DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae052

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38520141

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-27

التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي: توافق دلفي من المبادرة العالمية للقيادة في الضمور العضلي (GLIS)

– للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

معرف HAL: hal-04938140

https://hal.science/hal-04938140v1

https://doi.org/ل 0. 1 093/الشيخوخة/افاي052

© المؤلفون 2024. نُشر بواسطة مطبعة جامعة أكسفورد نيابة عن الجمعية البريطانية للشيخوخة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة بموجب شروط ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري.http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/الذي يسمح بإعادة الاستخدام غير التجاري، والتوزيع، والتكاثر في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاقتباس من العمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح. لإعادة الاستخدام التجاري، يرجى الاتصال بـjournals.permissions@oup.com

ورقة بحثية

التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي: توافق دلفي من المبادرة العالمية للقيادة في الضمور العضلي (GLIS)

الملخص

الأهمية: الساركوبينيا، وهي فقدان الكتلة العضلية والقوة/الوظيفة المرتبطة بالعمر، هي حالة سريرية مهمة. ومع ذلك، لا يوجد توافق دولي على التعريف. الهدف: كانت مبادرة القيادة العالمية في الساركوبينيا (GLIS) تهدف إلى معالجة ذلك من خلال إنشاء تعريف مفهومي عالمي للساركوبينيا. التصميم: تم تشكيل لجنة توجيهية لـ GLIS في 2019-21 مع ممثلين من جميع الجمعيات العلمية ذات الصلة في جميع أنحاء العالم. خلال هذه الفترة، وضعت اللجنة مجموعة من البيانات حول الموضوع ودعت أعضاء من هذه الجمعيات للمشاركة في دراسة دلفي الدولية ذات المرحلتين. بين 2022 و2023، قام المشاركون بتصنيف اتفاقهم مع مجموعة من البيانات باستخدام أداة استطلاع عبر الإنترنت (SurveyMonkey). تم تصنيف البيانات بناءً على عتبات محددة مسبقًا: اتفاق قوي (

النقاط الرئيسية

- السؤال: قامت عدة جمعيات ومنظمات بتطوير تعريفات للساركوبينيا، والتي هي محددة إقليميًا. في الوقت الحالي، لا يوجد توافق دولي حول كيفية تعريف الساركوبينيا.

- النتائج: قامت مبادرة القيادة العالمية في الساركوبينيا (GLIS)، وهي تعاون دولي من خبراء من جميع جمعيات/منظمات الساركوبينيا الرئيسية في جميع أنحاء العالم، بتطوير أول تعريف مفهومي عالمي للساركوبينيا. سيتم الآن استخدام هذا التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا لتطوير تعريف تشغيلي للساركوبينيا لكل من الإعدادات السريرية والبحثية.

- المعنى: تشير هذه الجهود التعاونية من GLIS إلى خطوة حاسمة نحو تعزيز فهمنا وإدارة الساركوبينيا على نطاق عالمي.

المقدمة

التي تصف الساركوبينيا في 2020 [20، 21]. تم تشكيل مبادرة القيادة العالمية في الساركوبينيا (GLIS) في محاولة لتنسيق هذه التعريفات المتنافسة في تصنيف موحد واحد سيتم استخدامه كمعيار ذهبي في تقييم الساركوبينيا.

الطرق

تطوير مبادرة GLIS

ب. كيرك وآخرون.

بدءًا من مسرد ومقالة مفاهيمية: نهج استراتيجي للتشغيل اللاحق

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

الإدراج/الاستبعاد

خصائص لجنة GLIS

| البيانات من الجولة 1 | الاتفاق (المتوسط

|

الاتفاق (%) | النتيجة |

| الساركوبينيا هي مرض عام للعضلات الهيكلية |

|

85.4% | مقبول |

| تزداد نسبة انتشار الساركوبينيا مع التقدم في العمر |

|

98.3% | مقبول |

| يجب ألا يختلف التعريف المفاهيمي للساركوبينيا حسب إعداد الرعاية (مثل، داخل المستشفى مقابل خارج المستشفى) |

|

91.2% | مقبول |

| يجب أن تظل التعريفات المفاهيمية للضمور العضلي ثابتة بغض النظر عن العمر أو الحالة (مثل فشل القلب، مرض الكلى، السرطان، إلخ). |

|

83.2٪ | مقبول |

| يجب أن تكون التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي هو نفسه للممارسة السريرية والبحث. |

|

92.0% | مقبول |

| يجب أن تكون كتلة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. |

|

89.4% | مقبول |

| يجب أن تكون الخصائص الشكلية للأنسجة العضلية (مثل تسرب الدهون إلى العضلات، وكثافة العضلات أو نسيجها) جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. |

|

69.9% | مرفوض |

| يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. |

|

93.1٪ | مقبول |

| يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. |

|

68.4٪ | مرفوض |

| تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر ضعف الأداء البدني |

|

97.9% | مقبول |

| يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر قيود الحركة (المشي) |

|

96.1٪ | مقبول |

| يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر قيود الحركة (الانتقال من الكرسي أو السرير إلى الوقوف) |

|

95.0% | مقبول |

| زيادة الساركوبينيا تزيد من خطر السقوط |

|

94.6٪ | مقبول |

| الساركوبينيا تزيد من خطر الكسور |

|

89.4٪ | مقبول |

| يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر عدم القدرة على أداء الأنشطة اليومية الأساسية المعقدة. |

|

٨٨.٦٪ | مقبول |

| يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر عدم القدرة على أداء الأنشطة اليومية الأساسية (الرعاية الذاتية) |

|

90.7% | مقبول |

| تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الدخول إلى المستشفى |

|

91.0% | مقبول |

| يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الدخول الجديد إلى دور الرعاية (دور التمريض) |

|

89.5% | مقبول |

| تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر تدني جودة الحياة |

|

91.8٪ | مقبول |

| زيادة الساركوبينيا تزيد من خطر الوفاة |

|

91.6% | مقبول |

| بيانات من الجولة الثانية | اتفاق

|

الاتفاقية (%) | نتيجة |

| يجب أن تكون القوة المحددة للعضلات (مثل، قوة العضلات/حجم العضلات) جزءًا من التعريف المفاهيمي للضمور العضلي. |

|

80.8٪ | مقبول |

| يجب أن يكون الأداء البدني جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. |

|

79.8٪ | مرفوض |

| يجب أن تكون التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا مرضًا قابلًا للعكس. |

|

84.1٪ | مقبول |

| يجب أن تتضمن التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي مستويات شدة المرض |

|

77.0% | مرفوض |

| ملاحظة: كانت هناك مقياس ليكرت من 11 نقطة يتراوح من أوافق بشدة (0) إلى أوافق بشدة (10) مصاحب لكل عبارة. | حساب الموازين الموزونة | ||

| بيانات مع اتفاق قوي (

|

استجابة | وزن | تفسير |

| بيانات ذات توافق منخفض

|

9,10 | 100% | أوافق بشدة |

| ٧، ٨ | 80٪ | لا أوافق ولا أعارض | |

| ٢، ٣ | 40٪ | يختلف | |

| 0,1 | 20٪ | أعارض بشدة | |

الجولة الأولى من عملية دلفي

- يجب أن تتضمن التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا مستويات شدة المرض”. الاتفاق: 77.9% (متوسط الدرجة:

). - يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. الاتفاق: 79.1% (متوسط الدرجة:

). - يجب أن تكون القوة العضلية المحددة (مثل، قوة العضلات/حجم العضلات) جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي”، الاتفاق:

(متوسط الدرجة: ). - “يجب أن يكون الأداء البدني جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي”. الاتفاق:

(متوسط الدرجة: ). - يجب أن يكون الأداء البدني علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي: الاتفاق: 82.2% (متوسط الدرجة:

).

- يجب أن تكون التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا مرضًا قابلًا للعكس.

الجولة الثانية من عملية دلفي

ب. كيرك وآخرون

| متغير | فئة فرعية | بشكل عام

|

| العمر، السنوات، المتوسط

|

|

|

| الجنس، الرجال، عدد (%) | 68 (64%) | |

| العرق/الاثنية، عدد (%) | ||

| أبيض/قوقازي | 73 (68%) | |

| آسيوي/جزيرة المحيط الهادئ | ٢٦ (٢٤٪) | |

| هسباني | 3 (3%) | |

| أسود أو أمريكي من أصل أفريقي | 1 (1%) | |

| يفضل عدم القول | 4 (4%) | |

| القارة/المنطقة، الإقامة الحالية، ن (%) | ||

| أوروبا | 43 (40%) | |

| آسيا | 23 (22%) | |

| أمريكا الشمالية | 20 (19%) | |

| أستراليا | 13 (12%) | |

| أمريكا الجنوبية | 4 (4%) | |

| أفريقيا | 3 (3%) | |

| أنتاركتيكا/نيوزيلندا | 1 (1%) | |

| الدولة، الإقامة الحالية، عدد (%) | ||

| أستراليا | 13 (12%) | |

| بلجيكا | 5 (5%) | |

| البرازيل | 3 (3%) | |

| الكاميرون | 1 (1%) | |

| كندا | 4 (4%) | |

| تشيلي | 1 (1%) | |

| الصين | 3 (3%) | |

| جمهورية التشيك | 1 (1%) | |

| الدنمارك | 1 (1%) | |

| فنلندا | 1 (1%) | |

| فرنسا | 2 (2%) | |

| ألمانيا | 4 (4%) | |

| إيطاليا | 5 (5%) | |

| اليابان | 5 (5%) | |

| المكسيك | 1 (1%) | |

| هولندا | 6 (6%) | |

| نيوزيلندا | 1 (1%) | |

| بولندا | 2 (2%) | |

| جمهورية كوريا | 4 (4%) | |

| المملكة العربية السعودية | 3 (3%) | |

| سنغافورة | 3 (3%) | |

| جنوب أفريقيا | 2 (2%) | |

| إسبانيا | 2 (2%) | |

| السويد | 1 (1%) | |

| سويسرا | 3 (3%) | |

| تايوان | 5 (5%) | |

| تركيا | 1 (1%) | |

| المملكة المتحدة لبريطانيا العظمى وأيرلندا الشمالية | 9 (8%) | |

| الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | 15 (14%) | |

| الدور الأساسي، عدد (%) | ||

| محترف أكاديمي | 76 (71%) | |

| أستاذ | 54 (71%) | |

| أستاذ مشارك | 11 (14%) | |

| زميل بحث (مثل: ما بعد الدكتوراه، أستاذ أول، أستاذ مساعد) | 6 (8%) | |

| محاضر | 2 (3%) | |

| غير محدد | 3 (4%) | |

| مهني صحي | 23 (22%) | |

| طبيب مسنّين | 18 (78%) | |

| طبيب | 3 (13%) | |

| إعادة تأهيل | 1 (4%) | |

| أخرى (يرجى التحديد)

|

1 (4%) | |

| محترف الصناعة | 3 (3%) | |

| المدير العلمي | 1 (33%) | |

| أخرى (يرجى التحديد)

|

2 (67%) | |

| أخرى (يرجى التحديد)

|

5 (5%) |

| رقم | بيان | اتفاق |

| الجوانب العامة للضمور العضلي | ||

| 1 | الساركوبينيا هي مرض عام يؤثر على العضلات الهيكلية | 85.4% |

| 2 | تزداد انتشار الساركوبينيا مع التقدم في العمر | 98.3% |

| ٣ | يجب أن لا تختلف التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا حسب بيئة الرعاية (مثل المرضى الداخليين مقابل المرضى الخارجيين). | 91.2% |

| ٤ | يجب أن لا تتغير التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا حسب العمر أو الحالة (مثل فشل القلب، مرض الكلى، السرطان، إلخ). | ٨٣.٢٪ |

| ٥ | يجب أن تكون التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي هو نفسه في الممارسة السريرية والبحث. | 92.0% |

| ٦ | يجب أن تكون التعريف المفهومي للساركوبينيا مرضًا قابلًا للعكس. | 84.1٪ |

| مكونات الساركوبينيا | ||

| ٧ | يجب أن تكون كتلة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 89.4% |

| ٨ | يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 93.1٪ |

| 9 | يجب أن تكون القوة المحددة للعضلات (مثل قوة العضلات/حجم العضلات) جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 80.8٪ |

| نتائج الساركوبينيا | ||

| 10 | تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر ضعف الأداء البدني | 97.9% |

| 11 | يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر قيود الحركة (المشي) | 96.1٪ |

| 12 | يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر قيود الحركة (الانتقال من الكرسي أو السرير إلى الوقوف). | 95.0% |

| ١٣ | الساركوبينيا تزيد من خطر السقوط | 94.6٪ |

| 14 | تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الكسور | 89.4% |

| 15 | يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر عدم القدرة على أداء الأنشطة اليومية الأساسية المعقدة. | ٨٨.٦٪ |

| 16 | يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر عدم القدرة على أداء الأنشطة اليومية الأساسية (الرعاية الذاتية) | 90.7% |

| 17 | تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الدخول إلى المستشفى | 91.0% |

| 18 | يزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الدخول الجديد إلى دور الرعاية (دور التمريض) | 89.5% |

| 19 | تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر تدني جودة الحياة | 91.8٪ |

| 20 | تزيد الساركوبينيا من خطر الوفاة | 91.6٪ |

| رقم | بيان | اتفاق |

| الجوانب العامة للضمور العضلي | ||

| 1 | يجب أن تكون الخصائص الشكلية للأنسجة العضلية (مثل تسرب الدهون إلى العضلات، وكثافة العضلات أو نسيج العضلات) جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 69.9% |

| 2 | يجب أن تتضمن التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي مستويات شدة المرض | 77.0% |

| مكونات الساركوبينيا | ||

| ٣ | يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 68.4٪ |

| ٤ | يجب أن يكون الأداء البدني جزءًا من التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. | 79.8٪ |

- “يجب أن تكون كتلة العضلات علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي.” الاتفاق:

(متوسط الدرجة: ; تم الإجابة = 93، تم تخطي = 14). - “يجب أن تكون قوة العضلات علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي.” الاتفاق:

(متوسط الدرجة: ; تم الإجابة = 94، تم تخطي = 13). - يجب أن تكون القوة العضلية المحددة (مثل، قوة العضلات/حجم العضلات) علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. الاتفاق: 68.6% (متوسط الدرجة: 6.1)

2.9؛ أجاب = 93، تخلف = 14). - يجب أن يكون الأداء البدني علامة على شدة التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي. الاتفاق: 81.9% (متوسط الدرجة:

; تم الإجابة = 93، تم تخطي = 14) (الشكل 2).

نقاش

القوة المحددة في التعريف المفهومي للضمور العضلي كانت أعلى بقليل من عتبة الاتفاق لدينا.

التعريف المفهومي العالمي للساركوبينيا

- ائتلاف الشيخوخة في الحركة (AIM) / التحالف من أجل أبحاث الشيخوخة (AAR) – جاك جيرالنك

- الجمعية الأمريكية لطب الشيخوخة (AGS) – إلين ف. بيندر

- الجمعية الأمريكية لأبحاث العظام والمعادن (ASBMR) – دوغلاس ب. كيل

- الرابطة الآسيوية للهشاشة والساركوبينيا (AAFS) – ليانغ-كونغ تشين

- الجمعية الأسترالية والنيوزيلندية لأبحاث الساركوبينيا والضعف (ANZSSFR) – غوستافو دوكي

- الرابطة الأوروبية لدراسة السمنة (EASO) روكو بارازوني

- الجمعية الأوروبية لطب الشيخوخة (EuGMS) – ألفونسو ج. كروز-خينتوت

- الجمعية الأوروبية للجوانب السريرية والاقتصادية لهشاشة العظام، والتهاب المفاصل، وأمراض الجهاز العضلي الهيكلي (ESCEO) – أوليفييه بروير

- الجمعية الأوروبية للتغذية السريرية والتمثيل الغذائي (ESPEN) – تومي سيدرهولم

- جمعية علم الشيخوخة الأمريكية (GSA) – بيغي م. كاوثون وروجر أ. فيلدينغ

- الرابطة الدولية لعلم الشيخوخة وطب الشيخوخة (IAGG) – خوسيه أ. أفيلا-فونيس

- المؤتمر الدولي حول أبحاث الهشاشة والضمور العضلي (ICFSR) – روجر أ. فيلدينغ

- الاتحاد الدولي لهشاشة العظام (IOF) – سايروس كوبر وجان-إيف ريجينستر

- جمعية الساركوبينيا، الكاشكسيا واضطرابات الهزال (SCWD) – ستيفان فون هايلينغ

يود المؤلفون أن يعبروا عن امتنانهم لكاترينا ويرنر-بيريز وليندسي كلارك، كلاهما من التحالف لأبحاث الشيخوخة، على دعمهما الإداري الذي ساعد بشكل كبير في هذه الدراسة دلفي.

إعلان تضارب المصالح: قبل بدء مبادرة GLIS، قدم جميع المؤلفين نموذج إعلان المصالح. هذا الإعلان، الذي هو أكثر تفصيلاً من نموذج تضارب المصالح القياسي، كان مفتوحًا للتدقيق العام ويمكن الاطلاع عليه هنا:https://www.eugms.org/fileadmin/images/news/2022/GLIS_Steering_Committee_Rev3.pdf.

لا تعكس بالضرورة آراء وزارة الزراعة الأمريكية. يمكن قراءة جميع إعلانات المؤلفين حول مصادر التمويل هنا:https://www.eugms.org/fileadmin/images/news/2022/GLIS_Steering_Committee_Rev3.pdf.

References

- Cawthon PM, Manini T, Patel SM et al. Putative cut-points in sarcopenia components and incident adverse health outcomes: an SDOC analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68: 1429-37.

- Cawthon PM, Blackwell T, Cummings SR et al. Muscle mass assessed by the D3-creatine dilution method and incident self-reported disability and mortality in a prospective observational study of community-dwelling older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021; 76: 123-30.

- Guralnik JM, Cawthon PM, Bhasin S et al. Limited physician knowledge of sarcopenia: a survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023; 71: 1595-602.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019; 393: 2636-46.

- Anker SD, Morley JE, von Haehling S. Welcome to the ICD10 code for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016; 7: 512-4.

- Mayhew AJ, Amog K, Phillips

et al. The prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults, an exploration of differences between studies and within definitions: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 48-56. - Kirk B, Mooney K, Amirabdollahian F, Khaiyat O. Exercise and dietary-protein as a countermeasure to skeletal muscle weakness: Liverpool Hope University – Sarcopenia Aging Trial (LHU-SAT). Front Physiol 2019; 10: 445.

- Kirk B, Mooney K, Cousins R et al. Effects of exercise and whey protein on muscle mass, fat mass, myoelectrical muscle fatigue and health-related quality of life in older adults: a secondary analysis of the Liverpool Hope UniversitySarcopenia Ageing Trial (LHU-SAT). Eur J Appl Physiol 2020; 120: 493-503.

- Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians: effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 1990; 263: 3029-34.

- Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311: 2387-96.

- Bernabei R, Landi F, Calvani R et al. Multicomponent intervention to prevent mobility disability in frail older adults: randomised controlled trial (SPRINTT project). BMJ 2022; 377: 1-13.

- Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 95-101.

- Chen L-K, Woo J, Assantachai P et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21: 300-307.e2.

- Zanker J, Sim M, Anderson K et al. Consensus guidelines for sarcopenia prevention, diagnosis and management in Australia and New Zealand. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023; 14: 142-56.

ب. كيرك وآخرون

- زانكر ج، سكوت د، رينيرس إي إم وآخرون. وضع تعريف تشغيلي للساركوبينيا في أستراليا ونيوزيلندا: بيان توافق قائم على طريقة دلفي. ج نوتريشن هيلث آ Aging 2019؛ 23: 105-10.

- كروز-جينتوف AJ، بايينز JP، باور JM وآخرون. ساركوبينيا: توافق أوروبي حول التعريف والتشخيص. العمر والشيخوخة 2010؛ 39: 412-23.

- كروز-جينتوف AJ، باهات G، باور J وآخرون. ساركوبينيا: توافق أوروبي مُعدل حول التعريف والتشخيص. الشيخوخة والشيخوخة 2019؛ 48: 16-31.

- ستودنسكي SA، بيترز KW، آلي DE وآخرون. مشروع فنيش لمكافحة الساركوبينيا: الأساس، وصف الدراسة، توصيات المؤتمر، والتقديرات النهائية. مجلة علم الشيخوخة A العلوم البيولوجية والعلوم الطبية 2014؛ 69: 547-58.

- فيلدينغ RA، فيلاس B، إيفانز WJ وآخرون. ساركوبينيا: حالة غير مشخصة لدى كبار السن. التعريف المتفق عليه حاليًا: الانتشار، الأسباب، والعواقب. المجموعة الدولية العاملة على الساركوبينيا. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية لإدارة الطب 2011؛ 12: 249-56.

- بهاسين س، ترافيسون تي جي، مانيني تي إم وآخرون. تعريف الساركوبينيا: بيانات الموقف من اتحاد تعريف الساركوبينيا والنتائج. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية للشيخوخة 2020؛ 68: 1410-8.

- كاوثون بي إم، ترافيسون تي جي، مانيني تي إم وآخرون. إنشاء الرابط بين كتلة العضلات ونقاط قطع قوة القبضة مع الإعاقة الحركية ونتائج صحية أخرى: وقائع مؤتمر تعريف الساركوبين ونتائجه. مجلة علم الشيخوخة A العلوم البيولوجية والعلوم الطبية 2020؛ 75: 1317-23.

- دونيني إل إم، بوسيتو إل، بيشوف إس سي وآخرون. تعريف ومعايير تشخيص السمنة الساركوبينية: بيان توافق ESPEN وEASO. التغذية السريرية 2022؛ 41: 990-1000.

- جينسن جي إل، سيدرهولم تي، كورييا إم آي تي دي وآخرون. معايير GLIM لتشخيص سوء التغذية: تقرير إجماعي من المجتمع العالمي للتغذية السريرية. مجلة JPEN للتغذية الوريدية والداخلية 2019؛ 43: 32-40.

- سيدر هولم تي، جنسن جي إل. لإنشاء توافق حول معايير تشخيص سوء التغذية: تقرير من مبادرة القيادة العالمية حول سوء التغذية (GLIM) في اجتماع مؤتمر ESPEN 2016. التغذية السريرية 2017؛ 36: 7-10.

- كاو إل، مورلي جي إي. تم التعرف على ساركوبينيا كحالة مستقلة من قبل التصنيف الدولي للأمراض، النسخة العاشرة، التعديل السريري (ICD-10-CM) كود. مجلة الجمعية الأمريكية لإدارة الطب 2016؛ 17: 675-7.

- رولاند واي، كروز-جينتوف AJ. تحرير: الساركوبينيا: الاستمرار في البحث عن أفضل تعريف تشغيلي. ج. التغذية والصحة والشيخوخة 2023؛ 27: 202-4.

- سانشيز-رودريغيز د، ماركو إ، كروز-خينتوف AJ. تعريف الساركوبينيا: بعض التحذيرات والتحديات. الرأي الحالي في التغذية السريرية ورعاية الأيض 2020؛ 23: 127-32.

- كروز-جينتوف AJ، غونزاليس MC، برادو CM. ساركوبينيا

كتلة عضلية منخفضة. Eur Geriatr Med 2023; 14: 225-8. - كاوثون بي إم، فيسر م، أراي إتش وآخرون. تعريف المصطلحات المستخدمة بشكل شائع في أبحاث ساركوبينيا: مسرد مقترح من قبل اللجنة التوجيهية للقيادة العالمية في ساركوبينيا (GLIS). الطب geriatr الأوروبي 2022؛ 13: 1239-44.

- كروز-جينتوف AJ. تشخيص الساركوبينيا: أعد تركيزك على المرضى. العمر والشيخوخة 2021؛ 50: 1904-5.

لم يتم الإبلاغ عن العمر. مهني صحي – آخر (يرجى التحديد): أخصائي قلب. محترف في الصناعة – أخرى (يرجى التحديد): المدير التنفيذي؛ قائد البرنامج. الدور الأساسي – آخر (يرجى التحديد): أكاديمي ومحترف صحي (مختلط)؛ فخري

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae052

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38520141

Publication Date: 2024-02-27

The Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS)

– To cite this version:

HAL Id: hal-04938140

https://hal.science/hal-04938140v1

https://doi.org/ l 0. 1 093/ageing/afae052

© The Author(s) 2024. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Geriatrics Society. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com

RESEARCH PAPER

The Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS)

Abstract

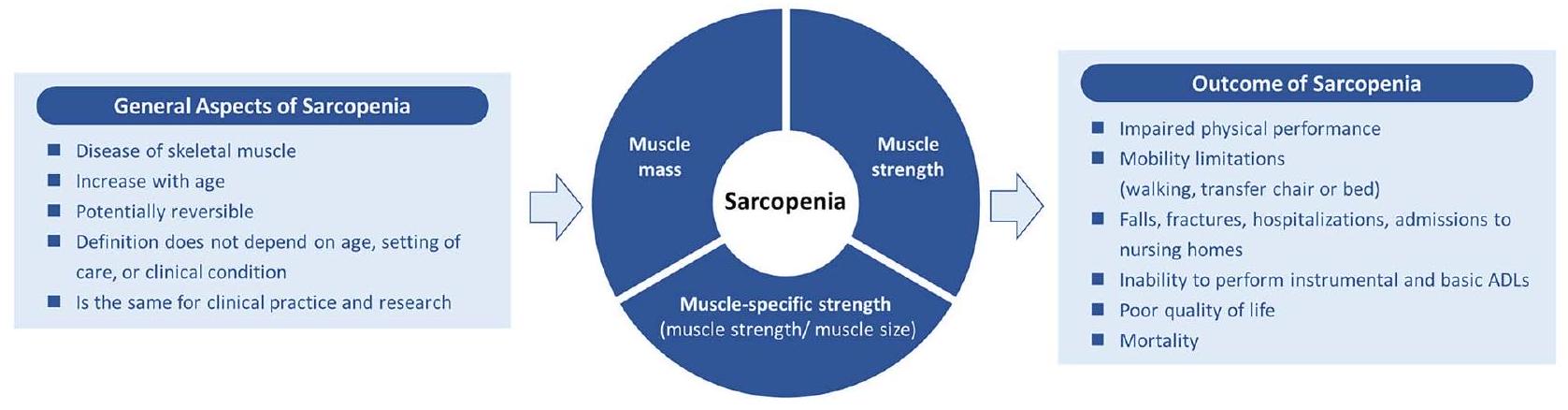

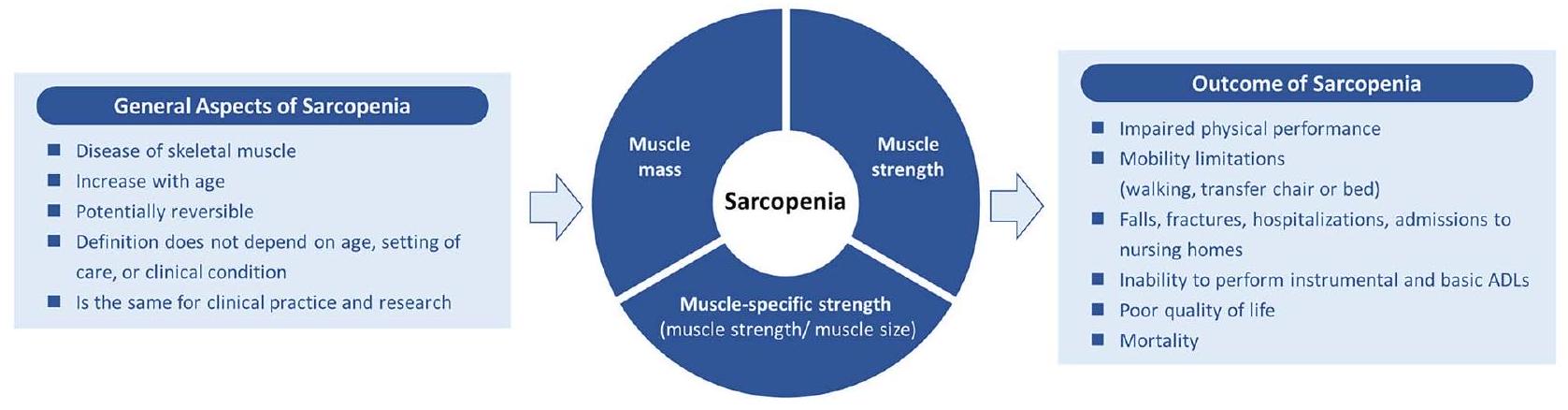

Importance: Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength/function, is an important clinical condition. However, no international consensus on the definition exists. Objective: The Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS) aimed to address this by establishing the global conceptual definition of sarcopenia. Design: The GLIS steering committee was formed in 2019-21 with representatives from all relevant scientific societies worldwide. During this time, the steering committee developed a set of statements on the topic and invited members from these societies to participate in a two-phase International Delphi Study. Between 2022 and 2023, participants ranked their agreement with a set of statements using an online survey tool (SurveyMonkey). Statements were categorised based on predefined thresholds: strong agreement (

Key Points

- Question: several societies and organisations have developed definitions of sarcopenia, which are region specific. At present, there is no international consensus on how to define sarcopenia.

- Findings: the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS), an international collaboration of experts from all major sarcopenia societies/organisations worldwide has developed the first global conceptual definition of sarcopenia. This conceptual definition of sarcopenia will now be used to develop an operational definition of sarcopenia for both clinical and research settings.

- Meaning: this collaborative effort by the GLIS signifies a critical step towards advancing our understanding and management of sarcopenia on a global scale.

Introduction

that characterise sarcopenia in 2020 [20, 21]. The Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS) was formed in an attempt to harmonise these competing definitions into one unifying common classification that would be used as the gold standard in sarcopenia assessment.

Methods

Development of the GLIS initiative

B. Kirk et al.

Initiating with a glossary and conceptual paper: a strategic approach for subsequent operationalization

Statistical analysis

Results

Inclusion/exclusion

Characteristics of the GLIS committee

| Statements from round 1 | Agreement (mean

|

Agreement (%) | Outcome |

| Sarcopenia is a generalised disease of skeletal muscle |

|

85.4% | Accepted |

| The prevalence of sarcopenia increases with age |

|

98.3% | Accepted |

| The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should not vary by setting of care (e.g., inpatient vs. outpatient) |

|

91.2% | Accepted |

| The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should not vary by age or condition (e.g., heart failure, kidney disease, cancer etc.) |

|

83.2% | Accepted |

| The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should be the same for clinical practice and research |

|

92.0% | Accepted |

| Muscle mass should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

89.4% | Accepted |

| Morphological characteristics of muscle tissue (e.g., muscle fat infiltration, muscle density or texture) should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

69.9% | Rejected |

| Muscle strength should be a part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

93.1% | Accepted |

| Muscle power should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

68.4% | Rejected |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of impaired physical performance |

|

97.9% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of mobility (walking) limitations |

|

96.1% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of mobility (transfer from chair or bed to rising) limitations |

|

95.0% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of falls |

|

94.6% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of fractures |

|

89.4% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of inability to perform instrumental ADLs |

|

88.6% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of inability to perform basic (self-care) ADLs |

|

90.7% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of hospitalizations |

|

91.0% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of new admission to care (nursing) homes |

|

89.5% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of poor quality of life |

|

91.8% | Accepted |

| Sarcopenia increases the risk of mortality |

|

91.6% | Accepted |

| Statements from round 2 | Agreement (mean

|

Agreement (%) | Outcome |

| Muscle specific strength (e.g., muscle strength/muscle size) should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

80.8% | Accepted |

| Physical performance should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia |

|

79.8% | Rejected |

| The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should be a potentially reversible disease |

|

84.1% | Accepted |

| The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should include levels of severity of the disease |

|

77.0% | Rejected |

| N.B. An 11-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (10) accompanied each statement | Weighted-scales calculation | ||

| Statements with strong agreement (

|

Response | Weight | Interpretation |

| Statements with low agreement (

|

9,10 | 100% | Strongly agree |

| 7, 8 | 80% | Agree Neither agree nor disagree | |

| 2, 3 | 40% | Disagree | |

| 0,1 | 20% | Strongly disagree | |

Round I of the Delphi process

- ‘The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should include levels of severity of the disease’. Agreement: 77.9% (mean score:

). - ‘Muscle strength should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement: 79.1% (mean score:

). - ‘Muscle-specific strength (e.g., muscle strength/muscle size) should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’, Agreement:

(mean score: ). - ‘Physical performance should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement:

(mean score: ). - Physical performance should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia: Agreement: 82.2% (mean score:

).

- ‘The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should be a potentially reversible disease’.

Round 2 of the Delphi process

B. Kirk et al.

| Variable | Sub-category | Overall (

|

| Age, years, mean

|

|

|

| Sex, men, n (%) | 68 (64%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 73 (68%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 26 (24%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (3%) | |

| Black or African American | 1 (1%) | |

| Preferred not to say | 4 (4%) | |

| Continent/region, currently residing, n (%) | ||

| Europe | 43 (40%) | |

| Asia | 23 (22%) | |

| North America | 20 (19%) | |

| Australia | 13 (12%) | |

| South America | 4 (4%) | |

| Africa | 3 (3%) | |

| Antarctica/New Zealand | 1 (1%) | |

| Country, currently residing, n (%) | ||

| Australia | 13 (12%) | |

| Belgium | 5 (5%) | |

| Brazil | 3 (3%) | |

| Cameroon | 1 (1%) | |

| Canada | 4 (4%) | |

| Chile | 1 (1%) | |

| China | 3 (3%) | |

| Czech Republic | 1 (1%) | |

| Denmark | 1 (1%) | |

| Finland | 1 (1%) | |

| France | 2 (2%) | |

| Germany | 4 (4%) | |

| Italy | 5 (5%) | |

| Japan | 5 (5%) | |

| Mexico | 1 (1%) | |

| Netherlands | 6 (6%) | |

| New Zealand | 1 (1%) | |

| Poland | 2 (2%) | |

| Republic of Korea | 4 (4%) | |

| Saudi Arabia | 3 (3%) | |

| Singapore | 3 (3%) | |

| South Africa | 2 (2%) | |

| Spain | 2 (2%) | |

| Sweden | 1 (1%) | |

| Switzerland | 3 (3%) | |

| Taiwan | 5 (5%) | |

| Turkey | 1 (1%) | |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 9 (8%) | |

| United States of America | 15 (14%) | |

| Primary role, n (%) | ||

| Academic professional | 76 (71%) | |

| Professor | 54 (71%) | |

| Associate Professor | 11 (14%) | |

| Research Fellow (e.g. postdoctoral, senior, assistant professor) | 6 (8%) | |

| Lecturer | 2 (3%) | |

| Not specified | 3 (4%) | |

| Health professional | 23 (22%) | |

| Geriatrician | 18 (78%) | |

| Physician | 3 (13%) | |

| Rehabilitation | 1 (4%) | |

| Other (please specify)

|

1 (4%) | |

| Industry professional | 3 (3%) | |

| Scientific Director | 1 (33%) | |

| Other (please specify)

|

2 (67%) | |

| Other (please specify)

|

5 (5%) |

| Number | Statement | Agreement |

| General aspects of sarcopenia | ||

| 1 | Sarcopenia is a generalised disease of skeletal muscle | 85.4% |

| 2 | The prevalence of sarcopenia increases with age | 98.3% |

| 3 | The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should not vary by setting of care (e.g. inpatient vs. outpatient) | 91.2% |

| 4 | The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should not vary by age or condition (e.g. heart failure, kidney disease, cancer etc.) | 83.2% |

| 5 | The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should be the same for clinical practice and research | 92.0% |

| 6 | The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should be a potentially reversible disease | 84.1% |

| Components of sarcopenia | ||

| 7 | Muscle mass should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 89.4% |

| 8 | Muscle strength should be a part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 93.1% |

| 9 | Muscle-specific strength (e.g. muscle strength/muscle size) should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 80.8% |

| Outcomes of sarcopenia | ||

| 10 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of impaired physical performance | 97.9% |

| 11 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of mobility (walking) limitations | 96.1% |

| 12 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of mobility (transfer from chair or bed to rising) limitations | 95.0% |

| 13 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of falls | 94.6% |

| 14 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of fractures | 89.4% |

| 15 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of inability to perform instrumental ADLs | 88.6% |

| 16 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of inability to perform basic (self-care) ADLs | 90.7% |

| 17 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of hospitalizations | 91.0% |

| 18 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of new admission to care (nursing) homes | 89.5% |

| 19 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of poor quality of life | 91.8% |

| 20 | Sarcopenia increases the risk of mortality | 91.6% |

| Number | Statement | Agreement |

| General aspects of sarcopenia | ||

| 1 | Morphological characteristics of muscle tissue (e.g. muscle fat infiltration, muscle density or muscle texture) should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 69.9% |

| 2 | The conceptual definition of sarcopenia should include levels of severity of the disease | 77.0% |

| Components of sarcopenia | ||

| 3 | Muscle power should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 68.4% |

| 4 | Physical performance should be part of the conceptual definition of sarcopenia | 79.8% |

- ‘Muscle mass should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement:

(mean score: ; answered = 93, skipped = 14). - ‘Muscle strength should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement:

(mean score: ; answered = 94, skipped = 13). - ‘Muscle-specific strength (e.g., muscle strength/muscle size) should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement: 68.6.% (mean score: 6.1

2.9; answered = 93, skipped = 14). - ‘Physical performance should be a marker of severity for the conceptual definition of sarcopenia’. Agreement: 81.9% (mean score:

; answered = 93, skipped = 14) (Figure 2).

Discussion

specific strength in the conceptual definition for sarcopenia was only slightly higher than our threshold for agreement

The Global Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia

- Aging in Motion (AIM) coalition/Alliance for Aging Research (AAR)-Jack Guralnik

- American Geriatrics Society (AGS)-Ellen F. Binder

- American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR)-Douglas P. Kiel

- Asian Association for Frailty and Sarcopenia (AAFS) -Liang-Kung Chen

- Australian and New Zealand Society for Sarcopenia and Frailty Research (ANZSSFR) – Gustavo Duque

- European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO)Rocco Barazzoni

- European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS)-Alfonso J. Cruz-Jentoft

- European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO)-Olivier Bruyere

- European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN)-Tommy Cederholm

- Gerontological Society of America (GSA)-Peggy M. Cawthon & Roger A. Fielding

- International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG)-José A. Ávila-Funes

- International Conference on Frailty and Sarcopenia Research (ICFSR)-Roger A. Fielding

- International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF)-Cyrus Cooper & Jean-Yves Reginster

- Society on Sarcopenia, Cachexia and Wasting Disorders (SCWD)-Stephan von Haehling

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Katrin Werner-Perez and Lindsay Clarke, both from the Alliance for Aging Research, for their administrative support which greatly assisted this Delphi study.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: Before starting the GLIS initiative, all authors submitted a Declaration of Interest form. This declaration, which is more detailed than the standard COI form, was open for public scrutiny and can be viewed here: https://www.eugms.org/fileadmin/images/ news/2022/GLIS_Steering_Committee_Rev3.pdf.

do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. All authors declarations of sources of funding can be read here: https://www.eugms.org/fileadmin/images/ news/2022/GLIS_Steering_Committee_Rev3.pdf.

References

- Cawthon PM, Manini T, Patel SM et al. Putative cut-points in sarcopenia components and incident adverse health outcomes: an SDOC analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68: 1429-37.

- Cawthon PM, Blackwell T, Cummings SR et al. Muscle mass assessed by the D3-creatine dilution method and incident self-reported disability and mortality in a prospective observational study of community-dwelling older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021; 76: 123-30.

- Guralnik JM, Cawthon PM, Bhasin S et al. Limited physician knowledge of sarcopenia: a survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023; 71: 1595-602.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet 2019; 393: 2636-46.

- Anker SD, Morley JE, von Haehling S. Welcome to the ICD10 code for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016; 7: 512-4.

- Mayhew AJ, Amog K, Phillips

et al. The prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults, an exploration of differences between studies and within definitions: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 48-56. - Kirk B, Mooney K, Amirabdollahian F, Khaiyat O. Exercise and dietary-protein as a countermeasure to skeletal muscle weakness: Liverpool Hope University – Sarcopenia Aging Trial (LHU-SAT). Front Physiol 2019; 10: 445.

- Kirk B, Mooney K, Cousins R et al. Effects of exercise and whey protein on muscle mass, fat mass, myoelectrical muscle fatigue and health-related quality of life in older adults: a secondary analysis of the Liverpool Hope UniversitySarcopenia Ageing Trial (LHU-SAT). Eur J Appl Physiol 2020; 120: 493-503.

- Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians: effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA 1990; 263: 3029-34.

- Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311: 2387-96.

- Bernabei R, Landi F, Calvani R et al. Multicomponent intervention to prevent mobility disability in frail older adults: randomised controlled trial (SPRINTT project). BMJ 2022; 377: 1-13.

- Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 95-101.

- Chen L-K, Woo J, Assantachai P et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21: 300-307.e2.

- Zanker J, Sim M, Anderson K et al. Consensus guidelines for sarcopenia prevention, diagnosis and management in Australia and New Zealand. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023; 14: 142-56.

B. Kirk et al.

- Zanker J, Scott D, Reijnierse EM et al. Establishing an operational definition of sarcopenia in Australia and New Zealand: Delphi method based consensus statement. J Nutr Health Aging 2019; 23: 105-10.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 412-23.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 16-31.

- Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014; 69: 547-58.

- Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011; 12: 249-56.

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Manini TM et al. Sarcopenia definition: the position statements of the sarcopenia definition and outcomes consortium. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68: 1410-8.

- Cawthon PM, Travison TG, Manini TM et al. Establishing the link between lean mass and grip strength cut points with mobility disability and other health outcomes: proceedings of the sarcopenia definition and outcomes consortium conference. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020; 75: 1317-23.

- Donini LM, Busetto L, Bischoff SC et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Clin Nutr 2022; 41: 990-1000.

- Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Correia MITD et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition: a consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2019; 43: 32-40.

- Cederholm T, Jensen GL. To create a consensus on malnutrition diagnostic criteria: a report from the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) meeting at the ESPEN Congress 2016. Clin Nutr 2017; 36: 7-10.

- Cao L, Morley JE. Sarcopenia is recognized as an independent condition by an international classification of disease, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) code. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016; 17: 675-7.

- Rolland Y, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Editorial: sarcopenia: keeping on search for the best operational definition. J Nutr Health Aging 2023; 27: 202-4.

- Sanchez-Rodriguez D, Marco E, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Defining sarcopenia: some caveats and challenges. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2020; 23: 127-32.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Gonzalez MC, Prado CM. Sarcopenia

low muscle mass. Eur Geriatr Med 2023; 14: 225-8. - Cawthon PM, Visser M, Arai H et al. Defining terms commonly used in sarcopenia research: a glossary proposed by the Global Leadership in Sarcopenia (GLIS) steering committee. Eur Geriatr Med 2022; 13: 1239-44.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Diagnosing sarcopenia: turn your eyes back on patients. Age Ageing 2021; 50: 1904-5.

did not report age. Health professional—Other (please specify): Cardiologist. Industry professional—Other (please specify): Executive Director; Programme leader. Primary role-Other (please specify): Academic and Health professional (Mixed); Emeritus.