DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-01

احترار المياه الجوفية العالمية بسبب تغير المناخ

تم القبول: 12 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 4 يونيو 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

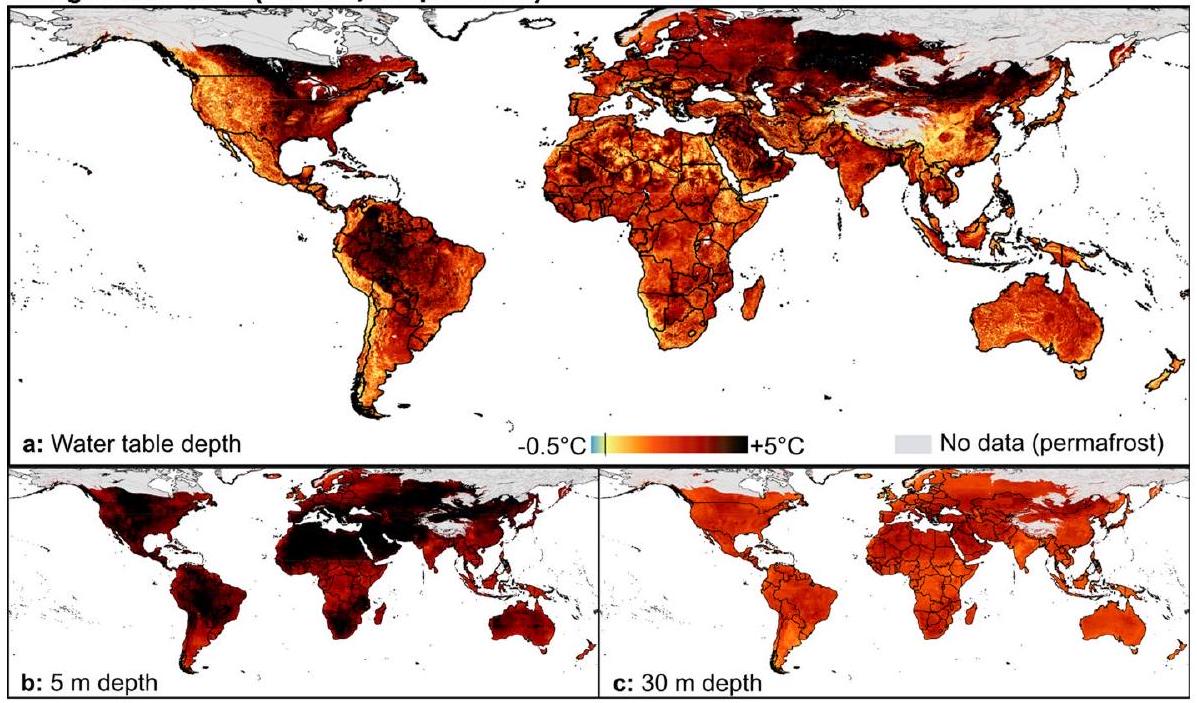

تحتوي الطبقات المائية على أكبر مخزون من المياه العذبة غير المتجمدة، مما يجعل المياه الجوفية حيوية للحياة على الأرض. من المدهش أن القليل جداً معروف عن كيفية استجابة المياه الجوفية لارتفاع درجات الحرارة السطحية عبر المقاييس المكانية والزمنية. من خلال التركيز على نقل الحرارة الانتشاري، نقوم بمحاكاة درجات حرارة المياه الجوفية الحالية والمتوقعة على المستوى العالمي. نوضح أن المياه الجوفية على عمق مستوى المياه (باستثناء مناطق التربة المتجمدة) من المتوقع أن ترتفع درجات حرارتها بمعدل

تغيرات درجة حرارة السطح قبل الملاحظة على نطاق عالمي

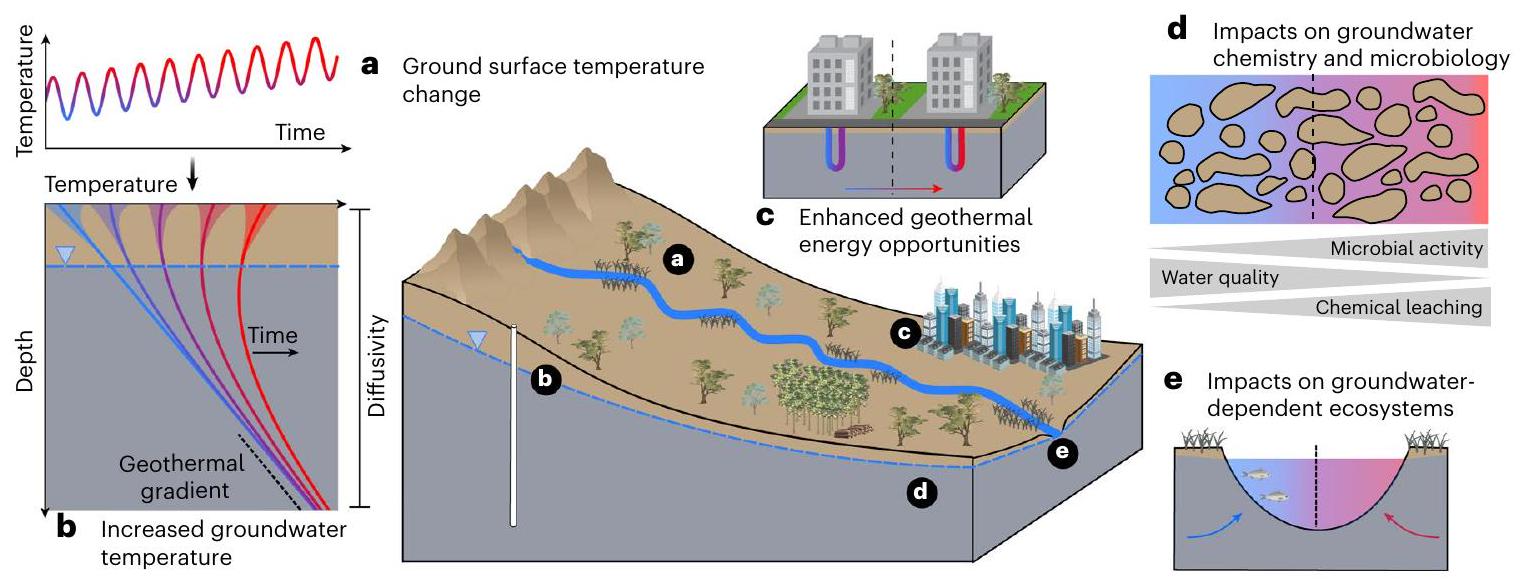

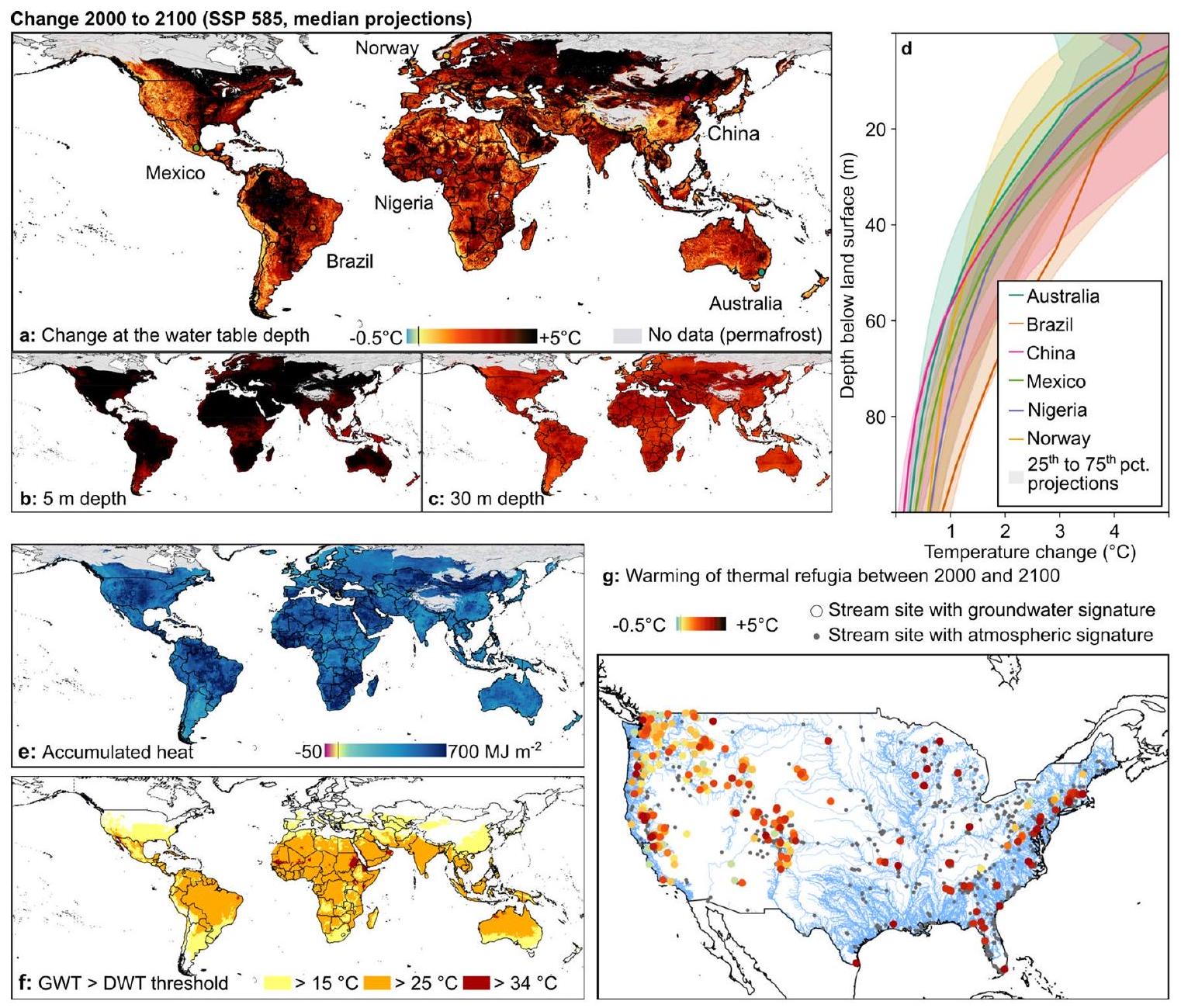

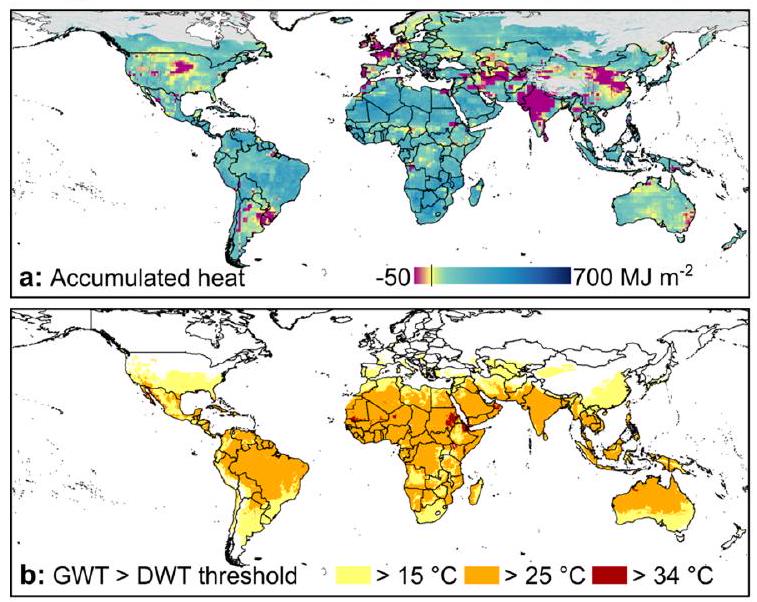

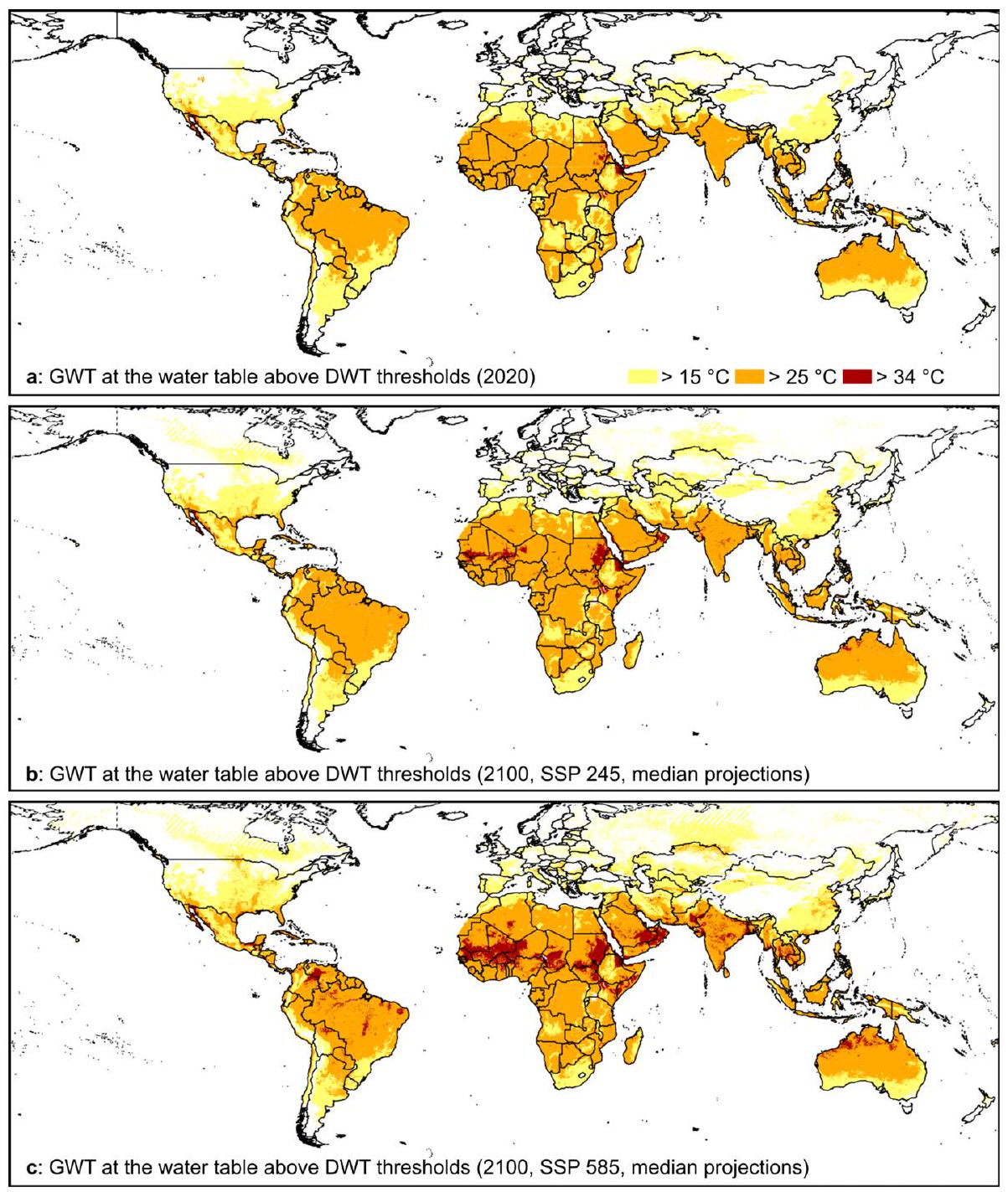

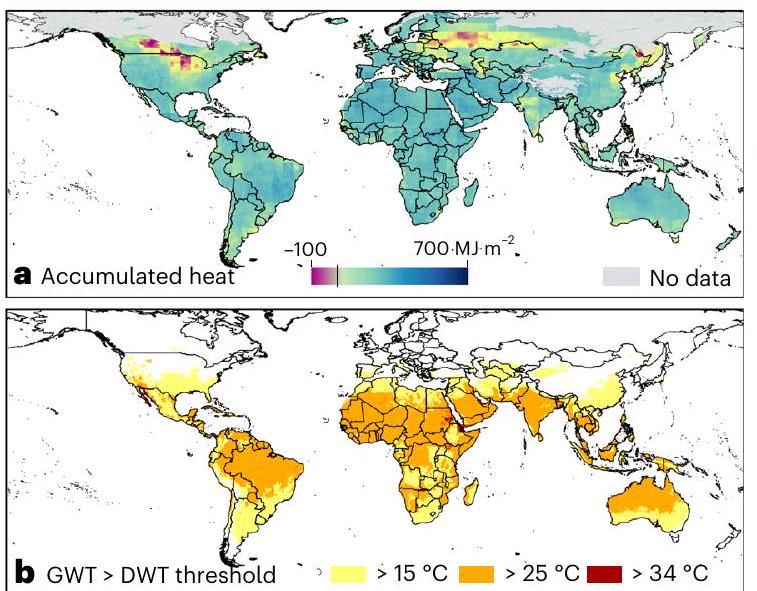

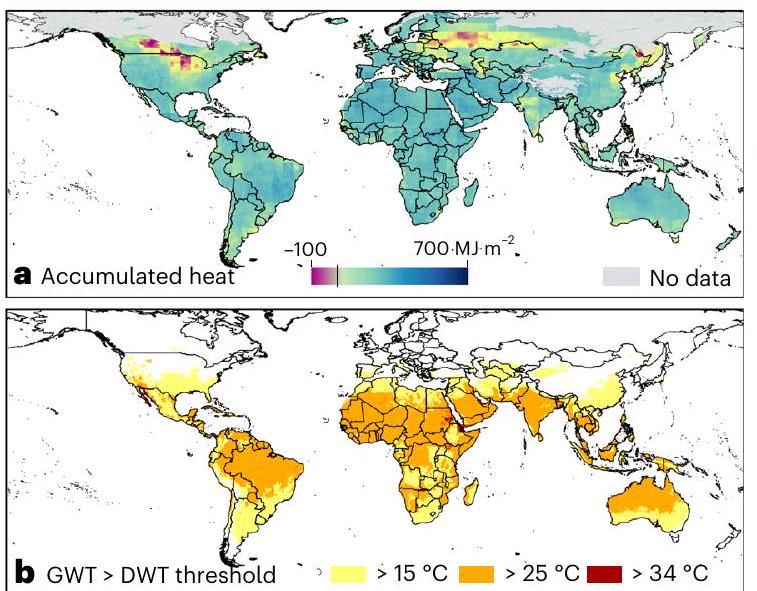

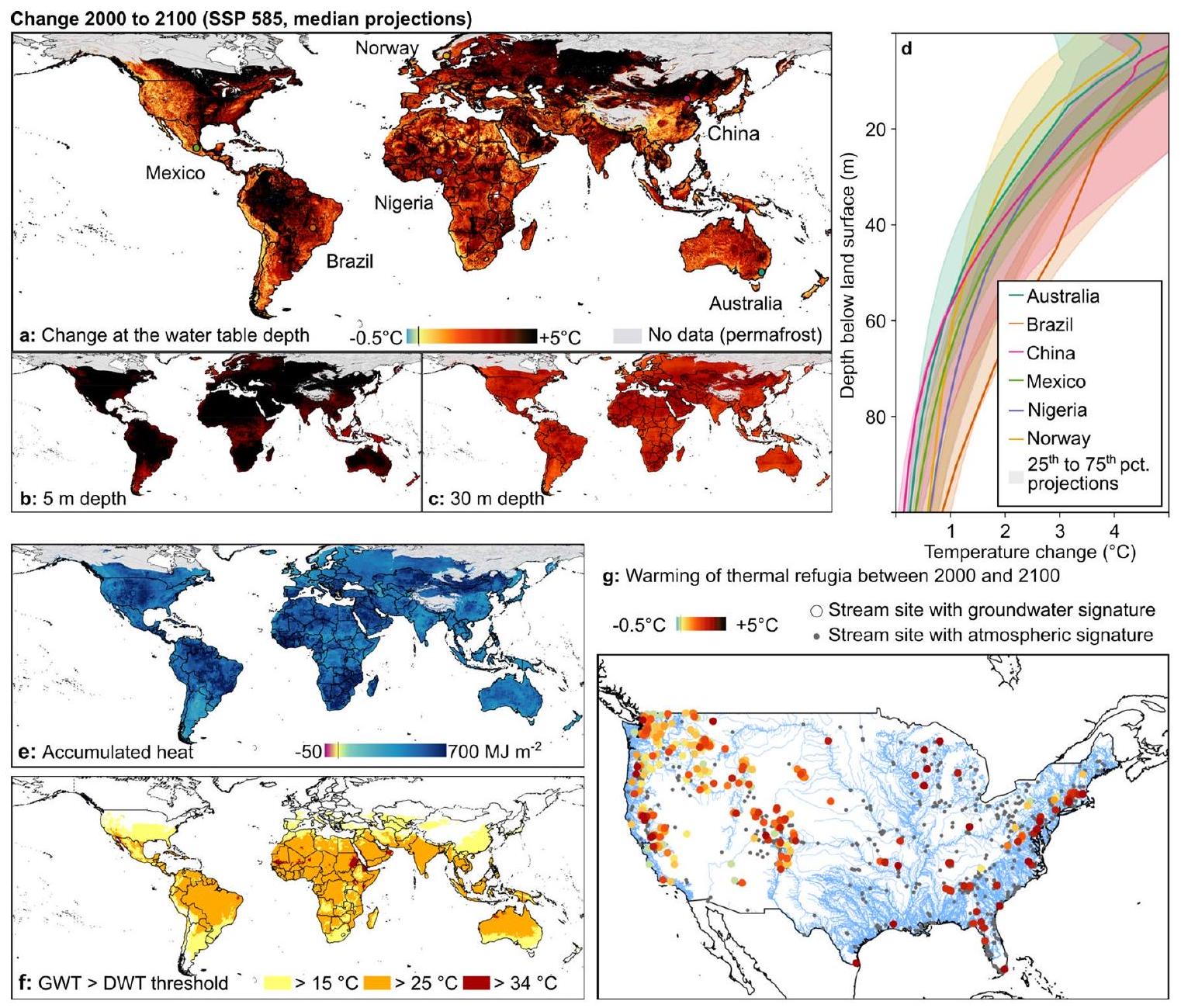

تم تحديدها بواسطة معايير مياه الشرب (الشكل 1d) و(3) حيث سيكون لتصريف المياه الجوفية الدافئة التأثير الأكثر وضوحًا على درجات حرارة الأنهار والأنظمة البيئية المائية (الشكل 1e). نموذجنا عالمي، وحدود دقته تحد من التقاط التفاصيل الدقيقة للعمليات الصغيرة، مما ينتج عنه نتائج محافظة بناءً على افتراضات هيدروليكية وحرارية تم اختبارها، بما في ذلك التدفق الواقعي من إعادة شحن على نطاق الحوض. قد تؤدي العمليات الأكثر محلية إلى درجات حرارة أعلى للمياه الجوفية في المناطق التي تشهد تدفقًا متزايدًا للأسفل (على سبيل المثال، إعادة الشحن المستندة إلى الأنهار) أو درجات حرارة سطح مرتفعة (على سبيل المثال، جزر الحرارة الحضرية) (تقدم الملاحظة التكميلية 1 التفاصيل).

