DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01887-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38539198

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-28

التأثيرات الوسيطة المزدوجة للقلق تجاه استخدام وتقبل تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي على العلاقة بين إدراك طلاب التمريض ونواياهم لاستخدامها: دراسة وصفية

الملخص

الخلفية: تقنيات الرعاية الصحية المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) تغير من أدوار الممرضين وتعزز من رعاية المرضى. ومع ذلك، قد لا يكون طلاب التمريض على دراية بالفوائد، وقد لا يتم تدريبهم على استخدام التقنيات المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي في ممارستهم، وقد تكون لديهم مخاوف أخلاقية بشأن استخدامها. تم إجراء هذه الدراسة لتحديد التأثيرات الوسيطة المزدوجة للقلق من الاستخدام والموقف القابل للتقبل تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي على العلاقة بين الإدراك والنوايا لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي بين طلاب التمريض في كوريا الجنوبية. الطرق: اتبع نموذج البحث نموذج PROCESS Macro 6 الذي اقترحه هايز. كان المشاركون 180 طالب تمريض في غيونغجي-دو. تم جمع البيانات من 5 إلى 16 يناير 2023، باستخدام استبيانات ذاتية التقرير. تم تحليل البيانات باستخدام برنامج SPSS/WIN 25.0، مع اختبارات t المستقلة، وتحليل التباين الأحادي، وارتباطات بيرسون، وطريقة PROCESS ماكرو لهايز للوساطة. النتائج: كان الإدراك للذكاء الاصطناعي مرتبطًا إيجابيًا بموقف القابلية للتقبل.

الخلفية

تُحدد الفائدة المدركة من خلال سهولة الاستخدام المدركة في التكنولوجيا الجديدة. تفترض نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (TAM) أن إدراك التكنولوجيا الجديدة يؤدي إلى قبولها، مما ينتج عنه الاستخدام الفعلي.

طرق

تصميم

المشاركون

القياسات

تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي

القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي

موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي

نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي

الاعتبارات الأخلاقية

تحليل البيانات

النتائج

الفروق في المتغيرات حسب الخصائص الديموغرافية

وفقًا للدرجة، كان لدى طلاب السنة الثانية إدراك أعلى بشكل ملحوظ لـ

| خاصية | فئة |

|

تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي | القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي | مواقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي | نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي | ||||

|

|

ص أو خ (ص) |

|

صحيح أو خطأ (ص) |

|

صحيح أو خطأ (ص) |

|

صحيح أو خطأ (ص) | |||

| العمر (بالسنوات) |

|

|||||||||

| جنس | رجال | ٢٦ (١٤.٤) |

|

0.055 |

|

٤.٠٦٤ |

|

1.266 |

|

1.542 |

| نساء | 154 (85.6) |

|

(0.956) |

|

(< 0.001) |

|

(0.207) |

|

(0.126) | |

| درجة | سنة

|

80 (44.4) |

|

٦.٥١٠ |

|

1.606 |

|

٤.٥٩١ |

|

0.823 |

| سنة

|

54 (30.0) |

|

(0.002) |

|

(0.204) |

|

(0.011) |

|

(0.441) | |

| سنة

|

٤٦ (٢٥.٦) |

|

ب، ج < أ |

|

|

|

|

|||

| تجربة التعليم بالذكاء الاصطناعي | نعم | 50 (27.8) |

|

2.076 |

|

-2.715 |

|

٣.٤٢٧ |

|

1.755 |

| لا | ١٣٠ (٧٢.٢) |

|

(0.039) |

|

(0.007) |

|

(0.001) |

|

(0.081) | |

| متغير | نطاق | من | ماكس | م

|

| تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي |

|

1.50 | ٤.٤٠ |

|

| القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي |

|

1.00 | ٥.٠٠ |

|

| موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي |

|

1.00 | ٥.٠٠ |

|

| نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي |

|

2.00 | ٥.٠٠ |

|

| متغير | تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي | القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي | موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي | نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي |

| ر (ب) | ر (ب) | ر (ب) | ر (ب) | |

| تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي | 1 | |||

| القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي | -0.27 (< 0.001) | 1 | ||

| موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي | 0.44 (< 0.001) | -0.36 (< 0.001) | 1 | |

| نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي | 0.38(<0.001) | -0.28 (< 0.001) | 0.43 (<0.001) | 1 |

