DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2306200121

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38285938

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-29

إعادة تقييم دور المساحات الخضراء الحضرية في التحكم في تلوث الهواء

الملخص

الافتراض بأن النباتات تحسن جودة الهواء شائع في الخطاب العلمي والشعبي والسياسي. ومع ذلك، تظهر الدراسات التجريبية والنمذجة أن تأثير المساحات الخضراء على تركيزات الملوثات الهوائية في البيئات الحضرية متغير للغاية ويعتمد على السياق. قمنا بإعادة زيارة الرابط بين النباتات وجودة الهواء باستخدام التغيرات المستمدة من الأقمار الصناعية للمساحات الخضراء الحضرية وتركيزات الملوثات الهوائية من 2,615 محطة مراقبة قائمة في أوروبا والولايات المتحدة. بين عامي 2010 و2019، سجلت المحطات انخفاضات في الهواء المحيط

الملخص

الأهمية تشير نتائجنا إلى أن العلاقة بين النباتات الحضرية وجودة الهواء أكثر تعقيدًا مما كان يُعتقد سابقًا. بينما للتشجير الحضري نتائج صحية إيجابية أخرى للسكان، تشير دراستنا إلى أنه قد لا يكون إجراءً فعالًا لتقليل تلوث الهواء. على الرغم من أننا وجدنا تأثيرات تحسين طفيفة للنباتات على نطاق الأحياء إلى المدينة، يمكن أن تعمل النباتات على مستوى الشارع على تفاقم تلوث الهواء. يجب أن يكون تقليل الانبعاثات البشرية بدلاً من التشجير الحضري هو التركيز الرئيسي لتحسين جودة الهواء.

النتائج والمناقشة

. كانت الانخفاضات متسقة نسبيًا عبر الولايات المتحدة وأوروبا، على الرغم من أن الزيادات في تركيزات الملوثات كانت واضحة في جنوب أوروبا وغرب الولايات المتحدة، خاصة بالنسبة لـ PM (الملحق SI، الشكل S1). التغيرات في جودة الهواء التي وجدت هنا تتماشى بشكل عام مع الاتجاهات المبلغ عنها في الدراسات السابقة التي استخدمت كل من شبكات محطات المراقبة التنظيمية وكذلك أدوات الأقمار الصناعية (على سبيل المثال، المراجع 19-22). القيم الاتجاهية التي وجدت هنا أعلى قليلاً من حيث الحجم من ورقة حديثة جدًا تدرس اتجاهات جودة الهواء الأوروبية لفترة 2005 إلى 2019 بعد تصحيح تأثير الأرصاد الجوية (23). وجدت الأخيرة اتجاهات متوسطة قدرها

كان للمساحات الخضراء تأثير إيجابي. كانت التغيرات داخل بيئة الغابات الصنوبرية تدفع هذا الاستجابة المتباينة (الشكل 3B). بالمقابل، كان لكل من المساحات الخضراء الإجمالية وتغطية الأشجار تأثيرات سلبية على تركيزات الجسيمات الدقيقة في بيئات السافانا/المراعي، على الرغم من وجود تباين أكبر في تأثيرها كما هو موضح بواسطة فترة الثقة 95%.

النتائج مثل المزاج والانتباه العقلي، مما يحسن في النهاية رفاهية المجتمع

المواد والأساليب

تم استخدامها في

- جي. ليليفلد وآخرون، فقدان متوسط العمر المتوقع بسبب تلوث الهواء مقارنة بعوامل الخطر الأخرى: منظور عالمي. أبحاث القلب والأوعية الدموية 116، 1910-1917 (2020).

- R. Burnett وآخرون، تقديرات عالمية للوفيات المرتبطة بالتعرض طويل الأمد لجزيئات الهواء الدقيقة الخارجية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 115، 9592-9597 (2018).

- س. تشودري وآخرون، العبء الصحي العالمي لجزيئات PM2.5 في الهواء والمساهمة من الكربون الأسود الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية والهباء العضوي. البيئة الدولية 159، 107020 (2022).

- منظمة الصحة العالمية، “إرشادات جودة الهواء العالمية من منظمة الصحة العالمية. الجسيمات الدقيقة (PM2.5 و PM10)، الأوزون، ثاني أكسيد النيتروجين، ثاني أكسيد الكبريت وأول أكسيد الكربون” (منظمة الصحة العالمية (WHO)، 2021).

- جي. ليليفلد وآخرون، آثار إزالة انبعاثات الوقود الأحفوري والانبعاثات البشرية الكلية على الصحة العامة والمناخ. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 7192-7197 (2019).

- برنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة، “إجراءات جودة الهواء: ملخص عالمي للسياسات والبرامج للحد من تلوث الهواء” (برنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة (UNEP)، 2021).

- J. González-Martín، N. J. R. Kraakman، C. Pérez، R. Lebrero، R. Muñoz، مراجعة متقدمة حول تلوث الهواء الداخلي واستراتيجيات السيطرة على تلوث الهواء الداخلي. Chemosphere 262، 128376 (2021).

- X. يوي وآخرون، التخفيف من تلوث الهواء الداخلي: مراجعة للتقدمات الحديثة في مواد الامتزاز والأكسدة الحفزية. مجلة المواد الخطرة 405، 124138 (2021).

- K. V. أبهيجيث وآخرون، أداء تقنيات البنية التحتية الخضراء في تقليل تلوث الهواء في بيئات الطرق المفتوحة والأزقة المبنية – مراجعة. أتموس. إنفيرون. 162، 71-86 (2017).

- A. دينر، P. مودي، كيف يمكن للنباتات أن تحمينا من تلوث الهواء؟ مراجعة نقدية حول قدرات المساحات الخضراء في التخفيف من الجسيمات المحمولة جواً من منظور الصحة العامة – مع تداعيات على التخطيط الحضري. Sci. Total Environ. 796، 148605 (2021).

- Y. Huang وآخرون، مراجعة لاستراتيجيات التخفيف من تلوث الهواء على جوانب الطرق في الأودية الحضرية. تلوث البيئة. 280، 116971 (2021).

- C. J. فيركامب وآخرون، مراجعة للدراسات التي تقيم خدمات النظام البيئي المقدمة من البنية التحتية الخضراء والزرقاء الحضرية. خدمات النظام البيئي 52، 101367 (2021).

- V. Traverso، أفضل الأشجار لتقليل تلوث الهواء. بي بي سي، 13 مارس 2023، (2020).https://www.bbc. com/future/article/20200504-which-trees-reduce-air-pollution-best. تم الوصول إليه في 20 سبتمبر 2023.

- الأمم المتحدة، “نظام المحاسبة البيئية-الاقتصادية – محاسبة النظام البيئي (SEEA EA)” (منشور ذو غلاف أبيض، 2021).https://seea.un.org/content/system-environmental-economic-accounting-ecosystem-accounting-white-cover-version. تم الوصول إليه في 20 سبتمبر 2023.

- س. يانهيل، مراجعة حول الغطاء النباتي الحضري وتلوث الهواء بالجسيمات – الترسيب والتشتت. أتموس. إنفيرون. 105، 130-137 (2015).

- بي. إي. ج. فوس، ب. مايهو، ج. فankerkom، س. يانسن، تحسين جودة الهواء المحلية في المدن: هل نزرع الأشجار أم لا؟ التلوث البيئي. 183، 113-122 (2013).

- Y. Barwise, P. Kumar، تصميم حواجز نباتية للحد من تلوث الهواء في المدن: مراجعة عملية لاختيار الأنواع النباتية المناسبة. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3، 1-19 (2020).

- سي. إم. نوسباومر، آر. سي. كوهين، تأثير الأيروسولات العضوية على الاعتماد الحراري لجزيئات PM 2.5 في حوض لوس أنجلوس. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 3549-3558 (2021).

- C. B. B. Guerreiro، V. Foltescu، F. de Leeuw، حالة وجودة الهواء والاتجاهات في أوروبا. Atmos. Environ. 98، 376-384 (2014).

- ب. شنايدر، و. أ. لاهوز، ر. فان دير أ، الاتجاهات الحديثة لثاني أكسيد النيتروجين في الطبقة السفلى من الغلاف الجوي المستندة إلى الأقمار الصناعية فوق التجمعات الحضرية الكبيرة في جميع أنحاء العالم. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 15، 1205-1220 (2015).

- بي. شنايدر، ر. فان دير إيه، تحليل عالمي باستخدام مستشعر واحد لاتجاهات ثاني أكسيد النيتروجين في الطبقة السفلى من الغلاف الجوي من 2002 إلى 2011 كما لوحظ من الفضاء. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. الغلاف الجوي 117، D16309 (2012).

- ل. ن. لامسال وآخرون، اتجاهات NO2 في الولايات المتحدة (2005-2013): بيانات نظام جودة الهواء التابع لوكالة حماية البيئة (EPA) مقابل الملاحظات المحسنة من أداة مراقبة الأوزون (OMI). أتموس. إنفيرون. 110، 130-143 (2015).

- س.-إي. ووكر، س. سولبرغ، ب. شنايدر، ج. غويريرو، نموذج اتجاه وتنبؤ جودة الهواء AirGAM 2022 r 1. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 16، 573-595 (2023).

- ق. تشانغ وآخرون، عوامل تحسين جودة الهواء من PM2.5 في الصين من 2013 إلى 2017. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 24463-24469 (2019).

