DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00921-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38238757

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-18

اختبار شرائط الاختبار: الأداء المختبري لشرائط اختبار الفنتانيل

الملخص

الخلفية: تستمر أزمة الجرعات الزائدة الناتجة عن الأفيونيات الاصطناعية في التصاعد في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قمنا بتقييم فعالية عدة دفعات تصنيع من شريط اختبار الفنتانيل (FTS) للكشف عن الفنتانيل ومشتقاته وقمنا بتقييم التفاعل المتبادل مع التداخلات المحتملة. الطرق: تم إذابة معايير المخدرات في الماء في بيئة مختبرية وتم تخفيفها بشكل متسلسل. تم اختبار تخفيفات المخدرات باستخدام خمسة دفعات تصنيع مختلفة من شرائط اختبار BTNX Rapid Response (

الخلفية

المادة الكيميائية الرئيسية، فإن مشتقات الفنتانيل تساهم بشكل كبير في وفيات الجرعات الزائدة. في المنطقة المتأثرة بشدة من 10 ولايات أمريكية، تم اكتشاف مشتقات الفنتانيل في سموم الجرعات الزائدة في 5,083 (19.5%) من 26,104 حالة وفاة تم فحصها [9]. تم تحديد أحد عشر نوعًا مختلفًا من مشتقات الفنتانيل والأفيونيات الاصطناعية في مصادرات المخدرات الأخيرة [10]، على الرغم من أن المئات معروفة بوجودها وأكثر من ذلك ممكن نظريًا [11، 12]. بالنسبة للمورفين، يُعتبر الفنتانيل أقوى بمقدار 100 مرة من حيث الوزن وبالتالي يُقدّر أنه أقوى بمقدار 40 مرة من الهيروين[13]. هناك

في السابق، كانت معظم IMF المتاحة في الولايات المتحدة تأتي في شكل هيروين ملوث بالفنتانيل أو هيروين مستبدل بالفنتانيل [16]. الأشخاص الذين يستخدمون هيروين ملوث بالفنتانيل أو مستبدل بالفنتانيل غالبًا ما يكونون غير مدركين للتلوث ولديهم آراء مختلطة حول جاذبيته [16-18]. يمكن لأولئك الذين لديهم خبرة تمييز الهيروين الملوث بالفنتانيل أو المستبدل بالفنتانيل من الهيروين باستخدام عدة استراتيجيات، لكن فائدة ذلك غير معروفة [16]. ومع ذلك، تشير الاتجاهات الأخيرة إلى أن الهيروين يتم استبداله بالفنتانيل كالأفيوني السائد في إمدادات المواد غير القانونية [19، 20]. بالإضافة إلى الهيروين، تم العثور على IMF في حبوب الأفيونيات المزيفة وحبوب البنزوديازيبين [6، 21-23]. تم ملاحظة زيادة التعرض لـ IMF بين مستخدمي المنشطات (مثل الكوكايين والميثامفيتامين) في كل من دراسات الفحص [24] ودراسات السموم بعد الوفاة [25].

يوصى بمزيد من المراقبة لـ IMF في إمدادات المواد غير القانونية لمعالجة الأزمة الأمريكية [13]. تم استخدام فحص المخدرات في نقطة الاستخدام في أوروبا وأستراليا لإبلاغ المستخدمين بالتلوث المحتمل لموادهم [26-29]. تتوفر مجموعة من خيارات الاختبار المناسبة لخدمات تقليل الأضرار [28]. يوجد اختبار سريع للفنتانيل كاختبار مناعي للبول، والذي يمكن تكييفه للاختبار المباشر للمخدرات. لقد ظهرت هذه الشرائط لاختبار الفنتانيل (FTSs) كاستراتيجية لتقليل الأضرار

على الرغم من وجود عدد من التحديات [16، 30-33]. تكشف النتائج المبكرة حول استخدام FTS بين عينات المجتمع في الولايات المتحدة عن قبول [34، 35] وتغييرات إيجابية كبيرة في سلوك استخدام المخدرات المبلغ عنه بعد اختبار إيجابي للفنتانيل [36-38]. مع تزايد إدراك انتشار الفنتانيل في معظم أنحاء الولايات المتحدة، هناك خطر أن يتناقص الحافز لمثل هذه التغييرات السلوكية الإيجابية حيث يُعتبر التعرض للفنتانيل أمرًا لا مفر منه من قبل الأشخاص الذين يستخدمون المخدرات [32، 36]. ومع ذلك، حتى عندما يُعتبر الفنتانيل أمرًا لا مفر منه، مما يمنع التأثيرات الإيجابية على المستوى الفردي، لا يزال الأشخاص الذين يستخدمون المخدرات يصفون FTS كأداة مفيدة على المستوى المجتمعي [39].

| الدراسة | السنة | حد الكشف عن الفنتانيل (نانوغرام/مل) | تفاعل مشتقات الفنتانيل | التداخلات |

| جرين وآخرون. | 2020 | 100 | 2 من 2 تم تقييمها تفاعلت | لم يتم تقييمها |

| بيرغ وآخرون. | 2021 | 50 | 25 من 28 تم تقييمها تفاعلت | لم يتم العثور على أي شيء بين المواد التي تم تقييمها |

| لوك وود وآخرون. | 2021 | 25 | لم يتم تقييمها | الميثامفيتامين، MDMA، ديفين هيدرامين |

| وارتون وآخرون. | 2021 | 100 | 19 من 29 تم تقييمها تفاعلت | لم يتم تقييمها |

| بارك وآخرون. | 2022 | 200 | 13 من 17 تم تقييمها تفاعلت | لم يتم تقييمها |

طرق

المعايير، الكواشف، شرائط الاختبار

تم إجراء الاختبارات في نفس مساحة المختبر. هذه الشرائط الاختبارية هي اختبارات مناعية تنافسية كروماتوغرافية بتدفق جانبي [50].

حساسية الشريط والتفاعل المتبادل

التداخلات

مقارنة بين البول والماء كمواد مذيبة

النتائج

حساسية شرائط اختبار الفنتانيل والتفاعل المتبادل

تم الكشف عن الألفنتانيل أو U-47700 بأي تركيز، حيث أن هذين الأفيونين الصناعيين والسوفنتانيل لهما اختلافات هيكلية أكثر أهمية عن الفنتانيل والأنالوجات الأخرى (انظر الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S1).

الكثير، ولكن لا يزال أقل من دفعات 2017). كانت الحساسية متفاوتة بين الثلاث دفعات من شرائط 2021 المستخرجة لعدة نظائر، مع تباين خاص للأكريلفينتانيل، الكارفنتانيل، والسيكلوبروبيلفينتانيل (الشكل 1).

