DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16431

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413365

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-27

استخدام الإباحية الإشكالي عبر البلدان، وال genders، والميول الجنسية: رؤى من المسح الدولي للجنس ومقارنة أدوات التقييم المختلفة

المراسلة

معلومات التمويل

الملخص

الخلفية والأهداف: استخدام المواد الإباحية بشكل إشكالي (PPU) هو تجلي شائع للتشخيص الجديد لاضطراب السلوك الجنسي القهري في الطبعة الحادية عشرة من التصنيف الدولي للأمراض والمشاكل الصحية ذات الصلة. على الرغم من توثيق الفروق الثقافية، والفروق المتعلقة بالجنس والميول الجنسية في السلوكيات الجنسية، إلا أن هناك غياب نسبي للبيانات حول PPU خارج البلدان الغربية وبين النساء وكذلك الأفراد المتنوعين جنسياً وميولاً. لقد عالجنا هذه الفجوات من خلال (أ) التحقق من صحة النسخ الطويلة والقصيرة من مقياس استهلاك المواد الإباحية الإشكالية (PPCS وPPCS-6، على التوالي) وشاشة المواد الإباحية المختصرة (BPS) و(ب) قياس مخاطر PPU عبر السكان المتنوعين. الطرق: باستخدام بيانات من المسح الدولي للجنس المسجل مسبقاً [

الكلمات الرئيسية

المقدمة

في انتشار PPU من اختلافات حقيقية بين المجموعات الثقافية، والفروق المتعلقة بالجنس والميول الجنسية [29].

مقاييس PPU

[31، 32]. بعد الدراسات الأصلية للتحقق من الصحة، تم تأكيد صلاحية وموثوقية كلا القياسين في الدراسات اللاحقة، بما في ذلك بين الأفراد من ثقافات مختلفة، ومجموعات عمرية، ومجموعات تسعى للعلاج وأخرى لا تسعى للعلاج [34، 36-38].

الطريقة

الإجراء

المشاركون

إجراءات

أسئلة سوسيو-ديموغرافية وأسئلة متعلقة بالمواد الإباحية

| المتغيرات |

|

% |

| بلد الإقامة | ||

| الجزائر | ٢٤ | 0.03 |

| أستراليا | 639 | 0.78 |

| النمسا | 746 | 0.91 |

| بنغلاديش | 373 | 0.45 |

| بلجيكا | 644 | 0.78 |

| بوليفيا | 385 | 0.47 |

| البرازيل | ٣٥٧٩ | ٤.٣٥ |

| كندا | 2541 | 3.09 |

| تشيلي | 1173 | 1.43 |

| الصين | 2428 | 2.95 |

| كولومبيا | 1913 | 2.33 |

| كرواتيا | 2390 | 2.91 |

| جمهورية التشيك | 1640 | 1.99 |

| الإكوادور | ٢٧٦ | 0.34 |

| فرنسا | 1706 | 2.07 |

| ألمانيا | ٣٢٧١ | 3.98 |

| جبل طارق | 64 | 0.08 |

| المجر | ١١٢٠٠ | ١٤.٥٨ |

| الهند | 194 | 0.24 |

| العراق | 99 | 0.12 |

| أيرلندا | 1702 | 2.07 |

| إسرائيل | ١٣٣٤ | 0.66 |

| إيطاليا | 2401 | 2.92 |

| اليابان | 562 | 0.68 |

| ليتوانيا | 2015 | ٢.٤٥ |

| ماليزيا | 1170 | 1.42 |

| المكسيك | 2137 | ٢.٦٠ |

| نيوزيلندا | ٢٨٣٤ | ٣.٤٥ |

| مقدونيا الشمالية | 1251 | 1.52 |

| بنما | ٣٣٣ | 0.40 |

| بيرو | 2672 | ٣.٢٥ |

| بولندا | 9892 | 12.03 |

| البرتغال | 2262 | ٢.٧٥ |

| سلوفاكيا | 1134 | 1.38 |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 1849 | ٢.٢٥ |

| كوريا الجنوبية | 1464 | 1.78 |

| إسبانيا | 2327 | 2.83 |

| سويسرا | 1144 | 1.39 |

| تايوان | ٢٦٦٨ | 3.24 |

| تركيا | ٨٢٠ | 1.00 |

| المملكة المتحدة | 1412 | 1.72 |

| الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | ٢٣٩٨ | 2.92 |

| آخر | 1177 | 1.43 |

| لغة | ||

| العربية | ١٤٢ | 0.17 |

| البنغالية | ٣٣٢ | 0.40 |

| المتغيرات | ن = 81 975-82 243 | % |

| الكرواتية | 2522 | 3.07 |

| التشيكية | 1583 | 1.92 |

| هولندي | 518 | 0.63 |

| الإنجليزية | ١٣٩٩٤ | 17.02 |

| فرنسي | ٣٩٤١ | ٤.٧٩ |

| ألماني | ٣٤٩٤ | ٤.٢٥ |

| العبرية | 1315 | 1.60 |

| هندي | 17 | 0.02 |

| هنغاري | ١٠٩٣٧ | ١٣:٣٠ |

| إيطالي | ٢٤٣٧ | 2.96 |

| ياباني | ٤٦٦ | 0.57 |

| كوري | 1437 | 1.75 |

| الليتوانية | ٢٠٩٤ | 2.55 |

| مقدوني | 1301 | 1.58 |

| الماندرين: مبسط | 2474 | 3.01 |

| الماندرين: التقليدي | ٢٦٨٥ | ٣.٢٦ |

| بولندي | ١٠٣٤٣ | 12.58 |

| البرتغالية: البرازيل | ٣٦٥٠ | ٤.٤٤ |

| البرتغالية: البرتغال | 2277 | 2.77 |

| روماني | 75 | 0.09 |

| سلوفاكي | 2118 | 2.58 |

| الإسبانية: أمريكا اللاتينية | 8926 | 10.85 |

| الإسبانية: إسبانيا | 2312 | 2.81 |

| تركي | 853 | 1.04 |

| الجنس المعين عند الولادة | ||

| ذكر | ٣٣٢٤٥ | ٤٠.٤٣ |

| أنثى | ٤٨٩٨٧ | ٥٩.٥٧ |

| الجنس (خيارات الإجابة الأصلية في الاستطلاع) | ||

| ذكري/رجل | ٣٢٥٤٩ | ٣٩.٥٨ |

| أنثوي/امرأة | ٤٦٨٧٤ | ٥٦.٩٩ |

| هوية الأقلية الثقافية أو الهوية الجندرية الأصلية (مثل: ذو الروحين) | 166 | 0.20 |

| غير ثنائي، سائل الجنس أو شيء آخر (مثل الجنس الكويري) | 2315 | 2.81 |

| آخر | 302 | 0.37 |

| الجنس (الفئات المستخدمة في التحليلات) | ||

| رجل | ٣٢٥٤٩ | ٣٩.٥٨ |

| امرأة | ٤٦٨٧٤ | ٥٦.٩٩ |

| الأفراد ذوو التنوع الجنسي | 2783 | 3.38 |

| حالة التحويل | ||

| لا، أنا لست شخصًا متحولًا | 79280 | ٩٦.٤٣ |

| نعم، أنا رجل متحول | ٣٥٧ | 0.43 |

| نعم، أنا امرأة متحولة جنسياً | ٢٩٥ | 0.36 |

| نعم، أنا شخص غير ثنائي ومتغير الجنس | ٨٨١ | 1.07 |

| أنا أشكك في هويتي الجنسية | 1137 | 1.38 |

| لا أعرف ما يعنيه | ٢٦٩ | 0.33 |

| التوجه الجنسي (خيارات الإجابة الأصلية في الاستطلاع) | ||

| مغاير الجنس/مستقيم | 56125 | 68.24 |

| المتغيرات |

|

% |

| مثلي الجنس أو مثلية الجنس أو مثلي | 4607 | ٥.٦٠ |

| مرن جنسيًا | 6200 | ٧.٥٤ |

| هوموفليكسible | 534 | 0.65 |

| ثنائي الجنس | 7688 | 9.35 |

| مغاير | 957 | 1.16 |

| بانسكسوال | 1969 | 2.39 |

| غير جنسي | 1064 | 1.29 |

| لا أعرف بعد أو أنني أستجوب ميولي الجنسية حاليًا | 1951 | 2.37 |

| لا شيء مما سبق | ٨٠٧ | 0.98 |

| لا أريد أن أجيب | ٣٠٨ | 0.37 |

| التوجه الجنسي (الفئات المستخدمة في التحليلات) | ||

| مغاير الجنس | 56125 | 68.24 |

| مثلي أو مثلية | 4607 | ٥.٦٠ |

| ثنائي الجنس | 7688 | 9.35 |

| متحول جنسيًا وبانسيكسيول | ٢٩٢٦ | ٣.٥٦ |

| الهويات المرنة المثلية وغير المثلية | 6734 | 8.19 |

| غير جنسي | 1064 | 1.29 |

| التساؤل | 1951 | 2.37 |

| آخر | ٨٠٧ | 0.98 |

| أعلى مستوى من التعليم | ||

| المرحلة الابتدائية (مثل: المدرسة الابتدائية) | 1002 | 1.22 |

| الثانوية (مثل: المدرسة الثانوية) | ٢٠٣٢٥ | ٢٤.٧١ |

| التعليم العالي (مثل: الكلية أو الجامعة) | 60896 | ٧٤.٠٤ |

| الحالة الحالية في التعليم | ||

| غير ملتحق بالتعليم | 49802 | 60.55 |

| في التعليم الابتدائي (مثل المدرسة الابتدائية) | 64 | 0.08 |

| في التعليم الثانوي (مثل المدرسة الثانوية) | 1571 | 1.91 |

| في التعليم العالي (مثل الكلية أو الجامعة) | 30762 | ٣٧.٤٠ |

| حالة العمل | ||

| لا يعمل | ٢٠٨٥٣ | 25.36 |

| العمل بدوام كامل | 42981 | ٥٢.٢٦ |

| العمل بدوام جزئي | ١١٣٥٦ | 13.81 |

| القيام بأعمال متنوعة | 7029 | ٨.٥٥ |

| الحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية | ||

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة من بين الأسوأ | 227 | 0.28 |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة أسوأ بكثير من المتوسط | ٧٧٣ | 0.94 |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة أسوأ من المتوسط | ٤٢٣٢ | 5.15 |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة متوسطة | 26742 | 32.52 |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة أفضل من المتوسط | 31567 | ٣٨.٣٨ |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة أفضل بكثير من المتوسط | 14736 | 17.92 |

| يعتبر ظروف الحياة من بين الأفضل | 3957 | ٤.٨١ |

| إقامة | ||

| مدينة كبيرة (عدد السكان أكثر من مليون نسمة) | 26441 | ٣٢.١٥ |

| مدينة (عدد السكان بين 100000 و 999999 نسمة) | ٢٩٩٢٠ | ٣٦.٣٨ |

| مدينة (عدد السكان بين 1000 و 99999 نسمة) | 21103 | ٢٥.٦٦ |

| قرية (عدد السكان أقل من 1000 شخص) | ٤٧٦٤ | ٥.٧٩ |

| المتغيرات |

|

% |

| حالة العلاقة | ||

| عازب | ٢٧٥٤١ | ٣٣.٤٩ |

| في علاقة | ٢٧٤٤٠ | ٣٣.٣٦ |

| الأزواج المتزوجون أو الشركاء في القانون العام | ٢٤٣٣٨ | ٢٩.٥٩ |

| أرملة أو أرمل | ٤٢٨ | 0.52 |

| مطلق | 2472 | 3.01 |

| عدد الأطفال | ||

| لا شيء | 57909 | 70.41 |

| 1 | 8417 | 10.23 |

| 2 | ١٠٣٥٣ | 12.59 |

| ٣ | ٣٨٤٣ | ٤.٦٧ |

| ٤ | 1014 | 1.23 |

| ٥ | ٢٩٠ | 0.35 |

| ٦-٩ | ١٢٥ | 0.15 |

| 10 أو أكثر | ٢٤ | 0.03 |

| معنى | SD | |

| العمر (بالسنوات) | ٣٢.٣٩ | 12.52 |

SD = الانحراف المعياري.

