DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.215900

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-08

الابتكارات المدفوعة بالتنسيق في العمليات التحفيزية منخفضة الطاقة: تعزيز الاستدامة في الإنتاج الكيميائي

نُشر في:

نسخة الوثيقة:

جامعة كوينز بلفاست – بوابة البحث:

حقوق الناشر

هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول نُشرت بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام مع الإشارة إلى المؤلفhttps://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/الذي يسمح بالاستخدام غير المقيد، والتوزيع، والاستنساخ في أي وسيلة، بشرط ذكر المؤلف والمصدر.

الحقوق العامة

سياسة الإزالة

الوصول المفتوح

الابتكارات المدفوعة بالتنسيق في العمليات التحفيزية منخفضة الطاقة: تعزيز الاستدامة في الإنتاج الكيميائي

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

كيمياء التنسيق

تحفيز ضوئي

الكهربائية التحفيزية

التحفيز الصناعي

تطبيقات التحفيز

الملخص

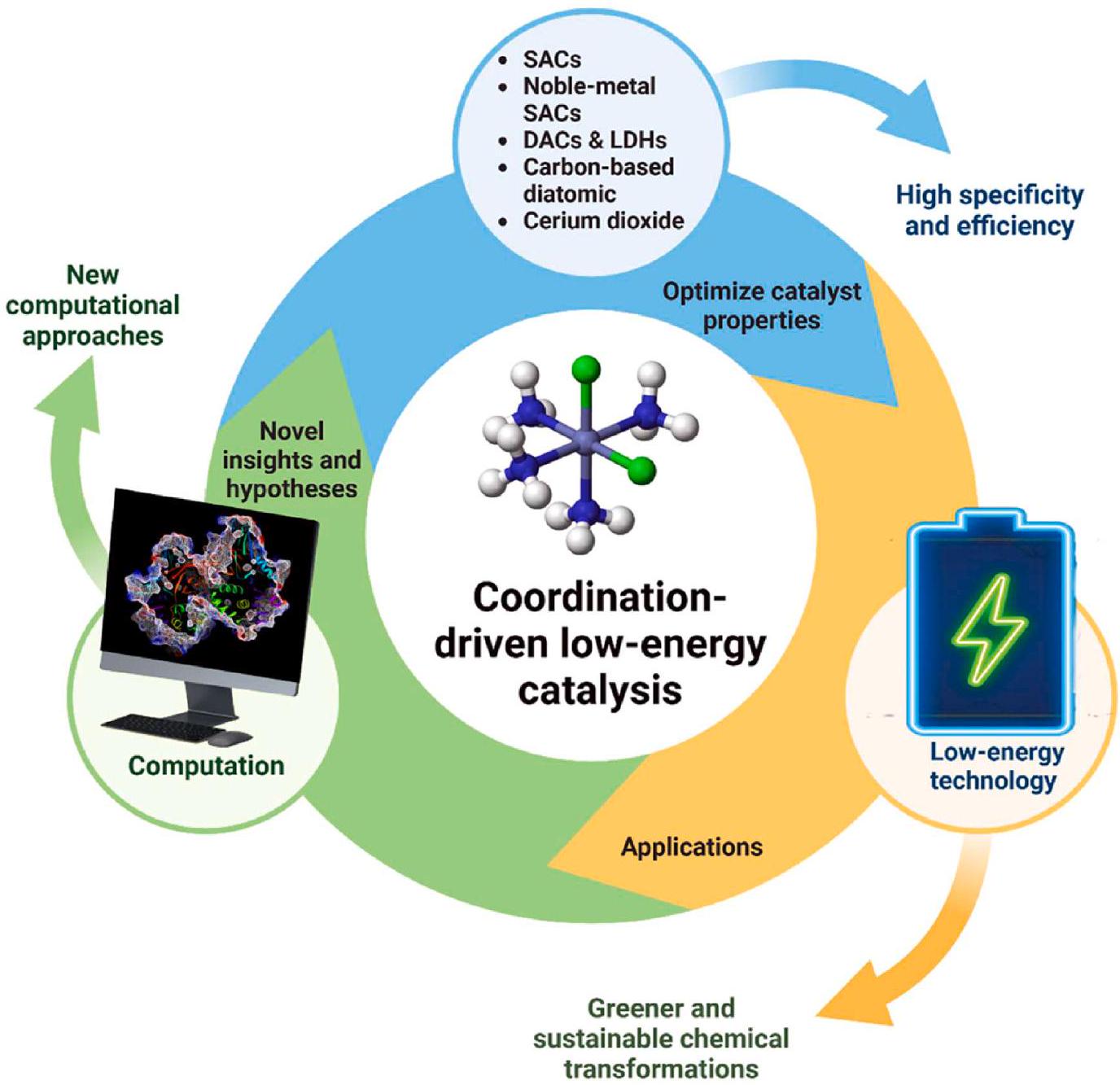

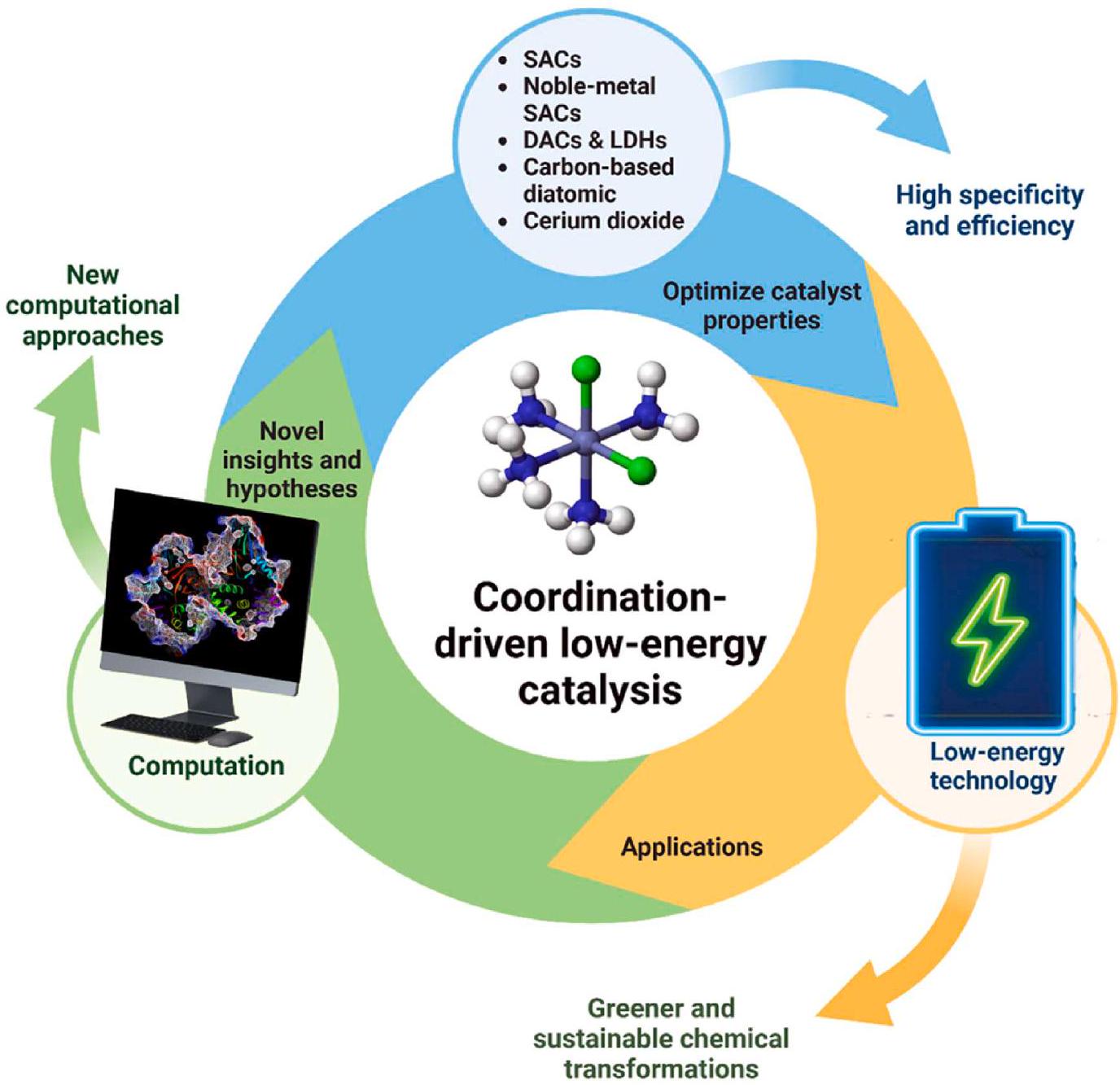

تعتبر الحفز حجر الزاوية في التخليق الكيميائي، حيث تلعب دورًا حيويًا في تعزيز مسارات التصنيع المستدام. لقد شهدت التطورات من العمليات الحفزية التي تتطلب طاقة عالية إلى العمليات الحفزية المستدامة تحولًا جذريًا، يتجلى بشكل خاص في الطرق الحفزية منخفضة الطاقة. تمثل هذه العمليات، التي تعمل تحت ظروف أكثر اعتدالًا وتؤكد على الانتقائية وإمكانية إعادة الاستخدام، طليعة الكيمياء المستدامة. تستعرض هذه المراجعة مجموعة من التفاعلات الكيميائية منخفضة الطاقة، مع تسليط الضوء على تطبيقاتها المتنوعة، وتختتم باستكشاف التقدمات الأخيرة في العمليات الحفزية منخفضة الطاقة. على سبيل المثال، تستكشف المراجعة استخدامات العمليات الحفزية منخفضة الطاقة في تطبيقات مثل تقليد الإنزيمات، وإنتاج الوقود الحيوي، والتقاط ثاني أكسيد الكربون، والتخليق العضوي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تغطي الحفز الإنزيمي والضوء الحفزي لتحويلات ثاني أكسيد الكربون، وتطبيقات الطاقة، ومعالجة المياه. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن المراجعة تؤكد على القدرات الحفزية منخفضة الطاقة للحفز ذي الذرة الواحدة (SAC) والحفازات ثنائية الذرات (DACs)، معترفًا بأدائها الاستثنائي في تحفيز التفاعلات عند طاقات تنشيط منخفضة مع الحفاظ على كفاءة عالية وانتقائية تحت ظروف معتدلة. من خلال توضيح تعديل الهيكل الإلكتروني وتقديم منظور ميكروإلكتروني، تهدف المراجعة إلى توضيح الآليات الكامنة وراء النشاط الحفزي لـ SAC و DACs. مع التأكيد على التفاعل بين مبادئ الكيمياء التنسيقية وفعالية الحفز، توضح المراجعة الدور الضروري للمركبات التنسيقية في تعزيز استدامة هذه العمليات. من خلال تسليط الضوء على دمج الكيمياء التنسيقية مع الحفز، تهدف هذه المراجعة إلى التأكيد على تأثيرهما المشترك في تشكيل مشهد الإنتاج الكيميائي المستدام.

1. المقدمة

التي تعتمد على درجات حرارة وضغوط عالية مصحوبة باستخدام موارد غير متجددة، تبرز الحاجة الملحة للبدائل المستدامة [8،9].

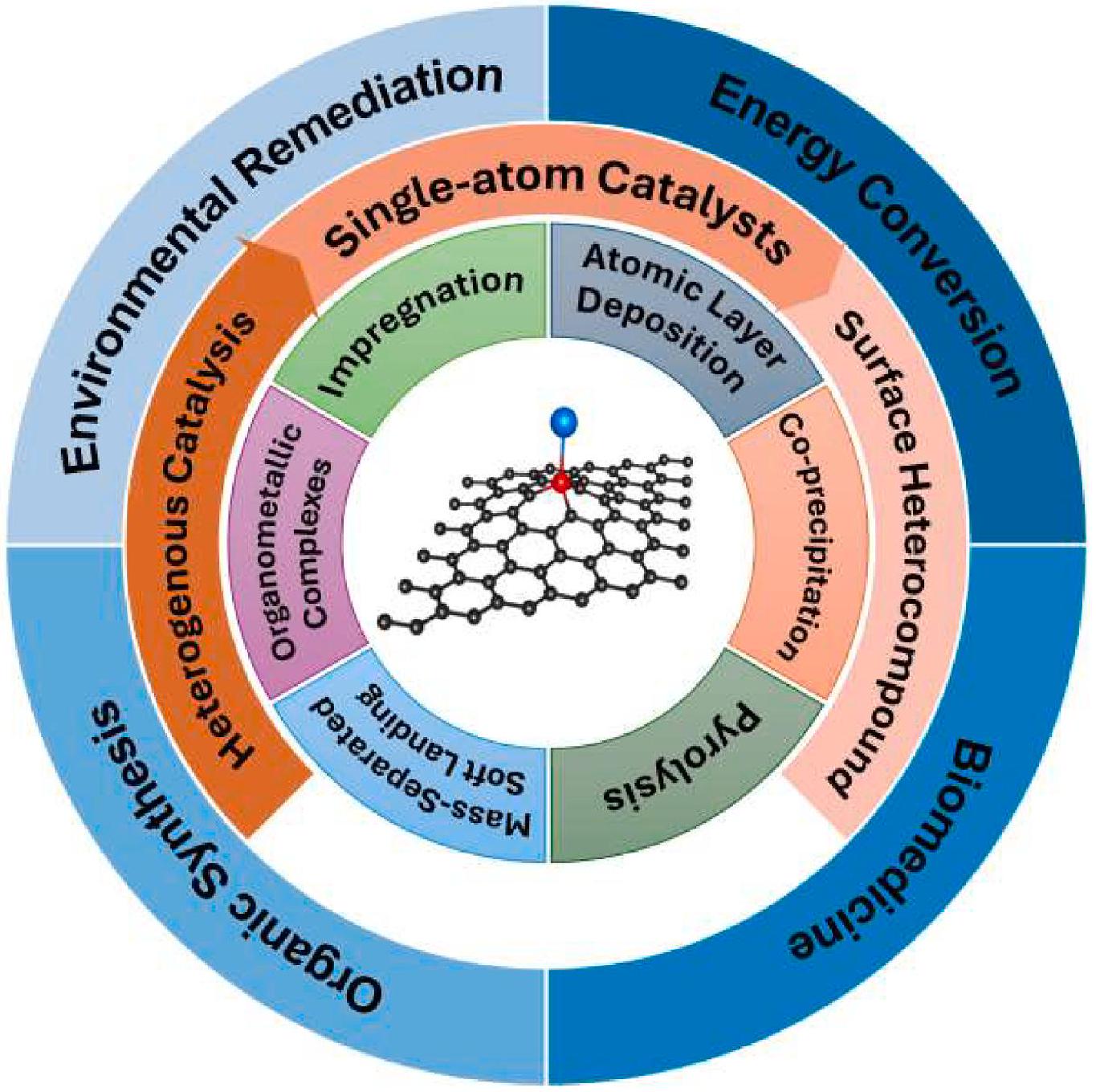

2. التطورات في الكيمياء التنسيقية: محفز لتحولات كيميائية أكثر خضرة واستدامة

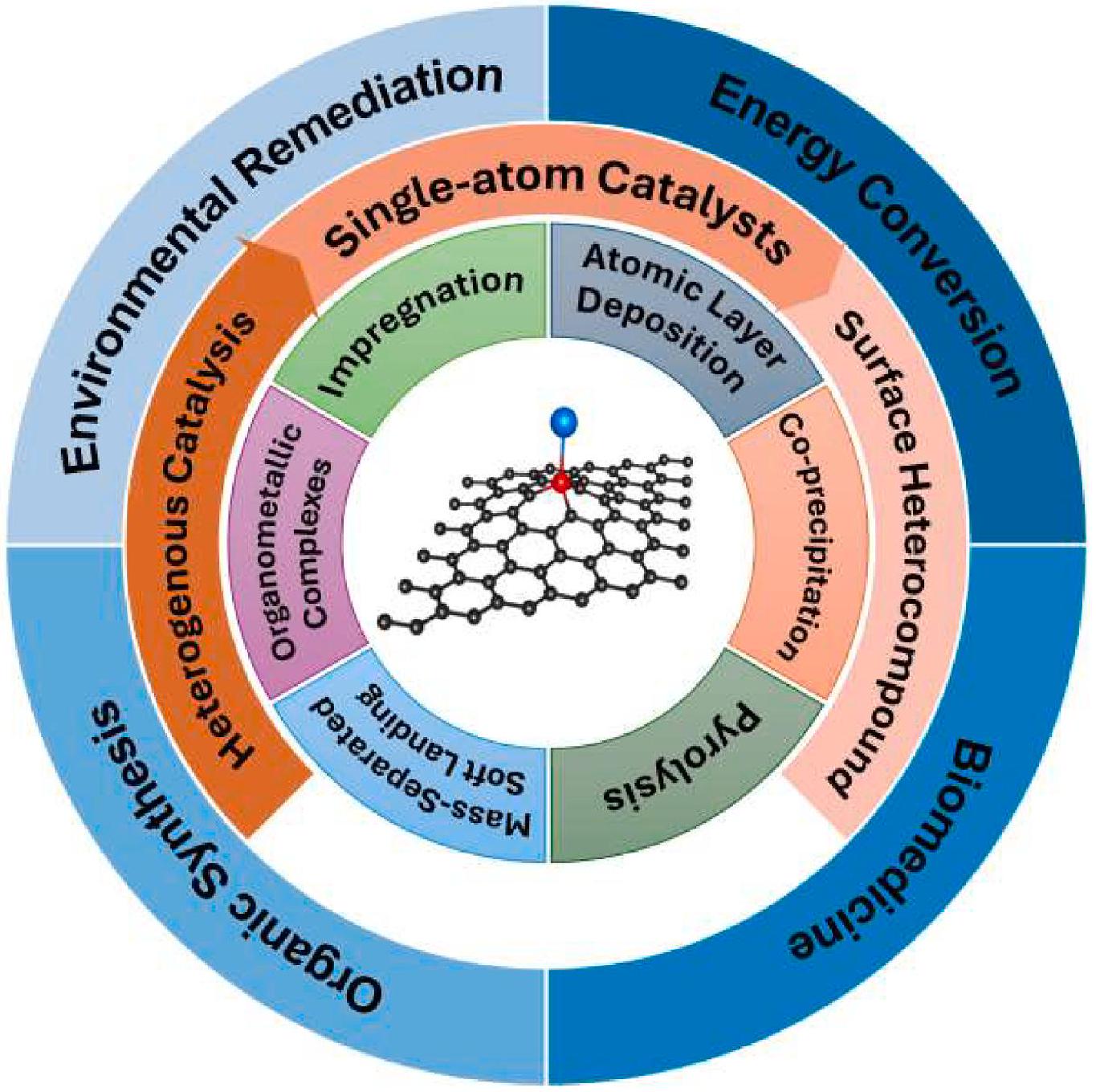

من كل من المحفزات المتجانسة وغير المتجانسة، التي تتميز بمواقع نشطة معزولة، وانتقائية عالية، وسهولة الفصل عن أنظمة التفاعل. توفر الشكل 2 تصويرًا موجزًا لعملية التخليق والتطبيقات الحفازة للمحفزات أحادية الذرة. على الرغم من استهلاك الطاقة المحتمل أثناء تخليق المحفزات أحادية الذرة، إلا أن هذه المحفزات تظهر القدرة الملحوظة على تحفيز التفاعلات الكيميائية عند طاقات تنشيط منخفضة للغاية بكفاءة استثنائية. تُظهر ذرات المعادن الموزعة على مواد الدعم كفاءة حفازة عالية وانتقائية. على الرغم من إمكانياتها، تواجه المحفزات أحادية الذرة تحديات تتعلق بتجمع ذرات المعادن أثناء عمليات التصنيع والتطبيق بسبب الطاقة السطحية العالية. ومع ذلك، فإن بناء روابط تنسيق قوية بين الذرات الفردية ودعائمها أثبت فعاليته في معالجة هذه المشكلة، مما يؤثر على النشاط والانتقائية للمحفزات أحادية الذرة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تلعب بيئات التنسيق للذرات الفردية النشطة في المحفزات أحادية الذرة دورًا حاسمًا في الاستقرار والخصائص الحفازة واستخدام مواد التحميل. تم تلخيص بيئات التنسيق وطرق تخليقها والتفاعلات القابلة للتطبيق، مما يظهر أن ذرات المعادن الفردية عادة ما تكون مستقرة على أسطح الركائز عبر روابط تساهمية أو أيونية. يتم تعريف الهياكل الهندسية والإلكترونية بشكل أساسي من خلال كيمياء التنسيق المحلية، مما يعمل كموصوفات قابلة للتنفيذ لاستكشاف علاقات الهيكل-النشاط في المحفزات أحادية الذرة. تشمل بيئات التنسيق

يثبت أنه فعال في خفض طاقة تنشيط التفاعل وتعزيز النشاط الحفزي [48]. تُعتبر المحفزات الثنائية القائمة على الكربون، كفئة هامة من هذا النوع من المحفزات، ذات تطبيقات واسعة في مجال التحفيز الكهربائي [43]. نجح زانغ وآخرون [48] في تخليق محفز ثنائي، يُشار إليه بـ

غالبًا ما يتم إدخالها في مصفوفة الكربون لتشكيل روابط N-C. إن دمج ذرات المعادن في هذا الهيكل الكربوني المدعوم بالذرات غير المعدنية، سواء كانت مثبتة بواسطة الذرة غير المعدنية أو البيئة السطحية الأساسية، يؤدي إلى تغييرات في الهيكل الإلكتروني لذرات المعادن، مما ينتج عنه تشكيل محفز بهيكل M-N-C. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن تصنيع محفزات ثنائية الذرات المدعومة عن طريق إدخال ثنائيات ذرية مباشرة على المواد القائمة على الكربون. تسهم الروابط القوية لموقع النشاط وتفاعله مع الدعم الكربوني في الكفاءة العالية والثبات في التحفيز الكهربائي في المحفزات ثنائية الذرات. يتضمن بناء محفز ثنائي الذرات مناسب تنظيم هيكله الإلكتروني، وخاصة من ثلاث وجهات نظر: الذرات المركزية ثنائية المعادن، والبيئة التنسيقية المحلية للذرات المركزية ثنائية المعادن، والبيئة القائمة على الكربون. يثبت تعديل الهيكل الإلكتروني هذا أنه ضروري لتحقيق تحفيز فعال عبر تفاعلات مختلفة، بما في ذلك تفاعل تطور الهيدروجين (HER)، وتفاعل تطور الأكسجين (OER)، وتفاعل اختزال الأكسجين (ORR)، وتفاعل اختزال ثاني أكسيد الكربون.

