DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07547-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38867037

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-12

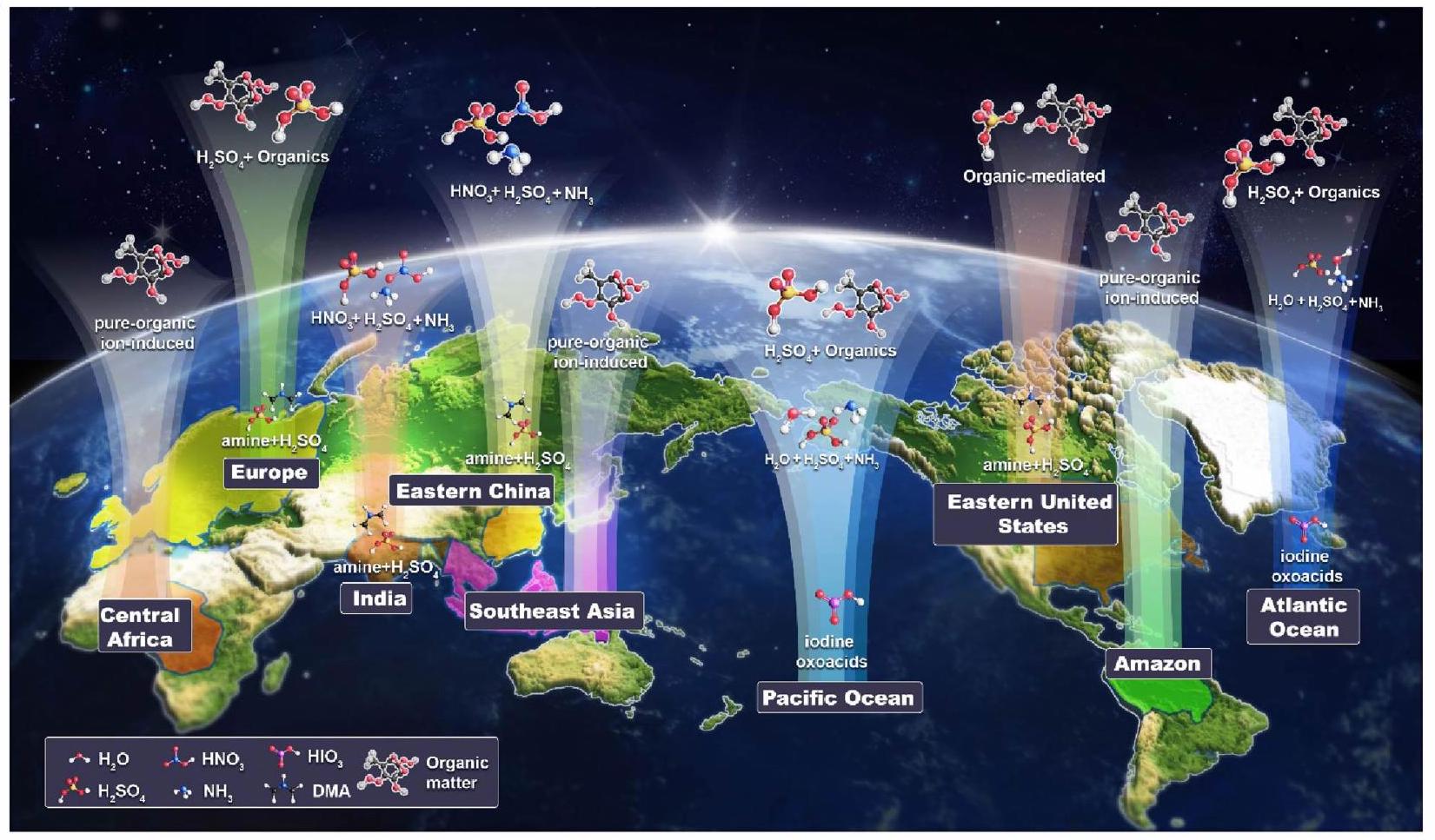

التنوع العالمي في آليات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة في الغلاف الجوي

تاريخ الاستلام: 21 أغسطس 2023

تم القبول: 9 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 12 يونيو 2024

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

تحدٍ رئيسي في دراسات تلوث الهباء الجوي وتقييم تغير المناخ هو فهم كيفية تكوين جزيئات الهباء الجوي في الغلاف الجوي في البداية.

نماذج الغلاف الجوي – أدوات لا غنى عنها لفهم الآليات وتأثيرات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة على المستويات العالمية والإقليمية – تفتقر إلى القدرة على تمثيل العديد من العمليات المهمة بشكل حاسم. تعتمد معظم النماذج العالمية المستخدمة على عمليات تكوين الجسيمات الثنائية والثلاثية التقليدية التي تشمل حمض الكبريتيك.

