DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-024-01044-y

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-08

التطورات الحديثة والتقنيات المستقبلية في كشف النانو والميكروبلاستيك

الملخص

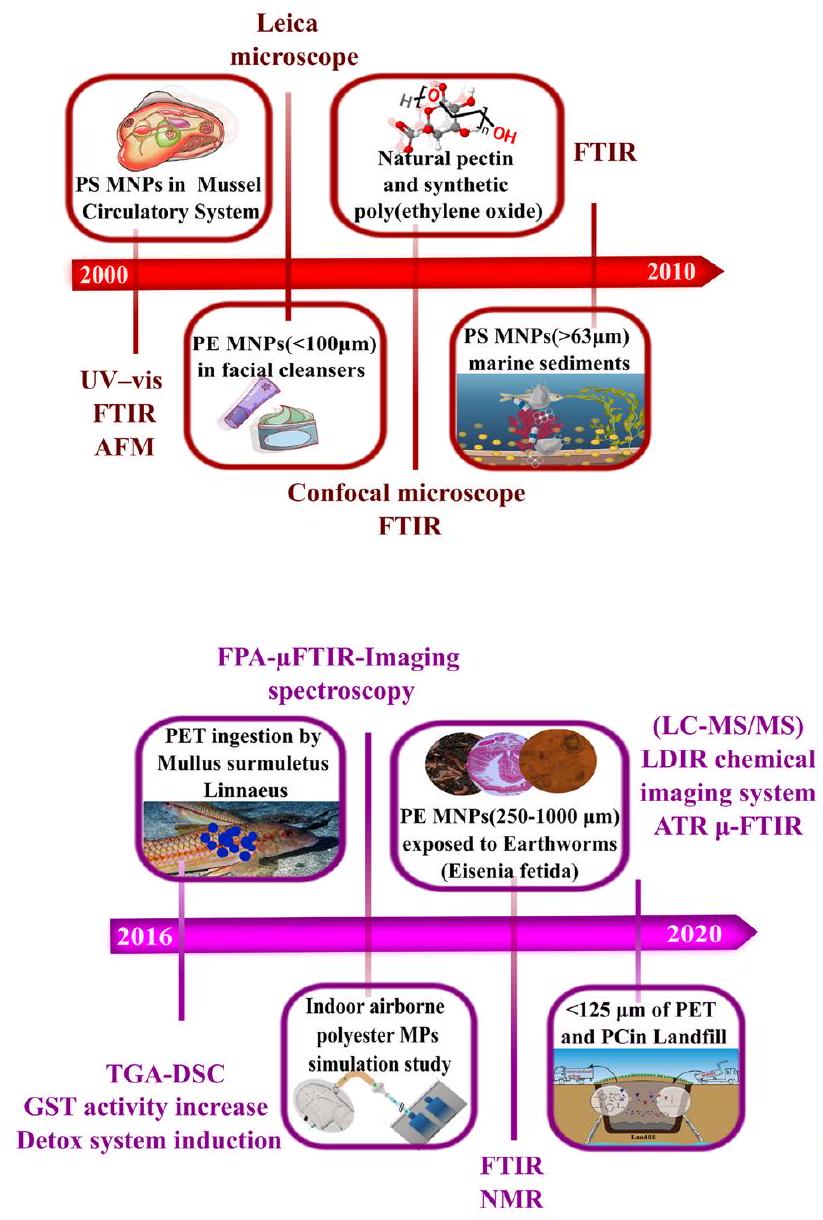

تؤدي تحلل النفايات البلاستيكية غير المدارة بشكل صحيح في البيئة إلى تكوين الميكروبلاستيك (MPs) والنانو بلاستيك (NPs)، والتي تشكل مخاطر كبيرة على النظم البيئية وصحة الإنسان. هذه الجسيمات موجودة في كل مكان، وتم اكتشافها حتى في المناطق النائية، ويمكن أن تدخل سلسلة الغذاء، وتتراكم في الكائنات الحية وتسبب ضررًا اعتمادًا على عوامل مثل حمولة الجسيمات، وجرعة التعرض، ووجود ملوثات مشتركة. إن الكشف عن وتحليل NMPs يواجه تحديات فريدة، خاصة مع انخفاض حجم الجسيمات، مما يجعل من الصعب بشكل متزايد التعرف عليها. علاوة على ذلك، فإن غياب البروتوكولات القياسية للكشف عنها وتحليلها يعيق التقييمات الشاملة لتأثيراتها البيئية والبيولوجية. تقدم هذه المراجعة نظرة عامة مفصلة عن أحدث التقدمات في التقنيات الخاصة بأخذ العينات، والفصل، والقياس، والتكميم لـ NMPs. تسلط الضوء على الأساليب الواعدة، مدعومة بأمثلة عملية من دراسات حديثة، بينما تتناول بشكل نقدي التحديات المستمرة في أخذ العينات، والتوصيف، والتحليل. تستعرض هذه العمل التطورات الرائدة في الكشف القائم على تكنولوجيا النانو، وتقنيات الطيف المجهري المتكاملة، وخوارزميات التصنيف المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، مقدمة حلولًا لسد الفجوات في أبحاث NMP. من خلال استكشاف المنهجيات الحديثة وتقديم وجهات نظر مستقبلية، توفر هذه المراجعة رؤى قيمة لتحسين قدرات الكشف على المقياس الميكروي والنانو، مما يمكّن من تحليل أكثر فعالية عبر سياقات بيئية متنوعة.

المقدمة

يمكن أن يبدأ التحلل البيئي لـ MPs من خلال عمليات حيوية (تشمل الإنزيمات، والمواد البيولوجية الأخرى، والبكتيريا، والفطريات، إلخ)، أو عمليات غير حيوية (مثل الأكسدة الحرارية، والأكسدة الضوئية، والتحلل الميكانيكي والأكسدة الجوية)، أو مزيج من الاثنين [8]. يمكن أن يتسبب التحلل الضوئي، خاصة من خلال الضوء فوق البنفسجي، في تفتت وسقوط سلاسل البوليمر، مما يؤدي إلى منتجات ثانوية تفاعلية [9]. تلوث NMPs موجود في كل مكان، يمتد إلى ما وراء المناطق الحضرية إلى المناطق النائية [10-12].

لذلك، فإن قياس وتوصيف NMPs باستخدام طرق فعالة من حيث التكلفة وبسيطة أمر ضروري. يمكن أن يقود تشتت NMPs في البيئة عوامل مناخية مثل الرياح والأمطار، مما يؤدي إلى ترسيب رطب وجاف في المناطق النائية [13، 14]. يتم تحديد وجود NMPs في المياه السطحية والمياه الجوفية بشكل أساسي من خلال الظروف الهيدروجيولوجية والقرب من مصادر التلوث الرئيسية [15]. على الرغم من الأبحاث المستمرة، لا تزال العديد من جوانب الدورة العالمية للبلاستيك وNMPs في البيئة غير واضحة [13]. يمكن أن تدخل NMPs الجسم وتتفاعل مع الخلايا، مما قد يؤدي إلى آثار سامة تتأثر بعوامل مثل حجم البلاستيك، والجرعة، ومدة التعرض. على المقياس النانوي، يمكن أن تطفو البوليمرات ذات كثافة أقل من

لتحقيق التفاعلات مع الكائنات الحية، حيث تزيد أحجام الجسيمات الأصغر من احتمال اختراق الأغشية البيولوجية [18].

على الرغم من التقارير العديدة حول وجود NMPs، لا يزال بروتوكول موحد لأخذ العينات، والمعالجة المسبقة، والقياس والتصنيف غائبًا [19، 20]. تعتبر المعالجة المسبقة للعينات خطوة حاسمة لتقليل وجود الجسيمات غير البلاستيكية والتركيز على الكشف عن NMPs. تشمل التحديات الحالية: (أ) فصل NMPs عن الملوثات العضوية والرواسب غير العضوية؛ (ب) تجنب النتائج الإيجابية الكاذبة والسلبية الكاذبة أثناء القياس والتصنيف؛ (ج) وضع بروتوكولات وإرشادات مقبولة عالميًا. بينما قد تكون التقنيات الحالية فعالة على مقياس الميكرومتر، فإن كفاءتها تتناقص بالنسبة للتلوثات الأصغر أو على المقياس النانوي، وغالبًا ما تصبح أكثر تكلفة وأقل موثوقية [21، 22]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن عدم تجانس العينات البيئية يعقد توصيف وكشف NMPs، مما يؤدي في كثير من الأحيان إلى أخطاء منهجية [22، 23].

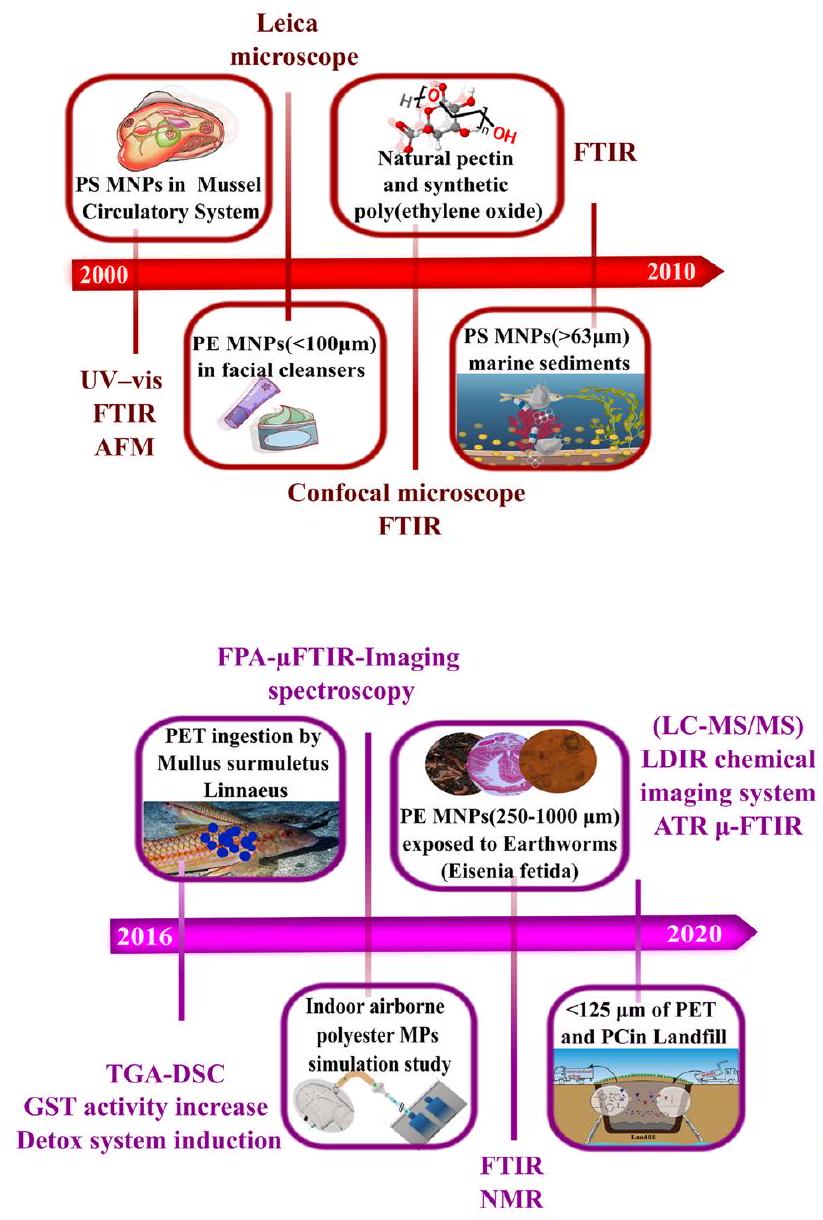

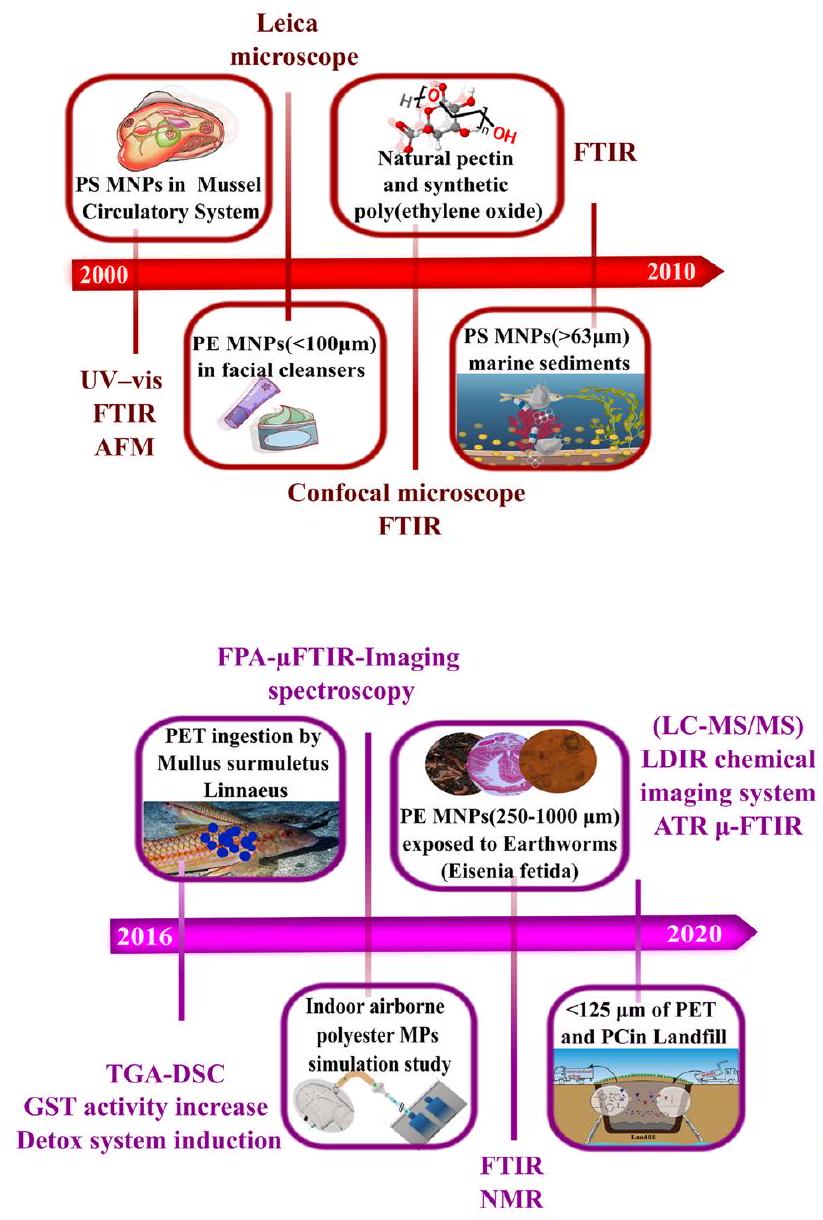

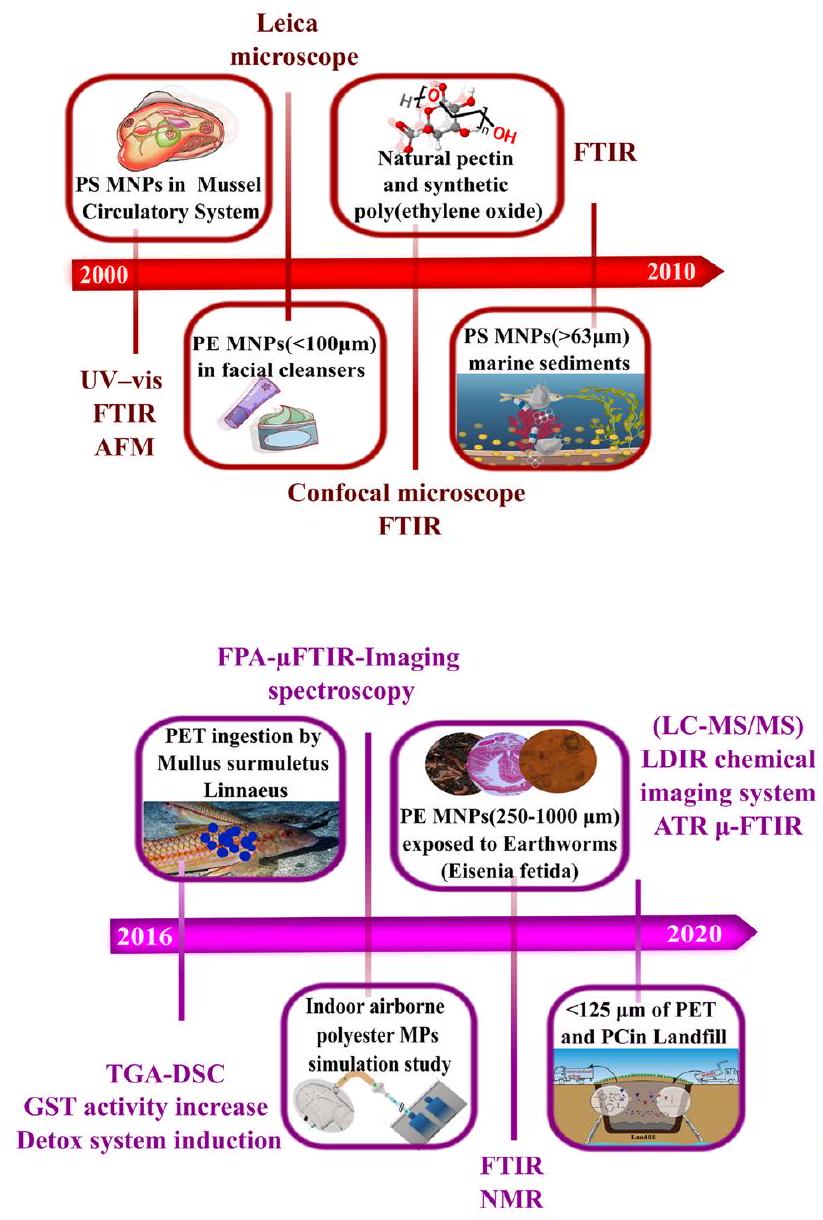

تتناول التقارير الحديثة جوانب عامة من أخذ العينات وفصل NMPs [26-28]؛ ومع ذلك، غالبًا ما تفتقر إلى المناقشات النقدية حول التقدمات، والتحديات، والحلول المبتكرة، جنبًا إلى جنب مع أمثلة بحثية عملية. تركز العديد من مراجعات الأدبيات بشكل أساسي على الأدوات التحليلية، مثل المجهر والطيف، للكشف عن NMPs. ومع ذلك، غالبًا ما تفشل في تقديم رؤى حول كيفية تحسين هذه التقنيات. كما أن المناقشات حول النتائج البحثية المهمة التي تعالج هذه القيود محدودة أيضًا [27-29]. تهدف هذه العمل إلى سد هذه الفجوات من خلال تقديم نظرة شاملة ونقدية عن الحالة الحالية للتقنيات المتطورة لأخذ العينات، والمعالجة المسبقة، والكشف التحليلي عن NMPs. تسلط الضوء على التقدمات الحديثة، خاصة الأساليب القائمة على تكنولوجيا النانو وتقنيات الطيف المجهري المدمجة، حيث يتم استخدام المواد النانوية بشكل فعال في طرق الفصل. أخيرًا، تستكشف هذه المراجعة دور خوارزميات التصنيف المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI)، التي لا تزال غير مستكشفة بشكل كافٍ في الأدبيات الحالية، على الرغم من قدرتها على تعزيز الدقة والكفاءة في الكشف عن NMPs.

إعداد العينات

تقدمات طرق أخذ العينات

أخذ عينات من المياه الجوفية أكثر تعقيدًا من المياه السطحية بسبب محدودية توفر نقاط أخذ العينات القابلة للوصول، مثل الينابيع أو آبار المياه أو آبار المراقبة. يمكن جمع مياه الينابيع مباشرة عند فم الينبوع دون إزعاج الديناميات الطبيعية للمياه الجوفية. بالمقابل، يتطلب جمع المياه الجوفية من آبار المراقبة عادةً مضخات أو أجهزة أخذ عينات حجمية، مما يمكن أن يزيد من خطر التلوث المتبادل [32]. تحدٍ آخر حاسم في أخذ عينات المياه الجوفية هو تحديد الحد الأدنى من الحجم المطلوب لتحقيق نتائج موثوقة إحصائيًا [33]. بالنسبة للمياه الجوفية ذات مستويات التلوث المنخفضة جدًا، تكون أنظمة الضخ ذات التدفق المنخفض المتصلة بالتصفية في الموقع مفيدة بشكل خاص، حيث تسمح بجمع مئات اللترات من المياه الجوفية. على العكس، في المواقع الأكثر تلوثًا، يمكن جمع بضع لترات من المياه الجوفية باستخدام أجهزة أخذ عينات حجمية [34]. بينما يمكن تكييف الطرق العامة لأخذ عينات التربة، هناك حاجة ملحة لتقنيات موحدة مصممة خصيصًا لتحديد كميات البلاستيكات النانوية والبلاستيكات الدقيقة في المياه الجوفية وغيرها من المصفوفات البيئية [35].

يمكن أن تستقر الجسيمات الدقيقة المحمولة جواً بسبب الجاذبية ويتم جمعها باستخدام حاويات، يمكن توصيلها بقمع في الأعلى كجهاز لجمع العينات بشكل سلبي [36]. جمع الغبار الداخلي باستخدام الفرشاة يتعامل مع الجسيمات الدقيقة وكذلك مزيج من مكونات الغبار الأخرى، وبالتالي يجب فصل الشوائب الأخرى عن الجسيمات الدقيقة. بينما يمكن أن تكون أجهزة أخذ العينات النشطة فعالة، إلا أنها غير مناسبة للمناطق التي يصعب الوصول إليها، مثل الجبال النائية. هذه الأنواع من الأجهزة معقدة ومكلفة [37].

التقدم في الفصل والمعالجة المسبقة

جزيئات التربة، والأيونات والمركبات المذابة، والمواد العضوية المتبقية. تشمل الاستراتيجيات الشائعة للمعالجة المسبقة اختيار الحجم (عبر المناخل)، والهضم (باستخدام الأكسدة، أو الهضم الإنزيمي، أو الهضم الحمضي القلوي)، وفصل الكثافة (مع محاليل الملح)، والتصفية.

يتم تحقيق الفصل بشكل أساسي من خلال فصل الكثافة والتصفية. يعتمد فصل الكثافة غالبًا على الطفو، ولكن هذه الطريقة أقل فعالية للجسيمات النانوية لأن القوى الطافية تكون ضئيلة عند النانو، ويمكن أن تتغير كثافة الجسيمات بسبب تلوث السطح. الطفو الرغوي، وهو تقنية فصل أخرى، غير مناسب عمومًا للبلاستيك بسبب فقد الجسيمات الكبير الناتج عن تفاعلات الفقاعات [38]. تعتمد فعالية فصل الكثافة أيضًا على كثافة المحلول الطافي. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تفصل المياه الخام فقط البلاستيكات ذات الكثافة المنخفضة مثل البوليسترين (PS)، والبولي إيثيلين (PE)، والبولي بروبيلين (PP) [39].

يمكن أن تصل المحاليل التي تحتوي على أملاح مثل

عادةً ما يتم استخدام المناخل الأولية لإزالة المواد الأكبر من العينة، ولكنها غير كافية للرواسب المعقدة، حيث يمكن أن تؤدي إلى آثار تتعلق بتعدد أشكال الجسيمات. الخطوة التالية عادةً ما تشمل هضم المادة العضوية، وغالبًا ما يتم تنفيذها باستخدام طريقة البيروكسيداز الرطبة أو كاشف فنتون، الذي يزيل بفعالية المواد العضوية المتبقية لتحسين دقة تحليل الجسيمات الدقيقة. يتطلب الأمر مزيدًا من الحذر في حالة استخدام كاشف فنتون لأن التفاعل الأكسيدي الشديد يمكن أن يغير أو يدمر الجسيمات الدقيقة [45]. على الرغم من أن طريقة البيروكسيداز الرطبة لا تؤثر على الجسيمات الدقيقة، فقد أظهرت بعض الدراسات أن هذه الطريقة قد تغير أو تهضم النايلون (البولي أميد، PA) والبولي إيثيلين منخفض الكثافة (LDPE) [46]. تعتمد طريقة أخرى في هضم المادة العضوية على الهضم الإنزيمي. هذه الطريقة أرخص ولكنها تستغرق وقتًا طويلاً؛ وقد تتفاعل الإنزيمات مع الشوائب الأخرى الموجودة في العينة مما يحد من فعاليتها [41].

على الرغم من التحديات والعيوب في الأساليب الحالية لمعالجة العينات والفصل، تبرز الدراسات الحديثة تطورات واعدة، خاصة للجسيمات النانوية، التي تتأثر بشكل كبير بالطرق المذكورة أعلاه. تناقش هذه القسم النتائج المهمة التي تم تحقيقها في عمليات الفصل، بما في ذلك التصفية والطرد المركزي، بالإضافة إلى الطرق المعتمدة على تكنولوجيا النانو التي تتضمن مواد نانوية جديدة. لفهم التطور في اكتشاف الجسيمات الدقيقة في

التقدم في عمليات التصفية والطرد المركزي

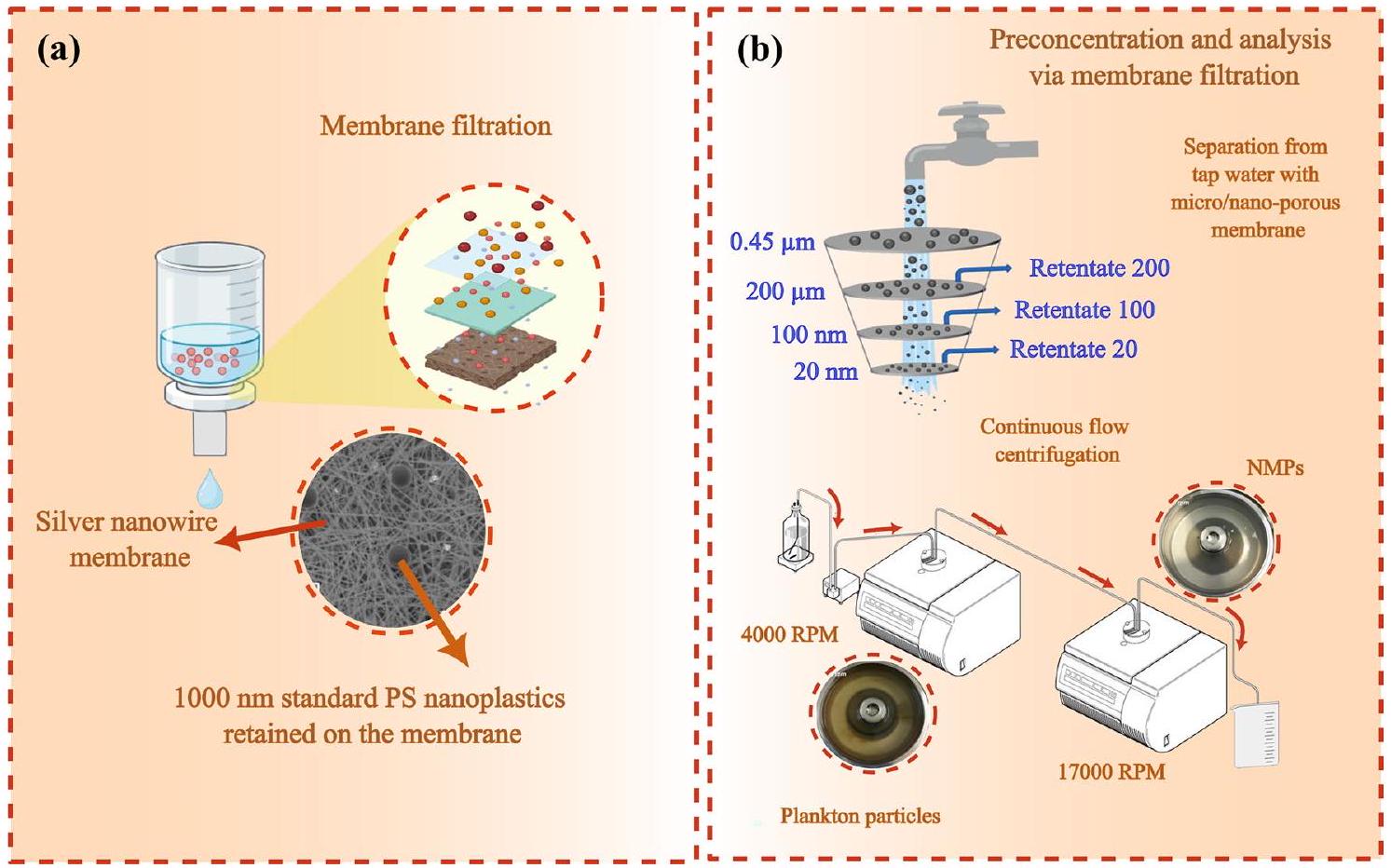

أبلغ هيلدبراندت وآخرون [50] عن جهازين طرد مركزي بتدفق مستمر (المخطط في الشكل 2c) مدمجين مع دوارات من التيتانيوم بسعة ترسيب تبلغ 300 مل.

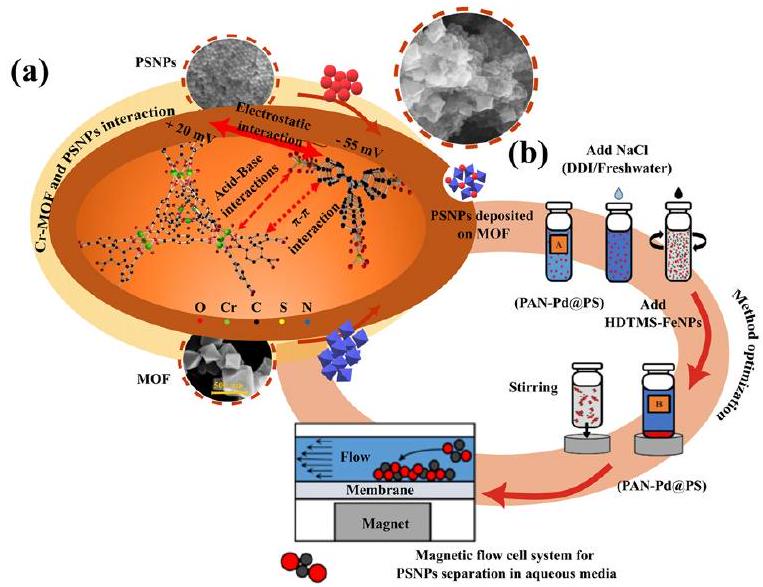

التطورات المعتمدة على تكنولوجيا النانو

التقدم في طرق قياس التيار التقدم في الطرق المجهرية المجهر الضوئي

بدون الفلورة أو التوسيم، يمكن أن يكون من الصعب تمييز الجسيمات الدقيقة البلاستيكية (NMPs) عن الجسيمات ذات الحجم المماثل مثل الحطام العضوي أو المعادن، مما يؤدي إلى سوء التعرف. يساعد التلوين بمواد مثل النيل الأحمر (NR)، وهو صبغة محبة للدهون، في تمييز الجسيمات الدقيقة البلاستيكية من خلال ارتباطها بالمواد الكارهة للماء وتنشيط الفلورة تحت أطوال موجية محددة. يقلل هذا التلوين التفضيلي للجسيمات البلاستيكية من خطر الخلط بينها وبين المواد غير البلاستيكية ويساعد في تحديد الجسيمات الأصغر التي تقل عن حد الانكسار. على سبيل المثال، تم استخدام النيل الأحمر للكشف عن الجسيمات الدقيقة البلاستيكية في مصفوفات معقدة وأنسجة من كائنات حية. للأسف، يمكن أن يعاني النيل الأحمر من آثار إيجابية زائفة، حيث يمكن أن يرتبط بمواد كارهة للماء أخرى مثل الدهون، مما يتطلب خطوات تأكيد إضافية.

على الرغم من التوسيم والفلورية، لا يزال التعرف الكيميائي على البوليمرات المختلفة يمثل تحديًا حيث إن عوامل الصبغ ليست محددة للبوليمرات. غالبًا ما يتطلب المجهر الضوئي العد اليدوي، مما يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً وعرضة للأخطاء، خاصةً بدون أدوات تحليل آلية. كما أن عمق المجال المحدود يعقد التركيز على الهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد في العينات السميكة. ومع ذلك، يمكن دمج المجهر الضوئي بسهولة مع تقنيات أخرى لتعزيز دقة الكشف.

المجهر الإلكتروني

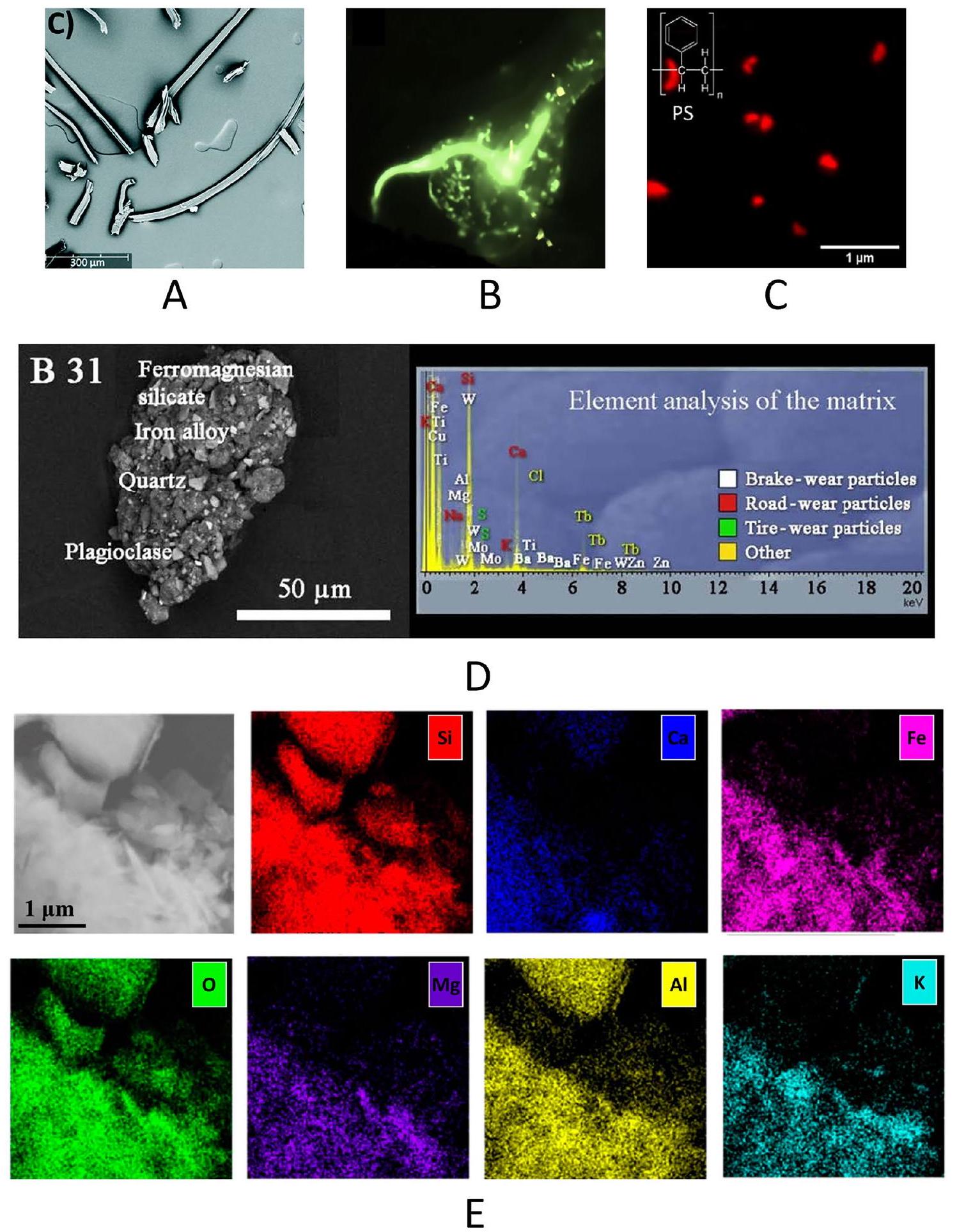

يوفر SEM تكبيرًا عاليًا ودقة، مما يسمح بملاحظة تفاصيل السطح الدقيقة مثل النسيج والعيوب والتلوث في MPs. عند دمجه مع التحليل الطيفي بالأشعة السينية المشتتة للطاقة (EDS/EDX)، يمكن أن يوفر SEM بيانات التركيب العنصري، مما يحدد الإضافات أو الملوثات. ومع ذلك، لا يمكن لرسم خرائط EDS التمييز بين أنواع البوليمرات/الإضافات المختلفة في المواد المعقدة [68]. من خلال تغيير عملية توليد شعاع الإلكترون، يوفر FE-SEM (المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح بإصدار المجال) تصويرًا عالي الدقة مقارنةً بـ SEM العادي. يضمن سطوعًا عاليًا وصورًا واضحة وتيار شعاع مستقر. تقدم الصورة 4a صورة FE-SEM بتكبير 350X تحدد ألياف السليلوز والبوليمر. الفلورية

يمكن أن ترتبط NPs بأصباغ متاحة تجاريًا ويمكن تحقيق التصوير فائق الدقة باستخدام STED (تقنية التصوير بالتحفيز بالإشعاع). تعتبر مجهر STED تقنية تصوير فلورية بعيدة المدى تتجاوز حد الانكسار عن طريق تبديل حالات جزيئات الصبغ بين الساطع والداكن، مما يصل إلى دقة 20 نانومتر. تم استخدام هذه التقنية مؤخرًا للتصوير عالي الدقة للبروتينات الملونة داخل الخلايا الحية [69].

