DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03274-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38355513

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-14

استكشاف العلاقة المحتملة بين ناهضات مستقبلات GLP-1 والسلوكيات الانتحارية أو الذاتية الجرح: دراسة مراقبة دوائية مستندة إلى قاعدة بيانات نظام الإبلاغ عن الأحداث الضارة التابع لإدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية

الملخص

الخلفية إن تحديد ما إذا كان هناك علاقة محتملة بين ناهضات مستقبلات الببتيد الشبيه بالجلوكاجون 1 (GLP-1RAs) والسلوكيات الانتحارية أو السلوكيات الذاتية الجرح (SSIBs) أمر بالغ الأهمية لسلامة الجمهور. وقد بحثت هذه الدراسة في العلاقة المحتملة بين GLP-1RAs وSSIBs من خلال استكشاف قاعدة بيانات نظام الإبلاغ عن الأحداث الضارة التابع لإدارة الغذاء والدواء (FAERS).

الطرق تم إجراء تحليل عدم التناسب باستخدام بيانات ما بعد التسويق من مستودع FAERS (الربع الأول من 2018 إلى الربع الرابع من 2022). تم تحديد حالات SSIB المرتبطة بمثبطات GLP-1RAs وتحليلها من خلال تحليل عدم التناسب باستخدام مكون المعلومات. تم استخدام التوزيع المعلمي مع اختبار ملاءمة لت分析 وقت بدء الأعراض، و

النتائج: تم تحديد 204 حالة من حالات السلوكيات الانتحارية المرتبطة بمستقبلات GLP-1RA، بما في ذلك السيماغلوتيد، والليراجلوتيد، والدولاجلوتيد، والإكسيناتيد، والألبiglوتيد، في قاعدة بيانات FAERS. أظهر تحليل وقت الظهور عدم وجود آلية متسقة لفترة تأخر السلوكيات الانتحارية في المرضى الذين يتلقون GLP-1RAs. لم يشير تحليل عدم التناسب إلى وجود ارتباط بين GLP-1RAs والسلوكيات الانتحارية. كشف تحليل الأدوية المشتركة عن 81 حالة مع مضادات الاكتئاب، ومضادات الذهان، والبنزوديازيبينات، والتي قد تكون مؤشرات على الاضطرابات النفسية المصاحبة. الاستنتاجات: لم نجد أي إشارة إلى تقارير غير متناسبة عن ارتباط استخدام GLP-1RA والسلوكيات الانتحارية. يحتاج الأطباء إلى الحفاظ على يقظة متزايدة تجاه المرضى الذين تم علاجهم مسبقًا بأدوية نفسية عصبية. وهذا يساهم في قبول أكبر لمستقبلات GLP-1RA في المرضى الذين يعانون من داء السكري من النوع الثاني أو السمنة.

أهم النقاط

- لتحديد ما إذا كان هناك علاقة محتملة بين ناهضات مستقبلات الببتيد الشبيه بالجلوكاجون 1 (GLP1RAs) والسلوكيات الانتحارية أو السلوكيات الذاتية الجرح (SSIBs).

- هل هناك ارتباط مباشر بين GLP-1RAs و SSIBs؟ لا توجد أدلة تشير بشكل معقول إلى وجود ارتباط بين GLP-1RAs و SSIBs بناءً على الخصائص السريرية، ومدة البداية، وعدم التناسب، وتحليل الأدوية المساعدة.

- يجب على الأطباء إيلاء المزيد من الاهتمام للحالة النفسية للمرضى الذين لديهم تاريخ من استخدام الأدوية النفسية العصبية، ويحتاج الأمر إلى مراقبة أكثر شمولاً للنظر بعناية في قابليتهم للإصابة بالآثار الجانبية النفسية.

الكلمات الرئيسية: GLP-1RAs، السلوكيات الانتحارية أو الذاتية الجرح، اليقظة الدوائية، قاعدة بيانات FAERS، داء السكري من النوع 2، السمنة

الملخص الرسومي

جيانشينغ زو، يو زينغ، باوهوا شيو، سونغجون لونغ، لي-إي زو، يونهوي ليو، تشينغليانغ لي، ييفان زانغ، ماوباي ليو، شيويمي وو*

تحليل وقت بدء الأعراض

جيانشينغ زو، يو زينغ، باوهوا شيو، سونغجون لونغ، لي-إي زو، يونهوي ليو، تشينغليانغ لي، ييفان زانغ، ماوباي ليو، شيويمي وو*

التحليل الوصفي

جيانشينغ زو، يو زينغ، باوهوا شيو، سونغجون لونغ، لي-إي زو، يونهوي ليو، تشينغليانغ لي، ييفان زانغ، ماوباي ليو، شيوماي وو*

تحليلات التزامن الدوائي

جيانشينغ زو، يو زينغ، باوهوا شيو، سونغجون لونغ، لي-إي زو، يونهوي ليو، تشينغليانغ لي، ييفان زانغ، ماوباي ليو، شيويمي وو*

على مستوى العالم، لم يتم الوفاء بمعايير برادفورد هيل

الخلفية

مرض الكلى المزمن) [5]. علاوة على ذلك، تظهر أدوية GLP-1RAs تأثيرات كبيرة في تقليل الوزن من خلال تسهيل امتصاص الجلوكوز وكبح الشهية [6]. وفقًا لمراكز السيطرة على الأمراض والوقاية منها، يحتل مرض السكري والسمنة المرتبتين بين أعلى 10 أمراض مزمنة من حيث العبء الاقتصادي في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. نظرًا للازدياد المتسارع في انتشار هذه الأمراض على مستوى العالم، هناك فرصة غير مسبوقة لتوسيع السوق العالمية لأدوية GLP-1RAs.

الموضوع والأنالوجات الجديدة يتم تقديمها باستمرار إلى السوق. في ديسمبر 2014، وافقت إدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية على الليراجلوتيد كدواء لفقدان الوزن. بعد ذلك مباشرة، أصبح السيماغلوتيد متاحًا مع دلالة مرض السكري في عام 2017، ثم في عام 2020، تم أيضًا الترخيص لعلاجه للسمنة. الطلب العالمي على السيماغلوتيد والليراجلوتيد يتجاوز العرض الحالي، والذي قد يكون مرتبطًا باستخداماتهما غير المصرح بها وسوء الاستخدام. على الرغم من الإمكانات الكبيرة والمزايا لمثبطات GLP-1RAs، إلا أنها مصحوبة حتمًا بمجموعة من ردود الفعل السلبية المحتملة (ADRs)، كما هو الحال مع أي دواء. تشمل أكثر ردود الفعل السلبية شيوعًا المرتبطة بعلاج GLP1RA أحداثًا معوية مثل الغثيان والقيء والإسهال. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه الردود غير الخطيرة مقبولة لدى الأفراد المصابين بالسكري والسمنة. ما يثير القلق هو بعض التقارير الأخيرة عن ردود الفعل السلبية الخطيرة المرتبطة بمثبطات GLP1RAs: (i) إفصاح شركة فايزر عن ارتفاع إنزيمات الكبد في مستخدمي اللوتيغليبرون (وهو مثبط GLP-1RA جديد عن طريق الفم) يدل على إصابة خلايا الكبد؛ (ii) كشفت الدراسات عن ارتفاع خطر الإصابة بسرطان الغدة الدرقية المرتبط والتهاب المرارة مع استخدام مثبطات GLP-1RAs؛ (iii) قدمت وكالة الأدوية الأيسلندية 150 تقريرًا عن سلوكيات انتحارية أو ذاتية الإصابة مرتبطة بمثبطات GLP-1RAs إلى وكالة الأدوية الأوروبية. بعد الحوادث المذكورة، تم إيقاف تطوير اللوتيغليبرون، وصنفت وكالات تنظيم الأدوية في عدة دول مثبطات GLP-1RAs كعامل خطر محتمل لسرطان الغدة الدرقية وأمراض المرارة والقنوات الصفراوية. ومع ذلك، لم تقم أي دراسات بالتحقيق في العلاقة بين مثبطات GLP-1RAs وسلوكيات الانتحار أو الإصابة الذاتية. تعتبر سلوكيات الانتحار أو الإصابة الذاتية، المعترف بها كردود فعل سلبية هامة، قد حظيت باعتراف واسع كعوامل حاسمة قد تعرض سلامة المرضى للخطر. أظهرت الدراسات تصاعدًا مستمرًا عامًا بعد عام في حالات انتحار المرضى المرتبطة باستخدام الأدوية، مما زاد من القلق بين الجمهور العام والمهنيين السريريين بشأن هذه الظاهرة. لذلك، في سياق الاستخدام العالمي الواسع لمثبطات GLP-1RAs، من الضروري التحقيق فيما إذا كانت هناك علاقة محتملة بين مثبطات GLP-1RAs وسلوكيات الانتحار أو الإصابة الذاتية، وهو أمر ذو أهمية قصوى لسلامة الأدوية العامة والسريرية.

طرق

مصادر البيانات وتصميم الدراسة

تعريف الحالات والأدوية ذات الاهتمام

أو إمكانية الانتحار في المواصفات أو الدراسات ذات الصلة. شملت الدراسة الحالية جميع الحالات التي تم فيها إعطاء GLP1RAs وتم إدراجها كأدوية مشتبه بها رئيسية، أدوية مشتبه بها ثانوية، أو أدوية مصاحبة لـ SSIBs.

