DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2024.109166

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-23

البحث عبر الإنترنت في جامعة LJMU

https://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/22428/

مقالة

دوبي، رhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-3913-030Xبرايد، دي جي، بلوم، سي، دويفيدي، واي، تشايلد، إس جي وفوروبون، سي (2024) التحالفات والتحول الرقمي أمران حاسمان للاستفادة من قدرات سلسلة التوريد الديناميكية خلال أوقات الأزمات: دراسة متعددة الطرق. الدولية

التحالفات والتحول الرقمي ضروريان للاستفادة من قدرات سلسلة التوريد الديناميكية خلال أوقات الأزمات: دراسة متعددة الأساليب

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

التحول الرقمي

مرونة سلسلة التوريد

قابلية التكيف في سلسلة الإمداد

أداء المنظمة

نظرية رؤية القدرة الديناميكية

الملخص

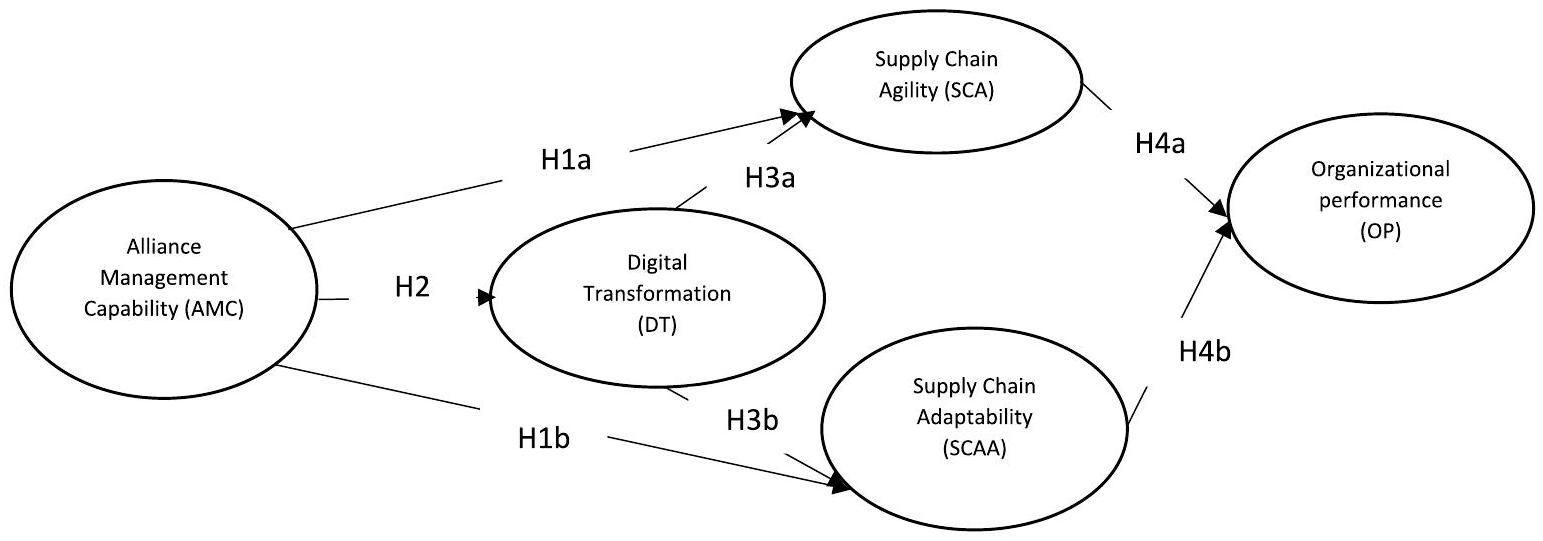

خلال أوقات الأزمات، تحتاج الشركات إلى شراكات استراتيجية وتحول رقمي للبقاء. من المهم فهم كيف يمكن أن يعمل التحول الرقمي وقدرة إدارة التحالفات معًا لتعزيز قدرات سلسلة التوريد خلال الأزمة. لقد طورنا إطارًا نظريًا يوضح كيف تساعد قدرة إدارة التحالفات، تحت التأثير الوسيط للتحول الرقمي، في بناء قدرات سلسلة التوريد للأزمات غير المسبوقة. يبرز هذا الإطار العوامل الرئيسية الممكنة مثل قدرة إدارة التحالفات، التحول الرقمي، مرونة سلسلة التوريد، وقابلية التكيف في سلسلة التوريد التي تعتبر ضرورية لأداء المنظمة. قمنا باختبار نموذجنا النظري باستخدام استبيان شمل 157 فردًا يعملون في صناعة التصنيع في الهند. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن دمج قدرة إدارة التحالفات والتحول الرقمي يعزز قدرات سلسلة التوريد، مما يحسن قدرة المنظمة على الاستجابة للأزمات. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التحول الرقمي، ومرونة سلسلة التوريد، وقابلية التكيف هي محددات حاسمة لأداء المنظمة خلال الأزمات. لذلك، فإن الشركات التي تستخدم التقنيات الرقمية لزيادة مرونتها وقابلية تكيفها من المرجح أن تؤدي بشكل جيد خلال أوقات الأزمات. لجمع البيانات النوعية، قمنا بمقابلة المشاركين الرئيسيين (

1. المقدمة

مثل هذه الأحداث (ألكسندر وآخرون، 2022؛ وولانداري وآخرون، 2022؛ جوان ولي، 2023). أشار باتروكو وكاهكونن (2021) إلى أن المرونة والقدرة على التكيف هما قدرات ديناميكية تساعد المنظمات على التنقل في الأزمات والحفاظ على النمو الاستراتيجي.

et وآخرون، 2021؛ باباناجنو وآخرون، 2022)، سيلعب دورًا حاسمًا في تقريب شركاء سلسلة التوريد من بعضهم البعض حيث يشاركون المعلومات وينسقون أنشطتهم بشكل أفضل (لي، 2021؛ إسكاميلا وآخرون، 2021). ومع ذلك، في العديد من الحالات، لم تحقق نتائج التحول الرقمي التوقعات (هيس وآخرون، 2016؛ قوه وآخرون، 2023)، وفي بعض الحالات، أدت قدرة التحول الرقمي إلى نتائج متفاوتة (شراغ وآخرون، 2022). لذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من التحقيق لفهم تأثيرات التحول الرقمي على قدرات سلسلة التوريد ونتائج الأداء (سينتوبيللي وآخرون، 2020؛ مينغ وآخرون، 2023). في الحالات التي يكون فيها التحول الرقمي قيد التنفيذ، يمكن أن يعمل إما كوسيط بين متغيرين (نايال وآخرون، 2022؛ تسو و تشين، 2023) أو أن يكون له تأثير تفاعلي (وانغ ودو، 2022) عليهما. وهذا يعني أن التغييرات التي يحدثها التحول الرقمي يمكن أن تؤثر إما على العلاقة بين متغيرين أو تؤثر عليهما مباشرة، اعتمادًا على السياق. على وجه التحديد، ليس من المفهوم جيدًا كيف يؤثر AMC على قدرات سلسلة التوريد والأداء التنظيمي (OP) تحت تأثير التحول الرقمي كوسيط. لمعالجة هذه الفجوة المعرفية، فإن سؤال البحث الثاني لدينا (RQ2) هو: ما هي تأثيرات AMC على SCA/SCAA و OP تحت تأثير التحول الرقمي كوسيط؟

2. تطوير النظرية

2.1. عملية بناء قدرات سلسلة التوريد الديناميكية

إطار العمل هو منظور متعدد التخصصات يشرح إدارة المخاطر وعدم اليقين (Teece et al., 2016, ص. 13). يقدم منظورًا نظريًا لبناء القدرات الاستراتيجية لتمكين المنظمات من الحفاظ على النمو المستمر خلال الأوقات المضطربة وتحقيق أداء متفوق (Mohamud و Sarpong, 2016). هناك مجموعة غنية من الأدبيات التي تُعزز فهمنا للقدرات الديناميكية، ولكن التناقضات في التصور والتعريفات غالبًا ما تحد من فهمنا للقدرات الديناميكية وارتباطها بالميزة التنافسية (Winter, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006; Fainshmidt et al., 2016; Hunt و Madhavaram, 2020; Ye et al., 2022; Yang و Yee, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023).

2.2. قدرة إدارة التحالفات (AMC)

تُبنى على مر الزمن من خلال تفاعلات متعددة. استنادًا إلى حجج RBV (انظر، Barney, 1991)، يُعتبر AMC تجميعًا للموارد غير المتجانسة وغير القابلة للتحرك لشركة، مما يشكل مصدرًا للميزة التنافسية المستدامة (Kauppila, 2015; Lioukas et al., 2016). غالبًا ما يُعتبر AMC ذا قيمة ونادرًا لأن التحالفات الاستراتيجية يصعب تشكيلها. تتطور التحالفات مع مرور الوقت، وغالبًا ما تواجه المنظمات التي تهتم فقط بالتعاون قصير الأجل صعوبات في تحقيق الفوائد؛ وبالتالي، غالبًا ما تفشل مثل هذه التحالفات الاستراتيجية (Prashant و Harbir, 2009). استنادًا إلى وجهة نظر تنسيق الموارد لـ Sirmon et al. (2011)، تتشكل AMC من خلال تجميع الموارد والقدرات لتوليد ميزة تنافسية مستدامة.

2.3. التحول الرقمي (DT)

2.4. الفرضيات

2.4.1. AMC و SCA/SCAA

2.4.2. AMC و DT

الأزمات (Karimi و Walter، 2015). من خلال تبني التقنيات الرقمية، يمكن للشركات تبسيط عملياتها، وتحسين مواردها، وزيادة مرونتها، مما يسمح لها بالاستجابة بسرعة وفعالية للظروف المتغيرة في السوق. وبالتالي، يمكن للمنظمات الاستفادة من تشكيل تحالفات استراتيجية مع شركات أخرى لتعزيز التحول الرقمي والبقاء تنافسية في بيئة الأعمال المتطورة بسرعة اليوم (Li et al.، 2018؛ Hanelt et al.، 2021). يمكن أن تساعد هذه التحالفات المنظمات في الوصول إلى خبرات وموارد قيمة يمكن الاستفادة منها لدفع الابتكار والنمو (Ghosh et al.، 2022). من خلال العمل عن كثب مع الشركاء، يمكن للمنظمات تطوير تقنيات جديدة وعمليات وحلول تلبي بشكل أفضل احتياجات وتوقعات العملاء، مع تحسين الكفاءة التشغيلية وتقليل التكاليف (Prashant و Harbir، 2009). لذلك، يمكن أن يكون تشكيل التحالفات الاستراتيجية ممكنًا رئيسيًا للتحول الرقمي وطريقة قوية للمنظمات للبقاء في المقدمة (Warner و Wäger، 2019). بناءً على المناقشات السابقة، يمكننا أن نفترض:

2.4.3. DT و SCA/SCAA

2.4.4. SCA/SCAA و

تتعلق SCAA بتعديل تصميم سلسلة التوريد للتعامل مع التغيرات السريعة وغير المتوقعة في بيئة الأعمال أو السوق (لي، 2004؛ إكشتاين وآخرون، 2015؛ فوسو وامبا وآخرون، 2020؛ لي، 2021). لبناء القدرة على التكيف، تحتاج المنظمات إلى تتبع التغيرات المستمرة في البيئة الخارجية بمساعدة التقنيات الرقمية وتطوير استراتيجيات توريد بديلة للتعامل مع أي نوع من قيود التجارة أو

الاضطراب الناجم عن الاضطرابات السياسية أو الأزمات الجيوسياسية. يجب عليهم خلق مرونة في سلاسل التوريد الخاصة بهم وأن يكون لديهم مصادر/أسواق متعددة للتعامل مع عدم اليقين في العرض/الطلب (لي، 2021). الفرق بين SCA و SCAA هو فرق في التوجه. SCA هو قصير الأجل، و SCAA هو استراتيجية طويلة الأجل (انظر لي، 2004؛ ريتشي وآخرون، 2022). تفترض الأدبيات السابقة أن SCAA ستؤثر بشكل إيجابي على مقاييس الأداء السوقي والمالي. ومن ثم، نفترض:

