DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38632481

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-17

الالتزام الاقتصادي بتغير المناخ

تاريخ الاستلام: 25 يناير 2023

تم القبول: 21 فبراير 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 17 أبريل 2024

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

ماكسيميليان كوتز

تأخذ التوقعات العالمية للأضرار الاقتصادية الكلية الناتجة عن تغير المناخ عادةً في الاعتبار التأثيرات الناتجة عن متوسط درجات الحرارة السنوية والوطنية على مدى فترات زمنية طويلة.

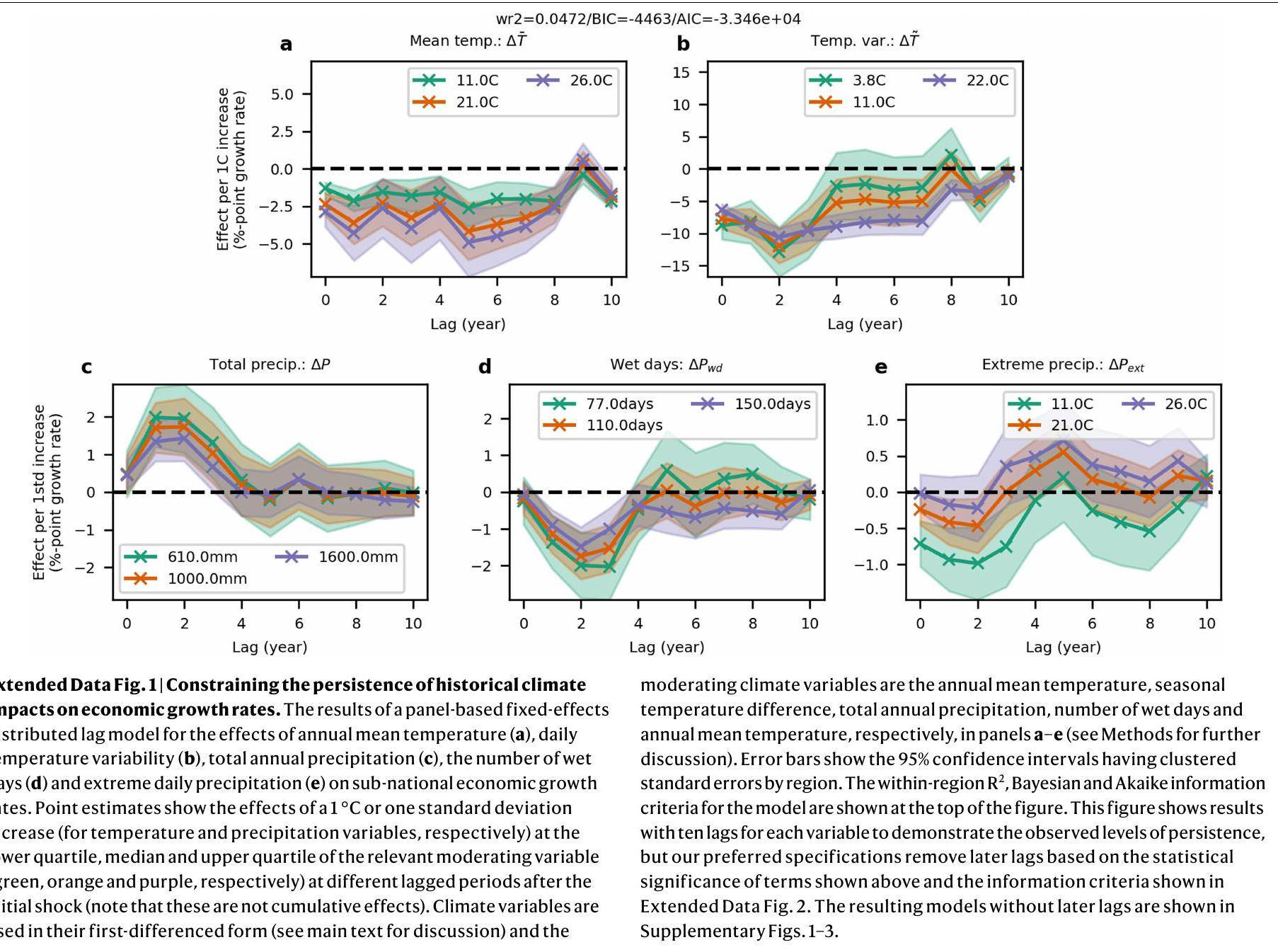

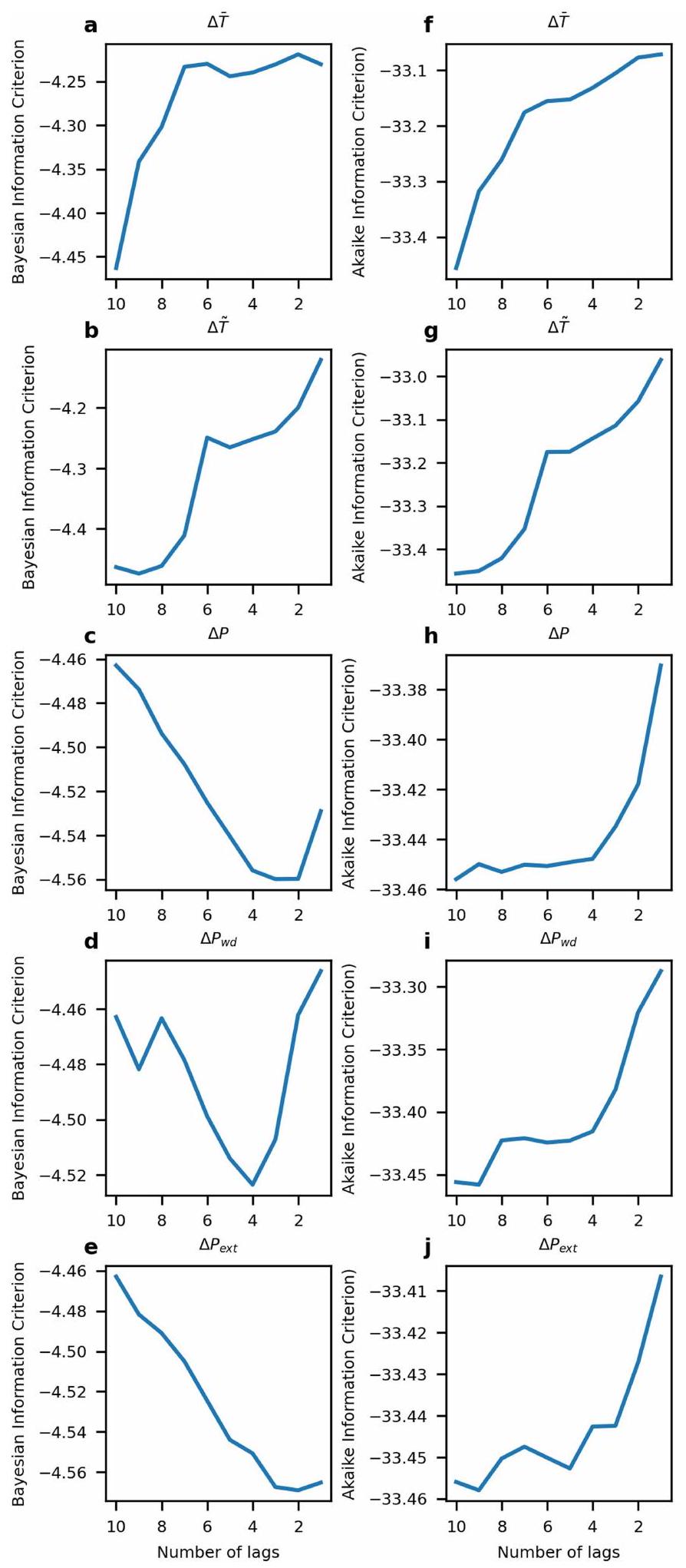

تقييد استمرارية التأثيرات

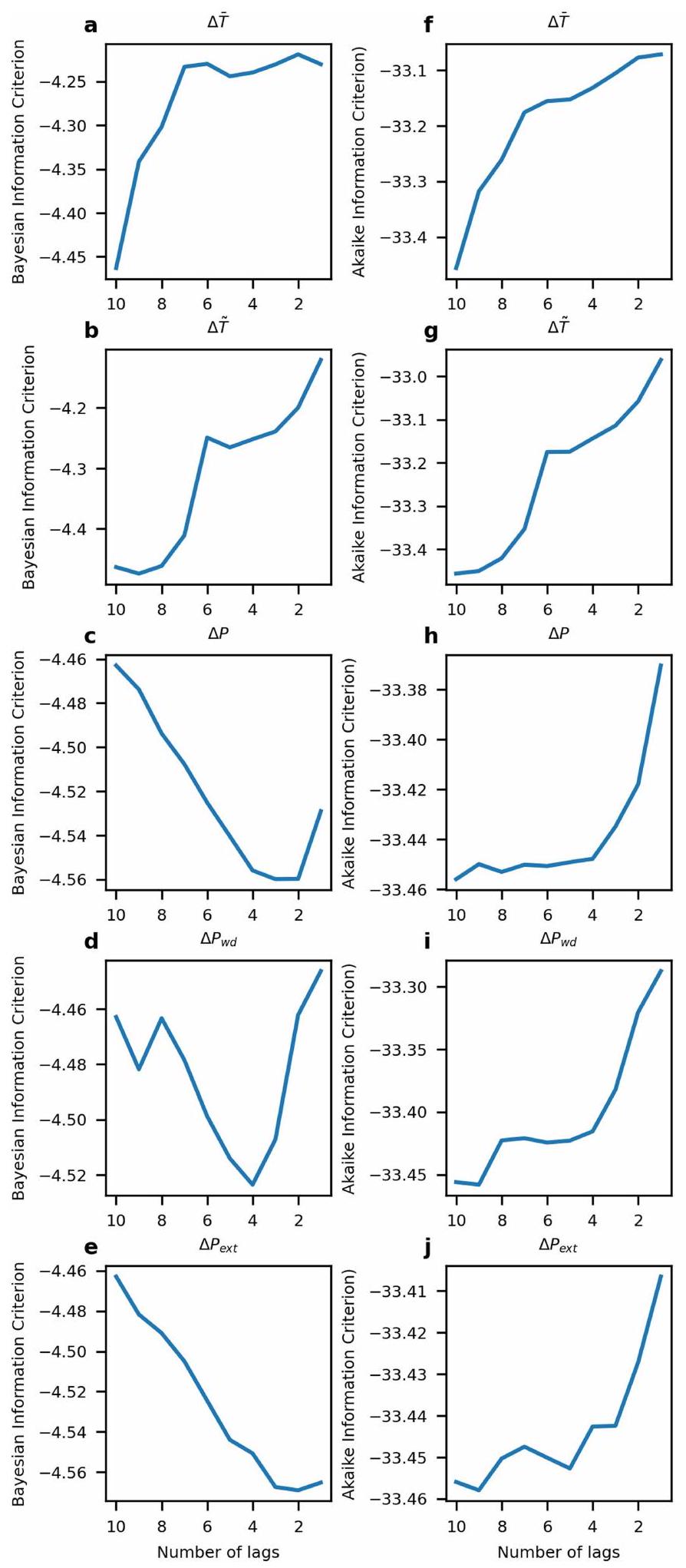

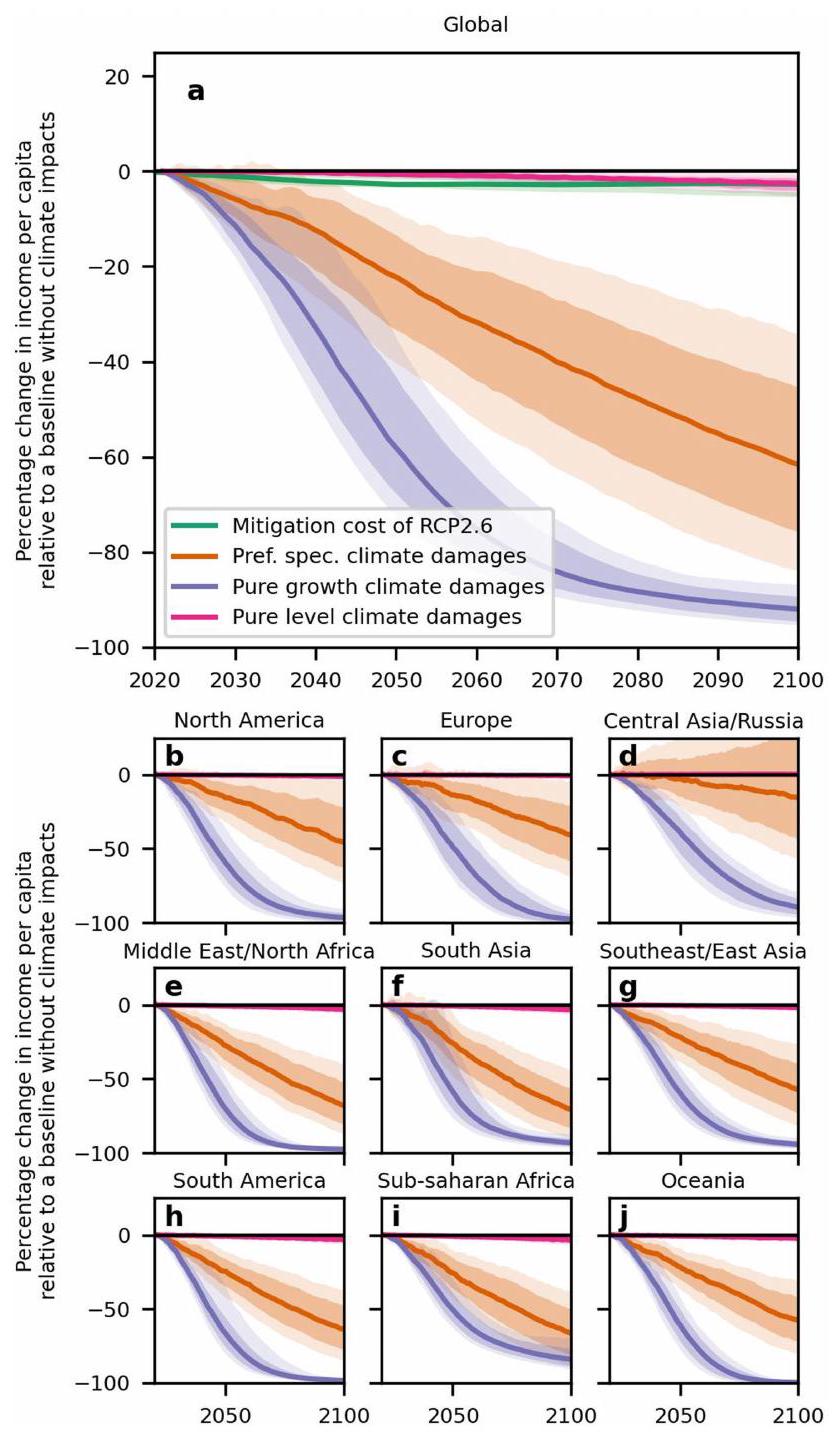

نبدأ تحليلنا التجريبي لاستمرارية تأثيرات المناخ على النمو باستخدام عشرة تأخيرات من المتغيرات المناخية ذات الفرق الأول في نماذج التأخير الموزعة ذات التأثيرات الثابتة. نكتشف تأثيرات كبيرة على النمو الاقتصادي في تأخيرات زمنية تصل إلى حوالي 8-10 سنوات بالنسبة لمصطلحات درجة الحرارة وحوالي 4 سنوات لمصطلحات الهطول (الشكل 1 من البيانات الموسعة والجدول 2 من البيانات الموسعة). علاوة على ذلك، تشير التقييمات من خلال معايير المعلومات إلى أن تضمين جميع المتغيرات المناخية الخمسة واستخدام هذه الأعداد من التأخيرات يوفر توازناً مفضلاً بين أفضل ملاءمة للبيانات وتضمين مصطلحات إضافية قد تسبب الإفراط في التخصيص، مقارنة بمواصفات النماذج التي تستبعد المتغيرات المناخية أو تتضمن المزيد أو القليل من التأخيرات (الشكل 3 من البيانات الموسعة، قسم الطرق التكميلية 1 والجدول 1 من البيانات التكميلية). لذلك، نقوم بإزالة المصطلحات غير المهمة إحصائياً في التأخيرات اللاحقة (الأشكال التكميلية 1-3 والجدول 2-4 من البيانات التكميلية). تظهر اختبارات إضافية باستخدام محاكاة مونت كارلو أن النماذج التجريبية قوية أمام الارتباط الذاتي في المتغيرات المناخية المتأخرة (قسم الطرق التكميلية 2 والأشكال التكميلية 4 و5)، وأن معايير المعلومات توفر مؤشراً فعالاً لاختيار التأخير (قسم الطرق التكميلية 2 والشكل التكميلية 6)، وأن النتائج قوية أمام مخاوف التعدد الخطي غير المثالي بين المتغيرات المناخية وأن تضمين عدة متغيرات مناخية ضروري فعلاً لعزل تأثيراتها المنفصلة (قسم الطرق التكميلية 3 والشكل التكميلية 7).