التحليل الوصفي

تحليل الوقت المبلغ عنه لبدء الأعراض

تحليل عدم التناسب

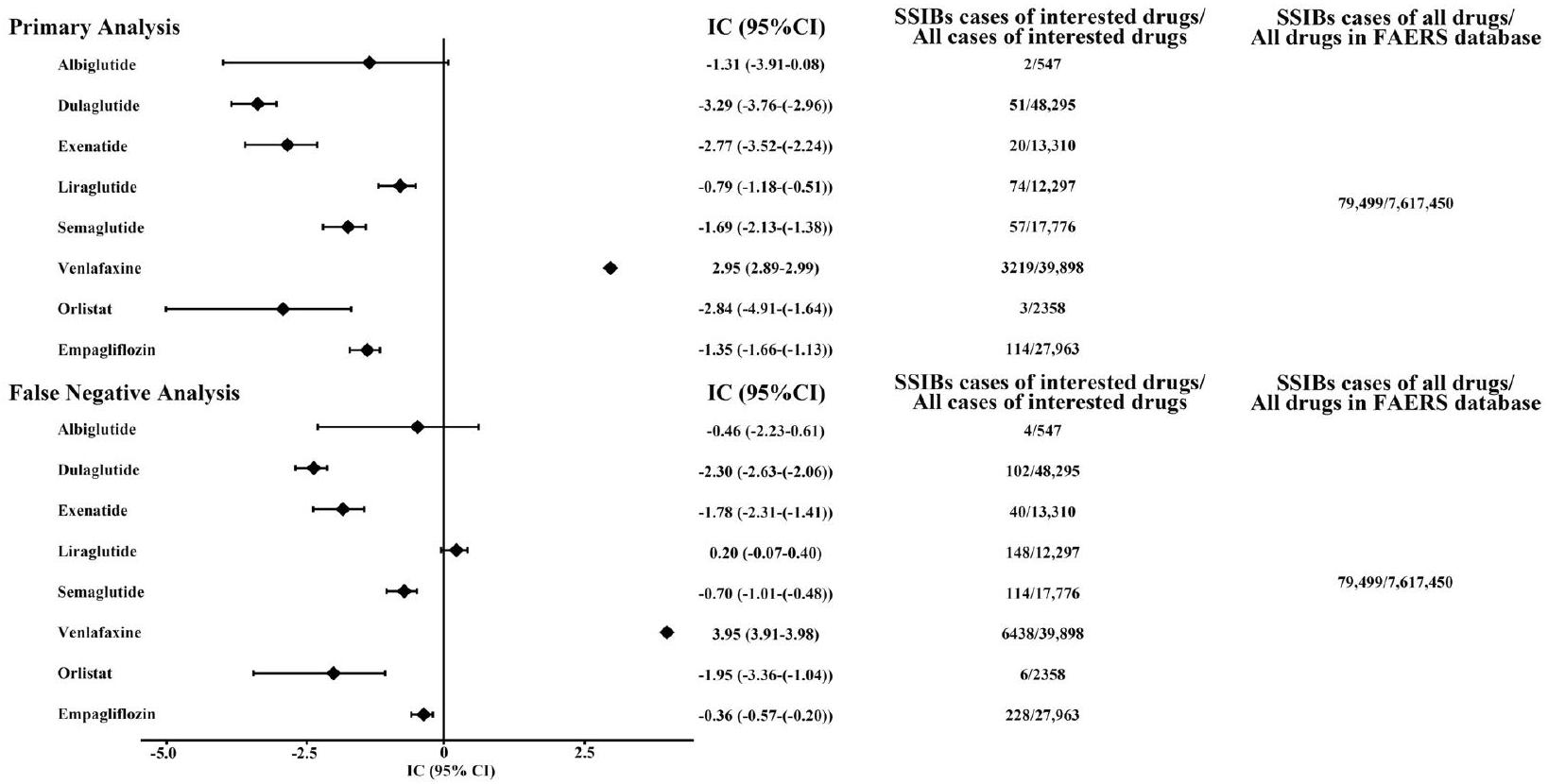

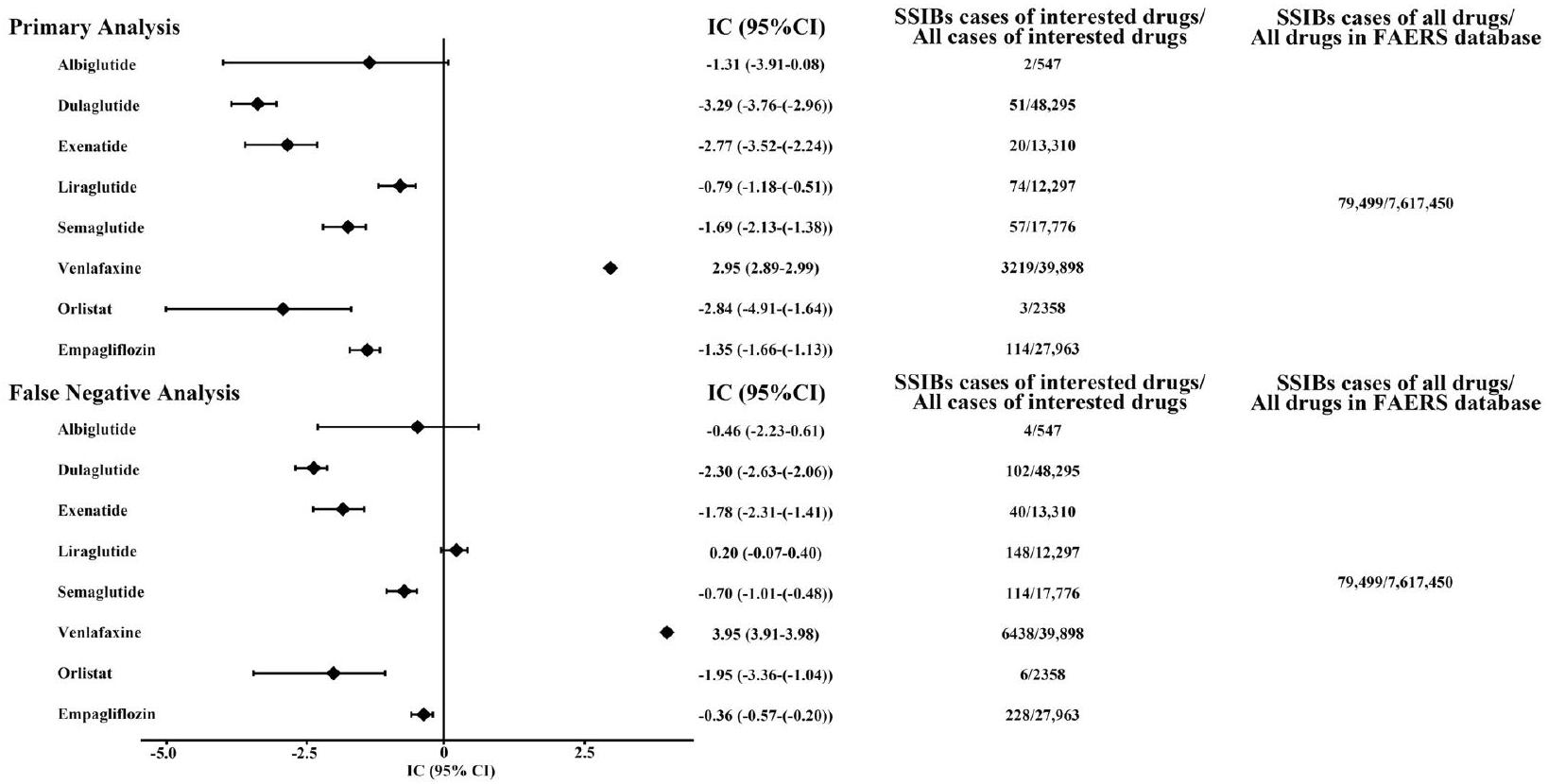

(1) نهج استكشافي غير متناسب يقارن بين GLP-1RAs وجميع الأدوية الأخرى المبلغ عنها في قاعدة بيانات FAERS، باستخدام فينلافاكسين كعنصر تحكم إيجابي وإمباغليفلوزين/أورليستات كعنصر تحكم سلبي. يمكن العثور على تعريف نهج عدم التناسب في الملف الإضافي 1: القسم 4 [29].

(2) استخدمنا مكون المعلومات البايزية (IC) لحساب الحد الأدنى من

(3) تم إجراء تحليل للنتائج السلبية الكاذبة من خلال زيادة معدل حدوث GLP-1RA المبلغ عنه بشكل مصطنع.

SSIBs المرتبطة بـ

(4) نظرًا للاختلافات الجوهرية والانحياز المحتمل في التقارير في قاعدة بيانات FAERS، قمنا بإجراء سلسلة من تحليلات الحساسية. أولاً، استبعدنا تقارير الحالات وغير الحالات التي تتعلق بالأحداث المعوية (جميع PTs تنتمي إلى اضطرابات الجهاز الهضمي في فئة الأعضاء النظامية) من مجموعة البيانات. كانت هذه الخطوة تهدف إلى تقليل تأثير التعتيم الناتج عن الأحداث المعوية لتجنب الانحياز التنافسي المحتمل. علاوة على ذلك، كانت المؤشرات الرئيسية في الحالات المشمولة هي داء السكري من النوع 2 والسمنة، وهما من عوامل الخطر المحتملة لـ SSIBs. لذلك، قمنا بتضييق مجموعة بيانات التحليل لتشمل الأفراد الذين يعانون من داء السكري من النوع 2 أو فقدان الوزن من خلال حقل indi_pt (الذي يمثل المؤشر). أظهرت الدراسات السابقة أن تقييد السكان الذين تم تحليلهم يمكن أن يخفف من انحياز المؤشر [21]. IC

(5) إن اعتبار عدد منخفض من الحالات المتوقعة قد يؤدي إلى حساسية غير كافية لاكتشاف عدم التناسب بالقوة ذات الصلة [31]، قمنا بالإبلاغ عن حساسية عينة تمثيلية

