DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02282-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38281026

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-27

التنقل في علاقة الطبيب بالمريض والذكاء الاصطناعي – دراسة مختلطة لآراء الأطباء تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية

الملخص

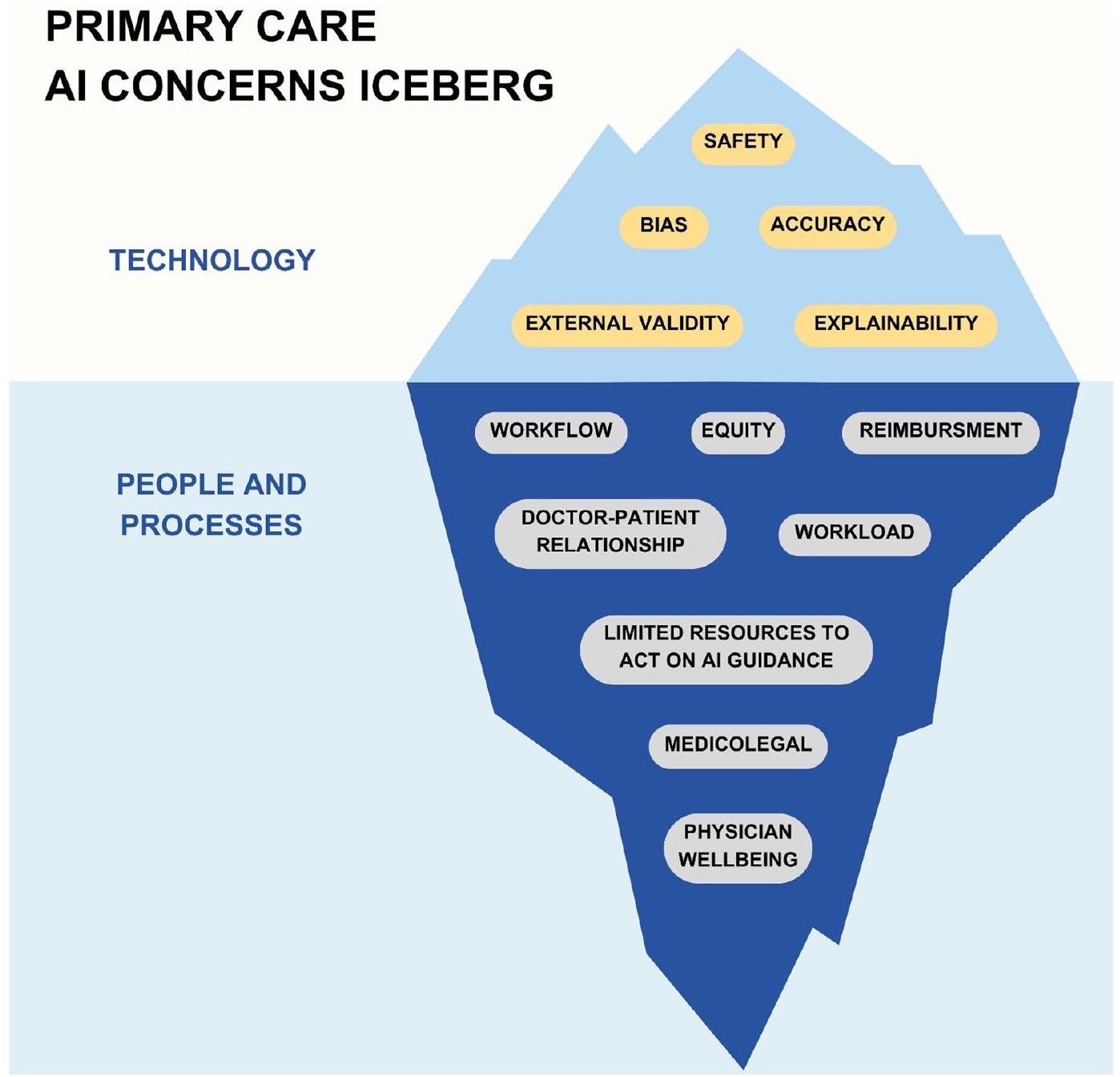

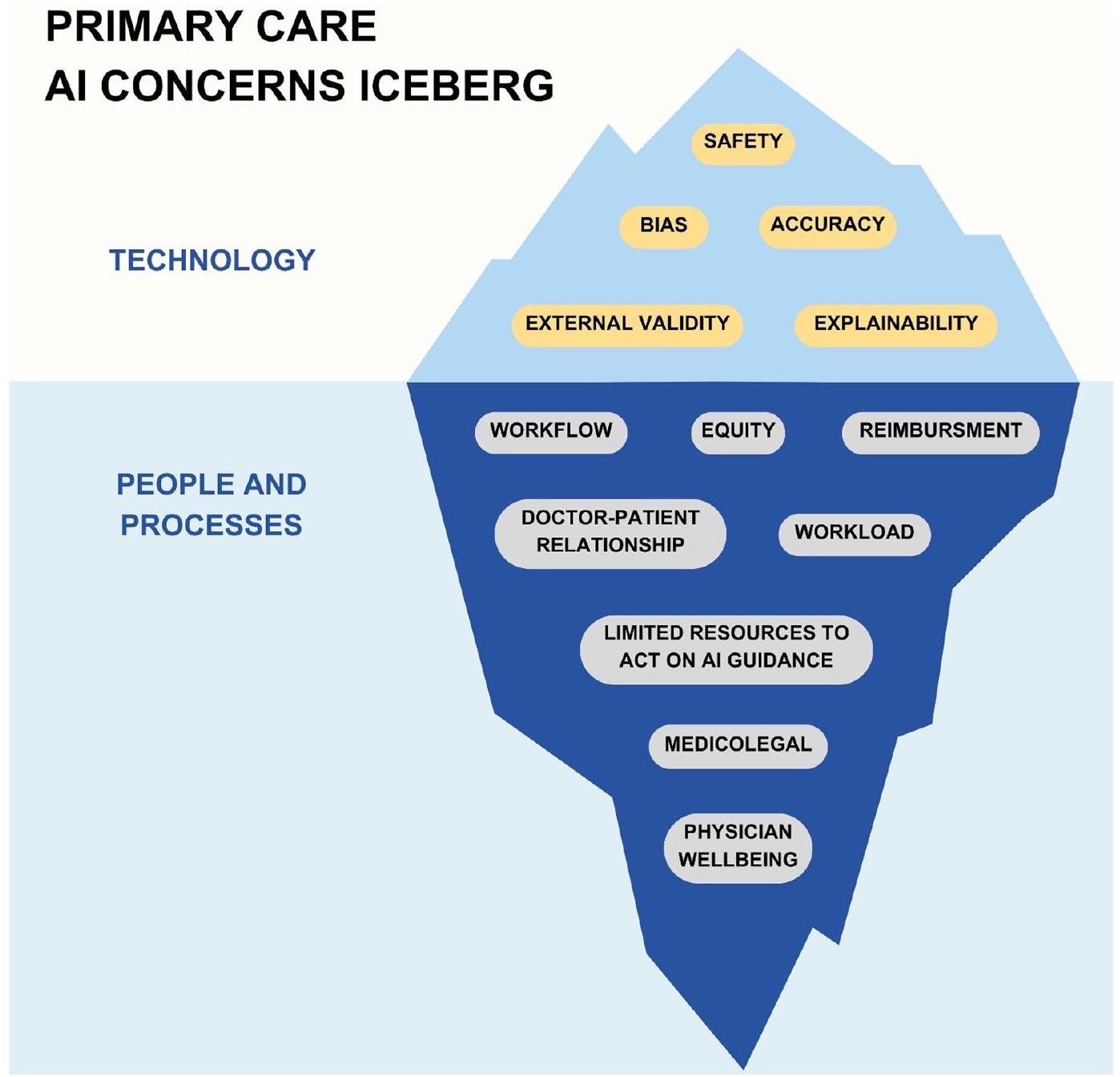

الخلفية: الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) هو مجال يتقدم بسرعة ويبدأ في دخول ممارسة الطب. الرعاية الأولية هي حجر الزاوية في الطب وتتعامل مع تحديات مثل نقص الأطباء والإرهاق الذي يؤثر على رعاية المرضى. يتم تقديم الذكاء الاصطناعي وتطبيقه عبر الصحة الرقمية بشكل متزايد كحل محتمل. ومع ذلك، هناك نقص في الأبحاث التي تركز على مواقف أطباء الرعاية الأولية (PCP) تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي. تدرس هذه الدراسة آراء PCP حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية. نستكشف تأثيره المحتمل على مواضيع ذات صلة بالرعاية الأولية مثل علاقة الطبيب بالمريض وسير العمل السريري. من خلال القيام بذلك، نهدف إلى إبلاغ أصحاب المصلحة في الرعاية الأولية لتشجيع الاستخدام الناجح والعادل لأدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي المستقبلية. دراستنا هي الأولى من نوعها، حسب علمنا، التي تستكشف مواقف PCP باستخدام حالات استخدام محددة للذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية بدلاً من مناقشة الذكاء الاصطناعي في الطب بشكل عام. الطرق: من يونيو إلى أغسطس 2023، أجرينا استطلاعًا بين 47 طبيب رعاية أولية مرتبطين بنظام صحي أكاديمي كبير في جنوب كاليفورنيا. قام الاستطلاع بتحديد مواقف تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل عام وكذلك فيما يتعلق بحالتين محددتين لاستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أجرينا مقابلات مع 15 من المشاركين في الاستطلاع. النتائج: تشير نتائجنا إلى أن PCPs لديهم آراء إيجابية إلى حد كبير حول الذكاء الاصطناعي. ومع ذلك، غالبًا ما كانت المواقف تعتمد على سياق التبني. بينما كانت بعض المخاوف التي أبلغ عنها PCPs بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية تركز على التكنولوجيا (الدقة، السلامة، التحيز)، كانت العديد منها تركز على عوامل تتعلق بالأشخاص والعمليات (سير العمل، العدالة، التعويض، علاقة الطبيب بالمريض). الخلاصة: تقدم دراستنا رؤى دقيقة حول مواقف PCP تجاه الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية وتبرز الحاجة إلى توافق أصحاب المصلحة في الرعاية الأولية حول القضايا الرئيسية التي أثارها PCPs. قد تواجه مبادرات الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تفشل في معالجة كل من المخاوف التكنولوجية ومخاوف الأشخاص والعمليات التي أثارها PCPs صعوبة في تحقيق تأثير.

الخلفية

الرعاية الأولية، التكنولوجيا والعدالة الصحية

قد عانى لفترة طويلة من نقص في الاهتمام والموارد والاعتراف مقارنة بالتخصصات الطبية الأخرى [31-33]. وقد ساهم ذلك في نقص نسبي في تقدم الذكاء الاصطناعي وتنفيذه في الرعاية الأولية على الرغم من الحاجة الكبيرة والإمكانات [9، 22، 34-36]. وبناءً عليه، فإن العدالة هي اعتبار رئيسي للذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية.

الهدف

الطرق

مشاركة المشاركين مع الذكاء الاصطناعي والصحة الرقمية

فحص الأمراض المعزز بالذكاء الاصطناعي: انقطاع النفس النومي الانسدادي

إدارة الأمراض الميسرة بالذكاء الاصطناعي: ارتفاع ضغط الدم