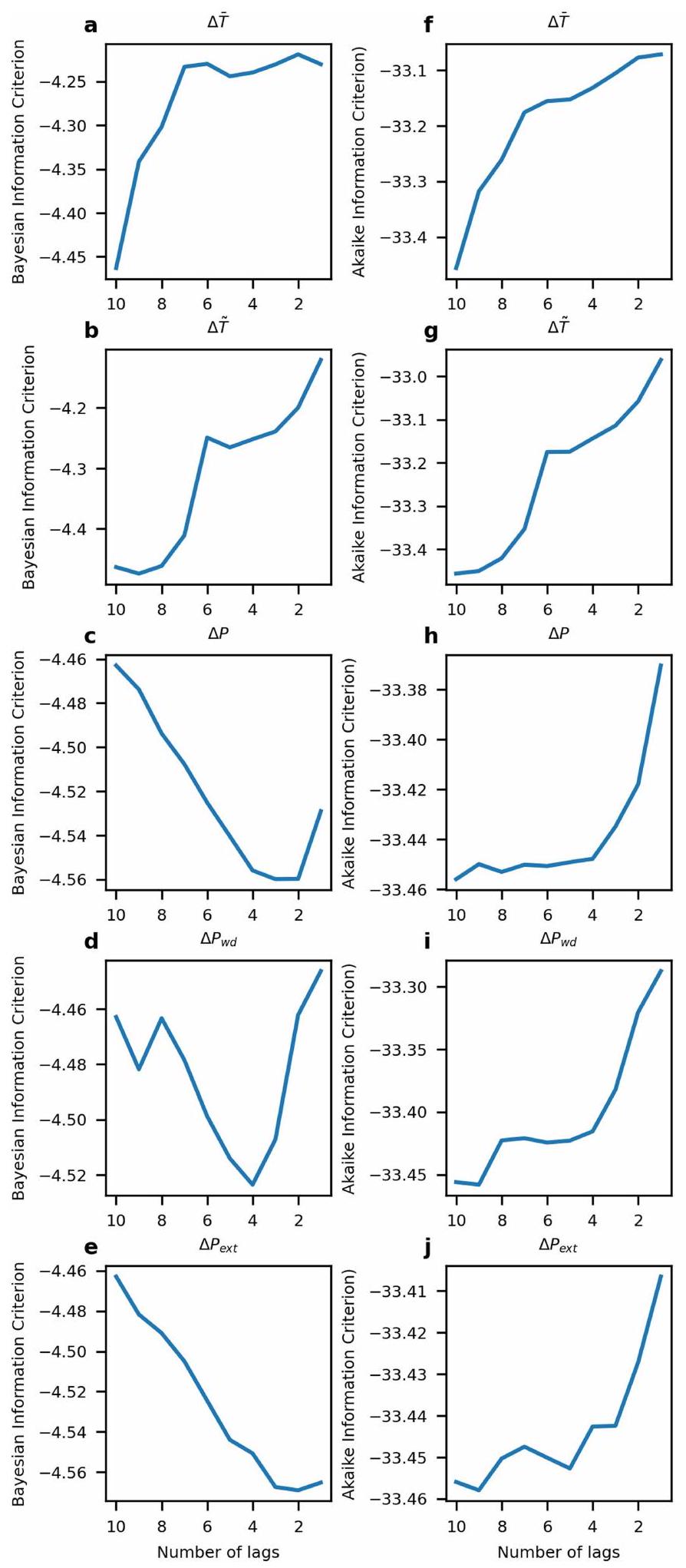

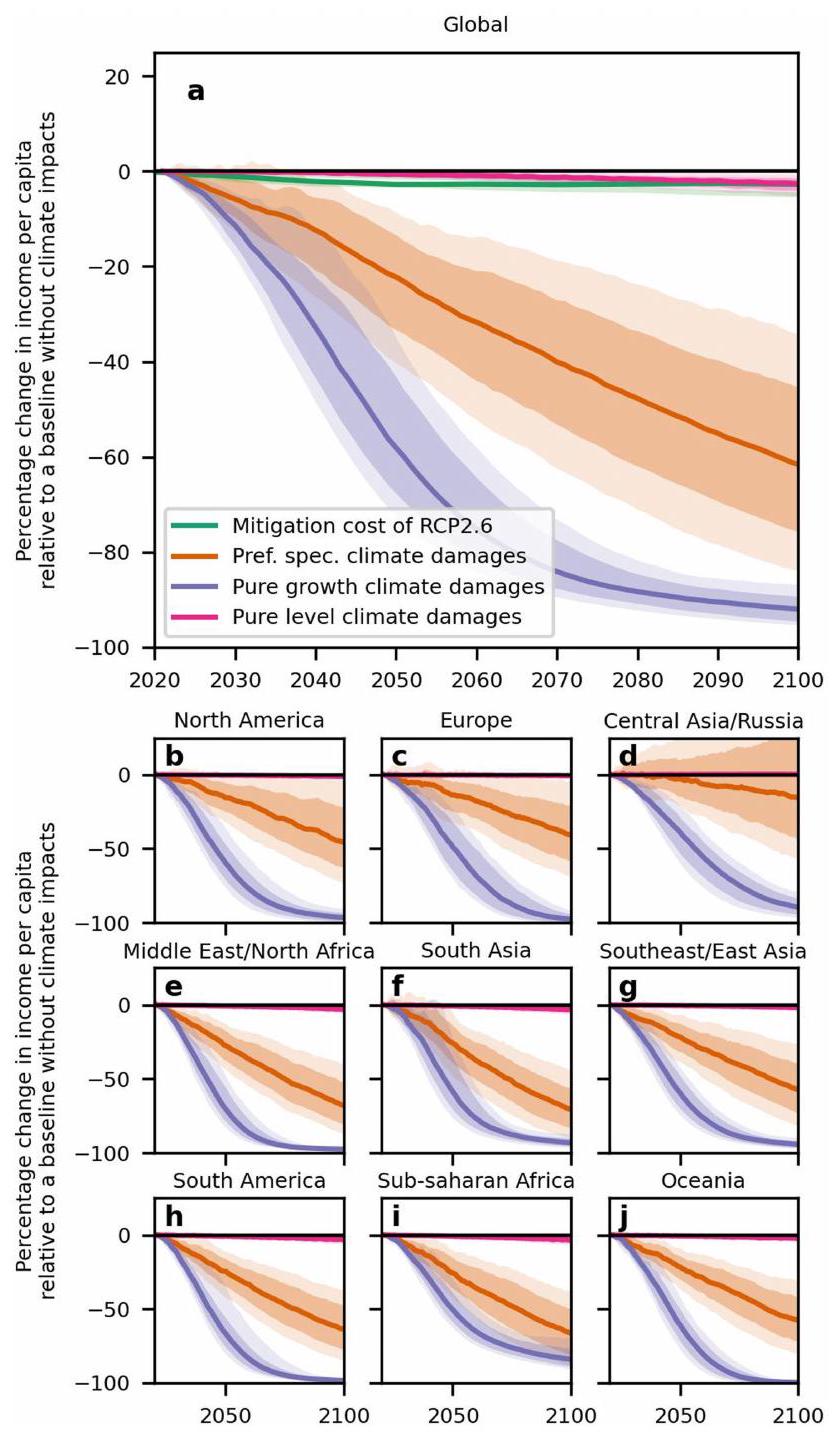

الأضرار الملتزمة حتى منتصف القرن

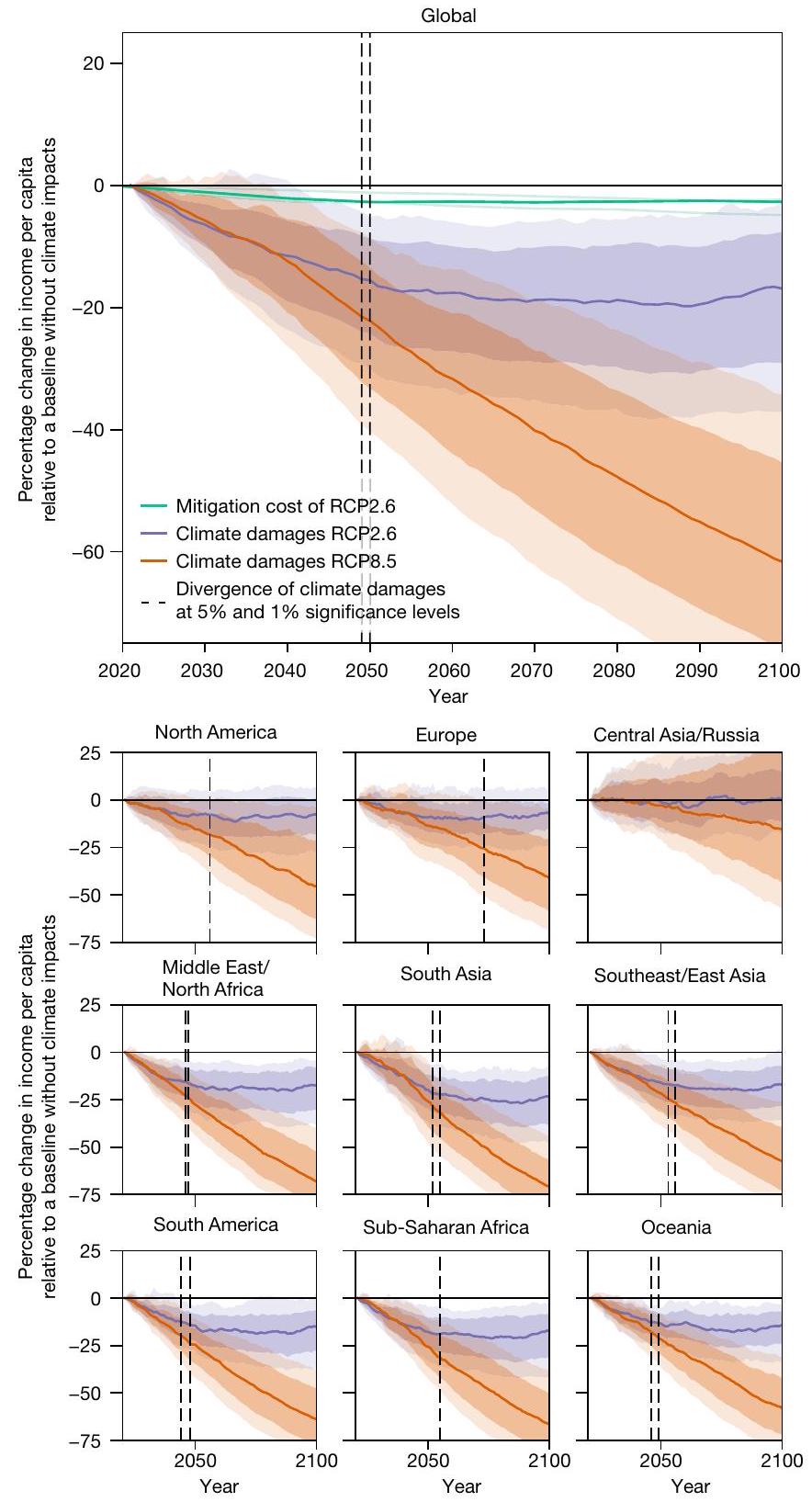

الأضرار تفوق بالفعل تكاليف التخفيف

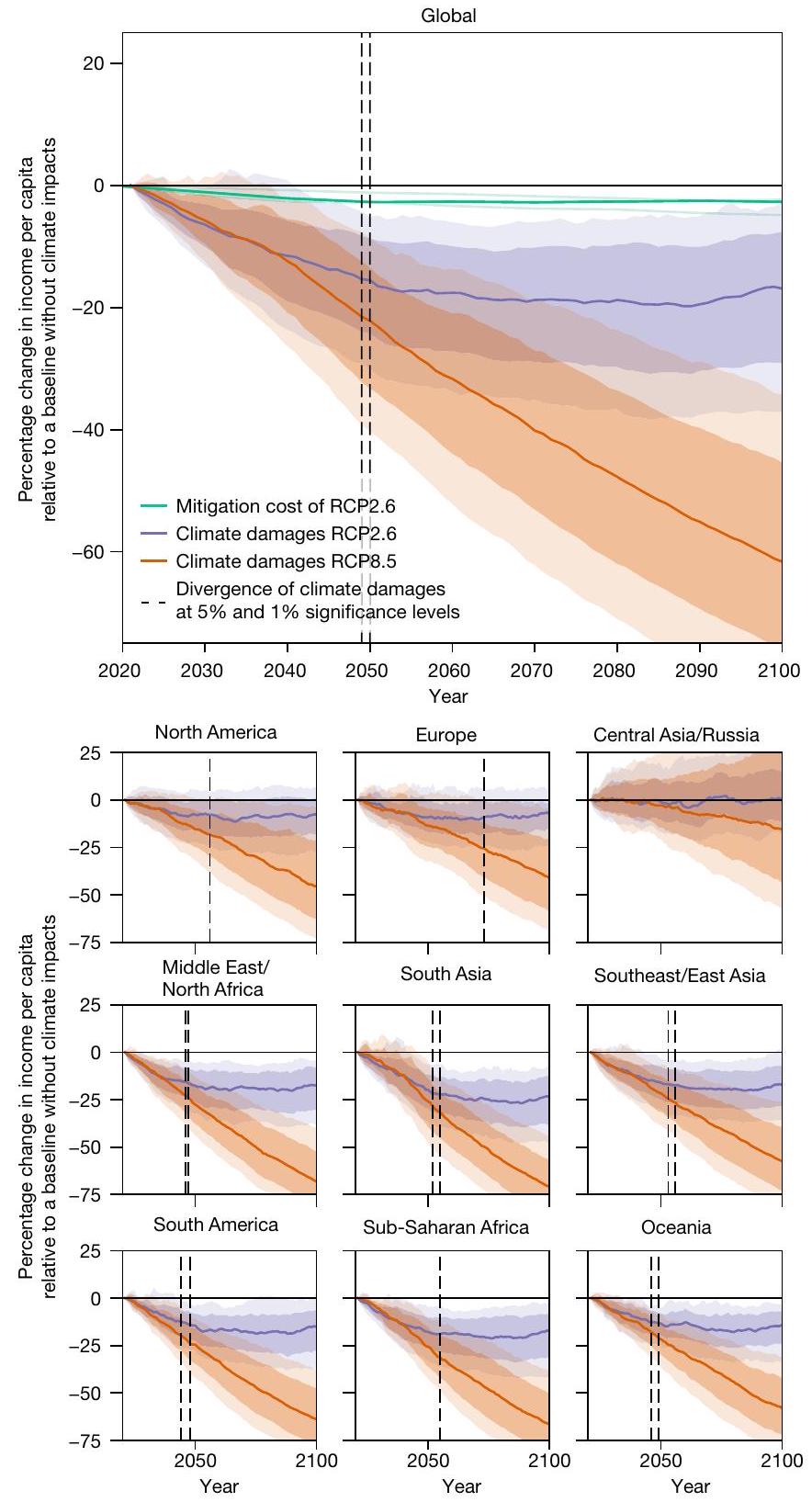

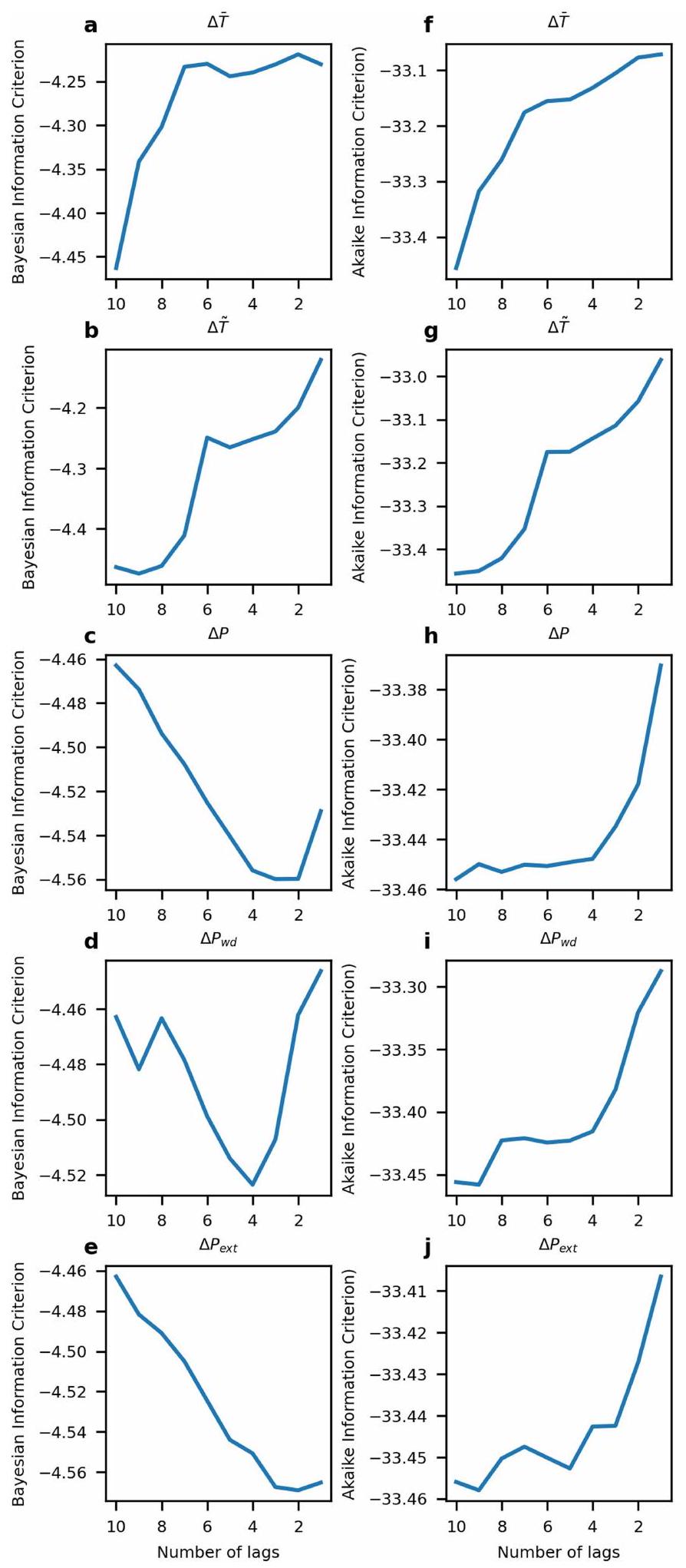

عادةً ما تجد تحليلات التكلفة والفائدة أن الفوائد الصافية للتخفيف تظهر فقط بعد عام 2050 (المرجع 5)، مما قد يقود البعض إلى الاستنتاج بأن الأضرار المادية الناتجة عن تغير المناخ ليست كبيرة بما يكفي لتفوق تكاليف التخفيف حتى النصف الثاني من القرن. توضح مقارنتنا البسيطة لحجمها أن الأضرار أكبر بالفعل بكثير من تكاليف التخفيف وأن ظهور الفوائد الصافية للتخفيف المتأخرة ناتج بشكل أساسي عن حقيقة أن الأضرار عبر مسارات الانبعاثات المختلفة لا يمكن تمييزها حتى منتصف القرن (الشكل 1).