تداخلات شرائط اختبار الفنتانيل

مقارنة بين البول والماء كإيليوت شريط الاختبار

نقاش

اختبار التداخل

تسلط هذه التغيرات الطولية في حساسية التداخل الضوء على الحاجة إلى تقييم مستمر لدفعات شرائط الاختبار الجديدة، وصعوبة تقديم مجموعة قوية من التعليمات لتخفيف العينات قبل استخدام شريط الاختبار. توصي بعض منظمات تقليل الأضرار بإرشادات تخفيف دقيقة لاستخدام شرائط BTNX-20، على سبيل المثال، لتخفيف الميثامفيتامين وMDMA إلى

المبنية في الأصل على نتائج اختبار التداخل مع دفعات 2017، ستترك الآن الشرائط عرضة لنتيجة إيجابية زائفة من ديفينهيدرامين أو MDMA مع الشرائط التي تؤدي على مستوى دفعات 2021. وبالمثل، نظرًا لانخفاض حساسية الفنتانيل لدفعات 2021 مقارنة بدفعات 2017، فإن النتائج السلبية الزائفة ممكنة مع تخفيف مفرط للفنتانيل ونظائره تحت حد الكشف. الملف الإضافي 3: الجدول S1 A-D يوضح كيف تجعل التغيرات الطولية في أداء FTS من دفعة إلى أخرى مع موازنة الاحتمالات الإيجابية الزائفة والسلبية الزائفة تحديد تركيز عينة مثالي أمرًا صعبًا.

التفاعل المتبادل المرغوب فيه وكشف نظائر الفنتانيل. أكدت عينات فحص المخدرات في كولومبيا البريطانية بواسطة طرق مرجعية مختبرية qNMR أن FTS فشلت في الكشف عن الفنتانيل في 4 من 173 (

يجب ملاحظة بعض القيود في هذه التحليلات. في هذه الدراسة، تم تقييم 13 من أكثر نظائر الفنتانيل استشهادًا من حيث التفاعل المتبادل مع اختبار فنتانيل السريع؛ ومع ذلك، توجد العديد من نظائر الفنتانيل الإضافية، ولا يزال مدى تفاعلها المتبادل غير معروف. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم تقييم 11 من المخدرات غير المشروعة والمواد المضافة فقط من حيث التفاعل المتبادل المحتمل، وقد تؤدي مواد أخرى لم يتم اختبارها إلى نتيجة إيجابية خاطئة في اختبار فنتانيل السريع. تحديد نتائج اختبار فنتانيل السريع من خلال الملاحظة البصرية لغياب أو وجود خط هو أمر ذاتي، وهو قيد حقيقي على استخدامه وقيد محتمل على نتائج هذه الدراسة. تم تقييم جميع النتائج من قبل شخصين أو أكثر في محاولات لتقليل الذاتية، ولكن هذه العملية

يمكن تحسين ذلك من خلال تسجيل تحليل المراجعين الفرديين بدلاً من الاعتماد فقط على قرار الإجماع لتسهيل حساب إحصائية كابا لتلخيص اتفاق المقيمين. من طبيعة نظام FTS أن ليست جميع النتائج واضحة بشكل إيجابي أو سلبي.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

الفنتانيل المصنع بشكل غير قانوني من قبل صندوق النقد الدولي

معلومات إضافية

(

الملف الإضافي 3. الجدول 1A. مثال على نتائج FTS المقدرة لعينة من الميثامفيتامين بدون تلوث بالفنتانيل، اعتمادًا على تركيز فحص المخدرات. يشير تركيز فحص المخدرات إلى التركيز الذي يتم تحقيقه عند إذابة عينة المخدر (خليط غير معروف وغير نقي من مكونات متعددة) في الماء تحضيرًا لاختبار FTS.

الجدول 1B. مثال على نتائج FTS المقدرة لعينة من الميثامفيتامين مع تلوث ضئيل بالفنتانيل، يعتمد على تركيز فحص المخدرات. يشير تركيز فحص المخدرات إلى التركيز الذي يتم تحقيقه عند إذابة عينة المخدر (خليط غير معروف وغير نقي من مكونات متعددة) في الماء تحضيرًا لاختبار FTS. الجدول 1C. مثال على نتائج FTS المقدرة لعينة من MDMA بدون تلوث بالفنتانيل، يعتمد على تركيز فحص المخدرات. يشير تركيز فحص المخدرات إلى التركيز الذي يتم تحقيقه عند إذابة عينة المخدر (خليط غير معروف وغير نقي من مكونات متعددة) في الماء تحضيرًا لاختبار FTS. الجدول 1D. مثال على نتائج FTS المقدرة لعينة من MDMA مع تلوث ضئيل بالفنتانيل، يعتمد على تركيز فحص المخدرات. يشير تركيز فحص المخدرات إلى التركيز الذي يتم تحقيقه عند إذابة عينة المخدر (خليط غير معروف وغير نقي من مكونات متعددة) في الماء تحضيرًا لاختبار FTS.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

References

- Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(71):183-8.

- Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2001-2021. NCHS Data Brief No 457 Natl Cent Health Stat. 2022; 457.

- Diversion Control Division. National Forensic Laboratory Information System: NFLIS-Drug 2021 Annual Report. US Department of Justice, US Drug Enforcement Administration; 2022.

- Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths-27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-43.

- O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700-10 States, July-December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(43):1197-202.

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, Seth P. Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region-United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(34):897-903.

- Unick GJ, Ciccarone D. US regional and demographic differences in prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose hospitalizations. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):112-9.

- Shover CL, Falasinnu TO, Dwyer CL, Santos NB, Cunningham NJ, Freedman RB, et al. Steep increases in fentanyl-related mortality west of the Mississippi River: recent evidence from county and state surveillance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;1(216): 108314.

- O’Donnell J. Notes from the field: opioid-involved overdose deaths with fentanyl or fentanyl analogs detected – 28 states and the District of Columbia, July 2016-December 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6910a4.htm

- Special testing and Research Laboratory. Drug Enforcement Administration Emerging Threat Report Mid-Year 2021. Drug Enforcement Administration; 2022.

- Mojica MA, Carter MD, Isenberg SL, Pirkle JL, Hamelin El, Shaner RL, et al. Designing traceable opioid material§ kits to improve laboratory testing during the U.S. opioid overdose crisis. Toxicol Lett. 2019;317:53-8.

- Zhang Y, Halifax JC, Tangsombatvisit C, Yun C, Pang S, Hooshfar S, et al. Development and application of a High-Resolution mass spectrometry method for the detection of fentanyl analogs in urine and serum. J Mass Spectrom Adv Clin Lab. 2022; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S2667145X22000232

- Ciccarone D. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: a rapidly changing risk environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:107-11.

- Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, Lynch KL. Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: a comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134:121-32.