2.4.5. التأثير الوسيط للتحول الرقمي

3. طرق البحث

3.1. بيئة البحث

خصائص المستجيبين (

| صناعة | عينة (ن) | % |

| طعام | ٣٦ | ٢٢.٩٣ |

| تصنيع الملابس | 23 | 14.65 |

| تصنيع أجهزة الكمبيوتر والإلكترونيات | 40 | 25.48 |

| تصنيع البلاستيك والمنتجات المطاطية | ٥٨ | ٣٦.٩٤ |

| حجم الشركة | ||

| <100 موظف | 21 | ١٣.٣٨ |

| 100-499 موظف | ٣٦ | ٢٢.٩٣ |

| 500-1499 موظف | 69 | ٤٣.٩٥ |

| 1500-4999 موظف | ٢٤ | 15.29 |

| >5000 موظف | ٧ | ٤.٤٦ |

| عمر الشركة (سنوات) | ||

| <10 | 12 | 7.64 |

| 10-19 سنة | 41 | ٢٦.١١ |

| 20-29 سنة | ٤٨ | 30.57 |

| >30 سنة | ٥٦ | ٣٥.٦٧ |

| تعيين | ||

| رئيس قسم سلسلة الإمداد | 72 | ٤٥.٨٦ |

| رئيس إقليمي | 61 | ٣٨.٨٥ |

| مستشار | ٢٤ | 15.29 |

| مدة خدمة المستجيب (سنوات) | ||

| <1 | 12 | 7.64 |

| 1-5 سنوات | ٣٦ | ٢٢.٩٣ |

| 6-10 سنوات | 62 | ٣٩.٤٩ |

| >10 سنوات | ٤٧ | ٢٩.٩٤ |

3.2. التدابير

3.3. جمع العينة والبيانات

بعد أسبوعين على الأقل من البريد الإلكتروني الأول. تلقينا أخيرًا 162 استبيانًا مكتملًا (معدل الاستجابة

4. تحليل البيانات

4.1. انحياز الطريقة الشائعة (CMB)

4.2. خصائص القياس للبنى

الصلاحية المتقاربة.

| بناء | عنصر | أحمال العوامل | التباين | خطأ | SCR | AVE | |

| AMC (

|

IC (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

IC1 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.72 |

| IC2 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | ||||

| IC3 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.20 | ||||

| APC (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

APC1 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| 0.91،

|

APC2 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| APC3 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | ||||

| APC4 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | ||||

| IL (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

IL1 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| 0.91،

|

IL2 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | |||

| IL3 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | ||||

| IL4 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | ||||

| AP (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

AP1 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.27 | |||

| 0.89،

|

AP2 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| AP3 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.40 | ||||

| AP4 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.32 | ||||

| SCA (

|

AGIL1 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.91 | 0.77 | |

| AGIL2 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| AGIL3 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | ||||

| سكا

|

ADAP1 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.92 | 0.79 | |

| ADAP2 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 | ||||

| ADAP3 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 | ||||

| OP (

|

العائد على الأصول | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.79 | |

| ITO | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| في مثل هذا اليوم | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | ||||

| دي تي (

|

DSS (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

دي تي_دي إس إس 1 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.86 |

| 0.95، AVE = 0.85) | دي تي_دي إس إس 2 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 | |||

| دي تي_دي إس إس 3 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| سيارة (بناء عاكس من الدرجة الأولى)

|

DT_CAR1 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.17 | |||

| 0.95،

|

DT_CAR2 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | |||

| DT_CAR3 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 |

صحة التمييز.

| نطاق المقياس | معنى | الانحراف المعياري | IC | APC | إل | AP | دي تي_دي إس إس | DT_CAR | SCA | سكا | OP | |

| IC | 1-7 | 5.62 | 1.00 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| APC | 1-7 | ٥.٧٧ | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.85 | |||||||

| إل | 1-7 | 5.69 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.85 | ||||||

| AP | 1-7 | ٥.٦٨ | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.82 | |||||

| دي تي_دي إس إس | 1-7 | ٥.٥٩ | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.92 | ||||

| DT_CAR | 1-7 | ٥.٦ | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.94 | |||

| SCA | 1-7 | ٥.٦٤ | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.93 | ||

| SCAA | 1-7 | ٥.٦٤ | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.89 | |

| OP | 1-7 | ٥.٧٥ | 0.96 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.89 |

قيم التباين المتغاير – التباين الأحادي (HTMT).

| IC | APC | إل | AP | دي تي_دي إس إس | DT_CAR | SCAG | سكا | OP | |

| IC | |||||||||

| APC | 0.72 | ||||||||

| إل | 0.84 | 0.82 | |||||||

| AP | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.89 | ||||||

| دي تي_دي إس إس | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | |||||

| DT_CAR | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||||

| SCAG | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | |||

| سكا | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.69 | ||

| OP | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.87 | |

تم إجراء اختبار HTMT (نسبة الارتباطات بين الصفات المختلفة والصفات الأحادية) (انظر الجدول 4). قيم HTMT أقل بكثير من القيم الحدية الموصى بها (انظر هنسلر وآخرون، 2015)، مما يشير إلى أن البنى تمتلك صلاحية تمييز كافية. بشكل عام، تمتلك البنى صلاحية بناء كافية لتمكين تفسير التقديرات الهيكلية.

