DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01278-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38175455

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

نانومتر-ميكرو ليت. (2024) 16:76

تم القبول: 8 نوفمبر 2023 نُشر على الإنترنت: 4 يناير 2024 © المؤلف(ون) 2024

إطار عضوي تساهمي ذو قنوات ثلاثية الأبعاد مرتبة ومجموعات متعددة الوظائف يمنح الأنود الزنك استقرارًا فائقًا

أبرز النقاط

- إطار عضوي تساهمي محب للزنك مفلور (COF-S-F) يحتوي على مجموعة حمض السلفونيك (-

) يتم تحضيره على سطح أنود الزنك، مما يعزز إزالة ذوبان أيونات الزنك المائية ويمنع التفاعلات الجانبية. - تعمل مجموعة -F ذات الكهروسالبية العالية في COF-S-F على تعزيز النقل السريع والمتجانس لأيونات الزنك عبر القنوات المترابطة، مما يساهم في عملية الترسيب الكهربائي المتجانسة لمعدن الزنك.

- خلية Zn@COF-S المتماثلة تحقق استقرارًا فائقًا من

و تقدم الخلية سعة نوعية عالية تبلغ عند كثافة التيار الحالية .

الملخص

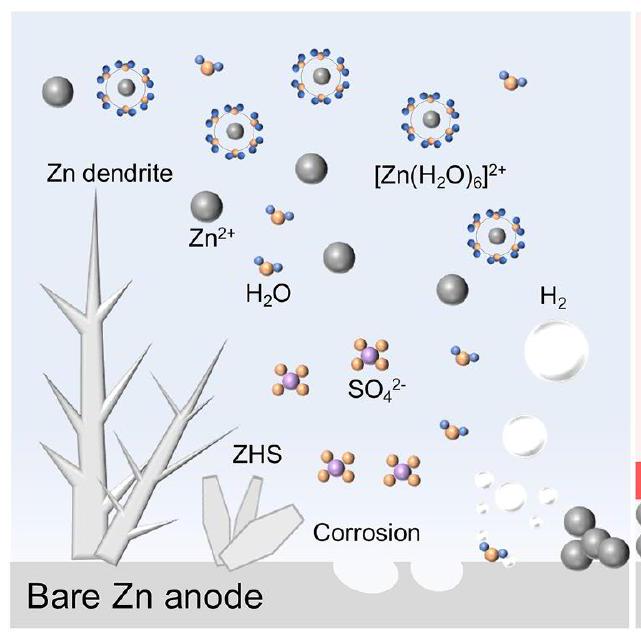

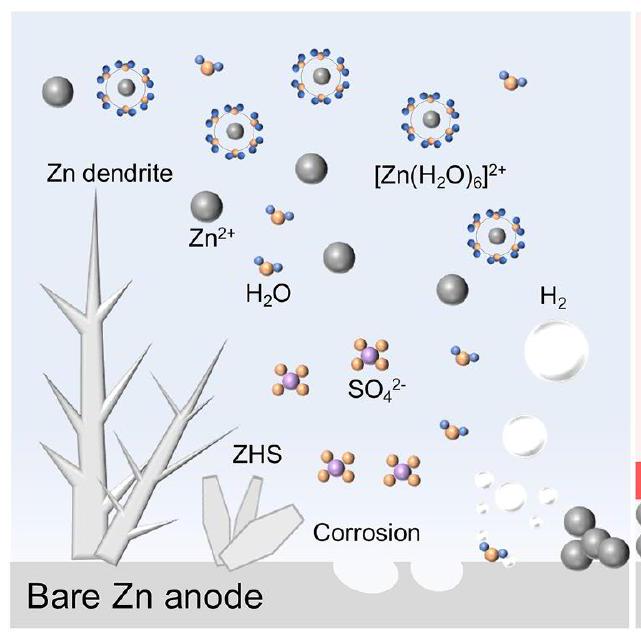

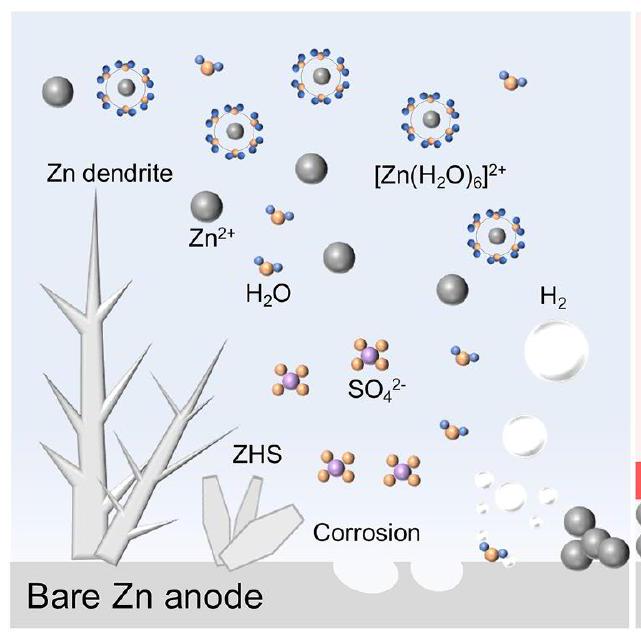

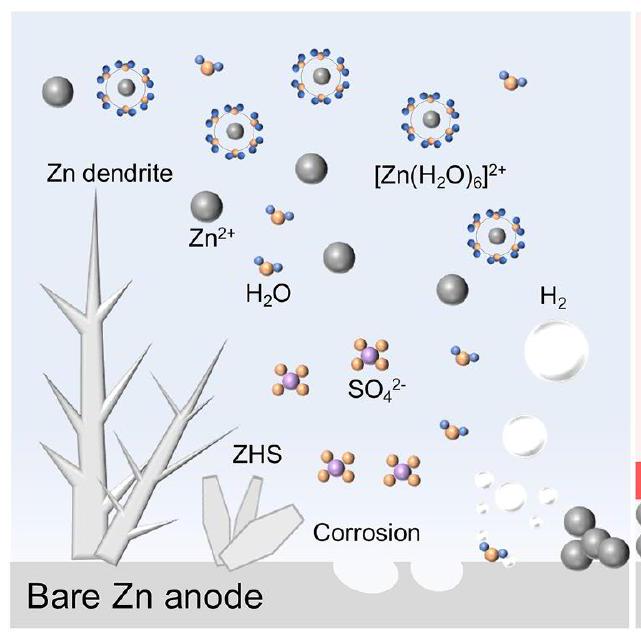

تحقيق أنود معدني من الزنك (Zn) عالي المتانة أمر بالغ الأهمية لتحسين أداء بطاريات أيونات الزنك المائية (AZIBs) من أجل تعزيز مجتمع “الحياد الكربوني”، والذي يعوقه النمو غير القابل للتحكم في أشواك الزنك والتفاعلات الجانبية الشديدة بما في ذلك تفاعل تطور الهيدروجين، والتآكل، والتخميل، وغيرها. هنا، طبقة وسطية تحتوي على مادة محبة للزنك مفلورة…

تم تطوير إطار عضوي تساهمي يحتوي على مجموعات حمض السلفونيك (COF-S-F) على معدن الزنك (Zn@COF-S-F) كواجهة إلكتروليت صلبة صناعية (SEI). مجموعة حمض السلفونيك (

تم تطوير إطار عضوي تساهمي يحتوي على مجموعات حمض السلفونيك (COF-S-F) على معدن الزنك (Zn@COF-S-F) كواجهة إلكتروليت صلبة صناعية (SEI). مجموعة حمض السلفونيك (