- Suzuki J, El-Haddad S. A review: fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;1(171):107-16.

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, Mars SG. Heroin uncertainties: exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin.’ Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):146-55.

- Carroll JJ, Marshall BDL, Rich JD, Green TC. Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island: a mixed methods study. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):136-45.

- McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC. Being “hooked up” during a sharp increase in the availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl: adaptations of drug using practices among people who use drugs (PWUD) in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;1(60):82-8.

- Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Browne EN, Wenger LD, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, et al. Transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl in San Francisco, California. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;1(227): 109003.

- Lambdin BH, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, Wenger L, Simpson K, Kral AH. Associations between perceived illicit fentanyl use and infectious disease risks among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(74):299-304.

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler P, Wall M. Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;1(178):501-11.

- McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocainerelated overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):430-2.

- Palamar JJ, Ciccarone D, Rutherford C, Keyes KM, Carr TH, Cottler LB. Trends in seizures of powders and pills containing illicit fentanyl in the United States, 2018 through 2021. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;234: 109398.

- Twillman RK, Dawson E, LaRue L, Guevara MG, Whitley P, Huskey A. Evaluation of trends of near-real-time urine drug test results for methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1): e1918514.

- Nolan ML, Shamasunder S, Colon-Berezin C, Kunins HV, Paone D. Increased presence of fentanyl in cocaine-involved fatal overdoses: implications for prevention. J Urban Health. 2019;96(1):49-54.

- Brunt T. Drug Checking as a Harm Reduction Tool for Recreational Drug Users: Opportunities and Challenges. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2017.

- Caudevilla F, Ventura M, Fornís I, Barratt MJ, Vidal C, Iladanosa CG, et al. Results of an international drug testing service for cryptomarket users. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;35:38-41.

- Harper L, Powell J, Pijl EM. An overview of forensic drug testing methods and their suitability for harm reduction point-of-care services. Harm Reduct J. 2017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5537996/

- Hondebrink L, Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen JJ, Van Der Gouwe D, Brunt TM. Monitoring new psychoactive substances (NPS) in The Netherlands: data from the drug market and the Poisons Information Centre. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:109-15.

- Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):172-9.

- Gilbert M, Dasgupta N. Silicon to syringe: cryptomarkets and disruptive innovation in opioid supply chains. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):160-7.

- McGowan CR, Harris M, Platt L, Hope V, Rhodes T. Fentanyl self-testing outside supervised injection settings to prevent opioid overdose: do we know enough to promote it? Int J Drug Policy. 2018;1(58):31-6.

- Socías ME, Wood E. Epidemic of deaths from fentanyl overdose. BMJ. 2017;28(358): j4355.

- Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Rich JD, et al. High willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):7.

- Sherman SG, Morales KB, Park JN, McKenzie M, Marshall BDL, Green TC. Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: baltimore, Boston and Providence. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(68):46-53.

- Goldman JE, Waye KM, Periera KA, Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Marshall BDL. Perspectives on rapid fentanyl test strips as a harm reduction practice among young adults who use drugs: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):3.

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:122-8.

- Park JN, Frankel S, Morris M, Dieni O, Fahey-Morrison L, Luta M, et al. Evaluation of fentanyl test strip distribution in two Mid-Atlantic syringe services programs. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;1(94): 103196.

- Weicker NP, Owczarzak J, Urquhart G, Park JN, Rouhani S, Ling R, et al. Agency in the fentanyl era: exploring the utility of fentanyl test strips in an opaque drug market. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;84: 102900.

- Maghsoudi N, Tanguay J, Scarfone K, Rammohan I, Ziegler C, Werb D, et al. Drug checking services for people who use drugs: a systematic review. Addiction. 2022;117(3):532-44.

- Park JN, Sherman SG, Sigmund V, Breaud A, Martin K, Clarke WA. Validation of a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for the detection of fentanyl in drug samples. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;1(240): 109610.

- BTNX INC. BTNX INC. Fentanyl Strips for Harm Reduction Use. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 4]. BTNX INC. Fentanyl strips for harm reduction use. https:// www.btnx.com/files/BTNX_Fentanyl_Strips_Harm_Reduction_Brochure. PDF

- Green TC, Park JN, Gilbert M, McKenzie M, Struth E, Lucas R, et al. An assessment of the limits of detection, sensitivity and specificity of three devices for public health-based drug checking of fentanyl in streetacquired samples. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;1(77): 102661.

- Bergh MSS, Øiestad ÅML, Baumann MH, Bogen IL. Selectivity and sensitivity of urine fentanyl test strips to detect fentanyl analogues in illicit drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;1(90): 103065.

- Lockwood TLE, Vervoordt A, Lieberman M. High concentrations of illicit stimulants and cutting agents cause false positives on fentanyl test strips. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):30.

- Wharton RE, Casbohm J, Hoffmaster R, Brewer BN, Finn MG, Johnson RC. Detection of 30 fentanyl analogs by commercial immunoassay kits. J Anal Toxicol. 2021;45(2):111-6.

- DanceSafe. How to Test Your Drugs for Fentanyl. DanceSafe; 2020. https:// dancesafe.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/DS-fentanly-instruction2020.pdf

- Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344-50.

- Clark R. URGENT: Recent batch of fentanyl strips requires different dilutions|DanceSafe. 2021. https://dancesafe.org/urgent-most-recent-batch-of-fentanyl-test-strips-requires-more-dilution-when-testi ng-mdma-and-meth/

- Matsuda R, Rodriguez E, Suresh D, Hage DS. Chromatographic immunoassays: strategies and recent developments in the analysis of drugs and biological agents. Bioanalysis. 2015;7(22):2947-66.

- Baumann MH, Tocco G, Papsun DM, Mohr AL, Fogarty MF, Krotulski AJ. U-47700 and its analogs: non-fentanyl synthetic opioids impacting the recreational drug market. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):895.

- Delcher C, Wang Y, Vega RS, Halpin J, Gladden RM, O’Donnell JK, et al. Carfentanil Outbreak-Florida, 2016-2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(5):125-9.

- Bhullar MK, Gilson TP, Singer ME. Trends in opioid overdose fatalities in Cuyahoga County, Ohio: multi-drug mixtures, the African-American community and carfentanil. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;1(4): 100069.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. 2020 Drug Enforcement Administration National Drug Threat Assessment. U.S. Department of Justice; 2021.

- Solomon N, Hayes J. Levamisole: a high performance cutting agent. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2017;7(3):469-76.

- Dinwiddie AT. Notes from the Field: Antihistamine Positivity and Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths—44 Jurisdictions, United States, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71. https://www.cdc. gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7141a4.htm

- McCrae K, Tobias S, Grant C, Lysyshyn M, Laing R, Wood E, et al. Assessing the limit of detection of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and immunoassay strips for fentanyl in a real-world setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(1):98-102.