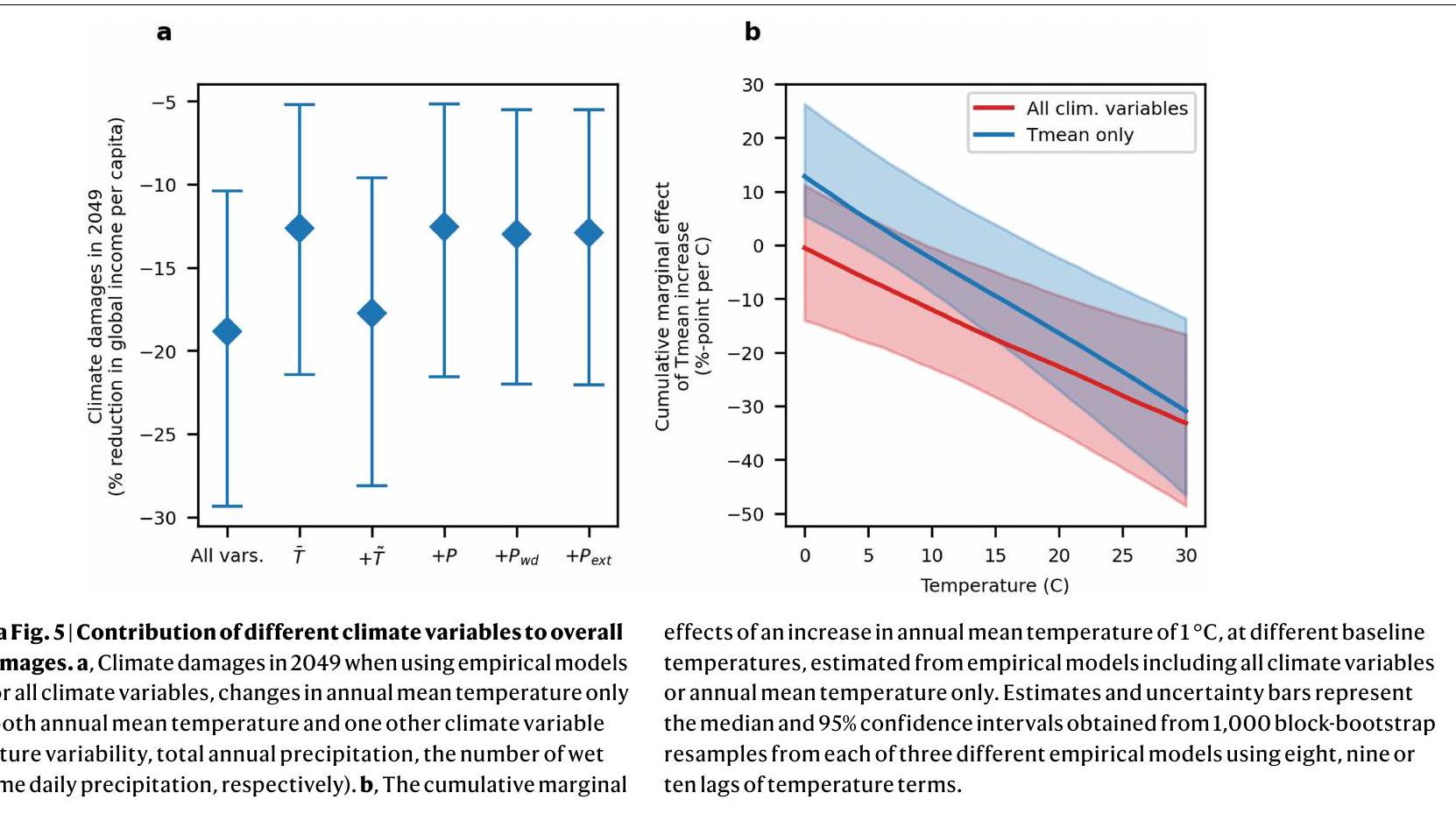

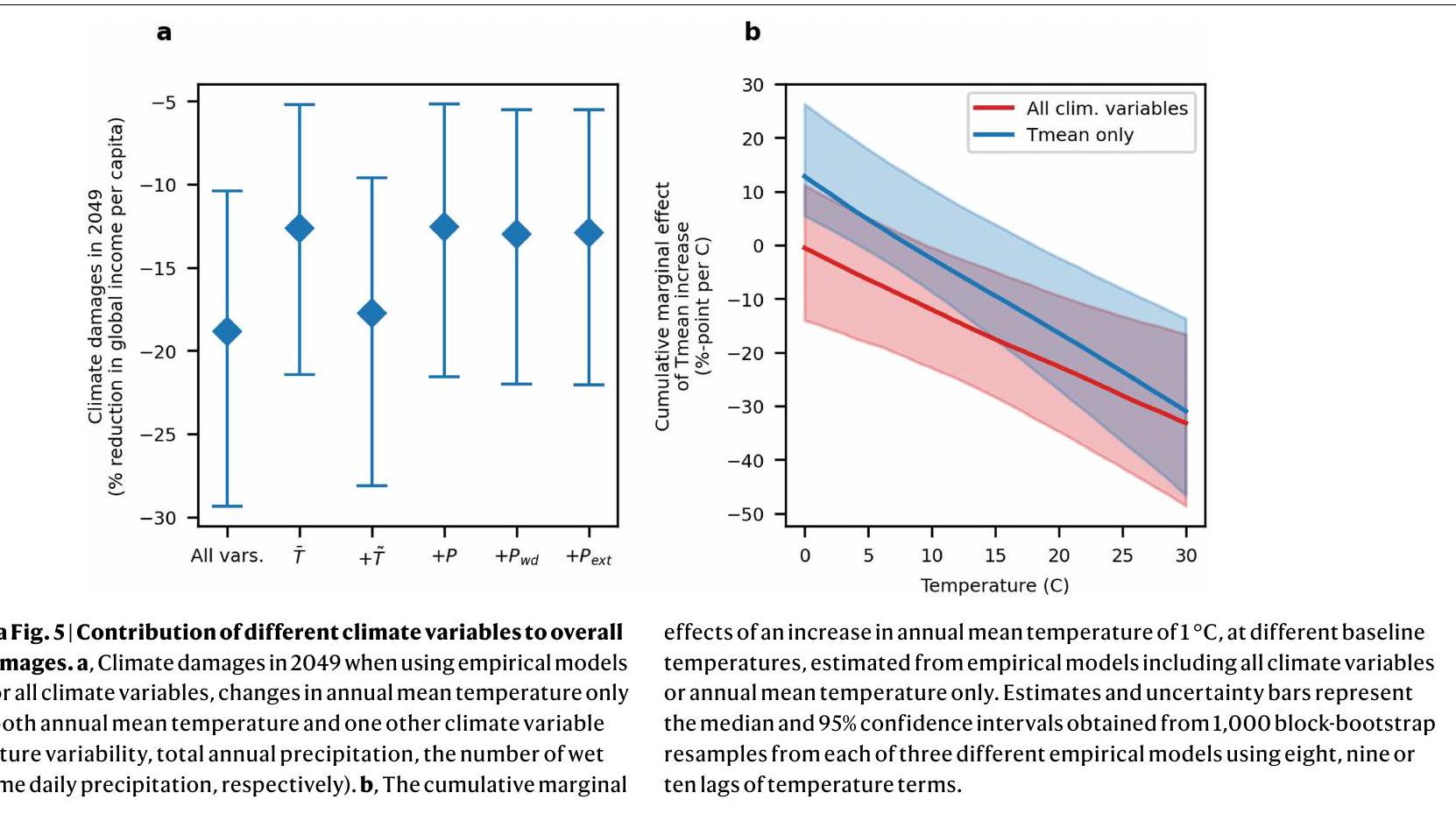

الأضرار الناتجة عن التباين والظواهر المتطرفة

(الشكل 5 من البيانات الموسعة أ، النطاق المحتمل 5-21%). وهذا يشير إلى أن الأخذ في الاعتبار المكونات الأخرى لتوزيع درجة الحرارة وهطول الأمطار يزيد الأضرار الصافية بنحو 50%. ينشأ هذا الارتفاع من الأضرار الإضافية التي تسببها هذه المكونات المناخية، ولكن أيضًا لأن إدراجها يكشف عن استجابة اقتصادية سلبية أقوى لدرجات الحرارة المتوسطة (الشكل 5 من البيانات الموسعة ب). يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع محاكاة مونت كارلو لدينا، التي تشير إلى أن حجم تأثير درجة الحرارة المتوسطة على النمو الاقتصادي يتم التقليل من قيمته ما لم يتم الأخذ في الاعتبار تأثيرات المتغيرات المناخية الأخرى المرتبطة (الشكل التكميلية 7).

0.36 نقطة مئوية (

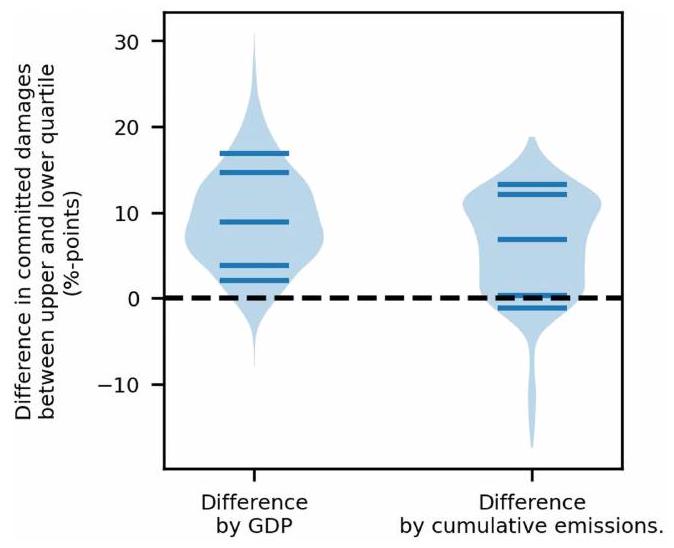

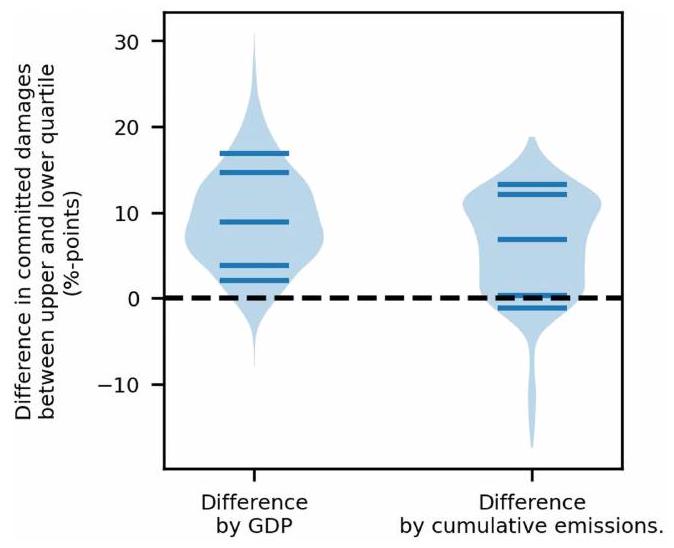

توزيع الأضرار الملتزمة

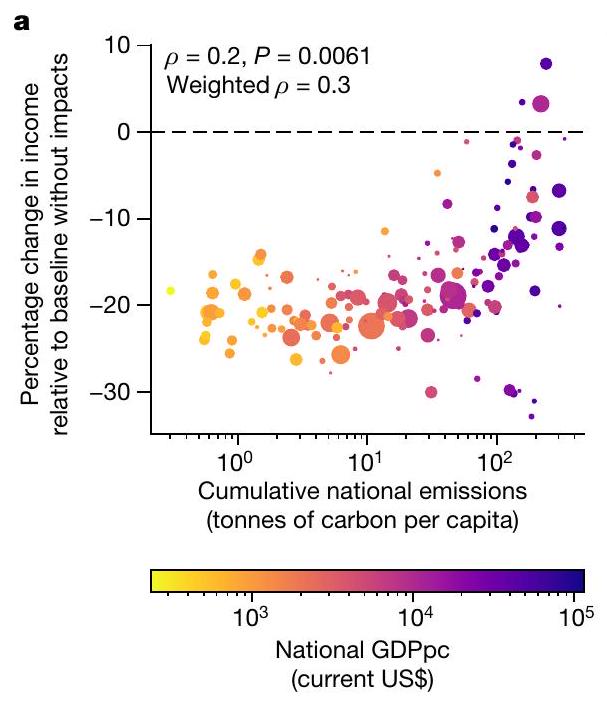

تصنيف الاحتمالية المعتمد من قبل الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ). وبالمثل، فإن الربع من الدول التي لديها انبعاثات تراكمية تاريخية أقل ملتزم بخسارة في الدخل تبلغ 6.9 نقطة مئوية (أو

تحديد حجم الأضرار

آثار مفقودة وتداعيات مكانية

الآثار السياسية

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- Glanemann, N., Willner, S. N. & Levermann, A. اتفاق باريس للمناخ يجتاز اختبار التكلفة والفائدة. Nat. Commun. 11, 110 (2020).

- Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. التأثير غير الخطي العالمي لدرجة الحرارة على الإنتاج الاقتصادي. Nature 527, 235-239 (2015).

- Kalkuhl, M. & Wenz, L. تأثير ظروف المناخ على الإنتاج الاقتصادي. أدلة من لوحة عالمية من المناطق. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 103, 102360 (2020).

- Moore, F. C. & Diaz, D. B. تأثيرات درجة الحرارة على النمو الاقتصادي تتطلب سياسة تخفيف صارمة. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 127-131 (2015).

- Drouet, L., Bosetti, V. & Tavoni, M. الفوائد الاقتصادية الصافية للسيناريوهات التي تقل عن

والشكوك المرتبطة بها. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2, kgac003 (2022). - Ueckerdt, F. et al. الحد الأمثل للاحتباس الحراري من الناحية الاقتصادية للكوكب. Earth Syst. Dyn. 10, 741-763 (2019).

- Kotz, M., Wenz, L., Stechemesser, A., Kalkuhl, M. & Levermann, A. تقلب درجة الحرارة من يوم لآخر يقلل من النمو الاقتصادي. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 319-325 (2021).

- Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. تأثير تغييرات الأمطار على الإنتاج الاقتصادي. Nature 601, 223-227 (2022).

- Kousky, C. إبلاغ التكيف المناخي: مراجعة للتكاليف الاقتصادية للكوارث الطبيعية. Energy Econ. 46, 576-592 (2014).

- Harlan, S. L. et al. في تغير المناخ والمجتمع: وجهات نظر سوسيولوجية (محرران Dunlap, R. E. & Brulle, R. J.) 127-163 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

- Bolton, P. et al. البجعة الخضراء (كتب BIS، 2020).

- Alogoskoufis, S. et al. اختبار الإجهاد المناخي على مستوى الاقتصاد: المنهجية والنتائج البنك المركزي الأوروبي، 2021).

- Weber, E. U. ما الذي يشكل تصورات تغير المناخ؟ Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1, 332-342 (2010).

- Markowitz, E. M. & Shariff, A. F. تغير المناخ والحكم الأخلاقي. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 243-247 (2012).

- Riahi, K. et al. المسارات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المشتركة وآثارها على الطاقة، واستخدام الأراضي، وانبعاثات غازات الدفيئة: نظرة عامة. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153-168 (2017).