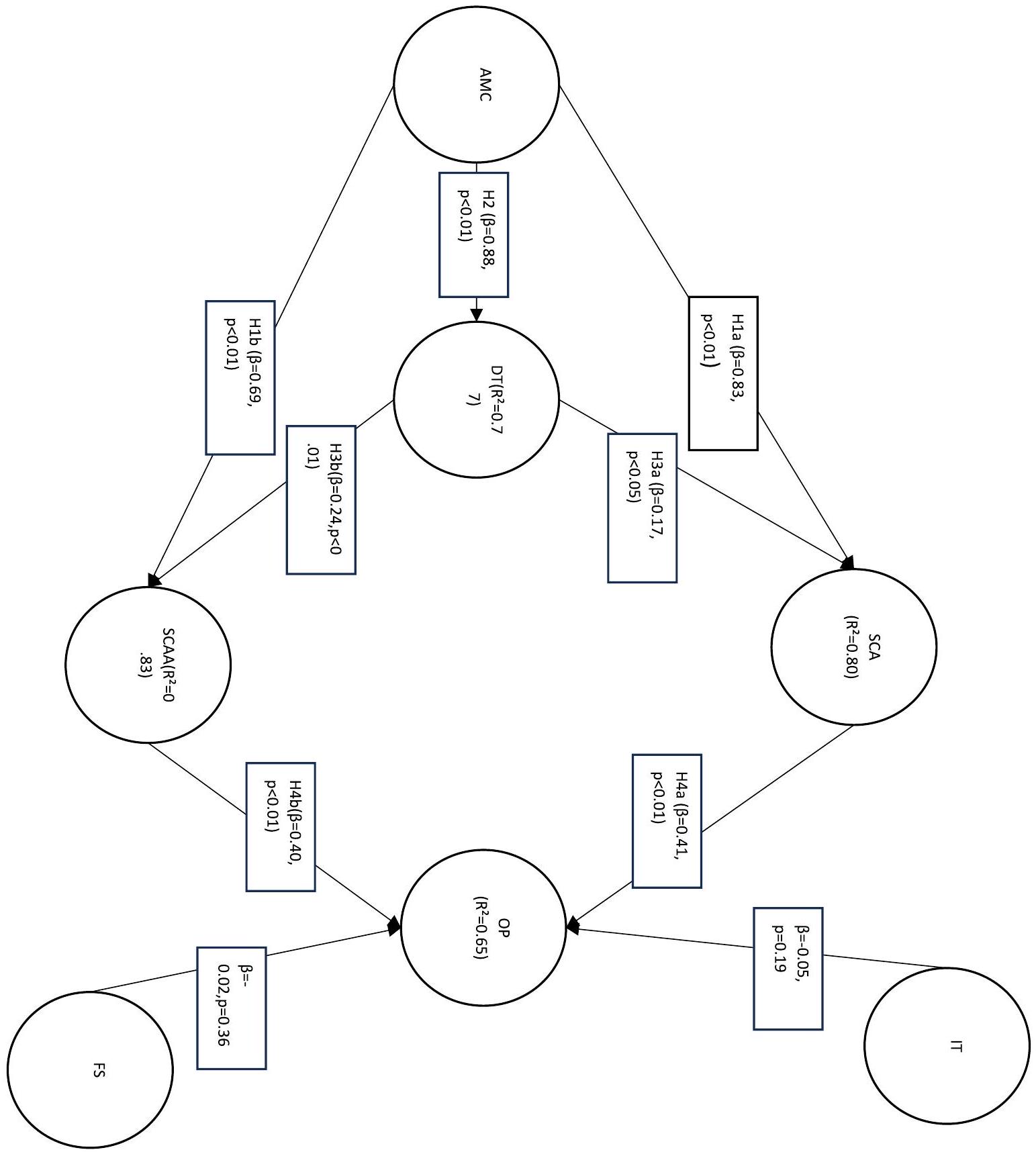

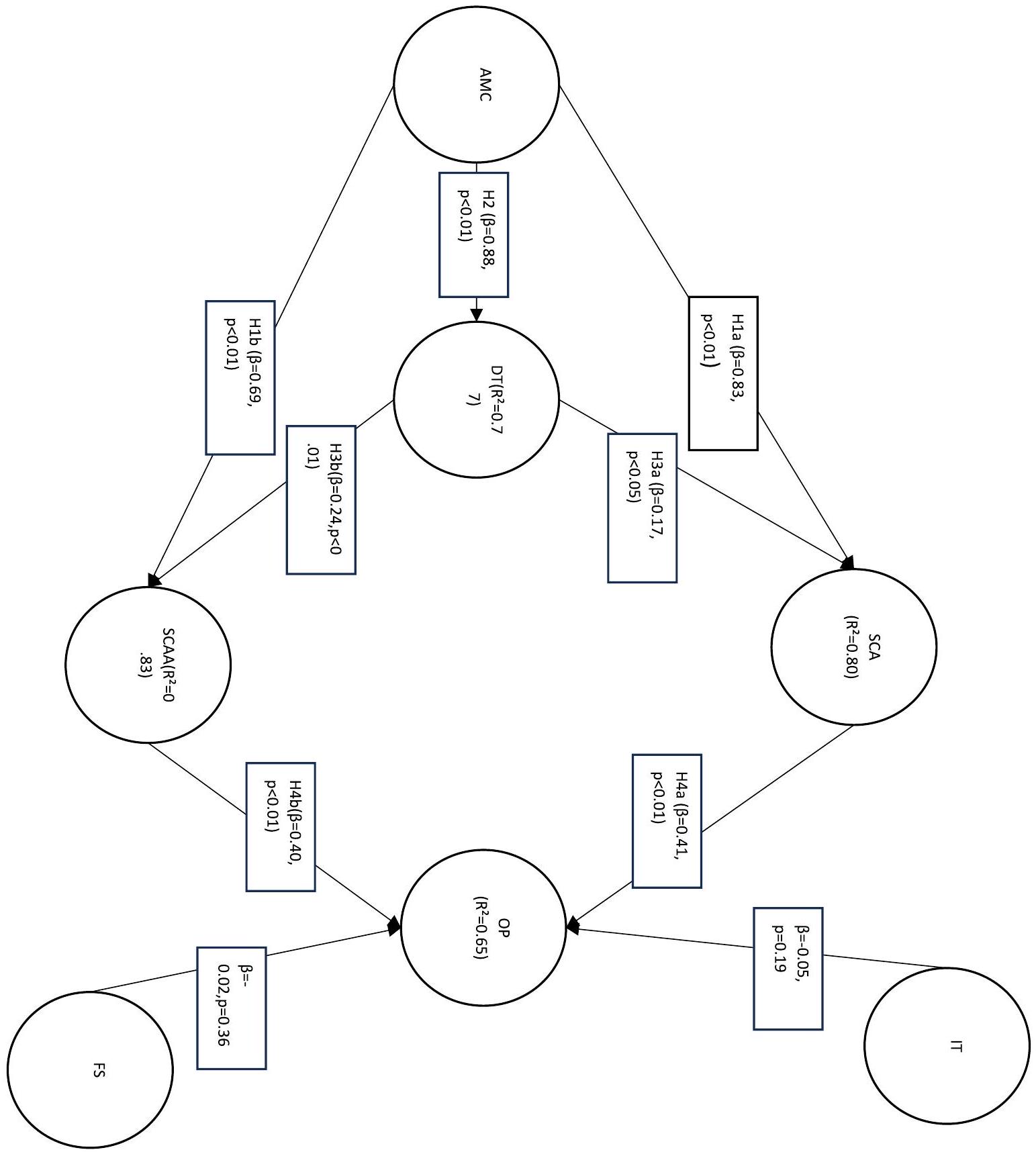

4.3. اختبار الفرضيات

قبل اختبار الفرضيات، من الضروري إجراء اختبار للداخلية. على الرغم من أن الباحثين اقترحوا عدة طرق لتحديد وتصحيح الداخلية، إلا أنها لا تزال قضية مثيرة للجدل. قمنا بإجراء اختبار طبيعة باستخدام اختبار كولموغوروف-سميرنوف مع تصحيح ليلييفورز على الدرجات المركبة الموحدة لـ AMC وDT وSCA وSCAA. نظرًا لأن أيًا من الدرجات لم يكن موزعًا بشكل طبيعي، اعتبرناها داخلية في تحليل الكوبولا الغاوسي. باستخدام ثلاثة نماذج انحدار، وجدنا أن الداخلية لم تكن مشكلة. علاوة على ذلك، استخدمنا نسبة مفارقة سيمبسون (SPR) ونسبة مساهمة R-squared (RSCR) ونسبة القمع الإحصائي (SSR) ونسبة اتجاه السببية الثنائية غير الخطية (NLBCDR) لتقييم العلاقات المفترضة. بعد تقييم العلاقات، استنتجنا أن العلاقات المفترضة كانت مدعومة، وأن المسار المعكوس كان إما ضعيفًا أو غير موجود. الشكل 2 يقدم النموذج النهائي.

نتائج اختبار الفرضيات.

| فرضية | متغير القيادة | متغير النتيجة |

|

| H1a | AMC | SCA | 0.83* |

| H1b | AMC | سكا | 0.69* |

| H2 | AMC | دي تي | 0.88* |

| H3a | دي تي | SCA | 0.17** |

| H3b | دي تي | سكا | 0.24* |

| H4a | SCA | OP | 0.41* |

| H4b | سكا | OP | 0.40* |

| اختبار الوساطة | |||

| فرضية | قيمة سوبل | الوساطة | |

| H5a (AMC-DT-SCA) | 2.89 عند

|

جزئي | |

| H5b (AMC-DT-SCAA) | 4.09 عند

|

جزئي | |

ملاحظات: AMC – قدرة إدارة التحالف؛ DT – التحول الرقمي؛ SC – مرونة سلسلة التوريد؛ SCA – قابلية التكيف في سلسلة التوريد؛ OP – الأداء التنظيمي.

العلاقة بين متغيرين (AMC و SCA/SCAA). قمنا بإجراء اختبار الوساطة بطريقتين. أولاً، اتبعنا توصيات بارون وكيني (1986). في المسار الأول، اختبرنا التأثير المباشر لـ AMC على SCA (

4.4. المقابلات الاستكشافية حول التفاعل بين التحول الرقمي وقدرات سلسلة التوريد

التأثيرات. تم تعديل إرشادات وأسئلة المقابلة الأولية خلال المناقشة، بناءً على الرؤى التي تم جمعها من المقابلات السابقة (انظر، جيويا وآخرون، 2013). وصلنا إلى التشبع النظري بعد 27 مقابلة (كوربين وستراوس، 2014).

5. المناقشة

5.1. الدلالات للنظرية

. نفحص التفاعل بين مختلف القدرات الديناميكية اللازمة للمنظمات للحفاظ على ميزة تنافسية. تشمل هذه القدرات قدرة إدارة التحالف، والتحول الرقمي، ومرونة سلسلة التوريد، وقدرة سلسلة التوريد على التكيف. من خلال فهم الرؤية الهرمية للقدرات الديناميكية، يمكن للمنظمات تطوير استراتيجيات فعالة للتنقل في تعقيدات بيئة الأعمال الحديثة والحفاظ على ميزة تنافسية مستدامة.

إدارة سلسلة الإمداد.

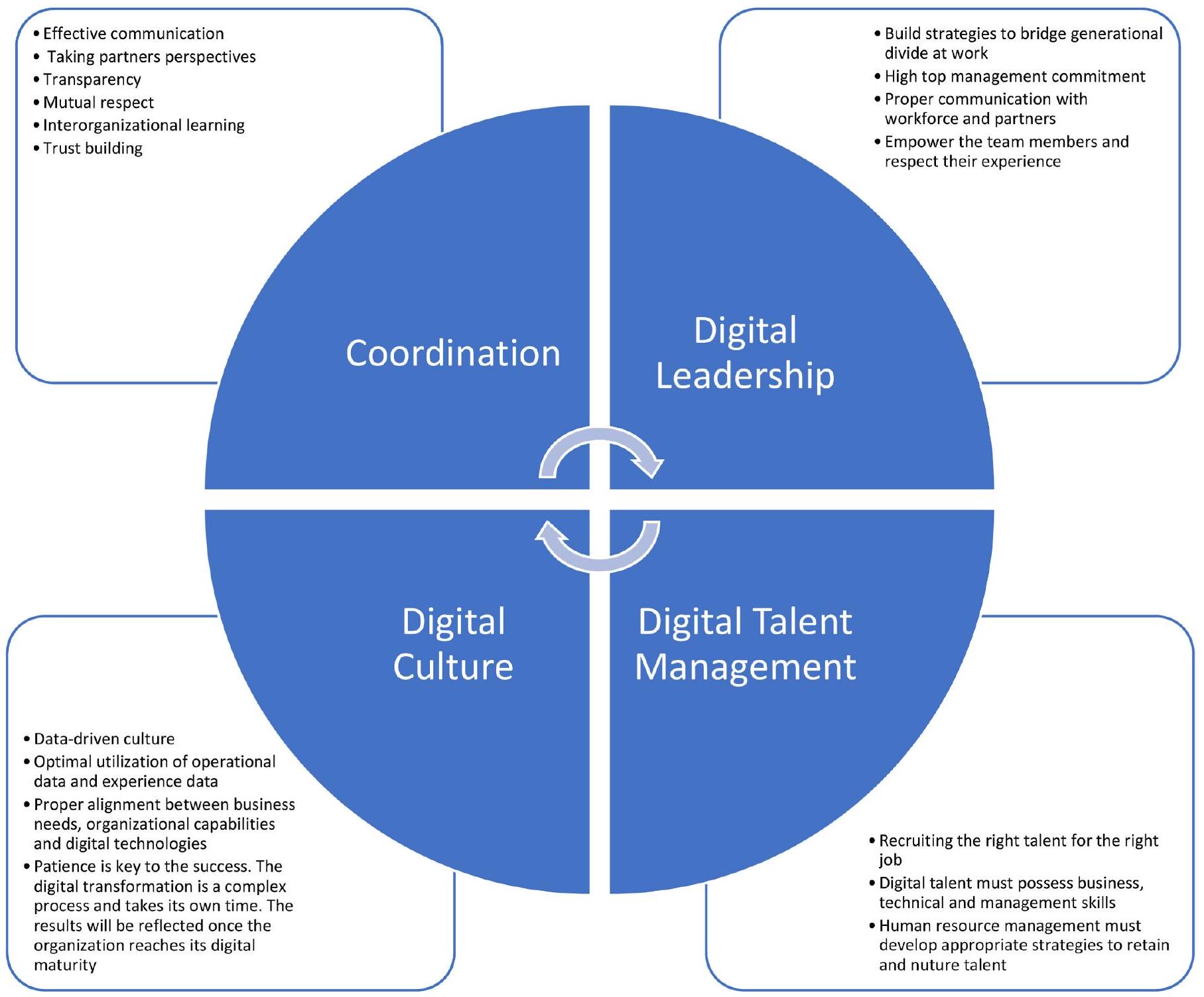

التحول الرقمي هو عملية معقدة تتطلب نهجًا منهجيًا للاستفادة من مزاياها وتحقيق النتائج المرغوبة بفعالية. لذلك، يجب على المديرين التنفيذيين أن يكونوا مستعدين لمواجهة تحدي هذه الموجة من التحول الرقمي، حيث لا يوجد قطاع أو منظمة محصنة من تأثيراتها. تركز دراستنا على الجوانب الديناميكية للتحول الرقمي، موفرة منصة لتقييم كيفية إنتاج القدرات الديناميكية للنتائج في ظل ظروف مختلفة، خاصة عندما تمر المنظمات بعملية التحول الرقمي.

5.2. الآثار على الممارسين وصانعي السياسات

5.3. قيود الدراسة واتجاهات البحث المستقبلية

6. الاستنتاجات

سلسلة التوريد والأداء التشغيلي:

- ما هي آثار AMC على SCA و SCAA؟

- ما هي آثار AMC على SCA/SCAA و OP تحت تأثير DT الوسيط؟

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

الملحق أ. مقاييس القياس والعناصر

| المقياس | المصدر | العناصر | |

| قدرة إدارة التحالفات (AMC) (موافق بشدة = 1؛ موافق بشدة = 7) | شيلكي (2014) | التنسيق بين المنظمات | |

| – نحن ننسق أنشطتنا في سلسلة التوريد مع شركائنا. | |||

| – نضمن التنسيق بين الشركاء في شبكة سلسلة التوريد لمشاركة الموارد الاستراتيجية. | |||

| – نحدد مجالات التعاون في شبكة سلسلة التوريد لدينا. | |||

| – نحدد بعناية أي تداخلات بين تحالفاتنا في شبكة سلسلة التوريد. التعلم بين المنظمات | |||

| – تتيح لنا شبكة سلسلة التوريد لدينا اكتساب معرفة لا تقدر بثمن من شركاء التحالف لدينا وتحسين عملياتنا باستمرار. | |||

| – يوفر لنا شركاء التحالف في سلسلة التوريد فرصًا قيمة لاكتساب معرفة جديدة وتعزيز كفاءاتنا الإدارية. | |||

| – قدراتنا كافية لتحليل المعلومات التي تم الحصول عليها من شركاء التحالف لدينا داخل شبكة سلسلة التوريد بفعالية. | |||

| – تأتي تعاوننا الناجح من دمج المعلومات المقدمة من شركاء التحالف لدينا مع معرفتنا الحالية. | |||

| الاستباقية في التحالف | |||

| – نحن دائمًا نسعى لفرص لإنشاء تحالفات مع شركاء سلسلة التوريد. | |||

| – نحن دائمًا نتخذ المبادرة في الاقتراب من شركاء سلسلة التوريد لدينا بمقترحات للتحالفات. | |||

|

|||

| التحول الرقمي (موافق بشدة

|

سوزا-زومر وآخرون (2020) | مهارات الذكاء الرقمي | |

| – تشجع منظمتنا موظفيها على أن يكونوا رياديين. | |||

| – تولي منظمتنا اهتمامًا كبيرًا بالشراكات الخارجية وتعزز التعاون لتحسين قدراتها الرقمية. | |||

| – تخصص منظمتنا ميزانيات كبيرة للاستثمار في القدرات الرقمية. | |||

| مرونة سلسلة التوريد (موافق بشدة

|

ألفالا-لوكي وآخرون (2018) | – تستثمر منظمتنا في القدرة الديناميكية للكشف عن أي تغييرات ديناميكية قصيرة الأجل في البيئة الخارجية. | |

| – يمكن لمنظمتنا تعديل قدراتها الإنتاجية بسرعة استجابةً للتغيرات السريعة في الطلب في السوق. | |||

| – في أوقات اضطرابات سلسلة التوريد، تكون منظمتنا جاهزة لتلبية الحاجة إلى تنوع المنتجات على الفور. | |||