- ك. وانغ، م. يان، ي. وانغ، ج.-ب. تشانغ، تأثير صرامة سياسة البيئة على جودة الهواء. أتموس. إنفيرون. 231، 117522 (2020).

- ج. جون، ب. أ. كول، أ. زانوبتي، ب. كوتراكيس، تأثير انخفاض تركيز أكاسيد النيتروجين على اتجاهات الأوزون في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. جودة الهواء. صحة الغلاف الجوي 8، 283-292 (2015).

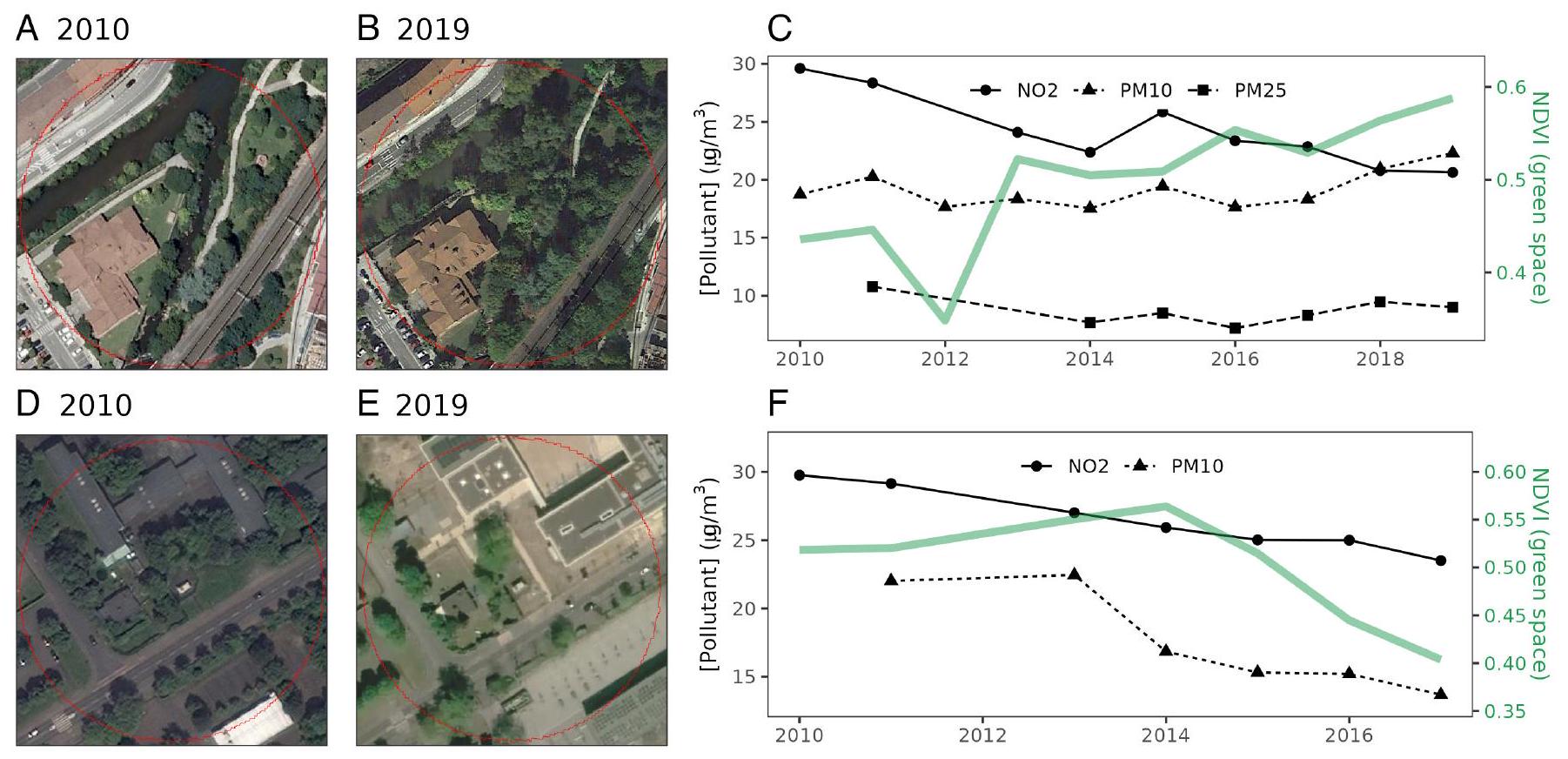

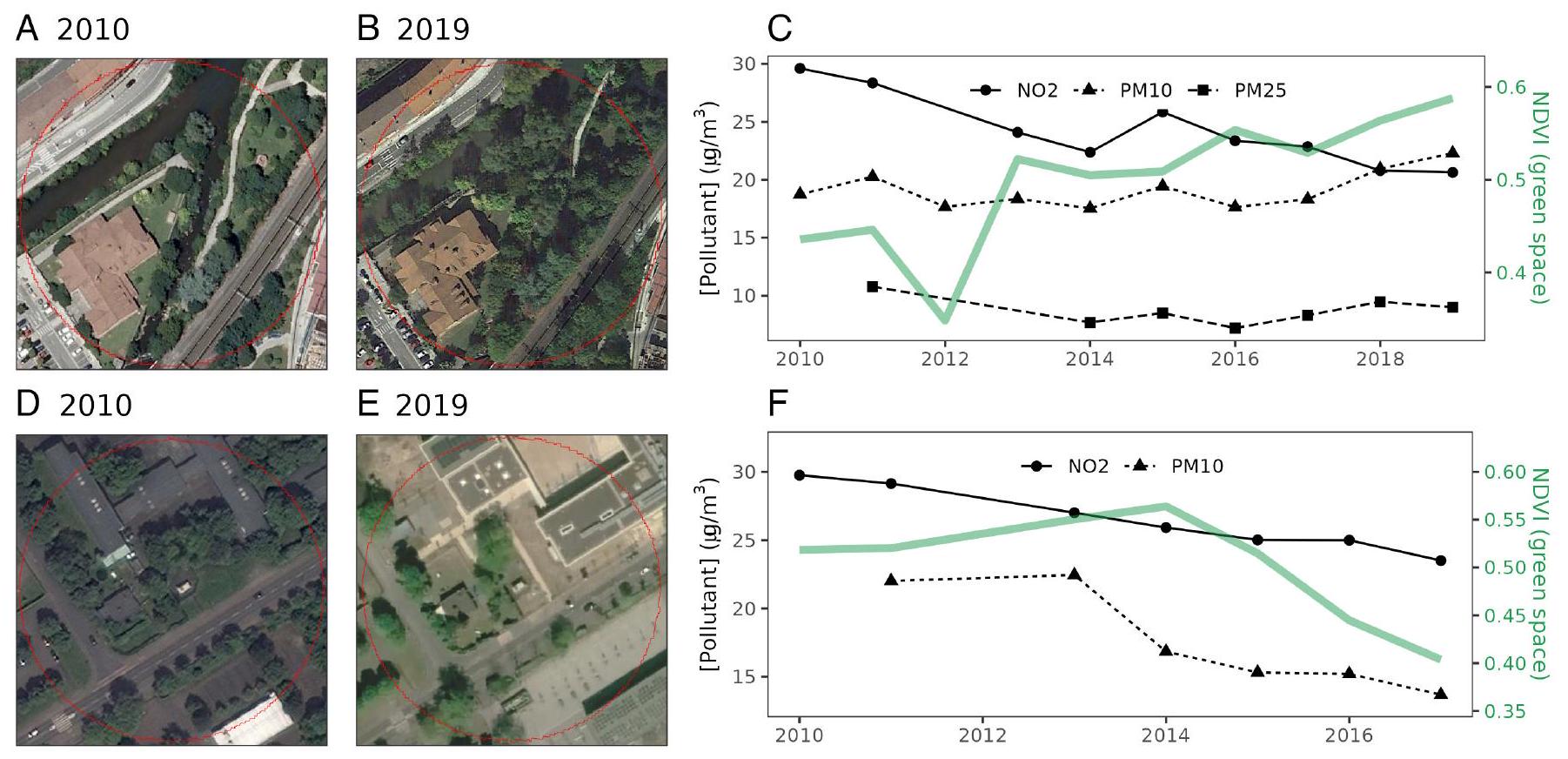

أي تأثيرات محددة للنموذج. تم تحويل تركيزات الملوثات الهوائية إلى لوغاريتمات لضمان توزيع المتبقيات بشكل طبيعي. ii) لت quantifying العلاقة بين المساحات الخضراء وتركيز الملوثات الهوائية على مر الزمن مع التحكم في تأثير الانبعاثات والمتغيرات المناخية، قمنا بتطبيق نفس هيكل النموذج الموصوف أعلاه، باستثناء إضافة المساحات الخضراء (NDVI وتغطية الأشجار) والانبعاثات والمتغيرات المناخية كأثر ثابت. تم تطبيق نماذج منفصلة لكل بيئة ولكل منطقة عازلة استخدمت لتجميع المساحات الخضراء حول المحطات. iii) تم استخدام المحطات التي تم فحصها يدويًا والتي شهدت تغييرات شديدة في NDVI لتطبيق نماذج مختلطة لاختبار ما إذا كانت الانخفاضات في تلوث الهواء أكبر في المحطات التي شهدت زيادة في المساحات الخضراء مقارنة بالمحطات التي شهدت انخفاضًا في المساحات الخضراء. تم تضمين الاتجاهات الخطية في المتغيرات المناخية وكسب/فقدان تصنيفي في المساحات الخضراء كأثر ثابت، بينما تم تضمين العينة كأثر عشوائي للتحكم في أي تحيزات محددة للعينة في تفسير الصور الجوية.

