DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/adc911

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41103619

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-30

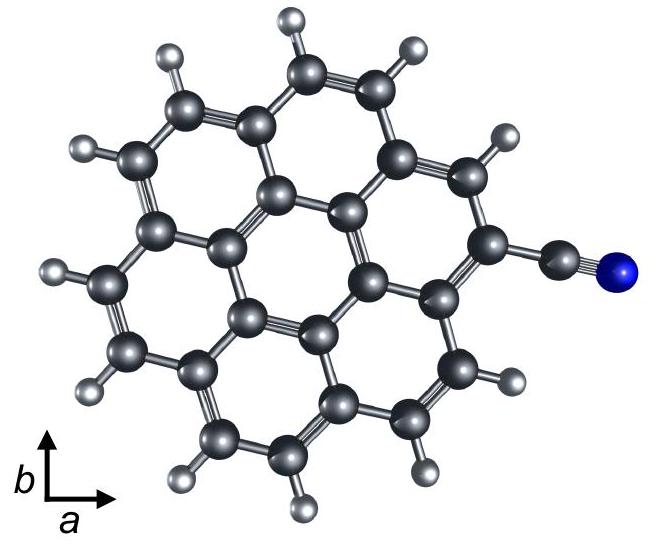

اكتشاف الهيدروكربون العطري متعدد الحلقات ذو السبعة حلقات سيانكورونين (C 24 H 11 CN) في ملاحظات GOTHAM لـ TMC-1

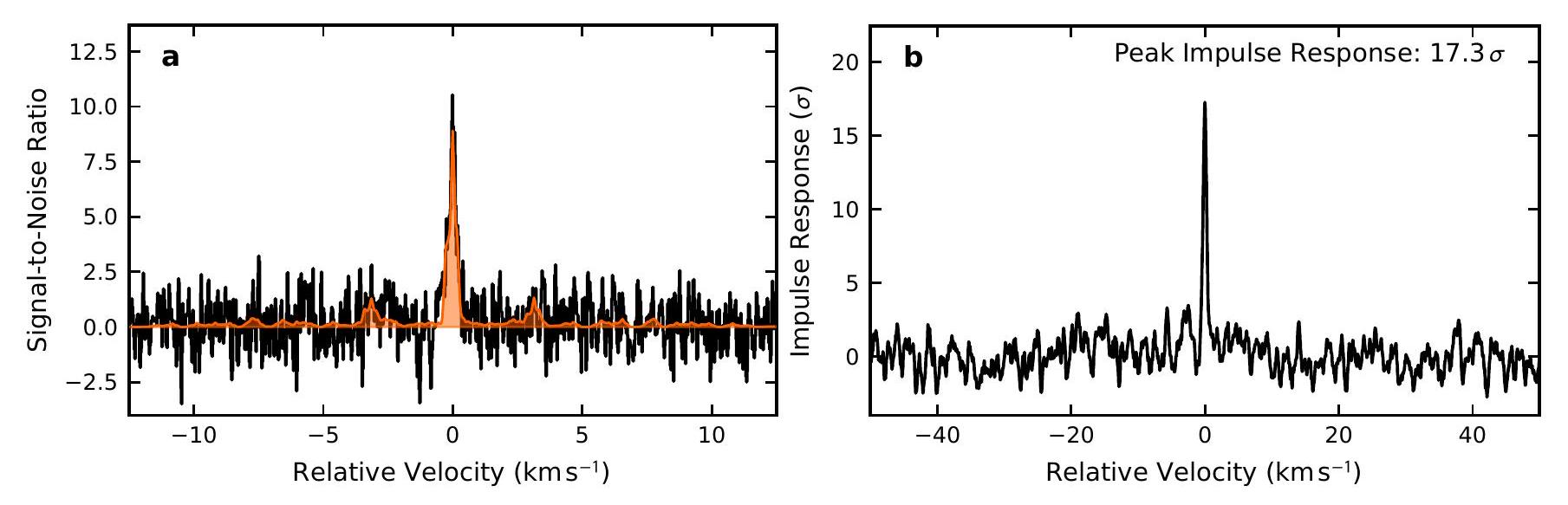

الملخص

نقدم تخليق وطيف الدوران المختبري للهيدروكربونات العطرية متعددة الحلقات ذات السبع حلقات

1. المقدمة

تمت مناقشة الأشرطة بين النجوم المنتشرة (DIBs). تم اقتراح الكورونين المنزوع الهيدروجين، والمُؤيّن، والمُؤيّن كحاملين محتملين للأشرطة (Pathak & Sarre 2008؛ Malloci et al. 2008)، لكن هذه الفرضيات تم دحضها (Garkusha et al. 2011؛ Useli-Bacchitta et al. 2010؛ Hardy et al. 2017). ومع ذلك، لا تزال بعض توزيعات PAHs مرشحة واعدة كحاملين للأشرطة بسبب علاقتها الوثيقة بعائلة الفوليرين (Campbell et al. 2015).

