DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44378-025-00041-8

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-03

مراجعة

البيوچار كإضافة للتربة: الآثار على صحة التربة، احتجاز الكربون، ومرونة المناخ

نُشر على الإنترنت: 03 مارس 2025

© المؤلفون 2025 مفتوح

الملخص

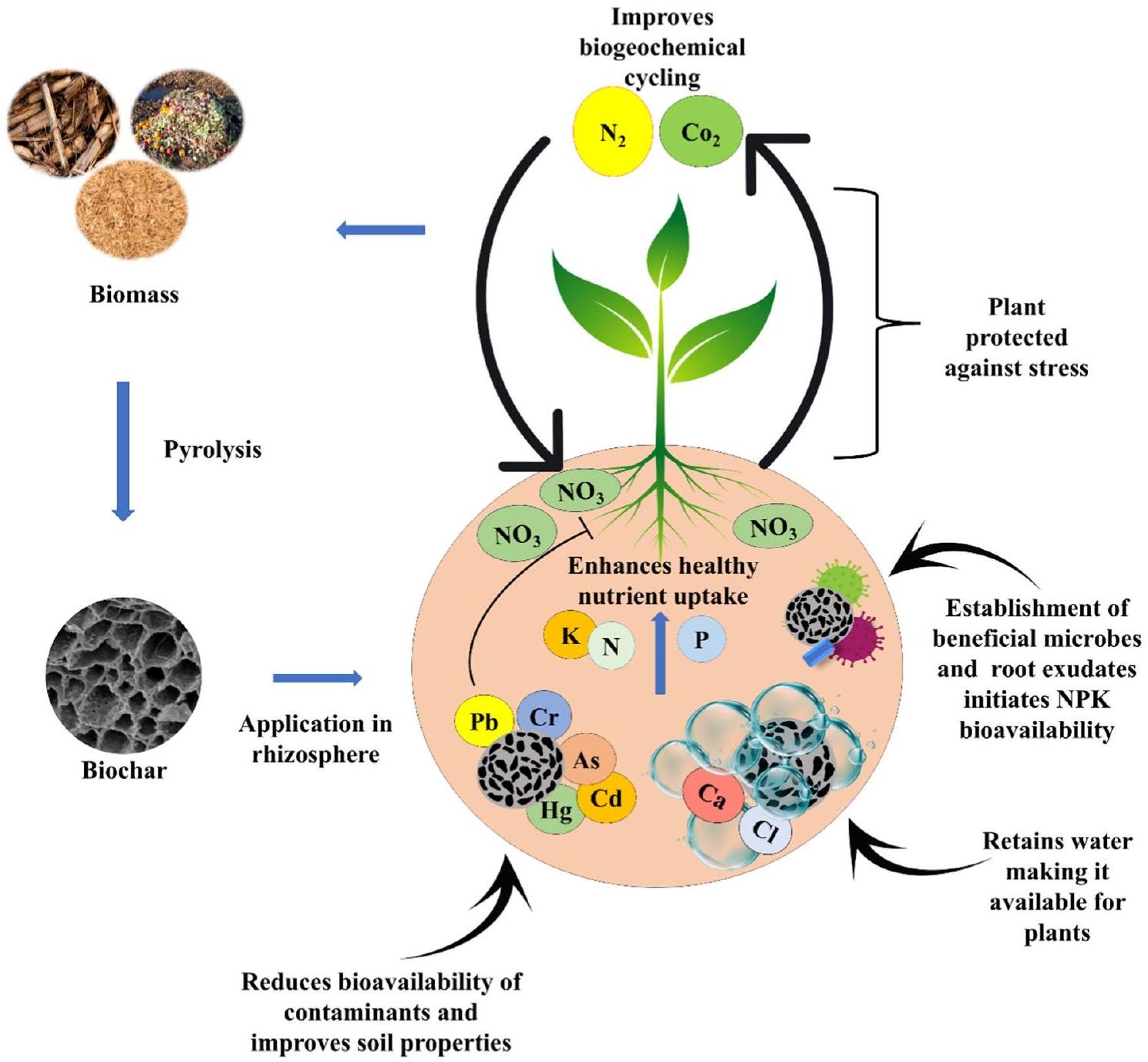

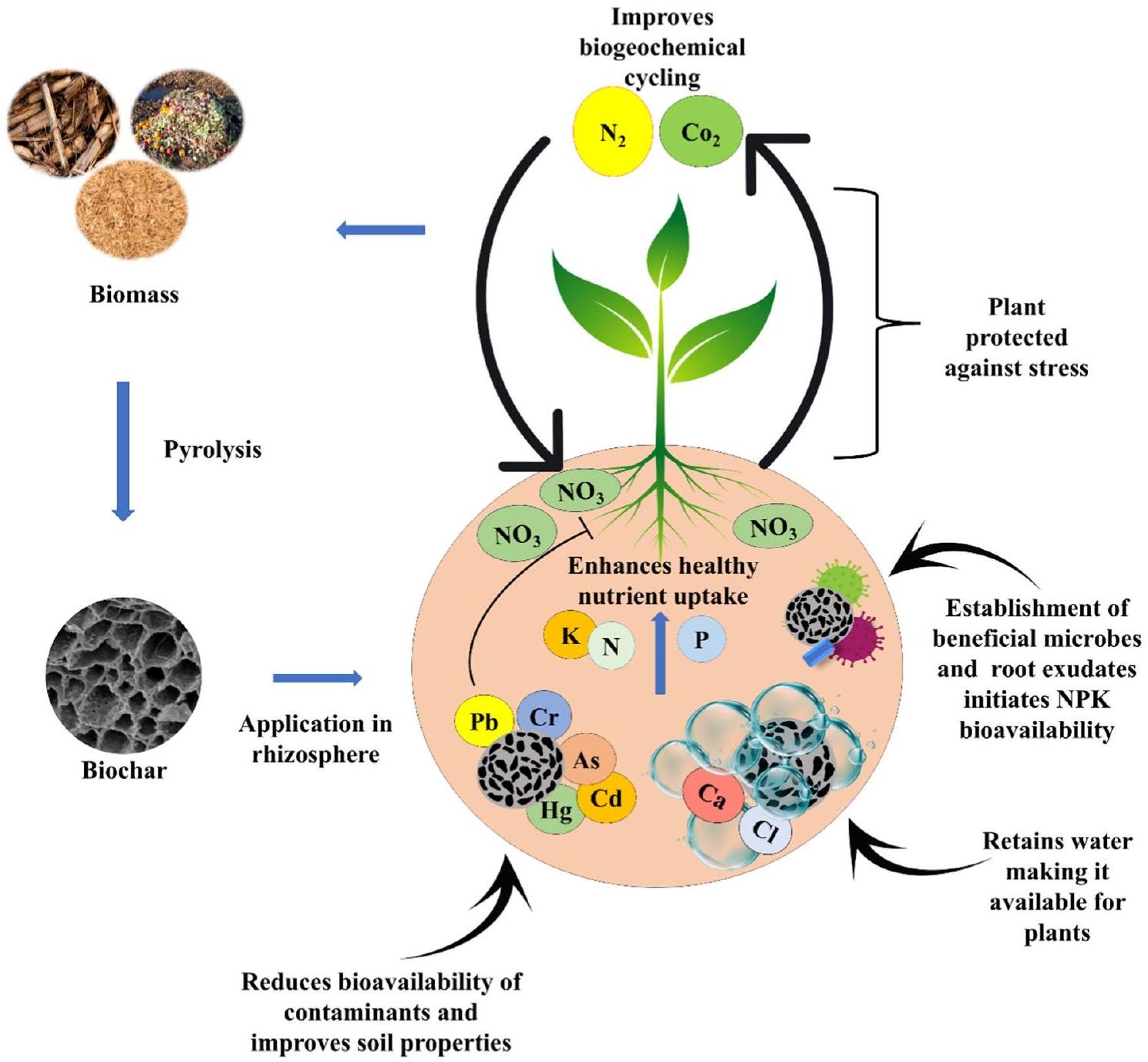

البيوچار، وهو مادة غنية بالكربون تُنتج من خلال التحلل الحراري للكتلة الحيوية العضوية، قد حظي باهتمام متزايد كسماد مستدام للتربة نظرًا لإمكاناته في تعزيز صحة التربة، وتحسين الإنتاجية الزراعية، والتخفيف من تغير المناخ. تستعرض هذه المراجعة الفوائد المتعددة للبيوچار، بما في ذلك قدرته على احتجاز الكربون لفترات طويلة، مما يقلل من غازات الدفيئة في الغلاف الجوي. الخصائص الفريدة للبيوچار، مثل هيكله المسامي، وسعته العالية لتبادل الكاتيونات، وقدراته على احتجاز المغذيات، تعزز بشكل كبير خصوبة التربة، وسعة احتفاظها بالمياه، ونشاط الميكروبات. هذه التحسينات تزيد من مرونة المحاصيل ضد الجفاف، وتآكل التربة، وفقدان المغذيات، مما يدعم أنظمة الزراعة المقاومة لتغير المناخ. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي تطبيق البيوچار إلى خفض انبعاثات أكسيد النيتروز والميثان من التربة، مما يساهم بشكل أكبر في التخفيف من تغير المناخ. ومع ذلك، فإن فعالية البيوچار تتأثر بعوامل مثل نوع المواد الخام، وظروف التحلل الحراري، ومعدلات التطبيق. فهم هذه المتغيرات أمر حاسم لتحسين استخدام البيوچار في أنواع التربة المختلفة والظروف البيئية.

أهم النقاط

- تمت مراجعة تقنيات التحلل الحراري لتحسين خصائص وتطبيقات الفحم الحيوي.

- يعزز احتفاظ التربة بالعناصر الغذائية، وسعة المياه، ودوام المادة العضوية.

- يقلل من انبعاثات الغازات الدفيئة بينما يعزز صحة التربة المستدامة.

- يحتجز الكربون لمدة تصل إلى 2000 عام، مما يدعم التخفيف من آثار تغير المناخ.