كان لديهم موقف قبول أعلى بشكل ملحوظ تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي مقارنةً بالطلاب في السنة الثالثة

الإدراك، القلق، موقف القبول، ونية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي

موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي،

العلاقات بين الإدراك، والقلق، وموقف القبول، ونية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي

التأثير الوسيط المزدوج للقلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي وموقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي

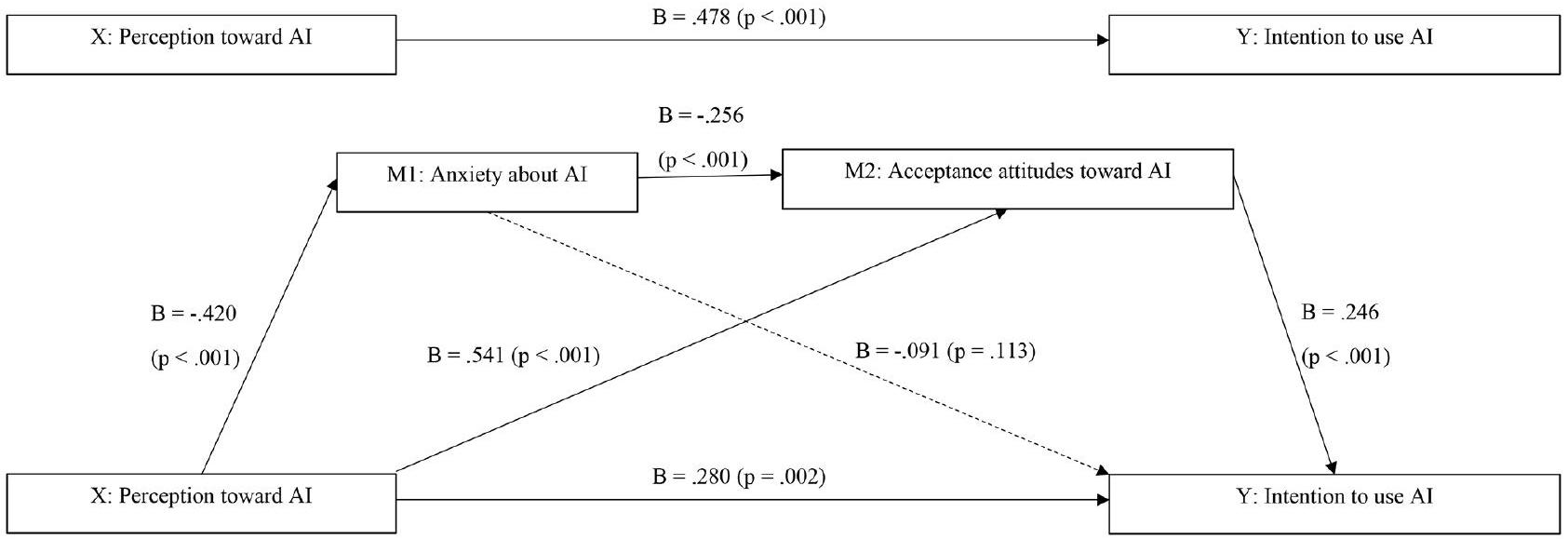

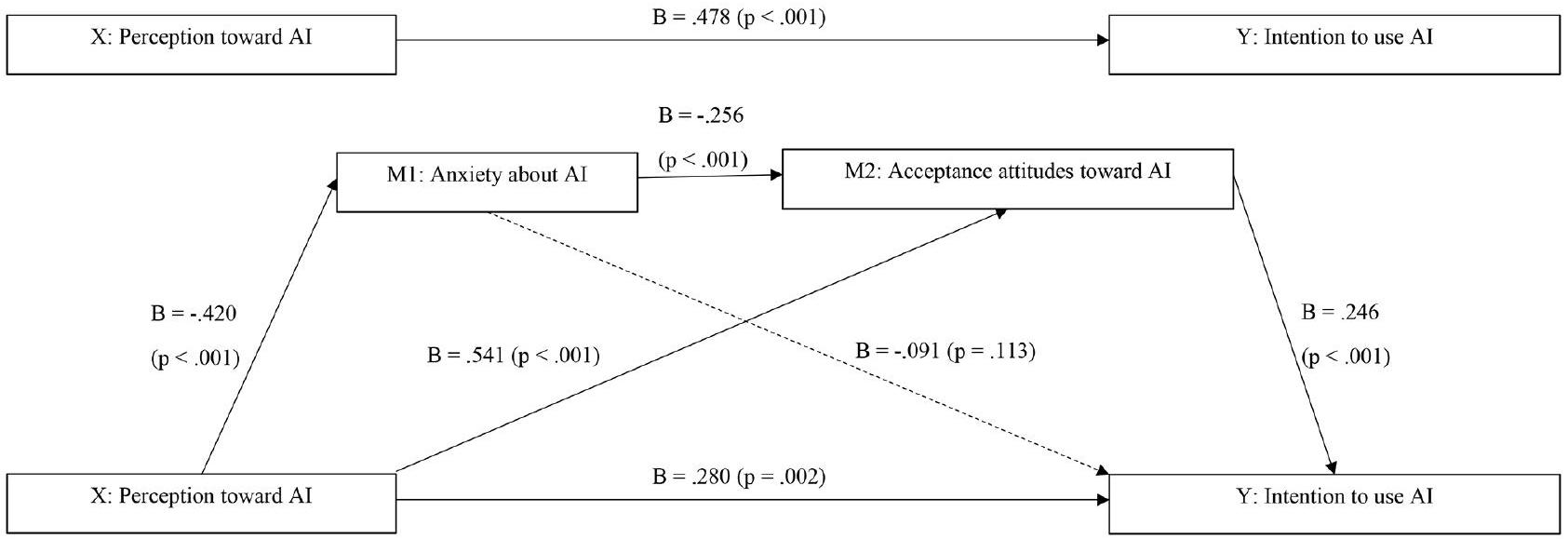

لفحص التأثيرات الوسيطة للقلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي وموقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي على العلاقة بين الإدراك والنية لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي، تم إجراء تحليلات باستخدام نموذج PROCESS Macro 6. يتكون النموذج من متغيرات مستقلة (X: إدراك الذكاء الاصطناعي)، ومتغير تابع (Y: النية لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي)، واثنين من المتغيرات الوسيطة (M1: القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي، M2: موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي).

| متغير | ب | SE | ت |

|

LLCI | ULCI |

| فترة الثقة 95% | فترة الثقة 95% | |||||

| تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي (X)

|

-0.420 | 0.111 | ٣.٧٧٣ | < 0.001 | -0.639 | -0.200 |

|

|

||||||

| تصور

|

0.541 | 0.100 | ٥.٤٢٤ | < 0.001 | 0.344 | 0.738 |

| القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي (M1)

|

-0.256 | 0.065 | ٣.٩٥٩ | < 0.001 | -0.384 | -0.129 |

|

|

||||||

| تصور

|

0.280 | 0.091 | ٣.٠٦٨ | 0.002 | 0.100 | 0.460 |

| القلق بشأن

|

-0.091 | 0.057 | 1.593 | 0.113 | -0.204 | 0.022 |

| مواقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي (M2)

|

0.246 | 0.064 | ٣.٨٥٦ | <0.001 | 0.120 | 0.371 |

|

|

||||||

| متغير | أثر | بوت SE | بوت LLCI | بوت ULCI |

| فترة الثقة 95% | 95% ثقة | |||

| تصور

|

0.038 | 0.027 | -0.007 | 0.098 |

| تصور

|

0.133 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.239 |

| تصور

|

0.026 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.066 |

| إجمالي | 0.198 | 0.058 | 0.095 | 0.322 |

| AI=الذكاء الاصطناعي؛ LLCI=فترة الثقة المنخفضة؛ ULCI=فترة الثقة العليا | ||||

يوضح الجدول 5 التأثير غير المباشر للمتغير المستقل على المتغيرات التابعة من خلال الوساطة بواسطة القلق والموقف من قبول الذكاء الاصطناعي. كان حجم التأثير الوسيط الكلي 0.198 (95% CI [0.095، 0.332])، وهو تأثير ذو دلالة، كما يتضح من غياب 0 في الـ

