DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44654-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177132

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

التخليق الحيوي الجديد للفلافونويد النشط زانثوهومول في الخميرة

تم القبول: 26 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 04 يناير 2024

(ط) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

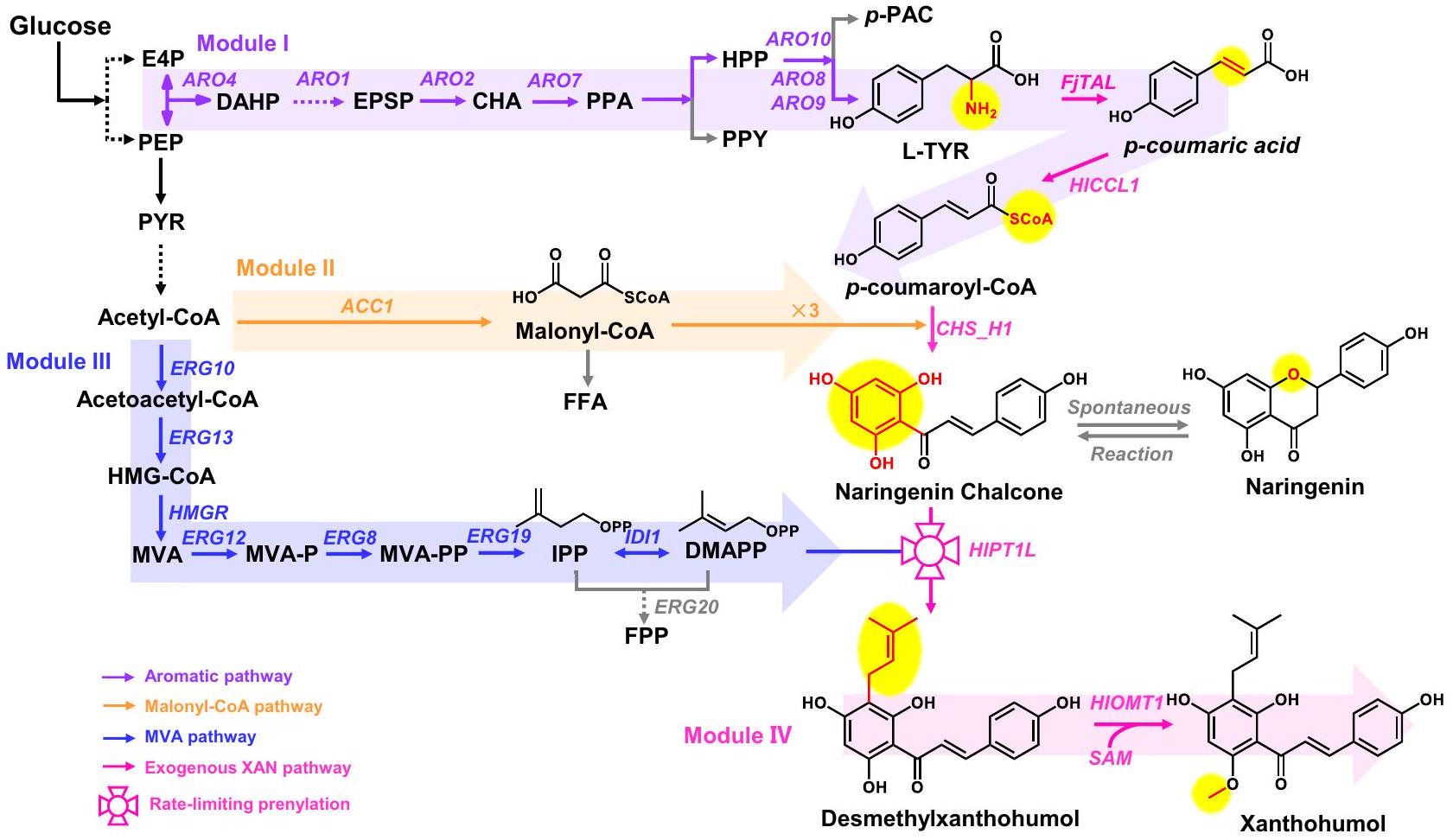

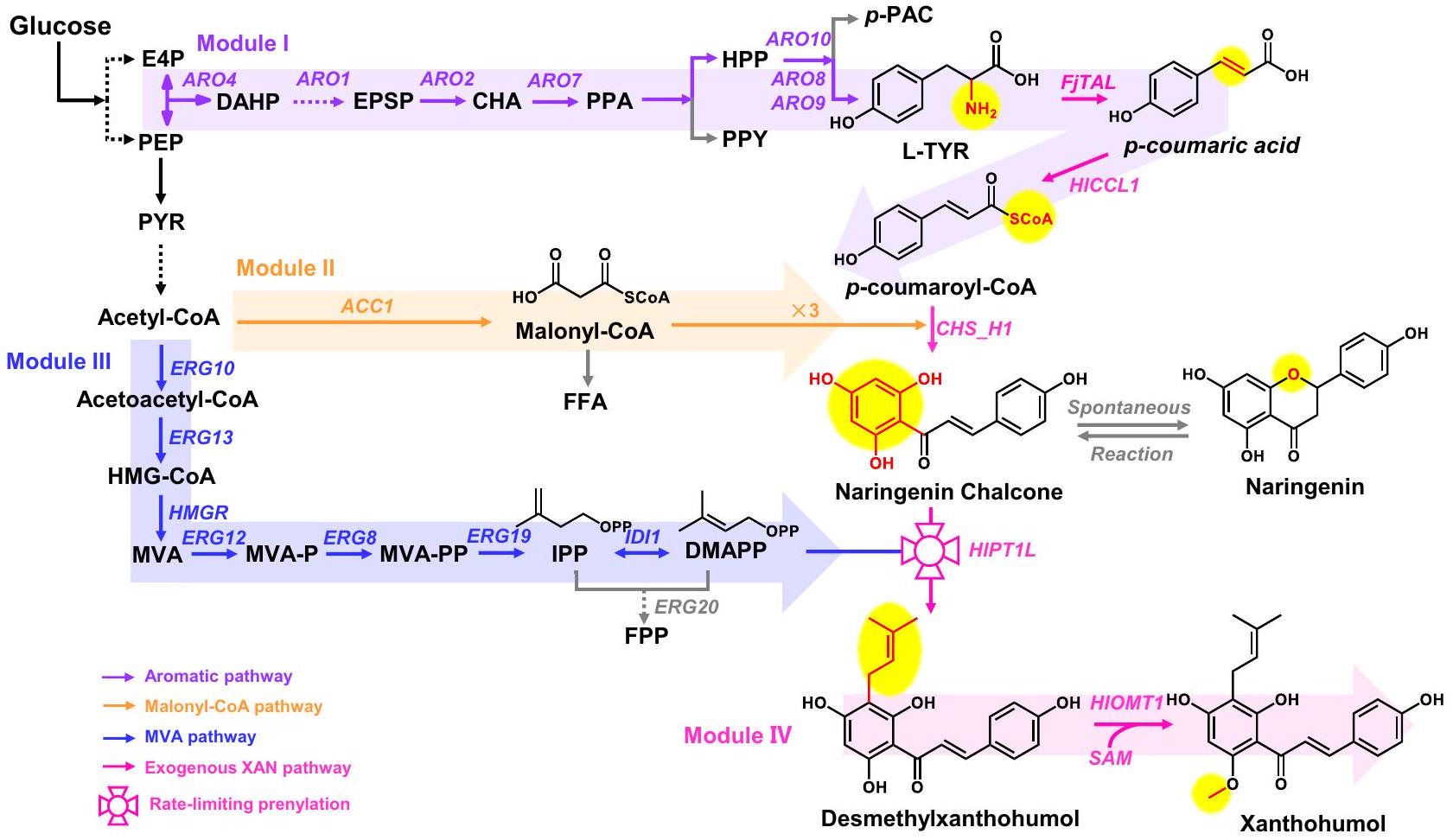

الفلافونويد زانثوهومول هو مادة نكهة مهمة في صناعة التخمير وله مجموعة واسعة من الأنشطة البيولوجية. ومع ذلك، فإن هيكله غير المستقر يؤدي إلى محتواه المنخفض في البيرة. يُعتبر التخليق الحيوي الميكروبي بديلاً مستدامًا وذو جدوى اقتصادية. هنا، نستخدم الخميرة Saccharomyces cerevisiae للتخليق الحيوي الجديد لزانثوهومول من الجلوكوز من خلال موازنة ثلاث مسارات تخليقية متوازية، هندسة إنزيم البرينيليترانسفيراز، تعزيز إمداد المتقدمات، بناء اندماج الإنزيمات، وهندسة البيروكسيسوم. تحسن هذه الاستراتيجيات إنتاج المتقدم الرئيسي لزانثوهومول، ديميثيلزانثوهومول (DMX)، بمقدار 83 ضعفًا وتحقق التخليق الحيوي الجديد لزانثوهومول في الخميرة. كما نكشف أن البرينيليشن هو الخطوة المحدودة الرئيسية في تخليق DMX ونطور استراتيجيات تنظيم أيضية مخصصة لتعزيز توفر DMAPP وكفاءة البرينيليشن. يوفر عملنا طرقًا قابلة للتطبيق لهندسة مصانع الخلايا الخميرية بشكل منهجي للتخليق الحيوي الجديد للمنتجات الطبيعية المعقدة.