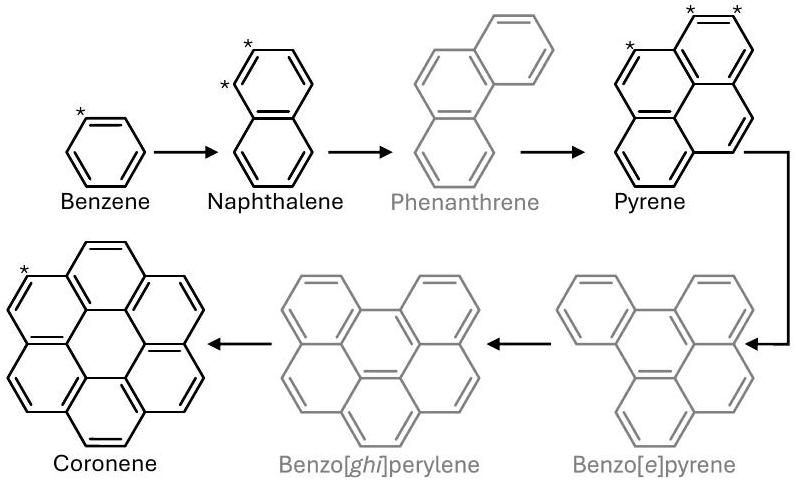

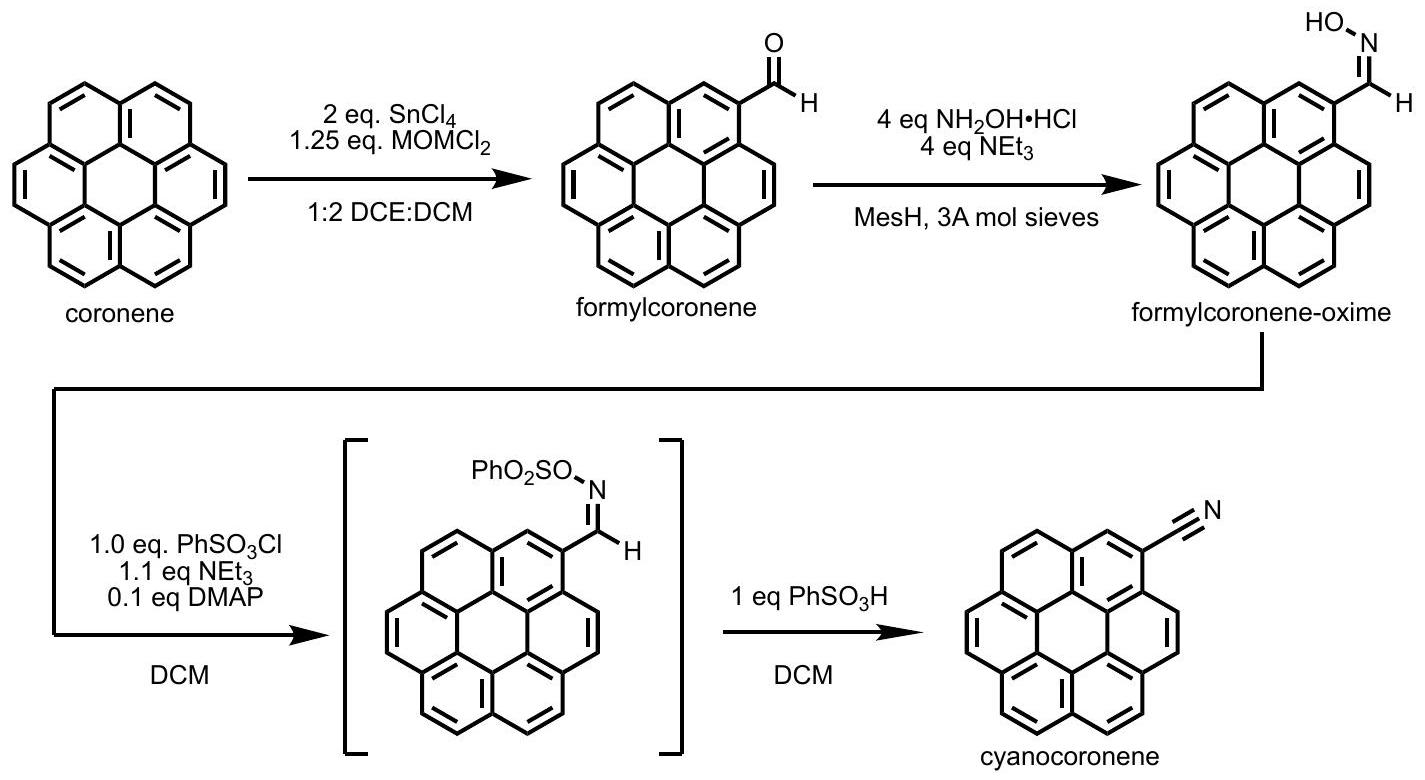

2. التركيب

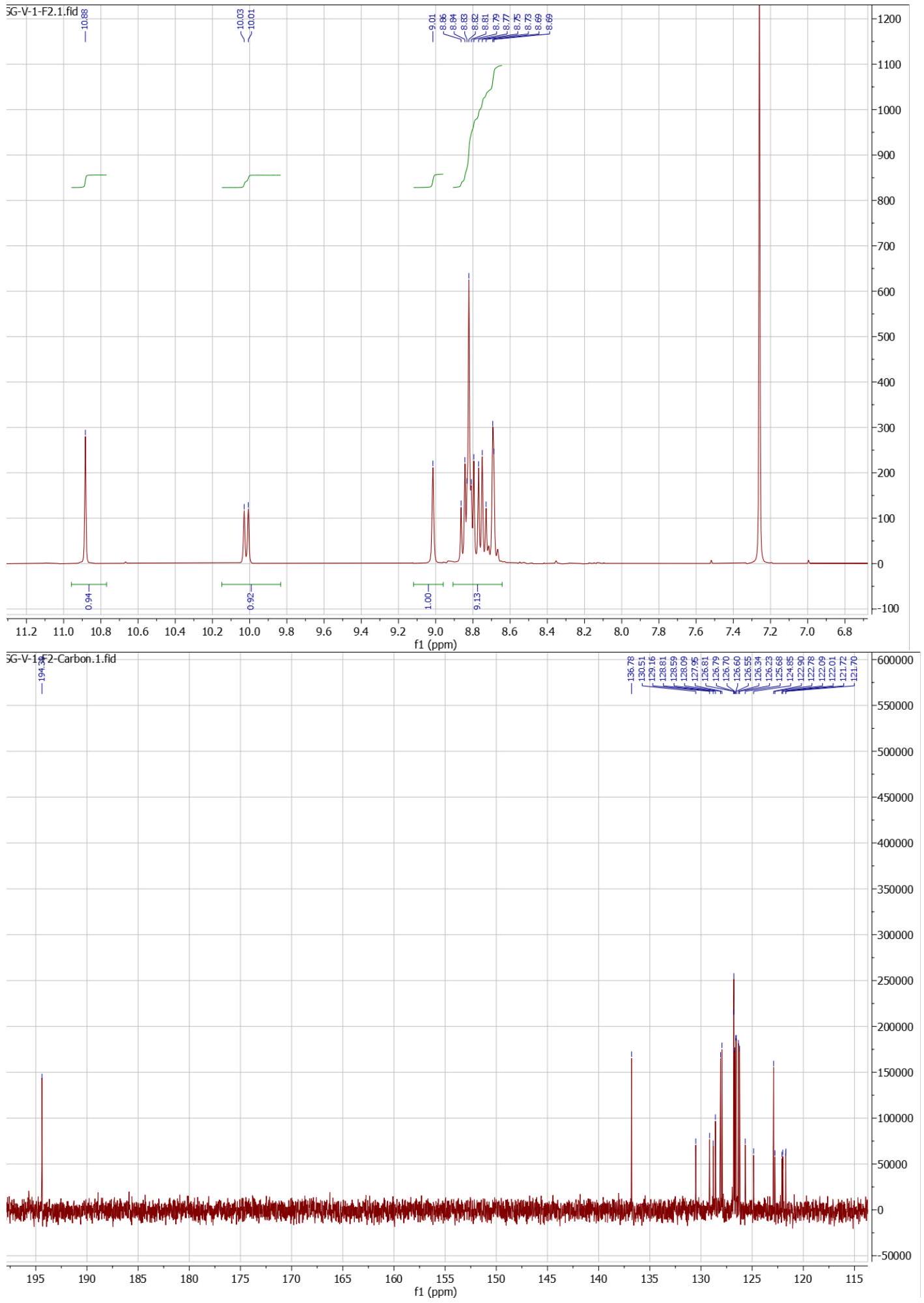

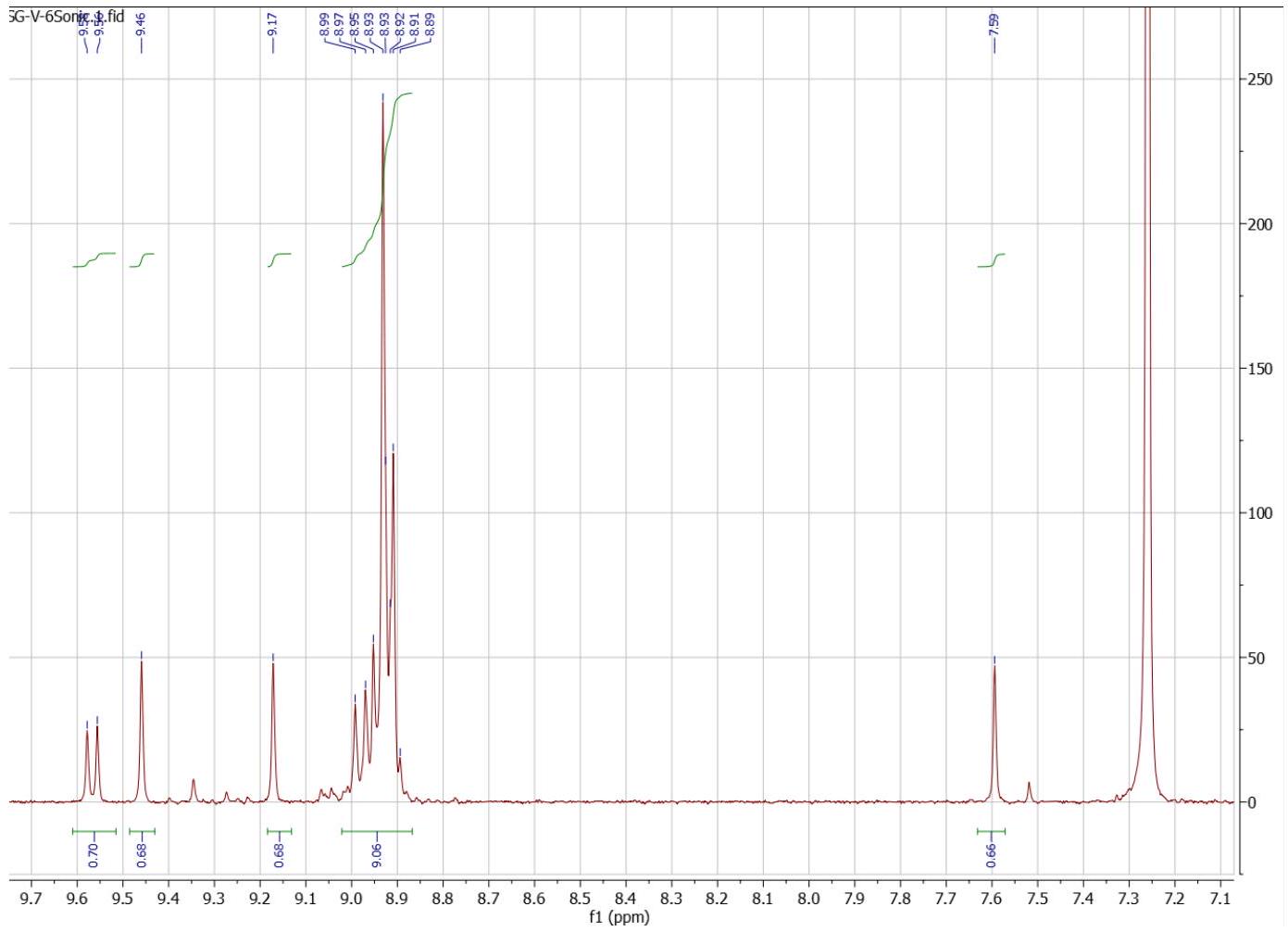

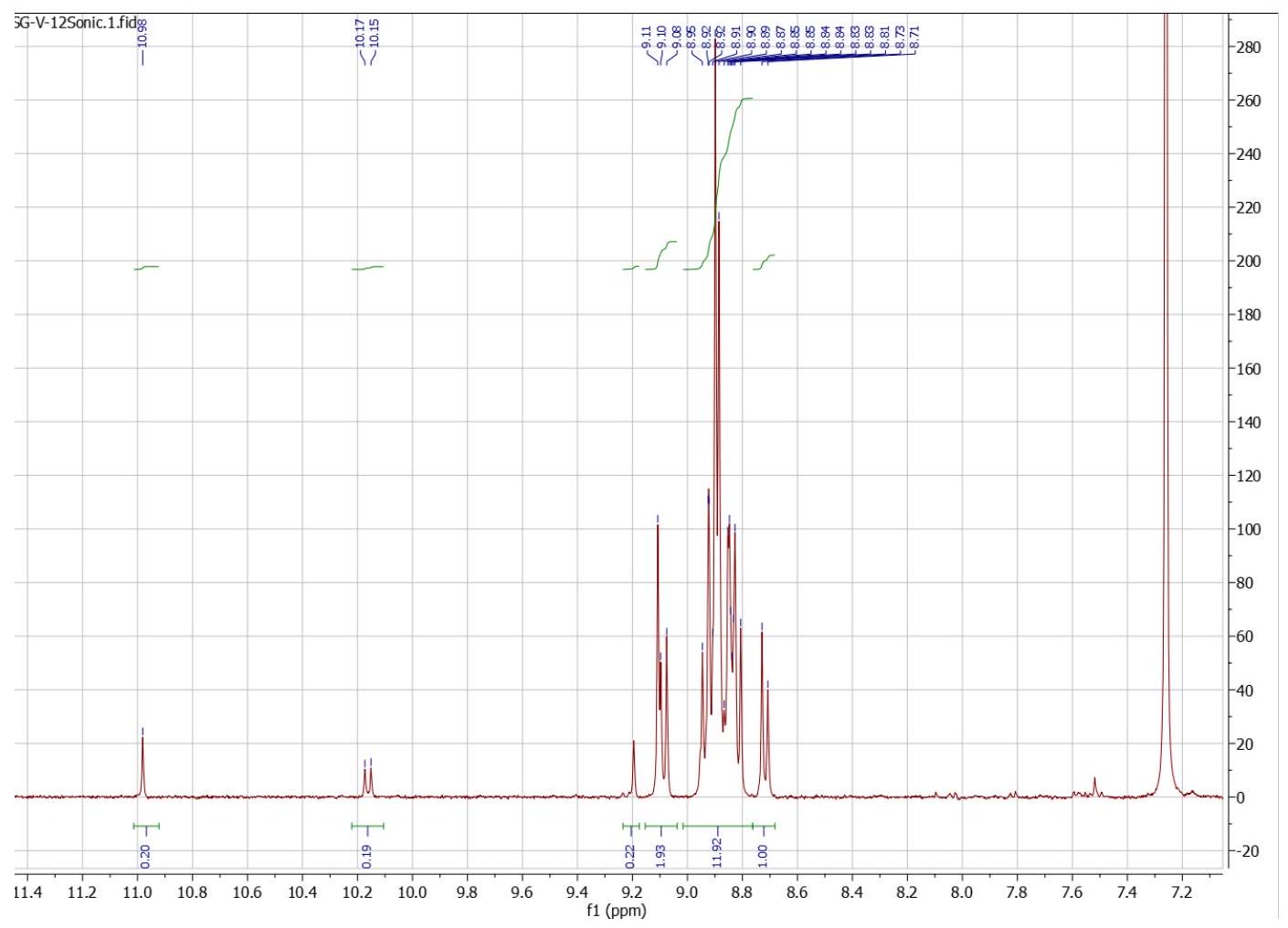

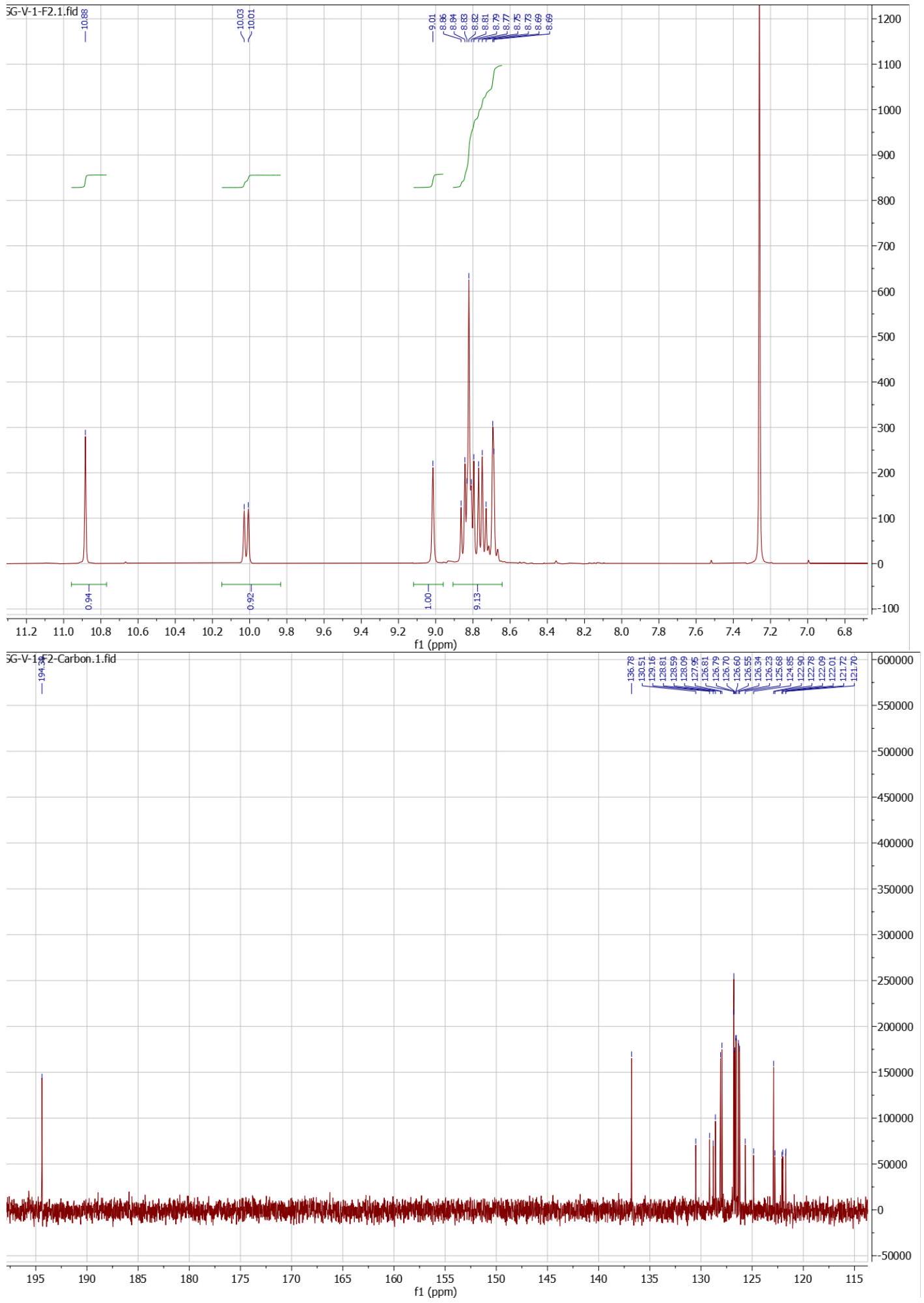

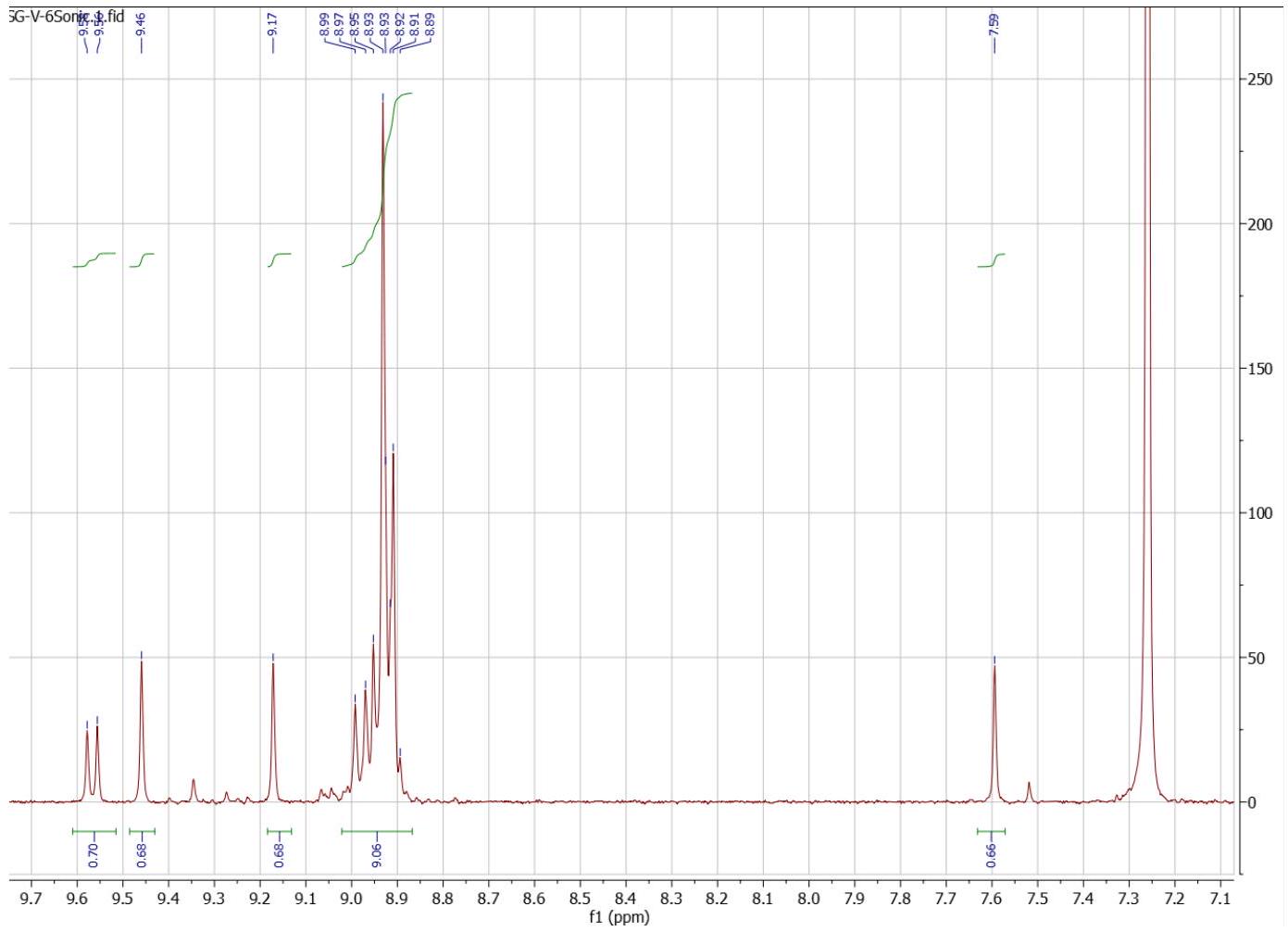

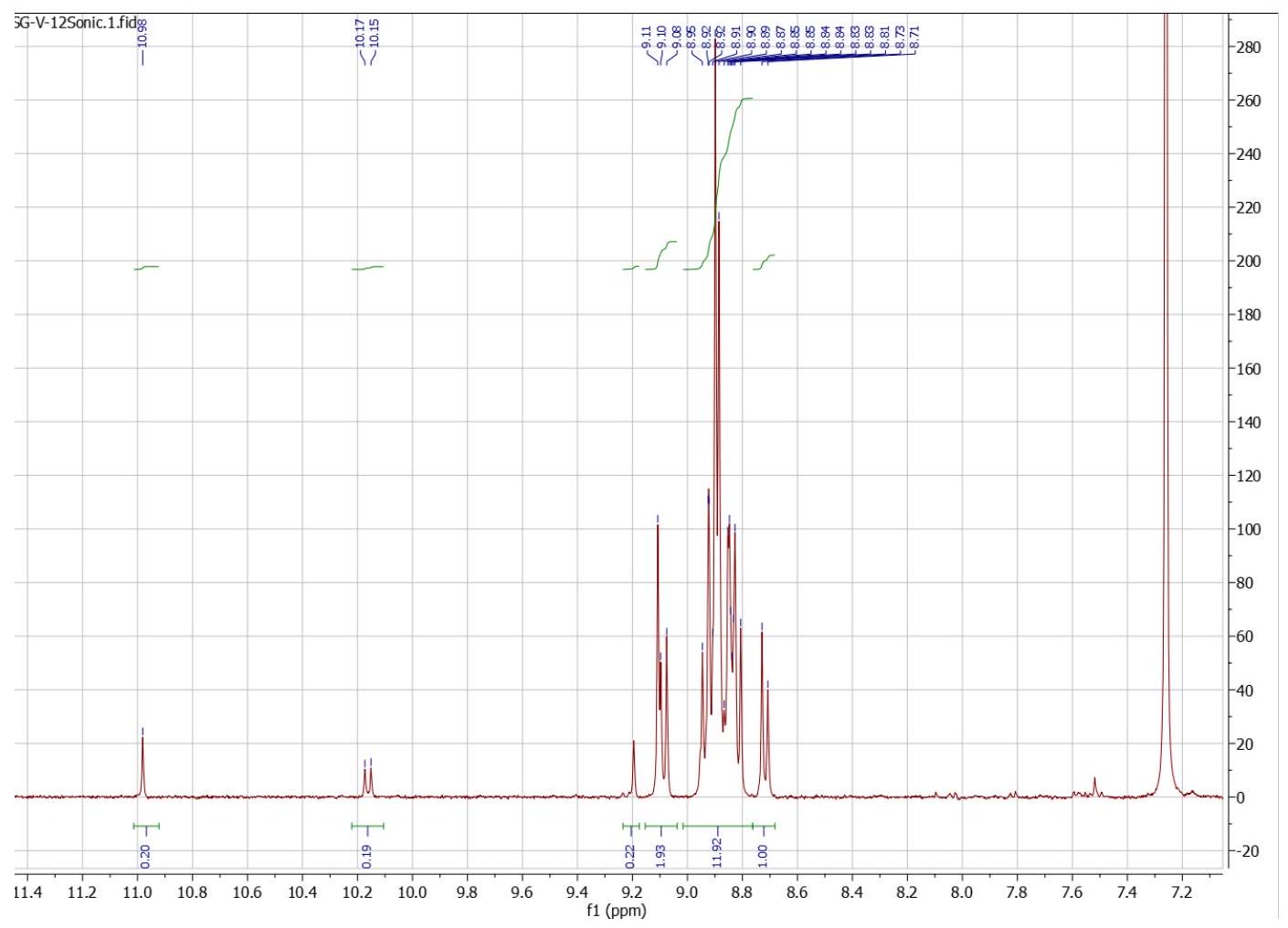

3. الطيفية المخبرية

| معامل | B3LYP aug-cc-pVTZ | تجريبي

|

|

|

335.393 | ٣٣٣.٨٥٢٩٨٩(٢٤٩) |

|

|

٢٢٢٫٠٣٥ | 221.2700880(838) |

|

|

١٣٣٫٥٩٤ | ١٣٣.١٠٨١٠١٥(١٢٢) |

|

|

0.669 | [0.669] |

|

|

-0.617 | [-0.617] |

|

|

0.011 | [0.011] |

|

|

-0.120 | [-0.120] |

|

|

-0.494 | [-0.494] |

|

|

71 | |

|

|

٣٨ | |

|

|

٢.٥٩٥ | |

|

|

|

|

ثوابت دورانية،

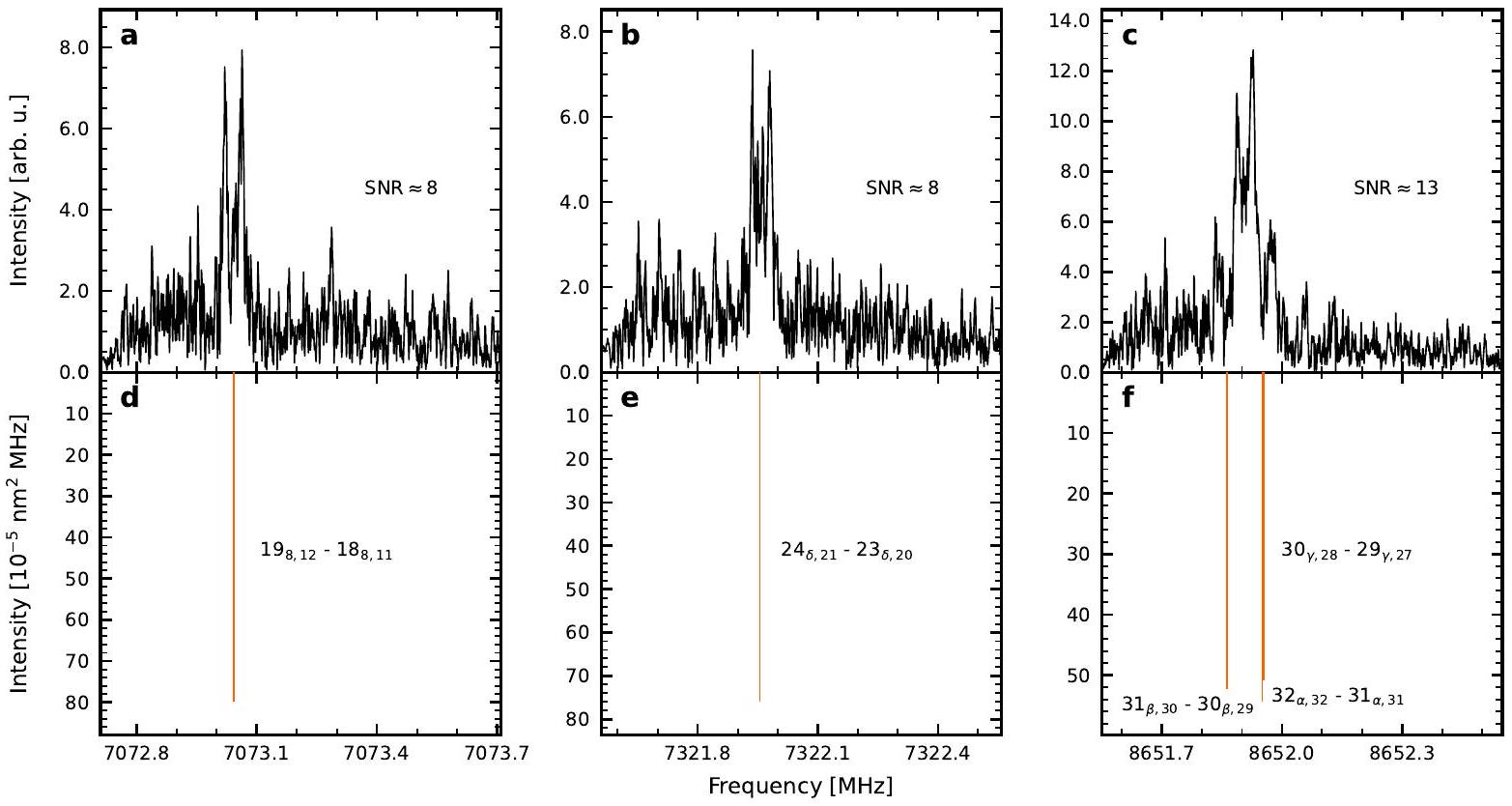

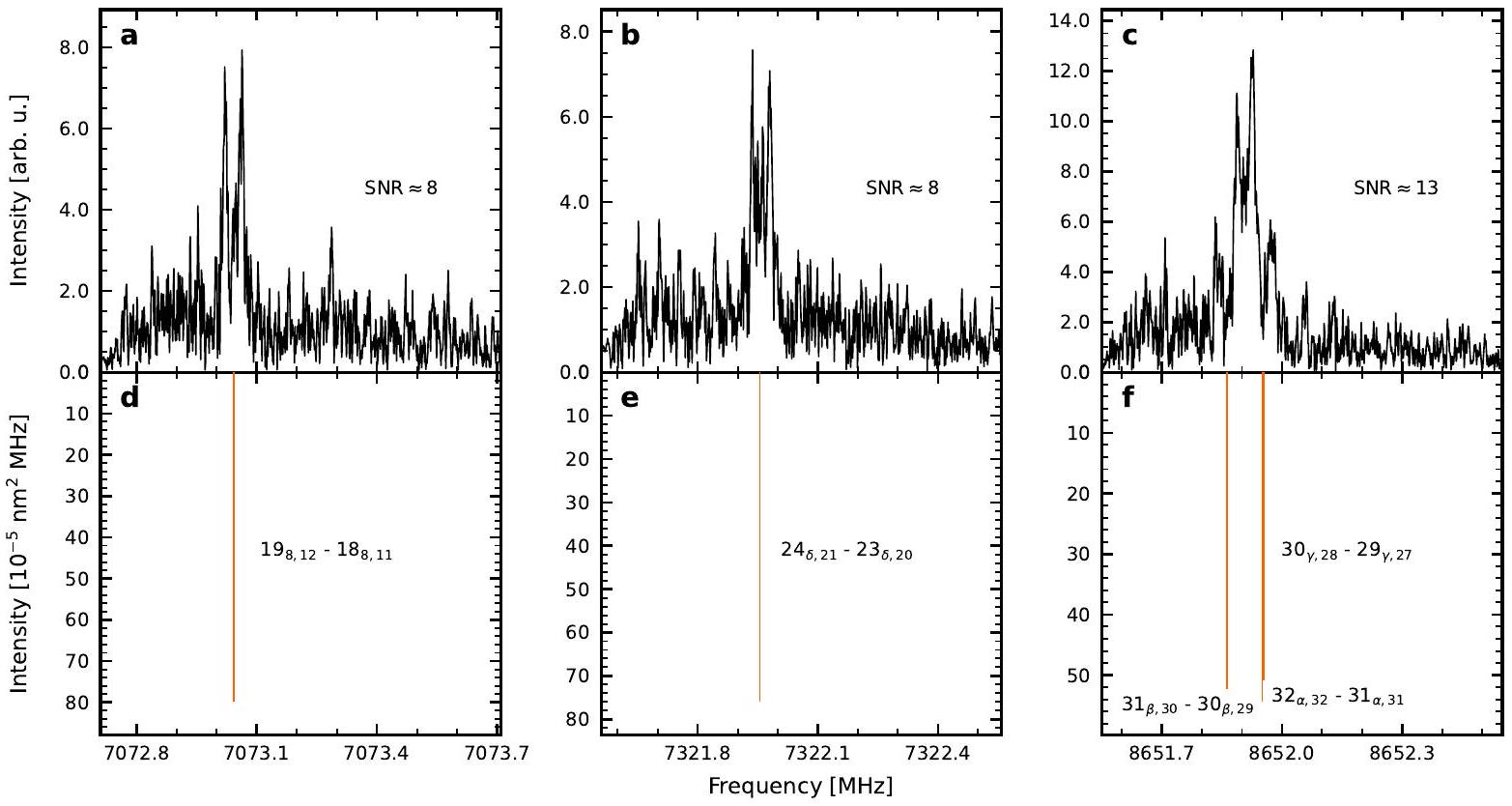

4. الملاحظات

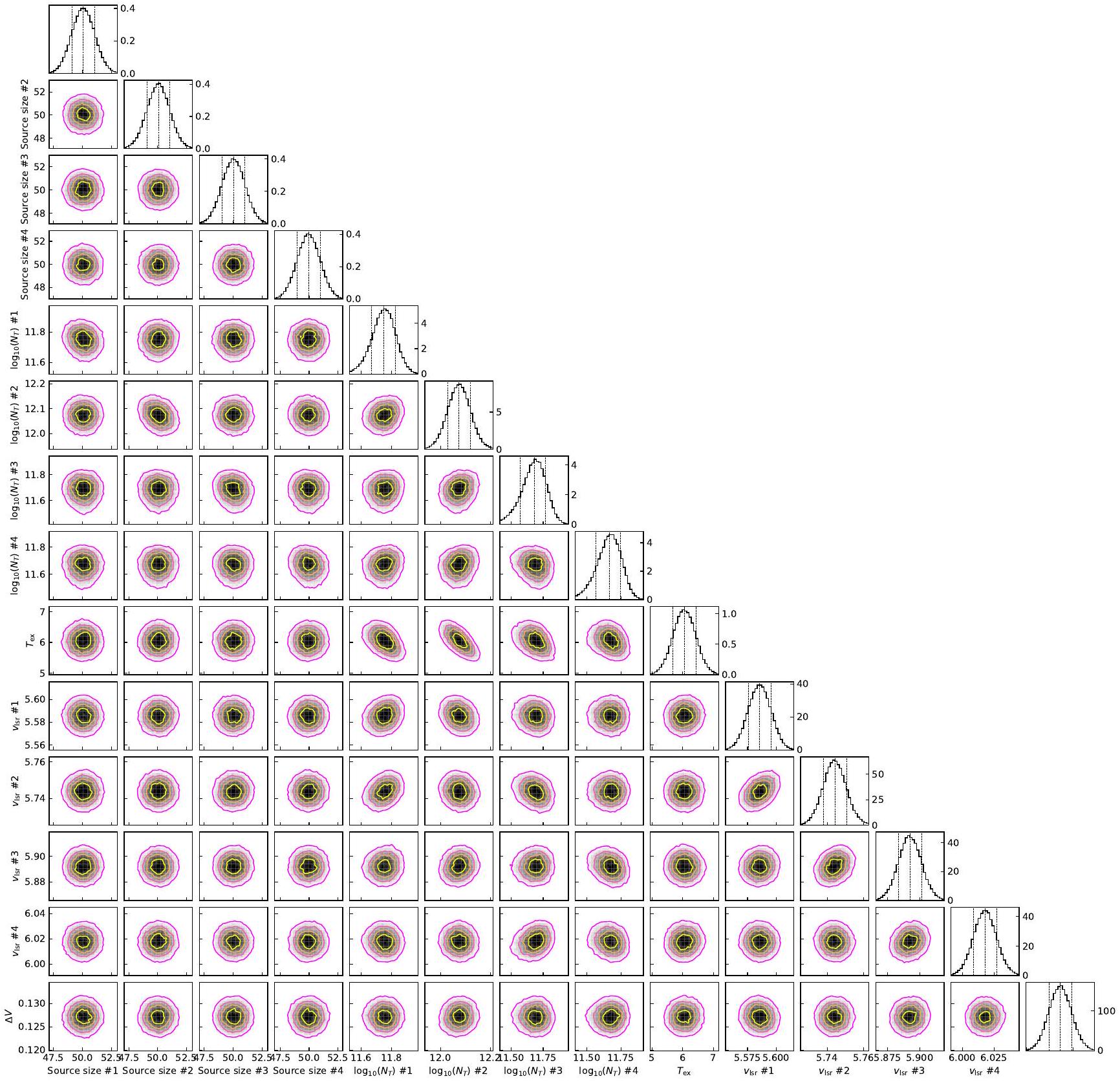

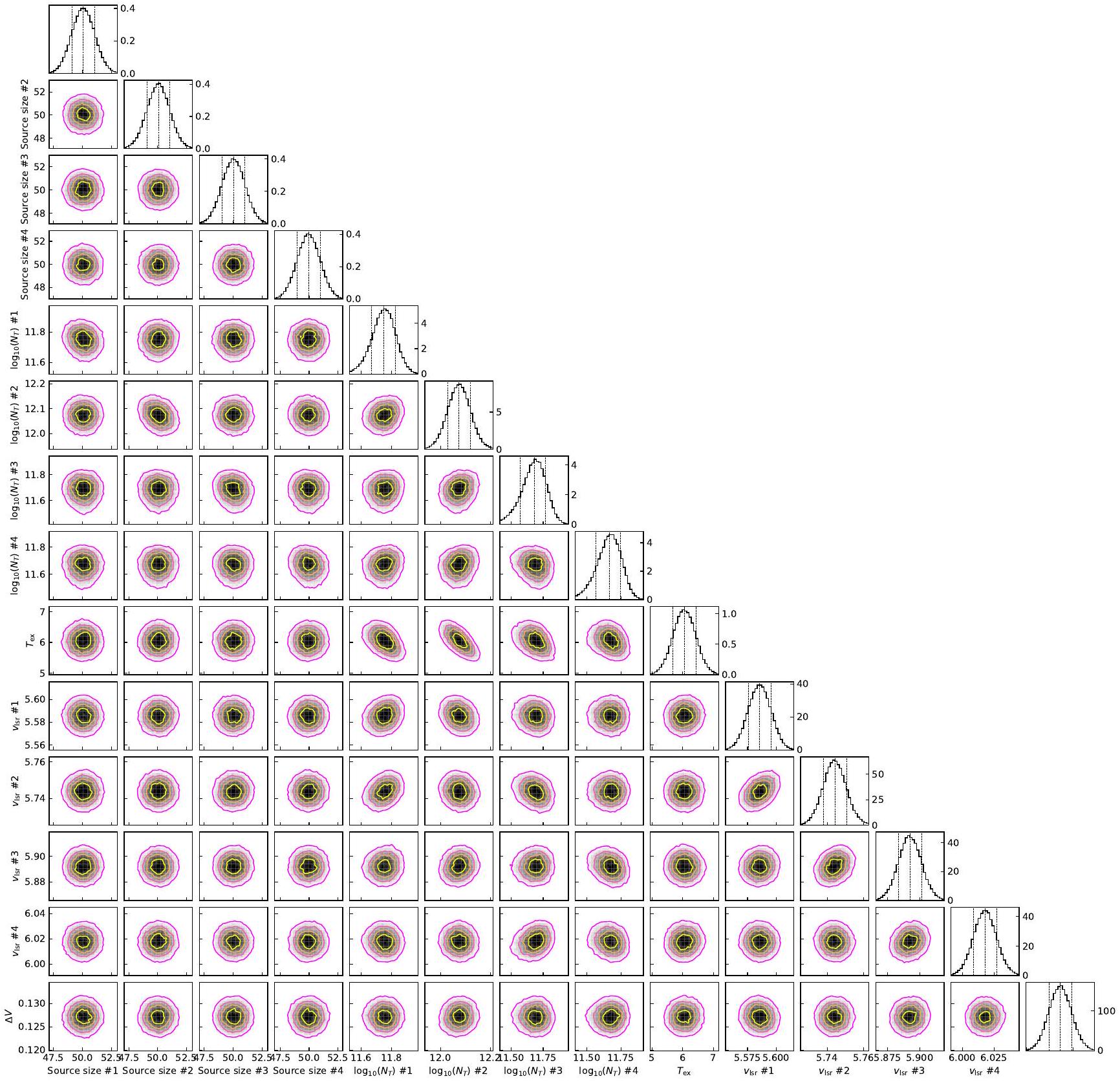

5. التحليل الفلكي

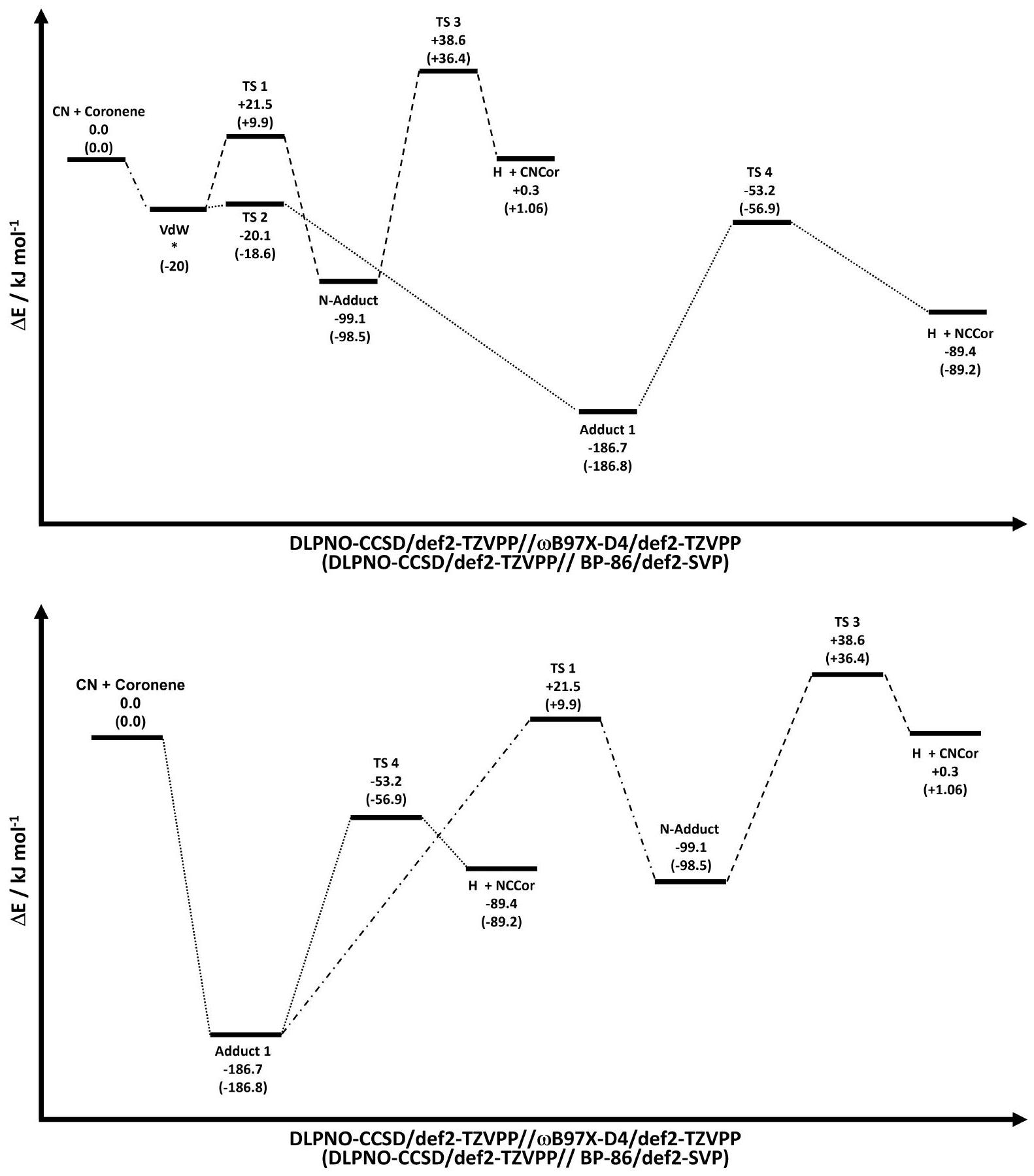

6. المناقشة

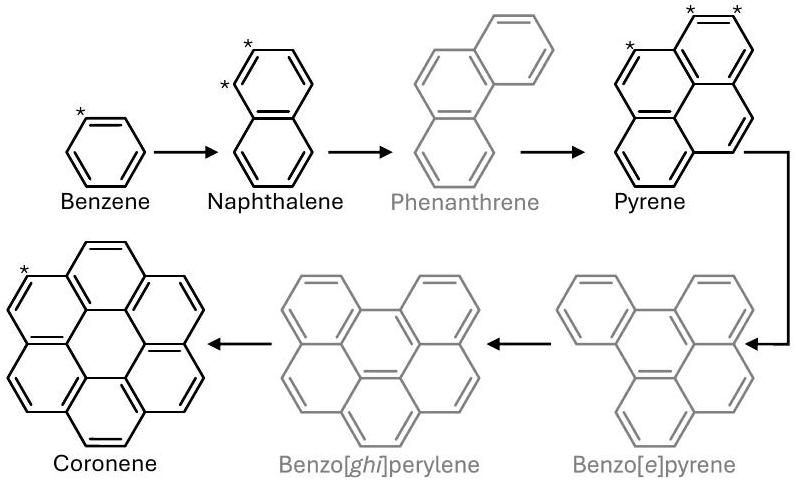

مسار تشكيل الطور لبايرين، بدءًا من الجذري 4-فينانثرينيل. في الواقع، الفينانثرين هو أيضًا عضو في أكثر مسارات بوليمرة PAH استقرارًا من الناحية الديناميكية الحرارية (انظر الشكل 5). ومع ذلك، لم تكن عمليات البحث السريعة عن مشتقه CN- 9-سيانوفيتانثرين، الذي يُعرف طيفه الدوراني (ماكنوتون وآخرون 2018)، ناجحة حتى الآن في ملاحظاتنا باستخدام GOTHAM. قد يكون ذلك بسبب أن الطيفية لواحد فقط من خمسة سيانوفيتانثرين المحتملة…

ويدل بول وآخرون (2025) على أن الهيكل الأساسي لمركبات PAH يمكن الحفاظ عليه من خلال التبريد الإشعاعي الفعال، مما يفتح إمكانية نوع من “إعادة التدوير” الكيميائي لمركبات PAH التي ستساهم بالتأكيد في الوفرة العالية الملحوظة، على سبيل المثال، السيانكورونين. عند الانتقال إلى النقص في الحبوب، أجرى دارتوا وآخرون (2022) تجارب على إنتاجية التبخير لمركب بيرلين الصلب والكورونين الذي تعرض لقصف من أيونات نشطة، وهو ما يشبه تعرض الأنواع لأشعة كونية في غلاف الثلج لحبوب الغبار. وقد وجدوا أن هذا التبخير الناتج عن الأشعة الكونية فعال تحت ظروف الوسط بين النجوم، ويتوقعون حتى وفرة جزئية في الطور الغازي للكورونين.

7. الاستنتاجات

8. الوصول إلى البيانات والرمز

المرافق: GBT

الشكر والتقدير

جائزة بيكمان للشباب الباحثين. يود ز.ت.ب.ف. و ب.أ.م. أن يعربا عن امتنانهما لدعم عائلة شميت. يقر إ.ر.س. بالدعم المقدم من جامعة كولومبيا البريطانية ومجلس أبحاث العلوم الطبيعية والهندسة في كندا (NSERC). يقر إ.ر.س. و ت.هـ.س. بالدعم المقدم من وكالة الفضاء الكندية (CSA) من خلال منحة 24AO3UBC14. يتلقى ب.ج.س. الدعم من NIST. المرصد الوطني للراديو الفلكي هو منشأة تابعة لمؤسسة العلوم الوطنية وتديرها اتفاقية تعاونية مع الجامعات المرتبطة، إنك. المرصد في غرين بانك هو منشأة تابعة لمؤسسة العلوم الوطنية وتديرها اتفاقية تعاونية مع الجامعات المرتبطة، إنك.

REFERENCES

Baer, T., & Hase, W. L. 1996, Unimolecular Reaction Dynamics: Theory and Experiments (Oxford University Press). https://academic.oup.com/book/40815

Bahou, M., Wu, Y.-J., & Lee, Y.-P. 2014, Angewandte Chemie, 126, 1039, doi: 10.1002/ange. 201308971

Bakes, E. L. O., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1998, The Astrophysical Journal, 499, 258, doi: 10.1086/305625

Balle, T. J., & Flygare, W. H. 1981, Review of Scientific Instruments, 52, 33, doi: 10.1063/1.1136443

Balucani, N., Asvany, O., Huang, L. C. L., et al. 2000, The Astrophysical Journal, 545, 892, doi: 10.1086/317848

Bauschlicher, C. W. 1998, The Astrophysical Journal, 509, L125, doi: 10.1086/311782

Becke, A. D. 1988, Physical Review A, 38, 3098, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098

-. 1993, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 98, 5648, doi: 10.1063/1.464913

Becke, A. D., & Johnson, E. R. 2006, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 124, 221101, doi: 10.1063/1.2213970

Bernstein, M. P., Elsila, J. E., Dworkin, J. P., et al. 2002, The Astrophysical Journal, 576, 1115, doi: 10.1086/341863

Berné, O., Foschino, S., Jalabert, F., & Joblin, C. 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 667, A159, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202243171

Boschman, L., Cazaux, S., Spaans, M., Hoekstra, R., & Schlathölter, T. 2015, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 579, A72, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201323165

Burkhardt, A. M., Long Kelvin Lee, K., Bryan Changala, P., et al. 2021, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 913, L18, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abfd3a

Caldeweyher, E., Bannwarth, C., & Grimme, S. 2017, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 147, 034112, doi: 10.1063/1.4993215

Campbell, E. K., Holz, M., Gerlich, D., & Maier, J. P. 2015, Nature, 523, 322, doi: 10.1038/nature14566

Carelli, F., & Gianturco, F. A. 2012, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 422, 3643, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20876.x

Cazaux, S., Boschman, L., Rougeau, N., et al. 2016, Scientific Reports, 6, 19835, doi: 10.1038/srep19835

Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Cabezas, C., et al. 2021a, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 649, L15, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202141156

Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2021b, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 652, L9, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202141660

—. 2021c, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 655, L1, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202142226

Cernicharo, J., Fuentetaja, R., Agúndez, M., et al. 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 663, L9, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202244399

