DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023ef003581

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

مستقبل الأرض

مقالة بحثية

10.1029/2023EF003581

قسم خاص:

- ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر تحت سيناريو مسار التركيز التمثيلي (RCP) 8.5 سيؤثر بشكل كبير على توفر المياه الجوفية العذبة في المناطق الساحلية المنخفضة.

- المناطق الساحلية التي تحتوي على أكثر من

فقدان المياه الجوفية العذبة بحلول عام 2100 سيؤثر على حوالي 60 مليون شخص ويمثل ناتجًا محليًا إجماليًا جماعيًا بمئات المليارات من الدولارات الأمريكية. - نتائجنا تشير إلى مؤشرات عالمية ولكن المقارنة مع الدراسات المحلية تظهر أن الشكوك مرتفعة.

المعلومات الداعمة:

المراسلة إلى:

d.zamrsky@uu.nl

اقتباس:

تم القبول في 31 أكتوبر 2023

© 2024 المؤلفون. تم نشر مستقبل الأرض بواسطة ويلي بيريوديكالز LLC نيابة عن الاتحاد الجيولوجي الأمريكي. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب شروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي، الذي يسمح بالاستخدام والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح.

الأثر العالمي لارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر على موارد المياه العذبة الساحلية

الملخص

المياه الجوفية هي المصدر الرئيسي للمياه العذبة في العديد من المناطق الساحلية ذات الكثافة السكانية العالية والصناعية حول العالم. من المحتمل أن يؤدي الطلب المتزايد على المياه العذبة في المستقبل إلى زيادة الضغط على المياه في هذه المناطق الساحلية، مما قد يؤدي إلى الإفراط في استغلال المياه الجوفية وتملحها. من المحتمل أن تتفاقم هذه الحالة بسبب تغير المناخ والارتفاع المتوقع في مستوى سطح البحر. هنا، نقوم بتقييم تأثير ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر بشكل حصري على موارد المياه الجوفية العذبة الساحلية في جميع أنحاء العالم (مقتصر على المناطق ذات الأنظمة الرسوبية غير المتماسكة) من خلال تقدير الانخفاض المستقبلي في أحجام المياه الجوفية العذبة الداخلية تحت ثلاثة سيناريوهات لارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر وفقًا لمسار التركيز التمثيلي (RCP) 2.6 و4.5 و8.5. لهذا، تم استخدام نماذج المياه الجوفية ثنائية الأبعاد في 1,200 منطقة ساحلية لتقدير ملوحة المياه الجوفية في الماضي والحاضر والمستقبل. تظهر نتائجنا أن حوالي 60 (نطاق 16-96) مليون شخص يعيشون ضمن 10 كم من الساحل الحالي قد يفقدون أكثر من