مقياس استهلاك المواد الإباحية الإشكالية – النسخة القصيرة (PPCS6) والنسخة الطويلة (PPCS) [31، 32]

فحص موجز للمواد الإباحية [33]

التحليلات الإحصائية

تتراوح بين 8.72 و

النتائج

الخصائص السيكومترية لـ PPCS و PPCS-6 و BPS

العلاقات بين PPU واستخدام المواد الإباحية

| نطاق | معنى | SD | الوسيط | 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | |

| 1. استخدام الإباحية الم problematic (PPCS) | 18-126 | 30.51 | 17.09 | ٢٣.٠٠ | – | |||||||

| 2. استخدام الإباحية الإشكالي (PPCS-6) | 6-42 | 10.54 | 6.16 | ٨.٠٠ | 0.95* | – | ||||||

| 3. استخدام الإباحية الم problematic (BPS) | 0-10 | 1.49 | 2.28 | 0.00 | 0.73* | 0.70* | – | |||||

| 4. العمر عند أول استخدام للمواد الإباحية | 3-88 | 14.48 | ٤.٩٣ | 14.00 | -0.21* | -0.19* | -0.16* | – | ||||

| 5. تكرار استخدام المواد الإباحية في السنة الماضية

|

0-10 | ٤.٢٢ | 3.02 | ٤.٠٠ | 0.68* | 0.66* | 0.51* | -0.30* | – | |||

| 6. الوقت المستغرق في استخدام المواد الإباحية لكل جلسة

|

0-1200 | 23.19 | ٢٤.٢٨ | 15.00 | 0.33* | 0.32* | 0.23* | -0.08* | 0.23* | – | ||

| 7. الإدمان الذاتي المدرك على المواد الإباحية

|

1-7 | 1.96 | 1.54 | 1.00 | 0.69* | 0.68* | 0.65* | -0.15* | 0.51* | 0.25* | – | |

| 8. الرفض الأخلاقي للمواد الإباحية

|

1-7 | ٢.٤٩ | 1.68 | 2.00 | 0.08* | 0.06* | 0.26* | 0.03* | -0.13* | -0.03* | 0.17* | – |

| 9. تكرار العادة السرية في السنة الماضية

|

0-10 | 5.36 | 2.61 | ٦.٠٠ | 0.46* | 0.45* | 0.35* | -0.25* | 0.69* | 0.10* | 0.35* | -0.09* |

| المتغيرات | PPCS | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

|

|

% | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | حد الثقة العلوي 95% |

|

% | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | حد الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| بلد الإقامة | ||||||||

| الجزائر | 20 | ٨٣.٣٣ | 67.26 | 99.41 | ٤ | ١٦.٦٧ | 0.59 | ٣٢.٧٤ |

| أستراليا | 567 | ٩٦.٢٦ | 94.73 | 97.80 | ٢٢ | 3.74 | 2.20 | 5.27 |

| النمسا | 672 | ٩٨.٩٧ | ٩٨.٢١ | 99.73 | ٧ | 1.03 | 0.27 | 1.79 |

| بنغلاديش | 291 | ٨٩.٢٦ | 85.89 | 92.64 | ٣٥ | 10.74 | 7.36 | 14.11 |

| بلجيكا | 579 | 97.80 | ٩٦.٦٢ | ٩٨.٩٩ | ١٣ | 2.20 | 1.01 | 3.38 |

| بوليفيا | ٣٥١ | 95.90 | 93.86 | 97.94 | 15 | ٤.١٠ | 2.06 | 6.14 |

| البرازيل | 3114 | 93.68 | 92.85 | 94.51 | ٢١٠ | 6.32 | ٥.٤٩ | 7.15 |

| كندا | 2328 | 97.73 | 97.13 | ٩٨.٣٣ | ٥٤ | ٢.٢٧ | 1.67 | 2.87 |

| تشيلي | 1066 | ٩٧.٣٥ | ٩٦.٤٠ | ٩٨.٣٠ | ٢٩ | 2.65 | 1.70 | ٣.٦٠ |

| الصين | ٢١٠٦ | 90.43 | 89.23 | 91.62 | ٢٢٣ | 9.57 | 8.38 | 10.77 |

| كولومبيا | 1714 | ٩٨.٠٥ | ٩٧.٤١ | ٩٨.٧٠ | ٣٤ | 1.95 | 1.30 | ٢.٥٩ |

| كرواتيا | 2158 | ٩٨.٤٥ | 97.93 | ٩٨.٩٧ | ٣٤ | 1.55 | 1.03 | 2.07 |

| جمهورية التشيك | 1291 | ٩٨.٤٠ | 97.72 | 99.08 | 21 | 1.60 | 0.92 | 2.28 |

| الإكوادور | ٢٥٠ | 95.79 | 93.33 | ٩٨.٢٤ | 11 | ٤.٢١ | 1.76 | 6.67 |

| فرنسا | 1512 | 97.05 | ٩٦.٢١ | ٩٧.٨٩ | ٤٦ | ٢.٩٥ | 2.11 | 3.79 |

| ألمانيا | ٢٧٦٢ | ٩٨.٧٥ | ٩٨.٣٤ | 99.16 | ٣٥ | 1.25 | 0.84 | 1.66 |

| جبل طارق | ٥٨ | 98.31 | 94.91 | ١٠١.٧٠ | 1 | 1.69 | -1.70 | 5.09 |

| المجر | 10050 | ٩٦.٣٧ | ٩٦.٠١ | ٩٦.٧٣ | ٣٧٩ | 3.63 | ٣.٢٧ | ٣.٩٩ |

| الهند | 168 | 92.82 | ٨٩.٠٢ | ٩٦.٦٢ | ١٣ | 7.18 | 3.38 | 10.98 |

| العراق | ٨٠ | ٨٦.٩٦ | 79.94 | 93.97 | 12 | 13.04 | 6.03 | ٢٠٫٠٦ |

| أيرلندا | 1515 | 97.93 | 97.22 | ٩٨.٦٤ | 32 | 2.07 | 1.36 | 2.78 |

| إسرائيل | ١١٢٧ | ٩٨.١٧ | ٩٧.٣٩ | ٩٨.٩٥ | 21 | 1.83 | 1.05 | 2.61 |

| إيطاليا | 2184 | 99.00 | ٩٨.٥٩ | 99.42 | ٢٢ | 1.00 | 0.58 | 1.41 |

| اليابان | 531 | ٩٦.٢٠ | 94.59 | 97.80 | 21 | 3.80 | 2.20 | 5.41 |

| ليتوانيا | 1715 | ٩٨.٢٨ | ٩٧.٦٧ | 98.89 | 30 | 1.72 | 1.11 | 2.33 |

| ماليزيا | 1046 | 93.48 | 92.03 | 94.93 | 73 | 6.52 | ٥.٠٧ | 7.97 |

| المكسيك | 1881 | ٩٨.٦٤ | 98.12 | 99.16 | 26 | 1.36 | 0.84 | 1.88 |

| نيوزيلندا | 2559 | ٩٨.٢٧ | 97.77 | ٩٨.٧٧ | ٤٥ | 1.73 | 1.23 | ٢.٢٣ |

| مقدونيا الشمالية | ١١٢٥ | ٩٧.٨٣ | ٩٦.٩٨ | ٩٨.٦٧ | ٢٥ | 2.17 | 1.33 | 3.02 |

| بنما | 298 | ٩٦.٤٤ | 94.36 | ٩٨.٥٢ | 11 | 3.56 | 1.48 | ٥.٦٤ |

| بيرو | 2420 | ٩٨.٢٥ | 97.74 | ٩٨.٧٧ | 43 | 1.75 | 1.23 | ٢.٢٦ |

| بولندا | 8757 | ٩٨.٩٢ | 98.70 | 99.13 | 96 | 1.08 | 0.87 | 1.30 |

| البرتغال | 1928 | ٩٨.٧٢ | ٩٨.٢٢ | 99.22 | ٢٥ | 1.28 | 0.78 | 1.78 |

| سلوفاكيا | 1009 | ٩٧.٤٩ | ٩٦.٥٣ | ٩٨.٤٤ | 26 | 2.51 | 1.56 | 3.47 |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 1638 | ٩٦.٩٢ | ٩٦.١٠ | 97.75 | 52 | 3.08 | ٢.٢٥ | 3.90 |

| كوريا الجنوبية | 1294 | 94.94 | 93.77 | ٩٦.١٠ | 69 | 5.06 | 3.90 | 6.23 |

| إسبانيا | ٢٠٥٨ | ٩٨.٤٢ | ٩٧.٨٩ | 98.96 | ٣٣ | 1.58 | 1.04 | 2.11 |

| سويسرا | ١٠٣١ | ٩٨.٣٨ | ٩٧.٦١ | 99.14 | 17 | 1.62 | 0.86 | 2.39 |

| تايوان | 2271 | ٨٨.٦٤ | ٨٧.٤١ | ٨٩.٨٧ | 291 | 11.36 | 10.13 | 12.59 |

| تركيا | 703 | 93.48 | 91.72 | 95.25 | ٤٩ | 6.52 | ٤.٧٥ | 8.28 |

| المملكة المتحدة | 1258 | ٩٧.٦٧ | ٩٦.٨٥ | 98.50 | 30 | 2.33 | 1.50 | ٣.١٥ |

| المتغيرات | PPCS | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

| ن | % | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | ن | % | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | ٢١٧٠ | ٩٦.٨٣ | ٩٦.١١ | ٩٧.٥٦ | 71 | 3.17 | 2.44 | 3.89 |

| جنس | ||||||||

| رجل | ٢٩٤٥٩ | 93.74 | 93.47 | 94.01 | 1967 | 6.26 | ٥.٩٩ | 6.53 |

| امرأة | ٤٠٦٩١ | 99.28 | 99.19 | 99.36 | 297 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.81 |

| فرد متنوع جنسياً | ٢٤٩٧ | 95.71 | 94.93 | ٩٦.٤٩ | ١١٢ | ٤.٢٩ | 3.51 | 5.07 |

| التوجه الجنسي | ||||||||

| مغاير الجنس | 49013 | ٩٧.٠٧ | ٩٦.٩٣ | 97.22 | 1478 | 2.93 | 2.78 | 3.07 |

| مثلي أو مثلية | ٤١٧٢ | 94.13 | 93.44 | 94.83 | ٢٦٠ | 5.87 | 5.17 | 6.56 |

| ثنائي الجنس | 7036 | ٩٦.٨٩ | ٩٦.٤٩ | ٩٧.٢٩ | 226 | 3.11 | 2.71 | ٣.٥١ |

| متحول جنسيًا وبانسي | ٢٧٠١ | 97.76 | ٩٧.٢٠ | 98.31 | 62 | ٢.٢٤ | 1.69 | 2.80 |

| الهويات المرنة المثلية وغير المثلية | 6071 | ٩٦.٢٤ | 95.77 | ٩٦.٧١ | 237 | 3.76 | 3.29 | ٤.٢٣ |

| غير جنسي | 952 | ٩٨.٥٥ | 97.80 | 99.31 | 14 | 1.45 | 0.69 | 2.20 |

| التساؤل | 1742 | ٩٦.٢٤ | 95.37 | 97.12 | 68 | 3.76 | 2.88 | ٤.٦٣ |

| آخر | 698 | ٩٦.٤١ | 95.05 | 97.77 | ٢٦ | ٣.٥٩ | ٢.٢٣ | ٤.٩٥ |

| المتغيرات | PPCS-6 | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

|

|

% | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% |

|

% | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| بلد الإقامة | ||||||||

| الجزائر | 16 | ٦٦.٦٧ | ٤٦.٣٣ | ٨٧.٠٠ | ٨ | ٣٣.٣٣ | ١٣:٠٠ | 53.67 |

| أستراليا | 531 | 90.15 | ٨٧.٧٤ | 92.57 | ٥٨ | 9.85 | 7.43 | 12.26 |

| النمسا | 634 | 93.37 | 91.50 | ٩٥.٢٥ | ٤٥ | 6.63 | ٤.٧٥ | ٨.٥٠ |

| بنغلاديش | 243 | ٧٤.٥٤ | 69.79 | 79.29 | 83 | ٢٥.٤٦ | ٢٠.٧١ | 30.21 |

| بلجيكا | ٥١٩ | ٨٧.٥٢ | 84.85 | 90.19 | 74 | 12.48 | 9.81 | 15.15 |

| بوليفيا | 318 | ٨٦.٨٩ | ٨٣.٤١ | 90.36 | ٤٨ | 13.11 | 9.64 | ١٦.٥٩ |

| البرازيل | ٢٧٣٧ | 82.32 | 81.02 | ٨٣.٦١ | ٥٨٨ | 17.68 | 16.39 | 18.98 |

| كندا | 2163 | 90.81 | ٨٩.٦٤ | 91.97 | ٢١٩ | 9.19 | 8.03 | 10.36 |

| تشيلي | 993 | 90.68 | ٨٨.٩٦ | 92.41 | ١٠٢ | 9.32 | ٧.٥٩ | 11.04 |

| الصين | 1764 | 75.74 | ٧٤.٠٠ | ٧٧.٤٨ | 565 | ٢٤.٢٦ | ٢٢.٥٢ | ٢٦.٠٠ |

| كولومبيا | 1647 | 94.22 | 93.13 | 95.32 | ١٠١ | ٥.٧٨ | ٤.٦٨ | 6.87 |

| كرواتيا | ٢٠٨٣ | 94.94 | 94.02 | 95.86 | 111 | 5.06 | ٤.١٤ | ٥.٩٨ |

| جمهورية التشيك | ١٢٢٨ | 93.60 | 92.27 | 94.92 | 84 | ٦.٤٠ | 5.08 | 7.73 |

| الإكوادور | 226 | ٨٦.٥٩ | 82.43 | 90.75 | ٣٥ | 13.41 | 9.25 | 17.57 |

| فرنسا | ١٣٩٥ | ٨٩.٥٤ | ٨٨.٠٢ | 91.06 | 163 | 10.46 | 8.94 | 11.98 |

| ألمانيا | 2627 | 93.92 | 93.04 | 94.81 | 170 | 6.08 | 5.19 | 6.96 |

| جبل طارق | ٥٦ | 94.92 | 89.14 | 100.69 | ٣ | 5.08 | -0.69 | 10.86 |

| المجر | 9313 | 89.29 | ٨٨.٧٠ | 89.88 | 1117 | 10.71 | 10.12 | 11.30 |

| الهند | 141 | ٧٧.٩٠ | 71.80 | ٨٤.٠٠ | 40 | 22.10 | 16.00 | ٢٨.٢٠ |

| العراق | 71 | ٧٧.١٧ | 68.43 | ٨٥.٩١ | 21 | ٢٢.٨٣ | 14.09 | 31.57 |

| أيرلندا | 1434 | 92.64 | 91.33 | 93.94 | 114 | 7.36 | 6.06 | 8.67 |

| إسرائيل | 1087 | 94.60 | 93.30 | 95.91 | 62 | ٥.٤٠ | ٤.٠٩ | ٦.٧٠ |

| إيطاليا | ٢٠٨٢ | ٩٤.٣٤ | 93.37 | 95.30 | ١٢٥ | ٥.٦٦ | ٤.٧٠ | 6.63 |

| اليابان | ٤٦٩ | 84.96 | 81.97 | ٨٧.٩٥ | 83 | 15.04 | ١٢.٠٥ | 18.03 |

| المتغيرات | PPCS-6 | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

| ن | % | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | ن | % | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| ليتوانيا | ١٦٣٧ | 93.81 | 92.68 | 94.94 | ١٠٨ | 6.19 | 5.06 | 7.32 |

