DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44652-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195701

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

استراتيجية استبدال لتنظيم البيئة المحلية للذرة المفردة

تم القبول: 21 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 10 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تتحكم البيئات التنسيقية المحلية في أداء المحفزات ذات الذرة الواحدة. هنا، تم تطوير استراتيجية استبدال حراري لتخليق المحفزات ذات الذرة الواحدة مع بيئات تنسيقية محلية مضبوطة وقابلة للتعديل بدقة. سلسلة من

النتائج

تم تصنيع سلسلة SACs من خلال عملية التحلل الحراري المنضبط لجزيئات نانوية من ZIF-8 المضافة بالكوبيك. أظهرت الدراسات السابقة أن M-

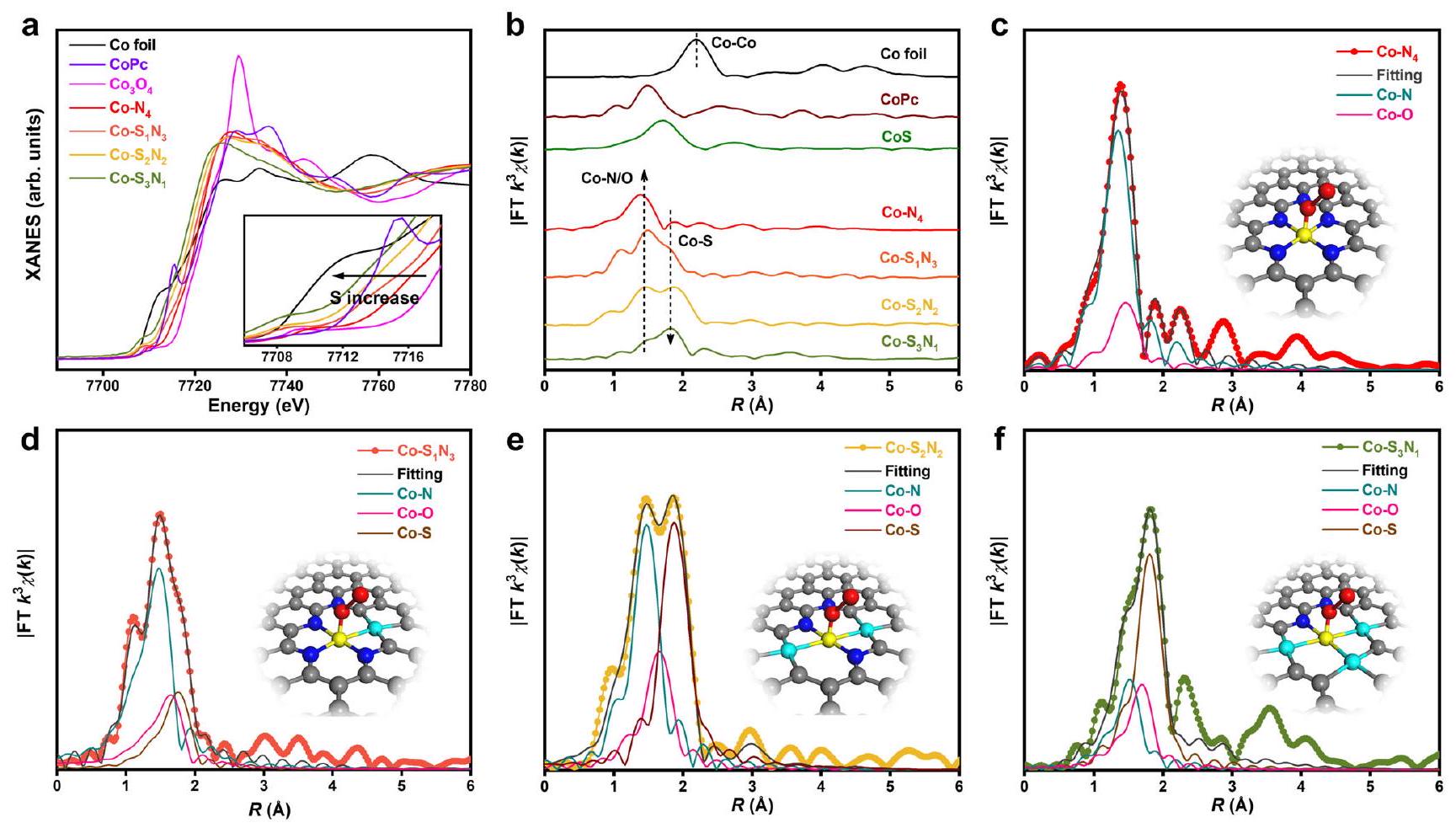

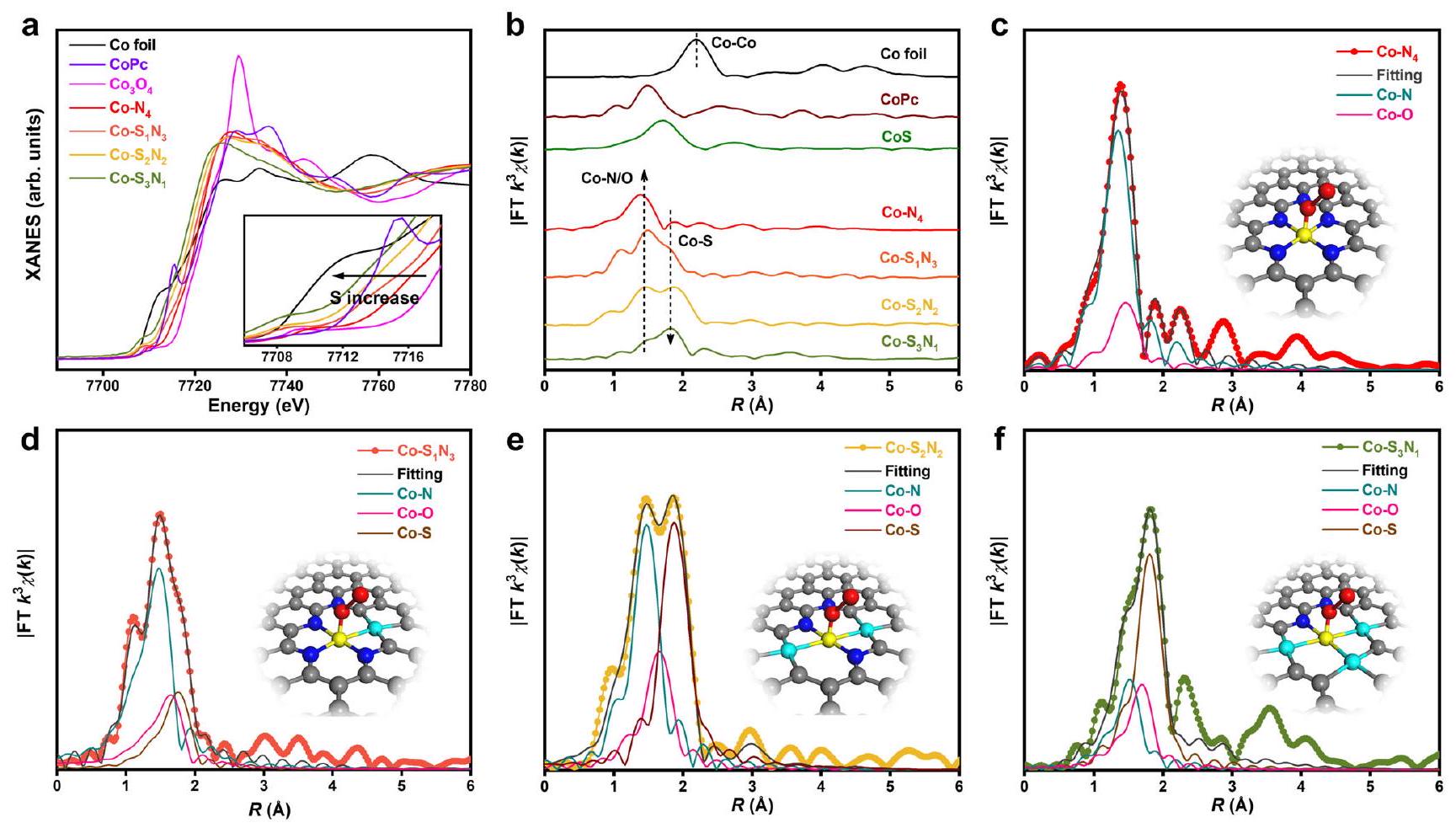

البيئات التنسيقية المحلية المفصلة لـ Co المستخرج

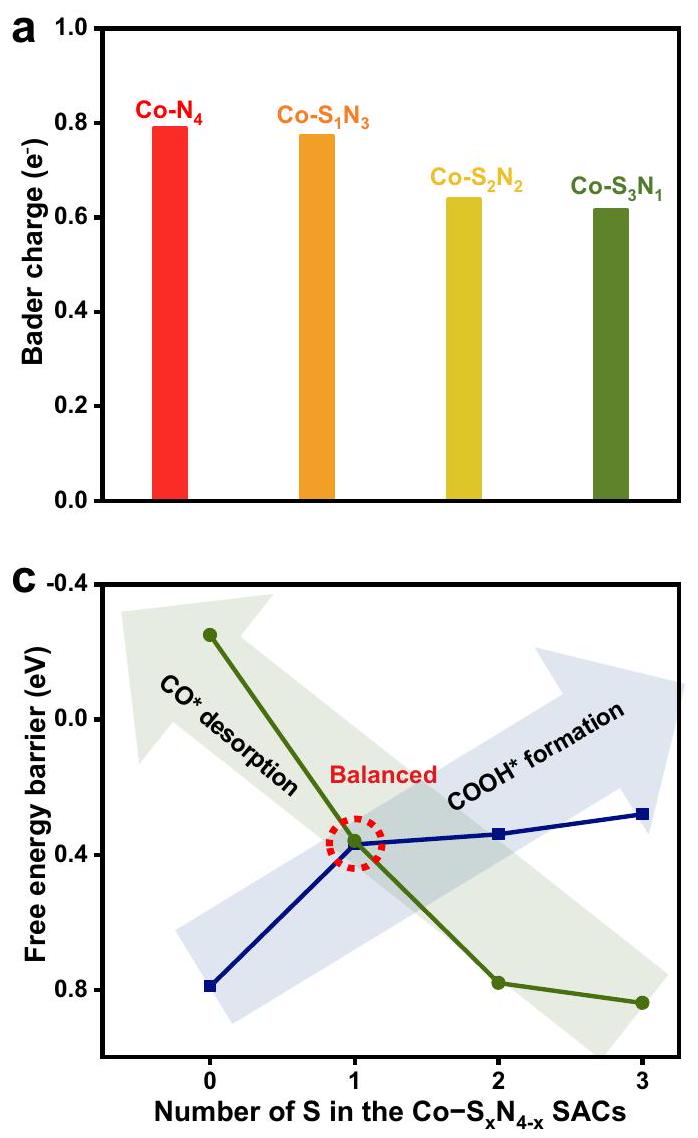

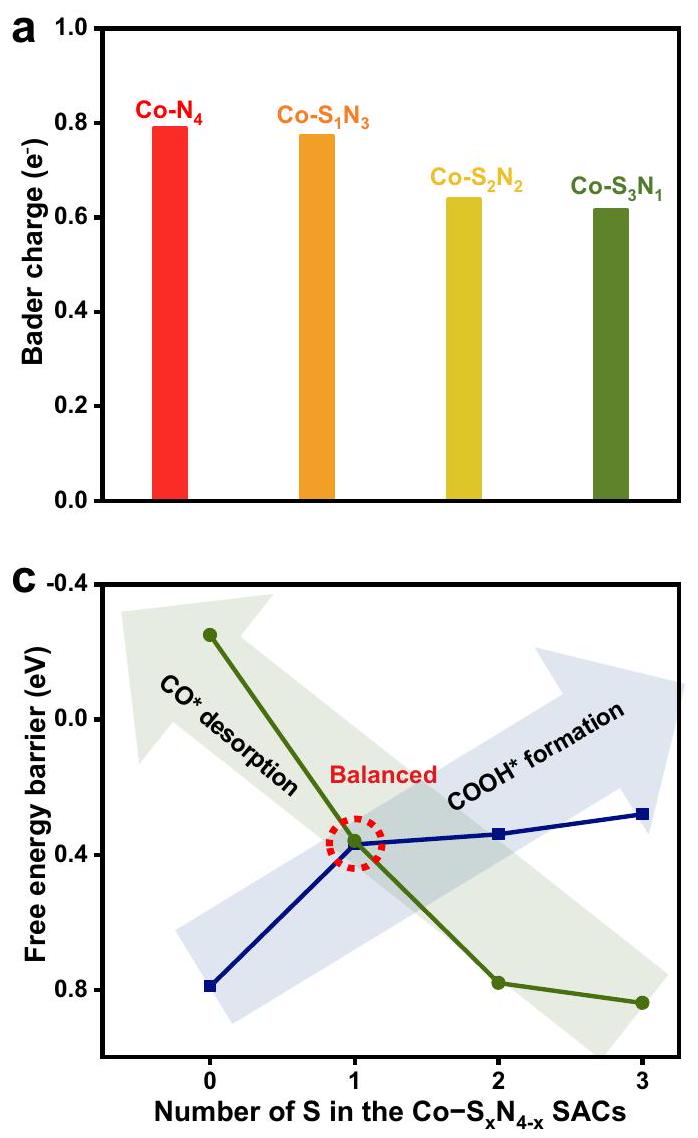

بيئات التنسيق لـ SACs. تم العثور على تأثير الضبط الإلكتروني على

تم تلخيص المعلمات الهيكلية في الجدول التكميلي 4.