Cernicharo, J., Cabezas, C., Fuentetaja, R., et al. 2024, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 690, L13, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202452196

Chai, J.-D., & Head-Gordon, M. 2008, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 128, 084106, doi: 10.1063/1.2834918

Chen, T., Luo, Y., & Li, A. 2020, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 633, A103, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201936873

Clar, E. 1964, Polycyclic Hydrocarbons (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-01668-8

-. 1983, in Mobile Source Emissions Including Policyclic Organic Species, ed. D. Rondia, M. Cooke, & R. K. Haroz (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 49-58, doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-7197-4_4

Cooke, I. R., Gupta, D., Messinger, J. P., & Sims, I. R. 2020, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 891, L41, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab7a9c

Crabtree, K. N., Martin-Drumel, M.-A., Brown, G. G., et al. 2016, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 144, 124201, doi: 10.1063/1.4944072

Dale, T. J., & Rebek, J. 2006, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 128, 4500, doi: 10.1021/ja057449i

Dartois, E., Chabot, M., Koch, F., et al. 2022, A&A, 663, A25, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202243274

Davidson, E. R. 1996, Chemical Physics Letters, 260, 514, doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00917-7

Davies, J. W., Green, N. J. B., & Pilling, M. J. 1986, Chemical Physics Letters, 126, 373, doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(86)80101-4

Dopfer, O. 2011, EAS Publications Series, 46, 103, doi: 10.1051/eas/1146010

Dunning, Jr., T. H. 1989, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 90, 1007, doi: 10.1063/1.456153

Dwek, E., Arendt, R. G., Fixsen, D. J., et al. 1997, The Astrophysical Journal, 475, 565, doi: 10.1086/303568

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., et al. 2016, Gaussian~16 revision C. 01

Garkusha, I., Fulara, J., Sarre, P. J., & Maier, J. P. 2011, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 115, 10972, doi: 10.1021/jp206188a

Gatchell, M., Ameixa, J., Ji, M., et al. 2021, Nature Communications, 12, 6646, doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26899-0

Georgievskii, Y., & Klippenstein, S. J. 2005, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 122, 194103, doi: 10.1063/1.1899603

Glowacki, D. R., Liang, C.-H., Morley, C., Pilling, M. J., & Robertson, S. H. 2012, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 116, 9545, doi: 10.1021/jp3051033

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S., & Goerigk, L. 2011, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 32, 1456, doi: 10.1002/jcc. 21759

Habart, E., Natta, A., & Krügel, E. 2004, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 427, 179, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20035916

Hardy, F.-X., Rice, C. A., & Maier, J. P. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal, 836, 37, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/836/1/37

Hill, G. 2016, ccRepo. http: //www.grant-hill.group.shef.ac.uk/ccrepo/index.html

Holbrook, K. A., Pilling, M. J., Robertson, S. H., & Robinson, P. J. 1996, Unimolecular reactions, Wiley

Hudgins, D. M., & Allamandola, L. J. 1995, The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 99, 3033, doi: 10.1021/j100010a011

Hyodo, K., Togashi, K., Oishi, N., Hasegawa, G., & Uchida, K. 2017, Organic Letters, 19, 3005, doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01263

Ishida, K., Morokuma, K., & Komornicki, A. 1977, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 66, 2153, doi: 10.1063/1.434152

Joblin, C., Boissel, P., Léger, A., D’Hendecourt, L., & Defourneau, D. 1995, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 299, 835. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995A%26A…299..835J

Joblin, C., Wenzel, G., Castillo, S. R., et al. 2020, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1412, 062002, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1412/6/062002

Johnson, R. I. 2022, NIST computational chemistry comparison and benchmark database. http://cccbdb.nist.gov/

Jurečka, P., Šponer, J., Černý, J., & Hobza, P. 2006, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 8, 1985, doi: 10.1039/B600027D

Kendall, R. A., Dunning, Jr., T. H., & Harrison, R. J. 1992, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 96, 6796, doi: 10.1063/1.462569

Kesharwani, M. K., Brauer, B., & Martin, J. M. L. 2015, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 119, 1701, doi: 10.1021/jp508422u

Le Page, V., Snow, T. P., & Bierbaum, V. M. 2009, The Astrophysical Journal, 704, 274, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/704/1/274

Lee, C., Yang, W., & Parr, R. G. 1988, Physical Review B, 37, 785, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785

Lee, K. L. K., Changala, P. B., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2021, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 910, L2, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abe764

Liakos, D. G., & Neese, F. 2012, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 116, 4801, doi: 10.1021/jp302096v

Linstrom, P., & Mallard, W. 2024, NIST chemistry WebBook, NIST standard reference database number 69. https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D303

Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., Shingledecker, C. N., et al. 2021, Nature Astronomy, 5, 188, doi: 10.1038/s41550-020-01261-4

