DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-023-01414-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38228849

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-16

الأريل سلفينيل أميدات الكيرالية كمواد تفاعلية لتفاعلات الألكينات الأمينية الأريلية تحت تأثير الضوء المرئي

تم القبول: 28 نوفمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 16 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

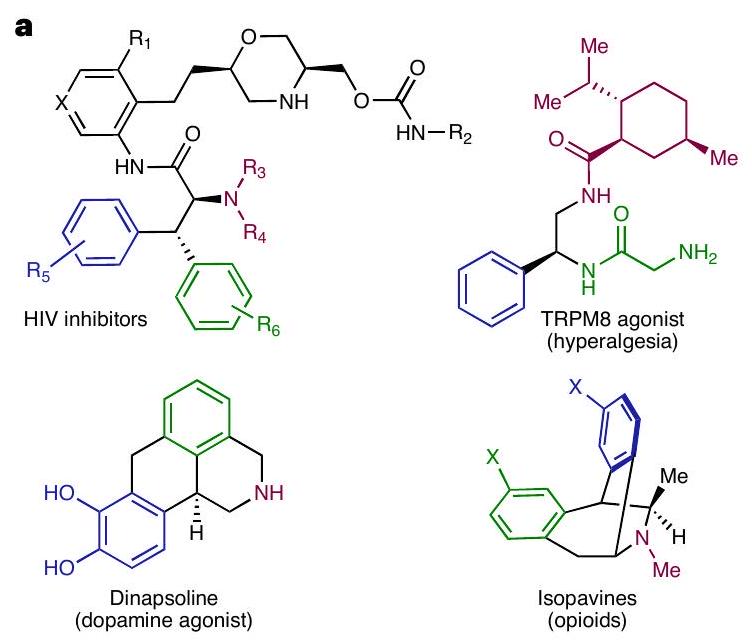

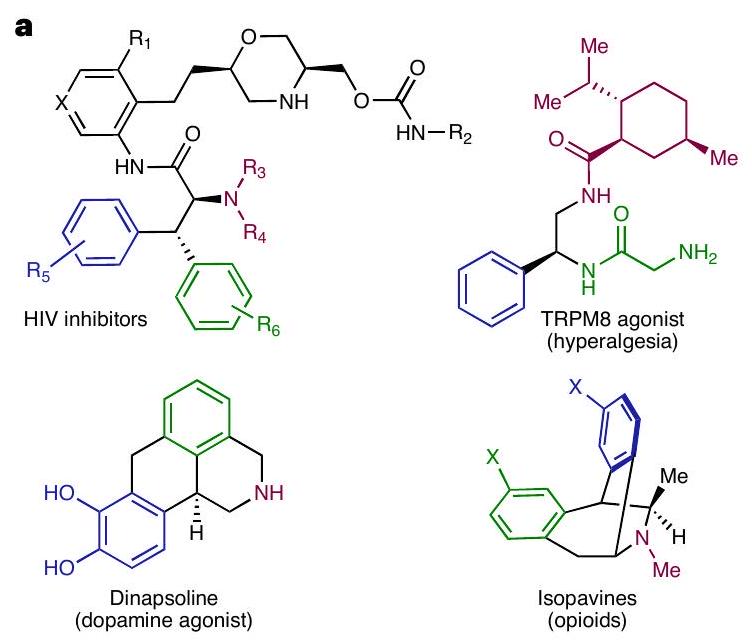

تمثل عمليات التفاعل المزدوجة التي تتوسطها إلكترونان أو إلكترون واحد للألكينات الداخلية طرقًا مباشرة لتجميع التعقيد الجزيئي من خلال التكوين المتزامن لاثنين من الجزيئات المتجاورة.

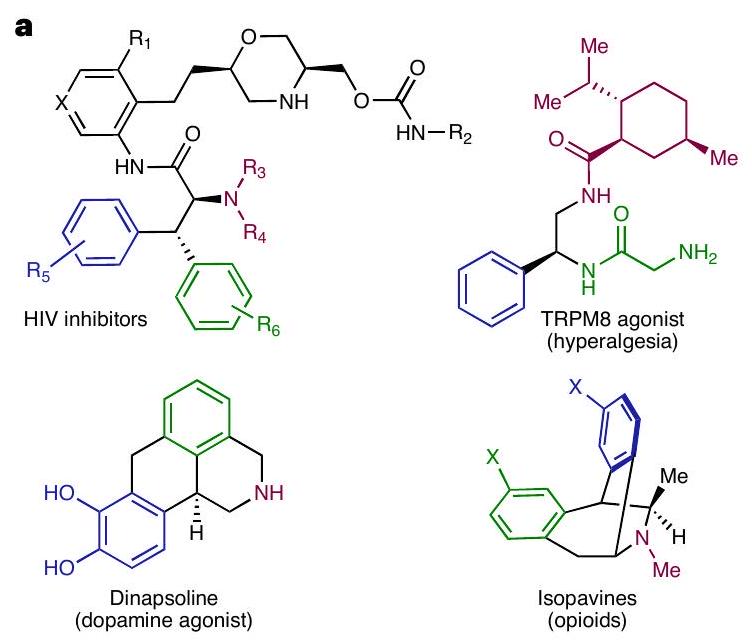

فتح الحلقة

بالإضافة إلى التحديد الممتاز للمنطقة، والديستيريو، والإنانتيومير، تبرز كل من العمومية والفائدة الاصطناعية لهذه التحولات في تجميع المخططات ذات الصلة التي تملأ الأدوية، والمنتجات الطبيعية النشطة حيوياً، والروابط لتحفيز المعادن الانتقالية.