درجات حرارة المياه الجوفية

وعلم الأحياء الدقيقة، الذي يؤثر بدوره على جودة المياه (د) والأنظمة البيئية المعتمدة على المياه الجوفية (هـ). تم إنشاء الشكل باستخدام صور من مكتبة الوسائط UMCES IAN بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي CC BY-SA 4.0.

ملفات النطاق مع تغييرات في درجة الحرارة

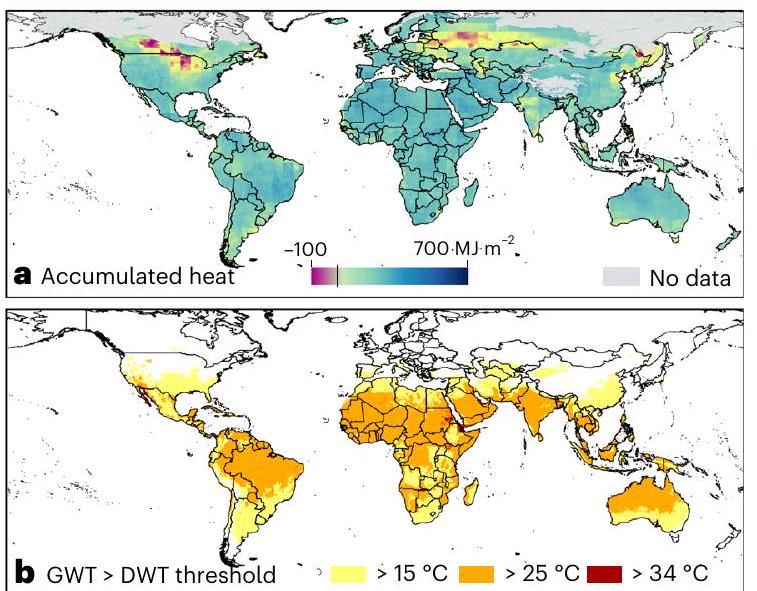

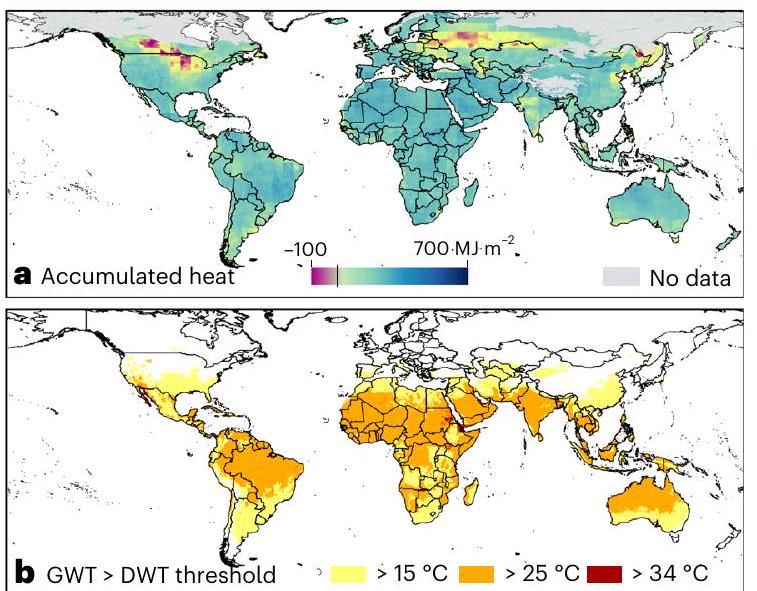

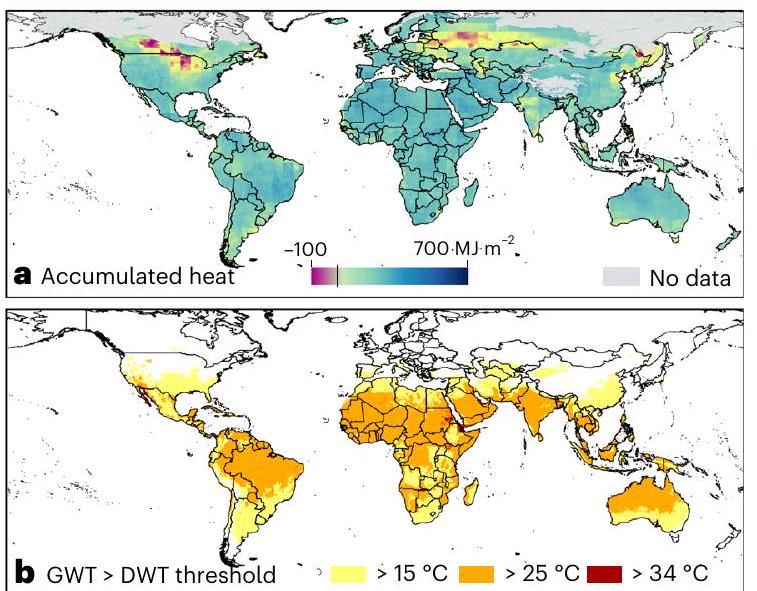

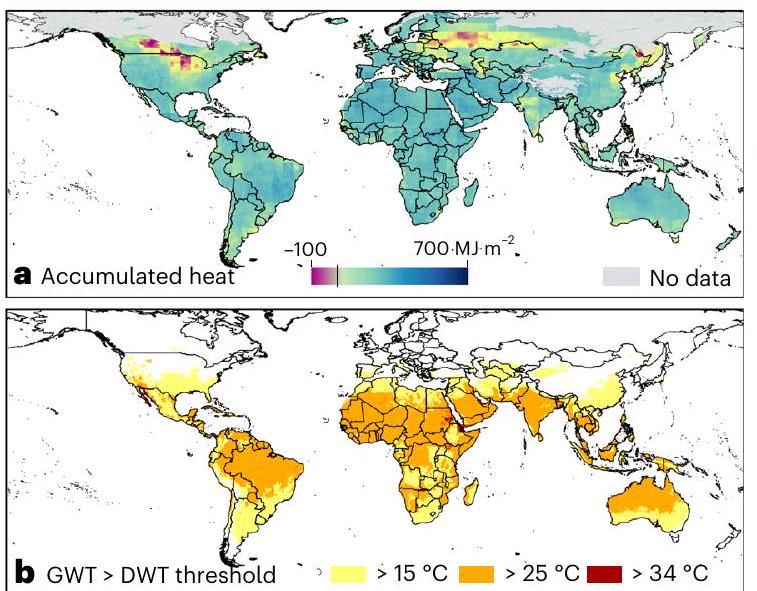

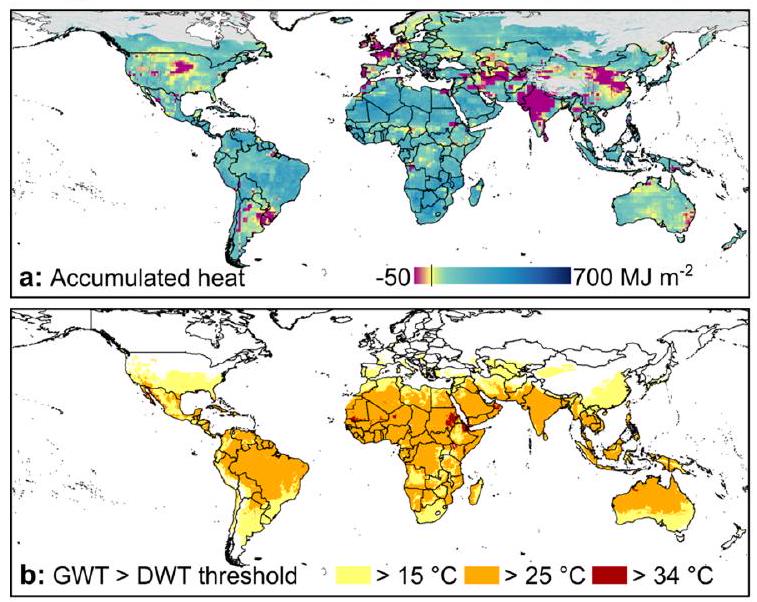

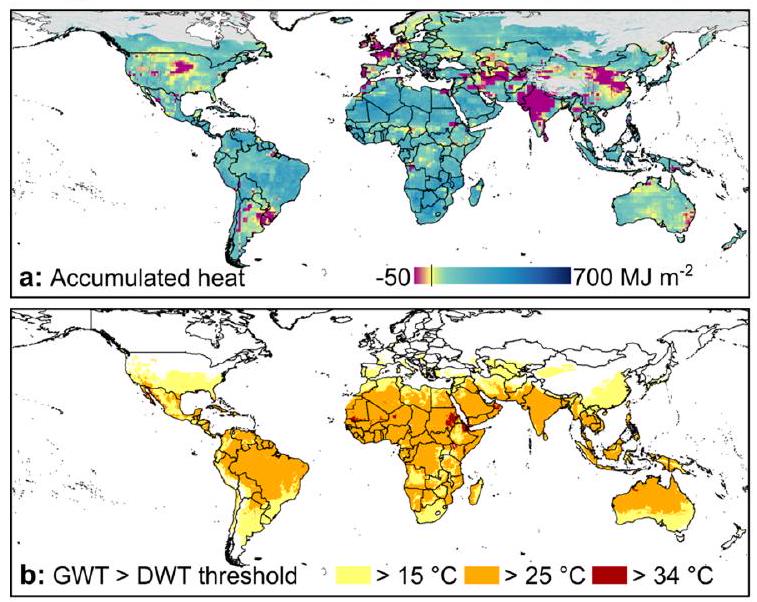

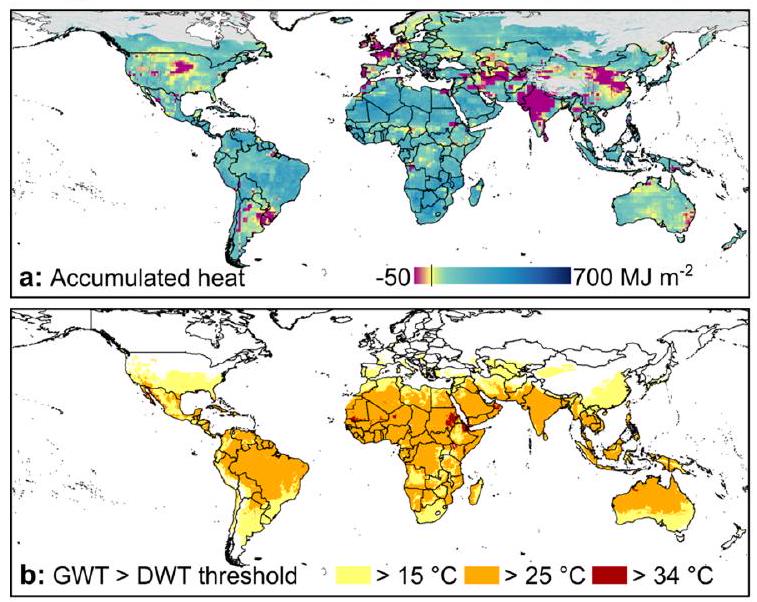

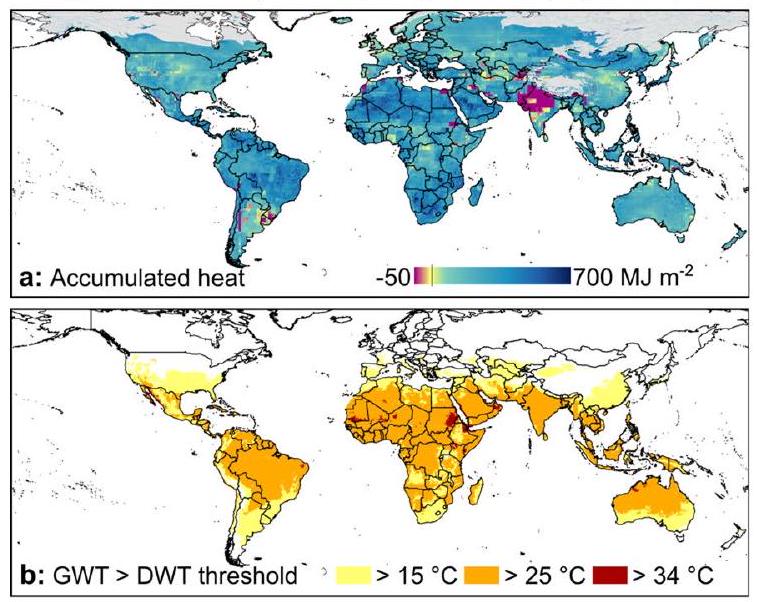

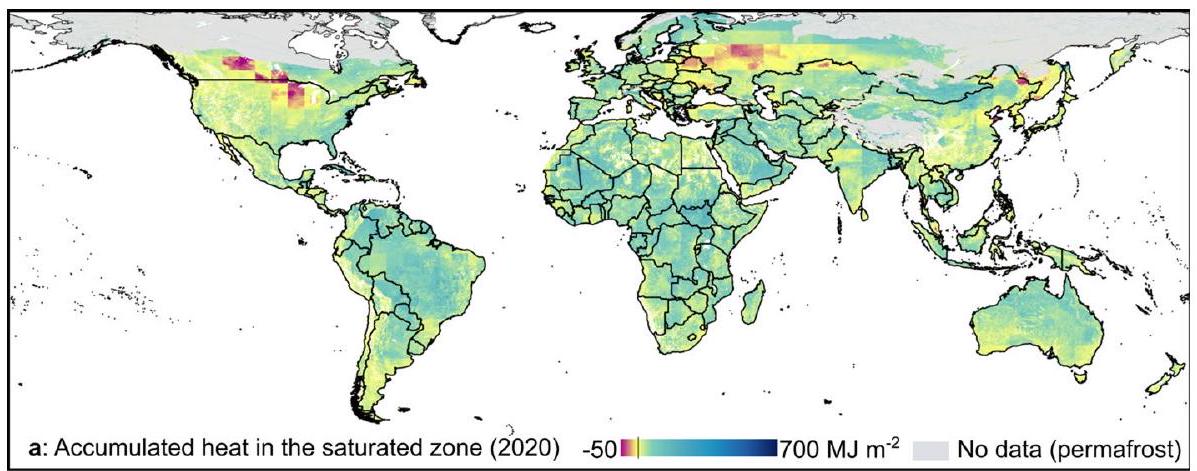

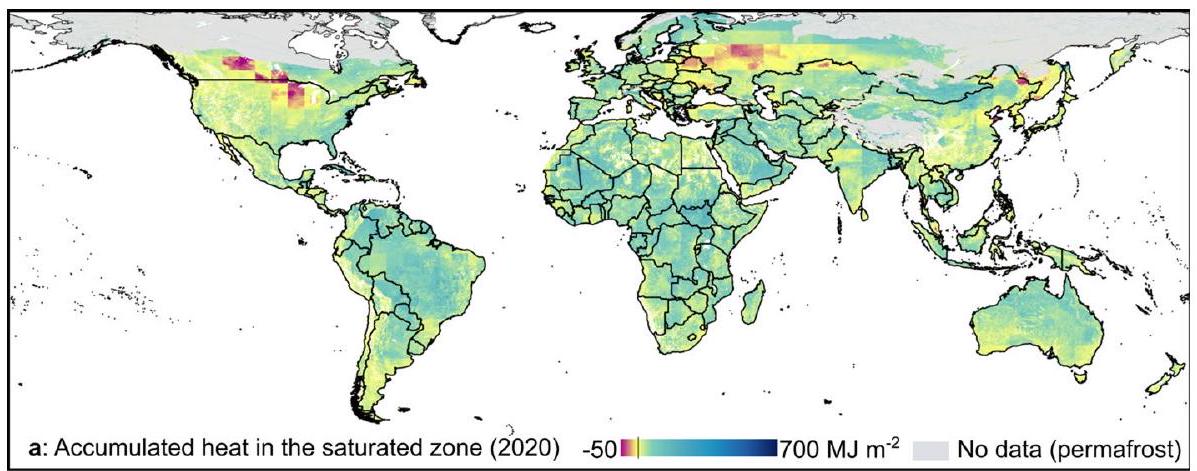

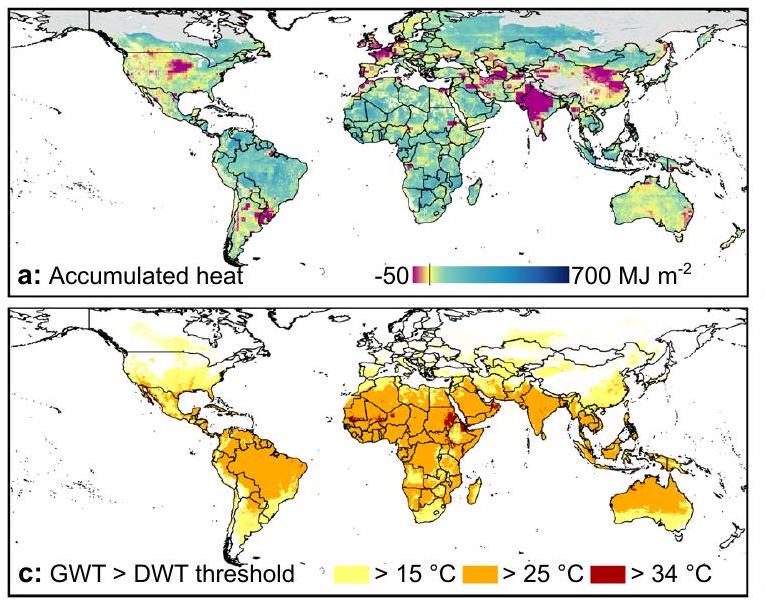

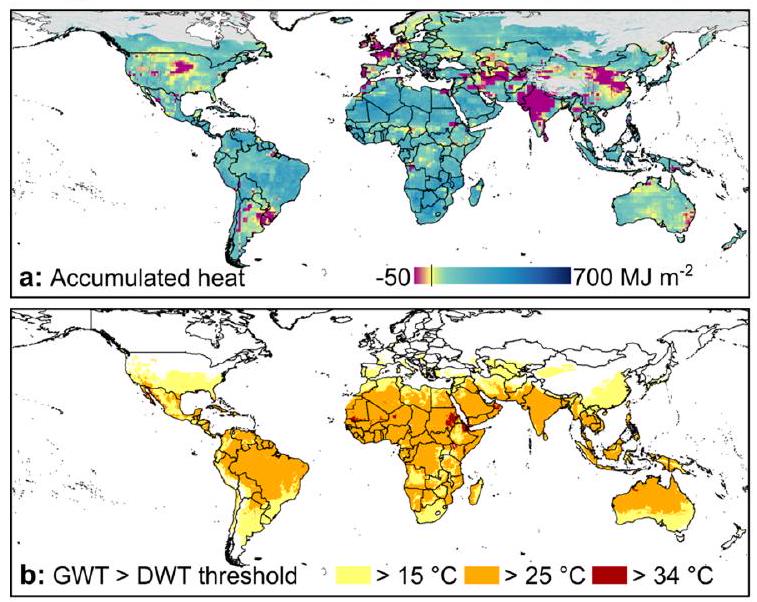

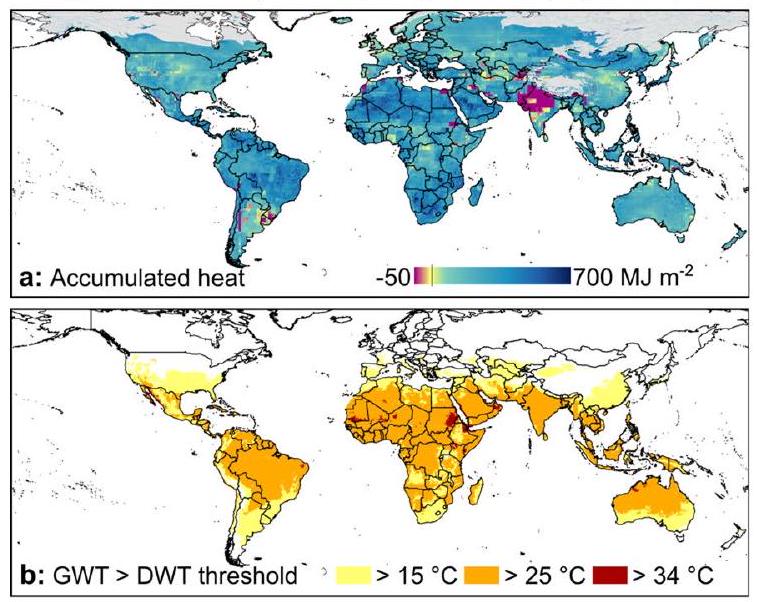

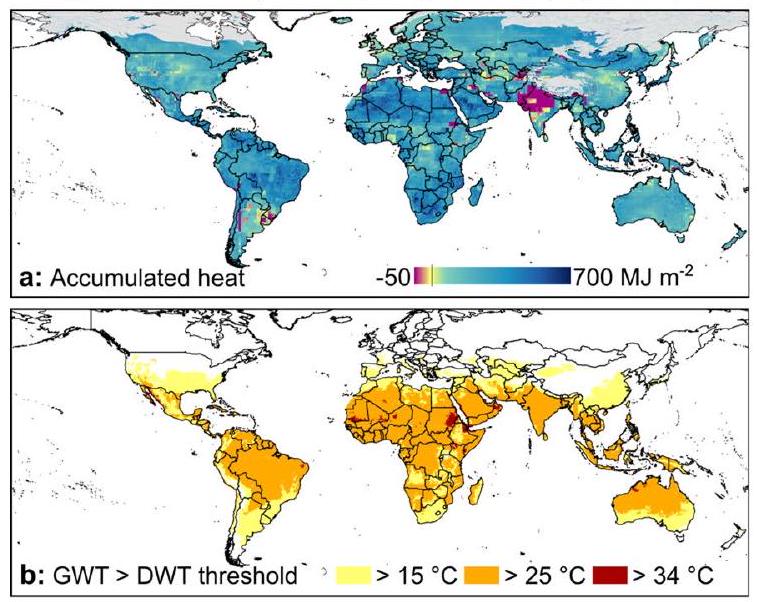

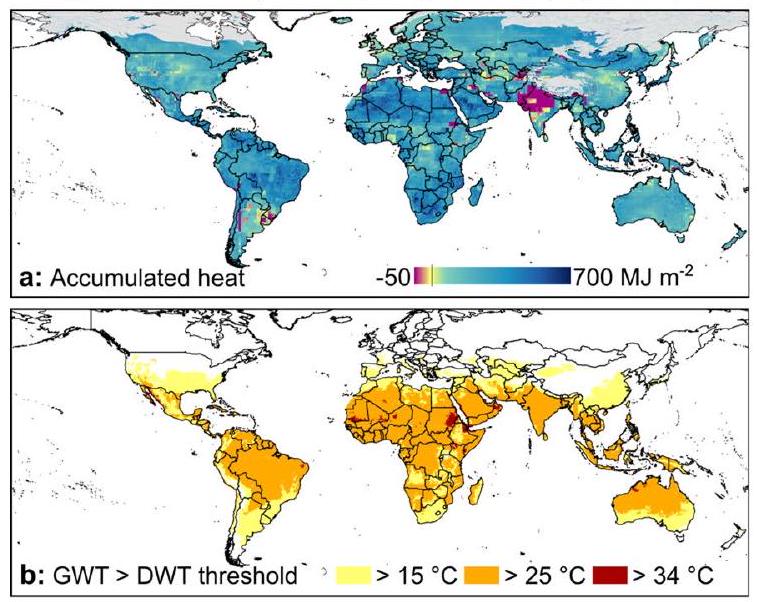

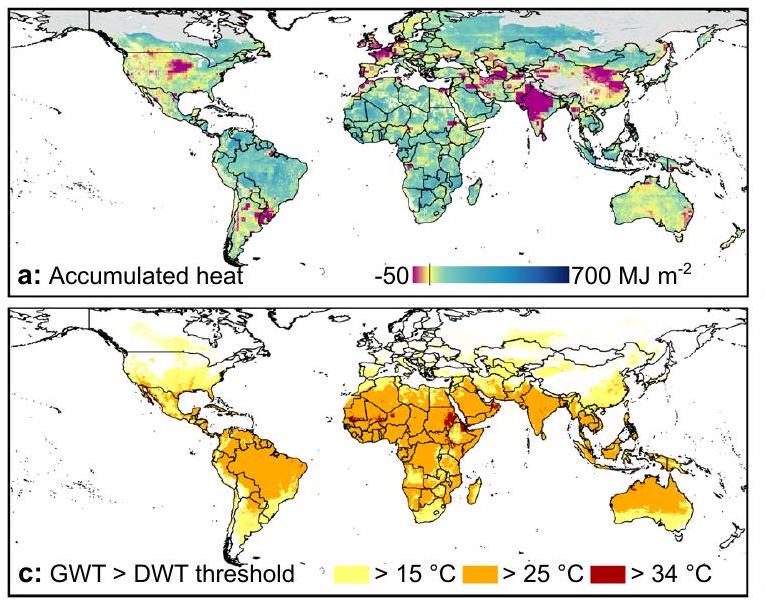

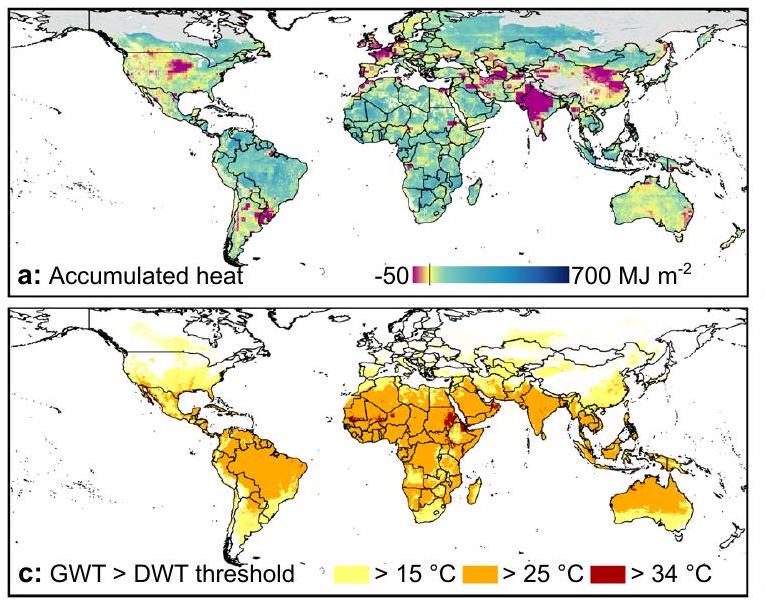

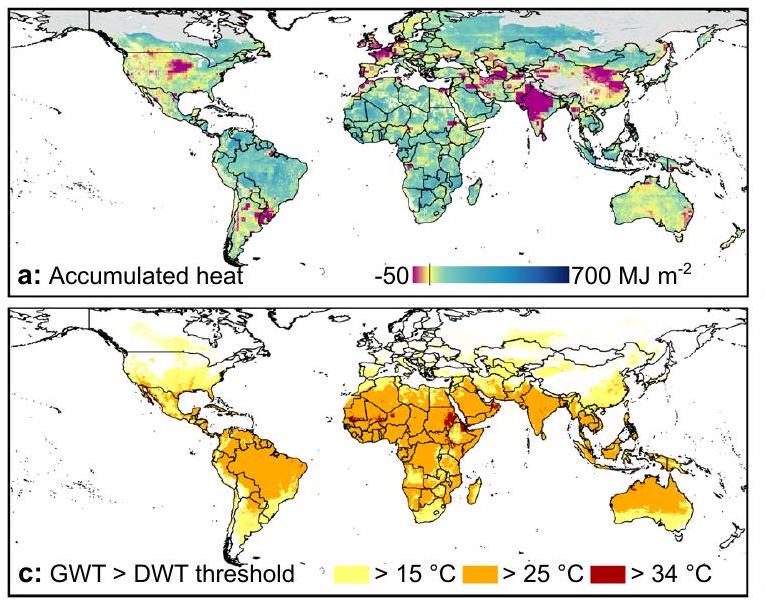

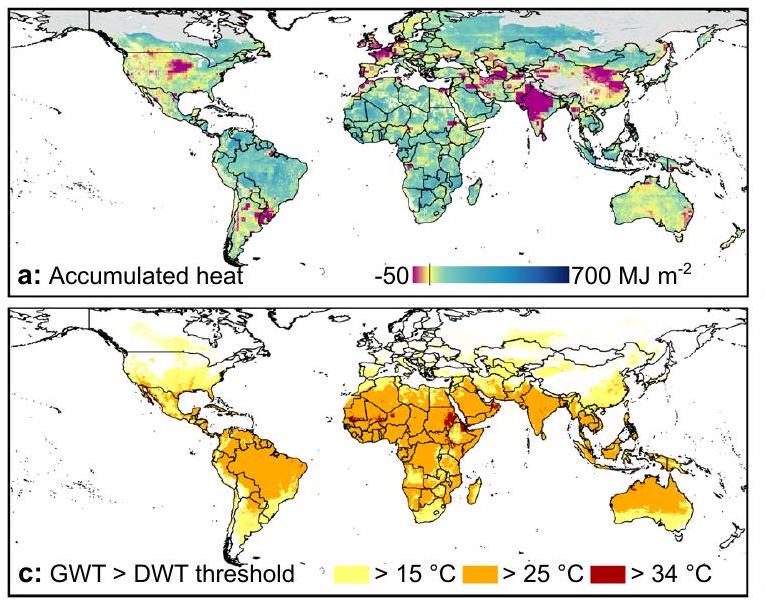

الطاقة المتراكمة

تداعيات على جودة مياه الشرب

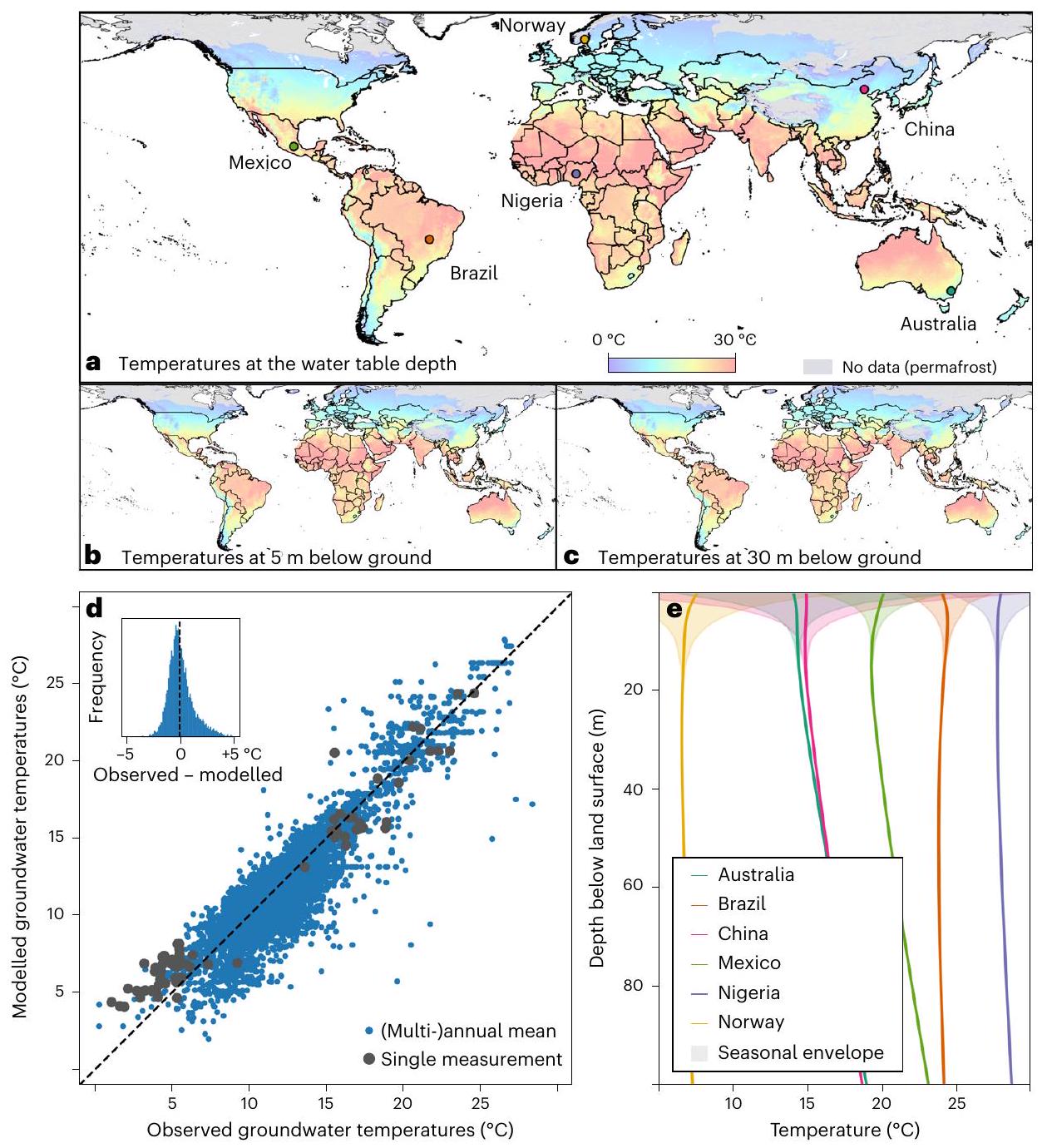

تُظهر درجات الحرارة لنقطة واحدة في الوقت مقابل درجات الحرارة المُحاكاة لنفس الوقت والعمق. يتم عرض هيستوجرام للأخطاء (الدرجات المُلاحظة ناقص الدرجات المُحاكاة) في الزاوية العلوية اليسرى. e، تُظهر ملفات درجات الحرارة والعمق المُحاكاة درجات الحرارة السنوية المتوسطة والغلاف الموسمي للمواقع المعروضة في a. يرجى ملاحظة أننا نستخدم الخصائص الحرارية الكلية، وبالتالي فإن عمق مستوى المياه ليس مدخلًا في نموذجنا.