Loru, D., Cabezas, C., Cernicharo, J., Schnell, M., & Steber, A. L. 2023, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 677, A166, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202347023

Lourderaj, U., & Hase, W. L. 2009, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 113, 2236, doi: 10.1021/jp806659f

Léger, A., & Puget, J. L. 1984, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 500, 279. https: //ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/1984A&A…137L…5L/abstract

Malloci, G., Mulas, G., Cecchi-Pestellini, C., & Joblin, C. 2008, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 489, 1183, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:200810177

McCarthy, M. C., Lee, K. L. K., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2021, Nature Astronomy, 5, 176, doi: 10.1038/s41550-020-01213-y

McGuire, B. A., Xue, C., Lee, K. L. K., El-Abd, S., & Loomis, R. A. 2024, molsim, v0.5.0, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo. 12697227

McGuire, B. A., Burkhardt, A. M., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2020, The Astrophysical Journal, 900, L10, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aba632

McGuire, B. A., Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., et al. 2021, Science, 371, 1265, doi: 10.1126/science.abb7535

McNaughton, D., Jahn, M. K., Travers, M. J., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 476, 5268, doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty557

Mennella, V., Hornekær, L., Thrower, J., & Accolla, M. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 745, L2, doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/745/1/L2

Miller, W. H. 1979, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 101, 6810, doi: 10.1021/ja00517a004

Neeman, E. M., Lesarri, A., & Bermúdez, C. 2025, ChemPhysChem, in press, e202401012, doi: 10.1002/cphc. 202401012

Neese, F. 2022, WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, e1606, doi: 10.1002/wcms. 1606

Oomens, J., Sartakov, B. G., Tielens, A. G. G. M., Meijer, G., & Helden, G. v. 2001, The Astrophysical Journal, 560, L99, doi: 10.1086/324170

Pathak, A., & Sarre, P. J. 2008, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 391, L10, doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00544.x

Perdew, J. P. 1986, Physical Review B, 33, 8822, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB. 33.8822

Pickett, H. M. 1991, Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy, 148, 371, doi: 10.1016/0022-2852(91)90393-O

Pinski, P., Riplinger, C., Valeev, E. F., & Neese, F. 2015, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 143, 034108, doi: 10.1063/1.4926879

Rauls, E., & Hornekær, L. 2008, The Astrophysical Journal, 679, 531, doi: 10.1086/587614

Reizer, E., Viskolcz, B., & Fiser, B. 2022, Chemosphere, 291, 132793, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132793

Riplinger, C., Pinski, P., Becker, U., Valeev, E. F., & Neese, F. 2016, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 144, 024109, doi: 10.1063/1.4939030

Sabbah, H., Bonnamy, A., Papanastasiou, D., et al. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal, 843, 34, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa73dd

Sabbah, H., Quitté, G., Demyk, K., & Joblin, C. 2024, Natural Sciences, 4, e20240010, doi: 10.1002/ntls. 20240010

Sephton, M. A., Love, G. D., Watson, J. S., et al. 2004, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 68, 1385, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2003.08.019

Siebert, M. A., Lee, K. L. K., Remijan, A. J., et al. 2022, The Astrophysical Journal, 924, 21, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac3238

Sita, M. L., Changala, P. B., Xue, C., et al. 2022, The Astrophysical Journal, 938, L12, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac92f4

Stein, S. 1978, The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 82, 566, doi: 10.1021/j100494a600

Stockett, M. H., Subramani, A., Liu, C., et al. 2025, Dissociation and radiative stabilization of the indene cation: The nature of the C-H bond and astrochemical implications. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20686

Thrower, J. D., Jørgensen, B., Friis, E. E., et al. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal, 752, 3, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/752/1/3

Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2008, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 46, 289, doi: 10.1146/annurev.astro.46.060407.145211

Useli-Bacchitta, F., Bonnamy, A., Mulas, G., et al. 2010, Chemical Physics, 371, 16, doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2010.03.012

Weigend, F., & Ahlrichs, R. 2005, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 7, 3297, doi: 10.1039/B508541A

Wenzel, G., Cooke, I. R., Changala, P. B., et al. 2024, Science, 386, 810, doi: 10.1126/science.adq6391

Wenzel, G., Speak, T. H., Changala, P. B., et al. 2025, Nature Astronomy, 9, 262, doi: 10.1038/s41550-024-02410-9

West, N. A., Millar, T. J., Van de Sande, M., et al. 2019, The Astrophysical Journal, 885, 134, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab480e

Xue, C. 2024, GBT Spectral Line Reduction Pipeline. https://github.com/cixue/gotham-spectral-pipeline

Zeichner, S. S., Aponte, J. C., Bhattacharjee, S., et al. 2023, Science, 382, 1411, doi: 10.1126/science.adg6304

Zhao, L., Kaiser, R. I., Xu, B., et al. 2018, Nature Astronomy, 2, 413, doi: 10.1038/s41550-018-0399-y

Zhen, J., Rodriguez Castillo, S., Joblin, C., et al. 2016, The Astrophysical Journal, 822, 113, doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/822/2/113

