DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44359-025-00037-1

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-04

التقنيات المعتمدة على الضوء لتحسين البيئة

الملخص

يمكن أن تؤدي العمليات الصناعية إلى تلوث الهواء والماء، لا سيما من الملوثات العضوية مثل التولوين والمضادات الحيوية، مما يشكل تهديدات لصحة الإنسان. تستفيد تقنيات الأكسدة الكيميائية المدعومة بالضوء من طاقة الضوء لتعدين هذه الملوثات. في هذه المراجعة، نناقش الآليات والكفاءات لعمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة المدعومة بالضوء لمعالجة مياه الصرف الصحي وتقنيات الفوتوحرارية لتنقية الهواء. يعزز دمج الطاقة الشمسية كفاءة التحلل ويقلل من استهلاك الطاقة، مما يمكّن من طرق معالجة أكثر كفاءة. نقيم الجوانب التكنولوجية للتقنيات المدعومة بالضوء، مثل الفوتو-فينتون، وتفعيل الفوتو-بيرسلفات، والفوتو-أوزون، والأكسدة الفوتو-كيميائية، مع التأكيد على إمكانياتها للتطبيقات العملية. أخيرًا، نناقش التحديات في توسيع نطاق التقنيات المدعومة بالضوء لتلبية احتياجات الترميم البيئي المحددة. لقد أظهرت التقنيات المدعومة بالضوء فعاليتها في الترميم البيئي، على الرغم من أن التطبيقات على نطاق واسع لا تزال مقيدة بالتكاليف العالية. ستتطلب التطبيقات المستقبلية المحتملة للتقنيات المدعومة بالضوء أن يتم اختيار التكنولوجيا وفقًا لسيناريوهات التلوث المحددة وأن يتم تحسين العمليات الهندسية لتقليل التكاليف.

الأقسام

تنقية المياه

تنقية الهواء

ملخص وآفاق المستقبل

النقاط الرئيسية

- تعمل عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة المدعومة بالصور بشكل فعال على معالجة مياه الصرف، بينما تُستخدم التقنيات الضوئية الحرارية في تنقية الهواء.

- يمكن أن يعزز دمج الطاقة الشمسية كفاءة عمليات المعالجة ويقلل من استهلاك الطاقة.

- تتفاعل الطاقة الشمسية مع عمليات الأكسدة الكيميائية، مما يؤدي إلى تكوين أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية التي تسرع من تحلل الملوثات.

- تستهلك عمليات معالجة مياه الصرف، مثل عملية أكسدة فينتون، كمية كبيرة من

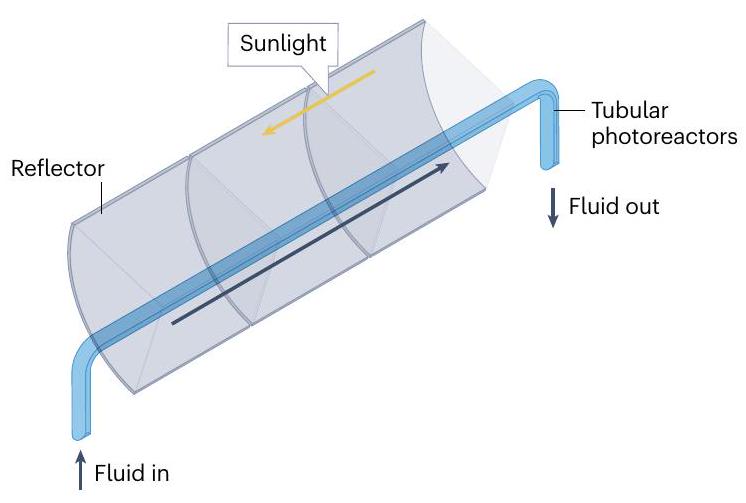

وهي بطيئة حركيًا. دمج الطاقة الشمسية يسرع العملية. - استخدام المجمعات البارابولية المركبة ومفاعلات برك السباق يُحسن من جمع الضوء ويمكّن من المعالجة عند تركيزات تصل إلى ملغرامات لكل لتر وأقل.

- يمكن أن يساعد دمج تقنيات الأكسدة المتقدمة المختلفة في تقليل استهلاك الطاقة وتوسيع نطاق الملوثات التي يمكن أن تتعادل.

مقدمة

يمكن أن تتداخل الوسائط الملوثة مع العملية التحفيزية، مما يقلل من توفر الأنواع التفاعلية المستحثة بالضوء اللازمة للتعافي الفعال.

تنقية المياه

أكسدة فنتون المعززة بالصور

مقالة مراجعة

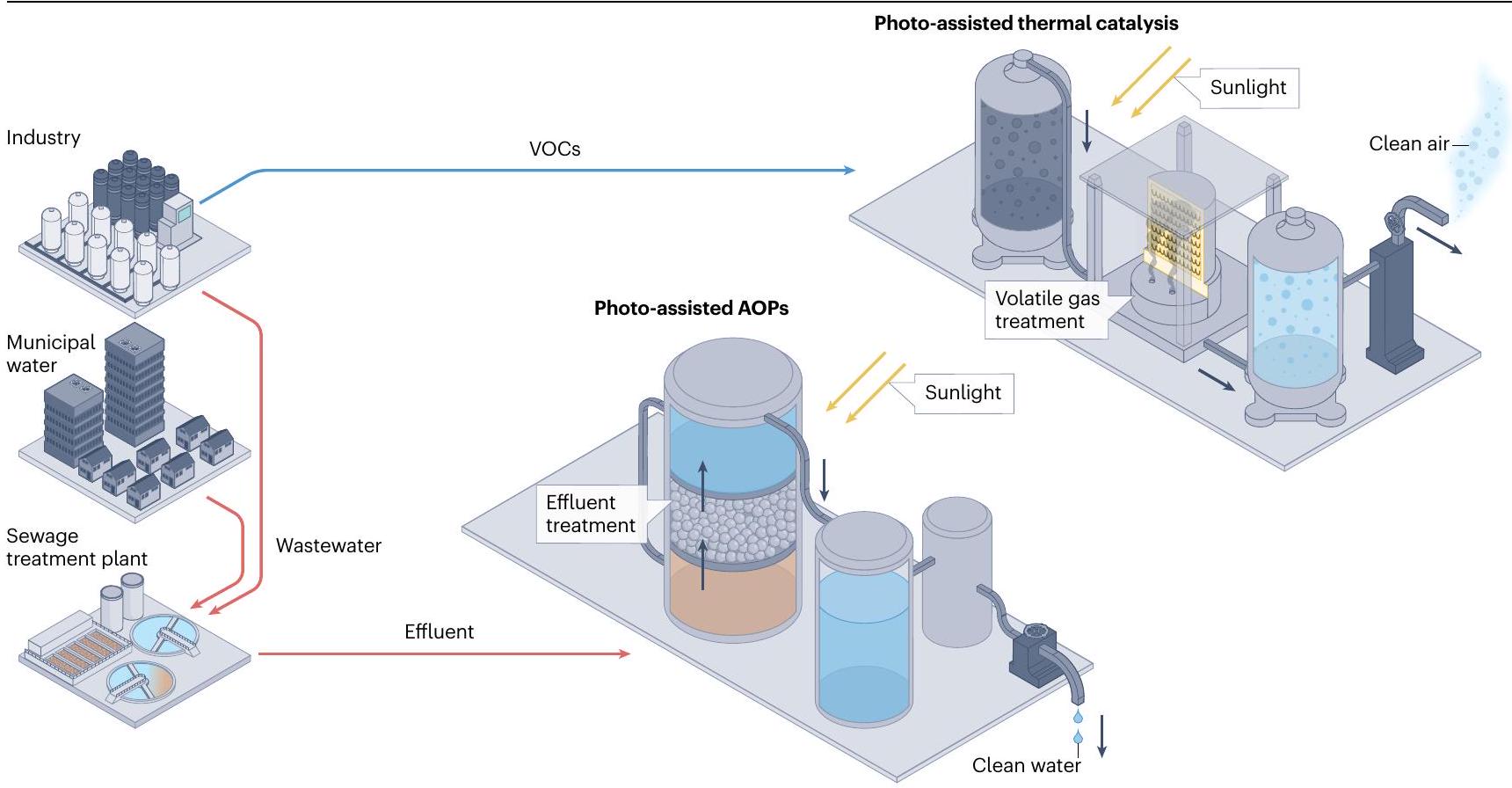

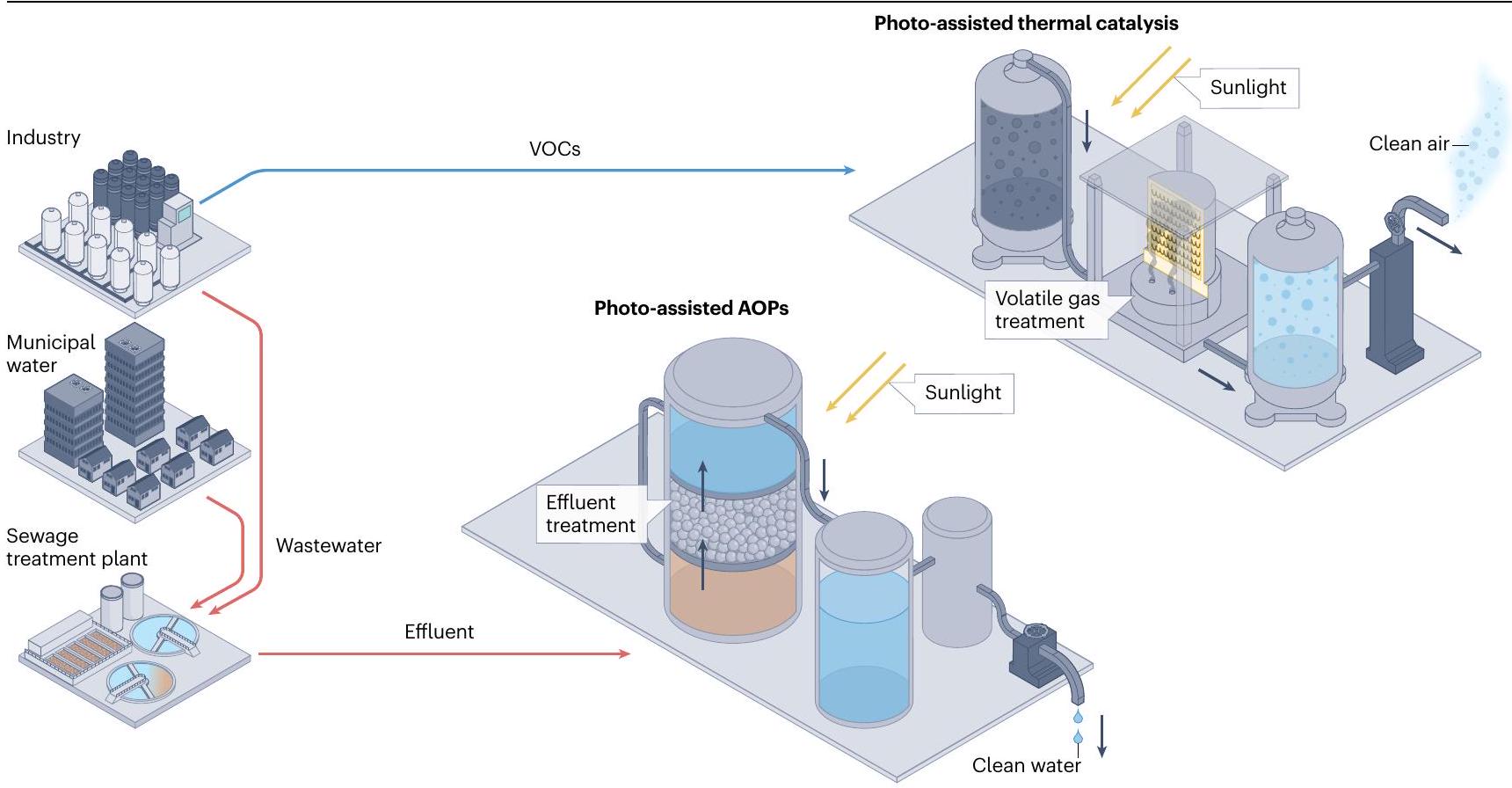

يمكن استخدام العمليات المتقدمة للأكسدة المدعومة بالضوء (AOPs) والتفاعل الحراري المدعوم بالضوء في معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي والهواء. يتم جمع مياه الصرف الصحي من الصناعات واستخدام المياه البلدية ونقلها إلى شبكة الصرف الصحي.

من حيث الحجم في

طلب (

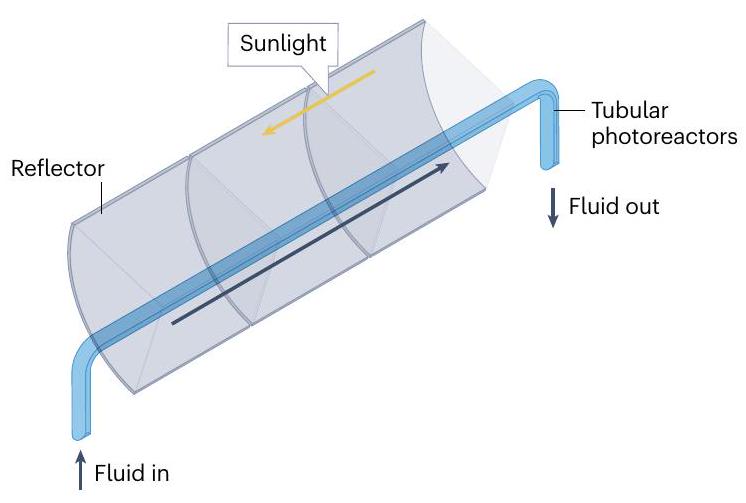

تكلفة إنتاج منخفضة مقارنةً بالمفاعلات الأخرى، حجم كبير بالنسبة للسطح، ومرونة في تحسين عمق السائل وفقًا لقوة الإشعاع

تنشيط البيرسلفات بمساعدة الصور

يمكن للجزيئات أن تعمل كقابلات للإلكترونات، حيث تلتقط الإلكترونات المتولدة على سطح المحفزات الضوئية المعرضة للضوء.

الأوزون المعزز بالصور

غير انتقائي

الأكسدة الكهروكيميائية المعززة بالصور

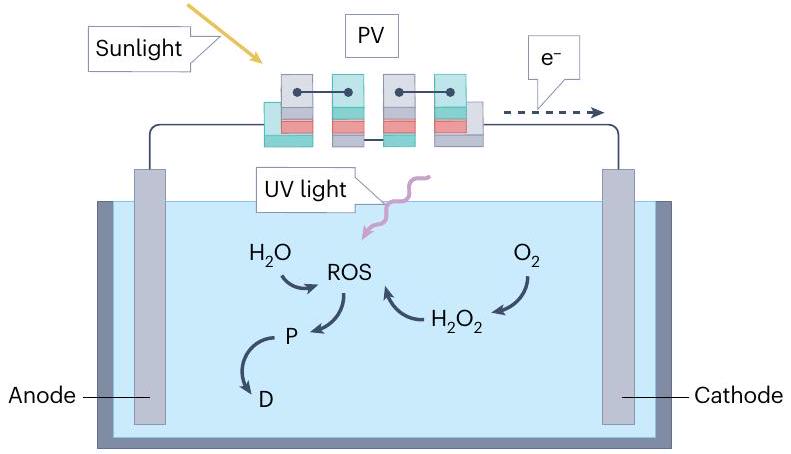

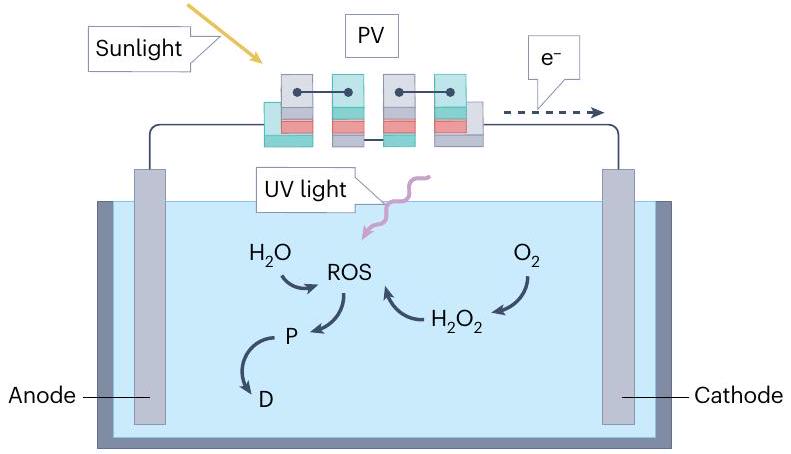

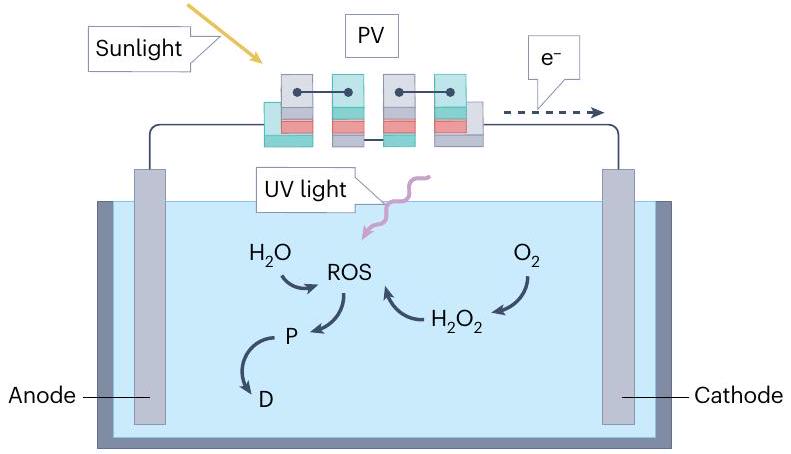

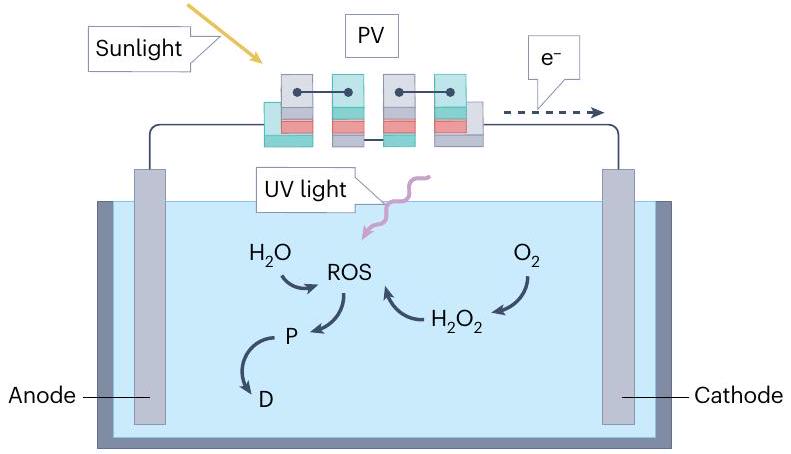

نظام إلكتروليزر UV و PV

الشكل 4 | عمليات الأكسدة الكهروكيميائية المعززة بالضوء.

نظام الأكسدة المتقدمة الكهروكيميائية الضوئية (PECAO). الخصائص الرئيسية لأنظمة الأكسدة المتقدمة الكهروكيميائية لتطبيقات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي العملية. يقلل المعالجة المسبقة من تداخل مياه المدخل، بينما يعزز وضع التدفق المستمر سعة الإنتاج واستقرار التشغيل. تحت ضوء الشمس، يمتص الأنود الضوئي طاقة الضوء لتوليد الفجوات والإلكترونات. طبقة رقيقة على الأنود الضوئي تحسن كفاءة استخدام الضوء. الكاثود يحفز اختزال الأكسجين إلى

تنتج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS)، مع إضافات الإلكتروليت التي تسرع من توليدها. تحدد المتانة الميكانيكية للأقطاب الكهربائية عمرها الافتراضي، مما يؤثر بشكل مباشر على طول عمر الجهاز بشكل عام. يقلل فقدان المقاومة المنخفض في النظام من استهلاك الطاقة غير الضروري ويحسن الاستقرار التشغيلي. من خلال ربط الأنود الضوئي والكاثود، يتم إزالة الملوثات العضوية بكفاءة. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي ضبط الخصائص الحفازة ومعلمات التشغيل إلى إنتاج منتجات ثانوية ذات قيمة مضافة مستهدفة، مما يعزز الجدوى الاقتصادية للعملية. D، منتجات التحلل؛ P، الملوثات.

يقلل الفوتوإلكترود من الجهد المطلوب لتحفيز التفاعلات، في حين أن الانحياز المطبق يسرع من عملية فصل الشحنات تحت تأثير حقل كهربائي.

للتحكم في توليد ROS بتراكيب محددة لمعالجة مياه الصرف المستهدفة

مقالة مراجعة

عمليات الأكسدة المدعومة بالضوء المتكاملة المتعددة

تحلل الملوثات وتحسن الكفاءة العامة للطاقة لعملية المعالجة

| عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة المدعومة بالضوء | المزايا | العيوب | السيناريوهات البيئية | ||||||||

| فوتو-فينتون |

|

|

نظام معالجة مياه الشرب؛ مياه الصرف الناتجة عن محطات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية؛ مياه الصرف الخام الزيتية | ||||||||

| فوتو-بيرسلفات |

|

|

مياه الصرف الصحي الصيدلانية؛ مياه الصرف الناتجة عن محطات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية | ||||||||

| فوتو-أوزون |

|

|

نظام معالجة مياه الشرب؛ المياه العادمة من محطات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية؛ مياه الصرف الصحي من الصناعات الدوائية | ||||||||

| الأكسدة الضوئية الكهروكيميائية |

|

|

مياه الصرف من مصافي النفط؛ المياه الناتجة عن محطات معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية |

تنقية الهواء

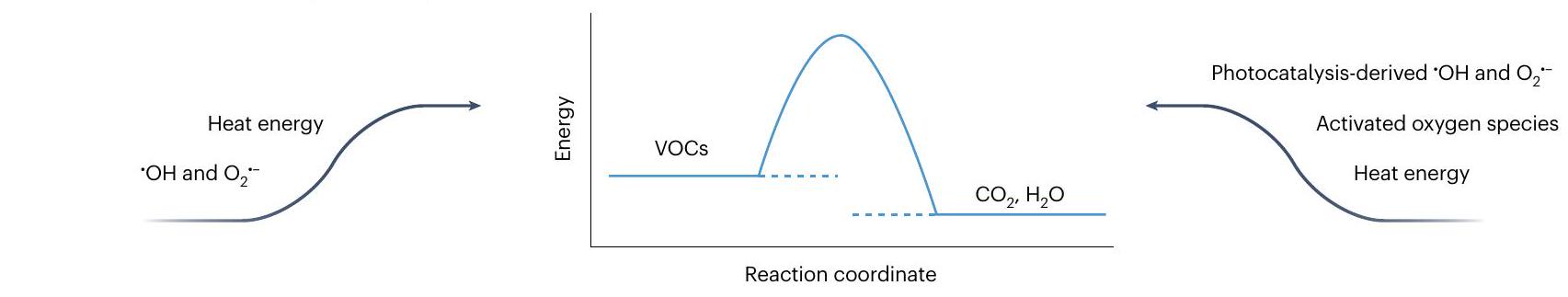

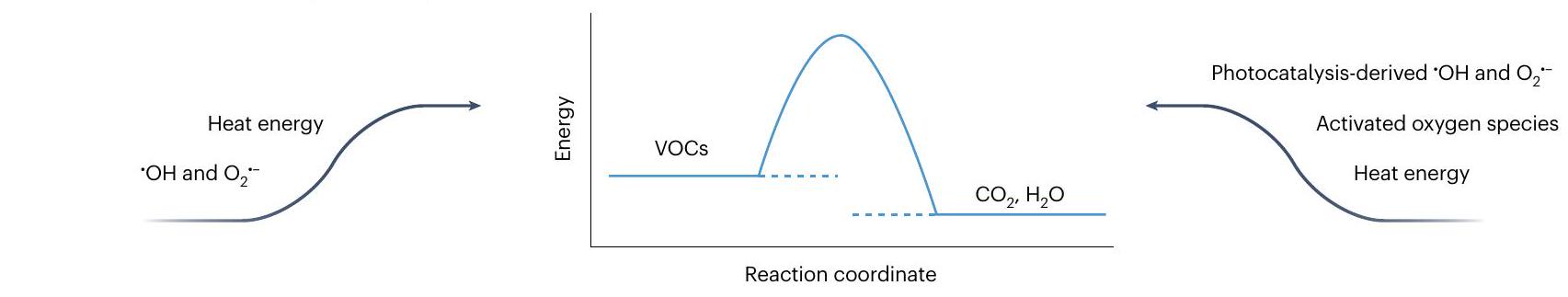

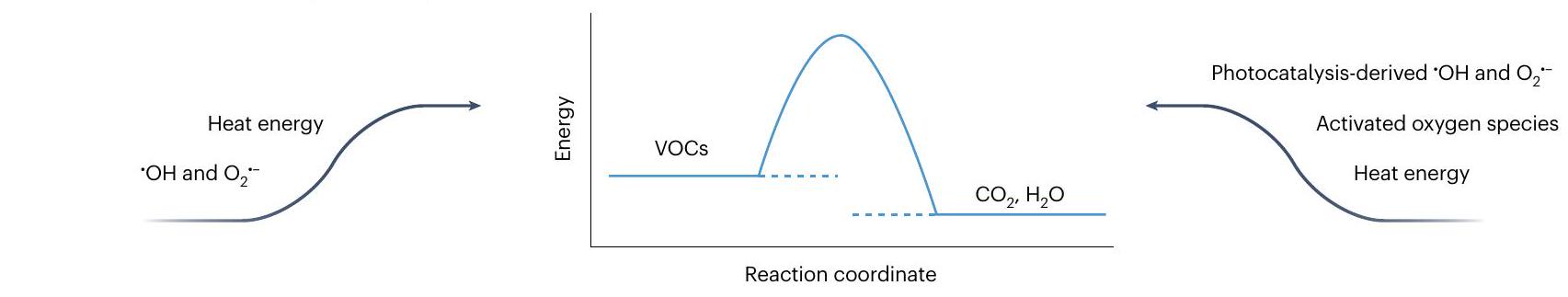

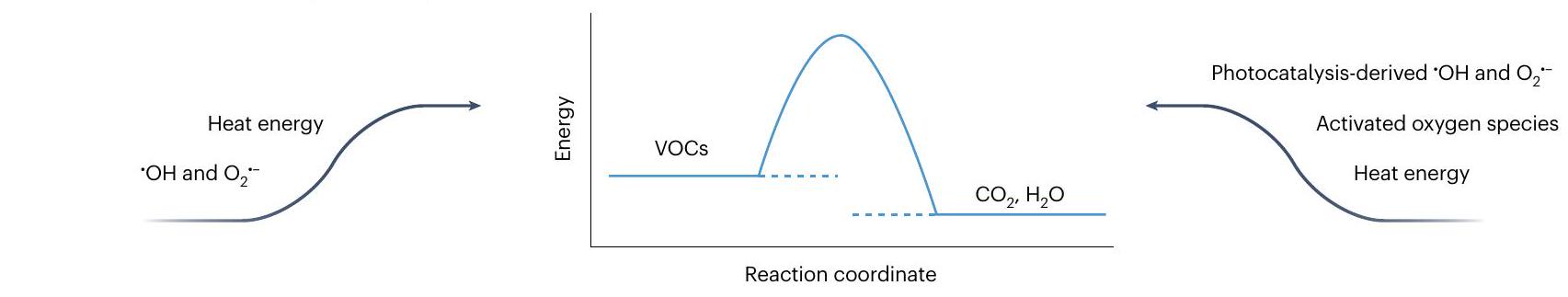

تحفيز حراري ضوئي للحصول على الطاقة من الطيف الشمسي (الشكل 5أ). يستخدم التحفيز الحراري المدعوم بالضوء العمليات الضوئية لتعزيز التفاعلات الحرارية من خلال إدخال ضوء إضافي في أنظمة التحفيز الحراري التقليدية.

تقنيات مساعدة بالصور لتنقية الهواء

بمساعدة إشعاع الضوء، يمكن أن تزيد كفاءة أداء نظام التفاعل التحفيزي الحراري – كفاءة تحويل المركبات العضوية المتطايرة – بمقدار لا يقل عن

كفاءة جمع الضوء والنشاط التحفيزي

مقالة مراجعة

ملخص وآفاق المستقبل

يمكن أن تعزز المفاعلات التي تقلل الحاجة لاختراق الضوء العميق، مثل المفاعلات المسطحة، فعالية التقنيات المعتمدة على الضوء. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من المهم تصميم مواد تحفيزية متقدمة ذات كفاءة عالية في امتصاص الضوء لاستخدام الفوتونات منخفضة الطاقة، مثل الضوء المرئي أو الأشعة تحت الحمراء. يمكن تحقيق تحسين امتصاص الضوء من خلال عدة استراتيجيات: اختيار محفزات ذات فجوة نطاق ضيقة، إدخال شوائب أو عيوب لإنشاء حالات منتصف الفجوة التي تضيق فجوة النطاق للموصلات، طلاء المحفزات بمواد تظهر تأثيرات الرنين السطحي المحلي (مثل المواد البلازمونية أو المواد القائمة على الكربون)، استخدام مواد حساسة للصبغة أو نقاط الكم، دمج مواد تحويل الطاقة لتحويل الضوء تحت الأحمر إلى ضوء فوق بنفسجي أو مرئي، وإنشاء مواد نانوية (مثل القضبان النانوية، الأسلاك النانوية، هياكل البلورات الضوئية وتشكيل السطح). سيفيد تحسين امتصاص الضوء في توليد أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية وزيادة كفاءة التحلل. بالنسبة لتنقية الهواء في المباني المكتبية والمصانع والمنازل، يمكن أن يوفر تطوير محفزات قادرة على استغلال الضوء الداخلي طريقًا نحو التنفيذ العملي للتقنية المعتمدة على الضوء لأنظمة تنقية الهواء.

References

- Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452, 301-310 (2008).

- Lin, J. et al. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 785-803 (2023).

- Wei, S. et al. Self-carbon-thermal-reduction strategy for boosting the Fenton-like activity of single

sites by carbon-defect engineering. Nat. Commun. 14, 7549 (2023). - Hodges, B. C., Cates, E. L. & Kim, J.-H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 642-650 (2018).

- He, F., Jeon, W. & Choi, W. Photocatalytic air purification mimicking the self-cleaning process of the atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 12, 2528 (2021).

- Weon, S., He, F. & Choi, W. Status and challenges in photocatalytic nanotechnology for cleaning air polluted with volatile organic compounds: visible light utilization and catalyst deactivation. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 3185-3214 (2019).

- Khin, M. M., Nair, A. S., Babu, V. J., Murugan, R. & Ramakrishna, S. A review on nanomaterials for environmental remediation. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8075-8109 (2012).

- Zheng, L. et al. Mixed scaling patterns and mechanisms of high-pressure nanofiltration in hypersaline wastewater desalination. Water Res. 250, 121023 (2024).

- Yang, X., Sun, H., Li, G., An, T. & Choi, W. Fouling of TiO

induced by natural organic matters during photocatalytic water treatment: mechanisms and regeneration strategy. Appl. Catal. B 294, 120252 (2021). - Le, N. T. H. et al. Freezing-enhanced non-radical oxidation of organic pollutants by peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 388, 124226 (2020).

- Weng, B., Lu, K.-Q., Tang, Z., Chen, H. M. & Xu, Y.-J. Stabilizing ultrasmall Au clusters for enhanced photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 9, 1543 (2018).

- Su, Y. et al. Unveiling the function of oxygen vacancy on facet-dependent

for the catalytic destruction of monochloromethane: guidance for industrial catalyst design. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 8086-8095 (2024). - Su, Y. et al. Surface-phosphorylated ceria for chlorine-tolerance catalysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 1369-1377 (2024).

- Yuan, X. et al. Anti-poisoning mechanisms of Sb on vanadia-based catalysts for NOx and chlorobenzene multi-pollutant control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 10211-10220 (2023).

- Su, Z. et al. Probing the actual role and activity of oxygen vacancies in toluene catalytic oxidation: evidence from in situ XPS/NEXAFS and DFT + U calculation. ACS Catal. 13, 3444-3455 (2023).

- Wang, B., Song, Z. & Sun, L. A review: comparison of multi-air-pollutant removal by advanced oxidation processes – industrial implementation for catalytic oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 409, 128136 (2021).

- Adeleye, A. S. et al. Engineered nanomaterials for water treatment and remediation: costs, benefits, and applicability. Chem. Eng. J. 286, 640-662 (2016).

- Brillas, E. Solar photoelectro-Fenton: a very effective and cost-efficient electrochemical advanced oxidation process for the removal of organic pollutants from synthetic and real wastewaters. Chemosphere 327, 138532 (2023).

- Wang, D., Junker, A. L., Sillanpää, M., Jiang, Y. & Wei, Z. Photo-based advanced oxidation processes for zero pollution: where are we now? Engineering 23, 19-23 (2023).

- Dey, A. K., Mishra, S. R. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. Solar light-based advanced oxidation processes for degradation of methylene blue dye using novel Zn-modified CeO2@ biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 53887-53903 (2023).

- Su, L., Wang, P., Ma, X., Wang, J. & Zhan, S. Regulating local electron density of iron single sites by introducing nitrogen vacancies for efficient photo-Fenton process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21261-21266 (2021).

- Yang, Q. et al. Recent advances in photo-activated sulfate radical-advanced oxidation process (SR-AOP) for refractory organic pollutants removal in water. Chem. Eng. J. 378, 122149 (2019).

- Yang, J., Zhu, M. & Dionysiou, D. D. What is the role of light in persulfate-based advanced oxidation for water treatment? Water Res. 189, 116627 (2021).

- Weng, B., Qi, M.-Y., Han, C., Tang, Z.-R. & Xu, Y.-J. Photocorrosion inhibition of semiconductor-based photocatalysts: basic principle, current development, and future perspective. ACS Catal. 9, 4642-4687(2019).

- Zhou, Q., Chen, Q., Tong, Y. & Wang, J. Light-induced ambient degradation of few-layer black phosphorus: mechanism and protection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11437-11441 (2016).

- Bi, Z. et al. The generation and transformation mechanisms of reactive oxygen species in the environment and their implications for pollution control processes: a review. Environ. Res. 260, 119592 (2024).

- Chen, M. et al. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots decorating

microspherical heterostructure and its efficient photocatalytic degradation of antibiotic norfloxacin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 109336 (2024). - Oh, V. B.-Y., Ng, S.-F. & Ong, W.-J. Is photocatalytic hydrogen production sustainable? Assessing the potential environmental enhancement of photocatalytic technology against steam methane reforming and electrocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134673 (2022).

- Wu, F., Zhou, Z. & Hicks, A. L. Life cycle impact of titanium dioxide nanoparticle synthesis through physical, chemical, and biological routes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4078-4087 (2019).

- Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 917 (2024).

- Ghanbarzadeh Lak, M., Sabour, M. R., Ghafari, E. & Amiri, A. Energy consumption and relative efficiency improvement of photo-Fenton – optimization by RSM for landfill leachate treatment, a case study. Waste Manage 79, 58-70 (2018).

- Barndõk, H., Blanco, L., Hermosilla, D. & Blanco, Á. Heterogeneous photo-Fenton processes using zero valent iron microspheres for the treatment of wastewaters contaminated with 1,4-dioxane. Chem. Eng. J. 284, 112-121 (2016).

- Santos, L. V. de S., Meireles, A. M. & Lange, L. C. Degradation of antibiotics norfloxacin by Fenton, UV and UV/

. J. Environ. Manage. 154, 8-12 (2015). - Kang, W. et al. Photocatalytic ozonation of organic pollutants in wastewater using a flowing through reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124277 (2021).

- Khaleel, G. F., Ismail, I. & Abbar, A. H. Application of solar photo-electro-Fenton technology to petroleum refinery wastewater degradation: optimization of operational parameters. Heliyon 9, e15062 (2023).

- Anipsitakis, G. P. & Dionysiou, D. D. Radical generation by the interaction of transition metals with common oxidants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 3705-3712 (2004).

- De Laat, J. & Gallard, H. Catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by Fe(III) in homogeneous aqueous solution: mechanism and kinetic modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2726-2732 (1999).

- Feng, W. & Nansheng, D. Photochemistry of hydrolytic iron(III) species and photoinduced degradation of organic compounds. A minireview. Chemosphere 41, 1137-1147 (2000).

- Sun, M. et al. New insights into photo-Fenton chemistry: the overlooked role of excited iron”

species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 10817-10827 (2024). - Yang, X.-j., Xu, X.-m., Xu, J. & Han, Y.-f. Iron oxychloride (FeOCl): an efficient Fenton-like catalyst for producing hydroxyl radicals in degradation of organic contaminants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16058-16061 (2013).

- Li, M. et al. Iron-organic frameworks as effective Fenton-like catalysts for peroxymonosulfate decomposition in advanced oxidation processes. npj Clean Water 6, 37 (2023).

- Wang, Y. et al. Comparison of Fenton, UV-Fenton and nano-

catalyzed UV-Fenton in degradation of phloroglucinol under neutral and alkaline conditions: role of complexation of with hydroxyl group in phloroglucinol. Chem. Eng. J. 313, 938-945 (2017). - Zheng, J., Li, Y. & Zhang, S. Engineered nanoconfinement activates Fenton catalyst at neutral pH: mechanism and kinetics study. Appl. Catal. B 343, 123555 (2024).

- Clarizia, L., Russo, D., Di Somma, I., Marotta, R. & Andreozzi, R. Homogeneous photo-Fenton processes at near neutral pH: a review. Appl. Catal. B 209, 358-371 (2017).

- Zhu, Y. et al. Strategies for enhancing the heterogeneous Fenton catalytic reactivity: a review. Appl. Catal. B 255, 117739 (2019).

- Brillas, E. Fenton, photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, and their combined treatments for the removal of insecticides from waters and soils. A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 284, 120290 (2022).

- Heidari, Z., Pelalak, R. & Zhou, M. A critical review on the recent progress in application of electro-Fenton process for decontamination of wastewater at near-neutral pH . Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145741 (2023).

- Ahile, U. J., Wuana, R. A., Itodo, A. U., Sha’Ato, R. & Dantas, R. F. A review on the use of chelating agents as an alternative to promote photo-Fenton at neutral pH: current trends, knowledge gap and future studies. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 134872 (2020).

- Vallés, I. et al. On the relevant role of iron complexation for the performance of photo-Fenton process at mild pH: role of ring substitution in phenolic ligand and interaction with halides. Appl. Catal. B 331, 122708 (2023).

- Li, W.-Q. et al. Boosting photo-Fenton process enabled by ligand-to-cluster charge transfer excitations in iron-based metal organic framework. Appl. Catal. B 302, 120882 (2022).

- Rodríguez, M., Bussi, J. & Andrea De León, M. Application of pillared raw clay-base catalysts and natural solar radiation for water decontamination by the photo-Fenton process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 259, 118167 (2021).

- Wu, Q. et al. Visible-light-driven iron-based heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalysts for wastewater decontamination: a review of recent advances. Chemosphere 313, 137509 (2023).

- Deng, G. et al. Ferryl ion in the photo-Fenton process at acidic pH: occurrence, fate, and implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 18586-18596 (2023).

- Gao, X. et al. New insight into the mechanism of symmetry-breaking charge separation induced high-valent iron(IV) for highly efficient photodegradation of organic pollutants. Appl. Catal. B 321, 122066 (2023).

- Jiang, J. et al. Spin state-dependent in-situ photo-Fenton-like transformation from oxygen molecule towards singlet oxygen for selective water decontamination. Water Res. 244, 120502 (2023).

- Lian, Z. et al. Photo-self-Fenton reaction mediated by atomically dispersed

photocatalysts toward efficient degradation of organic pollutants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318927 (2024). - Ciggin, A. S., Sarica, E. S., Doğruel, S. & Orhon, D. Impact of ultrasonic pretreatment on Fenton-based oxidation of olive mill wastewater – towards a sustainable treatment scheme. J. Clean. Prod. 313, 127948 (2021).

- Ahmed, Y., Zhong, J., Yuan, Z. & Guo, J. Roles of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic resistant bacteria inactivation and micropollutant degradation in Fenton and photo-Fenton processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 430, 128408 (2022).

- Li, Y. & Cheng, H. Autocatalytic effect of in situ formed (hydro)quinone intermediates in Fenton and photo-Fenton degradation of non-phenolic aromatic pollutants and chemical kinetic modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 449, 137812 (2022).

- Zhou, Y., Yu, M., Zhang, Q., Sun, X. & Niu, J. Regulating electron distribution of Fe/Ni-

single sites for efficient photo-Fenton process. J. Hazard. Mater. 440, 129724 (2022). - Gualda-Alonso, E. et al. Continuous solar photo-Fenton for wastewater reclamation in operational environment at demonstration scale. J. Hazard. Mater. 459, 132101 (2023).

- Silva, T. F. C. V., Fonseca, A., Saraiva, I., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Vilar, V. J. P. Scale-up and cost analysis of a photo-Fenton system for sanitary landfill leachate treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 283, 76-88 (2016).

- Miklos, D. B. et al. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – a critical review. Water Res. 139, 118-131 (2018).

- Gualda-Alonso, E. et al. Large-scale raceway pond reactor for CEC removal from municipal WWTP effluents by solar photo-Fenton. Appl. Catal. B 319, 121908 (2022).

- Gualda-Alonso, E., Soriano-Molina, P., García Sánchez, J. L., Casas López, J. L. & Sánchez Pérez, J. A. Mechanistic modeling of solar photo-Fenton with

-NTA for microcontaminant removal. Appl. Catal. B 318, 121795 (2022). - Duan, X., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Metal-free carbocatalysis in advanced oxidation reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 678-687 (2018).

- Han, B. et al. Microenvironment engineering of single-atom catalysts for persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 447, 137551 (2022).

- Lee, J., von Gunten, U. & Kim, J.-H. Persulfate-based advanced oxidation: critical assessment of opportunities and roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3064-3081 (2020).

- Zhang, S., Zheng, H. & Tratnyek, P. G. Advanced redox processes for sustainable water treatment. Nat. Water 1, 666-681(2023).

- Guo, R. et al. Catalytic degradation of lomefloxacin by photo-assisted persulfate activation on natural hematite: performance and mechanism. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 3809-3817 (2022).

- He, S., Chen, Y., Li, X., Zeng, L. & Zhu, M. Heterogeneous photocatalytic activation of persulfate for the removal of organic contaminants in water: a critical review. ACS EST. Eng 2, 527-546 (2022).

- Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Simultaneous nanocatalytic surface activation of pollutants and oxidants for highly efficient water decontamination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3005 (2022).

- Yin, R. et al. Near-infrared light to heat conversion in peroxydisulfate activation with

: a new photo-activation process for water treatment. Water Res. 190, 116720 (2021). - Weng, Z. et al. Site engineering of covalent organic frameworks for regulating peroxymonosulfate activation to generate singlet oxygen with

selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310934 (2023). - Yan, Y. et al. Merits and limitations of radical vs. nonradical pathways in persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12153-12179 (2023).

- Gan, P. et al. The degradation of municipal solid waste incineration leachate by UV/persulfate and UV/

processes: the different selectivity of and . Chemosphere 311, 137009 (2023). - Guerra-Rodríguez, S. et al. Pilot-scale sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation for wastewater reuse: simultaneous disinfection, removal of contaminants of emerging concern, and antibiotic resistance genes. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 146916 (2023).

- Wang, Y., Duan, X., Xie, Y., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Nanocarbon-based catalytic ozonation for aqueous oxidation: engineering defects for active sites and tunable reaction pathways. ACS Catal. 10, 13383-13414 (2020).

- Mundy, B. et al. A review of ozone systems costs for municipal applications. Report by the municipal committee – IOA Pan American group. Ozone Sci. Eng. 40, 266-274 (2018).

- Zhou, H. & Smith, D. W. Ozone mass transfer in water and wastewater treatment: experimental observations using a 2D laser particle dynamics analyzer. Water Res. 34, 909-921 (2000).

- Lu, J. et al. Efficient mineralization of aqueous antibiotics by simultaneous catalytic ozonation and photocatalysis using

as a bifunctional catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 358, 48-57 (2019). - Bessegato, G. G., Cardoso, J. C., da Silva, B. F. & Zanoni, M. V. B. Combination of photoelectrocatalysis and ozonation: a novel and powerful approach applied in Acid Yellow 1 mineralization. Appl. Catal. B 180, 161-168 (2016).

- Mehrjouei, M., Müller, S. & Möller, D. A review on photocatalytic ozonation used for the treatment of water and wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 263, 209-219 (2015).

- Beltrán, F. J., Aguinaco, A., García-Araya, J. F. & Oropesa, A. Ozone and photocatalytic processes to remove the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole from water. Water Res. 42, 3799-3808 (2008).

- Yu, D., Li, L., Wu, M. & Crittenden, J. C. Enhanced photocatalytic ozonation of organic pollutants using an iron-based metal-organic framework. Appl. Catal. B 251, 66-75 (2019).

- Xiao, J., Xie, Y., Rabeah, J., Brückner, A. & Cao, H. Visible-light photocatalytic ozonation using graphitic

catalysts: a hydroxyl radical manufacturer for wastewater treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1024-1033 (2020). - Xiao, J. et al. Is

chemically stable toward reactive oxygen species in sunlight-driven water treatment? Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13380-13387(2017). - Lincho, J., Zaleska-Medynska, A., Martins, R. C. & Gomes, J. Nanostructured photocatalysts for the abatement of contaminants by photocatalysis and photocatalytic ozonation: an overview. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155776 (2022).

- Ye, M., Chen, Z., Liu, X., Ben, Y. & Shen, J. Ozone enhanced activity of aqueous titanium dioxide suspensions for photodegradation of 4-chloronitrobenzene. J. Hazard. Mater. 167, 1021-1027 (2009).

- Andreozzi, R., Caprio, V., Insola, A. & Marotta, R. Advanced oxidation processes (AOP) for water purification and recovery. Catal. Today 53, 51-59 (1999).

- Mecha, A. C., Onyango, M. S., Ochieng, A. & Momba, M. N. B. Ultraviolet and solar photocatalytic ozonation of municipal wastewater: catalyst reuse, energy requirements and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 186, 669-676 (2017).

مقالة مراجعة

- مهرجوي، م.، مولر، س. ومولر، د. استهلاك الطاقة لثلاث طرق مختلفة من الأكسدة المتقدمة لمعالجة المياه: دراسة جدوى التكلفة. ج. نظافة. إنتاج. 65، 178-183 (2014).

- ميكا، أ. س.، أونيانغو، م. س.، أوشيينغ، أ.، فوري، ج. ج. س. ومومبا، م. ن. ب. التأثير التآزري للأوزون الضوئي باستخدام الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية والطاقة الشمسية على تحلل الفينول في مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية: دراسة مقارنة. مجلة الحفز 341، 116-125 (2016).

- مورييرا، ف. س.، بوافينتورا، ر. أ. ر.، بريلاس، إ. وفيلار، ف. ج. ب. عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة الكهروكيميائية: مراجعة حول تطبيقها على المياه العادمة الاصطناعية والحقيقية. تطبيقات الحفز ب 202، 217-261 (2017).

- باندي، أ. ك. وآخرون. استخدام الطاقة الشمسية في معالجة مياه الصرف: التحديات والاتجاهات البحثية المتقدمة. مجلة إدارة البيئة 297، 113300 (2021).

- Pham، C. V.، Escalera-López، D.، Mayrhofer، K.، Cherevko، S. & Thiele، S. أساسيات المحللات المائية عالية الأداء – من مواد طبقة المحفز إلى هندسة الأقطاب. Adv. Energy Mater. 11، 2101998 (2021).

- فاليرو، د.، غارسيا-غارسيا، ف.، إكسبوسيتو، إ.، ألداز، أ. ومونتييل، ف. المعالجة الكهروكيميائية لمياه الصرف من صناعة اللوز باستخدام أنودات من نوع DSA: الاتصال المباشر بمولد الطاقة الشمسية. تكنولوجيا الفصل والتنقية 123، 15-22 (2014).

- هوانغ، ي. وآخرون. التخفيف الفعال للملوثات ذات الاهتمام المتزايد بواسطة LED-UV

الكلور الكهروكيميائي لإعادة استخدام مياه الصرف الصحي: الحركيات، مسارات التحلل، والسمية الخلوية. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 480، 148032 (2024). - أوتير، ب. وآخرون. التقييم الاقتصادي لأنظمة إمداد المياه التي تعمل بالتعقيم الكهربائي المدفوع بالطاقة الشمسية في المناطق الريفية في نيبال ومصر وتنزانيا. مجلة المياه. 187، 116384 (2020).

- كوكي، ب. أ. وآخرون. الجذير الكبريتي في العمليات المتقدمة للأكسدة (الضوئية) الكهروكيميائية لمعالجة المياه: نهج متعدد الاستخدامات. ج. فيز. كيم. ليتر. 14، 8880-8889 (2023).

- سون، أ. وآخرون. تعزيز الأكسدة الضوئية الكهروكيميائية للملوثات العضوية باستخدام مواد ذاتية التخصيب.

مصفوفات الأنابيب النانوية: تأثير معلمات التشغيل ومصفوفة الماء. مياه. 191، 116803 (2021). - غارسيا-إسبينوزا، ج. د.، روبلز، إ.، دوران-مورينو، أ. و غودينز، ل. أ. العمليات المتقدمة للأكسدة الكهروكيميائية المدعومة بالضوء لتعقيم المحاليل المائية: مراجعة. كيموسفير 274، 129957 (2021).

- فاناجس، م. وآخرون. تخليق الاحتراق الذاتي بتقنية الجل-سول لـ

مساحيق نانوية من البراونميليريت والأفلام الرقيقة لمعالجة المياه الكهروكيميائية المتقدمة بواسطة الأكسدة تحت الضوء المرئي. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 103224 (2019). - ياو، ت.، آن، إكس.، هان، إتش.، تشين، ج. كيو. ولي، سي. مواد التحفيز الكهروضوئي لتفكيك الماء بالطاقة الشمسية. مواد الطاقة المتقدمة 8، 1800210 (2018).

- لو، س. وزانغ، ج. التقدمات الحديثة في تعطيل الكائنات الدقيقة الممرضة المنقولة بالماء بواسطة عمليات الأكسدة (الضوئية) الكهروكيميائية: استراتيجيات التصميم والتطبيق. مجلة المواد الخطرة 431، 128619 (2022).

- فكادو، س. وآخرون. معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي باستخدام عملية التجلط الكهروضوئي: نماذج تنبؤية لإزالة COD واللون واستهلاك الطاقة الكهربائية. ج. هندسة عمليات المياه 41، 102068 (2021).

- رينجيفو-هيريرا، ج. أ. وبولجارين، س. لماذا خمسة عقود من البحث الضخم في التحفيز الضوئي غير المتجانس، خاصة على

لم يقم بعد بتوجيه تطبيقات تعقيم المياه وإزالة السموم؟ مراجعة نقدية للعيوب والتحديات. Chem. Eng. J. 477، 146875 (2023). - زينغ، ج. وآخرون. المواد النانوية الممكنة للتحفيز الكهروضوئي لإزالة الملوثات في البيئة والغذاء. اتجاهات الكيمياء التحليلية 166، 117187 (2023).

- سونغ، ي.، تشانغ، ج.-ي.، يانغ، ج.، بو، ت. وما، ج.-ف. أكسدة فعالة للغاية للزرنيخ (III) باستخدام محفز ضوئي كهربائي قائم على معقد معدني عضوي معدل بواسطة بوليوكسوميتالات-ثياكالكس[4]أرين. الكيمياء الخضراء. 26، 3874-3883 (2024).

- جياو، ي.، ما، ل.، تيان، ي. وزو، م. عملية كهربائية فنتون متدفقة باستخدام كاثود من ألياف الكربون النشطة المعدلة لإزالة البرتقالي II. كيموسفير 252، 126483 (2020).

- تشو، و. وآخرون. معدلات

توليد الكهرباء عن طريق اختزال الأنود في أقطاب الرغوة RVC في خلايا الدفعة والتدفق. Electrochim. Acta 277، 185-196 (2018). - دانغ، ك. وآخرون. نظام كيميائي ضوئي مدعوم بالأيونات بدون تحيز لمعالجة مياه الصرف المستدامة. نات. كوميونيك. 14، 8413 (2023).

- ديبيا بريا، ج. وآخرون. معالجة المياه العادمة الحقيقية بواسطة الطرق الكهروضوئية: نظرة عامة. كيموسفير 276، 130188 (2021).

- تيديسكو، ج. س. ومورايش، ب. ب. تصميم مبتكر لمفاعل ضوئي كيميائي بتدفق مستمر: التصميم الهيدروليكي، محاكاة الديناميكا الهوائية، والنمذجة الأولية. مجلة هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 9، 105917 (2021).

- تاو، ي. وآخرون. الأكسدة الكهروضوئية المدفوعة بالأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة لليوريا على البيروفيسكايت القائم على اللانثانوم والنيكل. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 446، 137240 (2022).

- فيفار، م.، سكريابين، إ.، إيفريت، ف. و بلاكرز، أ. مفهوم لنظام هجين لتنقية المياه بالطاقة الشمسية ونظام الخلايا الشمسية. مواد الطاقة الشمسية وخلايا الشمس 94، 1772-1782 (2010).

- سبوعي، م. وآخرون. تصنيع مواد موصلة كهربائياً

أغشية مركبة للتفاعل الضوئي الكهربائي المتزامن والترشيح الدقيق لصبغة الأزوال من مياه الصرف. تطبيقات الحفز A 644، 118837 (2022). - غارغ، ر. وآخرون. ترسيب الأفلام الرقيقة: المواد، التطبيقات، التحديات والاتجاهات المستقبلية. علوم واجهة الكولود 330، 103203 (2024).

- نوكيد، م. وآخرون. الطبقات الرقيقة الكهروكيميائية في الهياكل النانوية لتخزين الطاقة. أكاديمي. كيم. ريس. 49، 2336-2346 (2016).

- جون، ت. هـ.، كو، م. س.، كيم، هـ. وتشوي، و. أنظمة التحفيز الضوئي والتحفيز الكهروضوئي ذات الوظائف المزدوجة لمعالجة المياه لاستعادة الطاقة والموارد. ACS Catal. 8، 11542-11563 (2018).

- غارزا-كامبوس، ب. وآخرون. تحلل حمض الساليسيليك بواسطة عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة. ربط عملية فوتو-فينتون الشمسية والضوء الشمسي المتغاير. مواد خطرة. 319، 34-42 (2016).

- وانغ، ي. وآخرون. تحفيز فتون ضوئي فعال لحمض البيرفلوروأوكتانويك باستخدام أوراق نانوية ثنائية الأبعاد من CoFe المستندة إلى MOFs: قدرة الامتصاص والتعدين المتوسطة بواسطة فراغات الأكسجين. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 483، 149385 (2024).

- مارينيو، ب. أ. وآخرون. التحلل الضوئي، التحلل الكهربائي والتحلل الضوئي الكهربائي للأدوية في الوسائط المائية: الطرق التحليلية، الآليات، المحاكاة، المحفزات والمفاعلات. ج. إنتاج نظيف. 343، 131061 (2022).

- تشنغ، ج.، تشانغ، ب.، لي، إكس.، جي، ل. ونيو، ج. نظرة على عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة المدعومة بالضوء لتفكيك الملوثات الدقيقة المضادة للبكتيريا: الآليات والفجوات البحثية. كيموسفير 343، 140211 (2023).

- براهم، ر. ج. وهاريس، أ. ت. مراجعة للاعتبارات الرئيسية في التصميم وتكبير الحجم لمفاعلات التحفيز الضوئي الشمسي. الهندسة الكيميائية الصناعية والبحوث 48، 8890-8905 (2009).

- سالازار، ل. م.، غريزاليس، س. م. وغارسيا، د. ب. كيف يؤثر التكثيف على الأداء التشغيلي والبيئي لعمليات فوتو-فينتون عند درجة حموضة حمضية وقريبة من المحايدة. علوم البيئة. بحث تلوث. 26، 4367-4380 (2019).

- مينغ، ت.، سون، و.، سو، إكس. وسون، ب. الجرعة المثلى من المؤكسدات في عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة المعتمدة على الأشعة فوق البنفسجية بالنسبة لتركيزات الجذور الأولية. مياه ريس. 206، 117738 (2021).

- شو، س.-ل. وآخرون. توسيع نطاق الرقم الهيدروجيني لتفاعلات شبيهة بفنتون لتحلل الملوثات: تأثير البيئات الدقيقة الحمضية. مياه البحث. 270، 122851 (2025).

- وانغ، ي. وآخرون. تحسين إزالة البرتقالي II باستخدام

-LDH نشط بيروكسيمونوكبريت: أكسدة جذرية تآزرية وامتصاص. المحفزات 14، 380 (2024). - بينجهيدي، ر.، موندال، ر. وموندال، س. مفاعل ضوئي مستمر: مراجعة نقدية حول التصميم والأداء. مجلة هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 10، 107746 (2022).

- غرجيć، إ. ولي بومة، ج. نماذج الامتصاص-التشتت ذات الستة تدفقات للتصوير الضوئي تحت مصادر الإشعاع واسعة الطيف في المفاعلات الحلزونية والمسطحة باستخدام محفزات ذات خصائص بصرية مختلفة. تطبيقات الحفز ب 211، 222-234 (2017).

- وو، ز. وآخرون. استشعار الألياف الضوئية بالأشعة تحت الحمراء في الموقع لمراقبة التغيرات في المتفاعلات والمنتجات خلال التفاعل الضوئي التحفيزي. التحليل الكيميائي 97، 1229-1235 (2025).

- لي، س.، لين، ي.، ليو، ج. وشي، ج. حالة البحث في تكنولوجيا إزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة (VOC) وآفاق الاستراتيجيات الجديدة: مراجعة. علوم البيئة. العمليات. التأثيرات 25، 727-740 (2023).

- هو، سي. وآخرون. التقدمات الحديثة في الأكسدة الحفزية للمركبات العضوية المتطايرة: مراجعة تستند إلى أنواع الملوثات ومصادرها. مراجعة الكيمياء 119، 4471-4568 (2019).

- Zhang، ك. وآخرون. تقدم البحث في محفز أكسيد المعادن المركب لتدهور المركبات العضوية المتطايرة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 9220-9236 (2022).

- يانغ، ي. وآخرون. التقدم الحديث والتحديات المستقبلية في التحفيز الضوئي الحراري لإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة: من تصميم المحفزات إلى التطبيقات. الطاقة الخضراء والبيئة. 8، 654-672 (2023).

- جيانغ، سي. وآخرون. تعديل حالات العيوب في

عن طريق إضافة الحديد: استراتيجية للأكسدة الحفزية للتولوين عند درجات حرارة منخفضة باستخدام ضوء الشمس. J. Hazard. Mater. 390، 122182 (2020). - سون، ب. وآخرون. تحويل ضوئي حراري بكفاءة في محفز ضوئي حراري أحادي قائم على MnOx لإزالة الفورمالديهايد الغازي. رسائل الكيمياء الصينية 33، 2564-2568 (2022).

- شان، سي. وآخرون. التقدمات الحديثة في أكسدة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة المحفزة على أكاسيد السبينل: تصميم المحفز وآلية التفاعل. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 57، 9495-9514 (2023).

- لي، ج.-ج. وآخرون. التحلل الفعال للمركبات العضوية المتطايرة المعزز بواسطة الضوء تحت الحمراء على المواد المستجيبة للضوء والحرارة

المركبات. تطبيقات الحفز. ب 233، 260-271 (2018). - هونغ، ج. وآخرون. الكيمياء الضوئية الحرارية المستندة إلى الطاقة الشمسية: من التأثيرات التآزرية إلى التطبيقات العملية. أدف. ساي. 9، 2103926 (2022).

- رين، ي. وآخرون. الطاقة الشمسية المركزة

تقليل في بخار مع كفاءة تحويل الطاقة. نات. كوم. 15، 4675 (2024). - لي، ج.، ليو، إكس.، وينغ، ب.، روفارس، م. ب. ج. وجيا، هـ. هندسة انتشار الضوء من أجل التحفيز الضوئي والحراري المتناغم نحو القضاء على المركبات العضوية المتطايرة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 461، 142022 (2023).

- كينيدي، ج. س. ودايت، أ. ك. الأكسدة غير المتجانسة للاثانول بواسطة الفوتوحرارية

. J. Catal. 179, 375-389 (1998). - تشانغ، م. وآخرون. البناء في الموقع لمحفزات الفوتوحرارية أكسيد المنغنيز لإزالة التولوين بعمق من خلال الاستفادة العالية من طاقة الشمس. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 57، 4286-4297 (2023).

- ما، ج.، وانغ، ج. و دانغ، ي. الأكسدة المساعدة بالضوء للبنزين الغازي على التنجستن المخلوط

عند درجة حرارة منخفضة. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية. 388، 124387 (2020). - يو، إكس، تشاو، سي، يانغ، إل، تشانغ، جي. & تشين، سي. الأكسدة التحفيزية الضوئية الحرارية للتولوين على

محفز نانو مركب. EES كاتال. 2، 811-822 (2024). - وو، ب.، جين، إكس.، تشيو، واي. ويي، د. التقدم الأخير في الأكسدة الحرارية الحفزية والأكسدة الضوئية/الحرارية الحفزية لتنقية المركبات العضوية المتطايرة باستخدام محفزات أكسيد المنغنيز. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 4268-4286 (2021).

- ماتيو، د.، سيريلو، ج. ل.، دوريني، س. وغاسكون، ج. أساسيات وتطبيقات التحفيز الضوئي الحراري. مراجعات الجمعية الكيميائية 50، 2173-2210 (2021).

- أجبوفهيمين إليميان، إ.، زانغ، م.، صن، ي.، هي، ج. وجيا، هـ. استغلال الطاقة الشمسية نحو الأكسدة التحفيزية الضوئية الحرارية التآزرية للمركبات العضوية المتطايرة. سول. آر. آر. إل 7، 2300238 (2023).

- شان، سي. وآخرون. النمو في الموقع الناتج عن الحفر الحمضي لـ

على سبينيل CoMn لأكسدة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة عند درجات حرارة منخفضة. علوم البيئة. التكنولوجيا 56، 10381-10390 (2022). - ما، ي. وآخرون. فهم الأدوار المختلفة للأكسجين الممتز على السطح وأنواع الأكسجين في الشبكة في الأداء التحفيزي المتميز لأكاسيد المعادن في أكسدة الأوكسيلين. ACS Catal. 14، 16624-16638 (2024).

- وانغ، هـ. وآخرون. تعزيز الأكسدة الضوحرارية التحفيزية للتولوين على

: تأثير التروس للضوء والحرارة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا. 58، 7662-7671 (2024). - وانغ، إكس. وآخرون. التآزر الكهرو-مساعد للحرارة الضوئية لإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة على ذرات الذهب المفردة المثبتة

أنابيب نانوية. تطبيقات التحفيز B 358، 124338 (2024). - رين، ل.، يانغ، إكس.، صن، إكس. ويوان، واي. مزامنة تنقية فعالة للمواد العضوية المتطايرة في تبخر المياه الشمسية المتينة على سطح عالي الاستقرار

مادة الجرافين. نانو ليت. 24، 715-723 (2024). - كوي، إكس. وآخرون. المواد النانوية الضوئية الحرارية: محول قوي من الضوء إلى الحرارة. مراجعة الكيمياء 123، 6891-6952 (2023).

- لي، ي. وآخرون. أكسدة تحفيزية ضوئية حرارية فعالة مدعومة بركيزات نانوية ثلاثية الأبعاد. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 58، 5153-5161 (2024).

- ليونغ، س.-ف. وآخرون. التقاط الفوتونات بكفاءة باستخدام مصفوفات آبار نانوية ثلاثية الأبعاد مرتبة. نانو ليت. 12، 3682-3689 (2012).

- وانغ، ف. وآخرون. أكاسيد المنغنيز بأشكال تشبه القضبان والأسلاك والأنابيب والزهور: محفزات فعالة للغاية لإزالة التولوين. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 46، 4034-4041 (2012).

- جيانغ، د.، وانغ، و.، صن، س.، تشانغ، ل. وزينغ، ي. تحقيق التوازن بين الأدوار البلازمونية والتحفيزية للهياكل النانوية المعدنية في الأكسدة الضوئية المعدلة بالذهب

. ACS كاتال. 5، 613-621 (2015). - Žerjav، ج. وآخرون. النشاط الضوئي والحراري والضوئي الحراري لـ

دعم المحفزات البلاتينية للتطبيقات البيئية المدفوعة بالبلاسمون. ج. هندسة الكيمياء البيئية 11، 110209 (2023). - تشينغ، ج. وآخرون. هندسة الواجهة لـ

تقنيات S-scheme للوصلات غير المتجانسة لتعزيز التحلل الضوئي الحراري للتولوين. مجلة المواد الخطرة. 452، 131249 (2023). - وانغ، ز.-ي. وآخرون. هيدروجيل MXene/CdS الضوئي الحراري-التحفيزي لتبخر المياه الشمسي الفعال والتحلل التآزري للمواد العضوية المتطايرة. مجلة مواد الكيمياء A 12، 10991-11003 (2024).

- إيليميان، إ. أ. وآخرون. بناء

محفز متعدد الوظائف غني بفجوات الأكسجين لتحسين التحلل الضوئي الحراري المدفوع بالضوء للتولوين. تطبيقات التحفيز B 307، 121203 (2022). - بي، ف. وآخرون. ذرة البالاديوم المفردة المنسقة بالكلور عززت مقاومة الكلور لتحلل المركبات العضوية المتطايرة: دراسة الآلية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 17321-17330 (2022).

- وانغ، ز. وآخرون. محاكاة تنقية التولوين المدفوعة بالضوء الشمسي باستخدام محفز Pt ذرة واحدة مدعوم بأكسيد الحديد. تطبيقات التحفيز B 298، 120612 (2021).

- كونغ، ج.، شيانغ، ز.، لي، ج. وآن، ت. يقدمون فراغات الأكسجين في

محفز لزيادة مقاومة الكوك أثناء الأكسدة الضوئية الحرارية الحفزية للمواد العضوية المتطايرة النموذجية. تطبيقات الحفز B 269، 118755 (2020). - وي، ل.، يو، ج.، يانغ، ك.، فان، ك. وجي، هـ. التقدمات الحديثة في إزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة وثاني أكسيد الكربون عبر التحفيز التآزري الضوئي الحراري. المجلة الصينية للتحفيز 42، 1078-1095 (2021).

- دينغ، إكس.، ليو، و.، تشاو، ج.، وانغ، ل. وزو، ز. التحفيز الضوئي الحراري لثاني أكسيد الكربون نحو تخليق وقود شمسي: من هندسة المواد والمفاعلات إلى التحليل التكنولوجي والاقتصادي. مواد متقدمة. 37، e2312093 (2025).

- يو، إكس. وآخرون. تقدمات في التحفيز الضوئي الحراري لملوثات الهواء. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 486، 150192 (2024).

- تاكيت، ب. م.، غوميز، إ. و تشين، ج. ج. التخفيض الصافي لـ

عبر تفاعلات التحول الحراري التحفيزي والتحول الكهربائي التحفيزي في العمليات القياسية والهجينة. نات. كاتال. 2، 381-386 (2019). - وانغ، س. وآخرون. إعادة تدوير النيكل من مياه الصرف الناتجة عن الطلاء الكهربائي من القبر إلى المهد إلى ضوء حراري

تحفيز. نات. كوميون. 13، 5305 (2022). - زينغ، م. وآخرون. التأثير التآزري بين التحفيز الضوئي على

والتحفيز الحراري على لأكسدة البنزين في الطور الغازي على نانومركبات. ACS Catal. 5، 3278-3286 (2015). - سونغ، سي. وآخرون. تقطير شمسي معتمد على غشاء نانوي ذو مسام مزدوجة الحجم لالتقاط المركبات العضوية المتطايرة بواسطة التأثير الضوئي الحراري/التحفيزي الضوئي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 9025-9033 (2020).

- سونغ، سي.، وانغ، زي.، يين، زي.، شياو، دي. وما، دي. مبادئ وتطبيقات التحفيز الضوئي الحراري. كيم. كاتال. 2، 52-83 (2022).

- لي، ج. وآخرون. التحفيز المتعدد الوظائف المدعوم بأشعة الشمس المحيطة للتقليل من التولوين عبر الانفصال في الموقع لـ

على والد البيروفيسكايت. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية. 412، 128560 (2021). - وانغ، هـ. وآخرون. مراجعة للتحكم في العملية الكاملة للمركبات العضوية المتطايرة الصناعية في الصين. مجلة العلوم البيئية 123، 127-139 (2023).

- وانغ، ر. وآخرون. خصائص انبعاثات وتفاعلية المركبات العضوية المتطايرة من الصناعات النموذجية ذات الاستهلاك العالي للطاقة في شمال الصين. العلوم. البيئة الكلية 809، 151134 (2022).

- غويتلا، أ.، ثيفينيت، ف.، بوزينات، إ.، غيارد، ج. ورسو، أ.

الأكسدة بواسطة البلازما تركيب: تأثير المسامية وآليات التحفيز الضوئي تحت تعرض البلازما. تطبيقات التحفيز B 80، 296-305 (2008). - ترانتو، ج.، فورتشوت، د. وبيشات، ب. دمج البلازما الباردة و

تحفيز ضوئي لتنقية الانبعاثات الغازية: دراسة أولية باستخدام هواء ملوث بالميثانول. الهندسة الكيميائية الصناعية والبحوث 46، 7611-7614 (2007). - ما، ر.، صن، ج.، لي، د. هـ. ووي، ج. ج. مراجعة للتفاعل التآزري للضوء والحرارة: الآليات والمواد والتطبيقات. المجلة الدولية لطاقة الهيدروجين 45، 30288-30324 (2020).

- وانغ، س.، أنغ، هـ. م. وتادي، م. أ. المركبات العضوية المتطايرة في البيئة الداخلية والأكسدة الضوئية: أحدث ما توصلت إليه الأبحاث. البيئة الدولية 33، 694-705 (2007).

- ناير، ف.، مونييز-باتيستا، م. ج.، فيرنانديز-غارسيا، م.، لوكي، ر. وكولميناريس، ج. س. التحفيز الضوئي الحراري: التطبيقات البيئية والطاقة. كيم ساس كيم 12، 2098-2116 (2019).

- تشانغ، ي. وآخرون. الأكسدة الضوئية لإزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة: من البحث الأساسي إلى التطبيقات العملية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 16582-16601 (2022).

- توماتيس، م. وآخرون. إزالة المركبات العضوية المتطايرة من الغازات النفايات باستخدام أكسدة حرارية متنوعة: دراسة مقارنة تعتمد على تقييم دورة الحياة وتحليل التكلفة في الصين. مجلة الإنتاج النظيف 233، 808-818 (2019).

- باسكاران، د.، ذاموداران، د.، بيهيرا، أ. س. & بيون، هـ.-س. مراجعة شاملة ورؤية بحثية في دمج التكنولوجيا لعلاج المركبات العضوية المتطايرة الغازية. البحث البيئي. 251، 118472 (2024).

- كونغ، ج. وآخرون. آلية التحلل التآزري والتعادل الضوئي الحراري للمعادن للمواد العضوية المتطايرة النموذجية على محفزات مسامية مرتبة PtCu/CeO2 تحت إشعاع شمسي محاكى. مجلة الحفز. 370، 88-96 (2019).

- زينغ، ي.، تشونغ، ج.، فنغ، ف.، يي، د. & هو، ي. التأكسد الضوئي الحراري التآزري لمزيج الميثانول والتولوين باستخدام محفز مشتق من Co-MOFs: تأثيرات الواجهة والترويج. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 485، 149720 (2024).

- سون، هـ. وآخرون. تنقية الهواء الداخلي الناتجة عن ضوء الغرفة باستخدام تقنية فعالة

المحفز الضوئي. تطبيقات التحفيز B 108-109، 127-133 (2011). - لو، هـ. وآخرون. تطبيقات فينتون على نطاق تجريبي ونطاق كبير مع محفزات نانوية معدنية: من وحدات التحفيز إلى تطبيقات التوسع. أبحاث المياه 266، 122425 (2024).

- بويجو، ي.، صن، هـ.، ليو، ج.، باريك، ف. ك. ووانغ، س. مراجعة حول التحفيز الضوئي لمعالجة الهواء: من تطوير المحفزات إلى تصميم المفاعلات. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 310، 537-559 (2017).

- فيدال، ج.، كارفاخال، أ.، هويليينير، ج. وسالازار، ر. معالجة مياه الصرف الصحي من المسالخ بواسطة عملية هضم لاهوائي مركب/عملية فوتوإلكترو-فينتون الشمسية التي تمت في تشغيل شبه مستمر. مجلة الهندسة الكيميائية 378، 122097 (2019).

- ميراليس-كويفاس، س. وآخرون. هل تعتبر مجموعة أغشية النانوترشيح وعمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة فعالة من حيث التكلفة لإزالة الملوثات الدقيقة في مياه الصرف الصحي البلدية الحقيقية؟ علوم البيئة. موارد المياه 2، 511-520 (2016).

- رودا-ماركيز، ج. ج.، ليفتشوك، إ.، مانزانو، م. وسيلانبا، م. تقليل السمية لمياه الصرف الصناعي والبلدي بواسطة عمليات الأكسدة المتقدمة (فوتو-فينتون، UVC

، فنتون الكهربائي وفنتون الجلفاني): مراجعة. المحفزات 10، 612 (2020). - نوت، ت.، فاهلنكامب، هـ. وسونتاج، س. معدل استهلاك الأوزون وعائد الجذور الحرة الهيدروكسيلية في أوزنة مياه الصرف الصحي. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 43، 5990-5995 (2009).

- مهرليبور، ج.، أكبرى، ح.، أديب زاده، أ. وأكبرى، ح. تحلل توسيليزوماب عبر عملية الأوزون الضوئي التحفيزي من المحاليل المائية. تقارير علمية 13، 22402 (2023).

- رادجينوفيتش، ج. وسيدلاك، د. ل. التحديات والفرص للعمليات الكهروكيميائية كتقنيات من الجيل التالي لمعالجة المياه الملوثة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 49، 11292-11302 (2015).

- لانزاريني-لوبيس، م.، غارسيا-سيغورا، س.، هريستوفسكي، ك. وويسترهوف، ب. الطاقة الكهربائية لكل طلب وكفاءة التيار للأكسدة الكهروكيميائية لحمض p-كلوروبنزويك باستخدام أنود ماسي مشوب بالبورون. كيموسفير 188، 304-311 (2017).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) شركة سبرينجر ناتشر المحدودة 2025

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لتكنولوجيا البيئة المتقدمة، معهد البيئة الحضرية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، شيامن، الصين. جامعة الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين، الصين. كلية الإلكترونيات وعلوم المعلومات، جامعة فوجيان جيانغشيا، فوزهو، الصين. قسم الهندسة الكهربائية وعلوم الحاسوب، جامعة تورونتو، تورونتو، كندا. مختبر المواد الحية في المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للتكنولوجيا المتقدمة لتخليق المواد ومعالجتها، جامعة ووهان للتكنولوجيا، ووهان، الصين. cMACS، قسم الأنظمة الميكروبية والجزيئية، جامعة KU Leuven، لوفين، بلجيكا. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة KU Leuven، لوفين، بلجيكا. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة تسينغhua، بكين، الصين. مدرسة الهندسة الكيميائية، جامعة أديلايد، أديلايد، جنوب أستراليا، أستراليا. قسم هندسة الطاقة، معهد كوريا لتكنولوجيا الطاقة (KENTECH)، ناجو، كوريا الجنوبية. البريد الإلكتروني: bweng@iue.ac.cn; jfxie@iue.ac.cn; hpjia@iue.ac.cn; ymzheng@iue.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44359-025-00037-1

Publication Date: 2025-03-04

Photo-assisted technologies for environmental remediation

Abstract

Industrial processes can lead to air and water pollution, particularly from organic contaminants such as toluene and antibiotics, posing threats to human health. Photo-assisted chemical oxidation technologies leverage light energy to mineralize these contaminants. In this Review, we discuss the mechanisms and efficiencies of photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment and photothermal technologies for air purification. The integration of solar energy enhances degradation efficiency and reduces energy consumption, enabling more efficient remediation methods. We evaluate the technological aspects of photo-assisted technologies, such as photo-Fenton, photo-persulfate activation, photo-ozonation and photoelectrochemical oxidation, emphasizing their potential for practical applications. Finally, we discuss the challenges in scaling up photo-assisted technologies for specific environmental remediation needs. Photo-assisted technologies have demonstrated effectiveness in environmental remediation, although large-scale applications remain constrained by high costs. Future potential applications of photo-assisted technologies will require that technology selection be tailored to specific pollution scenarios and engineering processes optimized to minimize costs.

Sections

Water purification

Air purification

Summary and future perspectives

Key points

- Photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes efficiently treat wastewater, whereas photothermal technologies are used in air purification.

- The integration of solar energy can enhance efficiency of remediation processes and reduce energy consumption.

- Solar energy interacts with chemical oxidation processes, which results in the formation of reactive oxygen species that accelerate the degradation of pollutants.

- Wastewater treatments, such as the Fenton oxidation process, consume a high quantity of

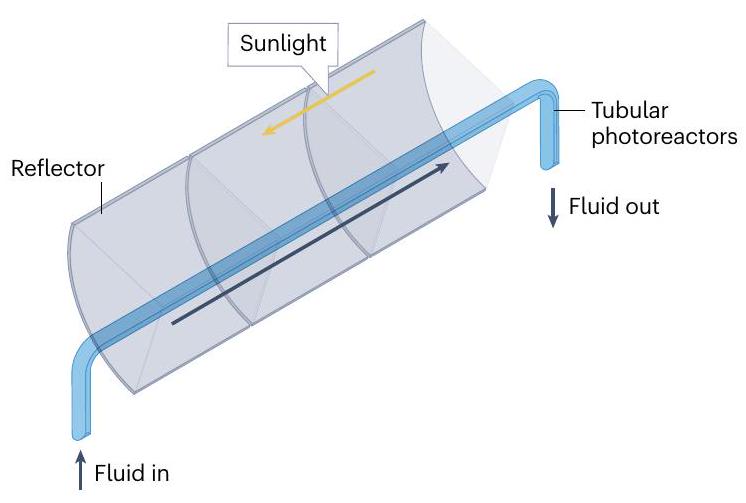

and are kinetically slow. Integrating solar energy accelerates the process. - Using compound parabolic collectors and raceway pond reactors optimizes light harvesting and enables remediation at concentrations of milligrams per litre and below.

- Combining different advanced oxidation technologies can help to reduce energy consumption and widen the range of contaminants that can be mineralized.

Introduction

polluted media can interfere with the catalytic process, diminishing the availability of the light-induced reactive species needed for effective remediations

Water purification

Photo-assisted Fenton oxidation

Review article

Photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) and photo-assisted thermal catalysis can be used for wastewater and air treatment. The wastewater from industries and municipal water usage is collected and transferred into a sewage

of magnitude in

order (

low production cost compared with other reactors, high volume to surface, and flexibility to optimize the liquid depth according to the radiation strength

Photo-assisted persulfate activation

molecules can act as electron acceptors, capturing electrons generated on the light-irradiated surface of solid photocatalysts

Photo-assisted ozonation

non-selective

Photo-assisted electrochemical oxidation

a UV- and PV-electrolyser system

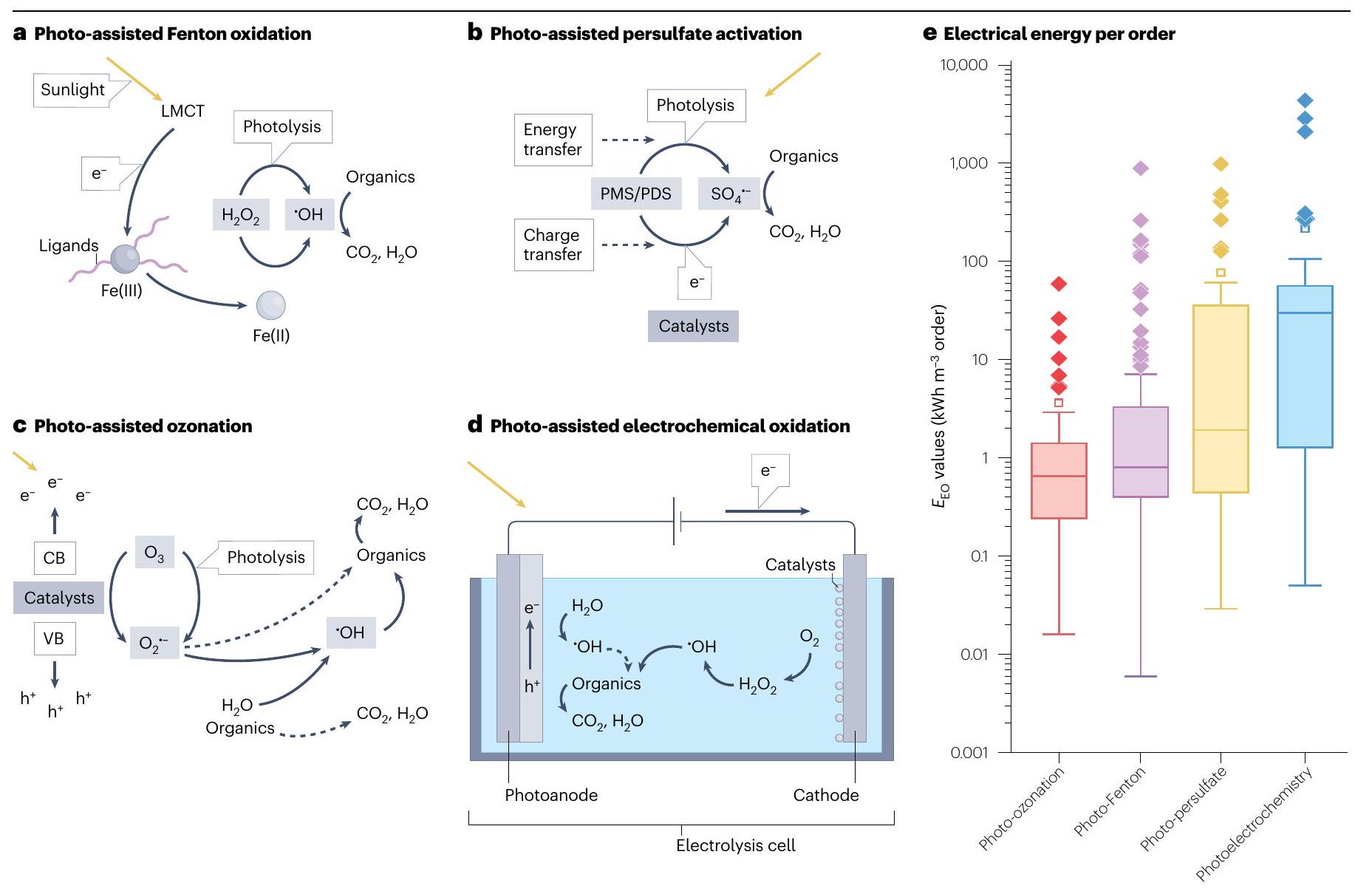

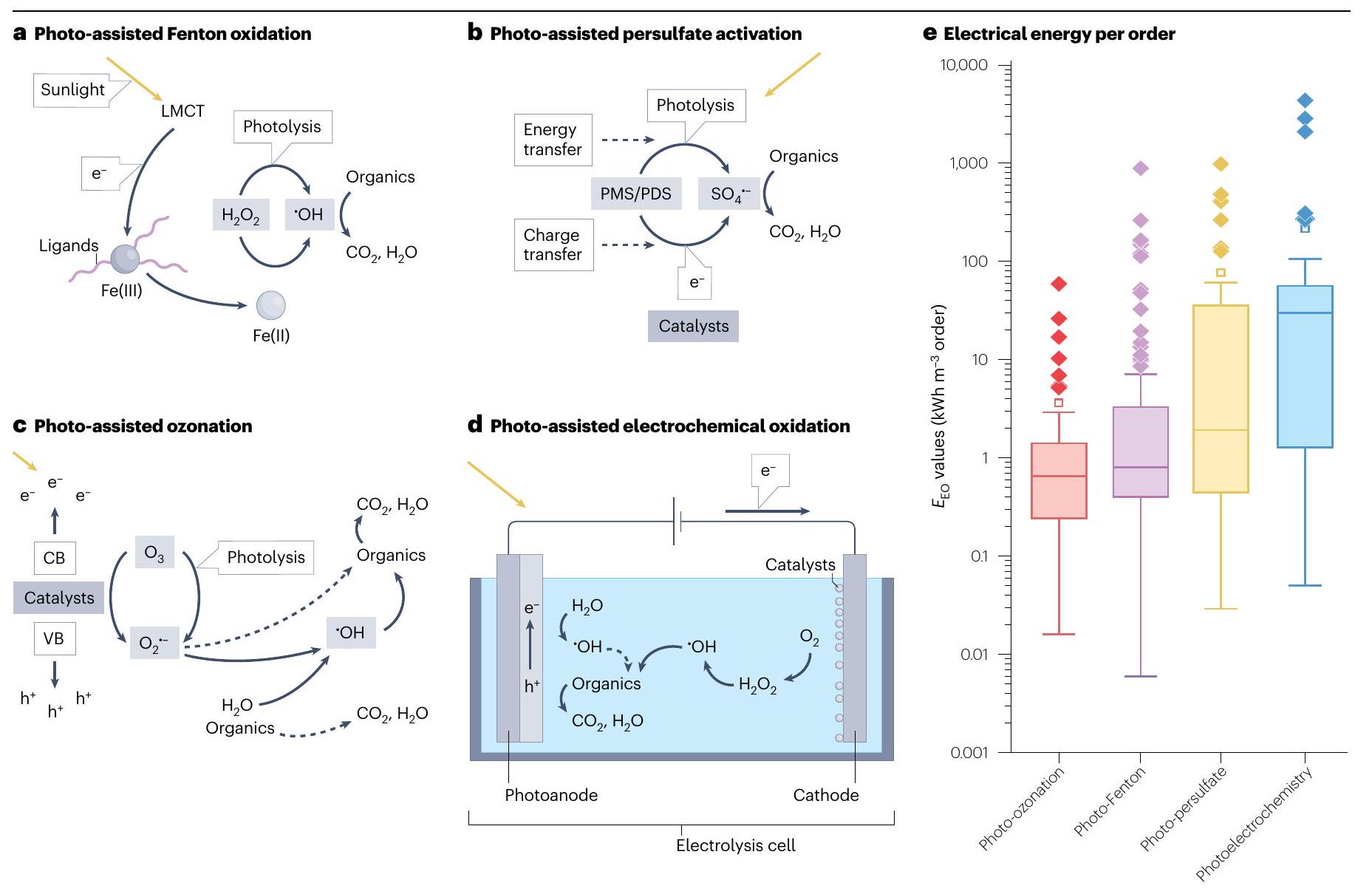

Fig. 4 | Photo-assisted electrochemical oxidation processes.

b, Photoelectrochemical advanced oxidation (PECAO) system. c, Key properties of electrochemical advanced oxidation systems for practical wastewater treatment applications. The pretreatment reduces the interference of the influent water, whereas the continuous-flow mode enhances throughput capacity and operational stability. Under sunlight, the photoanode absorbs light energy to generate holes and electrons. A thin layer on the photoanode improves light utilization efficiency. The cathode catalyses oxygen reduction to

produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), with electrolyte additives accelerating their generation. The mechanical durability of the electrodes determines their lifespan, directly influencing the overall device longevity. Low ohmic loss in the system minimizes unnecessary electrical consumption and improves operational stability. By coupling the photoanode and cathode, organic pollutants are efficiently removed. Furthermore, tuning catalytic properties and operating parameters can yield targeted value-added by-products, enhancing the economic viability of the process. D, degradation products; P, pollutants.

photoelectrode lowers the voltage required to drive the reactions, whereas the applied bias accelerates the charge separation process under an electric field

to control ROS generation with specific compositions for targeted wastewater treatment

Review article

Integrated multiple photo-assisted oxidation processes

can accelerate the degradation of pollutants and improve the overall energy efficiency of the remediation process

| Photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes | Advantages | Disadvantages | Environmental scenarios | ||||||||

| Photo-Fenton |

|

|

Drinking water treatment system; effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants; raw oily wastewater | ||||||||

| Photo-persulfate |

|

|

Pharmaceutical wastewater; effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants | ||||||||

| Photo-ozonation |

|

|

Drinking water treatment system; effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants; pharmaceutical wastewater | ||||||||

| Photoelectrochemical oxidation |

|

|

Petroleum refinery wastewater; effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants |

Air purification

(photo)thermal catalysis obtaining energy from the solar spectrum (Fig. 5a). Photo-assisted thermal catalysis uses photochemical processes to enhance thermal reactions by introducing additional light into traditional thermal catalytic systems

a Photo-assisted technologies for air purification

assistance of light irradiation, the thermal catalytic reaction system performance – VOC conversion efficiency – can increase by at least

light-harvesting efficiency and catalytic activity

Review article

Summary and future perspectives

reactors that minimize the need for deep light penetration, such as flat reactors, can enhance the effectiveness of photo-assisted technologies. Additionally, it is important to design advanced catalytic materials with high light absorption efficiency to use low-energy photons, such as visible or infrared light. Enhanced light absorption can be achieved through several strategies: selecting narrow-bandgap catalysts, introducing dopants or defects to create mid-gap states that narrow the bandgap of semiconductors, coating catalysts with substances that show localized surface plasmon resonance effects (such as plasmonic materials or carbon-based materials), using dye-sensitizers or quantum dots, integrating up-conversion materials to convert infrared light into UV or visible light, and creating nanostructured materials (such as nanorods, nanowires, photonic crystal structures and surface texturing). Improving light absorption will benefit the generation of ROS and increase the degradation efficiency. For air purification in office buildings, factories and homes, developing catalysts capable of harnessing indoor light could offer a pathway towards the practical implementation of photo-assisted technology for air purification systems

References

- Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452, 301-310 (2008).

- Lin, J. et al. Environmental impacts and remediation of dye-containing wastewater. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 785-803 (2023).

- Wei, S. et al. Self-carbon-thermal-reduction strategy for boosting the Fenton-like activity of single

sites by carbon-defect engineering. Nat. Commun. 14, 7549 (2023). - Hodges, B. C., Cates, E. L. & Kim, J.-H. Challenges and prospects of advanced oxidation water treatment processes using catalytic nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 642-650 (2018).

- He, F., Jeon, W. & Choi, W. Photocatalytic air purification mimicking the self-cleaning process of the atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 12, 2528 (2021).

- Weon, S., He, F. & Choi, W. Status and challenges in photocatalytic nanotechnology for cleaning air polluted with volatile organic compounds: visible light utilization and catalyst deactivation. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 3185-3214 (2019).

- Khin, M. M., Nair, A. S., Babu, V. J., Murugan, R. & Ramakrishna, S. A review on nanomaterials for environmental remediation. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8075-8109 (2012).

- Zheng, L. et al. Mixed scaling patterns and mechanisms of high-pressure nanofiltration in hypersaline wastewater desalination. Water Res. 250, 121023 (2024).

- Yang, X., Sun, H., Li, G., An, T. & Choi, W. Fouling of TiO

induced by natural organic matters during photocatalytic water treatment: mechanisms and regeneration strategy. Appl. Catal. B 294, 120252 (2021). - Le, N. T. H. et al. Freezing-enhanced non-radical oxidation of organic pollutants by peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 388, 124226 (2020).

- Weng, B., Lu, K.-Q., Tang, Z., Chen, H. M. & Xu, Y.-J. Stabilizing ultrasmall Au clusters for enhanced photoredox catalysis. Nat. Commun. 9, 1543 (2018).

- Su, Y. et al. Unveiling the function of oxygen vacancy on facet-dependent

for the catalytic destruction of monochloromethane: guidance for industrial catalyst design. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 8086-8095 (2024). - Su, Y. et al. Surface-phosphorylated ceria for chlorine-tolerance catalysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 1369-1377 (2024).

- Yuan, X. et al. Anti-poisoning mechanisms of Sb on vanadia-based catalysts for NOx and chlorobenzene multi-pollutant control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 10211-10220 (2023).

- Su, Z. et al. Probing the actual role and activity of oxygen vacancies in toluene catalytic oxidation: evidence from in situ XPS/NEXAFS and DFT + U calculation. ACS Catal. 13, 3444-3455 (2023).

- Wang, B., Song, Z. & Sun, L. A review: comparison of multi-air-pollutant removal by advanced oxidation processes – industrial implementation for catalytic oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 409, 128136 (2021).

- Adeleye, A. S. et al. Engineered nanomaterials for water treatment and remediation: costs, benefits, and applicability. Chem. Eng. J. 286, 640-662 (2016).

- Brillas, E. Solar photoelectro-Fenton: a very effective and cost-efficient electrochemical advanced oxidation process for the removal of organic pollutants from synthetic and real wastewaters. Chemosphere 327, 138532 (2023).

- Wang, D., Junker, A. L., Sillanpää, M., Jiang, Y. & Wei, Z. Photo-based advanced oxidation processes for zero pollution: where are we now? Engineering 23, 19-23 (2023).

- Dey, A. K., Mishra, S. R. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. Solar light-based advanced oxidation processes for degradation of methylene blue dye using novel Zn-modified CeO2@ biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 53887-53903 (2023).

- Su, L., Wang, P., Ma, X., Wang, J. & Zhan, S. Regulating local electron density of iron single sites by introducing nitrogen vacancies for efficient photo-Fenton process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21261-21266 (2021).

- Yang, Q. et al. Recent advances in photo-activated sulfate radical-advanced oxidation process (SR-AOP) for refractory organic pollutants removal in water. Chem. Eng. J. 378, 122149 (2019).

- Yang, J., Zhu, M. & Dionysiou, D. D. What is the role of light in persulfate-based advanced oxidation for water treatment? Water Res. 189, 116627 (2021).

- Weng, B., Qi, M.-Y., Han, C., Tang, Z.-R. & Xu, Y.-J. Photocorrosion inhibition of semiconductor-based photocatalysts: basic principle, current development, and future perspective. ACS Catal. 9, 4642-4687(2019).

- Zhou, Q., Chen, Q., Tong, Y. & Wang, J. Light-induced ambient degradation of few-layer black phosphorus: mechanism and protection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11437-11441 (2016).

- Bi, Z. et al. The generation and transformation mechanisms of reactive oxygen species in the environment and their implications for pollution control processes: a review. Environ. Res. 260, 119592 (2024).

- Chen, M. et al. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots decorating

microspherical heterostructure and its efficient photocatalytic degradation of antibiotic norfloxacin. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 109336 (2024). - Oh, V. B.-Y., Ng, S.-F. & Ong, W.-J. Is photocatalytic hydrogen production sustainable? Assessing the potential environmental enhancement of photocatalytic technology against steam methane reforming and electrocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 379, 134673 (2022).

- Wu, F., Zhou, Z. & Hicks, A. L. Life cycle impact of titanium dioxide nanoparticle synthesis through physical, chemical, and biological routes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4078-4087 (2019).

- Zhang, X. et al. Nanoconfinement-triggered oligomerization pathway for efficient removal of phenolic pollutants via a Fenton-like reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 917 (2024).

- Ghanbarzadeh Lak, M., Sabour, M. R., Ghafari, E. & Amiri, A. Energy consumption and relative efficiency improvement of photo-Fenton – optimization by RSM for landfill leachate treatment, a case study. Waste Manage 79, 58-70 (2018).

- Barndõk, H., Blanco, L., Hermosilla, D. & Blanco, Á. Heterogeneous photo-Fenton processes using zero valent iron microspheres for the treatment of wastewaters contaminated with 1,4-dioxane. Chem. Eng. J. 284, 112-121 (2016).

- Santos, L. V. de S., Meireles, A. M. & Lange, L. C. Degradation of antibiotics norfloxacin by Fenton, UV and UV/

. J. Environ. Manage. 154, 8-12 (2015). - Kang, W. et al. Photocatalytic ozonation of organic pollutants in wastewater using a flowing through reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 124277 (2021).

- Khaleel, G. F., Ismail, I. & Abbar, A. H. Application of solar photo-electro-Fenton technology to petroleum refinery wastewater degradation: optimization of operational parameters. Heliyon 9, e15062 (2023).

- Anipsitakis, G. P. & Dionysiou, D. D. Radical generation by the interaction of transition metals with common oxidants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 3705-3712 (2004).

- De Laat, J. & Gallard, H. Catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by Fe(III) in homogeneous aqueous solution: mechanism and kinetic modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 2726-2732 (1999).

- Feng, W. & Nansheng, D. Photochemistry of hydrolytic iron(III) species and photoinduced degradation of organic compounds. A minireview. Chemosphere 41, 1137-1147 (2000).

- Sun, M. et al. New insights into photo-Fenton chemistry: the overlooked role of excited iron”

species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 10817-10827 (2024). - Yang, X.-j., Xu, X.-m., Xu, J. & Han, Y.-f. Iron oxychloride (FeOCl): an efficient Fenton-like catalyst for producing hydroxyl radicals in degradation of organic contaminants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16058-16061 (2013).

- Li, M. et al. Iron-organic frameworks as effective Fenton-like catalysts for peroxymonosulfate decomposition in advanced oxidation processes. npj Clean Water 6, 37 (2023).

- Wang, Y. et al. Comparison of Fenton, UV-Fenton and nano-

catalyzed UV-Fenton in degradation of phloroglucinol under neutral and alkaline conditions: role of complexation of with hydroxyl group in phloroglucinol. Chem. Eng. J. 313, 938-945 (2017). - Zheng, J., Li, Y. & Zhang, S. Engineered nanoconfinement activates Fenton catalyst at neutral pH: mechanism and kinetics study. Appl. Catal. B 343, 123555 (2024).

- Clarizia, L., Russo, D., Di Somma, I., Marotta, R. & Andreozzi, R. Homogeneous photo-Fenton processes at near neutral pH: a review. Appl. Catal. B 209, 358-371 (2017).

- Zhu, Y. et al. Strategies for enhancing the heterogeneous Fenton catalytic reactivity: a review. Appl. Catal. B 255, 117739 (2019).

- Brillas, E. Fenton, photo-Fenton, electro-Fenton, and their combined treatments for the removal of insecticides from waters and soils. A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 284, 120290 (2022).

- Heidari, Z., Pelalak, R. & Zhou, M. A critical review on the recent progress in application of electro-Fenton process for decontamination of wastewater at near-neutral pH . Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145741 (2023).

- Ahile, U. J., Wuana, R. A., Itodo, A. U., Sha’Ato, R. & Dantas, R. F. A review on the use of chelating agents as an alternative to promote photo-Fenton at neutral pH: current trends, knowledge gap and future studies. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 134872 (2020).

- Vallés, I. et al. On the relevant role of iron complexation for the performance of photo-Fenton process at mild pH: role of ring substitution in phenolic ligand and interaction with halides. Appl. Catal. B 331, 122708 (2023).

- Li, W.-Q. et al. Boosting photo-Fenton process enabled by ligand-to-cluster charge transfer excitations in iron-based metal organic framework. Appl. Catal. B 302, 120882 (2022).

- Rodríguez, M., Bussi, J. & Andrea De León, M. Application of pillared raw clay-base catalysts and natural solar radiation for water decontamination by the photo-Fenton process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 259, 118167 (2021).

- Wu, Q. et al. Visible-light-driven iron-based heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalysts for wastewater decontamination: a review of recent advances. Chemosphere 313, 137509 (2023).

- Deng, G. et al. Ferryl ion in the photo-Fenton process at acidic pH: occurrence, fate, and implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 18586-18596 (2023).

- Gao, X. et al. New insight into the mechanism of symmetry-breaking charge separation induced high-valent iron(IV) for highly efficient photodegradation of organic pollutants. Appl. Catal. B 321, 122066 (2023).

- Jiang, J. et al. Spin state-dependent in-situ photo-Fenton-like transformation from oxygen molecule towards singlet oxygen for selective water decontamination. Water Res. 244, 120502 (2023).

- Lian, Z. et al. Photo-self-Fenton reaction mediated by atomically dispersed

photocatalysts toward efficient degradation of organic pollutants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318927 (2024). - Ciggin, A. S., Sarica, E. S., Doğruel, S. & Orhon, D. Impact of ultrasonic pretreatment on Fenton-based oxidation of olive mill wastewater – towards a sustainable treatment scheme. J. Clean. Prod. 313, 127948 (2021).

- Ahmed, Y., Zhong, J., Yuan, Z. & Guo, J. Roles of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic resistant bacteria inactivation and micropollutant degradation in Fenton and photo-Fenton processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 430, 128408 (2022).

- Li, Y. & Cheng, H. Autocatalytic effect of in situ formed (hydro)quinone intermediates in Fenton and photo-Fenton degradation of non-phenolic aromatic pollutants and chemical kinetic modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 449, 137812 (2022).

- Zhou, Y., Yu, M., Zhang, Q., Sun, X. & Niu, J. Regulating electron distribution of Fe/Ni-

single sites for efficient photo-Fenton process. J. Hazard. Mater. 440, 129724 (2022). - Gualda-Alonso, E. et al. Continuous solar photo-Fenton for wastewater reclamation in operational environment at demonstration scale. J. Hazard. Mater. 459, 132101 (2023).

- Silva, T. F. C. V., Fonseca, A., Saraiva, I., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Vilar, V. J. P. Scale-up and cost analysis of a photo-Fenton system for sanitary landfill leachate treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 283, 76-88 (2016).

- Miklos, D. B. et al. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – a critical review. Water Res. 139, 118-131 (2018).

- Gualda-Alonso, E. et al. Large-scale raceway pond reactor for CEC removal from municipal WWTP effluents by solar photo-Fenton. Appl. Catal. B 319, 121908 (2022).

- Gualda-Alonso, E., Soriano-Molina, P., García Sánchez, J. L., Casas López, J. L. & Sánchez Pérez, J. A. Mechanistic modeling of solar photo-Fenton with

-NTA for microcontaminant removal. Appl. Catal. B 318, 121795 (2022). - Duan, X., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Metal-free carbocatalysis in advanced oxidation reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 678-687 (2018).

- Han, B. et al. Microenvironment engineering of single-atom catalysts for persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 447, 137551 (2022).

- Lee, J., von Gunten, U. & Kim, J.-H. Persulfate-based advanced oxidation: critical assessment of opportunities and roadblocks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3064-3081 (2020).

- Zhang, S., Zheng, H. & Tratnyek, P. G. Advanced redox processes for sustainable water treatment. Nat. Water 1, 666-681(2023).

- Guo, R. et al. Catalytic degradation of lomefloxacin by photo-assisted persulfate activation on natural hematite: performance and mechanism. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 3809-3817 (2022).

- He, S., Chen, Y., Li, X., Zeng, L. & Zhu, M. Heterogeneous photocatalytic activation of persulfate for the removal of organic contaminants in water: a critical review. ACS EST. Eng 2, 527-546 (2022).

- Zhang, Y.-J. et al. Simultaneous nanocatalytic surface activation of pollutants and oxidants for highly efficient water decontamination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3005 (2022).

- Yin, R. et al. Near-infrared light to heat conversion in peroxydisulfate activation with

: a new photo-activation process for water treatment. Water Res. 190, 116720 (2021). - Weng, Z. et al. Site engineering of covalent organic frameworks for regulating peroxymonosulfate activation to generate singlet oxygen with

selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310934 (2023). - Yan, Y. et al. Merits and limitations of radical vs. nonradical pathways in persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12153-12179 (2023).

- Gan, P. et al. The degradation of municipal solid waste incineration leachate by UV/persulfate and UV/

processes: the different selectivity of and . Chemosphere 311, 137009 (2023). - Guerra-Rodríguez, S. et al. Pilot-scale sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation for wastewater reuse: simultaneous disinfection, removal of contaminants of emerging concern, and antibiotic resistance genes. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 146916 (2023).

- Wang, Y., Duan, X., Xie, Y., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Nanocarbon-based catalytic ozonation for aqueous oxidation: engineering defects for active sites and tunable reaction pathways. ACS Catal. 10, 13383-13414 (2020).

- Mundy, B. et al. A review of ozone systems costs for municipal applications. Report by the municipal committee – IOA Pan American group. Ozone Sci. Eng. 40, 266-274 (2018).

- Zhou, H. & Smith, D. W. Ozone mass transfer in water and wastewater treatment: experimental observations using a 2D laser particle dynamics analyzer. Water Res. 34, 909-921 (2000).

- Lu, J. et al. Efficient mineralization of aqueous antibiotics by simultaneous catalytic ozonation and photocatalysis using

as a bifunctional catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 358, 48-57 (2019). - Bessegato, G. G., Cardoso, J. C., da Silva, B. F. & Zanoni, M. V. B. Combination of photoelectrocatalysis and ozonation: a novel and powerful approach applied in Acid Yellow 1 mineralization. Appl. Catal. B 180, 161-168 (2016).

- Mehrjouei, M., Müller, S. & Möller, D. A review on photocatalytic ozonation used for the treatment of water and wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 263, 209-219 (2015).

- Beltrán, F. J., Aguinaco, A., García-Araya, J. F. & Oropesa, A. Ozone and photocatalytic processes to remove the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole from water. Water Res. 42, 3799-3808 (2008).

- Yu, D., Li, L., Wu, M. & Crittenden, J. C. Enhanced photocatalytic ozonation of organic pollutants using an iron-based metal-organic framework. Appl. Catal. B 251, 66-75 (2019).

- Xiao, J., Xie, Y., Rabeah, J., Brückner, A. & Cao, H. Visible-light photocatalytic ozonation using graphitic

catalysts: a hydroxyl radical manufacturer for wastewater treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1024-1033 (2020). - Xiao, J. et al. Is

chemically stable toward reactive oxygen species in sunlight-driven water treatment? Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13380-13387(2017). - Lincho, J., Zaleska-Medynska, A., Martins, R. C. & Gomes, J. Nanostructured photocatalysts for the abatement of contaminants by photocatalysis and photocatalytic ozonation: an overview. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155776 (2022).

- Ye, M., Chen, Z., Liu, X., Ben, Y. & Shen, J. Ozone enhanced activity of aqueous titanium dioxide suspensions for photodegradation of 4-chloronitrobenzene. J. Hazard. Mater. 167, 1021-1027 (2009).

- Andreozzi, R., Caprio, V., Insola, A. & Marotta, R. Advanced oxidation processes (AOP) for water purification and recovery. Catal. Today 53, 51-59 (1999).

- Mecha, A. C., Onyango, M. S., Ochieng, A. & Momba, M. N. B. Ultraviolet and solar photocatalytic ozonation of municipal wastewater: catalyst reuse, energy requirements and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 186, 669-676 (2017).

Review article

- Mehrjouei, M., Müller, S. & Möller, D. Energy consumption of three different advanced oxidation methods for water treatment: a cost-effectiveness study. J. Clean. Prod. 65, 178-183 (2014).

- Mecha, A. C., Onyango, M. S., Ochieng, A., Fourie, C. J. S. & Momba, M. N. B. Synergistic effect of UV-vis and solar photocatalytic ozonation on the degradation of phenol in municipal wastewater: a comparative study. J. Catal. 341, 116-125 (2016).

- Moreira, F. C., Boaventura, R. A. R., Brillas, E. & Vilar, V. J. P. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: a review on their application to synthetic and real wastewaters. Appl. Catal. B 202, 217-261 (2017).

- Pandey, A. K. et al. Utilization of solar energy for wastewater treatment: challenges and progressive research trends. J. Environ. Manage. 297, 113300 (2021).

- Pham, C. V., Escalera-López, D., Mayrhofer, K., Cherevko, S. & Thiele, S. Essentials of high performance water electrolyzers – from catalyst layer materials to electrode engineering. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101998 (2021).

- Valero, D., García-García, V., Expósito, E., Aldaz, A. & Montiel, V. Electrochemical treatment of wastewater from almond industry using DSA-type anodes: direct connection to a PV generator. Sep. Purif. Technol. 123, 15-22 (2014).

- Huang, Y. et al. The efficient abatement of contaminants of emerging concern by LED-UV

electrochemical chlorine for wastewater reuse: kinetics, degradation pathways, and cytotoxicity. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 148032 (2024). - Otter, P. et al. Economic evaluation of water supply systems operated with solar-driven electro-chlorination in rural regions in Nepal, Egypt and Tanzania. Water Res. 187, 116384 (2020).

- Koiki, B. A. et al. Sulfate radical in (photo)electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for water treatment: a versatile approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 8880-8889 (2023).

- Son, A. et al. Persulfate enhanced photoelectrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants using self-doped

nanotube arrays: effect of operating parameters and water matrix. Water Res. 191, 116803 (2021). - García-Espinoza, J. D., Robles, I., Durán-Moreno, A. & Godínez, L. A. Photo-assisted electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for the disinfection of aqueous solutions: a review. Chemosphere 274, 129957 (2021).

- Vanags, M. et al. Sol-gel auto-combustion synthesis of

brownmillerite nanopowders and thin films for advanced oxidation photoelectrochemical water treatment in visible light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 103224 (2019). - Yao, T., An, X., Han, H., Chen, J. Q. & Li, C. Photoelectrocatalytic materials for solar water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1800210 (2018).

- Lu, S. & Zhang, G. Recent advances on inactivation of waterborne pathogenic microorganisms by (photo) electrochemical oxidation processes: design and application strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 431, 128619 (2022).

- Fekadu, S. et al. Treatment of healthcare wastewater using the peroxiphotoelectrocoagulation process: predictive models for COD, color removal and electrical energy consumption. J. Water Process Eng. 41, 102068 (2021).

- Rengifo-Herrera, J. A. & Pulgarin, C. Why five decades of massive research on heterogeneous photocatalysis, especially on

, has not yet driven to water disinfection and detoxification applications? Critical review of drawbacks and challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 146875 (2023). - Zeng, J. et al. Nanomaterials enabled photoelectrocatalysis for removing pollutants in the environment and food. Trends Analyt. Chem. 166, 117187 (2023).

- Song, Y., Zhang, J.-Y., Yang, J., Bo, T. & Ma, J.-F. Highly efficient photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of arsenic(III) with a polyoxometalate-thiacalix[4]arene-based metal-organic complex-modified bismuth vanadate photoanode. Green Chem. 26, 3874-3883 (2024).

- Jiao, Y., Ma, L., Tian, Y. & Zhou, M. A flow-through electro-Fenton process using modified activated carbon fiber cathode for orange II removal. Chemosphere 252, 126483 (2020).

- Zhou, W. et al. Rates of

electrogeneration by reduction of anodic at RVC foam cathodes in batch and flow-through cells. Electrochim. Acta 277, 185-196 (2018). - Dang, Q. et al. Bias-free driven ion assisted photoelectrochemical system for sustainable wastewater treatment. Nat. Commun. 14, 8413 (2023).

- Divyapriya, G. et al. Treatment of real wastewater by photoelectrochemical methods: an overview. Chemosphere 276, 130188 (2021).

- Tedesco, G. C. & Moraes, P. B. Innovative design of a continuous flow photoelectrochemical reactor: hydraulic design, CFD simulation and prototyping. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105917 (2021).

- Tao, Y. et al. Near-infrared-driven photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of urea on La-Ni-based perovskites. Chem. Eng. J. 446, 137240 (2022).

- Vivar, M., Skryabin, I., Everett, V. & Blakers, A. A concept for a hybrid solar water purification and photovoltaic system. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell 94, 1772-1782 (2010).

- Sboui, M. et al. Fabrication of electrically conductive

composite membranes for simultaneous photoelectrocatalysis and microfiltration of azo dye from wastewater. Appl. Catal. A 644, 118837 (2022). - Garg, R. et al. Sputtering thin films: materials, applications, challenges and future directions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 330, 103203 (2024).

- Noked, M. et al. Electrochemical thin layers in nanostructures for energy storage. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 2336-2346 (2016).

- Jeon, T. H., Koo, M. S., Kim, H. & Choi, W. Dual-functional photocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic systems for energy- and resource-recovering water treatment. ACS Catal. 8, 11542-11563 (2018).

- Garza-Campos, B. et al. Salicylic acid degradation by advanced oxidation processes. Coupling of solar photoelectro-Fenton and solar heterogeneous photocatalysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 319, 34-42 (2016).

- Wang, Y. et al. Efficient photo-electro-Fenton catalysis of perfluorooctanoic acid with MOFs based 2D CoFe nanosheets: oxygen vacancy-mediated adsorption and mineralization ability. Chem. Eng. J. 483, 149385 (2024).

- Marinho, B. A. et al. Photocatalytic, electrocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals in aqueous media: analytical methods, mechanisms, simulations, catalysts and reactors. J. Clean. Prod. 343, 131061 (2022).

- Zheng, J., Zhang, P., Li, X., Ge, L. & Niu, J. Insight into typical photo-assisted AOPs for the degradation of antibiotic micropollutants: mechanisms and research gaps. Chemosphere 343, 140211 (2023).

- Braham, R. J. & Harris, A. T. Review of major design and scale-up considerations for solar photocatalytic reactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48, 8890-8905 (2009).

- Salazar, L. M., Grisales, C. M. & Garcia, D. P. How does intensification influence the operational and environmental performance of photo-Fenton processes at acidic and circumneutral pH. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 4367-4380 (2019).

- Meng, T., Sun, W., Su, X. & Sun, P. The optimal dose of oxidants in UV-based advanced oxidation processes with respect to primary radical concentrations. Water Res. 206, 117738 (2021).

- Xu, S.-L. et al. Expanding the pH range of Fenton-like reactions for pollutant degradation: the impact of acidic microenvironments. Water Res. 270, 122851 (2025).

- Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced orange II removal using

-LDH activated peroxymonosulfate: synergistic radical oxidation and adsorption. Catalysts 14, 380 (2024). - Binjhade, R., Mondal, R. & Mondal, S. Continuous photocatalytic reactor: critical review on the design and performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107746 (2022).

- Grčić, I. & Li Puma, G. Six-flux absorption-scattering models for photocatalysis under wide-spectrum irradiation sources in annular and flat reactors using catalysts with different optical properties. Appl. Catal. B 211, 222-234 (2017).

- Wu, Z. et al. In situ infared optical fiber sensor monitoring reactants and products changes during photocatalytic reaction. Anal. Chem. 97, 1229-1235 (2025).

- Li, S., Lin, Y., Liu, G. & Shi, C. Research status of volatile organic compound (VOC) removal technology and prospect of new strategies: a review. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 25, 727-740 (2023).

- He, C. et al. Recent advances in the catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds: a review based on pollutant sorts and sources. Chem. Rev. 119, 4471-4568 (2019).

- Zhang, K. et al. Research progress of a composite metal oxide catalyst for VOC degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9220-9236 (2022).

- Yang, Y. et al. Recent advancement and future challenges of photothermal catalysis for VOCs elimination: from catalyst design to applications. Green Energy Env. 8, 654-672 (2023).

- Jiang, C. et al. Modifying defect states in

by Fe doping: a strategy for low-temperature catalytic oxidation of toluene with sunlight. J. Hazard. Mater. 390, 122182 (2020). - Sun, P. et al. Efficiently photothermal conversion in a MnOx -based monolithic photothermocatalyst for gaseous formaldehyde elimination. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 2564-2568 (2022).

- Shan, C. et al. Recent advances of VOCs catalytic oxidation over spinel oxides: catalyst design and reaction mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 9495-9514 (2023).

- Li, J.-J. et al. Efficient infrared light promoted degradation of volatile organic compounds over photo-thermal responsive

composites. Appl. Catal. B 233, 260-271 (2018). - Hong, J. et al. Photothermal chemistry based on solar energy: from synergistic effects to practical applications. Adv. Sci. 9, 2103926 (2022).

- Ren, Y. et al. Concentrated solar