النتائج

تحسين التفاعل

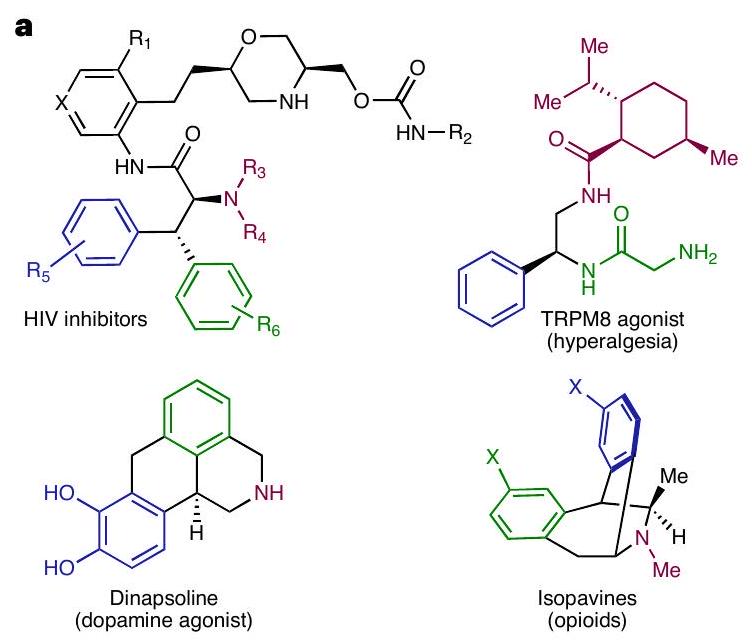

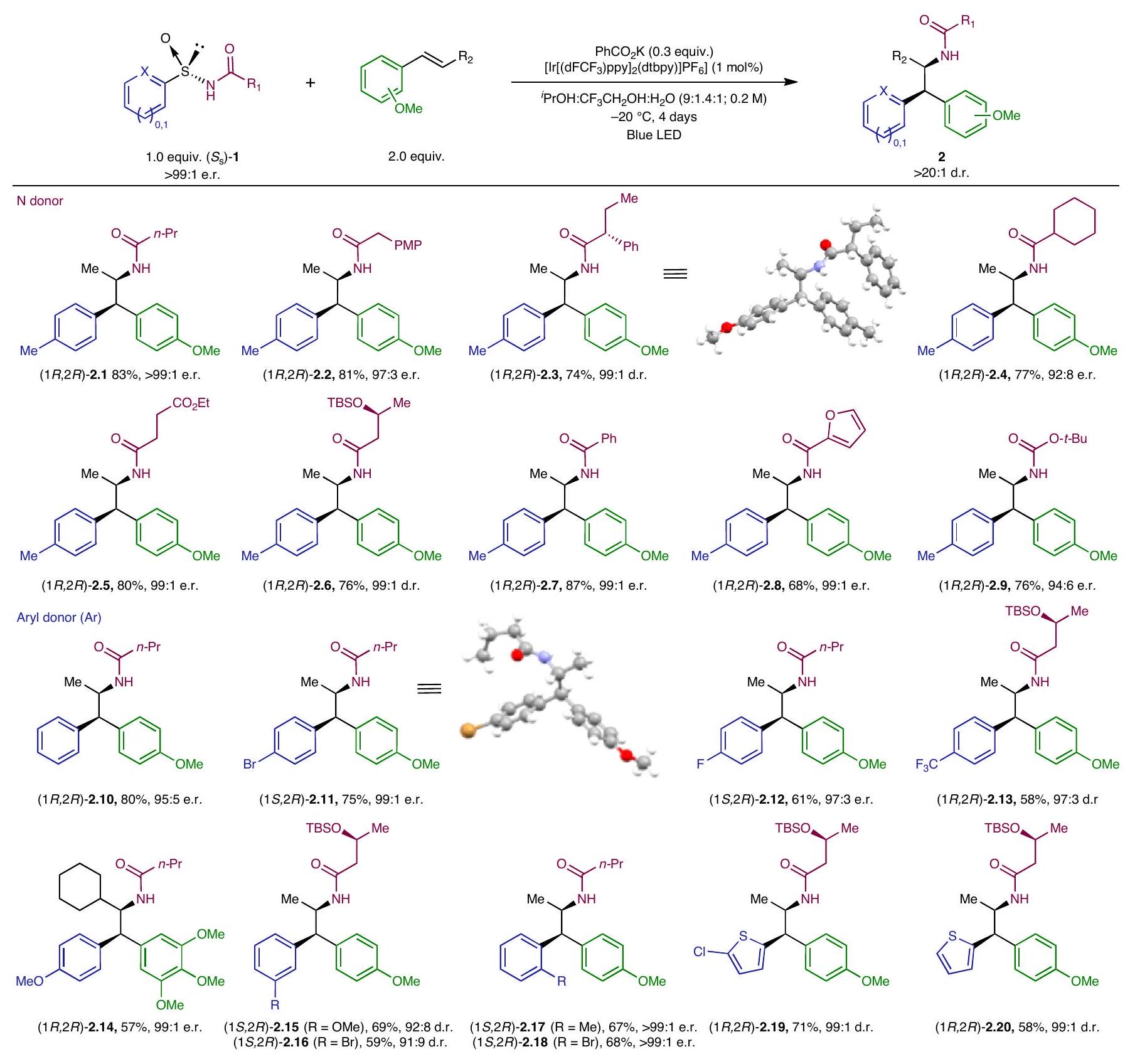

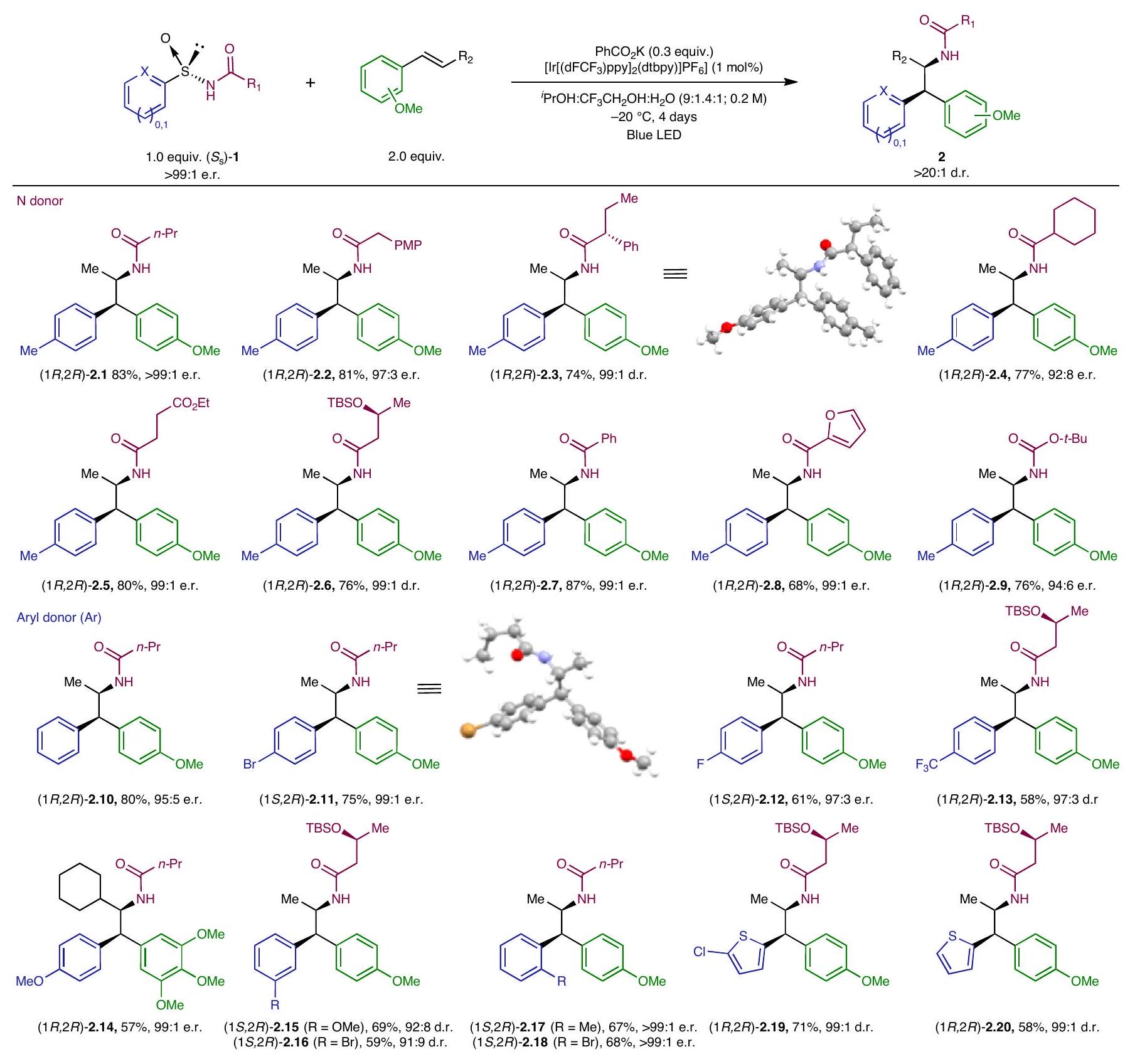

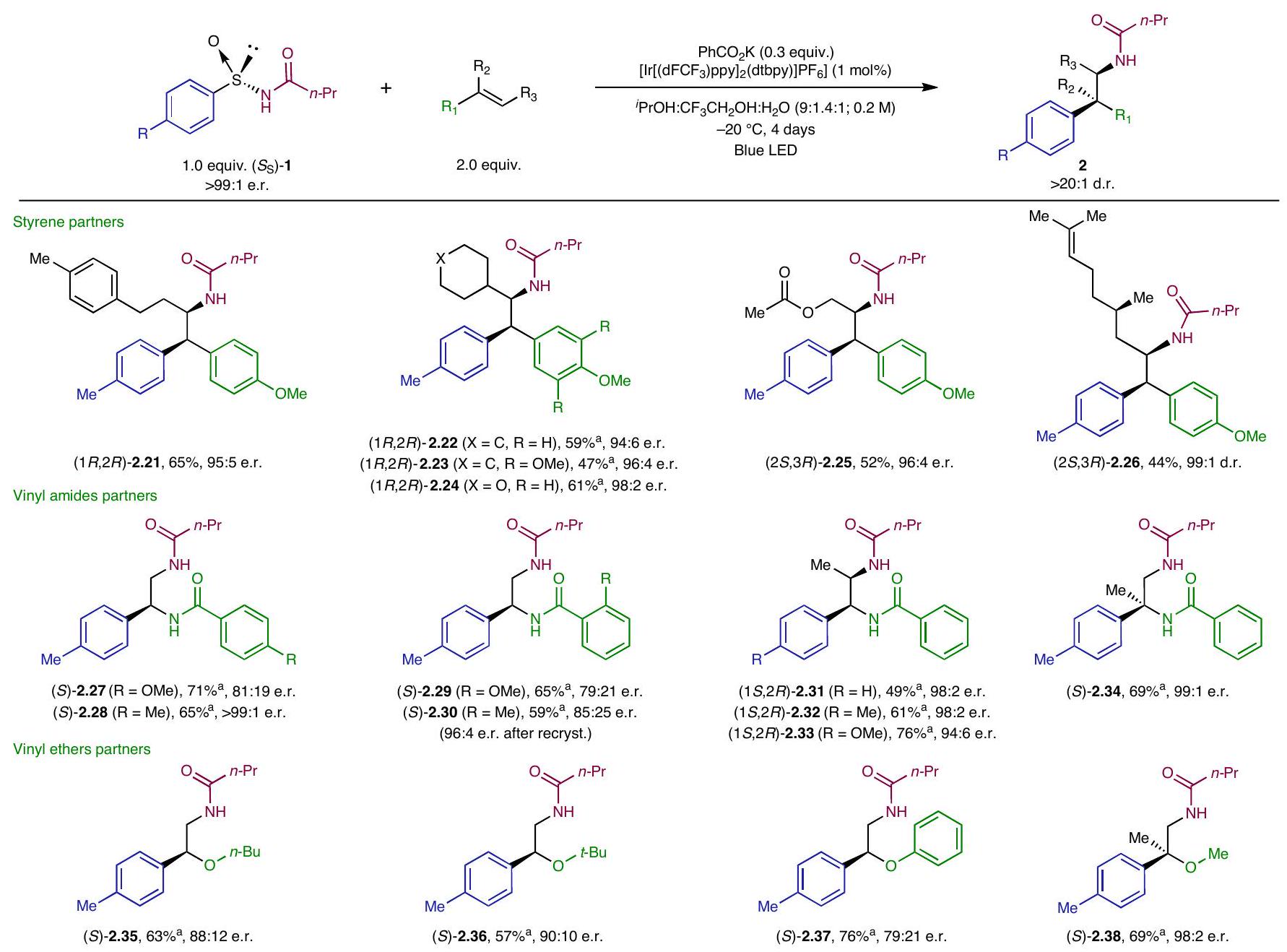

نطاق التفاعل

كانت الأنماط متوافقة أيضًا مع ظروف التفاعل القياسية، مما أدى إلى الحصول على المنتجات المقابلة

تمت العملية بسلاسة تحت ظروف قياسية لتعطي 2.10 بعائد مرتفع. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن الركائز التي تحمل مجموعات سحب الإلكترون ومجموعات منح الإلكترون في الموضع بارا من الأرين أثبتت أنها مقدّمات مناسبة، مما يوفر المركب المقابل.