نقاش

كان متوسط درجة إدراك الذكاء الاصطناعي بين طلاب التمريض

علاوة على ذلك، وجدنا أن موقف القبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي يلعب دورًا وساطيًا مزدوجًا. فهو لا يؤثر فقط بشكل مباشر على نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي، بل يؤثر أيضًا بشكل غير مباشر من خلال تعديل مستويات القلق. وهذا يبرز أهمية المواقف الإيجابية في تعزيز نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الصحية. يمكن أن تؤدي التصورات السلبية، مثل رؤية الذكاء الاصطناعي كتهديد لأمان الوظائف، إلى موقف قبول أكثر سلبية وبالتالي إلى انخفاض نية استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي.

من منظور تطبيق النتائج في تعليم التمريض وممارسة التمريض السريري، يبرز هذه الدراسة الدور الحاسم لكليهما في استغلال إمكانيات الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الصحية. تؤكد على الحاجة إلى تعليم شامل حول الذكاء الاصطناعي ضمن منهج التمريض لسد الفجوة التعليمية وتقليل القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي بين طلاب التمريض. يجب أن يغطي الإطار التعليمي الجوانب التقنية للذكاء الاصطناعي وتطبيقاته العملية في الرعاية الصحية لتعزيز وجهة نظر إيجابية وموقف قبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تتقدم ممارسة التمريض السريري من خلال تعزيز ثقافة صديقة للذكاء الاصطناعي، من خلال إظهار الاستخدام الناجح للذكاء الاصطناعي في المهام الروتينية للتمريض ورعاية المرضى لتخفيف المخاوف وزيادة الثقة في تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي. من خلال ورش العمل المحددة، والندوات، والجلسات العملية التي تعرض فوائد الذكاء الاصطناعي، بما في ذلك تقليل عبء العمل وتحسين جودة الرعاية، يمكن تحقيق فهم أفضل وموقف قبول تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي بين طلاب التمريض والمهنيين. قد يؤدي هذا النهج إلى استخدام أوسع وأكثر فعالية للذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الصحية، مما ينتج عنه نتائج أفضل للمرضى وممارسات تمريض أكثر كفاءة.

في الختام، تؤكد نتائجنا على الدور الحاسم للتدخلات التعليمية التي تعزز الفهم والقبول للذكاء الاصطناعي بين طلاب التمريض. مثل هذه

يمكن أن تؤثر المبادرات بشكل إيجابي على نيتهم في استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الصحية، مما قد يؤدي بالتالي إلى تحسين نتائج الرعاية الصحية.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

| الذكاء الاصطناعي | الذكاء الاصطناعي |

| تام | نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا |

| VIF | عامل تضخم التباين |

| كلور | فترة الثقة |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 27 أغسطس 2023 / تاريخ القبول: 21 مارس 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 28 مارس 2024

References

- Davenport T, Kalakota R. The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(2):94-8. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.6-2-94.

- Song YA, Kim HJ, Lee HK. Nursing, robotics, technological revolution: Robotics to support nursing work. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2018;20(S1):144-53. https:// doi.org/10.17079/jkgn.2018.20.s1.s144.

- Lee JY, Song YA, Jung JY, Kim HJ, Kim BR, Do HK, et al. Nurses’ needs for care robots in integrated nursing care services. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(9):2094-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13711.

- Ronquillo CE, Peltonen LM, Pruinelli L, Chu CH, Bakken S, Beduschi A, et al. Artificial intelligence in nursing: priorities and opportunities from an international invitational think-tank of the nursing and Artificial Intelligence Leadership Collaborative. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(9):3707-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jan. 14855.

- Swan BA. Assessing the knowledge and attitudes of registered nurses about artificial intelligence in nursing and health care. Nurs Econ. 2021;39(3):139-43.

- Kwak YH, Seo YH, Ahn JW. Nursing students’ intent to use AI-based healthcare technology: path analysis using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;119:105541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nedt.2022.105541.

