DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02235-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191388

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-08

الاتجاهات الحديثة في تحضير وتطبيقات الحديد أكسيد النانوية في الطب الحيوي

الملخص

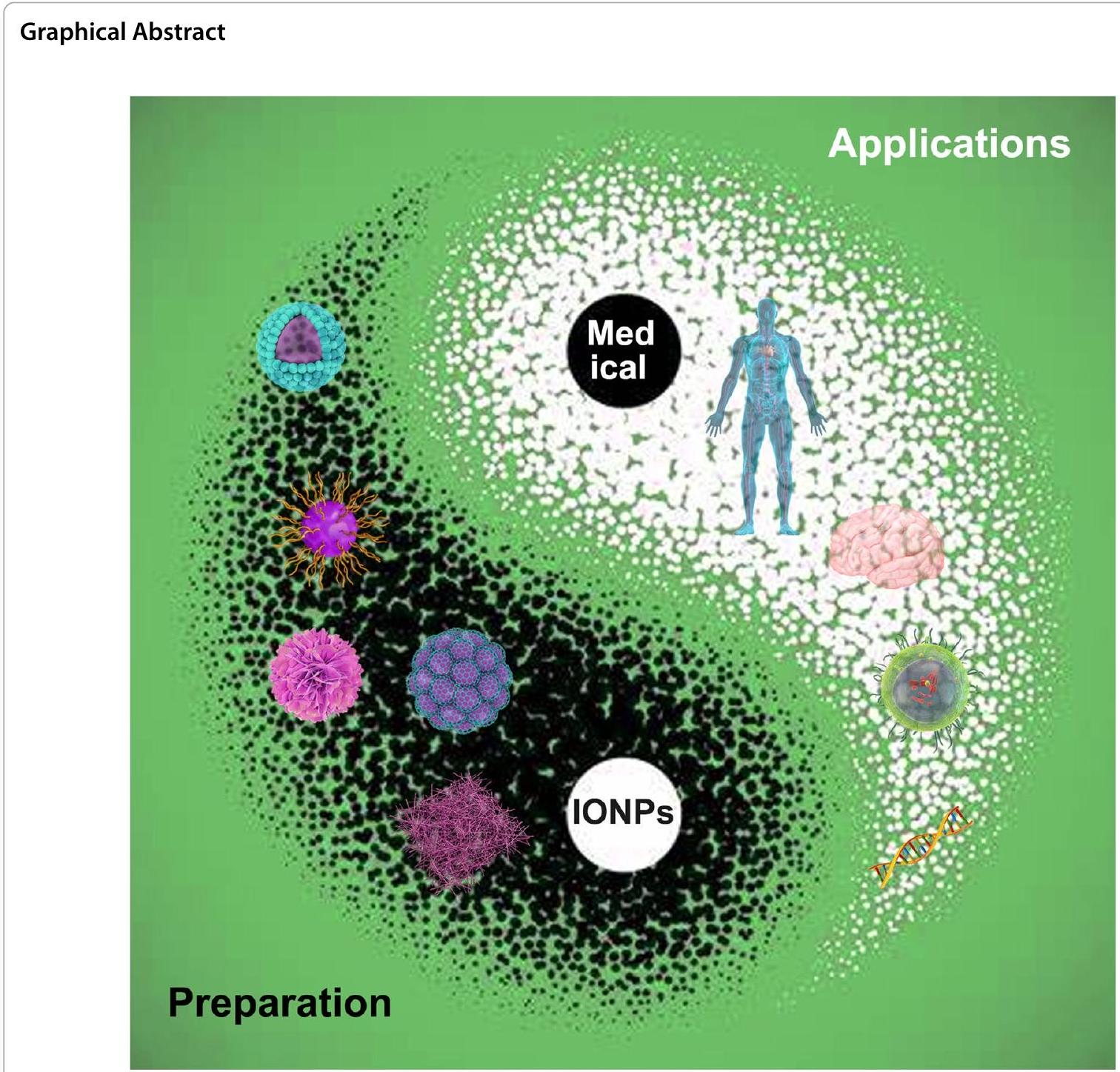

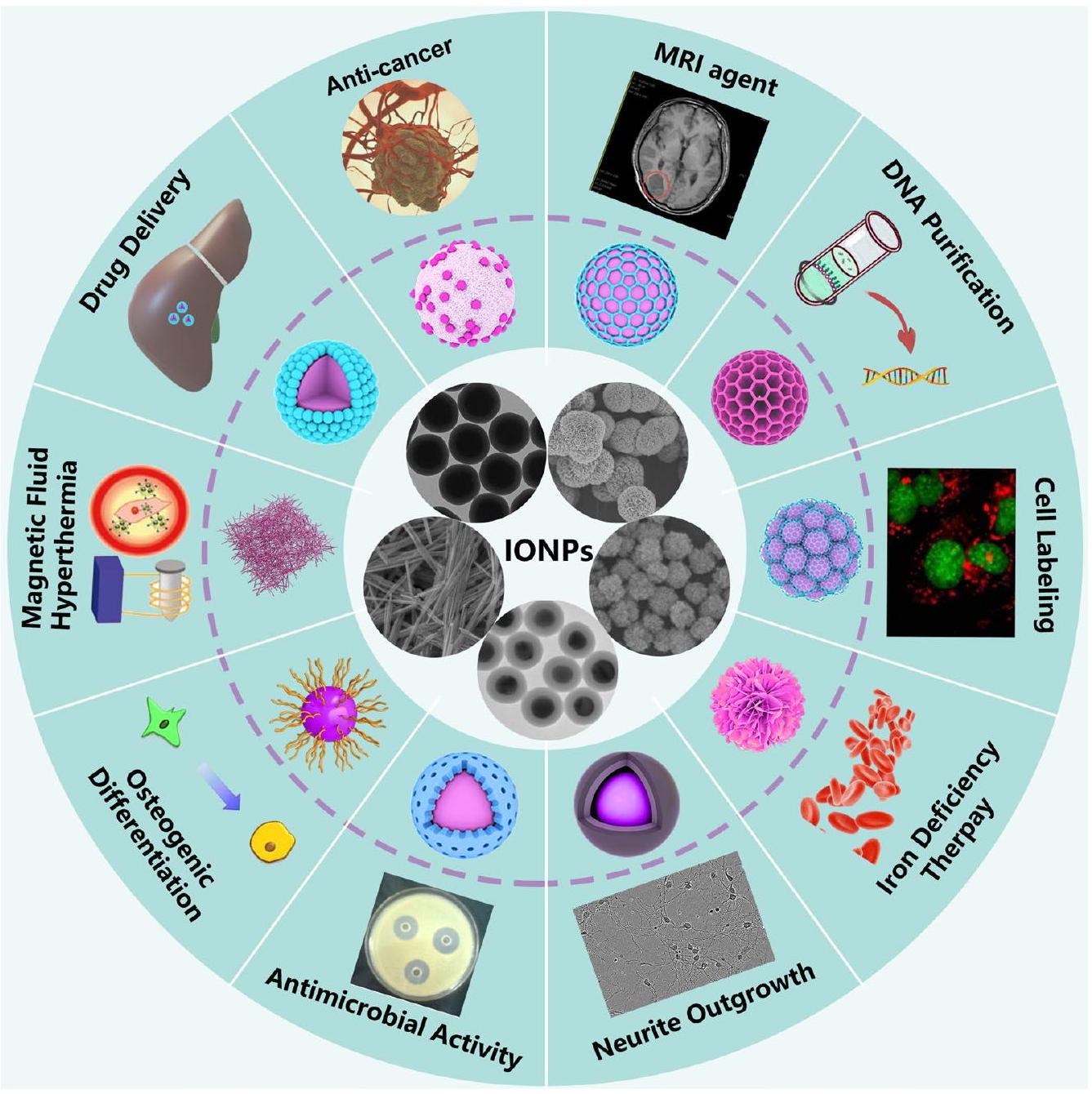

تُستخدم جزيئات أكسيد الحديد النانوية (IONPs)، التي تمتلك سلوكًا مغناطيسيًا وخصائص شبه موصلة، على نطاق واسع في مجالات الطب الحيوي المتعددة الوظائف نظرًا لتوافقها الحيوي، وقابليتها للتحلل البيولوجي، وانخفاض سمّيتها، مثل الأنشطة المضادة للسرطان، والمضادة للبكتيريا، وتوسيم الخلايا. ومع ذلك، هناك عدد قليل من جزيئات IONPs المستخدمة سريريًا في الوقت الحاضر. تم سحب بعض جزيئات IONPs المعتمدة للاستخدام السريري بسبب عدم الفهم الكافي لتطبيقاتها الطبية الحيوية. لذلك، فإن تلخيصًا منهجيًا لتحضير جزيئات IONPs وتطبيقاتها الطبية الحيوية أمر بالغ الأهمية للخطوة التالية للدخول في الممارسة السريرية من المرحلة التجريبية. تلخص هذه المراجعة الأبحاث الموجودة في العقد الماضي حول التفاعل البيولوجي لجزيئات IONPs مع نماذج الحيوانات/الخلايا، وتطبيقاتها السريرية في البشر. تهدف هذه المراجعة إلى تقديم معرفة متقدمة تتعلق بتأثيرات جزيئات IONPs البيولوجية في الجسم الحي وفي المختبر، وتحسين تصميمها وتطبيقها بشكل أذكى في أبحاث الطب الحيوي والتجارب السريرية.

مقدمة

أظهرت النتائج أن الجسيمات النانوية المغلفة بالكربوكسيميثيل دكستران تتفكك بشكل أسرع في سائل الجسم المحاكي مقارنة بتلك المغلفة بالسيليكا، وأظهرت أقل خصائص مسبب للتخثر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت السماكة عكسية بالنسبة لمعدل التفكك. علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت الدراسات أن نفس الجسيمات النانوية قد تظهر توافقًا حيويًا أو سمية مختلفة في أنواع خلايا مختلفة أو في البشر، وهو أيضًا السبب الرئيسي الذي يعيق تطبيق الجسيمات النانوية في المجال الطبي الحيوي. لذلك، من الضروري ليس فقط تلخيص الحجم، والتغليف السطحي، والمجموعات الوظيفية للجسيمات النانوية، ولكن أيضًا تلخيص التطبيقات الطبية الحيوية للجسيمات النانوية في نماذج حيوانية مختلفة، وأنواع خلايا، والبشر، من أجل تعزيز الفهم الشامل للجسيمات النانوية من قبل الباحثين وتقديم إرشادات لتسريع التطبيق السريري للطب النانوي القائم على الجسيمات النانوية.

تركيب جزيئات أكسيد الحديد النانوية

التفريز، طباعة الأشعة الإلكترونية، الهباء الجوي، وترسيب الطور الغازي. على الرغم من أن عائد الطرق الفيزيائية مرتفع، إلا أن

تطبيقات الجسيمات النانوية الحديدية في نماذج الحيوانات

الحالات المغناطيسية: المغناطيسية الحديدية (

حقن لمدة 24 ساعة، ثم تم التخلص منه بواسطة الكلى بعد 48 ساعة دون التسبب في أي ضرر أو آثار جانبية [46]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم استخدام سمكة الزرد، كنموذج ناشئ للتحقيق في السمية المحتملة، بنجاح لتقييم المخاطر المحتملة التي تسببها جزيئات النانو الحديدية. أظهرت النتائج أن الكربون المعدل

تم امتصاص بولي (إيثيلين جلايكول)-ل-أرجينين@IONPs (PEG-Arg@IONPs) بشكل رئيسي بواسطة الكبد، بالإضافة إلى الطحال والقلب والكلى في نموذج BALB/c خلال ساعتين. بعد 24 ساعة،

يمكن أن تزيد SPIONs الوظيفية من تراكم الميثوتريكسات (MTX) في موقع الورم وتقلل من سمية MTX في فئران BALB/c، مما يوفر خيارًا لتصوير الرنين المغناطيسي والعلاج المستهدف للورم [66].

التطبيقات في المختبر لجزيئات النانو الحديدية

جزيئات الحديد النانوية في خلايا الورم

خلايا سرطان الرئة

خلايا سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية الفموية

سرطان المبيض

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

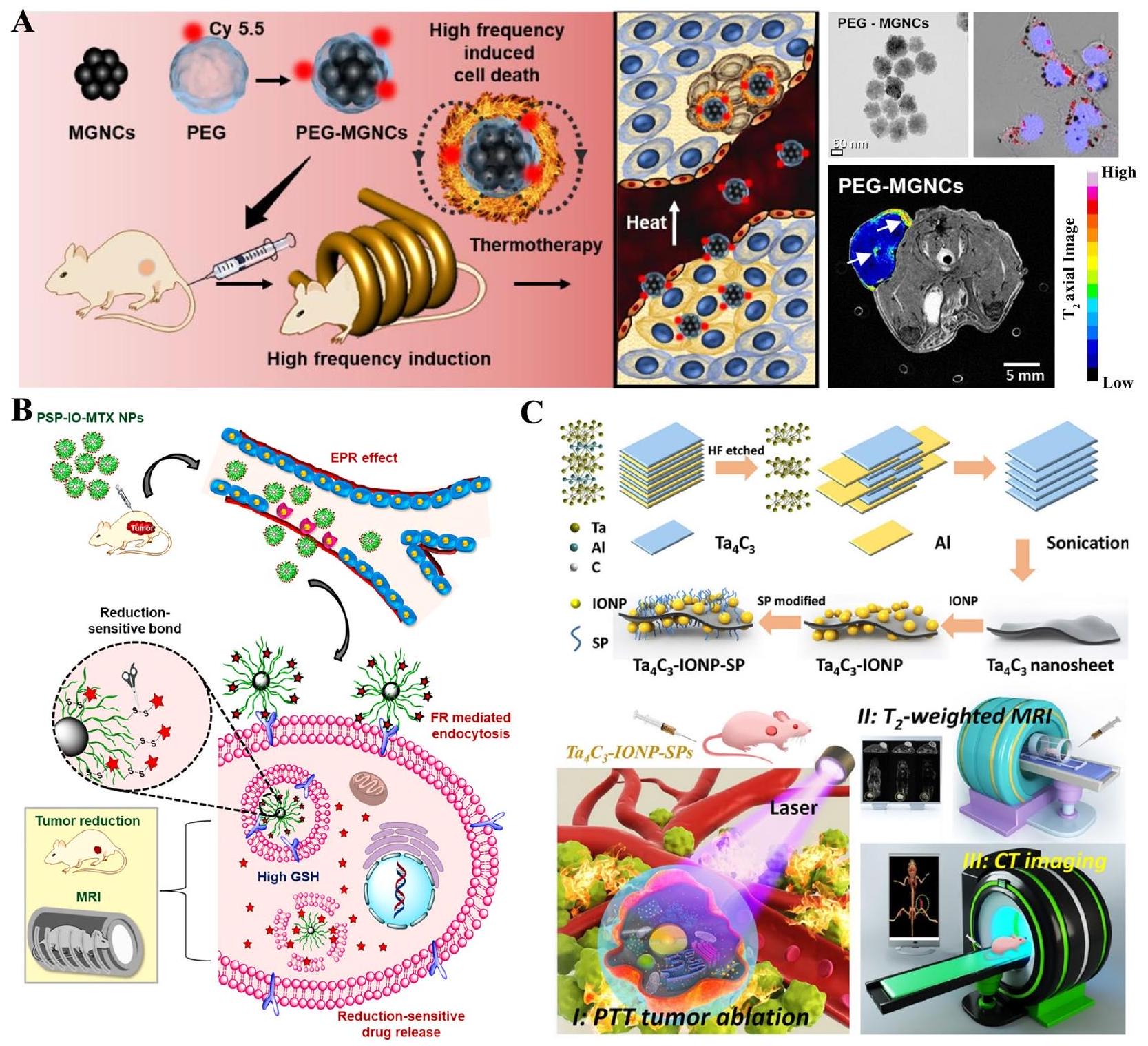

| بولي إيثيلين جلايكول | PEG-MGNCs | فأر مصاب بورم SCC7 |

|

8 أيام | تعزيز فعالية فرط الحرارة | [12] |

| سترات | سترات@جزيئات أكسيد الحديد النانوية | فئران مسنّة وصحية صغيرة |

|

28 يومًا | متوافق حيوياً بشكل معقول للفئران الصغيرة | [16] |

| بولي إيثيلين جلايكول | سانبس | خنزير |

|

90 يومًا | لا آثار سلبية | [٤٠] |

| كيتوزان |

|

فئران BALB/c |

|

|

لا سمية في الأعضاء الحيوية | [41] |

| c(RGDyK) و D-جلوكوزامين |

|

فئران BALB/c |

|

8 أيام | تم تثبيط الأورام على الفئران بشكل واضح | [42] |

| أغشية البلعميات |

|

فئران BALB/c |

|

16 يوم | تقليل حجم الورم بشكل كبير | [43] |

| سولفونات الدوبامين، سولفونات الدوبامين ثنائية الأيون، كلوريد الكورينين | جزيئات نانوية من أكسيد الحديد | فئران CD1 | 1 أو

