DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3652154

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-28

التنقل في تعقيد اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في هندسة البرمجيات

الملخص

تستكشف هذه الورقة اعتماد أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (AI) ضمن مجال هندسة البرمجيات، مع التركيز على العوامل المؤثرة على المستويات الفردية والتكنولوجية والاجتماعية. قمنا بتطبيق نهج مختلط متقارب لتقديم فهم شامل لديناميات اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي. بدأنا بإجراء استبيان مع 100 مهندس برمجيات، مستندين إلى نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (TAM) ونظرية انتشار الابتكار (DOI) ونظرية التعلم الاجتماعي المعرفي (SCT) كإطارات نظرية توجيهية. باستخدام منهجية جيويا، استخلصنا نموذجًا نظريًا لاعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي في هندسة البرمجيات: إطار التعاون والتكيف بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي (HACAF). تم التحقق من صحة هذا النموذج باستخدام نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية – المربعات الصغرى الجزئية (PLS-SEM) استنادًا إلى بيانات من 183 مهندس برمجيات. تشير النتائج إلى أنه في هذه المرحلة المبكرة من دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي، فإن توافق أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي مع سير العمل الحالي في التطوير هو ما يدفع اعتمادها بشكل أساسي، مما يتحدى نظريات قبول التكنولوجيا التقليدية. يبدو أن تأثير الفائدة المدركة والعوامل الاجتماعية والابتكار الشخصي أقل وضوحًا مما كان متوقعًا. تقدم الدراسة رؤى حاسمة لتصميم أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي المستقبلية وتوفر إطارًا لتطوير استراتيجيات تنفيذ تنظيمية فعالة.

تنسيق مرجع ACM:

1 المقدمة

في مسعانا لاستكشاف سؤال بحثنا، قمنا بتطبيق نهج مختلط متقارب، مستكشفين اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي ونماذج اللغة الكبيرة ضمن مجال هندسة البرمجيات. لتأطير فهمنا لاعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي، أشرنا إلى ثلاثة إطارات نظرية رئيسية تفحص التأثيرات على المستويات الفردية والتكنولوجية والاجتماعية. شملت هذه الإطارات نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (TAM) [110]، ونظرية انتشار الابتكار (DOI) [85]، ونظرية التعلم الاجتماعي المعرفي (SCT) [9]. من خلال دمج هذه النظريات المعتمدة جيدًا، تمكنا من فهم شامل لمحددات اعتماد نماذج اللغة واستكشاف الطرق المميزة التي يتم بها تشغيل هذه المتغيرات في مجال هندسة البرمجيات. بدأنا بحثنا بإجراء استبيان مع مجموعة من 100 مهندس برمجيات. تأثر تصميم هذا الاستبيان بالأبعاد الرئيسية لنظرياتنا المختارة. تم تحليل البيانات المجمعة باستخدام منهجية جيويا [38]، مما سهل تطوير نموذجنا النظري الأولي. تم التحقق من صحة هذا النموذج النظري المؤقت باستخدام نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية – المربعات الصغرى الجزئية (PLS-SEM)، مدعومًا بالبيانات التي تم جمعها من 183 مهندس برمجيات. تعزز تقارب الرؤى المستمدة من هذه التحقيق الشامل والمتعدد الأبعاد فهمنا لاعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي ضمن هندسة البرمجيات. علاوة على ذلك، من خلال فهم ديناميات الاعتماد وتأثير هذه التقنيات المدمرة، يحمل هذا البحث إمكانية توجيه تصميم أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي المستقبلية وتقديم توصيات ذات صلة لاستراتيجيات التنفيذ على مستوى المنظمة. في الواقع، تمثل أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية ابتكارًا مدمراً في مجال هندسة البرمجيات، كما عرّف مفهوم “الابتكار المدمر” لكريستنسن [18]. تستهدف هذه الأدوات، بينما تستهدف في البداية تطبيقات متخصصة أو شرائح سوق غير مخدومة، إمكانية إحداث ثورة في ممارسات هندسة البرمجيات التقليدية. إن قدرتها على أتمتة المهام المعقدة، وتوليد الشيفرة، وتقديم حلول استنادًا إلى مجموعات بيانات ضخمة تتحدى الوضع الراهن ويمكن أن تؤدي إلى تحول جذري في

كيف يتم الاقتراب من تطوير البرمجيات. مع مرور الوقت، ومع تزايد دقة هذه الأدوات واعتمادها على نطاق واسع، قد تحل محل المنهجيات والأدوات الراسخة، تمامًا كما تعيد الابتكارات المدمرة تشكيل الصناعات. من خلال فهم ديناميات اعتماد هذه التقنيات التحويلية، تقدم هذه الدراسة رؤى حول مسارها المحتمل وآثارها، مما يوجه تصميم أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي المستقبلية ويقدم توصيات لتنفيذها الاستراتيجي عبر المنظمات.

2 الأعمال ذات الصلة

2.1 تقييم الكود المُولد: الصحة والجودة

2.2 معايير التقييم: أساليب متنوعة

تؤكد هذه الاختلافات على الطبيعة المتعددة الأبعاد لتوليد الشيفرة بواسطة الذكاء الاصطناعي والأبعاد المختلفة التي تحتاج إلى تقييم.

2.3 تعزيز إنتاجية الكود

2.4 مقارنة الطرق

2.5 القضايا التربوية

2.6 تأثير الذكاء الاصطناعي على عملية تطوير البرمجيات

إمكانات وتحديات أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي في تطوير البرمجيات، كما أنها تقدم وجهات نظر فريدة، مما يوسع النقاش ليشمل جوانب مثل القضايا القانونية، وتغييرات سير العمل، وتكاليف الوقت.

2.7 تأثير المجتمع والثقة في أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي

2.8 الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في الأنشطة غير البرمجية

2.9 قابلية استخدام مساعدي البرمجة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

3 توليد النظرية

3.1 الأساس النظري

3.1.1 نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا (TAM). تم الإشادة بنموذج قبول التكنولوجيا على نطاق واسع لملاءمته وكفاءته في التنبؤ بشرح قبول أشكال مختلفة من التكنولوجيا [110]. تشكل مكوناته الأساسية – الفائدة المدركة وسهولة الاستخدام المدركة – نقطة انطلاق ممتازة لفهم سلوك الاعتماد. على سبيل المثال، إذا تم اعتبار نماذج اللغة مفيدة وسهلة الاستخدام، فمن المرجح أن يتبناها مهندسو البرمجيات. نظرًا لصلابته وبساطته، يوفر نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا أساسًا لفهم المحددات الأساسية لاعتماد التكنولوجيا ويساعد في تشخيص الحواجز الأساسية لاعتماد نماذج اللغة.

3.1.2 نظرية انتشار الابتكار (DOI). بينما يركز نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا بشكل أساسي على تصورات المستخدمين، تكمل نظرية انتشار الابتكار نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا من خلال معالجة الخصائص التكنولوجية التي تؤثر على الاعتماد. حدد روجرز [85] السمات الرئيسية للابتكارات – الميزة النسبية، والتوافق، والتعقيد، وقابلية التجربة، والملاحظة – التي تؤثر بشكل كبير على معدلات اعتمادها. كابتكار في هندسة البرمجيات، يمكن أن يتشكل قبول نماذج اللغة من خلال هذه السمات. على سبيل المثال، قد تكون الميزة النسبية لنماذج اللغة مقارنة بأساليب البرمجة التقليدية دافعًا قويًا للاعتماد. قد يلعب توافق نماذج اللغة مع الممارسات الحالية وتعقيد هذه النماذج أيضًا أدوارًا حاسمة. وبالتالي، تضيف نظرية انتشار الابتكار عمقًا إلى فهمنا للعوامل المحددة للتكنولوجيا التي تؤثر على اعتماد نماذج اللغة.

3.1.3 النظرية الاجتماعية المعرفية (SCT). لا تحدث قرار اعتماد تقنيات جديدة في فراغ. إنه يتأثر بالبيئة الاجتماعية التي يعمل فيها الأفراد. تدخل النظرية الاجتماعية المعرفية في اللعب

هنا من خلال التأكيد على العوامل الاجتماعية والبيئية التي تؤثر على سلوكيات الأفراد [9]. هندسة البرمجيات، مثل أي مهنة، لها ثقافتها الخاصة، ومعاييرها، ومعتقداتها المشتركة التي يمكن أن تشكل بشكل كبير اعتماد نماذج اللغة. على سبيل المثال، قد تشجع المعايير السائدة أو مدى استخدام الأقران على استخدام نماذج اللغة أو تثبطه. علاوة على ذلك، قد تؤثر الكفاءة الذاتية للأفراد – التي تتشكل جزئيًا من خلال بيئتهم الاجتماعية – على استعدادهم للتفاعل مع هذه الأداة الجديدة. لذلك، تضيف SCT طبقة اجتماعية إلى فهمنا لاعتماد نماذج اللغة.

3.2 إرشادات استبيان المسح

- الفائدة المدركة: “إلى أي مدى تعتقد أن استخدام نماذج اللغة يزيد من كفاءتك كمهندس برمجيات؟” تم تصميم هذا السؤال لقياس كيف يدرك مهندسو البرمجيات المكاسب المحتملة في الإنتاجية من استخدام LLMs.

- سهولة الاستخدام المدركة: “ما مدى سهولة تعلم كيفية استخدام نموذج لغة جديد بشكل فعال؟” يهدف هذا السؤال إلى التقاط الجهد المعرفي المدرك المطلوب لتعلم والتكيف مع LLMs.

- نية السلوك: “ما مدى احتمال استخدامك لنموذج لغة في عملك في الأشهر الستة المقبلة؟ ولأي مهام؟” تهدف هذه الأسئلة إلى تقييم نية مهندسي البرمجيات لاعتماد LLMs في مهامهم القريبة.

- التوافق: “كيف يختلف استخدام نموذج لغة عن ممارساتك الحالية في هندسة البرمجيات؟” يقيم هذا السؤال الملاءمة المدركة لـ LLMs مع الممارسات الحالية وسير العمل.

- الميزة النسبية: “ما الفوائد المحتملة التي تعتقد أن نماذج اللغة تقدمها مقارنة بأساليبك الحالية؟” يساعد هذا السؤال في تحديد الفوائد المدركة لـ LLMs مقارنة بالأساليب التقليدية.

- التعقيد: “ما المخاوف التي لديك بشأن استخدام نموذج لغة في عملك؟” يهدف هذا السؤال إلى تسليط الضوء على أي حواجز أو تحديات مدركة مرتبطة باعتماد LLM.

تشمل عوامل المستوى الاجتماعي، المستندة إلى نظرية الإدراك الاجتماعي، التأثير الاجتماعي، والعوامل البيئية، والكفاءة الذاتية: - التأثير الاجتماعي: “إلى أي مدى يؤثر زملاؤك أو أقرانك على قراراتك لاستخدام نماذج اللغة؟” يفحص هذا السؤال تأثير المعايير الاجتماعية وآراء الزملاء على قبول LLMs.

- العوامل البيئية: “في رأيك، إلى أي مدى تشعر أن منظمتك تدعم اعتماد نماذج اللغة كتكنولوجيا قياسية؟” يستكشف هذا السؤال دور الدعم التنظيمي في تعزيز اعتماد LLM.

- الكفاءة الذاتية: “ما مدى أهمية أن يُنظر إليك كشخص يستخدم التكنولوجيا المتطورة في عملك؟” يهدف هذا السؤال إلى التقاط ثقة الفرد في قدرته على استخدام تقنيات متقدمة مثل LLMs بشكل فعال.

من خلال هذه الأسئلة في استبيان المسح، نسعى لفهم التفاعل المعقد بين العوامل الفردية والتكنولوجية والاجتماعية التي تسهم في اعتماد واستخدام الأدوات المدعومة بـ LLM بين مهندسي البرمجيات.

3.3 المشاركون

3.4 تحليل البيانات النوعية

“تحسين الكفاءة”، الذي يمثل منطقة تأثير عامة في هندسة البرمجيات من خلال استخدام LLMs. يوضح هذا المثال التقدم التحليلي من اقتباسات المشاركين المحددة إلى فئات موضوعية أوسع، مما يوضح منهجية دراستنا.

4 النتائج

4.1 الفائدة المدركة لـ LLMs في هندسة البرمجيات

4.1.1 تحسين الكفاءة. واحدة من الفوائد المدركة الرئيسية لـ LLMs هي قدرتها على تحسين الكفاءة. كما هو موضح في الجدول 1، فإن تحسين الكفاءة هو البعد المجمّع الأكثر ذكرًا (55%). يدرك المهندسون أن LLMs يمكن أن تؤتمت بعض المهام، وتقلل من الوقت والجهد، وتبسط المهام المملة. على سبيل المثال، أشار R-15 إلى أن LLMs يمكن أن “تزيد من كفاءتي من خلال أتمتة بعض المهام وتقليل الوقت والجهد الذي يستغرقه الترميز اليدوي والوثائق.” يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع تأكيد نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا على الفائدة المدركة، الذي يفترض أن المستخدمين سيتبنون التكنولوجيا إذا رأوا أنها مفيدة في تعزيز أدائهم [29].

4.1.2 الفوائد الخاصة بالمهام. جانب آخر من الفائدة المدركة هو الفوائد الخاصة بالمهام التي تقدمها LLMs، مثل تصحيح الأخطاء، وتعلم الميزات الجديدة، وتوليد مقتطفات من الشيفرة. كما ذكر R-30، زادت LLMs بشكل كبير من كفاءتهم من خلال مساعدتهم في “تصحيح الشيفرة بشكل أسرع، وتعلم الميزات الجديدة دون الحاجة إلى مسح الوثائق بالكامل، وتوفير مقتطفات شيفرة مفيدة للعمل.” تمثل هذه الفئة

4.1.3 أداة تكميلية. تُعتبر LLMs أيضًا أداة تكميلية للخبرة البشرية والحكم. أشار R-17 إلى أن “نماذج اللغة لديها القدرة على تعزيز الإنتاجية والكفاءة في هندسة البرمجيات، ولكن يجب استخدامها كأداة جنبًا إلى جنب مع الخبرة البشرية والحكم.” يبرز هذا التصور أهمية تحقيق التوازن بين فوائد LLMs والحاجة إلى الإشراف البشري، وهو جانب قد يؤثر على الفائدة المدركة العامة للتكنولوجيا.

4.1.4 قابلية تطبيق محدودة ومخاوف تتعلق بالجودة. بينما أبلغ العديد من المستجيبين عن آراء إيجابية حول LLMs، أعرب البعض عن مخاوف بشأن قابلية تطبيقها المحدودة (

اعتماد واسع النطاق. ومع ذلك، تبرز المخاوف المتعلقة بقابلية التطبيق المحدودة والجودة أهمية معالجة هذه القيود لتعزيز الفائدة المدركة وبالتالي قبول LLMs. يتماشى هذا التحليل مع إطار نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا، الذي يؤكد أن الفائدة المدركة هي محدد حاسم لقبول التكنولوجيا [29].

| معرف | اقتباس | المفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات من الدرجة الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-15 | يمكن أن تزيد من كفاءتي بشكل كبير من خلال أتمتة بعض المهام وتقليل الوقت والجهد الذي يستغرقه الترميز اليدوي والوثائق | أتمتة المهام، تقليل الوقت والجهد، الترميز اليدوي، الوثائق | تحسينات الكفاءة الخاصة بالمهام | تحسين الكفاءة | 55 |

| R-28 | يزيد بشكل كبير من كفاءتي خاصة في المهام البسيطة | زيادة الكفاءة، المهام البسيطة | تحسينات الكفاءة الخاصة بالمهام | تحسين الكفاءة | 55 |

| R-52 | إنهم يساعدون فقط في المهام الرتيبة والبسيطة (مثل تعريف المنشئين وكتابة أنظمة التحقق من إدخال المستخدم على سبيل المثال). | المهام الرتيبة، المهام البسيطة | تحسينات الكفاءة الخاصة بالمهام | تحسين الكفاءة | 55 |

| R-67 | أوفر 10% – 20% من الوقت | توفير الوقت | توفير الوقت | توفير الوقت | 24 |

| R-30 | بالتأكيد يساعد كثيرًا، في الأيام القليلة الماضية التي كنت أستخدم فيها ChatGPT (مع GPT 3-5)، زادت كفاءتي بشكل كبير. يساعدني في تصحيح الأخطاء في الكود بشكل أسرع، والتعرف على ميزات جديدة دون الحاجة إلى مسح الوثائق بالكامل، وتزويدي بمقتطفات كود مفيدة لعملي. | زيادة الكفاءة، تصحيح الأخطاء، تعلم ميزات جديدة، مقتطفات كود | فوائد خاصة بالمهام، تعزيز التعلم | فوائد خاصة بالمهام | 26 |

| R-17 | أعتقد أن نماذج اللغة يمكن أن تزيد من كفاءة مهندسي البرمجيات من خلال أتمتة مهام معينة، مثل توليد الكود، والاختبار، والوثائق. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن تساعد نماذج اللغة في تحليل البيانات واتخاذ القرارات، مما يسمح للمهندسين باتخاذ خيارات مستنيرة بناءً على مجموعات بيانات كبيرة. بشكل عام، تمتلك نماذج اللغة القدرة على تعزيز الإنتاجية والكفاءة في هندسة البرمجيات، ولكن يجب استخدامها كأداة بجانب الخبرة البشرية والحكم. | أتمتة المهام، تحليل البيانات، اتخاذ القرار، الخبرة البشرية، الحكم | أداة مكملة، تحسين الكفاءة | أداة مكملة | 18 |

| R-21 | بشكل طفيف جدًا. إنه جيد للمهام العامة، لكن النماذج ليس لديها أي معرفة بواجهات برمجة التطبيقات الداخلية لدينا لذا يصعب تطبيقها. | قابلية تطبيق محدودة، واجهات برمجة التطبيقات الداخلية، المهام العامة | قابلية تطبيق محدودة | قابلية تطبيق محدودة | 15 |

| R-41 | أنا أكثر كفاءة بكثير عند استخدام نموذج لغة لأنه يساعدني على فهم كود الشركة بشكل أسرع. | زيادة الكفاءة، فهم كود الشركة، التعلم الأسرع | تعزيز التعلم | تعزيز التعلم | 12 |

| R-76 | بينما في معظم الأوقات، ترتكب نماذج اللغة أخطاء صغيرة، مما يتطلب وقتًا إضافيًا للتحقق من مخرجاتها، فإن الوقت الذي توفره من خلال القيام بالأجزاء المملة من البرمجة نيابة عنك بالتأكيد يفوق ذلك في رأيي. سأقول إن استخدام المساعد على سبيل المثال قد زاد من كفاءتي في البرمجة بحوالي

|

توفير الوقت، التحقق من المخرجات، زيادة الكفاءة | توفير الوقت، مخاوف الجودة | توفير الوقت، مخاوف الجودة | 24,9 |

| R-55 | أعتقد أنه يساعد ولكن عليك مراجعة وفهم الكود على أي حال. لذا لا أعرف إذا كان يجعلك أكثر كفاءة. | مراجعة الكود، الفهم، مخاوف الكفاءة | مخاوف الجودة | مخاوف الجودة | 9 |

4.2 سهولة استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

4.2.1 عملية التعلم. يكشف تحليلنا أن عملية التعلم هي عامل حاسم يؤثر على سهولة استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات. كما هو موضح في الجدول 2، أفاد R-54 بأنه “بمجرد أن تعودت على التكنولوجيا، أصبح من الأسهل بكثير استخدامها.” يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا المقترح من قبل [29]، الذي يقترح أن سهولة الاستخدام المدركة للتكنولوجيا مرتبطة مباشرة بتبنيها. علاوة على ذلك، أكدت الأبحاث السابقة على دور

التعلم في تبني التقنيات الجديدة [110]. في هذا السياق، يبدو أن منحنى التعلم المرتبط بنماذج اللغة الكبيرة هو محدد أساسي لسهولة استخدامها المدركة.

4.2.2 الخبرة السابقة. تؤكد بيانات استبيان الأسئلة أيضًا على أهمية الخبرة السابقة في تشكيل سهولة استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. على سبيل المثال، ذكر R-20 أنه “أعتقد أنه سهل عندما تعرف المفاهيم المختلفة.” يتماشى هذا الملاحظة مع الأدبيات حول تبني التكنولوجيا، التي تقترح أن الأفراد الذين لديهم خبرة سابقة في تقنيات ذات صلة هم أكثر عرضة لرؤية التكنولوجيا الجديدة على أنها سهلة الاستخدام [24]. في حالة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، يمكن أن يسهل وجود خلفية في لغات البرمجة أو معالجة اللغة الطبيعية (NLP) تبنيها في هندسة البرمجيات.

4.2.3 الفروق الفردية. موضوع رئيسي آخر ظهر من تحليلنا هو دور الفروق الفردية في تشكيل سهولة استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. كما أشار R-9، “يعتمد ذلك على الشخص وكيف اعتادوا على العمل.” يدعم هذا الاكتشاف الفكرة القائلة بأن الخصائص الفردية، مثل أسلوب التفكير والابتكار الشخصي، يمكن أن تؤثر على سهولة استخدام التكنولوجيا المدركة [94]. في سياق نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، قد يعتمد مدى رؤية مهندسي البرمجيات لها على أنها سهلة الاستخدام على تفضيلاتهم الفريدة، وأنماط التعلم، وطرق حل المشكلات.

4.2.4 الحدسية وواجهة المستخدم. كانت الحدسية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة وتصميم واجهة المستخدم الخاصة بها أيضًا عوامل مهمة في تحليلنا. على سبيل المثال، ذكر R-89 أن “تم تصميمها بشكل أساسي لتكون سهلة الاستخدام من قبل المستهلك العادي.” يتماشى هذا الملاحظة مع عمل [69]، الذي جادل بأن واجهة المستخدم المصممة بشكل جيد يمكن أن تعزز بشكل كبير سهولة استخدام التكنولوجيا المدركة. في حالة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، يمكن أن تسهل واجهة مستخدم حدسية وسهلة الاستخدام تبنيها بين مهندسي البرمجيات.

4.2.5 تعقيد المهام. أخيرًا، يبدو أن تعقيد المهام التي تستخدم من أجلها نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات يؤثر على سهولة استخدامها المدركة. كما أشار R-53، “يمكن أن يختلف صعوبة تعلم كيفية استخدامها بشكل فعال حسب كيفية استخدامك لها، ولكن في الغالب، يتراوح من ليس صعبًا جدًا إلى صعب جدًا.” يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع نموذج ملاءمة المهمة والتكنولوجيا [41]، الذي يفترض أن الملاءمة بين التكنولوجيا والمهمة التي تهدف إليها تؤثر على سهولة الاستخدام المدركة للتكنولوجيا، وفي النهاية، على تبنيها. في سياق نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، يبدو أن مهندسي البرمجيات قد يجدونها أسهل للاستخدام في مهام معينة، بينما قد تتطلب مهام أخرى مستوى أعلى من الخبرة والمعرفة.

4.3 النية السلوكية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

| ID | اقتباس | المفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-46 | سهل كلما مارست أكثر | الممارسة، التحسين | الممارسة والتحسين | عملية التعلم | 54 |

| R-4 | يستغرق بعض الوقت والتفاني | الوقت، التفاني | منحنى التعلم | عملية التعلم | 54 |

| R-96 | ومع ذلك، بالنسبة للمهام الأكثر تقدمًا، قد يستغرق الأمر بعض الوقت لصياغة أسئلتك بشكل صحيح | المهام المتقدمة، الوقت | منحنى التعلم | عملية التعلم | 54 |

| R-30 | في الأسبوع الأول من استخدامه، ستبدأ بالفعل في زيادة كفاءتك | الكفاءة، الوقت | الممارسة والتحسين | عملية التعلم | ٥٤ |

| R-33 | لكي تكون أكثر كفاءة، يتطلب الأمر تعلم العبارات المحددة التي تعطيك الإجابة الدقيقة التي تتوقعها. | الكفاءة، مطالب محددة | الممارسة والتحسين | عملية التعلم | ٥٤ |

| R-17 | يعتمد ذلك على تعقيد وقدرات النموذج، بالإضافة إلى خبرة ومعرفة المستخدم السابقة. | التعقيد، تجربة المستخدم، المعرفة السابقة | عوامل فردية | الأرض الفردية | 26 |

| R-98 | من السهل عندما تعرف لغة أخرى مشابهة لها | المعرفة السابقة، لغة مشابهة | عوامل فردية | الأرض الفردية | 26 |

| R-5 | سهل للغاية | سهولة الاستخدام | سهولة الاستخدام المدركة | سهولة التبني المدركة | ١٣ |

| R-52 | سهل الاستخدام، صعب الإتقان في التعليمات | سهولة الاستخدام، الإتقان | إتقان | سهولة التبني المدركة | ١٣ |

| R-74 | الجزء الصعب هو فهم ما إذا كانت الاستجابة المقدمة صحيحة ومرتبطة بما يحتاجه الشخص. | جودة الاستجابة، العلاقة بالاحتياجات | الصعوبة المدركة | فعالية النموذج | ٦ |

4.3.1 تحسين الكود والصيانة. أشار جزء كبير من مهندسي البرمجيات إلى نيتهم استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لتحسين وصيانة قاعدة الشيفرة الخاصة بهم. يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع مفهوم الفائدة المدركة في نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا، حيث يمكن أن يؤدي استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في إعادة هيكلة الكود، والالتزام بأنماط التصميم، وتنفيذ مبادئ SOLID إلى تحسين جودة البرمجيات وقابلية الصيانة. على سبيل المثال، ذكر R-8: “أفكر في شراء اشتراك في ChatGPT-4، بشكل أساسي لإعادة هيكلة (الكود القديم) أو لجعله يتماشى مع أنماط تصميم معينة. يمكن أن يساعد أيضًا في إعادة هيكلة الكود لجعله أكثر توافقًا مع مبادئ SOLID.” تسلط هذه الاقتباس الضوء على القيمة المحتملة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في معالجة التحديات الشائعة في هندسة البرمجيات.

4.3.2 الكفاءة والأتمتة. تم اعتبار نماذج اللغة الكبيرة مفيدة لأتمتة المهام المتكررة وزيادة الكفاءة. تتوافق هذه النظرة مع كل من الفائدة المدركة وسهولة الاستخدام المدركة في نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا، حيث يمكن أن تؤدي أتمتة المهام إلى توفير الوقت وتبسيط عملية التطوير. قال R-35: “أعتقد أنني قد أبدأ في استخدام نموذج لغة بشكل متزايد، خاصة لأتمتة المهام التي يمكن أن يؤديها نموذج اللغة والتي تستغرق وقتًا كبيرًا.” يمكن أن يؤدي اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لأتمتة المهام إلى تحسين إنتاجية مهندسي البرمجيات.

4.3.3 التعلم وحل المشكلات. كان استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للتعلم وحل المشكلات موضوعًا آخر تم تحديده، وهو متماشي مع الفائدة المدركة لنموذج قبول التكنولوجيا. أعرب مهندسو البرمجيات عن نيتهم في استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لمهام مثل العثور على الوثائق، وتوضيح الشيفرة المربكة، والبحث عن معلومات حول الأسئلة المتعلقة بالبرمجة. كما ذكر R-25، “من المحتمل جدًا. في الغالب للعثور على الوثائق الخاصة بالمكتبات، وإعادة هيكلة وتوضيح الشيفرة المربكة.” يمكن أن تكون نماذج اللغة الكبيرة أداة قيمة للتعلم وحل المشكلات لمهندسي البرمجيات، تدعم التطوير المهني المستمر.

4.3.4 التطبيقات المتخصصة. ذكر المستجيبون الاستخدام المحتمل لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة لمهام محددة، مثل كتابة الوظائف الأساسية، وتحديد المهام، وصياغة الرسائل الإلكترونية. يرتبط هذا الموضوع بالفائدة المتصورة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في تلبية احتياجات معينة في هندسة البرمجيات. على سبيل المثال، ذكر R-62، “من المحتمل جدًا. لكتابة الوظائف الأساسية، وتحديد المهام، وللرسائل الإلكترونية.

يمكن أن يوفر اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) لتطبيقات متخصصة فوائد مستهدفة لمهندسي البرمجيات في عملهم اليومي.