| ماليزيا | 899 | 80.34 | 78.01 | 82.67 | 220 | 19.66 | 17.33 | ٢١.٩٩ |

| المكسيك | 1808 | 94.81 | 93.81 | 95.81 | 99 | 5.19 | ٤.١٩ | 6.19 |

| نيوزيلندا | ٢٣٩٨ | 92.05 | 91.01 | 93.09 | ٢٠٧ | ٧.٩٥ | 6.91 | 8.99 |

| مقدونيا الشمالية | 1074 | 93.31 | 91.86 | 94.76 | 77 | 6.69 | 5.24 | 8.14 |

| بنما | 277 | ٨٩.٦٤ | ٨٦.٢٣ | 93.06 | 32 | 10.36 | 6.94 | ١٣.٧٧ |

| بيرو | 2268 | 92.05 | 90.98 | 93.11 | 196 | ٧.٩٥ | 6.89 | 9.02 |

| بولندا | 8485 | 95.82 | 95.40 | ٩٦.٢٤ | 370 | ٤.١٨ | 3.76 | ٤.٦٠ |

| البرتغال | 1854 | ٩٤.٨٨ | 93.90 | 95.86 | 100 | 5.12 | ٤.١٤ | 6.10 |

| سلوفاكيا | 938 | 90.63 | ٨٨.٨٥ | 92.41 | 97 | 9.37 | ٧.٥٩ | 11.15 |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 1496 | ٨٨.٤٧ | ٨٦.٩٤ | ٨٩.٩٩ | 195 | 11.53 | 10.01 | 13.06 |

| كوريا الجنوبية | 1180 | ٨٦.٥٧ | 84.76 | ٨٨.٣٩ | 183 | ١٣.٤٣ | 11.61 | 15.24 |

| إسبانيا | 1975 | 94.45 | 93.47 | 95.43 | ١١٦ | ٥.٥٥ | ٤.٥٧ | 6.53 |

| سويسرا | 971 | 92.65 | 91.07 | 94.23 | 77 | 7.35 | ٥.٧٧ | 8.93 |

| تايوان | 1878 | 73.30 | 71.59 | 75.02 | 684 | ٢٦.٧٠ | ٢٤.٩٨ | ٢٨.٤١ |

| تركيا | 625 | ٨٣.١١ | 80.43 | 85.80 | 127 | 16.89 | ١٤.٢٠ | 19.57 |

| المملكة المتحدة | 1204 | 93.48 | 92.13 | 94.83 | 84 | 6.52 | 5.17 | 7.87 |

| الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | 2016 | ٨٩.٩٦ | ٨٨.٧١ | 91.21 | 225 | 10.04 | 8.79 | 11.29 |

| جنس | ||||||||

| رجل | 25587 | 81.40 | 80.97 | 81.83 | 5845 | 18.60 | 18.17 | 19.03 |

| امرأة | 39782 | ٩٧.٠٤ | 96.87 | ٩٧.٢٠ | 1214 | 2.96 | 2.80 | 3.13 |

| فرد متنوع جنسياً | 2294 | ٨٧.٨٩ | ٨٦.٦٤ | 89.15 | 316 | 12.11 | 10.85 | ١٣.٣٦ |

| التوجه الجنسي | ||||||||

| مغاير الجنس | 45847 | 90.79 | 90.54 | 91.04 | 4652 | 9.21 | 8.96 | 9.46 |

| مثلي أو مثلية | ٣٥٩٢ | 81.03 | 79.87 | 82.18 | 841 | ١٨.٩٧ | 17.82 | ٢٠.١٣ |

| ثنائي الجنس | 6558 | 90.29 | 89.61 | 90.97 | ٧٠٥ | 9.71 | 9.03 | 10.39 |

| متحول جنسيًا وبانسي | 2564 | 92.76 | 91.80 | 93.73 | ٢٠٠ | 7.24 | 6.27 | 8.20 |

| الهويات المرنة المثلية وغير المثلية | 5641 | ٨٩.٤٠ | ٨٨.٦٤ | 90.16 | 669 | 10.60 | 9.84 | 11.36 |

| غير جنسي | 931 | ٩٦.٣٨ | 95.20 | ٩٧.٥٦ | ٣٥ | 3.62 | 2.44 | ٤.٨٠ |

| التساؤل | 1629 | 89.90 | ٨٨.٥١ | 91.29 | 183 | 10.10 | 8.71 | 11.49 |

| آخر | 664 | 91.71 | ٨٩.٧٠ | 93.73 | 60 | 8.29 | 6.27 | 10.30 |

| المتغيرات | بي بي إس | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

|

|

% | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% |

|

% | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | حد الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| بلد الإقامة | ||||||||

| الجزائر | 12 | 50.00 | ٢٨.٤٣ | ٧١.٥٧ | 12 | 50.00 | ٢٨.٤٣ | ٧١.٥٧ |

| أستراليا | ٤٩٣ | ٨٣.٧٠ | 80.71 | ٨٦.٦٩ | 96 | 16.30 | ١٣.٣١ | 19.29 |

| النمسا | 612 | 90.13 | ٨٧.٨٨ | 92.38 | 67 | 9.87 | 7.62 | 12.12 |

| بنغلاديش | 229 | 70.46 | 65.48 | 75.45 | 96 | ٢٩.٥٤ | ٢٤.٥٥ | ٣٤.٥٢ |

| بلجيكا | ٤٩٦ | ٨٣.٥٠ | 80.51 | ٨٦.٥٠ | 98 | ١٦.٥٠ | ١٣.٥٠ | 19.49 |

| بوليفيا | 261 | 71.51 | 66.85 | 76.16 | ١٠٤ | ٢٨.٤٩ | ٢٣.٨٤ | ٣٣.١٥ |

| (يستمر) | ||||||||

| المتغيرات | بي بي إس | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

|

|

% | الحد الأدنى 95% من فترة الثقة | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% |

|

% | الحد الأدنى 95% من فاصل الثقة | حد الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| البرازيل | ٢٤٩٧ | 75.10 | 73.63 | ٧٦.٥٧ | 828 | ٢٤.٩٠ | ٢٣.٤٣ | ٢٦.٣٧ |

| كندا | ٢٠٥٨ | ٨٦.٣٦ | ٨٤.٩٨ | ٨٧.٧٤ | ٣٢٥ | 13.64 | 12.26 | 15.02 |

| تشيلي | 840 | ٧٦.٦٤ | ٧٤.١٣ | 79.15 | 256 | ٢٣.٣٦ | ٢٠.٨٥ | ٢٥.٨٧ |

| الصين | 1539 | ٦٦.٠٨ | 64.16 | 68.00 | 790 | ٣٣.٩٢ | ٣٢.٠٠ | ٣٥.٨٤ |

| كولومبيا | 1416 | 80.91 | 79.07 | 82.76 | ٣٣٤ | 19.09 | 17.24 | ٢٠.٩٣ |

| كرواتيا | 1927 | ٨٧.٧٩ | ٨٦.٤٢ | ٨٩.١٦ | ٢٦٨ | 12.21 | 10.84 | ١٣.٥٨ |

| جمهورية التشيك | ١١٨٨ | 90.48 | ٨٨.٨٩ | 92.07 | ١٢٥ | 9.52 | 7.93 | 11.11 |

| الإكوادور | 183 | 70.66 | ٦٥.٠٧ | ٧٦.٢٤ | 76 | ٢٩.٣٤ | ٢٣.٧٦ | ٣٤.٩٣ |

| فرنسا | 1262 | ٨٠.٩٠ | 78.94 | 82.85 | 298 | 19.10 | 17.15 | 21.06 |

| ألمانيا | 2532 | 90.62 | ٨٩.٥٤ | 91.70 | 262 | 9.38 | 8.30 | 10.46 |

| جبل طارق | 50 | 84.75 | 75.30 | 94.20 | 9 | 15.25 | ٥.٨٠ | ٢٤.٧٠ |

| المجر | 8779 | 84.16 | ٨٣.٤٦ | 84.86 | 1652 | 15.84 | 15.14 | ١٦.٥٤ |

| الهند | ١١٩ | 66.48 | ٥٩.٥٠ | 73.46 | 60 | ٣٣.٥٢ | ٢٦.٥٤ | ٤٠.٥٠ |

| العراق | 57 | ٦١.٩٦ | ٥١.٨٥ | 72.07 | ٣٥ | ٣٨.٠٤ | ٢٧.٩٣ | ٤٨.١٥ |

| أيرلندا | 1318 | 85.14 | ٨٣.٣٧ | ٨٦.٩٢ | ٢٣٠ | 14.86 | 13.08 | 16.63 |

| إسرائيل | 991 | 86.25 | 84.25 | ٨٨.٢٤ | 158 | ١٣.٧٥ | 11.76 | 15.75 |

| إيطاليا | 1996 | 90.32 | ٨٩.٠٨ | 91.55 | ٢١٤ | 9.68 | 8.45 | 10.92 |

| اليابان | 473 | 85.69 | 82.76 | ٨٨.٦٢ | 79 | 14.31 | 11.38 | 17.24 |

| ليتوانيا | 1550 | ٨٨.٧٧ | ٨٧.٢٩ | 90.26 | 196 | 11.23 | 9.74 | 12.71 |

| ماليزيا | 747 | 66.76 | ٦٣.٩٩ | 69.52 | ٣٧٢ | ٣٣.٢٤ | 30.48 | ٣٦.٠١ |

| المكسيك | ١٦٠٩ | 84.46 | 82.83 | ٨٦.٠٩ | ٢٩٦ | 15.54 | 13.91 | 17.17 |

| نيوزيلندا | ٢٢٣٧ | ٨٥.٨٧ | 84.53 | ٨٧.٢١ | 368 | 14.13 | 12.79 | 15.47 |

| مقدونيا الشمالية | ١٠٢١ | ٨٨.٧١ | ٨٦.٨٧ | 90.54 | ١٣٠ | 11.29 | 9.46 | 13.13 |

| بنما | 249 | 80.58 | ٧٦.١٥ | 85.02 | 60 | 19.42 | 14.98 | ٢٣.٨٥ |

| بيرو | 1950 | 79.14 | ٧٧.٥٣ | 80.75 | 514 | ٢٠.٨٦ | 19.25 | ٢٢.٤٧ |

| بولندا | 8045 | 90.91 | 90.32 | 91.51 | 804 | 9.09 | 8.49 | 9.68 |

| البرتغال | 1810 | 92.73 | 91.57 | 93.88 | 142 | ٧.٢٧ | 6.12 | 8.43 |

| سلوفاكيا | ٨٤٧ | 81.91 | 79.56 | 84.26 | 187 | 18.09 | 15.74 | ٢٠.٤٤ |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 1285 | ٧٥.٩٠ | 73.86 | ٧٧.٩٤ | ٤٠٨ | ٢٤.١٠ | 22.06 | ٢٦.١٤ |

| كوريا الجنوبية | 1076 | 78.94 | ٧٦.٧٨ | 81.11 | 287 | 21.06 | 18.89 | ٢٣.٢٢ |

| إسبانيا | 1770 | 84.69 | ٨٣.١٤ | ٨٦.٢٣ | ٣٢٠ | 15.31 | ١٣.٧٧ | 16.86 |

| سويسرا | 890 | 84.84 | 82.67 | ٨٧.٠٢ | 159 | 15.16 | 12.98 | 17.33 |

| تايوان | 1838 | 71.74 | ٧٠.٠٠ | 73.49 | 724 | ٢٨.٢٦ | ٢٦.٥١ | 30.00 |

| تركيا | 561 | ٧٤.٦٠ | 71.48 | ٧٧.٧٢ | 191 | ٢٥.٤٠ | ٢٢.٢٨ | ٢٨.٥٢ |

| المملكة المتحدة | 1135 | ٨٨.١٢ | ٨٦.٣٥ | ٨٩.٨٩ | 153 | 11.88 | 10.11 | ١٣.٦٥ |

| الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | 1860 | 82.96 | 81.40 | 84.52 | ٣٨٢ | 17.04 | 15.48 | 18.60 |

| جنس | ||||||||

| رجل | ٢٢٣٤١ | 71.08 | 70.58 | 71.58 | 9090 | ٢٨.٩٢ | ٢٨.٤٢ | ٢٩.٤٢ |

| امرأة | 38117 | 92.99 | 92.75 | 93.24 | 2872 | 7.01 | 6.76 | ٧.٢٥ |

| فرد متنوع جنسياً | 2141 | 81.94 | 80.46 | ٨٣.٤١ | ٤٧٢ | 18.06 | ١٦.٥٩ | 19.54 |

| التوجه الجنسي | ||||||||

| مغاير الجنس | 42156 | ٨٣.٤٨ | ٨٣.١٥ | ٨٣.٨٠ | 8344 | 16.52 | ١٦.٢٠ | 16.85 |

| مثلي أو مثلية | ٣٤٣٣ | ٧٧.٣٩ | ٧٦.١٦ | 78.62 | 1003 | ٢٢.٦١ | ٢١.٣٨ | ٢٣.٨٤ |

| المتغيرات | بي بي إس | |||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|||||||

|

|

% | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | فاصل الثقة العلوي 95% | ن | % | حد الثقة الأدنى 95% | حد الثقة العلوي 95% | |

| ثنائي الجنس | 6115 | 84.22 | ٨٣.٣٨ | 85.06 | 1146 | 15.78 | ١٤.٩٤ | 16.62 |

| متحول جنسيًا وبانسيكشوال | 2415 | ٨٧.٤٠ | ٨٦.١٧ | ٨٨.٦٤ | 348 | 12.60 | 11.36 | 13.83 |

| الهويات المرنة المثلية وغير المثلية | 5316 | 84.29 | ٨٣.٣٩ | 85.19 | 991 | 15.71 | 14.81 | 16.61 |

| غير جنسي | 879 | 90.99 | ٨٩.١٩ | 92.80 | 87 | 9.01 | ٧.٢٠ | 10.81 |

| التساؤل | 1446 | 79.85 | ٧٨.٠٠ | 81.69 | ٣٦٥ | ٢٠.١٥ | 18.31 | ٢٢.٠٠ |

| آخر | 626 | ٨٦.٥٨ | 84.09 | ٨٩.٠٧ | 97 | ١٣.٤٢ | 10.93 | 15.91 |

CI = فترة الثقة.

