DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s447496

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38707615

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-01

التقدم في تكنولوجيا النانو لتعزيز الذوبانية والتوافر الحيوي للأدوية ذات الذوبانية الضعيفة

الملخص

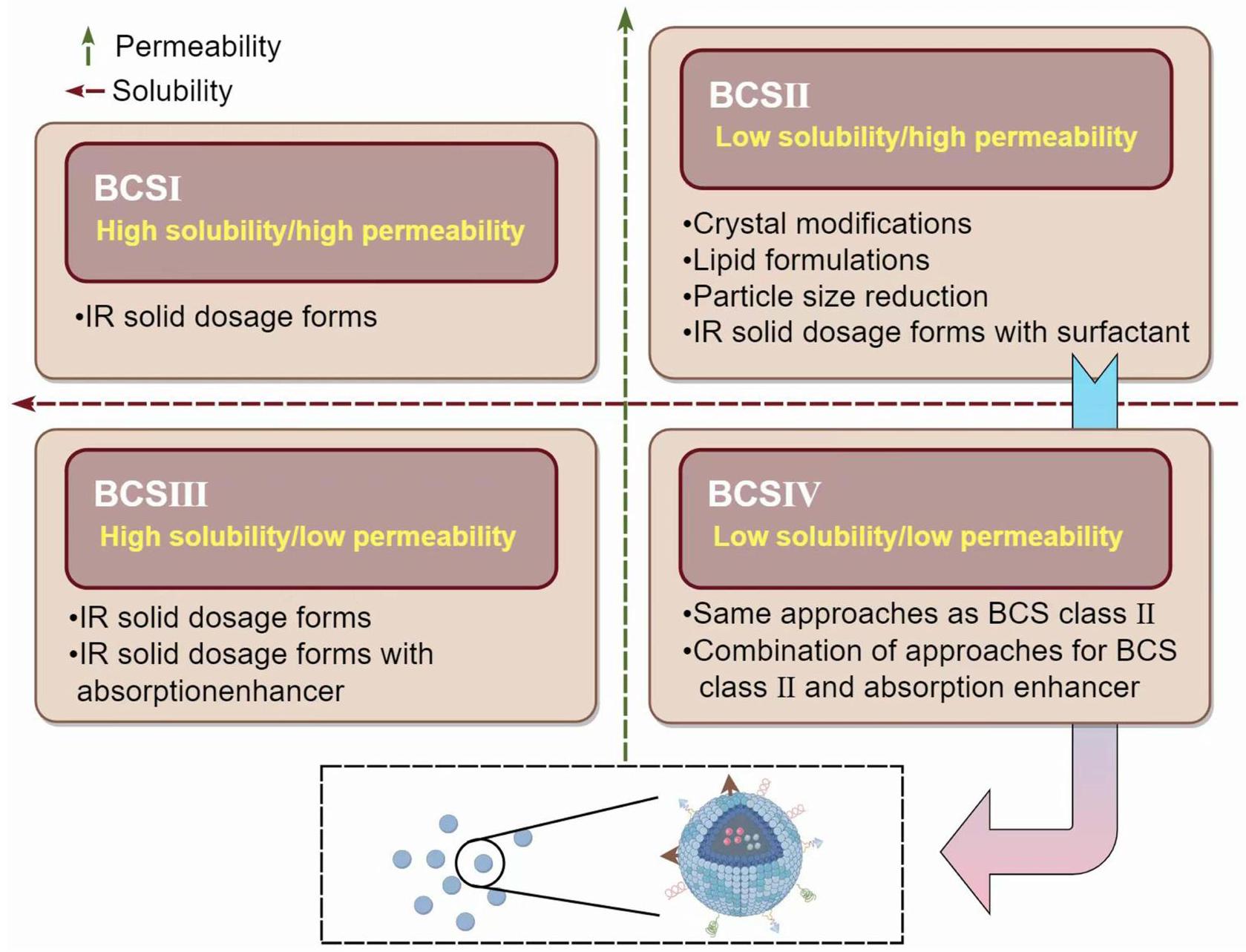

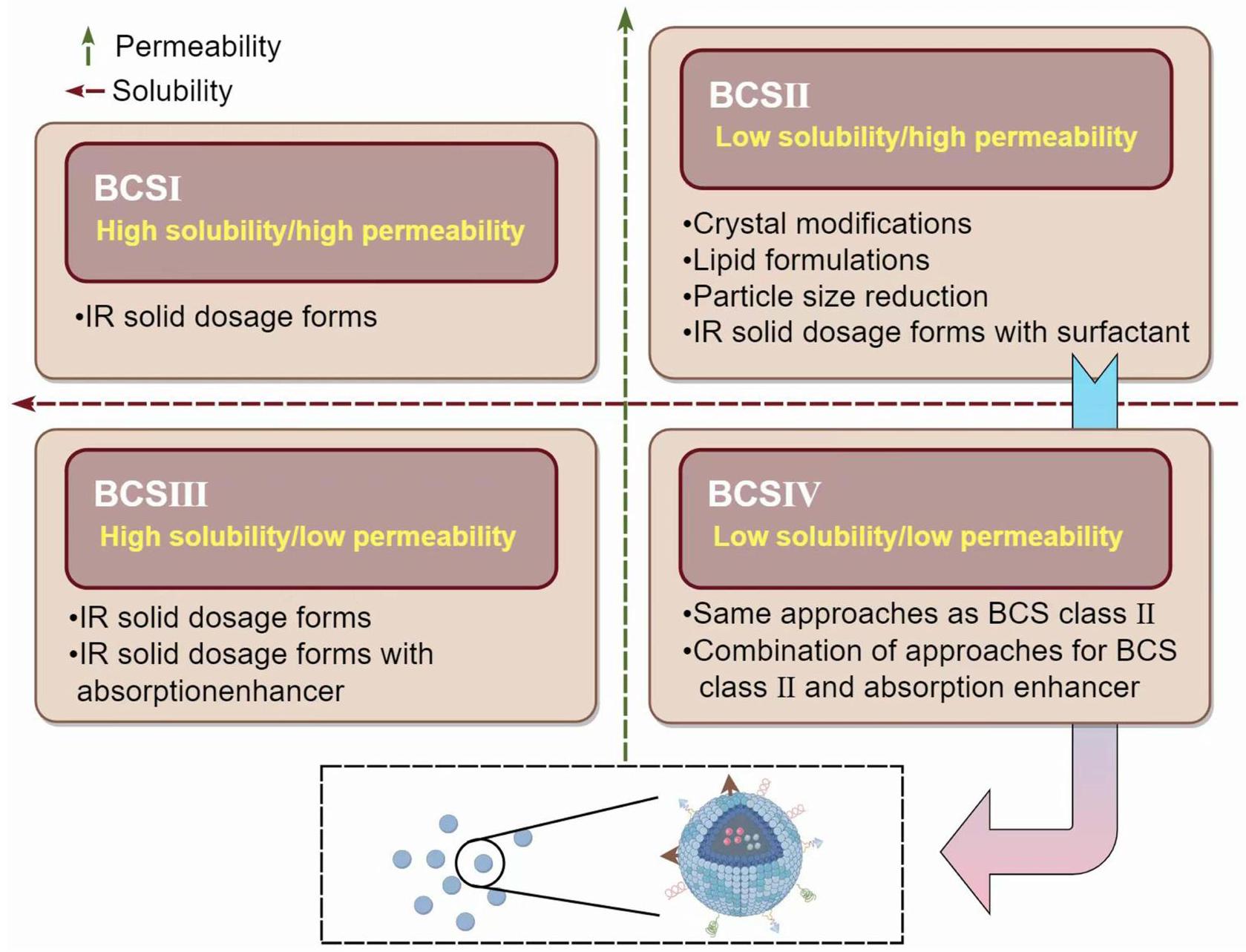

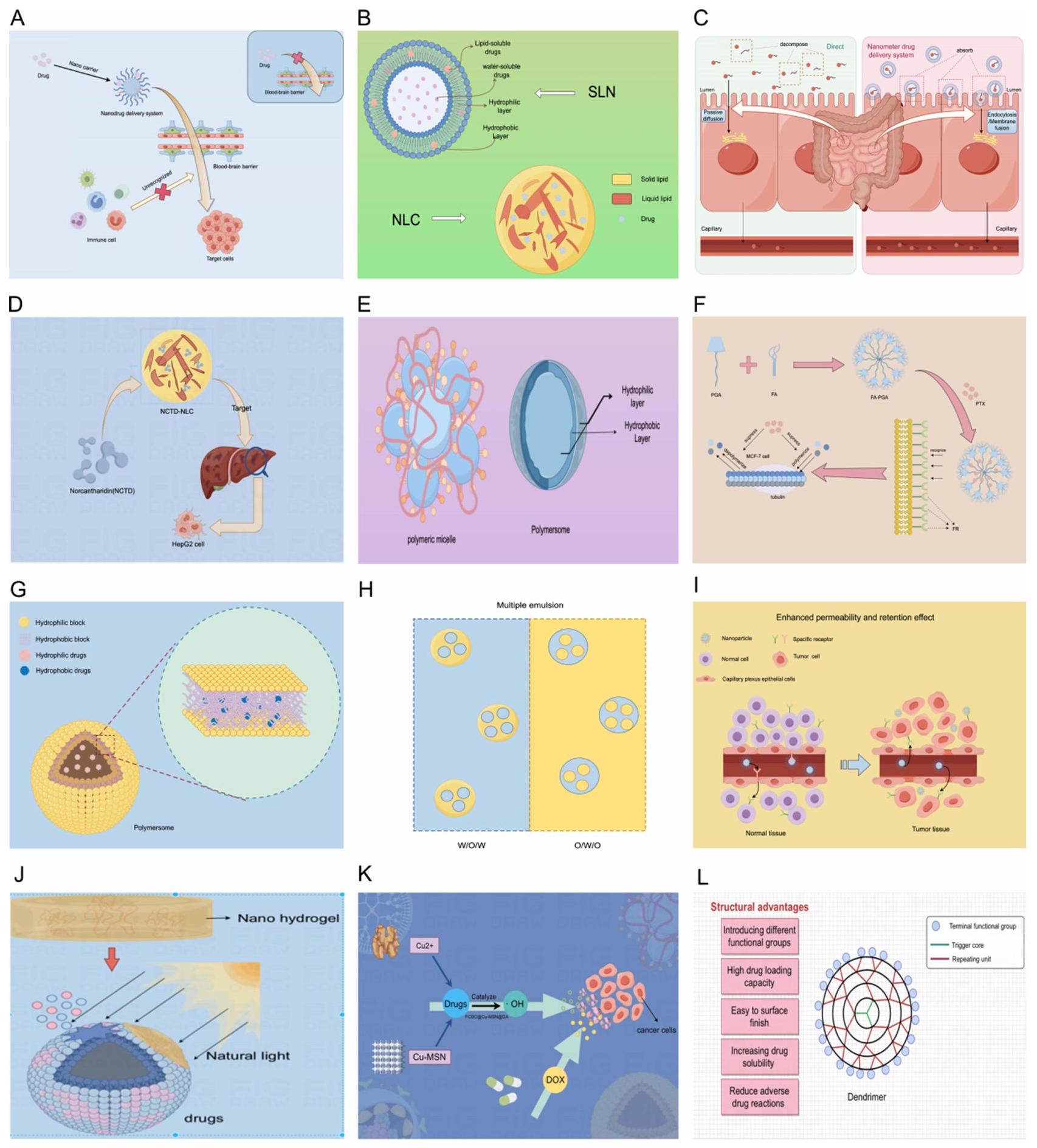

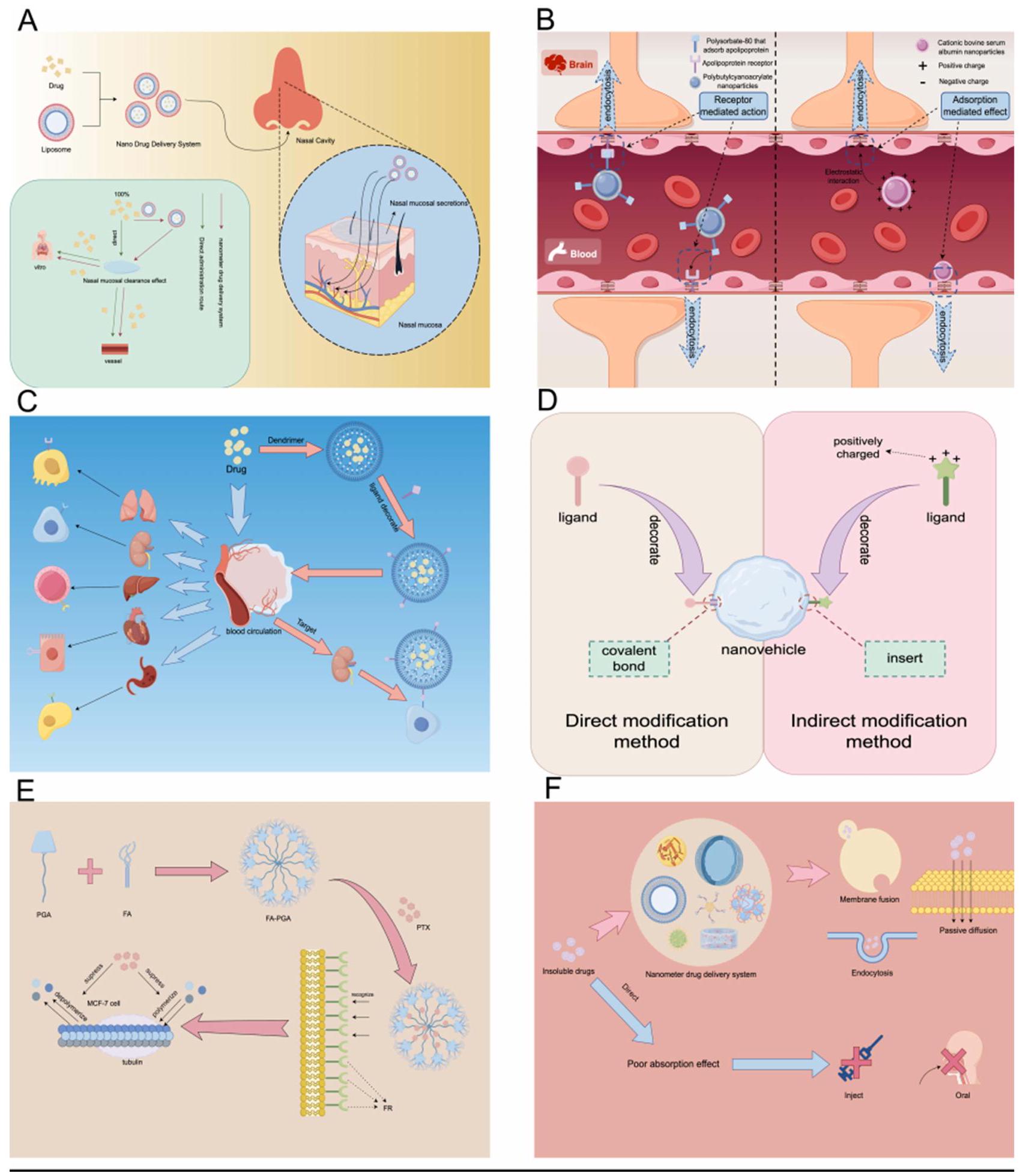

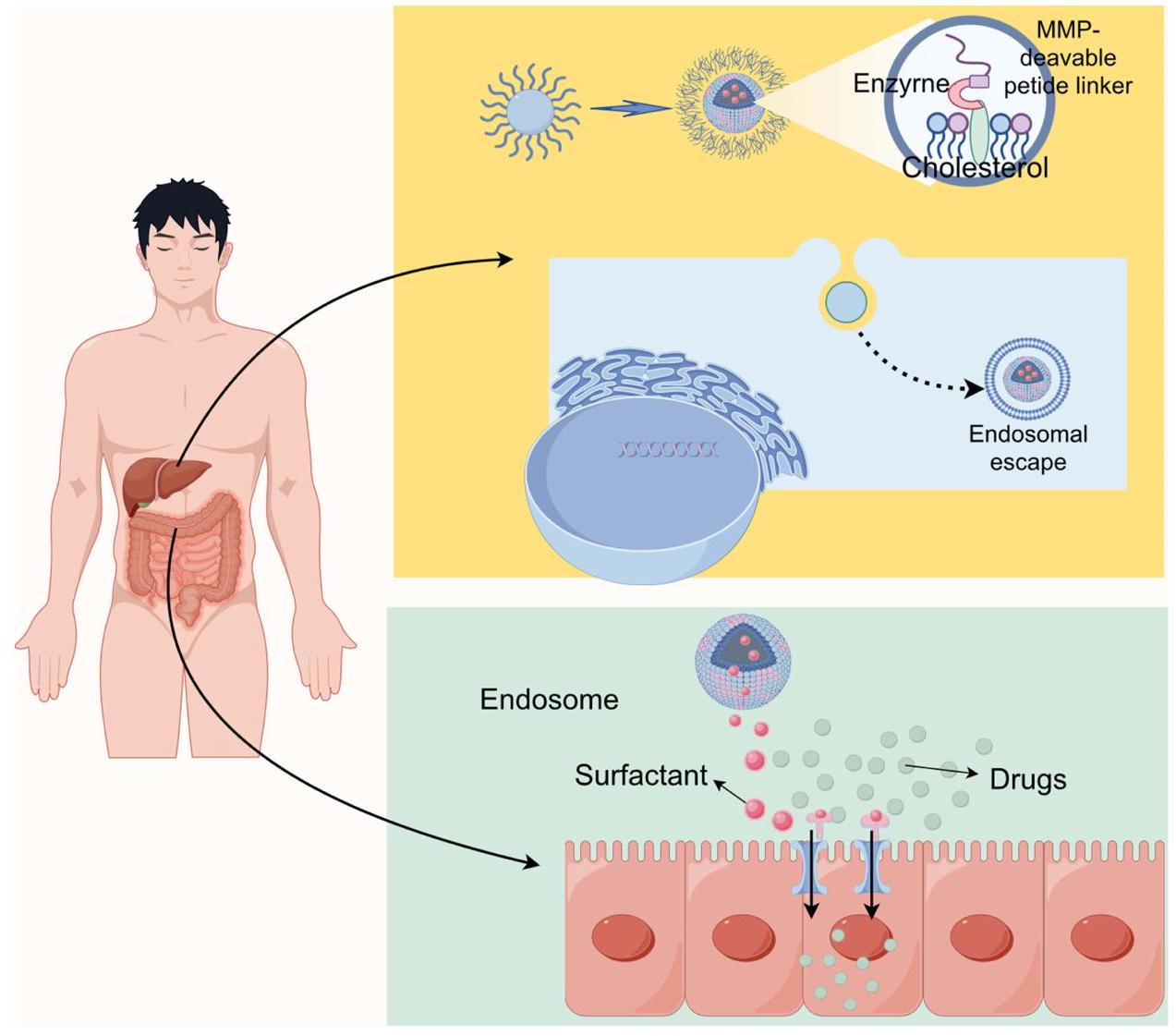

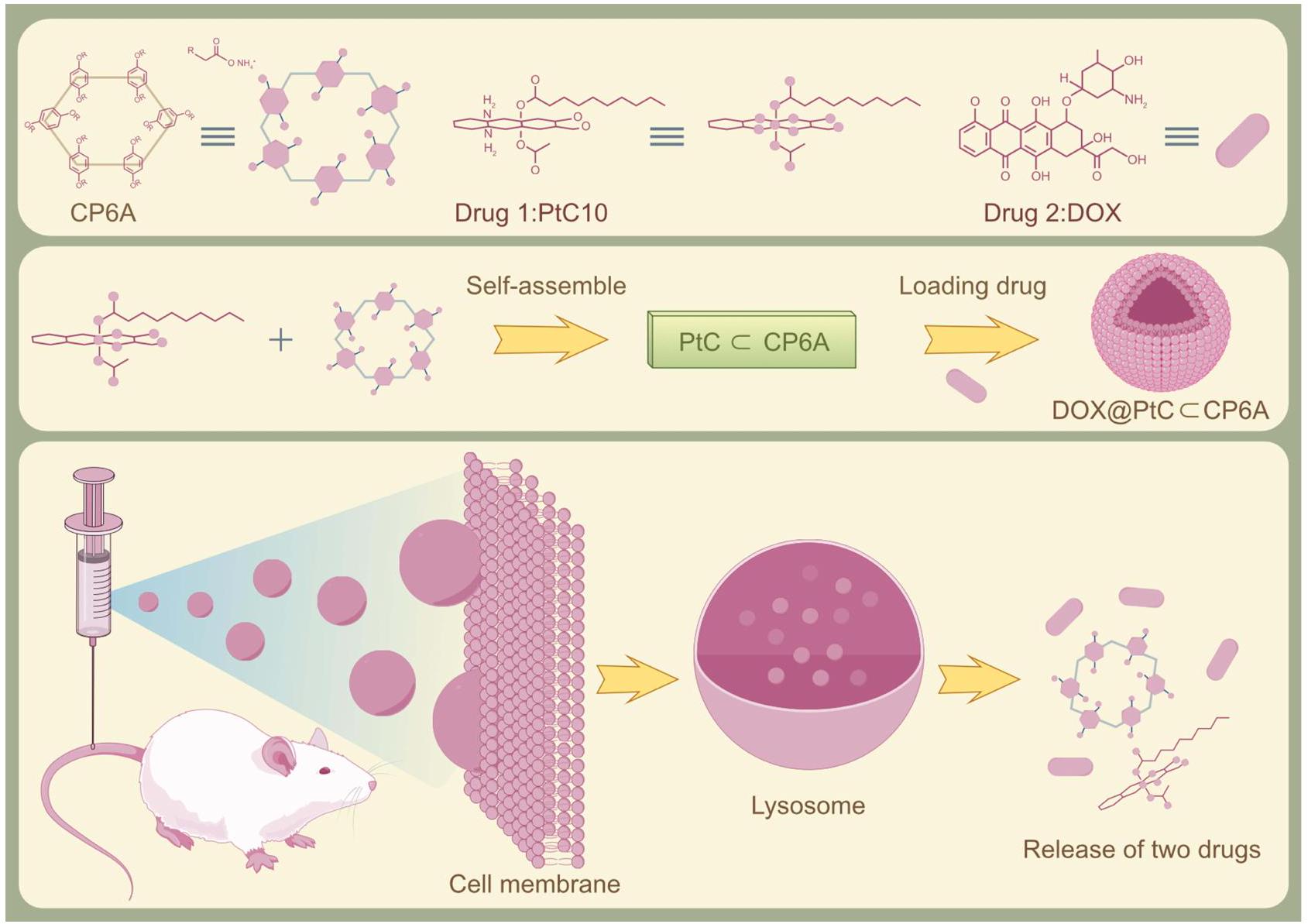

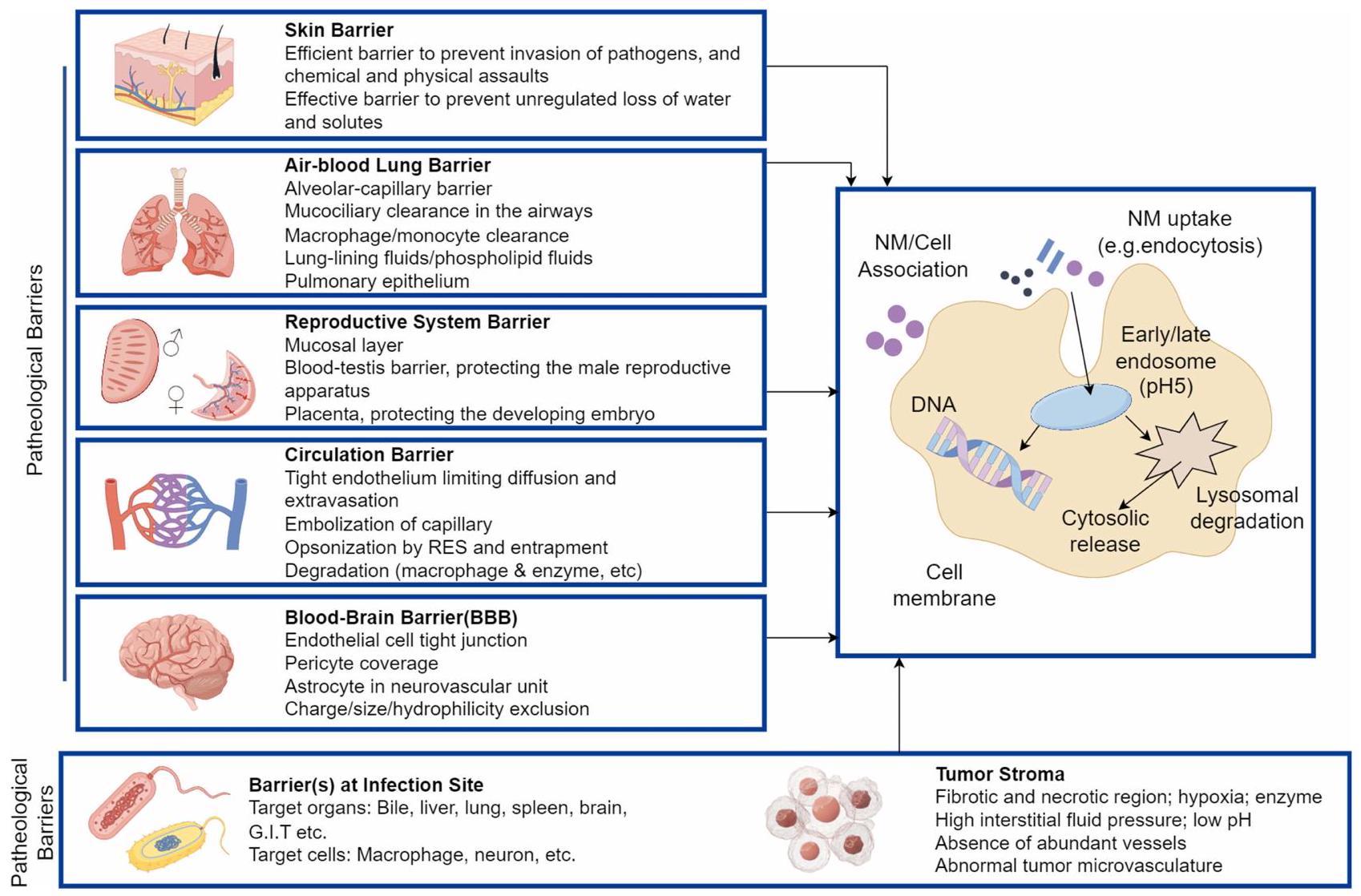

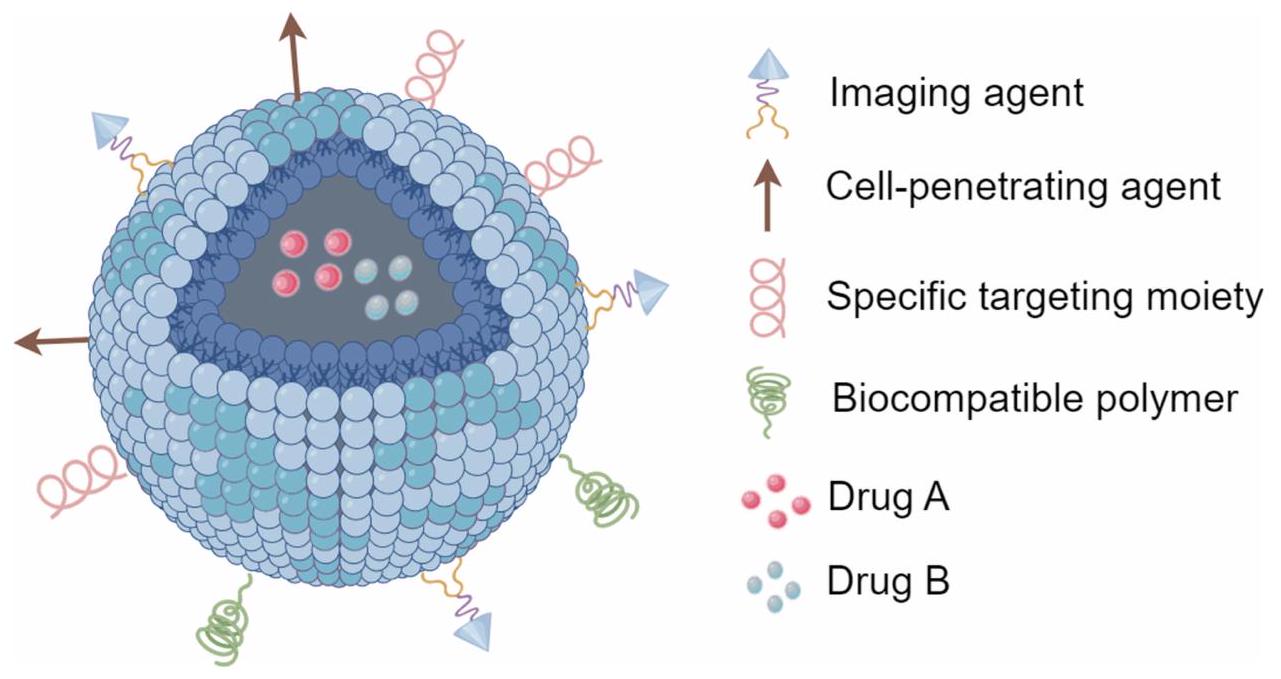

تقدم هذه المخطوطة نظرة شاملة على تأثير تكنولوجيا النانو على الذوبانية والتوافر البيولوجي للأدوية ذات الذوبانية الضعيفة، مع التركيز على الأدوية من الفئة الثانية والرابعة وفقًا لنظام تصنيف الأدوية (BCS). نستكشف أنظمة توصيل الأدوية على النانو (NDDSs) المختلفة، بما في ذلك الأنظمة القائمة على الدهون، والبوليمرات، والامولسيونات النانوية، والهلام النانوي، والناقلات غير العضوية. تقدم هذه الأنظمة فعالية دوائية محسنة، واستهدافًا، وتقليلًا للآثار الجانبية. مع التأكيد على الدور الحاسم لحجم الجسيمات النانوية وتعديلات السطح، تناقش المراجعة التقدم في NDDSs لتحقيق نتائج علاجية محسنة. يتم الاعتراف بالتحديات مثل تكلفة الإنتاج والسلامة، ومع ذلك يتم تسليط الضوء على إمكانيات NDDSs في تحويل طرق توصيل الأدوية. تؤكد هذه المساهمة على أهمية تكنولوجيا النانو في الهندسة الصيدلانية، مقترحةً أنها تقدم تقدمًا كبيرًا للتطبيقات الطبية ورعاية المرضى.

المقدمة

تقليل الأضرار التي تلحق بالأنسجة السليمة بشكل كبير. ثانيًا، يمكنها التحكم في معدل إطلاق الدواء، مما يضمن بقاء تركيز الدواء في الدم ضمن نطاق آمن وفعال، وبالتالي التخفيف أو تجنب التفاعلات السامة والسلبية.