- McCrae K, Tobias S, Stunden C. BCCSU drug checking operational technician manual version 2. British Columbia Centre on Sustance Use; 2022.

- Borden SA, Saatchi A, Vandergrift GW, Palaty J, Lysyshyn M, Gill CG. A new quantitative drug checking technology for harm reduction: pilot study in Vancouver, Canada using paper spray mass spectrometry. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41(2):410-8.

- Ciccarone D, Moran L, Outram S, Werb D, et al. Insights from drug checking programs: practicing bootstrap public health whilst tailoring to local drug user needs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):5999.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

جون سي. هاليفاكس

john.halifax@ucsf.edu

قسم طب المختبرات، مختبر زسفغ السريري، جامعة كاليفورنيا في سان فرانسيسكو، 1001 شارع بوتريو، مبنى 5 2M16، سان فرانسيسكو، كاليفورنيا 94110، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم طب الأسرة والمجتمع، جامعة كاليفورنيا في سان فرانسيسكو، 500 شارع بارناسوس، MU-3E، صندوق 900، سان فرانسيسكو، كاليفورنيا 94143، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00921-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38238757

Publication Date: 2024-01-18

Testing the test strips: laboratory performance of fentanyl test strips

Abstract

Background The overdose crisis driven by synthetic opioids continues to escalate in the USA. We evaluated the efficacy of multiple manufacturing lots of a fentanyl test strip (FTS) to detect fentanyl and fentanyl analogs and assessed cross-reactivity with possible interferences. Methods Drug standards were dissolved in water in a laboratory setting and serially diluted. Drug dilutions were tested using five different manufacturing lots of BTNX Rapid Response (

Background

main chemical, fentanyl analogs are significantly contributing to overdose deaths. In the highly impacted region of 10 US states, fentanyl analogs were detected in overdose toxicology in 5,083 (19.5%) of 26,104 examined overdose deaths [9]. Eleven different fentanyl analogs and synthetic opioids have been identified in recent drug seizures [10], although hundreds are known to exist and more theoretically possible [11, 12]. In relation to morphine, fentanyl is 100 times as potent by weight and thus estimated to be 40 times more potent than heroin[13]. There is a

Previously, most IMF available in the USA came in the form of fentanyl-adulterated or fentanyl-substituted heroin [16]. Persons who use fentanyl-adulterated or fentanyl-substituted heroin are often unaware of the adulteration and have mixed opinions about its desirability [16-18]. Those with experience can discern fentanyladulterated or fentanyl-substituted heroin from heroin with several strategies, but the utility of this is unknown [16]. Recent trends, however, indicate that heroin is being replaced by fentanyl as the dominant opioid in the illicit substance supply [19, 20]. In addition to heroin, IMF has been found in counterfeit opioid and benzodiazepine pills [6, 21-23]. Increasing exposure to IMF among stimulant users (e.g., cocaine and methamphetamine) has been noted in both screening [24] and post-mortem toxicology studies [25].

Greater surveillance for IMF in the illicit substance supply is recommended to address the US crisis [13]. Point-of-use drug checking has been used in Europe and Australia to inform users of potential contamination of their substances [26-29]. A range of testing options suitable for harm reduction services are available [28]. Rapid testing for fentanyl exists as a urine immunoassay, which can be adapted to direct drug testing. These fentanyl test strips (FTSs) have emerged as a harm reduction strategy

albeit with a number of challenges [16, 30-33]. Early findings on use of FTS among US community-based samples reveal acceptability [34, 35] and significant positive changes in reported drug use behavior following a positive fentanyl test [36-38]. As perceptions of fentanyl ubiquity become increasingly common in much of the USA, there is a risk the incentive for such positive behavioral changes decreases as fentanyl exposure is considered unavoidable by people who use drugs [32, 36]. However, even when fentanyl is considered unavoidable, precluding positive impacts at the individual level, people who use drugs still describe FTS as a useful tool at the community level [39].

| Study | Year | Fentanyl limit of detection (ng/mL) | Fentanyl analog cross-reactivity | Interferences |

| Green et al. | 2020 | 100 | 2 of 2 assessed cross-reacted | Not Assessed |

| Bergh et al. | 2021 | 50 | 25 of 28 assessed cross-reacted | None found among substances assessed |

| Lockwood et al. | 2021 | 25 | Not Assessed | Methamphetamine, MDMA, Diphenhydramine |

| Wharton et al. | 2021 | 100 | 19 of 29 assessed cross-reacted | Not Assessed |

| Park et al. | 2022 | 200 | 13 out of 17 assessed cross-reacted | Not Assessed |

Methods

Standards, reagents, test strips

of testing were performed in the same laboratory space. These test strips are lateral flow chromatographic competitive immunoassay tests [50].