| قابلية التكيف في سلسلة التوريد (موافق بشدة = 1؛ موافق بشدة = 7) | ألفالا-لوكي وآخرون (2018) | – منظمتنا قابلة للتكيف مع تغييرات السوق ويمكنها تعديل عملية وهيكل سلسلة التوريد الخاصة بها وفقًا لذلك. | |

| أداء المنظمة (أعارض بشدة)

|

ألفالا-لوك وآخرون (2018)؛ سوزا-زومر وآخرون (2020) | – العائد على الأصول (ROA) | |

| – نسبة دوران المخزون | |||

| – القيمة السوقية | |||

| – التسليم في الوقت المحدد | |||

| حجم الشركة | إكشتاين وآخرون (2015) | (عدد الموظفين) (ط) |

الملحق ب. مقابلات نموذجية

| مشارك | تعيين | مدة المقابلة | جنس | سنوات الخبرة |

| P1 | مهندس نظم موظف | 00: 29:32 | ف | 9 |

| P2 | مدير سلسلة الإمداد العالمية | 00:33:21 | M | 12 |

| P3 | المدير العام | 00: 36: 18 | M | 16 |

| P4 | مدير أول | 00: 28:37 | M | 11 |

| P5 | رئيس مجموعة B&I | 00: 37:23 | ف | ١٨ |

| P6 | مدير منتج المجموعة | 00: 28: 26 | M | 16 |

| P7 | محلل أعمال | 00:23:24 | M | ٨ |

| P8 | استشاري رئيسي | 00:37:25 | M | 12 |

| P9 | استشاري استراتيجية البيانات | 00:36:12 | ف | 10 |

| (يتبع في الصفحة التالية) |

| مشارك | تعيين | مدة المقابلة | جنس | سنوات الخبرة |

| P10 | رئيس اللوجستيات | 00:33:11 | M | ٢٢ |

| P11 | عالم بيانات أول | 00: 26:13 | ف | ٨ |

| P12 | نائب المدير العام | 00: 23:39 | M | 19 |

| P13 | مدير | 00:17:23 | M | 9 |

| P14 | استشاري أول – تصميم سلسلة الإمداد | 00:36:21 | M | 11 |

| P15 | مدير اللوجستيات | 00:19:21 | M | ١٣ |

| P16 | مدير أول – سلسلة إمداد المنتجات | 00:33:27 | M | ٩ |

| P17 | مدير التحول الرقمي | 00:37:21 | M | 11 |

| P18 | مخطط التوزيع | 00:16:38 | M | ٨ |

| P19 | استشاري أول – إدارة سلسلة الإمداد | 00:17:21 | M | 23 |

| P20 | مدير تخطيط سلسلة الإمداد | 00:28:21 | ف | 12 |

| P21 | مدير – تحليل البيانات | 00:23:11 | ف | 9 |

| P22 | نموذج بيانات | 00:19:13 | M | ٧ |

| P23 | استشاري رئيسي | 00:16:27 | M | 16 |

| P24 | مدير المشتريات | 00:31:12 | ف | ٧ |

| P25 | مدير استشارات التكنولوجيا | 00:26:33 | M | 9 |

| P26 | مدير مساعد | 00:25:21 | M | ٨ |

| P27 | مهندس مراقبة المشاريع الأول | 00:23:21 | M | 11 |

الملحق ج. بروتوكول المقابلة وتحليل الانعكاس وتدابير موثوقية المترجمين المتداخلين

الجزء 1

- كيف تتعامل شخصياً مع شركائك خلال الأزمات؟

- برأيك، ما الذي يجعل التحالفات بين الشركاء ناجحة؟

- هل يمكنك التفكير في كيفية استجابة منظمتك لاحتياجات المستهلكين خلال الأزمات؟

- برأيك، كيف يمكن للشركة تعديل نموذج عملها خلال الأزمات؟

الجزء 2

- ماذا تعرف عن مبادرات التحول الرقمي التي اتخذتها شركتك؟

- ما هي، برأيك، العوامل الرئيسية التي تؤثر على التحول الرقمي؟

- برأيك، إلى أي مدى تؤثر التحول الرقمي في شركتك على سلسلة الإمداد في شركتك خلال الأزمات الأخيرة (مثل COVID-19، التوترات الجيوسياسية، وأزمات أخرى)؟

- هل يمكنك تحديد القضايا الرئيسية المتعلقة بالتحول الرقمي في شركتك؟

- هل هناك أي تفاصيل أخرى ستكون مهمة لفهمنا؟

- هل هناك أي شيء تود أن تسأل عنه أو تشاركه بخصوص المقابلة؟

الملحق د. ملخص النتائج المستندة إلى المقابلات النوعية

| مشارك | مقتطفات من المقابلات | الأبعاد المجمعة | ||||||

| ب1، ب5، ب7، ب8، ب10، ب11 | تنسيق | |||||||

|

||||||||

| ب1، ب2، ب3، ب6 |

|

القدرة على التكيف | ||||||

| P4، P9، P13، P14 |

|

التكيف الرقمي |

| مشارك | مقتطفات من المقابلات | الأبعاد المجمعة | ||||||

|

||||||||

| ب12، ب15، ب27 | قيادة تحول التكنولوجيا من أجل القيم | |||||||

| P16، P17، P21، P19 |

|

غياب القيادة الرقمية | ||||||

| P18، P20، P22، P23 |

|

ثقافة رقمية مفقودة | ||||||

| ب24، ب25، ب26 |

|

إدارة المواهب الرقمية الضعيفة |

تنسيق بديل.

| الأبعاد المجمعة | مقتطفات من المقابلات | ||||||

| تنسيق |

|

||||||

| القدرة على التكيف |

|

||||||

| القدرة على التكيف الرقمي |

|

||||||

| قيادة تحول التكنولوجيا من أجل القيم |

|

||||||

| غياب القيادة الرقمية | P16: “أجد أنه على الرغم من مستوى الحماس العالي بين الموظفين الشباب، […] فإن الفجوة بين جيلين غالبًا ما تخلق اضطرابًا”. |

| الأبعاد المجمعة | مقتطفات من المقابلات | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

||||||

|

References

Aggarwal, V.A., 2020. Resource congestion in alliance networks: how a firm’s partners’ partners influence the benefits of collaboration. Strat. Manag. J. 41 (4), 627-655.

Aguinis, H., Edwards, J.R., Bradley, K.J., 2017. Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organ. Res. Methods 20 (4), 665-685.

Akter, S., Fosso Wamba, S., Dewan, S., 2017. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plann. Control 28 (11-12), 1011-1021.

Al-Tabbaa, O., Leach, D., Khan, Z., 2019. Examining alliance management capabilities in cross-sector collaborative partnerships. J. Bus. Res. 101, 268-284.

Alexander, A., Blome, C., Schleper, M.C., Roscoe, S., 2022. Managing the “new normal”: the future of operations and supply chain management in unprecedented times. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (8), 1061-1076.

Alicke, K., Barriball, E.D., Trautwein, V., 2021. How COVID-19 Is Reshaping Supply Chains. McKinsey and Company, pp. 2011-2020.

Alvarenga, M.Z., Oliveira, M.P.V.D., Oliveira, T.A.G.F.D., 2023. The impact of using digital technologies on supply chain resilience and robustness: the role of memory under the covid-19 outbreak. Supply Chain Manag.: Int. J. 28 (5), 825-842.

Anand, B.N., Khanna, T., 2000. Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strat. Manag. J. 21 (3), 295-315.

Apparel Resources (2017, November). https://vn.apparelresources.com/business-news /sourcing/supply-chain-leader-li-fung-focuses-speed-innovation-digitization-future /(date of access 22 July 2022).

Appio, F.P., Frattini, F., Petruzzelli, A.M., Neirotti, P., 2021. Digital transformation and innovation management: a synthesis of existing research and an agenda for future studies. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 38 (1), 4-20.

Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S., 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Market. Res. 14 (3), 396-402.

Aslam, H., Syed, T.A., Blome, C., Ramish, A., Ayaz, K., 2022. The multifaceted role of social capital for achieving organizational ambidexterity and supply chain resilience. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3174069.

Awan, U., Bhatti, S.H., Shamim, S., Khan, Z., Akhtar, P., Balta, M.E., 2022. The role of big data analytics in manufacturing agility and performance: moderation-mediation analysis of organizational creativity and of the involvement of customers as data analysts. Br. J. Manag. 33 (3), 1200-1220.

Bag, S., Rahman, M.S., Srivastava, G., Chan, H.L., Bryde, D.J., 2022. The role of big data and predictive analytics in developing a resilient supply chain network in the South African mining industry against extreme weather events. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 251, 108541.

Barney, J., 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 17 (1), 99-120.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173-1182.

Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., Schuberth, F., 2020. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 57 (2), 103168.

Berman, S.J., 2012. Digital transformation: opportunities to create new business models. Strat. Leader. 40 (2), 16-24.

Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O.A., Pavlou, P.A., Venkatraman, N.V., 2013. Digital business strategy: toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 37 (2), 471-482.

Borys, B., Jemison, D.B., 1989. Hybrid arrangements as strategic alliances: theoretical issues in organizational combinations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14 (2), 234-249.

Bosman, L., Hartman, N., Sutherland, J., 2020. How manufacturing firm characteristics can influence decision making for investing in Industry 4.0 technologies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 31 (5), 1117-1141.

Bouncken, R.B., Fredrich, V., Gudergan, S., 2022. Alliance management and innovation under uncertainty. J. Manag. Organ. 28 (3), 540-563.

Boyer, K.K., Pagell, M., 2000. Measurement issues in empirical research: improving measures of operations strategy and advanced manufacturing technology. J. Oper. Manag. 18 (3), 361-374.

Brammer, S., Branicki, L., Linnenluecke, M., 2023. Disrupting management research? Critical reflections on British journal of management COVID-19 research and an agenda for the future. Br. J. Manag. 34 (1), 3-15.

Cadden, T., McIvor, R., Cao, G., Treacy, R., Yang, Y., Gupta, M., Onofrei, G., 2022. Unlocking supply chain agility and supply chain performance through the development of intangible supply chain analytical capabilities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (9), 1329-1355.

Campbell, D.T., 1955. The informant in quantitative research. Am. J. Sociol. 60 (4), 339-342.

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Ertz, M., 2020. Agile supply chain management: where did it come from and where will it go in the era of digital transformation? Ind. Market. Manag. 90, 324-345.

Chen, H.Y., Das, A., Ivanov, D., 2019. Building resilience and managing post-disruption supply chain recovery: lessons from the information and communication technology industry. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 49, 330-342.

Chen, L., Liu, H., Zhou, Z., Chen, M., Chen, Y., 2022a. IT-business alignment, big data analytics capability, and strategic decision-making: moderating roles of event criticality and disruption of COVID-19. Decis. Support Syst. 161, 113745.

Chen, L., Lee, H.L., Tang, C.S., 2022b. Supply chain fairness. Prod. Oper. Manag. 31 (12), 4304-4318.

Cherbib, J., Chebbi, H., Yahiaoui, D., Thrassou, A., Sakka, G., 2021. Digital technologies and learning within asymmetric alliances: the role of collaborative context. J. Bus. Res. 125, 214-226.

Cheung, M.S., Myers, M.B., Mentzer, J.T., 2011. The value of relational learning in global buyer-supplier exchanges: a dyadic perspective and test of the pie-sharing premise. Strat. Manag. J. 32 (10), 1061-1082.

Cohen, M.A., Kouvelis, P., 2021. Revisit of AAA excellence of global value chains: robustness, resilience, and realignment. Prod. Oper. Manag. 30 (3), 633-643.

Conlon, C., Timonen, V., Elliott-O’Dare, C., O’Keeffe, S., Foley, G., 2020. Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qual. Health Res. 30 (6), 947-959.

Corbin, J., Strauss, A., 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Correani, A., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Petruzzelli, A.M., Natalicchio, A., 2020. Implementing a digital strategy: learning from the experience of three digital transformation projects. Calif. Manag. Rev. 62 (4), 37-56.

Cortez, R.M., Johnston, W.J., 2020. The Coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind. Market. Manag. 88, 125-135.

Cuevas-Rodríguez, G., Cabello-Medina, C., Carmona-Lavado, A., 2014. Internal and external social capital for radical product innovation: do they always work well together? Br. J. Manag. 25 (2), 266-284.

Del Giudice, M., Scuotto, V., Papa, A., Tarba, S.Y., Bresciani, S., Warkentin, M., 2021. A self-tuning model for smart manufacturing SMEs: effects on digital innovation. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 38 (1), 68-89.

Dhaundiyal, M., Coughlan, J., 2022. Extending alliance management capability in individual alliances in the post-formation stage. Ind. Market. Manag. 102, 12-23.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D.J., Foropon, C., Tiwari, M., Dwivedi, Y., Schiffling, S., 2021a. An investigation of information alignment and collaboration as complements to supply chain agility in humanitarian supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 59 (5), 1586-1605.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D.J., Blome, C., Roubaud, D., Giannakis, M., 2021b. Facilitating artificial intelligence powered supply chain analytics through alliance management during the pandemic crises in the B2B context. Ind. Market. Manag. 96, 135-146.

Dubey, R., Bryde, D.J., Dwivedi, Y.K., Graham, G., Foropon, C., Papadopoulos, T., 2023. Dynamic digital capabilities and supply chain resilience: the role of government effectiveness. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 258, 108790.

DuHadway, S., Carnovale, S., Hazen, B., 2019. Understanding risk management for intentional supply chain disruptions: risk detection, risk mitigation, and risk recovery. Ann. Oper. Res. 283, 179-198.

Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M.A., Peteraf, M.A., 2009. Dynamic capabilities: current debates and future directions. Br. J. Manag. 20, S1-S8.

Eckstein, D., Goellner, M., Blome, C., Henke, M., 2015. The performance impact of supply chain agility and supply chain adaptability: the moderating effect of product complexity. Int. J. Prod. Res. 53 (10), 3028-3046.

Eisenhardt, K.M., Martin, J.A., 2000. Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strat. Manag. J. 21 (10-11), 1105-1121.

Enrique, D.V., Lerman, L.V., de Sousa, P.R., Benitez, G.B., Santos, F.M.B.C., Frank, A.G., 2022. Being digital and flexible to navigate the storm: how digital transformation enhances supply chain flexibility in turbulent environments. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 250, 108668.

Faruquee, M., Paulraj, A., Irawan, C.A., 2021. Strategic supplier relationships and supply chain resilience: is digital transformation that precludes trust beneficial? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 41 (7), 1192-1219.

Fayezi, S., Zomorrodi, M., 2015. The role of relationship integration in supply chain agility and flexibility development: an Australian perspective. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 26 (8), 1126-1157.

Flynn, B.B., Sakakibara, S., Schroeder, R.G., Bates, K.A., Flynn, E.J., 1990. Empirical research methods in operations management. J. Oper. Manag. 9 (2), 250-284.

Forkmann, S., Henneberg, S.C., Mitrega, M., 2018. Capabilities in business relationships and networks: research recommendations and directions. Ind. Market. Manag. 74, 4-26.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F., 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18 (1), 39-50.

Forza, C., 2002. Survey research in operations management: a process-based perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 22 (2), 152-194.

Fosso Wamba, S., Akter, S., 2019. Understanding supply chain analytics capabilities and agility for data-rich environments. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 39 (6/7/8), 887-912.

Fosso Wamba, S., Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Akter, S., 2020a. The performance effects of big data analytics and supply chain ambidexterity: the moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 222, 107498.

Fosso Wamba, S., Queiroz, M.M., Trinchera, L., 2020b. Dynamics between blockchain adoption determinants and supply chain performance: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 229, 107791.

Friday, D., Savage, D.A., Melnyk, S.A., Harrison, N., Ryan, S., Wechtler, H., 2021. A collaborative approach to maintaining optimal inventory and mitigating stockout risks during a pandemic: capabilities for enabling health-care supply chain resilience. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 11 (2), 248-271.

Gabler, C.B., Richey Jr., R.G., Stewart, G.T., 2017. Disaster resilience through public-private short-term collaboration. J. Bus. Logist. 38 (2), 130-144.

Gereffi, G., Pananond, P., Pedersen, T., 2022. Resilience decoded: the role of firms, global value chains, and the state in COVID-19 medical supplies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 64 (2), 46-70.

Ghosh, S., Hughes, M., Hodgkinson, I., Hughes, P., 2022. Digital transformation of industrial businesses: a dynamic capability approach. Technovation 113, 102414.

Gioia, D.A., Corley, K.G., Hamilton, A.L., 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 16 (1), 15-31.

Glaser, B., Strauss, A., 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine Publishing Company, Hawthorne, New York.

Gligor, D.M., Esmark, C.L., Holcomb, M.C., 2015. Performance outcomes of supply chain agility: when should you be agile? J. Oper. Manag. 33, 71-82.

Grover, V., 2022. Digital agility: responding to digital opportunities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 31 (6), 709-715.

Guo, X., Li, M., Wang, Y., Mardani, A., 2023. Does digital transformation improve the firm’s performance? From the perspective of digitalization paradox and managerial myopia. J. Bus. Res. 163, 113868.

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Thiele, K.O., 2017. Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 45, 616-632.

Hamann-Lohmer, J., Bendig, M., Lasch, R., 2023. Investigating the impact of digital transformation on relationship and collaboration dynamics in supply chains and manufacturing networks-A multi-case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 262, 108932.

Hanelt, A., Bohnsack, R., Marz, D., Antunes Marante, C., 2021. A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J. Manag. Stud. 58 (5), 1159-1197.

Harju, A., Hallikas, J., Immonen, M., Lintukangas, K., 2023. The impact of procurement digitalization on supply chain resilience: empirical evidence from Finland. Supply Chain Manag.: Int. J. 28 (7), 62-76.

Hayes, A.F., 2009. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76 (4), 408-420.

Hayes, A.F., Preacher, K.J., 2010. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behav. Res. 45 (4), 627-660.

He, Q., Meadows, M., Angwin, D., Gomes, E., Child, J., 2020. Strategic alliance research in the era of digital transformation: perspectives on future research. Br. J. Manag. 31 (3), 589-617.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43, 115-135.

Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A., Wiesböck, F., 2016. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 15 (2), 123-139.

Homburg, C., Artz, M., Wieseke, J., 2012. Marketing performance measurement systems: does comprehensiveness really improve performance? J. Market. 76 (3), 56-77.

Huang, K., Wang, K., Lee, P.K., Yeung, A.C., 2023. The impact of industry 4.0 on supply chain capability and supply chain resilience: a dynamic resource-based view. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 262, 108913.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., Smith, K.M., 2018. Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 46, 92-108.

Hult, G.T.M., Hair Jr., J.F., Proksch, D., Sarstedt, M., Pinkwart, A., Ringle, C.M., 2018. Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. J. Int. Market. 26 (3), 1-21.

Hunt, S.D., Madhavaram, S., 2020. Adaptive marketing capabilities, dynamic capabilities, and renewal competences: the “outside vs. inside” and “static vs. dynamic” controversies in strategy. Ind. Market. Manag. 89, 129-139.

Ivanov, D., 2023. Intelligent digital twin (iDT) for supply chain stress-testing, resilience, and viability. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 263, 108938.

Jajja, M.S.S., Chatha, K.A., Farooq, S., 2018. Impact of supply chain risk on agility performance: mediating role of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 205, 118-138.

Juan, S.J., Li, E.Y., 2023. Financial performance of firms with supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of dynamic capability and supply chain resilience. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 43 (5), 712-737.

Ketchen Jr., D.J., Craighead, C.W., 2020. Research at the intersection of entrepreneurship, supply chain management, and strategic management: opportunities highlighted by COVID-19. J. Manag. 46 (8), 1330-1341.

Klimas, P., Sachpazidu, K., Stańczyk, S., 2023. The attributes of coopetitive relationships: what do we know and not know about them? Eur. Manag. J. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.emj.2023.02.005.

Kock, N., 2019. From composites to factors: bridging the gap between PLS and covariance-based structural equation modelling. Inf. Syst. J. 29 (3), 674-706.

Kumar, R., 2014. Managing ambiguity in strategic alliances. Calif. Manag. Rev. 56 (4), 82-102.

Kumar, N., Stern, L.W., Anderson, J.C., 1993. Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Acad. Manag. J. 36 (6), 1633-1651.

Kumar, V., Ramachandran, D., Kumar, B., 2021. Influence of new-age technologies on marketing: a research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 125, 864-877.

L’Hermitte, C., Tatham, P., Bowles, M., Brooks, B., 2016. Developing organisational capabilities to support agility in humanitarian logistics: an exploratory study. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 6 (1), 72-99.

Lee, H.L., 2021. The new AAA supply chain. Management and Business Review 1 (1), 173-176.

Lee, S.M., Rha, J.S., 2016. Ambidextrous supply chain as a dynamic capability: building a resilient supply chain. Manag. Decis. 54 (1), 2-23.

Levitt, B., March, J.G., 1988. Organizational learning. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 14 (1), 319-338.

Li, L., Su, F., Zhang, W., Mao, J.Y., 2018. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: a capability perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 28 (6), 1129-1157.

Lin, S., Lin, J., Han, F., Luo, X.R., 2022. How big data analytics enables the alliance relationship stability of contract farming in the age of digital transformation. Inf. Manag. 59 (6), 103680.

Lioukas, C.S., Reuer, J.J., Zollo, M., 2016. Effects of information technology capabilities on strategic alliances: implications for the resource-based view. J. Manag. Stud. 53 (2), 161-183.

Liu, S., Chan, F.T., Yang, J., Niu, B., 2018. Understanding the effect of cloud computing on organizational agility: an empirical examination. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 43, 98-111.

MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, P.M., 2012. Common method bias in marketing: causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retailing 88 (4), 542-555.

Mandal, S., Dubey, R.K., 2021. Effect of inter-organizational systems appropriation in agility and resilience development: an empirical investigation. Benchmark Int. J. 28 (9), 2656-2681.

Mohamud, M., Sarpong, D., 2016. Dynamic capabilities: towards an organizing framework. Journal of Strategy and Management 9 (4), 511-526.

Moshtari, M., 2016. Inter-organizational fit, relationship management capability, and collaborative performance within a humanitarian setting. Prod. Oper. Manag. 25 (9), 1542-1557.

Müller, J., Hoberg, K., Fransoo, J.C., 2022. Realizing supply chain agility under time pressure: ad hoc supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Oper. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1002/joom.1210.

Namagembe, S., 2022. Collaborative approaches and adaptability in disaster risk situations. Continuity Resilience Rev. 4 (2), 224-246.

Nasiri, M., Saunila, M., Ukko, J., 2022. Digital orientation, digital maturity, and digital intensity: determinants of financial success in digital transformation settings. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (13), 274-298.

Naughton, S., Golgeci, I., Arslan, A., 2020. Supply chain agility as an acclimatisation process to environmental uncertainty and organisational vulnerabilities: insights from British SMEs. Prod. Plann. Control 31 (14), 1164-1177.

Nayal, K., Raut, R.D., Yadav, V.S., Priyadarshinee, P., Narkhede, B.E., 2022. The impact of sustainable development strategy on sustainable supply chain firm performance in the digital transformation era. Bus. Strat. Environ. 31 (3), 845-859.

Niesten, E., Jolink, A., 2015. The impact of alliance management capabilities on alliance attributes and performance: a literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 17 (1), 69-100.

Ning, Y., Li, L., Xu, S.X., Yang, S., 2023. How do digital technologies improve supply chain resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Frontiers of Engineering Management 10 (1), 39-50.

Omrani, N., Rejeb, N., Maalaoui, A., Dabić, M., Kraus, S., 2022. Drivers of digital transformation in SMEs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/ TEM.2022.3215727.

Papanagnou, C., Seiler, A., Spanaki, K., Papadopoulos, T., Bourlakis, M., 2022. Datadriven digital transformation for emergency situations: the case of the UK retail sector. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 250, 108628.

Park, S., Braunscheidel, M.J., Suresh, N.C., 2023. The performance effects of supply chain agility with sensing and responding as formative capabilities. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-09-2022-0328.