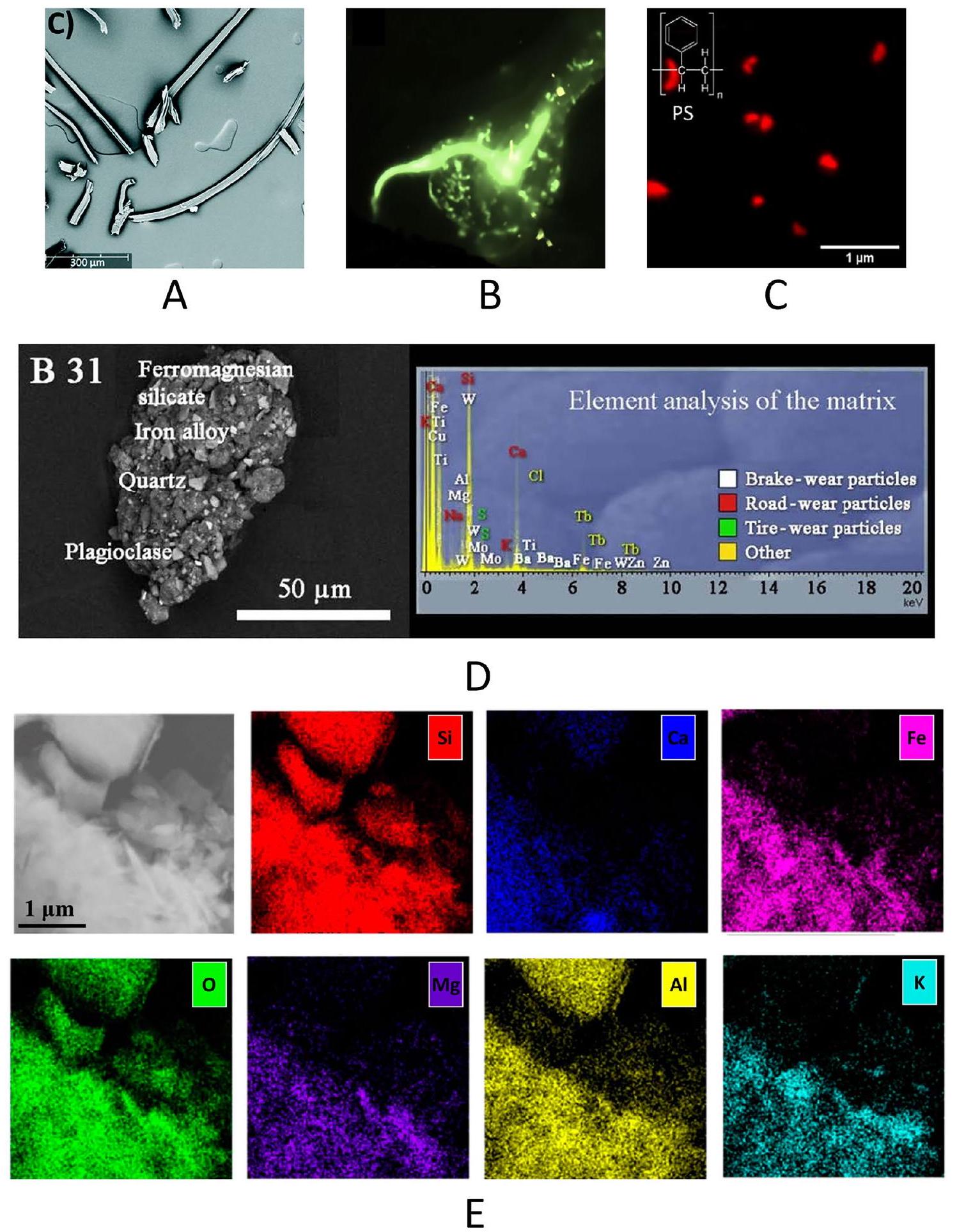

يمكن تحقيق تحسين تحليل MPs باستخدام تقنيات متقدمة مثل مجال الظلام الحلقي بزاوية عالية (HAADF) في TEM وتصوير الإلكترونات المرتدة (BSE) في SEM. يوفر HAADF صورًا عالية التباين بناءً على الرقم الذري (Z-contrast)، مما يجعله مفيدًا لتمييز الإضافات والمواد المالئة، حيث تظهر المواد ذات الأرقام الذرية الأعلى بشكل أكثر سطوعًا. مقترنًا مع EDX لرسم الخرائط العنصرية، تتيح هذه التقنيات الكمية الدقيقة وتحديد مواقع الإضافات أو الملوثات. تم تحليل جزيئات تآكل الإطارات في الغبار الجوي باستخدام BSE وEDX، مع خوارزميات التعلم الآلي للتشغيل الآلي. أظهرت صور SEM (الشكل 4d) لجزيئات تآكل الإطارات من المناطق الحضرية

تكتشف صور BSE في SEM الإلكترونات المشتتة المرتدة من سطح العينة. تعتمد شدة هذه الإلكترونات، وبالتالي سطوع الصورة، على الرقم الذري؛ حيث تشتت العناصر الأثقل المزيد من الإلكترونات، مما يخلق صورة أكثر سطوعًا. على سبيل المثال، استخدم سومر وآخرون BSE وEDX في SEM لتحليل شظايا MPs الفردية [72]، مما يوفر رؤى حول التأثير البيئي لتآكل الإطارات. استخدم بهات نفس التقنية لتحديد MPs من البيئة الداخلية [75].

باختصار، تعتبر أوضاع التصوير المتقدمة مثل HAADF في TEM وBSE في SEM حاسمة للتحليل التفصيلي لتكوين MPs. إنها توفر رؤى قيمة حول خصائص المواد والإضافات والملوثات والخصائص الهيكلية لـ MPs، والتي تعتبر ضرورية لفهم سلوكها البيئي وسميتها وتأثيراتها طويلة الأمد.

المجهر الذري

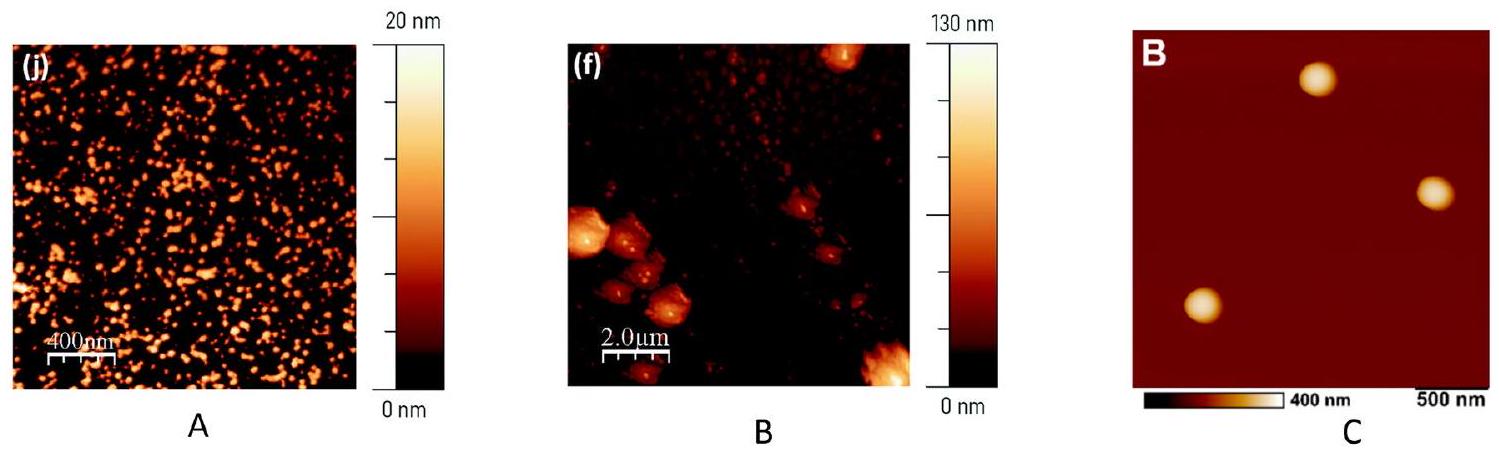

في دراسة مختلفة، [84] تم تصنيع نانو-

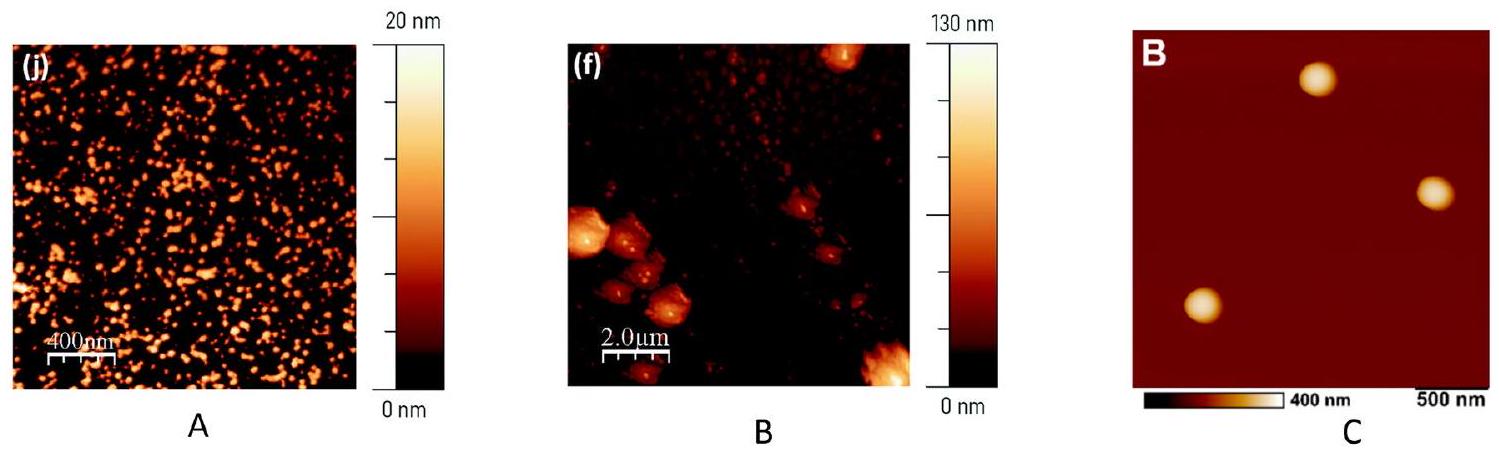

يوفر AFM بشكل أساسي بيانات طبوغرافية وميكانيكية، مع قدرة محدودة على تحديد التركيب الكيميائي للعينات. على عكس التقنيات الأخرى، لا يمكن لـ AFM التمييز بين أنواع البلاستيك المختلفة بناءً فقط على ميزات سطحها. يمكن تحقيق ذلك من خلال دمج AFM مع تقنيات مكملة للتعرف الكيميائي مما يؤدي إلى حل تحقيق قوي.

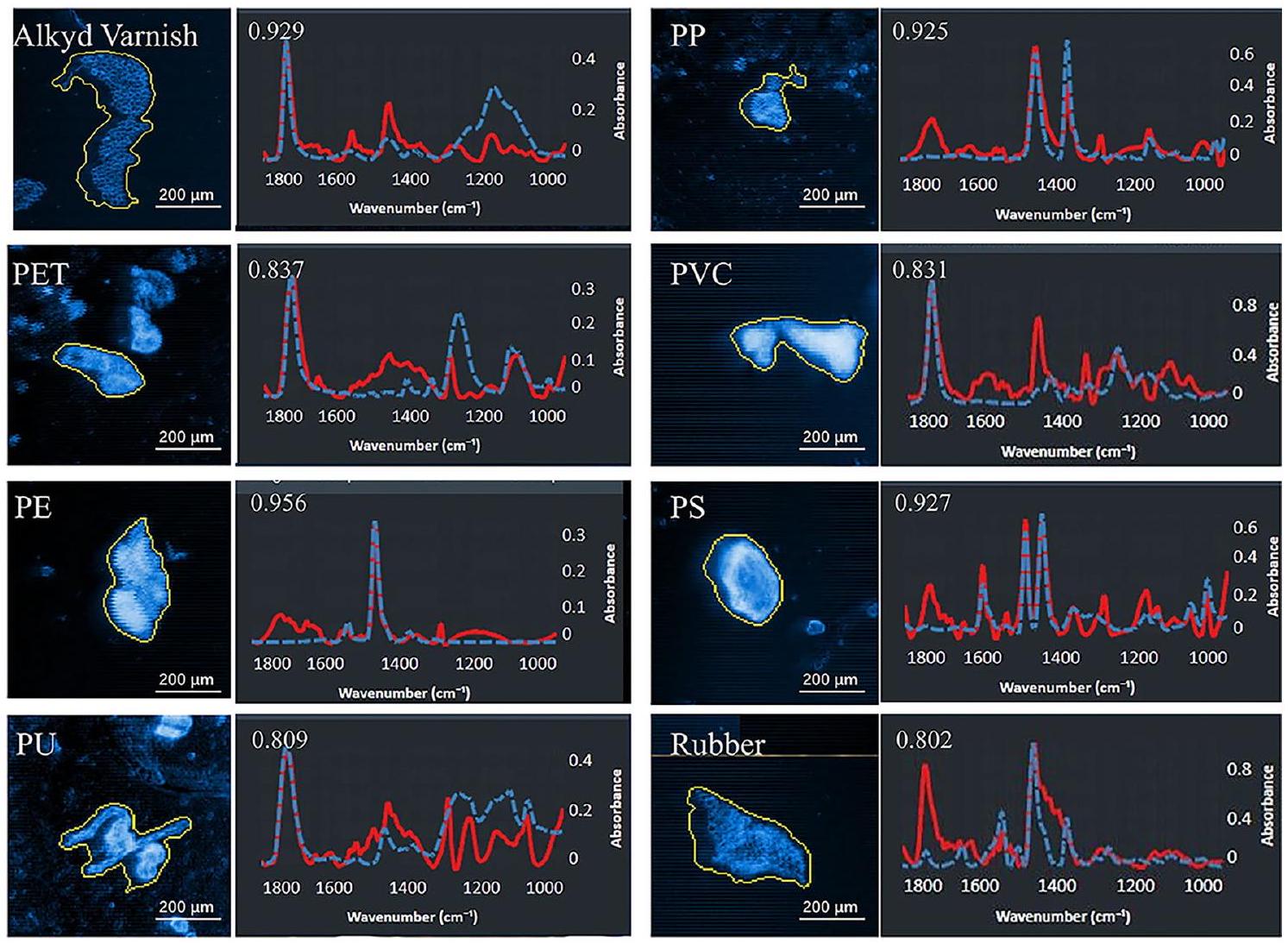

التطورات المعتمدة على الميكروسكوب الطيفي

التطورات المعتمدة على الأشعة تحت الحمراء

| نوع | طريقة | نطاق | التحديات | المزايا | المراجع. |

| الطيفية | DLS | 1 نانومتر إلى 3 مليمتر | الجسيمات الكبيرة، تأثير التوزيع المتعدد على النتائج | سريع، رخيص، غير جراحي | [86] |

| الطيفية | تشتت الليزر متعدد الزوايا (MALS) | 10 نانومتر إلى 1000 نانومتر | يتطلب عينة نظيفة ونماذج كروية فقط | ترابط عبر الإنترنت، نطاقات حجم كبيرة، سهل، سريع | [87] |

| الطيفية | تشتت الليزر (LD) | 10 نانومتر إلى 10 مليمتر | نموذج كروي فقط | سهل وسريع وآلي | [٨٨، ٨٩] |

| الطيفية | تحليل تتبع الجسيمات النانوية (NTA) | 10 نانومتر إلى

|

معقد في التشغيل | حجم وتركيز العدد | [90] |

| الطيفية | تشتت الضوء الكهربائي (ELS) |

|

التأثير الكهروأوزموزي | سريع، رخيص، غير جراحي | [٩١، ٩٢] |

| الطيفية | طيف رامان | حتى

|

صعوبة في تفسير البيانات للهياكل المعقدة, | غير مدمّر، سريع، موثوق | [93, 94] |

| ميكروسكوبي | المجهر الستيريو |

|

تحديد الطبيعة البلاستيكية، التركيب | سهل وسريع، تحديد الشكل والحجم واللون | [61] |

| ميكروسكوبي | تم | 0.1 نانومتر إلى

|

غير فعّال لتحديد النواب/ النواب الوطنيين | المعلومات الكيميائية والصور | [93] |

| ميكروسكوبي طيفي | تحليل المسح الإلكتروني للطاقة المشتتة | 5 نانومتر إلى 5 مليمتر | تقنية مكلفة | معلومات عن السطح الشكلي | [72] |

| ميكروسكوبي | AFM | حتى 0.1 نانومتر | مكلف، منطقة المسح محدودة

|

شكل السطح، الميكانيكا | [83] |

| ميكروسكوبي طيفي | AFM-IR | حتى 20 نانومتر | مكلف | شكل الجسيمات، التعرف الكيميائي | [95] |

| ميكروسكوبي طيفي | AFM-رامان | قدرة الكشف عن جزيء واحد | مكلف، قيد التطوير لتحليل المواد الكيميائية على نطاق نانوي بسرعة | شكل الجسيمات وبصمة كيميائية | [96] |

ATR-FTIR ذات صلة خاصة بالتحقيق في المواد الدقيقة غير المرغوب فيها (NMPs) لأنها تسمح بالتحليل المباشر للعينات الصلبة أو السائلة مع الحد الأدنى من التحضير. هذه التقنية تقدم الضوء تحت الأحمر مباشرة إلى العينة، مما يمكّن من استخراج المعلومات الهيكلية والتركيبية حتى من المصفوفات المعقدة. تُقدّر FTIR لقدرتها على توليد طيف عالي الجودة بسرعة، وسهولة الاستخدام، وقابلية التكرار. تشمل التحديات الشائعة التلوث المحتمل للخلفية، لكن ATR-FTIR تظل طريقة حساسة وفعالة من حيث التكلفة، قادرة على اكتشاف المواد الدقيقة.

على سبيل المثال، أظهر جهاز ATR-FTIR إشارات ذروة أقوى مع انخفاض قطر NMPS على مقياس الميكرومتر، مما سمح بالكشف عن NMPs بحساسية عالية في

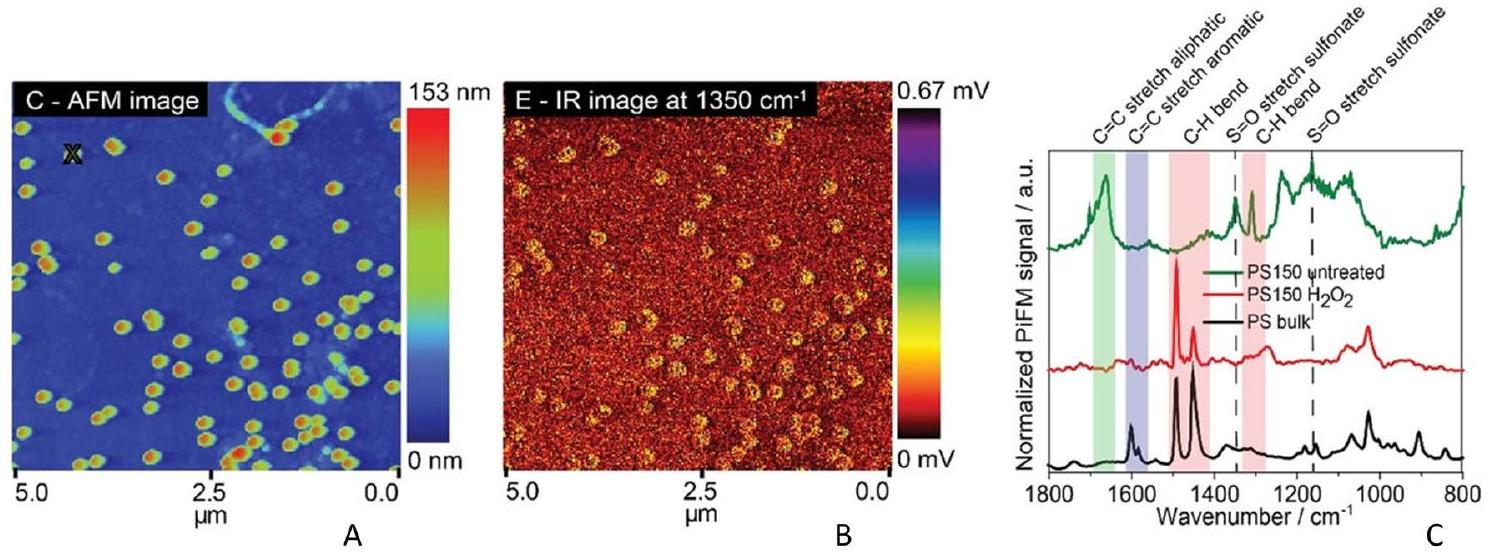

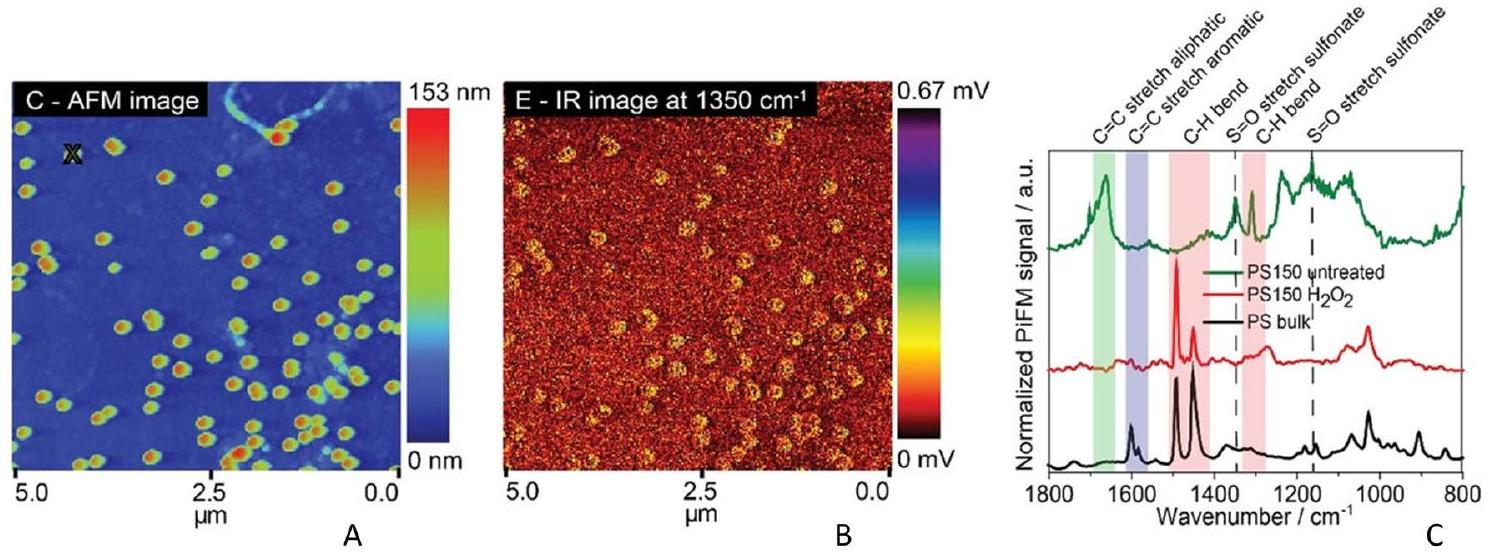

التضاريس والطيف الكيميائي. يوفر أوضاع رنين وبيانات عالية الجودة مع حساسية ممتازة، غير متأثرة بالواجهات الخلفية، ويتطابق مع الأطياف تحت الحمراء التقليدية للمواد الكتلية. ومع ذلك، فإنه بطيء ومعقد نسبيًا [103]. تم استخدام تقنية هجينة تجمع بين الدقة المكانية لتقنية AFM والمعلومات الكيميائية لطيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء لدراسة جزيئات PS على النانو. مكنت هذه الطريقة من الكشف عن وتحديد كميات الجسيمات النانوية التي تصل إلى 20 نانومتر في البيئات المائية [104]. مصدر IR قابل للتعديل بتردد نبضي مع

توضح الأشكال 6a-c فعالية تقنية AFM-IR في الكشف عن كرات PS بقطر 150 نانومتر بناءً على المجموعات السطحية. في الشكل 6b، يظهر السلفونات المميز

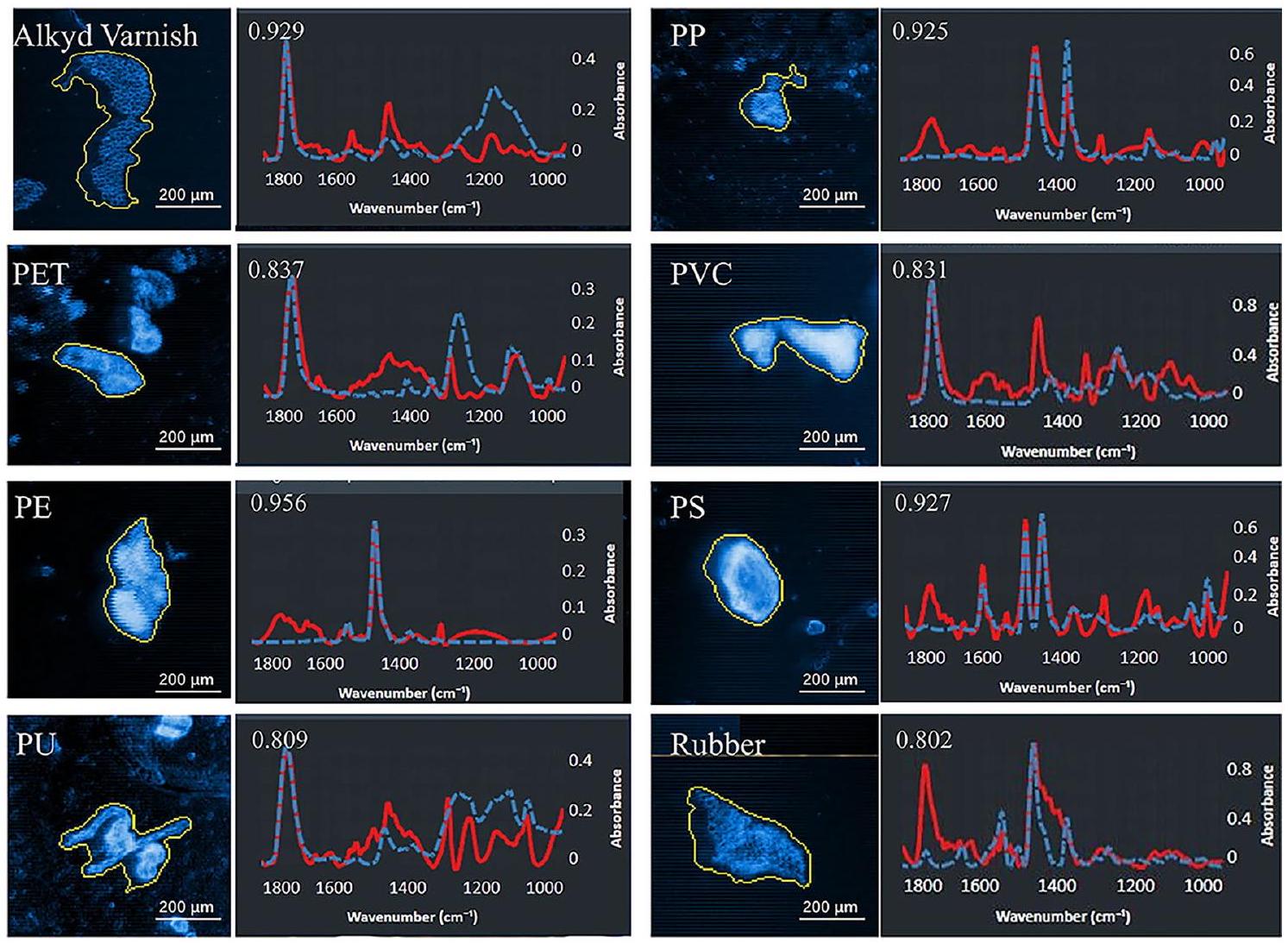

تظهر الشكل 7 طيف التصوير الكيميائي من تقنية LDIR. قام نظام LDIR بتحديد الجسيمات تلقائيًا ومطابقة الأطياف. أظهرت جميع الجسيمات الدقيقة في هذه الدراسة أكثر من

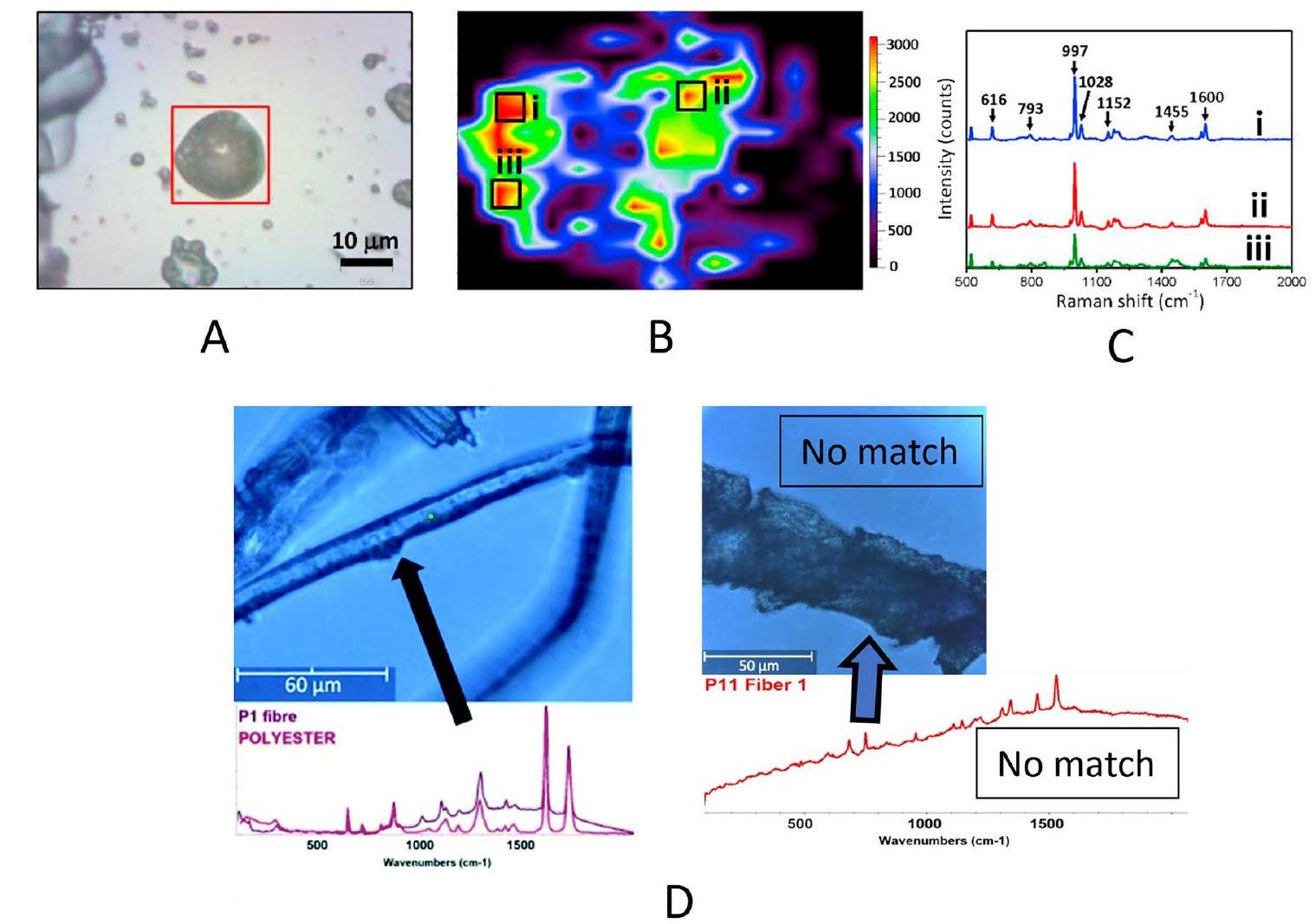

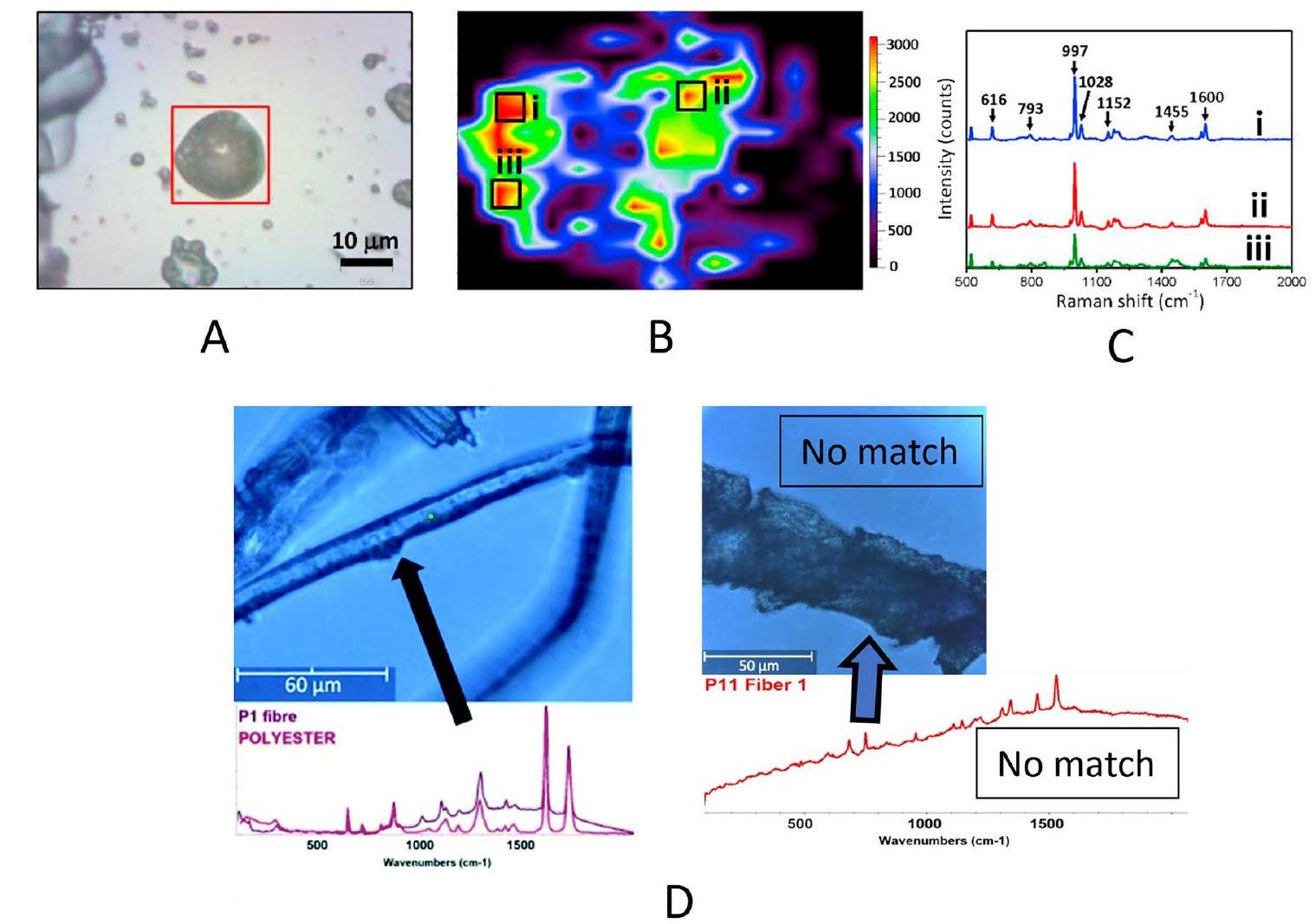

التطورات المعتمدة على طيف رامان

لمنع تدهور العينة والتألق، تم إجراء اختبارات معينة عند طاقة ليزر أقل. ومع ذلك، بالنسبة للجسيمات النانوية الأصغر من

تجمع تقنية طيف رامان المعززة بالرأس (TERS) بين الحساسية الكيميائية لـ SERS مع الدقة المكانية العالية لميكروسكوب المسبر الضوئي، مما يسمح بتصوير كيميائي على النطاق النانوي. يتم وضع رأس معدني حاد أو مغطى بالمعدن في مركز تركيز الليزر، حيث يتم حصر وتعزيز المجال الكهرومغناطيسي في قمة الرأس بواسطة الرنين البلازموني السطحي المحلي [115]. توفر TERS تقنية قوية لتحليل الأسطح بدقة نانومترية [116]. على مدار العقد الماضي، تم تطبيق هذه التقنية في مجموعة واسعة من مجالات البحث بما في ذلك أنابيب الكربون النانوية، الجرافين، البيولوجيا، الخلايا الشمسية، إلخ، ييو وآخرون [117]

أجروا استكشافًا على النطاق النانوي لطبقة رقيقة مختلطة من بولي إيزوبرين النشط رامان وPS للتحقيق في تركيبة السطح. على الرغم من صعوبة التشغيل، يمكن أن تستكشف هذه الطريقة الأفلام على مستويات السطح وتحت السطح وتميل إلى تمكين التحليل بدقة مكانية نانومترية.

التطورات في منهجيات أخرى تقدمات في طيف الكتلة

التطورات في التحليل الحراري

في TG-FTIR وTG-MS، يربط خط نقل أو شعري TGA مباشرة مع تحليل الغاز المتطور. هذه الطرق مفيدة لتحليل عينات المصفوفة المعروفة مع جزيئات دقيقة محددة وكشف PVC [124]. يمكن أن يكون التحليل الحراري-الاستخراج-التحليل الغازي لمطيافية الكتلة (TEDGC/MS) مفيدًا لتحليل عينات المصفوفة غير المعروفة مع أنواع متغيرة غير معروفة من الجسيمات الدقيقة والمحتوى ولكن الطريقة معقدة [125]. يمكن تطبيق مقياس الاحتراق المجهري (MCC) للت screening البسيط والسريع لتحديد الأحمال المحتملة للجسيمات الدقيقة من البوليمرات القياسية في عينات غير معروفة، لكن لا يوجد فرق بين البوليمرات المختلفة، حيث تساهم فقط PE وPP وPS بشكل كبير في الإشارة وتقتصر على 5 ملغ من العينة [124]. يمكن أن يحدد Py-GC-MS (التحليل الحراري-الغاز الكروماتوغرافي-مطيافية الكتلة) في الوقت نفسه ويقيس الجسيمات الدقيقة الأكثر انتشارًا في عينات معقدة.

التطورات في تقنية تشتت الضوء

تقدمات تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي

على سبيل المثال، ربط غوان وآخرون [126] بيانات المختبر حول امتصاص أيونات المعادن على NMPs بمراقبة البيئة باستخدام الشبكات العصبية للتنبؤ. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تجعل القيود في حجم مجموعة البيانات للامتصاص، وتنوع خصائص NMPs ومناطق أخذ العينات، هذا التنبؤ صعبًا. كفئة فرعية من الشبكات العصبية

الشبكات، الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية (CNN) غير حساسة للدوران والترجمة، مما يجعلها فعالة في التعرف على الصور. قام نج وآخرون [127] بتطبيق هذا الخوارزم لتصنيف مدى تلوث الجسيمات النانوية في عينات التربة حيث تم استخدام طيف الانعكاس المرئي بالقرب من الأشعة تحت الحمراء (vis-NIR) كمدخلات أحادية البعد. آلة الدعم الناقل (SVM) هي فئة من التعلم الآلي المراقب التي تصنف البيانات من خلال إيجاد مستوى فائق يعظم المسافة بين مجموعات البيانات المختلفة. تُستخدم للتصنيف العام، وتتطلب تدريبًا طويل الأمد، مما يجعلها غير مناسبة لمجموعات البيانات الكبيرة. قام شان وآخرون بدمج التصوير الطيفي الفائق (HSI) مع SVM لت quantifying تلوث الجسيمات النانوية في ترشيحات مياه البحر [128]. الغابة العشوائية وشجرة القرار هما طريقتان من طرق التعلم الآلي المستخدمة للتصنيف والانحدار. يمكنهما تحديد أو اكتشاف الميزات والأنماط، بالإضافة إلى توقع الفئات والقيم المستمرة. استخدم هوفناجل وآخرون هذه الطرق للتحليل التلقائي لـ

على الرغم من التقارير العديدة، لا يزال تطوير خوارزميات جديدة وقواعد بيانات لاكتشاف وتحليل الجزيئات النانوية غير المرئية باستخدام أساليب قائمة على التعلم الآلي أمرًا ضروريًا. تغطي مطيافية رامان، المستخدمة على نطاق واسع لاكتشاف الجزيئات النانوية غير المرئية، مجموعة متنوعة من النطاقات: التربة (

وجهات نظر

| طريقة | نهج | ميزة | عيب | المراجع. |

| إيه إن إن | توقع سعة الامتصاص لأيونات المعادن الثقيلة على NMPs | دراسة حالة ذات إمكانيات عالية مرتبطة بالتجارب المخبرية | تعيق بيانات الامتصاص المحدودة التطبيق الأوسع | [126] |

| سي إن إن | تصنيف بيانات الطيف تحت الأحمر المدخلة | فحص تلوث التربة المحتمل السريع لمواد NMP | عدم القدرة على تمييز الحالات المتوسطة | [127] |

| سي إن إن | هيكل GoogLeNet كنموذج تم تدريبه واختباره لتحليل الصور | تصنيف NMPs التلقائي المحتمل باستخدام الصور المجهرية | مقتصر على الكريات الدقيقة | [130] |

| SVM | لتحديد النواب من الصورة الطيفية الفائقة | القدرة على قياس وتحديد المواد غير المعروفة من مياه البحر ومرشحات مياه البحر | يمكن أن تؤثر حجم الجسيمات ونوع البوليمر والشوائب العضوية على الدقة | [128] |

| SVM | نموذج Repfile-EasyTL: استراتيجية التعلم الانتقالي لتحقيق النقل من نظام HIS إلى مستشعر NIR | سريع، دقيق، أقل تعقيداً | التداخل من المواد العضوية، النيتروجين القابل للهيدروlysis القلوي، والفوسفور المتاح | [131] |

| SVM | تصوير ثلاثي الأبعاد متماسك مع التعلم الآلي لاكتشاف الجزيئات النانوية | التوقيعات الهولوجرافية للمواد النانوية | في الوقت الحالي محدود بعينات المياه | [132] |

| RF |

|

يمكنه تمييز أنواع البوليمرات، ووفرتها وتوزيع حجمها | يمكن أن تؤثر ضوضاء التسمية والأبعاد المختلفة | [129] |

قد تلعب المواد النانوية الوظيفية المتقدمة دورًا حاسمًا في فصل الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة، مع إمكانية تصميم مواد تستهدف هذه الجسيمات بشكل محدد. ومع ذلك، فإن نقص العلامات الفريدة على الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة (المشابهة للعلامات الحيوية على أسطح الخلايا) يمثل تحديًا كبيرًا لفصلها واكتشافها بشكل مستهدف. إن معالجة هذا القيد أمر ضروري لتقدم طرق الكشف. من حيث تقنيات الكشف والتعرف التي تم مناقشتها في هذه المخطوطة، فإن المجهر الضوئي غير قادر على اكتشاف الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة التي تقل عن 200 نانومتر، بينما يمكن لطرق المجهر الإلكتروني اكتشاف الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة على النطاق النانوي ولكنها تفتقر إلى القدرة على التعرف عليها كيميائيًا. تعتبر تقنيات مثل FE-SEM وTEM أدوات قوية للتصوير عالي الدقة ولتحليل الشكل والبنية والتركيب العنصري للجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة. ومع ذلك، فإن إعداد العينات لهذه الطرق يمثل تحديًا، حيث يتطلب تجنب التلوث وتمييز الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة عن المواد الأخرى في العينات المعقدة. يمكن أن يميز المجهر الذري (AFM) الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة على النطاق النانوي ويوفر معلومات سطحية مفصلة، لكنه مكلف ويستغرق وقتًا طويلاً، مما يحد من عمليته للكشف الروتيني. تظهر أدوات المجهر الطيفي إمكانيات كبيرة لتحقيق التعرف الشكلي والكيميائي للجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة في وقت واحد. تعتبر تقنيات الطيف تحت الأحمر وطيف رامان، عند اقترانها بتقنيات مجهرية (مثل AFM-IR و

ورامان-المجهر التداخلي)، واعدة بالفعل بسبب قدرتها على توفير كل من التصوير والتعرف الكيميائي للجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة. من بين هذه التقنيات، يعتبر طيف رامان فعالًا بشكل خاص في اكتشاف الجسيمات حتى النطاق دون الميكرومتر، وهو نطاق غالبًا ما تكافح فيه تقنيات الطيف تحت الأحمر بسبب الإشارات الضعيفة الناتجة عن التركيزات الضئيلة وقيود الدقة المكانية المفروضة بواسطة الأطوال الموجية الأطول. بينما تعتبر مطيافية الكتلة دقيقة للغاية وحساسة وقادرة على تحليل مكونات متعددة، إلا أنها محدودة في اكتشاف الجسيمات التي تقل عن 50 نانومتر وتتطلب إعداد عينات معقدة ومكلفة. على الرغم من أن التحليل الحراري الوزني (TGA) مفيد لتقييم الخصائص الحرارية، إلا أنه لا يمكنه توفير معلومات جزيئية أو كيميائية، وهو قيد يمكن معالجته من خلال اقترانه بتقنيات مكملة. يوفر تشتت الضوء الديناميكي (DLS) تحليلًا سريعًا وغير مدمر للجسيمات في نطاق النانو إلى الميكرومتر، لكنه مقيد بالجسيمات المعلقة ويكافح مع العينات المتعددة الأشكال.

تلعب الذكاء الاصطناعي دورًا مهمًا في الكشف أو التعرف على الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة من خلال تحسين تحليل البيانات والدقة والكفاءة. يمكن لخوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي، وخاصة التعلم الآلي والتعلم العميق، معالجة بيانات الطيف والتصوير المعقدة لتحديد وتصنيف الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة بدقة. وبالتالي، فإن استخراج الميزات الآلي وتعزيز الإشارات يعززان قدرات التعرف، بينما يساعد النمذجة التنبؤية في تقييم التلوث وتحليل الأثر البيئي. تسهل هذه الخوارزميات إنشاء مكتبات شاملة أو قواعد بيانات لتوقيعات الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة، مما يمكّن من التعرف الفعال عبر أنواع العينات المختلفة والبيئات. يمكن أيضًا دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي مع تكنولوجيا الاستشعار لتمكين الاستشعار والت monitoring.

أحد الأمثلة الملحوظة هو الهولوجرافيا الرقمية (DH)، التي تقدم إمكانيات كبيرة للكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة. على عكس

تستخدم الهولوجرافيا الرقمية، على عكس الطرق التقليدية، مستشعرًا لعرض الهولوجرامات، مما يمكّن من تحديد عشرات الآلاف من العناصر في الساعة. عند دمجها مع الذكاء الاصطناعي، تصبح الهولوجرافيا الرقمية مناسبة للغاية لتحليل جودة المياه في الموقع، مما يوفر كفاءة لا مثيل لها في التطبيقات عالية الإنتاجية [132]. على الرغم من هذه التقدمات، لا تزال التحديات قائمة، خاصة في توحيد إجراءات معالجة العينات. يجب مراعاة عوامل مثل نوع العينة والمصدر والكمية بعناية لتجنب تغيير الخصائص الجوهرية للجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة. على سبيل المثال، بينما يظهر المجهر الذري (AFM) قدرات اكتشاف استثنائية على النطاق النانوي، إلا أنه لا يمكنه تحديد الأنواع الكيميائية للجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة. يمكن معالجة هذا القيد من خلال اقتران AFM بتقنيات أخرى، مثل AFM-IR أو TERS، لتوفير كل من التوصيف الشكلي والكيميائي. كما أظهرت مطيافية LDIR وعدًا كأداة متعددة الاستخدامات للكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة وتحديدها وتصنيفها. ومع ذلك، لا يزال تحقيق دقة عالية على النطاق النانوي يمثل تحديًا، مما يتطلب تقدمًا في المجهر النانوي ودمج التحقيقات الخاصة بالمواد. مع استمرار الابتكار وتطبيق الذكاء الاصطناعي، يمكن التغلب على هذه التحديات، مما يمهد الطريق لحلول أكثر فعالية وقابلية للتوسع في تحليل الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة.

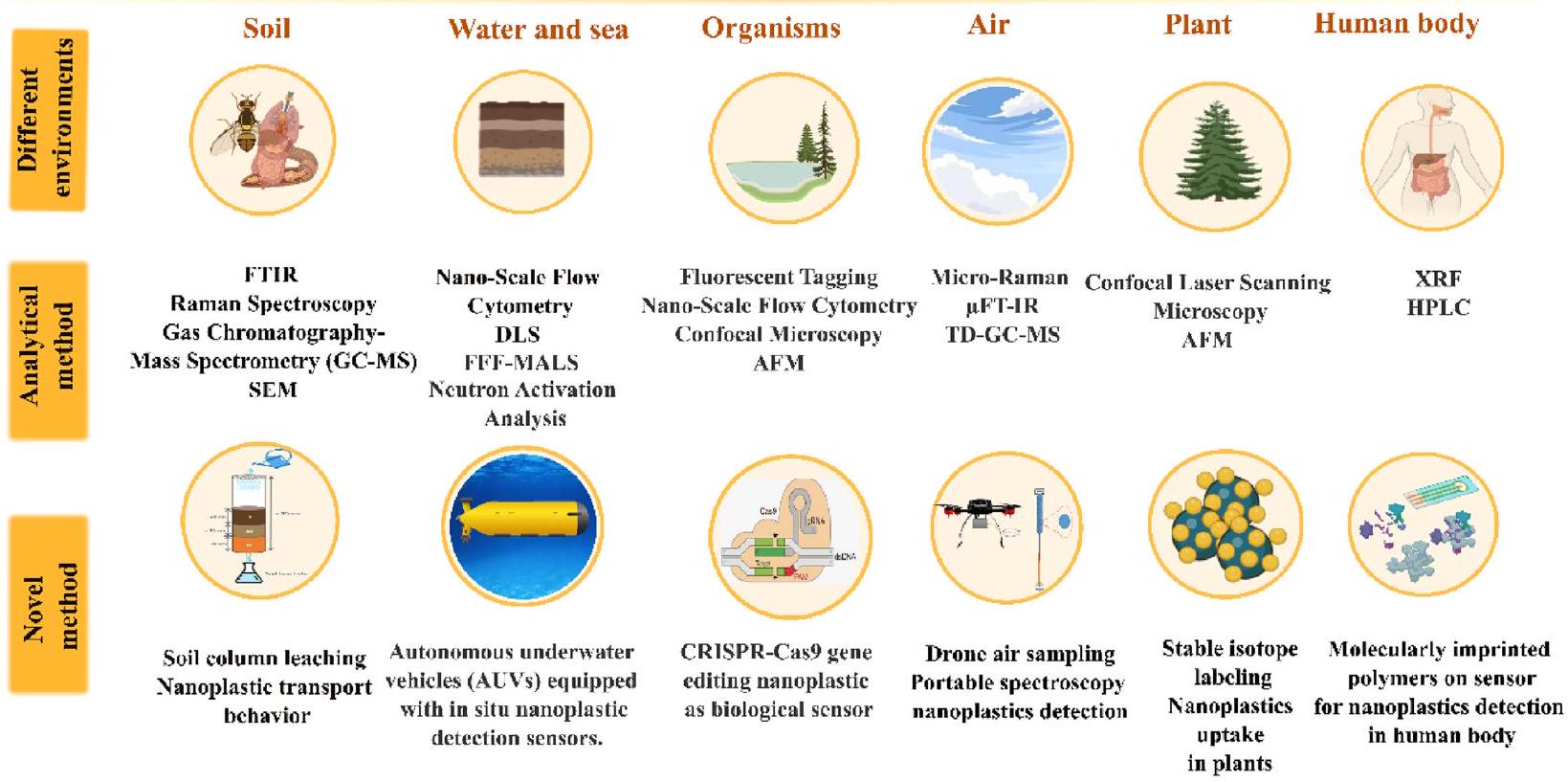

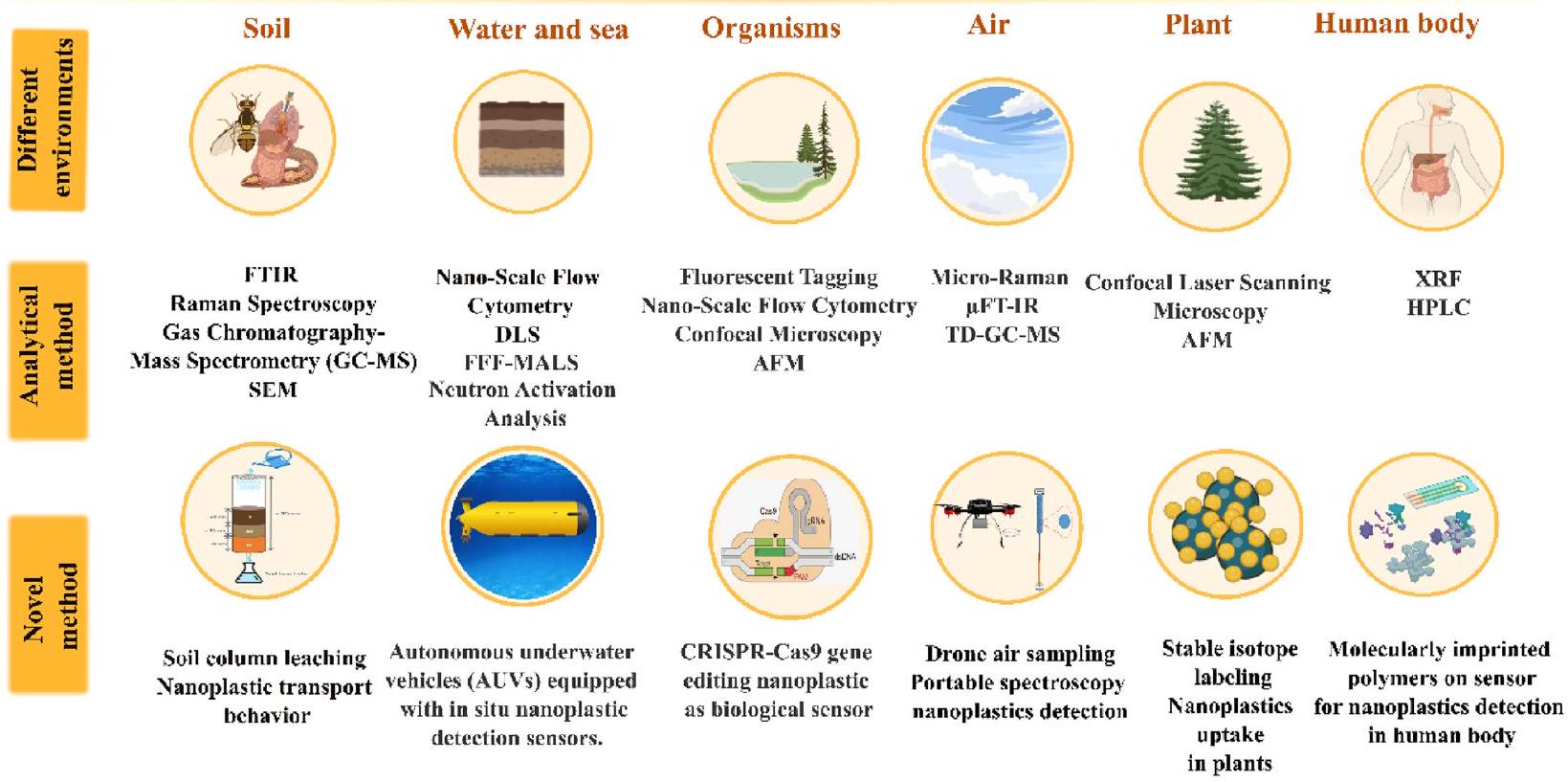

يوضح الشكل 9 النهج المحتملة التي يمكن تطويرها للكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة في سيناريوهات مختلفة، مما يوفر إطارًا شاملًا ورؤى متعمقة لتقدم تقنيات جديدة. بينما لا يوجد نهج واحد

فعال لكل سيناريو، تسلط الدراسات الحديثة الضوء على استراتيجيات مكملة وتحليل متعدد الخصائص في الطريق لحل مشكلة الكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة على النطاق النانوي. إن تطوير طرق موثوقة وجديدة أمر ضروري للتقدم المستمر في الكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة وتحليلها. يتطلب اتخاذ السياسات والقرارات الفعالة للتغلب على مشكلة الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة تلبية الاحتياجات العلمية والتنظيمية والاجتماعية الأساسية. يجب أن تملأ اتجاهات البحث المستمرة الفجوات المعرفية لضمان تطوير سياسات شاملة ضد الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة[135].

الخاتمة

تحديد الجسيمات الميكروية والنانوية أمر ضروري لإدارتها الفعالة. يجب إنشاء طريقة قوية للكشف والتعرف على الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة لمعالجة هذه التحديات. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يعتمد نجاح هذه الطرق على توحيد إجراءات معالجة العينات وتقنيات الفصل. لذلك، يشمل الكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة ثلاثة جوانب رئيسية: أخذ العينات، معالجة العينات، الفصل والكشف بالإضافة إلى التعرف. بشكل عام، هناك حاجة إلى جهود أكبر عبر هذه المجالات لتعزيز المعرفة والتقنيات الحالية في الكشف عن الجسيمات النانوية الدقيقة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 08 يناير 2025

References

- Ter Halle A, Ghiglione JF (2021) Nanoplastics: a complex, polluting terra incognita. Environ Sci Technol 55:14466-14469. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acs.est.1c04142

- Cai H, Xu EG, Du F, Li R, Liu J, Shi H (2021) Analysis of environmental nanoplastics: progress and challenges. Chem Eng J 410:128208. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.128208

- Kokilathasan N, Dittrich M (2022) Nanoplastics: detection and impacts in aquatic environments—a review. Sci Total Environ 849:157852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157852

- Ng EL, Huerta Lwanga E, Eldridge SM, Johnston P, Hu H, Geissen V, Chen D (2018) An overview of microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in agroecosystems. Sci Total Environ 627:1377-1388. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.341

- Ullah R, Tsui MTK, Chow A, Chen H, Williams C, Ligaba-Osena A (2023) Micro(nano)plastic pollution in terrestrial ecosystem: emphasis on impacts of polystyrene on soil biota, plants, animals, and humans. Environ Monit Assess 195:252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10769-3

- Lai H, Liu X, Qu M (2022) Nanoplastics and human health: hazard identification and biointerface. Nanomaterials 12(8):1298. https://doi.org/10. 3390/nano12081298

- Chamas A, Moon H, Zheng J, Qiu Y, Tabassum T, Jang JH, Abu-Omar M, Scott SL, Suh S (2020) Degradation rates of plastics in the environment. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 8:3494-3511. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssu schemeng.9b06635

- Pérez-Reverón R, Álvarez-Méndez SJ, González-Sálamo J, Socas-Hernández C, Díaz-Peña FJ, Hernández-Sánchez C, Hernández-Borges J (2023) Nanoplastics in the soil environment: analytical methods, occurrence, fate and ecological implications. Environ Pollut 317:120788. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120788

- Delre A, Goudriaan M, Morales VH, Vaksmaa A, Ndhlovu RT, Baas M, Keijzer E, de Groot T, Zeghal E, Egger M, Röckmann T, Niemann H (2023) Plastic photodegradation under simulated marine conditions. Mar PolIut Bull 187:114544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114544

- Yu J, Wang S, Zhang HQ, Song XR, Liu LF, Jinag Y, Chen R, Zhang Q, Chen YQ, Zhou HJ, Yang GP (2024) Effects of nanoplastics exposure on ingestion, life history traits, and dimethyl sulfide production in rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. Environ Pollut 344:123308. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.envpol.2024.123308

- Ouda M, Kadadou D, Swaidan B, Al-Othman A, Al-Asheh S, Banat F, Hasan SW (2021) Emerging contaminants in the water bodies of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): a critical review. Sci Total Environ 754:142177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142177

- Pedrotti ML, Petit S, Eyheraguibel B, Kerros ME, Elineau A, Ghiglione JF, Loret JF, Rostan A, Gorsky G (2021) Pollution by anthropogenic microfibers in North-West Mediterranean Sea and efficiency of microfiber removal by a wastewater treatment plant. Sci Total Environ 758:144195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144195

- Ryan AC, Allen D, Allen S, Maselli V, LeBlanc A, Kelleher L, Krause S, Walker TR, Cohen M (2023) Transport and deposition of ocean-sourced microplastic particles by a North Atlantic hurricane. Commun Earth Environ 4:442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01115-7

- Allen S, Allen D, Phoenix VR, Le Roux G, Jiménez PD, Simonneau A, Binet S, Galop D (2019) Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat Geosci 12:339-344. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0335-5

- Viaroli S, Lancia M, ReV (2022) Microplastics contamination of groundwater: current evidence and future perspectives. A Rev Sci Total Environ 824:153851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153851

- Mitrano DM, Wick P, Nowack B (2021) Placing nanoplastics in the context of global plastic pollution. Nat Nanotechnol 16:491-500. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41565-021-00888-2

- Wahl A, le Juge C, Davranche M, El Hadri H, Grassl B, Reynaud S, Gigault J (2021) Nanoplastic occurrence in a soil amended with plastic debris. Chemosphere 262:127784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere. 2020.127784

- Wang W, Zhang J, Qiu Z, Cui Z, Li N, Li X, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhao C (2022) Effects of polyethylene microplastics on cell membranes: a combined study of experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. J Hazard Mater 429:128323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022. 128323

- Barcelo D, Pico Y (2020) Case studies of macro- and microplastics pollution in coastal waters and rivers: Is there a solution with new removal technologies and policy actions? Case Stud Chem Environ Eng 2:100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100019

- Barchiesi M, Chiavola A, Di Marcantonio C, Boni MR (2021) Presence and fate of microplastics in the water sources: focus on the role of wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. J Water Process Eng 40:101787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101787

- Chia RW, Lee JY, Jang J, Cha J (2022) Errors and recommended practices that should be identified to reduce suspected concentrations of microplastics in soil and groundwater: a review. Environ Technol Innov 28:102933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2022.102933

- Huang J, Chen H, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Gao B (2021) Microplastic pollution in soils and groundwater: characteristics, analytical methods

and impacts. Chem Eng J 425:131870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej. 2021.131870 - He D, Luo Y, Lu S, Liu M, Song Y, Lei L (2018) Microplastics in soils: analytical methods, pollution characteristics and ecological risks. TrAC. Trends Anal Chem 109:163-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2018.10. 006

- Mahapatra S, Maity JP, Singha S, Mishra T, Dey G, Samal AC, Banerjee P, Biswas C, Chattopadhyay S, Patra RR, Patnaik S, Bhattacharya P (2024) Microplastics and nanoplastics in environment: sampling, characterization and analytical methods. Groundw Sustain Dev 26:101267. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.gsd.2024.101267

- Zheng K, Wang P, Lou X, Zhou Z, Zhou L, Hu Y, Luan Y, Quan C, Fang J, Zou H, Gao X (2024) A review of airborne micro- and nano-plastics: sampling methods, analytical techniques, and exposure risks. Environ Pollut 363:125074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125074

- Choi S, Lee S, Kim MK, Yu ES, Ryu YS (2024) Challenges and recent analytical advances in micro/nanoplastic detection. Anal Chem 96:88468854. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c05948

- Thomas C, Spatayeva T, Yu D, Loh A, Yim UH, Yoon JY (2024) A comparison of current analytical methods for detecting particulate matter and micro/nanoplastics. Appl Phys Rev 11:011313. https://doi.org/10. 1063/5.0153106

- Xue Y, Song K, Wang Z, Xia Z, Li R, Wang Q, Li L (2024) Nanoplastics occurrence, detection methods, and impact on the nitrogen cycle: a review. Environ Chem Lett 22:2241-2255. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10311-024-01764-w

- Saha N, Shourie A (2024) Detection and characterization of micro- and nano-plastics in wastewater: current status of preparatory & analytical techniques. Environ Qual Manage 34(2):e22267. https://doi.org/10. 1002/tqem. 22267

- Casella C, Vadivel D, Dondi D (2024) The current situation of the legislative gap on microplastics (MPs) as new pollutants for the environment. Water Air Soil Pollut 235:778. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11270-024-07589-1

- Jakubowicz I, Enebro J, Yarahmadi N (2021) Challenges in the search for nanoplastics in the environment-a critical review from the polymer science perspective. Polym Test 93:106953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. polymertesting.2020.106953

- Viaroli S, Lancia M, Lee JY, Ben Y, Giannecchini R, Castelvetro V, Petrini R, Zheng C, Re V (2024) Limits, challenges, and opportunities of sampling groundwater wells with plastic casings for microplastic investigations. Sci Total Environ 946:174259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024. 174259

- Lee JY, Jung J, Raza M (2022) Good field practice and hydrogeological knowledge are essential to determine reliable concentrations of microplastics in groundwater. Environ Pollut 308:119617. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.envpol.2022.119617

- Lee JY, Cha J, Ha K, Viaroli S (2024) Microplastic pollution in groundwater: a systematic review. Environ Pollut Bioavailabil 36:2299545. https:// doi.org/10.1080/26395940.2023.2299545

- Chia RW, Lee JY, Cha J, Rodríguez-Seijo A (2024) Methods of soil sampling for microplastic analysis: a review. Environ Chem Lett 22:227-238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01652-9

- Lai Y, Dong L, Li Q, Li P, Liu J (2021) Sampling of micro- and nanoplastics in environmental matrixes. TrAC Trends Anal Chem 145:116461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2021.116461

- Azari A, Vanoirbeek JAJ, Van Belleghem F, Vleeschouwers B, Hoet PHM, Ghosh M (2023) Sampling strategies and analytical techniques for assessment of airborne micro and nano plastics. Environ Int 174:107885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.107885

- Nguyen B, Claveau-Mallet D, Hernandez LM, Xu EG, Farner JM, Tufenkji N (2019) Separation and analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics in complex environmental samples. Acc Chem Res 52:858-866. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00602

- Vaughan R, Turner SD, Rose NL (2017) Microplastics in the sediments of a UK urban lake. Environ Pollut 229:10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envpol.2017.05.057

- Schütze B, Thomas D, Kraft M, Brunotte J, Kreuzig R (2022) Comparison of different salt solutions for density separation of conventional and biodegradable microplastic from solid sample matrices. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:81452-81467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21474-6

- Razeghi N, Hamidian AH, Mirzajani A et al (2022) Sample preparation methods for the analysis of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: a review. Environ Chem Lett 20:417-443. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10311-021-01341-5

- Merga LB, Redondo-Hasselerharm PE, Van den Brink PJ, Koelmans AA (2020) Distribution of microplastic and small macroplastic particles across four fish species and sediment in an African lake. Sci Total Environ 741:140527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140527

- Shruti VC, Jonathan MP, Rodriguez-Espinosa PF, Rodríguez-González F (2019) Microplastics in freshwater sediments of Atoyac River basin, Puebla City. Mexico Sci Total Environ 654:154-163. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.054

- Turner S, Horton AA, Rose NL, Hall C (2019) A temporal sediment record of microplastics in an urban lake, London. UK J Paleolimnol 61:449-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10933-019-00071-7

- Savino I, Campanale C, Trotti P, Massarelli C, Corriero G, Uricchio VF (2022) Effects and impacts of different oxidative digestion treatments on virgin and aged microplastic particles. Polymers 14(10):1958. https:// doi.org/10.3390/polym14101958

- Peng L, Mehmood T, Bao R, Wang Z, Fu D (2022) An overview of micro(nano)plastics in the environment: sampling, identification. Risk Assess Control Sustain 14(21):14338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142 114338

- Keerthana Devi M, Karmegam N, Manikandan S, Subbaiya R, Song H, Kwon EE, Sarkar B, Bolan N, Kim W, Rinklebe J, Govarthanan M (2022) Removal of nanoplastics in water treatment processes: a review. Sci Total Environ 845:157168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022. 157168

- Yang Q, Zhang S, Su J, Li S, Lv X, Chen J, Zhan LY (2022) Identification of trace polystyrene nanoplastics down to 50 nm by the hyphenated method of filtration and surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy based on silver nanowire membranes. Environ Sci Technol 56:10818-10828. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c02584

- Li Y, Wang Z, Guan B (2022) Separation and identification of nanoplastics in tap water. Environ Res 204:112134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envres.2021.112134

- Hildebrandt L, Mitrano DM, Zimmermann T, Pröfrock D (2020) A nanoplastic sampling and enrichment approach by continuous flow centrifugation. Front Environ Sci 8:89. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs. 2020.00089

- Ali I, Tan X, Mustafa G, Gao J, Peng C, Naz I, Duan Z, Zhu R, Ruan Y (2024) Removal of micro- and nanoplastics by filtration technology: performance and obstructions to market penetrations. J Clean Prod 470:143305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143305

- Juraij K, Ammed SP, Chingakham C, Ramasubramanian B, Ramakrishna S, Vasudevan S, Sujith A (2023) Electrospun polyurethane nanofiber membranes for microplastic and nanoplastic separation. ACS Appl Nano Mater 6(6):4636-4650. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c00112

- Lapointe M, Kurusu RS, Hernandez LM, Tufenkji N (2023) Removal of classical and emerging contaminants in water treatment using superbridging fiber-based materials. ACS EST Water 3:377-386. https://doi. org/10.1021/acsestwater.2c00443

- Grause G, Kuniyasu Y, Chien MF, Inoue C (2022) Separation of microplastic from soil by centrifugation and its application to agricultural soil. Chemosphere 288:132654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere. 2021.132654

- Modak S, Kasula M, Esfahani MR (2023) Nanoplastics removal from water using metal-organic framework: investigation of adsorption mechanisms, kinetics, and effective environmental parameters. ACS Appl Eng Mater 1:744-755. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaenm.2c00174

- Surette MC, Mitrano DM, Rogers KR (2023) Extraction and concentration of nanoplastic particles from aqueous suspensions using functionalized magnetic nanoparticles and a magnetic flow cell. Microplast Nanoplast 3:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43591-022-00051-1

- Liang Y, Hu S, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Guo G, Wang X (2022) Determination of nanoplastics using a novel contactless conductivity detector with controllable geometric parameters. Anal Chem 94:1552-1558. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c02752

- Liu P, Wu L, Guo Y, Huang X, Guo Z (2024) High crystalline LDHs with strong adsorption properties effectively remove oil and micro-nano

plastics. J Clean Prod 437:140628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024. 140628 - Wang H, Zhou Q (2024) Bioelectrochemical systems-a potentially effective technology for mitigating microplastic contamination in wastewater. J Clean Prod 450:141931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro. 2024.141931

- Ebnesajjad

(2014) Surface and Material Characterization Techniques. Surface Treatment of Materials for Adhesive Bonding. 39-75. https:// doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-26435-8.00004-6 - Song YK, Hong SH, Jang M, Han GM, Rani M, Lee J, Shim WJ (2015) A comparison of microscopic and spectroscopic identification methods for analysis of microplastics in environmental samples. Mar Pollut Bull 93:202-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.01.015

- Forte M, lachetta G, Tussellino M, Carotenuto R, Prisco M, De Falco M, Laforgia V, Valiante S (2016) Polystyrene nanoparticles internalization in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells. Toxicol in Vitro 31:126-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TIV.2015.11.006

- Maes T, Jessop R, Wellner N, Haupt K, Mayes AG (2017) A rapid-screening approach to detect and quantify microplastics based on fluorescent tagging with Nile Red. Sci Rep 7:44501. https://doi.org/10.1038/SREP4 4501

- Maxwell SH, Melinda KF, Matthew G (2020) Counterstaining to separate nile red-stained microplastic particles from terrestrial invertebrate biomass. Environ Sci Technol 54:5580-5588. https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.est.0c00711

- Nguyen B, Tufenkji N (2022) Single-particle resolution fluorescence microscopy of nanoplastics. Environ Sci Technol 56:6426-6435. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c08480

- Lee JJ, Kang J, Kim C (2024) A low-cost TICT-based staining agent for identification of microplastics: Theoretical studies and simple, costeffective smartphone-based fluorescence microscope application. J Hazard Mater 465:133168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023. 133168

- Tarafdar A, Choi SH, Kwon JH (2022) Differential staining lowers the false positive detection in a novel volumetric measurement technique of microplastics. J Hazard Mater 432:128755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jhazmat.2022.128755

- Silva AB, Bastos AS, Justino CIL, da Costa JP, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos TAP (2018) Microplastics in the environment: challenges in analytical chemistry—a review. Anal Chim Acta 1017:1-19. https://doi.org/10. 1016/J.ACA.2018.02.043

- Shang L, Gao P, Wang H, Popescu R, Gerthsen D, Nienhaus GU (2017) Protein-based fluorescent nanoparticles for super-resolution STED imaging of live cells. Chem Sci 8:2396-2400. https://doi.org/10.1039/ c6sc04664a

- Munoz LP, Baez AG, Purchase D, Jones H, Garelick H (2022) Release of microplastic fibres and fragmentation to billions of nanoplastics from period products: Preliminary assessment of potential health implications. Environ Sci Nano 9:606-620. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1en00755f

- Valsesia A, Parot J, Ponti J, Mehn D, Marino R, Melillo D, Muramoto S, Verkouteren M, Hackley VA, Colpo P (2021) Detection, counting and characterization of nanoplastics in marine bioindicators: a proof of principle study. Microplast Nanoplast 1:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s43591-021-00005-z

- Sommer F, Dietze V, Baum A, Sauer J, Gilge S, Maschowski C, Giere R (2018) Tire abrasion as a major source of microplastics in the environment. Aerosol Air Qual Res 18:2014-2028. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr. 2018.03.0099

- Riboni N, Ribezzi E, Nasi L, Mattarozzi M, Piergiovanni M, Masino M, Bianchi F, Careri M (2024) Characterization of small micro-and nanoparticles in antarctic snow by electron microscopy and raman micro-spectroscopy. Appl Sci 14(4):1597. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14041597

- Yang T, Xu Y, Liu G, Nowack B (2024) Oligomers are a major fraction of the submicrometre particles released during washing of polyester textiles. Nat Water 2:151-160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00191-5

- Bhat MA (2024) Airborne microplastic contamination across diverse university indoor environments: a comprehensive ambient analysis. Air Qual Atmos Health 17:1851-1866. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11869-024-01548-9

- Fu W, Zhang W (2017) Hybrid AFM for nanoscale physicochemical characterization: recent development and emerging applications. Small 13:1603525. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 201603525

- Cheng S, Bryant R, Doerr SH, Wright CJ, Williams PR (2009) Investigation of surface properties of soil particles and model materials with contrasting hydrophobicity using atomic force microscopy. Environ Sci Technol 43:6500-6506. https://doi.org/10.1021/es900158y

- Nguyen T, Petersen EJ, Pellegrin B, Lam GJM (2017) Impact of UV irradiation on multiwall carbon nanotubes in nanocomposites: formation of entangled surface layer and mechanisms of release resistance. Carbon 116:191-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBON.2017.01.097

- Zhang W, Crittenden J, Li K, Chen Y (2012) Attachment efficiency of nanoparticle aggregation in aqueous dispersions: modeling and experimental validation. Environ Sci Technol 46:7054-7062. https://doi. org/10.1021/es203623z

- Dussud C, Meistertzheim AL, Conan P, Pujo-Pay M, George M, Fabre P, Coudane J, Higgs P, Elineau A, Pedrotti ML, Gorsky G, Ghiglione JF (2018) Evidence of niche partitioning among bacteria living on plastics, organic particles and surrounding seawaters. Environ Pollut 236:807816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.027

- Dussud C, Hudec C, George M, Fabre P, Higgs P, Bruzaud S, Delort AM, Eyheraguibel B, Meistertzheim AL, Jacquin J, Cheng J, Callac N, Odobel C, Rabouille S, Ghiglione JF (2018) Colonization of non-biodegradable and biodegradable plastics by marine microorganisms. Front Microbiol 9:1571. https://doi.org/10.3389/FMICB.2018.01571

- Ducoli S, Federici S, Nicsanu R, Zendrini A, Marchesi C, Paolini L, Radeghieri A, Bergese P, Depero LE (2022) A different protein corona cloaks “true-to-life” nanoplastics with respect to synthetic polystyrene nanobeads. Environ Sci Nano 9:1414-1426. https://doi.org/10.1039/ d1en01016f

- Akhatova F, Ishmukhametov I (2022) Nanomechanical atomic force microscopy to probe cellular microplastics uptake and distribution. Int J Mol Sci 23(2):806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23020806

- Luo H, Xiang Y, Li Y, Zhao Y, Pan X (2021) Photocatalytic aging process of Nano-TiO2 coated polypropylene microplastics: combining atomic force microscopy and infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) for nanoscale chemical characterization. J Hazard Mater 404:124159. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2020.124159

- Dazzi A, Prater CB, Hu Q, Chase DB, Rabolt JF, Marcott C (2012) AFM-IR: combining atomic force microscopy and infrared spectroscopy for nanoscale chemical characterization. Appl Spectrosc 66:1365-1384. https://doi.org/10.1366/12-06804

- Stetefeld J, Mckenna SA, Patel TR (2016) Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophys Rev 8:409-427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-016-0218-6

- Austin J, Minelli C, Hamilton D, Wywijas M, Jones HJ (2020) Nanoparticle number concentration measurements by multi-angle dynamic light scattering. J Nanopart Res 22:108. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11051-020-04840-8

- Grubbs J, Tsaknopoulos K, Massar C, Young B, O’Connell A, Walde C, Birt A, Siopis M, Cote D (2021) Comparison of laser diffraction and image analysis techniques for particle size-shape characterization in additive manufacturing applications. Powder Technol 391:20-33. https://doi. org/10.1016/J.POWTEC.2021.06.003

- Keck CM, Müller RH (2008) Size analysis of submicron particles by laser diffractometry—

of the published measurements are false. Int J Pharm 355:150-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJPHARM.2007.12.004 - Gross J, Sayle S, Karow AR, Bakowsky U, Garidel P (2016) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of particle size and concentration detection in suspensions of polymer and protein samples: Influence of experimental and data evaluation parameters. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 104:30-41. https:// doi.org/10.1016/J.EJPB.2016.04.013

- Huang G, Xu B, Qiu J, Peng L, Luo K, Liu D, Han P (2020) Symmetric electrophoretic light scattering for determination of the zeta potential of colloidal systems. Colloids Surf A 587:124339. https://doi.org/10.1016/J. COLSURFA.2019.124339

- Carvalho PM, Felicio MR, Santos NC, Goncalves S, Domingues MM (2018) Application of light scattering techniques to nanoparticle characterization and development. Front Chem 6:237. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fchem.2018.00237

- Mariano S, Tacconi S, Fidaleo M, Rossi M, Dini L (2021) Micro and nanoplastics identification: classic methods and innovative detection techniques. Front Toxicol 3:636640. https://doi.org/10.3389/ftox.2021. 636640

- Prata JC, Paço A, Reis V, da Costa JP, Fernandes AJS, da Costa FM, Duarte AC, Rocha-Santos T (2020) Identification of microplastics in white wines capped with polyethylene stoppers using micro-Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem 331:127323. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2020. 127323

- Merzel RL, Purser L, Soucy TL, Olszewski M, Colón-Bernal I, Duhaime M, Elgin AK, Banaszak Holl MM (2019) Uptake and retention of nanoplastics in quagga mussels. Global Chall 4(6):1800104. https://doi.org/10. 1002/gch2.201800104

- Yeo BS, Stadler J, Schmid T, Zenobi R, Zhang W (2009) Tip-enhanced raman spectroscopy-its status, challenges and future directions. Chem Phys Lett 472:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2009.02.023

- Khan SA, Khan SB, Khan LU, Farooq A, Akhtar K, Asiri AM (2018) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: fundamentals and application in functional groups and nanomaterials characterization. Handbook Mater Char 10:317-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92955-2_9

- Asamoah BO, Uurasjärvi E, Räty J, Koistinen A, Roussey M, Peiponen KE (2021) Towards the development of portable and in situ optical devices for detection of micro and nanoplastics in water : a review on the current status. Polymers 13(5):730. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13050 730

- Chen Y, Wen D, Pei J, Fei Y, Ouyang D, Zhang H, Luo Y (2020) Identification and quantification of microplastics using fourier- transform infrared spectroscopy: current status and future prospects. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 18:14-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coesh.2020.05.004

- Othman AM, Elsayed AA, Sabry YM, Khalil D, Bourouina T (2023) Detection of Sub-20

m microplastic particles by attenuated total reflection fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and comparison with raman spectroscopy. ACS Omega 8:10335-10341. https://doi.org/10.1021/ acsomega.2c07998 - Jung MR, Horgen FD, Orski SV, Rodriguez CV, Beers KL, Balazs GH, Jones TT, Work TM, Brignac KC, Royer SJ, Hyrenbach KD, Jensen BA, Lynch JM (2018) Validation of ATR FT-IR to identify polymers of plastic marine debris, including those ingested by marine organisms. Mar Pollut Bull 127:704-716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.12.061

- Liong RMY, Hadibarata T, Yuniarto A, Tang KHD, Khamidun MH (2021) Microplastic occurrence in the water and sediment of miri river estuary. Borneo Island Water Air Soil Pollut 232:342. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s11270-021-05297-8

- Jafari M, Nowak DB, Huang S, Abrego JC, Yu T, Du Z, Hammouti B, Jeffali F, Touzani R, Ma D, Siaj M (2023) Photo-induced force microscopy applied to electronic devices and biosensors. Mater Today Proc 72:3904-3910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.10.216

- ten Have C (2021) Photoinduced force microscopy as an efficient method towards the detection of nanoplastics. Chem Methods 1:205-209. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmtd. 202100017

- Carruthers H, Clark D, Clarke FC, Faulds K, Graham D (2022) Evaluation of laser direct infrared imaging for rapid analysis of pharmaceutical tablets. Anal Methods 14:1862-1871. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ay0 0471b

- Hildebrandt L, El Gareb F, Zimmermann T, Klein O, Kerstan A, Emeis KC, Pröfrock D (2022) Spatial distribution of microplastics in the tropical Indian Ocean based on laser direct infrared imaging and microwave-assisted matrix digestion. Environ Pollut 307:119547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119547

- Ivleva NP (2021) Chemical analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics: challenges, advanced methods, and perspectives. Chem Rev 121:11886-11936. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev. 1 c00178

- Bao M, Huang Q, Lu Z, Collard F, Cai M, Huang P, Yu Y, Cheng S, An L, Wold A, Gabrielsen GW (2022) Investigation of microplastic pollution in Arctic fjord water: a case study of Rijpfjorden, Northern Svalbard. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:56525-56534. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11356-022-19826-3

- Ribeiro-Claro P, Nolasco MM, Araújo C (2017) Characterization of microplastics by raman spectroscopy. Comprehensive Anal Chem 75:119-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.COAC.2016.10.001

- Xie L, Gong K, Liu Y, Zhang L (2023) Strategies and challenges of identifying nanoplastics in environment by surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. Environ Sci Technol 57:25-43. https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.est.2c07416

- Zhang J, Peng M, Lian E, Xia L, Asimakopoulos AG, Luo S, Wang L (2023) Identification of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) nanoplastics in commercially bottled drinking water using surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. Environ Sci Technol 57:8365-8372. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acs.est.3c00842

- Gillibert R, Balakrishnan G, Deshoules Q, Tardivel M, MagazzùA DMG, Maragò OM, de La Chapelle ML, Colas F, Lagarde F, Gucciardi PG (2019) Raman tweezers for small microplastics and nanoplastics identification in seawater. Environ Sci Technol 53:9003-9013. https://doi. org/10.1021/acs.est.9b03105

- Mogha NK, Shin D (2023) Nanoplastic detection with surface enhanced raman spectroscopy: present and future. TrAC – Trends Anal Chem 158:116885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116885

- Zhou XX, Liu R, Hao LT, Liu JF (2021) Identification of polystyrene nanoplastics using surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Talanta 221:121552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121552

- Cao Y, Sun M (2022) Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Rev Phys 8:100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revip.2022.100067

- Kumar N, Mignuzzi S, Su W, Roy D (2015) Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: principles and applications. EPJ Tech Instrum 2:9. https:// doi.org/10.1140/epjti/s40485-015-0019-5

- Yeo BS, Amstad E, Schmid T, Stadler J, Zenobi R (2009) Nanoscale probing of a polymer-blend thin film with Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Small 5:952-960. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 20080 1101

- Lin Y, Huang X, Liu Q, Lin Z, Jinag G (2020) Thermal fragmentation enhanced identification and quantification of polystyrene micro/ nanoplastics in complex media. Talanta 208:120478. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120478

- Habumugisha T, Zhang Z, Fang C, Yan C, Zhang X (2023) Uptake, bioaccumulation, biodistribution and depuration of polystyrene nanoplastics in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci Total Environ 893:164840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164840

- Liu S, Zhao H, Liu Z, Zhang W, Lai C, Zhao S, Cai X, Qi Y, Zhao Q, Li R, Wang F (2022) High-performance micro/nanoplastics characterization by MALDI-FTICR mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 307:135601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135601

- Mansa R, Zou S (2021) Thermogravimetric analysis of microplastics: a mini review. Environ Adv 5:100117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv. 2021.100117

- Picó Y, Barceló D (2020) Pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in environmental analysis: focus on organic matter and microplastics. TrAC – Trends Anal Chem 130:115964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac. 2020.115964

- Majewsky M, Bitter H, Eiche E, Horn H (2016) Determination of microplastic polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) in environmental samples using thermal analysis (TGA-DSC). Sci Total Environ 568:507-511. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2016.06.017

- Goedecke C, Dittmann D, Eisentraut P et al (2020) Evaluation of thermoanalytical methods equipped with evolved gas analysis for the detection of microplastic in environmental samples. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 152:104961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2020.104961

- Duemichen E, Eisentraut P, Celina M, Braun U, Wiesner Y, Schartel B, Klack P, Braun U (2019) Automated thermal extraction-desorption gas chromatography mass spectrometry: a multifunctional tool for comprehensive characterization of polymers and their degradation products. J Chromatogr A 1592:133-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHROMA.2019. 01.033

- Guo X, Wang J (2021) Projecting the sorption capacity of heavy metal ions onto microplastics in global aquatic environments using artificial neural networks. J Hazard Mater 402:123709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jhazmat.2020.123709

- Ng W, Minasny B, McBratney A (2020) Convolutional neural network for soil microplastic contamination screening using infrared spectroscopy. Sci Total Environ 702:134723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019. 134723

- Shan J, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Liu L, Wu F, Wang X (2019) Simple and rapid detection of microplastics in seawater using hyperspectral imaging technology. Anal Chim Acta 1050:161-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aca.2018.11.008

- Hufnagl B, Steiner D, Renner E, Löder MGJ, Laforsch C, Lohninger H (2019) A methodology for the fast identification and monitoring of microplastics in environmental samples using random decision forest classifiers. Anal Methods 11:2277-2285. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9AY0 0252A

- Yurtsever M, Yurtsever U (2019) Use of a convolutional neural network for the classification of microbeads in urban wastewater. Chemosphere 216:271-280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.084

- Zhao S, Qiu Z, He Y (2021) Transfer learning strategy for plastic pollution detection in soil: calibration transfer from high-throughput HSI system to NIR sensor. Chemosphere 272:129908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chemosphere.2021.129908

- Bianco V, Memmolo P, Carcagnì P, Merola F, Paturzo M, Distante C, Ferraro

Microplastic identification via holographic imaging and machine learning. Adv Intell Syst 2:1900153. https://doi.org/10.1002/ aisy. 201900153 - Xie L, Luo S, Liu Y, Ruan X, Gong K, Ge Q, Li K, Valev VK, Liu G, Zhang L (2023) Automatic Identification of individual nanoplastics by Raman spectroscopy based on Machine Learning. Environ Sci Technol. https:// doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c03210

- Weber F, Zinnen A, Kerpen J (2023) Development of a machine learning-based method for the analysis of microplastics in environmental samples using

-Raman spectroscopy. Microplast Nanoplast 3:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43591-023-00057-3 - Duncan TV, Khan SA, Patri AK, Wiggins S (2024) Regulatory science perspective on the analysis of microplastics and nanoplastics in human food. Anal Chem 96:4343-4358. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem. 3c05408

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم أجيكيا نيني وسرور صادق زاده بالتساوي.

*المراسلة:

ماسيميليانو غالوتزي

galluzzi@siat.ac.cn

مختبر الالتهاب واللقاحات، معهد شنتشن للتكنولوجيا المتقدمة، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، شنتشن 518055، قوانغدونغ، الصين

المختبر الرئيسي لشنتشن للميكانيكا اللينة والتصنيع الذكي، قسم الميكانيكا وهندسة الفضاء، الجامعة الجنوبية للعلوم والتكنولوجيا، شنتشن 518055، الصين

كلية الهندسة، جامعة ويستليك، هانغتشو 310024، الصين

قسم علوم الأرض، جامعة بيزا، بيزا، إيطاليا

المختبر المشترك بين الصين وإيطاليا للبيوتكنولوجيا الدوائية لتعديل المناعة الطبية، شنتشن 518055، الصين

قسم العلوم والتكنولوجيا البيئية والبيولوجية والصيدلانية (DiSTABiF)، جامعة الدراسات في كامبانيا “لويجي فانفيتيلي”، كاسيرتا، إيطاليا

مدرسة الشرائح، كلية رواد الأعمال XJTLU (تايتسانغ)، جامعة شيان جياوتونغ-ليفربول تايتسانغ، سوتشو 215400، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-024-01044-y

Publication Date: 2025-01-08

Recent advances and future technologies in nano-microplastics detection

Abstract

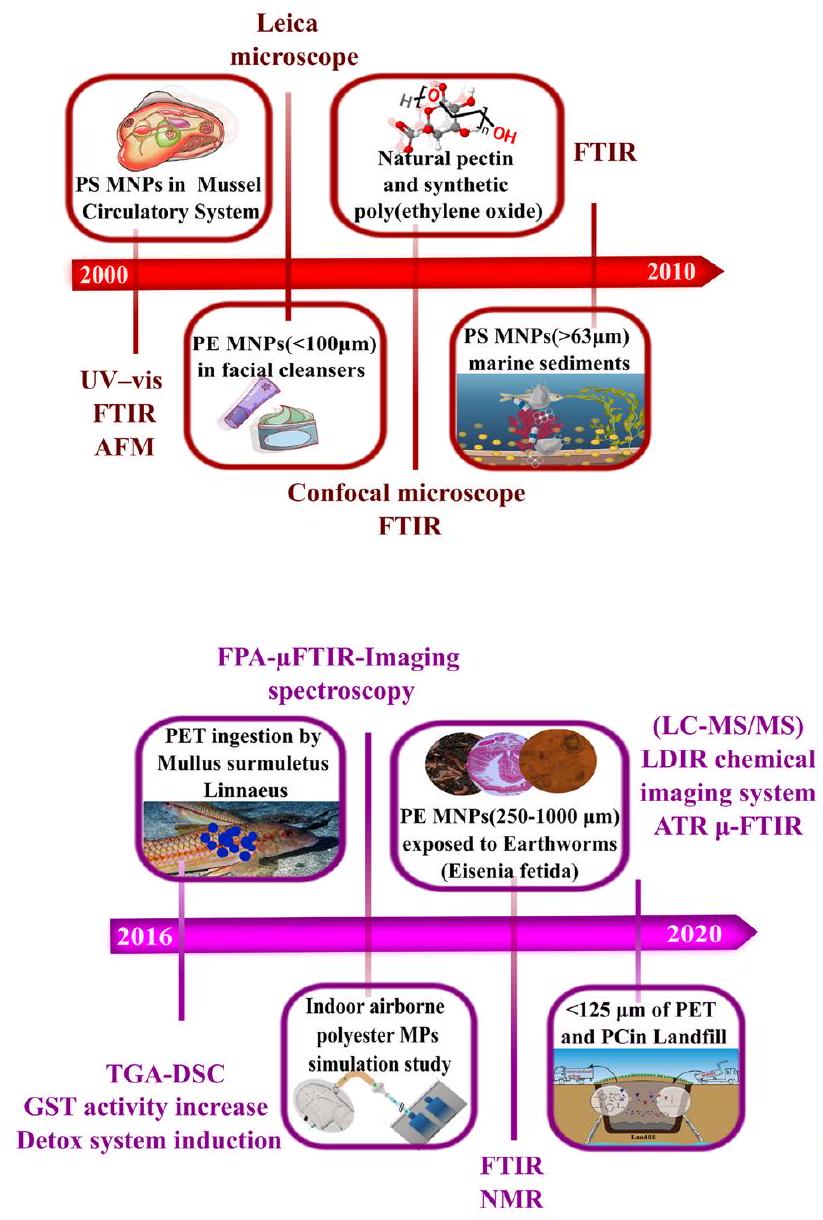

The degradation of mismanaged plastic waste in the environment results in the formation of microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs), which pose significant risks to ecosystems and human health. These particles are pervasive, detected even in remote regions, and can enter the food chain, accumulating in organisms and causing harm depending on factors such as particle load, exposure dose, and the presence of co-contaminants. Detecting and analyzing NMPs present unique challenges, particularly as particle size decreases, making them increasingly difficult to identify. Moreover, the absence of standardized protocols for their detection and analysis further hinders comprehensive assessments of their environmental and biological impacts. This review provides a detailed overview of the latest advancements in technologies for sampling, separation, measurement, and quantification of NMPs. It highlights promising approaches, supported by practical examples from recent studies, while critically addressing persistent challenges in sampling, characterization, and analysis. This work examines cutting-edge developments in nanotechnology-based detection, integrated spectro-microscopic techniques, and AI-driven classification algorithms, offering solutions to bridge gaps in NMP research. By exploring state-of-the-art methodologies and presenting future perspectives, this review provides valuable insights for improving detection capabilities at the microand nanoscale, enabling more effective analysis across diverse environmental contexts.

Introduction

Environmental degradation of MPs can be initiated by biotic processes (involving enzymes, other biomaterials, bacteria, fungi, etc.), abiotic processes (such as thermal oxidation, photo-oxidation, mechanical degradation and atmospheric oxidation), or a combination of both [8]. Photodegradation, particularly through UV light, can cause fragmentation and breakage of polymers chains, resulting in reactive byproducts [9]. NMPs pollution is ubiquitous, extending beyond urban areas to remote regions [10-12].

Therefore, quantifying and characterizing NMPs using cost-effective and straightforward methods is essential. The dispersion of NMPs in the environment can be driven by climatic factors such as wind and rainfall, leading to both wet and dry deposition in remote areas [13, 14]. The presence of NMPs in surface waters and groundwater is primarily determined by hydrogeological conditions and proximity to major pollution sources [15]. Despite ongoing research, many aspects of the global circulation of plastics and NMPs in the environment remain unclear [13]. NMPs can enter the body and interact with cells, potentially leading to toxic effects influenced by factors such as plastic size, dose, and exposure duration. At the nanoscale, polymers with a density of less than

important for investigating their interactions with biological organisms, as smaller particle sizes increase the likelihood of penetrating biological membranes [18].

Despite numerous reports on the presence of NMPs, a standardized protocol for sampling, pretreatment, quantification and classification remains absent [19, 20]. Sample pretreatment is a critical step to minimize the presence of non-plastic particles and focus on NMPs detection. Current challenges include: (a) separating NMPs from organic contaminants and inorganic sediment; (b) avoiding false-positive and false-negative during quantification and classification; (c) establishing universally accepted protocols and guidelines. While existing techniques may be effective at the micrometer scale, their efficiency diminishes for smaller contaminations or at the nanoscale, often becoming more expensive and less reliable [21, 22]. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of environmental samples complicates characterization and detection of NMPs, frequently leading to systematic errors [22,23].

Recent reports address generalized aspects of sampling and separation of NMPs [26-28]; however, they often lack critical discussions on advancements, challenges and innovative solutions, alongside practical research examples. Many literature reviews mainly focus on analytical tools, such as microscopy and spectroscopy, for NMPs detection. However, they often fail to provide insights into how these techniques can be improved. Discussions on significant research outcomes addressing these limitations are also limited [27-29]. This work aims to fill these gaps by providing a comprehensive and critical overview of the current state-of-art technologies for sampling, pretreatment, and analytical detection of NMPs. It highlights recent advancements, particularly nanotechnology-based approaches and combined spectro-microscopic techniques, where nanomaterials are effectively employed in separations methods. Finally, this review explores the role of artificial intelligence (AI)-based classification algorithms, which remain underexplored in the existing literature, despite their potential to enhance accuracy and efficiency in NMPs detection.

Sample preparation

Sampling methods advancements

Sampling groundwater samples is more complex than surface water due to the limited availability of accessible sampling points, such as springs, water wells or monitoring wells. Spring water can be directly collected at the spring’s mouth without perturbing the aquifer’s natural dynamics. In contrast, collecting groundwater from monitoring wells typically requires pumps or volumetric samplers, which can increase the risk of cross-contamination [32]. Another critical challenge in groundwater sampling is determining the minimum volume required to achieve statistically reliable results [33]. For aquifers with very low contamination levels, low-flow pumping systems connected to in situ filtration are particularly useful, as they allow for collection of hundreds of liters of groundwater. Conversely, in more contaminated sites, a few liters of groundwater can be collected using volumetric samplers [34]. While general methods for sampling soil can be adapted, there is a pressing need for standardized techniques specifically designed for the quantification of nanoplastics and microplastics in groundwater and other environmental matrices [35].

Airborne NMPs can settle due to gravity and be collected using containers, which can be connected to a funnel at top as a passive sample collector device [36]. Collecting indoor dust by brush deals with NMPs as well as other dust components mixture and hence other impurities must be separated from NMPs. While active sampling devices can be effective, they are not suitable for difficult-to-access areas, such as remote mountains. These types of devices are complex and expensive [37].

Separation and pretreatment advancements

soil particles, dissolved ions and molecules, and organic residues. Common strategies for pretreatment include size selection (via sieving), digestion (using oxidation, enzymatic digestion, or acid-alkaline digestion), density separation (with salt solutions), and filtration.

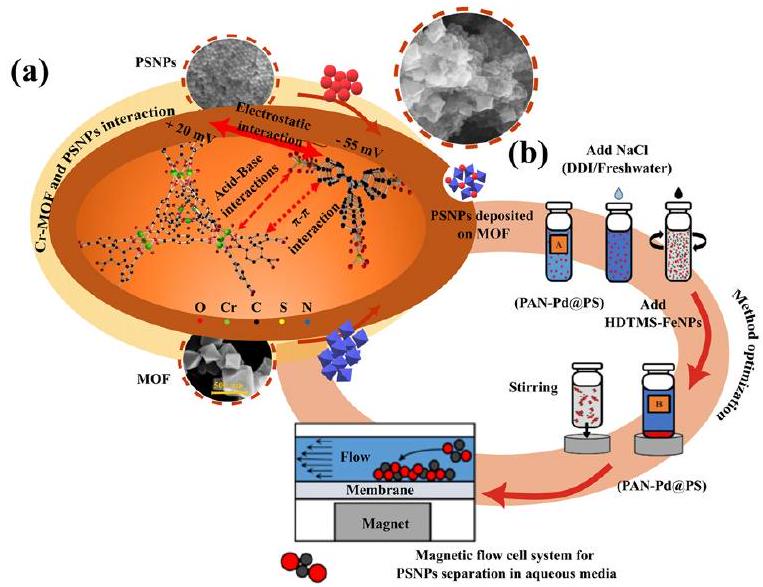

Separation is primarily achieved through density separation and filtration. Density separation often relies on flotation, but this approach is less effective for NPs because, at the nanoscale, buoyant forces are minimal, and particle density can be altered by surface fouling. Froth flotation, another separation technique, is generally unsuitable for plastics due to significant particle loss caused by bubble interactions [38]. The effectiveness of density separation also depends on the density of the floating solution. For example, raw water can only separate low-density plastics such as polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), and polypropylene (PP) [39].

Solutions containing salts like

Preliminary sieving is typically used to remove larger materials from the sample, but is insufficient for complex sediments, as it can lead to artifacts related to particle polydispersity. The subsequent step usually involves the digestion of organic matter, often performed using the wet peroxidase method or Fenton’s reagent, which effectively removes organic residues to improve the accuracy of NMP analysis. Additional care is requested in case of use of Fenton’s reagent because the intense oxidative reaction can alter or destroy NMPs [45]. Although the wet peroxidase method does not affect the NMPs, some studies have shown that this method may alter or digest nylon (polyamide, PA) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) [46]. Another approach in the organic matter digestion is based on enzymatic digestion. This method is cheaper but time-consuming; and enzymes may interact with other impurities present in sample limiting their efficacy [41].

Despite the challenges and drawbacks of existing approaches for sample pretreatment and separation, recent studies highlight promising developments, particularly for NPs, which are significantly affected by the aforementioned methods. This section discusses significant results achieved in separation processes, including filtration and centrifugation, as well as nanotechnologybased methods that incorporate novel nanomaterials. To understand the development in NMPs detection in

Filtration and centrifugation advancements

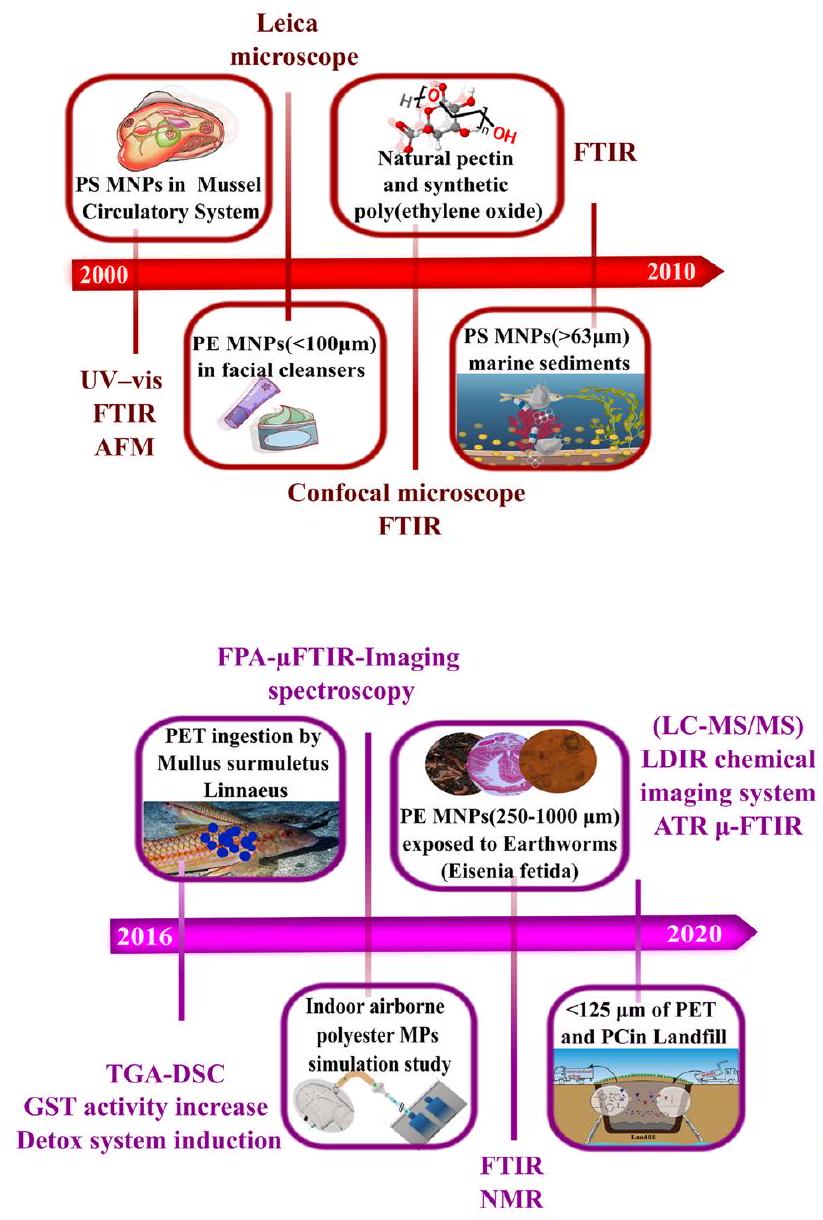

Hildebrandt et al. [50] reported two continuous-flow centrifuges (scheme in Fig. 2c) combined with two titanium rotors having 300 mL sedimentation capacity for

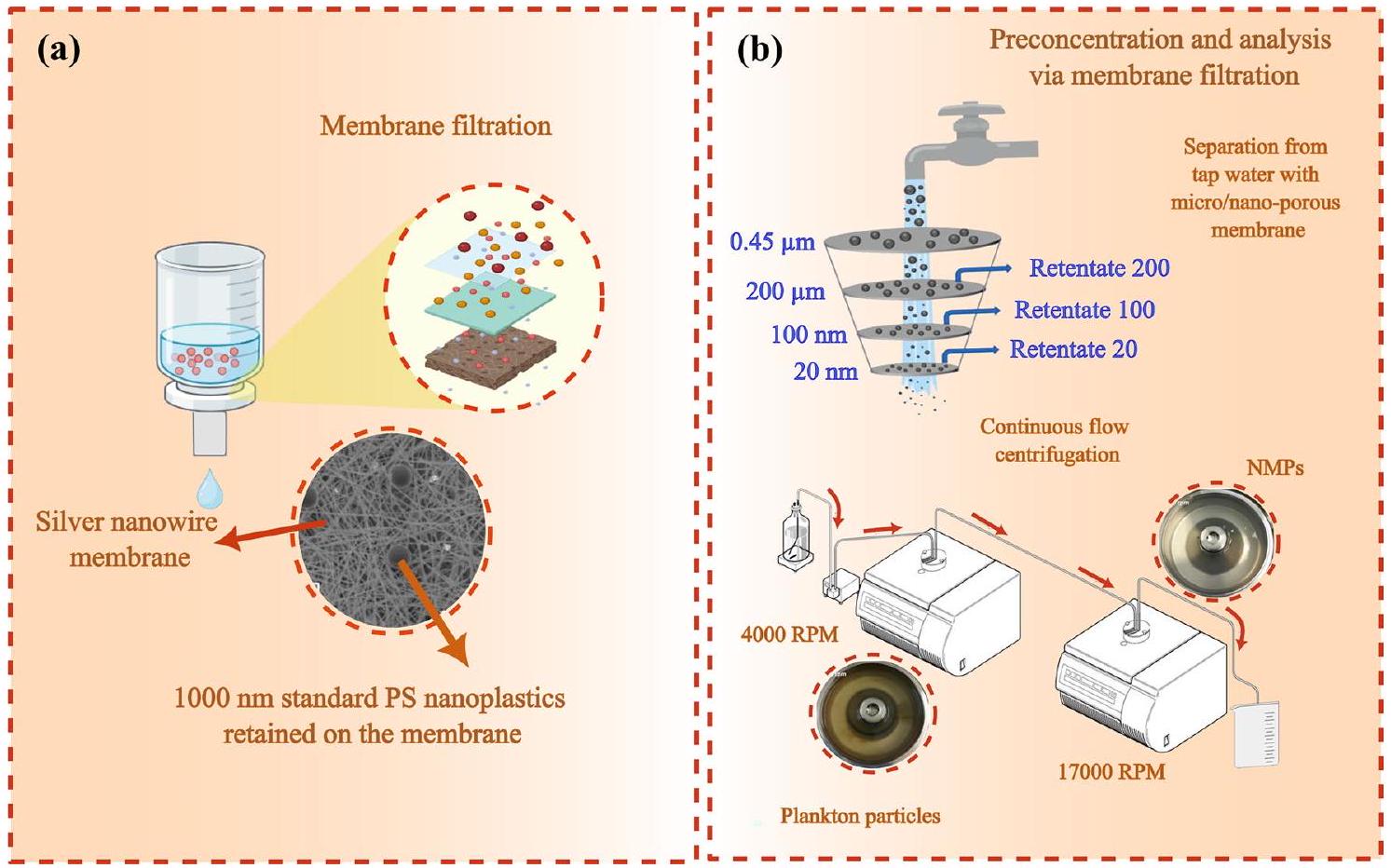

Nanotechnology-based advancements

Advances in current measurement methods Microscopic methods advancements Optical microscopy

Without fluorescence or labeling, differentiating NMPs from similarly sized particles like organic debris or minerals can be challenging, leading to misidentification. Staining with agents like Nile Red (NR), a lipophilic dye, helps distinguish NMPs by binding to hydrophobic substances and activating fluorescence under specific wavelengths. This preferential staining of plastic particles reduces the risk of mistaking them for non-plastic materials and aids in identifying smaller particles below the diffraction limit [63]. Nile red, for instance, was applied to detect NMPs in complex matrices and tissues from living organisms [64]. Unfortunately, Nile red can suffer from false-positive artifacts, as it can bind to other hydrophobic materials such as lipids, therefore requiring additional confirmation steps.

Despite labeling and fluorescence, chemical identification of different polymers remains challenging since staining agents are not polymer-specific. Optical microscopy often requires manual counting, which is time-consuming and prone to error, especially without automated analysis tools. Its limited depth of field also complicates focusing on 3D structures in thick samples. However, optical microscopy is easily integrated with other techniques to enhance accuracy of detection.

Electron microscopy

SEM offers high magnifications and resolutions, allowing observation of fine surface details like texture, defects, and contamination in MPs. When combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS/EDX), SEM can provide elemental composition data, identifying additives or contaminants. However, EDS mapping cannot distinguish between different polymer/additives types in complex materials [68]. By changing the electron beam generation process, FE-SEM (field emis-sion-scanning electron microscope) provides a very high-resolution imaging compared to regular SEM. It guarantees high brightness, crisp images and stable beam current. Figure 4a presents a 350X FE-SEM image identifying cellulose and polymer fibers. Fluorescent

NPs can get attached with commercially available dyes and super-resolution imaging can be achieved by using STED (STimulated Emission Depletion microscopy). STED microscopy is a far-field fluorescence imaging technique that overcomes the diffraction limit by switching the states of dye molecules between bright and dark, reaching 20 nm resolution. This technique was utilized recently for high-resolution imaging of stained proteins inside living cells [69].

Enhancing MPs analysis can be achieved by using advanced techniques like high-angle annular darkfield (HAADF) in TEM and backscattered electron (BSE) imaging in SEM. HAADF provides high-contrast images based on atomic number (Z-contrast), making it useful for distinguishing polymer additives and fillers, as materials with higher atomic numbers appear brighter. Coupled with EDX for elemental mapping, these techniques allow precise quantification and localization of additives or contaminants. Tire wear particles in airborne dust were analyzed using BSE and EDX, with machine learning algorithms for automation. SEM images (Fig. 4d) of tire wear particles from urban areas showed

BSE imaging on SEM detects electrons scattered back from the sample surface. The intensity of these electrons, and thus the image brightness, depends on the atomic number; heavier elements scatter more electrons, creating a brighter image. For example, Sommer et al. used BSE and EDX in SEM to analyze single MPs fragments [72], providing insights into the environmental impact of tire abrasion. Bhat used the same technique to identify MPs from indoor environment [75].

In summary, advanced imaging modes such as HAADF in TEM and BSE in SEM are crucial for detailed compositional analysis of MPs. They provide valuable insights into the material properties, additives, contaminants, and structural characteristics of MPs, which are essential for comprehending their environmental behavior, toxicity, and long-term impacts.

Atomic force microscopy

In a different study, [84] manufactured a nano-

AFM primarily provides topographical and mechanical data, with limited ability to determine the chemical composition of samples. Unlike other techniques, AFM cannot distinguish between different types of plastics based solely on their surface features. This can be achieved via integrating AFM with complementary techniques for chemical identification leading to a powerful investigation solution [85].

Spectro-microscopic based advancements

Infrared-based advancements

| Type | Method | Range | Challenges | Advantages | Refs. |

| Spectroscopy | DLS | 1 nm to 3 mm | Large particles, polydispersity affects results | Fast, cheap, non-invasive | [86] |

| Spectroscopy | Multiangle laser scattering (MALS) | 10 nm to 1000 nm | Require clean sample and only spherical models | Online coupling, large size ranges, easy, fast | [87] |

| Spectroscopy | Laser diffraction (LD) | 10 nm to 10 mm | Only spherical model | Easy, fast and automated | [88, 89] |

| Spectroscopy | Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) | 10 nm to

|

Complex in operation | Size and number concentration | [90] |

| Spectroscopy | Electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) |

|

Electro-osmotic effect | Rapid, cheap, non-invasive | [91, 92] |

| Spectroscopy | Raman spectroscopy | up to

|

difficulty with data interpretation for complex structures, | Nondestructive, fast, reliable | [93, 94] |

| Microscopic | Stereo microscopy |

|

Identifying plastic nature, composition | Easy and rapid, shape, size, color identification | [61] |

| Microscopic | TEM | 0.1 nm to

|

Not effective to identify MPs/ NPs | Chemical information and images | [93] |

| Spectro-microscopic | SEM-EDS | 5 nm to 5 mm | Expensive technique | Information about the morphological surface | [72] |

| Microscopic | AFM | Up to 0.1 nm | Expensive, limited scan area

|

Surface morphology, mechanics | [83] |

| Spectro-microscopic | AFM-IR | Down to 20 nm | Expensive | Particle morphology, chemical identification | [95] |

| Spectro-microscopic | AFM-Raman | Single molecule detection capability | Expensive, under-development for rapid nanoscale chemical analysis | Particle morphology and chemical fingerprint | [96] |

ATR-FTIR is particularly relevant for investigating NMPs because it allows direct analysis of solid or liquid samples with minimal preparation. This technique introduces infrared light directly to the sample, enabling the extraction of structural and compositional information even from complex matrices. FTIR is valued for its ability to quickly generate high-quality spectra, ease of use and reproducibility. Common challenges include potential background contamination, but ATRFTIR remains a sensitive and cost-effective method, capable of detecting MPs (about

For example, ATR-FTIR showed stronger peak signals with decreasing NMPS diameter at the micrometer scale, successfully detecting NMPs with high sensitivity in the

topography and chemical spectra. It provides resonant modes and high-quality data with excellent sensitivity, unaffected by background interfaces, and matches conventional IR spectra of bulk materials. However, it is relatively slow and complex [103]. A hybrid technique combining the spatial resolution of AFM with the chemical information of IR spectroscopy was employed to study nanoscale PS particles. This approach enabled the detection and quantification of NPs as small as 20 nm in aqueous environments [104]. A pulse tunable IR source with a

Figure 6a-c illustrates the efficacy of the AFM-IR technique in detecting 150 nm PS spheres based on surface groups. In Fig. 6b, characteristic sulfonate (

Figure 7 shows the chemical imaging spectra from LDIR technology. The LDIR system automatically identified particles and matched spectra. All MP particles in this study showed over

Raman spectroscopy-based advancements

To prevent sample degradation and luminescence, certain tests were conducted at lower laser power. However, for NPs smaller than

Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) merges the chemical sensitivity of SERS with the high spatial resolution of scanning probe microscopy, allowing for nanoscale chemical imaging. A sharp metal or metalcoated tip is placed at the center of a laser focus, where the electromagnetic field at the tip apex is confined and enhanced by localized surface plasmon resonance [115]. TERS provides a powerful technique for analyzing surfaces with nanometer precision [116]. Over the last decade, this technique has been applied in wide range of research areas including carbon nanotubes, graphene, biology, photovoltaics, etc., Yeo et al. [117]

conducted nano-scale probing of Raman active mixed polyisoprene and PS thin film to investigate surface composition. Although difficult to operate, this method could investigate films at surface and subsurface levels and tend to enable analysis at nanometer spatial resolution.

Advances in other methodologies Mass spectroscopy advancements

Thermal analysis advancements

In TG-FTIR and TG-MS, a transfer line or capillary connects the TGA directly with evolved gas analysis. These methods are useful for analyzing known matrix samples with specific MPs and detecting PVC [124]. Thermal extraction-desorption gas chromatography mass spectrometry (TEDGC/MS) can be useful for analyzing unknown matrix samples with unknown variable kinds of MPs and content but the method is complex [125]. Microscale combustion calorimeter (MCC) can be applied for simple and rapid screening to identify potential MP loads of standard polymers in unknown samples, but there is no difference between different polymers, where only PE, PP, PS contribute significantly to the signal and are limited to 5 mg of sample [124]. Py-GC-MS (pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) can simultaneously locate and measure the most prevalent MPs in complex samples.

Light scattering technique advancements

Al-based technologies advancements