DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.013

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38843834

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-05

اكتشاف الببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات في الميكروبيوم العالمي باستخدام التعلم الآلي

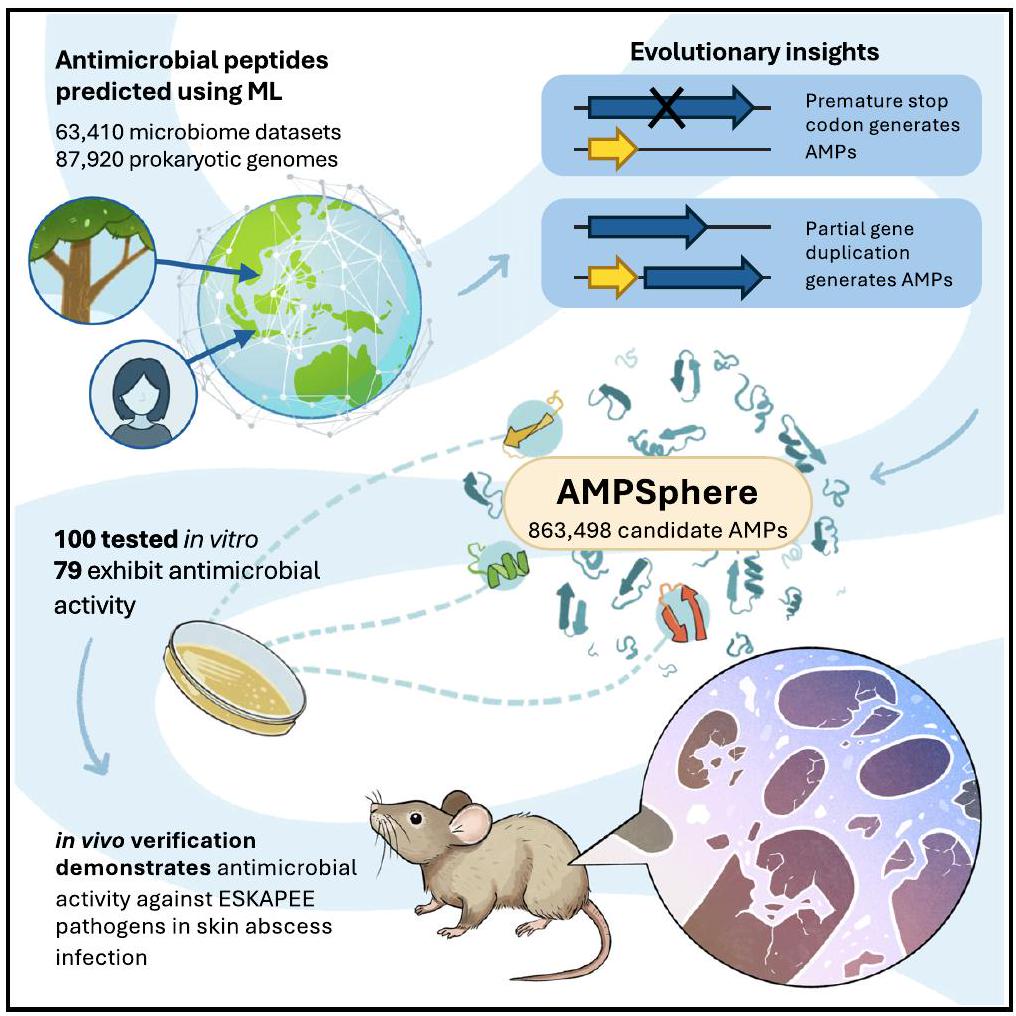

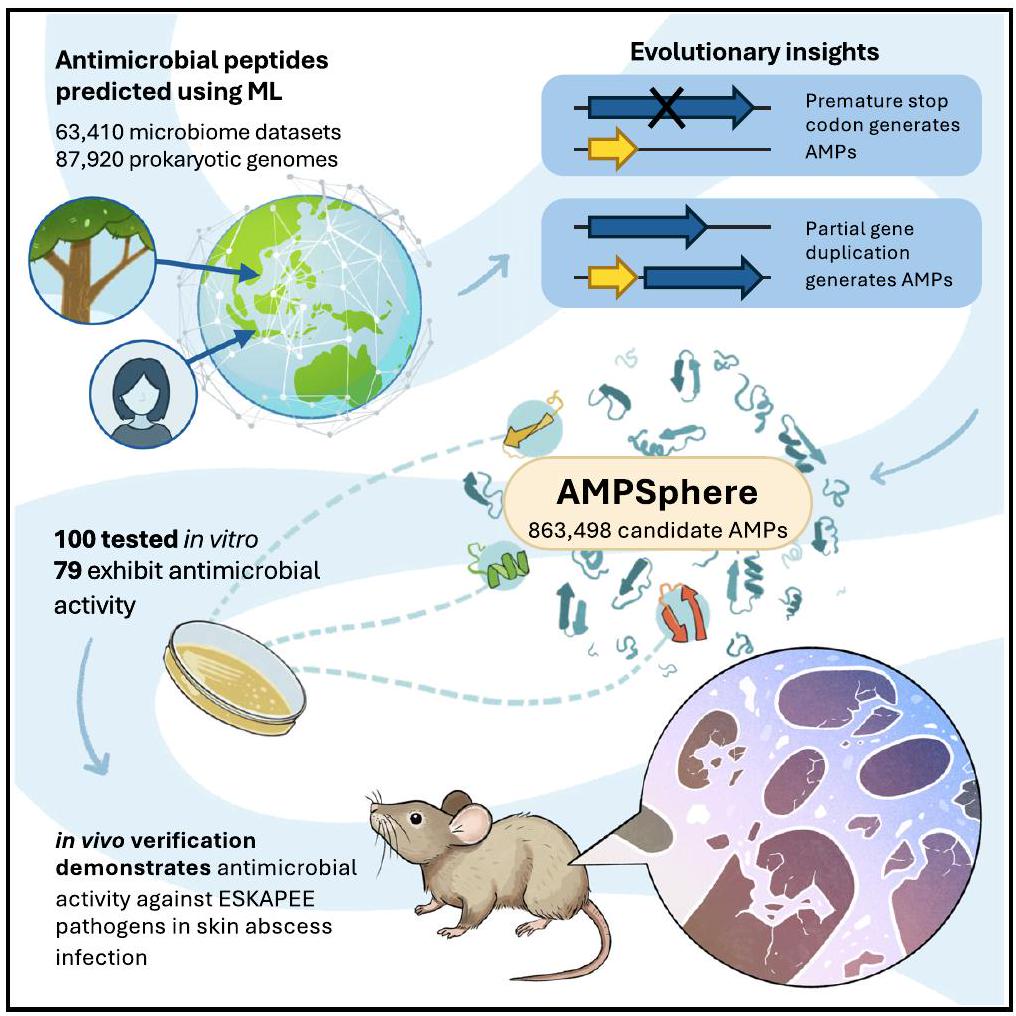

ملخص رسومي

أهم النقاط

- توقع التعلم الآلي ما يقرب من مليون مضاد حيوي جديد في الميكروبيوم العالمي

- خارج من

تم اختبار 79 ببتيدًا نشطًا في المختبر؛ 63 من هذه الببتيدات استهدفت مسببات الأمراض. - بعض الببتيدات قد تنشأ من تسلسلات أطول من خلال تجزئة الجينوم

- AMPSphere هو مورد مفتوح الوصول لتسريع اكتشاف المضادات الحيوية

المؤلفون

المراسلات

باختصار

اكتشاف الببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات في الميكروبيوم العالمي باستخدام التعلم الآلي

الملخص

الملخص: هناك حاجة ماسة لمضادات حيوية جديدة لمكافحة أزمة مقاومة المضادات الحيوية. نقدم نهجًا قائمًا على التعلم الآلي للتنبؤ بالببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات (AMPs) ضمن الميكروبيوم العالمي ونستفيد من مجموعة بيانات ضخمة تضم 63,410 ميتاجينومات و87,920 جينومًا بدائي النواة من المواطن البيئية والمترابطة مع المضيف لإنشاء AMPSphere، وهو كتالوج شامل يتضمن 863,498 ببتيد غير متكرر، القليل منها يتطابق مع قواعد البيانات الموجودة. يوفر AMPSphere رؤى حول الأصول التطورية للببتيدات، بما في ذلك من خلال التكرار أو تقصير الجينات من تسلسلات أطول، وقد لاحظنا أن إنتاج AMP يختلف حسب المواطن. للتحقق من تنبؤاتنا، قمنا بتخليق واختبار 100 AMP ضد مسببات الأمراض المقاومة للأدوية ذات الصلة سريريًا والميكروبات المعوية البشرية في كل من المختبر وفي الكائن الحي. كان هناك ما مجموعه 79 ببتيد نشط، مع 63 تستهدف مسببات الأمراض. أظهرت هذه AMPs النشطة نشاطًا مضادًا للبكتيريا من خلال تعطيل أغشية البكتيريا. في الختام، حدد نهجنا ما يقرب من مليون تسلسل AMP بدائي النواة، وهو مورد مفتوح الوصول لاكتشاف المضادات الحيوية.

مقدمة

في المختبر ضد مسببات الأمراض ESKAPEE ذات الأهمية السريرية، والتي تُعتبر من القضايا الصحية العامة.

النتائج

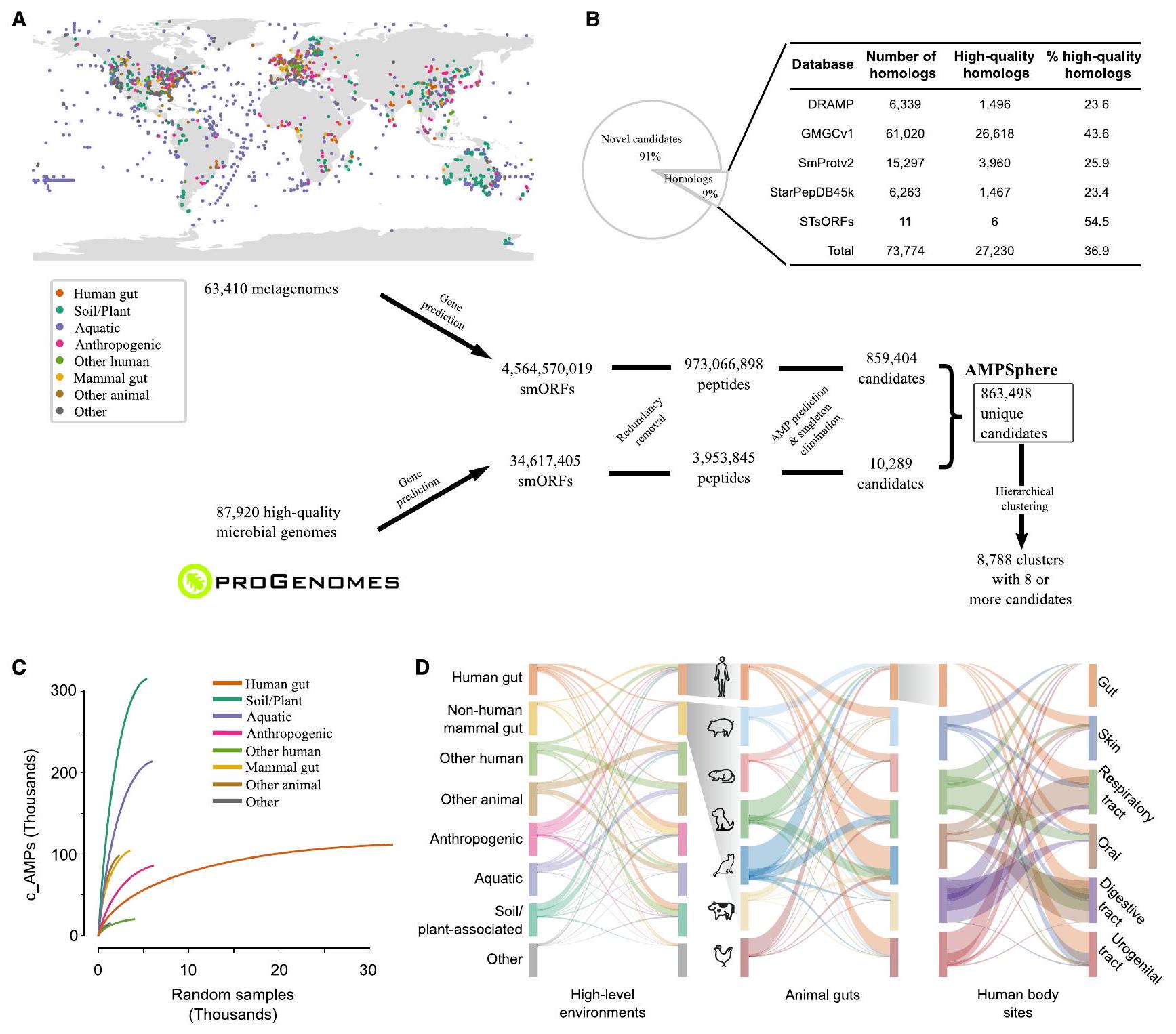

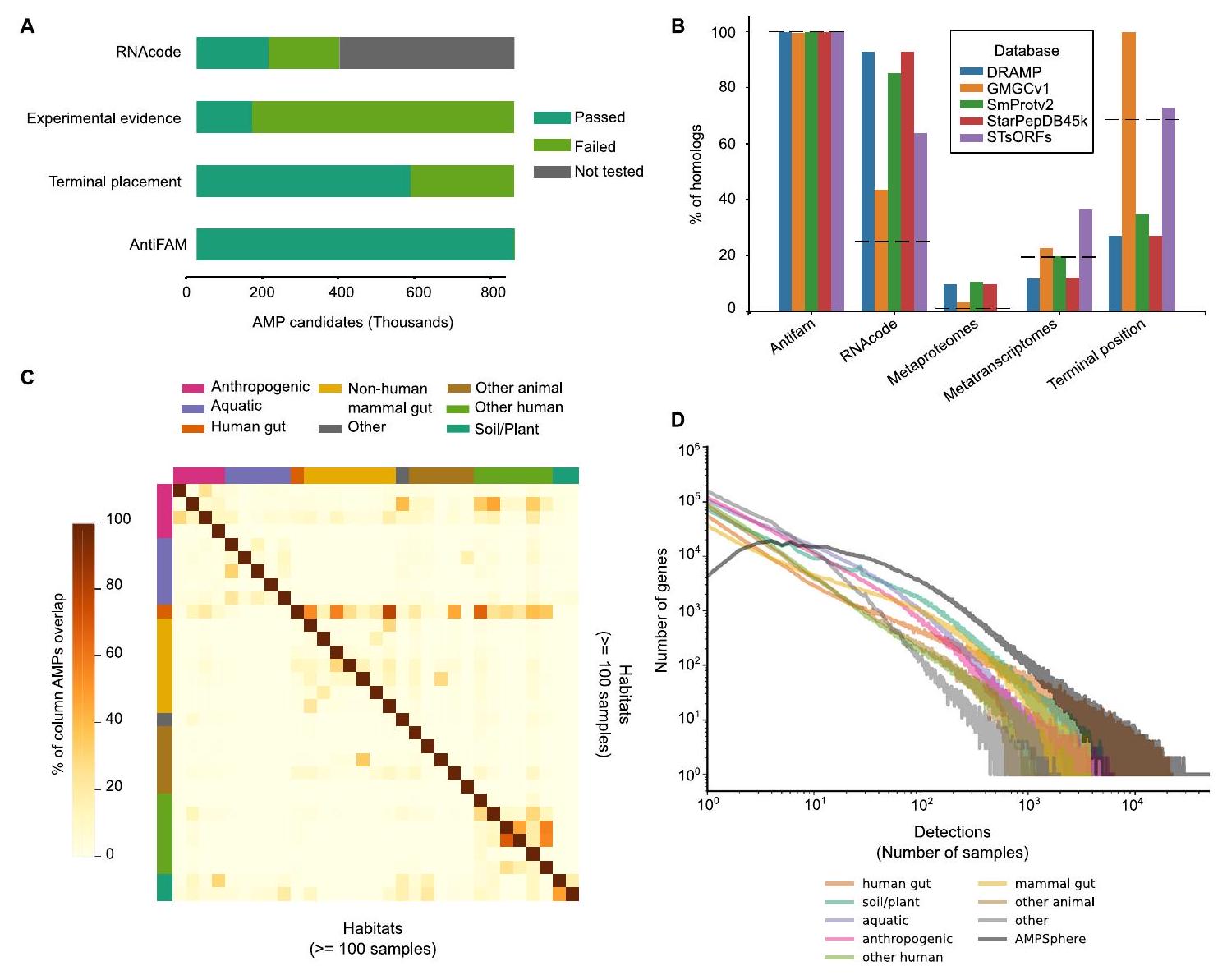

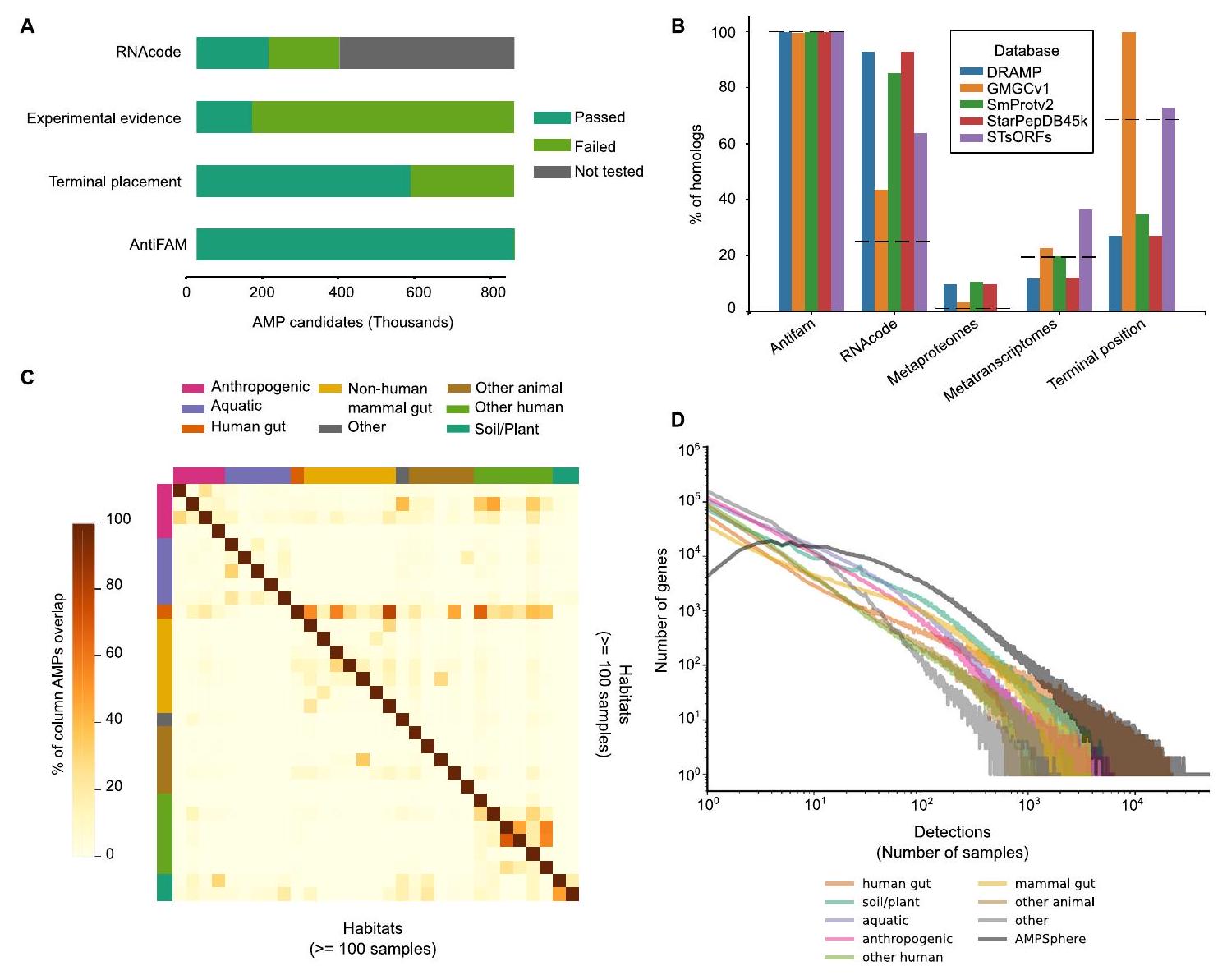

تتكون AMPSphere من ما يقرب من مليون c_AMPs من عدة موائل

(ب) فقط

(C) تظهر منحنيات التخفيف كيف يؤثر أخذ العينات على اكتشاف AMP، حيث تقدم معظم المواطن منحنيات أخذ عينات حادة.

(د) مشاركة c_AMPs بين المواطن محدودة. عرض الأشرطة يمثل نسبة c_AMPs المشتركة في المواطن على اليسار. انظر أيضًا الأشكال S2C و S2D والجداول S1 و S2.