تعريف وتصنيف الأدوية ذات الذوبانية الضعيفة

باستخدام الديجوكسين والغريزوفولفين كأمثلة، من الواضح أنه بالنسبة للديجوكسين، فإن حجم الجسيمات الأصغر (مما يشير إلى أعلى

الأدوية من الفئة الأولى BCSII

الأدوية من الفئة الرابعة BCS

المبادئ الأساسية لأنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية

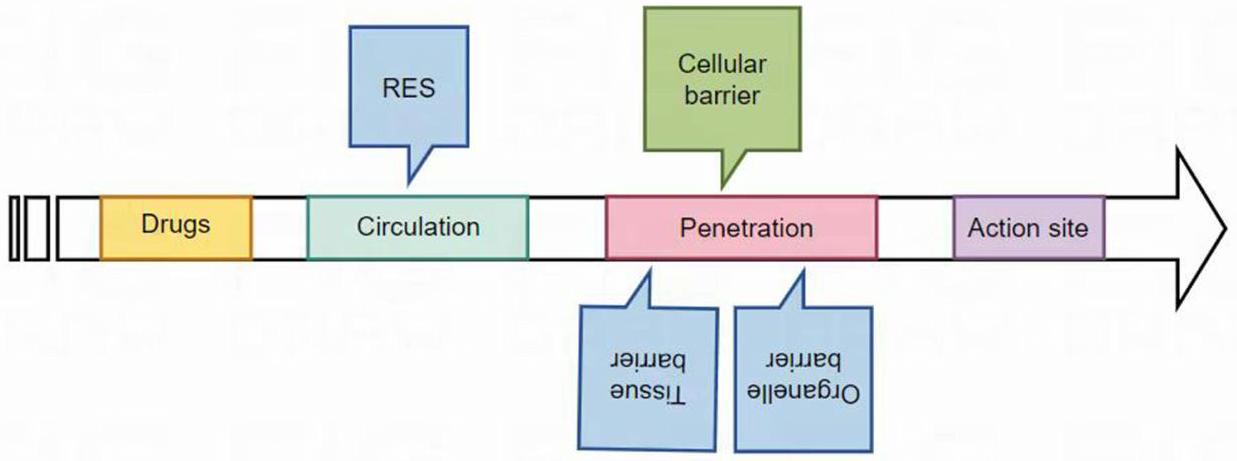

مبادئ عمل أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية

| رقم السجل. | مستحلب | نانو مستحلب |

| I | أقل استقرارًا حركيًا | أكثر استقرارًا حركيًا |

| 2 | المظهر – غائم/معتم | المظهر – واضح |

| 3 | حجم الجسيمات يتراوح من

|

حجم الجسيمات يتراوح من

|

| 4 | غير متجانس في الطبيعة | متجانس في الطبيعة |

| 5 | تركيز أعلى من السطحي (20-25%) | تركيز أقل من السطحي (5-10%) |

| 6 | تستخدم عادةً طريقة العجينة الرطبة وطريقة العجينة الجافة للتحضير | تستخدم طريقة الاستحلاب عالية الطاقة وطريقة الاستحلاب منخفضة الطاقة |

| 7 | قد تحدث مشاكل استقرار مثل التكتل، والانقلاب الطوري، والترسيب، إلخ. | لا تحدث هذه الأنواع من المشاكل. |

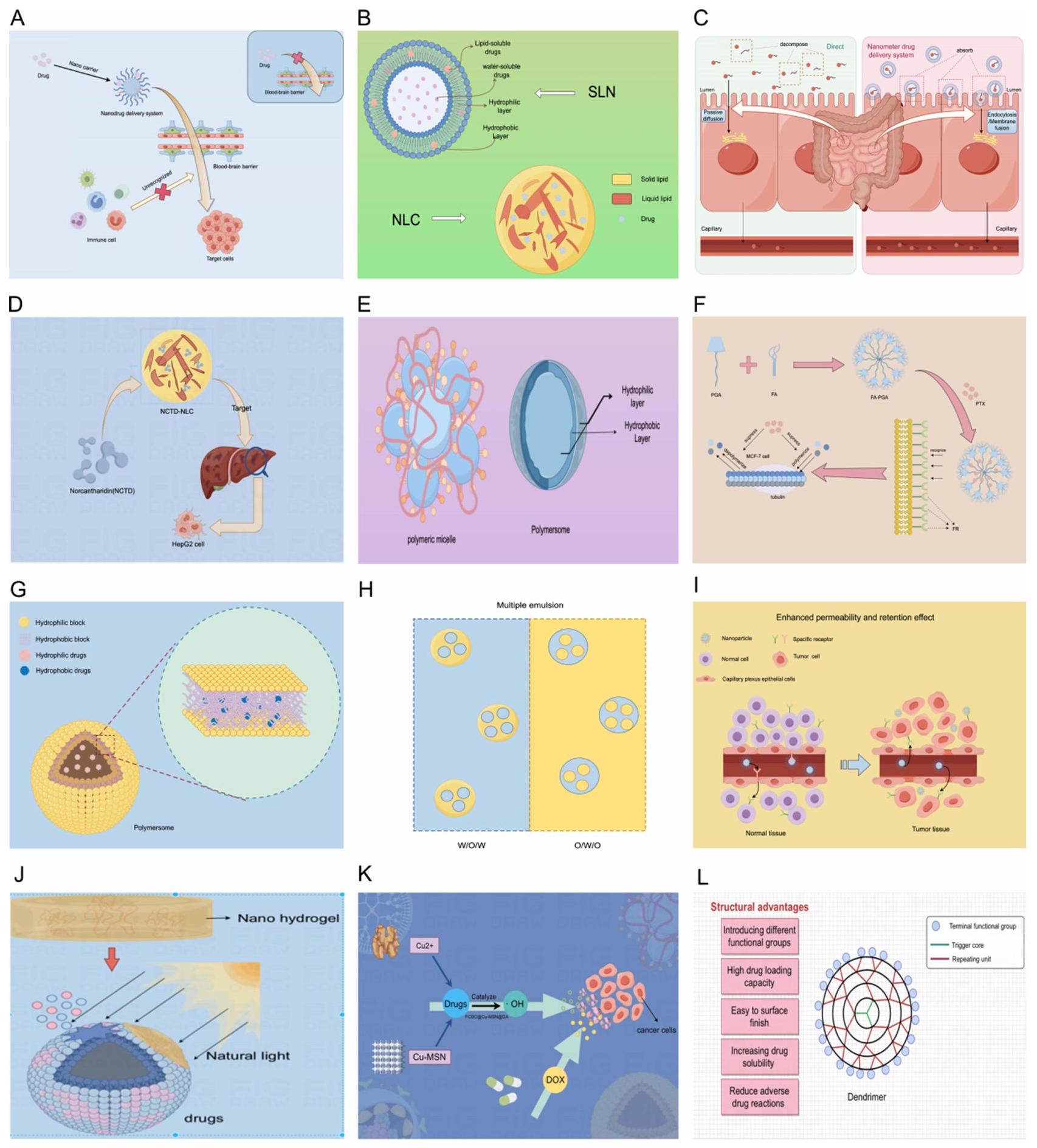

أنواع وخصائص أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية

حاملات نانوية ليفوسومية

ناقلات النانو البوليمر

الخاصية التخفي تسمح للميسيلات بالدوران لفترات طويلة، مما، بالتزامن مع تأثير النفاذية والاحتفاظ المعزز (EPR)، يمكنها من التراكم بشكل تفضيلي في أنسجة الورم من خلال آليات الاستهداف السلبي. يكون تأثير EPR بارزًا بشكل خاص في الحالات المرضية التي تعاني من تصريف لمفاوي compromised، مثل السرطان، حيث يمكن استغلاله لتوصيل تركيزات عالية من الدواء مباشرة إلى موقع الورم، مما يعزز فعالية العلاج مع تقليل السمية النظامية.