الآثار المترتبة على النظم البيئية المعتمدة على المياه الجوفية

أهمية الكربون العضوي المذاب في الطبقات تحت السطحية

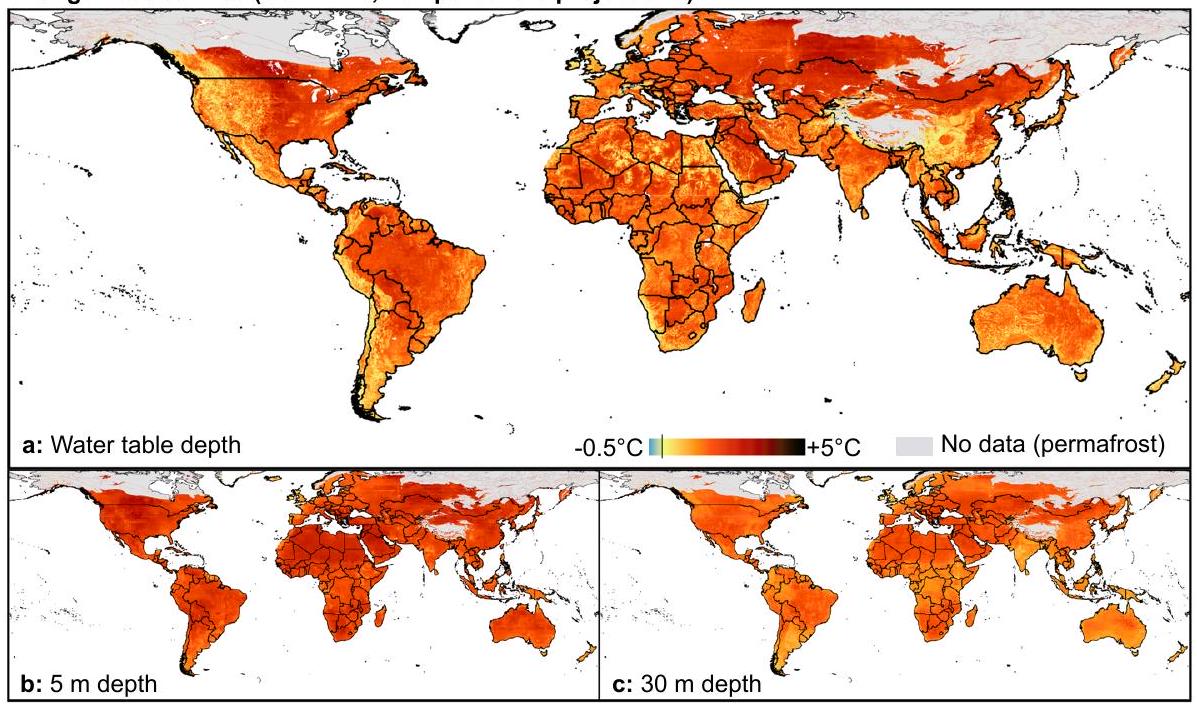

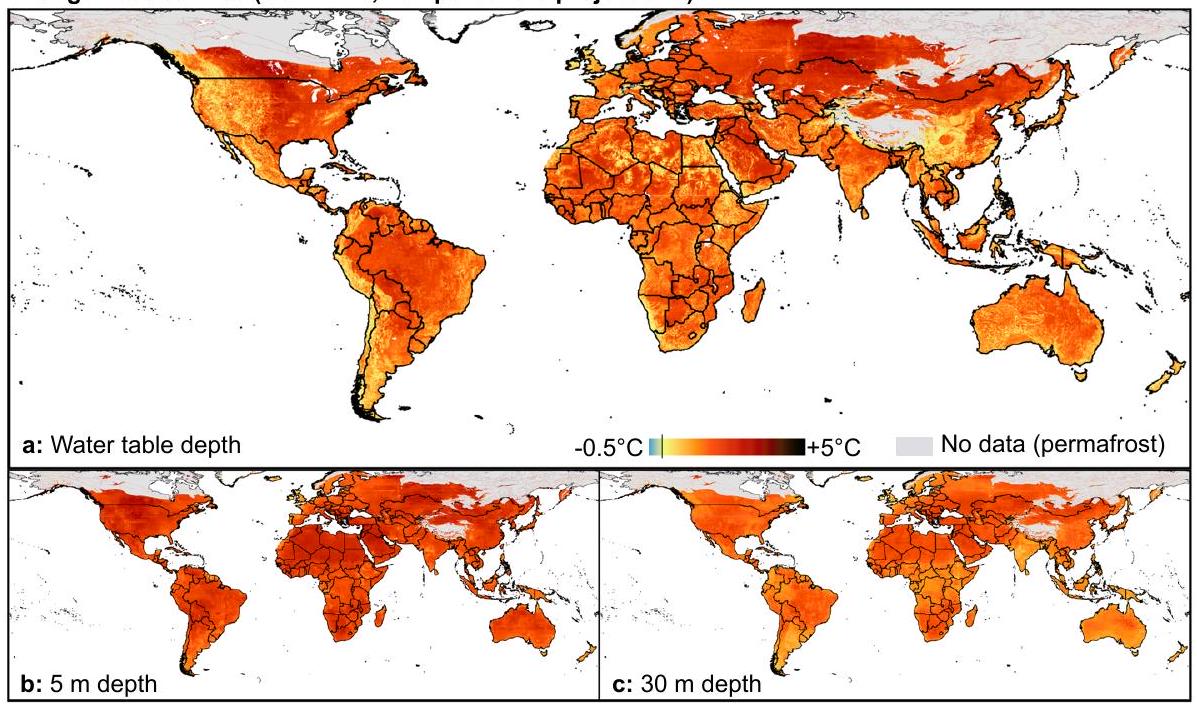

التغييرات. هـ-ز، التغييرات المتوقعة (2000-2100). أ، هـ، خريطة التغيير في متوسط درجة الحرارة السنوية عند عمق مستوى المياه الجوفية. الخط في الأسطورة يشير إلى

تحت سطح الأرض (ج، ط). د، ح، التغير في درجات الحرارة بين عامي 2000 و2020 (د) والفرق بين عامي 2000 و2100 (ح) كملفات عمق لمواقع مختارة (الرموز في

ملخص وتطبيق النموذج

تغير درجة حرارة المياه الجوفية حتى عام 2100 على نطاق عالمي. تعتمد تحليلاتنا على افتراضات هيدروليكية وحرارية معقولة توفر تقديرات محافظة وتسمح بكل من التنبؤات السابقة والتنبؤات المستقبلية لدرجات حرارة المياه الجوفية. تستند توقعات درجات حرارة المياه الجوفية المستقبلية إلى سيناريوهات المناخ SSP 2-4.5 و5-8.5. نقدم خرائط درجات الحرارة العالمية على عمق مستوى المياه، و5 و30 مترًا تحت سطح الأرض، وتبرز هذه الخرائط أن الأماكن ذات مستويات المياه الضحلة و/أو معدلات الاحترار الجوي العالية ستشهد أعلى معدلات احترار للمياه الجوفية على مستوى العالم. من المهم، نظرًا للبعد العمودي للطبقات تحت السطح، أن احترار المياه الجوفية هو ظاهرة ثلاثية الأبعاد (3D) بطبيعتها مع زيادة تأخر الاحترار مع العمق، مما يجعل ديناميات احترار المياه الجوفية مميزة عن احترار المياه السطحية الضحلة أو المختلطة جيدًا.

الحالة الحالية (2020)

تهدد النظم البيئية والصناعات المعتمدة عليها، وستؤدي إلى تدهور جودة مياه الشرب، بشكل أساسي في المناطق الأقل تطوراً.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Meinshausen, M. et al. Historical greenhouse gas concentrations for climate modelling (CMIP6). Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 2057-2116 (2017).

- Arias, P. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 33-144 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Kurylyk, B. L. & Irvine, D. J. Heat: an overlooked tool in the practicing hydrogeologist’s toolbox. Groundwater 57, 517-524 (2019).

- Bense, V. F. & Kurylyk, B. L. Tracking the subsurface signal of decadal climate warming to quantify vertical groundwater flow rates. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl076015 (2017).

- Smerdon, J. E. & Pollack, H. N. Reconstructing earth’s surface temperature over the past 2000 years: the science behind the headlines. WIREs Climate Change 7, 746-771 (2016).

- Döll, P. & Fiedler, K. Global-scale modeling of groundwater recharge. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 863-885 (2008).

- Famiglietti, J. S. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 945-948 (2014).

- Wada, Y. et al. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl044571 (2010).

- Gleeson, T., Befus, K. M., Jasechko, S., Luijendijk, E. & Cardenas, M. B. The global volume and distribution of modern groundwater. Nat. Geosci. 9, 161-167 (2015).

- Taylor, R. G. et al. Ground water and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 322-329 (2012).

- Green, T. R. et al. Beneath the surface of global change: impacts of climate change on groundwater. J. Hydrol. 405, 532-560 (2011).

- Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651-659 (2018).

- Hannah, D. M. & Garner, G. River water temperature in the United Kingdom. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 39, 68-92 (2015).

- Bosmans, J. et al. FutureStreams, a global dataset of future streamflow and water temperature. Sci. Data https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41597-022-01410-6 (2022).

- O’Reilly, C. M. et al. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi. org/10.1002/2015gl066235 (2015).

- Ferguson, G. et al. Crustal groundwater volumes greater than previously thought. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi. org/10.1029/2021gl093549 (2021).

- Zektser, I. S. & Everett, L. G. Groundwater Resources of the World and Their Use (UNESCO, 2004).

- Siebert, S. et al. Groundwater use for irrigation-a global inventory. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1863-1880 (2010).

- de Graaf, I. E. M., Gleeson, T., van Beek, L. P. H. R., Sutanudjaja, E. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Environmental flow limits to global groundwater pumping. Nature 574, 90-94 (2019).

- Chen, C.-H. et al. in Groundwater and Subsurface Environments (ed. Taniguchi, M.) 185-199 (Springer, 2011).

- Benz, S. A., Bayer, P., Winkler, G. & Blum, P. Recent trends of groundwater temperatures in Austria. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 3143-3154 (2018).

- Riedel, T. Temperature-associated changes in groundwater quality. J. Hydrol. 572, 206-212 (2019).

- Cogswell, C. & Heiss, J. W. Climate and seasonal temperature controls on biogeochemical transformations in unconfined coastal aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi. org/10.1029/2021jg006605 (2021).

- Griebler, C. et al. Potential impacts of geothermal energy use and storage of heat on groundwater quality, biodiversity, and ecosystem processes. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12665-016-6207-z (2016).

- Retter, A., Karwautz, C. & Griebler, C. Groundwater microbial communities in times of climate change. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 41, 509-538 (2021).

- Bonte, M. et al. Impacts of shallow geothermal energy production on redox processes and microbial communities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 14476-14484 (2013).

- Bonte, M., van Breukelen, B. M. & Stuyfzand, P. J. Temperature-induced impacts on groundwater quality and arsenic mobility in anoxic aquifer sediments used for both drinking water and shallow geothermal energy production. Water Res. 47, 5088-5100 (2013).

- Brookfield, A. E. et al. Predicting algal blooms: are we overlooking groundwater? Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144442 (2021).

- Bondu, R., Cloutier, V. & Rosa, E. Occurrence of geogenic contaminants in private wells from a crystalline bedrock aquifer in western Quebec, Canada: geochemical sources and health risks. J. Hydrol. 559, 627-637 (2018).

- Agudelo-Vera, C. et al. Drinking water temperature around the globe: understanding, policies, challenges and opportunities. Water 12, 1049 (2020).

- Mejia, F. H. et al. Closing the gap between science and management of cold-water refuges in rivers and streams. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5482-5508 (2023).

- Jyväsjärvi, J. et al. Climate-induced warming imposes a threat to north European spring ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 4561-4569 (2015).

- Stauffer, F., Bayer, P., Blum, P., Molina Giraldo, N. & Kinzelbach, W. Thermal Use of Shallow Groundwater (CRC Press, 2013).

- Epting, J., Müller, M. H., Genske, D. & Huggenberger, P. Relating groundwater heat-potential to city-scale heat-demand: a theoretical consideration for urban groundwater resource management. Appl. Energy 228, 1499-1505 (2018).

- Benz, S. A., Menberg, K., Bayer, P. & Kurylyk, B. L. Shallow subsurface heat recycling is a sustainable global space heating alternative. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31624-6 (2022).

- Schüppler, S., Fleuchaus, P. & Blum, P. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of an aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) in germany. Geotherm. Energy https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40517-019-0127-6 (2019).

- Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937-1958 (2016).

- Zhang, T. Influence of the seasonal snow cover on the ground thermal regime: an overview. Rev. Geophys. 43, RG4002 (2005).

- Zanna, L., Khatiwala, S., Gregory, J. M., Ison, J. & Heimbach, P. Global reconstruction of historical ocean heat storage and transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1126-1131 (2019).

- von Schuckmann, K. et al. Heat stored in the earth system: where does the energy go? Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2013-2041 (2020).

- Cuesta-Valero, F. J. et al. Continental heat storage: contributions from the ground, inland waters, and permafrost thawing. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 609-627 (2023).

- Nissler, E. et al. Heat transport from atmosphere through the subsurface to drinking-water supply pipes. Vadose Zone J. 22, 270-286 (2023).

- A Global Overview of National Regulations and Standards for Drinking-Water Quality 2nd edn (WHO, 2O21); https://apps.who.int/ iris/handle/10665/350981

- Griebler, C. & Avramov, M. Groundwater ecosystem services: a review. Freshw. Sci. 34, 355-367 (2015).

- Mammola, S. et al. Scientists’ warning on the conservation of subterranean ecosystems. BioScience 69, 641-650 (2019).

- McDonough, L. K. et al. Changes in global groundwater organic carbon driven by climate change and urbanization. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14946-1 (2020).

- Atawneh, D. A., Cartwright, N. & Bertone, E. Climate change and its impact on the projected values of groundwater recharge: a review. J. Hydrol. 601, 126602 (2021).

- Meisner, J. D., Rosenfeld, J. S. & Regier, H. A. The role of groundwater in the impact of climate warming on stream salmonines. Fisheries 13, 2-8 (1988).

- Hare, D. K., Helton, A. M., Johnson, Z. C., Lane, J. W. & Briggs, M. A. Continental-scale analysis of shallow and deep groundwater contributions to streams. Nat. Commun. 12, 1450 (2021).

- Caissie, D., Kurylyk, B. L., St-Hilaire, A., El-Jabi, N. & MacQuarrie, K. T. Streambed temperature dynamics and corresponding heat fluxes in small streams experiencing seasonal ice cover. J. Hydrol. 519, 1441-1452 (2014).

- Wondzell, S. M. The role of the hyporheic zone across stream networks. Hydrol. Process. 25, 3525-3532 (2011).

- Liu, S. et al. Global river water warming due to climate change and anthropogenic heat emission. Glob. Planet. Change 193, 103289 (2020).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

طرق

نقل الحرارة بالتشتت

عند سطح الأرض. ومع ذلك، يقوم Google Earth Engine تلقائياً بإعادة ضبط مقاييس الصور المعروضة على الخريطة بناءً على مستوى تكبير المستخدم. يتم إنشاء الرسوم البيانية التي تمثل درجات الحرارة في موقع معين بمقياس 5 كم من خلال النقر على الخريطة ويمكن تصديرها بتنسيقات ملفات CSV أو SVQ أو PNG. بالنسبة لجميع التحليلات التي تظهر بيانات سنوية متوسطة عند عمق مستوى المياه، نقوم أولاً بحساب درجات الحرارة الشهرية عند مستوى المياه الجوفية المرتبط قبل حساب متوسط النتائج.

درجات حرارة سطح الأرض

لتحليلنا نستخدم التوصيلية الحرارية الأرضية

التدرج الجيوحراري

عمق مستوى المياه

تقييم النموذج

أمثلة على المواقع

عمق نقطة انحناء التدرج الحراري الجيولوجي

الطاقة المتراكمة

حدود درجات حرارة مياه الشرب

أثر على المسطحات المائية السطحية

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Tissen, C., Benz, S. A., Menberg, K., Bayer, P. & Blum, P. Groundwater temperature anomalies in central Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 104012 (2019).

- Bodri, L. & Cermak, V. Borehole Climatology (Elsevier, 2007).

- Carslaw, H. S. & Jaeger, J. C. Conduction of Heat in Solids (Oxford Univ. Press, 1986).

- Turcotte, D. L. & Schubert, G. Geodynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

- Kurylyk, B. L., Irvine, D. J. & Bense, V. F. Theory, tools, and multidisciplinary applications for tracing groundwater fluxes from temperature profiles. WIREs Water https://doi.org/10.1002/ wat2.1329 (2018).

- Taylor, C. A. & Stefan, H. G. Shallow groundwater temperature response to climate change and urbanization. J. Hydrol. 375, 601-612 (2009).

- Bense, V. F., Kurylyk, B. L., van Daal, J., van der Ploeg, M. J. & Carey, S. K. Interpreting repeated temperature-depth profiles for groundwater flow. Water Resour. Res. 53, 8639-8647 (2017).

- Brown, J., Ferrians, O., Heginbottom, J. A. & Melnikov, E. CircumArctic map of permafrost and ground-ice conditions, version 2. NSIDC https://nsidc.org/data/GGD318/versions/2 (2002).

- Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18-27 (2017).

- ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 2001 to present. Copernicus Climate Data Store https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ doi/10.24381/cds.68d2bb30 (2019).

- Hansen, J. et al. Climate simulations for 1880-2003 with GISS modelE. Clim. Dyn. 29, 661-696 (2007).

- Soong, J. L., Phillips, C. L., Ledna, C., Koven, C. D. & Torn, M. S. CMIP5 models predict rapid and deep soil warming over the 21st century. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jg005266 (2020).

- Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J. & Börker, J. Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1897-1904 (2018).

- VDI 4640-Thermal Use of the Underground (VDI-Gesellschaft Energie und Umwelt, 2010).

- Börker, J., Hartmann, J., Amann, T. & Romero-Mujalli, G. Terrestrial sediments of the earth: development of a global unconsolidated sediments map database (GUM). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 997-1024 (2018).

- Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: a representation of rock properties at the earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/

(2012). - Clauser, C. in Thermal Storage and Transport Properties of Rocks, I: Heat Capacity and Latent Heat (ed. Gupta, H. K.) 1423-1431 (Springer, 2011).

- Clauser, C. in Thermal Storage and Transport Properties of Rocks, II: Thermal Conductivity and Diffusivity (ed. Gupta, H. K.) 1431-1448 (Springer, 2011).

- Rau, G. C., Andersen, M. S., McCallum, A. M., Roshan, H. & Acworth, R. I. Heat as a tracer to quantify water flow in near-surface sediments. Earth Sci. Rev. 129, 40-58 (2014).

- Halloran, L. J., Rau, G. C. & Andersen, M. S. Heat as a tracer to quantify processes and properties in the vadose zone: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 159, 358-373 (2016).

- Davies, J. H. Global map of solid earth surface heat flow. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 4608-4622 (2013).

- Fan, Y., Li, H. & Miguez-Macho, G. Global patterns of groundwater table depth. Science 339, 940-943 (2013).

- Fan, Y., Miguez-Macho, G., Jobbágy, E. G., Jackson, R. B. & Otero-Casal, C. Hydrologic regulation of plant rooting depth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10572-10577 (2017).

- Benz, S. A., Bayer, P. & Blum, P. Global patterns of shallow groundwater temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 034005 (2017).

- Jasechko, S. & Perrone, D. Global groundwater wells at risk of running dry. Science 372, 418-421 (2021).

- Gridded population of the world, version 4 (GPWv4): population density adjusted to match 2015 revision UN WPP country totals, revision 11. CIESIN https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/ data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-adjusted-to-2015-unwp p-country-totals-rev11 (2018).

- Gao, J. Global 1-km downscaled population base year and projection grids based on the shared socioeconomic pathways, revision 01. CIESIN https://doi.org/10.7927/q7z9-9r69 (2020).

- Gao, J. Downscaling Global Spatial Population Projections from 1/8-Degree to 1-km Grid Cells (NCAR/UCAR, 2017); https://opensky. ucar.edu/islandora/object/technotes:553

- Benz, S. Global groundwater warming due to climate change. Borealis https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/GE4VEQ (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x.

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x.

لا تزداد مع العمق كما هو متوقع بناءً على التدرج الحراري الأرضي.

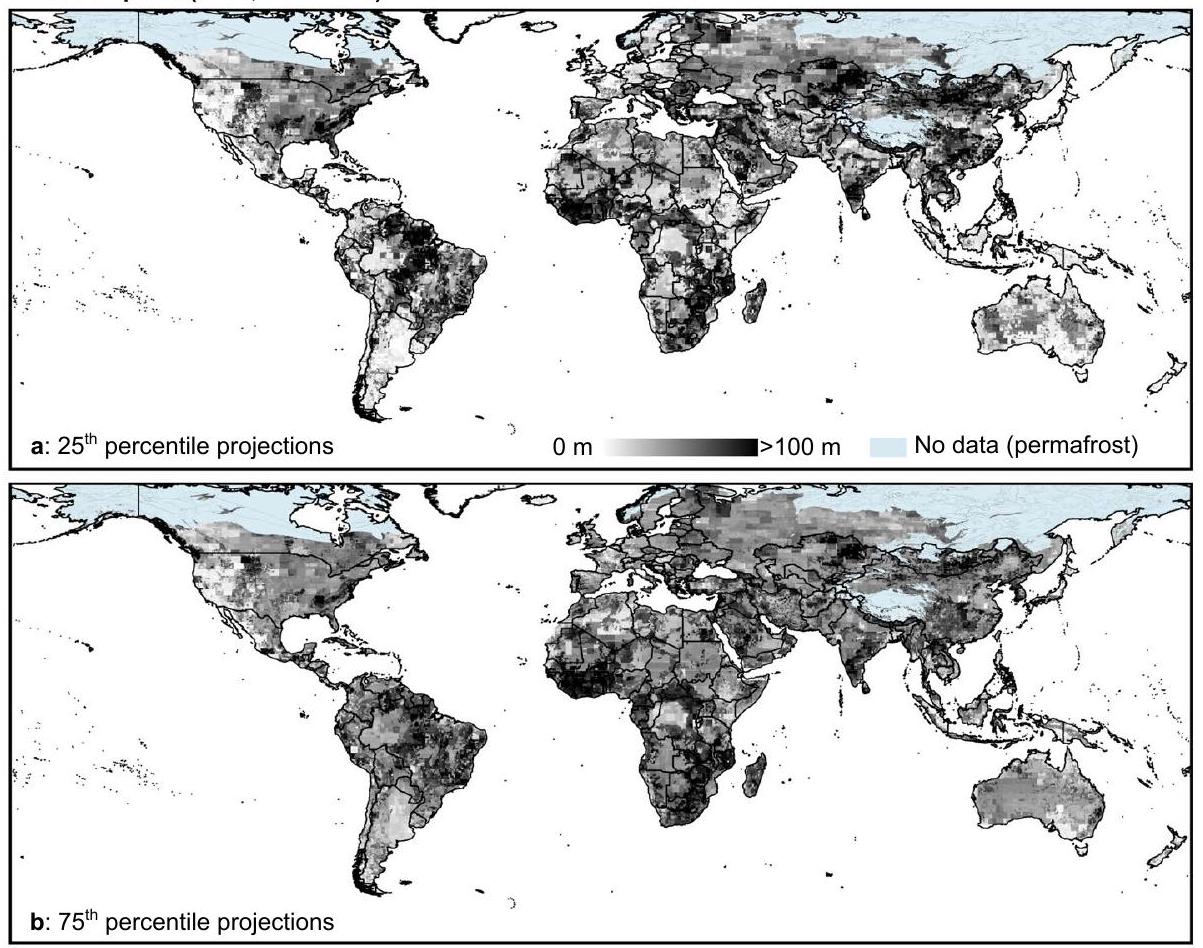

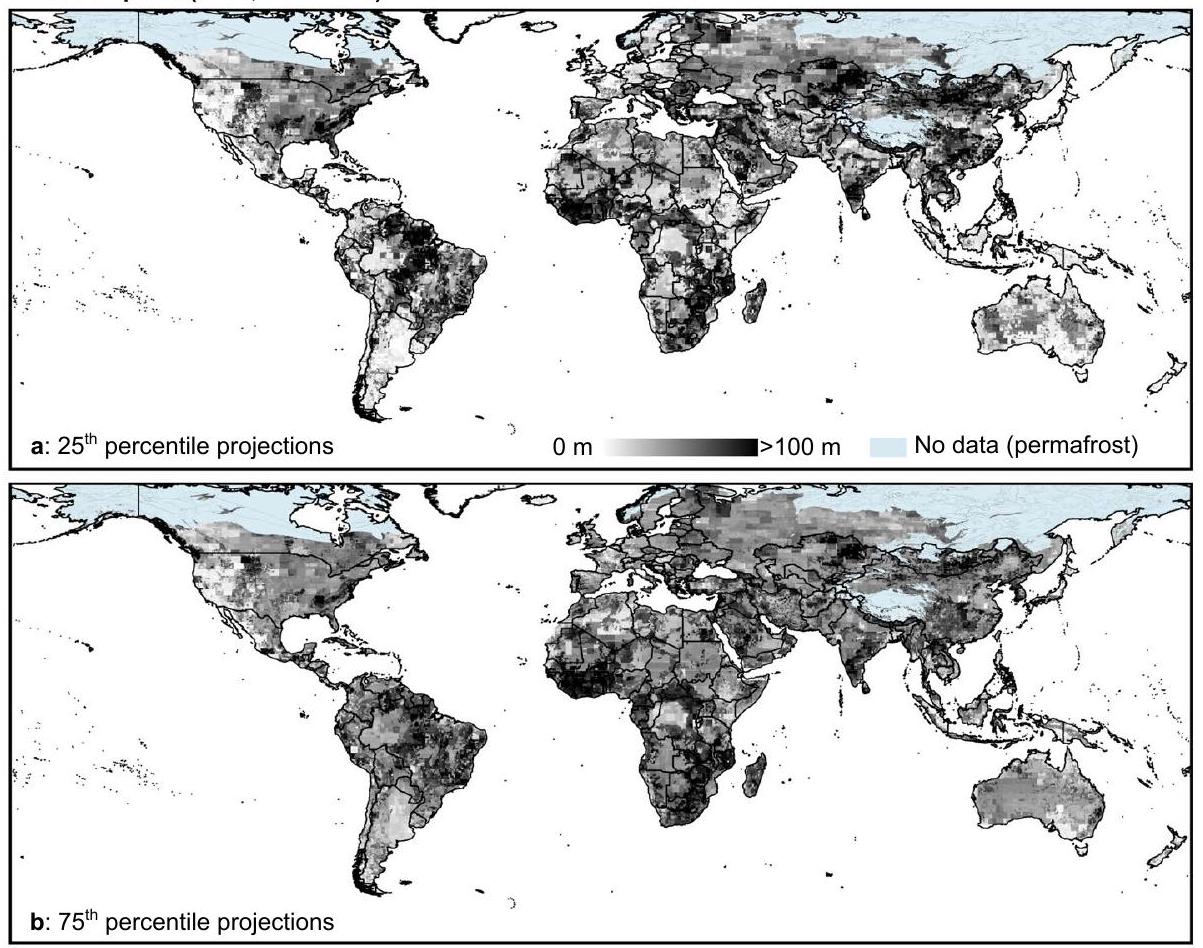

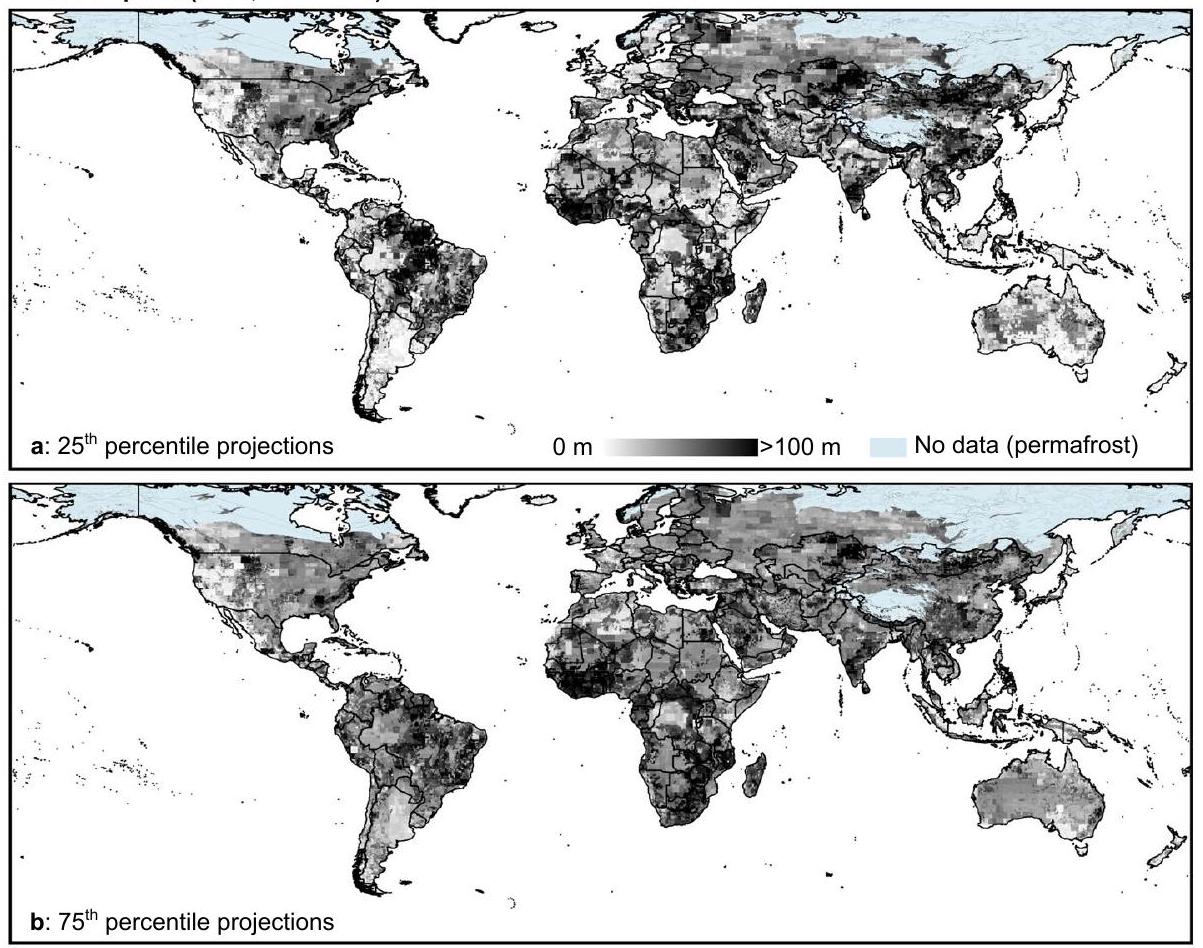

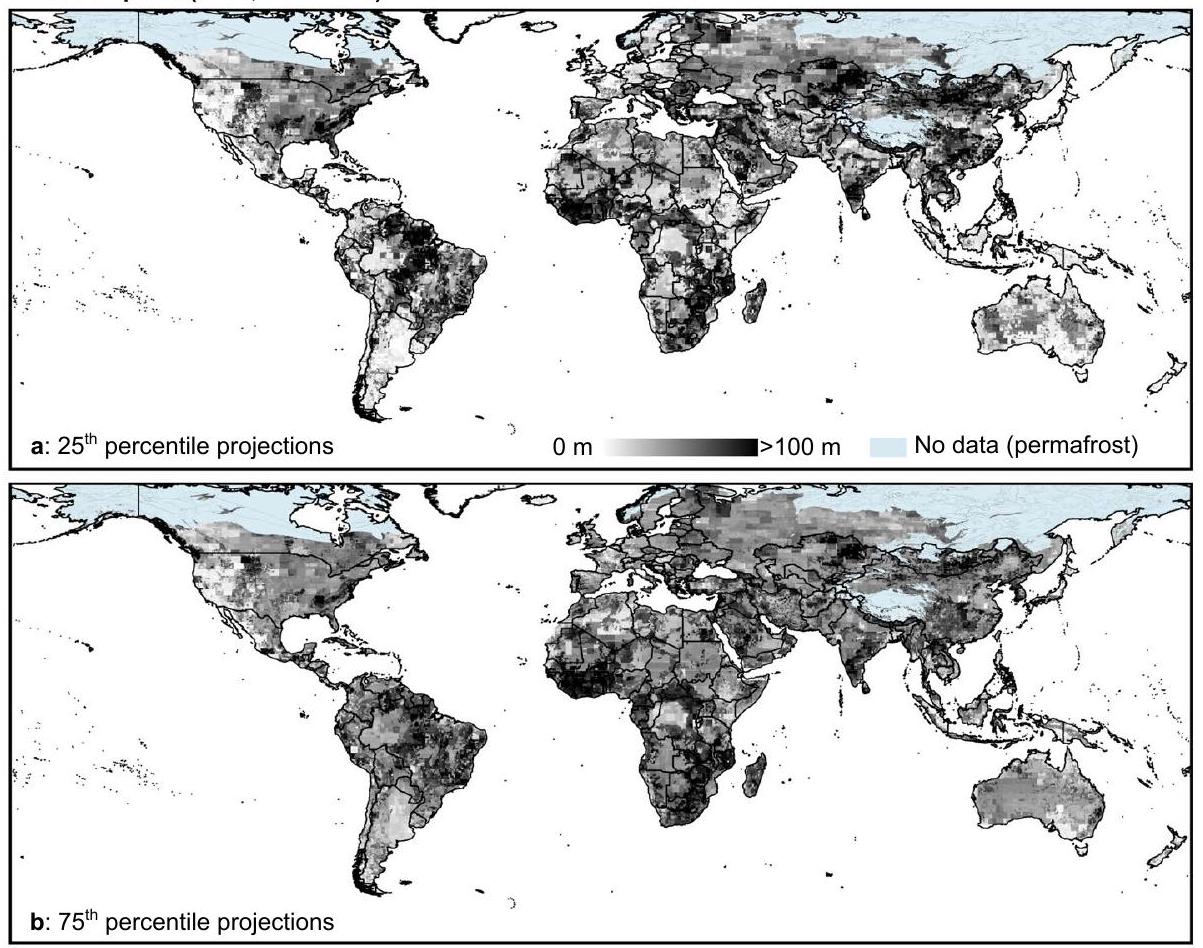

تغيرات متوقعة في متوسط درجة حرارة المياه الجوفية السنوية في النسبة المئوية 25.

تغيرات متوقعة في درجة حرارة المياه الجوفية السنوية في النسبة المئوية 75.

2000 و 2100 والآثار المترتبة على SSP 5-8.5. أ، خريطة التغير في متوسط درجة الحرارة السنوية بين 2000 و 2100 وفقًا لـ SSP 5-8.5 (توقعات الوسيط) عند عمق مستوى المياه الجوفية (مع الأخذ في الاعتبار تباينها الموسمي). تعتمد درجات الحرارة في 2000 على سيناريو CMIP6 التاريخي. تشير الخط في الأسطورة إلى

تدرج الحرارة الجيولوجية.

SSP 2-4.5،

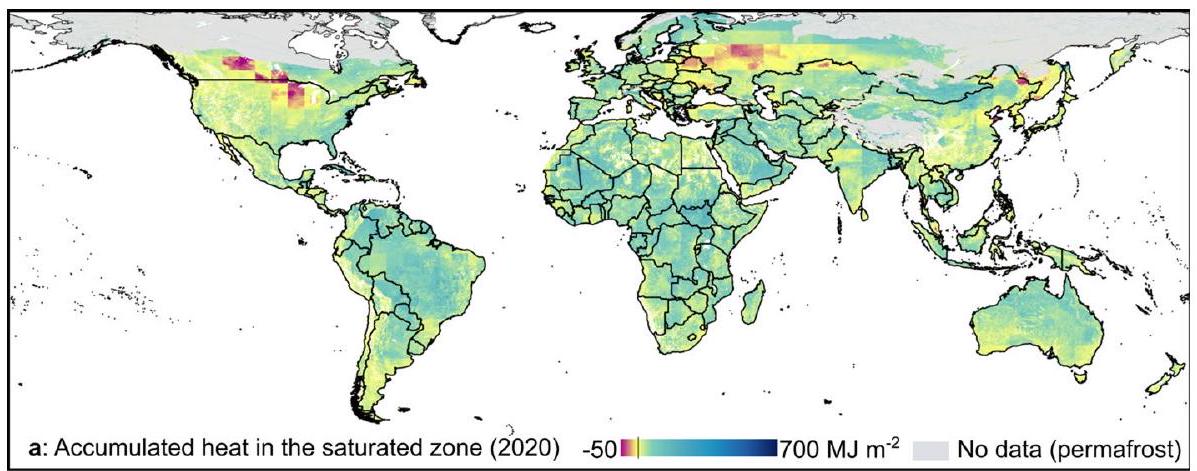

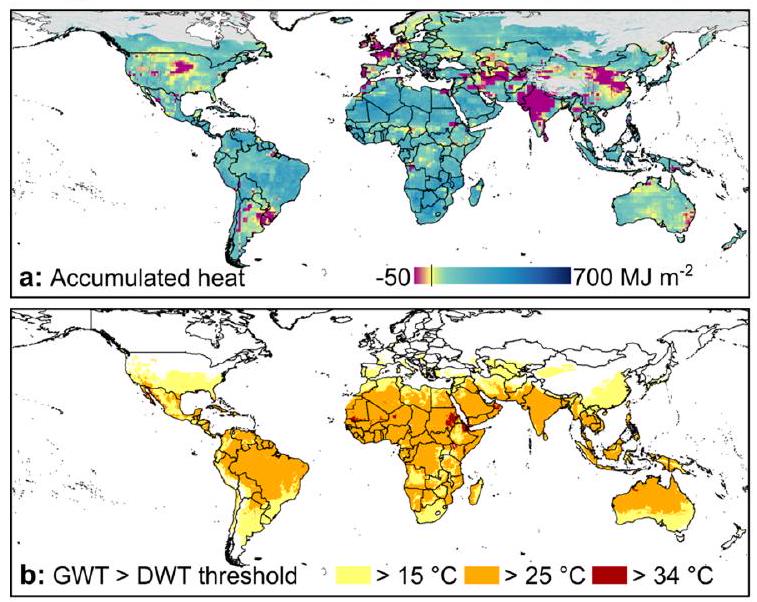

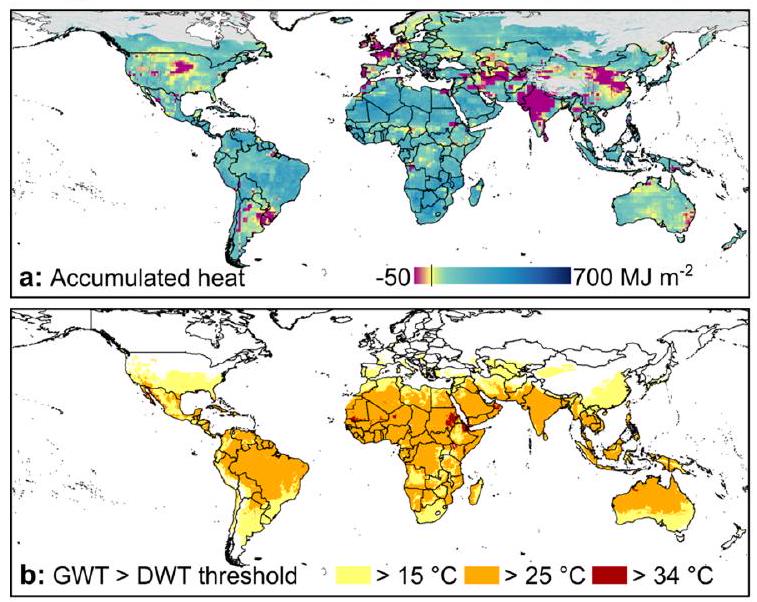

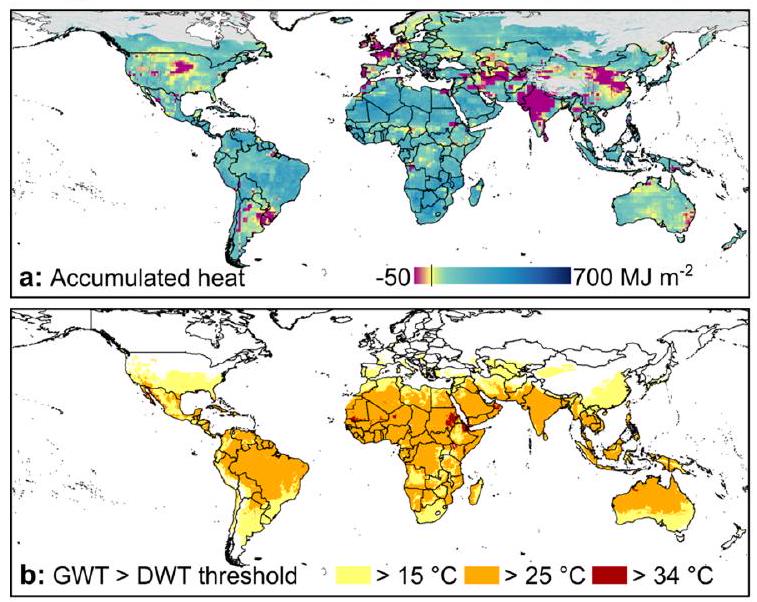

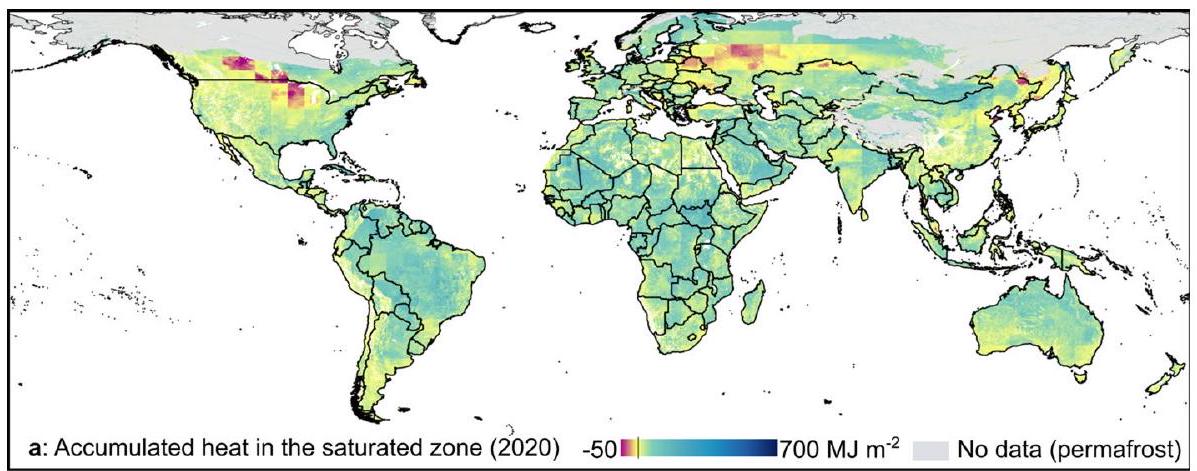

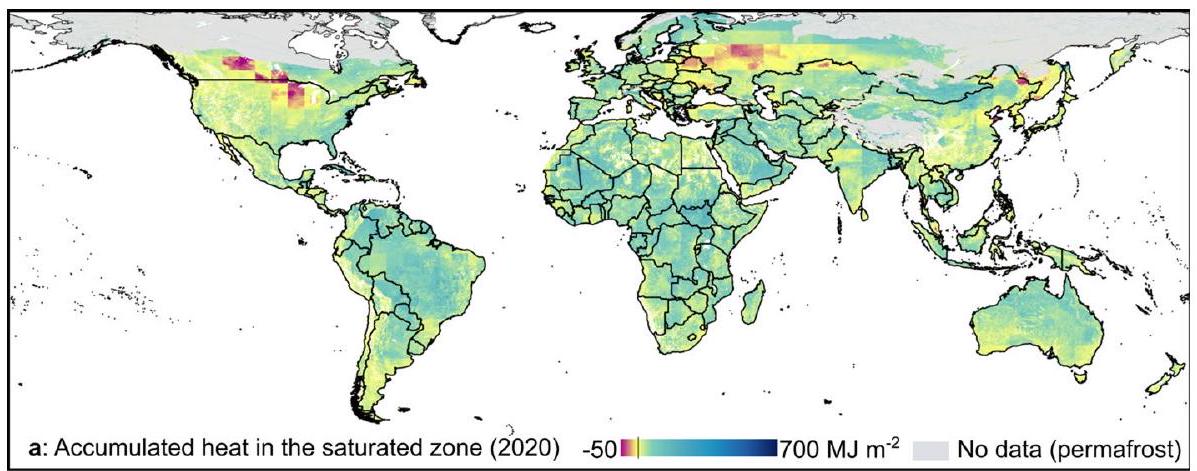

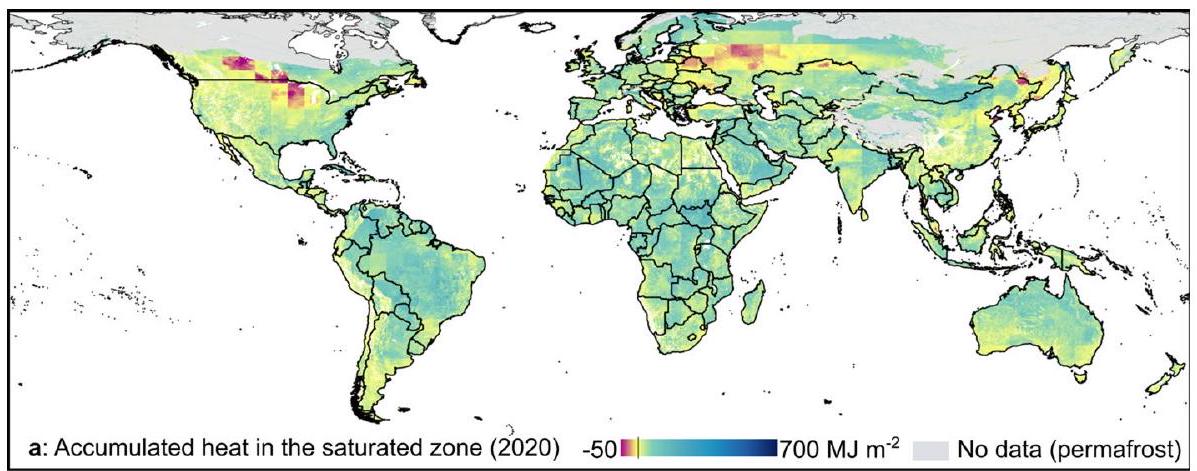

تجاوز الحدود الإرشادية لدرجات حرارة مياه الشرب (DWTs) لنماذج SSP 2-4.5 عند النسب المئوية 25 و75، على التوالي. هـ و و، الحرارة المتراكمة في المنطقة المشبعة لنماذج SSP 5-8.5 عند النسب المئوية 25 و75، على التوالي.

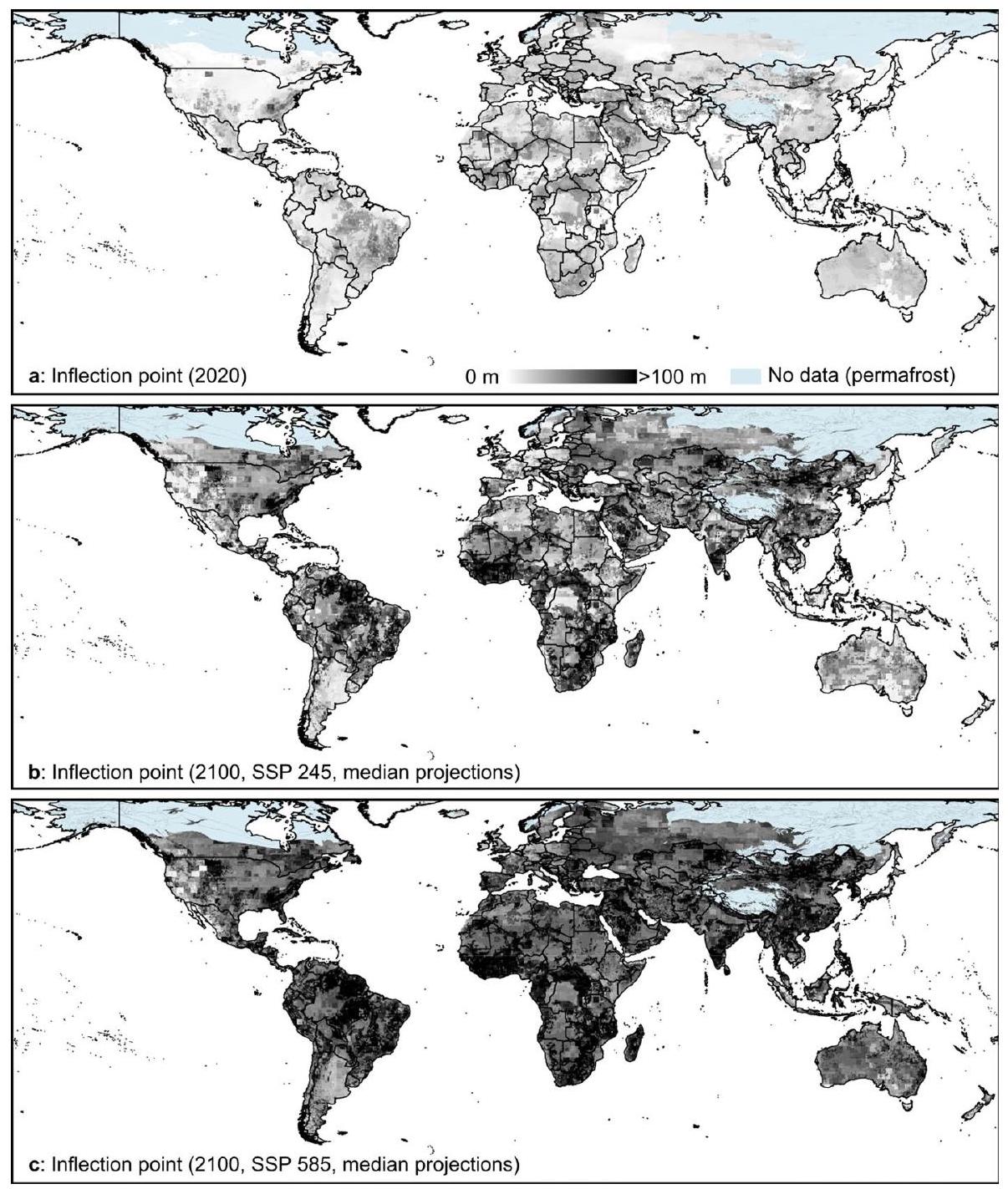

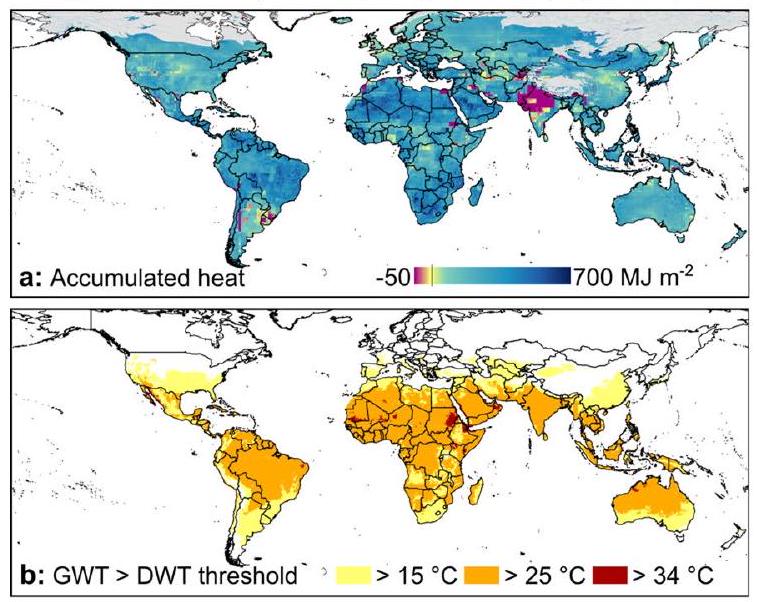

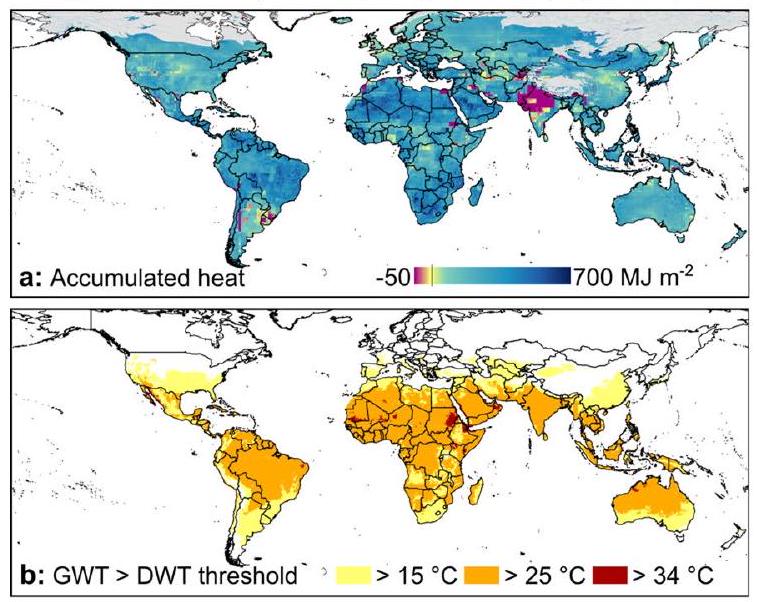

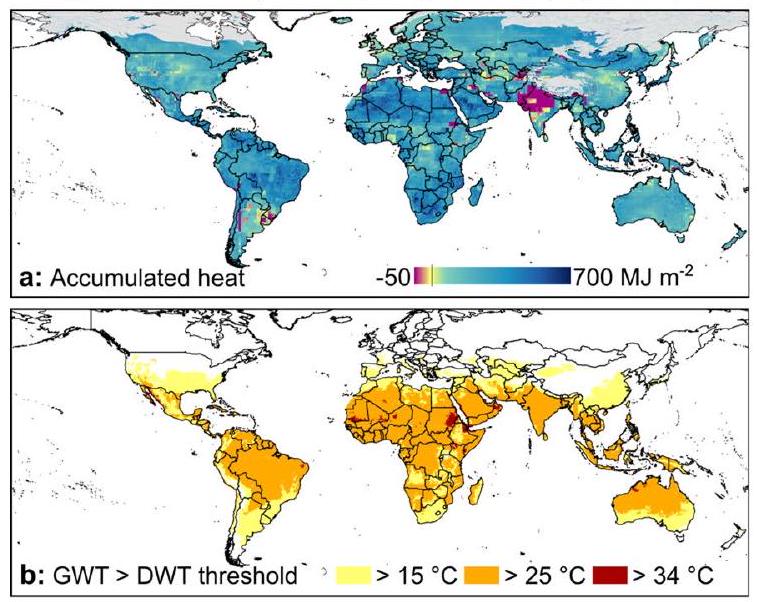

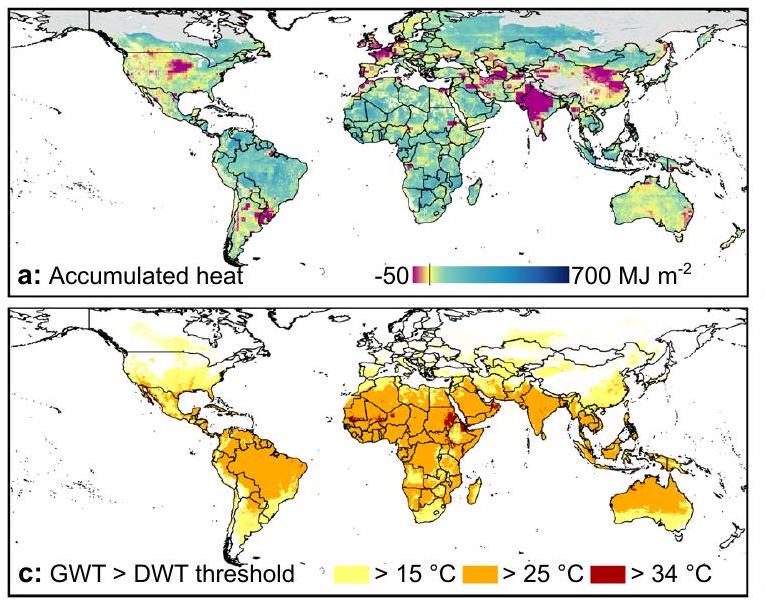

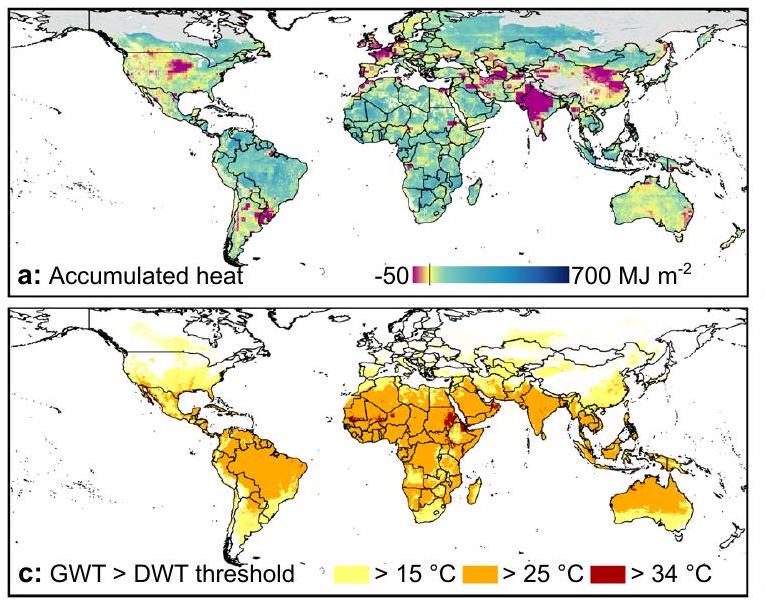

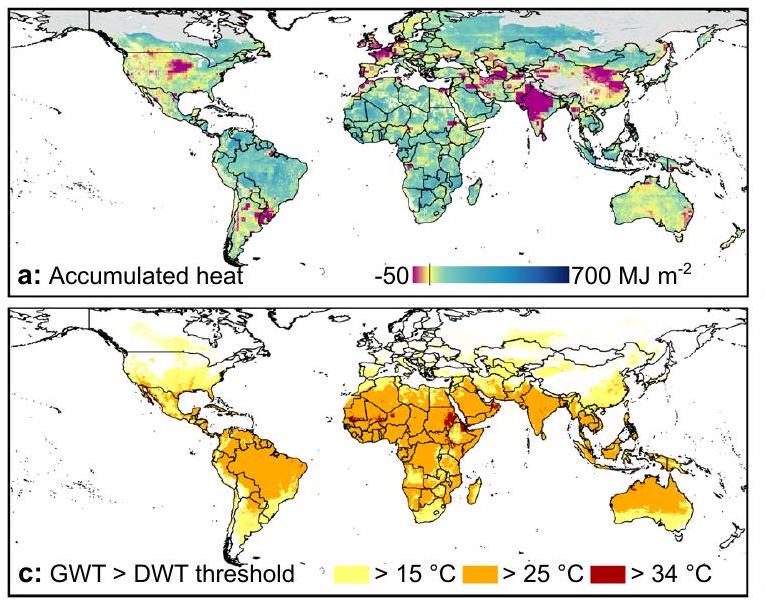

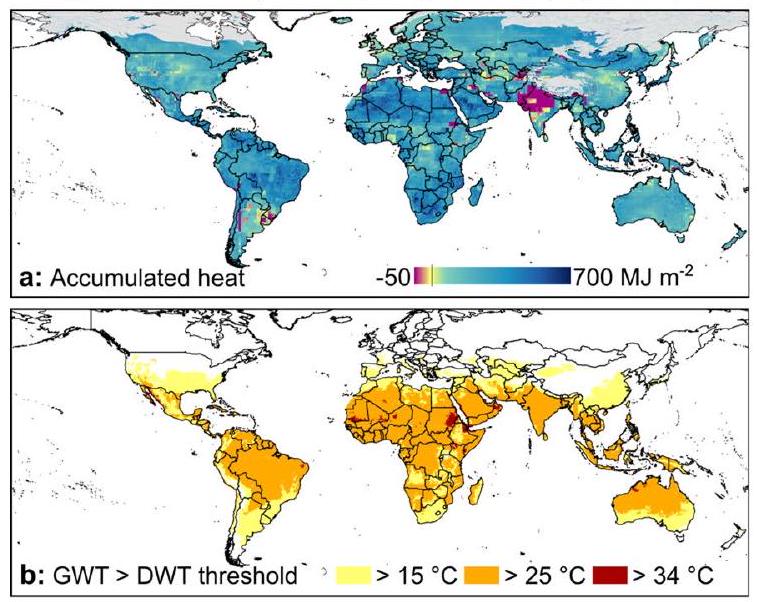

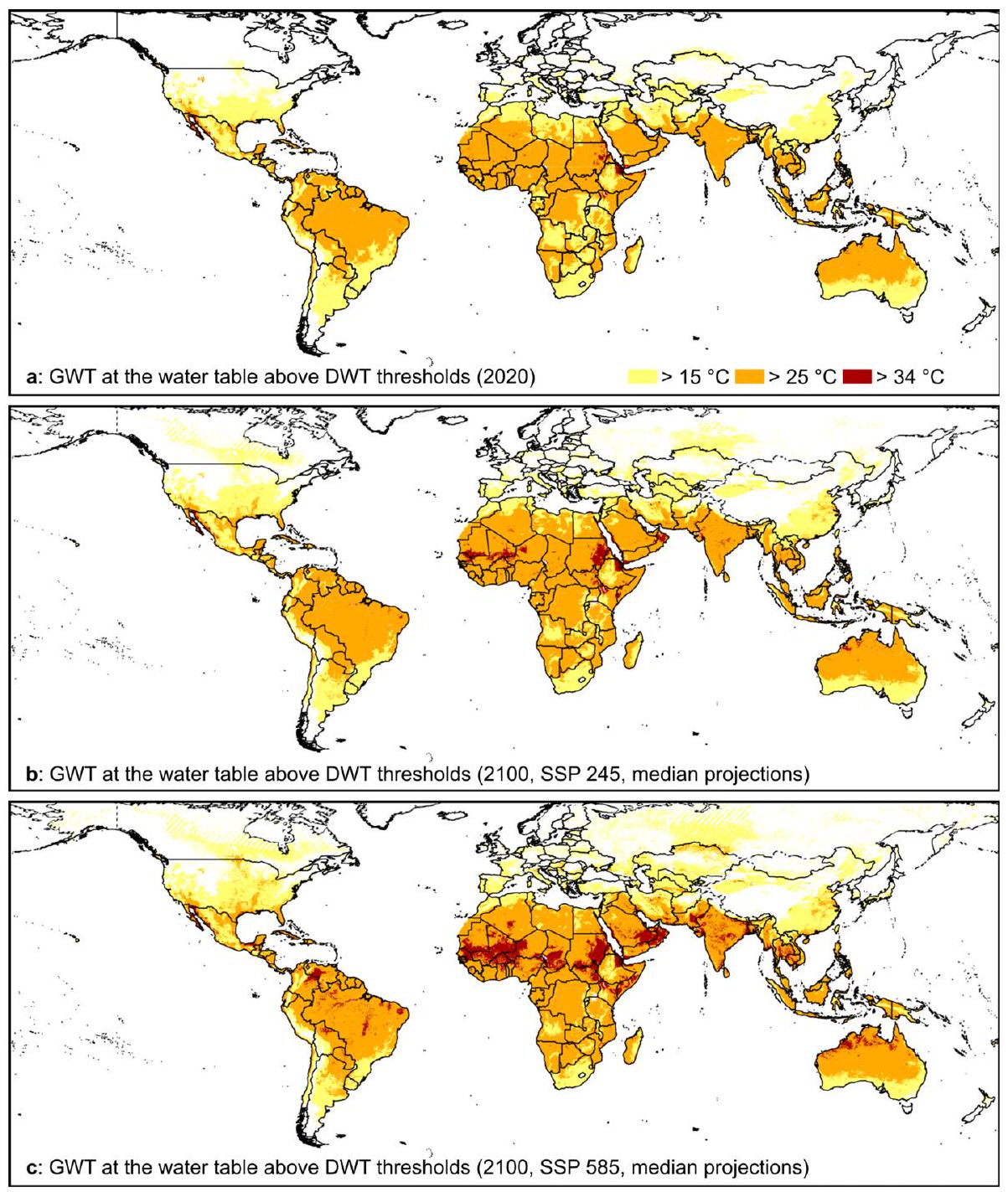

(DWTs). أ، الحد الأقصى لمستويات المياه الجوفية الشهرية عند عمق منسوب المياه الجوفية في عام 2020. ب وج، الحد الأقصى لمستويات المياه الجوفية الشهرية عند عمق منسوب المياه الجوفية في عام 2100 وفقًا للتوقعات المتوسطة لـ SSP2-4.5 و SSP5-8.5، على التوالي.

مركز دراسات موارد المياه وقسم الهندسة المدنية وموارد الهندسة، جامعة دالهوزي، هاليفاكس، نوفا سكوشا، كندا. معهد الفوتوغرامتري والاستشعار عن بُعد، معهد كارلسروه للتكنولوجيا، كارلسروه، ألمانيا. معهد الأبحاث للبيئة وسبل العيش، جامعة تشارلز داروين، كاسوارينا، الإقليم الشمالي، أستراليا. مدرسة العلوم البيئية والحياتية، جامعة نيوكاسل، كالاها، نيو ساوث ويلز، أستراليا. قسم الجيولوجيا التطبيقية، جامعة مارتن لوثر هاله-فيتنبرغ، هاله، ألمانيا. معهد علوم الأرض التطبيقية، معهد كارلسروه للتكنولوجيا، كارلسروه، ألمانيا. قسم البيئة الوظيفية والتطورية، جامعة فيينا، فيينا، النمسا. البريد الإلكتروني: سوزان.بينز@kit.edu; barret.kurylyk@dal.ca

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x

Publication Date: 2024-06-01

Global groundwater warming due to climate change

Accepted: 12 April 2024

Published online: 4 June 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

Aquifers contain the largest store of unfrozen freshwater, making groundwater critical for life on Earth. Surprisingly little is known about how groundwater responds to surface warming across spatial and temporal scales. Focusing on diffusive heat transport, we simulate current and projected groundwater temperatures at the global scale. We show that groundwater at the depth of the water table (excluding permafrost regions) is conservatively projected to warm on average by

pre-observational surface temperature changes at a global scale

set by drinking water standards (Fig. 1d) and (3) where discharge of warmed groundwater will have the most pronounced impact on river temperatures and aquatic ecosystems (Fig. 1e). Our model is global, and its resolution limits detailed capture of small-scale processes, producing conservative results based on tested hydraulic and thermal assumptions, including realistic advection from basin-scale recharge. More localized processes may lead to higher groundwater temperatures in areas with increased downward flow (for example, river-based recharge) or elevated surface temperatures (for example, urban heat islands) (Supplementary Note 1 provides details).

Groundwater temperatures

and microbiology, which in turn impacts water quality (d) and groundwaterdependent ecosystems (e). Figure created with images from the UMCES IAN Media Library under a Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0.

range profiles with temperature changes of

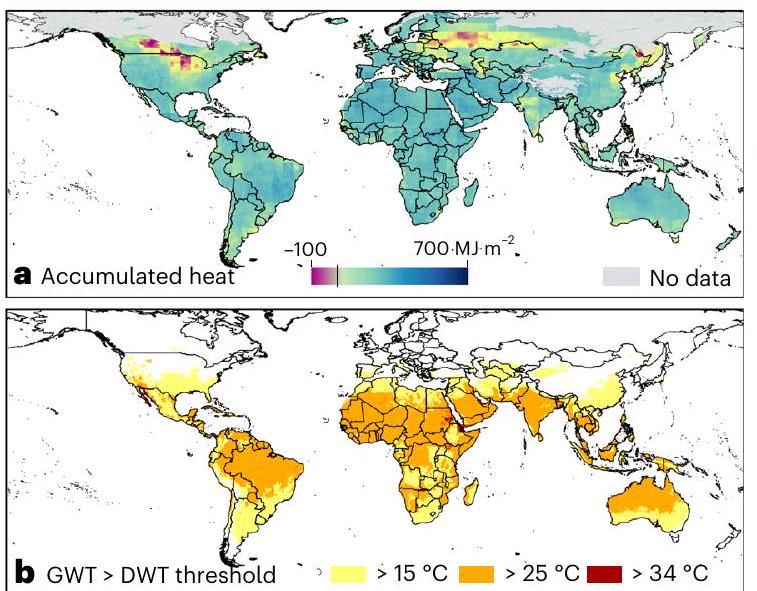

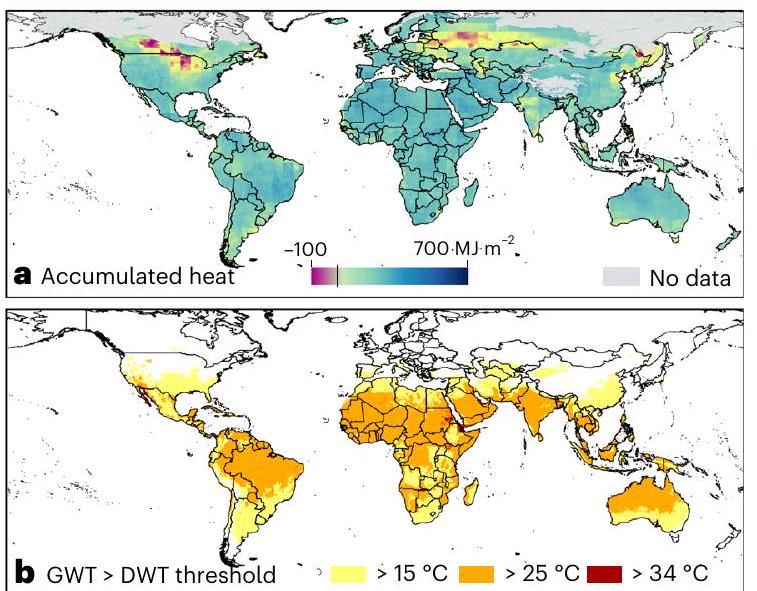

Accumulated energy

Implications for drinking water quality

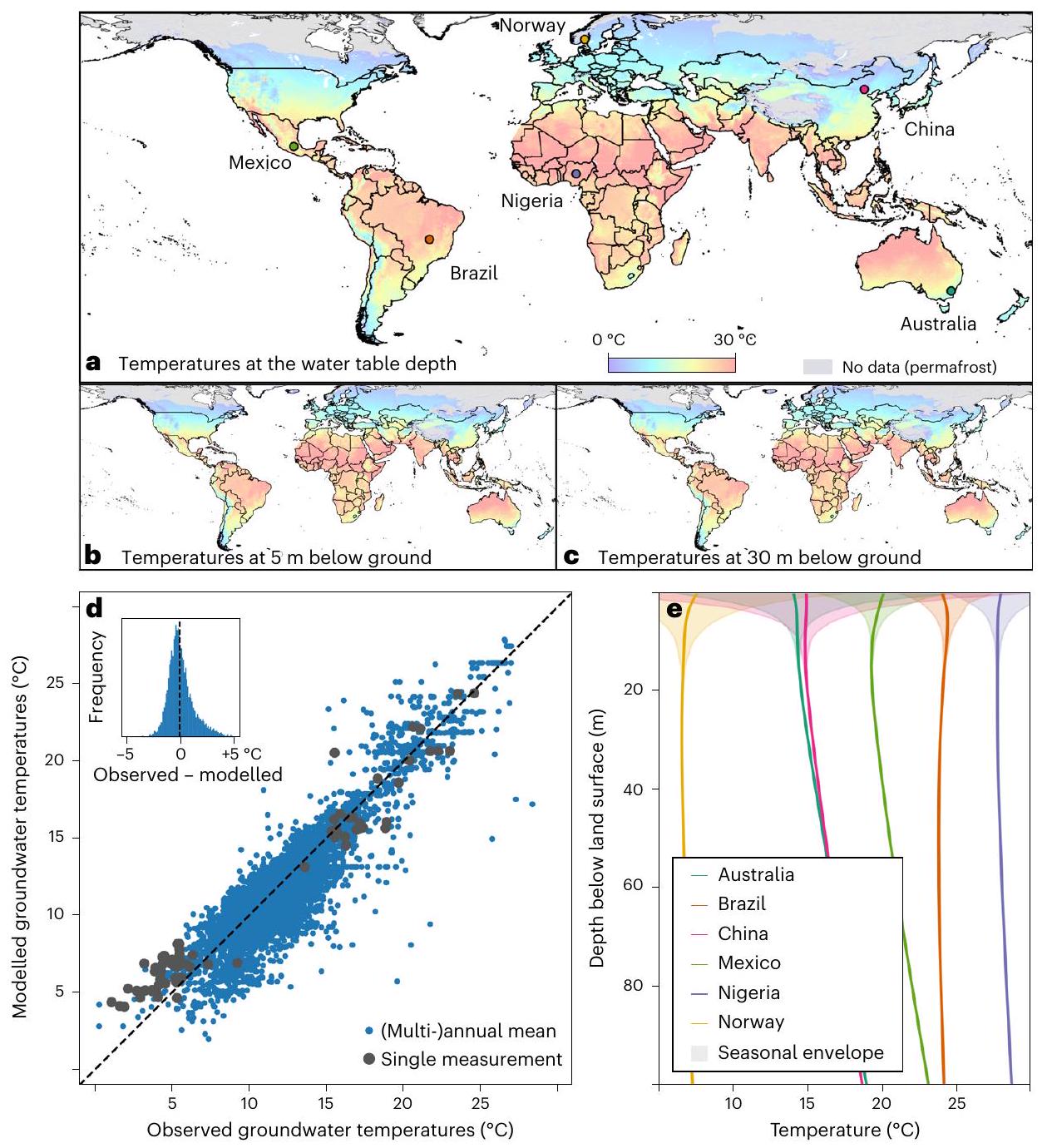

are temperatures of a single point in time versus modelled temperatures of the same time and depth. A histogram of the errors (observed minus modelled temperatures) is shown in the upper left corner. e, Modelled temperature-depth profiles showing mean annual temperatures and the seasonal envelope for the locations displayed in a. Please note that we use bulk thermal properties, and the water table depth is thus not an input parameter into our model.

Implications for groundwater-dependent ecosystems

importance of dissolved organic carbon to the subsurface

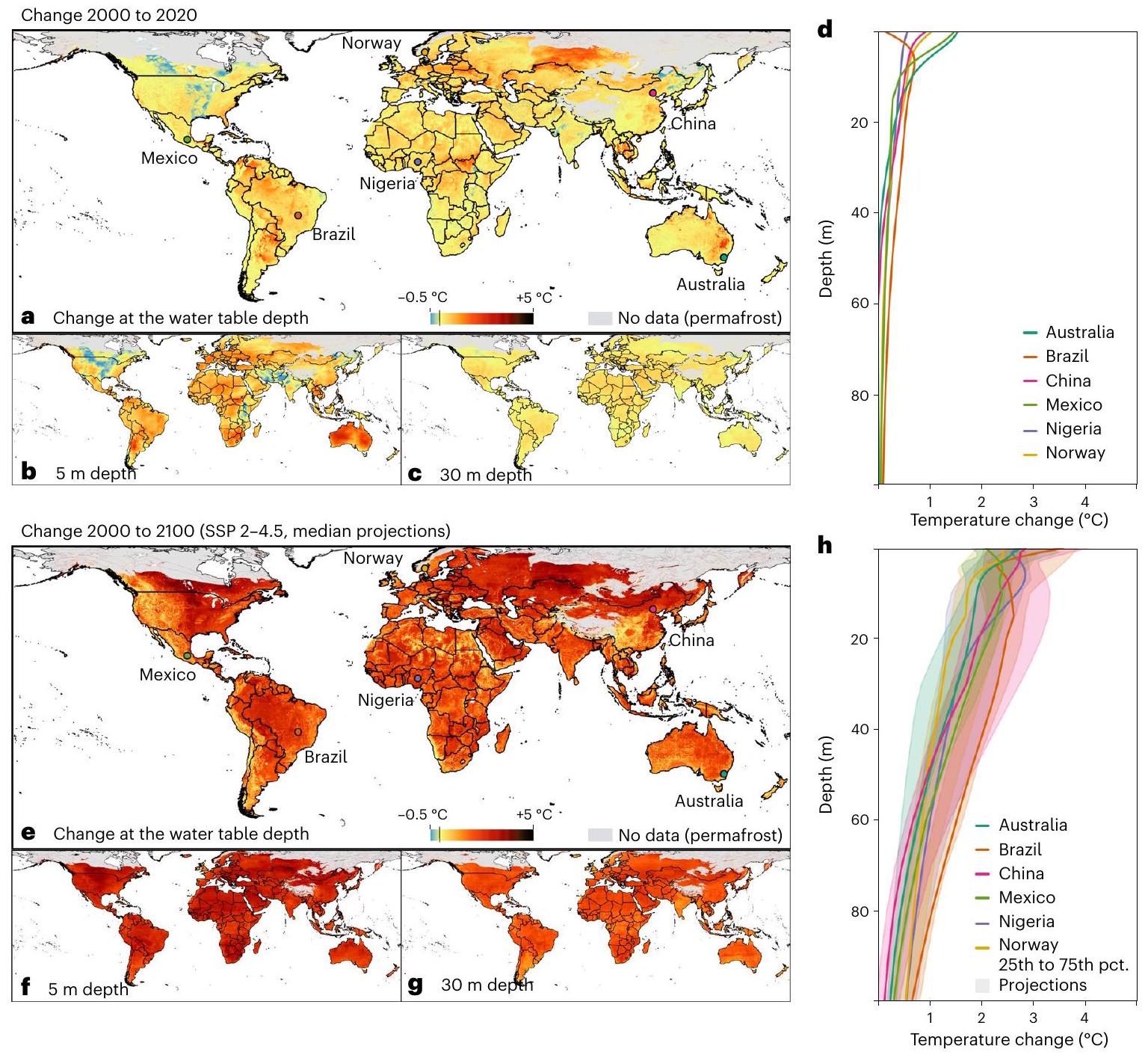

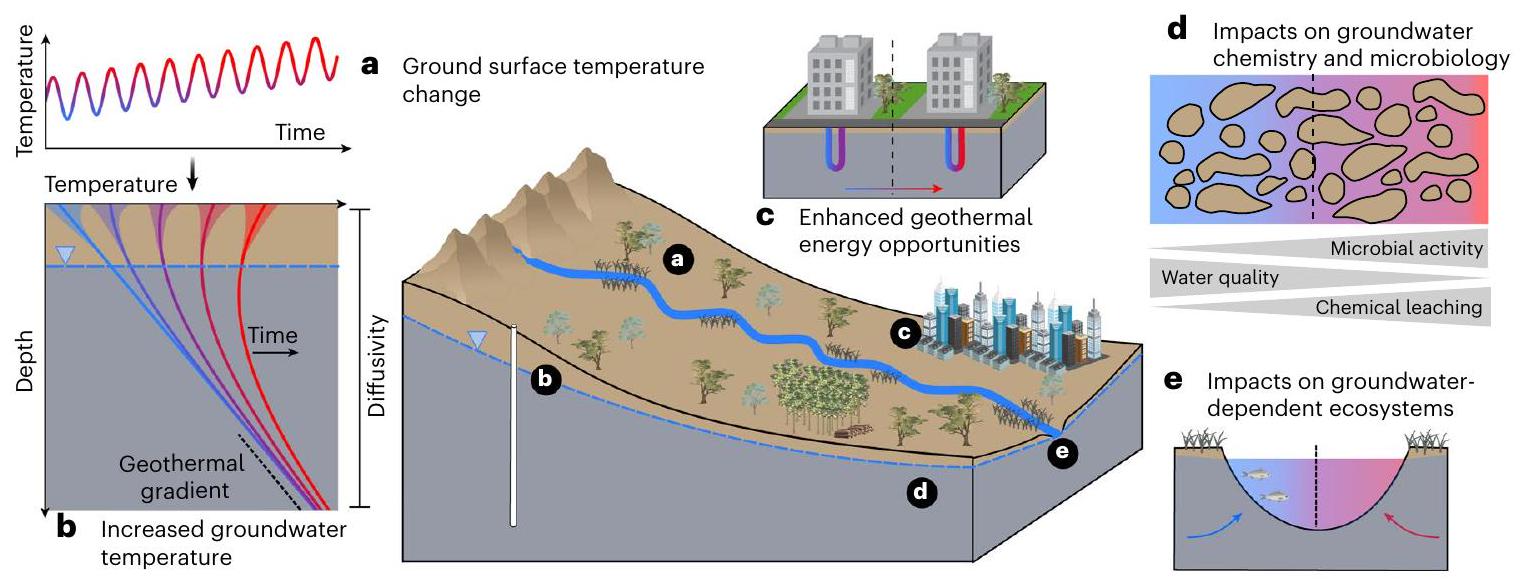

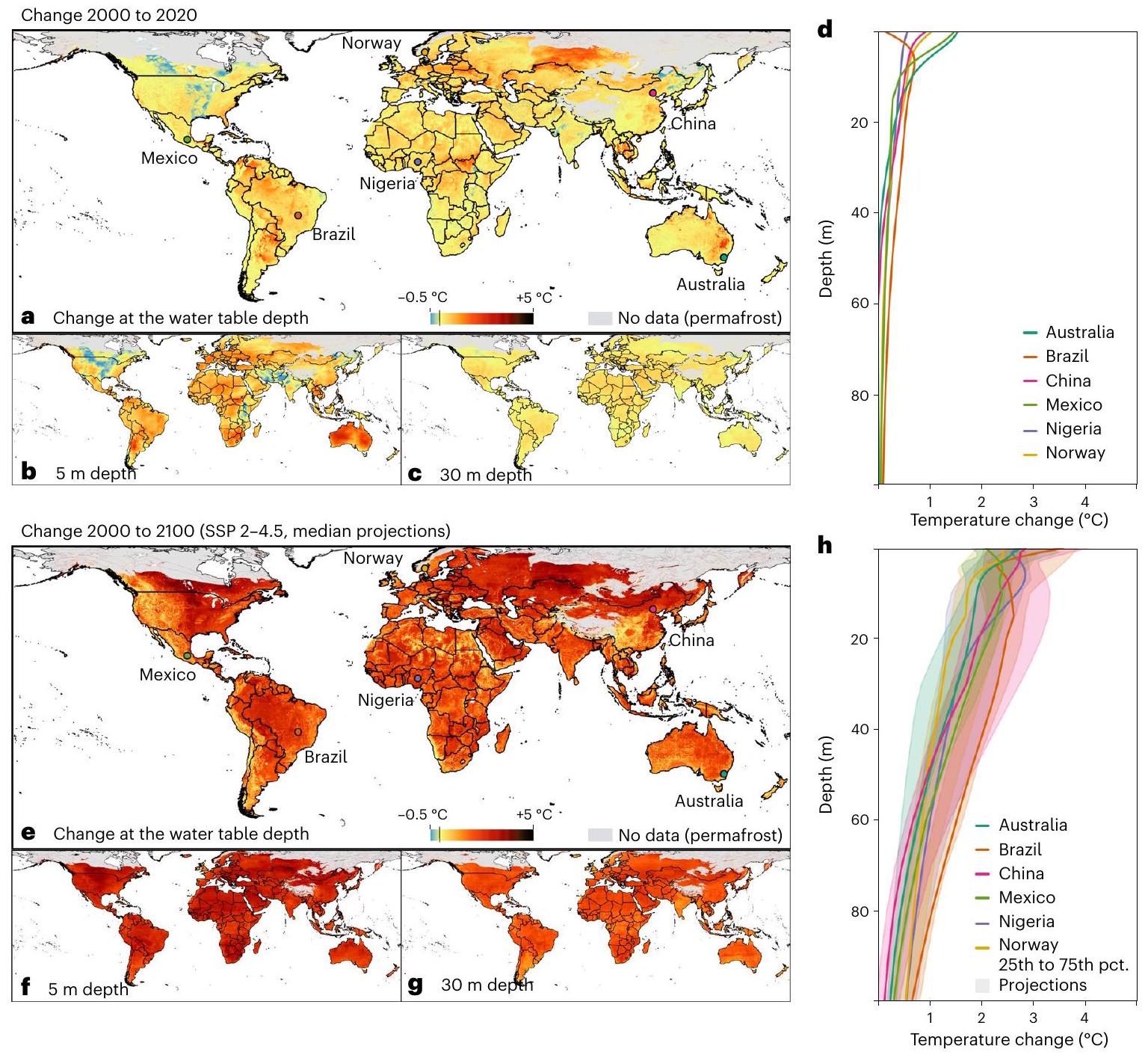

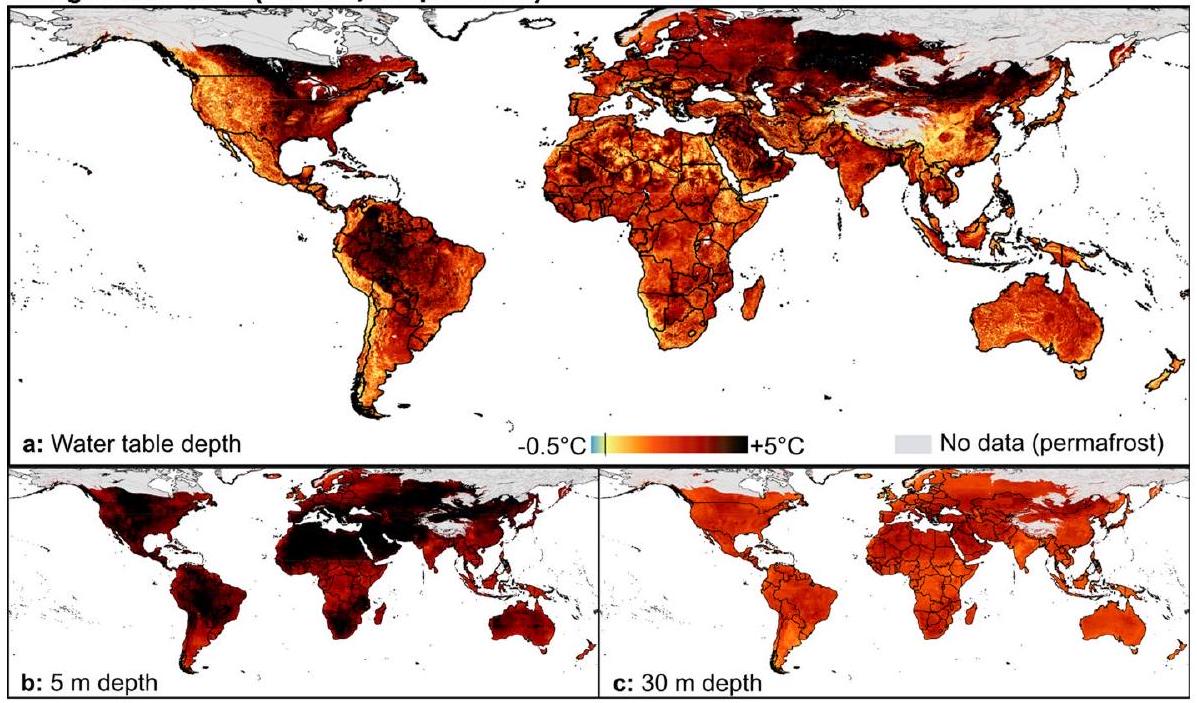

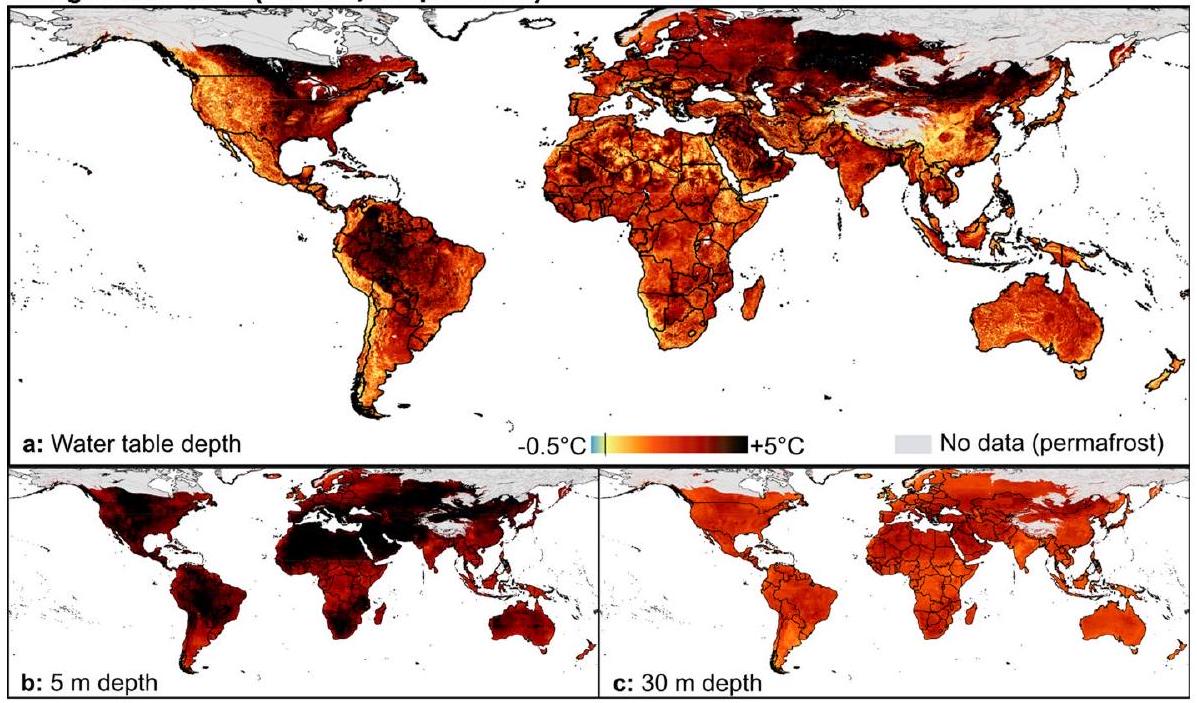

changes. e-h, Projected (2000-2100) changes. a,e, Map of the change in annual mean temperature at the depth of the water table. The line in the legend indicates

below the land surface (c,g). d,h, Change in temperatures between 2000 and 2020 (d) and difference between 2000 and 2100 (h) as depth profiles for selected locations (symbols in