- Carrington JM, Tiase VL. Nursing informatics year in review. Nurs Adm Q. 2013;37(2):136-43.

- Carrington JM. Summary of the nursing informatics year in review 2014. Nurs Adm Q. 2015;39(2):183-4.

- Carroll WM. The synthesis of nursing knowledge and predictive analytics. Nurs Manage. 2019;50(3):15-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. NUMA.0000553503.78274.f7.

- Buchanan C, Howitt ML, Wilson R, Booth RG, Risling T, Bamford M. Predicted influences of Artificial Intelligence on the domains of nursing: scoping review. JMIR Nurs. 2020;3(1):e23939. https://doi.org/10.2196/23939.

- McGrow K. Artificial intelligence: essentials for nursing. Nurs. 2019;49(9):46-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000577716.57052.8d.

- Rahimi B, Nadri H, Afshar HL, Timpka T. A systematic review of the Technology Acceptance Model in Health Informatics. Appl Clin Inf. 2018;9(3):604-34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1668091.

- Strudwick G. Predicting nurses’ use of healthcare technology using the technology acceptance model: an. Integr Rev Comput Inf Nurs 20153305189-198.

- Ahlan AR, Isma’eel AB. An overview of patient acceptance of health information technology in developing countries: a review and conceptual model. Int J Inf Syst Project Manage. 2015;3(01):29-48.

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13:319-40. https://doi. org/10.2307/249008.

- Holden RJ, Asan O, Wozniak EM, Flynn KE, Scanlon MC. Nurses’ perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2016;16:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0388-y.

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):267-86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267.

- Shinners L, Grace S, Smith S, Stephens A. Exploring healthcare professionals’ perceptions of artificial intelligence: piloting the Shinners artificial intelligence perception tool. Digit Health. 2022;8:1-8. https://doi. org/10.1177/20552076221078110.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425-78. https://doi. org/10.2307/30036540.

- Hayes AF. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013.

- Han SJ. Effect of nursing organizational culture, organizational silence, and organizational commitment on the intention of retention among nurses: applying the PROCESS macro model 6. Korean J Occup Health Nurs. 2022;31(1):31-41. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2022.31.1.31.

- Seo YH, Cho KA. Influence of AI knowledge, perception, and acceptance attitude on nursing students’ intention to use AI-based healthcare technologies. J Korean Nurs Res. 2022;6(3):81-90. https://doi.org/10.34089/jknr.2022.6.3.81.

- Kim JM. Study on intention and attitude of using artificial intelligence technology in healthcare. J Converg Inf Technol. 2017;7(4):53-60. https://doi. org/10.22156/CS4SMB.2017.7.4.053.

- Sit C, Srinivasan R, Amlani A, Muthuswamy K, Azam A, Monzon L, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of UK medical students towards artificial intelligence and radiology: a multicentre survey. Insights Imaging. 2020;11(14):1-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0830-7.

- Zhang B, Dafoe A. Artificial intelligence: American attitudes and trends. Available SSRN 3312874. 2019.

- Sindermann C, Yang H, Elhai JD, Yang S, Quan L, Li M, Montag C. Acceptance and Fear of Artificial Intelligence: associations with personality in a German and a Chinese sample. Discov Psychol. 2022;2(8). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s44202-022-00020-y.

- Ketikidis P, Dimitrovski T, Lazuras L, Bath PA. Acceptance of health information technology in health professionals: an application of the revised technology acceptance model. Health Inf J. 2012;18(2):124-34. https://doi. org/10.1177/1460458211435425.