معروض في الشكل التكميلية 21. الحد الأقصى

(TOF) مقارنةً بما تم الإبلاغ عنه سابقًا

نوع البركان

التحليل الكهربائي، والحفاظ عليه عند مستوى عالٍ من

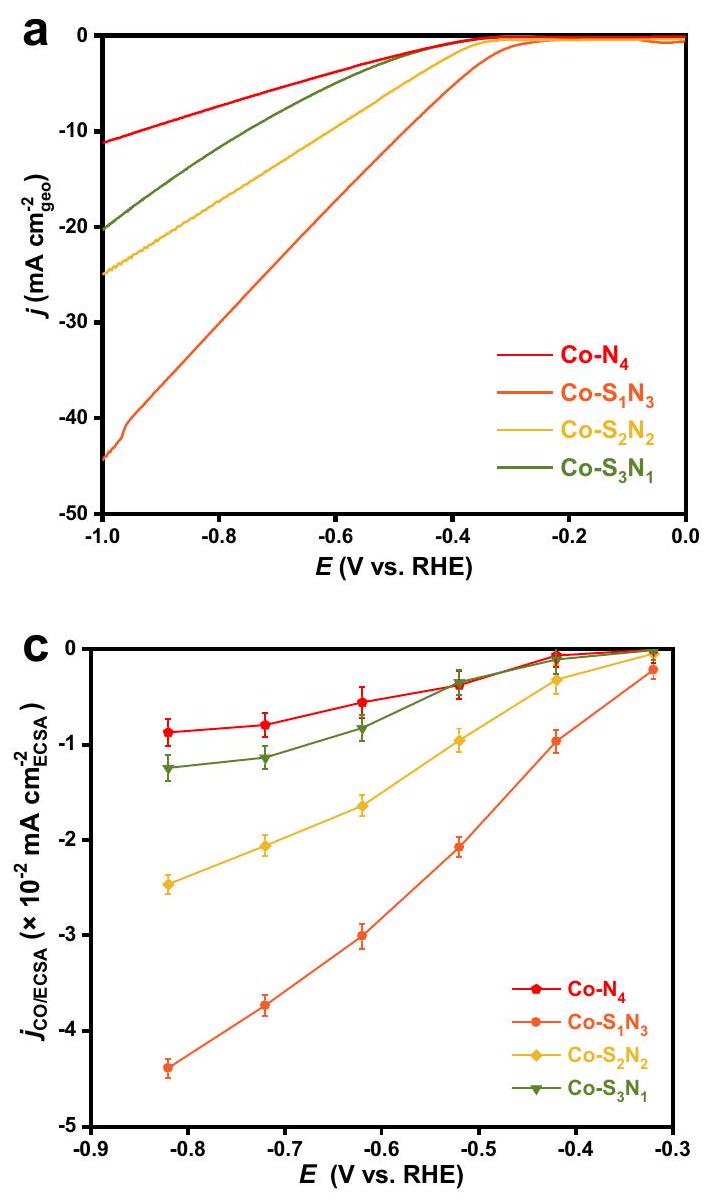

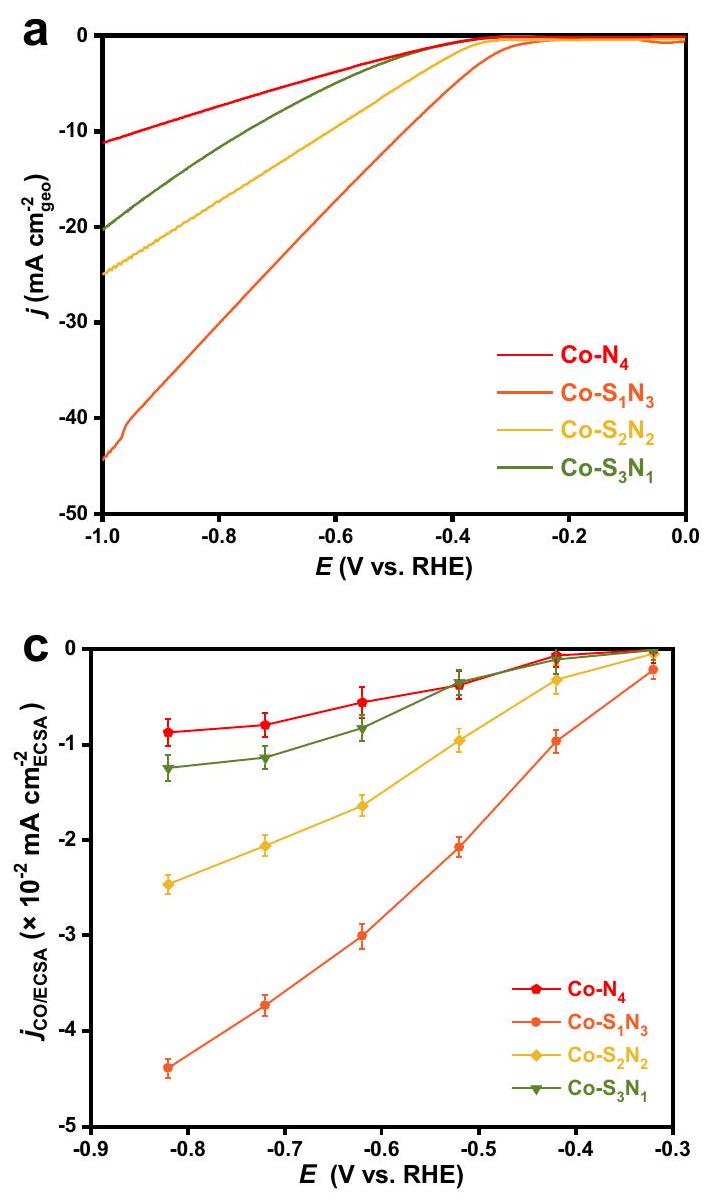

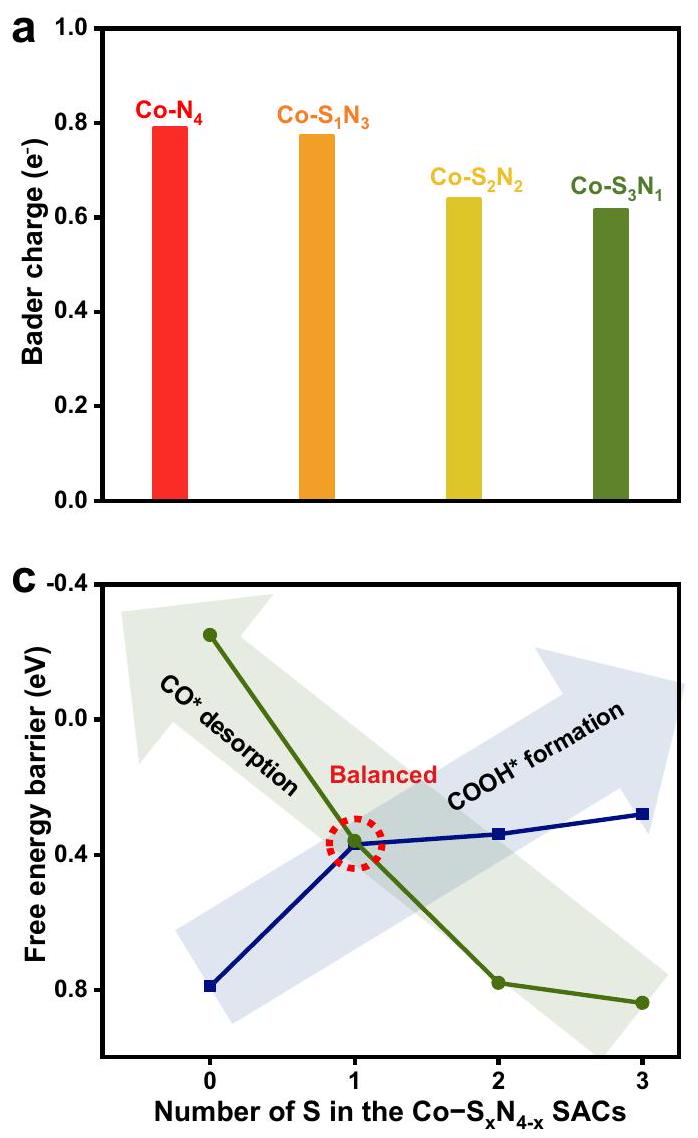

علاقة التنسيق بالأداء

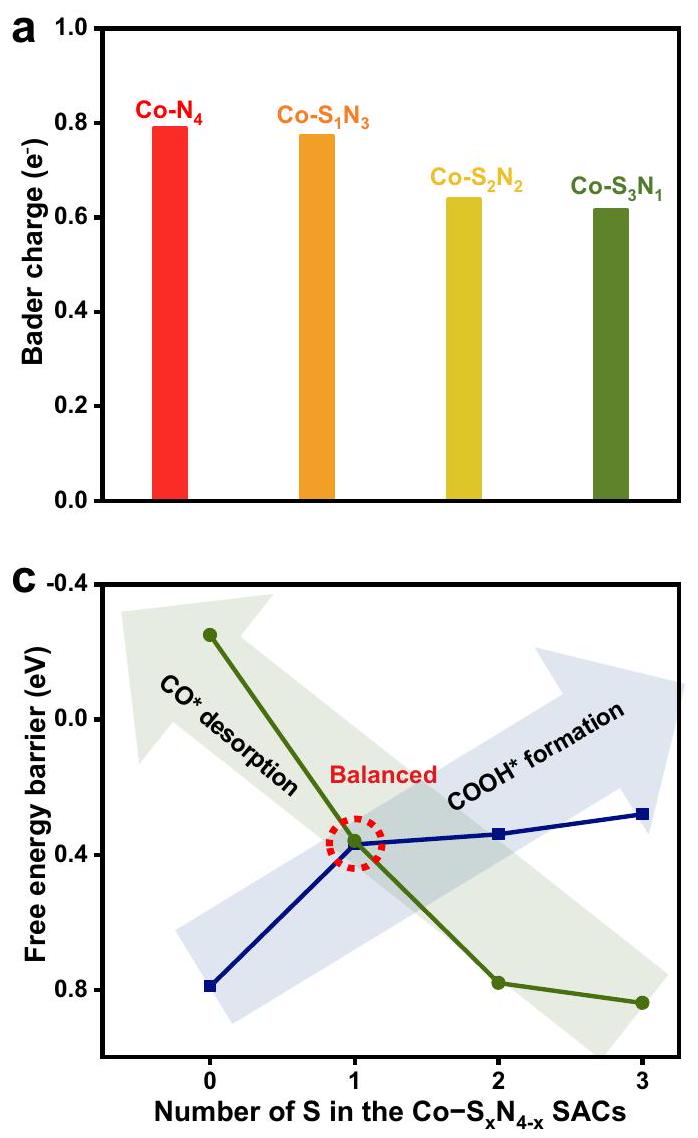

عدم الاتساق. بناءً على الحساب،

طرق

المواد الكيميائية

الخصائص الفيزيائية

قياسات XAFS

القياسات الكهروكيميائية لـ

تفاصيل الحساب

تم حسابه باستخدام نموذج الإلكترود الهيدروجيني الحاسوبي (CHE) كما طورته مجموعة نورسكو

توفر البيانات

References

- Guo, W., Wang, Z., Wang, X. & Wu, Y. General design concept for single-atom catalysts toward heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004287 (2021).

- Fei, H. et al. Single atom electrocatalysts supported on graphene or graphene-like carbons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 5207-5241 (2019).

- Zhang, N. et al. Single-atom site catalysts for environmental catalysis. Nano Res. 13, 3165-3182 (2020).

- Jin, S., Hao, Z., Zhang, K., Yan, Z. & Chen, J. Advances and challenges for the electrochemical reduction of

to CO : from fundamentals to industrialization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20627-20648 (2021). - Gawande, M. B., Fornasiero, P. & Zbořil, R. Carbon-based singleatom catalysts for advanced applications. ACS Catal. 10, 2231-2259 (2020).

- Li, M. et al. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysts for electrochemical

reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001848 (2020). - Han, S. G., Ma, D. D. & Zhu, Q. L. Atomically structural regulations of carbon-based single-atom catalysts for electrochemical

reduction. Small Methods 5, 2100102 (2021). - Zhu, S. et al. Recent advances in catalyst structure and composition engineering strategies for regulating

electrochemical reduction. Adv. Mater. 33, e2005484 (2021). - Wen, C. et al. Highly ethylene-selective electrocatalytic

reduction enabled by isolated Cu@SMotifs in metal-organic framework based precatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202111700 (2022). - Wang, J. et al. Linkage effect in the heterogenization of cobalt complexes by doped graphene for electrocatalytic

reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13532-13539 (2019). - Wang, D. et al. Palladium-catalyzed silacyclization of (hetero)arenes with a tetrasilane reagent through twofold C-H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 7066-7071 (2021).