Patrucco, A.S., Kähkönen, A.K., 2021. Agility, adaptability, and alignment: new capabilities for PSM in a post-pandemic world. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 27 (4), 100719.

Prashant, K., Harbir, S., 2009. Managing strategic alliances: what do we know now, and where do we go from here? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 23 (3), 45-62.

Preacher, K.J., Hayes, A.F., 2004. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36 (4), 717-731.

Queiroz, M., Tallon, P.P., Sharma, R., Coltman, T., 2018. The role of IT application orchestration capability in improving agility and performance. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 27 (1), 4-21.

Rai, A., Patnayakuni, R., Seth, N., 2006. Firm performance impacts of digitally enabled supply chain integration capabilities. MIS Q. 30 (2), 225-246.

Richey, R.G., Tokman, M., Dalela, V., 2010. Examining collaborative supply chain service technologies: a study of intensity, relationships, and resources. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 38, 71-89.

Richey, R.G., Roath, A.S., Adams, F.G., Wieland, A., 2022. A responsiveness view of logistics and supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 43 (1), 62-91.

Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., 2016. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: the importance-performance map analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 116 (9), 1865-1886.

Ringov, D., 2017. Dynamic capabilities and firm performance. Long. Range Plan. 50 (5), 653-664.

Roscoe, S., Aktas, E., Petersen, K.J., Skipworth, H.D., Handfield, R.B., Habib, F., 2022. Redesigning global supply chains during compounding geopolitical disruptions: the role of supply chain logics. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (9), 1407-1434.

Rothaermel, F.T., Deeds, D.L., 2006. Alliance type, alliance experience and alliance management capability in high-technology ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 21 (4), 429-460.

Sarker, S., Rashidi, K., Gölgeci, I., Gligor, D.M., Hsuan, J., 2022. Exploring pillars of supply chain competitiveness: insights from leading global supply chains. Prod. Plann. Control 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2022.2145246.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., Thiele, K.O., Gudergan, S.P., 2016. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: where the bias lies. J. Bus. Res. 69 (10), 3998-4010.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J.F., Pick, M., Liengaard, B.D., Radomir, L., Ringle, C.M., 2022. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Market. 39 (5), 1035-1064.

Schilke, O., 2014a. On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage: the nonlinear moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Strat. Manag. J. 35 (2), 179-203.

Schilke, O., 2014b. Second-order dynamic capabilities: how do they matter? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 28 (4), 368-380.

Schilke, O., Goerzen, A., 2010. Alliance management capability: an investigation of the construct and its measurement. J. Manag. 36 (5), 1192-1219.

Schilke, O., Hu, S., Helfat, C.E., 2018. Quo vadis, dynamic capabilities? A contentanalytic review of the current state of knowledge and recommendations for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 12 (1), 390-439.

Schoenherr, T., Swink, M., 2015. The roles of supply chain intelligence and adaptability in new product launch success. Decis. Sci. J. 46 (5), 901-936.

Schräge, M., Muttreja, V., Kwan, A., 2022. How the wrong KPIs doom digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 63 (3), 35-40.

Schreiner, M., Kale, P., Corsten, D., 2009. What really is alliance management capability and how does it impact alliance outcomes and success? Strat. Manag. J. 30 (13), 1395-1419.

Shen, Z.M., Sun, Y., 2023. Strengthening supply chain resilience during COVID-19: a case study of JD. com. J. Oper. Manag. 69 (3), 359-383.

Sheng, J., Amankwah-Amoah, J., Khan, Z., Wang, X., 2021. COVID-19 pandemic in the new era of big data analytics: methodological innovations and future research directions. Br. J. Manag. 32 (4), 1164-1183.

Shrey, A., Dutt, A., Roy, D., 2022. Impact Of COVID-19 Disruptions on the Supply Chain: Insights from India (No. WP 2022-06-01). Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department.

Sirmon, D.G., Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D., Gilbert, B.A., 2011. Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage: breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. J. Manag. 37 (5), 1390-1412.

Sodhi, M.S., Tang, C.S., 2021. Supply chain management for extreme conditions: research opportunities. J. Supply Chain Manag. 57 (1), 7-16.

Sodhi, M.S., Tang, C.S., Willenson, E.T., 2023. Research opportunities in preparing supply chains of essential goods for future pandemics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 61 (8), 2416-2431.

Sousa-Zomer, T.T., Neely, A., Martinez, V., 2020. Digital transforming capability and performance: a microfoundational perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 40 (7/8), 1095-1128.

Squire, B., Cousins, P.D., Brown, S., 2009. Cooperation and knowledge transfer within buyer-supplier relationships: the moderating properties of trust, relationship duration and supplier performance. Br. J. Manag. 20 (4), 461-477.

Stuart, F.I., 1997. Supply-chain strategy: organizational influence through supplier alliances. Br. J. Manag. 8 (3), 223-236.

Tallon, P.P., Queiroz, M., Coltman, T., Sharma, R., 2019. Information technology and the search for organizational agility: a systematic review with future research possibilities. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 28 (2), 218-237.

Teece, D.J., 2007. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 28 (13), 1319-1350.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A., 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 18 (7), 509-533.

Teece, D., Peteraf, M., Leih, S., 2016. Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 58 (4), 13-35.

Teng, B.S., 2007. Corporate entrepreneurship activities through strategic alliances: a resource-based approach toward competitive advantage. J. Manag. Stud. 44 (1), 119-142.

Turken, N., Geda, A., 2020. Supply chain implications of industrial symbiosis: a review and avenues for future research. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 161, 104974.

Vaia, G., Arkhipova, D., DeLone, W., 2022. Digital governance mechanisms and principles that enable agile responses in dynamic competitive environments. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 31 (6), 662-680.

Verbeke, A., 2020. Will the COVID-19 pandemic really change the governance of global value chains? Br. J. Manag. 31 (3), 444-446.

Verhoef, P.C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Dong, J.Q., Fabian, N., Haenlein, M., 2021. Digital transformation: a multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 122, 889-901.

Viswanathan, M., Kayande, U., 2012. Commentary on “common method bias in marketing: causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies”. J. Retailing 88 (4), 556-562.

Wang, Q., Du, Z.Y., 2022. Changing the impact of banking concentration on corporate innovation: the moderating effect of digital transformation. Technol. Soc. 71, 102124.

Warner, K.S., Wäger, M., 2019. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: an ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long. Range Plan. 52 (3), 326-349.

Whitten, G.D., Green, K.W., Zelbst, P.J., 2012. Triple-A supply chain performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 32 (1), 28-48.

Wieland, A., 2021. Dancing the supply chain: toward transformative supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 57 (1), 58-73.

Winter, S.G., 2003. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strat. Manag. J. 24 (10), 991-995.

Wright, L.T., Robin, R., Stone, M., Aravopoulou, D.E., 2019. Adoption of big data technology for innovation in B2B marketing. J. Bus. Bus. Market. 26 (3-4), 281-293.

Xu, D., Dai, J., Paulraj, A., Chong, A.Y.L., 2022. Leveraging digital and relational governance mechanisms in developing trusting supply chain relationships: the interplay between blockchain and norm of solidarity. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (12), 1878-1904.

Yang, L., Huo, B., Tian, M., Han, Z., 2021. The impact of digitalization and interorganizational technological activities on supplier opportunism: the moderating role of relational ties. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 41 (7), 1085-1118.

Ye, F., Liu, K., Li, L., Lai, K.H., Zhan, Y., Kumar, A., 2022. Digital supply chain management in the COVID-19 crisis: an asset orchestration perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 245, 108396.

Yeow, A., Soh, C., Hansen, R., 2018. Aligning with new digital strategy: a dynamic capabilities approach. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 27 (1), 43-58.

Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H.J., Davidsson, P., 2006. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: a review, model and research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 43 (4), 917-955.

Zhang, J., Chen, Y., Li, Q., Li, Y., 2023. A review of dynamic capabilities evolution-based on organisational routines, entrepreneurship and improvisational capabilities perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 168, 114214.

Zhao, N., Hong, J., Lau, K.H., 2023. Impact of supply chain digitalization on supply chain resilience and performance: a multi-mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 259, 108817.

- Corresponding author. Montpellier Business School, 2300 Avenue des Moulins, 34185, Montpellier, France.

E-mail addresses: r.dubey@montpellier-bs.com, r.dubey@ljmu.ac.uk (R. Dubey), D.J.Bryde@ljmu.ac.uk (D.J. Bryde), c.blome@lancaster.ac.uk (C. Blome), y.k. dwivedi@swansea.ac.uk (Y.K. Dwivedi), stephen.childe@plymouth.ac.uk (S.J. Childe), c.foropon@montpellier-bs.com (C. Foropon).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2024.109166

Publication Date: 2024-01-23

LJMU Research Online

https://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/22428/

Article

Dubey, R ORCID logoORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3913-030X, Bryde, DJ, Blome, C, Dwivedi, Y, Childe, SJ and Foropon, C (2024) Alliances and digital transformation are crucial for benefiting from dynamic supply chain capabilities during times of crisis: A multi-method studv. International

Alliances and digital transformation are crucial for benefiting from dynamic supply chain capabilities during times of crisis: A multi-method study

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Digital transformation

Supply chain agility

Supply chain adaptability

Organisational performance

Dynamic capability view theory

Abstract

During times of crisis, businesses need strategic partnerships and digital transformation to survive. Understanding how digital transformation and alliance management capability can work together to enhance supply chain capabilities during a crisis is important. We have developed a theoretical framework that explains how the alliance management capability, under the mediating influence of digital transformation, helps build supply chain capabilities for unprecedented crises. This framework highlights key enablers such as alliance management capability, digital transformation, supply chain agility, and supply chain adaptability that are essential for organisational performance. We tested our theoretical model using a survey of 157 individuals working in the manufacturing industry in India. Our findings suggest that combining alliance management capability and digital transformation enhances supply chain capabilities, which improves an organisation’s ability to respond to crises. Moreover, digital transformation, supply chain agility, and adaptability are critical determinants of organisational performance during crises. Therefore, companies that use digital technologies to increase their agility and adaptability are more likely to perform well during times of crisis. To collect qualitative data, we interviewed key participants (

1. Introduction

such events (Alexander et al., 2022; Wulandhari et al., 2022; Juan and Li, 2023). Patrucco and Kähkönen (2021) noted that agility and adaptability are dynamic capabilities that help organisations navigate crises and maintain strategic growth.

et al., 2021; Papanagnou et al., 2022), will play a critical role in bringing supply chain partners closer together as they share information and coordinate their activities better (Lee, 2021; Escamilla et al., 2021). However, in many cases, digital transformation results have not met expectations (Hess et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2023), and in some cases, digital transformation capability has yielded differential results (Schräge et al., 2022). Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand the effects of DT on supply chain capabilities and performance outcomes (Centobelli et al., 2020; Meng et al., 2023). In situations where digital transformation is at play, it can either act as a mediator between two variables (Nayal et al., 2022; Tsou and Chen, 2023) or have an interactive effect (Wang and Du, 2022) on them. This means that the changes brought about by digital transformation can either influence the relationship between two variables or directly impact them, depending on the context. Specifically, it is not well understood how AMC affects the supply chain capabilities and organisational performance (OP) under the mediating effect of digital transformation. To address this knowledge gap, our second research question (RQ2) is: What are the effects of AMC on the SCA/SCAA and OP under the mediating effect of DT?

2. Theory development

2.1. Dynamic supply chain capabilities-building process

framework is a multi-disciplinary perspective that explains risk management and uncertainties (Teece et al., 2016, p. 13). It offers a theoretical perspective on building strategic capabilities to enable organisations to sustain continuous growth during turbulent times and gain superior performance (Mohamud and Sarpong, 2016). There exists a rich body of literature that informs our understanding of dynamic capabilities, but contradictions in conceptualisation and definitions often limit our understanding of dynamic capabilities and their linkage with competitive advantage (Winter, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006; Fainshmidt et al., 2016; Hunt and Madhavaram, 2020; Ye et al., 2022; Yang and Yee, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023).