تم الإرسال من قواعد بيانات البروتينات غير المحددة لـ AMPs (الشكل 1B)، مثل قاعدة بيانات البروتينات الصغيرة (SmProt2)

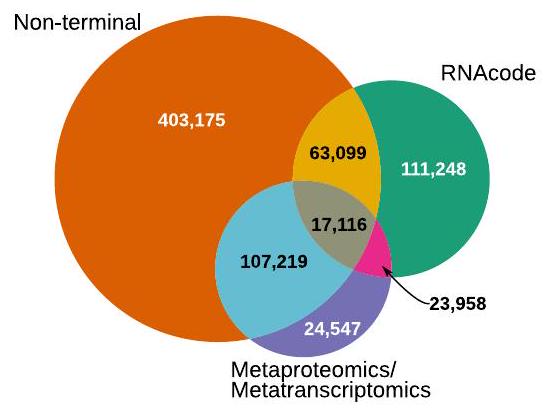

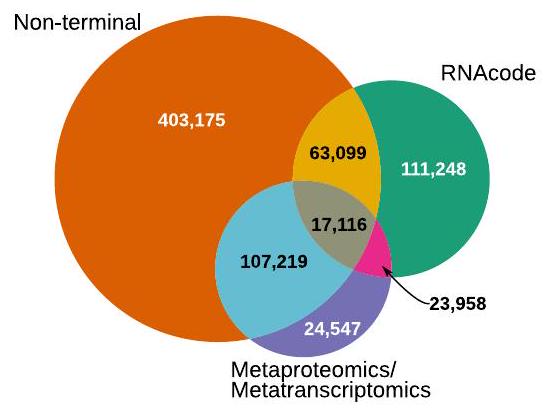

(أ) يتم عرض عدد مرشحي AMPSphere الذين اجتازوا كل اختبار مقترح للجودة. تتكون مجموعة الجودة العالية من

(ب) عدد المرشحين لمضادات الميكروبات الذين تم التنبؤ بهم بشكل مشترك بواسطة أنظمة التنبؤ بمضادات الميكروبات بخلاف ماكرل (AMPScanner v2،

مساحة تسلسل الببتيد التي لا توجد في هذه القواعد البيانات الأخرى. في المجموع، لم نتمكن من العثور إلا على 73,774 (

c_AMPs نادرة ومحددة الموائل

تولد الطفرات في الجينات الأكبر c_AMPs ككيانات جينومية مستقلة

| CD3:33 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTG G CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| F0106 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAAA TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| F0697 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| SAMN09837386 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTG A CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| SAMN09837387 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTGA CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| سامن09837388 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTGA CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_760 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_306 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_1566 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG G CAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| ATCC 25845 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG G CAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

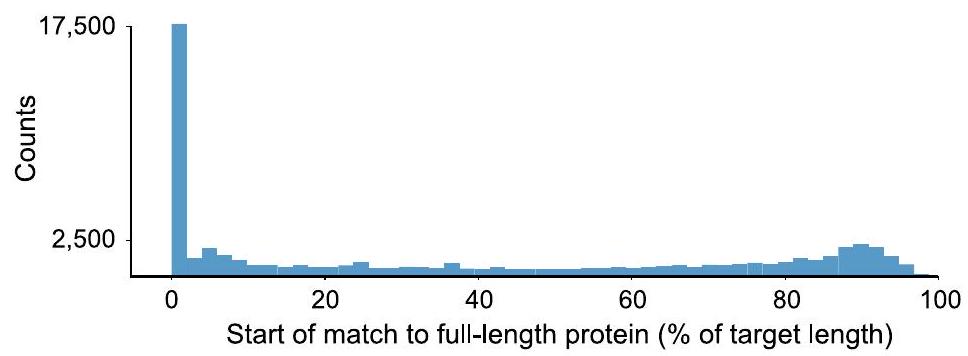

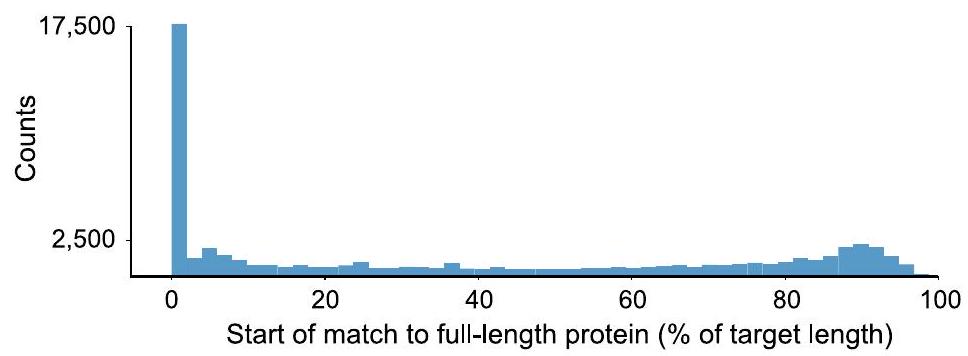

يوضح توزيع المواقع (كنسبة مئوية من طول البروتين الأكبر) التي تبدأ منها المتجانسات AMP محاذاتها. حوالي 7% من c_AMPs متجانسة مع بروتينات من GMGCv1،

(ب) كمثال توضيحي لمركب AMP متجانس مع بروتين كامل الطول، تم استرداد AMP10.271_016 من ثلاث عينات من لعاب الإنسان من نفس المتبرع.

(ج) توزيع AMPs حسب فئة OG (يسار) وغناها مقارنة بالبروتينات كاملة الطول من GMGCv1

قد تنشأ جينات c_AMP بعد أحداث تكرار الجينات

معظم c_AMPs هي أعضاء في الجينوم المساعد

الأنواع الأكثر قابلية للنقل لديها كثافة c_AMP أقل

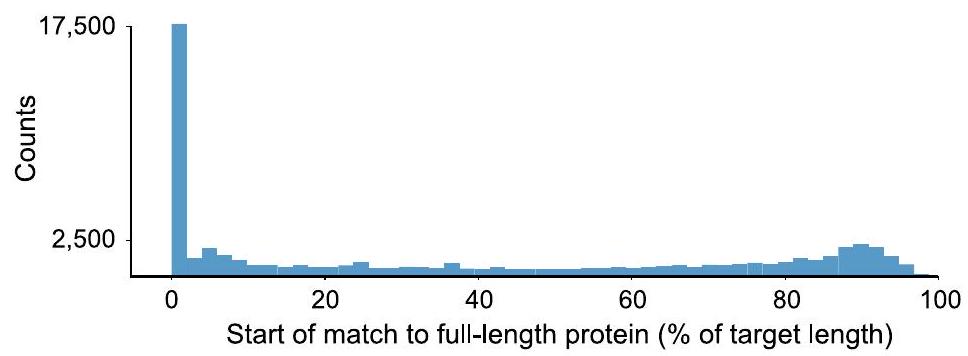

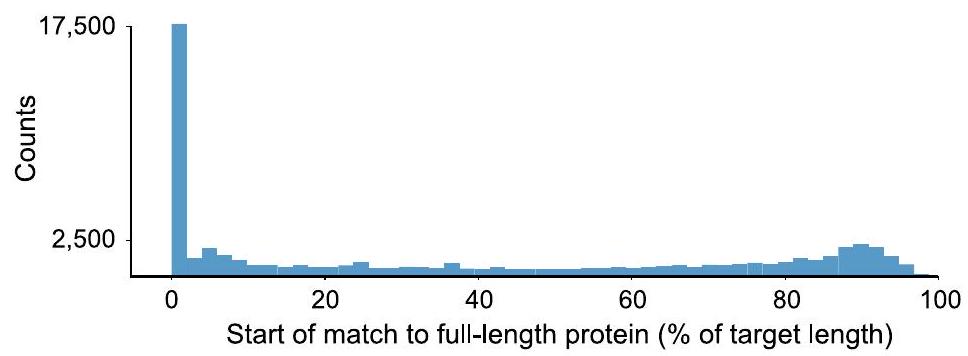

(أ) مقارنةً بالبروتينات الأخرى، تميل c_AMPs في الهياكل الجينومية المحفوظة إلى أن تكون أقرب إلى الجينات المتعلقة بآلية الريبوسوم من عائلات البروتينات ذات الأحجام المختلفة (جميع البروتينات ذات الطول الصغير و

(ب) نسبة c_AMPs في سياق الجينوم الذي يتضمن جينات مقاومة المضادات الحيوية أقل من تلك الموجودة في عائلات الجينات الأخرى.

(ج) نسبة c_AMPs في الأحياء المجاورة مع جينات مرتبطة بتخليق المضادات الحيوية صغيرة جدًا (

(د) يظهر السياق الجينومي المحفوظ للجين الذي يشفر AMP10.015_426 في جينومات مختلفة (الشجرة على اليسار توضح العلاقة التطورية للجينات المتجانسة له). هذا c_AMP متجانس مع البروتين الريبوسومي rpsH ويجد في سياق rpsH وجينات البروتينات الريبوسومية الأخرى. انظر أيضًا الجدول S4.

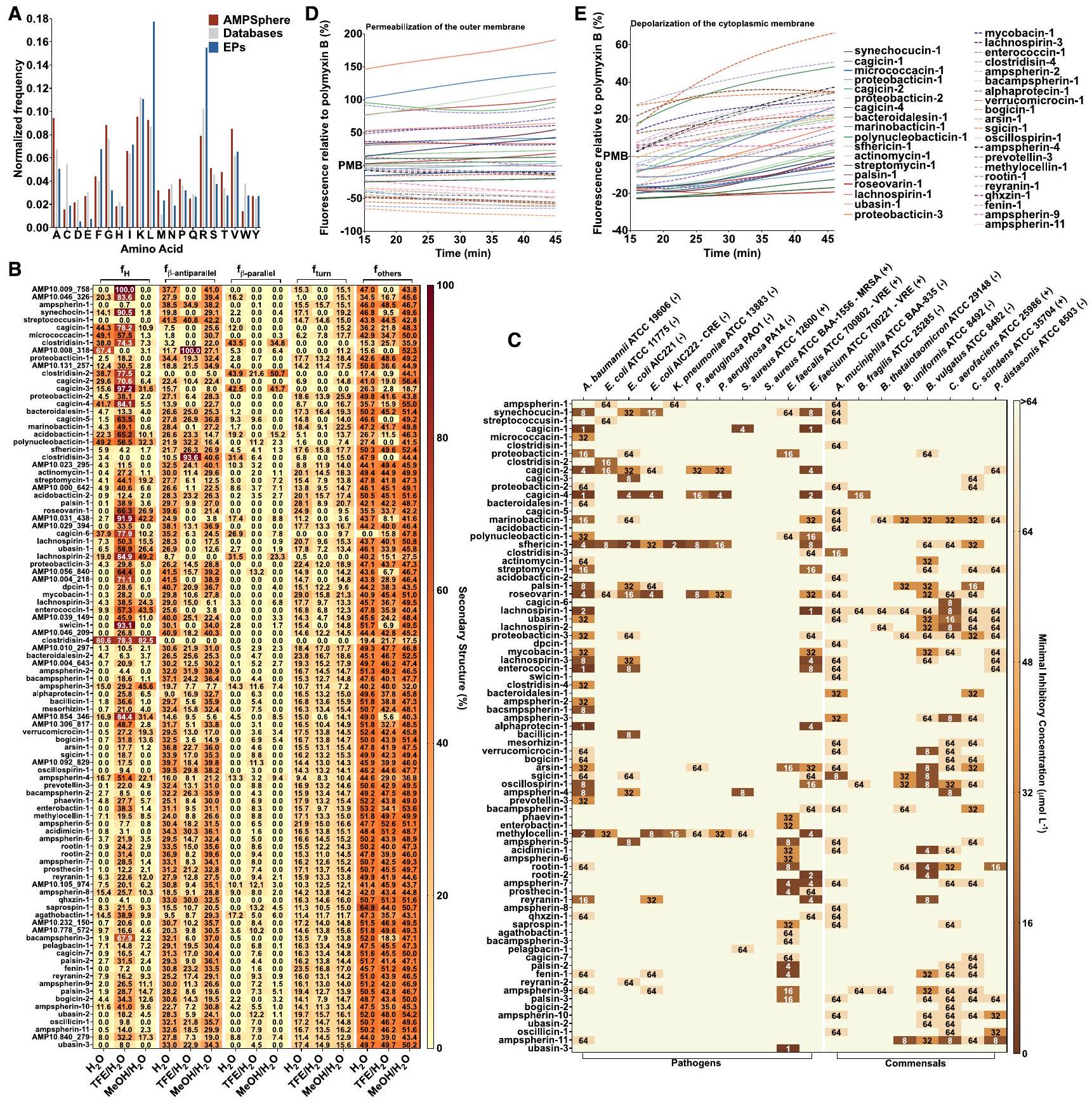

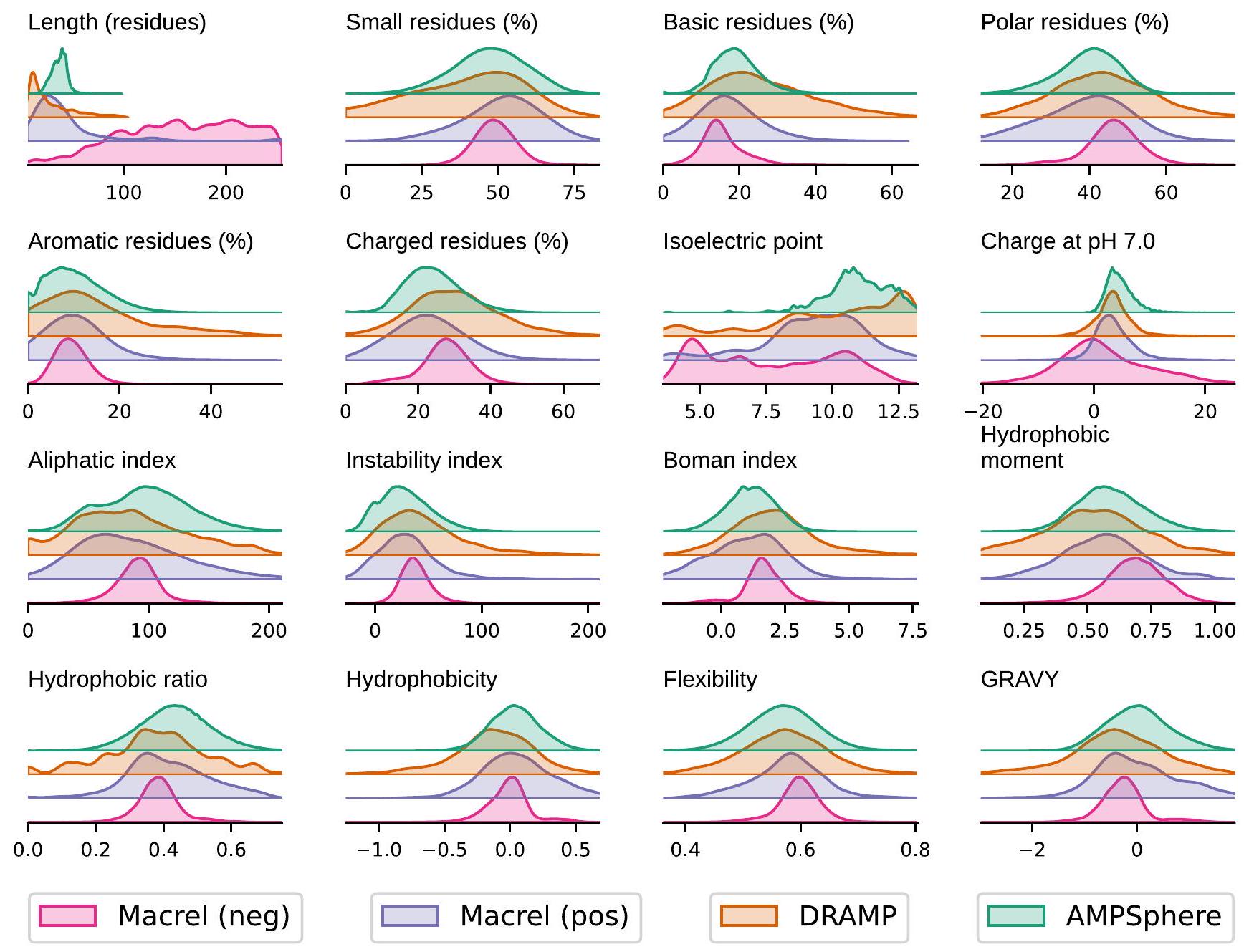

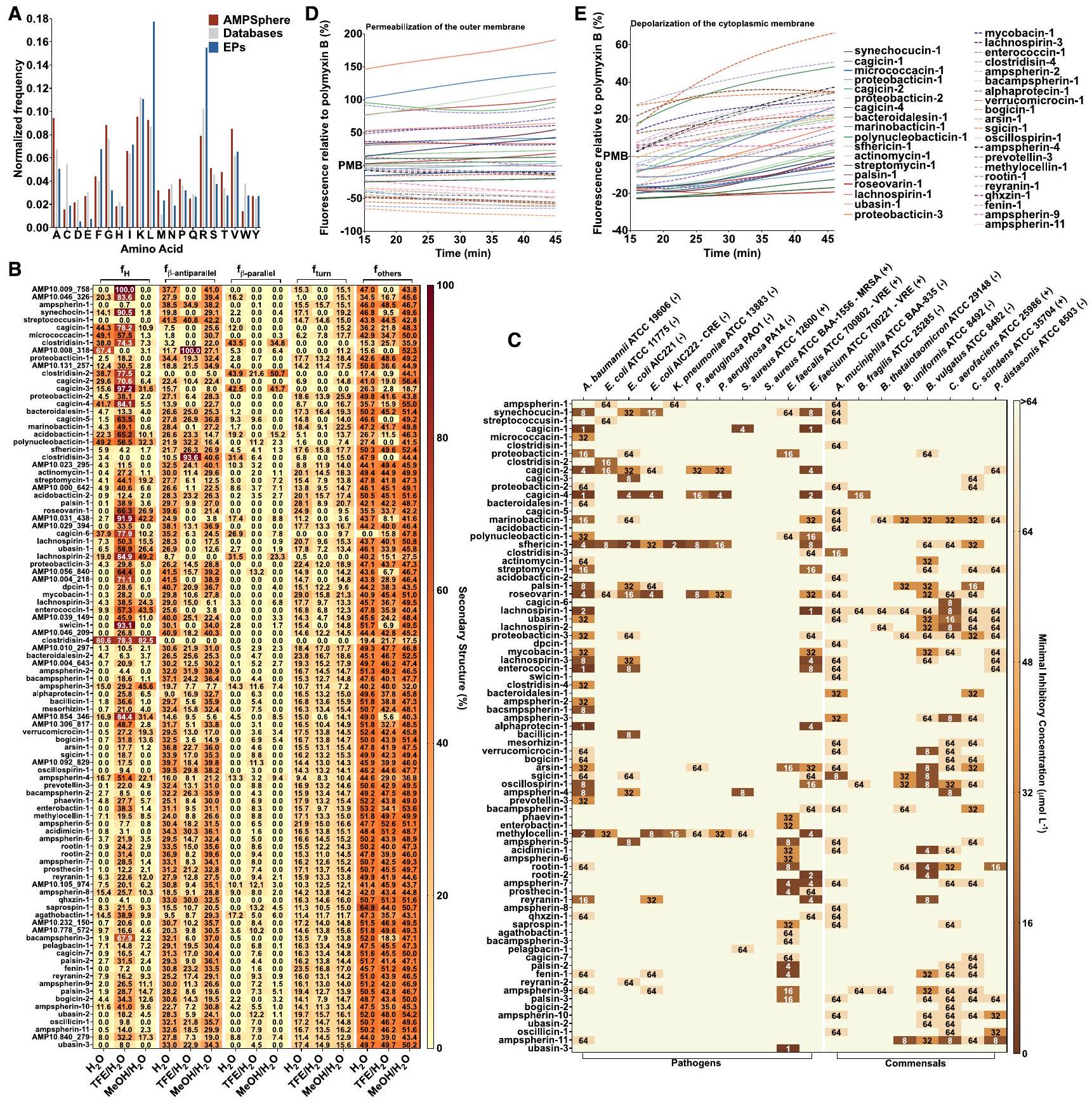

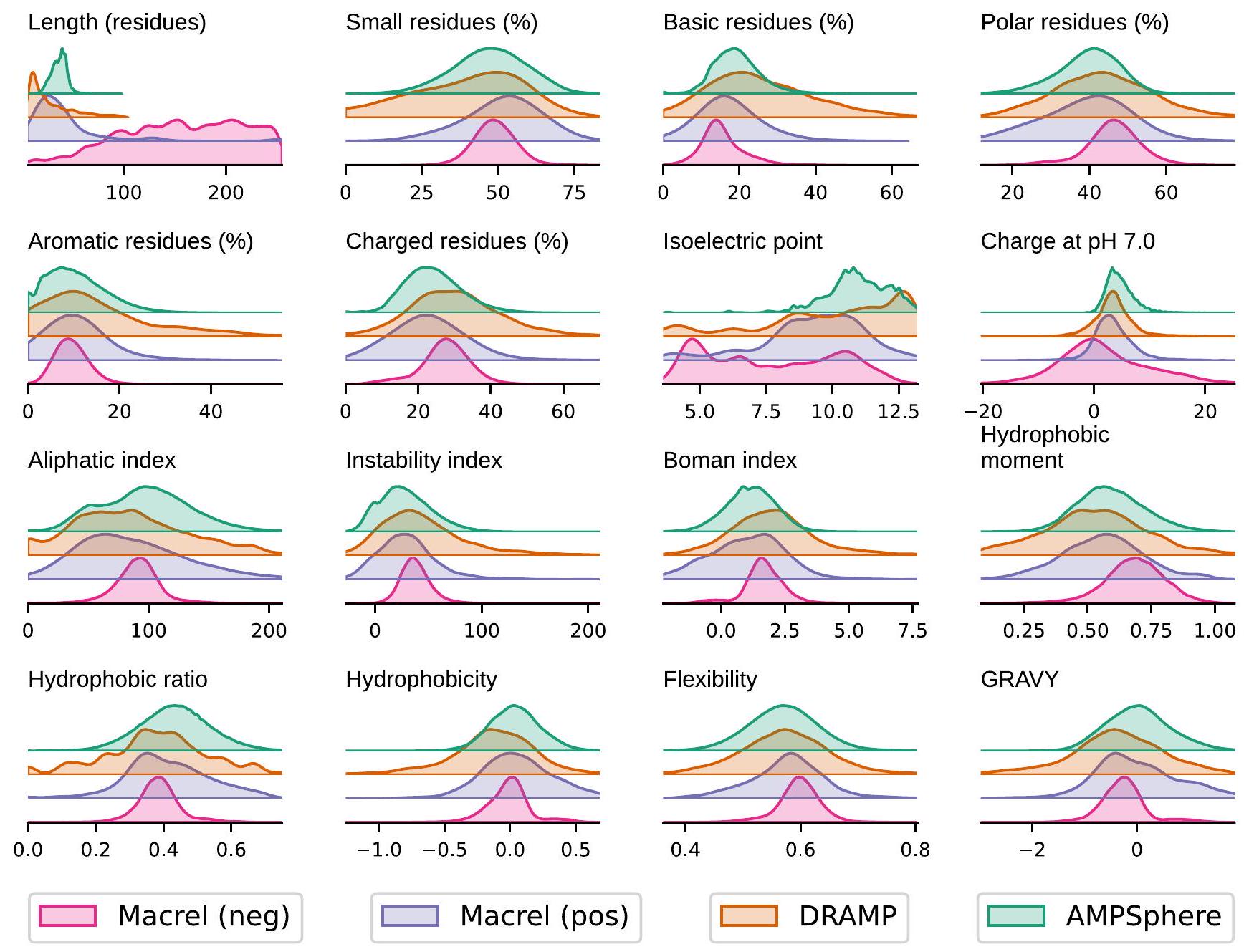

الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية والبنية الثانوية لـ AMPs