Strip sensitivity and cross-reactivity

Interferences

Urine and water eluent comparison

Results

Fentanyl test strip sensitivity and cross-reactivity

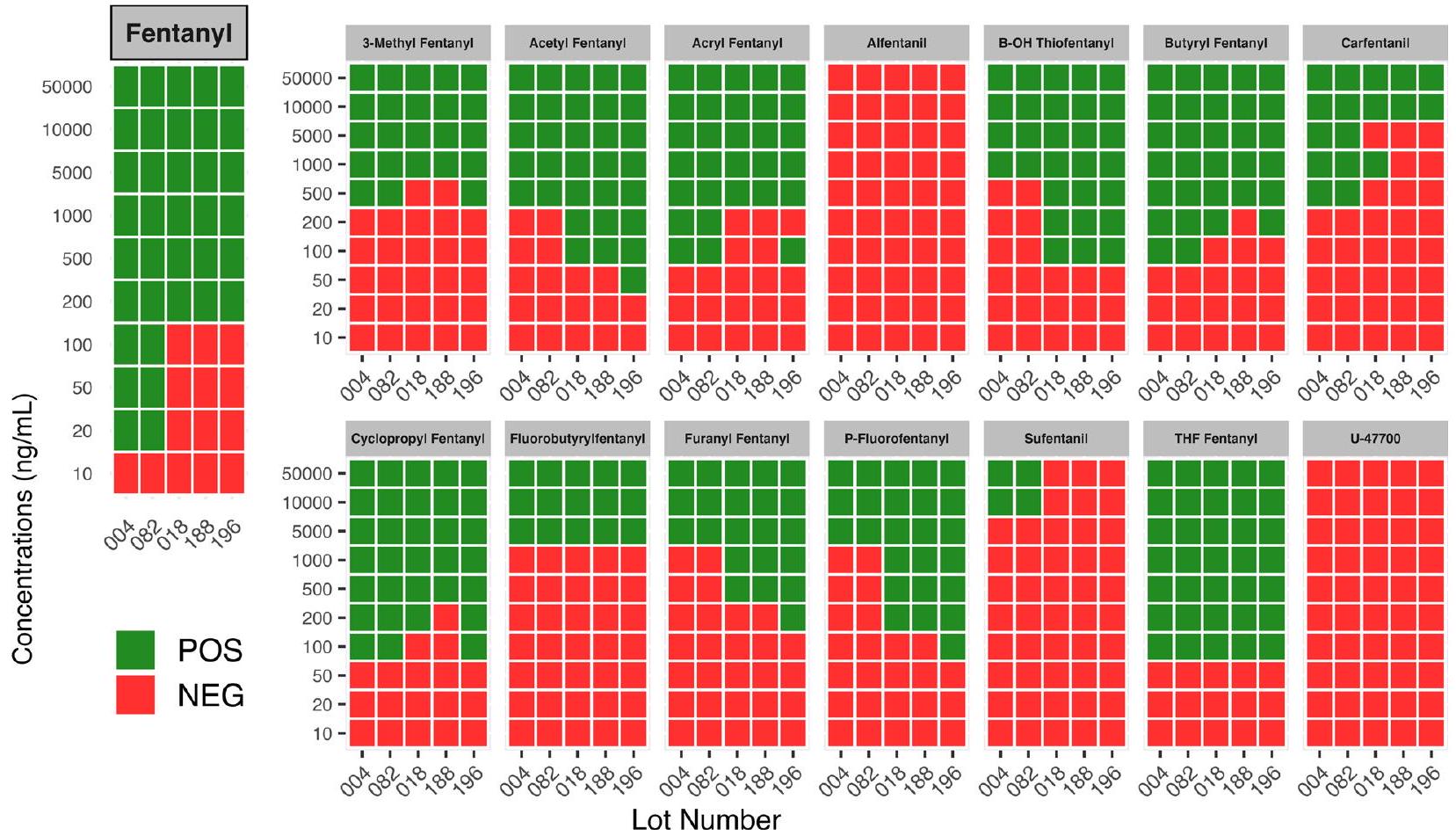

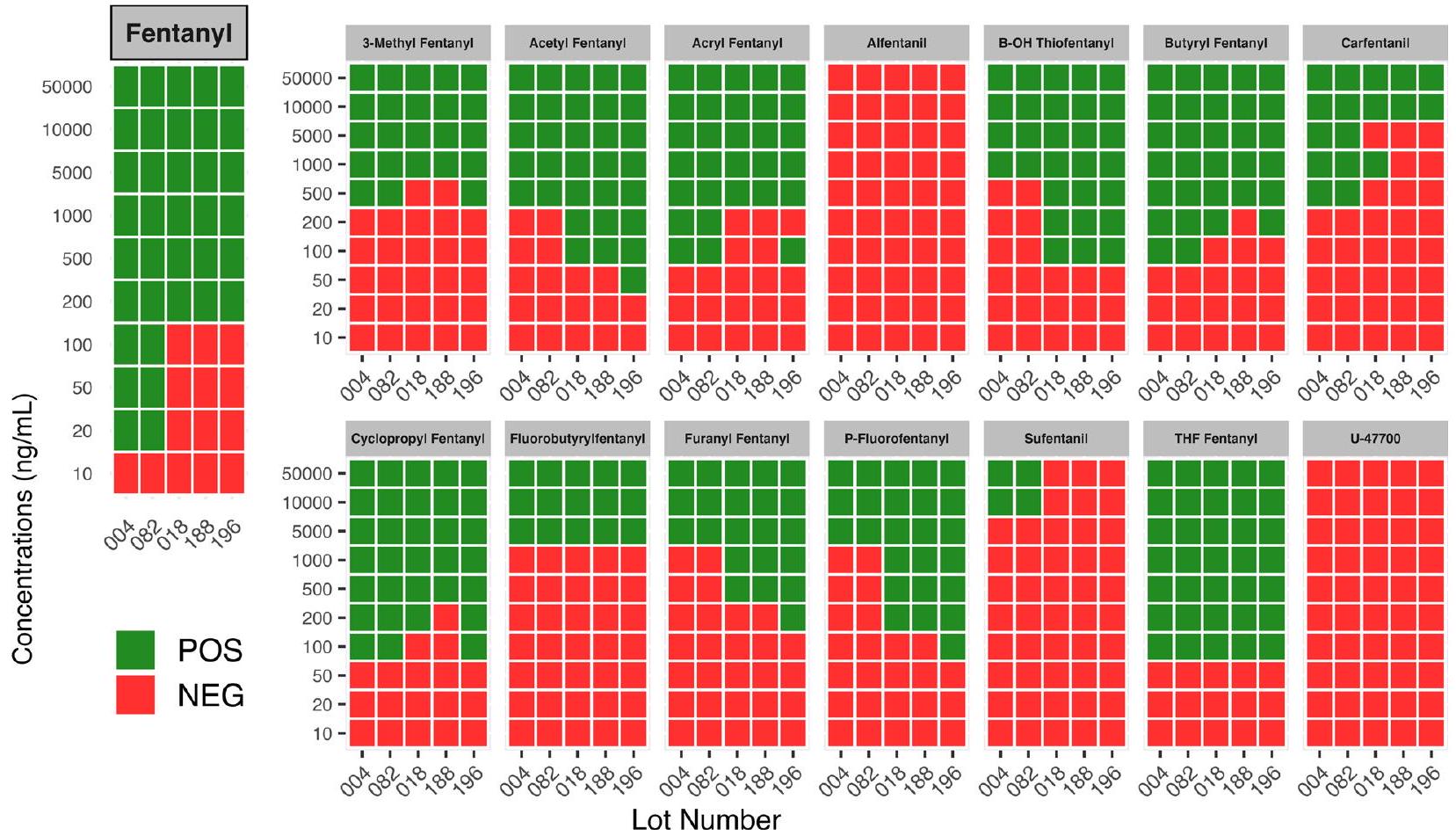

detected alfentanil or U-47700 at any concentration, with these two synthetic opioids and sufentanil having more significant structural differences from fentanyl and the other analogs (see Additional file 1: Fig.S1).

lots, but still inferior to the 2017 lots). Sensitivity varied between the three lots of 2021 sourced strips for multiple analogs, with particular variance for acrylfentanyl, carfentanil, and cyclopropylfentanyl (Fig. 1).