الان emulsions

الهيدروجيلات النانوية

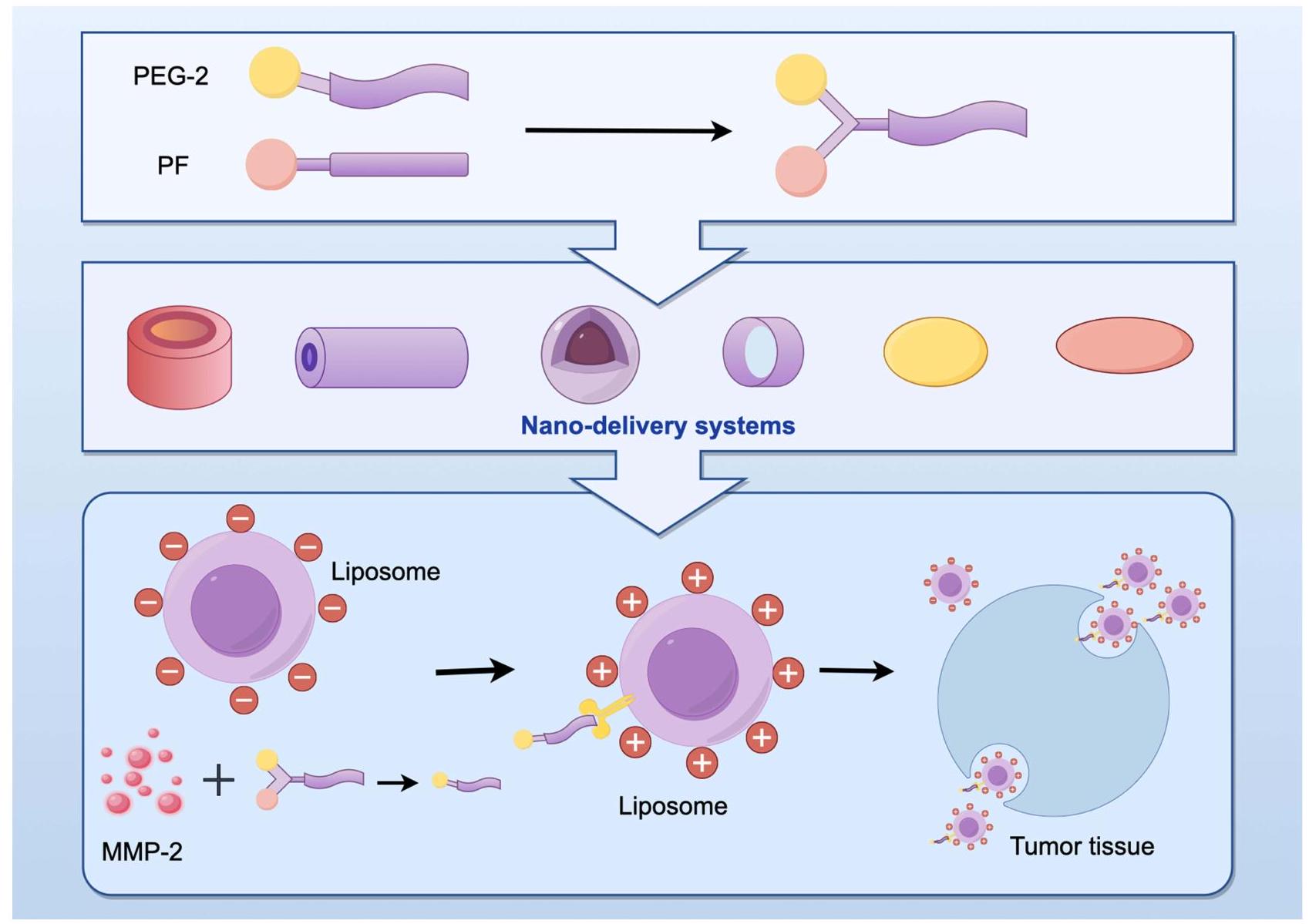

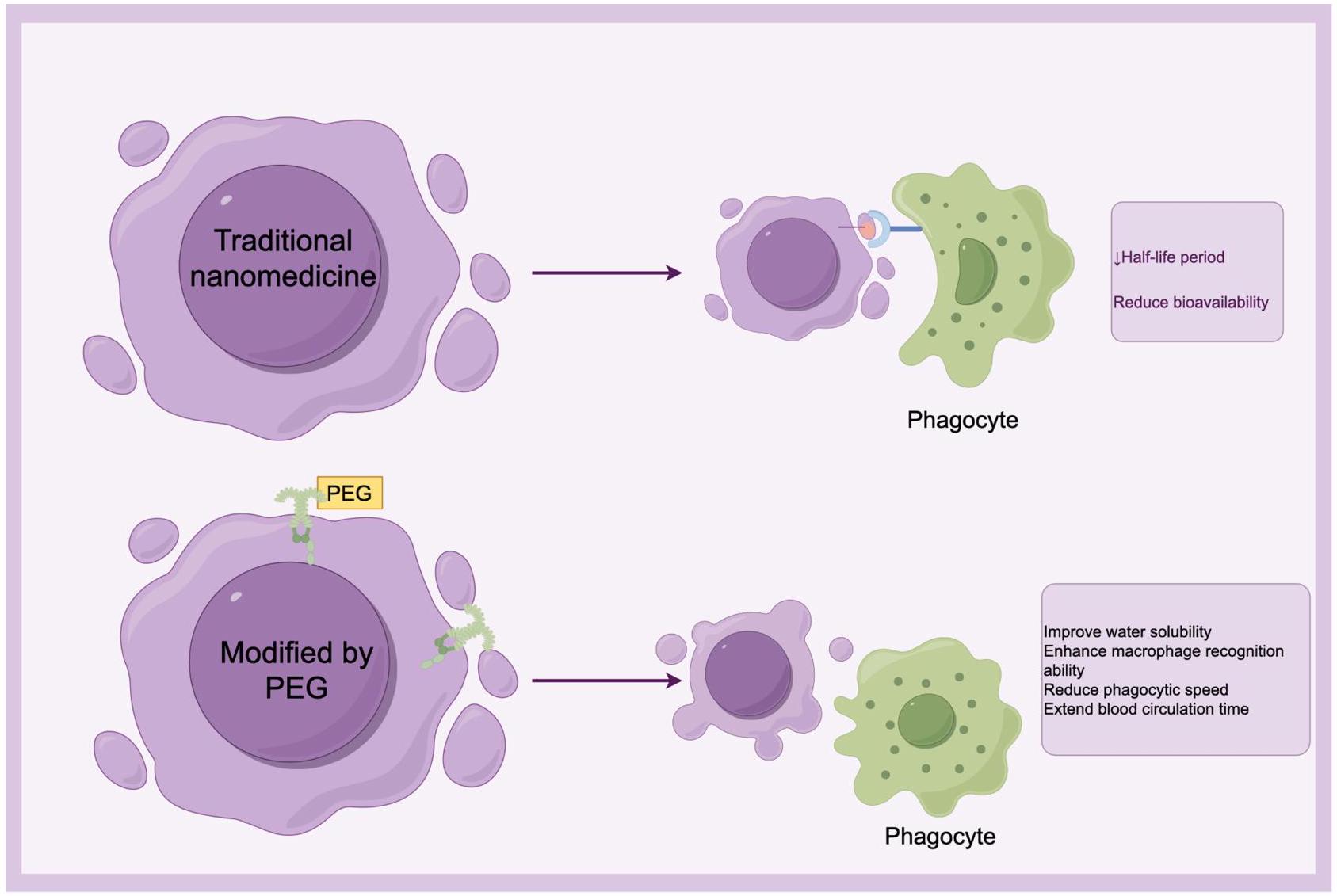

تجنب البلعمة من قبل البلعميات، وزيادة التعرف على الخلايا، مما يجعلها مناسبة لاستراتيجيات توصيل الأدوية المختلفة.

حاملات نانوية غير عضوية

حاملات بوليمرية شجرية

تتكون هذه المواد من نواة ابتدائية، وحدات تكرار داخلية، ومجموعات وظيفية نهائية، وقد تطورت من خلال عدة طرق تركيبية، بما في ذلك الطرق المتباينة، المتقاربة، مزيج من المتباينة والمتقاربة، وطرق التركيب في الطور الصلب. من خلال ربط مجموعات وظيفية مختلفة بأطراف البوليمرات الشجرية، يمكن لهذه المواد تلبية تطبيقات محددة. وهي معروفة بسعتها العالية لتحميل الأدوية، وسهولة تعديل السطح، وإطلاق الأدوية بشكل منظم، وزيادة ذوبانية الأدوية، وتقليل ردود الفعل السلبية للأدوية، كما هو موضح في الشكل

أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية الذكية المستجيبة

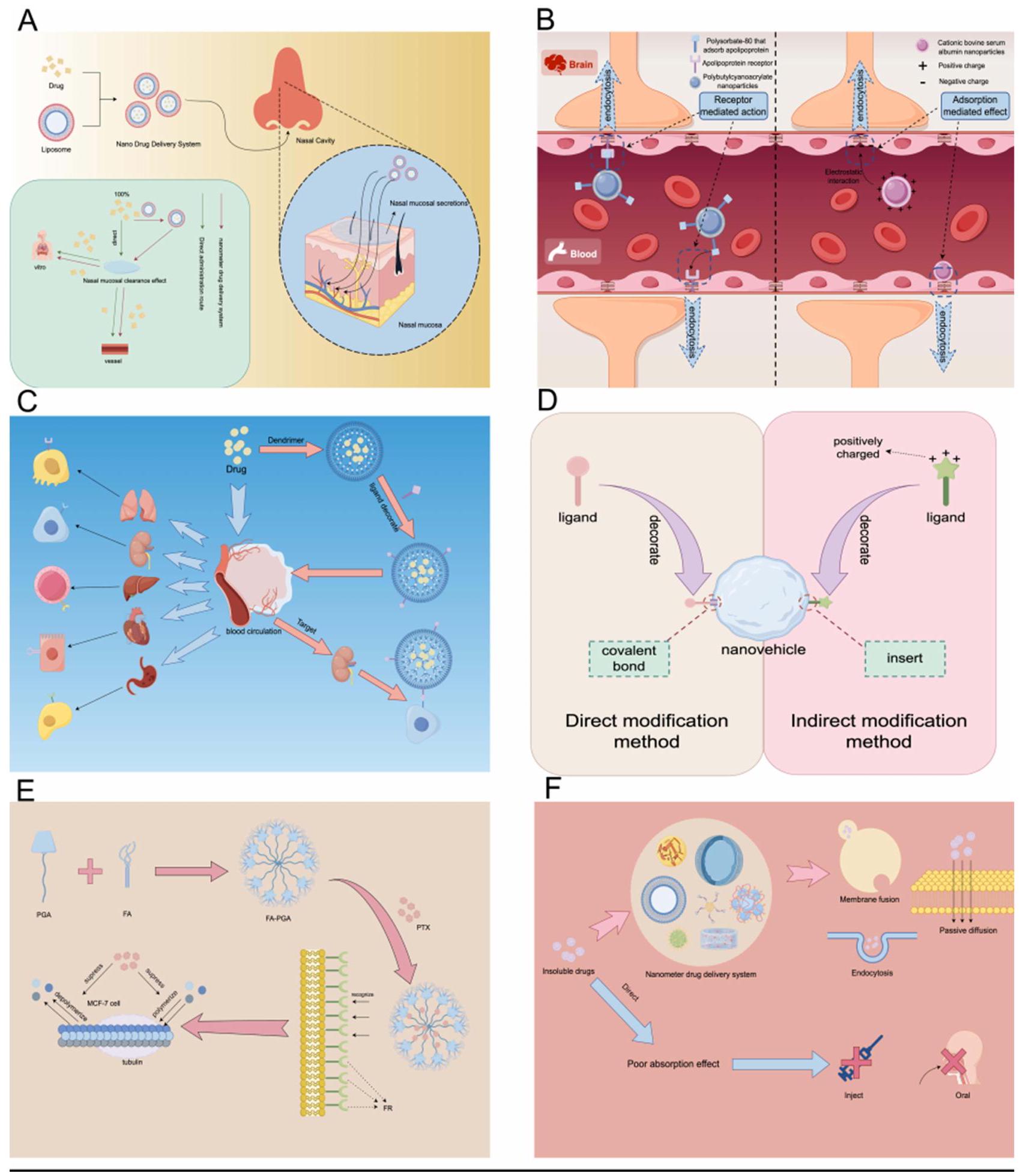

آليات أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية لتحسين ذوبانية الأدوية ذات الذوبانية الضعيفة

تكنولوجيا النانو

تقنيات تعديل السطح

مما يزيد من امتصاص الخلايا وبالتالي فعالية الدواء، كما هو موضح في الشكل 3C. هناك طريقتان رئيسيتان لتعديلات الاستهداف النشطة: واحدة تتضمن التعديل المباشر من خلال الربط التساهمي للروابط بحوامل الأدوية ذات المجموعات الوظيفية النشطة؛

تقنيات الوسيط الحامل

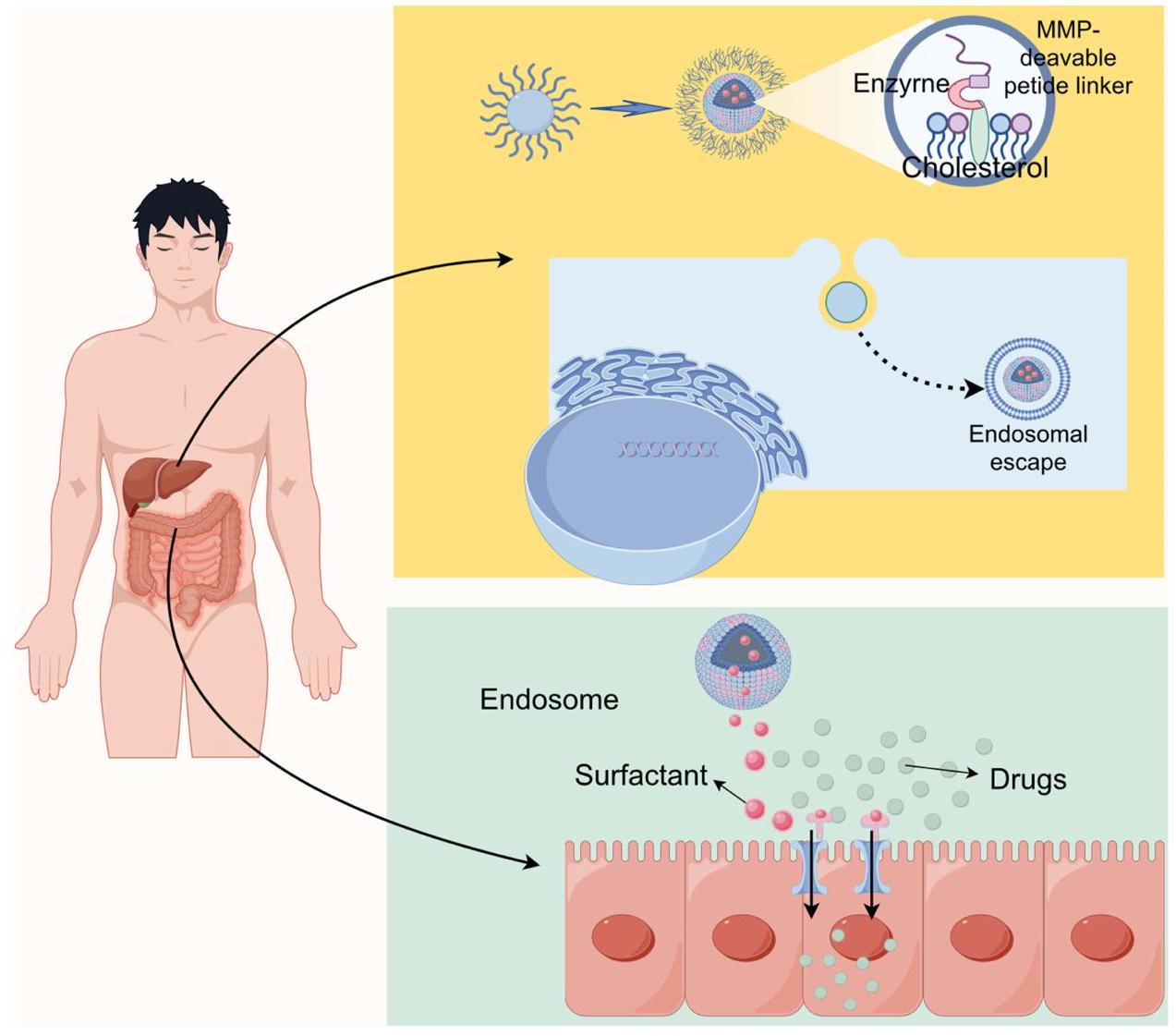

آليات تعزيز التوافر الحيوي في أنظمة توصيل الأدوية النانوية

تعزيز امتصاص الخلايا

وناقلات البيتاين.

تعزيز الإفراز داخل الخلايا

تجنب الأيض المبكر للأدوية

مزايا وتحديات أنظمة توصيل الأدوية في النانوميديسين

المزايا

تعزيز استقرار الأدوية

إطالة وقت الدورة الدموية

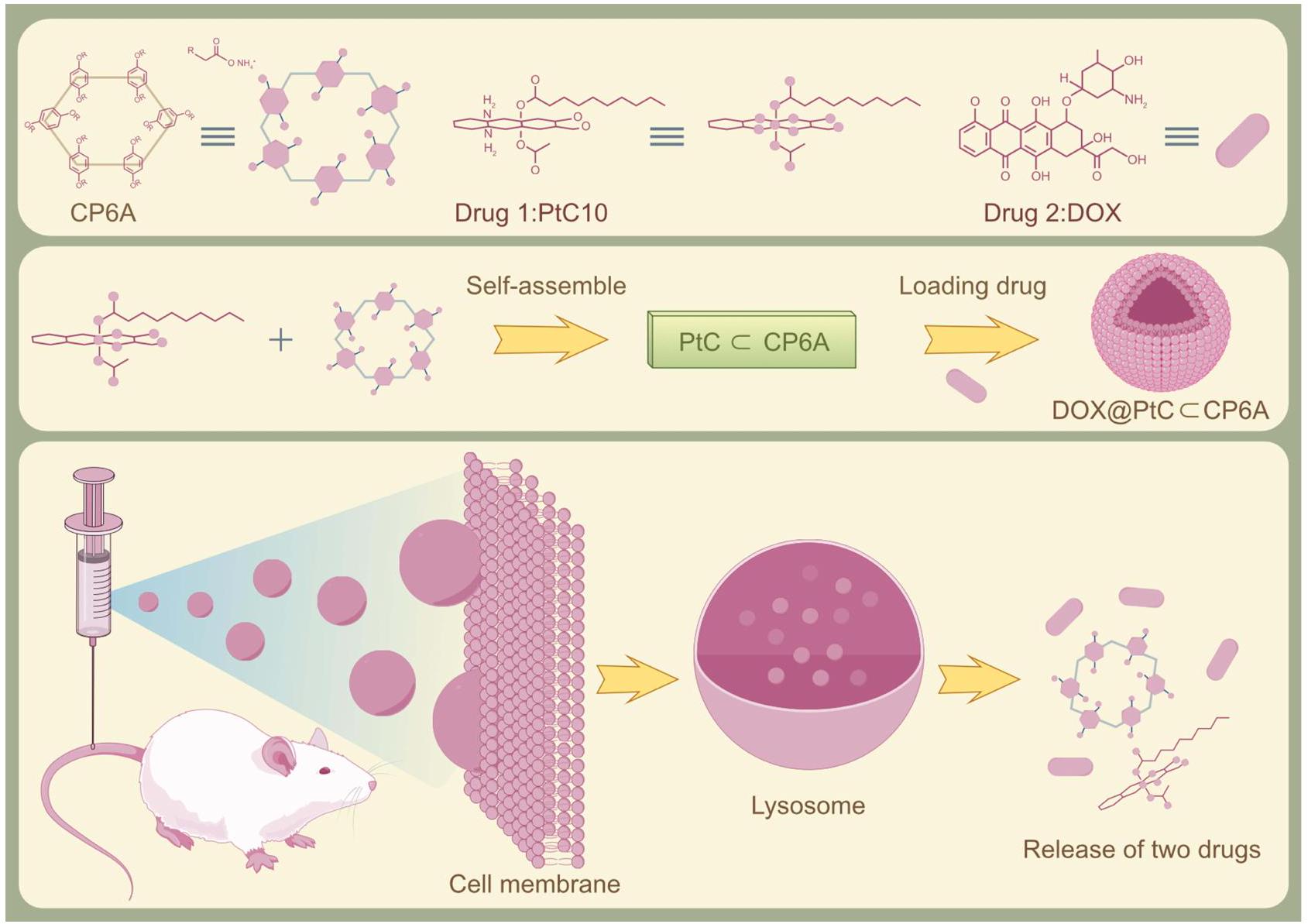

التوصيل المستهدف والعلاج المركب باستخدام أدوية متعددة

التحديات

قضايا التكلفة

مخاوف السلامة

نقص في التوحيد القياسي وقابلية التوسع

أحدث التطورات البحثية ودراسات الحالة

| فئات | سنة الموافقة | تركيبات دوائية | شركات | التطبيقات السريرية |

| جزيئات نانوية ليبوزومية | 2015 | إيرينوتيكان | ميريمك للأدوية (كامبريدج، المملكة المتحدة) | سرطان البنكرياس النقيلي |

| 2021 | بروتين CSP المؤتلف | كلاركسو سميث كلاين (ميدلسكس، المملكة المتحدة) | الملاريا | |

| 2021 | BNT162b2 | فايزر (نيويورك، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة) وبيونتيك (ماينز، ألمانيا) | كوفيد-19 |

| الفئات | سنة الموافقة | تركيبات دوائية | شركات | التطبيقات السريرية |

| جزيئات نانوية بوليمرية | 2012 | دوستكسل | شركة ساميانغ للأدوية (سيول، جمهورية كوريا) | سرطان الثدي، سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا، وسرطان المبيض |

| 2015 | بي تي إكس | أوزميا للأدوية (أوبسالا، السويد) | سرطان المبيض | |

| نانكرستالات الأدوية | 2018 | أريبيبرازول لوروكسيلي | ألكيرميس إنك (والثام، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) | الفصام |

| ٢٠٢١ | كابوتيجرافير | شركة فيي للرعاية الصحية (برينتفورد، لندن، المملكة المتحدة) | عدوى فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية من النوع الأول | |

| أدوية نانوية أخرى | 2010 | جزيء الحديد مع جزيئات الكربوهيدرات غير المتفرعة | فارماكوسموس (رورفانغسفي، هولباك، الدنمارك) | فقر الدم الناتج عن نقص الحديد |

| 2013 | جزيئات أكسيد هيدروكسيد الحديد الثلاثي متعدد النوى | فورلنت. (والثام، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) | فقر الدم الناتج عن نقص الحديد | |

| 2015 | عامل التخثر المضاد للهيموفيليا الثامن المؤتلف | باكزالتا (مونتغومري، ألاباما، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) | الهيموفيليا أ |

الخاتمة والتطلعات

داخل حوامل عالية الذوبانية، مما يؤدي إلى امتصاص الخلايا عبر الانتشار الساكن، واندماج الغشاء، والابتلاع الخلوي.

الاختصارات

مساهمات المؤلفين

الإفصاح

References

- Prabhu P, Patravale V. Dissolution enhancement of atorvastatin calcium by co-grinding technique. Drug Delivery Transl Res. 2016;6 (4):380-391. doi:10.1007/s13346-015-0271-x

- Khalid Q, Ahmad M, Minhas MU, et al. Synthesis of

-cyclodextrin hydrogel nanoparticles for improving the solubility of dexibuprofen: characterization and toxicity evaluation. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2017;43(11):1873-1884. doi:10.1080/03639045.2017.1350703 - Jermain SV, Brough C, Williams RO, et al. Amorphous solid dispersions and nanocrystal technologies for poorly water-soluble drug delivery An update. Int J Pharm. 2018;535(1-2):379-392. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.051

- Liu Y, Wang T, Ding W, et al. Dissolution and oral bioavailability enhancement of praziquantel by solid dispersions. Drug Delivery Transl Res. 2018;8(3):580-590. doi:10.1007/s13346-018-0487-7

- Baghel S, Cathcart H, O’Reilly NJ, et al. Polymeric Amorphous Solid Dispersions: a Review of Amorphization, Crystallization, Stabilization, Solid-State Characterization, and Aqueous Solubilization of Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II Drugs. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;105(9):2527-2544. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2015.10.008

- Hua S. Advances in Oral Drug Delivery for Regional Targeting in the Gastrointestinal Tract – Influence of Physiological, Pathophysiological and Pharmaceutical Factors. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11(524). doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00524

- Shreya AB, Raut SY, Managuli RS, et al. Active Targeting of Drugs and Bioactive Molecules via Oral Administration by Ligand-Conjugated Lipidic Nanocarriers: recent Advances. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2018;20(1):15. doi:10.1208/s12249-018-1262-2

- Siddiqui K, Waris A, Akber H, et al. Physicochemical Modifications and Nano Particulate Strategies for Improved Bioavailability of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Pharm nanotechnol. 2017;5(4):276-284. doi:10.2174/2211738506666171226120748

- Rubin KM, Vona K, Madden K, et al. Side effects in melanoma patients receiving adjuvant interferon alfa-2b therapy: a nurse’s perspective. Supportive Care Cancer. 2012;20(8):1601-1611. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1473-0

- Da Silva FL, Marques MB, Kato KC, et al. Nanonization techniques to overcome poor water-solubility with drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2020;15(7):853-864. doi:10.1080/17460441.2020.1750591

- Prakash S. Nano-based drug delivery system for therapeutics: a comprehensive review. Biomed Phys Eng Express. 2023;9(5):10.1088/20571976/acedb2. doi:10.1088/2057-1976/acedb2

- Harder BG, et al. Developments in Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrance and Drug Repurposing for Improved Treatment of Glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2018;8(462). doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00462

- Zhai X, Lademann J, Keck CM, et al. Nanocrystals of medium soluble actives–novel concept for improved dermal delivery and production strategy. Int J Pharm. 2014;470(1-2):141-150. doi:10.1016/j.jjpharm.2014.04.060

- Kataoka M, Yonehara A, Minami K, et al. Control of Dissolution and Supersaturation/Precipitation of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs from Cocrystals Based on Solubility Products: a Case Study with a Ketoconazole Cocrystal. Mol Pharmaceut. 2023;20(8):4100-4107. doi:10.1021/ acs.molpharmaceut.3c00237

- Haering B, Seyferth S, Schiffter HA, et al. The tangential flow absorption model (TFAM) – A novel dissolution method for evaluating the performance of amorphous solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble actives. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2020;154:74-88. doi:10.1016/j. ejpb.2020.06.013

- Yang M, Chen T, Wang L, et al. High dispersed phyto-phospholipid complex/TPGS 1000 with mesoporous silica to enhance oral bioavailability of tanshinol. Colloids Surf B. 2018;170:187-193. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.06.013

- Kawabata Y, Wada K, Nakatani M, et al. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: basic approaches and practical applications. Int J Pharm. 2011;420(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.032

- Takagi T, Ramachandran C, Bermejo M, et al. A provisional biopharmaceutical classification of the top 200 oral drug products in the United States, Great Britain, Spain, and Japan. Mol Pharmaceut. 2006;3(6):631-643. doi:10.1021/mp0600182

- Amidon GL, Lennernäs H, Shah VP, et al. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12(3):413-420. doi:10.1023/a:1016212804288

- Bhatt S, ROY D, KUMAR M, et al. Development and Validation of In Vitro Discriminatory Dissolution Testing Method for Fast Dispersible Tablets of BCS Class II Drug. Turkish j Pharm Sci. 2020;17(1):74-80. doi:10.4274/tjps.galenos.2018.90582

- Fraser EJ, Leach RH, Poston JW, et al. Dissolution and bioavailability of digoxin tablets. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1973;25(12):968-973. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1973.tb09988.x

- Johnson BF, O’Grady J, Bye C, et al. The influence of digoxin particle size on absorption of digoxin and the effect of propantheline and metoclopramide. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1978;5(5):465-467. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb01657.x

- Chi-Yuan W, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition via application of BCS: transport/absorption/ elimination interplay and development of a biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system. Pharm Res. 2005;22(1):11-23. doi:10.1007/s11095-004-9004-4

- Löbenberg R, Amidon GL. Modern bioavailability, bioequivalence and biopharmaceutics classification system. New scientific approaches to international regulatory standards. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2000;50(1):3-12. doi:10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00091-6

- Hattori Y, Haruna Y, Otsuka M, et al. Dissolution process analysis using model-free Noyes-Whitney integral equation. Colloids Surf B. 2013;102:227-231. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.017

- Kesisoglou F, Mitra A. Crystalline nanosuspensions as potential toxicology and clinical oral formulations for BCS II/IV compounds. AAPS J. 2012;14(4):677-687. doi:10.1208/s12248-012-9383-0

- Yang SG. Biowaiver extension potential and IVIVC for BCS ClassII drugs by formulation design:Case study for cyclosporine self-microemulsifying formulation. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33(11):1835-1842. doi:10.1007/s12272-010-1116-2

- Adachi M, Hinatsu Y, Kusamori K, et al. Improved dissolution and absorption of ketoconazole in the presence of organic acids as pH -modifiers. Eur

Pharm Sci. 2015;76:225-230. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2015.05.015 - Chi L, Wu D, Li Z, et al. Modified Release and Improved Stability of Unstable BCSII Drug by Using Cyclodextrin Complex as Carrier To Remotely Load Drug into Niosomes. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(1):113-124. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00566

- Verma H, Garg R. Development of a bio-relevant pH gradient dissolution method for a high-dose, weakly acidic drug, its optimization and IVIVC in Wistar rats: a case study of magnesium orotate dihydrate. Magnesium Res. 2022;35(3):88-95. doi:10.1684/mrh.2022.0505

- Efentakis M, Dressman JB. Gastric juice as a dissolution medium: surface tension and pH. Eur j Drug Metab Pharm. 1998;23(2):97-102. doi:10.1007/BF03189322

- Mithani SD, Bakatselou V, TenHoor CN, et al. Estimation of the increase in solubility of drugs as a function of bile salt concentration. Pharm Res. 1996;13(1):163-167. doi:10.1023/a:1016062224568

- Bakatselou V, Oppenheim RC, Dressman JB, et al. Solubilization and wetting effects of bile salts on the dissolution of steroids. Pharm Res. 1991;8(12):1461-1469. doi:10.1023/a:1015877929381

- Charman WN, Porter CJH, Mithani S, et al. Physiochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: the role of lipids and pH. J Pharmaceut Sci. 1997;86(3):269-282. doi:10.1021/js960085v

- La Sorella G, Sperni L, Canton P, et al. Selective Hydrogenations and Dechlorinations in Water Mediated by Anionic Surfactant-Stabilized Pd Nanoparticles. J Org Chem. 2018;83(14):7438-7446. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00314

- Singh KK, Vingkar SK. Formulation, antimalarial activity and biodistribution of oral lipid nanoemulsion of primaquine.Int. J Pharm. 2008;347 (1-2):567.

- Kalepu S, Nekkanti V. Insoluble drug delivery strategies: review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharma Sin. 2015;5 (5):442-453. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.003

- Hirose R, Sugano K. Effect of Food Viscosity on Drug Dissolution. Pharm Res. 2024;41(1):105-112. doi:10.1007/s11095-023-03620-y

- Amidon GL, Leesman GD, Elliott RL, et al. Improving intestinal absorption of water-insoluble compounds: a membrane metabolism strategy. J Pharmaceut Sci. 1980;69(12):1363-1368. doi:10.1002/jps. 2600691203

- Mistry A, Stolnik S, Illum L, et al. Nanoparticles for direct nose-to-brain delivery of drugs. Int J Pharm. 2009;379(1):146-157. doi:10.1016/j. ijpharm.2009.06.019

- Yuan S, Zhang Q. Application of One-Dimensional Nanomaterials in Catalysis at the Single-Molecule and Single-Particle Scale. Front Chem. 2021;9(812287). doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.812287

- Hegewald AB , Breitwieser K, Ottinger SM, et al. Extracellular miR-574-5p Induces Osteoclast Differentiation via TLR 7/8 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585282. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.585282

- Han L, Jiang C. Evolution of blood-brain barrier in brain diseases and related systemic nanoscale brain-targeting drug delivery strategies. Acta Pharma Sin. 2021;11(8):2306-2325. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.11.023

- Parodi A, Quattrocchi N, van de Ven AL, et al. Synthetic nanoparticles functionalized with biomimetic leukocyte membranes possess cell-like functions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(1):61-68. doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.212

- Ugwoke MI, AGU R, VERBEKE N, et al. Nasal mucoadhesive drug delivery: background, applications, trends and future perspectives. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2005;57(11):1640-1665. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.009

- Kanazawa T, Taki H, Tanaka K, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide-modified block copolymer micelles promote direct brain delivery via intranasal administration. Pharm Res. 2011;28(9):2130-2139. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0440-7

- Rafiei P, Haddadi A. Pharmacokinetic Consequences of PLGA Nanoparticles in Docetaxel Drug Delivery. Pharm nanotechnol. 2017;5(1):3-23. doi:10.2174/2211738505666161230110108

- Sridhar V, Gaud R, Bajaj A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intranasally administered selegiline nanoparticles with improved brain delivery in Parkinson’s disease. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(8):2609-2618. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2018.08.004

- Guo Q, Chang Z, Khan NU, et al. Nanosizing Noncrystalline and Porous Silica Material-Naturally Occurring Opal Shale for Systemic Tumor Targeting Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(31):25994-26004. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b06275

- Aslam M, Javed MN, Deeb HH, et al. Lipid Nanocarriers for Neurotherapeutics: introduction, Challenges, Blood-brain Barrier, and Promises of Delivery Approaches. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2022;21(10):952-965. doi:10.2174/1871527320666210706104240

- Large DE, Abdelmessih RG, Fink EA, et al. Liposome composition in drug delivery design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2021;176:113851. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.113851

- Harde H, Das M, Jain S, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles: an oral bioavailability enhancer vehicle. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2011;8 (11):1407-1424. doi:10.1517/17425247.2011.604311

- Damgé C, Michel C, Aprahamian M, et al. New approach for oral administration of insulin with polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanocapsules as drug carrier. Diabetes. 1988;37(2):246-251. doi:10.2337/diab.37.2.246

- Ponchel G, Montisci M-J, Dembri A, Durrer C, Duchêne D. Assia Dembri, Carlo Durrer, Dominique Duchêne,Mucoadhesion of colloidal particulate systems in the gastro-intestinal tract,European. J Pharm Biopharmaceutics. 1997;44(1):25-31. doi:10.1016/S0939-6411(97)00098-2

- Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, et al. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2016;99:28-51. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012

- Souto EB, Baldim I, Oliveira WP, et al. SLN and NLC for topical, dermal, and transdermal drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2020;17 (3):357-377. doi:10.1080/17425247.2020.1727883

- Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2002;54(1):S131-55. doi:10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00118-7

- Xiu-Yan L, Guan Q-X, Shang Y-Z, et al. Metal-organic framework IRMOFs coated with a temperature-sensitive gel delivering norcantharidin to treat liver. World j Gastroenterol. 2021;27(26):4208-4220. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i26.4208

- Pan M-S, Cao J, Fan Y-Z, et al. Insight into norcantharidin, a small-molecule synthetic compound with potential multi-target anticancer activities. ChinMed. 2020;15:55. doi:10.1186/s13020-020-00338-6

- Yan Z, Yang K, Tang X, et al. Norcantharidin Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NCTD-NLC) Suppresses the Viability of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells and Accelerates the Apoptosis. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:3851604. doi:10.1155/2022/3851604

- Akhter MH, Ahmad A, Ali J, et al. Formulation and Development of CoQ10-Loaded s-SNEDDS for Enhancement of Oral Bioavailability.

Pharm Innov. 2014;9:121-131. doi:10.1007/s12247-014-9179-0 - Soni K, Mujtaba A, Akhter MH, et al. Optimisation of ethosomal nanogel for topical nano-CUR and sulphoraphane delivery in effective skin cancer therapy. J Microencapsulation. 2020;37(2):91-108. doi:10.1080/02652048.2019.1701114

- Katari O, Jain S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carrier-based nanotherapeutics for the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2021;18(12):1857-1872. doi:10.1080/17425247.2021.2011857

- Carmen Gómez-Guillén M, Montero MP. Pilar Montero,Enhancement of oral bioavailability of natural compounds and probiotics by mucoadhesive tailored biopolymer-based nanoparticles: a review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;118:106772. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021. 106772

- Denora N, Trapani A, Laquintana V, et al. Recent advances in medicinal chemistry and pharmaceutical technology–strategies for drug delivery to the brain. Curr Top Med Chem 2009;9(2):182-196. doi:10.2174/156802609787521571

- Mikhail AS, Allen C. Block copolymer micelles for delivery of cancer therapy: transport at the whole body, tissue and cellular levels.

Control Release. 2009;138(3):214-223. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.04.010 - Lee Y. Preparation and characterization of folic acid linked poly(L-glutamate) nanoparticles for cancer targeting. Macromol Res. 2006;14:387-393. doi:10.1007/BF03219099

- Wang H, Zhao Y, Wu Y, et al. Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy by co-delivery of doxorubicin and paclitaxel with amphiphilic methoxy PEG-PLGA copolymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32(32):8281-8290. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.032

- Chen Q, Han X, Liu L, et al. Multifunctional Polymer Vesicles for Synergistic Antibiotic-Antioxidant Treatment of Bacterial Keratitis. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24(11):5230-5244. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00754

- Md S, Alhakamy NA, Neamatallah T, et al. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation of

-Mangostin-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticle Gel for Topical Therapy in Skin Cancer. Gels. 2021;7(4):230. doi:10.3390/gels7040230 - Shumin L, Xu Z, Alrobaian M, et al. EGF-functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles of 5-fluorouracil and sulforaphane with enhanced bioavailability and anticancer activity against colon carcinoma. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2022;69(5):2205-2221. doi:10.1002/bab.2279

- Karim S, Akhter MH, Burzangi AS, et al. Phytosterol-Loaded Surface-Tailored Bioactive-Polymer Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment: optimization, In Vitro Cell Viability, Antioxidant Activity, and Stability Studies. Gels. 2022;8:219. doi:10.3390/gels8040219

- Mir MA, Akhter MH, Afzal O, et al. Design-of-Experiment-Assisted Fabrication of Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles: in Vitro Characterization, Biological Activity, and In Vivo Assessment. ACS Omega. 2023;8(42):38806-38821. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01153

- Vozza G, Khalid M, Byrne HJ, Ryan SM, Jesus M. Frias,Nutraceutical formulation, characterisation, and in-vitro evaluation of methylselenocysteine and selenocystine using food derived chitosan:zein nanoparticles. Food Res Int. 2019;120:295-304. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.028

- Pauluk D, Krause Padilha A, Maissar Khalil N, Mainardes RM. Rubiana Mara Mainardes, Chitosan-coated zein nanoparticles for oral delivery of resveratrol: formation, characterization, stability, mucoadhesive properties and antioxidant activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;94:411-417. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.03.042

- Xia L, Cong Z, Liu Z, et al. Improvement of the solubility, photostability, antioxidant activity and UVB photoprotection of trans-resveratrol by essential oil based microemulsions for topical application. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2018;48:346-354. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2018.10.017

- Chatterjee B, Gorain B, Mohananaidu K, et al. Targeted drug delivery to the brain via intranasal nanoemulsion: available proof of concept and existing. Int j Pharma. 2019;565:258-268. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.05.032

- Pandey P, Gulati N, Makhija M, et al. Nanoemulsion: a Novel Drug Delivery Approach for Enhancement of Bioavailability. Recent Patents Nanotechnol. 2020;14(4):276-293. doi:10.2174/1872210514666200604145755

- Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Liang R, et al. Beta-carotene chemical stability in Nanoemulsions was improved by stabilized with beta-lactoglobulincatechin conjugates through free radical method. J Agr Food Chem. 2015;63(1):297-303. doi:10.1021/jf5056024

- Ding L, Tang S, Yu A, et al. Nanoemulsion-Assisted siRNA Delivery to Modulate the Nervous Tumor Microenvironment in the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(8):10015-10029. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c21997

- Niu Z, Acevedo-Fani A, McDowell A, et al. Nanoemulsion structure and food matrix determine the gastrointestinal fate and in vivo bioavailability of coenzyme Q10. J Control Release. 2020;327:444-455. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.025

- Bouchemal K, Briançon S, Perrier E, et al. Nano-emulsion formulation using spontaneous emulsification: solvent, oil and surfactant. Int j Pharm. 2004;280(1-2):241-251. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.016

- Weiss M, Steiner DF, Philipson LH, et al. Insulin Biosynthesis, Secretion, Structure, and Structure-Activity Relationships. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2014.

- Leber N, Nuhn L, Zentel R, et al. Cationic Nanohydrogel Particles for Therapeutic Oligonucleotide Delivery. Macromol biosci. 2017;17 (10):10.1002/mabi.201700092. doi:10.1002/mabi. 201700092

- Deng S, Gigliobianco M, Mijit E, et al. Dually Cross-Linked Core-Shell Structure Nanohydrogel with Redox-Responsive Degradability for Intracellular Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(12):2048. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13122048

- Granata G, Petralia S, Forte G, et al. Injectable supramolecular nanohydrogel from a micellar self-assembling calix[4] arene derivative and curcumin for a sustained drug release. Mater Sci Eng. 2020;111:110842. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2020.110842

- Raemdonck K, Demeester J, De Smedt S. Advanced nanogel engineering for drug delivery. Soft Matter. 2009;5(4):707-715. doi:10.1039/ B811923F

- El-Refaie WM, Elnaggar YSR, El-Massik MA, et al. Novel Self-assembled, Gel-core Hyaluosomes for Non-invasive Management of Osteoarthritis: in-vitro Optimization, Ex-vivo and In-vivo Permeation. Pharm Res. 2015;32(9):2901-2911. doi:10.1007/s11095-015-1672-8

- Udeni Gunathilake TMS, Ching YC, Chuah CH. Enhancement of Curcumin Bioavailability Using Nanocellulose Reinforced Chitosan Hydrogel. Polymers. 2017;9(2):64. doi:10.3390/polym9020064

- Ahmad I, Farheen M, Kukreti A, et al. Natural Oils Enhance the Topical Delivery of Ketoconazole by Nanoemulgel for Fungal Infections. ACS omega. 2023;8(31):28233-28248. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01571

- Yanchen H, Zhi Z, Zhao Q, et al. 3D cubic mesoporous silica microsphere as a carrier for poorly soluble drug carvedilol. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;147(1):94-101. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.06.001

- Zhang Y, Wang J, Bai X, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for increasing the oral bioavailability and permeation of poorly water soluble drugs. Mol Pharmaceut. 2012;9(3):505-513. doi:10.1021/mp200287c

- Pawlaczyk M, Schroeder G. Dual-Polymeric Resin Based on Poly (methyl vinyl ether-alt-maleic anhydride) and PAMAM Dendrimer as a Versatile Supramolecular Adsorbent. ACS Appl Polymer Mater. 2021;3(2):956-967. doi:10.1021/acsapm.0c01254

- Liu X, Peng Y, Qu X, et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube-chitosan/poly(amidoamine)/DNA nanocomposite modified gold electrode for determination of dopamine and uric acid under coexistence of ascorbic acid. J Electroanal Chem. 2011;654(1-2):72-78. doi:10.1016/j. jelechem.2011.01.024

- Zhuo RX, Du B, Lu ZR. In vitro release of 5-fluorouracil with cyclic core dendritic polymer. J Control Release. 1999;57(3):249-257. doi:10.1016/s0168-3659(98)00120-5

- Luo K, Li C, Li L, et al. Arginine functionalized peptide dendrimers as potential gene delivery vehicles. Biomaterials. 2012;33(19):4917-4927. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.030

- Conghua Y, Qinghe X, Yang D, Wang M. Miao Wang,A novel pH -responsive charge reversal nanospheres based on acetylated histidine-modified lignin for drug delivery. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;186:115193. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115193

- Guo F, Jiao Y, Du Y, et al. Enzyme-responsive nano-drug delivery system for combined antitumor therapy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;220:1133-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jjbiomac.2022.08.123

- Hui Y, Jin F, Liu D, et al. ROS-responsive nano-drug delivery system combining mitochondria-targeting ceria nanoparticles with atorvastatin for acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2020;10(5):2342-2357. doi:10.7150/thno. 40395

- Wang G, Maciel D, Wu Y, et al. Amphiphilic polymer-mediated formation of laponite-based nanohybrids with robust stability and pH sensitivity for anticancer drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(19):16687-16695. doi:10.1021/am5032874

- Ghadiri M, Young PM, Traini D. Strategies to Enhance Drug Absorption via Nasal and Pulmonary Routes. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(3):113. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11030113

- Pawar B, Vasdev N, Gupta T, et al. Current Update on Transcellular Brain Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12):2719. doi:10.3390/ pharmaceutics14122719

- Sosnik A, Das Neves J. Bruno Sarmento.Mucoadhesive polymers in the design of nano-drug delivery systems for administration by non-parenteral routes: a review. Prog Polym Sci. 2014;39(12):2030-2075.

- Costa CP, Moreira JN, Sousa Lobo JM, et al. Intranasal delivery of nanostructured lipid carriers, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsions: a current overview of in vivo studies. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2021;11(4):925-940. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.012

- Bhaskar S, Tian F, Stoeger T, et al. Multifunctional Nanocarriers for diagnostics, drug delivery and targeted treatment across blood-brain barrier: perspectives on tracking and neuroimaging. Particle Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:3. doi:10.1186/1743-8977-7-3

- Sun W, Xie C, Wang H, et al. Specific role of polysorbate 80 coating on the targeting of nanoparticles to the brain. Biomaterials. 2004; 25 (15):3065-3071. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.087

- Wei L, Tan Y-Z, Hu K-L, et al. Cationic albumin conjugated pegylated nanoparticle with its transcytosis ability and little toxicity against blood-brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2005;295(1-2):247-260. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.043

- Chai Z , Hu X, Wei X, et al. A facile approach to functionalizing cell membrane-coated nanoparticles with neurotoxin-derived peptide for brain-targeted drug delivery.

Control Release. 2017;264:102-111. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.027 - Fang RH, Hu C-MJ, Chen KNH, et al. Lipid-insertion enables targeting functionalization of erythrocyte membrane-cloaked nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2013;5(19):8884-8888. doi:10.1039/c3nr03064d

- Yan L, He H, Jia X, et al. A dual-targeting nanocarrier based on poly(amidoamine) dendrimers conjugated with transferrin and tamoxifen for treating brain gliomas. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3899-3908. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.004

- Habban Akhter M, Beg S, Tarique M, Malik A, Afaq S, Choudhry H. Salman Hosawi,Receptor-based targeting of engineered nanocarrier against solid tumors: recent progress and challenges ahead. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2021;1865(2):129777. doi:10.1016/j. bbagen.2020.129777

- Spanjers JM, Städler B. Cell Membrane Coated Particles. Adv Biosyst 2020;4(11):e2000174. doi:10.1002/adbi.202000174

- Ricordel C, Labalette-Tiercin M, Lespagnol A, et al. EFGR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma and Li-Fraumeni syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature. Lung Cancer. 2015;87(1):80-84. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.11.005

- Farheen M, Akhter MH, Chitme H, et al. Surface-Modified Biobased Polymeric Nanoparticles for Dual Delivery of Doxorubicin and Gefitinib in Glioma Cell Lines. ACS omega. 2023;8(31):28165-28184. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01375

- Wang Z-H, Liu J-M, Zhao N, et al. Cancer Cell Macrophage Membrane-Camouflaged Persistent-Luminescent Nanoparticles for Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy of Colorectal Cancer. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2020;XXXX. doi:10.1021/acsanm.0c01433

- Zhao K, Li D, Cheng G, et al. Targeted Delivery Prodigiosin to Choriocarcinoma by Peptide-Guided Dendrigraft Poly-1-lysines Nanoparticles. Int j Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5458. doi:10.3390/ijms20215458

- Wang Y, Cheng J, Zhao D, et al. Designed DNA nanostructure grafted with erlotinib for non-small-cell lung cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 2020;12 (47):23953-23958. doi:10.1039/d0nr06945k

- Gong Y, Mohd S, Wu S, et al. pH-responsive cellulose-based microspheres designed as an effective oral delivery system for insulin.

Mega. 2021;6:2734-2741. - Cikrikci S, Mert H, Oztop MH. Development of pH sensitive alginate/gum tragacanth based hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:11784-11796. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02525

- Qi X, Yuan Y, Zhang J, et al. Oral administration of salecan based hydrogels for controlled insulin delivery. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:10479-10489. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02879

- Zhang L, Qin H, Li J, et al. Preparation and characterization of layer-by-layer hypoglycemic nanoparticles with pH -sensitivity for oral insulin delivery. J Mater Chem. 2018;6:7451-7461.

- Shabana AM, Kambhampati SP, Hsia R-C, et al. Thermosensitive and Biodegradable Hydrogel Encapsulating Targeted Nanoparticles for the Sustained Co-Delivery of Gemcitabine and Paclitaxel to Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int J Pharm. 2020;593(6):120139. doi:10.1016/j. ijpharm.2020.120139

- Deodhar S, Dash AK, North EJ, et al. Development and In Vitro Evaluation of Long Circulating Liposomes for Targeted Delivery of Gemcitabine and Irinotecan in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2020;21(6). doi:10.1208/s12249-020-01745-6

- Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018; 16 (1):71. doi:10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8

- Ruan S, Li J, Ruan H, et al. Microneedle-mediated nose-to-brain drug delivery for improved Alzheimer’s disease treatment.

Controlled Release. 2024;366:712-731. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.01.013 - Jahangirian H, Ghasemian Lemraski E, Webster TJ, et al. A review of drug delivery systems based on nanotechnology and green chemistry: green nanomedicine. Int j Nanomed. 2017;12:2957-2978. doi:10.2147/IJN.S127683

- Hansen K, Kim G, Desai K-GH, et al. Feasibility Investigation of Cellulose Polymers for Mucoadhesive Nasal Drug Delivery Applications. Mol Pharmaceut. 2015;12(8):2732-2741. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00264

- Mignani S, El Kazzouli S, Bousmina M, et al. Expand classical drug administration ways by emerging routes using dendrimer drug delivery systems: a concise overview. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2013;65(10):1316-1330. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2013.01.001

- Miyata K, Christie RJ, Kataoka K. Polymeric micelles for nano-scale drug delivery. React Funct Polym. 2011;3(71). doi:10.1016/j. reactfunctpolym.2010.10.009

- Wei X, Ling P, Zhang T, et al. Polymeric micelles, a promising drug delivery system to enhance bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. J Drug Delivery. 2013;2013:340315. doi:10.1155/2013/340315

- Lam P-L, Wong W-Y, Bian Z, Chui C-H, Gambari R. Gambari R.Recent advances in green nanoparticulate systems for drug delivery: efficient delivery and safety concern. Nanomedicine. 2017;12:357-385. doi:10.2217/nnm-2016-0305

- Powell JJ, Faria N, Thomas-McKay E, et al. Origin and fate of dietary nanoparticles and microparticles in the gastrointestinal tract. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J226-33. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.006

- Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(11):799-809. doi:10.1038/nri2653

- Sahay G, Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV, et al. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. J Controlled Release. 2010;145(3):182-195. doi:10.1016/j. jconrel.2010.01.036

- Liang Q, Bie N, Yong T, et al. The softness of tumour-cell-derived microparticles regulates their drug-delivery efficiency. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019;3(9):729-740. doi:10.1038/s41551-019-0405-4

- Della Camera G, Madej M, Ferretti AM, et al. Personalised Profiling of Innate Immune Memory Induced by Nano-Imaging Particles in Human Monocytes. Front Immunol. 2021;12:692165. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.692165

- Wang J, Chen H-J, Hang T, et al. Physical activation of innate immunity by spiky particles. Nature Nanotechnol. 2018;13(11):1078-1086. doi:10.1038/s41565-018-0274-0

- Ejigah V, Owoseni O, Bataille-Backer P, et al. Approaches to Improve Macromolecule and Nanoparticle Accumulation in the Tumor Microenvironment by the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect. Polymers. 2022;14(13):2601. doi:10.3390/polym14132601

- Xiao M, Hu M, Dong M, et al. Folic Acid Decorated Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) Loaded with Baicalin as a Nano-Drug Delivery System for Breast Cancer Therapy. Int j Nanomed. 2021;16:8337-8352. doi:10.2147/IJN.S340764

- Kabanov AV, Lemieux P, Vinogradov S, et al. Pluronic block copolymers: novel functional molecules for gene therapy. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2002;54(2):223-233. doi:10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00018-2

- Jin P, Sha R, Zhang Y, et al. Blood Circulation-Prolonging Peptides for Engineered Nanoparticles Identified via Phage Display. Nano Lett. 2019;19(3):1467-1478. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b04007

- Aggarwal P, Hall JB, McLeland CB, et al. Nanoparticle interaction with plasma proteins as it relates to particle biodistribution, biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2009;61(6):428-437. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.009

- Hadidi N, Kobarfard F, Nafissi-Varcheh N, et al. PEGylated single-walled carbon nanotubes as nanocarriers for cyclosporin A delivery. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2013;14(2):593-600. doi:10.1208/s12249-013-9944-2

- Alimohammadi E, Nikzad A, Khedri M, et al. Molecular Tuning of the Nano-Bio Interface: alpha-Synuclein’s Surface Targeting with Doped Carbon Nanostructures. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2021;4(8):6073-6083. doi:10.1021/acsabm.1c00421

- Wohlfart S, Gelperina S, Kreuter J, et al. Transport of drugs across the blood-brain barrier by nanoparticles. J Controlled Release. 2012;161 (2):264-273. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.017

- Shen J, Zhao Z, Shang W, et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 nanoparticle penetrating the blood-brain barrier to improve the cerebral function of diabetic rats complicated with cerebral infarction. Int j Nanomed. 2017;12:6477-6486. doi:10.2147/IJN.S139602

- Wiley DT, Webster P, Gale A, et al. Transcytosis and brain uptake of transferrin-containing nanoparticles by tuning avidity to transferrin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(21):8662-8667. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307152110

- Liu Y, Zhang T, Li G, et al. Radiosensitivity enhancement by Co-NMS-mediated mitochondrial impairment in glioblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9623-9634. doi:10.1002/jcp. 29774

- Slepicka P, Kasalkova NS, Siegel J, et al. Nano-structured and functionalized surfaces for cytocompatibility improvement and bactericidal action. Biotechnol Adv 2015;33(6):1120-1129. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.01.001

- Luo X, Wu S, Xiao M, et al. Advances and Prospects of Prolamine Corn Protein Zein as Promising Multifunctional Drug Delivery System for Cancer Treatment. Int j Nanomed. 2023;18:2589-2621. doi:10.2147/IJN.S402891

- Canal F, Vicent MJ, Pasut G, et al. Relevance of folic acid/polymer ratio in targeted PEG-epirubicin conjugates. J Controlled Release. 2010;146 (3):388-399. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.027

- Yang Y, He Y, Deng Z, et al. Intelligent Nanoprobe: acid-Responsive Drug Release and In Situ Evaluation of Its Own Therapeutic Effect. Anal Chem 2020;92(18):12371-12378. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02099

- Desai N. Challenges in development of nanoparticle-based therapeutics. AAPS J. 2012;14(2):282-295. doi:10.1208/s12248-012-9339-4

- Higaki M, Ishihara T, Izumo N, et al. Treatment of experimental arthritis with poly(D, L-lactic/glycolic acid) nanoparticles encapsulating betamethasone sodium phosphate. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2005;64(8):1132-1136. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.030759

- McCully M, Sanchez-Navarro M, Teixido M, et al. Peptide Mediated Brain Delivery of Nano- and Submicroparticles: a Synergistic Approach. Curr Pharm Des 2018;24(13):1366-1376. doi:10.2174/1381612824666171201115126

- Tinkle S, McNeil SE, Mühlebach S, et al. Nanomedicines: addressing the scientific and regulatory gap. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1313:35-56. doi:10.1111/nyas. 12403

- Zcan I, et al. Effects of sterilization techniques on the PEGylated poly (

-benzyl-L-glutamate) (PBLG) nanoparticles. Acta Pharma Sci. 2009;51 (3):211-218. - Song Y , Li X , Du X, et al. Exposure to nanoparticles is related to pleural effusion, pulmonary fibrosis and granuloma. Europ resp J. 2009;34 (3):559-567. doi:10.1183/09031936.00178308

- Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, et al. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 2006;311(5761):622-627. doi:10.1126/science. 1114397

- Wacker MG, Proykova A, Santos GML, et al. Dealing with nanosafety around the globe-Regulation vs. innovation. Int J Pharm. 2016;509(1-2):95-106. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.05.015

- Mühlebach S. Regulatory challenges of nanomedicines and their follow-on versions: a generic or similar approach? Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018;131:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.06.024

- Paradise J. Regulating Nanomedicine at the Food and Drug Administration. AMA

Ethics. 2019;21(4):E347-355. doi:10.1001/ amajethics. 2019.347 - Resnik DB, Tinkle SS. Ethical issues in clinical trials involving nanomedicine. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2007;28(4):433-441. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2006.11.001

- Bawa R, Johnson S. The ethical dimensions of nanomedicine. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91(5):881-887. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2007.05.007

- Zhang J, Hu K, Di L, et al. Traditional herbal medicine and nanomedicine: converging disciplines to improve therapeutic efficacy and human health. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2021;178:113964. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.113964

- Majidinia M, Mirza-Aghazadeh-Attari M, Rahimi M, et al. Overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer: recent progress in nanotechnology and new horizons. IUBMB Life. 2020;72(5):855-871. doi:10.1002/iub. 2215

- Shen C-Y, Xu P-H, Shen B-D, et al. Nanogel for dermal application of the triterpenoids isolated from Ganoderma lucidum (GLT) for frostbite treatment. Drug Delivery. 2016;23(2):610-618. doi:10.3109/10717544.2014.929756

- Ventola CL. Progress in Nanomedicine: approved and Investigational Nanodrugs. PT. 2017;42(12):742-755.

- Sainz V, Conniot J, Matos AI, et al. Regulatory aspects on nanomedicines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;468(3):504-510. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.023

- Agrahari V, Agrahari V. Facilitating the translation of nanomedicines to a clinical product: challenges and opportunities. Drug Discovery Today. 2018;23(5):974-991. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.01.047

- Zhang N, Feng N, Xin X, et al. Nano-drug delivery system with enhanced tumour penetration and layered anti-tumour efficacy. Nanomedicine. 2022;45:102592. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2022.102592

- Ouyang Q, Meng Y, Zhou W, et al. New advances in brain-targeting nano-drug delivery systems for Alzheimer’s disease. J Drug Targeting. 2022;30(1):61-81. doi:10.1080/1061186X.2021.1927055

- Filipczak N, Yalamarty SSK, Li X, et al. Developments in Treatment Methodologies Using Dendrimers for Infectious Diseases. Molecules. 2021;26(11):3304. doi:10.3390/molecules26113304

- Cardoso RV, Pereira PR, Freitas CS, et al. Trends in Drug Delivery Systems for Natural Bioactive Molecules to Treat Health Disorders: the Importance of Nano-Liposomes. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12):2808. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14122808

- Manzari MT, Shamay Y, Kiguchi H, et al. Targeted drug delivery strategies for precision medicines. Nature Rev Mater. 2021;6(4):351-370. doi:10.1038/s41578-020-00269-6

- Taylor J, Sharp A, Rannard SP, et al. Nanomedicine strategies to improve therapeutic agents for the prevention and treatment of preterm birth and future directions. Nanoscale Adv. 2023;5(7):1870-1889. doi:10.1039/d2na00834c

- Savjani KT, Gajjar AK, Savjani JK, et al. Drug solubility: importance and enhancement techniques. ISRN Pharmaceutics. 2012;2012:195727. doi:10.5402/2012/195727

- Mistry A, Stolnik S, Illum L, et al. Nose-to-Brain Delivery: investigation of the Transport of Nanoparticles with Different Surface Characteristics and Sizes in Excised Porcine Olfactory Epithelium. Mol Pharmaceut. 2015;12(8):2755-2766. doi:10.1021/acs. molpharmaceut.5b00088

- Hegewald AB , et al. Extracellular miR-574-5p Induces Osteoclast Differentiation via TLR 7/8 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11 (585282). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.585282

- Motoyama K, Onodera R, Okamatsu A, et al. Potential use of the complex of doxorubicin with folate-conjugated methyl-

-cyclodextrin for tumor-selective cancer chemotherapy. J Drug Targeting. 2014;22(3):211-219. doi:10.3109/1061186X.2013.856012 - Date AA, Hanes J, Ensign LM, et al. Nanoparticles for oral delivery: design, evaluation and state-of-The-art. J Controlled Release. 2016;240:504-526. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.016

- Xiao S, Tang Y, Lv Z, et al. Nanomedicine – advantages for their use in rheumatoid arthritis theranostics. J Controlled Release. 2019;316:302-316. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.11.008

- Wang S, Lv J, Meng S, et al. Recent Advances in Nanotheranostics for Treat-to-Target of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2020;9 (6):e1901541. doi:10.1002/adhm. 201901541

انشر عملك في هذه المجلة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s447496

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38707615

Publication Date: 2024-05-01

Advances in Nanotechnology for Enhancing the Solubility and Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs

Abstract

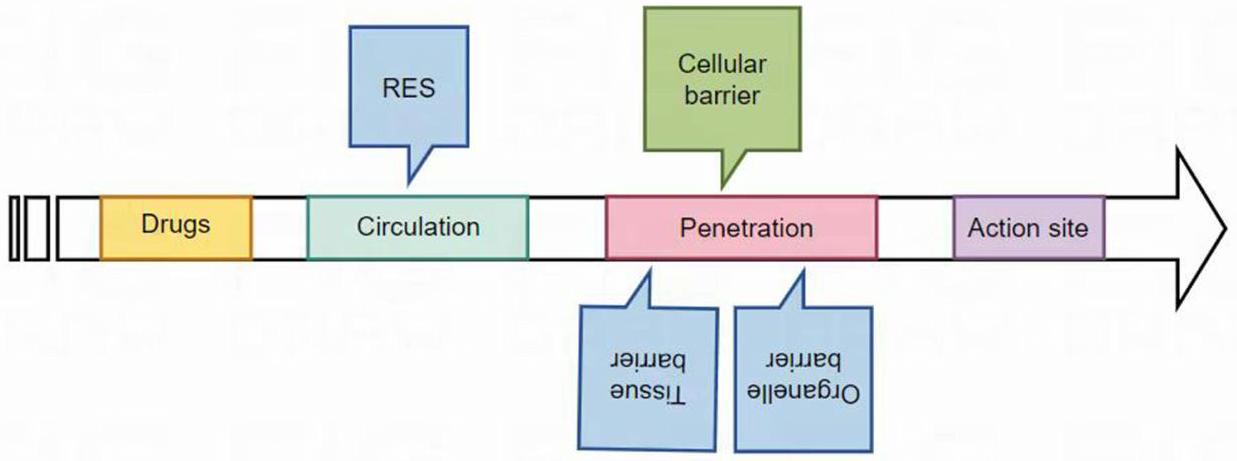

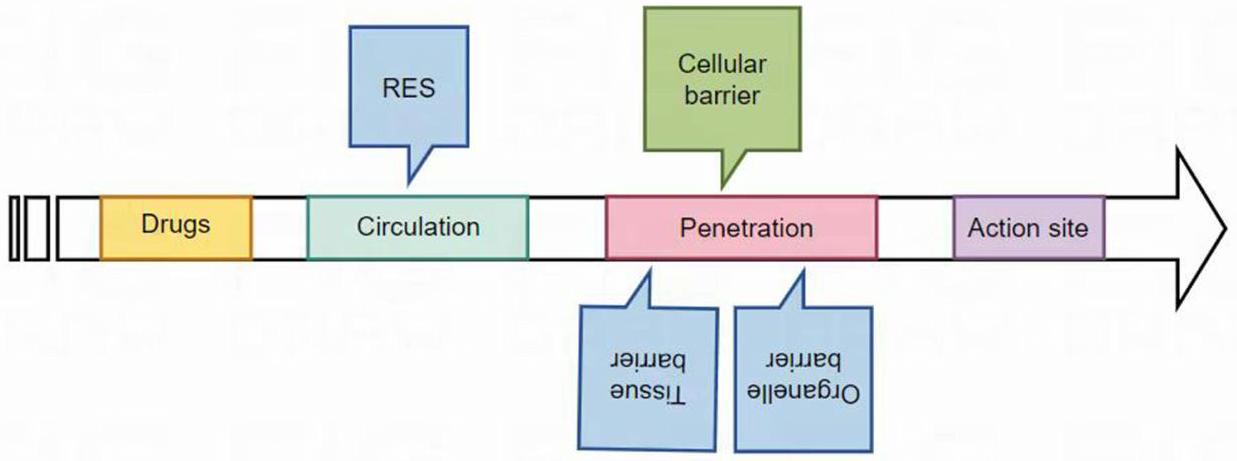

This manuscript offers a comprehensive overview of nanotechnology’s impact on the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs, with a focus on BCS Class II and IV drugs. We explore various nanoscale drug delivery systems (NDDSs), including lipid-based, polymer-based, nanoemulsions, nanogels, and inorganic carriers. These systems offer improved drug efficacy, targeting, and reduced side effects. Emphasizing the crucial role of nanoparticle size and surface modifications, the review discusses the advancements in NDDSs for enhanced therapeutic outcomes. Challenges such as production cost and safety are acknowledged, yet the potential of NDDSs in transforming drug delivery methods is highlighted. This contribution underscores the importance of nanotechnology in pharmaceutical engineering, suggesting it as a significant advancement for medical applications and patient care.

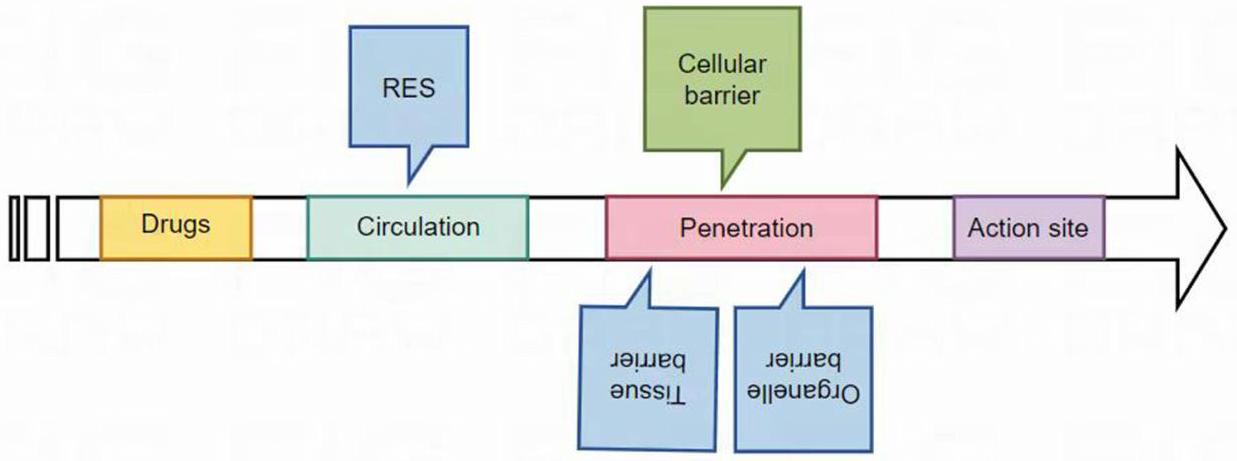

Introduction

significantly reducing damage to healthy tissues. Secondly, they can control the rate of drug release, ensuring that drug concentration in the blood remains within a safe and effective range, thus mitigating or avoiding toxic and adverse reactions.

Definition and Classification of Poorly Soluble Drugs

Using digoxin and griseofulvin as examples, it is evident that for digoxin, a smaller particle size (indicating a higher

Class I BCSII Drugs

BCS Class IV Drugs

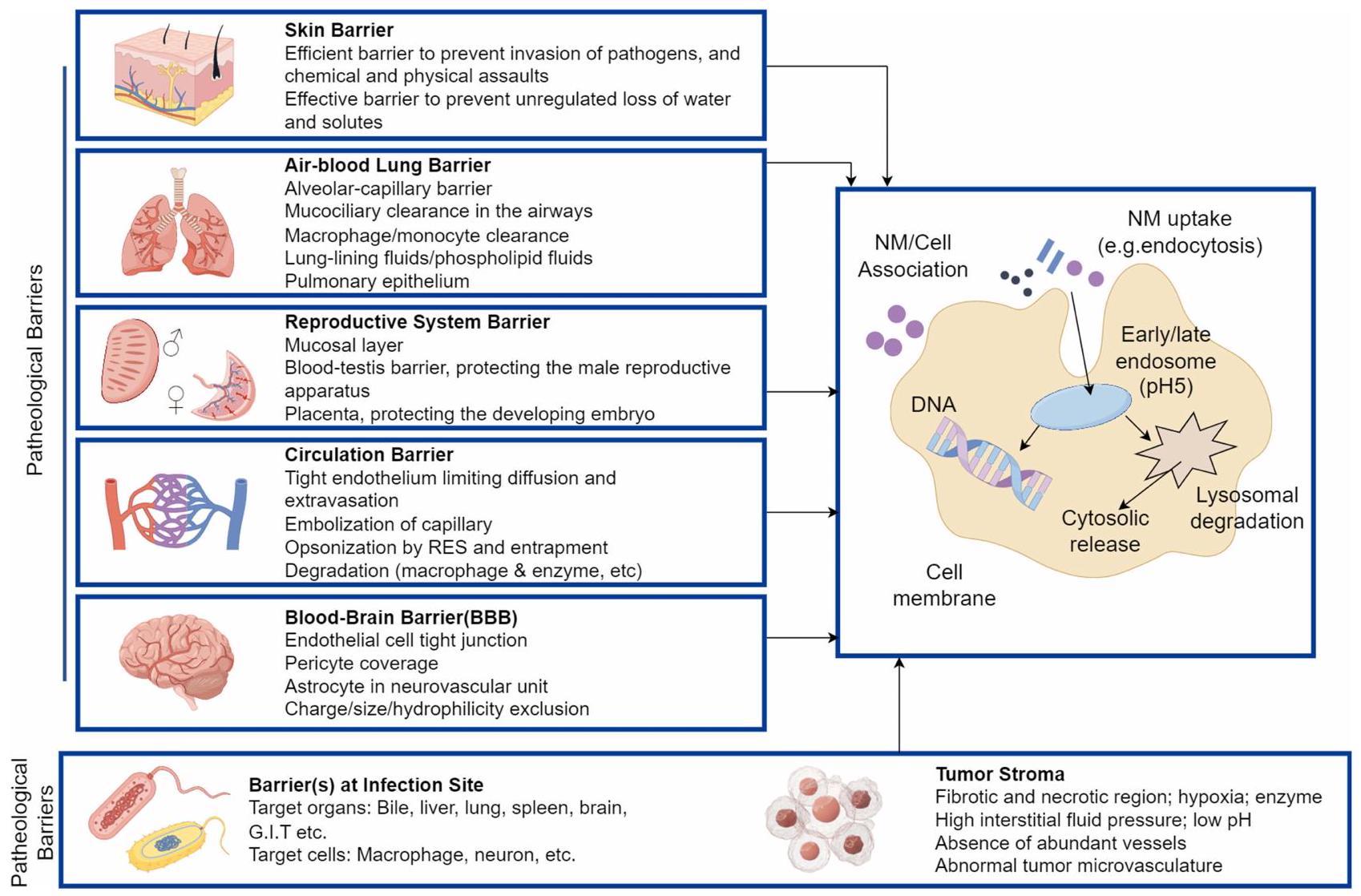

Fundamental Principles of Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

Working Principles of Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

| Sr.No. | Emulsion | Nanoemulsion |

| I | Kinetically less stable | Kinetically more stable |

| 2 | Appearance-cloudy/opaque | Appearance-clear |

| 3 | Particle size varies from

|

Particle size varies from

|

| 4 | Anisotropic in nature | Isotropic in nature |

| 5 | Higher surfactant concentration(20-25%) | Lower surfactant concentration(5-10%) |

| 6 | Wet gum method and dry gum method are generally used for preparation | High energy emulsification and low energy Emulsification method are used |

| 7 | Creaming, Phase inversion, and sedimentation, etc., stability problems may occur. | These types of problems not occur. |

Types and Characteristics of Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

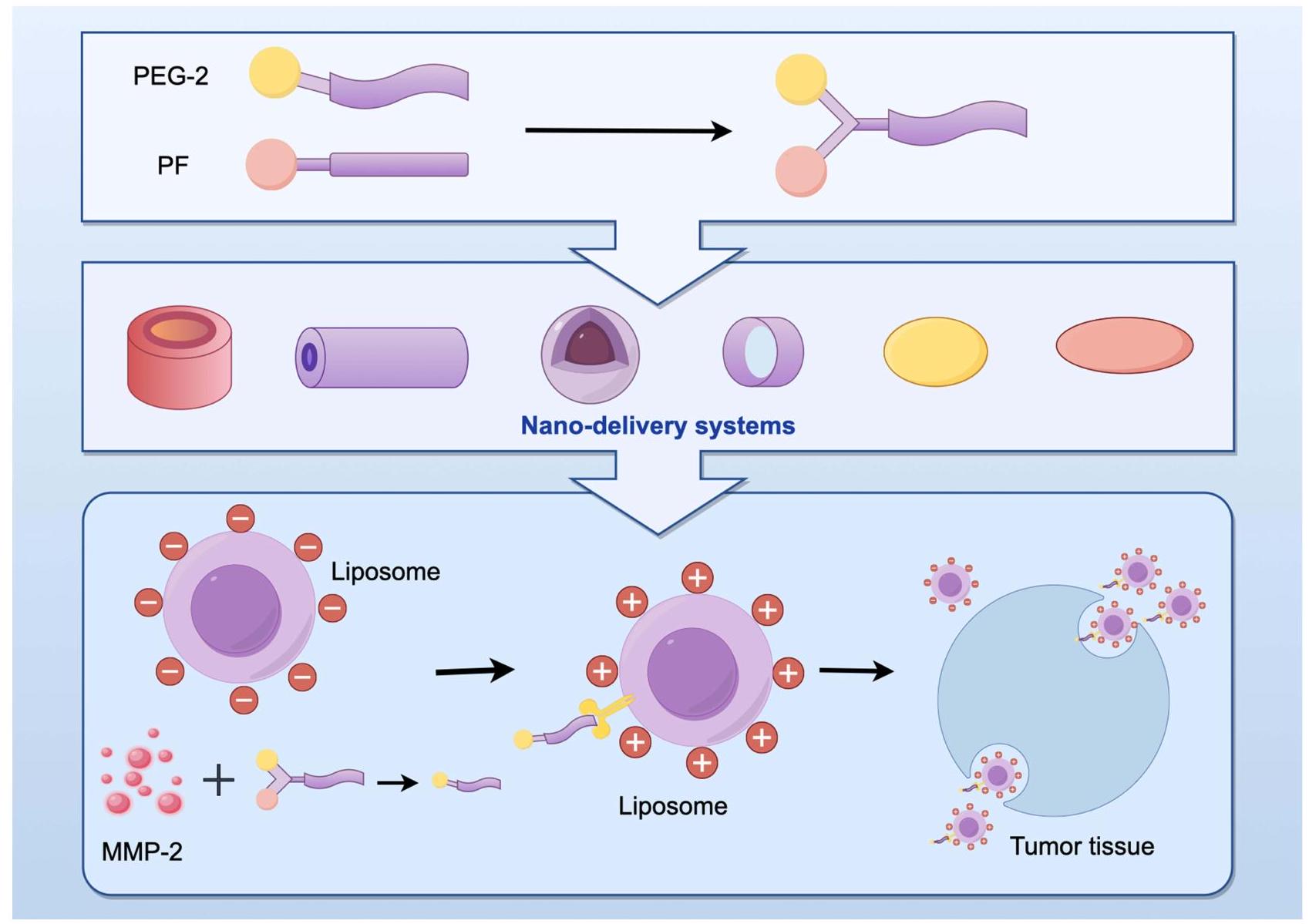

Liposomal Nanocarriers

Polymer Nanocarriers

stealth property allows for the micelles to circulate for extended periods, which, in conjunction with the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, enables them to accumulate preferentially in tumor tissues through passive targeting mechanisms. The EPR effect is especially pronounced in pathological conditions with compromised lymphatic drainage, such as cancer, where it can be exploited to deliver high drug concentrations directly to the site of the tumor, enhancing the efficacy of the treatment while reducing systemic toxicity.

Nanoemulsions

Nanohydrogels

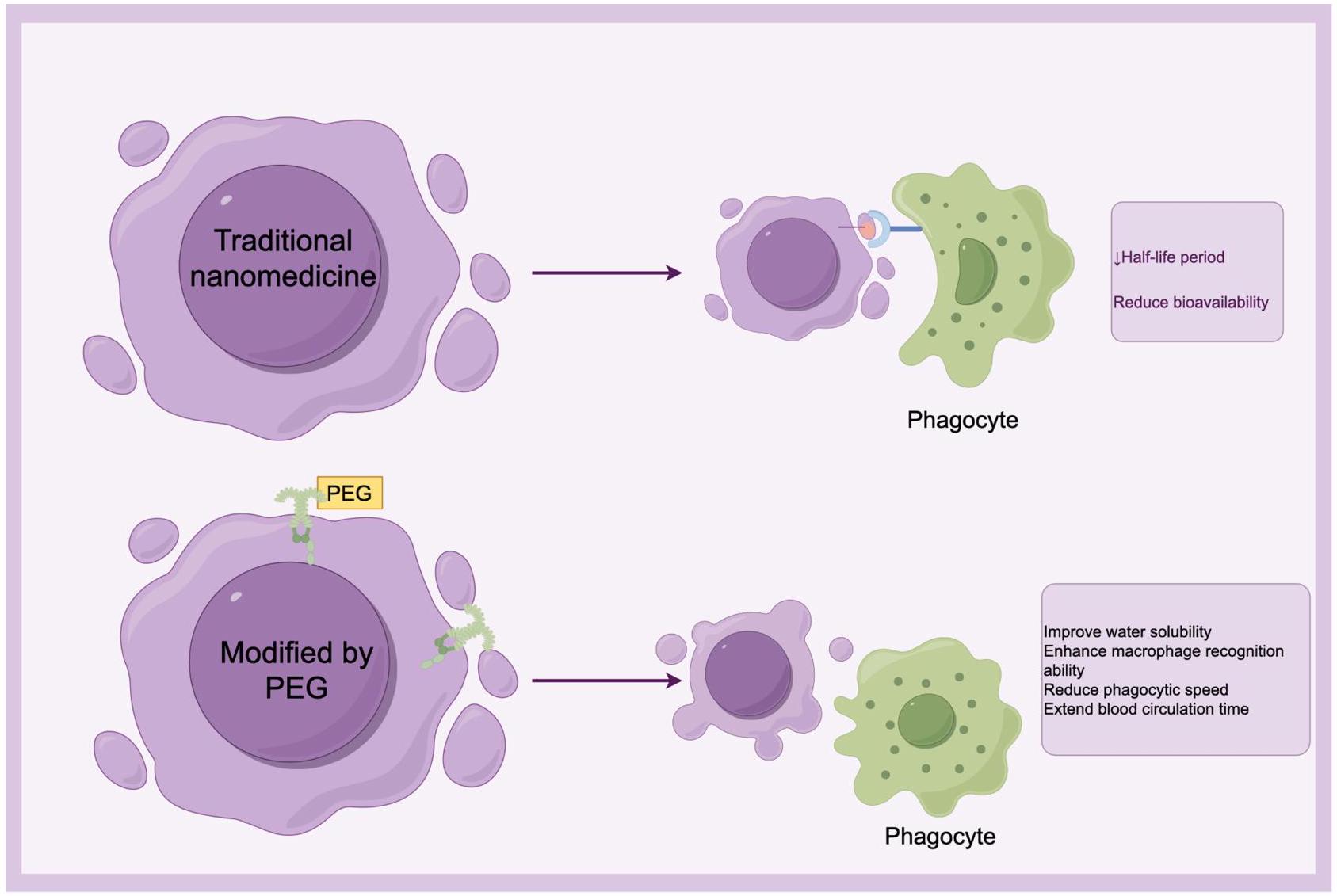

avoidance of macrophage phagocytosis, and enhanced cell recognition, making them suitable for various drug delivery strategies.

Inorganic Nanocarriers

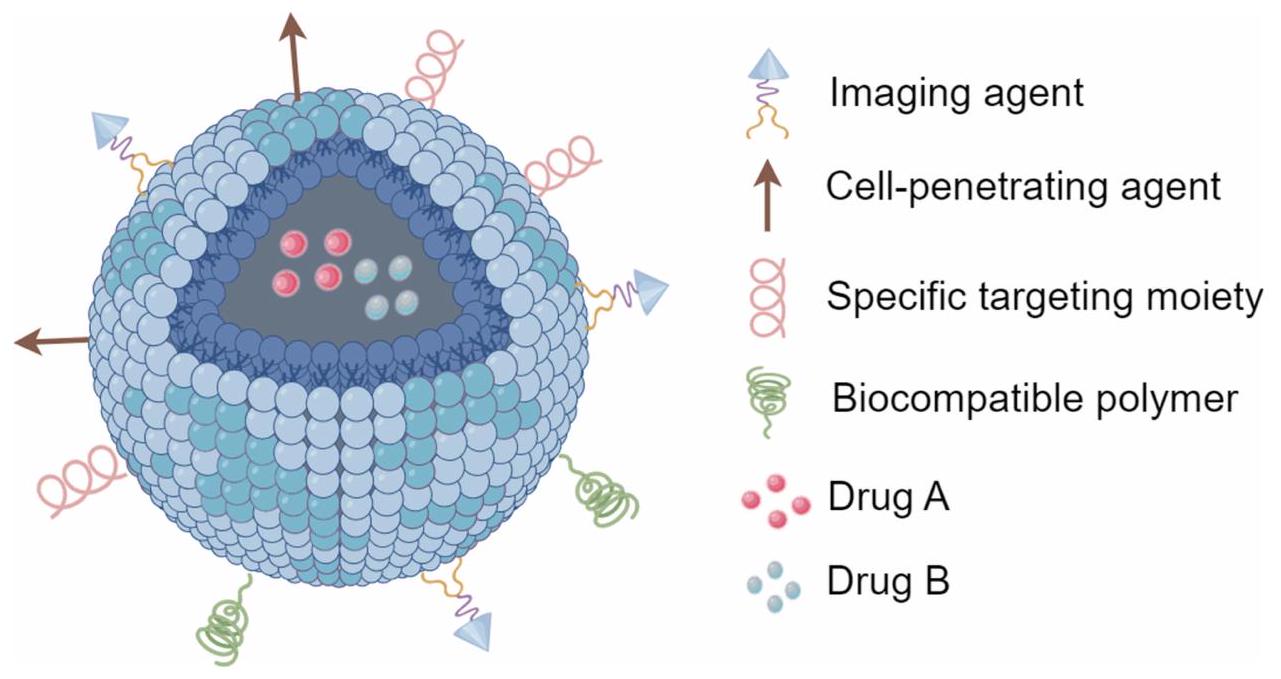

Dendritic Polymer Nanocarriers

composed of an initiating core, internal repeat units, and terminal functional groups, these materials have evolved through several synthetic approaches, including divergent, convergent, a hybrid of divergent-convergent, and solid-phase synthesis methods. By attaching different functional groups to the peripheries of dendritic polymers, these materials can fulfill specific applications. They are noted for their high drug loading capacity, ease of surface modification, controlled drug release, increased drug solubility, and reduced adverse drug reactions, as illustrated in Figure

Smart Responsive Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

Mechanisms of Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems for Improving Solubility of Poorly Soluble Drugs

Nanotechnology

Surface Modification Techniques

increasing cellular uptake and, consequently, drug efficacy, as illustrated in Figure 3C. There are primarily two methods for active targeting modifications: one involves the direct modification by covalently bonding ligands to drug carriers with active functional groups;

Carrier-Mediated Techniques

Mechanisms of Enhanced Bioavailability in Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

Enhancing Cellular Uptake

and betaine transporters.

Promoting Intracellular Release

Avoiding Early Metabolism of Drugs

Advantages and Challenges of Nanomedicine Drug Delivery Systems

Advantages

Enhancing Drug Stability

Prolonging Circulation Time

Targeted Delivery and Combination Therapy with Multiple Drugs

Challenges

Cost Issues

Safety Concerns

Lack of Standardization and Scalability

Latest Research Developments and Case Studies

| Categories | Year of Approval | Pharmaceutical Formulations | Companies | Clinical Applications |

| Liposomal Nanoparticles | 2015 | Irinotecan | Merrimack Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, UK) | Metastatic pancreatic cancer |

| 2021 | Recombinant CSP | ClaxoSmithKline (Middlesex, UK) | Malaria | |

| 2021 | BNT162b2 | Pfizer (NewYork, NY, USA) and BioNTech (Mainz, Germany) | COVID-19 |

| Categories | Year of Approval | Pharmaceutical Formulations | Companies | Clinical Applications |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | 2012 | Docetaxel | Samyang Pharmaceuticals (Seoul Republic of Korea) | MBC, NSCLC, and ovarian cancer |

| 2015 | PTX | Oasmia Pharmaceuticals (Uppsala, Sweden) | Ovarian cancer | |

| Drug Nanocrystals | 2018 | Aripiprazole lauroxil | AlkermesInc (Waltham, MA, USA) | Schizophrenia |

| 2021 | Cabotegravir | ViiyHealthcareCo. (Brentford, London, UK) | HIV-I infection | |

| Other Nanomedicines | 2010 | Ironmolecule with unbranched carbohydrateinon particles | Pharmacosmos (Rorvangsvei, Holbaek, Denmark) | Iron deficiency anemia |

| 2013 | Polynucleariron (III) oxyhydroxide iron particles | Forlnt. (Waltham, MA.USA) | Iron deficiency anemia | |

| 2015 | Recombinant anti-hemophilic factor VIII | Baxalta (Montgomery, Al, USA) | Hemophilia A |

Conclusion and Outlook

within high-solubility carriers, leading to cellular uptake via passive diffusion, membrane fusion, and endocytosis.

Abbreviations

Author Contributions

Disclosure

References

- Prabhu P, Patravale V. Dissolution enhancement of atorvastatin calcium by co-grinding technique. Drug Delivery Transl Res. 2016;6 (4):380-391. doi:10.1007/s13346-015-0271-x

- Khalid Q, Ahmad M, Minhas MU, et al. Synthesis of

-cyclodextrin hydrogel nanoparticles for improving the solubility of dexibuprofen: characterization and toxicity evaluation. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2017;43(11):1873-1884. doi:10.1080/03639045.2017.1350703 - Jermain SV, Brough C, Williams RO, et al. Amorphous solid dispersions and nanocrystal technologies for poorly water-soluble drug delivery An update. Int J Pharm. 2018;535(1-2):379-392. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.051

- Liu Y, Wang T, Ding W, et al. Dissolution and oral bioavailability enhancement of praziquantel by solid dispersions. Drug Delivery Transl Res. 2018;8(3):580-590. doi:10.1007/s13346-018-0487-7

- Baghel S, Cathcart H, O’Reilly NJ, et al. Polymeric Amorphous Solid Dispersions: a Review of Amorphization, Crystallization, Stabilization, Solid-State Characterization, and Aqueous Solubilization of Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II Drugs. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;105(9):2527-2544. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2015.10.008

- Hua S. Advances in Oral Drug Delivery for Regional Targeting in the Gastrointestinal Tract – Influence of Physiological, Pathophysiological and Pharmaceutical Factors. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11(524). doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00524

- Shreya AB, Raut SY, Managuli RS, et al. Active Targeting of Drugs and Bioactive Molecules via Oral Administration by Ligand-Conjugated Lipidic Nanocarriers: recent Advances. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2018;20(1):15. doi:10.1208/s12249-018-1262-2

- Siddiqui K, Waris A, Akber H, et al. Physicochemical Modifications and Nano Particulate Strategies for Improved Bioavailability of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Pharm nanotechnol. 2017;5(4):276-284. doi:10.2174/2211738506666171226120748

- Rubin KM, Vona K, Madden K, et al. Side effects in melanoma patients receiving adjuvant interferon alfa-2b therapy: a nurse’s perspective. Supportive Care Cancer. 2012;20(8):1601-1611. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1473-0

- Da Silva FL, Marques MB, Kato KC, et al. Nanonization techniques to overcome poor water-solubility with drugs. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2020;15(7):853-864. doi:10.1080/17460441.2020.1750591

- Prakash S. Nano-based drug delivery system for therapeutics: a comprehensive review. Biomed Phys Eng Express. 2023;9(5):10.1088/20571976/acedb2. doi:10.1088/2057-1976/acedb2

- Harder BG, et al. Developments in Blood-Brain Barrier Penetrance and Drug Repurposing for Improved Treatment of Glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2018;8(462). doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00462

- Zhai X, Lademann J, Keck CM, et al. Nanocrystals of medium soluble actives–novel concept for improved dermal delivery and production strategy. Int J Pharm. 2014;470(1-2):141-150. doi:10.1016/j.jjpharm.2014.04.060

- Kataoka M, Yonehara A, Minami K, et al. Control of Dissolution and Supersaturation/Precipitation of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs from Cocrystals Based on Solubility Products: a Case Study with a Ketoconazole Cocrystal. Mol Pharmaceut. 2023;20(8):4100-4107. doi:10.1021/ acs.molpharmaceut.3c00237

- Haering B, Seyferth S, Schiffter HA, et al. The tangential flow absorption model (TFAM) – A novel dissolution method for evaluating the performance of amorphous solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble actives. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2020;154:74-88. doi:10.1016/j. ejpb.2020.06.013

- Yang M, Chen T, Wang L, et al. High dispersed phyto-phospholipid complex/TPGS 1000 with mesoporous silica to enhance oral bioavailability of tanshinol. Colloids Surf B. 2018;170:187-193. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.06.013

- Kawabata Y, Wada K, Nakatani M, et al. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: basic approaches and practical applications. Int J Pharm. 2011;420(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.032

- Takagi T, Ramachandran C, Bermejo M, et al. A provisional biopharmaceutical classification of the top 200 oral drug products in the United States, Great Britain, Spain, and Japan. Mol Pharmaceut. 2006;3(6):631-643. doi:10.1021/mp0600182

- Amidon GL, Lennernäs H, Shah VP, et al. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12(3):413-420. doi:10.1023/a:1016212804288

- Bhatt S, ROY D, KUMAR M, et al. Development and Validation of In Vitro Discriminatory Dissolution Testing Method for Fast Dispersible Tablets of BCS Class II Drug. Turkish j Pharm Sci. 2020;17(1):74-80. doi:10.4274/tjps.galenos.2018.90582

- Fraser EJ, Leach RH, Poston JW, et al. Dissolution and bioavailability of digoxin tablets. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1973;25(12):968-973. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1973.tb09988.x

- Johnson BF, O’Grady J, Bye C, et al. The influence of digoxin particle size on absorption of digoxin and the effect of propantheline and metoclopramide. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1978;5(5):465-467. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb01657.x

- Chi-Yuan W, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition via application of BCS: transport/absorption/ elimination interplay and development of a biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system. Pharm Res. 2005;22(1):11-23. doi:10.1007/s11095-004-9004-4

- Löbenberg R, Amidon GL. Modern bioavailability, bioequivalence and biopharmaceutics classification system. New scientific approaches to international regulatory standards. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2000;50(1):3-12. doi:10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00091-6

- Hattori Y, Haruna Y, Otsuka M, et al. Dissolution process analysis using model-free Noyes-Whitney integral equation. Colloids Surf B. 2013;102:227-231. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.017

- Kesisoglou F, Mitra A. Crystalline nanosuspensions as potential toxicology and clinical oral formulations for BCS II/IV compounds. AAPS J. 2012;14(4):677-687. doi:10.1208/s12248-012-9383-0

- Yang SG. Biowaiver extension potential and IVIVC for BCS ClassII drugs by formulation design:Case study for cyclosporine self-microemulsifying formulation. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33(11):1835-1842. doi:10.1007/s12272-010-1116-2

- Adachi M, Hinatsu Y, Kusamori K, et al. Improved dissolution and absorption of ketoconazole in the presence of organic acids as pH -modifiers. Eur

Pharm Sci. 2015;76:225-230. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2015.05.015 - Chi L, Wu D, Li Z, et al. Modified Release and Improved Stability of Unstable BCSII Drug by Using Cyclodextrin Complex as Carrier To Remotely Load Drug into Niosomes. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(1):113-124. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00566

- Verma H, Garg R. Development of a bio-relevant pH gradient dissolution method for a high-dose, weakly acidic drug, its optimization and IVIVC in Wistar rats: a case study of magnesium orotate dihydrate. Magnesium Res. 2022;35(3):88-95. doi:10.1684/mrh.2022.0505

- Efentakis M, Dressman JB. Gastric juice as a dissolution medium: surface tension and pH. Eur j Drug Metab Pharm. 1998;23(2):97-102. doi:10.1007/BF03189322

- Mithani SD, Bakatselou V, TenHoor CN, et al. Estimation of the increase in solubility of drugs as a function of bile salt concentration. Pharm Res. 1996;13(1):163-167. doi:10.1023/a:1016062224568

- Bakatselou V, Oppenheim RC, Dressman JB, et al. Solubilization and wetting effects of bile salts on the dissolution of steroids. Pharm Res. 1991;8(12):1461-1469. doi:10.1023/a:1015877929381

- Charman WN, Porter CJH, Mithani S, et al. Physiochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: the role of lipids and pH. J Pharmaceut Sci. 1997;86(3):269-282. doi:10.1021/js960085v

- La Sorella G, Sperni L, Canton P, et al. Selective Hydrogenations and Dechlorinations in Water Mediated by Anionic Surfactant-Stabilized Pd Nanoparticles. J Org Chem. 2018;83(14):7438-7446. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00314

- Singh KK, Vingkar SK. Formulation, antimalarial activity and biodistribution of oral lipid nanoemulsion of primaquine.Int. J Pharm. 2008;347 (1-2):567.

- Kalepu S, Nekkanti V. Insoluble drug delivery strategies: review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharma Sin. 2015;5 (5):442-453. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.003

- Hirose R, Sugano K. Effect of Food Viscosity on Drug Dissolution. Pharm Res. 2024;41(1):105-112. doi:10.1007/s11095-023-03620-y

- Amidon GL, Leesman GD, Elliott RL, et al. Improving intestinal absorption of water-insoluble compounds: a membrane metabolism strategy. J Pharmaceut Sci. 1980;69(12):1363-1368. doi:10.1002/jps. 2600691203

- Mistry A, Stolnik S, Illum L, et al. Nanoparticles for direct nose-to-brain delivery of drugs. Int J Pharm. 2009;379(1):146-157. doi:10.1016/j. ijpharm.2009.06.019

- Yuan S, Zhang Q. Application of One-Dimensional Nanomaterials in Catalysis at the Single-Molecule and Single-Particle Scale. Front Chem. 2021;9(812287). doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.812287

- Hegewald AB , Breitwieser K, Ottinger SM, et al. Extracellular miR-574-5p Induces Osteoclast Differentiation via TLR 7/8 in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585282. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.585282

- Han L, Jiang C. Evolution of blood-brain barrier in brain diseases and related systemic nanoscale brain-targeting drug delivery strategies. Acta Pharma Sin. 2021;11(8):2306-2325. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.11.023

- Parodi A, Quattrocchi N, van de Ven AL, et al. Synthetic nanoparticles functionalized with biomimetic leukocyte membranes possess cell-like functions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(1):61-68. doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.212

- Ugwoke MI, AGU R, VERBEKE N, et al. Nasal mucoadhesive drug delivery: background, applications, trends and future perspectives. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2005;57(11):1640-1665. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.009

- Kanazawa T, Taki H, Tanaka K, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide-modified block copolymer micelles promote direct brain delivery via intranasal administration. Pharm Res. 2011;28(9):2130-2139. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0440-7

- Rafiei P, Haddadi A. Pharmacokinetic Consequences of PLGA Nanoparticles in Docetaxel Drug Delivery. Pharm nanotechnol. 2017;5(1):3-23. doi:10.2174/2211738505666161230110108

- Sridhar V, Gaud R, Bajaj A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intranasally administered selegiline nanoparticles with improved brain delivery in Parkinson’s disease. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(8):2609-2618. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2018.08.004

- Guo Q, Chang Z, Khan NU, et al. Nanosizing Noncrystalline and Porous Silica Material-Naturally Occurring Opal Shale for Systemic Tumor Targeting Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(31):25994-26004. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b06275

- Aslam M, Javed MN, Deeb HH, et al. Lipid Nanocarriers for Neurotherapeutics: introduction, Challenges, Blood-brain Barrier, and Promises of Delivery Approaches. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2022;21(10):952-965. doi:10.2174/1871527320666210706104240

- Large DE, Abdelmessih RG, Fink EA, et al. Liposome composition in drug delivery design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2021;176:113851. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.113851

- Harde H, Das M, Jain S, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles: an oral bioavailability enhancer vehicle. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2011;8 (11):1407-1424. doi:10.1517/17425247.2011.604311

- Damgé C, Michel C, Aprahamian M, et al. New approach for oral administration of insulin with polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanocapsules as drug carrier. Diabetes. 1988;37(2):246-251. doi:10.2337/diab.37.2.246

- Ponchel G, Montisci M-J, Dembri A, Durrer C, Duchêne D. Assia Dembri, Carlo Durrer, Dominique Duchêne,Mucoadhesion of colloidal particulate systems in the gastro-intestinal tract,European. J Pharm Biopharmaceutics. 1997;44(1):25-31. doi:10.1016/S0939-6411(97)00098-2

- Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, et al. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2016;99:28-51. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012

- Souto EB, Baldim I, Oliveira WP, et al. SLN and NLC for topical, dermal, and transdermal drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2020;17 (3):357-377. doi:10.1080/17425247.2020.1727883

- Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA, et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Delivery Rev 2002;54(1):S131-55. doi:10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00118-7

- Xiu-Yan L, Guan Q-X, Shang Y-Z, et al. Metal-organic framework IRMOFs coated with a temperature-sensitive gel delivering norcantharidin to treat liver. World j Gastroenterol. 2021;27(26):4208-4220. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i26.4208

- Pan M-S, Cao J, Fan Y-Z, et al. Insight into norcantharidin, a small-molecule synthetic compound with potential multi-target anticancer activities. ChinMed. 2020;15:55. doi:10.1186/s13020-020-00338-6

- Yan Z, Yang K, Tang X, et al. Norcantharidin Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NCTD-NLC) Suppresses the Viability of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells and Accelerates the Apoptosis. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:3851604. doi:10.1155/2022/3851604

- Akhter MH, Ahmad A, Ali J, et al. Formulation and Development of CoQ10-Loaded s-SNEDDS for Enhancement of Oral Bioavailability.

Pharm Innov. 2014;9:121-131. doi:10.1007/s12247-014-9179-0 - Soni K, Mujtaba A, Akhter MH, et al. Optimisation of ethosomal nanogel for topical nano-CUR and sulphoraphane delivery in effective skin cancer therapy. J Microencapsulation. 2020;37(2):91-108. doi:10.1080/02652048.2019.1701114

- Katari O, Jain S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carrier-based nanotherapeutics for the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2021;18(12):1857-1872. doi:10.1080/17425247.2021.2011857

- Carmen Gómez-Guillén M, Montero MP. Pilar Montero,Enhancement of oral bioavailability of natural compounds and probiotics by mucoadhesive tailored biopolymer-based nanoparticles: a review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;118:106772. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021. 106772

- Denora N, Trapani A, Laquintana V, et al. Recent advances in medicinal chemistry and pharmaceutical technology–strategies for drug delivery to the brain. Curr Top Med Chem 2009;9(2):182-196. doi:10.2174/156802609787521571

- Mikhail AS, Allen C. Block copolymer micelles for delivery of cancer therapy: transport at the whole body, tissue and cellular levels.

Control Release. 2009;138(3):214-223. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.04.010 - Lee Y. Preparation and characterization of folic acid linked poly(L-glutamate) nanoparticles for cancer targeting. Macromol Res. 2006;14:387-393. doi:10.1007/BF03219099

- Wang H, Zhao Y, Wu Y, et al. Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy by co-delivery of doxorubicin and paclitaxel with amphiphilic methoxy PEG-PLGA copolymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32(32):8281-8290. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.032

- Chen Q, Han X, Liu L, et al. Multifunctional Polymer Vesicles for Synergistic Antibiotic-Antioxidant Treatment of Bacterial Keratitis. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24(11):5230-5244. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00754

- Md S, Alhakamy NA, Neamatallah T, et al. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation of

-Mangostin-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticle Gel for Topical Therapy in Skin Cancer. Gels. 2021;7(4):230. doi:10.3390/gels7040230 - Shumin L, Xu Z, Alrobaian M, et al. EGF-functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles of 5-fluorouracil and sulforaphane with enhanced bioavailability and anticancer activity against colon carcinoma. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2022;69(5):2205-2221. doi:10.1002/bab.2279

- Karim S, Akhter MH, Burzangi AS, et al. Phytosterol-Loaded Surface-Tailored Bioactive-Polymer Nanoparticles for Cancer Treatment: optimization, In Vitro Cell Viability, Antioxidant Activity, and Stability Studies. Gels. 2022;8:219. doi:10.3390/gels8040219

- Mir MA, Akhter MH, Afzal O, et al. Design-of-Experiment-Assisted Fabrication of Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles: in Vitro Characterization, Biological Activity, and In Vivo Assessment. ACS Omega. 2023;8(42):38806-38821. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01153

- Vozza G, Khalid M, Byrne HJ, Ryan SM, Jesus M. Frias,Nutraceutical formulation, characterisation, and in-vitro evaluation of methylselenocysteine and selenocystine using food derived chitosan:zein nanoparticles. Food Res Int. 2019;120:295-304. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.028

- Pauluk D, Krause Padilha A, Maissar Khalil N, Mainardes RM. Rubiana Mara Mainardes, Chitosan-coated zein nanoparticles for oral delivery of resveratrol: formation, characterization, stability, mucoadhesive properties and antioxidant activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;94:411-417. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.03.042

- Xia L, Cong Z, Liu Z, et al. Improvement of the solubility, photostability, antioxidant activity and UVB photoprotection of trans-resveratrol by essential oil based microemulsions for topical application. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2018;48:346-354. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2018.10.017

- Chatterjee B, Gorain B, Mohananaidu K, et al. Targeted drug delivery to the brain via intranasal nanoemulsion: available proof of concept and existing. Int j Pharma. 2019;565:258-268. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.05.032

- Pandey P, Gulati N, Makhija M, et al. Nanoemulsion: a Novel Drug Delivery Approach for Enhancement of Bioavailability. Recent Patents Nanotechnol. 2020;14(4):276-293. doi:10.2174/1872210514666200604145755

- Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Liang R, et al. Beta-carotene chemical stability in Nanoemulsions was improved by stabilized with beta-lactoglobulincatechin conjugates through free radical method. J Agr Food Chem. 2015;63(1):297-303. doi:10.1021/jf5056024

- Ding L, Tang S, Yu A, et al. Nanoemulsion-Assisted siRNA Delivery to Modulate the Nervous Tumor Microenvironment in the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(8):10015-10029. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c21997

- Niu Z, Acevedo-Fani A, McDowell A, et al. Nanoemulsion structure and food matrix determine the gastrointestinal fate and in vivo bioavailability of coenzyme Q10. J Control Release. 2020;327:444-455. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.025

- Bouchemal K, Briançon S, Perrier E, et al. Nano-emulsion formulation using spontaneous emulsification: solvent, oil and surfactant. Int j Pharm. 2004;280(1-2):241-251. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.016

- Weiss M, Steiner DF, Philipson LH, et al. Insulin Biosynthesis, Secretion, Structure, and Structure-Activity Relationships. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2014.

- Leber N, Nuhn L, Zentel R, et al. Cationic Nanohydrogel Particles for Therapeutic Oligonucleotide Delivery. Macromol biosci. 2017;17 (10):10.1002/mabi.201700092. doi:10.1002/mabi. 201700092

- Deng S, Gigliobianco M, Mijit E, et al. Dually Cross-Linked Core-Shell Structure Nanohydrogel with Redox-Responsive Degradability for Intracellular Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(12):2048. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13122048

- Granata G, Petralia S, Forte G, et al. Injectable supramolecular nanohydrogel from a micellar self-assembling calix[4] arene derivative and curcumin for a sustained drug release. Mater Sci Eng. 2020;111:110842. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2020.110842

- Raemdonck K, Demeester J, De Smedt S. Advanced nanogel engineering for drug delivery. Soft Matter. 2009;5(4):707-715. doi:10.1039/ B811923F

- El-Refaie WM, Elnaggar YSR, El-Massik MA, et al. Novel Self-assembled, Gel-core Hyaluosomes for Non-invasive Management of Osteoarthritis: in-vitro Optimization, Ex-vivo and In-vivo Permeation. Pharm Res. 2015;32(9):2901-2911. doi:10.1007/s11095-015-1672-8

- Udeni Gunathilake TMS, Ching YC, Chuah CH. Enhancement of Curcumin Bioavailability Using Nanocellulose Reinforced Chitosan Hydrogel. Polymers. 2017;9(2):64. doi:10.3390/polym9020064

- Ahmad I, Farheen M, Kukreti A, et al. Natural Oils Enhance the Topical Delivery of Ketoconazole by Nanoemulgel for Fungal Infections. ACS omega. 2023;8(31):28233-28248. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01571

- Yanchen H, Zhi Z, Zhao Q, et al. 3D cubic mesoporous silica microsphere as a carrier for poorly soluble drug carvedilol. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;147(1):94-101. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.06.001

- Zhang Y, Wang J, Bai X, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for increasing the oral bioavailability and permeation of poorly water soluble drugs. Mol Pharmaceut. 2012;9(3):505-513. doi:10.1021/mp200287c

- Pawlaczyk M, Schroeder G. Dual-Polymeric Resin Based on Poly (methyl vinyl ether-alt-maleic anhydride) and PAMAM Dendrimer as a Versatile Supramolecular Adsorbent. ACS Appl Polymer Mater. 2021;3(2):956-967. doi:10.1021/acsapm.0c01254

- Liu X, Peng Y, Qu X, et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube-chitosan/poly(amidoamine)/DNA nanocomposite modified gold electrode for determination of dopamine and uric acid under coexistence of ascorbic acid. J Electroanal Chem. 2011;654(1-2):72-78. doi:10.1016/j. jelechem.2011.01.024

- Zhuo RX, Du B, Lu ZR. In vitro release of 5-fluorouracil with cyclic core dendritic polymer. J Control Release. 1999;57(3):249-257. doi:10.1016/s0168-3659(98)00120-5

- Luo K, Li C, Li L, et al. Arginine functionalized peptide dendrimers as potential gene delivery vehicles. Biomaterials. 2012;33(19):4917-4927. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.030

- Conghua Y, Qinghe X, Yang D, Wang M. Miao Wang,A novel pH -responsive charge reversal nanospheres based on acetylated histidine-modified lignin for drug delivery. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;186:115193. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115193

- Guo F, Jiao Y, Du Y, et al. Enzyme-responsive nano-drug delivery system for combined antitumor therapy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;220:1133-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jjbiomac.2022.08.123

- Hui Y, Jin F, Liu D, et al. ROS-responsive nano-drug delivery system combining mitochondria-targeting ceria nanoparticles with atorvastatin for acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2020;10(5):2342-2357. doi:10.7150/thno. 40395

- Wang G, Maciel D, Wu Y, et al. Amphiphilic polymer-mediated formation of laponite-based nanohybrids with robust stability and pH sensitivity for anticancer drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(19):16687-16695. doi:10.1021/am5032874

- Ghadiri M, Young PM, Traini D. Strategies to Enhance Drug Absorption via Nasal and Pulmonary Routes. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(3):113. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11030113

- Pawar B, Vasdev N, Gupta T, et al. Current Update on Transcellular Brain Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12):2719. doi:10.3390/ pharmaceutics14122719

- Sosnik A, Das Neves J. Bruno Sarmento.Mucoadhesive polymers in the design of nano-drug delivery systems for administration by non-parenteral routes: a review. Prog Polym Sci. 2014;39(12):2030-2075.

- Costa CP, Moreira JN, Sousa Lobo JM, et al. Intranasal delivery of nanostructured lipid carriers, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsions: a current overview of in vivo studies. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2021;11(4):925-940. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.02.012

- Bhaskar S, Tian F, Stoeger T, et al. Multifunctional Nanocarriers for diagnostics, drug delivery and targeted treatment across blood-brain barrier: perspectives on tracking and neuroimaging. Particle Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:3. doi:10.1186/1743-8977-7-3

- Sun W, Xie C, Wang H, et al. Specific role of polysorbate 80 coating on the targeting of nanoparticles to the brain. Biomaterials. 2004; 25 (15):3065-3071. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.087

- Wei L, Tan Y-Z, Hu K-L, et al. Cationic albumin conjugated pegylated nanoparticle with its transcytosis ability and little toxicity against blood-brain barrier. Int J Pharm. 2005;295(1-2):247-260. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.043

- Chai Z , Hu X, Wei X, et al. A facile approach to functionalizing cell membrane-coated nanoparticles with neurotoxin-derived peptide for brain-targeted drug delivery.

Control Release. 2017;264:102-111. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.027 - Fang RH, Hu C-MJ, Chen KNH, et al. Lipid-insertion enables targeting functionalization of erythrocyte membrane-cloaked nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2013;5(19):8884-8888. doi:10.1039/c3nr03064d

- Yan L, He H, Jia X, et al. A dual-targeting nanocarrier based on poly(amidoamine) dendrimers conjugated with transferrin and tamoxifen for treating brain gliomas. Biomaterials. 2012;33(15):3899-3908. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.004

- Habban Akhter M, Beg S, Tarique M, Malik A, Afaq S, Choudhry H. Salman Hosawi,Receptor-based targeting of engineered nanocarrier against solid tumors: recent progress and challenges ahead. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2021;1865(2):129777. doi:10.1016/j. bbagen.2020.129777

- Spanjers JM, Städler B. Cell Membrane Coated Particles. Adv Biosyst 2020;4(11):e2000174. doi:10.1002/adbi.202000174

- Ricordel C, Labalette-Tiercin M, Lespagnol A, et al. EFGR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma and Li-Fraumeni syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature. Lung Cancer. 2015;87(1):80-84. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.11.005

- Farheen M, Akhter MH, Chitme H, et al. Surface-Modified Biobased Polymeric Nanoparticles for Dual Delivery of Doxorubicin and Gefitinib in Glioma Cell Lines. ACS omega. 2023;8(31):28165-28184. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01375

- Wang Z-H, Liu J-M, Zhao N, et al. Cancer Cell Macrophage Membrane-Camouflaged Persistent-Luminescent Nanoparticles for Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy of Colorectal Cancer. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2020;XXXX. doi:10.1021/acsanm.0c01433

- Zhao K, Li D, Cheng G, et al. Targeted Delivery Prodigiosin to Choriocarcinoma by Peptide-Guided Dendrigraft Poly-1-lysines Nanoparticles. Int j Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5458. doi:10.3390/ijms20215458

- Wang Y, Cheng J, Zhao D, et al. Designed DNA nanostructure grafted with erlotinib for non-small-cell lung cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 2020;12 (47):23953-23958. doi:10.1039/d0nr06945k

- Gong Y, Mohd S, Wu S, et al. pH-responsive cellulose-based microspheres designed as an effective oral delivery system for insulin.

Mega. 2021;6:2734-2741. - Cikrikci S, Mert H, Oztop MH. Development of pH sensitive alginate/gum tragacanth based hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:11784-11796. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02525

- Qi X, Yuan Y, Zhang J, et al. Oral administration of salecan based hydrogels for controlled insulin delivery. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:10479-10489. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02879

- Zhang L, Qin H, Li J, et al. Preparation and characterization of layer-by-layer hypoglycemic nanoparticles with pH -sensitivity for oral insulin delivery. J Mater Chem. 2018;6:7451-7461.

- Shabana AM, Kambhampati SP, Hsia R-C, et al. Thermosensitive and Biodegradable Hydrogel Encapsulating Targeted Nanoparticles for the Sustained Co-Delivery of Gemcitabine and Paclitaxel to Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Int J Pharm. 2020;593(6):120139. doi:10.1016/j. ijpharm.2020.120139