DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02191-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40122855

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-24

التطعيم بالحمض النووي الريبي عبر الأنف يعزز استجابة قوية للخلايا التائية لعلاج سرطان الرئة

الملخص

لقد أثار النجاح السريع للقاحات RNA في الوقاية من SARS-CoV-2 اهتمامًا باستخدامها في العلاج المناعي للسرطان. على الرغم من أن العديد من السرطانات تنشأ في الأنسجة المخاطية، إلا أن لقاحات السرطان RNA الحالية تُعطى بشكل رئيسي بطريقة غير مخاطية. هنا، قمنا بتطوير لقاح سرطان غير جراحي عبر الأنف باستخدام RNA دائري محاط بجزيئات دهنية لتحفيز استجابات مناعية موضعية. هذه الاستراتيجية أثارت استجابات قوية للخلايا التائية المضادة للأورام في نماذج سرطان الرئة قبل السريرية مع تقليل الآثار الجانبية النظامية المرتبطة عادةً بالتطعيم الوريدي RNA. على وجه التحديد، كانت الخلايا التغصنية التقليدية من النوع 1 ضرورية لتفعيل الخلايا التائية بعد التطعيم، حيث كانت كل من البلعميات الهوائية والخلايا التغصنية التقليدية من النوع 1 تعزز استجابات الخلايا التائية المحددة للمستضد في أنسجة الرئة. علاوة على ذلك، سهل التطعيم توسيع كل من الخلايا التائية المحددة للمستضد الذاتية والمُنتقلة، مما أدى إلى فعالية قوية ضد الأورام. أظهرت تسلسلات RNA أحادية الخلية أن التطعيم يعيد برمجة الخلايا التائية الذاتية، مما يعزز سميتها ويحفز نمط ذاكرة شبيه. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن للقاح عبر الأنف تعديل استجابة خلايا CAR-T لزيادة الفعالية العلاجية ضد خلايا الورم التي تعبر عن مستضدات مرتبطة بالورم محددة. بشكل جماعي، تمثل استراتيجية لقاح RNA عبر الأنف نهجًا جديدًا واعدًا لتطوير لقاحات RNA تستهدف الأورام المخاطية.

; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02191-1

المقدمة

التكاليف.

النتائج

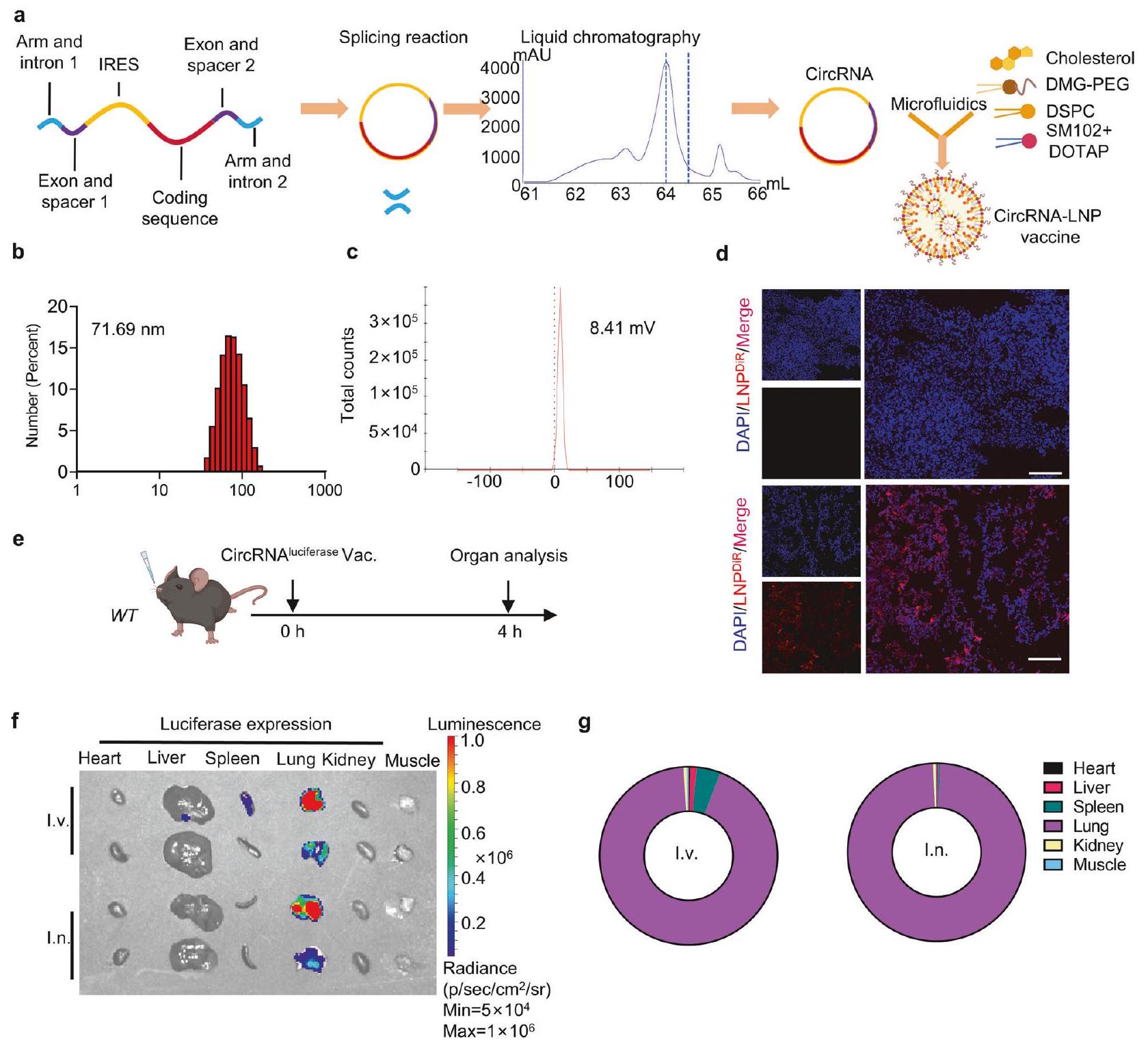

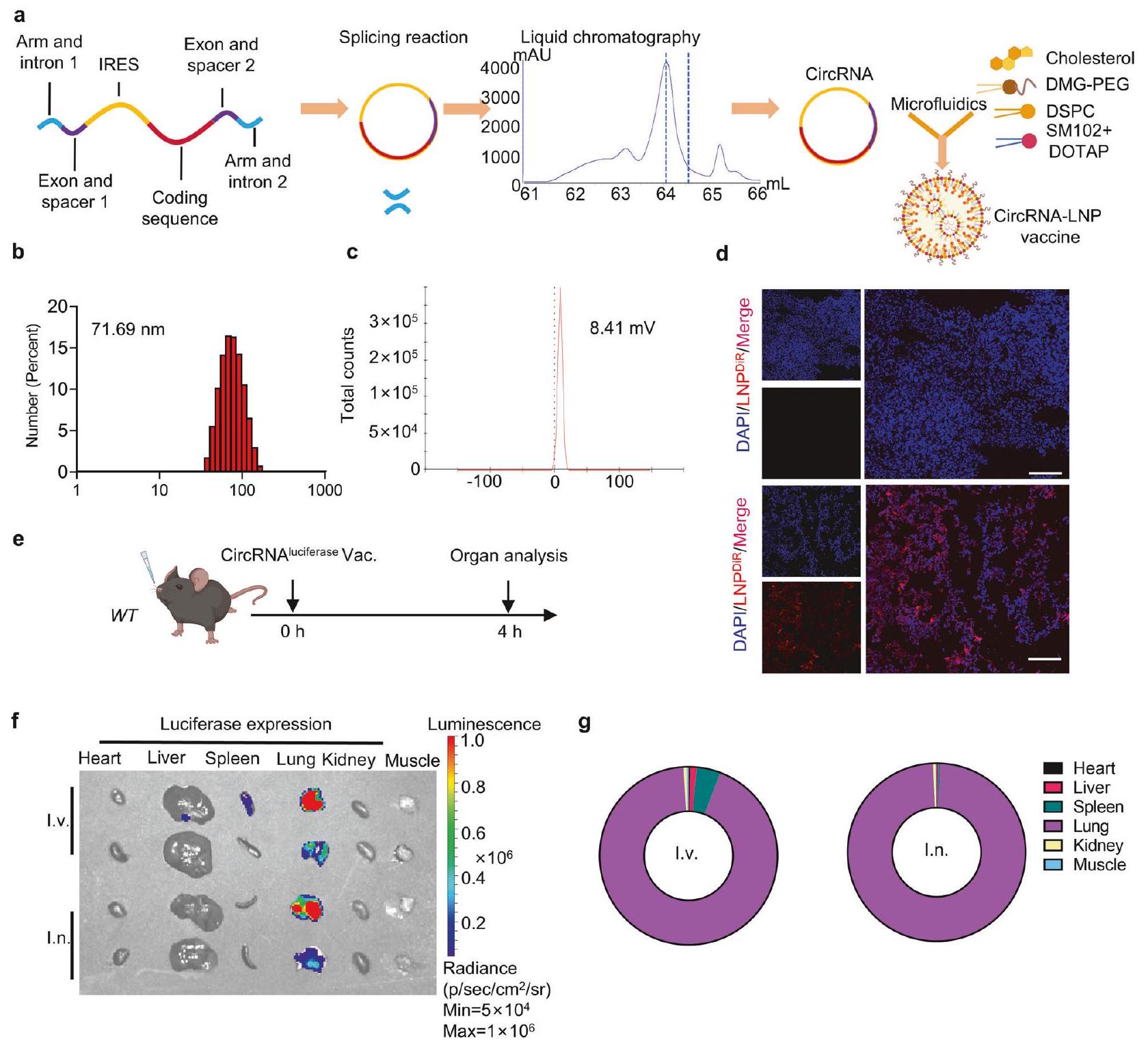

استنادًا إلى استراتيجية تحضير circRNA المنشورة سابقًا، تضمنت قوالب النسخ في المختبر زوجًا من الإكسونات والإنترونات، CVB3 IRES، الفواصل، الأذرع وتسلسلات الترميز.

أن LNP المعتمد على SM102 أظهر كثافة فلورية أعلى لتتبع الصبغة مقارنةً بـ ALC-0315 (الشكل التكميلي 2c، d). وفقًا للدراسات الحديثة، يمكن أن تعزز إضافة الدهون الكاتيونية، مثل 1،2-ديوليويل-3-تريميثيل أمونيوم-بروبان (DOTAP)، كفاءة استهداف الرئة بعد الإدارة الوريدية والأنفية.

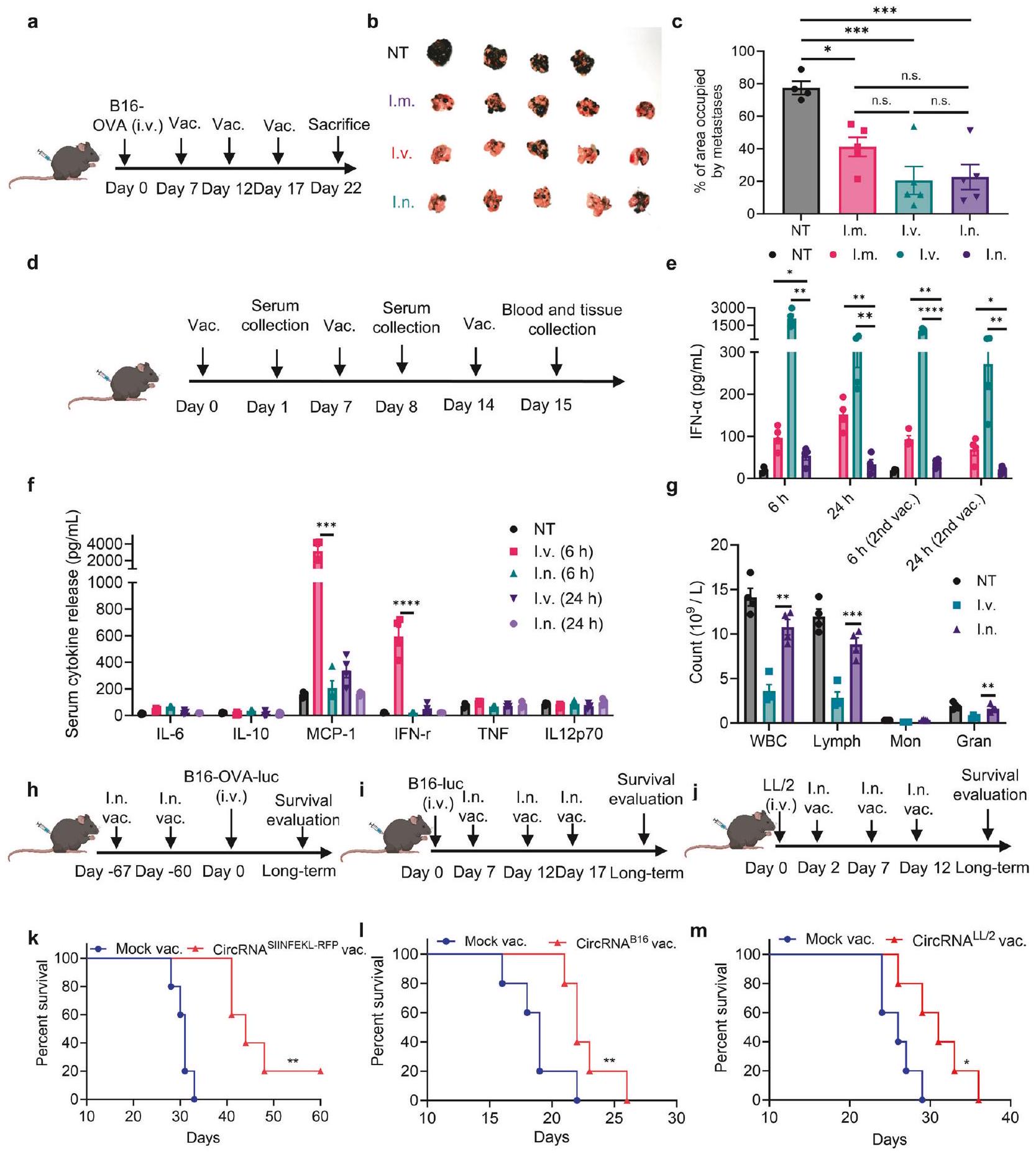

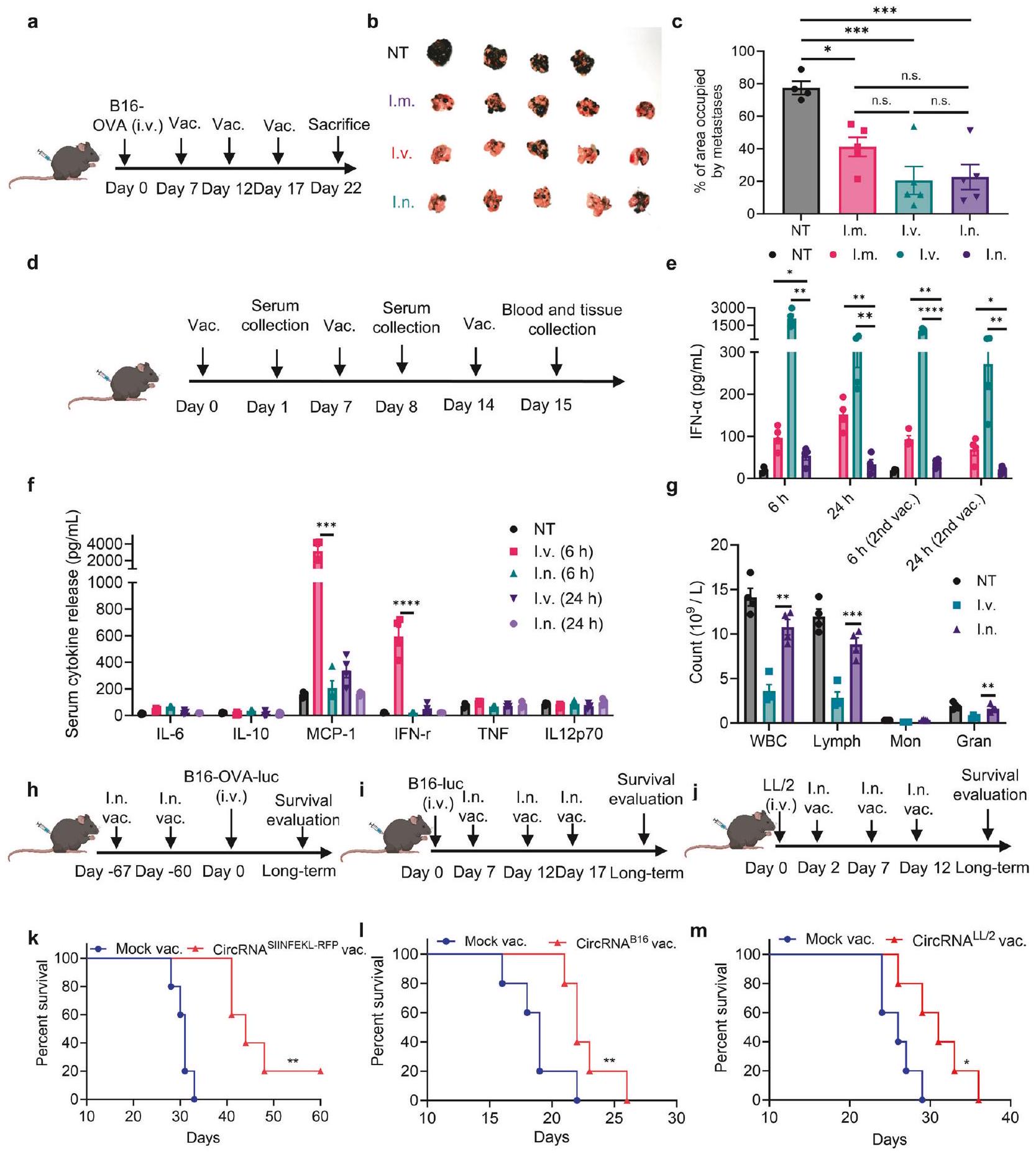

لمقارنة كفاءة اللقاح المضاد للورم المعطى عبر طرق مختلفة بشكل منهجي، أنشأنا نموذج ورم B16 النقوي في الرئة يعبر عن مستضد OVA. تلقت الفئران لقاحات circRNA المشفرة SIINFEKL (الجزء المحدود من مستضد OVA من الفئة I (Kb))-RFP في نقاط زمنية محددة (الشكل 2a). مقارنةً بالمجموعة غير المعالجة، أظهرت جميع طرق الإدارة الثلاثة فعالية مضادة للورم قابلة للمقارنة إحصائيًا (الشكل 2b، c). ومع ذلك، بدا أن نسبة أنسجة الرئة التي تحتلها بؤر النقائل كانت أقل في المجموعات الأنفية والوريدية مقارنةً بالمجموعة العضلية. ثم قمنا بتحليل السمية الحادة للقاح circRNA المعطى عبر طرق مختلفة. أشارت الدراسات السابقة إلى أن لقاحات RNA يمكن أن تحفز إفراز السيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهابات، مما يؤدي إلى آثار جانبية.

أن لقاح circRNA الأنفي يثير استجابة مضادة للورم قوية مع آثار جانبية أقل مقارنةً بطرق الإدارة الأخرى.

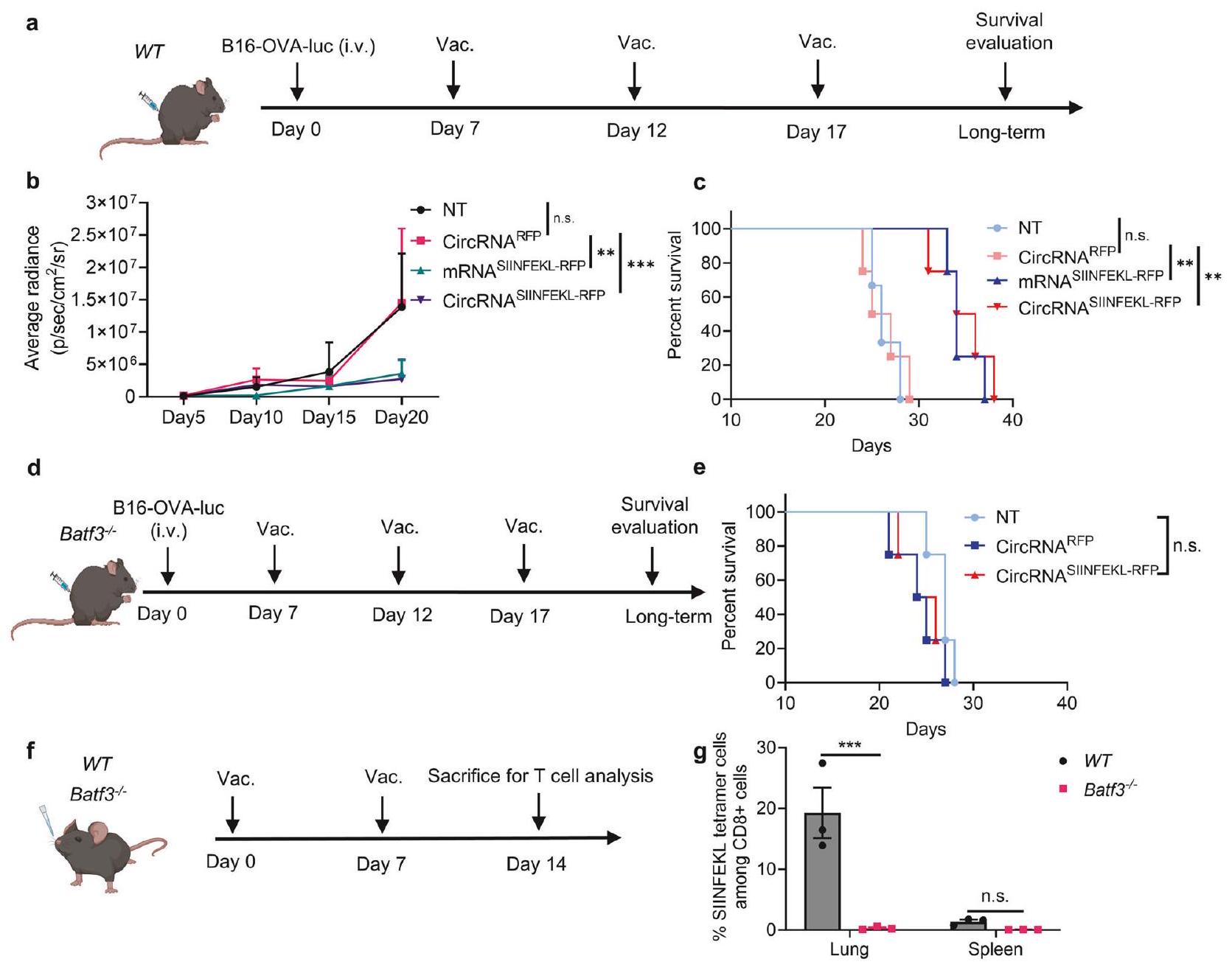

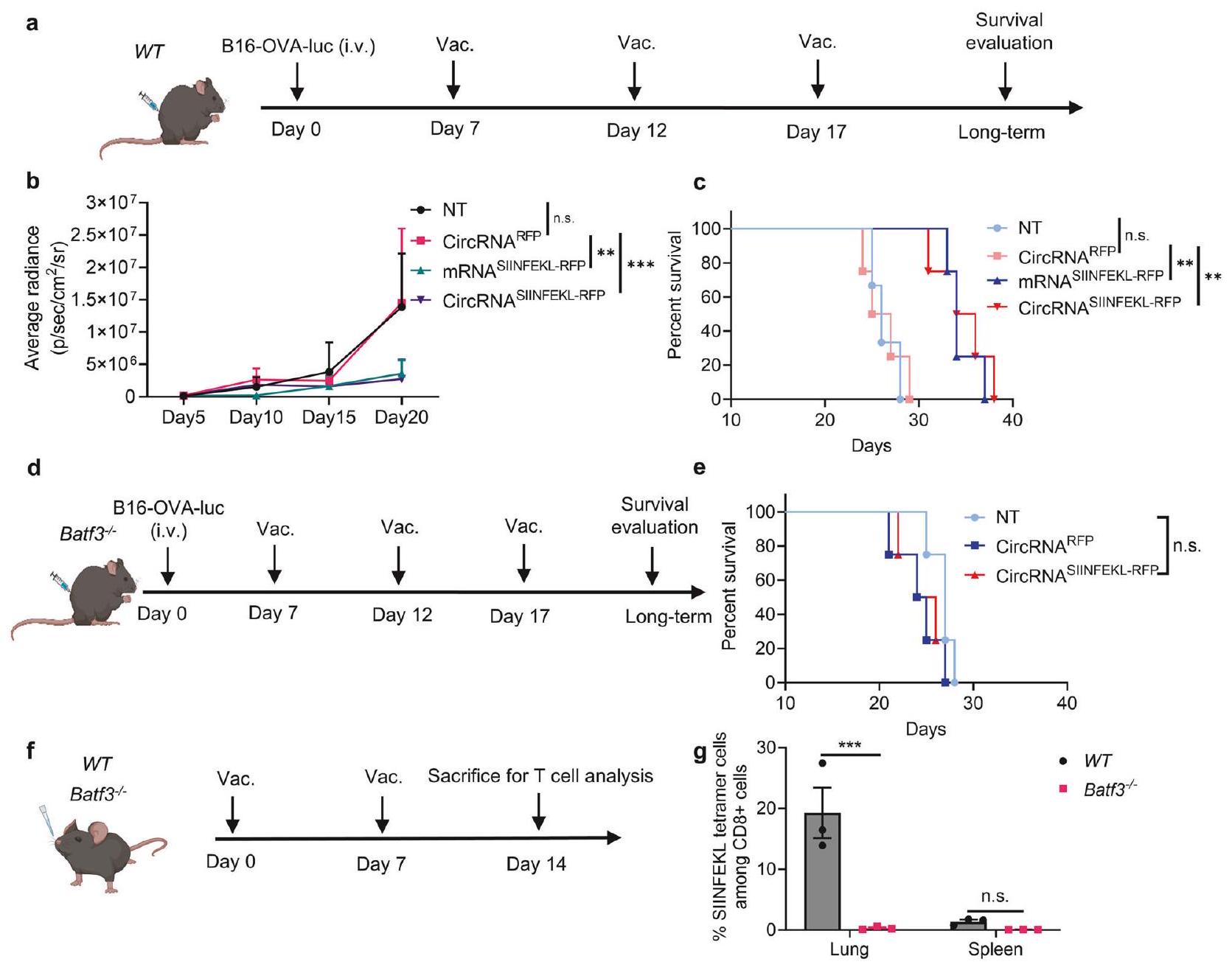

استلهمًا من الإمكانيات العلاجية للقاح الأنفي، هدفنا إلى التحقيق بشكل أكبر في المبادئ الأساسية وراء استجابته المناعية المضادة للورم. أولاً، أنشأنا نموذج نقائل الرئة B16-OVA-ليوسيفيراز وأكدنا الاستجابة المضادة للورم (الشكل 3a). تم استخدام RNA مشفر RFP كتحكم لمستضد غير ذي صلة. كما أعددنا لقاحات RNA خطية و circRNA مشفرة لـ SIINFEKL-RFP للتطعيم. أظهرت نتائج صور البيولومينسنس (الشكل 3b والشكل التكميلي 7a) ومنحنيات البقاء (الشكل 3c) أن لقاحات RNA المشفرة لمستضد الورم فقط يمكن أن توقف نمو خلايا الورم، دون ملاحظة فرق كبير بين لقاحات mRNA و circRNA في هذا

فئران knockout (الشكل 3d). من المثير للاهتمام أن كفاءة اللقاح الدائري RNA المضاد للورم عن طريق الأنف قد انخفضت، مما يشير إلى أن cDC1 ضروري للاستجابة المناعية المضادة للورم الناتجة عن اللقاح (الشكل 3e). قمنا أيضًا بتحليل خلايا CD8 + T المحددة للمستضد التي تم تحفيزها بواسطة اللقاح (الشكل 3f). WT و Batf3

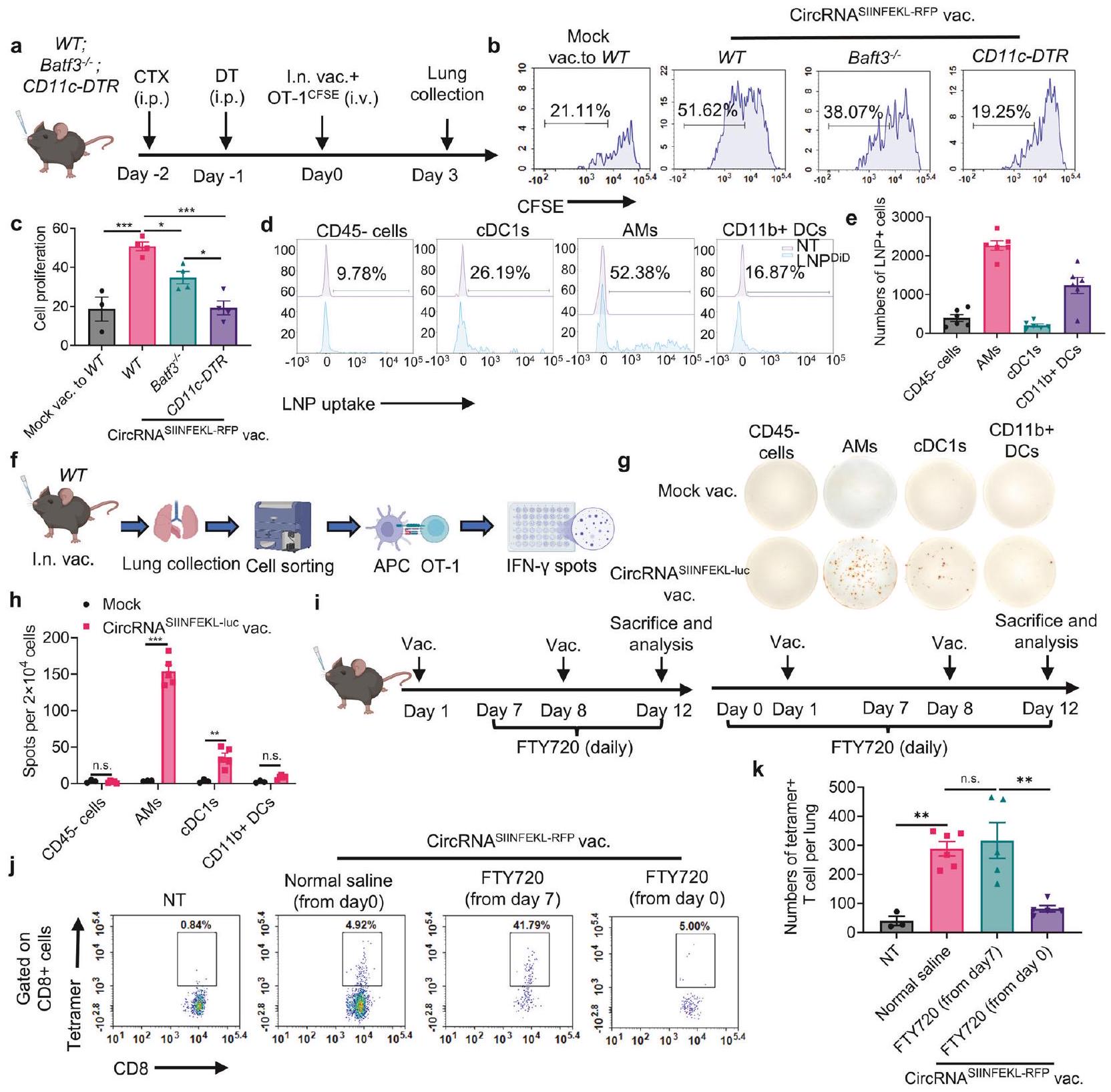

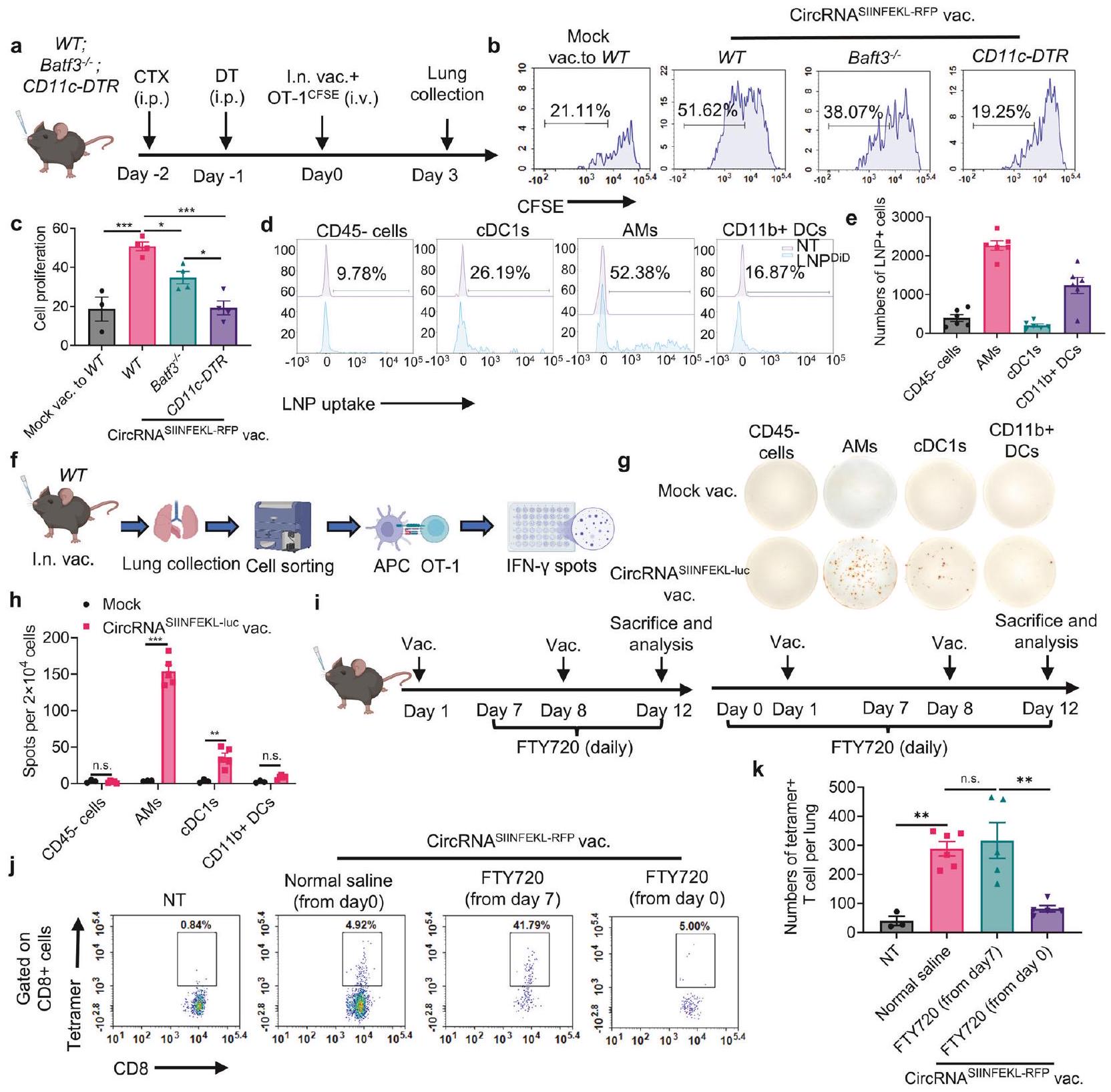

استكشاف عملية تعزيز خلايا T بعد التحصين عن طريق الأنف. استخدمنا فئران WT، وفئران بدون cDC1، وفئران بدون جميع خلايا CD11c+ لاختبار قدرتها على تعزيز خلايا T المحددة لل antigene المنشطة (الشكل 4a). على الرغم من أن استنفاد cDC1 قلل من تكاثر خلايا T، إلا أن نقص خلايا CD11c+

أوقف تمامًا تكاثر خلايا T الناتج عن اللقاح، مما يشير إلى أن كل من cDC1 وغيرها من خلايا تقديم antigene CD11c+ تشارك في تعزيز خلايا T (الشكل 4b، c والشكل التكميلي 9a). لتحديد أنواع الخلايا التي تدعم تكاثر خلايا T، تم وسم LNPs بصبغة DiD المحبة للدهون وتم إعطاؤها عن طريق الأنف للفئران. ثم قمنا بصبغ المجموعات الرئيسية من خلايا CD11c+ في أنسجة الرئة، بما في ذلك البلعميات الهوائية (AMs)، cDC1s، CD11b + DCs، وخلايا CD11c- CD45- كمجموعة تحكم. وجدنا أن LNPs تم ابتلاعها بشكل رئيسي بواسطة AMs، مع قدرة خلايا أخرى أيضًا على ابتلاع LNPs ولكن بأعداد أقل (الشكل 4d، e، الشكل التكميلي 9b-d). علاوة على ذلك، تم تعزيز إنتاج IFN-

استنادًا إلى النتائج المذكورة أعلاه، افترضنا أن لقاح RNA عن طريق الأنف قد يتعاون مع خلايا T المحددة لل antigene المُنتقلة لتعزيز القدرة المضادة للأورام. أجرينا تجارب باستخدام نموذج فأر WT. تم تحدي الفئران في البداية بخلايا ورم B16-OVAluciferase وخضعت لاستنفاد اللمف مع CTX قبل تلقي العلاج بلقاح circRNA، أو العلاج الخلوي التبني (ACT)، أو مجموعة من كلا العلاجين (الشكل 5a). أظهرت تصوير البيولومينسنس وفحص الأنسجة (صبغة HE) أنه بينما يمكن أن يمنع اللقاح بمفرده أو خلايا OT-1 مع اللقاح الوهمي نمو الورم، فإن العلاج المركب أدى إلى أقوى تحكم في الورم (الشكل 5b-d). كما قمنا بتحديد عدد خلايا T المحددة لل antigene لكل من خلايا T الذاتية والمُنتقلة، مما يكشف أن اللقاح وسع كلا المجموعتين بفعالية (الشكل 5e-g).

المعنية بالعلاج المناعي.

استنادًا إلى نتائجنا السابقة، هدفنا إلى فحص شامل للتغيرات في خلايا T الذاتية باستخدام تحليل RNAseq للخلايا الفردية من خلايا CD3+ من أنسجة الرئة في نماذج الفئران الحاملة للورم (الشكل 6a). حدد التجميع غير المراقب لبيانات النسخ تسعة مجموعات رئيسية من خلايا T: خلايا CD4 وCD8 الساذجة (المعلمة بتعبير Lef1 وTcf7 مع مستويات II7r وSell منخفضة نسبيًا)، خلايا CD4 وCD8 الذاكرة (التي تعبر عن II7r وSell)، خلايا CD8 التكاثرية (المميزة بتعبير Top2a وMki67)، خلايا CD4 وCD8 الفعالة (مع

بالإضافة إلى دراسة تأثير اللقاح على خلايا T الذاتية، قمنا أيضًا بالتحقيق في تأثيره المباشر على خلايا T المنقولة بالتبني. لتصور التوزيع الحيوي الديناميكي والأداء طويل الأمد لخلايا T المنقولة المعززة باللقاح خلال عملية مكافحة الورم، استخدمنا B16-OVA الحاملة لـ Rag1.

كشفت تصوير الإضاءة الحيوية أن اللقاح أدى إلى توسيع خلايا T في أنسجة الرئة، وأن الجرعات المتكررة حافظت على أعداد خلايا T عند مستوى مرتفع نسبيًا مقارنة بمجموعة اللقاح الوهمي (الشكل 7ب، ج). عند تقييم الكفاءة المضادة للورم لعلاجات مختلفة، لاحظنا أن التطعيم عن طريق الأنف زاد بشكل كبير من بقاء الفئران التي تم نقل خلايا T إليها (الشكل 7د). هذه

توضح النتائج أن تعزيز لقاح RNA عن طريق الأنف يمكّن خلايا T المحددة بمستضد من الانتشار في أنسجة الرئة، مما يعزز فعاليتها في علاج سرطان الرئة.

لا تستجيب فقط للقاح ولكن تستهدف أيضًا خلايا الورم التي تعبر عن مستضدات سطحية مرتبطة بالورم محددة. هذه المستضدات عادة ما تكون تحديًا لأساليب لقاح السرطان التقليدية التي تقتصر على استهداف الببتيدات المناعية المعروضة بواسطة MHC. تهدف هذه الطريقة إلى القضاء على خلايا الورم من خلال جزيء CAR بينما تعزز في الوقت نفسه تعزيز الاستجابات المناعية في الموقع من خلال آلية TCR (الشكل 7e). أظهرت خلايا CART القدرة على قتل خلايا ورم B16 التي تعبر عن EGFR بشكل مفرط في ظروف مختلفة.

نقاش

تظهر حقن لقاح circRNA تحكمًا أفضل في الورم مقارنةً بالحقن العضلي، كما أن اللقاح العضلي يثبط أيضًا نمو الورم. قد يُعزى هذا التباين عن الدراسات السابقة إلى مستويات مختلفة من تنشيط خلايا T الجهازية التي تسببها تركيبات اللقاح المختلفة بعد إعطاء الحقن. مجتمعة، تشير هذه النتائج جميعها إلى أن التطعيم غير الجراحي عن طريق الأنف مفيد بالفعل لعلاج سرطان الرئة المحلي مع الحد الأدنى من الالتهاب الجهازي.

تعزز اللقاحات الببتيدية تحت الجلد وظيفة خلايا CAR-T و TCR-T المنقولة،

استراتيجية العلاج في نموذج مستضد مرتبط بالورم مع خلايا CAR-T واللقاح عن طريق الأنف. توفر هذه الطريقة ميزتين هامتين، حيث تعزز من بقاء خلايا CAR-T وتمكن من إعادة توجيه خلايا T لاستهداف المستضدات المرتبطة بالورم بشكل مستقل عن تقديم MHC على خلايا الورم.

الملخص

الشكل 7 لقاح circRNA عن طريق الأنف يعزز فعالية العلاج بالخلايا CAR-T ضد خلايا الورم التي تعبر عن مستضدات مرتبطة بالورم محددة. أ مخطط للتجربة لتتبع هجرة وتوسع خلايا OT-1 المنقولة. تم تنشيط الخلايا، وإصابتها بفيروس ريتروفي، ثم تم نقلها إلى الفئران الحاملة للورم Rag1.

المواد والأساليب

الحيوانات وخطوط الخلايا

بلازميد

تحضير RNA

تحضير جزيئات الدهون النانوية (LNP)

توزيع LNP في الجسم

تم تصنيفها كخلايا CD11c+ و Siglec-F+. تم تصنيف cDC1s كخلايا CD11c+ و Siglec-F- و CD103+. تم تصنيف خلايا CD11b+ كخلايا CD11c+ و Siglec-F- و CD103- و CD11b+. تم تحليل العينات باستخدام مقياس التدفق الخلوي (BD Fortessa أو LSRII) وتم تقييم امتصاص LNP باستخدام قناة APC.

تم معالجة فئران بالبي/سي مسبقًا بالإيزوفلوران وتم إعطاؤها LNP عن طريق الحقن العضلي أو الوريدي أو الأنفي بجرعة من

في دراسات تحدي الورم الوقائية، تم تحصين فئران C57BL/6J باستخدام LNP تحتوي على SIINFEKL-RFP circRNA

لكل فأر) لجرعتين بفاصل 7 أيام. بعد 30 أو 60 يومًا، تم تحدي الفئران بـ

لتحقيق دور cDC1 في تنشيط خلايا T، WT و Batf3

علاج نقل الخلايا المتبناة

التحليل الإحصائي

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

معلومات إضافية

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينجر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

REFERENCES

- Waldman, A. D., Fritz, J. M. & Lenardo, M. J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 651-668 (2020).

- Lin, M. J. et al. Cancer vaccines: the next immunotherapy frontier. Nat. Cancer 3, 911-926 (2022).

- Blass, E. & Ott, P. A. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigenbased therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 215-229 (2021).

- Sayour, E. J., Boczkowski, D., Mitchell, D. A. & Nair, S. K. Cancer mRNA vaccines: clinical advances and future opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 489-500 (2024).

- Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403-416 (2021).

- Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603-2615 (2020).

- Miao, L., Zhang, Y. & Huang, L. mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 20, 41 (2021).

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M. J., Porter, F. W. & Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines – a new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 261-279 (2018).

- Rohner, E. et al. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1586-1600 (2022).

- Kristensen, L. S. et al. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 675-691 (2019).

- Qu, L. et al. Circular RNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Cell 185, 1728-1744 (2022).

- Li, H. et al. Circular RNA cancer vaccines drive immunity in hard-to-treat malignancies. Theranostics 12, 6422-6436 (2022).

- Baharom, F. et al. Systemic vaccination induces CD8(+) T cells and remodels the tumor microenvironment. Cell 185, 4317-4332 (2022).

- Lynn, G. M. et al. Peptide-TLR-7/8a conjugate vaccines chemically programmed for nanoparticle self-assembly enhance CD8 T-cell immunity to tumor antigens. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 320-332 (2020).

- Deng, W. et al. Recombinant Listeria promotes tumor rejection by CD8(+) T celldependent remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8179-8184 (2018).

- Baharom, F. et al. Intravenous nanoparticle vaccination generates stem-like TCF1(+) neoantigen-specific CD8(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol. 22, 41-52 (2021).

- Ramirez-Valdez, R. A. et al. Intravenous heterologous prime-boost vaccination activates innate and adaptive immunity to promote tumor regression. Cell Rep 42, 112599 (2023).

- Reinhard, K. et al. An RNA vaccine drives expansion and efficacy of claudin-CAR-T cells against solid tumors. Science 367, 446-453(2020).

- Kranz, L. M. et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 534, 396-401 (2016).

- Sahin, U. et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature 585, 107-112 (2020).

- Mendez-Gomez, H. R. et al. RNA aggregates harness the danger response for potent cancer immunotherapy. Cell 187, 2521-2535 (2024).

- Beatty, A. L. et al. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Type and Adverse Effects Following Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2140364 (2021).

- Kelly, J. D. et al. Incidence of Severe COVID-19 Illness Following Vaccination and Booster With BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S Vaccines. JAMA 328, 1427-1437 (2022).

- Russell, M. W., Moldoveanu, Z., Ogra, P. L. & Mestecky, J. Mucosal Immunity in COVID-19: A Neglected but Critical Aspect of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 11, 611337 (2020).

- Künzli, M. et al. Route of self-amplifying mRNA vaccination modulates the establishment of pulmonary resident memory CD8 and CD4 T cells. Sci. Immunol. 7, eadd3075 (2022).

- Mao, T. et al. Unadjuvanted intranasal spike vaccine elicits protective mucosal immunity against sarbecoviruses. Science 378, eabo2523 (2022).

- Lavelle, E. C. & Ward, R. W. Mucosal vaccines – fortifying the frontiers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 236-250 (2022).

- Illum, L. Nasal drug delivery: new developments and strategies. Drug Discov. Today 7, 1184-1189 (2002).

- Wesselhoeft, R. A., Kowalski, P. S. & Anderson, D. G. Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 2629 (2018).

- Wesselhoeft, R. A. et al. RNA Circularization Diminishes Immunogenicity and Can Extend Translation Duration In Vivo. Mol. Cell 74, 508-520 (2019).

- Lokugamage, M. P. et al. Optimization of lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of nebulized therapeutic mRNA to the lungs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1059-1068 (2021).

- Li, B. et al. Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1410-1415 (2023).

- Kauffman, K. J. et al. Rapid, Single-Cell Analysis and Discovery of Vectored mRNA Transfection In Vivo with a loxP-Flanked tdTomato Reporter Mouse. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 10, 55-63 (2018).

- Simon, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination responses in untreated, conventionally treated and anticytokine-treated patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1312-1316 (2024).

35. Lee, S. et al. Assessing the impact of mRNA vaccination in chronic inflammatory murine model. NPJ Vaccines 9, 34 (2024).

36. Tahtinen, S. IL-1 and IL-1ra are key regulators of the inflammatory response to RNA vaccines. Nat. Immunol. 23, 532-542 (2022).

37. Castle, J. C. et al. Exploiting the mutanome for tumor vaccination. Cancer Res 72, 1081-1091 (2012).

38. Zhang, R. et al. Personalized neoantigen-pulsed dendritic cell vaccines show superior immunogenicity to neoantigen-adjuvant vaccines in mouse tumor models. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 135-145 (2020).

39. Gulley, J. L. et al. Role of Antigen Spread and Distinctive Characteristics of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment. J. Nat.I Cancer Inst. 109, djw261 (2017).

40. Sandoval, F. et al. Mucosal imprinting of vaccine-induced

41. Nizard, M. et al. Induction of resident memory T cells enhances the efficacy of cancer vaccine. Nat. Commun. 24, 15221 (2017).

42. Li, C. et al. Mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity to the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat. Immunol. 23, 543-555 (2022).

43. Kawasaki, T. et al. Alveolar macrophages instruct CD8(+) T cell expansion by antigen cross-presentation in lung. Cell Rep 41, 111828 (2022).

44. Silva, M. et al. Single immunizations of self-amplifying or non-replicating mRNALNP vaccines control HPV-associated tumors in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabn3464 (2023).

45. Ma, L. et al. Vaccine-boosted CAR T crosstalk with host immunity to reject tumors with antigen heterogeneity. Cell 186, 3148-3165 (2023).

46. Birtel, M. et al. A TCR-like CAR Promotes Sensitive Antigen Recognition and Controlled T-cell Expansion Upon mRNA Vaccination. Cancer Res. Commun. 2, 827-841 (2022).

47. Ji, D. et al. An engineered influenza virus to deliver antigens for lung cancer vaccination. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 518-528 (2024).

© The Author(s) 2025

Institute for Immunology and School of Basic Medical Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; College of Future Technology, Peking University, Beijing 10084, China;

School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; Key Laboratory of Bioorganic Phosphorus Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Department of Chemistry, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; Changping Laboratory, Beijing 10084, China and Tsinghua-Peking Center for Life Sciences, Beijing 10084, China Correspondence: Xin Lin (linxin307@tsinghua.edu.cn)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02191-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40122855

Publication Date: 2025-03-24

Intranasal prime-boost RNA vaccination elicits potent T cell response for lung cancer therapy

Abstract

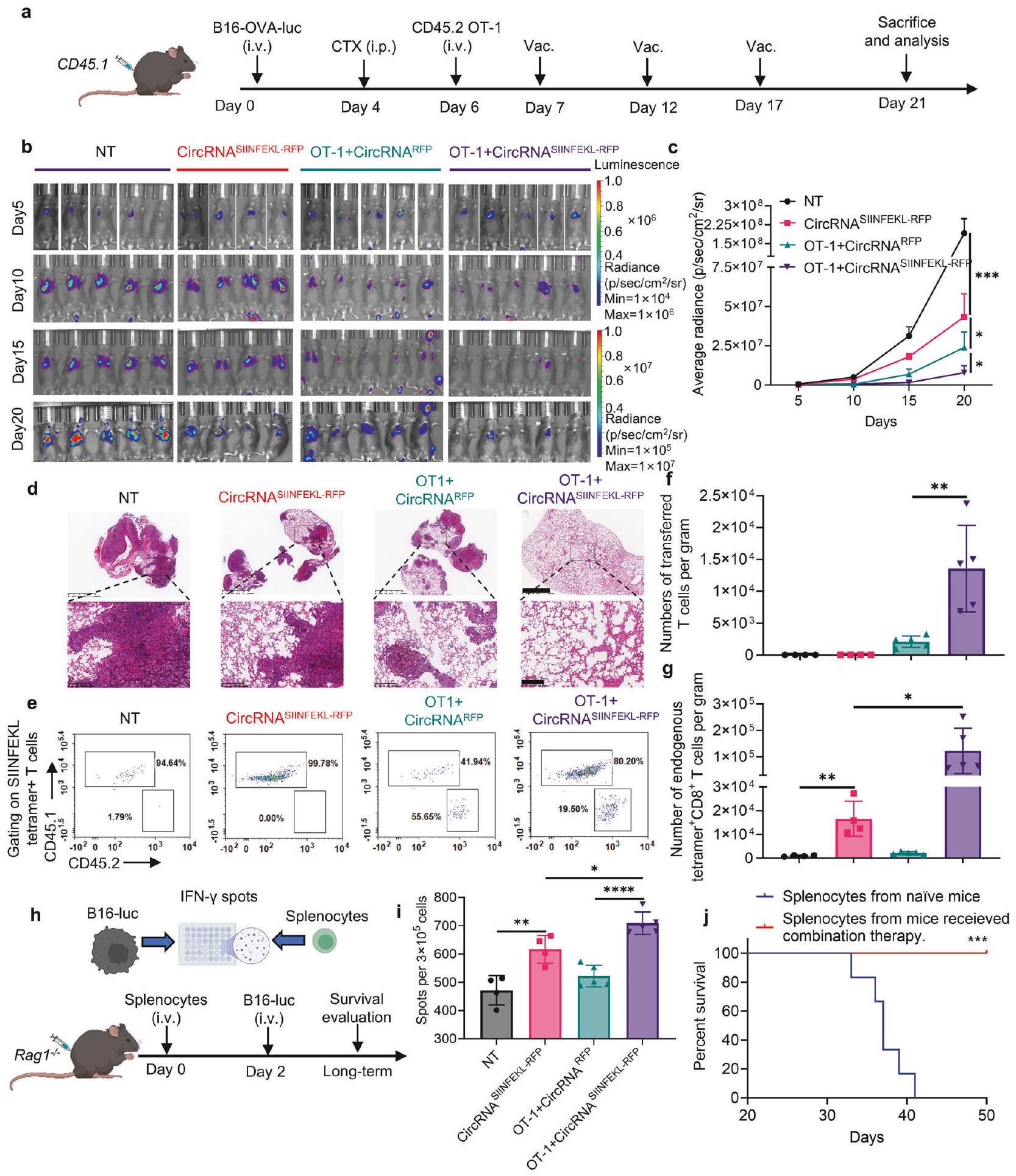

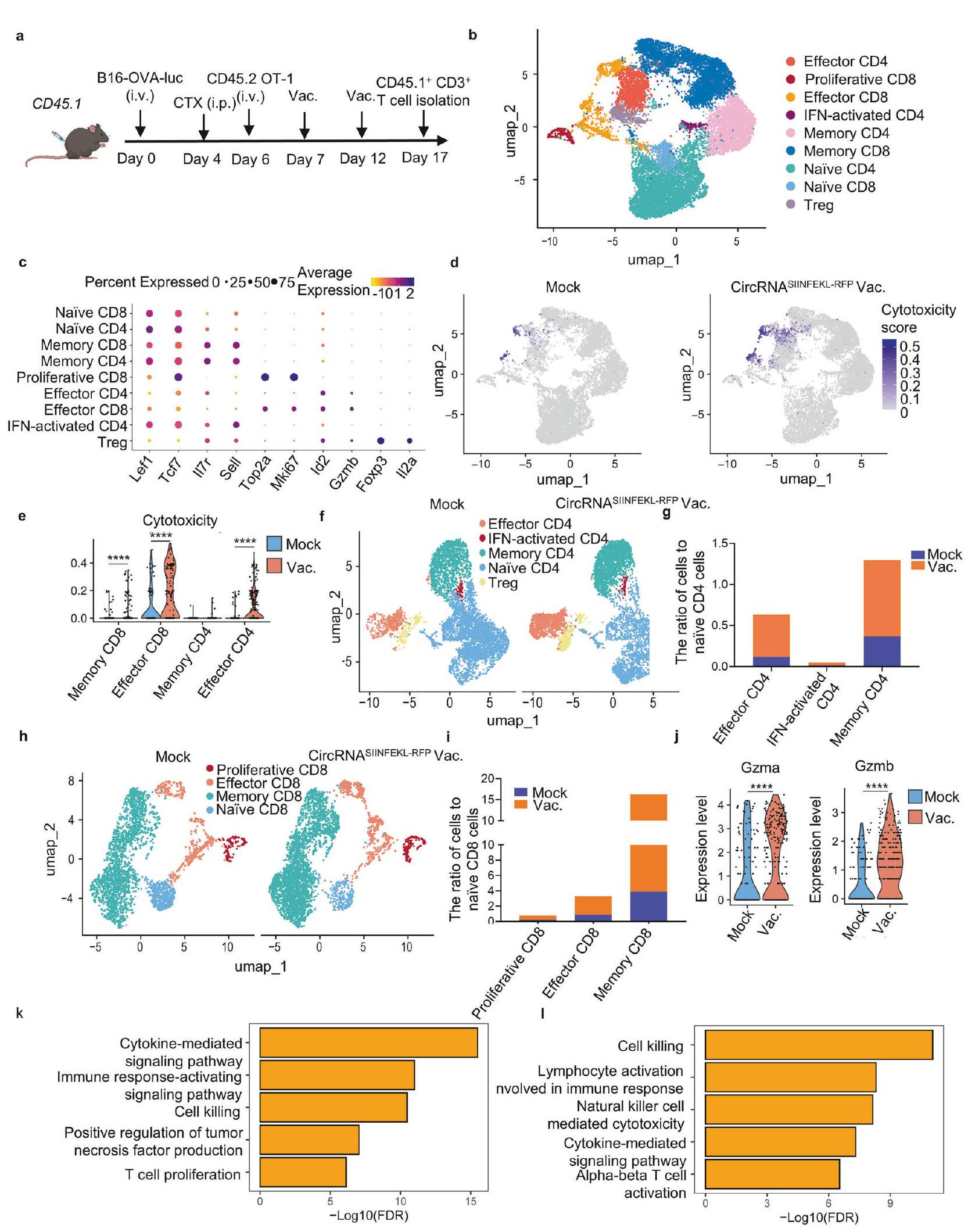

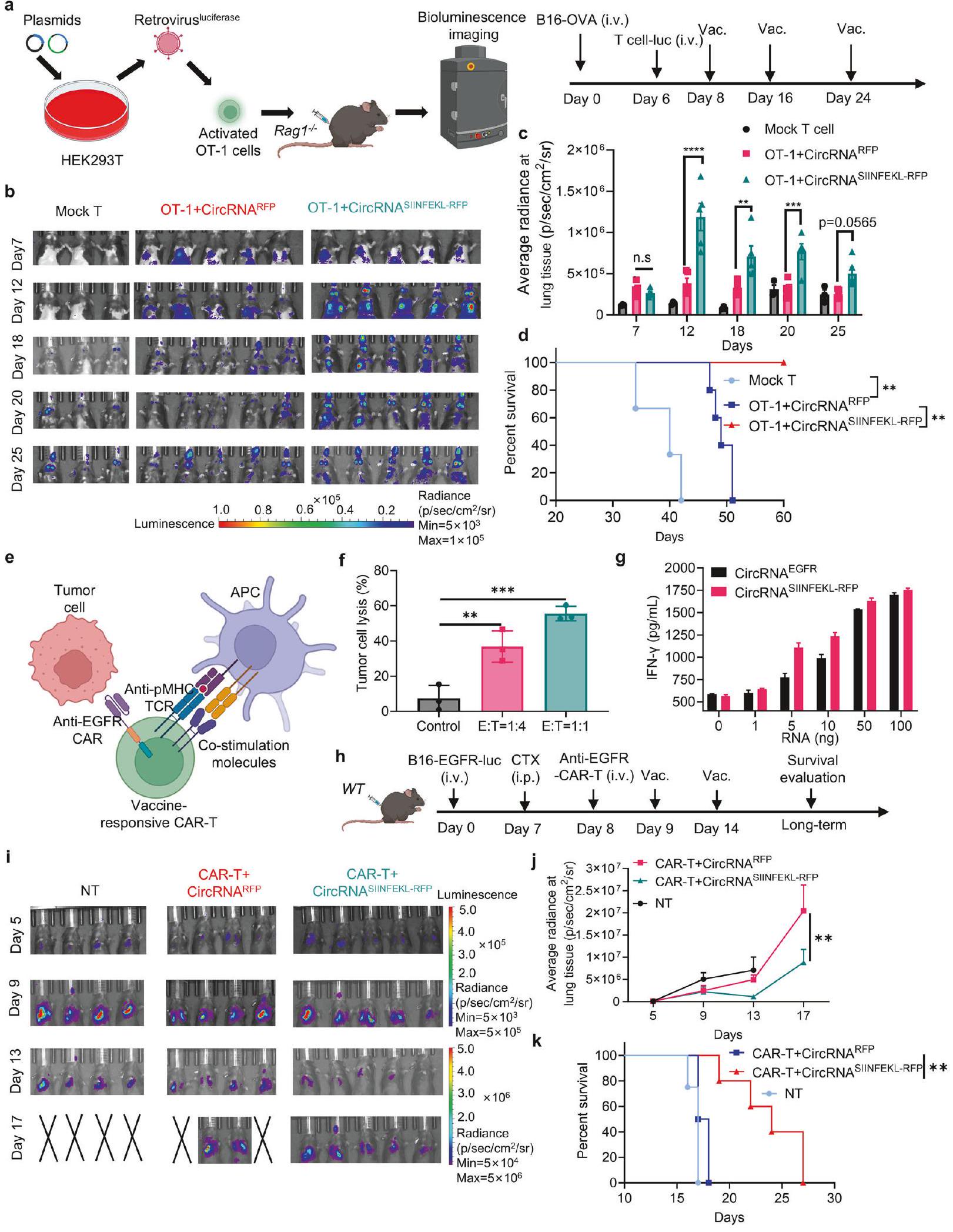

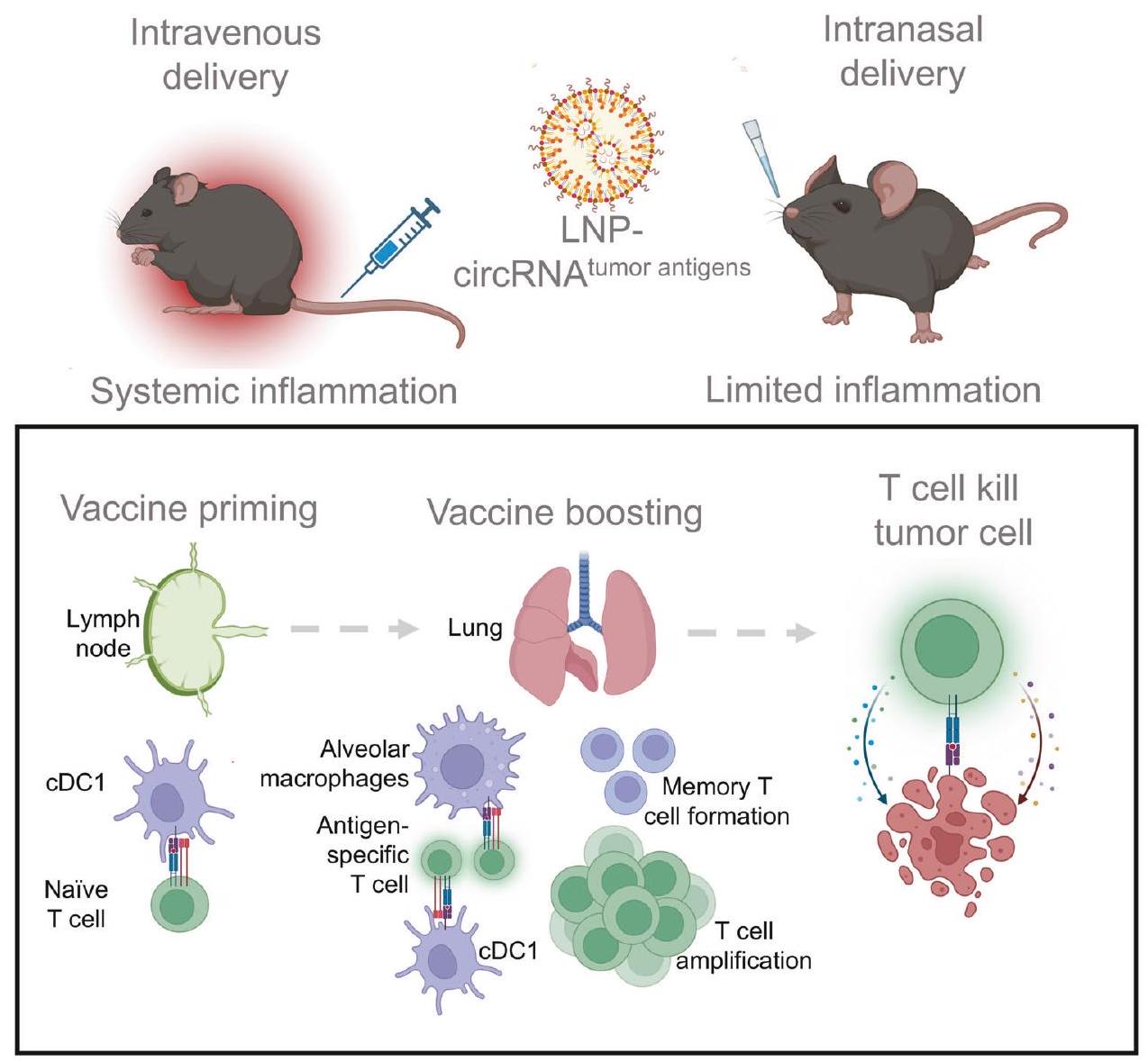

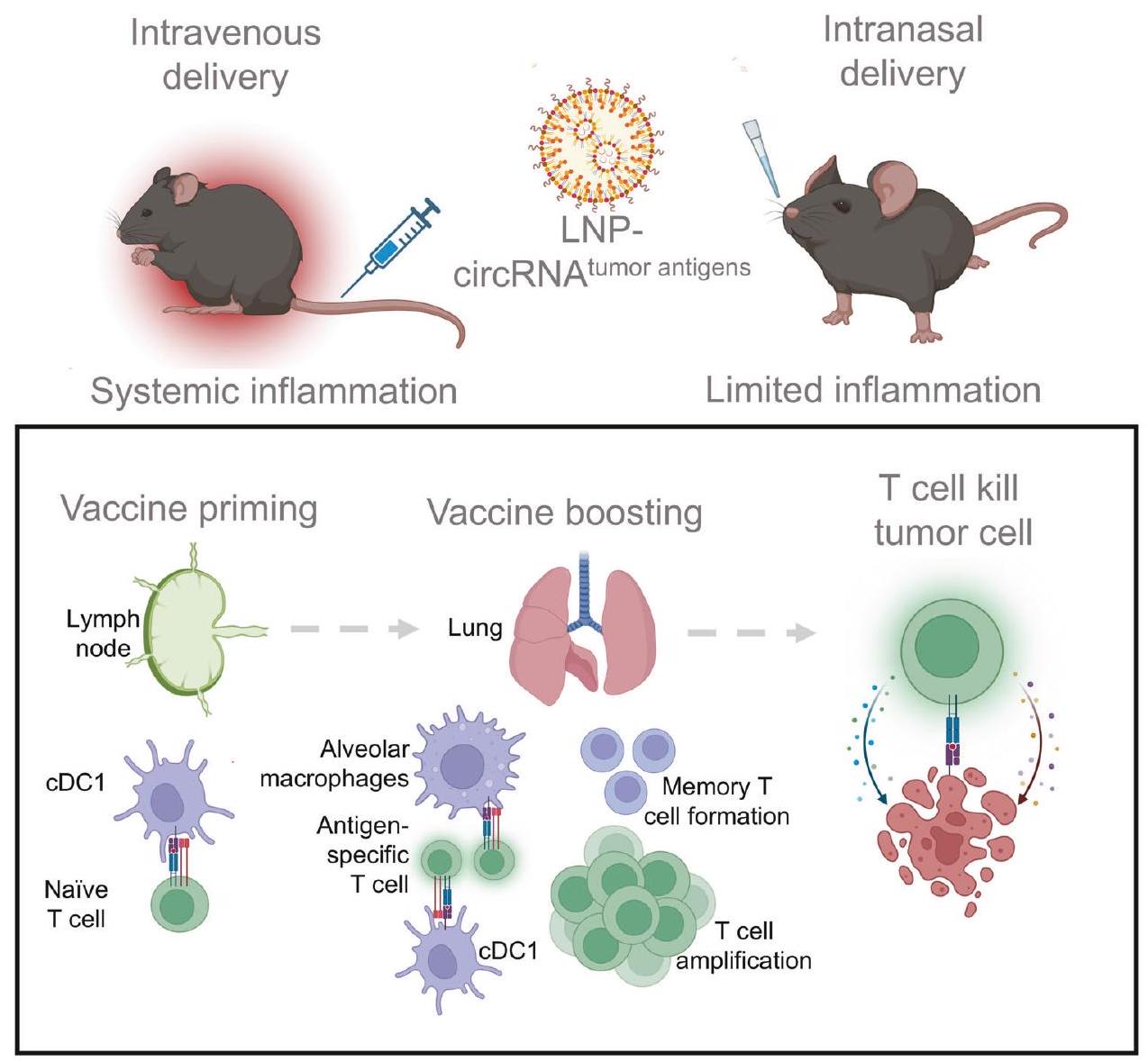

The rapid success of RNA vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 has sparked interest in their use for cancer immunotherapy. Although many cancers originate in mucosal tissues, current RNA cancer vaccines are mainly administered non-mucosally. Here, we developed a non-invasive intranasal cancer vaccine utilizing circular RNA encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles to induce localized mucosal immune responses. This strategy elicited potent anti-tumor T cell responses in preclinical lung cancer models while mitigating the systemic adverse effects commonly associated with intravenous RNA vaccination. Specifically, type 1 conventional dendritic cells were indispensable for T cell priming post-vaccination, with both alveolar macrophages and type 1 conventional dendritic cells boosting antigen-specific T cell responses in lung tissues. Moreover, the vaccination facilitated the expansion of both endogenous and adoptive transferred antigen-specific T cells, resulting in robust anti-tumor efficacy. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that the vaccination reprograms endogenous T cells, enhancing their cytotoxicity and inducing a memory-like phenotype. Additionally, the intranasal vaccine can modulate the response of CAR-T cells to augment therapeutic efficacy against tumor cells expressing specific tumor-associated antigens. Collectively, the intranasal RNA vaccine strategy represents a novel and promising approach for developing RNA vaccines targeting mucosal malignancies.

; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02191-1

INTRODUCTION

costs.

RESULTS

Based on the previously published circRNA preparation strategy, the in-vitro transcription templates included a pair of exons and introns, CVB3 IRES, spacers, arms and the coding sequences.

that SM102-based LNP showed higher dye-tracking fluorescence intensity compared to ALC-0315 (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). According to recent studies, the addition of cationic lipids, such as 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), can enhance lung-targeting efficiency after intravenous and intranasal administration.