1 المقدمة

إذا لم يتغير نمط التنمية، تقدر إدارة الشؤون الاقتصادية والاجتماعية التابعة للأمم المتحدة (2019) أن عدد سكان العالم سيصل إلى 9.4 إلى 10.1 مليار بحلول عام 2050. استنادًا إلى توقعات مختلفة، من المتوقع أن يزداد استهلاك الغذاء العالمي بـ

طرق إنتاج البيوچار

2.1 التحلل الحراري

| الكتلة الحيوية | درجة حرارة التحلل الحراري | درجة الحموضة | نسبة مئوية | N% | P% | K% | المراجع |

| نفايات مصنع الورق |

|

9.4 | 50.0 | 0.48 | – | 0.22 | [68] |

| النفايات الخضراء (قمامة القطن، العشب، وتقليم النباتات) |

|

6.2 | ٣٦.٠ | 0.18 | – | 1.00 | [69] |

| قش الأرز |

|

9.5 | ٤٨ | 10 | 15 | 20 | [70] |

| فضلات الدواجن |

|

9.9 | ٣٨.٠ | 2.00 | ٣٧.٤٢ | 0 | [71] |

| حمأة الصرف الصحي |

|

– | ٤٧.٠ | 6.4 | ٥.٦ | – | [72] |

| بقايا الذرة |

|

– | 79.0 | 9.2 | – | ٦.٧ | [73] |

| فحم الأوكاليبتوس |

|

– | 82.4 | 0.57 | 1.87 | – | [68] |

| قش القمح |

|

9.7 | 65.70 | 1.05 | 0.1 | 1.2 | [74] |

| خشب (صنوبر بونديروسا) | حرائق الغابات | ٦.٧ | 74.0 | 16.6 | 13.6 | – | [73] |

| قشرة الجوز الأمريكي (Carya illinoinensis) |

|

٧.٦ | ٨٣.٤ | 1.7 | – | – | [69] |

| نشارة الخشب الصلب |

|

12.1 | 66.5 | 0.3 | – | – | [75] |

2.1.1 التحلل الحراري البطيء

2.1.2 التحلل الحراري السريع

2.1.3 التحلل الفلاش

2.1.4 التحلل الفراغي

2.1.5 التحلل الوسيط

2.1.6 التحلل بمساعدة الميكروويف

2.2 الكربنة المائية

مقارنة بالتحلل الحراري، وهو فائدة إضافية. أحد الأسباب هو أن HTC تعمل عند درجات حرارة منخفضة مقارنة بالتحلل الحراري ولا تتطلب تجفيف المواد الخام [79]. يمكن أن تحسن بشكل كبير من ظروف التربة ويمكن استخدامها لالتقاط الكربون لتقليل انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة. أظهرت دراسات متعددة أن الهيدروكربون المنتج أثناء الكربنة المائية مقاوم للتغيير أو التحلل. عزز وجود البيوكربون كل من الجريان والاحتفاظ. تشير الأبحاث إلى أن دمج الهيدروكربون في التربة يمكن أن يعزز قدرتها على الاحتفاظ بالعناصر الغذائية والماء. تعزز مسام الهيدروكربون التخزين والتحكم في إطلاق العناصر الغذائية [84].

2.3 الغازification

2.4 التوريفيكت

له تأثير كبير على الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية للنانو-بيوكاربون. يتم إنتاج النانو-بيوكاربون الذي يحتوي على كميات منخفضة من الكربون والأكسجين عادةً من الكتلة الحيوية الغنية بالهيميسليلوز. العكس هو الصحيح بالنسبة للمواد التي تحتوي على نسبة عالية من اللجنين؛ حيث تنتج هذه المواد عادةً نانو-بيوكاربون يمكن أن يتجمع بشكل جيد. كانت النانو-بيوكاربونات المصنوعة من القصب وقش القمح تحتوي في الغالب على جزيئات صغيرة ذات هيكل مفتوح. على عكس النانو-بيوكاربونات الأولى، أظهرت نانو-بيوكاربونات الميسكانثوس تأثيرات تجميع أقل وكانت تحتوي على جزيئات كروية كبيرة. كان للنانو-بيوكاربون الناتج من النفايات الزراعية أيضًا تأثير متناسب مباشر على محتوى الرماد في البيوكاربون الكتلي، بينما لم يكن للنفايات البلدية تأثير مماثل. يتم صنع النانو-بيوكاربون من البيوكاربون الكتلي من خلال بعض الخطوات الإضافية.

2.4.1 طريقة الطحن

2.4.2 تقنية الموجات فوق الصوتية

3 خصائص للفحم الحيوي

المحتوى، القلوية السطحية، وانخفاض الحموضة السطحية. خلال التحلل الحراري السريع، يتم تسخين الكتلة الحيوية بسرعة إلى درجات حرارة تتراوح بين

4 تأثير الفحم الحيوي على ديناميات الطاقة في التربة

5 تأثير الفحم الحيوي على خصائص التربة

5.1 التأثيرات على بنية التربة وتركيبها

| نوع البيوچار | درجة حرارة التحلل الحراري | معدل التقديم | تم العثور على ردود | المراجع |

| نفايات مصنع الورق |

|

|

زيادة في الإنبات | [139] |

| قش الذرة |

|

0٪، 3٪، و5٪ | انخفض معدل التسلل مع زيادة معدل تطبيق الفحم الحيوي | [139] |

| قش الذرة |

|

10 و

|

انخفاض كثافة التربة الظاهرية | [140] |

| غبار الخشب |

|

|

يعزز قدرة التربة على احتباس الماء | [141] |

| قش الأرز |

|

0، 1، 3 و 9% | يعزز قدرة التربة على احتباس الماء | [140] |

| فحم قشرة الأكاسيا مانجيوم |

|

|

الفطريات الميكوريزية الجذرية زادت بـ

|

[٢٥، ١٤٢] |

| فحم قشور التبغ |

|

|

حسّن الرقم الهيدروجيني للتربة ومنع تسرب النيتروجين والبوتاسيوم في التربة ذات القوام الخفيف | [143] |

| النفايات الخضراء |

|

|

بأعلى المعدلات مع تطبيق N،

|

[15] |

| سماد الدواجن |

|

|

زيادة توفر النيتروجين والفوسفور والبوتاسيوم والكالسيوم والمغنيسيوم في التربة | [139] |

| قشور الفول السوداني |

|

0٪، 5٪، و20٪ | زيادة

|

[140] |

5.2 تأثيرات على قدرة احتفاظ التربة بالمياه

5.3 تأثيرات على نيتروجين التربة

5.4 تأثيرات على الفوسفور في التربة

5.5 التأثيرات على العناصر الغذائية الأخرى

6 إمكانيات احتجاز الكربون للفحم الحيوي وتأثيره على تغير المناخ

7 قيود للفحم الحيوي

8 الخاتمة والاتجاهات المستقبلية

بشأن تأثير الفحم الحيوي على غلات المحاصيل من خلال التركيز على أنواع التربة، وإدارة الأسمدة، والظروف البيئية. سيساعد ذلك في تحسين تطبيقات الفحم الحيوي للأنظمة الزراعية في العالم الحقيقي.

مساهمات المؤلفين: قامت سوبرتي شيام بمراجعة وإعداد المسودة الأولى من المخطوطة؛ جمعت سليماء أحمد البيانات وراجعت أجزاء من هذه المقالة؛ قام سانكيت ج. جوشي بتحرير ومراجعة المخطوطة؛ قام هيمن سارما بتصميم وتحرير المخطوطة.

توفر الشيفرة: غير قابل للتطبيق.

الإعلانات

References

- Malyan SK, Kumar SS, Fagodiya RK, Ghosh P, Kumar A, Singh R, et al. Biochar for environmental sustainability in the energy-wateragroecosystem nexus. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;149: 111379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111379.

- Vijay V, Shreedhar S, Adlak K, Payyanad S, Sreedharan V, Gopi G, et al. Review of large-scale biochar field-trials for soil amendment and the observed influences on crop yield variations. Front Energy Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.710766.

- Martínez-Gómez Á, Poveda J, Escobar C. Overview of the use of biochar from main cereals to stimulate plant growth. Front Plant Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.912264.

- Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Krupnik TJ, Rahut DB, Jat ML, Stirling CM. Factors affecting farmers’ use of organic and inorganic fertilizers in South Asia. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:51480-96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13975-7.

- Agegnehu G, Bass AM, Nelson PN, Bird MI. Benefits of biochar, compost, and biochar-compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in a tropical agricultural soil. Sci Total Environ. 2016;543:295-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.054.

- Singh B, Singh BP, Cowie AL. Characterisation and evaluation of biochars for their application as a soil amendment. Soil Research. 2010;48:516. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR10058.

- Rawat J, Saxena J, Biochar SP. A sustainable approach for improving plant growth and soil properties. Biochar – an imperative amendment for soil and the environment. IntechOpen. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82151.

- Beheshti M, Etesami H, Alikhani HA. Effect of different biochars amendment on soil biological indicators in a calcareous soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:14752-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1682-2.

- Amalina F, Abd Razak AS, Zularisam AW, Aziz MAA, Krishnan S, Nasrullah M. Comprehensive assessment of biochar integration in agricultural soil conditioning: advantages, drawbacks, and prospects. Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C. 2023;132: 103508. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.pce.2023.103508.

- Umair Hassan M, Huang G, Munir R, Khan TA, Noor MA. Biochar co-compost: a promising soil amendment to restrain greenhouse gases and improve rice productivity and soil fertility. Agronomy. 2024;14:1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071583.

- Gao S, Harrison BP, Thao T, Gonzales ML, An D, Ghezzehei TA, et al. Biochar co-compost improves nitrogen retention and reduces carbon emissions in a winter wheat cropping system. GCB Bioenergy. 2023;15:462-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.13028.

- Xu H. Analysis of the relationship between biochar and soil highlights in science. Eng Technol. 2022;26:59-64. https://doi.org/10.54097/ hset.v26i.3643.

- Aslam S, Nazir A. Valorizing combustible and compostable fractions of municipal solid waste to Biochar and compost as an alternative to chemical fertilizer for improving soil health and sunflower yield. Agronomy. 2024;14:1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071449.

- Sarma H, Shyam S, Zhang M, Guerriero G. Nano-biochar interactions with contaminants in the rhizosphere and their implications for plant-soil dynamics. Soil Environ Health. 2024;2: 100095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seh.2024.100095.

- Shareef TME, Zhao B. Review paper: the fundamentals of Biochar as a soil amendment tool and management in agriculture scope: an overview for farmers and gardeners. J Agric Chem Environ. 2017;06:38-61. https://doi.org/10.4236/jacen.2017.61003.

- Bo X, Zhang Z, Wang J, Guo S, Li Z, Lin H, et al. Benefits and limitations of biochar for climate-smart agriculture: a review and case study from China. Biochar. 2023;5:77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-023-00279-x.

- Joseph SD, Camps-Arbestain M, Lin Y, Munroe P, Chia CH, Hook J, et al. An investigation into the reactions of biochar in soil. Soil Research. 2010;48:501. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR10009.

- Barnes AD, Jochum M, Lefcheck JS, Eisenhauer N, Scherber C, O’Connor MI, et al. Energy flux: the link between multitrophic biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol Evol. 2018;33:186-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.12.007.

- LeCroy C, Masiello CA, Rudgers JA, Hockaday WC, Silberg JJ. Nitrogen, biochar, and mycorrhizae: alteration of the symbiosis and oxidation of the char surface. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;58:248-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.11.023.

- Wang M, Fu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Shen J, Liu X, et al. Pathways and mechanisms by which biochar application reduces nitrogen and phosphorus runoff losses from a rice agroecosystem. Sci Total Environ. 2021;797: 149193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149193.

- Sánchez-Monedero MA, Cayuela ML, Sánchez-García M, Vandecasteele B, D’Hose T, López G, et al. Agronomic evaluation of Biochar, compost and biochar-blended compost across different cropping systems: perspective from the european project FERTIPLUS. Agronomy. 2019;9:225. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9050225.

- Anand A, Kumar R, Kumar V, Kaushal P. Carbon sequestration in soil from paddy straw derived biochar in India. 2022 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Energy, Environment and Climate Change (ICUE), IEEE; 2022, p. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ ICUE55325.2022.10113534

- Murali M, Gayathri M, Singh V, Raj S, Singh V, Chaubey C, et al. Soil carbon sequestration in the age of climate change: a review. Int J Environ Climate Change. 2023;13:1668-77. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijecc/2023/v13i113322.

- Singh Yadav SP, Bhandari S, Bhatta D, Poudel A, Bhattarai S, Yadav P, et al. Biochar application: a sustainable approach to improve soil health. J Agric Food Res. 2023;11: 100498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100498.