الاحترار العالمي. ومع ذلك، فإن تفعيل

3. أنواع التفاعلات الكيميائية الموفرة للطاقة وتطبيقاتها في مجالات مختلفة

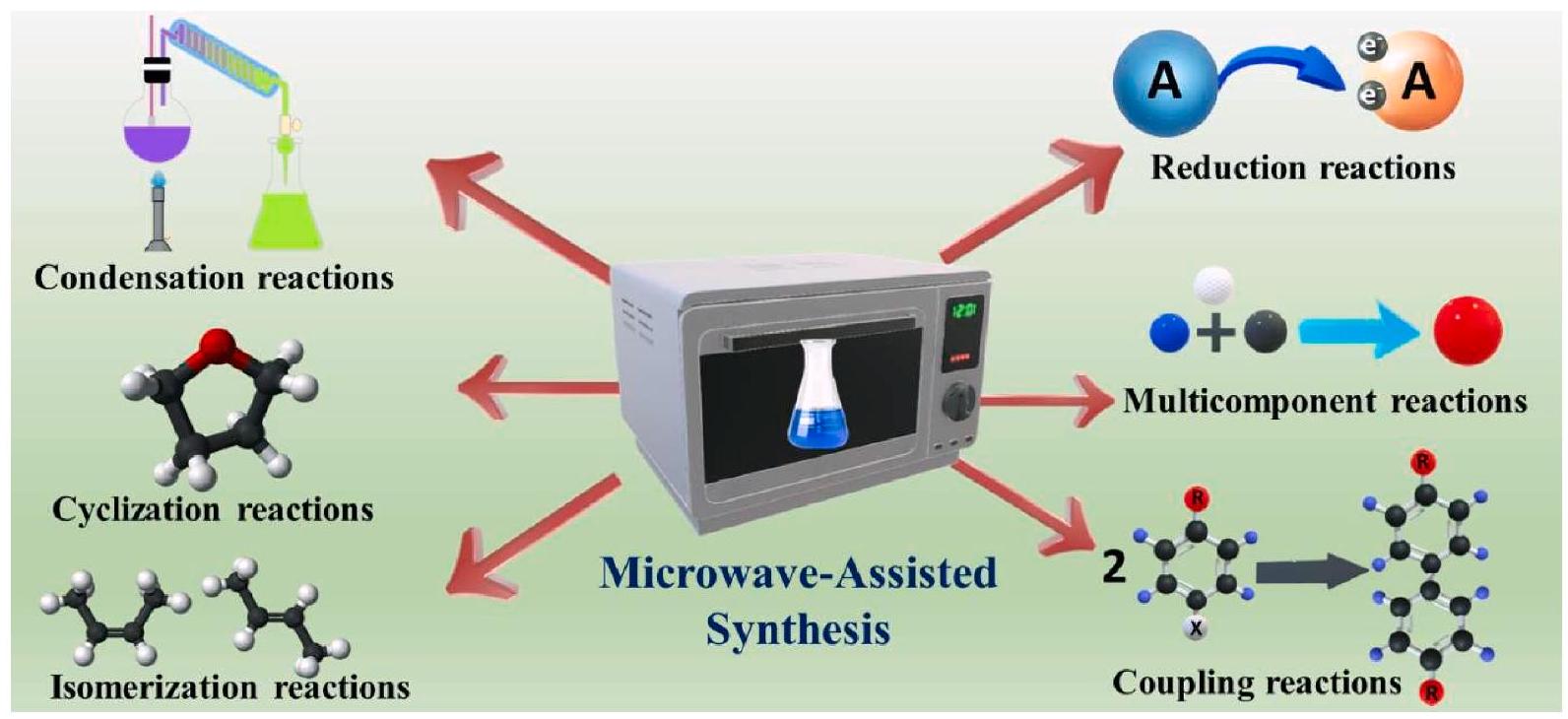

3.1. التفاعلات المساعدة بالموجات الدقيقة

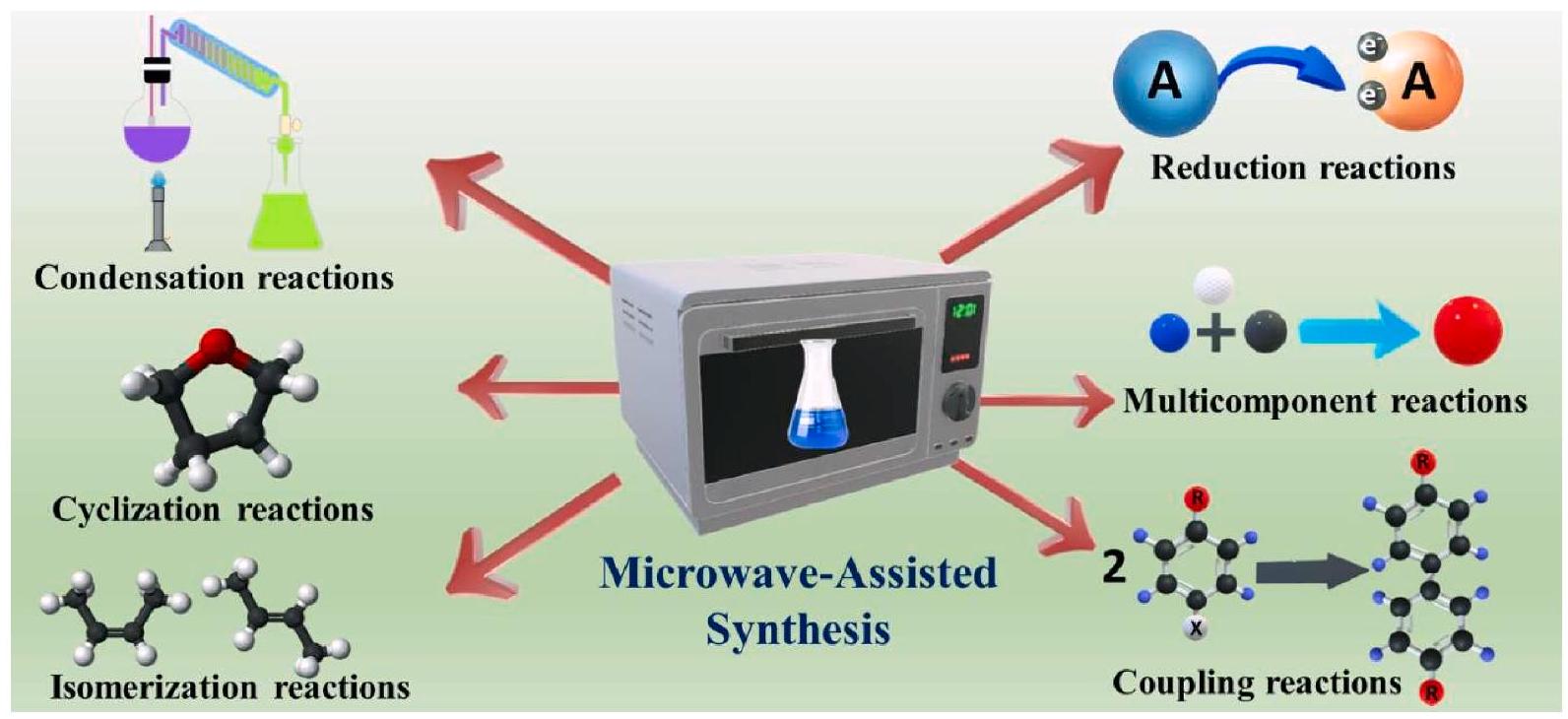

ديناميكا التفاعل، العائد العالي، والنقاء الأعلى هي بعض من المزايا الرئيسية للتفاعلات المعززة بالميكروويف. التسخين السريع وتقليل كبير في وقت التفاعل هما أكبر فوائدها. على سبيل المثال، تم تصنيع إطار عضوي معدني (DUT-67) باستخدام التصنيع المعزز بالميكروويف من خلال تقليل وقت التفاعل من 48 ساعة إلى ساعة واحدة، مقارنة بالطرق التقليدية المائية الحرارية.

زاوية الفقدان (

| مذيب | تان

|

مذيب | تان

|

| ماء | 0.123 | حمض الأسيتيك | 0.174 |

| ميثانول | 0.659 | الإيثيلين جلايكول | 1.350 |

| إيثانول | 0.941 | ثنائي ميثيل سلفوكسيد | 0.825 |

| كلوروفورم | 0.091 |

|

0.275 |

| التولوين | 0.040 | ثنائي ميثيل الفورماميد | 0.161 |

| الهكسان | 0.020 | 1,2-ثنائي كلوروبنزين | 0.280 |

| تيتراهيدروفوران | 0.047 | ثنائي كلورو ميثان | 0.042 |

| أسيتونيتريل | 0.062 | 1,2-ثنائي كلورو إيثان | 0.127 |

3.2. التفاعلات المساعدة بالموجات فوق الصوتية

المواد [135]، الممتزات [136،137]، المحفزات الضوئية [138]، والبوليمرات [48]. على سبيل المثال، تم استغلال نهج تقليل كيميائي بمساعدة الموجات فوق الصوتية لتخليق بلورات نانوية من النيكل أظهرت نشاطًا فعالًا في تفاعل تطور الهيدروجين [139].

[133]، يتم تطبيق تأثير التجويف الناتج عن الموجات فوق الصوتية القوية في السوائل تدريجياً لتحسين توزيع وقابلية بلل الجسيمات النانوية والميكروية. تم تحضير عدة ثنائي كبريتيدات المعادن الانتقالية باستخدام تقنيات مساعدة بالموجات فوق الصوتية [156،157] واستخدامها في تطبيقات مختلفة. على سبيل المثال، تحتوي الفوسفيدات المعدنية الانتقالية على ذرات كبريت تتفاعل مع البروتونات وتعزز تطور الهيدروجين. لقد حفزت النشاط الحفزي العالي لحواف ثنائي كبريتيد الموليبدينوم الباحثين على تحضير مركبات نانوية بكثافة حواف كبيرة وتكوين عيوب [158]. تم تطبيق طرق هيدروحرارية مساعدة بالموجات فوق الصوتية لتخليق محفزات كهربائية مسامية ثلاثية الأبعاد [159]. كانت سرعة انتقال الإلكترونات العالية، ومقاومة الاتصال الصغيرة مع الإلكتروليت، ووجود نقاط نشطة وفيرة هي الميزات التي تميزت بها.

عملية الأكسدة المتقدمة الكهروكيميائية، يتيح الصوت فوق الصوتي إنتاج كميات أكبر من الجذور في المحلول المائي، مما يحسن كفاءة التحلل. يتحلل بيروكسيد الهيدروجين المنتج كهربائياً إلى

الأنواع الناتجة [198]. في دراسة، درس محمودي وآخرون [199] أداء تقنيات فنتون الكهربائية وفنتون الصوتية الضوئية في تحلل مياه الصرف الملوثة بالأصباغ ووجدوا أن أقصى تحلل تم باستخدام فنتون الصوتية الضوئية من خلال زيادة توليد الجذور الحرة.

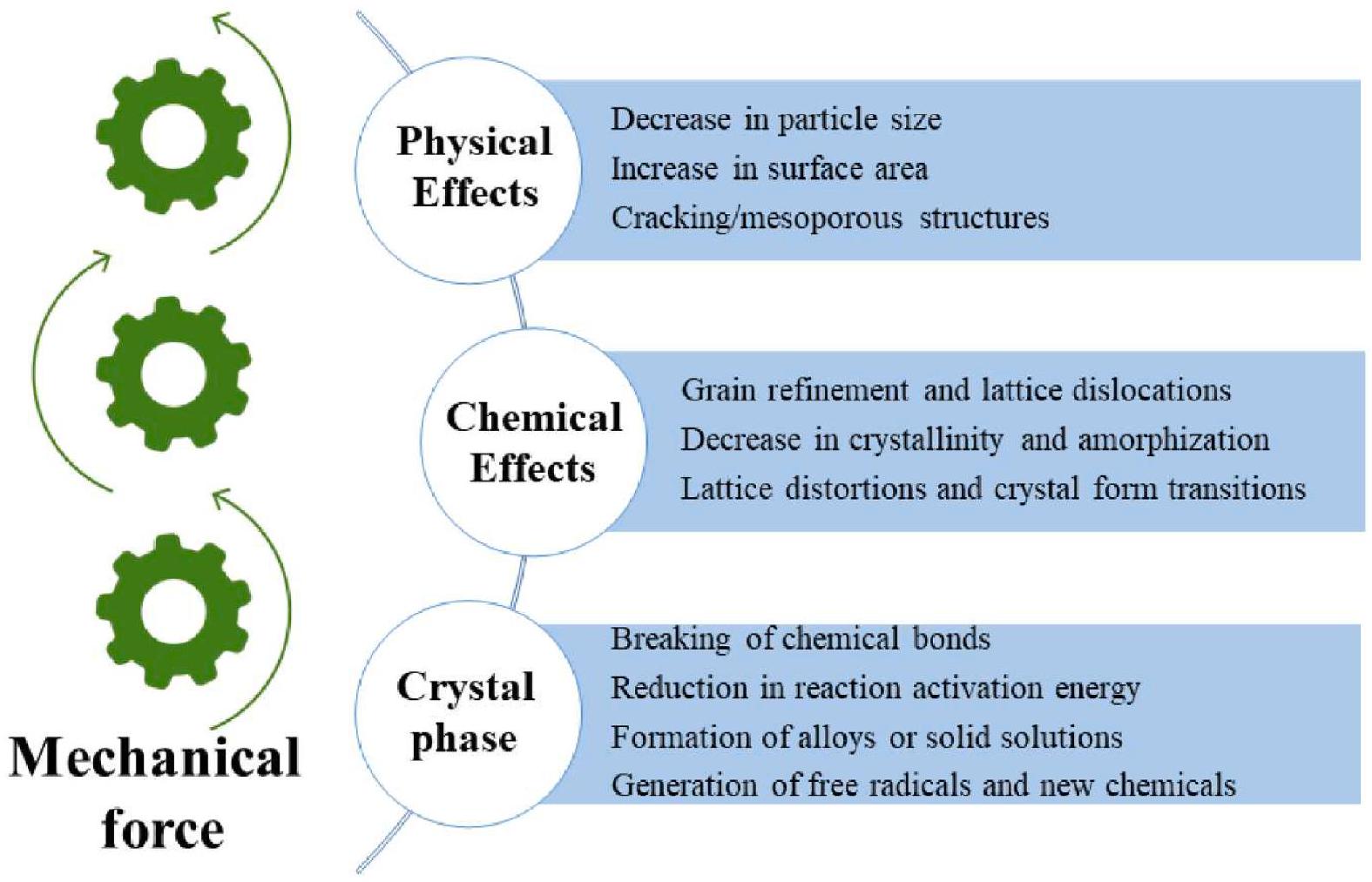

3.3. التفاعلات الميكانيكيميائية

4. التقدمات الحديثة في العمليات التحفيزية منخفضة الطاقة

4.1. تصميم المحفزات غير المتجانسة

4.1.1. المحفزات غير المتجانسة لمحاكاة الإنزيمات

الانتشارية. تم الحصول على

4.1.2. المحفزات غير المتجانسة لإنتاج الوقود الحيوي

عن طريق تحليل الأشعة السينية (XRD) ، وتحليل الطيف الكهرومغناطيسي بالأشعة تحت الحمراء (FTIR) ، وتحليل EDX ، وتحليل BET. أظهر تحليل XRD زيادة في بلورية المحفز بسبب تنشيط هيدروكسيد البوتاسيوم. بالمقارنة مع المواد الخام ، أظهر تحليل FTIR للمحفز وجود نطاقات امتصاص أكثر كثافة عند 3330-3350 ، 1600 ، و

نسبة المولات من الإيثانول إلى حمض الستاريك 11:1، ودرجة حرارة 353 كلفن.