4.3.5 حواجز القبول والمخاوف. على الرغم من الفوائد المحتملة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة، أعرب بعض مهندسي البرمجيات عن مخاوف وحواجز أمام القبول، مثل التكلفة، والاعتماد على خدمات الطرف الثالث، والمشاكل الأخلاقية المحتملة. تتماشى هذه المخاوف مع مفهوم سهولة الاستخدام المدركة في نموذج قبول التكنولوجيا، حيث يمكن أن تعيق اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة [110]. على سبيل المثال، ذكر R-60: “قد تكون التكلفة والاعتماد على خدمة طرف ثالث مصدر قلق.” فهم هذه المخاوف ومعالجتها أمر ضروري لتعزيز اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات.

| هوية | اقتباس | مفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات الثانية | الأبعاد الإجمالية | (% ) |

| R-8 | من المحتمل جداً. أنا أفكر في شراء اشتراك في ChatGPT-4، بشكل أساسي لإعادة هيكلة (الكود القديم) أو لجعله يتماشى مع أنماط تصميم معينة. يمكن أن يساعد أيضاً في إعادة هيكلة الكود لجعله أكثر توافقاً مع مبادئ SOLID. | إعادة هيكلة الكود، أنماط التصميم، مبادئ SOLID | توليد الشيفرة وإعادة هيكلتها | تحسين وصيانة الشيفرة | 42 |

| R-35 | أعتقد أنني قد أبدأ في استخدام لغة بشكل متزايد، خاصة لأتمتة المهام التي يمكن أن يؤديها نموذج اللغة والتي تستغرق وقتًا كبيرًا. | أتمتة المهام، توفير الوقت | أتمتة المهام وتحسينها | الكفاءة والأتمتة | ٣٥ |

| R-25 | من المحتمل جدًا. غالبًا ما يكون ذلك للعثور على الوثائق الخاصة بالمكتبات، وإعادة هيكلة الكود وتوضيح الكود المربك. | ابحث عن الوثائق، أعد هيكلة الكود، وضح الكود المربك | البحث عن المعلومات والتعلم | التعلم وحل المشكلات | ٢٨ |

| R-7 | جربته مع بعض الأسئلة الأساسية المتعلقة بالبرمجة بالفعل. | أسئلة البرمجة الأساسية | البحث عن المعلومات والتعلم | التعلم وحل المشكلات | ٢٨ |

| R-62 | من المحتمل جدًا. لكتابة الوظائف الأساسية، وتحديد المهام، وللرسائل الإلكترونية | كتابة الوظائف الأساسية، تحديد المهام، البريد الإلكتروني | حالات استخدام محددة بالمهام | التطبيقات المتخصصة | 20 |

| R-17 | من المحتمل جدًا في ترجمة اللغة، تلخيص النصوص وتوليد النصوص | ترجمة اللغة، تلخيص النص، توليد النص | مهام معالجة اللغة الطبيعية | معالجة اللغة الطبيعية وتوليد المحتوى | ١٨ |

| R-46 | كتابة اختبارات آلية | كتابة اختبارات آلية | اختبار والتحقق من الشيفرة | ضمان الجودة والتحقق | 15 |

| R-69 | ليس من المحتمل | عدم التبني | عدم اليقين أو عدم التبني | حواجز ومخاوف التبني | 12 |

| R-60 | قد تكون التكلفة والاعتماد على خدمة طرف ثالث مصدر قلق. | التكلفة، الاعتماد على خدمات الطرف الثالث | حواجز التبني | حواجز ومخاوف التبني | 12 |

4.4 توافق نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

4.4.1 تحسين الكفاءة. كان تحسين الكفاءة هو الموضوع الأكثر تكرارًا في البيانات، مع

4.4.2 المساعدة والدعم. ظهرت المساعدة والدعم كأكثر الموضوعات تكرارًا في البيانات، حيث تمثل

4.4.3 التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية. تم الإبلاغ عن التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية من قبل

4.4.4 التكيف والتعلم. تم الإبلاغ عن التكيف والتعلم من قبل

4.5 تعقيد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

| معرف | اقتباس | مفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | توافق | الموضوعات من الدرجة الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-19 | يمكن استخدام نماذج اللغة لأتمتة مهام معينة في هندسة البرمجيات… | أتمتة المهام، تسريع العملية | تحسين مهام هندسة البرمجيات | تحسين الكفاءة | 39 | |

| R-27 | ينقل عبء البحث مني إلى الخوارزمية. | نقل العبء، الخوارزمية | تحسين مهام هندسة البرمجيات | تحسين الكفاءة | 39 | |

| R-35 | سيسرع نموذج اللغة مهام البحث عن قطع معينة من الشيفرة من مواقع متعددة. | تسريع المهام، بحث الشيفرة | تحسين مهام هندسة البرمجيات | تحسين الكفاءة | 39 | |

| R-1 | يقدم يدًا إضافية ويمكن أن يوفر المساعدة للأشياء التي لا أعرفها ولا أستطيع العثور عليها باستخدام بحث تقليدي. | يد إضافية، مساعدة | تقديم المساعدة والدعم | المساعدة والدعم | 28 | |

| R-15 | لا يوجد فرق كبير حيث يتم استخدام نموذج اللغة فقط لمساعدتي في ممارسات هندسة البرمجيات الحالية. | تشابه، مساعدة | مساعدة | التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية | التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية | 16 |

| R-5 | ليس مختلفًا كثيرًا، إنه مثل البحث في جوجل لكنني لا أحتاج إلى تصفية الكثير من المعلومات. | تشابه، تصفية أقل | التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية | التشابه مع الممارسات الحالية | 16 | |

| R-46 | إنه شيء جديد: عليك أن تتعلم كيفية استخدامه. | تعلم، تكيف | الحاجة إلى التكيف والتعلم | التكيف والتعلم | 11 | |

| R-87 | يمثل استخدام نموذج اللغة نموذجًا جديدًا بالنسبة لي… | نموذج جديد، تكيف | الحاجة إلى التكيف والتعلم | التكيف والتعلم | 11 | |

| R-99 | أكثر تفاعلية وشخصية مقارنة بالبحث العادي في جوجل. | تفاعلي، شخصي | استخدام شخصي وتفاعلي | الشخصية والتفاعل | 10 | |

| R-58 | يقدم استجابة أكثر تحديدًا وتخصيصًا تم تجميعها من الكثير من المحتوى المتاح عبر الإنترنت… | محدد، استجابة مخصصة | استخدام شخصي وتفاعلي | الشخصية والتفاعل | 10 | |

4.5.1 مخاوف أمن الوظائف. ظهرت مخاوف فقدان الوظائف وتخفيض قيمة المهارات كقضية مهمة بين المستجيبين (

4.5.2 الاعتماد والركود. أعرب بعض المستجيبين (

4.5.3 أمان البيانات والخصوصية. تم تحديد مخاوف أمان البيانات والخصوصية من قبل

4.5.4 جودة ودقة الشيفرة المولدة. كما أعرب المستجيبون عن مخاوف بشأن جودة ودقة الشيفرة المولدة بواسطة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (13% تكرار). علق المستجيب R-49، “نماذج اللغة ليست مثالية، لذا سأكون خائفًا من أنها قد تسبب أخطاء.” إن ضمان موثوقية ودقة الشيفرة المولدة أمر ضروري لاعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة [81]. لمعالجة هذه القضية، يجب على المطورين وضع أفضل الممارسات لمراجعة الشيفرة والتحقق منها، بالإضافة إلى الاستثمار في تحسين أداء النماذج [115].

4.5.5 الاعتبارات الأخلاقية والقانونية. تم تحديد الاعتبارات الأخلاقية والقانونية، مثل حقوق التأليف وحقوق الملكية الفكرية، من قبل

4.5.6 التحيز وقابلية التفسير. أشار بعض المستجيبين (

4.5.7 التكامل والتوافق. تم ذكر قضايا التكامل والتوافق من قبل

| معرف | اقتباس | المفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات من الدرجة الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-15 | أنا قلق من أنها يمكن أن تؤتمت الكثير من المهام وتجعل معظم عملي عتيقًا. | الأتمتة، استبدال المهام، العتيقة | فقدان الوظائف، انخفاض قيمة المهارات | مخاوف أمان الوظائف | 25 |

| R-34 | قلقي هو أن المبرمجين المبتدئين الآخرين يستخدمونها دون فهم الكود ويتسببون في أخطاء (مزيد من العمل بالنسبة لي). | المبرمجون المبتدئون، نقص الفهم، الأخطاء | انخفاض في فهم الكود، الاعتماد على نماذج اللغة | الاعتماد والرضا | 16 |

| R-17 | من حيث الخصوصية، حيث يمكن تدريب نماذج اللغة على بيانات حساسة أو شخصية، مثل الرسائل الإلكترونية، الرسائل، أو الوثائق. قد يثير هذا مخاوف بشأن الخصوصية وحماية البيانات، خاصة إذا تم استخدام نموذج اللغة في بيئة سحابية أو تم مشاركته مع أطراف ثالثة. | الخصوصية، حماية البيانات، البيانات الحساسة | سرية البيانات، خطر التعرض | أمان البيانات والخصوصية | 15 |

| R-49 | نماذج اللغة ليست مثالية، لذا سأكون خائفًا من أنها ستسبب أخطاء. | عدم كمال نموذج اللغة، الأخطاء | كود غير صحيح أو غير مُدار بشكل جيد | جودة ودقة الكود الناتج | 13 |

| R-28 | حقوق المؤلفين من الصعب نسبها | الملكية، الحقوق | مخاوف قانونية | اعتبارات أخلاقية وقانونية | 8 |

| R-87 | المخاوف التي لدي بشأن استخدام نماذج اللغة في عملي تشمل قضايا التحيز، قابلية التفسير، والضعف الأمني المحتمل. | التحيز، قابلية التفسير، الثغرات الأمنية | الثقة في النتائج الناتجة، التداخل- | التحيز وقابلية التفسير | 7 |

| R-6 | قد لا تكون متوافقة مع الأنظمة في مكان عملي. | التوافق، الأنظمة | تحديات التكامل | التوافق والتكامل | 5 |

| R-5 | قد تصبح مهاراتي البرمجية “صدئة” إذا اعتمدت عليها كثيرًا، مثل التصحيح التلقائي، أشعر أن قواعدي اللغوية الآن أسوأ لأن هاتفي يفهم حتى الكلمات غير المكتملة ولا أستطيع تذكر الطريقة الصحيحة لكتابة بعض الكلمات بسبب ذلك. | الاعتماد على نماذج اللغة، تدهور المهارات، التصحيح التلقائي | انخفاض المهارات الشخصية | تدهور المهارات | 3 |

4.6 الميزة النسبية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

4.6.1 كفاءة الوقت. كان موضوعًا متكررًا في تحليلنا هو كفاءة الوقت التي توفرها نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، كما أفاد

4.6.2 جودة الكود. ظهرت تحسينات في جودة الكود كميزة رئيسية أخرى لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة، حيث أشار

4.6.3 تجربة المستخدم. لوحظ أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تعزز تجربة المستخدم العامة، حيث أشار

4.6.4 التعلم وتطوير المهارات. وُجد أيضًا أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تسهل التعلم وتطوير المهارات، كما أفاد

4.6.5 التخصيص والتخصيص الشخصي. أخيرًا، تم تسليط الضوء على التخصيص والتخصيص الشخصي كميزات من قبل

يمكن تسهيل هندسة البرمجيات من خلال قدرتها على تقديم فوائد واضحة مقارنة بالطرق الحالية [85]. علاوة على ذلك، تسلط نتائجنا الضوء على إمكانية نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في إحداث ثورة في مجال هندسة البرمجيات من خلال تبسيط العمليات، وتعزيز تجربة المستخدم، وتعزيز التعلم المستمر والتحسين.

| معرف | اقتباس | المفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات من الدرجة الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-25 | أعتقد أن أفضل شيء هو أن الوقت الذي يقضى في البحث عن أشياء معينة أقل بكثير مما كان عليه في السابق. | بحث موفر للوقت | إكمال المهام | كفاءة الوقت | 42 |

| R-37 | إنه يولد كودًا أبسط وأكثر قابلية للفهم، ويعمل بطريقة أكثر تنظيمًا ويقلل الأخطاء. | كود قابل للفهم، تقليل الأخطاء | بسيط وقوي | جودة الكود | 14 |

| R-67 | نماذج اللغة أسهل في الاستخدام وأسرع لأنك تستطيع إرسال رسائل كما لو كنت تتحدث مع إنسان | أسهل في الاستخدام، أسرع | سهولة التواصل | تجربة المستخدم | 11 |

| R-23 | أعتقد أنه مع نماذج اللغة لا تحتاج إلى قضاء الكثير من الوقت في تعلم الأشياء ‘التقنية’ | وقت أقل للتعلم | تعلم مبسط | التعلم وتطوير المهارات | 9 |

| R-64 | يمكن أن يساعدني في تخطي الكود النمطي والمقتطفات التي كتبتها مئات المرات من قبل. يمكن أن يساعد أيضًا في تعلم بناء الجمل للغات جديدة. | كود نمطي، تعلم لغات جديدة | توليد الكود والأتمتة | قابلية التكيف مع الأتمتة | 8 |

| R-35 | أعتقد أنه قد يكون أكثر كفاءة ويوفر بعض الوقت. | كفاءة، توفير الوقت | حلول مبتكرة | الإبداع والابتكار | 3 |

| R-11 | أعتقد أنه يمكن أن يقدم وجهات نظر واضحة لم تؤخذ في الاعتبار | وجهات نظر جديدة | وجهات نظر متنوعة | رؤى واتخاذ القرار | 4 |

| R-68 | حلول أسرع وأكثر فعالية للمشكلات | حلول أسرع للمشكلات | استكشاف فعال | حل المشكلات | 6 |

| R-53 | يمكن أن تساعد نماذج اللغة (برمجة زوجية) في تقليل الأخطاء وزيادة الكفاءة بشكل عام. | أخطاء أقل، زيادة الكفاءة | مساعدة تعاونية | العمل الجماعي والتعاون | 5 |

| R-94 | تقدم معلومات أكثر هضمًا، ويمكننا “تشكيل” المعلومات كما نريد (مثل: طلب من نموذج اللغة الرد باستخدام جمل قصيرة، أو الشرح بالتفصيل حول مواضيع معينة، إلخ) | معلومات سهلة الهضم، تخصيص | استجابات مرنة | تخصيص وتفصيل | 8 |

4.7 التأثير الاجتماعي لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

4.7.1 لا تأثير. كشف تحليلنا أن

4.7.2 تأثير منخفض. تم الإبلاغ عن تأثير منخفض من قبل

4.7.3 تأثير معتدل. كشف تحليلنا أن

4.7.4 تأثير عالي. أخيرًا، أفاد 26% من المستجيبين بتأثير عالي من أقرانهم وزملائهم (مثل: R-97، R-79، R-27). تشير هذه النتيجة إلى أن نسبة كبيرة من مهندسي البرمجيات تتأثر بشدة بالاستخدام الجماعي والحماس لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة ضمن دوائرهم المهنية. تتماشى هذه النتيجة مع تركيز نظرية الإدراك الاجتماعي على التفاعلات المتبادلة بين الأفراد وبيئتهم الاجتماعية، فضلاً عن الأدبيات حول اعتماد التكنولوجيا في المنظمات [85]. في هذه الحالة، قد ينبع مستوى التأثير العالي من الفوائد المدركة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة، والتعاون، والحماس المشترك لاستكشاف إمكانيات التكنولوجيا.

| معرف | اقتباس | مفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | مواضيع من الدرجة الثانية | أبعاد مجمعة | (%) |

| R-66 | زملائي لا يؤثرون على قراراتي لاستخدام نماذج اللغة | لا تأثير | اتخاذ قرارات مستقلة | لا تأثير | 29 |

| R-24 | ليس على الإطلاق. | لا تأثير | اتخاذ قرارات مستقلة | لا تأثير | 29 |

| R-58 | بعضهم مؤيد، لكن ذلك لا يؤثر على رأيي أو طريقة استخدامي له | آخرون مؤيدون، لا تأثير على الرأي أو الاستخدام | تقييم مستقل | لا تأثير | 29 |

| R-97 | كثيرًا، لأننا نستخدمه يوميًا ويتم تشجيعه. | استخدام يومي، تشجيع | اعتماد قوي | تأثير عالي | 26 |

| R-79 | نحن جميعًا نستخدمها، لذا نشجع بعضنا البعض على استخدامها أيضًا | استخدام جماعي، تشجيع متبادل | تعاون ودعم | تأثير عالي | 26 |

| R-27 | بشدة، كل من أعرفه حريص على استكشاف إمكانياتها. | تأثير قوي، استكشاف الإمكانيات | اعتماد متحمس | تأثير عالي | 26 |

| R-45 | ليس كثيرًا | تأثير ضئيل | مستوى منخفض من التأثير | تأثير منخفض | 24 |

| R-99 | ليس حقًا. | تأثير ضئيل | مستوى منخفض من التأثير | تأثير منخفض | 24 |

| R-9 | أتخذ قراراتي الخاصة … لكنني غالبًا ما أبحث عن مدخلات وتعليقات من زملائي وأقراني … | قرار مستقل، مدخلات وتعليقات من الأقران | تقدير آراء الأقران | تأثير معتدل | 21 |

| R-82 | هناك بعض التأثير لكن لا أعتقد أنه أمر كبير لأن الجميع يستخدمه بدافع الفضول | بعض التأثير، اعتماد مدفوع بالفضول | فضول واستكشاف | تأثير معتدل | 21 |

4.8 الكفاءة الذاتية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

يُنظر إليك على أنك متقدم. ستتم مناقشة هذه الأبعاد بالتفصيل في الفقرات الفرعية التالية، مع تسليط الضوء على دورها في تشكيل كفاءة المطورين الذاتية وسلوك اعتمادهم لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات. يمكن العثور على هيكل البيانات في الجدول 8.