إمكانات المنتجات الناتجة من الأمينوالريلاشن (المعلومات التكميلية، المركب 2.40). علاوة على ذلك، حدثت هجرة الهيدروكربونات غير المتجانسة أيضًا تحت الظروف القياسية، مما أدى إلى الحصول على مشتقات الثيوفين المقابلة.

تم استيعاب المجموعات في الموضع النهائي للرابطة المزدوجة بشكل فعال في عملية الأمينوالريlation. المعني

بوحدات

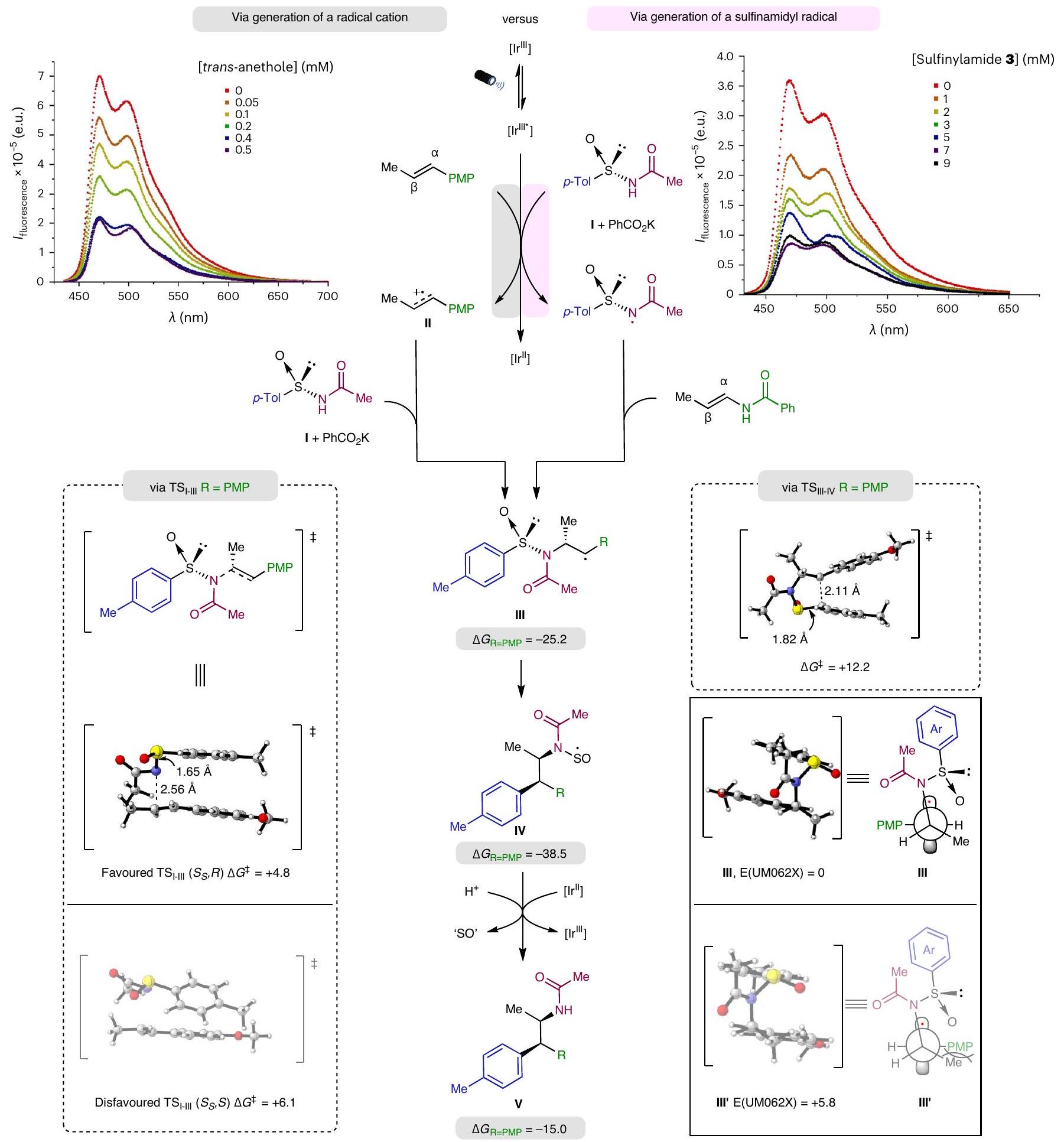

التحقيقات الميكانيكية

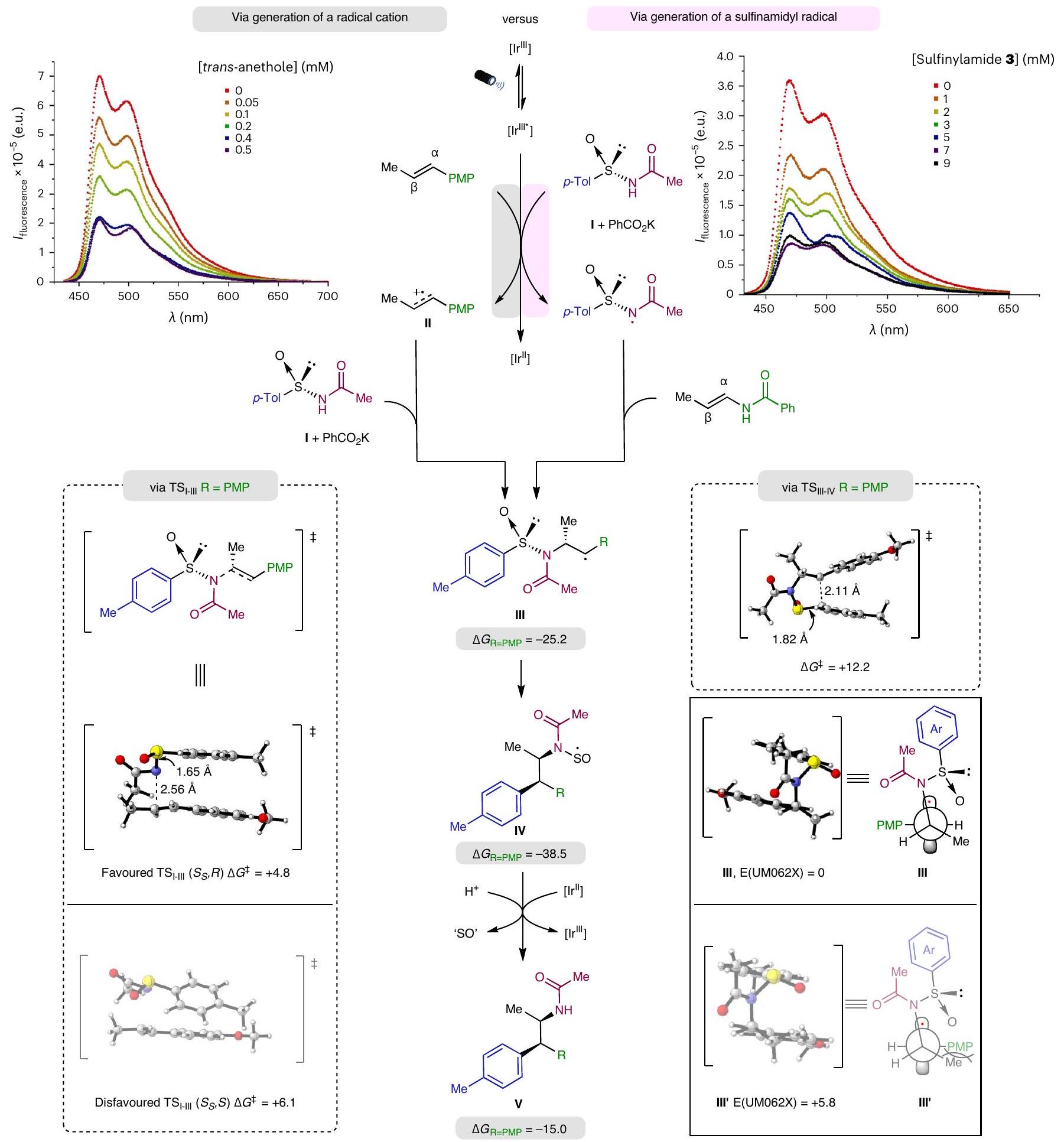

تحويل. تشير التحليلات الشكلية للوسيطين إلى أن انتقال الأريل يحدث بشكل تفضيلي من خلال مسار يتم فيه تقليل التفاعلات الحيزية بين مجموعة PMP والمجموعة الميثيلية داخل الأنثول.

الخاتمة

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- McCauley, J. A. et al. HIV protease inhibitors. PCT patent WO2014043019 A1 (2014).

- González-Muñiz, R., Bonache, M. A., Martín-Escura, C. & Gómez-Monterrey, I. Recent progress in TRPM8 modulation: an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2618 (2019).

- Sverrisdóttir, E. et al. A review of morphine and morphine-6glucuronide’s pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships in experimental and clinical pain. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 74, 45-62 (2015).

- Hanessian, S., Parthasarathy, S. & Mauduit, M. The power of visual imagery in drug design. Isopavines as a new class of morphinomimetics and their human opioid receptor binding activity. J. Med. Chem. 46, 34-48 (2003).

- Zhang, A., Neumeyer, J. L. & Baldessarini, R. J. Recent progress in development of dopamine receptor subtype-selective agents: potential therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Chem. Rev. 107, 274-302 (2007).

- Wang, Z.-Q., Feng, C.-G., Zhang, S.-S., Xu, M.-H. & Lin, G.-Q. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate addition of organoboronic acids to nitroalkenes using chiral bicyclo[3.3.0] diene ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5780-5783 (2010).

- He, F.-S. et al. Direct asymmetric synthesis of