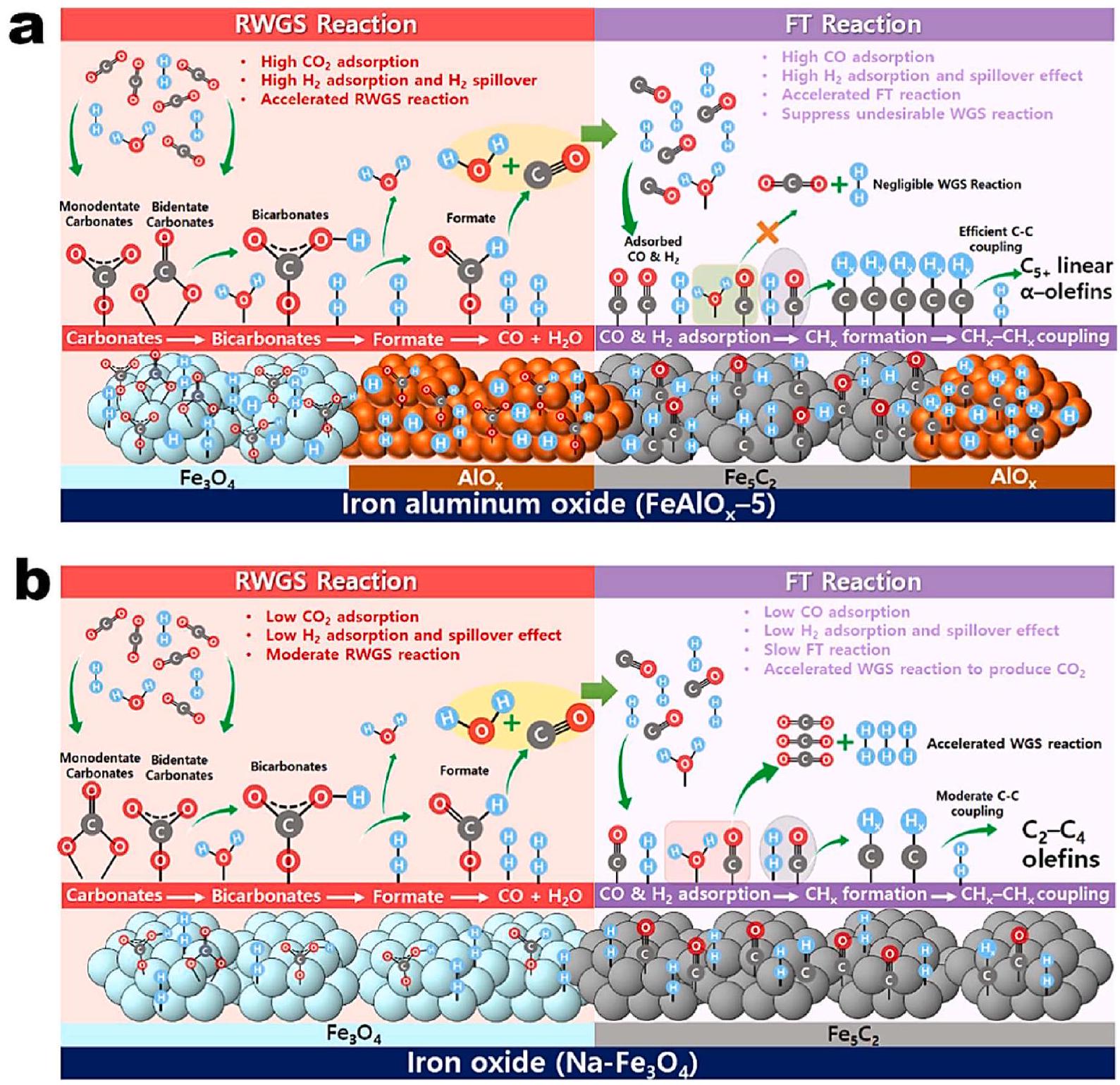

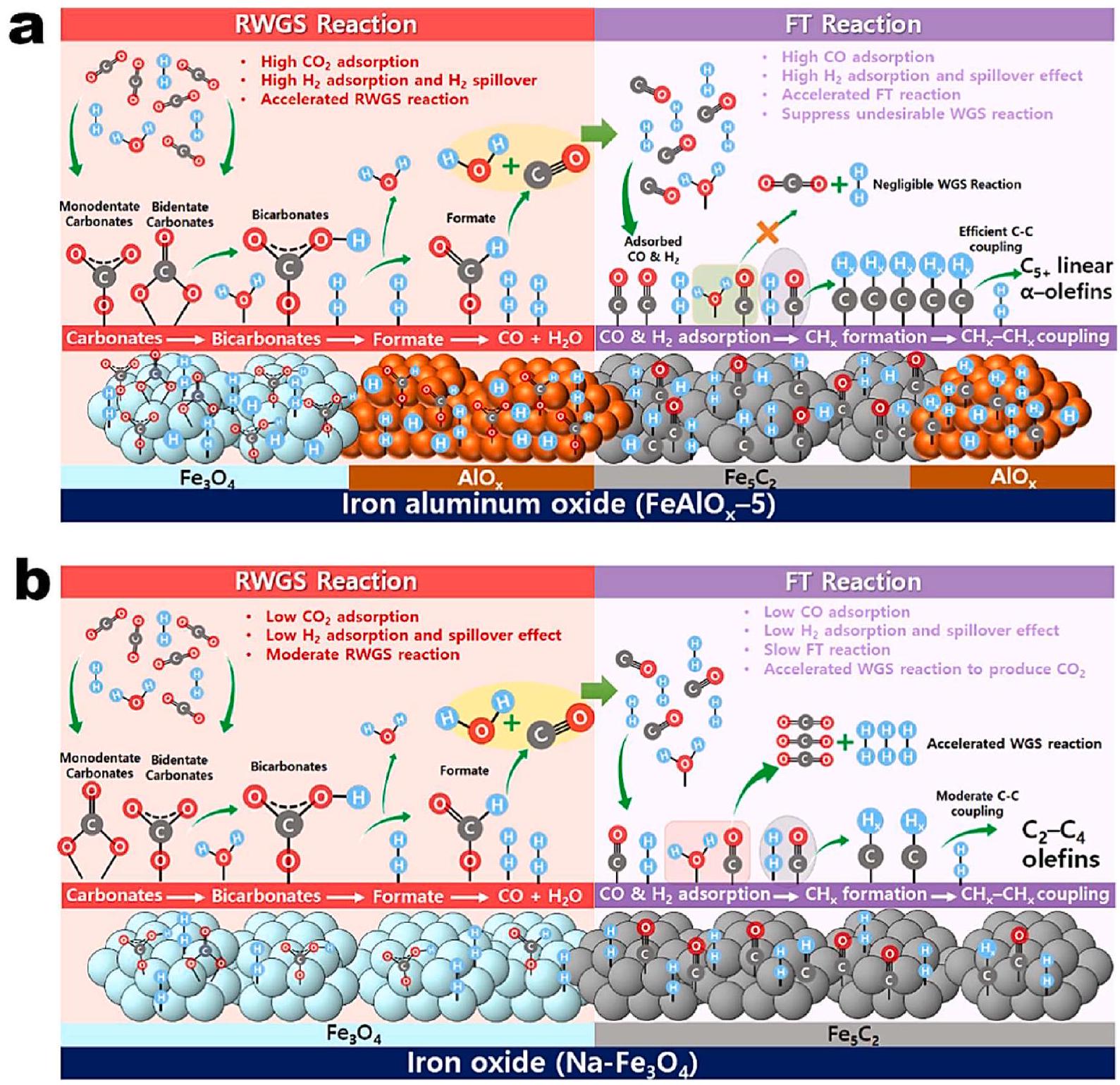

4.1.3. المحفزات غير المتجانسة لالتقاط ثاني أكسيد الكربون

السوائل المدعومة على المادة الصلبة القائمة على السيليكا، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى إنتاج المنتجات المرغوبة مثل الكربونات الحلقية أو مركبات عضوية أخرى. وُجد أن المواد التي تحتوي على سوائل أيونية لديها قدرة أعلى على امتصاص ثاني أكسيد الكربون، حيث

4.1.4. المحفزات غير المتجانسة للتخليق/التحولات العضوية

كفاءة عالية، انتقائية، وتنوع. تُستخدم لتنشيط وتسهيل انقسام الروابط الكيميائية في جزيئات المتفاعلات، مما يمكّن من بدء التحولات العضوية [22،242،243]. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تنشط المحفزات المعدنية

استرداد من خليط التفاعلات. هذا يمكّن من إعادة استخدام المحفزات لعدة دورات تفاعلية، مما يؤدي إلى توفير التكاليف، وتقليل توليد النفايات، وتحسين استدامة عمليات التخليق العضوي. على سبيل المثال، المحفزات المعدنية المدعومة مثل البلاتين على الألومينا.

علاوة على ذلك، تم تقليل كثافة القمة لمجموعة الهيدروكسيل عند

4.2. التحفيز الإنزيمي

4.2.1. التحفيز الإنزيمي لتحويلات/تثبيت ثاني أكسيد الكربون

دورة تثبيت ثاني أكسيد الكربون الموفرة للطاقة [268]. يمكن أن يقلل إنزيم Nmar_1308 من العدد الإجمالي للإنزيمات المطلوبة لتثبيت ثاني أكسيد الكربون في الثومارشيكوتا، مما يقلل من التكلفة الإجمالية للتخليق الحيوي. وذلك لأن دورة 3-هيدروكسي بروبيونات/ 4-هيدروكسي بيوتيرات الثومارشيكال تحتاج إلى روابط أنهدريد فوسفاتية منخفضة الطاقة من ATP لكل جزيء أسيتيل-CoA [269].

4.2.2. التحفيز الإنزيمي لالتقاط ثاني أكسيد الكربون

4.2.3. التحفيز الإنزيمي لتطبيقات الطاقة

تحلل اللجنين إلى مركبات عطرية متنوعة [296]. تعتبر التخمر في الحالة الصلبة نهجًا لتطوير الكائنات الدقيقة في غياب الماء الحر من خلال استخدام جزيئات صلبة مع مرحلة غازية مستمرة بين الجزيئات إما كركيزة أو دعم صلب غير نشط [297]. تم استخدام عدة أنواع من الكتلة الحيوية اللجنوسليلوزية، بما في ذلك نخالة الأرز، والحبوب المهدرة من مصانع الجعة، وقش القهوة، وبقايا العنب، ورقائق الخشب، وكعك الزيت، ونخالة القمح، وقش الذرة، وبقايا الزيتون، كركائز أساسية لتكوين إنزيمات بكتيرية وفطرية عبر التخمر في الحالة الصلبة [298،299]. على الرغم من الفوائد العديدة لتقنية التخمر في الحالة الصلبة، إلا أن قابليتها للاستخدام الصناعي محدودة حاليًا بسبب التغيرات في درجة الحرارة، ودرجة الحموضة، والرطوبة، والأكسجين، والمعلمات الأخرى التي تؤثر على تطوير الكائنات الدقيقة وتكوين المستقلبات داخل المفاعل الحيوي نتيجة لصعوبة تحريك الركيزة الصلبة [296]. لذلك، من الضروري إنشاء مفاعلات حيوية فعالة مع تحكم تلقائي لتعزيز إنتاجية المنتج.