|

يتم توزيعه بسرعة في الكبد والطحال، ويتم إخراجه عبر الجهاز البولي | [٤٤] | |

| / |

|

فئران سويسرية |

|

12.22 يوم | تقليل نمو الورم بشكل كبير | [٤٥] |

| 6-7 ألبومين مصل البقر |

|

جرذان SD |

|

|

تمت إزالته بكفاءة خلال 48 ساعة | [٤٦] |

| بوليمر (إيثيلين جلايكول)-L-أرجينين | PEG-Arg@IONPs | فئران BALB/c |

|

24 ساعة | يتم امتصاصه بشكل رئيسي بواسطة الكبد، بالإضافة إلى الطحال والقلب والكلى | [49] |

| سترات، كركمين، كيتوزان | IONPs@سترات، IONPs@كركمين، IONPs@كيتوزان | جرذان ويستار |

|

10 أيام | كانت جزيئات النانو الحديدية المغلفة بالكركم وجزيئات النانو الحديدية المغلفة بالكيتوزان سامة بشكل خفيف | [50] |

| كلوريد، لاكتات، نترات | IONPs@كلوريد، IONPs@لاكتات، وIONPs@نترات | جرذان ويستار |

|

14 يوم | لا علامات على السمية | [51] |

| الألبومين البشري | جزيئات النانو الحديدية المغلفة بالألبومين البشري | جرذان ويستار |

|

24 ساعة | أولاً يتم جمعه في الكبد، ثم في الطحال والكلى | [52] |

| حمض ثنائي الميركابتوسكسينيك | IONPs@DMSA | فئران C57BL/6 |

|

7، 30، 60، 90 يومًا | لا سمية | [53] |

| / | ES-IONPs | فئران عارية تحمل ورم U-87 MG |

|

28 يومًا | تراكم في الورم | [٥٤] |

| بوليمر (إيثيلين جلايكول) كربوكسي بولي(

|

PEG-PCCL-IONPs | فئران BALB/C المزروعة بأورام H22 |

|

48 ساعة | موزعة بشكل رئيسي في الطحال والكبد | [55] |

| ديكستران | سباينديكس | نموذج الخنزير |

|

30 دقيقة | لم يُلاحظ أي تفاعل زائف مرتبط بتنشيط المكملات | [56] |

| حمض اللاكتوبيونيك | MNP-LBA | أرنب ألبينو |

|

24 ساعة | تعزيز إطلاق السيفترياكسون | [57] |

| حمض البولي إيثيلين جلايكول، بولي إيثيلين جلايكول-

|

SPION@PEG-COOH و SPION@PEG-NH2 | فئران BALB/c |

|

28 يومًا | تراكمت بشكل رئيسي في الرئة | [58] |

| بولي إيثيلين جلايكول | PEG-SPIONs | فئران كونمينغ |

|

14 يوم | بشكل أساسي في الكبد والطحال والأمعاء | [٥٩] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

| بروميد ثنائي دوديليل-ثنائي ميثيل الأمونيوم، توكوفيريل-بولي إيثيلين غليكول-سكسينات | سبايون-ديمايب، سبايون-تي بي جي إس | فئران سويسرية ألبينو |

|

7 أيام | تراكمت SPION-DMAB بشكل رئيسي في الدماغ والطحال، بينما تم امتصاص SPION-TPGS في الكبد والكلى. | [60] |

| L-cysteine | سيستين-

|

فئران BALB/c |

|

7 أيام | زيادة الأنسجة الدهنية في الطبقة السفلية من البشرة لدى الفئران | [61] |

| بوليمر (لاكتيد) | PLA@SPIONs | جرذان سبرايج داولي |

|

6 أشهر | تدهور بطيء | [62] |

| حمض الأوليك وميثوكسي-بولي إيثيلين غليكول-فوسفوليبيد | سبايون-PEG2000 | فئران ألبينو سويسرية |

|

14 يوم | نخر مستحث في الكبد والكلى وت infiltrate التهابي في الرئة | [63] |

| سيليكا | سيو-في تحت 5 | فئران CD-1 |

|

7 أسابيع | لا توجد سمية حادة أو مزمنة واضحة | [64] |

| / | سبون | جرذان سبرايج داولي |

|

8 أسابيع | عزز تشكيل الغضروفية | [65] |

| جالاكتومانان | جزيئات PSP-IO | فئران BALB/c |

|

14 يوم | زيادة تراكم الميثوتريكسات في موقع الورم وتقليل سمية الميثوتريكسات | [66] |

| / | يو إس بيونز | فئران ICR |

|

7 أيام | لا سمية ملحوظة | [67] |

| أبتامير محدد لجليبيكان-3 | أبت-يو إس بي آي أو | فئران كونمينغ |

|

30 يومًا | متوافق حيوياً ممتاز | [68] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

| بوليمر (إيثيلين أمين)، بوليمر (أليلامين هيدروكلوريد)، بوليمر (داياليل ديميثيل أمونيوم كلوريد) | IONPs-PEI، IONPs-PAH، IONPs-PDADMAC | خط الخلايا A549 |

|

24 ساعة | كانت جزيئات الحديد النانوية المستقرة بواسطة بولي (أليل أمين هيدروكلوريد) الأفضل من حيث التوافق الحيوي. | [69] |

| بوليدوبامين |

|

خط الخلايا NK |

|

12 ساعة | يمكن أن ينظم خلايا المناعة، ويثبط نمو الورم | [70] |

| مغنيسيوم |

|

خط الخلايا A549 |

|

24 ساعة | آثار سامة خلوية ملحوظة | [71] |

| بوليمر الإيثيلين أمين – فوسفات الكالسيوم | SPIONs@PEI-CPs | خطوط خلايا A549 و HepG2 |

|

24 ساعة | كانت SPIONs@PEI-CPs تتمتع بتوافق حيوي ممتاز، بينما كانت SPIONs@PEI تتمتع بسمية خلوية ملحوظة. | [72] |

| بولي إيثيلين جلايكول | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خط الخلايا A549 |

|

لا سمية ملحوظة | [73] | |

| مضاد-اف

|

avß6-MIONPs | خطوط خلايا VB6 و H357 |

|

24 و 48 ساعة | يمكن أن تعزز الجسيمات النانوية المغناطيسية avß6- من قدرة قتل سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية الفموي عند دمجها مع مجال مغناطيسي. | [74] |

| كيتوزان | CS@IONPs | خط الخلايا HSC-2 |

|

48 ساعة | لا تآزر مع أدوية السرطان؛ لا تنقذ تمامًا من تلف الخلايا الناتج عن الأشعة السينية | [75] |

| فولات-كيتوزان-دوستكسل | SPIONs المغلفة بحمض الفوليك – كيتوزان – دوستكسل | خطوط خلايا L929 و KB و PC3 |

|

48 ساعة | السُميّة المستهدفة في خلايا السرطان | [76] |

| كيتوزان، مجال عامل النمو، مجال سوماتوميدين ب | IONPs/C، IONPs/C/GFD، IONPs/C/SMB | خط الخلايا SKOV3 |

|

|

أظهر GFD + SMB تأثيرًا تآزريًا | [77] |

| الكوبالت والمنغنيز | CoMn-IONP | خط الخلايا ES-2 |

|

24 ساعة | تشبع مغناطيسي عالي وكفاءة تسخين | [78] |

| / | مصل SPIONs | خط الخلايا SKOV3 |

|

24 ساعة | أثبط بشكل كبير تكاثر الخلايا | [79] |

| أجسام مضادة ذات سلسلة واحدة

|

|

خط الخلايا SKOV3 |

|

72 ساعة | استمر في تثبيط نمو خلايا سرطان المبيض Skov3 | [80] |

| كيتوزان | SPIONs المغلفة بـ Cs | خط الخلايا HEK-293 |

|

24، 48، 72 ساعة | غير سامة | [81] |

| / |

|

خطوط خلايا كاكو-2، HT-29، وSW-480 |

|

24 ساعة | الكربوهيدرات والبوليمرات المغلفة على سطح الجسيمات النانوية عززت التوافق الحيوي | [82] |

| بولي إيثيلين جلايكول |

|

خط الخلايا COLO-205 |

|

24 ساعة | السُمية الخلوية تجاه خلايا السرطان | [83] |

| سيليكا | جزيئات نانوية Fe@FeOx@SiO2 | خط الخلايا HCT116 |

|

72 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية | [84] |

| سيليكا | سيليكا@IONPs أقل من 5 نانومتر | خط الخلايا Caco-2 |

|

24 ساعة | حسن التوافق الحيوي | [85] |

| كربوكسيلات، أمين | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خط الخلايا C10 |

|

24 ساعة | السُمية الخلوية والإجهاد التأكسدي بطريقة تعتمد على الجرعة | [86] |

| أبتامير، ذهب | أبتامير-ذهب@SPIONs | خطوط خلايا HT-29 و CHO و L929 |

|

24 ساعة | تأثير التركيز على السمية الخلوية | [87] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

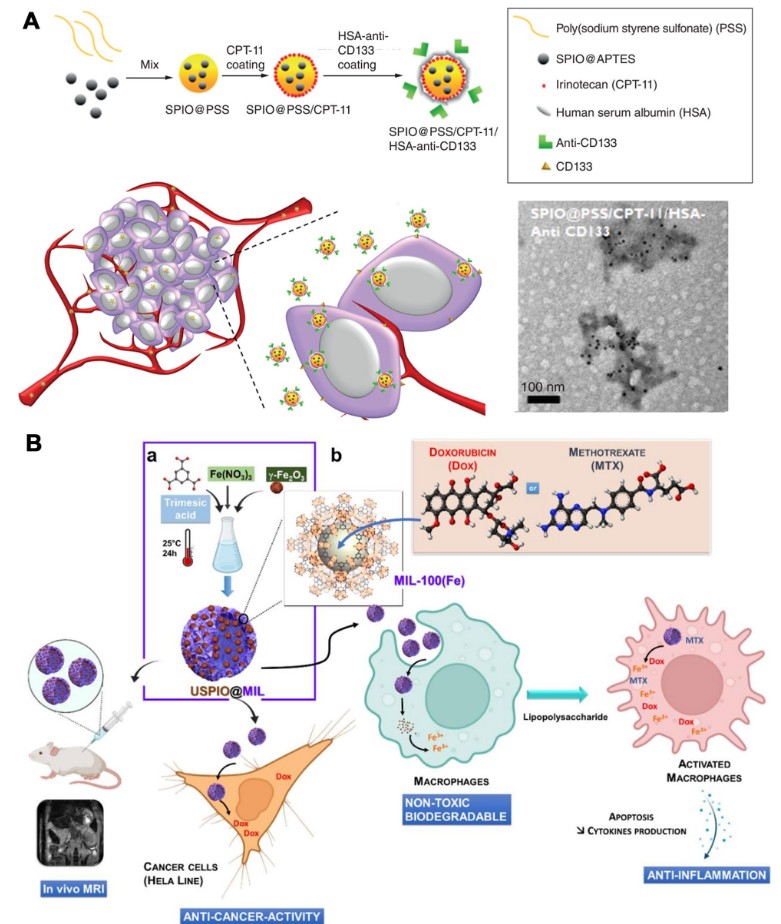

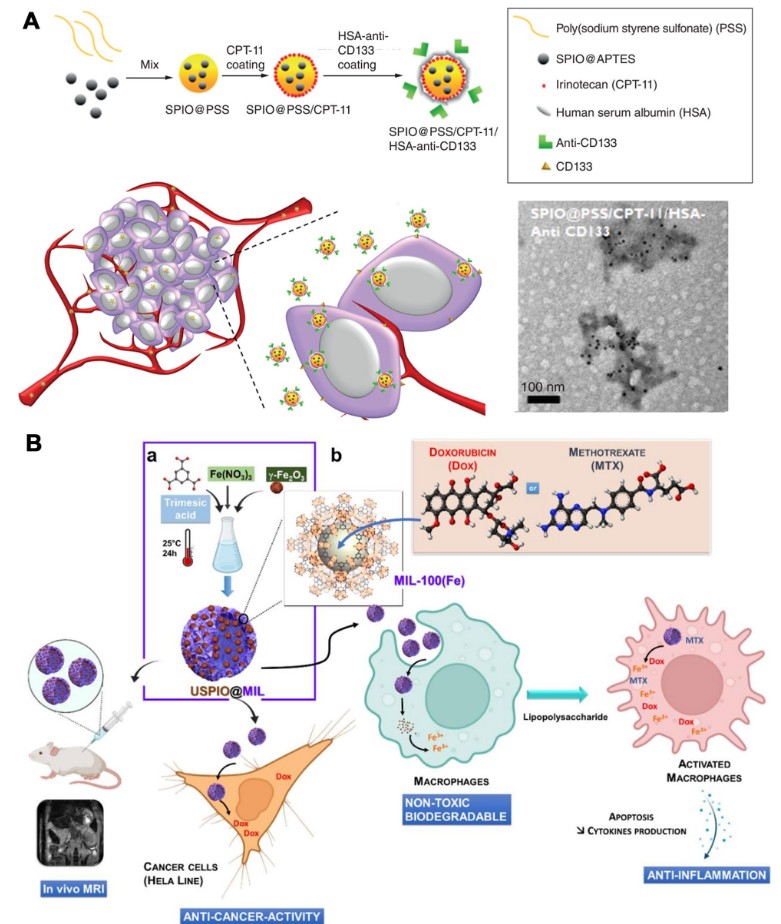

| بوليمر (صوديوم ستيرين سلفونات) / إيرينوتيكان / ألبومين مصل الإنسان – مضاد CD133 | SPIONs@PSS/HAS-مضاد-CD133 | خطوط خلايا Caco2 و HCT116 و DLD1 |

|

24 ساعة | أثبطت بقاء خلايا الورم بطريقة تعتمد على الجرعة | [88] |

| ديكستران | جامعة لوبيك – SPION مغطاة بالدكستران | خط الخلايا السرطانية الحرشفية للرأس والعنق |

|

120 ساعة | انخفاض تكاثر الخلايا | [89] |

| حمض الهيالورونيك، HA-PEG10 | HA-PEG10@SPIONs | خط الخلايا SCC7 |

|

2 ساعة | انخفاض ملحوظ في حيوية خلايا SCC7 | [90] |

| ديكستران، حمض الهيالورونيك، سيسبلاتين | سيون

|

خط الخلايا PC-3 |

|

24 ساعة | SPIONs مع السيسبلاتين تسبب موت الخلايا المبرمج والنخر | [91] |

| جي 591 | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خطوط خلايا LNCaP و PC3 و DU145 و 22RV1 | 48 ساعة | 48 ساعة | لا تأثير على بقاء الخلايا | [92] |

| بوليمر (N-إيزوبروبيل أكريلاميد – أكريلاميد – أليلامين) | R11-PIONPs | خطوط خلايا PC3 و LNCaP |

|

|

أثبطت بقاء خلايا الورم بطريقة تعتمد على الجرعة | [93] |

| دوستكسل |

|

خطوط خلايا DU145 و PC-3 و LNCaP |

|

72 ساعة | سمية خلوية طفيفة | [94] |

| ببتيد مستقبل هرمون اللوتين وهرمون الإفراز وببتيد مستقبل منشط البلازمينوجين من نوع يوروكيناز | LHRH-AE105-جزيئات نانوية مغناطيسية | خط الخلايا PC-3 |

|

24 ساعة | انخفاض ملحوظ في حيوية خلايا PC-3 | [95] |

| حمض الهيالورونيك | جزيئات نانوية FeO@HA | خلايا L929 الطبيعية وخلايا السرطان MDA-MB-231 |

|

|

استهداف عالي التخصص لخلايا السرطان | [96] |

| / | جزيئات نانوية صغيرة للغاية | خطوط خلايا MCF7 و 4T1 | 0.8 مللي مول من الحديد | 24 ساعة | عدم السمية الخلوية | [98] |

| / | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خط الخلايا 4T1 |

|

24 ساعة | خفضت قابلية بقاء خلايا 4T1 إلى 48.5% | [99] |

| أرجينين-ميثوتريكسات | في-أرج-متيكس | خطوط خلايا MCF-7، 4T1، HFF-2 |

|

|

انخفضت بشكل ملحوظ حيوية الخلايا | [100] |

| غشاء البلعمة | FeO@MM | خط الخلايا MCF-7 |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية | [43] |