Fentanyl test strip interferences

Urine and water as test strip eluent comparison

Discussion

Interference Testing

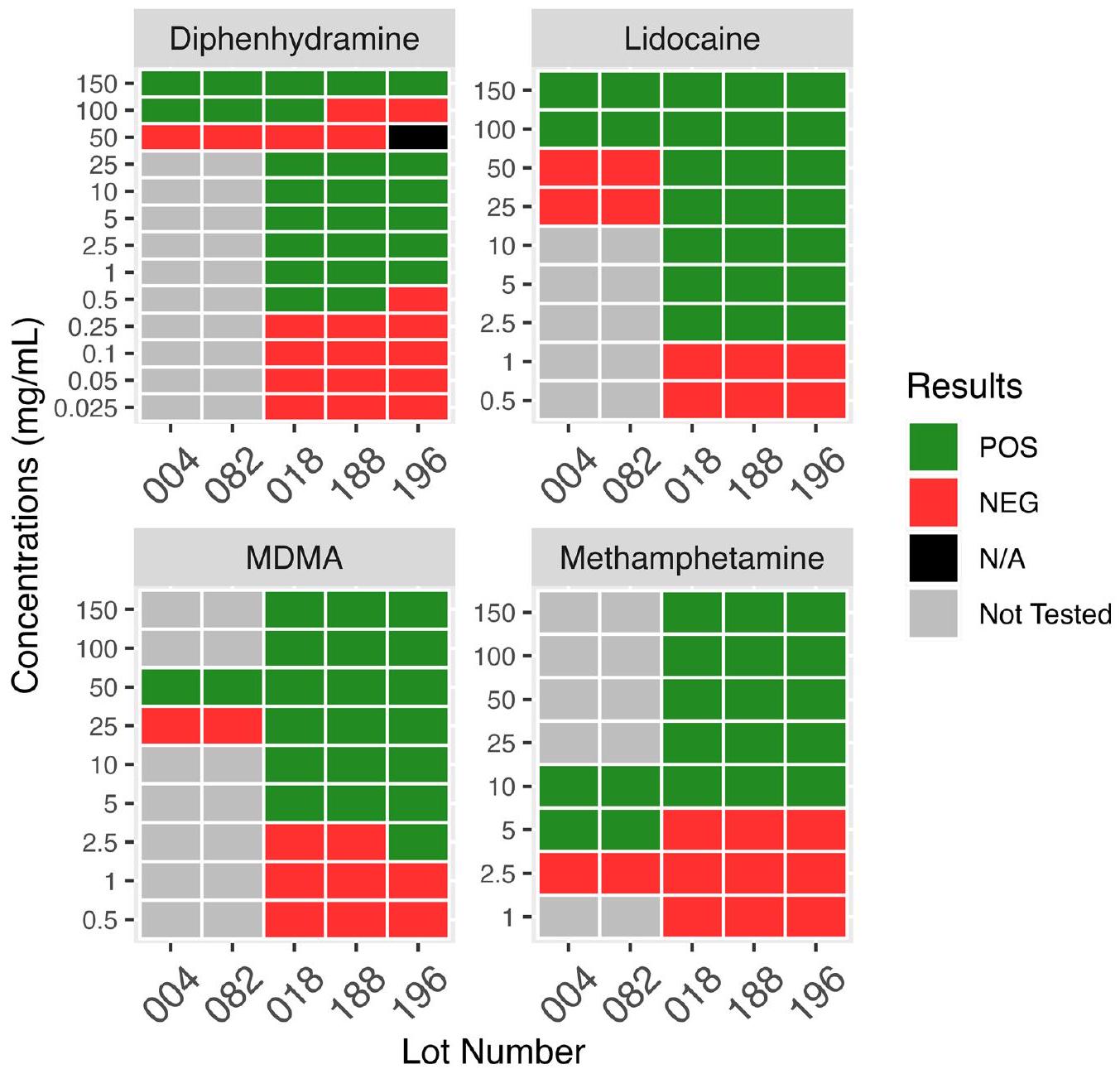

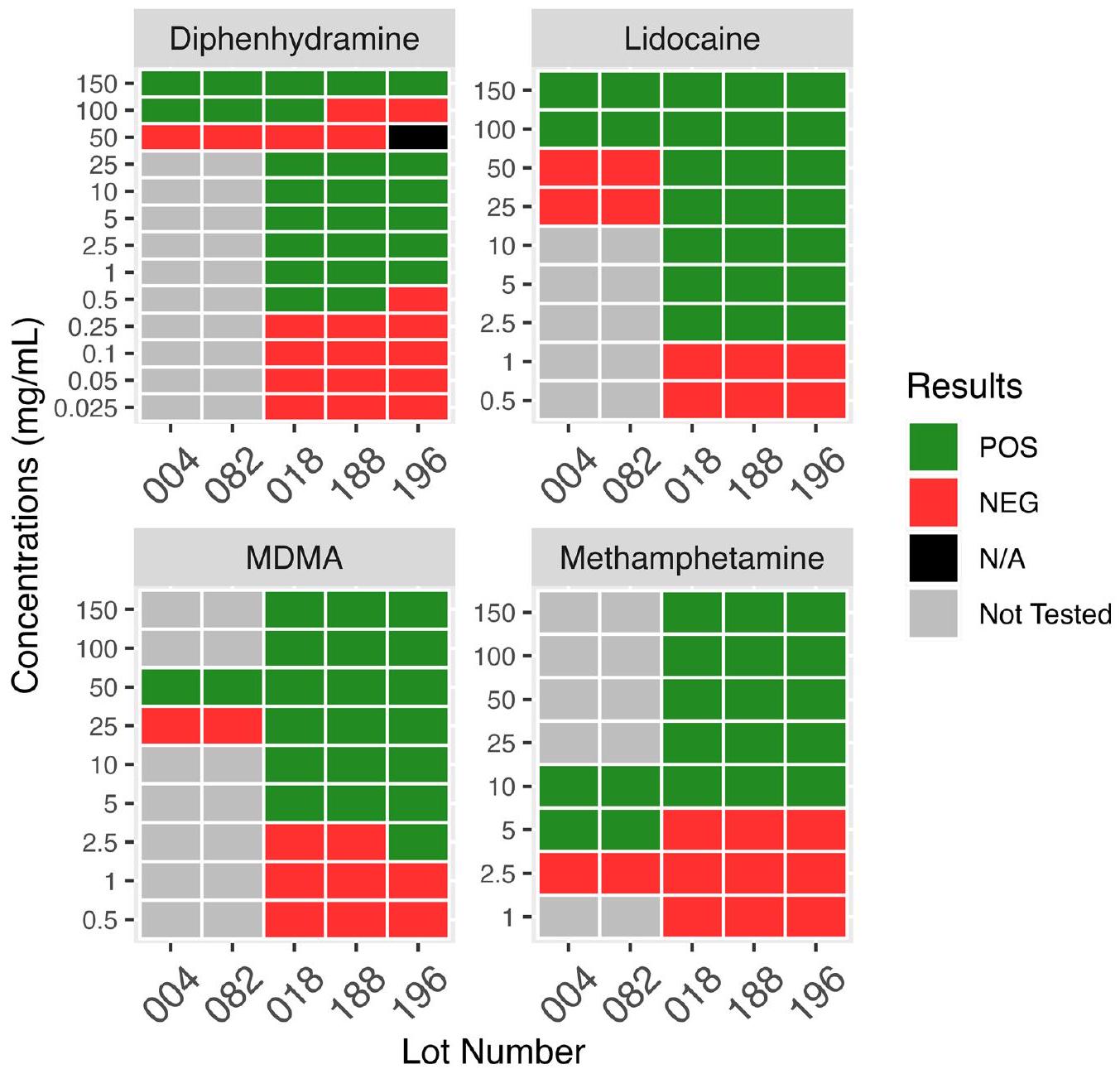

These longitudinal changes in interference sensitivities highlight the need for continued assessment of new test strip lots, and the difficulty of providing a robust set of instructions for sample dilution prior to test strip use. Some harm reduction organizations recommend precise dilution guidelines for use of the BTNX-20 strips, for example, to dilute methamphetamine and MDMA down to

originally based on the results of interference testing with the 2017 lots, would now leave the strips vulnerable to a diphenhydramine or MDMA false positive with strips performing at the level of the 2021 lots. Similarly, given the lower fentanyl sensitivity for the 2021 lots compared to the 2017 lots, false negatives are possible with excessive dilution of fentanyl and fentanyl analogs below the limit of detection. Additional file 3: Table S1 A-D illustrates how longitudinal changes in lot-to-lot FTS performance while balancing false-positive and false-negative possibilities make determining an ideal sample concentration difficult.

interference cross-reactivity and desired fentanyl analog detection cutoffs. Drug checking samples in British Columbia confirmed by laboratory reference qNMR methods determined that FTS failed to detect fentanyl in 4 of 173 (

Some limitations of these analyses should be noted. In this study, the 13 most cited fentanyl analogs were evaluated for cross-reactivity with the FTS; however, numerous additional fentanyl analogs exist, and their degree of cross-reactivity is still unknown. Additionally, only 11 illicit drugs and adulterants were evaluated for potential cross-reactivity and other untested substances could produce a false-positive FTS result. Determination of the FTS results by visual observation of the absence or presence of a line is subjective, which is a real-world limitation of their use and a potential limitation of the results of this study. All results were evaluated by 2 or more people in attempts to decrease subjectivity, but this process

could be improved by recording individual reviewer analysis instead of only consensus decision to facilitate calculation of a Kappa statistic to summarize evaluator agreement. It is the nature of the FTS that not all results are clearly positive or negative.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

IMF Illicitly manufactured fentanyls

Supplementary Information

(

Additional file 3. Table 1A. Example of estimated FTS results for a methamphetamine sample with no fentanyl contamination, dependent on drug check concentration. Drug check concentration refers to the concentration achieved when dissolving the drug sample (an unknown, impure mixture of multiple components) in water in preparation for FTS testing.

Table 1B. Example of estimated FTS results for a methamphetamine sample with trace fentanyl contamination, dependent on drug check concentration. Drug check concentration refers to the concentration achieved when dissolving the drug sample (an unknown, impure mixture of multiple components) in water in preparation for FTS testing. Table 1C. Example of estimated FTS results for an MDMA sample with no fentanyl contamination, dependent on drug check concentration. Drug check concentration refers to the concentration achieved when dissolving the drug sample (an unknown, impure mixture of multiple components) in water in preparation for FTS testing. Table 1D. Example of estimated FTS results for an MDMA sample with trace fentanyl contamination, dependent on drug check concentration. Drug check concentration refers to the concentration achieved when dissolving the drug sample (an unknown, impure mixture of multiple components) in water in preparation for FTS testing.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

References

- Ciccarone D. The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(71):183-8.

- Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2001-2021. NCHS Data Brief No 457 Natl Cent Health Stat. 2022; 457.