الملخص

Zn@COF-S-F ذو مورفولوجيا خالية من التشعبات وتفاعلات جانبية مكبوتة. وبناءً عليه، يمكن لخلية Zn@COF-S-F المتماثلة أن تعمل بشكل مستقر لفترة طويلة.

1 المقدمة

يُعاق التطور بسبب انخفاض قوته وهشاشته [27]. لذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مرونة مع قوة أعلى للطبقة الاصطناعية SEI لتتكيف مع تطور الشكل السطحي خلال عملية الترسيب الكهربائي لأنود الزنك. في الوقت نفسه، فإن الروابط القطبية الوفيرة (-CN، وغيرها) في طبقة SEI الخالية من المذيبات التجارية من السيانوأكريلات تمنع بشكل كبير حدوث التفاعلات الجانبية [28]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم الترويج للأطر العضوية التساهمية (COFs) التي تتميز بالمسامية، ونصف التوصيلية، والخصائص الكيميائية القابلة للتعديل، كمواد واعدة لبناء طبقة SEI اصطناعية على معدن الزنك لمواجهة القضايا المعقدة على السطح بشكل مشترك [29، 30]. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الأطر العضوية التساهمية ثلاثية الأبعاد (3D COFs) يمكن أن توفر قنوات مترابطة لنقل أيونات الزنك بشكل ملائم عبر الطبقة الاصطناعية SEI. لذلك، فإن تطوير أطر عضوية تساهمية متعددة الوظائف كطبقة تغطية باستخدام الهندسة الجزيئية يحمل إمكانات كبيرة في بناء أنود الزنك لبطاريات أيونات الزنك المائية عالية الأداء.

2 تجريبي

2.1 المواد

2.2 تحضير المواد

2.2.1 المعالجة المسبقة لـ COF-S-F

2.2.2 تحضير رقائق الزنك المطلية بـ COF-S-F (Zn@ COF-S-F)

2.2.3 التخليق

2.3 التوصيفات

2.4 القياسات الكهروكيميائية

ألياف زجاجية (

2.5 حسابات نظرية الدوال الكثافة

2.6 المحاكاة متعددة الفيزياء

3 النتائج والمناقشة

3.1 عملية التحضير وآلية العمل لـ COF-S-F

3.2 توصيفات Zn@COF-S-F

المنحنى الإيزوثيرمي من النوع الرابع القابل للعكس يظهر بنية المسام المميزة ومساحة سطح نوعية كبيرة (

3.3 الحسابات النظرية والمحاكاة لـ Zn @ COF-S-F

طاقة التفكك لـ

مع كثافة التيار (

3.4 الأداء الكهروكيميائي لخلايا Zn@COF-S-F المتماثلة

كثافات التيار الحالية أعلى من تلك الخاصة بخلية ZnITi غير المغطاة، مما يوضح أن الحركية الكهروكيميائية لترسيب/إزالة الزنك تتحسن مع طلاء COF-S-F. بعد ذلك، يتم تنفيذ أداء الترسيب/الإزالة طويل الأمد لخلية Zn غير المغطاة وخلية Zn@COF-S-F المتماثلة للتحقق من فعالية طبقة SEI الاصطناعية COF-S-F. عند كثافة التيار المنخفضة

عند كثافة تيار

3.5 الأداء الكهروكيميائي لخلايا Zn@ COF-S-FIMnO2 الكاملة

من المنتجات الثانوية. بسبب تأثير إزالة المذيب المحدد لـ COF-S-F، يحدث تلامس بين المادة الفعالة

القمة ليست واضحة. علاوة على ذلك، يتم إجراء المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح (SEM) والمجهر الماسح بالليزر المرافق (LSCM) للتحقيق في شكل معدن الزنك المحمي بواسطة فيلم COF-S-F. من صور SEM في الأشكال 5h، i وS20، يظهر عدد كبير من التفرعات الزنك على الأنود الزنك العاري، بينما سطح أنود Zn@COF-S-F يكون مستويًا نسبيًا مع شوائب ضئيلة. علاوة على ذلك، بالمقارنة مع الفرق الكبير في الارتفاع لأنود الزنك العاري

4 الخاتمة

الإعلانات

References

- X. Song, L. Bai, C. Wang, D. Wang, K. Xu et al., Synergistic cooperation of

texture and amorphous zinc phosphate for dendrite-free Zn anodes. ACS Nano 17, 15113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c04343 - Y. Shang, D. Kundu, A path forward for the translational development of aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Joule 7, 244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2023.01.011

- B. Qiu, K. Liang, W. Huang, G. Zhang, C. He et al., Crystalfacet manipulation and interface regulation via tmp-modulated solid polymer electrolytes toward high-performance Zn metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301193 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/aenm. 202301193

- J. Liu, M. Yue, S. Wang, Y. Zhao, J. Zhang, A review of performance attenuation and mitigation strategies of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107769 (2021). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202107769

- M. Ameziane, R. Mansell, V. Havu, P. Rinke, S. van Dijken, Lithium-ion battery technology for voltage control of perpendicular magnetization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2113118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202113118

- Z. Peng, Y. Li, P. Ruan, Z. He, L. Dai et al., Metal-organic frameworks and beyond: The road toward zinc-based batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 488, 215190 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215190

- J. Ruan, D. Ma, K. Ouyang, S. Shen, M. Yang et al., 3D artificial array interface engineering enabling dendrite-free stable Zn metal anode. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 37 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s40820-022-01007-z

- H. Ying, P. Huang, Z. Zhang, S. Zhang, Q. Han et al., Freestanding and flexible interfacial layer enables bottom-up Zn deposition toward dendrite-free aqueous Zn -ion batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 180 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00921-6

- H. Meng, Q. Ran, T.-Y. Dai, H. Shi, S.-P. Zeng et al., Surfacealloyed nanoporous zinc as reversible and stable anodes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion battery. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00867-9

- S. Zhao, Y. Zhang, J. Li, L. Qi, Y. Tang et al., A heteroanionic zinc ion conductor for dendrite-free Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202300195

- Z. Bie, Q. Yang, X. Cai, Z. Chen, Z. Jiao et al., One-step construction of a polyporous and zincophilic interface for stable zinc metal anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202683 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202202683

- G. Chen, Y. Kang, H. Yang, M. Zhang, J. Yang et al., Toward forty thousand-cycle aqueous zinc-iodine battery: Simultaneously inhibiting polyiodides shuttle and stabilizing zinc anode through a suspension electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300656 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202300656

- Z. Yi, J. Liu, S. Tan, Z. Sang, J. Mao et al., An ultrahigh rate and stable zinc anode by facet-matching-induced dendrite regulation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203835 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202203835

- Y. Zhao, Y. Huang, F. Wu, R. Chen, L. Li, High-performance aqueous zinc batteries based on organic/organic cathodes integrating multiredox centers. Adv. Mater. 33, 2106469 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202106469

- H. He, H. Qin, J. Wu, X. Chen, R. Huang et al., Engineering interfacial layers to enable Zn metal anodes for aqueous zincion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 43, 317 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2021.09.012

- F. Wu, Y. Chen, Y. Chen, R. Yin, Y. Feng et al., Achieving highly reversible zinc anodes via N, N-dimethylacetamide enabled Zn-ion solvation regulation. Small 18, 2202363 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202202363

- Y. Wu, T. Zhang, L. Chen, Z. Zhu, L. Cheng et al., Polymer chain-guided ion transport in aqueous electrolytes of Zn -ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300791 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/aenm. 202300719

- J. Shin, J. Lee, Y. Kim, Y. Park, M. Kim et al., Highly reversible, grain-directed zinc deposition in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100676 (2021). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/aenm. 202100676

- N. Maeboonruan, J. Lohitkarn, C. Poochai, T. Lomas, A. Wisitsoraat et al., Dendrite suppression with zirconium (IV) based metal-organic frameworks modified glass microfiber separator for ultralong-life rechargeable zinc-ion batteries. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 7, 100467 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jsamd.2022.100467

- T. Liu, J. Hong, J. Wang, Y. Xu, Y. Wang, Uniform distribution of zinc ions achieved by functional supramolecules for stable zinc metal anode with long cycling lifespan. Energy Storage Mater. 45, 1074 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2021. 11.002

- X. Zhao, N. Dong, M. Yan, H. Pan, Unraveling the interphasial chemistry for highly reversible aqueous Zn ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 4053 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsami.2c19022

- D. Yuan, X. Li, H. Yao, Y. Li, X. Zhu et al., A liquid crystal ionomer-type electrolyte toward ordering-induced regulation for highly reversible zinc ion battery. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206469 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 202206469

- J. Ji, Z. Zhu, H. Du, X. Qi, J. Yao et al., Zinc-contained alloy as a robustly adhered interfacial lattice locking layer for planar and stable zinc electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211961 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202211961

- Y. Yang, H. Yang, R. Zhu, H. Zhou, High reversibility at high current density: The zinc electrodeposition principle behind the “trick.” Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2723 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1039/d3ee00925d

- Y. Lin, Z. Mai, H. Liang, Y. Li, G. Yang et al., Dendrite-free Zn anode enabled by anionic surfactant-induced horizontal growth for highly-stable aqueous Zn -ion pouch cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 687-697 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1039/ d2ee03528f

- Y. Lin, Y. Li, Z. Mai, G. Yang, C. Wang, Interfacial regulation via anionic surfactant electrolyte additive promotes stable (002)-textured zinc anodes at high depth of discharge. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301999 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ aenm. 202301999

- Q. Zong, B. Lv, C.F. Liu, Y.F. Yu, Q.L. Kang et al., Dendrite-free and highly stable Zn metal anode with

coating. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2886 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.3c01017 - Z. Cao, X. Zhu, D. Xu, P. Dong, M.O.L. Chee et al., Eliminating Zn dendrites by commercial cyanoacrylate adhesive for zinc ion battery. Energy Storage Mater. 36, 132 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2020.12.022

- C. Guo, J. Zhou, Y. Chen, H. Zhuang, Q. Li et al., Synergistic manipulation of hydrogen evolution and zinc ion flux in metalcovalent organic frameworks for dendrite-free Zn -based aqueous batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210871 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie. 202210871

- X. Liu, Y. Jin, H. Wang, X. Yang, P. Zhang et al., In situ growth of covalent organic framework nanosheets on graphene as the cathode for long-life high-capacity lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203605 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adma. 202203605

- T. Huang, K. Xu, N. Jia, L. Yang, H. Liu et al., Intrinsic interfacial dynamic engineering of zincophilic microbrushes via regulating Zn deposition for highly reversible aqueous zinc ion battery. Adv. Mater. 35, 2205206 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202205206

- L. Hong, X. Wu, C. Ma, W. Huang, Y. Zhou et al., Boosting the zn-ion transfer kinetics to stabilize the zn metal interface

for high-performance rechargeable zn-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 16814 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/d1ta03967a - N. Guo, Z. Peng, W. Huo, Y. Li, S. Liu et al., Stabilizing Zn metal anode through regulation of Zn ion transfer and interfacial behavior with a fast ion conductor protective layer. Small (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202303963

- J. Zhao, Y. Ying, G. Wang, K. Hu, Y.D. Yuan et al., Covalent organic framework film protected zinc anode for highly stable rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 48, 82 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2022.02.054

- C. Hu, Z. Wei, L. Li, G. Shen, Strategy toward semiconducting

-MXene: Phenylsulfonic acid groups modified as photosensitive material for flexible visual sensoryneuromorphic system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202302188 - R. Kushwaha, C. Jain, P. Shekhar, D. Rase, R. Illathvalappil et al., Made to measure squaramide cof cathode for zinc dualion battery with enriched storage via redox electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301049 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ aenm. 202301049

- Z. Zhao, R. Wang, C. Peng, W. Chen, T. Wu et al., Horizontally arranged zinc platelet electrodeposits modulated by fluorinated covalent organic framework film for high-rate and durable aqueous zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 6606 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26947-9

- J. Xu, S. An, X. Song, Y. Cao, N. Wang et al., Towards high performance Li-S batteries via sulfonate-rich cof-modified separator. Adv. Mater. 33, 2105178 (2021). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202105178

- L. Wang, Z. Zhao, Y. Yao, Y. Zhang, Y. Meng et al., Highly fluorinated non-aqueous solid-liquid hybrid interface realizes water impermeability for anti-calendar aging zinc metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 62, 102920 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ensm.2023.102920

- I. Yoshimitsu, C. Shuo, H. Ryota, K. Takeshi, A. Tsubasa et al., Ultrafast water permeation through nanochannels with a densely fluorous interior surface. Science 376, 738 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd0966

- Y. Song, P. Ruan, C. Mao, Y. Chang, L. Wang et al., Metalorganic frameworks functionalized separators for robust aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 218 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00960-z

- C. Deng, X. Xie, J. Han, Y. Tang, J. Gao et al., A sieve-functional and uniform-porous kaolin layer toward stable zinc metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000599 (2020). https:// doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202000599

- H. Dong, X. Hu, R. Liu, M. Ouyang, H. He et al., Bio-inspired polyanionic electrolytes for highly stable zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311268 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/anie. 202311268

- K. Wu, X. Shi, F. Yu, H. Liu, Y. Zhang et al., Molecularly engineered three-dimensional covalent organic framework protection films for highly stable zinc anodes in aqueous electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 51, 391 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ensm.2022.06.032

- X. Jiao, X. Wang, X. Xu, Y. Wang, H.H. Ryu et al., Multiphysical field simulation: A powerful tool for accelerating exploration of high-energy-density rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301708 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/aenm. 202301708

- X. Xu, X. Jiao, O.O. Kapitanova, J. Wang, V.S. Volkov et al., Diffusion limited current density: A watershed in electrodeposition of lithium metal anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2200244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202200244

- X. Jiao, Y. Wang, O.O. Kapitanova, X. Xu, V.S. Volkov et al., Morphology evolution of electrodeposited lithium on metal substrates. Energy Storage Mater. 61, 102916 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2023.102916

- B. Li, S. Liu, Y. Geng, C. Mao, L. Dai et al., Achieving stable zinc metal anode via polyaniline interface regulation of Zn ion flux and desolvation. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202214033

- A.S. Chen, C.Y. Zhao, J.Z. Gao, Z.K. Guo, X.Y. Lu et al., Multifunctional sei-like structure coating stabilizing Zn anodes at a large current and capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 275 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ee02931f

- T. Wang, P. Wang, L. Pan, Z. He, L. Dai et al., Stabling zinc metal anode with polydopamine regulation through dual effects of fast desolvation and ion confinement. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203523 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202203523

- Y. Zeng, P.X. Sun, Z. Pei, Q. Jin, X. Zhang et al., Nitrogendoped carbon fibers embedded with zincophilic cu nanoboxes for stable Zn-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200342 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202200342

- W. Zhou, M. Chen, Q. Tian, J. Chen, X. Xu et al., Cottonderived cellulose film as a dendrite-inhibiting separator to stabilize the zinc metal anode of aqueous zinc ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 44, 57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ensm.2021.10.002

- Q. Dong, H. Ao, Z. Qin, Z. Xu, J. Ye et al., Synergistic chaotropic effect and cathode interface thermal release effect enabling ultralow temperature aqueous zinc battery. Small 18, 2203347 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202203347

- M. Sun, G. Ji, J. Zheng, A hydrogel electrolyte with ultrahigh ionic conductivity and transference number benefit from

“highways” for dendrite-free battery. Chem. Eng. J. 463, 142535 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023. 142535

- Bin Li and Pengchao Ruan have contributed equally to this work.

Zhangxing He, zxhe@ncst.edu.cn; Yangyang Liu, liuyy0510@hotmail.com; Jiang Zhou, zhou_jiang@csu.edu.cn

School of Chemical Engineering, North China University of Science and Technology, Tangshan 063009, People’s Republic of China

School of Materials Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, People’s Republic of China

State Key Laboratory for Mechanical Behavior of Materials, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, People’s Republic of China

Hunan Provincial Key Defense Laboratory of High Temperature Wear-Resisting Materials and Preparation Technology, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, People’s Republic of China

School of Physics and Electronics, Hunan University, Changsha 410082, People’s Republic of China

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01278-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38175455

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Nano-Micro Lett. (2024) 16:76

Accepted: 8 November 2023 Published online: 4 January 2024 © The Author(s) 2024

Covalent Organic Framework with 3D Ordered Channel and Multi-Functional Groups Endows Zn Anode with Superior Stability

HIGHLIGHTS

- A fluorinated zincophilic covalent organic framework (COF-S-F) with sulfonic acid group (-

) is prepared on the surface of Zn anode, which promotes the desolvation of hydrated Zn ions and inhibits the side reactions. - The highly electronegative -F group in COF-S-F promotes fast and uniform transport of Zn ions along the interconnected channels, which contributes to the uniform electrodeposition process of Zn metal.

- Zn@COF-S-F symmetric cell achieves a superior stability of

and cell delivers high specific capacity of at current density of .

Abstract

Achieving a highly robust zinc ( Zn ) metal anode is extremely important for improving the performance of aqueous Zn-ion batteries (AZIBs) for advancing “carbon neutrality” society, which is hampered by the uncontrollable growth of Zn dendrite and severe side reactions including hydrogen evolution reaction, corrosion, and passivation, etc. Herein, an interlayer containing fluorinated zincophilic

covalent organic framework with sulfonic acid groups (COF-S-F) is developed on Zn metal (Zn@COF-S-F) as the artificial solid electrolyte interface (SEI). Sulfonic acid group (

covalent organic framework with sulfonic acid groups (COF-S-F) is developed on Zn metal (Zn@COF-S-F) as the artificial solid electrolyte interface (SEI). Sulfonic acid group (

Abstract

Zn@COF-S-F with dendrite-free morphology and suppressed side reactions. Consequently, Zn@COF-S-F symmetric cell can stably cycle for

1 Introduction

development is hampered by its low strength and brittleness [27]. Hence, flexibility with higher strength is needed for the artificial SEI to adapt the interface-morphological evolution during the electrodeposition process of Zn anode. Meanwhile, the abundant polar bonds (-CN, etc.) in commercial solvent-free cyanoacrylate SEI greatly inhibit the occurrence of side reactions [28]. Apart from these, covalent organic frameworks (COFs) with the advantages of porosity, semi-conductivity, and adjustable chemical properties, have been promoted as promising materials for building artificial SEI on Zn metal to jointly tackle the complicated interfacial issues [29, 30]. Notably, three-dimensional (3D) COFs can provide interconnected channels for the favorable transport of Zn ions across the artificial SEI. Therefore, the development of multi-functional COFs as coating using molecular engineering has great potential in the construction of Zn anode for high-performance AZIBs.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

2.2 Preparation of Materials

2.2.1 Pretreatment of COF-S-F

2.2.2 Preparation of COF-S-F-Coated Zn Foil (Zn@ COF-S-F

2.2.3 Synthesis of

2.3 Characterizations

2.4 Electrochemical Measurements

glass fiber (

2.5 DFT Computations

2.6 Multi-physical Simulation

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Preparation Process and Action Mechanism of COF-S-F

3.2 Characterizations of Zn@COF-S-F

reversible type IV isotherm shows the distinct pore structure and large specific surface area (

3.3 Theoretical Calculations and Simulations of Zn @ COF-S-F

the dissociation energy for

with current density (

3.4 Electrochemical Performance of Zn@COF-S-F Symmetric Cells

current densities than that of bare ZnITi asymmetric cell, demonstrating that the electrochemical kinetics of Zn plating/stripping is fostered with COF-S-F coating. Following, the long-term plating/stripping performances of bare Zn and Zn@COF-S-F symmetric cells are implemented to verify the effectiveness of COF-S-F artificial SEI film. At the gentle current density of

at current density of

3.5 Electrochemical Performance of Zn@ COF-S-FIMnO2 Full Cells

of by-products. Because of the certain desolvation effect of COF-S-F, the contact between active

peak is not obvious. Furthermore, SEM and laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) are conducted to investigate the morphology of Zn metal that protected by COF-S-F film. From the SEM images in Figs. 5h, i and S20, a large number of Zn dendrites appear on the bare Zn anode, while the surface of Zn@COF-S-F anode is relatively flat with negligible impurities. Furthermore, compared with the giant height difference of bare Zn anode of

4 Conclusion

Declarations

References

- X. Song, L. Bai, C. Wang, D. Wang, K. Xu et al., Synergistic cooperation of

texture and amorphous zinc phosphate for dendrite-free Zn anodes. ACS Nano 17, 15113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c04343 - Y. Shang, D. Kundu, A path forward for the translational development of aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Joule 7, 244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2023.01.011

- B. Qiu, K. Liang, W. Huang, G. Zhang, C. He et al., Crystalfacet manipulation and interface regulation via tmp-modulated solid polymer electrolytes toward high-performance Zn metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301193 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/aenm. 202301193

- J. Liu, M. Yue, S. Wang, Y. Zhao, J. Zhang, A review of performance attenuation and mitigation strategies of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107769 (2021). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202107769

- M. Ameziane, R. Mansell, V. Havu, P. Rinke, S. van Dijken, Lithium-ion battery technology for voltage control of perpendicular magnetization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2113118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202113118

- Z. Peng, Y. Li, P. Ruan, Z. He, L. Dai et al., Metal-organic frameworks and beyond: The road toward zinc-based batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 488, 215190 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215190

- J. Ruan, D. Ma, K. Ouyang, S. Shen, M. Yang et al., 3D artificial array interface engineering enabling dendrite-free stable Zn metal anode. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 37 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1007/s40820-022-01007-z

- H. Ying, P. Huang, Z. Zhang, S. Zhang, Q. Han et al., Freestanding and flexible interfacial layer enables bottom-up Zn deposition toward dendrite-free aqueous Zn -ion batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 180 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40820-022-00921-6

- H. Meng, Q. Ran, T.-Y. Dai, H. Shi, S.-P. Zeng et al., Surfacealloyed nanoporous zinc as reversible and stable anodes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion battery. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00867-9

- S. Zhao, Y. Zhang, J. Li, L. Qi, Y. Tang et al., A heteroanionic zinc ion conductor for dendrite-free Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202300195

- Z. Bie, Q. Yang, X. Cai, Z. Chen, Z. Jiao et al., One-step construction of a polyporous and zincophilic interface for stable zinc metal anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202683 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202202683

- G. Chen, Y. Kang, H. Yang, M. Zhang, J. Yang et al., Toward forty thousand-cycle aqueous zinc-iodine battery: Simultaneously inhibiting polyiodides shuttle and stabilizing zinc anode through a suspension electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300656 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202300656

- Z. Yi, J. Liu, S. Tan, Z. Sang, J. Mao et al., An ultrahigh rate and stable zinc anode by facet-matching-induced dendrite regulation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203835 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202203835

- Y. Zhao, Y. Huang, F. Wu, R. Chen, L. Li, High-performance aqueous zinc batteries based on organic/organic cathodes integrating multiredox centers. Adv. Mater. 33, 2106469 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202106469

- H. He, H. Qin, J. Wu, X. Chen, R. Huang et al., Engineering interfacial layers to enable Zn metal anodes for aqueous zincion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 43, 317 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2021.09.012

- F. Wu, Y. Chen, Y. Chen, R. Yin, Y. Feng et al., Achieving highly reversible zinc anodes via N, N-dimethylacetamide enabled Zn-ion solvation regulation. Small 18, 2202363 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202202363

- Y. Wu, T. Zhang, L. Chen, Z. Zhu, L. Cheng et al., Polymer chain-guided ion transport in aqueous electrolytes of Zn -ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300791 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/aenm. 202300719

- J. Shin, J. Lee, Y. Kim, Y. Park, M. Kim et al., Highly reversible, grain-directed zinc deposition in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100676 (2021). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/aenm. 202100676

- N. Maeboonruan, J. Lohitkarn, C. Poochai, T. Lomas, A. Wisitsoraat et al., Dendrite suppression with zirconium (IV) based metal-organic frameworks modified glass microfiber separator for ultralong-life rechargeable zinc-ion batteries. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 7, 100467 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jsamd.2022.100467

- T. Liu, J. Hong, J. Wang, Y. Xu, Y. Wang, Uniform distribution of zinc ions achieved by functional supramolecules for stable zinc metal anode with long cycling lifespan. Energy Storage Mater. 45, 1074 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2021. 11.002

- X. Zhao, N. Dong, M. Yan, H. Pan, Unraveling the interphasial chemistry for highly reversible aqueous Zn ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 4053 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsami.2c19022

- D. Yuan, X. Li, H. Yao, Y. Li, X. Zhu et al., A liquid crystal ionomer-type electrolyte toward ordering-induced regulation for highly reversible zinc ion battery. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206469 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 202206469

- J. Ji, Z. Zhu, H. Du, X. Qi, J. Yao et al., Zinc-contained alloy as a robustly adhered interfacial lattice locking layer for planar and stable zinc electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211961 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202211961

- Y. Yang, H. Yang, R. Zhu, H. Zhou, High reversibility at high current density: The zinc electrodeposition principle behind the “trick.” Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 2723 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1039/d3ee00925d

- Y. Lin, Z. Mai, H. Liang, Y. Li, G. Yang et al., Dendrite-free Zn anode enabled by anionic surfactant-induced horizontal growth for highly-stable aqueous Zn -ion pouch cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 687-697 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1039/ d2ee03528f

- Y. Lin, Y. Li, Z. Mai, G. Yang, C. Wang, Interfacial regulation via anionic surfactant electrolyte additive promotes stable (002)-textured zinc anodes at high depth of discharge. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301999 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ aenm. 202301999

- Q. Zong, B. Lv, C.F. Liu, Y.F. Yu, Q.L. Kang et al., Dendrite-free and highly stable Zn metal anode with

coating. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2886 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.3c01017 - Z. Cao, X. Zhu, D. Xu, P. Dong, M.O.L. Chee et al., Eliminating Zn dendrites by commercial cyanoacrylate adhesive for zinc ion battery. Energy Storage Mater. 36, 132 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2020.12.022

- C. Guo, J. Zhou, Y. Chen, H. Zhuang, Q. Li et al., Synergistic manipulation of hydrogen evolution and zinc ion flux in metalcovalent organic frameworks for dendrite-free Zn -based aqueous batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210871 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie. 202210871

- X. Liu, Y. Jin, H. Wang, X. Yang, P. Zhang et al., In situ growth of covalent organic framework nanosheets on graphene as the cathode for long-life high-capacity lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203605 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/ adma. 202203605

- T. Huang, K. Xu, N. Jia, L. Yang, H. Liu et al., Intrinsic interfacial dynamic engineering of zincophilic microbrushes via regulating Zn deposition for highly reversible aqueous zinc ion battery. Adv. Mater. 35, 2205206 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202205206

- L. Hong, X. Wu, C. Ma, W. Huang, Y. Zhou et al., Boosting the zn-ion transfer kinetics to stabilize the zn metal interface

for high-performance rechargeable zn-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 16814 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/d1ta03967a - N. Guo, Z. Peng, W. Huo, Y. Li, S. Liu et al., Stabilizing Zn metal anode through regulation of Zn ion transfer and interfacial behavior with a fast ion conductor protective layer. Small (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202303963

- J. Zhao, Y. Ying, G. Wang, K. Hu, Y.D. Yuan et al., Covalent organic framework film protected zinc anode for highly stable rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 48, 82 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2022.02.054

- C. Hu, Z. Wei, L. Li, G. Shen, Strategy toward semiconducting

-MXene: Phenylsulfonic acid groups modified as photosensitive material for flexible visual sensoryneuromorphic system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202302188 - R. Kushwaha, C. Jain, P. Shekhar, D. Rase, R. Illathvalappil et al., Made to measure squaramide cof cathode for zinc dualion battery with enriched storage via redox electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301049 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/ aenm. 202301049

- Z. Zhao, R. Wang, C. Peng, W. Chen, T. Wu et al., Horizontally arranged zinc platelet electrodeposits modulated by fluorinated covalent organic framework film for high-rate and durable aqueous zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 6606 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26947-9

- J. Xu, S. An, X. Song, Y. Cao, N. Wang et al., Towards high performance Li-S batteries via sulfonate-rich cof-modified separator. Adv. Mater. 33, 2105178 (2021). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/adma. 202105178

- L. Wang, Z. Zhao, Y. Yao, Y. Zhang, Y. Meng et al., Highly fluorinated non-aqueous solid-liquid hybrid interface realizes water impermeability for anti-calendar aging zinc metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 62, 102920 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ensm.2023.102920

- I. Yoshimitsu, C. Shuo, H. Ryota, K. Takeshi, A. Tsubasa et al., Ultrafast water permeation through nanochannels with a densely fluorous interior surface. Science 376, 738 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd0966

- Y. Song, P. Ruan, C. Mao, Y. Chang, L. Wang et al., Metalorganic frameworks functionalized separators for robust aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 218 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00960-z

- C. Deng, X. Xie, J. Han, Y. Tang, J. Gao et al., A sieve-functional and uniform-porous kaolin layer toward stable zinc metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000599 (2020). https:// doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202000599

- H. Dong, X. Hu, R. Liu, M. Ouyang, H. He et al., Bio-inspired polyanionic electrolytes for highly stable zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311268 (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/anie. 202311268

- K. Wu, X. Shi, F. Yu, H. Liu, Y. Zhang et al., Molecularly engineered three-dimensional covalent organic framework protection films for highly stable zinc anodes in aqueous electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 51, 391 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ensm.2022.06.032

- X. Jiao, X. Wang, X. Xu, Y. Wang, H.H. Ryu et al., Multiphysical field simulation: A powerful tool for accelerating exploration of high-energy-density rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301708 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/aenm. 202301708

- X. Xu, X. Jiao, O.O. Kapitanova, J. Wang, V.S. Volkov et al., Diffusion limited current density: A watershed in electrodeposition of lithium metal anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2200244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202200244

- X. Jiao, Y. Wang, O.O. Kapitanova, X. Xu, V.S. Volkov et al., Morphology evolution of electrodeposited lithium on metal substrates. Energy Storage Mater. 61, 102916 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2023.102916

- B. Li, S. Liu, Y. Geng, C. Mao, L. Dai et al., Achieving stable zinc metal anode via polyaniline interface regulation of Zn ion flux and desolvation. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2023). https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm. 202214033

- A.S. Chen, C.Y. Zhao, J.Z. Gao, Z.K. Guo, X.Y. Lu et al., Multifunctional sei-like structure coating stabilizing Zn anodes at a large current and capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 275 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ee02931f

- T. Wang, P. Wang, L. Pan, Z. He, L. Dai et al., Stabling zinc metal anode with polydopamine regulation through dual effects of fast desolvation and ion confinement. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203523 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm. 202203523

- Y. Zeng, P.X. Sun, Z. Pei, Q. Jin, X. Zhang et al., Nitrogendoped carbon fibers embedded with zincophilic cu nanoboxes for stable Zn-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200342 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 202200342

- W. Zhou, M. Chen, Q. Tian, J. Chen, X. Xu et al., Cottonderived cellulose film as a dendrite-inhibiting separator to stabilize the zinc metal anode of aqueous zinc ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 44, 57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ensm.2021.10.002

- Q. Dong, H. Ao, Z. Qin, Z. Xu, J. Ye et al., Synergistic chaotropic effect and cathode interface thermal release effect enabling ultralow temperature aqueous zinc battery. Small 18, 2203347 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202203347

- M. Sun, G. Ji, J. Zheng, A hydrogel electrolyte with ultrahigh ionic conductivity and transference number benefit from

“highways” for dendrite-free battery. Chem. Eng. J. 463, 142535 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023. 142535

- Bin Li and Pengchao Ruan have contributed equally to this work.

Zhangxing He, zxhe@ncst.edu.cn; Yangyang Liu, liuyy0510@hotmail.com; Jiang Zhou, zhou_jiang@csu.edu.cn

School of Chemical Engineering, North China University of Science and Technology, Tangshan 063009, People’s Republic of China

School of Materials Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, People’s Republic of China

State Key Laboratory for Mechanical Behavior of Materials, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, People’s Republic of China

Hunan Provincial Key Defense Laboratory of High Temperature Wear-Resisting Materials and Preparation Technology, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, People’s Republic of China

School of Physics and Electronics, Hunan University, Changsha 410082, People’s Republic of China