توفر البيانات والمواد والبرمجيات. الشيفرة التي تدعم التحليل:https://github.com/zanderVenter/greenspace-air-pollutionتم استخدام بيانات منشورة سابقًا لهذا العمل وتم الاستشهاد بها في قسم الطرق.

الشكر والتقدير. نشكر مجلس البحث النرويجي على التمويل (رقم المنحة 326641). كما نشكر بامتنان على التمويل الإضافي من خلال مشروع SIS-EO (NILU #B121004). شكر خاص لسورانغسو تشودري على مساهمته في التصور وجمع البيانات. - Z. S. Venter، S. L. Scott، P. G. Desmet، M. T. Hoffman، تطبيق اتجاهات الغطاء النباتي المستمدة من لاندسات في جنوب أفريقيا: الإمكانية لرصد تدهور الأراضي واستعادتها. مؤشرات بيئية 113، 106206 (2020).

- جي. هي وآخرون، خصائص تلوث الهواء وعلاقتها بالظروف الجوية خلال 2014-2015 في المدن الكبرى الصينية. تلوث البيئة. 223، 484-496 (2017).

- Y. Liu، Y. Zhou، J. Lu، استكشاف العلاقة بين تلوث الهواء والظروف الجوية في الصين تحت إدارة البيئة. Sci. Rep. 10، 14518 (2020).

- R. Jayamurugan، B. Kumaravel، S. Palanivelraja، M. Chockalingam، تأثير درجة الحرارة والرطوبة النسبية والتغيرات الموسمية على جودة الهواء المحيط في منطقة حضرية ساحلية. المجلة الدولية لعلوم الغلاف الجوي 2013، 264046 (2013).

- H. تشين وآخرون، التعرض طويل الأمد لتلوث الهواء المرتبط بحركة المرور ووفيات القلب والأوعية الدموية. علم الأوبئة 24، 35-43 (2013).

- بي. كومار وآخرون، العلاقة بين تلوث الهواء والبنية التحتية الخضراء وصحة الإنسان. البيئة الدولية 133، 105181 (2019).

- V. جينينغز، C. E. ريد، C. H. فولر، يمكن أن تحد البنية التحتية الخضراء من الظلم الناتج عن تلوث الهواء ولكنها لا تحله. نات. كوميون. 12، 4681 (2021).

- N. E. يونغ وآخرون، دليل البقاء لمعالجة بيانات لاندسات. علم البيئة 98، 920-932 (2017).

- E. نيميتز وآخرون، الإمكانيات والقيود في تخفيف تلوث الهواء بواسطة النباتات وعدم اليقين في التقييمات المعتمدة على الترسيب. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. أ 378، 20190320 (2020).

- م. تاليس، ج. تايلور، د. سينيه، ب. فري-سميث، تقدير إزالة تلوث الجسيمات الجوية بواسطة مظلة الأشجار الحضرية في لندن، تحت الظروف الحالية والمستقبلية. تخطيط المناظر الطبيعية والمدن. 103، 129-138 (2011).

- دي. جي. نواك، إس. هيرابايشي، أ. بودين، إي. غرينفيلد، تأثيرات الأشجار والغابات على جودة الهواء وصحة الإنسان في الولايات المتحدة. تلوث البيئة. 193، 119-129 (2014).

- W. Y. تشين، “الطبيعة الحضرية وخدمات النظام البيئي الحضري” في مدن خضراء: الأشكال والوظائف، ب. تان، ج. جيم، محرران. (سبرينجر، سنغافورة، 2017)، الصفحات 181-199.

- X. P. Song، P. Y. Tan، P. Edwards، D. Richards، الفوائد الاقتصادية والتكاليف للأشجار في إدارة الغابات الحضرية: مراجعة منهجية. الغابات الحضرية. الأخضر الحضري. 29، 162-170 (2018).

- س. هيرابايشي، ج. ن. كرول، د. ج. نواك، أوصاف نموذج الترسيب الجاف i-Tree Eco (سايتسير، برينستون، نيو جيرسي، 2012).

- م. لطيف وآخرون، حول استخدام النمذجة العددية لتشتت الملوثات في الحقول القريبة في البيئات الحضرية – مراجعة. تلوث البيئة 208، 271-283 (2016).

- R. P. ريم، م. شروتر، ل. هاين، تطوير محاسبة بيئية مكانية للعديد من خدمات النظام البيئي. خدمات النظام البيئي 10، 6-18 (2014).

- ت. س. آيزنمان وآخرون، الأشجار الحضرية، جودة الهواء، والربو: مراجعة متعددة التخصصات. تخطيط المناظر الطبيعية والحضرية. 187، 47-59 (2019).

- تي. في. كوككونن وآخرون، تأثير الخصائص الشكلية الحضرية على التباين المكاني لجودة الهواء PM2.5 في وسط مدينة نانجينغ. علوم البيئة. الغلاف الجوي 1، 481-497 (2021).

- أ. ألكوك وآخرون، تغطية الأرض وتلوث الهواء مرتبطان بدخول المستشفى بسبب الربو: دراسة مقطعية. البيئة الدولية 109، 29-41 (2017).

- م. أ. بيلات وآخرون، تأثير غطاء الأشجار والنباتات على حدوث الربو لدى الأطفال في المناطق الإحصائية الحضرية في تكساس. هورت تكنول. 22، 631-637 (2012).

- جي. إس. لوفاسي وآخرون، غطاء الأشجار الحضرية والربو، الصفير، التهاب الأنف، والحساسية تجاه حبوب لقاح الأشجار في مجموعة ولادة في مدينة نيويورك. وجهات نظر الصحة البيئية 121، 494-500 (2013).

- S.P. جاروالا وآخرون، العلاقة بين عدد حبوب لقاح الأشجار وزيارات قسم الطوارئ بسبب الربو في مركز حضري ذو كثافة سكانية عالية. مجلة الربو 48، 442-448 (2011).

- Z. S. فنتير، N. H. كروغ، D. N. بارتون، ربط البنية التحتية الخضراء بالحرارة الحضرية وتخفيف مخاطر صحة الإنسان في أوسلو، النرويج. Sci. Total Environ. 709، 136193 (2020).

- أ. س. لي، ر. ماهيسواران، الفوائد الصحية للمساحات الخضراء الحضرية: مراجعة للأدلة. مجلة الصحة العامة 33، 212-222 (2011).

- M. C. كوند، J. M. فلوهر، T. مككيون، C. C. براناس، المساحات الخضراء الحضرية وتأثيرها على صحة الإنسان. المجلة الدولية للبحوث البيئية والصحة العامة 15، 445 (2018).

- أ. تيواري وآخرون، اعتبارات لتقييم تأثيرات البنية التحتية الخضراء في نماذج انتشار تلوث الهواء على المقياس الصغير والكبير. العلوم. البيئة الكاملة 672، 410-426 (2019).

- وكالة حماية البيئة الأمريكية، “نظام بيانات جودة الهواء [قاعدة بيانات على الإنترنت]”. https:// www.epa.gov/بيانات-جودة-الهواء-الخارجي. تم الوصول إليه في 14 أبريل 2023.

- الوكالة الأوروبية للبيئة، “سلاسل زمنية لجودة الهواء (مجموعات بيانات E1a و E2a)”.https://www.eea. europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/aqereporting-9/estatistics-e1a-e2a. تم الوصول إليه في 14 أبريل 2023.

- سي. جي. موري وآخرون، العبء العالمي لـ 87 عامل خطر في 204 دول وأقاليم، 1990-2019: تحليل منهجي لدراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض 2019. ذا لانسيت 396، 1223-1249 (2020).

- م. غرانستروم، هـ. بلييل، تأثير محدود لنباتات الأشجار الحضرية على

و تركيزات بالقرب من مسار حركة المرور. تلوث البيئة. 189، 73-76 (2014). - م. شيافينا، م. ميلكيوري، م. بيساريزي، “طبقات تسوية GHS-SMOD R2023A، تطبيق منهجية درجة التحضر (المرحلة الأولى) على GHS-POP R2023A وGHS-BUILT-S R2023A، متعددة الزمن (1975-2030)”. المفوضية الأوروبية، المركز المشترك للبحوث (JRC) [مجموعة بيانات] doi:https://doi.org/10.2905/A0DF7A6F-49DE-46EA-9BDE-563437A6E2BAمعرف العملية: http://data. europa.eu/89h/a0df7abf-49de-46ea-9bde-563437abe2ba. تم الوصول إليه في 20 سبتمبر 2023.

- س. سولبرغ، س.-إي. ووكر، ب. شنايدر، ج. غويريرو، قياس تأثير تدابير الإغلاق بسبب كوفيد-19 على مستويات ثاني أكسيد النيتروجين في جميع أنحاء أوروبا. الغلاف الجوي 12، 131 (2021).

- سي. جي. تاكر، التركيبات الخطية الحمراء والأشعة تحت الحمراء الضوئية لمراقبة الغطاء النباتي. الاستشعار عن بعد. البيئة 8، 127-150 (1979).

- سي. إم. دي ميسيلي وآخرون، الحقول المستمرة للنباتات العالمية الآلية السنوية (MOD44B) بدقة مكانية 250 م لسنوات البيانات بدءًا من اليوم 65 (الإصدار 6، جامعة ماريلاند، كوليج بارك، ماريلاند، 2017)، الصفحات 2000-2010.