علم الأحياء

النتائج

البناء المعياري لمسار التخليق الحيوي للزانثوهومول

بيروفوسفات إيزوبنتينيل، FPP بيروفوسفات فارنيسيل، SAM S-أدينوسيل-إل-ميثيونين،

إيزوميراز،

و

وبالتالي زادت توافر أسيتيل-كوإنزيم أ لتوفير مالونيل-كوإنزيم أ. ومع ذلك، كان لدى السلالة YS116 معدل نمو نوعي أقصى منخفض (

توصيف وهندسة إنزيم الفسفوتيرانسفيراز (PTase)

برنامج التنبؤ بالببتيدات TargetP (https://services.healthtech.dtu.

تحسين المسار لتحسين تخليق DMX الحيوي

طفرة في إنزيم HMG-CoA ريدوكتاز الداخلي (السلالة YS121)

حاول تحسين حجم المبيعات لـ

ترميز إيزوميراز الكالكون غير التحفيزي،

تجزئة البيروكسيسوم لتخليق DMX

المسارات (الشكل 5أ). استخدمنا مسارًا تم إنشاؤه سابقًا

تخليق الزانثوهومول الحيوي

على التوالي، وأكد تحليل الكروماتوغرافيا السائلة-مطياف الكتلة إنتاج الزانثوهومول (الشكل التكميلي 8). التراكم العالي لـ DMX (

مناقشة

يشارك العقدة الرئيسية أسيتيل-كوإنزيم أ مع مالونيل-كوإنزيم أ ويمكن تحويله بسهولة إلى FPP. قمنا بضبط تدفق المسار بعناية بين توفير كمية كافية من مجموعة البرينيل DMAPP وكمية كافية من مجموعة المالونيل مالونيل-كوإنزيم أ من خلال تعديل تعبير الجينات باستبدال المحفز، وتحوير الإنزيمات الرئيسية، وزيادة التعبير عن الإنزيمات المحددة لمعدل التفاعل. لاحظنا أن تعزيز توفر DMAPP من خلال تحور ERG20 أبطأ نمو الخلايا، مما يتطلب استراتيجيات تنظيم دقيقة لموازنة اللياقة الخلوية وتراكم DMAPP.

الطرق

السلالات، البلازميدات، والكواشف

الهندسة الوراثية

زراعة السلالة

استخلاص المنتج وتحديد كميته

تم استخدام مطياف الكتلة ThermoFisher Q Exactive Hybrid QuadrupoleOrbitrap في وضع التأين بالإلكترورش الساخن الإيجابي لتحليل الزانثوهومول كميًا.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Kubeš, J. Geography of world hop production 1990-2019. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 80, 84-91 (2022).

- Xu, H. et al. Characterization of the formation of branched shortchain fatty acid: CoAs for bitter acid biosynthesis in hop glandular trichomes. Mol. Plant. 6, 1301-1317 (2013).

- Stevens, J. F. & Page, J. E. Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: to your good health! Phytochemistry 65, 1317-1330 (2004).

- Miyata, S., Inoue, J., Shimizu, M. & Sato, R. Xanthohumol improves diet-induced obesity and fatty liver by suppressing sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP). Act. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 20565-20579 (2015).

- Miranda, C. L. et al. Antioxidant and prooxidant actions of prenylated and nonprenylated chalcones and flavanones in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 3876-3884 (2000).

- Legette, L. et al. Human pharmacokinetics of xanthohumol, an antihyperglycemic flavonoid from hops. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58, 248-255 (2014).

- Yong, W. K. & Abd Malek, S. N. Xanthohumol induces growth inhibition and apoptosis in ca ski human cervical cancer cells. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 921306 (2015).

- Liu, M. et al. Pharmacological profile of xanthohumol, a prenylated flavonoid from hops (Humulus lupulus). Molecules 20, 754-779 (2015).

- Amoriello, T., Mellara, F., Galli, V., Amoriello, M. & Ciccoritti, R. Technological properties and consumer acceptability of bakery products enriched with brewers’ spent grains. Foods 9, 1492 (2020).

- Chen, Q.-h et al. Preparative isolation and purification of xanthohumol from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) by high-speed countercurrent chromatography. Food Chem. 132, 619-623 (2012).

- Grudniewska, A. & Popłoński, J. Simple and green method for the extraction of xanthohumol from spent hops using deep eutectic solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 250, 117196 (2020).

- Keasling, J. D. Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science 330, 1355-1358 (2010).

- Li, S. J., Li, Y. R. & Smolke, C. D. Strategies for microbial synthesis of high-value phytochemicals. Nat. Chem. 10, 395-404 (2018).

- Galanie, S., Thodey, K., Trenchard, I. J., Interrante, M. F. & Smolke, C. D. Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science 349, 1095-1100 (2015).

- Paddon, C. J. et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 496, 528-532 (2013).

- Liu, X. et al. Engineering yeast for the production of breviscapine by genomic analysis and synthetic biology approaches. Nat. Commun. 9, 448 (2018).

- Denby, C. M. et al. Industrial brewing yeast engineered for the production of primary flavor determinants in hopped beer. Nat. Commun. 9, 965 (2018).

- Ban, Z. et al. Noncatalytic chalcone isomerase-fold proteins in Humulus lupulus are auxiliary components in prenylated flavonoid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E5223-E5232 (2018).

- Li, H. et al. A heteromeric membrane-bound prenyltransferase complex from hop catalyzes three sequential aromatic prenylations in the bitter acid pathway. Plant. Physiol. 167, 650-659 (2015).

- Nagel, J. et al. EST analysis of hop glandular trichomes identifies an O-methyltransferase that catalyzes the biosynthesis of xanthohumol. Plant Cell 20, 186-200 (2008).

- Novák, P., Matoušek, J. & Bříza, J. Valerophenone synthase-like chalcone synthase homologues in Humulus lupulus. Biol. Plant. 46, 375-381 (2003).

- Zhou, Y. J. et al. Modular pathway engineering of diterpenoid synthases and the mevalonic acid pathway for miltiradiene production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3234-3241 (2012).

- Jendresen, C. B. et al. Highly active and specific tyrosine ammoniaLyases from diverse origins enable enhanced production of aromatic compounds in bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4458-4476 (2015).

- Abe, I., Morita, H., Nomura, A. & Noguchi, H. Substrate specificity of chalcone synthase: enzymatic formation of unnatural polyketides from synthetic cinnamoyl-CoA. Anal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11242-11243 (2000).

- Rodriguez, A., Kildegaard, K. R., Li, M., Borodina, I. & Nielsen, J. Establishment of a yeast platform strain for production of

-coumaric acid through metabolic engineering of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. Metab. Eng. 31, 181-188 (2015). - Zhou, Y. J. et al. Production of fatty acid-derived oleochemicals and biofuels by synthetic yeast cell factories. Nat. Commun. 7, 11709 (2016).

- Ignea, C., Pontini, M., Maffei, M. E., Makris, A. M. & Kampranis, S. C. Engineering monoterpene production in yeast using a synthetic dominant negative geranyl diphosphate synthase. Acs. Synth. Biol. 3, 298-306 (2014).

- Martinez-Munoz, G. A. & Kane, P. Vacuolar and plasma membrane proton pumps collaborate to achieve cytosolic pH homeostasis in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20309-20319 (2008).

- Tsurumaru, Y. et al. An aromatic prenyltransferase-like gene HIPT-1 preferentially expressed in lupulin glands of hop. Plant Biotechnol. 27, 199-204 (2010).

- Wang, R. et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of two novel regio-specific flavonoid prenyltransferases from Morus alba and Cudrania tricuspidata. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 35815-35825 (2014).

- Li, J. et al. Biocatalytic access to diverse prenylflavonoids by combining a regiospecific C -prenyltransferase and a stereospecific chalcone isomerase. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 678-686 (2018).

- Sasaki, K., Tsurumaru, Y., Yamamoto, H. & Yazaki, K. Molecular characterization of a membrane-bound prenyltransferase specific for isoflavone from Sophora flavescens. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24125-24134 (2011).

- Chen, R. et al. Regio- and stereospecific prenylation of flavonoids by Sophora flavescens prenyltransferase. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 1817-1828 (2013).

- Shen, G. et al. Characterization of an isoflavonoid-specific prenyltransferase from Lupinus albus. Plant. Physiol. 159, 70-80 (2012).

- Yang, T. et al. Stilbenoid prenyltransferases define key steps in the diversification of peanut phytoalexins. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 28-46 (2018).

- He, J. et al. Regio-specific prenylation of pterocarpans by a membrane-bound prenyltransferase from Psoralea corylifolia. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 6760-6766 (2018).

- Rea, K. A. et al. Biosynthesis of cannflavins A and B from Cannabis sativa L. Phytochemistry 164, 162-171 (2019).

- Luo, X. et al. Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature 567, 123-126 (2019).

- Qian, S., Clomburg, J. M. & Gonzalez, R. Engineering Escherichia coli as a platform for the in vivo synthesis of prenylated aromatics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 1116-1127 (2019).

- Xie, W., Ye, L., Lv, X., Xu, H. & Yu, H. Sequential control of biosynthetic pathways for balanced utilization of metabolic intermediates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 28, 8-18 (2015).

- Ignea, C. et al. Orthogonal monoterpenoid biosynthesis in yeast constructed on an isomeric substrate. Nat. Commun. 10, 3799 (2019).

- Chen, R. et al. Engineering cofactor supply and recycling to drive phenolic acid biosynthesis in yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 520-529 (2022).

- Cao, X. et al. Engineering yeast for high-level production of diterpenoid sclareol. Metab. Eng. 75, 19-28 (2022).

- Chatzivasileiou, A. O., Ward, V., Edgar, S. M. & Stephanopoulos, G. Two-step pathway for isoprenoid synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 506-511 (2019).

- Hammer, S. K. & Avalos, J. L. Harnessing yeast organelles for metabolic engineering. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 823-832 (2017).

- Cao, X., Yang, S., Cao, C. & Zhou, Y. J. Harnessing sub-organelle metabolism for biosynthesis of isoprenoids in yeast. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 5, 179-186 (2020).

- Dusseaux, S., Wajn, W. T., Liu, Y., Ignea, C. & Kampranis, S. C. Transforming yeast peroxisomes into microfactories for the efficient production of high-value isoprenoids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 31789-31799 (2020).

- Cao, C. et al. Construction and optimization of nonclassical isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways in yeast peroxisomes for (+)-valencene production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 11124-11130 (2023).

- Gao, J. & Zhou, Y. J. Repurposing peroxisomes for microbial synthesis for biomolecules. Methods Enzymol. 617, 83-111 (2019).

- Peng, B. et al. A squalene synthase protein degradation method for improved sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 39, 209-219 (2017).

- Guo, X. et al. Enabling heterologous synthesis of lupulones in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 188, 787-797 (2019).

- Zirpel, B., Degenhardt, F., Martin, C., Kayser, O. & Stehle, F. Engineering yeasts as platform organisms for cannabinoid biosynthesis. J. Biotechnol. 259, 204-212 (2017).

- Chen, H. P. & Abe, I. Microbial soluble aromatic prenyltransferases for engineered biosynthesis. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 6, 51-62 (2021).

- Levisson, M. et al. Toward developing a yeast cell factory for the production of prenylated flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 13478-13486 (2019).

- Munakata, R. et al. Isolation of Artemisia capillaris membranebound di-prenyltransferase for phenylpropanoids and redesign of artepillin C in yeast. Commun. Biol. 2, 384 (2019).

- Bongers, M. et al. Adaptation of hydroxymethylbutenyl diphosphate reductase enables volatile isoprenoid production. eLife 9, e48685 (2020).

- Wang, P. et al. Complete biosynthesis of the potential medicine icaritin by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. Sci. Bull. 66, 1906-1916 (2021).

- Chen, R. et al. Molecular insights into the enzyme promiscuity of an aromatic prenyltransferase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 226-234 (2017).

- Yang, S., Cao, X., Yu, W., Li, S. & Zhou, Y. J. Efficient targeted mutation of genomic essential genes in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 3037-3047 (2020).

- Mans, R. et al. CRISPR/Cas9: a molecular Swiss army knife for simultaneous introduction of multiple genetic modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast. Res. 15, fov004 (2015).

- Inoue, H., Nojima, H. & Okayama, H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96, 23-28 (1990).

- Verduyn, C., Postma, E., Scheffers, W. A. & Van Dijken, J. P. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 8, 501-517 (1992).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

مادة تكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44654-5.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

قسم التكنولوجيا الحيوية، معهد داليان لفيزياء الكيمياء، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، داليان 116023، الصين. جامعة الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين 100049، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للدولة لعلم جينوم النبات، معهد الوراثة وعلم الأحياء التنموي، الأكاديمية الابتكارية لتصميم البذور، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين 100101، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي للأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم لعلوم الفصل في الكيمياء التحليلية، معهد داليان لفيزياء الكيمياء، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، داليان 116023، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي لداليان للتكنولوجيا الحيوية للطاقة، معهد داليان لفيزياء الكيمياء، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، داليان 116023، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني: zhouyongjin@dicp.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44654-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177132

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

De novo biosynthesis of the hops bioactive flavonoid xanthohumol in yeast

Accepted: 26 December 2023

Published online: 04 January 2024

(i) Check for updates

Abstract

The flavonoid xanthohumol is an important flavor substance in the brewing industry that has a wide variety of bioactivities. However, its unstable structure results in its low content in beer. Microbial biosynthesis is considered a sustainable and economically viable alternative. Here, we harness the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the de novo biosynthesis of xanthohumol from glucose by balancing the three parallel biosynthetic pathways, prenyltransferase engineering, enhancing precursor supply, constructing enzyme fusion, and peroxisomal engineering. These strategies improve the production of the key xanthohumol precursor demethylxanthohumol (DMX) by 83 -fold and achieve the de novo biosynthesis of xanthohumol in yeast. We also reveal that prenylation is the key limiting step in DMX biosynthesis and develop tailored metabolic regulation strategies to enhance the DMAPP availability and prenylation efficiency. Our work provides feasible approaches for systematically engineering yeast cell factories for the de novo biosynthesis of complex natural products.

biology

Results

Modular construction of the xanthohumol biosynthetic pathway

isopentenyl pyrophosphate, FPP farnesyl pyrophosphate, SAM S-adenosyl-Lmethionine,

isomerase,

and

and thus enhanced the acetyl-CoA availability for malonyl-CoA supply. However, strain YS116 had decreased maximum specific growth rate (

Characterizing and engineering PTase

peptide prediction software TargetP (https://services.healthtech.dtu.

Pathway optimization to improve DMX biosynthesis

mutant of endogenous HMG-CoA reductase (strain YS121)

tried to enhance the turnover of

encoding noncatalytic chalcone isomerase,

Peroxisome compartmentalization for DMX biosynthesis

pathways (Fig. 5a). We used a previously constructed

Biosynthesis of xanthohumol

respectively, and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis verified xanthohumol production (Supplementary Fig. 8). The high accumulation of DMX (

Discussion

shares the key node acetyl-CoA with malonyl-CoA and it can be easily converted to FPP. We carefully balanced the pathway flux between providing sufficient prenyl moiety DMAPP and sufficient malonyl moiety malonyl-CoA by tuning the gene expression with promoter replacement, mutating the key enzymes and overexpression of ratelimiting enzymes. We observed that enhancing DMAPP availability through ERG20 mutation retarded cell growth, which thus requires precise regulation strategies to balance cellular fitness and DMAPP accumulation.

Methods

Strains, plasmids, and reagents

Genetic engineering

Strain cultivation

Product extraction and quantification

spectrometer and a ThermoFisher Q Exactive Hybrid QuadrupoleOrbitrap Mass Spectrometer in positive heated electrospray ionization mode was used quantitatively analyze xanthohumol.

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Kubeš, J. Geography of world hop production 1990-2019. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 80, 84-91 (2022).

- Xu, H. et al. Characterization of the formation of branched shortchain fatty acid: CoAs for bitter acid biosynthesis in hop glandular trichomes. Mol. Plant. 6, 1301-1317 (2013).

- Stevens, J. F. & Page, J. E. Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: to your good health! Phytochemistry 65, 1317-1330 (2004).

- Miyata, S., Inoue, J., Shimizu, M. & Sato, R. Xanthohumol improves diet-induced obesity and fatty liver by suppressing sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP). Act. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 20565-20579 (2015).

- Miranda, C. L. et al. Antioxidant and prooxidant actions of prenylated and nonprenylated chalcones and flavanones in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 3876-3884 (2000).

- Legette, L. et al. Human pharmacokinetics of xanthohumol, an antihyperglycemic flavonoid from hops. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58, 248-255 (2014).

- Yong, W. K. & Abd Malek, S. N. Xanthohumol induces growth inhibition and apoptosis in ca ski human cervical cancer cells. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 921306 (2015).

- Liu, M. et al. Pharmacological profile of xanthohumol, a prenylated flavonoid from hops (Humulus lupulus). Molecules 20, 754-779 (2015).

- Amoriello, T., Mellara, F., Galli, V., Amoriello, M. & Ciccoritti, R. Technological properties and consumer acceptability of bakery products enriched with brewers’ spent grains. Foods 9, 1492 (2020).

