DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08409-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39814899

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-15

التدفق القاري والانتشار الواسع للعيش في منزل الأم في بريطانيا في عصر الحديد

تاريخ الاستلام: 7 مايو 2024

تم القبول: 14 نوفمبر 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2025

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

وجد الكتاب الرومان أن تمكين النساء السلتيكيات النسبي كان ملحوظًا

ومع ذلك، تُعتبر مثل هذه الأوصاف الاجتماعية مشبوهة، متحيزة نحو ما كان سيبدو غريبًا لجمهور البحر الأبيض المتوسط الذي كان غارقًا في عالم أبوي عميق.

تم تفسير توزيع الهدايا الجنائزية في العديد من المقابر السلتية في غرب أوروبا على أنه يدعم مكانة عالية للنساء.

الهجينة؛ يشير اللون الرمادي إلى مجموعات الهجينة الفردية. يتم الإشارة إلى فترة دوروتريجيان (الخط المتصل) ونطاق تواريخ أفراد العائلة (الخط المتقطع). كما يتم عرض العلاقة المجمعة في مخططات الصندوق (توكي) حسب الجنس للأفراد في النطاق الأخير؛ لوحظ فرق كبير بين الذكور (M) والإناث (F) (ويلش)

الموقع الأمومي في مجتمع دوروتريجيان

تم أخذ عينات من الموقع (الجدول التكميلي 1)، حيث حقق 40 منها تغطية عالية بما يكفي لتقدير النمط الجيني وتحديد قوي للمقاطع الجينومية التي كانت متطابقة بالوراثة (IBD) بين الأفراد.

من المدهش أن أكثر من ثلثي (24/34) الأقارب الذين تم تحديدهم وراثيًا ينتمون إلى سلالة نادرة من مجموعة الأليل الميتوكوندري U5b1 (الشكل 1د) التي لم يتم ملاحظتها سابقًا في العينات القديمة والتي لها تردد يبلغ فقط

أنه سيكون هناك حاجة إلى 420 ولادة أنثوية على الأقل من أمهات السلالة لتحقيق هذا المستوى من التنوع داخل السلالة (الملاحظة التكميلية 2.6)، مما يعني وجود ارتباط طويل الأمد بين هذا النمط الجيني و WBK. بالمقابل، نجد أن تنوع الكروموسوم Y مرتفع (الشكل 1د والملاحظة التكميلية 2.8)، وتشير سلاسل التماثل (ROH) إلى أن هذه كانت مجتمعًا من التزاوج الخارجي (الملاحظة التكميلية 5.5). لقد أظهرت النظرية والنمذجة واستطلاعات السكان الحديثين

عادة الزواج في مجتمع من عصر الحديد

الأمومية عبر بريطانيا في عصر الحديد

تظهر شرائح IBD الهيكل الإقليمي

تشمل المجموعات مواقع بريطانية قارية وساحلية، مما يشير إلى حركات عبر القناة.

الهجرة في عصر الحديد إلى جنوب إنجلترا

القناة. أ، المجموعات تعتمد على توافق 100 تشغيل لخوارزمية لايدن على رسم بياني موزون من IBD المشترك بين المواقع الأثرية وتظهر تكاملاً جغرافياً. تم تصنيف اثني عشر مجموعة رئيسية (عقد تعريفية محددة برموز) بناءً على الانتماءات الجغرافية، مع التأكيد على الهيكل الفرعي داخل المجموعات باستخدام درجات ألوان مختلفة. تم تمييز المجموعات عبر القناة بخطوط متقطعة تربط بين أقرب الجيران الجغرافيين عبر القناة. ب، خريطة متداخلة تظهر توزيع سلالة العصر البرونزي البريطاني عبر بريطانيا في العصر الحديدي، بناءً على القيم المتوسطة التي تم توليدها باستخدام ChromoPainter NNLS.

من المواقع من مجموعة دورست (الدوائر الحمراء) الموضوعة ضمن التوزيع الإقليمي لقطع النقود من نوع دوروتريجز. يتم الإشارة إلى WBK بـ ‘W’. تم رسم التوزيعات وفقًا للمراجع 34، 35. د، تُظهر نسبة سلالة EEF عبر الزمن لمنطقة القناة ذات التأثير القاري (باللون الأزرق؛ محددة بخط متقطع في ب) زيادة في أواخر العصر الحديدي لم تُلاحظ في العينة من بقية إنجلترا وويلز (باللون الأسود). منطقة القناة الأساسية تقع شرق خط الطول

في التخلص من الموتى، وهندسة المستوطنات والثقافة المادية على مر القرون، تشير إلى مستويات عالية من تنقل السكان.

تظهر تأثيرات تدفق الجينات القارية المحددة لمنطقة القناة الأساسية في تحليل المكونات الرئيسية (PCA) للأوروبيين الغربيين المعاصرين والقدامى (الشكل البياني الممتد 2)، بالإضافة إلى أنماط نسخ الهبلاي من السكان القاريين، والتي تم تمييزها باستخدام ChromoPainter.

استمرارية جزيرية

الاستنتاجات

اليقين الأبوي

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- ألاسان-جونز، ل. في رفيق النساء في العالم القديم (تحرير جيمس، س. ل. وديليون، س.) الفصل 34، 467-477 (بلاكويل، 2012).

- راسل، م.، سميث، م.، تشيثام، ب.، إيفانز، د. ومانلي، هـ. الفتاة ذات ميدالية العربة: دفن مزود جيدًا من العصر الحديدي المتأخر في دوروتريجيان من لانغتون هيرينغ، دورست. مجلة الآثار. 176، 196-230 (2019).

- كونليف، ب. بريطانيا تبدأ (أو بي يو أكسفورد، 2013).

- إمبر، سي. آر.، دروي، أ. ورسل، د. في شرح الثقافة البشرية (تحرير إمبر، سي. آر.) (ملفات العلاقات الإنسانية)I’m sorry, but I can’t access external links. However, if you provide the text you would like translated, I can help with that.، تم الوصول إليه في 01/10/2024).

- مردوك، ج. ب. وآخرون. مجموعة بيانات D-PLACE المستمدة من مردوك وآخرون 1999 ‘الأطلس الإثنوغرافي’ (الإصدار 3.0). زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10177061 (2023).

- كيربي، ك. ر. وآخرون. D-PLACE: قاعدة بيانات عالمية للتنوع الثقافي واللغوي والبيئي. PLoS ONE 11، eO158391 (2016).

- تشيلينسكي، م. وآخرون. النسب الأبوي والموقع السكني المرتبط بالصيادين وجامعي الثمار للسكان في شرق-وسط أوروبا خلال العصر البرونزي الأوسط. نات. كوم. 14، 4395 (2023).

- فاولر، سي. وآخرون. صورة عالية الدقة لممارسات القرابة في قبر من العصر الحجري الحديث المبكر. ناتشر 601، 584-587 (2022).

- شرويدر، هـ. وآخرون. فك شيفرة النسب، القرابة، والعنف في قبر جماعي من العصر الحجري الحديث المتأخر. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكيةhttps://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1820210116 (2019).

- فورتوانجلر، أ. وآخرون. الجينومات القديمة تكشف عن الهيكل الاجتماعي والوراثي لسويسرا في أواخر العصر النيوليثي. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 1915 (2020).

- فيلاالبا-موكو، ف. وآخرون. ممارسات القرابة في مجتمع الدولة المبكرة إيل أرجار من العصر البرونزي في إيبيريا. تقارير العلوم 12، 22415 (2022).

- ميتنيك، أ. وآخرون. عدم المساواة الاجتماعية القائمة على القرابة في أوروبا في عصر البرونز. ساينس 366، 731-734 (2019).

- سجورن، ك.-ج. وآخرون. القرابة والتنظيم الاجتماعي في أوروبا في عصر النحاس. تحليل متعدد التخصصات للآثار، الحمض النووي، النظائر، والأنثروبولوجيا من مقبرتين من ثقافة الجرس. PLoS ONE 15، e0241278 (2020).

- ماكاي، د. إيكولاندز: رحلة في البحث عن بوديكا (هاشيت المملكة المتحدة، 2023).

- البابا، ر. إعادة الاقتراب من السلتيين: الأصول، المجتمع، والتغيير الاجتماعي. بحوث الآثار. 30، 1-67 (2022).

- مورز، أ. وآخرون. الجينومات المستنتجة والتحليلات المعتمدة على الهابلوطايب للبيكتس في اسكتلندا في العصور الوسطى المبكرة تكشف عن علاقات دقيقة بين سكان العصر الحديدي والعصور الوسطى المبكرة والشعب الحديث في المملكة المتحدة. PLoS Genet. 19، e1010360 (2023).

- باترسون، ن. وآخرون. الهجرة على نطاق واسع إلى بريطانيا خلال العصر البرونزي الأوسط إلى المتأخر. نيتشر 601، 588-594 (2022).

- مارتينيانو، ر. وآخرون. إشارات جينومية للهجرة والاستمرارية في بريطانيا قبل الأنجلوساكسون. نات. كوم. 7، 10326 (2016).

- شيفلز، س. وآخرون. جينومات العصر الحديدي والأنجلو-ساكسوني من شرق إنجلترا تكشف تاريخ الهجرة البريطانية. نات. كوم. 7، 10408 (2016).

- راسل، م. وآخرون. مشروع دوروتريجس 2016: بيان مؤقت. وقائع جمعية تاريخ الطبيعة والآثار في دورست 138، 105-111 (2017).

- براونينغ، ب. ل. وبراونينغ، س. ر. تحسين دقة وكفاءة اكتشاف الهوية عن طريق السلف في بيانات السكان. علم الوراثة 194، 459-471 (2013).

- MITOMAP. قاعدة بيانات الجينوم الميتوكوندري البشري. FOSWIKIhttp://www.mitomap.org (2023).

- زايدي، أ. أ. وآخرون. عنق الزجاجة والاختيار في السلالة الجرثومية وعمر الأم يؤثران على نقل الحمض النووي الميتوكوندري في الأنساب البشرية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 25172-25178 (2019).

- لانسينغ، ج. س. وآخرون. تخلق هياكل القرابة قنوات دائمة لنقل اللغة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 114، 12910-12915 (2017).

- أوتا، هـ.، سيثيثام-إيشيدا، و.، تيوويتش، د.، إيشيدا، ت. وستونكينغ، م. تنوع mtDNA البشري والكروموسوم Y مرتبط بالإقامة الماتريلوكال مقابل الباتريلوكال. نات. جينيت. 29، 20-21 (2001).

- إنسور، ب. إ.، إيريش، ج. د. وكينغان، و. ف. علم الآثار الحيوي للقرابة: التعديلات المقترحة على الافتراضات التي توجه التفسير. الأنثروبولوجيا الحالية. 58، 739-761 (2017).

- فوكس، ر. القرابة والزواج: منظور أنثروبولوجي (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 1984).

- فورتوناتو، ل. تطور تنظيم القرابة الأمومية. وقائع العلوم البيولوجية 279، 4939-4945 (2012).

- ماتيسون، س. م. المساهمات التطورية في حل ‘لغز الأمومة’: اختبار لنموذج هولدن، سير، ومايس. الطبيعة البشرية 22، 64-88 (2011).

- سورويتش، أ.، سنايدر، ك. ت. وكريزانزا، ن. نظرة عالمية على الأمومية: استخدام التحليلات عبر الثقافات لتسليط الضوء على أنظمة القرابة البشرية. فلس. ترانس. ر. سوس. لندن. ب 374، 20180077 (2019).

- لي، ج. وآخرون. من الممارسات الزوجية إلى التنوع الجيني في السكان في جنوب شرق آسيا: بصمة اللغز الأمومي. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. لندن. ب 374، 20180434 (2019).

- بوث، ت. ج.، بروك، ج.، بريس، س. وبارنز، آي. حكايات من المعلومات التكميلية: تغير النسب في بريطانيا خلال العصر النحاسي – العصر البرونزي المبكر كان تدريجياً مع تنظيم قرابة متنوع. مجلة كامبريدج للآثار 31، 379-400 (2021).

- شينك، م. ك.، بيغلي، ر. أ.، نولين، د. أ. وسوياتيك، أ. متى تفشل الأمومية؟ الترددات وأسباب الانتقال إلى ومن الأمومية المقدرة من ترميز جديد لعينة عبر الثقافات. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. لندن. ب 374، 20190006 (2019).

- بابورث، م. البحث عن الدوروترجيز: دورست ومنطقة الغرب في أواخر العصر الحديدي (هيستوري برس، 2011).

- سيلوود، ل. في جوانب من العصر الحديدي في وسط وجنوب بريطانيا (تحرير كونليف، ب. ومايلز، د.) 191-204 (جامعة أكسفورد، مدرسة الآثار، 1984).

- لاوسون، د. ج.، هيلينثال، ج.، مايرز، س. وفالوش، د. استنتاج هيكل السكان باستخدام بيانات هابلوطايب كثيفة. PLoS Genet. 8، e1002453 (2012).

- تشاكون-دوكي، ج.-سي. وآخرون. يظهر الأمريكيون اللاتينيون أصول كونفيرسو واسعة الانتشار وأثر الأصول المحلية الأصلية على المظهر الجسدي. نات. كوميونيك. 9، 5388 (2018).

- ليزلي، س. وآخرون. الهيكل الجيني الدقيق للسكان البريطانيين. ناتشر 519، 309-314 (2015).

- كونليف، ب. مواجهة المحيط: الأطلسي وشعوبه 8000 قبل الميلاد – 1500 ميلادي (دار نشر جامعة أكسفورد، 2001).

- تايلور، أ.، ويال، أ. وفورد، س. المناظر الطبيعية لعصر البرونز، وعصر الحديد والرومان في السهول الساحلية، ودفن محارب من أواخر عصر الحديد في نورث بيرستيد، بوغنور ريجيس، ويست ساسكس (خدمات الآثار في وادي التايمز، 2014).

- فيشر، سي.-إي. وآخرون. أصل وتحرك مجموعات الغاليين في عصر الحديد في فرنسا الحالية كما كشفت عنه علم الجينوم الأثري. آي ساينس 25، 104094 (2022).

- بال، م. ج. ومولر، ن. (محرران) اللغات السلتية الطبعة الثانية (راوتليدج، 2009).

- غريتزينغر، ج. وآخرون. دليل على الخلافة السلالية بين النخب السلتية المبكرة في وسط أوروبا. نات. سلوك إنساني.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01888-7 (2024).

- هولدن، سي. جي.، سير، ر. وماس، ر. الأمومة كاستثمار موجه نحو البنات. سلوك الإنسان التطوري 24، 99-112 (2003).

- جونز، د. القبيلة المحلية: تنظيم التوسع الديموغرافي. الطبيعة البشرية 22، 177-200 (2011).

- كوروتاييف، أ. شكل الزواج، تقسيم العمل الجنسي، والإقامة بعد الزواج من منظور ثقافي مقارن: إعادة نظر. مجلة أبحاث الأنثروبولوجيا 59، 69-89 (2003).

- ديفال، و. ت. الهجرة، الحروب الخارجية، والإقامة في منزل الأم. بحوث العلوم السلوكية 9، 75-133 (1974).

- إمبر، م. وإمبر، س. ر. الظروف التي تفضل الإقامة في المناطق الأمومية مقابل الإقامة في المناطق الأبوية. الأنثروبولوجيا الأمريكية 73، 571-594 (1971).

- مورافيك، ج. س.، مارس لاند، س. وكوكس، م. ب. الحرب تؤدي إلى تغيير في مكان الإقامة بعد الزواج. مجلة البيولوجيا النظرية 474، 52-62 (2019).

- ريدفرن، ر. وتشامبرلين، أ. تحليل ديموغرافي لقلعة ميدن كاسل: دليل على الصراع في أواخر العصر الحديدي والفترة الرومانية المبكرة. مجلة علم الأمراض القديمة. 1، 68-73 (2011).

- Waddington، C. الحفريات في فين كوب، ديربيشاير: هل هو حصن تلة من العصر الحديدي في صراع؟ المجلة الأثرية 169، 159-236 (2012).

- سميث، م. الجروح القاتلة: الهيكل العظمي البشري كدليل على الصراع في الماضي (قلم وسيف، 2017).

- ثورب، ن. في تجسيد الصراعات/Materialisation of Conflicts (محرران هانسن، س. وكراوز، ر.) 259-276 (مشروع لووي للبحث في الصراعات ما قبل التاريخ جامعة فرانكفورت، 2020).

- ماتيسون، س. م.، كوينلان، ر. ج. وهير، د. فرضية الذكر القابل للاستغناء. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. لندن. ب 374، 20180080 (2019).

- روبنسون، أ. ل. وجوتليب، ج. كيفية سد الفجوة بين الجنسين في المشاركة السياسية: دروس من المجتمعات الأمومية في أفريقيا. المجلة البريطانية لعلوم السياسة 51، 68-92 (2021).

- لويس، س. هيكل القرابة والنساء: أدلة من الاقتصاد. ديدالوس 149، 119-133 (2020).

© المؤلفون 2025، نشر مصحح 2025

طرق

توليد البيانات

معالجة بيانات التسلسل

علامات أحادية الوالد

تحليل شبه أحادي الصيغة الصبغية

استخراج استدعاءات القاعدة على مواقع تعدد أشكال النوكليوتيدات المفردة (SNP) في

تقدير GLIMPSE

تحديد مقاطع IBD

بناء شجرة العائلة

ومشاركة مقاطع IBD؛ (3) أعداد وأطوال مقاطع IBD1 و IBD2 للجينومات التي لديها أكثر من

توليد ملفات تعريف الأنساب باستخدام ChromoPainter

تصوير البيانات

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

57. راسل، م. وآخرون. مشروع Durotriges، المرحلة الأولى: بيان مؤقت. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 135، 217-221 (2014).

58. راسل، م. وآخرون. مشروع Durotriges، المرحلة الثانية: بيان مؤقت. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 136، 157-161 (2015).

59. راسل، م. وآخرون. مشروع Durotriges، المرحلة الثالثة: بيان مؤقت. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 137، 173-177 (2016).

60. يانغ، د. ي.، إنغ، ب.، واي، ج. س.، دودار، ج. س. & سوندرز، س. ر. ملاحظة تقنية: تحسين استخراج الحمض النووي من العظام القديمة باستخدام أعمدة الدوران القائمة على السيليكا. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 105، 539-543 (1998).

61. غامبا، ج. وآخرون. تدفق الجينوم والثبات في مقطع يمتد لخمسة آلاف عام من ما قبل التاريخ الأوروبي. Nat. Commun. 5، 5257 (2014).