أول استخدام للمواد الإباحية

الفروق المستندة إلى البلد والجنس والميول الجنسية في PPU

مقارنة بين مجموعتي PPU و PPU+

نقاش

| نسخة مختصرة من مقياس استهلاك المواد الإباحية الإشكالية (PPCS-6) | |||||||||||||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

اختبارات مان-ويتني U | |||||||||||||||

| المتغيرات | معنى | SD | الوسيط | معنى | SD | الوسيط | أنت | ز |

|

كوهين

|

|||||||

| الوقت المستغرق في استخدام المواد الإباحية لكل جلسة

|

|||||||||||||||||

| الإدمان الذاتي المدرك على الإباحية

|

1.64 | 1.18 | 1.00 | ٤.٥٧ | 1.64 | ٥.٠٠ | 398955344.00 | 131.03 | < 0.001 | 0.99 | |||||||

| الرفض الأخلاقي للمواد الإباحية

|

2.42 | 1.64 | 2.00 | ٢.٩٩ | 1.90 | 2.00 | ٢٥٧٨٦٤٦٩١.٥٠ | ٢٥.٥١ | < 0.001 | 0.19 | |||||||

| تكرار العادة السرية في السنة الماضية

|

5.35 | ٢.٥٠ | ٦.٠٠ | ٧.٤٥ | 1.96 | ٨.٠٠ | ٣٧٣٨١١٧٧٧.٥٠ | 71.14 | < 0.001 | 0.53 | |||||||

| المتغيرات |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| ن | % |

|

% |

|

|

||||||||||||

| السعي للحصول على علاج لاستخدام المواد الإباحية | |||||||||||||||||

| نعم | 291 | 0.49% | 417 | 5.65% | 12 | < 0.001 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| لا، لأنه لم يكن لدي أي مشاكل مع مشاهدة المواد الإباحية. | 50388 | ٨٤.٦٦٪ | ٢٤٣٣ | 32.99% | |||||||||||||

| لا، لأنني لم أشعر أنه كان مشكلة خطيرة. | 7154 | 12.02% | ٢٦٩٩ | ٣٦.٦٠٪ | |||||||||||||

| لا، لأنني لم أعرف أين يجب أن أطلب المساعدة. | 238 | 0.40% | ٣٤٢ | ٤.٦٤٪ | |||||||||||||

| لا، لأنني كنت سأشعر بعدم الارتياح أو الإحراج. | 918 | 1.54% | ١١٥٧ | 15.69% | |||||||||||||

| لا، لأنني لم أستطع تحمل تكلفته. | ٢٥٠ | 0.42% | 239 | 3.24% | |||||||||||||

| لا، بسبب سبب آخر. | ٢٨٢ | 0.47% | ٨٨ | 1.19% | |||||||||||||

| تحت العلاج حاليًا بسبب استخدام المواد الإباحية | |||||||||||||||||

| نعم | 85 | 0.14% | 184 | 2.50% | ١٣ | < 0.001 | 0.45 | ||||||||||

| لا، لأنه لا يعاني من أي مشاكل في مشاهدة المواد الإباحية. |

|

||||||||||||||||

| لا، لأنه لا يشعر أنه مشكلة خطيرة | 5981 | 10.05% | 2548 | ٣٤.٥٦٪ | |||||||||||||

| لا، لأنه لا يعرف أين يجب أن يطلب المساعدة. | 218 |

|

|||||||||||||||

| لا، لأنني سأشعر بعدم الارتياح أو الإحراج. | 745 | 1.25% 1103 14.96% | |||||||||||||||

| لا، لأنه لم يكن بإمكاني تحمله | ٢٩٢ | 0.49% 349 4.73% | |||||||||||||||

| لا، بسبب أسباب أخرى | ٣٣١ | 0.56% 153 2.08% | |||||||||||||||

| شاشة الإباحية الموجزة (BPS) | |||||||||||||||||

| مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

اختبارات مان-ويتني U | |||||||||||||||

|

معنى | SD | الوسيط | أنت | ز | P | د كوهين | ||||||||||

| استخدام الإباحية الم problematic (BPS) | 0.61 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 5.92 | 1.85 | ٥.٠٠ | ٧٧٩١٥٤٩٤٨٫٠٠ | 192.18 | < 0.001 | 1.68 | |||||||

| العمر عند أول استخدام للمواد الإباحية | 14.47 | ٤.٨٠ | 14.00 | ١٣.١٩ | 3.98 | ١٣:٠٠ | ٢٧٢٧٥١٦٨٠.٠٠ | -32.14 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | |||||||

| تكرار استخدام المواد الإباحية في السنة الماضية

|

٤.١٨ | 2.77 | ٤.٠٠ | 6.87 | ٢.١٧ | ٧.٠٠ | ٥٩٩٦٨٧٢٤٨.٠٠ | 95.88 | < 0.001 | 0.74 | |||||||

| الوقت المستغرق في استخدام المواد الإباحية لكل جلسة

|

21.21 | 21.38 | 15.00 | 31.89 | ٣٢.٧٩ | ٢٠.٠٠ | ٤٢٦٩٦٢٣٢٥.٥٠ | ٤٧.٨٤ | < 0.001 | 0.37 | |||||||

| الإدمان الذاتي المدرك على الإباحية

|

1.51 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 3.94 | 1.77 | ٤.٠٠ | ٥٩٠٦٣٦٥٠١.٥٠ | 148.25 | < 0.001 | 1.16 | |||||||

| ٢.٢٨ | 1.55 | 2.00 | 3.38 | 1.93 | ٣.٠٠ | ٤٥٣٩٨٧١٦١.٠٠ | ٦١.٨٥ | < 0.001 | 0.47 | ||||||||

| شاشة الإباحية الموجزة (BPS) | |||||||||

| المتغيرات | مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

اختبارات مان-ويتني U | ||||||

| معنى | SD | الوسيط | معنى | SD | أنت | ز |

|

كوهين

|

|

| الرفض الأخلاقي للمواد الإباحية

|

|||||||||

| تكرار العادة السرية في السنة الماضية

|

5.29 | 2.52 | ٦.٠٠ | 6.92 | 2.15 | ٥٣٨٤٠٩٨٠٣.٥٠ | 68.52 | < 0.001 | 0.51 |

| المتغيرات | مجموعة PPU-

|

مجموعة PPU+

|

|

||||||

|

|

% |

|

% |

|

P | فاي كرامر | |||

| السعي للحصول على علاج لاستخدام المواد الإباحية | |||||||||

| نعم | ١٧٧ | 0.32% | 531 | ٤.٢٧٪ | ٢٠١٣١.٩٥ | < 0.001 | 0.55 | ||

| لا، لأنه لم أواجه أي مشاكل مع مشاهدة المواد الإباحية. | ٤٨٥٢٤ | 89.08% | 4297 | ٣٤.٥٧٪ | |||||

| لا، لأنني لم أشعر أنه كان مشكلة خطيرة. | 5012 | 9.20% | ٤٨٤١ | ٣٨.٩٥٪ | |||||

| لا، لأنني لم أعرف أين يجب أن أطلب المساعدة. | 96 | 0.18% | ٤٨٥ | 3.90% | |||||

| لا، لأنني كنت سأشعر بعدم الارتياح أو الإحراج. | ٣٣١ | 0.61% | 1746 | 14.05% | |||||

| لا، لأنه لم يكن بإمكاني تحمله. | ١٠٩ | 0.20% | 381 | 3.07% | |||||

| لا، بسبب أسباب أخرى | 221 | 0.41% | 148 | 1.19% | |||||

| تحت العلاج حاليًا بسبب استخدام المواد الإباحية | |||||||||

| نعم | ٤٨ | 0.09% | 221 | 1.78% | ٢٠٢٩٦.٠٨ | < 0.001 | 0.55 | ||

| لا، لأنه لا يعاني من أي مشاكل في مشاهدة المواد الإباحية. | 49727 | 91.31% | ٤٨٢٧ | ٣٨.٨٥٪ | |||||

| لا، لأنه لا يشعر أنه مشكلة خطيرة | 4021 | ٧.٣٨٪ | ٤٥١٢ | ٣٦.٣٢٪ | |||||

| لا، لأنه لا يعرف أين يجب أن يطلب المساعدة. | 65 | 0.12% | ٤٨٦ | 3.91% | |||||

| لا، لأنني سأشعر بعدم الارتياح أو الإحراج. | 227 | 0.42% | 1622 | ١٣٫٠٦٪ | |||||

| لا، لأنه لم يكن بإمكاني تحمله. | ١٢٩ | 0.24% | 512 | ٤.١٢٪ | |||||

| لا، بسبب أسباب أخرى | 241 | 0.44% | 244 | 1.96% | |||||

أظهرت خصائص نفسية قوية في الدراسات الحالية والسابقة [31-34، 36-38]. ومع ذلك، كانت قدراتها في التمييز بين الأفراد الذين لا يعانون من خطر PPU أو يعانون من خطر منخفض وبين الأفراد المعرضين لخطر PPU متفاوتة. قدمت BPS أعلى تقديرات لـ PPU، مما يتماشى مع

كونه أداة فحص (أي مقياس قصير مع خيارات استجابة محدودة) وتركيزه الوحيد على قضايا السيطرة المتعلقة باستخدام المواد الإباحية، حيث يهدف إلى اكتشاف جميع الحالات المحتملة التي تعاني من استخدام المواد الإباحية [33]. على النقيض من ذلك، قدمت أداة PPCS أدنى تقديرات لاستخدام المواد الإباحية لأنها تهدف إلى

تقييم PPU بشكل أكثر شمولاً على عدة عناصر استنادًا إلى نموذج الإدمان المكون من ستة عناصر [35]، وتقديم خيارات إجابة أكثر دقة [31].

يجب أيضًا أخذ بعض القيود الخاصة بالدراسة بعين الاعتبار. كانت العينات المستخدمة في الدراسة غير قائمة على الاحتمالات، وغير ممثلة على المستوى الوطني، وكانت تتكون بشكل رئيسي من أفراد ذوي تعليم عالٍ (أي…

الاستنتاجات

السكان [7,71]. لتحسين تقييم PPU وقابليته للمقارنة عبر الدراسات، قامت الدراسة الحالية بفحص ثلاثة مقاييس PPU متاحة مجانًا (PPCS وPPCS-6 وBPS) بين مجموعات سكانية متنوعة وأظهرت خصائصها النفسية القوية. تقديرنا المحافظ على الأرجح لحدوث

مساهمات المؤلفين

أعضاء اتحاد الاستطلاع الدولي للجنس

الانتماءات

فيينا، فيينا، النمسا

الطب النفسي، مركز الطب الجامعي هامبورغ-إيبندورف، هامبورغ، ألمانيا

كوريا

كيب تاون، جنوب أفريقيا

اجتماعية، جامعة تاراباكا، أريكا، تشيلي

كلية الطب، جامعة ساو باولو، ساو باولو، البرازيل

نيودلهي، الهند

علوم التأهيل، طهران، إيران

ترنافا، ترنافا، سلوفاكيا

جامعة العلوم الصحية، بالانغا، ليتوانيا

قسم الطب النفسي ومعهد علوم الأعصاب، جامعة

كيب تاون، كيب تاون، جنوب أفريقيا

علوم، جامعة زغرب، زغرب، كرواتيا

لاس فيغاس، نيفادا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

شكر وتقدير

بيان توافر البيانات

الأخلاق

إعلان المصالح

أوركيد

شين و. كراوس (د)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0404-9480

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 11th edn; 2022. Available at: https://icd.who.int/

- Reid RC, Carpenter BN, Hook JN, Garos S, Manning JC, Gilliland R, et al. Report of findings in a DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2868-77.

- Kraus SW, Krueger RB, Briken P, First MB, Stein DJ, Kaplan MS, et al. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11. World Psych. 2018;17:109-10.

- Grubbs JB, Perry SL. Moral incongruence and pornography use: a critical review and integration. J Sex Res. 2019;56:29-37.

- Grubbs JB, Perry SL, Wilt JA, Reid RC. Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: an integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:397-415.

- Kraus SW, Sweeney PJ. Hitting the target: considerations for differential diagnosis when treating individuals for problematic use of pornography. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:431-5.

- Grubbs JB, Hoagland C, Lee B, Grant JT, Davison P, Reid RC, et al. Sexual addiction 25 years on: a systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;8:101925.

- Gola M, Lewczuk K, Potenza MN, Kingston DA, Grubbs JB, Stark R, et al. What should be included in the criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder? J Behav Addict. 2022;11:160-5.

- Briken P, Turner D. What does ‘Sexual’ mean in compulsive sexual behavior disorder?: commentary to the debate: ‘Behavioral addictions in the ICD-11’. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:222-5.

- Jennings TL, Gleason N, Kraus SW. Assessment of compulsive sexual behavior disorder among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer clients: commentary to the debate: ‘Behavioral addictions in the ICD-11’. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:216-21.

- Bőthe B, Koós M, Demetrovics Z. Contradicting classification, nomenclature, and diagnostic criteria of compulsive sexual behavior disorder and future directions-commentary on ‘What should be included in the criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder?’ (Gola et al., 2020) and should compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) be considered as a behavioral addiction? A debate paper presenting the opposing view (Sassover and Weinstein, 2020). J Behav Addict. 2022;11:204-6.

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993-2007. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:21-38.

- Parker R. Sexuality, culture and society: shifting paradigms in sexuality research. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11:251-66.

- Khan T, Abimbola S, Kyobutungi C, Pai M. How we classify countries and people-and why it matters. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e009704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009704

- American Psychological Association. Inclusive Language Guide, 2nd edn. Available at: https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/language-guidelines.pdf

- Klein V, Savaş Ö, Conley TD. How WEIRD and androcentric is sex research? Global inequities in study populations. J Sex Res. 2022;59: 810-7.

- Kowalewska E, Gola M, Kraus SW, Lew-starowicz M. Spotlight on compulsive sexual behavior disorder: a systematic review of research on women. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;2025-43.

- Grubbs JB, Kraus SW, Perry SL. Self-reported addiction to pornography in a nationally representative sample: the roles of use habits, religiousness, and moral incongruence. J Behav Addict. 2019;8:88-93.

- Herbenick D, Fu TC, Wright P, Paul B, Gradus R, Bauer J, et al. Diverse sexual behaviors and pornography use: findings from a nationally representative probability survey of Americans aged 18 to 60 years. J Sex Med. 2020;17:623-33.

- Lewczuk K, Glica A, Nowakowska I, Gola M, Grubbs JB. Evaluating pornography problems due to moral incongruence model. J Sex Med. 2020;17:300-11.

- Rissel C, Richters J, de Visser RO, McKee A, Yeung A, Caruana T. A profile of pornography users in Australia: findings from the second Australian study of health and relationships. J Sex Res. 2017;54: 227-40.

- Træen B, Spitznogle K, Beverfjord A. Attitudes and use of pornography in the Norwegian population 2002. J Sex Res. 2004;41: 193-200.