4.8.1 أهمية أن يُنظر إليك على أنك متقدم. كما هو موضح في الجدول،

4.8.2 التركيز على العملية والكفاءة. كشفت تحليلاتنا أن

4.8.3 أهمية منخفضة لأن يُنظر إليهم على أنهم متطورون. مجموعة أصغر من المستجيبين (

4.9 العوامل البيئية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة في هندسة البرمجيات

| معرف | اقتباس | المفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | المواضيع من الدرجة الثانية | الأبعاد المجمعة | (%) |

| R-2 | البقاء على اطلاع بأحدث التقنيات أمر حاسم في مجالي. | أهمية التكنولوجيا المتطورة | التأكيد على أهمية التكنولوجيا المتطورة | أهمية أن يُنظر إليك على أنك متطور | 57 |

| R-30 | أمر مهم جدًا. لا أريد أن يتم استبدالي بشخص يُنظر إليه على أنه كذلك بينما لا أكون. | الخوف من الاستبدال | التأكيد على أهمية التكنولوجيا المتطورة | أهمية أن يُنظر إليك على أنك متطور | 57 |

| R-57 | من المهم أن أظهر أنني قادر على التكيف. | قدرة التكيف | التأكيد على أهمية التكنولوجيا المتطورة | أهمية أن يُنظر إليك على أنك متطور | 57 |

| R-77 | أعتقد أنه من المهم حقًا أن أكون دائمًا على اطلاع بأحدث التقنيات | أهمية البقاء على اطلاع | التأكيد على أهمية التكنولوجيا المتطورة | أهمية أن يُنظر إليك على أنك متطور | 57 |

| R-10 | من المهم بالنسبة لي لأنه يساعدني على البقاء في المقدمة وتقديم حلول مبتكرة تلبي احتياجات العملاء المتطورة. | البقاء في المقدمة، حلول مبتكرة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | 35 |

| R-19 | في عملي كمطور برمجيات، من المهم بالنسبة لي أن أبقى على اطلاع بأحدث الاتجاهات والتقنيات في هندسة البرمجيات، بما في ذلك نماذج اللغة. […] | تلبية احتياجات العملاء، التكنولوجيا المناسبة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | 35 |

| R-47 | ليس كثيرًا، عملي يعتمد في الغالب على التقنيات التي يقررها الآخرون. | استخدام التقنيات المحددة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | 35 |

| R-100 | قليلًا، لكن التكنولوجيا المتطورة لا تعني دائمًا كفاءة أعلى. والكفاءة هي المفتاح. | الكفاءة، ليست دائمًا متطورة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | التركيز على العملية والكفاءة | 35 |

| R-21 | ليس على الإطلاق. أبحث عن الاستقرار، وليس تنفيذ أحدث التقنيات المتطورة في سير العمل الخاص بي. | الاستقرار، رفض التكنولوجيا المتطورة | أهمية منخفضة لأن يُنظر إليهم على أنهم متطورون | أهمية منخفضة لأن يُنظر إليهم على أنهم متطورون | 8 |

| R-66 | لا أجد أنه من المهم أن يُنظر إلي كشخص يستخدم التكنولوجيا المتطورة في عملي. تركيزي هو على استخدام الأدوات الأكثر فعالية للمهام المطروحة. | أهمية منخفضة للتكنولوجيا المتطورة، أدوات فعالة | أهمية منخفضة لأن يُنظر إليهم على أنهم متطورون | أهمية منخفضة لأن يُنظر إليهم على أنهم متطورون | 8 |

4.9.2 الموقف المحايد. يعكس بعد الموقف المحايد المؤسسات التي لا تدعم ولا تعارض بنشاط اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (

4.9.3 الدعم المشروط. تظهر بعض المؤسسات في عيّنتنا بعد الدعم المشروط (

4.9.4 الدعم المحدود. يمثل بعد الدعم المحدود (

4.9.5 غياب الدعم. أخيرًا، يمثل بعد غياب الدعم (

| هوية | اقتباس | مفاهيم من الدرجة الأولى | الموضوعات الثانية | الأبعاد الإجمالية | (% ) |

| R-5 | الكثير، يدفعون ثمنه ويشجعوننا على استخدامه | تشجيع، دفع | ترويج نشط | موقف داعم | 42 |

| R-45 | داعم للغاية | دعم قوي | داعم للغاية | موقف داعم | 42 |

| R-84 | أعتقد أن منظمتنا محايدة، الأمر متروك للموظف. | محايد، خيار الموظف | نقص في الرأي القوي | موقف محايد | 20 |

| R-26 | إذا كان ذلك يجلب مزيدًا من المزايا للفريق وطريقة عملنا، ويجعل الأمور أسرع، فإنهم يدعمون اعتماد نماذج اللغة. | المزايا، الكفاءة، الدعم المشروط | الدعم بشروط | الدعم المشروط | 19 |

| R-21 | على الإطلاق. نحن ضد فن الذكاء الاصطناعي، وأيضًا ضد الذكاء الاصطناعي عندما يتعلق الأمر بالبرمجة. لقد فشل في تلبية متطلباتنا على أي حال أثناء الاختبار. | غير داعم، ضد الذكاء الاصطناعي | معارضة لتكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي | نقص الدعم | 15 |

| R-74 | ليس كثيرًا، لأنه قد ينتهك حقوق الطبع والنشر ويشكل أيضًا بعض المخاوف الأمنية بشأن الملكية الفكرية الخاصة. | مخاوف حقوق الطبع والنشر، مخاوف أمنية، دعم محدود | المخاوف التي تؤدي إلى نقص الدعم | نقص الدعم | 15 |

| R-92 | لا أعرف، لكنهم لا يعارضون ذلك. | عدم اليقين، لا معارضة | غير متأكد | عدم اليقين | 14 |

| R-61 | منظمتي تدعمني إلى حد ما لكنها غير متأكدة. | دعم جزئي، عدم اليقين | ازدواجية | عدم اليقين | 14 |

| R-79 | هم يدعمون استخدامه كأداة مساعدة، وليس كأداة رئيسية. | الدعم، سياق محدود | تطبيق محدود | دعم محدود | 12 |

| R-64 | هم يعارضونهم عند العمل على ميزات جديدة، لكنهم يمكن أن يكونوا مفيدين جدًا في تصحيح الأخطاء. | المعارضة، تصحيح الأخطاء، سياق محدد | الدعم في سياقات محددة | دعم محدود | 12 |

4.10 الرؤى الرئيسية للدراسة النوعية

5 إطار التعاون والتكيف بين الإنسان والذكاء الاصطناعي (HACAF)

تقييم نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بناءً على قدرتها على تبسيط عمليات البرمجة، وتعزيز جودة الكود، وتسريع جداول المشروع. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التركيز على العملية والكفاءة الموجود في دراستنا يبرز أهمية هذا البناء في التأثير على اعتماد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة.

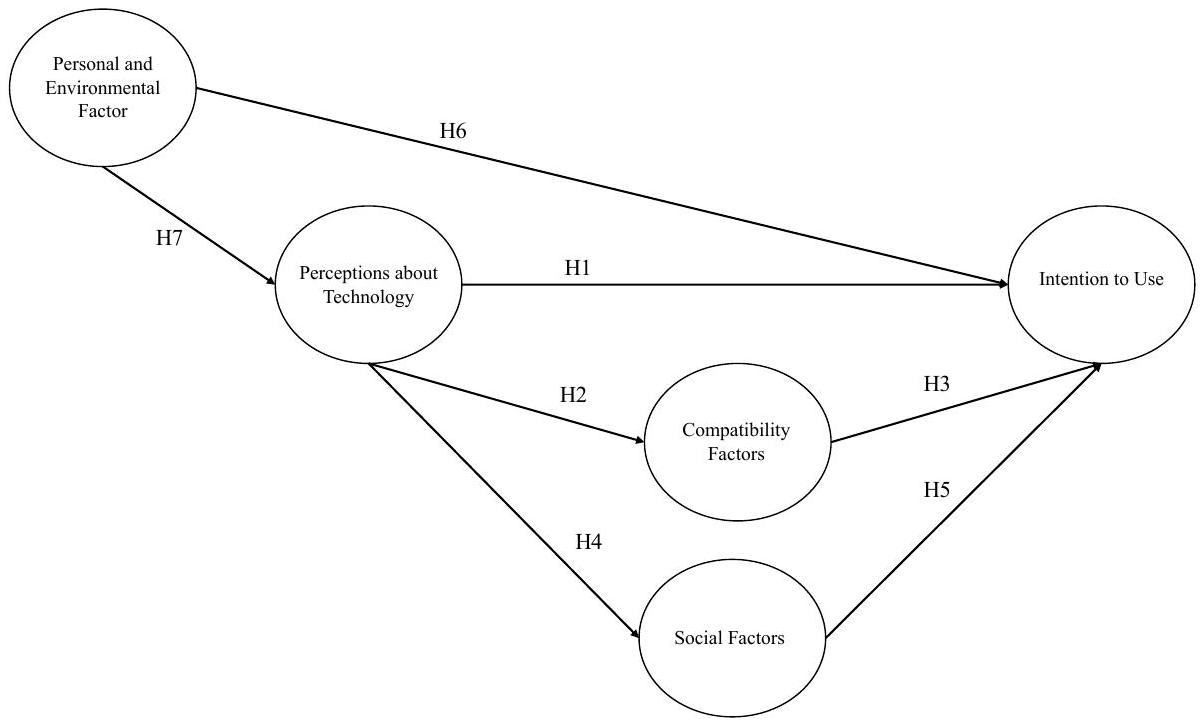

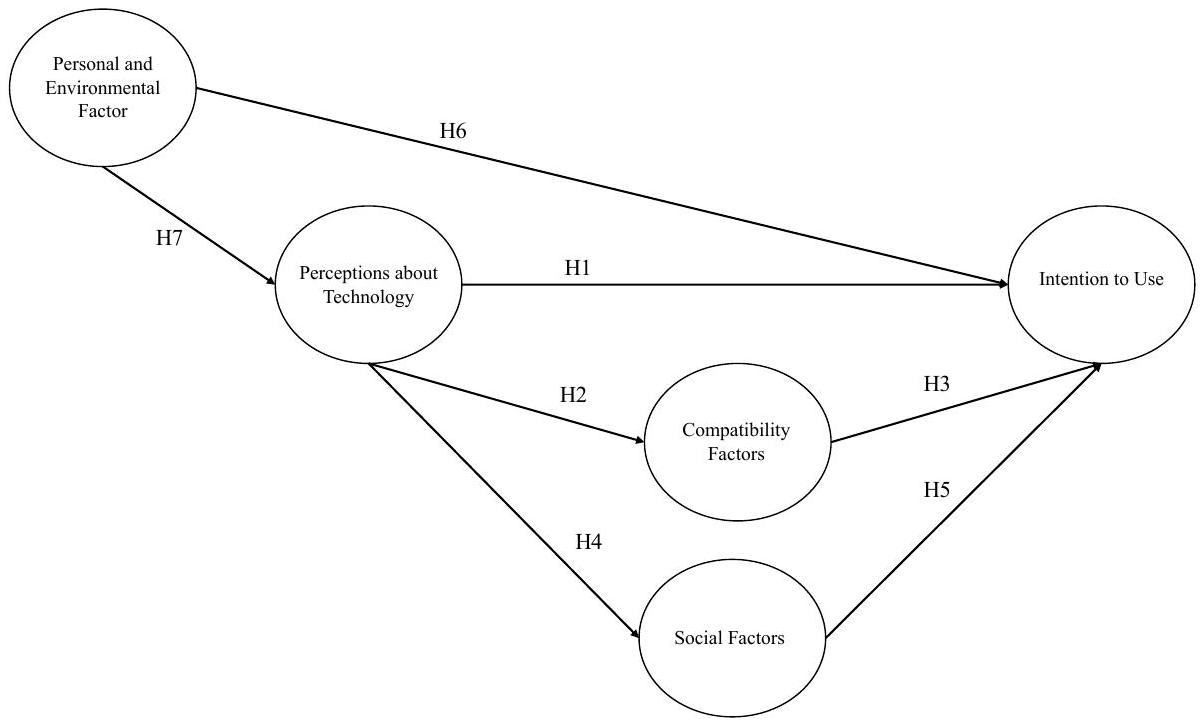

5.1 النموذج النظري والافتراضات

وتعزيز التأثير الإيجابي لتصورات حول التكنولوجيا على نية استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة.

6 التحقق من النظرية

6.1 النمذجة الهيكلية باستخدام المربعات الصغرى الجزئية

6.1.1 تطوير المقياس. تم إعداد الاستبيان بمساعدة نظرية إضافية. قمنا بتنظيم استبياننا من خلال تكييف الأدوات من الأبحاث السابقة. جميع العناصر المستخدمة لتعريف كل بنية والمراجع المستخدمة لتشكيل الأسئلة ملخصة في الجدول 20. تم تقييم كل بنية من خلال عناصر أحادية البعد على مقياس ليكرت من 7 نقاط تشير إلى مستويات الاتفاق.

6.1.2 جمع بيانات الاستبيان. تم تحديد الحد الأدنى لحجم العينة من خلال إجراء تحليل قوة مسبق باستخدام G*Power. مع حجم تأثير قدره

6.1.3 ديموغرافيات المشاركين. شمل استبياننا مجموعة متنوعة من 184 مستجيبًا، تتكون من

6.2 تقييم نموذج القياس

6.2.1 الصلاحية التمييزية. في هذا السياق، تشير الصلاحية التمييزية إلى تميز أو تفرد متغير كامن واحد مقارنة بآخر. هذا يعد معلمة أساسية لتحديد ما إذا كانت بنى معينة هي في الأساس نفس الشيء وتمثل جوانب مختلفة من المعرفة. لتقييمها، استخدمنا نسبة الارتباطات بين المتغيرات المختلفة (HTMT) المعروفة بأدائها المتفوق على اختبارات أخرى مثل معيار فورنل-لاركر. يجب أن تكون قيم HTMT مثالية أقل من 0.90.

| CF | IU | PEF | PT | |

| عوامل التوافق (CF) | ||||

| نية الاستخدام (IU) | 0.756 | |||

| العوامل الشخصية والبيئية (PEF) | 0.372 | 0.272 | ||

| المدركات حول التكنولوجيا (PT) | 0.848 | 0.633 | 0.338 | |

| العوامل الاجتماعية (SF) | 0.403 | 0.371 | 0.441 | 0.437 |

6.2.2 موثوقية الاتساق الداخلي. يسعى هذا الاختبار إلى تأكيد أن العناصر تقيس المتغيرات الكامنة بطريقة متسقة وموثوقة. على هذا النحو، نشير إلى قيم ألفا كرونباخ، وrho_a، وrho_c المعروضة في الجدول 11، والتي يجب أن تتجاوز جميعها 0.60 [70]. يمكننا أن نستنتج أن اختباراتنا تلبي معايير الموثوقية.

| ألفا كرونباخ | rho_a | rho_c | AVE | |

| عوامل التوافق (CF) | 0.856 | 0.866 | 0.902 | 0.699 |

| نية الاستخدام (IU) | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.961 | 0.891 |

| العوامل الشخصية والبيئية (PEF) | 0.876 | 0.905 | 0.914 | 0.727 |

| المدركات حول التكنولوجيا (PT) | 0.948 | 0.950 | 0.956 | 0.685 |

| العوامل الاجتماعية (SF) | 0.875 | 0.906 | 0.940 | 0.887 |

| عنصر | CF | آي يو | PEF | بي تي | SF |

| CF2 | 0.896 | 0.626 | 0.293 | 0.686 | 0.333 |

| CF3 | 0.856 | 0.657 | 0.352 | 0.666 | 0.305 |

| CF5 | 0.775 | 0.482 | 0.248 | 0.547 | 0.250 |

| CF6 | 0.811 | 0.505 | 0.236 | 0.654 | 0.289 |

| آي يو 1 | 0.662 | 0.935 | 0.238 | 0.560 | 0.293 |

| آي يو 2 | 0.602 | 0.945 | 0.235 | 0.558 | 0.337 |

| آي يو 3 | 0.671 | 0.951 | 0.267 | 0.577 | 0.330 |

| PEF4 | 0.293 | 0.198 | 0.811 | 0.276 | 0.277 |

| PEF5 | 0.156 | 0.130 | 0.838 | 0.214 | 0.250 |

| PEF6 | 0.362 | 0.316 | 0.892 | 0.300 | 0.394 |

| PEF7 | 0.298 | 0.200 | 0.867 | 0.258 | 0.391 |

| PT1 | 0.658 | 0.581 | 0.251 | 0.841 | 0.340 |

| PT11 | 0.641 | 0.521 | 0.178 | 0.855 | 0.318 |

| PT12 | 0.490 | 0.415 | 0.362 | 0.703 | 0.350 |

| بي تي 13 | 0.639 | 0.491 | 0.295 | 0.856 | 0.327 |

| بي تي 14 | 0.612 | 0.460 | 0.267 | 0.851 | 0.330 |

| PT2 | 0.663 | 0.545 | 0.281 | 0.827 | 0.378 |

| PT3 | 0.676 | 0.503 | 0.262 | 0.854 | 0.344 |

| بي تي 4 | 0.655 | 0.511 | 0.271 | 0.874 | 0.383 |

| بي تي 6 | 0.669 | 0.550 | 0.234 | 0.866 | 0.٣٢٣ |

| بي تي 7 | 0.622 | 0.353 | 0.191 | 0.727 | 0.243 |

| SF1 | 0.295 | 0.291 | 0.388 | 0.325 | 0.929 |

| SF2 | 0.365 | 0.342 | 0.359 | 0.427 | 0.955 |

6.3 تقييم النموذج الهيكلي

6.3.1 تحليل التداخل. في البداية، نقوم بتحليل العلاقة بين المتغير الخارجي (العوامل الشخصية والبيئية) وبقية المتغيرات الداخلية. يجب أن تكون هذه المتغيرات مستقلة لتجنب أي تحيز محتمل في تقديرات المسار. يجب أن تكون قيمة اختبار عامل تضخم التباين (VIF) أقل من خمسة [63]، والذي يكشف عن التعدد الخطي (أي، درجة متطرفة من التداخل). قيم VIF لدينا أقل من هذا العتبة، حيث تتراوح من 4.710 (للعنصر IU_3) إلى 2.034 (PEF_4). وبالتالي، نستنتج أن نموذجنا لا يعاني من مشاكل التعدد الخطي.

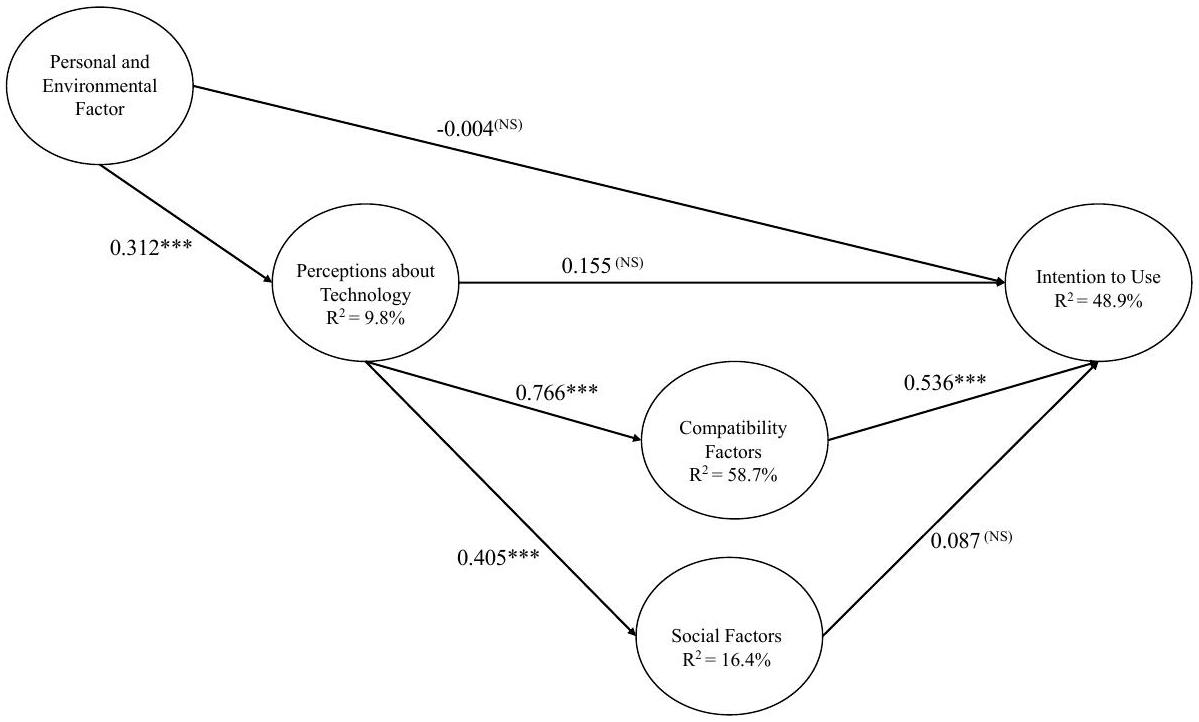

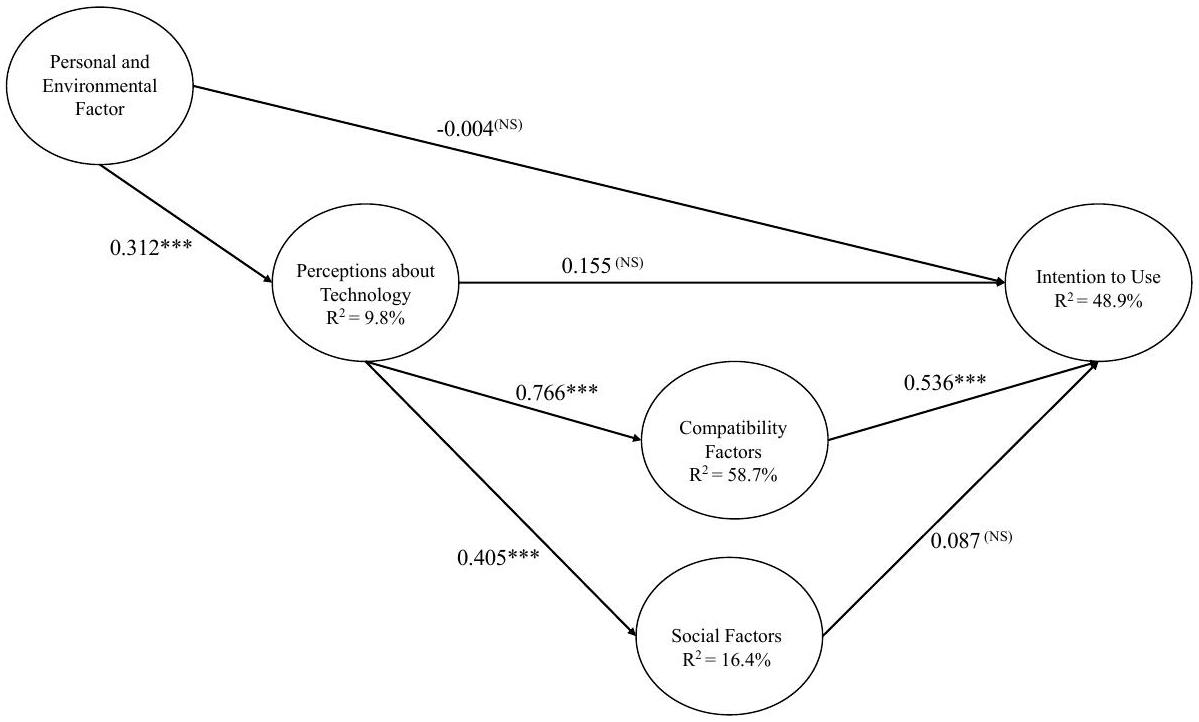

6.3.2 علاقات المسار: الأهمية والملاءمة. تمثل معاملات المسار العلاقات المفترضة بين المتغيرات الكامنة. إنها موحدة، مما يعني أن قيمها يمكن أن تتراوح

| فرضية | معامل | متوسط البوتستراب | الانحراف المعياري | ت |

|

| H1:

|

0.155 | 0.150 | 0.122 | 1.271 | 0.204 |

| H2: PT

|

0.766 | 0.766 | 0.047 | ١٦.٤٠٥ | 0.000 |

| H3:

|

0.536 | 0.537 | 0.090 | 5.936 | 0.000 |

| H4:

|

0.405 | 0.408 | 0.076 | ٥.٣٤٦ | 0.000 |

| H5: SF

|

0.087 | 0.090 | 0.064 | 1.373 | 0.170 |

| H6: PEF

|

-0.004 | -0.004 | 0.056 | 0.064 | 0.949 |

| H7: PEF

|

0.313 | 0.317 | 0.072 | ٤.٣١٣ | 0.000 |

| بناء |

|

|

| عوامل التوافق | 0.587 | 0.585 |

| نية الاستخدام | 0.489 | 0.477 |

| العوامل الشخصية والبيئية | 0.098 | 0.093 |

| العوامل الاجتماعية | 0.164 | 0.159 |

| بناء | جذر متوسط مربع الخطأ | ماي |

|

| عوامل التوافق | 0.089 | 0.984 | 0.752 |

| نية الاستخدام | 0.046 | 1.012 | 0.761 |

| الآراء حول التكنولوجيا | 0.076 | 0.998 | 0.733 |

| العوامل الاجتماعية | 0.078 | 0.971 | 0.755 |

| البنى | CF | آي يو | PEF | PT | SF |

| عوامل التوافق | 0.225 | ||||

| نية الاستخدام | |||||

| العوامل الشخصية والبيئية | 0.000 | 0.108 | |||

| الآراء حول التكنولوجيا | 1.426 | 0.196 | |||

| العوامل الاجتماعية | 0.018 | 0.011 |

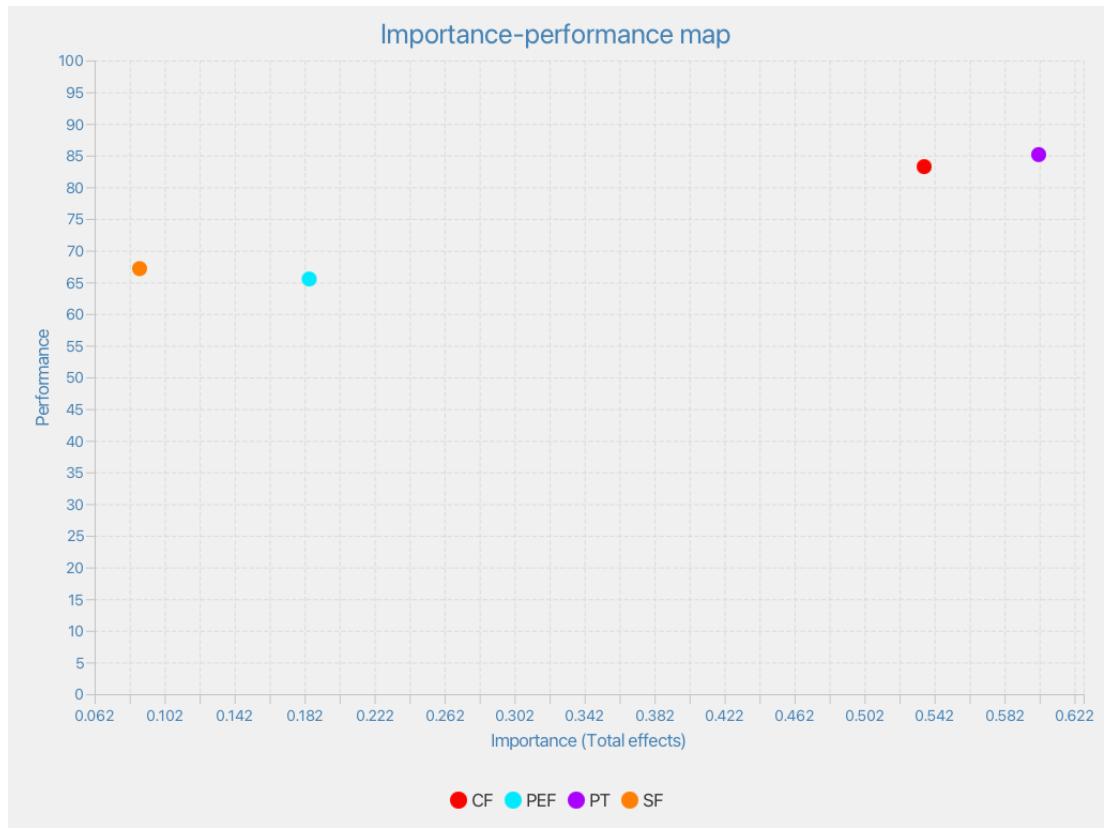

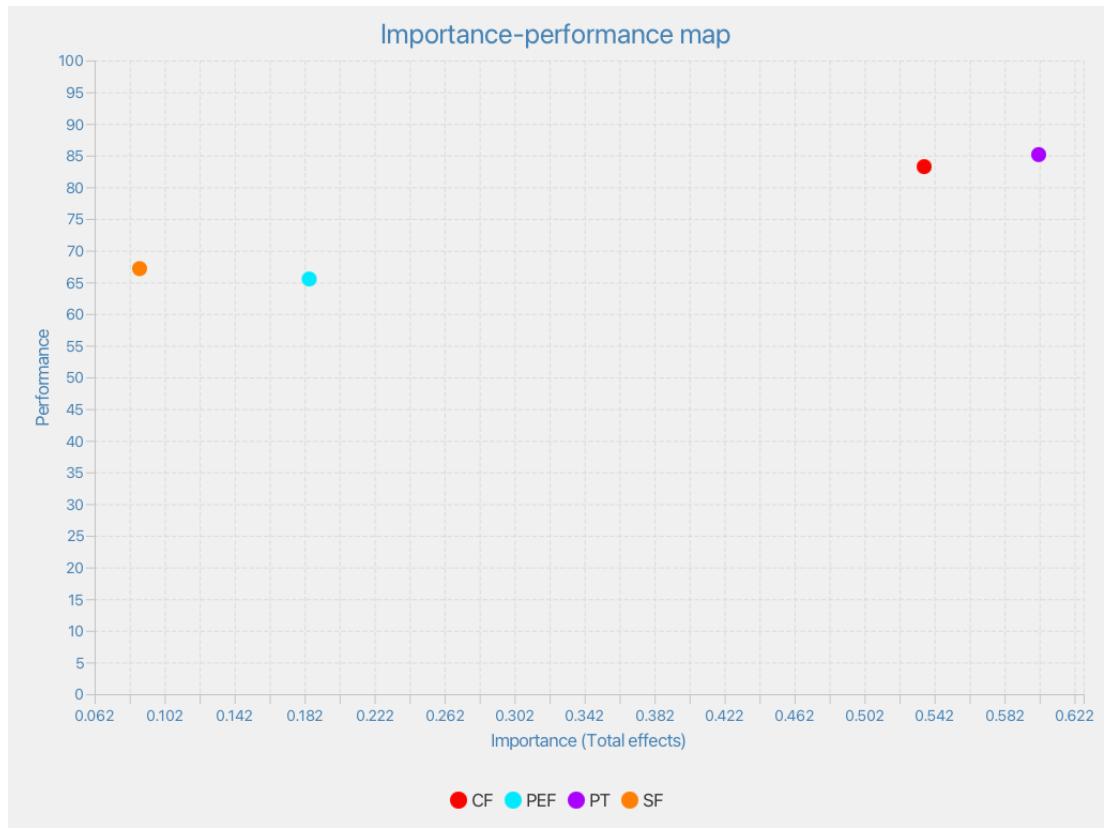

6.4 تحديد العوامل الرئيسية للتبني: تحليل باستخدام خريطة الأهمية والأداء

| البنية | أداء البنى |

| CF | 83.257 |

| PEF | 65.519 |

| PT | 85.138 |

| SF | 67.161 |

| البنية | CF | IU | PEF | PT | SF |

| CF | 0.646 | ||||

| IU | |||||

| PEF | 0.240 | 0.167 | 0.313 | 0.127 | |

| PT | 0.767 | 0.540 | 0.405 | ||

| SF | 0.110 |

7 المناقشة

| الفرضية | النتائج | التداعيات |

| H1: التصورات حول التكنولوجيا

|

غير مدعومة. لم نجد علاقة مباشرة بين التصورات حول التكنولوجيا والنية في الاستخدام. | تصور التكنولوجيا وحده لا يحفز اعتماد أداة ذكاء اصطناعي توليدي. |

| H2: التصورات حول التكنولوجيا

|

مدعومة. هذه العلاقة هي الأقوى في النموذج مع معامل مسار قدره 0.77 مع حجم تأثير كبير جدًا (1.43). | استيعاب قدرات أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي وإمكانية دمجها في سير العمل الحالي لتطوير البرمجيات أمر حاسم. |

| H3: عوامل التوافق

|

مدعومة. هذه العلاقة متناظرة مع فرضية H2 (مع معامل مسار كبير قدره 0.54 وحجم تأثير كبير قدره 0.66)، والتي تفسر في الغالب النية في استخدام LLMs. تظهر IPMA أن عوامل التوافق هي العنصر الأكثر أهمية لتحسين النية في الاستخدام. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تفسر، تقريبًا بمفردها، اعتماد أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي بحجم تأثير مرتفع جدًا

|

يعتمد اعتماد أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي بشكل كبير على تكاملها الناجح مع سير العمل الحالي لتطوير البرمجيات. |

| H4: التصورات حول التكنولوجيا

|

مدعومة. نبلغ عن معامل مسار كبير (0.40) مع حجم تأثير متوسط (0.20). الطريقة التي يتم بها تصور الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تؤثر بشكل إيجابي على كفاءة المطورين الذاتية. | يعتبر المطورون LLMs كعوامل تسهيل حيوية في إكمال المهام بشكل أكثر فعالية. |

| H5: العوامل الاجتماعية

|

غير مدعومة. العلاقة بين العوامل الاجتماعية والنية في الاستخدام ليست ذات دلالة. | على الرغم من أن أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي تعتبر عوامل تمكين مهمة لكفاءة المطورين الذاتية، إلا أن هذا التصور لا يترجم إلى اعتماد. |

| H6: العوامل الشخصية والبيئية

|

غير مدعومة. هذه العلاقة ليست ذات دلالة. | لا تؤثر الابتكارية الشخصية والدعم التنظيمي بشكل كبير على اعتماد المطورين لأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي. |

| H7: العوامل الشخصية والبيئية

|

مدعومة. وجدنا علاقة كبيرة بين العوامل الشخصية والبيئية والتصورات حول التكنولوجيا مع معامل مسار قدره 0.31 وحجم تأثير صغير إلى متوسط (0.11). | كما هو متوقع، فإن ميل المطور للتجربة مع أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الدعم التنظيمي المدرك، يؤثر بشكل إيجابي على تصور التكنولوجيا. |

أن يتم تأكيد العلاقات ضمن نموذج HACAF بشكل أكبر. إن عدم التحقق الحالي من جميع العلاقات ضمن نموذج إطار عملنا لا يقلل من فائدته ولكنه يقدم رؤى أولية حول العوامل التي تشكل اعتماد أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في هذه المرحلة.

7.1 الآثار

- تقييم الأدوات: يجب على المنظمات بدء تقييم شامل للأدوات المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي المتاحة، مع التركيز على توافقها مع العمليات الحالية والاحتياجات المحددة لفرق التطوير الخاصة بهم.

- اختبار تجريبي: قبل التنفيذ على نطاق واسع، قم بإجراء اختبارات تجريبية مع مجموعة فرعية من المشاريع لقياس تأثير الأداة على وقت التطوير، وجودة البرمجيات، ورضا المستخدم.

- برامج التدريب: تقديم جلسات تدريبية للمطورين لتعريفهم بتفاصيل الأدوات المدروسة، لضمان قدرتهم على الاستفادة القصوى من قدرات الأداة.

- حلقة التغذية الراجعة: إنشاء آلية للتغذية الراجعة حيث يمكن للمطورين الإبلاغ عن أداء الأداة، وأي تحديات واجهتهم، ومجالات التحسين. يمكن أن توجه هذه التغذية الراجعة التحسينات التكرارية وتضمن أن تظل الأداة متوافقة مع ممارسات التطوير المتطورة.

- تحليل التكلفة والفائدة: تقييم العائد على الاستثمار من اعتماد أداة الذكاء الاصطناعي بانتظام، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار عوامل مثل تحسين الكفاءة، وتقليل الأخطاء، ورضا المستخدمين.

نظرًا لنتائجنا حول أهمية عوامل التوافق في دفع اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي، هناك حاجة ملحة للتعليم والتدريب المستمر في الذكاء الاصطناعي مع تزايد انتشاره في هندسة البرمجيات. بشكل ملموس، نقترح: - وحدات تدريب مخصصة: يجب على المنظمات تطوير وتقديم وحدات تدريب مخصصة تركز على دمج أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي ضمن سير العمل الحالي لتطوير البرمجيات. يجب أن تتناول هذه الوحدات الجوانب التقنية والتعاونية لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في بيئات العمل الجماعي.

- ورش عمل منتظمة: استضافة ورش عمل وندوات منتظمة تضم خبراء في مجال الذكاء الاصطناعي. سيوفر ذلك للموظفين رؤى حول أحدث التطورات وأفضل الممارسات في تطوير البرمجيات المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي.

- التعاون مع مزودي أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي: إقامة شراكات مع مزودي أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي لتسهيل جلسات تدريب عملية، مما يضمن أن تكون القوى العاملة قادرة على الاستفادة الكاملة من إمكانيات هذه الأدوات.

- تعزيز التآزر بين الصناعة والأكاديميا: لسد الفجوة بين المعرفة النظرية والتطبيق العملي، يجب على المؤسسات الأكاديمية تعزيز التعاون الأعمق مع قادة الصناعة. من خلال تصميم مناهج هندسة البرمجيات التي تركز على التطوير المدفوع بالذكاء الاصطناعي، يمكننا ضمان أن يكون الخريجون ليسوا فقط على دراية بالتقنيات الحالية ولكن أيضًا متوافقين مع التحديات والفرص الحقيقية في الصناعة.

- التكرارات المدفوعة بالتغذية الراجعة: إنشاء آليات لجمع التغذية الراجعة من الموظفين الذين يخضعون للتدريب. يمكن أن تكون هذه التغذية الراجعة حاسمة في تحسين محتوى التدريب والأساليب، مما يضمن أنها تظل ذات صلة وفعالة.

تؤكد دراستنا أيضًا على أهمية نهج الإنسان في الحلقة عند دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي في هندسة البرمجيات. لاستخدام الإمكانات الكاملة لأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي مع ضمان أنها تعزز، بدلاً من استبدال، القدرات البشرية، يُوصى بالخطوات القابلة للتنفيذ التالية: - تصميم الذكاء الاصطناعي الموجه نحو المستخدم: يجب على مطوري أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي إعطاء الأولوية لفلسفة تصميم موجهة نحو المستخدم، مما يضمن أن تكون الأدوات بديهية وتتكامل بسلاسة في سير عمل المطورين.

- آليات الشفافية: تنفيذ آليات داخل أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي توضح عمليات اتخاذ القرار الخاصة بها. سيمكن ذلك المطورين من فهم واقتناع باقتراحات وقرارات الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- ميزات المعايرة: تجهيز أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي بميزات تسمح للمطورين بمعايرتها أو ضبطها بناءً على متطلبات المشروع المحددة وحكمهم المهني.

- حلقة التغذية الراجعة: إنشاء حلقات تغذية راجعة تكرارية حيث يمكن للمطورين تقديم ملاحظات حول مخرجات أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتي يمكن استخدامها بعد ذلك لتحسين أداء الأداة بمرور الوقت.

- مساحات العمل التعاونية: تصميم مساحات عمل تعاونية حيث يمكن لكل من أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي والمطورين المساهمة في الوقت الحقيقي، مما يعزز علاقة تكافلية تستفيد من نقاط القوة لدى كلا الطرفين.

- التدريب المستمر: مع تطور أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي، يجب توفير فرص تدريب مستمرة للمطورين لضمان قدرتهم على التعاون بفعالية مع أحدث إصدارات هذه الأدوات.

- تحليل المتطلبات: قبل الغوص في اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي، يجب على المنظمات إجراء تحليل شامل لاحتياجاتها المحددة. يتضمن ذلك فهم التحديات التي تواجهها وتحديد كيفية معالجة الذكاء الاصطناعي لها.

- تقييم الموارد: تقييم الموارد المتاحة، سواء من حيث الأجهزة أو الخبرة البشرية. سيساعد ذلك في اختيار حلول الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تمتلك المنظمة القدرة على نشرها وصيانتها.

- تحديد القيود: التعرف على أي قيود، سواء كانت ميزانية أو زمنية أو تقنية، قد تؤثر على نشر وتشغيل حلول الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- آلية التغذية الراجعة: إنشاء آلية للمطورين وغيرهم من أصحاب المصلحة لتقديم التغذية الراجعة حول أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي، مما يضمن تحسينها وتحسينها بمرور الوقت.

- المراجعة المستمرة: مراجعة استراتيجية اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل دوري لضمان أنها تظل متوافقة مع الاحتياجات والسياقات المتطورة للمنظمة.

- ثغرات أمنية: سلطت دراسات حديثة، مثل تلك التي أجراها تسامادوس وآخرون [106]، الضوء على الثغرات الأمنية الكامنة في الذكاء الاصطناعي، خاصة مع النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة. تؤكد نتائجهم على الحاجة إلى فهم شامل لقدرات هذه النماذج وثغراتها.

- مسؤولية مزود النموذج: يجب على مزودي النماذج، في سعيهم لتعزيز الاعتماد، أن يكونوا استباقيين في توضيح الثغرات المحتملة وتقديم إرشادات حول أفضل الممارسات لمواجهة هذه المخاطر. مع تطور تقنيات النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة بسرعة، فإن المراجعات والتدقيقات الدورية أمر بالغ الأهمية لضمان الشفافية والامتثال للمعايير الأخلاقية.

- تدابير أمان المنصة: يجب على المنصات التي تدمج النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة تعزيز بروتوكولات الأمان الخاصة بها، مما يضمن استعدادها لمواجهة التحديات الفريدة التي تطرحها هذه النماذج. عند اعتماد أو استخدام النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة، من الحكمة اختيار نماذج من مصادر موثوقة ومثبتة، مما يضمن كل من الاعتمادية والأمان.

- حوارات أصحاب المصلحة: يمكن أن تعزز المحادثات المفتوحة بين أصحاب المصلحة، بما في ذلك المطورين والمستخدمين والجهات التنظيمية، اعتمادًا أكثر مسؤولية وأخلاقية لأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية في هندسة البرمجيات.

باختصار، فإن دمج تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي، وخاصة أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية مثل النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة، في هندسة البرمجيات يحمل إمكانات هائلة لتعزيز عملية التطوير وتحسين جودة البرمجيات بشكل عام. من خلال الاعتراف بالتحديات المرتبطة

مع اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي – مع الأخذ في الاعتبار نتائجنا حول أهمية عوامل التوافق – يمكن للمنظمات الاستفادة بفعالية من أدوات وأساليب مدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي لتحقيق نتائج محسنة في مساعي تطوير البرمجيات الخاصة بهم.

7.2 القيود

8 الاستنتاج

المواد التكميلية

شكر وتقدير

REFERENCES

[2] Ritu Agarwal and Jayesh Prasad. 1999. Are individual differences germane to the acceptance of new information technologies? Decision Sciences 30, 2 (1999), 361-391.

[3] AI, B. 2023. BLACKBOX AI – useblackbox.io. https://www.useblackbox.io/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[4] Icek Ajzen. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 2 (1991), 179-211.

[5] Icek Ajzen. 2020. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2, 4 (2020), 314-324.

[6] Amazon Web Services. 2023. Code-Whisperer – Amazon Web Services. https://aws.amazon.com/es/codewhisperer/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[7] Alejandro Barredo Arrieta, Natalia Díaz-Rodríguez, Javier Del Ser, Adrien Bennetot, Siham Tabik, Alberto Barbado, Salvador Garcia, Sergio Gil-Lopez, Daniel Molina, Richard Benjamins, et al. 2020. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information Fusion 58 (2020), 82-115.

[8] S. Baltes and P. Ralph. 2020. Sampling in Software Engineering Research: A Critical Review and Guidelines. arXiv:2002.07764 (2020).

[9] Albert Bandura. 2014. Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In Handbook of moral behavior and development. Psychology press, 69-128.

[10] Albert Bandura, W. H. Freeman, and Richard Lightsey. 1999. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Fournal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 13, 2 (1999), 158-166.

[11] Shraddha Barke, Michael B James, and Nadia Polikarpova. 2023. Grounded copilot: How programmers interact with code-generating models. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 7 (2023), 85-111.

[12] James Bessen. 2019. Automation and jobs: When technology boosts employment. Economic Policy 34, 100 (2019), 589-626.

[13] Christian Bird, Denae Ford, Thomas Zimmermann, Nicole Forsgren, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Travis Lowdermilk, and Idan Gazit. 2022. Taking Flight with Copilot: Early insights and opportunities of AI-powered pair-programming tools. Queue 20, 6 (2022), 35-57.

[14] Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, et al. 2020. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 1877-1901.

[15] Javier Cámara, Javier Troya, Lola Burgueño, and Antonio Vallecillo. 2023. On the assessment of generative AI in modeling tasks: an experience report with ChatGPT and UML. Software and Systems Modeling (2023), 1-13.

[16] Ruijia Cheng, Ruotong Wang, Thomas Zimmermann, and Denae Ford. 2022. “It would work for me too”: How Online Communities Shape Software Developers’ Trust in AI-Powered Code Generation Tools. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.03491 (2022).

[17] W. W. Chin. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research 295, 2 (1998), 295-336.

[18] Clayton M. Christensen. 1997. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business Review Press.

[19] Michael Chui et al. 2023. The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier. [Accessed 03-Jul-2023].

[20] Victoria Clarke, Virginia Braun, and Nikki Hayfield. 2015. Thematic analysis. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods 3 (2015), 222-248.

[21] CodeComplete. 2023. CodeComplete: AI Coding Assistant for Enterprise. https://codecomplete.ai/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[22] Codeium. 2023. Codeium • Free AI Code Completion and Chat. https://codeium.com/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[23] J. Cohen. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge.

[24] Deborah R Compeau and Christopher A Higgins. 1995. Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly (1995), 189-211.

[25] J. Corbin and A. Strauss. 1990. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 13, 1 (1990), 3-21.

[26] J. Creswell. 2013. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

[27] Arghavan Moradi Dakhel, Vahid Majdinasab, Amin Nikanjam, Foutse Khomh, Michel C Desmarais, and Zhen Ming Jack Jiang. 2023. Github copilot ai pair programmer: Asset or liability? 7ournal of Systems and Software 203

(2023), 111734.

[28] Anastasia Danilova, Alena Naiakshina, Stefan Horstmann, and Matthew Smith. 2021. Do you really code? Designing and Evaluating Screening Questions for Online Surveys with Programmers. In International Conference on Software Engineering. IEEE, 537-548.

[29] F. Davis. 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 13, 3 (1989), 319-340.

[30] Fred D Davis, Richard P Bagozzi, and Paul R Warshaw. 1989. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management science 35, 8 (1989), 982-1003.

[31] Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2019).

[32] Paul Dourish. 2003. The appropriation of interactive technologies: Some lessons from placeless documents. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 12 (2003), 465-490.

[33] Christof Ebert and Panos Louridas. 2023. Generative AI for software practitioners. IEEE Software 40, 4 (2023), 30-38.

[34] Neil A Ernst and Gabriele Bavota. 2022. Ai-driven development is here: Should you worry? IEEE Software 39, 2 (2022), 106-110.

[35] Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A Osborne. 2017. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114 (2017), 254-280.

[36] Yanjie Gao, Xiaoxiang Shi, Haoxiang Lin, Hongyu Zhang, Hao Wu, Rui Li, and Mao Yang. 2023. An Empirical Study on Quality Issues of Deep Learning Platform. In International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice. IEEE, 455-466.

[37] D. Gefen, D. Straub, and M.-C. Boudreau. 2000. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 4, 1 (2000), 7.

[38] D. Gioia, K. Corley, and A. Hamilton. 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods 16, 1 (2013), 15-31.

[39] D. Gioia, J. Thomas, S. Clark, and K. Chittipeddi. 1994. Symbolism and strategic change in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organization Science 5, 3 (1994), 363-383.

[40] B. Glaser and A. Strauss. 2017. Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

[41] Dale L Goodhue and Ronald L Thompson. 1995. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS quarterly (1995), 213-236.

[42] Roberto Gozalo-Brizuela and Eduardo C Garrido-Merchán. 2023. A survey of Generative AI Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.02781 (2023).

[43] F. J. Gravetter and L.-A. B. Forzano. 2018. Research methods for the behavioral sciences. Cengage Learning.

[44] Stine Grodal, Michel Anteby, and Audrey L Holm. 2021. Achieving rigor in qualitative analysis: The role of active categorization in theory building. Academy of Management Review 46, 3 (2021), 591-612.

[45] E. Guba. 1981. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology fournal 29, 2 (1981), 75-91.

[46] J. F. Hair Jr, G T. M Hult, C. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2016. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

[47] Douglas M Hawkins. 2004. The problem of overfitting. Journal of chemical information and computer sciences 44, 1 (2004), 1-12.

[48] Ari Holtzman, Jan Buys, Li Du, Maxwell Forbes, and Yejin Choi. 2019. The curious case of neural text degeneration. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09751 (2019).

[49] Saki Imai. 2022. Is github copilot a substitute for human pair-programming? an empirical study. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings. 319-321.

[50] L. Isabella. 1990. Evolving interpretations as a change unfolds: How managers construe key organizational events. Academy of Management Journal 33, 1 (1990), 7-41.

[51] Mateusz Jaworski and Dariusz Piotrkowski. 2023. Study of software developers’ experience using the Github Copilot Tool in the software development process.

[52] Jared Kaplan, Sam McCandlish, Tom Henighan, Tom B Brown, Benjamin Chess, Rewon Child, Scott Gray, Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, and Dario Amodei. 2020. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 (2020).

[53] Ron Kohavi. 1995. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In Ijcai, Vol. 14. 1137-1145.

[54] Rajiv Kohli and Nigel P Melville. 2019. Digital innovation: A review and synthesis. Information Systems 7ournal 29, 1 (2019), 200-223.

[55] U. Kulkarni, S. Ravindran, and R. Freeze. 2006. A knowledge management success model: Theoretical development and empirical validation. Journal of Management Information Systems 23, 3 (2006), 309-347.

[56] W. Lewis, R. Agarwal, and V. Sambamurthy. 2003. Sources of influence on beliefs about information technology use: An empirical study of knowledge workers. MIS Quarterly (2003), 657-678.

[57] Y. Li, D. Choi, J. Chung, N. Kushman, J. Schrittwieser, R. Leblond, T. Eccles, J. Keeling, F. Gimeno, A. D. Lago, T. Hubert, P. Choy, C. de Masson d’Autume, I. Babuschkin, X. Chen, P.-S. Huang, J. Welbl, S. Gowal, A. Cherepanov, J. Molloy, D. J. Mankowitz, E. S. Robson, P. Kohli, N. de Freitas, K. Kavukcuoglu, and O. Vinyals. 2023. AlphaCode alphacode.deepmind.com. https://alphacode.deepmind.com/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[58] Jenny T Liang, Chenyang Yang, and Brad A Myers. 2023. Understanding the Usability of AI Programming Assistants. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17125 (2023).

[59] Y. Lincoln and E. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

[60] Mai Skjott Linneberg and Steffen Korsgaard. 2019. Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research fournal 19, 3 (2019), 259-270.

[61] K. Locke. 1996. Rewriting the discovery of grounded theory after 25 years? Journal of Management Inquiry 5, 3 (1996), 239-245.

[62] Antonio Mastropaolo, Luca Pascarella, Emanuela Guglielmi, Matteo Ciniselli, Simone Scalabrino, Rocco Oliveto, and Gabriele Bavota. 2023. On the robustness of code generation techniques: An empirical study on github copilot. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.00438 (2023).

[63] J. Miles. 2014. Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor. American Cancer Society.

[64] Brent Daniel Mittelstadt, Patrick Allo, Mariarosaria Taddeo, Sandra Wachter, and Luciano Floridi. 2016. The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society 3, 2 (2016).

[65] Geoffrey A Moore and Regis McKenna. 1999. Crossing the chasm. (1999).

[66] Hussein Mozannar, Gagan Bansal, Adam Fourney, and Eric Horvitz. 2022. Reading between the lines: Modeling user behavior and costs in AI-assisted programming. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.14306 (2022).

[67] mutable.ai. 2023. AI Accelerated Software Development. – mutable.ai. https://mutable.ai/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[68] Nhan Nguyen and Sarah Nadi. 2022. An empirical evaluation of GitHub copilot’s code suggestions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mining Software Repositories. 1-5.

[69] Oded Nov and Chen Ye. 2008. Users’ personality and perceived ease of use of digital libraries: The case for resistance to change. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 59, 5 (2008), 845-851.

[70] J. Nunnally. 1978. Psychometric methods. McGraw-Hill.

[71] General Assembly of the World Medical Association et al. 2014. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The 7ournal of the American College of Dentists 81, 3 (2014), 14.

[72] OpenAI. 2023. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv:2303.08774 [cs.CL]

[73] Ipek Ozkaya. 2023. The next frontier in software development: AI-augmented software development processes. IEEE Software 40, 4 (2023), 4-9.

[74] Stefan Palan and Christian Schitter. 2018. Prolific.ac–A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 17 (2018), 22-27.

[75] Sida Peng, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Peter Cihon, and Mert Demirer. 2023. The impact of ai on developer productivity: Evidence from github copilot. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06590 (2023).

[76] Anthony Peruma, Steven Simmons, Eman Abdullah AlOmar, Christian D Newman, Mohamed Wiem Mkaouer, and Ali Ouni. 2022. How do i refactor this? An empirical study on refactoring trends and topics in Stack Overflow. Empirical Software Engineering 27, 1 (2022), 11.

[77] James Prather, Brent N Reeves, Paul Denny, Brett A Becker, Juho Leinonen, Andrew Luxton-Reilly, Garrett Powell, James Finnie-Ansley, and Eddie Antonio Santos. 2023. ” It’s Weird That it Knows What I Want”: Usability and Interactions with Copilot for Novice Programmers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.02491 (2023).

[78] Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. 2019. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 1, 8 (2019), 9.

[79] Paul Ralph et al. 2020. Empirical standards for software engineering research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.03525 (2020).

[80] M. Ramkumar, T. Schoenherr, S. Wagner, and M. Jenamani. 2019. Q-TAM: A quality technology acceptance model for predicting organizational buyers’ continuance intentions for e-procurement services. International fournal of Production Economics 216 (2019), 333-348.

[81] Baishakhi Ray, Daryl Posnett, Vladimir Filkov, and Premkumar Devanbu. 2014. A large scale study of programming languages and code quality in github. In International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering. ACM, 155-165.

[82] replit. 2023. Ghostwriter – Code faster with AI – replit.com. https://replit.com/site/ghostwriter Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[83] C. M. Ringle and M. Sarstedt. 2016. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Industrial Management & Data Systems 116, 9 (2016), 1865-1886.

[84] C. M. Ringle, S. Wende, and J.-M. Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3.

[85] Everett M. Rogers. 2010. Diffusion of Innovations. Simon and Schuster.

[86] Daniel Russo. 2021. The agile success model: a mixed-methods study of a large-scale agile transformation. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology 30, 4 (2021), 1-46.

[87] D. Russo, P. Ciancarini, T. Falasconi, and M. Tomasi. 2018. A Meta Model for Information Systems Quality: a Mixed-Study of the Financial Sector. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 9, 3 (2018).

[88] Daniel Russo, Paul H P Hanel, Seraphina Altnickel, and Niels van Berkel. 2021. The daily life of software engineers during the covid-19 pandemic. In International Conference on Software Engineering. IEEE, 364-373.

[89] Daniel Russo, Paul H P Hanel, Seraphina Altnickel, and Niels van Berkel. 2021. Predictors of Well-being and Productivity among Software Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Longitudinal Study. Empirical Software Engineering 26, 62 (2021), 1-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-021-09945-9

[90] Daniel Russo and Klaas-Jan Stol. 2020. Gender Differences in Personality Traits of Software Engineers. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 48, 3 (2020), 16.

[91] Daniel Russo and Klaas-Jan Stol. 2021. PLS-SEM for software engineering research: An introduction and survey. Comput. Surveys 54, 4 (2021), 1-38.

[92] Mahadev Satyanarayanan. 2001. Pervasive computing: Vision and challenges. IEEE Personal Communications 8, 4 (2001), 10-17.

[93] Albrecht Schmidt. 2023. Speeding Up the Engineering of Interactive Systems with Generative AI. In ACM SIGCHI Symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems. 7-8.

[94] AH Segars and V Grover. 1993. Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: A confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Quarterly 17, 4 (1993), 517-525.

[95] Galit Shmueli, Soumya Ray, Juan Manuel Velasquez Estrada, and Suneel Babu Chatla. 2016. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. Journal of Business Research 69, 10 (2016), 4552-4564.

[96] G. Shmueli, M. Sarstedt, J. F. Hair, J Cheah, H. Ting, S. Vaithilingam, and C. M. Ringle. 2019. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. European fournal of Marketing 53, 11 (2019).

[97] Dominik Sobania, Martin Briesch, and Franz Rothlauf. 2022. Choose your programming copilot: A comparison of the program synthesis performance of github copilot and genetic programming. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference. 1019-1027.

[98] Klaas-Jan Stol and Brian Fitzgerald. 2018. The ABC of software engineering research. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology 27, 3 (2018), 11.

[99] A. Strauss and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage.

[100] Tabnine. 2023. AI Assistant for software developers – Tabnine. https://www.tabnine.com/ Accessed: October 17, 2023.

[101] Emmanuel Tenakwah. 2021. What do employees want?: Halting record-setting turnovers globally. Strategic HR Review 20, 6 (2021), 206-210.

[102] Ronald L Thompson, Christopher A Higgins, and Jane M Howell. 1991. Personal Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of Utilization. MIS Quarterly 15, 1 (1991), 125-143.

[103] Haoye Tian, Weiqi Lu, Tsz On Li, Xunzhu Tang, Shing-Chi Cheung, Jacques Klein, and Tegawendé F Bissyandé. 2023. Is ChatGPT the Ultimate Programming Assistant-How far is it? arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11938 (2023).

[104] Gholamreza Torkzadeh, Jerry Cha-Jan Chang, and Didem Demirhan. 2006. A contingency model of computer and Internet self-efficacy. Information & Management 43, 4 (2006), 541-550.

[105] Louis G. Tornatzky and Katherine J. Klein. 1982. Innovation characteristics and innovation adoption-implementation: A meta-analysis of findings. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 29, 1 (1982), 28-45.

[106] Andreas Tsamados, Luciano Floridi, and Mariarosaria Taddeo. 2023. The Cybersecurity Crisis of Artificial Intelligence: Unrestrained Adoption and Natural Language-Based Attacks. Available at SSRN 4578165 (2023).

[107] Priyan Vaithilingam, Tianyi Zhang, and Elena L Glassman. 2022. Expectation vs. experience: Evaluating the usability of code generation tools powered by large language models. In International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1-7.

[108] J. Van Maanen. 1979. The fact of fiction in organizational ethnography. Administrative Science Quarterly 24, 4 (1979), 539-550.

[109] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017).

[110] Viswanath Venkatesh and Fred D Davis. 2000. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Management science 46, 2 (2000), 186-204.

[111] Viswanath Venkatesh, Michael G Morris, Gordon B Davis, and Fred D Davis. 2003. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS quarterly (2003), 425-478.

[112] Viswanath Venkatesh, James YL Thong, and Xin Xu. 2016. Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 17, 5 (2016), 328-376.

[113] Vv.AA. 2023. The widespread adoption of AI by companies will take a while. https://www.economist.com/leaders/ 2023/06/29/the-widespread-adoption-of-ai-by-companies-will-take-a-while

[114] Ruotong Wang, Ruijia Cheng, Denae Ford, and Thomas Zimmermann. 2023. Investigating and Designing for Trust in AI-powered Code Generation Tools. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11248 (2023).

[115] Bolin Wei, Ge Li, Xin Xia, Zhiyi Fu, and Zhi Jin. 2019. Code generation as a dual task of code summarization. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. 6563-6573.

[116] Michel Wermelinger. 2023. Using GitHub Copilot to solve simple programming problems. In Proceedings of the ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education. 172-178.

[117] C. Wohlin, P. Runeson, M. Höst, M. Ohlsson, B. Regnell, and A. Wesslén. 2012. Experimentation in Software Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media.

[118] Burak Yetistiren, Isik Ozsoy, and Eray Tuzun. 2022. Assessing the quality of GitHub copilot’s code generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Predictive Models and Data Analytics in Software Engineering. 62-71.

[119] Beiqi Zhang, Peng Liang, Xiyu (Thomas) Zhou, Aakash Ahmad, and Muhammad Waseem. 2023. Practices and Challenges of Using GitHub Copilot: An Empirical Study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08733 (2023).

[120] Daniel Zhang, Saurabh Mishra, Erik Brynjolfsson, John Etchemendy, Deep Ganguli, Barbara Grosz, Terah Lyons, James Manyika, Juan Carlos Niebles, Michael Sellitto, et al. 2021. The AI index 2021 annual report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.06312 (2021).

[121] Q. Zheng, X. Xia, X. Zou, Y. Dong, S. Wang, Y. Xue, Z. Wang, L. Shen, A. Wang, Y. Li, T. Su, Z. Yang, and J. Tang. 2023. GitHub – THUDM/CodeGeeX: CodeGeeX: An Open Multilingual Code Generation Model. https: //github.com/THUDM/CodeGeeX Accessed: October 17, 2023.

أ الملحق أ (أداة الاستطلاع)

| البناء | معرف العنصر | الأسئلة | المرجع |

| الآراء حول التكنولوجيا | PT_1 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في عملي يمكنني من إنجاز المهام بشكل أسرع. | [29, 111] |

| PT_2 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيحسن من أدائي في العمل. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_3 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في عملي سيزيد من إنتاجيتي. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_4 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيعزز من فعاليتي في العمل. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_5 | (*) استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيجعل من الأسهل القيام بعملي. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_6 | سأجد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة مفيدة في عملي. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_7 | سأجد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سهلة الاستخدام. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_8 | (*) سيكون من السهل بالنسبة لي أن أصبح بارعًا في استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_9 | (*) سأجد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة مرنة للتفاعل معها. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_10 | (*) سيكون من السهل بالنسبة لي تعلم تشغيل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [65, 111] | |

| PT_11 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيمكنني من إنجاز المهام بشكل أسرع. | [29, 111] | |

| PT_12 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيحسن من جودة العمل الذي أقوم به. | [65, 111] | |

| PT_13 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيجعل من الأسهل القيام بعملي. | [65, 111] | |

| PT_14 | استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة سيعزز من فعاليتي في العمل. | [65, 111] | |

| PT_15 | (*) استخدام نموذج لغوي كبير يمنحني تحكمًا أكبر في عملي. | [4, 111] | |

| عوامل التوافق | CF_1 | (*) استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة متوافق مع جميع جوانب عملي. | [65, 111] |

| CF_2 | أعتقد أن استخدام نموذج اللغة الكبير يتناسب جيدًا مع الطريقة التي أحب أن أعمل بها. | [٦٥، ١١١] | |

| CF_3 | استخدام نموذج اللغة الكبير يتناسب مع أسلوب عملي. | [65, 111] | |

| CF_4 | (*) لدي السيطرة على استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [4, 111] | |

| CF_5 | لدي المعرفة اللازمة لاستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [4, 111] | |

| CF_6 | نظرًا للموارد والفرص والمعرفة اللازمة لاستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، سيكون من السهل بالنسبة لي استخدام هذه النماذج. | [4, 111] | |

| العوامل الاجتماعية | SF_1 | الأشخاص الذين يؤثرون على سلوكي يعتقدون أنه يجب علي استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [٤، ١١١] |

| SF_2 | الأشخاص الذين يهمونني يعتقدون أنه يجب علي استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [4, 111] | |

| SF_3 | (*) أستخدم نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بسبب نسبة الزملاء الذين يستخدمون النظام. | [١٠٢، ١١١] | |

| SF_4 | (*) الأشخاص في منظمتي الذين يستخدمون نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يتمتعون بمزيد من الهيبة مقارنةً بأولئك الذين لا يستخدمونها. | [٦٥، ١١١] | |

| العوامل الشخصية والبيئية | PEF_1 | (*) إذا سمعت عن تقنية جديدة مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، سأبحث عن طرق للتجربة معها. | [111] |

| PEF_2 | (*) بين أقراني، عادةً ما أكون الأول في تجربة تقنيات جديدة مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [1] | |

| PEF_3 | (*) أحب أن أجرب تقنيات جديدة. | [1] | |

| PEF_4 | منظمتي توفر الموارد اللازمة لاستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بفعالية. | [٥٥، ١١١] | |

| PEF_5 | منظمتنا تقدم جلسات تدريب كافية لتعزيز مهاراتنا في استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [٥٥، ١١١] | |

| PEF_6 | تشجع منظمتنا على استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في عملنا اليومي. | [٥٦، ١١١] | |

| PEF_7 | أشعر أن هناك دعمًا من الإدارة العليا في منظمتي لاستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. | [٥٦، ١١١] | |

| نية الاستخدام | آي يو_1 | أعتزم استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل أكثر شمولاً في الأشهر القادمة. | [٢٩، ١١١] |

| آي يو_2 | أتوقع أنني سأستخدم نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل أكثر شمولاً في الأشهر القادمة. | [٢٩، ١١١] | |

| آي يو_3 | أخطط لاستخدام LLM بشكل أكثر شمولاً في الأشهر القادمة. | [٢٩، ١١١] |

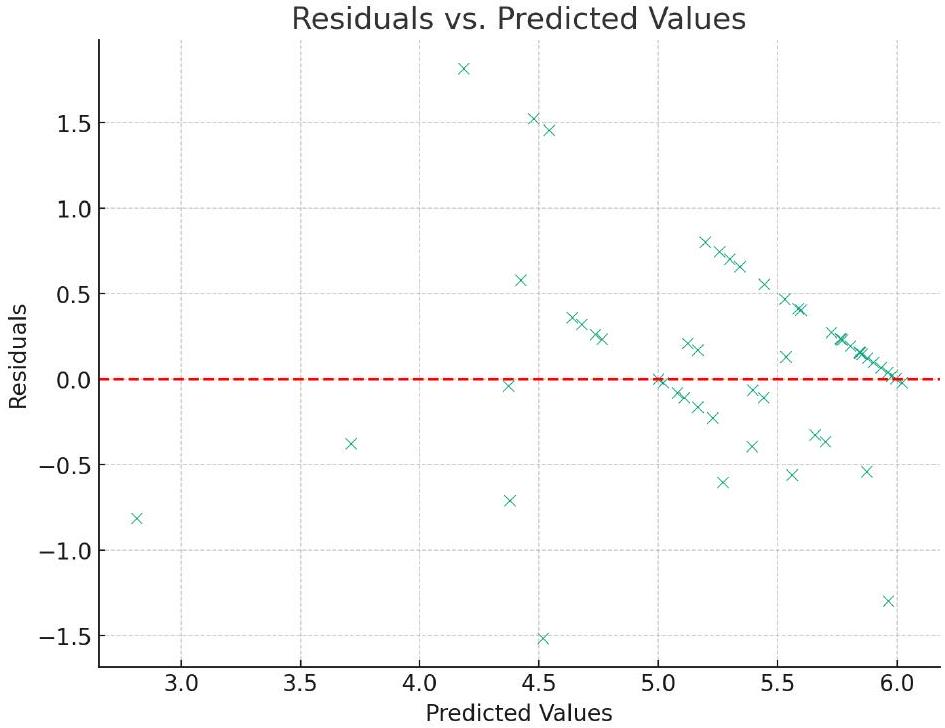

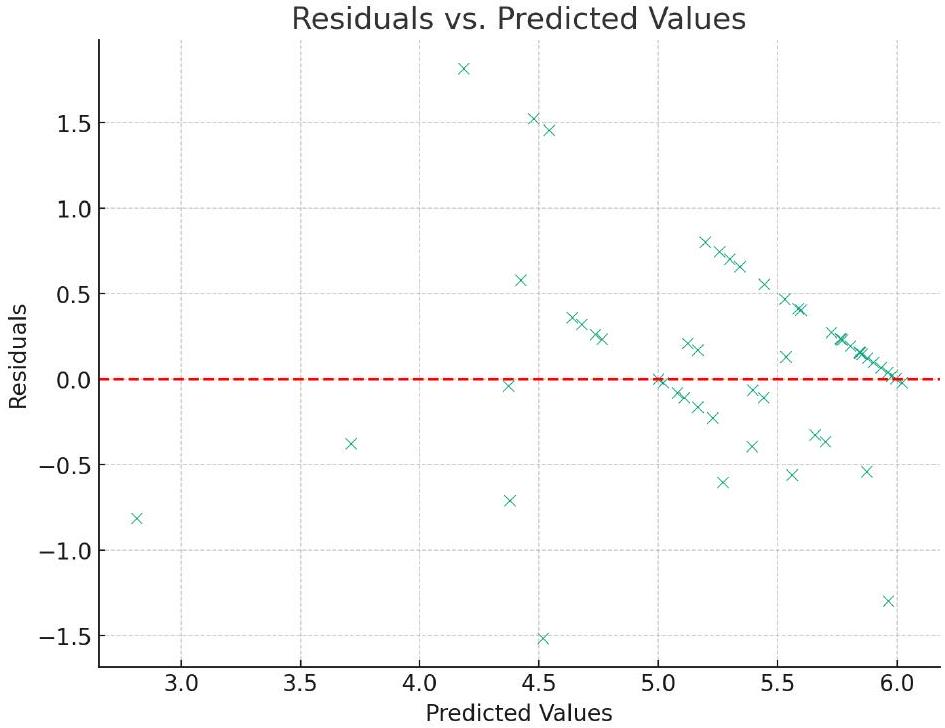

الملحق ب (تحليل الإفراط في التكيف)

- عنوان المؤلف: دانيال روسو،daniel.russo@cs.aau.dkقسم علوم الحاسوب، جامعة آلبورغ، شارع أ. سي. مايرز فايينغ، 15، 2450، كوبنهاغن، الدنمارك.يتم منح الإذن لعمل نسخ رقمية أو ورقية من كل أو جزء من هذا العمل للاستخدام الشخصي أو في الفصول الدراسية دون رسوم، بشرط ألا يتم صنع النسخ أو توزيعها لأغراض ربحية أو تجارية وأن تحمل النسخ هذا الإشعار والاستشهاد الكامل في الصفحة الأولى. يجب احترام حقوق الطبع والنشر للمكونات التي تعود ملكيتها لجهات أخرى غير ACM. يُسمح بالتلخيص مع الإشارة إلى المصدر. لنسخ أي شيء آخر، أو إعادة نشره، أو نشره على الخوادم أو إعادة توزيعه إلى القوائم، يتطلب إذنًا محددًا مسبقًا و/أو رسومًا. يرجى طلب الإذن منpermissions@acm.org.

لقد التزمنا باستمرار بالتعويض المقترح من قبل Prolific. للرجوع إليك، تم دفع المشاركين في الساعة مقابل وقتهم، أي، لهذا التحقيق. للحصول على مقارنة شاملة بين القياسات الانعكاسية والتكوينية، انظر روسو وستول (2021). على الرغم من أن أحجام التأثير الأكبر ليست مشكلة بحد ذاتها، إلا أنها قد تشير أحيانًا إلى خطر محتمل للإفراط في التكيف. ومع ذلك، فقد أجرينا فحصًا شاملاً لهذه المسألة المحتملة في الملحق ب وخلصنا إلى أن الإفراط في التكيف غير موجود في نموذجنا. رابط حزمة النسخ المتماثل:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8124332.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3652154

Publication Date: 2024-03-28

Navigating the Complexity of Generative AI Adoption in Software Engineering

Abstract

This paper explores the adoption of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools within the domain of software engineering, focusing on the influencing factors at the individual, technological, and social levels. We applied a convergent mixed-methods approach to offer a comprehensive understanding of AI adoption dynamics. We initially conducted a questionnaire survey with 100 software engineers, drawing upon the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DOI), and the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) as guiding theoretical frameworks. Employing the Gioia Methodology, we derived a theoretical model of AI adoption in software engineering: the Human-AI Collaboration and Adaptation Framework (HACAF). This model was then validated using Partial Least Squares – Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) based on data from 183 software engineers. Findings indicate that at this early stage of AI integration, the compatibility of AI tools within existing development workflows predominantly drives their adoption, challenging conventional technology acceptance theories. The impact of perceived usefulness, social factors, and personal innovativeness seems less pronounced than expected. The study provides crucial insights for future AI tool design and offers a framework for developing effective organizational implementation strategies.

ACM Reference Format:

1 INTRODUCTION