النهج لديه القدرة على مساعدة أطباء الرعاية الأولية في تقديم رعاية دقيقة لارتفاع ضغط الدم بناءً على الخصائص الفريدة للمرضى، مع تزويدهم أيضًا بالأدوات والكفاءات للقيام بذلك على مستوى السكان. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قدمت مؤسستنا خدمة صحة سكانية تتيح لأطباء الرعاية الأولية إحالة المرضى الذين يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم إلى إدارة الأدوية الرقمية التي تتم عن بُعد بواسطة الممرضين والصيادلة. هذه الحالة تمثل نموذجًا لإدارة الأمراض المزمنة في الرعاية الأولية وتثير تساؤلات مثل: كيف يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي تعزيز قدرات أطباء الرعاية الأولية أو تنسيق الرعاية بين أعضاء فريق الرعاية الأولية المختلفين؟

المهام الإدارية المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي: رسائل المرضى

استطلاع رقمي

سنوات

مقابلة شبه منظمة

النتائج

الآراء العامة حول الذكاء الاصطناعي في الطب

القلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي في الرعاية الأولية

| نطاق | مريح جداً | مريح إلى حد ما | محايد | غير مريح إلى حد ما | غير مريح للغاية |

| فحص الأمراض | ٢٩.٨٪ | ٤٦.٨٪ | ٨.٥٪ | ٨.٥٪ | 6.4% |

| إدارة الأمراض المزمنة | 25.5% | ٤٦.٨٪ | 12.8% | ٨.٥٪ | 6.4% |

| تشخيص الأمراض | ٨.٥٪ | 42.6% | 10.6% | ٢٣.٤٪ | 14.9% |

| المهام الإدارية | ٤٠.٤٪ | 25.5% | 12.8% | 14.9% | 6.4% |

لقد عرفت الكثير من مرضاي الآن لمدة 30 عامًا وأعرف الكثير عنهم. لا يمكن حقًا وضع ذلك في مجموعة بيانات يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي الاستناد إليها. [المشارك F]

في هذه المرحلة، أريد أن أتمكن من الحصول على تفسير منطقي. [المشارك ل]

أنا بخير تمامًا إذا كانت تجربتي مع الوقت تتحسن أكثر فأكثر وأشعر، كما تعلم، أنها تعمل. لا تسألني كيف تعمل، لكنها تعمل. [المشارك أ]

أعتقد تقريبًا أن الأداة تضيف المزيد إلى عملية اتخاذ القرار إذا كانت تعمل خارج تلك العملية العقلانية القابلة للوصول البشري. [المشارك ب]

إذا كان النظام يقول، ‘مرحبًا، هذه الشخص لديه انقطاع تنفس أثناء النوم الشديد، وماذا لو تعرض لحادث سيارة غدًا وكان لدينا تلك البيانات اليوم؟ [المشارك O]

عندما نقوم بتحميل نظامنا من هذا الجانب، نحتاج إلى أن تكون الموارد متاحة من الجانب الآخر. [المشارك E]

أعتقد أننا بحاجة إلى أن نكون مجهزين بشكل أفضل قبل أن نبدأ في إخبار الناس بهذا لأنه، كما تعلم، الأمر يشبه، مرحبًا، قد يكون لديك انقطاع النفس أثناء النوم. انتظر ستة أشهر لدراسة نومك… [المشارك ج]

قلقي هو أنه مثل كل شيء آخر حاولنا القيام به لتحسين الأمور في الطب، فإنه في الواقع يجعل الأمور أصعب على الطبيب ويخلق المزيد من العمل لنا بدلاً من تقليل العمل. [المشارك د]

هل يجب أن يتعامل الأطباء مع هذا في المقام الأول؟ [المشارك ك]

إنه مثل وجود طالب معي طوال الوقت، حيث يجب أن أتحقق من كل شيء مرتين. [المشارك د]

أو تركيز مفرط على الإنتاجية.

سنضيف مريضين إضافيين لكل جلسة لأنه الآن لدينا مساعدة هناك. لذا، للأسف، أحيانًا تُستخدم المزيد من المساعدة بطريقة سلبية. [المشارك هـ]

إذا كنت أستطيع رؤية 30 مريضًا في يوم واحد، وأنهيت سجلاتي بحلول الساعة 6 مساءً، مبتسمًا، وأعود إلى المنزل لتناول العشاء، سأكون سعيدًا. [المشارك ز]

ربما تكون أكثر تعاطفًا في اللقاء، لأنك لم تضطر إلى القيام بكل ذلك الحمل الذهني. [المشارك م]

للإشارة إلى أنهم لا يرغبون في أن يتم إبلاغهم. عندما سُئلوا عما إذا كانوا على علم بسجل إلكتروني موجود مسبقًا للمرضى الذين يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم، أجاب ما يقرب من نصفهم (45.83%) بلا. بالنسبة لأولئك الذين كانوا على علم بالسجل، أبلغ أكثر من نصفهم أن استخدامهم للسجل كان “نادراً” (

