المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97547-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40263348

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-22

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97547-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40263348

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-22

افتح

التعلم الجماعي مع الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير لتحسين توقعات أمراض القلب استنادًا إلى مجموعات بيانات متعددة

أمراض القلب هي واحدة من الأسباب الرئيسية للوفاة في جميع أنحاء العالم. إن التنبؤ بأمراض القلب واكتشافها مبكرًا أمر بالغ الأهمية، حيث يسمح للمهنيين الطبيين باتخاذ الإجراءات المناسبة والضرورية في مراحل مبكرة. يمكن لمتخصصي الرعاية الصحية تشخيص الحالات القلبية بدقة أكبر من خلال تطبيق تكنولوجيا التعلم الآلي. كانت هذه الدراسة تهدف إلى تعزيز التنبؤ بأمراض القلب باستخدام طرق التجميع والتصويت. تم تدريب خمسة عشر نموذجًا أساسيًا على مجموعتين مختلفتين من بيانات أمراض القلب. بعد تقييم تركيبات مختلفة، تم توصيل ستة نماذج أساسية لتطوير نماذج تجميعية باستخدام نموذج ميتا (التجميع) وتصويت الأغلبية (التصويت). تم مقارنة أداء نماذج التجميع والتصويت مع أداء النماذج الأساسية الفردية. لضمان قوة تقييم الأداء، قمنا بإجراء تحليل إحصائي باستخدام اختبار فريدمان للرتب المتوافقة ومقارنات زوجية بعد هولم. أشارت النتائج إلى أن النماذج التجميعية المطورة، وخاصة التجميع، تفوقت باستمرار على النماذج الأخرى، محققة دقة أعلى ونتائج تنبؤية محسنة. أكدت هذه التحقق الإحصائي الصارم موثوقية الطرق المقترحة. علاوة على ذلك، قمنا بإدماج الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير (XAI) من خلال تحليل SHAP لتفسير تنبؤات النموذج، مما يوفر الشفافية والرؤية حول كيفية تأثير الميزات الفردية على التنبؤ بأمراض القلب. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن دمج تنبؤات نماذج متعددة من خلال التجميع أو التصويت قد يعزز أداء التنبؤ بأمراض القلب ويكون أداة قيمة في اتخاذ القرارات السريرية.

الكلمات الرئيسية: توقع أمراض القلب، التعلم الجماعي، التكديس، التصويت، الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير، SHAP

تظل الأمراض القلبية الوعائية، وخاصة أمراض القلب، السبب الرئيسي للوفاة على مستوى العالم. وفقًا لبيانات من منظمات الرعاية الصحية الدولية، فإن 17.9 مليون شخص (

تظل الأمراض القلبية الوعائية، وخاصة أمراض القلب، السبب الرئيسي للوفاة على مستوى العالم. وفقًا لبيانات من منظمات الرعاية الصحية الدولية، فإن 17.9 مليون شخص (

أفضل طريقة لتقليل هذه الوفيات هي التنبؤ باحتمالية الإصابة بأمراض القلب أو اكتشافها في أقرب وقت ممكن، مما يسمح باتخاذ تدابير احترازية مسبقًا. تؤثر عدة عوامل، بما في ذلك العمر، والعادات الغذائية، ونمط الحياة الخامل، على الاضطرابات المتعلقة بالقلب.

التشخيص المبكر والدقيق أمر حاسم لتقليل معدلات المرض والوفيات. لقد ظهرت تقنيات التعلم الآلي كأداة واعدة للتنبؤ واكتشاف مختلف الأمراض في مراحلها المبكرة. وقد استكشفت العديد من الدراسات تطبيق التعلم الآلي في التنبؤ وتشخيص أمراض القلب، مستفيدة من مصادر بيانات متنوعة مثل السجلات الطبية وتخطيط القلب الكهربائي (ECGs).

على الرغم من أن نماذج التعلم الآلي الفردية قد أظهرت وعدًا في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب، إلا أن قيودها غالبًا ما تؤدي إلى أداء دون المستوى الأمثل.

تقنيات التعلم الآلي التقليدية، مما يؤدي إلى الإفراط في التكيف والحساسية لضوضاء البيانات. يمكن أن تؤثر عوامل مثل جودة البيانات، واختيار الميزات، ومعلمات النموذج بشكل كبير على أداء هذه الخوارزميات.

في التشخيص الطبي، يُعتبر التعلم الجماعي على نطاق واسع واحدًا من أكثر خوارزميات التعلم الآلي فعالية. تجمع طرق التجميع العديد من المتعلمين الأساسيين لإنشاء نموذج واحد أكثر قوة.

تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى إظهار فعالية التعلم الجماعي، وخاصة تجميع النماذج والتصويت، في تحسين توقعات أمراض القلب. نظرًا للطبيعة الحرجة لهذا التطبيق، فإن هدفنا هو تطوير نموذج يعرض دقة محسّنة، ومقاييس أداء إضافية، وموثوقية في توقع أمراض القلب. نعتقد أن هذا النهج يمكن أن يحسن من دقة وموثوقية وقابلية تفسير نماذج توقع أمراض القلب، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تحسين نتائج الرعاية الصحية للمرضى في جميع أنحاء العالم.

المساهمات الرئيسية لهذا البحث هي كما يلي:

- تصميم نماذج التكديس والتصويت لتوقع أمراض القلب: نقدم إطار عمل شاملاً يجمع بين خوارزميات تعلم الآلة المتنوعة لتعزيز الأداء التنبؤي.

- معالجة اختيار نماذج أساسية متنوعة: نحن نعتبر مجموعة من خوارزميات التعلم الآلي التي تتيح لنماذجنا التقاط نقاط القوة في أساليب مختلفة والتخفيف من نقاط ضعفها.

- إجراء تجارب على مجموعات بيانات متعددة: تم إجراء تجاربنا الدقيقة على مجموعتين متميزتين من بيانات أمراض القلب.

- تقييم شامل للنماذج: يتم تقييم النماذج المجمعة المقترحة بدقة باستخدام مقاييس متنوعة، مما يظهر تفوقها على النماذج الأساسية الفردية والنماذج المتطورة.

- تطبيق تحليل إحصائي صارم: لضمان الأهمية الإحصائية لتحسينات الأداء، يتم تنفيذ إطار إحصائي قوي – بما في ذلك اختبار رتب فريدمان المتوافقة وتحليل هولم بعد الاختبار.

- دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير (XAI) من خلال SHAP: تدمج دراستنا تقنيات XAI، وبشكل خاص SHAP (تفسيرات شابلي الإضافية)، لتفسير التنبؤات التي تقوم بها نماذج التجميع والتصويت. وهذا يمكننا من توفير الشفافية في تنبؤات النموذج وفهم أفضل لكيفية تأثير الميزات المختلفة على القرار النهائي، مما يعالج التحديات المتعلقة بالتفسير التي غالبًا ما ترتبط بالنماذج المركبة المعقدة.

يتكون باقي الورقة على النحو التالي: القسم 2 يستعرض الأعمال ذات الصلة، مقدماً لمحة عامة عن الدراسات الموجودة في توقع أمراض القلب ويبرز ضرورة استخدام طرق التجميع. القسم 3 يحدد منهجية البحث المعتمدة في هذه الدراسة، موضحاً الإطار والعمليات الرئيسية المعنية. القسم 4 يقدم معلومات شاملة عن مجموعات البيانات المستخدمة، بما في ذلك مصادرها وخصائصها وخطوات المعالجة المسبقة. القسم 5 يشرح إعداد التجارب ويعرض نتائج تقييم النماذج. القسم 6 يوفر تحليلاً شاملاً للنتائج التجريبية، متضمناً مناقشة نقدية للنتائج ومقارنة بين نماذج التجميع والتصويت مع أعمال أخرى قابلة للمقارنة. القسم 7 يختتم الدراسة، ملخصاً المساهمات الرئيسية ومشيراً إلى المجالات المحتملة للبحث المستقبلي.

الأعمال ذات الصلة

أدى انتشار التعلم الآلي إلى تطبيقه في العديد من المجالات، مثل تشخيص الأمراض والتنبؤ بها.

تشاندراسيخار وبيداكرشنا

تحليل فعالية التعلم الجماعي في تعزيز دقة التنبؤ بتشخيص أمراض القلب. من بين جميع المصنفات، أظهر التصويت نتائج ملحوظة على مجموعة بيانات أمراض القلب من UCI (UHDD)، محققًا دقة، ودرجة F1، واسترجاع، ودقة، ونوعية قدرها

تحليل فعالية التعلم الجماعي في تعزيز دقة التنبؤ بتشخيص أمراض القلب. من بين جميع المصنفات، أظهر التصويت نتائج ملحوظة على مجموعة بيانات أمراض القلب من UCI (UHDD)، محققًا دقة، ودرجة F1، واسترجاع، ودقة، ونوعية قدرها

تستند هذه الدراسة إلى الأبحاث السابقة التي استخدمت التجميع والتصويت للتنبؤ بأمراض القلب. ومع ذلك، تميزت من خلال الجوانب التالية:

- قمنا باستكشاف شامل لمجموعة متنوعة من النماذج الأساسية ذات الخصائص المختلفة لتطوير أطر العمل الخاصة بالتكديس والتصويت.

- قمنا بتصميم خطوط أنابيب فريدة لتعزيز الفعالية والعمومية والصلابة لهذه الأطر الخاصة بالتكديس والتصويت.

- قمنا بدراسة دور التكديس والتصويت في تقديم رؤى قيمة حول الميزات والنماذج الأساسية التي تؤثر على التنبؤ النهائي، مما يعزز فهمًا أفضل للمرض.

- استخدمنا اختبار رتب فريدمان المتوافقة مع تحليل هولم اللاحق لتأكيد الدلالة الإحصائية لأداء النموذج المصمم.

- على عكس العديد من الدراسات السابقة التي تعتبر نماذج التجميع كـ “صناديق سوداء”، يدمج عملنا الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير لتوفير الشفافية في توقعات النموذج. وهذا يميز دراستنا من خلال تقديم رؤى قابلة للتفسير حول كيفية تأثير الميزات الفردية على التوقع النهائي، مما يعالج القضية التي غالبًا ما يتم تجاهلها وهي قابلية تفسير النموذج في توقع أمراض القلب.

منهجية البحث

يوفر هذا القسم نظرة شاملة على إجراءات البحث التي تم اتخاذها وطرق التعلم الجماعي المستخدمة خلال التجربة.

سير عمل البحث

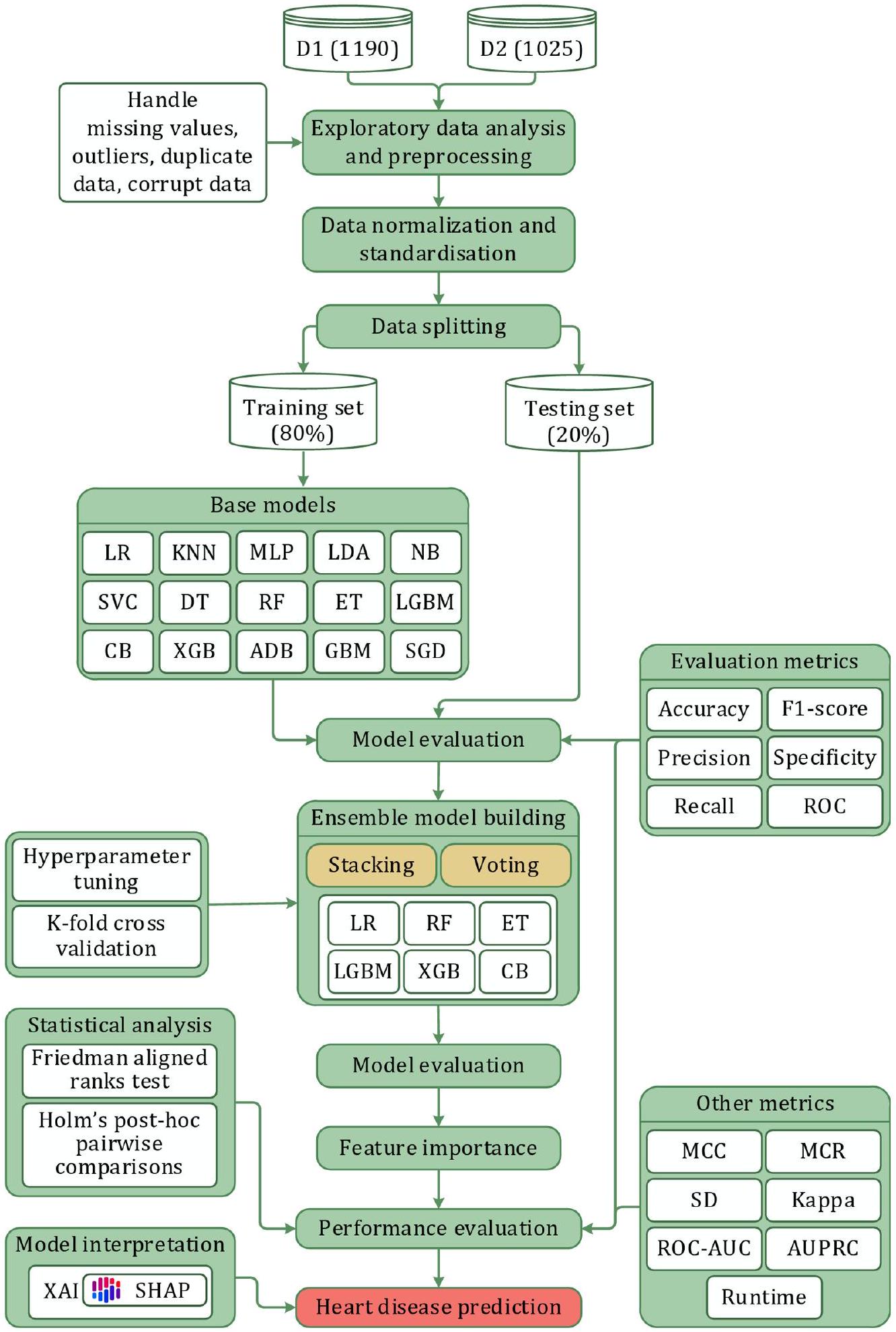

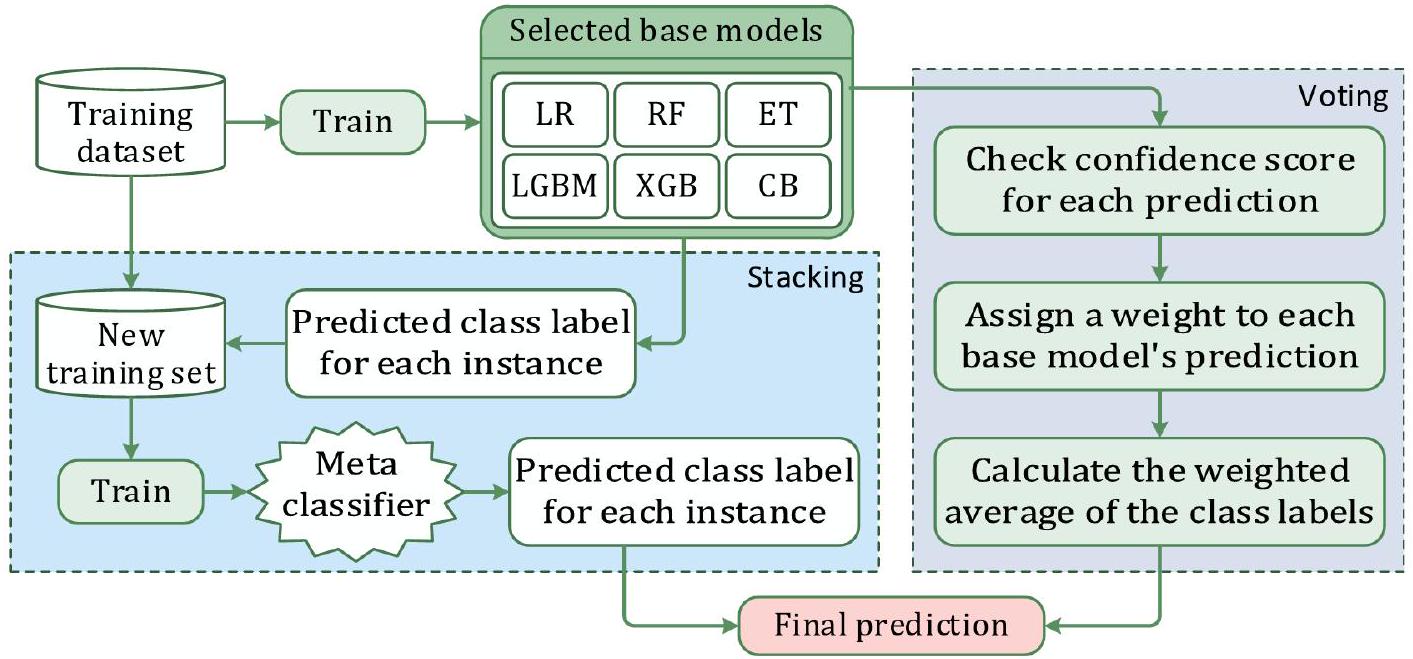

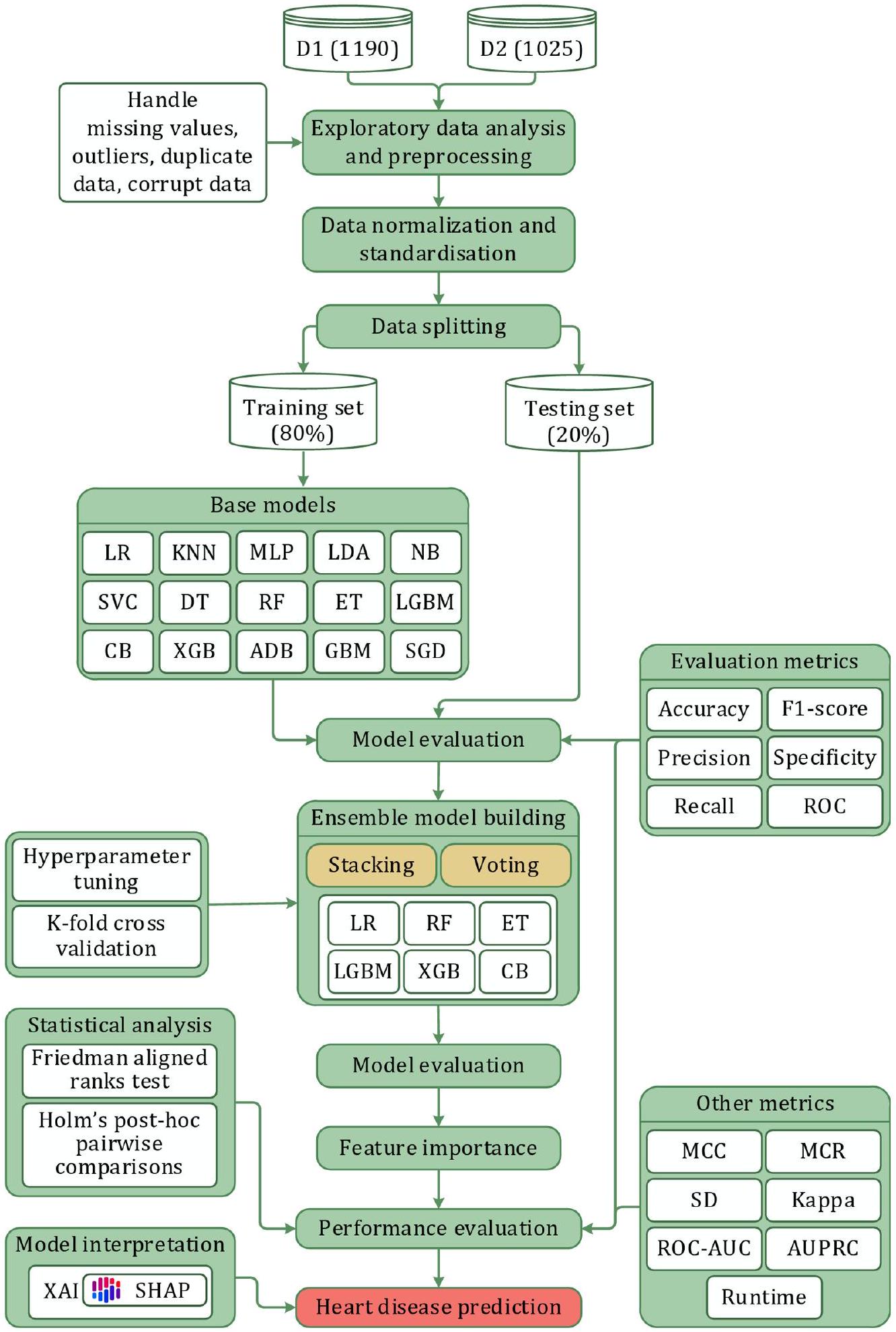

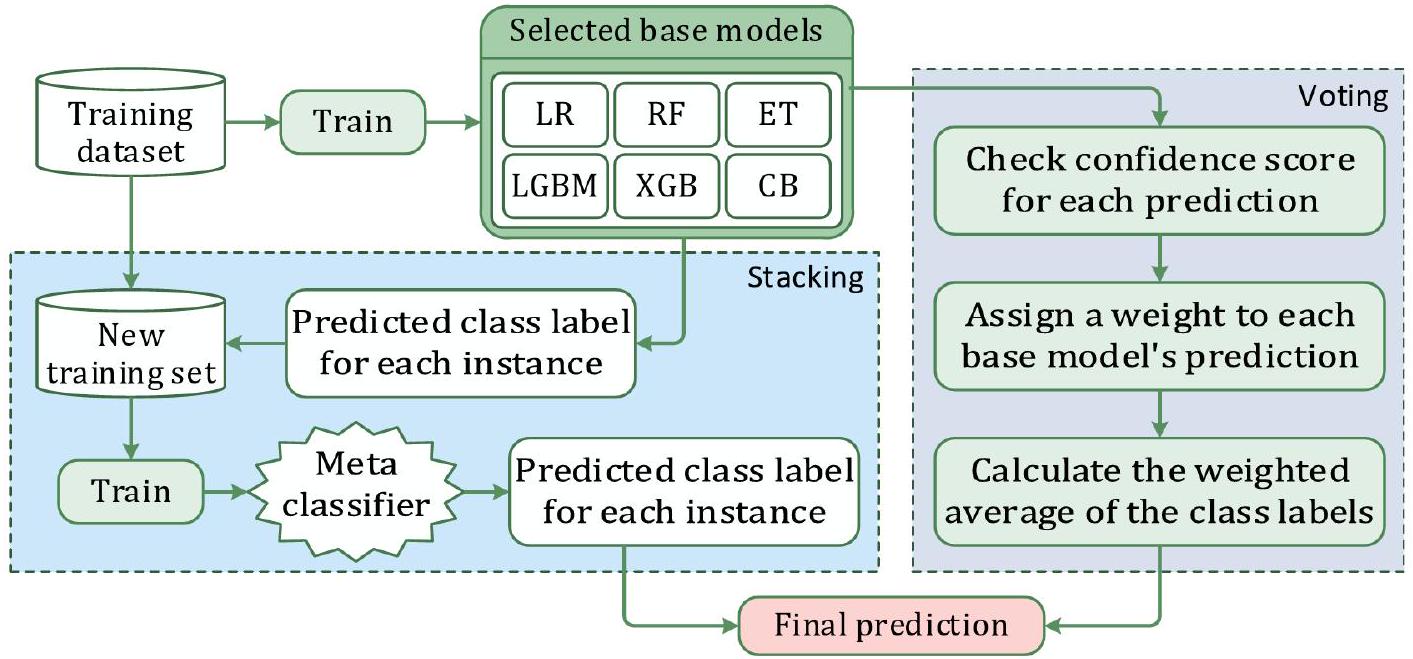

توضح الشكل 1 تدفق العمل المقترح. لقد اعتبرنا مجموعتين مختلفتين من بيانات أمراض القلب لهذه الدراسة. في البداية، قمنا بإجراء تحليل استكشافي للبيانات لتقييم وتعزيز جودة مجموعات البيانات. بحثنا عن القيم المفقودة والقيم الشاذة، لكن لم نجد أي حالات من هذا القبيل. بعد ذلك، تم تطبيع البيانات وتوحيدها وفقًا للإجراءات المعتمدة. ثم تم استخدام بيانات التدريب لبناء النموذج. قمنا أولاً بتقييم خمسة عشر نموذجًا أساسيًا. بعد التجريب مع تركيبات مختلفة من هذه النماذج الأساسية، اخترنا ستة لإنشاء نماذج التجميع والتصويت. تم تدريب النماذج المقترحة على

التكديس والتصويت

المفهوم الأساسي وراء التعلم الجماعي هو أن عدة نماذج تقليدية من التعلم الآلي يتم دمجها للتخفيف من عيوب أي نموذج واحد. النموذج المدمج الجديد يدمج نقاط القوة لمختلف النماذج، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين الأداء. تصف الأدبيات عدة طرق للتعلم الجماعي، مثل التكديس، والتصويت، والتعزيز، والتجميع.

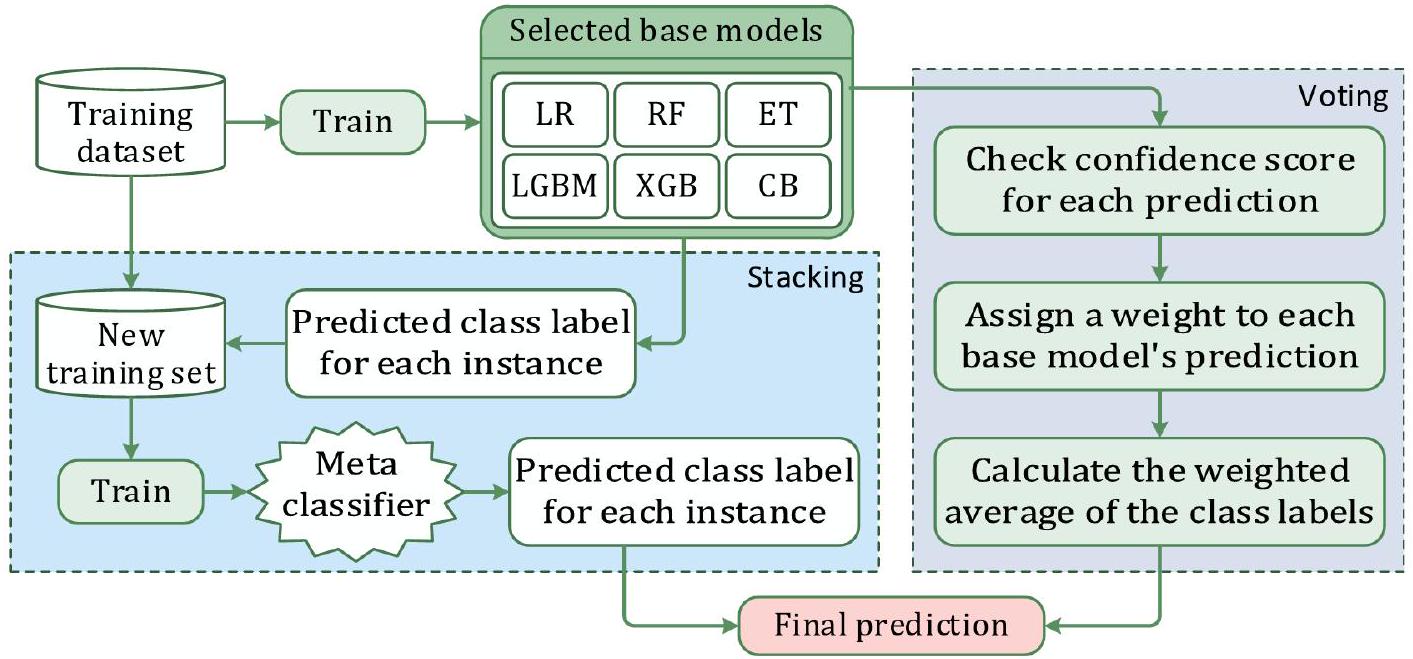

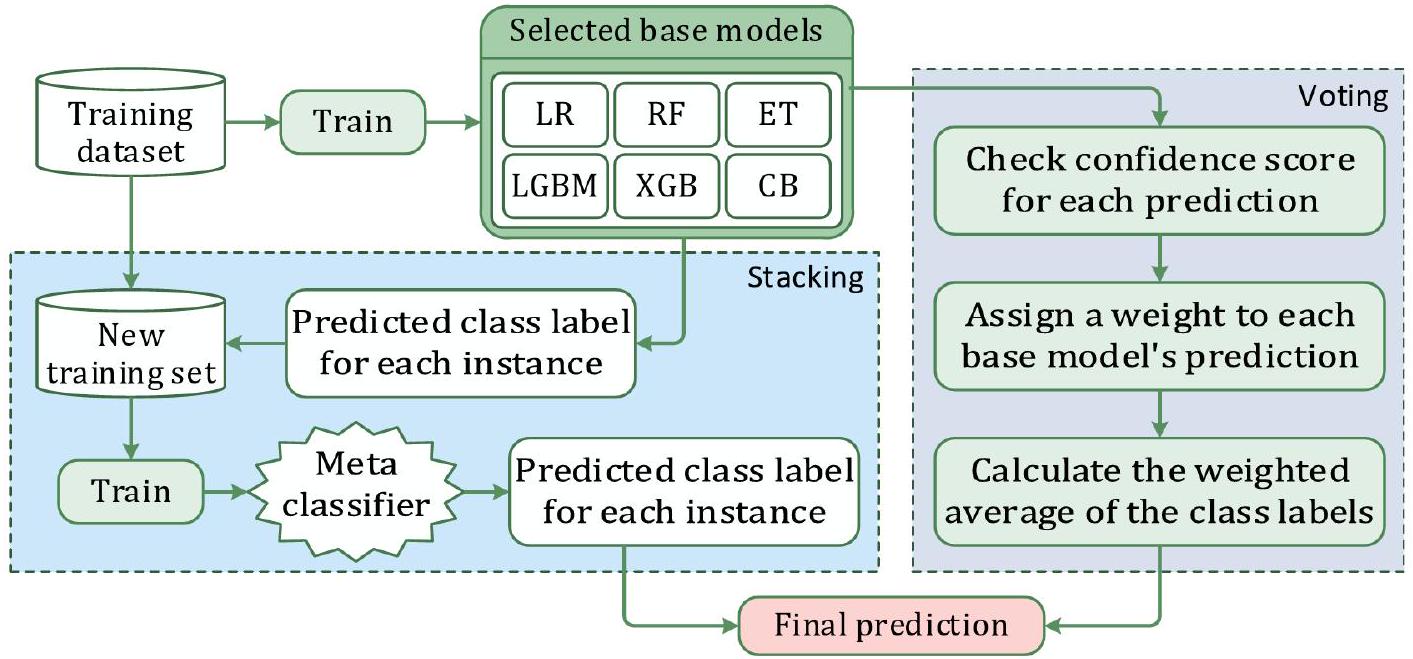

الشكل 1. المنهجية المقترحة للبحث.

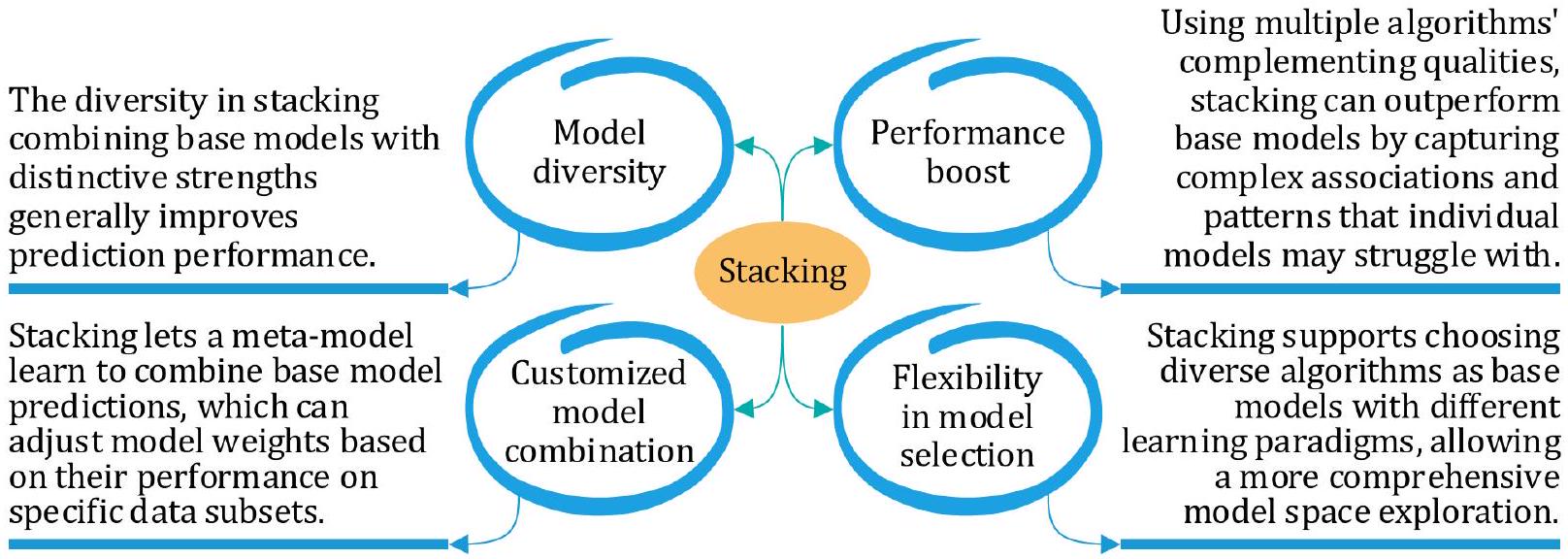

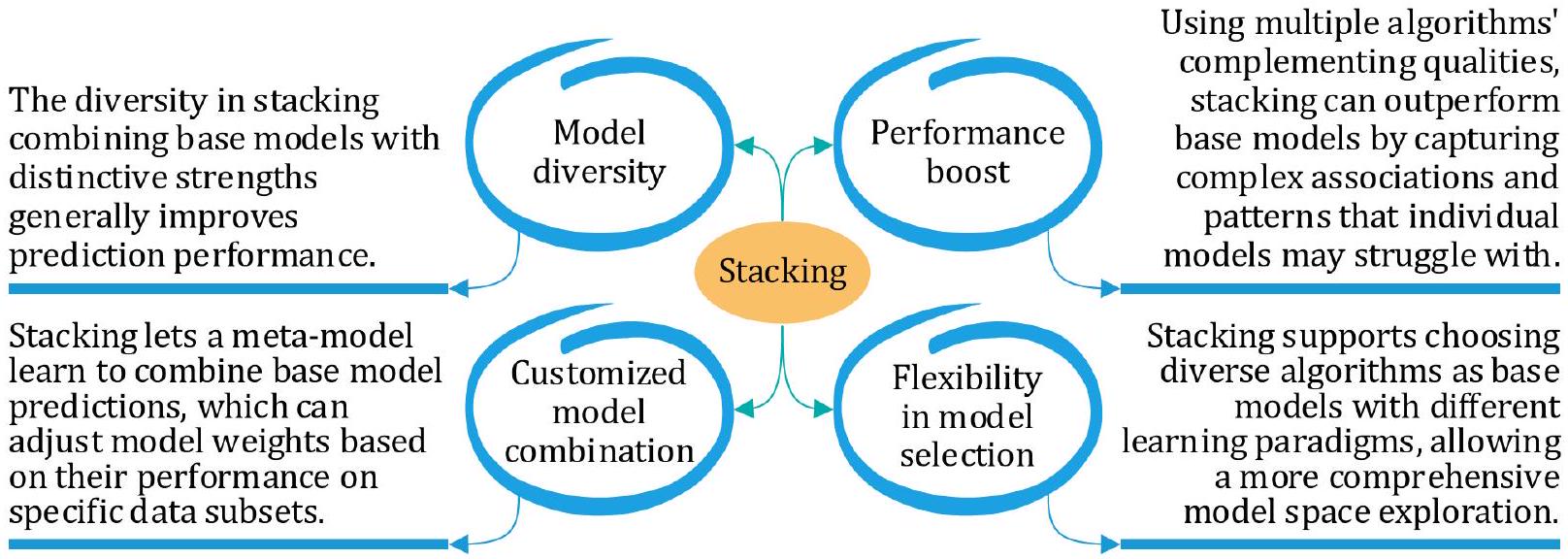

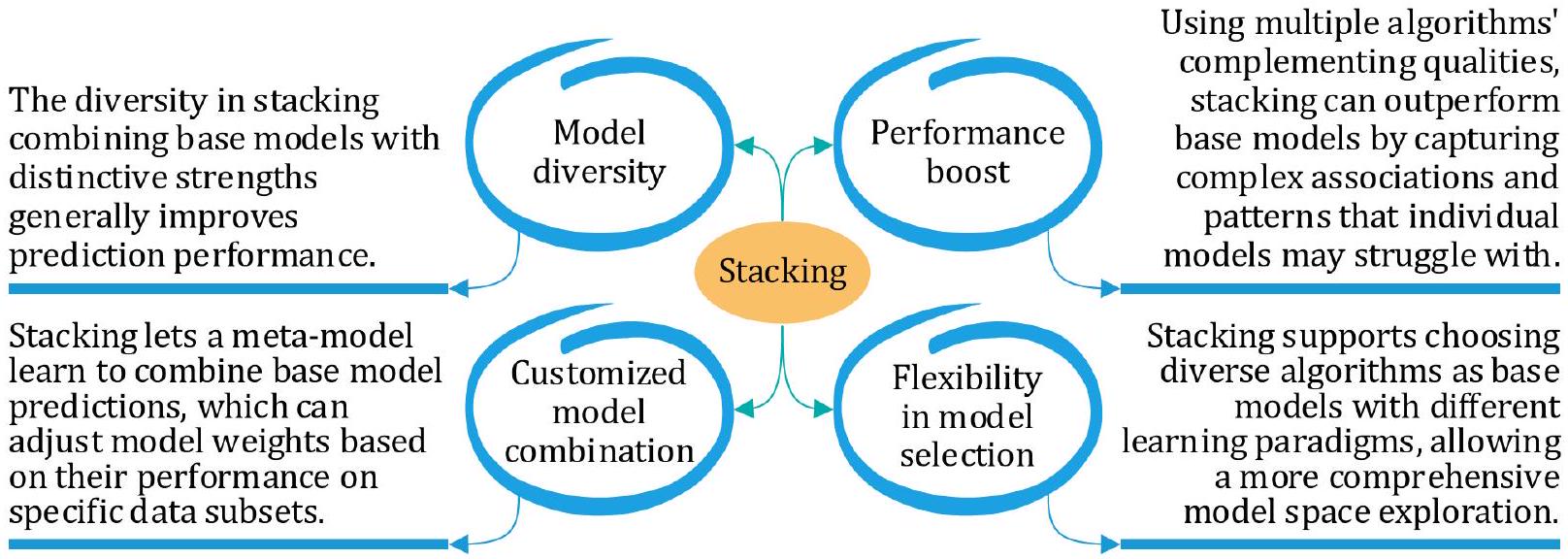

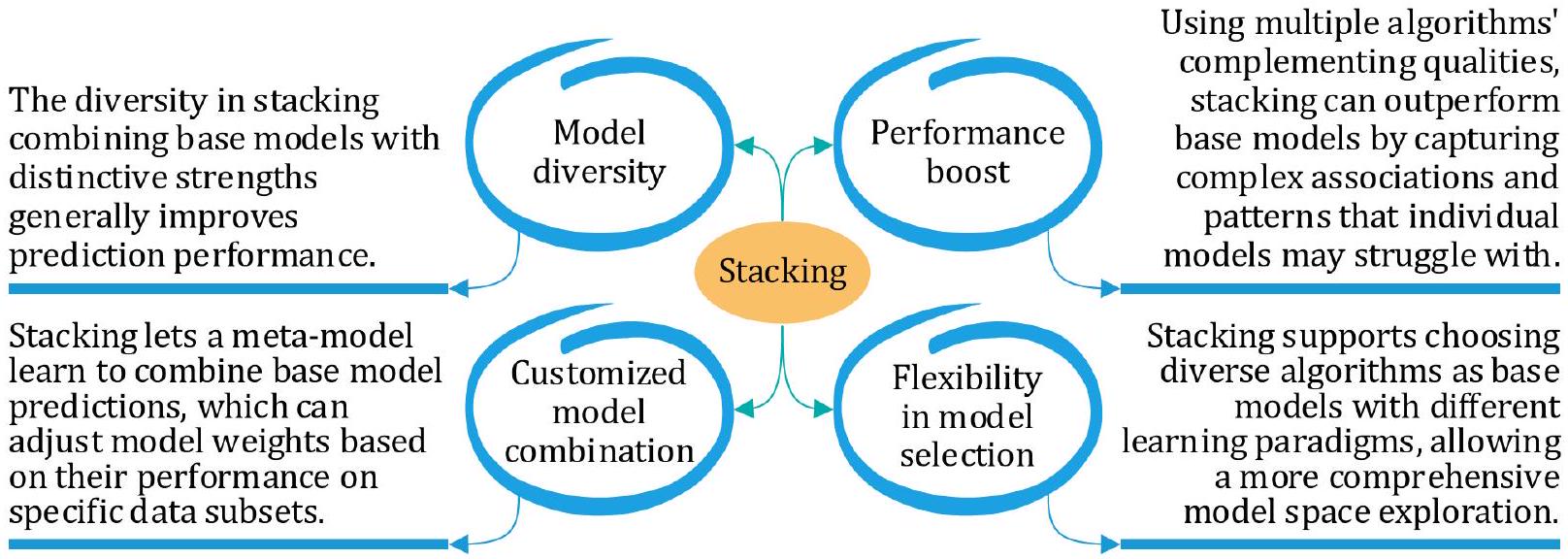

ومشكلة التنبؤ المطروحة. بشكل عام، توفر تقنيات التجميع والتصويت مرونة وموثوقية من خلال الاستفادة من خصائص النماذج المختلفة، بينما تركز تقنيات التعزيز والتجميع على تقليل التباين وتصحيح الأخطاء بشكل متسلسل. في هذه الدراسة، اخترنا طرق التجميع والتصويت نظرًا لمزاياها (كما هو موضح في الشكلين 2 و 3، على التوالي) مقارنةً بالتعزيز والتجميع. تعتبر كل من تقنيات التجميع والتصويت فعالة في استغلال تنوع النماذج المتعددة لتعزيز دقة التنبؤ وموثوقيتها في مهام التعلم الآلي. فيما يلي نظرة عامة موجزة عن طرق التجميع والتصويت.

الشكل 2. مزايا التكديس.

الشكل 3. مزايا التصويت.

تكديس

تكديس (التعميم المكدس) يتضمن تدريب نماذج فردية متعددة ثم دمج توقعاتها باستخدام نموذج آخر، غالبًا ما يُشار إليه باسم النموذج الفوقي. خلال مرحلة تدريب التكديس، تتضمن الخطوة الأولى تدريب مجموعة من النماذج الأساسية المتنوعة باستخدام بيانات التدريب المتاحة. يمكن اختيار هذه النماذج الأساسية بناءً على خوارزميات أو معلمات مختلفة، مما يسمح بتوقعات مختلفة. بمجرد تدريب هذه النماذج الأساسية، يتم استخدامها لتوليد توقعات لنفس بيانات التدريب التي تم تدريبها عليها. تؤدي هذه الخطوة إلى مجموعة جديدة من التوقعات، والتي يتم دمجها بعد ذلك مع الميزات الأصلية لإنشاء مجموعة بيانات جديدة. تتكون هذه المجموعة الجديدة من البيانات من الميزات الأصلية والتوقعات التي قدمتها النماذج الأساسية. في الخطوة النهائية من مرحلة التدريب، يتم تدريب نموذج فوقي باستخدام هذه المجموعة الجديدة من البيانات، مع كون المتغير المستهدف هو النتيجة الحقيقية أو التسمية. يتعلم هذا النموذج الفوقي كيفية تقديم توقعات بناءً على المعلومات المجمعة من النماذج الأساسية والميزات الأصلية، مما يحسن الأداء العام للنموذج. خلال مرحلة توقع التكديس، تكون الخطوة الأولى هي توليد توقعات لبيانات الاختبار من خلال استخدام النماذج الأساسية المدربة. يتم تحقيق ذلك من خلال تطبيق كل من النماذج الأساسية المدربة على بيانات الاختبار، مما يؤدي إلى مجموعة من التوقعات من كل نموذج. الخطوة التالية هي دمج هذه التوقعات لإنشاء مجموعة بيانات جديدة. تتكون هذه المجموعة الجديدة من البيانات فقط من التوقعات التي قدمتها النماذج الأساسية على بيانات الاختبار. في الخطوة النهائية من مرحلة التوقع، يتم استخدام النموذج الفوقي المدرب للوصول إلى التوقع النهائي بناءً على هذه المجموعة الجديدة من البيانات. يستخدم النموذج الفوقي المعلومات من توقعات النماذج الأساسية لتقديم توقع نهائي أكثر دقة لبيانات الاختبار. إن استخدام نموذج فوقي مدرب لاستنتاج توقع نهائي بناءً على توقعات نماذج أساسية متعددة يجعل التكديس تقنية قوية لتعزيز أداء نماذج التعلم الآلي.

التصويت

يتضمن التصويت دمج توقعات نماذج متعددة من خلال أخذ تصويت الأغلبية أو متوسط مخرجاتها. يمكن أن يتم ذلك بطريقتين رئيسيتين: التصويت الصارم والتصويت الناعم. في التصويت الصارم، ينتج كل نموذج في المجموعة توقعًا، ويتم تحديد التوقع النهائي من خلال اختيار الفئة التي تتلقى أغلبية الأصوات من النماذج. في حالة الانحدار، يمكن أن يكون التوقع النهائي هو متوسط التوقعات التي قدمتها النماذج. هذه الطريقة بسيطة وفعالة، حيث تسمح بالاستفادة من نقاط القوة لكل نموذج.

مما يؤدي إلى توقع أكثر دقة. على العكس من ذلك، يتضمن التصويت الناعم أن ينتج كل نموذج في المجموعة توزيع احتمالات على الفئات. ثم يتم حساب متوسط أو دمج الاحتمالات المتوقعة من كل نموذج بطريقة ما، ويتم اتخاذ التوقع النهائي من خلال اختيار الفئة ذات أعلى احتمال مجمع. يمكن إجراء التصويت بأوزان متساوية لكل نموذج، أو يمكن تعيين أوزان بناءً على أداء أو ثقة النماذج.

مما يؤدي إلى توقع أكثر دقة. على العكس من ذلك، يتضمن التصويت الناعم أن ينتج كل نموذج في المجموعة توزيع احتمالات على الفئات. ثم يتم حساب متوسط أو دمج الاحتمالات المتوقعة من كل نموذج بطريقة ما، ويتم اتخاذ التوقع النهائي من خلال اختيار الفئة ذات أعلى احتمال مجمع. يمكن إجراء التصويت بأوزان متساوية لكل نموذج، أو يمكن تعيين أوزان بناءً على أداء أو ثقة النماذج.

نماذج المكونات

تُعزز هذه الطريقة في التعلم الجماعي نتائج التنبؤ من خلال إنشاء ميزات جديدة لمجموعات التدريب من خلال دمج التنبؤات من المتعلمين الأساسيين. تُولد هذه الطريقة الميزات الميتا اللازمة للتنبؤ النهائي من خلال دمج كل من المصنفات التقليدية والمتقدمة. تقدم هذه القسم مناقشة موجزة حول المتعلمين الأساسيين المكونين المستخدمين لبناء نماذج التكديس والتصويت. يتم اختيار المتعلمين الأساسيين لضمان التنوع داخل الدراسة. تمتلك النماذج خصائص وآليات تعلم مختلفة.

نماذج ضعيفة

المتعلمون الضعفاء هم عمومًا نماذج بسيطة تؤدي بشكل أفضل قليلاً من الصدفة العشوائية في مهمة معينة. على الرغم من أنهم قد لا يكونون دقيقين بشكل خاص بمفردهم، إلا أنهم يعملون كأساس لنماذج أكثر تعقيدًا. تُعتبر الخوارزميات التقليدية التالية في تعلم الآلة نماذج ضعيفة.

الشبكة العصبية متعددة الطبقات (MLP) هي شبكة عصبية تغذية أمامية تتكون من عدة طبقات من العقد المترابطة (الخلايا العصبية). تستخدم دوال التنشيط والأوزان لتمثيل العلاقات غير الخطية المعقدة بين ميزات الإدخال والمتغيرات المستهدفة. إنها نموذج قوي وقابل للتكيف قادر على تقريب مجموعة واسعة من الدوال. تعمل بشكل جيد لمشاكل الانحدار والتصنيف ويمكنها التعامل مع الأنماط المعقدة.

تحليل التمييز الخطي (LDA) هو خوارزمية تصنيف خطي تحدد تركيبة خطية من الميزات لتعظيم فصل الفئات. يقوم بتحويل بيانات الإدخال إلى فضاء ذي أبعاد أقل مع الحفاظ على تمييز الفئات. إنها تقنية لتقليل الأبعاد تقلل من عدد ميزات الإدخال مع الاحتفاظ بمعلومات تمييز الفئات. تعمل بشكل أفضل مع الفئات المفصولة جيدًا وتوزيعات الميزات الغاوسية.

مصنف الدعم المتجه (SVC) هو خوارزمية تعلم تحت الإشراف تحدد أفضل مستوى فائق لتقسيم الفئات بأكبر هامش.

شجرة القرار (DT) هي هيكل هرمي يقسم بيانات الإدخال وفقًا لقيم الميزات بطريقة تكرارية.

نماذج التجميع

لجعل عملية التكديس والتصويت أكثر كفاءة وموثوقية، قمنا أيضًا بدراسة عدة نماذج تجميعية لبناء الأنابيب. تستخدم هذه الدراسة الخوارزميات التجميعية التالية بناءً على شعبيتها وقدرتها.

الأشجار الإضافية (ET) هي طريقة تعلم جماعي مشابهة للأشجار العشوائية (RF). تقوم ببناء عدة أشجار قرار باستخدام مجموعات فرعية عشوائية من البيانات ثم تقوم بمتوسط النتائج لتوليد التنبؤات. على عكس الأشجار العشوائية، تستخدم الأشجار الإضافية خوارزمية عشوائية أكثر عدوانية لاختيار الميزات. تقلل الأشجار الإضافية من تكاليف الحوسبة والتكيف الزائد من خلال استخدام المزيد من العشوائية في طريقة اختيار الميزات. يمكنها التعامل مع البيانات المزعجة والمفقودة وتؤدي بشكل جيد مع البيانات عالية الأبعاد.

LGBM هو إطار عمل يعتمد على طرق التعلم المعتمدة على الأشجار. يقوم ببناء نموذج قوي من خلال تدريب العديد من النماذج الضعيفة بشكل متتابع، حيث يقوم كل نموذج لاحق بتصحيح الأخطاء التي ارتكبتها النماذج السابقة. يوفر LGBM تدريبًا وتنبؤًا سريعًا وفعالًا، مما يجعله مثاليًا لمجموعات البيانات الكبيرة ووقت-

التطبيقات المقيدة. إنه يولد نماذج دقيقة وقوية، ويتعامل بكفاءة مع الميزات الفئوية، ويدعم تحليل أهمية الميزات وتخصيص المعلمات الفائقة.

التطبيقات المقيدة. إنه يولد نماذج دقيقة وقوية، ويتعامل بكفاءة مع الميزات الفئوية، ويدعم تحليل أهمية الميزات وتخصيص المعلمات الفائقة.

تعزيز الفئات (CB) هو طريقة تعزيز تدرج تعمل بشكل جيد مع الميزات الفئوية. تستخدم نوعًا من تعزيز التدرج المعروف باسم “تعزيز مرتب” وتقنيات فريدة للتعامل مع البيانات الفئوية دون الحاجة إلى معالجة بشرية مسبقة. لا يتطلب CatBoost ترميز واحد-ساخن أو ترميز تسميات لأنه يمكنه التعامل مع ميزات الفئات مباشرة. يعمل بشكل جيد مع المعلمات الفائقة الافتراضية ويتضمن دعمًا مدمجًا للقيم المفقودة. كما يدعم CatBoost تسريع GPU لتسريع التدريب والاستدلال.

XGB، تقنية أخرى من تقنيات GB، معروفة جيدًا بقابليتها للتوسع وكفاءتها. إنها تبني نموذج تجميعي قوي من خلال دمج طرق GB مع النماذج المعتمدة على الأشجار. يتعامل XGB بكفاءة مع مجموعات البيانات الكبيرة ذات الميزات عالية الأبعاد. يدعم مجموعة متنوعة من دوال الخسارة وقياسات التقييم ويقدم تقنيات تنظيمية لمنع الإفراط في التكيف. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يوفر XGBoost مرونة من حيث المعالجة المتوازية وخيارات التخصيص.

تعزيز التكيف (ADB) يستخدم التعلم الجماعي لإنتاج مصنف قوي من مصنفات أضعف. يمنح أوزانًا أكبر للحالات التي تم تصنيفها بشكل خاطئ في كل تكرار للتعامل مع العينات الصعبة ويعدل أوزان المصنفات الضعيفة بناءً على أدائها. ADB فعال في التعامل مع مشاكل التصنيف المعقدة ويحقق دقة عالية. حتى مع المصنفات الأساسية الضعيفة، فإنه يؤدي بشكل جيد وأقل عرضة للتكيف الزائد. ADB قادر على تصنيف كل من الحالات الثنائية والمتعددة الفئات.

الانحدار العشوائي التدرجي (SGD) هو تقنية تحسين شائعة لنماذج التعلم الآلي. في كل تكرار، يتم تغيير معلمات النموذج باستخدام مجموعة صغيرة عشوائية من بيانات التدريب، مما يجعله فعالاً من حيث الحوسبة. يعتبر SGD مثالياً لمجموعات البيانات الكبيرة وسيناريوهات التعلم عبر الإنترنت حيث تصل البيانات بشكل مستمر. يتعامل بشكل فعال مع البيانات عالية الأبعاد ويدعم مجموعة متنوعة من دوال الخسارة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن تنفيذ SGD بشكل متوازي ويكون موفرًا للذاكرة.

مجموعة البيانات للتجربة

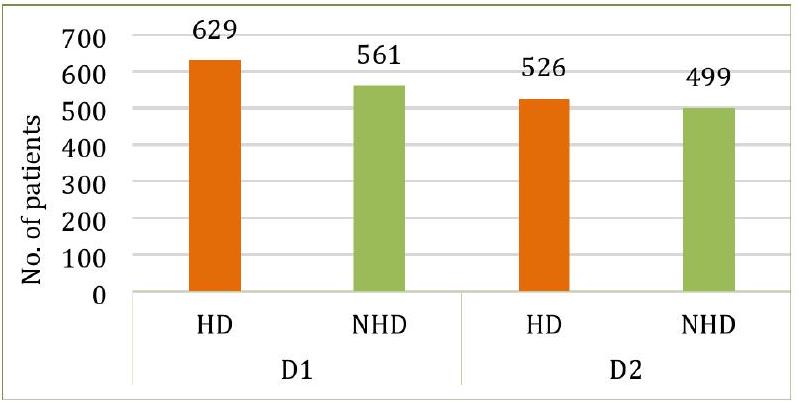

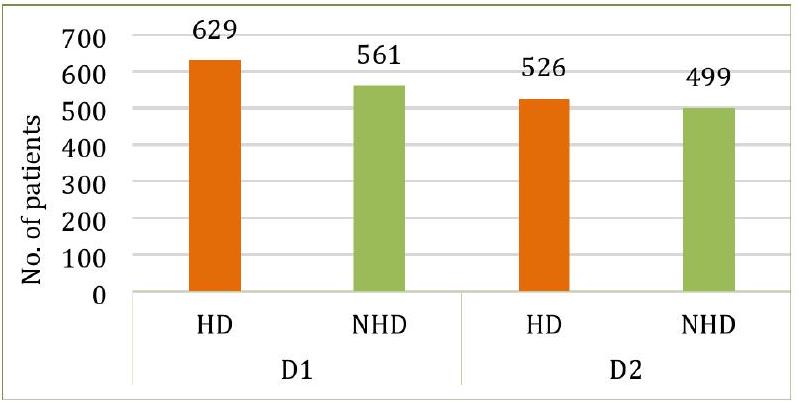

استخدمنا مجموعتين من البيانات تتضمن معلومات عن مرضى القلب. مجموعة البيانات الأولى (D1)، HDDC، ومجموعة البيانات الثانية (D2)، UHDD، تم جمعها من كاجل. توزيع المتغيرات المستهدفة في كلا مجموعتي البيانات موضح في الشكل 4. تحتوي D1 على سجلات لعدد إجمالي من 1,190 فردًا، حيث يعاني 629 منهم من مرض القلب، بينما لم يكن 561 منهم يعانون من ذلك. بالمقابل، كان 526 من أصل 1,025 فردًا في D2 يعانون من مرض القلب، مما يترك 499 خاليين من أمراض القلب. تتكون D1 من اثني عشر سمة لكل سجل، حيث السمة الحادية عشرة هي مستقلة (أو فرضية)، والسمة الأخيرة تعتمد (أو مستهدفة). بالإضافة إلى الاثني عشر سمة في D1، تتضمن D2 سمتين إضافيتين. تفاصيل جميع السمات في كلا مجموعتي البيانات موضحة في الجدول 1.

تم استخدام طرق IQRs والتعويض لتحديد أي قيم شاذة وقيم مفقودة في مجموعات البيانات. ومع ذلك، لم يتم العثور على مثل هذه الحالات في كل من D1 و D2. لتحديد وإدارة التعدد الخطي، استخدمنا عامل تضخم التباين (VIF)، وهو مقياس إحصائي يساعد في تحديد ومعالجة القضايا المحتملة للتعدد الخطي، مما يعزز من قابلية تفسير وموثوقية النموذج. يمكن أن يؤدي التعدد الخطي بين الميزات إلى تشويه معاملات النموذج التنبؤي، مما يؤدي إلى توقعات غير مستقرة. تشير الميزات ذات قيم VIF العالية إلى وجود تعدد خطي كبير، وفي مثل هذه الحالات، قد تحتاج إلى الاستبعاد أو التحويل.

في تحليلنا، أظهرت عدة ميزات قيم VIF مرتفعة (على سبيل المثال، AG: 34.318 في D1؛ RBP: 57.953 في D2)، كما هو موضح في الجدول 2. بينما يُعتبر VIF أكبر من 10 غالبًا مؤشرًا على وجود تعدد خطي كبير.

علاوة على ذلك، استخدمنا طريقة تحليل معامل الارتباط (CCA) لتحديد وتصوير العلاقات بين ميزات مجموعة البيانات. إنها تكشف عن قوة واتجاه العلاقة الخطية بين متغيرين وتستخدم لاختيار الميزات، وتحديد الميزات الزائدة، أو تقييم مدى صلة الميزات بالمتغير المستهدف. تساعد CCA في تحديد المتغيرات المرتبطة بقوة بنتيجة المرض وتلغي الميزات الزائدة التي ترتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا ببعضها البعض، مما قد يعقد النموذج دون إضافة قيمة. تؤثر بشكل مباشر على عملية بناء النموذج من خلال تحسين جودة البيانات المقدمة للنماذج، مما يضمن أن يتم تدريب طرق التجميع على مجموعة أكثر فعالية من الميزات. من خلال تقليل تكرار الميزات والتعدد الخطي، تقلل CCA بشكل أساسي من خطر الإفراط في التكيف، والذي في

الشكل 4. توزيع المتغيرات المستهدفة في كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

| صفة | اختصار | وحدة | من | ماكس | معنى | SD | 25% | 50٪ | 75% | |||||||

| D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | D1 | D2 | |||

| عمر | AG | رقمي | ٢٨ | ٢٩ | 77 | 77 | 53.72 | 54.43 | 9.35 | 9.07 | ٤٧ | ٤٨ | ٥٤ | ٥٦ | 60 | 61 |

| جنس | جي دي | فئوي (0: أنثى، 1: ذكر) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| نوع ألم الصدر | سي بي | رقمي | 1 | 0 | ٤ | ٣ | ٣.٢٣ | 0.94 | 0.93 | 1.02 | ٣ | 0 | ٤ | 1 | ٤ | 2 |

| ضغط الدم أثناء الراحة | RBP | مم زئبق | 0 | 94 | ٢٠٠ | ٢٠٠ | ١٣٢.١٥ | 131.61 | 18.36 | 17.51 | ١٢٠ | ١٢٠ | ١٣٠ | 130 | ١٤٠ | ١٤٠ |

| الكوليسترول في المصل | سي إل | ملغم/دل | 0 | ١٢٦ | ٦٠٣ | 564 | 210.36 | 246 | ١٠١.٤٢ | ٥١.٥٩ | 188 | 211 | 229 | ٢٤٠ | ٢٦٩.٧٥ | 275 |

| سكر الدم الصائم | FBS | ملغم/دل | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| نتائج تخطيط القلب أثناء الراحة | تسجيل | رقمي | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 0.52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ٢ | 1 |

| أقصى معدل ضربات قلب تم تحقيقه | MHR | رقمي | 60 | 71 | ٢٠٢ | ٢٠٢ | ١٣٩.٧٣ | 149.11 | 25.51 | 23 | 121 | 132 | ١٤٠.٥٠ | ١٥٢ | ١٦٠ | 166 |

| الذبحة الصدرية الناتجة عن التمارين | EA | فئوي (0: لا، 1: نعم) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| الانخفاض القديم (انخفاض ST الناتج عن التمرين مقارنة بالراحة) | OP | رقمي | 2.6 | 0 | ٦ | 6.2 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| ميل جزء ST في قمة التمرين | STS | رقمي | 0 | 0 | ٣ | 2 | 1.62 | 1.38 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ٢ | 2 |

| عدد الأوعية الرئيسية الملونة بواسطة الفلورسكوبي | CF | رقمي | – | 0 | – | ٤ | – | 0.75 | – | 1.03 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | 1 |

| ثال (معدل ضربات قلب الثاليوم) | ث | فئوي (0: طبيعي، 1: عيب ثابت، 2: عيب قابل للعكس) | – | 0 | – | ٣ | – | 2.32 | – | 0.62 | – | 2 | – | 2 | – | ٣ |

| أمراض القلب | إتش دي | فئوي (0: لا، 1: نعم) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

الجدول 1. معلومات السمات لكلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

| مجموعة بيانات | AG | جي دي | سي بي | RBP | سي إل | FBS | تسجيل | MHR | EA | OP | STS | CF | ث |

| D1 | ٣٤.٣١٨ | ٤.٤٥٠ | ١٤.٤٢٠ | ٤٦.٨١٤ | 6.387 | 1.413 | 1.757 | ٢٣.٢٨٧ | ٢.٤٢٤ | ٢.٤٩٩ | 11.932 | إكس | إكس |

| D2 | ٣٨.٦٩٩ | ٣.٦١٣ | ٢.٣٧٦ | ٥٧.٩٥٣ | ٢٦.١٨٥ | 1.272 | 2.052 | 42.598 | 2.073 | 3.117 | 9.854 | 1.830 | ١٦٫٧٢٤ |

الجدول 2. قيم VIF لكلا مجموعتي البيانات.

| AG | جي دي | سي بي | RBP | سي إل | FBS | تسجيل | MHR | EA | OP | STS | إتش دي | |

| AG | 1.000 | 0.015 | 0.150 | 0.260 | -0.046 | 0.180 | 0.190 | -0.370 | 0.190 | 0.250 | 0.240 | 0.260 |

| جي دي | 0.015 | 1.000 | 0.140 | -0.006 | -0.210 | 0.110 | -0.022 | -0.180 | 0.190 | 0.096 | 0.130 | 0.310 |

| سي بي | 0.150 | 0.140 | 1.000 | 0.010 | -0.110 | 0.076 | 0.036 | -0.340 | 0.400 | 0.220 | 0.280 | 0.460 |

| RBP | 0.260 | -0.006 | 0.010 | 1.000 | 0.099 | 0.088 | 0.096 | -0.100 | 0.140 | 0.180 | 0.089 | 0.120 |

| سي إل | -0.046 | -0.210 | -0.110 | 0.099 | 1.000 | -0.240 | 0.150 | 0.240 | -0.033 | 0.057 | -0.100 | -0.200 |

| FBS | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.076 | 0.088 | -0.240 | 1.000 | 0.032 | -0.120 | 0.053 | 0.031 | 0.150 | 0.220 |

| تسجيل | 0.190 | -0.022 | 0.036 | 0.096 | 0.150 | 0.032 | 1.000 | 0.059 | 0.038 | 0.130 | 0.094 | 0.073 |

| MHR | -0.370 | -0.180 | -0.340 | -0.100 | 0.240 | -0.120 | 0.059 | 1.000 | -0.380 | -0.180 | -0.350 | -0.410 |

| EA | 0.190 | 0.190 | 0.400 | 0.140 | -0.033 | 0.053 | 0.038 | -0.380 | 1.000 | 0.370 | 0.390 | 0.480 |

| OP | 0.250 | 0.096 | 0.220 | 0.180 | 0.057 | 0.031 | 0.130 | -0.180 | 0.370 | 1.000 | 0.520 | 0.400 |

| STS | 0.240 | 0.130 | 0.280 | 0.089 | -0.100 | 0.150 | 0.094 | -0.350 | 0.390 | 0.520 | 1.000 | 0.510 |

| إتش دي | 0.260 | 0.310 | 0.460 | 0.120 | -0.200 | 0.220 | 0.073 | -0.410 | 0.480 | 0.400 | 0.510 | 1.000 |

الشكل 5. تحليل معامل الارتباط لـ D1.

| AG | جي دي | سي بي | RBP | سي إل | FBS | تسجيل | MHR | EA | OP | STS | CF | ث | إتش دي | |

| AG | 1.000 | -0.100 | -0.072 | 0.270 | 0.220 | 0.120 | -0.130 | -0.390 | 0.088 | 0.210 | -0.170 | 0.270 | 0.072 | -0.230 |

| جي دي | -0.100 | 1.000 | -0.041 | -0.079 | -0.200 | 0.027 | -0.055 | -0.049 | 0.140 | 0.085 | -0.027 | 0.110 | 0.200 | -0.280 |

| سي بي | -0.072 | -0.041 | 1.000 | 0.038 | -0.082 | 0.079 | 0.044 | 0.310 | -0.400 | -0.170 | 0.130 | -0.180 | -0.160 | 0.430 |

| RBP | 0.270 | -0.079 | 0.038 | 1.000 | 0.130 | 0.180 | -0.120 | -0.039 | 0.061 | 0.190 | -0.120 | 0.100 | 0.059 | -0.140 |

| سي إل | 0.220 | -0.200 | -0.082 | 0.130 | 1.000 | 0.027 | -0.150 | -0.022 | 0.067 | 0.065 | -0.014 | 0.074 | 0.100 | -0.100 |

| FBS | 0.120 | 0.027 | 0.079 | 0.180 | 0.027 | 1.000 | -0.100 | -0.009 | 0.049 | 0.011 | -0.062 | 0.140 | -0.042 | -0.041 |

| تسجيل | -0.130 | -0.055 | 0.٠٤٤ | -0.120 | -0.150 | -0.100 | 1.000 | 0.048 | -0.066 | -0.050 | 0.086 | -0.078 | -0.021 | 0.130 |

| MHR | -0.390 | -0.049 | 0.310 | -0.039 | -0.022 | -0.009 | 0.048 | 1.000 | -0.380 | -0.350 | 0.400 | -0.210 | -0.098 | 0.420 |

| EA | 0.088 | 0.140 | -0.400 | 0.061 | 0.067 | 0.049 | -0.066 | -0.380 | 1.000 | 0.310 | -0.270 | 0.110 | 0.200 | -0.440 |

| OP | 0.210 | 0.085 | -0.170 | 0.190 | 0.065 | 0.011 | -0.050 | -0.350 | 0.310 | 1.000 | -0.580 | 0.220 | 0.200 | -0.440 |

| STS | -0.170 | -0.027 | 0.130 | -0.120 | -0.014 | -0.062 | 0.068 | 0.400 | -0.270 | -0.580 | 1.000 | -0.073 | -0.094 | 0.350 |

| CF | 0.270 | 0.110 | -0.180 | 0.100 | 0.074 | 0.140 | -0.078 | -0.210 | 0.110 | 0.220 | -0.073 | 1.000 | 0.150 | -0.380 |

| ث | 0.072 | 0.200 | -0.160 | 0.059 | 0.100 | -0.042 | -0.021 | -0.098 | 0.200 | 0.200 | -0.094 | 0.150 | 1.000 | -0.340 |

| إتش دي | -0.230 | -0.280 | 0.430 | -0.140 | -0.100 | -0.041 | 0.130 | 0.240 | -0.440 | -0.440 | 0.350 | -0.380 | -0.340 | 1.000 |

الشكل 6. تحليل معامل الارتباط لـ D2.

تحسن التدوير قدرة النموذج على التعميم

تتكون كلا المجموعتين من بيانات من مزيج من المتغيرات غير المتجانسة، بما في ذلك الميزات الفئوية والعشرية والعددية. كان من الضروري تطبيع البيانات لضمان أن تسهم جميع الميزات بشكل متساوٍ في أداء النموذج، حيث يمكن أن تهيمن بعض الميزات ذات النطاقات العددية الأكبر على عملية التعلم. لتطبيع قيم الميزات في كلا المجموعتين، استخدمنا المعادلة 1 التي تقوم بتعديل قيم الميزات من 0 إلى 1. تم اختيار مقياس الحد الأدنى والحد الأقصى بشكل خاص لأنه تقنية تطبيع مستخدمة على نطاق واسع تحول جميع الميزات إلى مقياس مشترك (عادةً بين 0 و 1)، وهو فعال بشكل خاص للمجموعات التي تحتوي على أنواع وقياسات ميزات متنوعة، كما هو الحال هنا. لاحظنا أن تطبيق مقياس الحد الأدنى والحد الأقصى حسّن من استقرار النماذج وتقاربها، حيث منع بعض الميزات من التأثير بشكل غير متناسب على المتعلمين الأساسيين.

أين

التجربة والنتائج

يقدم القسم التالي التفاصيل التجريبية لتوقع أمراض القلب باستخدام خوارزميات التعلم الجماعي. تحتوي الجدول 3 على تفاصيل إعداد التجربة وتكوين الكمبيوتر الذي تم إجراء التجربة عليه.

مقاييس التقييم

تقيم مقاييس التقييم مدى فعالية أداء النموذج بالنسبة لبيان المشكلة. يتم تطبيق مقاييس تقييم مختلفة اعتمادًا على طبيعة البيانات ونوع المشكلة التي يتم تحليلها. تلخص الجدول 4 مقاييس الأداء المستخدمة لتقييم النتائج التجريبية للنماذج المقدمة في هذه الدراسة. تستخدم هذه المقاييس التدابير الأساسية التالية:

- الإيجابي الحقيقي (TP) يعني أن المريض يعاني من مرض القلب، وأن النموذج يتنبأ بذلك بشكل صحيح.

- السلبية الحقيقية (TN) تعني أن المريض لا يعاني من مرض القلب، وأن النموذج يتنبأ بذلك بدقة.

- تشير الإيجابيات الكاذبة (FPs) إلى أن المريض لا يعاني من مرض القلب، ومع ذلك يتنبأ النموذج بشكل غير صحيح بنتيجة إيجابية لمرض القلب.

- يمثل السلبية الكاذبة (FN) حالة يكون فيها المريض مصابًا بأمراض القلب، لكن النموذج يتنبأ بشكل غير صحيح بنتيجة سلبية.

نتائج التنبؤ للنماذج الأساسية

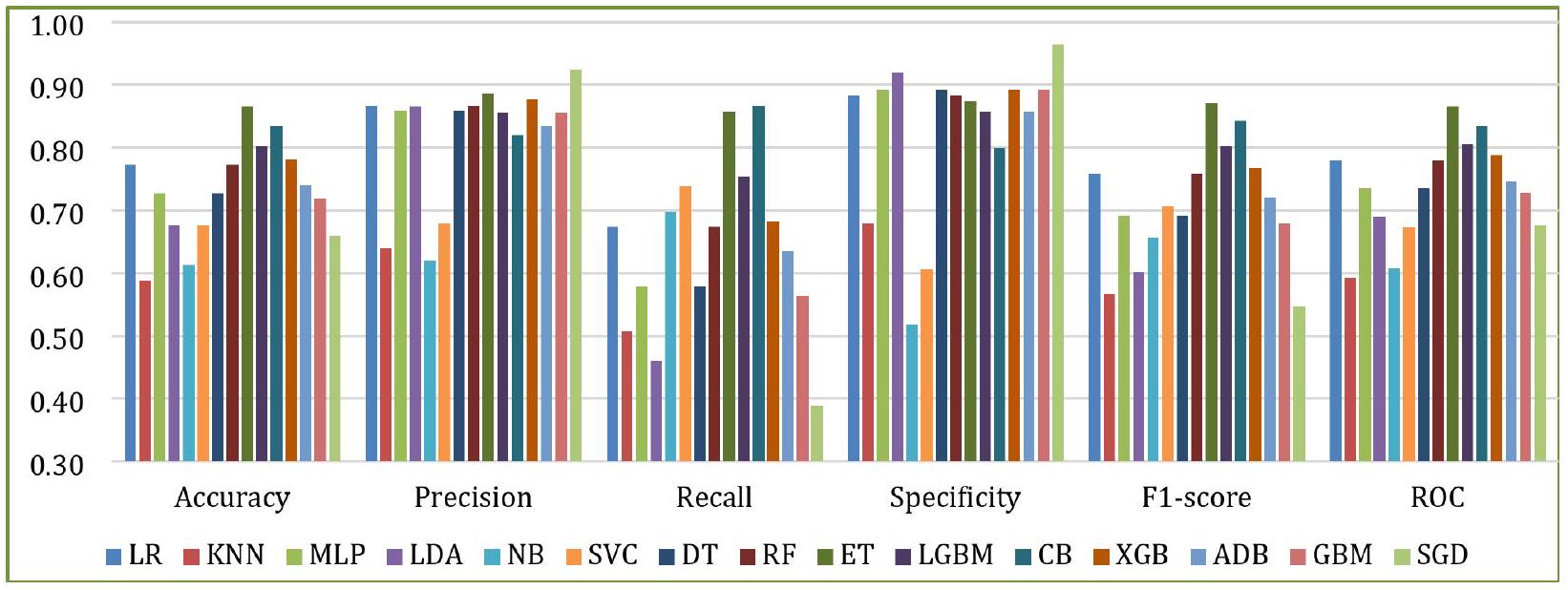

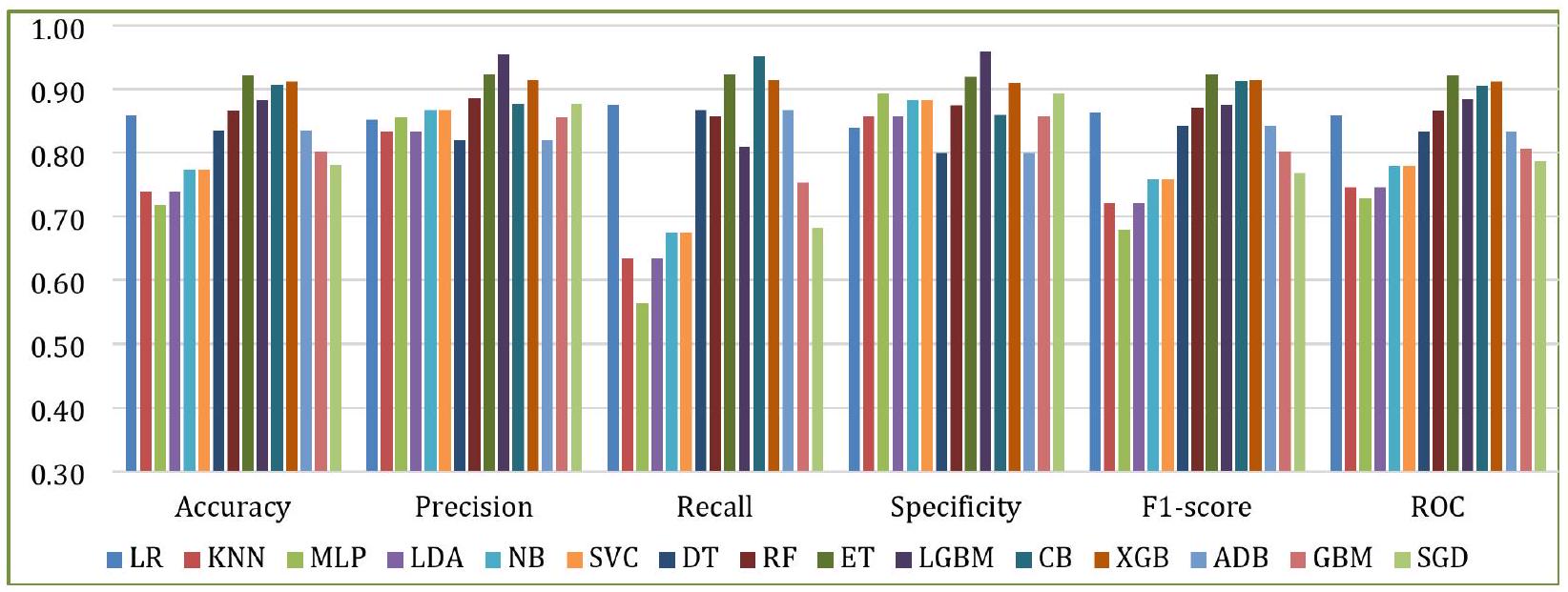

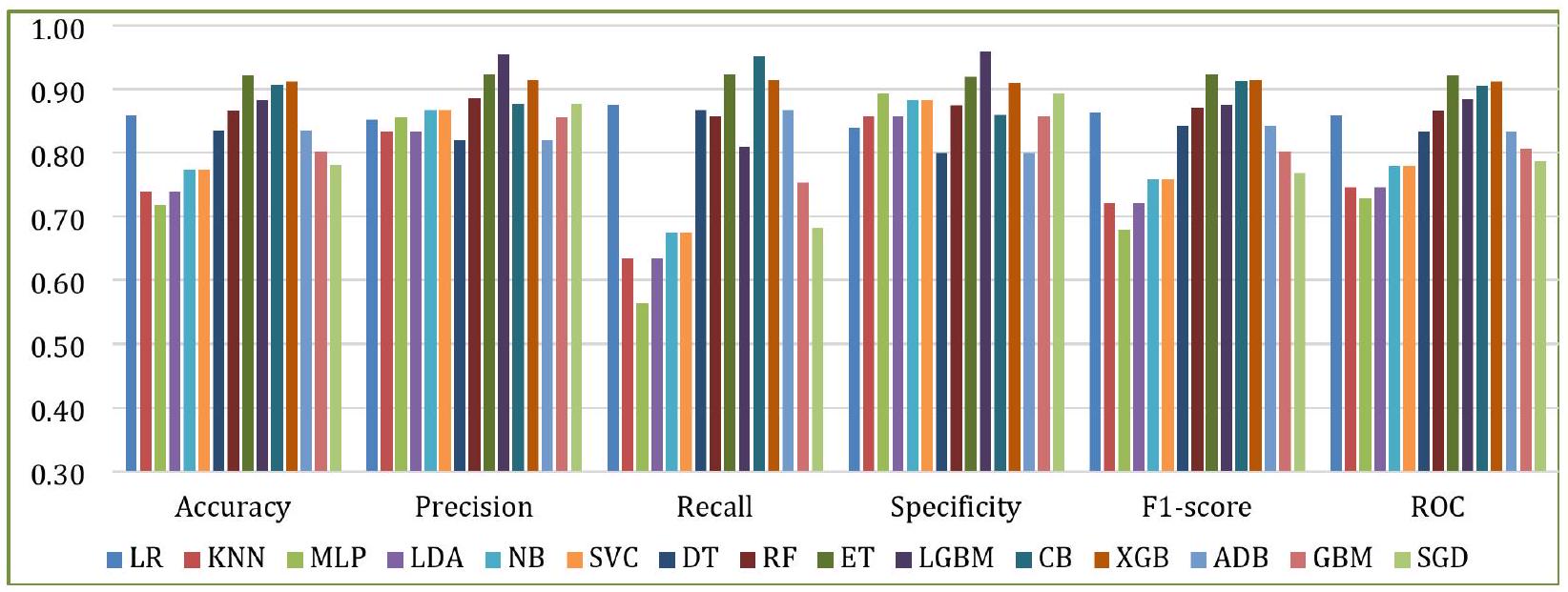

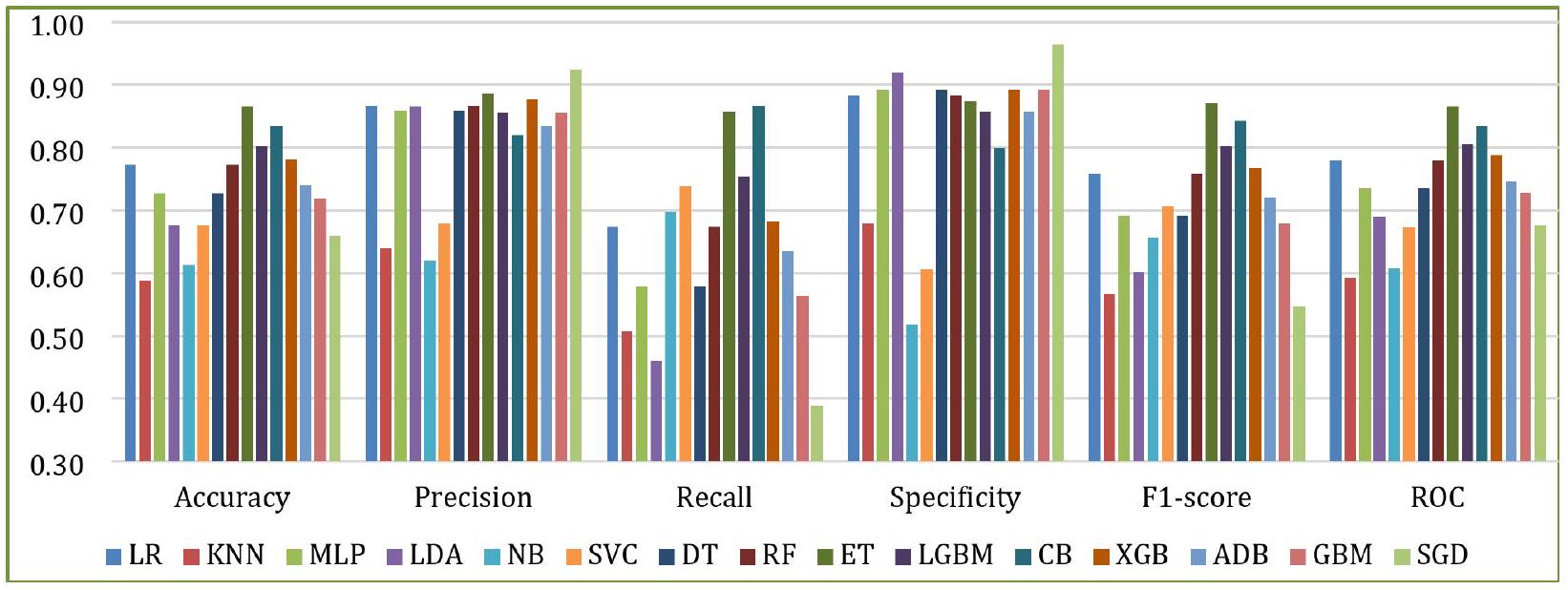

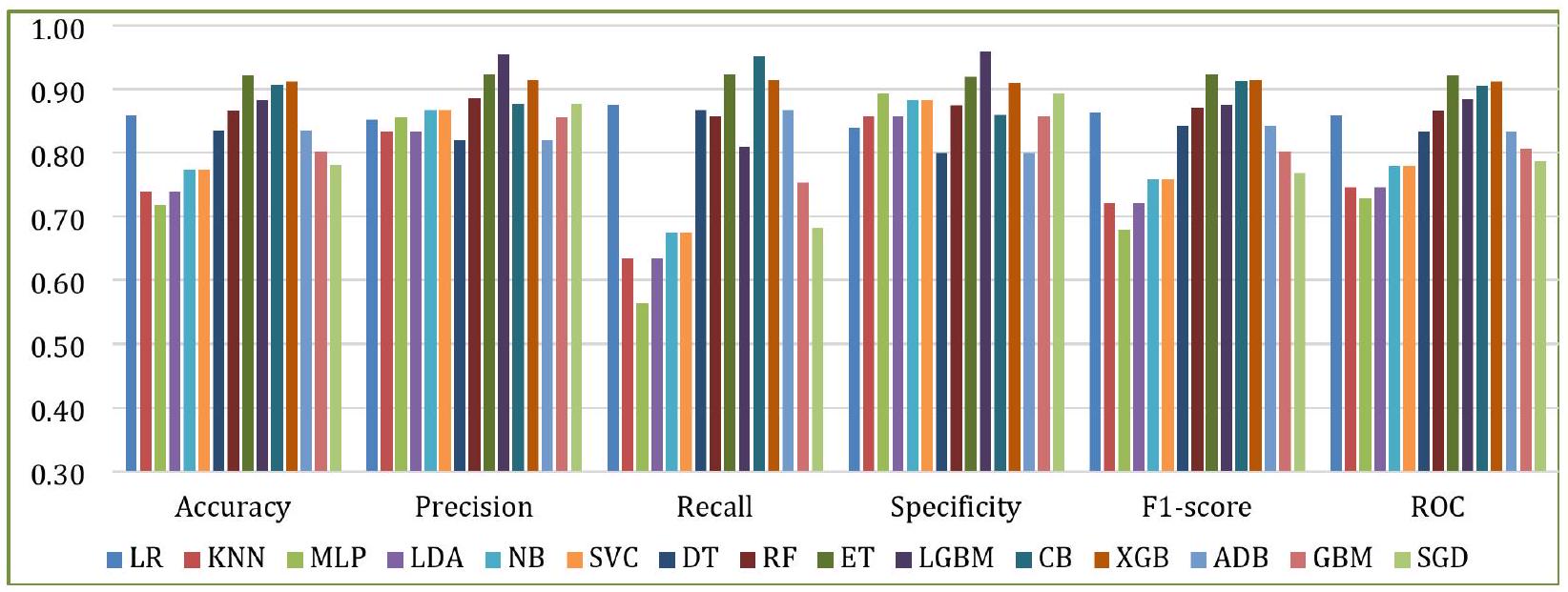

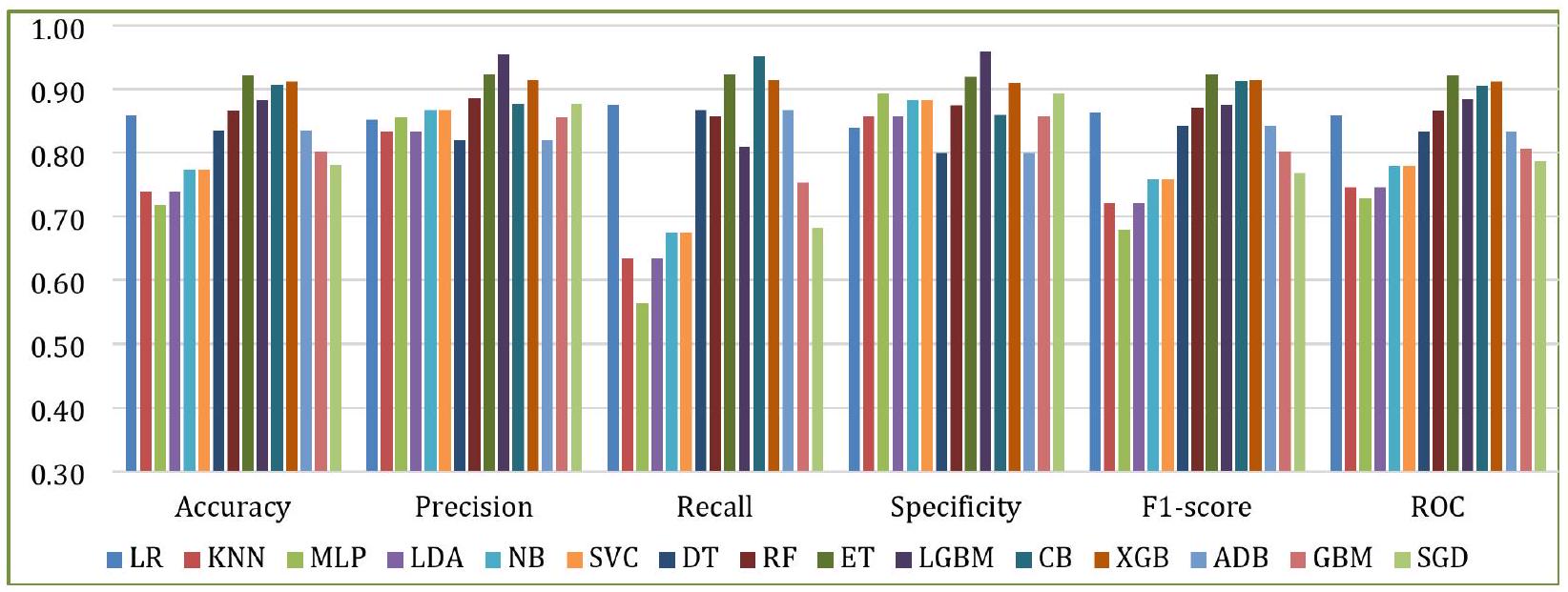

يقدم هذا القسم نتائج التنبؤ للمتعلمين الأساسيين، كما تم مناقشته في القسم 3.3. يتم تقييم النماذج بناءً على ستة مقاييس: الدقة، الدقة الإيجابية، الاسترجاع، الخصوصية، درجة F1، وROC. توضح الأشكال 7 و8 نتائج التنبؤ لـ D1 وD2، على التوالي. حقق ET أعلى دقة في كلا الحالتين، بينما كان لدى KNN أدنى دقة في D1، وكان لدى MLP أدنى دقة في D2. في المتوسط، أظهرت RF وET وLGBM وCB وXGB نتائج أفضل على كلا مجموعتي البيانات.

تصميم خط الأنابيب للتكديس والتصويت

لبناء نموذج تجميعي فعال، هدفنا إلى تحديد التركيبة المثلى من النماذج الأساسية. في البداية، جربنا خمسة عشر نموذجًا أساسيًا، كما تم مناقشته في القسم السابق. قمنا بتجربة مختلف التباديل والتركيبات، كما هو موضح في الشكل 9. في التركيبة الأولى، استخدمنا أفضل عشرة نماذج، بناءً بشكل أساسي على دقتها. في التركيبة الثانية، تم استخدام عشرة نماذج تم اختيارها عشوائيًا بواسطة البرنامج. تم اعتبار ستة نماذج مشتركة بين التركبتين للمجموعة النهائية. كانت هذه النماذج الستة هي الأفضل أداءً في كلا التركبتين.

باستخدام النماذج الستة المختارة (LR، ET، RF، CB، XGB، وLGBM)، قمنا ببناء خط أنابيب لكل من التكديس والتصويت، كما هو موضح في الشكل 10. يتم تقديم عمليات بناء خط الأنابيب للتكديس والتصويت في الخوارزمية 1 والخوارزمية 2، على التوالي.

كما هو موضح في الخوارزمية 1، تم استخدام الانحدار اللوجستي كنموذج ميتا في دراستنا للتكديس. كان اختيار الانحدار اللوجستي كالمصنف الميتا مستندًا إلى الأدبيات الأساسية والتحقق التجريبي. وولبرت

في هذه الدراسة، جربنا أيضًا مصنفات ميتا بديلة مثل KNN و LDA. ومع ذلك، كما هو متوقع، لم تحقق هذه النماذج أداءً تنافسيًا مقارنة بـ LR، سواء من حيث الدقة أو الاستقرار. يتم عرض الأداء المقارن لـ LR و KNN و LDA كمتعلمين ميتا في الشكل 11. أظهر LR قدرة تفوق في التعميم عند تجميع التنبؤات من متعلمين أساسيين متنوعين، ولهذا السبب تم الاحتفاظ به كنموذج ميتا في نموذج التكديس لدينا.

| الأجهزة/البرامج | المواصفات |

| المعالج | الجيل الحادي عشر من إنتل

|

| الذاكرة العشوائية | 8.00 جيجابايت (7.80 جيجابايت قابلة للاستخدام) (DDR4) |

| وحدة التخزين SSD | 256 جيجابايت (NVMe) |

| القرص الصلب | 2 تيرابايت (HDD) |

| نظام التشغيل | ويندوز 11 هوم بلغة واحدة 64 بت (10.0) |

| لغة البرمجة | بايثون |

| المنصة | دفتر جوبتر |

الجدول 3. الأجهزة والبرامج المستخدمة لإجراء التجربة.

| المقاييس | الحساب | الوصف |

| الدقة |

|

تقيس الدقة صحة التنبؤات العامة للنموذج، بما في ذلك كل من TPs و TNs. |

| الدقة |

|

تقيس الدقة نسبة التنبؤات الإيجابية الصحيحة من إجمالي التنبؤات الإيجابية التي قام بها النموذج، أي أنها تشير إلى قدرة النموذج على تحديد المرضى الذين يعانون من أمراض القلب بشكل صحيح. إنها مفيدة عندما يكون تقليل FPs أمرًا حاسمًا. |

| الاسترجاع |

|

يقيس الاسترجاع نسبة التنبؤات الإيجابية الصحيحة من الحالات الإيجابية الفعلية، أي أنه يعكس قدرة النموذج على اكتشاف المرضى الذين يعانون من أمراض القلب بشكل صحيح. إنه مهم في الحالات التي تكون فيها FNs حاسمة. |

| درجة F1 |

|

تعطي درجة F1 مقياسًا واحدًا يوازن بين الاسترجاع والدقة من خلال أخذ المتوسط التوافقي بين الاثنين. إنها مفيدة بشكل خاص عندما تكون مجموعة البيانات غير متوازنة أو عندما تكون الدقة والاسترجاع متساويين في الأهمية. تشير درجة F1 العالية إلى توازن جيد بين الدقة والاسترجاع. |

| الخصوصية |

|

تقيس الخصوصية عدد حالات أمراض القلب التي تم التنبؤ بها سلبًا والتي تبين أنها TN. تشير إلى قدرة النموذج على تحديد الأفراد الذين لا يعانون من أمراض القلب بشكل صحيح. الخصوصية مهمة عندما يكون تقليل FPs أمرًا حاسمًا، لأن FPs قد تؤدي إلى إجراءات طبية غير ضرورية. |

| المتوسط الكلي (MA) |

|

يحدد MA متوسط الأداء عبر جميع الفئات أو الفئات. هنا،

|

| المتوسط المرجح (WA) |

|

يوفر WA ملخصًا للأداء يأخذ في الاعتبار توزيع الفئات. إنه مفيد في مجموعات البيانات غير المتوازنة عندما تحتوي بعض الفئات على عدد أكبر بكثير من الحالات مقارنةً بأخرى. |

| الانحراف المعياري (SD) |

|

يقيم SD تباين مقاييس الأداء عبر عدة طيات، مما يوفر رؤى حول اتساق النموذج أو استقراره. يشير SD الأقل إلى نتائج أكثر اتساقًا. (

|

| كاررا |

|

كابا كوهين هو مقياس لقياس درجة الاتفاق بين التسميات الفعلية والمتوقعة للفئات التي تأخذ في الاعتبار الاتفاق المحتمل بالصدفة. عندما يكون توزيع الفئات منحرفًا، أو كانت الفئة الغالبة شائعة جدًا، فإنه يساعد في تقييم مدى جودة أداء النموذج. |

| معامل ارتباط ماثيو (MCC) |

|

يقيس MCC جودة التصنيفات الثنائية. يتراوح بين -1 و +1، حيث تشير +1 إلى تصنيف صحيح، و 0 تشير إلى تصنيف عشوائي، و -1 تشير إلى تصنيف خاطئ تمامًا. يشير MCC الأكبر إلى تحسين أداء النموذج. |

| منحنى خصائص التشغيل المستقبلية (ROC) | TPR (محور Y) مقابل FPR (محور X) | يوضح منحنى ROC التوازن بين الاسترجاع والخصوصية. يظهر مدى جودة أداء النموذج عند إعدادات عتبة مختلفة لتنبؤ أمراض القلب. يشير ROC الأعلى إلى أداء أفضل للنموذج. |

| المساحة تحت المنحنى (AUC) |

|

تمثل AUC المساحة تحت منحنى ROC وتوفر قيمة عددية واحدة تلخص الأداء العام لنموذج التنبؤ. تشير AUC الأعلى إلى تمييز أكثر دقة بين الحالات الإيجابية والسلبية لأمراض القلب بين المرضى. |

| المساحة تحت منحنى الدقة والاسترجاع (AUPRC) |

|

مؤشر على مدى جودة أداء النموذج على مجموعات البيانات غير المتوازنة، AUPRC هي المساحة تحت منحنى الدقة والاسترجاع. تأخذ في الاعتبار التوازن بين الدقة والاسترجاع. تشير AUPRC الأعلى إلى أداء أفضل، خاصة عند تحديد الحالات الإيجابية بشكل صحيح. |

| معدل التصنيف الخاطئ (MCR) |

|

نسبة الحالات التي تم تصنيفها بشكل خاطئ بالنسبة لإجمالي الحالات تُسمى MCR، وتُعرف أيضًا بمعدل الخطأ. تكمل الدقة من خلال إعطاء نسبة الأحداث المصنفة بشكل خاطئ. يشير انخفاض معدل التصنيف الخاطئ إلى تحسين أداء النموذج. |

| وقت التنفيذ | – | وقت تنفيذ الخوارزمية بالثواني. |

الجدول 4. مقاييس تقييم الأداء.

الشكل 7. أداء النماذج الأساسية مع D1.

الشكل 8. أداء النماذج الأساسية مع D2.

الشكل 9. اختيار النموذج.

الشكل 10. بناء خط الأنابيب للتكديس والتصويت.

الشكل 11. الأداء المقارن لـ LR و KNN و LDA كمتعلمين ميتا.

Input: a) Training/validation dataset $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}}=left{boldsymbol{x}_{boldsymbol{i}}, boldsymbol{y}_{boldsymbol{i}}right}_{boldsymbol{i}=mathbf{1}}^{boldsymbol{n}}, boldsymbol{n}$ is no. of instances

b) Base models: $boldsymbol{B}_{boldsymbol{L}}=left{boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{1}}+boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{2}}+ldots+boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{k}}right}$

c) A meta-classifier (LR)

Output: Ensemble stacking classifier S

Initialize an empty 2D array $boldsymbol{S}$ of size $n times k$ to store base learner predictions

For each base learner $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ in $boldsymbol{B}_{boldsymbol{L}}$ do

Initialize hyperparameters for $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$

Initialize an empty 1D array $boldsymbol{P}$ to store validation metrics $boldsymbol{P}_{i}$

For each instance $boldsymbol{i} in{1,2,3, ldots, n}$

Train $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ on $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}}^{(-boldsymbol{i})}$ // Train all instances except $i^{text {th }}$; keep one for cross-validation

Predict $boldsymbol{x}_{boldsymbol{i}}$ and compute performance metric $boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}}$

Append $boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}}$ to $boldsymbol{P}$

End

Compute average validation score $boldsymbol{P}=frac{mathbf{1}}{boldsymbol{n}} sum_{boldsymbol{i}=mathbf{1}}^{boldsymbol{n}} boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}} / /$ Aggregate performance

Adjust hyperparameters to maximize $boldsymbol{P}$ // Optimize hyperparameters

Go to Step 4 until $boldsymbol{P}$ improvement $<1 %$ || Saturation

Store the best hyperparameters for $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$

Train $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ on full $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}} / /$ Final training

Perform cross-validation using the remaining instance

Store the predicted class labels for $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}}$ in column $boldsymbol{j}$ of $boldsymbol{S}$

End

Initialize another $2 D$ array $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{N}}$ of size $n times(k+1) / /$ Prepare meta-dataset

Concatenate $boldsymbol{S}$ with original labels $boldsymbol{y}: boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{N}}=[boldsymbol{S} boldsymbol{y}]$

For each instance $boldsymbol{i} in{1,2,3, ldots, n} / /$ Train meta-learner (LR)

Train $boldsymbol{L} boldsymbol{R}$ on $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{N}}^{(-boldsymbol{i})}$ // Train all instances except $i^{text {th }}$; keep one for cross-validation

Predict $boldsymbol{x}_{boldsymbol{i}}$ and store the result in $boldsymbol{S}$

End

Return the predicted class labels in $boldsymbol{S}$

الخوارزمية 1. إجراء التكديس.

Input: a) Training/validation dataset $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}}=left{boldsymbol{x}_{boldsymbol{i}}, boldsymbol{y}_{boldsymbol{i}}right}_{boldsymbol{i}=mathbf{1}}^{boldsymbol{n}}, boldsymbol{n}$ is no. of instances

b) Base models: $boldsymbol{B}_{L}=left{boldsymbol{b}_{1}+boldsymbol{b}_{2}+ldots+boldsymbol{b}_{k}right}$

Output: Ensemble voting classifier $boldsymbol{V}$

Initialize an empty 2D array $boldsymbol{V}$ of size $n times k$ to store base learner predictions

Initialize an empty 2D array $boldsymbol{C}$ to store confidence scores for each prediction

For each base learner $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ in $boldsymbol{B}_{boldsymbol{L}}$ do

Initialize hyperparameters for $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$

Initialize an empty 1D array $boldsymbol{P}$ to store validation metrics $boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}}$

For each instance $boldsymbol{i} in{1,2,3, ldots, n}$

Train $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ on $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}}^{(-boldsymbol{i})}$ // Train all instances except $i^{text {th }}$; keep one for cross-validation

Predict $boldsymbol{x}_{boldsymbol{i}}$ and compute performance metric $boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}}$

Append $boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}}$ to $boldsymbol{P}$

End

Compute the average validation score $boldsymbol{P}=frac{mathbf{1}}{boldsymbol{n}} sum_{boldsymbol{i}=mathbf{1}}^{boldsymbol{n}} boldsymbol{P}_{boldsymbol{i}} / /$ Aggregate performance

Adjust hyperparameters to maximize $boldsymbol{P}$ // Optimize hyperparameters

Go to Step 4 until $boldsymbol{P}$ improvement < $1 %$ // Saturation

Store the best hyperparameters for $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$

Train $boldsymbol{b}_{boldsymbol{j}}$ on full $boldsymbol{T}_{boldsymbol{R}} / /$ Final training

Perform cross-validation using the remaining instance

Store the predicted class labels for $boldsymbol{T}_{R}$ in column $boldsymbol{j}$ of $boldsymbol{V}$ and confidence scores in $boldsymbol{C}$

End

Calculate the weighted vote for each class label based on the confidence scores in $boldsymbol{C}$

Assign the class label with the highest weighted vote to $V$ for this instance

Return the predicted class labels in $V$

الخوارزمية 2. إجراء التصويت.

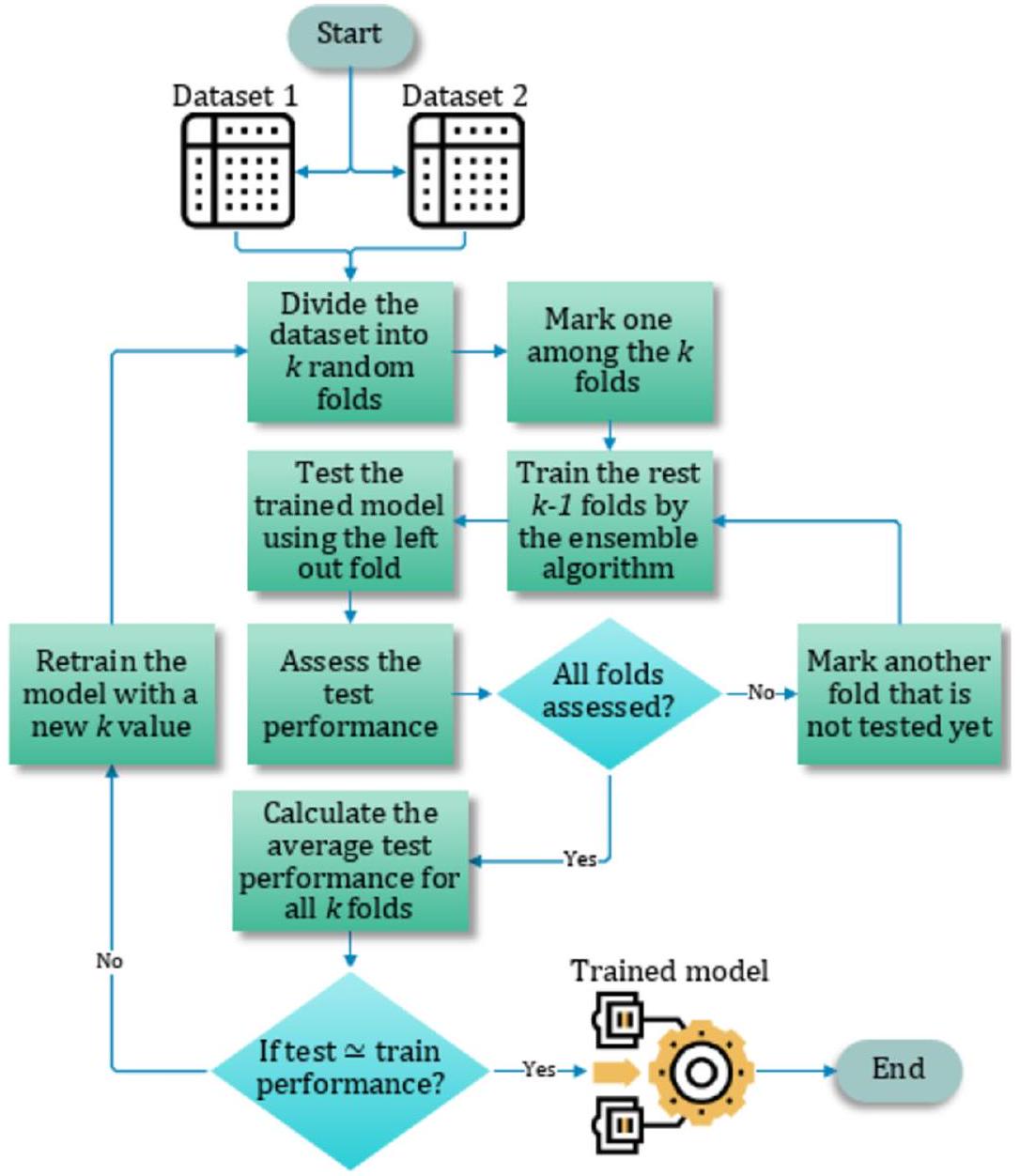

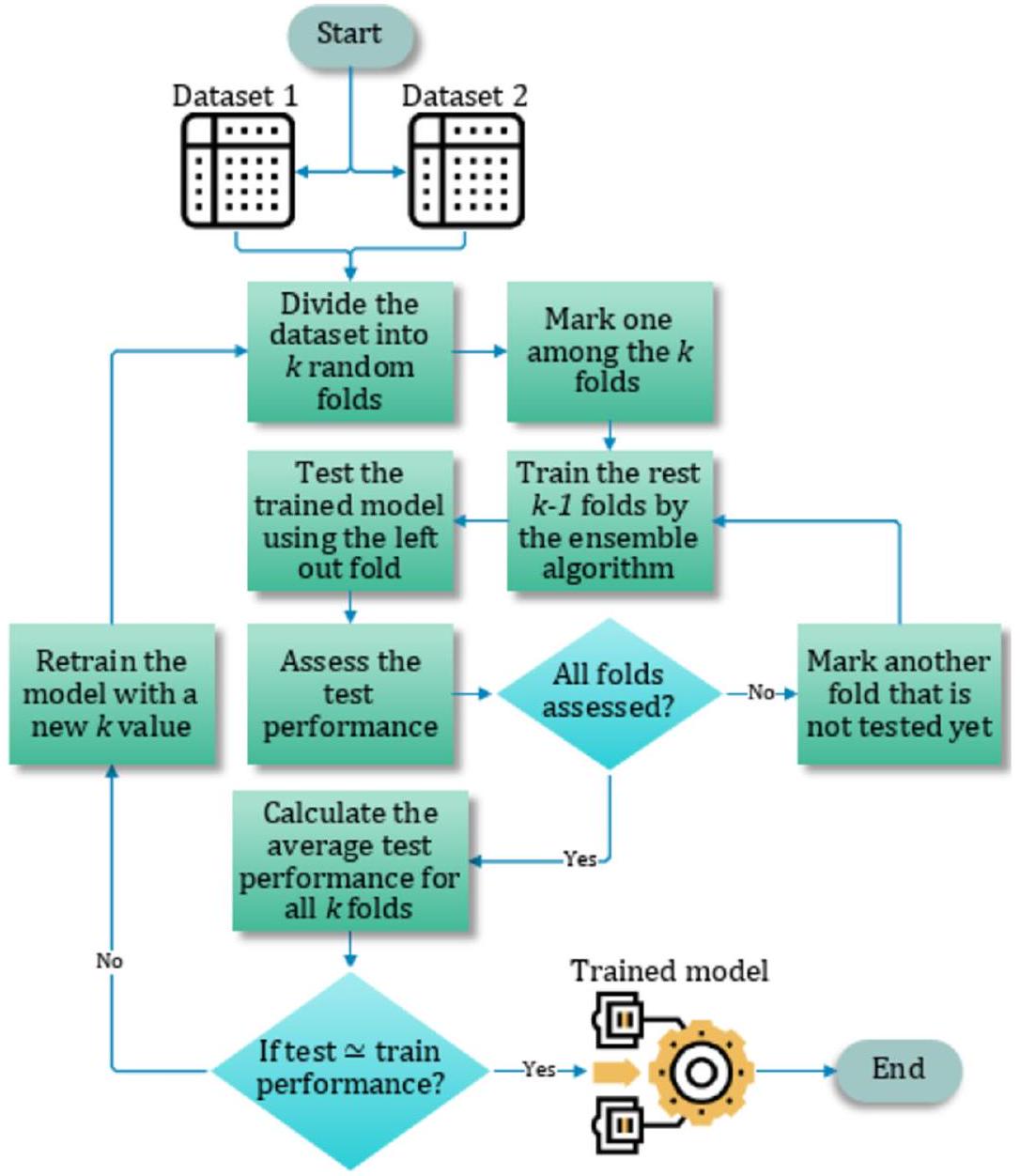

التحقق المتقاطع

يتم استخدام التحقق المتقاطع K -fold عادةً لتقليل التحيز الموجود في مجموعة البيانات. في هذه التقنية، يتم تقسيم مجموعة البيانات إلى

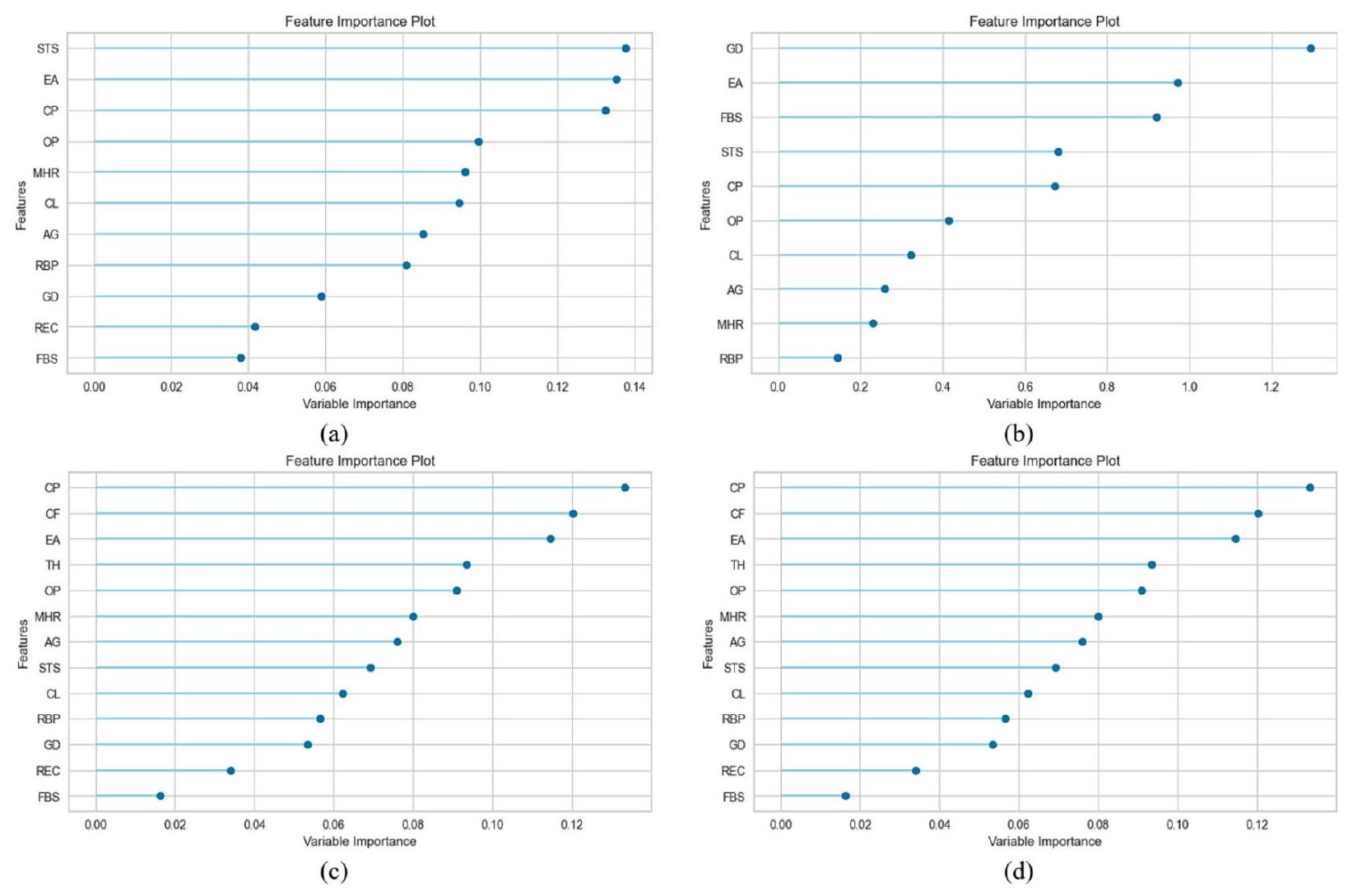

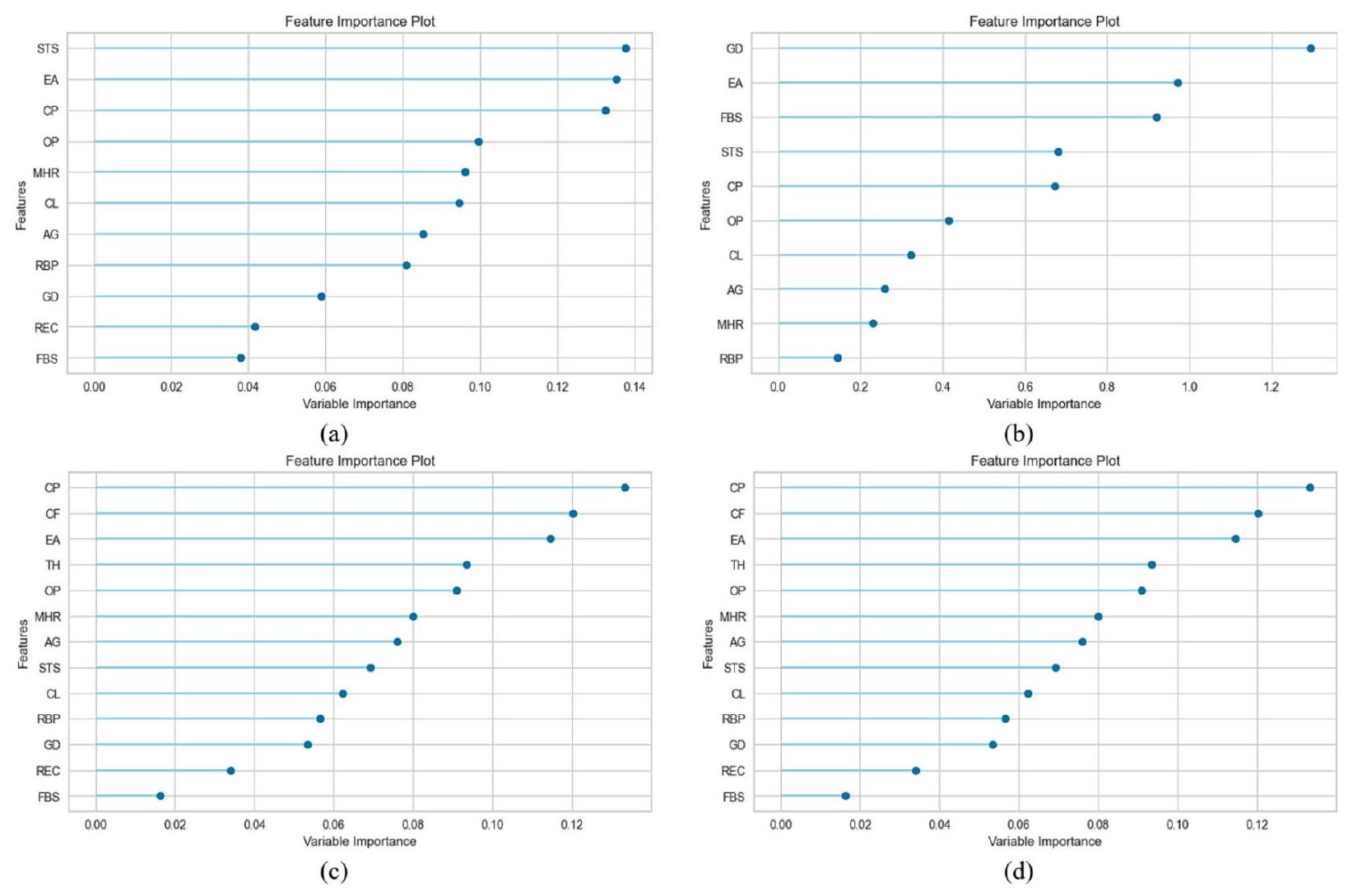

تقييم أهمية الميزات

يتم تصنيف المتغيرات المتنبئة (السمات المدخلة) في إجراء أهمية الميزات وفقًا للمدى الذي تساهم به في التنبؤ بالمتغير المستهدف (الميزة الناتجة). هذه المرحلة ضرورية لنماذج التعلم الآلي والتعلم الجماعي لتحقيق تنبؤات أكثر دقة. استخدمنا درجة أهمية الميزات (درجة F)، وهي مقياس يشير إلى مدى تكرار استخدام سمة ما للتقسيم أثناء عملية التدريب والتي يتم تعريفها بواسطة المعادلة

حيث،

الشكل 12. عملية التحقق المتقاطع

الشكل 13. أهمية الميزات لـ (أ) التكديس مع D1، (ب) التصويت مع D1، (ج) التكديس مع D2 و (د) التصويت مع D2.

الميزة i من الحالة السلبية k. يشير البسط إلى التمييز بين العينات الإيجابية والسلبية، بينما يحدد المقام التمييز داخل كل من العينتين. تشير درجة F الأكبر إلى أن هذه الميزة أكثر تمييزًا

تظهر المساهمات لكل معلمة تنبؤية تم استخدامها في هذه الدراسة في حدوث أمراض القلب في الشكل 13. عندما تم تطبيق التكديس على D1، ساهمت STS و FBS بأكبر وأقل مساهمة على التوالي. في سياق التصويت مع D1، ساهمت GD و RBP بأكبر وأقل مساهمة على التوالي. وبالمثل، أظهرت CP و FBS أكبر وأقل مساهمات على التوالي، مع D2 باستخدام كل من التكديس والتصويت.

تعديل المعلمات الفائقة

يعد تعديل المعلمات الفائقة عملية مهمة للغاية، حيث تتحكم في سلوك خوارزمية التدريب وتؤثر بشكل كبير على تقييم أداء النموذج. استخدمنا PyCaret (https://pycare t.org/)، أداة شائعة لأتمتة سير عمل تعلم الآلة، لضبط المعلمات الفائقة وتحقيق الأداء الأمثل في النموذج المقترح. تم تقديم تفاصيل المعلمات الفائقة لكل نموذج في الجدول 5. وقد حدد تجربتنا أن القيم المحددة لكل معلمة في النموذج المعني هي القيم المثلى.

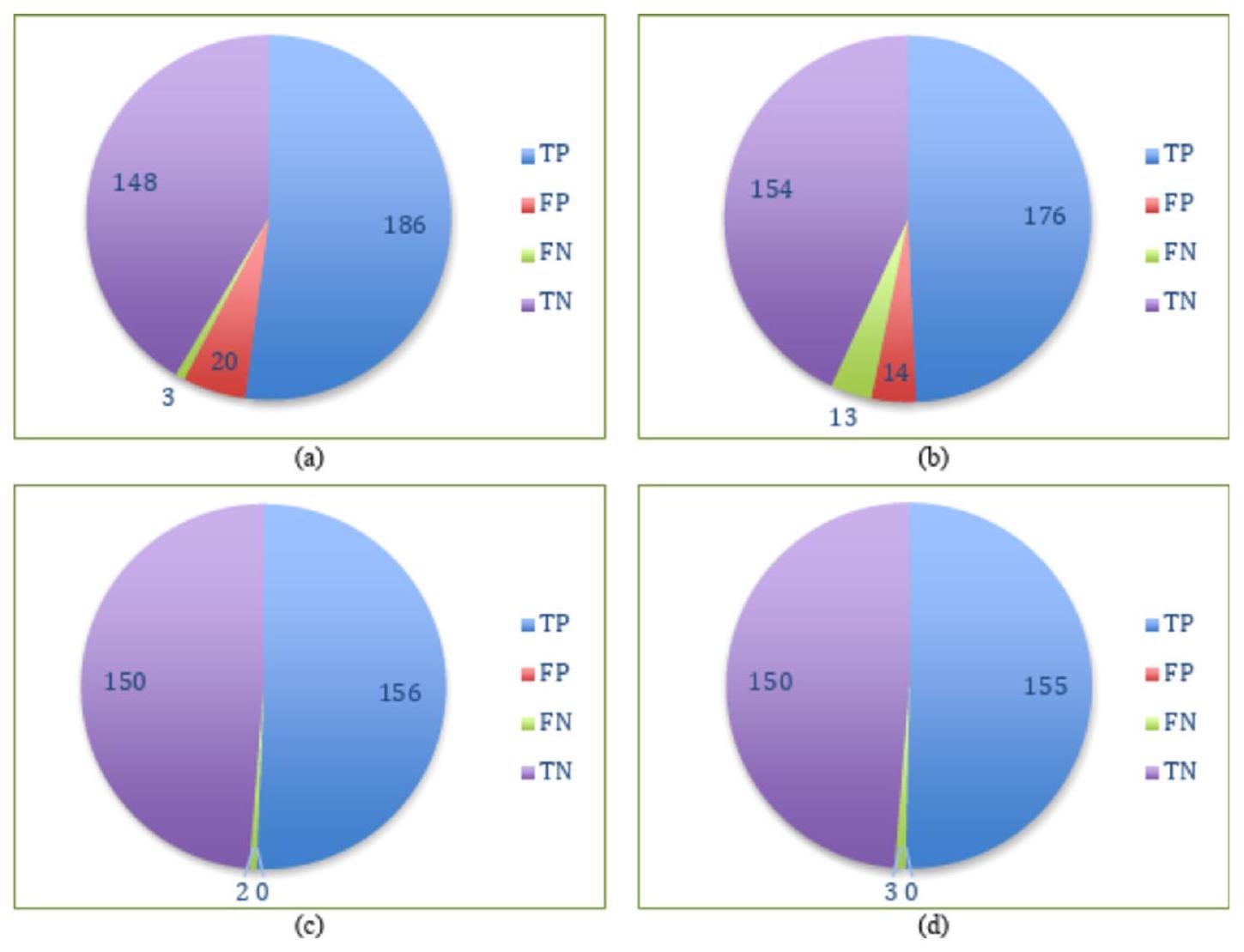

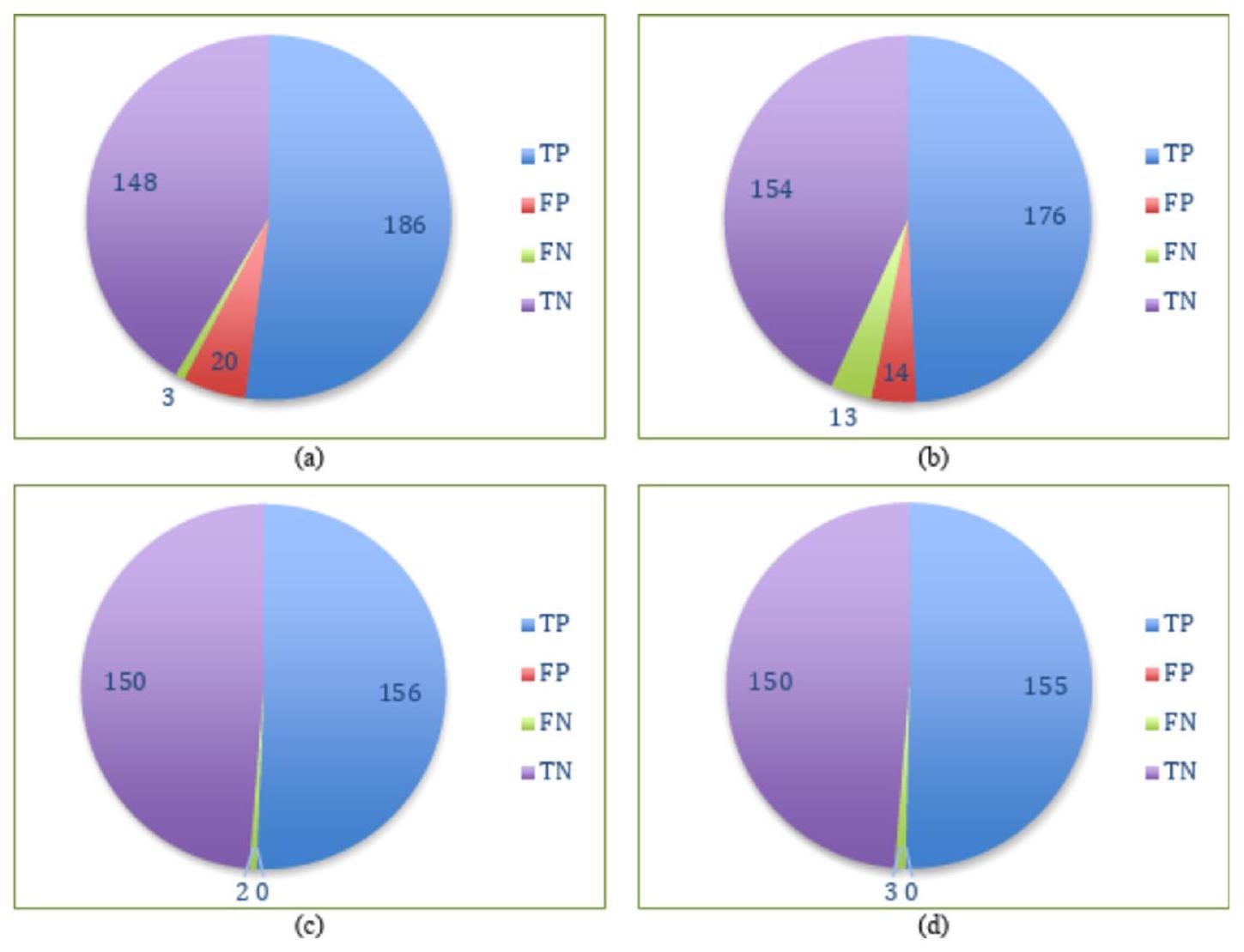

نتائج التنبؤ لنماذج التجميع والتصويت

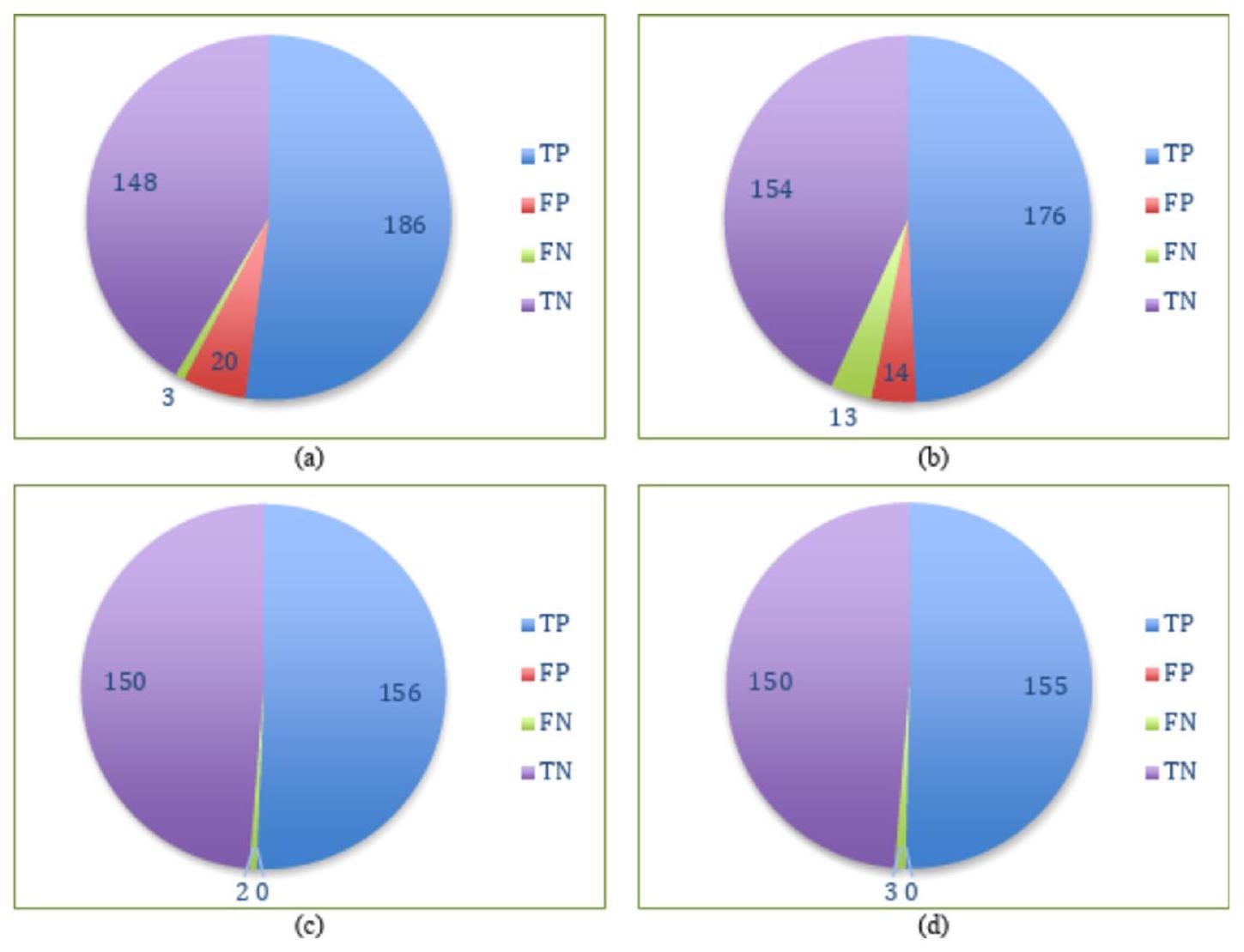

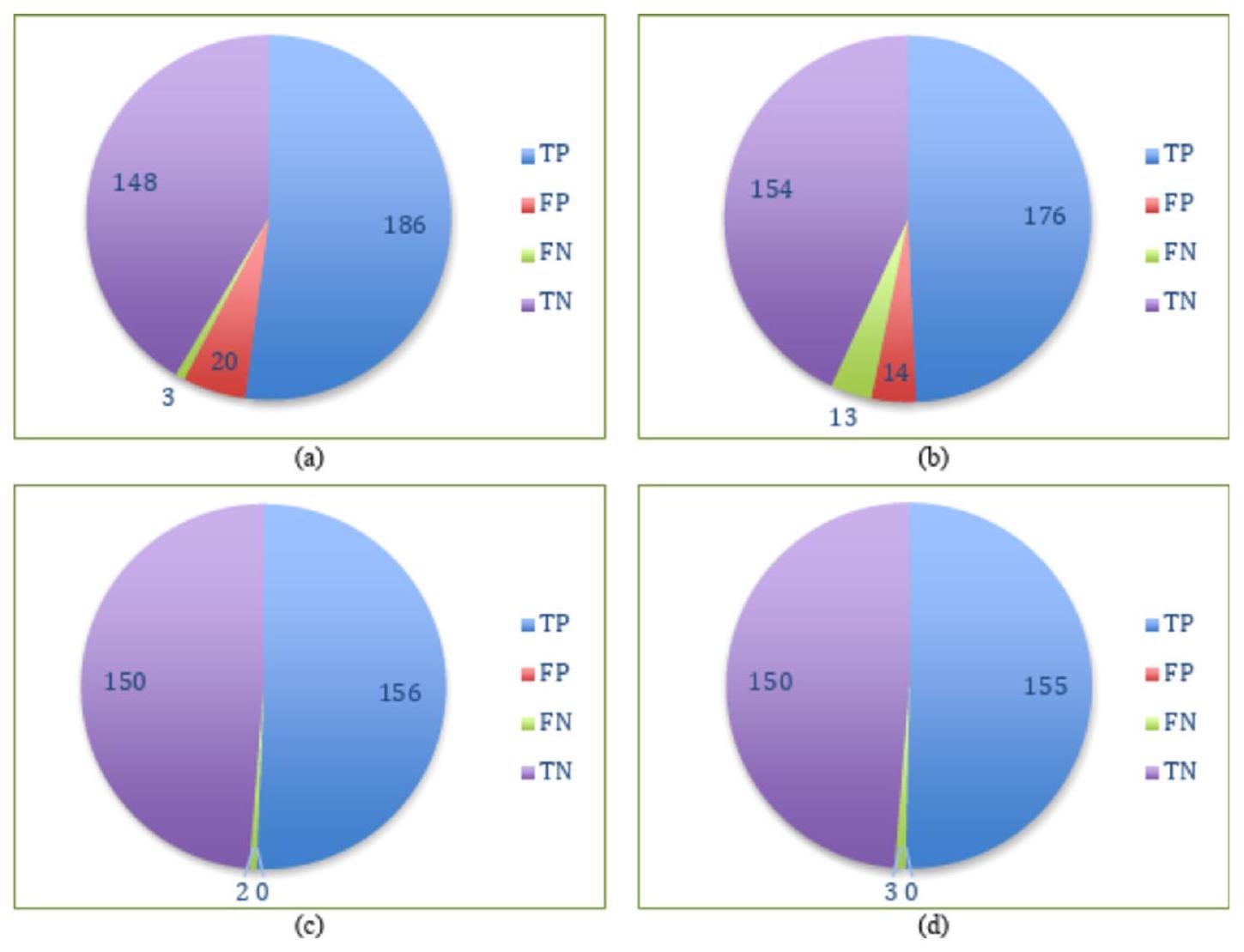

تم تقييم أداء التصنيف للخوارزميات باستخدام مصفوفة الالتباس. يتم عرض مصفوفات الالتباس من تجارب التكديس والتصويت على كلا المجموعتين في الشكل 14. يشير الشكل 14c إلى أن نموذج التكديس المصمم حقق أفضل أداء مع D2. من بين 308 حالات في D2، تم تصنيف جميع الحالات بشكل صحيح، بينما تم تصنيف حالتين بشكل خاطئ. بالمقابل، من بين 357 حالة في D1، كما هو موضح في الشكل 14b، قام نموذج التصويت المصمم بتصنيف 330 حالة بشكل صحيح بينما تم تصنيف 27 حالة بشكل خاطئ.

توضح دقة نماذج التجميع والتصويت لـ D1 و D2 في الشكل 15. يقدم الشكل دقة كل طية من كلا النموذجين المصممين بالإضافة إلى متوسط الـ 10 طيات. أظهر كل من التجميع والتصويت دقة متوسطة قدرها

تم تقديم انحرافات الأداء لنماذج التجميع والتصويت مع كلا المجموعتين عبر عشرة طيات لكل مقياس في الشكل 17. أظهر التجميع مع D1 أكبر قدر من الاتساق لكل مقياس باستثناء الاسترجاع. كان التصويت مع D1 الأكثر عدم اتساق عبر جميع المقاييس باستثناء الاسترجاع، حيث أظهر التجميع مع D1 انحرافًا أكبر.

| الهايبر بارامترز | LR | إي تي | RF | إكس جي بي | سي بي | LGBM |

| نسبة التعبئة | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7 |

| تكرار التعبئة | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| مصفوفة بايزيان للتسجيل | – | – | – | – | 0.1 | – |

| أفضل_نموذج_أدنى_عدد_من_الأشجار | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| تعزيز من المتوسط | – | – | – | – | زائف | – |

| معزز | – | – | – | شجرة جي بي | – | – |

| نوع التعزيز | – | – | – | – | سهل | gbdt |

| بوتستراب | – | خاطئ | صحيح | – | – | – |

| نوع الإقلاع | – | – | – | – | MVS | – |

| عدد الحدود | – | – | – | – | 254 | – |

| ج | 0.431 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ccp_alpha | – | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| أسماء الفئات | – | – | – | – | [0, 1] | – |

| وزن_الفئة | متوازن | – | – | – | – | – |

| عدد الفصول | – | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| نسبة العينة من الشجرة | – | – | – | 0.7 | – | 1 |

| معيار | – | جيني | جيني | – | – | – |

| عمق | – | – | – | – | ٦ | – |

| جهاز | – | – | – | وحدة المعالجة المركزية | – | – |

| ثنائي | زائف | – | – | – | – | – |

| تمكين الفئات | – | – | – | زائف | – | – |

| تقييم الكسر | – | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| مقياس التقييم | – | – | – | – | خسارة اللوغاريتم | – |

| نوع حدود الميزة | – | – | – | – | جمع السجل الجشع | – |

| نسبة الميزة | – | – | – | – | – | 0.5 |

| توافق التقاطع | صحيح | – | – | – | – | – |

| وزن_زوج_الوحدة_القوة_التلقائي | – | – | – | – | زائف | – |

| سياسة النمو | – | – | – | – | شجرة متناظرة | – |

| نوع الأهمية | – | – | – | – | – | انقسام |

| تعديل الاعتراض | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| تكرارات | – | – | – | – | 1000 | – |

| 12_ورقة_تنظيم | – | – | – | – | ٣ | – |

| تقدير_ورقة_التراجع | – | – | – | – | أي تحسين | – |

| عدد_iterations_تقدير_الورقة | – | – | – | – | 10 | – |

| طريقة تقدير الورقة | – | – | – | – | نيوتن | – |

| معدل التعلم | – | – | – | 0.0001 | 0.008938 | 0.0000001 |

| دالة الخسارة | – | – | – | – | خسارة اللوغاريتم | – |

| العمق الأقصى | – | – | – | ٨ | – | -1 |

| عدد الميزات القصوى | – | جذر | جذر | – | – | – |

| max_iter | 1000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| max_leaves | – | – | – | – | 64 | – |

| عدد العينات في الطفل الأدنى | – | – | – | – | – | 91 |

| وزن_الطفل_الأدنى | – | – | – | ٣ | – | 0.001 |

| min_data_in_leaf | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| انخفاض الشوائب الدنيا | – | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| عدد العينات في الورقة | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – |

| عدد العينات المطلوبة للتقسيم | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | – |

| حد الكسب الأدنى | – | – | – | – | – | 0.1 |

| نسبة الوزن الأدنى للورقة | – | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

| وضع تقليص النموذج | – | – | – | – | ثابت | – |

| معدل انكماش النموذج | – | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| حجم_النموذج_تنظيم | – | – | – | – | 0.5 | – |

| متعدد الفئات | سيارة | – | – | – | – | – |

| عدد النماذج | – | 100 | 100 | 10 | – | ٢٠٠ |

| عدد الوظائف | – | -1 | -1 | -1 | – | -1 |

| وضع نان | – | – | – | – | من | – |

| مستمر | ||||||

| الهايبر بارامترز | LR | إي تي | RF | إكس جي بي | СВ | LGBM |

| عدد الأوراق | – | – | – | – | – | ٨ |

| درجة خارجية | – | زائف | زائف | – | – | – |

| معامل العقوبات | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| عقوبة | ل2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| خيارات_معلومات_المسبح | – | – | – | – | {‘tags’: {}} | – |

| العينة اللاحقة | – | – | – | – | زائف | – |

| نوع_score_عشوائي | – | – | – | – | عادي مع تقليل حجم النموذج | – |

| حالة عشوائية | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| قوة عشوائية | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| الرجوع_ألفا | – | – | – | 0.001 | – | 0.000001 |

| اللامدا التنظيمية | – | – | – | 0.0005 | – | 0.0005 |

| رسم | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| تردد العينة | – | – | – | – | بير تري | – |

| وزن_مقياس_الإيجابية | – | – | – | 8.5 | – | – |

| دالة النتيجة | – | – | – | – | جيب التمام | – |

| حل | لبفغس | – | – | – | – | – |

| نسبة صراع الميزات النادرة | – | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| عينة فرعية | – | – | – | 1 | 0.8 | 1 |

| تحت عينة من أجل الصندوق | – | – | – | – | – | ٢٠٠,٠٠٠ |

| تردد العينة الفرعية | – | – | – | – | – | 0 |

| نوع المهمة | – | – | – | – | وحدة المعالجة المركزية | – |

| تول | 0.0001 | – | – | – | – | – |

| طريقة الشجرة | – | – | – | سيارة | – | – |

| استخدام أفضل نموذج | – | – | – | – | خاطئ | – |

| مُطوَّل | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| بدء دافئ | زائف | زائف | زائف | – | – | – |

الجدول 5. المعلمات الفائقة للنماذج المتسلسلة المستخدمة في التكديس والتصويت.

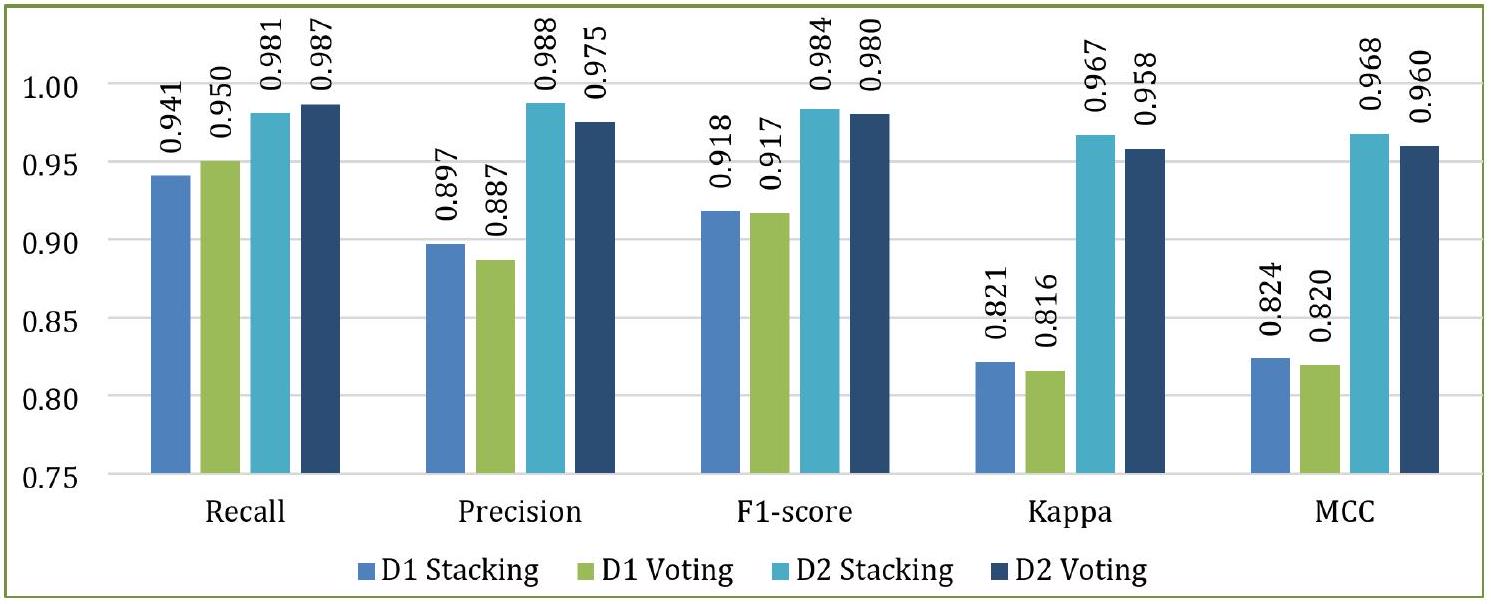

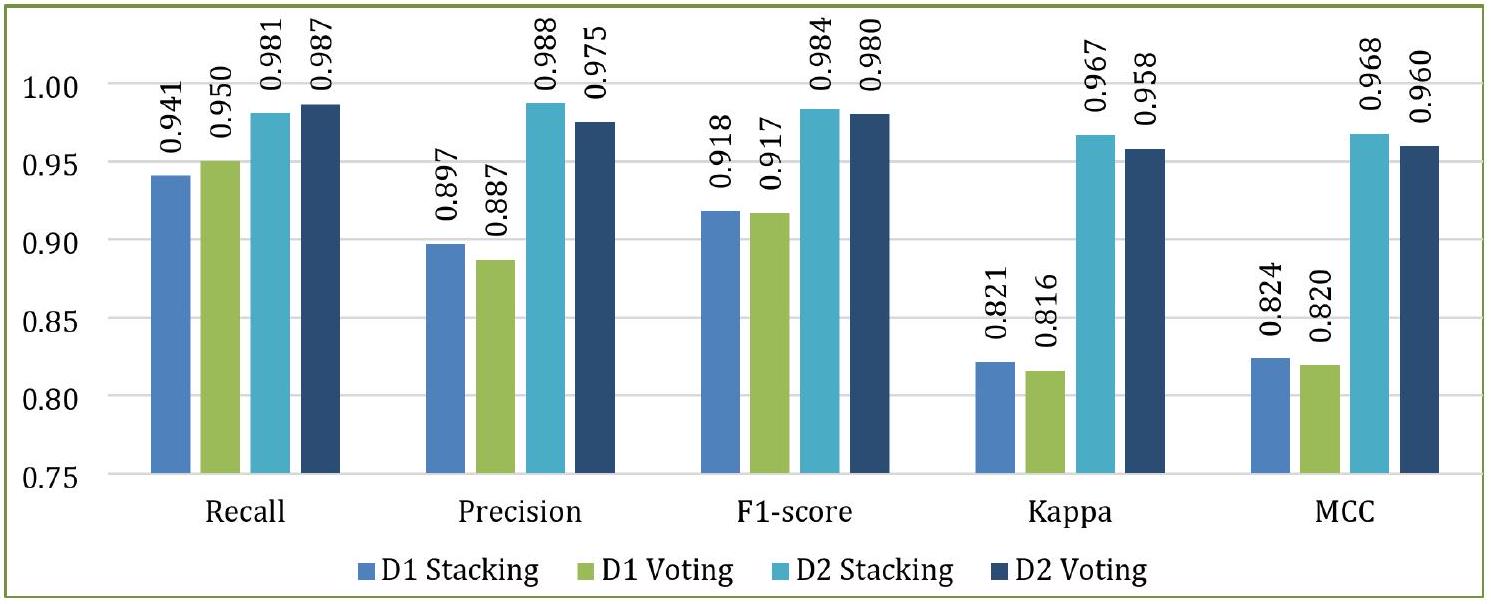

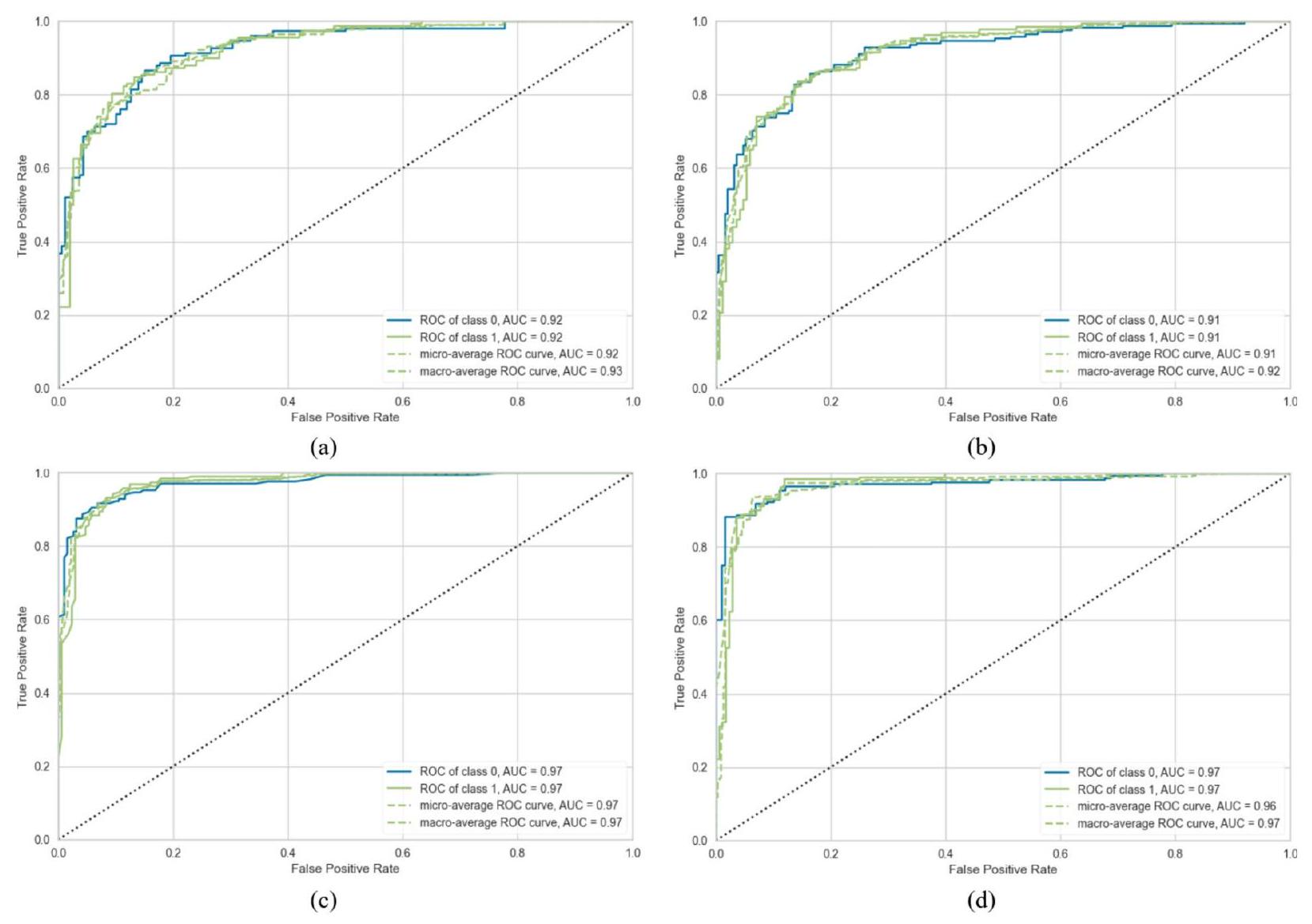

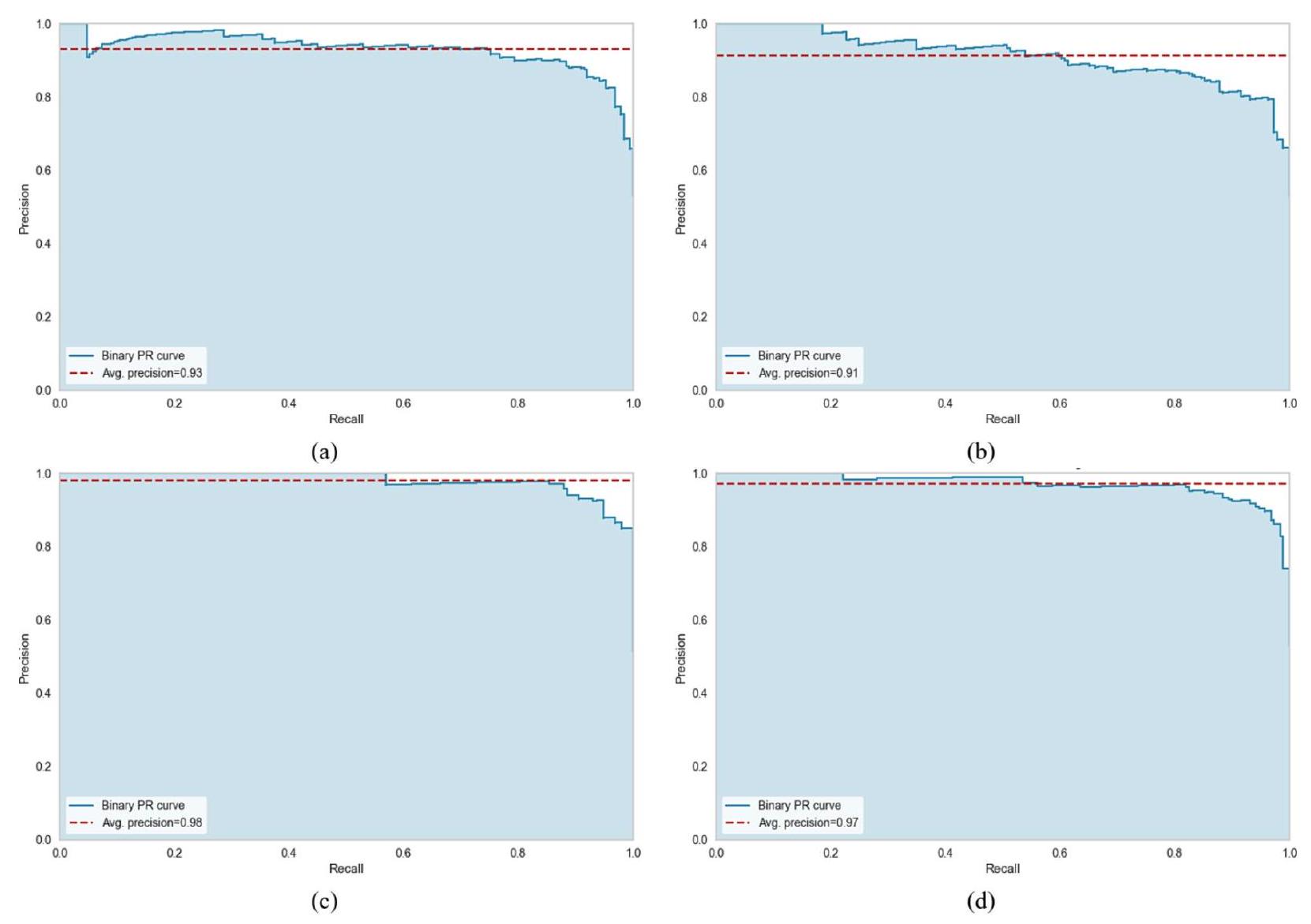

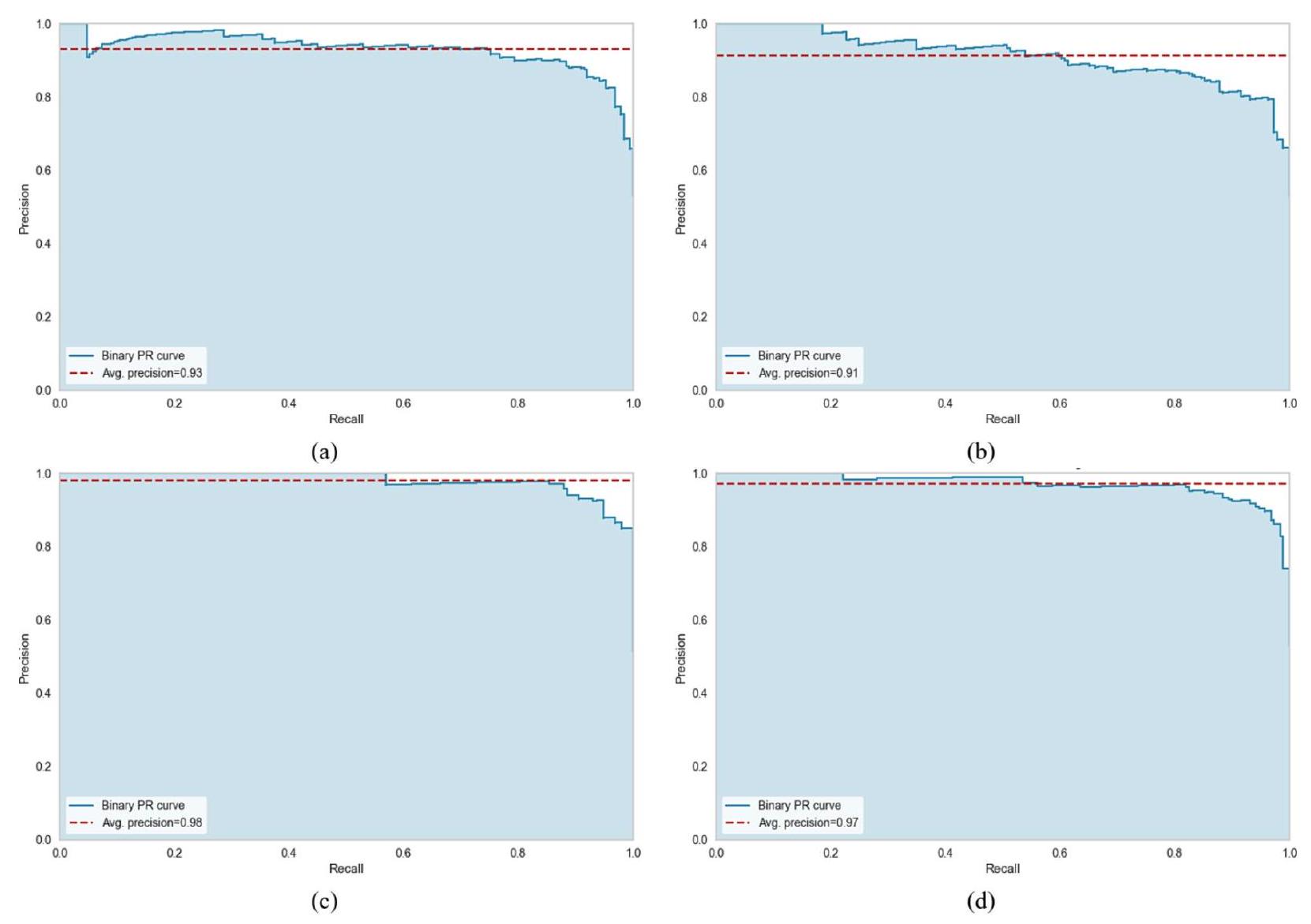

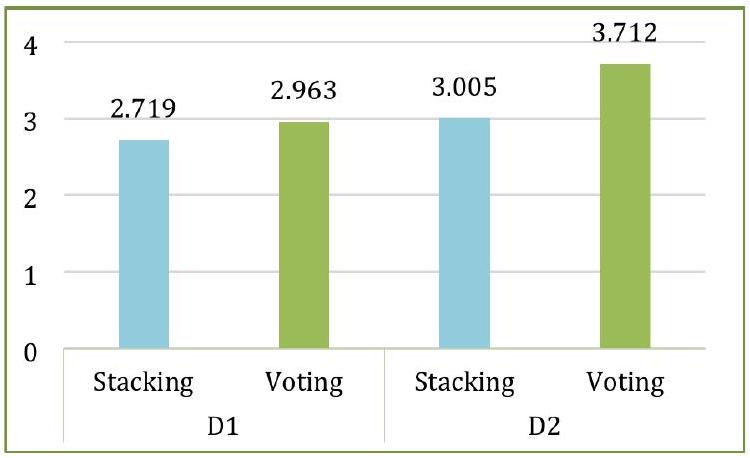

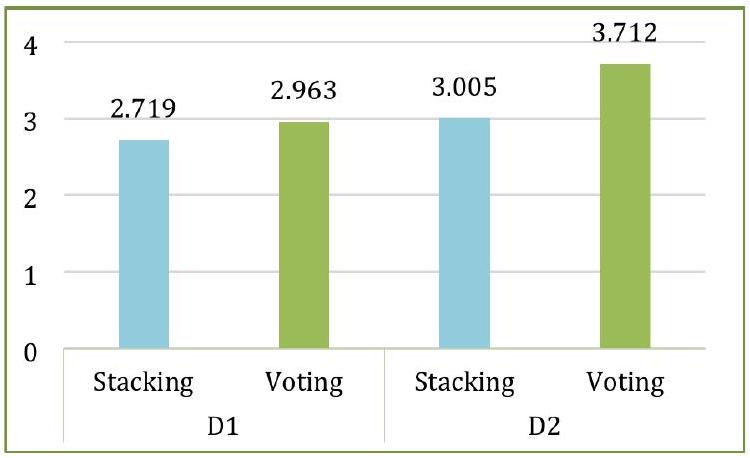

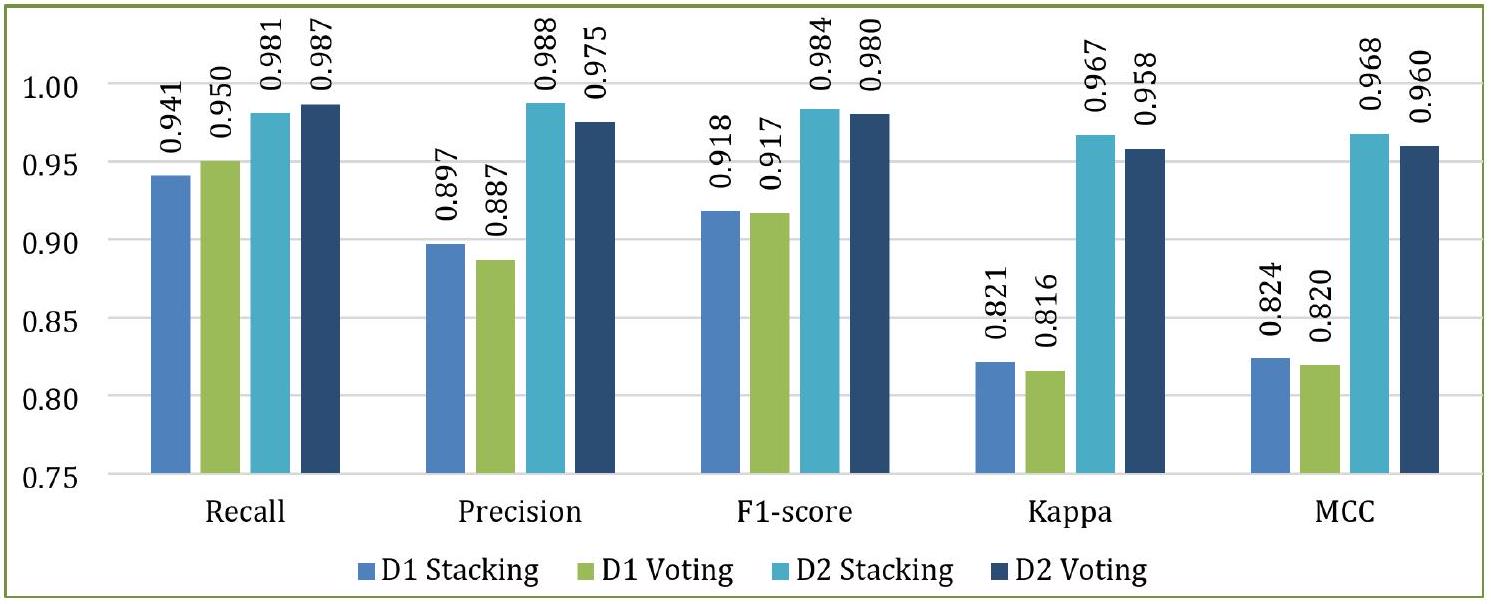

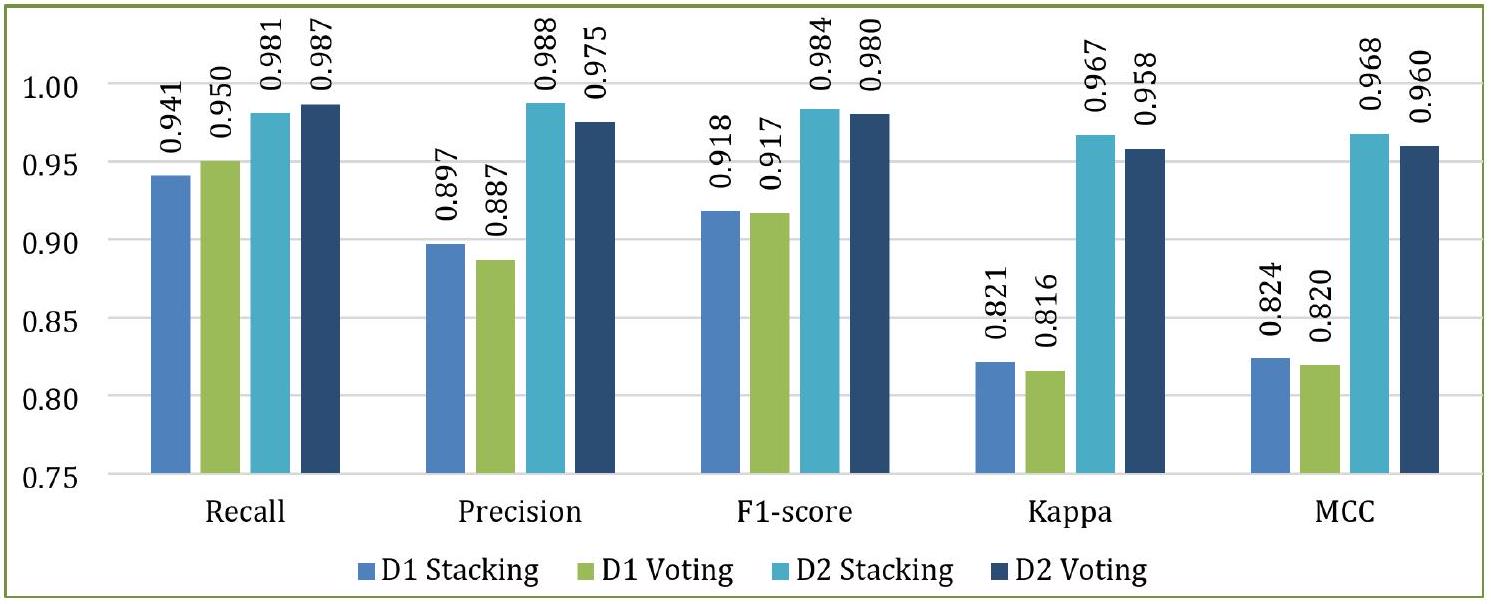

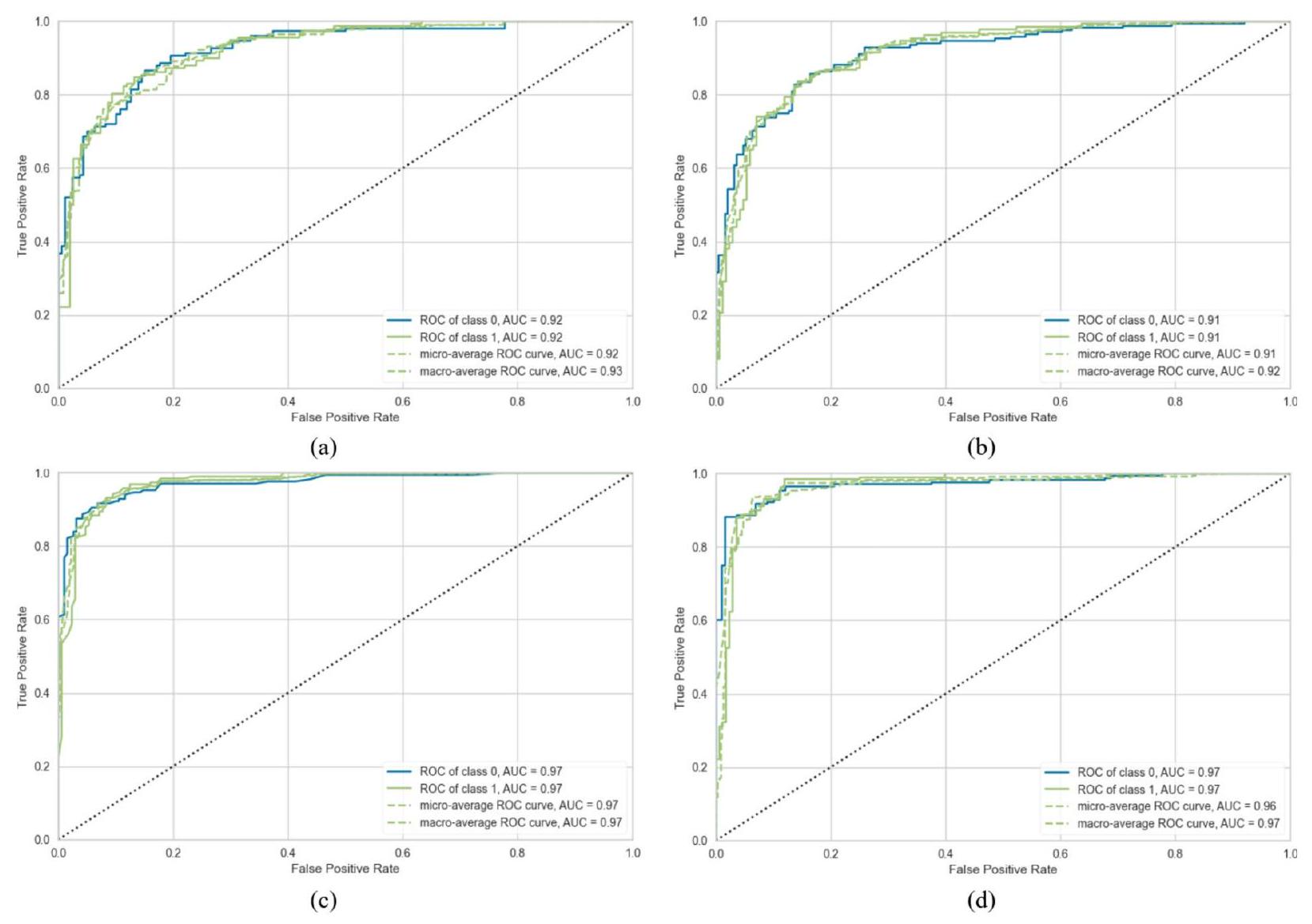

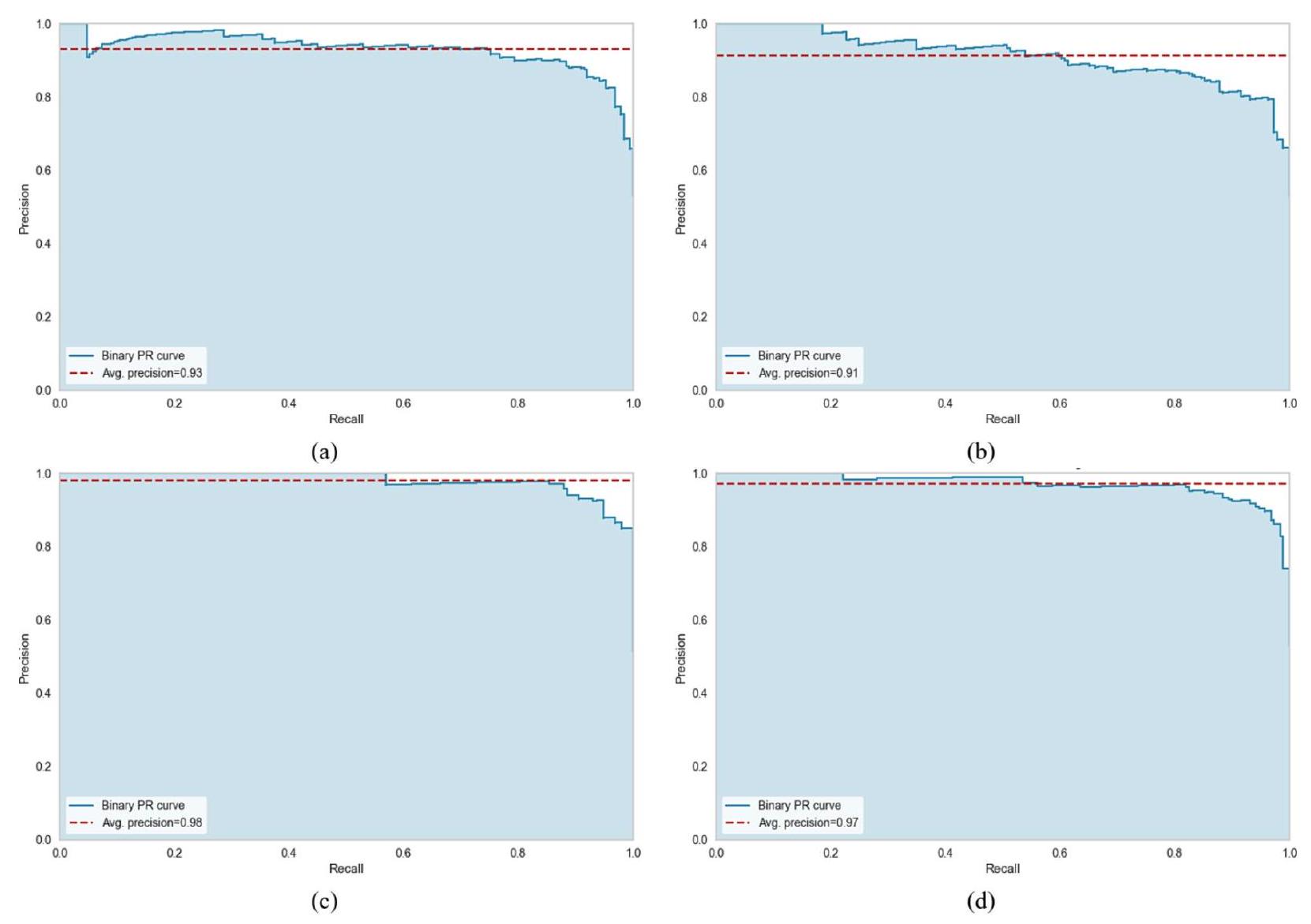

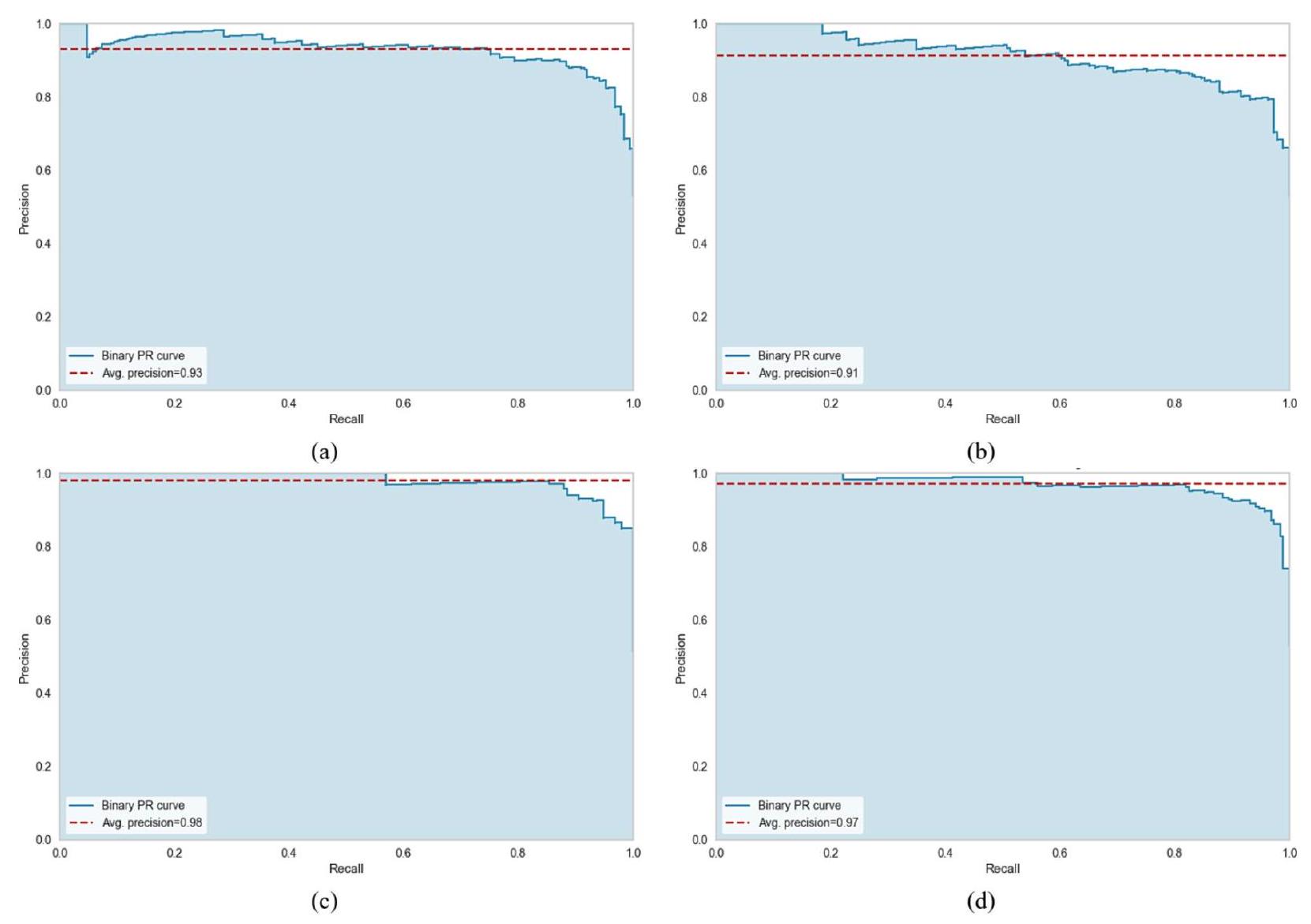

وفقًا لدرجات ROC-AUC، كما هو موضح في الشكل 18، كانت أداء التكديس والتصويت متشابهًا (0.97 لكلا الفئتين) بالنسبة لـ D2، بينما بالنسبة لـ D1، كان التكديس (0.92 لكلا الفئتين) متقدمًا قليلاً على التصويت (0.91 لكلا الفئتين). على العكس من ذلك، هناك تباين كبير في أداء التكديس والتصويت فيما يتعلق بـ AUPRC. كما هو موضح في الشكل 19، تم تحقيق أفضل AUPRC بواسطة التكديس مع D2 (0.98)، بينما أدى التصويت مع D2 إلى أدنى AUPRC (0.91). الشكل 20 أشار إلى أن MCR للتكديس مع D2 كان الأدنى عند 1.67، بينما كان التصويت مع D1 لديه أعلى MCR وهو 9.12.

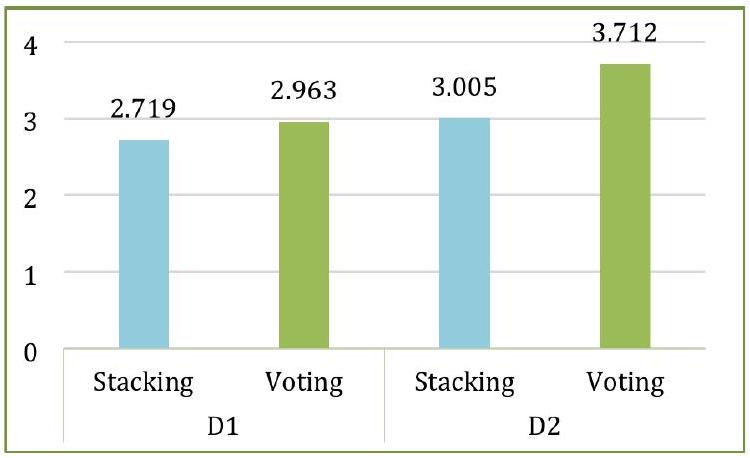

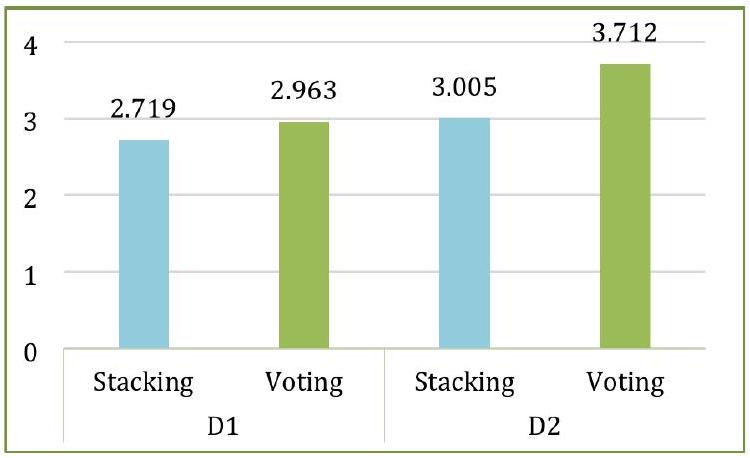

قمنا أيضًا بتسجيل وقت التشغيل لأربعة تركيبات من النماذج ومجموعات البيانات. كما هو موضح في الشكل 21، كانت عملية التجميع أسرع قليلاً من التصويت، وكما هو متوقع، كانت النماذج تحتاج إلى وقت أقل مع D1 مقارنة بـ D2 بسبب أن D1 أصغر حجمًا من D2.

التحليل والمناقشة

تحلل هذه القسم بدقة وتناقش الأداء التنبؤي لنماذج التجميع والتصويت المقترحة من زوايا مختلفة، مقارنتها بالنماذج الأساسية الفردية والأبحاث التجريبية التي استخدمت التجميع أو التصويت في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب.

نماذج التجميع والتصويت مقارنة بالنماذج الأساسية

تمت مقارنة أداء نماذج التجميع والتصويت المصممة مع أداء النماذج المكونة التي تم النظر فيها. كانت المقارنة مبنية على الدقة، والدقة الإيجابية، والاسترجاع، ودرجة F1، ومقاييس ROC لكلا مجموعتي البيانات. تم مقارنة أفضل الأداءات بين 15 نموذجًا لكل مقياس مع تلك الخاصة بنماذج التجميع والتصويت، كما هو موضح في الشكل 22. على سبيل المثال، كما تم مناقشته في القسم 5.2، أظهر نموذج ET أفضل دقة عبر كلا مجموعتي البيانات. يوضح الشكل 22a أن كلا من نماذج التجميع والتصويت تحقق دقة أعلى من ET. وبالمثل، أظهر نموذج CB أفضل استرجاع بين النماذج الـ 15. كما هو موضح في الشكل 22c، حققت نماذج التجميع والتصويت استرجاعًا أعلى من CB. لذلك، تتفوق نماذج التجميع والتصويت المقترحة على جميع النماذج المكونة ذات الأداء الأفضل عبر كلا مجموعتي البيانات، باستثناء الدقة على D1، حيث يتفوق نموذج SGD على نماذج التجميع والتصويت.

التحليل الإحصائي لنماذج التجميع والتصويت

لتقييم الأهمية الإحصائية للاختلافات في الأداء بين النماذج، قمنا بإجراء اختبار فريدمان المرتب غير المعلمي.

الشكل 14. مصفوفات الالتباس لـ (أ) التكديس مع D1، (ب) التصويت مع D1، (ج) التكديس مع D2 و (د) التصويت مع D2.

الشكل 15. دقة التجميع والتصويت بعشرة أضعاف على كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

تم استخدام اختبار الرتب المتوافقة مع فريدمان لمقارنة النماذج بشكل شامل عبر مجموعات البيانات والمعايير مع الأخذ في الاعتبار تباين مجموعة البيانات.

الشكل 16. مقاييس أداء أخرى للتكديس والتصويت على كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

الشكل 17. الانحراف المعياري للطيّات لمقاييس مختلفة للتكديس والتصويت مع كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

0.2059 ، وهو فوق عتبة الدلالة (

تحليل ما بعد الحدث. المقارنات بعد الحدث باستخدام طريقة هولم.

تفسير نماذج التكديس والتصويت باستخدام SHAP

تهدف XAI إلى تعزيز الشفافية وقابلية التفسير لنماذج التعلم الآلي، مما يسمح للمستخدمين بفهم الأسباب وراء التنبؤات. هذا أمر بالغ الأهمية بشكل خاص في المجالات الحساسة مثل الرعاية الصحية، حيث الثقة والمساءلة أمران أساسيان.

في سياق توقع أمراض القلب، يثبت SHAP أنه لا يقدر بثمن. إنه يساعد الأطباء والباحثين في تحديد السمات التي تلعب الأدوار الأكثر أهمية في تشخيص أمراض القلب. من خلال توضيح الأهمية النسبية لهذه الميزات، لا يعزز SHAP فقط قابلية تفسير النماذج، بل يعزز أيضًا الثقة في تطبيقها السريري، مما يضمن أن التوقعات دقيقة وقابلة للتنفيذ.

الشكل 18. ROC-AUC لـ (أ) التكديس مع D1، (ب) التصويت مع D1، (ج) التكديس مع D2 و (د) التصويت مع D2.

تفسير عالمي

تساعد التفسيرات العالمية في فهم كيفية أداء نموذج الذكاء الاصطناعي عبر مجموعة بيانات كاملة من خلال الكشف عن الاتجاهات العامة والعلاقات بين المتغيرات (مثل العمر، العلامات الجينية، نتائج المختبر) ونتائج النموذج. تحدد هذه التفسيرات الخصائص الأكثر تأثيرًا على التنبؤات، مما يمكّن من التحقق من صحة هذه التنبؤات مقابل المعرفة المتخصصة في المجال، مثل الإرشادات الطبية. يساعد ذلك في التحقق من أداء النموذج وتحديد المجالات التي تتطلب تحسينًا.

علاوة على ذلك، فإن التفسيرات العالمية ضرورية في اكتشاف التحيزات، وتعزيز العدالة عبر مجموعات سكانية متنوعة، وضمان الامتثال للمعايير الأخلاقية والتنظيمية مثل اللائحة العامة لحماية البيانات (GDPR) ومتطلبات قانون نقل التأمين الصحي والمساءلة (HIPAA) وإدارة الغذاء والدواء (FDA). مثل هذه الشفافية تبني الثقة في أنظمة الرعاية الصحية.

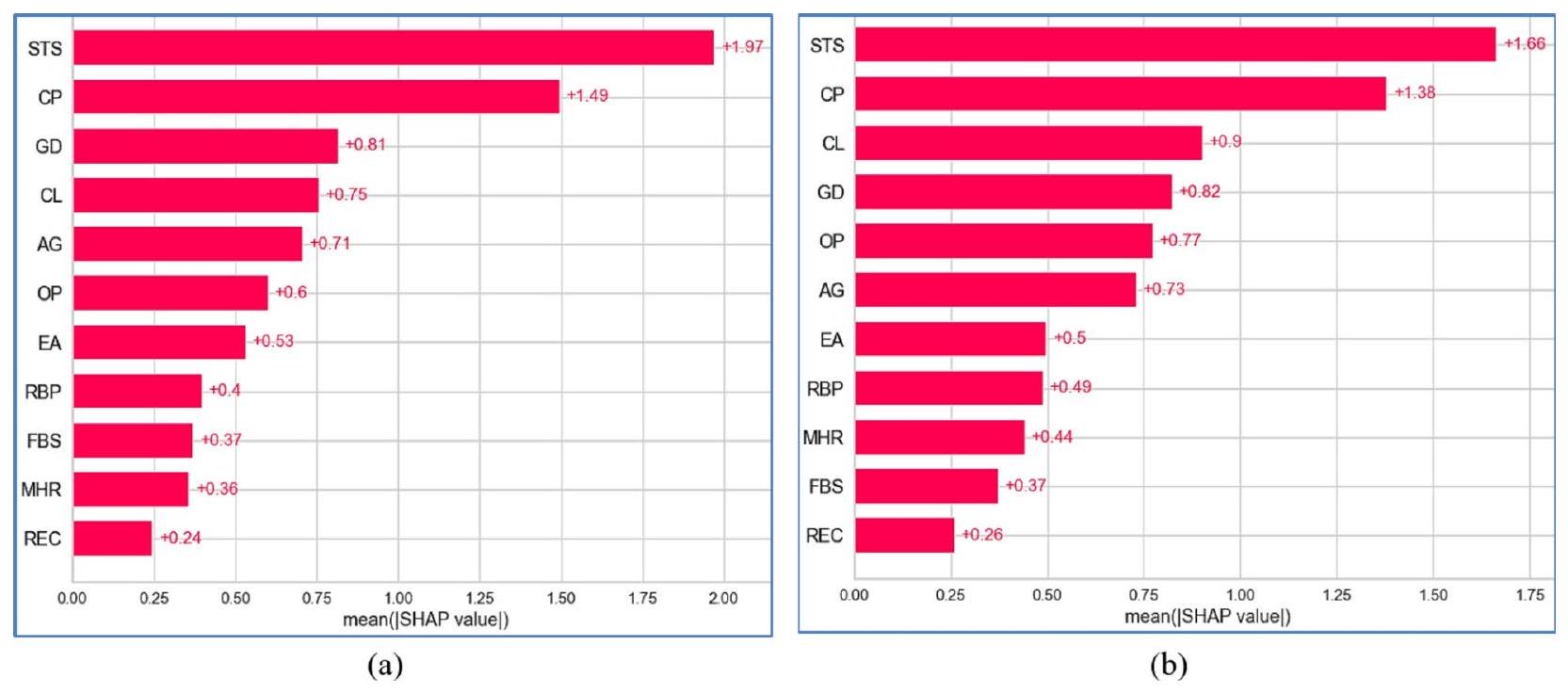

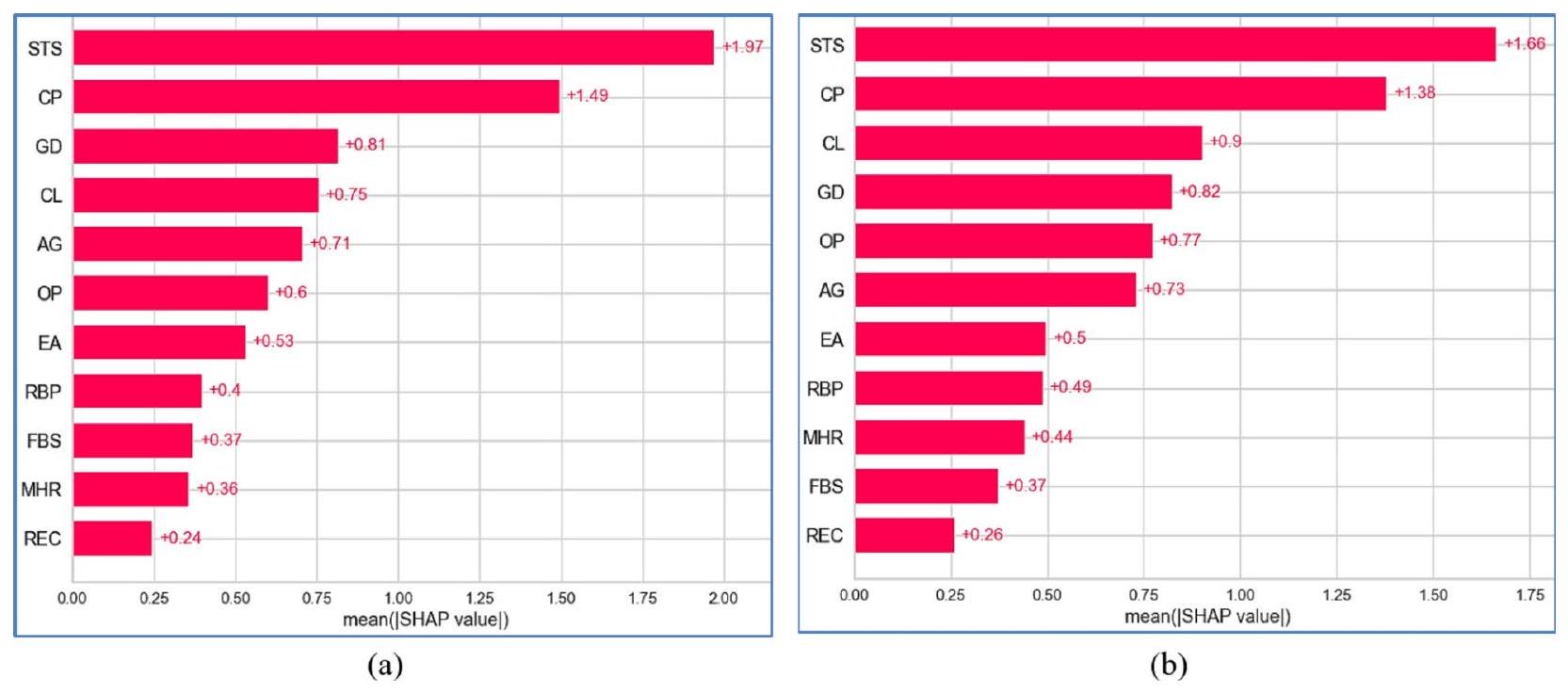

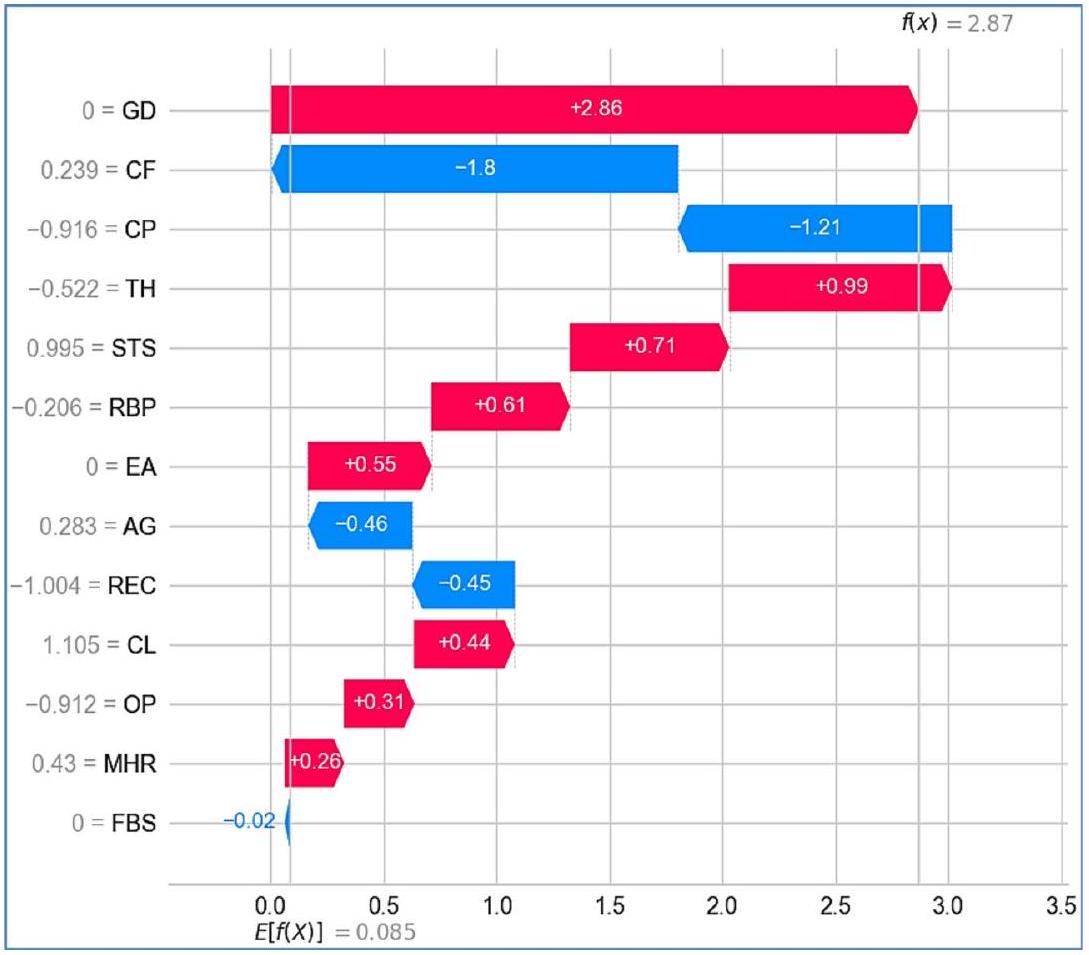

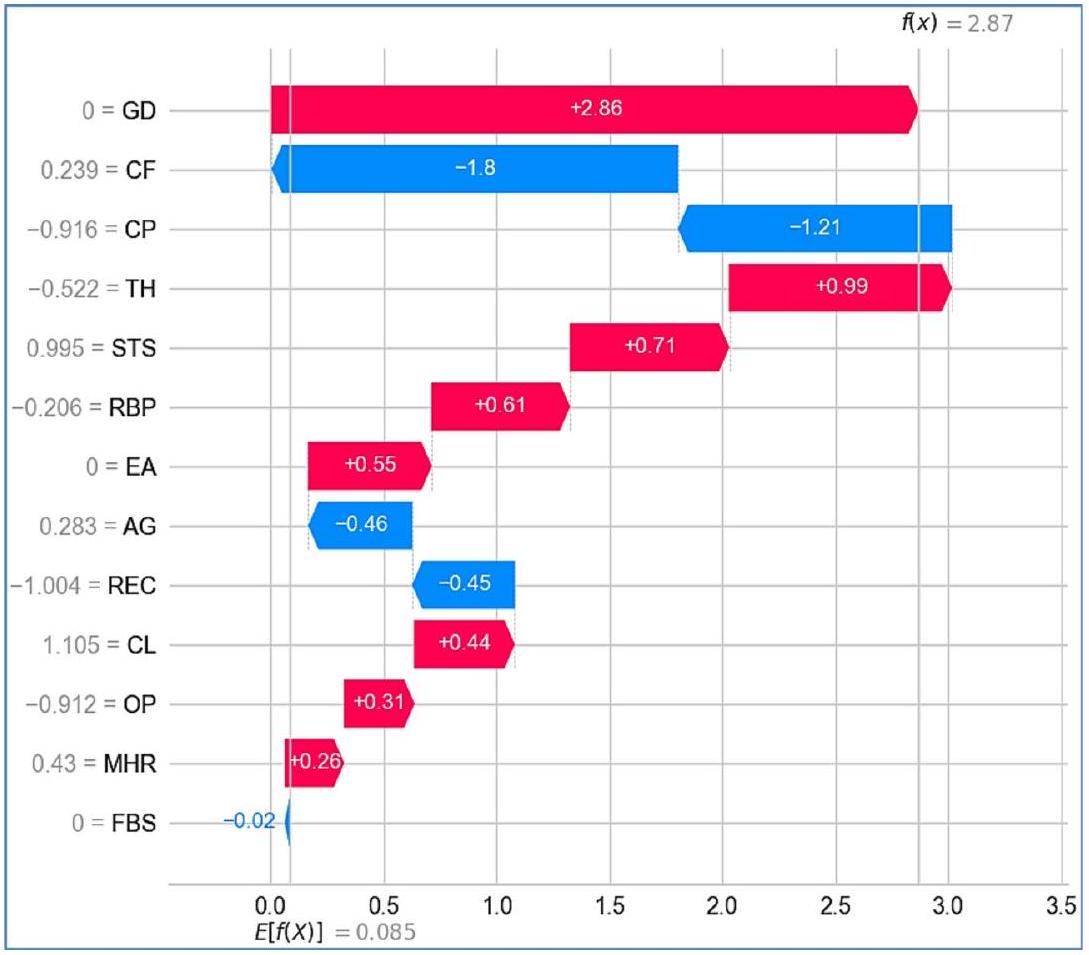

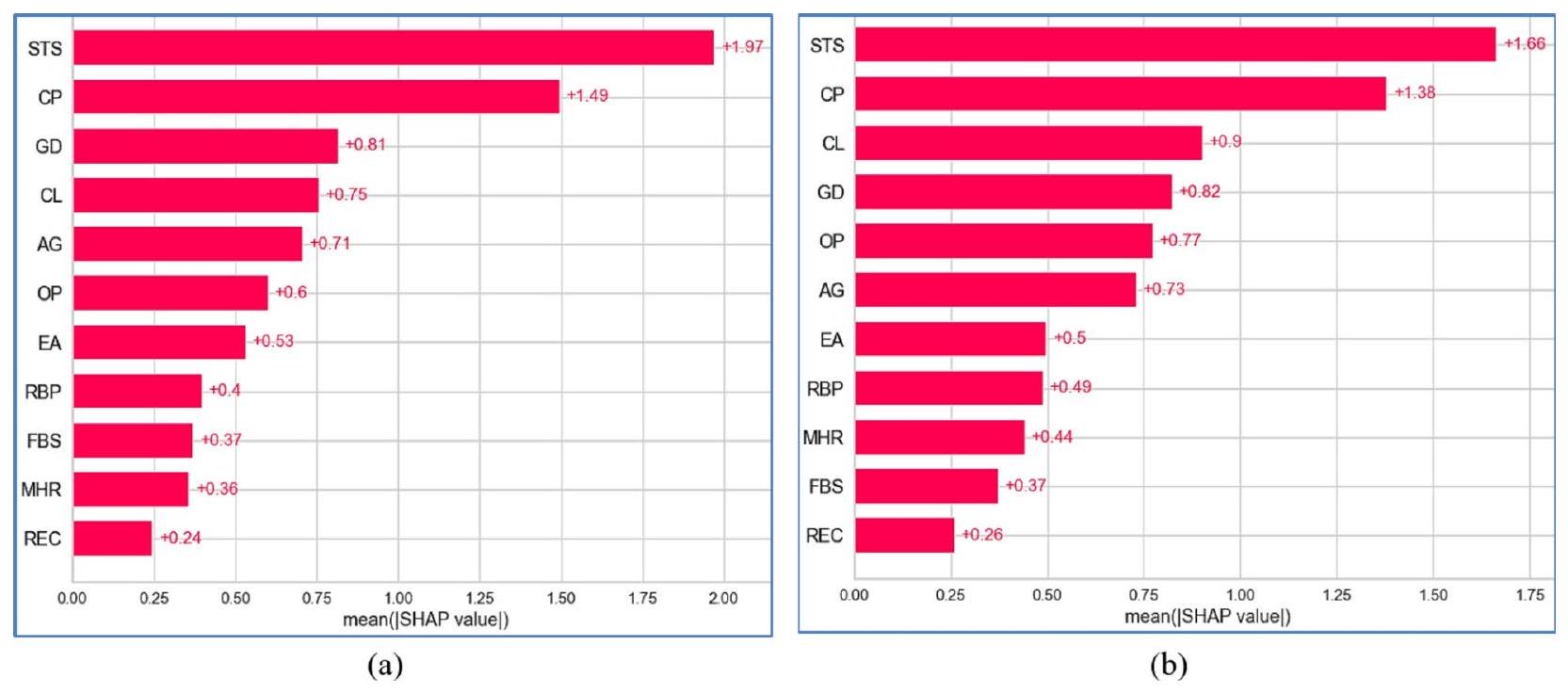

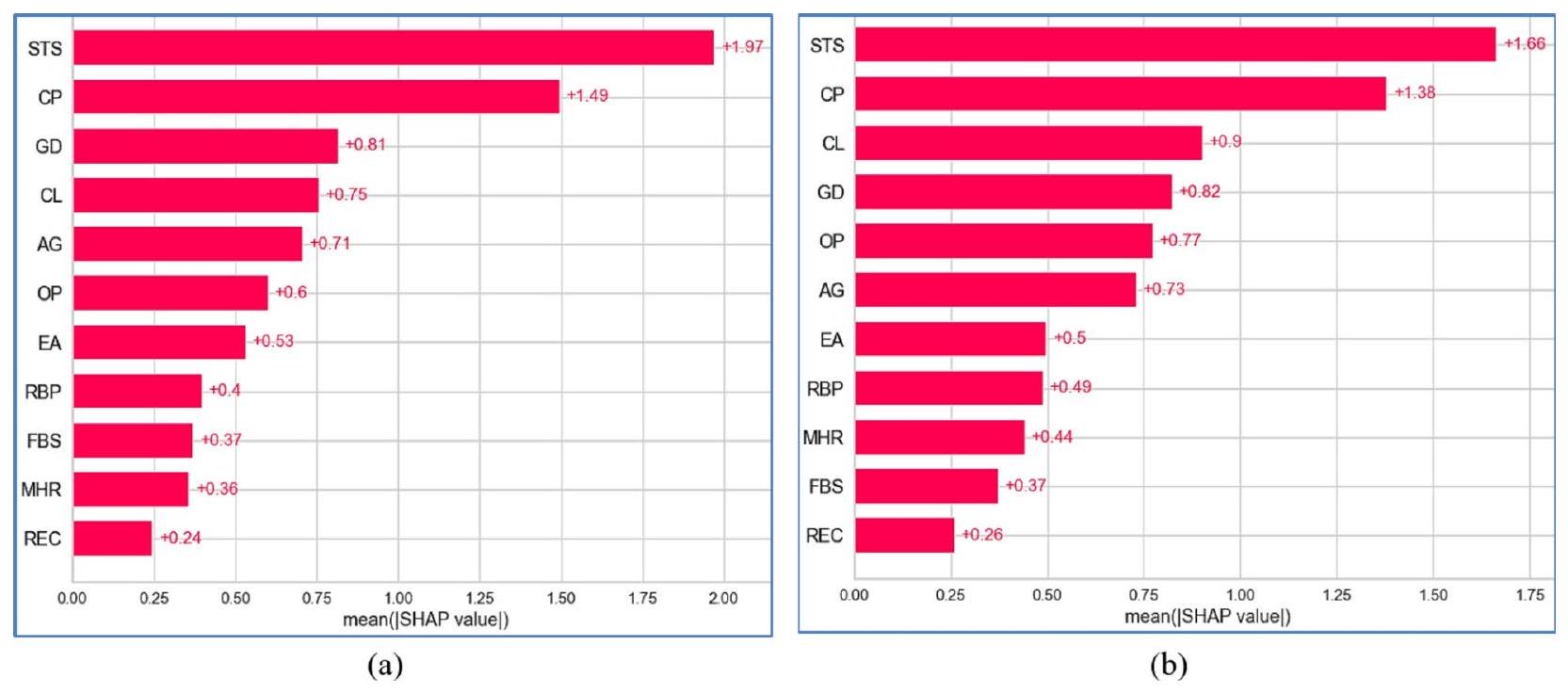

في تحليلنا، استخدمنا قيم أهمية ميزات SHAP المطلقة المتوسطة لترتيب الميزات وفقًا لتأثيرها العام على التنبؤات، بغض النظر عما إذا كان تأثيرها إيجابيًا أو سلبيًا. يتم توضيح التحليلات العالمية لنماذج التجميع والتصويت عبر D1 و D2 في الأشكال 23 و 24، على التوالي. يتم تنظيم الميزات حسب الأهمية على المحور الرأسي، مع عرض قيم SHAP المتوسطة على المحور الأفقي لرؤية غير متحيزة لأهميتها النسبية.

في نموذج التكديس المطبق على D1، يظهر ميل ذروة شريحة ST أثناء التمرين (STS) كأهم ميزة، مما يعكس ارتباطه القوي بأمراض القلب. وبالمثل، يعد نوع ألم الصدر (CP) عاملاً حاسماً، متماشياً مع أهميته التشخيصية المعروفة. تشمل الميزات المؤثرة الأخرى الكوليسترول في الدم (CL) والجنس (GD)، اللذان يساهمان بشكل معتدل في قوة النموذج التنبؤية. بالمقابل، تظهر ميزات مثل سكر الدم الصائم (FBS) ونتائج تخطيط القلب الكهربائي أثناء الراحة (REC) وأقصى معدل ضربات قلب تم تحقيقه (MHR) تأثيراً محدوداً، ربما بسبب الروابط الأضعف مع أمراض القلب في هذه المجموعة من البيانات.

بالنسبة لـ D2، يبرز نموذج التكديس عدد الأوعية الرئيسية الملونة بواسطة الفلوروسكوبي (CF) كمتنبئ رئيسي، مما يشير إلى أهميته في تمييز أمراض القلب ضمن هذه الفئة السكانية. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن CP يحتفظ بقيمة SHAP عالية، مما يبرز أهميته الشائعة عبر مجموعات البيانات. كما تكتسب ميزات مثل معدل ضربات القلب بالثاليوم (TH) وoldpeak (OP) أهمية في D2، مما يعكس زيادة أهميتها في التركيبة السكانية للمرضى في هذه المجموعة. تشير هذه الاختلافات إلى تأثير الخصائص المحددة لمجموعة البيانات على سلوك النموذج.

يقدم نموذج التصويت تأثيرًا أكثر توزيعًا للميزات، مع تباينات أكثر سلاسة في قيم SHAP. في D1، تظل STS و CP من أهم المتنبئين، لكن هيمنتهما تتقلص قليلاً مقارنةً بنموذج التكديس. تحافظ ميزات مثل CL والجنس على أهمية معتدلة، مما يعكس اتجاهًا ثابتًا. في الوقت نفسه، تظهر الخصائص ذات التأثير المنخفض مثل ضغط الدم أثناء الراحة (RBP) والذبحة الصدرية الناتجة عن التمارين (EA) مساهمة ضئيلة.

الشكل 19. AUPRC لـ (أ) التكديس مع D1، (ب) التصويت مع D1، (ج) التكديس مع D2 و (د) التصويت مع D2.

الشكل 20. MCR للتكديس والتصويت مع كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

في D2، يبرز نموذج التصويت مرة أخرى CP و CF كمتنبئين رئيسيين. ومع ذلك، فإن تأثير TH و GD أقل وضوحًا قليلاً مقارنةً بنموذج التكديس، مما يشير إلى اعتماد أكثر توازنًا على الميزات. قد تجعل التوزيع المتساوي لأهمية الميزات في نموذج التصويت أكثر قوة في مجموعات البيانات المتنوعة.

بشكل عام، يظهر CP باستمرار كأحد أفضل المؤشرات عبر جميع النماذج ومجموعات البيانات، مما يبرز قيمته التشخيصية العالمية. يؤكد D2 على أهمية CF وTH، اللذان يكونان أقل بروزًا في D1. يبدو أن نموذج التكديس أكثر ملاءمة لمجموعات البيانات ذات الميزات المميزة والواضحة، بينما يعد نموذج التصويت مفيدًا لمجموعات البيانات التي تتطلب تمثيلًا أوسع للميزات. تسلط هذه النتائج الضوء على الحاجة إلى تخصيص اختيار النموذج وتركيز الميزات وفقًا لخصائص مجموعة البيانات لتحقيق دقة تنبؤ مثلى.

تفسير محلي

تفسير محلي يركز على فهم الأسباب وراء توقع محدد قدمه نموذج الذكاء الاصطناعي لحالة فردية، مثل تشخيص مريض معين. هذه الطريقة ذات قيمة خاصة في الرعاية الصحية، حيث أن العلاج المخصص أمر حاسم. تفسيرات محلية تسلط الضوء على العوامل الفريدة، مثل

الشكل 21. وقت التنفيذ (بالثواني) للتكديس والتصويت على كلا المجموعتين البيانيّتين.

الشكل 22. مقارنة نماذج التكديس والتصويت مع نماذج الأداء الأعلى من حيث (أ) الدقة، (ب) الدقة الإيجابية، (ج) الاسترجاع، (د) درجة F1، و(هـ) ROC مع كلا المجموعتين البيانيات.

| مقياس | مجموعة بيانات | نموذج | إحصائية |

|

رتبة | تم قبول H0 |

| دقة | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | ٣.٥ | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | ٣.٥ | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| دقة | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | ٣.٥ | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | ٣.٥ | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| استدعاء | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | ٣.٥ | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | 3.5 | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| درجة F1 | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | ٣.٥ | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | 3.5 | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| كابا | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | ٣.٥ | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | ٣.٥ | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| MCC | D1 | تكديس | 1.6 | 0.2059 | 3.5 | نعم |

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم | ||||

| D2 | تكديس | ٣.٥ | نعم | |||

| التصويت | 1.5 | نعم |

الجدول 6. اختبار رينك المتراصة فريدمان لنماذج التجميع والتصويت.

| المقياس | نتائج الاختبار | D1 | D2 |

| الدقة | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم | |

| الدقة | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم | |

| الاسترجاع | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم | |

| درجة F1 | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم | |

| كابا | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم | |

| MCC | الإحصائية | 1.5492 | 1.5492 |

| قيمة p المعدلة | 0.1213 | 0.1213 | |

| تم قبول H0 | نعم | نعم |

الجدول 7. اختبار ما بعد hoc للتجميع مقابل التصويت لكلا مجموعتي البيانات.

المؤشرات الحيوية أو التاريخ الطبي، التي أثرت على قرار النموذج لمريض معين، مما يساعد في إنشاء استراتيجيات علاج مخصصة. من خلال تقديم هذه الرؤية الخاصة بالحالة، تعزز هذه التفسيرات أيضًا الثقة في القرارات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، خاصة في السيناريوهات الطبية الحرجة.

تساعد التفسيرات المحلية أيضًا في تحديد الأخطاء من خلال الكشف عن الميزات التي ساهمت في النتائج غير الصحيحة، مما يمكّن من تحسين النموذج وزيادة موثوقيته. كما أنها تسمح للمهنيين الطبيين بتقييم ما إذا كانت توقعات النموذج تتماشى مع الأبحاث الطبية المعتمدة، مما يعزز الشفافية في تشخيصات الذكاء الاصطناعي.

الشكل 23. متوسط SHAP المطلق لـ (أ) التجميع و (ب) التصويت على D1.

الشكل 24. متوسط SHAP المطلق لـ (أ) التجميع و (ب) التصويت على D2.

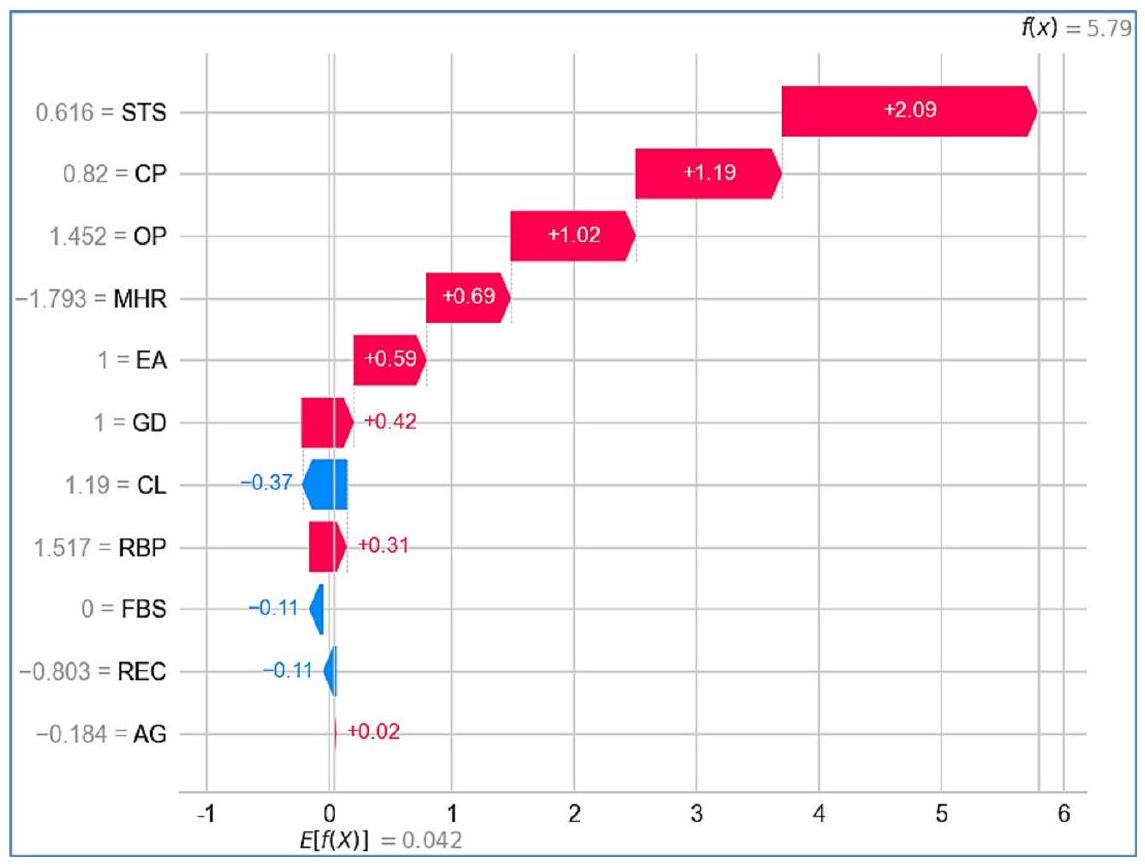

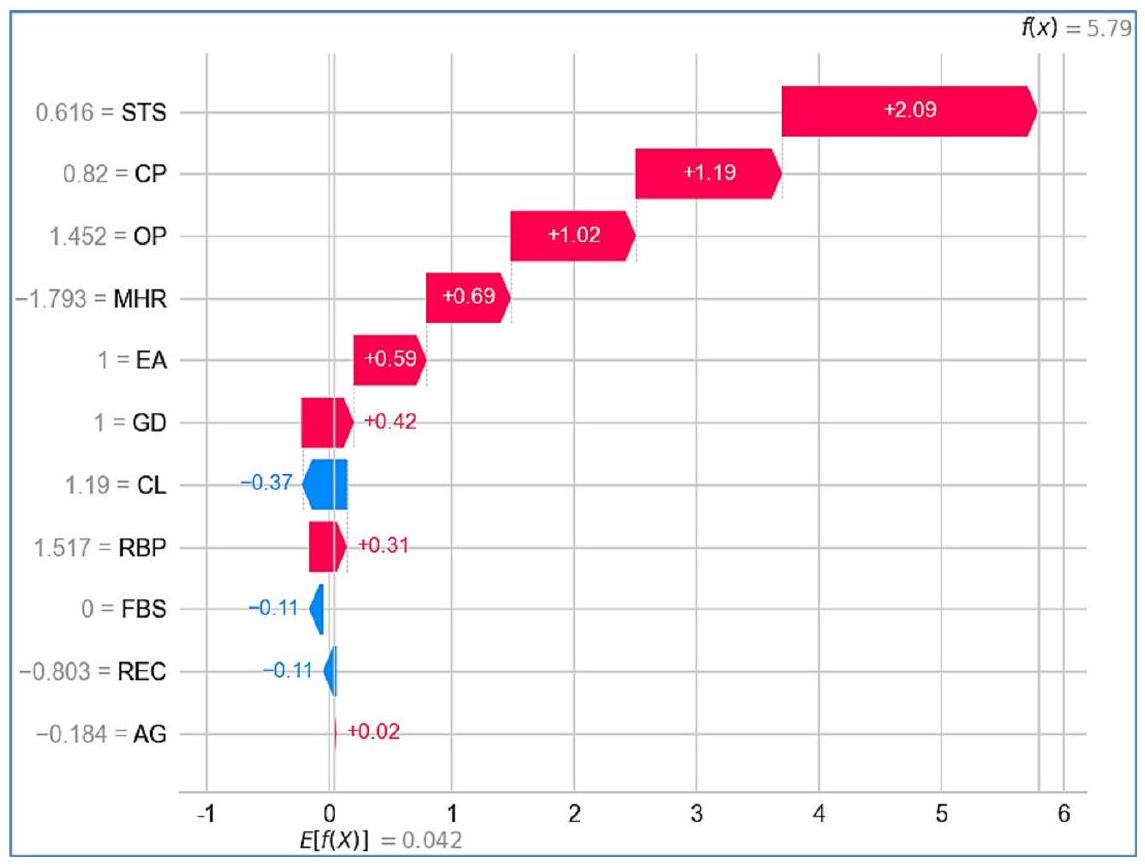

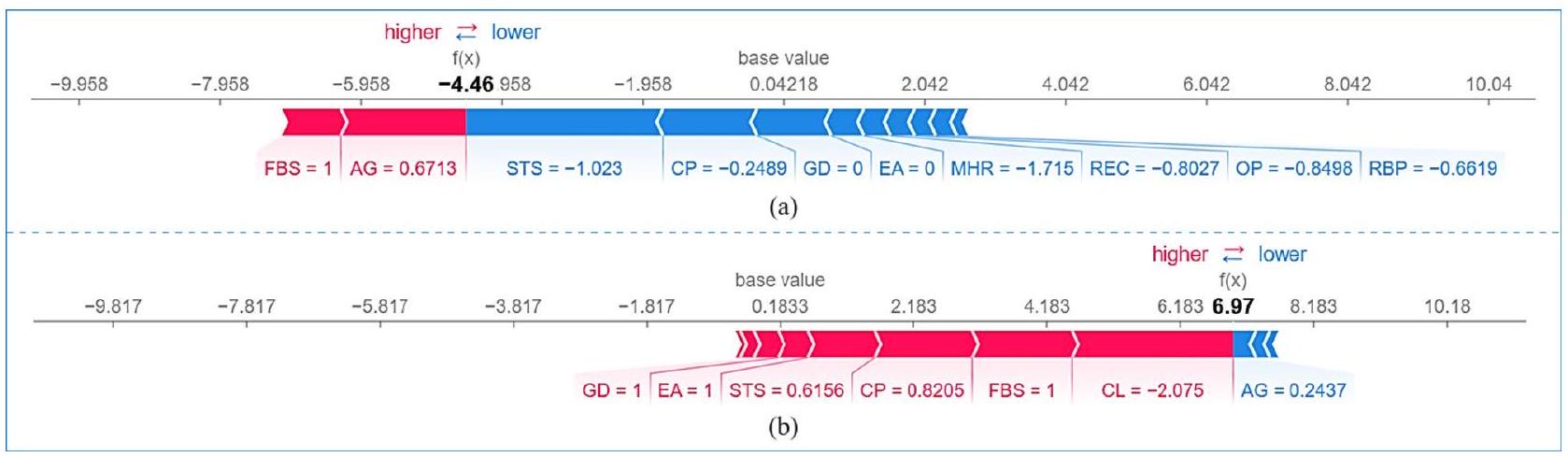

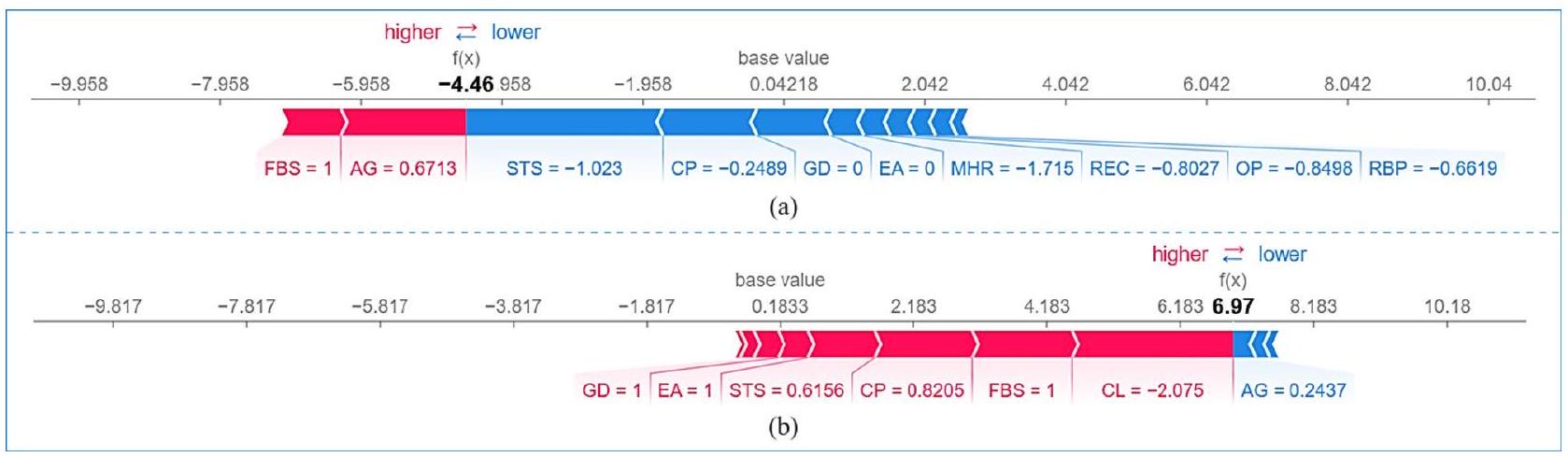

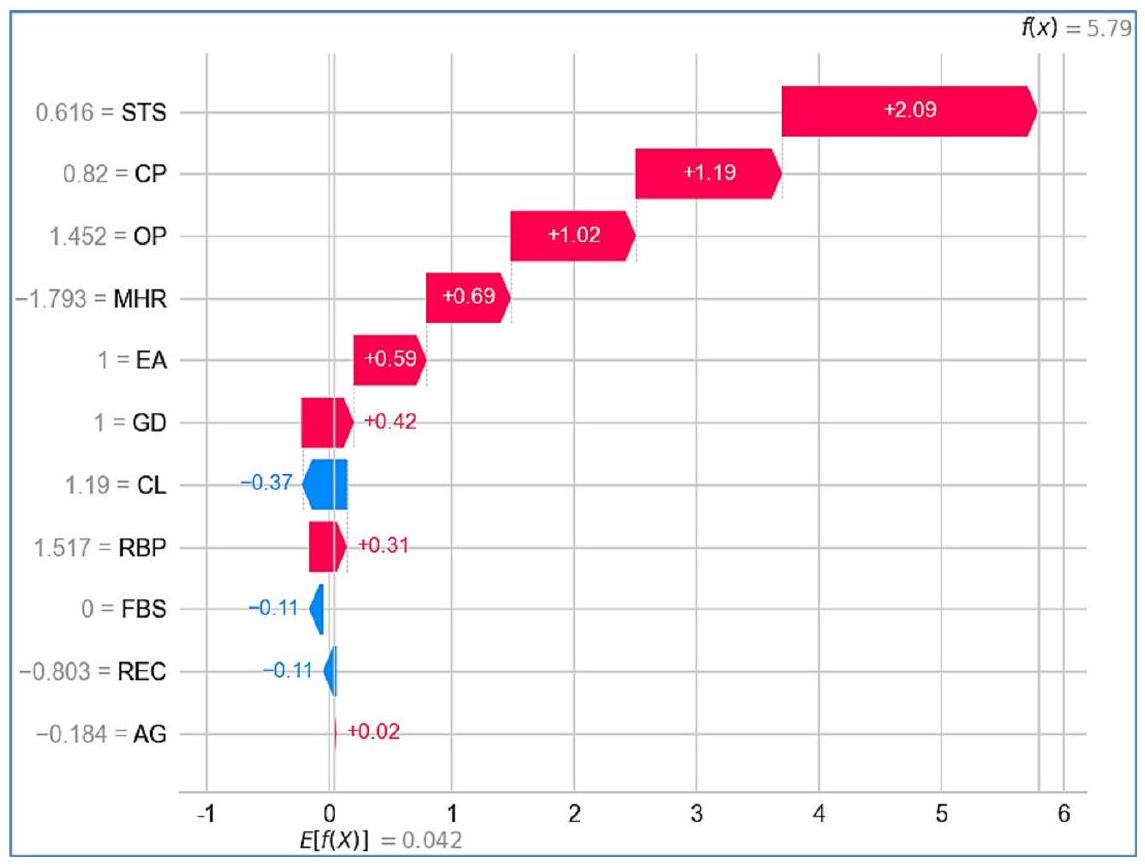

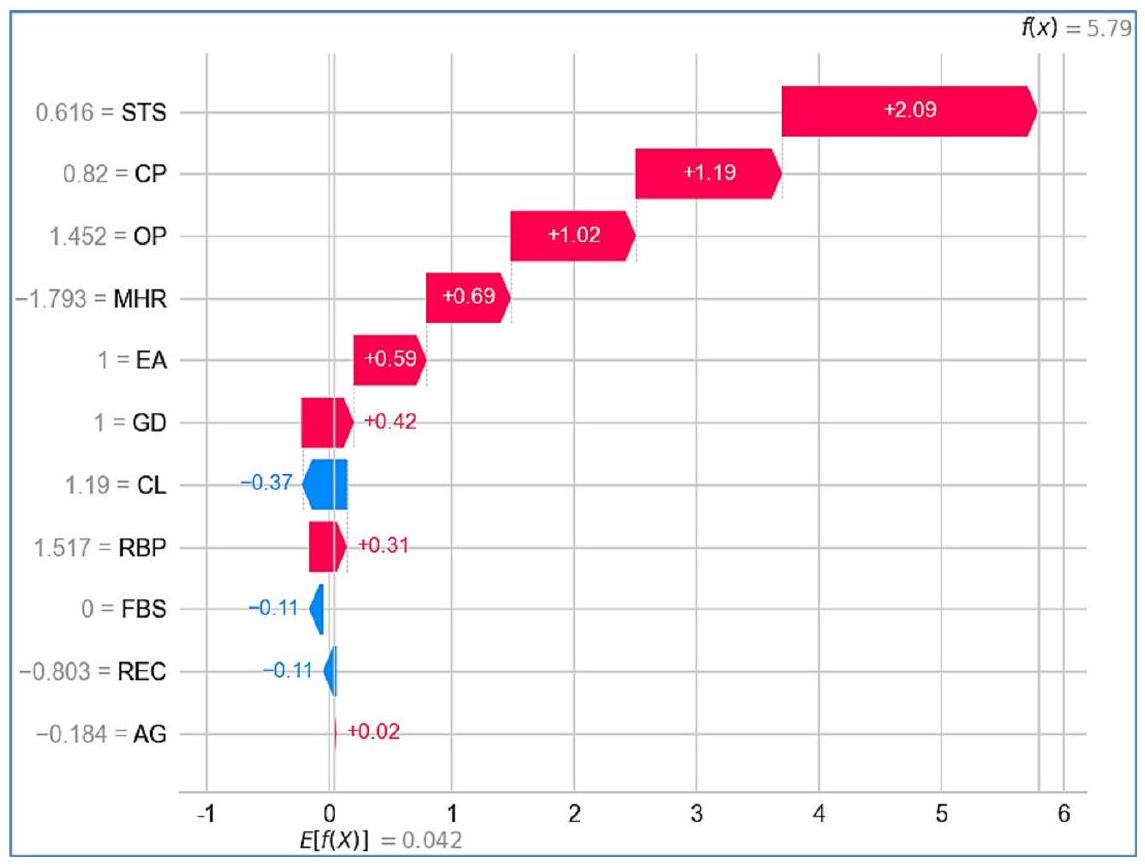

في هذا البحث، تم استخدام مخططات الشلال والقوة لـ SHAP لتقديم تفسيرات محلية للتوقعات التي قدمها نموذج التجميع في اكتشاف أمراض القلب. يكسر مخطط الشلال كيف تؤثر الميزات الفردية على التوقع خطوة بخطوة، بدءًا من الناتج الأساسي للنموذج. من ناحية أخرى، يمثل مخطط القوة بصريًا كيف تزيد أو تقلل ميزات معينة من التوقع، موضحًا بوضوح العوامل التي تؤثر على النتيجة.

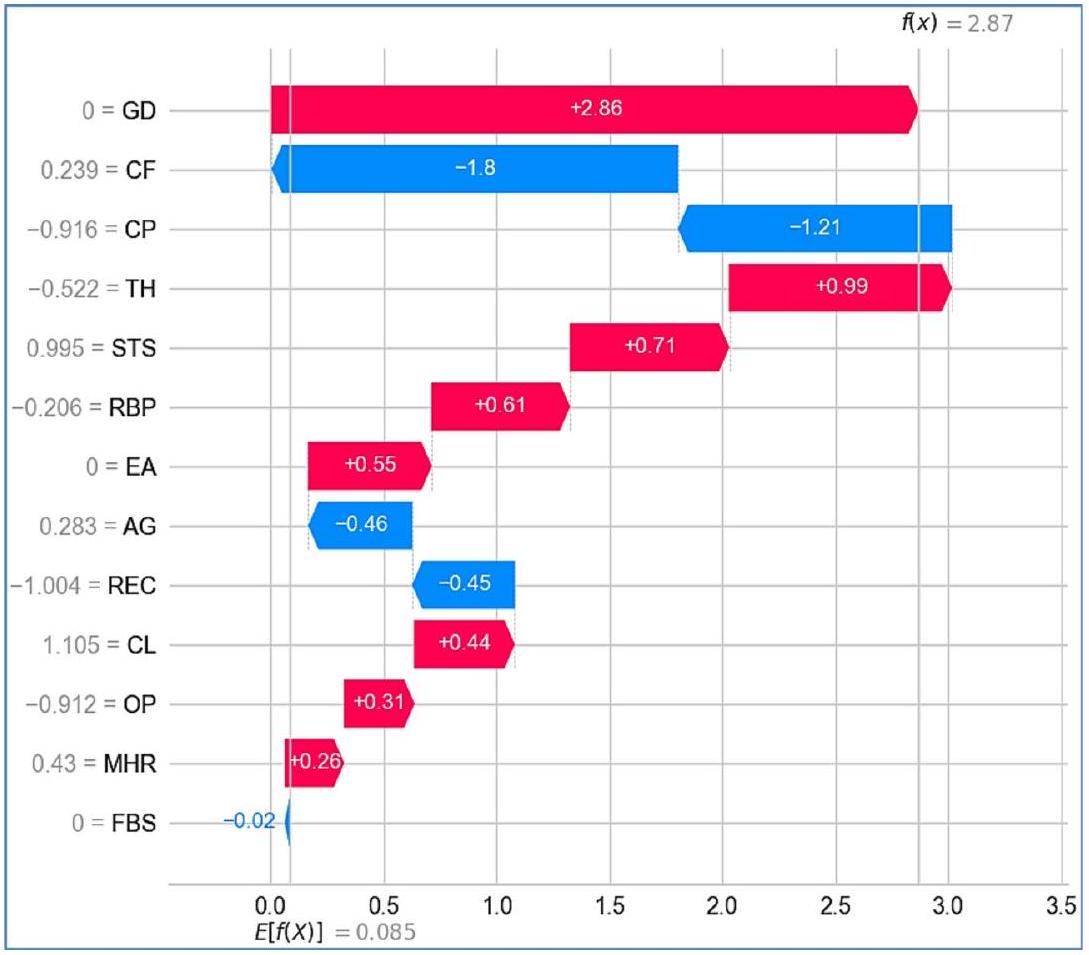

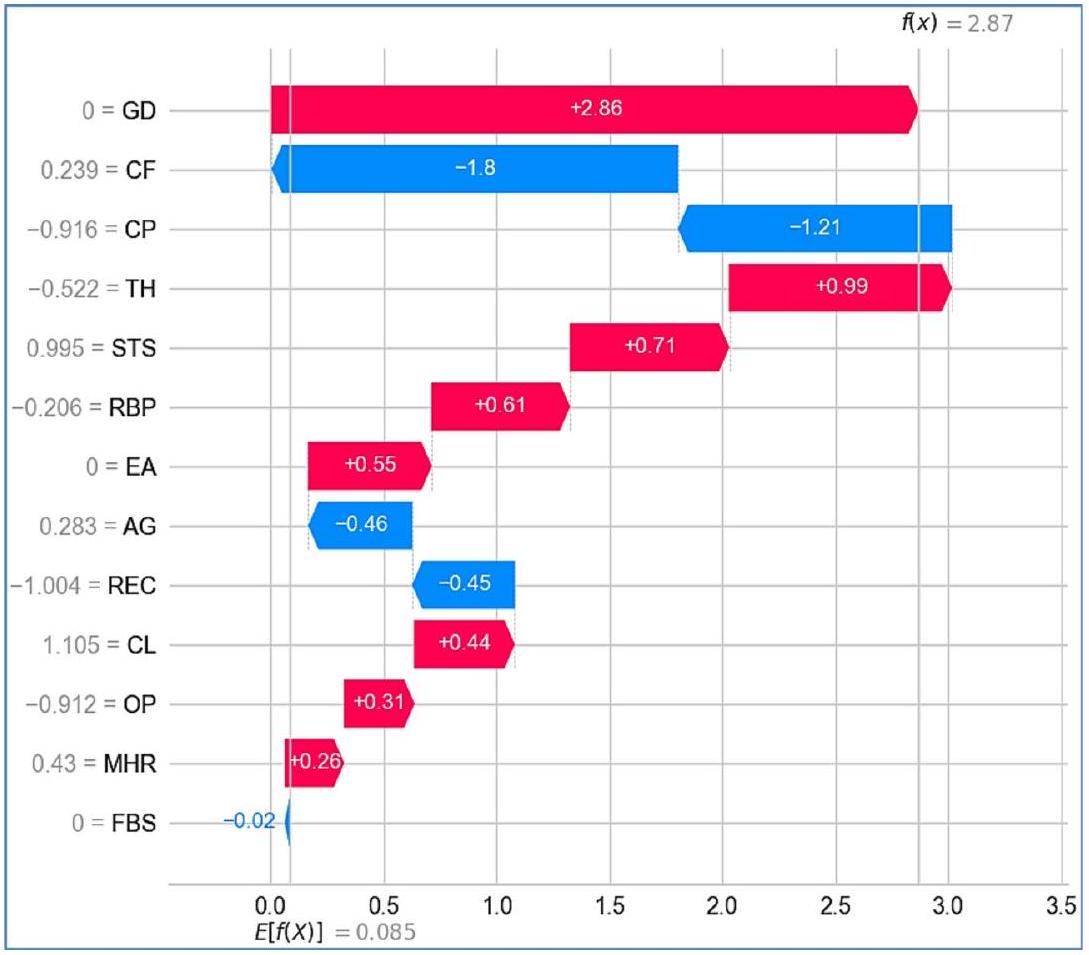

مخطط الشلال يعد مخطط الشلال لـ SHAP أداة تصور فعالة لفهم كيف تساهم الميزات الفردية في توقع النموذج بطريقة منهجية، خطوة بخطوة. يكسر هذا المخطط التوقع إلى مساهمات من ميزات محددة، مميزًا بوضوح بين التأثيرات الإيجابية والسلبية على المتغير المستهدف. يمثل المحور السيني القيمة المتوقعة، بينما يسرد المحور الصادي الميزات التي تؤثر على النتيجة. تُظهر الميزات التي تساهم إيجابيًا في التوقع باللون الأحمر. تُظهر الميزات التي تساهم سلبًا في التوقع باللون الأزرق. يمثل حجم كل شريط حجم التأثير على ناتج النموذج.

تعتبر هذه التصور ذات قيمة خاصة في توقع أمراض القلب. يبرز كيف أن عوامل مثل الحالات الصحية أو الخصائص الديموغرافية تشكل بشكل كبير التوقع لكل فرد، مما يعزز قابلية تفسير النموذج من خلال تحديد الميزات الأكثر أهمية في سياق محدد للمريض. تعرض الأشكال 25 و 26 مخططات الشلال لـ SHAP لـ D1 باستخدام التجميع والتصويت، على التوالي. مخططات الشلال لـ SHAP

الشكل 25. مخطط الشلال للتجميع على D1.

الشكل 26. مخطط الشلال للتصويت على D1.

لـ D2، باستخدام التجميع والتصويت، موضحة في الأشكال 27 و 28، على التوالي. في كل حالة، تم استخدام بيانات المريض رقم 5 لتحليل مخطط الشلال لـ SHAP.

في نموذج التجميع، على D1 (الشكل 25)، القيمة المتوقعة الإجمالية (

الشكل 27. مخطط الشلال للتجميع على D2.

الشكل 28. مخطط الشلال للتصويت على D2.

يمكن أن تقلل من خطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب. تساهم CL (-0.37) أيضًا بشكل سلبي، مما يشير إلى أن ارتفاع الكوليسترول في هذا السياق يقلل قليلاً من الخطر، ربما بسبب تفاعلات البيانات أو أنماط معينة تعلمها النموذج. أخيرًا، تلعب AG عند +0.02 دورًا ثانويًا، مع مساهمة إيجابية صغيرة، مما يشير إلى أنه على الرغم من أن العمر عامل، إلا أنه أقل تأثيرًا في هذه الحالة المحددة. تؤدي المساهمات المجمعة إلى توقع نهائي معدل قدره +5.79، مما يشير إلى أن المريض معرض لخطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب.

الشكل 29. مخطط القوة لـ (أ) التجميع و (ب) التصويت على D1.

الشكل 30. مخطط القوة لـ (أ) التجميع و (ب) التصويت على D2.

بالنسبة لنفس المريض، ينتج نموذج التصويت قيمة متوقعة قدرها 3.686 لخطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب على D1 (الشكل 26). هنا، تظل STS (+1.74) أقوى مساهم إيجابي، بينما تظهر AG (1.18)، OP (+0.98)، و GD (+0.73) تأثيرات إيجابية حاسمة، مما يشير إلى أهميتها المتزايدة في هذا السياق. من المثير للاهتمام أن CP (-0.249) تقدم أعلى مساهمة سلبية، مما يختلف عن دورها في نموذج التجميع. كما تم تغيير مساهمة MHR (-0.29) من نموذج التجميع.

على العكس من ذلك، على D2، في نموذج التجميع، تظهر ميزة GD كأهم مساهم إيجابي بقيمة +2.86 (الشكل 27)، مما يشير إلى أن المريضة مرتبطة بقوة بزيادة خطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب. بعد GD، تتمتع CF (-1.8) و CP (-1.21) بمساهمات سلبية ملحوظة، مما يشير إلى أن القيم الأعلى لهذه الميزات قد ترتبط بانخفاض خطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب. تشمل الميزات الأخرى التي تساهم إيجابيًا TH (+0.99)، STS (+0.71)، EA (+0.55) و RBP (+0.61) مما يشير إلى أن هذه العوامل تزيد أيضًا من الخطر. على العكس من ذلك، فإن الميزات مثل

ينتج نموذج التصويت قيمة متوقعة أعلى قدرها 5.455 لخطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب على D2 (الشكل 28). هنا، تظل GD مساهمًا إيجابيًا حاسمًا، بقيمة +2.6، مما يعزز أهميتها في توقع أمراض القلب. تساهم الميزة

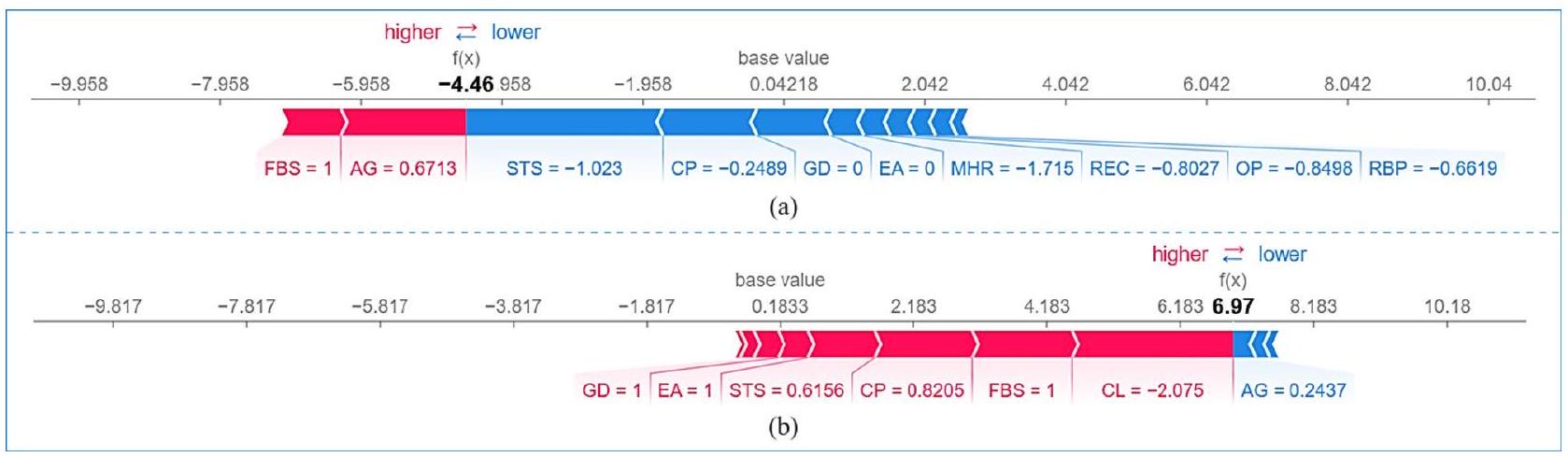

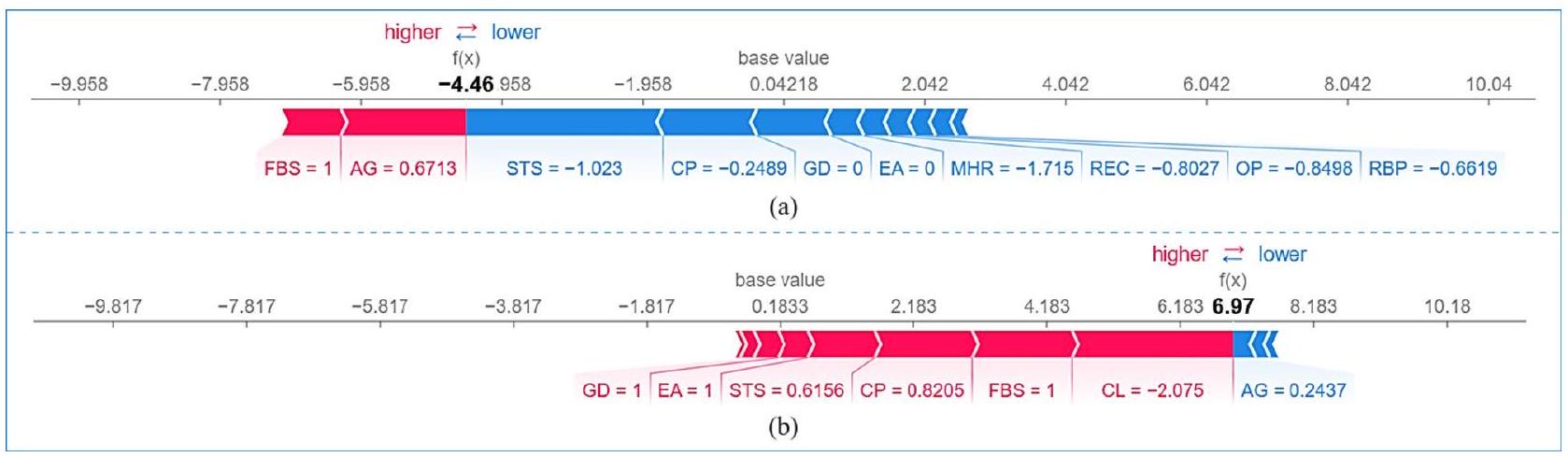

مخطط القوة بينما يقدم مخطط الشلال تحليلًا تسلسليًا لمساهمات الميزات، يبرز مخطط القوة لـ SHAP التأثير العام للميزات بالنسبة لقيمة أساسية. تنقل هذه المخططات بصريًا العوامل التي تؤثر على توقعات نموذج التجميع من خلال توضيح كيف تدعم ميزات معينة أو تعارض تصنيفًا معينًا. يتم تمثيل تأثير كل ميزة بأسهم تشير إلى اتجاهها (إيجابي أو سلبي) وحجمها، مما يوفر رؤية واضحة وقابلة للتفسير لقرارات النموذج. من خلال تقديم طريقة تفاعلية وسهلة الاستخدام لتحليل التوقعات، يسهل مخطط القوة فهمًا شاملاً لكيفية مساهمة الميزات الفردية في النتائج النهائية. تعرض الأشكال 29 و 30 مخططات القوة لـ SHAP لنماذج التجميع والتصويت على D1 و D2، على التوالي، لحالة معينة.

يظهر مخطط القوة لـ SHAP لنموذج التجميع على D1 (الشكل 29a) مساهمة سلبية بشكل أساسي من الميزات، مما يؤدي إلى درجة توقع منخفضة

بالنسبة لنموذج التصويت (الشكل 29ب) على نفس مجموعة البيانات (D1)، فإن التنبؤ مختلف بشكل ملحوظ، مع درجة تنبؤ إيجابية عالية (

تقدم نماذج التكديس والتصويت على D2 (الشكل 30) درجات تنبؤ إيجابية معتدلة (

التحليل النقدي تكشف مخططات SHAP المائية والقوة عن اختلافات كبيرة بين نماذج التكديس والتصويت في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب عبر مجموعتين من البيانات. يبرز مخطط الشلال تقييمات المخاطر المختلفة: على D1، يمنح نموذج التكديس درجة مخاطر أعلى (5.79) (الشكل 25) مقارنةً بنموذج التصويت (3.686) (الشكل 26)، بينما على D2، ينتج نموذج التصويت درجة أعلى (5.455) (الشكل 27) مقارنةً بالتكديس (2.87) (الشكل 28). تشير هذه الاختلافات إلى أن نموذج التكديس أكثر حساسية لتفاعلات الميزات الدقيقة، بينما يتفاعل نموذج التصويت بشكل أقوى مع مؤشرات المخاطر السائدة. تظهر الميزات الرئيسية مثل CP و MHR و REC على D1، و OP و CP و MHR على D2 اختلافات كبيرة في التفسير، مما يبرز كيف تؤثر استراتيجيات التعلم الجماعي المختلفة على أهمية الميزات. ومع ذلك، تبرز STS و GD باستمرار كعوامل مساهمة إيجابية سائدة، بينما يبقى FBS مساهمًا سلبيًا ضعيفًا باستمرار، مما يعزز دوره النسبي الضئيل في اتخاذ القرار للنموذج. تؤكد هذه الاختلافات على ضرورة مراعاة خصائص مجموعة البيانات واختيار النموذج عند إجراء التنبؤات السريرية.

يؤكد تحليل مخطط القوة هذه التمييزات. على D1، يتنبأ نموذج التكديس باحتمالية منخفضة للإصابة بأمراض القلب، مع اعتبار STS و CP و GD كعوامل وقائية، بينما تساهم العمر و FBS بشكل إيجابي في المخاطر (الشكل 29(أ)). في المقابل، يتنبأ نموذج التصويت باحتمالية عالية للإصابة بأمراض القلب، مدفوعًا بشكل أساسي بـ CL و FBS و CP و STS، مع لعب العمر دورًا سلبيًا طفيفًا فقط (الشكل 29(ب)). على D2، يتنبأ كلا النموذجين بمخاطر معتدلة، مع ظهور GD و OP و STS و CP و TH و RBP كعوامل خطر متسقة (الشكل 30). ومع ذلك، يختلف تفسير AG بشكل كبير – حيث يساهم بشكل إيجابي في نموذج التكديس (الشكل 30(أ)) ولكنه هو أقوى مساهم سلبي في التصويت (الشكل 30(ب))، مما يشير إلى أن النموذجين يقيمان العمر بشكل مختلف في تنبؤاتهما.

التمييز الرئيسي بين نماذج التكديس والتصويت ينشأ من استراتيجيات التعلم الجماعي المختلفة. يستخدم التكديس نماذج أساسية متعددة بطريقة هرمية، مما يلتقط تفاعلات الميزات المعقدة والاعتمادات، بينما يجمع التصويت التنبؤات بطريقة متوازية، مما يبرز المتنبئين الفرديين الأقوياء على التفاعلات الدقيقة.

أحد الأسباب الرئيسية لاختلاف تنبؤاتهما هو أن التكديس يصقل قراره النهائي من خلال نموذج ميتا، مما يجعله أكثر تكيفًا مع تأثيرات الميزات المتغيرة. يفسر هذا لماذا، على D1، يمنح التكديس أدوارًا تعزز المخاطر وأدوارًا وقائية لمميزات مختلفة، مما يؤدي إلى درجة تنبؤ أقل (الشكل 29(أ)). في المقابل، يميل التصويت، الذي يعتمد على قرار الأغلبية البسيطة، إلى المبالغة في التأكيد على عوامل الخطر السائدة، مثل الكوليسترول، مما يؤدي إلى درجة تنبؤ أعلى (الشكل 29(ب)).

تمييز آخر حاسم هو كيفية إدارة النماذج لارتباطات الميزات. يحدد التكديس التأثيرات التعويضية، مثل التأثير الوقائي لـ STS و CP في بعض الحالات (الشكل 29(أ))، مما يمنع المبالغة في تقدير مخاطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب. ومع ذلك، يعامل التصويت كل ميزة بشكل مستقل، مما يجعله أكثر عرضة للمبالغة في التأكيد على مؤشرات المخاطر العالية مثل CL و FBS (الشكل 29(ب)).

توضح معالجة العمر هذا الاختلاف بشكل أكبر. على D2، يعترف التكديس بالعمر كعامل خطر (الشكل 30(أ))، من المحتمل بالتزامن مع متغيرات طبية أخرى، بينما يمنح التصويت مساهمة سلبية كبيرة (الشكل 30(ب))، ربما بسبب تأثير العتبة حيث تقلل عوامل الخطر الأخرى من أهميته. يشير هذا إلى أن التصويت يعتمد أكثر على قوة الميزات المطلقة، بينما يقوم التكديس بتعديل التنبؤات بناءً على العلاقات المتداخلة بين الميزات.

في النهاية، يقدم التكديس تقييمًا أكثر وعيًا بالسياق ومتوازنًا من خلال دمج تفاعلات الميزات المتعددة، بينما يوفر التصويت نهجًا أكثر مباشرة وحساسية عالية من خلال إعطاء الأولوية للمتنبئين السائدين. يعد التكديس مفيدًا في الحالات المعقدة حيث تكون التفاعلات الدقيقة مهمة، بينما قد يُفضل التصويت عندما تتطلب عوامل الخطر الفردية القوية التأكيد.

على الرغم من التنبؤات المتوقعة عمومًا، تظهر بعض الملاحظات غير المتوقعة في كلا النموذجين. على سبيل المثال، في مخطط الشلال، تعمل CP (في التصويت على D1 (الشكل 26) والتكديس على D2 (الشكل 27)) و CL (في التكديس على D1 (الشكل 28)) كعوامل مساهمة سلبية، مما يتعارض مع المعرفة الطبية الراسخة. وبالمثل، في مخطط القوة للتصويت على D1 (الشكل 29(ب))، يكون الكوليسترول هو أقوى مساهم إيجابي، على الرغم من أن المريض لديه قيمة كوليسترول سلبية.

يمكن أن تُعزى هذه الشذوذات إلى عوامل مختلفة. أحد التفسيرات المحتملة هو الطبيعة غير الخطية للنموذج، حيث لا تزيد العلاقة بين الكوليسترول وأمراض القلب أو تنقص بشكل صارم. قد يكون النموذج قد حدد أن مستويات الكوليسترول المعتدلة تمثل خطرًا أقل من المستويات المنخفضة جدًا أو العالية جدًا، حيث يمكن أن تشير مستويات الكوليسترول المنخفضة جدًا أحيانًا إلى مشاكل صحية أساسية، مثل أمراض الكبد أو سوء التغذية.

عامل آخر هو التفاعلات بين الميزات في النموذج. تمثل قيم SHAP التأثير المشترك لعدة ميزات، مما يشير إلى أن تأثير الكوليسترول قد يعتمد على متغيرات أخرى مثل RBP و REC أو FBS. على سبيل المثال، إذا كان لدى المريض كوليسترول مرتفع معتدل ولكن علامات حيوية طبيعية بخلاف ذلك، قد يستنتج النموذج أن الكوليسترول لا يزيد من المخاطر بشكل كبير. علاوة على ذلك، قد تكون تقنيات المعالجة المسبقة مثل قياس الميزات والتحولات قد أثرت على هذه التفسيرات.

أخيرًا، قد تكون تحيزات مجموعة البيانات والارتباطات غير المتوقعة قد أثرت على هذه النتائج. إذا كانت مجموعة بيانات التدريب تتكون من عدد كبير من المرضى الذين لديهم كوليسترول منخفض والذين كانوا بالفعل يعانون من حالات قلبية وعائية (ربما بسبب علاجات خافضة للكوليسترول)، فقد يكون النموذج قد تعلم عن غير قصد رابطًا بين انخفاض الكوليسترول وزيادة خطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب. وهذا يبرز ضرورة تحليل توزيعات البيانات وارتباطات الميزات بدقة عند تفسير قيم SHAP.

مقارنة نماذج التكديس والتصويت مع أحدث التقنيات

تم تحديد أداء نموذجنا من خلال مقارنته بعدة أوراق بحثية مشابهة باستخدام مقاييس متنوعة، كما هو موضح في الجدول 8. في تجربتنا، أظهرت منهجية التكديس أفضل أداء بشكل عام في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب؛ وبالتالي، ركزنا فقط على النتائج التي تم الحصول عليها باستخدام التكديس. يمكن أن يُعزى التحسن في أداء نموذجنا مع التكديس إلى المنهجيات المطبقة، والتي تشمل اختيار النماذج الأساسية، واختيار المتعلم الميتا، والتحقق المتقاطع الفعال، وضبط المعلمات الفائقة بشكل صحيح.

الاستنتاجات، القيود، والاتجاهات المستقبلية

تستكشف هذه الورقة تطبيق تقنيات التعلم الجماعي، وبشكل خاص التجميع والتصويت، لتعزيز دقة التنبؤ بأمراض القلب. قام الباحثون بإجراء تجارب باستخدام مجموعات بيانات متعددة تتعلق بتنبؤ أمراض القلب وقارنوا أداء نماذج التجميع والتصويت مع نماذج فردية. أظهرت النتائج أن كلا من نماذج التجميع والتصويت تفوقت على النماذج الأساسية الفردية، بالإضافة إلى النماذج الموجودة، في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب، حيث أظهر نموذج التجميع دقة أعلى من نموذج التصويت. تؤكد التحليلات الإحصائية أيضًا تفوق نموذج التجميع. يمكن أن يُعزى التحسن في أداء نماذج التجميع والتصويت إلى المنهجيات المستخدمة، بما في ذلك اختيار النماذج الأساسية، واختيار المتعلم الميتا، والتقاطع الفعال، وضبط المعلمات الفائقة بشكل صحيح. بشكل خاص، سمح الجمع بين التنبؤات من نماذج متعددة بالاستفادة من نقاط القوة لكل نموذج فردي. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن التجميع والتصويت يمكن أن يكونا قيمين في اتخاذ القرارات السريرية لتنبؤ بأمراض القلب.

ومع ذلك، فإن مقارنة نماذج التكديس والتصويت في تحليل SHAP توضح أساليبها المميزة في توقع المخاطر. يأخذ التكديس في الاعتبار الاعتمادات المتبادلة بين الميزات وتأثيرات التعويض، مما يؤدي إلى توقعات أكثر حساسية للسياق، بينما يركز التصويت على المتنبئين الفرديين الأقوياء، مما يؤدي غالبًا إلى تقييمات مخاطر أعلى. تبرز هذه الاختلافات أهمية اختيار تقنية تجميع مناسبة بناءً على المتطلبات السريرية أو التنبؤية المحددة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التأثيرات غير المتوقعة للميزات تؤكد على الحاجة إلى تحليل بيانات دقيق، وهندسة ميزات، والتحقق، لضمان توافق العلاقات التي تعلمها النموذج مع المعرفة الطبية والأنماط الواقعية.

تتمتع هذه البحث بإمكانات كبيرة. يمكن أن تؤدي الدقة المحسّنة في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب إلى تشخيص مبكر، وأنظمة علاج مخصصة، وفي النهاية تحسين نتائج المرضى. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تحسين قابلية تفسير النموذج يساعد الأطباء في اتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة ووضع علاجات مخصصة. لتوسيع نطاق تطبيق هذه الدراسة، يمكن توسيع الطريقة المقترحة لتشمل مجموعات بيانات صحية إضافية ذات خصائص مشابهة.

بينما تُظهر هذه الدراسة فعالية تجميع النماذج والتصويت في التنبؤ بأمراض القلب، يجب الاعتراف بعدة قيود. أولاً، تقيّد قابلية تعميم النتائج استخدام مجموعات بيانات متاحة للجمهور، والتي قد لا تعكس تمامًا تنوع المرضى في العالم الحقيقي. من الضروري التحقق من هذه النتائج على مجموعات بيانات أكبر وأكثر تنوعًا لضمان قابليتها للتطبيق بشكل أوسع. ثانيًا، على الرغم من أن تحليل SHAP يعزز من قابلية التفسير، فإن بعض المساهمات غير المتوقعة للميزات تشير إلى وجود تحيزات أو شذوذات في البيانات تتطلب مزيدًا من التحقيق. يجب أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية سبل تحسين اختيار الميزات ومعالجة التحيزات المحتملة. ثالثًا، قد تشكل التعقيدات الحسابية لتجميع النماذج – خاصة فيما يتعلق بضبط المعلمات الفائقة والتحقق المتقاطع – تحديات للتنفيذ في بيئات الرعاية الصحية ذات الموارد المحدودة. يجب التحقيق في تقنيات تحسين فعالة وهياكل تجميع خفيفة الوزن للتخفيف من هذه المشكلة. أخيرًا، لم تفحص هذه الدراسة تحديات النشر في الوقت الحقيقي، مثل انحراف النموذج أو التكامل مع السجلات الصحية الإلكترونية (EHRs)، والتي تعتبر حاسمة للتبني العملي في البيئات السريرية. يجب أن تركز الأعمال المستقبلية على مواجهة هذه التحديات لتعزيز قابلية استخدام التعلم التجميعي في تطبيقات الرعاية الصحية في العالم الحقيقي.

لمعالجة قيود هذه الدراسة وتوسيع نطاق تطبيقها، يجب على الأبحاث المستقبلية استكشاف عدة اتجاهات رئيسية. أحد المسارات الواعدة هو تطوير التجميعات المتعددة الطبقات (MTSE)، حيث يمكن للهياكل الهرمية للتجميع مع طبقات متعددة من التعلم الميتا أن نمذج تفاعلات الميزات الأعمق. من خلال دمج مصادر بيانات متنوعة، يعزز MTSE القدرة على التكيف عبر السكان ويحسن من قابلية التفسير من خلال تحليل SHAP الهرمي، مما يجعل الرؤى المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي أكثر موثوقية للاستخدام السريري. قد تزيد تقنيات مثل وزن النموذج الديناميكي واختيار التجميع التكيفي من قدرة النماذج على التكيف عبر مجموعات المرضى المتنوعة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن دمج نماذج التجميع في سير العمل السريري المباشر جنبًا إلى جنب مع لوحات المعلومات التفاعلية للتفسير سيمكن الأطباء من التحقق من التنبؤات المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي وتنقيح خطط العلاج بشكل ديناميكي. منطقة أخرى مهمة هي مقارنة التجميعات المعتمدة على التكديس مع تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي المتقدمة، بما في ذلك هياكل التعلم العميق مثل المحولات والتجميعات الاحتمالية البايزية، لاكتشاف استراتيجيات لتعزيز كل من دقة التنبؤ وقياس عدم اليقين. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يساعد دمج بيانات المرضى الطولية وطرق الاستدلال السببي نماذج التجميع في التمييز بين الارتباط والسببية، مما يؤدي إلى تنبؤات ذات مغزى سريري أكبر. ستؤدي هذه التطورات إلى

| عمل بحثي | الخوارزميات المدروسة | مجموعة البيانات المستخدمة | أعلى دقة (%) | الدقة (%) | استرجاع (%) | درجة F1 (%) | الخصوصية (%) | منطقة تحت منحنى التشغيل/الاستقبال (%) | القيم المتوقعة السلبية (%) | نسبة MCC (%) | معدل الإيجابيات الكاذبة | معدل النتائج السلبية الخاطئة | معدل الاكتشافات الكاذبة | معدل التصنيف الخاطئ | التحليل الإحصائي | XAI |

| تشاندراسيخار وبيداكرشنا [31] | التصويت | HDDC و IDD | 95 مع IEEE Dataport | ٩٦.٠٤ | 93.27 | 94.63 | 95 | – | 91.57 | ٨٧.٩٤ | 0.0500 | 0.0673 | 0.0396 | 0.0500 | × | × |

| تيwari وآخرون [32] | تكديس | IDD | 92.34 | 92 | 93.49 | 92.74 | 91.07 | 92.28 | 93.49 | 84.64 | 0.0893 | 0.0651 | 0.0800 | 0.0766 | × | × |

| رازا [33] | التصويت | مجموعة بيانات أمراض القلب StatLog | ٨٨.٨٨ | 89 | 85 | 87 | 87 | ٨٨ | ٨٨ | – | 0.1300 | 0.1500 | 0.1000 | 0.1100 | × | × |

| مينيي وآخرون [34] | تكديس | HDDC و FHSD | 93 مع FHSD | 96 | 91 | 93 | – | 93.30 | 91 | 91 | – | 0.0900 | 0.0400 | 0.0700 | × | × |

| أمبروز وآخرون [35] | التصويت | FHSD و UHDD | 91.96 مع UHDD | 92.40 | 91.72 | 91.69 | 90.77 | – | 91.72 | – | 0.0923 | 0.0828 | 0.0760 | 0.0804 | × | × |

| أشفاق [36] | تكديس | HDDC | 87 | 83 | 83 | 83 | – | 83 | 83 | 83 | – | 0.0170 | 0.0170 | 0.0130 | × | × |

| حبيب وتسنيم [37] | التصويت | FHSD | ٨٨.٤٢ | 100 | 43 | 82 | – | 73 | 43 | 43 | – | 0.5700 | 0 | 0.1158 | × | × |

| موهباترا وآخرون [38] | تكديس | UHDD | 91.8 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 90.9 | 91.7 | 92.6 | ٨٣.٥ | 0.0910 | 0.0740 | 0.0740 | 0.0820 | × | × |

| ورقتنا | تكديس | HDDC | 91 | 89.7 | 98.1 | 91.8 | – | 92 | 98.1 | 82.4 | – | 0.0190 | 0.0130 | 0.0888 |

|

|

| UHDD | 98 | 98.8 | 98.7 | 98.4 | – | 98 | 98.7 | 96.8 | – | 0.0130 | 0.0120 | 0.0167 |

الجدول 8. مقارنة العمل المقترح مع الأدبيات الحديثة.

دفع المرحلة التالية من توقع أمراض القلب المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، مما يجعل النماذج أكثر قوة وقابلية للتفسير وملائمة عمليًا للنشر في بيئات الرعاية الصحية الواقعية.

دفع المرحلة التالية من توقع أمراض القلب المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، مما يجعل النماذج أكثر قوة وقابلية للتفسير وملائمة عمليًا للنشر في بيئات الرعاية الصحية الواقعية.

توفر البيانات

تتوفر مجموعات البيانات المستخدمة في الدراسة الحالية في مستودع كاجل، [HDDC: https://www.kaggle. com/datasets/sid321axn/heart-statlog-cleveland-hungary-final، UHDD: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/johnsmith88/مجموعة بيانات أمراض القلب

تاريخ الاستلام: 1 فبراير 2025؛ تاريخ القبول: 4 أبريل 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 أبريل 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 أبريل 2025

References

- WHO. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), 11 June 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/car diovascular-diseases-(cvds). [Accessed 17 December 2023].

- Ahmad, G. N., Ullah, S., Algethami, A., Fatima, H. & Akhter, S. M. H. Comparative study of optimum medical diagnosis of human heart disease using machine learning technique with and without sequential feature selection. IEEE Access. 10, 23808-23828 (2022).

- Gheorghe, A. et al. The economic burden of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public. Health. 18, 975 (2018). (Article number.

- Ruan, Y. et al. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and associated risk factors among older adults in six low-and middle-income countries: results from SAGE wave 1. BMC Public. Health. 18(1), 1-13 (2018).

- Biglu, M. H., Ghavami, M. & Biglu, S. Cardiovascular diseases in the mirror of science. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 8(4), 158-163 (2016).

- Ayano, Y. M., Schwenker, F., Dufera, B. D. & Debelee, T. G. Interpretable Machine Learning Techniques in ECG-Based Heart Disease Classification: A Systematic Review, Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 111, (2023).

- Rath, A., Mishra, D., Panda, G. & Satapathy, S. C. An exhaustive review of machine and deep learning based diagnosis of heart diseases. Multimedia Tools Appl. 81, 36069-36127 (2022).

- Ganie, S. M., Pramanik, P. K. D., Malik, M. B., Nayyar, A. & Kwak, K. S. An improved ensemble learning approach for heart disease prediction using boosting algorithms. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 46(3), 3993-4006 (2023).

- Brown, G. Ensemble learning, in Encyclopedia of Machine Learning, (eds Sammut, C. & Webb, G. I.) Boston, MA, Springer, 312-320. (2011).

- Ganie, S. M. & Malik, M. B. An ensemble machine learning approach for predicting type-II diabetes mellitus based on lifestyle indicators. Healthc. Analytics. 22, 100092 (2022). (Article number.

- Naveen, R. K., Sharma & Nair, A. R. Efficient breast cancer prediction using ensemble machine learning models, in 4 th International Conference on Recent Trends on Electronics, Information, Communication & Technology (RTEICT), Bangalore, India, (2019).

- Oswald, G. J., Sathwika & Bhattacharya, A. Prediction of cardiovascular disease (CVD) using ensemble learning algorithms, in 5th Joint International Conference on Data Science & Management of Data (9th ACM IKDD CODS and 27th COMAD), Bangalore, India, (2022).

- Shanbhag, G. A., Prabhu, K. A., Subba Reddy, N. V. & Rao, B. A. Prediction of lung cancer using ensemble classifiers, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 2161 (012007), (2022).

- Verma, A. K., Pal, S. & Tiwari, B. B. Skin disease prediction using ensemble methods and a new hybrid feature selection technique. Iran. J. Comput. Sci. 3, 207-216(2020).

- Ganie, S. M. & Malik, M. B. Comparative analysis of various supervised machine learning algorithms for the early prediction of type-II diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Med. Eng. Inf. 14(6), 473-483 (2022).

- Shaikh, F. J. & Rao, D. S. Prediction of cancer disease using machine learning approach, Materialstoday: Proceedings, vol. 50 (Part 1), pp. 40-47, (2022).

- Senthilkumar, B. et al. Ensemble modelling for early breast cancer prediction from diet and lifestyle, IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 429-435, (2022).

- Ganie, S. M. & Pramanik, P. K. D. Predicting chronic liver disease using boosting, in 1st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Innovations in Healthcare Industries (ICAIIHI-2023), Raipur, India, (2024).

- Ganie, S. M., Pramanik, P. K. D., Mallik, S. & Zhao, Z. Chronic kidney disease prediction using boosting techniques based on clinical parameters. PLoS ONE. 18(12), e0295234 (2023).

- Ganie, S. M., Pramanik, P. K. D., Malik, M. B., Mallik, S. & Qin, H. An ensemble learning approach for diabetes prediction using boosting techniques. Front. Genet. 14 (2023).

- Ganie, S. M. & Pramanik, P. K. D. A comparative analysis of boosting algorithms for chronic liver disease prediction. Healthc. Analytics 5, 100313 (2024).

- Shaik, H. S., RajyaLakshmi, G. V., Alane, V. & Kandimalla, N. D. Enhancing prediction of cardiovascular disease using bagging technique. in International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT).

- Yuan, X. et al. A High accuracy integrated bagging-fuzzy-GBDT prediction algorithm for heart disease diagnosis. in IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC)(2019).

- Deshmukh, V. M. Heart disease prediction using ensemble methods. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8(3), 8521-8526 (2019).

- Mary, N. et al. Investigating of classification algorithms for heart disease risk prediction. J. Intell. Med. Healthc. 1(1), 11-31 (2022).

- Budholiya, K., Shrivastava, S. K. & Sharma, V. An optimized XGBoost based diagnostic system for effective prediction of heart disease. J. King Saud Univ. – Comput. Inform. Sci. 34(7), 4514-4523 (2022).

- Pan, C., Poddar, A., Mukherjee, R. & Ray, A. K. Impact of categorical and numerical features in ensemble machine learning frameworks for heart disease prediction. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 76, 103666 (2022).

- Pouriyeh, S. et al. A comprehensive investigation and comparison of machine learning techniques in the domain of heart disease. in IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC) (2017).

- Shorewala, V. Early detection of coronary heart disease using ensemble techniques. Inf. Med. Unlocked, 26, 100655 (2021).

- Latha, C. B. C. & Jeeva, S. C. Improving the accuracy of prediction of heart disease risk based on ensemble classification techniques. Inf. Med. Unlocked 16, 100203 (2019).

- Chandrasekhar, N. & Peddakrishna, S. Enhancing heart disease prediction accuracy through machine learning techniques and optimization. Processes 11, (4), 1210 (2023).

- Tiwari, A., Chugh, A. & Sharma, A. Ensemble framework for cardiovascular disease prediction. Comput. Biol. Med. 146, 105624 (2022).

- Raza, K. Improving the prediction accuracy of heart disease with ensemble learning and majority voting rule. in U-Healthcare Monitoring Systems, Design and Applications (eds Dey, N. et al.) (Academic, 2019).

- Mienye, I. D., Sun, Y. & Wang, Z. An improved ensemble learning approach for the prediction of heart disease risk. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 20, 100402 (2020).

- Ambrews, A. B. et al. Ensemble based machine learning model for heart disease prediction. in International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES) (2022).

- Ashfaq, A. et al. Multi-model ensemble based approach for heart disease diagnosis. in International Conference on Recent Advances in Electrical Engineering & Computer Sciences (RAEE & CS) (2022).

- Habib, A. Z. S. B. & Tasnim, T. An Ensemble hard voting model for cardiovascular disease prediction. in 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI) (2020).

- Mohapatra, S. et al. A stacking classifiers model for detecting heart irregularities and predicting cardiovascular disease. Healthc. Analytics. 3, 100133 (2023).

- Saboor, A. et al. A method for improving prediction of human heart disease using machine learning algorithms, Mobile Inf. Syst. 2022, 1410169 (2022).

- Aldossary, Y., Ebrahim, M. & Hewahi, N. A comparative study of heart disease prediction using tree-based ensemble classification techniques. in International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI) (2022).

- Duraisamy, P., Natarajan, Y., Ebin, N. L. & Jawahar Raja, P. Efficient way of heart disease prediction and analysis using different ensemble algorithm: A comparative study. in 6th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (2023).

- Sagi, O. & Rokach, L. Ensemble learning: a survey. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 8(4), e1249 (2018).

- Zhang, C. & Ma, Y. (eds) Ensemble Machine Learning: Methods and Applications (Springer, 2012).

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (Springer, 2009).

- Schapire, R. E. & Singer, Y. Improved boosting algorithms using Confidence-rated predictions. Mach. Learn. 37, 297-336 (1999).

- Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A Decision-Theoretic generalization of On-Line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 55(1), 119-139 (1997).

- Weisberg, S. Applied Linear Regression (Wiley, 2005).