-bis-aryl- -amino acid esters via enantioselective copper-catalyzed addition of p-quinone methides. ACS Catal. 6, 652-656 (2016). - Li, W. et al. Enantioselective organocatalytic 1,6-addition of azlactones to para-quinone methides: an access to

-disubstituted and -diaryl- -amino acid esters. Org. Lett. 20,1142-1145 (2018). - Nishino, S., Miura, M. & Hirano, K. An umpolung-enabled copper-catalysed regioselective hydroamination approach to

-amino acids. Chem. Sci. 12, 11525-11537 (2021). - Röben, C., Souto, J. A., González, Y., Lishchynskyi, A. & Muñiz, K. Enantioselective metal-free diamination of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9478-9482 (2011).

- Molinaro, C. et al. Catalytic, asymmetric and stereodivergent synthesis of non-symmetric

-diaryl- -amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 999-1006 (2015). - Gao, W. et al. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of

-acylamino nitroolefins: an efficient approach to chiral amines. Chem. Sci. 8, 6419-6422 (2017). - Valdez, S. C. & Leighton, J. L. Tandem asymmetric aza-Darzens/ ring-opening reactions: dual functionality from the silane Lewis acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14638-14639 (2009).

- Takeda, Y., Ikeda, Y., Kuroda, A., Tanaka, S. & Minakata, S. Pd/ NHC-catalyzed enantiospecific and regioselective Suzuki-Miyaura arylation of 2-arylaziridines: synthesis of enantioenriched 2-arylphenethylamine derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8544-8547 (2014).

- Chai, Z. et al. Synthesis of chiral vicinal diamines by silver(I)catalyzed enantioselective aminolysis of

-tosylaziridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 650-654 (2017). - Gómez-Arrayás, R. & Carretero, J. C. Catalytic asymmetric direct Mannich reaction: a powerful tool for the synthesis of

-diamino acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1940-1948 (2009). - White, D. R., Hutt, J. T. & Wolfe, J. P. Asymmetric Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions for the synthesis of 2-aminoindane derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11246-11249 (2015).

- Ozols, K., Onodera, S., Woz’niak, L. & Cramer, N. Cobalt(III)catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular carboamination by C-H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 655-659 (2021).

- Schultz, D. M. & Wolfe, J. P. Recent developments in Pd-catalyzed alkene aminoarylation reactions for the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles. Synthesis 44, 351-361 (2012).

- Zhang, W., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Enantioselective palladium(II)catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes by dual N-H and aryl C-H bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5336-5340 (2017).

- Jiang, H. & Studer, A. Intermolecular radical carboamination of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1790-1811 (2020).

- Moon, Y. et al. Visible light induced alkene aminopyridylation using

-aminopyridinium salts as bifunctional reagents. Nat. Commun. 10, 4117 (2019). - Jiang, H., Yu, X., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Three-component aminoarylation of electron-rich alkenes by merging photoredox with nickel catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14399-14404 (2021).

- Muñoz-Molina, J. M., Belderrain, T. R. & Pérez, P. J. Coppercatalysed radical reactions of alkenes, alkynes and cyclopropanes with N-F reagents. Org. Biomol. Chem. 18, 8757-8770 (2020).

- Liu, Z. & Liu, Z.-Q. An intermolecular azidoheteroarylation of simple alkenes via free radical multicomponent cascade reactions. Org. Lett. 19, 5649-5652 (2017).

- Hari, D. P., Hering, T. & König, B. The photoredox-catalyzed Meerwein addition reaction: intermolecular amino-arylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 725-728 (2014).

- Fumagalli, G., Boyd, S. & Greaney, M. F. Oxyarylation and aminoarylation of styrenes using photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 15, 4398-4401 (2013).

- Brenzovich, W. E. et al. Gold-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes: C-C bond formation through bimolecular reductive elimination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5519-5522 (2010).

- Sahoo, B., Hopkinson, M. N. & Glorius, F. Combining gold and photoredox catalysis: visible light-mediated oxy- and aminoarylation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5505-5508 (2013).

- Tathe, A. G. et al. Gold-catalyzed 1,2-aminoarylation of alkenes with external amines. ACS Catal. 11, 4576-4582 (2021).

- Lee, S. & Rovis, T. Rh(III)-catalyzed three-component syn-carboamination of alkenes using arylboronic acids and dioxazolones. ACS Catal. 11, 8585-8590 (2021).

- Liu, Z. et al. Catalytic intermolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes via directed aminopalladation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11261-11270 (2017).

- Hajra, S., Maji, B. & Mal, D. A catalytic and enantioselective synthesis of trans-2-amino-1-aryltetralins. Adv. Synth. Catal. 351, 859-864 (2009).

- Akhtar, S. M. S., Bar, S. & Hajra, S. Asymmetric aminoarylation for the synthesis of trans-3-amino-4-aryltetrahydroquinolines: an access to aza-analogue of dihydrexidine. Tetrahedron 103, 132257 (2021).

- Kwon, Y. & Wang, Q. Recent advances in 1,2-amino(hetero) arylation of alkenes. Chem. Asian J. 17, e202200215 (2022).

- Ye, B. & Cramer, N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands as stereocontrolling element in asymmetric C-H functionalization. Science 338, 504-506 (2012).

- Bizet, V., Borrajo-Calleja, G., Besnard, C. & Mazet, C. Direct access to furoindolines by palladium-catalyzed intermolecular carboamination. ACS Catal. 6, 7183-7187 (2016).

- Wang, D. et al. Asymmetric copper-catalyzed intermolecular aminoarylation of styrenes: efficient access to optical 2,2-diarylethylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6811-6814 (2017).

- Zheng, D. & Studer, A. Asymmetric synthesis of heterocyclic Y -amino-acid and diamine derivatives by three-component radical cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15803-15807 (2019).

- Monos, T. M., McAtee, R. C. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents for alkene aminoarylation. Science 361, 1369-1373 (2018).

- Allen, A. R. et al. Mechanism of visible light-mediated alkene aminoarylation with arylsulfonylacetamides. ACS Catal. 12, 8511-8526 (2022).

- Noten, E., Ng, C., Wolesensky, R. & Stephenson, C. R. J. A general alkene aminoarylation enabled by N-centered radical reactivity of sulfinamides. Preprint at https://chemrxiv.org/ engage/chemrxiv/article-details/6347680bbb6d8b9cf1568f62 (2022).

- Allen, A. R., Noten, E. A. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Aryl transfer strategies mediated by photoinduced electron transfer. Chem. Rev. 122, 2695-2751 (2022).

- Hervieu, C. et al. Asymmetric, visible light-mediated radical sulfinyl-Smiles rearrangement to access all-carbon quaternary stereocentres. Nat. Chem. 13, 327-334 (2021).

- Desai, M. C., Lefkowitz, S. L., Bryce, D. K. & McLean, S. Articulating a pharmacophore driven synthetic strategy: discovery of a potent substance P antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 1865-1868 (1994).

- Saito, B. & Fu, G. C. Enantioselective alkyl-alkyl Suzuki cross-couplings of unactivated homobenzylic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6694-6695 (2008).

- Zhang, B., Wang, H., Lin, G.-Q. & Xu, M.-H. Ruthenium(II)catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation using unsymmetrical vicinal diamine-based ligands: dramatic substituent effect on catalyst efficiency. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4205-4211 (2011).

- Gehlen, M. H. The centenary of the Stern-Volmer equation of fluorescence quenching: from the single line plot to the SV quenching map. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 42, 100338 (2019).

- Cismesia, M. A. & Yoon, T. P. Characterizing chain processes in visible light photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 6, 5426-5434 (2015).

- Neveselý, T., Wienhold, M., Molloy, J. J. & Gilmour, R. Advances in the

isomerization of alkenes using small molecule photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 122, 2650-2694 (2022). - Okada, K. & Sekiguchi, S. Aromatic nucleophilic substitution. 9. Kinetics of the formation and decomposition of anionic

complexes in the Smiles rearrangements of -acetyl- -aminoethyl 2-X-4-nitro-1-phenyl or -acetyl- -aminoethyl 5-nitro-2-pyridyl ethers in aqueous dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Org. Chem. 43, 441-447 (1978). - Herron, J. T. & Huie, R. E. Rate constants at 298 K for the reactions

AND SO . Chem. Phys. Lett. 76, 322-324 (1980).

© The Author(s) 2024

طرق

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

قسم الكيمياء، جامعة زيورخ، زيورخ، سويسرا. جامعة ألكالا، قسم الكيمياء العضوية والكيمياء غير العضوية، معهد أبحاث أندريس م. ديل ريو (IQAR)، كلية الصيدلة، مدريد، إسبانيا. معهد رامون وكاخال للبحوث الصحية (IRYCIS)، مدريد، إسبانيا. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: يوان هو، سيرجيو كويستا-غاليستيو. البريد الإلكتروني: estibaliz.merino@uah.es; cristina.nevado@chem.uzh.ch

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-023-01414-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38228849

Publication Date: 2024-01-16

Chiral arylsulfinylamides as reagents for visible light-mediated asymmetric alkene aminoarylations

Accepted: 28 November 2023

Published online: 16 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

Two- or one-electron-mediated difunctionalizations of internal alkenes represent straightforward approaches to assemble molecular complexity by the simultaneous formation of two contiguous

ring-opening

combined with excellent regio-, diastereo- and enantioselectivity, highlight both the generality and synthetic utility of these transformations in the assembly of relevant blueprints populating pharmaceuticals, bioactive natural products and ligands for transition-metal catalysis.

Results

Reaction optimization

Reaction scope

patterns were also compatible with the standard reaction conditions, furnishing the corresponding adducts (

proceeded smoothly under standard conditions to give 2.10 in high yield. Interestingly, substrates bearing both electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups in the para-position of the arene proved to be suitable precursors, furnishing the corresponding

potential of the obtained aminoarylation products (Supplementary Information, compound 2.40). Moreover, heteroaryl migration also took place under the standard conditions, furnishing the corresponding thiophene derivatives

groups at the terminal position of the double bond were effectively accommodated in the aminoarylation process. The corresponding

in units of

Mechanistic investigations

transposition. Conformational analysis of the two intermediates suggests that the aryl translocation preferentially takes place through a trajectory in which the steric interactions between the PMP group and the methyl substituent within the anethole are minimized (

Conclusion

Online content

References

- McCauley, J. A. et al. HIV protease inhibitors. PCT patent WO2014043019 A1 (2014).

- González-Muñiz, R., Bonache, M. A., Martín-Escura, C. & Gómez-Monterrey, I. Recent progress in TRPM8 modulation: an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2618 (2019).

- Sverrisdóttir, E. et al. A review of morphine and morphine-6glucuronide’s pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships in experimental and clinical pain. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 74, 45-62 (2015).

- Hanessian, S., Parthasarathy, S. & Mauduit, M. The power of visual imagery in drug design. Isopavines as a new class of morphinomimetics and their human opioid receptor binding activity. J. Med. Chem. 46, 34-48 (2003).

- Zhang, A., Neumeyer, J. L. & Baldessarini, R. J. Recent progress in development of dopamine receptor subtype-selective agents: potential therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Chem. Rev. 107, 274-302 (2007).

- Wang, Z.-Q., Feng, C.-G., Zhang, S.-S., Xu, M.-H. & Lin, G.-Q. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate addition of organoboronic acids to nitroalkenes using chiral bicyclo[3.3.0] diene ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5780-5783 (2010).

- He, F.-S. et al. Direct asymmetric synthesis of

-bis-aryl- -amino acid esters via enantioselective copper-catalyzed addition of p-quinone methides. ACS Catal. 6, 652-656 (2016). - Li, W. et al. Enantioselective organocatalytic 1,6-addition of azlactones to para-quinone methides: an access to

-disubstituted and -diaryl- -amino acid esters. Org. Lett. 20,1142-1145 (2018). - Nishino, S., Miura, M. & Hirano, K. An umpolung-enabled copper-catalysed regioselective hydroamination approach to

-amino acids. Chem. Sci. 12, 11525-11537 (2021). - Röben, C., Souto, J. A., González, Y., Lishchynskyi, A. & Muñiz, K. Enantioselective metal-free diamination of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9478-9482 (2011).

- Molinaro, C. et al. Catalytic, asymmetric and stereodivergent synthesis of non-symmetric

-diaryl- -amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 999-1006 (2015). - Gao, W. et al. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of

-acylamino nitroolefins: an efficient approach to chiral amines. Chem. Sci. 8, 6419-6422 (2017). - Valdez, S. C. & Leighton, J. L. Tandem asymmetric aza-Darzens/ ring-opening reactions: dual functionality from the silane Lewis acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14638-14639 (2009).

- Takeda, Y., Ikeda, Y., Kuroda, A., Tanaka, S. & Minakata, S. Pd/ NHC-catalyzed enantiospecific and regioselective Suzuki-Miyaura arylation of 2-arylaziridines: synthesis of enantioenriched 2-arylphenethylamine derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8544-8547 (2014).

- Chai, Z. et al. Synthesis of chiral vicinal diamines by silver(I)catalyzed enantioselective aminolysis of

-tosylaziridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 650-654 (2017). - Gómez-Arrayás, R. & Carretero, J. C. Catalytic asymmetric direct Mannich reaction: a powerful tool for the synthesis of

-diamino acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1940-1948 (2009). - White, D. R., Hutt, J. T. & Wolfe, J. P. Asymmetric Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions for the synthesis of 2-aminoindane derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11246-11249 (2015).

- Ozols, K., Onodera, S., Woz’niak, L. & Cramer, N. Cobalt(III)catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular carboamination by C-H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 655-659 (2021).

- Schultz, D. M. & Wolfe, J. P. Recent developments in Pd-catalyzed alkene aminoarylation reactions for the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles. Synthesis 44, 351-361 (2012).

- Zhang, W., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Enantioselective palladium(II)catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes by dual N-H and aryl C-H bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5336-5340 (2017).

- Jiang, H. & Studer, A. Intermolecular radical carboamination of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1790-1811 (2020).

- Moon, Y. et al. Visible light induced alkene aminopyridylation using

-aminopyridinium salts as bifunctional reagents. Nat. Commun. 10, 4117 (2019). - Jiang, H., Yu, X., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Three-component aminoarylation of electron-rich alkenes by merging photoredox with nickel catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14399-14404 (2021).

- Muñoz-Molina, J. M., Belderrain, T. R. & Pérez, P. J. Coppercatalysed radical reactions of alkenes, alkynes and cyclopropanes with N-F reagents. Org. Biomol. Chem. 18, 8757-8770 (2020).

- Liu, Z. & Liu, Z.-Q. An intermolecular azidoheteroarylation of simple alkenes via free radical multicomponent cascade reactions. Org. Lett. 19, 5649-5652 (2017).

- Hari, D. P., Hering, T. & König, B. The photoredox-catalyzed Meerwein addition reaction: intermolecular amino-arylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 725-728 (2014).

- Fumagalli, G., Boyd, S. & Greaney, M. F. Oxyarylation and aminoarylation of styrenes using photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 15, 4398-4401 (2013).

- Brenzovich, W. E. et al. Gold-catalyzed intramolecular aminoarylation of alkenes: C-C bond formation through bimolecular reductive elimination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5519-5522 (2010).

- Sahoo, B., Hopkinson, M. N. & Glorius, F. Combining gold and photoredox catalysis: visible light-mediated oxy- and aminoarylation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5505-5508 (2013).

- Tathe, A. G. et al. Gold-catalyzed 1,2-aminoarylation of alkenes with external amines. ACS Catal. 11, 4576-4582 (2021).

- Lee, S. & Rovis, T. Rh(III)-catalyzed three-component syn-carboamination of alkenes using arylboronic acids and dioxazolones. ACS Catal. 11, 8585-8590 (2021).

- Liu, Z. et al. Catalytic intermolecular carboamination of unactivated alkenes via directed aminopalladation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11261-11270 (2017).

- Hajra, S., Maji, B. & Mal, D. A catalytic and enantioselective synthesis of trans-2-amino-1-aryltetralins. Adv. Synth. Catal. 351, 859-864 (2009).

- Akhtar, S. M. S., Bar, S. & Hajra, S. Asymmetric aminoarylation for the synthesis of trans-3-amino-4-aryltetrahydroquinolines: an access to aza-analogue of dihydrexidine. Tetrahedron 103, 132257 (2021).

- Kwon, Y. & Wang, Q. Recent advances in 1,2-amino(hetero) arylation of alkenes. Chem. Asian J. 17, e202200215 (2022).

- Ye, B. & Cramer, N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands as stereocontrolling element in asymmetric C-H functionalization. Science 338, 504-506 (2012).

- Bizet, V., Borrajo-Calleja, G., Besnard, C. & Mazet, C. Direct access to furoindolines by palladium-catalyzed intermolecular carboamination. ACS Catal. 6, 7183-7187 (2016).

- Wang, D. et al. Asymmetric copper-catalyzed intermolecular aminoarylation of styrenes: efficient access to optical 2,2-diarylethylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6811-6814 (2017).

- Zheng, D. & Studer, A. Asymmetric synthesis of heterocyclic Y -amino-acid and diamine derivatives by three-component radical cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 15803-15807 (2019).

- Monos, T. M., McAtee, R. C. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents for alkene aminoarylation. Science 361, 1369-1373 (2018).

- Allen, A. R. et al. Mechanism of visible light-mediated alkene aminoarylation with arylsulfonylacetamides. ACS Catal. 12, 8511-8526 (2022).

- Noten, E., Ng, C., Wolesensky, R. & Stephenson, C. R. J. A general alkene aminoarylation enabled by N-centered radical reactivity of sulfinamides. Preprint at https://chemrxiv.org/ engage/chemrxiv/article-details/6347680bbb6d8b9cf1568f62 (2022).

- Allen, A. R., Noten, E. A. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Aryl transfer strategies mediated by photoinduced electron transfer. Chem. Rev. 122, 2695-2751 (2022).

- Hervieu, C. et al. Asymmetric, visible light-mediated radical sulfinyl-Smiles rearrangement to access all-carbon quaternary stereocentres. Nat. Chem. 13, 327-334 (2021).

- Desai, M. C., Lefkowitz, S. L., Bryce, D. K. & McLean, S. Articulating a pharmacophore driven synthetic strategy: discovery of a potent substance P antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 1865-1868 (1994).

- Saito, B. & Fu, G. C. Enantioselective alkyl-alkyl Suzuki cross-couplings of unactivated homobenzylic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6694-6695 (2008).

- Zhang, B., Wang, H., Lin, G.-Q. & Xu, M.-H. Ruthenium(II)catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation using unsymmetrical vicinal diamine-based ligands: dramatic substituent effect on catalyst efficiency. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 4205-4211 (2011).

- Gehlen, M. H. The centenary of the Stern-Volmer equation of fluorescence quenching: from the single line plot to the SV quenching map. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 42, 100338 (2019).

- Cismesia, M. A. & Yoon, T. P. Characterizing chain processes in visible light photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 6, 5426-5434 (2015).

- Neveselý, T., Wienhold, M., Molloy, J. J. & Gilmour, R. Advances in the

isomerization of alkenes using small molecule photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 122, 2650-2694 (2022). - Okada, K. & Sekiguchi, S. Aromatic nucleophilic substitution. 9. Kinetics of the formation and decomposition of anionic

complexes in the Smiles rearrangements of -acetyl- -aminoethyl 2-X-4-nitro-1-phenyl or -acetyl- -aminoethyl 5-nitro-2-pyridyl ethers in aqueous dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Org. Chem. 43, 441-447 (1978). - Herron, J. T. & Huie, R. E. Rate constants at 298 K for the reactions

AND SO . Chem. Phys. Lett. 76, 322-324 (1980).

© The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

Department of Chemistry, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. Universidad de Alcalá, Departamento de Química Orgánica y Química Inorgánica, Instituto de Investigación Andrés M. del Río (IQAR), Facultad de Farmacia, Madrid, Spain. Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS), Madrid, Spain. These authors contributed equally: Yawen Hu, Sergio Cuesta-Galisteo. e-mail: estibaliz.merino@uah.es; cristina.nevado@chem.uzh.ch