- Lewczuk K, Wizła M, Glica A, Potenza MN, Lew-Starowicz M, Kraus SW. Withdrawal and tolerance as related to compulsive sexual behavior disorder and problematic pornography use-preregistered

study based on a nationally representative sample in Poland. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:979-93. - Grubbs JB, Lee BN, Hoagland KC, Kraus SW, Perry SL. Addiction or transgression? Moral incongruence and self-reported problematic pornography use in a nationally representative sample. Clin Psychol Sci. 2020;8:936-46.

- Költő A, Cosma A, Young H, Moreau N, Pavlova D, Tesler R, et al. Romantic attraction and substance use in 15-year-old adolescents from eight European countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3063.

- Borgogna NC, Mcdermott RC, Aita SL, Kridel MM. Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer, and questioning individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2019;6:54-63.

- Feinstein BA, Hurtado M, Dyar C, Davila J. Disclosure, minority stress, and mental health among bisexual, pansexual, and queer (Bi+) adults: the roles of primary sexual identity and multiple sexual identity label use. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2023;10:181-9.

- Kaestle CE, Ivory AH. A forgotten sexuality: content analysis of bisexuality in the medical literature over two decades. J Bisex. 2012; 12:35-48.

- Ahorsu DK, Adjorlolo S, Nurmala I, Ruckwongpatr K, Strong C, Lin CY. Problematic porn use and cross-cultural differences: a brief review. Curr Addict Rep. 2023;10:572-80.

- Fernandez DP, Griffiths MD. Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2021; 44:111-41.

- Bőthe B, Tóth-Király I, Zsila Á, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z, Orosz G. The development of the problematic pornography consumption scale (PPCS). J Sex Res. 2018;55:395-406.

- Bőthe B, Tóth-Király I, Demetrovics Z, Orosz G. The short version of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-6): a reliable and valid measure in general and treatment-seeking populations. J Sex Res. 2021;58:342-52.

- Kraus SW, Gola M, Grubbs JB, Kowalewska E, Hoff RA, LewStarowicz M, et al. Validation of a brief pornography screen across multiple samples. J Behav Addict. 2020;9:259-71.

- Chen L , Jiang X . The assessment of problematic internet pornography use: a comparison of three scales with mixed methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:488.

- Griffiths MD. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005;10:191-7.

- Chen

, Luo , Bőthe B, Jiang , Demetrovics , Potenza MN. Properties of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-18) in community and subclinical samples in China and Hungary. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106591. - Bőthe B, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Dion J, Štulhofer A, Bergeron S. Validity and reliability of the short version of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-6-A) in adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2021;35:486-500.

- Alidost F, Zareiyan A, Bőthe B, Farnam F. Psychometric properties of the Persian short version of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-6). Sex Health Compulsivity. 2022;29: 96-107.

- Kraus SW, Martino S, Potenza MN. Clinical characteristics of men interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography. J Behav Addict. 2016;5:169-78.

- Chen L , Jiang X , Luo X , Kraus SW , Bőthe B. The role of impaired control in screening problematic pornography use: evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in a large help-seeking male sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36:537-46.

- Grubbs JB, Floyd CG, Griffin KR, Jennings TL, Kraus SW. Moral incongruence and addiction: a registered report. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36:749-61.

- Kowalewska E, Gola M, Lew-Starowicz M, Kraus SW. Predictors of compulsive sexual behavior among treatment-seeking women. Sex Med. 2022;10:100525.

- Borgogna NC, Griffin KR, Grubbs JB, Kraus SW. Understanding differences in problematic pornography use: considerations for gender and sexual orientation. J Sex Med. 2022;19:1290-302.

- Lew-Starowicz M, Draps M, Kowalewska E, Obarska K, Kraus SW, Gola M. Tolerability and efficacy of paroxetine and naltrexone for treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:468-9.

- Bőthe B, Koós M, Nagy L, Kraus SW, Potenza MN, Demetrovics Z. International Sex Survey: study protocol of a large, cross-cultural collaborative study in 45 countries. J Behav Addict. 2021;10: 632-45.

- Jeong S, Lee Y. Consequences of not conducting measurement invariance tests in cross-cultural studies: a review of current research practices and recommendations. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2019;21: 466-83.

- Milfont TL, Fischer R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. Int J Psychol Res. 2010;3:2011-79.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics research suite. 2022.

- Kraus SW, Rosenberg H, Martino S, Nich C, Potenza MN. The development and initial evaluation of the pornography-use avoidance selfefficacy scale. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:354-63.

- Kohut T, Balzarini RN, Fisher WA, Grubbs JB, Campbell L, Prause N. Surveying pornography use: a shaky science resting on poor measurement foundations. J Sex Res. 2020;57:722-42.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2021.

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User’s Guide 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2022.

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:1198-202.

- Finney SJ, DiStefano C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editorsStructural Equation Modeling: a Second Course 2nd ed. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing; 2013. p. 439-92.

- Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Weighted least squares estimation with missing data; 2010.

- Islam MS, Tasnim R, Sujan MSH, Bőthe B, Ferdous MZ, Sikder MT, et al. Validation and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Bangla version of the brief pornography screen in men and women. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/ S11469-022-00903-0

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editorsTesting Structural Equation Models 21 Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. p. 136-62.

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive -goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res. 2003;8:23-74.

- Kenny DA, Kaniskan B, McCoach DB. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol Methods Res. 2015; 44:486-507.

- Millsap P. Statistical Approaches to Measurement Invariance Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2011.

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res Methods. 2000;3:4-70.

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. In: McGraw-Hill series in Psychology 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

- McDonald RP. The theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1970;23:1-21.

- McNeish D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’l take it from here. Psychol Methods. 2018;23:412-33.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297-334.

- Green SB, Yang Y. Commentary on coefficient alpha: a cautionary tale. Psychometrika. 2009;74:121-35.

- Revelle W, Zinbarg RE. Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika. 2009;74:145-54.

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. 2014;105:399-412.

- Reed GM, First MB, Billieux J, Cloitre M, Briken P, Achab S, et al. Emerging experience with selected new categories in the ICD-11: complex PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:189-213.

- Grubbs JB, Kraus SW. Pornography use and psychological science: a call for consideration. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2021;30:68-75.

- Griffin KR, Way BM, Kraus SW. Controversies and clinical recommendations for the treatment of compulsive sexual behavior disorder. Curr Addict Rep. 2021;8:546-55.

- Grubbs JB, Grant JT, Engelman J. Self-identification as a pornography addict: examining the roles of pornography use, religiousness, and moral incongruence. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2018;25:269-92.

- Bőthe B, Tóth-Király I, Potenza MN , Griffiths MD , Orosz G, Demetrovics Z. Revisiting the role of impulsivity and compulsivity in problematic sexual behaviors. J Sex Res. 2019;56:166-79.

- Carvalho J, Rosa PJ, Štulhofer A. Exploring hypersexuality pathways from eye movements: the role of (sexual) impulsivity. J Sex Med. 2021;18:1607-14.

- Lykke LC, Cohen PN. Widening gender gap in opposition to pornography, 1975-2012. Soc Curr. 2015;2:307-23.

- Chen L, Jiang X, Wang Q, Bőthe B, Potenza Marc N, Wu H. The association between the quantity and severity of pornography use: a meta-analysis. J Sex Res. 2022;509:704-19.

- Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Bergeron S. Self-perceived problematic pornography use: beyond individual differences and religiosity. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48:437-41.

- Baumeister RF, Mendoza JP. Cultural variations in the sexual marketplace: gender equality correlates with more sexual activity. J Soc Psychol. 2011;151:350-60.

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: a review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. J Sex Res. 2011;48:149-65.

- Grubbs JB, Floyd CG, Kraus SW. Pornography use and public health: examining the importance of online sexual behavior in the health sciences. Am J Public Health. 2023;113:22-6.

- Nelson KM, Rothman EF. Should public health professionals consider pornography a public health crisis? Am J Public Health. 2020;110: 151-3.

- McKay K, Poulin C, Muñoz-Laboy M. Claiming public health crisis to regulate sexual outlets: a critique of the state of Utah’s declaration on pornography. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50:401-5.

- Antons S, Engel J, Briken P, Krüger THC, Brand M, Stark R. Treatments and interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder with a focus on problematic pornography use: a preregistered systematic review. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:643-66.

- Borgogna NC, Garos S, Meyer CL, Trussell MR, Kraus SW. A review of behavioral interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder. Curr Addict Rep. 2022;9:99-108.

- Castro-Calvo J, Flayelle M, Perales JC, Brand M, Potenza MN, Billieux J. Compulsive sexual behavior disorder should not be

classified by solely relying on component/symptomatic features: commentary to the debate: ‘Behavioral addictions in the ICD-11’. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:210-5. - Starcevic V. Tolerance and withdrawal symptoms may not be helpful to enhance understanding of behavioural addictions. Addiction. 2016;111:1307-8.

- Sniewski L, Farvid P. Hidden in shame: heterosexual men’s experiences of self-perceived problematic pornography use. Psychol Men Masc. 2020;21:201-12.

- Wéry A, Schimmenti A, Karila L, Billieux J. Where the mind cannot dare: a case of addictive use of online pornography and its relationship with childhood trauma. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45: 114-27.

- Ford JJ, Durtschi JA, Franklin DL. Structural therapy with a couple battling pornography addiction. Am J Fam Ther. 2012;40: 336-48.

- Wéry A, Billieux J. Online sexual activities: an exploratory study of problematic and non-problematic usage patterns in a sample of men. Comput Human Behav. 2016;56:257-66.

- Grubbs JB, Kraus SW, Perry SL, Lewczuk K, Gola M. Moral incongruence and compulsive sexual behavior: results from cross-sectional interactions and parallel growth curve analyses. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129:266-78.

- Briken P, Wiessner C, Štulhofer A, Klein V, Fuß J, Reed GM, et al. Who feels affected by ‘out of control’ sexual behavior? Prevalence and correlates of indicators for ICD-11 Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder in the German Health and Sexuality Survey (GeSiD). J Behav Addict. 2022;11:900-11.

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Recent methods for the study of measurement invariance with many groups: alignment and random effects. Sociol Methods Res. 2018;47:637-64.

- Zhang Z, Braun TM, Peterson KE, Hu H, Téllez-Rojo MM, Sánchez BN. Extending tests of random effects to assess for measurement invariance in factor models. Stat Biosci. 2018;10:634-50.

- Kim ES, Cao C, Wang Y, Nguyen DT. Measurement invariance testing with many groups: a comparison of five approaches. Struct Equ Modeling. 2017;24:524-44.

- Rutkowski L, Svetina D. Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educ Psychol Meas. 2014;74:31-57.

- Jiang X, Wu Y, Zhang K, Bothe B, Hong Y, Chen L. Symptoms of problematic pornography use among help-seeking male adolescents: latent profile and network analysis. J Behav Addict. 2022;11:912-27.

- Štulhofer A, Rousseau A, Shekarchi R. A two-wave assessment of the structure and stability of self-reported problematic pornography use among male Croatian adolescents. Int J Sex Health. 2020;32: 151-64.

معلومات داعمة

- للاطلاع على الانتماءات، يرجى الرجوع إلى الصفحة 19هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب شروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري، والذي يسمح بالاستخدام والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح وألا يُستخدم لأغراض تجارية.

© 2024 المؤلفون. الإدمان نشرته شركة جون وايلي وأولاده نيابة عن جمعية دراسة الإدمان. - *تم تضمين مصر وإيران وباكستان ورومانيا في ورقة بروتوكول الدراسة كدول متعاونة [45]؛ ومع ذلك، لم يكن من الممكن الحصول على الموافقة الأخلاقية للدراسة في الوقت المناسب في هذه الدول. لم يتم تضمين تشيلي في ورقة بروتوكول الدراسة كدولة متعاونة [45]، حيث انضمت إلى الدراسة بعد نشر بروتوكول الدراسة. لذلك، بدلاً من 45 دولة مخطط لها [45]، يتم اعتبار 42 دولة فردية فقط في الدراسة الحالية؛ انظر التفاصيل فيhttps://osf.io/n3k2c/.

المنشورات: I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links. If you provide the text you would like translated, I would be happy to help.عروض المؤتمرات:https://osf.io/c695n/?view_only=7cae32e642b54d049e600ceb8971053e.

على الرغم من أن الدراسة تتبع ممارسات العلوم المفتوحة [45]، إلا أن مجموعة البيانات غير متاحة للجمهور بسبب الطبيعة الحساسة للبيانات. سيوفر المؤلف المقابل البيانات عند الطلب المبرر.

‘استخدام المواد الإباحية (البورنو) يعني النظر عمداً إلى، أو قراءة، أو الاستماع إلى: (أ) صور، أو مقاطع فيديو، أو أفلام تصور أفراد عراة أو أشخاص يمارسون الجنس؛ أو (ب) مواد مكتوبة أو صوتية تصف أفراد عراة أو أشخاص يمارسون الجنس. لا يتضمن استخدام البورنو مشاهدة أو التفاعل مع أفراد عراة حقيقيين، أو المشاركة في تجارب جنسية تفاعلية مع أشخاص آخرين شخصياً أو عبر الإنترنت. على سبيل المثال، المشاركة في دردشة جنسية مباشرة أو عرض كام والحصول على ‘رقصة حضن’ في نادي تعري لا تعتبر استخداماً للبورنو’. افتراض التكافؤ التاوي (أي تحميلات عوامل متساوية لجميع العناصر في نماذج العوامل) مطلوب لكي يكون ألفا قابلاً للمقارنة مع معامل الموثوقية [66]. إذا تم انتهاك هذا الافتراض (المشار إليه بالنماذج المتجانسة)، سيتم التقليل من قيمة الموثوقية اعتمادًا على شدة الانتهاك [67]. هنا، اخترنا التركيز على تفسير الأوميغا لأنها تصحح انحياز التقليل من ألفا في النماذج المتجانسة [68، 69]. - SD = الانحراف المعياري.

0: أبداً، 1: مرة واحدة في العام الماضي، 2: مرات في العام الماضي، 3: 7-11 مرة في العام الماضي، 4: شهرياً، 5: 2-3 مرات في الشهر، 6: أسبوعياً، 7: 2-3 مرات في الأسبوع، 8: 4-5 مرات في الأسبوع، 9: 6-7 مرات في الأسبوع، 10: أكثر من 7 مرات في الأسبوع.