الشحنة الصافية، والأمفيليتية مقارنةً بـ AMPs المستمدة من قواعد البيانات (الشكل S1). علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت ميلًا طفيفًا للتكوينات غير المرتبة (الشكل 6B) وكان لديها شحنة إيجابية صافية أقل مقارنةً بـ EPs الأخرى (الشكل 6A).

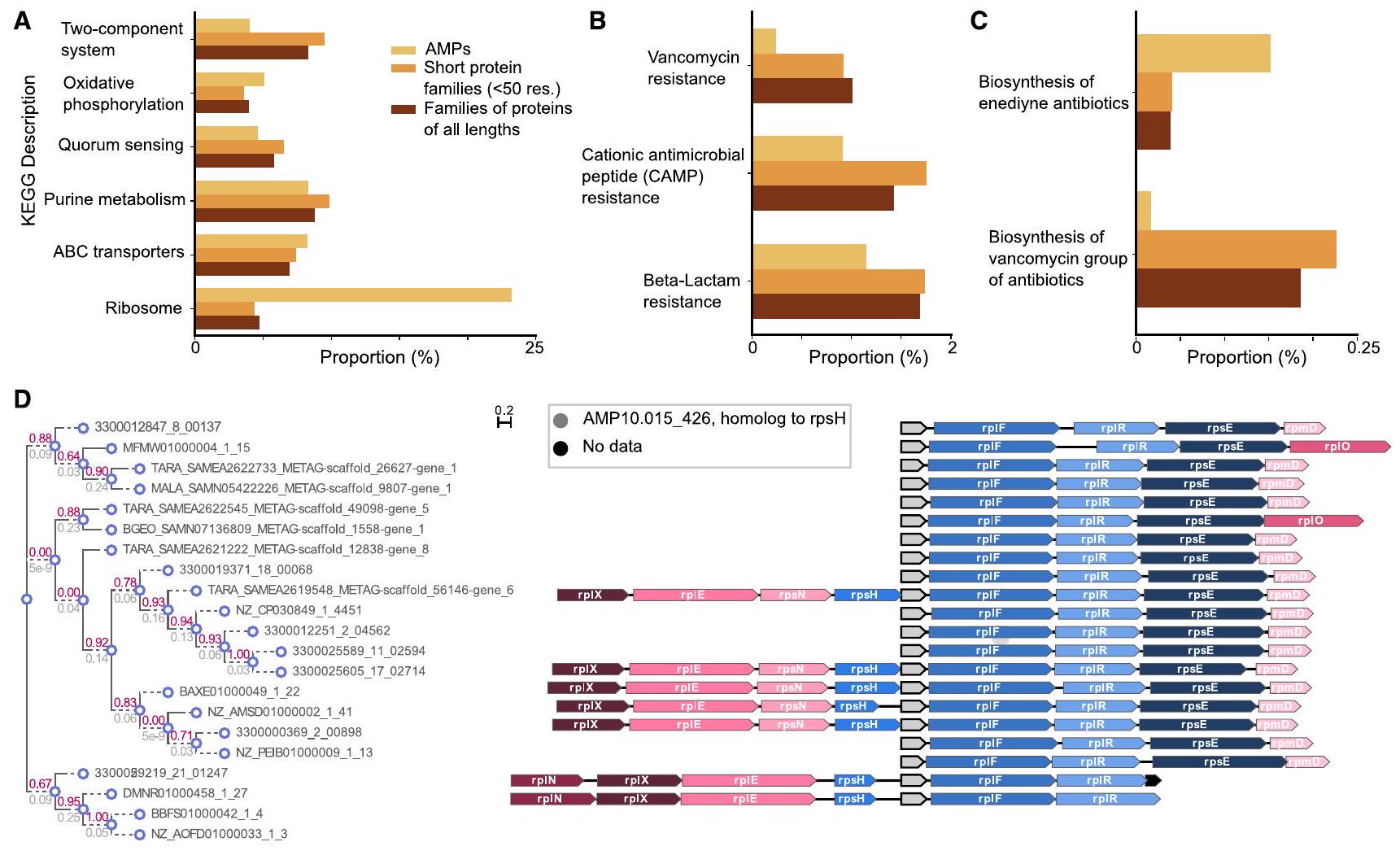

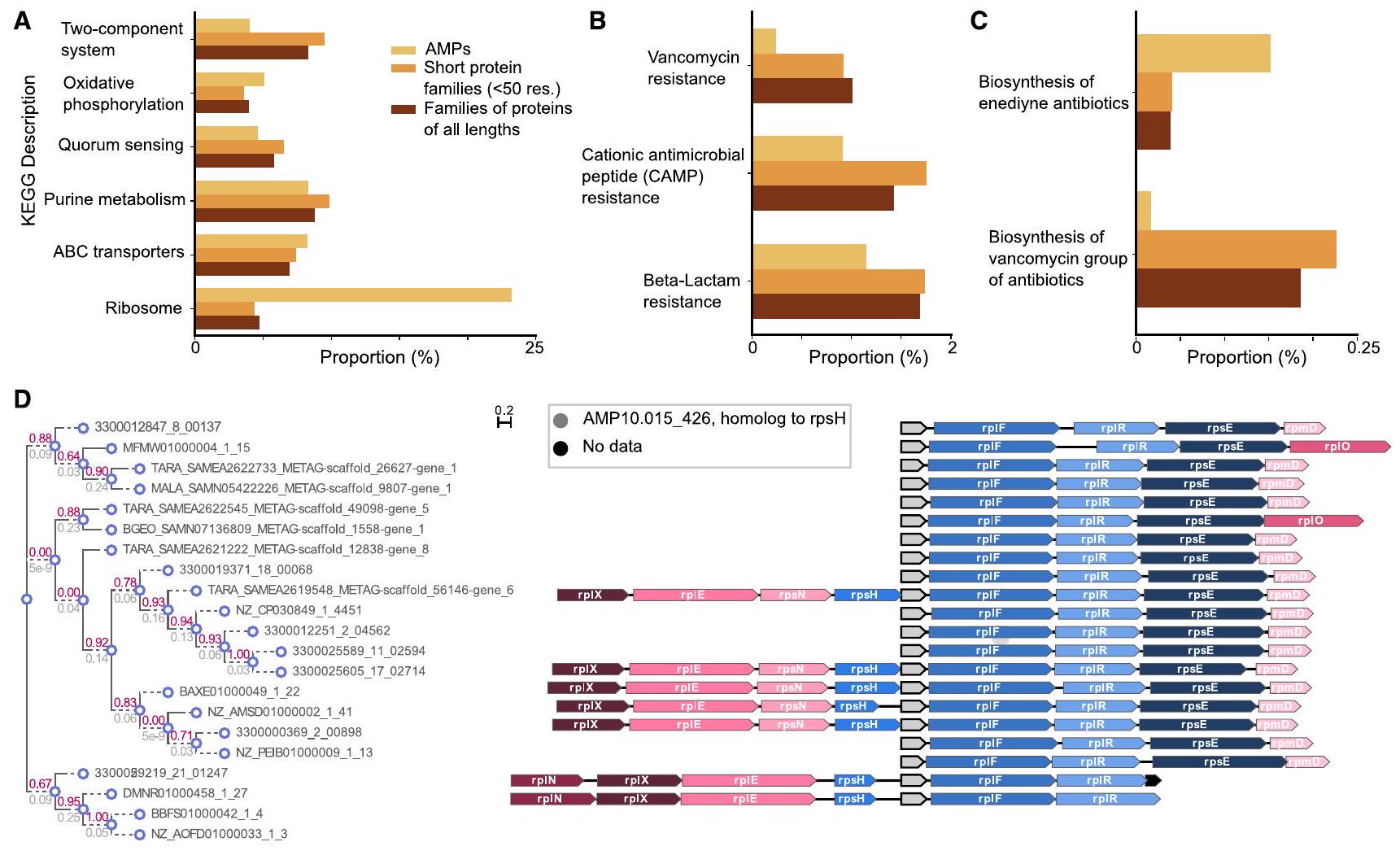

(أ) تظهر النسب المئوية لـ AMPs (أو عائلات AMP) التي هي مساعدة (موجودة في

(ب) توزيع أدنى مستوى تصنيفي تم توضيح c_AMPs فيه. بالتفصيل (اليمين) الأجناس العشرة الأولى التي تحتوي على أكبر عدد من c_AMPs المدرجة في AMPSphere. تساهم الأجناس المرتبطة بالحيوانات (مثل Prevotella وFaecalibacterium وCAG-110) بأكبر عدد من c_AMPs، مما يعكس على الأرجح أخذ العينات البيانية.

(ج) باستخدام

(د) يظهر تصنيف الأنواع المكتشفة في AMPSphere باستخدام GTDB

تحقق من فعالية c_AMPs كمضادات ميكروبية قوية من خلال اختبارات في المختبر

نمو واحد على الأقل من العوامل الممرضة المختبرة (الشكل 6C). ومن المRemarkably، في بعض الحالات، كانت AMP نشطة بتركيزات منخفضة تصل إلى

(أ) تكرار الأحماض الأمينية في c_AMPs من AMPSphere، AMPs من قواعد البيانات (DRAMP

(ب) خريطة حرارية مع النسبة المئوية للهيكل الثانوي الموجود لكل ببتيد في ثلاثة مذيبات مختلفة: الماء،

(ج) تم تقييم نشاط c_AMPs ضد مسببات الأمراض ESKAPEE وسلالات البكتيريا المعوية البشرية. باختصار،

تعيق c_AMPs نمو الكائنات الحية الدقيقة المعوية البشرية.

اختراق وإزالة الاستقطاب للغشاء البكتيري بواسطة c_AMPs من AMPSphere

في التحكم، استخدمنا بوليميكسين ب، وهو مضاد حيوي ببتيدي معروف بخصائصه في نفاذية الغشاء وإزالة الاستقطاب.

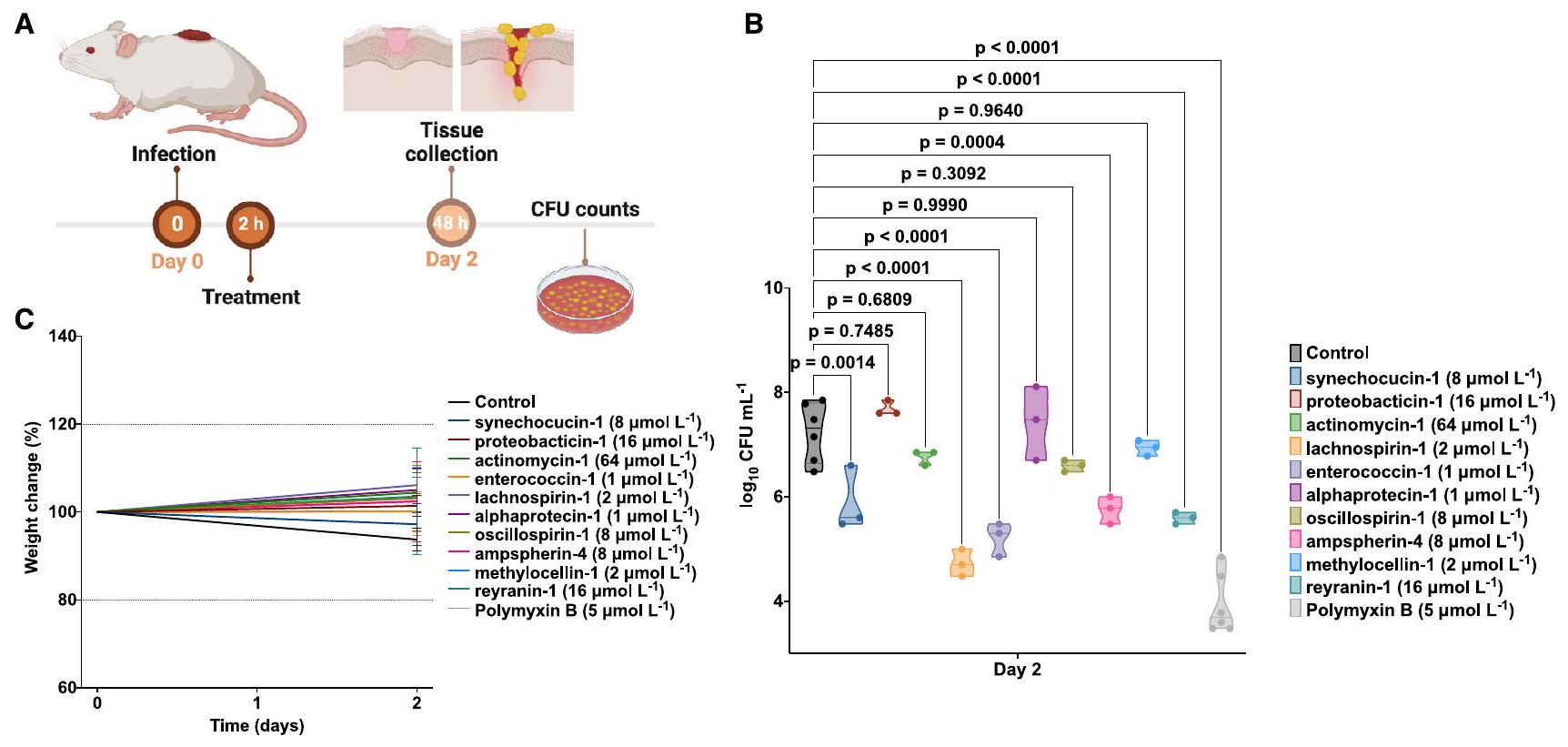

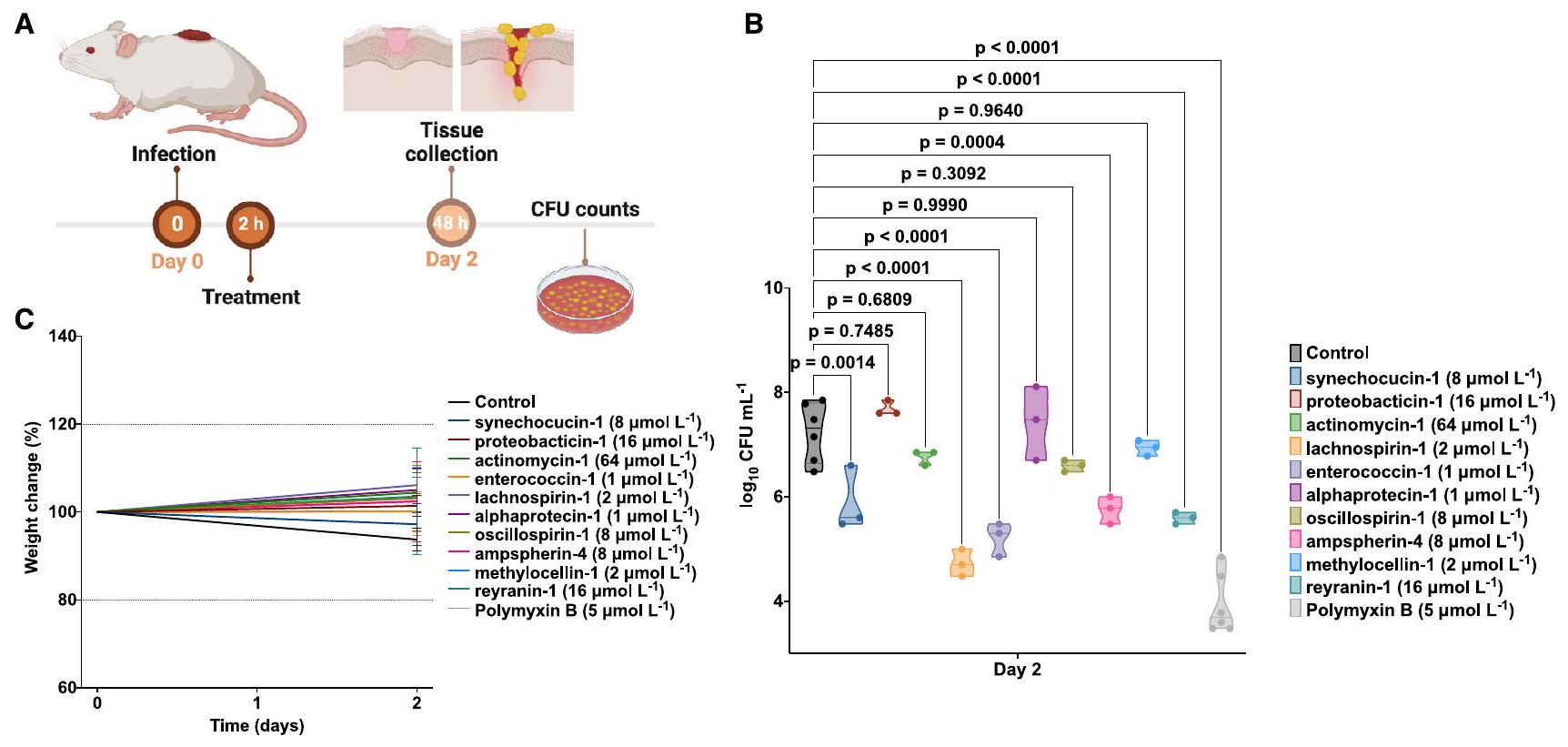

تظهر AMP فعالية مضادة للعدوى في نموذج الفأر

(أ) مخطط نموذج خراج الجلد في الفئران المستخدم لتقييم النشاط المضاد للعدوى للببتيدات ضد خلايا A. baumannii.

(ب) تم اختبار الببتيدات عند تركيزها المثبط الأدنى في جرعة واحدة بعد ساعتين من بدء العدوى. كانت كل مجموعة تتكون من ثلاثة فئران.

(ج) لاستبعاد التأثيرات السامة للببتيدات، تم مراقبة وزن الفئران طوال التجربة.

تم تحديد الدلالة الإحصائية في (B) باستخدام تحليل التباين الأحادي حيث تم مقارنة جميع المجموعات مع مجموعة التحكم غير المعالجة؛

القدرة العدوانية للببتيدات المختبرة من AMPSphere حيث تم إعطاؤها في وقت واحد مباشرة بعد تكوين الخراج. تم مراقبة وزن الفأر كبديل للسمية، ولم تُلاحظ تغييرات كبيرة (الأشكال 7C و S6D)، مما يشير إلى أن الببتيدات المختبرة لم تكن سامة.

نقاش

أنها كانت نشطة، بما في ذلك بياناتنا الخاصة في المختبر ووجود نظائر موثقة في قواعد البيانات الخارجية. من غير المرجح أن تمر الببتيدات ذات الانتشار المنخفض بالاختبارات (RNAcode

و لاكنوسبيرين-1 ضد الإشريكية القولونية المقاومة للفانكومايسين) قدمت قيم MIC منخفضة تصل إلى

قيود الدراسة

طرق النجوم

- جدول الموارد الرئيسية

- توافر الموارد

- جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

- توفر المواد

- توفر البيانات والشيفرة

- تفاصيل النموذج التجريبي وشارك الدراسة

- سلالات البكتيريا وظروف النمو

- نموذج الفأر لعدوى خراج الجلد

- تفاصيل الطريقة

- اختيار الجينومات الميكروبية (الميتاجينومية)

- قص و تجميع القراءات

- تنبؤ smORF و AMP

- تجميع عائلات AMP

- مراقبة جودة c_AMPs

- منحنيات تراكم c_AMPs المستندة إلى العينة

- cAMPs متعددة المواطن ونادرة

كثافة c_AMP في الأنواع الميكروبية

نقل c_AMPs وأنواع البكتيريا

تحديد مضخات الملحقات

توصيف AMP باستخدام مجموعات بيانات مختلفة

تحليل الحفاظ على السياق الجينومي

موارد ويب AMPSphere

اختيار الببتيدات للتخليق والاختبار

تحديد التركيز المثبط الأدنى (MIC)

اختبارات التشتت الدائري

اختبارات نفاذية الغشاء الخارجي

اختبارات إزالة الاستقطاب للغشاء السيتوبلازمي

- التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

- موارد إضافية

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

X.-M.Z. و C.F.-N.; التحقيق، C.D.S.-J. و L.P.C. و M.D.T.T. و C.F.-N.; المنهجية، C.D.S.-J. و Y.D. و J.H.-C. و A.R.d.R. و L.P.C. و M.D.T.T. و C.F.-N.; إدارة المشروع، L.P.C. و M.K. و X.-M.Z. و P.B. و C.F.-N.; الموارد، L.P.C. و X.-M.Z. و C.F.-N.; الإشراف، L.P.C. و C.F.-N.; التصور، C.D.S.-J. و J.H.-C. و J.S. و A.V. و A.H. و C.Z. و L.P.C. و M.D.T.T.; كتابة المسودة الأصلية، C.D.S.-J. و M.D.T.T. و C.F.-N. و L.P.C.; كتابة – مراجعة وتحرير، C.D.S.-J. و Y.D. و J.H.-C. و A.R.d.R. و T.S.B.S. و A.F. و P.B. و X.-M.Z. و L.P.C. و M.D.T.T. و C.F.-N.

إعلان المصالح

تمت المراجعة: 11 أبريل 2024

تم القبول: 6 مايو 2024

نُشر: 5 يونيو 2024

REFERENCES

- de la Fuente-Nunez, C., Torres, M.D., Mojica, F.J., and Lu, T.K. (2017). Next-generation precision antimicrobials: towards personalized treatment of infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37, 95-102. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.014.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629-655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

- Stokes, J.M., Yang, K., Swanson, K., Jin, W., Cubillos-Ruiz, A., Donghia, N.M., MacNair, C.R., French, S., Carfrae, L.A., Bloom-Ackermann, Z., et al. (2020). A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell 180, 688-702.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021.

- Torres, M.D.T., Melo, M.C.R., Flowers, L., Crescenzi, O., Notomista, E., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2022). Mining for encrypted peptide antibiotics in the human proteome. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 67-75. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41551-021-00801-1.

- Porto, W.F., Irazazabal, L., Alves, E.S.F., Ribeiro, S.M., Matos, C.O., Pires, Á.S., Fensterseifer, I.C.M., Miranda, V.J., Haney, E.F., Humblot, V., et al. (2018). In silico optimization of a guava antimicrobial peptide enables combinatorial exploration for peptide design. Nat. Commun. 9, 1490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03746-3.

- Ma, Y., Guo, Z., Xia, B., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Yu, Y., Tang, N., Tong, X., Wang, M., Ye, X., et al. (2022). Identification of antimicrobial peptides from the human gut microbiome using deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 921-931. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01226-0.

- Wong, F., de la Fuente-Nunez, C., and Collins, J.J. (2023). Leveraging artificial intelligence in the fight against infectious diseases. Science 381, 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh1114.

- Cesaro, A., Bagheri, M., Torres, M., Wan, F., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2023). Deep learning tools to accelerate antibiotic discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 18, 1245-1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441. 2023.2250721.

- Torres, M.D.T., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2019). Toward computermade artificial antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 51, 30-38. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.03.004.

- Maasch, J.R.M.A., Torres, M.D.T., Melo, M.C.R., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2023). Molecular de-extinction of ancient antimicrobial peptides enabled by machine learning. Cell Host Microbe 31, 1260-1274.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.07.001.

- Besse, A., Vandervennet, M., Goulard, C., Peduzzi, J., Isaac, S., Rebuffat, S., and Carré-Mlouka, A. (2017). Halocin C8: an antimicrobial peptide

distributed among four halophilic archaeal genera: Natrinema, Haloterrigena, Haloferax, and Halobacterium. Extremophiles 21, 623-638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-017-0931-5. - Cotter, P.D., Ross, R.P., and Hill, C. (2013). Bacteriocins – a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 95-105. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nrmicro2937.

- Wang, S., Zheng, Z., Zou, H., Li, N., and Wu, M. (2019). Characterization of the secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in archaea. Comput. Biol. Chem. 78, 165-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem. 2018.11.019.

- Zasloff, M. (2019). Antimicrobial Peptides of Multicellular Organisms: My Perspective. In Antimicrobial Peptides: Basics for Clinical Application, K. Matsuzaki, ed. (Springer Singapore), pp. 3-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-981-13-3588-4_1.

- Huang, K.-Y., Chang, T.-H., Jhong, J.-H., Chi, Y.-H., Li, W.-C., Chan, C.L., Robert Lai, K., and Lee, T.-Y. (2017). Identification of natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria through metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data of Taiwanese oolong teas. BMC Syst. Biol. 11, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12918-017-0503-4.

- Torres, M.D.T., Sothiselvam, S., Lu, T.K., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2019). Peptide Design Principles for Antimicrobial Applications. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3547-3567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2018.12.015.

- Pizzo, E., Cafaro, V., Di Donato, A., and Notomista, E. (2018). Cryptic Antimicrobial Peptides: Identification Methods and Current Knowledge of their Immunomodulatory Properties. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24, 10541066. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180327165012.

- Nolan, E.M., and Walsh, C.T. (2009). How nature morphs peptide scaffolds into antibiotics. Chembiochem 10, 34-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cbic. 200800438.

- Singh, N., and Abraham, J. (2014). Ribosomally synthesized peptides from natural sources. J. Antibiot. 67, 277-289. https://doi.org/10.1038/ ja.2013.138.

- García-Bayona, L., and Comstock, L.E. (2018). Bacterial antagonism in host-associated microbial communities. Science 361, eaat2456. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat2456.

- Anderson, M.C., Vonaesch, P., Saffarian, A., Marteyn, B.S., and Sansonetti, P.J. (2017). Shigella sonnei encodes a functional T6SS used for interbacterial competition and niche occupancy. Cell Host Microbe 21, 769-776.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.004.

- Krismer, B., Weidenmaier, C., Zipperer, A., and Peschel, A. (2017). The commensal lifestyle of Staphylococcus aureus and its interactions with the nasal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 675-687. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.104.

- Zhao, W., Caro, F., Robins, W., and Mekalanos, J.J. (2018). Antagonism toward the intestinal microbiota and its effect on Vibrio cholerae virulence. Science 359, 210-213. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8775.

- Quereda, J.J., Nahori, M.A., Meza-Torres, J., Sachse, M., Titos-Jiménez, P., Gomez-Laguna, J., Dussurget, O., Cossart, P., and Pizarro-Cerdá, J. (2017). Listeriolysin S is a streptolysin s-like virulence factor that targets exclusively prokaryotic cells in vivo. mBio 8, e00259-17. https://doi.org/

. - Quereda, J.J., Dussurget, O., Nahori, M.A., Ghozlane, A., Volant, S., Dillies, M.A., Regnault, B., Kennedy, S., Mondot, S., Villoing, B., et al. (2016). Bacteriocin from epidemic Listeria strains alters the host intestinal microbiota to favor infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5706-5711. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523899113.

- Gomes, B., Augusto, M.T., Felício, M.R., Hollmann, A., Franco, O.L., Gonçalves, S., and Santos, N.C. (2018). Designing improved active peptides for therapeutic approaches against infectious diseases. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 415-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.01.004.

- Lesiuk, M., Paduszyńska, M., and Greber, K.E. (2022). Synthetic Antimicrobial Immunomodulatory Peptides: Ongoing Studies and Clinical Tri-

als. Antibiotics (Basel) 11, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics 11081062. - Mahlapuu, M., Håkansson, J., Ringstad, L., and Björn, C. (2016). Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6, 235805.

- Baquero, F., Lanza, V.F., Baquero, M.R., Del Campo, R., and Bravo-Vázquez, D.A. (2019). Microcins in Enterobacteriaceae: peptide antimicrobials in the eco-active intestinal chemosphere. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2261. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02261.

- Kim, S.G., Becattini, S., Moody, T.U., Shliaha, P.V., Littmann, E.R., Seok, R., Gjonbalaj, M., Eaton, V., Fontana, E., Amoretti, L., et al. (2019). Micro-biota-derived lantibiotic restores resistance against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Nature 572, 665-669. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-019-1501-z.

- Nakatsuji, T., Hata, T.R., Tong, Y., Cheng, J.Y., Shafiq, F., Butcher, A.M., Salem, S.S., Brinton, S.L., Rudman Spergel, A.K., Johnson, K., et al. (2021). Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 27, 700-709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2.

- Spohn, R., Daruka, L., Lázár, V., Martins, A., Vidovics, F., Grézal, G., Méhi, O., Kintses, B., Számel, M., Jangir, P.K., et al. (2019). Integrated evolutionary analysis reveals antimicrobial peptides with limited resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 4538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12364-6.

- Cesaro, A., Torres, M.D.T., Gaglione, R., Dell’Olmo, E., Di Girolamo, R., Bosso, A., Pizzo, E., Haagsman, H.P., Veldhuizen, E.J.A., de la FuenteNunez, C., and Arciello, A. (2022). Synthetic Antibiotic Derived from Sequences Encrypted in a Protein from Human Plasma. ACS Nano 16, 1880-1895. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c04496.

- Hyatt, D., Chen, G.-L., LoCascio, P.F., Land, M.L., Larimer, F.W., and Hauser, L.J. (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinf. 11, 119. https://doi.org/10. 1186/1471-2105-11-119.

- Ahrens, C.H., Wade, J.T., Champion, M.M., and Langer, J.D. (2022). A Practical Guide to Small Protein Discovery and Characterization Using Mass Spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 204, e0035321. https://doi.org/10. 1128/JB.00353-21.

- Storz, G., Wolf, Y.I., and Ramamurthi, K.S. (2014). Small Proteins Can No Longer Be Ignored. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 753-777. https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070611-102400.

- Su, M., Ling, Y., Yu, J., Wu, J., and Xiao, J. (2013). Small proteins: untapped area of potential biological importance. Front. Genet. 4, 286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00286.

- Sberro, H., Fremin, B.J., Zlitni, S., Edfors, F., Greenfield, N., Snyder, M.P., Pavlopoulos, G.A., Kyrpides, N.C., and Bhatt, A.S. (2019). LargeScale Analyses of Human Microbiomes Reveal Thousands of Small, Novel Genes. Cell 178, 1245-1259.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell. 2019.07.016.

- Donia, M.S., Cimermancic, P., Schulze, C.J., Wieland Brown, L.C., Martin, J., Mitreva, M., Clardy, J., Linington, R.G., and Fischbach, M.A. (2014). A systematic analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters in the human microbiome reveals a common family of antibiotics. Cell 158, 1402-1414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.032.

- Fingerhut, L.C.H.W., Miller, D.J., Strugnell, J.M., Daly, N.L., and Cooke, I.R. (2021). ampir: an

package for fast genome-wide prediction of antimicrobial peptides. Bioinformatics 36, 5262-5263. https://doi.org/10. 1093/bioinformatics/btaa653. - Sugimoto, Y., Camacho, F.R., Wang, S., Chankhamjon, P., Odabas, A., Biswas, A., Jeffrey, P.D., and Donia, M.S. (2019). A metagenomic strategy for harnessing the chemical repertoire of the human microbiome. Science 366, eaax9176. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax9176.

- Santos-Júnior, C.D., Pan, S., Zhao, X.-M., and Coelho, L.P. (2020). Macrel: antimicrobial peptide screening in genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ 8, e10555. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj. 10555.

- Mende, D.R., Letunic, I., Maistrenko, O.M., Schmidt, T.S.B., Milanese, A., Paoli, L., Hernández-Plaza, A., Orakov, A.N., Forslund, S.K., Sunagawa, S., et al. (2020). proGenomes2: an improved database for accurate and consistent habitat, taxonomic and functional annotations of prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D621-D625. https://doi.org/10. 1093/nar/gkz1002.

- Navidinia, M. (2016). The clinical importance of emerging ESKAPE pathogens in nosocomial infections. Archives of Advances in Biosciences 7, 43-57. https://doi.org/10.22037/jps.v7i3.12584.

- Mulani, M.S., Kamble, E.E., Kumkar, S.N., Tawre, M.S., and Pardesi, K.R. (2019). Emerging Strategies to Combat ESKAPE Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 10, 539. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00539.

- Shi, G., Kang, X., Dong, F., Liu, Y., Zhu, N., Hu, Y., Xu, H., Lao, X., and Zheng, H. (2022). DRAMP 3.0: an enhanced comprehensive data repository of antimicrobial peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D488-D496. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab651.

- Zhang, L.-J., and Gallo, R.L. (2016). Antimicrobial peptides. Curr. Biol. 26, R14-R19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.017.

- Bhadra, P., Yan, J., Li, J., Fong, S., and Siu, S.W.I. (2018). AmPEP: Sequence-based prediction of antimicrobial peptides using distribution patterns of amino acid properties and random forest. Sci. Rep. 8, 1697. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19752-w.

- Hao, Y., Zhang, L., Niu, Y., Cai, T., Luo, J., He, S., Zhang, B., Zhang, D., Qin, Y., Yang, F., and Chen, R. (2018). SmProt: a database of small proteins encoded by annotated coding and non-coding RNA loci. Brief. Bioinform. 19, 636-643. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbx005.

- Venturini, E., Svensson, S.L., Maaß, S., Gelhausen, R., Eggenhofer, F., Li, L., Cain, A.K., Parkhill, J., Becher, D., Backofen, R., et al. (2020). A global data-driven census of Salmonella small proteins and their potential functions in bacterial virulence. microLife 1, uqaa002. https://doi.org/10. 1093/femsml/uqaa002.

- Aguilera-Mendoza, L., Marrero-Ponce, Y., Beltran, J.A., Tellez Ibarra, R., Guillen-Ramirez, H.A., and Brizuela, C.A. (2019). Graph-based data integration from bioactive peptide databases of pharmaceutical interest: toward an organized collection enabling visual network analysis. Bioinformatics 35, 4739-4747. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz260.

- Coelho, L.P., Alves, R., Del Río, Á.R., Myers, P.N., Cantalapiedra, C.P., Giner-Lamia, J., Schmidt, T.S., Mende, D.R., Orakov, A., Letunic, I., et al. (2022). Towards the biogeography of prokaryotic genes. Nature 601, 252-256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04233-4.

- Veltri, D., Kamath, U., and Shehu, A. (2018). Deep learning improves antimicrobial peptide recognition. Bioinformatics 34, 2740-2747. https://doi. org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty179.

- Lawrence, T.J., Carper, D.L., Spangler, M.K., Carrell, A.A., Rush, T.A., Minter, S.J., Weston, D.J., and Labbé, J.L. (2021). amPEPpy 1.0: a portable and accurate antimicrobial peptide prediction tool. Bioinformatics 37, 2058-2060. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa917.

- Su, X., Xu, J., Yin, Y., Quan, X., and Zhang, H. (2019). Antimicrobial peptide identification using multi-scale convolutional network. BMC Bioinf. 20, 730. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-019-3327-y.

- Lin, T.-T., Yang, L.-Y., Lu, I.-H., Cheng, W.-C., Hsu, Z.-R., Chen, S.-H., and Lin, C.-Y. (2021). Al4AMP: an Antimicrobial Peptide Predictor Using Physicochemical Property-Based Encoding Method and Deep Learning. mSystems 6, e0029921. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00299-21.

- Li, C., Sutherland, D., Hammond, S.A., Yang, C., Taho, F., Bergman, L., Houston, S., Warren, R.L., Wong, T., Hoang, L.M.N., et al. (2022). AMPlify: attentive deep learning model for discovery of novel antimicrobial peptides effective against whom priority pathogens. BMC Genom. 23, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08310-4.

- Murphy, L.R., Wallqvist, A., and Levy, R.M. (2000). Simplified amino acid alphabets for protein fold recognition and implications for folding. Protein Eng. 13, 149-152. https://doi.org/10.1093/protein/13.3.149.

- Heintz-Buschart, A., May, P., Laczny, C.C., Lebrun, L.A., Bellora, C., Krishna, A., Wampach, L., Schneider, J.G., Hogan, A., de Beaufort, C., and Wilmes, P. (2016). Integrated multi-omics of the human gut microbiome in a case study of familial type 1 diabetes. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.180.

- Huerta-Cepas, J., Szklarczyk, D., Heller, D., Hernández-Plaza, A., Forslund, S.K., Cook, H., Mende, D.R., Letunic, I., Rattei, T., Jensen, L.J., et al. (2019). eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D309-D314. https://doi.org/10.1093/ nar/gky1085.

- Rodríguez del Río, Á., Giner-Lamia, J., Cantalapiedra, C.P., Botas, J., Deng, Z., Hernández-Plaza, A., Munar-Palmer, M., Santamaría-Hernando, S., Rodríguez-Herva, J.J., Ruscheweyh, H.-J., et al. (2023). Functional and evolutionary significance of unknown genes from uncultivated taxa. Nature, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06955-z.

- Hurtado-Rios, J.J., Carrasco-Navarro, U., Almanza-Pérez, J.C., and Ponce-Alquicira, E. (2022). Ribosomes: The New Role of Ribosomal Proteins as Natural Antimicrobials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9123. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms23169123.

- Shoja, V., and Zhang, L. (2006). A Roadmap of Tandemly Arrayed Genes in the Genomes of Human, Mouse, and Rat. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 21342141. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msl085.

- Sukhodolets, V.V. (2006). Unequal crossing-over in Escherichia coli. Russ. J. Genet. 42, 1285-1293. https://doi.org/10.1134/S102279540611010X.

- Kim, M.K., Kang, T.H., Kim, J., Kim, H., and Yun, H.D. (2012). Evidence Showing Duplication and Recombination of cel Genes in Tandem from Hyperthermophilic Thermotoga sp. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 168, 1834-1848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-9901-7.

- Blaustein, R.A., McFarland, A.G., Ben Maamar, S., Lopez, A., CastroWallace, S., and Hartmann, E.M. (2019). Pangenomic Approach To Understanding Microbial Adaptations within a Model Built Environment, the International Space Station, Relative to Human Hosts and Soil. mSystems 4, e00281-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00281-18.

- Collins, F.W.J., Mesa-Pereira, B., O’Connor, P.M., Rea, M.C., Hill, C., and Ross, R.P. (2018). Reincarnation of Bacteriocins From the Lactobacillus Pangenomic Graveyard. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1298. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01298.

- Parks, D.H., Rinke, C., Chuvochina, M., Chaumeil, P.-A., Woodcroft, B.J., Evans, P.N., Hugenholtz, P., and Tyson, G.W. (2017). Recovery of nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes substantially expands the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1533-1542. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41564-017-0012-7.

- Parks, D.H., Chuvochina, M., Chaumeil, P.-A., Rinke, C., Mussig, A.J., and Hugenholtz, P. (2020). A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1079-1086. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41587-020-0501-8.

- Simmons, W.L., Daubenspeck, J.M., Osborne, J.D., Balish, M.F., Waites, K.B., and Dybvig, K. (2013). Type 1 and type 2 strains of Mycoplasma pneumoniae form different biofilms. Microbiology (Read.) 159, 737-747. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.064782-0.

- Diaz, M.H., Desai, H.P., Morrison, S.S., Benitez, A.J., Wolff, B.J., Caravas, J., Read, T.D., Dean, D., and Winchell, J.M. (2017). Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae genomes to investigate underlying population structure and type-specific determinants. PLoS One 12, e0174701. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174701.

- Valles-Colomer, M., Blanco-Míguez, A., Manghi, P., Asnicar, F., Dubois, L., Golzato, D., Armanini, F., Cumbo, F., Huang, K.D., Manara, S., et al. (2023). The person-to-person transmission landscape of the gut and oral microbiomes. Nature 614, 125-135. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-022-05620-1.

- Pirtskhalava, M., Amstrong, A.A., Grigolava, M., Chubinidze, M., Alimbarashvili, E., Vishnepolsky, B., Gabrielian, A., Rosenthal, A., Hurt, D.E., and Tartakovsky, M. (2021). DBAASP v3: database of antimicrobial/cytotoxic activity and structure of peptides as a resource for development of new therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D288-D297. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa991.

- Wang, G., Li, X., and Wang, Z. (2016). APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1087-D1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1278.

- Micsonai, A., Moussong, É., Wien, F., Boros, E., Vadászi, H., Murvai, N., Lee, Y.-H., Molnár, T., Réfrégiers, M., Goto, Y., et al. (2022). BeStSel: webserver for secondary structure and fold prediction for protein CD spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W90-W98. https://doi.org/10. 1093/nar/gkac345.

- Lifson, S., and Sander, C. (1979). Antiparallel and parallel

-strands differ in amino acid residue preferences. Nature 282, 109-111. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/282109a0. - Derrien, M., Collado, M.C., Ben-Amor, K., Salminen, S., and de Vos, W.M. (2008). The Mucin Degrader Akkermansia muciniphila Is an Abundant Resident of the Human Intestinal Tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1646-1648. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01226-07.

- Earley, H., Lennon, G., Balfe, Á., Coffey, J.C., Winter, D.C., and O’Connell, P.R. (2019). The abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila and its relationship with sulphated colonic mucins in health and ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep. 9, 15683. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51878-3.

- Daquigan, N., Seekatz, A.M., Greathouse, K.L., Young, V.B., and White, J.R. (2017). High-resolution profiling of the gut microbiome reveals the extent of Clostridium difficile burden. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 3, 35. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-017-0043-0.

- Saenz, C., Fang, Q., Gnanasekaran, T., Trammell, S.A.J., Buijink, J.A., Pisano, P., Wierer, M., Moens, F., Lengger, B., Brejnrod, A., and Arumugam, M. (2023). Clostridium scindens secretome suppresses virulence gene expression of Clostridioides difficile in a bile acid-independent manner. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0393322. https://doi.org/10.1128/spec-trum.03933-22.

- Geerlings, S.Y., Kostopoulos, I., De Vos, W.M., and Belzer, C. (2018). Akkermansia muciniphila in the Human Gastrointestinal Tract: When, Where, and How? Microorganisms 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/ microorganisms6030075.

- Cullen, T.W., Schofield, W.B., Barry, N.A., Putnam, E.E., Rundell, E.A., Trent, M.S., Degnan, P.H., Booth, C.J., Yu, H., and Goodman, A.L. (2015). Antimicrobial peptide resistance mediates resilience of prominent gut commensals during inflammation. Science 347, 170-175. https://doi. org/10.1126/science. 1260580.

- Torres, M.D.T., Pedron, C.N., Araújo, I., Silva, P.I., Silva, F.D., and Oliveira, V.X. (2017). Decoralin Analogs with Increased Resistance to Degradation and Lower Hemolytic Activity. ChemistrySelect 2, 18-23. https:// doi.org/10.1002/slct. 201601590.

- Torres, M.D.T., Pedron, C.N., Higashikuni, Y., Kramer, R.M., Cardoso, M.H., Oshiro, K.G.N., Franco, O.L., Silva Junior, P.I., Silva, F.D., Oliveira Junior, V.X., et al. (2018). Structure-function-guided exploration of the antimicrobial peptide polybia-CP identifies activity determinants and generates synthetic therapeutic candidates. Commun. Biol. 1, 221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-018-0224-2.

- Silva, O.N., Torres, M.D.T., Cao, J., Alves, E.S.F., Rodrigues, L.V., Resende, J.M., Lião, L.M., Porto, W.F., Fensterseifer, I.C.M., Lu, T.K., et al. (2020). Repurposing a peptide toxin from wasp venom into antiinfectives with dual antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26936-26945. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas. 2012379117.

- Morris, F.C., Dexter, C., Kostoulias, X., Uddin, M.I., and Peleg, A.Y. (2019). The Mechanisms of Disease Caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1601.

- Petruschke, H., Schori, C., Canzler, S., Riesbeck, S., Poehlein, A., Daniel, R., Frei, D., Segessemann, T., Zimmerman, J., Marinos, G., et al. (2021). Discovery of novel community-relevant small proteins in a simplified human intestinal microbiome. Microbiome 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40168-020-00981-z.

- Washietl, S., Findeiß, S., Müller, S.A., Kalkhof, S., von Bergen, M., Hofacker, I.L., Stadler, P.F., and Goldman, N. (2011). RNAcode: Robust discrimination of coding and noncoding regions in comparative sequence data. RNA 17, 578-594. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2536111.

- Galzitskaya, O.V. (2021). Exploring Amyloidogenicity of Peptides From Ribosomal S1 Protein to Develop Novel AMPs. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 705069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.705069.

- Ochman, H., Lawrence, J.G., and Groisman, E.A. (2000). Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405, 299-304. https://doi.org/10.1038/35012500.

- Zheng, D., and Gerstein, M.B. (2007). The ambiguous boundary between genes and pseudogenes: the dead rise up, or do they? Trends Genet. 23, 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.003.

- Lazzaro, B.P., Zasloff, M., and Rolff, J. (2020). Antimicrobial peptides: Application informed by evolution. Science 368, eaau5480. https://doi. org/10.1126/science.aau5480.

- Sun, S., Wang, H., Howard, A.G., Zhang, J., Su, C., Wang, Z., Du, S., Fodor, A.A., Gordon-Larsen, P., and Zhang, B. (2022). Loss of Novel Diversity in Human Gut Microbiota Associated with Ongoing Urbanization in China. mSystems 7, e0020022. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems. 00200-22.

- Piquer-Esteban, S., Ruiz-Ruiz, S., Arnau, V., Diaz, W., and Moya, A. (2022). Exploring the universal healthy human gut microbiota around the World. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 421-433. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.12.035.

- Dhakan, D.B., Maji, A., Sharma, A.K., Saxena, R., Pulikkan, J., Grace, T., Gomez, A., Scaria, J., Amato, K.R., and Sharma, V.K. (2019). The unique composition of Indian gut microbiome, gene catalogue, and associated fecal metabolome deciphered using multi-omics approaches. GigaScience 8, giz004. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz004.

- Coelho, L.P., Alves, R., Monteiro, P., Huerta-Cepas, J., Freitas, A.T., and Bork, P. (2019). NG-meta-profiler: fast processing of metagenomes using NGLess, a domain-specific language. Microbiome 7, 84. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0684-8.

- Coelho, L.P. (2017). Jug: Software for Parallel Reproducible Computation in Python. J. Open Res. Softw. 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.5334/jors.161.

- Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S., and Li, W. (2012). CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150-3152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565.

- Steinegger, M., and Söding, J. (2017). MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026-1028. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3988.

- Van Rossum, G. (2020). Python Release Python 3.8.2. Python.org. https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-382/.

- Hunter, J.D. (2007). Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2007.55.

- Harris, C.R., Millman, K.J., van der Walt, S.J., Gommers, R., Virtanen, P., Cournapeau, D., Wieser, E., Taylor, J., Berg, S., Smith, N.J., et al. (2020). Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357-362. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2.

- McKinney, W. (2010). Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, pp. 56-61. https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-00a.

- Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T.E., Haberland, M., Reddy, T., Cournapeau, D., Burovski, E., Peterson, P., Weckesser, W., Bright, J., et al. (2020). SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261-272. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2.

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V., et al. (2011). Sci-kit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Machine Learning In Python 12, 2825-2830.

- The scikit-bio development team (2020). scikit-bio: A Bioinformatics Library for Data Scientists, Students, and Developers. Version 0.5.5.

- Cock, P.J.A., Antao, T., Chang, J.T., Chapman, B.A., Cox, C.J., Dalke, A., Friedberg, I., Hamelryck, T., Kauff, F., Wilczynski, B., and de Hoon, M.J.L. (2009). Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25, 1422-1423. https:// doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163.

- Cantalapiedra, C.P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P., and Huerta-Cepas, J. (2021). eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825-5829. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/ msab293.

- Eddy, S.R. (2011). Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi. 1002195.

- Price, M.N., Dehal, P.S., and Arkin, A.P. (2010). FastTree 2 – Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS One 5, e9490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009490.

- Jain, C., Rodriguez-R, L.M., Phillippy, A.M., Konstantinidis, K.T., and Aluru, S. (2018). High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9.

- Li, D., Luo, R., Liu, C.M., Leung, C.M., Ting, H.F., Sadakane, K., Yamashita, H., and Lam, T.W. (2016). MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 102, 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016. 02.020.

- Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760. https://doi. org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324.

- Seabold, S., and Perktold, J. (2010). Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, pp. 92-96. https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011.

- Milanese, A., Mende, D.R., Paoli, L., Salazar, G., Ruscheweyh, H.-J., Cuenca, M., Hingamp, P., Alves, R., Costea, P.I., Coelho, L.P., et al. (2019). Microbial abundance, activity and population genomic profiling with mOTUs2. Nat. Commun. 10, 1014. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41467-019-08844-4.

- Li, H., Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N., Marth, G., Abecasis, G., and Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078-2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352.

- Quinlan, A.R., and Hall, I.M. (2010). BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841-842. https://doi. org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033.

- Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T.J., Karplus, K., Li, W., Lopez, R., McWilliam, H., Remmert, M., Söding, J., et al. (2011). Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539. https://doi.org/10.1038/msb. 2011.75.

- Buchfink, B., Xie, C., and Huson, D.H. (2015). Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59-60. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nmeth. 3176.

- Camacho, C., Coulouris, G., Avagyan, V., Ma, N., Papadopoulos, J., Bealer, K., and Madden, T.L. (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 10, 421. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421.

- UniProt Consortium (2021). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D480-D489. https://doi.org/10. 1093/nar/gkaa1100.

- Mistry, J., Chuguransky, S., Williams, L., Qureshi, M., Salazar, G.A., Sonnhammer, E.L.L., Tosatto, S.C.E., Paladin, L., Raj, S., Richardson, L.J., et al. (2021). Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D412-D419. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913.

- Eberhardt, R.Y., Haft, D.H., Punta, M., Martin, M., O’Donovan, C., and Bateman, A. (2012). AntiFam: a tool to help identify spurious ORFs in protein annotation. Database 2012, bas003. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bas003.

- NCBI Resource Coordinators (2015). Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D6-D17. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1130.

- Alcock, B.P., Raphenya, A.R., Lau, T.T.Y., Tsang, K.K., Bouchard, M., Edalatmand, A., Huynh, W., Nguyen, A.-L.V., Cheng, A.A., Liu, S., et al. (2020). CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D517D525. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz935.

- Kanehisa, M., and Sato, Y. (2020). KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Sci. 29, 28-35. https://doi. org/10.1002/pro.3711.

- Courtot, M., Cherubin, L., Faulconbridge, A., Vaughan, D., Green, M., Richardson, D., Harrison, P., Whetzel, P.L., Parkinson, H., and Burdett, T. (2019). BioSamples database: an updated sample metadata hub. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1172-D1178. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/ gky1061.

- Harrison, P.W., Ahamed, A., Aslam, R., Alako, B.T.F., Burgin, J., Buso, N., Courtot, M., Fan, J., Gupta, D., Haseeb, M., et al. (2021). The European Nucleotide Archive in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D82-D85. https:// doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1028.

- Jones, P., Côté, R.G., Martens, L., Quinn, A.F., Taylor, C.F., Derache, W., Hermjakob, H., and Apweiler, R. (2006). PRIDE: a public repository of protein and peptide identifications for the proteomics community. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D659-D663. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj138.

- Schmidt, T.S.B., Fullam, A., Ferretti, P., Orakov, A., Maistrenko, O.M., Ruscheweyh, H.-J., Letunic, I., Duan, Y., Van Rossum, T., Sunagawa, S., et al. (2024). SPIRE: a Searchable, Planetary-scale mlcrobiome REsource. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D777-D783. https://doi.org/10.1093/ nar/gkad943.

- Mirdita, M., Steinegger, M., Breitwieser, F., Söding, J., and Levy Karin, E. (2021). Fast and sensitive taxonomic assignment to metagenomic contigs. Bioinformatics 37, 3029-3031. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btab184.

- Oren, A., Arahal, D.R., Rosselló-Móra, R., Sutcliffe, I.C., and Moore, E.R.B. (2021). Emendation of Rules 5b, 8, 15 and 22 of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes to include the rank of phylum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 71. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.004851.

- Oren, A., and Garrity, G.M. (2021). Valid publication of the names of fortytwo phyla of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 71. https://doi.org/ 10.1099/ijsem.0.005056.

- Solis, A.D. (2015). Amino acid alphabet reduction preserves fold information contained in contact interactions in proteins. Proteins 83, 21982216. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.24936.

- Peterson, E.L., Kondev, J., Theriot, J.A., and Phillips, R. (2009). Reduced amino acid alphabets exhibit an improved sensitivity and selectivity in fold assignment. Bioinformatics 25, 1356-1362. https://doi.org/10. 1093/bioinformatics/btp164.

- Smith, T.F., and Waterman, M.S. (1981). Identification of Common Molecular Subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147, 195-197. https://doi.org/10. 1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5.

- Karlin, S., and Altschul, S.F. (1990). Methods for assessing the statistical significance of molecular sequence features by using general scoring schemes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 2264-2268. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2264.

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schäffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389-3402.

- Cena, J.A. de, Zhang, J., Deng, D., Damé-Teixeira, N., and Do, T. (2021). Low-Abundant Microorganisms: The Human Microbiome’s Dark Matter, a Scoping Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 689197.

- Mende, D.R., Sunagawa, S., Zeller, G., and Bork, P. (2013). Accurate and universal delineation of prokaryotic species. Nat. Methods 10, 881-884. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2575.

- Sélem-Mojica, N., Aguilar, C., Gutiérrez-García, K., Martínez-Guerrero, C.E., and Barona-Gómez, F. (2019). EvoMining reveals the origin and fate of natural product biosynthetic enzymes. Microb. Genom. 5, e000260. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000260.

- Rodriguez-R, L.M., Conrad, R.E., Viver, T., Feistel, D.J., Lindner, B.G., Venter, S.N., Orellana, L.H., Amann, R., Rossello-Mora, R., and Konstantinidis, K.T. (2024). An ANI gap within bacterial species that advances the definitions of intra-species units. mBio 15, e02696-23. https://doi.org/10. 1128/mbio.02696-23.

- Finn, R.D., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R.Y., Eddy, S.R., Mistry, J., Mitchell, A.L., Potter, S.C., Punta, M., Qureshi, M., Sangrador-Vegas, A., et al. (2016). The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D279-D285. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/ gkv1344.

- SolyPep: a fast generator of soluble peptides https://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot.fr/services/SolyPep/

- Ochoa, R., and Cossio, P. (2021). PepFun: Open Source Protocols for Peptide-Related Computational Analysis. Molecules 26, 1664. https:// doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061664.

- Kochendoerfer, G.G., and Kent, S.B. (1999). Chemical protein synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 665-671. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00024-1.

- Sheppard, R. (2003). The fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl group in solid phase synthesis. J. Pept. Sci. 9, 545-552. https://doi.org/10.1002/psc.479.

- Palomo, J.M. (2014). Solid-phase peptide synthesis: an overview focused on the preparation of biologically relevant peptides. RSC Adv. 4, 32658-32672. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA02458C.

- Schmidt, T.S.B., Li, S.S., Maistrenko, O.M., Akanni, W., Coelho, L.P., Dolai, S., Fullam, A., Glazek, A.M., Hercog, R., Herrema, H., et al. (2022). Drivers and determinants of strain dynamics following fecal microbiota transplantation. Nat. Med. 28, 1902-1912. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41591-022-01913-0.

- Wiegand, I., Hilpert, K., and Hancock, R.E.W. (2008). Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 3, 163-175. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nprot.2007.521.

- Santos-Júnior, C.D., Schmidt, T.S.B., Fullam, A., Duan, Y., Bork, P., Zhao, X.-M., and Coelho, L.P. (2021). AMPSphere : The Worldwide Survey of Prokaryotic Antimicrobial Peptides (Zenodo) https://doi.org/10. 5281/zenodo. 4606582.

طرق النجوم

جدول الموارد الرئيسية

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| سلالات البكتيريا والفيروسات | ||

| أسيتيتوباكتر باومانني | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 19606 |

| إشريشيا كولاي | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 11775 |

| إشريشيا كولاي | إشريشيا كولاي MG1655 phnE_2:FRT | AIC221 |

| إشريشيا كولاي | إشريشيا كولاي MG1655 pmrA53 phnE_2:FRT (سلالة مقاومة للبولي مكسين؛ سلالة مقاومة للكولستين) | AIC222 |

| كليبسيلا الرئوية | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 13883 |

| المُكَوِّرَة الزُرقاء | غير متوفر | PAO1 |

| المُكَوِّرَة الزُرقاء | غير متوفر | PA14 |

| المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 12600 |

| المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC BAA-1556 (سلالة مقاومة للميثيسيلين) |

| أكرمانسيا موكينيفيلا | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية | ATCC BAA-635 |

| باكتيرويدس فراجيلس | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 25285 |

| باكتيرويدس ثيتايوتاوميكرو | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية | ATCC 29148 |

| باكتيرويدس يونيformis | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية | ATCC 8492 |

| باكتيرويدس فulgatus (فوكايكولا فulgatus) | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 8482 |

| كولينسيلا أيروفاسيانس | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية | ATCC 25986 |

| كلوستريديوم سكيندينس | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية للأنواع | ATCC 35704 |

| باراباكتيرويدس ديستاسونيس | مجموعة الثقافة الأمريكية | ATCC 8503 |

| المواد الكيميائية، الببتيدات، والبروتينات المؤتلفة | ||

| مرق لوريا-بيرتاني | بي دي | 244620 |

| مرق الصويا التربتيك | سيغما | T8907-1KG |

| أجار | سيغما | 05039 |

| أجار ماكونكي | RPI | M42560-500.0 |

| محلول ملحي من فوسفات | سيغما | P3913-10PAK |

| جلوكوز | سيغما | G5767 |

| 1-(N-فينيل أمين) نافثالين | سيغما | ١٠٤٠٤٣ |

| يوديد 3,3′-ديبروبيل ثياديسكاربوكسيانين | سيغما | 43608 |

| هيبز | صياد | بي بي 310-100 |

| كلوريد البوتاسيوم (KCl) | سيغما | P3911 |

| البيانات المودعة | ||

| رمز لتوليد AMPSphere | هذه الدراسة | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11055585 |

| قاعدة بيانات AMPSphere | هذه الدراسة | https://zenodo.org/record/4606582 |

| نماذج تجريبية: الكائنات/السلالات | ||

| فأرة: CD-1 | نهر تشارلز | 18679700-022 |

| البرمجيات والخوارزميات | ||

| NGLess 1.3.0 | كويلو وآخرون

|

https://github.com/ngless-toolkit/ngless |

| جوج 2.1.1 | كويلو

|

https://github.com/luispedro/jug |

| بروجيكال 2.6.3 | هايات وآخرون

|

https://github.com/hyattpd/Prodigal |

| ماكرل v.1.0.0 | سانتوس-جونيور وآخرون

|

https://github.com/BigDataBiology/macrel |

| سي دي هيت 4.8.1 | فو وآخرون

|

https://github.com/weizhongli/cdhit |

| MMseqs2 | شتاينجر وسودينغ

|

https://github.com/soedinglab/MMseqs2 |

| مستمر | ||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| بايثون 3.8.2 | فان روسوم

|

https://www.python.org/ |

| ماتplotlib 3.4.3 | صياد

|

https://matplotlib.org/ |

| numpy 1.21.2 | هاريس وآخرون

|

https://numpy.org/ |

| باندا 1.3.2 | مكينى

|

https://pandas.pydata.org/ |

| بلوتلي 5.2.1 | شركة بلوتلي تكنولوجيز، 2015 | https://plot.ly |

| scipy 1.7.1 | فيرتانين وآخرون

|

https://www.scipy.org |

| scikit-learn 0.24 | بادريغوسا وآخرون

|

https://scikit-learn.org/ |

| scikit-bio 0.5.6 | فريق تطوير سكايكت-بايو،

|

http://scikit-bio.org/ |

| بايو بايثون 1.7.9 | كوك وآخرون

|

https://biopython.org/ |

| خريطة البيض المخفوق v2 | كانتالابيدرا وآخرون

|

https://github.com/eggnogdb/ eggnog-mapper |

| HMMer 3.3+dfsg2-1 | إيدي

|

http://hmmer.org/ |

| فاست تري 2.1 | برايس وآخرون

|

http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/ |

| فاست أيه إن آي v.1.33 | جاين وآخرون

|

https://github.com/ParBLiSS/FastANI |

| ميغاهيت 1.2.9 | لي وآخرون

|

https://github.com/voutcn/megahit/ |

| أمبليفاى | لي وآخرون

|

https://github.com/bcgsc/AMPlify |

| أمبير | فينجرهوت وآخرون

|

https://github.com/Legana/ampir |

| ماسح AMP الإصدار 2 | فيلتري وآخرون

|

https://www.dveltri.com/ascan/ v2/ascan.html |

| أبين | سو وآخرون

|

https://github.com/zhanglabNKU/APIN |

| amPEPpy 1.0 | لورنس وآخرون

|

https://github.com/tlawrence3/amPEPpy |

| أل4AMP | لين وآخرون

|

https://github.com/LinTzuTang/ AI4AMP_predictor |

| RNAcode 0.2-beta | واشييتل وآخرون

|

https://github.com/ViennaRNA/RNAcode |

| بوا 0.7.17 | لي وآخرون

|

https://github.com/lh3/bwa |

| ستاتس موديلز 0.14.0 | سيبولد و بيركتولد

|

https://www.statsmodels.org |

| mOTUs2 | ميلانيز وآخرون

|

https://github.com/motu-tool/mOTUs |

| سام توولز 1.18 | لي وآخرون

|

https://github.com/samtools/samtools |

| أدوات السرير v2.31.0 | كوينلان وهال

|

https://github.com/arq

|

| كلوستال أوميغا 1.2.2 | سيفرز وآخرون

|

http://clustal.org/omega/ |

| الماس v2.1.8 | بوشفينك وآخرون

|

https://github.com/bbuchfink/diamond |

| بلاست+ 2.13.0 | كاماشو وآخرون

|

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/doc/ blast-help/downloadblastdata.html |

| آخر | ||

| برو جينومز 2 | مند و آخرون

|

http://progenomes.embl.de/ |

| DRAMP – مستودع بيانات الببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات 3.0 | شي وآخرون

|

http://dramp.cpu-bioinfor.org/ |

| يونيبروتKB 2021_03 | اتحاد يوني بروت

|

https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| بيض بالكراميل النسخة 5.0 | هورتا-سيباس وآخرون

|

http://eggnog5.embl.de/ |

| قاعدة بيانات SmProt الإصدار 2.0 | هاو وآخرون

|

http://bigdata.ibp.ac.cn/ SmProt/index.html |

| ستاربيب45ك | أغيليرا-ميندوزا وآخرون

|

http://mobiosd-hub.com/starpep |

| PFAM 33.1. | ميستري وآخرون

|

http://pfam.xfam.org/ |

| أنتي فام 7.0 | إيبرهاردت وآخرون

|

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/research/bateman/software/antifam-tool-identify-spurious-proteins |

| جي تي دي بي 07-آر إس 95 | باركس وآخرون

|

https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/ |

| إصدار NCBI 207 | منسقو موارد NCBI

|

https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/refseq/release/ |

| مستمر | ||

| المُعَايِن أو المورد | المصدر | معرف |

| قاعدة بيانات النشاط المضاد للميكروبات وبنية الببتيدات – DBAASP | بيرتسخالافا وآخرون

|

https://dbaasp.org/home |

| قاعدة بيانات الببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات – APD3 | وانغ ووانغ

|

https://aps.unmc.edu/ |

| الأورف الصغيرة لسالمونيلا تايفيموريوم – STsORFs | فينتوريني وآخرون

|

https://academic.oup.com/microlife/article/1/1/uqaa002/5928550#supplementary-data |

| قاعدة بيانات مقاومة المضادات الحيوية الشاملة | ألكوك وآخرون

|

https://card.mcmaster.ca/ |

| إصدار 102 من موسوعة كيوتو للجينات والجينومات (KEGG) | كانهيسا وآخرون

|

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| قاعدة بيانات عينات الأحياء | كوروت وآخرون

|

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/biosamples |

| أرشيف النوكليوتيدات الأوروبي – ENA | هاريسون وآخرون

|

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena |

| قاعدة بيانات تحديد البروتيوم – PRIDE | جونز وآخرون

|

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/ |

توافر الموارد

جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

توفر المواد

توفر البيانات والشيفرة

- تتوفر بيانات الميتاجينومات والجينومات للجمهور في أرشيف النيوكليوتيدات الأوروبي (ENA) اعتبارًا من تاريخ النشر. أرقام الوصول الخاصة بها مدرجة في الجدول S1. AMPSphere متاحة كموارد عامة عبر الإنترنت.https://ampsphere. big-data-biology.org/)، وقد تم إيداع ملفاتها في زينودو وهي متاحة للجمهور اعتبارًا من تاريخ النشر. تم إدراج معرفات الكائن الرقمي (DOIs) في جدول الموارد الرئيسية.

- تم إيداع جميع الشيفرات الأصلية في Zenodo وهي متاحة للجمهور اعتبارًا من تاريخ النشر. تم إدراج معرفات الكائن الرقمي (DOIs) في جدول الموارد الرئيسية.

- أي معلومات إضافية مطلوبة لإعادة تحليل البيانات المبلغ عنها في هذه الورقة متاحة من جهة الاتصال الرئيسية عند الطلب.

تفاصيل النموذج التجريبي وشارك الدراسة

سلالات البكتيريا وظروف النمو

نموذج الفأر لعدوى خراج الجلد

تفاصيل الطريقة

اختيار الجينومات الميكروبية (الميتاجينومية)

قص و تجميع القراءات

تنبؤ smORF و AMP

تجميع عائلات AMP

مراقبة جودة c_AMPs

برنامج RNAcode

منحنيات تراكم c_AMPs المعتمدة على العينة

c_AMPs متعددة المواطن والنادرة

اختبار تداخل c_AMPs عبر المواطن

كثافة c_AMP في الأنواع الميكروبية

نقل c_AMPs وأنواع البكتيريا

تحديد مضخات الملحقات

استخدمت في هذا التحليل. عائلات c_AMPs وAMP موجودة في أقل من

توصيف AMP باستخدام مجموعات بيانات مختلفة

تحليل الحفاظ على السياق الجينومي

محسوبًا كعدد الجينات ذات التوصيف الوظيفي المحدد (مجموعة الأرتولوج، موسوعة كيوتو للجينات والجنوم (KEGG) المسار، الأرتولوجي KEGG، وحدة KEGG،

موارد الويب AMPSphere

اختيار الببتيدات للتخليق والاختبار

تحديد التركيز المثبط الأدنى (MIC)

اختبارات التشتت الدائري

تم الحصول على طيف ثنائي اللون عن طريق متوسط ثلاث تجميعات باستخدام قنينة كوارتز بطول مسار بصري يبلغ 1.0 مم. تم تسجيل الطيف في نطاق الطول الموجي من 260 إلى 190 نانومتر بمعدل مسح

اختبارات نفاذية الغشاء الخارجي

اختبارات إزالة الاستقطاب للغشاء السيتوبلازمي

التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

موارد إضافية

الرسوم التوضيحية التكميلية

موضحة هنا منحنيات الكثافة؛ وحدات الكثافة التعسفية غير معروضة، حيث تم تطبيع جميع المنحنيات بشكل مستقل بحيث تكون المساحة تحت المنحنى واحدة. لكل مجموعة بيانات وميزة، الأعلى

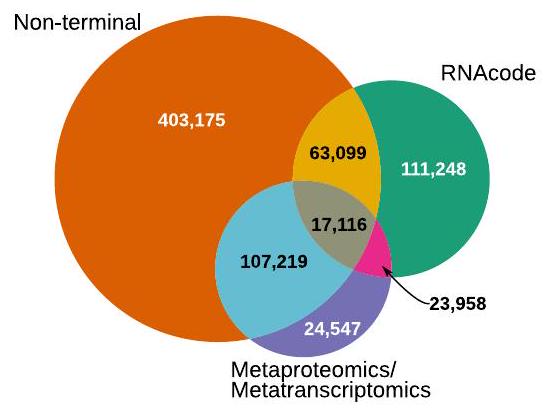

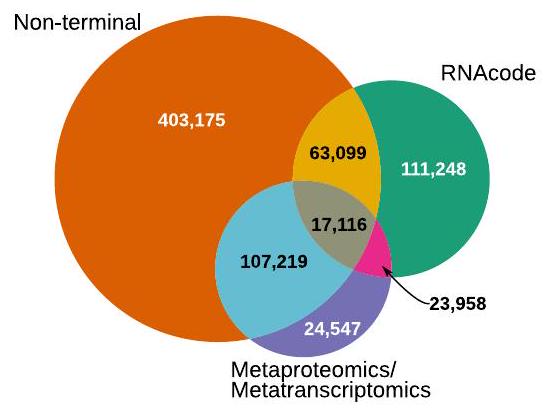

(أ) أظهر تقييم جودة AMPSphere أن معظم الببتيدات اجتازت على الأقل اختبارًا واحدًا. يعتمد اختبار RNAcode على تنوع الجينات، الذي يكون منخفضًا جدًا بالنسبة لـ AMPSphere، مما أدى إلى انخفاض معدل الإيجابيات بين مرشحينا.

(ب) أظهرت نظائر c_AMPs في قواعد بيانات الببتيدات الحيوية النشطة المعتمدة أيضًا جودة متوسطة أعلى لهذه المجموعات البيانية.

(ج) إن التداخل المحدود لمركبات c_AMPs بين المواطن يدعم استخدام مجموعات المواطن لتحقيق دقة أكبر. لاحظ أن مجموعة المواطن التي تحتوي على أعلى تداخل مزدوج تنتمي إلى مواقع الجسم البشري وعينات من أمعاء البشر وأمعاء الثدييات غير البشرية. تم عرض المواطن التي تحتوي على 100 عينة على الأقل فقط.

(د) لاحظنا نسبة كبيرة من الجينات النادرة في AMPSphere من مجموعات المواطن المختلفة.

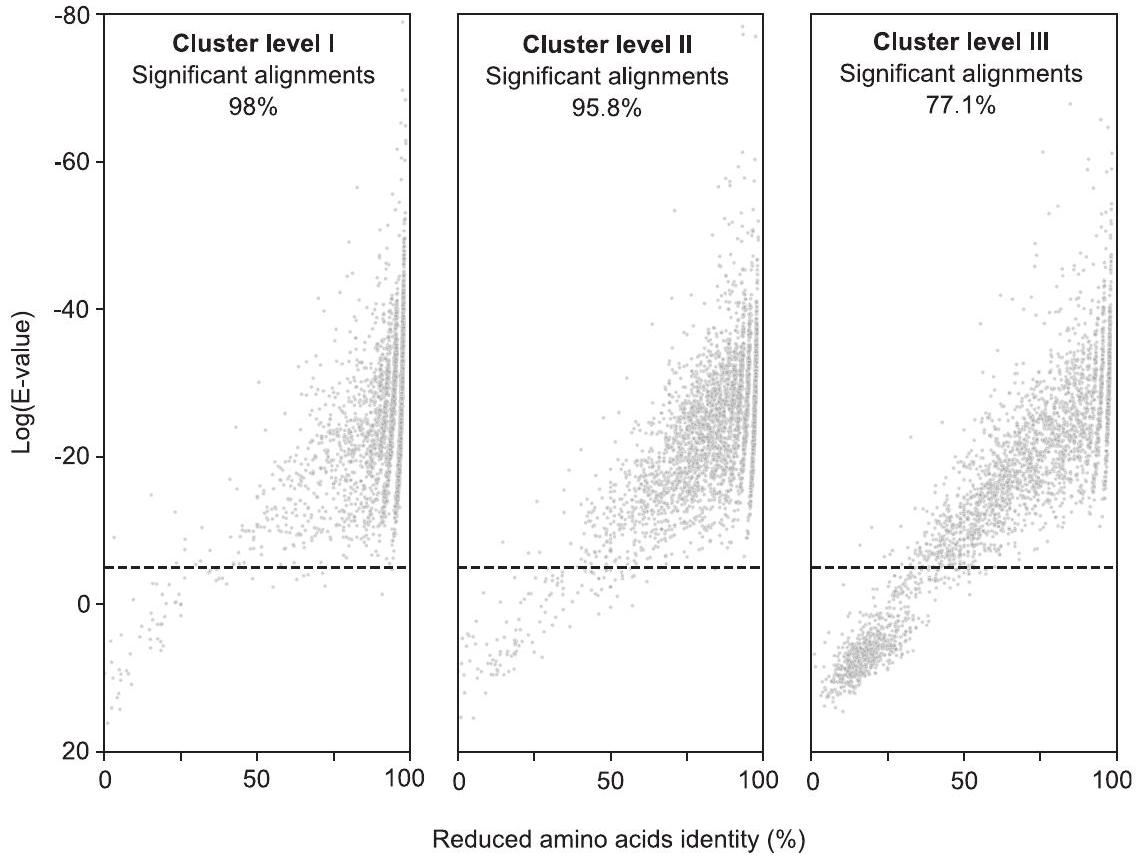

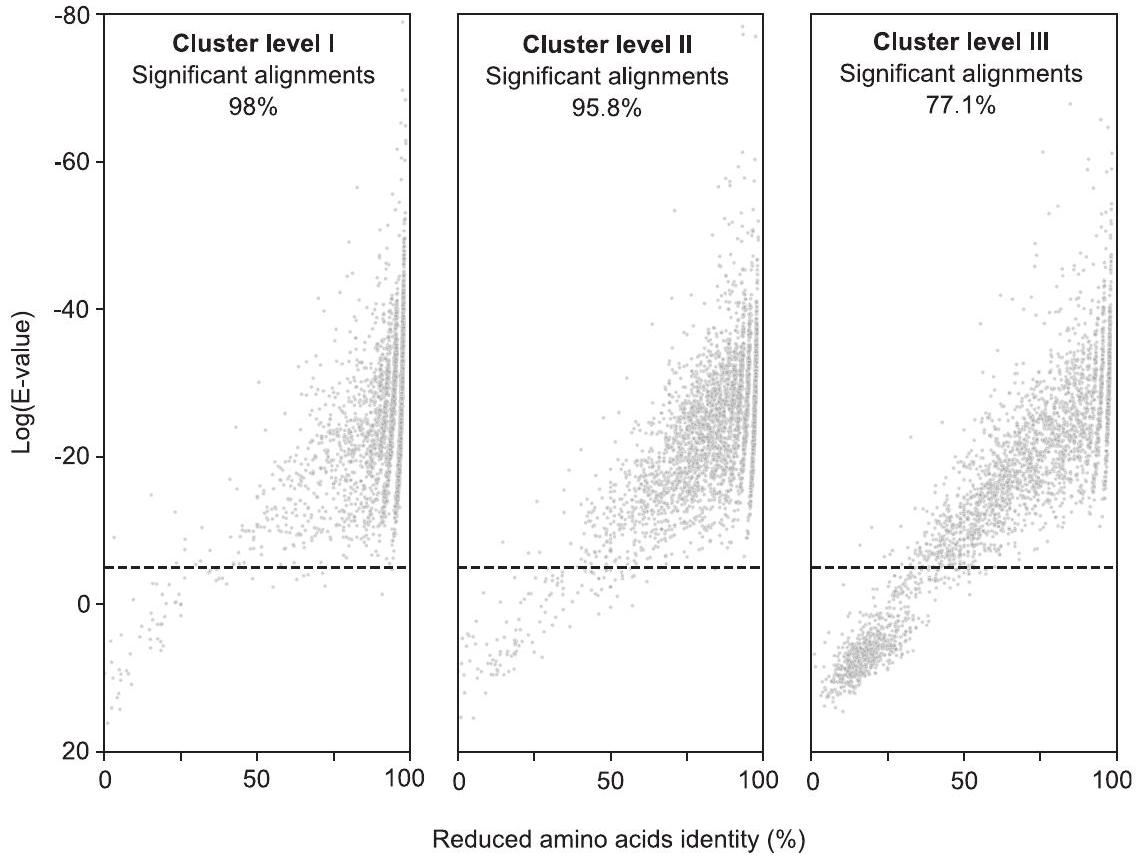

لتحقيق صحة إجراء التجميع باستخدام أبجدية الأحماض الأمينية المختزلة، تم سحب عينات من 1,000 ببتيد بشكل عشوائي من AMPSphere (باستثناء التسلسلات التمثيلية) وتم محاذاتها مع ممثلي مجموعاتها. تم اختبار ثلاثة مستويات مختلفة (الأول، الثاني، والثالث) من التجميع. تم حساب قيم E لكل محاذاة ورسمها مقابل هوية المحاذاة المقابلة. يتم عرض النسبة المتوسطة للمحاذات المهمة في كل رسم بياني أعلاه.

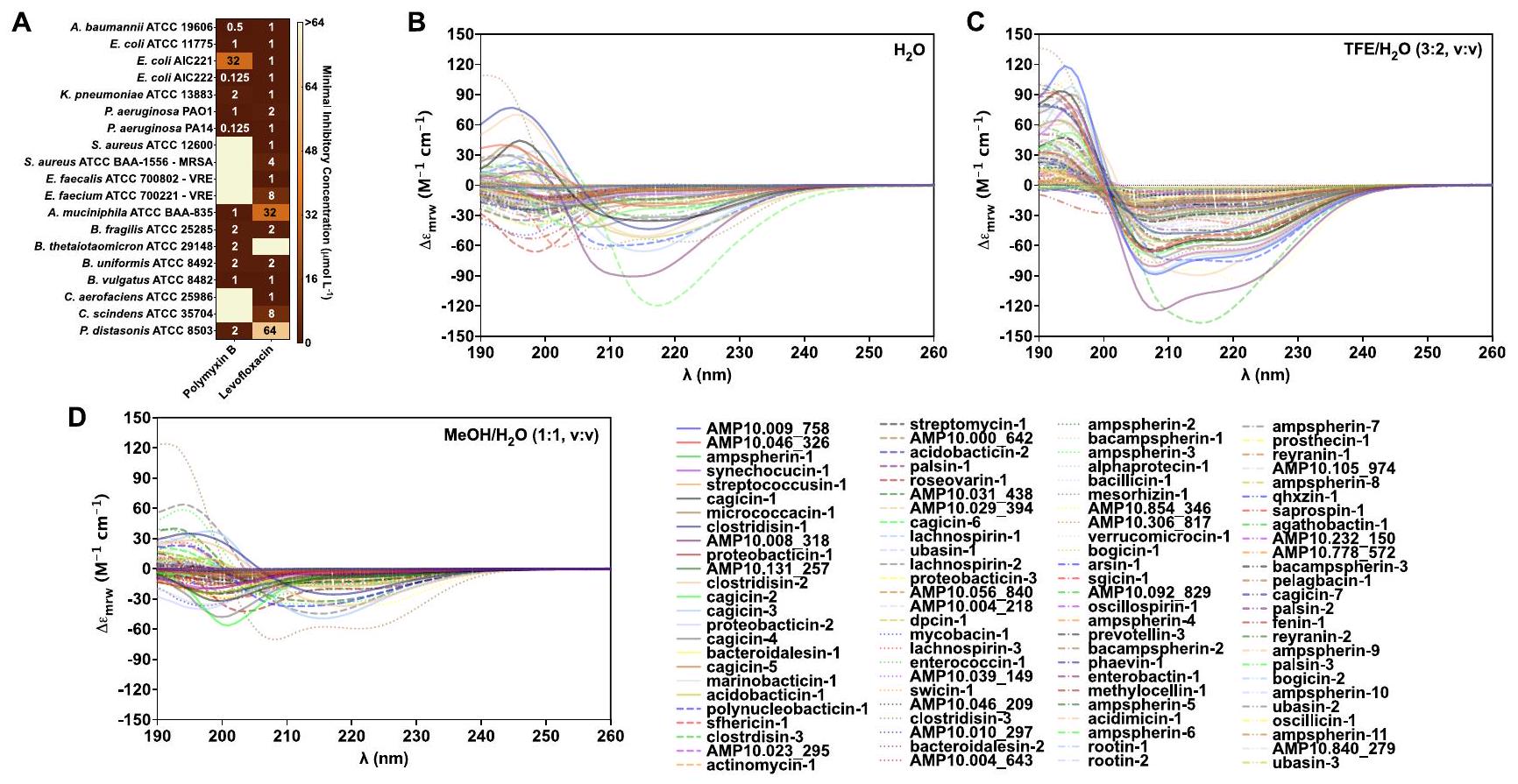

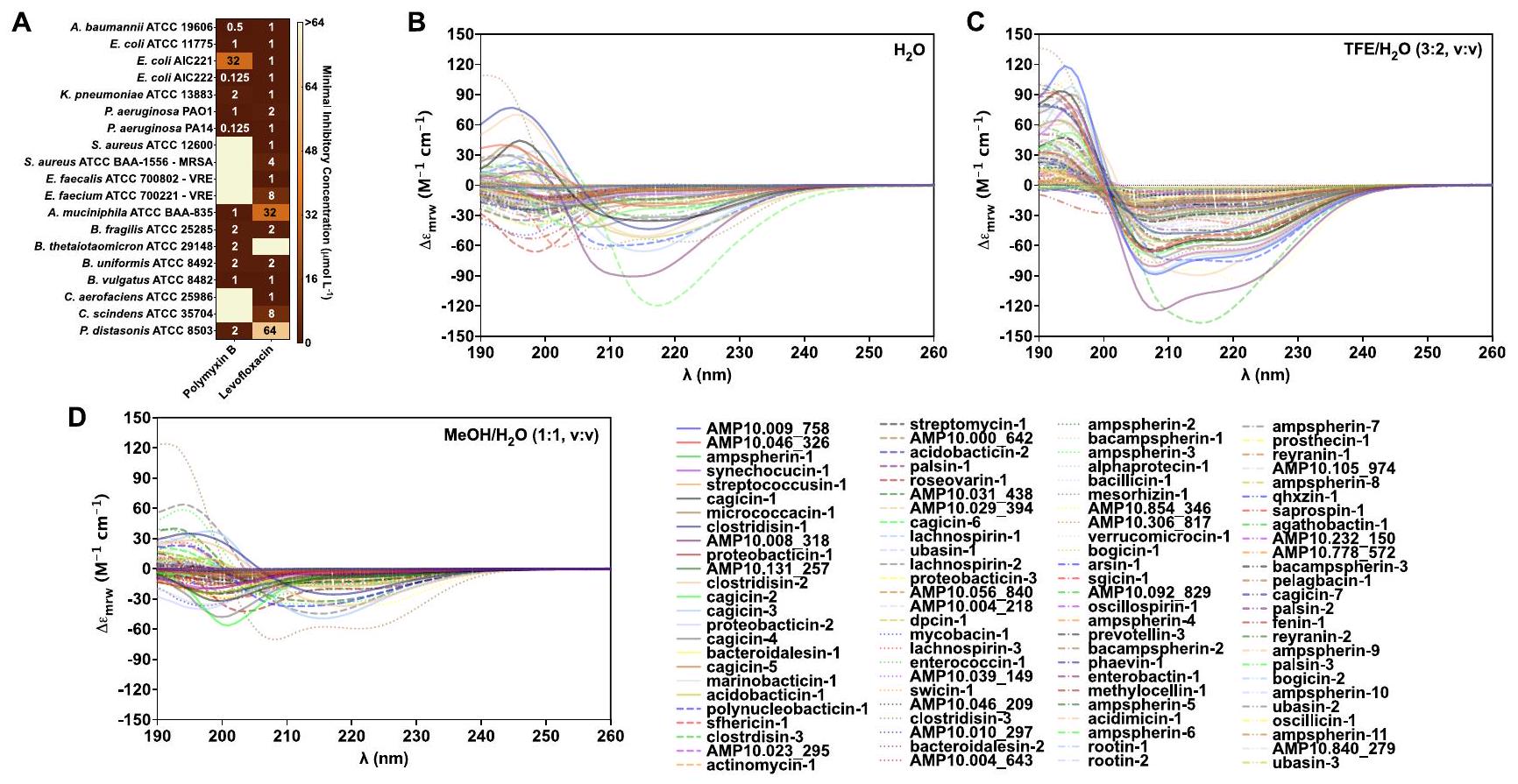

(أ) قيم التركيز المثبط الأدنى لبوليمكسين ب، وهو مضاد حيوي ببتيدي، وليفوفلوكساسين ضد جميع السلالات المختبرة. تم استخدام بوليمكسين ب وليفوفلوكساسين كضوابط إيجابية في جميع الاختبارات المضادة للميكروبات.

(B-D) تم تحليل الميل الهيكلي الثانوي لـ c_AMPs باستخدام ثلاثة مذيبات مختلفة: (B) الماء، (C) مزيج ثلاثي فلور الإيثانول (TFE) والماء.

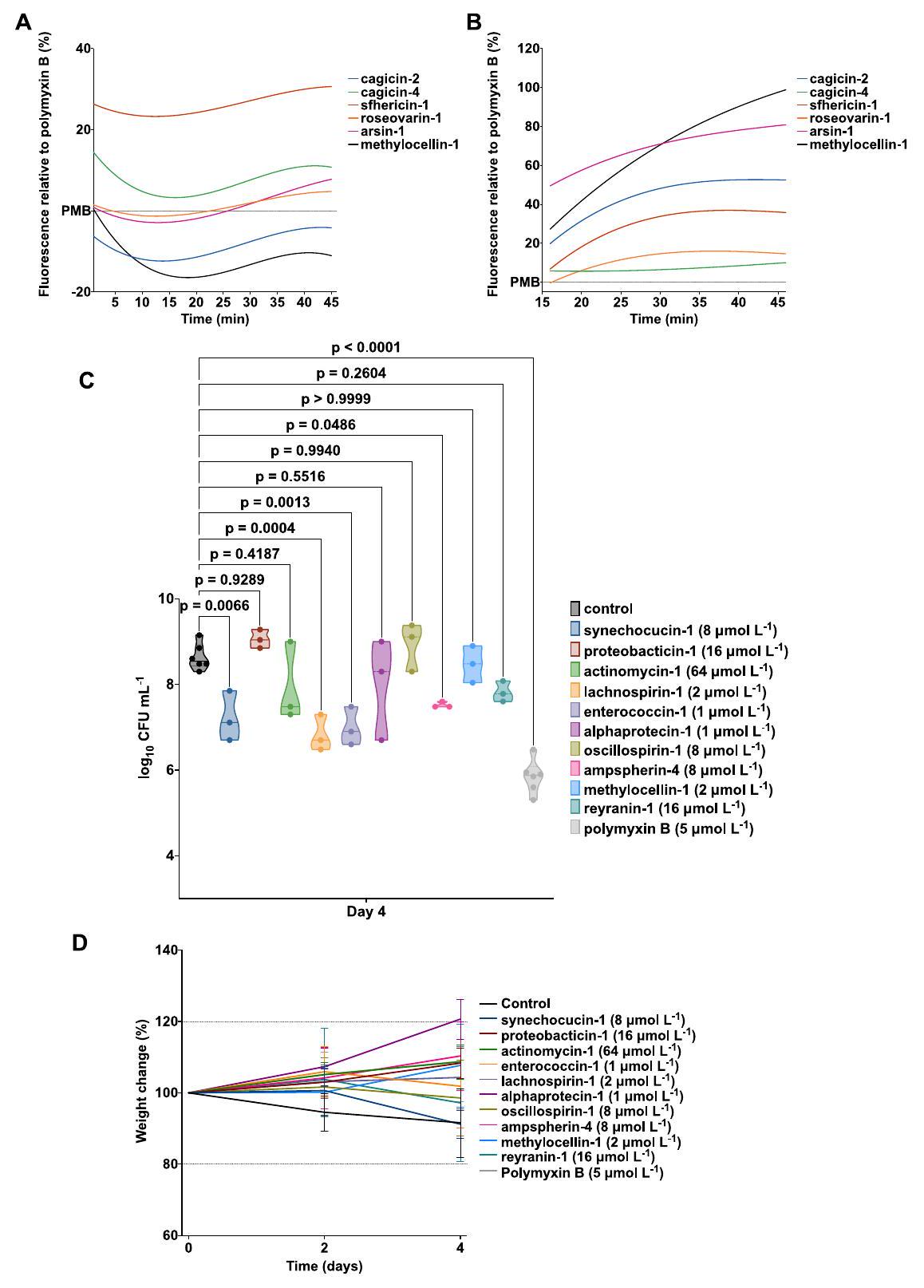

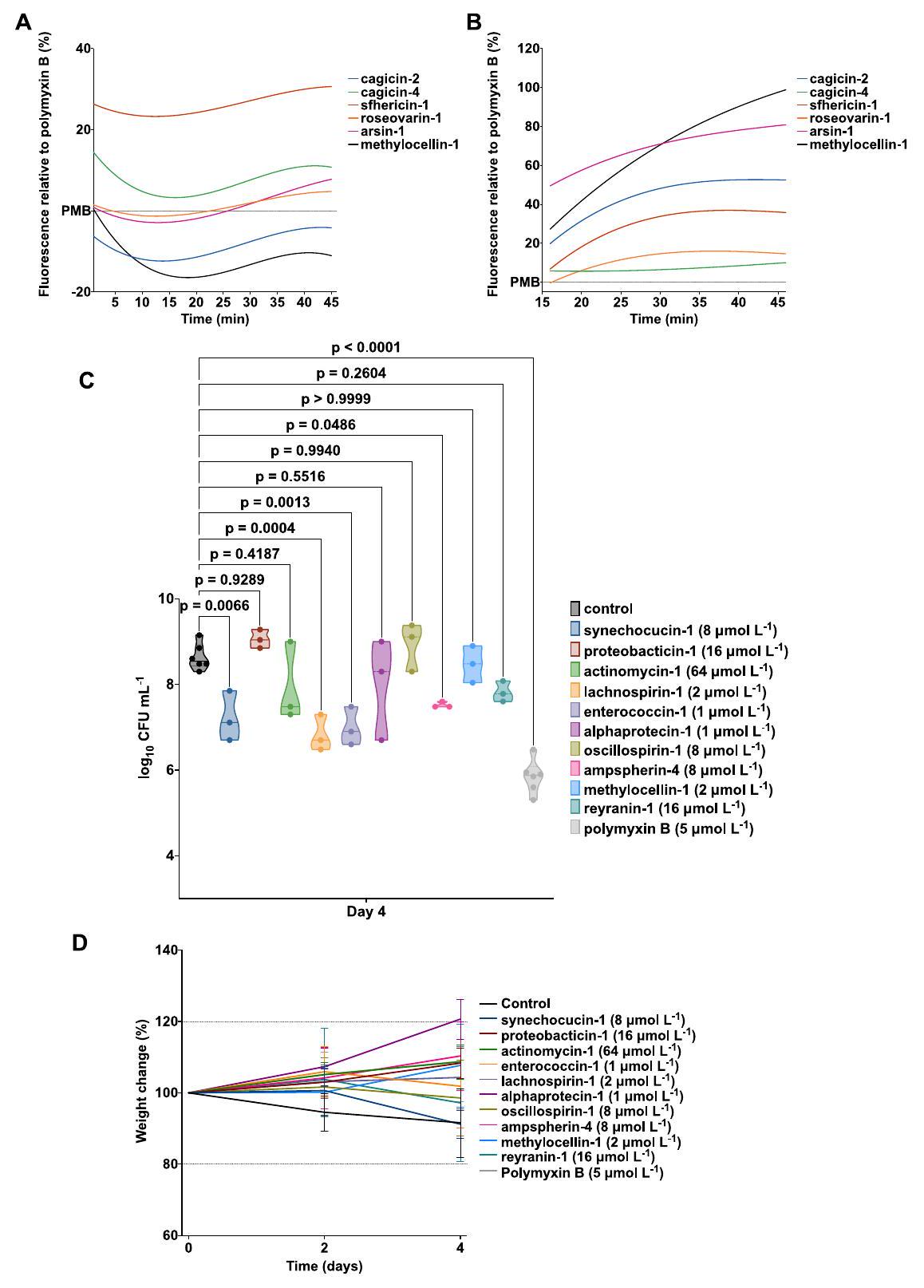

(أ) قيم الفلورية بالنسبة للبولي مكسين ب (PMB، التحكم الإيجابي) لمسبار الفلورسنت 1-(N-phenylamino)naphthalene (NPN) التي تشير إلى اختراق الغشاء الخارجي

(ب) قيم الفلورية بالنسبة لـ PMB (التحكم الإيجابي) لمادة 3,3′-ديبروبيلثياديديكاربوسيانيين يوديد

(ج) عدد البكتيريا بعد أربعة أيام من العدوى؛ تم اختبار c_AMPs عند تركيزه المثبط الأدنى في جرعة واحدة بعد ساعة من بدء العدوى. كل مجموعة تتكون من ثلاثة فئران.

وزن الفئران طوال التجربة (المتوسط

تم تحديد الدلالة الإحصائية في (C) باستخدام تحليل التباين الأحادي حيث تم مقارنة جميع المجموعات مع مجموعة التحكم غير المعالجة؛

- (D) قيم الفلورية بالنسبة للبوليماكسين ب (PMB، التحكم الإيجابي) لمسبار الفلورسنت 1-(N-phenylamino)naphthalene (NPN) التي تشير إلى اختراق الغشاء الخارجي لخلايا A. baumannii ATCC 19606.

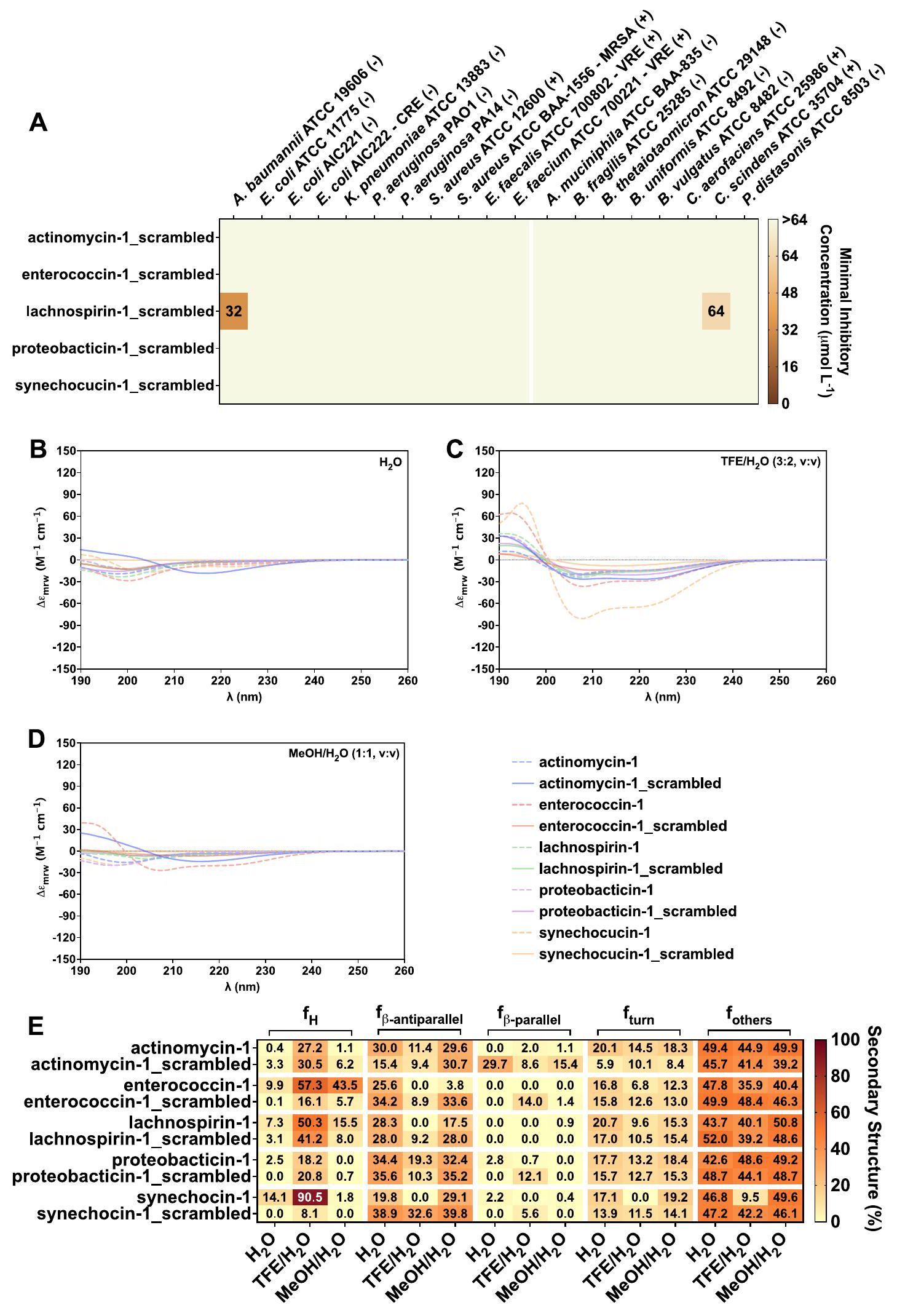

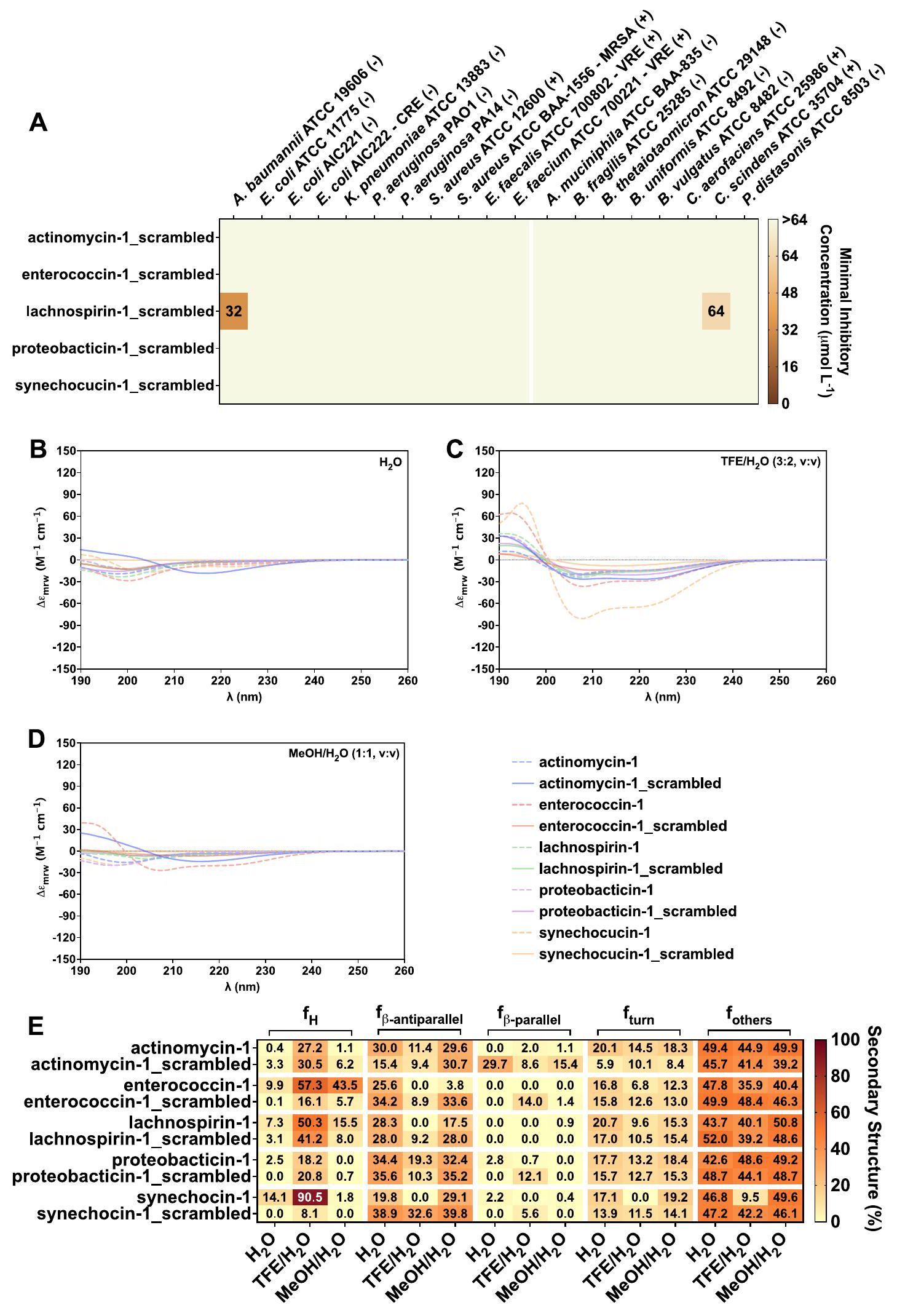

قيم الفلورية بالنسبة لـ PMB (التحكم الإيجابي) لـ-ديبروميد ثياديسكاربوكسيانين مسبار فلوري هيدروفوبي يُستخدم للإشارة إلى إزالة استقطاب الغشاء السيتوبلازمي لـ حدثت إزالة استقطاب الغشاء السيتوبلازمي ببطء مقارنة بتمرير الغشاء الخارجي واستغرقت حوالي 20 دقيقة للاستقرار. - الشكل S5. النشاط المضاد للميكروبات والبنية الثانوية للإصدارات المختلطة لبعض من المركبات الرائدة c_AMPs، المتعلقة بالشكلين 6 و7 (A) قيم MIC للإصدارات المختلطة من خمسة من المركبات الرائدة c_AMPs من AMPSphere التي تم اختبارها ضد نفس 11 سلالة مرضية وثماني سلالات متعايشة في الأمعاء المستخدمة لتقييم نشاط المركبات c_AMPs.

(B-D) تم تحليل الميل الهيكلي الثانوي للببتيدات المخلوطة باستخدام ثلاثة مذيبات مختلفة: (B) الماء، (C) خليط TFE والماء ()، و(D) خليط MeOH والماء ( ). تم إجراء التجارب في نفس الظروف المستخدمة لـ AMPs. تم تطبيق فلتر تحويل فورييه لتقليل تأثيرات الخلفية.