| حمض ثنائي الميركابتوسكسينيك | DMSA-SPION | خط الخلايا MCF-7 |

|

|

استهداف خلايا سرطان الثدي | [101] |

| كربيد التنتالوم |

|

خط الخلايا 4T1 |

|

24 ساعة | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [102] |

| دندريمير بولي (أميدوأمين) بلورونيك P123/HSP90a | منارة نانوية IPP/MB | خطوط خلايا MDA-MB-231 و MCF-10A |

|

48 ساعة | توافق حيوي جيد | [103] |

| ثلاثة ألياف حيوية مهندسة (MS1Fe1 و MS1Fe2 و MS1Fe1Fe2) | H2.1MS1: MS1Fe1/IONPs | خطوط خلايا SKBR3 و MSU1.1 |

|

72 ساعة | تمت ملاحظة السمية عندما كانت التركيزات أكثر من

|

[104] |

| سيليكا | PVPMSFe | خطوط خلايا MCF-7 و HFF2 |

|

|

لا سمية للخلايا | [105] |

| حمض الأوليك، جيلاتين | جزيئات النانو المغناطيسية المغلفة بغلاف من حمض الأوليك والجيلاتين | خط خلايا هيلا |

|

|

فعالية علاجية أعلى | [106] |

| بوليمر الكابرو لاكتون | PCL-IONPs | خط خلايا هيلا |

|

24 ساعة | التأثيرات السامة للخلايا على خلايا هيلا | [107] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

| حمض الجلوتاريك المرتبط بالبروتين | برو-غلو-في أو | خطوط خلايا WI26VA و MCF-7 و HeLa |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية في خلايا الرئة البشرية الطبيعية، سمية طفيفة في خلايا MCF-7 و HeLa | [108] |

| دوكسوروبيسين أو ميثوتريكسات | USPIO(20)@MIL، USPIO(20)@MIL/MTX و USPIO(20)@MIL/Dox | خطوط خلايا هلا و RAW 264.7 |

|

|

أظهر USPIO(20)@MIL سمية خلوية منخفضة تجاه خلايا هيلا، ولكن لم يظهر سمية خلوية تجاه البلعميات. قام USPIO(20)@MIL/MTX و USPIO(20)@MIL/Dox بشكل ملحوظ بتثبيط بقاء الخلايا في كلا خطي الخلايا. | [109] |

| 3-أمينوبروبيل-ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين، أمينودكستران، وحمض ثنائي الميركابتوسكسينيك | IONPs-AD، IONPs-DMSA، IONPs-APS | خط خلايا هيلا |

|

72 ساعة | سمية منخفضة دون تغيير شكلي | [110] |

| هيبارين-بولوكسامر | SPION@HP | خط خلايا هيلا |

|

48 ساعة | متوافق حيوياً بدرجة عالية | [111] |

| بولي (إيثيلين جلايكول) |

|

خط الخلايا SGC7901/ADR |

|

48 ساعة | زيادة موت الخلايا مع سمية منخفضة | [112] |

|

|

|

خط الخلايا MGC-803 |

|

24 ساعة | تم امتصاصه بشكل انتقائي بواسطة خلايا سرطان المعدة | [113] |

| سيللوز كربوكسي ميثيل، 5-فلورويوراسيل |

|

خط الخلايا SGC7901 |

|

24، 48، 72 ساعة | تأثير مضاد للأورام على ما يبدو | [114] |

| أترانورين | أترانورين@SPIONs | خط الخلايا الجذعية لسرطان المعدة |

|

24، 48، 72 ساعة | من الواضح أنه يعيق تكاثر خلايا سرطان المعدة الجذعية | [115] |

| بولي (إيثيلين جلايكول) |

|

خط الخلايا U87MG |

|

|

موت الخلايا المستحث | [116] |

| زنك | زنك@SPIONs | خط الخلايا U-87 MG |

|

|

لا سمية خلوية | [117] |

| ألبومين مصل الإنسان (باكليتاكسيل) – ببتيدات أرج-جلاي-أسب | SPIOCs@HSA(PTX)-RGD | خط الخلايا U-87 MG |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية | [118] |

| ذهب أوروشيل | أوروشيل الذهب@الهيماتيت | خط الخلايا U-87 MG |

|

72 ساعة | قتل خلايا سرطان الجليوبلاستوما بشكل ملحوظ | [119] |

| دوكسوروبيسين | دوكس-أيون بي | خطوط خلايا U251 و bEnd.3 و MDCK-MDR1 |

|

48 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية | [120] |

| حمض الأكريليك المتعدد، استر السيرين المتعدد، بولي (إيثيلين جلايكول) | صور | خطوط خلايا MC3T3-E1 و HepG2 | 0.751 إلى

|

24 ساعة | سمية خلوية منخفضة | [121] |

| جلوتاثيون وسيستين | جزيئات نانوية من FePd | خطوط خلايا هيب جي 2، أي جي إس، إس كي-ميل-2، إم جي 63، و إن سي آي-إتش 460 |

|

1-7 أيام | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [122] |

| سيليكا | slONPs | خط الخلايا HuH7 | 0-160 جزيئات نانوية معدنية مغناطيسية لكل خلية | 24,48 ساعة | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [123] |

| / | يوسبينز | خط الخلايا PLC/PRF5 |

|

48 ساعة | متوافق للغاية | [124] |

| بوليلان | P-SPIONs | خطوط خلايا HepG2 و L-929 |

|

24 ساعة | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [125] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

| زنك، كوبالت | جزيئات نانوية من الزنك، جزيئات نانوية من الكوبالت | خطوط خلايا جذعية ميزانشيمية مشتقة من نخاع العظام البشري MG-63 |

|

72 ساعة | سمية خلوية حادة على المدى القصير | [126] |

| عامل نمو البطانة الوعائية، ن-هيدروكسي سكسينيميد | IONPs@CD80+VEGF | خط الخلايا ATCCTM CRL-2836 |

|

24 ساعة | تقليل كبير في تكاثر الخلايا الشاذة | [127] |

| هيدروكسيباتيت | IONPs@HA | خط الخلايا العظمية MG-63 |

|

|

سمية ملحوظة | [128] |

| كيتوزان، أنهدريد السكسينيك، حمض الفوليك | IONPs@CS-FA/CS-SA | خط الخلايا العظمية MG-63 |

|

72 ساعة | تثبيط كبير في تكاثر الخلايا | [129] |

| البوليستر متفرع بشكل مفرط، أنهدريد السكسينيك دوديكنيل | FeO/HBPE-DDSA | خط الخلية OCI-LY3 |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية | [130] |

| / | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خط الخلايا لورم ليمفاوي كبير الخلايا B |

|

|

أثبط بشكل ملحوظ نمو الخلايا | [131] |

| أجسام مضادة لريتوكسيماب وبولي (إيثيلين جلايكول) |

|

راجعي الخلية لي |

|

72 ساعة | طريقة تعتمد على الفالنس لموت خلايا راجي | [132] |

| ميثوتريكسات | FeO@MTX | خط خلية ليمفاوية كبيرة B منتشرة |

|

24 ساعة | تحفيز موت الخلايا المبرمج | [133] |

| / | نقاط الكم من الجسيمات النانوية الحديدية | خط الخلايا اللمفاوية B-الليمفاوية A20 |

|

12، 24، 48، 72 ساعة | تنظيم البلعمة الذاتية | [134] |

| سيليبيين | IONPs@silibinin | خط الخلايا A-498 |

|

96 ساعة | أثبط بشكل ملحوظ نمو الخلايا | [135] |

| المضاد الأحادي G250 | mAb G250-SPIONs | خط الخلايا السرطانية الكلوية 786-0 |

|

12 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية | [136] |

| جيلاتين، أكيرمانيت | جل/أكر/

|

خلايا أستيو بلاست G292 |

|

24، 48، 72 ساعة | سمية خلوية منخفضة | [145] |

| هيدروكسي أباتيت، كولاجين | FeHA/Coll | خط الخلايا الشبيهة بالخلايا العظمية البشرية MG63 | قطر 8.00 مم وارتفاع 3.00 مم | 72 ساعة | عزز بشكل كبير تكاثر الخلايا | [146] |

| / | جزيئات النانو الحديدية | خط الخلايا الجذعية المشتقة من الدهون البشرية |

|

24 ساعة | أثر على التمايز الدهني والعظمي | [147] |

| ببتيد المستضد | a-AP-fmNPs | خطوط خلايا BMDCs وخلايا الشجرة 2.4 |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية للخلايا | [148] |

| / | SPIONs | خط الخلايا الشجرية |

|

24 ساعة | تم وسم ما يقرب من 100% من الخلايا بواسطة SPIONs | [149] |

| حمض الستريك، ديكستران | IONPs-CIT، IONPs-DEXT | خطوط خلايا THP1 و NCTC 1469 |

|

24 ساعة | لا سمية | [150] |

| / | SPIONs | نيوريت | 10 مللي مول | 48 ساعة | زيادة طول ومساحة النوريت | [151] |

| غلوكوزامين، بولي (حمض الأكريليك) | سبايون-بّا، يو إس بي آي أو-بّا، يو إس بي آي أو بّا جي سي إن | خط الخلايا الجذعية الميزانشيمية |

|

24 ساعة | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [152] |

| حمض 2,3-ثنائي الميركابتوسكسينيك |

|

خط الخلايا الجذعية البشرية |

|

2، 6، 24 ساعة | لا سمية خلوية ملحوظة | [153] |

| / | رويسون | خط الخلايا MSCs |

|

24 ساعة | توافق حيوي ممتاز | [154] |

| الكركمين | جزيئات النانو الحديدية مع الكركمين | خط الخلايا الجذعية المشتقة من نخاع العظام |

|

24 ساعة | التوافق الخلوي المعتمد على الجرعة | [155] |

| جزيء الطلاء | اسم | نموذج | جرعة | أيام | نتيجة | المراجع |

| بوليمرات مطبوعة جزيئيًا محددة للبروتين | مخططات التحفيز | خط الخلايا الجذعية الميزانشيمية البشرية |

|

24 ساعة | توافق حيوي عالي وسميّة خلوية منخفضة | [156] |

| حمض الستريك | IONPs@CA | الخلايا البطانية وخطوط خلايا MC3T3-E1 |

|

|

فقط أثر على حيوية الخلايا | [157] |

| / | ماغنيتوفيريتين | خط الخلايا الجذعية المشتقة من الإنسان |

|

1 دقيقة | التوافق الحيوي | [158] |

| الفبرين الحريري | SPION@بروتين الحرير | خط الخلايا المشتقة من نخاع العظام البشري MSCs | 2.5 ملغ حديد | 21 يوم | تنظيم الالتصاق والتكاثر بشكل إيجابي | [159] |

| دي مانوز | دي مانوز

|

خط الخلايا الجذعية العصبية |

|

48 ساعة | سمية طفيفة | [160] |

[79].

سرطان القولون والمستقيم

سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في الرأس والعنق

سرطان البروستاتا

تم تطويره كنظام توصيل دوائي. تم تفضيل LHRH-AE105IONPs وامتصاصها من قبل خلايا PC-3 أكثر من خلايا البروستاتا الطبيعية. تم تحميل LHRH-AE105-IONPs مع باكليتاكسيل (

سرطان الثدي

سرطان عنق الرحم

سرطان المعدة

كان يعتمد على

ورم دبقي

سرطان الكبد

الساركوما العظمية

لمفوما

حتى التركيز كان يصل إلى

سرطان الكلى

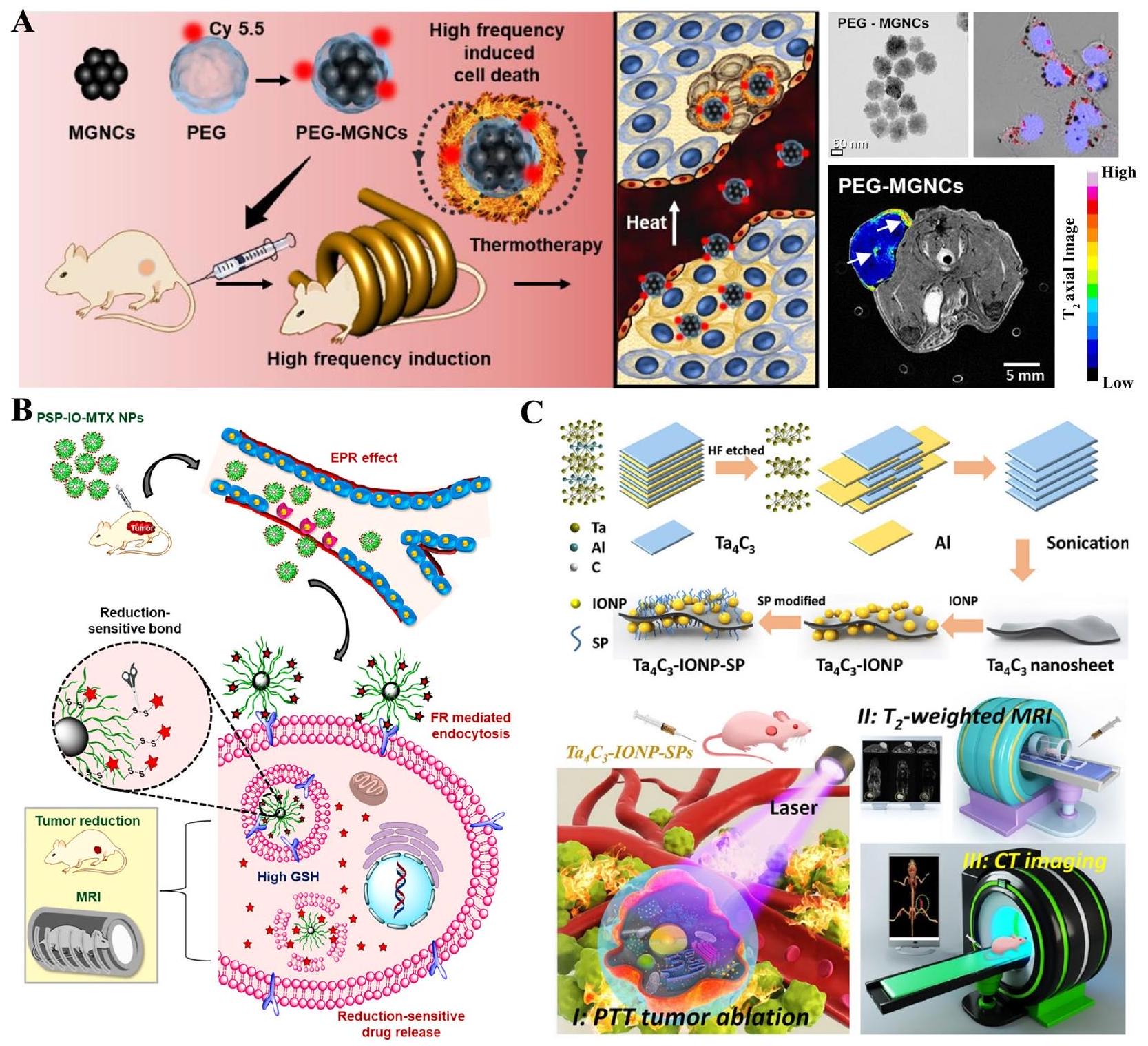

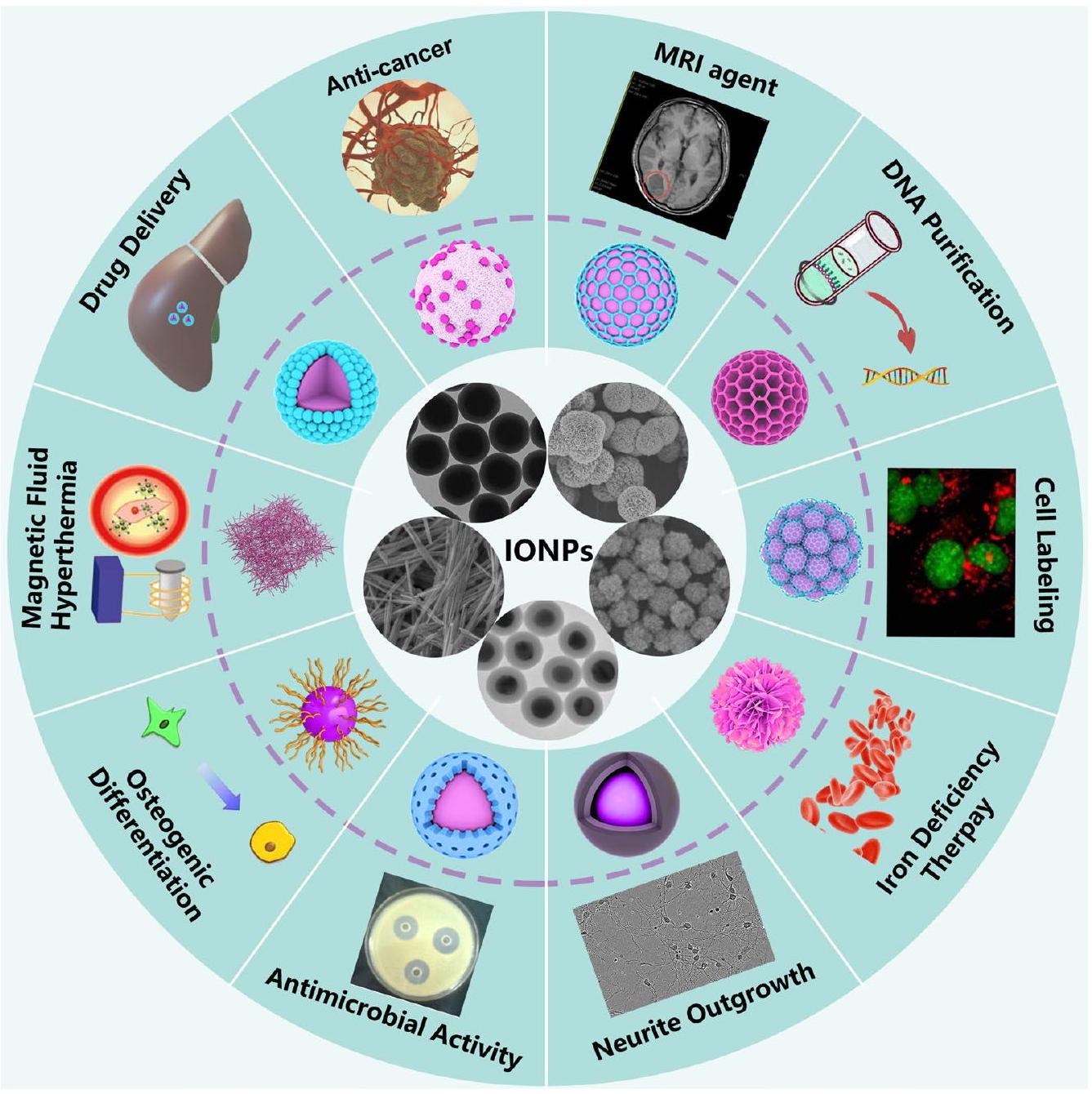

بشكل عام، يمكن لجزيئات النانو المغناطيسية الحديدية أن تثبط تقريبًا بقاء الخلايا لجميع أنواع خلايا السرطان، مما يظهر آفاقًا كبيرة في علاجات السرطان. السبب الرئيسي وراء التأثير الواعد لمضادات السرطان لجزيئات النانو المغناطيسية الحديدية هو تدهور نواة أكسيد الحديد، الذي يمكن أن يحفز إنتاج ROS المفرط عبر تفاعل فنتون، ثم يؤثر على حالة الأكسدة والاختزال داخل الخلايا وعمليات الأيض للحديد. بالمقارنة مع الجزيئات الصغيرة التقليدية، يمكن لجزيئات النانو المغناطيسية الحديدية أن تطلق كمية كبيرة من أيونات الحديد، وتزيد من محتوى ROS في الخلايا، وبالتالي تحفز الموت الخلوي الحديدي بشكل أكثر فعالية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نظمت جزيئات النانو المغناطيسية الحديدية البيئة الدقيقة المناعية للورم من خلال التأثير على موت الخلايا المبرمج والالتهام الذاتي للبلاعم، مما يثبط تطور الورم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تركز التطبيقات المحتملة لجزيئات النانو المغناطيسية الحديدية في علاج السرطان على إطلاق وتفعيل أدوية العلاج الكيميائي، وزيادة درجة الحرارة في موقع الورم تحت ضوء الأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة أو المجال المغناطيسي، والعلاج الجيني، والتوصيل المستهدف (بما في ذلك التوجيه النشط، السلبي أو المغناطيسي).

ومع ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الأبحاث البيولوجية المستندة إلى آلية التفاعل لتعزيز تطبيق جزيئات النانو الحديدية في علاج السرطان.

جزيئات الحديد النانوية في الخلايا غير الورمية

باني العظم

خلايا المناعة

نوع البلعميات قرر بشكل رئيسي أيض الحديد لـ IONPs [150].

خلايا الساق

التطبيقات السريرية لـ IONPs في البشر

(SNB) بناءً على SPION

تم تجنيد 28 مريضة لتInvestigate دور الالتهاب الذي يتوسطه البلعميات في الصداع النصفي بدون هالة. تم اعتماد التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي المعزز بـ USPIO للكشف عن الالتهاب الذي يتوسطه البلعميات عند حدوث نوبة شبيهة بالصداع النصفي. أظهرت نتائج التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي أن الالتهاب الذي يتوسطه البلعميات لم يكن مرتبطًا بالصداع النصفي بدون هالة [178]. تم تجنيد 18 مريضًا أطفال و8 مراهقين أصحاء لتقييم تأثير التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي المعزز بـ USPIO. كشفت النتائج أن 5 ملغ من الحديد لكل كغ من الفيروموكسيترول يمكن أن تطيل بشكل واضح أوقات الاسترخاء T2* إلى 37.0 مللي ثانية بسبب انخفاض التروية وزيادة الوذمة [179]. تم تطوير التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي المعزز بالفيروموكسيترول للكشف عن خلايا نخاع العظام المزروعة في نخر العظام. يمكن أن يطيل الفيروموكسيترول أوقات الاسترخاء T2* لخلايا نخاع العظام المعلّمة بالحديد دون التأثير على إصلاح العظام [180]. باختصار، تم تطبيق IONPs في الممارسة السريرية بسبب إشعاعها المنخفض وخصائصها المضادة للحساسية. ومع ذلك، كان الفيروموكسيترول، كأحد IONPs المستخدمة بشكل شائع في التجارب السريرية، يستخدم بشكل رئيسي لتحديد أو تشخيص سرطان الثدي.

الاستنتاجات وآفاق المستقبل

تهدف هذه المراجعة إلى وصف الآثار البيولوجية والتجارب السريرية لـ IONPs بشكل كامل. أولاً، قمنا بتلخيص التوافق الحيوي، والتوزيع الحيوي، والتمثيل الغذائي، والتخلص الحيوي لـ IONPs في نماذج حيوانية مختلفة. كانت الغالبية العظمى من IONPs غير سامة ومتوافقة حيويًا بشكل جيد مع الأعضاء الحيوية للحيوانات، وتوزعت بشكل رئيسي في الكبد والطحال، ثم تم التخلص منها بسرعة بواسطة الكلى. ثانيًا، وصفنا تطبيق IONPs في أنواع مختلفة من خلايا الأورام وخلايا غير الأورام. استهدفت IONPs بشكل انتقائي أنواعًا مختلفة من خلايا الأورام وأدت إلى موت خلايا الأورام دون التأثير على حيوية ونشاط الخلايا الطبيعية. كانت سمية IONPs تجاه خلايا الأورام مرتبطة بشكل رئيسي بالشكل، وتعديل السطح، والحجم، والتركيز، وحالة التكافؤ. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، عرض مجال مغناطيسي خارجي، ومولد تردد راديوي،

الإشعاع، وتصوير الرنين المغناطيسي والعلاج الضوئي الحراري تأثيرًا مضادًا للسرطان تآزريًا. في الوقت نفسه، تتمتع IONPs أيضًا بمجموعة واسعة من التطبيقات في خلايا غير الأورام مع توافق خلوي جيد. يلعب تعديل السطح وأنواع الخلايا دورًا حيويًا في تحديد استقلاب الحديد في الخلايا. أخيرًا، قمنا بمراجعة التطبيق السريري لـ IONPs في السنوات العشر الماضية. على الرغم من أن مجموعة متنوعة من الأدوية النانوية المعتمدة على IONPs قد تم الموافقة عليها سريريًا أو في التجارب السريرية من قبل وكالة الأدوية الأوروبية (EMA) وإدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية (FDA) مثل NanoTherm

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 08 يناير 2024

References

- Panda PK, Verma SK, Suar M. Nanoparticle-biological interactions: the renaissance of bionomics in the myriad nanomedical technologies. Nanomedicine. 2021;16(25):2249-54.

- Chen Y, Hou S. Recent progress in the effect of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles on cells and extracellular vesicles. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:195.

- Yang Y, Liu Y, Song L, Cui X, Zhou J, Jin G, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticlebased nanocomposites in biomedical application. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;S0167-7799(23):00175.

- Dash S, Das T, Patel P, Panda PK, Suar M, Verma SK. Emerging trends in the nanomedicine applications of functionalized magnetic nanoparticles as novel therapies for acute and chronic diseases. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):393.

- Simnani FZ, Singh D, Patel P, Choudhury A, Sinha A, Nandi A, et al. Nanocarrier vaccine therapeutics for global infectious and chronic diseases. Mater Today. 2023;66:371-408.

- Al-Musawi S, Albukhaty S, Al-Karagoly H, Almalki F. Design and synthesis of multi-functional superparamagnetic core-gold shell nanoparticles coated with chitosan and folate for targeted antitumor therapy. Nanomaterials. 2020;11:32.

- Albukhaty S, Al-Musawi S, Abdul Mahdi S, Sulaiman GM, Alwahibi MS, Dewir YH, et al. Investigation of dextran-coated superparamagnetic nanoparticles for targeted vinblastine controlled release, delivery, apoptosis induction, and gene expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Molecules. 2020;25:4721.

- Albukhaty S, Naderi-Manesh H, Tiraihi T, Sakhi JM. Poly-I-lysine-coated superparamagnetic nanoparticles: a novel method for the transfection of pro-BDNF into neural stem cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:125-32.

- Shirazi M , Allafchian A, Salamati H. Design and fabrication of magnetic

-QSM nanoparticles loaded with ciprofloxacin as a potential antibacterial agent. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;241: 124517. - Sinha A, Simnani FZ, Singh D, Nandi A, Choudhury A, Patel P, et al. The translational paradigm of nanobiomaterials: biological chemistry to modern applications. Mater Today Bio. 2022;17: 100463.

- Yang J, Feng J, Yang S, Xu Y, Shen Z. Exceedingly small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and imaging-guided therapy of tumors. Small. 2023. https://doi.org/10. 1002/smll. 202302856.

- Jeon S, Park BC, Lim S, Yoon HY, Jeon YS, Kim BS, et al. Heat-generating iron oxide multigranule nanoclusters for enhancing hyperthermic efficacy in tumor treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:33483-91.

- Peng Y, Gao Y, Yang C, Guo R, Shi X, Cao X. Low-molecular-weight poly(ethylenimine) nanogels loaded with ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles for T(1)-weighted MR imaging-guided gene therapy of sarcoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:27806-13.

- Turrina C, Schoenen M, Milani D, Klassen A, Rojas Gonzaléz DM, Cvirn G, et al. Application of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: thrombotic activity, imaging and cytocompatibility of silica-coated and carboxymethyl dextrane-coated particles. Colloids Surf, B. 2023;228: 113428.

- Mushtaq S, Shahzad K, Saeed T, Ul-Hamid A, Abbasi BH, Ahmad N. Surface functionalized drug loaded spinel ferrite MFe2O4 (

, ) nanoparticles, their biocompatibility and cytotoxicity in vitro: a comparison. Beilstein Arch. 2021;2021:56. - Pinheiro WO, Fascineli ML, Farias GR, Horst FH, Andrade LR, Correa LH , et al. The influence of female mice age on biodistribution and biocompatibility of citrate-coated magnetic nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:3375-88.

- Dadfar SM, Roemhild K, Drude NI, Stillfried S, Knüchel R, Kiessling F, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles: diagnostic, therapeutic and theranostic applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;138:302-25.

- Patel P, Nandi A, Jha E, Sinha A, Mohanty S, Panda PK, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles: fabrication, characterization, properties, and application for environment sustainability. Magn Nanopart-Based Hybrid Mater. 2021;17:33-62.

- Ling D, Lee N, Hyeon T. Chemical synthesis and assembly of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for medical applications. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1276-85.

- Ali A, Zafar H, Zia M, Haq I, Phull AR, Ali JS, et al. Synthesis, characterization, applications, and challenges of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2016;9:49-67.

- Verma SK, Suar M, Mishra YK. Editorial: green perspective of nanobiotechnology: nanotoxicity horizon to biomedical applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10: 919226.

- Jacinto MJ, Silva VC, Valladão DMS, Souto RS. Biosynthesis of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: a review. Biotechnol Lett. 2020;43:1-12.

- Verma SK, Patel P, Panda PK, Kumari P, Patel P, Arunima A, et al. Determining factors for the nano-biocompatibility of cobalt oxide nanoparticles: proximal discrepancy in intrinsic atomic interactions at differential vicinage. Green Chem. 2021;23:3439.

- Sheel R, Kumari P, Panda PK, Ansari MDJ, Patel P, Singh S, et al. Molecular intrinsic proximal interaction infer oxidative stress and apoptosis modulated in vivo biocompatibility of P. niruri contrived antibacterial iron oxide nanoparticles with zebrafish. Environ Pollut. 2020;267:115482.

- Ngnintedem Yonti C, Kenfack Tsobnang P, Lontio Fomekong R, Devred F, Mignolet E, Larondelle Y, et al. Green synthesis of iron-doped cobalt oxide nanoparticles from palm kernel oil via co-precipitation and structural characterization. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2833.

- Rezaei B, Yari P, Sanders SM, Wang H, Chugh VK, Liang S, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles: a review on synthesis, characterization, functionalization, and biomedical applications. Small. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202304848.

- Zhang G, Liao Y, Baker I. Surface engineering of core/shell iron/iron oxide nanoparticles from microemulsions for hyperthermia. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2010;30:92-7.

- AI-Kinani MA, Haider AJ, Al-Musawi S. High uniformity distribution of Fe@Au preparation by a micro-emulsion method. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;987: 012013.

- Bustamante-Torres M, Romero-Fierro D, Estrella-Nuñez J, ArcentalesVera B, Chichande-Proaño E, Bucio E. Polymeric composite of magnetite iron oxide nanoparticles and their application in biomedicine: a review. Polymers. 2022;14:752.

- Bokov D, Turki Jalil A, Chupradit S, Suksatan W, Javed Ansari M, Shewael IH, et al. Nanomaterial by sol-gel method: synthesis and application. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2021;2021:1-21.

- Hufschmid R, Arami H, Ferguson RM, Gonzales M, Teeman E, Brush LN, et al. Synthesis of phase-pure and monodisperse iron oxide nanoparticles by thermal decomposition. Nanoscale. 2015;7:11142-54.

- Patsula V, Kosinová L, Lovrić M, Ferhatovic Hamzić L, Rabyk M, Konefal R , et al. Superparamagnetic

nanoparticles: synthesis by thermal decomposition of iron(III) glucuronate and application in magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:7238-47. - Valdiglesias V, Fernández-Bertólez N, Kiliç G, Costa C, Costa S, Fraga S, et al. Are iron oxide nanoparticles safe? Current knowledge and future perspectives. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2016;38:53-63.

- Roca AG, Gutiérrez L, Gavilán H, Fortes Brollo ME, Veintemillas-Verdaguer S, Morales MDP. Design strategies for shape-controlled magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;138:68-104.

- Abakumov MA, Semkina AS, Skorikov AS, Vishnevskiy DA, Ivanova AV, Mironova E. Toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles: size and coating effects. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2018;32(12):e22225.

- Wu L, Wang C, Li Y. Iron oxide nanoparticle targeting mechanism and its application in tumor magnetic resonance imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2022;17(21):1567-83.

- Das S, Ross A, Ma XX, Becker S, Schmitt C, Duijn F, et al. Anisotropic long-range spin transport in canted antiferromagnetic orthoferrite

. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6140. - Jungwirth T, Marti X, Wadley P, Wunderlich J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat Nanotechnol. 2016;11(3):231-41.

- Mehmood S, Ali Z, Khan SR, Aman S, Elnaggar AY, Ibrahim MM, et al. Mechanically stable magnetic metallic materials for biomedical applications. Materials. 2022;15:8009.

- Kraus S, Rabinovitz R, Sigalov E, Eltanani M, Khandadash R, Tal C, et al. Self-regulating novel iron oxide nanoparticle-based magnetic hyperthermia in swine: biocompatibility, biodistribution, and safety assessments. Arch Toxicol. 2022;96:2447-64.

- Fernandez-Alvarez F, Caro C, Garcia-Garcia G, Garcia-Martin ML, Arias JL. Engineering of stealth (maghemite/PLGA)/chitosan (core/shell)/shell nanocomposites with potential applications for combined MRI and hyperthermia against cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9:4963-80.

- Chen L, Wu Y, Wu H, Li J, Xie J, Zang F. Magnetic targeting combined with active targeting of dual-ligand iron oxide nanoprobes to promote the penetration depth in tumors for effective magnetic resonance imaging and hyperthermia. Acta Biomater. 2019;96:491-504.

- Meng QF, Rao L, Zan M, Chen M, Yu GT, Wei X, et al. Macrophage membrane-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal tumor therapy. Nanotechnology. 2018;29: 134004.

- Ferretti AM, Usseglio S, Mondini S, Drago C, La MR, Chini B, et al. Towards bio-compatible magnetic nanoparticles: Immune-related effects, in-vitro internalization, and in-vivo bio-distribution of zwitterionic ferrite nanoparticles with unexpected renal clearance. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2021;582:678-700.

- Gogoi M, Jaiswal MK, Sarma HD, Bahadur D, Banerjee R. Biocompatibility and therapeutic evaluation of magnetic liposomes designed for self-controlled cancer hyperthermia and chemotherapy. Integr Biol (Camb). 2017;9:555-65.

- Xu S, Wang J, Wei Y, Zhao H, Tao T, Wang H, et al. In situ one-pot synthesis of

core-shell nanoparticles as enhanced -weighted magnetic resonance imagine contrast agents. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:56701-11. - Verma SK, Nandi A, Sinha A, Patel P, Jha E, Mohanty S, et al. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an ecotoxicological model for Nanomaterial induced toxicity profiling. Precis Nanomed. 2021;4(1):750-81.

- Verma SK, Thirumurugan A, Panda PK, Patel P, Nandi A, Jha E, et al. Altered electrochemical properties of iron oxide nanoparticles by carbon enhance molecular biocompatibility through discrepant atomic interaction. Materials Today Bio. 2021;12: 100131.

- Nosrati H, Salehiabar M, Fridoni M, Abdollahifar MA, Kheiri Manjili H, Davaran S , et al. new insight about biocompatibility and biodegradability of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles: stereological and in vivo MRI monitor. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7173.

- Fahmy HM, El-Daim TM, Ali OA, Hassan AA, Mohammed FF, Fathy MM. Surface modifications affect iron oxide nanoparticles’ biodistribution after multiple-dose administration in rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021;35: e22671.

- Mabrouk M, Ibrahim Fouad G, El-Sayed SAM, Rizk MZ, Beherei HH. Hepatotoxic and neurotoxic potential of iron oxide nanoparticles in wistar rats: a biochemical and ultrastructural study. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;200:3638-65.

- Toropova YG, Zelinskaya IA, Gorshkova MN, Motorina DS, Korolev DV, Velikonivtsev FS, et al. Albumin covering maintains endothelial function upon magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles intravenous injection in rats. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2021;109:2017-26.

- Mejias R, Gutierrez L, Salas G, Perez-Yague S, Zotes TM, Lazaro FJ, et al. Long term biotransformation and toxicity of dimercaptosuccinic

acid-coated magnetic nanoparticles support their use in biomedical applications. J Control Release. 2013;171:225-33. - Shen Z, Chen T, Ma X, Ren W, Zhou Z, Zhu G, et al. Multifunctional theranostic nanoparticles based on exceedingly small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and chemotherapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:10992-1004.

- Li X, Yang Y, Jia Y, Pu X, Yang T, Wang Y, et al. Enhanced tumor targeting effects of a novel paclitaxel-loaded polymer: PEG-PCCL-modified magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. 2017;24:1284-94.

- Unterweger H, Janko C, Schwarz M, Dezsi L, Urbanics R, Matuszak J, et al. Non-immunogenic dextran-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: a biocompatible, size-tunable contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:5223-38.

- Kawish M, Jabri T, Elhissi A, Zahid H, Muhammad K, Rao K, et al. Galactosylated iron oxide nanoparticles for enhancing oral bioavailability of ceftriaxone. Pharm Dev Technol. 2021;26:291-301.

- AI Faraj A, Shaik AP, Shaik AS. Effect of surface coating on the biocompatibility and in vivo MRI detection of iron oxide nanoparticles after intrapulmonary administration. Nanotoxicology. 2015;9:825-34.

- Dai L, Liu Y, Wang Z, Guo F, Shi D, Zhang B. One-pot facile synthesis of PEGylated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for MRI contrast enhancement. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;41:161-7.

- Ghosh S, Ghosh I, Chakrabarti M, Mukherjee A. Genotoxicity and biocompatibility of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of surface modification on biodistribution, retention, DNA damage and oxidative stress. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;136: 110989.

- Britos TN, Castro CE, Bertassoli BM, Petri G, Fonseca FLA, Ferreira FF, et al. In vivo evaluation of thiol-functionalized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;99:171-9.

- Awada H, Sene S, Laurencin D, Lemaire L, Franconi F, Bernex F, et al. Long-term in vivo performances of polylactide/iron oxide nanoparticles core-shell fibrous nanocomposites as MRI-visible magneto-scaffolds. Biomater Sci. 2021;9:6203-13.

- Silva AH, Lima E, Mansilla MV, Zysler RD, Troiani H, Pisciotti MLM, et al. Superparamagnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles mPEG350- and mPEG2000-coated: cell uptake and biocompatibility evaluation. Nanomedicine. 2016;12:909-19.

- Ledda M, Fioretti D, Lolli MG, Papi M, Gioia C, Carletti R, et al. Biocompatibility assessment of sub- 5 nm silica-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in human stem cells and in mice for potential application in nanomedicine. Nanoscale. 2020;12:1759-v1778.

- Chen X, Qin Z, Zhao J, Yan X, Ye J, Ren E, et al. Pulsed magnetic field stimuli can promote chondrogenic differentiation of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles-labeled mesenchymal stem cells in rats. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2018;14:2135-45.

- Shiji R, Joseph MM, Sen A, Unnikrishnan BS, Sreelekha TT. Galactomannan armed superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as a folate receptor targeted multi-functional theranostic agent in the management of cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;219:740-53.

- Wu L, Wen W, Wang X, Huang D, Cao J, Qi X, et al. Ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles cause significant toxicity by specifically inducing acute oxidative stress to multiple organs. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2022;19:24.

- Zhao M, Liu Z, Dong L, Zhou H, Yang S, Wu W, et al. A GPC3-specific aptamer-mediated magnetic resonance probe for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:4433-43.

- Rozhina E, Danilushkina A, Akhatova F, Fakhrullin R, Rozhin A, Batasheva S. Biocompatibility of magnetic nanoparticles coating with polycations using A549 cells. J Biotechnol. 2021;325:25-34.

- Wu L, Zhang F, Wei Z, Li X, Zhao H, Lv H, et al. Magnetic delivery of

@polydopamine nanoparticle-loaded natural killer cells suggest a promising anticancer treatment. Biomater Sci. 2018;6:2714-25. - Nowicka AM, Ruzycka-Ayoush M, Kasprzak A, Kowalczyk A, Bamburow-icz-Klimkowska M, Sikorska M, et al. Application of biocompatible and ultrastable superparamagnetic iron(III) oxide nanoparticles doped with magnesium for efficient magnetic fluid hyperthermia in lung cancer cells. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:4028-41.

- Tang Z, Zhou Y, Sun H, Li D, Zhou S. Biodegradable magnetic calcium phosphate nanoformulation for cancer therapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;87:90-100.

- Reynders H, Zundert I, Silva R, Carlier B, Deschaume O, Bartic C, et al. Label-free iron oxide nanoparticles as multimodal contrast agents in

cells using multi-photon and magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:8375-89. - Legge CJ, Colley HE, Lawson MA, Rawlings AE. Targeted magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia for the treatment of oral cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48:803-9.

- Paulino-Gonzalez AD, Sakagami H, Bandow K, Kanda Y, Nagasawa Y, Hibino Y, et al. Biological properties of the aggregated form of chitosan magnetic nanoparticle. In Vivo. 2020;34:1729-38.

- Shanavas A, Sasidharan S, Bahadur D, Srivastava R. Magnetic core-shell hybrid nanoparticles for receptor targeted anti-cancer therapy and magnetic resonance imaging. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;486:112-20.

- Shahdeo D, Roberts A, Kesarwani V, Horvat M, Chouhan RS, Gandhi S. Polymeric biocompatible iron oxide nanoparticles labeled with peptides for imaging in ovarian cancer. Biosci Rep. 2022;42(2):BSR20212622.

- Albarqi HA, Wong LH, Schumann C, Sabei FY, Korzun T, Li X, et al. Biocompatible nanoclusters with high heating efficiency for systemically delivered magnetic hyperthermia. ACS Nano. 2019;13:6383-95.

- Zhang Y, Xia M, Zhou Z, Hu X, Wang J, Zhang M, et al. p53 promoted ferroptosis in ovarian cancer cells treated with human serum incubatedsuperparamagnetic iron oxides. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:283-96.

- Huang

, Yi C, Fan Y, Zhang Y, Zhao L, Liang Z, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles grafted with single-chain antibody (scFv) and docetaxel loaded beta-cyclodextrin potential for ovarian cancer dual-targeting therapy. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;42:325-32. - Braim FS, Razak NN, Aziz AA, Ismael LQ, Sodipo BK. Ultrasound assisted chitosan coated iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of ultrasonic irradiation on the crystallinity, stability, toxicity and magnetization of the functionalized nanoparticles. Ultrason Sonochem. 2022;88: 106072.

- Moskvin M, Babic M, Reis S, Cruz MM, Ferreira LP, Carvalho MD, et al. Biological evaluation of surface-modified magnetic nanoparticles as a platform for colon cancer cell theranostics. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;161:35-41.

- Chen L, Xie J, Wu H, Zang F, Ma M, Hua Z, et al. Improving sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging by using a dual-targeted magnetic iron oxide nanoprobe. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;161:339-46.

- Mathieu P, Coppel Y, Respaud M, Nguyen QT, Boutry S, Laurent S, et al. Silica coated iron/iron oxide nanoparticles as a nano-platform for T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Molecules. 2019;24(24):4629.

- Foglia S, Ledda M, Fioretti D, lucci G, Papi M, Capellini G, et al. In vitro biocompatibility study of sub- 5 nm silica-coated magnetic iron oxide fluorescent nanoparticles for potential biomedical application. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46513.

- Sharma G, Kodali V, Gaffrey M, Wang W, Minard KR, Karin NJ, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticle agglomeration influences dose rates and modulates oxidative stress-mediated dose-response profiles in vitro. Nanotoxicology. 2014;8:663-75.

- Azhdarzadeh M, Atyabi F, Saei AA, Varnamkhasti BS, Omidi Y, Fateh M, et al. Theranostic MUC-1 aptamer targeted gold coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging and photothermal therapy of colon cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2016;143:224-32.

- Yang SJ, Tseng SY, Wang CH, Young TH, Chen KC, Shieh MJ. Magnetic nanomedicine for CD133-expressing cancer therapy using locoregional hyperthermia combined with chemotherapy. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:2543-61.

- Lindemann A, Ludtke-Buzug K, Fraderich BM, Grafe K, Pries R, Wollenberg

. Biological impact of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic particle imaging of head and neck cancer cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:5025-40. - Thomas RG, Moon MJ, Lee H, Sasikala ARK, Kim CS, Park IK, et al. Hyaluronic acid conjugated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle for cancer diagnosis and hyperthermia therapy. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;131:439-46.

- Unterweger H, Tietze R, Janko C, Zaloga J, Lyer S, Durr S, et al. Development and characterization of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with a cisplatin-bearing polymer coating for targeted drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:3659-76.

- Tse BW, Cowin GJ, Soekmadji C, Jovanovic L, Vasireddy RS, Ling MT, et al. PSMA-targeting iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles enhance MRI of preclinical prostate cancer. Nanomedicine. 2015;10:375-86.

- Wadajkar AS, Menon JU, Tsai YS, Gore C, Dobin T, Gandee L, Kangasniemi K, et al. Prostate cancer-specific thermo-responsive polymercoated iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3618-25.

- Sato A, Itcho N, Ishiguro H, Okamoto D, Kobayashi N, Kawai K, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles of

enhance docetaxel-induced prostate cancer cell death. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:3151-60. - Ahmed MSU, Salam AB, Yates C, Willian K, Jaynes J, Turner T, et al. Double-receptor-targeting multifunctional iron oxide nanoparticles drug delivery system for the treatment and imaging of prostate cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:6973-84.

- Soleymani M, Velashjerdi M, Shaterabadi Z, Barati A. One-pot preparation of hyaluronic acid-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia therapy and targeting CD44-overexpressing cancer cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;237: 116130.

- Zhang T, Wang Z, Xiang H, Xu X, Zou J, Lu C. Biocompatible superparamagnetic europium-doped iron oxide nanoparticle clusters as multifunctional nanoprobes for multimodal in vivo imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:33850-61.

- Lu X, Zhou H, Liang Z, Feng J, Lu Y, Huang L, et al. Biodegradable and biocompatible exceedingly small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of tumors. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20:350.

- Gao H, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Liu B, Wu J, et al. Ellipsoidal magnetite nanoparticles: a new member of the magnetic-vortex nanoparticles family for efficient magnetic hyperthermia. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:515-22.

- Attari E, Nosrati H, Danafar H, Kheiri MH. Methotrexate anticancer drug delivery to breast cancer cell lines by iron oxide magnetic based nanocarrier. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2019;107:2492-500.

- Calero M, Chiappi M, Lazaro-Carrillo A, Rodriguez MJ, Chichon FJ, Crosbie-Staunton K, et al. Characterization of interaction of magnetic nanoparticles with breast cancer cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 2015;13:16.

- Liu Z, Lin H, Zhao M, Dai C, Zhang S, Peng W, et al. 2D superparamagnetic tantalum carbide composite mxenes for efficient breast-cancer theranostics. Theranostics. 2018;8:1648-64.

- Chen Z, Peng Y, Xie X, Feng Y, Li T, Li S, et al. Dendrimer-functionalized superparamagnetic nanobeacons for real-time detection and depletion of HSP90alpha mRNA and MR imaging. Theranostics. 2019;9:5784-96.

- Kucharczyk K, Kaczmarek K, Jozefczak A, Slachcinski M, Mackiewicz A, Dams-Kozlowska H. Hyperthermia treatment of cancer cells by the application of targeted silk/iron oxide composite spheres. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;120: 111654.

- Kermanian M, Sadighian S, Naghibi M, Khoshkam M. PVP Surface-protected silica coated iron oxide nanoparticles for MR imaging application. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2021;32:1356-69.

- Tran TT, Tran PH, Yoon TJ, Lee BJ. Fattigation-platform theranostic nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;75:1161-7.

- Serio F, Silvestri N, Kumar Avugadda S, Nucci GEP, Nitti S, Onesto V, et al. Co-loading of doxorubicin and iron oxide nanocubes in polycaprolactone fibers for combining Magneto-Thermal and chemotherapeutic effects on cancer cells. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;607:34-44.

- Gawali SL, Shelar SB, Gupta J, Barick KC, Hassan PA. Immobilization of protein on

nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;166:851-60. - Zhao H, Sene S, Mielcarek AM, Miraux S, Menguy N, Ihiawakrim D, et al. Hierarchical superparamagnetic metal-organic framework nanovectors as anti-inflammatory nanomedicines. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:3195-211.

- Calero M, Gutierrez L, Salas G, Luengo Y, Lazaro A, Acedo P, et al. Efficient and safe internalization of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: two fundamental requirements for biomedical applications. Nanomedicine. 2014;10:733-43.

- Hoang Thi TT, Nguyen Tran DH, Bach LG, Vu-Quang H, Nguyen DC, Park KD, et al. Functional magnetic core-shell system-based iron oxide nanoparticle coated with biocompatible copolymer for anticancer drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(3):120.

- Sun Z, Song X, Li X, SuT, Qi S, Qiao R, et al. In vivo multimodality imaging of miRNA-16 iron nanoparticle reversing drug resistance to chemotherapy in a mouse gastric cancer model. Nanoscale. 2014;6:14343-53.

- Guo H, Zhang Y, Liang W, Tai F, Dong Q, Zhang R, et al. An inorganic magnetic fluorescent nanoprobe with favorable biocompatibility for dual-modality bioimaging and drug delivery. J Inorg Biochem. 2019;192:72-81.

- Liu X, Deng X, Li X, Xue D, Zhang H, Liu T, et al. A visualized investigation at the atomic scale of the antitumor effect of magnetic nanomedicine on gastric cancer cells. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1389-402.

- Ni Z, Nie X, Zhang H, Wang L, Geng Z, Du X, et al. Atranorin driven by nano materials SPION lead to ferroptosis of gastric cancer stem cells by weakening the mRNA 5-hydroxymethylcytidine modification of the Xc-/GPX4 axis and its expression. Int J Med Sci. 2022;19:1680-94.

- Moskvin M, Huntosova V, Herynek V, Matous P, Michalcova A, Lobaz V, et al. In vitro cellular activity of maghemite/cerium oxide magnetic nanoparticles with antioxidant properties. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2021;204: 111824.

- Das P, Salvioni L, Malatesta M, Vurro F, Mannucci S, Gerosa M, et al. Colloidal polymer-coated Zn -doped iron oxide nanoparticles with high relaxivity and specific absorption rate for efficient magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic hyperthermia. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;579:186-94.

- Li X, Wang Z, Ma M, Chen Z, Tang X, Wang Z. Self-assembly iron oxide nanoclusters for photothermal-mediated synergistic chemo/chemodynamic therapy. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:9958239.

- Alahdal HM, Abdullrezzaq SA, Amin HIM, Alanazi SF, Jalil AT, et al. Trace elements-based Auroshell gold@hematite nanostructure: green synthesis and their hyperthermia therapy. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2023;17:22-31.

- Norouzi M, Yathindranath V, Thliveris JA, Kopec BM, Siahaan TJ, Miller DW. Doxorubicin-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy: a combinational approach for enhanced delivery of nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11292.

- Wang B, Sandre O, Wang K, Shi H, Xiong K, Huang YB, et al. Autodegradable and biocompatible superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles/polypeptides colloidal polyion complexes with high density of magnetic material. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;104: 109920.

- Kwon J, Mao X, Lee HA, Oh S, Tufa LT, Choi JY, et al. Iron-Palladium magnetic nanoparticles for decolorizing rhodamine

and scavenging reactive oxygen species. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;588:646-56. - Kluge M, Leder A, Hillebrandt KH, Struecker B, Geisel D, Denecke T, et al. The magnetic field of magnetic resonance imaging systems does not affect cells labeled with micrometer-sized iron oxide particles. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2017;23:412-21.

- Chee HL, Gan CRR, Ng M, Low L, Fernig DG, Bhakoo KK, et al. Biocompatible peptide-coated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for in vivo contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Nano. 2018;12:6480-91.

- Saraswathy A, Nazeer SS, Nimi N, Santhakumar H, Suma PR, Jibin K, et al. Asialoglycoprotein receptor targeted optical and magnetic resonance imaging and therapy of liver fibrosis using pullulan stabilized multi-functional iron oxide nanoprobe. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18324.

- Moise S, Cespedes E, Soukup D, Byrne JM, El Haj AJ, Telling ND. The cellular magnetic response and biocompatibility of biogenic zincand cobalt-doped magnetite nanoparticles. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39922.

- Kovach AK, Gambino JM, Nguyen V, Nelson Z, Szasz T, Liao J, et al. Prospective preliminary in vitro investigation of a magnetic iron oxide nanoparticle conjugated with ligand CD80 and VEGF antibody as a targeted drug delivery system for the induction of cell death in rodent osteosarcoma cells. Biores Open Access. 2016;5:299-307.

- Mondal S, Manivasagan P, Bharathiraja S, Santha Moorthy M, Nguyen VT, Kim HH, et al. Hydroxyapatite coated iron oxide nanoparticles: a promising nanomaterial for magnetic hyperthermia cancer treatment. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(12):426.

- Amiryaghoubi N, Abdolahinia ED, Nakhlband A, Aslzad S, Fathi M, Barar J, et al. Smart chitosan-folate hybrid magnetic nanoparticles for targeted delivery of doxorubicin to osteosarcoma cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;220: 112911.

- Zhao C, Han Q, Qin H, Yan H, Qian Z, Ma Z, et al. Biocompatible hyperbranched polyester magnetic nanocarrier for stimuli-responsive drug release. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2017;28:616-28.

- Huang QT, Hu QQ, Wen ZF, Li YL. Iron oxide nanoparticles inhibit tumor growth by ferroptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:498-508.

- Song L, Chen Y, Ding J, Wu H, Zhang W, Ma M, et al. Rituximab conjugated iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted imaging and enhanced treatment against CD20-positive lymphoma. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:895-907.

- Dai X, Yao J, Zhong Y, Li Y, Lu Q, Zhang Y, et al. Preparation and characterization of

@MTX magnetic nanoparticles for thermochemotherapy of primary central nervous system lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:9647-63. - Lin YR, Chan CH, Lee HT, Cheng SJ, Yang JW, Chang SJ, et al. Remote magnetic control of autophagy in mouse B-lymphoma cells with iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2019;9(4):551.

- Takke A, Shende P. Magnetic-core-based silibinin nanopolymeric carriers for the treatment of renal cell cancer. Life Sci. 2021;275: 119377.

- Lu C, Li J, Xu K, Yang C, Wang J, Han C, et al. Fabrication of mAb G250SPIO molecular magnetic resonance imaging nanoprobe for the specific detection of renal cell carcinoma in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e101898.

- Alphandéry E. Iron oxide nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:141-9.

- Li Y, Wei X, Tao F, Deng C, Lv C, Chen C, et al. The potential application of nanomaterials for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy. Biomed Mater. 2021;16: 042013.

- Mulens-Arias V, Rojas JM, Barber DF. The use of iron oxide nanoparticles to reprogram macrophage responses and the immunological tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2021;12(12): 693709.

- Lorkowski ME, Atukorale PU, Ghaghada KB, Karathanasis E. Stimuliresponsive iron oxide nanotheranostics: a versatile and powerful approach for cancer therapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(5): e2001044.

- Alphandéry E. Biodistribution and targeting properties of iron oxide nanoparticles for treatments of cancer and iron anemia disease. Nanotoxicology. 2019;13:573-96.

- Fèvre RL, Durand-Dubief M, Chebbi I, Mandawala C, Lagroix F, Valet JP, et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of biocompatible magnetosomes for the magnetic hyperthermia treatment of glioblastoma. Theranostics. 2017;7:4618-31.

- Mahajan UM, Teller S, Sendler M, Palankar R, Brandt C, Schwaiger T, et al. Tumour-specific delivery of siRNA-coupled superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, targeted against PLK1, stops progression of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2016;65:1838-49.

- Saadat M, Manshadi MKD, Mohammadi M, Zare MJ, Zarei M, Kamali R, et al. Magnetic particle targeting for diagnosis and therapy of lung cancers. J Contr Release. 2020;328:776-91.

- Saber-Samandari S, Mohammadi-Aghdam M, Saber-Samandari S. A novel magnetic bifunctional nanocomposite scaffold for photothermal therapy and tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;138:810-8.

- Tampieri A, lafisco M, Sandri M, Panseri S, Cunha C, Sprio S, et al. Magnetic bioinspired hybrid nanostructured collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffolds supporting cell proliferation and tuning regenerative process. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:15697-707.

- Labusca L, Herea DD, Danceanu CM, Minuti AE, Stavila C, Grigoras M, et al. The effect of magnetic field exposure on differentiation of magnetite nanoparticle-loaded adipose-derived stem cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;109: 110652.

- Jin H, Qian Y, Dai Y, Qiao S, Huang C, Lu L, et al. Magnetic enrichment of dendritic cell vaccine in lymph node with fluorescent-magnetic nanoparticles enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2016;6:2000-14.

- Su H, Mou Y, An Y, Han W, Huang X, Xia G, et al. The migration of synthetic magnetic nanoparticle labeled dendritic cells into lymph nodes with optical imaging. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:3737-44.

- Rojas JM, Gavilan H, Dedo V, Lorente-Sorolla E, Sanz-Ortega L, Silva GB, et al. Time-course assessment of the aggregation and metabolization of magnetic nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2017;58:181-95.

- Funnell JL, Ziemba AM, Nowak JF, Awada H, Prokopiou N, Samuel J, Guari Y, et al. Assessing the combination of magnetic field stimulation, iron oxide nanoparticles, and aligned electrospun fibers for promoting neurite outgrowth from dorsal root ganglia in vitro. Acta Biomater. 2021;131:302-13.

- Guldris N, Argibay B, Gallo J, Iglesias-Rey R, Carbó-Argibay E, Kolenko YV, et al. Magnetite nanoparticles for stem cell labeling with high efficiency and long-term in vivo tracking. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;28:362-70.

- Silva LH, Silva JR, Ferreira GA, Silva RC, Lima EC, Azevedo RB, et al. Labeling mesenchymal cells with DMSA-coated gold and iron oxide nanoparticles: assessment of biocompatibility and potential applications. J Nanobiotechnology. 2016;14:59.

- Xie Y, Liu W, Zhang B, Wang B, Wang L, Liu S, et al. Systematic intracelIular biocompatibility assessments of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in human umbilical cord mesenchyme stem cells in testifying its reusability for inner cell tracking by MRI. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2019;15:2179-92.

- Daya R, Xu C, Nguyen NT, Liu HH. Angiogenic hyaluronic acid hydrogels with curcumin-coated magnetic nanoparticles for tissue repair. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14:11051-67.

- Boitard C, Curcio A, Rollet AL, Wilhelm C, Menager C, Griffete N. Biological fate of magnetic protein-specific molecularly imprinted polymers: toxicity and degradation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:35556-65.

- Schneider MG, Azcona P, Campelo A, Massheimer V, Agotegaray M, Lassalle V. Magnetic nanoplatform with novel potential for the treatment of bone pathologies: drug loading and biocompatibility on blood and bone cells. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2023;22:11-8.

- Carreira SC, Armstrong JP, Seddon AM, Perriman AW, Hartley-Davies R, Schwarzacher W. Ultra-fast stem cell labelling using cationised magnetoferritin. Nanoscale. 2016;8:7474-83.

- Bianco LD, Spizzo F, Yang Y, Greco G, Gatto ML, Barucca G, et al. Silk fibroin films with embedded magnetic nanoparticles: evaluation of the magneto-mechanical stimulation effect on osteogenic differentiation of stem cells. Nanoscale. 2022;14:14558-74.

- Pongrac IM, Radmilovic MD, Ahmed LB, Mlinaric H, Regul J, Skokic S, et al. D-mannose-coating of maghemite nanoparticles improved labeling of neural stem cells and allowed their visualization by ex vivo MRI after transplantation in the mouse brain. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:553-67.

- Taruno K, Kurita T, Kuwahata A, Yanagihara K, Enokido K, Katayose Y, et al. Multicenter clinical trial on sentinel lymph node biopsy using superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and a novel handheld magnetic probe. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:1391-6.

- Sekino M, Kuwahata A, Ookubo T, Shiozawa M, Ohashi K, Kaneko M, et al. Handheld magnetic probe with permanent magnet and hall sensor for identifying sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1195.

- Vural V, Yilmaz OC. The Turkish SentiMAG feasibility trial: preliminary results. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:261-5.

- Karakatsanis A, Olofsson H, Stalberg P, Bergkvist L, Abdsaleh S, Warnberg F . Simplifying logistics and avoiding the unnecessary in patients with breast cancer undergoing sentinel node biopsy. A prospective feasibility trial of the preoperative injection of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Scand J Surg. 2018;107:130-7.

- Alvarado MD, Mittendorf EA, Teshome M, Thompson AM, Bold RJ, Gittleman MA. SentimagIC: a non-inferiority trial comparing superparamagnetic iron oxide versus technetium- 99 m and blue dye in the detection of axillary sentinel nodes in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3510-6.

- Houpeau JL, Chauvet MP, Guillemin F, Bendavid-Athias C, Charitansky H, Kramar A, et al. Sentinel lymph node identification using superparamagnetic iron oxide particles versus radioisotope: The French Sentimag feasibility trial. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:501-7.

- Karakatsanis A, Christiansen PM, Fischer L, Hedin C, Pistioli L, Sund

, et al. The Nordic SentiMag trial: a comparison of super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles versus Tc(99) and patent blue in the detection of sentinel node (SN) in patients with breast cancer and a meta-analysis of earlier studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;157:281-94. - Rubio IT, Rodriguez-Revuelto R, Espinosa-Bravo M, Siso C, Rivero J, Esgueva A. A randomized study comparing different doses of superparamagnetic iron oxide tracer for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: the SUNRISE study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:2195-201.

- Man V, Suen D, Kwong A. Use of superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) versus conventional technique in sentinel lymph node detection

for breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:3237-44. - Aldenhoven L, Frotscher C, Korver-Steeman R, Martens MH, Kuburic D, Janssen A, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping with superparamagnetic iron oxide for melanoma: a pilot study in healthy participants to establish an optimal MRI workflow protocol. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:1062.

- Birkhauser FD, Studer UE, Froehlich JM, Triantafyllou M, Bains LJ, Petralia G , et al. Combined ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide-enhanced and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging facilitates detection of metastases in normal-sized pelvic lymph nodes of patients with bladder and prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;64:953-60.

- Muehe AM, Siedek F, Theruvath AJ, Seekins J, Spunt SL, Pribnow A, et al. Differentiation of benign and malignant lymph nodes in pediatric patients on ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MRI. Theranostics. 2020;10:3612-21.

- Yilmaz A, Dengler MA, Kuip H, Yildiz H, Rosch S, Klumpp S, et al. Imaging of myocardial infarction using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: a human study using a multi-parametric cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging approach. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:462-75.

- Stirrat CG, Alam SR, MacGillivray TJ, Gray CD, Dweck MR, Dibb K, et al. Ferumoxytol-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in acute myocarditis. Heart. 2018;104:300-5.

- Florian A, Ludwig A, Rösch S, Yildiz H, Sechtem U, Yilmaz A. Positive effect of intravenous iron-oxide administration on left ventricular remodelling in patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction-a cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;173(2):184-9.

- Aoki T, Saito M, Koseki H, Tsuji K, Tsuji A, Murata K, et al. Investigators, macrophage imaging of cerebral aneurysms with ferumoxytol: an exploratory study in an animal model and in patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2055-64.

- Investigators MRS. Aortic wall inflammation predicts abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion, rupture, and need for surgical repair. Circulation. 2017;136:787-97.

- Khan S, Amin FM, Fliedner FP, Christensen CE, Tolnai D, Younis S, et al. Investigating macrophage-mediated inflammation in migraine using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced 3T magnetic resonance imaging. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:1407-20.

- Aghighi M, Pisani L, Theruvath AJ, Muehe AM, Donig J, Khan R, et al. Ferumoxytol is not retained in kidney allografts in patients undergoing acute rejection. Mol Imaging Biol. 2018;20:139-49.

- Theruvath AJ, Nejadnik H, Muehe AM, Gassert F, Lacayo NJ, Goodman SB, et al. Tracking cell transplants in femoral osteonecrosis with magnetic resonance imaging: a proof-of-concept study in patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:6223-9.

- Guo X, Mao F, Wang W, Yang Y, Bai Z. Sulfhydryl-modified

core/shell nanocomposite: synthesis and toxicity assessment in vitro. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:14983-91. - Bona KD, Xu Y, Gray M, Fair D, Hayles H, Milad L, et al. Short- and longterm effects of prenatal exposure to iron oxide nanoparticles: influence of surface charge and dose on developmental and reproductive toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:30251-68.

- Agotegaray MA, Campelo AE, Zysler RD, Gumilar F, Bras C, Gandini A, et al. Magnetic nanoparticles for drug targeting: from design to insights into systemic toxicity. Preclinical evaluation of hematological, vascular and neurobehavioral toxicology. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:772-83.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم يو تشينغ مينغ، يا نان شي ويونغ بينغ زو بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

جون زهي زانغ

jzzhang@icmm.ac.cn

تشونغ تشيو

cqiu@icmm.ac.cn

جي غانغ وانغ

jgwang@icmm.ac.cn

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02235-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191388

Publication Date: 2024-01-08

Recent trends in preparation and biomedical applications of iron oxide nanoparticles

Abstract

The iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), possessing both magnetic behavior and semiconductor property, have been extensively used in multifunctional biomedical fields due to their biocompatible, biodegradable and low toxicity, such as anticancer, antibacterial, cell labelling activities. Nevertheless, there are few IONPs in clinical use at present. Some IONPs approved for clinical use have been withdrawn due to insufficient understanding of its biomedical applications. Therefore, a systematic summary of IONPs’ preparation and biomedical applications is crucial for the next step of entering clinical practice from experimental stage. This review summarized the existing research in the past decade on the biological interaction of IONPs with animal/cells models, and their clinical applications in human. This review aims to provide cutting-edge knowledge involved with IONPs’ biological effects in vivo and in vitro, and improve their smarter design and application in biomedical research and clinic trials.

Introduction

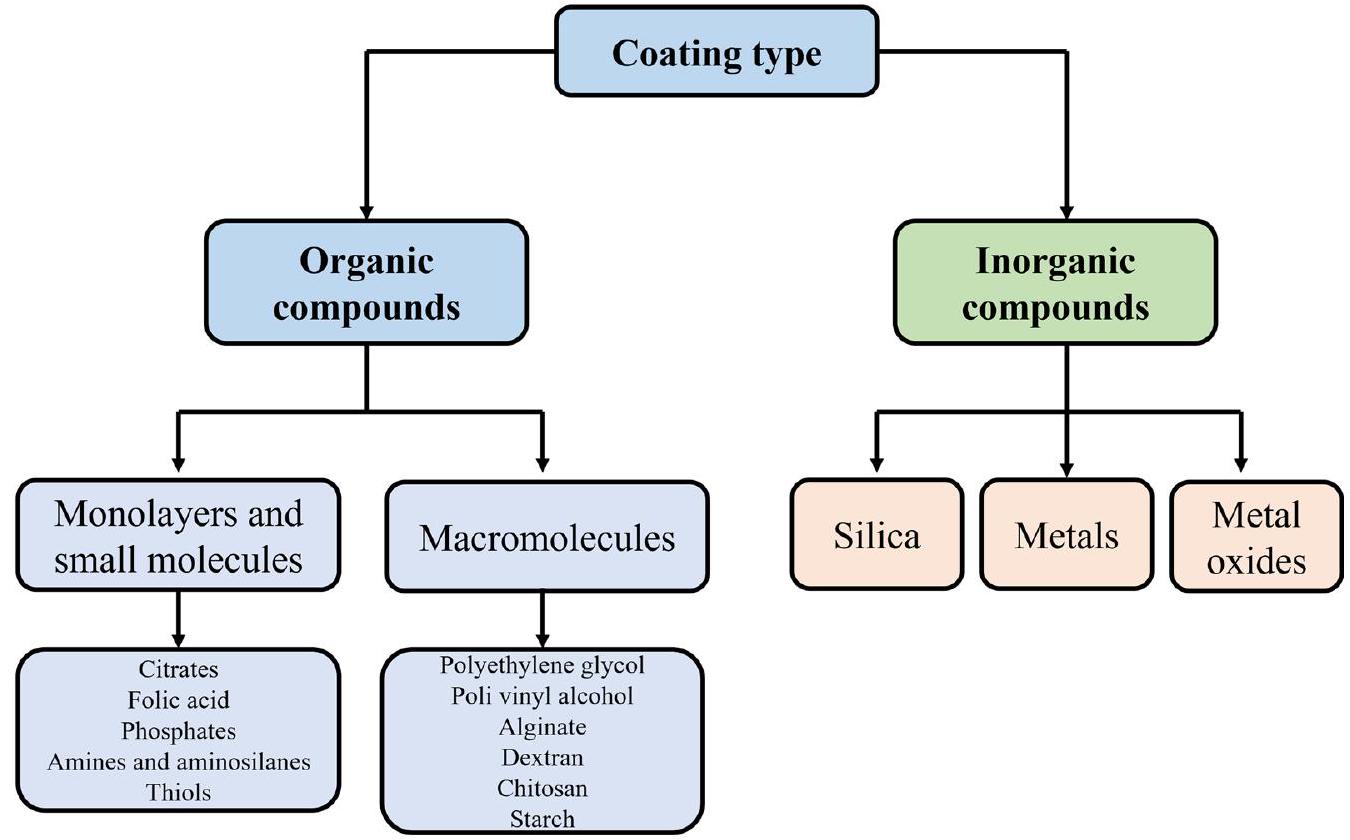

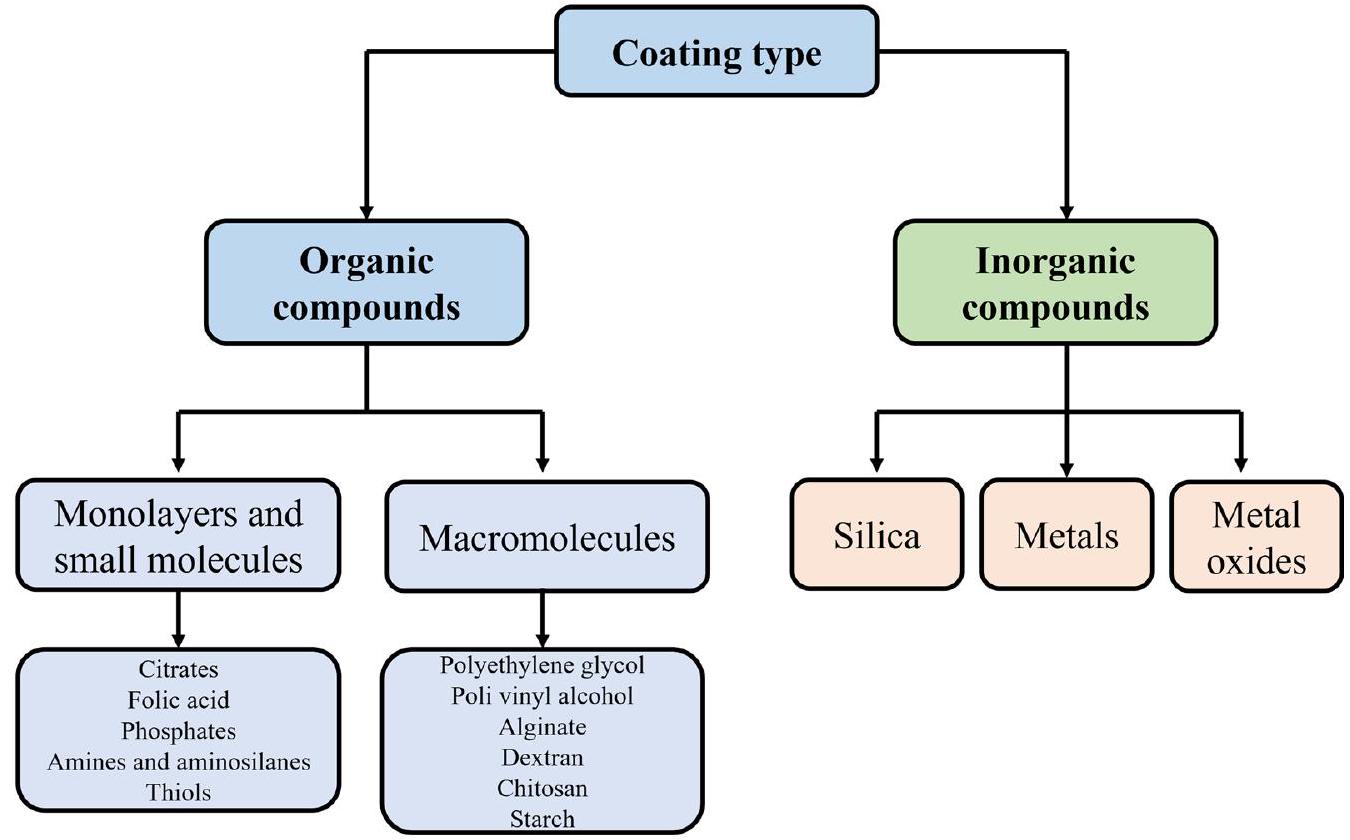

[14]. The results showed that carboxymethyl dextran coated IONPs degraded faster in simulated body fluid than those coated with silica, and showed the least prothrombotic properties. In addition, the thickness was inversely proportional to the degradation rate. Besides, studies have demonstrated that the same IONP might show different biocompatibility or toxicity in different cell type or humans, which is also the predominant reason to hinder the application of IONPs in biomedical field [15, 16]. Hence, it is necessary not only to summarize the size, surface coatings and functional groups of IONPs (Fig. 2), but also to summarize the biomedical applications of IONPs in different animal models, cell types and humans, so as to promote the comprehensive understanding of IONPs by researchers and provide guidance for accelerating the clinical application of IONPs-based nanomedicine.

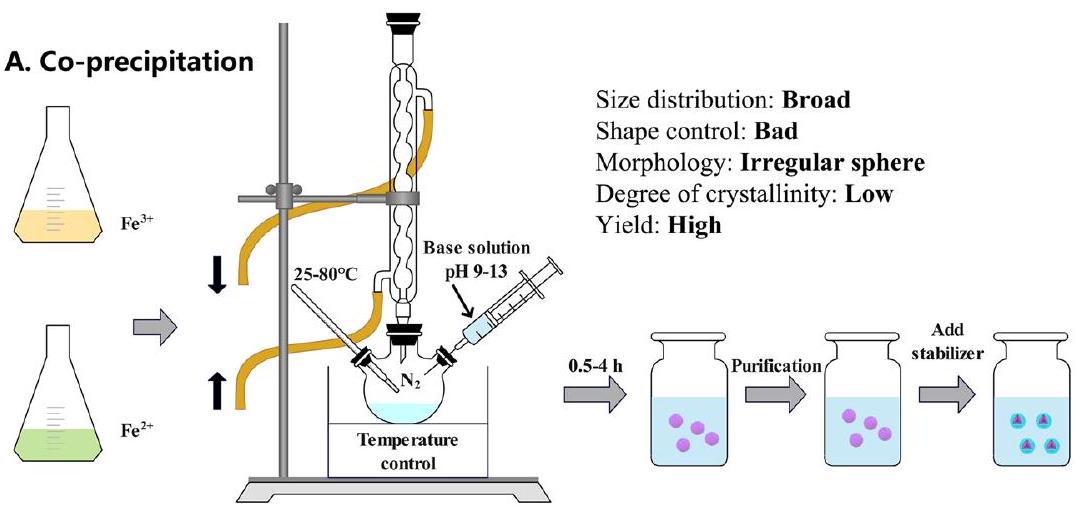

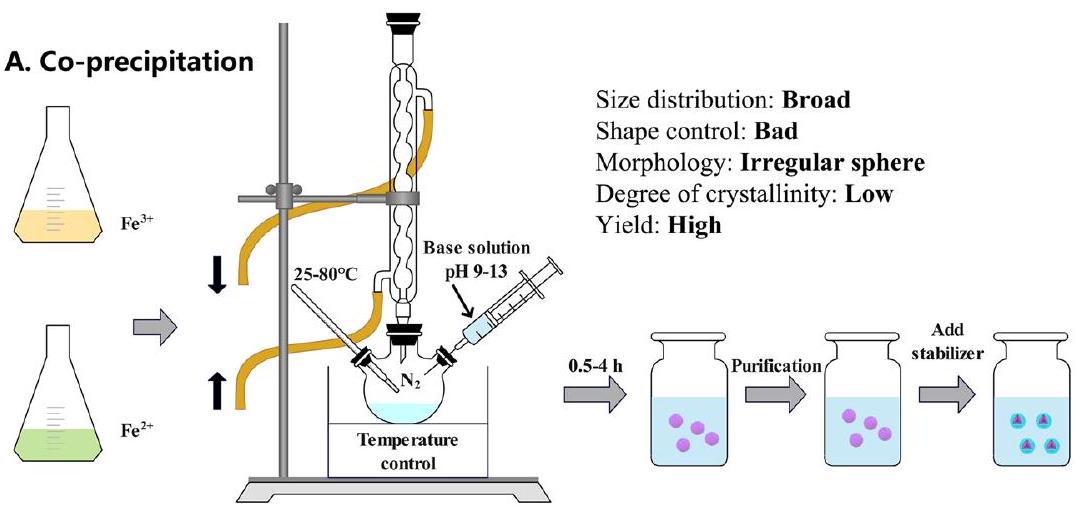

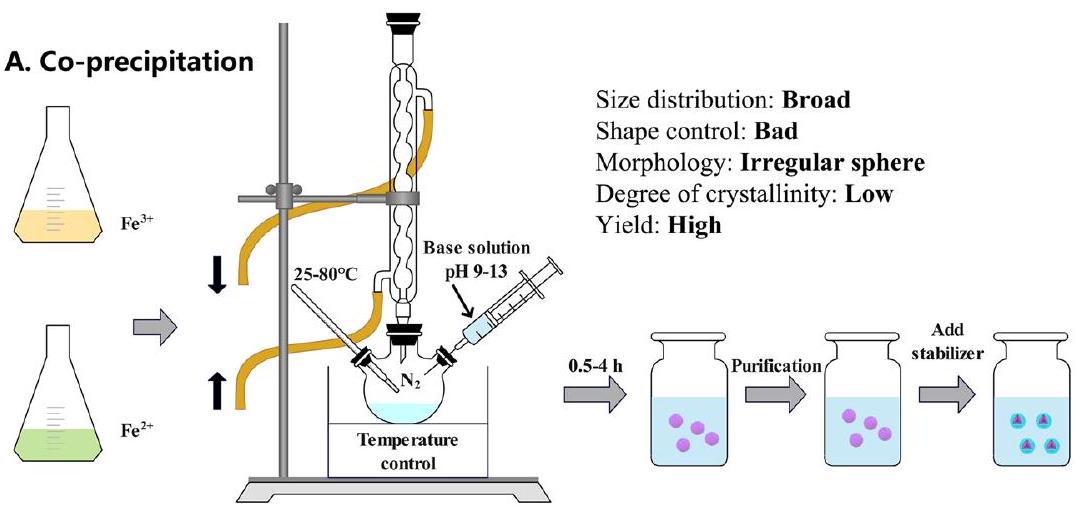

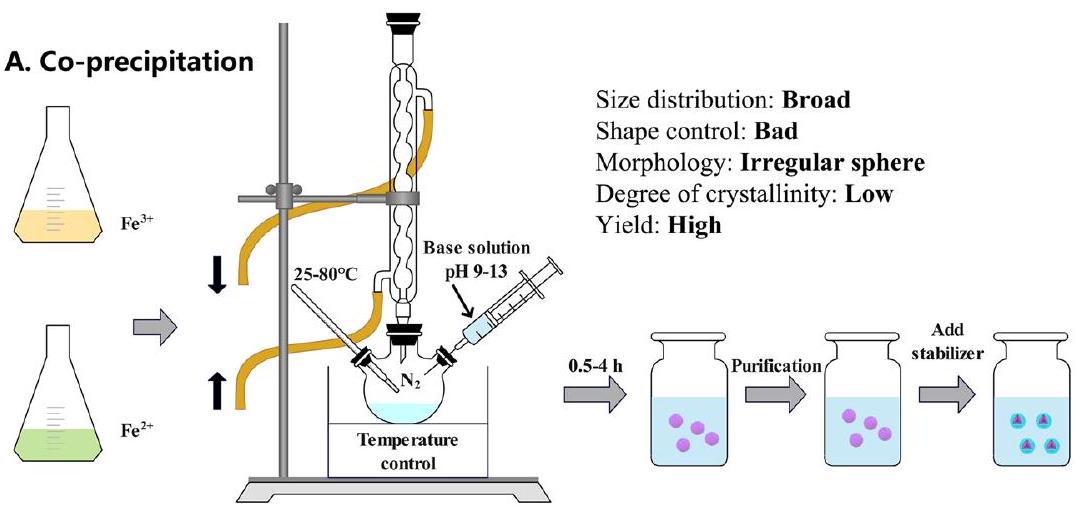

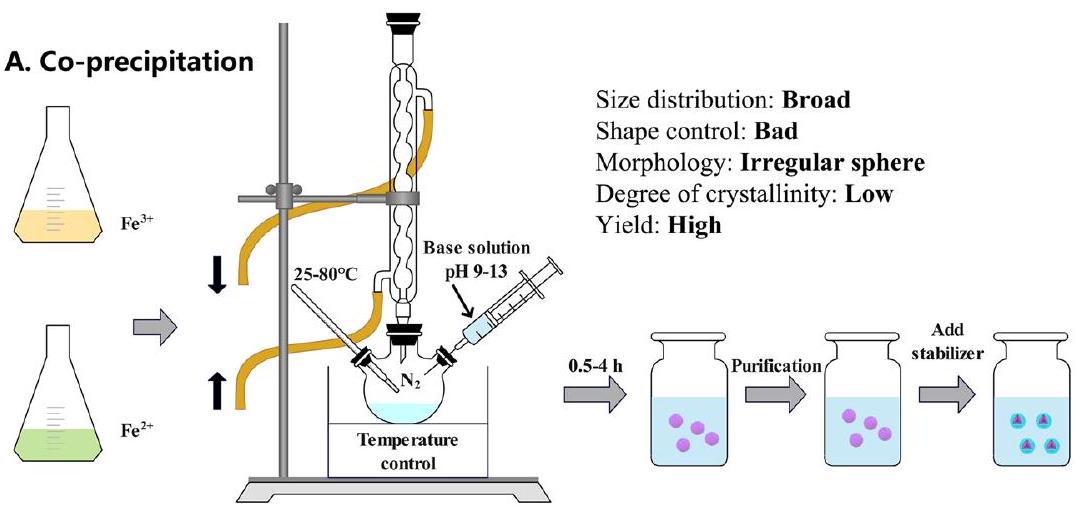

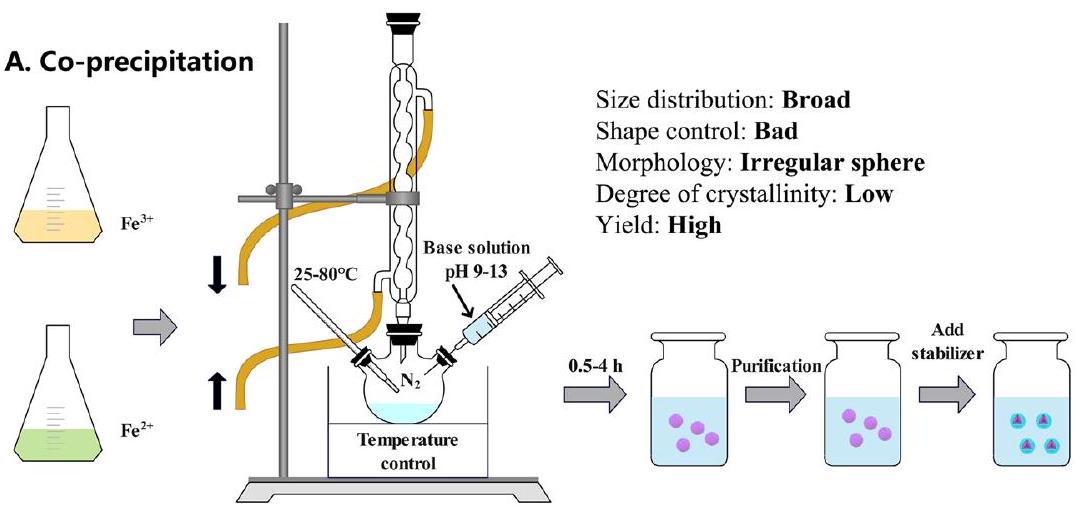

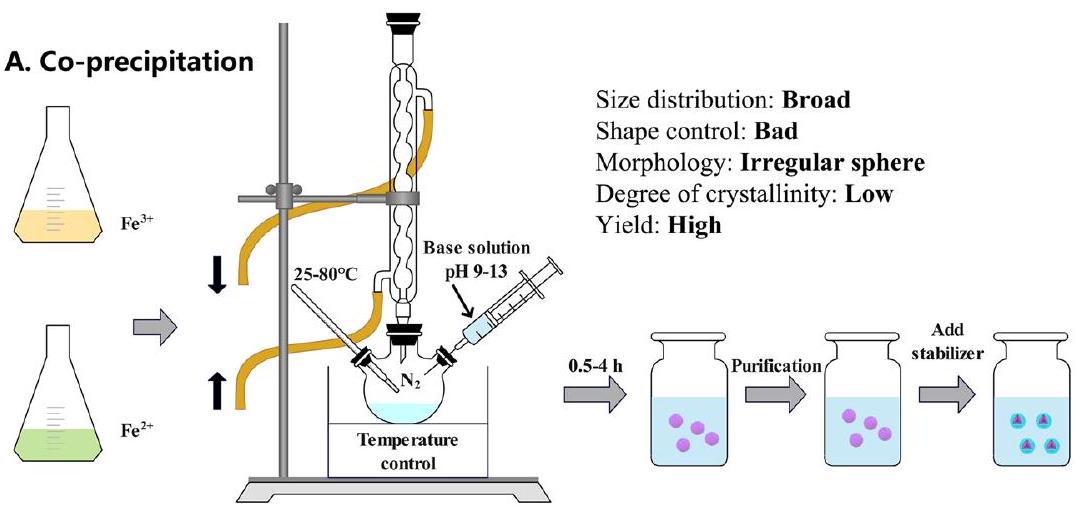

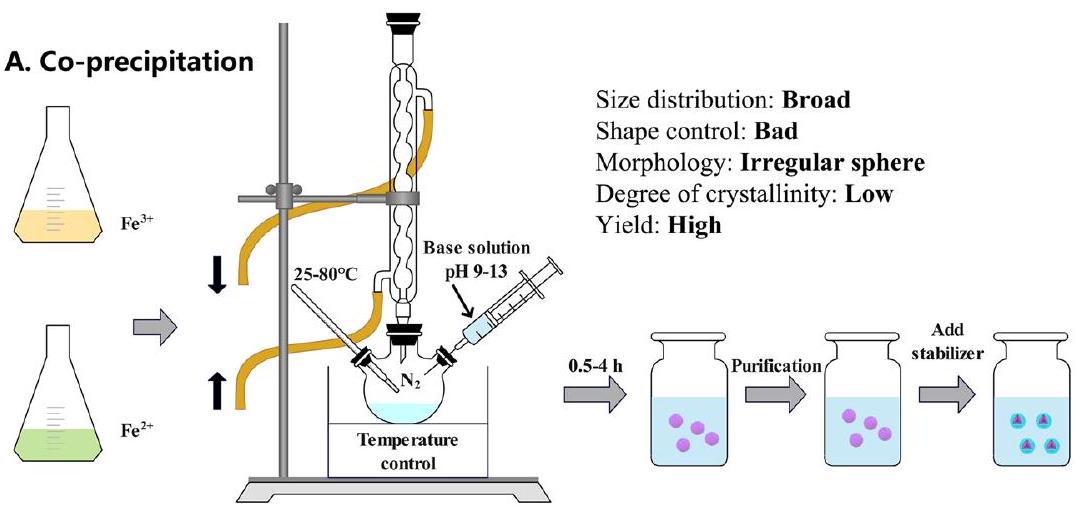

Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles

milling, electron beam lithography, aerosol, and gas phase deposition. Although the yield of physical methods is high, only

Applications of IONPs in animal models

magnetic states: ferromagnetism (

injection for 24 h , then cleared by kidney at 48 h without inducing any damage and side effects [46]. Additionally, zebrafish, as an emerging model to investigate the potential toxicity, has been used successfully to assess the potential risks induced by the IONPs. The result showed that carbon-modified

Poly (ethylene glycol)-l-arginine@IONPs (PEG-Arg@ IONPs) were mainly uptake by liver, besides spleen, heart and kidneys in BALB/c model within 2 h . After 24 h , the

functioned SPIONs could increase the accumulation of methotrexate (MTX) in the tumor site and decrease the toxicity of MTX in BALB/c mice, which provided an option for MRI imaging and targeted tumor therapy [66].

In vitro applications of IONPs

IONPs in tumor cells

Lung carcinoma cells

Oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

Ovarian carcinoma

| Coating molecule | Name | Model | Dose | Days | Outcome | References |

| Polyethylene glycol | PEG-MGNCs | SCC7 tumor-bearing mouse |

|

8 days | Enhance the hyperthermia efficacy | [12] |

| Citrate | Citrate@IONPs | Elderly and young healthy mice |

|

28 days | Reasonably biocompatible for young mice | [16] |

| Polyethylene glycol | SaNPs | Swine |

|

90 days | No adverse effects | [40] |

| Chitosan |

|

BALB/c mice |

|

|

No toxicity in vital organs | [41] |

| c(RGDyK)and D-glucosamine |

|

BALB/c mice |

|

8 days | Tumors on mice were obviously inhibited | [42] |

| Macrophage membranes |

|

BALB/c mice |

|

16 days | Significantly reduce the tumor size | [43] |

| Dopamine sulfonate, zwitterionic dopamine sulfonate, coryneine chloride | FeOx NPs | CD1 mice | 1 or

|

Rapidly distributed in liver and spleen, and excreted via urinary system | [44] | |

| / |

|

Swiss mice |

|

12,22 days | Significantly reduce the tumor growth | [45] |

| 6-7 bovine serum albumin |

|

SD rats |

|

|

Efficiently cleared within 48 h | [46] |

| Poly (ethylene glycol)-L-arginine | PEG-Arg@IONPs | BALB/c mice |

|

24 h | Mainly uptake by liver, besides spleen, heart and kidneys | [49] |

| Citrate, curcumin, chitosan | IONPs@citrate, IONPs@curcumin, IONPs@chitosan | Wistar rats |

|

10 days | IONPs@curcumin and IONPs@ chitosan were mild toxic | [50] |

| Chloride, lactate, nitrate | IONPs@chloride, IONPs@lactate, and IONPs@nitrate | Wistar rats |

|

14 days | No signs of toxicity | [51] |

| Human albumin | IONPs@human albumin | Wistar rats |

|

24 h | Firstly gathered in liver, then in spleen and kidney | [52] |

| Dimercaptosuccinic acid | IONPs@DMSA | C57BL/6 mice |

|

7, 30, 60, 90 days | No toxicity | [53] |

| / | ES-IONPs | U-87 MG tumor-bearing nude mice |

|

28 days | Accumulate in tumor | [54] |

| Poly (ethylene glycol) carboxylpoly(

|

PEG-PCCL-IONPs | H22 tumor xenograft BALB/C mice |

|

48 h | Mainly distributed in the spleen and liver | [55] |

| Dextran | SPIONdex | Pig model |

|

30 min | No complement activationrelated pseudoallergy observed | [56] |

| Lactobionic acid | MNP-LBA | Albino rabbit |

|

24 h | Enhance the release of ceftriaxone | [57] |

| Polyethylene glycol-COOH, Polyethylene glycol-

|

SPION@PEG-COOH and SPION@ PEG-NH2 | BALB/c mice |

|

28 days | Mainly accumulated in the lung | [58] |

| Polyethylene glycol | PEG-SPIONs | Kunming mice |

|

14 days | Primarily in the liver, spleen, and intestine, | [59] |

| Coating molecule | Name | Model | Dose | Days | Outcome | References |

| Didodecyl-dimethyl-ammoniumbromide, tocopheryl-polyethele-neglycol-succinate | SPION-DMAB, SPION-TPGS | Swiss albino mice |

|

7 days | SPION-DMAB mainly accumulated in brain and spleen, while SPION-TPGS internalized in liver and kidney | [60] |

| L-cysteine | Cys-

|

BALB/c mice |

|

7 days | Increase the adipose tissue in the inferior layer of the epidermis of mice | [61] |

| Poly(lactide) | PLA@SPIONs | Sprague Dawley rats |

|

6 months | Slow degradation | [62] |

| Oleic acid and methoxy-polyethylene glycol-phospholipid | SPION-PEG2000 | Swiss albino mice |

|

14 days | Induced necrosis in liver and kidney and inflammatory infiltration in lung | [63] |

| Silica | sub-5 SIO-FI | CD-1 mice |

|

7 weeks | No obviously acute and chronic toxicity | [64] |

| / | SPION | Sprague Dawley rats |

|

8 weeks | Enhanced the formation of chondrogenesis | [65] |

| Galactomannan | PSP-IO NPs | BALB/c mice |

|

14 days | Increased the accumulation of methotrexate in the tumor site and decrease the toxicity of methotrexate | [66] |

| / | USPIONs | ICR mice |

|

7 days | No significantly toxicity | [67] |

| Glypican-3-specific aptamer | Apt-USPIO | Kunming mice |

|

30 days | Excellent biocompatible | [68] |

| Coating molecule | Name | Model | Dose | Days | Outcome | References |

| Poly (ethylenimine), poly(allylamine hydrochloride), poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) | IONPs-PEI, IONPs-PAH, IONPsPDADMAC | A549 cell line |

|

24 h | poly(allylamine hydrochloride) stabilized IONPs were the best biocompatibility | [69] |

| Polydopamine |

|

NK cell line |

|

12 h | It could regulate immune cells, inhibit tumor growth | [70] |

| Magnesium |

|

A549 cell line |

|

24 h | Significant cytotoxic effects | [71] |

| Polyethylenimine-calcium phosphate | SPIONs@PEI-CPs | A549 and HepG2 cell lines |

|

24 h | SPIONs@PEI-CPs were excellent biocompatibility, while SPIONs@ PEI were remarkable cytotoxicity | [72] |

| Polyethylene glycol | IONPs | A549 cell line |

|

No significantly toxicity | [73] | |

| Anti-av

|

avß6-MIONPs | VB6 and H357 cell lines |

|

24 and 48 h | avß6- magnetic NP could enhance the killing potential of OSCC when combined with magnetic field | [74] |

| Chitosan | CS@IONPs | HSC-2 cell line |

|

48 h | No synergism with anticancer drugs; not completely rescue the X-ray-induced cell damage | [75] |

| Folate-chitosan-docetaxel | SPIONs coated with folate-chi-tosan-docetaxel | L929, KB and PC3 cell lines |

|

48 h | targeted cytotoxicity in cancer cells | [76] |

| Chitosan, growth factor domain, somatomedin B domain | IONPs/C, IONPs/C/GFD, IONPs/C/ SMB | SKOV3 cell line |

|

|

GFD + SMB showed synergistic effect | [77] |

| Cobalt and manganese | CoMn-IONP | ES-2 cell line |

|

24 h | High saturation magnetization and heating efficiency | [78] |

| / | SPIONs-Serum | SKOV3 cell line |

|

24 h | Significantly inhibited the cell proliferation | [79] |

| Single-chain antibody,

|

|

SKOV3 cell line |

|

72 h | Continuously inhibited the growth of Skov3 ovarian cancer cells | [80] |

| Chitosan | Cs-coated SPIONs | HEK-293 cell line |

|

24,48,72 h | Non-toxic | [81] |

| / |

|

Caco-2, HT-29, and SW-480 cell lines |

|

24 h | Carbohydrate and polymer coated on the surface of NPs enhanced the biocompatibility | [82] |

| Polyethylene glycol |

|

COLO-205 cell line |

|

24 h | Cytotoxicity to cancer cells | [83] |

| Silica | Fe@FeOx@SiO2 NPs | HCT116 cell line |

|

72 h | No cytotoxicity | [84] |

| Silica | Sub-5 nm silica@IONPs | Caco-2 cell line |

|

24 h | Well biocompatible | [85] |

| Carboxylate, amine | IONPs | C10 cell line |

|

24 h | Cytotoxicity and oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner | [86] |

| Aptamer, Au | Aptamer-Au@SPIONs | HT-29, CHO and L929 cell lines |

|

24 h | Concentration influenced the cytotoxicity | [87] |

| Coating molecule | Name | Model | Dose | Days | Outcome | References |

| Poly (sodium styrene sulfonate)/ irinotecan/human serum albumin-anti-CD133 | SPIONs@PSS/HAS-anti-CD133 | Caco2, HCT116, DLD1 cell lines |

|

24 h | Inhibited the tumor cell viability in a dose-dependent manner | [88] |

| Dextran | University of Luebeck-Dextran coated SPION | Head and neck squamous cancer cell line |

|

120 h | Decreased cell proliferation | [89] |

| Hyaluronic acid, HA-PEG10 | HA-PEG10@SPIONs | SCC7 cell line |

|

2 h | Remarkably decreased SCC7 cell viability | [90] |

| Dextran, hyaluronic acid, cisplatin | SEON

|

PC-3 cell line |

|

24 h | SPIONs with cisplatin induced apoptosis and necrosis | [91] |

| J591 | IONPs | LNCaP, PC3, DU145, 22RV1 cell lines | 48 h | 48 h | No effect on cell viability | [92] |

| Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-acrylamide-allylamine) | R11-PIONPs | PC3 and LNCaP cell lines |

|

|

Inhibited the tumor cell viability in a dose-dependent manner | [93] |

| Docetaxel |

|

DU145, PC-3, and LNCaP cell lines |

|

72 h | Slightly cytotoxicity | [94] |

| Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptor peptide and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor peptide | LHRH-AE105-IONPs | PC-3 cell line |

|

24 h | Remarkably decreased PC-3 cell viability | [95] |

| Hyaluronic acid | FeO@HA NPs | L929 normal cell and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell |

|

|

High targeting specificity to cancer cells | [96] |

| / | Exceedingly small IONPs | MCF7 and 4T1 cell lines | 0.8 mM Fe | 24 h | Non-cytotoxicity | [98] |

| / | IONPs | 4T1 cell line |

|

24 h | Decreased 4T1 cell viability to 48.5% | [99] |

| Arginine-methotrexate | Fe-Arg-MTX | MCF-7, 4T1, HFF-2 cell lines |

|

|

Significantly decreased the cell viability | [100] |

| Macrophage membrane | FeO@MM | MCF-7 cell line |

|

24 h | No toxicity | [43] |

| Dimercaptosuccinic acid | DMSA-SPION | MCF-7 cell line |

|

|

Targeting breast cancer cells | [101] |

| Tantalum carbide |

|

4T1 cell line |

|

24 h | Excellent biocompatibility | [102] |