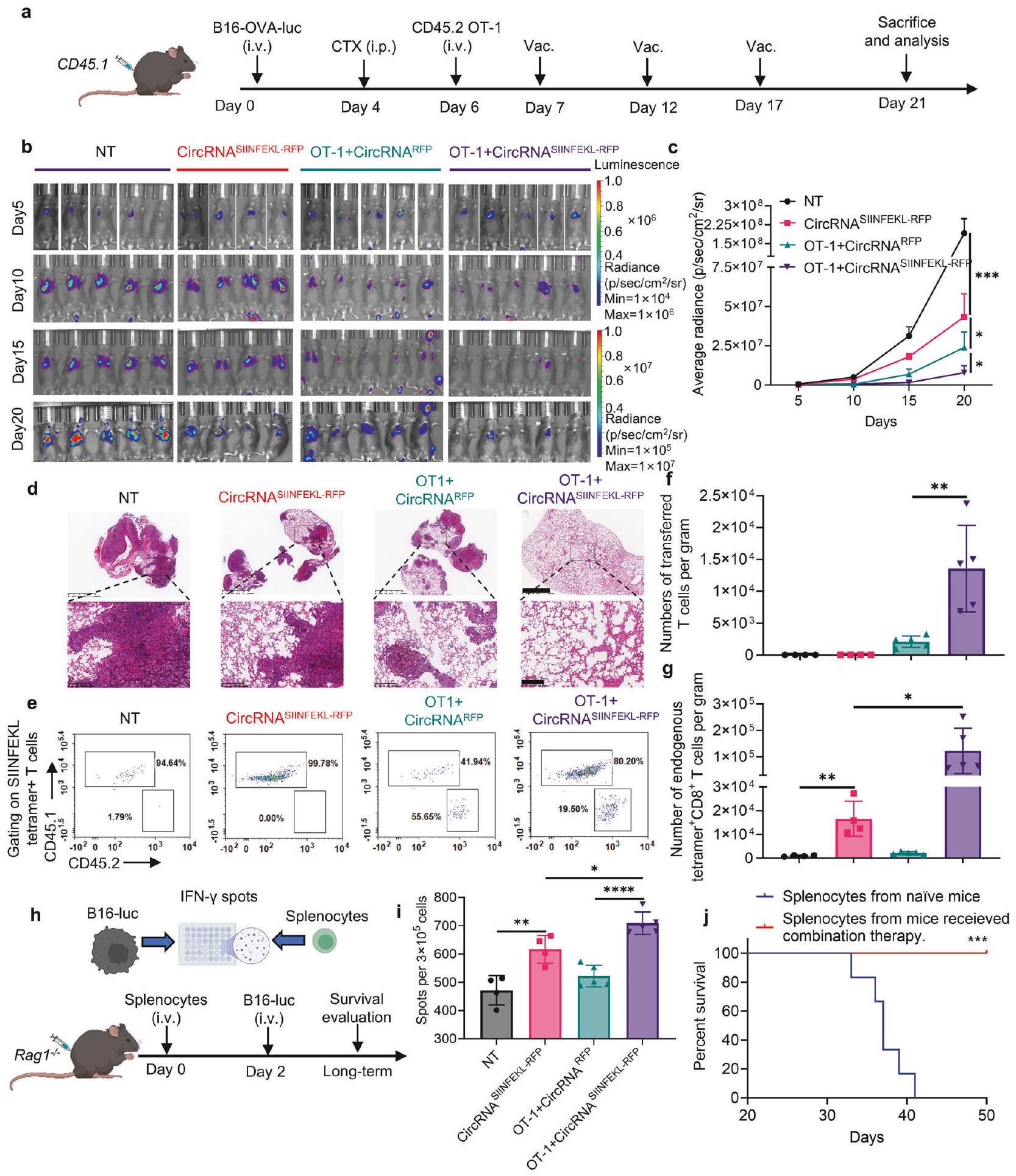

To systematically compare the anti-tumor efficiency of the circRNA vaccine administered through different routes, we established a lung metastasis B16 tumor model expressing the OVA antigen. Mice received SIINFEKL (class I (Kb)-restricted epitope of OVA antigen)-RFP-coding circRNA vaccines at specified time points (Fig. 2a). Compared to the untreated group, all three administration routes exhibited statistically comparable antitumor efficacy (Fig. 2b, c). However, the percentage of lung tissue occupied by metastatic foci appeared lower in the intranasal and intravenous groups compared to the intramuscular group. Then, we analyzed the acute toxicity of the circRNA vaccine administered through different routes. Previous studies have indicated that RNA vaccines can induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in adverse effects.

that the intranasal circRNA vaccine elicits a potent anti-tumor response with fewer side effects compared to other routes of administration.

Inspired by the therapeutic potential of the intranasal vaccine, we aimed to further investigate the principles underlying its antitumor immune response. We first established a B16-OVAluciferase lung metastasis model and confirmed the anti-tumor response (Fig. 3a). An RFP-coding RNA was used as an irrelevant antigen control. We also prepared linear mRNA and circRNA vaccines encoding SIINFEKL-RFP for vaccination. Bioluminescence image results (Fig. 3b and supplementary Fig. 7a) and survival curves (Fig. 3c) demonstrated that only tumor antigen-coding RNA vaccines could inhibit tumor cell growth, with no significant difference observed between mRNA and circRNA vaccines in this

knockout mice (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, the anti-tumor efficiency of the intranasal circRNA vaccine was diminished, suggesting that cDC1 is crucial for the vaccine-induced anti-tumor immune response (Fig. 3e). We further analyzed the antigenspecific CD8 + T cells induced by the vaccine (Fig. 3f). WT and Batf3

further explore the T cell boosting process following intranasal immunization. We employed WT mice, mice without cDC1, and mice without all CD11c+ cells to test their ability to boost activated antigen-specific T cells (Fig. 4a). Although depletion of cDC1 reduced T cell proliferation, the deficiency of CD11c+ cells

completely blocked vaccine-induced T cell proliferation, suggesting that both cDC1 and other CD11c+ antigen-presenting cells are involved in boosting T cells (Fig. 4b, c and supplementary Fig. 9a). To identify the cell types that support T cell proliferation, LNPs were labeled with DiD lipophilic dye and intranasally administered to mice. We then stained the major populations of CD11c+ cells at lung tissues, including alveolar macrophages (AMs), cDC1s, CD11b + DCs, and CD11c- CD45- cells as the control group. We found that LNPs were predominantly engulfed by AMs, with other cells also capable of engulfing LNPs but in smaller numbers (Fig. 4d, e, supplementary Fig. 9b-d). Moreover, the production of IFN-

Based on the above findings, we hypothesized that intranasal RNA vaccine may synergize with transferred antigen-specific T cells for enhanced anti-tumor ability. We conducted experiments using a WT mouse model. Mice were initially challenged with B16-OVAluciferase tumor cells and underwent lymphodepletion with CTX before receiving treatment with circRNA vaccine, adoptive cell therapy (ACT), or a combination of both therapies (Fig. 5a). Bioluminescence imaging and histopathological examination (HE staining) demonstrated that while vaccine alone or OT-1 cells with mock vaccine could inhibit tumor growth, the combination therapy resulted in the most pronounced tumor control (Fig. 5b-d). We also quantified antigen-specific T cell numbers for both endogenous and transferred T cells, revealing that the vaccine effectively expanded both populations (Fig. 5e-g).

studies involving immunotherapy.

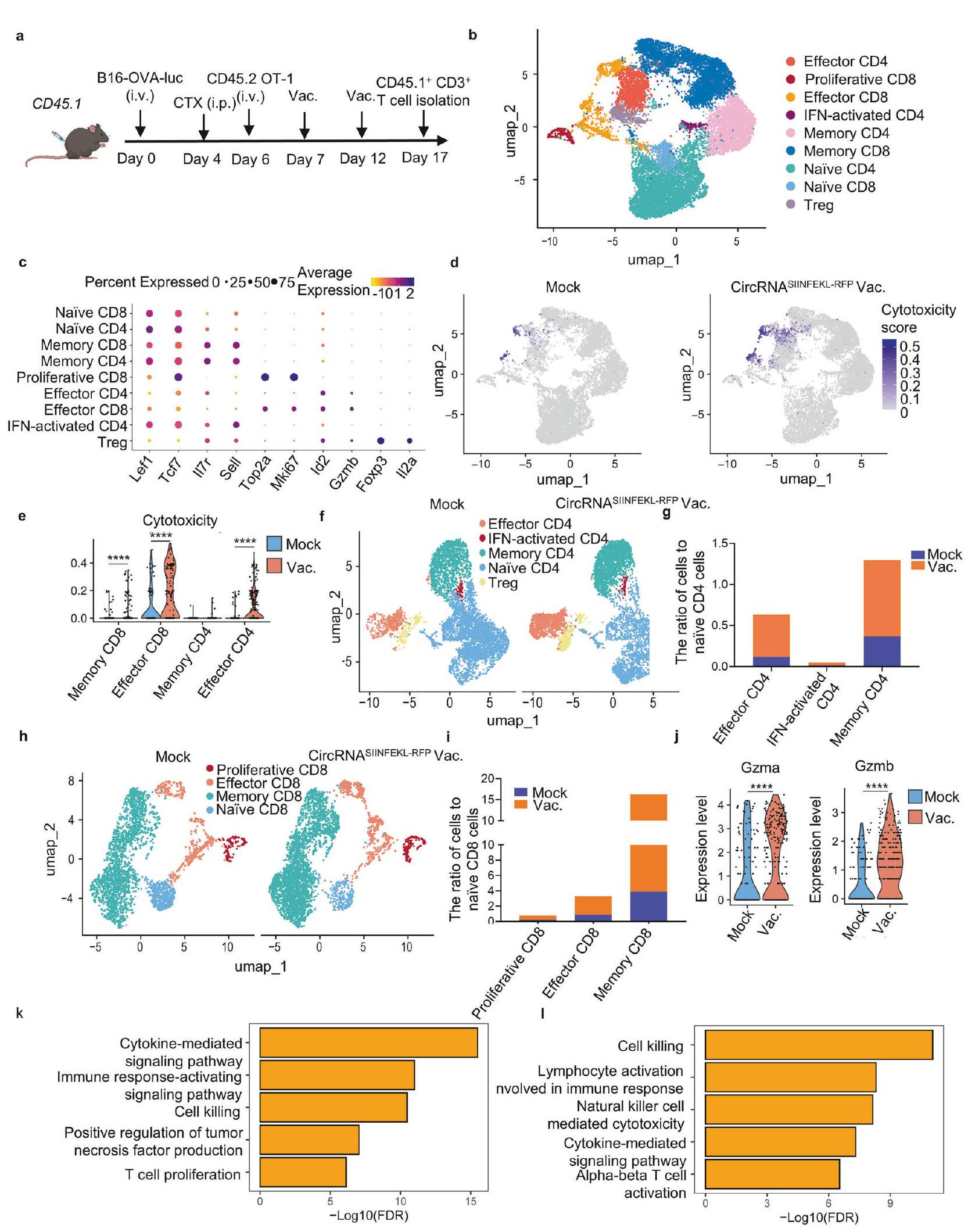

Building on our previous findings, we aimed to comprehensively examine alterations in endogenous T cells using single-cell RNAseq analysis of CD3+ cells from lung tissues in tumor-bearing mouse models (Fig. 6a). Unsupervised clustering of the transcriptome data identified nine major T cell subsets: naïve CD4 and CD8 cells (marked by Lef1 and Tcf7 expression with relatively low II7r and Sell levels), memory CD4 and CD8 cells (expressing II7r and Sell), proliferative CD8 cells (characterized by Top2a and Mki67 expression), effector CD4 and CD8 cells (with

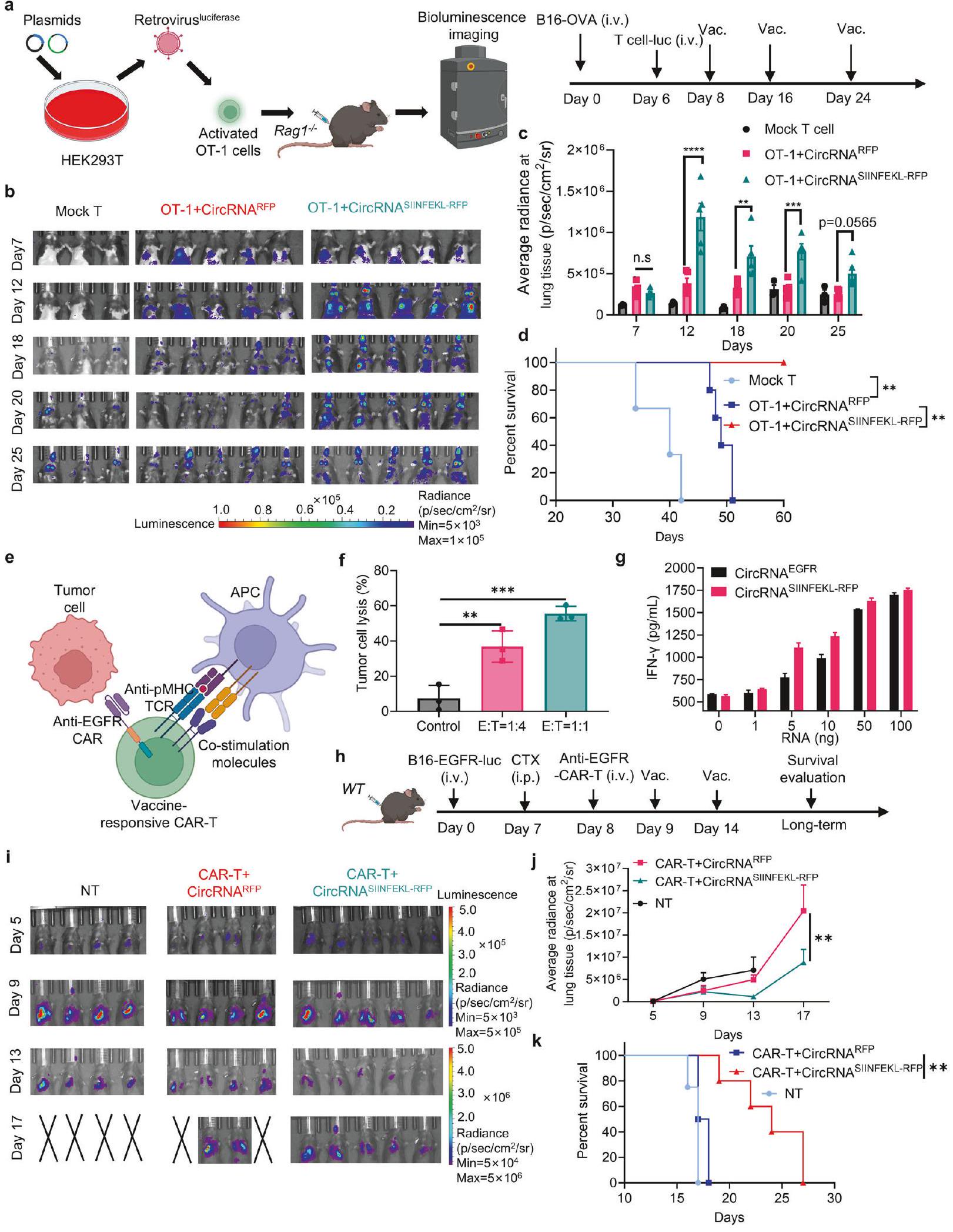

In addition to examining the effects of the vaccine on endogenous T cells, we also investigated its direct impact on adoptive transferred T cells. To visualize the dynamic biodistribution and long-term performance of vaccine-boosted transferred T cells during the anti-tumor process, we used B16-OVA bearing Rag1

bioluminescence imaging revealed that the vaccine drove T cell expansion in lung tissues, and repeated doses sustained T cell numbers at a relatively high level compared to the mock vaccine group (Fig. 7b, c). Assessing the anti-tumor efficiency of various treatments, we observed that intranasal vaccination significantly prolonged the survival of T cell-transferred mice (Fig. 7d). These

findings illustrate that intranasal RNA vaccine boosting enables transferred antigen-specific T cells to expand in lung tissues, thereby enhancing their efficiency in lung cancer treatment.

only responds to the vaccination but also targets tumor cells expressing specific surface tumor-associated antigens. These antigens are typically challenging for conventional cancer vaccine approaches which are limited to target MHC-presented immunogenic peptides. This approach aims to eliminate tumor cells via the CAR molecule while simultaneously promoting in-situ boosting of immune responses through the TCR machinery (Fig. 7e). The CART cells showed the ability to kill EGFR-overexpressing B16 tumor cells at different

DISCUSSION

injections of the circRNA vaccine appear better tumor control compared with intramuscular injection, the intramuscular vaccine also inhibit tumor growth. This discrepancy from previous studies may be attributed to differing levels of systemic T cell activation induced by distinct vaccine formulations following injection administration. Taken together, these results all suggest that the noninvasive intranasal immunization is indeed beneficial for local lung cancer treatment with minimal systemic inflammation.

subcutaneously peptide vaccines enhance the function of transferred CAR-T and TCR-T cells,

treatment strategy in a tumor-associate-antigen model with CAR-T cells and the intranasal vaccine. The approach provides two significant advantages, enhancing CAR-T cell persistence and enabling redirection of T cells to target tumor-associated antigens independent of MHC presentation on tumor cells.

Abstract

Fig. 7 Intranasal circRNA vaccine augments the anti-tumor efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy against tumor cells expressing specific tumorassociated antigens. a Scheme of the experiment to track the migration and expansion of transferred OT-1 cells. Cells were activated, infected with luciferase-coding retrovirus and then transferred to tumor-bearing Rag1

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and cell lines

Plasmid

Preparation of RNA

Preparation of lipid nanoparticle (LNP)

Biodistribution of LNP

were gated as CD11c+ and Siglec-F+ cells. cDC1s were gated as CD11c + , Siglec-F- and CD103 + cells. CD11b + cells were gated as CD11c + , Siglec-F-, CD103- and CD11b+ cells. Samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer (BD Fortessa or LSRII) and cellular uptake of LNP was evaluated using APC channel.

Balb/c mice were pre-treated with isoflurane and administrated with LNP via i.m., i.v. or i.n. at a dose of

For prophylactic tumor challenge studies, C57BL/6J mice were immunized with LNP containing SIINFEKL-RFP circRNA (

per mouse) for two doses at an interval of 7 days. 30 or 60 days later, mice were challenged with

To investigate the role of cDC1 on T cell priming, WT and Batf3

Adoptive cell transfer therapy

Statistical analysis

DATA AVAILABILITY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- Waldman, A. D., Fritz, J. M. & Lenardo, M. J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 651-668 (2020).

- Lin, M. J. et al. Cancer vaccines: the next immunotherapy frontier. Nat. Cancer 3, 911-926 (2022).

- Blass, E. & Ott, P. A. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigenbased therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 215-229 (2021).

- Sayour, E. J., Boczkowski, D., Mitchell, D. A. & Nair, S. K. Cancer mRNA vaccines: clinical advances and future opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 489-500 (2024).

- Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403-416 (2021).

- Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603-2615 (2020).

- Miao, L., Zhang, Y. & Huang, L. mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 20, 41 (2021).

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M. J., Porter, F. W. & Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines – a new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 261-279 (2018).

- Rohner, E. et al. Unlocking the promise of mRNA therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1586-1600 (2022).

- Kristensen, L. S. et al. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 675-691 (2019).

- Qu, L. et al. Circular RNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Cell 185, 1728-1744 (2022).

- Li, H. et al. Circular RNA cancer vaccines drive immunity in hard-to-treat malignancies. Theranostics 12, 6422-6436 (2022).

- Baharom, F. et al. Systemic vaccination induces CD8(+) T cells and remodels the tumor microenvironment. Cell 185, 4317-4332 (2022).

- Lynn, G. M. et al. Peptide-TLR-7/8a conjugate vaccines chemically programmed for nanoparticle self-assembly enhance CD8 T-cell immunity to tumor antigens. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 320-332 (2020).

- Deng, W. et al. Recombinant Listeria promotes tumor rejection by CD8(+) T celldependent remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8179-8184 (2018).

- Baharom, F. et al. Intravenous nanoparticle vaccination generates stem-like TCF1(+) neoantigen-specific CD8(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol. 22, 41-52 (2021).

- Ramirez-Valdez, R. A. et al. Intravenous heterologous prime-boost vaccination activates innate and adaptive immunity to promote tumor regression. Cell Rep 42, 112599 (2023).

- Reinhard, K. et al. An RNA vaccine drives expansion and efficacy of claudin-CAR-T cells against solid tumors. Science 367, 446-453(2020).

- Kranz, L. M. et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 534, 396-401 (2016).

- Sahin, U. et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature 585, 107-112 (2020).

- Mendez-Gomez, H. R. et al. RNA aggregates harness the danger response for potent cancer immunotherapy. Cell 187, 2521-2535 (2024).

- Beatty, A. L. et al. Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccine Type and Adverse Effects Following Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2140364 (2021).

- Kelly, J. D. et al. Incidence of Severe COVID-19 Illness Following Vaccination and Booster With BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S Vaccines. JAMA 328, 1427-1437 (2022).

- Russell, M. W., Moldoveanu, Z., Ogra, P. L. & Mestecky, J. Mucosal Immunity in COVID-19: A Neglected but Critical Aspect of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 11, 611337 (2020).

- Künzli, M. et al. Route of self-amplifying mRNA vaccination modulates the establishment of pulmonary resident memory CD8 and CD4 T cells. Sci. Immunol. 7, eadd3075 (2022).

- Mao, T. et al. Unadjuvanted intranasal spike vaccine elicits protective mucosal immunity against sarbecoviruses. Science 378, eabo2523 (2022).

- Lavelle, E. C. & Ward, R. W. Mucosal vaccines – fortifying the frontiers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 236-250 (2022).

- Illum, L. Nasal drug delivery: new developments and strategies. Drug Discov. Today 7, 1184-1189 (2002).

- Wesselhoeft, R. A., Kowalski, P. S. & Anderson, D. G. Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 2629 (2018).

- Wesselhoeft, R. A. et al. RNA Circularization Diminishes Immunogenicity and Can Extend Translation Duration In Vivo. Mol. Cell 74, 508-520 (2019).

- Lokugamage, M. P. et al. Optimization of lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of nebulized therapeutic mRNA to the lungs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1059-1068 (2021).

- Li, B. et al. Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1410-1415 (2023).

- Kauffman, K. J. et al. Rapid, Single-Cell Analysis and Discovery of Vectored mRNA Transfection In Vivo with a loxP-Flanked tdTomato Reporter Mouse. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 10, 55-63 (2018).

- Simon, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination responses in untreated, conventionally treated and anticytokine-treated patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1312-1316 (2024).

35. Lee, S. et al. Assessing the impact of mRNA vaccination in chronic inflammatory murine model. NPJ Vaccines 9, 34 (2024).

36. Tahtinen, S. IL-1 and IL-1ra are key regulators of the inflammatory response to RNA vaccines. Nat. Immunol. 23, 532-542 (2022).

37. Castle, J. C. et al. Exploiting the mutanome for tumor vaccination. Cancer Res 72, 1081-1091 (2012).

38. Zhang, R. et al. Personalized neoantigen-pulsed dendritic cell vaccines show superior immunogenicity to neoantigen-adjuvant vaccines in mouse tumor models. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 135-145 (2020).

39. Gulley, J. L. et al. Role of Antigen Spread and Distinctive Characteristics of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment. J. Nat.I Cancer Inst. 109, djw261 (2017).

40. Sandoval, F. et al. Mucosal imprinting of vaccine-induced

41. Nizard, M. et al. Induction of resident memory T cells enhances the efficacy of cancer vaccine. Nat. Commun. 24, 15221 (2017).

42. Li, C. et al. Mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity to the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat. Immunol. 23, 543-555 (2022).

43. Kawasaki, T. et al. Alveolar macrophages instruct CD8(+) T cell expansion by antigen cross-presentation in lung. Cell Rep 41, 111828 (2022).

44. Silva, M. et al. Single immunizations of self-amplifying or non-replicating mRNALNP vaccines control HPV-associated tumors in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabn3464 (2023).

45. Ma, L. et al. Vaccine-boosted CAR T crosstalk with host immunity to reject tumors with antigen heterogeneity. Cell 186, 3148-3165 (2023).

46. Birtel, M. et al. A TCR-like CAR Promotes Sensitive Antigen Recognition and Controlled T-cell Expansion Upon mRNA Vaccination. Cancer Res. Commun. 2, 827-841 (2022).

47. Ji, D. et al. An engineered influenza virus to deliver antigens for lung cancer vaccination. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 518-528 (2024).

© The Author(s) 2025

Institute for Immunology and School of Basic Medical Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; College of Future Technology, Peking University, Beijing 10084, China;

School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; Key Laboratory of Bioorganic Phosphorus Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Department of Chemistry, Tsinghua University, Beijing 10084, China; Changping Laboratory, Beijing 10084, China and Tsinghua-Peking Center for Life Sciences, Beijing 10084, China Correspondence: Xin Lin (linxin307@tsinghua.edu.cn)