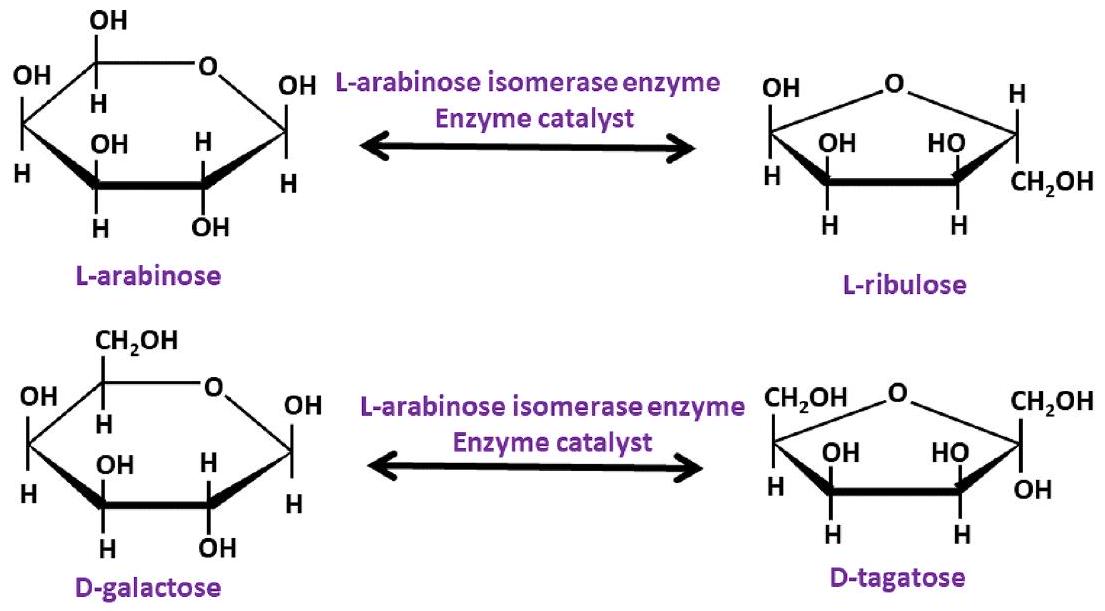

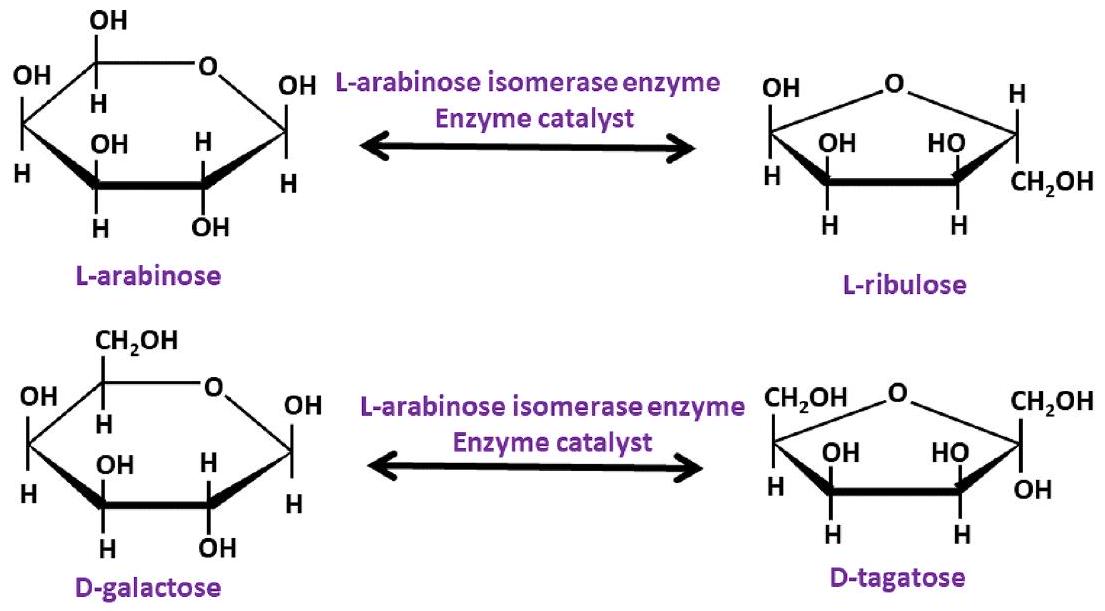

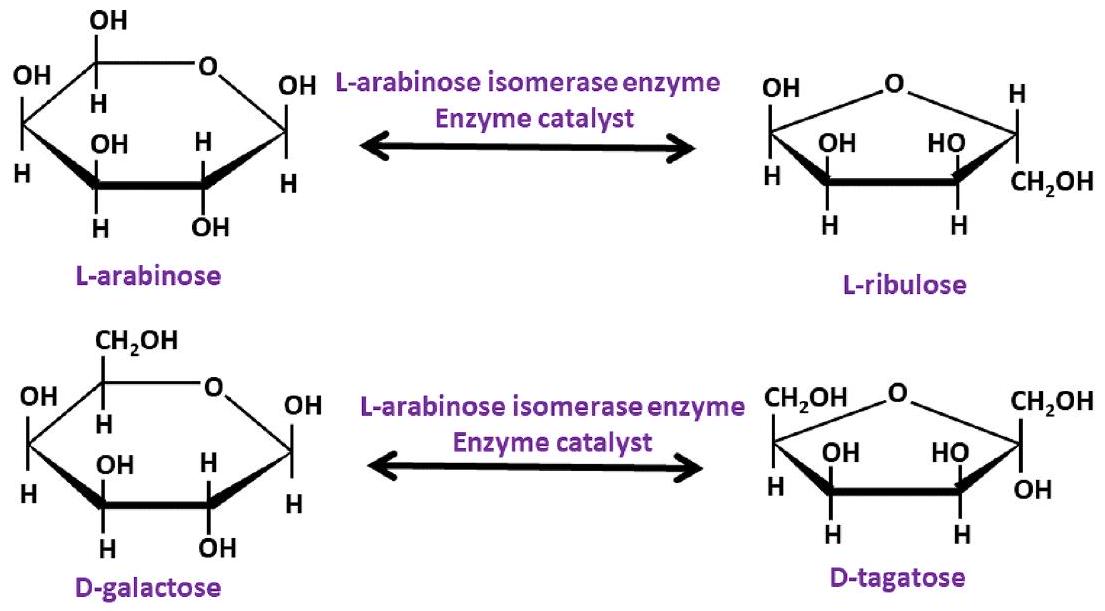

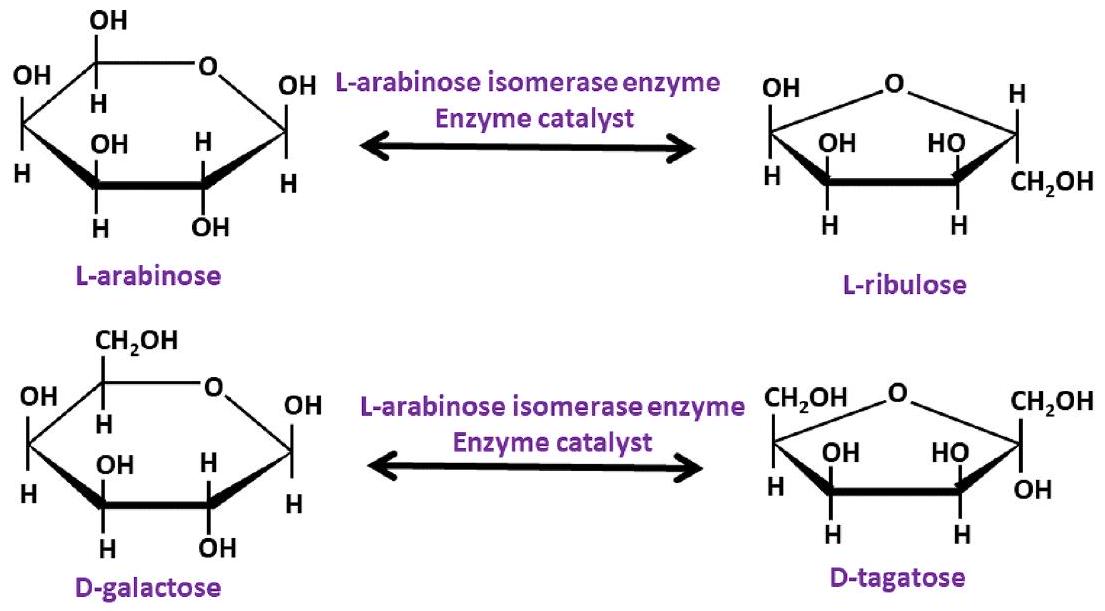

4.2.4. التحفيز الإنزيمي للتخليق/التحويل العضوي

4.3. التحفيز الضوئي

4.3.1. التحفيز الضوئي لإنتاج الهيدروجين

4.3.2. التحفيز الضوئي لإنتاج الوقود الحيوي

4.3.3. التحفيز الضوئي للتخليق/التحويل العضوي

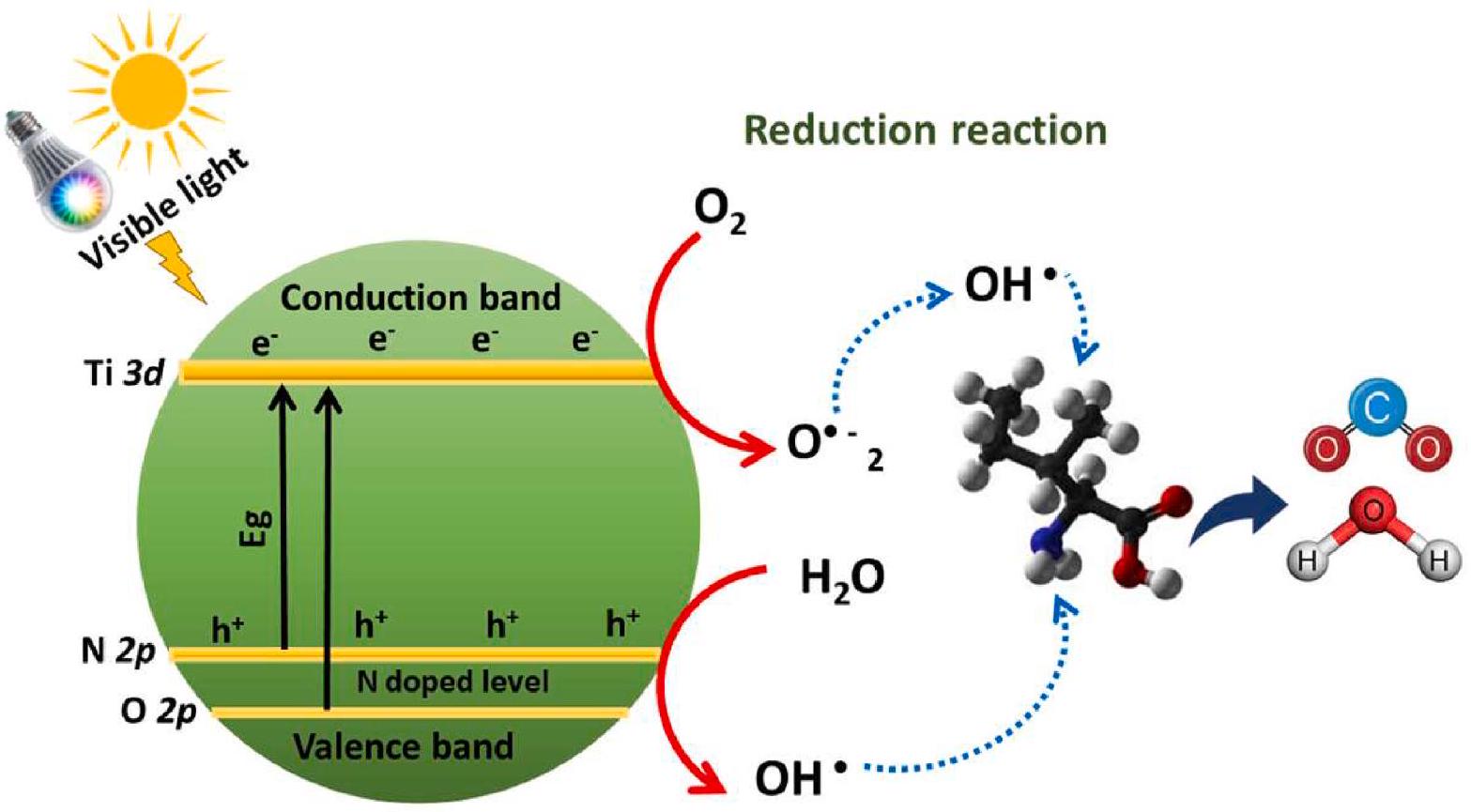

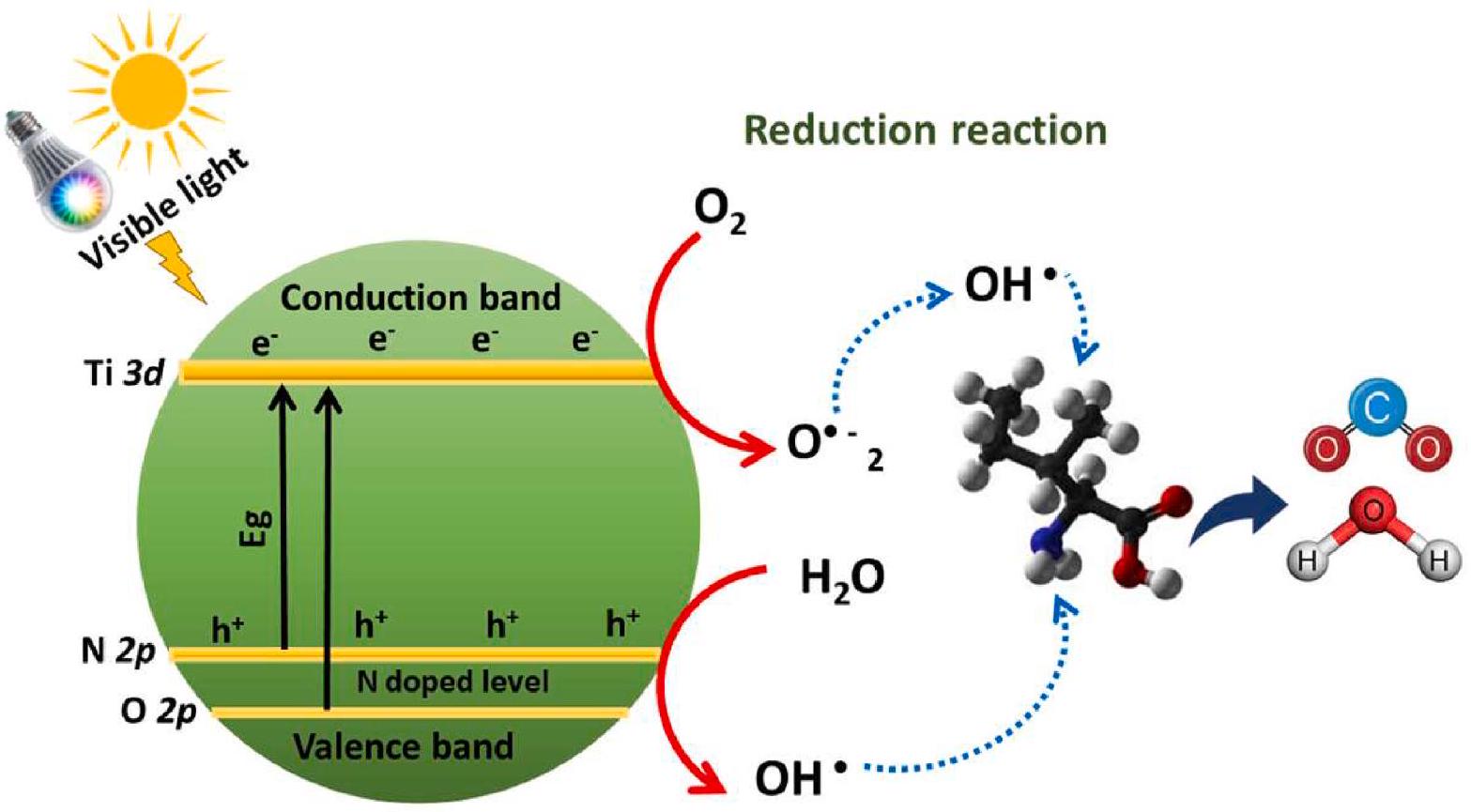

4.3.4. التحفيز الضوئي لمعالجة المياه ومياه الصرف الصحي

داخل مياه الصرف الصحي. تشمل المتغيرات الرئيسية التي تؤثر على هذه العملية اختيار المحفز الضوئي، وخصائص الضوء، ووجود المواد المضافة، والشكل الهيكلي للمحفز الضوئي. بشكل عام، تعتمد تقنية التحفيز الضوئي على استخدام محفزات ضوئية شبه موصلة (مثل

5. التأثير على الإنتاج الكيميائي المستدام

5.1. إزالة الكربون وتوفير الطاقة المحتمل

من المتوقع زيادة كبيرة في هذه المستويات من ثاني أكسيد الكربون على مدى السنوات القادمة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يأتي أكثر من (

بنسبة (

تحتاج التجديد إلى حوالي

5.2. الفوائد البيئية

يمكن أن يؤدي الجمع بين الطاقة المتجددة كتكنولوجيا منخفضة الطاقة إلى عواقب إيجابية على البيئة. يُبلغ عن أن إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية العالمية يطلق حوالي 100 مليار طن متري من الكربون سنويًا. يتم إدارة مصادر الكتلة الحيوية المحددة بشكل غير كافٍ من خلال الاحتراق في الموقع، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة انبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكربون. لذلك، يمكن أن يقلل استخدام الكتلة الحيوية في تكنولوجيا التحليل الكهربائي منخفضة الطاقة من إمكانات الاحترار العالمي. على وجه الخصوص، يمكن استخدام الكتلة الحيوية اللجنوسليلوزية لإنتاج إنزيمات تعمل كعوامل مساعدة في تقنيات التحفيز الإنزيمي منخفضة الطاقة. يمكن أن يقلل استخدام الكتلة الحيوية اللجنوسليلوزية في التحفيز الإنزيمي من تأثيراتها البيئية المرتبطة وانبعاثات غازات الدفيئة بسبب الاحتراق في الموقع والتخلص في مدافن النفايات.

رماد الطين السائل إلى محفزات كاليوبيلت ذات تركيب شبيه بالزيوليت لإنتاج الديزل الحيوي [227]. يتم تلقي اهتمام متزايد في إنتاج الديزل الحيوي من خلال تفاعلات الاسترification التي تحفزها المحفزات غير المتجانسة بسبب الفوائد البيئية لهذه الطريقة. يمكن أن تحل هذه الطريقة مشكلات مثل تآكل الأدوات، وإنتاج النفايات من عملية تحييد الحمض، وتحديات فصل المنتجات الناتجة عن استخدام الأحماض السائلة المتجانسة مثل حمض الكبريتيك [388-390].

6. الخاتمة

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

References

[2] A.I. Osman, A.M. Elgarahy, A.S. Eltaweil, E.M. Abd El-Monaem, H.G. El-Aqapa, Y. Park, Y. Hwang, A. Ayati, M. Farghali, I. Ihara, A.H. Al-Muhtaseb, D. W. Rooney, P.S. Yap, M. Sillanpää, Environ. Chem. Lett. 21 (2023) 1315-1379.

[3] H. Li, X. Qin, K. Wang, T. Ma, Y. Shang, Sep. Purif. Technol. 333 (2024) 125900.

[4] Y. Chen, X. Jiang, J. Xu, D. Lin, X. Xu, Environ. Funct. Mater. (2023).

[5] F.-X. Wang, Z.-C. Zhang, C.-C. Wang, Chem. Eng. J. 459 (2023) 141538.

[6] F. Karimi, N. Zare, R. Jahanshahi, Z. Arabpoor, A. Ayati, P. Krivoshapkin, R. Darabi, E.N. Dragoi, G.G. Raja, F. Fakhari, H. Karimi-Maleh, Environ. Res. 238 (2023) 117202.

[7] Y. Sun, Y. Zhao, Y. Zhou, L. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Qi, D. Fu, P. Zhang, K. Zhao, Mater. Today Energy 37 (2023) 101397.

[8] P.K. Verma, Coord. Chem. Rev. 472 (2022) 214805.

[9] H.-S. Xu, W. Xie, Coord. Chem. Rev. 501 (2024) 215591.

[10] I. Huskić, C.B. Lennox, T. Friščić, Green Chem. 22 (2020) 5881-5901.

[11] S. Eon Jun, S. Choi, J. Kim, K.C. Kwon, S.H. Park, H.W. Jang, Chin. J. Catal. 50 (2023) 195-214.

[12] Q.-N. Zhan, T.-Y. Shuai, H.-M. Xu, C.-J. Huang, Z.-J. Zhang, G.-R. Li, Chin. J. Catal. 47 (2023) 32-66.

[13] A. Noor, Coord. Chem. Rev. 476 (2023) 214941.

[14] S.S.M. Bandaru, J. Shah, S. Bhilare, C. Schulzke, A.R. Kapdi, J. Roger, J.C. Hierso, Coord. Chem. Rev. 491 (2023) 215250.

[15] Z. Wu, M. Tallu, G. Stuhrmann, S. Dehnen, Coord. Chem. Rev. 497 (2023) 215424.

[16] H. Wang, M. Gu, X. Huang, A. Gao, X. Liu, P. Sun, X. Zhang, J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023) 7239-7245.

[17] W. Matsuoka, Y. Harabuchi, S. Maeda, ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 5697-5711.

[18] Y. Zhang, J. Yang, R. Ge, J. Zhang, J.M. Cairney, Y. Li, M. Zhu, S. Li, W. Li, Coord. Chem. Rev. 461 (2022) 214493.

[19] C. Wang, Z. Wang, S. Mao, Z. Chen, Y. Wang, Chin. J. Catal. 43 (2022) 928-955.

[20] L. Li, G. Zhao, Z. Lv, P. An, J. Ao, M. Song, J. Zhao, G. Liu, Chem. Eng. J. 474 (2023) 145647.

[21] S. Tian, H. Tang, Q. Wang, X. Yuan, Q. Ma, M. Wang, Sci. Total Environ. 772 (2021) 145049.

[22] D. Roy, P. Kumar, A. Soni, M. Nemiwal, Tetrahedron 138 (2023) 133408.

[23] C. Xia, J. Wu, S.A. Delbari, A.S. Namini, Y. Yuan, Q. Van Le, D. Kim, R.S. Varma, A.T. Raissi, H.W. Jang, M. Shokouhimehr, Mol. Catal. 546 (2023) 113217.

[24] S.S. Stahl, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 8524-8525.

[25] G.A. Bhat, D.J. Darensbourg, Coord. Chem. Rev. 492 (2023) 215277.

[26] P.J. Craig, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 7 (1993) 224.

[27] W. Chen, P. Cai, H.-C. Zhou, S.T. Madrahimov, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63 (2024) e202315075.

[28] G. Li, B. Wang, D.E. Resasco, Surf. Sci. Rep. 76 (2021) 100541.

[29] Y. Tian, D. Deng, L. Xu, M. Li, H. Chen, Z. Wu, S. Zhang, Nano-Micro Lett. 15 (2023) 122.

[30] J. Li, C. Chen, L. Xu, Y. Zhang, W. Wei, E. Zhao, Y. Wu, C. Chen, JACS Au 3 (2023) 736-755.

[31] A.C.M. Loy, S.Y. Teng, B.S. How, X. Zhang, K.W. Cheah, V. Butera, W.D. Leong, B. L.F. Chin, C.L. Yiin, M.J. Taylor, G. Kyriakou, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 96 (2023) 101074.

[32] Y. Chen, S. Ji, C. Chen, Q. Peng, D. Wang, Y. Li, Joule 2 (2018) 1242-1264.

[33] R. Qin, P. Liu, G. Fu, N. Zheng, Small Methods 2 (2018) 1700286.

[34] L. DeRita, S. Dai, K. Lopez-Zepeda, N. Pham, G.W. Graham, X. Pan, P. Christopher, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 14150-14165.

[35] J. Liu, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 34-59.

[36] L. Liu, A. Corma, Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 4981-5079.

[37] R. Jiang, L. Li, T. Sheng, G. Hu, Y. Chen, L. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 11594-11598.

[38] C. Tang, Y. Jiao, B. Shi, J.-N. Liu, Z. Xie, X. Chen, Q. Zhang, S.-Z. Qiao, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 9171-9176.

[39] J. Hulva, M. Meier, R. Bliem, Z. Jakub, F. Kraushofer, M. Schmid, U. Diebold, C. Franchini, G.S. Parkinson, Science 371 (2021) 375-379.

[40] H. Yang, L. Shang, Q. Zhang, R. Shi, G.I.N. Waterhouse, L. Gu, T. Zhang, Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4585.

[41] L. Wang, M.-X. Chen, Q.-Q. Yan, S.-L. Xu, S.-Q. Chu, P. Chen, Y. Lin, H.-W. Liang, Sci. Adv. 5, eaax6322.

[42] E. Jung, H. Shin, B.-H. Lee, V. Efremov, S. Lee, H.S. Lee, J. Kim, W. Hooch Antink, S. Park, K.-S. Lee, S.-P. Cho, J.S. Yoo, Y.-E. Sung, T. Hyeon, Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 436-442.

[43] T. Tang, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Coord. Chem. Rev. 492 (2023) 215288.

[44] W.H. Li, J. Yang, D. Wang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202213318.

[45] T. Tang, Y. Wang, J. Han, Q. Zhang, X. Bai, X. Niu, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Chin. J. Catal. 46 (2023) 48-55.

[46] T. Tang, Z. Duan, D. Baimanov, X. Bai, X. Liu, L. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Nano Res. 16 (2023) 2218-2223.

[47] X. Zheng, B. Li, Q. Wang, D. Wang, Y. Li, Nano Res. 15 (2022) 7806-7839.

[48] H. Zhang, X. Jin, J.-M. Lee, X. Wang, ACS Nano 16 (2022) 17572-17592.

[49] Y. Song, B. Xu, T. Liao, J. Guo, Y. Wu, Z. Sun, Small 17 (2021) 2002240.

[50] Y. Lei, Y. Wang, Y. Liu, C. Song, Q. Li, D. Wang, Y. Li, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 20794-20812.

[51] D.-S. Bin, Y.-S. Xu, S.-J. Guo, Y.-G. Sun, A.-M. Cao, L.-J. Wan, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 221-231.

[52] S. Zhang, Y. Wu, Y.-X. Zhang, Z. Niu, Sci. China Chem. 64 (2021) 1908-1922.

[53] T. Hu, Z. Gu, G.R. Williams, M. Strimaite, J. Zha, Z. Zhou, X. Zhang, C. Tan, R. Liang, Chem. Soc. Rev. (2022).

[54] C. Ning, S. Bai, J. Wang, Z. Li, Z. Han, Y. Zhao, D. O’Hare, Y.-F. Song, Coord. Chem. Rev. 480 (2023) 215008.

[55] Z.-Z. Yang, C. Zhang, G.-M. Zeng, X.-F. Tan, D.-L. Huang, J.-W. Zhou, Q.-Z. Fang, K.-H. Yang, H. Wang, J. Wei, K. Nie, Coord. Chem. Rev. 446 (2021) 214103.

[56] G. Wang, D. Huang, M. Cheng, S. Chen, G. Zhang, L. Lei, Y. Chen, L. Du, R. Li, Y. Liu, Coord. Chem. Rev. 460 (2022) 214467.

[57] H. Ye, S. Liu, D. Yu, X. Zhou, L. Qin, C. Lai, F. Qin, M. Zhang, W. Chen, W. Chen, L. Xiang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 450 (2022) 214253.

[58] Z. Cai, D. Zhou, M. Wang, S.-M. Bak, Y. Wu, Z. Wu, Y. Tian, X. Xiong, Y. Li, W. Liu, S. Siahrostami, Y. Kuang, X.-Q. Yang, H. Duan, Z. Feng, H. Wang, X. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 9392-9396.

[59] P. Li, X. Duan, Y. Kuang, Y. Li, G. Zhang, W. Liu, X. Sun, Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018) 1703341.

[60] X. Li, Y. Sun, J. Xu, Y. Shao, J. Wu, X. Xu, Y. Pan, H. Ju, J. Zhu, Y. Xie, Nat. Energy 4 (2019) 690-699.

[61] X. Hao, L. Tan, Y. Xu, Z. Wang, X. Wang, S. Bai, C. Ning, J. Zhao, Y. Zhao, Y.F. Song, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59 (2020) 3008-3015.

[62] K. Teramura, S. Iguchi, Y. Mizuno, T. Shishido, T. Tanaka, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 8008-8011.

[63] Y. Li, J. Hao, H. Song, F. Zhang, X. Bai, X. Meng, H. Zhang, S. Wang, Y. Hu, J. Ye, Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 2359.

[64] L. Tan, S.-M. Xu, Z. Wang, Y. Xu, X. Wang, X. Hao, S. Bai, C. Ning, Y. Wang, W. Zhang, Y.K. Jo, S.-J. Hwang, X. Cao, X. Zheng, H. Yan, Y. Zhao, H. Duan, Y.F. Song, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) (1867) 11860-11861.

[65] L. Tan, S.-M. Xu, Z. Wang, X. Hao, T. Li, H. Yan, W. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Y.-F. Song, Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2 (2021) 100322.

[66] Z. Wang, S.-M. Xu, L. Tan, G. Liu, T. Shen, C. Yu, H. Wang, Y. Tao, X. Cao, Y. Zhao, Y.-F. Song, Appl. Catal. B 270 (2020) 118884.

[67] J. Ren, S. Ouyang, H. Xu, X. Meng, T. Wang, D. Wang, J. Ye, Adv. Energy Mater. 7 (2017) 1601657.

[68] X. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Sun, K. Li, T. Shang, Y. Wan, Front. Chem. 10 (2022) 1089708.

[69] Y. Li, W. Shen, Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (2014) 1543-1574.

[70] M. Melchionna, P. Fornasiero, Mater. Today 17 (2014) 349-357.

[71] D. Gao, Y. Zhang, Z. Zhou, F. Cai, X. Zhao, W. Huang, Y. Li, J. Zhu, P. Liu, F. Yang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 5652-5655.

[72] Q. Li, L. Song, Z. Liang, M. Sun, T. Wu, B. Huang, F. Luo, Y. Du, C.-H. Yan, Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2 (2021) 2000063.

[73] J. Kong, Z. Xiang, G. Li, T. An, Appl. Catal. B 269 (2020) 118755.

[74] S.A. Galema, Chem. Soc. Rev. 26 (1997) 233-238.

[75] C.O. Kappe, D. Dallinger, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5 (2006) 51-63.

[76] S.-T. Chen, S.-H. Chiou, K.-T. Wang, J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 38 (1991) 85-91.

[77] D. Dallinger, C.O. Kappe, Chem. Rev. 107 (2007) 2563-2591.

[78] B.-X. Jiang, H. Wang, Y.-T. Zhang, S.-B. Li, Polyhedron 243 (2023) 116569.

[79] V. Bon, I. Senkovska, I.A. Baburin, S. Kaskel, Cryst. Growth Des. 13 (2013) 1231-1237.

[80] G. Bond, R.B. Moyes, D.A. Whan, Catal. Today 17 (1993) 427-437.

[81] R. Gedye, F. Smith, K. Westaway, H. Ali, L. Baldisera, L. Laberge, J. Rousell, Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (1986) 279-282.

[82] R.J. Giguere, T.L. Bray, S.M. Duncan, G. Majetich, Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (1986) 4945-4948.

[83] M.B. Gawande, S.N. Shelke, R. Zboril, R.S. Varma, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 1338-1348.

[84] M.B. Gawande, V.D.B. Bonifácio, R. Luque, P.S. Branco, R.S. Varma, ChemSusChem 7 (2014) 24-44.

[85] H. Cho, F. Török, B. Török, Green Chem. 16 (2014) 3623-3634.

[86] J.D. Moseley, C.O. Kappe, Green Chem. 13 (2011) 794-806.

[87] V. Polshettiwar, R.S. Varma, Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (2008) 629-639.

[88] A. Pons-Balagué, M.J.H. Ojea, M. Ledezma-Gairaud, D.R. Mañeru, S.J. Teat, J. S. Costa, G. Aromí, E.C. Sanudo, Polyhedron 52 (2013) 781-787.

[89] B. Borah, K.D. Dwivedi, B. Kumar, L.R. Chowhan, Arab. J. Chem. 15 (2022) 103654.

[90] A.K. Rathi, M.B. Gawande, R. Zboril, R.S. Varma, Coord. Chem. Rev. 291 (2015) 68-94.

[91] Q. You, M. Liao, H. Feng, J. Huang, Org. Biomol. Chem. 20 (2022) 8569-8583.

[92] K. Kumar, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 59 (2022) 205-238.

[93] B.R. Reddy, V. Sridevi, T.H. Kumar, C.S. Rao, V.C.S. Palla, D.V. Suriapparao, G. S. Undi, Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 164 (2022) 354-372.

[94] P.C. Dhanush, P.V. Saranya, G. Anilkumar, Tetrahedron 105 (2022) 132614.

[95] G.B. Dudley, R. Richert, A.E. Stiegman, Chem. Sci. 6 (2015) 2144-2152.

[96] T.V. de Medeiros, J. Manioudakis, F. Noun, J.-R. Macairan, F. Victoria, R. Naccache, J. Mater. Chem. C 7 (2019) 7175-7195.

[97] Y. Li, W. Yang, J. Membr. Sci. 316 (2008) 3-17.

[98] C. Gabriel, S. Gabriel, E.H. Grant, E.H. Grant, B.S.J. Halstead, D. Michael, P. Mingos, Chem. Soc. Rev. 27 (1998) 213-224.

[99] W. Liang, D.M. D’Alessandro, Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 3706-3708.

[100] M. Nüchter, B. Ondruschka, W. Bonrath, A. Gum, Green Chem. 6 (2004) 128-141.

[101] A. Stadler, B.H. Yousefi, D. Dallinger, P. Walla, E. Van der Eycken, N. Kaval, C. O. Kappe, Org. Process Res. Dev. 7 (2003) 707-716.

[102] A. Adhikari, S. Bhakta, T. Ghosh, Tetrahedron 126 (2022) 133085.

[103] S.V. Giofrè, R. Romeo, R. Mancuso, N. Cicero, N. Corriero, U. Chiacchio, G. Romeo, B. Gabriele, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 20777-20780.

[104] C.O. Kappe, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 4977-4990.

[105] Z. Wu, E. Borretto, J. Medlock, W. Bonrath, G. Cravotto, ChemCatChem 6 (2014) 2762-2783.

[106] H.K.M. Ng, G.K. Lim, C.P. Leo, Microchem. J. 165 (2021) 106116.

[107] G.S. Singh, Asian J. Org. Chem. 11 (2022) 165-182.

[108] M. Nishioka, M. Miyakawa, Y. Daino, H. Kataoka, H. Koda, K. Sato, T.M. Suzuki, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52 (2013) 4683-4687.

[109] T. Razzaq, J.M. Kremsner, C.O. Kappe, J. Org. Chem. 73 (2008) 6321-6329.

[110] N.A.A. Elkanzi, H. Hrichi, R.A. Alolayan, W. Derafa, F.M. Zahou, R.B. Bakr, ACS Omega 7 (2022) 27769-27786.

[111] Z.-X. Wu, G.-W. Hu, Y.-X. Luan, ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 11716-11733.

[112] S.S. Gupta, S. Kumari, I. Kumar, U. Sharma, Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 56 (2020) 433-444.

[113] E.S. Yun, M.S. Akhtar, S. Mohandoss, Y.R. Lee, Org. Biomol. Chem. 20 (2022) 3397-3407.

[114] M. Henary, C. Kananda, L. Rotolo, B. Savino, E.A. Owens, G. Cravotto, RSC Adv. 10 (2020) 14170-14197.

[115] S. Sahoo, R. Kumar, G. Dhakal, J.-J. Shim, J. Storage Mater. 74 (2023) 109427.

[116] H. Park, K.Y. Hwang, Y.H. Kim, K.H. Oh, J.Y. Lee, K. Kim, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18 (2008) 3711-3715.

[117] A. Jha, Y.L.N. Murthy, G. Durga, T.T. Sundari, E-J. Chem. 7 (2010) 569605.

[118] S.M. Sondhi, J. Singh, P. Roy, S.K. Agrawal, A.K. Saxena, Med. Chem. Res. 20 (2011) 887-897.

[119] E.-I. Negishi, L. Anastasia, Chem. Rev. 103 (2003) 1979-2018.

[120] J. Sedelmeier, S.V. Ley, H. Lange, I.R. Baxendale, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009 (2009) 4412-4420.

[121] G.-R. Qu, P.-Y. Xin, H.-Y. Niu, X. Jin, X.-T. Guo, X.-N. Yang, H.-M. Guo, Tetrahedron 67 (2011) 9099-9103.

[122] B.R. Vaddula, A. Saha, J. Leazer, R.S. Varma, Green Chem. 14 (2012) 2133-2136.

[123] M. Sako, M. Arisawa, Synthesis 53 (2021) 3513-3521.

[124] L. Bai, J.X. Wang, Synfacts 2008 (2008) 0434.

[125] M. Rahman, S. Ghosh, D. Bhattacherjee, G.V. Zyryanov, A. Kumar Bagdi, A. Hajra, Asian J. Org. Chem. (2022).

[126] V. Polshettiwar, B. Baruwati, R.S. Varma, Green Chem. 11 (2009) 127-131.

[127] B. Desai, P. Satani, R.S. Patil, H. Bhukya, T. Naveen, ChemistrySelect 8 (2023) e202302849.

[128] M.N. Nadagouda, V. Polshettiwar, R.S. Varma, J. Mater. Chem. 19 (2009) 2026-2031.

[129] V. Polshettiwar, B. Baruwati, R.S. Varma, ACS Nano 3 (2009) 728-736.

[130] J. Kou, R.S. Varma, Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 692-694.

[131] J. Kou, C. Bennett-Stamper, R.S. Varma, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 1 (2013) 810-816.

[132] J. Kou, R.S. Varma, RSC Adv. 2 (2012) 10283-10290.

[133] C. An, T. Wang, S. Wang, X. Chen, X. Han, S. Wu, Q. Deng, L. Zhao, N. Hu, Ultrason. Sonochem. 98 (2023) 106503.

[134] S.J. Doktycz, K.S. Suslick, Science 247 (1990) 1067-1069.

[135] P.R. Kumar, P.L. Suryawanshi, S.P. Gumfekar, S.H. Sonawane, Chem. Eng. Process. 121 (2017) 50-56.

[136] R. Eizi, T.R. Bastami, V. Mahmoudi, A. Ayati, H. Babaei, J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 145 (2023) 104844.

[137] M. Najafi, T.R. Bastami, N. Binesh, A. Ayati, S. Emamverdi, J. Ind. Eng. Chem. (2022).

[138] A.I. Osman, A.M. Elgarahy, A.S. Eltaweil, E.M. Abd El-Monaem, H.G. El-Aqapa, Y. Park, Y. Hwang, A. Ayati, M. Farghali, I. Ihara, A.a.H. Al-Muhtaseb, D. W. Rooney, P.-S. Yap, M. Sillanpää, Environ. Chem. Lett. (2023).

[139] Q. Wu, J. Ouyang, K. Xie, L. Sun, M. Wang, C. Lin, J. Hazard. Mater. 199-200 (2012) 410-417.

[140] A. Hassani, M. Malhotra, A.V. Karim, S. Krishnan, P.V. Nidheesh, Environ. Res. 205 (2022) 112463.

[141] Q. Ren, C. Kong, Z. Chen, J. Zhou, W. Li, D. Li, Z. Cui, Y. Xue, Y. Lu, Microchem. J. 164 (2021) 106059.

[142] A.V. Karim, A. Shriwastav, Chem. Eng. J. 392 (2020) 124853.

[143] D.Y. Hoo, Z.L. Low, D.Y.S. Low, S.Y. Tang, S. Manickam, K.W. Tan, Z.H. Ban, Ultrason. Sonochem. 90 (2022) 106176.

[144] R. Hamidi, M. Damizia, P.D. Filippis, D. Patrizi, N. Verdone, G. Vilardi, B. d. Caprariis, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. (2023) 110819.

[145] J. Zheng, Y. Guo, L. Zhu, H. Deng, Y. Shang, Ultrasonics 115 (2021) 106456.

[146] L. Ye, X. Zhu, Y. Liu, Ultrason. Sonochem. 59 (2019) 104744.

[147] F. Guittonneau, A. Abdelouas, B. Grambow, S. Huclier, Ultrason. Sonochem. 17 (2010) 391-398.

[148] M.J. Lo Fiego, A.S. Lorenzetti, G.F. Silbestri, C.E. Domini, Ultrason. Sonochem. 80 (2021) 105834.

[149] Z. Li, T. Zhuang, J. Dong, L. Wang, J. Xia, H. Wang, X. Cui, Z. Wang, Ultrason. Sonochem. 71 (2021) 105384.

[150] J. Dong, Z. Wang, F. Yang, H. Wang, X. Cui, Z. Li, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 305 (2022) 102683.

[151] M.D. Kass, Mater. Lett. 42 (2000) 246-250.

[152] K.R. Gopi, R. Nagarajan, IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 7 (2008) 532-537.

[153] U. Teipel, K. Leisinger, I. Mikonsaari, Int. J. Miner. Process. 74 (2004) S183-S190.

[154] Y. Hernandez, V. Nicolosi, M. Lotya, F.M. Blighe, Z. Sun, S. De, I.T. McGovern, B. Holland, M. Byrne, Y.K. Gun’Ko, J.J. Boland, P. Niraj, G. Duesberg, S. Krishnamurthy, R. Goodhue, J. Hutchison, V. Scardaci, A.C. Ferrari, J. N. Coleman, Nat. Nanotechnol. 3 (2008) 563-568.

[155] B.W. Zeiger, K.S. Suslick, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (2011) 14530-14533.

[156] R. Nehru, Y.-F. Hsu, S.-F. Wang, C.-W. Chen, C.-D. Dong, ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4 (2021) 7497-7508.

[157] A.V. Bogolubsky, Y.S. Moroz, P.K. Mykhailiuk, E.N. Ostapchuk, A. V. Rudnichenko, Y.V. Dmytriv, A.N. Bondar, O.A. Zaporozhets, S.E. Pipko, R. A. Doroschuk, L.N. Babichenko, A.I. Konovets, A. Tolmachev, ACS Comb. Sci. 17 (2015) 348-354.

[158] T.F. Jaramillo, K.P. Jørgensen, J. Bonde, J.H. Nielsen, S. Horch, I. Chorkendorff, Science 317 (2007) 100-102.

[159] A.A. Yadav, Y.M. Hunge, S.-W. Kang, Ultrason. Sonochem. 72 (2021) 105454.

[160] P. Cui, X. Yang, Q. Liang, S. Huang, F. Lu, J. Owusu, X. Ren, H. Ma, Ultrason. Sonochem. 62 (2020) 104859.

[161] S. Anandan, V. Kumar Ponnusamy, M. Ashokkumar, Ultrason. Sonochem. 67 (2020) 105130.

[162] A. Khataee, P. Eghbali, M.H. Irani-Nezhad, A. Hassani, Ultrason. Sonochem. 48 (2018) 329-339.

[163] F. Ghanbari, A. Hassani, S. Wacławek, Z. Wang, G. Matyszczak, K.-Y.-A. Lin, M. Dolatabadi, Sep. Purif. Technol. 266 (2021) 118533.

[164] S. Merouani, O. Hamdaoui, Z. Boutamine, Y. Rezgui, M. Guemini, Ultrason. Sonochem. 28 (2016) 382-392.

[165] A.V. Karim, A. Shriwastav, Environ. Res. 200 (2021) 111515.

[166] P. Eghbali, A. Hassani, B. Sündü, Ö. Metin, J. Mol. Liq. 290 (2019) 111208.

[167] A. Hassani, G. Çelikdağ, P. Eghbali, M. Sevim, S. Karaca, Ö. Metin, Ultrason. Sonochem. 40 (2018) 841-852.

[168] R. Patidar, V.C. Srivastava, Sep. Purif. Technol. 258 (2021) 117903.

[169] L. Hou, H. Zhang, L. Wang, L. Chen, Chem. Eng. J. 229 (2013) 577-584.

[170] A. Khataee, T. Sadeghi Rad, S. Nikzat, A. Hassani, M.H. Aslan, M. Kobya, E. Demirbaş, Chem. Eng. J. 375 (2019) 122102.

[171] S. Heidari, M. Haghighi, M. Shabani, Ultrason. Sonochem. 43 (2018) 61-72.

[172] R. Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani, S. Jorfi, H. Ramezani, S. Purfadakari, Ultrason. Sonochem. 28 (2016) 69-78.

[173] L. Wang, D. Luo, O. Hamdaoui, Y. Vasseghian, M. Momotko, G. Boczkaj, G. Z. Kyzas, C. Wang, Sci. Total Environ. 876 (2023) 162551.

[174] A. Khataee, S. Arefi-Oskoui, L. Samaei, Ultrason. Sonochem. 40 (2018) 703-713.

[175] Ö. Görmez, E. Yakar, B. Gözmen, B. Kayan, A. Khataee, Chemosphere 288 (2022) 132663.

[176] R. Patidar, V.C. Srivastava, Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2021) 1667-1701.

[177] P. Ritesh, V.C. Srivastava, J. Water Process Eng. 37 (2020) 101378.

[178] W.L. Ang, P.J. McHugh, M.D. Symes, Chem. Eng. J. 444 (2022) 136573.

[179] R. Patidar, V.C. Srivastava, Chemosphere 257 (2020) 127121.

[180] H. Li, H. Lei, Q. Yu, Z. Li, X. Feng, B. Yang, Chem. Eng. J. 160 (2010) 417-422.

[181] Y.-C. Wu, S.-J. Wu, C.-H. Lin, Microsyst. Technol. 23 (2017) 293-298.

[182] M. Lounis, M.E. Samar, O. Hamdaoui, Desalin. Water Treat. 57 (2016) 22533-22542.

[183] M. Zhang, Z. Zhang, S. Liu, Y. Peng, J. Chen, S. Yoo Ki, Ultrason. Sonochem. 65 (2020) 105058.

[184] P. Menon, T.S. Anantha Singh, N. Pani, P.V. Nidheesh, Chemosphere 269 (2021) 128739.

[185] Y. Liu, H.-Y. Xu, S. Komarneni, Appl. Catal. A 670 (2024) 119550.

[186] H. Shi, Y. Liu, Y. Bai, H. Lv, W. Zhou, Y. Liu, D.-G. Yu, Sep. Purif. Technol. 330 (2024) 125247.

[187] Y. Zhu, H. Chen, L. Wang, L. Ye, H. Zhou, Q. Peng, H. Zhu, Y. Huang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108884.

[188] Y. Wu, H. Shangs, X. Pan, G. Zhou, Mol. Catal. 556 (2024) 113820.

[189] F. Yang, P. Wang, J. Hao, J. Qu, Y. Cai, X. Yang, C.M. Li, J. Hu, Nano Energy 118 (2023) 108993.

[190] H. Shaukat, A. Ali, S. Bibi, S. Mehmood, W.A. Altabey, M. Noori, S.A. Kouritem, Energy Rep. 9 (2023) 4306-4324.

[191] H. Fadhlina, A. Atiqah, Z. Zainuddin, Mater. Today Commun. 33 (2022) 104835.

[192] T. Zheng, J. Wu, D. Xiao, J. Zhu, Prog. Mater. Sci. 98 (2018) 552-624.

[193] M. Moradi, Y. Vasseghian, H. Arabzade, A. Mousavi Khaneghah, Chemosphere 263 (2021) 128314.

[194] P.V. Nidheesh, J. Scaria, D.S. Babu, M.S. Kumar, Chemosphere 263 (2021) 127907.

[195] C.-C. He, C.-Y. Hu, S.-L. Lo, Sep. Purif. Technol. 165 (2016) 107-113.

[196] N. Dizge, C. Akarsu, Y. Ozay, H.E. Gulsen, S.K. Adiguzel, M.A. Mazmanci, J. Water Process. Eng. 21 (2018) 52-60.

[197] A. Raschitor, J. Llanos, P. Cañizares, M.A. Rodrigo, Sep. Purif. Technol. 231 (2020) 115926.

[198] M.J.M.d. Vidales, S. Barba, C. Sáez, P. Cañizares, M.A. Rodrigo, Electrochim. Acta 140 (2014) 20-26.

[199] N. Mahmoudi, M. Farhadian, A.R. Solaimany Nazar, P. Eskandari, K.N. Esfahani, Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19 (2022) 1671-1682.

[200] L. Takacs, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 7649-7659.

[201] S.L. James, C.J. Adams, C. Bolm, D. Braga, P. Collier, T. Friščić, F. Grepioni, K.D. M. Harris, G. Hyett, W. Jones, A. Krebs, J. Mack, L. Maini, A.G. Orpen, I.P. Parkin, W.C. Shearouse, J.W. Steed, D.C. Waddell, Chem. Soc. Rev. 41 (2012) 413-447.