- Diversion Control Division. National Forensic Laboratory Information System: NFLIS-Drug 2021 Annual Report. US Department of Justice, US Drug Enforcement Administration; 2022.

- Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths-27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-43.

- O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700-10 States, July-December 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(43):1197-202.

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, Seth P. Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region-United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(34):897-903.

- Unick GJ, Ciccarone D. US regional and demographic differences in prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose hospitalizations. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):112-9.

- Shover CL, Falasinnu TO, Dwyer CL, Santos NB, Cunningham NJ, Freedman RB, et al. Steep increases in fentanyl-related mortality west of the Mississippi River: recent evidence from county and state surveillance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;1(216): 108314.

- O’Donnell J. Notes from the field: opioid-involved overdose deaths with fentanyl or fentanyl analogs detected – 28 states and the District of Columbia, July 2016-December 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6910a4.htm

- Special testing and Research Laboratory. Drug Enforcement Administration Emerging Threat Report Mid-Year 2021. Drug Enforcement Administration; 2022.

- Mojica MA, Carter MD, Isenberg SL, Pirkle JL, Hamelin El, Shaner RL, et al. Designing traceable opioid material§ kits to improve laboratory testing during the U.S. opioid overdose crisis. Toxicol Lett. 2019;317:53-8.

- Zhang Y, Halifax JC, Tangsombatvisit C, Yun C, Pang S, Hooshfar S, et al. Development and application of a High-Resolution mass spectrometry method for the detection of fentanyl analogs in urine and serum. J Mass Spectrom Adv Clin Lab. 2022; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S2667145X22000232

- Ciccarone D. Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: a rapidly changing risk environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:107-11.

- Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, Lynch KL. Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: a comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134:121-32.

- Suzuki J, El-Haddad S. A review: fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;1(171):107-16.

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, Mars SG. Heroin uncertainties: exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin.’ Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):146-55.

- Carroll JJ, Marshall BDL, Rich JD, Green TC. Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island: a mixed methods study. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):136-45.

- McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC. Being “hooked up” during a sharp increase in the availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl: adaptations of drug using practices among people who use drugs (PWUD) in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;1(60):82-8.

- Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Browne EN, Wenger LD, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, et al. Transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl in San Francisco, California. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;1(227): 109003.

- Lambdin BH, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, Wenger L, Simpson K, Kral AH. Associations between perceived illicit fentanyl use and infectious disease risks among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(74):299-304.

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler P, Wall M. Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;1(178):501-11.

- McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocainerelated overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):430-2.

- Palamar JJ, Ciccarone D, Rutherford C, Keyes KM, Carr TH, Cottler LB. Trends in seizures of powders and pills containing illicit fentanyl in the United States, 2018 through 2021. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;234: 109398.