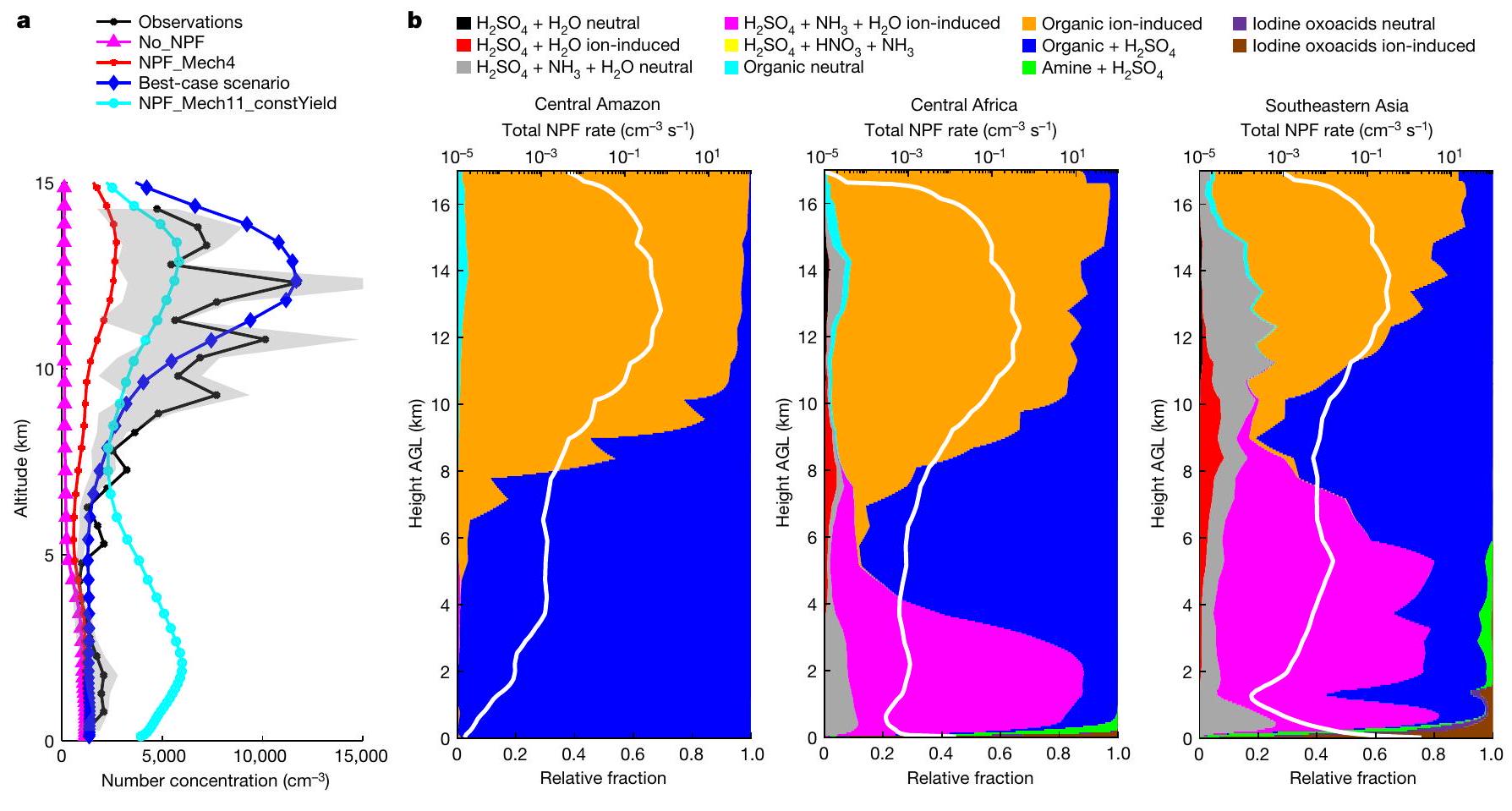

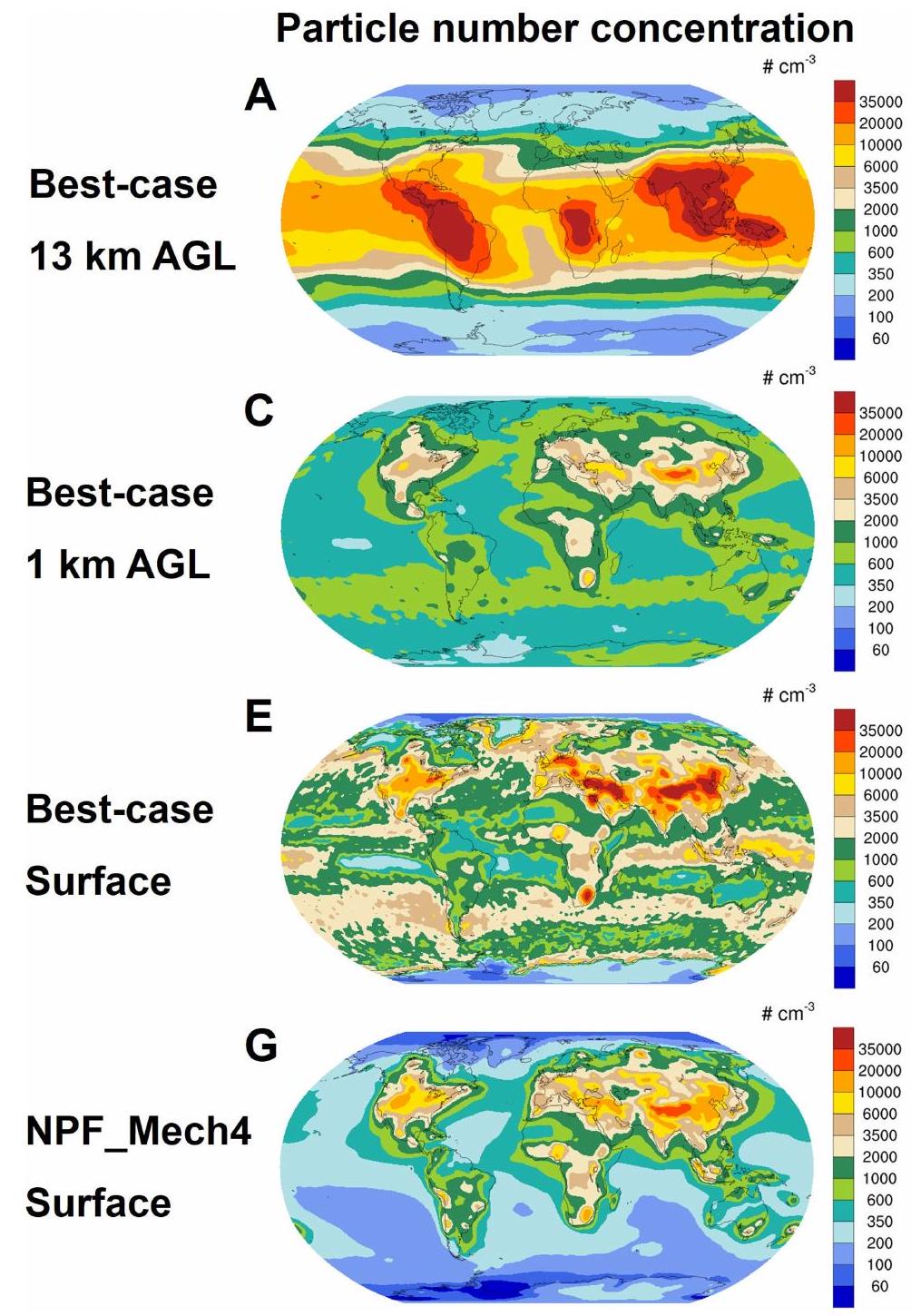

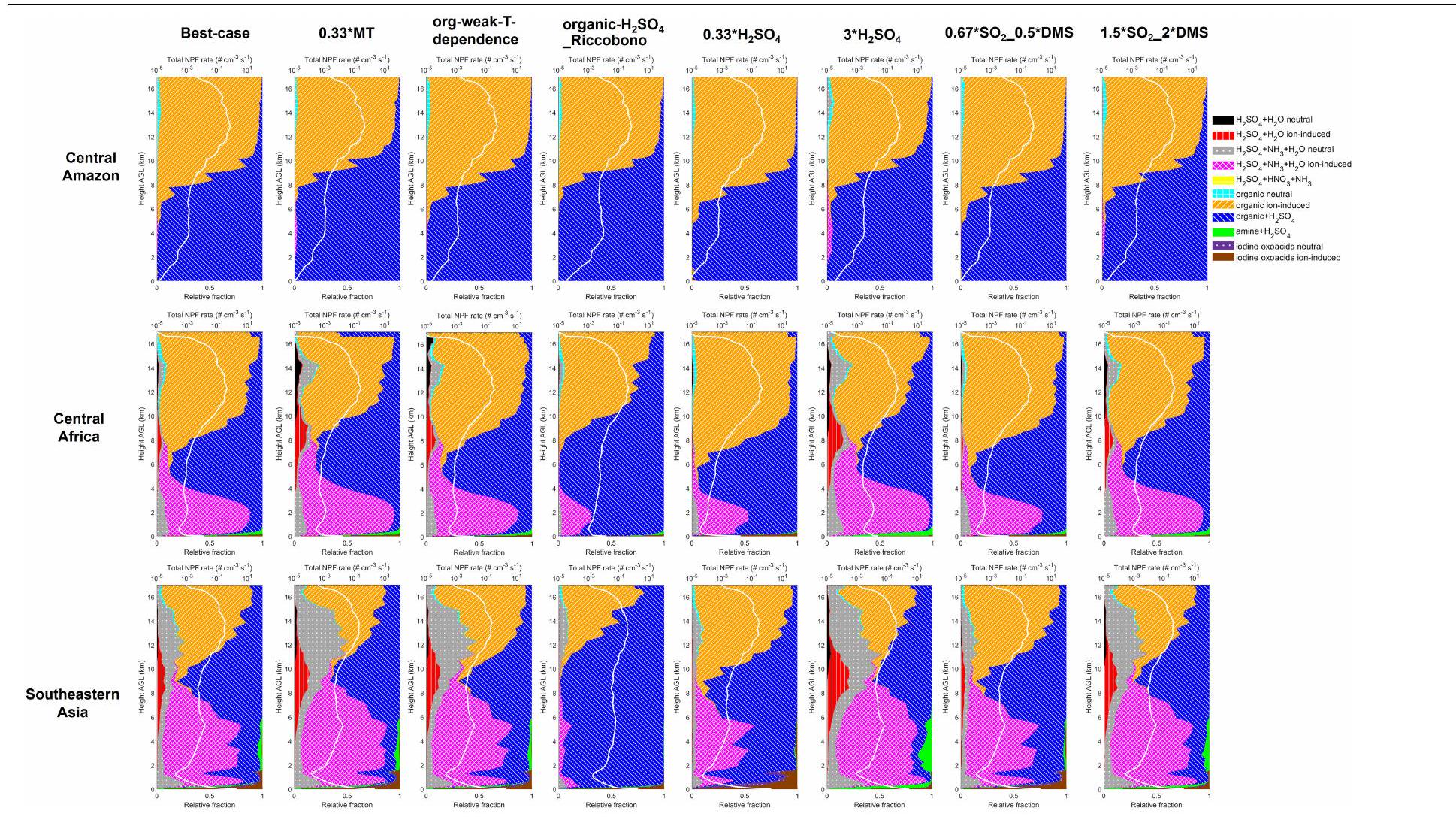

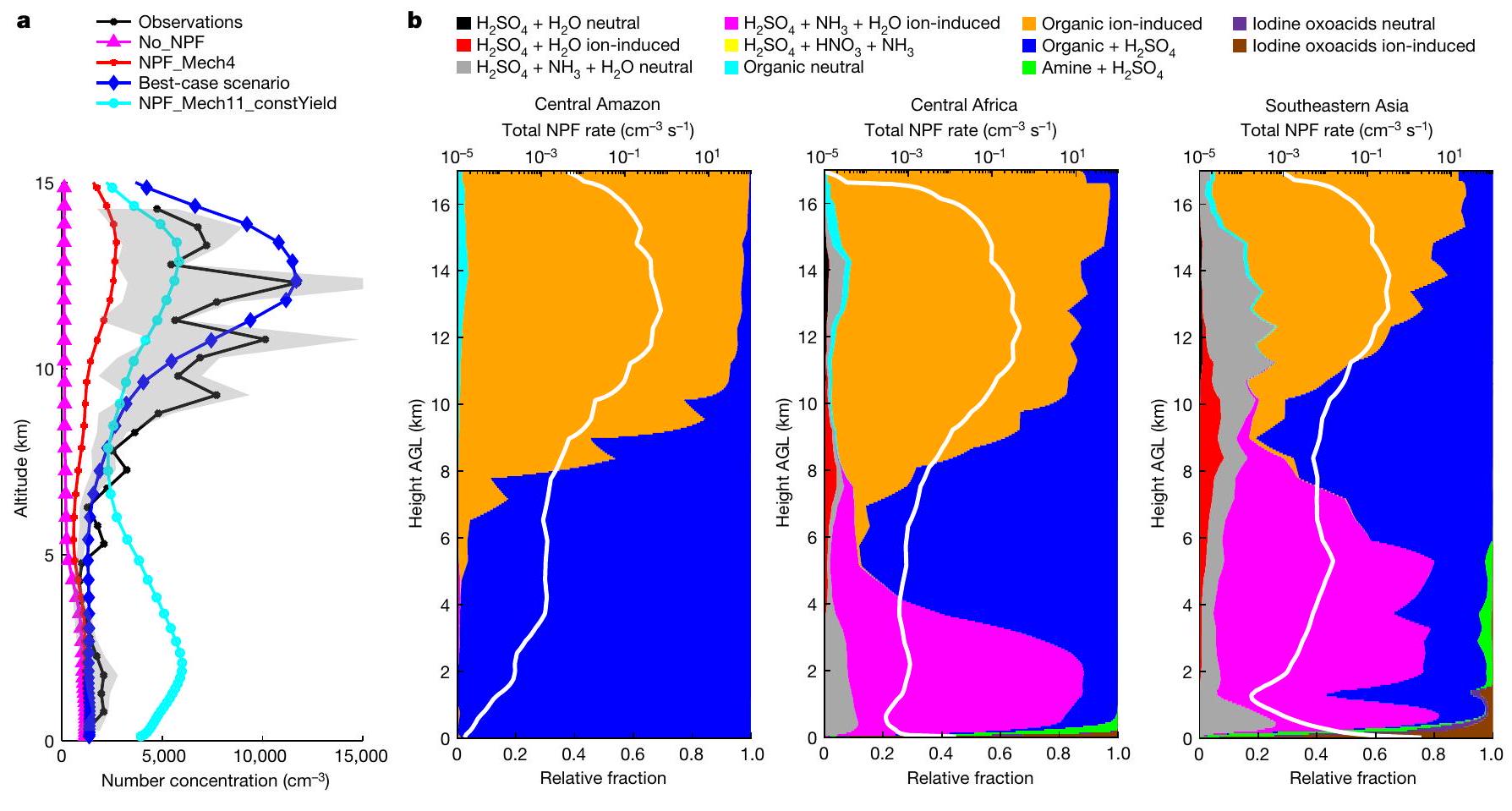

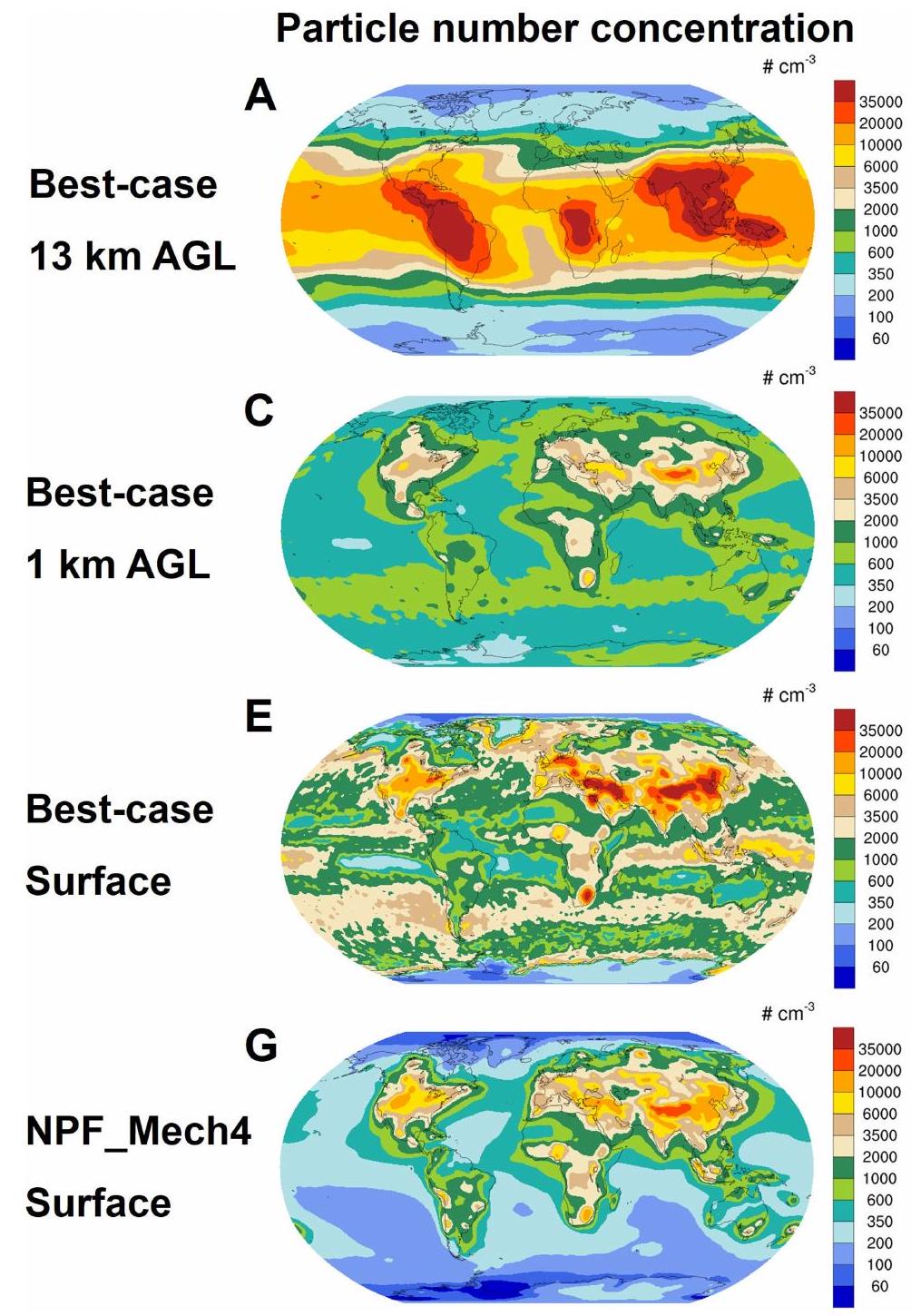

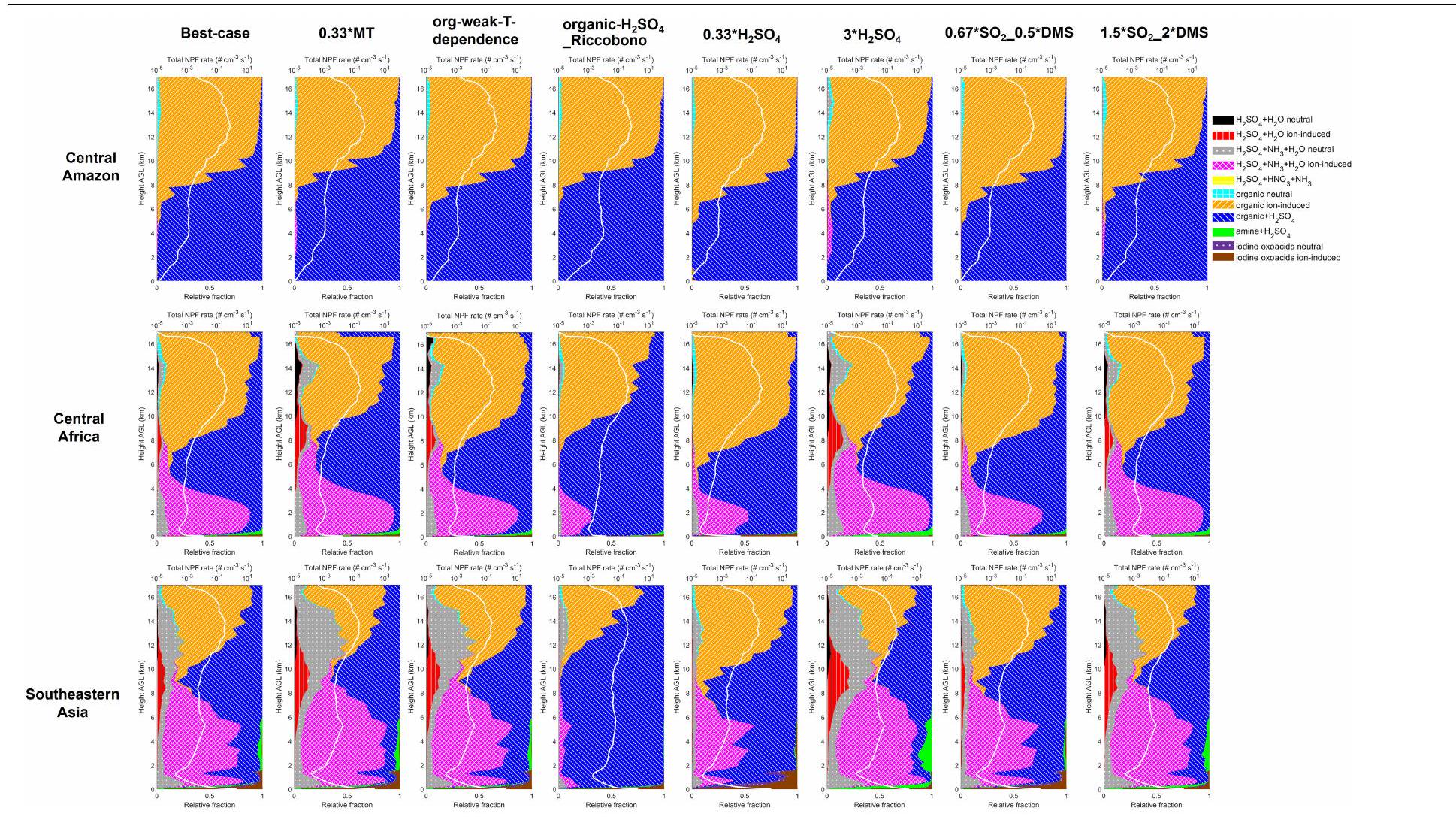

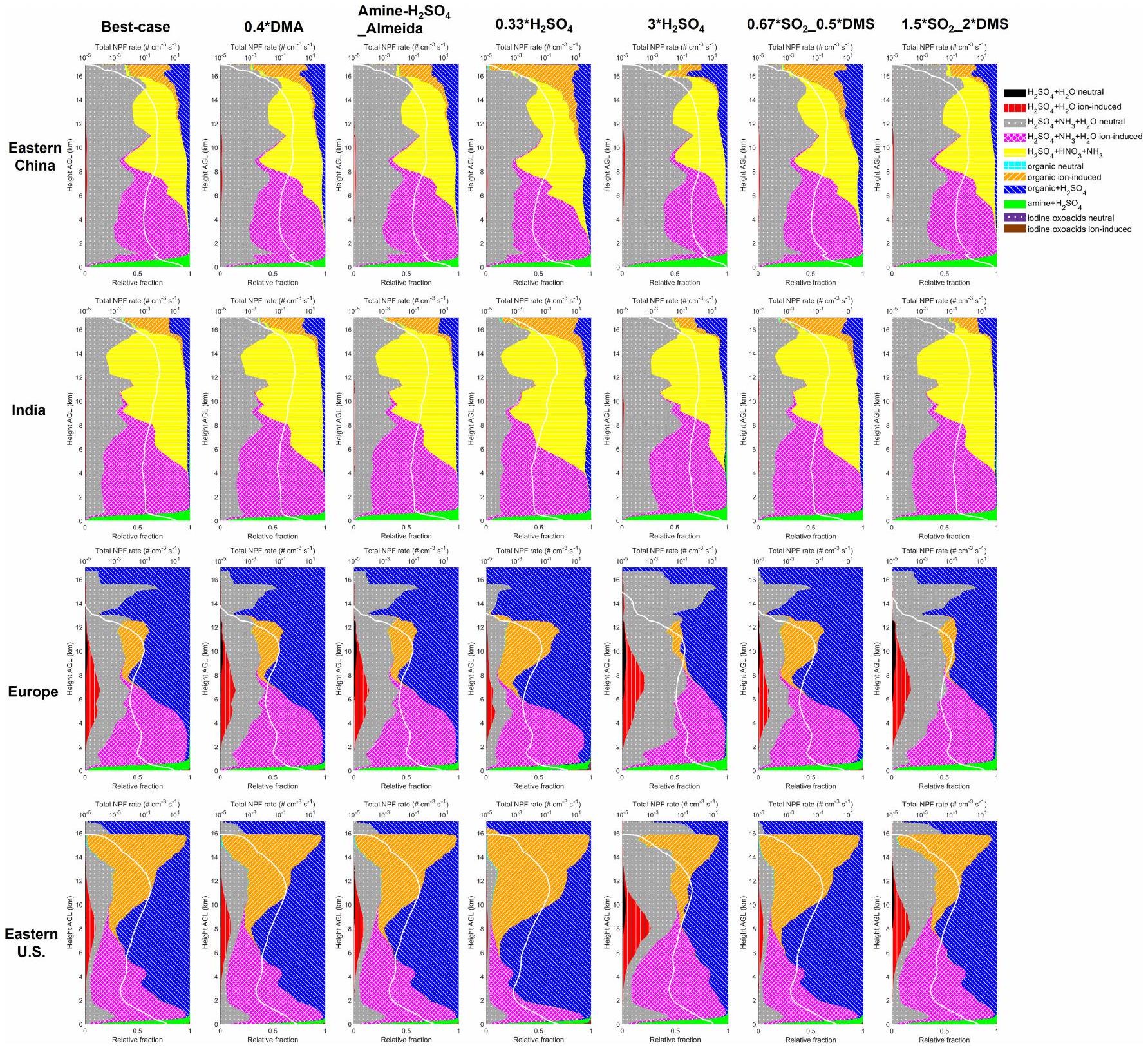

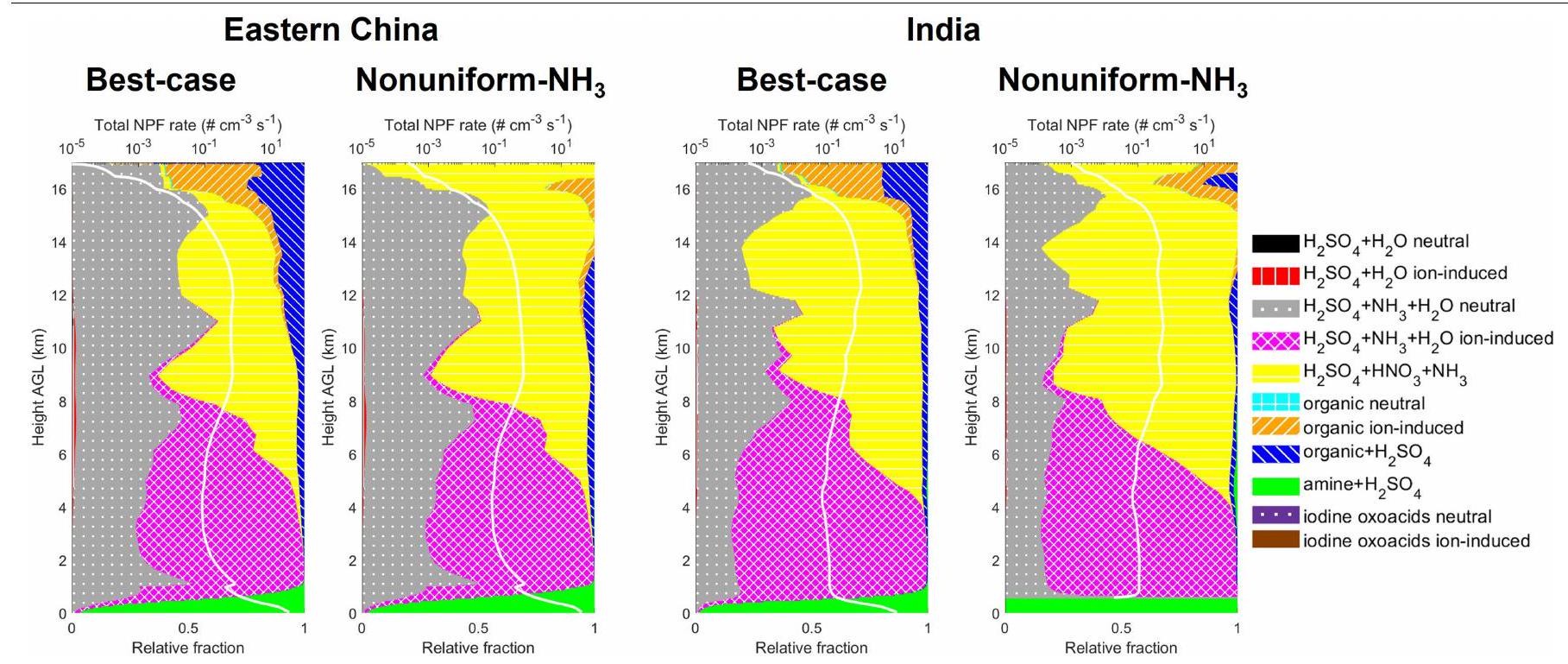

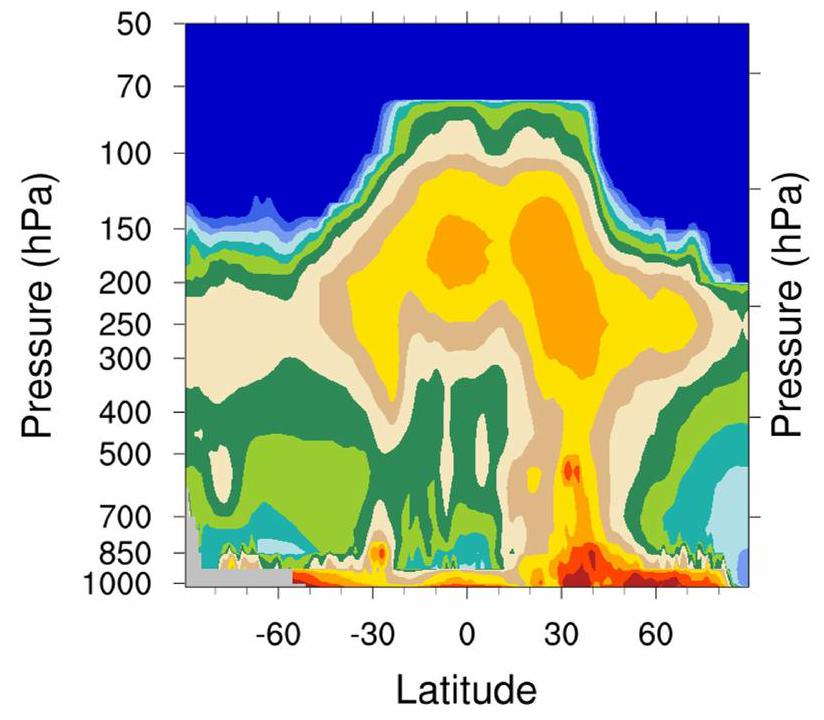

مُعَيار إلى درجة حرارة وضغط قياسيين (273.15 كلفن و101.325 كيلو باسكال). تُعطى تعريفات سيناريوهات النموذج في النص الرئيسي والجدول التكميلي 1.b، ومعدلات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة كدالة للارتفاع عن سطح الأرض فوق الأمازون المركزي، وأفريقيا الوسطى، وجنوب شرق آسيا. تمثل الخطوط البيضاء إجمالي معدلات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة لجميع الآليات عند قطر 1.7 نانومتر.

هنا قمنا بتجميع تجارب مختبرية على المستوى الجزيئي لتطوير تمثيلات نموذجية شاملة لتكوين الجسيمات الجديدة (NPF) والتحول الكيميائي لغازات السلف. يأخذ النموذج في الاعتبار 11 آلية نواة، من بينها أربع آليات حاسمة تم تجاهلها إلى حد كبير سابقًا، بما في ذلك نواة الأحماض الأكسجينية لليود المحايدة والمحفزة بالأيونات، والتآزر.

قوة الإشعاع السحابية للجسيمات الهوائية الكبيرة

آليات NPF فوق الغابات المطيرة

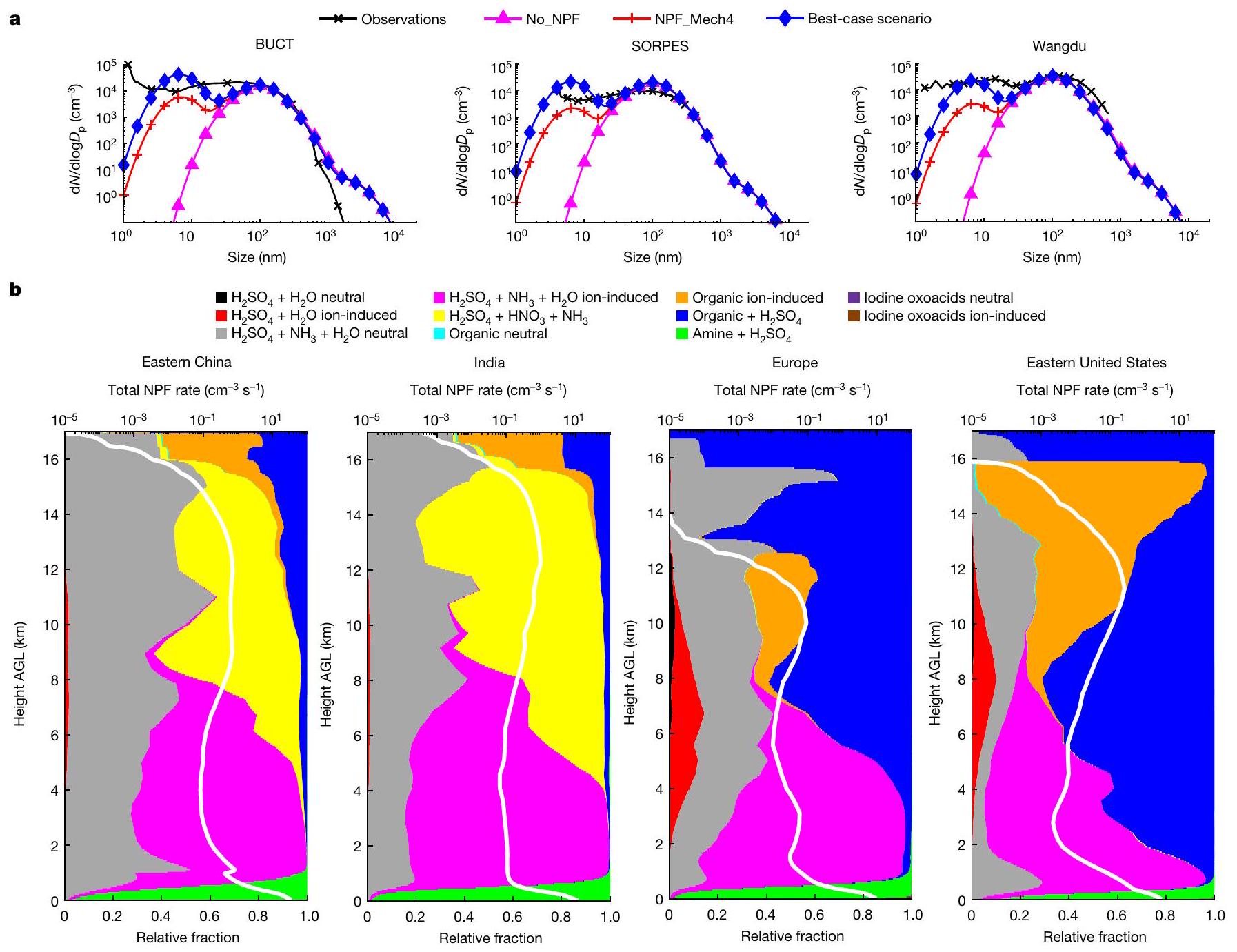

آليات NPF في المناطق الملوثة بالبشر

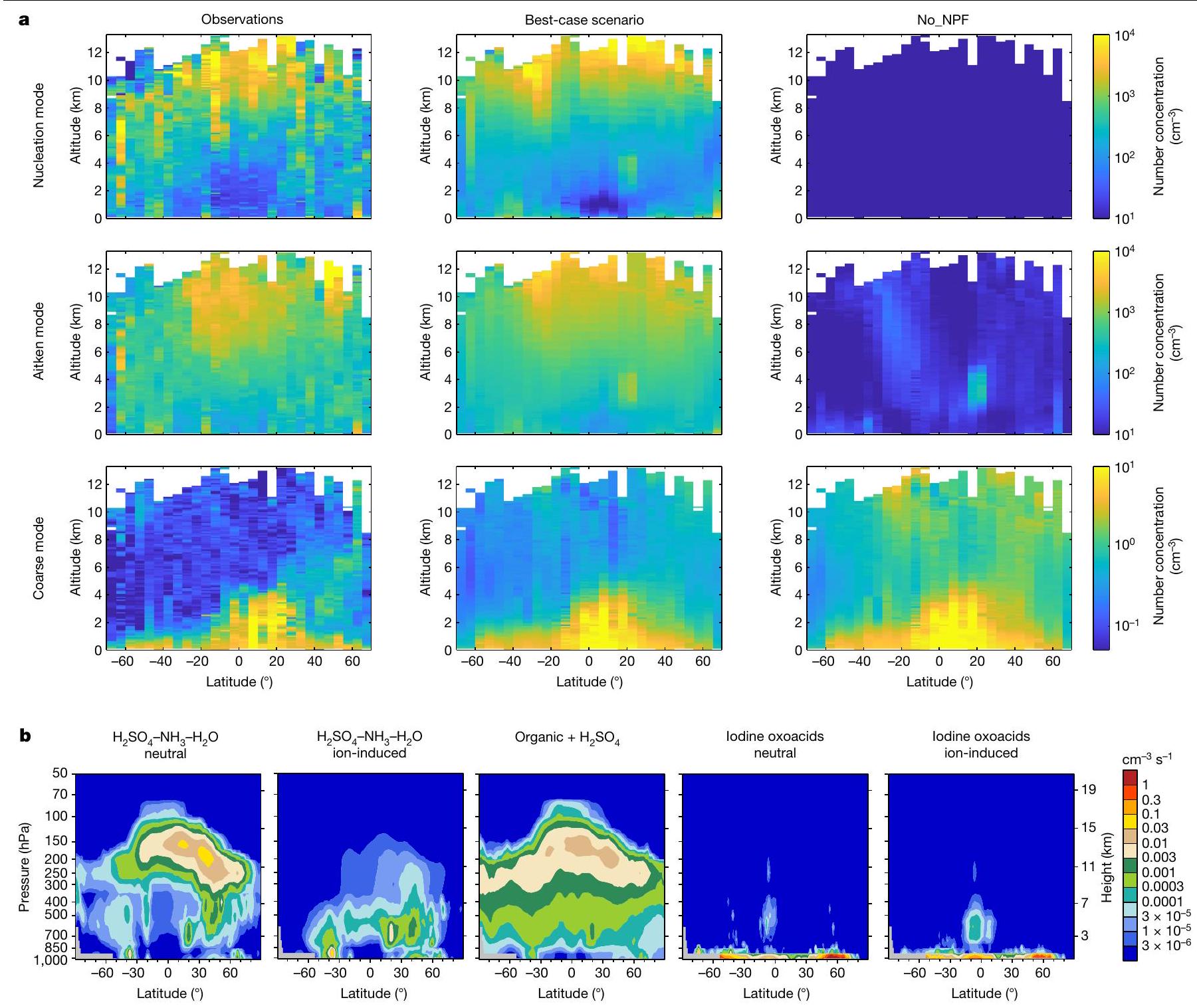

آليات NPF فوق المحيطات

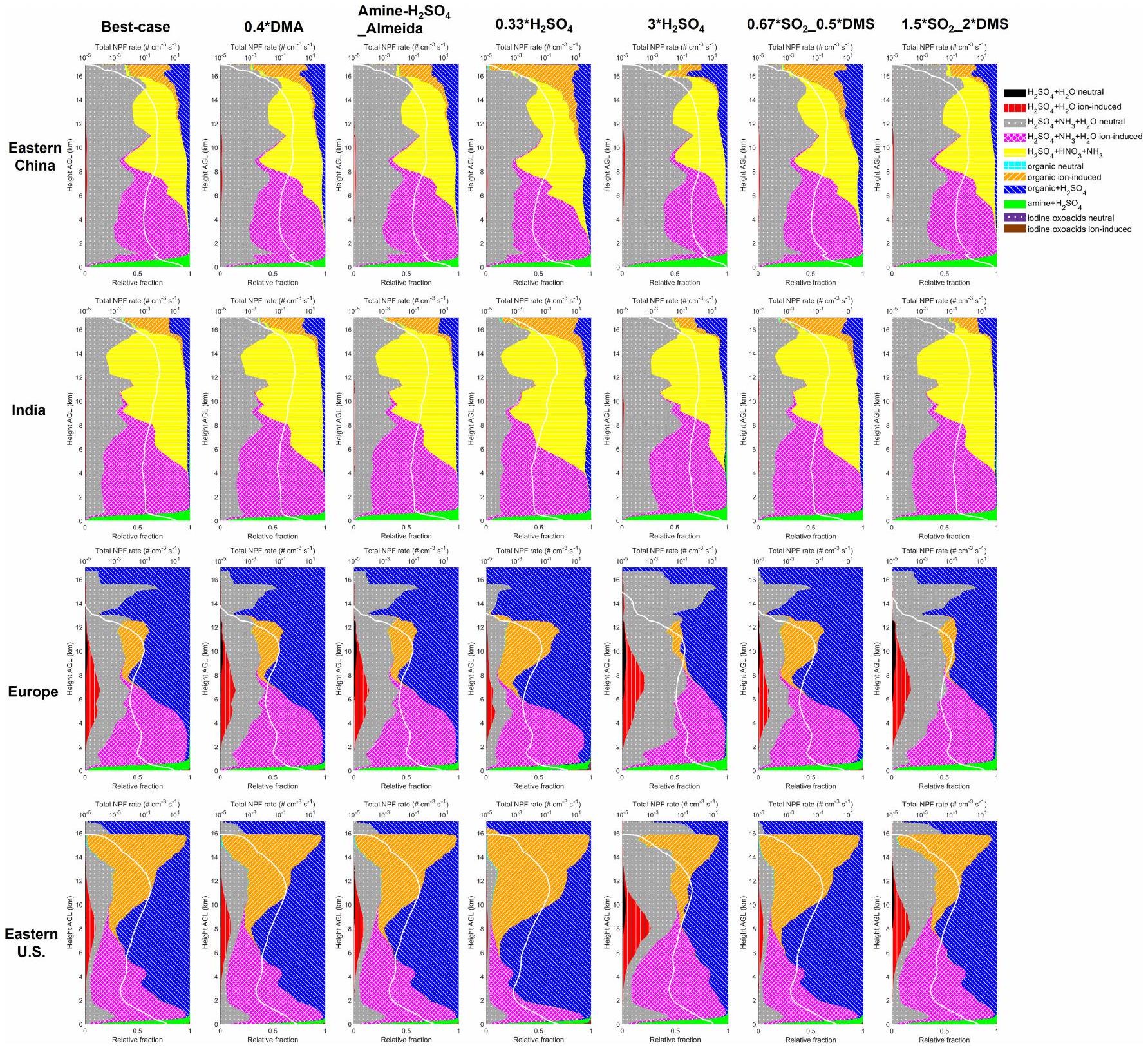

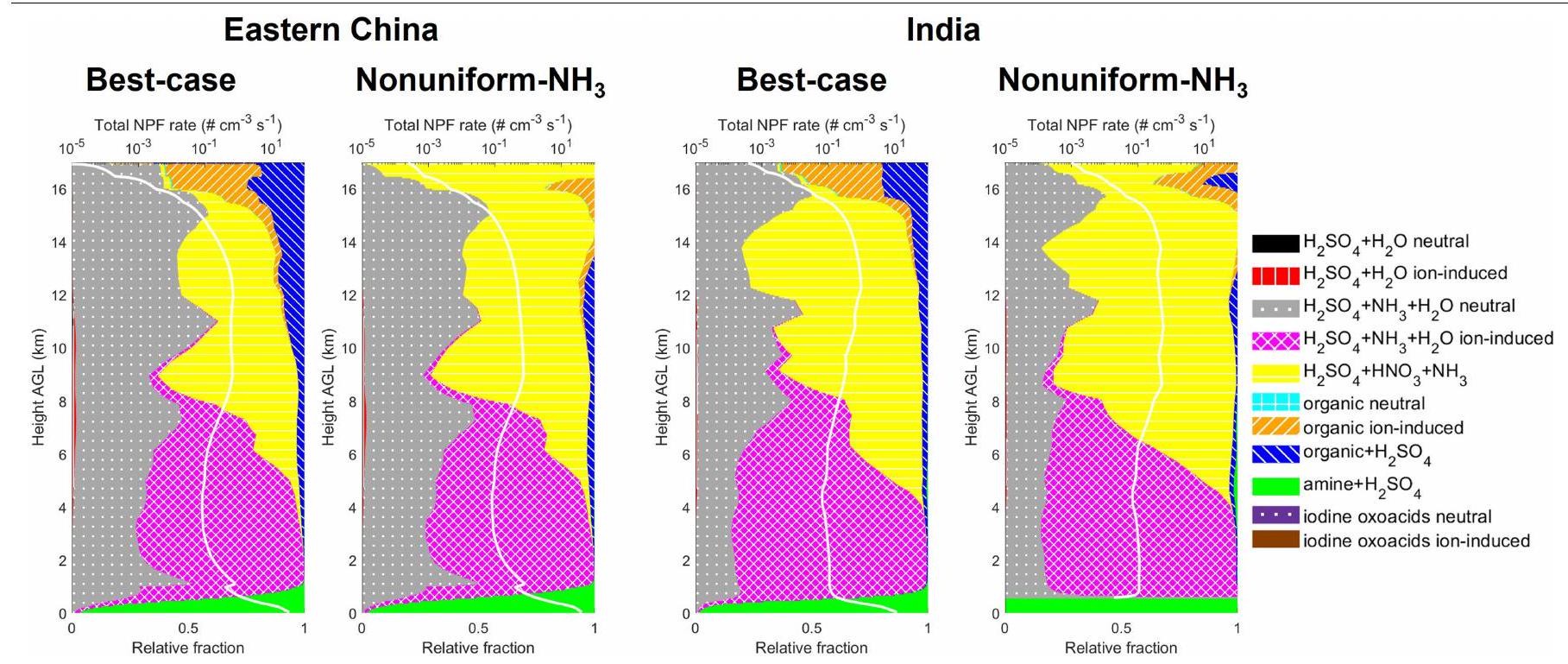

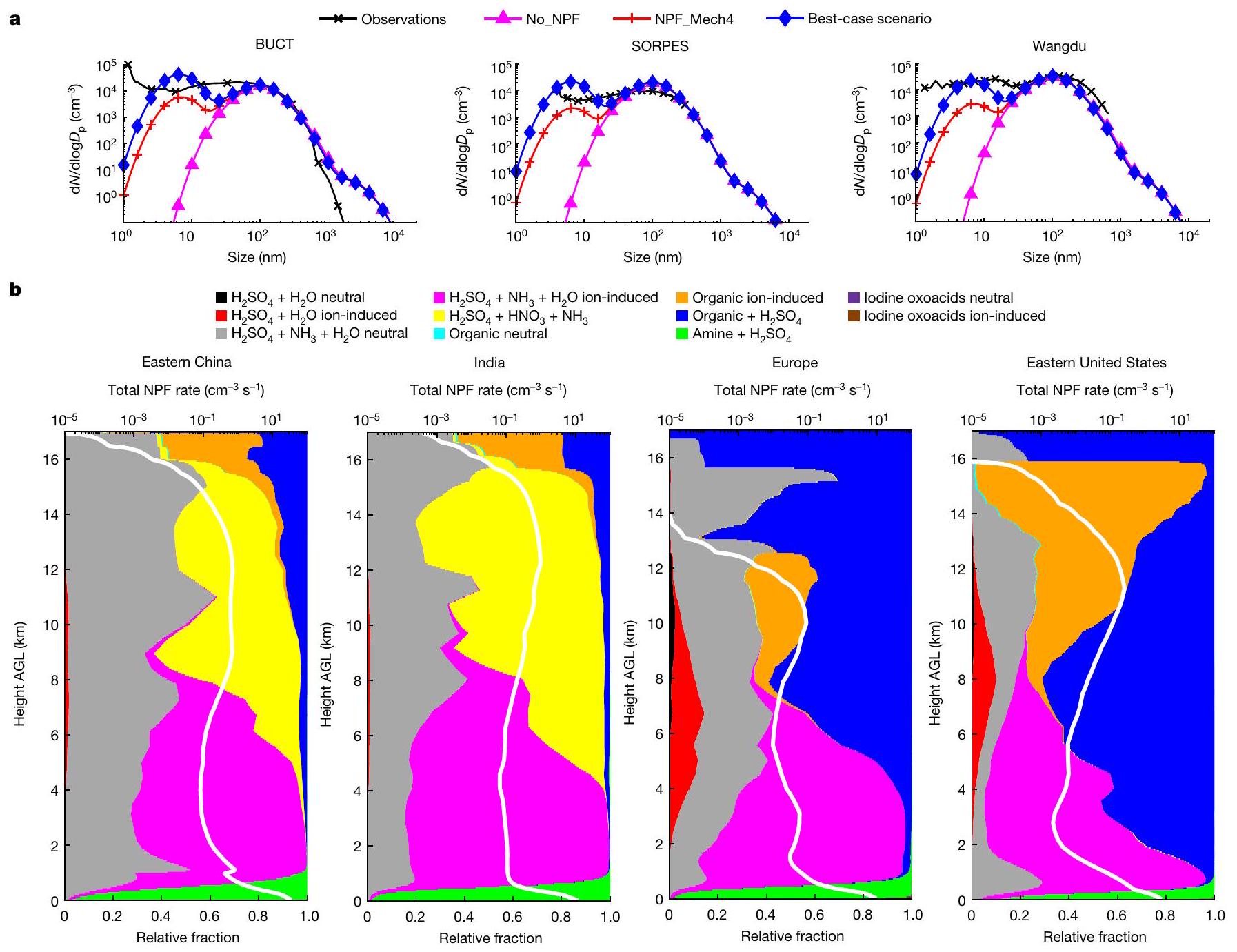

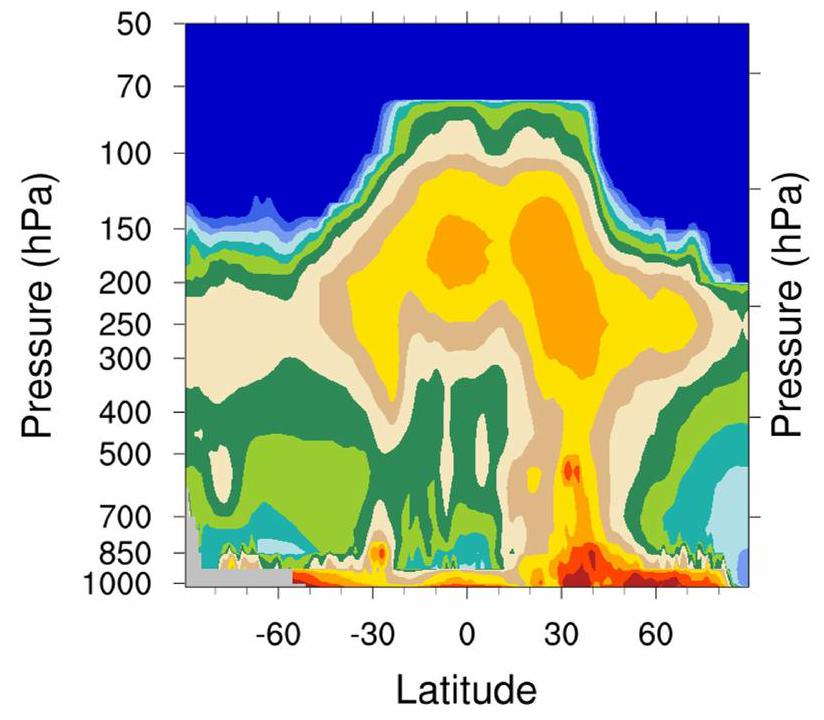

التقاط شكل توزيع حجم الأعداد الدقيقة للغاية لأن النموذج يستخدم نهج الوضع لتمثيل حجم الجسيمات. ب، معدلات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة كدالة للارتفاع فوق مستوى سطح البحر في شرق الصين والهند وأوروبا والشرق الأمريكي. تمثل الخطوط البيضاء إجمالي معدلات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة عند قطر

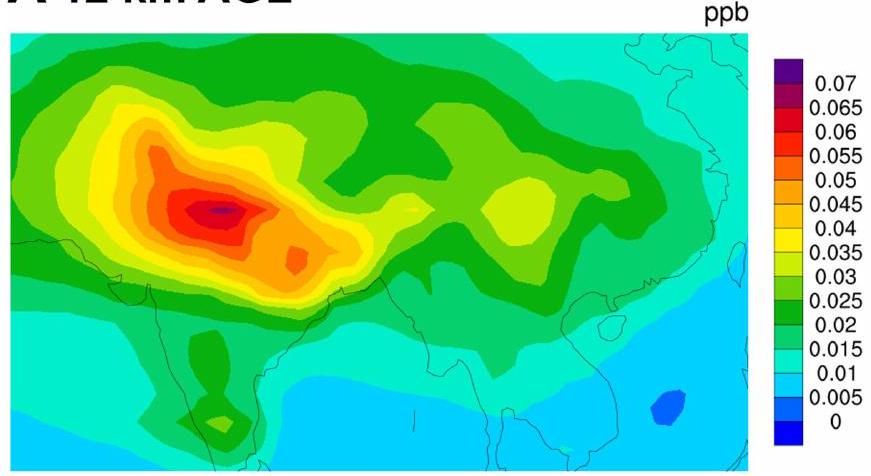

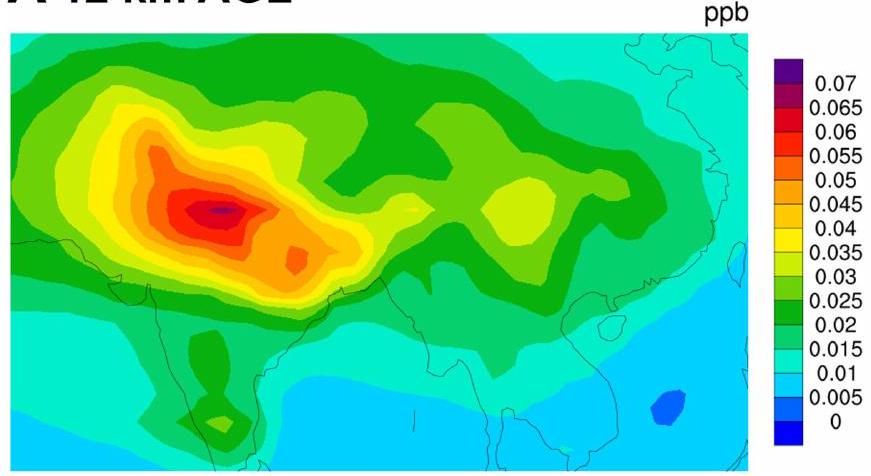

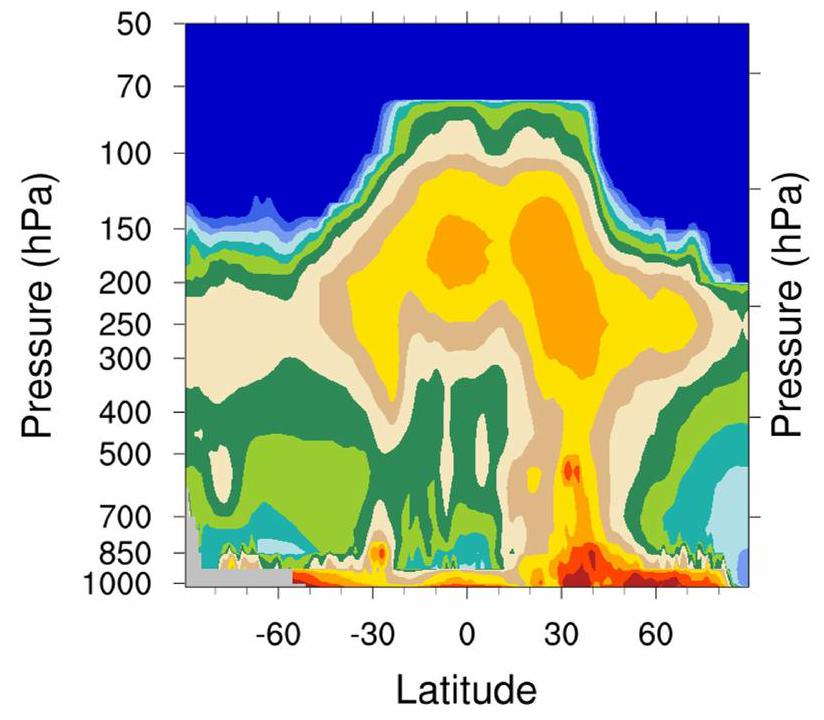

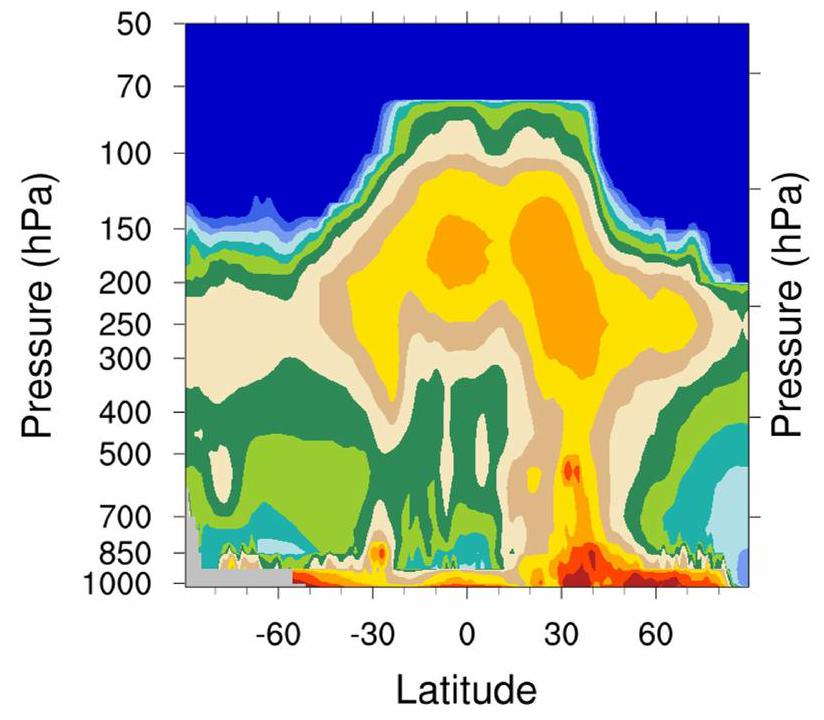

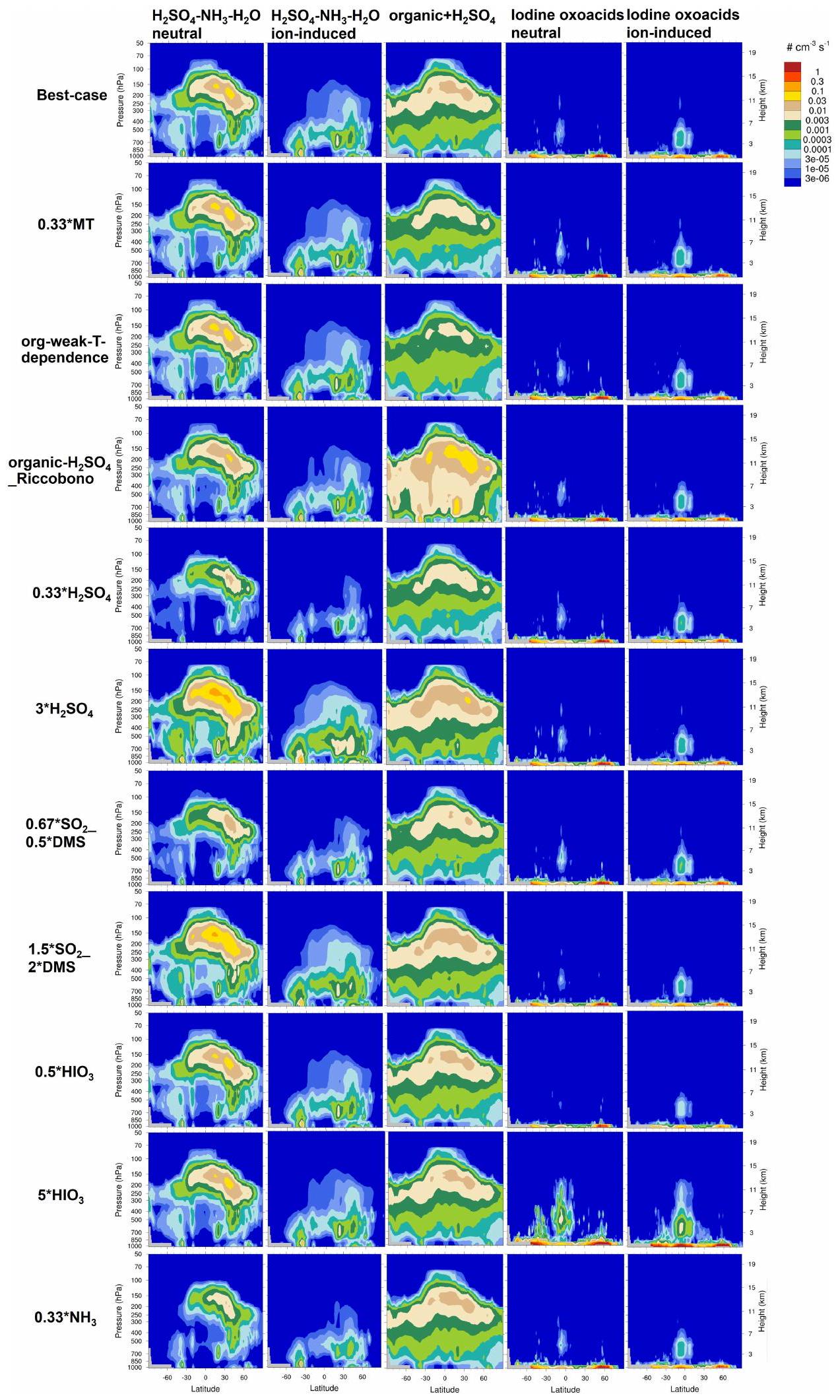

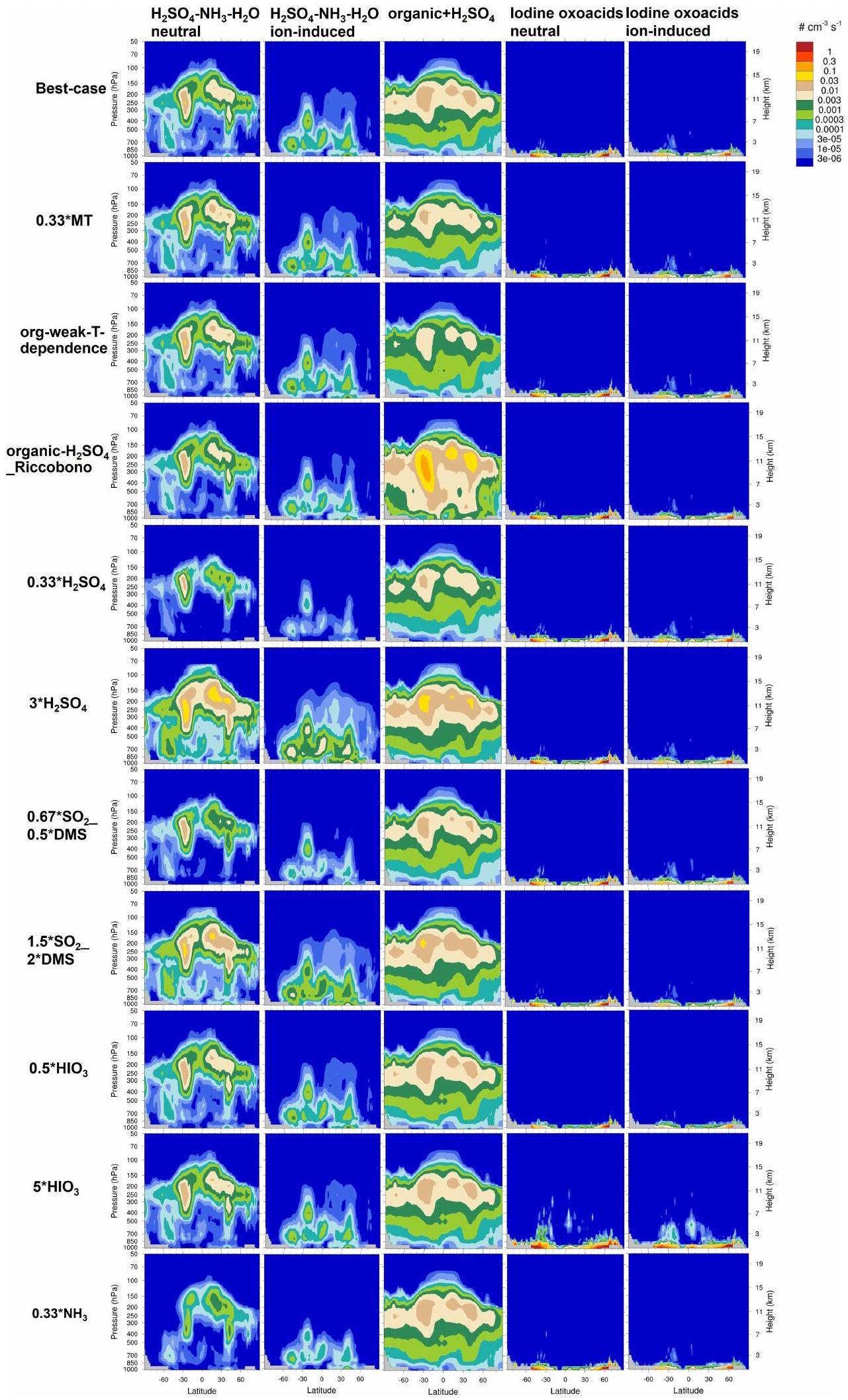

مع خط العرض. تشير محاكاتنا إلى أن المواد العضوية-

نظرة عامة عالمية وتحليل الحساسية

(كل 100 م) وتم حساب وترتيب متوسط تركيز عدد الجسيمات في كل حاوية. تم تطبيع جميع تركيزات عدد الجسيمات إلى درجة حرارة وضغط قياسيين. ب، متوسط معدلات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة للآليات الفردية فوق المحيط الهادئ (

التحكم في النقل الحراري بناءً على أفضل سيناريو لدينا. تشير النتائج إلى أن اكتشافاتنا الرئيسية حول آليات تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة (NPF) تظل صحيحة تحت هذه المحاكاة الحساسة في جميع المناطق الرئيسية ذات الأهمية. ومع ذلك، قد تؤثر هذه المصادر من عدم اليقين على المساهمات الكمية الدقيقة للآليات الفردية، سواء في المناطق الرئيسية المذكورة أعلاه أو في مناطق أخرى لم يتم مناقشتها بالتفصيل بشكل فردي.

مساهمة NPF في الجسيمات و CCN

مستوى)، تتفاوت نسب الجسيمات وCCNO.5% الناتجة عن NPF إقليمياً. فوق المحيطات الاستوائية والمعتدلة حيث تكون تأثيرات الإشعاع السحابي حساسة للغاية لتوافر CCN، فإن NPF بشكل عام يمثل

المستويات الرأسية في 2016. أ، ج، هـ، التوزيع المكاني لتركيزات CCN في

نقاش

مناطق الرياح الموسمية، الغابات المطيرة والمحيطات الاستوائية خلال العصر الصناعي. كمثال آخر، ما إذا كانت NPF في طبقات الحدود المحيطية تحكمها أحماض اليود الأكسجينية أو

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- لي، س.-هـ. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة في الغلاف الجوي: من الكتل الجزيئية إلى المناخ العالمي. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. 124، 7098-7146 (2019).

- كولمالا، م. وآخرون. هل تقليل تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة هو حل محتمل للتخفيف من تلوث الهواء الجزيئي في بكين وغيرها من المدن الكبرى في الصين؟ مناقشات فاراداي. 226، 334-347 (2021).

- ياو، ل. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة في الغلاف الجوي من حمض الكبريتيك والأمينات في مدينة صينية كبيرة. ساينس 361، 278-281 (2018).

- كاي، ر. وآخرون. نواة حمض الكبريتيك والأمين في بكين الحضرية. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 21، 2457-2468 (2021).

- باكاريني، أ. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة بشكل متكرر فوق جليد القطب الشمالي العالي بسبب زيادة انبعاثات اليود. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 4924 (2020).

- بيانكي، ف. وآخرون. تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة في الطبقة الجوية الحرة: سؤال عن الكيمياء والتوقيت. ساينس 352، 1109-1112 (2016).

- ويليامسون، سي. جي. وآخرون. مصدر كبير لنوى تكثف السحب من تكوين جزيئات جديدة في المناطق الاستوائية. ناتشر 574، 399-403 (2019).

- كوهن، أ. ج. وآخرون. تقديرات واتجاهات على مدى 25 عامًا للعبء العالمي للأمراض الناتج عن تلوث الهواء المحيط: تحليل لبيانات من دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض 2015. لانسيت 389، 1907-1918 (2017).

- غوردون، هـ. وآخرون. أسباب وأهمية تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة في الغلاف الجوي الحالي وما قبل الصناعي. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. الغلاف الجوي 122، 8739-8760 (2017).

- يو، ف. ولوا، ج. محاكاة توزيع حجم الجسيمات باستخدام نموذج عالمي للهباء الجوي: مساهمة النواة في تركيزات عدد الهباء الجوي وCCN. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 9، 7691-7710 (2009).

- زافيري، ر. أ. وآخرون. النمو السريع للجزيئات العضوية النانوية الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية يغير بشكل كبير دورة حياة السحب في غابة الأمازون المطيرة. ساي. أدف. 8، eabjO329 (2022).

- كيركبي، ج. وآخرون. دور حمض الكبريتيك، الأمونيا وأشعة الكون المجرية في نواة الهباء الجوي في الغلاف الجوي. ناتشر 476، 429-433 (2011).

- تشاو، ب. وآخرون. تركيز عالٍ من الجسيمات فائقة الدقة في طبقة التروبوسفير الحرة في الأمازون الناتجة عن تكوين جزيئات جديدة عضوية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 117، 25344-25351 (2020).

- تشين، م. وآخرون. نموذج تفاعل كيميائي حمضي-قاعدي لمعدلات النواة في طبقة الغلاف الجوي الملوثة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 109، 18713-18718 (2012).

- وانغ، م. وآخرون. التآزرية

تكوين الجسيمات في الطبقة العليا من التروبوسفير. الطبيعة 605، 483-489 (2022). - سايز-لوبيز، أ. وآخرون. الكيمياء الجوية لليود. مراجعة الكيمياء 112، 1773-1804 (2012).

- هوفمان، ت.، أودو، ك. د. وسينفيلد، ج. هـ. نواة أكسيد اليود المتجانسة: تفسير لإنتاج جزيئات جديدة على السواحل. رسائل الأبحاث الجيوفيزيائية 28، 1949-1952 (2001).

- بيرغمان، ت. وآخرون. الميزات الجغرافية واليومية لتكوين طبقة الحدود المعززة بالأمينات. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 120، 9606-9624 (2015).

- لاي، س. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة نشطة فوق طبقة الحدود الملوثة في سهل شمال الصين. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 49، e2022GL100301 (2022).

- كيركبي، ج. وآخرون. النواة الناتجة عن الأيونات لجزيئات بيولوجية نقية. ناتشر 533، 521-526 (2016).

- ريكو بونو، ف. وآخرون. منتجات الأكسدة من الانبعاثات البيولوجية تساهم في نواة الجسيمات الجوية. العلوم 344، 717-721 (2014).

- يو، ف.، لو، ج.، نادكوتو، أ. ب. & هيرب، ج. تأثير الاعتماد على درجة الحرارة على المساهمة المحتملة للمواد العضوية في تكوين جزيئات جديدة في الغلاف الجوي. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 17، 4997-5005 (2017).

- تشين، إكس. وآخرون. تحسين محاكاة تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة من خلال ربط وحدة الهباء العضوي القائمة على تقلبات (VBS) في NAQPMS+APM. البيئة الجوية. 204، 1-11 (2019).

- وانغ، إكس.، غوردون، إتش.، غروسفينور، دي. بي.، أندريا، م. أو. وكارسلاو، ك. إس. مساهمة نواة الهباء الإقليمي في CCN منخفضة المستوى في بيئة الحمل العميق في الأمازون: نتائج من نموذج عالمي متداخل إقليمياً. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 23، 4431-4461 (2023).

- زو، ج. وآخرون. انخفاض في القوة الإشعاعية بسبب نواة الهباء العضوي، المناخ، وتغير استخدام الأراضي. نات. كوم. 10، 423 (2019).

- شرفيش، م. ودونهيو، ن. م. كيمياء الجذور البيروكسي وقاعدة تقلبات المواد. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 20، 1183-1199 (2020).

- فريجي، سي. وآخرون. تأثير درجة الحرارة على التركيب الجزيئي للأيونات والعناقيد المشحونة خلال النواة البيولوجية النقية. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 18، 65-79 (2018).

- ي، ق. وآخرون. التركيب الجزيئي والتطايرية للجزيئات المتكونة من أكسدة ألفا-بينين بين

و . Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12357-12365 (2019). - يان، سي. وآخرون. التأثير المعتمد على الحجم لـ

عن معدلات نمو جزيئات الهباء العضوي. Sci. Adv. 6، eaay4945 (2020). - أندريا، م. أ. وآخرون. خصائص الهباء الجوي وإنتاج الجسيمات في الطبقة العليا من التروبوسفير فوق حوض الأمازون. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 18، 921-961 (2018).

- ويجل، ر. وآخرون. المراقبة في الموقع لتكوين جزيئات جديدة (NPF) في طبقة التروبوسفير الاستوائية خلال إعصار الرياح الموسمية الآسيوية لعام 2017 – الجزء 1: ملخص لنتائج StratoClim. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 21، 11689-11722 (2021).

- زو، ي. وآخرون. تركيزات عدد الجسيمات المحمولة جواً في الصين: مراجعة نقدية. تلوث البيئة. 307، 119470 (2022).

- كارسلوا، ك. س. وآخرون. مساهمة كبيرة من الهباء الجوي الطبيعي في عدم اليقين في التأثير غير المباشر. ناتشر 503، 67-71 (2013).

- وانغ، سي.، سودن، ب. ج.، يانغ، و. وفكّي، ج. أ. التعويض بين ردود فعل السحب وتفاعل الهباء الجوي مع السحب في نماذج CMIP6. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 48، e2020GL091024 (2021).

- كواس، ج.، بوشيه، أ.، بيلوين، ن. وكيني، س. تقدير قائم على الأقمار الصناعية للقوة المناخية المباشرة وغير المباشرة للجسيمات الهوائية. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 113، D05204 (2008).

- مكوي، د. ت. وآخرون. التأثير غير المباشر الأول للغلاف الجوي العالمي على السحب مقدر باستخدام MODIS وMERRA وAeroCom. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 122، 1779-1796 (2017).

- ريدينغتون، سي. إل. وآخرون. المساهمات الأولية مقابل الثانوية في تركيزات عدد الجسيمات في طبقة الحدود الأوروبية. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 11، 12007-12036 (2011).

- شيلينغ، ج. إي. وآخرون. ملاحظات الطائرات حول التركيب الكيميائي وعمر الهباء الجوي في سحابة ماناوس الحضرية خلال GoAmazon 2014/5. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 18، 10773-10797 (2018).

- لانغفورد، ب. وآخرون. تدفقات وتركيزات المركبات العضوية المتطايرة من غابة استوائية في جنوب شرق آسيا. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 10، 8391-8412 (2010).

- يو، ف. ولوا، ج. نمذجة الميثيلامينات الغازية في الغلاف الجوي العالمي: تأثيرات الأكسدة وامتصاص الهباء الجوي. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 14، 12455-12464 (2014).

- كاي، سي. وآخرون. دمج تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة وعلاجات النمو المبكر في WRF/Chem: تحسين النموذج، التقييم، وتأثيرات الهباء الجوي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية في شرق آسيا. أتموس. إنف. 124، 262-284 (2016).

- هوفنر، م. وآخرون. أول اكتشاف للأمونيا (

) في طبقة التروبوسفير العليا لموسم الرياح الموسمية الصيفية الآسيوية. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 16، 14357-14369 (2016). - هوفنر، م. وآخرون. جزيئات نترات الأمونيوم المتكونة في الطبقة العليا من الغلاف الجوي من مصادر الأمونيا الأرضية خلال مواسم الرياح الموسمية الآسيوية. نات. جيوسي. 12، 608-612 (2019).

- أوريوبولوس، ل. وبلاتنيك، س. قابلية الإشعاع للغلاف الجوي السحابي لت perturbations عدد القطرات: 2. تحليل عالمي من MODIS. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. الغلاف الجوي 113، D14S21 (2008).

- غريسبيردت، إ. وآخرون. تقييد التأثير الفوري للجسيمات الهوائية على البياض السحابي. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 114، 4899-4904 (2017).

- بروك، سي. إيه. وآخرون. توزيع أحجام الهباء الجوي خلال مهمة التصوير الجوي (ATom): الطرق، وعدم اليقين، ومنتجات البيانات. تقنيات قياس الغلاف الجوي 12، 3081-3099 (2019).

- إلم، ج. وآخرون. نمذجة تشكيل ونمو الكتل الجزيئية في الغلاف الجوي: مراجعة. مجلة علوم الهباء الجوي 149، 105621 (2020).

- ين، ر. وآخرون. تجمعات الحمض والقاعدة خلال تشكيل جزيئات جديدة في الغلاف الجوي في بكين الحضرية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 10994-11005 (2021).

- غلاسو، و. أ. وآخرون. نواة حمض الكبريتيك: دراسة تجريبية لتأثير سبعة قواعد. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. 120، 1933-1950 (2015).

- ليو، ل. وآخرون. تكوين سريع لحمض الكبريتيك-ثنائي ميثيل الأمين المعزز بواسطة حمض النيتريك في المناطق الملوثة. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 118، e2108384118 (2021).

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

وحدة NPF مع 11 آلية نواة

للتآزر

بدقة عند

R2D-VBS ومعاملاته

هو درجة الحرارة (الوحدة: ك).

بسبب معدلاتها الأبطأ بكثير. إن امتصاص الهباء لـ DMA يخضع لعدم اليقين الأعلى لأن معامل الامتصاص يتفاوت على نطاق واسع نسبيًا في الأدبيات (

تمثيل المصادر والمصارف لأحماض اليود الأكسجينية

تكوين E3SM المعدل

بالنسبة لكيمياء الغاز، يمثل النموذج بشكل صريح أكسدة DMS إلى

وصف البيانات الملاحظة

على متن الطائرة الألمانية عالية الارتفاع وطويلة المدى (HALO). يمتلك جهاز CPC قطر قطع اسمي يبلغ 4 أميال بحرية، ولكن بسبب خسائر المدخل، فإن قطر القطع الفعلي يبلغ حوالي 10 أميال بحرية بالقرب من السطح ويزداد إلى حوالي 20 ميلاً بحرياً عند 150 هكتوباسكال (حوالي 13.8 كم). نظرًا لأن المونوتيربينات لها ارتباطات مثبتة مع تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة المدعوم بالمواد العضوية، قمنا أيضًا بتقييم النموذج مقابل تركيزات المونوتيربينات التي تم قياسها بواسطة مطياف الكتلة لنقل البروتونات عالي الحساسية من نوع أيونيكون (PTR-MS) على متن طائرة G-1 خلال حملة GoAmazon (الملاحظات والنمذجة للمحيط الأخضر في الأمازون).

تحليل حساسية آليات NPF

أن

تركيزات لأنها لن تتحدى الأدوار الرائدة للتكوين الذي يتم بوساطة المواد العضوية فوق المناطق المعنية. تُظهر البيانات الموسعة الأشكال 5 و7 و8 أنه، حتى مع تقليل انبعاثات المونوتربين، لا يزال التكوين الذي يتم بوساطة المواد العضوية هو أكبر آلية لتكوين الجسيمات الجديدة في الطبقة العليا من الغلاف الجوي فوق المناطق الثلاث للغابات المطيرة وواحدة من الآليتين الرئيسيتين في الطبقة العليا من الغلاف الجوي فوق المحيطين الهادئ والأطلسي.

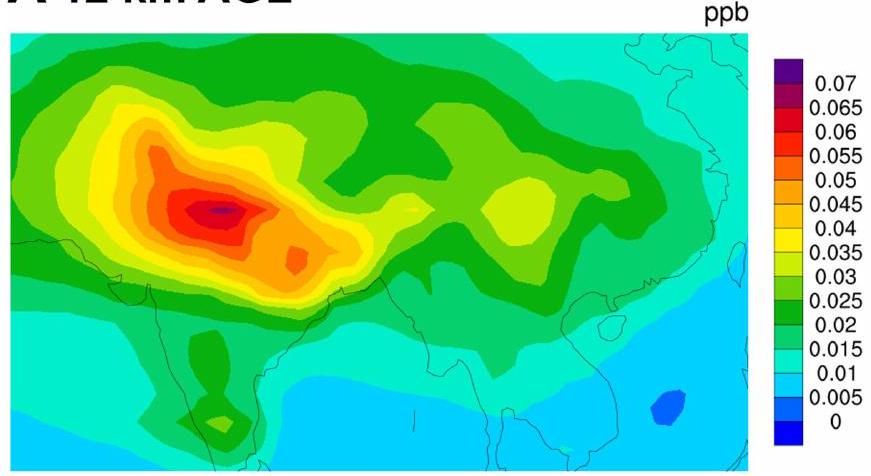

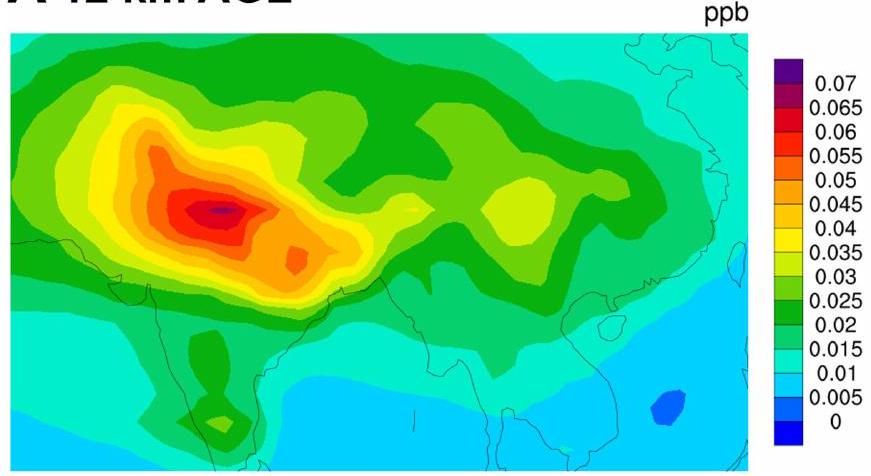

الطبقة الجوية فوق شرق الصين والهند، في حين أن العضوي-

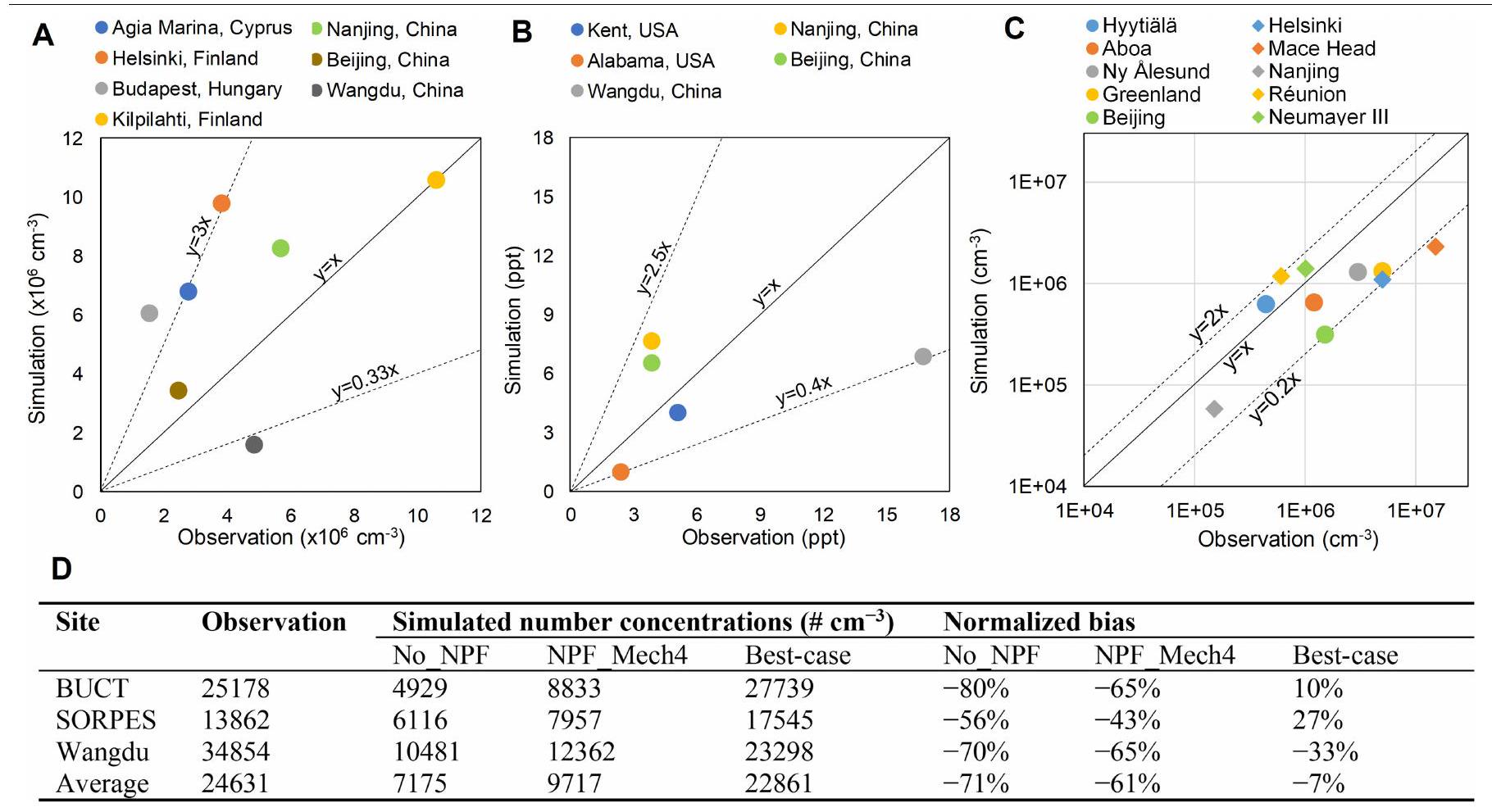

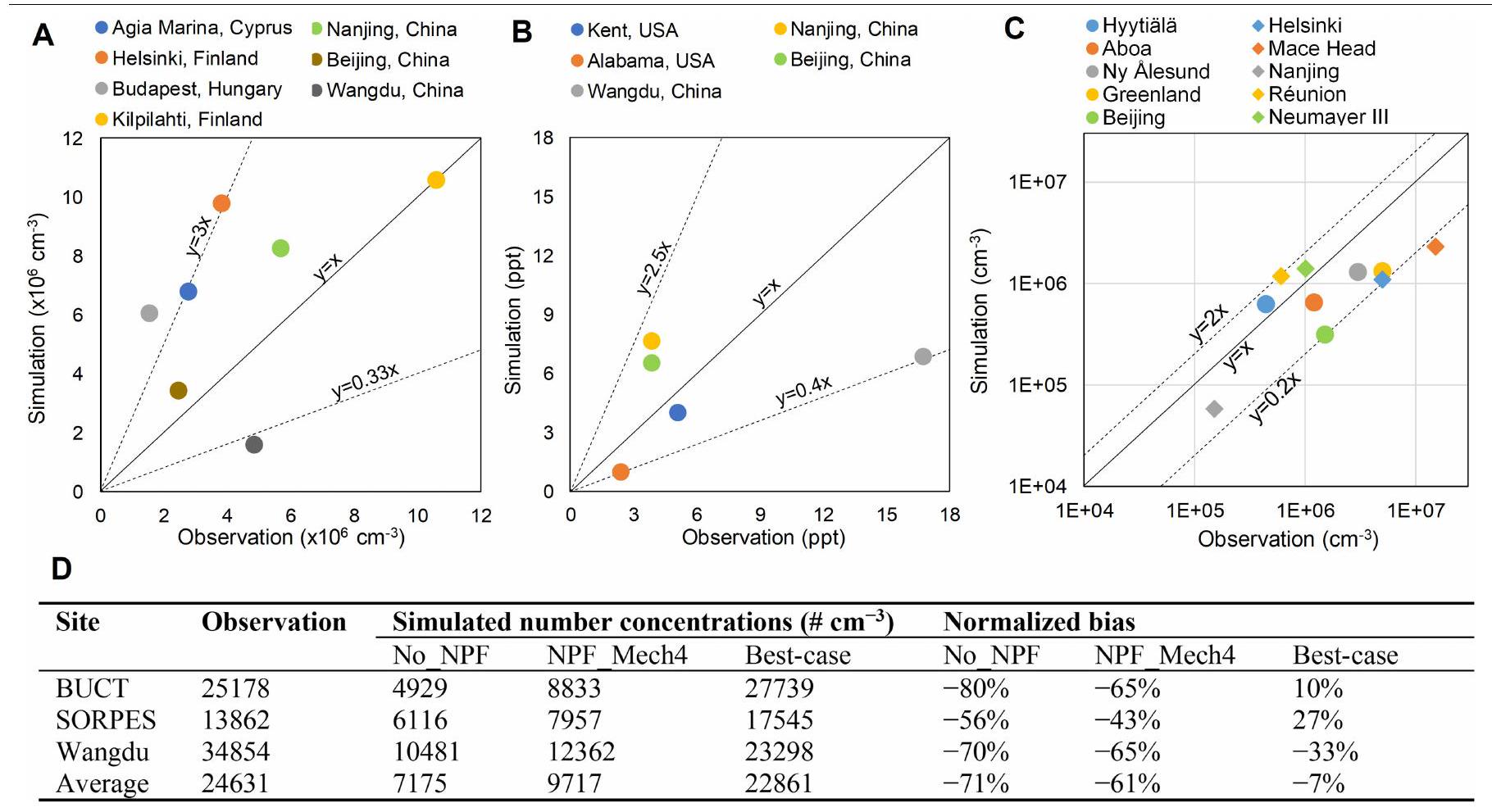

تقييم

معلمات نظام الحمل ZM المطبق في نموذج الغلاف الجوي المجتمعي الإصدار 5. لمعالجة قلق المراجع بشكل أفضل، قمنا أيضًا بإجراء محاكاة حساسية إضافية (‘upper_tau’ و ‘lower_tau’) التي تحدد قيمة تاو عند الحدود العليا والسفلى (14,400 و

مزيد من المناقشة حول آليات NPF في مناطق مختلفة

نتائج إضافية ومناقشة حول مساهمة NPF في الجسيمات وCCN

النقاش في سياق النماذج العالمية السابقة

تركيزات فوق المحيطات وفوق طبقة الحدود

المنتجات لتحفيز النواة، كما هو موضح أعلاه. كشفت محاكاة أنهم وجدوا أن تقريبًا جميع عمليات النواة في الغلاف الجوي الحالي تتضمن الأمونيا أو المركبات العضوية البيولوجية، بالإضافة إلى

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

51. غولاز، ج.-س. وآخرون. نموذج DOE E3SM المترابط الإصدار 1: نظرة عامة وتقييم عند الدقة القياسية. مجلة النمذجة المتقدمة في نظم الأرض 11، 2089-2129 (2019).