- Premalatha RP, Poorna Bindu J, Nivetha E, Malarvizhi P, Manorama K, Parameswari E, et al. A review on biochar’s effect on soil properties and crop growth. Front Energy Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1092637.

- Gul S, Whalen JK, Thomas BW, Sachdeva V, Deng H. Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: Mechanisms and future directions. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015;206:46-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.03.015.

- Han L, Sun K, Yang Y, Xia X, Li F, Yang Z, et al. Biochar’s stability and effect on the content, composition and turnover of soil organic carbon. Geoderma. 2020;364: 114184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114184.

- Waheed QMK, Nahil MA, Williams PT. Pyrolysis of waste biomass: investigation of fast pyrolysis and slow pyrolysis process conditions on product yield and gas composition. J Energy Inst. 2013;86:233-41. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743967113Z.00000000067.

- Pecha MB, Garcia-Perez M. Pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: oil, char, and gas. Bioenergy. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815497-7.00029-4.

- Czernik S, Bridgwater AV. Overview of applications of biomass fast pyrolysis oil. Energy Fuels. 2004;18:590-8. https://doi.org/10. 1021/ef034067u.

- Zhang P, Duan W, Peng H, Pan B, Xing B. Functional biochar and its balanced design. ACS Environmental Au. 2022;2:115-27. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acsenvironau.1c00032.

- Torri IDV, Paasikallio V, Faccini CS, Huff R, Caramão EB, Sacon V, et al. Bio-oil production of softwood and hardwood forest industry residues through fast and intermediate pyrolysis and its chromatographic characterization. Bioresour Technol. 2016;200:680-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.086.

- Kwaku Armah E, Chetty M, Adebisi Adedeji J, Erwin Estrice D, Mutsvene B, Singh N, et al. Biochar: production, application and the future. Biochar – productive technologies, properties and applications. IntechOpen. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen. 105070.

- Lee Y, Eum P-R-B, Ryu C, Park Y-K, Jung J-H, Hyun S. Characteristics of biochar produced from slow pyrolysis of Geodae-Uksae 1. Bioresour Technol. 2013;130:345-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.012.

- Lu J-S, Chang Y, Poon C-S, Lee D-J. Slow pyrolysis of municipal solid waste (MSW): A review. Bioresour Technol. 2020;312: 123615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123615.

- Sonowal S, Koch N, Sarma H, Prasad K, Prasad R. A review on magnetic nanobiochar with their use in environmental remediation and high-value applications. J Nanomater. 2023;2023:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4881952.

- Li C, Zhang L, Gao Y, Li A. Facile synthesis of nano ZnO/ZnS modified biochar by directly pyrolyzing of zinc contaminated corn stover for

and removals. Waste Manage. 2018;79:625-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.08.035. - Venderbosch RH. Fast Pyrolysis. Thermochemical Processing of Biomass, Wiley; 2019, p. 175-206. https://doi.org/10.1002/97811 19417637.ch6.

- Onay O, Kockar OM. Slow, fast and flash pyrolysis of rapeseed. Renew Energy. 2003;28:2417-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(03)00137-X.

- Kim KH, Kim J-Y, Cho T-S, Choi JW. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on physicochemical properties of biochar obtained from the fast pyrolysis of pitch pine (Pinus rigida). Bioresour Technol. 2012;118:158-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.094.

- Bridgwater AV, Meier D, Radlein D. An overview of fast pyrolysis of biomass. Org Geochem. 1999;30:1479-93. https://doi.org/10. 1016/S0146-6380(99)00120-5.

- Graham RG, Bergougnou MA, Overend RP. Fast pyrolysis of biomass. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 1984;6:95-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/ 0165-2370(84)80008-X.

- Ighalo JO, Iwuchukwu FU, Eyankware OE, Iwuozor KO, Olotu K, Bright OC, et al. Flash pyrolysis of biomass: a review of recent advances. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2022;24:2349-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-022-02339-5.

- Nyoni B, Fouda-Mbanga BG, Hlabano-Moyo BM, Nthwane YB, Yalala B, Tywabi-Ngeva Z, et al. The Potential of Agricultural Waste Chars as Low-Cost Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal From Water, 2024, p. 244-70. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-1618-4. ch011.

- Scott DS, Piskorz J. The continuous flash pyrolysis of biomass. Can J Chem Eng. 1984;62:404-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.54506 20319.

- Sowmya Dhanalakshmi C, Kaliappan S, Mohammed Ali H, Sekar S, Depoures MV, Patil PP, et al. Flash pyrolysis experiment on albizia odoratissima biomass under different operating conditions: a comparative study on bio-oil, biochar, and noncondensable gas products. J Chem. 2022;2022:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9084029.

- Madhu P, Kanagasabapathy H, Manickam IN. Flash pyrolysis of palmyra palm ( Borassus flabellifer) using an electrically heated fluidized bed reactor. Energy Sources. 2016;38:1699-705. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2014.956192.

- Miranda R, Pakdel H, Roy C, Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of commingled plastics containing PVC II. Product analysis Polym Degrad Stab. 2001;73:47-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(01)00066-0.

- Nugroho RAA, Alhikami AF, Wang W-C. Thermal decomposition of polypropylene plastics through vacuum pyrolysis. Energy. 2023;277: 127707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127707.

- Miranda R, Yang J, Roy C, Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of PVC I. Kinetic study Polym Degrad Stab. 1999;64:127-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0141-3910(98)00186-4.

- Boucher ME, Chaala A, Pakdel H, Roy C. Bio-oils obtained by vacuum pyrolysis of softwood bark as a liquid fuel for gas turbines. Part II: Stability and ageing of bio-oil and its blends with methanol and a pyrolytic aqueous phase. Biomass Bioenergy. 2000;19:351-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00044-1.

- Carrier M, Hardie AG, Uras Ü, Görgens J. Knoetze J Production of char from vacuum pyrolysis of South-African sugar cane bagasse and its characterization as activated carbon and biochar. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2012;96:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2012. 02.016.

- Bardestani R, Kaliaguine S. Steam activation and mild air oxidation of vacuum pyrolysis biochar. Biomass Bioenergy. 2018;108:101-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2017.10.011.

- Kazawadi D, Ntalikwa J, Kombe G. A review of intermediate pyrolysis as a technology of biomass conversion for coproduction of biooil and adsorption biochar. Journal of Renewable Energy. 2021;2021:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5533780.

- Yang Y, Brammer JG, Mahmood ASN, Hornung A. Intermediate pyrolysis of biomass energy pellets for producing sustainable liquid, gaseous and solid fuels. Bioresour Technol. 2014;169:794-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.044.

- Ibrahim MD, Abakr YA, Gan S, Lee LY, Thangalazhy-Gopakumar S. Intermediate pyrolysis of bambara groundnut shell (BGS) in various inert gases (N2, CO2, and N2/CO2). Energies (Basel). 2022;15:8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228421.

- Oh S, Lee J, Lam SS, Kwon EE, Ha J-M, Tsang DCW, et al. Fast hydropyrolysis of biomass conversion: a comparative review. Bioresour Technol. 2021;342: 126067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126067.

- Stummann MZ, Høj M, Gabrielsen J, Clausen LR, Jensen PA, Jensen AD. A perspective on catalytic hydropyrolysis of biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;143: 110960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110960.

- Marker TL, Felix LG, Linck MB, Roberts MJ. Integrated hydropyrolysis and hydroconversion (IH 2) for the direct production of gasoline and diesel fuels or blending components from biomass, part 1: Proof of principle testing. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2012;31:191-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep. 10629.

- Yin C. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass for liquid biofuels production. Bioresour Technol. 2012;120:273-84. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.biortech.2012.06.016.

- Zhang Y, Chen P, Liu S, Peng P, Min M, Cheng Y, et al. Effects of feedstock characteristics on microwave-assisted pyrolysis – A review. Bioresour Technol. 2017;230:143-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.01.046.

- Zhu L, Lei H, Wang L, Yadavalli G, Zhang X, Wei Y, et al. Biochar of corn stover: Microwave-assisted pyrolysis condition induced changes in surface functional groups and characteristics. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2015;115:149-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2015.07.012.

- Wan Y, Chen P, Zhang B, Yang C, Liu Y, Lin X, et al. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass: Catalysts to improve product selectivity. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2009;86:161-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2009.05.006.

- Priecel P, Lopez-Sanchez JA. Advantages and limitations of microwave reactors: from chemical synthesis to the catalytic valorization of biobased chemicals. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7:3-21. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03286.

- Amalina F, Razak ASA, Krishnan S, Sulaiman H, Zularisam AW, Nasrullah M. Biochar production techniques utilizing biomass waste-derived materials and environmental applications – a review. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2022;7: 100134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100134.

- Zhu L, Zhang Y, Lei H, Zhang X, Wang L, Bu Q, et al. Production of hydrocarbons from biomass-derived biochar assisted microwave catalytic pyrolysis. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2018;2:1781-90. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8SE00096D.

- Mohamed BA, Ellis N, Kim CS, Bi X, Emam AE. Engineered biochar from microwave-assisted catalytic pyrolysis of switchgrass for increasing water-holding capacity and fertility of sandy soil. Sci Total Environ. 2016;566-567:387-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016. 04.169.

- Layek J, Narzari R, Hazarika S, Das A, Rangappa K, Devi S, et al. Prospects of biochar for sustainable agriculture and carbon sequestration: an overview for eastern himalayas. Sustainability. 2022;14:6684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116684.

- Zhu X, Chen B, Zhu L, Xing B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ Pollut. 2017;227:98-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.04.032.

- Liu D, Zhang W, Lin H, Li Y, Lu H, Wang Y. A green technology for the preparation of high capacitance rice husk-based activated carbon. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:1190-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.005.

- Gunes A, Inal A, Taskin MB, Sahin O, Kaya EC, Atakol A. Effect of phosphorus-enriched biochar and poultry manure on growth and mineral composition of lettuce L actuca sativa L. cv. grown in alkaline soil. Soil Use Manag. 2014;30:182-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12114.

- Sakhiya AK, Anand A, Kaushal P. Production, activation, and applications of biochar in recent times. Biochar. 2020;2:253-85. https://doi. org/10.1007/s42773-020-00047-1.

- Jatav HS, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Singh SK, Chejara S, Gorovtsov A, et al. Sustainable approach and safe use of biochar and its possible consequences. Sustainability. 2021;13:10362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810362.

- Yin Y, Li J, Zhu S, Chen Q, Chen C, Rui Y, et al. Effect of biochar application on rice, wheat, and corn seedlings in hydroponic culture. J Environ Sci. 2024;135:379-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.01.023.

- Agegnehu G, Srivastava AK, Bird MI. The role of biochar and biochar-compost in improving soil quality and crop performance: A review. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;119:156-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.06.008.

- Che CA, Heynderickx PM. Hydrothermal carbonization of plastic waste: A review of its potential in alternative energy applications. Fuel Communications. 2024;18: 100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfueco.2023.100103.

- Funke A, Ziegler F. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: A summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuels, Bioprod Biorefin. 2010;4:160-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.198.

- Nizamuddin S, Baloch HA, Griffin GJ, Mubarak NM, Bhutto AW, Abro R, et al. An overview of effect of process parameters on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;73:1289-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.122.

- Fang J, Zhan L, Ok YS, Gao B. Minireview of potential applications of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J Ind Eng Chem. 2018;57:15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.08.026.

- Heidari M , Dutta A , Acharya B , Mahmud S . A review of the current knowledge and challenges of hydrothermal carbonization for biomass conversion. J Energy Inst. 2019;92:1779-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2018.12.003.

- Sharma R, Jasrotia K, Singh N, Ghosh P, et al. A Comprehensive review on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass and its applications. Chemistry Africa. 2020;3:1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42250-019-00098-3.

- Magdziarz A, Wilk M, Wądrzyk M. Pyrolysis of hydrochar derived from biomass – experimental investigation. Fuel. 2020;267: 117246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117246.

- Zhang X, Zhang L, Li A. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass and waste polyvinyl chloride for high-quality solid fuel production: Hydrochar properties and its combustion and pyrolysis behaviors. Bioresour Technol. 2019;294: 122113. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122113.

- Czerwińska K, Śliz M, Wilk M. Hydrothermal carbonization process: Fundamentals, main parameter characteristics and possible applications including an effective method of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation in sewage sludge. A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;154:111873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111873.

- Yaashikaa PR, Kumar PS, Varjani S, Saravanan A. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol Rep. 2020;28: e00570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00570.

- Higman C, van der Burgt M. Gasification Processes. Gasification, Elsevier; 2008, p. 91-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8528-3.00005-5.

- Arumugasamy SK, Selvarajoo A, Tariq MA. Artificial neural networks modelling: gasification behaviour of palm fibre biochar. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2020;3:868-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2020.10.010.

- Yu T, Abudukeranmu A, Anniwaer A, Situmorang YA, Yoshida A, Hao X, et al. Steam gasification of biochars derived from pruned apple branch with various pyrolysis temperatures. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45:18321-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene. 2019.02.226.

- Cahyanti MN, Doddapaneni TRKC, Kikas T. Biomass torrefaction: An overview on process parameters, economic and environmental aspects and recent advancements. Bioresour Technol. 2020;301: 122737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122737.

- Shankar Tumuluru J, Sokhansanj S, Hess JR, Wright CT, Boardman RD. REVIEW: A review on biomass torrefaction process and product properties for energy applications. Ind Biotechnol. 2011;7:384-401. https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2011.7.384.

- Nhuchhen D, Basu P, Acharya B. A comprehensive review on biomass torrefaction. Int J Renew Energy Biofuels. 2014. https://doi. org/10.5171/2014.506376.

- Kanwal S, Chaudhry N, Munir S, Sana H. Effect of torrefaction conditions on the physicochemical characterization of agricultural waste (sugarcane bagasse). Waste Manage. 2019;88:280-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.053.

- Zhang C, Ho S-H, Chen W-H, Fu Y, Chang J-S, Bi X. Oxidative torrefaction of biomass nutshells: Evaluations of energy efficiency as well as biochar transportation and storage. Appl Energy. 2019;235:428-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.090.

- Khitab A, Ahmad S, Khan RA, Arshad MT, Anwar W, Tariq J, et al. Production of biochar and its potential application in cementitious composites. Crystals (Basel). 2021;11:527. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11050527.

- Jiang M, He L, Niazi NK, Wang H, Gustave W, Vithanage M, et al. Nanobiochar for the remediation of contaminated soil and water: challenges and opportunities. Biochar. 2023;5:2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-022-00201-x.

- Rajput VD, Minkina T, Ahmed B, Singh VK, Mandzhieva S, Sushkova S, et al. Nano-biochar: A novel solution for sustainable agriculture and environmental remediation. Environ Res. 2022;210: 112891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112891.

- Tan X, Liu Y, Gu Y, Xu Y, Zeng G, Hu X, et al. Biochar-based nano-composites for the decontamination of wastewater: A review. Bioresour Technol. 2016;212:318-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.04.093.

- Bhushan B, Gupta V, Kotnala S. Development of magnetic-biochar nano-composite: Assessment of its physico-chemical properties. Mater Today Proc. 2020;26:3271-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.911.

- Ramanayaka S, Tsang DCW, Hou D, Ok YS, Vithanage M. Green synthesis of graphitic nanobiochar for the removal of emerging contaminants in aqueous media. Sci Total Environ. 2020;706: 135725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135725.

- Naghdi M, Taheran M, Brar SK, Rouissi T, Verma M, Surampalli RY, et al. A green method for production of nanobiochar by ball mill-ing- optimization and characterization. J Clean Prod. 2017;164:1394-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.084.

- Xing T, Sunarso J, Yang W, Yin Y, Glushenkov AM, Li LH, et al. Ball milling: a green mechanochemical approach for synthesis of nitrogen doped carbon nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2013;5:7970. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr02328a.

- Amusat SO, Kebede TG, Dube S, Nindi MM. Ball-milling synthesis of biochar and biochar-based nanocomposites and prospects for removal of emerging contaminants: A review. J Water Process Eng. 2021;41: 101993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.101993.

- Tan M, Li Y, Chi D, Wu Q. Efficient removal of ammonium in aqueous solution by ultrasonic magnesium-modified biochar. Chem Eng J. 2023;461: 142072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142072.

- Chaubey AK, Pratap T, Preetiva B, Patel M, Singsit JS, Pittman CU, et al. Definitive review of nanobiochar. ACS Omega. 2024. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c07804.

- Song B, Chen M, Zhao L, Qiu H, Cao X. Physicochemical property and colloidal stability of micron- and nano-particle biochar derived from a variety of feedstock sources. Sci Total Environ. 2019;661:685-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.193.

- Chausali N, Saxena J, Prasad R. Nanobiochar and biochar based nanocomposites: advances and applications. J Agric Food Res. 2021;5: 100191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100191.

- Nair VD, Nair PKR, Dari B, Freitas AM, Chatterjee N, Pinheiro FM. Biochar in the agroecosystem-climate-change-sustainability nexus. Front Plant Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02051.

- Kalus K, Koziel J, Opaliński S. A review of biochar properties and their utilization in crop agriculture and livestock production. Appl Sci. 2019;9:3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9173494.

- Li S, Harris S, Anandhi A, Chen G. Predicting biochar properties and functions based on feedstock and pyrolysis temperature: a review and data syntheses. J Clean Prod. 2019;215:890-902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.106.

- Tomczyk A, Sokołowska Z, Boguta P. Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2020;19:191-215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-020-09523-3.

- Khatun M, Hossain M, Joardar JC. Quantifying the acceptance and adoption dynamics of biochar and co-biochar as a sustainable soil amendment. Plant Sci Today. 2024. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.3242.

- El-Naggar A, Jiang W, Tang R, Cai Y, Chang SX. Biochar and soil properties affect remediation of Zn contamination by biochar: A global meta-analysis. Chemosphere. 2024;349: 140983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140983.

- Hussain R, Kumar H, Bordoloi S, Jaykumar S, Salim S, Garg A, et al. Effect of biochar type and amendment rates on soil physicochemical properties: potential application in bioengineered structures. Adv Civ Eng Mater. 2024;13:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1520/ACEM202001 02.

- Wacha K, Philo A, Hatfield JL. Soil energetics: A unifying framework to quantify soil functionality. Agrosyst Geosci Environ. 2022. https:// doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20314.

- Zhu B, Wan B, Liu T, Zhang C, Cheng L, Cheng Y, et al. Biochar enhances multifunctionality by increasing the uniformity of energy flow through a soil nematode food web. Soil Biol Biochem. 2023;183: 109056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109056.

- Marzeddu S, Cappelli A, Ambrosio A, Décima MA, Viotti P, Boni MR. A Life cycle assessment of an energy-biochar chain involving a gasification plant in Italy. Land (Basel). 2021;10:1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111256.

- Yang Q, Mašek O, Zhao L, Nan H, Yu S, Yin J, et al. Country-level potential of carbon sequestration and environmental benefits by utilizing crop residues for biochar implementation. Appl Energy. 2021;282: 116275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116275.

- Woo SH. Biochar for soil carbon sequestration. Clean Technology. 2013;19:201-11. https://doi.org/10.7464/ksct.2013.19.3.201.

- Lyu H, Zhang H, Chu M, Zhang C, Tang J, Chang SX, et al. Biochar affects greenhouse gas emissions in various environments: A critical review. Land Degrad Dev. 2022;33:3327-42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4405.

- Luo L, Wang J, Lv J, Liu Z, Sun T, Yang Y, et al. Carbon sequestration strategies in soil using biochar: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Environ Sci Technol. 2023;57:11357-72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c02620.

- Allohverdi T, Mohanty AK, Roy P, Misra M. A review on current status of biochar uses in agriculture. Molecules. 2021;26:5584. https://doi. org/10.3390/molecules26185584.

- Sun J, Jia Q, Li Y, Zhang T, Chen J, Ren Y, et al. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and biochar on growth, nutrient absorption, and physiological properties of Maize (Zea mays L.). J Fungi. 2022;8:1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8121275.

- Zhang Q, Ge T, Dippold M, Gunina A. Long-term action of biochar in paddy soils: effect on organic carbon and functioning of microbial communities 2023. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu23-5811.

- Ali I, Yuan P, Ullah S, Iqbal A, Zhao Q, Liang H, et al. Biochar amendment and nitrogen fertilizer contribute to the changes in soil properties and microbial communities in a paddy field. Front Microbiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.834751.

- Chen Y, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu X, Qin X, Chen Q, et al. Biochar and flooding increase and change the diazotroph communities in tropical paddy fields. Agriculture. 2024;14:211. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020211.

- Su Y, Wang Y, Liu G, Zhang Z, Li X, Chen G, et al. Nitrogen (N) “supplementation, slow release, and retention” strategy improves N use efficiency via the synergistic effect of biochar, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and dicyandiamide. Sci Total Environ. 2024;908: 168518. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168518.

- Sindhu SS, Rakshiya YS, Sahu G. Biological control of soilborne plant pathogens with rhizosphere bacteria. Pest Technology. 2009;3:10-21.

- Fatima R, Basharat U, Safdar A, Haidri I, Fatima A, Mahmood A, et al. Availability of phosphorous to the soil, their significance for roots of plants and environment. EPH Int J Agriculture Environ Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.53555/eijaer.v10i1.97.

- Palansooriya KN, Wong JTF, Hashimoto Y, Huang L, Rinklebe J, Chang SX, et al. Response of microbial communities to biochar-amended soils: a critical review. Biochar. 2019;1:3-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-019-00009-2.

- Li Q, Zhang J, Ye J, Liu Y, Lin Y, Yi Z, et al. Biochar affects organic carbon composition and stability in highly acidic tea plantation soil. J Environ Manage. 2024;370: 122803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122803.

- Landrat M, Abawalo M, Pikoń K, Fufa PA, Seyid S. Assessing the potential of teff husk for biochar production through slow pyrolysis: effect of pyrolysis temperature on biochar yield. Energies (Basel). 2024;17:1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17091988.

- Feng Z, Fan Z, Song H, Li K, Lu H, Liu Y, et al. Biochar induced changes of soil dissolved organic matter: The release and adsorption of dissolved organic matter by biochar and soil. Sci Total Environ. 2021;783: 147091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147091.

- Enaime G, Lübken M. Agricultural waste-based biochar for agronomic applications. Appl Sci. 2021;11:8914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ app11198914.

- Kabir E, Kim K-H, Kwon EE. Biochar as a tool for the improvement of soil and environment. Front Environ Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fenvs.2023.1324533.

- Li L, Zhang Y-J, Novak A, Yang Y, Wang J. Role of biochar in improving sandy soil water retention and resilience to drought. Water (Basel). 2021;13:407. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13040407.