Summary and model application

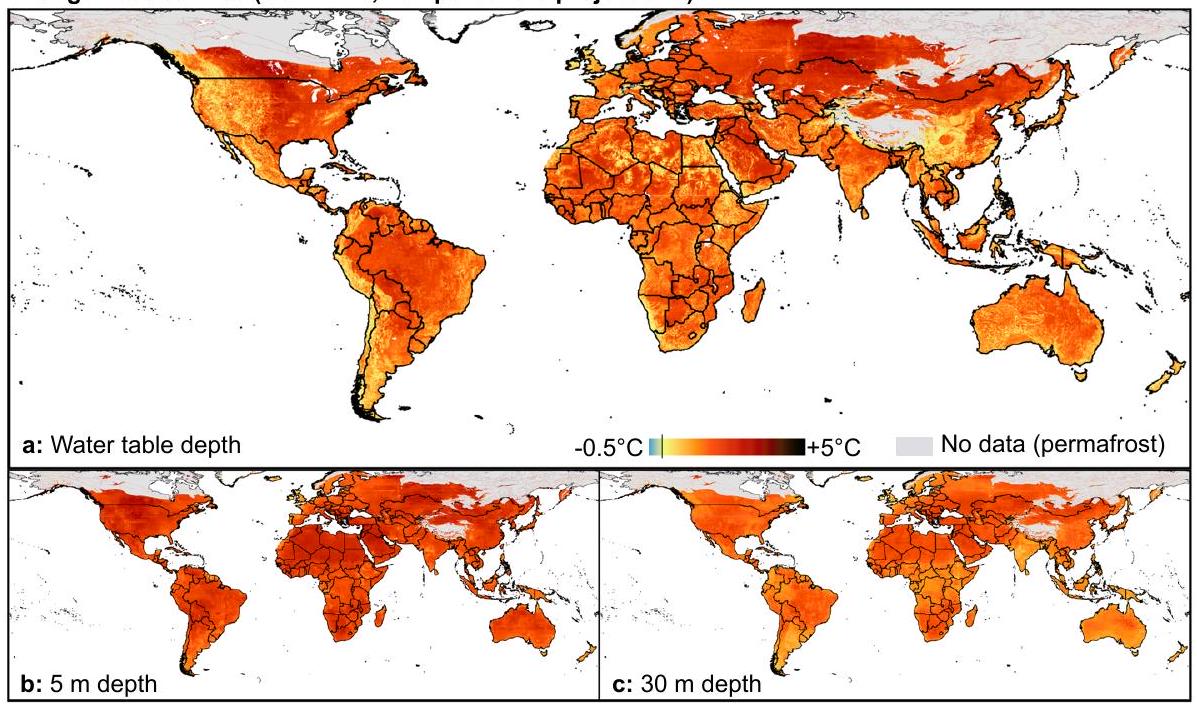

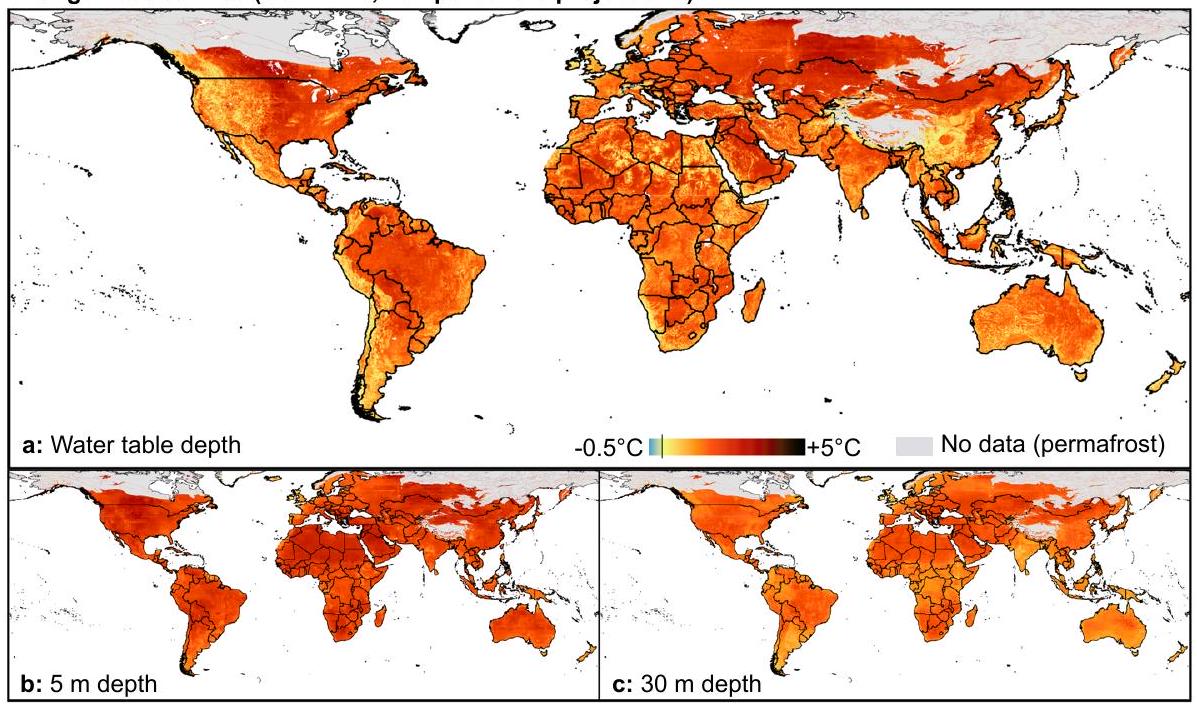

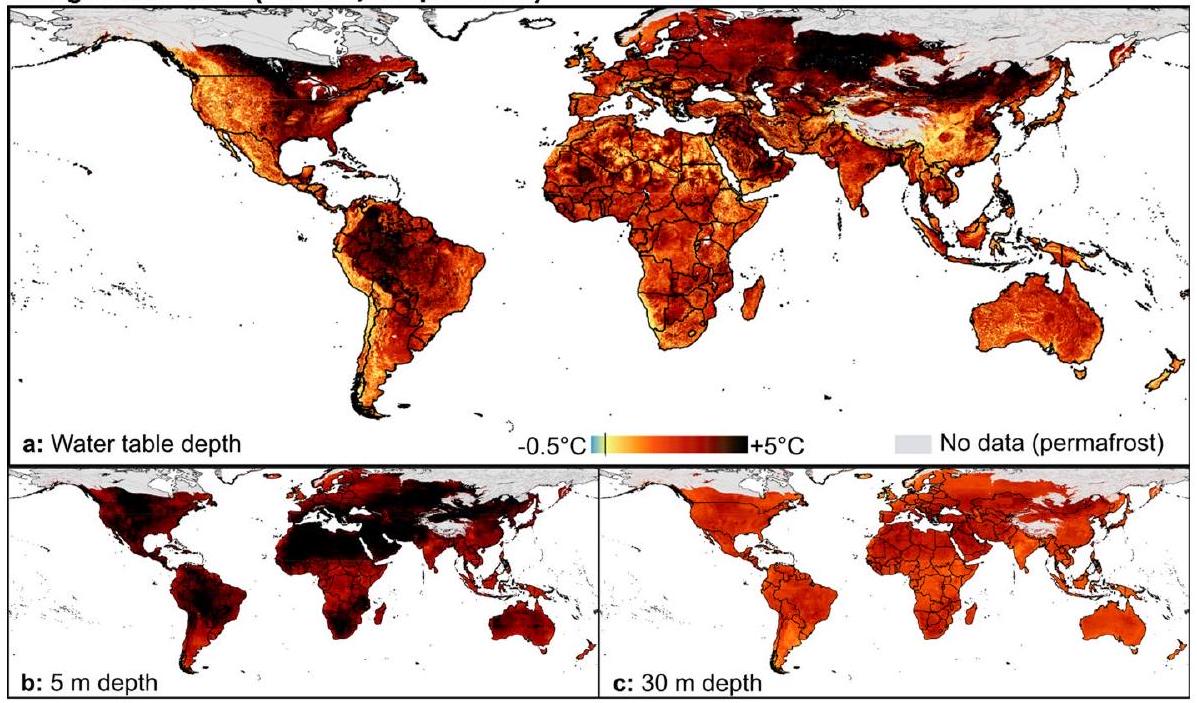

groundwater temperature change to 2100 at a global scale. Our analyses are based on reasonable hydraulic and thermal assumptions providing conservative estimates and allow for both the hindcasting and forecasting of groundwater temperatures. Future groundwater temperature forecasts are based on both SSP 2-4.5 and 5-8.5 climate scenarios. We provide global temperature maps at the depth of the water table, 5 and 30 m below land surface, and these highlight that places with shallow water tables and/or high rates of atmospheric warming will experience the highest groundwater warming rates globally. Importantly, given the vertical dimension of the subsurface, groundwater warming is inherently a three-dimensional (3D) phenomenon with increased lagging of warming with depth, making aquifer warming dynamics distinct from the warming of shallow or well-mixed surface water bodies.

Current status (2020)

threatens ecosystems and the industries depending on them, and it will degrade drinking water quality, primarily in less-developed regions.

Online content

References

- Meinshausen, M. et al. Historical greenhouse gas concentrations for climate modelling (CMIP6). Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 2057-2116 (2017).

- Arias, P. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 33-144 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- Kurylyk, B. L. & Irvine, D. J. Heat: an overlooked tool in the practicing hydrogeologist’s toolbox. Groundwater 57, 517-524 (2019).

- Bense, V. F. & Kurylyk, B. L. Tracking the subsurface signal of decadal climate warming to quantify vertical groundwater flow rates. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl076015 (2017).

- Smerdon, J. E. & Pollack, H. N. Reconstructing earth’s surface temperature over the past 2000 years: the science behind the headlines. WIREs Climate Change 7, 746-771 (2016).

- Döll, P. & Fiedler, K. Global-scale modeling of groundwater recharge. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 863-885 (2008).

- Famiglietti, J. S. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 945-948 (2014).

- Wada, Y. et al. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl044571 (2010).

- Gleeson, T., Befus, K. M., Jasechko, S., Luijendijk, E. & Cardenas, M. B. The global volume and distribution of modern groundwater. Nat. Geosci. 9, 161-167 (2015).

- Taylor, R. G. et al. Ground water and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 322-329 (2012).

- Green, T. R. et al. Beneath the surface of global change: impacts of climate change on groundwater. J. Hydrol. 405, 532-560 (2011).

- Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651-659 (2018).

- Hannah, D. M. & Garner, G. River water temperature in the United Kingdom. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 39, 68-92 (2015).

- Bosmans, J. et al. FutureStreams, a global dataset of future streamflow and water temperature. Sci. Data https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41597-022-01410-6 (2022).

- O’Reilly, C. M. et al. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi. org/10.1002/2015gl066235 (2015).

- Ferguson, G. et al. Crustal groundwater volumes greater than previously thought. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi. org/10.1029/2021gl093549 (2021).

- Zektser, I. S. & Everett, L. G. Groundwater Resources of the World and Their Use (UNESCO, 2004).

- Siebert, S. et al. Groundwater use for irrigation-a global inventory. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1863-1880 (2010).

- de Graaf, I. E. M., Gleeson, T., van Beek, L. P. H. R., Sutanudjaja, E. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Environmental flow limits to global groundwater pumping. Nature 574, 90-94 (2019).

- Chen, C.-H. et al. in Groundwater and Subsurface Environments (ed. Taniguchi, M.) 185-199 (Springer, 2011).

- Benz, S. A., Bayer, P., Winkler, G. & Blum, P. Recent trends of groundwater temperatures in Austria. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 3143-3154 (2018).

- Riedel, T. Temperature-associated changes in groundwater quality. J. Hydrol. 572, 206-212 (2019).

- Cogswell, C. & Heiss, J. W. Climate and seasonal temperature controls on biogeochemical transformations in unconfined coastal aquifers. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi. org/10.1029/2021jg006605 (2021).

- Griebler, C. et al. Potential impacts of geothermal energy use and storage of heat on groundwater quality, biodiversity, and ecosystem processes. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12665-016-6207-z (2016).

- Retter, A., Karwautz, C. & Griebler, C. Groundwater microbial communities in times of climate change. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 41, 509-538 (2021).

- Bonte, M. et al. Impacts of shallow geothermal energy production on redox processes and microbial communities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 14476-14484 (2013).

- Bonte, M., van Breukelen, B. M. & Stuyfzand, P. J. Temperature-induced impacts on groundwater quality and arsenic mobility in anoxic aquifer sediments used for both drinking water and shallow geothermal energy production. Water Res. 47, 5088-5100 (2013).

- Brookfield, A. E. et al. Predicting algal blooms: are we overlooking groundwater? Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144442 (2021).

- Bondu, R., Cloutier, V. & Rosa, E. Occurrence of geogenic contaminants in private wells from a crystalline bedrock aquifer in western Quebec, Canada: geochemical sources and health risks. J. Hydrol. 559, 627-637 (2018).

- Agudelo-Vera, C. et al. Drinking water temperature around the globe: understanding, policies, challenges and opportunities. Water 12, 1049 (2020).

- Mejia, F. H. et al. Closing the gap between science and management of cold-water refuges in rivers and streams. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5482-5508 (2023).

- Jyväsjärvi, J. et al. Climate-induced warming imposes a threat to north European spring ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 4561-4569 (2015).

- Stauffer, F., Bayer, P., Blum, P., Molina Giraldo, N. & Kinzelbach, W. Thermal Use of Shallow Groundwater (CRC Press, 2013).

- Epting, J., Müller, M. H., Genske, D. & Huggenberger, P. Relating groundwater heat-potential to city-scale heat-demand: a theoretical consideration for urban groundwater resource management. Appl. Energy 228, 1499-1505 (2018).

- Benz, S. A., Menberg, K., Bayer, P. & Kurylyk, B. L. Shallow subsurface heat recycling is a sustainable global space heating alternative. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31624-6 (2022).

- Schüppler, S., Fleuchaus, P. & Blum, P. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of an aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) in germany. Geotherm. Energy https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40517-019-0127-6 (2019).

- Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937-1958 (2016).

- Zhang, T. Influence of the seasonal snow cover on the ground thermal regime: an overview. Rev. Geophys. 43, RG4002 (2005).

- Zanna, L., Khatiwala, S., Gregory, J. M., Ison, J. & Heimbach, P. Global reconstruction of historical ocean heat storage and transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1126-1131 (2019).

- von Schuckmann, K. et al. Heat stored in the earth system: where does the energy go? Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2013-2041 (2020).

- Cuesta-Valero, F. J. et al. Continental heat storage: contributions from the ground, inland waters, and permafrost thawing. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 609-627 (2023).

- Nissler, E. et al. Heat transport from atmosphere through the subsurface to drinking-water supply pipes. Vadose Zone J. 22, 270-286 (2023).

- A Global Overview of National Regulations and Standards for Drinking-Water Quality 2nd edn (WHO, 2O21); https://apps.who.int/ iris/handle/10665/350981

- Griebler, C. & Avramov, M. Groundwater ecosystem services: a review. Freshw. Sci. 34, 355-367 (2015).

- Mammola, S. et al. Scientists’ warning on the conservation of subterranean ecosystems. BioScience 69, 641-650 (2019).

- McDonough, L. K. et al. Changes in global groundwater organic carbon driven by climate change and urbanization. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14946-1 (2020).

- Atawneh, D. A., Cartwright, N. & Bertone, E. Climate change and its impact on the projected values of groundwater recharge: a review. J. Hydrol. 601, 126602 (2021).

- Meisner, J. D., Rosenfeld, J. S. & Regier, H. A. The role of groundwater in the impact of climate warming on stream salmonines. Fisheries 13, 2-8 (1988).

- Hare, D. K., Helton, A. M., Johnson, Z. C., Lane, J. W. & Briggs, M. A. Continental-scale analysis of shallow and deep groundwater contributions to streams. Nat. Commun. 12, 1450 (2021).

- Caissie, D., Kurylyk, B. L., St-Hilaire, A., El-Jabi, N. & MacQuarrie, K. T. Streambed temperature dynamics and corresponding heat fluxes in small streams experiencing seasonal ice cover. J. Hydrol. 519, 1441-1452 (2014).

- Wondzell, S. M. The role of the hyporheic zone across stream networks. Hydrol. Process. 25, 3525-3532 (2011).

- Liu, S. et al. Global river water warming due to climate change and anthropogenic heat emission. Glob. Planet. Change 193, 103289 (2020).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Diffusive heat transport

resolution at Earth’s surface. However, Google Earth Engine automatically rescales images shown on the map based on the zoom level of the user. Charts that represent temperatures at a given location at a 5 km scale are created by clicking on the map and can be exported in CSV, SVQ or PNG file formats. For all analyses showing annual mean data at the water table depth, we first calculate monthly temperatures at the associated monthly groundwater level before averaging the results.

Ground surface temperatures

For our analysis we use the ground thermal diffusivity

Geothermal gradient

Water table depth

Model evaluation

Example locations

Depth of the geothermal gradient ‘inflection point’

Accumulated energy

Drinking water temperature thresholds

Impact on surface water bodies

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Tissen, C., Benz, S. A., Menberg, K., Bayer, P. & Blum, P. Groundwater temperature anomalies in central Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 104012 (2019).

- Bodri, L. & Cermak, V. Borehole Climatology (Elsevier, 2007).

- Carslaw, H. S. & Jaeger, J. C. Conduction of Heat in Solids (Oxford Univ. Press, 1986).

- Turcotte, D. L. & Schubert, G. Geodynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

- Kurylyk, B. L., Irvine, D. J. & Bense, V. F. Theory, tools, and multidisciplinary applications for tracing groundwater fluxes from temperature profiles. WIREs Water https://doi.org/10.1002/ wat2.1329 (2018).

- Taylor, C. A. & Stefan, H. G. Shallow groundwater temperature response to climate change and urbanization. J. Hydrol. 375, 601-612 (2009).

- Bense, V. F., Kurylyk, B. L., van Daal, J., van der Ploeg, M. J. & Carey, S. K. Interpreting repeated temperature-depth profiles for groundwater flow. Water Resour. Res. 53, 8639-8647 (2017).

- Brown, J., Ferrians, O., Heginbottom, J. A. & Melnikov, E. CircumArctic map of permafrost and ground-ice conditions, version 2. NSIDC https://nsidc.org/data/GGD318/versions/2 (2002).

- Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18-27 (2017).

- ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 2001 to present. Copernicus Climate Data Store https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ doi/10.24381/cds.68d2bb30 (2019).

- Hansen, J. et al. Climate simulations for 1880-2003 with GISS modelE. Clim. Dyn. 29, 661-696 (2007).

- Soong, J. L., Phillips, C. L., Ledna, C., Koven, C. D. & Torn, M. S. CMIP5 models predict rapid and deep soil warming over the 21st century. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jg005266 (2020).

- Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J. & Börker, J. Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1897-1904 (2018).

- VDI 4640-Thermal Use of the Underground (VDI-Gesellschaft Energie und Umwelt, 2010).

- Börker, J., Hartmann, J., Amann, T. & Romero-Mujalli, G. Terrestrial sediments of the earth: development of a global unconsolidated sediments map database (GUM). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 997-1024 (2018).

- Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: a representation of rock properties at the earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/

(2012). - Clauser, C. in Thermal Storage and Transport Properties of Rocks, I: Heat Capacity and Latent Heat (ed. Gupta, H. K.) 1423-1431 (Springer, 2011).

- Clauser, C. in Thermal Storage and Transport Properties of Rocks, II: Thermal Conductivity and Diffusivity (ed. Gupta, H. K.) 1431-1448 (Springer, 2011).

- Rau, G. C., Andersen, M. S., McCallum, A. M., Roshan, H. & Acworth, R. I. Heat as a tracer to quantify water flow in near-surface sediments. Earth Sci. Rev. 129, 40-58 (2014).

- Halloran, L. J., Rau, G. C. & Andersen, M. S. Heat as a tracer to quantify processes and properties in the vadose zone: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 159, 358-373 (2016).

- Davies, J. H. Global map of solid earth surface heat flow. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 4608-4622 (2013).

- Fan, Y., Li, H. & Miguez-Macho, G. Global patterns of groundwater table depth. Science 339, 940-943 (2013).

- Fan, Y., Miguez-Macho, G., Jobbágy, E. G., Jackson, R. B. & Otero-Casal, C. Hydrologic regulation of plant rooting depth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10572-10577 (2017).

- Benz, S. A., Bayer, P. & Blum, P. Global patterns of shallow groundwater temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 034005 (2017).

- Jasechko, S. & Perrone, D. Global groundwater wells at risk of running dry. Science 372, 418-421 (2021).

- Gridded population of the world, version 4 (GPWv4): population density adjusted to match 2015 revision UN WPP country totals, revision 11. CIESIN https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/ data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-adjusted-to-2015-unwp p-country-totals-rev11 (2018).

- Gao, J. Global 1-km downscaled population base year and projection grids based on the shared socioeconomic pathways, revision 01. CIESIN https://doi.org/10.7927/q7z9-9r69 (2020).

- Gao, J. Downscaling Global Spatial Population Projections from 1/8-Degree to 1-km Grid Cells (NCAR/UCAR, 2017); https://opensky. ucar.edu/islandora/object/technotes:553

- Benz, S. Global groundwater warming due to climate change. Borealis https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/GE4VEQ (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01453-x.

not increasing with depth as expected based on the geothermal gradient.

a-c, Annual mean groundwater temperature 25 th percentile projected changes.

d-f, Annual mean groundwater temperature 75th percentile projected changes.

2000 and 2100 and implications following SSP 5-8.5. a, Map of the change in annual mean temperature between 2000 and 2100 following SSP 5-8.5 (median projections) at the depth of the water table (under consideration of its seasonal variation). Temperatures in 2000 are based on the historic CMIP6 scenario. The line in the legend indicates

geothermal gradient.

SSP 2-4.5,

exceed guideline thresholds for drinking water temperatures (DWTs) for SSP 2-4.5 25th and 75th percentile projections, respectively. e and f, Accumulated heat in the saturated zone for SSP 5-8.5 25th and 75th percentile projections, respectively.

(DWTs). a, Maximum monthly GWTs at the depth of the water table in 2020. b and c, Maximum monthly GWTs at the depth of the water table in 2100 following median projections of SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, respectively.

Centre for Water Resources Studies and Department of Civil and Resource Engineering, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany. Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Casuarina, Northern Territory, Australia. School of Environmental and Life Sciences, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia. Department of Applied Geology, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany. Institute of Applied Geosciences, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany. Department of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. e-mail: susanne.benz@kit.edu; barret.kurylyk@dal.ca