62. بوسينكول، س. وآخرون. الجمع بين التبييض والهضم الخفيف يحسن استرداد الحمض النووي القديم من العظام. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17، 742-751 (2017).

63. دابني، ج. & ماير، م. استخراج الحمض النووي المتدهور بشدة من العظام والأسنان القديمة. Methods Mol. Biol. 1963، 25-29 (2019).

64. ماير، م. & كيرشر، م. إعداد مكتبة تسلسل إلومينا لالتقاط الأهداف المتعددة التسلسل. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010، db.prot5448 (2010).

65. مارتن، م. Cutadapt يزيل تسلسلات المحولات من قراءات التسلسل عالية الإنتاج. EMBnet.journal 17، 10-12 (2011).

66. شوبيرت، م.، ليندغرين، س. & أورلاندو، ل. AdapterRemoval v2: تقليم المحولات بسرعة، والتعرف، ودمج القراءات. BMC Res. Notes 9، 88 (2016).

67. لي، هـ. & دوربين، ر. محاذاة سريعة ودقيقة للقراءات القصيرة باستخدام تحويل بوروز-ويلر. Bioinformatics 25، 1754-1760 (2009).

68. لي، هـ. وآخرون. تنسيق محاذاة التسلسل/الخريطة و SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25، 2078-2079 (2009).

69. مكينا، أ. وآخرون. مجموعة أدوات تحليل الجينوم: إطار عمل MapReduce لتحليل بيانات تسلسل الحمض النووي من الجيل التالي. Genome Res. 20، 1297-1303 (2010).

70. دانسيك، ب. وآخرون. اثنا عشر عامًا من SAMtools و BCFtools. Gigascience 10، giab008 (2021).

71. وايسنشتاينر، هـ. وآخرون. HaploGrep 2: تصنيف مجموعة الهالوجين في عصر التسلسل عالي الإنتاج. Nucleic Acids Res. 44، W58-W63 (2016).

72. فان أوفن، م. & كايسر، م. شجرة النسب الشاملة المحدثة لتنوع الحمض النووي الميتوكوندري البشري العالمي. Hum. Mutat. 30، E386-E394 (2009).

73. ناي، م. & رويشودوري، أ. ك. تباينات أخذ العينات من التغايرية والمسافة الجينية. Genetics 76، 379-390 (1974).

74. ناي، م. & تاجيما، ف. تعدد أشكال الحمض النووي القابل للاكتشاف بواسطة إنزيمات القطع التقييدية. Genetics 97، 145-163 (1981).

75. ماثيسون، I. وآخرون. أنماط الانتقاء على مستوى الجينوم في 230 من الأوراسيين القدماء. الطبيعة 528، 499-503 (2015).

76. برونيل، س. وآخرون. الجينومات القديمة من فرنسا الحالية تكشف عن 7000 سنة من تاريخها الديموغرافي. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 117، 12791-12798 (2020).

77. دولياس، ك. وآخرون. الحمض النووي القديم في أقصى العالم: الهجرة القارية واستمرار سلالات الذكور النيوثية في عصر البرونز في أوركني. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 119، e2108001119 (2022).

78. مارغاريان، أ. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني لعالم الفايكنج. ناتشر 585، 390-396 (2020).

79. ألينتوف، م. إي. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني في عصر البرونز في أوراسيا. ناتشر 522، 167-172 (2015).

80. دامغارد، ب. وآخرون. 137 جينوم بشري قديم من سهول أوراسيا. نيتشر 557، 369-374 (2018).

81. اتحاد جينات التصلب المتعدد الدولي ومؤسسة ويلكوم للسيطرة على الحالات 2. المخاطر الجينية ودور أساسي لآليات المناعة الخلوية في التصلب المتعدد. الطبيعة 476، 214-219 (2011).

82. باترسون، ن.، برايس، أ. ل. ورايش، د. هيكل السكان والتحليل الذاتي. PLoS Genet. 2، e190 (2006).

83. باترسون، ن. وآخرون. الاختلاط القديم في تاريخ البشر. علم الوراثة 192، 1065-1093 (2012).

84. بروشكي، ف. وآخرون. جينومات العصر الحجري الحديث المبكر من الهلال الخصيب الشرقي. ساينس 353، 499-503 (2016).

85. لازاريديس، إ. وآخرون. الجينومات البشرية القديمة تشير إلى ثلاثة تجمعات سكانية أسلاف للأوروبيين الحاليين. ناتشر 513، 409-413 (2014).

86. بريس، س. وآخرون. الجينومات القديمة تشير إلى استبدال السكان في بريطانيا في العصر الحجري الحديث المبكر. نات. إيكول. إيفول. 3، 765-771 (2019).

87. كاسيدي، ل. م. وآخرون. نخب سلالية في المجتمع النيوليثي الضخم. نيتشر 582، 384-388 (2020).

88. يكا، ر. وآخرون. أنماط القرابة المتغيرة في الأناضول النيوليثي تم الكشف عنها بواسطة الجينومات القديمة. البيولوجيا الحالية 31، 2455-2468 (2021).

89. جونز، إ. ر. وآخرون. لم يكن الانتقال النيوليثي في البلطيق مدفوعًا بالاختلاط مع المزارعين الأوروبيين الأوائل. بيولوجيا حالية 27، 576-582 (2017).

90. غونزاليس-فورتس، ج. وآخرون. أدلة باليوجينية على الاختلاط عبر أجيال متعددة بين المزارعين النيوليثيين وجامعي الصيد في حوض الدانوب الأدنى. بيولوجيا حالية 27، 1801-1810 (2017).

91. مالك، س. وآخرون. مشروع تنوع جينوم سيمونز: 300 جينوم من 142 مجموعة سكانية متنوعة. ناتشر 538، 201-206 (2016).

92. روبيناتشي، س.، ريبيرو، د. م.، هوفمايستر، ر. ج. وديلانو، أ. استخدام لوحات مرجعية كبيرة في تحديد المراحل والتقدير الفعال لبيانات التسلسل ذات التغطية المنخفضة. نات. جينيت. 53، 120-126 (2021).

93. مجموعة مشروع الجينوم البشري. مرجع عالمي للتنوع الجيني البشري. ناتشر 526، 68-74 (2015).

94. براونينغ، ب. ل.، تيان، إكس.، زو، واي. وبراونينغ، س. ر. مرحلة سريعة من مرحلتين لبيانات التسلسل على نطاق واسع. المجلة الأمريكية لعلم الوراثة البشرية 108، 1880-1890 (2021).

95. تراج، ف. أ.، والت مان، ل. و فان إيك، ن. ج. من لوفيان إلى لايدن: ضمان المجتمعات المتصلة بشكل جيد. Sci. Rep. 9، 5233 (2019).

96. خارشينكو، ب.، بيتوكوف، ف.، وانغ، ي. وبييدرستيدت، إ. leidenAlg: ينفذ خوارزمية لايدن عبر واجهة R. GitHubhttps://github.com/kharchenkolab/leidenAlg (2023).

97. شلييب، ك. ب. phangorn: تحليل النشوء والتطور في R. المعلومات الحيوية 27، 592-593 (2011).

98. كاباليرو، م. وآخرون. تداخل التقاطع والخرائط الجينية المحددة حسب الجنس تشكل المشاركة المتطابقة عن طريق النسب في الأقارب المقربين. PLoS Genet. 15، e1007979 (2019).

99. أنطونيو، م. ل. وآخرون. روما القديمة: تقاطع جيني لأوروبا والبحر الأبيض المتوسط. ساينس 366، 708-714 (2019).

100. فيرنانديز، د. م. وآخرون. مقطع زمني جينومي من العصر الحجري الحديث لامتزاج الصيادين والمزارعين في وسط بولندا. تقارير العلوم 8، 14879 (2018).

101. فريليش، س. وآخرون. إعادة بناء التاريخ الجيني والتنظيم الاجتماعي في كرواتيا في العصر الحجري الحديث وعصر البرونز. تقارير العلوم 11، 16729 (2021).

102. جريتزينجر، ج. وآخرون. هجرة الأنجلوساكسون وتشكيل مجموعة الجينات الإنجليزية المبكرة. ناتشر 610، 112-119 (2022).

103. أولالد، إ. وآخرون. ظاهرة الكوب والانتقال الجيني في شمال غرب أوروبا. ناتشر 555، 190-196 (2018).

104. سيغوين-أورلاندو، أ. وآخرون. أسلاف غير متجانسة من الصيادين وجامعي الثمار وأصول متعلقة بالسافانا في جينومات العصر الحجري الحديث المتأخر وجرات الجرس من فرنسا الحالية. بيولوجيا حالية 31، 1072-1083 (2021).

105. زيجاراك، أ. وآخرون. توفر الجينومات القديمة رؤى حول هيكل الأسرة ووراثة الوضع الاجتماعي في العصر البرونزي المبكر في جنوب شرق أوروبا. ساي. ريب. 11، 10072 (2021).

106. ماثيسون، I. وآخرون. التاريخ الجينومي لجنوب شرق أوروبا. ناتشر 555، 197-203 (2018).

107. ديلانو، أ.، زاجوري، ج.-ف. ومارشيني، ج. تحسين تحديد الكروموسومات بالكامل لدراسات الأمراض والوراثة السكانية. نات. ميثودز 10، 5-6 (2013).

السماح وتسهيل جميع جوانب العمل الميداني الأثري. تم تمويل هذا العمل من قبل مؤسسة العلوم الأيرلندية / مجلس أبحاث الصحة / جائزة شراكة أبحاث العلوم الحيوية من ويلكوم ترست رقم 205072 لد.ج.ب، ‘الجينوميات القديمة والعبء الأطلسي’، وجائزة تايخ إيرلندا – جائزة باحث أيرلندا (IRCLA/2022/126) لـ ل.م.ك، ‘الجزيرة القديمة’. نشكر إ. كيني والفريق في ترينسيك (كلية ترينيتي دبلن) على دعم التسلسل.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى لارا م. كاسيدي. معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر نيتشر المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة الأقران لهذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

مقالة

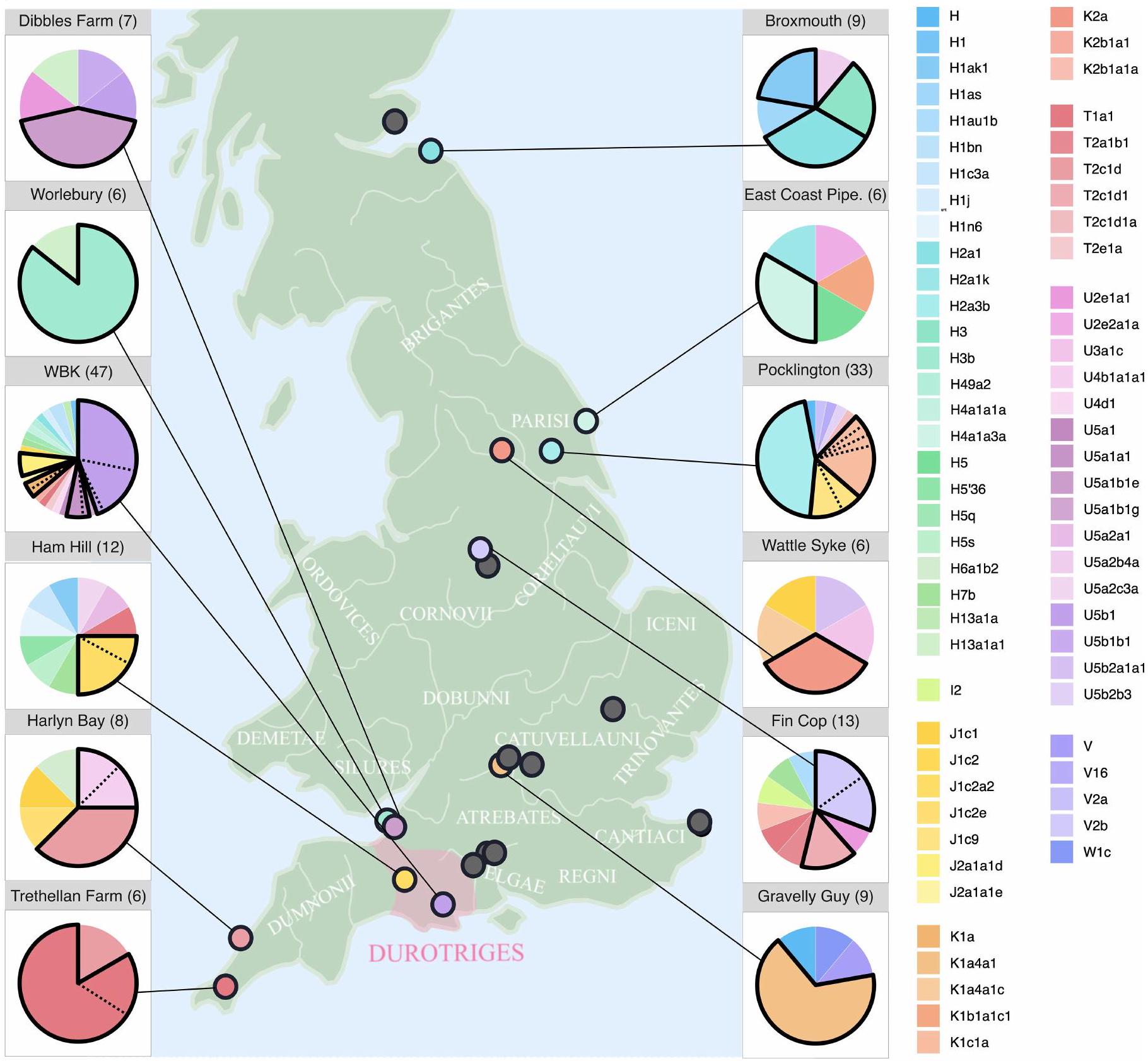

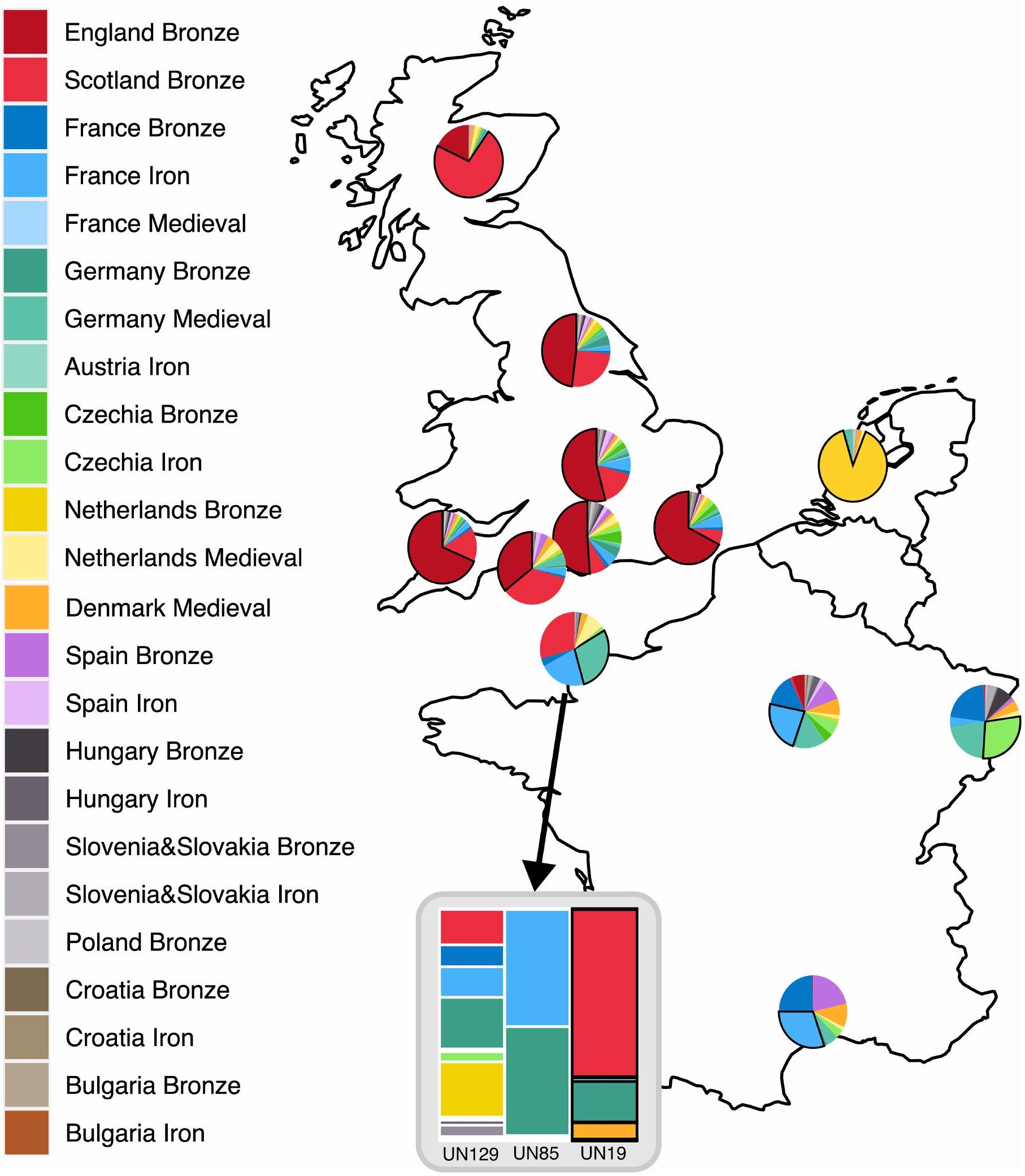

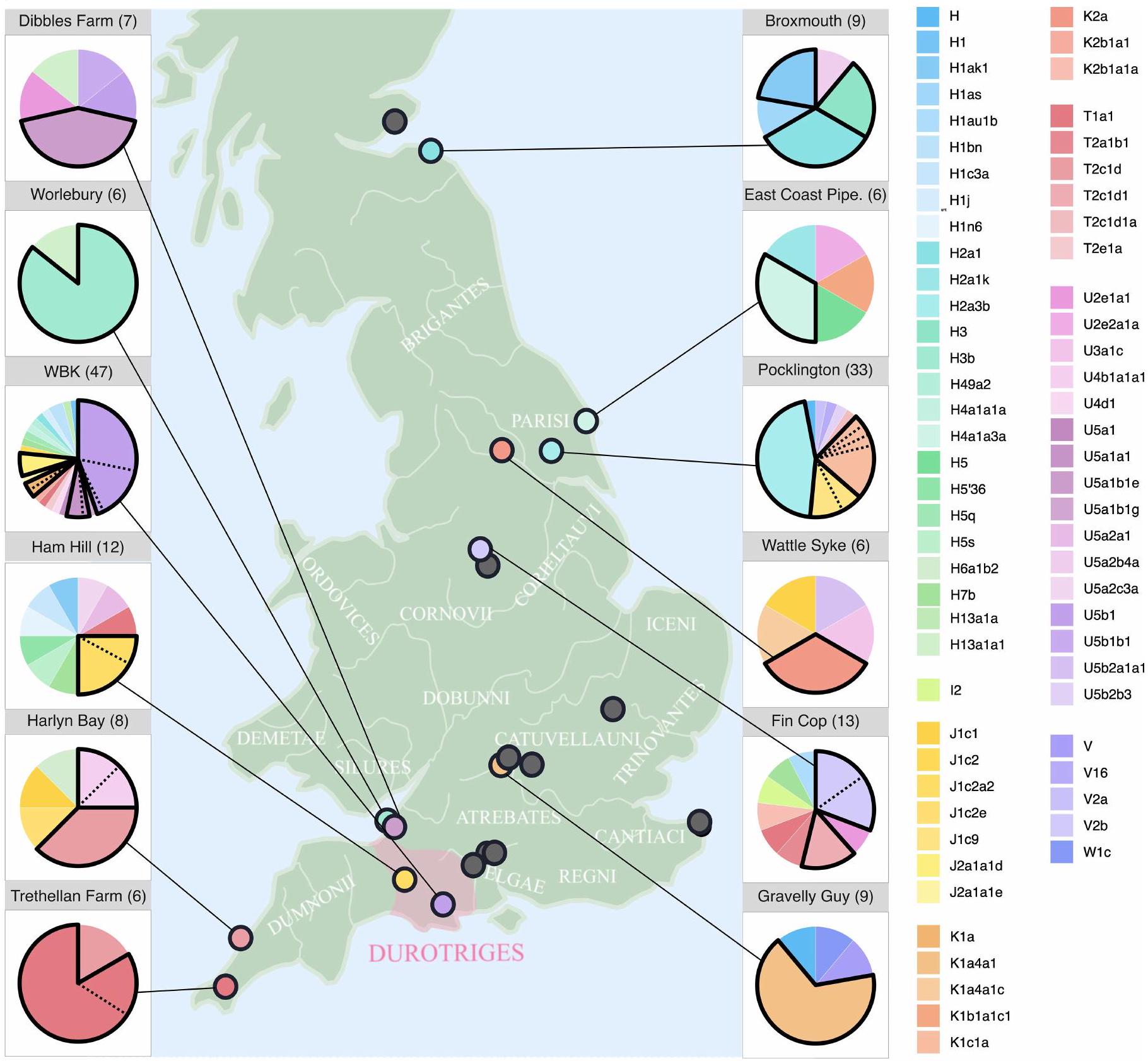

الشكل 1 من البيانات الموسعة | ترددات مجموعة الهيموغلوبين الميتوكوندري في بريطانيا

المواقع الاثني عشر المتبقية. يتم تمييز المجموعات الوراثية التي تحتوي على عدد يزيد عن واحد بخط أسود في الرسوم البيانية الدائرية. تُستخدم الخطوط المنقطة لتقسيم المجموعات الوراثية إلى فروع فرعية بناءً على طفرات إضافية. يتم عرض أسماء القبائل في عصر الحديد التي سجلها الكتاب الكلاسيكيون ومواقعها الجغرافية التقريبية. يتم تقديم الأنماط الوراثية لجميع عينات عصر الحديد البريطانية المستخدمة في هذا التحليل في الجدول التكميلي 12.

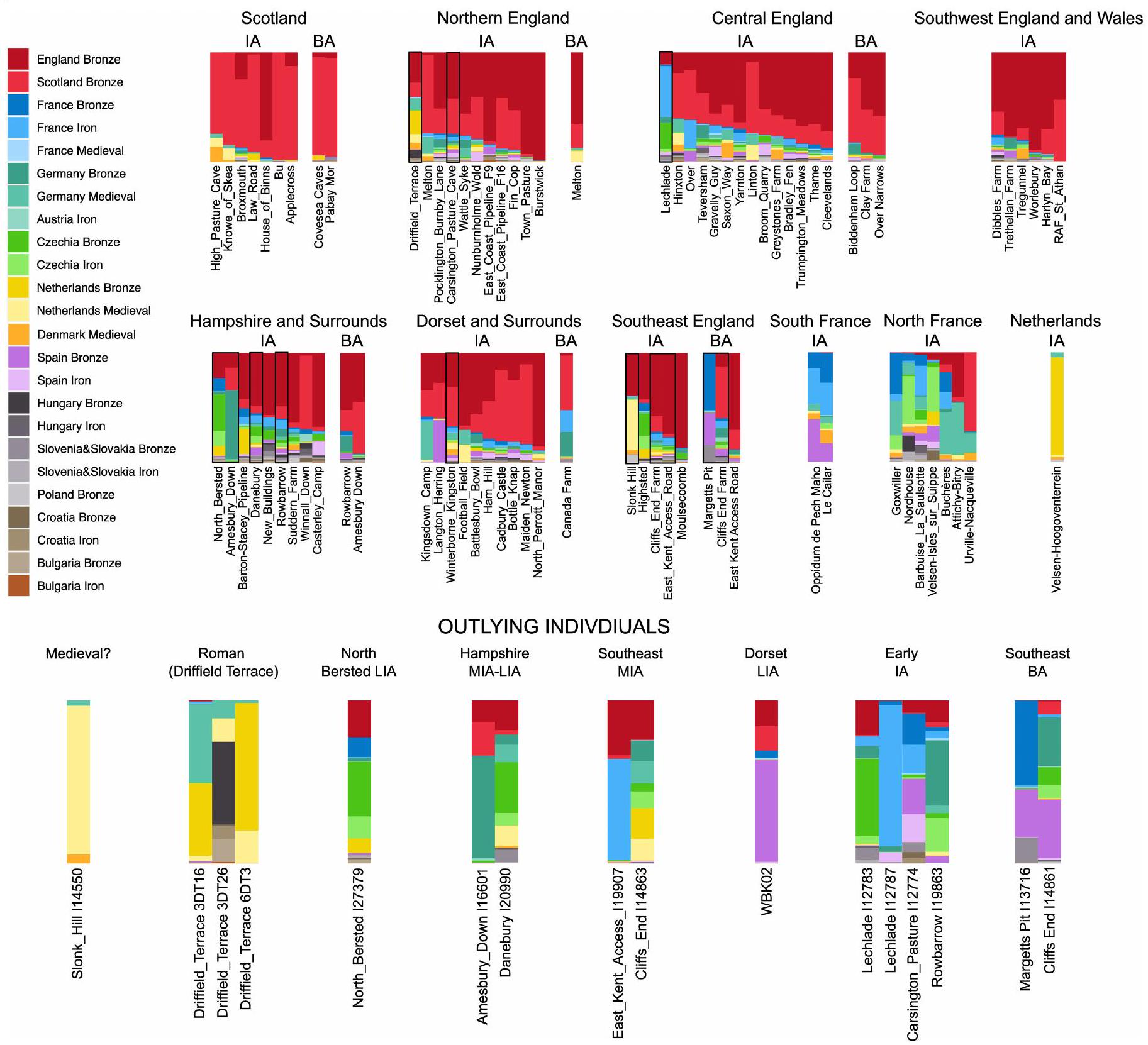

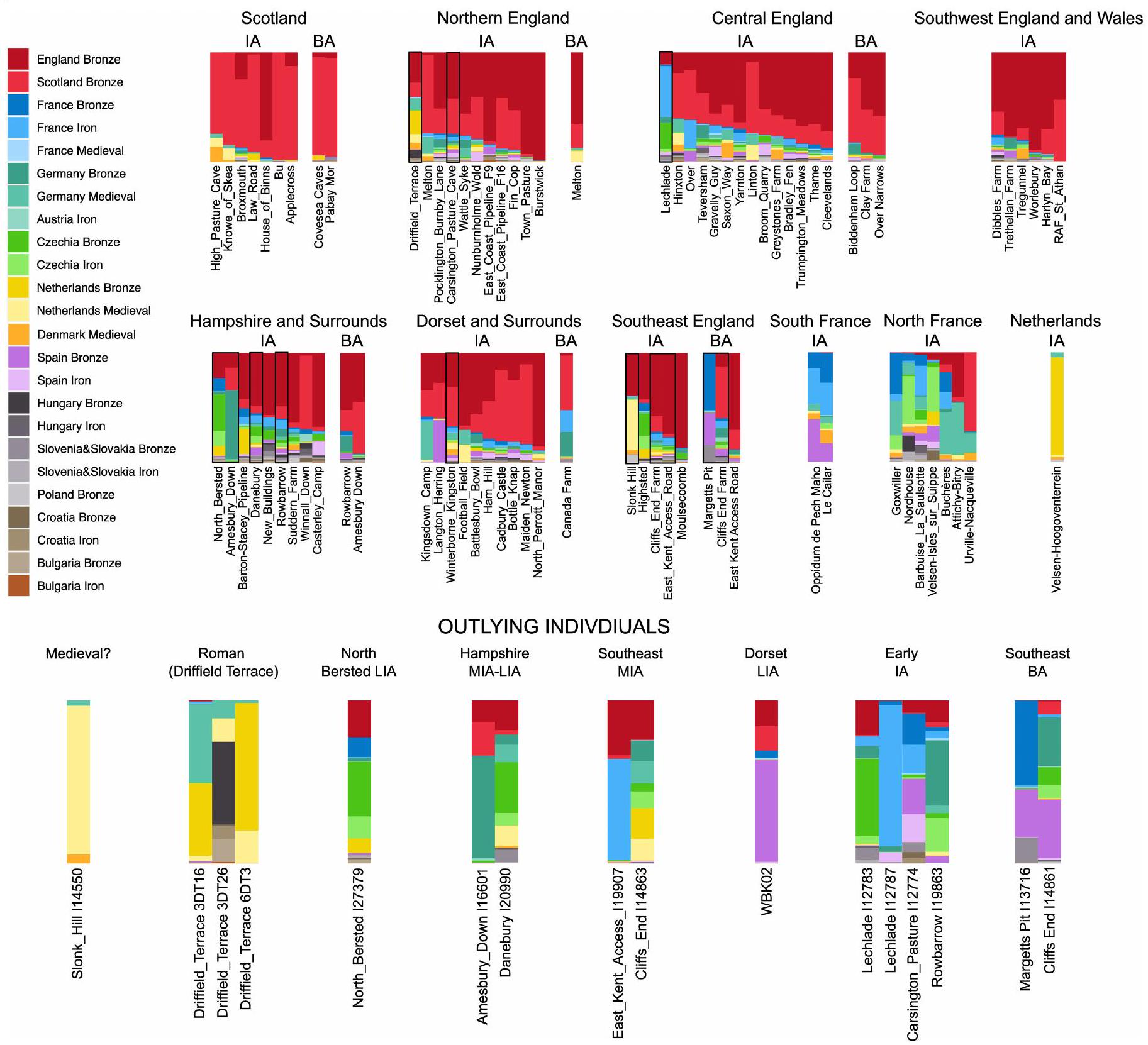

مع معرفات السكان الخاصة بهم في الجدول التكميلي 12. القيم الخام متاحة في الجدول التكميلي 17. الصفوف العليا تظهر ملفات متوسطة لمواقع أثرية من العصر البرونزي والعصر الحديدي في بريطانيا وفرنسا وهولندا. يتم تحديد ملفات المواقع البريطانية باللون الأسود إذا كان الموقع يحتوي على فرد واحد أو أكثر من القيم الشاذة (التي تمتلك مستوى من السلالة البريطانية من العصر البرونزي المبكر بمقدار معيارين)

الانحرافات دون متوسط السكان). الصف السفلي يظهر ملفات النسب لهذه الجينومات الشاذة. نلاحظ أن جميع الشواذ من عصر الحديد الأوسط والمتأخر تأتي من منطقة القناة الأساسية. نحن نحدد اثنين من التقارير السابقة

مقالة

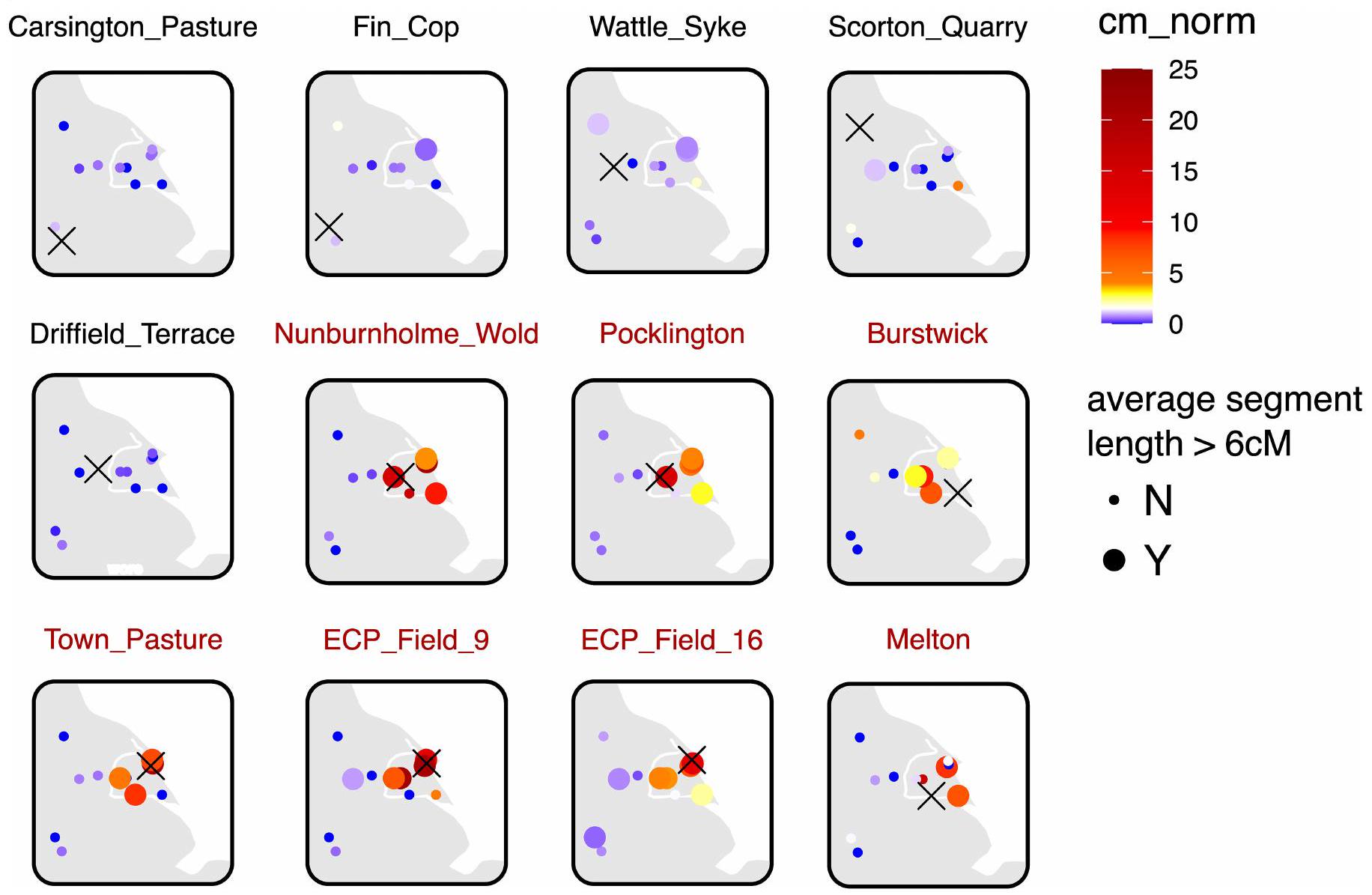

(المميز بالأبيض) ويظهر تبادل مفرط لمرض التهاب الأمعاء فيما بينهم. المدافن الرومانية في تيراس دريفيلد

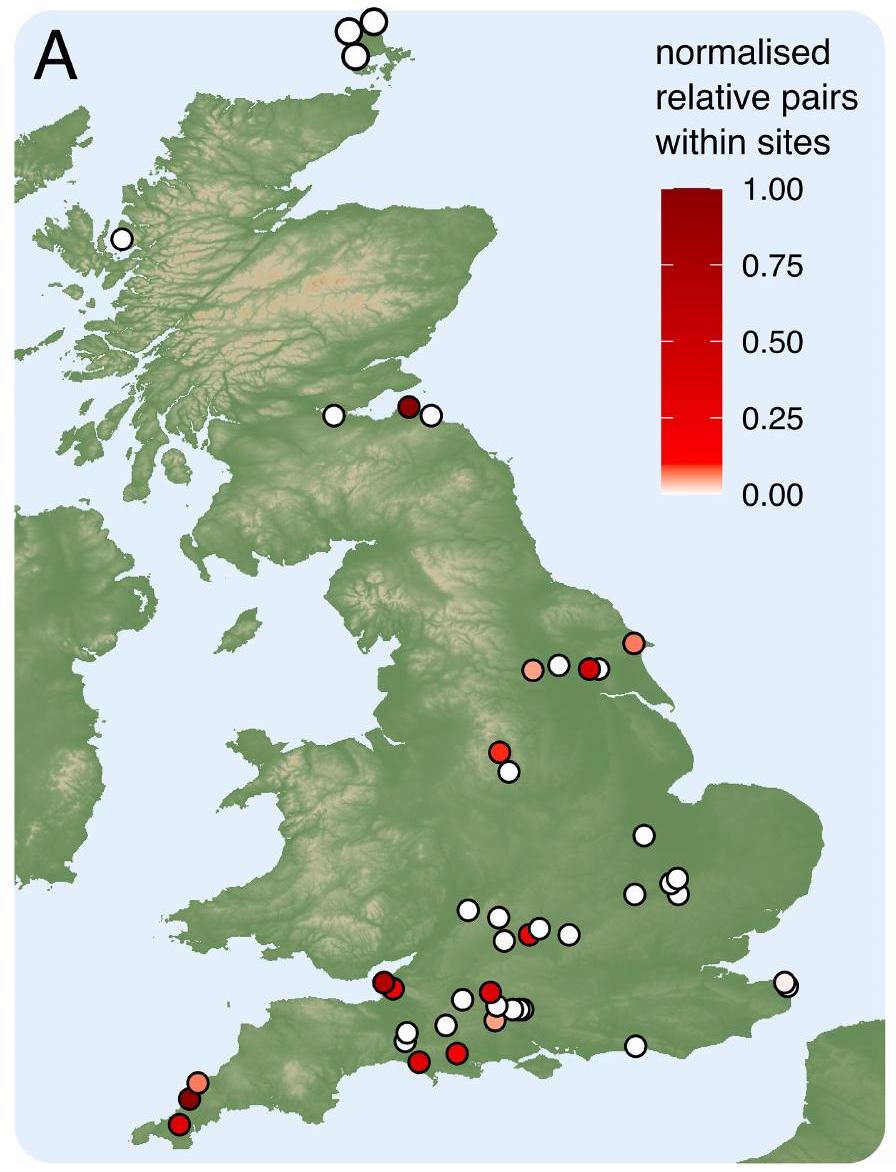

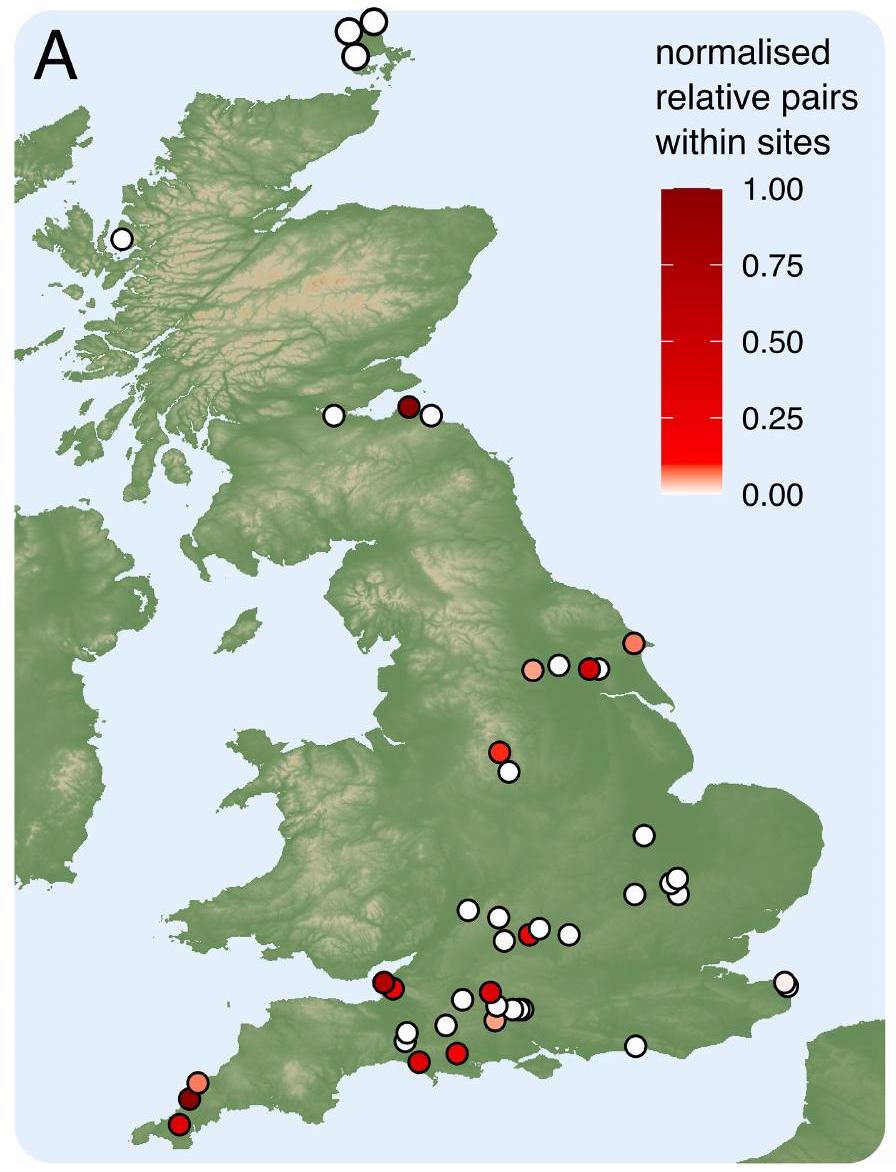

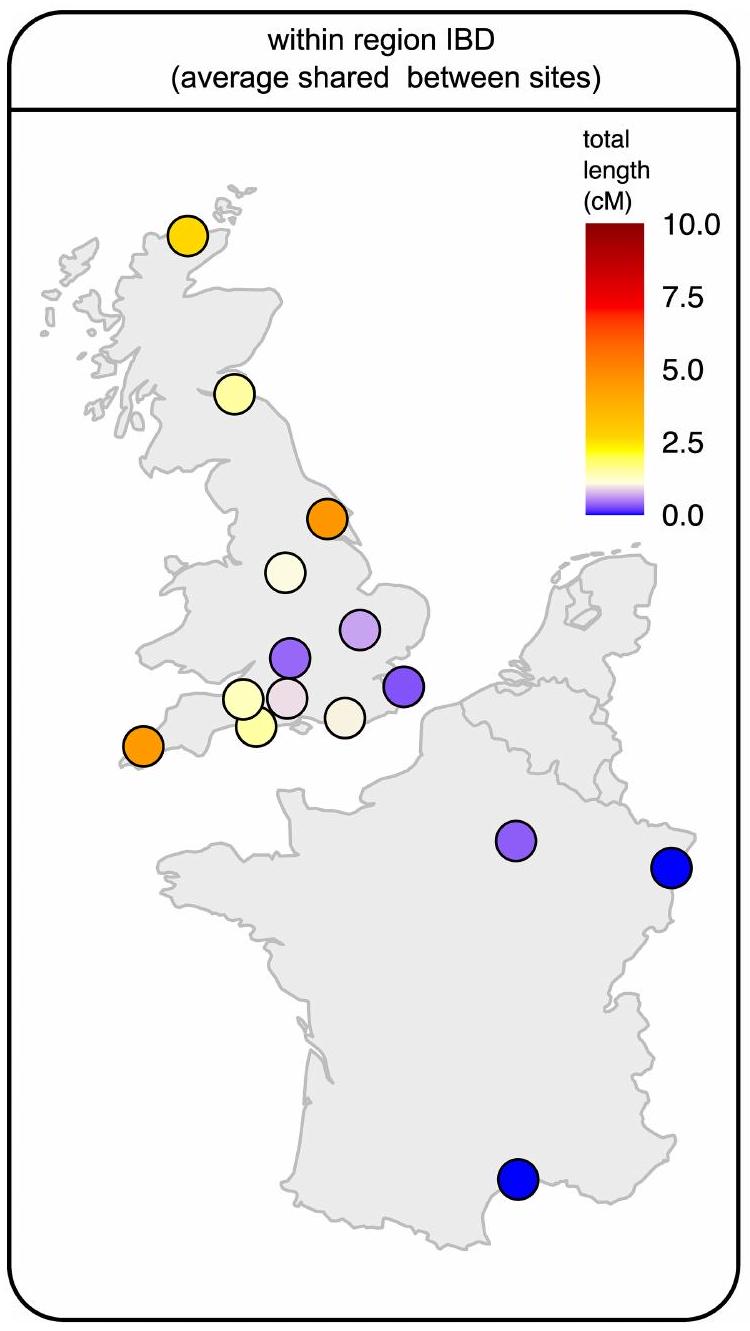

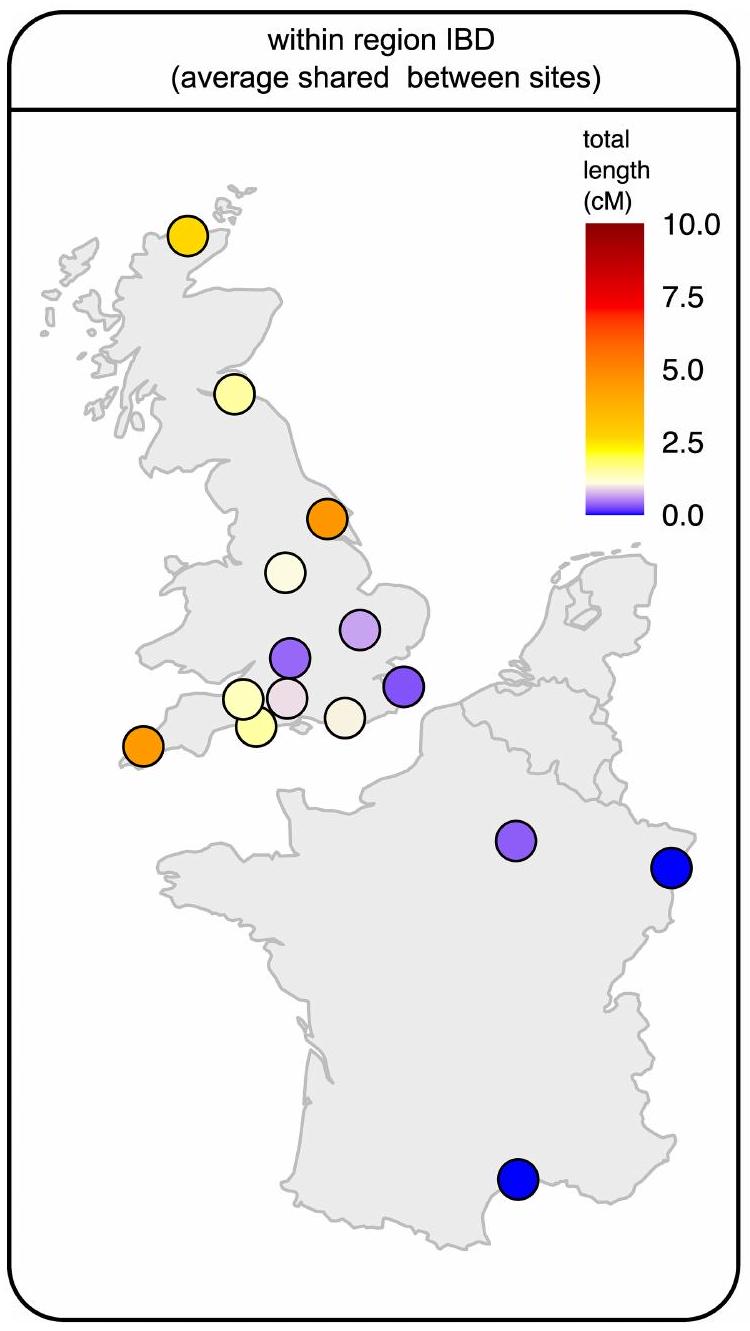

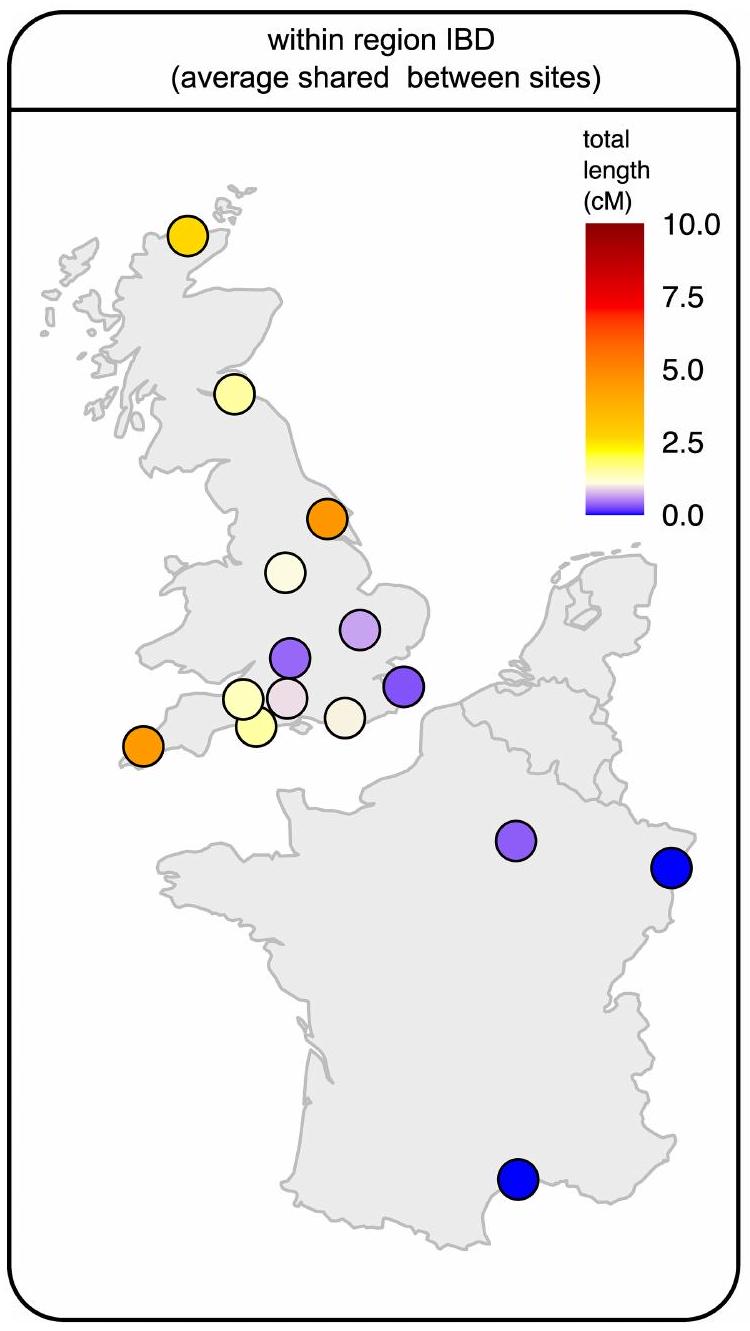

القرابة والممارسات الثقافية مثل الزواج الأقاربي. نرى أدنى القيم لمشاركة IBD داخل المنطقة في فرنسا وجنوب شرق إنجلترا. بالنسبة لمشاركة IBD داخل الجينوم، نأخذ متوسط السكان لطول إجمالي فترات التماثل الوراثي لكل موقع أثري. إذا كان متوسط الطول الإجمالي فوق 3 سم، نقوم برسم الموقع في اللوحة السفلية. في بريطانيا، تتركز المواقع ذات فترات التماثل الوراثي المنخفضة (اللوحة العلوية) في المناطق الوسطى الجنوبية والجنوبية الشرقية، مما يدل على أحجام سكانية أكبر. يتم رسم مشاركة IBD داخل الموقع (متوسط الطول المشترك بين الأفراد في موقع) بطريقة مشابهة.

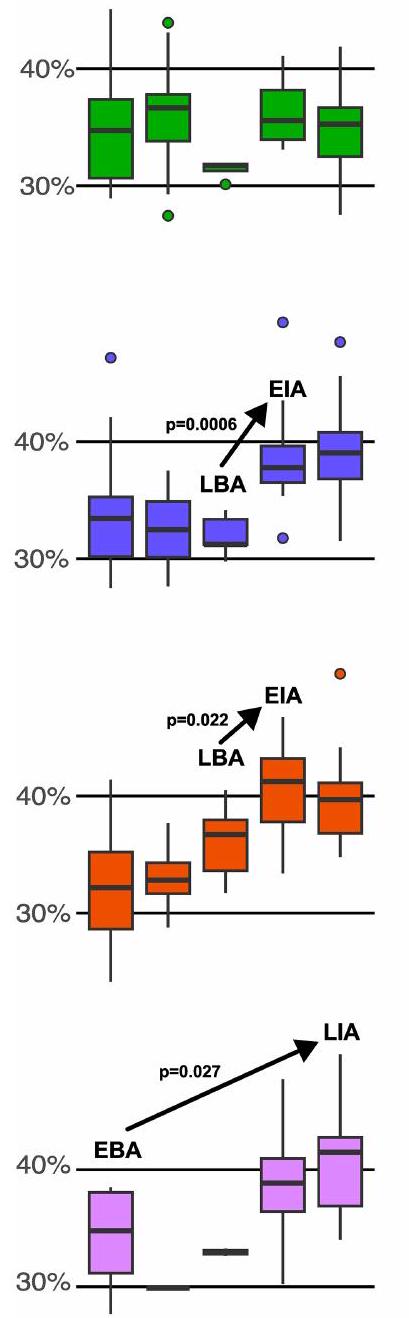

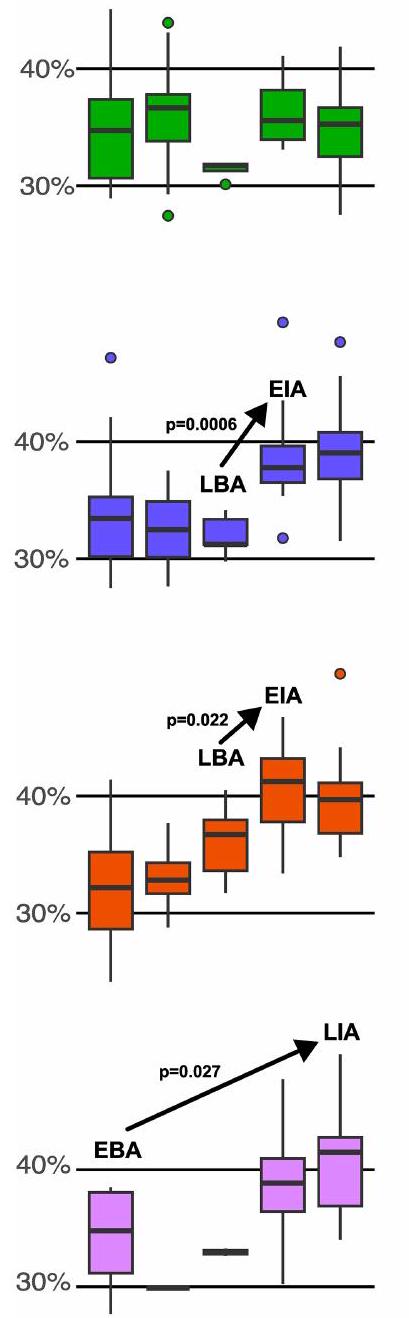

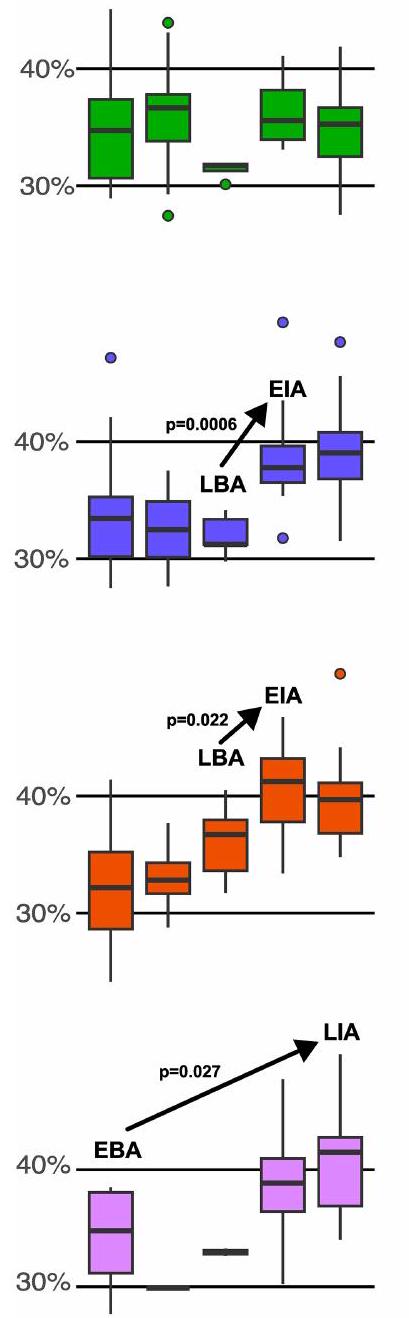

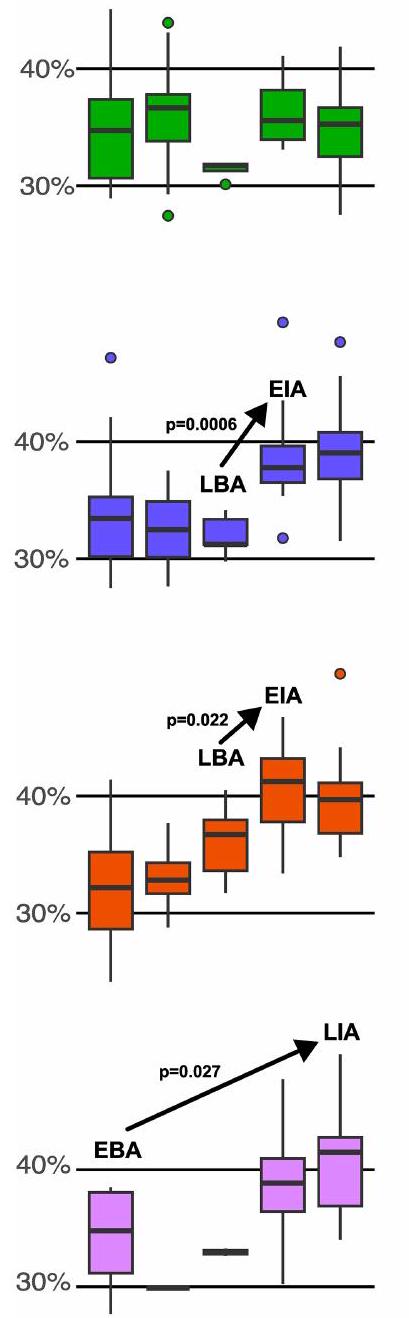

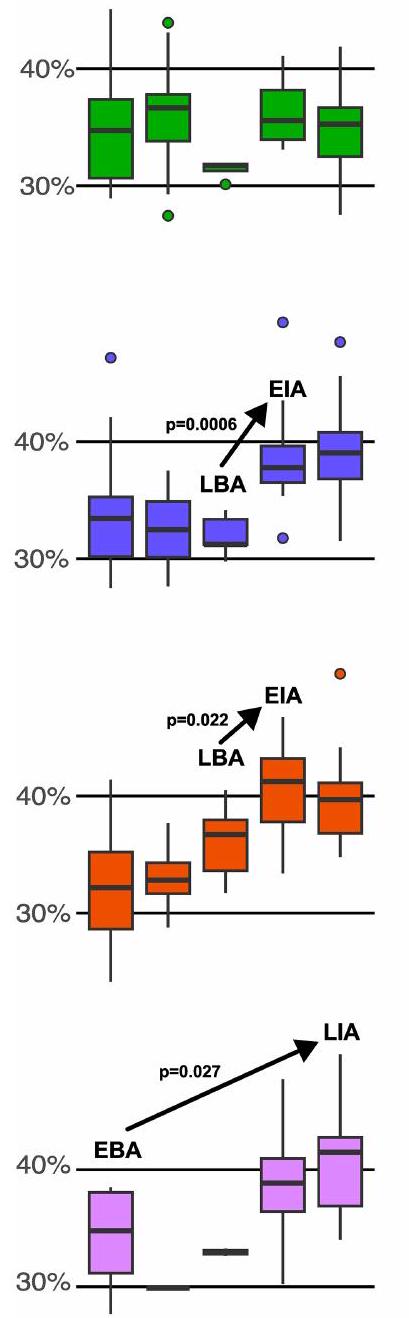

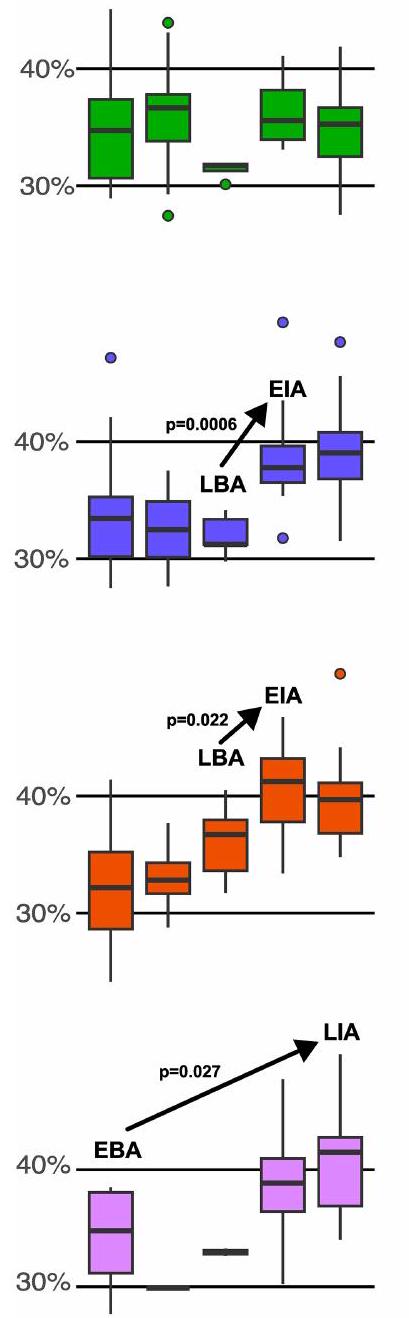

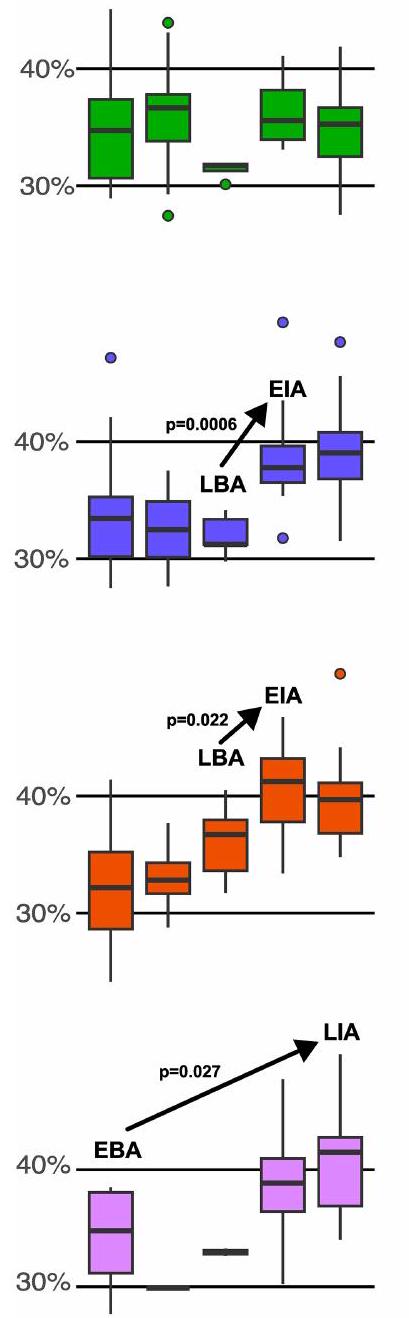

قيم لفترات زمنية مختلفة مدتها 500 عام لكل منطقة. يتم تمييز هذه الفترات بخطوط متقطعة رمادية على مخطط المتوسط المتحرك. تم وضع تسميات لنطاقات تواريخ الفترات الزمنية بالنسبة للفترة الأثرية التقريبية التي تتركز عليها (EBA: العصر البرونزي المبكر، MBA: العصر البرونزي الأوسط، LBA: العصر البرونزي المتأخر، EIA: العصر الحديدي المبكر، LIA: العصر الحديدي المتأخر). تغييرات كبيرة (اختبار ويلش)

محفظة الطبيعة

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

غير متوفر

□

X

□

□

لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية، فإن إحصائية الاختبار (على سبيل المثال،

□

□ لتحليل بايزي، معلومات حول اختيار القيم الأولية وإعدادات سلسلة ماركوف مونت كارلو

□ لتصميمات هرمية ومعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة للنتائج

□ تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين)

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات تتناول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

تم التأكيد

□ حجم العينة الدقيق

□ بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات متميزة أو ما إذا كانت نفس العينة قد تم قياسها عدة مرات

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

□ وصف لجميع المتغيرات المرافقة التي تم اختبارها

□ وصف لأي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات الطبيعية والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

□ وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو تقديرات أساسية أخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) وَ التباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو تقديرات مرتبطة بعدم اليقين (مثل فترات الثقة)

البرمجيات والشيفرة

جمع البيانات

FASTQC v0.11.5

قطع التكيف v1.9.1

إزالة المحول v2.3.1

بوا الإصدار 0.7.5a-r405

سام تولز الإصدار 1.7

جي إيه تي كيه v3.7.0

أدوات بيكارد v2.0.1

BCFtools v1.10.2

هابلوجريب 2 الإصدار 2.2.9

سمارت بي سي إيه v16000 (EIGENSOFT)

ADMIXTOOLS2 v2.0.4

لمحة1 الإصدار 1.1.0

بيجل 5 v05 مايو 22.33أ

refinedIBD v17Jan20.102

لايدن ألغ v1.1.1

فهانغورن v2.11.1

SHAPEIT2 v2.r837

SOURCEFIND v2

هيكل دقيق v2

محاكاة المشاة

بيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا.

البحث الذي يتضمن مشاركين بشريين، بياناتهم، أو مواد بيولوجية

| التقارير عن الجنس والنوع الاجتماعي | تم تعريف العينات على أنها ذكور أو إناث بناءً على تغطية القراءة عبر الكروموسومات الجنسية. لم تُلاحظ أي شذوذ في الكروموسومات الجنسية. تم إجراء مقارنات بين السكان الذكور والإناث المدفونين في وينتربورن كينغستون لاستنتاج معلومات حول القرابة وعادات الزواج. عند مناقشة هذه العادات وغيرها من الظواهر الثقافية، نستخدم مصطلحي الرجال والنساء. |

| التقارير عن العرق أو الإثنية أو غيرها من المجموعات الاجتماعية ذات الصلة | نحن لا نصنف العينات حسب الفئات الاجتماعية المبنية على العرق أو الإثنية. نحن نجمع العينات حسب المنطقة الجغرافية أو الكتلة الجينية (المعرفة بناءً على بيانات الهابلوتيب). |

| خصائص السكان | جميع العينات البشرية ذات طبيعة أثرية. تم إجراء تقييم عظامي لعمر الوفاة، والأمراض، والصدمة. |

| التوظيف | غير متوفر |

| رقابة الأخلاقيات | غير متوفر |

التقارير المتخصصة في المجال

علوم الحياة

العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية □ العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة بجميع الأقسام، انظرnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم الحياتية

| حجم العينة | قمنا بأخذ عينات شاملة من جميع المدافن التي تم التنقيب عنها في وينتر بورن كينغستون. تم تحليل هذه العينات مع جميع البيانات المتاحة للجمهور من العصر الحديدي في شمال غرب أوروبا. | ||||||

| استثناءات البيانات |

|

||||||

| استنساخ | غير متوفر |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | |

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر |

| إكس | □ الأجسام المضادة | إكس |

| إكس | □ | إكس |

| □ | علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار | إكس |

| إكس | □ | |

| – | □ | |

| إكس | □ | |

| ف | □ | |

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار

أصل العينة

رقابة الأخلاقيات

النباتات

غير متوفر

غير متوفر

غير متوفر

- ¹قسم الوراثة، كلية ترينيتي دبلن، دبلن، أيرلندا. ²قسم الآثار والأنثروبولوجيا، جامعة بورنموث، بورنموث، المملكة المتحدة. ³قسم علوم الحياة والبيئة، جامعة بورنموث، بورنموث، المملكة المتحدة.

مدرسة الرياضيات، جامعة بريستول، بريستول، المملكة المتحدة. معهد الجينوم، جامعة تارتي، تارتي، إستونيا. قسم اللغويات، جامعة هاواي في مانو، مانو، هاواي، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز DFG للدراسات المتقدمة، جامعة توبنغن، توبنغن، ألمانيا. الإيكو-أنثروبولوجيا، متحف الإنسان، باريس، فرنسا.

البريد الإلكتروني: cassidl1@tcd.ie

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08409-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39814899

Publication Date: 2025-01-15

Continental influx and pervasive matrilocality in Iron Age Britain

Received: 7 May 2024

Accepted: 14 November 2024

Published online: 15 January 2025

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Roman writers found the relative empowerment of Celtic women remarkable

husbands (De Bello Gallico). However, such social descriptions are seen as suspect, biased towards what would have seemed exotic to a Mediterranean audience that was immersed in a deeply patriarchal world

The distributions of grave goods in multiple western European Celtic cemeteries have been interpreted as supporting high female status

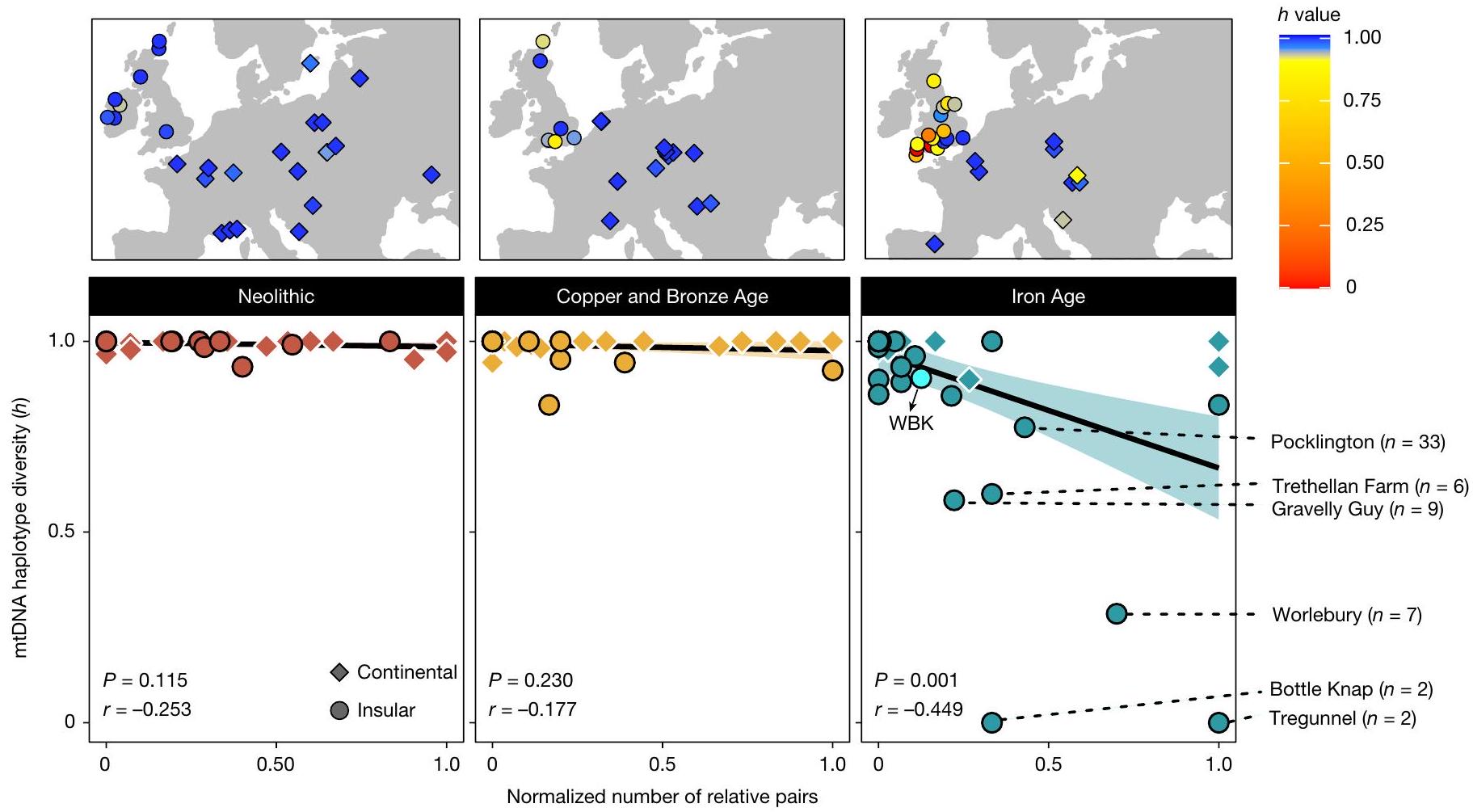

haplotype; grey indicates singleton haplogroups. The Durotrigian period (solid line) and the range of dates of family members (dashed line) are indicated. The summed relatedness is also shown in box plots (Tukey) by sex for individuals in the latter range; a significant difference between males (M) and females (F) is observed (Welch’s

Matrilocality in Durotrigian society

samples taken from the site (Supplementary Table 1), with 40 achieving a coverage high enough for genotype imputation and robust identification of genomic segments that were identical by descent (IBD) between individuals