- Jindo K, Audette Y, Higashikawa FS, Silva CA, Akashi K, Mastrolonardo G, et al. Role of biochar in promoting circular economy in the agriculture sector. Part 1: A review of the biochar roles in soil N, P and K cycles. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2020;7:15. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s40538-020-00182-8.

- Johan PD, Ahmed OH, Omar L, Hasbullah NA. Phosphorus transformation in soils following co-application of charcoal and wood ash. Agronomy. 2021;11:2010. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11102010.

- Kannan P, Krishnaveni D, Ponmani S. Biochars and Its Implications on Soil Health and Crop Productivity in Semi-Arid Environment. Biochar Applications in Agriculture and Environment Management, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020, p. 99-122. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-030-40997-5_5.

- Sanchez-Reinoso AD, Ávila-Pedraza EA, Restrepo H. Use of Biochar in agriculture. Acta Biolo Colomb. 2020;25:327-38. https://doi.org/ 10.15446/abc.v25n2.79466.

- Murtaza G, Ahmed Z, Usman M, Tariq W, Ullah Z, Shareef M, et al. Biochar induced modifications in soil properties and its impacts on crop growth and production. J Plant Nutr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2021.1871746.

- Shaaban A, Se S-M, Mitan NMM, Dimin MF. Characterization of biochar derived from rubber wood sawdust through slow pyrolysis on surface porosities and functional groups. Procedia Eng. 2013;68:365-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2013.12.193.

- Reyes Moreno G, Elena Fernández M, Darghan CE. Balanced mixture of biochar and synthetic fertilizer increases seedling quality of Acacia mangium. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2021;20:371-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2021.04.004.

- Dong CD, Lung SCC, Chen CW, Lee JS, Chen YC, Wang WCV, et al. Assessment of the pulmonary toxic potential of nano-tobacco stempyrolyzed biochars. Environ Sci Nano. 2019;6:1527-35. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EN00968F.

- Purakayastha TJ, Das KC, Gaskin J, Harris K, Smith JL, Kumari S. Effect of pyrolysis temperatures on stability and priming effects of C3 and C4 biochars applied to two different soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2016;155:107-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.07.011.

- Oni BA, Oziegbe O, Olawole OO. Significance of biochar application to the environment and economy. Ann Agric Sci. 2019;64:222-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aoas.2019.12.006.

- Lin Y, Cai Q, Chen B, Garg A. A review of the negative effects of biochar on soil in green infrastructure with consideration of soil properties. Indian Geotech J. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40098-024-00875-z.

- Lentz RD, Ippolito JA. Biochar and manure affect calcareous soil and corn silage nutrient concentrations and uptake. J Environ Qual. 2012;41:1033-43. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2011.0126.

- Yao Y, Gao B, Zhang M, Inyang M, Zimmerman AR. Effect of biochar amendment on sorption and leaching of nitrate, ammonium, and phosphate in a sandy soil. Chemosphere. 2012;89:1467-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.06.002.

- Borchard N, Wolf A, Laabs V, Aeckersberg R, Scherer HW, Moeller A, et al. Physical activation of biochar and its meaning for soil fertility and nutrient leaching – a greenhouse experiment. Soil Use Manag. 2012;28:177-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2012.00407.x.

- Godlewska P, Ok YS, Oleszczuk P. THE DARK SIDE OF BLACK GOLD: Ecotoxicological aspects of biochar and biochar-amended soils. J Hazard Mater. 2021;403: 123833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123833.

- Nogueira Cardoso EJB, Lopes Alves PR. Soil Ecotoxicology. Ecotoxicology, InTech; 2012. https://doi.org/10.5772/28447.

- Lu W, Ding W, Zhang J, Li Y, Luo J, Bolan N, et al. Biochar suppressed the decomposition of organic carbon in a cultivated sandy loam soil: A negative priming effect. Soil Biol Biochem. 2014;76:12-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.04.029.

- Tang Y, Li Y, Cockerill TT. Environmental and economic spatial analysis system for biochar production – Case studies in the East of England and the East Midlands. Biomass Bioenergy. 2024;184: 107187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2024.107187.

- Meyer S, Glaser B, Quicker P. Technical, economical, and climate-related aspects of biochar production technologies: a literature review. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:9473-83. https://doi.org/10.1021/es201792c.

- You S, Li W, Zhang W, Lim H, Kua HW, Park Y-K, et al. Energy, economic, and environmental impacts of sustainable biochar systems in rural China. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2022;52:1063-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2020.1848170.

- Supraja KV, Kachroo H, Viswanathan G, Verma VK, Behera B, Doddapaneni TRKC, et al. Biochar production and its environmental applications: Recent developments and machine learning insights. Bioresour Technol. 2023;387: 129634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech. 2023.129634.

- Ahmed SF, Mehejabin F, Chowdhury AA, Almomani F, Khan NA, Badruddin IA, et al. Biochar produced from waste-based feedstocks: Mechanisms, affecting factors, economy, utilization, challenges, and prospects. GCB Bioenergy. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb. 13175.

- Lee M, Lin Y-L, Chiueh P-T, Den W. Environmental and energy assessment of biomass residues to biochar as fuel: A brief review with recommendations for future bioenergy systems. J Clean Prod. 2020;251: 119714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119714.

- Kuppusamy S, Thavamani P, Megharaj M, Venkateswarlu K, Naidu R. Agronomic and remedial benefits and risks of applying biochar to soil: Current knowledge and future research directions. Environ Int. 2016;87:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.018.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44378-025-00041-8

Publication Date: 2025-03-03

Review

Biochar as a Soil amendment: implications for soil health, carbon sequestration, and climate resilience

Published online: 03 March 2025

© The Author(s) 2025 OPEN

Abstract

Biochar, a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of organic biomass, has gained increasing attention as a sustainable soil amendment due to its potential to enhance soil health, improve agricultural productivity, and mitigate climate change. This review explores the multifaceted benefits of biochar, including its ability to sequester carbon for long periods, thereby reducing atmospheric greenhouse gases. Biochar’s unique properties, such as its porous structure, high cation exchange capacity, and nutrient retention capabilities, significantly enhance soil fertility, water-holding capacity, and microbial activity. These improvements increase crop resilience against drought, soil erosion, and nutrient loss, supporting climate-resilient agricultural systems. Additionally, biochar’s application can lower nitrous oxide and methane emissions from soils, further contributing to climate change mitigation. However, the effectiveness of biochar is influenced by factors such as feedstock type, pyrolysis conditions, and application rates. Understanding these variables is crucial for optimizing biochar’s use in different soil types and environmental conditions.

Highlights

- Pyrolysis techniques were reviewed to optimize biochar properties and applications.

- Boosts soil nutrient retention, water capacity, and organic matter durability.

- Cuts greenhouse gases while enhancing sustainable soil health.

- Sequesters carbon for up to 2,000 years, supporting climate change mitigation.

1 Introduction

of development does not change, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ Population Division (2019) estimates that the world’s population will reach 9.4 to 10.1 billion by 2050 . Based on various projections, global food consumption is projected to increase by