2.2. Alliance management capability (AMC)

built over time through multiple interactions. Following RBV arguments (see, Barney, 1991), AMC is conceived as marshalling heterogeneous and immobile resources of a firm, thus forming a source of sustained competitive advantage (Kauppila, 2015; Lioukas et al., 2016). AMC is often considered valuable and rare because strategic alliances are difficult to form. Alliances develop over time, and organisations that are purely interested in short-term collaboration often face difficulties in realizing the benefits; thus, such strategic alliances often fail (Prashant and Harbir, 2009). Following Sirmon et al.. (2011) resource orchestration view, AMC forms through the bundling of resources and capability to generate sustained competitive advantage.

2.3. Digital transformation (DT)

2.4. Hypotheses

2.4.1. AMC and SCA/SCAA

2.4.2. AMC and DT

of crisis (Karimi and Walter, 2015). By embracing digital technologies, companies can streamline their operations, optimise their resources, and increase their agility, allowing them to respond quickly and effectively to changing market conditions. Thus, organisations can benefit from forming strategic alliances with other companies to foster digital transformation and stay competitive in today’s rapidly evolving business landscape (Li et al., 2018; Hanelt et al., 2021). Such alliances can help organisations access valuable expertise and resources that can be leveraged to drive innovation and growth (Ghosh et al., 2022). By working closely with partners, organisations can develop new technologies, processes, and solutions that better meet the needs and expectations of customers, while also improving operational efficiency and reducing costs (Prashant and Harbir, 2009). Therefore, forming strategic alliances can be a key enabler of digital transformation and a powerful way for organisations to stay ahead of the curve (Warner and Wäger, 2019). Based on the preceding discussions, we can hypothesise:

2.4.3. DT and SCA/SCAA

2.4.4. SCA/SCAA and

SCAA is about adjusting supply chain design to address the rapid and unexpected changes in the business environment or market (Lee, 2004; Eckstein et al., 2015; Fosso Wamba et al. 2020; Lee, 2021). To build adaptability, organisations need to track continuous changes in the external environment with the help of digital technologies and develop alternate sourcing strategies to handle any kind of trade restriction or

disruption caused by political turbulence or geopolitical crises. They must create flexibility in their supply chains and have multiple sources/markets to address supply/demand uncertainties (Lee, 2021). The difference between SCA and SCAA is one of orientation. SCA is short-term, and SCAA is a long-term strategy (see Lee, 2004; Richey et al., 2022). The prior literature posits that SCAA will positively influence the market and financial performance measures. Hence, we hypothesise:

2.4.5. The mediating effect of digital transformation

3. Research methods

3.1. Research setting

Respondents characteristics (

| Industry | Sample (n) | % |

| Food | 36 | 22.93 |

| Apparel Manufacturing | 23 | 14.65 |

| Computer and electronics goods manufacturing | 40 | 25.48 |

| Plastics and Rubber goods manufacturing | 58 | 36.94 |

| Firm Size | ||

| <100 employees | 21 | 13.38 |

| 100-499 employees | 36 | 22.93 |

| 500-1499 employees | 69 | 43.95 |

| 1500-4999 employees | 24 | 15.29 |

| >5000 employees | 7 | 4.46 |

| Firm age (years) | ||

| <10 | 12 | 7.64 |

| 10-19 years | 41 | 26.11 |

| 20-29 years | 48 | 30.57 |

| >30 years | 56 | 35.67 |

| Designation | ||

| Head of Supply Chain Department | 72 | 45.86 |

| Regional Head | 61 | 38.85 |

| Consultant | 24 | 15.29 |

| Tenure of the respondent (years) | ||

| <1 | 12 | 7.64 |

| 1-5 years | 36 | 22.93 |

| 6-10 years | 62 | 39.49 |

| >10 years | 47 | 29.94 |

3.2. Measures

3.3. Sample and data collection

least two weeks after the initial email. We finally received 162 completed questionnaires (response rate

4. Data analysis

4.1. Common method bias (CMB)

4.2. Measurement properties of constructs

Convergent validity.

| Construct | Item | Factor loadings | Variance | Error | SCR | AVE | |

| AMC (

|

IC (first-order reflective construct)

|

IC1 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.72 |

| IC2 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | ||||

| IC3 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.20 | ||||

| APC (first-order reflective construct)

|

APC1 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| 0.91,

|

APC2 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | |||

| APC3 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.30 | ||||

| APC4 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | ||||

| IL (first-order reflective construct) (

|

IL1 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.30 | |||

| 0.91,

|

IL2 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.26 | |||

| IL3 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | ||||

| IL4 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | ||||

| AP (first-order reflective construct) (

|

AP1 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.27 | |||

| 0.89,

|

AP2 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.29 | |||

| AP3 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.40 | ||||

| AP4 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.32 | ||||

| SCA (

|

AGIL1 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 0.91 | 0.77 | |

| AGIL2 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| AGIL3 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | ||||

| SCAA (

|

ADAP1 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.92 | 0.79 | |

| ADAP2 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 | ||||

| ADAP3 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.19 | ||||

| OP (

|

ROA | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.79 | |

| ITO | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| OTD | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.18 | ||||

| DT (

|

DSS (first-order reflective construct) (

|

DT_DSS1 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.86 |

| 0.95, AVE = 0.85) | DT_DSS2 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 | |||

| DT_DSS3 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.23 | ||||

| CAR (first-order reflective construct) (

|

DT_CAR1 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.17 | |||

| 0.95,

|

DT_CAR2 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.10 | |||

| DT_CAR3 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.11 |

Discriminant validity.

| Scale Range | Mean | Standard Deviation | IC | APC | IL | AP | DT_DSS | DT_CAR | SCA | SCAA | OP | |

| IC | 1-7 | 5.62 | 1.00 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| APC | 1-7 | 5.77 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.85 | |||||||

| IL | 1-7 | 5.69 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.85 | ||||||

| AP | 1-7 | 5.68 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.82 | |||||

| DT_DSS | 1-7 | 5.59 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.92 | ||||

| DT_CAR | 1-7 | 5.6 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.94 | |||

| SCA | 1-7 | 5.64 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.93 | ||

| SCAA | 1-7 | 5.64 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.89 | |

| OP | 1-7 | 5.75 | 0.96 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.89 |

Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) values.

| IC | APC | IL | AP | DT_DSS | DT_CAR | SCAG | SCAA | OP | |

| IC | |||||||||

| APC | 0.72 | ||||||||

| IL | 0.84 | 0.82 | |||||||

| AP | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.89 | ||||||

| DT_DSS | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | |||||

| DT_CAR | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||||

| SCAG | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | |||

| SCAA | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.69 | ||

| OP | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.87 | |

performed the HTMT (hetrotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations) test (see Table 4). The HTMT values are well below the recommended threshold values (see Henseler et al., 2015), which indicates that the constructs possess sufficient discriminant validity. In totality, the constructs possess construct validity that is sufficient to enable the interpretation of structural estimates.

4.3. Hypothesis testing

before hypothesis testing, it is essential to perform an endogeneity test. Although scholars have suggested several methods for identifying and correcting endogeneity, it remains a contentious issue. We conducted a normality test using Kolmogorov-Smirnov with Lilliefors correction on the standardized composite scores of AMC, DT, SCA, and SCAA. Since none of the scores were normally distributed, we considered them endogenous in the Gaussian copula analysis. Using three regression models, we found that endogeneity was not an issue. Moreover, we used Simpson’s paradox ratio (SPR), r-squared contribution ratio (RSCR), statistical suppression ratio (SSR), and non-linear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) to evaluate the hypothesised relationships. After assessing the relationships, we concluded that the hypothesised relationships were supported, and the reversed path was either weak or did not exist. Fig. 2 presents the final model.

Results of hypothesis testing.

| Hypothesis | Driving variable | Outcome variable |

|

| H1a | AMC | SCA | 0.83* |

| H1b | AMC | SCAA | 0.69* |

| H2 | AMC | DT | 0.88* |

| H3a | DT | SCA | 0.17** |

| H3b | DT | SCAA | 0.24* |

| H4a | SCA | OP | 0.41* |

| H4b | SCAA | OP | 0.40* |

| Mediation test | |||

| Hypothesis | Sobel value | Mediation | |

| H5a (AMC-DT-SCA) | 2.89 at

|

partial | |

| H5b (AMC-DT-SCAA) | 4.09 at

|

partial | |

Notes: AMC-alliance management capability; DT-digital transformation; SCAsupply chain agility; SCAA-supply chain adaptability; OP-organisational performance.

relationship between two variables (AMC and SCA/SCAA). We conducted the mediation test in two ways. Firstly, we followed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommendations. In the first path, we tested the direct impact of AMC on SCA (

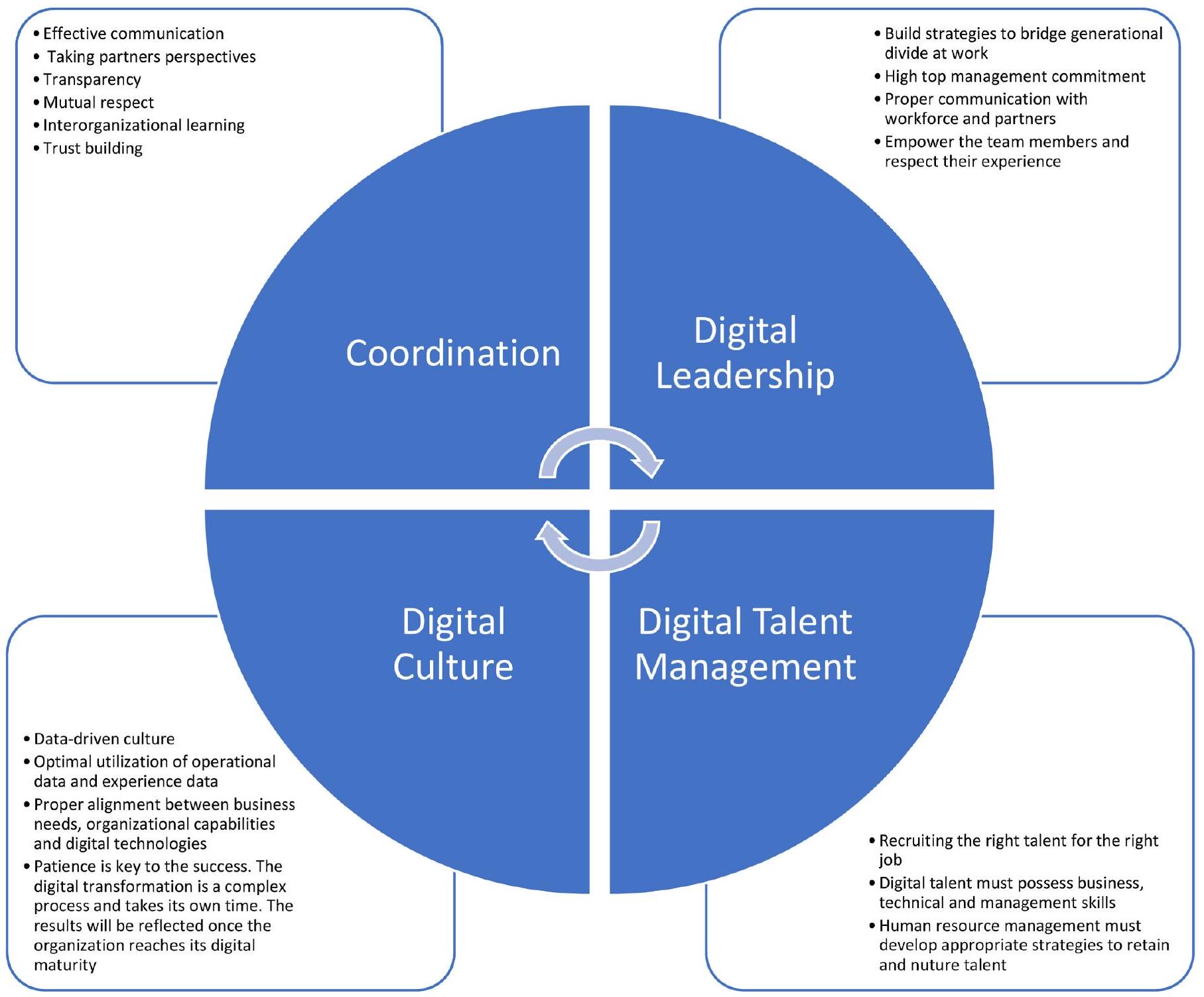

4.4. Exploratory interviews on the interaction between digital transformation and supply chain capabilities

impacts. The initial interview guidelines and questions were adjusted during the discussion, based on the insights gathered from previous interviews (see, Gioia et al., 2013). We reached theoretical saturation after 27 interviews (Corbin and Strauss, 2014).

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for theory

environment. We examine the interplay of various dynamic capabilities necessary for organisations to maintain a competitive advantage. These capabilities include alliance management capability, digital transformation, supply chain agility, and supply chain adaptability. By understanding the hierarchical view of dynamic capabilities, organisations can develop effective strategies to navigate the complexities of the modern business environment and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage.

supply chain management.

Digital transformation is a complex process requiring a systematic approach to leverage its benefits and achieve desired outcomes effectively. As such, senior managers must be ready to meet the challenge of this wave of digital transformation, as no sector or organisation is immune to its effects. Our study focuses on the dynamic aspects of digital transformation, providing a platform to evaluate how dynamic capabilities can produce results under different conditions, especially when organisations are undergoing digital transformation.

5.2. Implications for practitioners and policymakers

5.3. Limitations of the study and future research directions

6. Conclusions

the supply chain and operational performance:

- What are the effects of AMC on SCA and SCAA?

- What are the effects of AMC on the SCA/SCAA and OP under the mediating effect of DT?

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Data availability

Acknowledgement

Appendix A. Measurement scales and items

| Scale | Source | Items | |

| Alliance management capability (AMC) (strongly disagree =1; strongly agree = 7) | Schilke (2014) | Interorganisational coordination | |

| – We coordinate our activities in the supply chain with our partners. | |||

| – We ensure coordination among the partners in the supply chain network to share strategic resources. | |||

| – We determine the areas of collaboration in our supply chain network. | |||

| – We carefully determine any overlaps between our alliances in the supply chain network. Interorganisational learning | |||

| – Our supply chain network allows us to gain invaluable knowledge from our alliance partners and continuously improve our operations. | |||

| – Our supply chain alliance partners provide valuable opportunities to acquire new knowledge and enhance our managerial competencies. | |||

| – Our capabilities are sufficient to effectively analyse the information obtained from our alliance partners within the supply chain network. | |||

| – Our successful collaboration results from integrating the information provided by our alliance partners with our existing knowledge. | |||

| Alliance Proactiveness | |||

| – We always seek opportunities to establish alliances with supply chain partners. | |||

| – We always take the initiative in approaching our supply chain partners with proposals for alliances. | |||

|

|||

| Digital transformation (strongly disagree

|

Sousa-Zomer et al. (2020) | Digital savvy skills | |

| – Our organisation encourages its employees to be entrepreneurial. | |||

| – Our organisation pays significant attention to external partnerships and fosters collaboration to help improve its digital capabilities. | |||

| – Our organisation makes significant fund allocations on investment in digital capabilities. | |||

| Supply chain agility (strongly disagree

|

Alfalla-Luque et al. (2018) | – Our organisation invests in the dynamic sensing capability to detect any short-term dynamic changes in the external environment. | |

| – Our organisation can quickly adjust its production capabilities in response to rapid changes in market demand. | |||

| – In times of supply chain disruptions, our organisation stands ready to promptly meet the need for product variety. | |||

| Supply chain adaptability (strongly disagree = 1; strongly agree = 7) | Alfalla-Luque et al. (2018) | – Our organisation is adaptable to market changes and can modify its supply chain process and structure accordingly. | |

| Organizational performance (strongly disagree

|

Alfalla-Luque et al. (2018); Sousa-Zomer et al. (2020) | – Return on Asset (ROA) | |

| – Inventory turnover ratio | |||

| – Market capitalisation | |||

| – On-time delivery | |||

| Firm size | Eckstein et al. (2015) | (Number of employees) (ln) |

Appendix B. Sample Interviews

| Participant | Designation | Interview duration | Gender | Experience (years) |

| P1 | Staff Systems Engineer | 00: 29:32 | F | 9 |

| P2 | Global Supply Chain Manager | 00:33:21 | M | 12 |

| P3 | Chief Manager | 00: 36: 18 | M | 16 |

| P4 | Senior Manager | 00: 28:37 | M | 11 |

| P5 | Cluster B&I Head | 00: 37:23 | F | 18 |

| P6 | Group Product Manager | 00: 28: 26 | M | 16 |

| P7 | Business Analyst | 00:23:24 | M | 8 |

| P8 | Principal Consultant | 00:37:25 | M | 12 |

| P9 | Data Strategy Consultant | 00:36:12 | F | 10 |

| (continued on next page) |

| Participant | Designation | Interview duration | Gender | Experience (years) |

| P10 | Head-Logistics | 00:33:11 | M | 22 |

| P11 | Senior Data Scientist | 00: 26:13 | F | 8 |

| P12 | Deputy General Manager | 00: 23:39 | M | 19 |

| P13 | Manager | 00:17:23 | M | 9 |

| P14 | Senior Consultant-Supply Chain Design | 00:36:21 | M | 11 |

| P15 | Manager-Logistics | 00:19:21 | M | 13 |

| P16 | Senior Manager-Product Supply Chain | 00:33:27 | M | 9 |

| P17 | Manager-Digital Transformation | 00:37:21 | M | 11 |

| P18 | Distribution Planner | 00:16:38 | M | 8 |

| P19 | Senior Consultant-Supply Chain Management | 00:17:21 | M | 23 |

| P20 | Manager-Supply Chain Planning | 00:28: 21 | F | 12 |

| P21 | Manager-Data Analytics | 00:23:11 | F | 9 |

| P22 | Data Modeller | 00:19:13 | M | 7 |

| P23 | Lead Consultant | 00:16:27 | M | 16 |

| P24 | Procurement Manager | 00:31: 12 | F | 7 |

| P25 | Technology Consulting Manager | 00:26:33 | M | 9 |

| P26 | Associate Manager | 00:25:21 | M | 8 |

| P27 | Senior Project Controls Engineer | 00:23:21 | M | 11 |

Appendix C. Interview protocol and the reflective analysis and intercoder reliability measures

Part 1

- How do you personally deal with your partners during crises?

- In your opinion, what makes alliances between partners successful?

- Can you think about how your organisation responds to the needs of the consumers during the crises?

- In your opinion, how a company can adapt its business model during crises?

Part 2

- What do you know about the digital transformation initiatives taken by your company?

- What, in your view, are the key factors that impact digital transformation?

- In your opinion, to what extent does the digital transformation in your company impact the supply chain of your company during the recent crises (e.g., COVID-19, geopolitical tensions, and other crises)?

- Can you identify the main issues related to digital transformation in your company?

- Are there any other details that would be important for us to comprehend?

- Is there anything you would like to ask or share about the interview?

Appendix D. Summary of findings based on qualitative interviews

| Participant | Excerpt from interviews | Aggregate dimensions | ||||||

| P1, P5, P7, P8, P10, P11 | Coordination | |||||||

|

||||||||

| P1, P2, P3, P6 |

|

Agile capability | ||||||

| P4, P9, P13, P14 |

|

Digital adaptability |

| Participant | Excerpt from interviews | Aggregate dimensions | ||||||

|

||||||||

| P12, P15, P27 | Driving technology transformation for values | |||||||

| P16, P17, P21, P19 |

|

Missing digital leadership | ||||||

| P18, P20, P22, P23 |

|

Missing digital culture | ||||||

| P24, P25, P26 |

|

Poor digital talent management |

Alternative format.

| Aggregate dimensions | Excerpt from interviews | ||||||

| Coordination |

|

||||||

| Agile capability |

|

||||||

| Digital adaptability |

|

||||||

| Driving technology transformation for values |

|

||||||

| Missing digital leadership | P16: “I find despite the high level of enthusiasm among the young staff, […] the generational divide between two generations often creates disruption”. |

| Aggregate dimensions | Excerpt from interviews | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

||||||

|

References

Aggarwal, V.A., 2020. Resource congestion in alliance networks: how a firm’s partners’ partners influence the benefits of collaboration. Strat. Manag. J. 41 (4), 627-655.

Aguinis, H., Edwards, J.R., Bradley, K.J., 2017. Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organ. Res. Methods 20 (4), 665-685.

Akter, S., Fosso Wamba, S., Dewan, S., 2017. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plann. Control 28 (11-12), 1011-1021.

Al-Tabbaa, O., Leach, D., Khan, Z., 2019. Examining alliance management capabilities in cross-sector collaborative partnerships. J. Bus. Res. 101, 268-284.

Alexander, A., Blome, C., Schleper, M.C., Roscoe, S., 2022. Managing the “new normal”: the future of operations and supply chain management in unprecedented times. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (8), 1061-1076.

Alicke, K., Barriball, E.D., Trautwein, V., 2021. How COVID-19 Is Reshaping Supply Chains. McKinsey and Company, pp. 2011-2020.

Alvarenga, M.Z., Oliveira, M.P.V.D., Oliveira, T.A.G.F.D., 2023. The impact of using digital technologies on supply chain resilience and robustness: the role of memory under the covid-19 outbreak. Supply Chain Manag.: Int. J. 28 (5), 825-842.

Anand, B.N., Khanna, T., 2000. Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strat. Manag. J. 21 (3), 295-315.

Apparel Resources (2017, November). https://vn.apparelresources.com/business-news /sourcing/supply-chain-leader-li-fung-focuses-speed-innovation-digitization-future /(date of access 22 July 2022).

Appio, F.P., Frattini, F., Petruzzelli, A.M., Neirotti, P., 2021. Digital transformation and innovation management: a synthesis of existing research and an agenda for future studies. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 38 (1), 4-20.

Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S., 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Market. Res. 14 (3), 396-402.

Aslam, H., Syed, T.A., Blome, C., Ramish, A., Ayaz, K., 2022. The multifaceted role of social capital for achieving organizational ambidexterity and supply chain resilience. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3174069.

Awan, U., Bhatti, S.H., Shamim, S., Khan, Z., Akhtar, P., Balta, M.E., 2022. The role of big data analytics in manufacturing agility and performance: moderation-mediation analysis of organizational creativity and of the involvement of customers as data analysts. Br. J. Manag. 33 (3), 1200-1220.

Bag, S., Rahman, M.S., Srivastava, G., Chan, H.L., Bryde, D.J., 2022. The role of big data and predictive analytics in developing a resilient supply chain network in the South African mining industry against extreme weather events. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 251, 108541.

Barney, J., 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 17 (1), 99-120.

Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173-1182.

Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., Schuberth, F., 2020. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Inf. Manag. 57 (2), 103168.

Berman, S.J., 2012. Digital transformation: opportunities to create new business models. Strat. Leader. 40 (2), 16-24.

Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O.A., Pavlou, P.A., Venkatraman, N.V., 2013. Digital business strategy: toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q. 37 (2), 471-482.

Borys, B., Jemison, D.B., 1989. Hybrid arrangements as strategic alliances: theoretical issues in organizational combinations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14 (2), 234-249.

Bosman, L., Hartman, N., Sutherland, J., 2020. How manufacturing firm characteristics can influence decision making for investing in Industry 4.0 technologies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 31 (5), 1117-1141.

Bouncken, R.B., Fredrich, V., Gudergan, S., 2022. Alliance management and innovation under uncertainty. J. Manag. Organ. 28 (3), 540-563.

Boyer, K.K., Pagell, M., 2000. Measurement issues in empirical research: improving measures of operations strategy and advanced manufacturing technology. J. Oper. Manag. 18 (3), 361-374.

Brammer, S., Branicki, L., Linnenluecke, M., 2023. Disrupting management research? Critical reflections on British journal of management COVID-19 research and an agenda for the future. Br. J. Manag. 34 (1), 3-15.

Cadden, T., McIvor, R., Cao, G., Treacy, R., Yang, Y., Gupta, M., Onofrei, G., 2022. Unlocking supply chain agility and supply chain performance through the development of intangible supply chain analytical capabilities. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 42 (9), 1329-1355.