- Cai, Y. et al. Insights on forming N,O-coordinated Cu single-atom catalysts for electrochemical reduction

to methane. Nat. Commun. 12, 586 (2021). - Feng, J. et al. A

single-atom catalyst embedded in graphitic carbon nitride for efficient electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4341 (2020). - Zheng, T., Jiang, K. & Wang, H. Recent advances in electrochemical

-to-CO conversion on heterogeneous catalysts. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802066 (2018). - Zhao, K. et al. Selective electroreduction of

to acetone by single copper atoms anchored on N-doped porous carbon. Nat. Commun. 11, 2455 (2020). - Tang, C. et al. Coordination tunes selectivity: Two-electron oxygen reduction on high-loading molybdenum single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9171-9176 (2020).

- Ren, Y. et al. Unraveling the coordination structure-performance relationship in

single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 4500 (2019). - Wang, G. et al. Photoinduction of Cu single atoms decorated on UiO-66-

for enhanced photocatalytic reduction of to liquid fuels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19339-19345 (2020). - Zhang, H. et al. Dynamic traction of lattice-confined platinum atoms into mesoporous carbon matrix for hydrogen evolution reaction. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao6657 (2018).

- Zhang, H., Liu, G., Shi, L. & Ye, J. Single-atom catalysts: emerging multifunctional materials in heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701343 (2017).

- Xu, H., Cheng, D., Cao, D. & Zeng, X. C. A universal principle for a rational design of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 1, 339-348 (2018).

- Liu, J. Catalysis by supported single metal atoms. ACS Catal. 7, 34-59 (2016).

- Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 355, 146 (2017).

- Liu, P. & Zheng, N. Coordination chemistry of atomically dispersed catalysts. Natl Sci. Rev. 5, 636-638 (2018).

- Long, X. et al. Graphitic phosphorus coordinated single Fe atoms for hydrogenative transformations. Nat. Commun. 11, 4074 (2020).

- Shen, H. et al. Synergistic effects between atomically dispersed Fe-N-C and C-S-C for the oxygen reduction reaction in acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13800-13804 (2017).

- Haile, A. S., Hansen, H. A., Yohannes, W. & Mekonnen, Y. S. The role of nitrogen and sulfur dual coordination of cobalt in

single atom catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction. Sustain. Energy Fuels 6, 179-187 (2022). - Wang, X. et al. Regulation of coordination number over single Co sites: triggering the efficient electroreduction of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1944-1948 (2018). - Rong, X., Wang, H. J., Lu, X. L., Si, R. & Lu, T. B. Controlled synthesis of a vacancy-defect single-atom catalyst for boosting

electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1961-1965 (2020). - Hou, Y. et al. Atomically dispersed nickel-nitrogen-sulfur species anchored on porous carbon nanosheets for efficient water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1392 (2019).

- Wan, J. et al. In situ phosphatizing of triphenylphosphine encapsulated within metal-organic frameworks to design atomic

interfacial structure for promoting catalytic performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8431-8439 (2020). - Cheng, Q. et al. Carbon-defect-driven electroless deposition of Pt atomic clusters for highly efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5594-5601 (2020).

- Yan, C. et al. Coordinatively unsaturated nickel-nitrogen sites towards selective and high-rate

electroreduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1204-1210 (2018). - Zhang, L. et al. Atomic layer deposited Pt-Ru dual-metal dimers and identifying their active sites for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 10, 4936 (2019).

- Hai, X. et al. Engineering local and global structures of single co atoms for a superior oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 10, 5862-5870 (2020).

- Tong, M. et al. Operando cooperated catalytic mechanism of atomically dispersed

and for promoting oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14005-14012 (2021). - Yang, Q. et al. Understanding the activity of

in atomic metal catalysts for oxygen reduction catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6122-6127 (2020). - Gong, Y. N. et al. Regulating the coordination environment of MOFtemplated single-atom nickel electrocatalysts for boosting

reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2705-2709 (2020). - Hu, L. et al. Metal-triazolate-framework-derived

singleatom catalysts with hierarchical porosity for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 27324-27329 (2021). - Jiao, L. et al. From metal-organic frameworks to single-atom Fe implanted N -doped porous carbons: efficient oxygen reduction in both alkaline and acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8525-8529 (2018).

- Johnson, C . et al. Near stoichiometric

binding on metal centers in Co(salen) nanoparticles. AIChE J. 55, 1040-1045 (2009). - Chen, Y. et al. Isolated single iron atoms anchored on N-Doped porous carbon as an efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6937-6941 (2017).

- Fei, H. et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of

single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 1, 63-72 (2018). - Yang, H. B. et al. Atomically dispersed Ni(i) as the active site for electrochemical

reduction. Nat. Energy 3, 140-147 (2018). - Lin, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic

reduction in water. Science 349, 1208-1213 (2015). - Zhu, M. et al. Covalently grafting cobalt porphyrin onto carbon nanotubes for efficient

electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6595-6599 (2019). - Pan, Y . et al. Design of single-atom

catalytic site: A robust electrocatalyst for reduction with nearly 100% CO selectivity and remarkable stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4218-4221 (2018). - Gu, J., Hsu, C.-S., Bai, L., Chen, H. M. & Hu, X. Atomically dispersed

sites catalyze efficient electroreduction to co. Science 364, 1091-1094 (2019). - Zhao, C. et al. lonic exchange of metal-organic frameworks to access single nickel sites for efficient electroreduction of

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8078-8081 (2017). - Kornienko, N. et al. Metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14129-14135 (2015).

- Morlanés, N., Takanabe, K. & Rodionov, V. Simultaneous reduction of

and splitting of by a single immobilized cobalt phthalocyanine electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 6, 3092-3095 (2016). - Han, N. et al. Supported cobalt polyphthalocyanine for highperformance electrocatalytic

reduction. Chem 3, 652-664 (2017). - Zhang, B. et al. Manganese acting as a high-performance heterogeneous electrocatalyst in carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 2980 (2019).

- Cheng, W., Su, H. & Liu, Q. Tracking the oxygen dynamics of solidliquid electrochemical interfaces by correlative in situ synchrotron spectroscopies. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1949-1959 (2022).

- Yin, P. et al. Single cobalt atoms with precise N-coordination as superior oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10800-10805 (2016).

- Kortlever, R., Shen, J., Schouten, K. J., Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. Catalysts and reaction pathways for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4073-4082 (2015).

- Shi, C., Hansen, H. A., Lausche, A. C. & Norskov, J. K. Trends in electrochemical

reduction activity for open and close-packed metal surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 4720-4727 (2014). - Kim, D. et al. Electrochemical activation of

through atomic ordering transformations of AuCu nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8329-8336 (2017). - Ren, W. et al. Isolated diatomic Ni-Fe metal-nitrogen sites for synergistic electroreduction of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6972-6976 (2019). - Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using

. Nat. Chem. 3, 634-641 (2011). - Zitolo, A. et al. Identification of catalytic sites for oxygen reduction in Iron- and Nitrogen-doped graphene materials. Nat. Mater. 14, 937-942 (2015).

- Briois, V. et al. Spectroscopie d’absorption des rayons X au seuil K : complexes moléculaires du cobalt. J. Chim. Phys. 86, 1623-1634 (1989).

- Liu, Y. et al. Determining the coordination environment and electronic structure of polymer-encapsulated cobalt phthalocyanine under electrocatalytic

reduction conditions using in situ X-Ray absorption spectroscopy. Dalton Trans. 49, 16329-16339 (2020). - Obreja, V. V. N. On the performance of supercapacitors with electrodes based on carbon nanotubes and carbon activated materiala review. Phys. E 40, 2596-2605 (2008).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15-50 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953-17979 (1994).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413-7421 (1999).

- Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886-17892 (2004).

- Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311-1315 (2010).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية المتاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44652-7.

© المؤلفون 2024

المختبر الرئيسي للدراسات العضوية وغير العضوية ومركز الابتكار المتقدم للعلوم والهندسة للمواد اللينة، جامعة بكين للتكنولوجيا الكيميائية، بكين 100029، الصين. مركز الطاقة والتحفيز، كلية علوم المواد والهندسة، معهد بكين للتكنولوجيا، بكين 100081، الصين. كلية الكيمياء وعلوم المواد، جامعة آنهوي العادية، ووهو 241002، الصين. مركز التركيب الضوئي الاصطناعي للوقود الشمسية، كلية العلوم، جامعة ويستلايك، هانغتشو 310024، الصين. مرافق إشعاع السنكروترون في شنغهاي، معهد شنغهاي للفيزياء التطبيقية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، شنغهاي 201204، الصين. مركز التحليل والاختبار، معهد بكين للتكنولوجيا، معهد بكين للتكنولوجيا، بكين 100081، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للطاقة والبيئة الحفازة، جامعة بكين للتكنولوجيا الكيميائية، 100029 بكين، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: جياجينغ بي، هويشان شانغ، جونجي ماو. البريد الإلكتروني:twang@westlake.edu.cn; wxchen@bit.edu.cn; zhuangzb@mail.buct.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44652-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195701

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

A replacement strategy for regulating local environment of single-atom

Accepted: 21 December 2023

Published online: 10 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

The performances of single-atom catalysts are governed by their local coordination environments. Here, a thermal replacement strategy is developed for the synthesis of single-atom catalysts with precisely controlled and adjustable local coordination environments. A series of

Results

The series of SACs was synthesized by the controlled pyrolysis process of the Co-doped ZIF-8 nanoparticles. The previous studies showed that the M-

The detailed local coordination environments of the obtained Co

coordination environments of the SACs. The electronic tuning effect is found on the

structural parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The

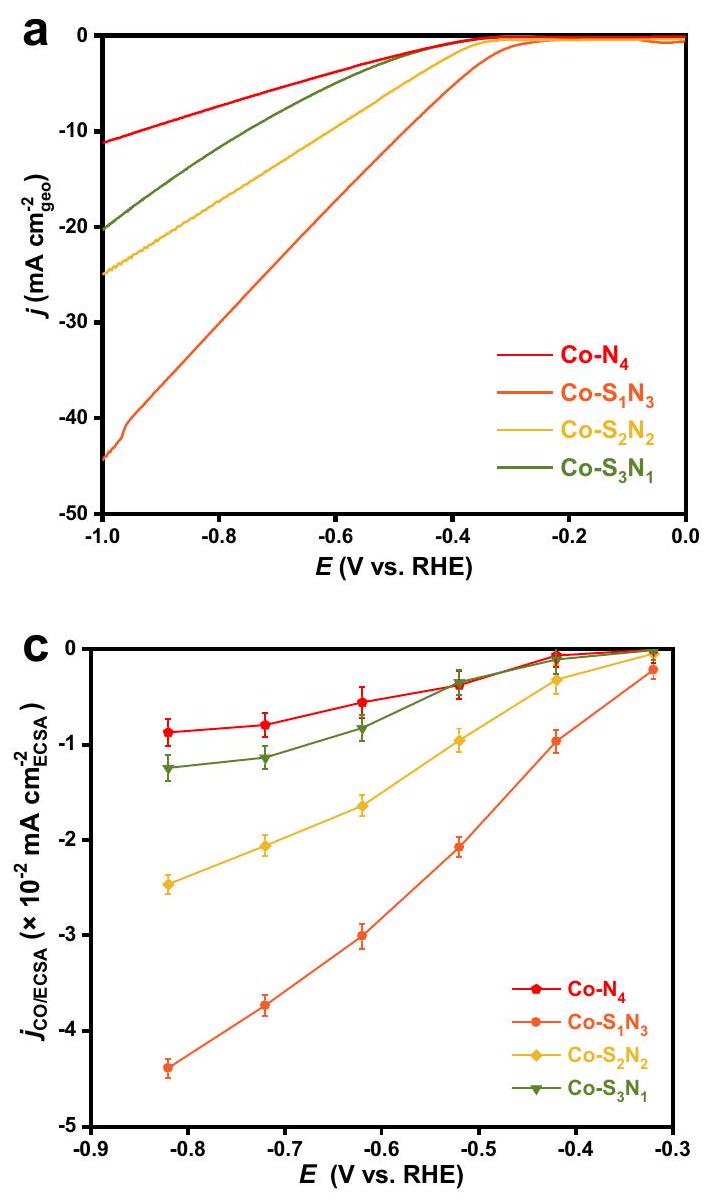

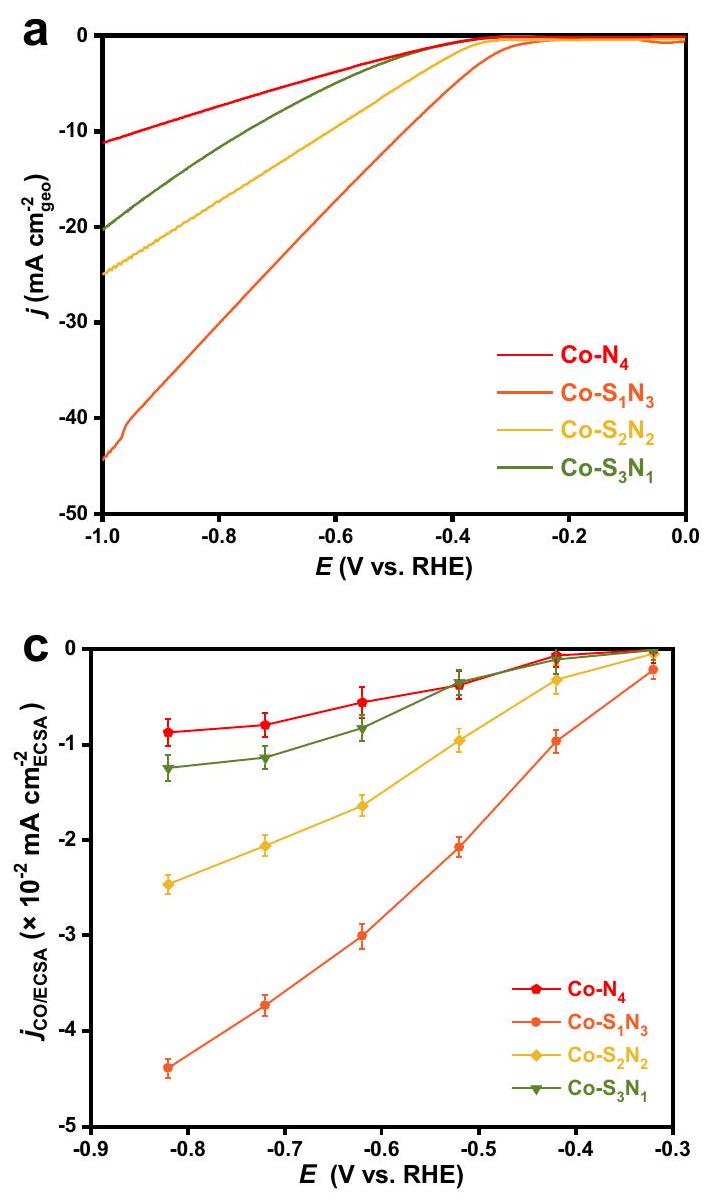

displayed in Supplementary Fig. 21. The maximum

(TOF) compared with the previously reported

volcano-type

of electrolysis, and maintained at a high level of

The coordination-performance relationship

inconsistency. Based on the calculation, the

Methods

Chemicals

Physical characterizations

XAFS measurements

Electrochemical measurements for

Calculation details

calculated with computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model as developed by Norskov group

Data availability

References

- Guo, W., Wang, Z., Wang, X. & Wu, Y. General design concept for single-atom catalysts toward heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004287 (2021).

- Fei, H. et al. Single atom electrocatalysts supported on graphene or graphene-like carbons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 5207-5241 (2019).

- Zhang, N. et al. Single-atom site catalysts for environmental catalysis. Nano Res. 13, 3165-3182 (2020).

- Jin, S., Hao, Z., Zhang, K., Yan, Z. & Chen, J. Advances and challenges for the electrochemical reduction of

to CO : from fundamentals to industrialization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20627-20648 (2021). - Gawande, M. B., Fornasiero, P. & Zbořil, R. Carbon-based singleatom catalysts for advanced applications. ACS Catal. 10, 2231-2259 (2020).

- Li, M. et al. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysts for electrochemical

reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001848 (2020). - Han, S. G., Ma, D. D. & Zhu, Q. L. Atomically structural regulations of carbon-based single-atom catalysts for electrochemical

reduction. Small Methods 5, 2100102 (2021). - Zhu, S. et al. Recent advances in catalyst structure and composition engineering strategies for regulating

electrochemical reduction. Adv. Mater. 33, e2005484 (2021). - Wen, C. et al. Highly ethylene-selective electrocatalytic

reduction enabled by isolated Cu@SMotifs in metal-organic framework based precatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202111700 (2022). - Wang, J. et al. Linkage effect in the heterogenization of cobalt complexes by doped graphene for electrocatalytic

reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13532-13539 (2019). - Wang, D. et al. Palladium-catalyzed silacyclization of (hetero)arenes with a tetrasilane reagent through twofold C-H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 7066-7071 (2021).

- Cai, Y. et al. Insights on forming N,O-coordinated Cu single-atom catalysts for electrochemical reduction

to methane. Nat. Commun. 12, 586 (2021). - Feng, J. et al. A

single-atom catalyst embedded in graphitic carbon nitride for efficient electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4341 (2020). - Zheng, T., Jiang, K. & Wang, H. Recent advances in electrochemical

-to-CO conversion on heterogeneous catalysts. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802066 (2018). - Zhao, K. et al. Selective electroreduction of

to acetone by single copper atoms anchored on N-doped porous carbon. Nat. Commun. 11, 2455 (2020). - Tang, C. et al. Coordination tunes selectivity: Two-electron oxygen reduction on high-loading molybdenum single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9171-9176 (2020).

- Ren, Y. et al. Unraveling the coordination structure-performance relationship in

single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 10, 4500 (2019). - Wang, G. et al. Photoinduction of Cu single atoms decorated on UiO-66-

for enhanced photocatalytic reduction of to liquid fuels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19339-19345 (2020). - Zhang, H. et al. Dynamic traction of lattice-confined platinum atoms into mesoporous carbon matrix for hydrogen evolution reaction. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao6657 (2018).

- Zhang, H., Liu, G., Shi, L. & Ye, J. Single-atom catalysts: emerging multifunctional materials in heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701343 (2017).

- Xu, H., Cheng, D., Cao, D. & Zeng, X. C. A universal principle for a rational design of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 1, 339-348 (2018).

- Liu, J. Catalysis by supported single metal atoms. ACS Catal. 7, 34-59 (2016).

- Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 355, 146 (2017).

- Liu, P. & Zheng, N. Coordination chemistry of atomically dispersed catalysts. Natl Sci. Rev. 5, 636-638 (2018).

- Long, X. et al. Graphitic phosphorus coordinated single Fe atoms for hydrogenative transformations. Nat. Commun. 11, 4074 (2020).

- Shen, H. et al. Synergistic effects between atomically dispersed Fe-N-C and C-S-C for the oxygen reduction reaction in acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13800-13804 (2017).

- Haile, A. S., Hansen, H. A., Yohannes, W. & Mekonnen, Y. S. The role of nitrogen and sulfur dual coordination of cobalt in

single atom catalysts in the oxygen reduction reaction. Sustain. Energy Fuels 6, 179-187 (2022). - Wang, X. et al. Regulation of coordination number over single Co sites: triggering the efficient electroreduction of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1944-1948 (2018). - Rong, X., Wang, H. J., Lu, X. L., Si, R. & Lu, T. B. Controlled synthesis of a vacancy-defect single-atom catalyst for boosting

electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1961-1965 (2020). - Hou, Y. et al. Atomically dispersed nickel-nitrogen-sulfur species anchored on porous carbon nanosheets for efficient water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1392 (2019).

- Wan, J. et al. In situ phosphatizing of triphenylphosphine encapsulated within metal-organic frameworks to design atomic

interfacial structure for promoting catalytic performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8431-8439 (2020). - Cheng, Q. et al. Carbon-defect-driven electroless deposition of Pt atomic clusters for highly efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5594-5601 (2020).

- Yan, C. et al. Coordinatively unsaturated nickel-nitrogen sites towards selective and high-rate

electroreduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1204-1210 (2018). - Zhang, L. et al. Atomic layer deposited Pt-Ru dual-metal dimers and identifying their active sites for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 10, 4936 (2019).

- Hai, X. et al. Engineering local and global structures of single co atoms for a superior oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 10, 5862-5870 (2020).

- Tong, M. et al. Operando cooperated catalytic mechanism of atomically dispersed

and for promoting oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14005-14012 (2021). - Yang, Q. et al. Understanding the activity of

in atomic metal catalysts for oxygen reduction catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6122-6127 (2020). - Gong, Y. N. et al. Regulating the coordination environment of MOFtemplated single-atom nickel electrocatalysts for boosting

reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2705-2709 (2020). - Hu, L. et al. Metal-triazolate-framework-derived

singleatom catalysts with hierarchical porosity for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 27324-27329 (2021). - Jiao, L. et al. From metal-organic frameworks to single-atom Fe implanted N -doped porous carbons: efficient oxygen reduction in both alkaline and acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8525-8529 (2018).

- Johnson, C . et al. Near stoichiometric

binding on metal centers in Co(salen) nanoparticles. AIChE J. 55, 1040-1045 (2009). - Chen, Y. et al. Isolated single iron atoms anchored on N-Doped porous carbon as an efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6937-6941 (2017).

- Fei, H. et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of

single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 1, 63-72 (2018). - Yang, H. B. et al. Atomically dispersed Ni(i) as the active site for electrochemical

reduction. Nat. Energy 3, 140-147 (2018). - Lin, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic

reduction in water. Science 349, 1208-1213 (2015). - Zhu, M. et al. Covalently grafting cobalt porphyrin onto carbon nanotubes for efficient

electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6595-6599 (2019). - Pan, Y . et al. Design of single-atom

catalytic site: A robust electrocatalyst for reduction with nearly 100% CO selectivity and remarkable stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4218-4221 (2018). - Gu, J., Hsu, C.-S., Bai, L., Chen, H. M. & Hu, X. Atomically dispersed

sites catalyze efficient electroreduction to co. Science 364, 1091-1094 (2019). - Zhao, C. et al. lonic exchange of metal-organic frameworks to access single nickel sites for efficient electroreduction of

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8078-8081 (2017). - Kornienko, N. et al. Metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14129-14135 (2015).

- Morlanés, N., Takanabe, K. & Rodionov, V. Simultaneous reduction of

and splitting of by a single immobilized cobalt phthalocyanine electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 6, 3092-3095 (2016). - Han, N. et al. Supported cobalt polyphthalocyanine for highperformance electrocatalytic

reduction. Chem 3, 652-664 (2017). - Zhang, B. et al. Manganese acting as a high-performance heterogeneous electrocatalyst in carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 10, 2980 (2019).

- Cheng, W., Su, H. & Liu, Q. Tracking the oxygen dynamics of solidliquid electrochemical interfaces by correlative in situ synchrotron spectroscopies. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1949-1959 (2022).

- Yin, P. et al. Single cobalt atoms with precise N-coordination as superior oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 10800-10805 (2016).

- Kortlever, R., Shen, J., Schouten, K. J., Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. Catalysts and reaction pathways for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4073-4082 (2015).

- Shi, C., Hansen, H. A., Lausche, A. C. & Norskov, J. K. Trends in electrochemical

reduction activity for open and close-packed metal surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 4720-4727 (2014). - Kim, D. et al. Electrochemical activation of

through atomic ordering transformations of AuCu nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8329-8336 (2017). - Ren, W. et al. Isolated diatomic Ni-Fe metal-nitrogen sites for synergistic electroreduction of

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6972-6976 (2019). - Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using

. Nat. Chem. 3, 634-641 (2011). - Zitolo, A. et al. Identification of catalytic sites for oxygen reduction in Iron- and Nitrogen-doped graphene materials. Nat. Mater. 14, 937-942 (2015).

- Briois, V. et al. Spectroscopie d’absorption des rayons X au seuil K : complexes moléculaires du cobalt. J. Chim. Phys. 86, 1623-1634 (1989).

- Liu, Y. et al. Determining the coordination environment and electronic structure of polymer-encapsulated cobalt phthalocyanine under electrocatalytic

reduction conditions using in situ X-Ray absorption spectroscopy. Dalton Trans. 49, 16329-16339 (2020). - Obreja, V. V. N. On the performance of supercapacitors with electrodes based on carbon nanotubes and carbon activated materiala review. Phys. E 40, 2596-2605 (2008).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15-50 (1996).

- Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169-11186 (1996).

- Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953-17979 (1994).

- Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758-1775 (1999).

- Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413-7421 (1999).

- Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886-17892 (2004).

- Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311-1315 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44652-7.

© The Author(s) 2024

State Key Lab of Organic-Inorganic Composites and Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Soft Matter Science and Engineering, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing 100029, China. Energy & Catalysis Center, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China. College of Chemistry and Materials Science, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu 241002, China. Center of Artificial Photosynthesis for Solar Fuels, School of Science, Westlake University, Hangzhou 310024, China. Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facilities, Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai 201204, China. Analysis and Testing Center, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China. Beijing Key Laboratory of Energy Environmental Catalysis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, 100029 Beijing, China. These authors contributed equally: Jiajing Pei, Huishan Shang, Junjie Mao. e-mail: twang@westlake.edu.cn; wxchen@bit.edu.cn; zhuangzb@mail.buct.edu.cn