- Auffhammer, M., Hsiang, S. M., Schlenker, W. & Sobel, A. استخدام بيانات الطقس ومخرجات نماذج المناخ في التحليلات الاقتصادية لتغير المناخ. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 7, 181-198 (2013).

- Kolstad, C. D. & Moore, F. C. تقدير التأثيرات الاقتصادية لتغير المناخ باستخدام ملاحظات الطقس. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 14, 1-24 (2020).

- Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. صدمات درجة الحرارة والنمو الاقتصادي: أدلة من النصف الأخير من القرن. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 4, 66-95 (2012).

- Newell, R. G., Prest, B. C. & Sexton, S. E. العلاقة بين الناتج المحلي الإجمالي ودرجة الحرارة: الآثار المترتبة على أضرار تغير المناخ. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 108, 102445 (2021).

- Kikstra, J. S. et al. التكلفة الاجتماعية لثاني أكسيد الكربون تحت تأثيرات المناخ والاقتصاد وتقلبات درجة الحرارة. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 094037 (2021).

- Bastien-Olvera, B. & Moore, F. التأثير المستمر لدرجة الحرارة على الناتج المحلي الإجمالي المحدد من تقلبات درجة الحرارة ذات التردد المنخفض. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 084038 (2022).

- Eyring, V. et al. نظرة عامة على تصميم وتنظيم مشروع المقارنة بين النماذج المتصلة المرحلة 6 (CMIP6). Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937-1958 (2016).

- Byers, E. et al. قاعدة بيانات سيناريوهات AR6. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/7197970 (2022).

- Burke, M., Davis, W. M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. تقليل كبير محتمل في الأضرار الاقتصادية بموجب أهداف التخفيف التابعة للأمم المتحدة. Nature 557, 549-553 (2018).

- Kotz, M., Wenz, L. & Levermann, A. بصمة التأثيرات الناتجة عن الاحتباس الحراري في تقلبات درجة الحرارة اليومية. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2103294118 (2021).

- Myhre, G. et al. تزداد وتيرة الأمطار الغزيرة بشكل كبير مع ندرة الأحداث تحت الاحتباس الحراري العالمي. Sci. Rep. 9, 16063 (2019).

- Min, S.-K., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. W. & Hegerl, G. C. المساهمة البشرية في زيادة شدة الأمطار الغزيرة. Nature 470, 378-381 (2011).

- إنجلترا، م. ر.، آيزنمان، إ.، لوتسكو، ن. ج. وواجنر، ت. ج. الظهور الحديث لتضخيم القطب الشمالي. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 48، e2021GL094086 (2021).

- فيشر، إ. م. وكنوتي، ر. المساهمة البشرية في حدوث الأمطار الغزيرة وارتفاع درجات الحرارة على مستوى العالم. نات. مناخ. تغيير 5، 560-564 (2015).

- Pfahl، س.، O’Gorman، ب. أ. و Fischer، إ. م. فهم النمط الإقليمي للتغيرات المستقبلية المتوقعة في الأمطار الغزيرة. Nat. Clim. Change 7، 423-427 (2017).

- كالاهان، سي. دبليو. ومانكين، جي. إس. التأثير غير المتساوي عالميًا للحرارة الشديدة على النمو الاقتصادي. ساينس أدفانس. 8، eadd3726 (2022).

- ديفنباخ، ن. س. وبورك، م. الاحتباس الحراري قد زاد من عدم المساواة الاقتصادية العالمية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم 116، 9808-9813 (2019).

- كالاهان، سي. دبليو. ومانكين، جي. إس. النسبة الوطنية للأضرار المناخية التاريخية. تغير المناخ 172، 40 (2022).

- بورك، م. وتاناتاما، ف. القيود المناخية على الناتج الاقتصادي الإجمالي. المكتب الوطني للبحوث الاقتصادية، ورقة عمل 25779.https://doi.org/10.3386/w25779 (2019).

- خان، م. إ. وآخرون. الآثار الاقتصادية الكلية طويلة الأجل لتغير المناخ: تحليل عبر البلدان. اقتصاد الطاقة. 104، 105624 (2021).

- ديسميت، ك. وآخرون. تقييم التكلفة الاقتصادية للفيضانات الساحلية. المكتب الوطني للبحوث الاقتصادية، ورقة عمل 24918.https://doi.org/10.3386/w24918 (2018).

- شيانغ، س. م. وجينا، أ. س. التأثير السببي لكارثة بيئية على النمو الاقتصادي على المدى الطويل: أدلة من 6700 إعصار. المكتب الوطني للبحوث الاقتصادية، ورقة عمل 20352.https://doi.org/10.3386/w2035 (2014).

- ريتش، ب. د. وآخرون. التحولات في استخدام الأراضي الوطنية وإنتاج الغذاء في بريطانيا العظمى بعد نقطة تحول مناخية. نات. فود 1، 76-83 (2020).

- ديتس، س.، رايزينغ، ج.، ستورك، ت. وواجنر، ج. التأثيرات الاقتصادية لنقاط التحول في نظام المناخ. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم 118، e2103081118 (2021).

- باستيان-أولفيرا، ب. أ. ومور، ف. س. قيمة الاستخدام وعدم الاستخدام للطبيعة والتكلفة الاجتماعية للكربون. الطبيعة. الاستدامة. 4، 101-108 (2021).

- كارلتون، ت. وآخرون. تقييم العواقب العالمية للوفيات الناتجة عن تغير المناخ مع الأخذ في الاعتبار تكاليف وفوائد التكيف. ربع سنوي. ج. اقتصاد. 137، 2037-2105 (2022).

- باستيان-أولفيرا، ب. أ. وآخرون. تأثيرات المناخ غير المتكافئة على القيم العالمية لرأس المال الطبيعي. ناتشر 625، 722-727 (2024).

- مالك، أ. وآخرون. تأثيرات تغير المناخ والطقس القاسي على سلاسل إمداد الغذاء تتساقط عبر القطاعات والمناطق في أستراليا. نات. فود 3، 631-643 (2022).

- كوهلا، ك.، ويلنر، س. ن.، أوتو، ج.، جيجر، ت. ولفرمان، أ. تأثير رنين التموج يعزز فقدان الرفاهية الاقتصادية الناتج عن الظروف الجوية المتطرفة. رسائل البحث البيئي 16، 114010 (2021).

- شلايبن، ج. ر.، ميستري، م. ن.، سعيد، ف. وداسغوبتا، س. مشاركة العبء: قياس تأثيرات تغير المناخ في الاتحاد الأوروبي بموجب اتفاق باريس. تحليل الاقتصاد المكاني 17، 67-82 (2022).

- داسغوبتا، س.، بوسيلو، ف.، دي سيان، إ. ومستري، م. تأثيرات درجة الحرارة العالمية على النشاط الاقتصادي والعدالة: تحليل مكاني. المعهد الأوروبي للاقتصاد والبيئة، ورقة عمل 22-1 (2022).

- نيل، ت. أهمية تأثيرات الطقس الخارجي في توقع الآثار الاقتصادية الكلية لتغير المناخ. ورقة عمل اقتصادية من جامعة UNSW 2023-09 (2023).

- ديريوغينا، ت. وشيانغ، س. م. هل لا يزال للبيئة أهمية؟ درجة الحرارة اليومية والدخل في الولايات المتحدة. المكتب الوطني للبحوث الاقتصادية، ورقة عمل 20750.https://doi.org/10.3386/w20750 (2014).

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

بيانات المناخ التاريخية

بيانات المناخ المستقبلية

البيانات الاقتصادية التاريخية

البيانات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المستقبلية

التوزيع الواقعي على المستوى دون الوطني غير متوفر بسهولة لسيناريوهات التنمية المشتركة (SSPs). لذلك، نستخدم توقعات الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد (GDPpc) على المستوى الوطني لجميع المناطق دون الوطنية في بلد معين، مع افتراض التجانس داخل البلدان من حيث الناتج المحلي الإجمالي للفرد الأساسي. هنا نستخدم التوقعات التي تم تحديثها لأخذ تأثير جائحة COVID-19 في الاعتبار على مسار الدخل المستقبلي، مع الحفاظ على التوافق مع التنمية طويلة الأجل لسيناريوهات التنمية المشتركة.

متغيرات المناخ

قمنا أيضًا بحساب الانحرافات المعيارية الموزونة لمجموع الأمطار الشهرية كما تم استخدامه في المرجع 8، لكننا لا ندرجها في توقعاتنا لأننا نجد أنه عند أخذ التأثيرات المتأخرة في الاعتبار، يصبح تأثيرها غير واضح إحصائيًا ومن الأفضل التقاطه من خلال التغيرات في مجموع الأمطار السنوية.

التجميع المكاني

تحديد النموذج التجريبي: نماذج التأخير الموزع ذات التأثيرات الثابتة

نموذج التأخير المكاني

بناء توقعات الأضرار الاقتصادية الناتجة عن تغير المناخ في المستقبل

كلا من التغير المناخي الفيزيائي وعدم اليقين الهيكلي والعيني للنماذج التجريبية.

تقديرات تكاليف التخفيف

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

49. هيرسباخ، هـ. وآخرون. إعادة التحليل العالمية ERA5. مجلة الجمعية الملكية للأرصاد الجوية 146، 1999-2049 (2020).

50. كوتشي، م. وآخرون. WFDE5: بيانات إعادة تحليل ERA5 المعدلة لتناسب التحيز لدراسات التأثير. بيانات علوم الأرض 12، 2097-2120 (2020).

51. أدلر، ر. وآخرون. النسخة الجديدة 2.3 من مشروع المناخ العالمي لهطول الأمطار (GPCP) منتج التحليل الشهري 1072-1084 (جامعة ماريلاند، 2016).

52. لانج، س. تعديل الانحياز الذي يحافظ على الاتجاه والتقليل الإحصائي باستخدام ISIMIP3BASD (الإصدار 1.0). تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 12، 3055-3070 (2019).

53. وينز، ل.، كار، ر. د.، كوجل، ن.، كوتز، م. وكالكول، م. DOSE – مجموعة بيانات عالمية للإنتاج الاقتصادي المبلغ عنه على المستوى دون الوطني. بيانات علمية 10، 425 (2023).

54. جينايولي، ن.، لا بورتا، ر.، لوبيز دي سيلانيس، ف. وشلايفر، أ. النمو في المناطق. مجلة نمو الاقتصاد 19، 259-309 (2014).

55. مجلس محافظي النظام الاحتياطي الفيدرالي (الولايات المتحدة). سعر صرف الدولار الأمريكي مقابل اليورو.https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/AEXUSEU (2022).

56. البنك الدولي. مُعَدِّل الناتج المحلي الإجمالي.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.ZS (2022).

57. جونز، ب. وأونيل، ب. سي. سيناريوهات سكانية عالمية محددة مكانيًا تتماشى مع المسارات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية المشتركة. رسائل البحث البيئي 11، 084003 (2016).

58. موراكامي، د. وياماغاتا، ي. تقدير سيناريوهات السكان والناتج المحلي الإجمالي الموزعة على الشبكة باستخدام تقنيات التحجيم الإحصائي المكاني. الاستدامة 11، 2106 (2019).

59. كوتش، ج. وليمباخ، م. تحديث توقعات الناتج المحلي الإجمالي لبرنامج SSP: التقاط التغيرات الأخيرة في المحاسبة الوطنية، تحويل القوة الشرائية وتأثيرات كوفيد 19. الاقتصاد البيئي 206 (2023).

60. كارلتون، ت. أ. و هسيانغ، س. م. الآثار الاجتماعية والاقتصادية للمناخ. العلوم 353، aad9837 (2016).

61. بيرجي، ل. تقدير فعال لنماذج الاحتمالية القصوى مع تأثيرات ثابتة متعددة: حزمة R FENmlm. سلسلة أوراق مناقشة DEM 18-13 (2018).

62. كالكوهل، م.، كوتز، م. و وينز، ل. DOSE – قاعدة بيانات الناتج الاقتصادي دون الوطني من MCC-PIK. زينودوhttps://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo. 4681305 (2021).

63. كوتز، م.، وينز، ل. وليفرمان، أ. البيانات والرمز لـ “الالتزام الاقتصادي لتغير المناخ”. زينودوhttps://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo. 10562951 (2024).

64. داسغوبتا، س. وآخرون. آثار تغير المناخ على إنتاجية العمل المجمعة والإمداد: دراسة تجريبية متعددة النماذج. لانسيت كوكب. الصحة 5، e455-e465 (2021).

65. لوبيلي، د. ب. وآخرون. الدور الحاسم للحرارة الشديدة في إنتاج الذرة في الولايات المتحدة. نات. مناخ. تغيير 3، 497-501 (2013).

66. زهاو، سي. وآخرون. زيادة درجة الحرارة تقلل من الغلات العالمية للمحاصيل الرئيسية في أربع تقديرات مستقلة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم 114، 9326-9331 (2017).

67. ويلر، ت. ر.، كراوفورد، ب. كيو.، إليس، ر. هـ.، بورتير، ج. ر. & براساد، ب. ف. تقلب درجة الحرارة وعائد المحاصيل السنوية. البيئة الزراعية والنظم البيئية 82، 159-167 (2000).

68. روحاني، ب.، لوبي، د. ب.، ليندرمان، م. ورامانكوتي، ن. تقلب المناخ وإنتاج المحاصيل في تنزانيا. الزراعة والغابات والأرصاد الجوية 151، 449-460 (2011).

69. سيجلار، أ.، توتي، أ.، ليسيرف، ر.، فان دير فيلدي، م. ودينتينر، ف. تأثير العوامل الجوية على تباين محصول المحاصيل الإقليمي بين السنوات في فرنسا. الأرصاد الجوية الزراعية والغابات 216، 58-67 (2016).

70. شي، ل.، كلوج، إ.، زانوبتي، أ.، ليو، ب. وشوارتز، ج. د. تأثيرات درجة الحرارة وتقلبها على الوفيات في نيو إنجلاند. نات. مناخ. تغيير 5، 988-991 (2015).

71. شيو، تي، زو، تي، تشنغ، واي وزانغ، كيو. تراجع في الصحة النفسية مرتبط بتلوث الهواء وتقلبات درجة الحرارة في الصين. نات. كوميونيك. 10، 2165 (2019).

72. ليانغ، إكس.-زد. وآخرون. تحديد تأثيرات المناخ على إجمالي الإنتاجية الزراعية في الولايات المتحدة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم 114، E2285-E2292 (2017).

73. ديسبورو، س. وروديلا، أ.-س. الجفاف في المدينة: الأثر الاقتصادي لنقص المياه في المناطق الحضرية في أمريكا اللاتينية. التنمية العالمية. 114، 13-27 (2019).

74. دامانيا، ر. اقتصاد ندرة المياه وتغيرها. مراجعة أكسفورد للسياسة الاقتصادية 36، 24-44 (2020).

75. دافنبورت، ف. ف.، بيرك، م. وديفنباخ، ن. س. مساهمة تغير هطول الأمطار التاريخي في أضرار الفيضانات في الولايات المتحدة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم 118، e2017524118 (2021).

76. ديف، ر.، سوبرا مانيان، س. س. وبهاتيا، أ. الأحداث المتزامنة الناتجة عن هطول الأمطار الشديدة تؤدي إلى اضطرابات طويلة الأمد في شبكات الطرق الإقليمية. رسائل البحث البيئي 16، 104050 (2021).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى ليوني وينز.

تُعرب مجلة Nature عن شكرها لـ Xin-Zhong Liang و Chad Thackeray والمراجعين الآخرين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل. تقارير مراجعي الأقران متاحة.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

مقالة

مقالة

تقديرات الأضرار المستقبلية كما هو موضح في الشكل 1 ولكن تحت سيناريو الانبعاثات RCP8.5 لثلاثة مواصفات تجريبية منفصلة: باللون البرتقالي، مواصفتنا المفضلة، التي توفر حدًا أدنى تجريبيًا لاستمرارية تأثيرات المناخ على معدلات النمو الاقتصادي مع تجنب افتراضات الاستمرارية اللانهائية (انظر النص الرئيسي لمزيد من المناقشة)؛ باللون الأرجواني، مواصفة ‘تأثيرات النمو الخالص’ التي لا يتم فيها أخذ الفرق الأول من متغيرات المناخ ولا يتم تضمين متغيرات مناخية متأخرة (المواصفة الأساسية في المرجع 2)؛ وباللون الوردي، مواصفة ‘تأثيرات المستوى الخالص’ التي يتم فيها أخذ الفرق الأول من متغيرات المناخ ولكن لا يتم تضمين أي مصطلحات متأخرة.

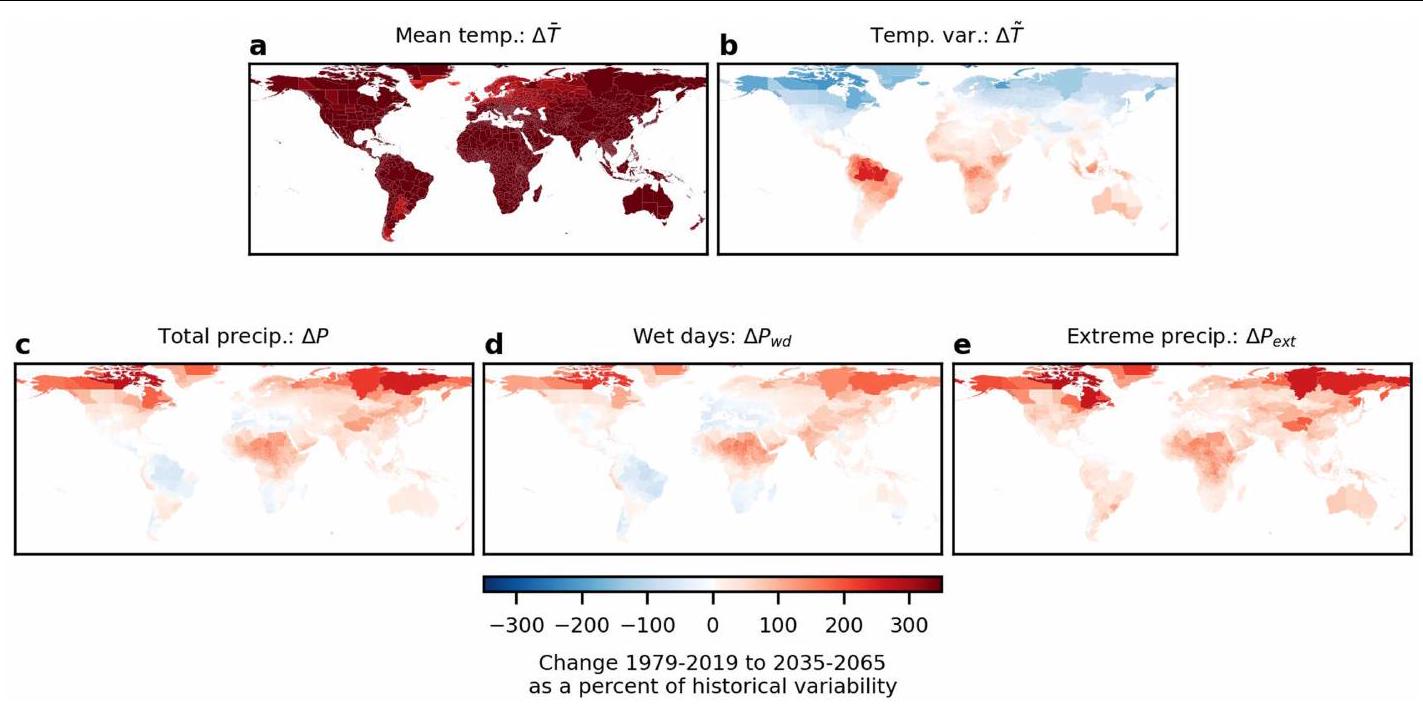

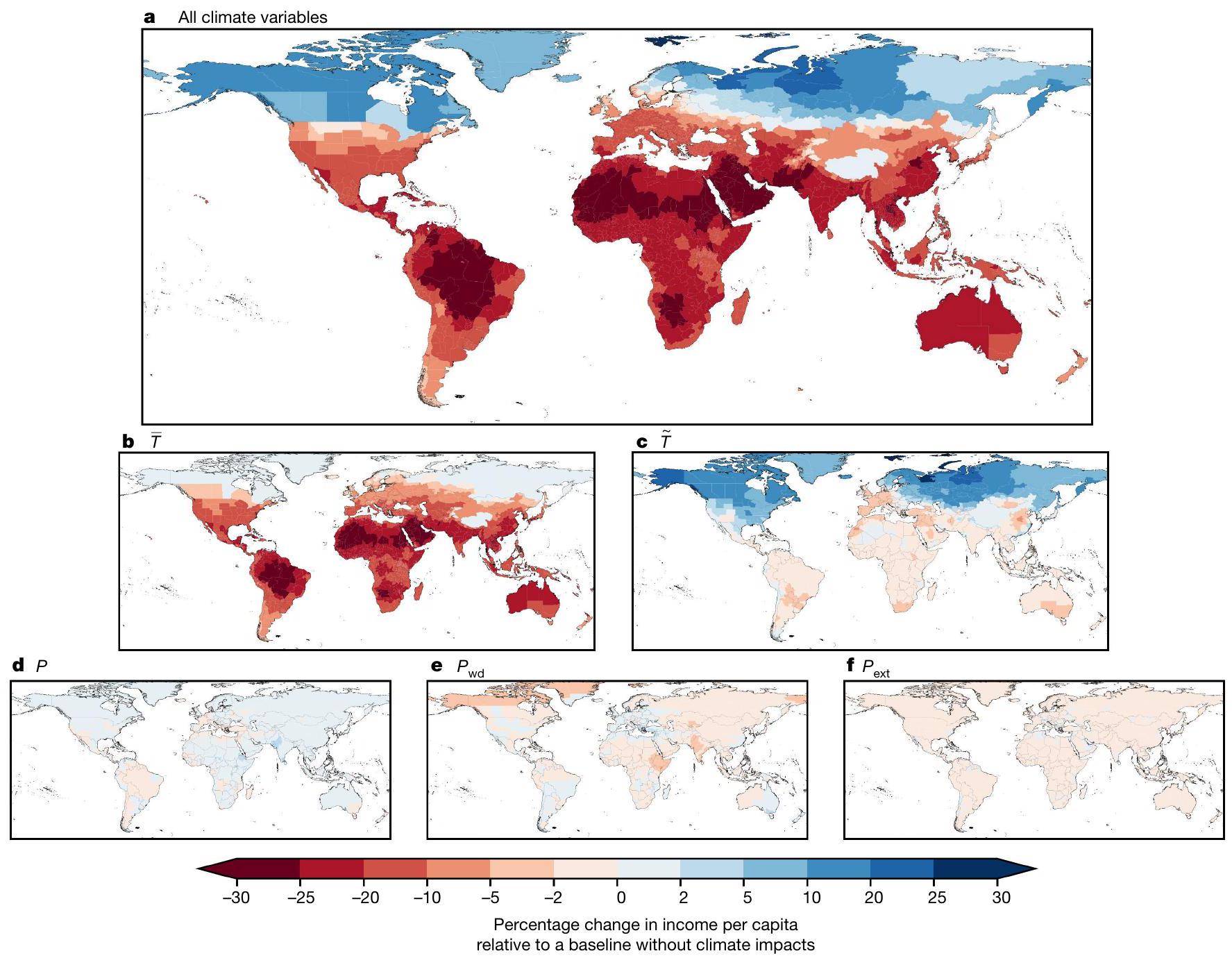

تم تحديد (إن إزالة الاتجاهات مناسبة بسبب تضمين الاتجاهات الزمنية الخطية الخاصة بالمنطقة في النماذج التجريبية). انظر الشكل التكميلي 13 للتغييرات المعبر عنها بوحدات قياسية. تم الحصول على بيانات الحدود الإدارية الوطنية من قاعدة بيانات GADM الإصدار 3.6 وهي متاحة مجانًا للاستخدام الأكاديمي.https://gadm.org/).

مقالة

مقالة

| متغير المناخ | آليات فيزيائية | المراجع |

| متوسط درجة الحرارة السنوية | إنتاجية العمل والإمداد؛ إنتاجية الزراعة | داسغوبتا وآخرون (2021)

|

| تغير درجة الحرارة اليومية | الإنتاجية الزراعية؛ الصحة البدنية؛ الصحة النفسية | ويلر وآخرون

|

| إجمالي هطول الأمطار السنوي | إنتاجية الزراعة؛ نتائج العمل في المناطق الحضرية؛ الصراع | ليانغ وآخرون (2017)

|

| عدد الأيام الممطرة | اضطراب في السفر | يفتقر |

| هطول الأمطار الشديد اليومي | أضرار الفيضانات؛ اضطراب | دافنبورت وآخرون (2021)

|

| متغير | صيغة | تأخير 0 | تأخير 1 | لاج 2 | لاج 3 | لاج 4 | تأخر 5 | تأخر 6 | لاج 7 | لاج 8 | لاج 9 | تأخر 10 |

| متوسط درجة الحرارة السنوي |

|

-0.17 | -0.57 | -0.78 | -0.23 | -0.79 | -0.96 | -0.23 | -0.71 | -1.8** | -1.1* | -2.5*** |

| (0.32) | (0.5) | (0.54) | (0.57) | (0.57) | (0.65) | (0.67) | (0.73) | (0.63) | (0.48) | (0.35) | ||

|

|

-0.0011*** (0.00029) | -0.0014** (0.00049) | -0.00072 (0.00051) | -0.0015** (0.00055) | -0.00072 (0.00047) | -0.0015** (0.0005) | -0.0017*** (0.00046) | -0.0012** (0.00047) | -0.00029 (0.0004) | 0.00065* (0.00032) | 0.00029 (0.00023) | |

| تغير درجة الحرارة اليومية |

|

-9.3*** | -8.1*** | -13*** | -9.3*** | -1.5 | -1.2 | -2.4 | -1.8 | 3.3 | -5.3** | -0.34 |

| (1.3) | (2) | (2.3) | (2.7) | (3.1) | (3.2) | (3) | (2.9) | (2.5) | (1.9) | (1.3) | ||

|

|

0.0013* (0.00054) | -0.0003 (0.00083) | 0.0013 (0.00087) | -0.00011 (0.0011) | -0.0034** (0.0012) | -0.0032* (0.0013) | -0.0025* (0.0012) | -0.0029* (0.0012) | -0.003** (0.0011) | 0.00079 (0.00078) | -0.00037 (0.00057) | |

| إجمالي هطول الأمطار السنوي |

|

0.002 (0.0016) | 0.0094*** (0.002) | 0.009*** (0.0023) | 0.0068** (0.0024) | 0.0021 (0.0024) | -0.0012 (0.0025) | 0.0013 (0.0025) | -0.001 (0.0023) | -0.0001 (0.0021) | 0.0012 (0.0019) | 0.0005 (0.0015) |

|

|

|

-2.6e-08** (8.5e-09) |

|

-2.6e-08** (9.8e-09) |

|

|

|

|

-1.2e-09 (8.6e-09) | -1.3e-08 (7.8e-09) | -9.4e-09 (6.1e-09) | |

| عدد الأيام الممطرة السنوي |

|

-0.028 (0.038) | -0.12** (0.043) | -0.17** (0.055) | -0.2*** (0.055) | -0.038 (0.052) | 0.12 (0.065) | 0.037 (0.068) | 0.079 (0.058) | 0.1 * (0.048) | 0.045 (0.04) | -0.03 (0.032) |

|

|

|

|

|

9.2e-06* (3.6e-06) |

|

-1e-05* (4.1e-06) | -5.5e-06 (4.1e-06) | -7.1e-06 (3.6e-06) | -9e-06** (3e-06) | -5.6e-06 * (2.5e-06) | 2.2e-06 (1.9e-06) | |

| أقصى هطول للأمطار |

|

-0.023*** (0.0053) | -0.028*** (0.0073) | -0.029*** (0.0084) | -0.029** (0.0094) | -0.01 (0.0098) | -0.0032 (0.01) | -0.013 (0.011) | -0.017 (0.01) | -0.019* (0.0093) | -0.013 (0.0079) | 0.0054 (0.0052) |

|

|

8.8e-06*** (2.5e-06) | 9.6e-06** (3.4e-06) | 9.6e-06* (

|

1.4e-05** (4.6e-06) |

|

|

8e-06 (4.9e-06) | 8.8e-06 (4.8e-06) |

|

8.1e-06* (

|

-1.2e-06 (2.7e-06) | |

|

|

0.291 | |||||||||||

|

|

0.0472 | |||||||||||

| بيك | -٤.٤٦e+٠٣ | |||||||||||

| إيه آي سي |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

34855 | |||||||||||

مع عشرة تأخيرات لكل متغير مناخي (أي أن كل إدخال في الجدول يدل على معامل انحدار محدد)

مع عشرة تأخيرات لكل متغير مناخي (أي أن كل إدخال في الجدول يدل على معامل انحدار محدد)

داخل المنطقة

داخل المنطقة

مقالة

| دراسة | قرار | عدد المتغيرات المناخية | المواصفات الأساسية لتأثيرات النمو أو المستوى | عدد التأخيرات | الأضرار بحلول عام 2100 تحت سيناريو RCP8.5 |

| بورك وآخرون (2015)

|

وطني | واحد | النمو | لا شيء | 25% |

| خان وآخرون (2019)

|

وطني | واحد | مستوى | أربعة | 7.2% |

| كالكول و وينز (2020)

|

دون الوطني | واحد | مستوى | واحد | 14.2% |

| هذه الدراسة | دون الوطني | خمسة | مستوى | ثمانية-عشرة/أربعة | 61.6% |

- تستخدم جميع الدراسات انحدارات بانل ذات تأثيرات ثابتة. تصف الأعمدة الأربعة الأولى الفروقات في البيانات الأساسية والمواصفات التجريبية. يوضح العمود الثالث طبيعة المواصفة الأساسية بدون تأخيرات فيما يتعلق بتأثيرات النمو أو المستوى (انظر النص الرئيسي لمزيد من المناقشة). يقارن العمود الأخير توقعات الأضرار الاقتصادية المستقبلية تحت RCP8.5 بحلول عام 2100 كما ورد في الدراسة المعنية.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38632481

Publication Date: 2024-04-17

The economic commitment of climate change

Received: 25 January 2023

Accepted: 21 February 2024

Published online: 17 April 2024

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Maximilian Kotz

Global projections of macroeconomic climate-change damages typically consider impacts from average annual and national temperatures over long time horizons