1. المقدمة

2. المنهجية

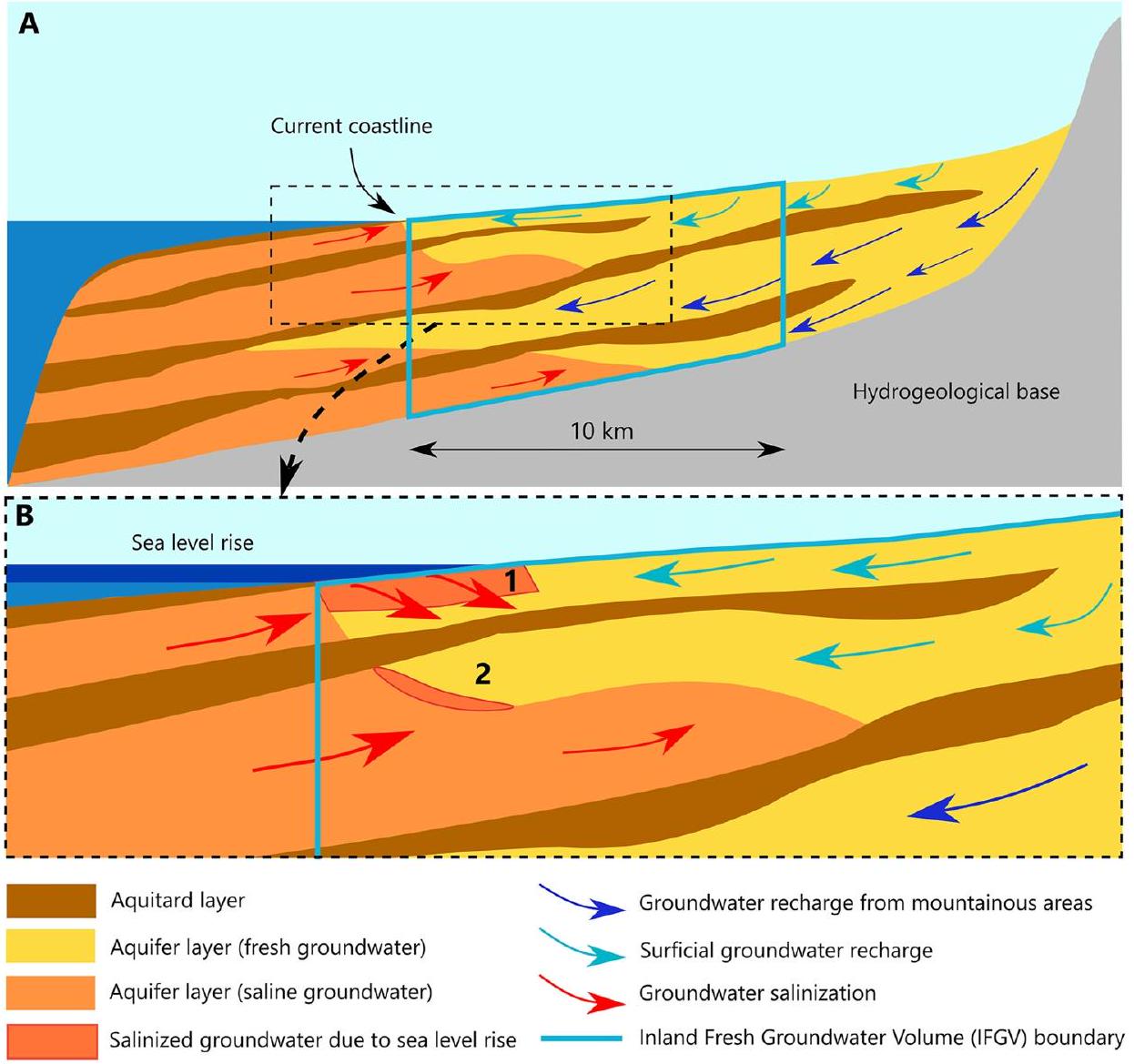

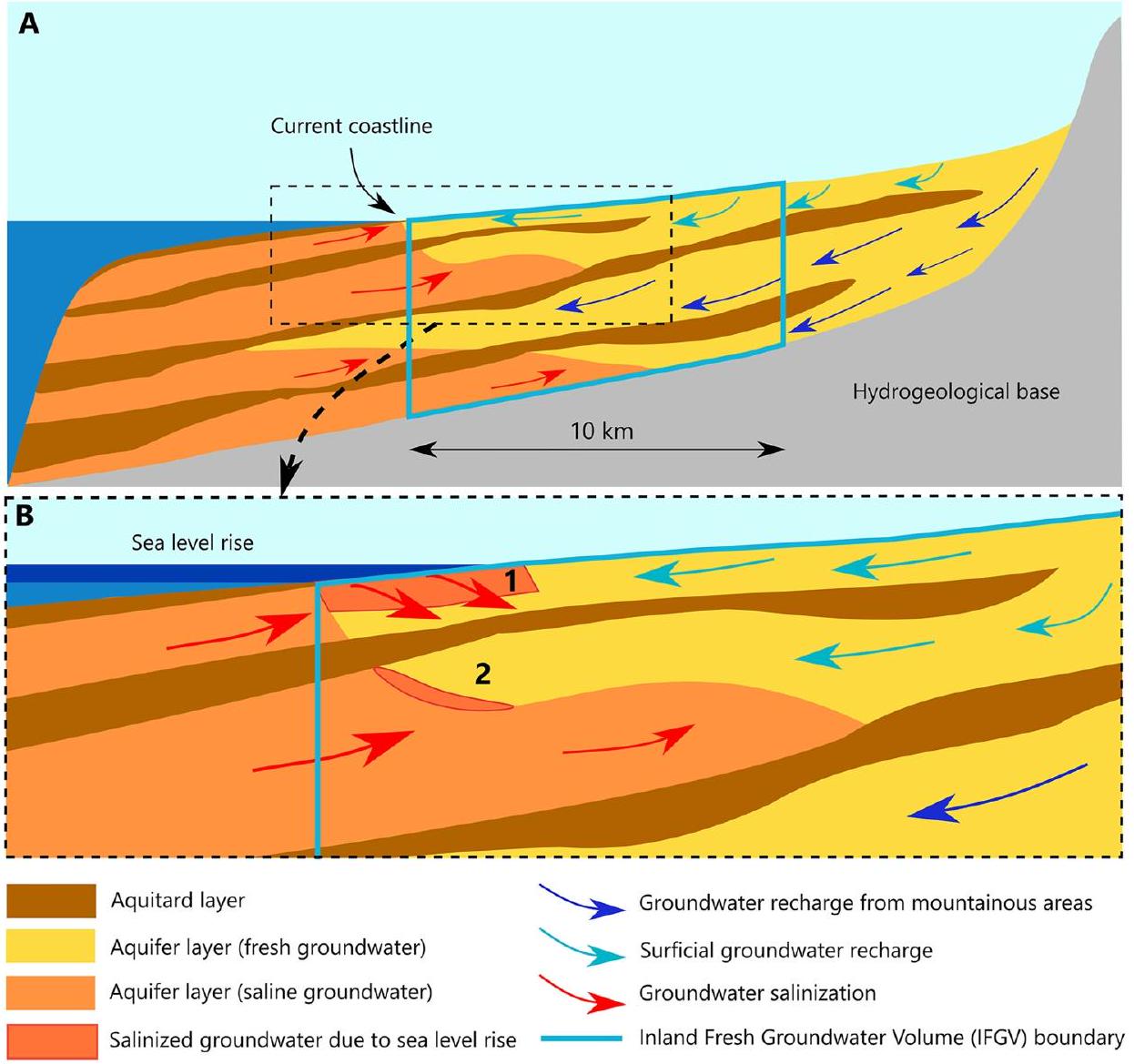

(نموذج المياه الجوفية العرضي) العمودي على الساحل لكل SRM. تساعدنا مجموعات البيانات العالمية المجمعة في تحديد SRMs الفردية مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الخصائص المحلية، وتوضيح الظروف الهيدروجيولوجية المحلية وتحديد شروط الحدود. كان لتغير مستويات البحر السريع في الـ 20,000 سنة الماضية وتأثيرات المناخ المرتبطة بها تأثير كبير على ديناميات المياه الجوفية في المناطق الساحلية (Post et al., 2013). لالتقاط هذه الديناميات بشكل صحيح، تتبع نماذج المياه الجوفية ثنائية الأبعاد ارتفاع مستوى البحر السريع في الماضي وتطور المناخ. يتم تنفيذ ذلك من خلال تقدير معدلات إعادة شحن المياه الجوفية القديمة (انظر النص S1 في المعلومات الداعمة S1) التي يتم حسابها بناءً على معدلات التبخر المحتمل السابقة (المحسوبة من سجلات درجة الحرارة)، والهطول، واستخدام الأراضي ومحتوى الطين في التربة. نقوم أيضًا بإجراء دراسة حساسية لتقييم مدى تأثير نتائج نموذج المياه الجوفية ثنائي الأبعاد على دقة النموذج المكاني (النص S2 في المعلومات الداعمة S1) واختيار DEM المستخدم (النص S3 في المعلومات الداعمة S1).

2.1. تعريف SRMs

2.2. تدفق المياه الجوفية بكثافة متغيرة مقترن بنمذجة نقل الملح

الملف الشخصي. مثال على إنشاء نموذج إدارة الموارد الساحلية (SRM) من ملفات تعريف ساحلية فردية موضح في الشكل S1 في المعلومات الداعمة S1.

2.3. الظروف الهيدروجيولوجية

2.4. شروط الحدود في نماذج المياه الجوفية ثنائية الأبعاد

2.5. انخفاض حجم المياه الجوفية العذبة الداخلية

3. النتائج

3.1. آثار ارتفاع مستوى البحر على أحجام المياه الجوفية العذبة المستقبلية

3.2. تأثير الارتفاع على تقديرات IFGV

3.3. التأثيرات على المجتمعات الساحلية والاقتصادات

إجمالي عدد الأشخاص الذين يعيشون في نماذج الممثلين الفرعيين (حتى 10 كم من الساحل الحالي) ملخص لكل سيناريو لمسار التركيز التمثيلي وخطوة زمنية

| RCP | سنة | إجمالي عدد الأشخاص المتأثرين (بالملايين) بانخفاض نسبة IFGV مقارنة بسنة 2000 | ||||

| <5٪ | 5%-10% | 10%-25% | 25%-50% | >50% | ||

| 2.6 | ٢٠٥٠ | 215.6 (179.0-222.5) | 7.0 (0.0-26.6) | 0.0 (0.0-17.7) | 0.0 (0.0-3.4) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) |

| ٢١٠٠ | 214.6 (176.6-222.5) | 7.8 (0.0-28.8) | 0.1 (0.0-17.5) | 0.0 (0.0-3.8) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | |

| ٢٢٠٠ | 209.5 (164.8-221.7) | 6.3 (0.1-36.3) | 7.9 (0.9-14.2) | 0.0 (0.0-11.7) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | |

| 2300 | 207.5 (151.4-221.5) | 5.5 (0.1-47.2) | 10.7 (1.0-16.0) | 0.1 (0.0-12.6) | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | |

| ٤.٥ | ٢٠٥٠ | 191.3 (159.5-215.1) | 22.0 (6.5-23.3) | 11.3 (1.1-28.1) | 0.1 (0.0-14.6) | 0.0 (0.0-1.7) |

| ٢١٠٠ | 191.2 (159.2-215.2) | 22.8 (6.5-23.8) | 10.5 (1.1-27.4) | 0.1 (0.0-15.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.7) | |

| ٢٢٠٠ | 182.0 (145.8-214.4) | 27.9 (0.9-30.8) | 8.9 (7.3-32.7) | 7.9 (0.0-11.1) | 0.0 (0.0-8.3) | |

| ٢٣٠٠ | 171.1 (135.4-211.3) | 27.6 (3.3-34.4) | 19.7 (1.1-29.3) | 1.9 (7.2-20.2) | 6.6 (0.0-8.9) | |

| 85 | ٢٠٥٠ | 168.0 (132.9-205.5) | 27.3 (9.2-36.2) | 21.2 (1.2-29.8) | 10.4 (7.2-21.3) | 0.1 (0.0-9.5) |

| ٢١٠٠ | 167.4 (133.4-205.8) | 22.0 (9.0-36.0) | 27.1 (1.1-27.2) | 10.3 (7.2-23.5) | 0.1 (0.0-9.5) | |

| ٢٢٠٠ | ١٣٨.٠ (١١٥.٤-١٩١.٥) | ٣٤.٧ (١٧.٤-٢٨.٩) | ٣٦.١ (٦.٠-٤٣.٩) | 11.3 (1.6-26.5) | 7.6 (7.1-14.0) | |

| ٢٣٠٠ | 107.6 (78.0-148.1) | 21.0 (17.9-35.0) | 53.9 (44.0-54.0) | 28.4 (8.4-34.8) | 17.4 (10.4-36.9) | |

بين

3.4. التحقق من الأبعاد وتأثيرها

4. المناقشة

4.1. تبسيط نموذج المياه الجوفية وتأثيراته

يجب أخذ مثل هذه التغيرات الإقليمية في ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر في الاعتبار حيث يمكن التقاط الاختلافات المحلية في الارتفاع في مثل هذه الحالات.

4.2. عدم اليقين في نموذج المياه الجوفية

4.3. تأثيرات ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر على موارد المياه الجوفية العذبة الساحلية المستقبلية

إلى أن حوالي 225 (150-453) مليون شخص يعيشون بالقرب من الساحل الحالي (حتى 10 كم) سيكونون مهددين بانخفاض في IFGV (على الرغم من أنه أقل من

5. الاستنتاج

الشكر والتقدير

مليارات دولار أمريكي. تختلف شدة هذه التأثيرات السلبية بشكل كبير بين سيناريوهات RCP 2.6 و RCP 8.5. على الرغم من أن نماذج المياه الجوفية ثنائية الأبعاد تهدف إلى تمثيل التباين على النطاق الإقليمي، إلا أن درجة كبيرة من عدم اليقين تبقى، ناتجة عن استخدام مجموعات بيانات الإدخال العالمية ومن المنهجية المطبقة (باستخدام نماذج إقليمية تمثيلية في إطار احتمالي). على هذا النحو، فإنها توفر فقط منظورًا محدودًا على نطاق واسع حول تأثيرات ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر على موارد المياه الجوفية العذبة المستقبلية في المناطق الساحلية. للحصول على رؤى جديدة وأكثر تفصيلًا، يجب الانتقال نحو البيانات المحلية ونماذج المياه الجوفية ثلاثية الأبعاد في المستقبل.

بيان توفر البيانات

References

Becker, M., Papa, F., Karpytchev, M., Delebecque, C., Krien, Y., Khan, J. U., et al. (2020). Water level changes, subsidence, and sea level rise in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(4), 1867-1876. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1912921117

Berghuijs, W. R., Luijendijk, E., Moeck, C., van der Velde, Y., & Allen, S. T. (2022). Global recharge data set indicates strengthened groundwater connection to surface fluxes. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(23), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099010

Carrard, N., Foster, T., & Willetts, J. (2020). Correction: Groundwater as a source of drinking water in Southeast Asia and the Pacific: A multi-country review of current reliance and resource concerns. Water, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010298

CIESIN. (2017). Center for international Earth science information network (CIESIN), Columbia University. Documentation for the gridded population of the world, version 4 (GPWv4), revision 11 data sets. NASA Socioeconomic Data and Application Center (SEDAC), Palisades, NY. https://doi.org/10.7927/H45Q4T5F

Cohen, D., Person, M., Wang, P., Gable, C. W., Hutchinson, D., Marksamer, A., et al. (2010). Origin and extent of fresh paleowaters on the Atlantic continental shelf, USA. Groundwater, 48(1), 143-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2009.00627.x

Custodio, E. (2002). Aquifer overexploitation: What does it mean? Hydrogeology Journal, 10(2), 254-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10040-002-0188-6

Daliakopoulos, I. N., Tsanis, I. K., Koutroulis, A., Kourgialas, N. N., Varouchakis, A. E., Karatzas, G. P., & Ritsema, C. J. (2016). The threat of soil salinity: A European scale review. Science of the Total Environment, 573, 727-739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.177

Delsman, J. R., Hu-a-ng, K. R. M., Vos, P. C., de Louw, P. G. B., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Stuyfzand, P. J., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2014). Paleo-modeling of coastal saltwater intrusion during the Holocene: An application to The Netherlands. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 18(10), 3891-3905. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-3891-2014

Dutkiewicz, A., Dietmar Müller, R., Simon, O. ‘C., & Jónasson, H. (2015). Census of seafloor sediments in the world’s ocean. Geology, 43(9), 795-798. https://doi.org/10.1130/G36883.1

Engelen, J. V., GualbertEssink, H. P. O., Kooi, H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2018). On the origins of hypersaline groundwater in the Nile Delta aquifer. Journal of Hydrology, 560, 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.03.029

Engelen, J. V., Verkaik, J., King, J., Nofal, E. R., Bierkens, M. F. P., & Oude Essink, G. H. (2019). A three-dimensional palaeohydrogeological reconstruction of the groundwater salinity distribution in the Nile Delta aquifer. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 23(12), 5175-5198. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-5175-2019

Faneca Sànchez, M., Bashar, K., Janssen, G. M. C. M., Vogels, M., Snel, J., Zhou, Y., et al. (2015). SWIBANGLA: Managing salt water intrusion impacts in coastal groundwater systems of Bangladesh. 153.

FAO. (2021). Global map of salt-affected soils: GSASmap V1.0. Fao 20.

Ferguson, G., & Gleeson, T. (2012). Vulnerability of coastal aquifers to groundwater use and climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2(5), 342-345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1413

Feseker, T. (2007). Numerical studies on saltwater intrusion in a coastal aquifer in Northwestern Germany. Hydrogeology Journal, 15(2), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-006-0151-z

Fox-Kemper, B., Hewitt, H. T., Xiao, C., Aðalgeirsdóttir, G., Drijfhout, S. S., Edwards, T. L., et al. (2023). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

Gingerich, S. B., & Voss, C. I. (2005). Three-dimensional variable-density flow simulation of a coastal aquifer in southern Oahu, Hawaii, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 13(2), 436-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-004-0371-z

Gleeson, T., Moosdorf, N., Hartmann, J., & Van Beek, L. P. H. (2014). A glimpse beneath Earth’s surface: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS (GLHYMPS) of permeability and porosity. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(11), 3891-3898. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059856

Gossel, W., Ahmed, S., & Peter, W. (2010). Modelling of paleo-saltwater intrusion in the northern part of the Nubian aquifer system, Northeast Africa. Hydrogeology Journal, 18(6), 1447-1463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-010-0597-x

Hartmann, J., & Moosdorf, N. (2012). The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 13(12), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GC004370

He, F. J., & MacGregor, G. A. (2009). A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. Journal of Human Hypertension, 23(6), 363-384. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2008.144

Hengl, T., Mendes De Jesus, J., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Ribeiro, E., et al. (2014). SoilGrids 1km – Global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One, 9(8), e105992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0105992

Herrera-García, G., Ezquerro, P., Tomas, R., Béjar-Pizarro, M., López-Vinielles, J., Rossi, M., et al. (2021). Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science, 371(6524), 34-36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8549

Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J., & Börker, J. (2018). Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated Earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophysical Research Letters, 45(4), 1897-1904. https://doi. org/10.1002/2017GL075860

Ketabchi, H., Mahmoodzadeh, D., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., & CraigSimmons, T. (2016). Sea-level rise impacts on seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers: Review and integration. Journal of Hydrology, 535, 235-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.01.083

Ketabchi, H., Mahmoodzadeh, D., Ataie-ashtiani, B., Werner, A. D., & Simmons, C. T. (2014). Sea-level rise impact on fresh groundwater lenses in two-layer small islands. Hydrological Processes, 28(24), 5938-5953. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp. 10059

Khan, M. R., Voss, C. I., Yu, W., & Michael, H. A. (2014). Water resources management in the Ganges basin: A comparison of three strategies for conjunctive use of groundwater and surface water. Water Resources Management, 28(5), 1235-1250. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11269-014-0537-y

Kirezci, E., Young, I. R., Ranasinghe, R., Muis, S., Nicholls, R. J., Lincke, D., & Hinkel, J. (2020). Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st century. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67736-6

Kulp, S. A., & Strauss, B. H. (2019). New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal floodin. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z

Kummu, M., Taka, M., & JosephGuillaume, H. A. (2018). Gridded global datasets for gross domestic product and human development index over 1990-2015. Scientific Data, 5, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.4

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y., & Sambridge, M. (2014). Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(43), 15296-15303. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas. 1411762111

Langevin, C. D., Thorne, D. T., Jr., Dausman, A. M., Sukop, M. C., & Guo, W. (2008). SEAWAT version 4: A computer program for simulation of multi-species solute and heat transport. In U.S. Geological survey techniques and methods book (Vol. 6, p. 39).

Larsen, F., Tran, L. V., Van Hoang, H., Tran, L. T., Christiansen, A. V., & Pham, N. Q. (2017). Groundwater salinity influenced by Holocene seawater trapped in incised valleys in the Red River Delta plain. Nature Geoscience, 10(5), 376-381. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2938

Laruelle, G. G., Dürr, H. H., Lauerwald, R., Hartmann, J., Slomp, C. P., Goossens, N., & Regnier, P. A. G. (2013). Global multi-scale segmentation of continental and coastal waters from the watersheds to the continental margins. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17(5), 20292051. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-2029-2013

Mabrouk, M., Jonoski, A., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Uhlenbrook, S. (2018). Impacts of sea level rise and groundwater extraction scenarios on fresh groundwater resources in the Nile Delta Governorates, Egypt. Water, 10(11), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111690

Meisler, H., Leahy, P. P., & Knobel, L. L. (1984). Effect of eustatic sea-level changes on saltwater-freshwater in the Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain. USGS Water Supply Paper: 2255 (p. 33).

Merkens, J. L., Jan, L., Reimann, L., Hinkel, J., & AthanasiosVafeidis, T. (2016). Gridded population projections for the coastal zone under the shared socioeconomic Pathways. Global and Planetary Change, 145, 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.08.009

Meybeck, M., Dürr, H. H., & Vörösmarty, C. J. (2006). Global coastal segmentation and its river catchment contributors: A new look at land-ocean linkage. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 20(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002540

Meyer, R., Engesgaard, P., & TorbenSonnenborg, O. (2019). Origin and dynamics of saltwater intrusion in a regional aquifer: Combining 3-D saltwater modeling with geophysical and geochemical data. Water Resources Research, 55(3), 1792-1813. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023624

Michael, H. A., Post, V. E. A., Wilson, A. M., & Werner, A. D. (2000). Science, society, and the coastal groundwater squeeze. Water Resources Research, 36(1), 11-12. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999WR900293

Michael, H. A., Russoniello, C. J., & Byron, L. A. (2013). Global assessment of vulnerability to sea-level rise in topography-limited and recharge-limited coastal groundwater systems. Water Resources Research, 49(4), 2228-2240. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr. 20213

Michael, H. A., Scott, K. C., Koneshloo, M., Yu, X., Khan, M. R., & Li, K. (2016). Geologic influence on groundwater salinity drives large seawater circulation through the continental shelf. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(20), 10782-10791. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070863

Michael, H. A., & Voss, C. I. (2009). Estimation of regional-scale groundwater flow properties in the Bengal basin of India and Bangladesh. Hydrogeology Journal, 17(6), 1329-1346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0443-1

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Coumou, L., Erkens, G., Middelkoop, H., & Stouthamer, E. (2019). Mekong delta much lower than previously assumed in seasea-level rise impact assessments. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11602-1

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Erkens, G., Pham, V. H., Bui, V. T., Erban, L., Kooi, H., & Stouthamer, E. (2017). Impacts of 25 years of groundwater extraction on subsidence in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Environmental Research Letters, 12(6), 064006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7146

Moeck, C., Grech-Cumbo, N., Podgorski, J., Bretzler, A., Gurdak, J. J., Berg, M., & Schirmer, M. (2020). A global-scale dataset of direct natural groundwater recharge rates: A review of variables, processes and relationships. Science of the Total Environment, 717(May), 137042. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137042

Mohan, C., Western, A. W., Wei, Y., & Saft, M. (2018). Predicting groundwater recharge for varying land cover and climate conditions – A global meta-study. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(22), 2689-2703. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2689-2018

Montzka, C., Herbst, M., Weihermüller, L., Verhoef, A., & Vereecken, H. (2017). A global data set of soil hydraulic properties and sub-grid variability of soil water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.5194/ essd-2017-13

Muis, S., Verlaan, M., Winsemius, H. C., JeroenAerts, C. J. H., & Ward, P. J. (2016). A global reanalysis of storm surges and extreme sea levels. Nature Communications, 7(1), 51-69. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11969

Nicholls, R. J., & Cazenave, A. (2010). Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science, 328(5985), 1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1126/ science. 1185782

Nicholls, R. J., Lincke, D., Hinkel, J., Brown, S., Vafeidis, A. T., Meyssignac, B., et al. (2021). A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 338-342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00993-z

O’Neill, B. C., Kriegler, E., Riahi, K., Ebi, K. L., Hallegatte, S., Carter, T. R., et al. (2014). A new scenario framework for climate change research: The concept of shared socioeconomic Pathways. Climatic Change, 122(3), 387-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0905-2

Perriquet, M., Leonardi, V., Henry, T., & Jourde, H. (2014). Saltwater wedge variation in a non-anthropogenic coastal Karst aquifer influenced by a strong tidal range (Burren, Ireland). Journal of Hydrology, 519(PB), 2350-2365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.10.006

Pham, V. H., FransVan Geer, C., Tran, V. B., Dubelaar, W., & GualbertOude Essink, H. P. (2019). Paleo-hydrogeological reconstruction of the fresh-saline groundwater distribution in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta since the late Pleistocene. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 23(July 2018), 100594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2019.100594

Pickering, M. D., Horsburgh, K. J., Blundell, J. R., Hirschi, J. J. M., Nicholls, R. J., Verlaan, M., & Wells, N. C. (2017). The impact of future sea-level rise on the global tides. Continental Shelf Research, 142(September 2016), 50-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2017.02.004

Pitman, M. G., & Läuchli, A. (2002). Global impact of salinity and agricultural ecosystems. In A. Läuchli & U. Lüttge (Eds.), Salinity: Environment-Plants-Molecules (pp. 3-20). Springer Netherlands.

Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., et al. (2019). The Ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate: A special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1-765. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/

Post, V. E. A., Groen, J., Kooi, H., Person, M., Ge, S., & Mike Edmunds, W. (2013). Offshore fresh groundwater reserves as a global phenomenon. Nature, 504(7478), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12858

Qadir, M., Quillérou, E., Nangia, V., Murtaza, G., Singh, M., Thomas, R. J., et al. (2014). Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Natural Resources Forum, 38(4), 282-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12054

Rodriguez, E., Morris, C., & Belz, J. (2006). An assessment of the SRTM topographic products. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 72(3), 249-260.

Small, C., & Nicholls, R. J. (2003). A global analysis of human settlement in coastal zones. Journal of Coastal Research, 19(3), 584-599.

Sutanudjaja, E. H., Van Beek, R., Wanders, N., Wada, Y., Bosmans, J. H. C., Drost, N., et al. (2018). PCR-GLOBWB 2: A 5 arcmin global hydrological and water resources model. Geoscientific Model Development, 08(6), 2429-2453. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-2429-2018

Syvitski, J. P. M., Kettner, A. J., Overeem, I., Hutton, E. W. H., Hannon, M. T., Brakenridge, G. R., et al. (2009). Sinking deltas due to human activites. Nature Geoscience, 2(10), 681-686. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo629

Terry, J. P., & Chui, T. F. M. (2012). Evaluating the fate of freshwater lenses on Atoll islands after eustatic sea-level rise and cyclone-driven inundation: A modelling approach. Global and Planetary Change, 88(89), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.03.008

Tessler, Z. D., Vörösmarty, C. J., Grossberg, M., Gladkova, I., Aizenman, H., Syvitski, J. P. M., & Foufoula-Georgiou, E. (2015). Profiling risk and sustainability in coastal deltas of the world. Science, 349(6248), 638-643. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3574

Thomas, A. T., Reiche, S., Riedel, M., & Clauser, C. (2019). The fate of submarine fresh groundwater reservoirs at the New Jersey shelf, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 27(7), 2673-2694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-019-01997-y

Tiggeloven, T., De Moel, H., Winsemius, H. C., Eilander, D., Erkens, G., Gebremedhin, E., et al. (2020). Global-scale benefit-cost analysis of coastal flood adaptation to different flood risk drivers using structural measures. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 20(4), 1025-1044. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-1025-2020

Van Camp, M., Mtoni, Y., Mjemah, I. C., Bakundukize, C., & Walraevens, K. (2014). Investigating seawater intrusion due to groundwater pumping with schematic model simulations: The example of the Dar es Salaam coastal aquifer in Tanzania. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 96, 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.02.012

Vandenbohede, A., & Lebbe, L. (2006). Occurrence of salt water above fresh water in dynamic equilibrium in a coastal groundwater flow system near De Panne, Belgium. Hydrogeology Journal, 14(4), 462-472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-005-0446-5

van Vuuren, D. P., Detlef, P., Edmonds, J., Kainuma, M., Riahi, K., Thomson, A., et al. (2011). The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Climatic Change, 109(1-2), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z

Været, L., Leijnse, A., Cuamba, F., & Haldorsen, S. (2012). Holocene dynamics of the salt-fresh groundwater interface under a sand island, Inhaca, Mozambique. Quaternary International, 257, 74-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2011.11.020

Vousdoukas, M. I., Voukouvalas, E., Annunziato, A., Giardino, A., & Feyen, L. (2016). Projections of extreme storm surge levels along Europe. Climate Dynamics, 47(9-10), 3171-3190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3019-5

Wahl, T. (2017). Sea-level rise and storm surges, relationship status: Complicated. Environmental Research Letters, 12(11), 111001. https://doi. org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8eba

Warner, K., Hamza, M., Oliver-Smith, A., Renaud, F., & Julca, A. (2010). Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards, 55(3), 689-715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9419-7

Weatherall, P., Marks, K. M., Jakobsson, M., Schmitt, T., Tani, S., Arndt, J. E., et al. (2015). A new digital bathymetric model of the world’s oceans. Earth and Space Science, 2(8), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015EA000107

Wu, W. Y., Lo, M. H., Wada, Y., Famiglietti, J. S., Reager, J. T., Yeh, P. J. F., et al. (2020). Divergent effects of climate change on future groundwater availability in key mid-latitude aquifers. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17581-y

Xiao, H., Wang, D., Medeiros, S. C., Hagen, S. C., & Hall, C. R. (2018). Assessing sea-level rise impact on saltwater intrusion into the root zone of a geo-typical area in coastal east-central Florida. Science of the Total Environment, 630, 211-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scitotenv.2018.02.184

Yamazaki, D., Ikeshima, D., Tawatari, R., Yamaguchi, T., O’Loughlin, F., Neal, J. C., et al. (2017). A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(11), 5844-5853. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL072874

Zamrsky, D., Karssenberg, M. E., Cohen, K. M., Bierkens, M. F. P., & Oude Essink, G. H. P. (2020). Geological heterogeneity of coastal unconsolidated groundwater systems worldwide and its influence on offshore fresh groundwater occurrence. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00339

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2018). Estimating the thickness of unconsolidated coastal aquifers along the global coastline. Earth System Science Data, 10(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA. 880771

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2023a). SRM groundwater salinity estimates as 2D profiles in .netcdf format (folder GW_models_SLR) and paleo groundwater recharge estimates (folder GW_recharge) [Datataset]. https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-X9I1YR

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2023b). dzamrsky/SLR_gw_impacts: SLR_gw_impacts_v1.0. [Software]. https://doi. org/10.5281/zenodo. 8143802

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Sutanudjaja, E. H., (Rens) van Beek, L. P. H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2021). Offshore fresh groundwater in coastal unconsolidated sediment systems as a potential fresh water source in the 21st century. Environmental Research Letters, 17 (1), 14021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac4073

References From the Supporting Information

Abu-alnaeem, M. F., Yusoff, I., Ng, T. F., Alias, Y., & Raksmey, M. (2018). Assessment of groundwater salinity and quality in Gaza coastal aquifer, Gaza Strip, Palestine: An integrated statistical, geostatistical and hydrogeochemical approaches study. Science of the Total Environment, 615, 972-989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.320

Alfarrah, N., & Walraevens, K. (2018). Groundwater overexploitation and seawater intrusion in coastal areas of arid and semi-arid regions. Water, 10(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020143

Barlow, P. M., & Reichard, E. G. (2010). L’intrusion d’eau salée dans les régions côtières d’Amérique du Nord. Hydrogeology Journal, 18(1), 247-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0514-3

Carretero, S., Rapaglia, J., Perdomo, S., Albino Martínez, C., Rodrigues Capítulo, L., Gómez, L., & Kruse, E. (2019). A multi-parameter study of groundwater-seawater interactions along Partido de La Costa, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Environmental Earth Sciences, 78(16), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8532-5

Casillas-Trasvina, A., Zhou, Y., Stigter, T. Y., Mussáa, F. E. F., & Juízo, D. (2019). Application of numerical models to assess multi-source saltwater intrusion under natural and pumping conditions in the Great Maputo aquifer, Mozambique. Hydrogeology Journal, 27(8), 2973-2992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-019-02053-5

De Graaf, I. E. M., Sutanudjaja, E. H., van Beek, L. P. H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2015). A high-resolution global-scale groundwater model. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 19(2), 823-837. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-823-2015

Dibaj, M., Javadi, A. A., Akrami, M., Ke, K. Y., Farmani, R., Tan, Y. C., & Chen, A. S. (2020). Modelling seawater intrusion in the Pingtung coastal aquifer in Taiwan, under the influence of sea-level rise and changing abstraction regime. Hydrogeology Journal, 28(6), 2085-2103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02172-4

Döll, P. (2009). Vulnerability to the impact of climate change on renewable groundwater resources: A global-scale assessment. Environmental Research Letters, 4(3), 035006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/3/035006

El Yaouti, F., El Mandour, A., Khattach, D., Benavente, J., & Kaufmann, O. (2009). Salinization processes in the unconfined aquifer of Bou-Areg (NE Morocco): A geostatistical, geochemical, and tomographic study. Applied Geochemistry, 24(1), 16-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. apgeochem.2008.10.005

Faneca Sànchez, M., Gunnink, J. L., Van Baaren, E. S., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Siemon, B., Auken, E., et al. (2012). Modelling climate change effects on a Dutch coastal groundwater system using airborne electromagnetic measurements. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 16(12), 4499-4516. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-4499-2012

Fick, S. E., & Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 37(12), 4302-4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 5086

Gardner, L. R. (2009). Assessing the effect of climate change on mean annual runoff. Journal of Hydrology, 379(3-4), 351-359. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.10.021

Giambastiani, B. M. S., Antonellini, M., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Stuurman, R. J. (2007). Saltwater intrusion in the unconfined coastal aquifer of Ravenna (Italy): A numerical model. Journal of Hydrology, 340(1-2), 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.04.001

Goldewijk, K. K., Beusen, A., Doelman, J., & Stehfest, E. (2017). Anthropogenic land use estimates for the Holocene – HYDE 3.2. Earth System Science Data, 9(2), 927-953. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-927-2017

Hamzah, U., Samsudin, A. R., & Malim, E. P. (2007). Groundwater investigation in Kuala Selangor using vertical electrical sounding (VES) surveys. Environmental Geology, 51(8), 1349-1359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0433-8

Han, D., Cao, G., Currell, M. J., Priestley, S. C., & Love, A. J. (2020). Groundwater salinization and flushing during glacial-interglacial cycles: Insights from aquitard porewater tracer profiles in the North China plain. Water Resources Research, 56(11), 1-23. https://doi. org/10.1029/2020WR027879

Han, D., & Currell, M. J. (2018). Delineating multiple salinization processes in a coastal plain aquifer, northern China: Hydrochemical and isotopic evidence. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(6), 3473-3491. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-3473-2018

Han, D., Kohfahl, C., Song, X., Xiao, G., & Yang, J. (2011). Geochemical and isotopic evidence for palaeo-seawater intrusion into the south coast aquifer of Laizhou Bay, China. Applied Geochemistry, 26(5), 863-883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2011.02.007

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J., & Lister, D. H. (2014). Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – The CRU TS3.10 Dataset. International Journal of Climatology, 34(3), 623-642. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 3711

Hasan, M., Shang, Y., Metwaly, M., Jin, W., Khan, M., & Gao, Q. (2020). Assessment of groundwater resources in coastal areas of Pakistan for sustainable water quality management using joint geophysical and geochemical approach: A case study. Sustainability, 12(22), 1-23. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su12229730

Hengl, T., De Jesus, J. M., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Ribeiro, E., et al. (2014). SoilGrids 1km – global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One, 9(8), e105992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0105992

Hermans, T., & Paepen, M. (2020). Combined inversion of land and marine electrical resistivity tomography for submarine groundwater discharge and saltwater intrusion characterization. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(3), 0-1. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085877

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G., & Jarvis, A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 25(15), 1965-1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 1276

Huizer, S., Karaoulis, M. C., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2017). Monitoring and simulation of salinity changes in response to tide and storm surges in a sandy coastal aquifer system. Water Resources Research, 53(8), 6487-6509. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR020339

Huizer, S., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2016). Fresh groundwater resources in a large sand replenishment. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 20(8), 3149-3166. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-3149-2016

Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J., & Börker, J. (2018). Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated Earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophysical Research Letters, 45(4), 1897-1904. https://doi. org/10.1002/2017GL075860

Kalbus, E., Zekri, S., & Karimi, A. (2016). Intervention scenarios to manage seawater intrusion in a coastal agricultural area in Oman. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 9(6), 472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-016-2442-6

Karamouz, M., Mahmoodzadeh, D., & Oude Essink, G. H. P. (2020). A risk-based groundwater modeling framework in coastal aquifers: A case study on long island, New York, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 28(7), 2519-2541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02197-9

Kulp, S. A., & Strauss, B. H. (2019). New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal floodin. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z

Lakfifi, L., Larabi, A., Bziou, M., Benbibai, M., & Lahmouri, A. (2004). Regional model for seawater intrusion in the Chaouia Coastal aquifer (Morocco).

Langevin, C. D., Thorne, D. T. J., Dausman, A. M., Sukop, M. C., & Guo, W. (2008). SEAWAT version 4: A computer program for simulation of multi-species solute and heat transport. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods Book, 6, 39. http://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/tm6a22/

Lemieux, J. M., Hassaoui, J., Molson, J., Therrien, R., Therrien, P., Chouteau, M., & Ouellet, M. (2015). Simulating the impact of climate change on the groundwater resources of the Magdalen Islands, Québec, Canada. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 3, 400-423. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2015.02.011

Li, Q., Zhang, Y., Chen, W., & Yu, S. (2018). The integrated impacts of natural processes and human activities on groundwater salinization in the coastal aquifers of Beihai, southern China. Hydrogeology Journal, 26(5), 1513-1526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-018-1756-8

Lin, J., Snodsmith, J. B., Zheng, C., & Wu, J. (2009). A modeling study of seawater intrusion in Alabama Gulf Coast, USA. Environmental Geology, 57(1), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-008-1288-y

Liu, S., Gao, M., Hou, G., & Jia, C. (2020). Groundwater characteristics and mixing processes during the development of a modern Estuarine Delta (Luanhe River Delta, China). Journal of Coastal Research, 37(2), 349-363. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-20-00022.1

Mabrouk, M., Jonoski, A., Essink, G. H. P. O., & Uhlenbrook, S. (2019). Assessing the fresh-saline groundwater distribution in the Nile Delta aquifer using a 3D variable-density groundwater flow model. Water (Switzerland), 11(9), 1946. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091946

Mastrocicco, M., Busico, G., Colombani, N., Vigliotti, M., & Ruberti, D. (2019). Modelling actual and future seawater intrusion in the variconi coastal wetland (Italy) due to climate and landscape changes. Water (Switzerland), 11(7), 1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11071502

Maurya, P., Kumari, R., & Mukherjee, S. (2019). Hydrochemistry in integration with stable isotopes (

Misut, P. E., & Voss, C. I. (2007). Freshwater-saltwater transition zone movement during aquifer storage and recovery cycles in Brooklyn and Queens, New York City, USA. Journal of Hydrology, 337(1-2), 87-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.01.035

Mohan, C., Western, A. W., Wei, Y., & Saft, M. (2018). Predicting groundwater recharge for varying land cover and climate conditions – A global meta-study. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(5), 2689-2703. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2689-2018

Najib, S., Fadili, A., Mehdi, K., Riss, J., & Makan, A. (2017). Contribution of hydrochemical and geoelectrical approaches to investigate salinization process and seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifers of Chaouia, Morocco. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 198, 24-36. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2017.01.003

Narayan, K. A., Schleeberger, C., & Bristow, K. L. (2007). Modelling seawater intrusion in the Burdekin delta irrigation area, North Queensland, Australia. Agricultural Water Management, 89(3), 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2007.01.008

Nishikawa, T., Siade, A. J., Reichard, E. G., Ponti, D. J., Canales, A. G., & Johnson, T. A. (2009). Stratigraphic controls on seawater intrusion and implications for groundwater management. Dominguez Gap area of Los Angeles. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0481-8

Palacios, A., José Ledo, J., Linde, N., Luquot, L., Bellmunt, F., Folch, A., et al. (2020). Time-lapse cross-hole electrical resistivity tomography (CHERT) for monitoring seawater intrusion dynamics in a Mediterranean aquifer. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 24(4), 2121-2139. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-2121-2020

Paldor, A., Aharonov, E., & Katz, O. (2020). Thermo-haline circulations in subsea confined aquifers produce saline, steady-state deep submarine groundwater discharge. Journal of Hydrology, 580, 124276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124276

Perera, E. D. P., Jinno, K., Tsutsumi, A., & Hiroshiro, Y. (2008). Development and verification of a three dimensional density dependent solute transport model for seawater intrusion. Memoirs of the Faculty of Engineering, Kyushu University, 68(2), 93-106.

Qahman, K., & Larabi, A. (2004). Three dimensional numerical models of seawater intrusion in the Gaza aquifer, Palestine (pp. 215-230).

Qahman, K., & Larabi, A. (2006). Evaluation and numerical modeling of seawater intrusion in the Gaza aquifer (Palestine). Hydrogeology Journal, 14(5), 713-728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-005-003-2

Sae-Ju, J., Chotpantarat, S., & Thitimakorn, T. (2020). Hydrochemical, geophysical and multivariate statistical investigation of the seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifer at Phetchaburi Province, Thailand. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 191(November 2019), 104165. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2019.104165

Sanford, W. E., & Pope, J. P. (2010). Défis actuels de l’utilisation des modèles pour prédire l’intrusion d’eau de mer: Des leçons de la côte est de la Virginie, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 18(1), 73-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0513-4

Sankaran, S., Sonkamble, S., Krishnakumar, K., & Mondal, N. C. (2012). Integrated approach for demarcating subsurface pollution and saline water intrusion zones in SIPCOT area: A case study from Cuddalore in Southern India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 184(8), 5121-5138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-011-2327-9

Sathish, S., & Elango, L. (2016). An integrated study on the characterization of freshwater lens in a coastal aquifer of Southern India. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 9(14), 643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-016-2656-7

Sherif, M., Kacimov, A., Javadi, A., & Ebraheem, A. A. (2012). Modeling groundwater flow and seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifer of Wadi Ham, UAE. Water Resources Management, 26(3), 751-774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-011-9943-6

Siemon, B., van Baaren, E., Dabekaussen, W., Delsman, J., Karaoulis, M., de Louw, P., et al. (2017). Frequency-domain helicopter-borne EM survey for delineation of the 3D chloride distribution in Zeeland, The Netherlands. Frequency-domain Helicopter-borne EM Survey for Delineation of the 3D Chloride Distribution in Zeeland, the Netherlands, 2017(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.3997/2214-4609.201702177

Siemon, B., Steuer, A., Meyer, U., & Rehli, H. J. (2007). HELP ACEH – A post-tsunami helicopter-borne groundwater project along the coasts of Aceh, Northern Sumatra. Near Surface Geophysics, 5(4), 231-240. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2007005

Sindhu, G., Ashitha, M., Jairaj, P. G., & Raghunath, R. (2012). Modelling of coastal aquifers of Trivandrum. Procedia Engineering, 38, 34343448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.06.397

Telahigue, F., Souid, F., Agoubi, B., Chahlaoui, A., & Kharroubi, A. (2020). Hydrogeochemical and isotopic evidence of groundwater salinization in a coastal aquifer: A case study in Jerba Island, southeastern Tunisia. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 118-119(January), 102886. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2020.102886

Van Baaren, E. S., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Janssen, G. M. C. M., De Louw, P. G. B., Heerdink, R., & Goes, B. J. M. (2016). Verzoeting en verzilting freatisch grondwater in de Provincie Zeeland, Rapportage 3D regionaal zoet-zout grondwater model.

Vandenbohede, A., Lebbe, L., Adams, R., Cosyns, E., Durinck, P., & Zwaenepoel, A. (2010). Hydrogeological study for improved nature restoration in dune ecosystems-Kleyne Vlakte case study, Belgium. Journal of Environmental Management, 91(11), 2385-2395. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.06.023

Vandenbohede, A. (2016). The hydrogeology of the military inundation at the 1914-1918 Yser front (Belgium). Hydrogeology Journal, 24(2), 521-534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-015-1344-0

Verkaik, J., van Engelen, J., Huizer, S., Bierkens, M. F. P., Lin, H. X., & Oude Essink, G. H. P. (2021). Distributed memory parallel computing of three-dimensional variable-density groundwater flow and salt transport. Advances in Water Resources, 154(May), 103976. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2021.103976

Vu, D. T., Yamada, T., & Ishidaira, H. (2018). Assessing the impact of sea level rise due to climate change on seawater intrusion in Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Water Science and Technology: A Journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research, 77(5-6), 1632-1639. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2018.038

Walther, M., Delfs, J. O., Grundmann, J., Kolditz, O., & Liedl, R. (2012). Saltwater intrusion modeling: Verification and application to an agricultural coastal arid region in Oman. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 236(18), 4798-4809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cam.2012.02.008

Wu, J., Meng, F., Wang, X., & Wang, D. (2008). The development and control of the seawater intrusion in the eastern coastal of Laizhou Bay, China. Environmental Geology, 54(8), 1763-1770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-007-0954-9

Xiao, H., Wang, D., Medeiros, S. C., Hagen, S. C., & Hall, C. R. (2018). Assessing sea-level rise impact on saltwater intrusion into the root zone of a geo-typical area in coastal east-central Florida. Science of the Total Environment, 630, 211-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scitotenv.2018.02.184

Yamazaki, D., Ikeshima, D., Tawatari, R., Yamaguchi, T., O’Loughlin, F., Neal, J. C., et al. (2017). A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(11), 5844-5853. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL072874

Zghibi, A., Mirchi, A., Zouhri, L., Taupin, J. D., Chekirbane, A., & Tarhouni, J. (2019). Implications of groundwater development and seawater intrusion for sustainability of a Mediterranean coastal aquifer in Tunisia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 191(11), 696. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10661-019-7866-5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2023ef003581

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

Earth’s Future

RESEARCH ARTICLE

10.1029/2023EF003581

Special Section:

- Sea level rise under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenario will severely impact fresh groundwater availability in low lying coastal regions

- Coastal areas with more than

loss of fresh groundwater by 2100 harbor around 60 million people and represent a collective gross domestic product of hundreds of billion USD - Our results are globally indicative but comparison with local studies show that uncertainties are high

Supporting Information:

Correspondence to:

d.zamrsky@uu.nl

Citation:

Accepted 31 OCT 2023

© 2024 The Authors. Earth’s Future published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of American Geophysical Union. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Global Impact of Sea Level Rise on Coastal Fresh Groundwater Resources

Abstract

Groundwater is the main freshwater source in many densely populated and industrialized coastal areas around the world. Growing future freshwater demand is likely to increase the water stress in these coastal areas, possibly leading to groundwater overexploitation and salinization. This situation will likely be aggravated by climate change and the associated projected sea level rise. Here, we assess the impact of sea level rise exclusively on coastal fresh groundwater resources worldwide (limited to areas with unconsolidated sedimentary systems) by estimating future decline in inland fresh groundwater volumes under three sea level rise scenarios following Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5. For that, 2D groundwater models in 1,200 coastal regions estimate the past, present and future groundwater salinity. Our results show that roughly 60 (range 16-96) million people living within 10 km from current coastline could lose more than

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

(cross-sectional) groundwater models perpendicular to the coastline for each SRM. The collected global data sets help us to define individual SRMs while taking into account local characteristics, illustrate the local hydrogeological conditions and define boundary conditions. Rapid changing sea levels in the past 20,000 years and associated climate variations had a significant impact on groundwater dynamics in coastal areas (Post et al., 2013). To properly pick up these dynamics, the 2D groundwater models follow past rapid sea level rise and climate evolution. The latter is implemented via estimated paleo groundwater recharge rates (see Text S1 in Supporting Information S1) which are calculated based on past potential evapotranspiration rates (calculated via temperature records), precipitation, land use and soil clay content. We also perform a sensitivity study to assess to what extent 2D groundwater model results are affected by spatial model resolution (Text S2 in Supporting Information S1) and the choice of the used DEM (Text S3 in Supporting Information S1).

2.1. Defining the SRMs

2.2. Variable Density Groundwater Flow Coupled With Salt Transport Modeling

profile. An example of creating a single SRM from individual coastal profiles is given in Figure S1 in Supporting Information S1.

2.3. Hydrogeological Conditions

2.4. Boundary Conditions in the 2D Groundwater Models

2.5. Inland Fresh Groundwater Volume Decline

3. Results

3.1. Sea Level Rise Effects on Future Fresh Groundwater Volumes

3.2. Elevation Impacts on IFGV Estimates

3.3. Impacts on Coastal Communities and Economies

Total Number of People Living in the Sub-Regional Representative Models (Up to 10 km From Current Coastline) Summarized for Each Representative Concentration Pathway Scenario and Time Step

| RCP | Year | Total number of people affected (millions) by % decline in IFGV compared to year 2000 | ||||

| <5% | 5%-10% | 10%-25% | 25%-50% | >50% | ||

| 2.6 | 2050 | 215.6 (179.0-222.5) | 7.0 (0.0-26.6) | 0.0 (0.0-17.7) | 0.0 (0.0-3.4) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) |

| 2100 | 214.6 (176.6-222.5) | 7.8 (0.0-28.8) | 0.1 (0.0-17.5) | 0.0 (0.0-3.8) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | |

| 2200 | 209.5 (164.8-221.7) | 6.3 (0.1-36.3) | 7.9 (0.9-14.2) | 0.0 (0.0-11.7) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | |

| 2300 | 207.5 (151.4-221.5) | 5.5 (0.1-47.2) | 10.7 (1.0-16.0) | 0.1 (0.0-12.6) | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | |

| 4.5 | 2050 | 191.3 (159.5-215.1) | 22.0 (6.5-23.3) | 11.3 (1.1-28.1) | 0.1 (0.0-14.6) | 0.0 (0.0-1.7) |

| 2100 | 191.2 (159.2-215.2) | 22.8 (6.5-23.8) | 10.5 (1.1-27.4) | 0.1 (0.0-15.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.7) | |

| 2200 | 182.0 (145.8-214.4) | 27.9 (0.9-30.8) | 8.9 (7.3-32.7) | 7.9 (0.0-11.1) | 0.0 (0.0-8.3) | |

| 2300 | 171.1 (135.4-211.3) | 27.6 (3.3-34.4) | 19.7 (1.1-29.3) | 1.9 (7.2-20.2) | 6.6 (0.0-8.9) | |

| 85 | 2050 | 168.0 (132.9-205.5) | 27.3 (9.2-36.2) | 21.2 (1.2-29.8) | 10.4 (7.2-21.3) | 0.1 (0.0-9.5) |

| 2100 | 167.4 (133.4-205.8) | 22.0 (9.0-36.0) | 27.1 (1.1-27.2) | 10.3 (7.2-23.5) | 0.1 (0.0-9.5) | |

| 2200 | 138.0 (115.4-191.5) | 34.7 (17.4-28.9) | 36.1 (6.0-43.9) | 11.3 (1.6-26.5) | 7.6 (7.1-14.0) | |

| 2300 | 107.6 (78.0-148.1) | 21.0 (17.9-35.0) | 53.9 (44.0-54.0) | 28.4 (8.4-34.8) | 17.4 (10.4-36.9) | |

between

3.4. Validation and Impact of Dimensionality

4. Discussion

4.1. Groundwater Model Simplifications and Their Implications

analyses using 3D groundwater models such regional changes in sea level rise should be taken into account since in such cases local differences in elevation can be captured.

4.2. Groundwater Model Uncertainty

4.3. Sea Level Rise Effects on Future Coastal Fresh Groundwater Resources

suggest that approximately 225 (150-453) million people that live in close proximity to current coastline (up to 10 km ) will be threatened by a decline in IFGV (albeit lower than

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

billions USD. The severity of these negative impacts differs largely between RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 scenarios. Although the 2D groundwater models are meant to represent regional-scale variability a large degree of uncertainty remains, stemming both from the use of global input data sets and from the methodology applied (using representative regional models in a probabilistic framework). As such, they only provide a limited large-scale perspective into the effects of sea level rise on future fresh groundwater resources in coastal zones. To gain new and more detailed insights a shift toward local data and 3D groundwater models needs to be made in future.

Data Availability Statement

References

Becker, M., Papa, F., Karpytchev, M., Delebecque, C., Krien, Y., Khan, J. U., et al. (2020). Water level changes, subsidence, and sea level rise in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(4), 1867-1876. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1912921117

Berghuijs, W. R., Luijendijk, E., Moeck, C., van der Velde, Y., & Allen, S. T. (2022). Global recharge data set indicates strengthened groundwater connection to surface fluxes. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(23), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099010

Carrard, N., Foster, T., & Willetts, J. (2020). Correction: Groundwater as a source of drinking water in Southeast Asia and the Pacific: A multi-country review of current reliance and resource concerns. Water, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010298

CIESIN. (2017). Center for international Earth science information network (CIESIN), Columbia University. Documentation for the gridded population of the world, version 4 (GPWv4), revision 11 data sets. NASA Socioeconomic Data and Application Center (SEDAC), Palisades, NY. https://doi.org/10.7927/H45Q4T5F

Cohen, D., Person, M., Wang, P., Gable, C. W., Hutchinson, D., Marksamer, A., et al. (2010). Origin and extent of fresh paleowaters on the Atlantic continental shelf, USA. Groundwater, 48(1), 143-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2009.00627.x

Custodio, E. (2002). Aquifer overexploitation: What does it mean? Hydrogeology Journal, 10(2), 254-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10040-002-0188-6

Daliakopoulos, I. N., Tsanis, I. K., Koutroulis, A., Kourgialas, N. N., Varouchakis, A. E., Karatzas, G. P., & Ritsema, C. J. (2016). The threat of soil salinity: A European scale review. Science of the Total Environment, 573, 727-739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.177

Delsman, J. R., Hu-a-ng, K. R. M., Vos, P. C., de Louw, P. G. B., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Stuyfzand, P. J., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2014). Paleo-modeling of coastal saltwater intrusion during the Holocene: An application to The Netherlands. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 18(10), 3891-3905. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-3891-2014

Dutkiewicz, A., Dietmar Müller, R., Simon, O. ‘C., & Jónasson, H. (2015). Census of seafloor sediments in the world’s ocean. Geology, 43(9), 795-798. https://doi.org/10.1130/G36883.1

Engelen, J. V., GualbertEssink, H. P. O., Kooi, H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2018). On the origins of hypersaline groundwater in the Nile Delta aquifer. Journal of Hydrology, 560, 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.03.029

Engelen, J. V., Verkaik, J., King, J., Nofal, E. R., Bierkens, M. F. P., & Oude Essink, G. H. (2019). A three-dimensional palaeohydrogeological reconstruction of the groundwater salinity distribution in the Nile Delta aquifer. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 23(12), 5175-5198. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-5175-2019

Faneca Sànchez, M., Bashar, K., Janssen, G. M. C. M., Vogels, M., Snel, J., Zhou, Y., et al. (2015). SWIBANGLA: Managing salt water intrusion impacts in coastal groundwater systems of Bangladesh. 153.

FAO. (2021). Global map of salt-affected soils: GSASmap V1.0. Fao 20.

Ferguson, G., & Gleeson, T. (2012). Vulnerability of coastal aquifers to groundwater use and climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2(5), 342-345. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1413

Feseker, T. (2007). Numerical studies on saltwater intrusion in a coastal aquifer in Northwestern Germany. Hydrogeology Journal, 15(2), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-006-0151-z

Fox-Kemper, B., Hewitt, H. T., Xiao, C., Aðalgeirsdóttir, G., Drijfhout, S. S., Edwards, T. L., et al. (2023). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

Gingerich, S. B., & Voss, C. I. (2005). Three-dimensional variable-density flow simulation of a coastal aquifer in southern Oahu, Hawaii, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 13(2), 436-450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-004-0371-z

Gleeson, T., Moosdorf, N., Hartmann, J., & Van Beek, L. P. H. (2014). A glimpse beneath Earth’s surface: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS (GLHYMPS) of permeability and porosity. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(11), 3891-3898. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059856

Gossel, W., Ahmed, S., & Peter, W. (2010). Modelling of paleo-saltwater intrusion in the northern part of the Nubian aquifer system, Northeast Africa. Hydrogeology Journal, 18(6), 1447-1463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-010-0597-x

Hartmann, J., & Moosdorf, N. (2012). The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 13(12), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GC004370

He, F. J., & MacGregor, G. A. (2009). A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. Journal of Human Hypertension, 23(6), 363-384. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2008.144

Hengl, T., Mendes De Jesus, J., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Ribeiro, E., et al. (2014). SoilGrids 1km – Global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One, 9(8), e105992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0105992

Herrera-García, G., Ezquerro, P., Tomas, R., Béjar-Pizarro, M., López-Vinielles, J., Rossi, M., et al. (2021). Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science, 371(6524), 34-36. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8549

Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J., & Börker, J. (2018). Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated Earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophysical Research Letters, 45(4), 1897-1904. https://doi. org/10.1002/2017GL075860

Ketabchi, H., Mahmoodzadeh, D., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., & CraigSimmons, T. (2016). Sea-level rise impacts on seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers: Review and integration. Journal of Hydrology, 535, 235-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.01.083

Ketabchi, H., Mahmoodzadeh, D., Ataie-ashtiani, B., Werner, A. D., & Simmons, C. T. (2014). Sea-level rise impact on fresh groundwater lenses in two-layer small islands. Hydrological Processes, 28(24), 5938-5953. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp. 10059

Khan, M. R., Voss, C. I., Yu, W., & Michael, H. A. (2014). Water resources management in the Ganges basin: A comparison of three strategies for conjunctive use of groundwater and surface water. Water Resources Management, 28(5), 1235-1250. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11269-014-0537-y

Kirezci, E., Young, I. R., Ranasinghe, R., Muis, S., Nicholls, R. J., Lincke, D., & Hinkel, J. (2020). Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st century. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67736-6

Kulp, S. A., & Strauss, B. H. (2019). New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal floodin. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z

Kummu, M., Taka, M., & JosephGuillaume, H. A. (2018). Gridded global datasets for gross domestic product and human development index over 1990-2015. Scientific Data, 5, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.4

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y., & Sambridge, M. (2014). Sea level and global ice volumes from the last glacial maximum to the Holocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(43), 15296-15303. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas. 1411762111

Langevin, C. D., Thorne, D. T., Jr., Dausman, A. M., Sukop, M. C., & Guo, W. (2008). SEAWAT version 4: A computer program for simulation of multi-species solute and heat transport. In U.S. Geological survey techniques and methods book (Vol. 6, p. 39).

Larsen, F., Tran, L. V., Van Hoang, H., Tran, L. T., Christiansen, A. V., & Pham, N. Q. (2017). Groundwater salinity influenced by Holocene seawater trapped in incised valleys in the Red River Delta plain. Nature Geoscience, 10(5), 376-381. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2938

Laruelle, G. G., Dürr, H. H., Lauerwald, R., Hartmann, J., Slomp, C. P., Goossens, N., & Regnier, P. A. G. (2013). Global multi-scale segmentation of continental and coastal waters from the watersheds to the continental margins. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17(5), 20292051. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-2029-2013

Mabrouk, M., Jonoski, A., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Uhlenbrook, S. (2018). Impacts of sea level rise and groundwater extraction scenarios on fresh groundwater resources in the Nile Delta Governorates, Egypt. Water, 10(11), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111690

Meisler, H., Leahy, P. P., & Knobel, L. L. (1984). Effect of eustatic sea-level changes on saltwater-freshwater in the Northern Atlantic Coastal Plain. USGS Water Supply Paper: 2255 (p. 33).

Merkens, J. L., Jan, L., Reimann, L., Hinkel, J., & AthanasiosVafeidis, T. (2016). Gridded population projections for the coastal zone under the shared socioeconomic Pathways. Global and Planetary Change, 145, 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.08.009

Meybeck, M., Dürr, H. H., & Vörösmarty, C. J. (2006). Global coastal segmentation and its river catchment contributors: A new look at land-ocean linkage. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 20(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002540

Meyer, R., Engesgaard, P., & TorbenSonnenborg, O. (2019). Origin and dynamics of saltwater intrusion in a regional aquifer: Combining 3-D saltwater modeling with geophysical and geochemical data. Water Resources Research, 55(3), 1792-1813. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023624

Michael, H. A., Post, V. E. A., Wilson, A. M., & Werner, A. D. (2000). Science, society, and the coastal groundwater squeeze. Water Resources Research, 36(1), 11-12. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999WR900293

Michael, H. A., Russoniello, C. J., & Byron, L. A. (2013). Global assessment of vulnerability to sea-level rise in topography-limited and recharge-limited coastal groundwater systems. Water Resources Research, 49(4), 2228-2240. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr. 20213

Michael, H. A., Scott, K. C., Koneshloo, M., Yu, X., Khan, M. R., & Li, K. (2016). Geologic influence on groundwater salinity drives large seawater circulation through the continental shelf. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(20), 10782-10791. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070863

Michael, H. A., & Voss, C. I. (2009). Estimation of regional-scale groundwater flow properties in the Bengal basin of India and Bangladesh. Hydrogeology Journal, 17(6), 1329-1346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0443-1

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Coumou, L., Erkens, G., Middelkoop, H., & Stouthamer, E. (2019). Mekong delta much lower than previously assumed in seasea-level rise impact assessments. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11602-1

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Erkens, G., Pham, V. H., Bui, V. T., Erban, L., Kooi, H., & Stouthamer, E. (2017). Impacts of 25 years of groundwater extraction on subsidence in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Environmental Research Letters, 12(6), 064006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7146

Moeck, C., Grech-Cumbo, N., Podgorski, J., Bretzler, A., Gurdak, J. J., Berg, M., & Schirmer, M. (2020). A global-scale dataset of direct natural groundwater recharge rates: A review of variables, processes and relationships. Science of the Total Environment, 717(May), 137042. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137042

Mohan, C., Western, A. W., Wei, Y., & Saft, M. (2018). Predicting groundwater recharge for varying land cover and climate conditions – A global meta-study. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(22), 2689-2703. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2689-2018

Montzka, C., Herbst, M., Weihermüller, L., Verhoef, A., & Vereecken, H. (2017). A global data set of soil hydraulic properties and sub-grid variability of soil water retention and hydraulic conductivity curves. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.5194/ essd-2017-13

Muis, S., Verlaan, M., Winsemius, H. C., JeroenAerts, C. J. H., & Ward, P. J. (2016). A global reanalysis of storm surges and extreme sea levels. Nature Communications, 7(1), 51-69. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11969

Nicholls, R. J., & Cazenave, A. (2010). Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science, 328(5985), 1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1126/ science. 1185782

Nicholls, R. J., Lincke, D., Hinkel, J., Brown, S., Vafeidis, A. T., Meyssignac, B., et al. (2021). A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 338-342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00993-z

O’Neill, B. C., Kriegler, E., Riahi, K., Ebi, K. L., Hallegatte, S., Carter, T. R., et al. (2014). A new scenario framework for climate change research: The concept of shared socioeconomic Pathways. Climatic Change, 122(3), 387-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0905-2

Perriquet, M., Leonardi, V., Henry, T., & Jourde, H. (2014). Saltwater wedge variation in a non-anthropogenic coastal Karst aquifer influenced by a strong tidal range (Burren, Ireland). Journal of Hydrology, 519(PB), 2350-2365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.10.006

Pham, V. H., FransVan Geer, C., Tran, V. B., Dubelaar, W., & GualbertOude Essink, H. P. (2019). Paleo-hydrogeological reconstruction of the fresh-saline groundwater distribution in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta since the late Pleistocene. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 23(July 2018), 100594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2019.100594

Pickering, M. D., Horsburgh, K. J., Blundell, J. R., Hirschi, J. J. M., Nicholls, R. J., Verlaan, M., & Wells, N. C. (2017). The impact of future sea-level rise on the global tides. Continental Shelf Research, 142(September 2016), 50-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2017.02.004

Pitman, M. G., & Läuchli, A. (2002). Global impact of salinity and agricultural ecosystems. In A. Läuchli & U. Lüttge (Eds.), Salinity: Environment-Plants-Molecules (pp. 3-20). Springer Netherlands.

Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., et al. (2019). The Ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate: A special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1-765. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/

Post, V. E. A., Groen, J., Kooi, H., Person, M., Ge, S., & Mike Edmunds, W. (2013). Offshore fresh groundwater reserves as a global phenomenon. Nature, 504(7478), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12858

Qadir, M., Quillérou, E., Nangia, V., Murtaza, G., Singh, M., Thomas, R. J., et al. (2014). Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Natural Resources Forum, 38(4), 282-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12054

Rodriguez, E., Morris, C., & Belz, J. (2006). An assessment of the SRTM topographic products. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 72(3), 249-260.

Small, C., & Nicholls, R. J. (2003). A global analysis of human settlement in coastal zones. Journal of Coastal Research, 19(3), 584-599.

Sutanudjaja, E. H., Van Beek, R., Wanders, N., Wada, Y., Bosmans, J. H. C., Drost, N., et al. (2018). PCR-GLOBWB 2: A 5 arcmin global hydrological and water resources model. Geoscientific Model Development, 08(6), 2429-2453. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-2429-2018

Syvitski, J. P. M., Kettner, A. J., Overeem, I., Hutton, E. W. H., Hannon, M. T., Brakenridge, G. R., et al. (2009). Sinking deltas due to human activites. Nature Geoscience, 2(10), 681-686. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo629

Terry, J. P., & Chui, T. F. M. (2012). Evaluating the fate of freshwater lenses on Atoll islands after eustatic sea-level rise and cyclone-driven inundation: A modelling approach. Global and Planetary Change, 88(89), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.03.008

Tessler, Z. D., Vörösmarty, C. J., Grossberg, M., Gladkova, I., Aizenman, H., Syvitski, J. P. M., & Foufoula-Georgiou, E. (2015). Profiling risk and sustainability in coastal deltas of the world. Science, 349(6248), 638-643. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab3574

Thomas, A. T., Reiche, S., Riedel, M., & Clauser, C. (2019). The fate of submarine fresh groundwater reservoirs at the New Jersey shelf, USA. Hydrogeology Journal, 27(7), 2673-2694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-019-01997-y

Tiggeloven, T., De Moel, H., Winsemius, H. C., Eilander, D., Erkens, G., Gebremedhin, E., et al. (2020). Global-scale benefit-cost analysis of coastal flood adaptation to different flood risk drivers using structural measures. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 20(4), 1025-1044. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-1025-2020

Van Camp, M., Mtoni, Y., Mjemah, I. C., Bakundukize, C., & Walraevens, K. (2014). Investigating seawater intrusion due to groundwater pumping with schematic model simulations: The example of the Dar es Salaam coastal aquifer in Tanzania. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 96, 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.02.012

Vandenbohede, A., & Lebbe, L. (2006). Occurrence of salt water above fresh water in dynamic equilibrium in a coastal groundwater flow system near De Panne, Belgium. Hydrogeology Journal, 14(4), 462-472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-005-0446-5

van Vuuren, D. P., Detlef, P., Edmonds, J., Kainuma, M., Riahi, K., Thomson, A., et al. (2011). The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Climatic Change, 109(1-2), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z

Været, L., Leijnse, A., Cuamba, F., & Haldorsen, S. (2012). Holocene dynamics of the salt-fresh groundwater interface under a sand island, Inhaca, Mozambique. Quaternary International, 257, 74-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2011.11.020

Vousdoukas, M. I., Voukouvalas, E., Annunziato, A., Giardino, A., & Feyen, L. (2016). Projections of extreme storm surge levels along Europe. Climate Dynamics, 47(9-10), 3171-3190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3019-5

Wahl, T. (2017). Sea-level rise and storm surges, relationship status: Complicated. Environmental Research Letters, 12(11), 111001. https://doi. org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8eba

Warner, K., Hamza, M., Oliver-Smith, A., Renaud, F., & Julca, A. (2010). Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards, 55(3), 689-715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9419-7

Weatherall, P., Marks, K. M., Jakobsson, M., Schmitt, T., Tani, S., Arndt, J. E., et al. (2015). A new digital bathymetric model of the world’s oceans. Earth and Space Science, 2(8), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015EA000107

Wu, W. Y., Lo, M. H., Wada, Y., Famiglietti, J. S., Reager, J. T., Yeh, P. J. F., et al. (2020). Divergent effects of climate change on future groundwater availability in key mid-latitude aquifers. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17581-y

Xiao, H., Wang, D., Medeiros, S. C., Hagen, S. C., & Hall, C. R. (2018). Assessing sea-level rise impact on saltwater intrusion into the root zone of a geo-typical area in coastal east-central Florida. Science of the Total Environment, 630, 211-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. scitotenv.2018.02.184

Yamazaki, D., Ikeshima, D., Tawatari, R., Yamaguchi, T., O’Loughlin, F., Neal, J. C., et al. (2017). A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(11), 5844-5853. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL072874

Zamrsky, D., Karssenberg, M. E., Cohen, K. M., Bierkens, M. F. P., & Oude Essink, G. H. P. (2020). Geological heterogeneity of coastal unconsolidated groundwater systems worldwide and its influence on offshore fresh groundwater occurrence. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00339

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2018). Estimating the thickness of unconsolidated coastal aquifers along the global coastline. Earth System Science Data, 10(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA. 880771

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2023a). SRM groundwater salinity estimates as 2D profiles in .netcdf format (folder GW_models_SLR) and paleo groundwater recharge estimates (folder GW_recharge) [Datataset]. https://doi.org/10.24416/UU01-X9I1YR

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2023b). dzamrsky/SLR_gw_impacts: SLR_gw_impacts_v1.0. [Software]. https://doi. org/10.5281/zenodo. 8143802

Zamrsky, D., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Sutanudjaja, E. H., (Rens) van Beek, L. P. H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2021). Offshore fresh groundwater in coastal unconsolidated sediment systems as a potential fresh water source in the 21st century. Environmental Research Letters, 17 (1), 14021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac4073

References From the Supporting Information

Abu-alnaeem, M. F., Yusoff, I., Ng, T. F., Alias, Y., & Raksmey, M. (2018). Assessment of groundwater salinity and quality in Gaza coastal aquifer, Gaza Strip, Palestine: An integrated statistical, geostatistical and hydrogeochemical approaches study. Science of the Total Environment, 615, 972-989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.320

Alfarrah, N., & Walraevens, K. (2018). Groundwater overexploitation and seawater intrusion in coastal areas of arid and semi-arid regions. Water, 10(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10020143

Barlow, P. M., & Reichard, E. G. (2010). L’intrusion d’eau salée dans les régions côtières d’Amérique du Nord. Hydrogeology Journal, 18(1), 247-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0514-3

Carretero, S., Rapaglia, J., Perdomo, S., Albino Martínez, C., Rodrigues Capítulo, L., Gómez, L., & Kruse, E. (2019). A multi-parameter study of groundwater-seawater interactions along Partido de La Costa, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Environmental Earth Sciences, 78(16), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8532-5

Casillas-Trasvina, A., Zhou, Y., Stigter, T. Y., Mussáa, F. E. F., & Juízo, D. (2019). Application of numerical models to assess multi-source saltwater intrusion under natural and pumping conditions in the Great Maputo aquifer, Mozambique. Hydrogeology Journal, 27(8), 2973-2992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-019-02053-5

De Graaf, I. E. M., Sutanudjaja, E. H., van Beek, L. P. H., & Bierkens, M. F. P. (2015). A high-resolution global-scale groundwater model. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 19(2), 823-837. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-823-2015

Dibaj, M., Javadi, A. A., Akrami, M., Ke, K. Y., Farmani, R., Tan, Y. C., & Chen, A. S. (2020). Modelling seawater intrusion in the Pingtung coastal aquifer in Taiwan, under the influence of sea-level rise and changing abstraction regime. Hydrogeology Journal, 28(6), 2085-2103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02172-4

Döll, P. (2009). Vulnerability to the impact of climate change on renewable groundwater resources: A global-scale assessment. Environmental Research Letters, 4(3), 035006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/3/035006

El Yaouti, F., El Mandour, A., Khattach, D., Benavente, J., & Kaufmann, O. (2009). Salinization processes in the unconfined aquifer of Bou-Areg (NE Morocco): A geostatistical, geochemical, and tomographic study. Applied Geochemistry, 24(1), 16-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. apgeochem.2008.10.005

Faneca Sànchez, M., Gunnink, J. L., Van Baaren, E. S., Oude Essink, G. H. P., Siemon, B., Auken, E., et al. (2012). Modelling climate change effects on a Dutch coastal groundwater system using airborne electromagnetic measurements. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 16(12), 4499-4516. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-4499-2012

Fick, S. E., & Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 37(12), 4302-4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 5086

Gardner, L. R. (2009). Assessing the effect of climate change on mean annual runoff. Journal of Hydrology, 379(3-4), 351-359. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.10.021

Giambastiani, B. M. S., Antonellini, M., Oude Essink, G. H. P., & Stuurman, R. J. (2007). Saltwater intrusion in the unconfined coastal aquifer of Ravenna (Italy): A numerical model. Journal of Hydrology, 340(1-2), 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.04.001

Goldewijk, K. K., Beusen, A., Doelman, J., & Stehfest, E. (2017). Anthropogenic land use estimates for the Holocene – HYDE 3.2. Earth System Science Data, 9(2), 927-953. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-927-2017

Hamzah, U., Samsudin, A. R., & Malim, E. P. (2007). Groundwater investigation in Kuala Selangor using vertical electrical sounding (VES) surveys. Environmental Geology, 51(8), 1349-1359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0433-8

Han, D., Cao, G., Currell, M. J., Priestley, S. C., & Love, A. J. (2020). Groundwater salinization and flushing during glacial-interglacial cycles: Insights from aquitard porewater tracer profiles in the North China plain. Water Resources Research, 56(11), 1-23. https://doi. org/10.1029/2020WR027879

Han, D., & Currell, M. J. (2018). Delineating multiple salinization processes in a coastal plain aquifer, northern China: Hydrochemical and isotopic evidence. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(6), 3473-3491. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-3473-2018

Han, D., Kohfahl, C., Song, X., Xiao, G., & Yang, J. (2011). Geochemical and isotopic evidence for palaeo-seawater intrusion into the south coast aquifer of Laizhou Bay, China. Applied Geochemistry, 26(5), 863-883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2011.02.007

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J., & Lister, D. H. (2014). Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – The CRU TS3.10 Dataset. International Journal of Climatology, 34(3), 623-642. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 3711

Hasan, M., Shang, Y., Metwaly, M., Jin, W., Khan, M., & Gao, Q. (2020). Assessment of groundwater resources in coastal areas of Pakistan for sustainable water quality management using joint geophysical and geochemical approach: A case study. Sustainability, 12(22), 1-23. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su12229730

Hengl, T., De Jesus, J. M., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Ribeiro, E., et al. (2014). SoilGrids 1km – global soil information based on automated mapping. PLoS One, 9(8), e105992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0105992

Hermans, T., & Paepen, M. (2020). Combined inversion of land and marine electrical resistivity tomography for submarine groundwater discharge and saltwater intrusion characterization. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(3), 0-1. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085877

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G., & Jarvis, A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 25(15), 1965-1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc. 1276