- Labrague LJ, Aguilar-Rosales R, Yboa BC, Sabio JB, de los Santos JA. Student nurses’ attitudes, perceived utilization, and intention to adopt artificial intelligence (AI) technology in nursing practice: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Educ Today. 2023;73:103815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103815.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

يون هي سيو

yseo017@naver.com

¹قسم التمريض، جامعة غوانغجو، 277، طريق هيو دوك، نام-غو، غوانغجو، كوريا الجنوبية

قسم التمريض، جامعة أندونغ الوطنية، 1375، شارع جيونغدونغ، مدينة أندونغ، مقاطعة جيونغسانغبوك-do، كوريا الجنوبية

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01887-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38539198

Publication Date: 2024-03-28

Dual mediating effects of anxiety to use and acceptance attitude of artificial intelligence technology on the relationship between nursing students’ perception of and intention to use them: a descriptive study

Abstract

Background Artificial intelligence (AI)-based healthcare technologies are changing nurses’ roles and enhancing patient care. However, nursing students may not be aware of the benefits, may not be trained to use AI-based technologies in their practice, and could have ethical concerns about using them. This study was conducted to identify the dual mediating effects of anxiety to use and acceptance attitude toward AI on the relationship between perception of and intentions to use AI among nursing students in South Korea. Methods The research model followed the PROCESS Macro model 6 proposed by Hayes. The participants were 180 nursing students in Gyeonggi-do. Data were collected from January 5-16, 2023, using self-reported questionnaires. Data were analyzed using the SPSS/WIN 25.0 program, with independent t-tests, one-way analysis of variance, Pearson’s correlations, and Hayes’s PROCESS macro method for mediation. Results AI perception positively correlated with acceptance attitude (

Background

by perceived usefulness, and perceived usefulness is predicted by perceived ease of use in the novel technology. TAM posits that the perception of the novel technology leads to its acceptance, which results in actual use [16].

Methods

Design

Participants

Measurements

Perception of AI

Anxiety about AI

Acceptance attitude toward AI

Intention to use the AI

Ethical considerations

Data analysis

Results

Differences in variables by demographic characteristics

According to grade, second-year students had a significantly higher perception of

| Characteristic | Category |

|

Perception of AI | Anxiety about AI | Acceptance attitudes toward AI | Intention to use AI | ||||

|

|

t or F (p) |

|

t or F (p) |

|

t or F (p) |

|

t or F (p) | |||

| Age (years) |

|

|||||||||

| Sex | Men | 26 (14.4) |

|

0.055 |

|

4.064 |

|

1.266 |

|

1.542 |

| Women | 154 (85.6) |

|

(0.956) |

|

(< 0.001) |

|

(0.207) |

|

(0.126) | |

| Grade | Year

|

80 (44.4) |

|

6.510 |

|

1.606 |

|

4.591 |

|

0.823 |

| Year

|

54 (30.0) |

|

(0.002) |

|

(0.204) |

|

(0.011) |

|

(0.441) | |

| Year

|

46 (25.6) |

|

b, c < a |

|

|

|

|

|||

| AI education experience | Yes | 50 (27.8) |

|

2.076 |

|

-2.715 |

|

3.427 |

|

1.755 |

| No | 130 (72.2) |

|

(0.039) |

|

(0.007) |

|

(0.001) |

|

(0.081) | |

| Variable | Range | Min | Max | M

|

| Perception of Al |

|

1.50 | 4.40 |

|

| Anxiety about Al |

|

1.00 | 5.00 |

|

| Acceptance attitude toward Al |

|

1.00 | 5.00 |

|

| Intention to use Al |

|

2.00 | 5.00 |

|

| Variable | Perception of Al | Anxiety about AI | Acceptance attitude toward AI | Intention to use Al |

| r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | |

| Perception of AI | 1 | |||

| Anxiety about AI | -0.27 (< 0.001) | 1 | ||

| Acceptance attitude toward AI | 0.44 (< 0.001) | -0.36 (< 0.001) | 1 | |

| Intention to use AI | 0.38(<0.001) | -0.28 (< 0.001) | 0.43 (<0.001) | 1 |

had a significantly higher acceptance attitude toward AI than third-year students (

Perception, anxiety, acceptance attitude, and intention to use AI

acceptance attitude toward AI,

Correlations between perception, anxiety, acceptance attitude, and intention to use AI

The dual mediating effect of anxiety about AI and acceptance attitude toward AI

To examine the mediating effects of anxiety about AI and acceptance attitude toward AI on the relationship between perception of and intention to use AI, analyses were performed using PROCESS Macro model 6. The model consisted of independent variables ( X : perception of AI), a dependent variable ( Y : intention to use AI), and two mediating variables (M1: anxiety about AI, M2: acceptance attitude toward AI).