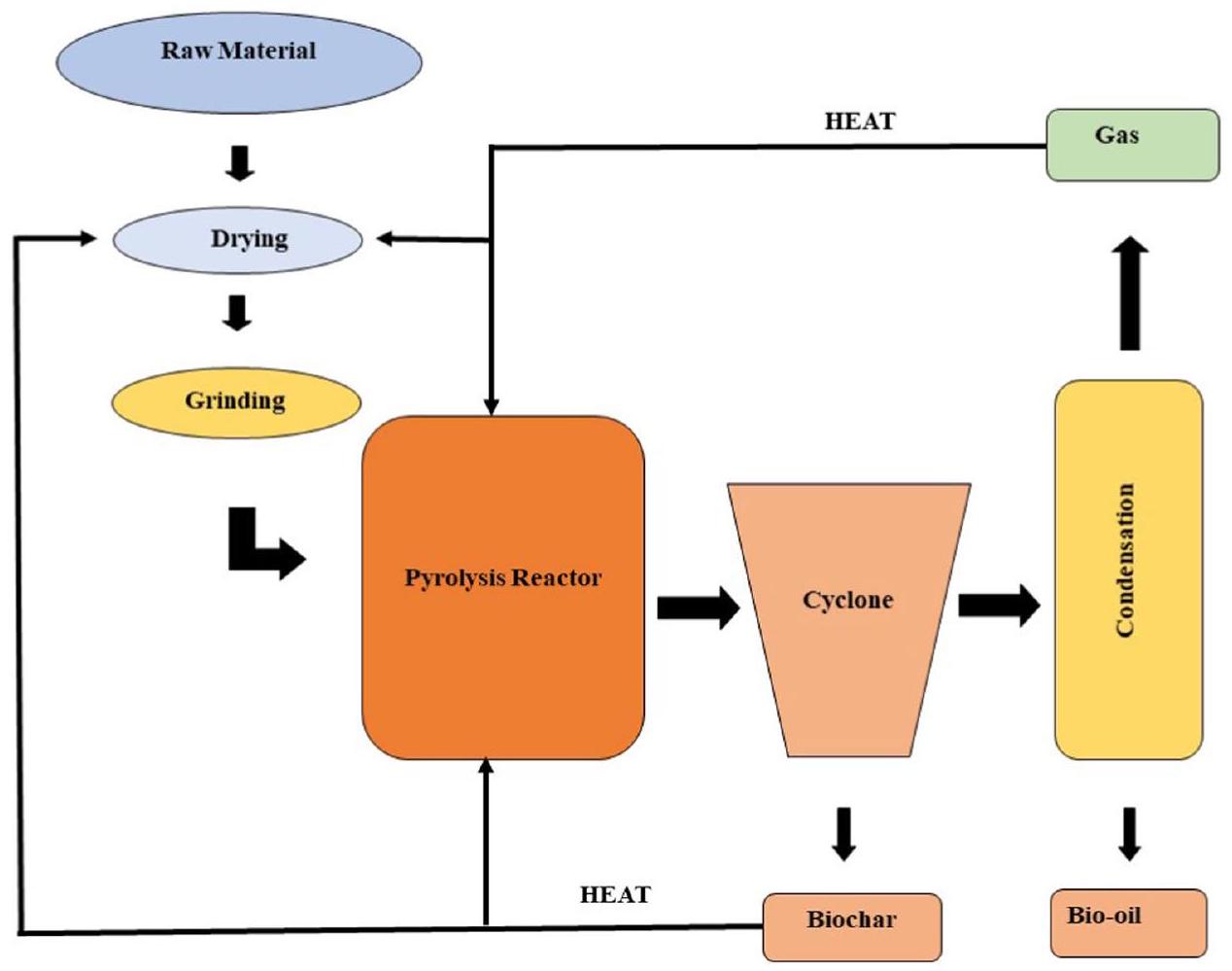

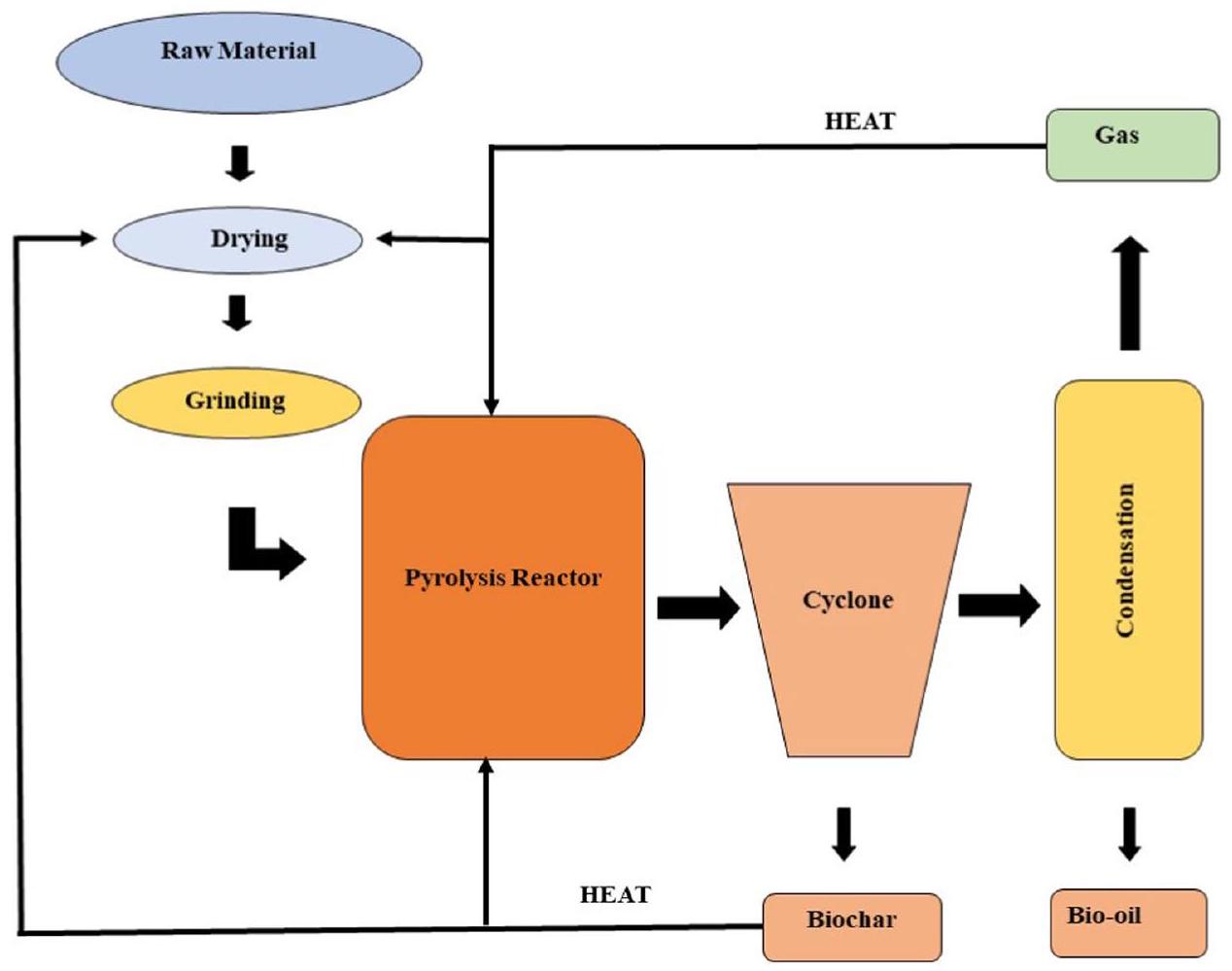

2 Biochar production methods

2.1 Pyrolysis

| Biomass | Pyrolysis temperature | pH | C% | N% | P% | K% | References |

| Paper mill waste |

|

9.4 | 50.0 | 0.48 | – | 0.22 | [68] |

| Green waste (cotton trash, grass, and plant pruning) |

|

6.2 | 36.0 | 0.18 | – | 1.00 | [69] |

| Rice husk |

|

9.5 | 48 | 10 | 15 | 20 | [70] |

| Poultry litter |

|

9.9 | 38.0 | 2.00 | 37.42 | 0 | [71] |

| Sewage sludge |

|

– | 47.0 | 6.4 | 5.6 | – | [72] |

| Corn residue |

|

– | 79.0 | 9.2 | – | 6.7 | [73] |

| Eucalyptus biochar |

|

– | 82.4 | 0.57 | 1.87 | – | [68] |

| Wheat straw |

|

9.7 | 65.70 | 1.05 | 0.1 | 1.2 | [74] |

| Wood (Pinus ponderosa) | Wildfire | 6.7 | 74.0 | 16.6 | 13.6 | – | [73] |

| Pecan shell (Carya illinoinensis) |

|

7.6 | 83.4 | 1.7 | – | – | [69] |

| Hardwood sawdust |

|

12.1 | 66.5 | 0.3 | – | – | [75] |

2.1.1 Slow pyrolysis

2.1.2 Fast pyrolysis

2.1.3 Flash pyrolysis

2.1.4 Vacuum pyrolysis

2.1.5 Intermediate pyrolysis

2.1.6 Microwave-assisted pyrolysis

2.2 Hydrothermal carbonization

compared to pyrolysis, which is an added benefit. One reason is that HTC functions at reduced temperatures compared to pyrolysis and does not necessitate feedstock drying [79]. It can greatly improve soil conditions and can be utilized to capture carbon to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Multiple studies have shown that the hydrochar produced during hydrothermal carbonization is resistant to change or decomposition. The presence of biocarbon enhanced both runoff and retention. Research suggests that incorporating hydrochar into soil can enhance its capacity to hold nutrients and water. The hydrochar pores promote storage and control of nutrient release [84].

2.3 Gasification

2.4 Torrefaction

has a significant effect on the physiochemical attributes of nano-BC. Nanobiochar containing low amounts of carbon and oxygen is usually produced from biomass that is rich in hemicellulose [98]. The opposite is true for materials with a high lignin content; these materials usually produce nano-BC that can clump together quite well. Nanobiochars made from wicker and wheat straw contained mostly small particles with an open structure. Unlike the first two nano-BCs, miscanthus nano-BC exhibited fewer aggregation effects and had big spherical particles. Agricultural waste nano-BC also had a direct proportionate effect on the bulk biochar’s ash content, whereas municipal waste nano-BC did not [99]. From bulk biochar, nano-BC is made with a couple of additional steps.

2.4.1 Milling method

2.4.2 Ultra-sonication technique

3 Properties of Biochar

content, surface basicity, and decrease in surface acidity. During rapid pyrolysis, biomass is rapidly heated to temperatures between

4 Biochar impact on soil energy dynamics

5 Biochar impact on soil properties

5.1 Effects on soil structure and composition

| Type of biochar | Pyrolysis temperature | Rate of application | Responses found | References |

| Paper mill waste |

|

|

Increased germination | [139] |

| Corn straw |

|

0%, 3%, and 5% | The infiltration rate diminished as the biochar application rate increased | [139] |

| Corn stover |

|

10 and

|

Lowered soil bulk density | [140] |

| Sawdust |

|

|

Enhances the soil’s water retention capacity | [141] |

| Rice husk |

|

0, 1, 3 and 9% | Enhances the soil’s water retention capacity | [140] |

| Acacia mangium bark biochar |

|

|

Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungi increased by

|

[25, 142] |

| Tobacco stalk biochar |

|

|

Improved the soil pH and inhibited N and K leaching in light-textured soils | [143] |

| Green waste |

|

|

At the highest rates with N application,

|

[15] |

| Poultry manure |

|

|

Increased N, P, K, Ca, and Mg availability in the soil | [139] |

| Peanut shells |

|

0%, 5%, and 20% | Increased

|

[140] |

5.2 Effects on soil water retention capacity

5.3 Effects on soil nitrogen

5.4 Effects on soil phosphorous

5.5 Effects on other nutrients

6 Carbon sequestration potential of biochar and its effect on climate change

7 Limitations of Biochar

8 Conclusion and future directions

regarding biochar’s impact on crop yields by focusing on soil types, fertilizer management, and environmental conditions. This will aid in optimizing biochar applications for real-world agricultural systems.

Author contributions Suprity Shyam has reviewed and prepared the first draft of the manuscript; Selima Ahmed collected data and reviewed parts of this article; Sanket J Joshi edited and reviwed the manuscript; Hemen Sarma has conceptualized and edited the manuscript.

Code availability Not applicable.

Declarations

References

- Malyan SK, Kumar SS, Fagodiya RK, Ghosh P, Kumar A, Singh R, et al. Biochar for environmental sustainability in the energy-wateragroecosystem nexus. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;149: 111379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111379.

- Vijay V, Shreedhar S, Adlak K, Payyanad S, Sreedharan V, Gopi G, et al. Review of large-scale biochar field-trials for soil amendment and the observed influences on crop yield variations. Front Energy Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.710766.

- Martínez-Gómez Á, Poveda J, Escobar C. Overview of the use of biochar from main cereals to stimulate plant growth. Front Plant Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.912264.

- Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Krupnik TJ, Rahut DB, Jat ML, Stirling CM. Factors affecting farmers’ use of organic and inorganic fertilizers in South Asia. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:51480-96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13975-7.

- Agegnehu G, Bass AM, Nelson PN, Bird MI. Benefits of biochar, compost, and biochar-compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in a tropical agricultural soil. Sci Total Environ. 2016;543:295-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.054.

- Singh B, Singh BP, Cowie AL. Characterisation and evaluation of biochars for their application as a soil amendment. Soil Research. 2010;48:516. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR10058.

- Rawat J, Saxena J, Biochar SP. A sustainable approach for improving plant growth and soil properties. Biochar – an imperative amendment for soil and the environment. IntechOpen. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82151.

- Beheshti M, Etesami H, Alikhani HA. Effect of different biochars amendment on soil biological indicators in a calcareous soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:14752-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1682-2.

- Amalina F, Abd Razak AS, Zularisam AW, Aziz MAA, Krishnan S, Nasrullah M. Comprehensive assessment of biochar integration in agricultural soil conditioning: advantages, drawbacks, and prospects. Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C. 2023;132: 103508. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.pce.2023.103508.

- Umair Hassan M, Huang G, Munir R, Khan TA, Noor MA. Biochar co-compost: a promising soil amendment to restrain greenhouse gases and improve rice productivity and soil fertility. Agronomy. 2024;14:1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071583.

- Gao S, Harrison BP, Thao T, Gonzales ML, An D, Ghezzehei TA, et al. Biochar co-compost improves nitrogen retention and reduces carbon emissions in a winter wheat cropping system. GCB Bioenergy. 2023;15:462-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.13028.

- Xu H. Analysis of the relationship between biochar and soil highlights in science. Eng Technol. 2022;26:59-64. https://doi.org/10.54097/ hset.v26i.3643.

- Aslam S, Nazir A. Valorizing combustible and compostable fractions of municipal solid waste to Biochar and compost as an alternative to chemical fertilizer for improving soil health and sunflower yield. Agronomy. 2024;14:1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071449.

- Sarma H, Shyam S, Zhang M, Guerriero G. Nano-biochar interactions with contaminants in the rhizosphere and their implications for plant-soil dynamics. Soil Environ Health. 2024;2: 100095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seh.2024.100095.

- Shareef TME, Zhao B. Review paper: the fundamentals of Biochar as a soil amendment tool and management in agriculture scope: an overview for farmers and gardeners. J Agric Chem Environ. 2017;06:38-61. https://doi.org/10.4236/jacen.2017.61003.

- Bo X, Zhang Z, Wang J, Guo S, Li Z, Lin H, et al. Benefits and limitations of biochar for climate-smart agriculture: a review and case study from China. Biochar. 2023;5:77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-023-00279-x.