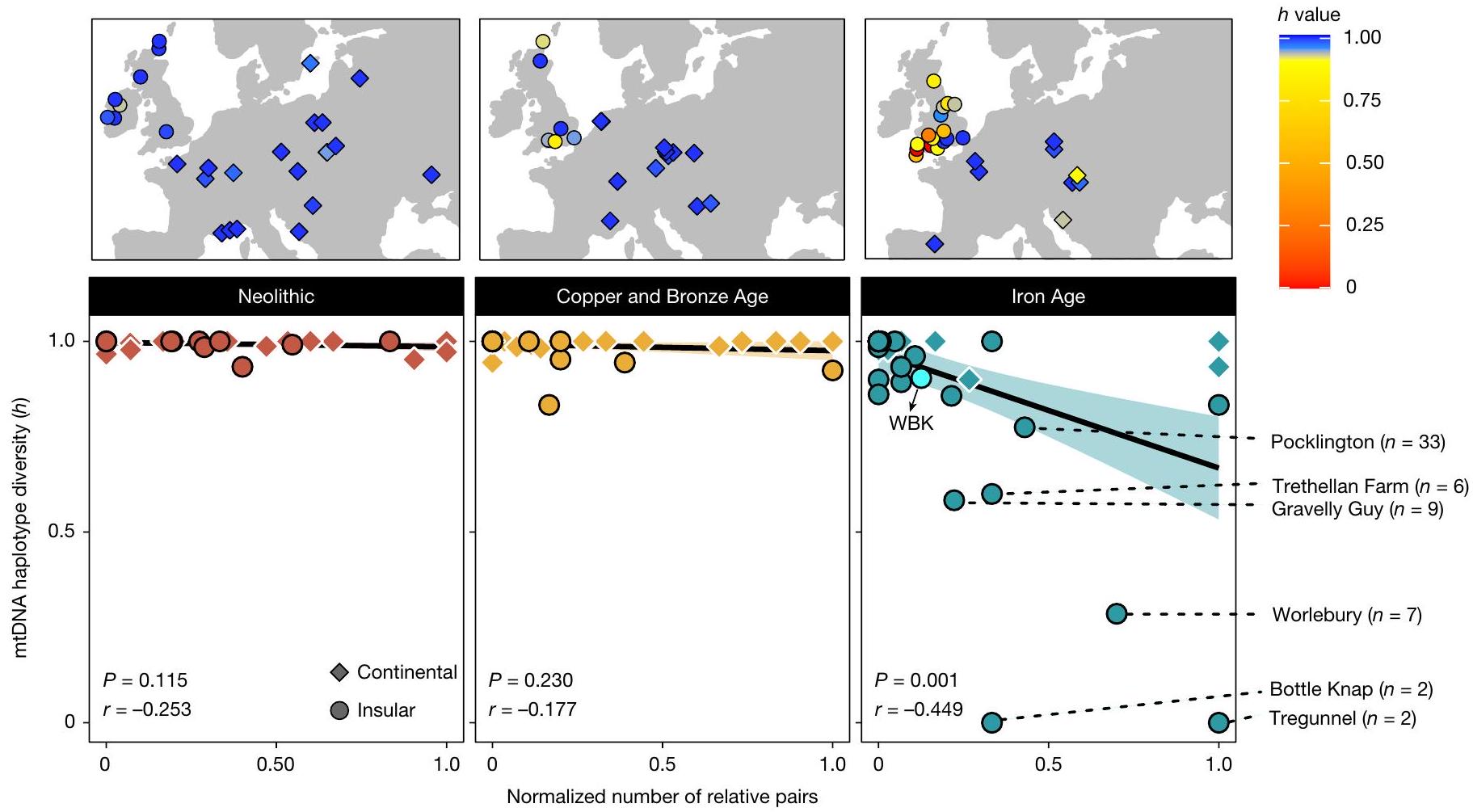

Strikingly, more than two thirds (24/34) of the genetically identified kin belong to a rare lineage of mitochondrial haplogroup U5b1 (Fig. 1d) that has not been observed previously in ancient sampling and that has a frequency of only

that at least 420 female births to lineage mothers would be required to result in this level of within-clade diversity (Supplementary Note 2.6), implying a long-term association between this haplotype and WBK. By contrast, we find that Y chromosome diversity is high (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Note 2.8), and runs of homozygosity (ROH) indicate that this was an outbreeding community (Supplementary Note 5.5). Theory, modelling and surveys of modern populations

Marriage custom in an Iron Age community

Matrilocality across Iron Age Britain

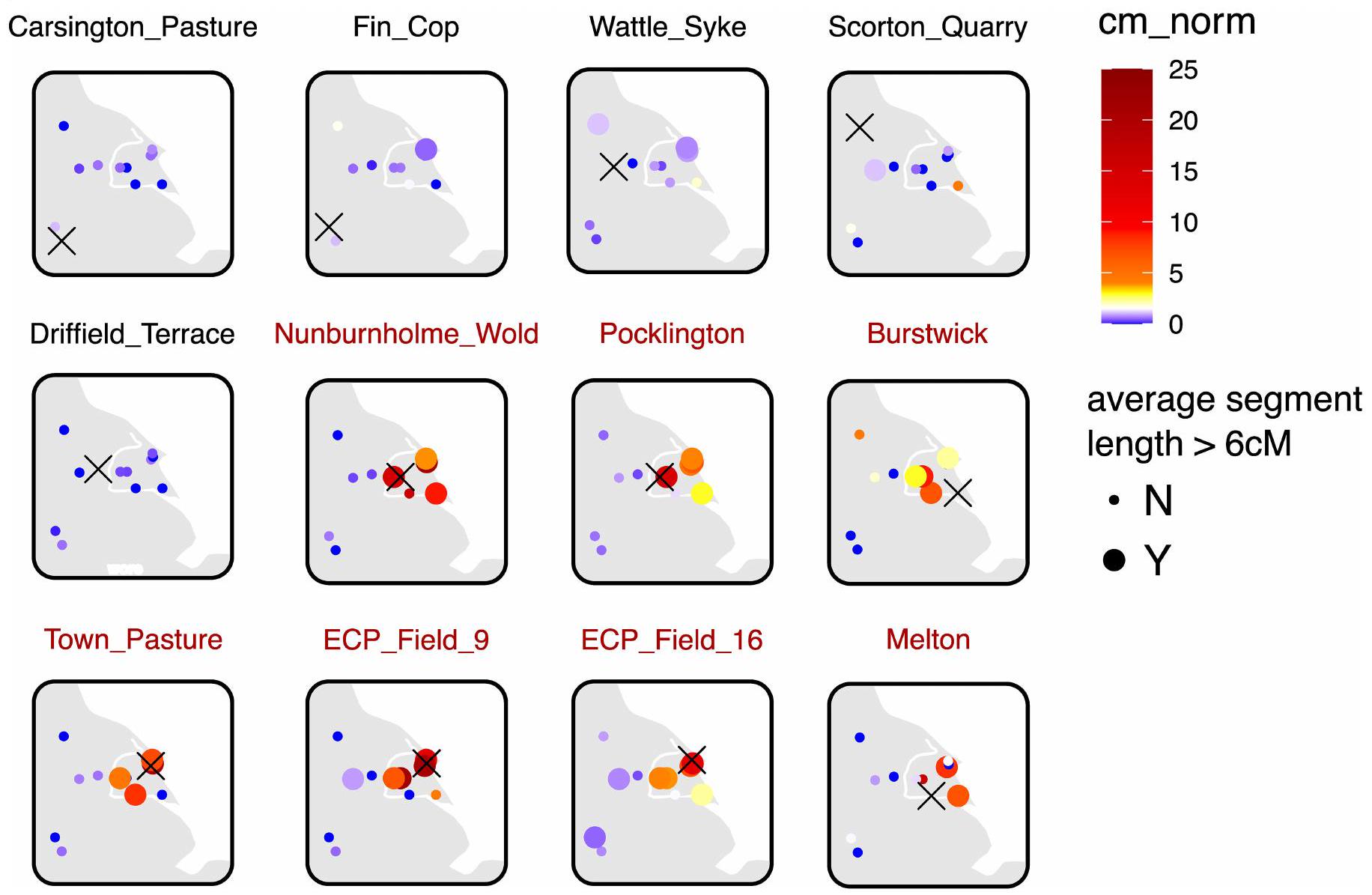

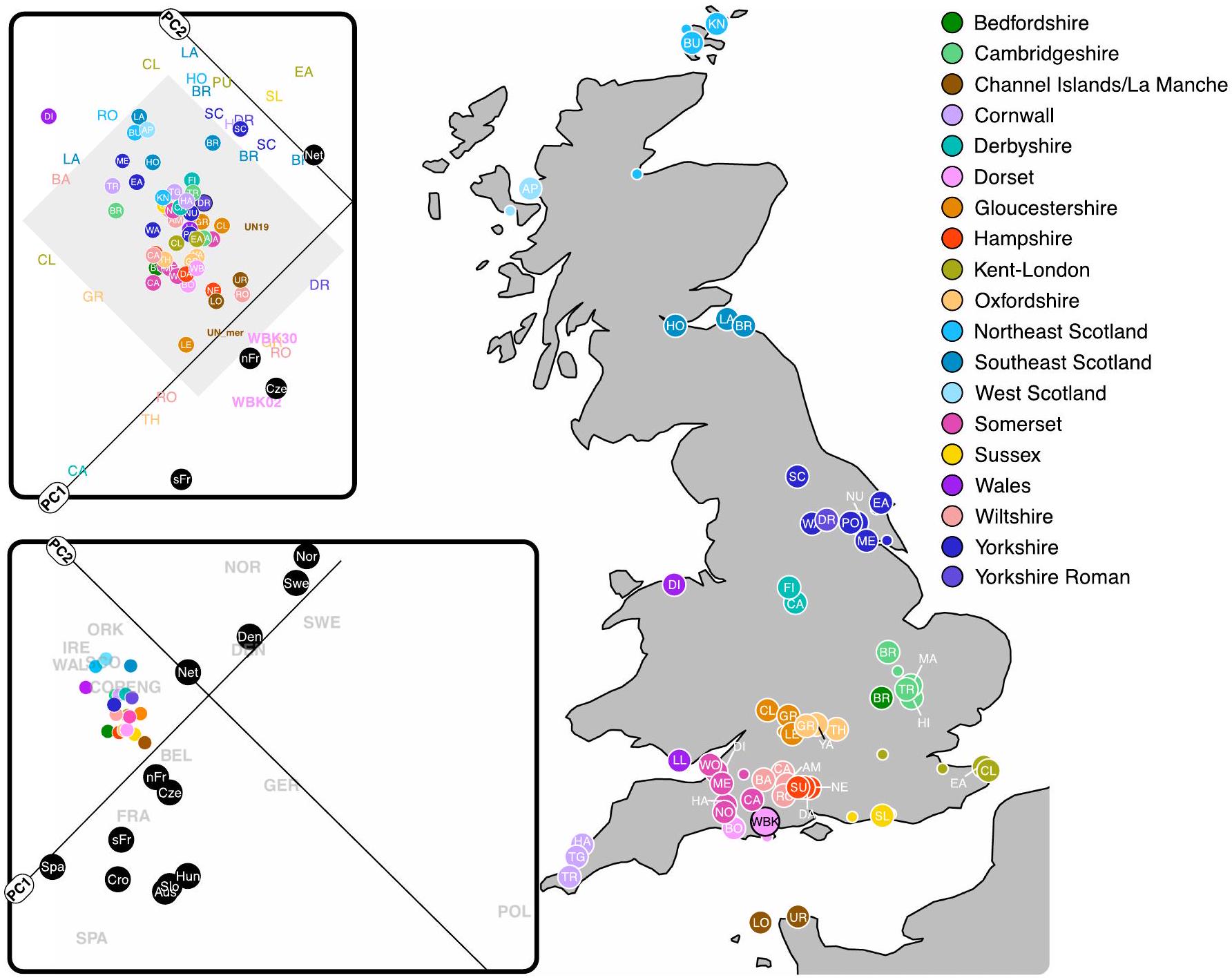

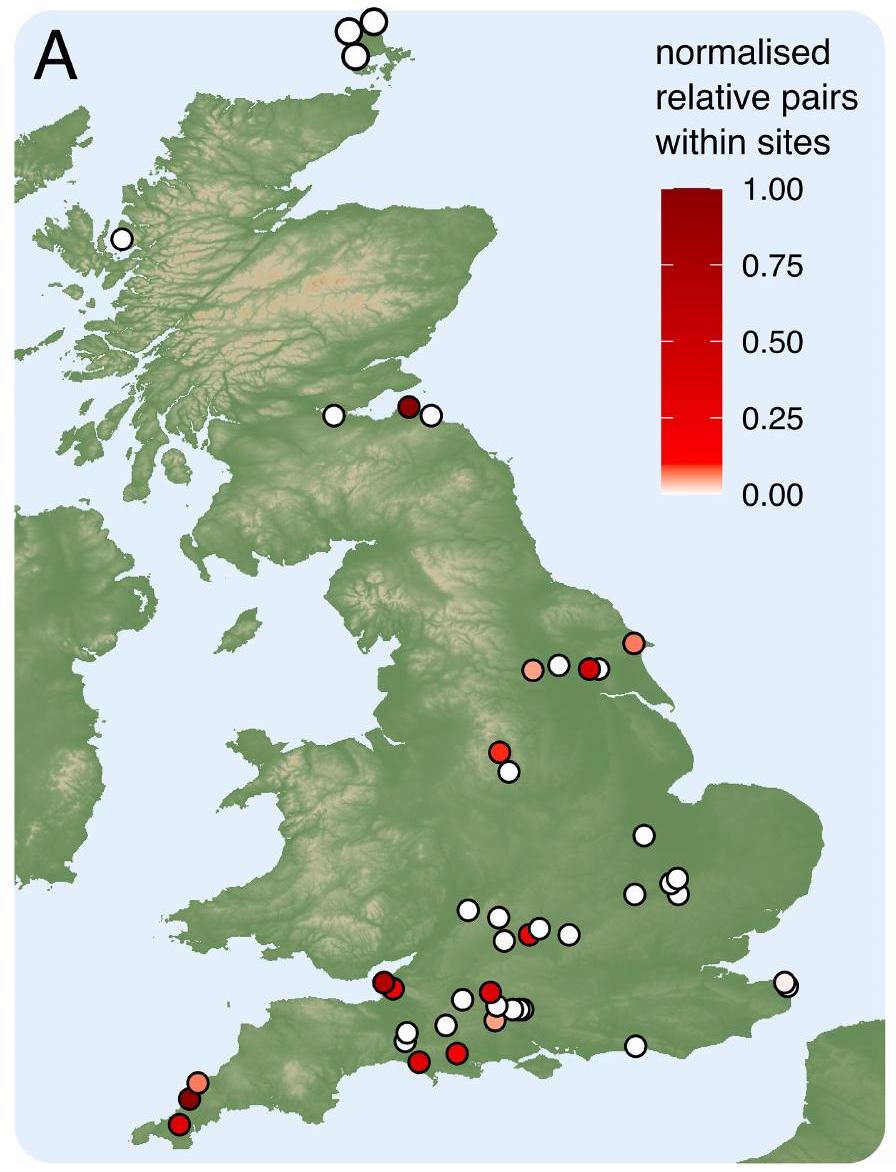

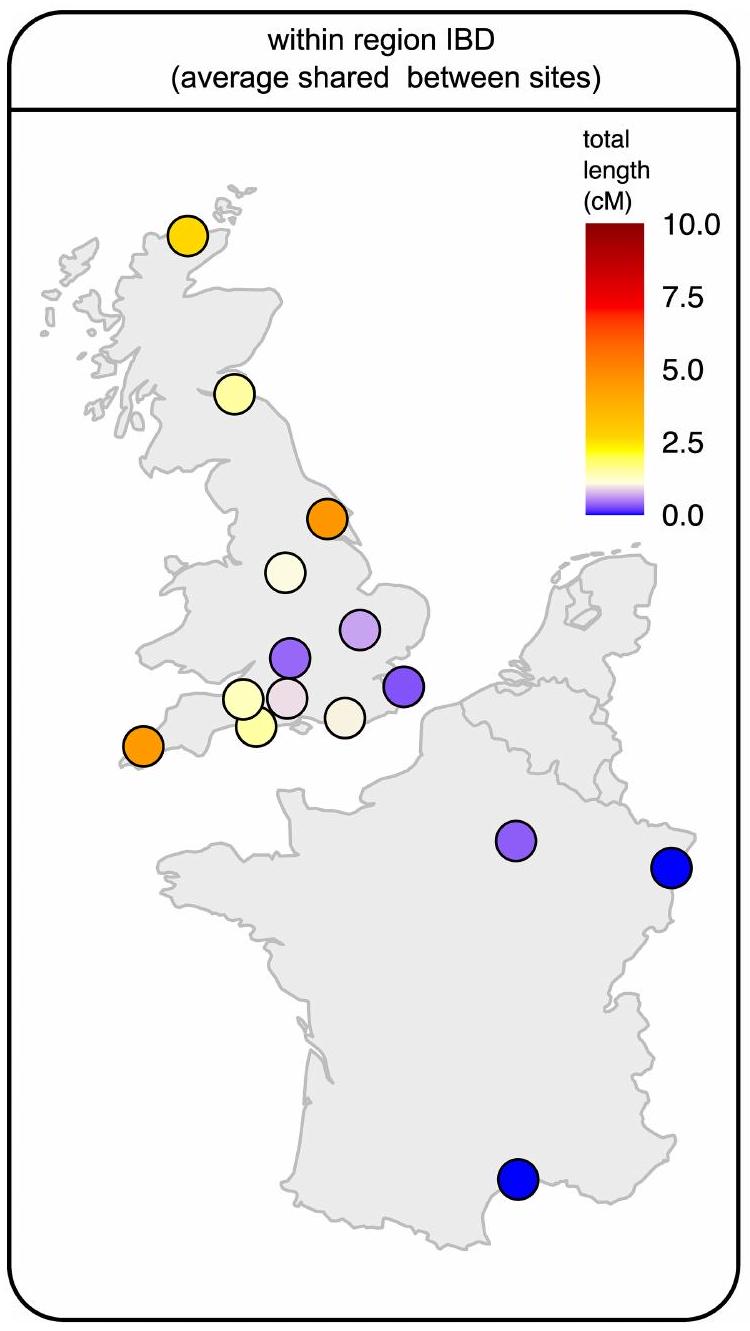

IBD segments reveal regional structure

clusters encompass both continental and coastal British sites, pointing to cross-channel movements.

