effects approach. Gondwana Res 116:73-88

Kaika D, Zervas E (2013a) The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) theory-Part A: concept, causes and the

Kaika D, Zervas E (2013b) The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) theory. Part B: critical issues. Energy Policy 62:1403-1411

Karim S, Appiah M, Naeem MA, Lucey BM, Li M (2022) Modelling the role of institutional quality on carbon emissions in Sub-Saharan African countries. Renew Energy 198:213-221

Koondhar MA, Shahbaz M, Memon KA, Ozturk I, Kong R (2021) A visualization review analysis of the last two decades for environmental Kuznets curve “EKC” based on co-citation analysis theory and pathfinder network scaling algorithms. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:16690-16706

Kuznets

Lantz V, Feng Q (2006) Assessing income, population, and technology impacts on

Lark TJ, Spawn SA, Bougie M, Gibbs HK (2020) Cropland expansion in the United States produces marginal yields at high costs to wildlife. Nat Commun 11(1):4295

Le HP, Ozturk I (2020) The impacts of globalization, financial development, government expenditures, and institutional quality on

Leal PH, Marques AC (2022) The evolution of the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis assessment: a literature review under a critical analysis perspective. Heliyon

Li R, Wang Q, Guo J (2024) Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis of carbon emissions: exploring the impact of geopolitical risks, natural resource rents, corrupt governance, and energy intensity. J Environ Manag 351:119663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119663

Li R, Wang Q, Li L, Hu S (2023) Do natural resource rent and corruption governance reshape the environmental Kuznets curve for ecological footprint? Evidence from 158 countries. Resour Policy 85:103890

Li R, Wang Q, Liu Y, Jiang R (2021) Per-capita carbon emissions in 147 countries: the effect of economic, energy, social, and trade structural changes. Sustain Prod Consum 27:1149-1164

Li Y, Zhang Y, Pan A, Han M, Veglianti E (2022) Carbon emission reduction effects of industrial robot applications: Heterogeneity characteristics and influencing mechanisms. Technol Soc 70:102034

Liu B, Yang X, Zhang J (2024) Nonlinear effect of industrial robot applications on carbon emissions: evidence from China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 104:107297

Lorente DB, Álvarez-Herranz A (2016) Economic growth and energy regulation in the environmental Kuznets curve. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:16478-16494

Luan F, Yang X, Chen Y, Regis PJ (2022) Industrial robots and air environment: a moderated mediation model of population density and energy consumption. Sustain Prod Consum 30:870-888

Mao F, Miller JD, Young SL, Krause S, Hannah DM (2022) Inequality of household water security follows a Development Kuznets Curve. Nat Commun 13(1):4525

Naeem MA, Appiah M, Taden J, Amoasi R, Gyamfi BA (2023) Transitioning to clean energy: assessing the impact of renewable energy, bio-capacity and access to clean fuel on carbon emissions in OECD economies. Energy Econ 127:107091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107091

Naseem S, Guang Ji T, Kashif U (2020) Asymmetrical ARDL correlation between fossil fuel energy, food security, and carbon emission: providing fresh information from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:31369-31382

Nguyen KH, Kakinaka M (2019) Renewable energy consumption, carbon emissions, and development stages: some evidence from panel cointegration analysis. Renew Energy 132:1049-1057

Numan U, Ma B, Meo MS, Bedru HD (2022) Revisiting the N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve for economic complexity and ecological footprint. J Clean Prod 365:132642

PRS (2023) ICRG. The International Country Risk Guide. https://www.prsgroup. com/explore-our-products/icrg/

Rashdan MOJ, Faisal F, Tursoy T, Pervaiz R (2021) Investigating the N-shape EKC using capture fisheries as a biodiversity indicator: empirical evidence from selected 14 emerging countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:36344-36353

Ray DK, Gerber JS, MacDonald GK, West PC (2015) Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat Commun 6(1):5989

Roelfsema M, van Soest HL, Harmsen M, van Vuuren DP, Bertram C, den Elzen M et al. (2020) Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat Commun 11(1):2096

Rojas-Vallejos J, Lastuka A (2020) The income inequality and carbon emissions trade-off revisited. Energy Policy 139:111302