- Joseph SD, Camps-Arbestain M, Lin Y, Munroe P, Chia CH, Hook J, et al. An investigation into the reactions of biochar in soil. Soil Research. 2010;48:501. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR10009.

- Barnes AD, Jochum M, Lefcheck JS, Eisenhauer N, Scherber C, O’Connor MI, et al. Energy flux: the link between multitrophic biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol Evol. 2018;33:186-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.12.007.

- LeCroy C, Masiello CA, Rudgers JA, Hockaday WC, Silberg JJ. Nitrogen, biochar, and mycorrhizae: alteration of the symbiosis and oxidation of the char surface. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;58:248-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.11.023.

- Wang M, Fu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Shen J, Liu X, et al. Pathways and mechanisms by which biochar application reduces nitrogen and phosphorus runoff losses from a rice agroecosystem. Sci Total Environ. 2021;797: 149193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149193.

- Sánchez-Monedero MA, Cayuela ML, Sánchez-García M, Vandecasteele B, D’Hose T, López G, et al. Agronomic evaluation of Biochar, compost and biochar-blended compost across different cropping systems: perspective from the european project FERTIPLUS. Agronomy. 2019;9:225. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9050225.

- Anand A, Kumar R, Kumar V, Kaushal P. Carbon sequestration in soil from paddy straw derived biochar in India. 2022 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Energy, Environment and Climate Change (ICUE), IEEE; 2022, p. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ ICUE55325.2022.10113534

- Murali M, Gayathri M, Singh V, Raj S, Singh V, Chaubey C, et al. Soil carbon sequestration in the age of climate change: a review. Int J Environ Climate Change. 2023;13:1668-77. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijecc/2023/v13i113322.

- Singh Yadav SP, Bhandari S, Bhatta D, Poudel A, Bhattarai S, Yadav P, et al. Biochar application: a sustainable approach to improve soil health. J Agric Food Res. 2023;11: 100498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100498.

- Premalatha RP, Poorna Bindu J, Nivetha E, Malarvizhi P, Manorama K, Parameswari E, et al. A review on biochar’s effect on soil properties and crop growth. Front Energy Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1092637.

- Gul S, Whalen JK, Thomas BW, Sachdeva V, Deng H. Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: Mechanisms and future directions. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015;206:46-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.03.015.

- Han L, Sun K, Yang Y, Xia X, Li F, Yang Z, et al. Biochar’s stability and effect on the content, composition and turnover of soil organic carbon. Geoderma. 2020;364: 114184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114184.

- Waheed QMK, Nahil MA, Williams PT. Pyrolysis of waste biomass: investigation of fast pyrolysis and slow pyrolysis process conditions on product yield and gas composition. J Energy Inst. 2013;86:233-41. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743967113Z.00000000067.

- Pecha MB, Garcia-Perez M. Pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: oil, char, and gas. Bioenergy. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815497-7.00029-4.

- Czernik S, Bridgwater AV. Overview of applications of biomass fast pyrolysis oil. Energy Fuels. 2004;18:590-8. https://doi.org/10. 1021/ef034067u.

- Zhang P, Duan W, Peng H, Pan B, Xing B. Functional biochar and its balanced design. ACS Environmental Au. 2022;2:115-27. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acsenvironau.1c00032.

- Torri IDV, Paasikallio V, Faccini CS, Huff R, Caramão EB, Sacon V, et al. Bio-oil production of softwood and hardwood forest industry residues through fast and intermediate pyrolysis and its chromatographic characterization. Bioresour Technol. 2016;200:680-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.086.

- Kwaku Armah E, Chetty M, Adebisi Adedeji J, Erwin Estrice D, Mutsvene B, Singh N, et al. Biochar: production, application and the future. Biochar – productive technologies, properties and applications. IntechOpen. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen. 105070.

- Lee Y, Eum P-R-B, Ryu C, Park Y-K, Jung J-H, Hyun S. Characteristics of biochar produced from slow pyrolysis of Geodae-Uksae 1. Bioresour Technol. 2013;130:345-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.012.

- Lu J-S, Chang Y, Poon C-S, Lee D-J. Slow pyrolysis of municipal solid waste (MSW): A review. Bioresour Technol. 2020;312: 123615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123615.

- Sonowal S, Koch N, Sarma H, Prasad K, Prasad R. A review on magnetic nanobiochar with their use in environmental remediation and high-value applications. J Nanomater. 2023;2023:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4881952.

- Li C, Zhang L, Gao Y, Li A. Facile synthesis of nano ZnO/ZnS modified biochar by directly pyrolyzing of zinc contaminated corn stover for

and removals. Waste Manage. 2018;79:625-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.08.035. - Venderbosch RH. Fast Pyrolysis. Thermochemical Processing of Biomass, Wiley; 2019, p. 175-206. https://doi.org/10.1002/97811 19417637.ch6.

- Onay O, Kockar OM. Slow, fast and flash pyrolysis of rapeseed. Renew Energy. 2003;28:2417-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-1481(03)00137-X.

- Kim KH, Kim J-Y, Cho T-S, Choi JW. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on physicochemical properties of biochar obtained from the fast pyrolysis of pitch pine (Pinus rigida). Bioresour Technol. 2012;118:158-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.094.

- Bridgwater AV, Meier D, Radlein D. An overview of fast pyrolysis of biomass. Org Geochem. 1999;30:1479-93. https://doi.org/10. 1016/S0146-6380(99)00120-5.

- Graham RG, Bergougnou MA, Overend RP. Fast pyrolysis of biomass. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 1984;6:95-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/ 0165-2370(84)80008-X.

- Ighalo JO, Iwuchukwu FU, Eyankware OE, Iwuozor KO, Olotu K, Bright OC, et al. Flash pyrolysis of biomass: a review of recent advances. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2022;24:2349-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-022-02339-5.

- Nyoni B, Fouda-Mbanga BG, Hlabano-Moyo BM, Nthwane YB, Yalala B, Tywabi-Ngeva Z, et al. The Potential of Agricultural Waste Chars as Low-Cost Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal From Water, 2024, p. 244-70. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-1618-4. ch011.

- Scott DS, Piskorz J. The continuous flash pyrolysis of biomass. Can J Chem Eng. 1984;62:404-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.54506 20319.

- Sowmya Dhanalakshmi C, Kaliappan S, Mohammed Ali H, Sekar S, Depoures MV, Patil PP, et al. Flash pyrolysis experiment on albizia odoratissima biomass under different operating conditions: a comparative study on bio-oil, biochar, and noncondensable gas products. J Chem. 2022;2022:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9084029.

- Madhu P, Kanagasabapathy H, Manickam IN. Flash pyrolysis of palmyra palm ( Borassus flabellifer) using an electrically heated fluidized bed reactor. Energy Sources. 2016;38:1699-705. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2014.956192.

- Miranda R, Pakdel H, Roy C, Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of commingled plastics containing PVC II. Product analysis Polym Degrad Stab. 2001;73:47-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(01)00066-0.

- Nugroho RAA, Alhikami AF, Wang W-C. Thermal decomposition of polypropylene plastics through vacuum pyrolysis. Energy. 2023;277: 127707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127707.

- Miranda R, Yang J, Roy C, Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of PVC I. Kinetic study Polym Degrad Stab. 1999;64:127-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0141-3910(98)00186-4.

- Boucher ME, Chaala A, Pakdel H, Roy C. Bio-oils obtained by vacuum pyrolysis of softwood bark as a liquid fuel for gas turbines. Part II: Stability and ageing of bio-oil and its blends with methanol and a pyrolytic aqueous phase. Biomass Bioenergy. 2000;19:351-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00044-1.

- Carrier M, Hardie AG, Uras Ü, Görgens J. Knoetze J Production of char from vacuum pyrolysis of South-African sugar cane bagasse and its characterization as activated carbon and biochar. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2012;96:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2012. 02.016.

- Bardestani R, Kaliaguine S. Steam activation and mild air oxidation of vacuum pyrolysis biochar. Biomass Bioenergy. 2018;108:101-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2017.10.011.

- Kazawadi D, Ntalikwa J, Kombe G. A review of intermediate pyrolysis as a technology of biomass conversion for coproduction of biooil and adsorption biochar. Journal of Renewable Energy. 2021;2021:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5533780.

- Yang Y, Brammer JG, Mahmood ASN, Hornung A. Intermediate pyrolysis of biomass energy pellets for producing sustainable liquid, gaseous and solid fuels. Bioresour Technol. 2014;169:794-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.044.

- Ibrahim MD, Abakr YA, Gan S, Lee LY, Thangalazhy-Gopakumar S. Intermediate pyrolysis of bambara groundnut shell (BGS) in various inert gases (N2, CO2, and N2/CO2). Energies (Basel). 2022;15:8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228421.

- Oh S, Lee J, Lam SS, Kwon EE, Ha J-M, Tsang DCW, et al. Fast hydropyrolysis of biomass conversion: a comparative review. Bioresour Technol. 2021;342: 126067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126067.

- Stummann MZ, Høj M, Gabrielsen J, Clausen LR, Jensen PA, Jensen AD. A perspective on catalytic hydropyrolysis of biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;143: 110960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110960.

- Marker TL, Felix LG, Linck MB, Roberts MJ. Integrated hydropyrolysis and hydroconversion (IH 2) for the direct production of gasoline and diesel fuels or blending components from biomass, part 1: Proof of principle testing. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2012;31:191-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep. 10629.

- Yin C. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass for liquid biofuels production. Bioresour Technol. 2012;120:273-84. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.biortech.2012.06.016.

- Zhang Y, Chen P, Liu S, Peng P, Min M, Cheng Y, et al. Effects of feedstock characteristics on microwave-assisted pyrolysis – A review. Bioresour Technol. 2017;230:143-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.01.046.

- Zhu L, Lei H, Wang L, Yadavalli G, Zhang X, Wei Y, et al. Biochar of corn stover: Microwave-assisted pyrolysis condition induced changes in surface functional groups and characteristics. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2015;115:149-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2015.07.012.

- Wan Y, Chen P, Zhang B, Yang C, Liu Y, Lin X, et al. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass: Catalysts to improve product selectivity. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2009;86:161-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2009.05.006.

- Priecel P, Lopez-Sanchez JA. Advantages and limitations of microwave reactors: from chemical synthesis to the catalytic valorization of biobased chemicals. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7:3-21. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03286.

- Amalina F, Razak ASA, Krishnan S, Sulaiman H, Zularisam AW, Nasrullah M. Biochar production techniques utilizing biomass waste-derived materials and environmental applications – a review. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2022;7: 100134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100134.

- Zhu L, Zhang Y, Lei H, Zhang X, Wang L, Bu Q, et al. Production of hydrocarbons from biomass-derived biochar assisted microwave catalytic pyrolysis. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2018;2:1781-90. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8SE00096D.

- Mohamed BA, Ellis N, Kim CS, Bi X, Emam AE. Engineered biochar from microwave-assisted catalytic pyrolysis of switchgrass for increasing water-holding capacity and fertility of sandy soil. Sci Total Environ. 2016;566-567:387-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016. 04.169.

- Layek J, Narzari R, Hazarika S, Das A, Rangappa K, Devi S, et al. Prospects of biochar for sustainable agriculture and carbon sequestration: an overview for eastern himalayas. Sustainability. 2022;14:6684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116684.

- Zhu X, Chen B, Zhu L, Xing B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ Pollut. 2017;227:98-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.04.032.

- Liu D, Zhang W, Lin H, Li Y, Lu H, Wang Y. A green technology for the preparation of high capacitance rice husk-based activated carbon. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:1190-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.005.

- Gunes A, Inal A, Taskin MB, Sahin O, Kaya EC, Atakol A. Effect of phosphorus-enriched biochar and poultry manure on growth and mineral composition of lettuce L actuca sativa L. cv. grown in alkaline soil. Soil Use Manag. 2014;30:182-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12114.

- Sakhiya AK, Anand A, Kaushal P. Production, activation, and applications of biochar in recent times. Biochar. 2020;2:253-85. https://doi. org/10.1007/s42773-020-00047-1.

- Jatav HS, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Singh SK, Chejara S, Gorovtsov A, et al. Sustainable approach and safe use of biochar and its possible consequences. Sustainability. 2021;13:10362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810362.

- Yin Y, Li J, Zhu S, Chen Q, Chen C, Rui Y, et al. Effect of biochar application on rice, wheat, and corn seedlings in hydroponic culture. J Environ Sci. 2024;135:379-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.01.023.

- Agegnehu G, Srivastava AK, Bird MI. The role of biochar and biochar-compost in improving soil quality and crop performance: A review. Appl Soil Ecol. 2017;119:156-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.06.008.

- Che CA, Heynderickx PM. Hydrothermal carbonization of plastic waste: A review of its potential in alternative energy applications. Fuel Communications. 2024;18: 100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfueco.2023.100103.

- Funke A, Ziegler F. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: A summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuels, Bioprod Biorefin. 2010;4:160-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.198.

- Nizamuddin S, Baloch HA, Griffin GJ, Mubarak NM, Bhutto AW, Abro R, et al. An overview of effect of process parameters on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;73:1289-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.122.

- Fang J, Zhan L, Ok YS, Gao B. Minireview of potential applications of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. J Ind Eng Chem. 2018;57:15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.08.026.

- Heidari M , Dutta A , Acharya B , Mahmud S . A review of the current knowledge and challenges of hydrothermal carbonization for biomass conversion. J Energy Inst. 2019;92:1779-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2018.12.003.

- Sharma R, Jasrotia K, Singh N, Ghosh P, et al. A Comprehensive review on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass and its applications. Chemistry Africa. 2020;3:1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42250-019-00098-3.

- Magdziarz A, Wilk M, Wądrzyk M. Pyrolysis of hydrochar derived from biomass – experimental investigation. Fuel. 2020;267: 117246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117246.

- Zhang X, Zhang L, Li A. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass and waste polyvinyl chloride for high-quality solid fuel production: Hydrochar properties and its combustion and pyrolysis behaviors. Bioresour Technol. 2019;294: 122113. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122113.

- Czerwińska K, Śliz M, Wilk M. Hydrothermal carbonization process: Fundamentals, main parameter characteristics and possible applications including an effective method of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation in sewage sludge. A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;154:111873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111873.

- Yaashikaa PR, Kumar PS, Varjani S, Saravanan A. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol Rep. 2020;28: e00570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00570.

- Higman C, van der Burgt M. Gasification Processes. Gasification, Elsevier; 2008, p. 91-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8528-3.00005-5.

- Arumugasamy SK, Selvarajoo A, Tariq MA. Artificial neural networks modelling: gasification behaviour of palm fibre biochar. Mater Sci Energy Technol. 2020;3:868-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2020.10.010.

- Yu T, Abudukeranmu A, Anniwaer A, Situmorang YA, Yoshida A, Hao X, et al. Steam gasification of biochars derived from pruned apple branch with various pyrolysis temperatures. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45:18321-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene. 2019.02.226.

- Cahyanti MN, Doddapaneni TRKC, Kikas T. Biomass torrefaction: An overview on process parameters, economic and environmental aspects and recent advancements. Bioresour Technol. 2020;301: 122737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122737.

- Shankar Tumuluru J, Sokhansanj S, Hess JR, Wright CT, Boardman RD. REVIEW: A review on biomass torrefaction process and product properties for energy applications. Ind Biotechnol. 2011;7:384-401. https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2011.7.384.

- Nhuchhen D, Basu P, Acharya B. A comprehensive review on biomass torrefaction. Int J Renew Energy Biofuels. 2014. https://doi. org/10.5171/2014.506376.

- Kanwal S, Chaudhry N, Munir S, Sana H. Effect of torrefaction conditions on the physicochemical characterization of agricultural waste (sugarcane bagasse). Waste Manage. 2019;88:280-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.053.

- Zhang C, Ho S-H, Chen W-H, Fu Y, Chang J-S, Bi X. Oxidative torrefaction of biomass nutshells: Evaluations of energy efficiency as well as biochar transportation and storage. Appl Energy. 2019;235:428-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.090.

- Khitab A, Ahmad S, Khan RA, Arshad MT, Anwar W, Tariq J, et al. Production of biochar and its potential application in cementitious composites. Crystals (Basel). 2021;11:527. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11050527.

- Jiang M, He L, Niazi NK, Wang H, Gustave W, Vithanage M, et al. Nanobiochar for the remediation of contaminated soil and water: challenges and opportunities. Biochar. 2023;5:2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-022-00201-x.

- Rajput VD, Minkina T, Ahmed B, Singh VK, Mandzhieva S, Sushkova S, et al. Nano-biochar: A novel solution for sustainable agriculture and environmental remediation. Environ Res. 2022;210: 112891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112891.

- Tan X, Liu Y, Gu Y, Xu Y, Zeng G, Hu X, et al. Biochar-based nano-composites for the decontamination of wastewater: A review. Bioresour Technol. 2016;212:318-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.04.093.

- Bhushan B, Gupta V, Kotnala S. Development of magnetic-biochar nano-composite: Assessment of its physico-chemical properties. Mater Today Proc. 2020;26:3271-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.911.

- Ramanayaka S, Tsang DCW, Hou D, Ok YS, Vithanage M. Green synthesis of graphitic nanobiochar for the removal of emerging contaminants in aqueous media. Sci Total Environ. 2020;706: 135725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135725.

- Naghdi M, Taheran M, Brar SK, Rouissi T, Verma M, Surampalli RY, et al. A green method for production of nanobiochar by ball mill-ing- optimization and characterization. J Clean Prod. 2017;164:1394-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.084.

- Xing T, Sunarso J, Yang W, Yin Y, Glushenkov AM, Li LH, et al. Ball milling: a green mechanochemical approach for synthesis of nitrogen doped carbon nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2013;5:7970. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr02328a.

- Amusat SO, Kebede TG, Dube S, Nindi MM. Ball-milling synthesis of biochar and biochar-based nanocomposites and prospects for removal of emerging contaminants: A review. J Water Process Eng. 2021;41: 101993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.101993.

- Tan M, Li Y, Chi D, Wu Q. Efficient removal of ammonium in aqueous solution by ultrasonic magnesium-modified biochar. Chem Eng J. 2023;461: 142072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142072.

- Chaubey AK, Pratap T, Preetiva B, Patel M, Singsit JS, Pittman CU, et al. Definitive review of nanobiochar. ACS Omega. 2024. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c07804.

- Song B, Chen M, Zhao L, Qiu H, Cao X. Physicochemical property and colloidal stability of micron- and nano-particle biochar derived from a variety of feedstock sources. Sci Total Environ. 2019;661:685-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.193.

- Chausali N, Saxena J, Prasad R. Nanobiochar and biochar based nanocomposites: advances and applications. J Agric Food Res. 2021;5: 100191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100191.

- Nair VD, Nair PKR, Dari B, Freitas AM, Chatterjee N, Pinheiro FM. Biochar in the agroecosystem-climate-change-sustainability nexus. Front Plant Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02051.

- Kalus K, Koziel J, Opaliński S. A review of biochar properties and their utilization in crop agriculture and livestock production. Appl Sci. 2019;9:3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9173494.

- Li S, Harris S, Anandhi A, Chen G. Predicting biochar properties and functions based on feedstock and pyrolysis temperature: a review and data syntheses. J Clean Prod. 2019;215:890-902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.106.

- Tomczyk A, Sokołowska Z, Boguta P. Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2020;19:191-215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-020-09523-3.

- Khatun M, Hossain M, Joardar JC. Quantifying the acceptance and adoption dynamics of biochar and co-biochar as a sustainable soil amendment. Plant Sci Today. 2024. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.3242.

- El-Naggar A, Jiang W, Tang R, Cai Y, Chang SX. Biochar and soil properties affect remediation of Zn contamination by biochar: A global meta-analysis. Chemosphere. 2024;349: 140983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140983.

- Hussain R, Kumar H, Bordoloi S, Jaykumar S, Salim S, Garg A, et al. Effect of biochar type and amendment rates on soil physicochemical properties: potential application in bioengineered structures. Adv Civ Eng Mater. 2024;13:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1520/ACEM202001 02.

- Wacha K, Philo A, Hatfield JL. Soil energetics: A unifying framework to quantify soil functionality. Agrosyst Geosci Environ. 2022. https:// doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20314.

- Zhu B, Wan B, Liu T, Zhang C, Cheng L, Cheng Y, et al. Biochar enhances multifunctionality by increasing the uniformity of energy flow through a soil nematode food web. Soil Biol Biochem. 2023;183: 109056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109056.

- Marzeddu S, Cappelli A, Ambrosio A, Décima MA, Viotti P, Boni MR. A Life cycle assessment of an energy-biochar chain involving a gasification plant in Italy. Land (Basel). 2021;10:1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111256.

- Yang Q, Mašek O, Zhao L, Nan H, Yu S, Yin J, et al. Country-level potential of carbon sequestration and environmental benefits by utilizing crop residues for biochar implementation. Appl Energy. 2021;282: 116275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116275.

- Woo SH. Biochar for soil carbon sequestration. Clean Technology. 2013;19:201-11. https://doi.org/10.7464/ksct.2013.19.3.201.

- Lyu H, Zhang H, Chu M, Zhang C, Tang J, Chang SX, et al. Biochar affects greenhouse gas emissions in various environments: A critical review. Land Degrad Dev. 2022;33:3327-42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4405.

- Luo L, Wang J, Lv J, Liu Z, Sun T, Yang Y, et al. Carbon sequestration strategies in soil using biochar: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Environ Sci Technol. 2023;57:11357-72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c02620.

- Allohverdi T, Mohanty AK, Roy P, Misra M. A review on current status of biochar uses in agriculture. Molecules. 2021;26:5584. https://doi. org/10.3390/molecules26185584.

- Sun J, Jia Q, Li Y, Zhang T, Chen J, Ren Y, et al. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and biochar on growth, nutrient absorption, and physiological properties of Maize (Zea mays L.). J Fungi. 2022;8:1275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8121275.

- Zhang Q, Ge T, Dippold M, Gunina A. Long-term action of biochar in paddy soils: effect on organic carbon and functioning of microbial communities 2023. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu23-5811.

- Ali I, Yuan P, Ullah S, Iqbal A, Zhao Q, Liang H, et al. Biochar amendment and nitrogen fertilizer contribute to the changes in soil properties and microbial communities in a paddy field. Front Microbiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.834751.

- Chen Y, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu X, Qin X, Chen Q, et al. Biochar and flooding increase and change the diazotroph communities in tropical paddy fields. Agriculture. 2024;14:211. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14020211.