الوقت المستغرق في استخدام المواد الإباحية لكل جلسة بالدقائق.

البند: ‘أنا مدمن على البورنو’، أعارض بشدة، أعارض، أعارض إلى حد ما، لا أوافق ولا أعارض، أوافق إلى حد ما، أوافق، 7 = أوافق بشدة.

البند: ‘أعتقد أن استخدام البورنو خطأ من الناحية الأخلاقية’، أعارض بشدة، أعارض، أعارض إلى حد ما، لا أوافق ولا أعارض، أوافق إلى حد ما، أوافق، أوافق بشدة.

. - #اللغة متغير منهجي وقد تعكس اختلافات قائمة على الدول. لذلك، لم نقم بفحص الفروق المتوسطة القائمة على اللغة بالتفصيل.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16431

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413365

Publication Date: 2024-02-27

Problematic pornography use across countries, genders, and sexual orientations: Insights from the International Sex Survey and comparison of different assessment tools

Correspondence

Funding information

Abstract

Background and aims: Problematic pornography use (PPU) is a common manifestation of the newly introduced Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder diagnosis in the 11th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Although cultural, gender- and sexual orientation-related differences in sexual behaviors are well documented, there is a relative absence of data on PPU outside Western countries and among women as well as gender- and sexually-diverse individuals. We addressed these gaps by (a) validating the long and short versions of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS and PPCS-6, respectively) and the Brief Pornography Screen (BPS) and (b) measuring PPU risk across diverse populations. Methods: Using data from the pre-registered International Sex Survey [

KEYWORDS

INTRODUCTION

in PPU prevalence may stem from real differences between cultural, gender- and sexual orientation-related groups [29].

PPU measures

[31, 32]. After the original validation studies, both measures’ validity and reliability were corroborated in subsequent studies, including among individuals from different cultures, age groups, and treatmentseeking and non-treatment-seeking groups [34, 36-38].

METHOD

Procedure

Participants

Measures

Socio-demographic and pornography-related questions

| Variables |

|

% |

| Country of residence | ||

| Algeria | 24 | 0.03 |

| Australia | 639 | 0.78 |

| Austria | 746 | 0.91 |

| Bangladesh | 373 | 0.45 |

| Belgium | 644 | 0.78 |

| Bolivia | 385 | 0.47 |

| Brazil | 3579 | 4.35 |

| Canada | 2541 | 3.09 |

| Chile | 1173 | 1.43 |

| China | 2428 | 2.95 |

| Colombia | 1913 | 2.33 |

| Croatia | 2390 | 2.91 |

| Czech Republic | 1640 | 1.99 |

| Ecuador | 276 | 0.34 |

| France | 1706 | 2.07 |

| Germany | 3271 | 3.98 |

| Gibraltar | 64 | 0.08 |

| Hungary | 11200 | 14.58 |

| India | 194 | 0.24 |

| Iraq | 99 | 0.12 |

| Ireland | 1702 | 2.07 |

| Israel | 1334 | 0.66 |

| Italy | 2401 | 2.92 |

| Japan | 562 | 0.68 |

| Lithuania | 2015 | 2.45 |

| Malaysia | 1170 | 1.42 |

| Mexico | 2137 | 2.60 |

| New Zealand | 2834 | 3.45 |

| North Macedonia | 1251 | 1.52 |

| Panama | 333 | 0.40 |

| Peru | 2672 | 3.25 |

| Poland | 9892 | 12.03 |

| Portugal | 2262 | 2.75 |

| Slovakia | 1134 | 1.38 |

| South Africa | 1849 | 2.25 |

| South Korea | 1464 | 1.78 |

| Spain | 2327 | 2.83 |

| Switzerland | 1144 | 1.39 |

| Taiwan | 2668 | 3.24 |

| Turkey | 820 | 1.00 |

| United Kingdom | 1412 | 1.72 |

| United States of America | 2398 | 2.92 |

| Other | 1177 | 1.43 |

| Language | ||

| Arabic | 142 | 0.17 |

| Bangla | 332 | 0.40 |

| Variables | n = 81 975-82 243 | % |

| Croatian | 2522 | 3.07 |

| Czech | 1583 | 1.92 |

| Dutch | 518 | 0.63 |

| English | 13994 | 17.02 |

| French | 3941 | 4.79 |

| German | 3494 | 4.25 |

| Hebrew | 1315 | 1.60 |

| Hindi | 17 | 0.02 |

| Hungarian | 10937 | 13.30 |

| Italian | 2437 | 2.96 |

| Japanese | 466 | 0.57 |

| Korean | 1437 | 1.75 |

| Lithuanian | 2094 | 2.55 |

| Macedonian | 1301 | 1.58 |

| Mandarin: simplified | 2474 | 3.01 |

| Mandarin: traditional | 2685 | 3.26 |

| Polish | 10343 | 12.58 |

| Portuguese: Brazil | 3650 | 4.44 |

| Portuguese: Portugal | 2277 | 2.77 |

| Romanian | 75 | 0.09 |

| Slovak | 2118 | 2.58 |

| Spanish: Latin America | 8926 | 10.85 |

| Spanish: Spain | 2312 | 2.81 |

| Turkish | 853 | 1.04 |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||

| Male | 33245 | 40.43 |

| Female | 48987 | 59.57 |

| Gender (original answer options in the survey) | ||

| Masculine/man | 32549 | 39.58 |

| Feminine/woman | 46874 | 56.99 |

| Indigenous or other cultural gender minority identity (e.g. two-spirit) | 166 | 0.20 |

| Non-binary, gender fluid or something else (e.g. genderqueer) | 2315 | 2.81 |

| Other | 302 | 0.37 |

| Gender (categories used in the analyses) | ||

| Man | 32549 | 39.58 |

| Woman | 46874 | 56.99 |

| Gender-diverse individuals | 2783 | 3.38 |

| Trans status | ||

| No, I am not a trans person | 79280 | 96.43 |

| Yes, I am a trans man | 357 | 0.43 |

| Yes, I am a trans woman | 295 | 0.36 |

| Yes, I am a non-binary trans person | 881 | 1.07 |

| I am questioning my gender identity | 1137 | 1.38 |

| I do not know what it means | 269 | 0.33 |

| Sexual orientation (original answer options in the survey) | ||

| Heterosexual/straight | 56125 | 68.24 |

| Variables |

|

% |

| Gay or lesbian or homosexual | 4607 | 5.60 |

| Heteroflexible | 6200 | 7.54 |

| Homoflexible | 534 | 0.65 |

| Bisexual | 7688 | 9.35 |

| Queer | 957 | 1.16 |

| Pansexual | 1969 | 2.39 |

| Asexual | 1064 | 1.29 |

| I do not know yet or I am currently questioning my sexual orientation | 1951 | 2.37 |

| None of the above | 807 | 0.98 |

| I do not want to answer | 308 | 0.37 |

| Sexual orientation (categories used in the analyses) | ||

| Heterosexual | 56125 | 68.24 |

| Gay or lesbian | 4607 | 5.60 |

| Bisexual | 7688 | 9.35 |

| Queer and pansexual | 2926 | 3.56 |

| Homo- and heteroflexible identities | 6734 | 8.19 |

| Asexual | 1064 | 1.29 |

| Questioning | 1951 | 2.37 |

| Other | 807 | 0.98 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary (e.g. elementary school) | 1002 | 1.22 |

| Secondary (e.g. high school) | 20325 | 24.71 |

| Tertiary (e.g. college or university) | 60896 | 74.04 |

| Current status in education | ||

| Not in education | 49802 | 60.55 |

| In primary education (e.g. elementary school) | 64 | 0.08 |

| In secondary education (e.g. high school) | 1571 | 1.91 |

| In tertiary education (e.g. college or university) | 30762 | 37.40 |

| Work status | ||

| Not working | 20853 | 25.36 |

| Working full-time | 42981 | 52.26 |

| Working part-time | 11356 | 13.81 |

| Doing odd jobs | 7029 | 8.55 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Considers life circumstances among the worst | 227 | 0.28 |

| Considers life circumstances much worse than average | 773 | 0.94 |

| Considers life circumstances worse than average | 4232 | 5.15 |

| Considers life circumstances average | 26742 | 32.52 |

| Considers life circumstances better than average | 31567 | 38.38 |

| Considers life circumstances much better than average | 14736 | 17.92 |

| Considers life circumstances among the best | 3957 | 4.81 |

| Residence | ||

| Metropolis (population is more than 1 million people) | 26441 | 32.15 |

| City (population is between 100000 and 999999 people) | 29920 | 36.38 |

| Town (population is between 1000 and 99999 people) | 21103 | 25.66 |

| Village (population is below 1000 people) | 4764 | 5.79 |

| Variables |

|

% |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 27541 | 33.49 |

| In a relationship | 27440 | 33.36 |

| Married or common-law partners | 24338 | 29.59 |

| Widow or widower | 428 | 0.52 |

| Divorced | 2472 | 3.01 |

| Number of children | ||

| None | 57909 | 70.41 |

| 1 | 8417 | 10.23 |

| 2 | 10353 | 12.59 |

| 3 | 3843 | 4.67 |

| 4 | 1014 | 1.23 |

| 5 | 290 | 0.35 |

| 6-9 | 125 | 0.15 |

| 10 or more | 24 | 0.03 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 32.39 | 12.52 |

SD = standard deviation.

Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale-short (PPCS6) and long (PPCS) versions [31, 32]

Brief Pornography Screen [33]