Salman M, Long X, Dauda L, Mensah CN (2019) The impact of institutional quality on economic growth and carbon emissions: Evidence from Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand. J Clean Prod 241:118331

Schiermeier Q (2020) The US has left the Paris climate deal-what’s next? Nature 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03066-x

Tapio P (2005) Towards a theory of decoupling: degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp Policy 12(2):137-151

Tollefson J (2022) What the war in Ukraine means for energy, climate and food. Nature 604(7905):232-233

Ullah A, Khan S, Khamjalas K, Ahmad M, Hassan A, Uddin I (2023) Environmental regulation, renewable electricity, industrialization, economic complexity, technological innovation, and sustainable environment: testing the N-shaped EKC hypothesis for the G-10 economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(44):99713-99734

Usman O, Alola AA, Sarkodie SA (2020) Assessment of the role of renewable energy consumption and trade policy on environmental degradation using innovation accounting: evidence from the US. Renew Energy 150:266-277

Vakulchuk R, Overland I, Scholten D (2020) Renewable energy and geopolitics: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 122:109547

Wang K, Zhu Y, Zhang J (2021) Decoupling economic development from municipal solid waste generation in China’s cities: Assessment and prediction based on Tapio method and EKC models. Waste Manag 133:37-48

Wang Q, Ge Y, Li R (2024a) Does improving economic efficiency reduce ecological footprint? The role of financial development, renewable energy, and industrialization. Energy Environ 0958305X231183914. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0958305X231183914

Wang Q, Hu S, Li R (2024b) Could information and communication technology (ICT) reduce carbon emissions? The role of trade openness and financial development. Telecommunications Policy, 102699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. telpol.2023.102699

Wang Q, Ren F, Li R (2023a) Exploring the impact of geopolitics on the environmental Kuznets curve research. Sustain Dev 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd. 2743

Wang Q, Wang L, Li R (2023b) Trade openness helps move towards carbon neutrality-insight from 114 countries. Sustain Dev 2023. https://doi.org/10. 1002/sd. 2720

Worldbank (2023a) WDI. World Development Index. https://datatopics. worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

Worldbank (2023b) WGI. World Governance Index. https://www.govindicators.org/

Xiaoman W, Majeed A, Vasbieva DG, Yameogo CEW, Hussain N (2021) Natural resources abundance, economic globalization, and carbon emissions: advancing sustainable development agenda. Sustain Dev 29(5):1037-1048

Yi M, Liu Y, Sheng MS, Wen L (2022) Effects of digital economy on carbon emission reduction: new evidence from China. Energy Policy 171:113271

Zhang J, Lyu Y, Li Y, Geng Y (2022a) Digital economy: an innovation driving factor for low-carbon development. Environ Impact Assess Rev 96:106821

Zhang L, Mu R, Zhan Y, Yu J, Liu L, Yu Y et al. (2022b) Digital economy, energy efficiency, and carbon emissions: evidence from provincial panel data in China. Sci Total Environ 852:158403

Zhao J, Shahbaz M, Dong X, Dong K (2021a) How does financial risk affect global

Zhao S, Hafeez M, Faisal CMN (2022) Does ICT diffusion lead to energy efficiency and environmental sustainability in emerging Asian economies? Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:12198-12207

Zhao W, Zhong R, Sohail S, Majeed MT, Ullah S (2021b) Geopolitical risks, energy consumption, and

Zhao Z, Gozgor G, Lau MCK, Mahalik MK, Patel G, Khalfaoui R (2023) The impact of geopolitical risks on renewable energy demand in OECD countries. Energy Econ 122:106700

Zhengxia T, Haseeb M, Usman M, Shuaib M, Kamal M, Khan MF (2023) The role of monetary and fiscal policies in determining environmental pollution: revisiting the N-shaped EKC hypothesis for China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(38):89756-89769

Zou T, Zhang X, Davidson E (2022) Global trends of cropland phosphorus use and sustainability challenges. Nature 611(7934):81-87

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Ethical approval

Informed consent

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

© The Author(s) 2024

School of Economics and Management, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao 266580, People’s Republic of China. School of Economics and Management, Xinjiang University, Wulumuqi 830046, People’s Republic of China. email: wangqiang7@upc.edu.cn; lirr@upc.edu.cn