| Variable | B | SE | t |

|

LLCI | ULCI |

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Perception of AI (X)

|

-0.420 | 0.111 | 3.773 | < 0.001 | -0.639 | -0.200 |

|

|

||||||

| Perception of

|

0.541 | 0.100 | 5.424 | < 0.001 | 0.344 | 0.738 |

| Anxiety about AI (M1)

|

-0.256 | 0.065 | 3.959 | < 0.001 | -0.384 | -0.129 |

|

|

||||||

| Perception of

|

0.280 | 0.091 | 3.068 | 0.002 | 0.100 | 0.460 |

| Anxiety about

|

-0.091 | 0.057 | 1.593 | 0.113 | -0.204 | 0.022 |

| Acceptance attitudes toward AI (M2)

|

0.246 | 0.064 | 3.856 | <0.001 | 0.120 | 0.371 |

|

|

||||||

| Variable | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| 95% CI | 95% Cl | |||

| Perception of

|

0.038 | 0.027 | -0.007 | 0.098 |

| Perception of

|

0.133 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.239 |

| Perception of

|

0.026 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.066 |

| Total | 0.198 | 0.058 | 0.095 | 0.322 |

| AI=artificial intelligence; LLCI=lower level confidence interval; ULCI=upper | ||||

Table 5 shows the indirect effect of the independent variable on dependent variables through mediation by anxiety and acceptance attitude toward AI. The size of the overall mediating effect was 0.198 (95% CI [0.095, 0.332]), which was significant, as evidenced by the absence of 0 in the

Discussion

The average perception score of AI among nursing students was

Furthermore, we found that an acceptance attitude toward AI plays a dual mediating role. Not only does it directly influence the intention to use AI, but it also does so indirectly by modulating anxiety levels. This underscores the importance of positive attitudes in fostering an intention to use AI in healthcare [6, 28]. Negative perceptions, such as viewing AI as a threat to job security, can conversely lead to a more negative acceptance attitude and, consequently, a decreased intention to use AI.

From the perspective of applying results in nursing education and clinical nursing practice, this study highlights the critical role of both in leveraging AI’s potential in healthcare. It stresses the need for comprehensive AI education within the nursing curriculum to close the educational gap and reduce anxiety about AI among nursing students. The educational framework should cover AI’s technical aspects and its practical healthcare applications to foster a positive view and acceptance attitude toward AI. Furthermore, clinical nursing practice can advance by promoting an AI-friendly culture, demonstrating AI’s successful use in routine nursing tasks and patient care to mitigate fears and enhance confidence in AI technologies. Through specific workshops, seminars, and hands-on sessions that showcase AI’s benefits, including workload reduction and improved care quality, a better understanding and acceptance attitude toward AI among nursing students and professionals can be achieved. This approach could lead to broader and more effective AI use in healthcare, resulting in better patient outcomes and more efficient nursing practices.

In conclusion, our findings emphasize the crucial role of educational interventions that enhance understanding and acceptance of AI among nursing students. Such

initiatives can positively impact their intention to use AI in healthcare, thus potentially leading to improved healthcare outcomes.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| Cl | Confidence interval |

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Received: 27 August 2023 / Accepted: 21 March 2024

Published online: 28 March 2024

References

- Davenport T, Kalakota R. The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(2):94-8. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.6-2-94.

- Song YA, Kim HJ, Lee HK. Nursing, robotics, technological revolution: Robotics to support nursing work. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2018;20(S1):144-53. https:// doi.org/10.17079/jkgn.2018.20.s1.s144.

- Lee JY, Song YA, Jung JY, Kim HJ, Kim BR, Do HK, et al. Nurses’ needs for care robots in integrated nursing care services. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(9):2094-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13711.

- Ronquillo CE, Peltonen LM, Pruinelli L, Chu CH, Bakken S, Beduschi A, et al. Artificial intelligence in nursing: priorities and opportunities from an international invitational think-tank of the nursing and Artificial Intelligence Leadership Collaborative. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(9):3707-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jan. 14855.

- Swan BA. Assessing the knowledge and attitudes of registered nurses about artificial intelligence in nursing and health care. Nurs Econ. 2021;39(3):139-43.