Statistical analyses

ranged between 8.72 and

RESULTS

Psychometric properties of the PPCS, PPCS-6, and BPS

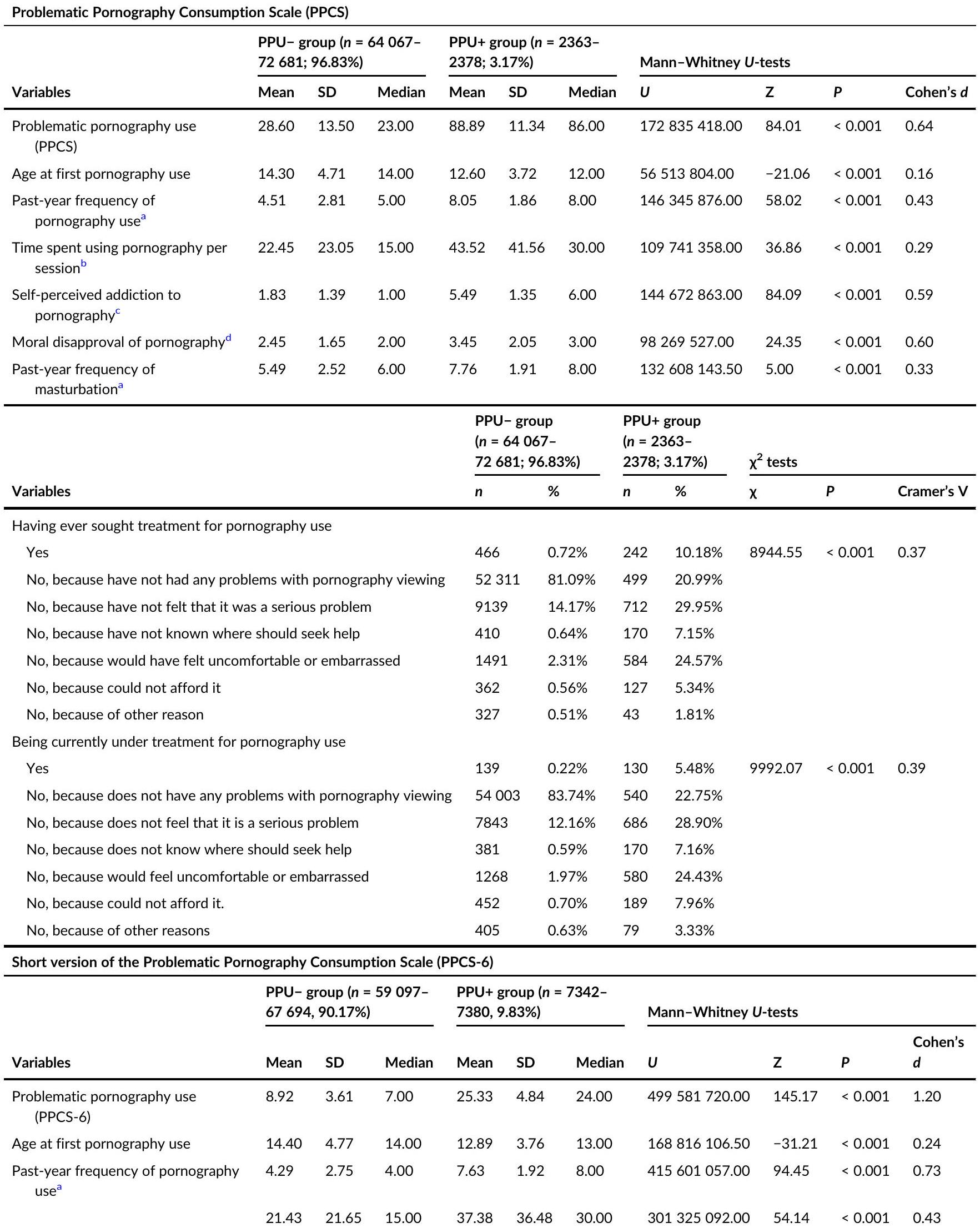

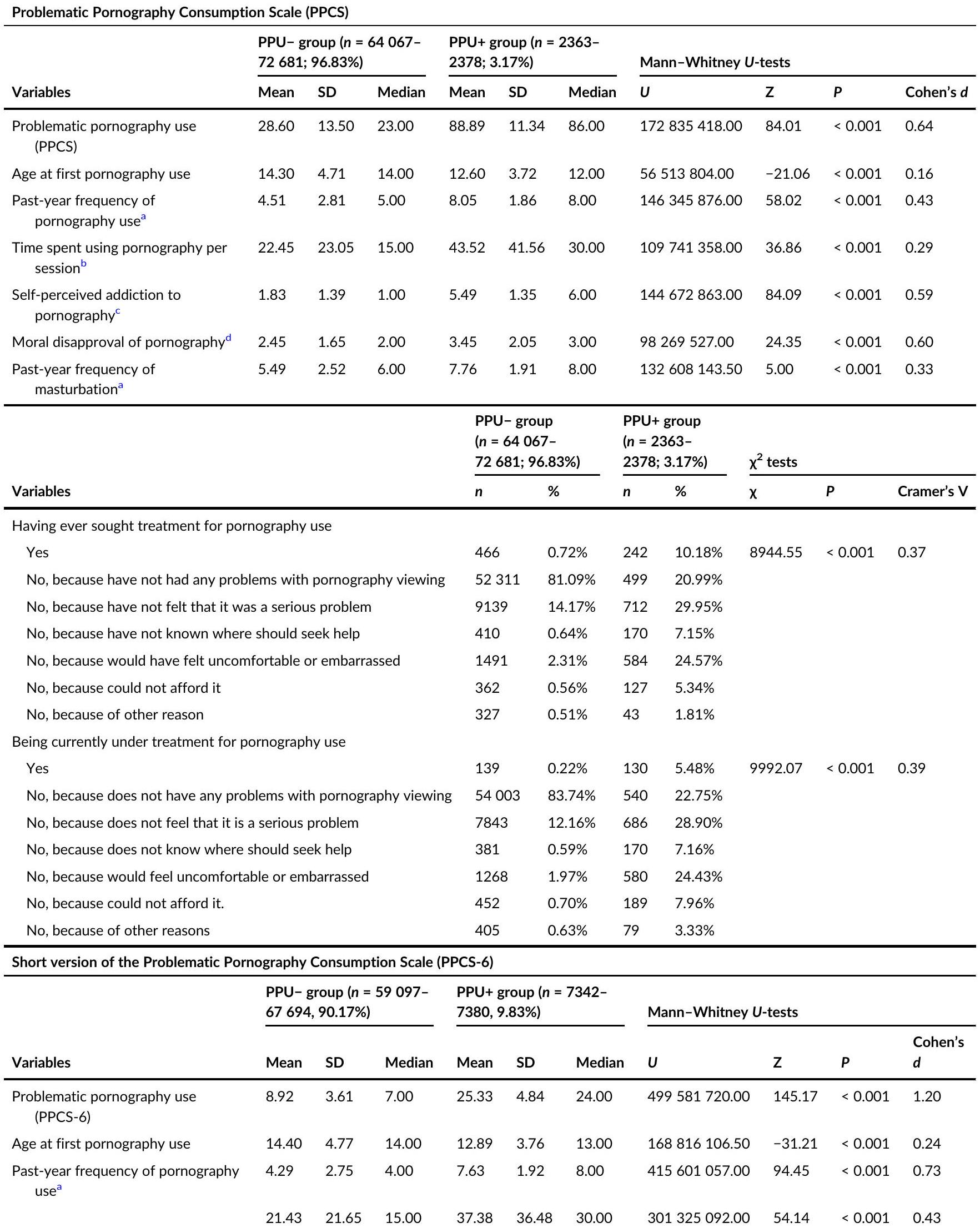

Associations between PPU and pornography use

| Range | Mean | SD | Median | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| 1. Problematic pornography use (PPCS) | 18-126 | 30.51 | 17.09 | 23.00 | – | |||||||

| 2. Problematic pornography use (PPCS-6) | 6-42 | 10.54 | 6.16 | 8.00 | 0.95* | – | ||||||

| 3. Problematic pornography use (BPS) | 0-10 | 1.49 | 2.28 | 0.00 | 0.73* | 0.70* | – | |||||

| 4. Age at first pornography use | 3-88 | 14.48 | 4.93 | 14.00 | -0.21* | -0.19* | -0.16* | – | ||||

| 5. Past-year frequency of pornography use

|

0-10 | 4.22 | 3.02 | 4.00 | 0.68* | 0.66* | 0.51* | -0.30* | – | |||

| 6. Time spent using pornography per session

|

0-1200 | 23.19 | 24.28 | 15.00 | 0.33* | 0.32* | 0.23* | -0.08* | 0.23* | – | ||

| 7. Self-perceived addiction to pornography

|

1-7 | 1.96 | 1.54 | 1.00 | 0.69* | 0.68* | 0.65* | -0.15* | 0.51* | 0.25* | – | |

| 8. Moral disapproval of pornography

|

1-7 | 2.49 | 1.68 | 2.00 | 0.08* | 0.06* | 0.26* | 0.03* | -0.13* | -0.03* | 0.17* | – |

| 9. Past-year frequency of masturbation

|

0-10 | 5.36 | 2.61 | 6.00 | 0.46* | 0.45* | 0.35* | -0.25* | 0.69* | 0.10* | 0.35* | -0.09* |

| Variables | PPCS | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

|

|

% | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI |

|

% | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Country of residence | ||||||||

| Algeria | 20 | 83.33 | 67.26 | 99.41 | 4 | 16.67 | 0.59 | 32.74 |

| Australia | 567 | 96.26 | 94.73 | 97.80 | 22 | 3.74 | 2.20 | 5.27 |

| Austria | 672 | 98.97 | 98.21 | 99.73 | 7 | 1.03 | 0.27 | 1.79 |

| Bangladesh | 291 | 89.26 | 85.89 | 92.64 | 35 | 10.74 | 7.36 | 14.11 |

| Belgium | 579 | 97.80 | 96.62 | 98.99 | 13 | 2.20 | 1.01 | 3.38 |

| Bolivia | 351 | 95.90 | 93.86 | 97.94 | 15 | 4.10 | 2.06 | 6.14 |

| Brazil | 3114 | 93.68 | 92.85 | 94.51 | 210 | 6.32 | 5.49 | 7.15 |

| Canada | 2328 | 97.73 | 97.13 | 98.33 | 54 | 2.27 | 1.67 | 2.87 |

| Chile | 1066 | 97.35 | 96.40 | 98.30 | 29 | 2.65 | 1.70 | 3.60 |

| China | 2106 | 90.43 | 89.23 | 91.62 | 223 | 9.57 | 8.38 | 10.77 |

| Colombia | 1714 | 98.05 | 97.41 | 98.70 | 34 | 1.95 | 1.30 | 2.59 |

| Croatia | 2158 | 98.45 | 97.93 | 98.97 | 34 | 1.55 | 1.03 | 2.07 |

| Czech Republic | 1291 | 98.40 | 97.72 | 99.08 | 21 | 1.60 | 0.92 | 2.28 |

| Ecuador | 250 | 95.79 | 93.33 | 98.24 | 11 | 4.21 | 1.76 | 6.67 |

| France | 1512 | 97.05 | 96.21 | 97.89 | 46 | 2.95 | 2.11 | 3.79 |

| Germany | 2762 | 98.75 | 98.34 | 99.16 | 35 | 1.25 | 0.84 | 1.66 |

| Gibraltar | 58 | 98.31 | 94.91 | 101.70 | 1 | 1.69 | -1.70 | 5.09 |

| Hungary | 10050 | 96.37 | 96.01 | 96.73 | 379 | 3.63 | 3.27 | 3.99 |

| India | 168 | 92.82 | 89.02 | 96.62 | 13 | 7.18 | 3.38 | 10.98 |

| Iraq | 80 | 86.96 | 79.94 | 93.97 | 12 | 13.04 | 6.03 | 20.06 |

| Ireland | 1515 | 97.93 | 97.22 | 98.64 | 32 | 2.07 | 1.36 | 2.78 |

| Israel | 1127 | 98.17 | 97.39 | 98.95 | 21 | 1.83 | 1.05 | 2.61 |

| Italy | 2184 | 99.00 | 98.59 | 99.42 | 22 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 1.41 |

| Japan | 531 | 96.20 | 94.59 | 97.80 | 21 | 3.80 | 2.20 | 5.41 |

| Lithuania | 1715 | 98.28 | 97.67 | 98.89 | 30 | 1.72 | 1.11 | 2.33 |

| Malaysia | 1046 | 93.48 | 92.03 | 94.93 | 73 | 6.52 | 5.07 | 7.97 |

| Mexico | 1881 | 98.64 | 98.12 | 99.16 | 26 | 1.36 | 0.84 | 1.88 |

| New Zealand | 2559 | 98.27 | 97.77 | 98.77 | 45 | 1.73 | 1.23 | 2.23 |

| North Macedonia | 1125 | 97.83 | 96.98 | 98.67 | 25 | 2.17 | 1.33 | 3.02 |

| Panama | 298 | 96.44 | 94.36 | 98.52 | 11 | 3.56 | 1.48 | 5.64 |

| Peru | 2420 | 98.25 | 97.74 | 98.77 | 43 | 1.75 | 1.23 | 2.26 |

| Poland | 8757 | 98.92 | 98.70 | 99.13 | 96 | 1.08 | 0.87 | 1.30 |

| Portugal | 1928 | 98.72 | 98.22 | 99.22 | 25 | 1.28 | 0.78 | 1.78 |

| Slovakia | 1009 | 97.49 | 96.53 | 98.44 | 26 | 2.51 | 1.56 | 3.47 |

| South Africa | 1638 | 96.92 | 96.10 | 97.75 | 52 | 3.08 | 2.25 | 3.90 |

| South Korea | 1294 | 94.94 | 93.77 | 96.10 | 69 | 5.06 | 3.90 | 6.23 |

| Spain | 2058 | 98.42 | 97.89 | 98.96 | 33 | 1.58 | 1.04 | 2.11 |

| Switzerland | 1031 | 98.38 | 97.61 | 99.14 | 17 | 1.62 | 0.86 | 2.39 |

| Taiwan | 2271 | 88.64 | 87.41 | 89.87 | 291 | 11.36 | 10.13 | 12.59 |

| Turkey | 703 | 93.48 | 91.72 | 95.25 | 49 | 6.52 | 4.75 | 8.28 |

| United Kingdom | 1258 | 97.67 | 96.85 | 98.50 | 30 | 2.33 | 1.50 | 3.15 |

| Variables | PPCS | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

| n | % | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI | n | % | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI | |

| United States of America | 2170 | 96.83 | 96.11 | 97.56 | 71 | 3.17 | 2.44 | 3.89 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Man | 29459 | 93.74 | 93.47 | 94.01 | 1967 | 6.26 | 5.99 | 6.53 |

| Woman | 40691 | 99.28 | 99.19 | 99.36 | 297 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.81 |

| Gender-diverse individual | 2497 | 95.71 | 94.93 | 96.49 | 112 | 4.29 | 3.51 | 5.07 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 49013 | 97.07 | 96.93 | 97.22 | 1478 | 2.93 | 2.78 | 3.07 |

| Gay or lesbian | 4172 | 94.13 | 93.44 | 94.83 | 260 | 5.87 | 5.17 | 6.56 |

| Bisexual | 7036 | 96.89 | 96.49 | 97.29 | 226 | 3.11 | 2.71 | 3.51 |

| Queer and pansexual | 2701 | 97.76 | 97.20 | 98.31 | 62 | 2.24 | 1.69 | 2.80 |

| Homo- and heteroflexible identities | 6071 | 96.24 | 95.77 | 96.71 | 237 | 3.76 | 3.29 | 4.23 |

| Asexual | 952 | 98.55 | 97.80 | 99.31 | 14 | 1.45 | 0.69 | 2.20 |

| Questioning | 1742 | 96.24 | 95.37 | 97.12 | 68 | 3.76 | 2.88 | 4.63 |

| Other | 698 | 96.41 | 95.05 | 97.77 | 26 | 3.59 | 2.23 | 4.95 |

| Variables | PPCS-6 | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

|

|

% | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|

% | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI | |

| Country of residence | ||||||||

| Algeria | 16 | 66.67 | 46.33 | 87.00 | 8 | 33.33 | 13.00 | 53.67 |

| Australia | 531 | 90.15 | 87.74 | 92.57 | 58 | 9.85 | 7.43 | 12.26 |

| Austria | 634 | 93.37 | 91.50 | 95.25 | 45 | 6.63 | 4.75 | 8.50 |

| Bangladesh | 243 | 74.54 | 69.79 | 79.29 | 83 | 25.46 | 20.71 | 30.21 |

| Belgium | 519 | 87.52 | 84.85 | 90.19 | 74 | 12.48 | 9.81 | 15.15 |

| Bolivia | 318 | 86.89 | 83.41 | 90.36 | 48 | 13.11 | 9.64 | 16.59 |

| Brazil | 2737 | 82.32 | 81.02 | 83.61 | 588 | 17.68 | 16.39 | 18.98 |

| Canada | 2163 | 90.81 | 89.64 | 91.97 | 219 | 9.19 | 8.03 | 10.36 |

| Chile | 993 | 90.68 | 88.96 | 92.41 | 102 | 9.32 | 7.59 | 11.04 |

| China | 1764 | 75.74 | 74.00 | 77.48 | 565 | 24.26 | 22.52 | 26.00 |

| Colombia | 1647 | 94.22 | 93.13 | 95.32 | 101 | 5.78 | 4.68 | 6.87 |

| Croatia | 2083 | 94.94 | 94.02 | 95.86 | 111 | 5.06 | 4.14 | 5.98 |

| Czech Republic | 1228 | 93.60 | 92.27 | 94.92 | 84 | 6.40 | 5.08 | 7.73 |

| Ecuador | 226 | 86.59 | 82.43 | 90.75 | 35 | 13.41 | 9.25 | 17.57 |

| France | 1395 | 89.54 | 88.02 | 91.06 | 163 | 10.46 | 8.94 | 11.98 |

| Germany | 2627 | 93.92 | 93.04 | 94.81 | 170 | 6.08 | 5.19 | 6.96 |

| Gibraltar | 56 | 94.92 | 89.14 | 100.69 | 3 | 5.08 | -0.69 | 10.86 |

| Hungary | 9313 | 89.29 | 88.70 | 89.88 | 1117 | 10.71 | 10.12 | 11.30 |

| India | 141 | 77.90 | 71.80 | 84.00 | 40 | 22.10 | 16.00 | 28.20 |

| Iraq | 71 | 77.17 | 68.43 | 85.91 | 21 | 22.83 | 14.09 | 31.57 |

| Ireland | 1434 | 92.64 | 91.33 | 93.94 | 114 | 7.36 | 6.06 | 8.67 |

| Israel | 1087 | 94.60 | 93.30 | 95.91 | 62 | 5.40 | 4.09 | 6.70 |

| Italy | 2082 | 94.34 | 93.37 | 95.30 | 125 | 5.66 | 4.70 | 6.63 |

| Japan | 469 | 84.96 | 81.97 | 87.95 | 83 | 15.04 | 12.05 | 18.03 |

| Variables | PPCS-6 | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

| n | % | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | n | % | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI | |

| Lithuania | 1637 | 93.81 | 92.68 | 94.94 | 108 | 6.19 | 5.06 | 7.32 |

| Malaysia | 899 | 80.34 | 78.01 | 82.67 | 220 | 19.66 | 17.33 | 21.99 |

| Mexico | 1808 | 94.81 | 93.81 | 95.81 | 99 | 5.19 | 4.19 | 6.19 |

| New Zealand | 2398 | 92.05 | 91.01 | 93.09 | 207 | 7.95 | 6.91 | 8.99 |

| North Macedonia | 1074 | 93.31 | 91.86 | 94.76 | 77 | 6.69 | 5.24 | 8.14 |

| Panama | 277 | 89.64 | 86.23 | 93.06 | 32 | 10.36 | 6.94 | 13.77 |

| Peru | 2268 | 92.05 | 90.98 | 93.11 | 196 | 7.95 | 6.89 | 9.02 |

| Poland | 8485 | 95.82 | 95.40 | 96.24 | 370 | 4.18 | 3.76 | 4.60 |

| Portugal | 1854 | 94.88 | 93.90 | 95.86 | 100 | 5.12 | 4.14 | 6.10 |

| Slovakia | 938 | 90.63 | 88.85 | 92.41 | 97 | 9.37 | 7.59 | 11.15 |

| South Africa | 1496 | 88.47 | 86.94 | 89.99 | 195 | 11.53 | 10.01 | 13.06 |

| South Korea | 1180 | 86.57 | 84.76 | 88.39 | 183 | 13.43 | 11.61 | 15.24 |

| Spain | 1975 | 94.45 | 93.47 | 95.43 | 116 | 5.55 | 4.57 | 6.53 |

| Switzerland | 971 | 92.65 | 91.07 | 94.23 | 77 | 7.35 | 5.77 | 8.93 |

| Taiwan | 1878 | 73.30 | 71.59 | 75.02 | 684 | 26.70 | 24.98 | 28.41 |

| Turkey | 625 | 83.11 | 80.43 | 85.80 | 127 | 16.89 | 14.20 | 19.57 |

| United Kingdom | 1204 | 93.48 | 92.13 | 94.83 | 84 | 6.52 | 5.17 | 7.87 |

| United States of America | 2016 | 89.96 | 88.71 | 91.21 | 225 | 10.04 | 8.79 | 11.29 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Man | 25587 | 81.40 | 80.97 | 81.83 | 5845 | 18.60 | 18.17 | 19.03 |

| Woman | 39782 | 97.04 | 96.87 | 97.20 | 1214 | 2.96 | 2.80 | 3.13 |

| Gender-diverse individual | 2294 | 87.89 | 86.64 | 89.15 | 316 | 12.11 | 10.85 | 13.36 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 45847 | 90.79 | 90.54 | 91.04 | 4652 | 9.21 | 8.96 | 9.46 |

| Gay or lesbian | 3592 | 81.03 | 79.87 | 82.18 | 841 | 18.97 | 17.82 | 20.13 |

| Bisexual | 6558 | 90.29 | 89.61 | 90.97 | 705 | 9.71 | 9.03 | 10.39 |

| Queer and pansexual | 2564 | 92.76 | 91.80 | 93.73 | 200 | 7.24 | 6.27 | 8.20 |

| Homo- and heteroflexible identities | 5641 | 89.40 | 88.64 | 90.16 | 669 | 10.60 | 9.84 | 11.36 |

| Asexual | 931 | 96.38 | 95.20 | 97.56 | 35 | 3.62 | 2.44 | 4.80 |

| Questioning | 1629 | 89.90 | 88.51 | 91.29 | 183 | 10.10 | 8.71 | 11.49 |

| Other | 664 | 91.71 | 89.70 | 93.73 | 60 | 8.29 | 6.27 | 10.30 |

| Variables | BPS | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

|

|

% | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|

% | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Country of residence | ||||||||

| Algeria | 12 | 50.00 | 28.43 | 71.57 | 12 | 50.00 | 28.43 | 71.57 |

| Australia | 493 | 83.70 | 80.71 | 86.69 | 96 | 16.30 | 13.31 | 19.29 |

| Austria | 612 | 90.13 | 87.88 | 92.38 | 67 | 9.87 | 7.62 | 12.12 |

| Bangladesh | 229 | 70.46 | 65.48 | 75.45 | 96 | 29.54 | 24.55 | 34.52 |

| Belgium | 496 | 83.50 | 80.51 | 86.50 | 98 | 16.50 | 13.50 | 19.49 |

| Bolivia | 261 | 71.51 | 66.85 | 76.16 | 104 | 28.49 | 23.84 | 33.15 |

| (Continues) | ||||||||

| Variables | BPS | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

|

|

% | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI |

|

% | Lower 95% Cl | Upper 95% CI | |

| Brazil | 2497 | 75.10 | 73.63 | 76.57 | 828 | 24.90 | 23.43 | 26.37 |

| Canada | 2058 | 86.36 | 84.98 | 87.74 | 325 | 13.64 | 12.26 | 15.02 |

| Chile | 840 | 76.64 | 74.13 | 79.15 | 256 | 23.36 | 20.85 | 25.87 |

| China | 1539 | 66.08 | 64.16 | 68.00 | 790 | 33.92 | 32.00 | 35.84 |

| Colombia | 1416 | 80.91 | 79.07 | 82.76 | 334 | 19.09 | 17.24 | 20.93 |

| Croatia | 1927 | 87.79 | 86.42 | 89.16 | 268 | 12.21 | 10.84 | 13.58 |

| Czech Republic | 1188 | 90.48 | 88.89 | 92.07 | 125 | 9.52 | 7.93 | 11.11 |

| Ecuador | 183 | 70.66 | 65.07 | 76.24 | 76 | 29.34 | 23.76 | 34.93 |

| France | 1262 | 80.90 | 78.94 | 82.85 | 298 | 19.10 | 17.15 | 21.06 |

| Germany | 2532 | 90.62 | 89.54 | 91.70 | 262 | 9.38 | 8.30 | 10.46 |

| Gibraltar | 50 | 84.75 | 75.30 | 94.20 | 9 | 15.25 | 5.80 | 24.70 |

| Hungary | 8779 | 84.16 | 83.46 | 84.86 | 1652 | 15.84 | 15.14 | 16.54 |

| India | 119 | 66.48 | 59.50 | 73.46 | 60 | 33.52 | 26.54 | 40.50 |

| Iraq | 57 | 61.96 | 51.85 | 72.07 | 35 | 38.04 | 27.93 | 48.15 |

| Ireland | 1318 | 85.14 | 83.37 | 86.92 | 230 | 14.86 | 13.08 | 16.63 |

| Israel | 991 | 86.25 | 84.25 | 88.24 | 158 | 13.75 | 11.76 | 15.75 |

| Italy | 1996 | 90.32 | 89.08 | 91.55 | 214 | 9.68 | 8.45 | 10.92 |

| Japan | 473 | 85.69 | 82.76 | 88.62 | 79 | 14.31 | 11.38 | 17.24 |

| Lithuania | 1550 | 88.77 | 87.29 | 90.26 | 196 | 11.23 | 9.74 | 12.71 |

| Malaysia | 747 | 66.76 | 63.99 | 69.52 | 372 | 33.24 | 30.48 | 36.01 |

| Mexico | 1609 | 84.46 | 82.83 | 86.09 | 296 | 15.54 | 13.91 | 17.17 |

| New Zealand | 2237 | 85.87 | 84.53 | 87.21 | 368 | 14.13 | 12.79 | 15.47 |

| North Macedonia | 1021 | 88.71 | 86.87 | 90.54 | 130 | 11.29 | 9.46 | 13.13 |

| Panama | 249 | 80.58 | 76.15 | 85.02 | 60 | 19.42 | 14.98 | 23.85 |

| Peru | 1950 | 79.14 | 77.53 | 80.75 | 514 | 20.86 | 19.25 | 22.47 |

| Poland | 8045 | 90.91 | 90.32 | 91.51 | 804 | 9.09 | 8.49 | 9.68 |

| Portugal | 1810 | 92.73 | 91.57 | 93.88 | 142 | 7.27 | 6.12 | 8.43 |

| Slovakia | 847 | 81.91 | 79.56 | 84.26 | 187 | 18.09 | 15.74 | 20.44 |

| South Africa | 1285 | 75.90 | 73.86 | 77.94 | 408 | 24.10 | 22.06 | 26.14 |

| South Korea | 1076 | 78.94 | 76.78 | 81.11 | 287 | 21.06 | 18.89 | 23.22 |

| Spain | 1770 | 84.69 | 83.14 | 86.23 | 320 | 15.31 | 13.77 | 16.86 |

| Switzerland | 890 | 84.84 | 82.67 | 87.02 | 159 | 15.16 | 12.98 | 17.33 |

| Taiwan | 1838 | 71.74 | 70.00 | 73.49 | 724 | 28.26 | 26.51 | 30.00 |

| Turkey | 561 | 74.60 | 71.48 | 77.72 | 191 | 25.40 | 22.28 | 28.52 |

| United Kingdom | 1135 | 88.12 | 86.35 | 89.89 | 153 | 11.88 | 10.11 | 13.65 |

| United States of America | 1860 | 82.96 | 81.40 | 84.52 | 382 | 17.04 | 15.48 | 18.60 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Man | 22341 | 71.08 | 70.58 | 71.58 | 9090 | 28.92 | 28.42 | 29.42 |

| Woman | 38117 | 92.99 | 92.75 | 93.24 | 2872 | 7.01 | 6.76 | 7.25 |

| Gender-diverse individual | 2141 | 81.94 | 80.46 | 83.41 | 472 | 18.06 | 16.59 | 19.54 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 42156 | 83.48 | 83.15 | 83.80 | 8344 | 16.52 | 16.20 | 16.85 |

| Gay or lesbian | 3433 | 77.39 | 76.16 | 78.62 | 1003 | 22.61 | 21.38 | 23.84 |

| Variables | BPS | |||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

|||||||

|

|

% | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | n | % | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Bisexual | 6115 | 84.22 | 83.38 | 85.06 | 1146 | 15.78 | 14.94 | 16.62 |

| Queer and pansexual | 2415 | 87.40 | 86.17 | 88.64 | 348 | 12.60 | 11.36 | 13.83 |

| Homo- and heteroflexible identities | 5316 | 84.29 | 83.39 | 85.19 | 991 | 15.71 | 14.81 | 16.61 |

| Asexual | 879 | 90.99 | 89.19 | 92.80 | 87 | 9.01 | 7.20 | 10.81 |

| Questioning | 1446 | 79.85 | 78.00 | 81.69 | 365 | 20.15 | 18.31 | 22.00 |

| Other | 626 | 86.58 | 84.09 | 89.07 | 97 | 13.42 | 10.93 | 15.91 |

CI = confidence interval.

first pornography use (

Country-, gender- and sexual orientation-based differences in PPU

Comparison of the PPU- and PPU+ groups

DISCUSSION

| Short version of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-6) | |||||||||||||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

Mann-Whitney U-tests | |||||||||||||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | U | Z |

|

Cohen’s

|

|||||||

| Time spent using pornography per session

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Self-perceived addiction to pornography

|

1.64 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 4.57 | 1.64 | 5.00 | 398955344.00 | 131.03 | < 0.001 | 0.99 | |||||||

| Moral disapproval of pornography

|

2.42 | 1.64 | 2.00 | 2.99 | 1.90 | 2.00 | 257864691.50 | 25.51 | < 0.001 | 0.19 | |||||||

| Past-year frequency of masturbation

|

5.35 | 2.50 | 6.00 | 7.45 | 1.96 | 8.00 | 373811777.50 | 71.14 | < 0.001 | 0.53 | |||||||

| Variables |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| n | % |

|

% |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Having ever sought treatment for pornography use | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 291 | 0.49% | 417 | 5.65% | 12 | < 0.001 | 0.44 | ||||||||||

| No, because have not had any problems with pornography viewing | 50388 | 84.66% | 2433 | 32.99% | |||||||||||||

| No, because have not felt that it was a serious problem | 7154 | 12.02% | 2699 | 36.60% | |||||||||||||

| No, because have not known where should seek help | 238 | 0.40% | 342 | 4.64% | |||||||||||||

| No, because would have felt uncomfortable or embarrassed | 918 | 1.54% | 1157 | 15.69% | |||||||||||||

| No, because could not afford it | 250 | 0.42% | 239 | 3.24% | |||||||||||||

| No, because of other reason. | 282 | 0.47% | 88 | 1.19% | |||||||||||||

| Being currently under treatment for pornography use | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 85 | 0.14% | 184 | 2.50% | 13 | < 0.001 | 0.45 | ||||||||||

| No, because does not have any problems with pornography viewing |

|

||||||||||||||||

| No, because does not feel that it is a serious problem | 5981 | 10.05% | 2548 | 34.56% | |||||||||||||

| No, because does not know where should seek help | 218 |

|

|||||||||||||||

| No, because would feel uncomfortable or embarrassed | 745 | 1.25% 1103 14.96% | |||||||||||||||

| No, because could not afford it | 292 | 0.49% 349 4.73% | |||||||||||||||

| No, because of other reasons | 331 | 0.56% 153 2.08% | |||||||||||||||

| Brief Pornography Screen (BPS) | |||||||||||||||||

| PPU- group (

|

PPU+ group (

|

Mann-Whitney U-tests | |||||||||||||||

|

Mean | SD | Median | U | Z | P | Cohen’s d | ||||||||||

| Problematic pornography use (BPS) | 0.61 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 5.92 | 1.85 | 5.00 | 779154948.00 | 192.18 | < 0.001 | 1.68 | |||||||

| Age at first pornography use | 14.47 | 4.80 | 14.00 | 13.19 | 3.98 | 13.00 | 272751680.00 | -32.14 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | |||||||

| Past-year frequency of pornography use

|

4.18 | 2.77 | 4.00 | 6.87 | 2.17 | 7.00 | 599687248.00 | 95.88 | < 0.001 | 0.74 | |||||||

| Time spent using pornography per session

|