DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165241237136

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39234612

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-18

التهديد الروسي وتوحيد الغرب: كيف يشكل الشعبوية والشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي دعم الأحزاب لأوكرانيا

للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links or content from URLs. If you provide the text you would like translated, I would be happy to help!

تم التقديم في 3 أبريل 2024

التهديد الروسي وتوحيد الغرب: كيف تشكل الشعبوية والشكوك في الاتحاد الأوروبي دعم الأحزاب لأوكرانيا

الملخص

كان الدعم لأوكرانيا ضد العدوان الروسي قويًا في جميع أنحاء أوروبا، لكنه بعيد عن أن يكون موحدًا. تكشف دراسة خبراء حول المواقف التي اتخذتها الأحزاب السياسية في 29 دولة أجريت في منتصف عام 2023 أن 97 من أصل 269 حزبًا ترفض واحدًا أو أكثر من الأمور التالية: تقديم الأسلحة، استضافة اللاجئين، دعم مسار أوكرانيا نحو عضوية الاتحاد الأوروبي، أو قبول ارتفاع تكاليف الطاقة. حيثما كانت التهديدات المتصورة من روسيا أكثر حدة، نجد أعلى مستويات الدعم لأوكرانيا. ومع ذلك، يبدو أن الأيديولوجيا لها تأثير أكبر بكثير. يفسر مستوى خطاب الحزب الشعبوي وشكوكه تجاه الاتحاد الأوروبي الجزء الأكبر من التباين في الدعم لأوكرانيا على الرغم من أننا وجدنا أن العديد من الأحزاب الشعبوية بشدة والتي تشكك في الاتحاد الأوروبي تتبنى مواقف معتدلة مؤيدة لأوكرانيا عندما تكون في الحكومة.

الكلمات الرئيسية

مقدمة

التعاون لتعزيز نطاق المقاومة. من ناحية أخرى، ينتج التضامن ضد المعتدي داخل الدول المهددة.

النظرية والتوقعات

تهديد خارجي

تفعيل الغضب أو القلق الذي يمكن أن يدفع إلى تأثير “التجمع حول المجموعة” (لامبرت وآخرون، 2011؛ كيزيلوفا ونوريس، 2023). قد يؤدي ذلك إلى دفع الأفراد لتحديث أو تكثيف أو تعزيز هويتهم حيث يضعون قيمة أكبر على الصفات التي يشتركون فيها مع أعضاء المجموعة الآخرين (دهداري وجيرينغ، 2021؛ غايتنر ودوفيديو، 2012؛ أونوتش وهيل، 2023؛ شولت-كلوس ودرازانوفا، 2023).

H1 (أطروحة التهديد): كلما زادت حدة التهديد الأمني من روسيا، زادت الدعم لأوكرانيا.

الإيديولوجيا

الذين يتهمونهم بأنهم ضارون ثقافياً. يعتبرون مجموعتهم، “الشعب”، حصرية عرقياً، ويقومون بحملة لتقليل الموارد والحقوق للمجموعات الخارجية (جين، 2018؛ فاشودوفا، 2020، 2021). من ناحية أخرى، يستهدف الشعبويون اليساريون، مثل بوديموس في إسبانيا وسيريزا في اليونان، المؤسسات الأجنبية التي يُنظر إليها على أنها تستغل الناس العاديين؛ وهم مشبوهون من التعددية التي تقودها الولايات المتحدة، والعسكرة، والإمبريالية (غوميز وآخرون، 2016؛ زوليانييلو ولارسون، 2024).

المشاركة في الحكومة

البيانات والتدابير

تقييم كل حزب في أربعة مجالات: (أ) الأيديولوجية الاقتصادية اليسارية-اليمينية؛ (ب) الأيديولوجية الخضراء/ البديلة/ الليبرالية مقابل التقليدية/ الاستبدادية/ القومية (GAL-TAN)؛ (ج) الخطاب المناهض للنخبة؛ و (د) الموقف العام بشأن الاندماج الأوروبي (جولي وآخرون، 2022). تم التحقق من صحة العناصر الأساسية في بيانات CHES عبر عدة موجات ضد تقديرات موقف الحزب المستمدة من البيانات الانتخابية، واستطلاعات النخبة، والتدابير المستمدة من الرأي العام (باكر وآخرون، 2015؛ ماركس وستينبرغن، 2007). لقد أظهرت مواضع الأحزاب على المقاييس الأيديولوجية أنها قابلة للمقارنة عبر الدول (باكر وآخرون، 2014، 2022).