Constraining the persistence of impacts

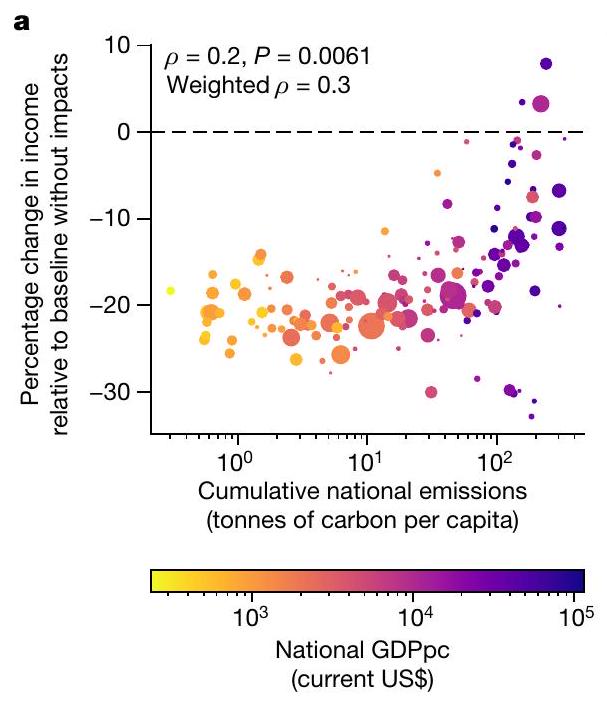

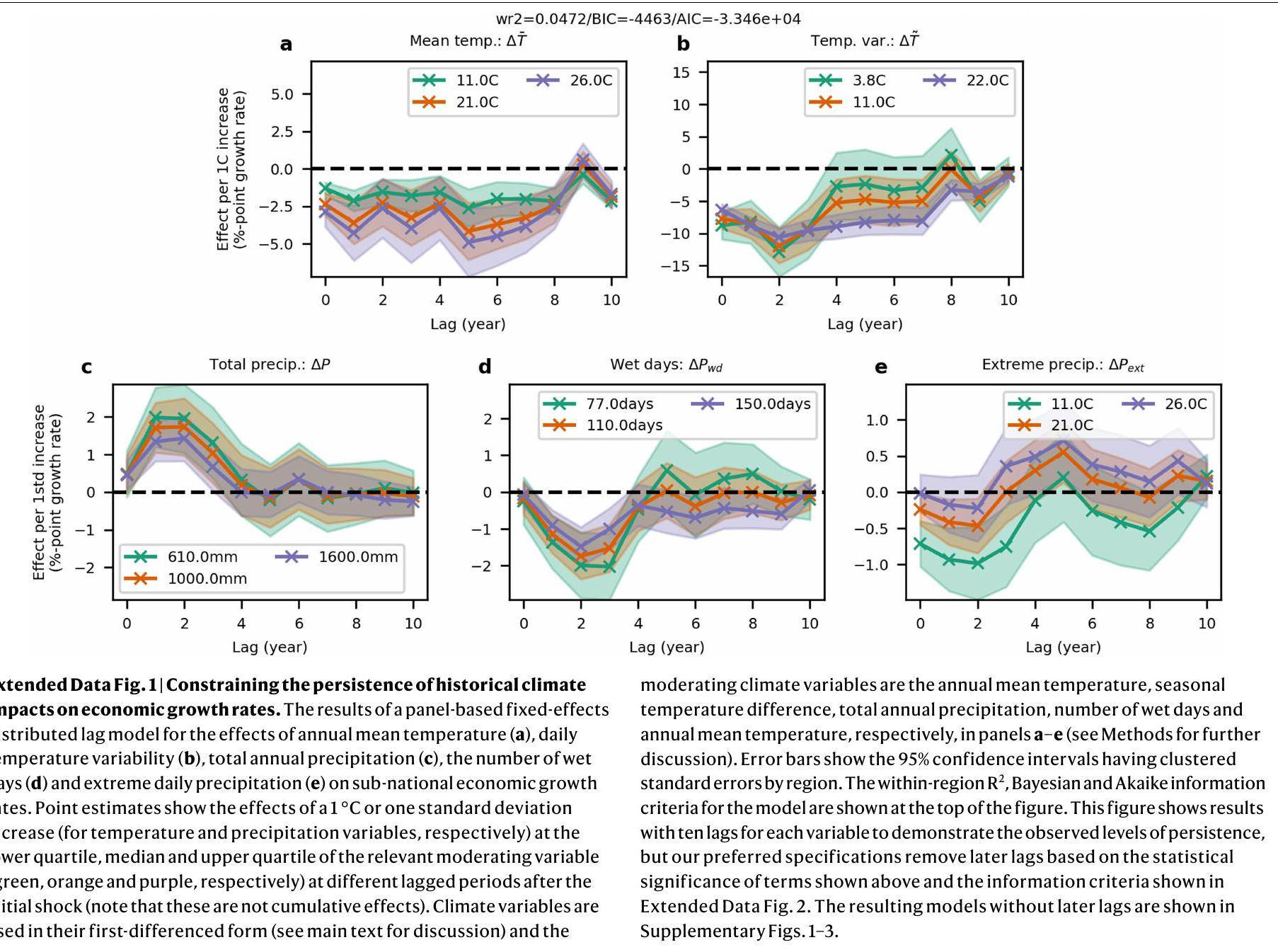

We begin our empirical analysis of the persistence of climate impacts on growth using ten lags of the first-differenced climate variables in fixed-effects distributed lag models. We detect substantial effects on economic growth at time lags of up to approximately 8-10 years for the temperature terms and up to approximately 4 years for the precipitation terms (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2). Furthermore, evaluation by means of information criteria indicates that the inclusion of all five climate variables and the use of these numbers of lags provide a preferable trade-off between best-fitting the data and including further terms that could cause overfitting, in comparison with model specifications excluding climate variables or including more or fewer lags (Extended Data Fig. 3, Supplementary Methods Section 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We therefore remove statistically insignificant terms at later lags (Supplementary Figs. 1-3 and Supplementary Tables 2-4). Further tests using Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that the empirical models are robust to autocorrelation in the lagged climate variables (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), that information criteria provide an effective indicator for lag selection (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6), that the results are robust to concerns of imperfect multicollinearity between climate variables and that including several climate variables is actually necessary to isolate their separate effects (Supplementary Methods Section 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7).

Committed damages until mid-century

Damages already outweigh mitigation costs

cost-benefit analyses typically find that the net benefits of mitigation only emerge after 2050 (ref. 5), which may lead some to conclude that physical damages from climate change are simply not large enough to outweigh mitigation costs until the second half of the century. Our simple comparison of their magnitudes makes clear that damages are actually already considerably larger than mitigation costs and the delayed emergence of net mitigation benefits results primarily from the fact that damages across different emission paths are indistinguishable until mid-century (Fig. 1).

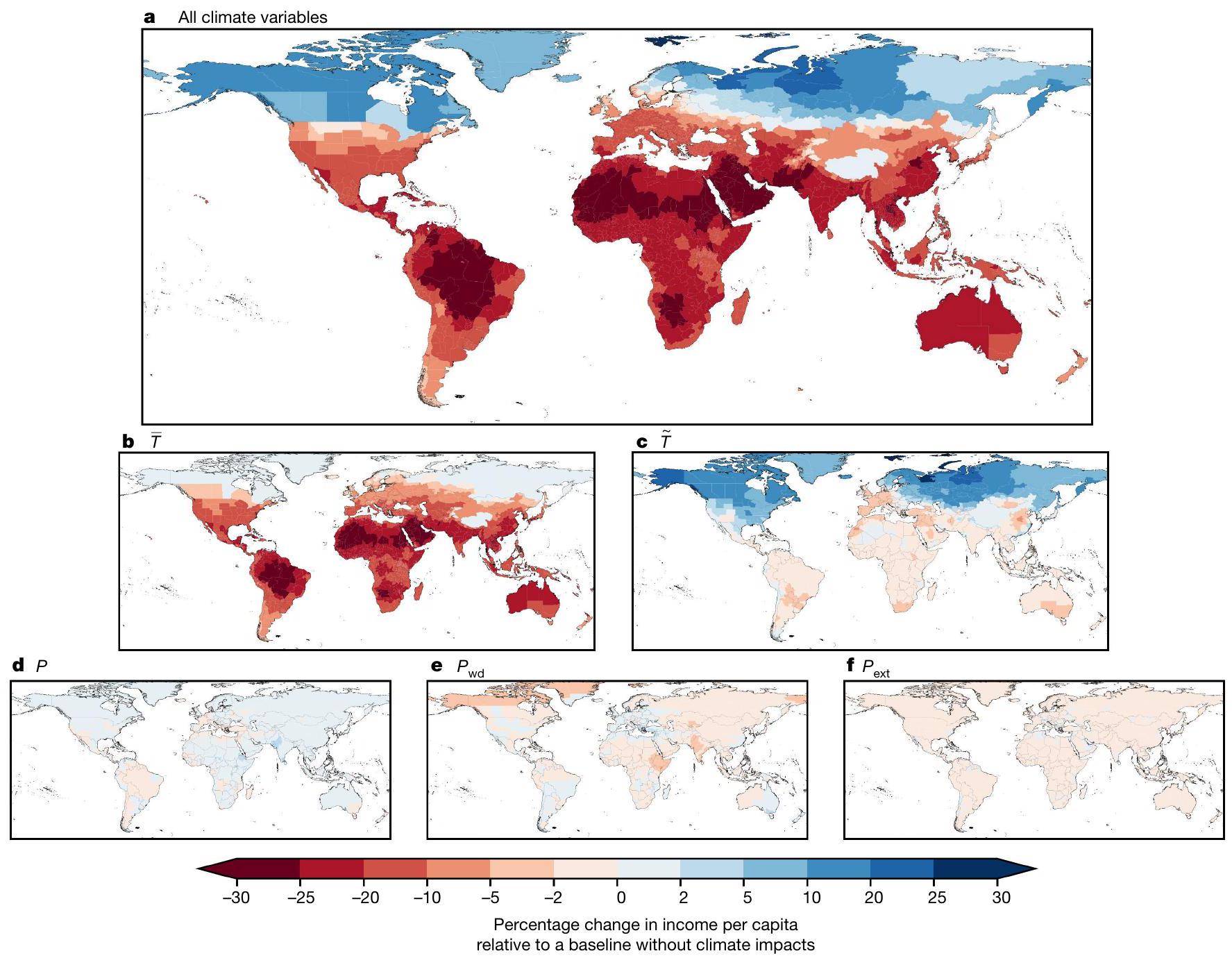

Damages from variability and extremes

(Extended Data Fig. 5a, likely range 5-21%). This suggests that accounting for the other components of the distribution of temperature and precipitation raises net damages by nearly 50%. This increase arises through the further damages that these climatic components cause, but also because their inclusion reveals a stronger negative economic response to average temperatures (Extended Data Fig. 5b). The latter finding is consistent with our Monte Carlo simulations, which suggest that the magnitude of the effect of average temperature on economic growth is underestimated unless accounting for the impacts of other correlated climate variables (Supplementary Fig. 7).

0.36 percentage points (

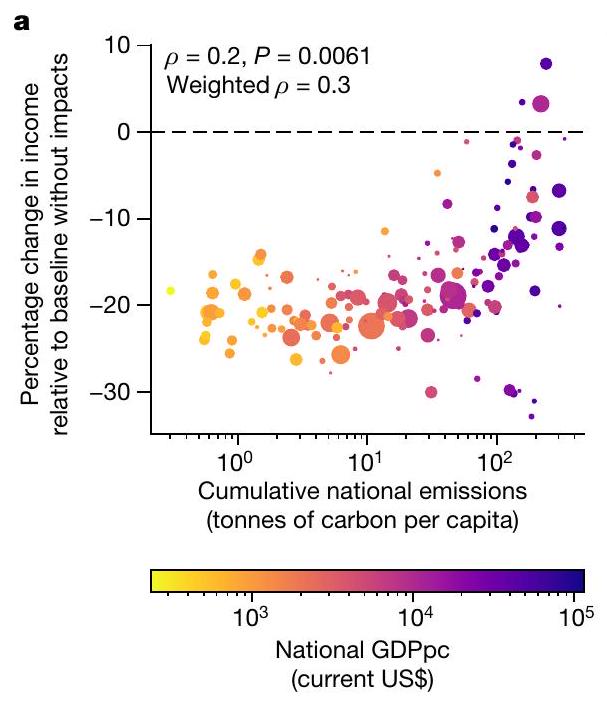

The distribution of committed damages

likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC). Similarly, the quartile of countries with lower historical cumulative emissions are committed to an income loss that is 6.9 percentage points (or

Contextualizing the magnitude of damages

Missing impacts and spatial spillovers

Policy implications

Online content

- Glanemann, N., Willner, S. N. & Levermann, A. Paris Climate Agreement passes the cost-benefit test. Nat. Commun. 11, 110 (2020).

- Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235-239 (2015).

- Kalkuhl, M. & Wenz, L. The impact of climate conditions on economic production. Evidence from a global panel of regions. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 103, 102360 (2020).

- Moore, F. C. & Diaz, D. B. Temperature impacts on economic growth warrant stringent mitigation policy. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 127-131 (2015).

- Drouet, L., Bosetti, V. & Tavoni, M. Net economic benefits of well-below

- Ueckerdt, F. et al. The economically optimal warming limit of the planet. Earth Syst. Dyn. 10, 741-763 (2019).

- Kotz, M., Wenz, L., Stechemesser, A., Kalkuhl, M. & Levermann, A. Day-to-day temperature variability reduces economic growth. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 319-325 (2021).

- Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The effect of rainfall changes on economic production. Nature 601, 223-227 (2022).

- Kousky, C. Informing climate adaptation: a review of the economic costs of natural disasters. Energy Econ. 46, 576-592 (2014).

- Harlan, S. L. et al. in Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives (eds Dunlap, R. E. & Brulle, R. J.) 127-163 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

- Bolton, P. et al. The Green Swan (BIS Books, 2020).

- Alogoskoufis, S. et al. ECB Economy-wide Climate Stress Test: Methodology and Results European Central Bank, 2021).

- Weber, E. U. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1, 332-342 (2010).

- Markowitz, E. M. & Shariff, A. F. Climate change and moral judgement. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 243-247 (2012).

- Riahi, K. et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153-168 (2017).

- Auffhammer, M., Hsiang, S. M., Schlenker, W. & Sobel, A. Using weather data and climate model output in economic analyses of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 7, 181-198 (2013).

- Kolstad, C. D. & Moore, F. C. Estimating the economic impacts of climate change using weather observations. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 14, 1-24 (2020).

- Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 4, 66-95 (2012).

- Newell, R. G., Prest, B. C. & Sexton, S. E. The GDP-temperature relationship: implications for climate change damages. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 108, 102445 (2021).

- Kikstra, J. S. et al. The social cost of carbon dioxide under climate-economy feedbacks and temperature variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 094037 (2021).

- Bastien-Olvera, B. & Moore, F. Persistent effect of temperature on GDP identified from lower frequency temperature variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 084038 (2022).

- Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937-1958 (2016).

- Byers, E. et al. AR6 scenarios database. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/7197970 (2022).

- Burke, M., Davis, W. M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature 557, 549-553 (2018).

- Kotz, M., Wenz, L. & Levermann, A. Footprint of greenhouse forcing in daily temperature variability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2103294118 (2021).

- Myhre, G. et al. Frequency of extreme precipitation increases extensively with event rareness under global warming. Sci. Rep. 9, 16063 (2019).

- Min, S.-K., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. W. & Hegerl, G. C. Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 470, 378-381 (2011).

- England, M. R., Eisenman, I., Lutsko, N. J. & Wagner, T. J. The recent emergence of Arctic Amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094086 (2021).

- Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavyprecipitation and high-temperature extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 560-564 (2015).

- Pfahl, S., O’Gorman, P. A. & Fischer, E. M. Understanding the regional pattern of projected future changes in extreme precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 423-427 (2017).

- Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. Globally unequal effect of extreme heat on economic growth. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd3726 (2022).

- Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 9808-9813 (2019).

- Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. National attribution of historical climate damages. Clim. Change 172, 40 (2022).

- Burke, M. & Tanutama, V. Climatic constraints on aggregate economic output. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 25779. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25779 (2019).

- Kahn, M. E. et al. Long-term macroeconomic effects of climate change: a cross-country analysis. Energy Econ. 104, 105624 (2021).

- Desmet, K. et al. Evaluating the economic cost of coastal flooding. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 24918. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24918 (2018).

- Hsiang, S. M. & Jina, A. S. The causal effect of environmental catastrophe on long-run economic growth: evidence from 6,700 cyclones. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 20352. https://doi.org/10.3386/w2035 (2014).

- Ritchie, P. D. et al. Shifts in national land use and food production in Great Britain after a climate tipping point. Nat. Food 1, 76-83 (2020).

- Dietz, S., Rising, J., Stoerk, T. & Wagner, G. Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2103081118 (2021).

- Bastien-Olvera, B. A. & Moore, F. C. Use and non-use value of nature and the social cost of carbon. Nat. Sustain. 4, 101-108 (2021).

- Carleton, T. et al. Valuing the global mortality consequences of climate change accounting for adaptation costs and benefits. Q. J. Econ. 137, 2037-2105 (2022).

- Bastien-Olvera, B. A. et al. Unequal climate impacts on global values of natural capital. Nature 625, 722-727 (2024).

- Malik, A. et al. Impacts of climate change and extreme weather on food supply chains cascade across sectors and regions in Australia. Nat. Food 3, 631-643 (2022).

- Kuhla, K., Willner, S. N., Otto, C., Geiger, T. & Levermann, A. Ripple resonance amplifies economic welfare loss from weather extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114010 (2021).

- Schleypen, J. R., Mistry, M. N., Saeed, F. & Dasgupta, S. Sharing the burden: quantifying climate change spillovers in the European Union under the Paris Agreement. Spat. Econ. Anal. 17, 67-82 (2022).

- Dasgupta, S., Bosello, F., De Cian, E. & Mistry, M. Global temperature effects on economic activity and equity: a spatial analysis. European Institute on Economics and the Environment, Working Paper 22-1 (2022).

- Neal, T. The importance of external weather effects in projecting the macroeconomic impacts of climate change. UNSW Economics Working Paper 2023-09 (2023).

- Deryugina, T. & Hsiang, S. M. Does the environment still matter? Daily temperature and income in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 20750. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20750 (2014).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Historical climate data

Future climate data

Historical economic data

Future socio-economic data

realistic distribution at the sub-national level are not readily available for the SSPs. We therefore use national-level GDP per capita (GDPpc) projections for all sub-national regions of a given country, assuming homogeneity within countries in terms of baseline GDPpc. Here we use projections that have been updated to account for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the trajectory of future income, while remaining consistent with the long-term development of the SSPs

Climate variables

We also calculated weighted standard deviations of monthly rainfall totals as also used in ref. 8 but do not include them in our projections as we find that, when accounting for delayed effects, their effect becomes statistically indistinct and is better captured by changes in total annual rainfall.

Spatial aggregation

Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models

Spatial-lag model

Constructing projections of economic damage from future climate change

both physical climate change and the structural and sampling uncertainty of the empirical models.

Estimates of mitigation costs

Data availability

Code availability

49. Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999-2049 (2020).

50. Cucchi, M. et al. WFDE5: bias-adjusted ERA5 reanalysis data for impact studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2097-2120 (2020).

51. Adler, R. et al. The New Version 2.3 of the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly Analysis Product 1072-1084 (University of Maryland, 2016).

52. Lange, S. Trend-preserving bias adjustment and statistical downscaling with ISIMIP3BASD (v1.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 3055-3070 (2019).

53. Wenz, L., Carr, R. D., Kögel, N., Kotz, M. & Kalkuhl, M. DOSE – global data set of reported sub-national economic output. Sci. Data 10, 425 (2023).

54. Gennaioli, N., La Porta, R., Lopez De Silanes, F. & Shleifer, A. Growth in regions. J. Econ. Growth 19, 259-309 (2014).

55. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). U.S. dollars to euro spot exchange rate. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/AEXUSEU (2022).

56. World Bank. GDP deflator. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.ZS (2022).

57. Jones, B. & O’Neill, B. C. Spatially explicit global population scenarios consistent with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 084003 (2016).

58. Murakami, D. & Yamagata, Y. Estimation of gridded population and GDP scenarios with spatially explicit statistical downscaling. Sustainability 11, 2106 (2019).

59. Koch, J. & Leimbach, M. Update of SSP GDP projections: capturing recent changes in national accounting, PPP conversion and Covid 19 impacts. Ecol. Econ. 206 (2023).

60. Carleton, T. A. & Hsiang, S. M. Social and economic impacts of climate. Science 353, aad9837 (2016).

61. Bergé, L. Efficient estimation of maximum likelihood models with multiple fixed-effects: the R package FENmlm. DEM Discussion Paper Series 18-13 (2018).

62. Kalkuhl, M., Kotz, M. & Wenz, L. DOSE – The MCC-PIK Database Of Subnational Economic output. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo. 4681305 (2021).

63. Kotz, M., Wenz, L. & Levermann, A. Data and code for “The economic commitment of climate change”. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo. 10562951 (2024).

64. Dasgupta, S. et al. Effects of climate change on combined labour productivity and supply: an empirical, multi-model study. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e455-e465 (2021).

65. Lobell, D. B. et al. The critical role of extreme heat for maize production in the United States. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 497-501 (2013).

66. Zhao, C. et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 9326-9331 (2017).

67. Wheeler, T. R., Craufurd, P. Q., Ellis, R. H., Porter, J. R. & Prasad, P. V. Temperature variability and the yield of annual crops. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 82, 159-167 (2000).

68. Rowhani, P., Lobell, D. B., Linderman, M. & Ramankutty, N. Climate variability and crop production in Tanzania. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 449-460 (2011).

69. Ceglar, A., Toreti, A., Lecerf, R., Van der Velde, M. & Dentener, F. Impact of meteorological drivers on regional inter-annual crop yield variability in France. Agric. For. Meteorol. 216, 58-67 (2016).

70. Shi, L., Kloog, I., Zanobetti, A., Liu, P. & Schwartz, J. D. Impacts of temperature and its variability on mortality in New England. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 988-991 (2015).

71. Xue, T., Zhu, T., Zheng, Y. & Zhang, Q. Declines in mental health associated with air pollution and temperature variability in China. Nat. Commun. 10, 2165 (2019).

72. Liang, X.-Z. et al. Determining climate effects on US total agricultural productivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, E2285-E2292 (2017).

73. Desbureaux, S. & Rodella, A.-S. Drought in the city: the economic impact of water scarcity in Latin American metropolitan areas. World Dev. 114, 13-27 (2019).

74. Damania, R. The economics of water scarcity and variability. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 36, 24-44 (2020).

75. Davenport, F. V., Burke, M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Contribution of historical precipitation change to US flood damages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2017524118 (2021).

76. Dave, R., Subramanian, S. S. & Bhatia, U. Extreme precipitation induced concurrent events trigger prolonged disruptions in regional road networks. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 104050 (2021).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Leonie Wenz.

Peer review information Nature thanks Xin-Zhong Liang, Chad Thackeray and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

Article

Article

effects. Estimates of future damages as shown in Fig. 1 but under the emission scenario RCP8.5 for three separate empirical specifications: in orange our preferred specification, which provides an empirical lower bound on the persistence of climate impacts on economic growth rates while avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence (see main text for further discussion); in purple a specification of ‘pure growth effects’ in which the first difference of climate variables is not taken and no lagged climate variables are included (the baseline specification of ref. 2); and in pink a specification of ‘pure level effects’ in which the first difference of climate variables is taken but no lagged terms are included.

identified (detrending is appropriate because of the inclusion of region-specific linear time trends in the empirical models). See Supplementary Fig. 13 for changes expressed in standard units. Data on national administrative boundaries are obtained from the GADM database version 3.6 and are freely available for academic use (https://gadm.org/).

Article

Article

| Climate variable | Physical mechanisms | References |

| Average annual temperature | Labour productivity and supply; agricultural productivity | Dasgupta et al. (2021)

|

| Daily temperature variability | Agricultural productivity; physical health; mental health | Wheeler et al.

|

| Total annual precipitation | Agricultural productivity; metropolitan labour outcomes; conflict | Liang et al. (2017)

|

| Number of wet days | Travel disruption | Lacking |

| Extreme daily precipitation | Flood damages; disruption | Davenport et al. (2021)

|

| Variable | Formula | Lag 0 | Lag 1 | Lag 2 | Lag 3 | Lag 4 | Lag 5 | Lag 6 | Lag 7 | Lag 8 | Lag 9 | Lag 10 |

| Annual mean temperature |

|

-0.17 | -0.57 | -0.78 | -0.23 | -0.79 | -0.96 | -0.23 | -0.71 | -1.8** | -1.1* | -2.5*** |

| (0.32) | (0.5) | (0.54) | (0.57) | (0.57) | (0.65) | (0.67) | (0.73) | (0.63) | (0.48) | (0.35) | ||

|

|

-0.0011*** (0.00029) | -0.0014** (0.00049) | -0.00072 (0.00051) | -0.0015** (0.00055) | -0.00072 (0.00047) | -0.0015** (0.0005) | -0.0017*** (0.00046) | -0.0012** (0.00047) | -0.00029 (0.0004) | 0.00065* (0.00032) | 0.00029 (0.00023) | |

| Daily temp. variability |

|

-9.3*** | -8.1*** | -13*** | -9.3*** | -1.5 | -1.2 | -2.4 | -1.8 | 3.3 | -5.3** | -0.34 |

| (1.3) | (2) | (2.3) | (2.7) | (3.1) | (3.2) | (3) | (2.9) | (2.5) | (1.9) | (1.3) | ||

|

|

0.0013* (0.00054) | -0.0003 (0.00083) | 0.0013 (0.00087) | -0.00011 (0.0011) | -0.0034** (0.0012) | -0.0032* (0.0013) | -0.0025* (0.0012) | -0.0029* (0.0012) | -0.003** (0.0011) | 0.00079 (0.00078) | -0.00037 (0.00057) | |

| Total annual precipitation |

|

0.002 (0.0016) | 0.0094*** (0.002) | 0.009*** (0.0023) | 0.0068** (0.0024) | 0.0021 (0.0024) | -0.0012 (0.0025) | 0.0013 (0.0025) | -0.001 (0.0023) | -0.0001 (0.0021) | 0.0012 (0.0019) | 0.0005 (0.0015) |

|

|

|

-2.6e-08** (8.5e-09) |

|

-2.6e-08** (9.8e-09) |

|

|

|

|

-1.2e-09 (8.6e-09) | -1.3e-08 (7.8e-09) | -9.4e-09 (6.1e-09) | |

| Annual no. wet days |

|

-0.028 (0.038) | -0.12** (0.043) | -0.17** (0.055) | -0.2*** (0.055) | -0.038 (0.052) | 0.12 (0.065) | 0.037 (0.068) | 0.079 (0.058) | 0.1* (0.048) | 0.045 (0.04) | -0.03 (0.032) |

|

|

|

|

|

9.2e-06* (3.6e-06) |

|

-1e-05* (4.1e-06) | -5.5e-06 (4.1e-06) | -7.1e-06 (3.6e-06) | -9e-06** (3e-06) | -5.6e-06* (2.5e-06) | 2.2e-06 (1.9e-06) | |

| Precipitation extremes |

|

-0.023*** (0.0053) | -0.028*** (0.0073) | -0.029*** (0.0084) | -0.029** (0.0094) | -0.01 (0.0098) | -0.0032 (0.01) | -0.013 (0.011) | -0.017 (0.01) | -0.019* (0.0093) | -0.013 (0.0079) | 0.0054 (0.0052) |

|

|

8.8e-06*** (2.5e-06) | 9.6e-06** (3.4e-06) | 9.6e-06* (

|

1.4e-05** (4.6e-06) |

|

|

8e-06 (4.9e-06) | 8.8e-06 (4.8e-06) |

|

8.1e-06* (

|

-1.2e-06 (2.7e-06) | |

|

|

0.291 | |||||||||||

|

|

0.0472 | |||||||||||

| BIC | -4.46e+03 | |||||||||||

| AIC |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

34855 | |||||||||||

with ten lags for each climate variable (that is, each table entry denotes a specific regression coefficient

with ten lags for each climate variable (that is, each table entry denotes a specific regression coefficient

within-region

within-region

Article

| Study | Resolution | Number of climate variables | Baseline specification of growth- or level-effects | Number of lags | Damages by 2100 under RCP8.5 |

| Burke et al. (2015)

|

National | One | Growth | None | 25% |

| Kahn et al. (2019)

|

National | One | Level | Four | 7.2% |

| Kalkuhl & Wenz (2020)

|

Sub-national | One | Level | One | 14.2% |

| This study | Sub-national | Five | Level | Eight-ten/four | 61.6% |

- All studies use fixed-effects panel regressions. The first four columns describe differences in the underlying data and empirical specification. The third column shows the nature of the baseline specification without lags with regards to growth or level effects (see main text for further discussion). The last column compares projections of future economic damage under RCP8.5 by 2100 as reported by the respective study.