- Chen, Q.-h et al. Preparative isolation and purification of xanthohumol from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) by high-speed countercurrent chromatography. Food Chem. 132, 619-623 (2012).

- Grudniewska, A. & Popłoński, J. Simple and green method for the extraction of xanthohumol from spent hops using deep eutectic solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 250, 117196 (2020).

- Keasling, J. D. Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science 330, 1355-1358 (2010).

- Li, S. J., Li, Y. R. & Smolke, C. D. Strategies for microbial synthesis of high-value phytochemicals. Nat. Chem. 10, 395-404 (2018).

- Galanie, S., Thodey, K., Trenchard, I. J., Interrante, M. F. & Smolke, C. D. Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science 349, 1095-1100 (2015).

- Paddon, C. J. et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 496, 528-532 (2013).

- Liu, X. et al. Engineering yeast for the production of breviscapine by genomic analysis and synthetic biology approaches. Nat. Commun. 9, 448 (2018).

- Denby, C. M. et al. Industrial brewing yeast engineered for the production of primary flavor determinants in hopped beer. Nat. Commun. 9, 965 (2018).

- Ban, Z. et al. Noncatalytic chalcone isomerase-fold proteins in Humulus lupulus are auxiliary components in prenylated flavonoid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E5223-E5232 (2018).

- Li, H. et al. A heteromeric membrane-bound prenyltransferase complex from hop catalyzes three sequential aromatic prenylations in the bitter acid pathway. Plant. Physiol. 167, 650-659 (2015).

- Nagel, J. et al. EST analysis of hop glandular trichomes identifies an O-methyltransferase that catalyzes the biosynthesis of xanthohumol. Plant Cell 20, 186-200 (2008).

- Novák, P., Matoušek, J. & Bříza, J. Valerophenone synthase-like chalcone synthase homologues in Humulus lupulus. Biol. Plant. 46, 375-381 (2003).

- Zhou, Y. J. et al. Modular pathway engineering of diterpenoid synthases and the mevalonic acid pathway for miltiradiene production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3234-3241 (2012).

- Jendresen, C. B. et al. Highly active and specific tyrosine ammoniaLyases from diverse origins enable enhanced production of aromatic compounds in bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4458-4476 (2015).

- Abe, I., Morita, H., Nomura, A. & Noguchi, H. Substrate specificity of chalcone synthase: enzymatic formation of unnatural polyketides from synthetic cinnamoyl-CoA. Anal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11242-11243 (2000).

- Rodriguez, A., Kildegaard, K. R., Li, M., Borodina, I. & Nielsen, J. Establishment of a yeast platform strain for production of

-coumaric acid through metabolic engineering of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. Metab. Eng. 31, 181-188 (2015). - Zhou, Y. J. et al. Production of fatty acid-derived oleochemicals and biofuels by synthetic yeast cell factories. Nat. Commun. 7, 11709 (2016).

- Ignea, C., Pontini, M., Maffei, M. E., Makris, A. M. & Kampranis, S. C. Engineering monoterpene production in yeast using a synthetic dominant negative geranyl diphosphate synthase. Acs. Synth. Biol. 3, 298-306 (2014).

- Martinez-Munoz, G. A. & Kane, P. Vacuolar and plasma membrane proton pumps collaborate to achieve cytosolic pH homeostasis in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20309-20319 (2008).

- Tsurumaru, Y. et al. An aromatic prenyltransferase-like gene HIPT-1 preferentially expressed in lupulin glands of hop. Plant Biotechnol. 27, 199-204 (2010).

- Wang, R. et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of two novel regio-specific flavonoid prenyltransferases from Morus alba and Cudrania tricuspidata. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 35815-35825 (2014).

- Li, J. et al. Biocatalytic access to diverse prenylflavonoids by combining a regiospecific C -prenyltransferase and a stereospecific chalcone isomerase. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 678-686 (2018).

- Sasaki, K., Tsurumaru, Y., Yamamoto, H. & Yazaki, K. Molecular characterization of a membrane-bound prenyltransferase specific for isoflavone from Sophora flavescens. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24125-24134 (2011).

- Chen, R. et al. Regio- and stereospecific prenylation of flavonoids by Sophora flavescens prenyltransferase. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 1817-1828 (2013).

- Shen, G. et al. Characterization of an isoflavonoid-specific prenyltransferase from Lupinus albus. Plant. Physiol. 159, 70-80 (2012).

- Yang, T. et al. Stilbenoid prenyltransferases define key steps in the diversification of peanut phytoalexins. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 28-46 (2018).