- N. غورليك وآخرون، محرك جوجل الأرض: تحليل جغرافي مكاني على مستوى الكوكب للجميع. الاستشعار عن بعد. البيئة 202، 18-27 (2017).

- دي. بي. روي وآخرون، توصيف طول الموجة الانعكاسية للاقمار الصناعية لاندسات-7 إلى لاندسات-8 واستمرارية مؤشر الفرق النباتي المعدل. الاستشعار عن بعد. البيئة 185، 57-70 (2016).

- م. كريبا وآخرون، انبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكربون والغازات الدفيئة من جميع دول العالم (مكتب نشر الاتحاد الأوروبي، لوكسمبورغ، 2019).

- J. Muñoز-Sاباطر وآخرون، ERA5-Land: مجموعة بيانات إعادة تحليل عالمية متطورة لتطبيقات الأراضي. بيانات علوم الأرض 13، 4349-4383 (2021).

- دي. بيتيز، تركيب نماذج مختلطة خطية في R. أخبار R 5، 27-30 (2005).

- مساهمات المؤلفين: صمم ز.س.ف.، أ.هـ.، إ.س.، ب.س.، و ن.س. البحث؛ أجرى ز.س.ف. البحث؛ قام ز.س.ف. و أ.هـ. بتحليل البيانات؛ و كتب ز.س.ف.، أ.هـ.، إ.س.، ب.س.، و ن.س. الورقة.

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

هذه المقالة هي تقديم مباشر إلى PNAS. م.غ. هو محرر ضيف تم دعوته من قبل هيئة التحرير.حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 المؤلف(ون). نُشر بواسطة PNAS. يتم توزيع هذه المقالة المفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام المنسوب 4.0 (CC BY).على الرغم من أن PNAS تطلب من المؤلفين الالتزام بتسميات الأمم المتحدة للخرائط (https://www.un.org/الجغرافيا المكانية/الخرائط الجغرافية)، سياستنا هي نشر الخرائط كما قدمها المؤلفون.

إلى من يمكن توجيه المراسلات. البريد الإلكتروني:زاندير.فينتر@نينا.no. تحتوي هذه المقالة على معلومات داعمة على الإنترنت فيhttps://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas. 2306200121/-/DCSupplemental.

نُشر في 29 يناير 2024.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2306200121

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38285938

Publication Date: 2024-01-29

Reassessing the role of urban green space in air pollution control

Abstract

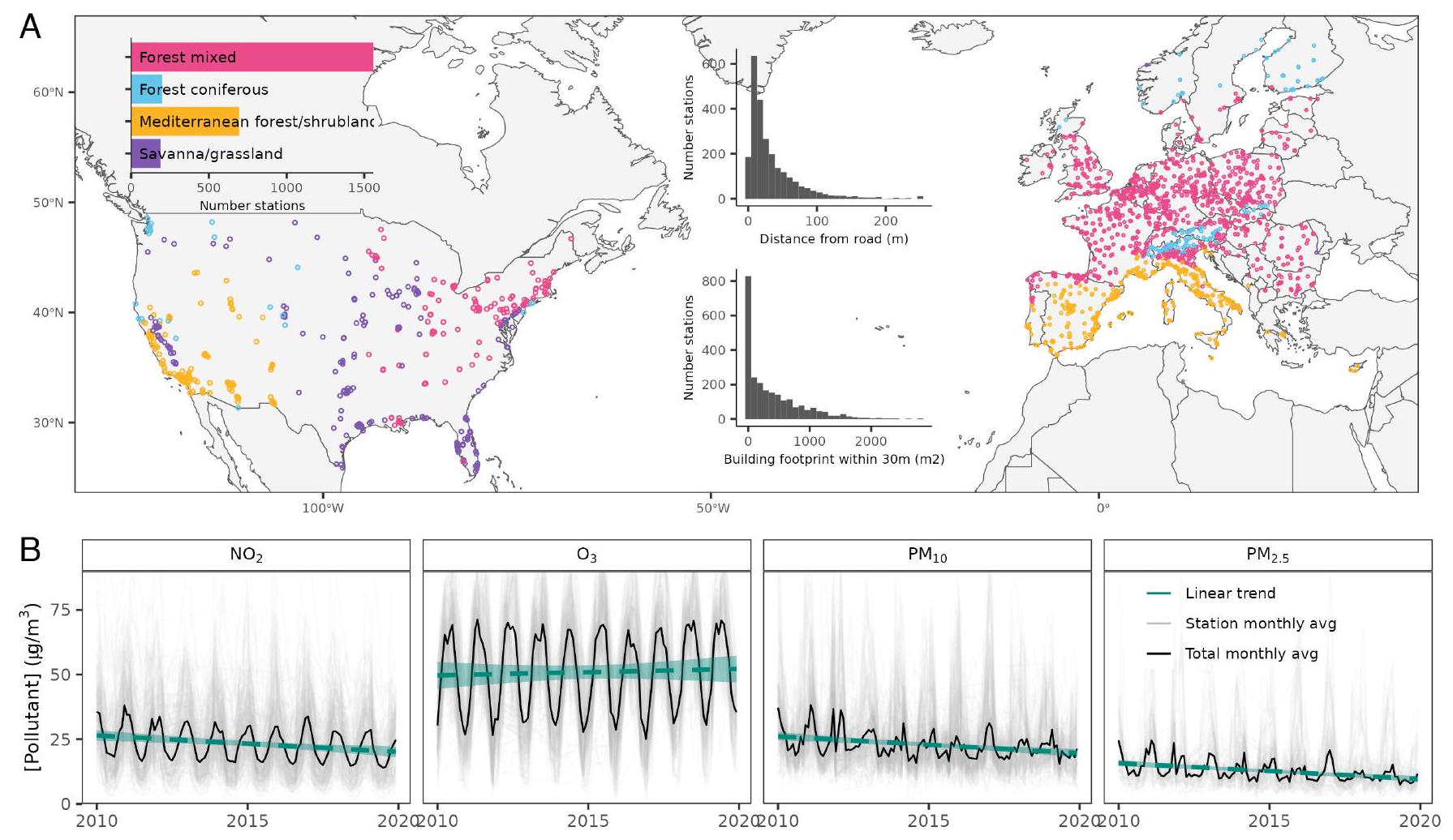

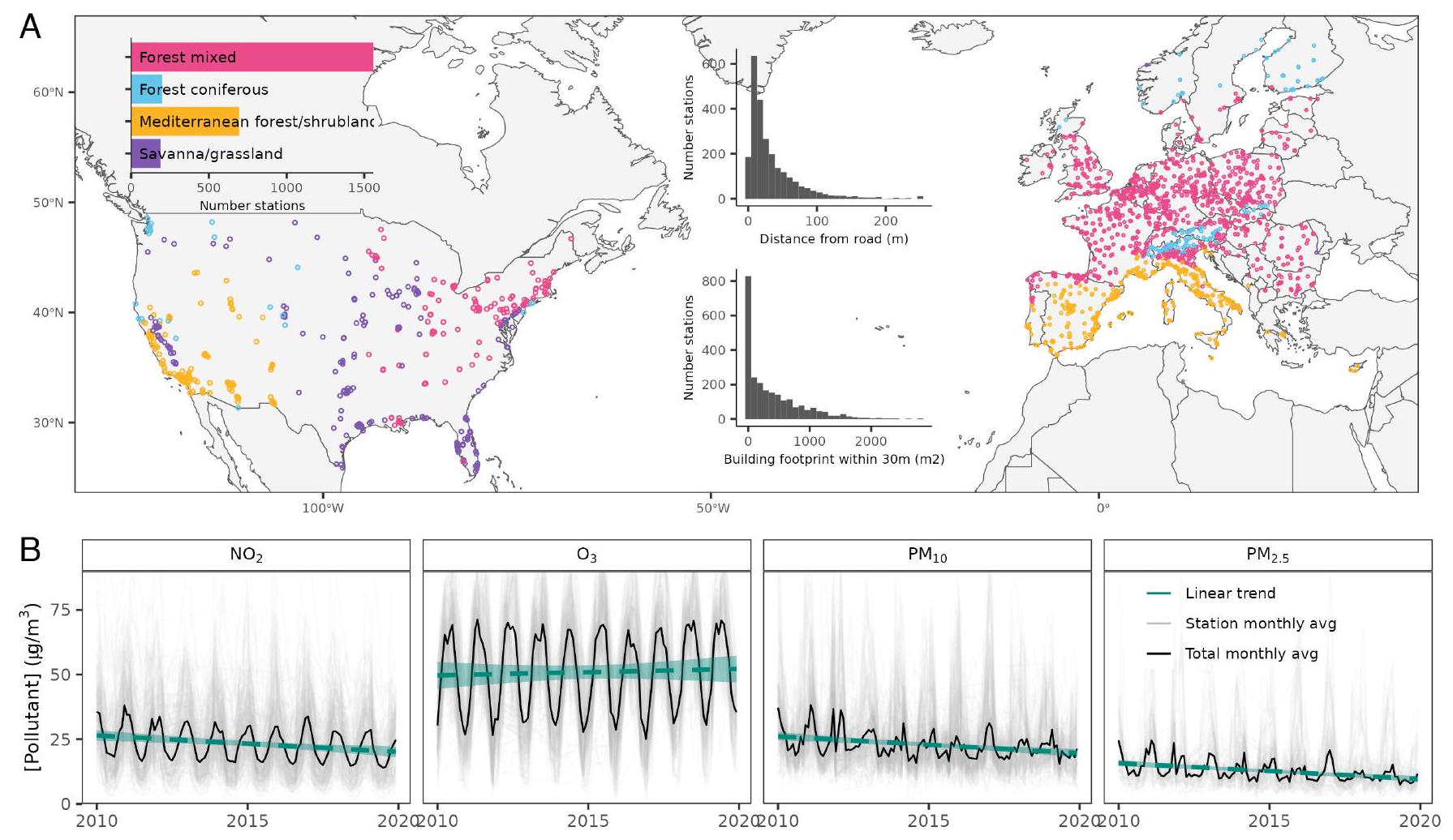

The assumption that vegetation improves air quality is prevalent in scientific, popular, and political discourse. However, experimental and modeling studies show the effect of green space on air pollutant concentrations in urban settings is highly variable and context specific. We revisited the link between vegetation and air quality using satellite-derived changes of urban green space and air pollutant concentrations from 2,615 established monitoring stations over Europe and the United States. Between 2010 and 2019, stations recorded declines in ambient

Abstract

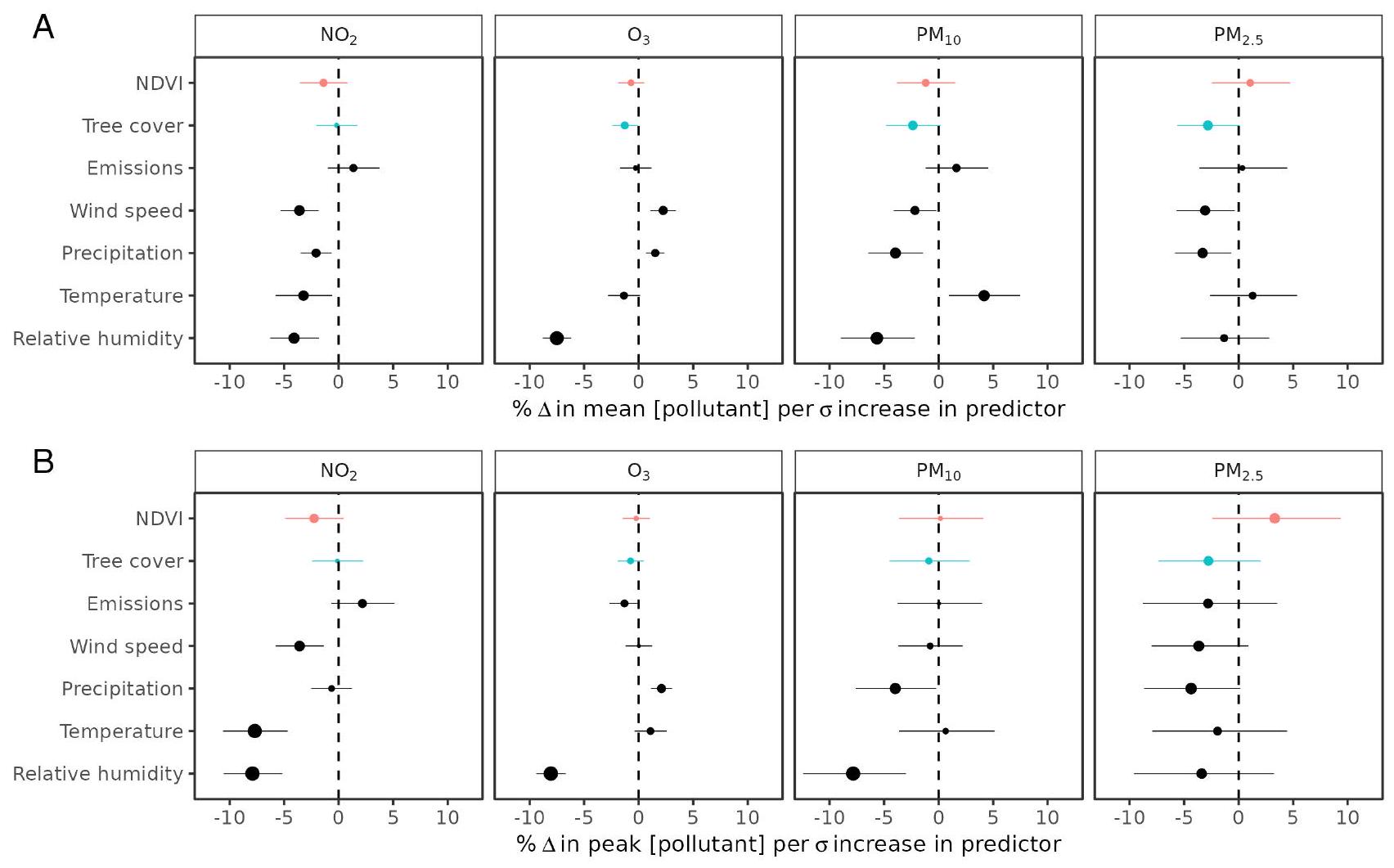

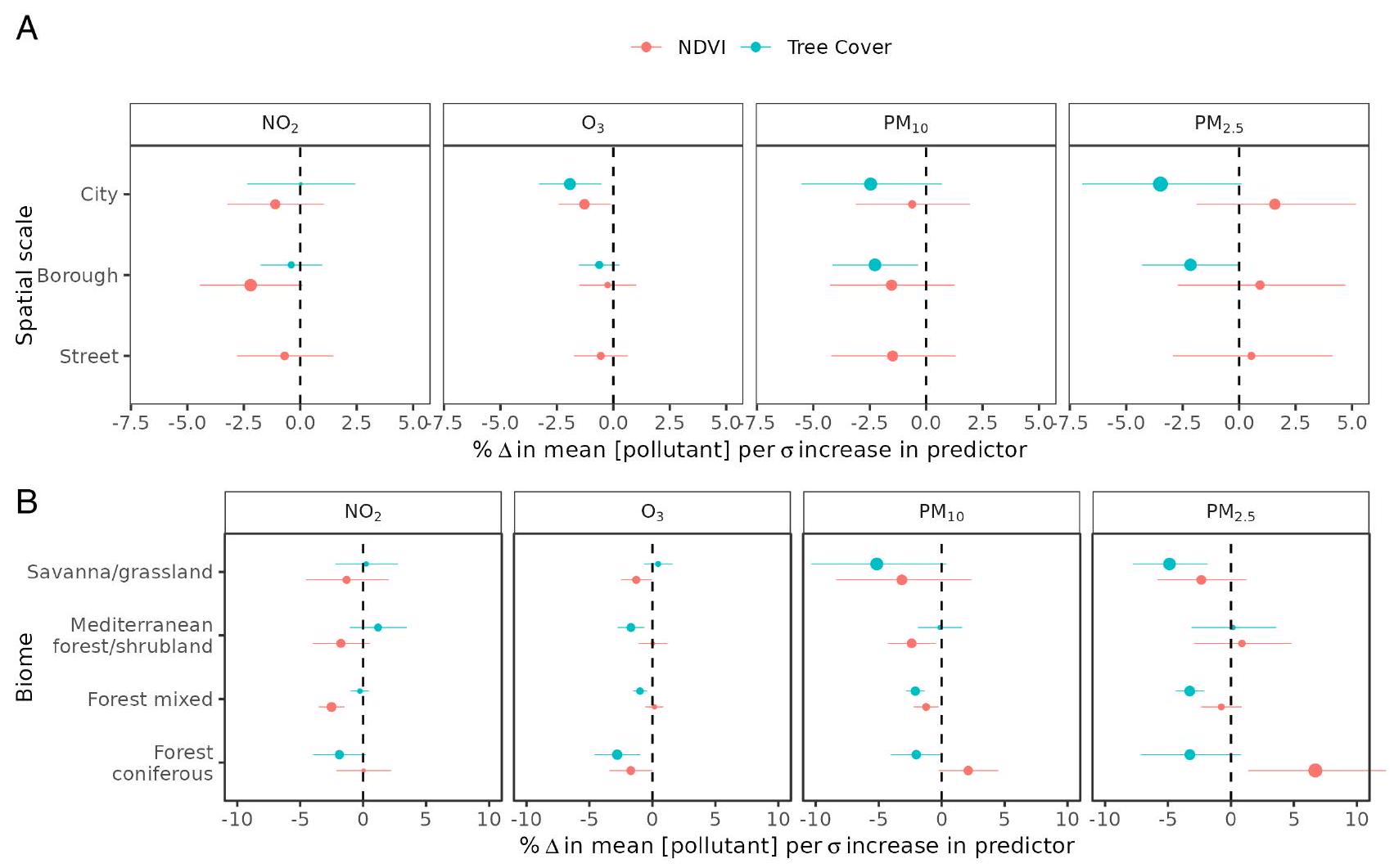

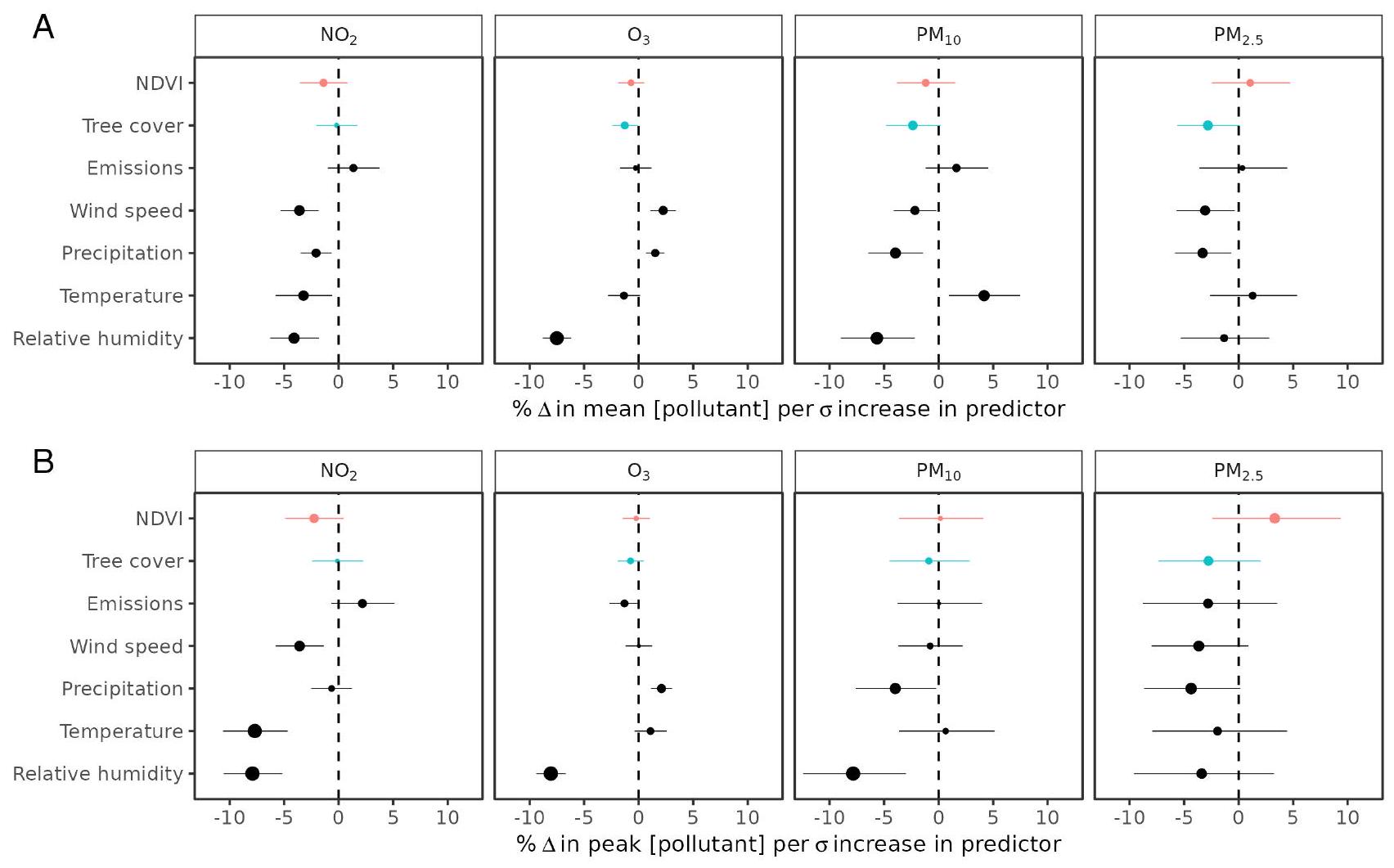

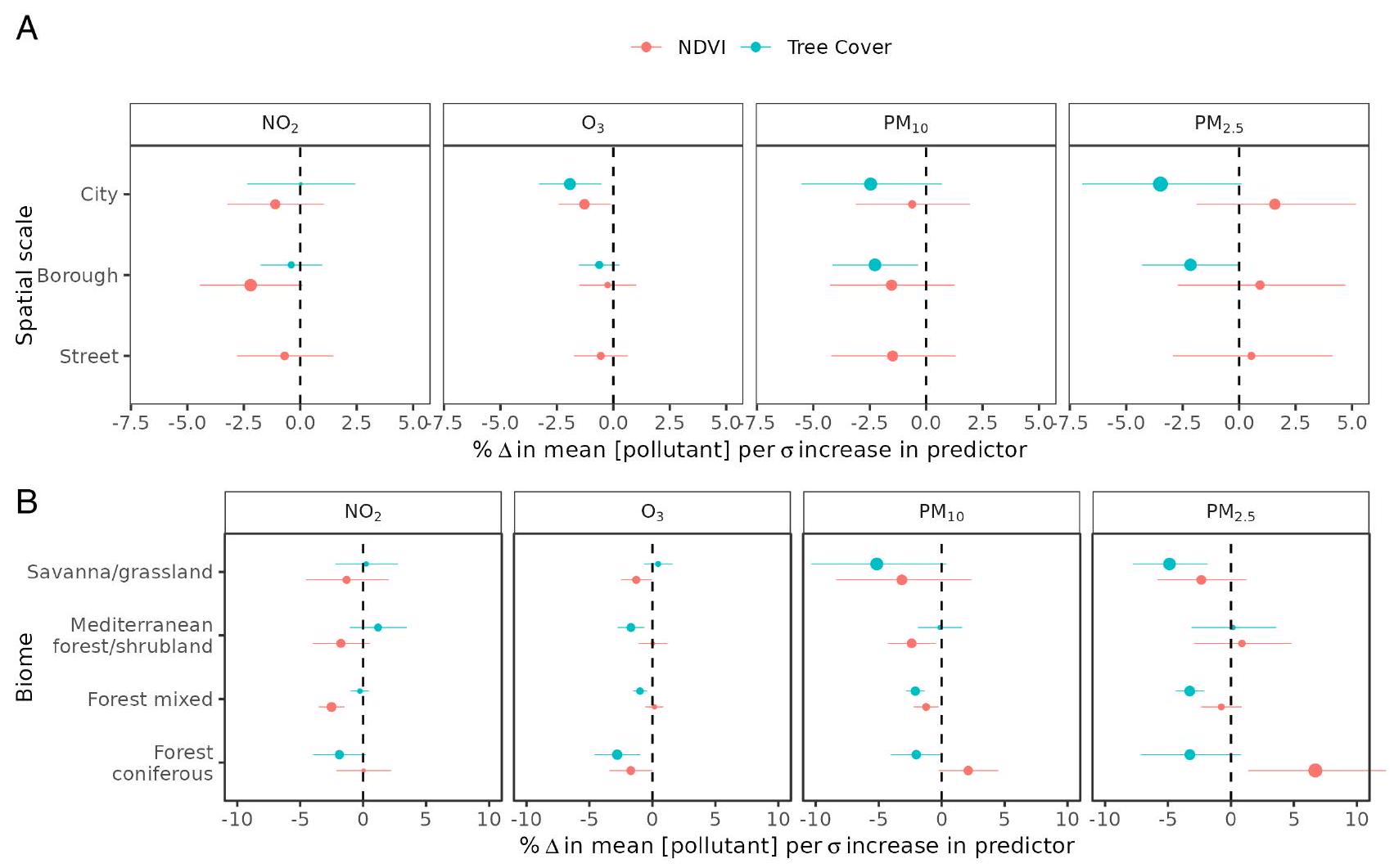

Significance Our findings indicate that the relationship between urban vegetation and air quality is more complex than previously thought. While urban greening has other positive health outcomes for residents, our study suggests that it may not be an efficient abatement measure for air pollution. Although we found minor amelioration effects of vegetation at the borough to city scale, street-level vegetation can act to exacerbate air pollution. Reducing anthropogenic emissions instead of urban greening should be the primary focus for improving air quality.

Results and Discussion

concentrations were evident in Southern Europe and Western United States, especially for PM (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The changes in air quality found here are broadly consistent with the trends reported in earlier studies using both the regulatory monitoring station networks as well as satellite instruments (e.g., refs. 19-22). The trend values found here are slightly higher in magnitude than a very recent paper studying European air quality trends for the 2005 to 2019 period after correcting for the impact of meteorology (23). The latter found median trends of

green space had a positive effect. Changes within the coniferous forest biome were driving this divergent response (Fig. 3B). In contrast, both total green space and tree cover in particular had negative effects on PM concentrations in the savanna/grassland biomes, albeit with greater variation in their effect as indicated by 95% CI.

outcomes such as mood and mental attention, which ultimately improve community wellbeing

Materials and Methods

were used in

- J. Lelieveld et al., Loss of life expectancy from air pollution compared to other risk factors: A worldwide perspective. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, 1910-1917 (2020).

- R. Burnett et al., Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9592-9597 (2018).

- S. Chowdhury et al., Global health burden of ambient PM2. 5 and the contribution of anthropogenic black carbon and organic aerosols. Environ. Int. 159, 107020 (2022).

- World Health Organization, “WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide” (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021).

- J. Lelieveld et al., Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7192-7197 (2019).

- United Nations Environment Programme, “Actions on air quality: A global summary of policies and programmes to reduce air pollution” (United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2021).

- J. González-Martín, N. J. R. Kraakman, C. Pérez, R. Lebrero, R. Muñoz, A state-of-the-art review on indoor air pollution and strategies for indoor air pollution control. Chemosphere 262, 128376 (2021).

- X. Yue et al., Mitigation of indoor air pollution: A review of recent advances in adsorption materials and catalytic oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124138 (2021).

- K. V. Abhijith et al., Air pollution abatement performances of green infrastructure in open road and built-up street canyon environments-A review. Atmos. Environ. 162, 71-86 (2017).

- A. Diener, P. Mudu, How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces’ mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective-With implications for urban planning Sci. Total Environ. 796, 148605 (2021).

- Y. Huang et al., A review of strategies for mitigating roadside air pollution in urban street canyons. Environ. Pollut. 280, 116971 (2021).

- C. J. Veerkamp et al., A review of studies assessing ecosystem services provided by urban green and blue infrastructure. Ecosyst. Serv. 52, 101367 (2021).

- V. Traverso, The best trees to reduce air pollution. BBC, 13 March 2023, (2020). https://www.bbc. com/future/article/20200504-which-trees-reduce-air-pollution-best. Accessed 20 September 2023.

- United Nations, “System of Environmental-Economic Accounting-Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA)” (White cover publication, 2021). https://seea.un.org/content/system-environmental-economic-accounting-ecosystem-accounting-white-cover-version. Accessed 20 September 2023.

- S. Janhäll, Review on urban vegetation and particle air pollution-Deposition and dispersion. Atmos. Environ. 105, 130-137 (2015).

- P. E. J. Vos, B. Maiheu, J. Vankerkom, S. Janssen, Improving local air quality in cities: To tree or not to tree? Environ. Pollut. 183, 113-122 (2013).

- Y. Barwise, P. Kumar, Designing vegetation barriers for urban air pollution abatement: A practical review for appropriate plant species selection. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 1-19 (2020).

- C. M. Nussbaumer, R. C. Cohen, Impact of OA on the temperature dependence of PM 2.5 in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3549-3558 (2021).

- C. B. B. Guerreiro, V. Foltescu, F. de Leeuw, Air quality status and trends in Europe. Atmos. Environ. 98, 376-384 (2014).

- P. Schneider, W. A. Lahoz, R. van der A, Recent satellite-based trends of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide over large urban agglomerations worldwide. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 1205-1220 (2015).

- P. Schneider, R. Van der A, A global single-sensor analysis of 2002-2011 tropospheric nitrogen dioxide trends observed from space. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D16309 (2012).

- L. N. Lamsal et al., U.S. NO2 trends (2005-2013): EPA Air Quality System (AQS) data versus improved observations from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI). Atmos. Environ. 110, 130-143 (2015).

- S.-E. Walker, S. Solberg, P. Schneider, C. Guerreiro, The AirGAM 2022 r 1 air quality trend and prediction model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 573-595(2023).

- Q. Zhang et al., Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 24463-24469 (2019).

- K. Wang, M. Yan, Y. Wang, C.-P. Chang, The impact of environmental policy stringency on air quality. Atmos. Environ. 231, 117522 (2020).

- I. Jhun, B. A. Coull, A. Zanobetti, P. Koutrakis, The impact of nitrogen oxides concentration decreases on ozone trends in the USA. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 8, 283-292 (2015).

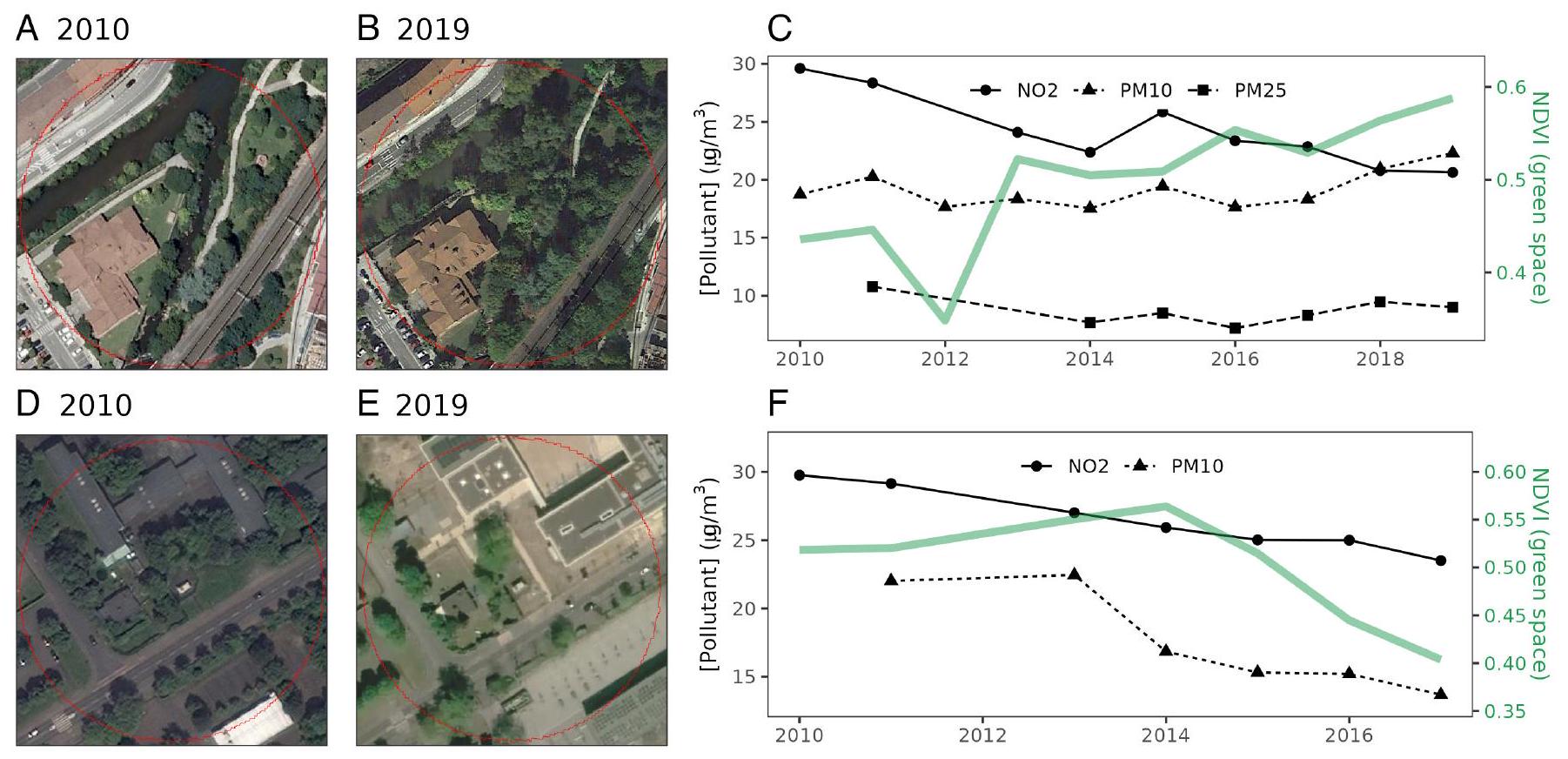

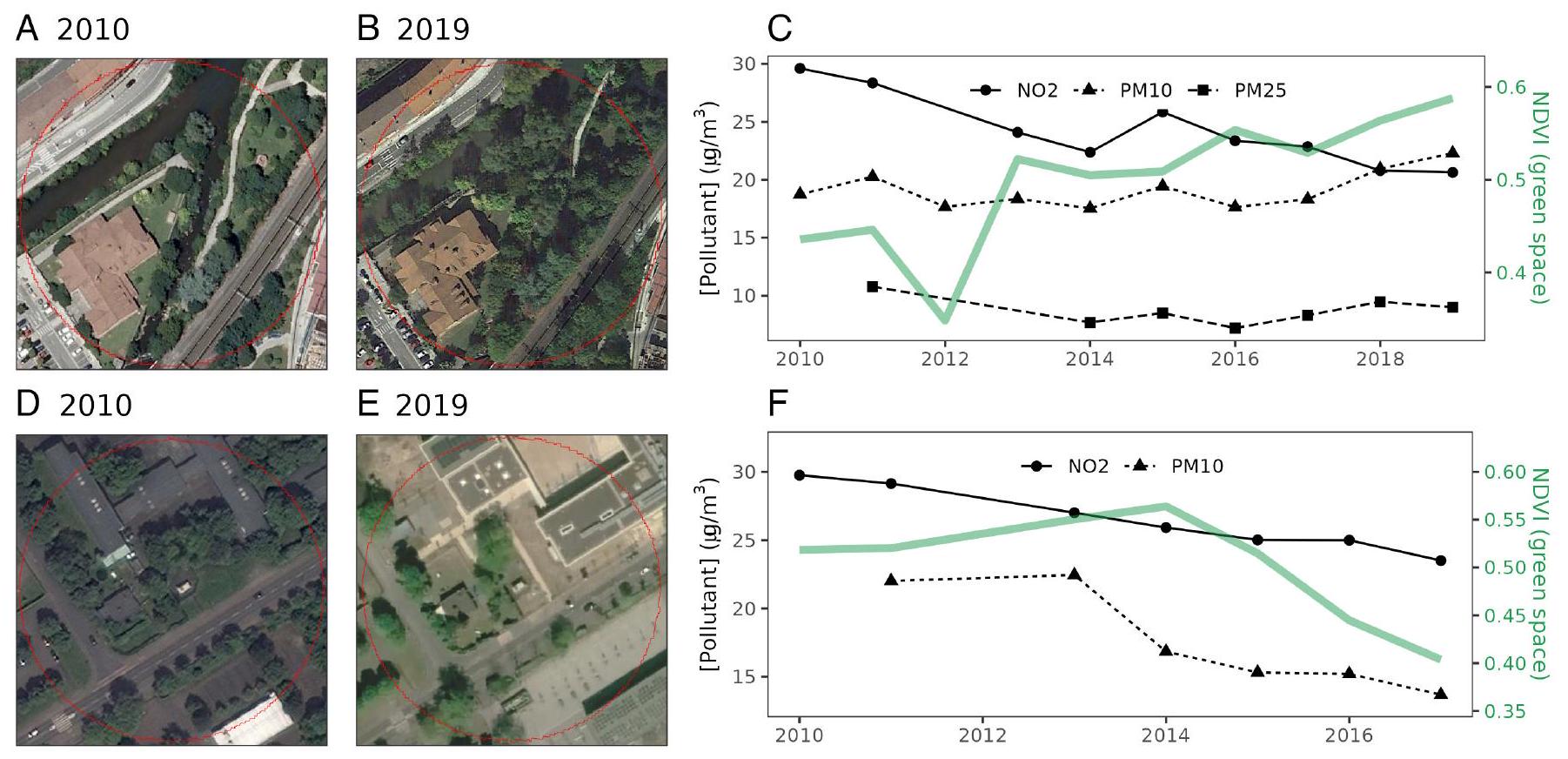

any model-specific effects. Air pollutant concentrations were log-transformed to ensure residuals were normally distributed. ii) To quantify the association between green space and air pollution concentration over time while controlling for the effect of emissions and climate variables, we fitted the same model structure described above, except adding green space (NDVI and tree cover), emissions, and climate covariates as fixed-effects. Separate models were fit for each biome and each buffer zone used to aggregate green space around the stations. iii) The manually screened stations with extreme NDVI changes were used to fit mixed-effects models to test whether air pollution declines were greater at stations with gains in green space than at stations with losses in green space. Linear trends in climate variables and a categorical gain/loss in green space were included as fixed effects, while sampler was included as a random effect to control for any sampler-specific biases in interpretation of aerial imagery.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability. Code supporting the analysis: https://github.com/zanderVenter/greenspace-air-pollution. Previously published data were used for this work and are cited in the methods section.

acknowledgments. We acknowledge funding from the Research Council of Norway (grant number 326641). Additional funding through the project SIS-EO (NILU #B121004) is gratefully acknowledged. Thanks to Sourangsu Chowdhury for input into the conceptualization and data collection. - Z. S. Venter, S. L. Scott, P. G. Desmet, M. T. Hoffman, Application of Landsat-derived vegetation trends over South Africa: Potential for monitoring land degradation and restoration. Ecol. Indicators 113, 106206 (2020).

- J. He et al., Air pollution characteristics and their relation to meteorological conditions during 2014-2015 in major Chinese cities. Environ. Pollut. 223, 484-496 (2017).

- Y. Liu, Y. Zhou, J. Lu, Exploring the relationship between air pollution and meteorological conditions in China under environmental governance. Sci. Rep. 10, 14518 (2020).

- R. Jayamurugan, B. Kumaravel, S. Palanivelraja, M. Chockalingam, Influence of temperature, relative humidity and seasonal variability on ambient air quality in a coastal urban area. Int. J. Atmos. Sci. 2013, 264046 (2013).

- H. Chen et al., Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and cardiovascular mortality. Epidemiology 24, 35-43 (2013).

- P. Kumar et al., The nexus between air pollution, green infrastructure and human health. Environ. Int. 133, 105181 (2019).

- V. Jennings, C. E. Reid, C. H. Fuller, Green infrastructure can limit but not solve air pollution injustice. Nat. Commun. 12, 4681 (2021).

- N. E. Young et al., A survival guide to Landsat preprocessing. Ecology 98, 920-932 (2017).

- E. Nemitz et al., Potential and limitation of air pollution mitigation by vegetation and uncertainties of deposition-based evaluations. Philos. Trans. R Soc. A 378, 20190320 (2020).

- M. Tallis, G. Taylor, D. Sinnett, P. Freer-Smith, Estimating the removal of atmospheric particulate pollution by the urban tree canopy of London, under current and future environments. Landscape Urban Plann. 103, 129-138 (2011).

- D. J. Nowak, S. Hirabayashi, A. Bodine, E. Greenfield, Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environ. Pollut. 193, 119-129 (2014).

- W. Y. Chen, “Urban nature and urban ecosystem services” in Greening Cities: Forms and Functions, P. Tan, C. Jim, Eds. (Springer, Singapore, 2017), pp. 181-199.

- X. P. Song, P. Y. Tan, P. Edwards, D. Richards, The economic benefits and costs of trees in urban forest stewardship: A systematic review. Urban Forest. Urban Green. 29, 162-170 (2018).

- S. Hirabayashi, C. N. Kroll, D. J. Nowak, i-Tree Eco Dry Deposition Model Descriptions (Citeseer, Princeton, NJ, 2012).

- M. Lateb et al., On the use of numerical modelling for near-field pollutant dispersion in urban environments-A review. Environ. Pollut. 208, 271-283 (2016).

- R. P. Remme, M. Schröter, L. Hein, Developing spatial biophysical accounting for multiple ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 10, 6-18 (2014).

- T. S. Eisenman et al., Urban trees, air quality, and asthma: An interdisciplinary review. Landscape Urban Plann. 187, 47-59 (2019).

- T.V. Kokkonen et al., The effect of urban morphological characteristics on the spatial variation of PM2.5 air quality in downtown Nanjing. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 1, 481-497 (2021).

- I. Alcock et al., Land cover and air pollution are associated with asthma hospitalisations: A crosssectional study. Environ. Int. 109, 29-41 (2017).

- M. A. Pilat et al., The effect of tree cover and vegetation on incidence of childhood asthma in metropolitan statistical areas of Texas. HortTechnol. 22, 631-637 (2012).

- G. S. Lovasi et al., Urban tree canopy and asthma, wheeze, rhinitis, and allergic sensitization to tree pollen in a New York City birth cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 494-500 (2013).

- S.P. Jariwala et al., Association between tree pollen counts and asthma ED visits in a high-density urban center. J. Asthma 48, 442-448 (2011).

- Z. S. Venter, N. H. Krog, D. N. Barton, Linking green infrastructure to urban heat and human health risk mitigation in Oslo, Norway. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 136193 (2020).

- A. C. Lee, R. Maheswaran, The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public Health 33, 212-222 (2011).

- M. C. Kondo, J. M. Fluehr, T. McKeon, C. C. Branas, Urban green space and its impact on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 445 (2018).

- A. Tiwari et al., Considerations for evaluating green infrastructure impacts in microscale and macroscale air pollution dispersion models. Sci. Total Environ. 672, 410-426 (2019).

- US Environmental Protection Agency, “Air quality system data mart [internet database]”. https:// www.epa.gov/outdoor-air-quality-data. Accessed 14 April 2023.

- European Environmental Agency, “Air quality time series (E1a & E2a data sets)”. https://www.eea. europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/aqereporting-9/estatistics-e1a-e2a. Accessed 14 April 2023.

- C. J. Murray et al., Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396, 1223-1249 (2020).

- M. Grundström, H. Pleijel, Limited effect of urban tree vegetation on

and concentrations near a traffic route. Environ. Pollut. 189, 73-76 (2014). - M. Schiavina, M. Melchiorri, M. Pesaresi, “GHS-SMOD R2023A-GHS settlement layers, application of the degree of urbanisation methodology (stage I) to GHS-POP R2023A and GHS-BUILT-S R2023A, multitemporal (1975-2030)”. European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC) [Dataset] doi: https://doi.org/10.2905/A0DF7A6F-49DE-46EA-9BDE-563437A6E2BA PID: http://data. europa.eu/89h/a0df7abf-49de-46ea-9bde-563437abe2ba. Accessed 20 September 2023.

- S. Solberg, S.-E. Walker, P. Schneider, C. Guerreiro, Quantifying the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown measures on nitrogen dioxide levels throughout Europe. Atmosphere 12, 131 (2021).

- C. J. Tucker, Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8, 127-150 (1979).

- C. M. DiMiceli et al., Annual Global Automated MODIS Vegetation Continuous Fields (MOD44B) at 250 m Spatial Resolution for Data Years Beginning Day 65 (Version 6, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, 2017), pp. 2000-2010.

- N. Gorelick et al., Google earth engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18-27 (2017).

- D. P. Roy et al., Characterization of Landsat-7 to Landsat-8 reflective wavelength and normalized difference vegetation index continuity. Remote Sens. Environ. 185, 57-70 (2016).

- M. Crippa et al., Fossil CO and GHG Emissions of All World Countries (Publication Office of the European Union, Luxemburg, 2019).

- J. Muñoz-Sabater et al., ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349-4383 (2021).

- D. Bates, Fitting linear mixed models in R. R News 5, 27-30 (2005).

- Author contributions: Z.S.V., A.H., E.S., P.S., and N.C. designed research; Z.S.V. performed research; Z.S.V. and A.H. analyzed data; and Z.S.V., A.H., E.S., P.S., and N.C. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.Copyright © 2024 the Author(s). Published by PNAS. This open access article is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY).Although PNAS asks authors to adhere to United Nations naming conventions for maps (https://www.un.org/ geospatial/mapsgeo), our policy is to publish maps as provided by the authors.

To whom correspondence may be addressed. Email: zander.venter@nina.no. This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas. 2306200121/-/DCSupplemental.

Published January 29, 2024.