[202] K. Tanaka, F. Toda, Chem. Rev. 100 (2000) 1025-1074.

[203] G.-W. Wang, K. Komatsu, Y. Murata, M. Shiro, Nature 387 (1997) 583-586.

[204] K. Kubota, H. Ito, Trends Chem. 2 (2020) 1066-1081.

[205] X. Guo, D. Xiang, G. Duan, P. Mou, Waste Manag. 30 (2010) 4-10.

[206] Z. Ou, J. Li, Z. Wang, Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts 17 (2015) 1522-1530.

[207] Q. Tan, J. Li, Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (2015) 5849-5861.

[208] K. Liu, M. Wang, D.C.W. Tsang, L. Liu, Q. Tan, J. Li, J. Hazard. Mater. 440 (2022) 129638.

[209] Q. Tan, C. Deng, J. Li, J. Clean. Prod. 142 (2017) 2187-2191.

[210] W. Yuan, J. Li, Q. Zhang, F. Saito, Powder Technol. 230 (2012) 63-66.

[211] K. Liu, Q. Tan, L. Liu, J. Li, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8 (2020) 3547-3552.

[212] F. Delogu, L. Takacs, J. Mater. Sci. 53 (2018) 13331-13342.

[213] M.H. Barbee, T. Kouznetsova, S.L. Barrett, G.R. Gossweiler, Y. Lin, S.K. Rastogi, W.J. Brittain, S.L. Craig, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 12746-12750.

[214] A. Boscoboinik, D. Olson, H. Adams, N. Hopper, W.T. Tysoe, Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 7730-7733.

[215] E. Fan, L. Li, X. Zhang, Y. Bian, Q. Xue, J. Wu, F. Wu, R. Chen, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6 (2018) 11029-11035.

[216] M.-M. Wang, C.-C. Zhang, F.-S. Zhang, Waste Manag. 67 (2017) 232-239.

[217] K. Liu, Q. Tan, L. Liu, J. Li, Environ. Sci. Tech. 53 (2019) 9781-9788.

[218] C. Bolm, J.G. Hernández, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 3285-3299.

[219] B. Xu, P. Dong, J. Duan, D. Wang, X. Huang, Y. Zhang, Ceram. Int. 45 (2019) (1801) 11792-111791.

[220] M. Wang, Q. Tan, Q. Huang, L. Liu, J.F. Chiang, J. Li, J. Hazard. Mater. 413 (2021) 125222.

[221] J. Wu, X. Wang, Q. Wang, Z. Lou, S. Li, Y. Zhu, L. Qin, H. Wei, Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 1004-1076.

[222] Y. Huang, J. Ren, X. Qu, Chem. Rev. 119 (2019) 4357-4412.

[223] M. Liang, X. Yan, Acc. Chem. Res. 52 (2019) 2190-2200.

[224] S. Sarkar, Y. Negishi, T. Pal, Dalton Trans. 51 (2022) 12904-12914.

[225] H. Baek, K. Kashimura, T. Fujii, S. Tsubaki, Y. Wada, S. Fujikawa, T. Sato, Y. Uozumi, Y.M. Yamada, ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 2148-2156.

[226] X. Li, P. Bohn, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77 (2000) 2572-2574.

[227] P.Y. He, Y.J. Zhang, H. Chen, Z.C. Han, L.C. Liu, Fuel 257 (2019) 116041.

[228] R.A. Quevedo-Amador, H.E. Reynel-Avila, D.I. Mendoza-Castillo, M. Badawi, A. Bonilla-Petriciolet, Fuel 312 (2022) 122731.

[229] W. Liu, P. Yin, X. Liu, W. Chen, H. Chen, C. Liu, R. Qu, Q. Xu, Energ. Conver. Manage. 76 (2013) 1009-1014.

[230] X.G. Zhang, A. Buthiyappan, J. Jewaratnam, H.S.C. Metselaar, A.A.A. Raman, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12 (2024) 111799.

[231] Sahil, N. Gupta, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 193 (2024) 114297.

[232] Y. Xu, L. Wang, Q. Zhou, Y. Li, L. Liu, W. Nie, R. Xu, J. Zhang, Z. Cheng, H. Wang, Y. Huang, T. Wei, Z. Fan, L. Wang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 508 (2024) 215775.

[233] D.Y.Z.Q.Y.U.D. Zhang Zhen, Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 43 (2022) 20220255.

[234] Z. Zhang, J.-H. Ye, D.-S. Wu, Y.-Q. Zhou, D.-G. Yu, Chemistry – An Asian J. 13 (2018) 2292-2306.

[235] N. Martín, F.G. Cirujano, J. CO2 Util. 65 (2022) 102176.

[236] X. Zhao, B. Deng, H. Xie, Y. Li, Q. Ye, F. Dong, Chin. Chem. Lett. (2023) 109139.

[237] M.K. Khan, P. Butolia, H. Jo, M. Irshad, D. Han, K.-W. Nam, J. Kim, ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 10325-10338.

[238] M.S. Alivand, O. Mazaheri, Y. Wu, A. Zavabeti, G.W. Stevens, C.A. Scholes, K. A. Mumford, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 57294-57305.

[239] D. Rodrigues, J. Wolf, B. Polesso, P. Micoud, C. Le Roux, F. Bernard, F. Martin, S. Einloft, Fuel 346 (2023) 128304.

[240] X.H. Liu, J.G. Ma, Z. Niu, G.M. Yang, P. Cheng, Angew. Chem. 127 (2015) 1002-1005.

[241] R.R. Kuruppathparambil, R. Babu, H.M. Jeong, G.-Y. Hwang, G.S. Jeong, M.I. Kim, D.-W. Kim, D.-W. Park, Green Chem. 18 (2016) 6349-6356.

[242] N. Ahmed, J. Organomet. Chem. 1009 (2024) 123071.

[243] A. Simon, S. Mathai, J. Organomet. Chem. 996 (2023) 122768.

[244] A. Ayati, M.M. Heravi, M. Daraie, B. Tanhaei, F.F. Bamoharram, M. Sillanpaa, J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 13 (2016) 2301-2308.

[245] G. Rahimzadeh, M. Tajbakhsh, M. Daraie, A. Ayati, Sci. Rep. 12 (2022) 17027.

[246] F.F. Bamoharram, M.M. Heravi, S. Saneinezhad, A. Ayati, Prog. Org. Coat. 76 (2013) 384-387.

[247] A. Ebrahimi, L. Krivosudský, A. Cherevan, D. Eder, Coord. Chem. Rev. 508 (2024) 215764.

[248] D. Sharma, P. Choudhary, P. Mittal, S. Kumar, A. Gouda, V. Krishnan, ACS Catal. 14 (2024) 4211-4248.

[249] Y. Gao, Y. Ding, Chemistry – A Eur. J. 26 (2020) 8845-8856.

[250] D. Hayes, S. Alia, B. Pivovar, R. Richards, Chem Catal. 4 (2024) 100905.

[251] X. Wang, Y. Liu, W. Ge, Y. Xu, H. Jia, Q. Li, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11 (2023) 110712.

[252] L. Jurado, J. Esvan, L.A. Luque-Álvarez, L.F. Bobadilla, J.A. Odriozola, S. PosadaPérez, A. Poater, A. Comas-Vives, M.R. Axet, Cat. Sci. Technol. 13 (2023) 1425-1436.

[253] D. Gaviña, M. Escolano, J. Torres, G. Alzuet-Piña, M. Sánchez-Roselló, C. del Pozo, Adv. Synth. Catal. 363 (2021) 3439-3470.

[254] M.C. Carson, M.C. Kozlowski, Nat. Prod. Rep. 41 (2024) 208-227.

[255] Y. Gambo, R.A. Lucky, M.S. Ba-Shammakh, M.M. Hossain, Mol. Catal. 551 (2023) 113554.

[256] X. Le, Z. Dong, Z. Jin, Q. Wang, J. Ma, Catal. Commun. 53 (2014) 47-52.

[257] P. Bhattacharjee, A. Dewan, P.K. Boruah, M.R. Das, S.P. Mahanta, A.J. Thakur, U. Bora, Green Chem. 24 (2022) 7208-7219.

[258] P.-I. Dassie, R. Haddad, M. Lenez, A. Chaumonnot, M. Boualleg, P. Legriel, A. Styskalik, B. Haye, M. Selmane, D.P. Debecker, Green Chem. 25 (2023) 2800-2814.

[259] M. RezaáNaimi-Jamal, RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 46022-46027.

[260] R.O. Araujo, V.O. Santos, F.C. Ribeiro, J.d.S. Chaar, N.P. Falcão, L.K. de Souza, React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 134 (2021) 199-220.

[261] A. Alissandratos, C.J. Easton, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 11 (2015) 2370-2387.

[262] U.T. Bornscheuer, G. Huisman, R. Kazlauskas, S. Lutz, J. Moore, K. Robins, Nature 485 (2012) 185-194.

[263] R. Wohlgemuth, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21 (2010) 713-724.

[264] S.M. Glueck, S. Gümüs, W.M. Fabian, K. Faber, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 313-328.

[265] A.S. Hawkins, P.M. McTernan, H. Lian, R.M. Kelly, M.W. Adams, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24 (2013) 376-384.

[266] R. Matthessen, J. Fransaer, K. Binnemans, D.E. De Vos, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 10 (2014) 2484-2500.

[267] D.C. Ducat, P.A. Silver, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16 (2012) 337-344.

[268] E. Destan, B. Yuksel, B.B. Tolar, E. Ayan, S. Deutsch, Y. Yoshikuni, S. Wakatsuki, C.A. Francis, H. DeMirci, Sci. Rep. 11 (2021) 22849.

[269] M. Könneke, D.M. Schubert, P.C. Brown, M. Hügler, S. Standfest, T. Schwander, L. Schada von Borzyskowski, T.J. Erb, D.A. Stahl, I.A. Berg, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (2014) 8239-8244.

[270] J.K. Yong, G.W. Stevens, F. Caruso, S.E. Kentish, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 90 (2015) 3-10.

[271] B.A. Oyenekan, G.T. Rochelle, Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 3 (2009) 121-132.

[272] J. da Costa Ores, L. Sala, G.P. Cerveira, S.J. Kalil, Chemosphere 88 (2012) 255-259.

[273] S. Bhattacharya, A. Nayak, M. Schiavone, S.K. Bhattacharya, Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86 (2004) 37-46.

[274] A.Y. Shekh, K. Krishnamurthi, S.N. Mudliar, R.R. Yadav, A.B. Fulke, S.S. Devi, T. Chakrabarti, Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (2012) 1419-1440.

[275] S. Lindskog, Pharmacol. Ther. 74 (1997) 1-20.

[276] Y.-T. Zhang, L. Zhang, H.-L. Chen, H.-M. Zhang, Chem. Eng. Sci. 65 (2010) 3199-3207.

[277] M.E. Russo, G. Olivieri, A. Marzocchella, P. Salatino, P. Caramuscio, C. Cavaleiro, Sep. Purif. Technol. 107 (2013) 331-339.

[278] R. Cowan, J.J. Ge, Y.J. Qin, M. McGregor, M. Trachtenberg, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 984 (2003) 453-469.

[279] B.C. Tripp, K. Smith, J.G. Ferry, J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2001) 48615-48618.

[280] K. Yao, Z. Wang, J. Wang, S. Wang, Chem. Commun. 48 (2012) 1766-1768.

[281] S. Zhang, Z. Zhang, Y. Lu, M. Rostam-Abadi, A. Jones, Bioresour. Technol. 102 (2011) 10194-10201.

[282] E. Ozdemir, Energy Fuel 23 (2009) 5725-5730.

[283] S. Bachu, Energ. Conver. Manage. 41 (2000) 953-970.

[284] F. Migliardini, V. De Luca, V. Carginale, M. Rossi, P. Corbo, C.T. Supuran, C. Capasso, J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 29 (2014) 146-150.

[285] S. Zhang, Y. Lu, X. Ye, Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 13 (2013) 17-25.

[286] M. Vinoba, M. Bhagiyalakshmi, S.K. Jeong, Y.I. Yoon, S.C. Nam, Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 90 (2012) 91-96.

[287] P. Billsten, P.-O. Freskgård, U. Carlsson, B.-H. Jonsson, H. Elwing, FEBS Lett. 402 (1997) 67-72.

[288] A. Crumbliss, K. McLachlan, J. O’Daly, R. Henkens, Biotechnol. Bioeng. 31 (1988) 796-801.

[289] R. Yadav, S. Wanjari, C. Prabhu, V. Kumar, N. Labhsetwar, T. Satyanarayanan, S. Kotwal, S. Rayalu, Energy Fuel 24 (2010) 6198-6207.

[290] P.C. Sahoo, Y.-N. Jang, S.-W. Lee, J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 82 (2012) 37-45.

[291] M. Vinoba, K.S. Lim, S.H. Lee, S.K. Jeong, M. Alagar, Langmuir 27 (2011) 6227-6234.

[292] L. Xu, L. Zhang, H. Chen, Desalination 148 (2002) 309-313.

[293] Y.-T. Zhang, T.-T. Zhi, L. Zhang, H. Huang, H.-L. Chen, Polymer 50 (2009) 5693-5700.

[294] D.T. Arazawa, H.-I. Oh, S.-H. Ye, C.A. Johnson Jr, J.R. Woolley, W.R. Wagner, W. J. Federspiel, J. Membr. Sci. 403 (2012) 25-31.

[295] I. Ichinose, K. Kuroiwa, Y. Lvov, T. Kunitake, Multilayer Thin Films: Sequential Assembly of Nanocomposite Materials, (2002) 155-175.

[296] P. Nargotra, V. Sharma, Y.-C. Lee, Y.-H. Tsai, Y.-C. Liu, C.-J. Shieh, M.-L. Tsai, C.D. Dong, C.-H. Kuo, Catalysts 13 (2022) 83.

[297] G. Šelo, M. Planinić, M. Tišma, S. Tomas, D. Koceva Komlenić, A. Bucić-Kojić, Foods 10 (2021) 927.

[298] P. Leite, D. Sousa, H. Fernandes, M. Ferreira, A.R. Costa, D. Filipe, M. Gonçalves, H. Peres, I. Belo, J.M. Salgado, Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem. 27 (2021) 100407.

[299] J. Liu, J. Yang, R. Wang, L. Liu, Y. Zhang, H. Bao, J.M. Jang, E. Wang, H. Yuan, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 152 (2020) 288-294.

[300] W. Mei, L. Wang, Y. Zang, Z. Zheng, J. Ouyang, BMC Biotech. 16 (2016) 1-11.

[301] N. Salonen, K. Salonen, M. Leisola, A. Nyyssölä, Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 36 (2013) 489-497.

[302] H. Hosney, A. Mustafa, J. Oleo Sci. 69 (2020) 31-41.

[303] A. Mustafa, F. Niikura, Clean. Eng. Technol. 8 (2022) 100516.

[304] N. Zhong, W. Chen, L. Liu, H. Chen, Food Chem. 271 (2019) 739-746.

[305] Y. Li, N. Zhong, L.-Z. Cheong, J. Huang, H. Chen, S. Lin, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120 (2018) 886-895.

[306] A. Mustafa, R. Ramadan, F. Niikura, A. Inayat, H. Hafez, Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57 (2023) 103200.

[307] H. Li, C. Lai, Z. Wei, X. Zhou, S. Liu, L. Qin, H. Yi, Y. Fu, L. Li, M. Zhang, F. Xu, H. Yan, M. Xu, D. Ma, Y. Li, Chemosphere 344 (2023) 140395.

[308] D. Chen, Y.-T. Zheng, N.-Y. Huang, Q. Xu, EnergyChem (2023) 100115.

[309] Y. Orooji, B. Tanhaei, A. Ayati, S.H. Tabrizi, M. Alizadeh, F.F. Bamoharram, F. Karimi, S. Salmanpour, J. Rouhi, S. Afshar, M. Sillanpää, R. Darabi, H. KarimiMaleh, Chemosphere 281 (2021) 130795.

[310] H. Luo, J. Barrio, N. Sunny, A. Li, L. Steier, N. Shah, I.E. Stephens, M.M. Titirici, Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 2101180.

[311] X. Lu, S. Xie, H. Yang, Y. Tong, H. Ji, Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (2014) 7581-7593.

[312] M. Rafique, S. Hajra, M. Irshad, M. Usman, M. Imran, M.A. Assiri, W.M. Ashraf, ACS Omega 8 (2023) 25640-25648.

[313] K.C. Christoforidis, P. Fornasiero, ChemCatChem 9 (2017) 1523-1544.

[314] I. Rossetti, ISRN Chem. Eng. 2012 (2012) 964936.

[315] A. Piątkowska, M. Janus, K. Szymański, S. Mozia, Catalysts 11 (2021) 144.

[316] S. Bahrami, A. Ahmadpour, T. Rohani Bastami, A. Ayati, S. Mirzaei, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 160 (2024) 111986.

[317] M. de Oliveira Melo, L.A. Silva, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 226 (2011) 36-41.

[318] J. Fang, L. Xu, Z. Zhang, Y. Yuan, S. Cao, Z. Wang, L. Yin, Y. Liao, C. Xue, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5 (2013) 8088-8092.

[319] S. Zinoviev, F. Müller-Langer, P. Das, N. Bertero, P. Fornasiero, M. Kaltschmitt, G. Centi, S. Miertus, ChemSusChem 3 (2010) 1106-1133.

[320] T. Sakata, T. Kawai, Chem. Phys. Lett. 80 (1981) 341-344.

[321] D.I. Kondarides, V.M. Daskalaki, A. Patsoura, X.E. Verykios, Catal. Lett. 122 (2008) 26-32.

[322] B. Rusinque, S. Escobedo, H. de Lasa, Catalysts 11 (2021) 405.

[323] P. Pradhan, P. Karan, R. Chakraborty, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. (2021) 1-14.

[324] A. Gautam, V.B. Khajone, P.R. Bhagat, S. Kumar, D.S. Patle, Environ. Chem. Lett. 21 (2023) 3105-3126.

[325] D. Franchi, Z. Amara, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8 (2020) 15405-15429.

[326] T. Noël, E. Zysman-Colman, Chem. Catal. 2 (2022) 468-476.

[327] W. Sun, Y. Zheng, J. Zhu, Mater. Today Sustain. 23 (2023) 100465.

[328] R. Rashid, I. Shafiq, M.R.H.S. Gilani, M. Maaz, P. Akhter, M. Hussain, K.-E. Jeong, E.E. Kwon, S. Bae, Y.-K. Park, Chemosphere 349 (2024) 140703.

[329] X. Yu, Y. Hu, C. Shao, W. Huang, Y. Li, Mater. Today (2023).

[330] K. Prajapat, M. Dhonde, K. Sahu, P. Bhojane, V.V.S. Murty, P.M. Shirage, J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 55 (2023) 100586.

[331] S. Gonuguntla, R. Kamesh, U. Pal, D. Chatterjee, J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 57 (2023) 100621.

[332] F. Akbari Beni, A. Gholami, A. Ayati, M. Niknam Shahrak, M. Sillanpää, Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 303 (2020) 110275.

[333] Y. Ahmadi, K.-H. Kim, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 189 (2024) 113948.

[334] A. Ayati, A. Ahmadpour, F.F. Bamoharram, M.M. Heravi, H. Rashidi, Chin. J. Catal. 32 (2011) 978-982.

[335] S.A. Ansari, M.M. Khan, M.O. Ansari, M.H. Cho, New J. Chem. 40 (2016) 3000-3009.

[336] A.C. Mecha, M.S. Onyango, A. Ochieng, M.N. Momba, Chemosphere 186 (2017) 669-676.

[337] C. Zhang, Y. Li, C. Wang, X. Zheng, Sci. Total Environ. 755 (2021) 142588.

[338] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, J. Hazard. Mater. 338 (2017) 491-501.

[339] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, Chem. Eng. J. 338 (2018) 411-421.

[340] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, Chemosphere 237 (2019) 124487.

[341] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, Chem. Eng. J. 382 (2020) 122930.

[342] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, S. Farzana, Chemosphere 256 (2020) 127094.

[343] A. Abdelhaleem, W. Chu, X. Liang, Appl. Catal. B 244 (2019) 823-835.

[344] Y. Wang, J. Gu, J. Ni, Biogeotechnics 1 (2023) 100040.

[345] A. Islam, S.H. Teo, C.H. Ng, Y.H. Taufiq-Yap, S.Y.T. Choong, M.R. Awual, Prog. Mater. Sci. 132 (2023) 101033.

[346] J.G. Olivier, G. Janssens-Maenhout, M. Muntean, J. Peters, Institute for Environment and Sustainability of the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, (2012).

[347] A. Dibenedetto, A. Angelini, P. Stufano, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 89 (2014) 334-353.

[348] T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, P.M. Midgley, Comput. Geom. 18 (2013) 95-123.

[349] M. da Graça Carvalho, Energy 40 (2012) 19-22.

[350] K. Zakaria, R. Thimmappa, M. Mamlouk, K. Scott, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45 (2020) 8107-8117.

[351] Y. Chen, Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 4036.

[352] S. Uhm, H. Jeon, T.J. Kim, J. Lee, J. Power Sources 198 (2012) 218-222.

[353] C. Lamy, T. Jaubert, S. Baranton, C. Coutanceau, J. Power Sources 245 (2014) 927-936.

[354] P. De Luna, C. Hahn, D. Higgins, S.A. Jaffer, T.F. Jaramillo, E.H. Sargent, Science 364 (2019) eaav3506.

[355] R. Davy, Energy Proc. 1 (2009) 885-892.

[356] A. Samanta, A. Zhao, G.K. Shimizu, P. Sarkar, R. Gupta, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51 (2012) 1438-1463.

[357] C.-H. Yu, C.-H. Huang, C.-S. Tan, Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 12 (2012) 745-769.

[358] P. Luis, T. Van Gerven, B. Van der Bruggen, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 38 (2012) 419-448.

[359] C.A. Scholes, K.H. Smith, S.E. Kentish, G.W. Stevens, Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 4 (2010) 739-755.

[360] A. Brunetti, F. Scura, G. Barbieri, E. Drioli, J. Membr. Sci. 359 (2010) 115-125.

[361] C. Song, Y. Kitamura, S. Li, Energy 65 (2014) 580-589.

[362] C.-G. Xu, Z.-Y. Chen, J. Cai, X.-S. Li, Energy Fuel 28 (2014) 1242-1248.

[363] M. Yang, Y. Song, L. Jiang, Y. Zhao, X. Ruan, Y. Zhang, S. Wang, Appl. Energy 116 (2014) 26-40.

[364] A.J. Reynolds, T.V. Verheyen, S.B. Adeloju, E. Meuleman, P. Feron, Environ. Sci. Tech. 46 (2012) 3643-3654.

[365] S. Li, D.J. Rocha, S.J. Zhou, H.S. Meyer, B. Bikson, Y. Ding, J. Membr. Sci. 430 (2013) 79-86.

[366] H.H. Weetall, Anal. Chem. 46 (1974) 602A-615A.

[367] M. Onda, K. Ariga, T. Kunitake, J. Biosci. Bioeng. 87 (1999) 69-75.

[368] F. Caruso, C. Schüler, Langmuir 16 (2000) 9595-9603.

[369] K.N. Rajnish, M.S. Samuel, S. Datta, N. Chandrasekar, R. Balaji, S. Jose, E. Selvarajan, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 182 (2021) 1793-1802.

[370] U.H. Bhatti, W.W. Kazmi, H.A. Muhammad, G.H. Min, S.C. Nam, I.H. Baek, Green Chem. 22 (2020) 6328-6333.

[371] X. Zhang, Y. Huang, H. Gao, X. Luo, Z. Liang, P. Tontiwachwuthikul, Appl. Energy 240 (2019) 827-841.

[372] X. Zhang, Y. Huang, J. Yang, H. Gao, Y. Huang, X. Luo, Z. Liang, P. Tontiwachwuthikul, Chem. Eng. J. 383 (2020) 123077.

[373] M.S. Alivand, O. Mazaheri, Y. Wu, G.W. Stevens, C.A. Scholes, K.A. Mumford, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8 (2020) 18755-18788.

[374] M. Leimbrink, S. Sandkämper, L. Wardhaugh, D. Maher, P. Green, G. Puxty, W. Conway, R. Bennett, H. Botma, P. Feron, Appl. Energy 208 (2017) 263-276.

[375] H. Tang, X. Liu, Y. Li, J. Tian, C. Hou, M. Tian, T. Zhu, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (2023) 53492-53504.

[376] D. Kim, J. Han, Appl. Energy 264 (2020) 114711.

[377] D. Kim, J. Choi, G.-J. Kim, S.K. Seol, Y.-C. Ha, M. Vijayan, S. Jung, B.H. Kim, G. D. Lee, S.S. Park, Bioresour. Technol. 102 (2011) 3639-3641.

[378] Y. Liu, Q. Zhong, P. Xu, H. Huang, F. Yang, M. Cao, L. He, Q. Zhang, J. Chen, Matter 5 (2022) 1305-1317.

[379] V. Sharma, M.-L. Tsai, P. Nargotra, C.-W. Chen, C.-H. Kuo, P.-P. Sun, C.-D. Dong, Catalysts 12 (2022) 1373.

[380] G.-A. Martău, P. Unger, R. Schneider, J. Venus, D.C. Vodnar, J.P. López-Gómez, J. Fungi 7 (2021) 766.

[381] P. Mirjafari, K. Asghari, N. Mahinpey, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 46 (2007) 921-926.

[382] M. Loi, O. Glazunova, T. Fedorova, A.F. Logrieco, G. Mulè, J. Fungi 7 (2021) 1048.

[383] A. Dewan, M. Sarmah, P. Bharali, A.J. Thakur, P.K. Boruah, M.R. Das, U. Bora, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9 (2021) 954-966.

[384] A. Dewan, M. Sarmah, P. Bhattacharjee, P. Bharali, A.J. Thakur, U. Bora, Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 23 (2021) 100502.

[385] A.J. Onyianta, D. O’Rourke, D. Sun, C.-M. Popescu, M. Dorris, Cellul. 27 (2020) 7997-8010.

[386] B.E. Yoldas, J. Appl. Chem. Biotech. 23 (1973) 803-809.

[387] R. Qiu, F. Cheng, H. Huang, J. Clean. Prod. 172 (2018) 1918-1927.

[388] A. Tropecêlo, M. Casimiro, I. Fonseca, A. Ramos, J. Vital, J. Castanheiro, Appl. Catal. A 390 (2010) 183-189.

[389] C. Caetano, L. Guerreiro, I. Fonseca, A. Ramos, J. Vital, J. Castanheiro, Appl. Catal. A 359 (2009) 41-46.

[390] J.R. Kastner, J. Miller, D.P. Geller, J. Locklin, L.H. Keith, T. Johnson, Catal. Today 190 (2012) 122-132.

- Corresponding authors at: School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Queen’s University Belfast, David Keir Building, Stranmillis Road, Belfast BT9 5AG, Northern Ireland, UK.

E-mail addresses: aosmanahmed01@qub.ac.uk (A.I. Osman), PowSeng.Yap@xjtlu.edu.cn (P.-S. Yap), amal.elsonbaty@ejust.edu.eg (A. Abdelhaleem).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.215900

Publication Date: 2024-05-08

Coordination-driven innovations in low-energy catalytic processes: advancing sustainability in chemical production

Published in:

Document Version:

Queen’s University Belfast – Research Portal:

Publisher rights

This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited.

General rights

Take down policy

Open Access

Coordination-driven innovations in low-energy catalytic processes: Advancing sustainability in chemical production

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Coordination chemistry

Photocatalysis

Electrocatalysis

Industrial catalysis

Catalysis applications

Abstract

Catalysis stands as a cornerstone in chemical synthesis, pivotal in advancing sustainable manufacturing pathways. The evolution from energy-intensive to sustainable catalytic processes has marked a transformative shift, notably exemplified by low-energy catalytic methods. These processes, operating under milder conditions and emphasizing selectivity and recyclability, represent the forefront of sustainable chemistry. This review navigates through an array of low-energy chemical reactions, highlighting their diverse applications and culminating in exploration of recent strides within low-energy catalytic processes. For example, the review explores the uses of low-energy catalytic processes in applications such as enzyme mimicking, biodiesel production, carbon dioxide capture, and organic synthesis. Additionally, it covers enzymatic catalysis and photocatalysis for carbon dioxide transformations, energy applications, and water treatment. Notably, the review emphasizes the low-energy catalytic capabilities of single-atom catalysis (SAC) and diatomic catalysts (DACs), recognizing their exceptional performance in catalyzing reactions at minimal activation energies while maintaining high efficiency and selectivity under mild conditions. By elucidating the modulation of electronic structure and offering a microelectronic perspective, the review aims to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the catalytic activity of SAC and DACs. Emphasizing the interplay between coordination chemistry principles and catalytic efficacy, the review elucidates the indispensable role of coordination complexes in fortifying the sustainability of these processes. By spotlighting the fusion of coordination chemistry with catalysis, this review aims to underscore their collective influence in shaping the landscape of sustainable chemical production.

1. Introduction

that rely on high temperatures and pressures coupled with nonrenewable resource utilization, underscore the urgency for sustainable alternatives [8,9].

2. Advancements in coordination chemistry: a catalyst for greener and sustainable chemical transformations

from both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, featuring isolated active sites, high selectivity, and easy separation from reaction systems [18]. Fig. 2 provides a succinct portrayal of the synthesis process and catalytic applications of SACs. Despite the potential energy consumption during SACs synthesis [30], these catalysts exhibit the remarkable ability to catalyze chemical reactions at extremely low activation energies with exceptional efficiency [31]. Metal atoms dispersed on support materials demonstrate high catalytic efficiency and selectivity [30]. Despite their potential, SACs face challenges related to metal atom agglomeration during fabrication and application processes due to high surface energy. However, constructing strong coordination bonds between single atoms and their supports has proven effective in addressing this issue, influencing the activity and selectivity of SACs. Additionally, the coordination environments of active single atoms in SACs play a crucial role in stability, catalytic properties, and loading material utilization. Coordination environments, their synthesis methods, and applicable reactions have been summarized, showcasing metal single atoms typically stabilized on substrate surfaces via covalent or ionic bonds. The geometric and electronic structures are primarily defined by local coordination chemistry, serving as executable descriptors for exploring structure-activity relationships in SACs. Coordination environments include

proves instrumental in effectively lowering reaction activation energy and enhancing catalytic activity [48]. Carbon-based diatomic catalysts, as a significant subset of this catalyst type, find widespread application in the field of electrocatalysis [43]. Zhang et al. [48] successfully synthesized a diatomic catalyst, denoted as

are commonly introduced into the carbon matrix to form N-C bonds [51,52]. The incorporation of metal atoms into this heteroatom-doped carbon structure, whether fixed by the heteroatom or the base surface environment, induces changes in the electronic structure of the metal atoms, resulting in the formation of a catalyst with an M-N-C structure. Additionally, supported diatomic catalysts can be synthesized by directly introducing atomic dimers onto carbon-based materials. The robust bonding of the active site and its interaction with the carbon support contribute to the high efficiency and stability of electrocatalysis in diatomic catalysts. The construction of a suitable diatomic catalyst involves the regulation of its electronic structure, particularly from three perspectives: bimetallic central atoms, the local coordination environment of bimetallic central atoms, and the carbon-based environment. This electronic structure modulation proves essential for achieving efficient catalysis across various reactions, including the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), oxygen evolution reaction (OER), oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), carbon dioxide reduction reaction (

global warming. However, the activation of

3. Types of energy-saving chemical reactions and their applications in various fields

3.1. Microwave-assisted reactions

reaction kinetics, high yield, and higher purity are some of the main advantages of microwave-assisted reactions [78]. Rapid heating and a significant reduction in reaction time, are their greatest benefits. For instance, a metal-organic framework (DUT-67) was fabricated using microwave-assisted fabrication by reducing the reaction time from 48 h to 1 h , compared to traditional solvothermal methods [79].

Loss Tangent (

| Solvent | Tan

|

Solvent | Tan

|

| Water | 0.123 | Acetic acid | 0.174 |

| Methanol | 0.659 | Ethylene glycol | 1.350 |

| Ethanol | 0.941 | dimethyl sulfoxide | 0.825 |

| Chloroform | 0.091 |

|

0.275 |

| Toluene | 0.040 | Dimethylformamide | 0.161 |

| Hexane | 0.020 | 1,2-dichlorobenzene | 0.280 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 0.047 | dichloromethane | 0.042 |

| Acetonitrile | 0.062 | 1,2-dichloroethane | 0.127 |

3.2. Ultrasonic-assisted reactions

materials [135], adsorbents [136,137], photocatalysts [138], and polymers [48]. For example, an ultrasound-assisted chemical reduction approach was exploited to synthesize nickel nanocrystals that exhibited efficient activity in the hydrogen evolution reaction [139].

[133], the cavitation effect produced by strong ultrasonic waves in liquids is gradually being applied to improve the dispersal and wettability of nano- and microparticles. Several transition metal dichalcogenides have been prepared using ultrasound-assisted technologies [156,157] and used for different applications. Transition metal phosphides, for instance, have sulfur atoms that interact with protons and promote hydrogen evolution. The high catalytic activity of molybdenum disulfide edges has motivated researchers to prepare nanocompounds with large edge density and defect formation [158]. Ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal methods were applied to synthesize three-dimensional porous electrocatalysts [159]. A high electron transition rate, tiny electrolyte contact resistance, and abundant active spots were the features that distinguished

electro-advanced oxidation process, ultrasound enables the production of greater quantities of radicals in aqueous solution, thus improving the efficiency of degradation [180,181]. Hydrogen peroxide produced electrolytically decomposes into

generated species [198]. In a study, Mahmoudi et al. [199] studied the performance of electro-Fenton-based and sono-photoelectro-Fentonbased in dye wastewater degradation and found the maximum degradation using sono-photoelectro-Fenton via higher radical generation.

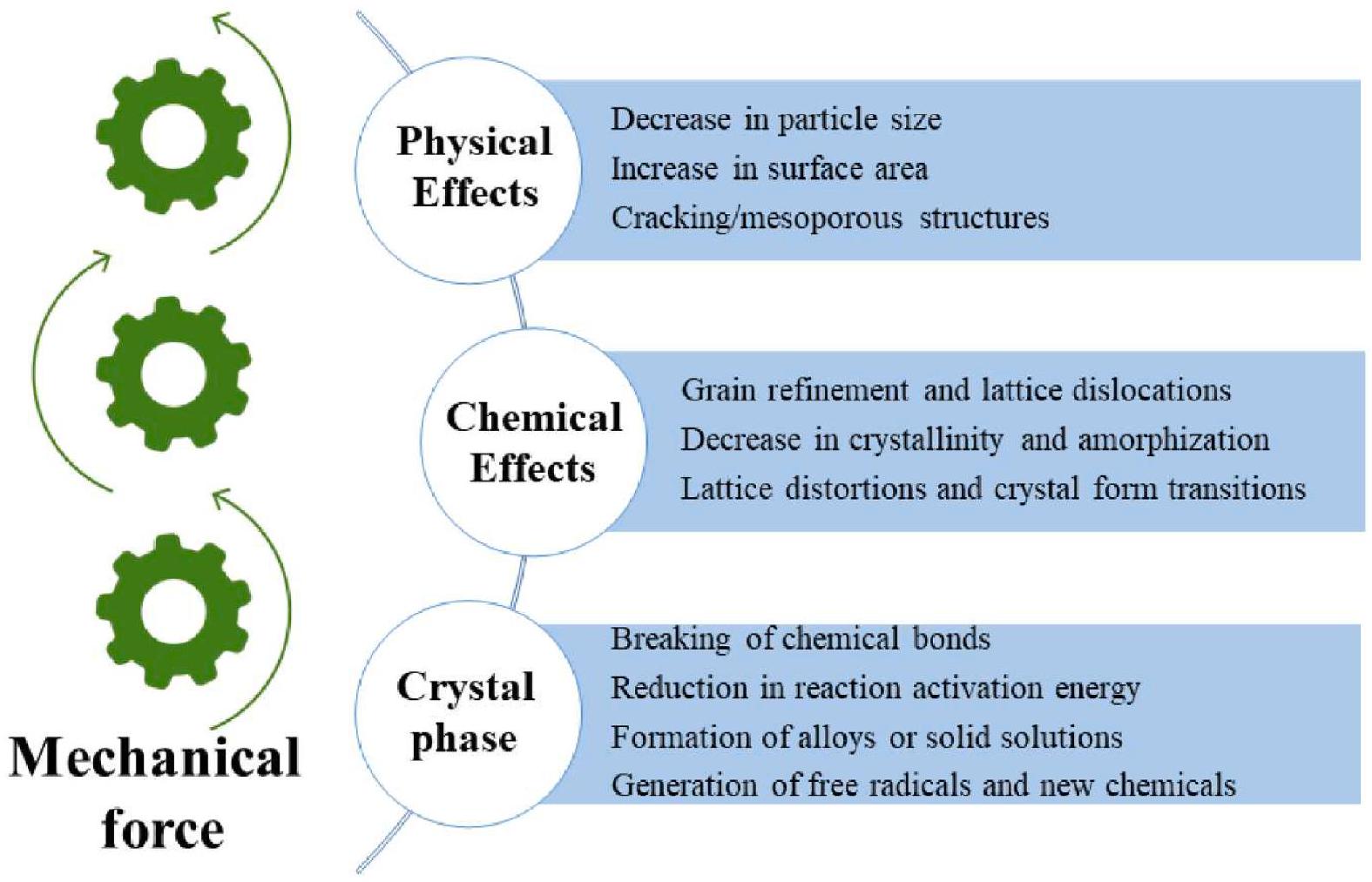

3.3. Mechanochemical reactions

4. Recent advances in low-energy catalytic processes

4.1. Heterogeneous catalyst design

4.1.1. Heterogeneous catalysts for enzyme mimicking

diffusivities. The obtained

4.1.2. Heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel production

by XRD, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, EDX, and BET analyses. The XRD analysis revealed an increase in the catalyst crystallinity because of potassium hydroxide activation. In comparison with the raw materials, the catalyst’s FTIR analysis showed more intense absorption bands at 3330-3350, 1600, and

mole ratio of ethanol to stearic acid of 11:1, and a temperature of 353 K .

4.1.3. Heterogeneous catalysts for carbon dioxide capture

liquids supported on the silica-based solid, ultimately yielding desired products such as cyclic carbonates or other organic compounds. It was found that materials containing ionic liquids have higher carbon dioxide adsorption capacity, where

4.1.4. Heterogeneous catalysts for organic synthesis/transformations

high efficiency, selectivity, and versatility. They are used to activate and facilitate the cleavage of chemical bonds in reactant molecules, enabling the initiation of organic transformations [22,242,243]. For example, metal catalysts can activate

recovery from reaction mixtures. This enables the reuse of catalysts for multiple reaction cycles, leading to cost savings, reduced waste generation, and improved sustainability of organic synthesis processes. For example, supported metal catalysts such as Pt on alumina

spectrum. Moreover, the reduction in the peak intensity of the hydroxyl group at

4.2. Enzymatic catalysis

4.2.1. Enzymatic catalysis for carbon dioxide transformations/fixation

energy-efficient carbon dioxide fixation cycle [268]. Nmar_1308 enzyme could lower the total number of enzymes required for carbon dioxide fixation in Thaumarchaeota, reducing the overall cost of biosynthesis. This is because the thaumarchaeal 3-hydroxypropionate/ 4-hydroxybutyrate cycle needs lower energy phosphoric anhydride bonds of ATP per acetyl-CoA molecule [269].

4.2.2. Enzymatic catalysis for carbon dioxide capture

4.2.3. Enzymatic catalysis for energy applications

degrade lignin into various aromatic compounds [296]. Solid-state fermentation is an approach for developing microorganisms in the absence of free water by using solid particles with an inter-particle continuous gaseous phase either as a substrate or inert solid support [297]. Several types of lignocellulosic biomasses, including rice bran, brewer’s wasted grain, coffee husk, grape pomace, wood chips, oilseed cakes, wheat bran, corn stover, and olive pomace, were employed as basic substrates for the formation of bacterial and fungal enzymes via solid-state fermentation [298,299]. Despite the various benefits of solidstate fermentation technology, its applicability for industrial use is currently limited due to variations in temperature, pH , moisture, oxygen, and other parameters that affect the development of microorganisms and the formation of metabolites inside the bioreactor as a result of the difficult agitation of the solid substrate [296]. Hence, it is crucial to establish effective bioreactors with automatic control to enhance product yield.

4.2.4. Enzymatic catalysis for organic synthesis/transformation

4.3. Photocatalysis

4.3.1. Photocatalysis for hydrogen production

4.3.2. Photocatalysis for biodiesel production

4.3.3. Photocatalysis for organic synthesis/transformation

4.3.4. Photocatalysis for water and wastewater treatment

within the wastewater. Key variables affecting this process include the selection of the photocatalyst, the light’s characteristics, the presence of dopants, and the structural morphology of the photocatalyst. In general, photocatalysis technology is based on the use of semiconductor photocatalysts (e.g.

5. Impact on sustainable chemical production

5.1. Decarbonization and potential energy savings

a substantial increment of these carbon dioxide levels is anticipated over the coming years. Additionally, more than

by

regeneration needs around

5.2. Environmental benefits

coupled with renewable energy as a low-energy technology could induce positive consequences for the environment. Global biomass production is reported to release about 100 billion metric tonnes of carbon annually. Specific biomass sources are inadequately managed through in-situ burning, leading to elevated carbon dioxide emissions. Therefore, biomass utilization in low-energy biomass electrolysis technology could minimize global warming potential. In particular, lignocellulosic biomass can be used for producing enzymes that function as catalysts in low-energy enzymatic catalysis technologies. The utilization of lignocellulosic biomass in enzymatic catalysis can minimize its associated environmental impacts and greenhouse gas emissions due to in-situ burning and landfill disposal.

circulating fluidized bed fly ash into kaliophilite catalysts with a zeolitelike composition for biodiesel production [227]. Growing interest is being received in biodiesel production through esterification reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous catalysts due to the environmental benefits of this approach. This approach could solve issues like instrument corrosion, waste production from the acid neutralization process, and product separation challenges caused by the use of homogeneous liquid acids like sulphuric acid [388-390].

6. Conclusion

Declaration of competing interest

Data availability

Acknowledgments

References

[2] A.I. Osman, A.M. Elgarahy, A.S. Eltaweil, E.M. Abd El-Monaem, H.G. El-Aqapa, Y. Park, Y. Hwang, A. Ayati, M. Farghali, I. Ihara, A.H. Al-Muhtaseb, D. W. Rooney, P.S. Yap, M. Sillanpää, Environ. Chem. Lett. 21 (2023) 1315-1379.

[3] H. Li, X. Qin, K. Wang, T. Ma, Y. Shang, Sep. Purif. Technol. 333 (2024) 125900.

[4] Y. Chen, X. Jiang, J. Xu, D. Lin, X. Xu, Environ. Funct. Mater. (2023).

[5] F.-X. Wang, Z.-C. Zhang, C.-C. Wang, Chem. Eng. J. 459 (2023) 141538.

[6] F. Karimi, N. Zare, R. Jahanshahi, Z. Arabpoor, A. Ayati, P. Krivoshapkin, R. Darabi, E.N. Dragoi, G.G. Raja, F. Fakhari, H. Karimi-Maleh, Environ. Res. 238 (2023) 117202.

[7] Y. Sun, Y. Zhao, Y. Zhou, L. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Qi, D. Fu, P. Zhang, K. Zhao, Mater. Today Energy 37 (2023) 101397.

[8] P.K. Verma, Coord. Chem. Rev. 472 (2022) 214805.

[9] H.-S. Xu, W. Xie, Coord. Chem. Rev. 501 (2024) 215591.

[10] I. Huskić, C.B. Lennox, T. Friščić, Green Chem. 22 (2020) 5881-5901.

[11] S. Eon Jun, S. Choi, J. Kim, K.C. Kwon, S.H. Park, H.W. Jang, Chin. J. Catal. 50 (2023) 195-214.

[12] Q.-N. Zhan, T.-Y. Shuai, H.-M. Xu, C.-J. Huang, Z.-J. Zhang, G.-R. Li, Chin. J. Catal. 47 (2023) 32-66.

[13] A. Noor, Coord. Chem. Rev. 476 (2023) 214941.

[14] S.S.M. Bandaru, J. Shah, S. Bhilare, C. Schulzke, A.R. Kapdi, J. Roger, J.C. Hierso, Coord. Chem. Rev. 491 (2023) 215250.

[15] Z. Wu, M. Tallu, G. Stuhrmann, S. Dehnen, Coord. Chem. Rev. 497 (2023) 215424.

[16] H. Wang, M. Gu, X. Huang, A. Gao, X. Liu, P. Sun, X. Zhang, J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023) 7239-7245.

[17] W. Matsuoka, Y. Harabuchi, S. Maeda, ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 5697-5711.

[18] Y. Zhang, J. Yang, R. Ge, J. Zhang, J.M. Cairney, Y. Li, M. Zhu, S. Li, W. Li, Coord. Chem. Rev. 461 (2022) 214493.

[19] C. Wang, Z. Wang, S. Mao, Z. Chen, Y. Wang, Chin. J. Catal. 43 (2022) 928-955.

[20] L. Li, G. Zhao, Z. Lv, P. An, J. Ao, M. Song, J. Zhao, G. Liu, Chem. Eng. J. 474 (2023) 145647.

[21] S. Tian, H. Tang, Q. Wang, X. Yuan, Q. Ma, M. Wang, Sci. Total Environ. 772 (2021) 145049.

[22] D. Roy, P. Kumar, A. Soni, M. Nemiwal, Tetrahedron 138 (2023) 133408.

[23] C. Xia, J. Wu, S.A. Delbari, A.S. Namini, Y. Yuan, Q. Van Le, D. Kim, R.S. Varma, A.T. Raissi, H.W. Jang, M. Shokouhimehr, Mol. Catal. 546 (2023) 113217.

[24] S.S. Stahl, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 8524-8525.

[25] G.A. Bhat, D.J. Darensbourg, Coord. Chem. Rev. 492 (2023) 215277.

[26] P.J. Craig, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 7 (1993) 224.

[27] W. Chen, P. Cai, H.-C. Zhou, S.T. Madrahimov, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63 (2024) e202315075.

[28] G. Li, B. Wang, D.E. Resasco, Surf. Sci. Rep. 76 (2021) 100541.

[29] Y. Tian, D. Deng, L. Xu, M. Li, H. Chen, Z. Wu, S. Zhang, Nano-Micro Lett. 15 (2023) 122.

[30] J. Li, C. Chen, L. Xu, Y. Zhang, W. Wei, E. Zhao, Y. Wu, C. Chen, JACS Au 3 (2023) 736-755.

[31] A.C.M. Loy, S.Y. Teng, B.S. How, X. Zhang, K.W. Cheah, V. Butera, W.D. Leong, B. L.F. Chin, C.L. Yiin, M.J. Taylor, G. Kyriakou, Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 96 (2023) 101074.

[32] Y. Chen, S. Ji, C. Chen, Q. Peng, D. Wang, Y. Li, Joule 2 (2018) 1242-1264.

[33] R. Qin, P. Liu, G. Fu, N. Zheng, Small Methods 2 (2018) 1700286.

[34] L. DeRita, S. Dai, K. Lopez-Zepeda, N. Pham, G.W. Graham, X. Pan, P. Christopher, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 14150-14165.

[35] J. Liu, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 34-59.

[36] L. Liu, A. Corma, Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 4981-5079.

[37] R. Jiang, L. Li, T. Sheng, G. Hu, Y. Chen, L. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 11594-11598.

[38] C. Tang, Y. Jiao, B. Shi, J.-N. Liu, Z. Xie, X. Chen, Q. Zhang, S.-Z. Qiao, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 9171-9176.

[39] J. Hulva, M. Meier, R. Bliem, Z. Jakub, F. Kraushofer, M. Schmid, U. Diebold, C. Franchini, G.S. Parkinson, Science 371 (2021) 375-379.

[40] H. Yang, L. Shang, Q. Zhang, R. Shi, G.I.N. Waterhouse, L. Gu, T. Zhang, Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4585.

[41] L. Wang, M.-X. Chen, Q.-Q. Yan, S.-L. Xu, S.-Q. Chu, P. Chen, Y. Lin, H.-W. Liang, Sci. Adv. 5, eaax6322.

[42] E. Jung, H. Shin, B.-H. Lee, V. Efremov, S. Lee, H.S. Lee, J. Kim, W. Hooch Antink, S. Park, K.-S. Lee, S.-P. Cho, J.S. Yoo, Y.-E. Sung, T. Hyeon, Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 436-442.

[43] T. Tang, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Coord. Chem. Rev. 492 (2023) 215288.

[44] W.H. Li, J. Yang, D. Wang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202213318.

[45] T. Tang, Y. Wang, J. Han, Q. Zhang, X. Bai, X. Niu, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Chin. J. Catal. 46 (2023) 48-55.

[46] T. Tang, Z. Duan, D. Baimanov, X. Bai, X. Liu, L. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Guan, Nano Res. 16 (2023) 2218-2223.

[47] X. Zheng, B. Li, Q. Wang, D. Wang, Y. Li, Nano Res. 15 (2022) 7806-7839.

[48] H. Zhang, X. Jin, J.-M. Lee, X. Wang, ACS Nano 16 (2022) 17572-17592.

[49] Y. Song, B. Xu, T. Liao, J. Guo, Y. Wu, Z. Sun, Small 17 (2021) 2002240.

[50] Y. Lei, Y. Wang, Y. Liu, C. Song, Q. Li, D. Wang, Y. Li, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 20794-20812.

[51] D.-S. Bin, Y.-S. Xu, S.-J. Guo, Y.-G. Sun, A.-M. Cao, L.-J. Wan, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 221-231.

[52] S. Zhang, Y. Wu, Y.-X. Zhang, Z. Niu, Sci. China Chem. 64 (2021) 1908-1922.

[53] T. Hu, Z. Gu, G.R. Williams, M. Strimaite, J. Zha, Z. Zhou, X. Zhang, C. Tan, R. Liang, Chem. Soc. Rev. (2022).

[54] C. Ning, S. Bai, J. Wang, Z. Li, Z. Han, Y. Zhao, D. O’Hare, Y.-F. Song, Coord. Chem. Rev. 480 (2023) 215008.

[55] Z.-Z. Yang, C. Zhang, G.-M. Zeng, X.-F. Tan, D.-L. Huang, J.-W. Zhou, Q.-Z. Fang, K.-H. Yang, H. Wang, J. Wei, K. Nie, Coord. Chem. Rev. 446 (2021) 214103.

[56] G. Wang, D. Huang, M. Cheng, S. Chen, G. Zhang, L. Lei, Y. Chen, L. Du, R. Li, Y. Liu, Coord. Chem. Rev. 460 (2022) 214467.

[57] H. Ye, S. Liu, D. Yu, X. Zhou, L. Qin, C. Lai, F. Qin, M. Zhang, W. Chen, W. Chen, L. Xiang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 450 (2022) 214253.

[58] Z. Cai, D. Zhou, M. Wang, S.-M. Bak, Y. Wu, Z. Wu, Y. Tian, X. Xiong, Y. Li, W. Liu, S. Siahrostami, Y. Kuang, X.-Q. Yang, H. Duan, Z. Feng, H. Wang, X. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 9392-9396.

[59] P. Li, X. Duan, Y. Kuang, Y. Li, G. Zhang, W. Liu, X. Sun, Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018) 1703341.

[60] X. Li, Y. Sun, J. Xu, Y. Shao, J. Wu, X. Xu, Y. Pan, H. Ju, J. Zhu, Y. Xie, Nat. Energy 4 (2019) 690-699.

[61] X. Hao, L. Tan, Y. Xu, Z. Wang, X. Wang, S. Bai, C. Ning, J. Zhao, Y. Zhao, Y.F. Song, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59 (2020) 3008-3015.

[62] K. Teramura, S. Iguchi, Y. Mizuno, T. Shishido, T. Tanaka, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 8008-8011.

[63] Y. Li, J. Hao, H. Song, F. Zhang, X. Bai, X. Meng, H. Zhang, S. Wang, Y. Hu, J. Ye, Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 2359.

[64] L. Tan, S.-M. Xu, Z. Wang, Y. Xu, X. Wang, X. Hao, S. Bai, C. Ning, Y. Wang, W. Zhang, Y.K. Jo, S.-J. Hwang, X. Cao, X. Zheng, H. Yan, Y. Zhao, H. Duan, Y.F. Song, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) (1867) 11860-11861.

[65] L. Tan, S.-M. Xu, Z. Wang, X. Hao, T. Li, H. Yan, W. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Y.-F. Song, Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2 (2021) 100322.

[66] Z. Wang, S.-M. Xu, L. Tan, G. Liu, T. Shen, C. Yu, H. Wang, Y. Tao, X. Cao, Y. Zhao, Y.-F. Song, Appl. Catal. B 270 (2020) 118884.

[67] J. Ren, S. Ouyang, H. Xu, X. Meng, T. Wang, D. Wang, J. Ye, Adv. Energy Mater. 7 (2017) 1601657.

[68] X. Wang, J. Wang, Y. Sun, K. Li, T. Shang, Y. Wan, Front. Chem. 10 (2022) 1089708.

[69] Y. Li, W. Shen, Chem. Soc. Rev. 43 (2014) 1543-1574.

[70] M. Melchionna, P. Fornasiero, Mater. Today 17 (2014) 349-357.

[71] D. Gao, Y. Zhang, Z. Zhou, F. Cai, X. Zhao, W. Huang, Y. Li, J. Zhu, P. Liu, F. Yang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 5652-5655.

[72] Q. Li, L. Song, Z. Liang, M. Sun, T. Wu, B. Huang, F. Luo, Y. Du, C.-H. Yan, Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2 (2021) 2000063.

[73] J. Kong, Z. Xiang, G. Li, T. An, Appl. Catal. B 269 (2020) 118755.

[74] S.A. Galema, Chem. Soc. Rev. 26 (1997) 233-238.

[75] C.O. Kappe, D. Dallinger, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5 (2006) 51-63.

[76] S.-T. Chen, S.-H. Chiou, K.-T. Wang, J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 38 (1991) 85-91.

[77] D. Dallinger, C.O. Kappe, Chem. Rev. 107 (2007) 2563-2591.

[78] B.-X. Jiang, H. Wang, Y.-T. Zhang, S.-B. Li, Polyhedron 243 (2023) 116569.

[79] V. Bon, I. Senkovska, I.A. Baburin, S. Kaskel, Cryst. Growth Des. 13 (2013) 1231-1237.

[80] G. Bond, R.B. Moyes, D.A. Whan, Catal. Today 17 (1993) 427-437.

[81] R. Gedye, F. Smith, K. Westaway, H. Ali, L. Baldisera, L. Laberge, J. Rousell, Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (1986) 279-282.

[82] R.J. Giguere, T.L. Bray, S.M. Duncan, G. Majetich, Tetrahedron Lett. 27 (1986) 4945-4948.

[83] M.B. Gawande, S.N. Shelke, R. Zboril, R.S. Varma, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 1338-1348.

[84] M.B. Gawande, V.D.B. Bonifácio, R. Luque, P.S. Branco, R.S. Varma, ChemSusChem 7 (2014) 24-44.

[85] H. Cho, F. Török, B. Török, Green Chem. 16 (2014) 3623-3634.

[86] J.D. Moseley, C.O. Kappe, Green Chem. 13 (2011) 794-806.

[87] V. Polshettiwar, R.S. Varma, Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (2008) 629-639.

[88] A. Pons-Balagué, M.J.H. Ojea, M. Ledezma-Gairaud, D.R. Mañeru, S.J. Teat, J. S. Costa, G. Aromí, E.C. Sanudo, Polyhedron 52 (2013) 781-787.

[89] B. Borah, K.D. Dwivedi, B. Kumar, L.R. Chowhan, Arab. J. Chem. 15 (2022) 103654.

[90] A.K. Rathi, M.B. Gawande, R. Zboril, R.S. Varma, Coord. Chem. Rev. 291 (2015) 68-94.

[91] Q. You, M. Liao, H. Feng, J. Huang, Org. Biomol. Chem. 20 (2022) 8569-8583.

[92] K. Kumar, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 59 (2022) 205-238.

[93] B.R. Reddy, V. Sridevi, T.H. Kumar, C.S. Rao, V.C.S. Palla, D.V. Suriapparao, G. S. Undi, Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 164 (2022) 354-372.

[94] P.C. Dhanush, P.V. Saranya, G. Anilkumar, Tetrahedron 105 (2022) 132614.

[95] G.B. Dudley, R. Richert, A.E. Stiegman, Chem. Sci. 6 (2015) 2144-2152.

[96] T.V. de Medeiros, J. Manioudakis, F. Noun, J.-R. Macairan, F. Victoria, R. Naccache, J. Mater. Chem. C 7 (2019) 7175-7195.

[97] Y. Li, W. Yang, J. Membr. Sci. 316 (2008) 3-17.

[98] C. Gabriel, S. Gabriel, E.H. Grant, E.H. Grant, B.S.J. Halstead, D. Michael, P. Mingos, Chem. Soc. Rev. 27 (1998) 213-224.

[99] W. Liang, D.M. D’Alessandro, Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 3706-3708.

[100] M. Nüchter, B. Ondruschka, W. Bonrath, A. Gum, Green Chem. 6 (2004) 128-141.

[101] A. Stadler, B.H. Yousefi, D. Dallinger, P. Walla, E. Van der Eycken, N. Kaval, C. O. Kappe, Org. Process Res. Dev. 7 (2003) 707-716.

[102] A. Adhikari, S. Bhakta, T. Ghosh, Tetrahedron 126 (2022) 133085.

[103] S.V. Giofrè, R. Romeo, R. Mancuso, N. Cicero, N. Corriero, U. Chiacchio, G. Romeo, B. Gabriele, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 20777-20780.

[104] C.O. Kappe, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 4977-4990.

[105] Z. Wu, E. Borretto, J. Medlock, W. Bonrath, G. Cravotto, ChemCatChem 6 (2014) 2762-2783.

[106] H.K.M. Ng, G.K. Lim, C.P. Leo, Microchem. J. 165 (2021) 106116.

[107] G.S. Singh, Asian J. Org. Chem. 11 (2022) 165-182.

[108] M. Nishioka, M. Miyakawa, Y. Daino, H. Kataoka, H. Koda, K. Sato, T.M. Suzuki, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52 (2013) 4683-4687.

[109] T. Razzaq, J.M. Kremsner, C.O. Kappe, J. Org. Chem. 73 (2008) 6321-6329.

[110] N.A.A. Elkanzi, H. Hrichi, R.A. Alolayan, W. Derafa, F.M. Zahou, R.B. Bakr, ACS Omega 7 (2022) 27769-27786.

[111] Z.-X. Wu, G.-W. Hu, Y.-X. Luan, ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 11716-11733.

[112] S.S. Gupta, S. Kumari, I. Kumar, U. Sharma, Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 56 (2020) 433-444.

[113] E.S. Yun, M.S. Akhtar, S. Mohandoss, Y.R. Lee, Org. Biomol. Chem. 20 (2022) 3397-3407.