52. راش، ب. ج. وآخرون. نظرة عامة على المكون الجوي لنموذج نظام الأرض على نطاق الطاقة. مجلة النمذجة المتقدمة لنظام الأرض 11، 2377-2411 (2019).

53. دن، إ. م. وآخرون. تشكيل الجسيمات الجوية العالمية من قياسات CERN CLOUD. ساينس 354، 1119-1124 (2016).

54. ألميدا، ج. وآخرون. الفهم الجزيئي لتكوين جزيئات حمض الكبريتيك والأمينات في الغلاف الجوي. ناتشر 502، 359-363 (2013).

55. هو، إكس.-سي. وآخرون. دور أحماض اليود الأكسجينية في نواة الهباء الجوي في الغلاف الجوي. ساينس 371، 589-595 (2021).

56. كيركبي، ج. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة في الغلاف الجوي من تجربة CERN CLOUD. نات. جيوساي. 16، 948-957 (2023).

57. ليهتيبالو، ك. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة متعددة المكونات من حمض الكبريتيك، الأمونيا، وبخار المواد البيولوجية. ساينس أدفانس 4، eaau5363 (2018).

58. ميتزجر، أ. وآخرون. دليل على دور المواد العضوية في تشكيل جزيئات الهباء الجوي تحت الظروف الجوية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 107، 6646-6651 (2010).

59. جين، سي. إن.، مك موري، بي. إتش. وهانسون، دي. آر. استقرار ثنائيات حمض الكبريتيك بواسطة الأمونيا، ميثيلامين، ثنائي ميثيلامين، وثلاثي ميثيلامين. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. الغلاف الجوي 119، 7502-7514 (2014).

60. كاي، ر. وآخرون. الجزيئات الأساسية المفقودة في نواة الحمض-القاعدة في الغلاف الجوي. مراجعة العلوم الوطنية. 9، nwac137 (2022).

61. كيرمينين، ف. م. وكولمالا، م. صيغ تحليلية تربط بين معدل النواة “الحقيقي” و”الظاهر” وتركيز عدد النوى لظواهر النواة الجوية. مجلة علوم الهباء الجوي 33، 609-622 (2002).

62. كورتن، أ. وآخرون. تشكيل جزيئات جديدة في نظام حمض الكبريتيك-ثنائي ميثيل الأمين-الماء: إعادة تقييم قياسات غرفة CLOUD ومقارنتها بنموذج نواة الهباء الجوي والنمو. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 18، 845-863 (2018).

63. وانغ، م. وآخرون. النمو السريع لجزيئات جوية جديدة بواسطة تكثف حمض النيتريك والأمونيا. ناتشر 581، 184-189 (2020).

64. زانغ، ر. وآخرون. الدور الحاسم لحمض اليودوز في نواة الأحماض الأكسجينية المحايدة لليود. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 56، 14166-14177 (2022).

65. بيرس، ج. ر. وآدامز، ب. ج. طريقة فعالة حسابياً لتكوين/تكثيف الهباء الجوي: حمض الكبريتيك في حالة شبه مستقرة. علوم وتقنية الهباء الجوي 43، 216-226 (2009).

66. زهاو، ب. وآخرون. تأثير التلوث الحضري على تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة المدعوم بالمواد العضوية وتركيز عدد الجسيمات في غابة الأمازون المطيرة. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 4357-4367 (2021).

67. كيندلر-شار، أ. وآخرون. تكوين جزيئات جديدة في الغابات مثبط بواسطة انبعاثات الإيزوبرين. ناتشر 461، 381-384 (2009).

68. لي، س.-هـ. وآخرون. تثبيط الإيزوبرين لتكوين جزيئات جديدة: الآليات المحتملة والآثار المترتبة. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 121، 14621-14635 (2016).

69. هاينريتي، م. وآخرون. الفهم الجزيئي لقمع تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة بواسطة الإيزوبرين. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 20، 11809-11821 (2020).

70. يونغ، ل. هـ. وآخرون. تم رصد نمو الجسيمات الجديدة وانكماشها في البيئات شبه الاستوائية. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 13، 547-564 (2013).

71. لو، س. وآخرون. علاجات SOA الجديدة ضمن نموذج نظام الأرض إكساسكال للطاقة (E3SM): الإنتاج القوي والمصارف تحكم توزيعات SOA الجوية والقوة الإشعاعية. مجلة النمذجة المتقدمة. أنظمة الأرض 12، e2020MS002266 (2020).

72. ماو، ج. وآخرون. النمذجة عالية الدقة للميثيلامينات الغازية فوق منطقة ملوثة في الصين: انبعاثات تعتمد على المصدر وآثار التغيرات المكانية. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 18، 7933-7950 (2018).

73. تشين، د. وآخرون. رسم خرائط ثنائي ميثيل الأمين، ثلاثي ميثيل الأمين، الأمونيا، ونظائرها الجسيمية في الأجواء البحرية لبحار الصين الهامشية – الجزء 1: تمييز الانبعاثات البحرية عن النقل القاري. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 21، 16413-16425 (2021).

74. كارل، س. أ. وكراولي، ج. ن. امتصاص الفوتونات الزرقاء المتتابعة

75. وانغ، ل.، لال، ف.، خاليزوف، أ. ف. وزانغ، ر. كيمياء غير متجانسة للألكيل أمينات مع حمض الكبريتيك: الآثار المترتبة على التكوين الجوي لألكيل أمونيوم سلفات. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 44، 2461-2465 (2010).

76. تشيو، سي.، وانغ، ل.، لال، ف.، خاليزوف، أ. ف. وزانغ، ر. تفاعلات غير متجانسة للألكيل أمينات مع كبريتات الأمونيوم وكبريتات الأمونيوم الهيدروجينية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 45، 4748-4755 (2011).

77. ساندر، ر. تجميع ثوابت قانون هنري (الإصدار 4.0) للماء كمذيب. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزيائية 15، 4399-4981 (2015).

78. كاراغودين-دوينيل، أ. وآخرون. كيمياء اليود في نموذج الكيمياء-المناخ SOCOL-AERv2-I. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 14، 6623-6645 (2021).

79. كونيغ، ت. ك. وآخرون. الكشف الكمي عن اليود في الستراتوسفير. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 117، 1860-1866 (2020).

80. سايز-لوبيز، أ. وآخرون. كيمياء اليود في التروبوسفير وتأثيرها على الأوزون. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 14، 13119-13143 (2014).

81. فينكزيلر، هـ. وآخرون. آلية تكوين حمض اليود في الطور الغازي كمصدر للهباء الجوي. نات. كيم. 15، 129-135 (2022).

82. بلين، ج. م. سي، جوزيف، د. م.، ألان، ب. ج.، أشورث، س. هـ. وفرانسيسكو، ج. س. دراسة تجريبية ونظرية للتفاعلات

83. كونيغ، ت. ك. وآخرون. استنفاد الأوزون بسبب إطلاق الغبار لليود في الطبقة التروبوسفيرية الحرة. ساينس أدفانس. 7، eabj6544 (2021).

84. كويفاس، سي. أ. وآخرون. تأثير اليود على ثقب الأوزون في الستراتوسفير القطبي الجنوبي. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 119، e2110864119 (2022).

85. وانغ، هـ. وآخرون. الهباء الجوي في النسخة 1 من E3SM: التطورات الجديدة وتأثيراتها على الإشعاع القسري. مجلة النمذجة المتقدمة في نظم الأرض 12، e2019MS001851 (2020).

86. ليو، إكس. وآخرون. وصف وتقييم نسخة جديدة بأربعة أوضاع من وحدة الهباء الجوي النمطي (MAM4) ضمن النسخة 5.3 من نموذج الغلاف الجوي المجتمعي. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 9، 505-522 (2016).

87. ليو، إكس. وآخرون. نحو تمثيل بسيط للجسيمات الهوائية في نماذج المناخ: الوصف والتقييم في نموذج الغلاف الجوي المجتمعي CAM5. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 5، 709-739 (2012).

88. زافيري، ر. أ.، إيستر، ر. س.، فاست، ج. د. وبيترز، ل. ك. نموذج لمحاكاة تفاعلات وهندسة الهباء الجوي (MOSAIC). مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء: الغلاف الجوي 113، D132O4 (2008).

89. إصدار WCRP-CMIP CMIP6_CVs: 6.2.58.68https://wcrp-cmip.github.io/CMIP6_CVs/docs/CMIP6_source_id.html.

90. كازيل، ج. وآخرون. نواة الهباء الجوي ودورها في السحب وتأثيرها الإشعاعي على الأرض في نموذج المناخ ECHAM5-HAM. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 10، 10733-10752 (2010).

91. غوردون، هـ. وآخرون. تقليل التأثير الإشعاعي للهباء الجوي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية بسبب تكوين جزيئات جديدة بيولوجية. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 113، 12053-12058 (2016).

92. مكونن، ر.، سيلاند، أ.، كيركيفاج، أ.، إيفرسن، ت. وكريستيانسون، ج. إ. تقييم تركيزات عدد الهباء الجوي في NorESM مع تحسين معلمات النواة. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 14، 5127-5152 (2014).

93. بيرغمان، ت. وآخرون. وصف وتقييم مخطط للهباء العضوي الثانوي وتكوين جزيئات جديدة ضمن TM5-MP v1.2. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 15، 683-713 (2022).

94. مكونن، ر. وآخرون. حساسية تركيزات الهباء الجوي وخصائص السحب للتكوين وتوزيع المواد العضوية الثانوية في نموذج الدورة الجوية العالمية ECHAM5-HAM. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 9، 1747-1766 (2009).

95. مان، ج. و. وآخرون. مقارنة بين تمثيلات الميكروفيزياء الهوائية النمطية والقطاعية ضمن نفس نموذج النقل الكيميائي العالمي ثلاثي الأبعاد. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 12، 4449-4476 (2012).

96. فيجناتي، إ.، ويلسون، ج. وستير، ب. نموذج M7: وحدة ميكروفزيائية فعالة لحجم الجسيمات الهوائية لنماذج النقل الهوائي على نطاق واسع. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. الغلاف الجوي 109، D222O2 (2004).

97. مان، ج. و. وآخرون. وصف وتقييم نموذج GLOMAP-mode: نموذج ميكروفيزياء الهباء الجوي العالمي النمطي لنموذج UKCA لتكوين المناخ. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 3، 519-551 (2010).

98. وانغ، هـ. وآخرون. حساسية توزيع الهباء الجوي عن بُعد لتمثيل تفاعلات السحاب والهباء الجوي في نموذج مناخ عالمي. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 6، 765-782 (2013).

99. إيمونز، ل. ك. وآخرون. وصف وتقييم نموذج الأوزون والمتتبعات الكيميائية ذات الصلة، الإصدار 4 (MOZART-4). تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 3، 43-67 (2010).

100. بوشولز، ر. ر.، إيمونز، ل. ك.، تيلميس، س. وفريق تطوير CESM2. مخرجات CESM2.1/ CAM-chem الفورية لظروف الحدود.https://doi.org/10.5065/ NMP7-EP60 (يوكار/إنكار – مختبر ملاحظات ونمذجة الكيمياء الجوية، 2019).

101. هودزيتش، أ. وآخرون. اعتماد التقلب على ثوابت قانون هنري للمواد العضوية القابلة للتكثف: تطبيق لتقدير فقد الإيداع للهباء العضوي الثانوي. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 41، 4795-4804 (2014).

102. صن، ج. وآخرون. تأثير استراتيجية الدفع على تمثيل المناخ ومهارة التنبؤ في محاكاة EAMv1 المقيدة. مجلة النمذجة المتقدمة في أنظمة الأرض 11، 3911-3933 (2019).

103. هويسلي، ر. م. وآخرون. الانبعاثات البشرية التاريخية (1750-2014) للغازات التفاعلية والهباء الجوي من نظام بيانات انبعاثات المجتمع (CEDS). تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 11، 369-408 (2018).

104. فنغ، ل. وآخرون. إنتاج بيانات انبعاثات شبكية لـ CMIP6. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 13، 461-482 (2020).

105. وانغ، س.، مالترود، م.، إليوت، س.، كاميرون-سميث، ب. وجونكو، أ. تأثير ثنائي ميثيل كبريتيد على دورة الكربون والإنتاج البيولوجي. الكيمياء الحيوية 138، 49-68 (2018).

106. وانغ، س. إكس. وآخرون. اتجاهات الانبعاثات وخيارات التخفيف للملوثات الجوية في شرق آسيا. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 14، 6571-6603 (2014).

107. دينغ، د.، شينغ، ج.، وانغ، س. إكس.، ليو، ك. واي. & هاو، ج. م. التقديرات المتعلقة بمساهمات ضوابط الانبعاثات، والعوامل الجوية، ونمو السكان، والتغيرات في معدل الوفيات الأساسي في تقليل مستويات التلوث البيئي

108. غينتر، أ. وآخرون. تقديرات انبعاثات الإيزوبرين الأرضية العالمية باستخدام MEGAN (نموذج انبعاثات الغازات والهباء من الطبيعة). الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 6، 3181-3210 (2006).

109. وينديش، م. وآخرون. حملة ACRIDICON-CHUVA: دراسة السحب العميقة التكتونية الاستوائية وهطول الأمطار فوق الأمازون باستخدام الطائرة البحثية الألمانية الجديدة HALO. نشرة الجمعية الأمريكية للأرصاد الجوية 97، 1885-1908 (2016).

110. دينغ، أ. وآخرون. المراقبة طويلة الأمد لتفاعلات تلوث الهواء والطقس/المناخ في محطة SORPES: مراجعة وآفاق. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 10، 15 (2016).

111. دينغ، أ. وآخرون. انخفاض كبير في

112. جيانغ، ج.، تشين، م.، كوانغ، ج.، أتووي، م. ومك موري، ب. هـ. مقياس الحركة الكهربائية باستخدام عداد جزيئات تكثيف ثنائي إيثيلين جلايكول لقياس توزيعات حجم الهباء الجوي حتى 1 نانومتر. علوم وتقنية الهباء الجوي 45، 510-521 (2011).

113. ليو، ج.، جيانغ، ج.، تشانغ، ق.، دينغ، ج. & هاو، ج. جهاز طيفي لقياس توزيعات حجم الجسيمات في نطاق 3 نانومتر إلى

114. كاي، ر.، تشين، د.-ر.، هاو، ج. وجيانغ، ج. محلل حركة تفاضلي أسطواني مصغر لتحديد حجم الجسيمات أقل من 3 نانومتر. مجلة علوم الهباء الجوي 106، 111-119 (2017).

115. ليو، ي. وآخرون. تشكيل أبخرة عضوية قابلة للتكثف من المركبات العضوية المتطايرة (VOCs) الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية والبيولوجية يتأثر بشدة بـ

116. سميث، س. ج. وآخرون. انبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكبريت الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية: 1850-2005. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 11، 1101-1116 (2011).

117. كريبا، م. وآخرون. انبعاثات ملوّثات الهواء الموزعة جغرافياً للفترة من 1970 إلى 2012 ضمن EDGAR v4.3.2. بيانات علوم الأرض 10، 1987-2013 (2018).

118. وانغ، س.، إليوت، س.، مالترود، م. وكاميرون-سميث، ب. تأثير التوصيفات الصريحة لفايوسيستيس على التوزيع العالمي للثنائي ميثيل كبريتيد البحري. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. البيوجيوكيمياء 120، 2158-2177 (2015).

119. لانا، أ. وآخرون. علم المناخ المحدث لتركيزات ثنائي ميثيل كبريتيد السطح وتدفقات الانبعاثات في المحيط العالمي. دوريات الدورات البيوجيوكيميائية العالمية 25، Gb1004 (2011).

120. كوبك، أ. وآخرون. الدور المحتمل للمواد العضوية في تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة والنمو الأولي في الطبقة العليا من الغلاف الجوي الاستوائي النائي. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 20، 15037-15060 (2020).

121. غونتر، أ. ب. وآخرون. نموذج انبعاثات الغازات والهباء الجوي من الطبيعة النسخة 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): إطار موسع ومحدث لنمذجة الانبعاثات البيوجينية. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 5، 1471-1492 (2012).

122. مكدوفي، إ. إ. وآخرون. جرد عالمي للانبعاثات البشرية من الملوثات الجوية من مصادر محددة حسب القطاع والوقود (1970-2017): تطبيق نظام بيانات انبعاثات المجتمع (CEDS). بيانات علوم الأرض 12، 3413-3442 (2020).

123. بومان، أ. ف. وآخرون. جرد انبعاثات عالمي عالي الدقة للأمونيا. الدورات البيوجيوكيميائية العالمية 11، 561-587 (1997).

124. فاولر، د. وآخرون. آثار التغيرات العالمية خلال القرن الحادي والعشرين على دورة النيتروجين. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 15، 13849-13893 (2015).

125. بولوت، ف. وآخرون. الانبعاثات العالمية للأمونيا من المحيطات: قيود من ملاحظات مياه البحر والغلاف الجوي. الدورات البيوجيوكيميائية العالمية 29، 1165-1178 (2015).

126. ليفسي، ن. ج.، فان سنايدر، و.، ريد، و. ج. وواجنر، ب. أ. خوارزميات الاسترجاع لجهاز قياس الأطياف الميكروويفية في الأطراف (MLS). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44، 1144-1155 (2006).

127. ليفسي، ن. ج. وآخرون. نظام مراقبة الأرض (EOS). جهاز قياس الموجات الدقيقة في الطبقة العليا (MLS). الإصدار

128. زانغ، جي. جي. ومكفارلين، ن. أ. حساسية محاكاة المناخ لتحديد معلمات الحمل السحابي في نموذج الدورة العامة للمناخ في المركز الكندي للمناخ. أتموس.-أوشن 33، 407-446 (1995).

129. تشيان، ي. وآخرون. حساسية المعلمات وتقدير عدم اليقين في النسخة 1 من نموذج الغلاف الجوي E3SM استنادًا إلى محاكاة مجموعة المعلمات المضطربة القصيرة. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 123، 13046-13073 (2018).

130. شو، إكس. وآخرون. العوامل المؤثرة على معدل الإدخال في السحب الحملية العميقة والمعلمات. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 126، e2021JD034881 (2021).

131. يانغ، ب. وآخرون. تحديد عدم اليقين وضبط المعلمات في مخطط الحمل في CAM5 زانغ-ماكفارلين وتأثير الحمل المحسن على الدورة الجوية العالمية والمناخ. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 118، 395-415 (2013).

132. ويمر، د. وآخرون. المراقبة الأرضية للتجمعات وجزيئات وضع النواة في الأمازون. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 18، 13245-13264 (2018).

133. فرانكو، م. أ. وآخرون. حدوث ونمو جزيئات الهباء الجوي أقل من 50 نانومتر في طبقة الحدود الأمازونية. الكيمياء والفيزياء الجوية 22، 3469-3492 (2022).

134. زهاو، ب. وآخرون. عملية تشكيل الجسيمات ونوى تكثف السحب فوق غابة الأمازون المطيرة: دور تشكيل الجسيمات الجديدة المحلية والبعيدة. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 49، e2022GL100940 (2022).

135. ستير، ب. وآخرون. نموذج الهباء الجوي والمناخ ECHAM5-HAM. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 5، 1125-1156 (2005).

136. لوكاس، د. د. وأكي موتو، هـ. تقييم معلمات تكوين الهباء في نموذج جوي عالمي. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 33، L10808 (2006).

137. بيرس، ج. ر. وآدامز، ب. ج. عدم اليقين في تركيزات CCN العالمية نتيجة عدم اليقين في معدلات تكوين الهباء الجوي والانبعاثات الأولية. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 9، 1339-1356 (2009).

138. يو، ف. وآخرون. تركيزات عدد الجسيمات وتوزيعات الحجم في الستراتوسفير: تداعيات آليات النواة والميكروفيزياء الجسيمات. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء. 23، 1863-1877 (2023).

139. ميريكانتو، ج.، سبركلن، د. ف.، مان، ج. و.، بيكيرينغ، س. ج. وكارسلاو، ك. س. تأثير النواة على CCN العالمية. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 9، 8601-8616 (2009).

140. يو، ف. وآخرون. التوزيعات المكانية لتركيزات عدد الجسيمات في الغلاف الجوي العالمي: المحاكاة، الملاحظات، والآثار على آليات النواة. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء: الغلاف الجوي 115، D17205 (2010).

141. ويسترفيلت، د. م. وآخرون. تشكيل ونمو الجسيمات المنوية إلى نوى تكاثف السحب: مقارنة بين النموذج والقياس. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 13، 7645-7663 (2013).

142. سبراكيلن، د. ف. وآخرون. تفسير تركيزات عدد الجسيمات الهوائية السطحية العالمية من حيث الانبعاثات الأولية وتكوين الجسيمات. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 10، 4775-4793 (2010).

143. كولمالا، م.، ليتينين، ك. إ. ج. & لاكسونين، أ. نظرية تنشيط الكتل كشرح للاعتماد الخطي بين معدل تكوين جزيئات بحجم 3 نانومتر وتركيز حمض الكبريتيك. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 6، 787-793 (2006).

144. كوانغ، سي.، مك موري، بي. إتش.، مك كورميك، إيه. في. وإيسل، إف. إل. اعتماد معدلات النواة على تركيز بخار حمض الكبريتيك في مواقع جوية متنوعة. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. أتموس. 113، D10209 (2008).

145. سكوت، سي. إي. وآخرون. التأثيرات الإشعاعية المباشرة وغير المباشرة للهباء الجوي العضوي الثانوي البيولوجي. الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 14، 447-470 (2014).

146. دادا، ل. وآخرون. المصادر والمصارف التي تؤثر على تركيزات حمض الكبريتيك في بيئات متباينة: الآثار على حسابات المؤشرات. أتموس. كيم. فيز. 20، 11747-11766 (2020).

147. يانغ، ل. وآخرون. نحو بناء نموذج مادي لتركيز حمض الكبريتيك في الطور الغازي استنادًا إلى تحليل ميزانيته في دلتا نهر يانغتسي الملوثة، شرق الصين. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 55، 6665-6676 (2021).

148. دينغ، سي. وآخرون. الخصائص الموسمية لتكوين الجسيمات الجديدة ونموها في بكين الحضرية. علوم البيئة والتكنولوجيا 54، 8547-8557 (2020).

149. وانغ، ي. وآخرون. الكشف عن ثنائي ميثيل الأمين الغازي باستخدام مطياف الكتلة بتفاعل نقل البروتون من نوع فوكوس. البيئة الجوية 243، 117875 (2020).

150. أنت، ي. وآخرون. الأمينات الجوية والأمونيا المقاسة باستخدام مطياف الكتلة بتأين كيميائي (CIMS). الكيمياء الجوية والفيزياء 14، 12181-12194 (2014).

151. تشنغ، ج. وآخرون. قياس الأمينات الجوية والأمونيا باستخدام مطياف الكتلة بتقنية التأين الكيميائي عالي الدقة. البيئة الجوية. 102، 249-259 (2015).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى بين زهاو.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر مجلة Nature المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل. تقارير مراجعي الأقران متاحة.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

عضوي-

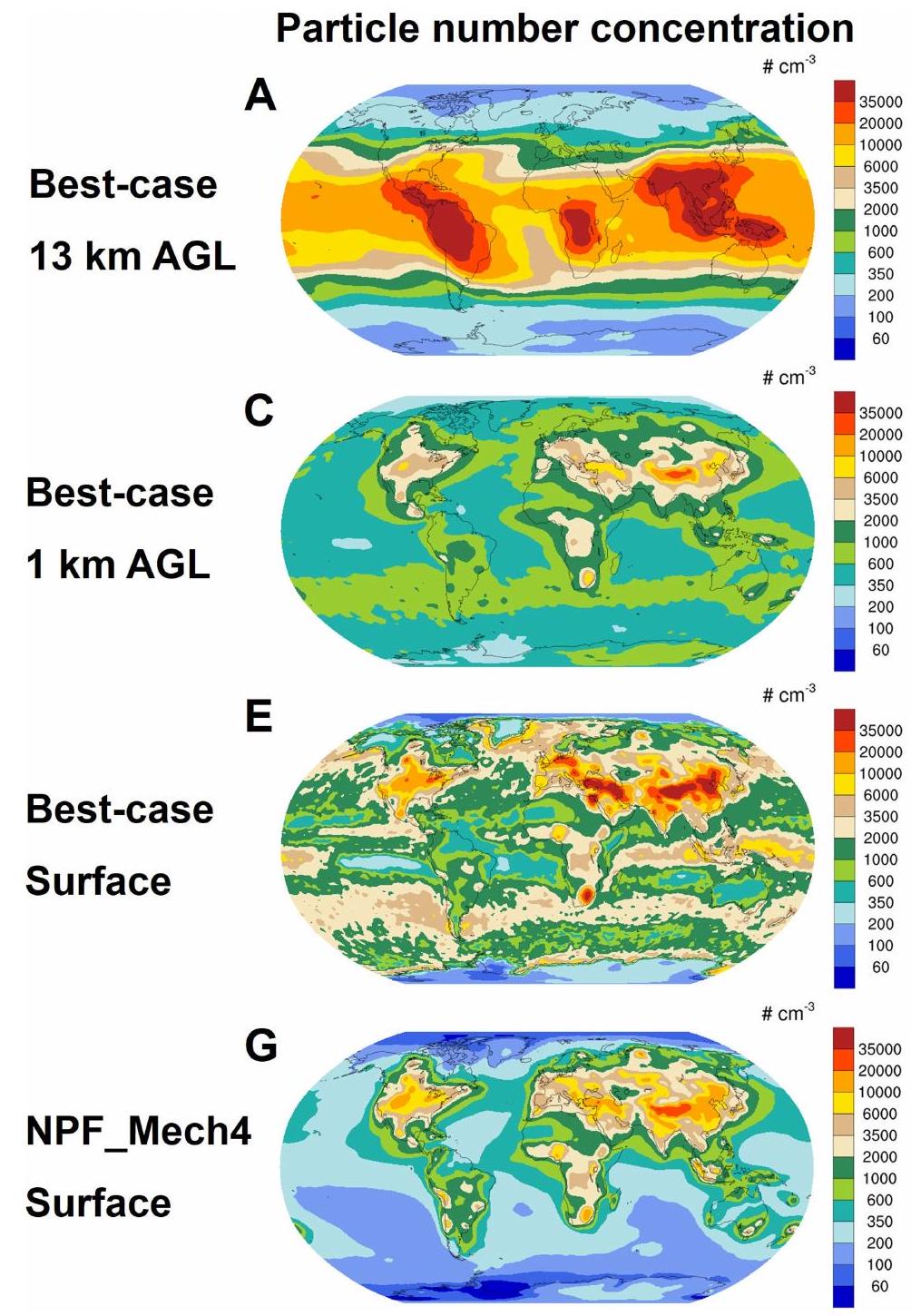

ن، كسور تركيزات عدد الجسيمات الناتجة عن تكوين الجسيمات الجديدة عند مستوى السطح، بناءً على

على الفرق بين سيناريوهات NPF_Mech4 و No_NPF. تم تقديم تعريفات السيناريوهات في الطرق والجدول التكميلي 1. تغطي تركيزات عدد الجسيمات النطاق الكامل للحجم (لاحظ أن الملاحظات الميدانية تتم عادة للجسيمات الأكبر من حجم قطع معين) ويتم تطبيعها إلى درجة حرارة وضغط قياسيين (273.15 كلفن و 101.325 كيلو باسكال). تم تقديم متوسط تركيز عدد الجسيمات في المناطق والفئات الناتجة عن NPF في الشكل التكميلي 12. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام لغة أوامر NCAR (الإصدار 6.6.2).https://doi.org/10.5065/D6WD3XH5.

مقارنة بين المحاكاة

كلاهما متوسط في عام 2016 عبر المناطق المحددة في الشكل 1b من البيانات الموسعة. تم تقديم تعريفات تجارب الحساسية في الطرق والجدول التكميلي 1.

المساهمات النسبية لآليات مختلفة، تم حسابها في عام 2016 عبر المناطق المحددة في الشكل التوضيحي 1b. تم تقديم تعريفات تجارب الحساسية في الطرق والجدول التكميلي 1.

آليات التأثير ضئيلة في هذه المناطق. تم تقديم تعريفات تجارب الحساسية في الطرق والجدول التكميلي 1.

آليات مختلفة، تم حسابها في عام 2016 عبر المناطق المحددة في الشكل 1b من البيانات الموسعة. بالنسبة لسيناريو متوسط بين أفضل محاكاة للحالة وأسفل محاكاة الحساسية المذكورة أعلاه، فإن مساهمة

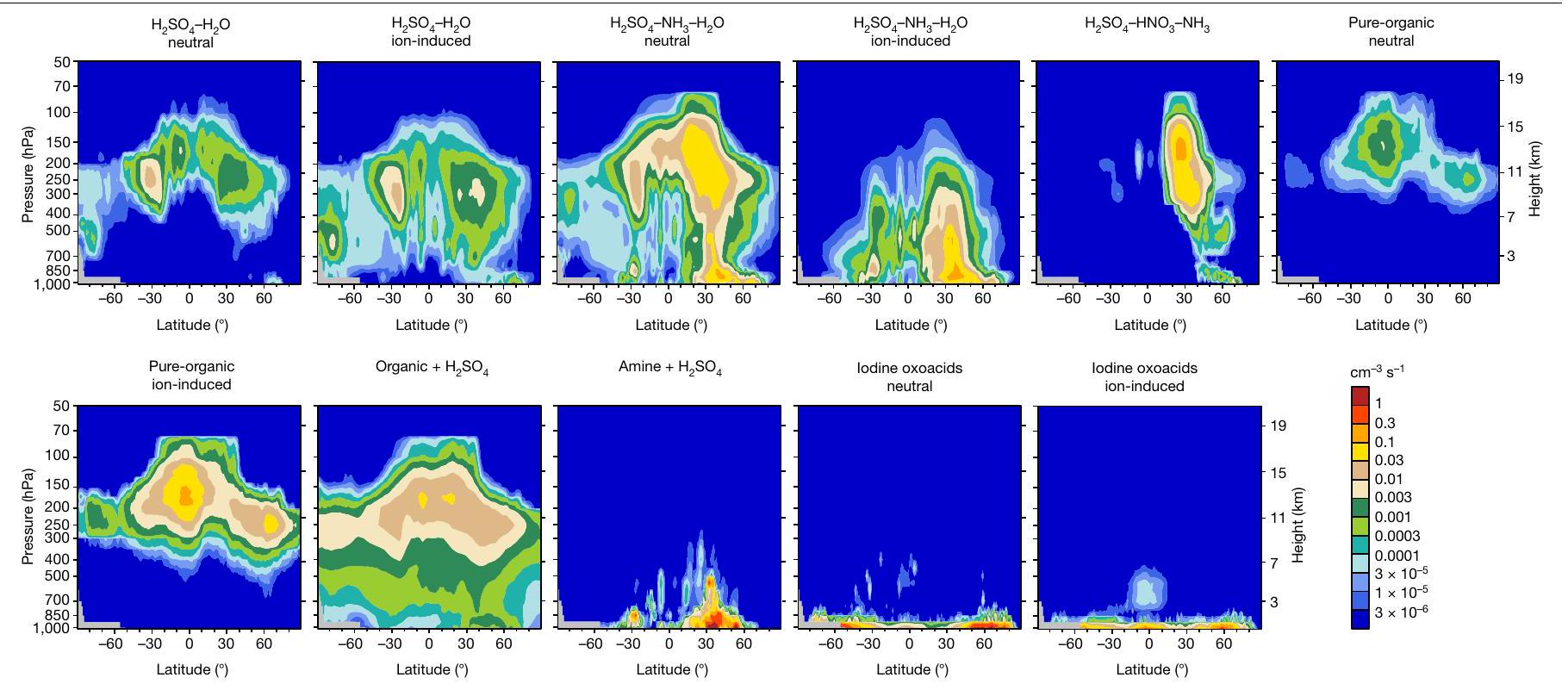

معدلات في سيناريوهين. أ، محاكاة أفضل حالة تشمل 11 آلية نواة. ب، محاكاة حساسية تشمل فقط أربع آليات تقليدية

المختبر المشترك الرئيسي للدولة لمحاكاة البيئة ومراقبة التلوث، كلية البيئة، جامعة تسينغhua، بكين، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي لحماية البيئة للدولة لمصادر ومراقبة تلوث الهواء المعقد، بكين، الصين. المختبر الوطني في شمال غرب المحيط الهادئ، ريتشلاند، واشنطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز دراسات الجسيمات الجوية، جامعة كارنيجي ميلون، بيتسبرغ، بنسلفانيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الهندسة الكيميائية، جامعة كارنيجي ميلون، بيتسبرغ، بنسلفانيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الكيمياء، جامعة كارنيجي ميلون، بيتسبرغ، بنسلفانيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الهندسة والسياسة العامة، جامعة كارنيجي ميلون، بيتسبرغ، بنسلفانيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. المركز الوطني للبحوث الجوية، بولدر، كولورادو، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الكيمياء والهندسة الكيميائية، معهد كاليفورنيا للتكنولوجيا، باسادينا، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. المختبر الرئيسي للبيئة البحرية والبيئة، وزارة التعليم، جامعة المحيط في الصين، كينغداو، الصين. المختبر الدولي المشترك للبحوث في علوم الغلاف الجوي ونظام الأرض، كلية علوم الغلاف الجوي، جامعة نانجينغ، نانجينغ، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي لتلوث الجسيمات الجوية والوقاية (LAP )، قسم علوم البيئة والهندسة، جامعة فودان، شنغهاي، الصين. العنوان الحالي: كلية علوم المحيطات والأرض، جامعة شيامن، شيامن، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني:bzhao@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07547-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38867037

Publication Date: 2024-06-12

Global variability in atmospheric new particle formation mechanisms

Received: 21 August 2023

Accepted: 9 May 2024

Published online: 12 June 2024

Open access

Abstract

A key challenge in aerosol pollution studies and climate change assessment is to understand how atmospheric aerosol particles are initially formed

atmospheric models-tools indispensable for understanding the mechanisms and impacts of NPF on global and regional scales-lack the ability to represent many critically important processes. Most widely used global models are built on traditional binary and ternary particle nucleation processes involving sulfuric acid (

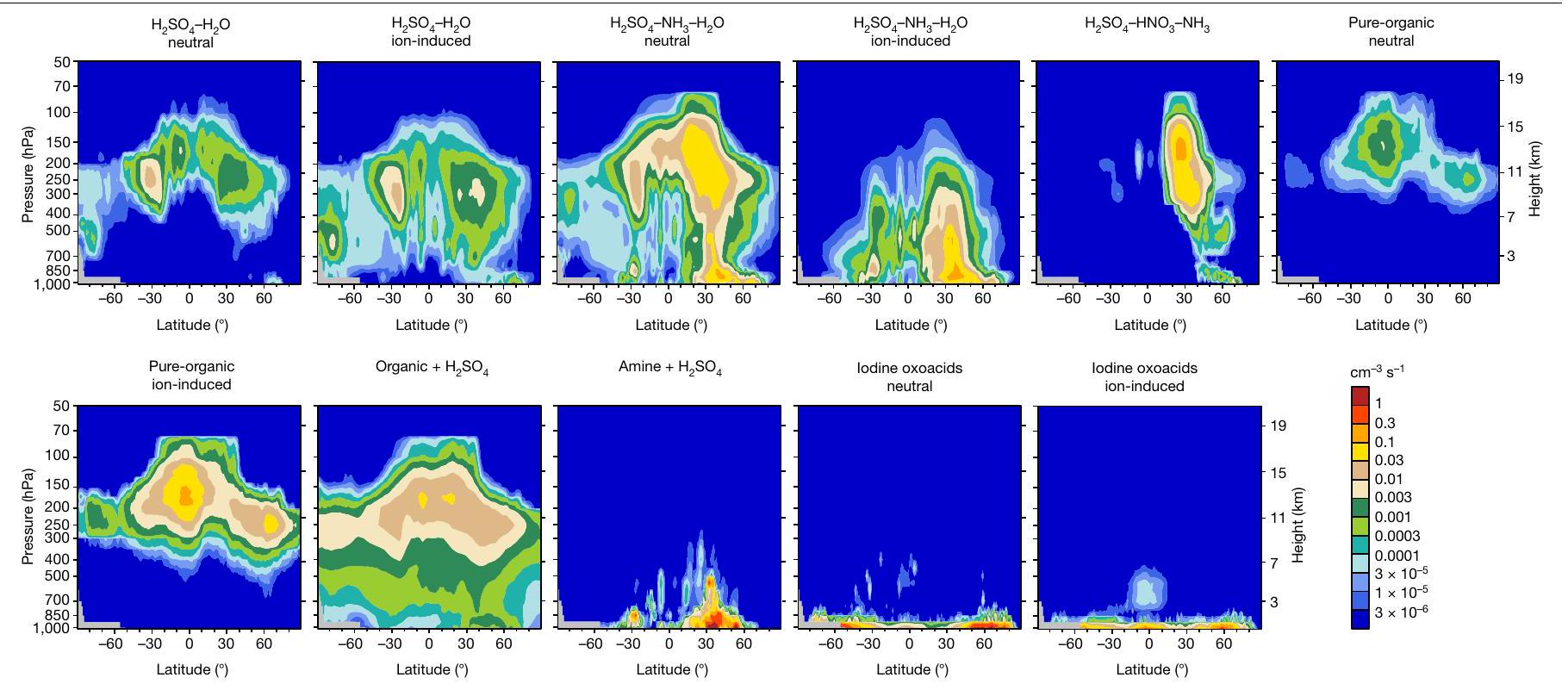

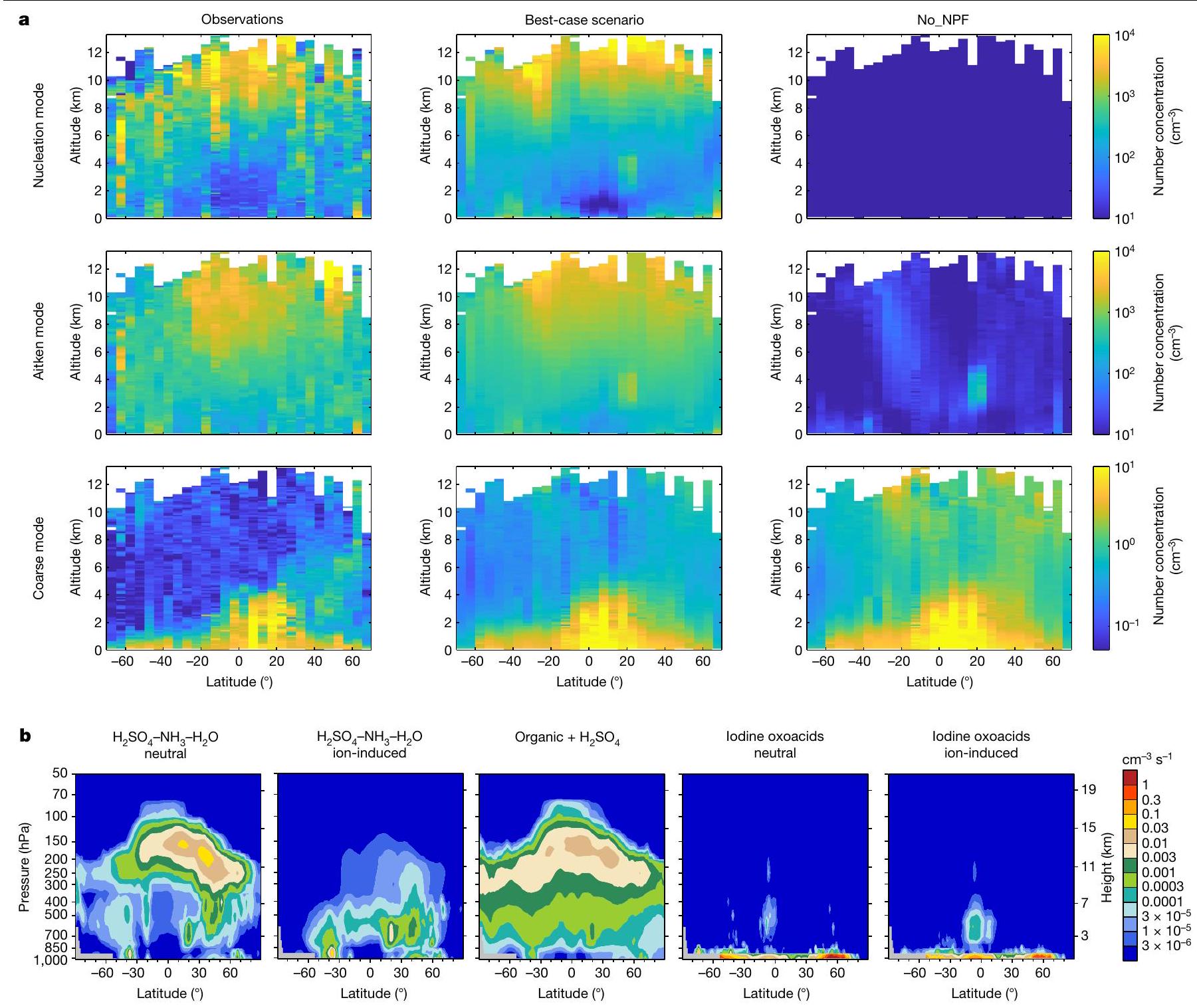

normalized to standard temperature and pressure ( 273.15 K and 101.325 kPa ). Definitions of the model scenarios are given in the main text and Supplementary Table1.b, NPF rates as a function of height AGL over the Central Amazon, Central Africa and Southeastern Asia. White lines represent the total NPF rates of all mechanisms at a diameter of 1.7 nm (

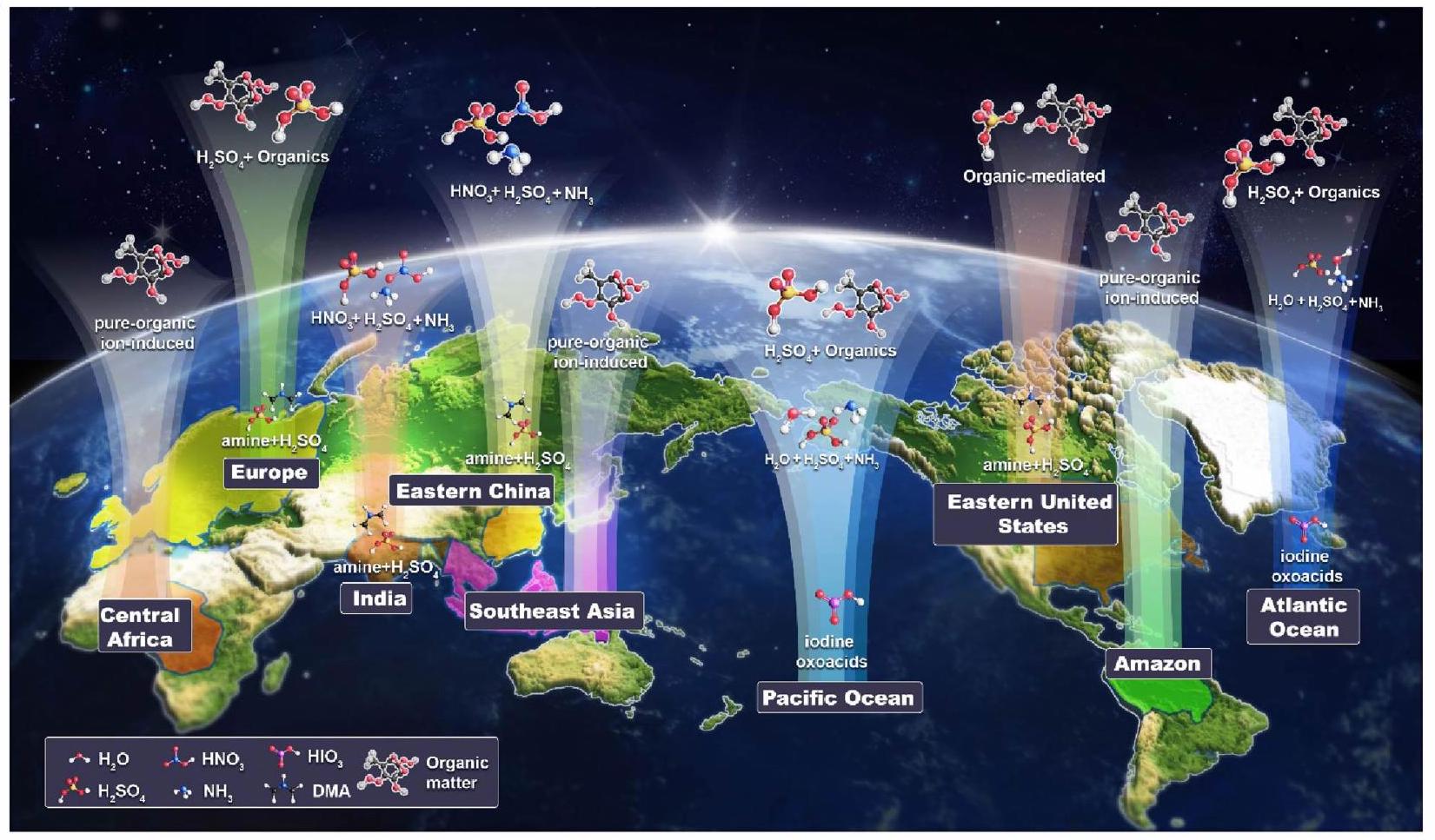

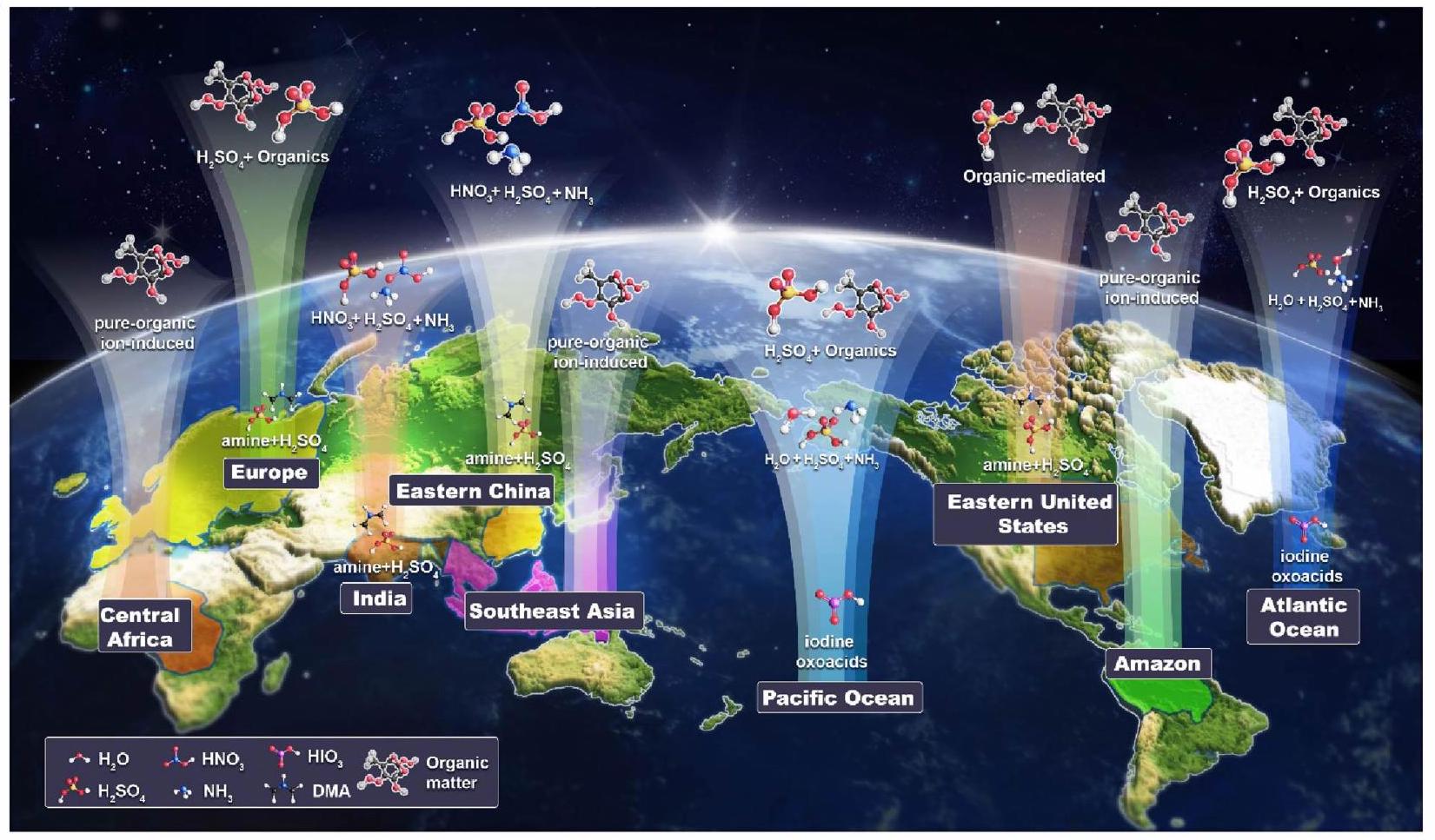

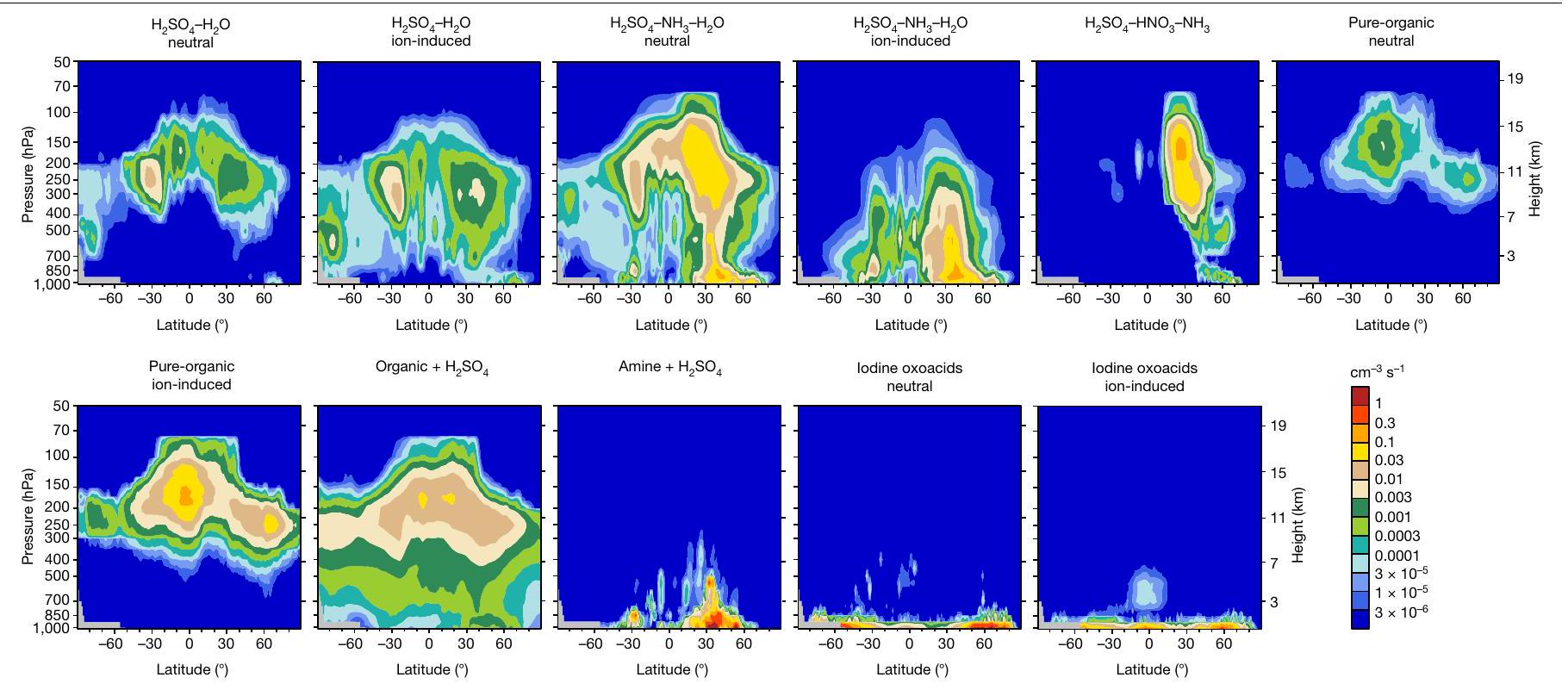

Here we synthesized molecular-level laboratory experiments to develop comprehensive model representations of NPF and the chemical transformation of precursor gases in a fully coupled global climate model. The model considers 11 nucleation mechanisms, among which four crucial mechanisms were largely overlooked previously, including iodine oxoacids neutral and ion-induced nucleation, synergistic

large aerosol-cloud radiative forcing

NPF mechanisms over rainforests

NPF mechanisms in human-polluted regions

NPF mechanisms over the oceans

capture the shape of the ultrafine number size distribution because the model uses a mode approach to represent particle size.b, NPF rates as a function of height AGL over Eastern China, India, Europe and the Eastern United States. White lines represent the total NPF rates at a diameter of

with latitude. Our simulation suggests that organic-

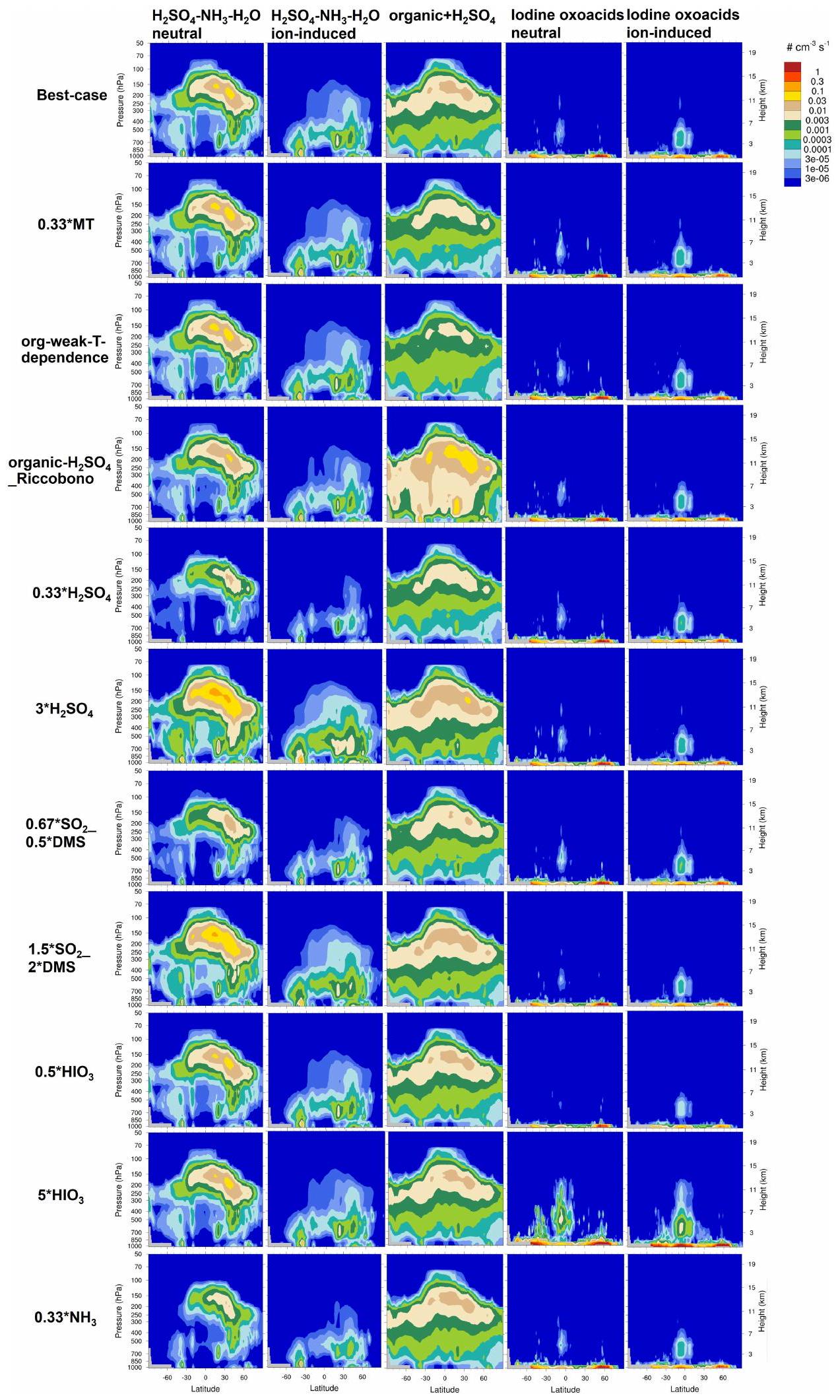

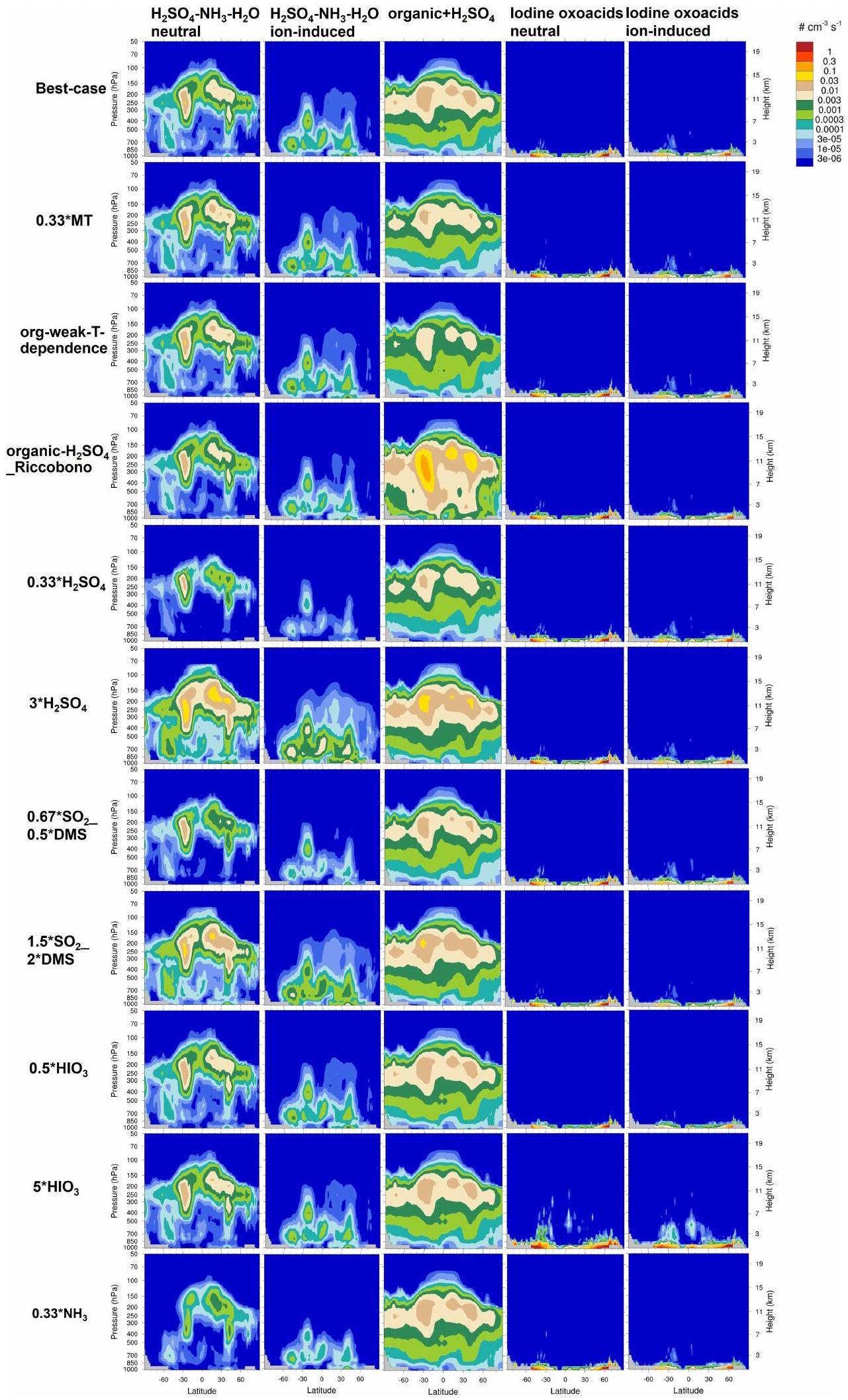

Global overview and sensitivity analysis

(every 100 m ) and the average particle number concentrations in each bin are calculated and plotted. All particle number concentrations are normalized to standard temperature and pressure. b, Zonal mean NPF rates of individual mechanisms over the Pacific Ocean (

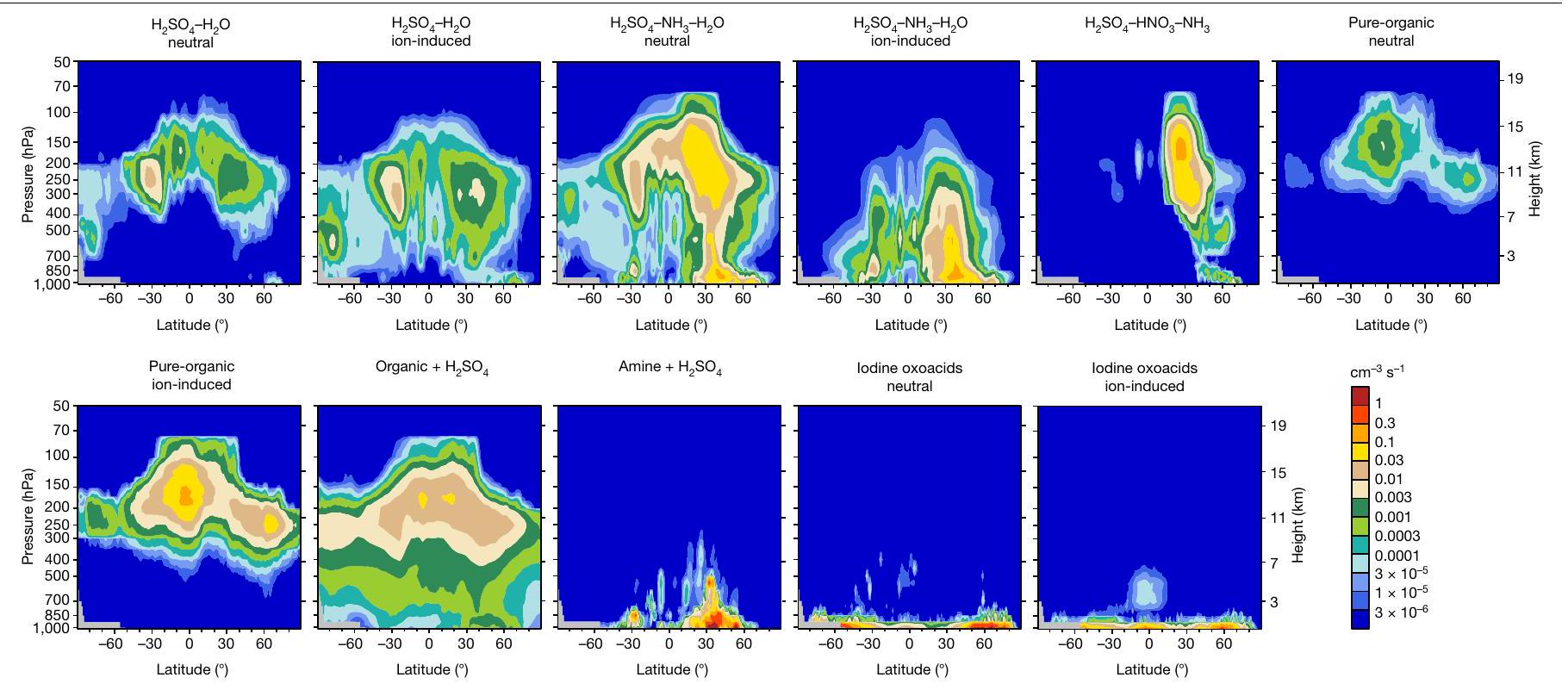

governing convective transport based on our best-case scenario. The results indicate that our main findings about the leading NPF mechanisms hold true under these sensitivity simulations in all key regions of interest. Nevertheless, these sources of uncertainty might affect the precise quantitative contributions of individual mechanisms, both in the above key regions and in other areas not discussed in detail individually.

Contribution of NPF to particles and CCN

level), the fractions of particles and CCNO.5% caused by NPF vary regionally. Over the tropical and mid-latitude oceans at which cloud radiative effects are highly susceptible to CCN availability, NPF generally accounts for

vertical levels in 2016. a,c,e, Spatial distribution of CCN concentrations at

Discussion

monsoon regions, rainforests and tropical oceans during the industrial era. For another example, whether NPF in oceanic boundary layers is governed by iodine oxoacids or

Online content

- Lee, S.-H. et al. New particle formation in the atmosphere: from molecular clusters to global climate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 7098-7146 (2019).

- Kulmala, M. et al. Is reducing new particle formation a plausible solution to mitigate particulate air pollution in Beijing and other Chinese megacities? Faraday Discuss. 226, 334-347 (2021).

- Yao, L. et al. Atmospheric new particle formation from sulfuric acid and amines in a Chinese megacity. Science 361, 278-281 (2018).

- Cai, R. et al. Sulfuric acid-amine nucleation in urban Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 2457-2468 (2021).

- Baccarini, A. et al. Frequent new particle formation over the high Arctic pack ice by enhanced iodine emissions. Nat. Commun. 11, 4924 (2020).

- Bianchi, F. et al. New particle formation in the free troposphere: a question of chemistry and timing. Science 352, 1109-1112 (2016).

- Williamson, C. J. et al. A large source of cloud condensation nuclei from new particle formation in the tropics. Nature 574, 399-403 (2019).

- Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907-1918 (2017).

- Gordon, H. et al. Causes and importance of new particle formation in the present-day and preindustrial atmospheres. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 8739-8760 (2017).

- Yu, F. & Luo, G. Simulation of particle size distribution with a global aerosol model: contribution of nucleation to aerosol and CCN number concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 7691-7710 (2009).

- Zaveri, R. A. et al. Rapid growth of anthropogenic organic nanoparticles greatly alters cloud life cycle in the Amazon rainforest. Sci. Adv. 8, eabjO329 (2022).

- Kirkby, J. et al. Role of sulphuric acid, ammonia and galactic cosmic rays in atmospheric aerosol nucleation. Nature 476, 429-433 (2011).

- Zhao, B. et al. High concentration of ultrafine particles in the Amazon free troposphere produced by organic new particle formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 25344-25351 (2020).

- Chen, M. et al. Acid-base chemical reaction model for nucleation rates in the polluted atmospheric boundary layer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18713-18718 (2012).

- Wang, M. et al. Synergistic

upper tropospheric particle formation. Nature 605, 483-489 (2022). - Saiz-Lopez, A. et al. Atmospheric chemistry of iodine. Chem. Rev. 112, 1773-1804 (2012).

- Hoffmann, T., O’Dowd, C. D. & Seinfeld, J. H. lodine oxide homogeneous nucleation: an explanation for coastal new particle production. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 1949-1952 (2001).

- Bergman, T. et al. Geographical and diurnal features of amine-enhanced boundary layer nucleation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 9606-9624 (2015).

- Lai, S. et al. Vigorous new particle formation above polluted boundary layer in the North China Plain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100301 (2022).

- Kirkby, J. et al. Ion-induced nucleation of pure biogenic particles. Nature 533, 521-526 (2016).

- Riccobono, F. et al. Oxidation products of biogenic emissions contribute to nucleation of atmospheric particles. Science 344, 717-721 (2014).

- Yu, F., Luo, G., Nadykto, A. B. & Herb, J. Impact of temperature dependence on the possible contribution of organics to new particle formation in the atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4997-5005 (2017).

- Chen, X. et al. Improving new particle formation simulation by coupling a volatility-basis set (VBS) organic aerosol module in NAQPMS+APM. Atmos. Environ. 204, 1-11 (2019).

- Wang, X., Gordon, H., Grosvenor, D. P., Andreae, M. O. & Carslaw, K. S. Contribution of regional aerosol nucleation to low-level CCN in an Amazonian deep convective environment: results from a regionally nested global model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 4431-4461 (2023).

- Zhu, J. et al. Decrease in radiative forcing by organic aerosol nucleation, climate, and land use change. Nat. Commun. 10, 423 (2019).

- Schervish, M. & Donahue, N. M. Peroxy radical chemistry and the volatility basis set. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 1183-1199 (2020).

- Frege, C. et al. Influence of temperature on the molecular composition of ions and charged clusters during pure biogenic nucleation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 65-79 (2018).

- Ye, Q. et al. Molecular composition and volatility of nucleated particles from a-pinene oxidation between

and . Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12357-12365 (2019). - Yan, C. et al. Size-dependent influence of

on the growth rates of organic aerosol particles. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay4945 (2020). - Andreae, M. O. et al. Aerosol characteristics and particle production in the upper troposphere over the Amazon Basin. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 921-961 (2018).

- Weigel, R. et al. In situ observation of new particle formation (NPF) in the tropical tropopause layer of the 2017 Asian monsoon anticyclone – part 1: summary of StratoClim results. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 11689-11722 (2021).

- Zhu, Y. et al. Airborne particle number concentrations in China: a critical review. Environ. Pollut. 307, 119470 (2022).

- Carslaw, K. S. et al. Large contribution of natural aerosols to uncertainty in indirect forcing. Nature 503, 67-71 (2013).

- Wang, C., Soden, B. J., Yang, W. & Vecchi, G. A. Compensation between cloud feedback and aerosol-cloud interaction in CMIP6 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091024 (2021).

- Quaas, J., Boucher, O., Bellouin, N. & Kinne, S. Satellite-based estimate of the direct and indirect aerosol climate forcing. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D05204 (2008).

- McCoy, D. T. et al. The global aerosol-cloud first indirect effect estimated using MODIS, MERRA, and AeroCom. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 1779-1796 (2017).

- Reddington, C. L. et al. Primary versus secondary contributions to particle number concentrations in the European boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 12007-12036 (2011).

- Shilling, J. E. et al. Aircraft observations of the chemical composition and aging of aerosol in the Manaus urban plume during GoAmazon 2014/5. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 10773-10797 (2018).

- Langford, B. et al. Fluxes and concentrations of volatile organic compounds from a South-East Asian tropical rainforest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 8391-8412 (2010).

- Yu, F. & Luo, G. Modeling of gaseous methylamines in the global atmosphere: impacts of oxidation and aerosol uptake. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 12455-12464 (2014).

- Cai, C. et al. Incorporation of new particle formation and early growth treatments into WRF/Chem: model improvement, evaluation, and impacts of anthropogenic aerosols over East Asia. Atmos. Environ. 124, 262-284 (2016).

- Höpfner, M. et al. First detection of ammonia (

) in the Asian summer monsoon upper troposphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 14357-14369 (2016). - Höpfner, M. et al. Ammonium nitrate particles formed in upper troposphere from ground ammonia sources during Asian monsoons. Nat. Geosci. 12, 608-612 (2019).

- Oreopoulos, L. & Platnick, S. Radiative susceptibility of cloudy atmospheres to droplet number perturbations: 2. Global analysis from MODIS. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D14S21 (2008).

- Gryspeerdt, E. et al. Constraining the instantaneous aerosol influence on cloud albedo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4899-4904 (2017).

- Brock, C. A. et al. Aerosol size distributions during the Atmospheric Tomography Mission (ATom): methods, uncertainties, and data products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 3081-3099 (2019).

- Elm, J. et al. Modeling the formation and growth of atmospheric molecular clusters: a review. J. Aerosol Sci. 149, 105621 (2020).

- Yin, R. et al. Acid-base clusters during atmospheric new particle formation in urban Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 10994-11005 (2021).

- Glasoe, W. A. et al. Sulfuric acid nucleation: an experimental study of the effect of seven bases. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 1933-1950 (2015).

- Liu, L. et al. Rapid sulfuric acid-dimethylamine nucleation enhanced by nitric acid in polluted regions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2108384118 (2021).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

NPF module with 11 nucleation mechanisms

For the synergistic

accurately at

R2D-VBS and its parameterizations

Representation of the source and sinks of DMA

uptake of DMA is subject to higher uncertainty because the uptake coefficient varies over a relatively large range in the literature (

Representation of sources and sinks of iodine oxoacids

Configuration of the revised E3SM

For gas chemistry, the model explicitly represents the oxidation of DMS to

Descriptions of observational data

aboard the German High Altitude and LOng range (HALO) aircraft. The CPC has a nominal cutoff diameter of 4 nm , but owing to inlet losses, the effective cutoff diameter is approximately 10 nm near the surface and increases to approximately 20 nm at 150 hPa (approximately 13.8 km ). Because monoterpenes have established connections to organic-mediated NPF, we also evaluated the model against monoterpene concentrations measured by an Ionicon quadrupole high-sensitivity proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS) aboard the G-1 aircraft during the GoAmazon (Observations and Modeling of the Green Ocean Amazon) campaign

Sensitivity analysis of NPF mechanisms

that

concentrations because they would not challenge the leading roles of organic-mediated nucleation over the regions of interest. Extended Data Figs. 5,7 and 8 show that, even with reduced monoterpene emissions, organic-mediated nucleation remains the largest NPF mechanism in the upper troposphere above the three rainforest regions and one of the two primary mechanisms in the upper troposphere above the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

troposphere above Eastern China and India, whereas organic-

evaluation

parameters for the ZM convection scheme implemented in the Community Atmosphere Model version 5. To better address the reviewer’s concern, we further performed two sensitivity simulations (‘upper_tau’ and ‘lower_tau’) that set the value of tau to the upper and lower bounds ( 14,400 and

Further discussion about NPF mechanisms in different regions

Further results and discussion about the NPF contribution to particles and CCN

Discussion in the context of previous global models

concentrations over the oceans and above the boundary layer

products to drive nucleation, as described above. Their simulations revealed that nearly all nucleation throughout the present-day atmosphere involves ammonia or biogenic organic compounds, as well as

Data availability

Code availability

51. Golaz, J.-C. et al. The DOE E3SM coupled model version 1: overview and evaluation at standard resolution. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2089-2129 (2019).

52. Rasch, P. J. et al. An overview of the atmospheric component of the Energy Exascale Earth System Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2377-2411 (2019).

53. Dunne, E. M. et al. Global atmospheric particle formation from CERN CLOUD measurements. Science 354, 1119-1124 (2016).

54. Almeida, J. et al. Molecular understanding of sulphuric acid-amine particle nucleation in the atmosphere. Nature 502, 359-363 (2013).

55. He, X.-C. et al. Role of iodine oxoacids in atmospheric aerosol nucleation. Science 371, 589-595 (2021).

56. Kirkby, J. et al. Atmospheric new particle formation from the CERN CLOUD experiment. Nat. Geosci. 16, 948-957 (2023).

57. Lehtipalo, K. et al. Multicomponent new particle formation from sulfuric acid, ammonia, and biogenic vapors. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau5363 (2018).

58. Metzger, A. et al. Evidence for the role of organics in aerosol particle formation under atmospheric conditions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6646-6651 (2010).

59. Jen, C. N., McMurry, P. H. & Hanson, D. R. Stabilization of sulfuric acid dimers by ammonia, methylamine, dimethylamine, and trimethylamine. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 7502-7514 (2014).

60. Cai, R. et al. The missing base molecules in atmospheric acid-base nucleation. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwac137 (2022).

61. Kerminen, V. M. & Kulmala, M. Analytical formulae connecting the “real” and the “apparent” nucleation rate and the nuclei number concentration for atmospheric nucleation events. J. Aerosol Sci. 33, 609-622 (2002).

62. Kürten, A. et al. New particle formation in the sulfuric acid-dimethylamine-water system: reevaluation of CLOUD chamber measurements and comparison to an aerosol nucleation and growth model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 845-863 (2018).

63. Wang, M. et al. Rapid growth of new atmospheric particles by nitric acid and ammonia condensation. Nature 581, 184-189 (2020).

64. Zhang, R. et al. Critical role of iodous acid in neutral iodine oxoacid nucleation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14166-14177 (2022).

65. Pierce, J. R. & Adams, P. J. A computationally efficient aerosol nucleation/condensation method: pseudo-steady-state sulfuric acid. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 43, 216-226 (2009).

66. Zhao, B. et al. Impact of urban pollution on organic-mediated new-particle formation and particle number concentration in the Amazon rainforest. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 4357-4367 (2021).

67. Kiendler-Scharr, A. et al. New particle formation in forests inhibited by isoprene emissions. Nature 461, 381-384 (2009).

68. Lee, S.-H. et al. Isoprene suppression of new particle formation: potential mechanisms and implications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 14621-14635 (2016).

69. Heinritzi, M. et al. Molecular understanding of the suppression of new-particle formation by isoprene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 11809-11821 (2020).

70. Young, L. H. et al. New particle growth and shrinkage observed in subtropical environments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 547-564 (2013).

71. Lou, S. et al. New SOA treatments within the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM): strong production and sinks govern atmospheric SOA distributions and radiative forcing. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2020MS002266 (2020).

72. Mao, J. et al. High-resolution modeling of gaseous methylamines over a polluted region in China: source-dependent emissions and implications of spatial variations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 7933-7950 (2018).

73. Chen, D. et al. Mapping gaseous dimethylamine, trimethylamine, ammonia, and their particulate counterparts in marine atmospheres of China’s marginal seas – part 1: differentiating marine emission from continental transport. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 16413-16425 (2021).

74. Carl, S. A. & Crowley, J. N. Sequential two (blue) photon absorption by

75. Wang, L., Lal, V., Khalizov, A. F. & Zhang, R. Heterogeneous chemistry of alkylamines with sulfuric acid: implications for atmospheric formation of alkylaminium sulfates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 2461-2465 (2010).

76. Qiu, C., Wang, L., Lal, V., Khalizov, A. F. & Zhang, R. Heterogeneous reactions of alkylamines with ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4748-4755 (2011).

77. Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4399-4981 (2015).

78. Karagodin-Doyennel, A. et al. Iodine chemistry in the chemistry-climate model SOCOL-AERv2-I. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 6623-6645 (2021).

79. Koenig, T. K. et al. Quantitative detection of iodine in the stratosphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 1860-1866 (2020).

80. Saiz-Lopez, A. et al. lodine chemistry in the troposphere and its effect on ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 13119-13143 (2014).

81. Finkenzeller, H. et al. The gas-phase formation mechanism of iodic acid as an atmospheric aerosol source. Nat. Chem. 15, 129-135 (2022).

82. Plane, J. M. C., Joseph, D. M., Allan, B. J., Ashworth, S. H. & Francisco, J. S. An experimental and theoretical study of the reactions

83. Koenig, T. K. et al. Ozone depletion due to dust release of iodine in the free troposphere. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj6544 (2021).

84. Cuevas, C. A. et al. The influence of iodine on the Antarctic stratospheric ozone hole. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2110864119 (2022).

85. Wang, H. et al. Aerosols in the E3SM Version 1: new developments and their impacts on radiative forcing. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001851 (2020).

86. Liu, X. et al. Description and evaluation of a new four-mode version of the Modal Aerosol Module (MAM4) within version 5.3 of the Community Atmosphere Model. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 505-522 (2016).

87. Liu, X. et al. Toward a minimal representation of aerosols in climate models: description and evaluation in the Community Atmosphere Model CAM5. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 709-739 (2012).

88. Zaveri, R. A., Easter, R. C., Fast, J. D. & Peters, L. K. Model for Simulating Aerosol Interactions and Chemistry (MOSAIC). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D132O4 (2008).

89. WCRP-CMIP CMIP6_CVs version: 6.2.58.68 https://wcrp-cmip.github.io/CMIP6_CVs/docs/ CMIP6_source_id.html.

90. Kazil, J. et al. Aerosol nucleation and its role for clouds and Earth’s radiative forcing in the aerosol-climate model ECHAM5-HAM. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 10733-10752 (2010).

91. Gordon, H. et al. Reduced anthropogenic aerosol radiative forcing caused by biogenic new particle formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 12053-12058 (2016).

92. Makkonen, R., Seland, O., Kirkevag, A., Iversen, T. & Kristjansson, J. E. Evaluation of aerosol number concentrations in NorESM with improved nucleation parameterization. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 5127-5152 (2014).

93. Bergman, T. et al. Description and evaluation of a secondary organic aerosol and new particle formation scheme within TM5-MP v1.2. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 683-713 (2022).

94. Makkonen, R. et al. Sensitivity of aerosol concentrations and cloud properties to nucleation and secondary organic distribution in ECHAM5-HAM global circulation model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1747-1766 (2009).

95. Mann, G. W. et al. Intercomparison of modal and sectional aerosol microphysics representations within the same 3-D global chemical transport model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 4449-4476 (2012).

96. Vignati, E., Wilson, J. & Stier, P. M7: an efficient size-resolved aerosol microphysics module for large-scale aerosol transport models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D222O2 (2004).

97. Mann, G. W. et al. Description and evaluation of GLOMAP-mode: a modal global aerosol microphysics model for the UKCA composition-climate model. Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 519-551 (2010).

98. Wang, H. et al. Sensitivity of remote aerosol distributions to representation of cloudaerosol interactions in a global climate model. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 765-782 (2013).

99. Emmons, L. K. et al. Description and evaluation of the Model for Ozone and Related chemical Tracers, version 4 (MOZART-4). Geosci. Model Dev. 3, 43-67 (2010).

100. Buchholz, R. R., Emmons, L. K., Tilmes, S. & The CESM2 Development Team. CESM2.1/ CAM-chem Instantaneous Output for Boundary Conditions. https://doi.org/10.5065/ NMP7-EP60 (UCAR/NCAR – Atmospheric Chemistry Observations and Modeling Laboratory, 2019).

101. Hodzic, A. et al. Volatility dependence of Henry’s law constants of condensable organics: application to estimate depositional loss of secondary organic aerosols. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 4795-4804 (2014).

102. Sun, J. et al. Impact of nudging strategy on the climate representativeness and hindcast skill of constrained EAMv1 simulations. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 3911-3933 (2019).

103. Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750-2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369-408 (2018).

104. Feng, L. et al. The generation of gridded emissions data for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 461-482 (2020).

105. Wang, S., Maltrud, M., Elliott, S., Cameron-Smith, P. & Jonko, A. Influence of dimethyl sulfide on the carbon cycle and biological production. Biogeochemistry 138, 49-68 (2018).

106. Wang, S. X. et al. Emission trends and mitigation options for air pollutants in East Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 6571-6603 (2014).

107. Ding, D., Xing, J., Wang, S. X., Liu, K. Y. & Hao, J. M. Estimated contributions of emissions controls, meteorological factors, population growth, and changes in baseline mortality to reductions in ambient

108. Guenther, A. et al. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3181-3210 (2006).

109. Wendisch, M. et al. ACRIDICON-CHUVA campaign: studying tropical deep convective clouds and precipitation over Amazonia using the new German research aircraft HALO. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 1885-1908 (2016).

110. Ding, A. et al. Long-term observation of air pollution-weather/climate interactions at the SORPES station: a review and outlook. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 10, 15 (2016).

111. Ding, A. et al. Significant reduction of

112. Jiang, J., Chen, M., Kuang, C., Attoui, M. & McMurry, P. H. Electrical mobility spectrometer using a diethylene glycol condensation particle counter for measurement of aerosol size distributions down to 1 nm . Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45, 510-521 (2011).

113. Liu, J., Jiang, J., Zhang, Q., Deng, J. & Hao, J. A spectrometer for measuring particle size distributions in the range of 3 nm to

114. Cai, R., Chen, D.-R., Hao, J. & Jiang, J. A miniature cylindrical differential mobility analyzer for sub-3 nm particle sizing. J. Aerosol Sci. 106, 111-119 (2017).

115. Liu, Y. et al. Formation of condensable organic vapors from anthropogenic and biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) is strongly perturbed by

116. Smith, S. J. et al. Anthropogenic sulfur dioxide emissions: 1850-2005. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1101-1116 (2011).

117. Crippa, M. et al. Gridded emissions of air pollutants for the period 1970-2012 within EDGAR v4.3.2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 1987-2013 (2018).

118. Wang, S., Elliott, S., Maltrud, M. & Cameron-Smith, P. Influence of explicit Phaeocystis parameterizations on the global distribution of marine dimethyl sulfide. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 120, 2158-2177 (2015).

119. Lana, A. et al. An updated climatology of surface dimethlysulfide concentrations and emission fluxes in the global ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25, Gb1004 (2011).

120. Kupc, A. et al. The potential role of organics in new particle formation and initial growth in the remote tropical upper troposphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 15037-15060 (2020).

121. Guenther, A. B. et al. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1471-1492 (2012).

122. McDuffie, E. E. et al. A global anthropogenic emission inventory of atmospheric pollutants from sector- and fuel-specific sources (1970-2017): an application of the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3413-3442 (2020).

123. Bouwman, A. F. et al. A global high-resolution emission inventory for ammonia. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 11, 561-587 (1997).

124. Fowler, D. et al. Effects of global change during the 21st century on the nitrogen cycle. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 13849-13893 (2015).

125. Paulot, F. et al. Global oceanic emission of ammonia: constraints from seawater and atmospheric observations. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1165-1178 (2015).

126. Livesey, N. J., Van Snyder, W., Read, W. G. & Wagner, P. A. Retrieval algorithms for the EOS Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 1144-1155 (2006).

127. Livesey, N. J. et al. Earth Observing System (EOS). Aura Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS). Version

128. Zhang, G. J. & McFarlane, N. A. Sensitivity of climate simulations to the parameterization of cumulus convection in the Canadian Climate Centre general circulation model. Atmos.-Ocean 33, 407-446 (1995).

129. Qian, Y. et al. Parametric sensitivity and uncertainty quantification in the version 1 of E3SM atmosphere model based on short perturbed parameter ensemble simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 13046-13073 (2018).

130. Xu, X. et al. Factors affecting entrainment rate in deep convective clouds and parameterizations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD034881 (2021).

131. Yang, B. et al. Uncertainty quantification and parameter tuning in the CAM5 ZhangMcFarlane convection scheme and impact of improved convection on the global circulation and climate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 395-415 (2013).

132. Wimmer, D. et al. Ground-based observation of clusters and nucleation-mode particles in the Amazon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 13245-13264 (2018).

133. Franco, M. A. et al. Occurrence and growth of sub-50 nm aerosol particles in the Amazonian boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3469-3492 (2022).

134. Zhao, B. et al. Formation process of particles and cloud condensation nuclei over the Amazon rainforest: the role of local and remote new-particle formation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100940 (2022).

135. Stier, P. et al. The aerosol-climate model ECHAM5-HAM. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5, 1125-1156 (2005).

136. Lucas, D. D. & Akimoto, H. Evaluating aerosol nucleation parameterizations in a global atmospheric model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L10808 (2006).

137. Pierce, J. R. & Adams, P. J. Uncertainty in global CCN concentrations from uncertain aerosol nucleation and primary emission rates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1339-1356 (2009).

138. Yu, F. et al. Particle number concentrations and size distributions in the stratosphere: implications of nucleation mechanisms and particle microphysics. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 1863-1877 (2023).

139. Merikanto, J., Spracklen, D. V., Mann, G. W., Pickering, S. J. & Carslaw, K. S. Impact of nucleation on global CCN. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 8601-8616 (2009).

140. Yu, F. et al. Spatial distributions of particle number concentrations in the global troposphere: simulations, observations, and implications for nucleation mechanisms. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D17205 (2010).

141. Westervelt, D. M. et al. Formation and growth of nucleated particles into cloud condensation nuclei: model-measurement comparison. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 7645-7663 (2013).

142. Spracklen, D. V. et al. Explaining global surface aerosol number concentrations in terms of primary emissions and particle formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 4775-4793 (2010).

143. Kulmala, M., Lehtinen, K. E. J. & Laaksonen, A. Cluster activation theory as an explanation of the linear dependence between formation rate of 3 nm particles and sulphuric acid concentration. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 787-793 (2006).

144. Kuang, C., McMurry, P. H., McCormick, A. V. & Eisele, F. L. Dependence of nucleation rates on sulfuric acid vapor concentration in diverse atmospheric locations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D10209 (2008).

145. Scott, C. E. et al. The direct and indirect radiative effects of biogenic secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 447-470 (2014).

146. Dada, L. et al. Sources and sinks driving sulfuric acid concentrations in contrasting environments: implications on proxy calculations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 11747-11766 (2020).

147. Yang, L. et al. Toward building a physical proxy for gas-phase sulfuric acid concentration based on its budget analysis in polluted Yangtze River Delta, East China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6665-6676 (2021).

148. Deng, C. et al. Seasonal characteristics of new particle formation and growth in urban Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8547-8557 (2020).

149. Wang, Y. et al. Detection of gaseous dimethylamine using vocus proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Atmos. Environ. 243, 117875 (2020).

150. You, Y. et al. Atmospheric amines and ammonia measured with a chemical ionization mass spectrometer (CIMS). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 12181-12194 (2014).

151. Zheng, J. et al. Measurement of atmospheric amines and ammonia using the high resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Atmos. Environ. 102, 249-259 (2015).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Bin Zhao.

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

organic-

h, Fractions of particle number concentrations from NPF at surface level, based

on the difference between the NPF_Mech4 and No_NPF scenarios. Definitions of the scenarios are presented in Methods and Supplementary Table 1. Particle number concentrations cover the entire size range (note that field observations are mostly made for particles larger than a certain cutoff size) and are normalized to standard temperature and pressure ( 273.15 K and 101.325 kPa ). The zonal mean particle number concentrations and the fractions caused by NPF are presented in Supplementary Fig. 12. Maps were created using the NCAR Command Language (version 6.6.2), https://doi.org/10.5065/D6WD3XH5.

Comparison of simulated

both averaged in 2016 over the regions specified in Extended Data Fig.1b. Definitions of the sensitivity experiments are presented in Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

relative contributions of different mechanisms, both averaged in 2016 over the regions specified in Extended Data Fig. 1b. Definitions of the sensitivity experiments are presented in Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

mechanisms are negligible in these regions. Definitions of the sensitivity experiments are presented in Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

different mechanisms, both averaged in 2016 over the regions specified in Extended Data Fig. 1b. For a scenario intermediate between the best-case simulation and the above sensitivity simulation, the contribution of

rates in two scenarios. a, Best-case simulation including 11 nucleation mechanisms. b, A sensitivity simulation that includes only four traditional

State Key Joint Laboratory of Environmental Simulation and Pollution Control, School of Environment, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China. State Environmental Protection Key Laboratory of Sources and Control of Air Pollution Complex, Beijing, China. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, USA. Center for Atmospheric Particle Studies, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Chemical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Department of Engineering and Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, USA. Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA. Key Laboratory of Marine Environment and Ecology, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China. Joint International Research Laboratory of Atmospheric and Earth System Sciences, School of Atmospheric Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China. Shanghai Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Particle Pollution and Prevention (LAP ), Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. Present address: College of Ocean and Earth Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. e-mail: bzhao@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn