DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50800-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39085268

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-31

الأدوار المزدوجة للميكروبات في التوسط في ديناميات الكربون في التربة استجابةً للاحتباس الحراري

تم القبول: 22 يوليو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 31 يوليو 2024

(د) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

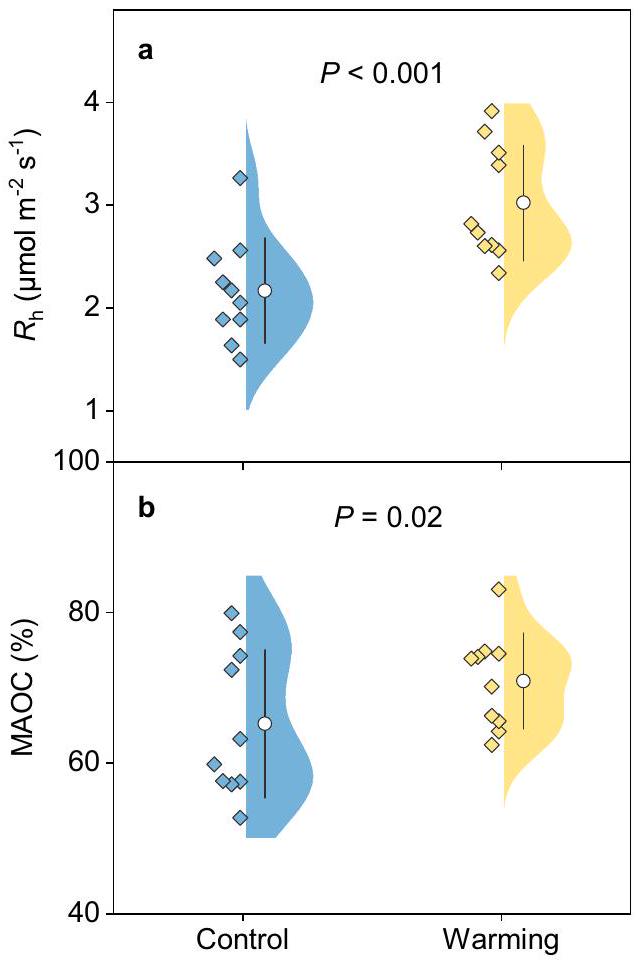

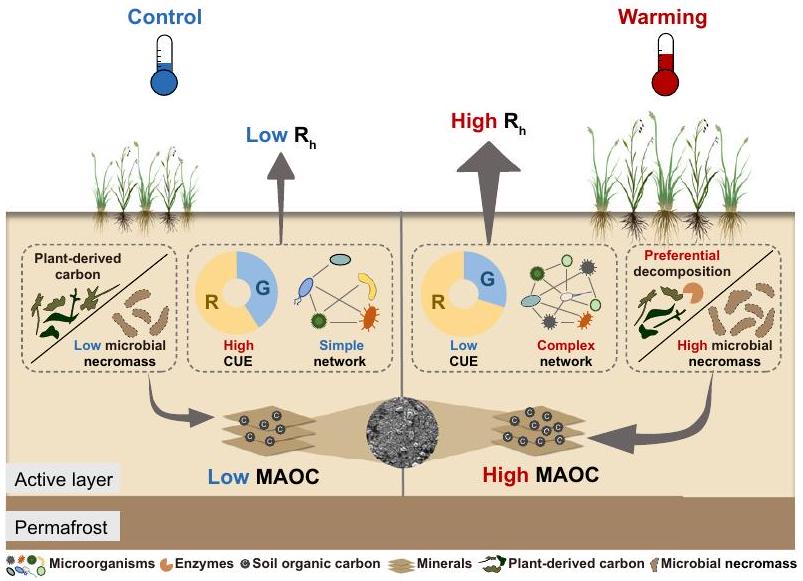

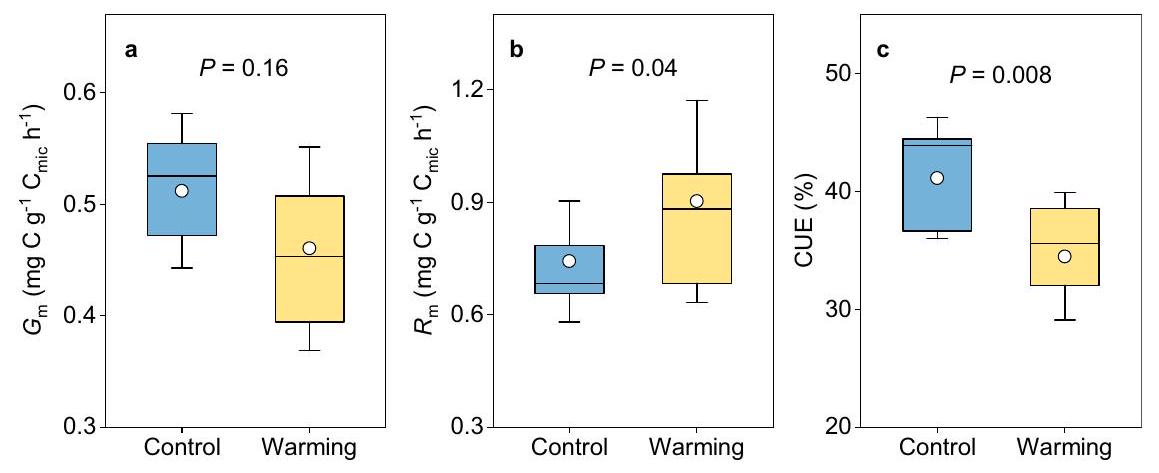

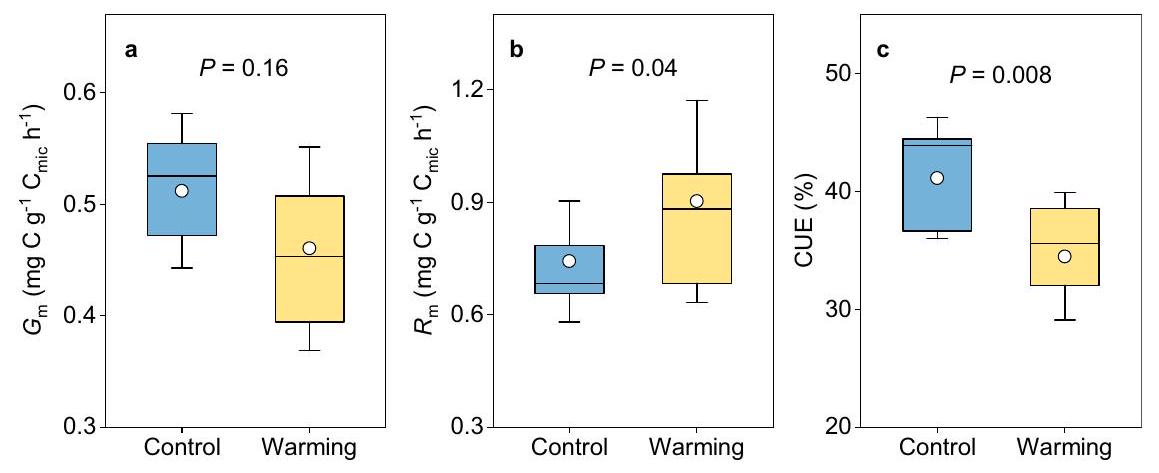

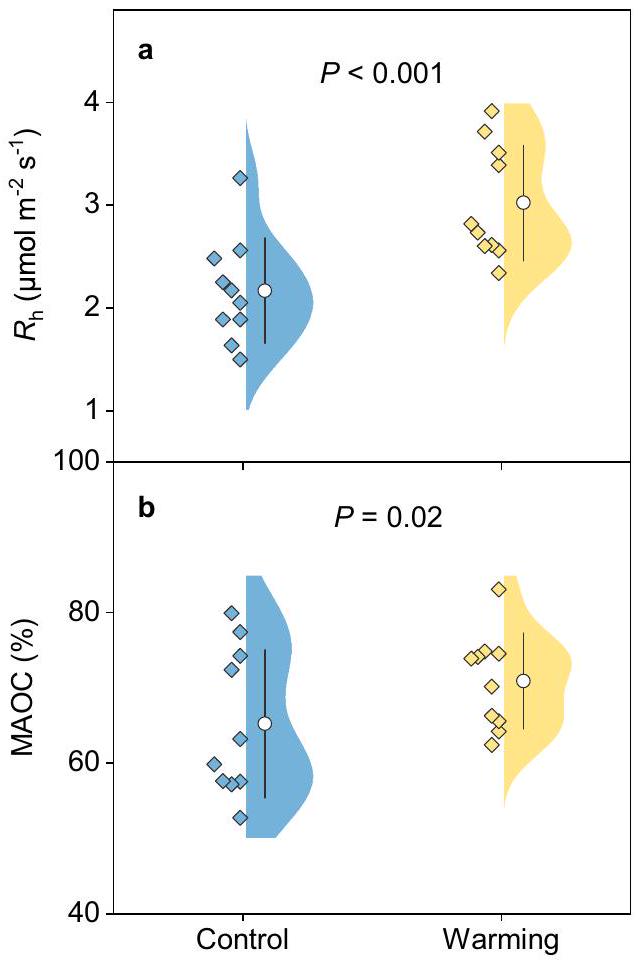

فهم التغيرات في المجتمعات الميكروبية في التربة استجابةً للاحترار المناخي والسيطرة عليها على عمليات الكربون (C) في التربة أمر بالغ الأهمية لتوقع ردود الفعل بين الكربون في التربة والمناخ. ومع ذلك، ركزت الدراسات السابقة بشكل رئيسي على إطلاق الكربون من التربة الذي يتم بوساطة الميكروبات، ولا يُعرف الكثير عن ما إذا كان وكيف يؤثر الاحترار المناخي على الأيض الميكروبي والإدخال اللاحق للكربون في مناطق التربة المتجمدة. هنا، استنادًا إلى تجربة تسخين في الموقع استمرت لأكثر من نصف عقد، نوضح أنه مقارنةً بالتحكم البيئي، يقلل الاحترار بشكل كبير من كفاءة استخدام الكربون من قبل الميكروبات ويعزز تعقيد الشبكة الميكروبية، مما يعزز التنفس غير الذاتي في التربة. في الوقت نفسه، تتراكم الكتلة الميكروبية الميتة بشكل ملحوظ تحت تأثير الاحترار، على الأرجح بسبب التحلل الميكروبي المفضل للكربون المشتق من النباتات، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة الكربون العضوي المرتبط بالمعادن. مجتمعة، تظهر هذه النتائج الأدوار المزدوجة للميكروبات في التأثير على إطلاق الكربون من التربة واستقراره، مما يوحي بأن ردود الفعل بين الكربون في التربة والمناخ ستضعف مع مرور الوقت مع تراجع استجابة التنفس الميكروبي وزيادة نسبة حوض الكربون المستقر.

كشفت أن التسخين التجريبي لم يغير التركيب العام لمجتمع الميكروبات، ولكنه قلل من كفاءة استخدام الكربون الميكروبي وشكل شبكة أكثر تعقيدًا، والتي كانت مسؤولة عن الزيادة

النتائج

آثار الاحترار على تركيب المجتمع الميكروبي والشبكة

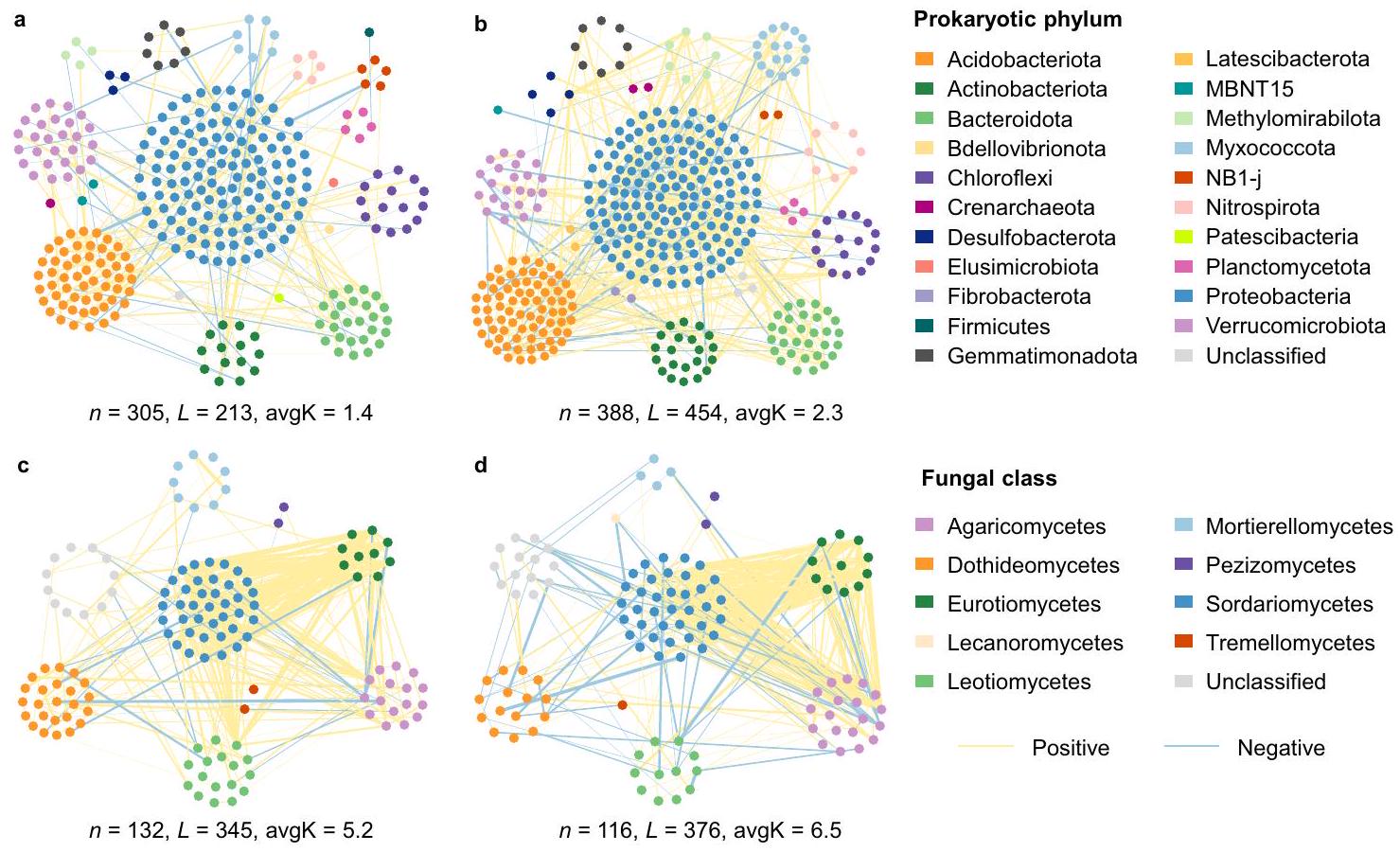

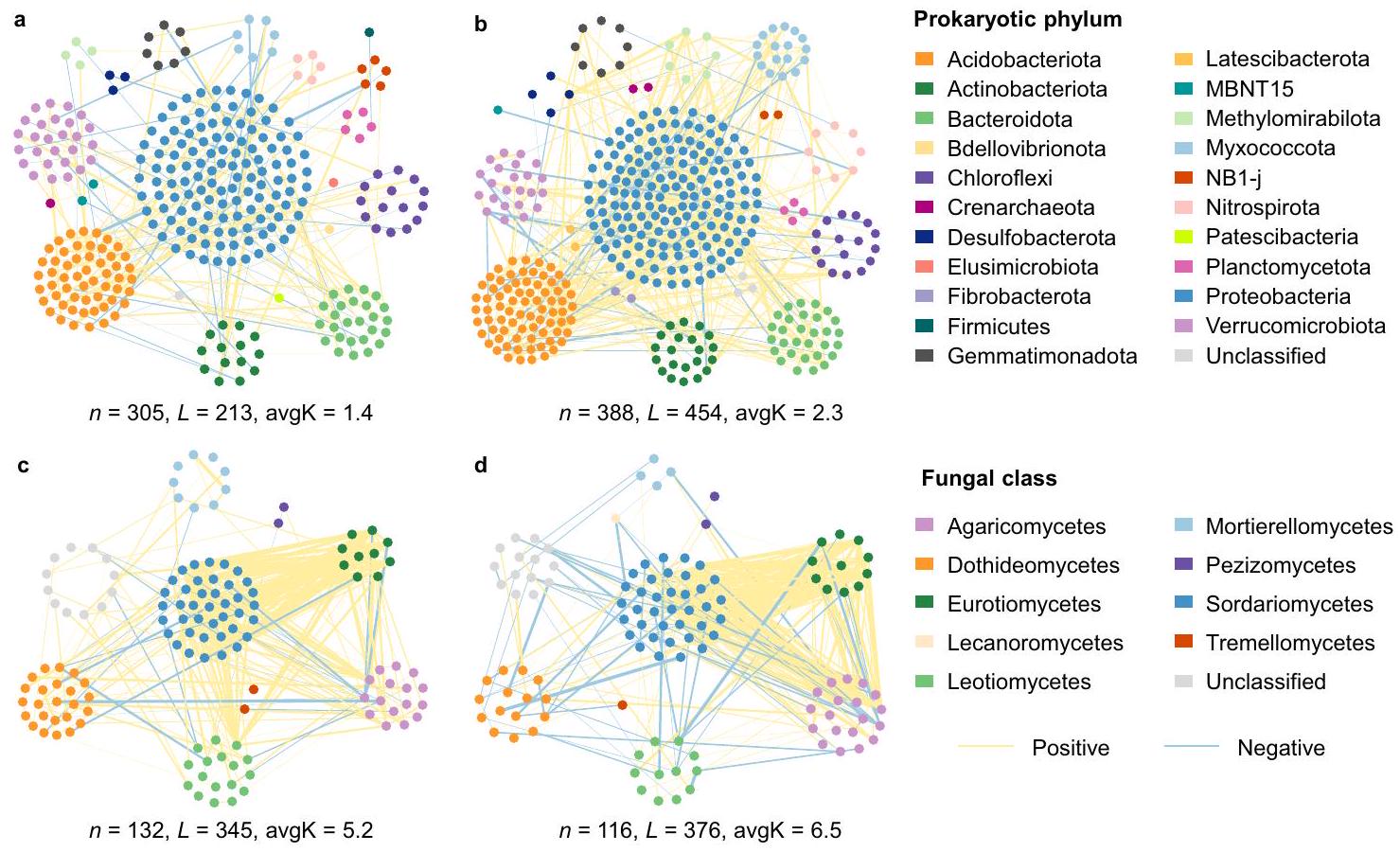

تمثل العقد ارتباطات هامة، حيث تشير الألوان الصفراء والزرقاء إلى الارتباط الإيجابي والسلبي على التوالي. عرض الخط يتناسب مع قوة العلاقة.

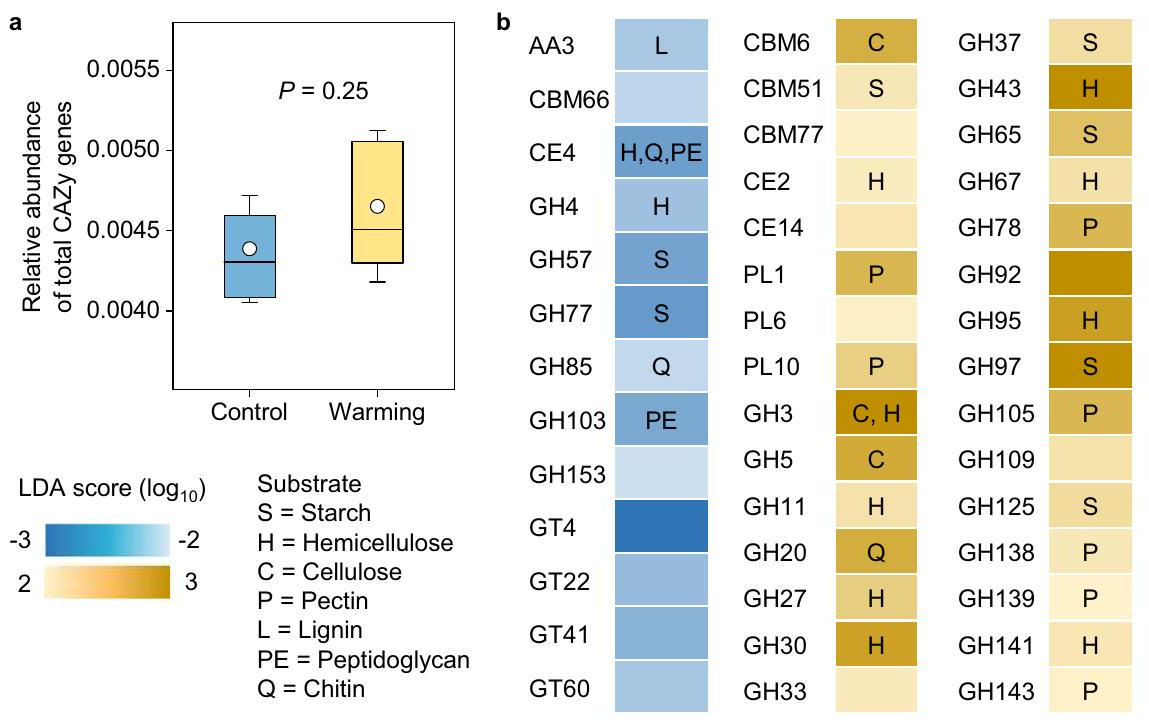

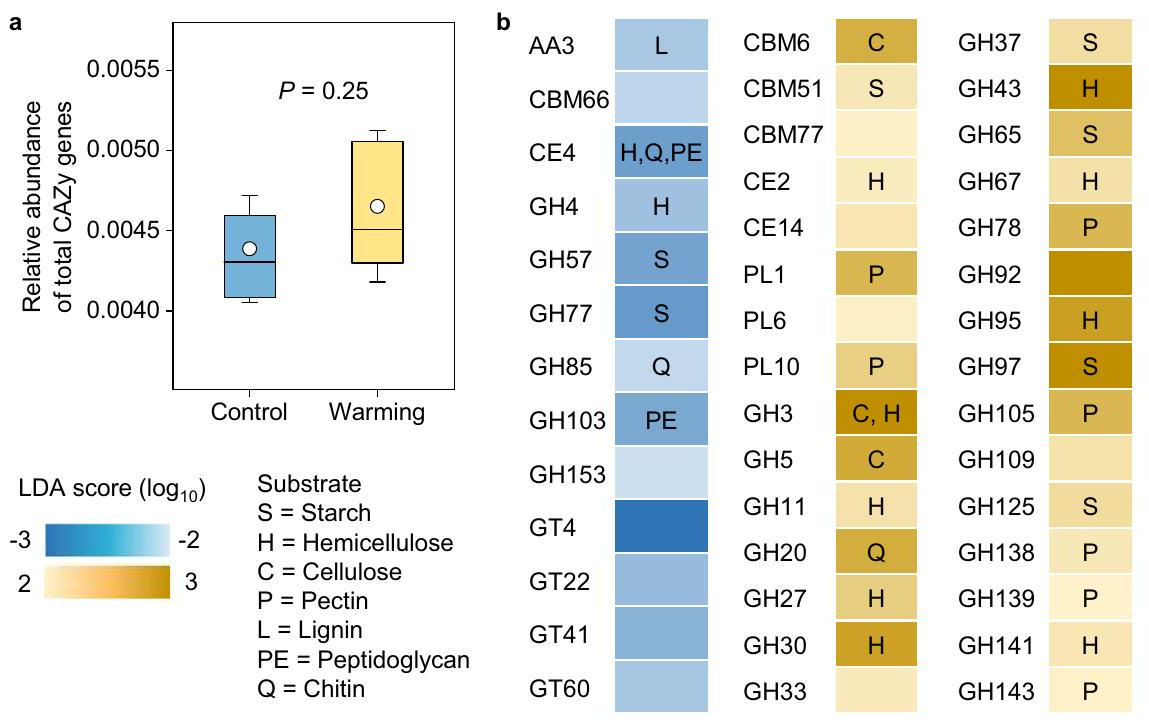

وفرة (درجة LDA

كان عدد متغيرات تسلسل الأمبليكون (ASV) المستخدمة في بناء الشبكة أقل، ولكنها أظهرت حجم شبكة نهائية أكبر للبكتيريا كما يتضح من إجمالي العقد (الشكل 1 أ، ب والجدول التكميلي 4). كما أظهرت الشبكة البكتيرية تحت تأثير الاحترار أيضًا اتصالًا أعلى (إجمالي الروابط)، ومتوسط اتصال (avgK؛ متوسط الروابط لكل عقدة)، ومتوسط معامل التجميع (مدى تجميع العقد) (الجدول التكميلي 4). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، زاد الاحترار التجريبي من إجمالي الروابط وavgK لشبكة الفطريات (الشكل 1 ج، د)، كما رفع أيضًا من النسب النسبية للهيكلية ونسبة العقد الأساسية لكل من الشبكات البكتيرية والفطرية (الشكل التكميلي 3). تشير هذه النتائج مجتمعة إلى تغيير في هيكل الشبكة وزيادة في تعقيد الشبكة نتيجة لمعالجة الاحترار. كشفت التحليلات الإضافية أن تكوين المجتمعات البكتيرية والفطرية المكتشفة في الشبكة اختلف بشكل ملحوظ بين معالجات الاحترار والتحكم.

آثار الاحترار التجريبي على القدرات الأيضية للميكروبات

آثار التسخين التجريبي على فسيولوجيا الميكروبات

الكتلة الحيوية الميكروبية

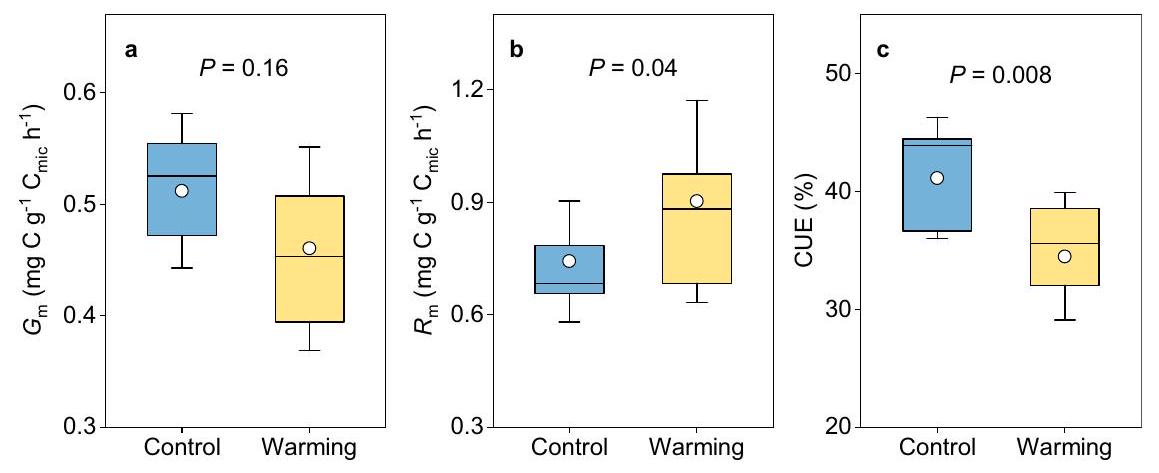

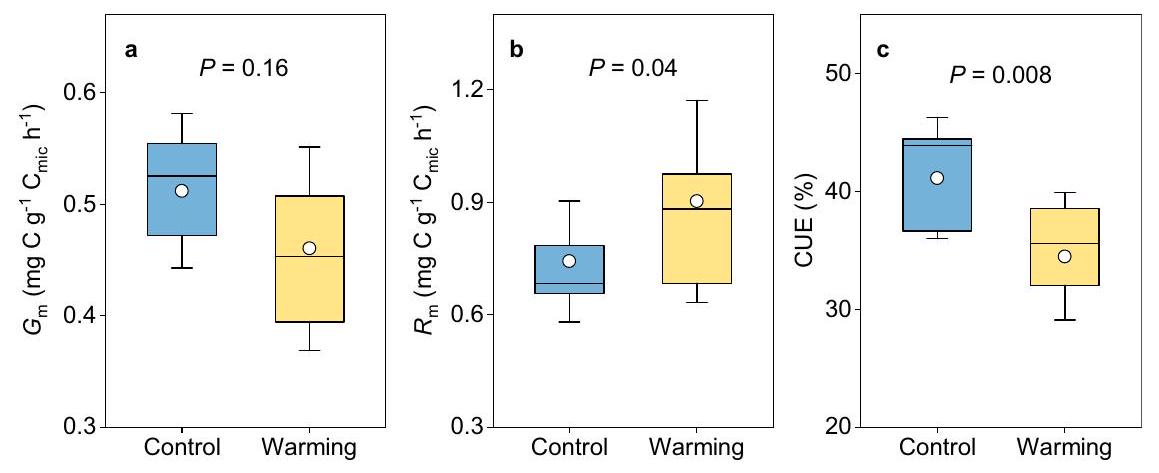

القيمة المتوسطة والقيمة المتوسطة، على التوالي. تشير الشعيرات إلى

نطاق الربيع الربعي، مع الإشارة إلى التحكم والتسخين باللونين الأزرق والأصفر، على التوالي. الخط الأفقي والدائرة داخل الصندوق يوضحان القيمة الوسيطة والمتوسطة، على التوالي. تشير الشعيرات إلى الانحراف المعياري.

كانت محتويات GluN و MurA والسكر الأميني الكلي كمجموع للثلاثة الفردية أعلى بشكل ملحوظ تحت تأثير الاحترار

تحذير عندما

نقاش

أنواع مختلفة

طرق

وصف الموقع وتصميم التجربة

قياسات التنفس غير الذاتي وتحليلات التربة الكيميائية

تم اعتبار هذا الطوق “الخالي من الجذور” كـ

تجزئة المادة العضوية في التربة

استخراج الحمض النووي، تسلسل الأمبليكون والتحليلات المعلوماتية

تسلسل الميتاجينوم ومعالجة البيانات

تحديد الفسيولوجيا الميكروبية

تحليلات السكريات الأمينية

التحليلات الإحصائية

يعني بين ظروف التحكم والتسخين باستخدام عينات متزاوجة

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Zhang, T., Barry, R. G., Knowles, K., Heginbottom, J. A. & Brown, J. Statistics and characteristics of permafrost and ground-ice distribution in the Northern Hemisphere. Pol. Geogr. 23, 132-154 (1999).

- Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature 520, 171-179 (2015).

- Mishra, U. et al. Spatial heterogeneity and environmental predictors of permafrost region soil organic carbon stocks. Sci. Adv. 7, eaaz5236 (2021).

- Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Permafrost and climate change: carbon cycle feedbacks from the warming Arctic. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 343-371 (2022).

- Harris, L. I. et al. Permafrost thaw causes large carbon loss in boreal peatlands while changes to peat quality are limited. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5720-5735 (2023).

- Liu, F. et al. Divergent changes in particulate and mineralassociated organic carbon upon permafrost thaw. Nat. Commun. 13, 5073 (2022).

- Plaza, C. et al. Direct observation of permafrost degradation and rapid soil carbon loss in tundra. Nat. Geosci. 12, 627-631 (2019).

- Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

- Miner, K. R. et al. Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 55-67 (2022).

- Wieder, W. R. et al. Explicitly representing soil microbial processes in Earth system models. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 29, 1782-1800 (2015).

- Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B. & Allison, S. D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 909-912 (2013).

- Liang, C., Schimel, J. P. & Jastrow, J. D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17105 (2017).

- Schimel, J. & Schaeffer, S. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 3, 348 (2012).

- Liang, C. & Balser, T. C. Warming and nitrogen deposition lessen microbial residue contribution to soil carbon pool. Nat. Commun. 3, 1222 (2012).

- Hicks Pries, C. E., Castanha, C., Porras, R. C. & Torn, M. S. The wholesoil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 355, 1420-1423 (2017).

- Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104-108 (2016).

- Johnston, E. R. et al. Responses of tundra soil microbial communities to half a decade of experimental warming at two critical depths. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 15096-15105 (2019).

- Xue, K. et al. Tundra soil carbon is vulnerable to rapid microbial decomposition under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 595-600 (2016).

- Wu, L. et al. Permafrost thaw with warming reduces microbial metabolic capacities in subsurface soils. Mol. Ecol. 31, 1403-1415 (2022).

- Wang, G. et al. Enhanced response of soil respiration to experimental warming upon thermokarst formation. Nat. Geosci. 17, 532-538 (2024).

- Hagerty, S. B. et al. Accelerated microbial turnover but constant growth efficiency with warming in soil. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 903-906 (2014).

- Frey, S. D., Lee, J., Melillo, J. M. & Six, J. The temperature response of soil microbial efficiency and its feedback to climate. Nat. Clim. Chang 3, 395-398 (2013).

- Allison, S. D., Wallenstein, M. D. & Bradford, M. A. Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology. Nat. Geosci. 3, 336-340 (2010).

- Yang, M., Nelson, F. E., Shiklomanov, N. I., Guo, D. & Wan, G. Permafrost degradation and its environmental effects on the Tibetan Plateau: a review of recent research. Earth Sci. Rev. 103, 31-44 (2010).

- Zou, D. et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 11, 2527-2542 (2017).

- Kuang, X. & Jiao, J. J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 3979-4007 (2016).

- Ding, J. et al. Decadal soil carbon accumulation across Tibetan permafrost regions. Nat. Geosci. 10, 420-424 (2017).

- Li, F. et al. Warming effects on permafrost ecosystem carbon fluxes associated with plant nutrients. Ecology 98, 2851-2859 (2017).

- Walker, T. W. N. et al. Microbial temperature sensitivity and biomass change explain soil carbon loss with warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 885-889 (2018).

- Liang, C., Amelung, W., Lehmann, J. & Kästner, M. Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 3578-3590 (2019).

- Li, F. et al. Warming alters surface soil organic matter composition despite unchanged carbon stocks in a Tibetan permafrost ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 34, 911-922 (2020).

- Sinsabaugh, R. L., Manzoni, S., Moorhead, D. L. & Richter, A. Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol. Lett. 16, 930-939 (2013).

- Chen, W. et al. Soil microbial network complexity predicts ecosystem function along elevation gradients on the Tibetan Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 172, 108766 (2022).

- Wagg, C., Schlaeppi, K., Banerjee, S., Kuramae, E. E. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4841 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Decreased soil multifunctionality is associated with altered microbial network properties under precipitation reduction in a semiarid grassland. iMeta 2, e106 (2023).

- Montoya, J. M., Pimm, S. L. & Solé, R. V. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 442, 259-264 (2006).

- Zhou, J. et al. Phylogenetic molecular ecological network of soil microbial communities in response to elevated

. mBio 2, e00122-11 (2011). - Yuan, M. M. et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 343-348 (2021).

- Goberna, M. & Verdú, M. Cautionary notes on the use of cooccurrence networks in soil ecology. Soil Biol. Biochem. 166, 108534 (2022).

- Maes, S. L. et al. Environmental drivers of increased ecosystem respiration in a warming tundra. Nature 629, 105-113 (2024).

- Prommer, J. et al. Increased microbial growth, biomass, and turnover drive soil organic carbon accumulation at higher plant diversity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 669-681 (2020).

- Sokol, N. W. et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 415-430 (2022).

- Buckeridge, K. M. et al. Environmental and microbial controls on microbial necromass recycling, an important precursor for soil carbon stabilization. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 36 (2020).

- Conant, R. T. et al. Temperature and soil organic matter decomposition rates-synthesis of current knowledge and a way forward. Glob. Chang. Biol. 17, 3392-3404 (2011).

- Daugherty, E. E., Lobo, G. P., Young, R. B., Pallud, C. & Borch, T. Temperature effects on sorption of dissolved organic matter on ferrihydrite under dynamic flow and batch conditions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 86, 224-237 (2022).

- Alteio, L. V. et al. A critical perspective on interpreting amplicon sequencing data in soil ecological research. Soil Biol. Biochem. 160, 108357 (2021).

- Fraser, L. H. et al. Coordinated distributed experiments: an emerging tool for testing global hypotheses in ecology and environmental science. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 147-155 (2013).

- Wei, B. et al. Experimental warming altered plant functional traits and their coordination in a permafrost ecosystem. N. Phytol. 240, 1802-1816 (2023).

- Kuzyakov, Y. Sources of

efflux from soil and review of partitioning methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 425-448 (2006). - Mielnick, P. C. & Dugas, W. A. Soil CO2 flux in a tallgrass prairie. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32, 221-228 (2000).

- Hasselquist, N. J., Metcalfe, D. B. & Högberg, P. Contrasting effects of low and high nitrogen additions on soil

flux components and ectomycorrhizal fungal sporocarp production in a boreal forest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 18, 3596-3605 (2012). - Dorrepaal, E. et al. Carbon respiration from subsurface peat accelerated by climate warming in the subarctic. Nature 460, 616-619 (2009).

- Nottingham, A. T., Meir, P., Velasquez, E. & Turner, B. L. Soil carbon loss by experimental warming in a tropical forest. Nature 584, 234-237 (2020).

- Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L. & Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 261-273 (2020).

- Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16 S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4516-4522 (2011).

- White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. in PCR Protocols (eds Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J. & White, T. J.) (Academic Press, 1990).

- Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460-2461 (2010).

- Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852-857 (2019).

- Edgar, R. C. UNOISE2: improved error-correction for Illumina 16 S and ITS amplicon sequencing. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/ 081257 (2016).

- Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590-D596 (2013).

- Kõljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271-5277 (2013).

- Edgar, R. C. SINTAX: a simple non-Bayesian taxonomy classifier for 16S and ITS sequences. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/074161 (2016).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674-1676 (2015).

- Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 119 (2010).

- Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 9, 2542 (2018).

- Lombard, V., Ramulu, H. G., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490-D495 (2014).

- Zhang, H. et al. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W95-W101 (2018).

- Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59-60 (2015).

- Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27-30 (2000).

- Kang, L. et al. Metagenomic insights into microbial community structure and metabolism in alpine permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 15, 5920 (2024).

- Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760 (2009).

- Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55-60 (2012).

- Spohn, M., Klaus, K., Wanek, W. & Richter, A. Microbial carbon use efficiency and biomass turnover times depending on soil depth-implications for carbon cycling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 96, 74-81 (2016).

- Wu, J., Joergensen, R. G., Pommerening, B., Chaussod, R. & Brookes, P. C. Measurement of soil microbial biomass

by fumi-gation-extraction-an automated procedure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 22, 1167-1169 (1990). - Zhang, X. & Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine, and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28, 1201-1206 (1996).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Oksanen, J. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. (2022).

- Feng, K. et al. iNAP: an integrated network analysis pipeline for microbiome studies. iMeta 1, e13 (2022).

- Olesen, J. M., Bascompte, J., Dupont, Y. L. & Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19891-19896 (2007).

- Guimerà, R. & Nunes Amaral, L. A. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433, 895-900 (2005).

- Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498-2504 (2003).

- Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

- Qin, S., Zhang, D., Wei, B. & Yang Y. Dual roles of microbes in mediating soil carbon dynamics in response to warming. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25974622.v2 (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للنباتات وتغير البيئة، معهد علم النبات، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، 100093 بكين، الصين. الحديقة الوطنية النباتية الصينية، 100093 بكين، الصين. جامعة الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، 100049 بكين، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني: yhyang@ibcas.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50800-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39085268

Publication Date: 2024-07-31

Dual roles of microbes in mediating soil carbon dynamics in response to warming

Accepted: 22 July 2024

Published online: 31 July 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

Understanding the alterations in soil microbial communities in response to climate warming and their controls over soil carbon (C) processes is crucial for projecting permafrost C -climate feedback. However, previous studies have mainly focused on microorganism-mediated soil C release, and little is known about whether and how climate warming affects microbial anabolism and the subsequent C input in permafrost regions. Here, based on a more than halfdecade of in situ warming experiment, we show that compared with ambient control, warming significantly reduces microbial C use efficiency and enhances microbial network complexity, which promotes soil heterotrophic respiration. Meanwhile, microbial necromass markedly accumulates under warming likely due to preferential microbial decomposition of plant-derived C , further leading to the increase in mineral-associated organic C. Altogether, these results demonstrate dual roles of microbes in affecting soil C release and stabilization, implying that permafrost C-climate feedback would weaken over time with dampened response of microbial respiration and increased proportion of stable C pool.

revealed that experimental warming did not alter the overall microbial community composition, but decreased microbial CUE and structured more complex network, which was responsible for the increased

Results

Warming effects on microbial community composition and network

nodes represent significant correlations, with yellow and blue indicating positive and negative correlation, respectively. Line width is proportional to the strength of the relationship.

abundant (LDA score

had less amplicon sequence variant (ASV) numbers used for network construction, but showed larger final network size for prokaryotes as reflected by total nodes (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 4). Prokaryotic network under warming also exhibited higher connectivity (total links), average connectivity (avgK; average links per node), and average clustering coefficient (the extent of node clustering) (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, experimental warming increased total links and avgK of fungal network (Fig. 1c, d), and also elevated relative modularity and the proportion of keystone nodes for both prokaryotic and fungal networks (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results collectively indicated altered network structure and enhanced network complexity by the warming treatment. Further analyses revealed that the composition of prokaryotic and fungal communities detected in the network markedly differed between the warming and control treatments (

Impacts of experimental warming on microbial metabolic capacities

Effects of experimental warming on microbial physiology

Microbial necromass

the median and mean value, respectively. The whisker denotes

the interquartile range, with blue and yellow indicating control and warming, respectively. Horizontal line and circle within the box show the median and mean value, respectively. The whisker denotes SD (

contents of GluN, MurA, and total amino sugars as the sum of three individual ones were significantly higher under warming (

warming when

Discussion

different species

Methods

Site description and experimental design

Heterotrophic respiration measurements and soil chemical analyses

this “root-free” collar was considered as

Soil organic matter fractionation

DNA extraction, amplicon sequencing and bioinformatic analyses

Metagenomic sequencing and data processing

Determination of microbial physiology

Analyses of amino sugars

Statistical analyses

means between control and warming conditions using paired samples

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Zhang, T., Barry, R. G., Knowles, K., Heginbottom, J. A. & Brown, J. Statistics and characteristics of permafrost and ground-ice distribution in the Northern Hemisphere. Pol. Geogr. 23, 132-154 (1999).

- Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature 520, 171-179 (2015).

- Mishra, U. et al. Spatial heterogeneity and environmental predictors of permafrost region soil organic carbon stocks. Sci. Adv. 7, eaaz5236 (2021).

- Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Permafrost and climate change: carbon cycle feedbacks from the warming Arctic. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 343-371 (2022).

- Harris, L. I. et al. Permafrost thaw causes large carbon loss in boreal peatlands while changes to peat quality are limited. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 5720-5735 (2023).

- Liu, F. et al. Divergent changes in particulate and mineralassociated organic carbon upon permafrost thaw. Nat. Commun. 13, 5073 (2022).

- Plaza, C. et al. Direct observation of permafrost degradation and rapid soil carbon loss in tundra. Nat. Geosci. 12, 627-631 (2019).

- Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

- Miner, K. R. et al. Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 55-67 (2022).

- Wieder, W. R. et al. Explicitly representing soil microbial processes in Earth system models. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 29, 1782-1800 (2015).

- Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B. & Allison, S. D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 909-912 (2013).

- Liang, C., Schimel, J. P. & Jastrow, J. D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17105 (2017).

- Schimel, J. & Schaeffer, S. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 3, 348 (2012).

- Liang, C. & Balser, T. C. Warming and nitrogen deposition lessen microbial residue contribution to soil carbon pool. Nat. Commun. 3, 1222 (2012).

- Hicks Pries, C. E., Castanha, C., Porras, R. C. & Torn, M. S. The wholesoil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 355, 1420-1423 (2017).

- Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104-108 (2016).

- Johnston, E. R. et al. Responses of tundra soil microbial communities to half a decade of experimental warming at two critical depths. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 15096-15105 (2019).

- Xue, K. et al. Tundra soil carbon is vulnerable to rapid microbial decomposition under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 595-600 (2016).

- Wu, L. et al. Permafrost thaw with warming reduces microbial metabolic capacities in subsurface soils. Mol. Ecol. 31, 1403-1415 (2022).

- Wang, G. et al. Enhanced response of soil respiration to experimental warming upon thermokarst formation. Nat. Geosci. 17, 532-538 (2024).

- Hagerty, S. B. et al. Accelerated microbial turnover but constant growth efficiency with warming in soil. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 903-906 (2014).

- Frey, S. D., Lee, J., Melillo, J. M. & Six, J. The temperature response of soil microbial efficiency and its feedback to climate. Nat. Clim. Chang 3, 395-398 (2013).

- Allison, S. D., Wallenstein, M. D. & Bradford, M. A. Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology. Nat. Geosci. 3, 336-340 (2010).

- Yang, M., Nelson, F. E., Shiklomanov, N. I., Guo, D. & Wan, G. Permafrost degradation and its environmental effects on the Tibetan Plateau: a review of recent research. Earth Sci. Rev. 103, 31-44 (2010).

- Zou, D. et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 11, 2527-2542 (2017).

- Kuang, X. & Jiao, J. J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 3979-4007 (2016).

- Ding, J. et al. Decadal soil carbon accumulation across Tibetan permafrost regions. Nat. Geosci. 10, 420-424 (2017).

- Li, F. et al. Warming effects on permafrost ecosystem carbon fluxes associated with plant nutrients. Ecology 98, 2851-2859 (2017).

- Walker, T. W. N. et al. Microbial temperature sensitivity and biomass change explain soil carbon loss with warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 885-889 (2018).

- Liang, C., Amelung, W., Lehmann, J. & Kästner, M. Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 3578-3590 (2019).

- Li, F. et al. Warming alters surface soil organic matter composition despite unchanged carbon stocks in a Tibetan permafrost ecosystem. Funct. Ecol. 34, 911-922 (2020).

- Sinsabaugh, R. L., Manzoni, S., Moorhead, D. L. & Richter, A. Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol. Lett. 16, 930-939 (2013).

- Chen, W. et al. Soil microbial network complexity predicts ecosystem function along elevation gradients on the Tibetan Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 172, 108766 (2022).

- Wagg, C., Schlaeppi, K., Banerjee, S., Kuramae, E. E. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4841 (2019).

- Wang, X. et al. Decreased soil multifunctionality is associated with altered microbial network properties under precipitation reduction in a semiarid grassland. iMeta 2, e106 (2023).

- Montoya, J. M., Pimm, S. L. & Solé, R. V. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 442, 259-264 (2006).

- Zhou, J. et al. Phylogenetic molecular ecological network of soil microbial communities in response to elevated

. mBio 2, e00122-11 (2011). - Yuan, M. M. et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 343-348 (2021).

- Goberna, M. & Verdú, M. Cautionary notes on the use of cooccurrence networks in soil ecology. Soil Biol. Biochem. 166, 108534 (2022).

- Maes, S. L. et al. Environmental drivers of increased ecosystem respiration in a warming tundra. Nature 629, 105-113 (2024).

- Prommer, J. et al. Increased microbial growth, biomass, and turnover drive soil organic carbon accumulation at higher plant diversity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 669-681 (2020).

- Sokol, N. W. et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: how ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 415-430 (2022).

- Buckeridge, K. M. et al. Environmental and microbial controls on microbial necromass recycling, an important precursor for soil carbon stabilization. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 36 (2020).

- Conant, R. T. et al. Temperature and soil organic matter decomposition rates-synthesis of current knowledge and a way forward. Glob. Chang. Biol. 17, 3392-3404 (2011).

- Daugherty, E. E., Lobo, G. P., Young, R. B., Pallud, C. & Borch, T. Temperature effects on sorption of dissolved organic matter on ferrihydrite under dynamic flow and batch conditions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 86, 224-237 (2022).

- Alteio, L. V. et al. A critical perspective on interpreting amplicon sequencing data in soil ecological research. Soil Biol. Biochem. 160, 108357 (2021).

- Fraser, L. H. et al. Coordinated distributed experiments: an emerging tool for testing global hypotheses in ecology and environmental science. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 147-155 (2013).

- Wei, B. et al. Experimental warming altered plant functional traits and their coordination in a permafrost ecosystem. N. Phytol. 240, 1802-1816 (2023).

- Kuzyakov, Y. Sources of

efflux from soil and review of partitioning methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 425-448 (2006). - Mielnick, P. C. & Dugas, W. A. Soil CO2 flux in a tallgrass prairie. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32, 221-228 (2000).

- Hasselquist, N. J., Metcalfe, D. B. & Högberg, P. Contrasting effects of low and high nitrogen additions on soil

flux components and ectomycorrhizal fungal sporocarp production in a boreal forest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 18, 3596-3605 (2012). - Dorrepaal, E. et al. Carbon respiration from subsurface peat accelerated by climate warming in the subarctic. Nature 460, 616-619 (2009).

- Nottingham, A. T., Meir, P., Velasquez, E. & Turner, B. L. Soil carbon loss by experimental warming in a tropical forest. Nature 584, 234-237 (2020).

- Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L. & Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 261-273 (2020).

- Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16 S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4516-4522 (2011).

- White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. in PCR Protocols (eds Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J. & White, T. J.) (Academic Press, 1990).

- Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460-2461 (2010).

- Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852-857 (2019).

- Edgar, R. C. UNOISE2: improved error-correction for Illumina 16 S and ITS amplicon sequencing. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/ 081257 (2016).

- Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590-D596 (2013).

- Kõljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271-5277 (2013).

- Edgar, R. C. SINTAX: a simple non-Bayesian taxonomy classifier for 16S and ITS sequences. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/074161 (2016).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674-1676 (2015).

- Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 119 (2010).

- Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 9, 2542 (2018).

- Lombard, V., Ramulu, H. G., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490-D495 (2014).

- Zhang, H. et al. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W95-W101 (2018).

- Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59-60 (2015).

- Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27-30 (2000).

- Kang, L. et al. Metagenomic insights into microbial community structure and metabolism in alpine permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 15, 5920 (2024).

- Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760 (2009).

- Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55-60 (2012).

- Spohn, M., Klaus, K., Wanek, W. & Richter, A. Microbial carbon use efficiency and biomass turnover times depending on soil depth-implications for carbon cycling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 96, 74-81 (2016).

- Wu, J., Joergensen, R. G., Pommerening, B., Chaussod, R. & Brookes, P. C. Measurement of soil microbial biomass

by fumi-gation-extraction-an automated procedure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 22, 1167-1169 (1990). - Zhang, X. & Amelung, W. Gas chromatographic determination of muramic acid, glucosamine, mannosamine, and galactosamine in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28, 1201-1206 (1996).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Oksanen, J. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. (2022).

- Feng, K. et al. iNAP: an integrated network analysis pipeline for microbiome studies. iMeta 1, e13 (2022).

- Olesen, J. M., Bascompte, J., Dupont, Y. L. & Jordano, P. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19891-19896 (2007).

- Guimerà, R. & Nunes Amaral, L. A. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433, 895-900 (2005).

- Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498-2504 (2003).

- Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

- Qin, S., Zhang, D., Wei, B. & Yang Y. Dual roles of microbes in mediating soil carbon dynamics in response to warming. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25974622.v2 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100093 Beijing, China. China National Botanical Garden, 100093 Beijing, China. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China. e-mail: yhyang@ibcas.ac.cn