(E) خريطة حرارية مع النسبة المئوية للهيكل الثانوي الموجود لكل ببتيد في ثلاثة مذيبات مختلفة: الماء،TFE في الماء، و في الماء. تم حساب الهيكل الثانوي باستخدام خادم BeStSel.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.013

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38843834

Publication Date: 2024-06-05

Discovery of antimicrobial peptides in the global microbiome with machine learning

Graphical abstract

Highlights

- Machine learning predicts nearly 1 million new antibiotics in the global microbiome

- Out of

tested peptides, 79 were active in vitro; 63 of these targeted pathogens - Some peptides may originate from longer sequences through genomic fragmentation

- The AMPSphere is an open-access resource to accelerate antibiotic discovery

Authors

Correspondence

In brief

Discovery of antimicrobial peptides in the global microbiome with machine learning

Abstract

SUMMARY Novel antibiotics are urgently needed to combat the antibiotic-resistance crisis. We present a machine-learning-based approach to predict antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) within the global microbiome and leverage a vast dataset of 63,410 metagenomes and 87,920 prokaryotic genomes from environmental and host-associated habitats to create the AMPSphere, a comprehensive catalog comprising 863,498 nonredundant peptides, few of which match existing databases. AMPSphere provides insights into the evolutionary origins of peptides, including by duplication or gene truncation of longer sequences, and we observed that AMP production varies by habitat. To validate our predictions, we synthesized and tested 100 AMPs against clinically relevant drug-resistant pathogens and human gut commensals both in vitro and in vivo. A total of 79 peptides were active, with 63 targeting pathogens. These active AMPs exhibited antibacterial activity by disrupting bacterial membranes. In conclusion, our approach identified nearly one million prokaryotic AMP sequences, an open-access resource for antibiotic discovery.

INTRODUCTION

ity in vitro against clinically significant ESKAPEE pathogens, which are recognized as public health concerns.

RESULTS

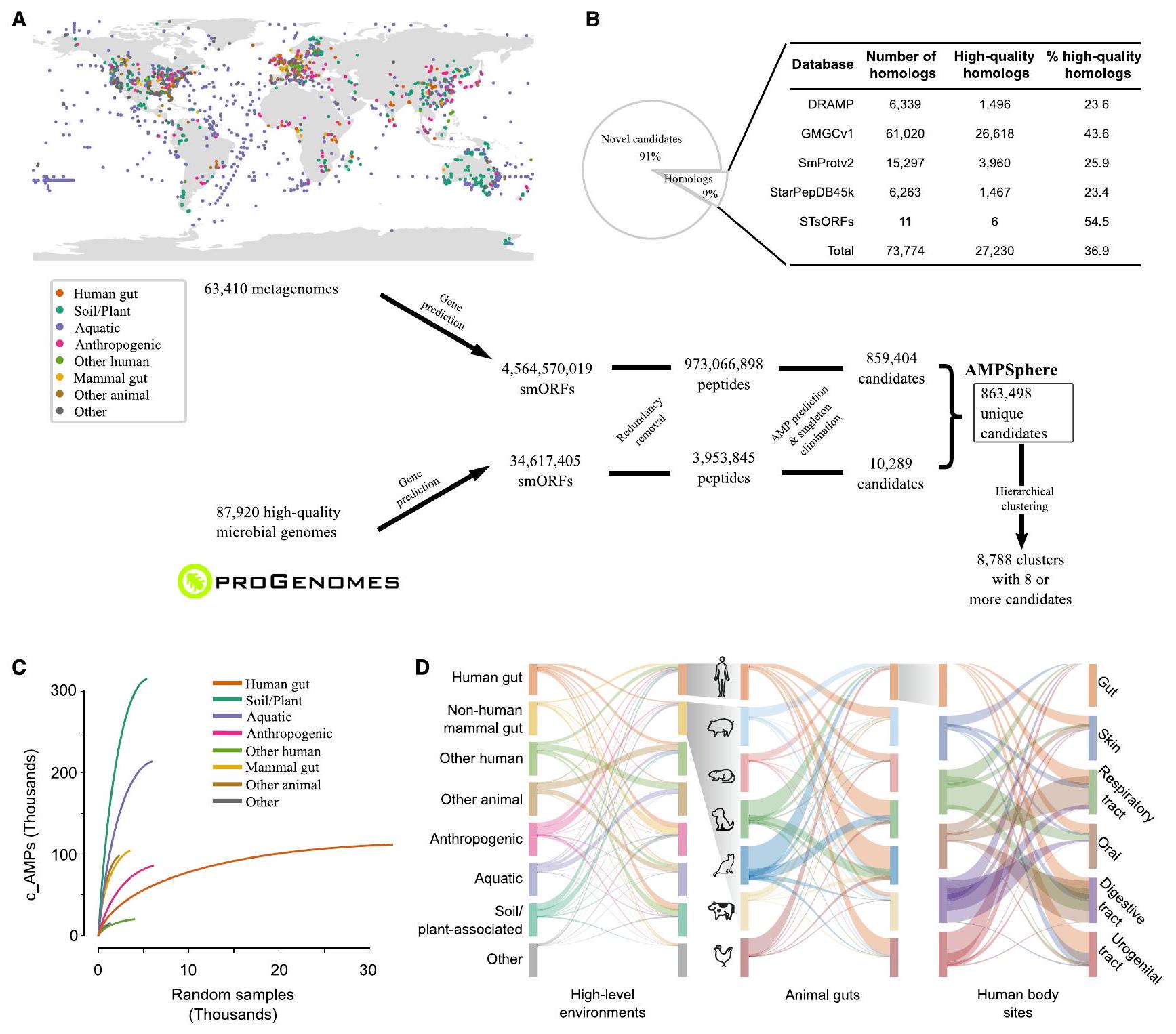

AMPSphere comprises almost 1 million c_AMPs from several habitats

(B) Only

(C) Shown are rarefaction curves showing how AMP discovery is impacted by sampling, with most of the habitats presenting steep sampling curves.

(D) Sharing of c_AMPs between habitats is limited. The width of ribbons represents the proportion of the shared c_AMPs in the habitat on the left. See also Figures S2C and S2D and Tables S1 and S2.

sent from protein databases not specific to AMPs (Figure 1B), such as the Small Proteins database (SmProt2)

(A) The number of AMPSphere candidates passing each of the tests proposed for quality is shown. The high-quality set is composed of

(B) The number of AMP candidates co-predicted by AMP prediction systems beyond Macrel (AMPScanner v2,

peptide sequence space that is not present in these other databases. In total, we could find only 73,774 (

c_AMPs are rare and habitat-specific

Mutations in larger genes generate c_AMPs as independent genomic entities

| CD3:33 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTG G CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| F0106 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAAA TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| F0697 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| SAMN09837386 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTG A CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| SAMN09837387 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTGA CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| SAMN09837388 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGT AAGAGTGGCTGA CAAG TAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_760 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_306 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG GCAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| FDAARGOS_1566 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG G CAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

| ATCC 25845 | GCTATGGTATCTGTAAGTTTTTAGGCAAGAGTGGCTG G CAGGTAATCGTTGGTGC |

(A) The distribution of positions (as a percentage of the length of the larger protein) from which the AMP homologs start their alignment is shown. About 7% of c_AMPs are homologous to proteins from GMGCv1,

(B) As an illustrative example of an AMP homologous to a full-length protein, AMP10.271_016 was recovered from three samples of human saliva from the same donor.

(C) The distribution of AMPs per OG class (left) and their enrichment in comparison to full-length proteins from GMGCv1

c_AMP genes may arise after gene duplication events

Most c_AMPs are members of the accessory pangenome

More transmissible species have lower c_AMP density

(A) Compared to other proteins, c_AMPs in conserved genomic architectures tend to be closer to ribosomal-machinery-related genes than families of proteins with different sizes (all length and small proteins with

(B) The proportion of c_AMPs in a genome context involving antibiotic resistance genes is lower than in other gene families.

(C) The proportion of c_AMPs in neighborhoods with antibiotic-synthesis-related genes is very small (

(D) The conserved genomic context of the gene encoding AMP10.015_426 is shown in different genomes (the tree on the left depicts the phylogenetic relationship of the genes homologous to it). This c_AMP is homologous to the ribosomal protein rpsH and is found in the context of rpsH and other ribosomal protein genes. See also Table S4.

Physicochemical features and secondary structure of AMPs

bicity, net charge, and amphiphilicity to AMPs sourced from databases (Figure S1). Furthermore, they displayed a slight propensity for disordered conformations (Figure 6B) and had a lower net positive charge compared to other EPs (Figure 6A).

(A) Shown are the fractions of AMPs (or AMP families) that are accessory (present in

(B) Distribution of the lowest taxonomic level at which c_AMPs were annotated. In detail (right) are the top 10 genera with the highest numbers of c_AMPs included in AMPSphere. Animal-associated genera (e.g., Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, and CAG-110) contribute the most c_AMPs, possibly reflecting data sampling.

(C) Using the

(D) Taxonomy of the detected taxa in AMPSphere is shown using the GTDB

Validation of c_AMPs as potent antimicrobials through in vitro assays

the growth of at least one of the pathogens tested (Figure 6C). Remarkably, in some cases, the AMPs were active at concentrations as low as

(A) Amino acid frequency in c_AMPs from AMPSphere, AMPs from databases (DRAMP

(B) Heatmap with the percentage of secondary structure found for each peptide in three different solvents: water,

(C) Activity of c_AMPs assessed against ESKAPEE pathogens and human gut commensal strains. Briefly,

The growth of human gut commensals is impaired by c_AMPs

Permeabilization and depolarization of the bacterial membrane by c_AMPs from AMPSphere

control, we used polymyxin B, a peptide antibiotic known for its membrane permeabilization and depolarization properties.

AMPs exhibit anti-infective efficacy in a mouse model

(A) Schematic of the skin abscess mouse model used to assess the anti-infective activity of the peptides against A. baumannii cells.

(B) Peptides were tested at their MIC in a single dose 2 h after the establishment of the infection. Each group consisted of three mice (

(C) To rule out toxic effects of the peptides, mouse weight was monitored throughout the experiment.

Statistical significance in (B) was determined using one-way ANOVA where all groups were compared to the untreated control group;

infective potential of the tested peptides from AMPSphere as they were administered at a single time immediately after the establishment of the abscess. Mouse weight was monitored as a proxy for toxicity, and no significant changes were observed (Figures 7C and S6D), suggesting that the peptides tested were not toxic.

DISCUSSION

that they were active, including our own in vitro data and the existence of validated homologs in external databases. Low-prevalence peptides will be less likely to pass the tests (RNAcode

and lachnospirin-1 against vancomycin-resistant E. faecium) presented MIC values as low as

Limitations of the study

STAR*METHODS

- Key RESOURCES TABLE

- RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

- Lead contact

- Materials availability

- Data and code availability

- EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

- Bacterial strains and growth conditions

- Skin abscess infection mouse model

- METHOD DETAILS

- Selection of microbial (meta)genomes

- Reads trimming and assembly

- smORF and AMP prediction

- Clustering of AMP families

- Quality control of c_AMPs

- Sample-based c_AMPs accumulation curves

- Multi-habitat and rare c_AMPs

c_AMP density in microbial species

c_AMPs and bacterial species transmissibility

Determination of accessory AMPs

Annotation of AMPs using different datasets

Genomic context conservation analysis

AMPSphere web resource

Peptide selection for synthesis and testing

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination

Circular dichroism assays

Outer membrane permeabilization assays

Cytoplasmic membrane depolarization assays

- QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

- ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.-M.Z., and C.F.-N.; Investigation, C.D.S.-J., L.P.C., M.D.T.T., and C.F.-N.; Methodology, C.D.S.-J., Y.D., J.H.-C., A.R.d.R., L.P.C., M.D.T.T., and C.F.-N.; Project administration, L.P.C., M.K., X.-M.Z., P.B., and C.F.-N.; Resources, L.P.C., X.-M.Z., and C.F.-N.; Supervision, L.P.C. and C.F.-N.; Visualization, C.D.S.-J., J.H.-C., J.S., A.V., A.H., C.Z., L.P.C., and M.D.T.T.; Writing original draft, C.D.S.-J., M.D.T.T., C.F.-N., and L.P.C.; Writing – review & editing, C.D.S.-J., Y.D., J.H.-C., A.R.d.R., T.S.B.S., A.F., P.B., X.-M.Z., L.P.C., M.D.T.T., and C.F.-N.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Revised: April 11, 2024

Accepted: May 6, 2024

Published: June 5, 2024

REFERENCES

- de la Fuente-Nunez, C., Torres, M.D., Mojica, F.J., and Lu, T.K. (2017). Next-generation precision antimicrobials: towards personalized treatment of infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37, 95-102. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.014.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629-655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

- Stokes, J.M., Yang, K., Swanson, K., Jin, W., Cubillos-Ruiz, A., Donghia, N.M., MacNair, C.R., French, S., Carfrae, L.A., Bloom-Ackermann, Z., et al. (2020). A Deep Learning Approach to Antibiotic Discovery. Cell 180, 688-702.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.021.

- Torres, M.D.T., Melo, M.C.R., Flowers, L., Crescenzi, O., Notomista, E., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2022). Mining for encrypted peptide antibiotics in the human proteome. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 67-75. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41551-021-00801-1.

- Porto, W.F., Irazazabal, L., Alves, E.S.F., Ribeiro, S.M., Matos, C.O., Pires, Á.S., Fensterseifer, I.C.M., Miranda, V.J., Haney, E.F., Humblot, V., et al. (2018). In silico optimization of a guava antimicrobial peptide enables combinatorial exploration for peptide design. Nat. Commun. 9, 1490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03746-3.

- Ma, Y., Guo, Z., Xia, B., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Yu, Y., Tang, N., Tong, X., Wang, M., Ye, X., et al. (2022). Identification of antimicrobial peptides from the human gut microbiome using deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 921-931. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01226-0.

- Wong, F., de la Fuente-Nunez, C., and Collins, J.J. (2023). Leveraging artificial intelligence in the fight against infectious diseases. Science 381, 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh1114.

- Cesaro, A., Bagheri, M., Torres, M., Wan, F., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2023). Deep learning tools to accelerate antibiotic discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 18, 1245-1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441. 2023.2250721.

- Torres, M.D.T., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2019). Toward computermade artificial antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 51, 30-38. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.03.004.

- Maasch, J.R.M.A., Torres, M.D.T., Melo, M.C.R., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2023). Molecular de-extinction of ancient antimicrobial peptides enabled by machine learning. Cell Host Microbe 31, 1260-1274.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.07.001.

- Besse, A., Vandervennet, M., Goulard, C., Peduzzi, J., Isaac, S., Rebuffat, S., and Carré-Mlouka, A. (2017). Halocin C8: an antimicrobial peptide

distributed among four halophilic archaeal genera: Natrinema, Haloterrigena, Haloferax, and Halobacterium. Extremophiles 21, 623-638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-017-0931-5. - Cotter, P.D., Ross, R.P., and Hill, C. (2013). Bacteriocins – a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 95-105. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nrmicro2937.

- Wang, S., Zheng, Z., Zou, H., Li, N., and Wu, M. (2019). Characterization of the secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in archaea. Comput. Biol. Chem. 78, 165-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem. 2018.11.019.

- Zasloff, M. (2019). Antimicrobial Peptides of Multicellular Organisms: My Perspective. In Antimicrobial Peptides: Basics for Clinical Application, K. Matsuzaki, ed. (Springer Singapore), pp. 3-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-981-13-3588-4_1.

- Huang, K.-Y., Chang, T.-H., Jhong, J.-H., Chi, Y.-H., Li, W.-C., Chan, C.L., Robert Lai, K., and Lee, T.-Y. (2017). Identification of natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria through metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data of Taiwanese oolong teas. BMC Syst. Biol. 11, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12918-017-0503-4.

- Torres, M.D.T., Sothiselvam, S., Lu, T.K., and de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2019). Peptide Design Principles for Antimicrobial Applications. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3547-3567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2018.12.015.

- Pizzo, E., Cafaro, V., Di Donato, A., and Notomista, E. (2018). Cryptic Antimicrobial Peptides: Identification Methods and Current Knowledge of their Immunomodulatory Properties. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24, 10541066. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180327165012.

- Nolan, E.M., and Walsh, C.T. (2009). How nature morphs peptide scaffolds into antibiotics. Chembiochem 10, 34-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cbic. 200800438.

- Singh, N., and Abraham, J. (2014). Ribosomally synthesized peptides from natural sources. J. Antibiot. 67, 277-289. https://doi.org/10.1038/ ja.2013.138.

- García-Bayona, L., and Comstock, L.E. (2018). Bacterial antagonism in host-associated microbial communities. Science 361, eaat2456. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat2456.

- Anderson, M.C., Vonaesch, P., Saffarian, A., Marteyn, B.S., and Sansonetti, P.J. (2017). Shigella sonnei encodes a functional T6SS used for interbacterial competition and niche occupancy. Cell Host Microbe 21, 769-776.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.004.

- Krismer, B., Weidenmaier, C., Zipperer, A., and Peschel, A. (2017). The commensal lifestyle of Staphylococcus aureus and its interactions with the nasal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 675-687. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.104.

- Zhao, W., Caro, F., Robins, W., and Mekalanos, J.J. (2018). Antagonism toward the intestinal microbiota and its effect on Vibrio cholerae virulence. Science 359, 210-213. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8775.

- Quereda, J.J., Nahori, M.A., Meza-Torres, J., Sachse, M., Titos-Jiménez, P., Gomez-Laguna, J., Dussurget, O., Cossart, P., and Pizarro-Cerdá, J. (2017). Listeriolysin S is a streptolysin s-like virulence factor that targets exclusively prokaryotic cells in vivo. mBio 8, e00259-17. https://doi.org/

. - Quereda, J.J., Dussurget, O., Nahori, M.A., Ghozlane, A., Volant, S., Dillies, M.A., Regnault, B., Kennedy, S., Mondot, S., Villoing, B., et al. (2016). Bacteriocin from epidemic Listeria strains alters the host intestinal microbiota to favor infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5706-5711. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523899113.

- Gomes, B., Augusto, M.T., Felício, M.R., Hollmann, A., Franco, O.L., Gonçalves, S., and Santos, N.C. (2018). Designing improved active peptides for therapeutic approaches against infectious diseases. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 415-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.01.004.

- Lesiuk, M., Paduszyńska, M., and Greber, K.E. (2022). Synthetic Antimicrobial Immunomodulatory Peptides: Ongoing Studies and Clinical Tri-

als. Antibiotics (Basel) 11, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics 11081062. - Mahlapuu, M., Håkansson, J., Ringstad, L., and Björn, C. (2016). Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6, 235805.

- Baquero, F., Lanza, V.F., Baquero, M.R., Del Campo, R., and Bravo-Vázquez, D.A. (2019). Microcins in Enterobacteriaceae: peptide antimicrobials in the eco-active intestinal chemosphere. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2261. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02261.

- Kim, S.G., Becattini, S., Moody, T.U., Shliaha, P.V., Littmann, E.R., Seok, R., Gjonbalaj, M., Eaton, V., Fontana, E., Amoretti, L., et al. (2019). Micro-biota-derived lantibiotic restores resistance against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Nature 572, 665-669. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-019-1501-z.

- Nakatsuji, T., Hata, T.R., Tong, Y., Cheng, J.Y., Shafiq, F., Butcher, A.M., Salem, S.S., Brinton, S.L., Rudman Spergel, A.K., Johnson, K., et al. (2021). Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 27, 700-709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2.

- Spohn, R., Daruka, L., Lázár, V., Martins, A., Vidovics, F., Grézal, G., Méhi, O., Kintses, B., Számel, M., Jangir, P.K., et al. (2019). Integrated evolutionary analysis reveals antimicrobial peptides with limited resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 4538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12364-6.

- Cesaro, A., Torres, M.D.T., Gaglione, R., Dell’Olmo, E., Di Girolamo, R., Bosso, A., Pizzo, E., Haagsman, H.P., Veldhuizen, E.J.A., de la FuenteNunez, C., and Arciello, A. (2022). Synthetic Antibiotic Derived from Sequences Encrypted in a Protein from Human Plasma. ACS Nano 16, 1880-1895. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c04496.

- Hyatt, D., Chen, G.-L., LoCascio, P.F., Land, M.L., Larimer, F.W., and Hauser, L.J. (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinf. 11, 119. https://doi.org/10. 1186/1471-2105-11-119.

- Ahrens, C.H., Wade, J.T., Champion, M.M., and Langer, J.D. (2022). A Practical Guide to Small Protein Discovery and Characterization Using Mass Spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 204, e0035321. https://doi.org/10. 1128/JB.00353-21.

- Storz, G., Wolf, Y.I., and Ramamurthi, K.S. (2014). Small Proteins Can No Longer Be Ignored. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 753-777. https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070611-102400.

- Su, M., Ling, Y., Yu, J., Wu, J., and Xiao, J. (2013). Small proteins: untapped area of potential biological importance. Front. Genet. 4, 286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00286.

- Sberro, H., Fremin, B.J., Zlitni, S., Edfors, F., Greenfield, N., Snyder, M.P., Pavlopoulos, G.A., Kyrpides, N.C., and Bhatt, A.S. (2019). LargeScale Analyses of Human Microbiomes Reveal Thousands of Small, Novel Genes. Cell 178, 1245-1259.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell. 2019.07.016.