- He, J. et al. Regio-specific prenylation of pterocarpans by a membrane-bound prenyltransferase from Psoralea corylifolia. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 6760-6766 (2018).

- Rea, K. A. et al. Biosynthesis of cannflavins A and B from Cannabis sativa L. Phytochemistry 164, 162-171 (2019).

- Luo, X. et al. Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature 567, 123-126 (2019).

- Qian, S., Clomburg, J. M. & Gonzalez, R. Engineering Escherichia coli as a platform for the in vivo synthesis of prenylated aromatics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 1116-1127 (2019).

- Xie, W., Ye, L., Lv, X., Xu, H. & Yu, H. Sequential control of biosynthetic pathways for balanced utilization of metabolic intermediates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 28, 8-18 (2015).

- Ignea, C. et al. Orthogonal monoterpenoid biosynthesis in yeast constructed on an isomeric substrate. Nat. Commun. 10, 3799 (2019).

- Chen, R. et al. Engineering cofactor supply and recycling to drive phenolic acid biosynthesis in yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 520-529 (2022).

- Cao, X. et al. Engineering yeast for high-level production of diterpenoid sclareol. Metab. Eng. 75, 19-28 (2022).

- Chatzivasileiou, A. O., Ward, V., Edgar, S. M. & Stephanopoulos, G. Two-step pathway for isoprenoid synthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 506-511 (2019).

- Hammer, S. K. & Avalos, J. L. Harnessing yeast organelles for metabolic engineering. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 823-832 (2017).

- Cao, X., Yang, S., Cao, C. & Zhou, Y. J. Harnessing sub-organelle metabolism for biosynthesis of isoprenoids in yeast. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 5, 179-186 (2020).

- Dusseaux, S., Wajn, W. T., Liu, Y., Ignea, C. & Kampranis, S. C. Transforming yeast peroxisomes into microfactories for the efficient production of high-value isoprenoids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 31789-31799 (2020).

- Cao, C. et al. Construction and optimization of nonclassical isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways in yeast peroxisomes for (+)-valencene production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 11124-11130 (2023).

- Gao, J. & Zhou, Y. J. Repurposing peroxisomes for microbial synthesis for biomolecules. Methods Enzymol. 617, 83-111 (2019).

- Peng, B. et al. A squalene synthase protein degradation method for improved sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 39, 209-219 (2017).

- Guo, X. et al. Enabling heterologous synthesis of lupulones in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 188, 787-797 (2019).

- Zirpel, B., Degenhardt, F., Martin, C., Kayser, O. & Stehle, F. Engineering yeasts as platform organisms for cannabinoid biosynthesis. J. Biotechnol. 259, 204-212 (2017).

- Chen, H. P. & Abe, I. Microbial soluble aromatic prenyltransferases for engineered biosynthesis. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 6, 51-62 (2021).

- Levisson, M. et al. Toward developing a yeast cell factory for the production of prenylated flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 13478-13486 (2019).

- Munakata, R. et al. Isolation of Artemisia capillaris membranebound di-prenyltransferase for phenylpropanoids and redesign of artepillin C in yeast. Commun. Biol. 2, 384 (2019).

- Bongers, M. et al. Adaptation of hydroxymethylbutenyl diphosphate reductase enables volatile isoprenoid production. eLife 9, e48685 (2020).

- Wang, P. et al. Complete biosynthesis of the potential medicine icaritin by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli. Sci. Bull. 66, 1906-1916 (2021).

- Chen, R. et al. Molecular insights into the enzyme promiscuity of an aromatic prenyltransferase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 226-234 (2017).

- Yang, S., Cao, X., Yu, W., Li, S. & Zhou, Y. J. Efficient targeted mutation of genomic essential genes in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 3037-3047 (2020).

- Mans, R. et al. CRISPR/Cas9: a molecular Swiss army knife for simultaneous introduction of multiple genetic modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast. Res. 15, fov004 (2015).

- Inoue, H., Nojima, H. & Okayama, H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96, 23-28 (1990).

- Verduyn, C., Postma, E., Scheffers, W. A. & Van Dijken, J. P. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 8, 501-517 (1992).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44654-5.

© The Author(s) 2024

Division of Biotechnology, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dalian 116023, China. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China. State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, The Innovative Academy of Seed Design, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China. CAS Key Laboratory of Separation Science for Analytical Chemistry, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dalian 116023, China. Dalian Key Laboratory of Energy Biotechnology, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dalian 116023, China. e-mail: zhouyongjin@dicp.ac.cn