الملحق

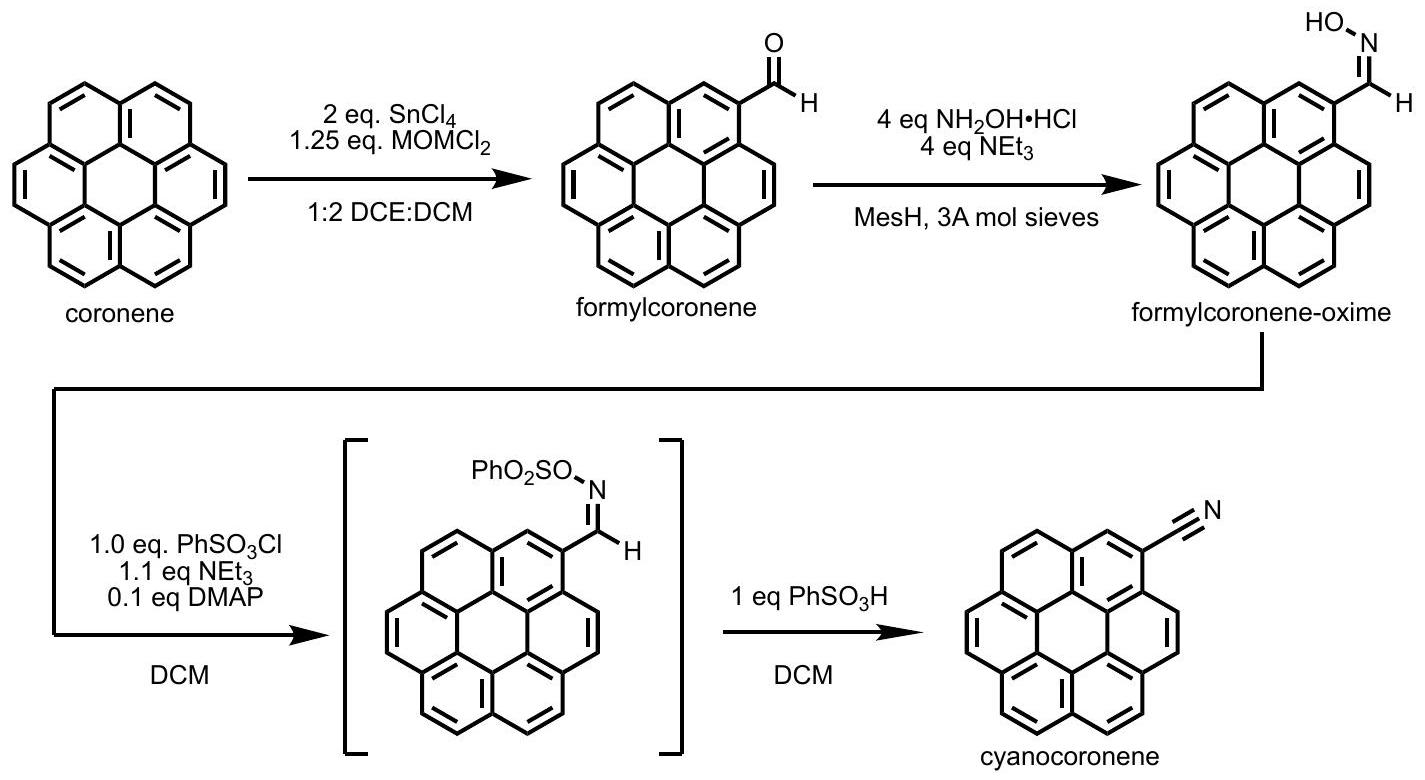

أ. مسار التخليق الكامل إلى سيانكورونين

أ.1. تخليق الفورميلكورونين

- سوف تطلق التفاعل غاز HCl أثناء التسخين. يُنصح بالحذر.

- لم تُظهر التفاعل أي تحسين في العائد بعد مضاعفة المعادلة.

و . ومع ذلك، فإن معظم المواد الأولية قابلة للاسترداد. - المنتج والمواد الأولية غير المتفاعلة كلاهما ذو قابلية ذوبان ضعيفة في مجموعة واسعة من المذيبات العضوية. وبالتالي، فإن كميات كبيرة (قد تتجاوز 6 لترات) من DCM مطلوبة لإجراء الكروماتوغرافيا على هذا النطاق.

أ.2. تخليق الفورميلكورونين-أوكسيما

- خليط التفاعل غير متجانس ويمكن أن يلتصق بجدران الوعاء إذا تم تحريكه بعنف شديد، مما يؤدي إلى تفاعل غير مكتمل. يُفضل التحريك البطيء.

أ.3. تخليق السيانكورونين

- التحويل المباشر للفورميلكورونين إلى سيانكورونين وفقًا لبروتوكول الأدبيات (هايو دو وآخرون 2017) صعب بسبب التفاعل المحدود للفورميلكورونين في درجة حرارة الغرفة. يتم تحقيق تحويل ملحوظ فقط بشكل موثوق في التولوين المغلي أو الكلوروبنزين أو الميسيتيلين. ومع ذلك، فإن ظروف التفاعل الحمضية المدمجة مع درجات الحرارة العالية غالبًا ما تؤدي إلى تدهور كبير في المادة الأولية وتقلل بشكل كبير من العوائد.

- المتوسط O-sulfonyl oxime حساس للتحلل المائي. لا يُوصى بعزله.

- خليط التفاعل غير متجانس ويمكن أن يلتصق بجدران الوعاء إذا تم تحريكه بعنف شديد، مما يؤدي إلى تفاعل غير مكتمل. يُفضل التحريك البطيء.

- كميات وفيرة

كان من الضروري إكمال عملية الكروماتوغرافيا بسبب انخفاض قابلية ذوبان المنتج. يمكن التخفيف من انسداد الترسيب عن طريق إزعاج الجزء العلوي من العمود برفق.

ب. معيار مستوى النظرية

| معامل | 1-سيانوبييرين | ||

| نظري | تجريبي

|

نظري + تجريبي

|

|

|

|

٨٥٠.١٤١ | 843.140191(128) | 843.141827(128) |

|

|

٣٧٢.٩٣١ | ٣٧٢.٥٠٠١٧٥(٥٦) | ٣٧٢.٥٠٠١٨٣(٥٦) |

|

|

٢٥٩٫٢١٩ | 258.4249175(164) | 258.4248913(164) |

|

|

1.977 | ٢.٢٤٠(٨٠) | 2.153(80)) |

|

|

-5.556 | -5.52(101) | -5.88(101) |

|

|

٢٠.٣١٠ | [0] | [20.310] |

|

|

0.724 | 0.826(40) | 0.795(40) |

|

|

٣.٠٥٩ | 5.26(74) | ٤.٢٠(٧٤) |

| معامل | 2-سيانوبييرين | ||

| نظري | تجريبي

|

نظري + تجريبي

|

|

|

|

١٠١٥٫٢٣٩ | 1009.19382(60) | 1009.19356(39) |

|

|

314.479 | 313.1345299(202) | 313.1345270(195) |

|

|

٢٤٠.١٠٥ | 239.0427225(184) | 239.0427270(167) |

|

|

0.706 | 0.7008(109) | 0.7023(106) |

|

|

٥.٣٧٥ | 5.814(94) | 5.818(94) |

|

|

8.785 | 15.3(114) | [8.785] |

|

|

0.184 | 0.1759(60) | 0.1766(59) |

|

|

٤.٥١٠ | 4.22(39) | ٤.١٢(٣٥) |

| معامل | 4-سيانوبييرين | ||

| نظري | تجريبي

|

نظري + تجريبي

|

|

|

|

652.155 | 651.383034(69) | 651.382955(64) |

|

|

٤٥٦٫٦٧٠ | 453.731352(45) | 453.731444(41) |

|

|

٢٦٨٫٥٩٠ | 267.5078168(224) | 267.5078004(221) |

|

|

1.893 | 1.780(98) | 2.026(69) |

|

|

-1.553 | 0.43(58) | [-1.553] |

|

|

14.821 | 10.89(73) | 12.61(53) |

|

|

0.756 | 0.677(49) | 0.803(35) |

|

|

1.971 | 2.56(33) | 2.40(33) |

ج. خطوط قياس السيانكورونين

| الانتقال

|

التردد

|

|

|

6788.4098 |

|

|

6788.4098 |

|

|

6788.4443 |

|

|

6788.4443 |

|

|

6788.7145 |

|

|

6788.7145 |

|

|

6789.9187 |

|

|

6789.9187 |

|

|

6815.8858 |

|

|

7005.2518 |

|

|

٧٠٥٤.٦١٠٦ |

|

|

7054.6106 |

|

|

7054.6617 |

|

|

7054.6617 |

|

|

٧٠٥٤.٨٧٥٩ |

|

|

٧٠٥٤.٨٧٥٩ |

|

|

7055.9209 |

|

|

7055.9209 |

|

|

٧٠٥٨.٧٨٥٧ |

|

|

7058.7857 |

|

|

7073.0418 |

|

|

٧٠٨٠.٦٣٥٣ |

|

|

٧٠٨٨.٦٠٠٤ |

|

|

٧٢٩١.٤٧١٠ |

|

|

٧٣٢٠.٨١٧٩ |

|

|

٧٣٢٠.٨١٧٩ |

|

|

٧٣٢٠.٨٧٨٠ |

|

|

٧٣٢٠.٨٧٨٠ |

|

|

7321.0420 |

|

|

7321.0420 |

|

|

7321.9574 |

|

|

7321.9574 |

|

|

٧٣٢٤.٤٣٩٣ |

|

|

٧٣٢٤.٤٣٩٣ |

| الانتقال

|

التردد

|

|

|

7587.0283 |

|

|

7587.0283 |

|

|

7587.0875 |

|

|

7587.0875 |

|

|

8377.6038 |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٦٥٠٥ |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٦٥٠٥ |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٧٣٤٧ |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٧٣٤٧ |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٧٦٣٦ |

|

|

٨٣٨٥.٧٦٣٦ |

|

|

8391.1806 |

|

|

8391.1806 |

|

|

8651.8594 |

|

|

٨٦٥١.٨٥٩٤ |

|

|

8651.9466 |

|

|

8651.9466 |

|

|

8651.9537 |

|

|

8651.9537 |

|

|

8652.4539 |

|

|

8652.4539 |

|

|

8653.7843 |

|

|

8653.7843 |

|

|

8656.7527 |

|

|

8656.7527 |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٣٤٣٧ |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٣٤٣٧ |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٣٤٣٧ |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٣٤٣٧ |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٤٥٢٩ |

|

|

١٠٥١٥.٤٥٢٩ |

|

|

١٠٥١٦.٢٣٥٦ |

|

|

١٠٥١٦.٢٣٥٦ |

|

|

١٠٥١٧.٦٧٠٣ |

|

|

١٠٥١٧.٦٧٠٣ |

|

|

١٠٥٢٠.٤٣١٣ |

|

|

١٠٥٢٠.٤٣١٣ |

د. دالة التقسيم لسيانكورونين

| درجة الحرارة [ك] | دالة التقسيم |

| 1.0 | 1703.7230 |

| 2.0 | ٤٨١٣.٧٢٤٥ |

| 3.0 | 8840.2413 |

| ٤.٠ | ١٣٦٠٨.٠٣٣٣ |

| 5.0 | ١٩٠١٥.٧٨٩٧ |

| 6.0 | ٢٤٩٩٥.١٤٣٧ |

| 7.0 | 31495.9011 |

| 8.0 | 38479.1687 |

| 9.375 | ٤٨٨١٢.٤٩٢٩ |

| 18.75 | 138047.6140 |

| 37.5 | 390439.4924 |

| 75.0 | ١١٠٤٣١٧.٣٢٩٢ |

| 150.0 | ٣١٢٠٠٧٨.٨٦٥٧ |

| ٢٢٥.٠ | ٥٦٨٦٧٥٩٫١٢٤١ |

| ٣٠٠.٠ | ٨٥٨٩٥٢٦.٦٧٢٥ |

| ٤٠٠.٠ | ١٢٦٧٨٧٤٢.٢٠٦٠ |

| ٥٠٠.٠ | 16744897.1786 |

تحليل MCMC للسيانكورونين في TMC-1

| رقم المكون |

|

الحجم (“) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

||||

| ٢ |

|

|

|

|

|

| ٣ |

|

||||

| ٤ |

|

||||

| من | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 0.1 |

| ماكس | 10.0 | 100 | ١٣.٠ | 15.0 | 0.3 |

| رقم المكون |

|

الحجم (“) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

50 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

50 |

|

||

| ٣ |

|

50 |

|

||

| ٤ |

|

٤٩ |

|

||

|

|

|||||

F. كثافات الأعمدة للهيدروكربونات الحلقية في TMC-1

| جزيء |

|

كثافة العمود (

|

مرجع |

|

|

٥ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2021أ) |

|

|

٦ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2021ب) |

|

|

٦ |

|

لي وآخرون (2021) |

|

|

٦ |

|

لي وآخرون (2021) |

|

|

٧ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2021ج) |

|

|

٧ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2021ج) |

|

|

٧ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2022) |

|

|

٧ |

|

مكغواير وآخرون (2021) |

|

|

٨ |

|

لور و آخرون (2023) |

|

|

9 |

|

سيتا وآخرون (2022) |

|

|

10 |

|

سيتا وآخرون (2022) |

|

|

11 |

|

ماكغواير وآخرون (2021) |

|

|

11 |

|

ماكغواير وآخرون (2021) |

|

|

١٣ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2024) |

|

|

١٣ |

|

سيرنيتشارو وآخرون (2024) |

|

|

17 |

|

وينزل وآخرون (2024) |

|

|

17 |

|

وينزل وآخرون (2025) |

|

|

17 |

|

وينزل وآخرون (2025) |

|

|

16 |

|

وينزل وآخرون (2025) |

|

|

25 |

|

هذا العمل |

|

|

٢٤ |

|

هذا العمل |

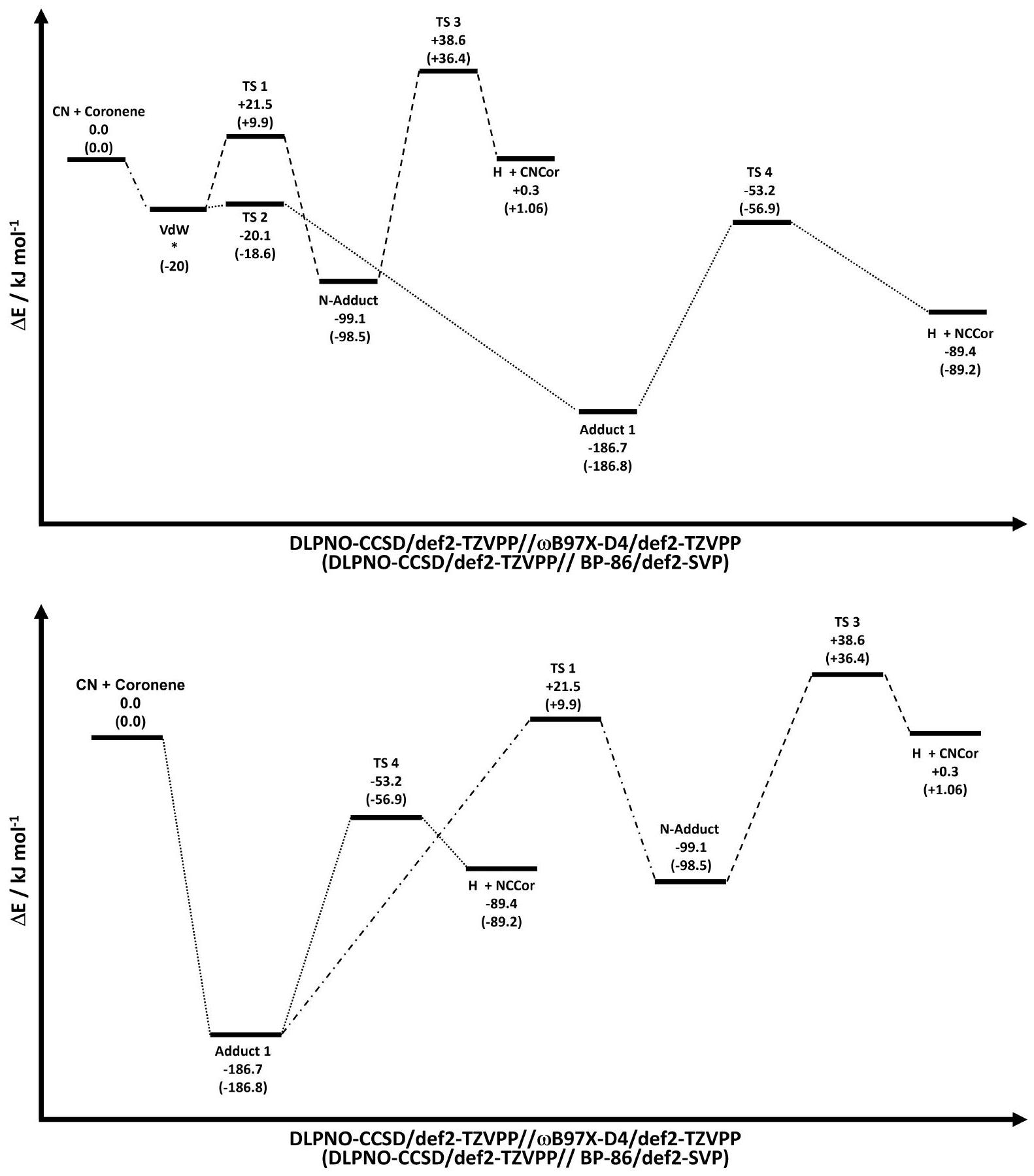

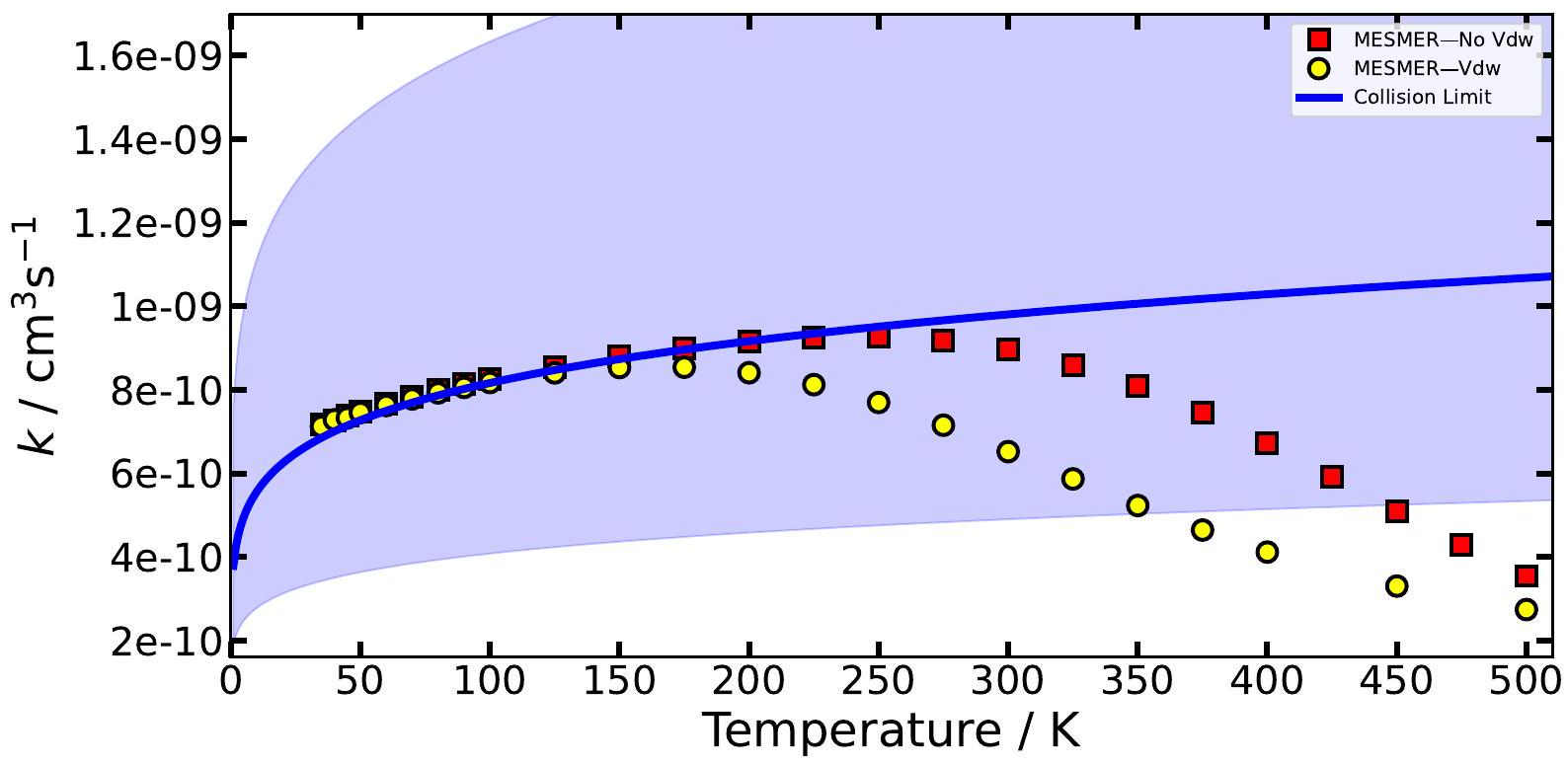

حسابات الكيمياء الكمومية من البداية

ج.1. المنهجية الحاسوبية

في هذه المسوحات، تم السماح لجميع الإحداثيات باستثناء الرابطة التي يتم مسحها بالاسترخاء بينما تم تغيير الإحداثية الممسوحة. تم استخدام القيم القصوى الناتجة كإدخالات للهندسة في تحسينات حالة الانتقال، وتم تحسين القيم الدنيا بعيدة المدى قبل إضافة CN إلى مركب مرتبط فضفاض في قناة الدخول.

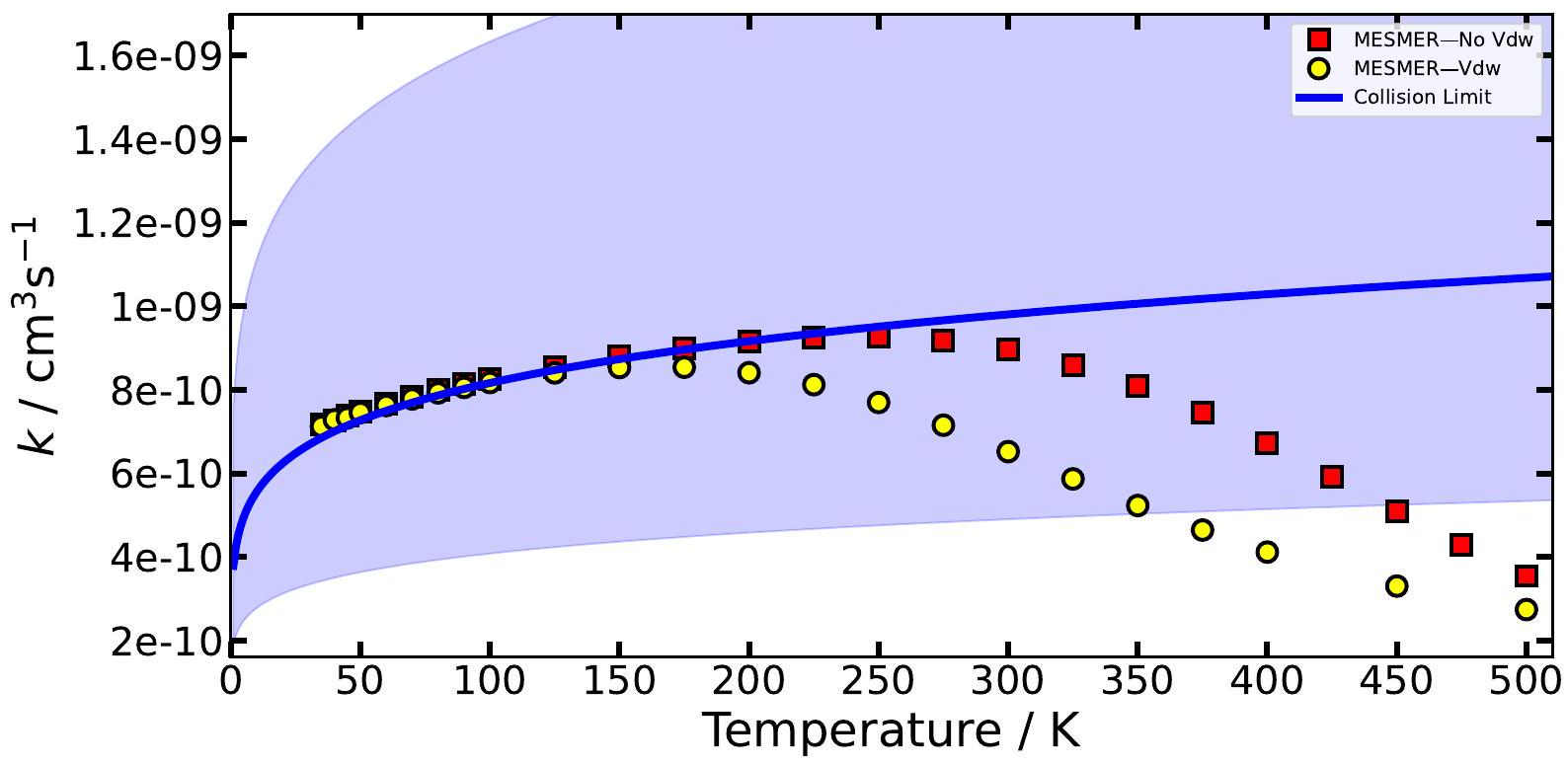

ج.2. توقعات الديناميكا للمعادلة الرئيسية

| 1-1 | 1-2 | 1-3 | 1-4 | 1-5 | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 2-5 | |

| CN + كورونين | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| فدW | -20.57 | -20.26 | -25.82 | * | * | * | ||||

| TS 1 (إضافة CN) | 9.87 | 14.42 | 3.83 | 21.48 | 25.03 | 13.18 | ||||

| N-أدكت 1 | -98.48 | -90.90 | -98.57 | -99.08 | -91.60 | -101.41 | ||||

| إزالة TS 3 H | ٣٦.٣٥ | 42.57 | ٣٣.٣٨ | ٣٨.٥٥ | ٤٥.٣٧ | ٣٤.٢٣ | ||||

| H + إيزوسيانوكورونين | 1.06 | 0.14 | 1.72 | 1.12 | -١٦.٢٠ | 0.33 | -0.68 | 0.20 | 0.94 | -14.17 |

| TS 2 (إضافة NC) | -18.57 | -18.27 | -23.82 | -20.09 | -18.52 | -25.05 | ||||

| العضلة المضافة 1 | -186.80 | -179.23 | -184.50 | -186.68 | -179.22 | -186.00 | ||||

| إزالة TS 4 H | -56.87 | -50.57 | -57.91 | -53.20 | -٤٦.٢٧ | -54.98 | ||||

| H + سيانكورونين | -89.15 | -89.97 | -86.33 | -89.88 | -106.47 | -89.39 | -90.31 | -86.53 | -88.90 | -١٠٣.٦٧ |

https://greenbankobservatory.org/portal/gbt/gbt-legacy-archive/gotham-data/ عدم اليقين التجريبي هو 2 كيلوهرتز. - *تم التقدير باستخدام كثافات عمود السيانوبيرين والسيانكورونين، ومعاملات المعدل المحسوبة لإضافة CN، ونسبة CN/H قدرها 0.15 (انظر الملحق G و وينزل وآخرون 2025).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/adc911

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41103619

Publication Date: 2025-04-30

Discovery of the

Abstract

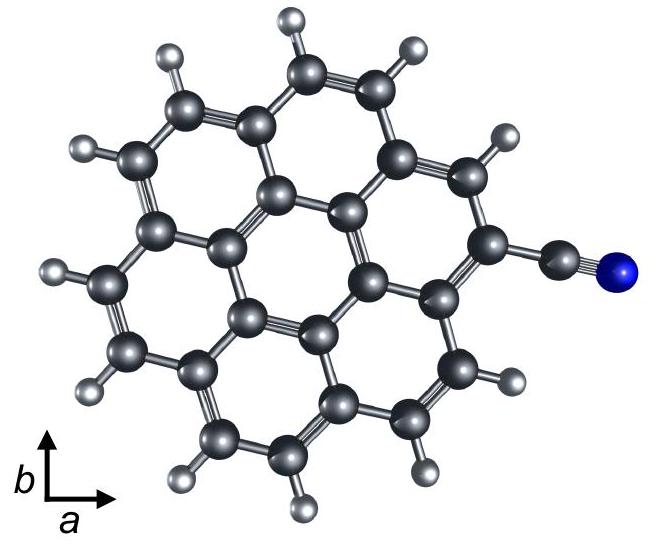

We present the synthesis and laboratory rotational spectroscopy of the 7 -ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

1. INTRODUCTION

diffuse interstellar bands (DIBs) has been debated. Dehydrogenated, protonated, and cationic coronene were proposed as potential carriers of DIBs (Pathak & Sarre 2008; Malloci et al. 2008), but these hypotheses were disproven (Garkusha et al. 2011; Useli-Bacchitta et al. 2010; Hardy et al. 2017). Nevertheless, some distribution of PAHs remain promising DIB carrier candidates due to their close relation to the fullerene family (Campbell et al. 2015).

2. SYNTHESIS

3. LABORATORY SPECTROSCOPY

| Parameter | B3LYP aug-cc-pVTZ | Experimental

|

|

|

335.393 | 333.852989(249) |

|

|

222.035 | 221.2700880(838) |

|

|

133.594 | 133.1081015(122) |

|

|

0.669 | [0.669] |

|

|

-0.617 | [-0.617] |

|

|

0.011 | [0.011] |

|

|

-0.120 | [-0.120] |

|

|

-0.494 | [-0.494] |

|

|

71 | |

|

|

38 | |

|

|

2.595 | |

|

|

|

|

rotational constants,

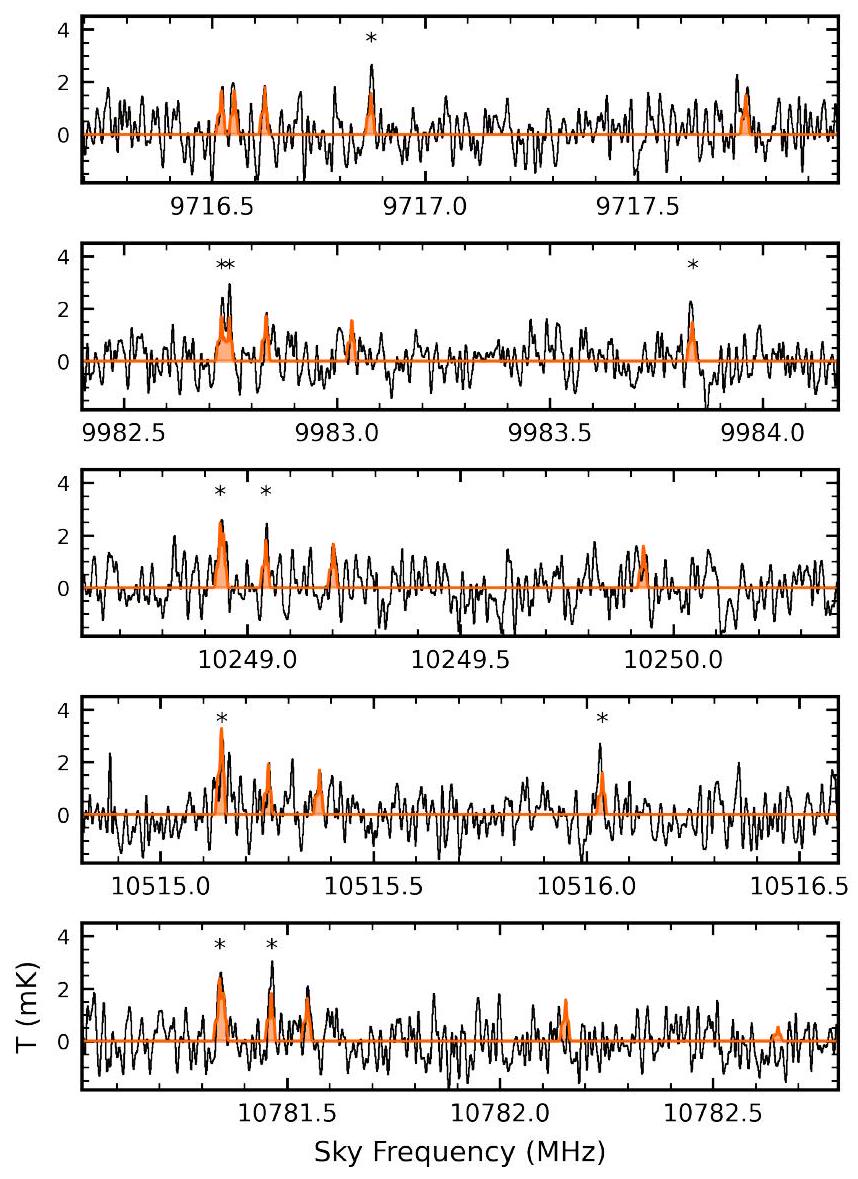

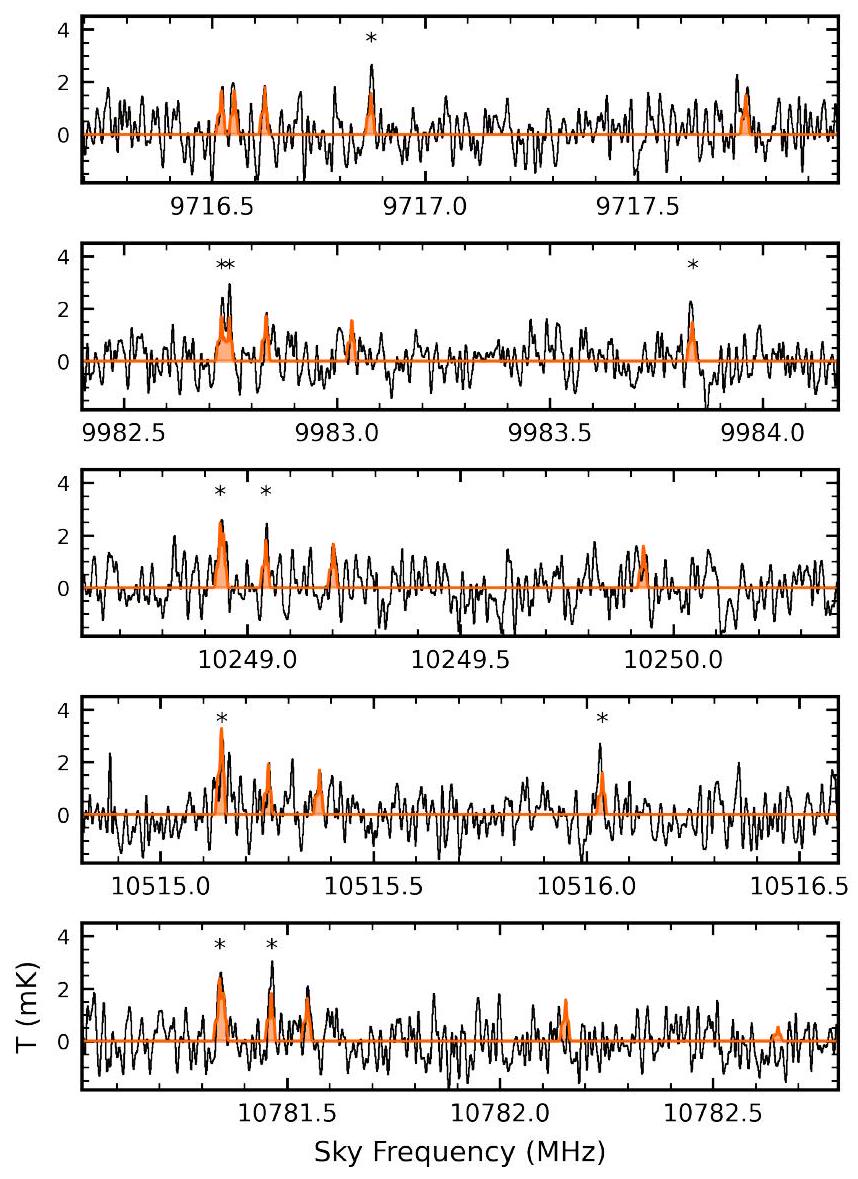

4. OBSERVATIONS

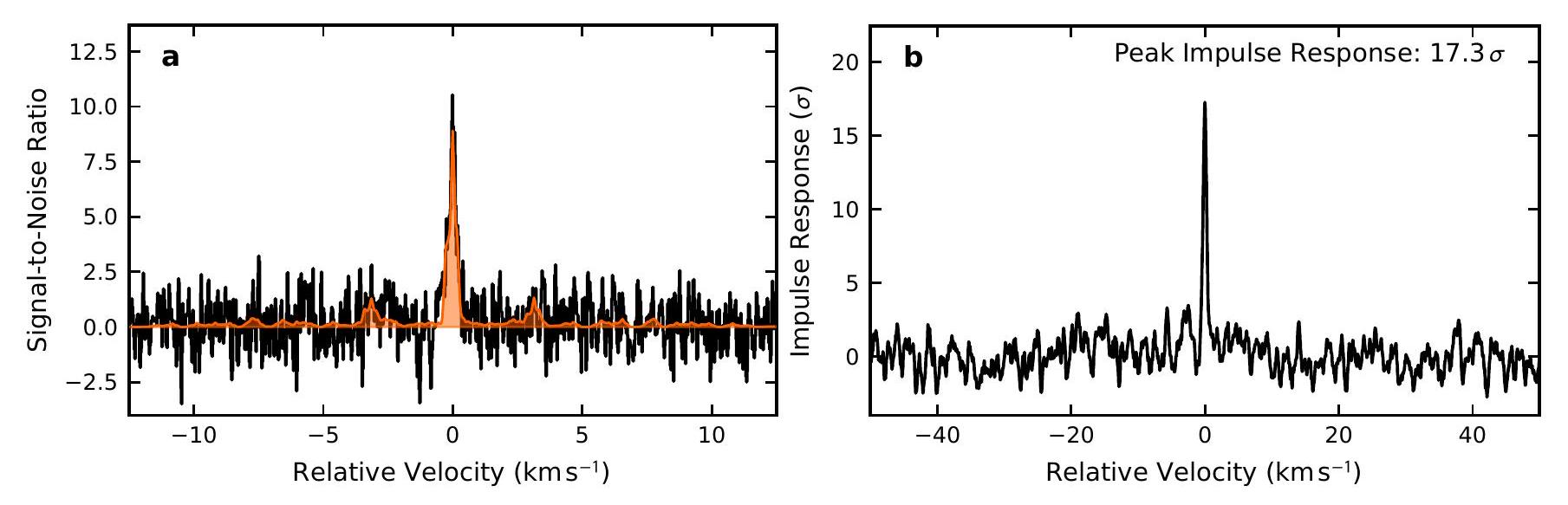

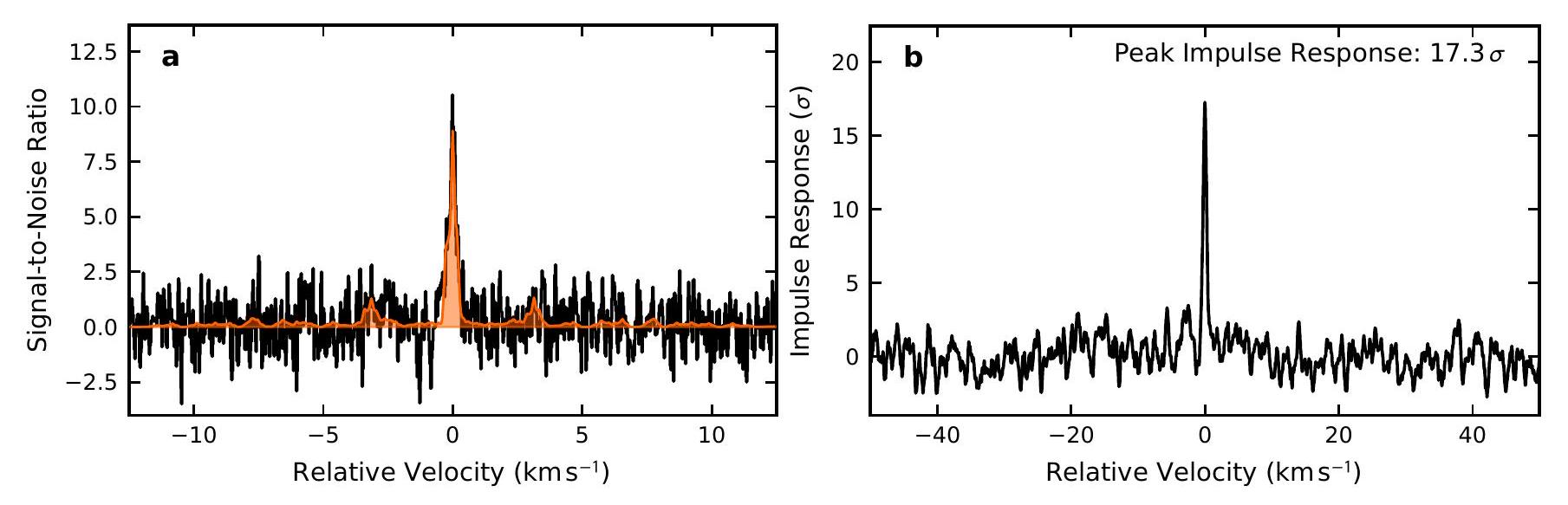

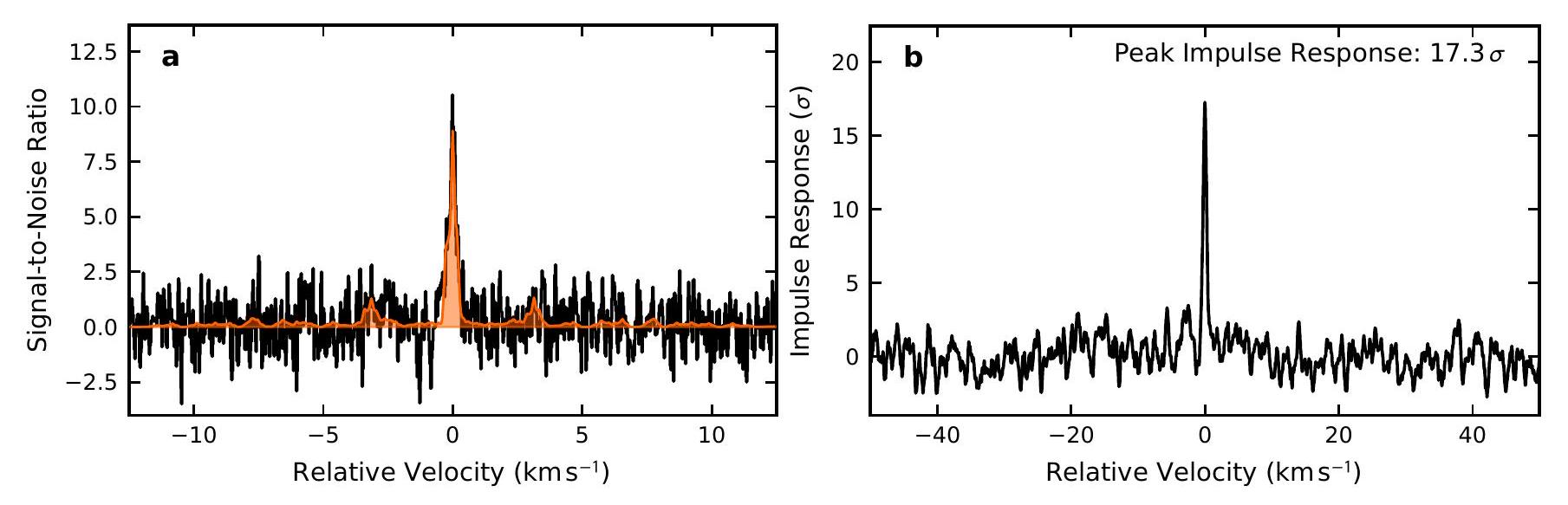

5. ASTRONOMICAL ANALYSIS

6. DISCUSSION

phase formation route for pyrene, starting from 4phenanthrenyl radical. Indeed, phenanthrene is also a member of the most thermodynamically stable PAH polymerization route (see Fig 5). However, cursory searches for its CN-derivative 9-cyanophenanthrene, whose rotational spectrum is known (McNaughton et al. 2018), in our GOTHAM observations have not yet been successful. This could be due to the fact that the spectroscopy of only one of the five possible cyanophenan-

and Bull et al. (2025) indicate that the underlying PAH backbone can be maintained via efficient radiative cooling, thereby opening up the possibility of a kind of chemical “recycling” of PAHs that would certainly contribute to the high observed abundance of, e.g., cyanocoronene. Turning to depletion onto grains, Dartois et al. (2022) conducted experiments on the sputtering yield of solidphase perylene and coronene bombarded by energetic ions, analogous to the cosmic ray exposure of species in dust-grain ice mantles. They found that such cosmic ray-induced sputtering is efficient under ISM conditions, and even predict a gas-phase fractional abundance of coronene over

7. CONCLUSIONS

8. DATA ACCESS & CODE

Facilities: GBT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

tion Beckman Young Investigator Award. Z.T.P.F. and B.A.M. gratefully acknowledge the support of Schmidt Family Futures. I.R.C. acknowledges support from the University of British Columbia and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). I.R.C. and T.H.S. acknowledge the support of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) through grant 24AO3UBC14. P.B.C. is supported by NIST. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc. The Green Bank Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

REFERENCES

Baer, T., & Hase, W. L. 1996, Unimolecular Reaction Dynamics: Theory and Experiments (Oxford University Press). https://academic.oup.com/book/40815

Bahou, M., Wu, Y.-J., & Lee, Y.-P. 2014, Angewandte Chemie, 126, 1039, doi: 10.1002/ange. 201308971

Bakes, E. L. O., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1998, The Astrophysical Journal, 499, 258, doi: 10.1086/305625

Balle, T. J., & Flygare, W. H. 1981, Review of Scientific Instruments, 52, 33, doi: 10.1063/1.1136443

Balucani, N., Asvany, O., Huang, L. C. L., et al. 2000, The Astrophysical Journal, 545, 892, doi: 10.1086/317848

Bauschlicher, C. W. 1998, The Astrophysical Journal, 509, L125, doi: 10.1086/311782

Becke, A. D. 1988, Physical Review A, 38, 3098, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098

-. 1993, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 98, 5648, doi: 10.1063/1.464913

Becke, A. D., & Johnson, E. R. 2006, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 124, 221101, doi: 10.1063/1.2213970

Bernstein, M. P., Elsila, J. E., Dworkin, J. P., et al. 2002, The Astrophysical Journal, 576, 1115, doi: 10.1086/341863

Berné, O., Foschino, S., Jalabert, F., & Joblin, C. 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 667, A159, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202243171

Boschman, L., Cazaux, S., Spaans, M., Hoekstra, R., & Schlathölter, T. 2015, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 579, A72, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201323165

Burkhardt, A. M., Long Kelvin Lee, K., Bryan Changala, P., et al. 2021, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 913, L18, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abfd3a

Caldeweyher, E., Bannwarth, C., & Grimme, S. 2017, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 147, 034112, doi: 10.1063/1.4993215

Campbell, E. K., Holz, M., Gerlich, D., & Maier, J. P. 2015, Nature, 523, 322, doi: 10.1038/nature14566

Carelli, F., & Gianturco, F. A. 2012, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 422, 3643, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20876.x

Cazaux, S., Boschman, L., Rougeau, N., et al. 2016, Scientific Reports, 6, 19835, doi: 10.1038/srep19835

Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Cabezas, C., et al. 2021a, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 649, L15, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202141156

Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2021b, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 652, L9, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202141660

—. 2021c, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 655, L1, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202142226

Cernicharo, J., Fuentetaja, R., Agúndez, M., et al. 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 663, L9, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202244399

Cernicharo, J., Cabezas, C., Fuentetaja, R., et al. 2024, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 690, L13, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202452196

Chai, J.-D., & Head-Gordon, M. 2008, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 128, 084106, doi: 10.1063/1.2834918

Chen, T., Luo, Y., & Li, A. 2020, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 633, A103, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201936873

Clar, E. 1964, Polycyclic Hydrocarbons (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-01668-8

-. 1983, in Mobile Source Emissions Including Policyclic Organic Species, ed. D. Rondia, M. Cooke, & R. K. Haroz (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 49-58, doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-7197-4_4

Cooke, I. R., Gupta, D., Messinger, J. P., & Sims, I. R. 2020, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 891, L41, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab7a9c

Crabtree, K. N., Martin-Drumel, M.-A., Brown, G. G., et al. 2016, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 144, 124201, doi: 10.1063/1.4944072

Dale, T. J., & Rebek, J. 2006, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 128, 4500, doi: 10.1021/ja057449i

Dartois, E., Chabot, M., Koch, F., et al. 2022, A&A, 663, A25, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202243274

Davidson, E. R. 1996, Chemical Physics Letters, 260, 514, doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00917-7

Davies, J. W., Green, N. J. B., & Pilling, M. J. 1986, Chemical Physics Letters, 126, 373, doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(86)80101-4

Dopfer, O. 2011, EAS Publications Series, 46, 103, doi: 10.1051/eas/1146010

Dunning, Jr., T. H. 1989, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 90, 1007, doi: 10.1063/1.456153

Dwek, E., Arendt, R. G., Fixsen, D. J., et al. 1997, The Astrophysical Journal, 475, 565, doi: 10.1086/303568

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., et al. 2016, Gaussian~16 revision C. 01

Garkusha, I., Fulara, J., Sarre, P. J., & Maier, J. P. 2011, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 115, 10972, doi: 10.1021/jp206188a

Gatchell, M., Ameixa, J., Ji, M., et al. 2021, Nature Communications, 12, 6646, doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26899-0

Georgievskii, Y., & Klippenstein, S. J. 2005, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 122, 194103, doi: 10.1063/1.1899603

Glowacki, D. R., Liang, C.-H., Morley, C., Pilling, M. J., & Robertson, S. H. 2012, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 116, 9545, doi: 10.1021/jp3051033

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S., & Goerigk, L. 2011, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 32, 1456, doi: 10.1002/jcc. 21759

Habart, E., Natta, A., & Krügel, E. 2004, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 427, 179, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20035916

Hardy, F.-X., Rice, C. A., & Maier, J. P. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal, 836, 37, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/836/1/37

Hill, G. 2016, ccRepo. http: //www.grant-hill.group.shef.ac.uk/ccrepo/index.html

Holbrook, K. A., Pilling, M. J., Robertson, S. H., & Robinson, P. J. 1996, Unimolecular reactions, Wiley

Hudgins, D. M., & Allamandola, L. J. 1995, The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 99, 3033, doi: 10.1021/j100010a011

Hyodo, K., Togashi, K., Oishi, N., Hasegawa, G., & Uchida, K. 2017, Organic Letters, 19, 3005, doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01263

Ishida, K., Morokuma, K., & Komornicki, A. 1977, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 66, 2153, doi: 10.1063/1.434152

Joblin, C., Boissel, P., Léger, A., D’Hendecourt, L., & Defourneau, D. 1995, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 299, 835. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995A%26A…299..835J

Joblin, C., Wenzel, G., Castillo, S. R., et al. 2020, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1412, 062002, doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1412/6/062002

Johnson, R. I. 2022, NIST computational chemistry comparison and benchmark database. http://cccbdb.nist.gov/

Jurečka, P., Šponer, J., Černý, J., & Hobza, P. 2006, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 8, 1985, doi: 10.1039/B600027D

Kendall, R. A., Dunning, Jr., T. H., & Harrison, R. J. 1992, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 96, 6796, doi: 10.1063/1.462569

Kesharwani, M. K., Brauer, B., & Martin, J. M. L. 2015, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 119, 1701, doi: 10.1021/jp508422u

Le Page, V., Snow, T. P., & Bierbaum, V. M. 2009, The Astrophysical Journal, 704, 274, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/704/1/274

Lee, C., Yang, W., & Parr, R. G. 1988, Physical Review B, 37, 785, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785

Lee, K. L. K., Changala, P. B., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2021, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 910, L2, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abe764

Liakos, D. G., & Neese, F. 2012, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 116, 4801, doi: 10.1021/jp302096v

Linstrom, P., & Mallard, W. 2024, NIST chemistry WebBook, NIST standard reference database number 69. https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D303

Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., Shingledecker, C. N., et al. 2021, Nature Astronomy, 5, 188, doi: 10.1038/s41550-020-01261-4

Loru, D., Cabezas, C., Cernicharo, J., Schnell, M., & Steber, A. L. 2023, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 677, A166, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202347023

Lourderaj, U., & Hase, W. L. 2009, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 113, 2236, doi: 10.1021/jp806659f

Léger, A., & Puget, J. L. 1984, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 500, 279. https: //ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/1984A&A…137L…5L/abstract

Malloci, G., Mulas, G., Cecchi-Pestellini, C., & Joblin, C. 2008, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 489, 1183, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:200810177

McCarthy, M. C., Lee, K. L. K., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2021, Nature Astronomy, 5, 176, doi: 10.1038/s41550-020-01213-y

McGuire, B. A., Xue, C., Lee, K. L. K., El-Abd, S., & Loomis, R. A. 2024, molsim, v0.5.0, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo. 12697227

McGuire, B. A., Burkhardt, A. M., Loomis, R. A., et al. 2020, The Astrophysical Journal, 900, L10, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aba632

McGuire, B. A., Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., et al. 2021, Science, 371, 1265, doi: 10.1126/science.abb7535

McNaughton, D., Jahn, M. K., Travers, M. J., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 476, 5268, doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty557

Mennella, V., Hornekær, L., Thrower, J., & Accolla, M. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 745, L2, doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/745/1/L2

Miller, W. H. 1979, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 101, 6810, doi: 10.1021/ja00517a004

Neeman, E. M., Lesarri, A., & Bermúdez, C. 2025, ChemPhysChem, in press, e202401012, doi: 10.1002/cphc. 202401012

Neese, F. 2022, WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12, e1606, doi: 10.1002/wcms. 1606

Oomens, J., Sartakov, B. G., Tielens, A. G. G. M., Meijer, G., & Helden, G. v. 2001, The Astrophysical Journal, 560, L99, doi: 10.1086/324170

Pathak, A., & Sarre, P. J. 2008, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 391, L10, doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00544.x

Perdew, J. P. 1986, Physical Review B, 33, 8822, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB. 33.8822

Pickett, H. M. 1991, Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy, 148, 371, doi: 10.1016/0022-2852(91)90393-O

Pinski, P., Riplinger, C., Valeev, E. F., & Neese, F. 2015, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 143, 034108, doi: 10.1063/1.4926879

Rauls, E., & Hornekær, L. 2008, The Astrophysical Journal, 679, 531, doi: 10.1086/587614

Reizer, E., Viskolcz, B., & Fiser, B. 2022, Chemosphere, 291, 132793, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132793

Riplinger, C., Pinski, P., Becker, U., Valeev, E. F., & Neese, F. 2016, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 144, 024109, doi: 10.1063/1.4939030

Sabbah, H., Bonnamy, A., Papanastasiou, D., et al. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal, 843, 34, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa73dd

Sabbah, H., Quitté, G., Demyk, K., & Joblin, C. 2024, Natural Sciences, 4, e20240010, doi: 10.1002/ntls. 20240010

Sephton, M. A., Love, G. D., Watson, J. S., et al. 2004, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 68, 1385, doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2003.08.019

Siebert, M. A., Lee, K. L. K., Remijan, A. J., et al. 2022, The Astrophysical Journal, 924, 21, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac3238

Sita, M. L., Changala, P. B., Xue, C., et al. 2022, The Astrophysical Journal, 938, L12, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac92f4

Stein, S. 1978, The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 82, 566, doi: 10.1021/j100494a600

Stockett, M. H., Subramani, A., Liu, C., et al. 2025, Dissociation and radiative stabilization of the indene cation: The nature of the C-H bond and astrochemical implications. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20686

Thrower, J. D., Jørgensen, B., Friis, E. E., et al. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal, 752, 3, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/752/1/3

Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2008, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 46, 289, doi: 10.1146/annurev.astro.46.060407.145211

Useli-Bacchitta, F., Bonnamy, A., Mulas, G., et al. 2010, Chemical Physics, 371, 16, doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2010.03.012

Weigend, F., & Ahlrichs, R. 2005, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 7, 3297, doi: 10.1039/B508541A

Wenzel, G., Cooke, I. R., Changala, P. B., et al. 2024, Science, 386, 810, doi: 10.1126/science.adq6391

Wenzel, G., Speak, T. H., Changala, P. B., et al. 2025, Nature Astronomy, 9, 262, doi: 10.1038/s41550-024-02410-9

West, N. A., Millar, T. J., Van de Sande, M., et al. 2019, The Astrophysical Journal, 885, 134, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab480e

Xue, C. 2024, GBT Spectral Line Reduction Pipeline. https://github.com/cixue/gotham-spectral-pipeline

Zeichner, S. S., Aponte, J. C., Bhattacharjee, S., et al. 2023, Science, 382, 1411, doi: 10.1126/science.adg6304

Zhao, L., Kaiser, R. I., Xu, B., et al. 2018, Nature Astronomy, 2, 413, doi: 10.1038/s41550-018-0399-y

Zhen, J., Rodriguez Castillo, S., Joblin, C., et al. 2016, The Astrophysical Journal, 822, 113, doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/822/2/113

APPENDIX

A. FULL SYNTHESIS ROUTE TO CYANOCORONENE

A.1. Synthesis of Formylcoronene

- The reaction will release HCl gas during heating. Caution is advised.

- The reaction did not show improvement in yield after doubling the equivalence of

and . However, most of the starting material is recoverable. - The product and unreacted starting material are both poorly soluble in a wide range of organic solvents. As such, copious amounts (potentially exceeding 6 L ) of DCM are required to perform chromatography at the scale

A.2. Synthesis of Formylcoronene-Oxime

- The reaction mixture is heterogeneous and can stick on the walls of the vessel if stirred too violently, thus leading to incomplete reaction. Slow stirring is preferred.

A.3. Synthesis of Cyanocoronene

- Direct conversion of formylcoronene to cyanocoronene according to literature protocol (Hyodo et al. 2017) is difficult due to the limited reactivity of formylcoronene at room temperature. Noticeable conversion is only reliably achieved in refluxing toluene, chlorobenzene, or mesitylene. However, the acidic reaction conditions combined with high temperatures frequently resulted in significant degradation of the starting material and severely decreased yields.

- The O-sulfonyl oxime intermediate is sensitive to hydrolysis. Its isolation is not recommended.

- The reaction mixture is heterogeneous and can stick on the walls of the vessel if stirred too violently, thus leading to incomplete reaction. Slow stirring is preferred.

- Copious amounts (

of DCM) were required to complete the chromatography due to the low solubility of the product. Precipitation-induced clogging can be mitigated by gently disturbing the top of the column.

B. BENCHMARK OF LEVEL OF THEORY

| Parameter | 1-cyanopyrene | ||

| Theoretical | Experimental

|

Theoretical+Experimental

|

|

|

|

850.141 | 843.140191(128) | 843.141827(128) |

|

|

372.931 | 372.500175(56) | 372.500183(56) |

|

|

259.219 | 258.4249175(164) | 258.4248913(164) |

|

|

1.977 | 2.240(80) | 2.153(80)) |

|

|

-5.556 | -5.52(101) | -5.88(101) |

|

|

20.310 | [0] | [20.310] |

|

|

0.724 | 0.826(40) | 0.795(40) |

|

|

3.059 | 5.26(74) | 4.20(74) |

| Parameter | 2-cyanopyrene | ||

| Theoretical | Experimental

|

Theoretical+Experimental

|

|

|

|

1015.239 | 1009.19382(60) | 1009.19356(39) |

|

|

314.479 | 313.1345299(202) | 313.1345270(195) |

|

|

240.105 | 239.0427225(184) | 239.0427270(167) |

|

|

0.706 | 0.7008(109) | 0.7023(106) |

|

|

5.375 | 5.814(94) | 5.818(94) |

|

|

8.785 | 15.3(114) | [8.785] |

|

|

0.184 | 0.1759(60) | 0.1766(59) |

|

|

4.510 | 4.22(39) | 4.12(35) |

| Parameter | 4-cyanopyrene | ||

| Theoretical | Experimental

|

Theoretical+Experimental

|

|

|

|

652.155 | 651.383034(69) | 651.382955(64) |

|

|

456.670 | 453.731352(45) | 453.731444(41) |

|

|

268.590 | 267.5078168(224) | 267.5078004(221) |

|

|

1.893 | 1.780(98) | 2.026(69) |

|

|

-1.553 | 0.43(58) | [-1.553] |

|

|

14.821 | 10.89(73) | 12.61(53) |

|

|

0.756 | 0.677(49) | 0.803(35) |

|

|

1.971 | 2.56(33) | 2.40(33) |

C. MEASURED LINES OF CYANOCORONENE

| Transition (

|

Frequency

|

|

|

6788.4098 |

|

|

6788.4098 |

|

|

6788.4443 |

|

|

6788.4443 |

|

|

6788.7145 |

|

|

6788.7145 |

|

|

6789.9187 |

|

|

6789.9187 |

|

|

6815.8858 |

|

|

7005.2518 |

|

|

7054.6106 |

|

|

7054.6106 |

|

|

7054.6617 |

|

|

7054.6617 |

|

|

7054.8759 |

|

|

7054.8759 |

|

|

7055.9209 |

|

|

7055.9209 |

|

|

7058.7857 |

|

|

7058.7857 |

|

|

7073.0418 |

|

|

7080.6353 |

|

|

7088.6004 |

|

|

7291.4710 |

|

|

7320.8179 |

|

|

7320.8179 |

|

|

7320.8780 |

|

|

7320.8780 |

|

|

7321.0420 |

|

|

7321.0420 |

|

|

7321.9574 |

|

|

7321.9574 |

|

|

7324.4393 |

|

|

7324.4393 |

| Transition (

|

Frequency

|

|

|

7587.0283 |

|

|

7587.0283 |

|

|

7587.0875 |

|

|

7587.0875 |

|

|

8377.6038 |

|

|

8385.6505 |

|

|

8385.6505 |

|

|

8385.7347 |

|

|

8385.7347 |

|

|

8385.7636 |

|

|

8385.7636 |

|

|

8391.1806 |

|

|

8391.1806 |

|

|

8651.8594 |

|

|

8651.8594 |

|

|

8651.9466 |

|

|

8651.9466 |

|

|

8651.9537 |

|

|

8651.9537 |

|

|

8652.4539 |

|

|

8652.4539 |

|

|

8653.7843 |

|

|

8653.7843 |

|

|

8656.7527 |

|

|

8656.7527 |

|

|

10515.3437 |

|

|

10515.3437 |

|

|

10515.3437 |

|

|

10515.3437 |

|

|

10515.4529 |

|

|

10515.4529 |

|

|

10516.2356 |

|

|

10516.2356 |

|

|

10517.6703 |

|

|

10517.6703 |

|

|

10520.4313 |

|

|

10520.4313 |

D. PARTITION FUNCTION FOR CYANOCORONENE

| Temperature [K] | Partition function |

| 1.0 | 1703.7230 |

| 2.0 | 4813.7245 |

| 3.0 | 8840.2413 |

| 4.0 | 13608.0333 |

| 5.0 | 19015.7897 |

| 6.0 | 24995.1437 |

| 7.0 | 31495.9011 |

| 8.0 | 38479.1687 |

| 9.375 | 48812.4929 |

| 18.75 | 138047.6140 |

| 37.5 | 390439.4924 |

| 75.0 | 1104317.3292 |

| 150.0 | 3120078.8657 |

| 225.0 | 5686759.1241 |

| 300.0 | 8589526.6725 |

| 400.0 | 12678742.2060 |

| 500.0 | 16744897.1786 |

E. MCMC ANALYSIS OF CYANOCORONENE IN TMC-1

| Component No. |

|

Size (“) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

||||

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

||||

| 4 |

|

||||

| Min | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 0.1 |

| Max | 10.0 | 100 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 0.3 |

| Component No. |

|

Size (“) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

50 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

50 |

|

||

| 3 |

|

50 |

|

||

| 4 |

|

49 |

|

||

|

|

|||||

F. COLUMN DENSITIES OF CYCLIC HYDROCARBONS IN TMC-1

| Molecule |

|

Column Density (

|

Reference |

|

|

5 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2021a) |

|

|

6 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2021b) |

|

|

6 |

|

Lee et al. (2021) |

|

|

6 |

|

Lee et al. (2021) |

|

|

7 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2021c) |

|

|

7 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2021c) |

|

|

7 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2022) |

|

|

7 |

|

McGuire et al. (2021) |

|

|

8 |

|

Loru et al. (2023) |

|

|

9 |

|

Sita et al. (2022) |

|

|

10 |

|

Sita et al. (2022) |

|

|

11 |

|

McGuire et al. (2021) |

|

|

11 |

|

McGuire et al. (2021) |

|

|

13 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2024) |

|

|

13 |

|

Cernicharo et al. (2024) |

|

|

17 |

|

Wenzel et al. (2024) |

|

|

17 |

|

Wenzel et al. (2025) |

|

|

17 |

|

Wenzel et al. (2025) |

|

|

16 |

|

Wenzel et al. (2025) |

|

|

25 |

|

This work |

|

|

24 |

|

This work |

G. AB-INITIO QUANTUM CHEMICAL CALCULATIONS

G.1. Computational Methodology

bonds. In these scans, all coordinates except the bond being scanned were allowed to relax while the scanned coordinate was varied. The resultant maxima were used as input geometries for transition state optimizations and the long-range minima prior to CN addition were optimized to a loose bound complex on the entrance channel.

G.2. Master equation kinetic predictions

| 1-1 | 1-2 | 1-3 | 1-4 | 1-5 | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 2-5 | |

| CN + Coronene | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| VdW | -20.57 | -20.26 | -25.82 | * | * | * | ||||

| TS 1 (CN addition) | 9.87 | 14.42 | 3.83 | 21.48 | 25.03 | 13.18 | ||||

| N-Adduct 1 | -98.48 | -90.90 | -98.57 | -99.08 | -91.60 | -101.41 | ||||

| TS 3 H elimination | 36.35 | 42.57 | 33.38 | 38.55 | 45.37 | 34.23 | ||||

| H + Isocyanocoronene | 1.06 | 0.14 | 1.72 | 1.12 | -16.20 | 0.33 | -0.68 | 0.20 | 0.94 | -14.17 |

| TS 2 (NC addition) | -18.57 | -18.27 | -23.82 | -20.09 | -18.52 | -25.05 | ||||

| Adduct 1 | -186.80 | -179.23 | -184.50 | -186.68 | -179.22 | -186.00 | ||||

| TS 4 H elimination | -56.87 | -50.57 | -57.91 | -53.20 | -46.27 | -54.98 | ||||

| H + Cyanocoronene | -89.15 | -89.97 | -86.33 | -89.88 | -106.47 | -89.39 | -90.31 | -86.53 | -88.90 | -103.67 |

https://greenbankobservatory.org/portal/gbt/ gbt-legacy-archive/gotham-data/ Experimental uncertainties are 2 kHz . - *Estimated using the cyanopyrene and cyanocoronene column densities, calculated rate coefficients for CN addition, and an CN/H ratio of 0.15 (see Appendix G and Wenzel et al. 2025).