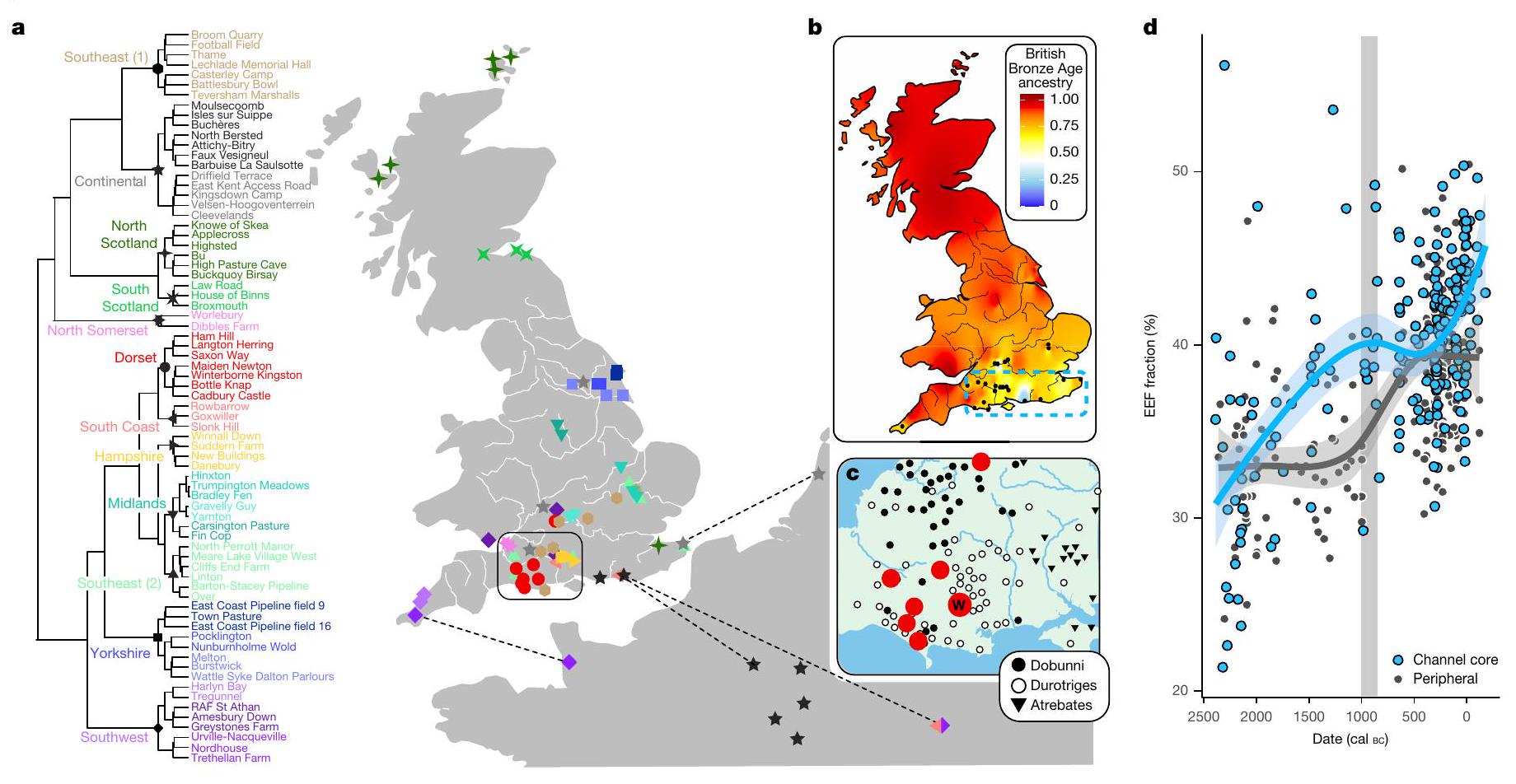

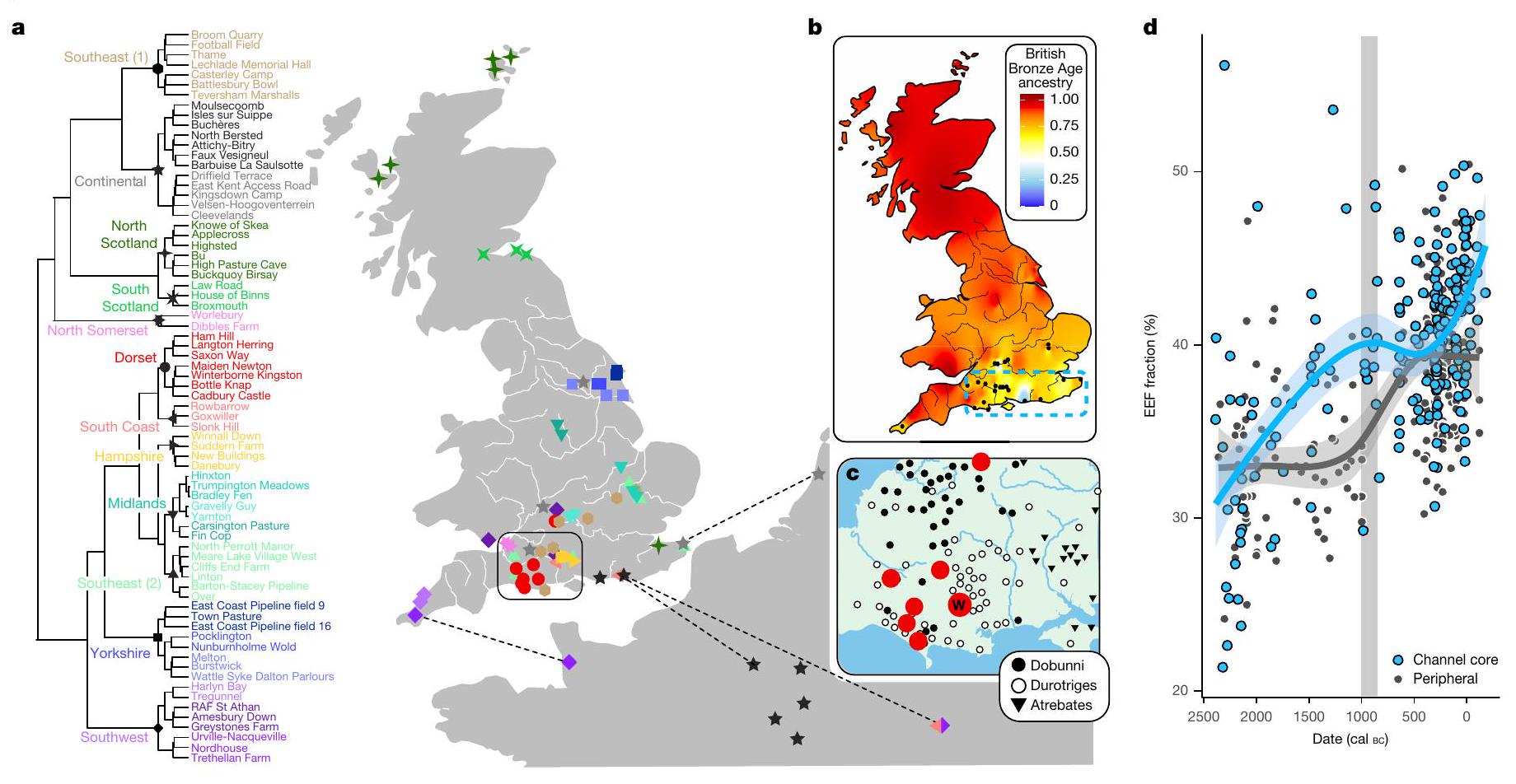

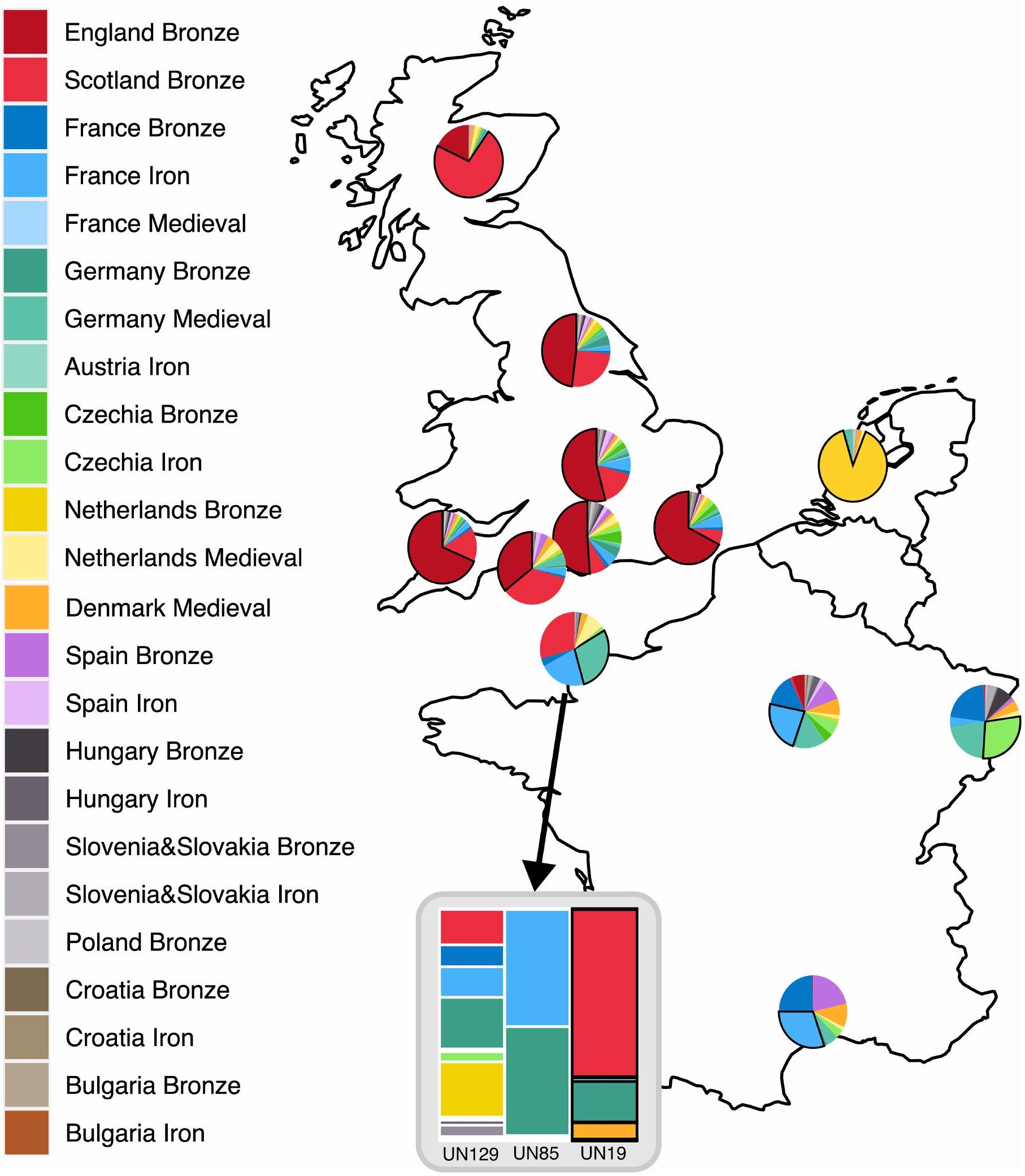

Iron Age migration into southern England

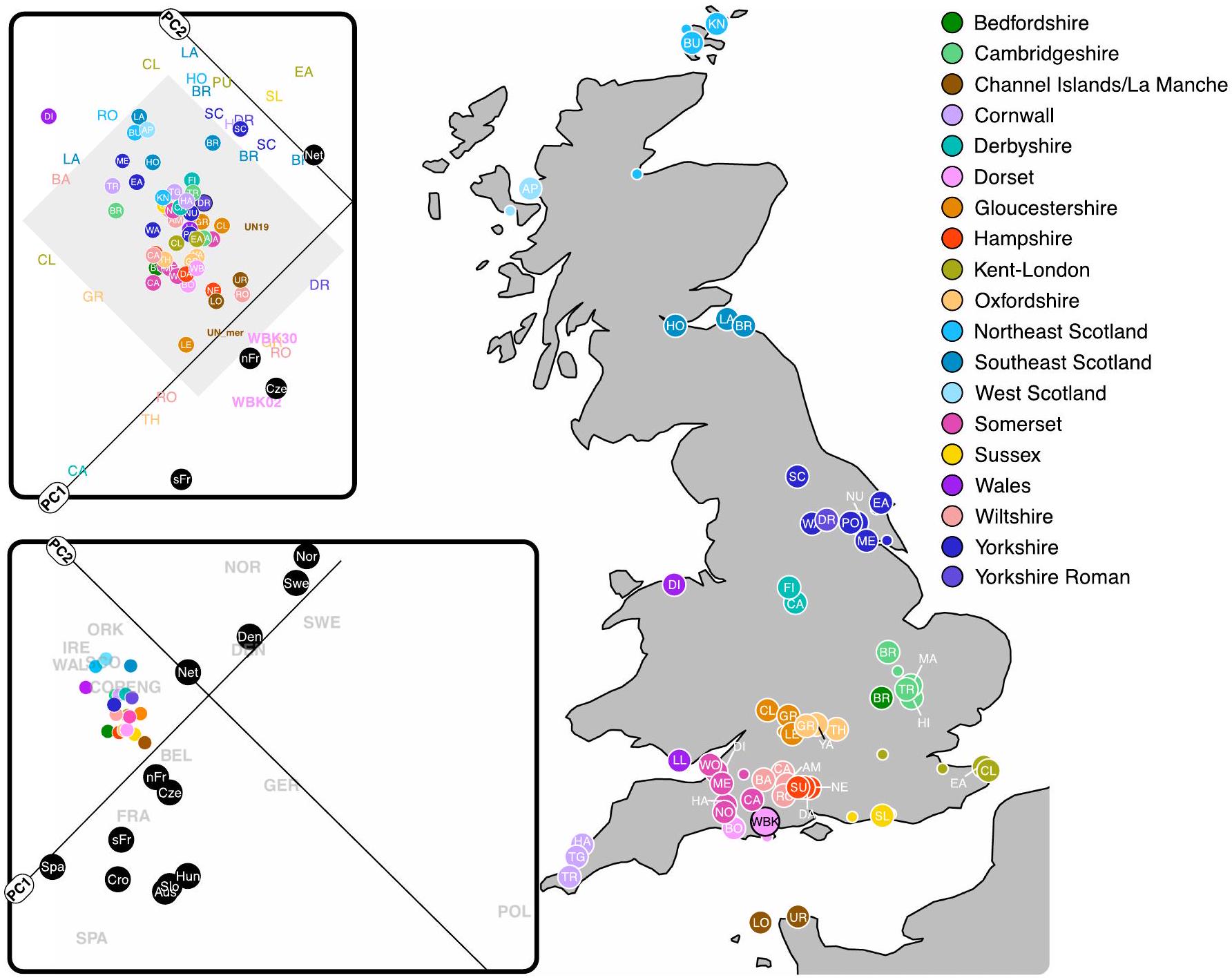

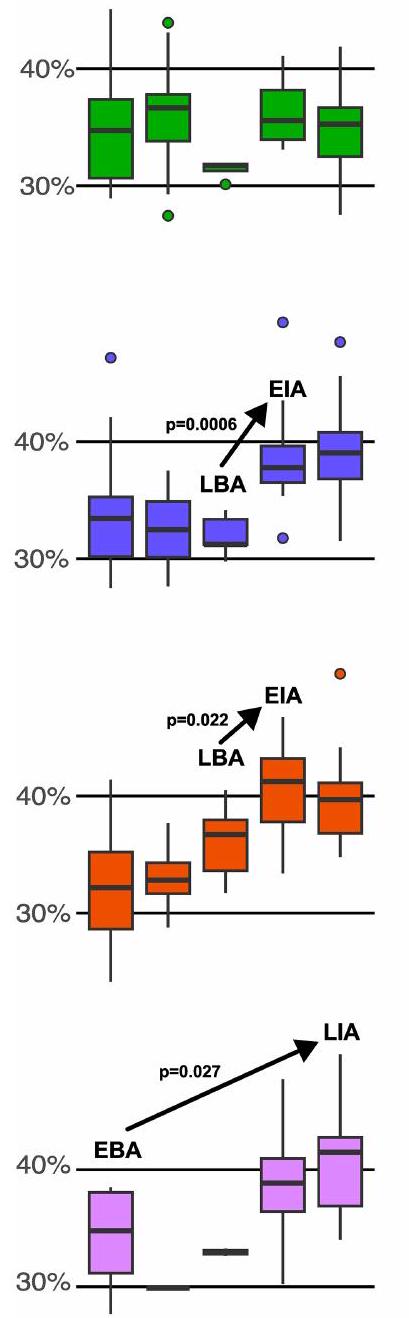

Channel. a, The clusters are based on the consensus of 100 runs of the Leiden algorithm on a weighted graph of IBD shared between archaeological sites and show geographical integrity. Twelve major clusters (defining nodes marked with symbols) are labelled on the basis of geographical affiliations, with further substructure within clusters emphasized using different colour shades. The cross-channel clusters are highlighted with dashed lines joining nearest geographical neighbours across the channel.b, An interpolated map showing the distribution of British Bronze Age ancestry across Iron Age Britain, based on average values generated using ChromoPainter NNLS

of the sites from the Dorset cluster (red circles) placed within the regional distribution of Durotriges coin finds. WBK is denoted by ‘W’. The distributions are plotted according to refs. 34,35 . d, The EEF ancestry proportion through time for the channel core region of continental influence (blue; outlined with dashed line in b) shows a Late Iron Age increase not observed in the sample from the rest of England and Wales (black). The channel core zone is east of longitude

in disposal of the dead, settlement architecture and material culture over centuries, suggestive of high levels of population mobility

The impact of continental gene flow specific to the channel core zone is visible in principal-components analysis (PCA) of modern and ancient western Europeans (Extended Data Fig. 2), as well as patterns of haplotype copying from continental populations, characterized using ChromoPainter

Insular continuity

Conclusions

paternity certainty

Online content

- Allason-Jones, L. in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World (eds James, S. L. & Dillon, S.) Ch. 34, 467-477 (Blackwell, 2012).

- Russell, M., Smith, M., Cheetham, P., Evans, D. & Manley, H. The girl with the chariot medallion: a well-furnished, Late Iron Age Durotrigian burial from Langton Herring, Dorset. Archaeol. J. 176, 196-230 (2019).

- Cunliffe, B. Britain Begins (OUP Oxford, 2013).

- Ember, C. R., Droe, A. & Russell, D. in Explaining Human Culture (ed. Ember, C. R.) (Human Relations Area Files https://hraf.yale.edu/ehc/summaries/residence-and-kinship, accessed 01/10/2024).

- Murdock, G. P. et al. D-PLACE dataset derived from Murdock et al. 1999 ‘Ethnographic Atlas’ (v3.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10177061 (2023).

- Kirby, K. R. et al. D-PLACE: a global database of cultural, linguistic and environmental diversity. PLoS ONE 11, eO158391 (2016).

- Chyleński, M. et al. Patrilocality and hunter-gatherer-related ancestry of populations in East-Central Europe during the Middle Bronze Age. Nat. Commun. 14, 4395 (2023).

- Fowler, C. et al. A high-resolution picture of kinship practices in an Early Neolithic tomb. Nature 601, 584-587(2022).

- Schroeder, H. et al. Unraveling ancestry, kinship, and violence in a Late Neolithic mass grave. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1820210116 (2019).

- Furtwängler, A. et al. Ancient genomes reveal social and genetic structure of Late Neolithic Switzerland. Nat. Commun. 11, 1915 (2020).

- Villalba-Mouco, V. et al. Kinship practices in the early state El Argar society from Bronze Age Iberia. Sci. Rep. 12, 22415 (2022).

- Mittnik, A. et al. Kinship-based social inequality in Bronze Age Europe. Science 366, 731-734 (2019).

- Sjögren, K.-G. et al. Kinship and social organization in Copper Age Europe. A cross-disciplinary analysis of archaeology, DNA, isotopes, and anthropology from two Bell Beaker cemeteries. PLoS ONE 15, e0241278 (2020).

- Mackay, D. Echolands: A Journey in Search of Boudica (Hachette UK, 2023).

- Pope, R. Re-approaching Celts: origins, society, and social change. J. Archaeol. Res. 30, 1-67 (2022).

- Morez, A. et al. Imputed genomes and haplotype-based analyses of the Picts of early medieval Scotland reveal fine-scale relatedness between Iron Age, early medieval and the modern people of the UK. PLoS Genet. 19, e1010360 (2023).

- Patterson, N. et al. Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. Nature 601, 588-594 (2022).

- Martiniano, R. et al. Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons. Nat. Commun. 7, 10326 (2016).

- Schiffels, S. et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat. Commun. 7, 10408 (2016).

- Russell, M. et al. The Durotriges Project 2016: an interim statement. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 138, 105-111 (2017).

- Browning, B. L. & Browning, S. R. Improving the accuracy and efficiency of identity-bydescent detection in population data. Genetics 194, 459-471 (2013).

- MITOMAP. A human mitochondrial genome database. FOSWIKI http://www.mitomap.org (2023).

- Zaidi, A. A. et al. Bottleneck and selection in the germline and maternal age influence transmission of mitochondrial DNA in human pedigrees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25172-25178 (2019).

- Lansing, J. S. et al. Kinship structures create persistent channels for language transmission. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12910-12915 (2017).

- Oota, H., Settheetham-Ishida, W., Tiwawech, D., Ishida, T. & Stoneking, M. Human mtDNA and Y-chromosome variation is correlated with matrilocal versus patrilocal residence. Nat. Genet. 29, 20-21 (2001).

- Ensor, B. E., Irish, J. D. & Keegan, W. F. The bioarchaeology of kinship: proposed revisions to assumptions guiding interpretation. Curr. Anthropol. 58, 739-761 (2017).

- Fox, R. Kinship and Marriage: An Anthropological Perspective (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1984).

- Fortunato, L. The evolution of matrilineal kinship organization. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 4939-4945 (2012).

- Mattison, S. M. Evolutionary contributions to solving the ‘matrilineal puzzle’: a test of Holden, Sear, and Mace’s model. Hum. Nat. 22, 64-88 (2011).

- Surowiec, A., Snyder, K. T. & Creanza, N. A worldwide view of matriliny: using crosscultural analyses to shed light on human kinship systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 374, 20180077 (2019).

- Ly, G. et al. From matrimonial practices to genetic diversity in Southeast Asian populations: the signature of the matrilineal puzzle. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 374, 20180434 (2019).

- Booth, T. J., Brück, J., Brace, S. & Barnes, I. Tales from the Supplementary Information: ancestry change in Chalcolithic-Early Bronze Age Britain was gradual with varied kinship organization. Cambr. Archaeol. J. 31, 379-400 (2021).

- Shenk, M. K., Begley, R. O., Nolin, D. A. & Swiatek, A. When does matriliny fail? The frequencies and causes of transitions to and from matriliny estimated from a de novo coding of a cross-cultural sample. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 374, 20190006 (2019).

- Papworth, M. The Search for the Durotriges: Dorset and the West Country in the Late Iron Age (History Press, 2011).

- Sellwood, L. in Aspects of the Iron Age in Central Southern Britain (eds Cunliffe, B. & Miles, D.) 191-204 (Oxford Univ. School of Archaeology, 1984).

- Lawson, D. J., Hellenthal, G., Myers, S. & Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002453 (2012).

- Chacón-Duque, J.-C. et al. Latin Americans show wide-spread Converso ancestry and imprint of local Native ancestry on physical appearance. Nat. Commun. 9, 5388 (2018).

- Leslie, S. et al. The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature 519, 309-314 (2015).

- Cunliffe, B. Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and Its Peoples 8000 BC-AD 1500 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2001).

- Taylor, A., Weale, A. & Ford, S. Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman Landscapes of the Costal Plain, and a Late Iron Age Warrior Burial at North Bersted, Bognor Regis, West Sussex (Thames Valley Archaeological Services, 2014).

- Fischer, C.-E. et al. Origin and mobility of Iron Age Gaulish groups in present-day France revealed through archaeogenomics. iScience 25, 104094 (2022).

- Ball, M. J. & Müller, N. (eds) The Celtic Languages 2nd edn (Routledge, 2009).

- Gretzinger, J. et al. Evidence for dynastic succession among early Celtic elites in Central Europe. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01888-7 (2024).

- Holden, C. J., Sear, R. & Mace, R. Matriliny as daughter-biased investment. Evol. Hum. Behav. 24, 99-112 (2003).

- Jones, D. The matrilocal tribe: an organization of demic expansion. Hum. Nat. 22, 177-200 (2011).

- Korotayev, A. Form of marriage, sexual division of labor, and postmarital residence in cross-cultural perspective: a reconsideration. J. Anthropol. Res. 59, 69-89 (2003).

- Divale, W. T. Migration, external warfare, and matrilocal residence. Behav. Sci. Res. 9, 75-133 (1974).

- Ember, M. & Ember, C. R. The conditions favoring matrilocal versus patrilocal residence. Am. Anthropol. 73, 571-594 (1971).

- Moravec, J. C., Marsland, S. & Cox, M. P. Warfare induces post-marital residence change. J. Theor. Biol. 474, 52-62 (2019).

- Redfern, R. & Chamberlain, A. Demographic analysis of Maiden Castle hillfort: evidence for conflict in Late Iron Age and Early Roman period. J. Paleopathol. 1, 68-73 (2011).

- Waddington, C. Excavations at Fin Cop, Derbyshire: an Iron Age hillfort in conflict? Archaeol. J. 169, 159-236 (2012).

- Smith, M. Mortal Wounds: The Human Skeleton as Evidence for Conflict in the Past (Pen and Sword, 2017).

- Thorpe, N. in Materialisierung von Konflikten/Materialisation of Conflicts (eds Hansen, S. & Krause, R.) 259-276 (LOEWE-Schwerpunkt Prähistorische Konfliktforschung Universität Frankfurt, 2020).

- Mattison, S. M., Quinlan, R. J. & Hare, D. The expendable male hypothesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 374, 20180080 (2019).

- Robinson, A. L. & Gottlieb, J. How to close the gender gap in political participation: lessons from matrilineal societies in Africa. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 68-92 (2021).

- Lowes, S. Kinship structure & women: evidence from economics. Daedalus 149, 119-133 (2020).

© The Author(s) 2025, corrected publication 2025

Methods

Data generation

Sequence data processing

Uniparental markers

Pseudo-haploid analysis

extract base calls over single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) sites in the

GLIMPSE imputation

IBD segment identification

Pedigree construction

methods and IBD segment sharing; (3) IBD1 and IBD2 segment numbers and lengths for genomes with more than

Generating ancestry profiles with ChromoPainter

Data visualization

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

57. Russell, M. et al. The Durotriges Project, phase one: an interim statement. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 135, 217-221 (2014).

58. Russell, M. et al. The Durotriges Project, phase two: an interim statement. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 136, 157-161 (2015).

59. Russell, M. et al. The Durotriges Project, phase three: an interim statement. Proc. Dorset Nat. Hist. Archeol. Soc. 137, 173-177 (2016).

60. Yang, D. Y., Eng, B., Waye, J. S., Dudar, J. C. & Saunders, S. R. Technical note: improved DNA extraction from ancient bones using silica-based spin columns. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 105, 539-543 (1998).

61. Gamba, C. et al. Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory. Nat. Commun. 5, 5257 (2014).

62. Boessenkool, S. et al. Combining bleach and mild predigestion improves ancient DNA recovery from bones. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 742-751 (2017).

63. Dabney, J. & Meyer, M. Extraction of highly degraded DNA from ancient bones and teeth. Methods Mol. Biol. 1963, 25-29 (2019).

64. Meyer, M. & Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, db.prot5448 (2010).

65. Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17, 10-12 (2011).

66. Schubert, M., Lindgreen, S. & Orlando, L. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res. Notes 9, 88 (2016).

67. Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760 (2009).

68. Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078-2079 (2009).

69. McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297-1303 (2010).

70. Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, giab008 (2021).

71. Weissensteiner, H. et al. HaploGrep 2: mitochondrial haplogroup classification in the era of high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W58-W63 (2016).

72. van Oven, M. & Kayser, M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum. Mutat. 30, E386-E394 (2009).

73. Nei, M. & Roychoudhury, A. K. Sampling variances of heterozygosity and genetic distance. Genetics 76, 379-390 (1974).

74. Nei, M. & Tajima, F. DNA polymorphism detectable by restriction endonucleases. Genetics 97, 145-163 (1981).

75. Mathieson, I. et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, 499-503 (2015).

76. Brunel, S. et al. Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12791-12798 (2020).

77. Dulias, K. et al. Ancient DNA at the edge of the world: continental immigration and the persistence of Neolithic male lineages in Bronze Age Orkney. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2108001119 (2022).

78. Margaryan, A. et al. Population genomics of the Viking world. Nature 585, 390-396 (2020).

79. Allentoft, M. E. et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, 167-172 (2015).

80. Damgaard, P. et al. 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes. Nature 557, 369-374 (2018).

81. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476, 214-219 (2011).

82. Patterson, N., Price, A. L. & Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2, e190 (2006).

83. Patterson, N. et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192, 1065-1093 (2012).

84. Broushaki, F. et al. Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent. Science 353, 499-503 (2016).

85. Lazaridis, I. et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature 513, 409-413 (2014).

86. Brace, S. et al. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 765-771 (2019).

87. Cassidy, L. M. et al. A dynastic elite in monumental Neolithic society. Nature 582, 384-388 (2020).

88. Yaka, R. et al. Variable kinship patterns in Neolithic Anatolia revealed by ancient genomes. Curr. Biol. 31, 2455-2468 (2021).

89. Jones, E. R. et al. The Neolithic transition in the Baltic was not driven by admixture with Early European Farmers. Curr. Biol. 27, 576-582 (2017).

90. González-Fortes, G. et al. Paleogenomic evidence for multi-generational mixing between Neolithic farmers and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in the Lower Danube Basin. Curr. Biol. 27, 1801-1810 (2017).

91. Mallick, S. et al. The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations. Nature 538, 201-206 (2016).

92. Rubinacci, S., Ribeiro, D. M., Hofmeister, R. J. & Delaneau, O. Efficient phasing and imputation of low-coverage sequencing data using large reference panels. Nat. Genet. 53, 120-126 (2021).

93. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68-74 (2015).

94. Browning, B. L., Tian, X., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1880-1890 (2021).

95. Traag, V. A., Waltman, L. & van Eck, N. J. From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 9, 5233 (2019).

96. Kharchenko, P., Petukhov, V., Wang, Y. & Biederstedt, E. leidenAlg: implements the Leiden algorithm via an R interface. GitHub https://github.com/kharchenkolab/leidenAlg (2023).

97. Schliep, K. P. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592-593 (2011).

98. Caballero, M. et al. Crossover interference and sex-specific genetic maps shape identical by descent sharing in close relatives. PLoS Genet. 15, e1007979 (2019).

99. Antonio, M. L. et al. Ancient Rome: a genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean. Science 366, 708-714 (2019).

100. Fernandes, D. M. et al. A genomic Neolithic time transect of hunter-farmer admixture in central Poland. Sci. Rep. 8, 14879 (2018).

101. Freilich, S. et al. Reconstructing genetic histories and social organisation in Neolithic and Bronze Age Croatia. Sci. Rep. 11, 16729 (2021).

102. Gretzinger, J. et al. The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool. Nature 610, 112-119 (2022).

103. Olalde, I. et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, 190-196 (2018).

104. Seguin-Orlando, A. et al. Heterogeneous hunter-gatherer and steppe-related ancestries in Late Neolithic and Bell Beaker genomes from present-day France. Curr. Biol. 31, 1072-1083 (2021).

105. Žegarac, A. et al. Ancient genomes provide insights into family structure and the heredity of social status in the early Bronze Age of southeastern Europe. Sci. Rep. 11, 10072 (2021).

106. Mathieson, I. et al. The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature 555, 197-203 (2018).

107. Delaneau, O., Zagury, J.-F. & Marchini, J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat. Methods 10, 5-6 (2013).

permitting and facilitating all aspects of archaeological fieldwork. This work was funded by Science Foundation Ireland/Health Research Board/Wellcome Trust Biomedical Research Partnership Investigator Award no. 205072 to D.G.B., ‘Ancient Genomics and the Atlantic Burden’, and a Taighde Éireann – Research Ireland Laureate Award (IRCLA/2022/126) to L.M.C., ‘Ancient Isle’. We thank E. Kenny and the team at Trinseq (Trinity College Dublin) for sequencing support.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Lara M. Cassidy. Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

Article

Extended Data Fig. 1|Mitochondrial haplogroup frequencies at British

remaining 12 sites. Haplogroups with a count above one are emphasised with a black outline in the pie charts. Dotted lines are used to split haplogroups into downstream subclades based on additional mutations. Iron Age tribe names recorded by classical writers and their approximate geographic locations are shown. The haplotypes of all British Iron Age samples used in this analysis are given in Supplementary Table 12.

with their population IDs in Supplementary Table 12. Raw values are available in Supplementary Table 17. The top rows show averaged profiles for Bronze and Iron Age archaeological sites in Britain, France and the Netherlands. British site profiles are outlined in black if the site contains one or more individual outliers (those possessing a level of British Early Bronze Age ancestry two standard

deviations below the population mean). The bottom row shows ancestry profiles for these outlying genomes. We note that all Middle and Late Iron Age outliers derive from the channel core region. We identify two previously reported

Article

(highlighted in white) and show excessive IBD sharing with one another. The Roman burials of Driffield Terrace

kinship and cultural practices such as consanguineous marriage. We see lowest values for within region IBD sharing in France and the southeast of England. For within genome IBD sharing, we take the population average of the total length of runs of homozygosity for each archaeological site. If the average total length is above 3 cM we plot the site in the bottom panel. In Britain, sites with reduced runs of homozygosity (top panel) are concentrated in south central and southeastern regions indicative of larger population sizes. Within site IBD sharing (average length shared between individuals in a site) is plotted in a similar fashion.

values for different 500-year time bins for each region. These bins are demarcated with grey dashed lines on the rolling average plot. Time bin date ranges are labelled with respect to the approximate archaeological period they centre on (EBA:Earlier Bronze Age, MBA: Middle Bronze Age, LBA: Later Bronze Age, EIA:Earlier Iron Age, LIA: Later Iron Age). Significant changes (Welch’s

natureportfolio

Reporting Summary

Statistics

n/a

□

X

□

□

For null hypothesis testing, the test statistic (e.g.

□

□ For Bayesian analysis, information on the choice of priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo settings

□ For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

□ Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Confirmed

□ The exact sample size

□ A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

□ A description of all covariates tested

□ A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

□ A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

Software and code

Data collection

FASTQC v0.11.5

cutadapt v1.9.1

AdapterRemoval v2.3.1

BWA v0.7.5a-r405

SAMtools v1.7

GATK v3.7.0

Picard Tools v2.0.1

BCFtools v1.10.2

Haplogrep2 v2.2.9

smartpca v16000 (EIGENSOFT)

ADMIXTOOLS2 v2.0.4

GLIMPSE1 v1.1.0

Beagle5 v05May22.33a

refinedIBD v17Jan20.102

leidenAlg v1.1.1

phangorn v2.11.1

SHAPEIT2 v2.r837

SOURCEFIND v2

fineSTRUCTURE v2

ped-sim

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

| Reporting on sex and gender | Samples were defined as male or female based on read coverage across the sex chromosomes. No sex chromosome aneuploidies were observed. Comparisons were made between the male and female populations buried at Winterborne Kingston to draw inferences about kinship and marriage customs. When discussing these customs and other cultural phenomena we use the terms men and women. |

| Reporting on race, ethnicity, or other socially relevant groupings | We do not bin samples by the socially constructed categories of race or ethnicity. We group samples by geographical region or genetic cluster (defined based on haplotypic data). |

| Population characteristics | All human samples are archaeological in nature. An osteological assessment of age-at-death, pathologies and trauma was carried out. |

| Recruitment | N/A |

| Ethics oversight | N/A |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences

Behavioural & social sciences □ Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | We exhaustively sampled all burials excavated at Winterborne Kingston. These were analysed with all publicly available data from the Iron Age of northwestern Europe. | ||||||

| Data exclusions |

|

||||||

| Replication | N/A |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | |

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a |

| X | □ Antibodies | X |

| X | □ | X |

| □ | 【 Palaeontology and archaeology | X |

| X | □ | |

| – | □ | |

| X | □ | |

| V | □ | |

Palaeontology and Archaeology

Specimen provenance

Ethics oversight

Plants

N/A

N/A

N/A

- ¹Department of Genetics, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. ²Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK. ³Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK.

School of Mathematics, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia. Department of Linguistics, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Mānoa, HI, USA. DFG Center for Advanced Studies, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. Éco-anthropologie, Musée de l’Homme, Paris, France.

e-mail: cassidl1@tcd.ie