نقاش

الذكاء الاصطناعي كحد سيفين

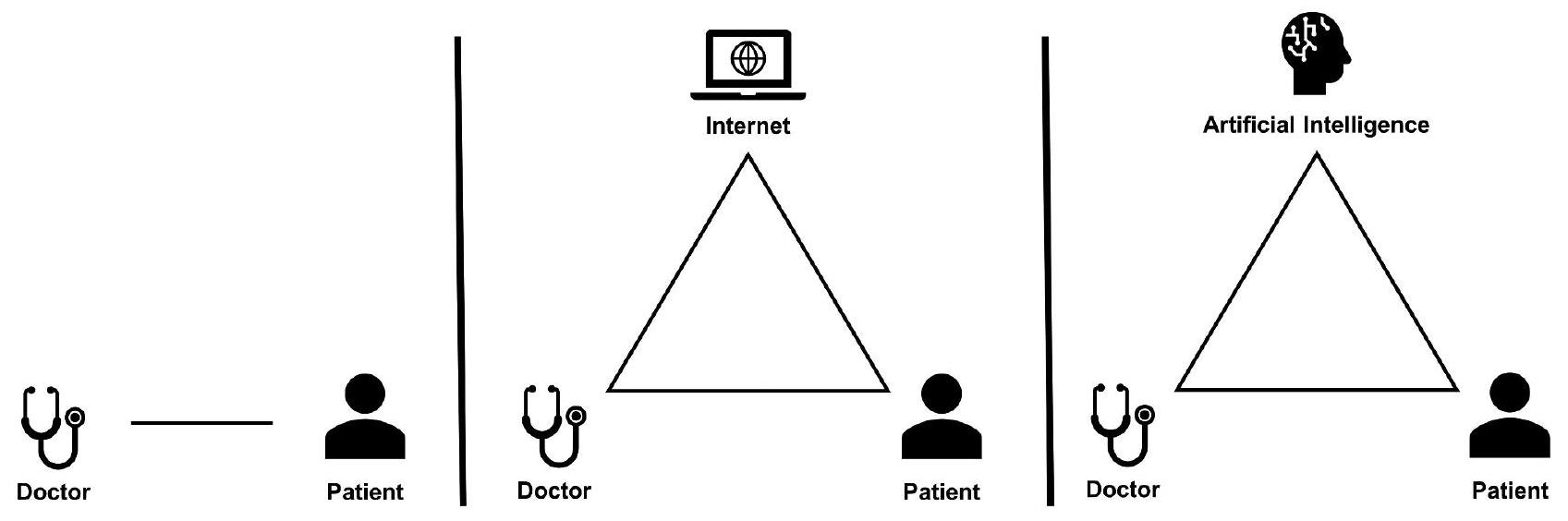

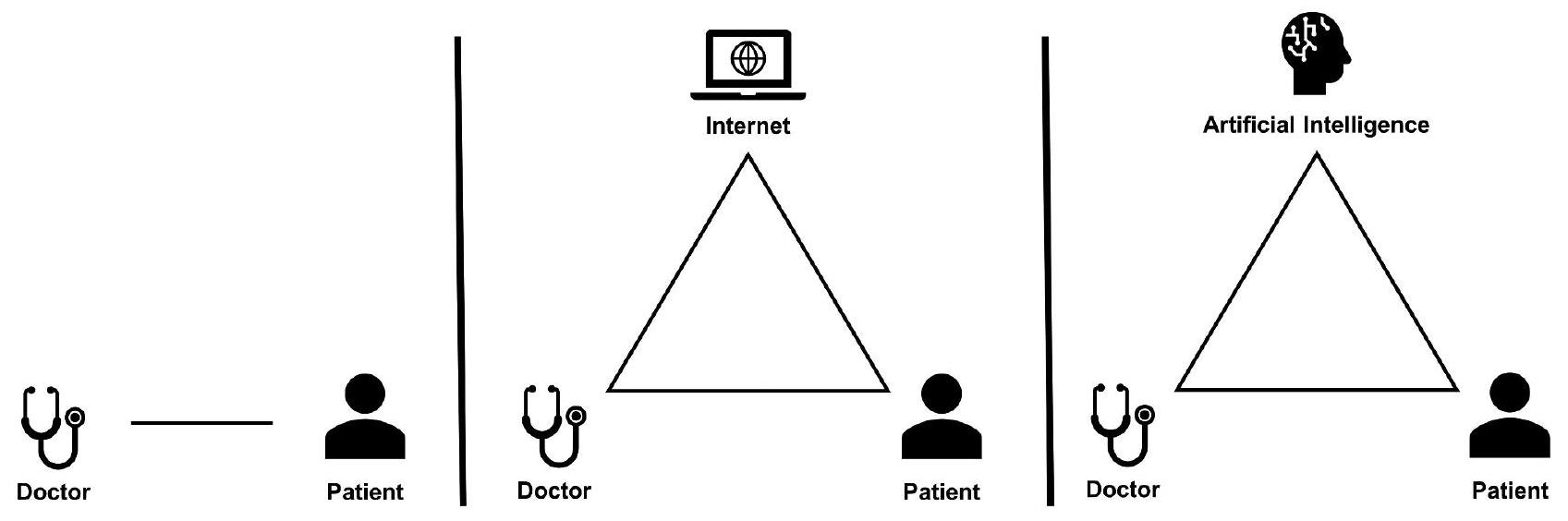

التنقل في العلاقة بين الطبيب والمريض والذكاء الاصطناعي

يجب تكرار وتوسيع الكثير من الأبحاث التي أجريت لاستكشاف تأثير معلومات الصحة على الإنترنت على علاقة الطبيب بالمريض في سياق الذكاء الاصطناعي. على عكس المعلومات الثابتة على الإنترنت، فإن أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التفاعلية مستعدة لتولي دور أكثر نشاطًا في تشكيل التفاعلات بين المرضى والأطباء. إن ضمان تأثير إيجابي للذكاء الاصطناعي على علاقة الطبيب بالمريض أمر ضروري للحفاظ على العقد الاجتماعي للطب مع المجتمع.

دور الذكاء الاصطناعي في تزويد المرضى بالمعلومات، سواء كانت دقيقة أو مضللة، يمكن أن يربك الديناميكية بين الطبيب والمريض. المرضى الذين يصلون بمعلومات مستندة إلى الذكاء الاصطناعي

يمكن أن تعقد المعلومات اتخاذ القرارات التعاونية. تشمل العواقب المحتملة الالتزام الصارم بنصائح الذكاء الاصطناعي دون النظر في التاريخ الطبي الفردي أو الصعوبات التي يواجهها الأطباء في محاولة التوفيق بين خبراتهم واقتراحات الذكاء الاصطناعي. لا يهدد هذا فقط بتآكل دور طبيب الرعاية الأولية، بل يمكن أن يعيد تشكيل العلاقة بين الطبيب والمريض إلى نموذج المستهلك والمزود.

أنا قلق بشأن الذكاء الاصطناعي، حيث يتم تعزيز المعلومات المضللة… إذا جاء مريض وقال، مرحبًا، كما تعلم، أخبرني WebMD.GPT أنني بحاجة إلى تصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي، فهناك شيء آخر قوي أجادل ضده. [المشارك ب]

“بدلاً من مجرد الإفصاح عن الأمر ورؤية ما سيحدث، تريد التأكد من أن كل من سيتفاعل مع ذلك لديه توقعات دقيقة وقد تم توعيته بالدور الذي من المفترض أن يلعبه.” [المشارك ج]

مستقبل سير العمل في الرعاية الأولية

معظم رعايتنا تُقدم عبر MyChart. دعونا نكون صادقين، هكذا يتم تقديمها. [المشارك ج]

العواقب [77]. من المحتمل أن تصبح الأدوات الرقمية المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي لإدارة الأمراض المزمنة وفحص الأمراض، المعززة بأنظمة مراقبة المرضى عن بُعد، أكثر شيوعًا [78، 79]. وبناءً عليه، يجب النظر في كيفية تخصيص وقت الأطباء بشكل أفضل لدعم الصحة الرقمية. النجاح في الصحة الرقمية يتجاوز مجرد حل مشكلة تراكم الرسائل الواردة أو إرهاق الإنذارات، بل يتعلق بتحقيق تحول أساسي في كيفية تفاعل الرعاية الأولية مع المرضى ورعايتهم [6]. نقترح أن تجربة جداول العمل الهجينة التي تجمع بين الحضور الشخصي والافتراضي يمكن أن تمكن الأطباء من تحقيق إمكانيات الصحة الرقمية [80].

اعتبارات لأصحاب المصلحة في الرعاية الأولية

| المعنيون | توصية |

| الدافعين | تنفيذ نماذج سداد مبتكرة لمقدمي الرعاية الأولية وأعضاء فريق الرعاية الأولية الآخرين المشاركين في الصحة الرقمية |

| أنظمة الرعاية الصحية | جدولة الوقت وتحديد المعايير لمقدمي الرعاية الأولية للمشاركة في الصحة الرقمية |

| أنظمة الرعاية الصحية | تزويد مقدمي الرعاية الأولية بأعضاء فريق إضافيين مثل الصيادلة أو منسقي المرضى الذين يمكنهم التفاعل رقميًا مع المرضى |

| أنظمة الرعاية الصحية | تطوير وتوزيع مواد تعليمية حول الدور الصحيح للأدوات الجديدة للذكاء الاصطناعي للمرضى والأطباء قبل تنفيذ الأداة |

| الباحثون | قم بإجراء تجارب عشوائية محكومة، تجارب عملية، أو أبحاث قائمة على الممارسة بين سير العمل التقليدي وسير العمل المعزز رقميًا لمقدمي الرعاية الأولية. |

| الباحثون | تقييم أدوات الرقمية المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي الجديدة في سياق سير عمل الأطباء بدلاً من بيئة معزولة |

| PCPs | الدفاع بشكل فردي وجماعي عن أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تحسن جودة رعاية الأطباء، والرفاهية، وعلاقة الطبيب بالمريض |

الذكاء الاصطناعي والعدالة

أننا سنستبعد أفقر الناس من الحصول على أفضل رعاية. – المشارك ج.