- Twillman RK, Dawson E, LaRue L, Guevara MG, Whitley P, Huskey A. Evaluation of trends of near-real-time urine drug test results for methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1): e1918514.

- Nolan ML, Shamasunder S, Colon-Berezin C, Kunins HV, Paone D. Increased presence of fentanyl in cocaine-involved fatal overdoses: implications for prevention. J Urban Health. 2019;96(1):49-54.

- Brunt T. Drug Checking as a Harm Reduction Tool for Recreational Drug Users: Opportunities and Challenges. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2017.

- Caudevilla F, Ventura M, Fornís I, Barratt MJ, Vidal C, Iladanosa CG, et al. Results of an international drug testing service for cryptomarket users. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;35:38-41.

- Harper L, Powell J, Pijl EM. An overview of forensic drug testing methods and their suitability for harm reduction point-of-care services. Harm Reduct J. 2017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5537996/

- Hondebrink L, Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen JJ, Van Der Gouwe D, Brunt TM. Monitoring new psychoactive substances (NPS) in The Netherlands: data from the drug market and the Poisons Information Centre. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:109-15.

- Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):172-9.

- Gilbert M, Dasgupta N. Silicon to syringe: cryptomarkets and disruptive innovation in opioid supply chains. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;1(46):160-7.

- McGowan CR, Harris M, Platt L, Hope V, Rhodes T. Fentanyl self-testing outside supervised injection settings to prevent opioid overdose: do we know enough to promote it? Int J Drug Policy. 2018;1(58):31-6.

- Socías ME, Wood E. Epidemic of deaths from fentanyl overdose. BMJ. 2017;28(358): j4355.

- Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Rich JD, et al. High willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):7.

- Sherman SG, Morales KB, Park JN, McKenzie M, Marshall BDL, Green TC. Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: baltimore, Boston and Providence. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;1(68):46-53.

- Goldman JE, Waye KM, Periera KA, Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Marshall BDL. Perspectives on rapid fentanyl test strips as a harm reduction practice among young adults who use drugs: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16(1):3.

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:122-8.

- Park JN, Frankel S, Morris M, Dieni O, Fahey-Morrison L, Luta M, et al. Evaluation of fentanyl test strip distribution in two Mid-Atlantic syringe services programs. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;1(94): 103196.

- Weicker NP, Owczarzak J, Urquhart G, Park JN, Rouhani S, Ling R, et al. Agency in the fentanyl era: exploring the utility of fentanyl test strips in an opaque drug market. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;84: 102900.

- Maghsoudi N, Tanguay J, Scarfone K, Rammohan I, Ziegler C, Werb D, et al. Drug checking services for people who use drugs: a systematic review. Addiction. 2022;117(3):532-44.

- Park JN, Sherman SG, Sigmund V, Breaud A, Martin K, Clarke WA. Validation of a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for the detection of fentanyl in drug samples. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;1(240): 109610.

- BTNX INC. BTNX INC. Fentanyl Strips for Harm Reduction Use. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 4]. BTNX INC. Fentanyl strips for harm reduction use. https:// www.btnx.com/files/BTNX_Fentanyl_Strips_Harm_Reduction_Brochure. PDF

- Green TC, Park JN, Gilbert M, McKenzie M, Struth E, Lucas R, et al. An assessment of the limits of detection, sensitivity and specificity of three devices for public health-based drug checking of fentanyl in streetacquired samples. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;1(77): 102661.

- Bergh MSS, Øiestad ÅML, Baumann MH, Bogen IL. Selectivity and sensitivity of urine fentanyl test strips to detect fentanyl analogues in illicit drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;1(90): 103065.

- Lockwood TLE, Vervoordt A, Lieberman M. High concentrations of illicit stimulants and cutting agents cause false positives on fentanyl test strips. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):30.

- Wharton RE, Casbohm J, Hoffmaster R, Brewer BN, Finn MG, Johnson RC. Detection of 30 fentanyl analogs by commercial immunoassay kits. J Anal Toxicol. 2021;45(2):111-6.

- DanceSafe. How to Test Your Drugs for Fentanyl. DanceSafe; 2020. https:// dancesafe.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/DS-fentanly-instruction2020.pdf

- Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344-50.

- Clark R. URGENT: Recent batch of fentanyl strips requires different dilutions|DanceSafe. 2021. https://dancesafe.org/urgent-most-recent-batch-of-fentanyl-test-strips-requires-more-dilution-when-testi ng-mdma-and-meth/

- Matsuda R, Rodriguez E, Suresh D, Hage DS. Chromatographic immunoassays: strategies and recent developments in the analysis of drugs and biological agents. Bioanalysis. 2015;7(22):2947-66.

- Baumann MH, Tocco G, Papsun DM, Mohr AL, Fogarty MF, Krotulski AJ. U-47700 and its analogs: non-fentanyl synthetic opioids impacting the recreational drug market. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):895.

- Delcher C, Wang Y, Vega RS, Halpin J, Gladden RM, O’Donnell JK, et al. Carfentanil Outbreak-Florida, 2016-2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(5):125-9.

- Bhullar MK, Gilson TP, Singer ME. Trends in opioid overdose fatalities in Cuyahoga County, Ohio: multi-drug mixtures, the African-American community and carfentanil. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;1(4): 100069.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. 2020 Drug Enforcement Administration National Drug Threat Assessment. U.S. Department of Justice; 2021.

- Solomon N, Hayes J. Levamisole: a high performance cutting agent. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2017;7(3):469-76.

- Dinwiddie AT. Notes from the Field: Antihistamine Positivity and Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths—44 Jurisdictions, United States, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022; 71. https://www.cdc. gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7141a4.htm

- McCrae K, Tobias S, Grant C, Lysyshyn M, Laing R, Wood E, et al. Assessing the limit of detection of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and immunoassay strips for fentanyl in a real-world setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(1):98-102.

- McCrae K, Tobias S, Stunden C. BCCSU drug checking operational technician manual version 2. British Columbia Centre on Sustance Use; 2022.

- Borden SA, Saatchi A, Vandergrift GW, Palaty J, Lysyshyn M, Gill CG. A new quantitative drug checking technology for harm reduction: pilot study in Vancouver, Canada using paper spray mass spectrometry. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41(2):410-8.

- Ciccarone D, Moran L, Outram S, Werb D, et al. Insights from drug checking programs: practicing bootstrap public health whilst tailoring to local drug user needs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):5999.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

John C. Halifax

john.halifax@ucsf.edu

Department of Laboratory Medicine, ZSFG Clinical Laboratory, UCSF, 1001 Potrero Ave. Bldg. 5 2M16, San Francisco, CA 94110, USA

Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco, 500 Parnassus Avenue, MU-3E, Box 900, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA