DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12865

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-15

الأرشيف المفتوح UNIGE

https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch

التقشف، الضعف الاقتصادي، والشعبوية

كيفية الاقتباس

رقم التعريف الرقمي للنشر: 10.1111/ajps.12865

© المؤلف(ون). هذا العمل مرخص بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب (CC BY 4.0)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

التقشف، الضعف الاقتصادي، والشعبوية

المراسلات

الملخص

لقد قامت الحكومات بتعديل السياسة المالية بشكل متكرر في العقود الأخيرة. نحن ندرس الآثار السياسية لهذه التعديلات في أوروبا منذ التسعينيات باستخدام نتائج الانتخابات على مستوى الدوائر وبيانات التصويت على المستوى الفردي. نتوقع أن تؤدي سياسة التقشف إلى زيادة الأصوات المؤيدة للشعبوية، ولكن فقط بين الناخبين المعرضين اقتصاديًا، الذين يتأثرون بشدة بالتقشف. نحدد المناطق المعرضة اقتصاديًا على أنها تلك التي تحتوي على نسبة عالية من العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة، والعمال في التصنيع، وفي الوظائف ذات الكثافة العالية من المهام الروتينية. تُظهر تحليل الانتخابات على مستوى الدوائر أن التقشف يزيد من الدعم للأحزاب الشعبوية في المناطق المعرضة اقتصاديًا، ولكنه له تأثير ضئيل في المناطق الأقل تعرضًا. تؤكد التحليلات على المستوى الفردي هذه النتائج. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن نجاح الأحزاب الشعبوية يعتمد على فشل الحكومة في حماية الخاسرين من التغيير الاقتصادي الهيكلي. وبالتالي، فإن الأصول الاقتصادية للشعبوية ليست خارجية بحتة؛ بل إن رد الفعل الشعبوي يتم تحفيزه بواسطة عوامل داخلية، ولا سيما السياسات العامة.

أقل مما سيكونون عليه في دراسة حالة تحتوي على حلقة واحدة من التقشف، والتي تختلف على المستوى دون الوطني. نحن نتبادل افتراضات تحديد أقوى من أجل صلاحية خارجية أقوى.

التقشف والأصول الاقتصادية للشعبوية

التعديلات المالية في أوقات زيادة المخاطر الاقتصادية

الناخبون المعرضون للخطر، مثل التحويلات الاجتماعية وغيرها من سياسات دولة الرفاه. يظهر الشكل 2 أن التحويلات الحكومية مركزية في حزم التقشف. تتفاوت متوسط تحويلات الضمان الاجتماعي في الدول الصناعية بشكل كبير على مر الزمن وانخفضت بشكل خاص خلال التسعينيات ومرة أخرى من 2013 فصاعدًا. تتزامن هذه الانخفاضات في التحويلات مع موجات كبيرة من التقشف التي نفذتها الحكومات في العقود الأخيرة (انظر أيضًا أرمينجيون وآخرون، 2016). كما يظهر الملحق الإلكتروني أ على الصفحة 2، يتم تقليص التحويلات الحكومية أكثر من أي فئة ميزانية أخرى. نجد نمطًا مشابهًا للإنفاق العام على إعانات البطالة والتعليم والمعاشات في الشكل C1 في الملحق الإلكتروني C على الصفحة.

الناخبون المعرضون للخطر وردود أفعالهم السياسية

من المرجح أن تفقد الوظائف الروتينية وظائفها بسبب نقلها إلى الخارج أو الأتمتة (غاليغو وآخرون، 2022؛ جينغريتش، 2019؛ أوين، 2020).

الانتخابات على مستوى المقاطعة

بيانات

قياس الشعبوية

قياس التقشف

قياس الضعف الاقتصادي

الاستراتيجية التجريبية

التعريف

الناخبين الضعفاء. لمعالجة هذه النقطة، نستفيد من حقيقة أن تدابير التقشف لا تتوافق تمامًا مع الظروف الاقتصادية السلبية في دول غرب أوروبا. بعبارة أخرى، بينما يرتبط التقشف سلبًا بالنمو الاقتصادي والتوازن المالي، تشير بياناتنا إلى أن مثل هذه التدابير قد تم تنفيذها أيضًا خلال فترات من الاستقرار والنمو الاقتصادي. وبالتالي، لتحديد ما إذا كانت فترات الأزمات الاقتصادية تدفع تقديراتنا، نقوم بتشغيل نماذجنا الرئيسية على عينتين فرعيتين: (1) الملاحظات التي تشهد نموًا اقتصاديًا بطيئًا وتوازنًا ماليًا سلبيًا و(2) الملاحظات التي تشهد نموًا اقتصاديًا متوسطًا أو سريعًا وتوازنًا ماليًا متوسطًا أو إيجابيًا.

النتائج

الشعبوية

| درجة الشعبوية | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف | 1.041** (.356) | 1.037** (.302) |

|

||||

| نسبة عمال التصنيع * التقشف | 1.248** (.334) | 1.459** (.456) | 1.107** (.341) | ||||

| نسبة العمال المعرضين للأتمتة * التقشف | 1.581** (.513) | 1.525* (.620) | |||||

| ثابت | 4.352** (.105) | 4.439** (.058) | 4.198** (.154) | 4.360** (.121) | 4.502** (.059) | 4.205** (.199) | 4.290** (.110) |

| الملاحظات | 14,110 | 14,158 | 14,435 | 11,607 | 11,607 | 11,583 | 14,110 |

|

|

. 867 | . 868 | . 870 | . 847 | . 849 | . 848 | . 868 |

| التحكم | لا | لا | لا | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

| آثار ثابتة NUTS-2 | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

| آثار ثابتة لبلد-سنة الانتخابات | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

التحكم (النماذج 4-6). تعطي نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة، ونسبة عمال التصنيع، ونسبة العمال المعرضين للأتمتة نتائج مشابهة؛ تظل معاملاتهن إيجابية وذات دلالة، حتى عندما ندرج كلاهما في نفس الوقت على الجانب الأيمن من النماذج (النموذج 7).

| درجة الشعبوية | |||

| توازن مالي منخفض فقط | توازن مالي مرتفع فقط | العينة الكاملة | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف |

|

|

.950* (.371) |

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التوازن المالي | -. 057 (.068) | ||

| ثابت | 4.551** (.240) | 4.277** (.133) | 4.367** (.106) |

| الملاحظات | 3497 | 10,602 | 14,110 |

|

|

. 789 | . 884 | . 867 |

| التحكم | لا | لا | لا |

| آثار ثابتة NUTS-2 | نعم | نعم | نعم |

| آثار ثابتة لبلد-سنة الانتخابات | نعم | نعم | نعم |

دور الأزمات

أنواع التقشف

| درجة الشعبوية | ||||||||

| عينة كاملة | عينة كاملة | عينة كاملة | عينة كاملة | رفاهية منخفضة فقط | رفاهية عالية فقط | عينة كاملة | عينة كاملة | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف (الخفضات) | 1.089 * (.545) | 1.470** (.412) | ||||||

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * نسبة تخفيضات الإنفاق | 1.779 * (.690) | |||||||

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * تخفيضات الإنفاق بشكل أساسي | 1.011 * (.493) | |||||||

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف (التوحيد) |

|

1.118 * (.492) | ||||||

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف (منخفض) | -. 373 (.546) | -. 482 (.345) | ||||||

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف (مرتفع) | 1.655** (.559) | 1.492** (.468) | ||||||

| ثابت | 4.431** (.114) | 4.362** (.119) | 4.368** (.065) | 4.451** (.041) | 5.206** (.120) | 3.824** (.162) | 4.459** (.134) | 4.523** (.102) |

| ملاحظات | 14,110 | 11,607 | 12,439 | 12,439 | ٥٣٣٤ | 8776 | ١٤١١٠ | 11,607 |

|

|

. 867 | . ٨٤٧ | . 871 | . 871 | . 856 | . 809 | . 868 | . 848 |

| التحكمات | لا | نعم | نعم | نعم | لا | لا | لا | نعم |

| تأثيرات ثابتة NUTS-2 | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

| آثار ثابتة لسنة الانتخابات في الدول | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

العمال المعرضون للخطر اقتصاديًا، مما قد يفسر سبب تحولهم إلى التصويت للأحزاب الشعبوية. في الملحق الإلكتروني E في الصفحة 21، نوضح أن نتائجنا مشابهة عندما نستخدم مؤشرات أخرى للهشاشة الاقتصادية.

التقشف والأيديولوجيا

فحوصات المتانة

| نسبة الأصوات للأحزاب اليسارية الراديكالية | نسبة الأصوات للأحزاب اليمينية المتطرفة | |||||

| عينة كاملة | اليسار فقط | الحق فقط للمستفيد | عينة كاملة | اليسار فقط | الحق فقط للمستفيد | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة * التقشف | -0.006 (0.071) | -0.084** (0.025) | 0.013 (0.054) | 0.152** (0.049) | 0.183* (0.071) | 0.136* (0.055) |

| ثابت | 0.042* (0.021) | 0.070** (0.006) | 0.029 (0.018) | 0.017 (0.014) | 0.025 (0.016) | 0.012 (0.019) |

| ملاحظات | ١٤١١١ | 5624 | ٨٤٧٨ | ١٤١١١ | 5624 | ٨٤٧٨ |

|

|

. 640 | . 739 | . 612 | . ٨٣٣ | . 918 | . 767 |

| التحكمات | لا | لا | لا | لا | لا | لا |

| تأثيرات ثابتة NUTS-2 | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

| آثار ثابتة لسنة الانتخابات في الدول | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

لا يوجد دعم للشعبوية. ثانياً، نتائجنا مشابهة إذا استخدمنا القيمة الخام للتقشف بدلاً من قيمتها المسجلة. ثالثاً، لا نجد أي دليل على أن التقشف يؤثر على نسبة المشاركة. رابعاً، نوضح أن نتائجنا ليست مدفوعة بفترة ما بعد 2010. أخيراً، نوضح أن نتائجنا تظل صحيحة إذا استبعدنا دولة واحدة في كل مرة؛ وبالتالي فهي لا تعتمد على تضمين أي دولة معينة في عيّنتنا.

التصويت على مستوى الأفراد

بيانات

| درجة الشعبوية | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (٤) | (5) | (6) | |

| التعليم الثانوي الأدنى | . ٠٥٤ (.٠٥٥) | . ٠٤٧ (.٠٥٩) | ||||

| التعليم الثانوي العلوي | .096* (.037) | .090* (.037) | ||||

| التصنيع | -. 011 (.021) | -. 016 (.021) | ||||

| RTI | -. 026 (.035) | . 011 (.039) | ||||

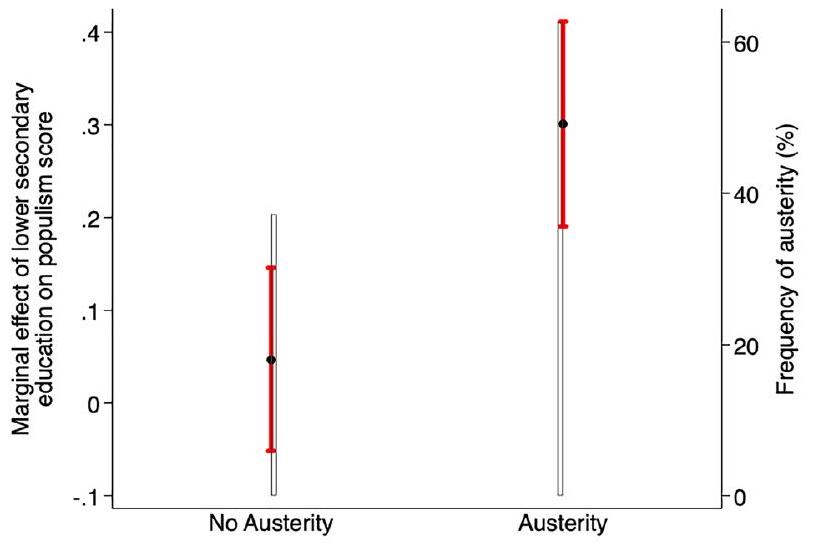

| التعليم الثانوي الأدنى * التقشف (نموذج) | .221** (.083) | .254** (.089) | ||||

| التعليم الثانوي العلوي * التقشف (نموذج) | .164** (.062) | .173** (.062) | ||||

| التصنيع * التقشف (نموذج) | .093* (.038) | .085* (.039) | ||||

| RTI * التقشف (نموذج) |

|

.111* (.055) | ||||

| ثابت | 4.621** (.040) | 4.471** (.162) | 4.843** (.005) | 4.670** (.147) | 4.779** (.017) | 4.521** (.168) |

| ملاحظات | ٨٦,٩٣٩ | ٨٦٧١٧ | 82,317 | 82,128 | 72,613 | 72,449 |

|

|

. 301 | . 303 | . 299 | . 301 | . 299 | . 301 |

| التحكمات | لا | نعم | لا | نعم | لا | نعم |

| تأثيرات ثابتة على مستوى الدولة | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم | نعم |

(2019)، نقوم بتجميع مقياس RTI إلى خمسة خُمس، مع إعادة قياسه من 0 (الأقل تأثراً) إلى 1 (الأكثر تأثراً)، مما يتيح لنا تحديد فئات واسعة من التعرض.

استراتيجية تجريبية

أين

النتائج

الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

REFERENCES

Arias, Eric, and David Stasavage. 2019. “How Large Are the Political Costs of Fiscal Austerity.” Journal of Politics 81(4): 1517-22.

Armingeon, Klaus, Kai Guthmann, and David Weisstanner. 2016. “Choosing the Path of Austerity: A Neo-Functionalist Explanation of Welfare-Policy Choices in Periods of Fiscal Consolidation.” West European Politics 39(4): 628-47.

Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfeland David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler. 2019. “Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2017.” Electronic Database, http://www.cpds-data.org.

Baccini, Leonardo, Pablo M. Pinto, and Stephen Weymouth. 2017. “The Distributional Consequences of Preferential Trade Liberalization: Firm-Level Evidence.” International Organization 71(2): 373-95.

Baccini, Leonardo, and Stephen Weymouth. 2021. “Gone for Good: Deindustrialization, White Voter Backlash, and U.S. Presidential Voting.” American Political Science Review 115(2): 550-67.

Ballard-Rosa, Cameron, Mashail Malik, Stephanie Rickard, and Ken Scheve. 2021. “The Economic Origins of Authoritarian Values: Evidence from Local Trade Shocks in the United Kingdom.” Comparative Political Studies (Online First).

Bambra, Clare, Julia Lynch, and Katherine E. Smith. 2021. The Unequal Pandemic: Covid-10 and Health Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press.

Bansak, Kirk, Michael Bechtel, and Yotam Margalit. 2021. “Why Austerity? The Mass Politics of a Contested Policy.” American Political Science Review 115(2): 486-505.

Barnes, Lucy, and Timothy Hicks. 2018. “Making Austerity Popular: The Media and Mass Attitudes Towards Fiscal Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 62(2): 340-54.

Barta, Zsófia, and Alison Johnston. 2018. “Rating Politics? Partisan Discrimination in Credit Ratings in Developed Economies.” Comparative Political Studies 51(5): 587-620.

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bisbee, James, Layna Mosley, Thomas B. Pepinsky, and B. Peter Rosendorff. 2020. “Decompensating Domestically: The Political Economy of Anti-Globalism.” Journal of European Public Policy 27(7): 1090-102.

Blyth, Mark. 2013. Austerity-The History of a Dangerous Idea. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bodea, Cristina, and Masaaki Higashijima. 2017. “Central Bank Independence and Fiscal Policy: Can the Central Bank Restrain Deficit Spending?” British Journal of Political Science 47(1): 47-70.

Bremer, Björn, Swen Hutter, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2020. “Dynamics of Protest and Electoral Politics in the Great Recession.” European Journal of Political Research 59(4): 842-66.

Colantone, Italo, and Piero Stanig. 2018. “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe.” American Journal of Political Science 62(4): 936-53.

Copelovitch, Mark, Jeffry Frieden, and Stefanie Walter. 2016. “The Political Economy of the Euro Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 49(7): 811-40.

Cremaschi, Simone, Paula Rettl, Marco Cappelluti, and Catherine De Vries. 2023. “Geographies of Discontent: Public Service Deprivation and the Rise of the Far Right in Italy.” Harvard Business School Working Paper 24-024. Available at: https:// www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication Files/24-024_da5e436e-b4e8-4215-b788-f6043dbc7d1f.pdf

De Vries, Catherine, and Sara Hobolt. 2020. Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Devries, Pete, Jaime Guajardo, Daniel Leigh, and Andrea Pescatori. 2011. “A New Action-Based Dataset of Fiscal Consolidation.” IMF Working Paper

Enggist, Matthias, and Michael Pinggera. 2022. “Radical Right Parties and Their Welfare State Stances: Not so Blurry After All?” West European Politics 45(1): 102-28.

Fetzer, Thiemo. 2019. “Did Austerity Cause Brexit?” American Economic Review 109(11): 3849-86.

Frieden, Jeffry A. 2000. Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century. New York: Norton & Company.

Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. 2017. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” British Journal of Sociology 68(S1): S57-S84.

Giger, Nathalie, and Moira Nelson. 2011. “The Electoral Consequences of Welfare State Retrenchment: Blame Avoidance or Credit Claiming in the Era of Permanent Austerity.” European Journal of Political Research 50(1): 1-23.

Gingrich, Jane. 2019. “Did State Responses to Automation Matter for Voters?” Research and Politics 6(1): 1-9.

Gingrich, Jane, and Ben Ansell. 2012. “Preferences in Context: Micro Preferences, Macro Contexts, and the Demand for Social Policy.” Comparative Political Studies 45(12): 1624-54.

Goos, Maarten, Alan Manning, and Anna Salomons. 2014. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Based Technological Change and Offshoring.” American Economic Review 104(8): 2509-26.

Grittersová, Jana, Indridi H. Indridason, Christina C. Gregory, and Ricardo Crespo. 2016. “Austerity and Niche Parties: The Electoral Consequences of Fiscal Reforms.” Electoral Studies 42(June): 27689.

Hallerberg, Mark, and Guntram Wolff. 2008. “Fiscal Institutions, Fiscal Policy and Sovereign Risk Premia in EMU.” Public Choice 136(3): 379-96.

Hays, Jude C. 2009. Globalization and the New Politics of Embedded Liberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hellwig, Timothy, and David Samuels. 2007. “Voting in Open Economies-The Electoral Consequences of Globalization.” Comparative Political Studies 40(3): 283-306.

Hopkin, Jonathan. 2020. Anti-System Politics: The Crisis of Market Capitalism in Rich Democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hübscher, Evelyne, and Thomas Sattler. 2017. “Fiscal Consolidation under Electoral Risk.” European Journal of Political Research 56(1): 151-68.

Hübscher, Evelyne, Thomas Sattler, and Markus Wagner. 2021. “Voter Responses to Fiscal Austerity.” British Journal of Political Science 51(4): 1751-60.

Hübscher, Evelyne, Thomas Sattler, and Markus Wagner. 2023. “Does Austerity Cause Polarization?” British Journal of Political Science 53(4): 1170-88.

Jensen, J. Bradford, Dennis P. Quinn, and Stephen Weymouth. 2017. “Winners and Losers in International Trade: The Effects on US Presidential Voting.” International Organization 71(3): 423-57.

Kayser, Mark A., and Michael Peress. 2012. “Benchmarking across Borders: Electoral Accountability and the Necessity of Comparison.” American Political Science Review 106(3): 661-84.

Kollman, Ken, Allen Hicken, Daniele Caramani, David Backer, and David Lublin. 2019. Constituency-Level Elections Archive. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Political Studies, University of Michigan [producer and distributor]. http://www.electiondataarchive.org.

Konstantinidis, Nikitas, Konstantinos Matakos, and Hande HutluEren. 2019. “‘Take Back Control’? The effects of Supranational Integration on Party-System Polarization.” Review of International Organizations 14(2): 297-333.

Margalit, Yotam. 2011. “Costly Jobs: Trade-Related Layoffs, Government Compensation, and Voting in U.S. Elections.” American Political Science Review 105(1): 166-88.

Milner, Helen V. 1988. Resisting Protectionism: Global Industries and the Politics of International Trade. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Milner, Helen V. 2021. “Voting for Populism in Europe: Globalization, Technological Change, and the Extreme Right.” Comparative Political Studies 54(13): 2286-320.

Mosley, Layna. 2003. Global Capital and National Governments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2019. “The Global Party Survey (V1.0).” https://www. globalpartysurvey.org.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and the Rise of Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, Erica. 2020. “Firms vs. Workers? The Politics of Openness in an Era of Global Production and Automation.” Paper presented in the Global Research in International Political Economy (GRIPE) Seminar, June 10, online.

Owen, Erica, and Noel Johnston. 2017. “Occupation and the Political Economy of Trade: Job Routineness, Offshoreability and Protectionist Sentiment.” International Organization 71(4): 665-99.

Pierson, Paul, ed. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press.

Richtie, Melinda, and Hye Young You. 2020. “Trump and Trade: Protectionist Politics and Redistributive Policy.” Working Paper, UC Riverside and New York University.

Rickard, Stephanie J. 2015. “Compensating the Losers: An Examination of Congressional Votes on Trade Adjustment Assistance.” International Interactions 41(1): 46-60.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, Stijn Van Kessel, Caterina Froio, Andrea Pirro, Sarah De Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart. 2019. “The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe.” www. popu-list.org.

Rudra, Nita. 2005. “Globalization and the Strengthening of Democracy in the Developing World.” American Journal of Political Science 49(4): 704-30.

Sambanis, Nicholas, Anna Schultz, and Elena Nikolova. 2018. “Austerity as Violence: Measuring the Effects of Economic Austerity on Pro-Sociality.” EBRD Working Paper No. 220.

Sattler, Thomas. 2013. “Do Markets Punish Left Governments?” Journal of Politics 75(2): 343-56.

Scheve, Kenneth, and Matthew J. Slaughter. 2001. “What Determines Individual Trade Policy Preferences?” Journal of International Economics 54(2): 267-92.

Talving, Liisa. 2017. “The Electoral Consequences of Austerity: Economic Policy Voting in Europe in Times of Crisis.” West European Politics 40(3): 560-83.

Vlandas, Tim, and Daphne Halikiopoulou. 2022. “Welfare State Policies and Far Right Party Support: Moderating ‘Insecurity Effects’ Among Different Social Groups.” West European Politics 45(1): 24-49.

Walter, Stefanie. 2010. “Globalization and the Welfare State: Testing the Microfoundations of the Compensation Hypothesis.” International Studies Quarterly 54(2): 403-26.

معلومات داعمة

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps. 12865

- بيان التحقق: المواد المطلوبة للتحقق من إمكانية إعادة إنتاج النتائج والإجراءات والتحليلات في هذه الورقة متاحة على قاعدة بيانات المجلة الأمريكية لعلوم السياسة ضمن شبكة هارفارد لقاعدة البيانات، على الرابط:https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1OPRYA

- هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب شروط رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام، والتوزيع، وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة، بشرط أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح.

© 2024 المؤلفون. المجلة الأمريكية للعلوم السياسية نشرتها وايلي بيريوديكالز LLC نيابة عن جمعية العلوم السياسية في الغرب الأوسط. نركز على خيارات السياسات بدلاً من التغيرات الفعلية في النفقات العامة والإيرادات. يمكن أن تُنسب الأولى مباشرةً إلى الحكومة، بينما يمكن أن تتغير الثانية لأسباب أخرى، مثل الصدمات الاقتصادية الكلية، التي تتجاوز السيطرة المباشرة للحكومة.

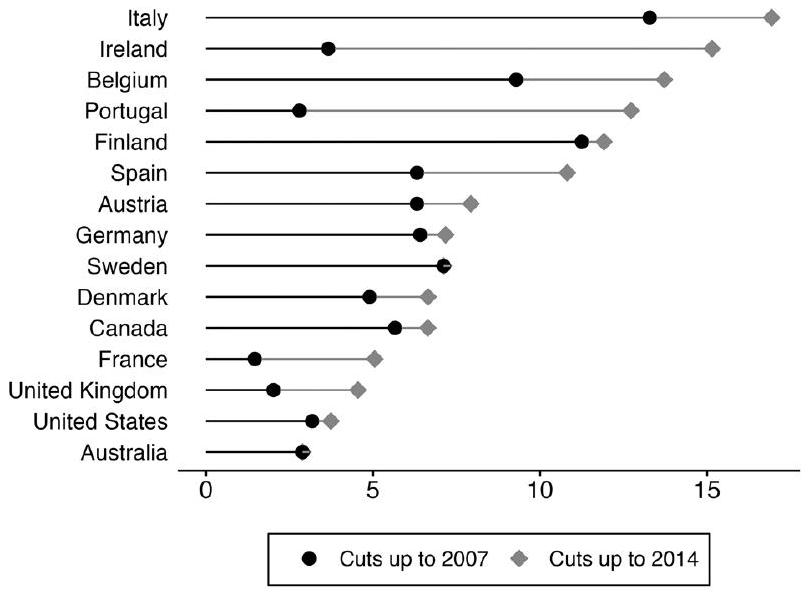

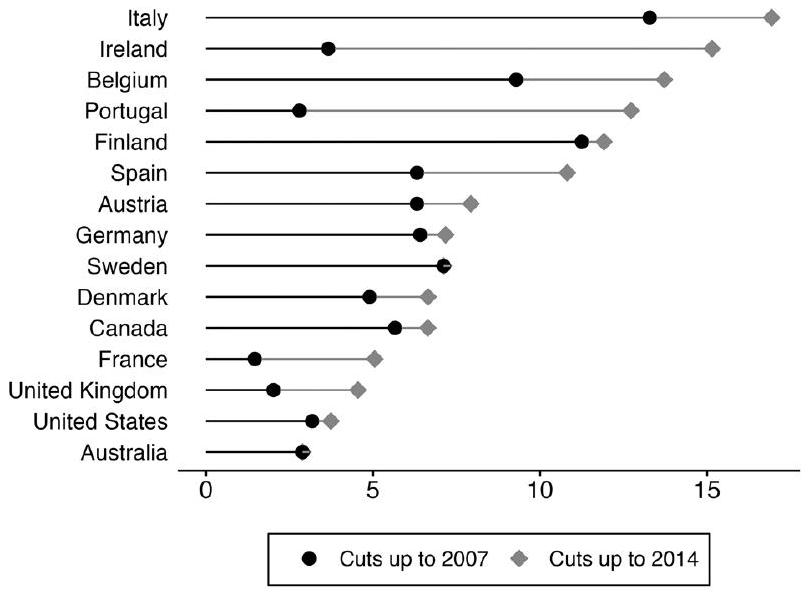

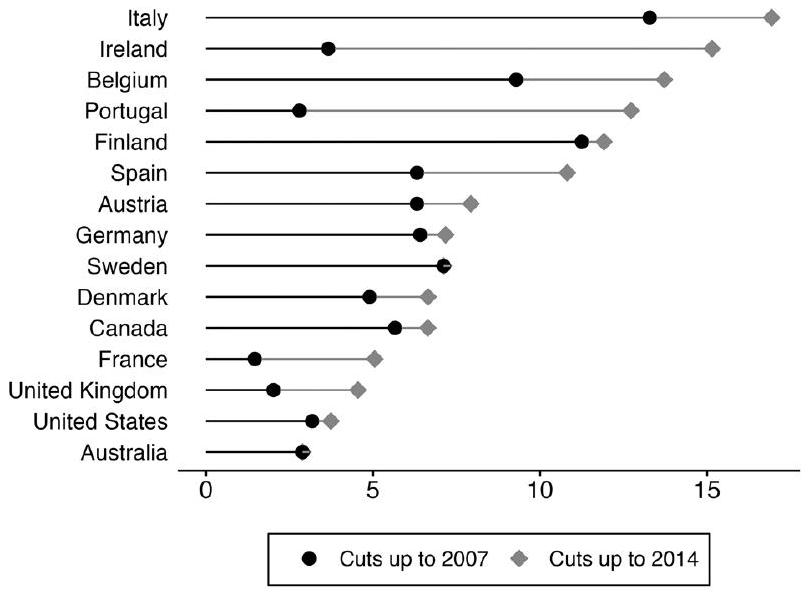

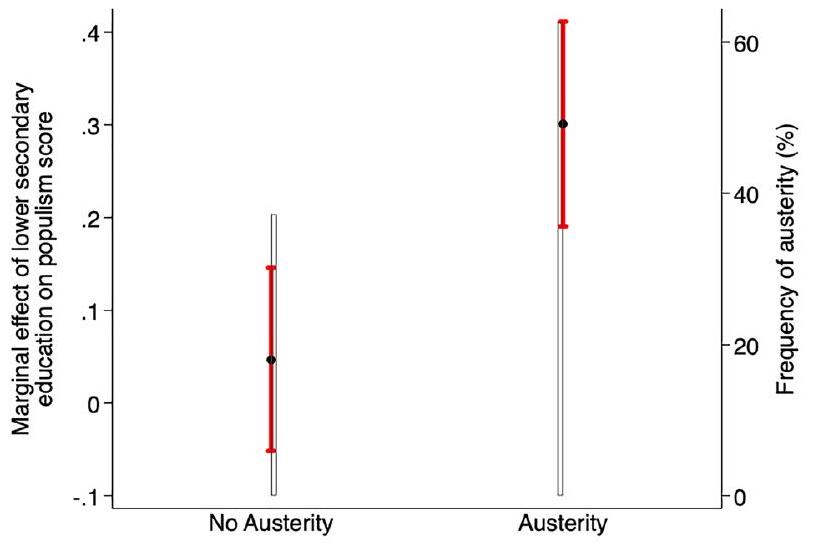

نناقش قياس التقشف المستخدم في هذه الصورة بالتفصيل في قسم “الانتخابات على مستوى المقاطعة”. في هذه الشكل، نقدم أيضًا نفس المؤشرات المعدلة بالنسبة لنسبة المواطنين المستحقين، لاستبعاد أن هذا النمط هو ببساطة تأثيرات دورة الأعمال.

بينما زادت النفقات الاجتماعية الإجمالية تدريجياً مع مرور الوقت، فإن هذا ليس هو الحال بالنسبة لبنود الإنفاق التي تعتبر مركزية في حجتنا. الزيادة في النفقات الاجتماعية الإجمالية تعود في الغالب إلى المعاشات والرعاية الصحية. من الصعب جداً سياسياً إجراء تخفيضات في هذه المجالات المتعلقة بما يسمى بمخاطر دورة الحياة (بييرسون، 2001). وهذا يزيد الضغط للتركيز على تخفيضات في فئات الإنفاق الاجتماعي الأخرى. هذا يعني أن الناخبين المعرضين للخطر يستجيبون بطرق مشابهة في أنواع مختلفة من دول الرفاه. تحليلنا التجريبي يفحص ما إذا كان هذا هو الحال بالفعل.

يمكن للناخبين غير الراضين أيضًا الامتناع عن التصويت للتعبير عن استيائهم، وقد يصوتون للأحزاب الشعبوية في وقت لاحق. نحن نفحص هذه الإمكانية بشكل تجريبي إلى الحد الذي تسمح به بياناتنا.

هناك أسباب متعددة محتملة لهذه النزعة، بما في ذلك الضغط المالي (بارتا وجونستون، 2018؛ هالربرغ وولف، 2008؛ ساتلر، 2013). - الاندماج الدولي (كونستانتينيديس وآخرون، 2019؛ موسلي، 2003)، انتشار أفكار التقشف (بلايث، 2013)، والقيود المؤسسية (بوديا وهيغاشيجيم، 2017).

في هذه المجموعة من البيانات، يتم تصنيف الأحزاب وفقًا لمجموعة من الأبعاد استنادًا إلى استطلاعات الخبراء. يعتمد مفهوم وتطبيق الشعبوية على نوريس وإنغلهارت (2019)، الذي يعتبر الخطاب الشعبوي متعارضًا مع الخطاب التعددي. اللغة الشعبوية “تتحدى عادةً شرعية المؤسسات السياسية القائمة وتؤكد أن إرادة الشعب يجب أن تسود”، بينما اللغة التعددية “ترفض هذه الأفكار، معتقدة أن القادة المنتخبين يجب أن يحكموا مقيدين بحقوق الأقليات، والتفاوض والتسوية، فضلاً عن الضوابط والتوازنات على السلطة التنفيذية” (دليل مسح الأحزاب العالمية، ص. 10). يتم قياس الخطاب الشعبوي من 0 (أقل شعبوية) إلى 10 (أكثر شعبوية).

تصنيف استطلاع الأحزاب العالمية للأحزاب ثابت لأنه من الصعب الحكم على درجة الخطاب الشعبوي في الماضي البعيد باستخدام استطلاعات الخبراء الحالية. ومع ذلك، تتفاوت درجات الشعبوية مع مرور الوقت وعبر المناطق عندما تتغير حصص تصويت الأحزاب في منطقة معينة. وبالتالي، يقيس مقياسنا آثار جانب الطلب التي تنشأ عندما يتحول الناخبون إلى حزب سياسي مختلف، ويستبعد آثار جانب العرض التي تُنشأ عندما تصبح الأحزاب الرئيسية أكثر شعبوية. وهذا يولد تقديرات أكثر تحفظًا. كما نقوم بفحص حصة التصويت للأحزاب الشعبوية القوية، والتي يمكن القول إنها تشمل تلك التي كانت شعبوية طوال الفترة. نعتمد أيضًا على مقاييس زمنية متغيرة مختلفة (لكنها ذات صلة)، مثل درجة الوطنية لكولانتوني وستانيج (2018)، ونجد آثارًا مشابهة. تتميز البيانات بين سنة الإعلان وسنة التنفيذ. في حالة خطط التعديل متعددة السنوات، يتم عادةً تنفيذ جزء كبير من الخطة في السنة التي يتم الإعلان عنها. ومع ذلك، فإن بعض التغييرات السياسية المعلنة لا تدخل حيز التنفيذ إلا في السنوات اللاحقة. حيثما كان هذا هو الحال، نستخدم السنة التي يتم فيها تنفيذ السياسة بشكل فعلي. نظرًا لأننا نقيس التقشف عبر الفترات الانتخابية بدلاً من السنوات، فإن الإعلانات والتنفيذ تتزامن في الغالب في مجموعة بياناتنا.

في الأصل، كانت متغيرات التقشف سلسلة زمنية سنوية لكل دولة: حيث تعكس مقدار التدابير التي تتخذها الحكومة لتقليل العجز في سنة معينة. نقوم بجمع هذه القيم السنوية لكل فترة انتخابية، مما يعطينا إجمالي مقدار التقشف (كنسبة من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي) الذي تم تنفيذه خلال فترة انتخابية. من السهل نسب التوحيد السنوي إلى فترة انتخابية في السنوات التي لا توجد فيها انتخابات. ولكن الأمر أكثر تعقيدًا في سنوات الانتخابات حيث كان علينا اتخاذ بعض القرارات التقديرية. قمنا بنسب التوحيدات المالية في سنوات الانتخابات إلى واحدة من فترتين انتخابيتين بأكبر قدر ممكن من الدقة. نسبة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة هي نسبة الموظفين الحاصلين على تعليم ثانوي أدنى وما دونه في منطقة معينة، وفقًا لإحصاءات يوروستات الإقليمية. نسبة عمال التصنيع هي نسبة الموظفين في منطقة معينة الذين يعملون في قطاع التصنيع، وفقًا ليوروستات والمكاتب الإحصائية الوطنية. يتم تحديد قطاع التصنيع باستخدام رموز NACE المكونة من حرفين أبجديين (DA إلى DN).

نستخدم القيمة الأساسية لتجنب أن تقيس مقياس الضعف المتغير مع الزمن تأثير التقشف. بسبب التحولات الاقتصادية السريعة، مثل إزالة التصنيع والأتمتة، قد تنحرف الضعف عند القيمة الأساسية عن الضعف في الفترات اللاحقة التي نفحصها. هذا أكثر صلة بحصة العمال في التصنيع وRTI مقارنة بحصة العمال ذوي المهارات المنخفضة. للتغلب على هذا التحدي، نستخدم عدة مقاييس للضعف، التي تلتقط أجزاء مختلفة من المجتمع.

الأرقام للمتغيرين الآخرين متاحة عند الطلب. نستخدم قيمة الربع الأدنى لتقسيم العينة. نحن غير قادرين على تضمين حصة العمال المعرضين للأتمتة مع التدبيرين الآخرين للضعف الاقتصادي بسبب تداخلها العالي جداً، أي، .

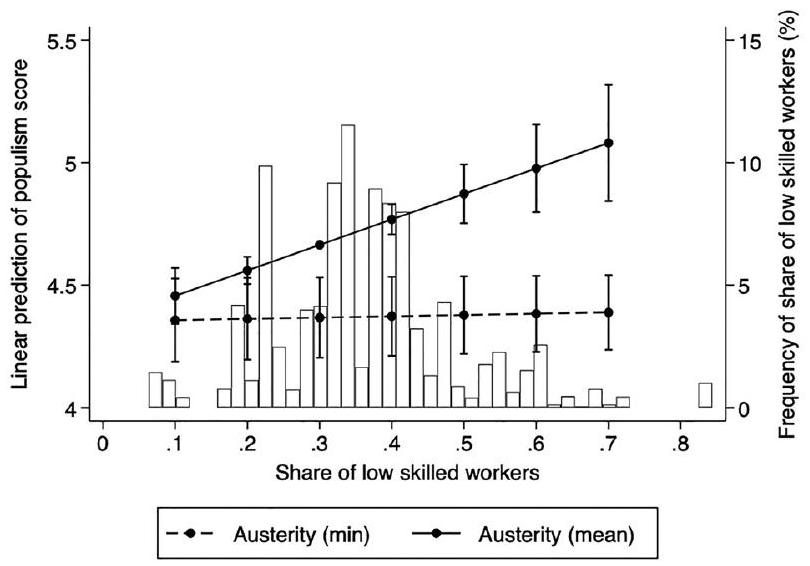

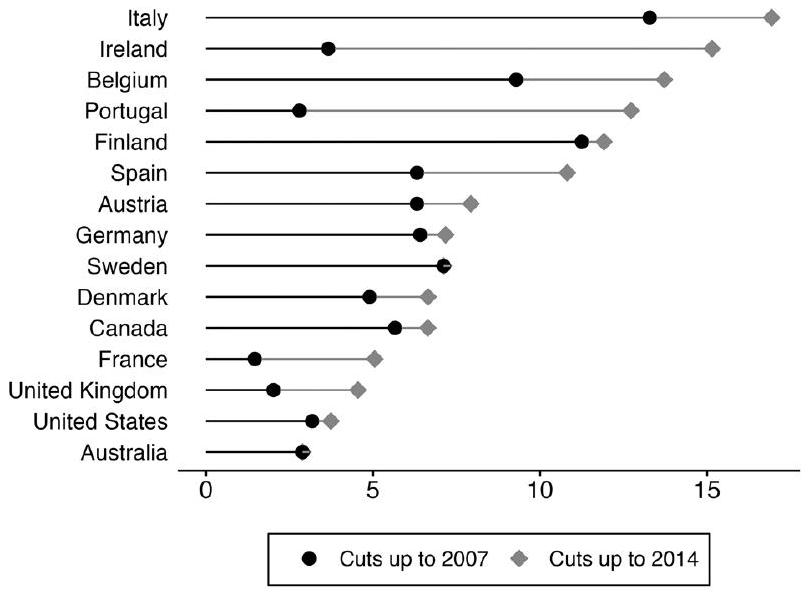

في الملحق الإلكتروني د في الصفحات 12 و 13، نعرض التنبؤات الخطية للمناطق ذات الضعف الاقتصادي العالي (انحراف معياري واحد فوق المتوسط) والضعف الاقتصادي المنخفض (انحراف معياري واحد تحت المتوسط) مع الحد الأدنى أو المتوسط من التقشف. تشير النتائج إلى أن الدعم للشعبوية يزداد في كلا المجموعتين من المناطق، لكن الزيادة أكبر بشكل ملحوظ في المناطق ذات الضعف الاقتصادي العالي. النتيجة مشابهة لنسبة العمال في التصنيع ونسبة العمال المعرضين للأتمتة (انظر الملحق الإلكتروني د في الصفحة 10). هذه التأثيرات تتماشى مع التأثيرات المقدرة من قبل كولانتوني وستانيج (2018)، الذين - يستفيدون من حدث واحد، وهو صدمة التجارة مع الصين، على مدى فترة زمنية قصيرة نسبياً، بينما حدوث التقشف أكثر تكراراً في عينتنا ومدة زمننا أطول.

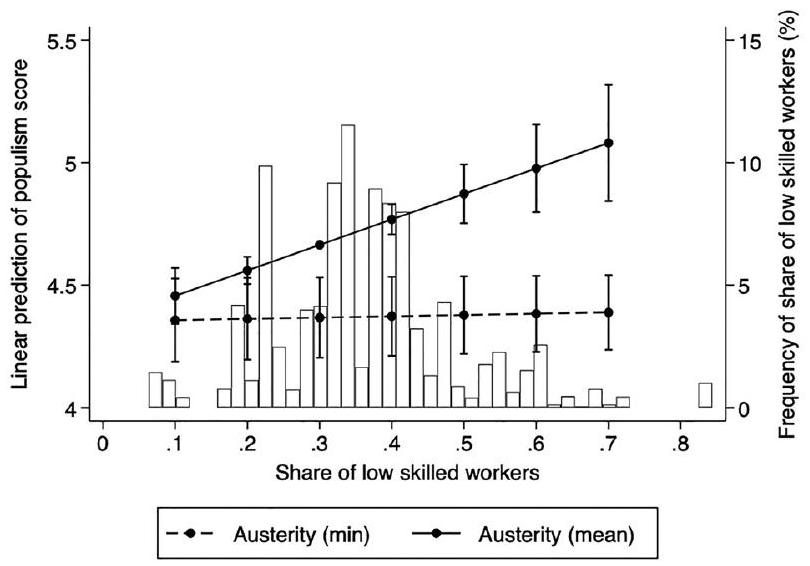

تحويلات الحكومة، التي تتعلق بأمان الوظائف، واستهلاك الحكومة، الذي يؤثر بشكل غير متناسب على الناخبين ذوي الدخل المنخفض، تدفع هذه النتائج. نستخدم بيانات عن الإنفاق الاجتماعي الأساسي لتمييز بين الدول ذات مستويات الإنفاق على الرفاهية المنخفضة (أي أقل من المتوسط) والعالية (أعلى من المتوسط).

نظرياً، دور حجم دولة الرفاهية غير واضح. من ناحية، قد يتفاعل الناخبون في دول الرفاهية الكبيرة بشكل أقوى مع التقشف لأن لديهم توقعات أعلى من دعم الدولة. من ناحية أخرى، قد يتفاعل الناخبون في دول الرفاهية الصغيرة بشكل أقوى لأن وضعهم يصبح أكثر هشاشة بعد تقليص الدعم المعادل. هذه النتائج قوية عند استخدام مؤشرات أخرى للضعف الاقتصادي وقياسات مختلفة للدعم للأحزاب اليسارية واليمينية المتطرفة (انظر الملحق الإلكتروني ف في الصفحات 24 و 26).

تقيس مقاييس اليسار/اليمين وجودة الحكومة قبل الانتخابات باستخدام المتوسط لموقف اليسار-اليمين لجميع الأحزاب في الحكومة. تأتي البيانات من مشروع البيانات المقارنة للبرامج الانتخابية. على سبيل المثال، تلتقط موجة ESS 6 من عام 2012 تصويت المستجيبين الأيرلنديين في الانتخابات الوطنية لعام 2011. في مثال الانتخابات الأيرلندية لعام 2011 المسجل في موجة ESS 6، تعكس متغيرات التقشف التوحيد المالي الذي نفذته الحكومة الأيرلندية بين الانتخابات السابقة في عام 2007 وانتخابات 2011.

في تحليلات إضافية (متاحة عند الطلب)، نوضح أن نتائجنا هي تقريباً نفسها بالنسبة للتعليم إذا استخدمنا مقياساً مستمراً للتقشف. وهي أضعف بالنسبة للتصنيع وRTI، على الرغم من أن إشارة المعامل الرئيسي تبقى كما هي.

تصنف مؤشر RTI المهن بناءً على المهارات الأكثر تأثراً بالأتمتة في الثمانينيات والتسعينيات. هذه القياسات مفقودة لثلاثة - مجموعات مهنية رئيسية (ISCO 23 و33 و61)، والتي تم استبعادها من التحليل.

النتائج مشابهة إذا استخدمنا النسخة المستمرة من RTI التي طورها غوس وآخرون (2014). لا يمكننا استخدام القيم الأساسية لمقاييسنا للضعف الاقتصادي، حيث أن ESS هو مقطع عرضي متكرر بدلاً من أن يكون لوحة: يشارك مستجيبون مختلفون في كل موجة. تشمل جميع التقديرات أوزان ما بعد التصنيف، بما في ذلك أوزان التصميم.

تذكر أننا نحصل على هذه التأثيرات الهامشية مع التحكم في حالة الطالب، وحالة العاطلين عن العمل، والعمر. وبالتالي، فإن سنوات الدراسة لا تعكس (البطالة) الشباب. النتيجة مشابهة لعمال التصنيع وللعمال المعرضين للأتمتة (انظر الملحق الإلكتروني ح).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12865

Publication Date: 2024-05-15

Archive ouverte UNIGE

https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch

Austerity, Economic Vulnerability, and Populism

How to cite

Publication DOI: 10.1111 /ajps. 12865

© The author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0)

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Austerity, economic vulnerability, and populism

Correspondence

Abstract

Governments have repeatedly adjusted fiscal policy in recent decades. We examine the political effects of these adjustments in Europe since the 1990s using both district-level election outcomes and individual-level voting data. We expect austerity to increase populist votes, but only among economically vulnerable voters, who are hit the hardest by austerity. We identify economically vulnerable regions as those with a high share of low-skilled workers, workers in manufacturing and in jobs with a high routine-task intensity. The analysis of district-level elections demonstrates that austerity increases support for populist parties in economically vulnerable regions, but has little effect in less vulnerable regions. The individual-level analysis confirms these findings. Our results suggest that the success of populist parties hinges on the government’s failure to protect the losers of structural economic change. The economic origins of populism are thus not purely external; the populist backlash is triggered by internal factors, notably public policies.

ing than they would be in a case study with a single episode of austerity, which varies subnationally. We trade off stronger identification assumptions for a stronger external validity.

AUSTERITY AND THE ECONOMIC ORIGINS OF POPULISM

Fiscal adjustments in times of enhanced economic risk

vulnerable voters, such as social transfers and other welfare state policies. Figure 2 shows that government transfers are central to austerity packages. Average social security transfers in industrialized countries vary considerably over time and declined particularly strongly during the 1990s and again from 2013 onwards. These declines in transfers coincide with the large waves of austerity that governments have implemented in recent decades (see also Armingeon et al., 2016). As the Online Appendix A shows on p.2, government transfers are cut more than any other budgetary category. We find a similar pattern for public spending on unemployment benefits, education, and pensions in Figure C1 in Online Appendix C on p.

Vulnerable voters and their political reactions

routine jobs are most likely to lose their jobs due to offshoring or automation (Gallego et al., 2022; Gingrich, 2019; Owen, 2020).

DISTRICT-LEVEL ELECTIONS

Data

Measuring populism

Measuring austerity

Measuring economic vulnerability

Empirical strategy

Identification

vulnerable voters. To address this point, we leverage the fact that austerity measures do not perfectly correlate with negative economic conditions in Western European countries. In other words, while austerity correlates negatively with economic growth and fiscal balance, our data indicate that such measures have also been implemented during periods of economic stability and growth. Thus, to determine whether periods of economic crisis are driving our estimates, we run our main models on two subsamples: (1) observations experiencing sluggish economic growth and negative fiscal balance and (2) observations experiencing average or fast economic growth and average or positive fiscal balance.

Results

Populism

| Populism Score | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity | 1.041** (.356) | 1.037** (.302) |

|

||||

| Share of manufacturing workers * Austerity | 1.248** (.334) | 1.459** (.456) | 1.107** (.341) | ||||

| Share of workers exposed to automation * Austerity | 1.581** (.513) | 1.525* (.620) | |||||

| Constant | 4.352** (.105) | 4.439** (.058) | 4.198** (.154) | 4.360** (.121) | 4.502** (.059) | 4.205** (.199) | 4.290** (.110) |

| Observations | 14,110 | 14,158 | 14,435 | 11,607 | 11,607 | 11,583 | 14,110 |

|

|

. 867 | . 868 | . 870 | . 847 | . 849 | . 848 | . 868 |

| Controls | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NUTS-2 fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-election year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

controls (Models 4-6). The share of low-skilled workers, share of manufacturing workers, and share of workers exposed to automation give similar results; their coefficients remain positive and significant, even when we include both at the same time on the right-hand side of the models (Model 7).

| Populism score | |||

| Low fiscal balance only | High fiscal balance only | Full sample | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity |

|

|

.950* (.371) |

| Share of low-skilled workers * Fiscal balance | -. 057 (.068) | ||

| Constant | 4.551** (.240) | 4.277** (.133) | 4.367** (.106) |

| Observations | 3497 | 10,602 | 14,110 |

|

|

. 789 | . 884 | . 867 |

| Controls | No | No | No |

| NUTS-2 fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-election year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The role of crises

Types of austerity

| Populism score | ||||||||

| Full sample | Full sample | Full sample | Full sample | Low welfare only | High welfare only | Full sample | Full sample | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity (cuts) | 1.089* (.545) | 1.470** (.412) | ||||||

| Share of low-skilled workers * Share of spending cuts | 1.779* (.690) | |||||||

| Share of low-skilled workers * Predominantly spending cuts | 1.011* (.493) | |||||||

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity (consolidation) |

|

1.118* (.492) | ||||||

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity (low) | -. 373 (.546) | -. 482 (.345) | ||||||

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity (high) | 1.655** (.559) | 1.492** (.468) | ||||||

| Constant | 4.431** (.114) | 4.362** (.119) | 4.368** (.065) | 4.451** (.041) | 5.206** (.120) | 3.824** (.162) | 4.459** (.134) | 4.523** (.102) |

| Observations | 14,110 | 11,607 | 12,439 | 12,439 | 5334 | 8776 | 14,110 | 11,607 |

|

|

. 867 | . 847 | . 871 | . 871 | . 856 | . 809 | . 868 | . 848 |

| Controls | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| NUTS-2 fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-election year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ically vulnerable workers, which may explain why they turn their vote to populist parties. In Online Appendix E on p. 21, we show that our results are similar when we use other proxies for economic vulnerability.

Austerity and ideology

Robustness checks

| Share of votes for radical left parties | Share of votes for radical right parties | |||||

| Full sample | Left incumbent only | Right incumbent only | Full sample | Left incumbent only | Right incumbent only | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Share of low-skilled workers * Austerity | -0.006 (0.071) | -0.084** (0.025) | 0.013 (0.054) | 0.152** (0.049) | 0.183* (0.071) | 0.136* (0.055) |

| Constant | 0.042* (0.021) | 0.070** (0.006) | 0.029 (0.018) | 0.017 (0.014) | 0.025 (0.016) | 0.012 (0.019) |

| Observations | 14,111 | 5624 | 8478 | 14,111 | 5624 | 8478 |

|

|

. 640 | . 739 | . 612 | . 833 | . 918 | . 767 |

| Controls | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| NUTS-2 fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-election year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

of support for populism. Second, our results are similar if we use the raw value of austerity rather than its logged value. Third, we find no evidence that austerity affects turnout. Fourth, we show that our results are not driven by the post-2010 period. Finally, we show that our results hold if we exclude one country at a time; thus they do not depend on the inclusion of any specific country in our sample.

INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL VOTING

Data

| Populism score | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Lower secondary education | . 054 (.055) | . 047 (.059) | ||||

| Upper secondary education | .096* (.037) | .090* (.037) | ||||

| Manufacturing | -. 011 (.021) | -. 016 (.021) | ||||

| RTI | -. 026 (.035) | . 011 (.039) | ||||

| Lower secondary education * Austerity (dummy) | .221** (.083) | .254** (.089) | ||||

| Upper secondary education * Austerity (dummy) | .164** (.062) | .173** (.062) | ||||

| Manufacturing * Austerity (dummy) | .093* (.038) | .085* (.039) | ||||

| RTI * Austerity (dummy) |

|

.111* (.055) | ||||

| Constant | 4.621** (.040) | 4.471** (.162) | 4.843** (.005) | 4.670** (.147) | 4.779** (.017) | 4.521** (.168) |

| Observations | 86,939 | 86,717 | 82,317 | 82,128 | 72,613 | 72,449 |

|

|

. 301 | . 303 | . 299 | . 301 | . 299 | . 301 |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Country-wave fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

(2019), we aggregate the RTI measure into five quintiles, rescaled to 0 (least affected) to 1 (most affected), which allows us to identify broad categories of exposure.

Empirical strategy

where

Results

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REFERENCES

Arias, Eric, and David Stasavage. 2019. “How Large Are the Political Costs of Fiscal Austerity.” Journal of Politics 81(4): 1517-22.

Armingeon, Klaus, Kai Guthmann, and David Weisstanner. 2016. “Choosing the Path of Austerity: A Neo-Functionalist Explanation of Welfare-Policy Choices in Periods of Fiscal Consolidation.” West European Politics 39(4): 628-47.

Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfeland David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler. 2019. “Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2017.” Electronic Database, http://www.cpds-data.org.

Baccini, Leonardo, Pablo M. Pinto, and Stephen Weymouth. 2017. “The Distributional Consequences of Preferential Trade Liberalization: Firm-Level Evidence.” International Organization 71(2): 373-95.

Baccini, Leonardo, and Stephen Weymouth. 2021. “Gone for Good: Deindustrialization, White Voter Backlash, and U.S. Presidential Voting.” American Political Science Review 115(2): 550-67.

Ballard-Rosa, Cameron, Mashail Malik, Stephanie Rickard, and Ken Scheve. 2021. “The Economic Origins of Authoritarian Values: Evidence from Local Trade Shocks in the United Kingdom.” Comparative Political Studies (Online First).

Bambra, Clare, Julia Lynch, and Katherine E. Smith. 2021. The Unequal Pandemic: Covid-10 and Health Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press.

Bansak, Kirk, Michael Bechtel, and Yotam Margalit. 2021. “Why Austerity? The Mass Politics of a Contested Policy.” American Political Science Review 115(2): 486-505.

Barnes, Lucy, and Timothy Hicks. 2018. “Making Austerity Popular: The Media and Mass Attitudes Towards Fiscal Policy.” American Journal of Political Science 62(2): 340-54.

Barta, Zsófia, and Alison Johnston. 2018. “Rating Politics? Partisan Discrimination in Credit Ratings in Developed Economies.” Comparative Political Studies 51(5): 587-620.

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bisbee, James, Layna Mosley, Thomas B. Pepinsky, and B. Peter Rosendorff. 2020. “Decompensating Domestically: The Political Economy of Anti-Globalism.” Journal of European Public Policy 27(7): 1090-102.

Blyth, Mark. 2013. Austerity-The History of a Dangerous Idea. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bodea, Cristina, and Masaaki Higashijima. 2017. “Central Bank Independence and Fiscal Policy: Can the Central Bank Restrain Deficit Spending?” British Journal of Political Science 47(1): 47-70.

Bremer, Björn, Swen Hutter, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2020. “Dynamics of Protest and Electoral Politics in the Great Recession.” European Journal of Political Research 59(4): 842-66.

Colantone, Italo, and Piero Stanig. 2018. “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe.” American Journal of Political Science 62(4): 936-53.

Copelovitch, Mark, Jeffry Frieden, and Stefanie Walter. 2016. “The Political Economy of the Euro Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 49(7): 811-40.

Cremaschi, Simone, Paula Rettl, Marco Cappelluti, and Catherine De Vries. 2023. “Geographies of Discontent: Public Service Deprivation and the Rise of the Far Right in Italy.” Harvard Business School Working Paper 24-024. Available at: https:// www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication Files/24-024_da5e436e-b4e8-4215-b788-f6043dbc7d1f.pdf

De Vries, Catherine, and Sara Hobolt. 2020. Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Devries, Pete, Jaime Guajardo, Daniel Leigh, and Andrea Pescatori. 2011. “A New Action-Based Dataset of Fiscal Consolidation.” IMF Working Paper

Enggist, Matthias, and Michael Pinggera. 2022. “Radical Right Parties and Their Welfare State Stances: Not so Blurry After All?” West European Politics 45(1): 102-28.

Fetzer, Thiemo. 2019. “Did Austerity Cause Brexit?” American Economic Review 109(11): 3849-86.

Frieden, Jeffry A. 2000. Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century. New York: Norton & Company.

Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. 2017. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” British Journal of Sociology 68(S1): S57-S84.

Giger, Nathalie, and Moira Nelson. 2011. “The Electoral Consequences of Welfare State Retrenchment: Blame Avoidance or Credit Claiming in the Era of Permanent Austerity.” European Journal of Political Research 50(1): 1-23.

Gingrich, Jane. 2019. “Did State Responses to Automation Matter for Voters?” Research and Politics 6(1): 1-9.

Gingrich, Jane, and Ben Ansell. 2012. “Preferences in Context: Micro Preferences, Macro Contexts, and the Demand for Social Policy.” Comparative Political Studies 45(12): 1624-54.

Goos, Maarten, Alan Manning, and Anna Salomons. 2014. “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Based Technological Change and Offshoring.” American Economic Review 104(8): 2509-26.

Grittersová, Jana, Indridi H. Indridason, Christina C. Gregory, and Ricardo Crespo. 2016. “Austerity and Niche Parties: The Electoral Consequences of Fiscal Reforms.” Electoral Studies 42(June): 27689.

Hallerberg, Mark, and Guntram Wolff. 2008. “Fiscal Institutions, Fiscal Policy and Sovereign Risk Premia in EMU.” Public Choice 136(3): 379-96.

Hays, Jude C. 2009. Globalization and the New Politics of Embedded Liberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hellwig, Timothy, and David Samuels. 2007. “Voting in Open Economies-The Electoral Consequences of Globalization.” Comparative Political Studies 40(3): 283-306.

Hopkin, Jonathan. 2020. Anti-System Politics: The Crisis of Market Capitalism in Rich Democracies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hübscher, Evelyne, and Thomas Sattler. 2017. “Fiscal Consolidation under Electoral Risk.” European Journal of Political Research 56(1): 151-68.

Hübscher, Evelyne, Thomas Sattler, and Markus Wagner. 2021. “Voter Responses to Fiscal Austerity.” British Journal of Political Science 51(4): 1751-60.

Hübscher, Evelyne, Thomas Sattler, and Markus Wagner. 2023. “Does Austerity Cause Polarization?” British Journal of Political Science 53(4): 1170-88.

Jensen, J. Bradford, Dennis P. Quinn, and Stephen Weymouth. 2017. “Winners and Losers in International Trade: The Effects on US Presidential Voting.” International Organization 71(3): 423-57.

Kayser, Mark A., and Michael Peress. 2012. “Benchmarking across Borders: Electoral Accountability and the Necessity of Comparison.” American Political Science Review 106(3): 661-84.

Kollman, Ken, Allen Hicken, Daniele Caramani, David Backer, and David Lublin. 2019. Constituency-Level Elections Archive. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Political Studies, University of Michigan [producer and distributor]. http://www.electiondataarchive.org.

Konstantinidis, Nikitas, Konstantinos Matakos, and Hande HutluEren. 2019. “‘Take Back Control’? The effects of Supranational Integration on Party-System Polarization.” Review of International Organizations 14(2): 297-333.

Margalit, Yotam. 2011. “Costly Jobs: Trade-Related Layoffs, Government Compensation, and Voting in U.S. Elections.” American Political Science Review 105(1): 166-88.

Milner, Helen V. 1988. Resisting Protectionism: Global Industries and the Politics of International Trade. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Milner, Helen V. 2021. “Voting for Populism in Europe: Globalization, Technological Change, and the Extreme Right.” Comparative Political Studies 54(13): 2286-320.

Mosley, Layna. 2003. Global Capital and National Governments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2019. “The Global Party Survey (V1.0).” https://www. globalpartysurvey.org.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and the Rise of Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, Erica. 2020. “Firms vs. Workers? The Politics of Openness in an Era of Global Production and Automation.” Paper presented in the Global Research in International Political Economy (GRIPE) Seminar, June 10, online.

Owen, Erica, and Noel Johnston. 2017. “Occupation and the Political Economy of Trade: Job Routineness, Offshoreability and Protectionist Sentiment.” International Organization 71(4): 665-99.

Pierson, Paul, ed. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press.

Richtie, Melinda, and Hye Young You. 2020. “Trump and Trade: Protectionist Politics and Redistributive Policy.” Working Paper, UC Riverside and New York University.

Rickard, Stephanie J. 2015. “Compensating the Losers: An Examination of Congressional Votes on Trade Adjustment Assistance.” International Interactions 41(1): 46-60.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, Stijn Van Kessel, Caterina Froio, Andrea Pirro, Sarah De Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Paul Lewis, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart. 2019. “The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe.” www. popu-list.org.

Rudra, Nita. 2005. “Globalization and the Strengthening of Democracy in the Developing World.” American Journal of Political Science 49(4): 704-30.

Sambanis, Nicholas, Anna Schultz, and Elena Nikolova. 2018. “Austerity as Violence: Measuring the Effects of Economic Austerity on Pro-Sociality.” EBRD Working Paper No. 220.

Sattler, Thomas. 2013. “Do Markets Punish Left Governments?” Journal of Politics 75(2): 343-56.

Scheve, Kenneth, and Matthew J. Slaughter. 2001. “What Determines Individual Trade Policy Preferences?” Journal of International Economics 54(2): 267-92.

Talving, Liisa. 2017. “The Electoral Consequences of Austerity: Economic Policy Voting in Europe in Times of Crisis.” West European Politics 40(3): 560-83.

Vlandas, Tim, and Daphne Halikiopoulou. 2022. “Welfare State Policies and Far Right Party Support: Moderating ‘Insecurity Effects’ Among Different Social Groups.” West European Politics 45(1): 24-49.

Walter, Stefanie. 2010. “Globalization and the Welfare State: Testing the Microfoundations of the Compensation Hypothesis.” International Studies Quarterly 54(2): 403-26.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps. 12865

- Verification statement: The materials required to verify the computational reproducibility of the results, procedures and analyses in this paper are available on the American Journal of Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1OPRYA

- This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

© 2024 The Authors. American Journal of Political Science published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Midwest Political Science Association. We concentrate on policy choices rather than actual changes in public expenditures and revenues. The former can be directly attributed to the government, while the latter can also vary for other reasons, such as macroeconomic shocks, which are beyond the government’s direct control.

We discuss the measurement of austerity used in this figure in detail in Section “District-level elections”. In this figure, we also present the same indicators adjusted for the percentage of entitled citizens, to rule out that this pattern is simply catching business cycle effects.

While total social expenditures have gradually increased over time, this is not the case for the spending items that are central to our argument. The increase in total social expenditures is mostly due to pensions and health care. It is politically very difficult to make cuts in these areas related to so-called lifecycle risks (Pierson, 2001). This increases the pressure to concentrate cuts in other social spending categories. This implies that vulnerable voters respond in similar ways in different types of welfare states. Our empirical analysis examines whether this is indeed the case.

Dissatisfied voters can also abstain to express their discontent, and may vote for populist parties at a later point in time. We empirically examine this possibility to the extent that our data allow.

There are multiple possible reasons for this tendency, including financial pressure (Barta & Johnston, 2018; Hallerberg & Wolff, 2008; Sattler, 2013), - international integration (Konstantinidis et al., 2019; Mosley, 2003), the diffusion of proausterity ideas (Blyth, 2013), and institutional constraints (Bodea & Higashijima, 2017).

In this data set, parties are classified according to a range of dimensions based on expert surveys. The conceptualization and operationalization of populism relies on Norris and Inglehart (2019), which treats populist rhetoric as antithetical to pluralist rhetoric. Populist language “typically challenges the legitimacy of established political institutions and emphasizes that the will of the people should prevail,” while pluralist language “rejects these ideas, believing that elected leaders should govern constrained by minority rights, bargaining and compromise, as well as checks and balances on executive power” (Global Party Survey codebook, p. 10). Populist rhetoric is measured from 0 (less populist) to 10 (more populist).

The Global Party Survey’s classification of parties is fixed since it is difficult to judge the degree of populist rhetoric in the more distant past using current expert surveys. Nonetheless, populism scores vary over time and across districts when party vote shares in a district change. Our measure thus captures the demand-side effects that arise when voters switch to a different political party, and rules out supply-side effects that are created when mainstream parties become more populist. This generates more conservative estimates. We also examine the vote share of strongly populist parties, which arguably includes those that have been populist for the entire period. We also rely on different (but related) time-varying measures, such as Colantone and Stanig’s (2018) nationalism score, and find similar effects. The data distinguish between the year of announcement and the year of implementation. In case of multiyear adjustment plans, a large part of the plan is usually implemented in the year in which it is announced. Some of the announced policy changes, however, only take effect in later years. Where this is the case, we use the year in which the policy is effectively implemented. Since we measure austerity across electoral periods rather than years, the announcements and implementation mostly coincide in our data set.

Originally, the austerity variable was an annual time series for each country: It captures the amount of deficit-reducing measures that a government implements in a particular year. We sum these annual values for each electoral period, which gives us the total amount of austerity (as % of GDP) implemented during an electoral period. It is straightforward to attribute the annual consolidations to an election period in years without elections. It is trickier for election years where we had to make some judgment calls. We manually attributed fiscal consolidations in election years to one of the two election periods as accurately as possible. The share of low-skilled workers is the share of employees with a lower secondary education and below in a region, according to Eurostat Regional Statistics. The share of manufacturing workers is the share of employees in a region who work in the manufacturing sector, according to Eurostat and national statistical offices. The manufacturing sector is identified using NACE two-character alphabetical codes (DA to DN).

We use the baseline value to avoid that a time-varying vulnerability measure picks up the effect of austerity. Due to fast-moving economic transformations, such as deindustrialization and automation, vulnerability at the baseline value may deviate from vulnerability in the later periods that we examine. This is more relevant for the share of manufacturing and RTI workers than for share of low-skilled workers. To overcome this challenge, we use several measures of vulnerability, which capture different parts of the society.

The figures for the other two variables are available upon request. We use the value of the lower quartile to split the sample. We are unable to include the share of workers exposed to automation with the other two measures of economic vulnerability due to their very high collinearity, that is, .

In Online Appendix D on pp. 12 and 13, we show the linear predictions of regions with high economic vulnerability (one standard deviation above the mean) and low economic vulnerability (one standard deviation below the mean) with minimum or average value of austerity. Results indicate that support for populism increases in both sets of regions, but the increase is significantly larger in regions with high economic vulnerability. The result is similar for Share of Manufacturing Workers and Share of Workers Exposed to Automation (see Online Appendix D on p. 10). These effects are in line with the effects estimated by Colantone and Stanig (2018), who - leverage a single event, that is, the China trade shock, over a relatively short period of time, whereas the occurrence of austerity is more frequent in our sample and our time span is longer.

Government transfers, which are relevant for job security, and government consumption, which disproportionately hits lower income voters, drive these results. We use data on baseline social expenditure to distinguish between countries with low (i.e. below average) and high (above average) levels of welfare spending.

Theoretically, the role of welfare state size is ambiguous. On the one hand, voters in large welfare states may react more strongly to austerity because they have higher expectations on state support. On the other hand, voters in small welfare states may react more strongly because their situation becomes even more precarious after an equivalent reduction in support. These results are robust to the use of other proxies for economic vulnerability and different measures of support for radical left and right parties (see Online Appendix F on pp. 24 and 26).

Left/right incumbency measures the ideology of the cabinet before the election using the average left-right position of all parties in government. The data come from the Comparative Manifestos Project. For instance, ESS wave 6 from 2012 captures the vote of Irish respondents in the 2011 national election. In the example of the 2011 Irish election recorded in ESS wave 6, the austerity variable reflects the fiscal consolidation that the Irish government implemented between the preceding election in 2007 and the 2011 election.

In additional analyses (available upon request), we show that our results are virtually the same for education if we use a continuous measure of austerity. They are weaker for manufacturing and RTI, though the sign of the main coefficient remains the same.

The RTI index categorizes occupations based on the skills most affected by automation in the 1980s and 1990s. This measure is missing for three - major occupational groups (ISCO 23, 33, and 61), which are excluded from the analysis.

The results are similar if we use the continuous version of the RTI developed by Goos et al. (2014). We are unable to use the baseline values of our measures of economic vulnerability, since the ESS is a repeated cross-section rather than a panel: Different respondents take part in each wave. All estimates include poststratification weights, including design weights.

Recall that we obtain these marginal effects controlling for student status, unemployed status, and age. Thus, years in school does not proxy for (youth) unemployment. The result is similar for manufacturing workers and for workers exposed to automation (see Online Appendix H).