نقاط القوة، والقيود، والاتجاهات للبحوث المستقبلية

ومقدمي الرعاية المتقدمين مثل ممارسي التمريض ومساعدي الأطباء. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث حول كيفية تجربة المرضى – وخاصة أولئك الذين قد يكونون مهمشين – للتحول نحو الذكاء الاصطناعي والصحة الرقمية في الرعاية الأولية. أخيرًا، يجب أن يتوسع البحث المستقبلي أيضًا ليشمل تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخرى ذات الصلة بالرعاية الأولية.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

طبيب الرعاية الأولية PCP

مركز AMC الطبي الأكاديمي

انقطاع النفس النومي الانسدادي (OSA)

سجل الصحة الإلكتروني (EHR)

معلومات إضافية

المادة التكميلية 2: أسئلة مستمدة من المقابلة شبه المنظمة

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 27 يناير 2024

References

- Strohm L, Hehakaya C, Ranschaert ER, Boon WPC, Moors EHM. Implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in radiology: hindering and facilitating factors. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5525-32.

- Park CJ, Yi PH, Siegel EL. Medical Student perspectives on the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the practice of Medicine. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50(5):614-9.

- Briganti G, Le Moine O. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Today and Tomorrow. Front Med [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 6];7. Available from: https:// www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00027.

- Seneviratne MG, Shah NH, Chu L. Bridging the implementation gap of machine learning in healthcare. BMJ Innov. 2020;6(2):45-7.

- Zimlichman E, Nicklin W, Aggarwal R, Bates D, Health Care. 2030: The Coming Transformation. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv [Internet]. (March 1, 2021). Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1056/ CAT.20.0569.

- Pagliari C. Digital health and primary care: past, pandemic and prospects. J Glob Health. 2021;11:01005.

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-3.

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the Residency Expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-14.

- Lin SA, Clinician’s, Guide to Artificial Intelligence (AI). Why and how primary care should lead the Health Care AI revolution. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):175-84.

- Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, Sherritt KM. Professional Dissonance and Burnout in Primary Care: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):395.

- Amano A, Brown-Johnson CG, Winget M, Sinha A, Shah S, Sinsky CA, et al. Perspectives on the Intersection of Electronic Health Records and Health Care Team Communication, function, and well-being. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2313178.

- Kearley KE, Freeman GK, Heath A. An exploration of the value of the personal doctor-patient relationship in general practice. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):712-8.

- Aminololama-Shakeri S, López JE. The Doctor-Patient Relationship with Artificial Intelligence. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(2):308-10.

- Nagy M, Sisk B. How will Artificial Intelligence Affect Patient-Clinician relationships? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E395-400.

- Blease C, Kaptchuk TJ, Bernstein MH, Mandl KD, Halamka JD, DesRoches CM. Artificial Intelligence and the future of primary care: exploratory qualitative study of UK General practitioners’ views. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12802.

- Buck C, Doctor E, Hennrich J, Jöhnk J, Eymann T. General practitioners’ attitudes toward Artificial intelligence-enabled systems: interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e28916.

- Kueper JK, Terry AL, Zwarenstein M, Lizotte DJ. Artificial Intelligence and Primary Care Research: a scoping review. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):250-8.

- Marwaha JS, Landman AB, Brat GA, Dunn T, Gordon WJ. Deploying digital health tools within large, complex health systems: key considerations for adoption and implementation. Npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):1-7.

- Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA. Physician burnout in the Electronic Health Record Era: are we ignoring the Real cause? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):50.

- López L, Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, King RS, Betancourt JR. Bridging the Digital divide in Health Care: the role of Health Information Technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(10):437-45.

- Latulippe K, Hamel C, Giroux D. Social Health Inequalities and eHealth: A literature review with qualitative synthesis of theoretical and empirical studies. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e136.

- Weiss D, Rydland HT, Øversveen E, Jensen MR, Solhaug S, Krokstad S. G Virgili editor 2018 Innovative technologies and social inequalities in health: a scoping review of the literature. PLOS ONE 134 e0195447.

- Ramsetty A, Adams C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19.J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1147-8.

- Yao R, Zhang W, Evans R, Cao G, Rui T, Shen L. Inequities in Health Care services caused by the Adoption of Digital Health Technologies: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e34144.

- Joyce K, Smith-Doerr L, Alegria S, Bell S, Cruz T, Hoffman SG, et al. Toward a sociology of Artificial Intelligence: a call for Research on inequalities and Structural Change. Socius Sociol Res Dyn World. 2021;7:237802312199958.

- Salhi RA, Dupati A, Burkhardt JC. Interest in serving the Underserved: role of race, gender, and Medical Specialty Plans. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):933-41.

- Jetty A, Hyppolite J, Eden AR, Taylor MK, Jabbarpour Y. Underrepresented Minority Family Physicians more likely to care for vulnerable populations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(2):223-4.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Blumenthal D, Mort E, Edwards J. The efficacy of primary care for vulnerable population groups. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1 Pt 2):253-73.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority Physicians’ role in the Care of Underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing Health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289.

- Lambert SI, Madi M, Sopka S, Lenes A, Stange H, Buszello CP, et al. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):1-14.

- Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The Paradox of Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293-9.

- Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica. 2012;2012:1-22.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA. Primary care Artificial Intelligence: a branch hiding in Plain Sight. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):194-5.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA. Artificial Intelligence and Family Medicine: better together. Fam Med. 2020;52(1):8-10.

- Lin SY, Mahoney MR, Sinsky CA. Ten ways Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1626-30.

- Fatehi F, Samadbeik M, Kazemi A. What is Digital Health? Review of definitions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;275:67-71.

- Motamedi KK, McClary AC, Amedee RG. Obstructive sleep apnea: a growing problem. Ochsner J. 2009;9(3):149-53.

- Ramesh J, Keeran N, Sagahyroon A, Aloul F. Towards validating the effectiveness of obstructive sleep apnea classification from Electronic Health Records Using Machine Learning. Healthc Basel Switz. 2021;9(11):1450.

- Maniaci A, Riela PM, lannella G, Lechien JR, La Mantia I, De Vincentiis M, et al. Machine learning identification of obstructive sleep apnea severity through the patient clinical features: a retrospective study. Life Basel Switz. 2023;13(3):702.

- Molina-Ortiz El, Vega AC, Calman NS. Patient registries in primary care: essential element for Quality Improvement: P ATIENT R EGISTRIES IN P RIMARY C ARE. Mt Sinai. J Med J Transl Pers Med. 2012;79(4):475-80.

- Hu Y, Huerta J, Cordella N, Mishuris RG, Paschalidis IC. Personalized hypertension treatment recommendations by a data-driven model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):44.

- Fisher NDL, Fera LE, Dunning JR, Desai S, Matta L, Liquori V, et al. Development of an entirely remote, non-physician led hypertension management program. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42(2):285-91.

- Visco V, Izzo C, Mancusi C, Rispoli A, Tedeschi M, Virtuoso N, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Hypertension Management: an Ace up your sleeve. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10(2):74.

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-60.

- University NCS, Payton F, Pare G, Montréal HEC, Le Rouge C, Saint L et al. University,. Health Care IT: Process, People, Patients and Interdisciplinary Considerations. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2011;12(2):I-XIII.

- the Precise4Q consortium, Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, Frey D, Madai VI. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):310.

- Challen R, Denny J, Pitt M, Gompels L, Edwards T, Tsaneva-Atanasova K. Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):231-7.

- Wong A, Otles E, Donnelly JP, Krumm A, McCullough J, DeTroyer-Cooley O, et al. External validation of a widely implemented proprietary Sepsis prediction model in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(8):1065.

- Yu KH, Kohane IS. Framing the challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):238-41.

- Terry AL, Kueper JK, Beleno R, Brown JB, Cejic S, Dang J, et al. Is primary health care ready for artificial intelligence? What do primary health care stakeholders say? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):237.

- Phillips RL, Bazemore AW, Newton WP. PURSUING PRACTICAL PROFESSIONALISM: FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(5):472-5.

- Relman AS. The New Medical-Industrial Complex. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(17):963-70.

- Tai-Seale M, Baxter S, Millen M, Cheung M, Zisook S, Çelebi J et al. Association of physician burnout with perceived EHR work stress and potentially actionable factors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023;ocad136.

- Bodenheimer TS, Smith MD. Primary care: proposed solutions to the physician shortage without training more Physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1881-6.

- Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and Electronic Communication. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):11-9.

- Raffoul M, Moore M, Kamerow D, Bazemore A. A primary care panel size of 2500 is neither Accurate nor reasonable. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2016;29(4):496-9.

- Harrington C. Considerations for patient panel size. Del J Public Health. 2022;8(5):154-7.

- Salisbury C, Murphy M, Duncan P. The impact of Digital-First Consultations on workload in General Practice: modeling study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e18203.

- Halbesleben JRB, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29-39.

- Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608-10.

- Streeter RA, Snyder JE, Kepley H, Stahl AL, Li T, Washko MM. The geographic alignment of primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas

with markers for social determinants of health. Shah TI, editor. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231443. - Liu J, Jason. Health Professional Shortage and Health Status and Health Care Access. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(3):590-8.

- Ahuja AS. The impact of artificial intelligence in medicine on the future role of the physician. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7702.

- Van Riel N, Auwerx K, Debbaut P, Van Hees S, Schoenmakers B. The effect of Dr Google on doctor-patient encounters in primary care: a quantitative, observational, cross-sectional study. BJGP Open. 2017;1(2):bjgpopen17X100833.

- Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, Catania J, White M, et al. The impact of Health Information on the internet on the physician-patient relationship: patient perceptions. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(14):1727.

- Tan SSL, Goonawardene N. Internet Health Information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e9.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA, Yang Z. Is Artificial Intelligence the Key to Reclaiming relationships in Primary Care? Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):558-9.

- Luo A, Qin L, Yuan Y, Yang Z, Liu F, Huang P, et al. The Effect of Online Health Information seeking on Physician-Patient relationships: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e23354.

- Cruess SR. Professionalism and Medicine’s Social Contract with Society. Clin Orthop. 2006;449:170-6.

- Resnicow K, Catley D, Goggin K, Hawley S, Williams GC. Shared decision making in Health Care: theoretical perspectives for why it works and for whom. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2022;42(6):755-64.

- Verlinde E, De Laender N, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Willems S. The social gradient in doctor-patient communication. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):12.

- Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Derese A, De Maeseneer J. Socioeconomic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):139-46.

- Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan WJ, Sinsky CA, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-26.

- Tai-Seale M, Olson CW, Li J, Chan AS, Morikawa C, Durbin M, et al. Electronic Health Record logs Indicate that Physicians Split Time evenly between seeing patients and Desktop Medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):655-62.

- Murphy DR, Meyer AND, Russo E, Sittig DF, Wei L, Singh H. The Burden of Inbox Notifications in Commercial Electronic Health Records. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):559.

- Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, Nordgren R, Steinberg RL, Nauenberg T, et al. Physicians’ well-being linked to In-Basket messages generated by Algorithms in Electronic Health Records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1073-8.

- Muller AE, Berg RC, Jardim PSJ, Johansen TB, Ormstad SS. Can remote patient monitoring be the New Standard in Primary Care of Chronic Diseases, Post-COVID-19? Telemed E-Health. 2022;28(7):942-69.

- Willis VC, Thomas Craig KJ, Jabbarpour Y, Scheufele EL, Arriaga YE, Ajinkya M, et al. Digital Health Interventions To Enhance Prevention in Primary Care: scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2022;10(1):e33518.

- Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a New Medical Specialty? The Medical Virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437.

- Goldberg DG, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, Love LE, Carver MC. Team-Based Care: a critical element of Primary Care Practice Transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(3):150-6.

- American College of Physicians, Smith CD, Balatbat C, National Academy of Medicine, Corbridge S. University of Illinois at Chicago, Implementing Optimal Team-Based Care to Reduce Clinician Burnout. NAM Perspect [Internet]. 2018 Sep 17 [cited 2023 Aug 1];8(9). Available from: https://nam.edu/ implementing-optimal-team-based-care-to-reduce-clinician-burnout.

- Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Candrian C, deGruy FV, Binswanger IA. Primary care providers’ experiences caring for complex patients in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):34.

- Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Coleman K, Phillips KE, Sugarman JR. Improving care coordination in primary care. Med Care. 2014;52(11 Suppl 4):33-8.

- Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, Stone JA, Smith PD, Wetterneck TB. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2016;23(1):29-37.

- Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care [Internet]. McCauley L, Phillips RL, Meisnere M, Robinson SK, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ; 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/ catalog/25983.

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time Allocation in Primary Care Office visits: Time Allocation in Primary Care. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1871-94.

- Hilty DM, Torous J, Parish MB, Chan SR, Xiong G, Scher L, et al. A literature review comparing clinicians’ approaches and skills to In-Person, Synchronous, and Asynchronous Care: moving toward competencies to ensure Quality Care. Telemed E-Health. 2021;27(4):356-73.

- Rotenstein LS, Holmgren AJ, Healey MJ, Horn DM, Ting DY, Lipsitz S, et al. Association between Electronic Health Record Time and Quality of Care Metrics in Primary Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2237086.

- Saag HS, Shah K, Jones SA, Testa PA, Horwitz LI. Pajama Time: Working after Work in the Electronic Health Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1695-6.

- Pellegrino ED, Altruism. Self-interest, and Medical Ethics. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1987;258(14):1939.

- Sajjad M, Qayyum S, Iltaf S, Khan RA. The best interest of patients, not selfinterest: how clinicians understand altruism. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):477.

- Jones R. Declining altruism in medicine. BMJ. 2002;324(7338):624-5.

- Yin J, Ngiam KY, Teo HH. Role of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Real-Life Clinical Practice: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e25759.

- Choudhury A, Asan O, Medow JE. Clinicians’ perceptions of an Artificial Intelligence-based blood utilization calculator: qualitative exploratory study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(4):e38411.

- Thomas Craig KJ, Willis VC, Gruen D, Rhee K, Jackson GP. The burden of the digital environment: a systematic review on organization-directed workplace interventions to mitigate physician burnout. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2021;28(5):985-97.

- Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I, Sutton M, Leese B, Giuffrida A et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2000 Jul 24 [cited 2023 Jul 31];2011(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002215.

- Diaz N. More health systems charging for MyChart messages. Becker’s Health IT [Internet]. 2022 Aug 28 [cited 2023 Aug 17]; Available from: https:// www.beckershospitalreview.com/ehrs/more-health-systems-charging-for-mychart-messages.html.

- Porter ME, Pabo EA, Lee TH. Redesigning primary care: a Strategic Vision to improve Value by Organizing around patients’ needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(3):516-25.

- AMA Future of Health issue brief: Commercial Payer Coverage for Digital Medicine Codes. American Medical Association [Internet]. 2023 Sep 18 [cited 2023 Sep 26]; Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/ digital/ama-future-health-issue-brief-commercial-payer-coverage-digital.

- Richardson S, Lawrence K, Schoenthaler AM, Mann D. A framework for digital health equity. Npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):119.

- Frimpong JA, Jackson BE, Stewart LM, Singh KP, Rivers PA, Bae S. Health information technology capacity at federally qualified health centers: a mechanism for improving quality of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):35.

- Guo J, Li B. The application of Medical Artificial Intelligence Technology in Rural areas of developing countries. Health Equity. 2018;2(1):174-81.

- Davlyatov G, Borkowski N, Feldman S, Qu H, Burke D, Bronstein J, et al. Health Information Technology Adoption and Clinical Performance in Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Healthc Qual. 2020;42(5):287-93.

- Iyanna S, Kaur P, Ractham P, Talwar S, Najmul Islam AKM. Digital transformation of healthcare sector. What is impeding adoption and continued usage of technology-driven innovations by end-users? J Bus Res. 2022;153:150-61.

- Richardson JP, Smith C, Curtis S, Watson S, Zhu X, Barry B, et al. Patient apprehensions about the use of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Npj Digit Med. 2021;4(1):140.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

ماثيو ر. ألين

Mattallen876@gmail.com; maa007@health.ucsd.edu

قسم طب الأسرة، جامعة كاليفورنيا سان دييغو، لا

جولا، كاليفورنيا 92093، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم المعلوماتية الحيوية، جامعة كاليفورنيا سان دييغو، لا

جولا، كاليفورنيا 92093، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02282-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38281026

Publication Date: 2024-01-27

Navigating the doctor-patient-AI relationship a mixed-methods study of physician attitudes toward artificial intelligence in primary care

Abstract

Background Artificial intelligence (AI) is a rapidly advancing field that is beginning to enter the practice of medicine. Primary care is a cornerstone of medicine and deals with challenges such as physician shortage and burnout which impact patient care. AI and its application via digital health is increasingly presented as a possible solution. However, there is a scarcity of research focusing on primary care physician (PCP) attitudes toward AI. This study examines PCP views on AI in primary care. We explore its potential impact on topics pertinent to primary care such as the doctorpatient relationship and clinical workflow. By doing so, we aim to inform primary care stakeholders to encourage successful, equitable uptake of future AI tools. Our study is the first to our knowledge to explore PCP attitudes using specific primary care AI use cases rather than discussing AI in medicine in general terms. Methods From June to August 2023, we conducted a survey among 47 primary care physicians affiliated with a large academic health system in Southern California. The survey quantified attitudes toward AI in general as well as concerning two specific AI use cases. Additionally, we conducted interviews with 15 survey respondents. Results Our findings suggest that PCPs have largely positive views of AI. However, attitudes often hinged on the context of adoption. While some concerns reported by PCPs regarding AI in primary care focused on technology (accuracy, safety, bias), many focused on people-and-process factors (workflow, equity, reimbursement, doctorpatient relationship). Conclusion Our study offers nuanced insights into PCP attitudes towards AI in primary care and highlights the need for primary care stakeholder alignment on key issues raised by PCPs. AI initiatives that fail to address both the technological and people-and-process concerns raised by PCPs may struggle to make an impact.

Background

Primary care, technology and health equity

has long endured a lack of attention, resources, and recognition compared to other medical specialties [31-33]. This has contributed to a comparative lack of AI progress and implementation in primary care in spite of huge need and potential [9, 22, 34-36]. Accordingly, equity is a key consideration for AI in primary care.

Objective

Methods

Participant engagement with AI and digital health

Al-enhanced disease screening: obstructive sleep apnea

Al-facilitated disease management: hypertension

approach has potential to help primary care physicians give precise hypertension care based on unique patient characteristics while also giving them tools and efficiencies to do so at a population level [42-44]. Additionally, our institution has introduced a population health service enabling PCPs to refer patients with hypertension to digital medication management facilitated remotely by nurses and pharmacists. This use case is an archetype for chronic disease management in primary care and raises questions such as: how can AI augment PCP abilities or coordinate care between different primary care team members?

AI-facilitated administrative tasks: patient messaging

Digital survey

years

Semi-structured interview

Results

General perceptions of a.i. in medicine

Concerns about AI in primary care

| Domain | Very Comfortable | Somewhat Comfortable | Neutral | Somewhat Uncomfortable | Very Uncomfortable |

| Disease Screening | 29.8% | 46.8% | 8.5% | 8.5% | 6.4% |

| Chronic Disease Management | 25.5% | 46.8% | 12.8% | 8.5% | 6.4% |

| Disease Diagnosis | 8.5% | 42.6% | 10.6% | 23.4% | 14.9% |

| Administrative Tasks | 40.4% | 25.5% | 12.8% | 14.9% | 6.4% |

I’ve known a lot of my patients now for 30 years and know a lot about them. That can’t really be put into a data set that AI can draw upon. [Participant F]

At this point, I want to be able to get a logical explanation. [Participant L]

I’m perfectly okay if my own experience with time goes better and better and I feel like, you know, it works. Don’t ask me how it works, but it works. [Participant A]

I almost think that the tool adds more to the deci-sion-making process if it’s operating outside of that human accessible reasoning process. [Participant B]

If the system is saying, ‘Hey, this person has severe sleep apnea, and what if they get in a car accident tomorrow and we had that data today? [Participant O]

When we are loading our system from this side, we need to have the resources on the other side. [Participant E]

I think we need to be better equipped before we start telling people this because, you know, it’s like, Hey, you might have sleep apnea. Wait six months for your sleep study… [Participant C]

My concern is that like everything else that we have tried to do to make things better in medicine is that it actually makes things harder on the physician and creates more work for us instead of less work. [Participant D]

Is it really the physicians that should deal with this in the first place? [Participant K]

It’s like having a student with me all the time, where I’ve got to just double check everything. [Participant D]

or an excessive focus on productivity.

We are going to add two extra patients per session because now we have help there. So unfortunately, sometimes more help is used in a negative way. [Participant E]

If I could see 30 patients in a day, and actually close out my charts by 6pm, smiling, and get home for dinner, I’d be happy. [Participant G]

Maybe you are actually then more compassionate in an encounter, because you haven’t had to do all of that mental lifting. [Participant M]

to indicate that they would not like to be notified. When asked if they were aware of a pre-existing EHR registry of patients with hypertension, nearly half (45.83%) responded no. For those that were aware of the registry, more than half reported that their usage of the registry was “infrequently” (

Discussion

Al as a double-edged sword

Navigating the doctor-patient-AI relationship

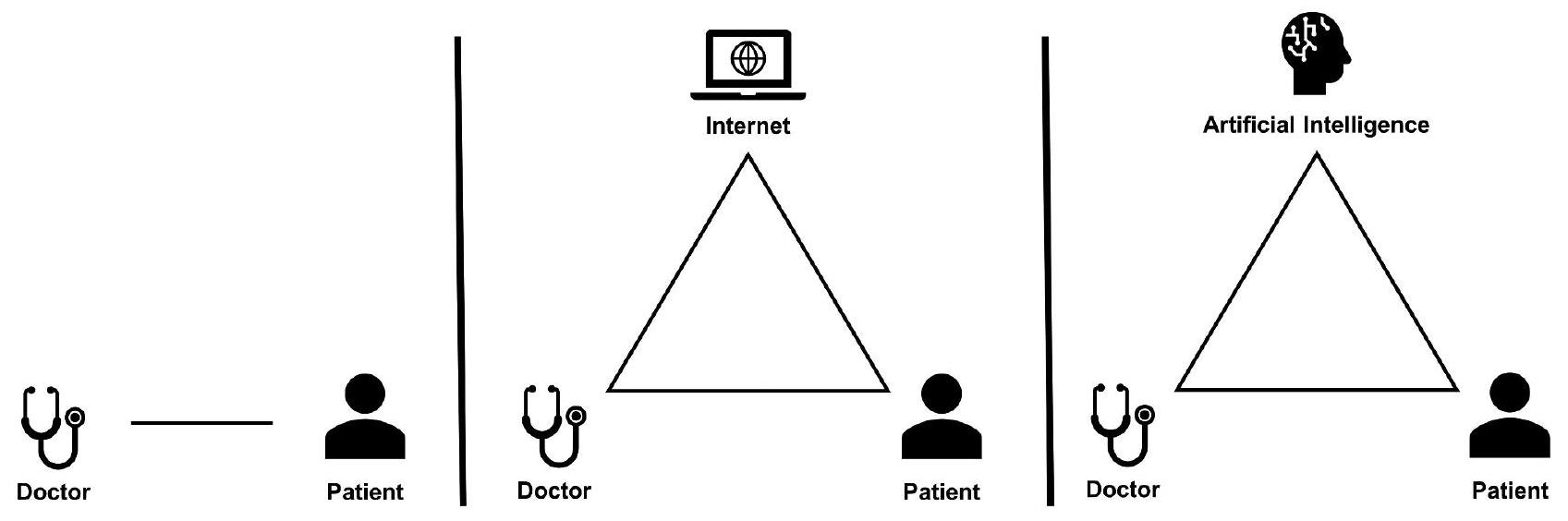

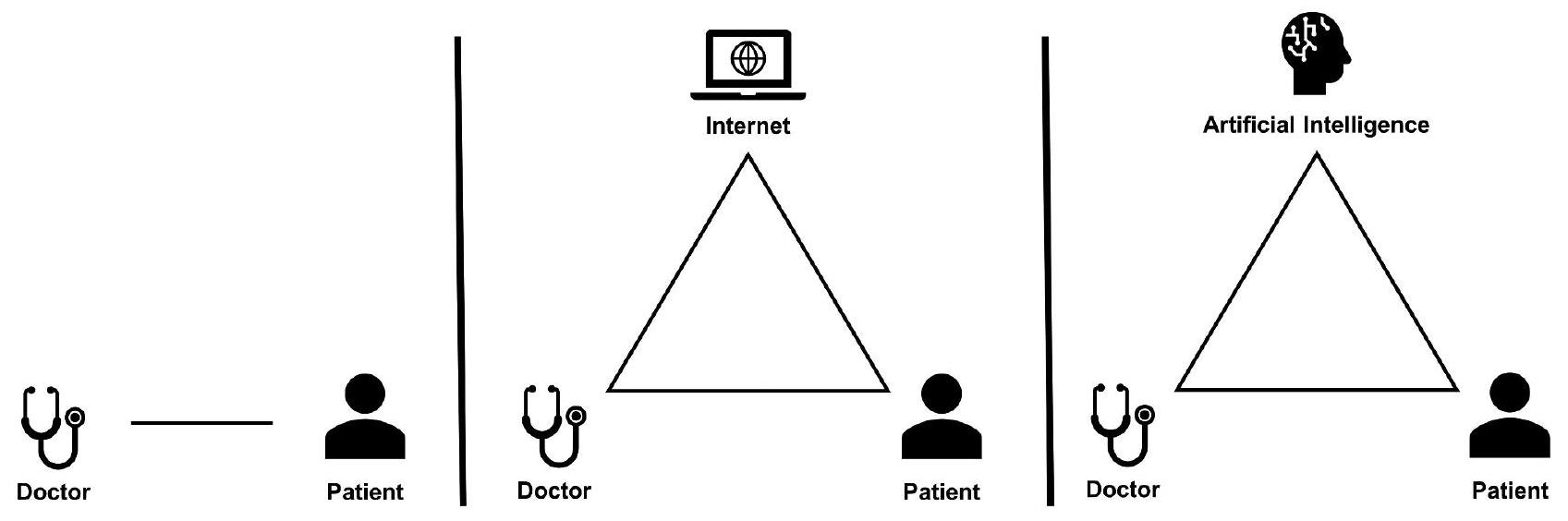

Much of the same research that was done to explore the impact of internet health information on the doctorpatient relationship needs to be repeated and expanded upon in the context of AI. Unlike static online information, interactive AI systems are poised to assume a more active role in shaping the interactions between patients and physicians. Ensuring a positive impact of AI on the doctor-patient relationship is essential to maintaining medicine’s social contract with society [70].

AI’s role in providing patients with information, be it accurate or misleading, could confound the physicianpatient dynamic. Patients arriving with AI-informed

information could complicate collaborative decisionmaking [71]. Possible consequences include rigid adherence to AI-driven advice without considering individual medical history or difficulties for physicians attempting to reconcile their expertise with AI suggestions. This not only risks eroding the PCP’s role but also could reshape the doctor-patient relationship into a consumer-provider model.

I’m worried about AI, introducing a dynamic where misinformation is enhanced… if a patient comes in and they’re like, hey, like, you know, WebMD.GPT told me that I need an MRI then there’s another powerful thing that I’m arguing against. [Participant B]

Instead of just letting the cat out of the bag and seeing what happens, you want to make sure that everyone that is going to be interacting with it has accurate expectations and has been educated on what role this is supposed to play. [Participant J]

The future of primary care workflow

“Most of our care is delivered in MyChart. Like let’s just be honest, that’s how it’s getting delivered. [Participant G]

consequences [77]. AI-powered digital tools for chronic disease management and disease screening augmented by remote patient monitoring systems will likely become increasingly common [78, 79]. Accordingly, consideration needs to be given to how best to allocate physician time to support digital health. Succeeding in digital health is more than solving inbox overload or alarm fatigue but rather realizing a fundamental shift in how primary care interacts with and takes care of patients [6]. We propose that experimenting with hybrid in-person and virtual work schedules could empower physicians to actualize the potential of digital health [80].

Considerations for primary care stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Recommendation |

| Payors | Implement innovative reimbursement models for PCPs and other primary care team members engaging in digital health |

| Healthcare Systems | Schedule time and establish standards for PCPs to engage in digital health |

| Healthcare Systems | Provide PCPs with additional team members such as pharmacists or patient coordinators who can engage digitally with patients |

| Healthcare Systems | Develop and disseminate educational materials on the proper role of new AI tools to patients and physicians before tool implementation |

| Researchers | Run RCTs, pragmatic trials, or practice-based research between traditional and digitally enhanced PCP workflows |

| Researchers | Evaluate new AI-powered digital tools in the context of physician workflow instead of an isolated environment |

| PCPs | Advocate individually and collectively for Al tools that improve physician care quality, wellbeing, and the doctor-patient relationship |

Al and equity

that we will leave out the poorest people from getting the best care. – Participant G.

Strengths, limitations, and directions for future research

and advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. In addition, greater research is needed on how patients-especially those that may be marginalized-are experiencing a shift toward AI and digital health in primary care [105, 106]. Finally, future research should also expand beyond our selected AI use cases to incorporate other AI applications pertinent to primary care.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

PCP Primary Care Physician

AMC Academic Medical Center

OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea

EHR Electronic Health Record

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 2: Questions stems from the semi-structured interview

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 27 January 2024

References

- Strohm L, Hehakaya C, Ranschaert ER, Boon WPC, Moors EHM. Implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in radiology: hindering and facilitating factors. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5525-32.

- Park CJ, Yi PH, Siegel EL. Medical Student perspectives on the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the practice of Medicine. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50(5):614-9.

- Briganti G, Le Moine O. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Today and Tomorrow. Front Med [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Aug 6];7. Available from: https:// www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00027.

- Seneviratne MG, Shah NH, Chu L. Bridging the implementation gap of machine learning in healthcare. BMJ Innov. 2020;6(2):45-7.

- Zimlichman E, Nicklin W, Aggarwal R, Bates D, Health Care. 2030: The Coming Transformation. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv [Internet]. (March 1, 2021). Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1056/ CAT.20.0569.

- Pagliari C. Digital health and primary care: past, pandemic and prospects. J Glob Health. 2021;11:01005.

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-3.

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the Residency Expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-14.

- Lin SA, Clinician’s, Guide to Artificial Intelligence (AI). Why and how primary care should lead the Health Care AI revolution. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):175-84.

- Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, Sherritt KM. Professional Dissonance and Burnout in Primary Care: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):395.

- Amano A, Brown-Johnson CG, Winget M, Sinha A, Shah S, Sinsky CA, et al. Perspectives on the Intersection of Electronic Health Records and Health Care Team Communication, function, and well-being. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2313178.

- Kearley KE, Freeman GK, Heath A. An exploration of the value of the personal doctor-patient relationship in general practice. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):712-8.

- Aminololama-Shakeri S, López JE. The Doctor-Patient Relationship with Artificial Intelligence. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(2):308-10.

- Nagy M, Sisk B. How will Artificial Intelligence Affect Patient-Clinician relationships? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(5):E395-400.

- Blease C, Kaptchuk TJ, Bernstein MH, Mandl KD, Halamka JD, DesRoches CM. Artificial Intelligence and the future of primary care: exploratory qualitative study of UK General practitioners’ views. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12802.

- Buck C, Doctor E, Hennrich J, Jöhnk J, Eymann T. General practitioners’ attitudes toward Artificial intelligence-enabled systems: interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e28916.

- Kueper JK, Terry AL, Zwarenstein M, Lizotte DJ. Artificial Intelligence and Primary Care Research: a scoping review. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):250-8.

- Marwaha JS, Landman AB, Brat GA, Dunn T, Gordon WJ. Deploying digital health tools within large, complex health systems: key considerations for adoption and implementation. Npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):1-7.

- Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA. Physician burnout in the Electronic Health Record Era: are we ignoring the Real cause? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):50.

- López L, Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, King RS, Betancourt JR. Bridging the Digital divide in Health Care: the role of Health Information Technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(10):437-45.

- Latulippe K, Hamel C, Giroux D. Social Health Inequalities and eHealth: A literature review with qualitative synthesis of theoretical and empirical studies. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e136.

- Weiss D, Rydland HT, Øversveen E, Jensen MR, Solhaug S, Krokstad S. G Virgili editor 2018 Innovative technologies and social inequalities in health: a scoping review of the literature. PLOS ONE 134 e0195447.

- Ramsetty A, Adams C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19.J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1147-8.

- Yao R, Zhang W, Evans R, Cao G, Rui T, Shen L. Inequities in Health Care services caused by the Adoption of Digital Health Technologies: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e34144.

- Joyce K, Smith-Doerr L, Alegria S, Bell S, Cruz T, Hoffman SG, et al. Toward a sociology of Artificial Intelligence: a call for Research on inequalities and Structural Change. Socius Sociol Res Dyn World. 2021;7:237802312199958.

- Salhi RA, Dupati A, Burkhardt JC. Interest in serving the Underserved: role of race, gender, and Medical Specialty Plans. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):933-41.

- Jetty A, Hyppolite J, Eden AR, Taylor MK, Jabbarpour Y. Underrepresented Minority Family Physicians more likely to care for vulnerable populations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(2):223-4.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Blumenthal D, Mort E, Edwards J. The efficacy of primary care for vulnerable population groups. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1 Pt 2):253-73.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority Physicians’ role in the Care of Underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing Health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289.

- Lambert SI, Madi M, Sopka S, Lenes A, Stange H, Buszello CP, et al. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):1-14.

- Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The Paradox of Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293-9.

- Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica. 2012;2012:1-22.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA. Primary care Artificial Intelligence: a branch hiding in Plain Sight. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):194-5.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA. Artificial Intelligence and Family Medicine: better together. Fam Med. 2020;52(1):8-10.

- Lin SY, Mahoney MR, Sinsky CA. Ten ways Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1626-30.

- Fatehi F, Samadbeik M, Kazemi A. What is Digital Health? Review of definitions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;275:67-71.

- Motamedi KK, McClary AC, Amedee RG. Obstructive sleep apnea: a growing problem. Ochsner J. 2009;9(3):149-53.

- Ramesh J, Keeran N, Sagahyroon A, Aloul F. Towards validating the effectiveness of obstructive sleep apnea classification from Electronic Health Records Using Machine Learning. Healthc Basel Switz. 2021;9(11):1450.

- Maniaci A, Riela PM, lannella G, Lechien JR, La Mantia I, De Vincentiis M, et al. Machine learning identification of obstructive sleep apnea severity through the patient clinical features: a retrospective study. Life Basel Switz. 2023;13(3):702.

- Molina-Ortiz El, Vega AC, Calman NS. Patient registries in primary care: essential element for Quality Improvement: P ATIENT R EGISTRIES IN P RIMARY C ARE. Mt Sinai. J Med J Transl Pers Med. 2012;79(4):475-80.

- Hu Y, Huerta J, Cordella N, Mishuris RG, Paschalidis IC. Personalized hypertension treatment recommendations by a data-driven model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):44.

- Fisher NDL, Fera LE, Dunning JR, Desai S, Matta L, Liquori V, et al. Development of an entirely remote, non-physician led hypertension management program. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42(2):285-91.

- Visco V, Izzo C, Mancusi C, Rispoli A, Tedeschi M, Virtuoso N, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Hypertension Management: an Ace up your sleeve. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10(2):74.

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-60.

- University NCS, Payton F, Pare G, Montréal HEC, Le Rouge C, Saint L et al. University,. Health Care IT: Process, People, Patients and Interdisciplinary Considerations. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2011;12(2):I-XIII.

- the Precise4Q consortium, Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, Frey D, Madai VI. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):310.

- Challen R, Denny J, Pitt M, Gompels L, Edwards T, Tsaneva-Atanasova K. Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):231-7.

- Wong A, Otles E, Donnelly JP, Krumm A, McCullough J, DeTroyer-Cooley O, et al. External validation of a widely implemented proprietary Sepsis prediction model in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(8):1065.

- Yu KH, Kohane IS. Framing the challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):238-41.

- Terry AL, Kueper JK, Beleno R, Brown JB, Cejic S, Dang J, et al. Is primary health care ready for artificial intelligence? What do primary health care stakeholders say? BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):237.

- Phillips RL, Bazemore AW, Newton WP. PURSUING PRACTICAL PROFESSIONALISM: FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(5):472-5.

- Relman AS. The New Medical-Industrial Complex. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(17):963-70.

- Tai-Seale M, Baxter S, Millen M, Cheung M, Zisook S, Çelebi J et al. Association of physician burnout with perceived EHR work stress and potentially actionable factors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023;ocad136.

- Bodenheimer TS, Smith MD. Primary care: proposed solutions to the physician shortage without training more Physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1881-6.

- Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and Electronic Communication. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):11-9.

- Raffoul M, Moore M, Kamerow D, Bazemore A. A primary care panel size of 2500 is neither Accurate nor reasonable. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2016;29(4):496-9.

- Harrington C. Considerations for patient panel size. Del J Public Health. 2022;8(5):154-7.

- Salisbury C, Murphy M, Duncan P. The impact of Digital-First Consultations on workload in General Practice: modeling study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e18203.

- Halbesleben JRB, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29-39.

- Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608-10.

- Streeter RA, Snyder JE, Kepley H, Stahl AL, Li T, Washko MM. The geographic alignment of primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas

with markers for social determinants of health. Shah TI, editor. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231443. - Liu J, Jason. Health Professional Shortage and Health Status and Health Care Access. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(3):590-8.

- Ahuja AS. The impact of artificial intelligence in medicine on the future role of the physician. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7702.

- Van Riel N, Auwerx K, Debbaut P, Van Hees S, Schoenmakers B. The effect of Dr Google on doctor-patient encounters in primary care: a quantitative, observational, cross-sectional study. BJGP Open. 2017;1(2):bjgpopen17X100833.

- Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, Catania J, White M, et al. The impact of Health Information on the internet on the physician-patient relationship: patient perceptions. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(14):1727.

- Tan SSL, Goonawardene N. Internet Health Information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e9.

- Liaw W, Kakadiaris IA, Yang Z. Is Artificial Intelligence the Key to Reclaiming relationships in Primary Care? Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):558-9.

- Luo A, Qin L, Yuan Y, Yang Z, Liu F, Huang P, et al. The Effect of Online Health Information seeking on Physician-Patient relationships: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e23354.

- Cruess SR. Professionalism and Medicine’s Social Contract with Society. Clin Orthop. 2006;449:170-6.

- Resnicow K, Catley D, Goggin K, Hawley S, Williams GC. Shared decision making in Health Care: theoretical perspectives for why it works and for whom. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2022;42(6):755-64.

- Verlinde E, De Laender N, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Willems S. The social gradient in doctor-patient communication. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):12.

- Willems S, De Maesschalck S, Deveugele M, Derese A, De Maeseneer J. Socioeconomic status of the patient and doctor-patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):139-46.

- Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan WJ, Sinsky CA, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-26.

- Tai-Seale M, Olson CW, Li J, Chan AS, Morikawa C, Durbin M, et al. Electronic Health Record logs Indicate that Physicians Split Time evenly between seeing patients and Desktop Medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):655-62.

- Murphy DR, Meyer AND, Russo E, Sittig DF, Wei L, Singh H. The Burden of Inbox Notifications in Commercial Electronic Health Records. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):559.

- Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, Nordgren R, Steinberg RL, Nauenberg T, et al. Physicians’ well-being linked to In-Basket messages generated by Algorithms in Electronic Health Records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1073-8.

- Muller AE, Berg RC, Jardim PSJ, Johansen TB, Ormstad SS. Can remote patient monitoring be the New Standard in Primary Care of Chronic Diseases, Post-COVID-19? Telemed E-Health. 2022;28(7):942-69.

- Willis VC, Thomas Craig KJ, Jabbarpour Y, Scheufele EL, Arriaga YE, Ajinkya M, et al. Digital Health Interventions To Enhance Prevention in Primary Care: scoping review. JMIR Med Inform. 2022;10(1):e33518.

- Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a New Medical Specialty? The Medical Virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437.

- Goldberg DG, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, Love LE, Carver MC. Team-Based Care: a critical element of Primary Care Practice Transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(3):150-6.

- American College of Physicians, Smith CD, Balatbat C, National Academy of Medicine, Corbridge S. University of Illinois at Chicago, Implementing Optimal Team-Based Care to Reduce Clinician Burnout. NAM Perspect [Internet]. 2018 Sep 17 [cited 2023 Aug 1];8(9). Available from: https://nam.edu/ implementing-optimal-team-based-care-to-reduce-clinician-burnout.

- Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Candrian C, deGruy FV, Binswanger IA. Primary care providers’ experiences caring for complex patients in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):34.

- Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Coleman K, Phillips KE, Sugarman JR. Improving care coordination in primary care. Med Care. 2014;52(11 Suppl 4):33-8.

- Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, Stone JA, Smith PD, Wetterneck TB. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2016;23(1):29-37.

- Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care [Internet]. McCauley L, Phillips RL, Meisnere M, Robinson SK, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ; 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/ catalog/25983.

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time Allocation in Primary Care Office visits: Time Allocation in Primary Care. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1871-94.

- Hilty DM, Torous J, Parish MB, Chan SR, Xiong G, Scher L, et al. A literature review comparing clinicians’ approaches and skills to In-Person, Synchronous, and Asynchronous Care: moving toward competencies to ensure Quality Care. Telemed E-Health. 2021;27(4):356-73.

- Rotenstein LS, Holmgren AJ, Healey MJ, Horn DM, Ting DY, Lipsitz S, et al. Association between Electronic Health Record Time and Quality of Care Metrics in Primary Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2237086.

- Saag HS, Shah K, Jones SA, Testa PA, Horwitz LI. Pajama Time: Working after Work in the Electronic Health Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1695-6.

- Pellegrino ED, Altruism. Self-interest, and Medical Ethics. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1987;258(14):1939.

- Sajjad M, Qayyum S, Iltaf S, Khan RA. The best interest of patients, not selfinterest: how clinicians understand altruism. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):477.

- Jones R. Declining altruism in medicine. BMJ. 2002;324(7338):624-5.

- Yin J, Ngiam KY, Teo HH. Role of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Real-Life Clinical Practice: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e25759.

- Choudhury A, Asan O, Medow JE. Clinicians’ perceptions of an Artificial Intelligence-based blood utilization calculator: qualitative exploratory study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(4):e38411.

- Thomas Craig KJ, Willis VC, Gruen D, Rhee K, Jackson GP. The burden of the digital environment: a systematic review on organization-directed workplace interventions to mitigate physician burnout. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA. 2021;28(5):985-97.

- Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I, Sutton M, Leese B, Giuffrida A et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2000 Jul 24 [cited 2023 Jul 31];2011(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002215.

- Diaz N. More health systems charging for MyChart messages. Becker’s Health IT [Internet]. 2022 Aug 28 [cited 2023 Aug 17]; Available from: https:// www.beckershospitalreview.com/ehrs/more-health-systems-charging-for-mychart-messages.html.

- Porter ME, Pabo EA, Lee TH. Redesigning primary care: a Strategic Vision to improve Value by Organizing around patients’ needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(3):516-25.

- AMA Future of Health issue brief: Commercial Payer Coverage for Digital Medicine Codes. American Medical Association [Internet]. 2023 Sep 18 [cited 2023 Sep 26]; Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/ digital/ama-future-health-issue-brief-commercial-payer-coverage-digital.

- Richardson S, Lawrence K, Schoenthaler AM, Mann D. A framework for digital health equity. Npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):119.

- Frimpong JA, Jackson BE, Stewart LM, Singh KP, Rivers PA, Bae S. Health information technology capacity at federally qualified health centers: a mechanism for improving quality of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):35.

- Guo J, Li B. The application of Medical Artificial Intelligence Technology in Rural areas of developing countries. Health Equity. 2018;2(1):174-81.

- Davlyatov G, Borkowski N, Feldman S, Qu H, Burke D, Bronstein J, et al. Health Information Technology Adoption and Clinical Performance in Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Healthc Qual. 2020;42(5):287-93.

- Iyanna S, Kaur P, Ractham P, Talwar S, Najmul Islam AKM. Digital transformation of healthcare sector. What is impeding adoption and continued usage of technology-driven innovations by end-users? J Bus Res. 2022;153:150-61.

- Richardson JP, Smith C, Curtis S, Watson S, Zhu X, Barry B, et al. Patient apprehensions about the use of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Npj Digit Med. 2021;4(1):140.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Matthew R. Allen

Mattallen876@gmail.com; maa007@health.ucsd.edu

Department of Family Medicine, University of California San Diego, La

Jolla, CA 92093, USA

Division of Biomedical Informatics, University of California San Diego, La

Jolla, CA 92093, USA