تحليل التداخل الدوائي

تقييم عالمي للأدلة

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

التحليل الوصفي

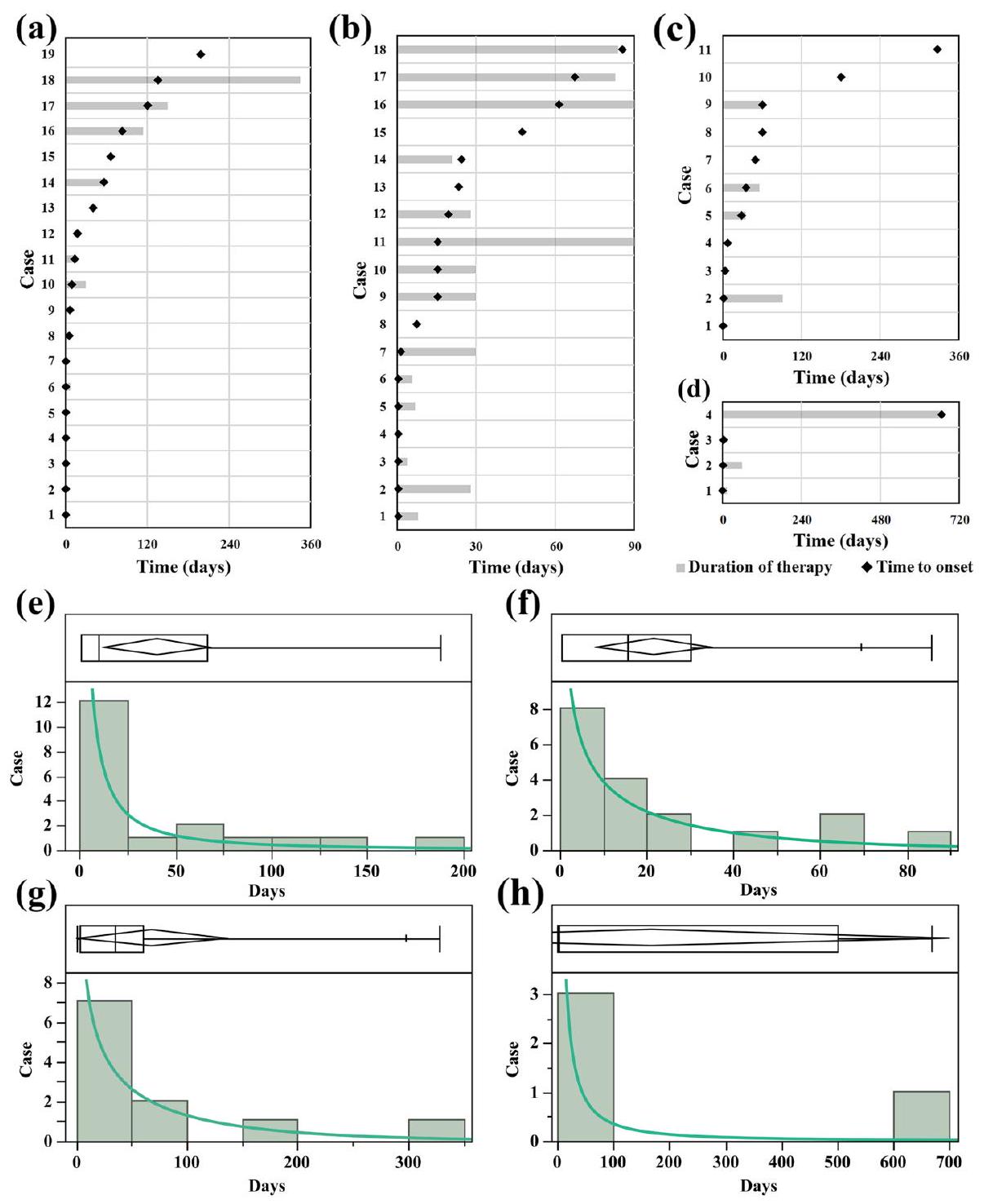

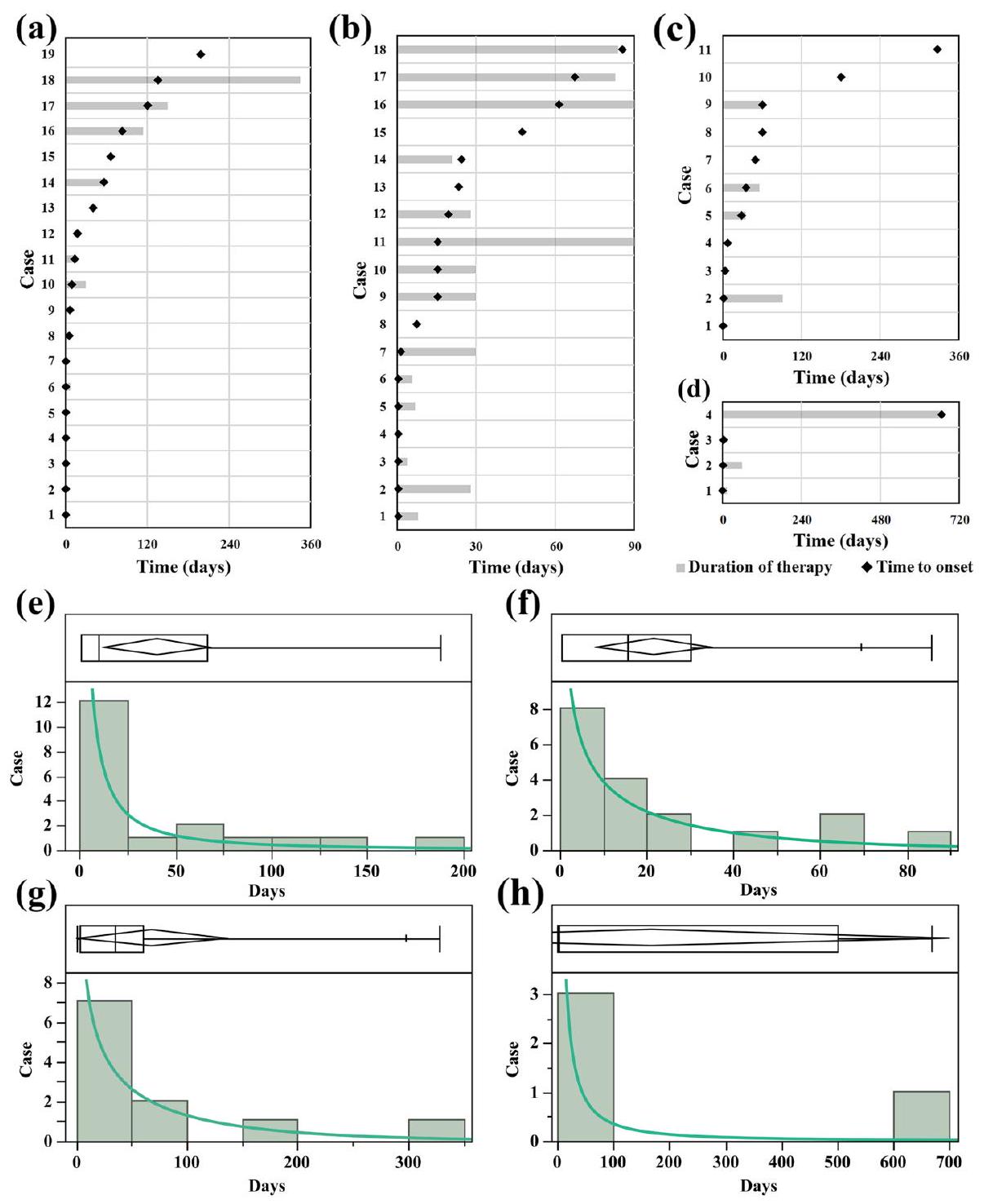

تحليل الوقت المبلغ عنه لبدء الأعراض

liraglutide وحالتين لـ semaglutide، والتي قد تكون مرتبطة بتأخر ردود الفعل الضارة الناتجة عن الأدوية المعنية.

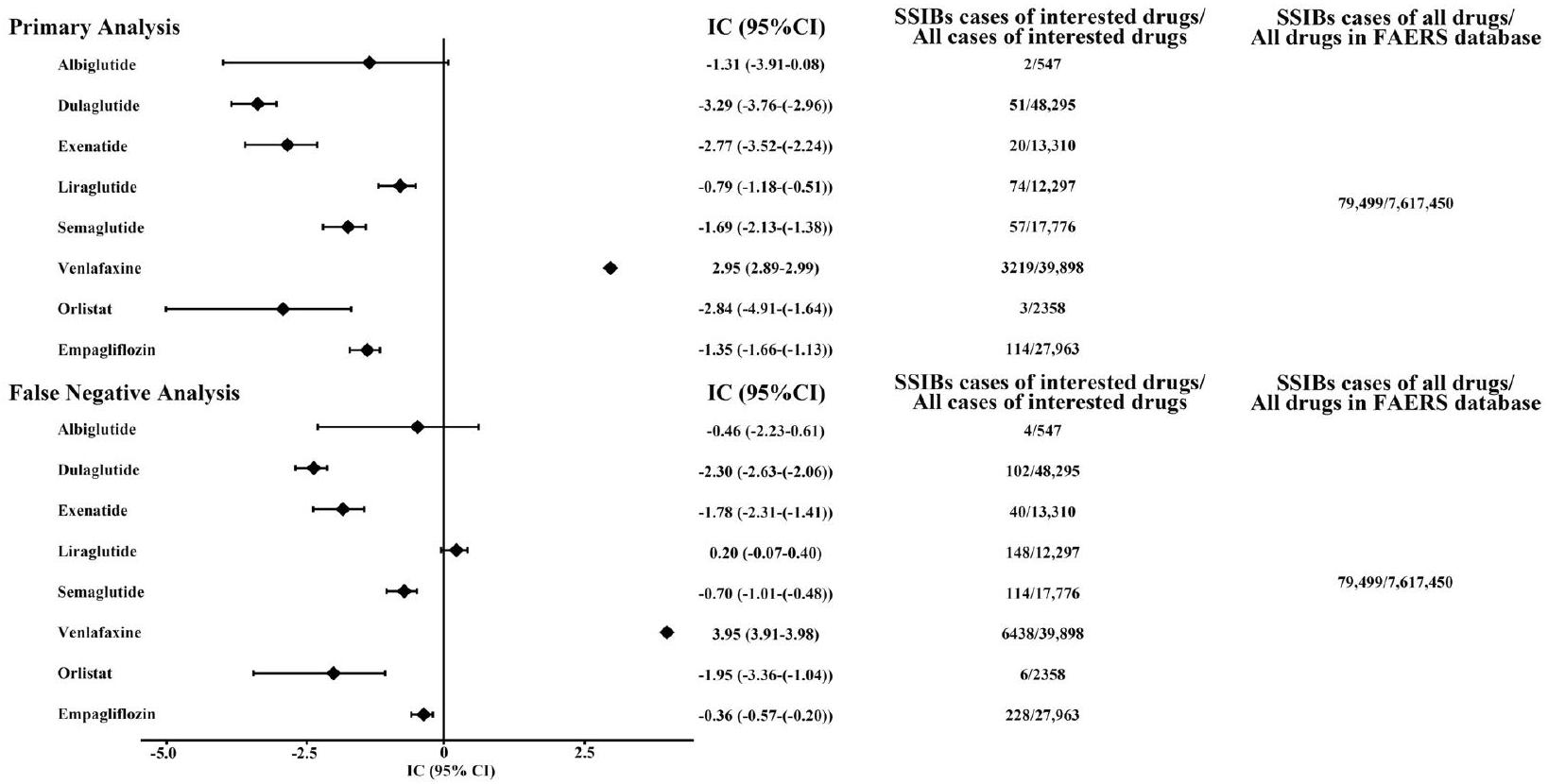

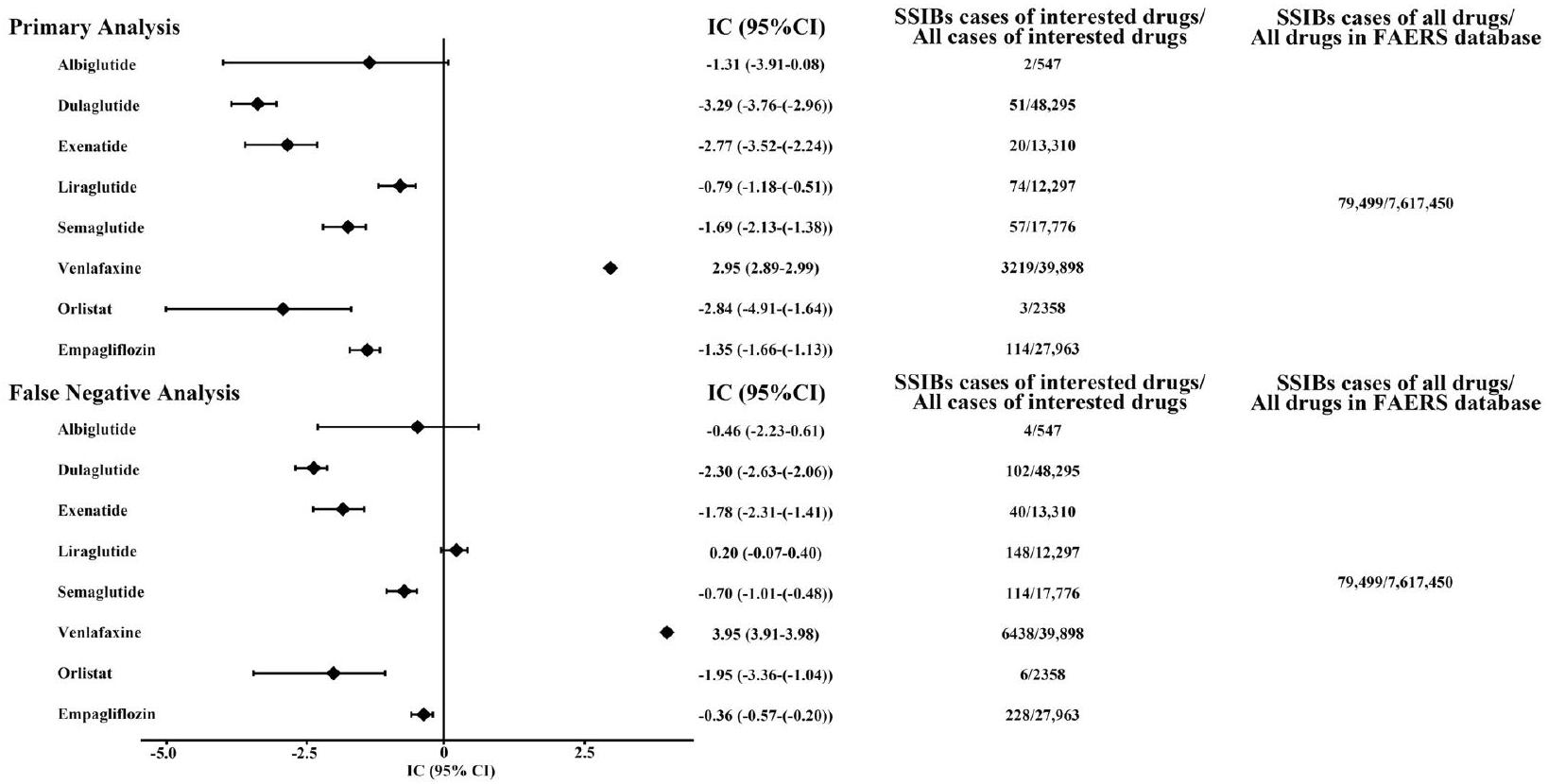

تحليل عدم التناسب

تحليل التداخل الدوائي

| فئات | سيماجلوتيد

|

ليراجلوتيد

|

دولاجلوتيد

|

إكسيناتيد

|

ألبجليتيد

|

الإجمالي

|

| تقارير SSIBs | ٥٧ | 74 | 51 | 20 | 2 | 204 |

| سنة التقرير | ||||||

| 2018 | 2 (3.51) | 16 (21.62) | 12 (23.53) | 4 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | ٣٥ (١٧.١٦) |

| 2019 | 4 (7.02) | 11 (14.86) | 7 (13.73) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | ٢٩ (١٤.٢٢) |

| ٢٠٢٠ | 8 (14.04) | 19 (25.68) | 10 (19.61) | 4 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | 42 (20.59) |

| 2021 | 16 (28.07) | 12 (16.22) | 8 (15.69) | 2 (10.00) | 0 | ٣٨ (١٨.٦٣) |

| 2022 | ٢٧ (٤٧.٣٧) | 16 (21.62) | 14 (27.45) | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 60 (29.41) |

| مراسل

|

||||||

| محترف الرعاية الصحية | 30 (52.63) | 53 (71.62) | 19 (37.25) | 9 (45.00) | 1 (50.00) | ١١٢ (٥٤.٩٠) |

| غير متخصص في الرعاية الصحية | ٢٦ (٤٥.٦١) | 21 (28.38) | 31 (60.78) | 6 (30.00) | 1 (50.00) | 85 (41.67) |

| غير معروف أو مفقود | 1 (1.75) | 0 | 1 (1.96) | 5 (25.00) | 0 | 7 (3.43) |

| جنس | ||||||

| ذكر | 18 (31.58) | 20 (27.03) | 19 (37.25) | 9 (45.00) | 1 (50.00) | 67 (32.84) |

| أنثى | ٣٨ (٦٦.٦٧) | 52 (70.27) | ٢٩ (٥٦.٨٦) | 11 (55.00) | 1 (50.00) | 131 (64.22) |

| غير معروف أو مفقود | 1 (1.75) | 2 (2.70) | 3 (5.88) | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.94) |

| فئة العمر، سنوات | ||||||

| قاصر (< 18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 3 (1.47) |

| بالغ (18-65) | ٢٨ (٤٩.١٢) | ٤٣ (٥٨.١١) | ٢٤ (٤٧.٠٦) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | ١٠٢ (٥٠.٠٠) |

| كبار السن (>65) | 1 (1.75) | 7 (9.46) | 10 (19.61) | 2 (10.00) | 0 | 20 (9.80) |

| غير معروف أو مفقود | ٢٨ (٤٩.١٢) | ٢٤ (٣٢.٤٣) | 17 (33.33) | 8 (40.00) | 2 (100.00) | 79 (38.73) |

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | ٤٣ (٣٥-٥٢) | ٤٧ (٣٦-٥٧) | ٥٥ (٤٦-٦٧) | 40 (25-54) | / | / |

| إشارة | ||||||

| داء السكري من النوع الثاني | 13 (22.81) | 14 (18.92) | 30 (58.82) | 13 (65.00) | 1 (50.00) | 71 (34.80) |

| فقدان الوزن | 15 (26.32) | 15 (20.27) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 (14.71) |

| الآخرون | 1 (1.75) | ٤ (٥.٤١) | 0 | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 8 (3.92) |

| غير معروف أو مفقود | ٢٨ (٤٩.١٢) | 41 (55.41) | 21 (41.18) | ٤ (٢٠.٠٠) | 1 (50.00) | 95 (46.57) |

| النتائج

|

||||||

| الموت | 1 (1.75) | 17 (22.97) | 3 (5.88) | 1 (5.00) | 0 | 22 (10.78) |

| يهدد الحياة | 6 (10.53) | 6 (8.11) | 3 (5.88) | 5 (25.00) | 0 | 20 (9.80) |

| الاستشفاء | 8 (14.04) | 20 (27.03) | 19 (37.25) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | 54 (26.47) |

| إعاقة | 2 (3.51) | 1 (1.35) | 2 (3.92) | 1 (5.00) | 0 | 6 (2.94) |

| أمراض خطيرة أخرى | 52 (91.23) | 55 (74.32) | ٣٧ (٧٢.٥٥) | 12 (60.00) | 2 (100) | 158 (77.45) |

الأدوية النفسية العصبية، واستخدم 63 مريضًا أكثر من دواء نفسي عصبي واحد (الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S4). بعد ذلك

تقييم العلاقة السببية العالمية

العلاقات، والاحتمالية البيولوجية، وبالتالي عدم دعم ارتباط سببي محتمل بين مثبطات GLP-1 (سيماجلوتيد، ليراجلوتيد، دولاجلوتيد، إكسيناتيد، ليكسيزيناتيد، وألبiglوتيد) و SSIBs (الجدول 2).

نقاش

في البداية، قمنا بمقارنة الخصائص السريرية للمرضى الذين تم علاجهم بمثبطات GLP-1RAs و SSIBs. أظهرت التقارير من 2018 إلى 2021 توزيعًا متوسطًا عامًا. ومع ذلك، كان هناك اتجاه تصاعدي في كل من ADR مع الحالة و

لم يتم ملاحظة أي حالة في عام 2022، مما قد يعكس الزيادة في وصف أدوية GLP-1RAs في السنوات الأخيرة. من بين البيانات المتاحة حول الأحداث السلبية، كانت النسبة أعلى بشكل ملحوظ من الإناث (64.22%) مقارنة بالذكور.

بين الإناث أكثر من الذكور. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن هذه الفجوة تكون ملحوظة بشكل خاص لدى الأفراد البدينين [40، 41]. فيما يتعلق بالعمر، يجب على الأطباء توخي الحذر بشكل أكبر

| معايير | وصف | المصدر/الطريقة |

| قوة الارتباط | على الرغم من أن مؤشرات التناسب ليست مقاييس للمخاطر، فإن قوة عدم التناسب سواء في التحليل الأساسي (مقارنة بجميع الأدوية الأخرى) أو في تحليل النتائج السلبية الكاذبة تشير إلى إشارة سلبية. | تحليل عدم التناسب |

| تشبيه | تم إثبات عدم الصلة أيضًا بالنسبة لأدوية مضادة للسكري/مضادة للسمنة الأخرى (إمباغليفلوزين وأورليستات)، التي تم استخدامها كتحكم سلبي في هذه الدراسة. | تحليل عدم التناسب والتسميات |

| الاحتمالية البيولوجية / الأدلة التجريبية | يُقترح أن يكون لمستقبلات GLP-1 تأثيرات إيجابية على الإدراك. خاصة من حيث الآليات العلاجية المزدوجة التي قد تحسن كل من العجز في الجهاز العصبي المركزي والعبء الأيضي. لا توجد أدلة تدعم أن مستقبلات GLP-1 ستسبب سلوكيات تناول الطعام غير الطبيعية. | تحليل عدم التناسب والأدبيات |

| الاتساق | كانت نتائج أساليب عدم التناسب متسقة في النتائج السلبية الكاذبة | تحليل عدم التناسب |

| التماسك | تقرير تجربة عشوائية محكومة يذكر ثلاث حالات مراهقين مرتبطة بأفكار/سلوكيات انتحارية باستخدام الليراجلوتيد. ومع ذلك، فإن المشارك الذي انتحر، والذي كان في مجموعة الليراجلوتيد، كان لديه تاريخ من اضطراب نقص الانتباه مع فرط النشاط وكان هناك محاولة انتحار واحدة في مجموعتي الليراجلوتيد والدواء الوهمي، على التوالي [37]. أبلغ تحليل استكشافي مجمع عن 34 من أصل 3291 أفكار انتحارية مع الليراجلوتيد. لكن لم يتم ملاحظة أي اختلالات بين العلاجات في أفكار/سلوكيات انتحارية أو اكتئاب من خلال تقييمات استبيانات مستقبلية [38]. يصف تقرير حالة حالتين من الاكتئاب المرتبط بالسيماجلوتيد [39]. | بحث أدبي |

| خصوصية | أظهرت نتائج التحليل الأولي وتحليل النتائج السلبية الكاذبة عدم وجود ارتباط بين أدوية GLP-1RAs وSSIBs. وأشارت تحليل الأدوية المشتركة إلى أن حدوث SSIBs كان أكثر احتمالاً أن يرتبط بالحالة النفسية للمريض نفسه. | تحليل عدم التناسب والتداوي المشترك |

| علاقة زمنية | تشير البيانات المتاحة إلى وجود حالات من SSIBs بعد التوقف عن استخدام GLP-1RA، ولكن لم يكن بالإمكان إجراء دراسات إضافية بسبب نقص البيانات. | تحليل وقت البدء |

| الرجعية | هذا المعيار ذو قيمة محدودة هنا حيث لا توجد بيانات كافية عن إعادة التحدي وإلغاء التحدي في قاعدة بيانات FAERS. | وصفي |

بعد ذلك، استكشفنا العلاقة المحتملة بين GLP-1RAs وTTO لـ SSIBs. كان هدف تحليلنا هو تحديد ما إذا كانت هذه الأدوية قد تؤثر على تطور SSIBs من خلال بعض الآليات المشتركة. GLP-1RAs هي فئة من الأدوية المستخدمة لعلاج داء السكري من النوع 2 والتي يمكن أن تحاكي التأثير التنظيمي لـ GLP-1 على

مستويات الجلوكوز في الدم. على الرغم من أن هذه الأدوية من فئة GLP-1RAs تختلف في التركيب الجزيئي ومدة الفعالية، إلا أن آلياتها الدوائية متشابهة. لذلك، افترضنا أنه إذا كانت هناك ارتباطات ميكانيكية محتملة بين GLP-1RAs وSSIBs، فإن أنماطها المسببة للأمراض ستكون مشابهة. ومع ذلك، كشفت نتائجنا عن اكتشافات غير متوقعة. لاحظنا ثلاثة نماذج مسببة للأمراض مختلفة للأدوية في تحليل TTO. على سبيل المثال، تم تصنيف السيماغلوتيد والدولاجلوتيد كأنواع فشل مبكر، بينما تم تحديد الإكسيناتيد كنوع فشل عشوائي، وتم تصنيف الليراجلوتيد كنوع فشل نتيجة التآكل. وهذا يشير إلى أنه لا يوجد آلية واحدة (تأثير التحمل/تأثير التراكم) تفسر الارتباط الزمني لظهور GLP-1RAs وSSIBs. وبالتالي، يبدو أن تنوع أنماط الظهور التي لوحظت لـ GLP-1RAs يتحدى الافتراضات المذكورة أعلاه، مما يجعل من الصعب استنتاج علاقة واضحة بينها.

قاعدة البيانات. كانت الأورليستات والإمباغليفلوزين بمثابة ضوابط سلبية، بينما كانت الفينلافاكسين بمثابة ضابط إيجابي. كانت النتائج لهذه الأدوية الضابطة متسقة مع المعلومات المتاحة في الأدبيات والملصقات، مما يؤكد موثوقية دراستنا من حيث المنهجية وتحليل البيانات. أظهرت نتائج التحليل غير المتناسب أنه لم يظهر أي من GLP-1RAs إشارات مع SSIBs. تشير هذه النتائج السلبية إلى عدم وجود ارتباط مباشر بين GLP-1RAs وSSIBs. بالنظر إلى أننا استبعدنا ثلاث حالات تتعلق بالاستخدام المتزامن لعدة GLP-1RAs، قمنا أيضًا بإجراء تحليل للنتائج السلبية الكاذبة لتجنب النتائج السلبية الكاذبة. ومع ذلك، حتى مع

مع الأدوية النفسية العصبية. عند الجمع مع الأدوية النفسية العصبية، لم تزد GLP-1RAs من خطر تطوير SSIBs. علاوة على ذلك، فإن GLP-1RAs لها تأثيرات تعزز الإدراك وت activates مسار GLP-1R/cAMP/PKA، مما يوفر تدخلاً جديداً لعلاج الاكتئاب وتقليل SSIBs. توفر هذه الدراسات منظوراً بيولوجياً شاملاً ودقيقاً لفهم أعمق للعلاقة بين GLP-1RAs وSSIBs. وجهة نظرنا بدأت تميل نحو فكرة أن حدوث SSIBs من المرجح أن يكون مرتبطاً بالحالة العقلية للمريض بدلاً من GLP-1RAs.

قد تكون غير كافية. وبالتالي، يجب اعتبار الاستنتاجات المستخلصة من تحليل TTO كأدلة ذات جودة منخفضة. ثالثًا، تحليل النتائج السلبية الكاذبة هو اختبار نقترحه بناءً على الوضع المحدد لهذه الدراسة. ومع ذلك، لم يتم استخدامه على نطاق واسع بعد في مجال اليقظة الدوائية. لذلك، فإن تطبيقه يتطلب اعتبارات دقيقة. رابعًا، كانت SSIBs المحددة في دراستنا هي PTs المضمنة للسلوكيات الانتحارية والسلوكيات الذاتية الجرح (على مستوى HLGT). نظرًا للاختلافات في قواعد تصنيف MedDRA، قد توجد بعض PTs المحتملة التي لم يتم تضمينها، مثل الاكتئاب الانتحاري (الذي ينتمي إلى مستوى HLGT، اضطرابات المزاج الاكتئابية والاضطرابات) والجرعة الزائدة المتعمدة (التي تنتمي إلى مستوى HLGT، الجرعات الزائدة والجرعات الناقصة NEC).

الاستنتاجات

سلوكيات انتحارية أو ذاتية الإصابة

الوكالة الأوروبية للأدوية

إدارة الغذاء والدواء

نظام الإبلاغ عن الأحداث السلبية التابع لإدارة الغذاء والدواء

مدرا – المعجم الطبي للأنشطة التنظيمية

وقت بدء TTO

فترة الثقة

مكون معلومات IC

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

العرض السابق

مساهمات المؤلفين

حسابات تويتر للمؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

الاختصارات

الببتيد الشبيه بالجلوكاجون 1

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 فبراير 2024

References

- Lingvay I, Leiter LA. Use of GLP-1 RAs in cardiovascular disease prevention: a practical guide. Circulation. 2018;137:2200-2.

- Patorno E, Htoo PT, Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Wexler DJ, Pawar A, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and the risk for cardiovascular outcomes in routine care patients with diabetes across categories of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1528-41.

- Ma X, Liu Z, Ilyas I, Little PJ, Kamato D, Sahebka A, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs): cardiovascular actions and therapeutic potential. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:2050-68.

- Barritt AS, Marshman E, Noureddin M. Review article: role of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, obesity and diabetes-what hepatologists need to know. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:944-59.

- Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, Gabbay RA, Green J, Maruthur NM, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, A consensus report by the american diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022;45(11):2753-86.

- Jastreboff AM, Kushner RF. New frontiers in obesity treatment: GLP-1 and nascent nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:125-39.

- Bailey CJ, Flatt PR, Conlon JM. An update on peptide-based therapies for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Peptides. 2023;161:170939.

- O’Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, Wharton S, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:637-49.

- Chadda KR, Cheng TS, Ong KK. GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13177.

- Tan B, Pan X-H, Chew HSJ, Goh RSJ, Lin C, Anand VV, et al. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide for treatment of overweight or obesity. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47:677-85.

- Pfizer Provides Update on GLP-1-RA Clinical Development Program for Adults with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Pfizer. https://www. pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-provides-update-glp-1-ra-clinical-development. Accessed 8 Aug 2023.

- Bezin J, Gouverneur A, Pénichon M, Mathieu C, Garrel R, Hillaire-Buys D, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and the risk of thyroid cancer. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:384-90.

- He L, Wang J, Ping F, Yang N, Huang J, Li Y, et al. Association of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonist use with risk of gallbladder and biliary diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:513-9.

- EMA. EMA statement on ongoing review of GLP-1 receptor agonists. European Medicines Agency. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ news/ema-statement-ongoing-review-glp-1-receptor-agonists. Accessed 20 Jul 2023.

- Fine KL , Rickert

‘Reilly LM , Sujan AC, Boersma K, Chang Z, et al. Initiation of opioid prescription and risk of suicidal behavior among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2022;149:e2020049750. - Takeuchi T, Takenoshita S, Taka F, Nakao M, Nomura K. The relationship between psychotropic drug use and suicidal behavior in Japan: Japanese adverse drug event report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50:69-73.

- Gonda

, Dome , Serafini . How to save a life: From neurobiological underpinnings to psychopharmacotherapies in the prevention of suicide. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;244:108390. - Hughes JL, Horowitz LM, Ackerman JP, Adrian MC, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Suicide in young people: screening, risk assessment, and intervention. BMJ. 2023;381:e070630.

- Jing Y, Liu J, Ye Y, Pan L, Deng H, Wang Y, et al. Multi-omics prediction of immune-related adverse events during checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4946.

- Raschi E, Fusaroli M, Giunchi V, Repaci A, Pelusi C, Mollica V, et al. adrenal insufficiency with anticancer tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor: analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4610.

- Xia S, Gong H, Zhao Y, Guo L, Wang Y, Ma R, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome associated with monoclonal antibodies in patients with multiple myeloma: a pharmacovigilance study based on the FAERS database. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;114:211-9.

- Zhou J, Wei Z, Xu B, Liu M, Xu R, Wu X. Pharmacovigilance of triazole antifungal agents: analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1039867.

- Ren W, Wang W, Guo Y. Analysis of adverse reactions of aspirin in prophylaxis medication Based on FAERS database. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:7882277.

- Yu RJ, Krantz MS, Phillips EJ, Stone CA. Emerging causes of drug-induced anaphylaxis: a review of anaphylaxis-associated reports in the fda adverse event reporting system (FAERS). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:819829.e2.

- Hu Y, Bai Z, Tang Y, Liu R, Zhao B, Gong J, et al. Fournier gangrene associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study with data from the U.S. FDA Adverse event reporting system. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:3695101.

- Liu L, Chen J, Wang L, Chen C, Chen L. Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal adverse reactions: a realworld disproportionality study based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1043789.

- Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller CI, Badcock PB, et al. New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD013674.

- Sauzet O, Carvajal A, Escudero A, Molokhia M, Cornelius VR. Illustration of the weibull shape parameter signal detection tool using electronic healthcare record data. Drug Saf. 2013;36:995-1006.

- van Puijenbroek EP, Bate A, Leufkens HGM, Lindquist M, Orre R, Egberts ACG. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:3-10.

- Norén GN, Hopstadius J, Bate A. Shrinkage observed-to-expected ratios for robust and transparent large-scale pattern discovery. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:57-69.

- Trillenberg P, Sprenger A, Machner B. Sensitivity and specificity in signal detection with the reporting odds ratio and the information component. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023;32:910-7.

- Noguchi Y, Tachi T, Teramachi H. Comparison of signal detection algorithms based on frequency statistical model for drug-drug interaction using spontaneous reporting systems. Pharm Res. 2020;37:86.

- Anderson N, Borlak J. Correlation versus causation? Pharmacovigilance of the analgesic flupirtine exemplifies the need for refined spontaneous ADR reporting. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25221.

- Fusaroli M, Raschi E, Giunchi V, Menchetti M, Rimondini Giorgini R, De Ponti F, et al. Impulse control disorders by dopamine partial agonists: a pharmacovigilance-pharmacodynamic assessment through the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:727-36.

- Raschi E, Fusaroli M, Ardizzoni A, Poluzzi E, De Ponti F. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors and interstitial lung disease in the FDA adverse event reporting system: a pharmacovigilance assessment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;186:219-27.

- Horska K, Ruda-Kucerova J, Skrede S. GLP-1 agonists: superior for mind and body in antipsychotic-treated patients? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33:628-38.

- Kelly AS, Auerbach P, Barrientos-Perez M, Gies I, Hale PM, Marcus C, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of liraglutide for adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2117-28.

- O’Neil PM, Aroda VR, Astrup A, Kushner R, Lau DCW, Wadden TA, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety with liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management: Results from randomized controlled phase 2 and 3a trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1529-36.

- Li J-R, Cao J, Wei J, Geng W. Case report: Semaglutide-associated depression: a report of two cases. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1238353.

- Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Blüher M, Kersting A, Wagner B. Obesity and suicide risk in adults-a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:277-84.

- da Silva Bandeira BE, Dos Santos Júnior A, Dalgalarrondo P, de Azevedo RCS, Celeri EHVR. Nonsuicidal self-injury in undergraduate students: a cross-sectional study and association with suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2022;318:114917.

- Yan Y, Gong Y, Jiang M, Gao Y, Guo S, Huo J, et al. Utilization of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents in China: a real-world study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1170127.

- Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998.

- Yaribeygi H, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms by which GLP-1 RA and DPP-4i induce insulin sensitivity. Life Sci. 2019;234:116776.

- Jespersen MJ, Knop FK, Christensen M. GLP-1 agonists for type 2 diabetes: pharmacokinetic and toxicological considerations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:17-29.

- Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment of patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1500-6.

- Battini V, Van Manen RP, Gringeri M, Mosini G, Guarnieri G, Bombelli A, et al. The potential antidepressant effect of antidiabetic agents: New insights from a pharmacovigilance study based on data from the reporting system databases FAERS and VigiBase. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1128387.

- Darwish AB, El Sayed NS, Salama AAA, Saad MA. Dulaglutide impedes depressive-like behavior persuaded by chronic social defeat stress model in male C57BL/6 mice: Implications on GLP-1R and cAMP/PKA signaling pathway in the hippocampus. Life Sci. 2023;320:121546.

- Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, O’Neil PM, Rosenstock J, Sørrig R, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327:138-50.

- Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, Hesse D, Greenway FL, Jensen C, et al. Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1414-25.

- Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, Davies M, Frias JP, Koroleva A, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1403-13.

- Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, Pakseresht A, Pedersen SD, Perreault L, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double-blind, doubledummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:971-84.

- Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:796-803.

- Khaleel MA, Khan AH, Ghadzi SMS, Adnan AS, Abdallah QM. A Standardized dataset of a spontaneous adverse event reporting system. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:420.

- McIntyre RS, Mansur RB, Rosenblat JD, Kwan ATH. The association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and suicidality: reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;1-9. Online ahead of print.

- Chen C, Zhou R, Fu F, Xiao J. Postmarket safety profile of suicide/ self-injury for GLP-1 receptor agonist: a real-world pharmacovigilance analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2023;66:e99.

- Wang W, Volkow ND, Berger NA, Davis PB, Kaelber DC, Xu R. Association of semaglutide with risk of suicidal ideation in a real-world cohort. Nat Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02672-2.

ملاحظة الناشر

ماوباي ليو وشيوماي وو قدما مساهمة متساوية في هذا العمل ككاتبين متعاونين.

*المراسلة:

ماوباي ليو

liumb0591@fjmu.edu.cn

شيو مي وو

wuxuemei@fjmu.edu.cn

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03274-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38355513

Publication Date: 2024-02-14

Check for updates

Exploration of the potential association between GLP-1 receptor agonists and suicidal or self-injurious behaviors: a pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database

Abstract

Background Establishing whether there is a potential relationship between glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and suicidal or self-injurious behaviors (SSIBs) is crucial for public safety. This study investigated the potential association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs by exploring the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database.

Methods A disproportionality analysis was conducted using post-marketing data from the FAERS repository (2018 Q1 to 2022 Q4). SSIB cases associated with GLP-1RAs were identified and analyzed through disproportionality analysis using the information component. The parametric distribution with a goodness-of-fit test was employed to analyze the time-to-onset, and the

Results In total, 204 cases of SSIBs associated with GLP-1RAs, including semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, and albiglutide, were identified in the FAERS database. Time-of-onset analysis revealed no consistent mechanism for the latency of SSIBs in patients receiving GLP-1RAs. The disproportionality analysis did not indicate an association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. Co-medication analysis revealed 81 cases with antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines, which may be proxies of mental health comorbidities. Conclusions We found no signal of disproportionate reporting of an association between GLP-1RA use and SSIBs. Clinicians need to maintain heightened vigilance on patients premedicated with neuropsychotropic drugs. This contributes to the greater acceptance of GLP-1RAs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or obesity.

Highlights

- To determine whether there is a potential relationship between glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP1RAs) and suicidal or self-injurious behaviors (SSIBs).

- Is there a direct association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs? No evidence reasonably suggests an association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs based on clinical characteristics, time-onset, disproportionality, and co-medication analysis.

- Clinicians should pay more attention to the psychiatric status of patients with a history of neuropsychotropic drugs, and more comprehensive monitoring is needed to consider their susceptibility to SSIBs carefully.

Keywords GLP-1RAs, Suicidal or self-injurious behaviors, Pharmacovigilance, FAERS database, Type 2 diabetes, Obesity

Graphical Abstract

Jianxing Zhou, You Zheng, Baohua Xu, Songjun Long, Li-e Zhu, Yunhui Liu, Chengliang Li, Yifan Zhang, Maobai Liu, Xuemei Wu*

Time to onset analysis

Jianxing Zhou, You Zheng, Baohua Xu, Songjun Long, Li-e Zhu, Yunhui Liu, Chengliang Li, Yifan Zhang, Maobai Liu, Xuemei Wu*

Descriptive analysis

Jianxing Zhou, You Zheng, Baohua Xu, Songjun Long, Li-e Zhu, Yunhui Liu, Chengliang Li, Yifan Zhang, Maobai Liu, Xuemei Wu*

Co-medication analyses

Jianxing Zhou, You Zheng, Baohua Xu, Songjun Long, Li-e Zhu, Yunhui Liu, Chengliang Li, Yifan Zhang, Maobai Liu, Xuemei Wu*

Globally, Bradford Hill Criteria were unfulfilled

Background

chronic kidney disease) [5]. Furthermore, GLP-1RAs exhibit substantial weight reduction effects by facilitating glucose uptake and suppressing appetite [6]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, diabetes and obesity rank among the top 10 most economically burdensome chronic diseases in the USA. Given the escalating global prevalence of these diseases, there is an unprecedented opportunity to expand the global market for GLP-1RAs.

topic and new analogs are constantly being introduced to the market. In December 2014, the FDA approved liraglutide as a weight loss drug. Right after this, semaglutide became available with the indication of diabetes in 2017, and then in 2020, its treatment for obesity was also authorized. Global demand for semaglutide and liraglutide exceeds the present supply, which might be related to their off label uses and misuse [7]. Despite the significant potential and advantages of GLP-1RAs, they are inevitably accompanied by a range of possible adverse drug reactions (ADRs), as is the case with any medication. The most prevalent ADRs associated with GLP1RA therapy encompass gastrointestinal events such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, these nonserious ADRs are tolerable in individuals with diabetes and obesity [8-10]. What raises concerns are some of the recent reports of serious ADRs associated with GLP1RAs: (i) Pfizer’s disclosure of elevated aminotransferases in users of lotiglipron (a novel oral GLP-1RA) is indicative of hepatocellular injury [11]; (ii) Studies revealed an elevated risk of thyroid cancer associated and cholecystitis with the use of GLP-1RAs [12, 13]; (iii) The Icelandic Medicines Agency has submitted 150 reports of GLP-1RAs-related suicidal or self-injurious behaviors (SSIBs) to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [14]. Following the aforementioned incidents, the development of lotiglipron was discontinued, and drug regulatory agencies in several countries classified GLP-1RAs as a potential risk factor for thyroid cancer, gallbladder, and biliary diseases. However, no studies have investigated the association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. SSIBs, recognized as significant ADRs, have garnered widespread acknowledgment as critical factors that may jeopardize patient safety [15]. Studies have demonstrated a consistent year-on-year escalation in patient suicides associated with medication use, intensifying concerns among the general public and clinical professionals regarding this phenomenon [16-18]. Therefore, in the context of the widespread global utilization of GLP-1RAs, it is imperative to investigate whether a potential relationship exists between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs, which is of paramount importance for public and clinical medication safety.

Methods

Data sources and study design

Definition of cases and drugs of interest

or suicide potential in the specification or related studies. The current study encompassed all cases in which GLP1RAs were administered and listed as primary suspect drugs, secondary suspect drugs, or concomitant drugs for SSIBs.

Descriptive analysis

Reported timeto-onset analysis

Disproportionality analysis

(1) An exploratory disproportionality approach comparing GLP-1RAs with all other drugs reported in the FAERS database, using venlafaxine as the positive control and empagliflozin/orlistat as the negative control. The definition of the disproportionality approach can be found in Additional file 1: section 4 [29].

(2) We utilized the Bayesian Information Component (IC) to calculate the lower limit of the

(3) False-negative analysis was conducted by artificially augmenting the reported incidence of GLP-1RA-

associated SSIBs by

(4) Given the inherent heterogeneity and potential reporting bias in the FAERS database, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we excluded case and non-case reports with gastrointestinal events (all PTs belonged to gastrointestinal disorders in the system organ class) in the dataset. This step aimed to reduce the masking effect of gastrointestinal events to avoid possible competitive bias. Furthermore, the main indications in the included cases were type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which are potential risk factors for SSIBs. Therefore, we narrowed the analysis dataset to subject with type 2 diabetes mellitus or weight loss through the indi_pt field (which represents the indication). Previous studies have shown that restricting the analyzed population can mitigate indication bias [21]. IC

(5) Considering a low number of expected cases could lead to an insufficient sensitivity to detect disproportionality of relevant strength [31], we reported the sensitivity of a representative

Co-medication analysis

Global assessment of the evidence

Statistical analysis

Results

Descriptive analysis

Reported time-to-onset analysis

liraglutide and 2 cases for semaglutide), which might be related to the delayed ADR caused by the interested drugs.

Disproportionality analysis

Co-medication analysis

| Categories | Semaglutide

|

Liraglutide

|

Dulaglutide

|

Exenatide

|

Albiglutide

|

Total

|

| Reports of SSIBs | 57 | 74 | 51 | 20 | 2 | 204 |

| Report year | ||||||

| 2018 | 2 (3.51) | 16 (21.62) | 12 (23.53) | 4 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | 35 (17.16) |

| 2019 | 4 (7.02) | 11 (14.86) | 7 (13.73) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | 29 (14.22) |

| 2020 | 8 (14.04) | 19 (25.68) | 10 (19.61) | 4 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | 42 (20.59) |

| 2021 | 16 (28.07) | 12 (16.22) | 8 (15.69) | 2 (10.00) | 0 | 38 (18.63) |

| 2022 | 27 (47.37) | 16 (21.62) | 14 (27.45) | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 60 (29.41) |

| Reporter

|

||||||

| Healthcare professional | 30 (52.63) | 53 (71.62) | 19 (37.25) | 9 (45.00) | 1 (50.00) | 112 (54.90) |

| Nonhealthcare professional | 26 (45.61) | 21 (28.38) | 31 (60.78) | 6 (30.00) | 1 (50.00) | 85 (41.67) |

| Unknown or missing | 1 (1.75) | 0 | 1 (1.96) | 5 (25.00) | 0 | 7 (3.43) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 18 (31.58) | 20 (27.03) | 19 (37.25) | 9 (45.00) | 1 (50.00) | 67 (32.84) |

| Female | 38 (66.67) | 52 (70.27) | 29 (56.86) | 11 (55.00) | 1 (50.00) | 131 (64.22) |

| Unknown or missing | 1 (1.75) | 2 (2.70) | 3 (5.88) | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.94) |

| Age category, years | ||||||

| Juvenile (< 18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 3 (1.47) |

| Adult (18-65) | 28 (49.12) | 43 (58.11) | 24 (47.06) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | 102 (50.00) |

| Seniors (>65) | 1 (1.75) | 7 (9.46) | 10 (19.61) | 2 (10.00) | 0 | 20 (9.80) |

| Unknown or missing | 28 (49.12) | 24 (32.43) | 17 (33.33) | 8 (40.00) | 2 (100.00) | 79 (38.73) |

| Median (IQR) | 43 (35-52) | 47 (36-57) | 55 (46-67) | 40 (25-54) | / | / |

| Indication | ||||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 13 (22.81) | 14 (18.92) | 30 (58.82) | 13 (65.00) | 1 (50.00) | 71 (34.80) |

| Weight loss | 15 (26.32) | 15 (20.27) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 (14.71) |

| Others | 1 (1.75) | 4 (5.41) | 0 | 3 (15.00) | 0 | 8 (3.92) |

| Unknown or missing | 28 (49.12) | 41 (55.41) | 21 (41.18) | 4 (20.00) | 1 (50.00) | 95 (46.57) |

| Outcomes

|

||||||

| Death | 1 (1.75) | 17 (22.97) | 3 (5.88) | 1 (5.00) | 0 | 22 (10.78) |

| Life-threatening | 6 (10.53) | 6 (8.11) | 3 (5.88) | 5 (25.00) | 0 | 20 (9.80) |

| Hospitalization | 8 (14.04) | 20 (27.03) | 19 (37.25) | 7 (35.00) | 0 | 54 (26.47) |

| Disability | 2 (3.51) | 1 (1.35) | 2 (3.92) | 1 (5.00) | 0 | 6 (2.94) |

| Other serious illness | 52 (91.23) | 55 (74.32) | 37 (72.55) | 12 (60.00) | 2 (100) | 158 (77.45) |

neuropsychiatric drugs, and 63 patients used more than one neuropsychiatric drug (Additional file 1: Fig S4). Subsequent

Causal relationship global assessment

relationships, and biological plausibility, thus unsupporting a likely causal association between GLP-1RAs (semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, lixisenatide, and albiglutide) and SSIBs (Table 2).

Discussion

Initially, we compared the clinical characteristics of patients treated with GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. Reports from 2018 to 2021 exhibited an overall average distribution. However, an uptrend in both ADR with case and

non-case was observed in 2022, possibly reflecting the increased prescription of GLP-1RAs in recent years. Among the available data on adverse events, a significantly higher proportion of females (64.22%) than males

females than among males. Notably, this disparity is particularly pronounced in obese individuals [40, 41]. With regard to age, physicians should exert heightened caution

| Criteria | Description | Source/method |

| Strength of the association | Although ICs are not measures of risk, the strength of the disproportionality both in primary (vs. all other drugs) and false negative analysis suggests a negative signal | Disproportionality analysis |

| Analogy | The irrelevance was also demonstrated for other anti-diabetic/anti-obesity drugs (empagliflozin and Orlistat), which were used as a negative control in this study | Disproportionality analysis and labels |

| Biological plausibility/ empirical evidence | GLP-1RAs are also proposed to have pro-cognitive effects. Particularly in terms of dual therapeutic mechanisms potentially improving both central nervous system deficits and metabolic burden [36]. There is no evidence to support that GLP-1RA will cause SSIBs | Disproportionality analysis and literature |

| Consistency | Results of disproportionality approaches were consistent in false negative | Disproportionality analysis |

| Coherence | A randomized, controlled trial reports three adolescent cases associated with suicidal ideation/behavior using liraglutide. However, the participant who committed suicide, who was in the liraglutide group, had a history of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and there was one suicide attempt in the liraglutide and placebo groups, respectively [37]. An exploratory pooled analysis reported 34/3291 suicidal ideation with liraglutide. But no between-treatment imbalances in suicidal ideation/behavior or depression were noted through prospective questionnaire assessments [38]. A case report describes two instances of depression associated with semaglutide [39]. | literature search |

| Specificity | The results of primary and false-negative analysis showed no association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. The co-medication analysis indicated that the occurrence of SSIBs was more likely to be related to the patient’s own mental state. | Disproportionality and co-medication analysis |

| Temporal relationship | Available data suggested that there were cases of SSIBs after discontinuation of GLP-1RA, but further studies could not be performed due to missing data | Time-to-onset analysis |

| Reversibility | This criterion is of limited value here as there is not enough data on rechallenge and de-challenge in the FAERS database | Descriptive |

Next, we delved into the potential association between GLP-1RAs and TTO of SSIBs. Our analysis aimed to determine whether these drugs might influence the development of SSIBs by some common mechanism. GLP-1RAs are a class of drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes that can simulate the regulatory effect of GLP-1 on

blood glucose levels. Although these GLP-1RAs differ in molecular structure and duration of action, their pharmacological mechanisms are similar [44, 45]. Therefore, we hypothesized that if GLP-1RAs had potential mechanistic associations with SSIBs, their pathogenic patterns would be similar. However, our results revealed unexpected findings. We observed three different pathogenic models for the drugs in the TTO analysis. For example, semaglutide and dulaglutide were categorized as earlyfailure types, exenatide was determined to be a random failure type, and liraglutide was classified as a wear-out failure type. This suggests that no single mechanism (tolerance effect/accumulation effect) explains the temporal association of onset between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. Thus, the diversity of the onset patterns observed for GLP1RAs appears to challenge the above assumptions, making it difficult to conclude a clear relationship between them.

database. Orlistat and empagliflozin served as negative controls, and venlafaxine served as a positive control. The results for these control drugs were consistent with the information available in the literature and labels, confirming the reliability of our study in terms of methodology and data analysis. The results of the disproportionate analysis showed that none of the GLP-1RAs showed signaling with SSIBs. These negative results imply no direct association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. Considering that we discarded three cases involving the concurrent use of multiple GLP-1RAs, we further performed a falsenegative analysis to avoid false-negative results. However, even with a

with neuropsychiatric drugs. In combination with neuropsychiatric drugs, GLP-1RAs did not increase the risk of developing SSIBs. Moreover, GLP-1RAs have cogni-tion-promoting effects and activate the GLP-1R/cAMP/ PKA pathway, thus providing a new intervention for the treatment of depression and reduction of SSIBs [36, 47, 48]. These studies provide a comprehensive and accurate biological perspective for a deeper understanding of the association between GLP-1RAs and SSIBs. Our view is beginning to lean toward the idea that the occurrence of SSIBs is more likely to be related to the mental state of the patient rather than GLP-1RAs.

may be inadequate. Consequently, the conclusions drawn from the TTO analysis should be regarded as low-quality evidence. Third, false-negative analysis is a test that we propose based on the specific situation of this study. However, it is not yet widely used in the field of pharmacovigilance. Therefore, its application warrants careful consideration. Fourth, the SSIBs defined in our study were PTs included for Suicidal and self-injurious behaviors (HLGT level). Given the differences in the MedDRA’s categorization rules, some potential PTs that were not included may exist, e.g., depression suicidal (belonging to HLGT level, depressed mood disorders and disturbances) and intentional overdose (belonging to HLGT level, overdoses, and underdoses NEC).

Conclusions

SSIBs Suicidal or self-injurious behaviors

EMA European Medicines Agency

FDA The Food and Drug Administration

FAERS The Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System

MedDRA The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

TTO Time-to-onset

Cl Confidence interval

IC Information Component

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Prior presentation

Authors’ contributions

Authors’ Twitter handles

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Abbreviations

GLP-1 Glucagon-like peptide 1

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 14 February 2024

References

- Lingvay I, Leiter LA. Use of GLP-1 RAs in cardiovascular disease prevention: a practical guide. Circulation. 2018;137:2200-2.

- Patorno E, Htoo PT, Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Wexler DJ, Pawar A, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and the risk for cardiovascular outcomes in routine care patients with diabetes across categories of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1528-41.

- Ma X, Liu Z, Ilyas I, Little PJ, Kamato D, Sahebka A, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs): cardiovascular actions and therapeutic potential. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:2050-68.

- Barritt AS, Marshman E, Noureddin M. Review article: role of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, obesity and diabetes-what hepatologists need to know. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:944-59.

- Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, Gabbay RA, Green J, Maruthur NM, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, A consensus report by the american diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022;45(11):2753-86.

- Jastreboff AM, Kushner RF. New frontiers in obesity treatment: GLP-1 and nascent nutrient-stimulated hormone-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:125-39.

- Bailey CJ, Flatt PR, Conlon JM. An update on peptide-based therapies for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Peptides. 2023;161:170939.

- O’Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, Wharton S, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:637-49.

- Chadda KR, Cheng TS, Ong KK. GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13177.

- Tan B, Pan X-H, Chew HSJ, Goh RSJ, Lin C, Anand VV, et al. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide for treatment of overweight or obesity. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47:677-85.

- Pfizer Provides Update on GLP-1-RA Clinical Development Program for Adults with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Pfizer. https://www. pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-provides-update-glp-1-ra-clinical-development. Accessed 8 Aug 2023.

- Bezin J, Gouverneur A, Pénichon M, Mathieu C, Garrel R, Hillaire-Buys D, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and the risk of thyroid cancer. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:384-90.

- He L, Wang J, Ping F, Yang N, Huang J, Li Y, et al. Association of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonist use with risk of gallbladder and biliary diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:513-9.

- EMA. EMA statement on ongoing review of GLP-1 receptor agonists. European Medicines Agency. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ news/ema-statement-ongoing-review-glp-1-receptor-agonists. Accessed 20 Jul 2023.

- Fine KL , Rickert

‘Reilly LM , Sujan AC, Boersma K, Chang Z, et al. Initiation of opioid prescription and risk of suicidal behavior among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2022;149:e2020049750. - Takeuchi T, Takenoshita S, Taka F, Nakao M, Nomura K. The relationship between psychotropic drug use and suicidal behavior in Japan: Japanese adverse drug event report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50:69-73.

- Gonda

, Dome , Serafini . How to save a life: From neurobiological underpinnings to psychopharmacotherapies in the prevention of suicide. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;244:108390. - Hughes JL, Horowitz LM, Ackerman JP, Adrian MC, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Suicide in young people: screening, risk assessment, and intervention. BMJ. 2023;381:e070630.

- Jing Y, Liu J, Ye Y, Pan L, Deng H, Wang Y, et al. Multi-omics prediction of immune-related adverse events during checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4946.

- Raschi E, Fusaroli M, Giunchi V, Repaci A, Pelusi C, Mollica V, et al. adrenal insufficiency with anticancer tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor: analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4610.

- Xia S, Gong H, Zhao Y, Guo L, Wang Y, Ma R, et al. Tumor lysis syndrome associated with monoclonal antibodies in patients with multiple myeloma: a pharmacovigilance study based on the FAERS database. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;114:211-9.

- Zhou J, Wei Z, Xu B, Liu M, Xu R, Wu X. Pharmacovigilance of triazole antifungal agents: analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1039867.

- Ren W, Wang W, Guo Y. Analysis of adverse reactions of aspirin in prophylaxis medication Based on FAERS database. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:7882277.

- Yu RJ, Krantz MS, Phillips EJ, Stone CA. Emerging causes of drug-induced anaphylaxis: a review of anaphylaxis-associated reports in the fda adverse event reporting system (FAERS). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:819829.e2.

- Hu Y, Bai Z, Tang Y, Liu R, Zhao B, Gong J, et al. Fournier gangrene associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study with data from the U.S. FDA Adverse event reporting system. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:3695101.

- Liu L, Chen J, Wang L, Chen C, Chen L. Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal adverse reactions: a realworld disproportionality study based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1043789.

- Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller CI, Badcock PB, et al. New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD013674.

- Sauzet O, Carvajal A, Escudero A, Molokhia M, Cornelius VR. Illustration of the weibull shape parameter signal detection tool using electronic healthcare record data. Drug Saf. 2013;36:995-1006.

- van Puijenbroek EP, Bate A, Leufkens HGM, Lindquist M, Orre R, Egberts ACG. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:3-10.

- Norén GN, Hopstadius J, Bate A. Shrinkage observed-to-expected ratios for robust and transparent large-scale pattern discovery. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:57-69.

- Trillenberg P, Sprenger A, Machner B. Sensitivity and specificity in signal detection with the reporting odds ratio and the information component. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023;32:910-7.

- Noguchi Y, Tachi T, Teramachi H. Comparison of signal detection algorithms based on frequency statistical model for drug-drug interaction using spontaneous reporting systems. Pharm Res. 2020;37:86.

- Anderson N, Borlak J. Correlation versus causation? Pharmacovigilance of the analgesic flupirtine exemplifies the need for refined spontaneous ADR reporting. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25221.

- Fusaroli M, Raschi E, Giunchi V, Menchetti M, Rimondini Giorgini R, De Ponti F, et al. Impulse control disorders by dopamine partial agonists: a pharmacovigilance-pharmacodynamic assessment through the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:727-36.

- Raschi E, Fusaroli M, Ardizzoni A, Poluzzi E, De Ponti F. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors and interstitial lung disease in the FDA adverse event reporting system: a pharmacovigilance assessment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;186:219-27.

- Horska K, Ruda-Kucerova J, Skrede S. GLP-1 agonists: superior for mind and body in antipsychotic-treated patients? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33:628-38.

- Kelly AS, Auerbach P, Barrientos-Perez M, Gies I, Hale PM, Marcus C, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of liraglutide for adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2117-28.

- O’Neil PM, Aroda VR, Astrup A, Kushner R, Lau DCW, Wadden TA, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety with liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management: Results from randomized controlled phase 2 and 3a trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1529-36.

- Li J-R, Cao J, Wei J, Geng W. Case report: Semaglutide-associated depression: a report of two cases. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1238353.

- Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Blüher M, Kersting A, Wagner B. Obesity and suicide risk in adults-a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:277-84.

- da Silva Bandeira BE, Dos Santos Júnior A, Dalgalarrondo P, de Azevedo RCS, Celeri EHVR. Nonsuicidal self-injury in undergraduate students: a cross-sectional study and association with suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2022;318:114917.

- Yan Y, Gong Y, Jiang M, Gao Y, Guo S, Huo J, et al. Utilization of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents in China: a real-world study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1170127.

- Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998.

- Yaribeygi H, Sathyapalan T, Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms by which GLP-1 RA and DPP-4i induce insulin sensitivity. Life Sci. 2019;234:116776.

- Jespersen MJ, Knop FK, Christensen M. GLP-1 agonists for type 2 diabetes: pharmacokinetic and toxicological considerations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:17-29.

- Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment of patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1500-6.

- Battini V, Van Manen RP, Gringeri M, Mosini G, Guarnieri G, Bombelli A, et al. The potential antidepressant effect of antidiabetic agents: New insights from a pharmacovigilance study based on data from the reporting system databases FAERS and VigiBase. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1128387.

- Darwish AB, El Sayed NS, Salama AAA, Saad MA. Dulaglutide impedes depressive-like behavior persuaded by chronic social defeat stress model in male C57BL/6 mice: Implications on GLP-1R and cAMP/PKA signaling pathway in the hippocampus. Life Sci. 2023;320:121546.

- Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, O’Neil PM, Rosenstock J, Sørrig R, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327:138-50.

- Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, Hesse D, Greenway FL, Jensen C, et al. Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1414-25.

- Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, Davies M, Frias JP, Koroleva A, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1403-13.

- Davies M, Færch L, Jeppesen OK, Pakseresht A, Pedersen SD, Perreault L, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double-blind, doubledummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:971-84.

- Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:796-803.

- Khaleel MA, Khan AH, Ghadzi SMS, Adnan AS, Abdallah QM. A Standardized dataset of a spontaneous adverse event reporting system. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:420.

- McIntyre RS, Mansur RB, Rosenblat JD, Kwan ATH. The association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and suicidality: reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;1-9. Online ahead of print.

- Chen C, Zhou R, Fu F, Xiao J. Postmarket safety profile of suicide/ self-injury for GLP-1 receptor agonist: a real-world pharmacovigilance analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2023;66:e99.

- Wang W, Volkow ND, Berger NA, Davis PB, Kaelber DC, Xu R. Association of semaglutide with risk of suicidal ideation in a real-world cohort. Nat Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02672-2.

Publisher’s Note

Maobai Liu and Xuemei Wu contributed equally to this work as cocorresponding authors.

*Correspondence:

Maobai Liu

liumb0591@fjmu.edu.cn

Xuemei Wu

wuxuemei@fjmu.edu.cn

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article