- Kwak YH, Seo YH, Ahn JW. Nursing students’ intent to use AI-based healthcare technology: path analysis using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;119:105541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nedt.2022.105541.

- Carrington JM, Tiase VL. Nursing informatics year in review. Nurs Adm Q. 2013;37(2):136-43.

- Carrington JM. Summary of the nursing informatics year in review 2014. Nurs Adm Q. 2015;39(2):183-4.

- Carroll WM. The synthesis of nursing knowledge and predictive analytics. Nurs Manage. 2019;50(3):15-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. NUMA.0000553503.78274.f7.

- Buchanan C, Howitt ML, Wilson R, Booth RG, Risling T, Bamford M. Predicted influences of Artificial Intelligence on the domains of nursing: scoping review. JMIR Nurs. 2020;3(1):e23939. https://doi.org/10.2196/23939.

- McGrow K. Artificial intelligence: essentials for nursing. Nurs. 2019;49(9):46-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000577716.57052.8d.

- Rahimi B, Nadri H, Afshar HL, Timpka T. A systematic review of the Technology Acceptance Model in Health Informatics. Appl Clin Inf. 2018;9(3):604-34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1668091.

- Strudwick G. Predicting nurses’ use of healthcare technology using the technology acceptance model: an. Integr Rev Comput Inf Nurs 20153305189-198.

- Ahlan AR, Isma’eel AB. An overview of patient acceptance of health information technology in developing countries: a review and conceptual model. Int J Inf Syst Project Manage. 2015;3(01):29-48.

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13:319-40. https://doi. org/10.2307/249008.

- Holden RJ, Asan O, Wozniak EM, Flynn KE, Scanlon MC. Nurses’ perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2016;16:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0388-y.

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):267-86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267.

- Shinners L, Grace S, Smith S, Stephens A. Exploring healthcare professionals’ perceptions of artificial intelligence: piloting the Shinners artificial intelligence perception tool. Digit Health. 2022;8:1-8. https://doi. org/10.1177/20552076221078110.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003;27(3):425-78. https://doi. org/10.2307/30036540.

- Hayes AF. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013.

- Han SJ. Effect of nursing organizational culture, organizational silence, and organizational commitment on the intention of retention among nurses: applying the PROCESS macro model 6. Korean J Occup Health Nurs. 2022;31(1):31-41. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2022.31.1.31.

- Seo YH, Cho KA. Influence of AI knowledge, perception, and acceptance attitude on nursing students’ intention to use AI-based healthcare technologies. J Korean Nurs Res. 2022;6(3):81-90. https://doi.org/10.34089/jknr.2022.6.3.81.

- Kim JM. Study on intention and attitude of using artificial intelligence technology in healthcare. J Converg Inf Technol. 2017;7(4):53-60. https://doi. org/10.22156/CS4SMB.2017.7.4.053.

- Sit C, Srinivasan R, Amlani A, Muthuswamy K, Azam A, Monzon L, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of UK medical students towards artificial intelligence and radiology: a multicentre survey. Insights Imaging. 2020;11(14):1-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-019-0830-7.

- Zhang B, Dafoe A. Artificial intelligence: American attitudes and trends. Available SSRN 3312874. 2019.

- Sindermann C, Yang H, Elhai JD, Yang S, Quan L, Li M, Montag C. Acceptance and Fear of Artificial Intelligence: associations with personality in a German and a Chinese sample. Discov Psychol. 2022;2(8). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s44202-022-00020-y.

- Ketikidis P, Dimitrovski T, Lazuras L, Bath PA. Acceptance of health information technology in health professionals: an application of the revised technology acceptance model. Health Inf J. 2012;18(2):124-34. https://doi. org/10.1177/1460458211435425.

- Labrague LJ, Aguilar-Rosales R, Yboa BC, Sabio JB, de los Santos JA. Student nurses’ attitudes, perceived utilization, and intention to adopt artificial intelligence (AI) technology in nursing practice: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Educ Today. 2023;73:103815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103815.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Yon Hee Seo

yseo017@naver.com

¹Department of Nursing, Gwangju University, 277, Hyodeok-ro, Nam-gu, GwangJu, South Korea

Department of Nursing, Andong National University, 1375, Gyeongdongro, Andong-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea