DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07548-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38898275

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-19

التعديل المباشر للجذور الوظيفية للسكريات الأصلية

تاريخ الاستلام: 10 نوفمبر 2023

تم القبول: 9 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 19 يونيو 2024

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

تحتوي السكريات والكربوهيدرات الطبيعية (المحلية) على العديد من مجموعات الهيدروكسيل ذات التفاعل المماثل.

على النقيض من الطبيعة الانتقائية العالية للموقع للإنزيمات

السكريات الأصلية غير المحمية (أكثر الأشكال وفرة في الطبيعة) إلى سلفيات جليكوسيل مصممة تحتوي على مجموعات مغادرة أنوميرية مثل الهاليدات

لتحقيق تفاعل أنوميري انتقائي من حيث الموقع والاستيريو. R، مجموعة وظيفية؛ LG، مجموعة مغادرة؛ B، قاعدة؛ NTP، ثلاثي فوسفات النوكليوزيد؛ NDP، ثنائي فوسفات النوكليوزيد؛ Dha، ديهيدرو ألانين؛

لنجاح هذه الاستراتيجية ‘التغطية والجليكوزيل’، يجب أولاً تمييز مجموعات الهيدروكسيل المتعددة لضمان التغطية الانتقائية للهيمياستال لتشكيل مانح ثيوغليكوزيل مؤقت. ثانياً، يجب أن يكون المانح تفاعلياً بما فيه الكفاية للمشاركة في الربط المتقاطع دون تدخل تنافسي أو تفاعل مع مواقع الهيدروكسيل الأخرى، مما قد يؤدي إلى تفاعلات غير مرغوب فيها ومخاليط يصعب التعامل معها. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، هناك تحدي التحكم في النتيجة الاستيريوكيميائية لوظيفة الأنومير في سياق بقايا كربوهيدراتية معقدة ومتعددة الهيدروكسيل.

تسريع إعداد مركبات الكربو-، الثيو- والسيلينوغليكوزيل القوية بالإضافة إلى

تحليل الكروماتوغرافيا-مطيافية الكتلة (LC-MS). DMC، كلوريد 2-كلورو-1،3-ثنائي ميثيل إيميدازوليوم؛ CDMT، 2-كلورو-4،6-ثنائي ميثوكسي-1،3،5-تريازين؛ NMM،

الشروط الأساسية (الشكل 2أ). في وجود 2-كلورو-1،3-ثنائي ميثيل إيميدازوليوم كلوريد (DMC) المتاح تجارياً كمحفز وثلاثي إيثيل أمين كقاعدة، تم الحصول على 2 في

مع تحديد DMC كأكثر المحفزات فعالية، استخدمنا ظروف الاستبدال النووي لتخليق ليس فقط 2 ولكن أيضًا مجموعة من الثيوغلوكوزيدات (الهيدرو) أريل غير المحمية (6-9) للمقارنة. لدفع عملية الجليكوزيل، خضعنا الثيوغلوكوزيدات لتفاعل مع الأكريلات.

على النقيض، لوحظ تحويل ضعيف مع المواد الأقل نشاطًا في الأكسدة والاختزال

إمكانات الاختزال (الأشكال التكميلية 2-6)، والتي تقارن بتلك الخاصة بسلفون جليكوزيل هيتروأريل النشط في التفاعل الأكسدة-اختزال

الترابط. تم تحديد العوائد بواسطة

الميزة المميزة للاستراتيجية الحالية في تحويل خلطات من متساويات السكر الأصلية غير المحمية، من خلال مشتقاتها من الثيوغليكوزيد، إلى جليكوزيدات نقية من حيث التماثل بطريقة سلسة. في دراسة منفصلة، تم إضافة مواد خارجية (

تحويل 2 إلى 11 (الشكل 3ب). أظهر تحليل مطيافية الكتلة عالية الدقة (HRMS) تكوين مركب يمكن أن يُنسب إلى إضافة جليكوسيد TEMPO 16، مما يوفر دليلاً على أن نوع الجذري الجليكوزي (الأنوميري) الذي يعيش لفترة كافية يتم توليده خلال العملية. هذه العمليات تتناقض مع الجليكوزيلات الهتروتوليدية التي تفتقر أساسًا إلى تكوين نوع وسيط واضح (على سبيل المثال، كاتيون الجليكوزيل).

لا تحدث ولا يمكن استبعادها تمامًا (الشكل التوضيحي 7). يُفترض أن الوسيط الثيوغليكوزيدي الناتج يرتبط بإستر هانتزتش وDABCO في المحلول، مما يوفر معقد ثلاثي يمكنه امتصاص الضوء المرئي لتحفيز نقل الإلكترون المعتمد على الضوء (PET).

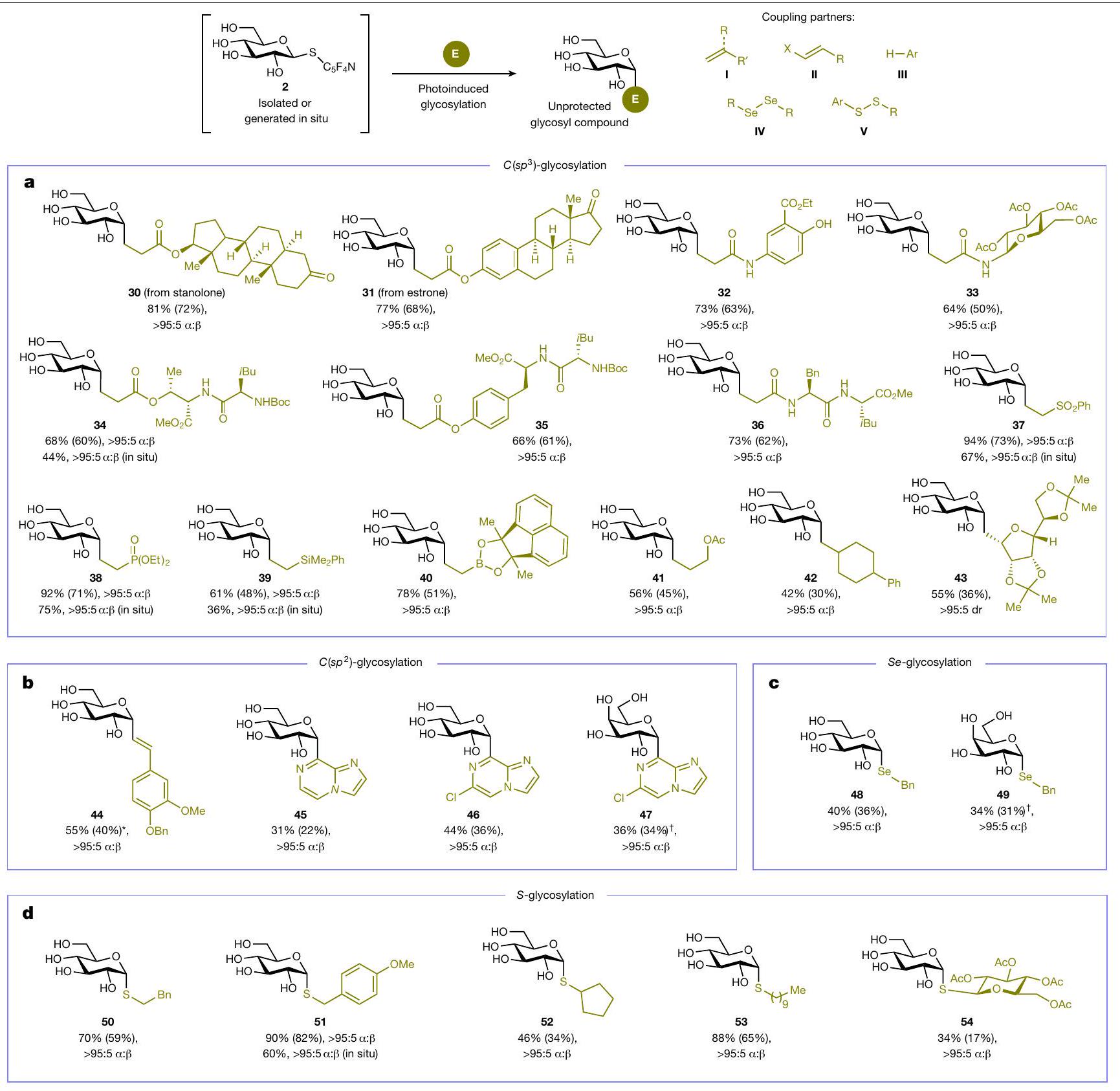

الأكريلات والأكرلاميدات المفعلة المرتبطة بالمركبات النشطة بيولوجيًا (30، 31)، والأمينوساليسيلات (32)، والسكر الأميني (33) والبيبتيدات الصغيرة (34-36) كانت ركائز متوافقة، مما يوفر الوصول إلى مواد قطبية عالية.

وجود ألكين مستبدل بألكيل أقل تنشيطًا (42). أوليغوسكاريد زائف مستقر من الناحية الأيضية

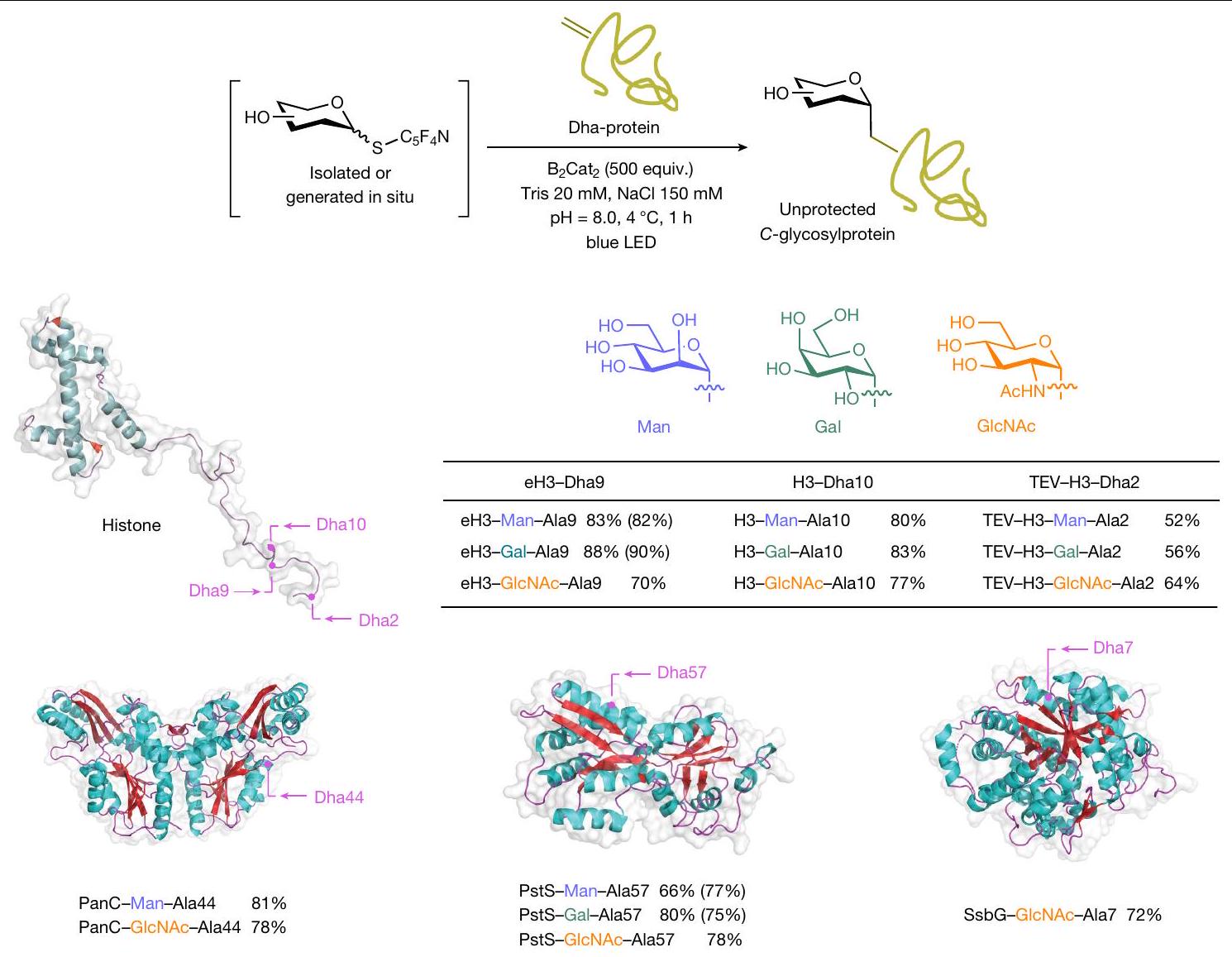

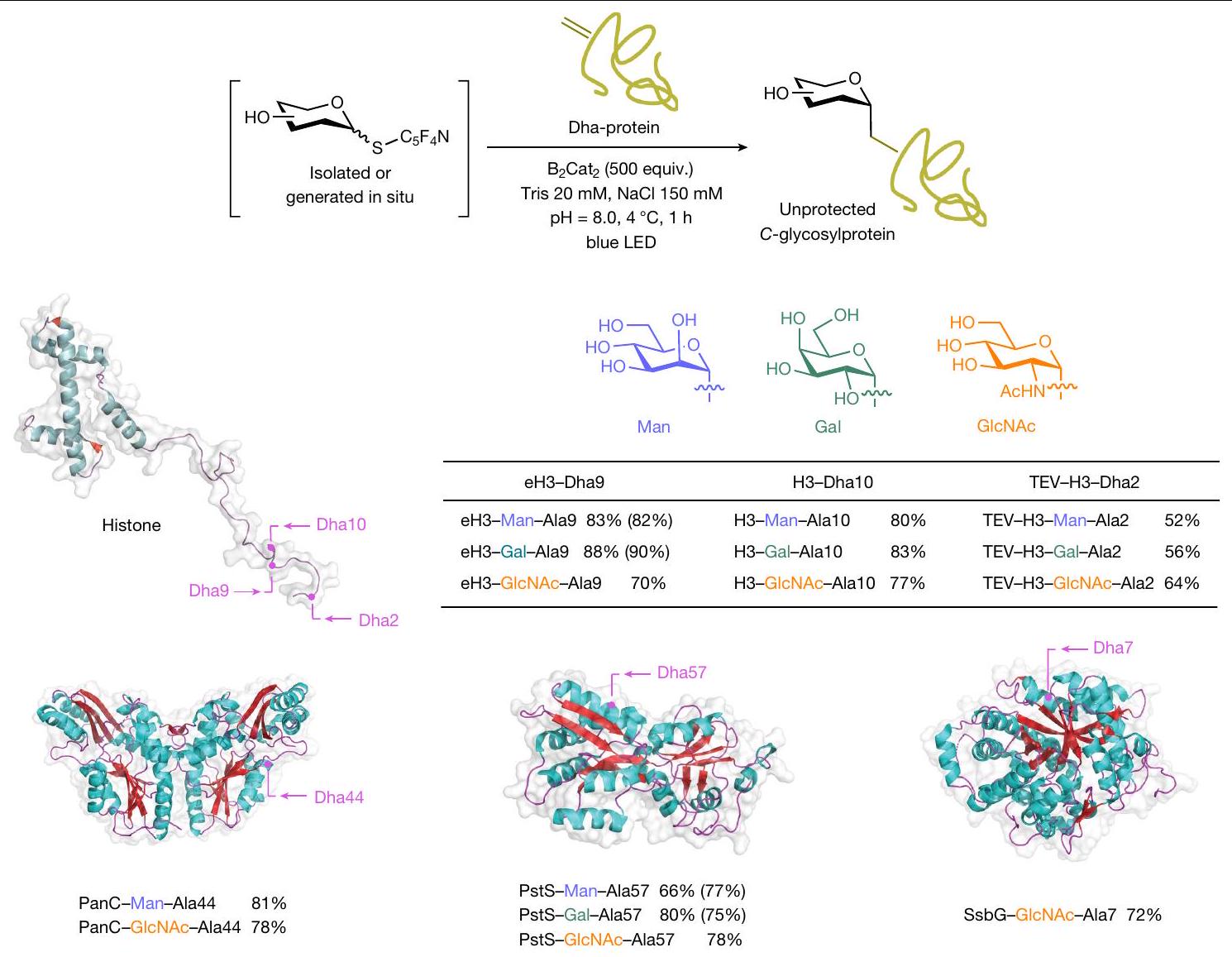

لركيزة البروتين؛ تشير العوائد بين قوسين إلى التفاعلات مع مانحي الثيوغليكوزيل الناتجين في الموقع وغير المنقين. تريس، 2-أمينو-2-(هيدروكسي ميثيل)-بروبان-1،3-ديول؛

مع الهتروأرينات تحت ظروف خالية من الحمض، مما يؤدي إلى الحصول على 45-47 غير محمية بشكل انتقائي في أكثر المواقع نقصًا في الإلكترونات، وهو ما يتوافق مع تقرير سابق يتضمن جذور جليكوزيل محمية بالكامل.

ثنائي البورون (بيس كاتيكولات)

بعد تحديد الظروف المثلى (500 مكافئ من

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- باتي، ج.، هي، ج. إكس.، بال، ك. ب. وليو، إكس. و. جليكوزيلشن انتقائي ستيريو وإقليمي مع مشتقات السكر بدون حماية: استراتيجية جذابة للوصول إلى الجليكوزات والمنتجات الطبيعية. مراجعات الجمعية الكيميائية 48، 4006-4018 (2019).

- ديماكوس، ف. وتايلور، م. س. التوظيف الانتقائي للمجموعات الهيدروكسيلية في مشتقات الكربوهيدرات. مراجعة الكيمياء 118، 11457-11517 (2018).

- فولبد، أ. ج.، فان دير ماريل، ج. أ. وكودي، ج. د. س. في استراتيجيات وتطبيقات المجموعات الواقية في كيمياء الكربوهيدرات (تحرير: فيدال، س.) الفصل 1، 1-24 (وايلي-فيتش، 2019).

- رود، ب. م.، إليوت، ت.، كريسويل، ب.، ويلسون، آي. أ. ودويك، ر. أ. الجليكوزيل والتفاعل المناعي. ساينس 291، 2370-2376 (2001).

- فاركي، أ. الأدوار البيولوجية للجليكوز. علم الجليكوز 27، 3-49 (2017).

- رايلي، سي.، ستيوارت، تي. جي.، رينفرو، إم. بي. ونوفاك، جي. الجليكوزيل في الصحة والمرض. نات. ريف. نيفرول. 15، 346-366 (2019).

- شولداغر، ك. ت.، ناريماتسو، ي.، جوشي، هـ. ج. و كلاوسن، هـ. نظرة عالمية على مسارات ووظائف جليكوزيلاتي البروتينات البشرية. نات. ريف. مول. سيل. بيول. 21، 729-749 (2020).

- إرنست، ب. وماغناني، ج. ل. من الرصاصات الكربوهيدراتية إلى الأدوية المقلدة للجليكوز. نات. ريف. دراج ديسكوف. 8، 661-677 (2009).

- شيفاتاري، س.، س. ف.، شيفاتاري، ف. س. سي.-هـ. وونغ، س.-هـ. الجليكوكوجينات: التركيب، الدراسات الوظيفية، والتطورات العلاجية. مراجعة الكيمياء 122، 15603-15671 (2022).

- سيبرجر، ب. هـ. اكتشاف لقاحات كربوهيدرات شبه صناعية وكاملة الاصطناع ضد العدوى البكتيرية باستخدام نهج الكيمياء الطبية. مراجعة الكيمياء 121، 3598-3626 (2021).

- زو، إكس. وشميت، ر. ر. مبادئ جديدة لتكوين روابط الجليكوسيد. أنجيو. كيم. إن. إيد. 48، 1900-1934 (2009).

- مكاى، م. ج. و نغوين، هـ. م. التقدمات الحديثة في الجليكوزيلation المحفز بواسطة المعادن الانتقالية. ACS Catal. 2، 1563-1595 (2012).

- يانغ، ي. ويو، ب. التقدمات الحديثة في التخليق الكيميائي للغليكوسيدات C. مراجعة الكيمياء 117، 12281-12356 (2017).

- كولكارني، س. س. وآخرون. “حماية من وعاء واحد”، استراتيجيات الجليكوزيل والحمائية للجليكوزيلات. مراجعة الكيمياء 118، 8025-8104 (2018).

- نيلسن، م. م. وبيدرسن، س. م. التفاعلات التحفيزية في تخليق الأوليغوسكاريد. مراجعة الكيمياء 118، 8285-8358 (2018).

- لي، و.، مك آرثر، ج. ب. و تشين، إكس. استراتيجيات للتخليق الكيميائي الإنزيمي للكربوهيدرات. أبحاث الكربوهيدرات 472، 86-97 (2019).

- بوتكارادزه، ن.، تيزي، د.، فريدسلوند، ف. و ويلنر، د. هـ. ناقلات C-جليكوسيل الطبيعية نشاط إنزيمي قليل التوصيف مع إمكانيات بيولوجية تكنولوجية. تقرير المنتجات الطبيعية 38، 432-443 (2021).

- فرانك، ر. و. & تسوجي، م. أ-سي-غالاكتوسيلسيراميدات: التركيب وعلم المناعة. أك. كيم. ريس. 39، 692-701 (2006).

- تشاو، إي. سي. & هنري، ر. ر. مثبطات SGLT2 – استراتيجية جديدة لعلاج السكري. نات. ريف. دراج ديسكوف. 9، 551-559 (2010).

- أداك، ل. وآخرون. تخليق جليكوسيدات C-aril عبر اقتران متقاطع محفز بالحديد للسكريات الهالوجينية: الأريلة الانتقائية للأنومر من الجذور الجليكوسيلية. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية للكيمياء 139، 10693-10701 (2017).

- وانغ، ق. وآخرون. تفاعل جليكوزيل C-H المحفز بالبلاتين لتخليق جليكوزيدات C-أريل. نات. كاتال. 2، 793-800 (2019).

- Lv، و.، تشين، ي.، وين، س.، با، د. وتشينغ، ج. التركيب المودولي والانتقائي للستيريو لجليكوسيدات C-أريل عبر تفاعل كاتيلاني. ج. أم. كيم. سوس. 142، 14864-14870 (2020).

- جيانغ، ي.، وانغ، ق.، تشانغ، إكس. وكوه، م. ج. تخليق C-glycosides بواسطة تفاعل جذر الجليكوزيل الانتقائي بالتحفيز بواسطة التيتانيوم. كيم 7، 3377-3392 (2021).

- وانغ، ق. وآخرون. التفاعل المتقاطع الاختزالي المحفز بالحديد للجذور الجليكوسيلية من أجل التخليق الانتقائي للـ C-جليكوسيدات. نات. سينث. 1، 235-244 (2022).

- وي، ي.، بن زفي، ب. و دياو، ت. التخليق الانتقائي للديستيريو من جليكوسيدات C-aril من استرات الجليكوسيل عبر تحلل رابطة C-O. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 60، 9433-9438 (2021).

- وي، ي.، لام، ج. و دياو، ت. تخليق الفورانوسيدات C-acyl عبر الاقتران المتقاطع للإسترات الجليكوسيلية مع الأحماض الكربوكسيلية. كيم. ساي. 12، 11414-11419 (2021).

- روميو، ج. ر.، لوكيرا، ج. د.، جنسن، د.، ديفيس، ل. م. وبينيت، س. س. تطبيق تحفيز الإستر النشط بالأكسدة والاختزال في تخليق جليكوسيدات C-الكيل من البيرانو. رسائل عضوية 25، 3760-3765 (2023).

- شانغ، و. وآخرون. توليد الجذور الجليكوزيلية من السلفوكسيدات الجليكوزيلية واستخدامها في تخليق الجليكوكوجينات المرتبطة بـ C. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 60، 385-390 (2021).

- شيا، د.، وانغ، ي.، تشانغ، إكس.، فو، ز. & نيو، د. السلفوكسيدات الألكيلية/الجليكوسيلية كمقدمات جذرية واستخدامها في تخليق مشتقات البيريدين. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إيد. 61، e202204922 (2022).

- وانغ، ق. وآخرون. تفعيل الضوء المرئي يمكّن من الربط المتقاطع لإزالة السلفونيل من سلفونات الجلوكوز. نات. سينث. 1، 967-974 (2022).

- وانغ، ق.، لي، ب. ج.، سونغ، ن. وكوه، م. ج. التفاعل الانتقائي للغليكوزيل C-أريل بواسطة الربط المتقاطع التحفيزي لسلفونات الغليكوزيل الهتروأريل. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إيد. 62، e202301081 (2023).

- تشانغ، سي. وآخرون. التخليق المباشر للغليكوسيدات C-aril غير المحمية بواسطة التفاعل المتقاطع المحفز بواسطة النيكل في الفوتو ريدوكس. نات. سينث. 2، 251-260 (2023).

- لي، ق.، ليفي، س. م.، واغن، س. س.، ويندلاندت، أ. إ. وجاكوبسن، إ. ن. جليكوزيلشن انتقائي الموقع، تحت السيطرة الاستيريو، للسكريات المحمية بشكل ضئيل. ناتشر 608، 74-79 (2022).

- باتشاموثو، ك. وشميت، ر. ر. طرق تركيب الثيوأوليغوسكاريد والثيوغليكوببتيد. مراجعة الكيمياء 106، 160-187 (2006).

- هوغان، أ. إ. وآخرون. تنشيط خلايا القاتل الطبيعي T البشرية غير المتغيرة باستخدام نظير ثيوغليكوسيد من أ-غالكتوسيلسيراميد. المناعة السريرية 140، 196-207 (2011).

- كونيا، ز. وآخرون. السيلينوجليكوسيدات الأرالكيلية والسكر السيليني المرتبط بها في شكل أسيتيل تنشط الفوسفاتاز البروتيني-1 و-2A. الكيمياء الطبية الحيوية العضوية 26، 1875-1884 (2018).

- غانت، ر. و.، غوف، ر. د.، ويليامز، ج. ج. وثورسن، ج. س. استكشاف تعدد استخدامات الأجليكوزيد لإنزيم نقل السكر المهندَس. أنجيو. كيم. إنترن. إد. 47، 8889-8892 (2008).

- فوجينامي، د. وآخرون. تحقيقات هيكلية وآلية لبروتينات S-غليكوزيل ترانسفيراز. كيمياء الخلية. بيولوجيا 28، 1740-1749 (2021).

- بانفيروفا، ل. إ. وديلمان، أ. د. تبادل الكبريت والبورون بواسطة الضوء. رسائل عضوية. 23، 3919-3922 (2021).

- Worp، ب. أ.، كوسوبوكوف، م. د. وديلمان، أ. د. تبادل قابل للعكس بين الكبريتيدات/ اليوديدات المعزز بالضوء المرئي في الكبريتيدات الفلورية المدعوم بتكوين معقد مانح-مستقبل للإلكترون. ChemPhotoChem 5، 565-570 (2021).

- فو، إكس.-بي. وآخرون. تحرير البروتين بعد الترجمة مع الاحتفاظ بالاستريو. ACS Cent. Sci. 9، 405-416 (2023).

- جيوركسيك، ب. وناجي، ل. الكربوهيدرات كعوامل ربط: توازنات التنسيق وبنية معقدات المعادن. مراجعات كيمياء التنسيق 203، 81-149 (2000).

- فيربانكس، أ. ج. تطبيقات مادة شودا (DMC) ونظائرها لتنشيط المركز الأنوميري للكربوهيدرات غير المحمية. أبحاث الكربوهيدرات 499، 108197 (2021).

- فوسيت، أ. وآخرون. البوريلين الناتج عن إزالة الكربوكسيل المحفز بالضوء للأحماض الكربوكسيلية. العلوم 357، 283-286 (2017).

- فو، م.-سي، شانغ، ر، تشاو، ب، وانغ، ب. وفو، ي. الألكلة إزالة الكربوكسيل المحفزة ضوئيًا بواسطة ثلاثي فينيل الفوسفين واليوديد الصوديوم. العلوم 363، 1429-1434 (2019).

- سيلفي، م. وملكيور، ب. تعزيز إمكانيات التحفيز العضوي الانتقائي باستخدام الضوء. ناتشر 554، 41-49 (2018).

- جيزي، ب. ودوبيس، ج. تخليق ديستيريوانتقائي لمركبات C-جليكوبيرانويد. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. إنجل. 22، 622-623 (1983).

- أبي، هـ.، شوتو، س. وماتسودا، أ. عالي أ- و

جذري انتقائي تفاعلات -غليكوزيل باستخدام تأثير أنوميري مسيطر عليه يعتمد على استراتيجية تقييد التوافق. دراسة عن علاقة التوافق-تأثير الأنوميري-الانتقائية الاستيريو في تفاعلات الجذور الأنوميرية. ج. أم. كيم. سوس. 123، 11870-11882 (2001). - يوان، إكس. ولينهاردت، ج. ر. التقدمات الحديثة في تخليق أوليغوسكاريد C. المواضيع الحالية في الكيمياء الطبية 5، 1393-1430 (2005).

- شيا، ل.، فان، و.، يوان، إكس.-أ. ويو، س. التخليق الانتقائي للستيريو باستخدام التحفيز الضوئي من نظائر C-nucleoside من بروميدات الجليكوسيل والهيدروأرينات. ACS Catal. 11، 9397-9406 (2021).

- دونغ، ز. وماكميلان، د. و. س. تفاعل الأريل المزيل للأكسجين المعتمد على الفوتوريدوكس من الكحوليات. ناتشر 598، 451-456 (2021).

- زو، ف. وآخرون. استراتيجيات تحفيزية وضوئية لتثبيت الجذور بناءً على النيوكليوفيلات الأنوميرية. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية للكيمياء 142، 11102-11113 (2020).

- Zhang، C. وآخرون. تفعيل الجذور بمساعدة الروابط الهالوجينية للمانحين الجليكوزيل يمكّن من جليكوزيل 1،2-سيز معتدل ومتقارب في الت stereochemistry. نات. كيم. 14، 686-694 (2022).

- غامبلين، د. ب.، سكنلان، إ. م. وديفيس، ب. ج. تخليق الجليكوبروتين: تحديث. مراجعة الكيمياء 109، 131-163 (2009).

- بوتورييرا، أ. وبيرنارديس، ج. ج. تقدمات في تعديل البروتينات الكيميائية. مراجعة الكيمياء 115، 2174-2195 (2015).

- دادوفا، ج.، غالان، س. ر. وديفيس، ب. ج. تخليق البروتينات المعدلة من خلال تفعيل الديهيدروألانين. الرأي الحالي في الكيمياء الحيوية. 46، 71-81 (2018).

- جوزيفسون، ب. وآخرون. تركيب سلاسل جانبية بروتينية تفاعلية مدفوعة بالضوء بعد الترجمة. ناتشر 585، 530-537 (2020).

- تشنغ، ر. وبلانشارد، ج. س. تحليل الحركية في الحالة المستقرة وما قبل الحالة المستقرة لإنزيم بانثوثينات سينثيتاز من المتفطرة السلية. الكيمياء الحيوية 40، 12904-12912 (2001).

- Qi، ي.، كوباياشي، ي. و هوليت، ف. م. يحتوي operon pst في Bacillus subtilis على محفز منظم بواسطة الفوسفات ويشارك في نقل الفوسفات ولكن ليس في تنظيم مجموعة pho. J. Bacteriol. 179، 2534-2539 (1997).

- أغيلار، سي. إف. وآخرون. التركيب البلوري لـ

-غليكوسيداز من الأركيون الفائق الحرارة سولفولوبوس سولفاتاريكوس: المرونة كعامل رئيسي في الثبات الحراري. ج. مول. بيول. 271، 789-802 (1997). - تعديل الهيستونات بواسطة السكر

– -أسيتيلغلوكوزامين (GlcNAc) يحدث على عدة بقايا، بما في ذلك الهيستون H3 سيرين 10، وهو منظم لدورة الخلية. J. Biol. Chem. 286، 37483-37495 (2011). - بارسونز، ت. ب. وآخرون. التعديل الجليكوزي الاصطناعي الأمثل للأجسام المضادة العلاجية. أنجيو. كيم. إنترناش. إد. 55، 2361-2367 (2016).

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

مقالة

توفر البيانات

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى بنيامين جي. ديفيس أو مينغ جو كو.

تُعرب Nature عن شكرها للمراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة على http://www.nature.com/reprints.

قسم الكيمياء، الجامعة الوطنية في سنغافورة، سنغافورة، سنغافورة. معهد روزاليند فرانكلين، حرم هارويل للعلوم والابتكار، ديدكوت، المملكة المتحدة. قسم علم الأدوية، جامعة أكسفورد، أكسفورد، المملكة المتحدة. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة جنوب الصين للتكنولوجيا، شنتشن، الصين. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة أكسفورد، أكسفورد، المملكة المتحدة. قسم الكيمياء الحيوية، جامعة أكسفورد، أكسفورد، المملكة المتحدة. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: يي جيانغ، يي وي. أشرف هؤلاء المؤلفون بشكل مشترك على هذا العمل: بنيامين ج. ديفيس، مينغ جو كو. البريد الإلكتروني: ben.davis@chem.ox.ac.uk; chmkmj@nus.edu.sg

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07548-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38898275

Publication Date: 2024-06-19

Direct radical functionalization of native sugars

Received: 10 November 2023

Accepted: 9 May 2024

Published online: 19 June 2024

Open access

Abstract

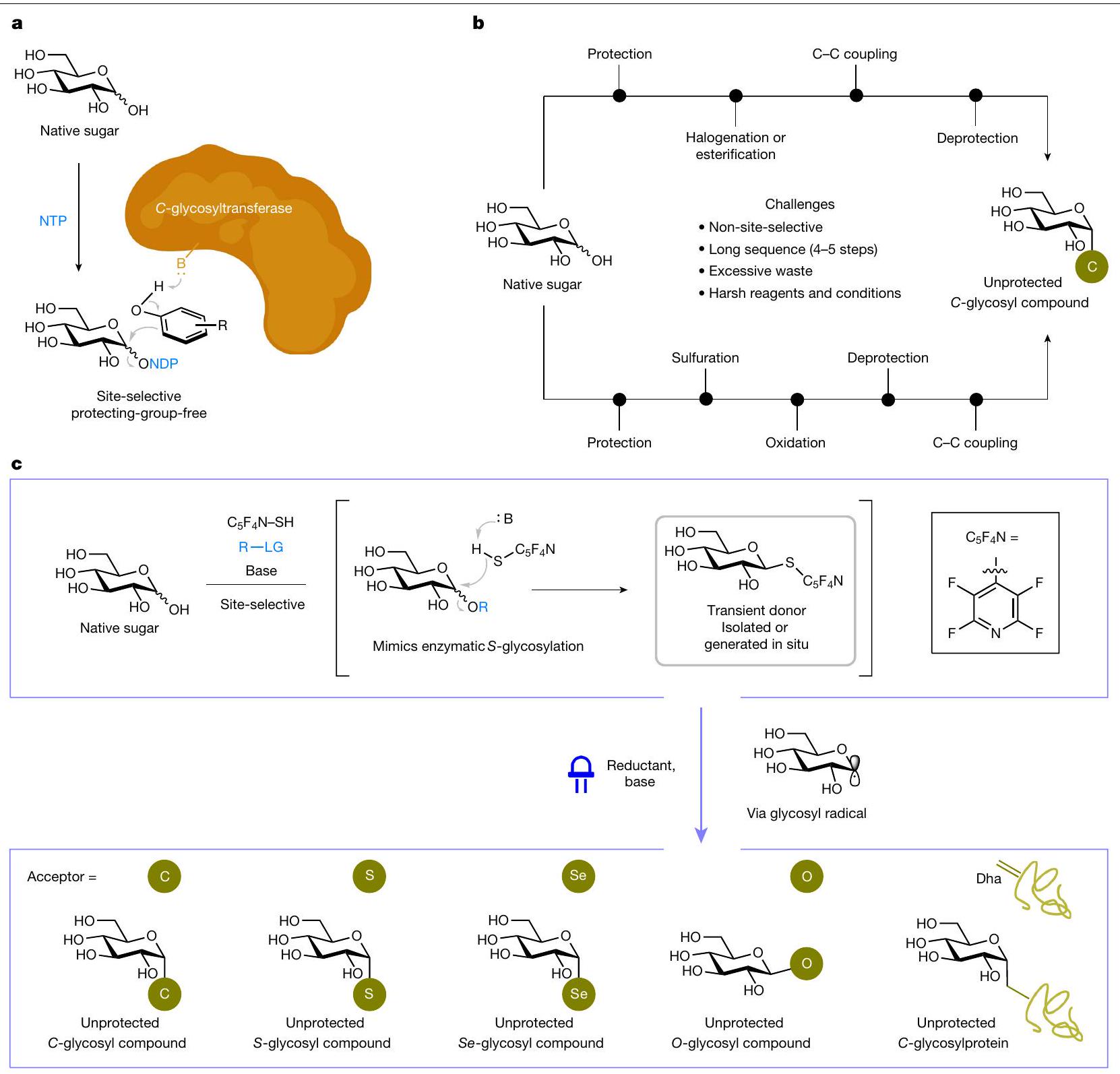

Naturally occurring (native) sugars and carbohydrates contain numerous hydroxyl groups of similar reactivity

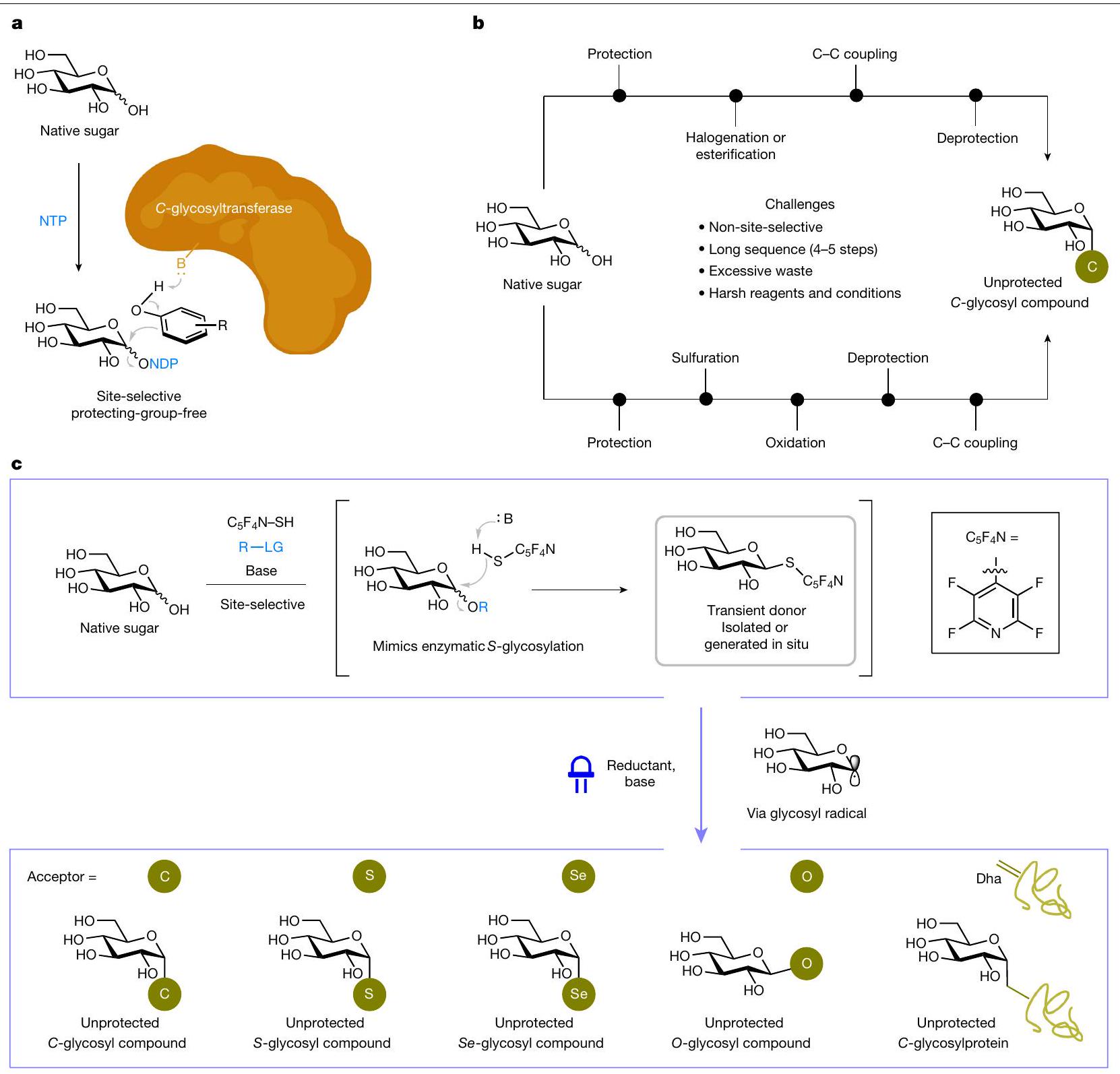

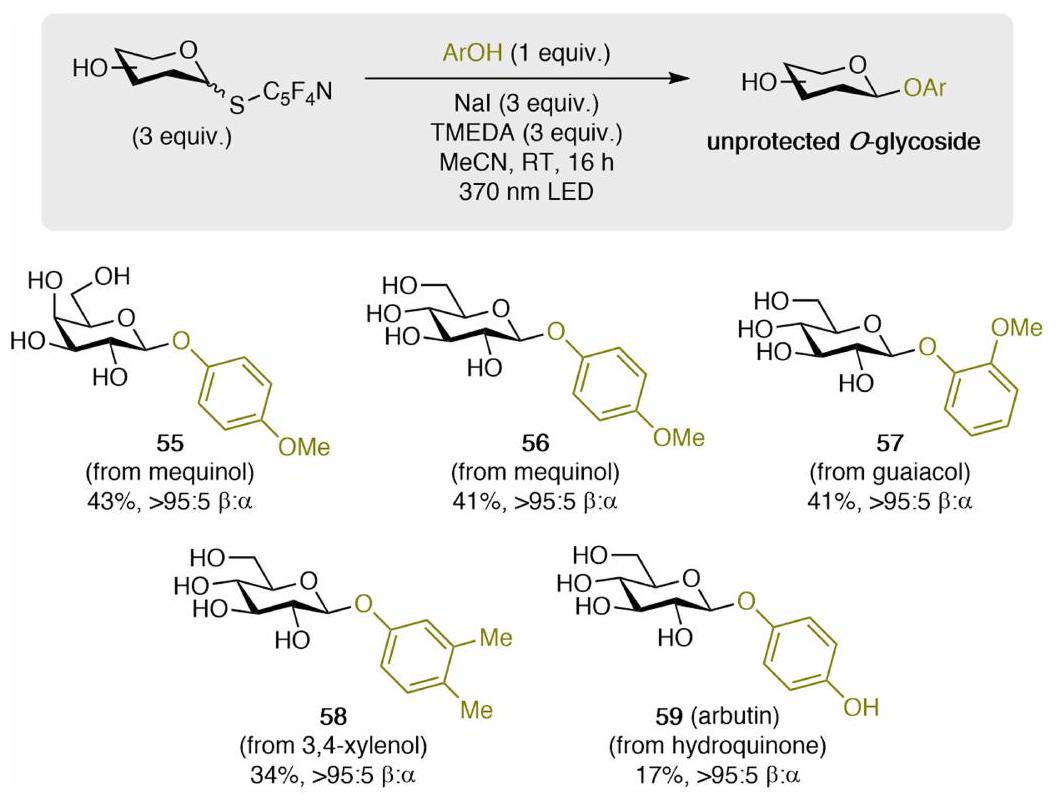

In contrast to the highly site-selective nature of enzymatic

unprotected native sugars (the most abundant form in nature) into tailored glycosyl precursors containing anomeric leaving groups such as halides

to achieve site- and stereoselective anomeric functionalization of native sugars. R, functional group; LG, leaving group; B, base; NTP, nucleoside triphosphate; NDP, nucleoside diphosphate; Dha, dehydroalanine;

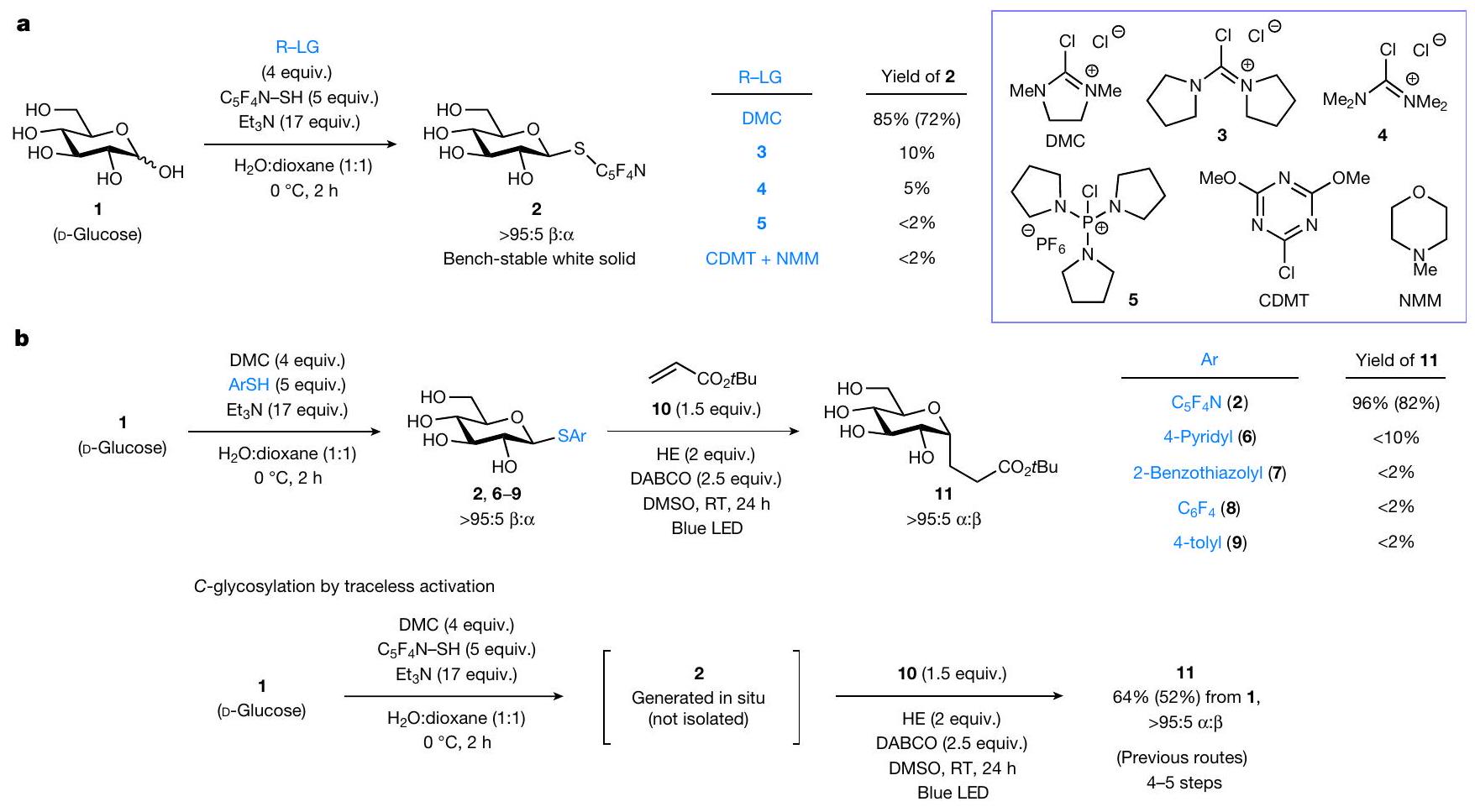

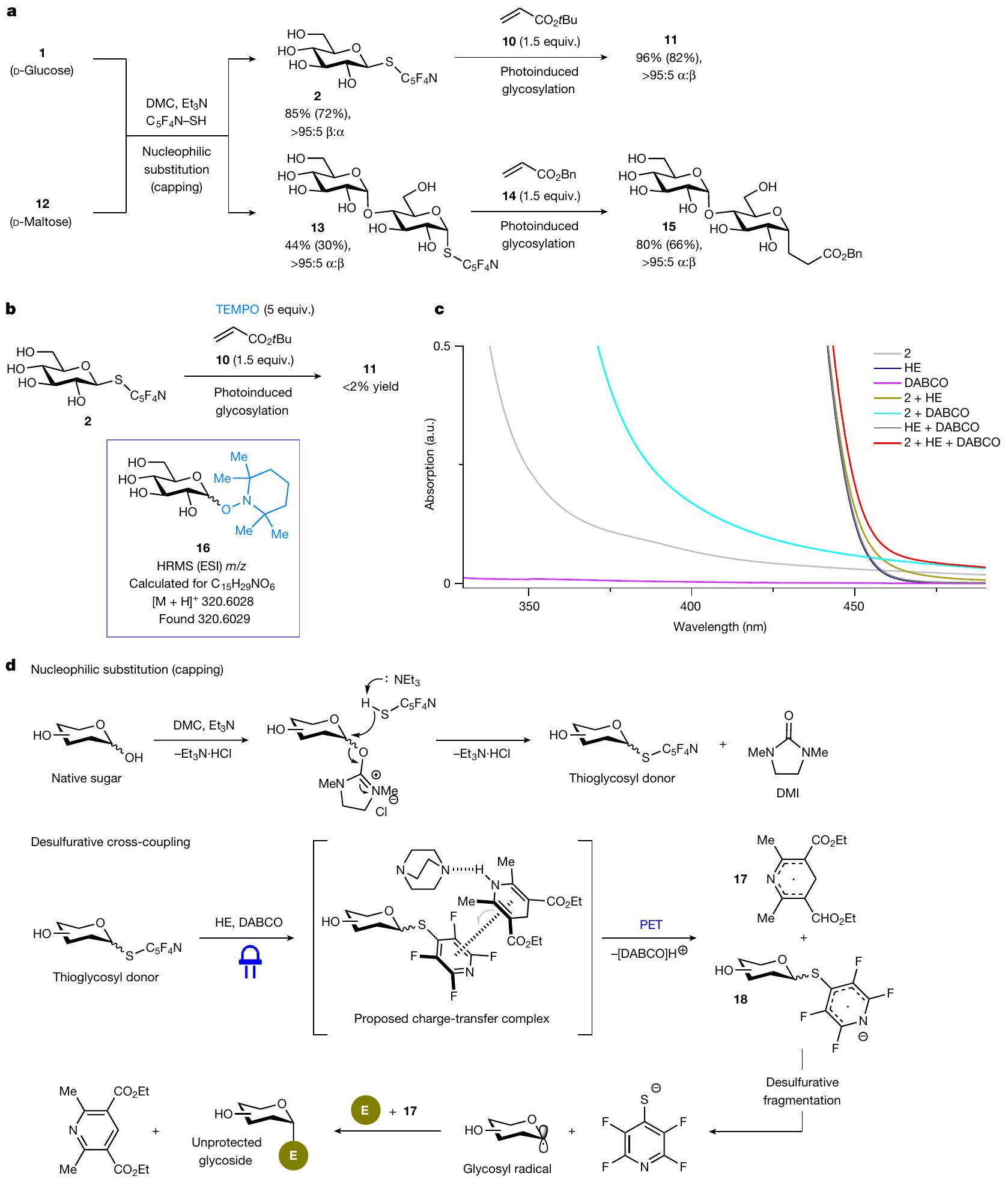

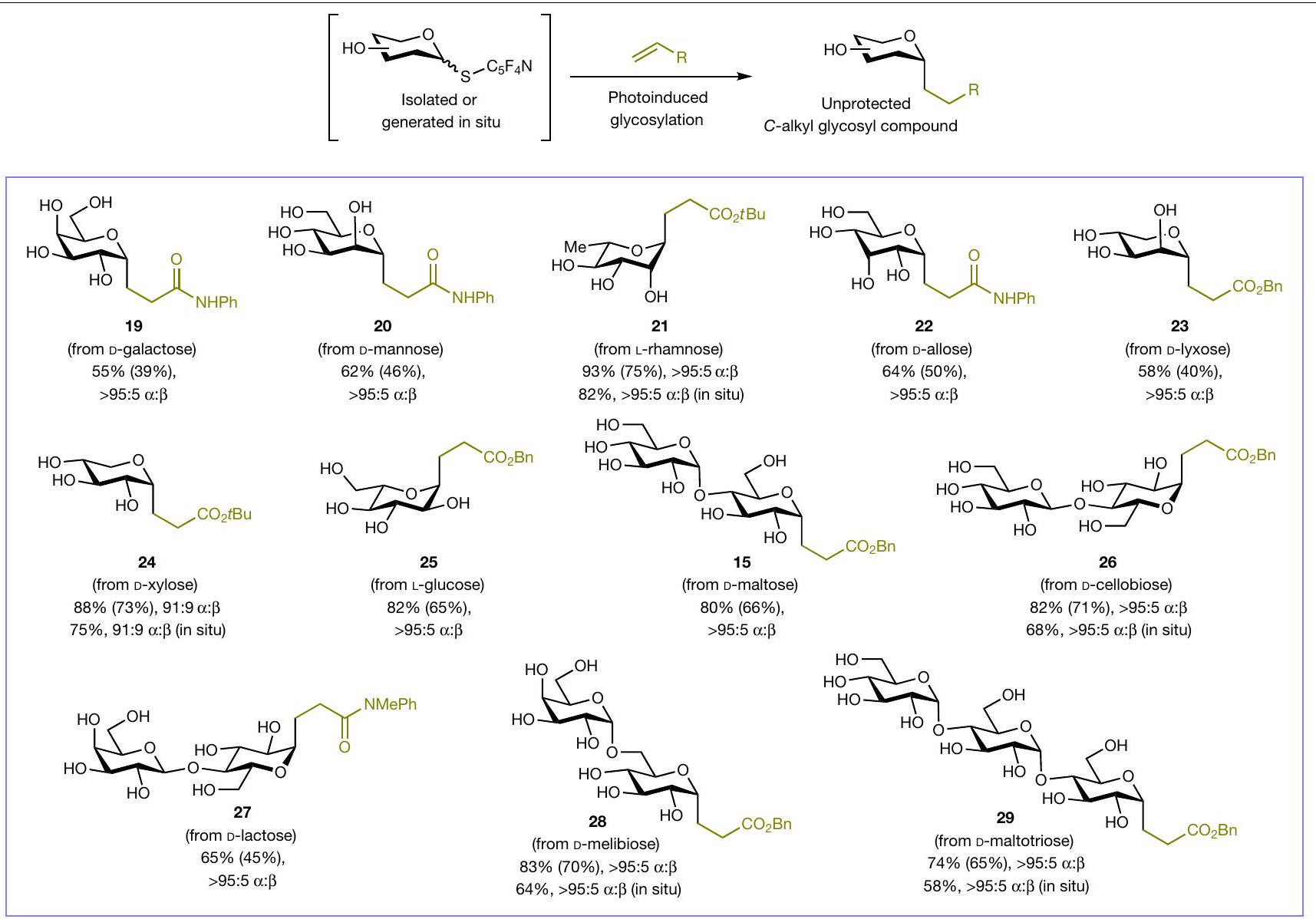

for the success of this ‘cap and glycosylate’ strategy. First, the multiple hydroxyl groups must be distinguished to ensure selective masking of the hemiacetal to form a transient thioglycosyl donor. Second, the donor must be sufficiently reactive to participate in cross-coupling without competitive interference or reaction on other hydroxyl sites, which would otherwise result in undesired reactions and intractable mixtures. Added to these is the challenge of controlling the stereochemical outcome of anomeric functionalization in the context of a complex, polyhydroxylated carbohydrate residue.

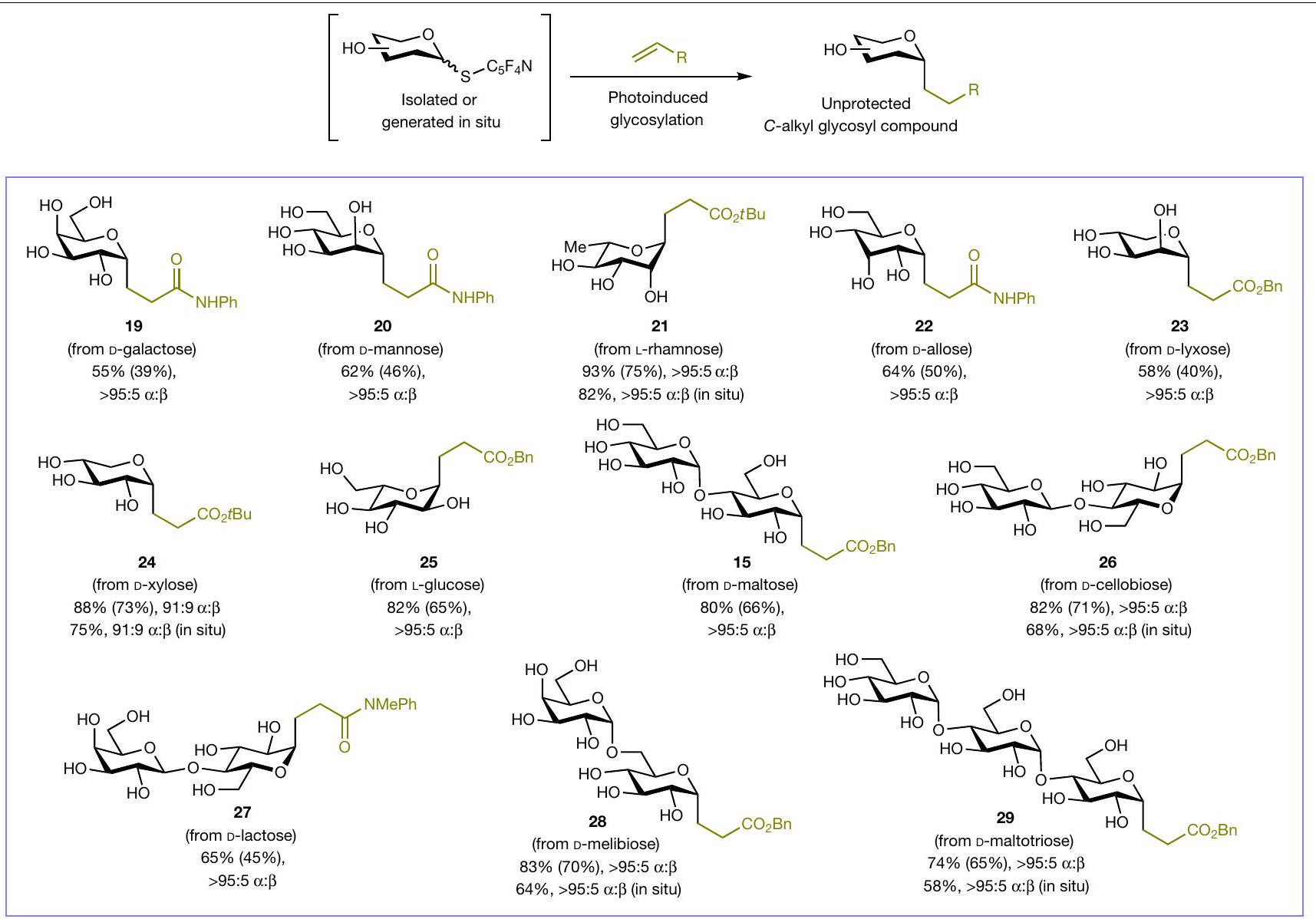

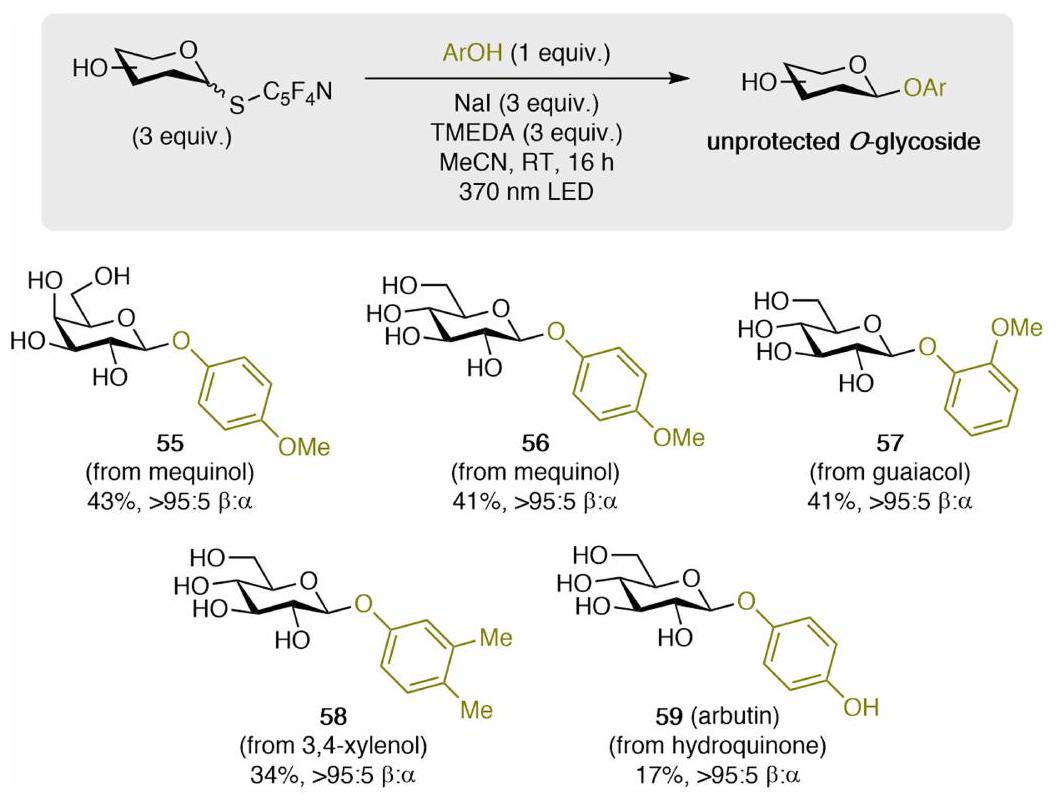

accelerate the preparation of robust carbo-, thio- and selenoglycosyl compounds as well as

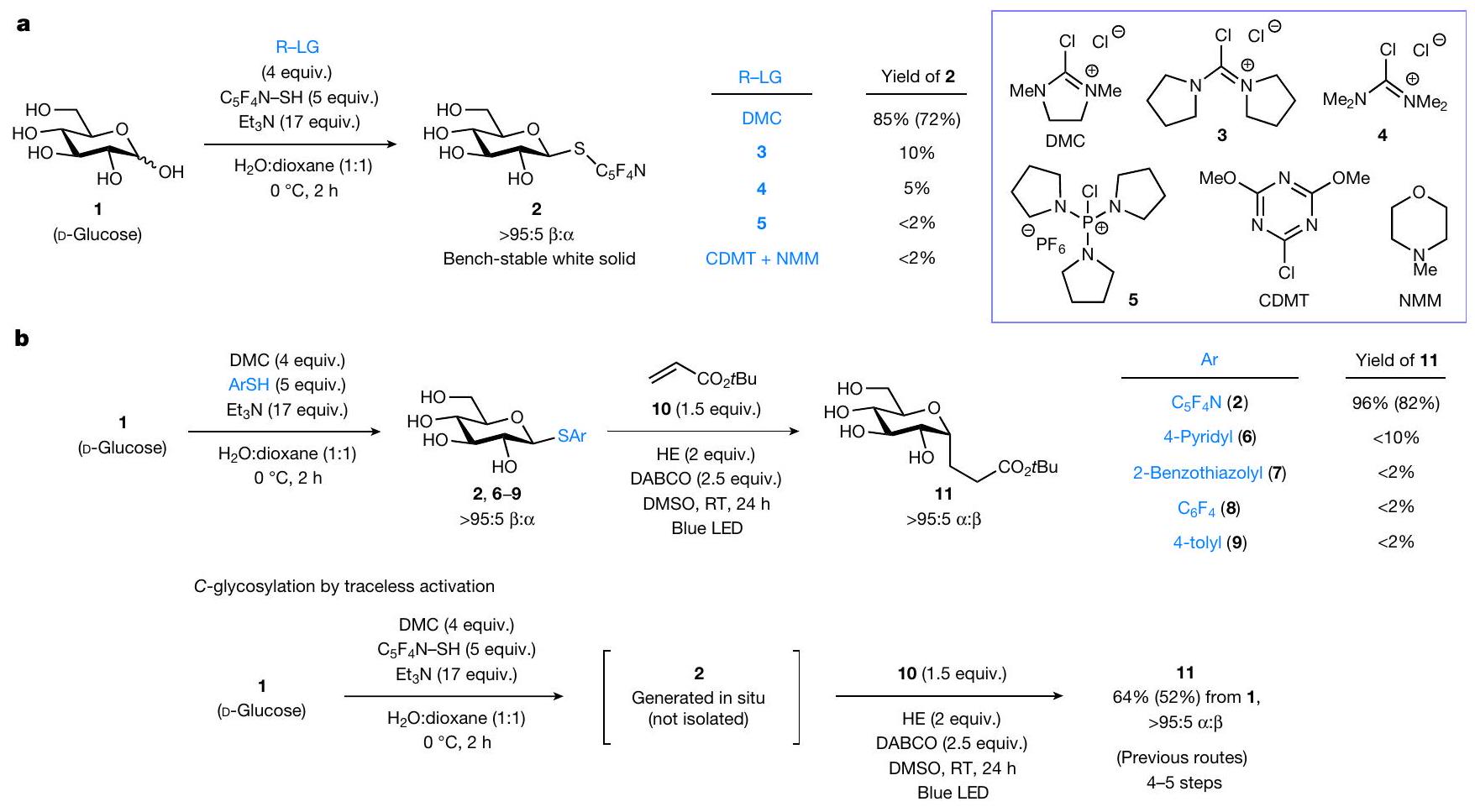

chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. DMC, 2-chloro-1,3-dimethylimidazolinium chloride; CDMT, 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine; NMM,

basic conditions (Fig. 2a). In the presence of commercially available 2-chloro-1,3-dimethylimidazolinium chloride (DMC) as activator and triethylamine as base, 2 was obtained in

With DMC identified as the most effective activator, we used the nucleophilic substitution conditions to synthesize not only 2 but also a range of unprotected (hetero)aryl thioglucosides (6-9) for comparison. To drive glycosylation, we subjected the thioglucosides to a reaction with acrylate

By contrast, poor conversion was observed with the less redox-active

reduction potential (Supplementary Figs. 2-6), which is comparable to that of a redox-active heteroaryl glycosyl sulfone

coupling. Yields were determined by

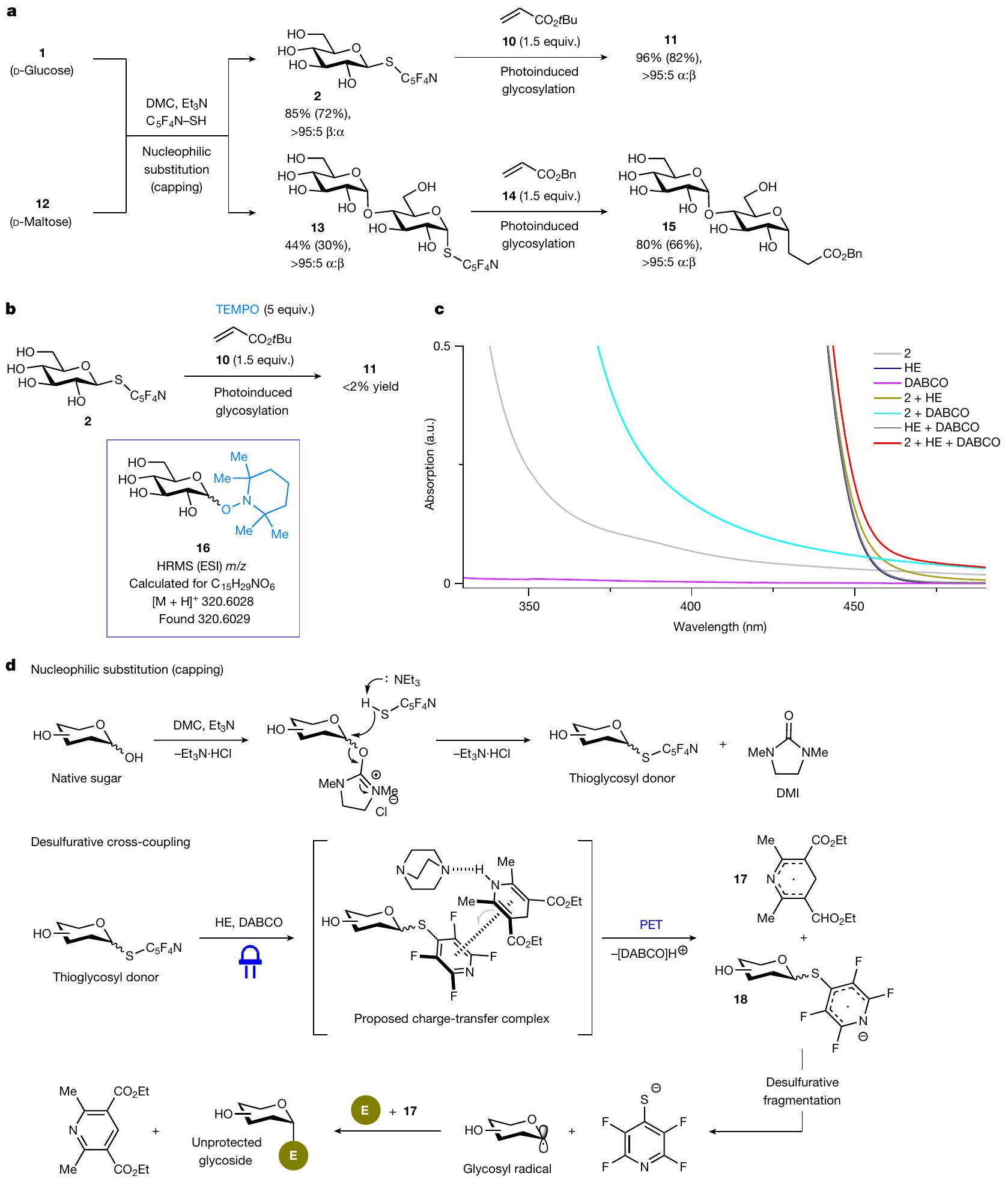

distinct advantage of the present strategy in transforming mixtures of unprotected native sugar isomers, through their thioglycoside derivatives, into stereoisomerically pure glycosides in a streamlined fashion. In a separate study, the addition of exogenous (

transformation of 2 to 11 (Fig. 3b). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis revealed the formation of a complex that can be ascribed to a TEMPO-glycoside adduct 16, providing evidence that a sufficiently long-lived glycosyl (anomeric) radical species is generated during the process. These processes are in contrast to heterolytic glycosylations that essentially lack the formation of a clear intermediate species (for example, glycosyl cation).

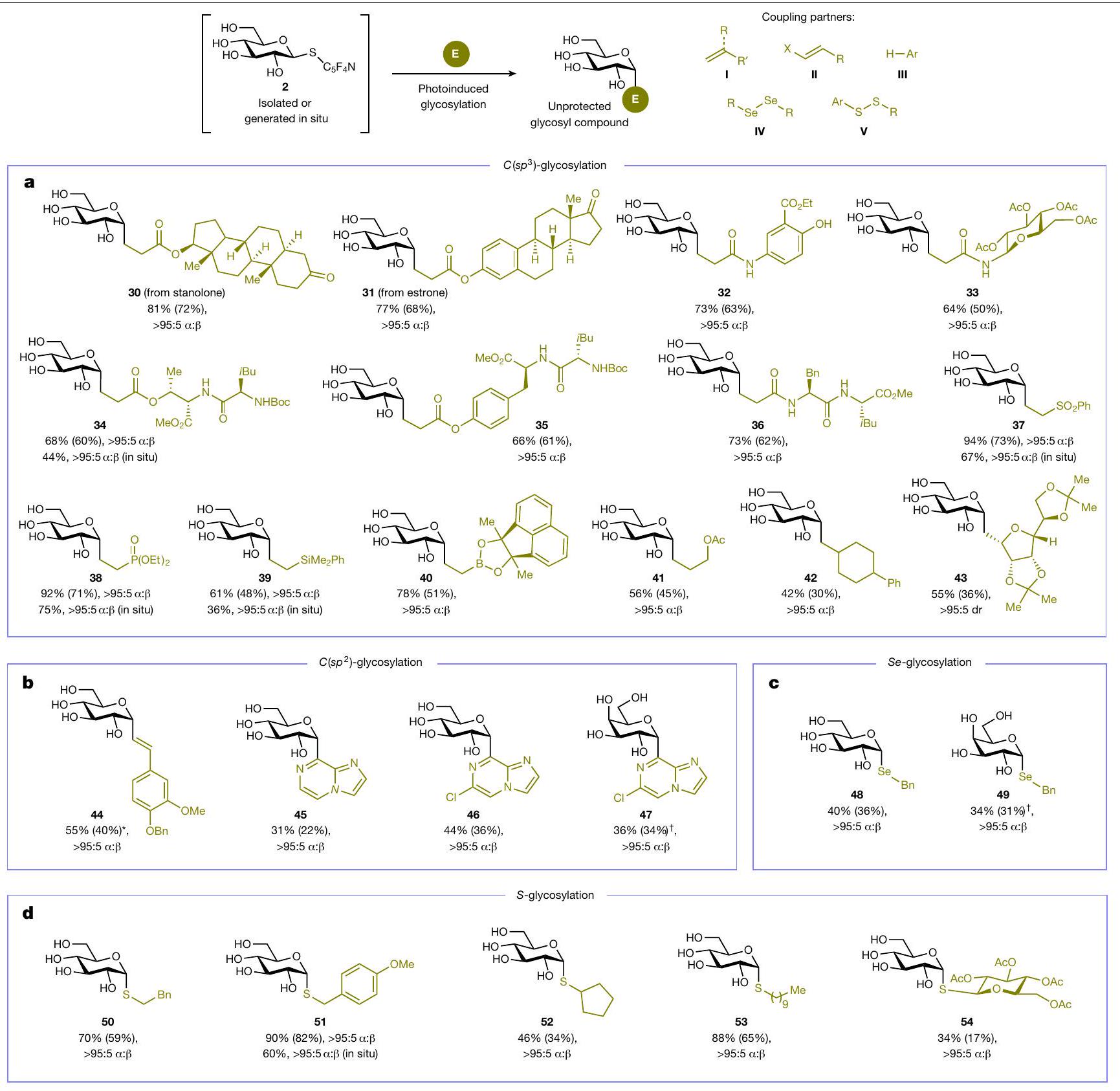

occur and cannot be completely ruled out (Supplementary Fig. 7). The resulting thioglycoside intermediate is postulated to associate with Hantzsch ester and DABCO in solution, affording a ternary complex that can absorb visible light to trigger photoinduced electron transfer (PET)

functionalized acrylates and acrylamides conjugated to biologically active compounds (30, 31), an aminosalicylate (32), an amino sugar (33) and oligopeptides (34-36) were compatible substrates, providing access to highly polar

presence of a less-activated alkyl-substituted alkene (42). Metabolically stable pseudo-oligosaccharide

of the protein substrate; yields in parentheses denote reactions with in situgenerated and unpurified thioglycosyl donors. Tris, 2-amino-2-(hydroxylmethyl)-propane-1,3-diol;

with heteroarenes under acid-free conditions, delivering unprotected 45-47 selectively at the most electron-deficient sites, which is congruent with a previous report involving fully protected glycosyl radicals

bis(catecholato)diboron (

After identifying the optimal conditions ( 500 equiv. of

Online content

- Bati, G., He, J. X., Pal, K. B. & Liu, X. W. Stereo- and regioselective glycosylation with protection-less sugar derivatives: an alluring strategy to access glycans and natural products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4006-4018 (2019).

- Dimakos, V. & Taylor, M. S. Site-selective functionalization of hydroxyl groups in carbohydrate derivatives. Chem. Rev. 118, 11457-11517 (2018).

- Volbeda, A. G., van der Marel, G. A. & Codée, J. D. C. in Protecting Groups Strategies and Applications in Carbohydrate Chemistry (ed. Vidal, S.) Ch. 1, 1-24 (Wiley-VCH, 2019).

- Rudd, P. M., Elliott, T., Cresswell, P., Wilson, I. A. & Dwek, R. A. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 291, 2370-2376 (2001).

- Varki, A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 27, 3-49 (2017).

- Reily, C., Stewart, T. J., Renfrow, M. B. & Novak, J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 346-366 (2019).

- Schjoldager, K. T., Narimatsu, Y., Joshi, H. J. & Clausen, H. Global view of human protein glycosylation pathways and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 729-749 (2020).

- Ernst, B. & Magnani, J. L. From carbohydrate leads to glycomimetic drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 661-677 (2009).

- Shivatare, S., SV, S., Shivatare, V. S. C.-H. & Wong, C.-H. Glycoconjugates: synthesis, functional studies, and therapeutic developments. Chem. Rev. 122, 15603-15671 (2022).

- Seeberger, P. H. Discovery of semi- and fully-synthetic carbohydrate vaccines against bacterial infections using a medicinal chemistry approach. Chem. Rev. 121, 3598-3626 (2021).

- Zhu, X. & Schmidt, R. R. New principles for glycoside-bond formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 1900-1934 (2009).

- McKay, M. J. & Nguyen, H. M. Recent advances in transition metal-catalyzed glycosylation. ACS Catal. 2, 1563-1595 (2012).

- Yang, Y. & Yu, B. Recent advances in the chemical synthesis of C-glycosides. Chem. Rev. 117, 12281-12356 (2017).

- Kulkarni, S. S. et al. “One-pot” protection, glycosylation, and protection-glycosylation strategies of carbohydrates. Chem. Rev. 118, 8025-8104 (2018).

- Nielsen, M. M. & Pedersen, C. M. Catalytic glycosylations in oligosaccharide synthesis. Chem. Rev. 118, 8285-8358 (2018).

- Li, W., McArthur, J. B. & Chen, X. Strategies for chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Res. 472, 86-97 (2019).

- Putkaradze, N., Teze, D., Fredslund, F. & Welner, D. H. Natural product C-glycosyltransferases a scarcely characterised enzymatic activity with biotechnological potential. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 432-443 (2021).

- Franck, R. W. & Tsuji, M. a-C-Galactosylceramides: synthesis and immunology. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 692-701 (2006).

- Chao, E. C. & Henry, R. R. SGLT2 inhibition – a novel strategy for diabetes treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 551-559 (2010).

- Adak, L. et al. Synthesis of aryl C-glycosides via iron-catalyzed cross coupling of halosugars: stereoselective anomeric arylation of glycosyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10693-10701 (2017).

- Wang, Q. et al. Palladium-catalysed C-H glycosylation for synthesis of C-aryl glycosides. Nat. Catal. 2, 793-800 (2019).

- Lv, W., Chen, Y., Wen, S., Ba, D. & Cheng, G. Modular and stereoselective synthesis of C-aryl glycosides via Catellani reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14864-14870 (2020).

- Jiang, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, X. & Koh, M. J. Synthesis of C-glycosides by Ti-catalyzed stereoselective glycosyl radical functionalization. Chem 7, 3377-3392 (2021).

- Wang, Q. et al. Iron-catalysed reductive cross-coupling of glycosyl radicals for the stereoselective synthesis of C-glycosides. Nat. Synth. 1, 235-244 (2022).

- Wei, Y., Ben-Zvi, B. & Diao, T. Diastereoselective synthesis of aryl C-glycosides from glycosyl esters via C-O bond homolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9433-9438 (2021).

- Wei, Y., Lam, J. & Diao, T. Synthesis of C-acyl furanosides via the cross-coupling of glycosyl esters with carboxylic acids. Chem. Sci. 12, 11414-11419 (2021).

- Romeo, J. R., Lucera, J. D., Jensen, D., Davis, L. M. & Bennett, C. S. Application of redoxactive ester catalysis to the synthesis of pyranose alkyl C-glycosides. Org. Lett. 25, 3760-3765 (2023).

- Shang, W. et al. Generation of glycosyl radicals from glycosyl sulfoxides and its use in the synthesis of C-linked glycoconjugates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 385-390 (2021).

- Xie, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Fu, Z. & Niu, D. Alkyl/glycosyl sulfoxides as radical precursors and their use in the synthesis of pyridine derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204922 (2022).

- Wang, Q. et al. Visible light activation enables desulfonylative cross-coupling of glycosyl sulfones. Nat. Synth. 1, 967-974 (2022).

- Wang, Q., Lee, B. C., Song, N. & Koh, M. J. Stereoselective C-aryl glycosylation by catalytic cross-coupling of heteroaryl glycosyl sulfones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301081 (2023).

- Zhang, C. et al. Direct synthesis of unprotected aryl C-glycosides by photoredox Ni-catalysed cross-coupling. Nat. Synth. 2, 251-260 (2023).

- Li, Q., Levi, S. M., Wagen, C. C., Wendlandt, A. E. & Jacobsen, E. N. Site-selective, stereocontrolled glycosylation of minimally protected sugars. Nature 608, 74-79 (2022).

- Pachamuthu, K. & Schmidt, R. R. Synthetic routes to thiooligosaccharides and thioglycopeptides. Chem. Rev. 106, 160-187 (2006).

- Hogan, A. E. et al. Activation of human invariant natural killer T cells with a thioglycoside analogue of a-galactosylceramide. Clin. Immunol. 140, 196-207 (2011).

- Kónya, Z. et al. Aralkyl selenoglycosides and related selenosugars in acetylated form activate protein phosphatase-1 and -2A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26, 1875-1884 (2018).

- Gantt, R. W., Goff, R. D., Williams, G. J. & Thorson, J. S. Probing the aglycon promiscuity of an engineered glycosyltransferase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8889-8892 (2008).

- Fujinami, D. et al. Structural and mechanistic investigations of protein S-glycosyltransferases. Cell Chem. Biol. 28, 1740-1749 (2021).

- Panferova, L. I. & Dilman, A. D. Light-mediated sulfur-boron exchange. Org. Lett. 23, 3919-3922 (2021).

- Worp, B. A., Kosobokov, M. D. & Dilman, A. D. Visible-light-promoted reversible sulfide/ iodide exchange in fluoroalkyl sulfides enabled by electron donor-acceptor complex formation. ChemPhotoChem 5, 565-570 (2021).

- Fu, X.-P. et al. Stereoretentive post-translational protein editing. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 405-416 (2023).

- Gyurcsik, B. & Nagy, L. Carbohydrates as ligands: coordination equilibria and structure of the metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 203, 81-149 (2000).

- Fairbanks, A. J. Applications of Shoda’s reagent (DMC) and analogues for activation of the anomeric centre of unprotected carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Res. 499, 108197 (2021).

- Fawcett, A. et al. Photoinduced decarboxylative borylation of carboxylic acids. Science 357, 283-286 (2017).

- Fu, M.-C., Shang, R., Zhao, B., Wang, B. & Fu, Y. Photocatalytic decarboxylative alkylations mediated by triphenylphosphine and sodium iodide. Science 363, 1429-1434 (2019).

- Silvi, M. & Melchiorre, P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 554, 41-49 (2018).

- Giese, B. & Dupis, J. Diastereoselective syntheses of C-glycopyranosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 22, 622-623 (1983).

- Abe, H., Shuto, S. & Matsuda, A. Highly a- and

-selective radical -glycosylation reactions using a controlling anomeric effect based on the conformational restriction strategy. A study on the conformation-anomeric effect-stereoselectivity relationship in anomeric radical reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11870-11882 (2001). - Yuan, X. & Linhardt, J. R. Recent advances in the synthesis of C-oligosaccharides. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 5, 1393-1430 (2005).

- Xia, L., Fan, W., Yuan, X.-A. & Yu, S. Photoredox-catalyzed stereoselective synthesis of C-nucleoside analogues from glycosyl bromides and heteroarenes. ACS Catal. 11, 9397-9406 (2021).

- Dong, Z. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative arylation of alcohols. Nature 598, 451-456 (2021).

- Zhu, F. et al. Catalytic and photochemical strategies to stabilized radicals based on anomeric nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11102-11113 (2020).

- Zhang, C. et al. Halogen-bond-assisted radical activation of glycosyl donors enables mild and stereoconvergent 1,2-cis-glycosylation. Nat. Chem. 14, 686-694 (2022).

- Gamblin, D. P., Scanlan, E. M. & Davis, B. G. Glycoprotein synthesis: an update. Chem. Rev. 109, 131-163 (2009).

- Boutureira, O. & Bernardes, G. J. Advances in chemical protein modification. Chem. Rev. 115, 2174-2195 (2015).

- Dadová, J., Galan, S. R. & Davis, B. G. Synthesis of modified proteins via functionalization of dehydroalanine. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 46, 71-81 (2018).

- Josephson, B. et al. Light-driven post-translational installation of reactive protein side chains. Nature 585, 530-537 (2020).

- Zheng, R. & Blanchard, J. S. Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pantothenate synthetase. Biochemistry 40, 12904-12912 (2001).

- Qi, Y., Kobayashi, Y. & Hulett, F. M. The pst operon of Bacillus subtilis has a phosphateregulated promoter and is involved in phosphate transport but not in regulation of the pho regulon. J. Bacteriol. 179, 2534-2539 (1997).

- Aguilar, C. F. et al. Crystal structure of the

-glycosidase from the hyperthermophilic archeon sulfolobus solfataricus: resilience as a key factor in thermostability. J. Mol. Biol. 271, 789-802 (1997). - Zhang, S., Roche, K., Nasheuer, H. P. & Lowndes, N. F. Modification of histones by sugar

– -acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) occurs on multiple residues, including histone H3 serine 10, and is cell cycle-regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37483-37495 (2011). - Parsons, T. B. et al. Optimal synthetic glycosylation of a therapeutic antibody. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2361-2367 (2016).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Article

Data availability

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Benjamin G. Davis or Ming Joo Koh.

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

Department of Chemistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore. The Rosalind Franklin Institute, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, UK. Department of Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Department of Chemistry, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China. Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. These authors contributed equally: Yi Jiang, Yi Wei. These authors jointly supervised this work: Benjamin G. Davis, Ming Joo Koh. e-mail: ben.davis@chem.ox.ac.uk; chmkmj@nus.edu.sg