رسم دعم أوكرانيا

النتائج

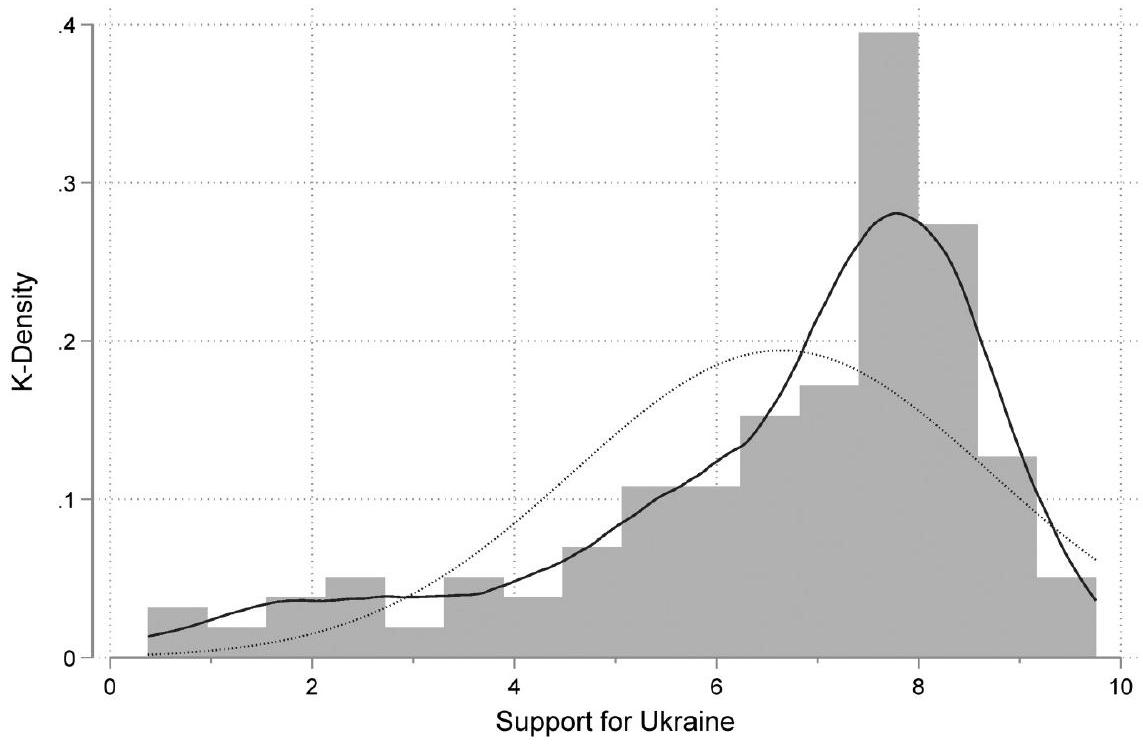

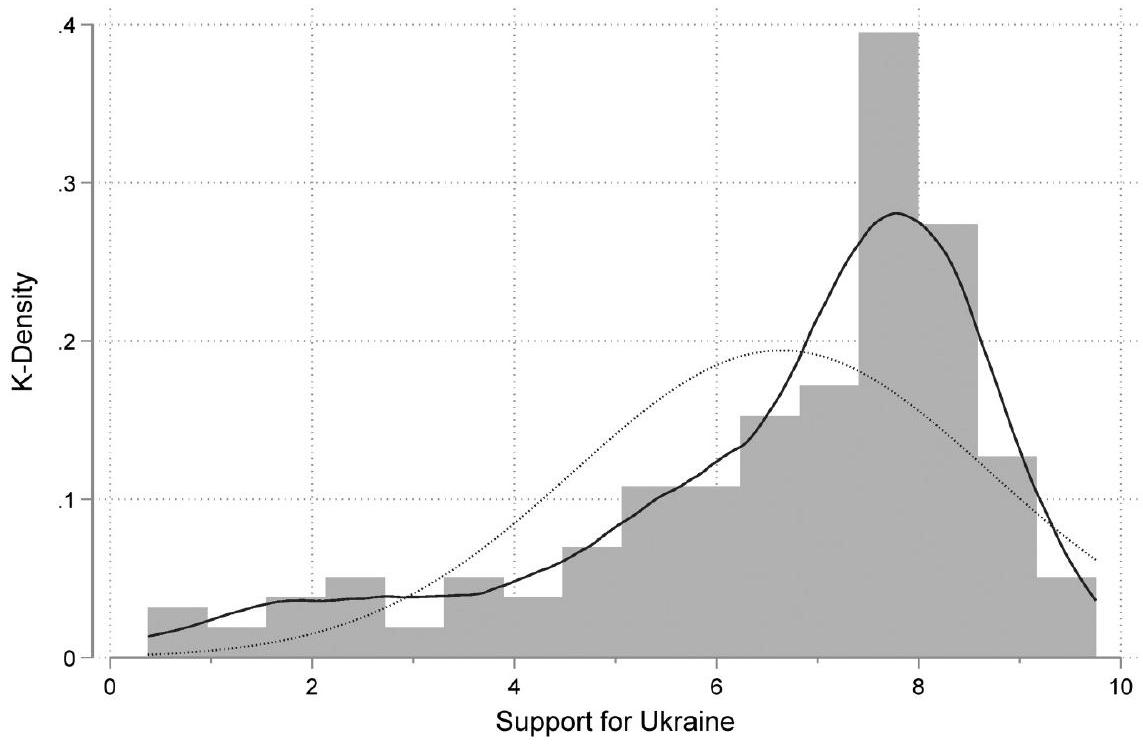

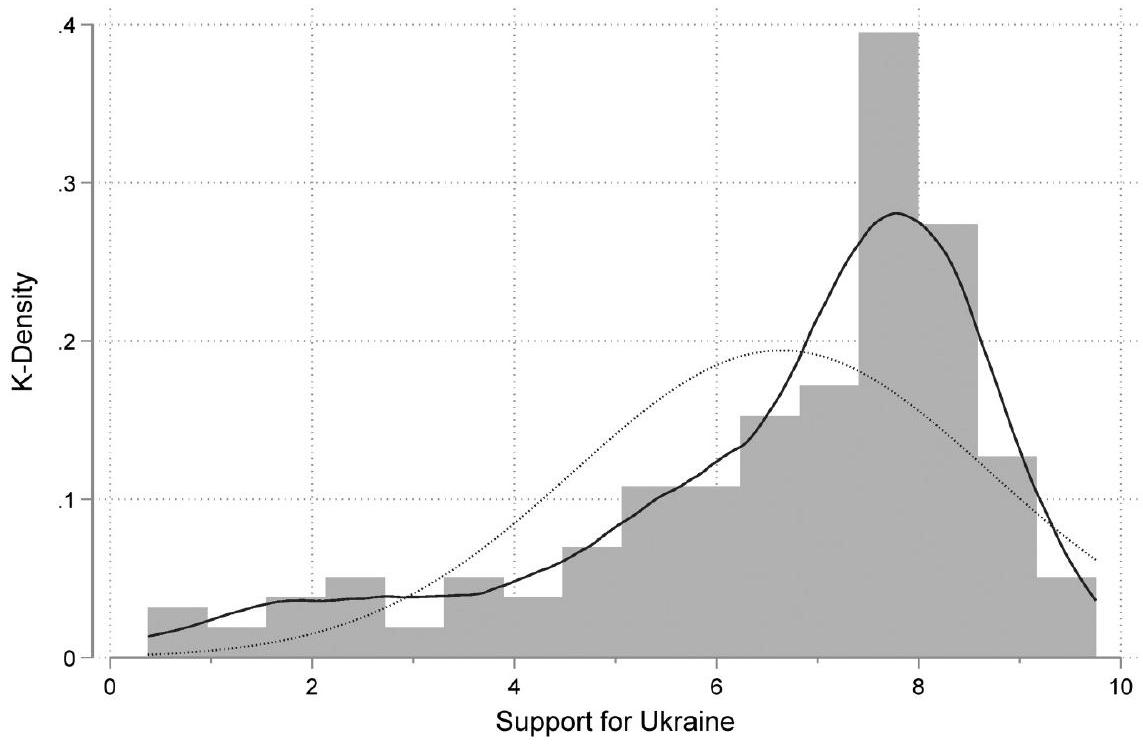

ملاحظة: نرسم توزيع الدعم بين 269 حزبًا لكل من أربع سياسات تتعلق بأوكرانيا. التوزيعات هي نواة Epanechnikov مع عرض نطاق ثابت عند 0.5. تمثل القيم الأعلى على المحور

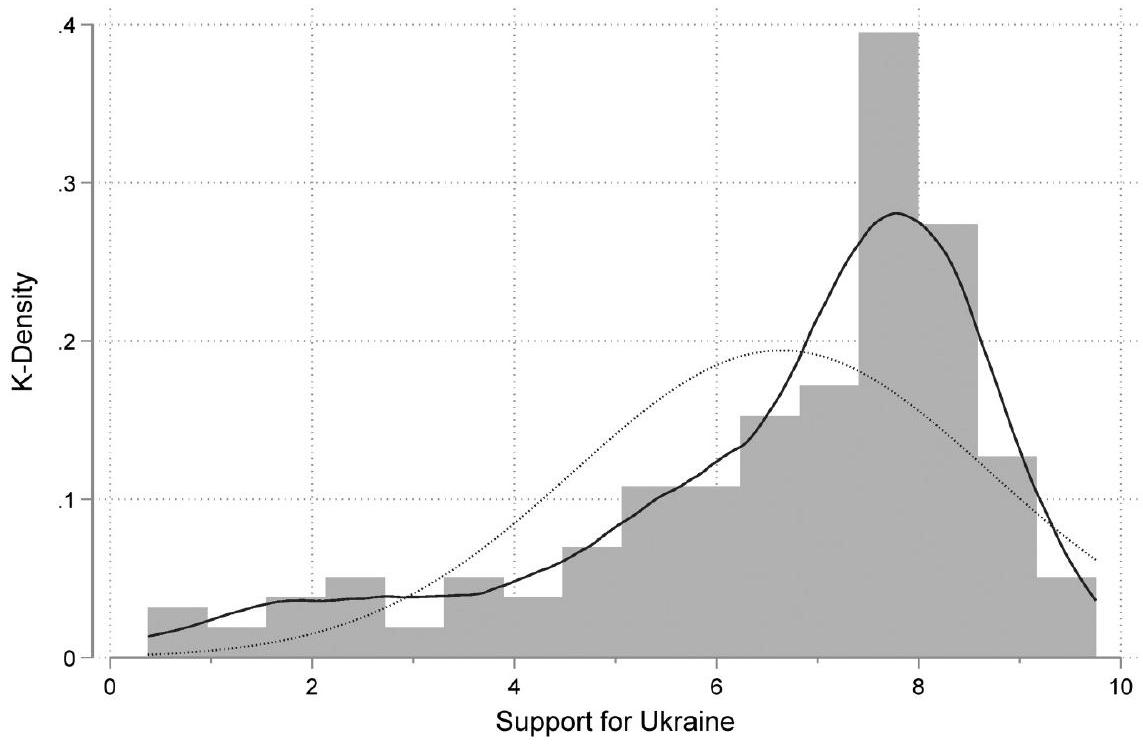

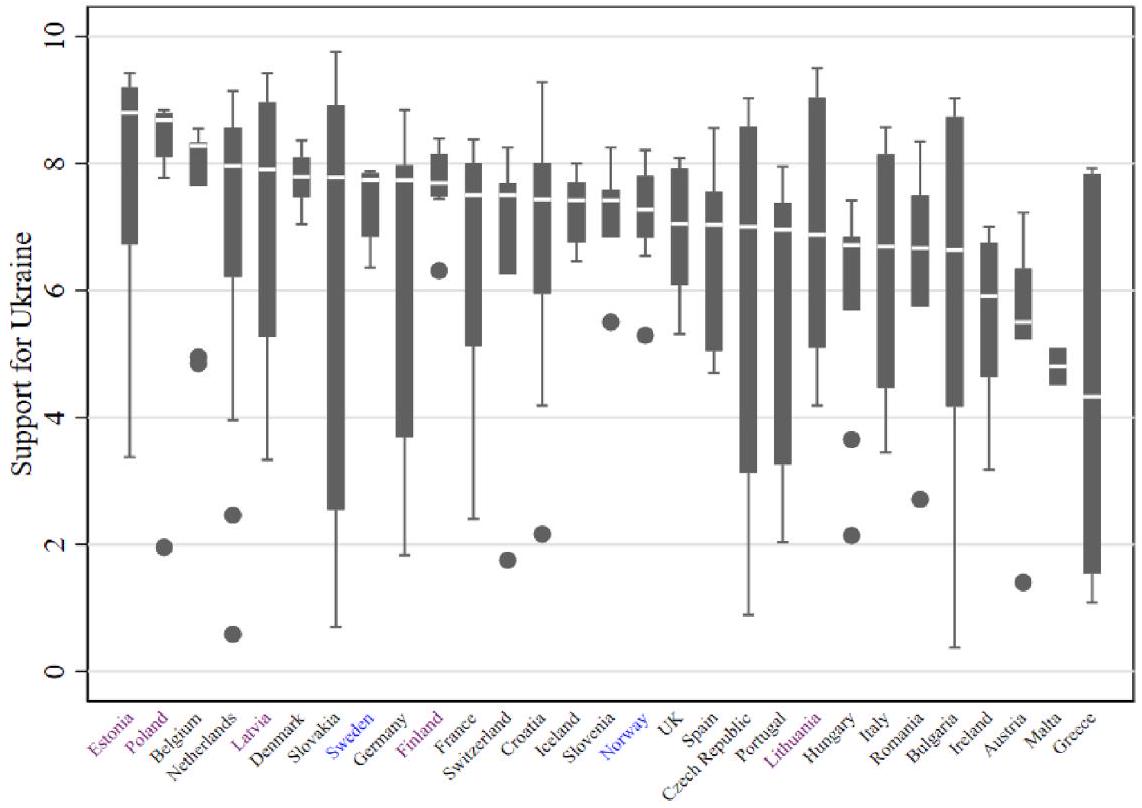

ملاحظة: نرسم الدعم لأوكرانيا في كل من 29 دولة باستخدام مخططات الصندوق على مقياس من 0 إلى 10، مرتبة من اليسار إلى اليمين، من أعلى إلى أدنى دعم وسطي لأوكرانيا. الدول باللون الأزرق لها حدود مشتركة مع روسيا، والدول باللون الأرجواني تم احتلالها وضمها جزئيًا أو كليًا من قبل الاتحاد السوفيتي في الحرب العالمية الثانية (جميعها تشترك أيضًا في حدود مع روسيا). تمثل القيم الأعلى على المحور

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| تهديد أمني (تأثيرات بين الدول) | |||

| محتلة من قبل الاتحاد السوفيتي | 0.92** (0.35) | 0.95** (0.33) | 0.95** (0.33) |

| الأيديولوجيا (تأثيرات داخل الدولة) | |||

| الشعبوية | -1.88*** (0.44) | -2.42*** (0.47) | -1.73*** (0.43) |

| الشكوك حول الاتحاد الأوروبي | -3.66*** (0.46) | -3.52*** (0.46) | -4.27*** (0.49) |

| في الحكومة | 0.34* (0.16) | -0.36 (0.28) | -0.29 (0.24) |

| في الحكومة

|

2.04** (0.67) | ||

| في الحكومة

|

2.13** (0.61) | ||

| الضوابط | |||

| تأثيرات بين الدول | |||

| تباين التحالف الأمريكي |

|

|

|

| الديمقراطية الليبرالية | 0.87 (0.60) | 0.89 (0.58) |

|

| اعتماد الغاز الروسي |

|

-0.83* (0.41) |

|

| تأثيرات داخل الدولة | |||

| اليسار-اليمين الاقتصادي | 1.07** (0.34) | 1.12** (0.34) | 0.96** (0.34) |

| غال-تان |

|

|

|

| ثابت | 8.54*** (0.62) | 8.70*** (0.60) | 8.60*** (0.59) |

| ملاحظات | ٢٦٩ | ٢٦٩ | ٢٦٩ |

| بين R-squared | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.57 |

| داخل R-squared | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| معامل التحديد الكلي | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| معامل الارتباط داخل الفئة (ICC) | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

نتوقع أن تشعر هذه الدول بتهديد مباشر من الانتقام الروسي. ومع ذلك، يتوازن ذلك مع الإرث السوفيتي المحلي لوجود أقليات ناطقة بالروسية كبيرة في إستونيا ولاتفيا وليتوانيا (روفي، 2014). تكشف تحليلاتنا أن الدول السابقة في روسيا/الاتحاد السوفيتي لديها مستويات أعلى من الدعم في

أكد أن الأحزاب السياسية في دولة مجاورة لروسيا لديها مستويات دعم تتراوح في المتوسط

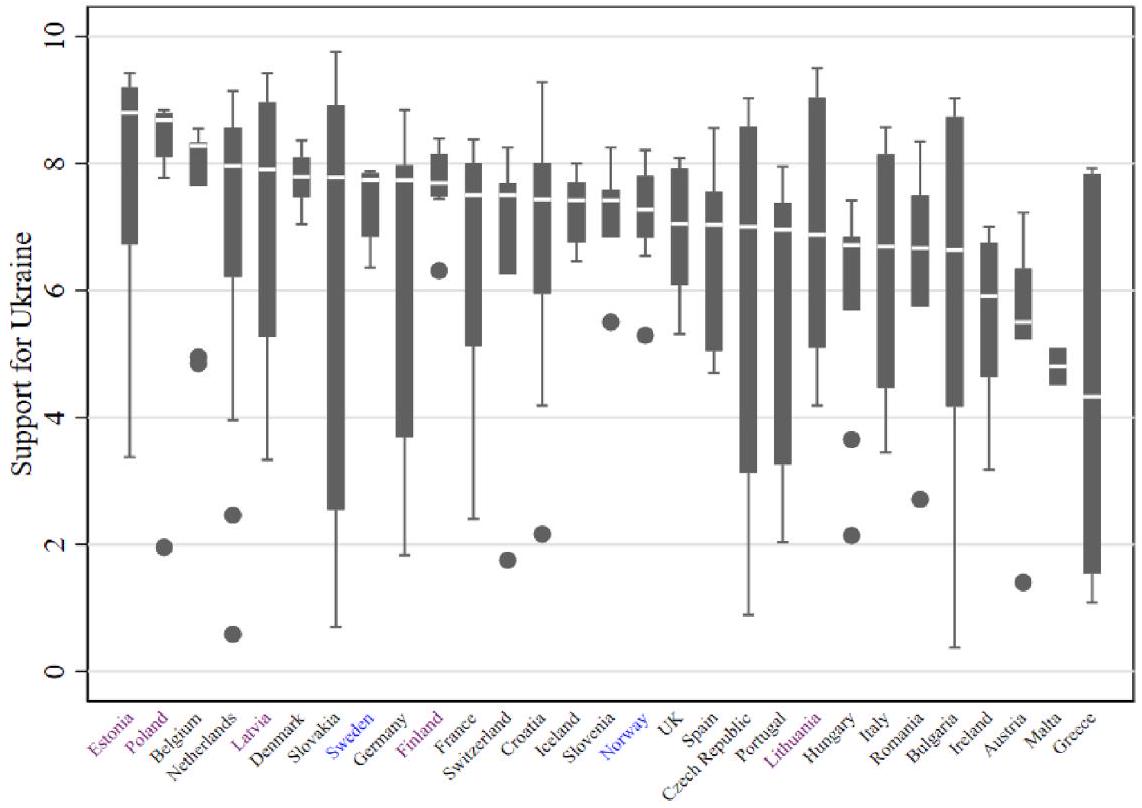

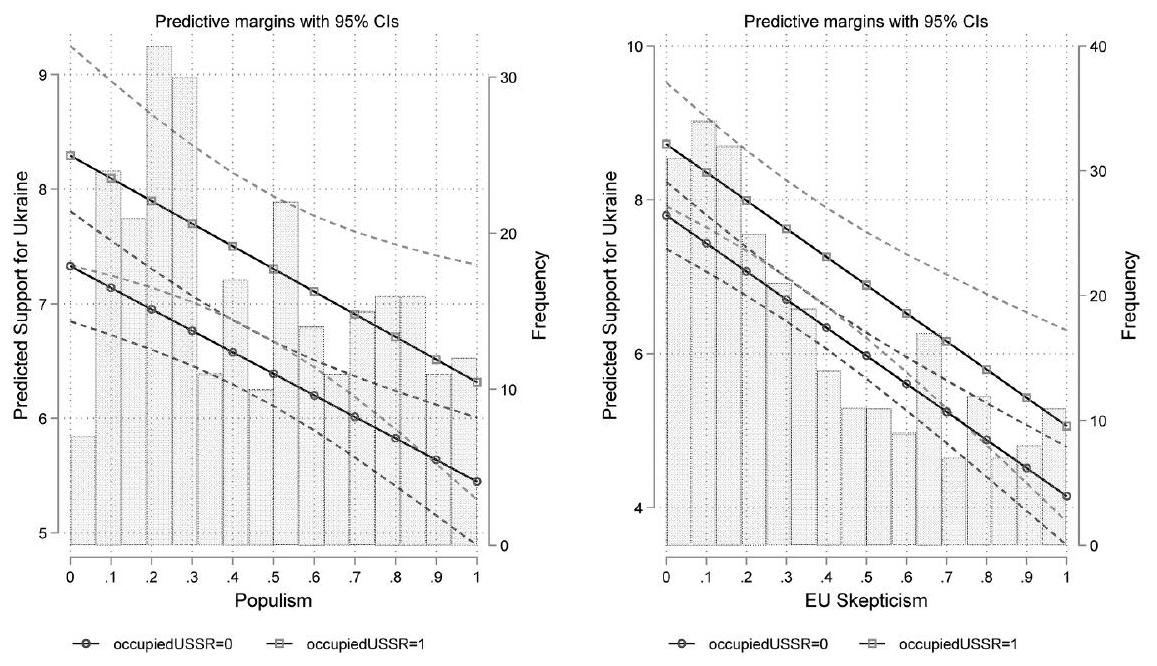

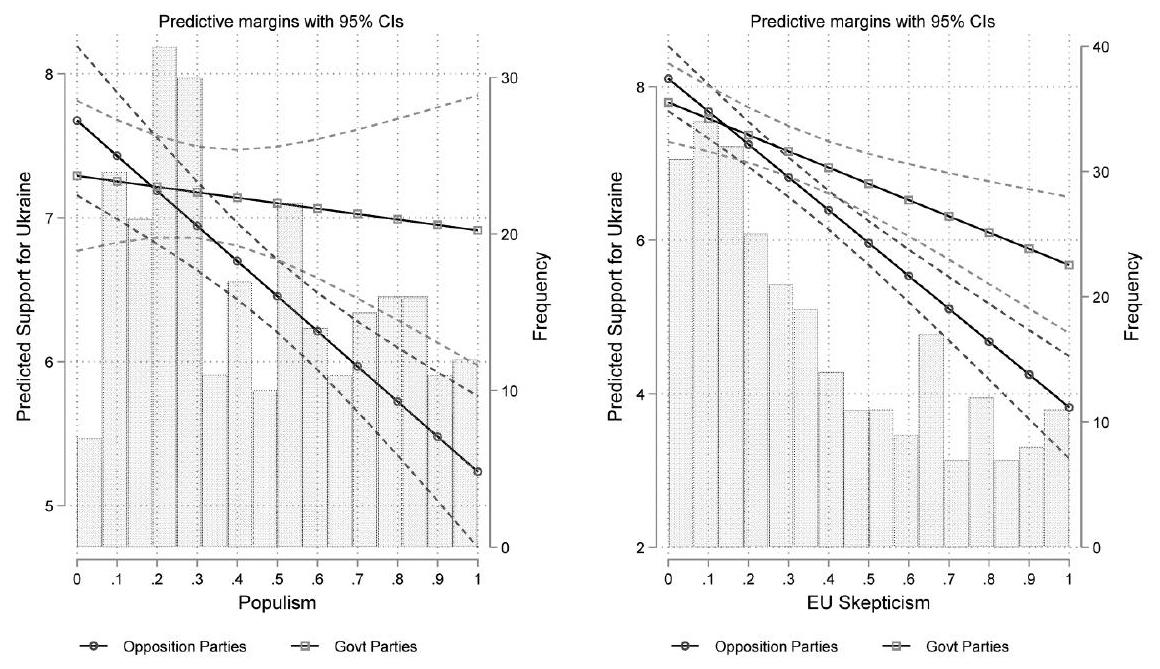

ملاحظة: هذه الصورة تقارن الدعم المتوقع لأوكرانيا بين الأحزاب المعارضة والأحزاب الحكومية عند مستويات مختلفة من الشعبوية (اللوحة اليسرى) أو مستويات مختلفة من الشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي (اللوحة اليمنى) مع الرسوم البيانية المتكررة للمتغيرات المستقلة لعرض توزيع الشعبوية والشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي. تمثل المنحدرات العلاقة، تحت السيطرة، بين الشعبوية (الشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي) والدعم لأوكرانيا، ضمن

هل تهديدات الأمن تؤثر على الأيديولوجيا؟

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| تهديد أمني (آثار بين الدول) | |||

| محتل من قبل الاتحاد السوفيتي | 0.79 * (0.33) | 0.85 * (0.33) | 0.84 * (0.34) |

| الإيديولوجيا (آثار داخل البلد) | |||

| الشعبوية في عام 2019 | -2.28*** (0.51) | -3.07 (0.55) | -1.99*** (0.50) |

| الشكوك في الاتحاد الأوروبي في عام 2019 | -2.28*** (0.51) | -2.14*** (0.50) | -3.15*** (0.56) |

| في الحكومة في عام 2023 | 0.61** (0.20) | -0.32 (0.34) | -0.04 (0.28) |

| في الحكومة

|

2.62** (0.78) | ||

| في الحكومة

|

2.17** (0.67) | ||

| التحكمات | |||

| آثار بين الدول | |||

| تباين التحالفات الأمريكية | -1.39* (0.59) | -1.34* (0.58) | -1.37* (0.60) |

| الديمقراطية الليبرالية | 0.60 (0.58) | 0.70 (0.58) | 0.91 (0.60) |

| اعتماد الغاز الروسي | -0.57 (0.42) | -0.64 (0.42) | -0.59 (0.42) |

| آثار داخل الدولة | |||

| اليسار واليمين الاقتصادي في 2019 | 1.62*** (0.45) | 1.61*** (0.44) | 1.50** (0.44) |

| غال-تان في 2019 | -1.29** (0.45) | -1.32** (0.44) | -1.20** (0.44) |

| ثابت | 8.41*** (0.63) | 8.67*** (0.63) | 8.37*** (0.63) |

| ملاحظات | ٢٣٠ | ٢٣٠ | ٢٣٠ |

| بين R-squared | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| داخل R-squared | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| معامل التحديد الكلي | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| معامل الارتباط داخل الفئة (ICC) | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

أخطاء معيارية بين قوسين، ***

هل تكون الدول القريبة من الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية أقل انقسامًا بسبب الشعبوية أو الشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي مقارنة بتلك التي هي أكثر بُعدًا؟ هل الأحزاب الشعبوية أو المشككة في الاتحاد الأوروبي في هذه الدول أكثر استعدادًا للتجمع حول العلم عندما تكون التهديدات على عتبة منازلهم؟

مما يشير إلى أن الأيديولوجية تؤثر على الأحزاب في الدول الموجودة في الخطوط الأمامية بنفس الطريقة التي تؤثر بها على تلك التي هي أكثر بعدًا. تؤكد اختبارات المنحدر المتناقضة هذا (

التحقق من السببية العكسية

مع الادعاء بأن العلاقة بين الأيديولوجية والدعم لأوكرانيا تعكس تثبيت الحزب الأيديولوجي الذي يسبق ويشكل استجابته لأزمة أوكرانيا.

هل تأثير المشاركة في الحكومة زائف؟

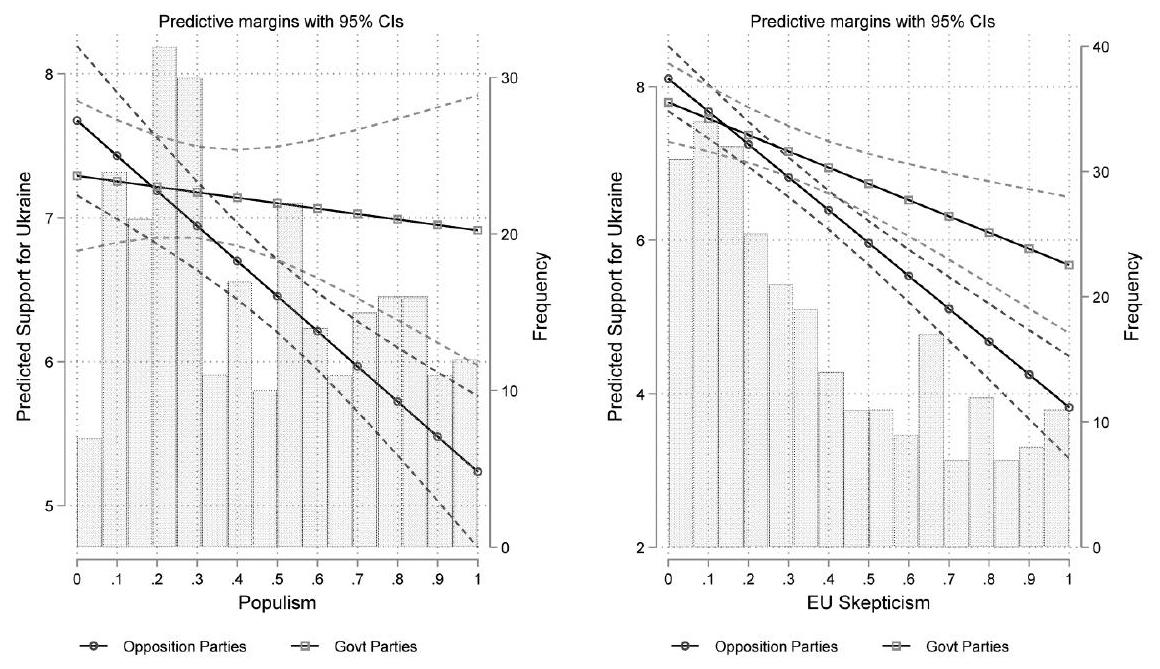

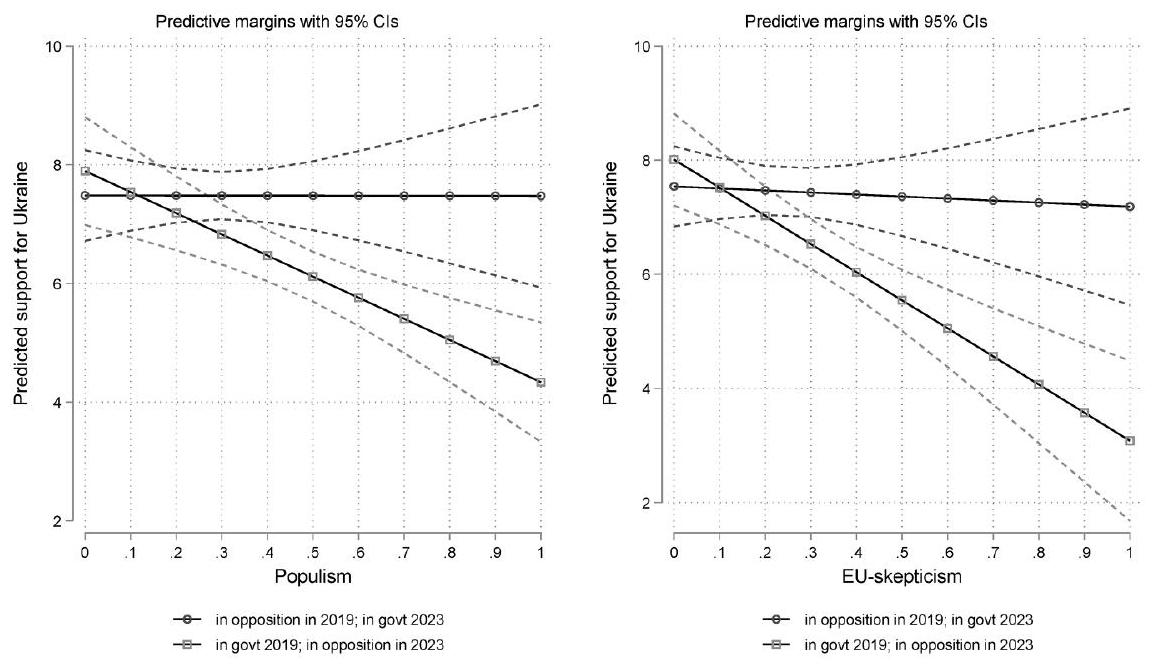

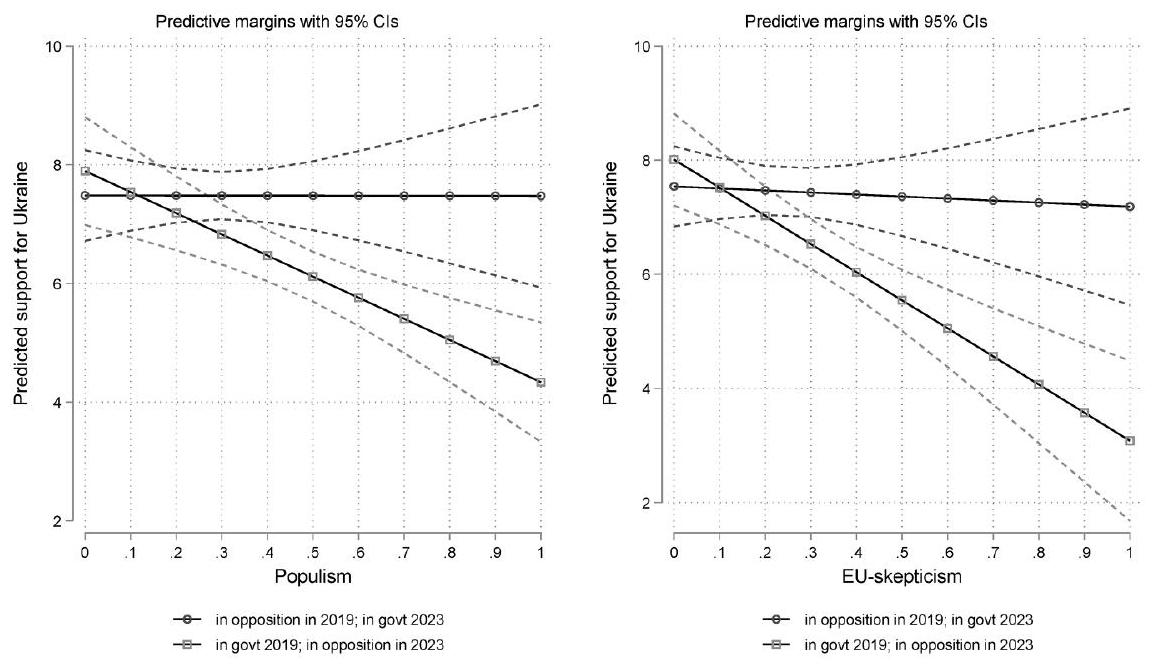

ملاحظة: يقارن هذا الشكل الدعم المتوقع لأوكرانيا بين (أ) الأحزاب التي انتقلت من المعارضة في 2019 إلى الحكومة في 2023؛ و (ب) الأحزاب التي انتقلت من الحكومة في 2019 إلى المعارضة في 2023 عند مستويات مختلفة من الشعبوية (اللوحة اليسرى) أو الشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي (اللوحة اليمنى). ترسم المنحدرات العلاقة، تحت السيطرة، بين الشعبوية (الشك في الاتحاد الأوروبي) والدعم لأوكرانيا، ضمن

الخاتمة

التكاليف، مرحبًا أوكرانيا في الاتحاد الأوروبي، أو حتى استضافة اللاجئين الأوكرانيين. هذه العلاقة بين أيديولوجية الحزب والدعم لأوكرانيا قوية بشكل خاص فيما يتعلق بموقف الأحزاب من الاندماج الأوروبي. معظم الأحزاب المؤيدة للاتحاد الأوروبي مؤيدة لأوكرانيا؛ بينما تظهر معظم الأحزاب المعادية للاتحاد الأوروبي ترددًا أو معارضة. من المثير للاهتمام أن هذه الأنماط قوية عندما نتحكم في الأيديولوجية الاقتصادية والاجتماعية الثقافية الأوسع للأحزاب، والتي تشكل الهيكل الأساسي لعلامات الأحزاب، والتي، فيما يتعلق بأزمات أخرى مثل جائحة COVID-19 أو أزمة الهجرة، شكلت استجابة الأحزاب (Ferwerda et al.، 2023؛ Rovny et al.، 2022). آثار الشعبوية والشكوك في الاتحاد الأوروبي أكبر بكثير من عمق التحالف في السياسة الخارجية مع الولايات المتحدة، أو قوة الديمقراطية الليبرالية في بلد ما، أو اعتماد بلد ما على الغاز الروسي.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

تمويل

معرفات ORCID

غاري ماركس (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1331-0975

رايان باكر (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7695-9467

جوناثان بولك (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0125-8850

ميلادا آنا فاشودوفا (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8587-5081

بيان توفر البيانات

المواد التكميلية

ملاحظات

- تفصيل ما تعارضه الأحزاب هو كما يلي: توفير الأسلحة (77)، السماح للاجئين الأوكرانيين (25)، قبول أوكرانيا في الاتحاد الأوروبي (55)، تحمل تكاليف الطاقة المرتفعة (67).

- يلاحظ ثيوسيديدس (1998) أن خوف الكورينثيين من أثينا زاد عندما احتلت أثينا ميغارا في برزخ كورنث: “كانت هذه هي السبب الرئيسي في تصور الكورينثيين كراهية قاتلة ضد أثينا” والسبب الذي جعل كورنث تقترب من سبارتا لتشكيل رابطة بيلوبونيز (الكتاب 1: الفصل الرابع).

- TAN تعني تقليدي، استبدادي، قومي.

- الارتباط المبلغ عنه في الملحق عبر الإنترنت بين عامل والمقياس الإضافي هو 0.99، واستخدام العامل ينتج نتائج متطابقة تقريبًا.

- تم احتلال إستونيا ولاتفيا وليتوانيا في يونيو 1940 وضمها في أغسطس 1940. تم احتلال أجزاء من فنلندا خلال حرب الاستمرار (يونيو 1941 إلى سبتمبر 1944). نتيجة لمعادلة مولوتوف-ريبنتروب، تم احتلال شرق بولندا من سبتمبر 1939 حتى يونيو 1941.

- تقدير التصويت على مدى فترة زمنية أطول تبلغ 10 سنوات ينتج أنماطًا متطابقة تقريبًا (

). - نموذج في الملحق عبر الإنترنت مع حجم الحزب كتحكم ينتج نتائج متطابقة تقريبًا، كما يفعل الانحدار الخطي الذي يزن الملاحظات حسب تصويت الحزب.

- يمكن أيضًا توسيع تعريف التهديد ليشمل أي دولة تحد أوكرانيا أو روسيا، مما يجذب ثلاث دول أخرى إلى فئة التهديد (المجر ورومانيا وسلوفاكيا)، وينتج تأثيرًا كبيرًا، على الرغم من أنه أضعف (انظر الملحق عبر الإنترنت).

References

Bailey MA, Strezhnev A and Voeten E (2017) Estimating dynamic state preferences from united nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution 61(2): 430-456.

Bakker R, De Vries C, Edwards E, et al. (2015) Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999-2010. Party Politics 21(1): 143-153.

Bakker R, Jolly S and Polk J (2022) Analyzing the cross-national comparability of party positions on the socio-cultural and EU dimensions in Europe. Political Science Research and Methods 10(2): 408-418.

Bakker R, Jolly S, Poole K, et al. (2014) The European common space: Extending the use of anchoring vignettes. The Journal of Politics 76(4): 1089-1101.

Bayer L (2023) Slovakia election: pro-Moscow former PM on course to win with almost all votes counted. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/01/slovakia-election-pro-moscow-former-pm-on-course-to-win-with-almost-all-votes-counted (accessed 16 February 2024).

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, et al. (2023) V-Dem Codebook v13 -Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Coser LA (1959) The Functions of Social Conflict. New York: The Free Press.

Dehdari SH and Gehring K (2021) The origins of common identity: Evidence from Alsace-Lorraine. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(1): 261-292.

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni M (2022) The anachronism of bellicist state-building. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1901-1915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141825.

European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy regulators (n.d.) Estimated number and diversity of supply sources 2021. Available at: https://aegis.acer.europa.eu/chest/dataitems/ 214/view (accessed 16 February 2024).

Farrell N (2022) Could Giorgia Meloni become Italy’s next prime minister? Available at: https:// www.spectator.co.uk/article/could-giorgia-meloni-become-italy-s-next-prime-minister/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Freudlsperger C and Schimmelfennig F (2022) Transboundary crises and political development: Why war is not necessary for European state-building. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1871-1884.

Freudlsperger C and Schimmelfennig F (2023) Rebordering Europe in the Ukraine War: Community building without capacity building. West European Politics 46(5): 843-871.

Gaetner SL and Dovidio JF (2012) The common ingroup identity model. In: Nelson TD (eds) Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology II. New York: Sage, 433-454.

Gehring K (2022) Can external threats foster a European Union identity? Evidence from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. The Economic Journal 132(644): 1489-1516.

Genschel P (2022) Bellicist integration? The war in Ukraine, the European Union, and core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1885-1990.

Gomez R, Morales L and Ramiro L (2016) Varieties of radicalism: Examining the diversity of radical left parties and voters in Western Europe. West European Politics 39(2): 351-379.

Havlík V and Kluknavská A (2023) Our people first (again)! The impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on the populist radical right in the Czech Republic. In: Ivaldi G and Zankina E (eds) The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies, 91-101.

Hechter M (1987) Principles of Group Solidarity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hooghe L and Marks G (2009) A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1-23.

Hooghe L and Marks G (2018) Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy 25(1): 109-135.

Ivaldi G and Zankina E (2023) The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies.

Jackson D and Jolly S (2021) A new divide? Assessing the transnational-nationalist dimension among political parties and the public across the EU. European Union Politics 22(2): 316-339.

Jenne E (2018) Is nationalism or ethno-populism on the rise Today? Ethnopolitics 17(5): 546-552.

Jolly S, Bakker R, Hooghe L, et al. (2022) Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999-2019. Electoral Studies 75: 1-8.

Kelemen RD and McNamara KR (2022) State-building and the European union: Markets, war, and Europe’s uneven political development. Comparative Political Studies 55(6): 963-991.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy (n.d.) Ukraine support tracker. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Kizilova K and Norris P (2023) ‘Rally around the flag’ effects in the Russian – Ukrainian war. European Political Science. Epub ahead of print 27 September 2023. DOI: 10.1057/ s41304-023-00450-9.

Kleider H and Stoeckel F (2019) The politics of international redistribution: Explaining public support for fiscal transfers in the EU. European Journal of Political Research 58(1): 4-29.

Lambert AJ, Schott JP and Scherer L (2011) Threat, politics, and attitudes: Toward a greater understanding of rally-’round-the-flag effects. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20(6): 343-348.

Lijphart A (1999) Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mader M, Gavras K, Hofmann SC, et al. (2023) International threats and support for European security and defence integration: Evidence from 25 countries. European Journal of Political Research. Epub ahead of print 17 June 2023. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6765.12605.

Mader M, Neubert M, Münchow F, et al. (2024) Crumbling in the face of cost? How cost considerations affect public support for European security and defence cooperation. European Union Politics. Epub ahead of print.

Marcos-Marne H, Llamazares I and Shikano S (2022) Left-right radicalism and populist attitudes in France and Spain. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30(4): 608-622.

Marks G and Steenbergen M (2007) Evaluating expert judgments. European Journal of Political Research 46(3): 347-366.

McNamara KR and Kelemen RD (2022) Seeing Europe like a state. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1916-1927.

Meijers MJ and Zaslove A (2021) Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach. Comparative Political Studies 54(2): 372-407.

Morgenthau H (1948) Politics among Nations: The struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Knopf.

Mudde C and Kaltwasser CR (2013) Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition 48(2): 147-174.

Noury A and Roland G (2020) Identity politics and populism in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science 23: 421-439.

Onuch O and Hale H (2023) The Zelensky Effect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Otjes S, Van Der Veer H and Wagner W (2022) Party ideologies and European foreign policy: Examining a transnational foreign policy space. Journal of European Public Policy 30(9): 1793-1819.

Pedersen HH (2011) Policy-seeking parties in multiparty systems: Influence or purity? Party Politics 18(3): 297-314.

Polk J and Rovny J (2023) European integration and the populist challenge. Available at: https:// epsanet.org (accessed 16 February 2024).

Raunio T and Wagner W (2020) The party politics of foreign and security policy. Foreign Policy Analysis 16(4): 515-531.

Richter M (2023) Opinion: Why the Polish elections are good news for Ukraine. The Kyiv Independent, 1 November. Available at: https://kyivindependent.com/opinion-why-the-polish-elections-are-good-news-for-ukraine/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Riker WH (1964) Federalism: Origin, Operation, Significance. New York: Little, Brown.

Rooduijn M and Akkerman T (2017) Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics 23(3): 193-204.

Rovny J (2014) Communism, federalism, and ethnic minorities: Explaining party competition patterns in Eastern Europe. World Politics 66(4): 669-708.

Rovny J, Bakker R, Hooghe L, Jolly S, Marks G, Polk J, Steenbergen M and Vachudova MA (2022) Contesting COVID: The ideological bases of partisan responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Political Research 61(4): 1155-1164.

Schulte-Cloos J and Dražanová L (2023) Shared identity in crisis : a comparative study of support for the EU in the face of the Russian threat. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=4558773 (accessed 16 February 2024).

Steiner ND, Berlinschi R, Farvaque E, Fidrmuc J, Harms P, Mihailov A, Neugart M and Stanek P (2023) Rallying around the EU flag: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and attitudes toward European integration. Journal of Common Market Studies 61(2): 283-301.

Stolle D (2023) Aiding Ukraine in the Russian War: Unity or new dividing line among Europeans? European Political Science. Epub ahead of print 12 October 2023. DOI: 10.1057/s41304-023-00444-7.

Strøm K and Müller W (1999) Political parties and hard choices. In: Müller W and Strøm K (eds) Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Choices. Cambridge: CUP, 1-35.

Tajfel H and Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S and Austin LW (eds) Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall, 2-24.

Thucydides (1998) The Peloponnesian War. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Tilly C (1990) Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Truchlewski Z, Oana IE and Moise AD (2023) A missing link? Maintaining support for the European polity after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Journal of European Public Policy 30(8): 1162-1178.

Vachudova MA (2020) Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in central Europe. East European Politics 36(3): 318-340.

Vachudova MA (2021) Populism, democracy, and party system change in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science 24: 471-498.

Voeten E (2021) Ideology and international institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Walter S (2021) The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science 24: 421-442.

Waltz K (1979) Theory of International Politics. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

Whitehouse Press Release (2023) Remarks by President Biden and Prime Minister Meloni of the Italian Republic Before Bilateral Meeting, 27 July. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/07/27/remarks-by-president-biden-and-prime-minister-meloni-of-the-italian-republic-before-bilateral-meeting/#:~:text=And%20also%20for%20that% 2C%20our,much%20than%20some%20have%20believed (accessed 16 February 2024).

Wondreys J (2023) Putin’s puppets in the west? The far right’s reaction to the 2022 Russian (re) invasion of Ukraine. Party Politics. Epub ahead of print 31 October 2023. DOI: 10.1177/ 13540688231210.

- Corresponding author:

Liesbet Hooghe, Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina, USA, Hamilton Hall, Chapel Hill NC 27514, USA; RSCAS, European University Institute, Florence, Italy; Robert Schuman Centre, Via dei Roccettini 9, Fiesole, 50014 IT.

Email: hooghe@unc.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165241237136

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39234612

Publication Date: 2024-03-18

The Russian threat and the consolidation of the West: How populism and EU-skepticism shape party support for Ukraine

To cite this version:

The Russian threat and the consolidation of the West: How populism and EU-skepticism shape party support for Ukraine

Abstract

Support for Ukraine against Russian aggression has been strong across Europe, but it is far from uniform. An expert survey of the positions taken by political parties in 29 countries conducted mid-2023 reveals that 97 of 269 parties reject one or more of the following: providing weapons, hosting refugees, supporting Ukraine’s path to European Union membership, or accepting higher energy costs. Where the perceived threat from Russia is most severe, we find the greatest levels of support for Ukraine. However, ideology appears to be far more influential. The level of a party’s populist rhetoric and its European Union skepticism explain the bulk of variation in support for Ukraine despite our finding that many strongly populist and European Union-skeptical parties take moderate pro-Ukraine positions when in government.

Keywords

Introduction

collaboration to enhance the scale of resistance. On the other, it produces solidarity against the aggressor within threatened countries.

Theory and expectations

External threat

activate anger or anxiety that can drive a “rally around the group” effect (Lambert et al., 2011; Kizilova and Norris, 2023). This may induce individuals to update, intensify, or scale up their identity as they put more value on attributes they share with other group members (Dehdari and Gehring, 2021; Gaetner and Dovidio, 2012; Onuch and Hale, 2023; Schulte-Cloos and Dražanová, 2023).

H1 (threat thesis): The more intense the security threat from Russia, the greater the support for Ukraine.

Ideology

which they accuse of being culturally harmful. They consider their ingroup, “the people,” as ethnically exclusive, and campaign on reducing the resources and rights for outgroups (Jenne, 2018; Vachudova, 2020, 2021). Left populists, on the other hand, such as Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece, target foreign institutions that are perceived to exploit ordinary people; they are suspicious of US-led multilateralism, militarism, and imperialism (Gomez et al., 2016; Zulianello and Larsen, 2024).

Participation in government

Data and measures

were asked to rate each party in four areas: (a) economic left-right ideology; (b) Green/ Alternative/Libertarian versus Traditional/Authoritarian/Nationalist (GAL-TAN) ideology; (c) anti-elite rhetoric; and (d) general position on European integration (Jolly et al., 2022). Core items in the CHES data have been cross-validated across several waves against party position estimates derived from manifestos, elite surveys, and measures derived from public opinion (Bakker et al., 2015; Marks and Steenbergen, 2007). Party placements on ideological scales have been shown to be cross-nationally comparable (Bakker et al., 2014, 2022).

Mapping support for Ukraine

Results

Note: We plot the distribution of support among 269 parties for each of four policies with respect to Ukraine. The distributions are kernel Epanechnikov with bandwidth held constant at 0.5 . Higher values on the

Note: We plot support for Ukraine in each of 29 countries using boxplots on a 0 to 10 scale, ordered from left to right, from highest to lowest median support for Ukraine. Countries in blue have a common border with Russia, and countries in purple were occupied and partially or fully annexed by the USSR in WWII (all also share a border with Russia). Higher values on the

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Security threat (between-country effects) | |||

| Occupied by USSR | 0.92** (0.35) | 0.95** (0.33) | 0.95** (0.33) |

| Ideology (within-country effects) | |||

| Populism | -1.88*** (0.44) | -2.42*** (0.47) | -1.73*** (0.43) |

| EU-skepticism | -3.66*** (0.46) | -3.52*** (0.46) | -4.27*** (0.49) |

| In government | 0.34* (0.16) | -0.36 (0.28) | -0.29 (0.24) |

| In govt

|

2.04** (0.67) | ||

| In govt

|

2.13** (0.61) | ||

| Controls | |||

| Between-country effects | |||

| US alliance divergence |

|

|

|

| Liberal democracy | 0.87 (0.60) | 0.89 (0.58) |

|

| Russian gas dependency |

|

-0.83* (0.41) |

|

| Within-country effects | |||

| Economic left-right | 1.07** (0.34) | 1.12** (0.34) | 0.96** (0.34) |

| GAL-TAN |

|

|

|

| Constant | 8.54*** (0.62) | 8.70*** (0.60) | 8.60*** (0.59) |

| Observations | 269 | 269 | 269 |

| Between R-squared | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.57 |

| Within R-squared | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Overall R-squared | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| Intra-class correlation (ICC) | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

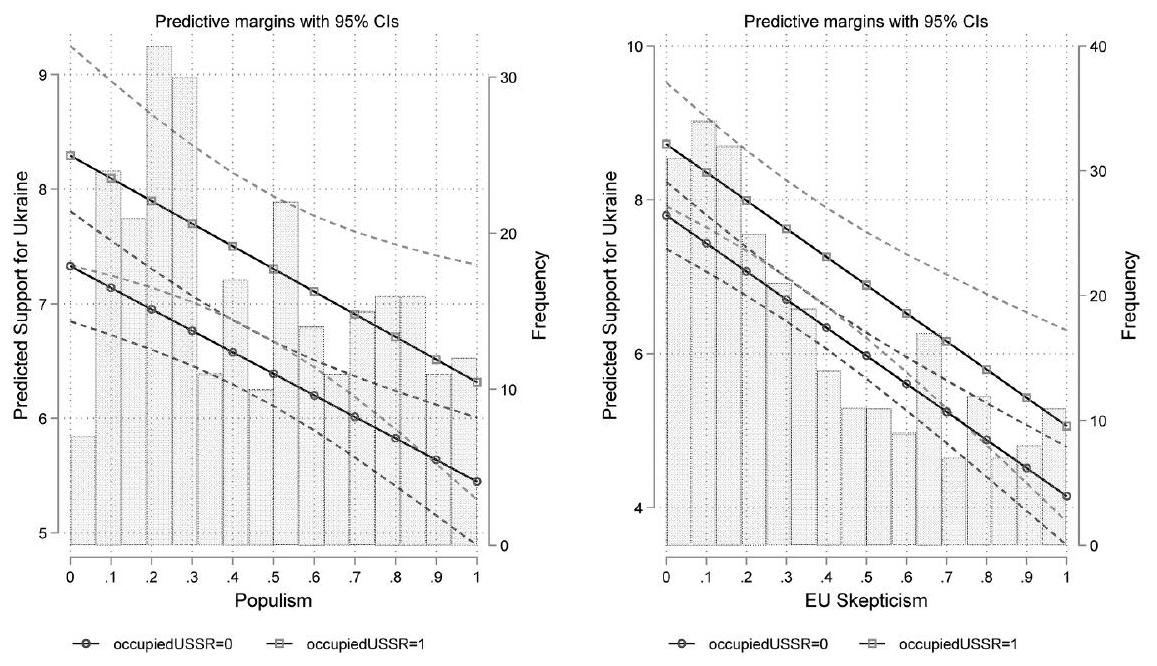

expect these countries to feel directly threatened by Russian revanchism. However, this is balanced by the domestic Soviet legacy of large Russian-speaking minorities in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (Rovny, 2014). Our analysis reveals that Former Russia/USSR countries have higher levels of support at

confirm that political parties in a country bordering Russia have support levels that are on average

Note: This figure compares the predicted support for Ukraine among opposition parties and government parties at different levels of populism (left panel) or different levels of EU-skepticism (right panel) with histograms of the independent variables to display the distribution of populism and EU-skepticism. The slopes plot the relationship, under controls, between populism (EU-skepticism) and support for Ukraine, within

Do security threats moderate ideology?

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Security threat (between-country effects) | |||

| Occupied by USSR | 0.79* (0.33) | 0.85* (0.33) | 0.84* (0.34) |

| Ideology (within-country effects) | |||

| Populism in 2019 | -2.28*** (0.51) | -3.07 (0.55) | -1.99*** (0.50) |

| EU-skepticism in 2019 | -2.28*** (0.51) | -2.14*** (0.50) | -3.15*** (0.56) |

| In government in 2023 | 0.61** (0.20) | -0.32 (0.34) | -0.04 (0.28) |

| In govt

|

2.62** (0.78) | ||

| In govt

|

2.17** (0.67) | ||

| Controls | |||

| Between-country effects | |||

| US alliance divergence | -1.39* (0.59) | -1.34* (0.58) | -1.37* (0.60) |

| Liberal democracy | 0.60 (0.58) | 0.70 (0.58) | 0.91 (0.60) |

| Russian gas dependency | -0.57 (0.42) | -0.64 (0.42) | -0.59 (0.42) |

| Within-country effects | |||

| Economic left-right in 2019 | 1.62*** (0.45) | 1.61*** (0.44) | 1.50** (0.44) |

| GAL-TAN in 2019 | -1.29** (0.45) | -1.32** (0.44) | -1.20** (0.44) |

| Constant | 8.41*** (0.63) | 8.67*** (0.63) | 8.37*** (0.63) |

| Observations | 230 | 230 | 230 |

| Between R-squared | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Within R-squared | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Overall R-squared | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| Intra-class correlation (ICC) | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

Standard errors in parentheses, ***

of the Ukrainian-Russian war be less divided by populism or EU-skepticism than those that are more distant? Are populist or EU-skeptic parties in these countries more willing to rally around the flag when the threat is at their doorstep?

indicating that ideology affects parties in countries on the frontline in the same way as those that are more remote. Contrast slope tests confirm this (

Checking reverse causality

with the claim that the association between ideology and support for Ukraine reflects a party’s ideological anchoring that precedes and shapes its response to the Ukraine crisis.

Is the effect of participation in government spurious?

Note: This figure compares the predicted support for Ukraine among (a) parties that transitioned from opposition in 2019 to government in 2023; and (b) parties that transitioned from government in 2019 to opposition in 2023 at different levels of populism (left panel) or EU-skepticism (right panel). The slopes plot the relationship, under controls, between populism (EU-skepticism) and support for Ukraine, within

Conclusion

costs, welcome Ukraine in the EU, or even host Ukrainian refugees. This relationship between party ideology and support for Ukraine is particularly strong with respect to parties’ stance on European integration. Most pro-EU parties are pro-Ukraine; most anti-EU parties display ambivalence or opposition. Interestingly, these patterns are robust when we control for parties’ broader economic and socio-cultural ideology, which constitute the scaffolding for party brands and which, with respect to other crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the migration crisis, have shaped party response (Ferwerda et al., 2023; Rovny et al., 2022). The effects of populism and EU-skepticism are also much larger than the depth of foreign policy alliance with the US, the strength of a country’s liberal democracy, or a country’s dependence on Russian gas.

Acknowledgment

Author contributions

Declaration of conflicting interests

Funding

ORCID iDs

Gary Marks (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1331-0975

Ryan Bakker (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7695-9467

Jonathan Polk (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0125-8850

Milada Anna Vachudova (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8587-5081

Data availability statement

Supplemental material

Notes

- The breakdown of what parties oppose is as follows: provision of weapons (77), allowing Ukrainian refugees (25), accepting Ukraine into the EU (55), tolerating higher energy costs (67).

- Thucydides (1998) observes that Corinthian fear of Athens intensified when Athens occupied Megara on the Isthmus of Corinth: “This was the principal cause of the Corinthians conceiving such a deadly hatred against Athens” and the reason Corinth approached Sparta to form the Peloponnesian League (Book 1: Chapter IV).

- TAN stands for traditionalist, authoritarian, nationalist.

- The correlation reported in the online Appendix between a factor and the additive scale is 0.99 , and using the factor produces virtually identical results.

- Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were occupied in June 1940 and annexed in August 1940. Parts of Finland were occupied during the Continuation War (June 1941 to September 1944). As a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, eastern Poland was occupied from September 1939 until June 1941.

- Estimating voting over a longer time period of 10 years produces virtually identical patterns (

). - A model in the online Appendix with party size as control produces nearly identical results, as does a linear regression weighting observations by party vote.

- One might also broaden the definition of threat to include any country that borders either Ukraine or Russia, which draws three more countries into the threat category (Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia), and produces a significant, though weaker, effect (see online Appendix).

References

Bailey MA, Strezhnev A and Voeten E (2017) Estimating dynamic state preferences from united nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution 61(2): 430-456.

Bakker R, De Vries C, Edwards E, et al. (2015) Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999-2010. Party Politics 21(1): 143-153.

Bakker R, Jolly S and Polk J (2022) Analyzing the cross-national comparability of party positions on the socio-cultural and EU dimensions in Europe. Political Science Research and Methods 10(2): 408-418.

Bakker R, Jolly S, Poole K, et al. (2014) The European common space: Extending the use of anchoring vignettes. The Journal of Politics 76(4): 1089-1101.

Bayer L (2023) Slovakia election: pro-Moscow former PM on course to win with almost all votes counted. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/01/slovakia-election-pro-moscow-former-pm-on-course-to-win-with-almost-all-votes-counted (accessed 16 February 2024).

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, et al. (2023) V-Dem Codebook v13 -Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Coser LA (1959) The Functions of Social Conflict. New York: The Free Press.

Dehdari SH and Gehring K (2021) The origins of common identity: Evidence from Alsace-Lorraine. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14(1): 261-292.

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni M (2022) The anachronism of bellicist state-building. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1901-1915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141825.

European Union Agency for the Cooperation of Energy regulators (n.d.) Estimated number and diversity of supply sources 2021. Available at: https://aegis.acer.europa.eu/chest/dataitems/ 214/view (accessed 16 February 2024).

Farrell N (2022) Could Giorgia Meloni become Italy’s next prime minister? Available at: https:// www.spectator.co.uk/article/could-giorgia-meloni-become-italy-s-next-prime-minister/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Freudlsperger C and Schimmelfennig F (2022) Transboundary crises and political development: Why war is not necessary for European state-building. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1871-1884.

Freudlsperger C and Schimmelfennig F (2023) Rebordering Europe in the Ukraine War: Community building without capacity building. West European Politics 46(5): 843-871.

Gaetner SL and Dovidio JF (2012) The common ingroup identity model. In: Nelson TD (eds) Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology II. New York: Sage, 433-454.

Gehring K (2022) Can external threats foster a European Union identity? Evidence from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. The Economic Journal 132(644): 1489-1516.

Genschel P (2022) Bellicist integration? The war in Ukraine, the European Union, and core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1885-1990.

Gomez R, Morales L and Ramiro L (2016) Varieties of radicalism: Examining the diversity of radical left parties and voters in Western Europe. West European Politics 39(2): 351-379.

Havlík V and Kluknavská A (2023) Our people first (again)! The impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on the populist radical right in the Czech Republic. In: Ivaldi G and Zankina E (eds) The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies, 91-101.

Hechter M (1987) Principles of Group Solidarity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hooghe L and Marks G (2009) A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1-23.

Hooghe L and Marks G (2018) Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy 25(1): 109-135.

Ivaldi G and Zankina E (2023) The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies.

Jackson D and Jolly S (2021) A new divide? Assessing the transnational-nationalist dimension among political parties and the public across the EU. European Union Politics 22(2): 316-339.

Jenne E (2018) Is nationalism or ethno-populism on the rise Today? Ethnopolitics 17(5): 546-552.

Jolly S, Bakker R, Hooghe L, et al. (2022) Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999-2019. Electoral Studies 75: 1-8.

Kelemen RD and McNamara KR (2022) State-building and the European union: Markets, war, and Europe’s uneven political development. Comparative Political Studies 55(6): 963-991.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy (n.d.) Ukraine support tracker. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Kizilova K and Norris P (2023) ‘Rally around the flag’ effects in the Russian – Ukrainian war. European Political Science. Epub ahead of print 27 September 2023. DOI: 10.1057/ s41304-023-00450-9.

Kleider H and Stoeckel F (2019) The politics of international redistribution: Explaining public support for fiscal transfers in the EU. European Journal of Political Research 58(1): 4-29.

Lambert AJ, Schott JP and Scherer L (2011) Threat, politics, and attitudes: Toward a greater understanding of rally-’round-the-flag effects. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20(6): 343-348.

Lijphart A (1999) Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mader M, Gavras K, Hofmann SC, et al. (2023) International threats and support for European security and defence integration: Evidence from 25 countries. European Journal of Political Research. Epub ahead of print 17 June 2023. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6765.12605.

Mader M, Neubert M, Münchow F, et al. (2024) Crumbling in the face of cost? How cost considerations affect public support for European security and defence cooperation. European Union Politics. Epub ahead of print.

Marcos-Marne H, Llamazares I and Shikano S (2022) Left-right radicalism and populist attitudes in France and Spain. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30(4): 608-622.

Marks G and Steenbergen M (2007) Evaluating expert judgments. European Journal of Political Research 46(3): 347-366.

McNamara KR and Kelemen RD (2022) Seeing Europe like a state. Journal of European Public Policy 29(12): 1916-1927.

Meijers MJ and Zaslove A (2021) Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach. Comparative Political Studies 54(2): 372-407.

Morgenthau H (1948) Politics among Nations: The struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Knopf.

Mudde C and Kaltwasser CR (2013) Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition 48(2): 147-174.

Noury A and Roland G (2020) Identity politics and populism in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science 23: 421-439.

Onuch O and Hale H (2023) The Zelensky Effect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Otjes S, Van Der Veer H and Wagner W (2022) Party ideologies and European foreign policy: Examining a transnational foreign policy space. Journal of European Public Policy 30(9): 1793-1819.

Pedersen HH (2011) Policy-seeking parties in multiparty systems: Influence or purity? Party Politics 18(3): 297-314.

Polk J and Rovny J (2023) European integration and the populist challenge. Available at: https:// epsanet.org (accessed 16 February 2024).

Raunio T and Wagner W (2020) The party politics of foreign and security policy. Foreign Policy Analysis 16(4): 515-531.

Richter M (2023) Opinion: Why the Polish elections are good news for Ukraine. The Kyiv Independent, 1 November. Available at: https://kyivindependent.com/opinion-why-the-polish-elections-are-good-news-for-ukraine/ (accessed 16 February 2024).

Riker WH (1964) Federalism: Origin, Operation, Significance. New York: Little, Brown.

Rooduijn M and Akkerman T (2017) Flank attacks: Populism and left-right radicalism in Western Europe. Party Politics 23(3): 193-204.

Rovny J (2014) Communism, federalism, and ethnic minorities: Explaining party competition patterns in Eastern Europe. World Politics 66(4): 669-708.

Rovny J, Bakker R, Hooghe L, Jolly S, Marks G, Polk J, Steenbergen M and Vachudova MA (2022) Contesting COVID: The ideological bases of partisan responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Political Research 61(4): 1155-1164.

Schulte-Cloos J and Dražanová L (2023) Shared identity in crisis : a comparative study of support for the EU in the face of the Russian threat. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=4558773 (accessed 16 February 2024).

Steiner ND, Berlinschi R, Farvaque E, Fidrmuc J, Harms P, Mihailov A, Neugart M and Stanek P (2023) Rallying around the EU flag: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and attitudes toward European integration. Journal of Common Market Studies 61(2): 283-301.

Stolle D (2023) Aiding Ukraine in the Russian War: Unity or new dividing line among Europeans? European Political Science. Epub ahead of print 12 October 2023. DOI: 10.1057/s41304-023-00444-7.

Strøm K and Müller W (1999) Political parties and hard choices. In: Müller W and Strøm K (eds) Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Choices. Cambridge: CUP, 1-35.

Tajfel H and Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S and Austin LW (eds) Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall, 2-24.

Thucydides (1998) The Peloponnesian War. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Tilly C (1990) Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Truchlewski Z, Oana IE and Moise AD (2023) A missing link? Maintaining support for the European polity after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Journal of European Public Policy 30(8): 1162-1178.

Vachudova MA (2020) Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in central Europe. East European Politics 36(3): 318-340.

Vachudova MA (2021) Populism, democracy, and party system change in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science 24: 471-498.

Voeten E (2021) Ideology and international institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Walter S (2021) The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science 24: 421-442.

Waltz K (1979) Theory of International Politics. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

Whitehouse Press Release (2023) Remarks by President Biden and Prime Minister Meloni of the Italian Republic Before Bilateral Meeting, 27 July. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/07/27/remarks-by-president-biden-and-prime-minister-meloni-of-the-italian-republic-before-bilateral-meeting/#:~:text=And%20also%20for%20that% 2C%20our,much%20than%20some%20have%20believed (accessed 16 February 2024).

Wondreys J (2023) Putin’s puppets in the west? The far right’s reaction to the 2022 Russian (re) invasion of Ukraine. Party Politics. Epub ahead of print 31 October 2023. DOI: 10.1177/ 13540688231210.

- Corresponding author:

Liesbet Hooghe, Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina, USA, Hamilton Hall, Chapel Hill NC 27514, USA; RSCAS, European University Institute, Florence, Italy; Robert Schuman Centre, Via dei Roccettini 9, Fiesole, 50014 IT.

Email: hooghe@unc.edu