DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08020-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39385053

تاريخ النشر: 2024-10-09

الثقة المفرطة في تجاوز المناخ

– للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

معرف HAL: hal-04741921

https://hal.science/hal-04741921v1

الثقة المفرطة في تجاوز المناخ

تاريخ الاستلام: 17 أكتوبر 2023

تم القبول: 29 أغسطس 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 9 أكتوبر 2024

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تستمر جهود خفض الانبعاثات العالمية في كونها غير كافية لتحقيق هدف درجة الحرارة في اتفاق باريس

من المتوقع أن تؤدي انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الصفرية (GHG)، كما هو مذكور في المادة 4.1 من الاتفاق، إلى انخفاض درجات الحرارة.

| فئة المسار | خصائص درجة الحرارة | خصائص الانبعاثات (أفضل التقديرات) |

| مسارات الذروة والانحدار | مسارات تهدف إلى تحقيق ذروة درجة الحرارة وانخفاض مستدام في درجة الحرارة على المدى الطويل لمدة لا تقل عن عدة عقود | خفض الانبعاثات في جميع غازات الدفيئة نحو تحقيق صافي الصفر

|

| PD-OS: مسارات التجاوز | تحدد مسارات التنمية المستدامة مستوى استهداف الاحترار الذي يجب تحقيقه في وقت ما في المستقبل البعيد، لكنها تسمح بتجاوزه مع احتمال كبير على المدى القريب، وذلك بناءً على القناعة بأنه يمكن عكس الاحترار مرة أخرى في مرحلة لاحقة. عادةً ما تتصور هذه المسارات أن يتم الحفاظ على درجة الحرارة عند المستوى المستهدف عند العودة بعد التجاوز. | كطرق الذروة والانخفاض، ولكن معدل تقليل الانبعاثات، ميزانية الكربون، توقيت الوصول إلى صافي الصفر

|

| PD-EP: مسارات حماية معززة | مسارات التنمية المستدامة التي تهدف إلى الحفاظ على ارتفاع درجة حرارة الأرض العالمية عند أدنى مستوى ممكن، وعكس الاحترار تدريجياً بعد ذلك لتقليل مخاطر المناخ. نظراً للفترات الزمنية المعنية لعكس الاحترار، فإن هذه المسارات عادةً لا تصل إلى مستوى درجة حرارة هدف نهائي أدنى ضمن الإطار الزمني للسيناريو المعني. | خفض انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة بشكل صارم وسريع قدر الإمكان وفي أقرب وقت ممكن، لتحقيق صافي صفر

|

ذروة الاحترار لنتائج المناخ المتوسطة

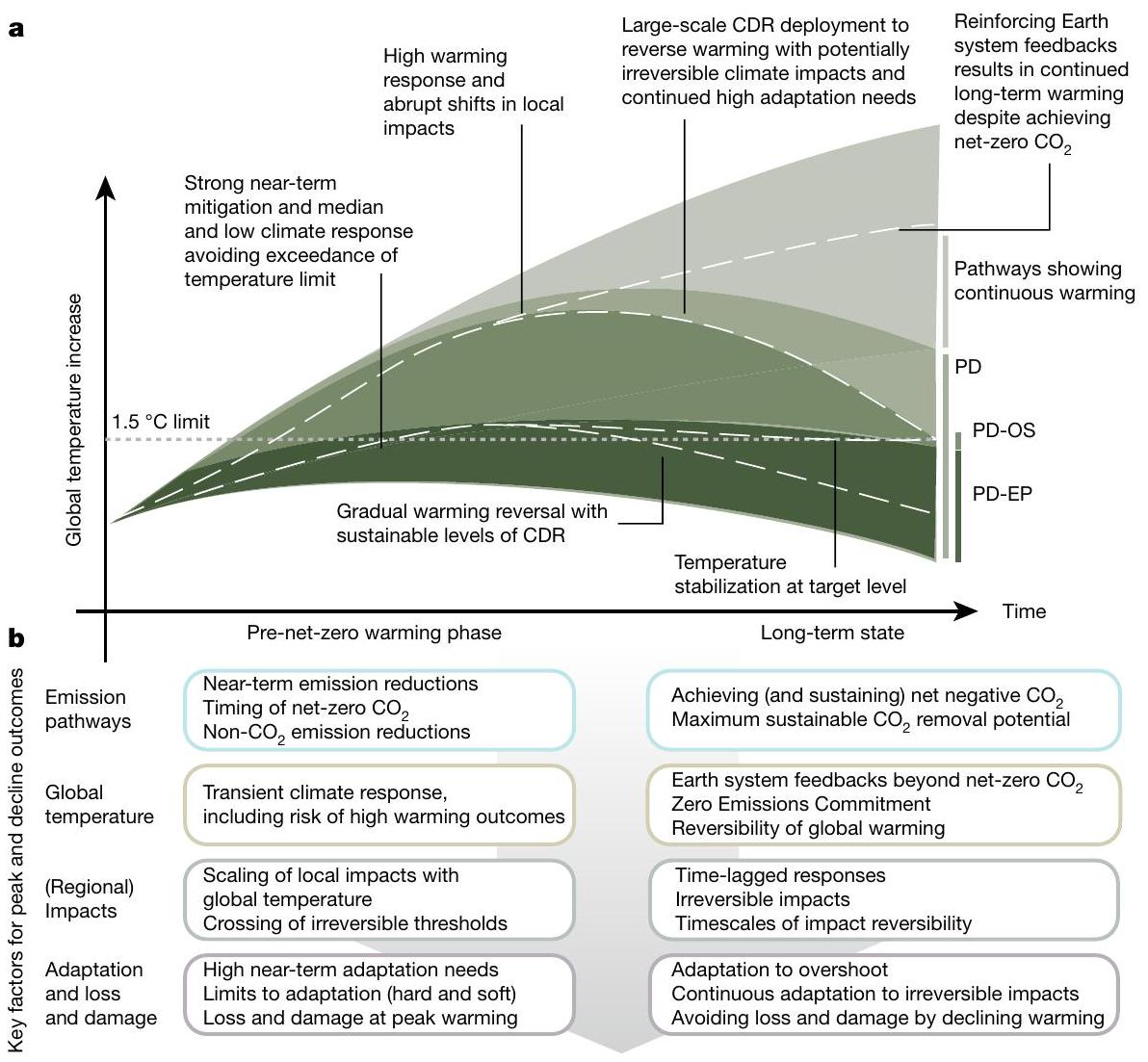

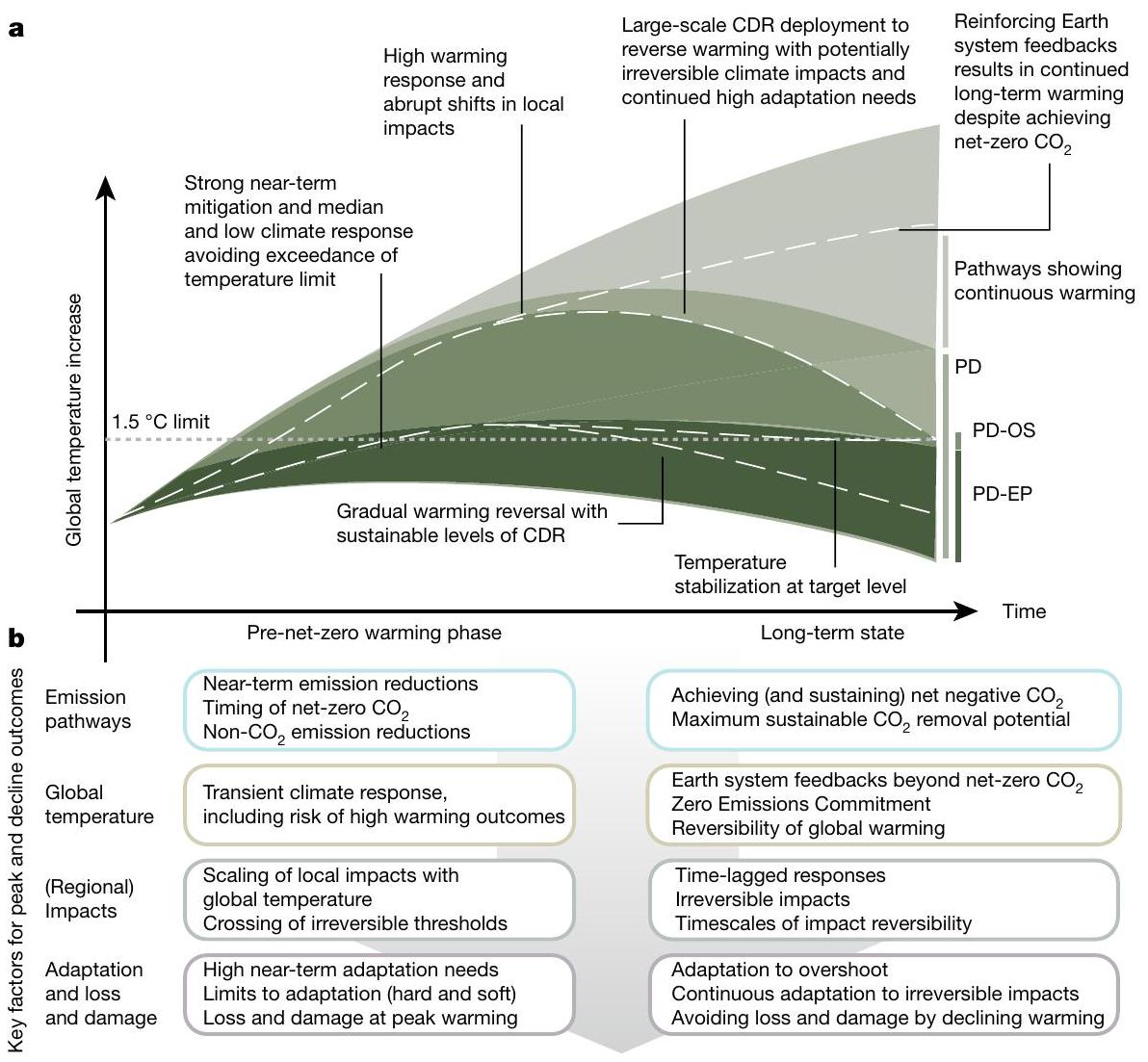

تم اقتراح عدة فئات من مسارات الذروة والانحدار في الأدبيات العلمية

على الرغم من تعريفه من حيث احتمالات تجاوز المؤقت

ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر. أخيرًا، نناقش ما يعنيه اعتبار أو تجربة تجاوز درجات الحرارة بالنسبة لتكيف التغير المناخي. استنادًا إلى هذه النظرة الشاملة، نرى أنه من الضروري إعادة توجيه مناقشة التجاوز نحو إعطاء الأولوية لتقليل مخاطر المناخ على المدى القريب والبعيد، وأنه يجب تجنب الثقة المفرطة في إمكانية التحكم في تجاوز المناخ ورغبيته.

استجابة المناخ غير المؤكدة والعكس

نظرة عامة على العوامل الرئيسية التي تؤثر على المسار والنتائج المحتملة للذروة والانخفاض على طول سلسلة التأثير خلال مرحلة الاحترار حتى الوصول إلى الصفر الصافي

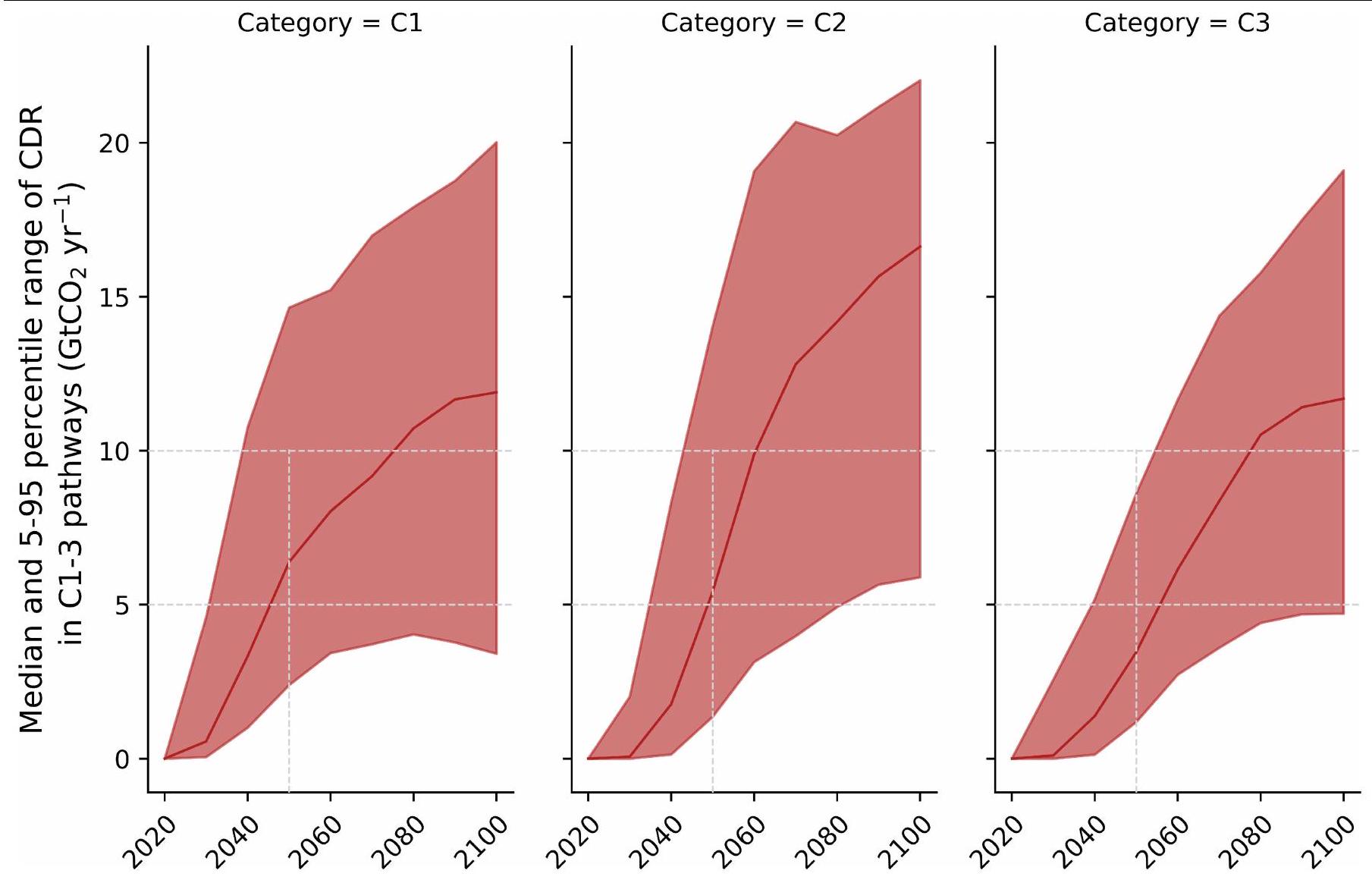

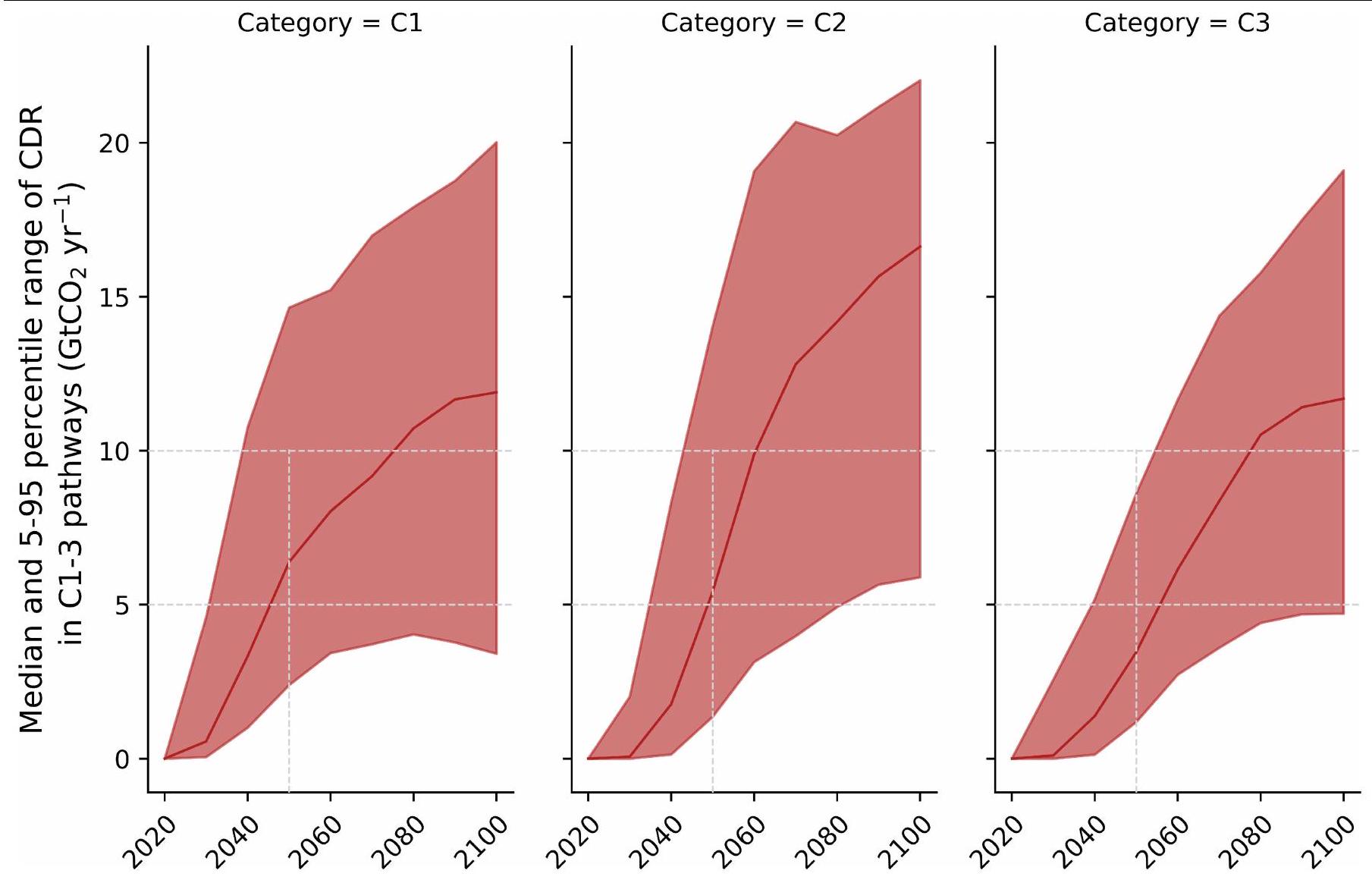

الاعتماد على CDR

استخدام CDR المفترض (الجدول البياني الموسع 2). قد يكون توسيع CDR مقيدًا بشكل كبير

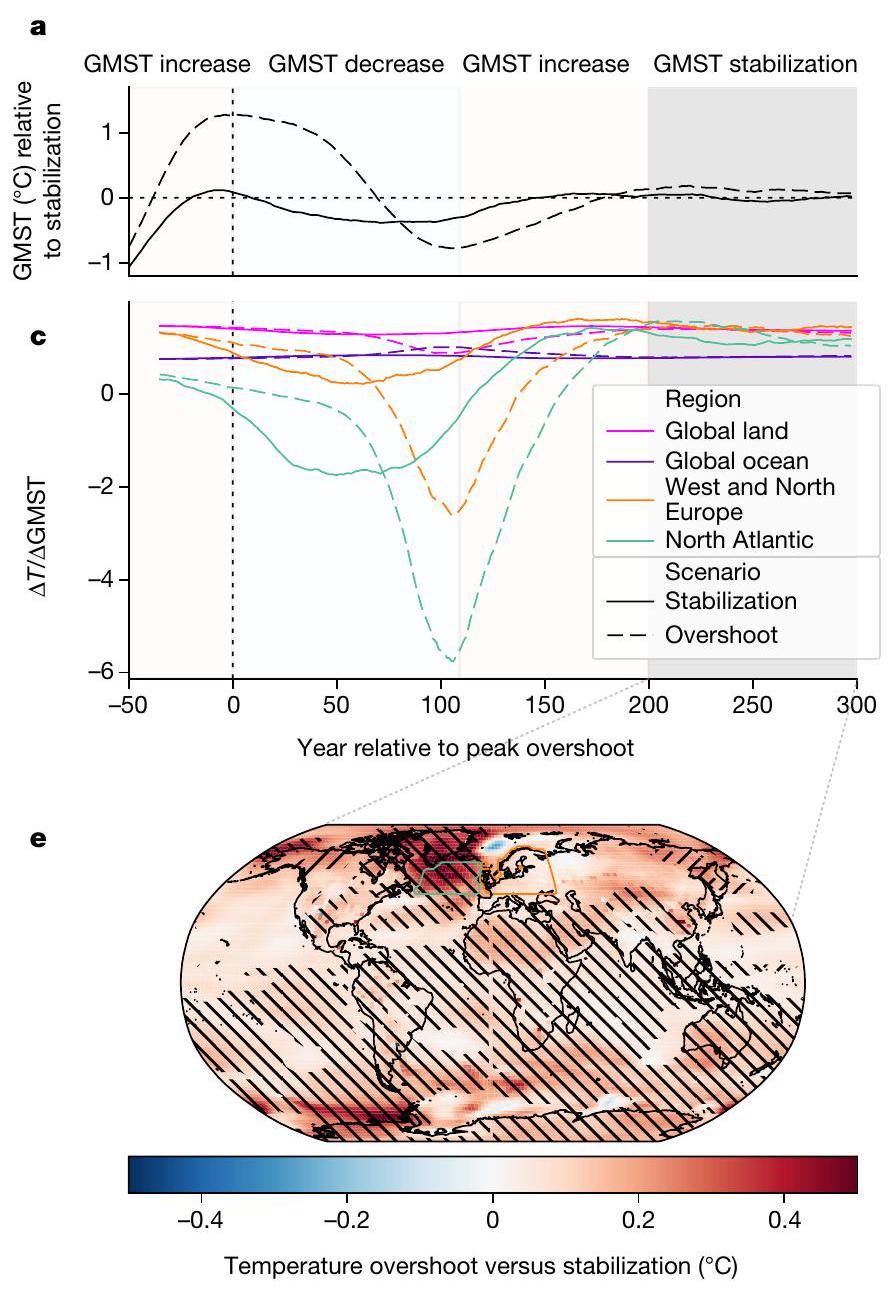

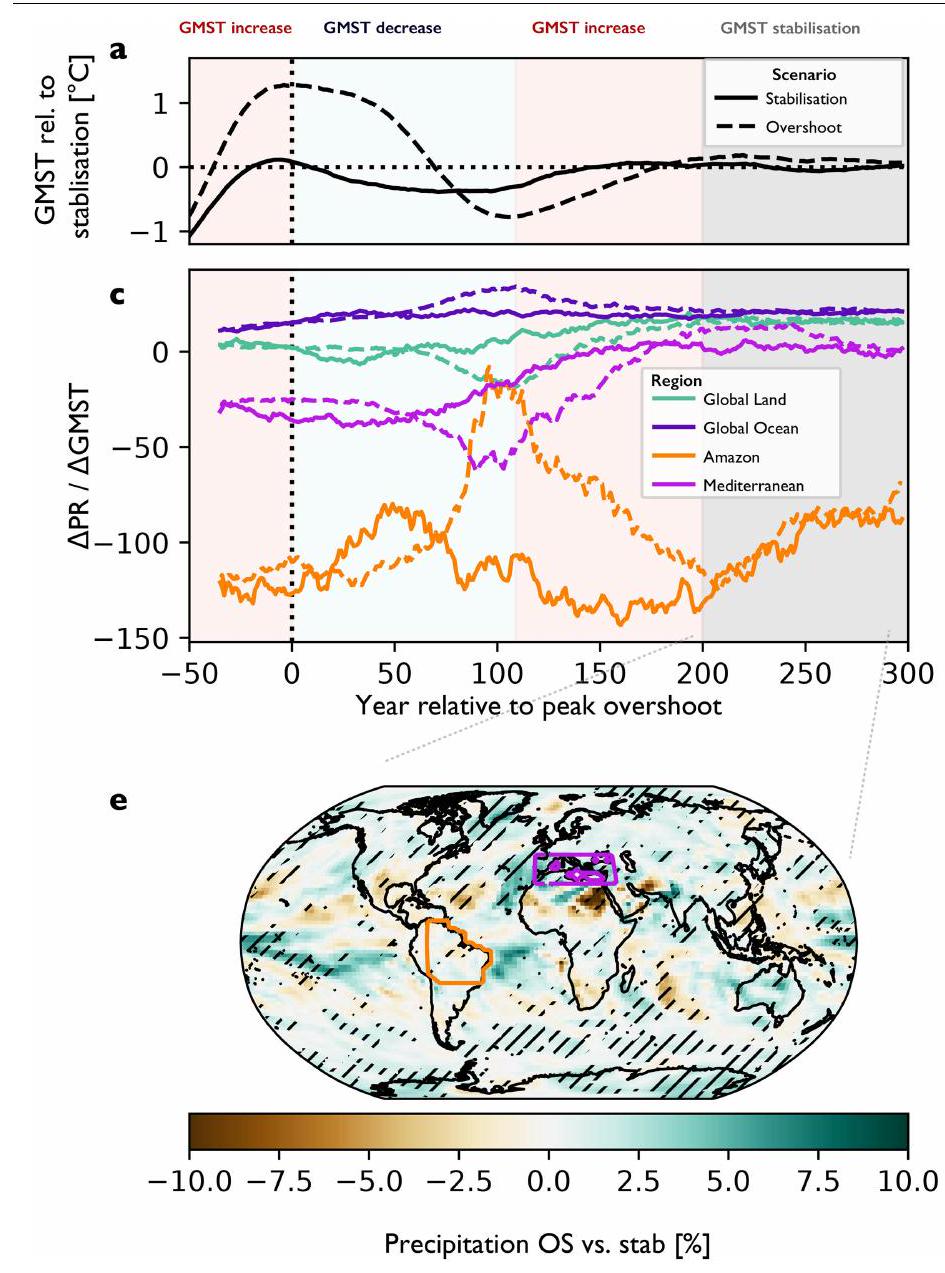

قابلية عكس تغير المناخ الإقليمي

تحذير لكل نتيجة ارتفاع في درجة الحرارة موضحة في

التغيرات المناخية. لذلك، فإن فهم تداعيات تجاوز درجة الحرارة العالمية للتغيرات الإقليمية أمر مهم. حتى إذا تم استقرار الاحترار العالمي عند مستوى معين دون تجاوز، فإن النظام المناخي يستمر في التغير حيث تستمر مكوناته في التكيف والتوازن.

كلا النموذجين، على وجه الخصوص، يتعلقان بحركات منطقة التقارب الاستوائية في استجابة للتغيرات في AMOC

آثار متأخرة وغير قابلة للعكس

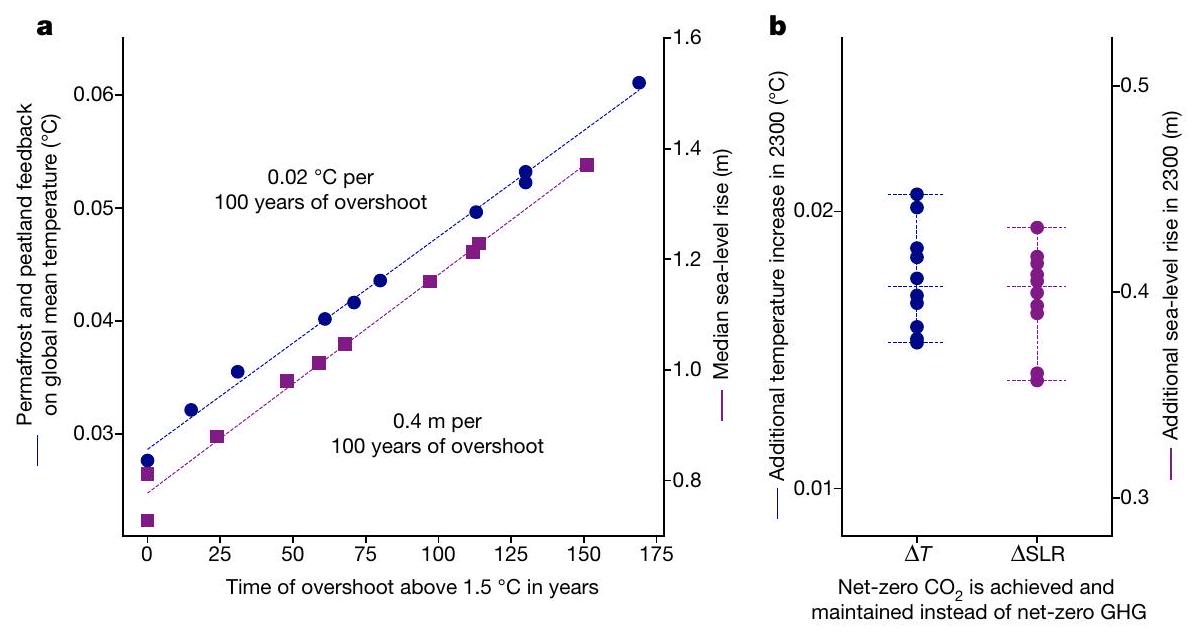

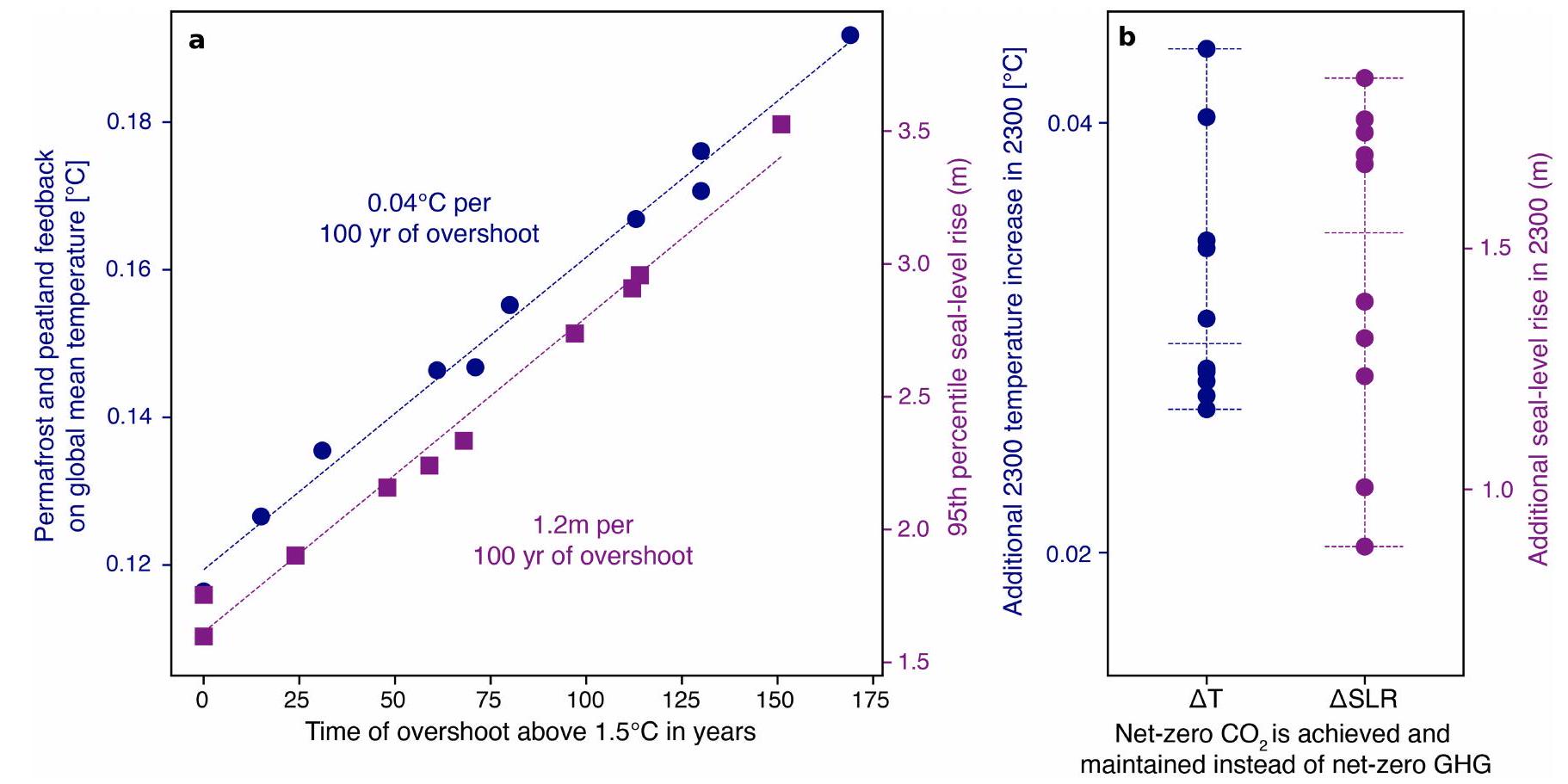

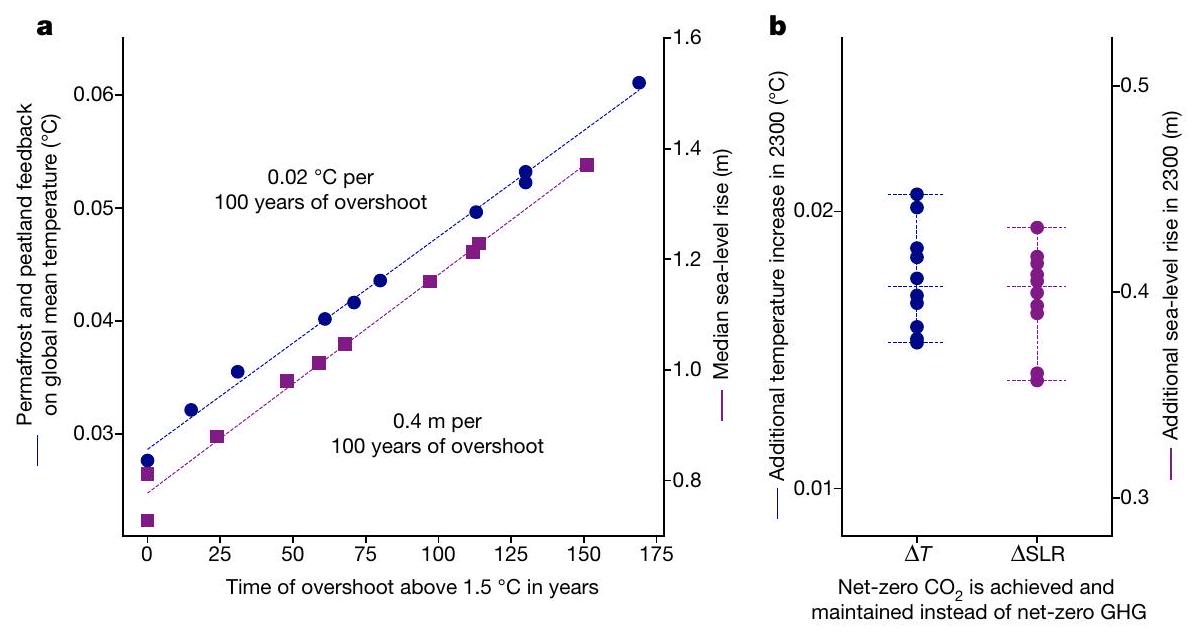

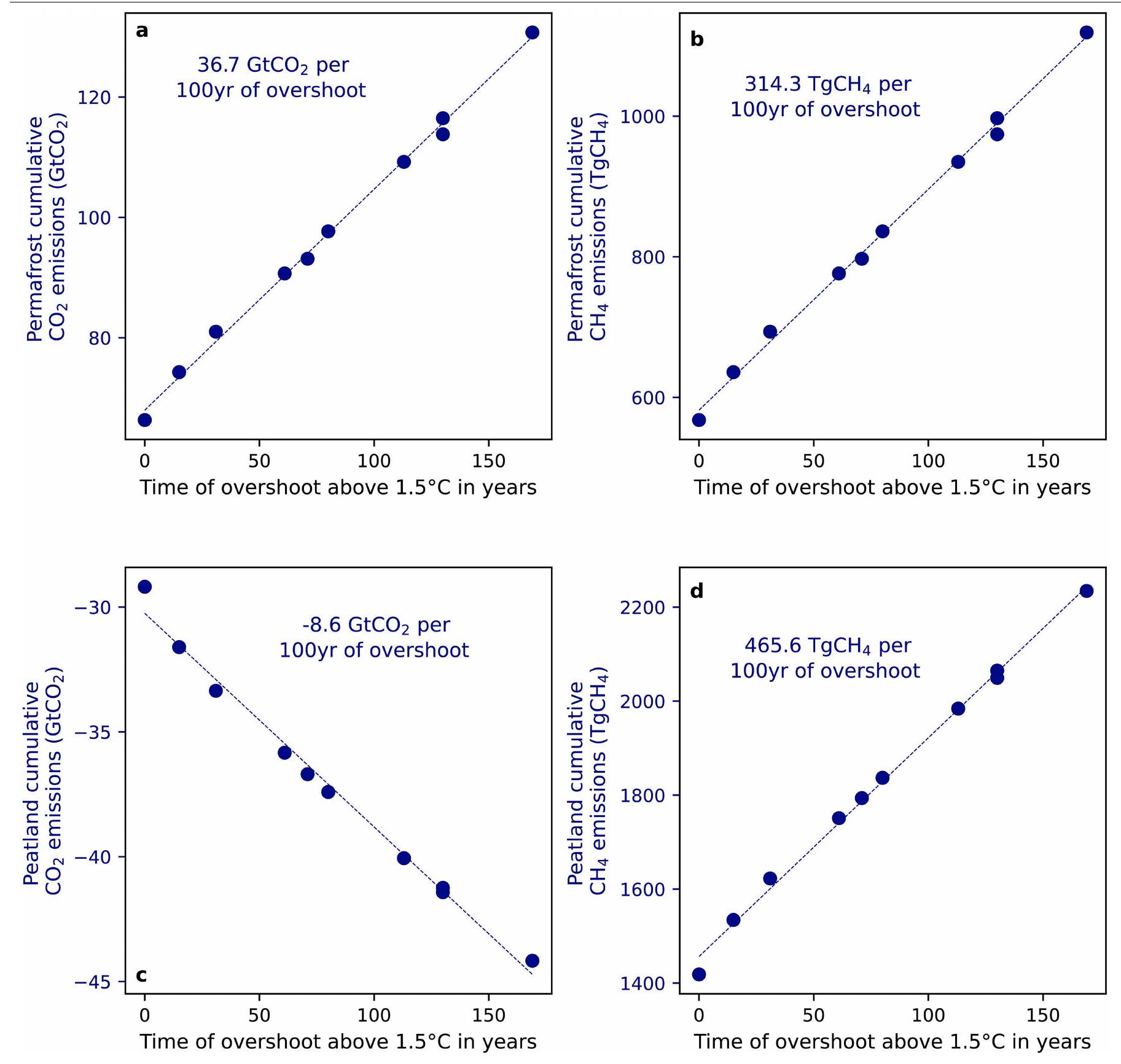

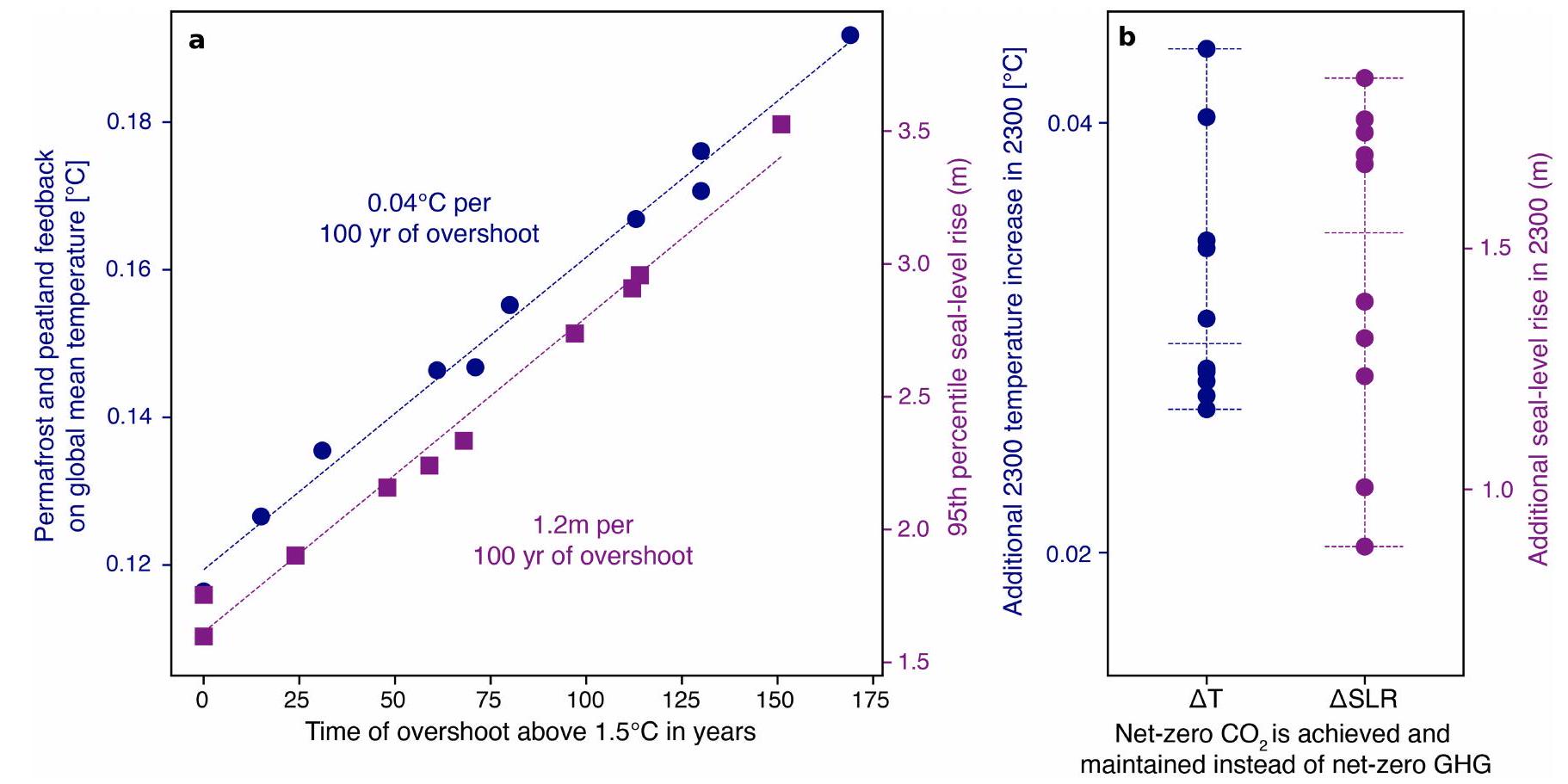

بالنسبة لارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر العالمي، نجد أن كل 100 عام من التجاوز فوق

يظهر نمط مشابه لذوبان الجليد الدائم في 2300 وارتفاع درجة حرارة الأراضي الخثية الشمالية مما يؤدي إلى زيادة تحلل الكربون في التربة و

زيادة بنفس ترتيب الحجم. نحذر من أن العلاقة الخطية المشخصة بين طول التجاوز ونتيجة التأثير قد تعتمد على مجموعة المسارات التي تم اشتقاقها منها. تفترض المسارات الأساسية حدوث التجاوزات بدءًا من فترة تأخير في العمل المناخي تليها تقليص ثابت إلى انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الصفرية، مما يعني معدل مشابه لانخفاض درجة الحرارة على المدى الطويل في جميع المسارات. قد تكون العلاقة مختلفة بالنسبة لنتائج التجاوز الأكثر أو الأقل تطرفًا.

التأثيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية

زيادة متوسط درجة الحرارة الناتجة عن انبعاثات التربة المتجمدة والأراضي الخثية بسبب الاحترار وارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر الناتج عن تثبيت درجات الحرارة عند ذروة الاحترار (تحقيق والحفاظ على صافي انبعاثات صفرية

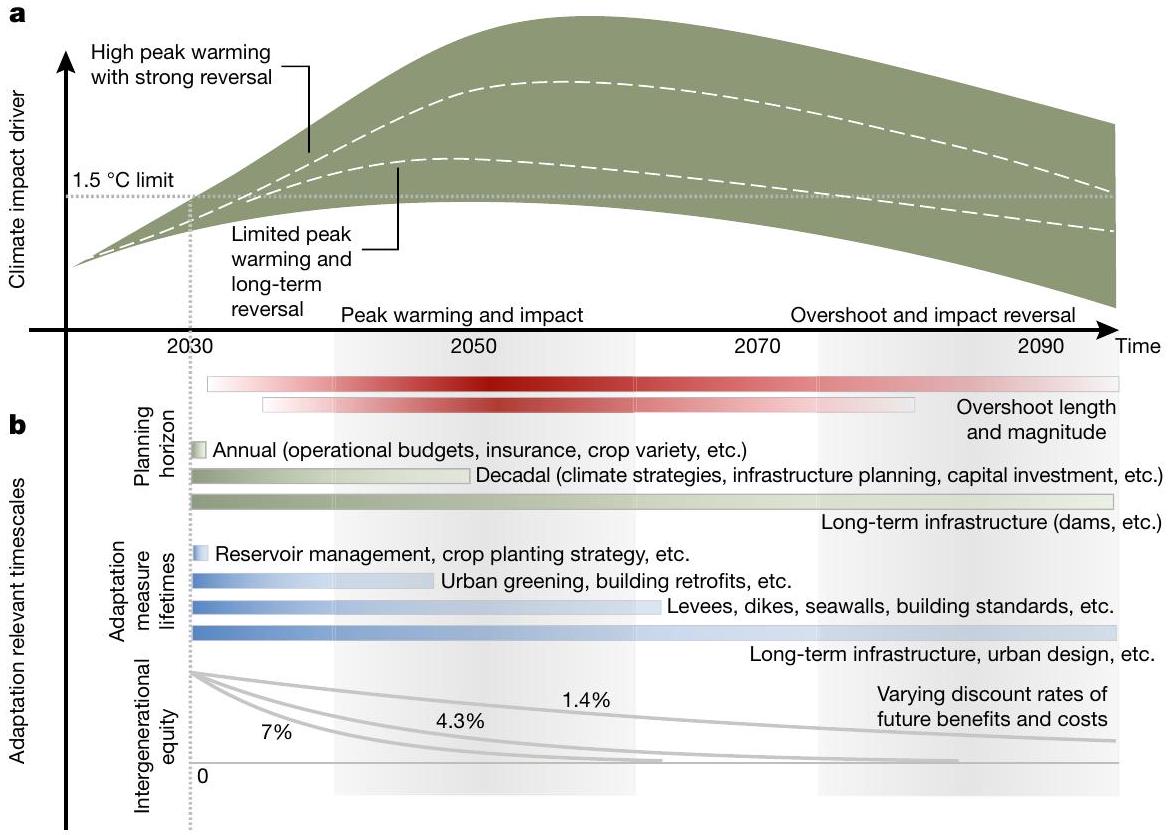

اتخاذ قرارات التكيف وتجاوز الحدود

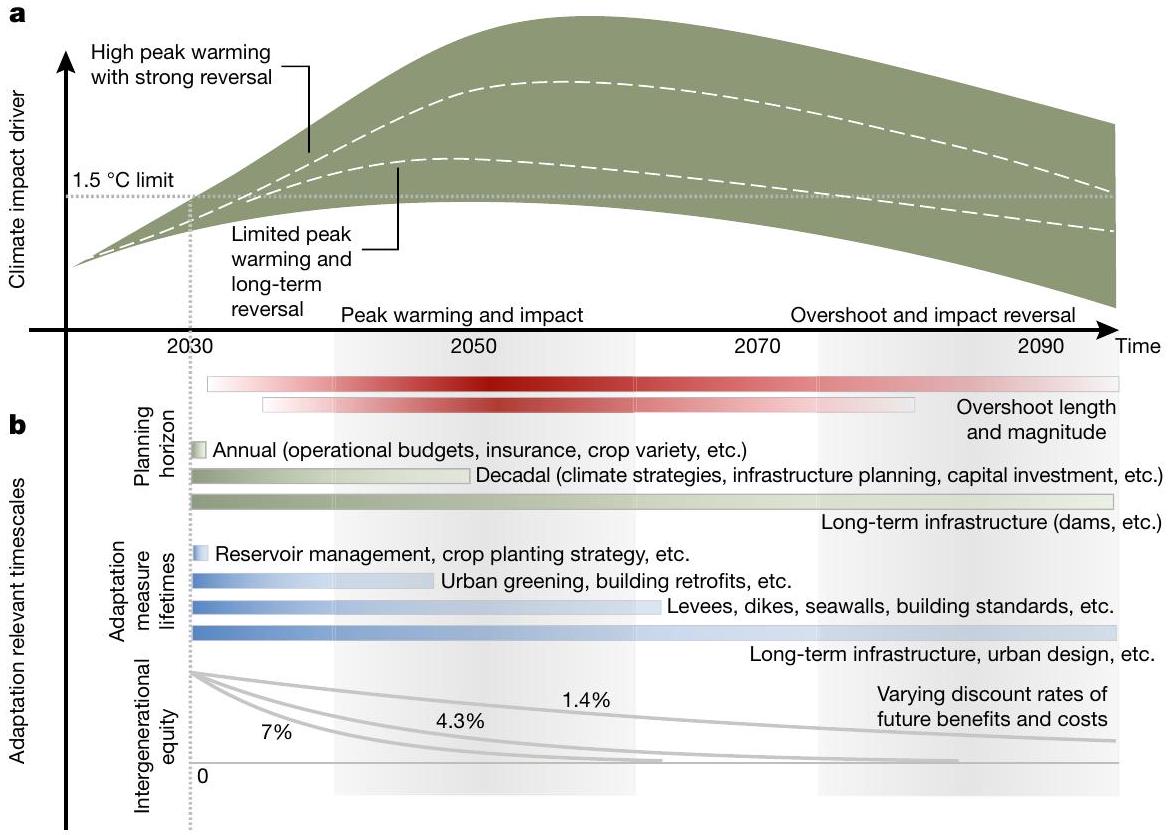

حتى تحت الافتراض المتفائل بوجود قابلية عكسية شبه كاملة لمؤثرات المناخ تحت تجاوز الحدود، قد يتطلب الأمر أفق تخطيط يمتد إلى 50 عامًا أو أكثر قبل أن تبدأ آفاق الانخفاض على المدى الطويل في التأثير على قرارات التكيف اليوم أو في المستقبل القريب (الشكل 5أ). القليل من خطط وسياسات التكيف تعمل على هذه الأطر الزمنية: على سبيل المثال، تمتد استراتيجية التكيف الخاصة بالاتحاد الأوروبي على مدى ثلاثة عقود، في حين أن خطط التكيف الوطنية الأخرى لها آفاق زمنية مماثلة أو أقصر.

يتطلب تطبيق أساليب التكلفة والفائدة في تدابير التكيف، والفترة الزمنية التي يتم تقييمها خلالها، اتخاذ قرارات بشأن العدالة بين الأجيال كما يتجلى في اختيار معدل الخصم الزمني.

لذا يبدو أن قابلية عكس تأثير السائق على المدى الطويل بعد تجاوز الحد قد تكون ذات صلة فقط في حالات محددة من التكيف.

صنع القرار. استثناء ملحوظ هو التكيف ضد التأثيرات غير القابلة للعكس المتأخرة في الزمن مثل ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر، حيث ستؤثر الزيادات الزائدة على التوقعات على المدى الطويل (الشكل 4). ومع ذلك، كما أظهرنا أعلاه، لا يمكن الاعتماد على انخفاض درجة حرارة الأرض العالمية على المدى الطويل بشكل مؤكد. وبالتالي، لا يمكن أن تستند استراتيجية التكيف المرنة إلى المراهنة على الزيادات الزائدة، ولا يمكن أن يقلل من احتياجات التكيف إلا الحد من ارتفاع درجات الحرارة القصوى.

إعادة صياغة مناقشة التجاوز

افتراضات قوية حول قابلية تطبيق وتفعيل وحوكمة تدخلات الهندسة الجيولوجية. إن الأخذ في الاعتبار عدم اليقين في الاستجابة المناخية الفيزيائية، وفي تطور الانبعاثات المستقبلية بعد نشر الهندسة الجيولوجية، يعني أن تدخلًا في الهندسة الجيولوجية يهدف إلى تقليل الذروة في حالة تجاوز الحدود قد يؤدي إلى التزام يمتد لعدة قرون لكل من نشر الهندسة الجيولوجية وإزالة الكربون.

القطاعات التي يصعب تقليل انبعاثاتها. وهذا يبرز أهمية تخفيضات الانبعاثات الصارمة على المدى القريب للحد من المخاطر على المدى الطويل. على الرغم من أننا نؤكد أن بناء قدرة احتجاز الكربون الوقائية مطلوب للتأمين ضد نتائج الاحترار العالية، فإن هذه القدرة نفسها يمكن، في حال عدم حدوث نتائج احترار عالية، أن تُستخدم أيضًا لخفض درجات الحرارة على المدى الطويل وبالتالي تقليل المخاطر المناخية.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- روجيل، ج. وآخرون. فجوة المصداقية في أهداف المناخ الصفرية الصافية تترك العالم في خطر كبير. ساينس 380، 1014-1016 (2023).

- الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ. ملخص لصانعي السياسات. في تغير المناخ 2022: التخفيف من تغير المناخ. مساهمة الفريق العامل الثالث في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير شوقلا، ب. ر. وآخرون) 1-48 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2022).

- برُوتز، ر.، ستريفلر، ج.، روجيل، ج. وفوس، س. فهم نطاق إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون في

مسارات متوافقة وعالية الارتفاع. اتصالات البحث البيئي 5، 041005 (2023). - شوينجر، ج.، أسعدي، أ.، شتاينرت، ن. ج. ولي، هـ. انبعاث الآن، تخفيف لاحقاً؟ قابلية عكس نظام الأرض تحت تجاوزات بمقادير وفترات زمنية مختلفة. ديناميات نظام الأرض 13، 1641-1665 (2022).

- بلايدرر، ب.، شلاوسنر، ج.-ف. وسيلمان، ج. عكس محدود للإشارات المناخية الإقليمية في سيناريوهات التجاوز. البحث البيئي والمناخي 3، 015005 (2024).

- الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ. ملخص لصانعي السياسات. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة الفريق العامل الأول في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير ماسون-ديلموت، ف. وآخرون) 3-32 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

- ماكدوجال، أ. هـ. وآخرون. هل هناك احترار في الأفق؟ تحليل متعدد النماذج لالتزام الصفر من الانبعاثات من

علوم الأحياء الجيولوجية 17، 2987-3016 (2020). - سميث، س. وآخرون. حالة إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون الطبعة الأولى (MCC، 2023).

- ديبريز، أ. وآخرون. الحدود اللازمة للاستدامة لـ

إزالة. العلوم 383، 484-486 (2024). - شنايدر، س. هـ. وماستراندريا، م. د. تقييم احتمالي لتغير المناخ “الخطير” ومسارات الانبعاثات. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 102، 15728-15735 (2005).

- ويغلي، ت. م. ل.، ريتشيلز، ر. وإدموندز، ج. أ. الخيارات الاقتصادية والبيئية في استقرار الغلاف الجوي

تركيزات. الطبيعة 379، 240-243 (1996). - أزار، سي.، يوهانسون، د. ج. أ. وماتسون، ن. تحقيق أهداف درجة الحرارة العالمية – دور الطاقة الحيوية مع احتجاز الكربون وتخزينه. رسائل البحث البيئي 8، 034004 (2013).

- شلاوسنر، سي.-إف. وآخرون. خصائص العلم والسياسة لهدف درجة حرارة اتفاق باريس. نات. مناخ. تغيير 6، 827-835 (2016).

- راجاماني، ل. وويركسمن، ج. الطابع القانوني والأهمية التشغيلية لهدف درجة حرارة اتفاق باريس. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. رياضيات. فيزيائية. هندسية. علوم. 376، 20160458 (2018).

- رياحي، ك. وآخرون. مسارات التخفيف المتوافقة مع الأهداف طويلة الأجل. في الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ، 2022: تغير المناخ 2022: التخفيف من تغير المناخ. مساهمة الفريق العامل الثالث في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير: شوكلا، ب. ر. وآخرون) 295-408 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2022).

- روجيل، ج. وآخرون. منطق سيناريو جديد لهدف درجة الحرارة على المدى الطويل لاتفاق باريس. ناتشر 573، 357-363 (2019).

- شلاوسنر، سي.-إف.، غانتي، جي.، روجيل، جي. & جيدن، إم. جي. تصنيف مسارات الانبعاثات الذي يعكس أهداف اتفاق باريس المناخية. اتصالات. الأرض والبيئة 3، 135 (2022).

- فورستر، ب. وآخرون. ميزانية الطاقة في الأرض، ردود الفعل المناخية، وحساسية المناخ. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة الفريق العامل الأول في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ 923-1054 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2023).

- بالازو كورنر، س. وآخرون. الالتزام بصفر انبعاثات واستقرار المناخ. فرونت. ساينس. 1، 1170744 (2023).

- غراسي، ج. وآخرون. تنسيق تقديرات تدفقات استخدام الأراضي للنماذج العالمية والمخزونات الوطنية للفترة 2000-2020. بيانات علوم الأرض 15، 1093-1114 (2023).

- مينهاوزن، م. وآخرون. وجهة نظر حول الجيل القادم من سيناريوهات نماذج نظام الأرض: نحو مسارات انبعاث تمثيلية (REPs). تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 17، 4533-4559 (2024).

- زيكفيلد، ك.، أزيفيدو، د.، ماثيسيوس، س. وماثيوز، هـ. د. عدم التماثل في استجابة دورة المناخ والكربون لانبعاثات ثاني أكسيد الكربون الإيجابية والسلبية. نات. مناخ. تغيير 11، 613-617 (2021).

- باور، س.، ناويلز، أ.، نيكولز، ز.، ساندرسون، ب. م. وشلاوسنر، س.-ف. طول فترة نشر تعديل الإشعاع الشمسي: تفاعل التخفيف، والانبعاثات السلبية الصافية، وعدم اليقين المناخي. ديناميات نظام الأرض 14، 367-381 (2023).

- كاناديل، ج. ج. وآخرون. الكربون العالمي ودورات الكيمياء الحيوية الأخرى والتغذية الراجعة. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة مجموعة العمل الأولى في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ 673-816 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

- ماكلارين، د.، ويليس، ر.، شيرزينسكي، ب.، تايفيلد، د. وماركوسون، ن. جاذبية التأخير: استخدام المشاركة المدروسة للتحقيق في الآثار السياسية والاستراتيجية لتقنيات إزالة غازات الدفيئة. التخطيط البيئي. E الفضاء الطبيعي 6، 578-599 (2023).

- باويس، سي. إم.، سميث، إس. إم.، مينكس، جي. سي. وغاسر، تي. قياس نشر إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون على مستوى العالم. رسائل البحث البيئي 18، 024022 (2023).

- لامب، و. ف. وآخرون. فجوة إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون. نات. مناخ. تغيير 14، 644-651 (2024).

- برودز، ر.، فوس، س.، لوك، س.، ستيفان، ل. وروجيل، ج. تصنيف لرسم الأدلة حول الفوائد المشتركة، التحديات، وحدود إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون. اتصالات. الأرض والبيئة 5، 197 (2024).

- ستيوارت-سميث، ر. ف.، راجاماني، ل.، روجيل، ج. وويتزر، ت. الحدود القانونية لاستخدام

الإزالة. العلوم 382، 772-774 (2023). - كينغ، أ. د. وآخرون. الاستعداد لعالم ما بعد الصفر الصافي. نات. مناخ. تغيير 12، 775-777 (2022).

- بيلومو، ك.، أنجيلوني، م.، كورتّي، س. وفون هاردنبرغ، ج. تغير المناخ المستقبلي الذي تشكله الاختلافات بين النماذج في استجابة الدورة الدموية العمودية الأطلسية. نات. كوميونيك. 12، 3659 (2021).

- شوينغر، ج.، أسعدي، أ.، غوريس، ن. ولي، هـ. إمكانية حدوث تبريد قوي في نصف الكرة الشمالي عند خطوط العرض العالية تحت انبعاثات سلبية. نات. كوميونيك. 13، 1095 (2022).

- مولر، ت. وآخرون. تحقيق صافي انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الصفرية أمر حاسم للحد من مخاطر تغير المناخ. نات. كوم. 15، 6192 (2024).

- سانتانا-فالكون، ي. وآخرون. فقدان لا رجعة فيه في قابلية الحياة في النظام البيئي البحري بعد تجاوز درجة الحرارة. اتصالات. الأرض والبيئة. 4، 343 (2023).

- شلاوسنر، سي.-إف. وآخرون. تغييرات في إنتاجية المحاصيل في

و عوالم تحت عدم اليقين في حساسية المناخ. رسائل البحث البيئي 13، 064007 (2018). - ماير، أ. ل. س.، بينتلي، ج.، أودولامي، ر. س.، بيغوت، أ. ل. و تريزوس، س. هـ. المخاطر التي تهدد التنوع البيولوجي نتيجة مسارات تجاوز درجات الحرارة. فلسفة. ترانس. ر. سوس. ب. بيولوجيا. علوم. 377، 20210394 (2022).

- مينجل، م.، ناويلز، أ.، روجيل، ج. وشلاوسنر، س.-ف. ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر الملتزم بموجب اتفاق باريس وإرث تأخير إجراءات التخفيف. نات. كوم. 9، 601 (2018).

- أندرييفيتش، م. وآخرون. نحو تمثيل السيناريو لقدرة التكيف لتقييمات تغير المناخ العالمي. نات. مناخ. تغيير 13، 778-787 (2023).

- توماس، أ. وآخرون. أدلة عالمية على القيود والحدود لتكيف الإنسان. تغيير البيئة الإقليمية 21، 85 (2021).

- بيركمان، ج. وآخرون. الفقر وسبل العيش والتنمية المستدامة. في تغير المناخ 2022: الآثار والتكيف والضعف. مساهمة الفريق العامل الثاني في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ 1171-1274 (IPCC، 2022).

- بورك، م.، هسيانغ، س. م. وميغيل، إ. التأثير غير الخطي العالمي لدرجة الحرارة على الإنتاج الاقتصادي. ناتشر 527، 235-239 (2015).

- بارى، م.، لو، ج. وهانسون، س. تجاوز، تكيف واستعد. ناتشر 458، 1102-1103 (2009).

- ويليامز، ج. و.، أوردونيز، أ. وسفينينغ، ج.-س. إطار موحد لدراسة وإدارة معدلات التغيير البيئي المدفوعة بالمناخ. نات. إيكول. إيفول. 5، 17-26 (2021).

- الاتفاقية الإطارية للأمم المتحدة بشأن تغير المناخ. خطط التكيف الوطنية 2021. التقدم في صياغة وتنفيذ خطط التكيف الوطنية (الاتفاقية الإطارية للأمم المتحدة، 2022).

- كاني، س. تغير المناخ، العدالة بين الأجيال ومعدل الخصم الاجتماعي. فلسفة السياسة والاقتصاد 13، 320-342 (2014).

- ماك مارتن، د. ج.، ريك، ك. ل. وكيث، د. و. الهندسة الجيولوجية الشمسية كجزء من استراتيجية شاملة لتحقيق

هدف باريس. فلس. ترانس. ر. سوس. رياض. فيز. إنج. سا. 376، 20160454 (2018). - بييرمان، ف. وآخرون. الهندسة الجيولوجية الشمسية: الحالة من أجل اتفاق دولي بعدم الاستخدام. WIREs تغير المناخ 13، e754 (2022).

- فيسون، سي. إل.، باور، س.، جيدن، م. وشلاوسنر، سي. إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون العادل تزيد من مسؤولية المصدرين الرئيسيين. نات. مناخ. تغيير 10، 836-841 (2020).

- سيلفي، ي. وآخرون. AERA-MIP: مسارات الانبعاثات، الميزانيات المتبقية وديناميات دورة الكربون المتوافقة مع

و استقرار الاحتباس الحراري. مسودة مسبقة فيhttps://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-488 (2024). - هاليغاتي، س. استراتيجيات التكيف مع تغير المناخ غير المؤكد. التغيير البيئي العالمي 19، 240-247 (2009).

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

تقييم الصافي السلبي

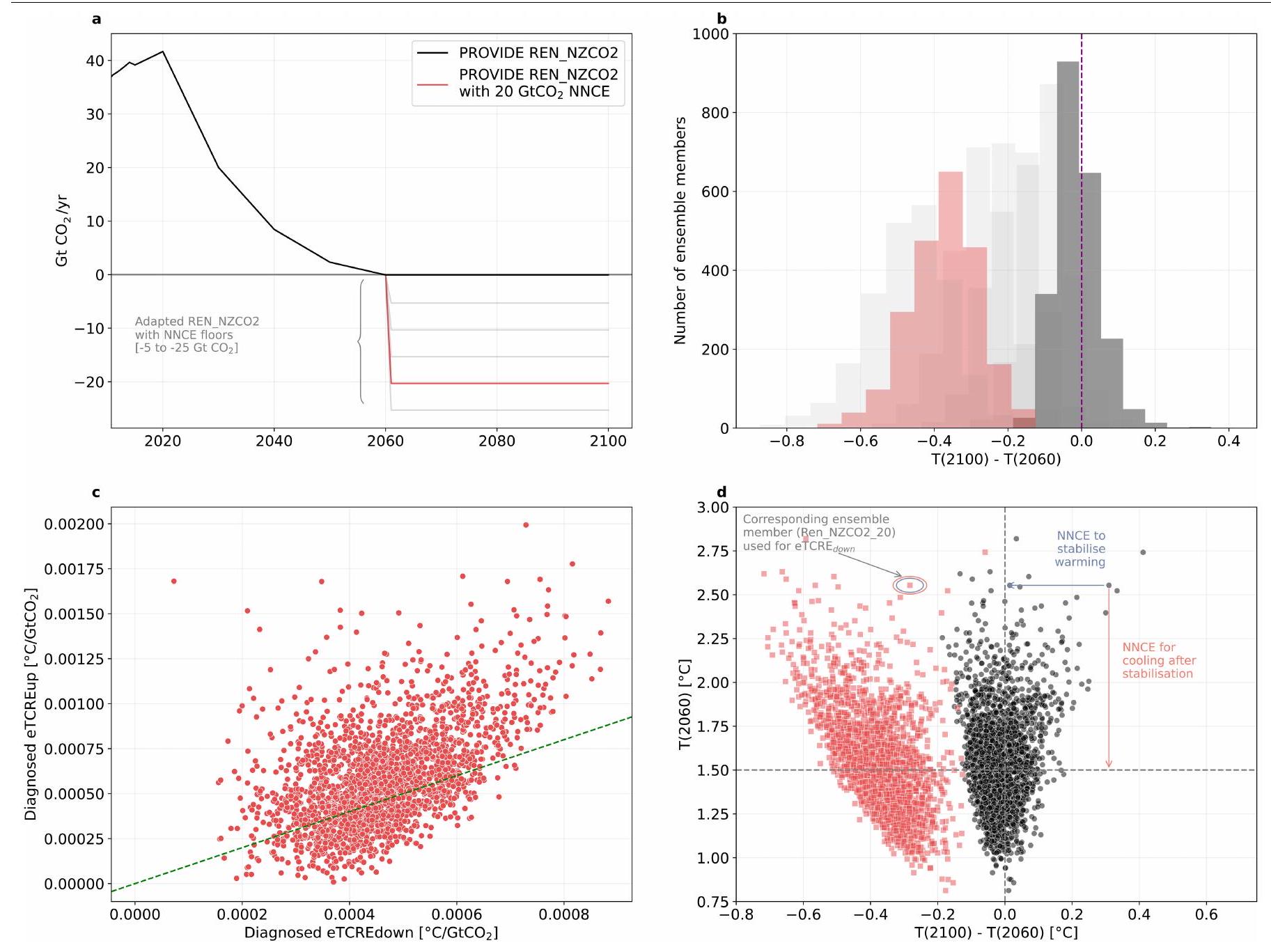

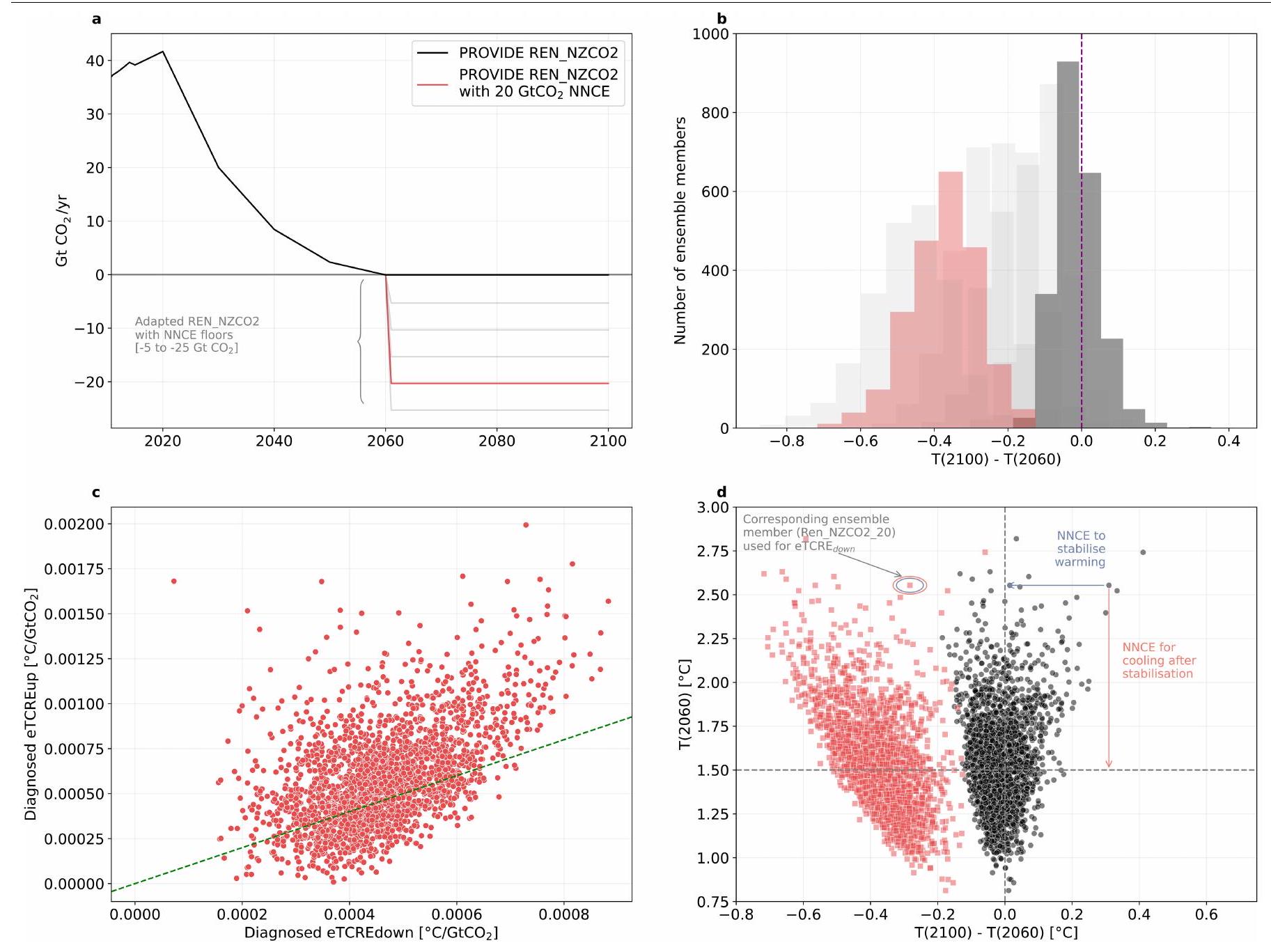

- الاستجابة العابرة الفعالة لانبعاثات التراكمية (للزيادة)، أو eTCREup: هذه المقياس يلتقط الاحترار المتوقع لكمية معينة من الانبعاثات التراكمية حتى الوصول إلى صافي الصفر.

. - الاستجابة العابرة الفعالة للانبعاثات التراكمية (الأسفل)، أو eTCREdown: هذه المقياس يلتقط الاحترار أو التبريد المتوقع لكمية معينة من الانبعاثات السلبية الصافية التراكمية بعد الوصول إلى صافي الصفر.

. هذه مقياس تشخيصي بحت ويشمل أيضًا تأثيرات الالتزام الفعّال بانبعاثات صفرية (eZEC). - eZEC: الاستجابة المستمرة لدرجة الحرارة بعد الصفر الصافي

تتحقق الانبعاثات وتستمر هنا يتم تقييم eZEC على مدى 40 عامًا (بين 2060 و 2100).

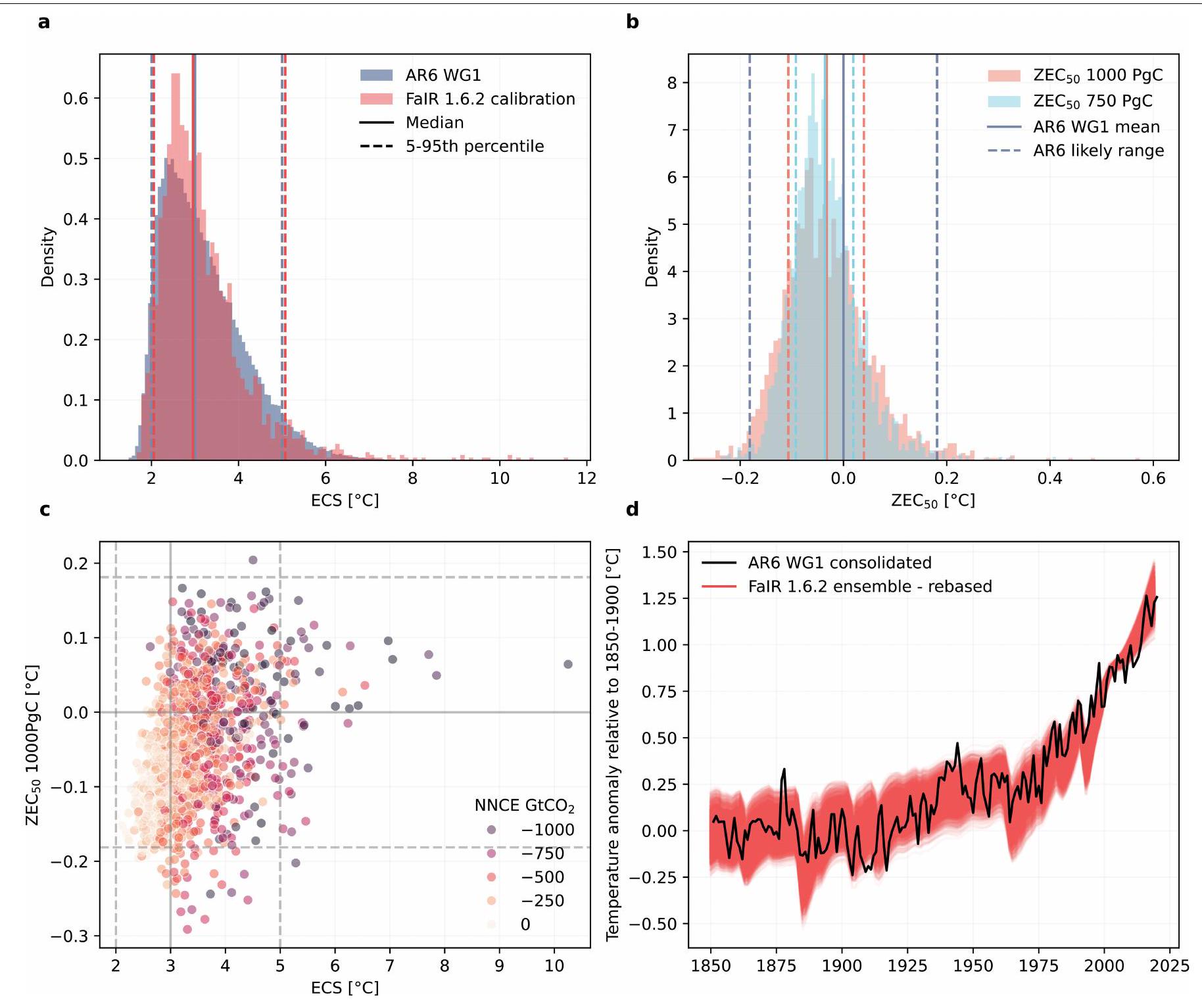

نحتاج إلى اتخاذ نهج مختلف لتقدير المقياس الثاني (eTCRE)

(لكل عضو في الفرقة) الذي هو ضروري لضمان التبريد بعد الذروة إلى

لا يمكننا استبعاد أعضاء مجموعة ECS/ZEC العالية التي تؤثر على ذيل توزيع NNCE لدينا (الشكل 2c من البيانات الموسعة). ومع ذلك، نجد أن النتائج العالية لـ NNCE تظهر أيضًا في حالات ECS وZEC المتوسطة إلى العالية.

تجاوز القابلية للعكس لدرجة الحرارة ومتوسط هطول الأمطار السنوي

يتوافق مع خلايا الشبكة الأرضية في غرب وسط أوروبا (WCE) وشمال أوروبا (NEU). يتوافق NAO45 مع خلايا الشبكة البحرية في منطقة شمال الأطلسي.

ثم نقوم بتقدير تغير درجة الحرارة العالمية (

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

51. لامبول، ر.، روجيل، ج. وشلاوسنر، ك.-ف. دليل السيناريوهات لمشروع PROVIDE. أرشيف ESS المفتوحhttps://doi.org/10.1002/essoar. 10511875.2 (2022).

52. لوديرر، ج. وآخرون. تأثير انخفاض تكاليف الطاقة المتجددة على الكهربة في السيناريوهات ذات الانبعاثات المنخفضة. نات. إنرجي 7، 32-42 (2022).

53. رياحي، ك. وآخرون. مسارات التخفيف المتوافقة مع الأهداف طويلة الأجل. في الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ، 2022: تغير المناخ 2022: التخفيف من تغير المناخ. مساهمة الفريق العامل الثالث في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير شوقلا، ب. ر. وآخرون) (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2022).

54. بايرز، إ. وآخرون. قاعدة بيانات سيناريوهات AR6. زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5886912 (2022).

55. سميث، سي. جي. وآخرون. FAIR v1.3: نموذج استجابة دافعة بسيط قائم على الانبعاثات ودورة الكربون. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 11، 2273-2297 (2018).

56. نيكولز، ز. وآخرون. صندوق عبر الفصول 7.1: المحاكاة الفيزيائية لنماذج نظام الأرض لتصنيف السيناريوهات ودمج المعرفة في التقرير السادس لتقييم المناخ. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة مجموعة العمل الأولى في التقرير السادس للجنة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير ماسون-ديلموتي، ف. وآخرون) (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

57. الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ. الملحق السابع: المعجم. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة مجموعة العمل الأولى في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير ماثيوز، ج. ب. ر. وآخرون) 2215-2256 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2021).

58. شيروود، س. وآخرون. تقييم حساسية مناخ الأرض باستخدام خطوط متعددة من الأدلة. مراجعة الجيوفيزياء 58، e2019RG000678 (2020).

59. دن، ج. ب. وآخرون. نماذج نظام الأرض المناخي الكربوني المتكاملة GFDL’s ESM2. الجزء الثاني: صياغة نظام الكربون وخصائص المحاكاة الأساسية. مجلة المناخ 26، 2247-2267 (2013).

60. برجر، ف. أ.، جون، ج. ج. وفرويشلر، ت. ل. زيادة في تباين حموضة المحيطات والظواهر القصوى تحت زيادة الغلاف الجوي

61. تيرها، ج.، فريوليشر، ت. ل.، أشواندن، م. ت.، فريدلينغستين، ب. وجوس، ف. نهج تخفيض الانبعاثات التكيفية للوصول إلى أي هدف من أهداف الاحترار العالمي. نات. مناخ. تغيير 12، 1136-1142 (2022).

62. فريوليش، ت. ل.، ينس، ت.، فورتونات، ج. ويونا، س. بروتوكول لمحاكاة نهج تقليل الانبعاثات التكيفية (AERA). زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7473133 (2022).

63. سيلاند،

64. جونز، سي. دي. وآخرون. مساهمة مشروع مقارنة نماذج الالتزام بالانبعاثات الصفرية (ZECMIP) في C4MIP: قياس التغيرات المناخية الملتزمة بعد انبعاثات كربونية صفرية. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 12، 4375-4385 (2019).

65. دي هيرتوج، س. ج. وآخرون. التأثيرات البيوجغرافية والفيزيائية لتغييرات الغطاء الأرضي وإدارة الأراضي المثالية في نماذج نظام الأرض. ديناميات نظام الأرض 14، 629-667 (2023).

66. أونيل، ب. س. وآخرون. مشروع المقارنة بين نماذج السيناريو (ScenarioMIP) لـ CMIP6. مناقشات تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 9، 3461-3482 (2016).

67. كويلكايل، ي.، غاسر، ت.، سياس، ب. وبوشيه، أ. محاكاة CMIP6 باستخدام نموذج النظام الأرضي المدمج OSCAR v3.1. تطوير نماذج علوم الأرض 16، 1129-1161 (2023).

68. تشيو، سي. وآخرون. سيناريو تخفيف قوي يحافظ على الحياد المناخي للأراضي الخثية الشمالية. ون إيرث 5، 86-97 (2022).

69. لامبول، ر.، روجيل، ج. وشلاوسنر، ك.-ف. بيانات انبعاثات السيناريو ودرجات الحرارة لمشروع PROVIDE (الإصدار 1.1.1). زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6963586 (2022).

70. لاكروا، ف.، برجر، ف.، سيلفي، ي.، شلاوسنر، ج.-ف.، وفرويشلر، ت. بيانات تجاوز GFDL-ESM2M. زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11091132 (2024).

71. شلاوسنر، سي.-إف. وآخرون. النصوص المرافقة لشلاوسنر وآخرون. الثقة المفرطة في تجاوز المناخ. زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13208166 (2024).

72. لين، ج.، غريغ، س. & غارنيت، أ. آفاق التخزين غير المؤكدة تخلق معضلة لطموحات التقاط الكربون وتخزينه. نات. مناخ. تغيير 11، 925-936 (2021).

73. فوس، س. وآخرون. الانبعاثات السلبية – الجزء 2: التكاليف، الإمكانيات والآثار الجانبية. رسائل البحث البيئي 13، 063002 (2018).

74. أندرغ، و. ر. ل. وآخرون. المخاطر المدفوعة بالمناخ على إمكانيات التخفيف المناخي للغابات. ساينس 368، eaaz7005 (2020).

75. هيكنين، ج.، كيسكينن، ر.، كوستنسالو، ج. ونوتينن، ف. تغير المناخ يؤدي إلى فقدان الكربون من التربة المعدنية القابلة للزراعة في الظروف الشمالية. التغير العالمي في البيولوجيا 28، 3960-3973 (2022).

76. تشيكير، س.، باتريزيو، ب.، بوي، م.، سوني، ن. ودويل، ن. م. تحليل مقارن لكفاءة وتوقيت وديمومة مسارات إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون. علوم الطاقة والبيئة 15، 4389-4403 (2022).

77. Mengis, N.، Paul, A. & Fernández-Méndez, M. العد (على) الكربون الأزرق – التحديات والطرق المستقبلية لمحاسبة الكربون لإزالة الكربون المعتمدة على النظام البيئي في البيئات البحرية. PLoS Clim. 2، e0000148 (2023).

78. جونز، سي. دي. وآخرون. محاكاة استجابة نظام الأرض للانبعاثات السلبية. رسائل البحث البيئي 11، 095012 (2016).

79. ريالمنت، ج. وآخرون. تقييم بين النماذج لدور التقاط الهواء المباشر في مسارات التخفيف العميق. نات. كوميونيك. 10، 3277 (2019).

80. كراوس، أ. وآخرون. عدم اليقين الكبير في إمكانيات امتصاص الكربون لجهود التخفيف من تغير المناخ على اليابسة. بيولوجيا التغير العالمي 24، 3025-3038 (2018).

81. مينكس، ج. س. وآخرون. الانبعاثات السلبية – الجزء 1: مشهد البحث والتلخيص. رسائل البحث البيئي 13، 063001-063001 (2018).

82. غرانت، ن.، هاوكز، أ.، ميتال، س. وغامبير، أ. مواجهة ردع التخفيف في سيناريوهات منخفضة الكربون. رسائل البحث البيئي 16، 64099-64099 (2021).

83. كارتون، و.، هوغارد، إ.-م.، ماركوسون، ن. ولوند، ج. ف. هل تؤخر إزالة الكربون تقليل الانبعاثات؟ مراجعات وايلي متعددة التخصصات لتغير المناخ 14، e826 (2023).

84. دونيسون، سي. وآخرون. الطاقة الحيوية مع احتجاز الكربون وتخزينه (BECCS): إيجاد الفوائد المتبادلة للطاقة، والانبعاثات السلبية، وخدمات النظام البيئي – الحجم مهم. التغير العالمي في البيولوجيا. الطاقة الحيوية 12، 586-604 (2020).

85. هيك، ف.، هوف، هـ.، ويرسينياس، س.، ماير، ج. وكريفت، هـ. خيارات استخدام الأراضي للبقاء ضمن الحدود الكوكبية – التآزر والمقايضات بين الأهداف العالمية والمحلية للاستدامة. التغيير البيئي العالمي 49، 73-84 (2018).

86. دويلمان، ج. س. وآخرون. التشجير للتخفيف من تغير المناخ: الإمكانيات والمخاطر والمقايضات. بيولوجيا التغير العالمي 26، 1576-1591 (2020).

87. لي، ك.، فيسون، س. & شلاوسنر، س. ف. توزيعات عادلة لالتزامات إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون وآثارها على الأهداف الوطنية الفعالة للوصول إلى صافي انبعاثات صفرية. رسائل البحث البيئي 16، 094001 (2021).

88. غانتي، ج. وآخرون. المطالب غير المعوضة لمساحة الانبعاثات العادلة تعرض أهداف اتفاق باريس للخطر. رسائل البحث البيئي 18، 024040 (2023).

89. يوانو، ب. وآخرون. القيام بمشاركة الأعباء بشكل صحيح لتقديم حلول المناخ الطبيعية لإزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون. الحلول المستندة إلى الطبيعة 3، 100048 (2023).

طور تصنيف المسار وصمم الشكل 1، الجدول 1 والجدول الممتد 1 بدعم من G.G. قاد قسم استجابة المناخ العالمي، بما في ذلك التحليل الذي يستند إليه الشكل 2 والأشكال الممتدة 1 و2، G.G. بدعم من Z.N. وC.J.S. وR.L. وC.-F.S. وJ.R. قاد قسم إزالة الكربون، بما في ذلك الجدول الممتد 2 والشكل الممتد 3، R.P. بدعم من S.F. وC.-F.S. وM.J.G. وJ.R. قاد قسم قابلية عكس تغير المناخ، بما في ذلك الشكل 3 والأشكال الممتدة 4-8، P.P. بدعم من N.J.S. وT.L.F. وF.L. وB.S. وC.-F.S.؛ قامت F.L. بإجراء محاكاة تجاوز GFDL ESM2M والاستقرار بدعم من T.L.F. قاد التحليل الذي يستند إليه قسم التأثيرات المتأخرة الزمنية B.Z. بدعم من M. Mengel وT.G. وP.C. مع مدخلات من R.W. وJ.P. وF.M. وC.-F.S. قاد قسم اتخاذ قرارات التكيف C.M.K. وJ.W.M. وE.T. وR.M. مع مدخلات من J.S. وC.-F.S.؛ قدم S.I.S. وY.Q. وM. Meinshausen مدخلات حول تصوّر المقالة بأكملها. ساهم جميع المؤلفين في كتابة الورقة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى كارل-فريدريش شلاوسنر.

تُعرب مجلة Nature عن شكرها لأيمي لورز، نادين مينغيس والمراجعين الآخرين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذه العمل. تقارير مراجعي الأقران متاحة.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

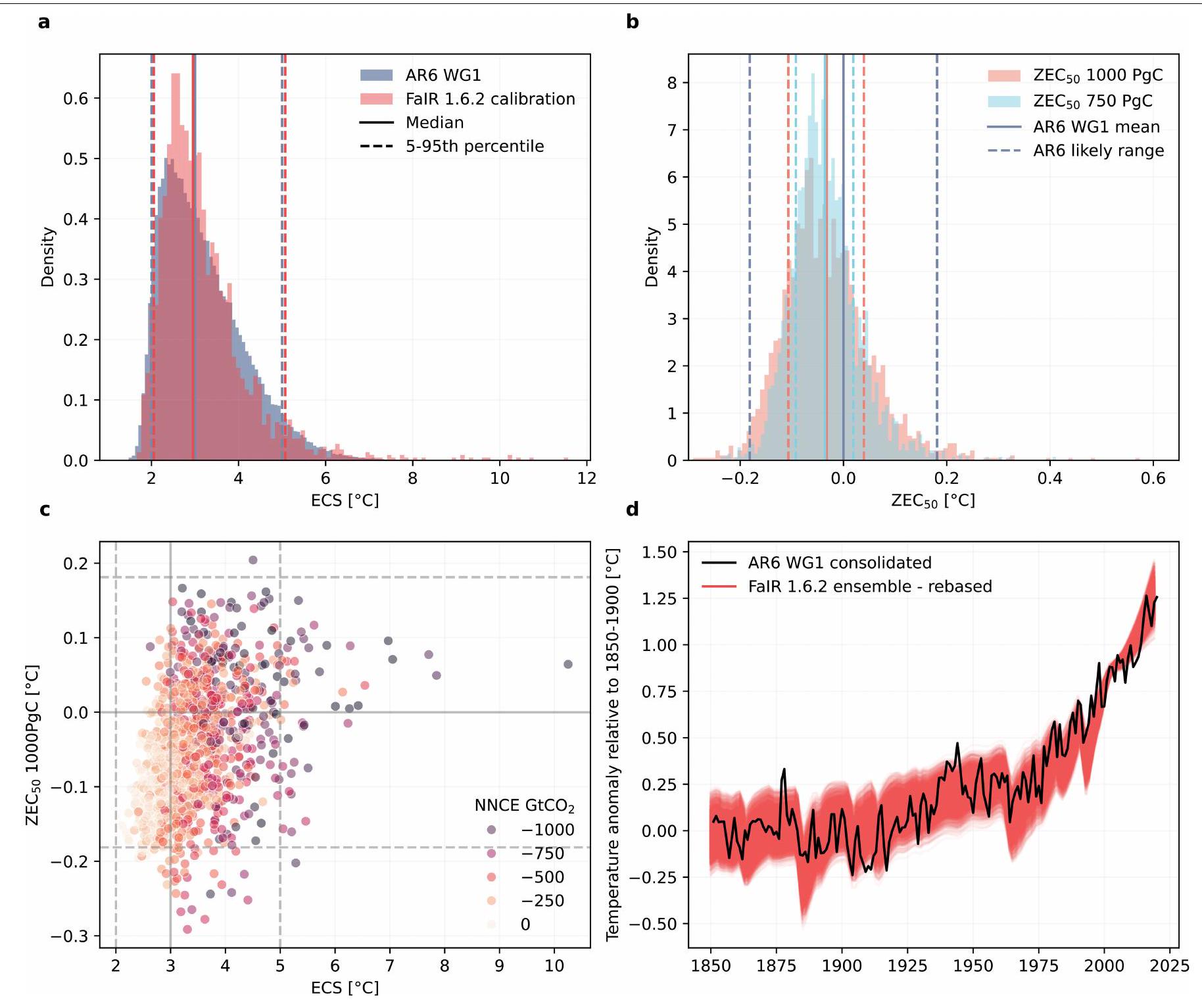

تشير التقديرات إلى يمين الخط الأرجواني إلى استمرار الاحترار بعد عام 2060. ج، تم تشخيص eTCREup و eTCREdown (المقدرة من PROVIDEREN_NZCO2_20)، د، التبريد بين عامي 2100 و2060 مقابل الاحترار في عام 2060 لـ PROVIDE REN_NZCO2 و PROVIDE REN_NZCO2_20.

أعضاء المجموعة. تشير الخطوط الأفقية الصلبة والمقطعة (العمودية) إلى الوسيط و

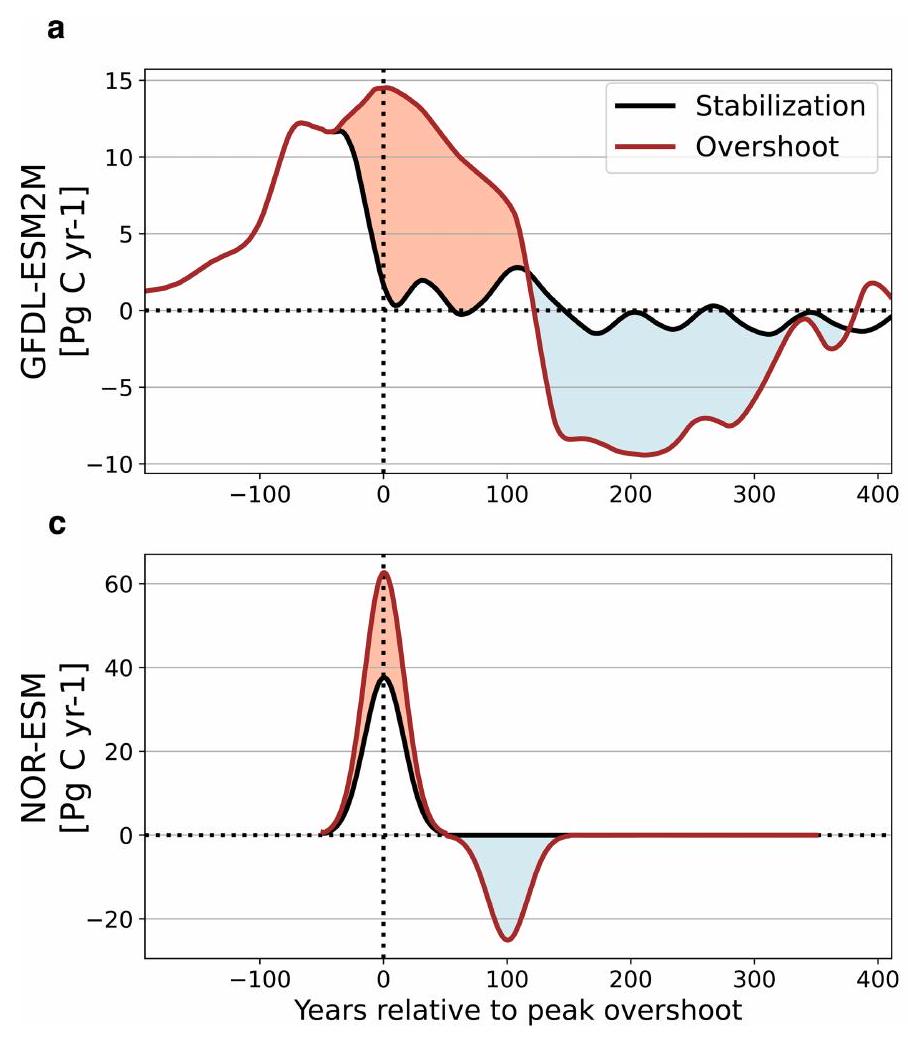

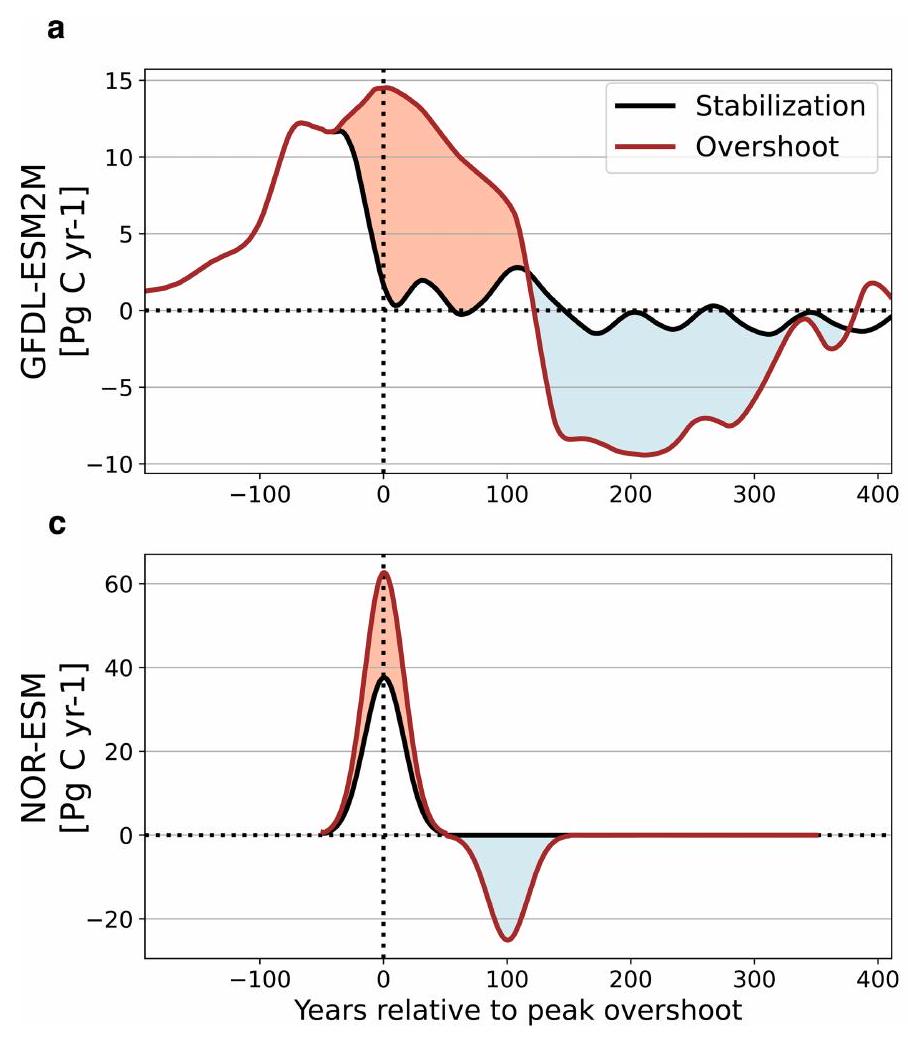

التجارب. أ، ج تظهر متوسط 31 عامًا مؤقت

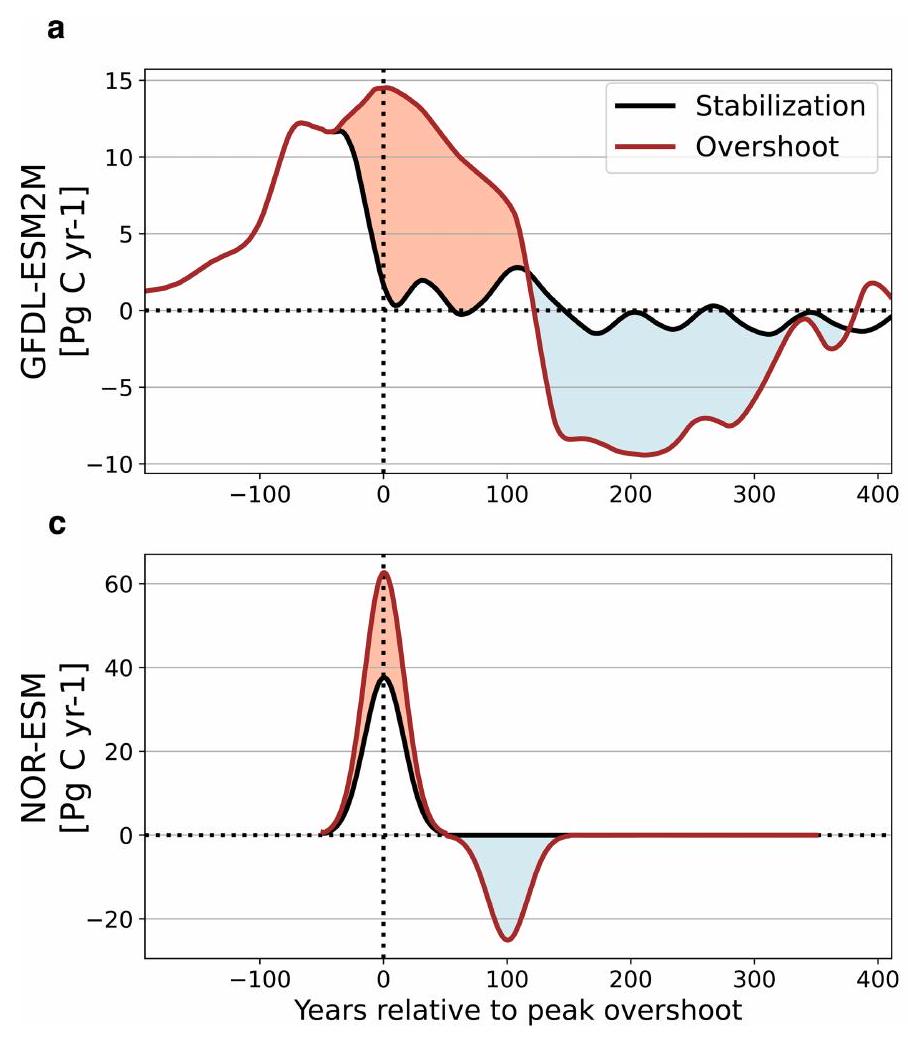

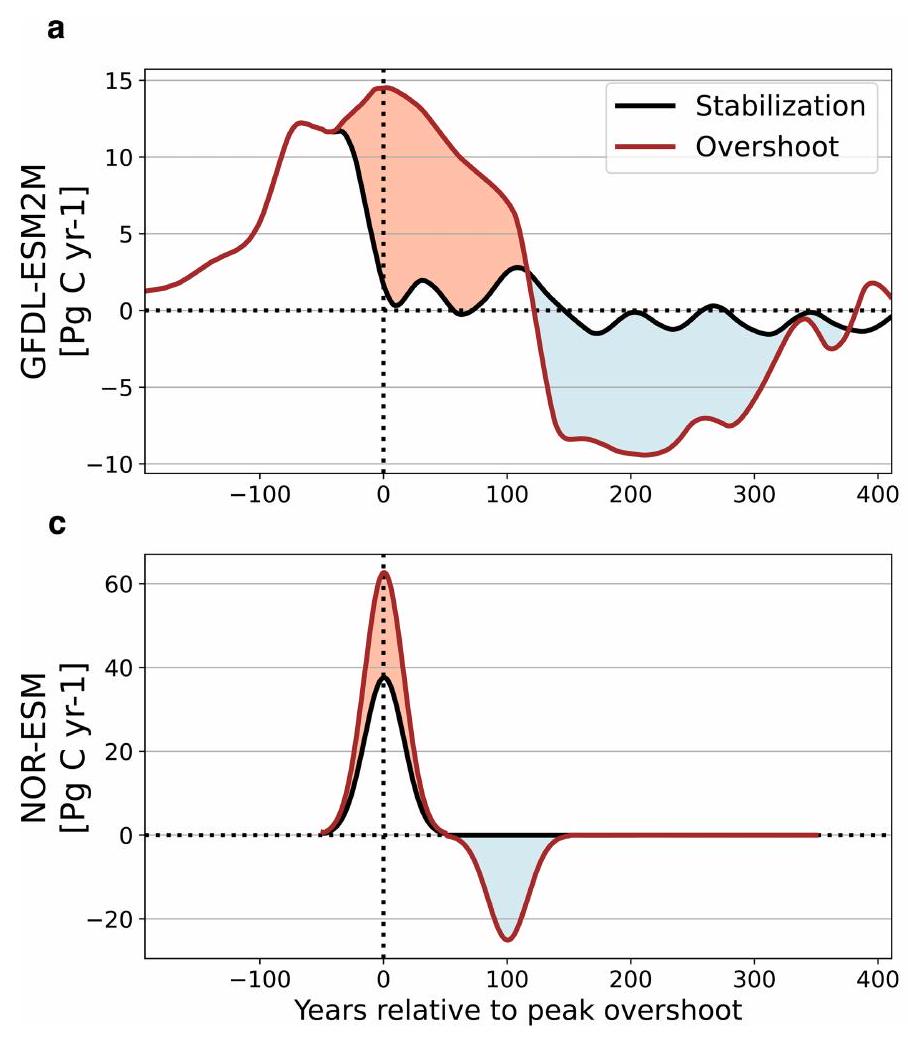

فرق ميزانية الكربون بين تجارب تجاوز الحدود وتجارب الاستقرار لنموذج GFDL-ESM2M ونموذج NorESM خلال المراحل الصاعدة (البرتقالي) والهابطة (الأزرق) التي تم تسليط الضوء عليها أيضًا في الأشكال a و c.

المنطقة (انحرافات متوسطة على مدى 31 عامًا بالنسبة للفترة من 1850 إلى 1900). e، f الفروق الإقليمية في هطول الأمطار السنوي بين سيناريوهات التجاوز وسيناريوهات الاستقرار على مدى مئة عام من استقرار درجة حرارة الأرض على المدى الطويل (المنطقة المظللة باللون الرمادي في اللوحات)

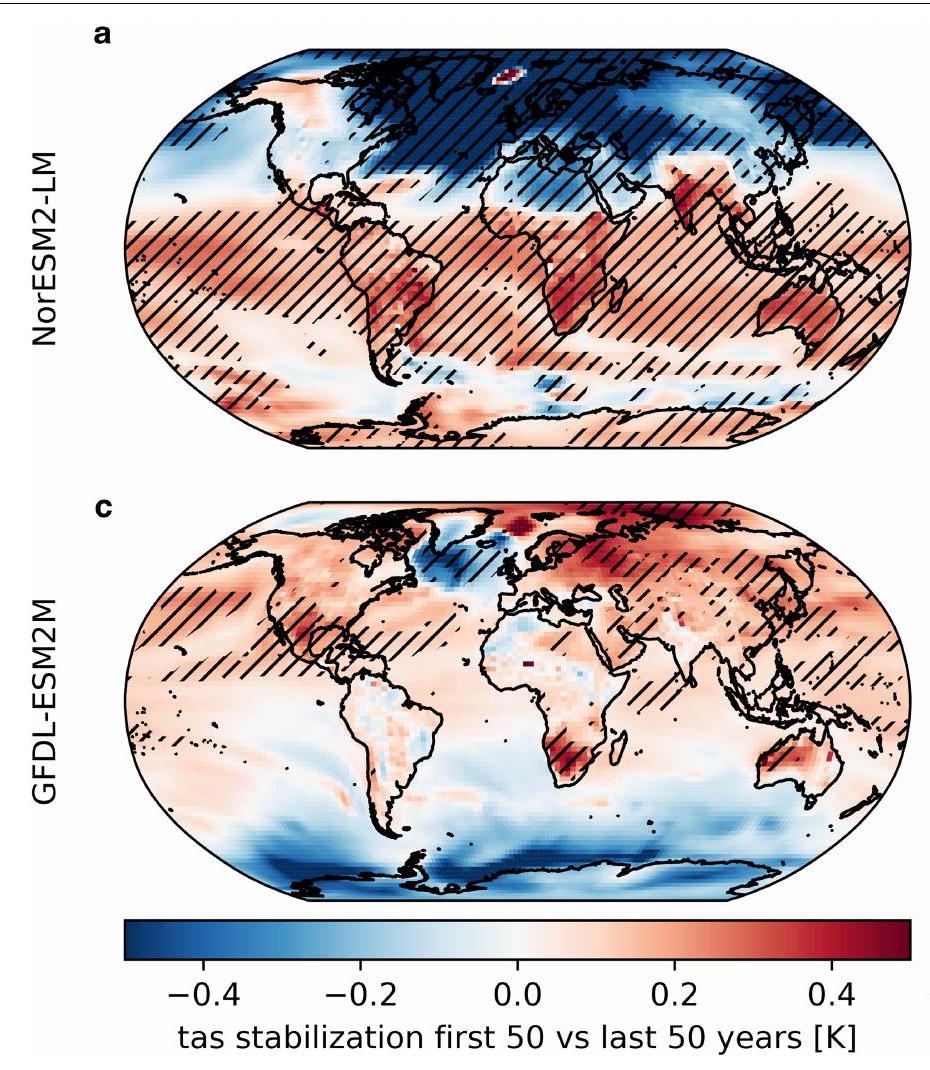

السيناريو. أ، ب تظهر النتائج لنموذج NorESM، ج، د لنموذج GFDL-ESM2M، أ، ج لدرجة الحرارة السنوية على مدى الخمسين عامًا الأولى من استقرار GMT مقابل الخمسين عامًا الأخيرة (قارن الشكل 3أ). القيم السلبية تعني أن الفترة الأولى أبرد من

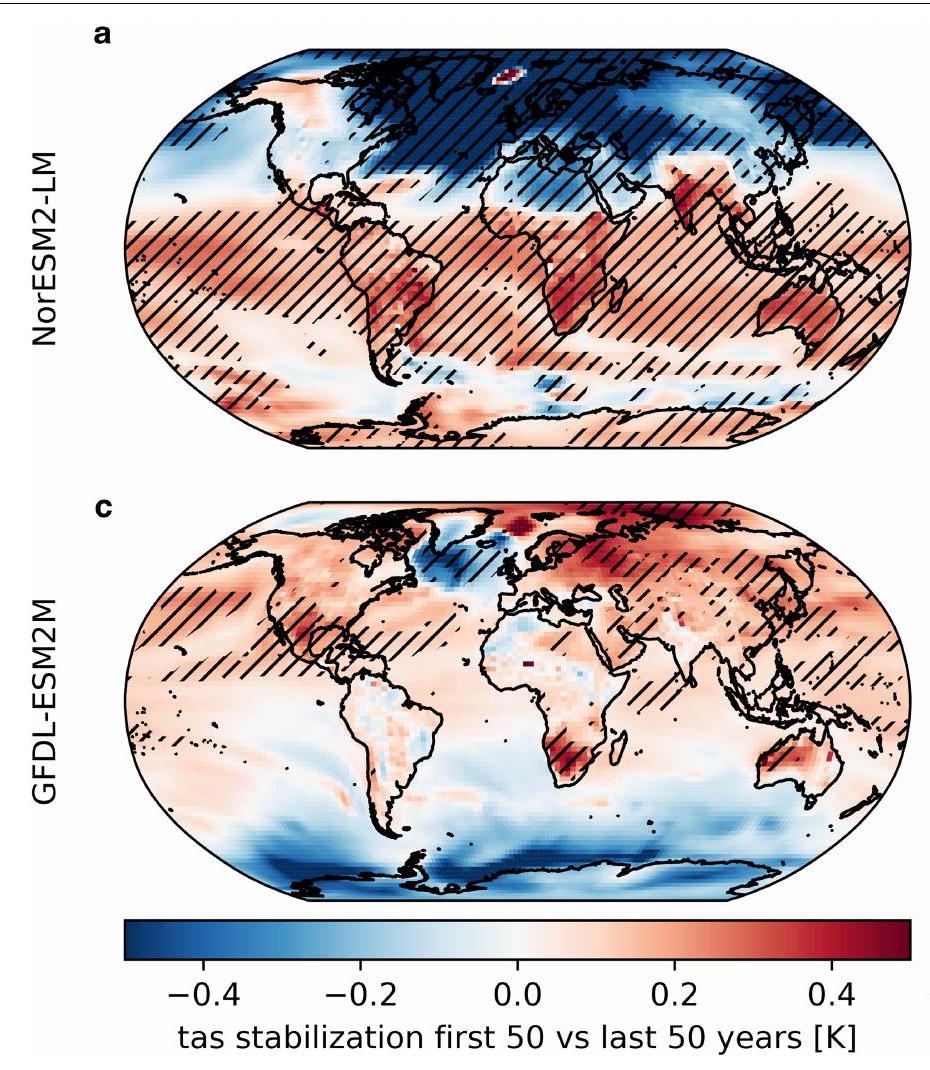

ثانياً، يشبه c و d a و c ولكن لهطول الأمطار السنوي. يبرز التظليل خلايا الشبكة حيث يتجاوز الفرق النسبة المئوية 95 (أو يكون أقل من النسبة المئوية 5) للاختلافات في الفترات المقارنة في محاكاة piControl (انظر الطرق).

النسبة المئوية 95 (تكون أقل من النسبة المئوية 5) للاختلافات في الفترات المقارنة في محاكاة piControl (انظر الطرق). بالنسبة للوسيط الجماعي (اللوحة الأخيرة)، تشير النقاط المتقطعة إلى توافق النماذج في اتجاه التغيير بنسبة لا تقل عن 66% من النماذج.

متوسط درجة الحرارة الناتجة عن انبعاثات التربة المتجمدة والأراضي الخثية بسبب الاحترار وزيادة مستوى سطح البحر الناتجة عن استقرار درجات الحرارة عند ذروة الاحترار من خلال تحقيق صافي انبعاثات صفرية

| فئة المسار | خصائص درجة الحرارة | خصائص الانبعاثات (أفضل التقديرات) | |||||||

| مسارات تحد من الاحترار إلى

|

|

|

|||||||

| مسارات تعيد الاحترار إلى

|

|

|

|||||||

| مسارات متوافقة مع اتفاق باريس

|

|

|

| وصف القيود والإمكانات للثقة المفرطة | |

| الاستعداد | تظل قدرات الإزالة الحالية بعيدة عن المتطلبات اللازمة لتكون متوافقة مع اتفاق باريس. في السنوات القادمة، يجب أن تتزايد مقاييس الإزالة بينما يجب أن تنخفض التكاليف على مستويات طموحة للغاية. تظهر فجوات في التنفيذ بالفعل، مما قد يمنع الاعتماد على إزالة الكربون للتراجع عن تجاوز الحدود.

|

| الدوام والمرونة | التخزين الدائم والآمن للكربون المزال هو أمر أساسي. قد تنشأ الثقة المفرطة من تجاهل عدم اليقين في الإمكانيات الجيولوجية للتخزين.

|

| تغذية راجعة للنظام | قد يتم تعويض آثار التخفيف الناتجة عن إزالة ثاني أكسيد الكربون من الغلاف الجوي من خلال ضعف وعودة محتملة لامتصاص الكربون في اليابسة والمحيطات، بالإضافة إلى ردود فعل غير مرغوب فيها في النظام.

|

| استجابة السياسة والحوكمة | قد يؤدي الاعتماد على فعالية تقنيات إزالة الكربون (CDR) إلى تقليل غير كافٍ في الانبعاثات إذا كانت هذه التقنيات أقل أداءً مما هو متوقع، أو إذا كانت ردود الفعل المناخية الفيزيائية أقوى من المتوقع. قد تؤدي توقعات توفر تقنيات إزالة الكربون في المستقبل إلى تثبيط جهود التخفيف، مما يعني أن التخفيضات الإجمالية المطلوبة في الانبعاثات قد تتأخر و/أو تضعف.

|

| الاستدامة والقبول | قد يهدد البصمة الواسعة لاستخدام الأراضي المرتبطة بتقنيات إزالة الكربون على نطاق واسع سلامة البيئة.

|

المعهد الدولي لتحليل النظم التطبيقية (IIASA)، لاكسنبورغ، النمسا. قسم الجغرافيا ومعهد IRITHESys، جامعة هومبولت في برلين، برلين، ألمانيا. المناخ

هامبورغ، ألمانيا.

هامبورغ، ألمانيا.

معهد ميركاتور للبحوث حول المشاعات العالمية وتغير المناخ (MCC)، برلين، ألمانيا. معهد غرانثام لتغير المناخ والبيئة، كلية إمبريال لندن، لندن، المملكة المتحدة. فيزياء المناخ والبيئة، معهد الفيزياء، جامعة برن، برن، سويسرا. مركز أوشجر لبحوث تغير المناخ، جامعة برن، برن، سويسرا. معهد بوتسدام لأبحاث تأثير المناخ، بوتسدام، ألمانيا. قسم علوم نظم البيئة، ETH زيورخ، زيورخ، سويسرا. المكتب الفيدرالي للأرصاد الجوية والمناخ، ميتيو سويس، زيورخ، سويسرا. معهد الجغرافيا، جامعة برن، برن، سويسرا. مركز السياسة البيئية، إمبريال كوليدج لندن، لندن، المملكة المتحدة. قسم علوم الغلاف الجوي والثلوج، جامعة إنسبروك، إنسبروك، النمسا. مدرسة العلوم الجغرافية، جامعة بريستول، بريستول، المملكة المتحدة. مدرسة الجغرافيا وعلوم الأرض والجو، جامعة ملبورن، ملبورن، فيكتوريا، أستراليا. موارد المناخ، ملبورن، فيكتوريا، أستراليا. مركز أوسلو الدولي لأبحاث المناخ والبيئة، النرويج. مكتب الأرصاد الجوية – مركز هادلي، إكستر، المملكة المتحدة. مدرسة الأرض والبيئة، جامعة ليدز، ليدز، المملكة المتحدة. مركز تيندال لأبحاث تغير المناخ ومدرسة العلوم البيئية، جامعة إيست أنجليا، نورويتش، المملكة المتحدة. العنوان الحالي: مركز أبحاث المناخ والبيئة الدولية، أوسلو، النرويج. البريد الإلكتروني: schleussner@iiasa.ac.at

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08020-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39385053

Publication Date: 2024-10-09

Overconfidence in climate overshoot

– To cite this version:

HAL Id: hal-04741921

https://hal.science/hal-04741921v1

Overconfidence in climate overshoot

Received: 17 October 2023

Accepted: 29 August 2024

Published online: 9 October 2024

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Global emission reduction efforts continue to be insufficient to meet the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement

net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, as implied by Article 4.1 of the Agreement, is expected to lead to declining temperatures

| Pathway category | Temperature characteristics | Emission characteristics (best estimates) |

| PD: peak and decline pathways | Pathways that aim to achieve temperature peak and a sustained long-term temperature decline of at least several decades in duration | Emission reductions in all GHGs towards achieving net-zero

|

| PD-OS: overshoot pathways | PD pathways establish a target warming level to be achieved at some point in the far future but allow it to be exceeded with high likelihood over the near term in the conviction that warming can be reversed again at a later stage. These pathways typically envision temperature to be kept at the target level upon returning after overshoot | As peak and decline pathways, but rate of emission reduction, carbon budget, timing of net-zero

|

| PD-EP: enhanced protection pathways | PD pathways that aim to keep peak global warming as low as possible and gradually reverse warming thereafter to reduce climate risks. Given the timescales involved for warming reversal, these pathways typically do not reach an ultimate lower target temperature level within the scenario time frame considered | Stringent and rapid GHG emission reduction as much and as early as possible, achieving net-zero

|

of peak warming for median climate outcomes

Several categories of peak and decline pathways have been proposed in the scientific literature

Although defined in terms of probabilities of temporarily exceeding

as sea-level rise. Finally, we discuss what considering or experiencing temperature overshoot implies for climate change adaptation. Based on this comprehensive perspective, we contend that it is essential to redirect the overshoot discussion towards prioritizing the reduction of climate risks in both the near term and long term and that overconfidence in the controllability and desirability of climate overshoot should be avoided.

Uncertain climate response and reversal

b, An overview of key factors affecting pathway and potential peak and decline outcomes along the impact chain for the warming phase until net-zero

Relying on CDR

assumed use of CDR (Extended Data Table 2). Upscaling of CDR may be constrained considerably

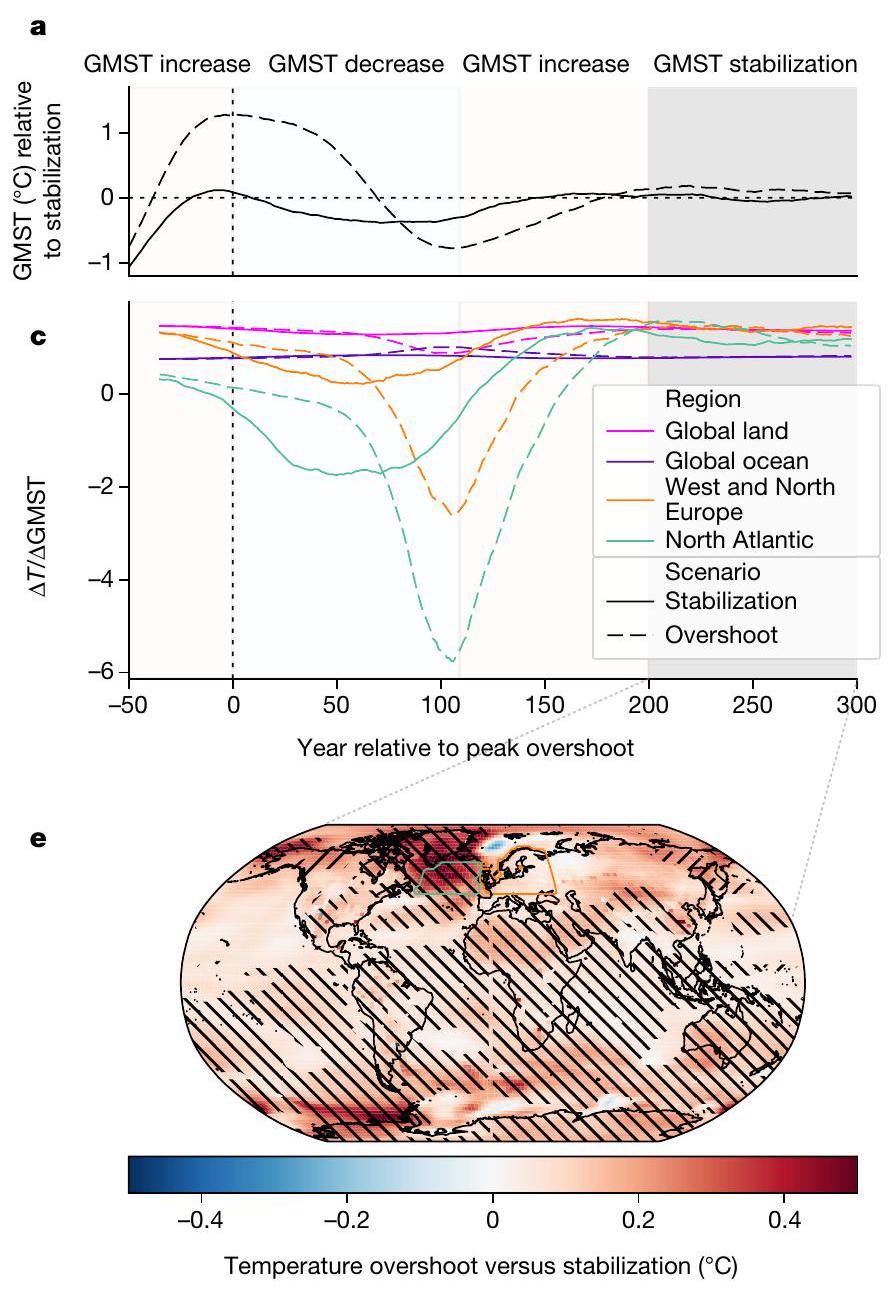

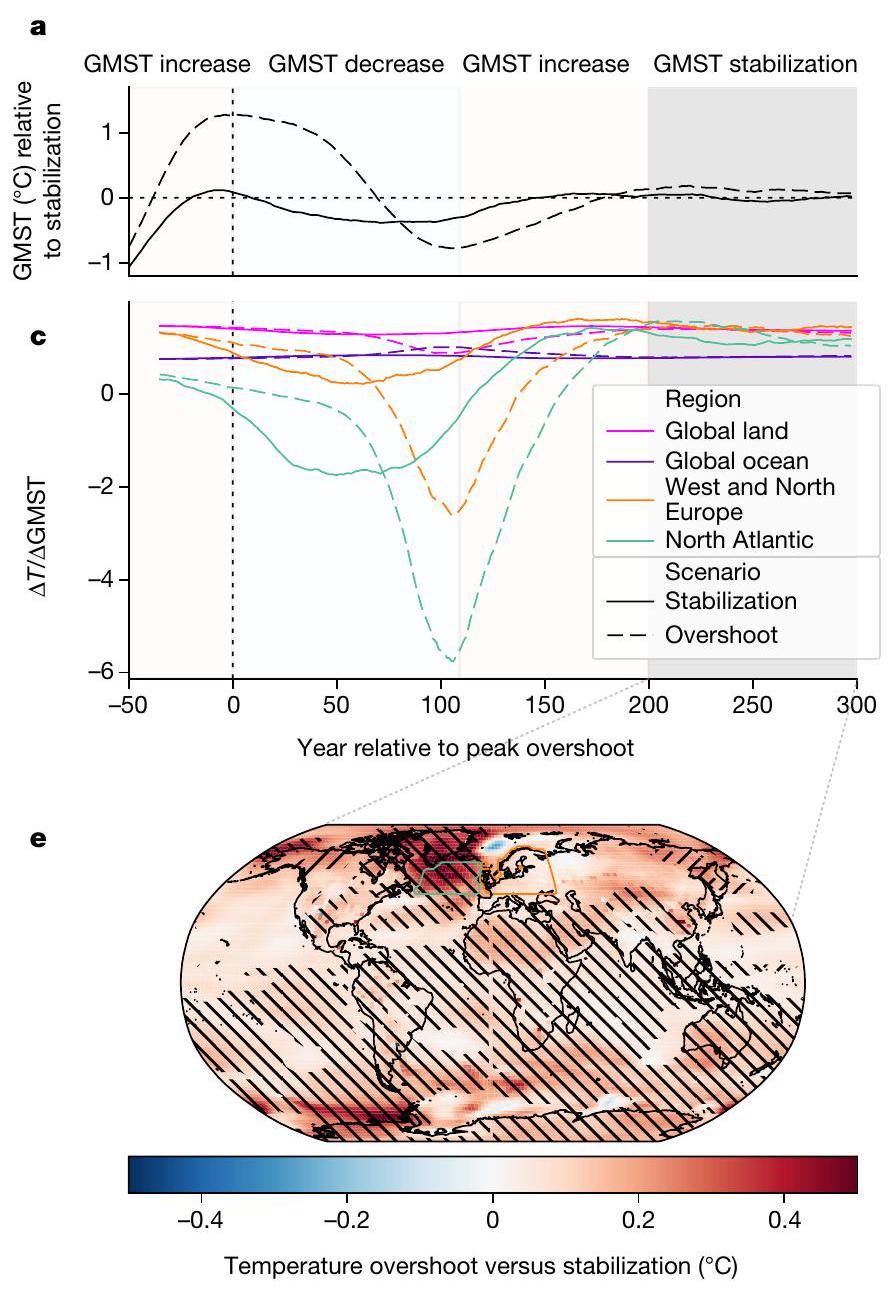

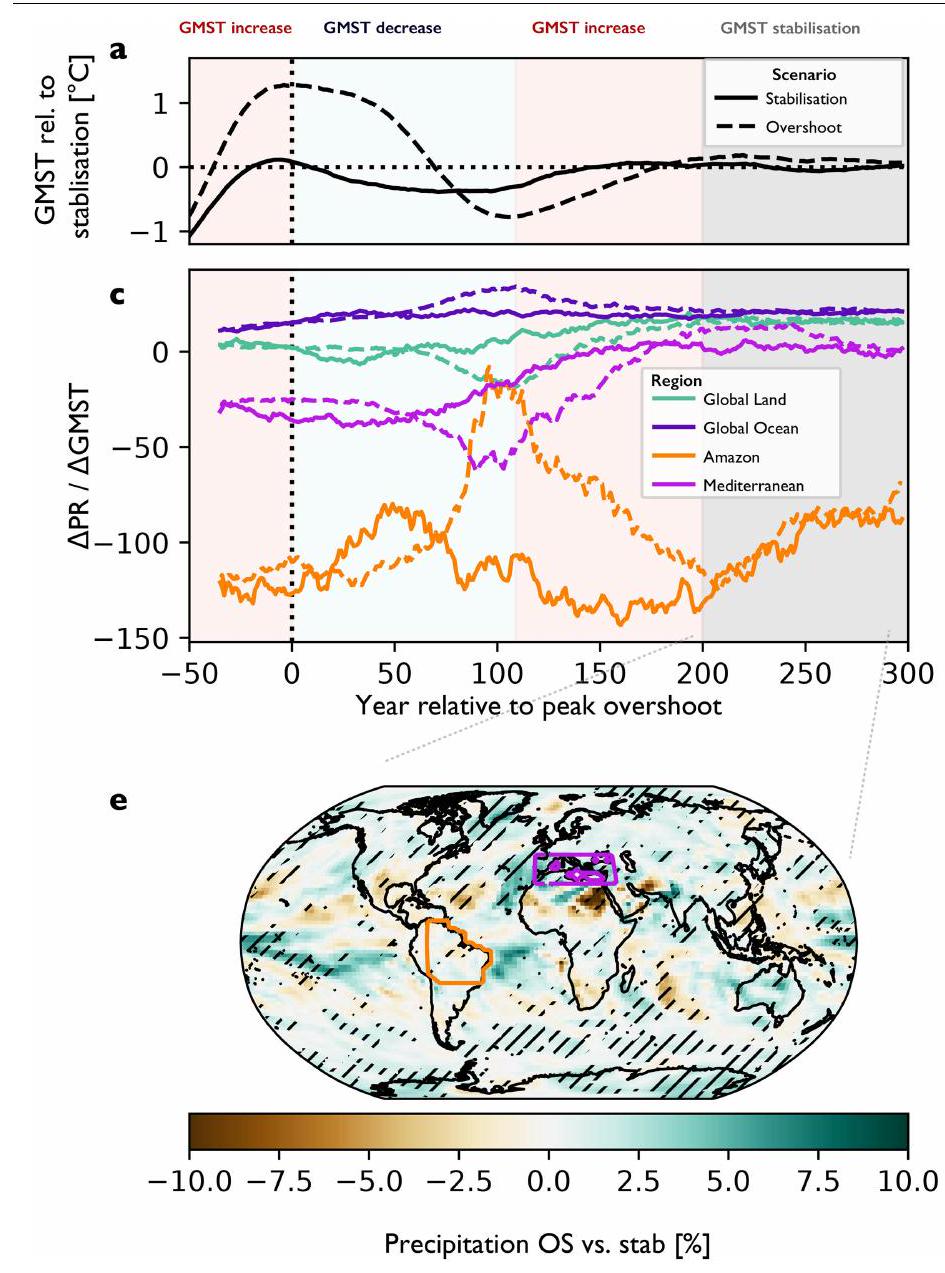

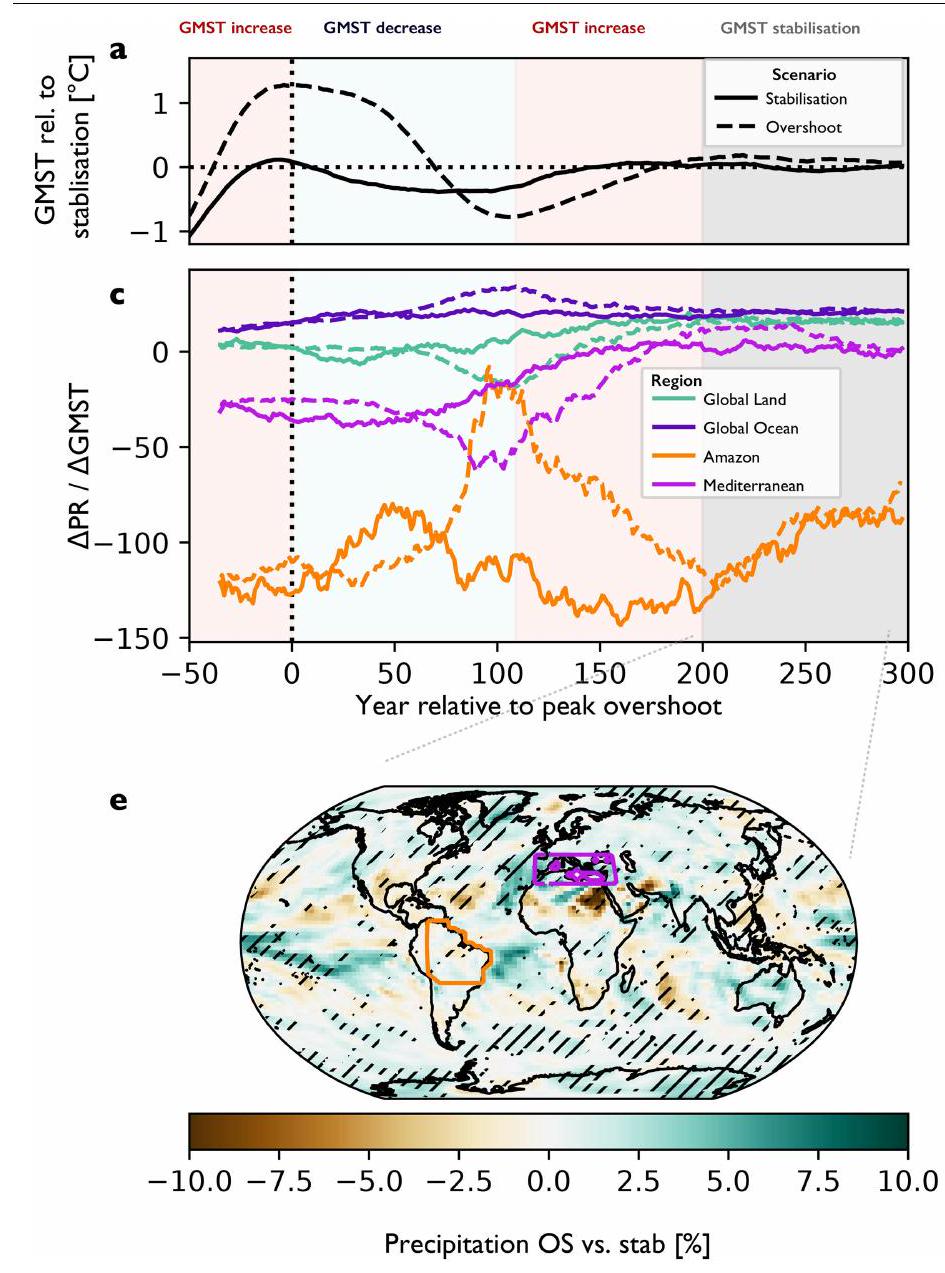

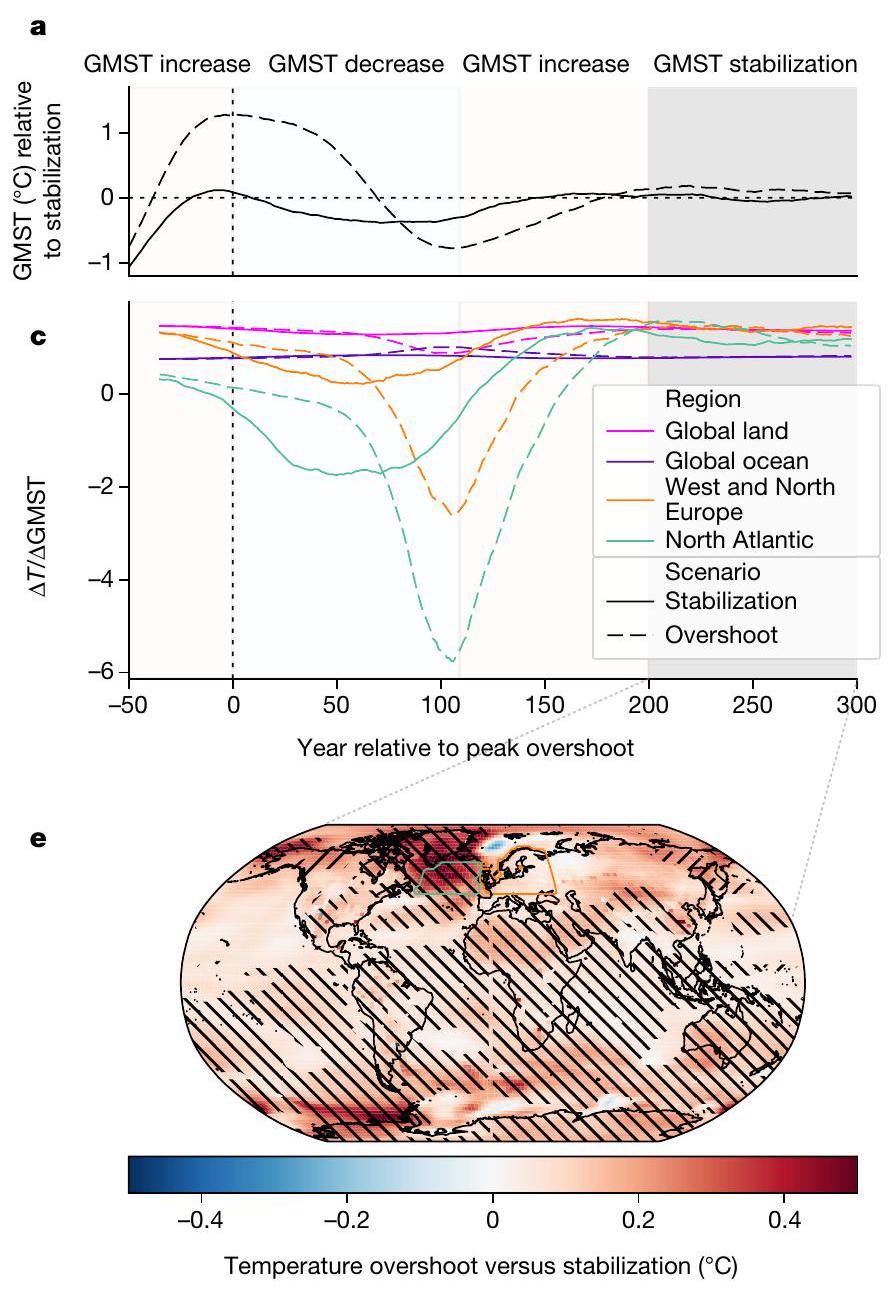

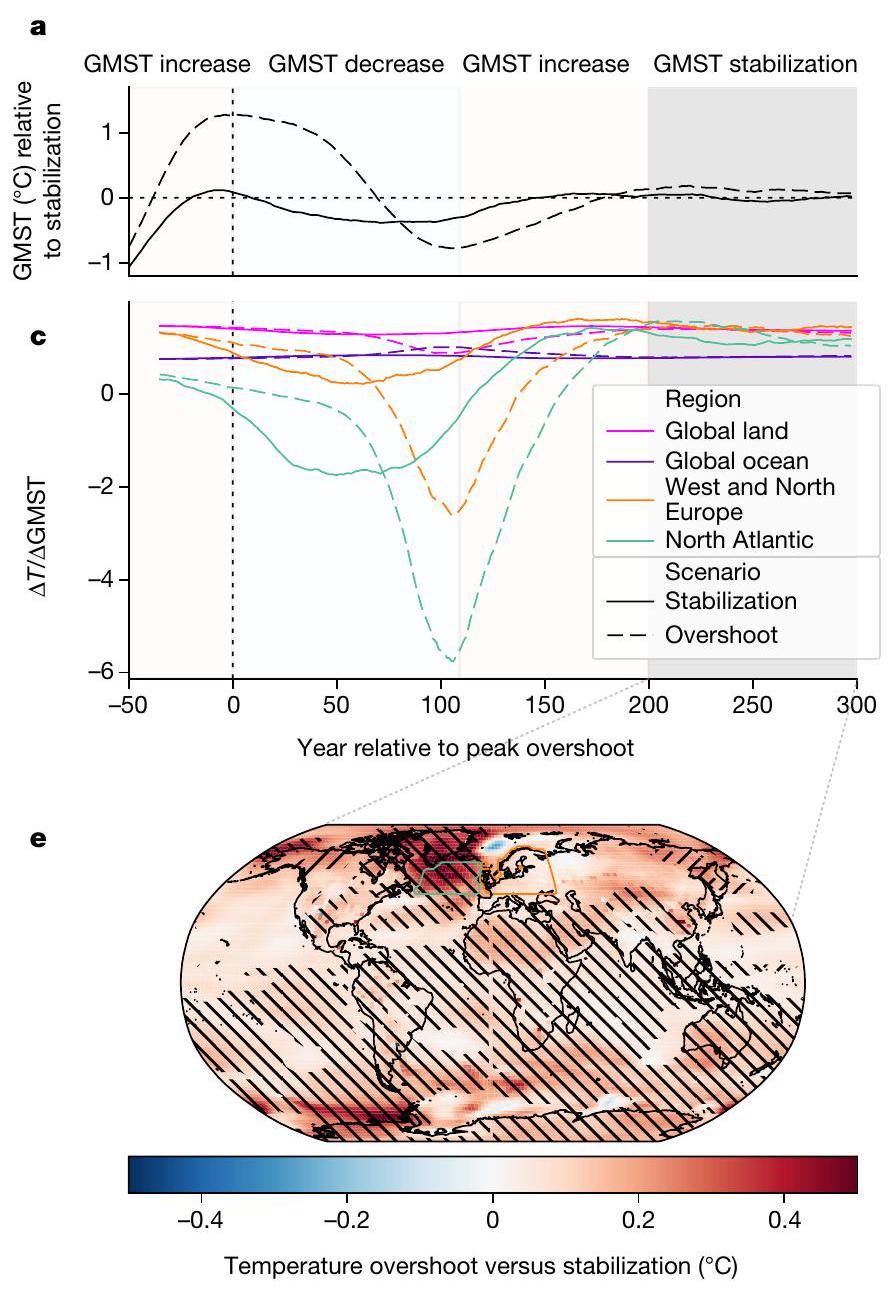

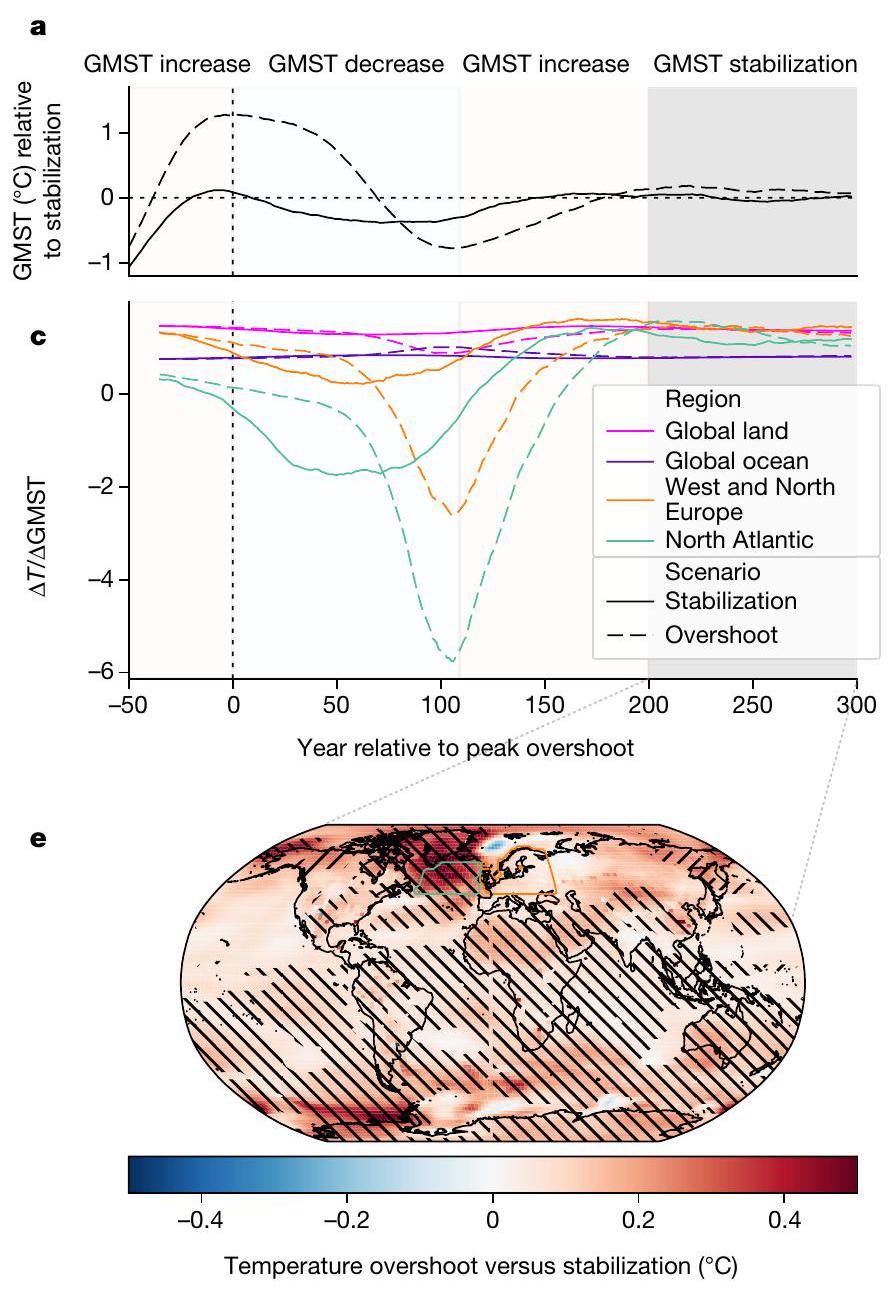

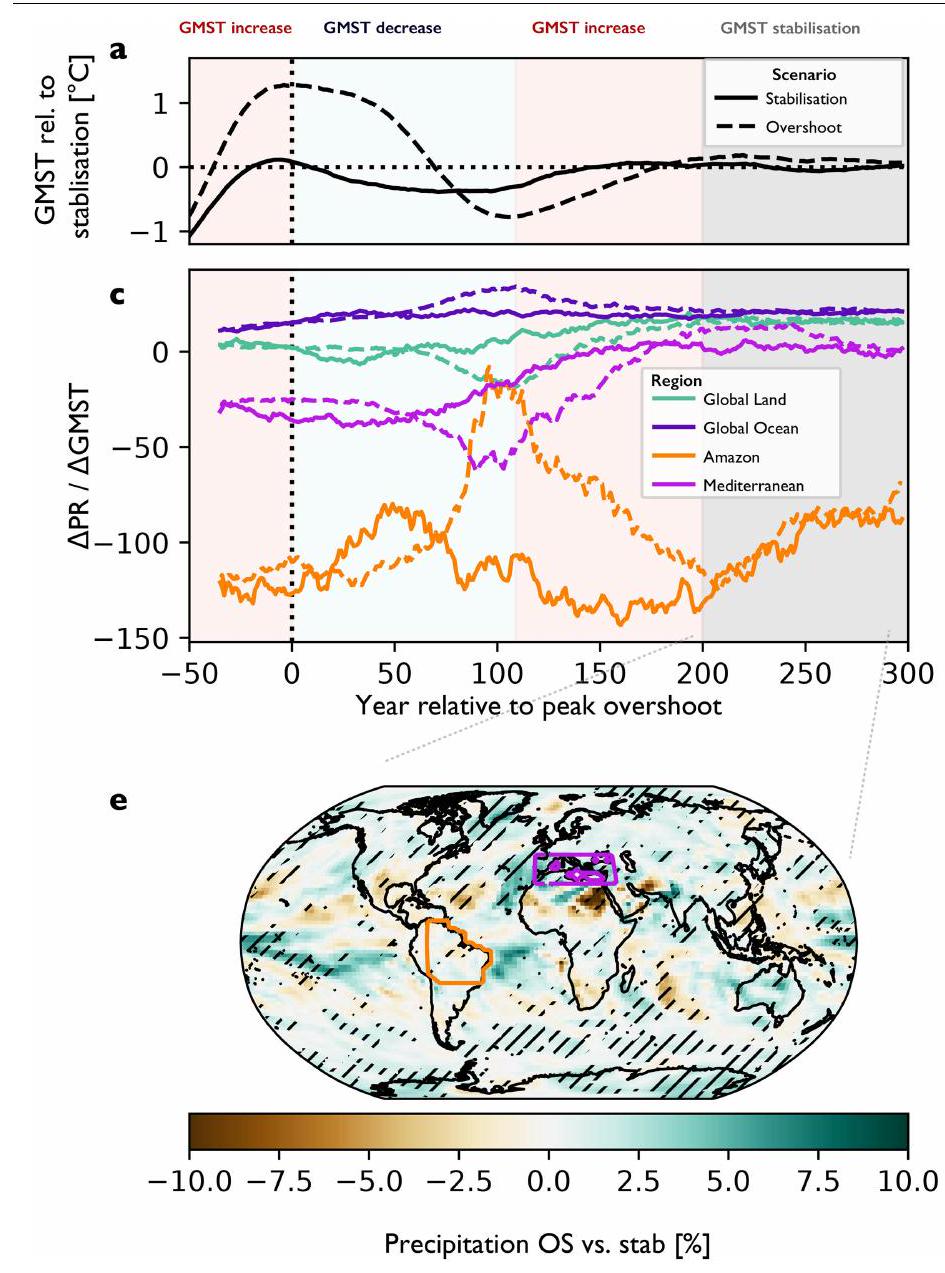

Regional climate change reversibility

warming for each peak warming outcome shown in

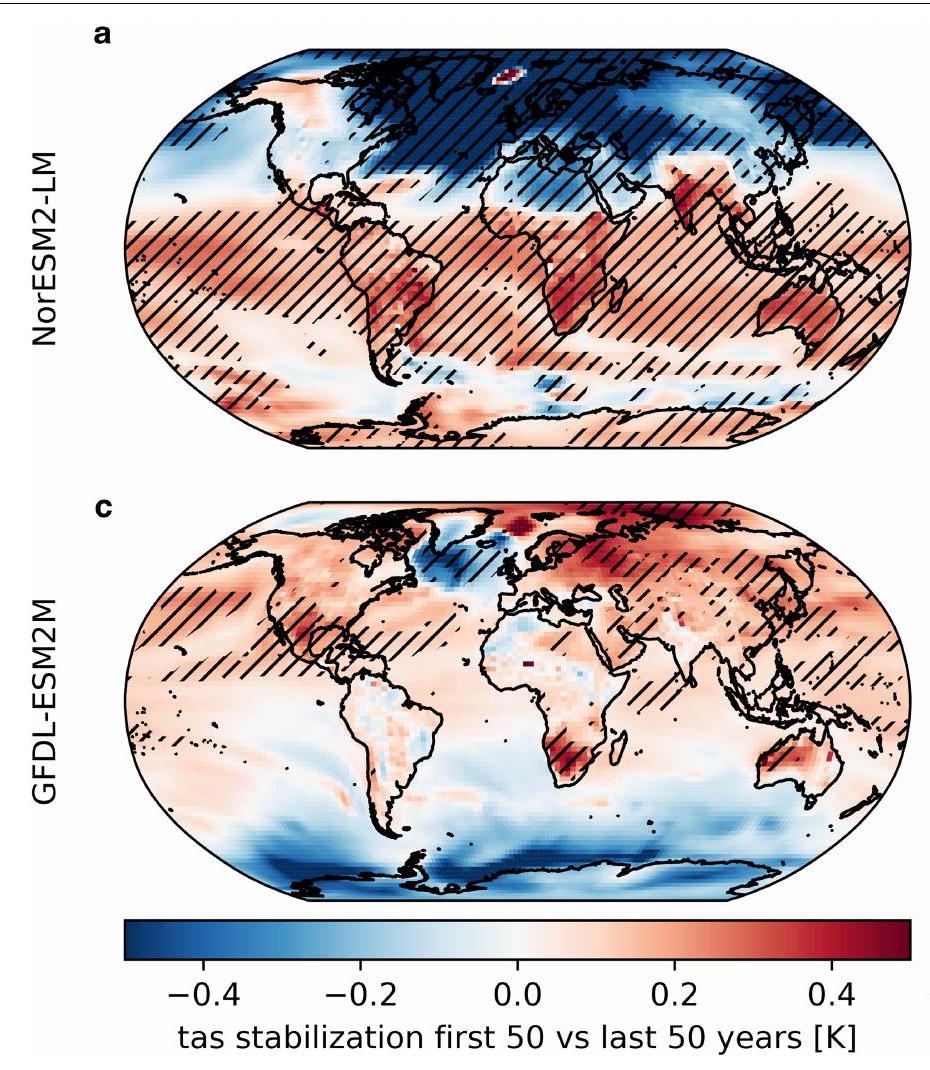

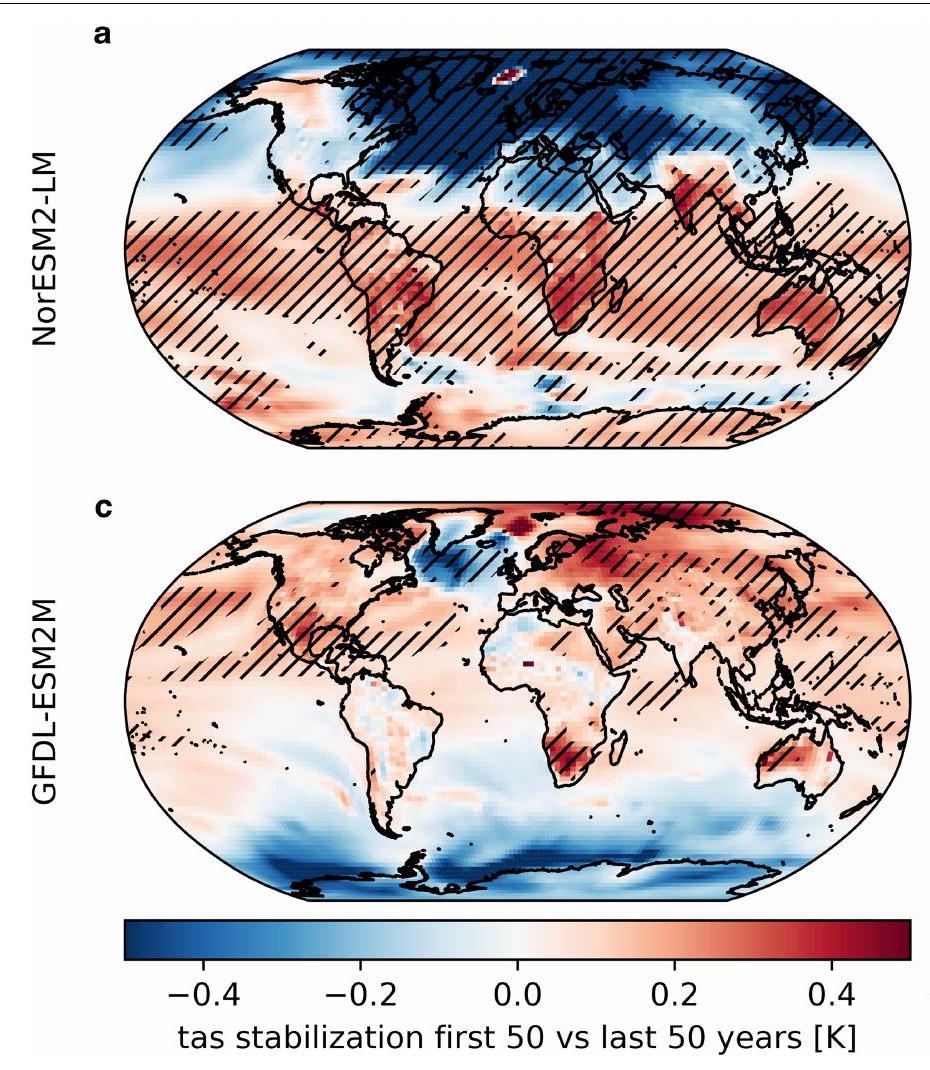

climatic changes. Therefore, understanding the implications of a global temperature overshoot for regional changes is important. Even if global warming is stabilized at a certain level without overshoot, the climate system continues to change as its components keep adjusting and equilibrate

both models, in particular, related to movements of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone in response to changes in the AMOC

Time-lagged and irreversible impacts

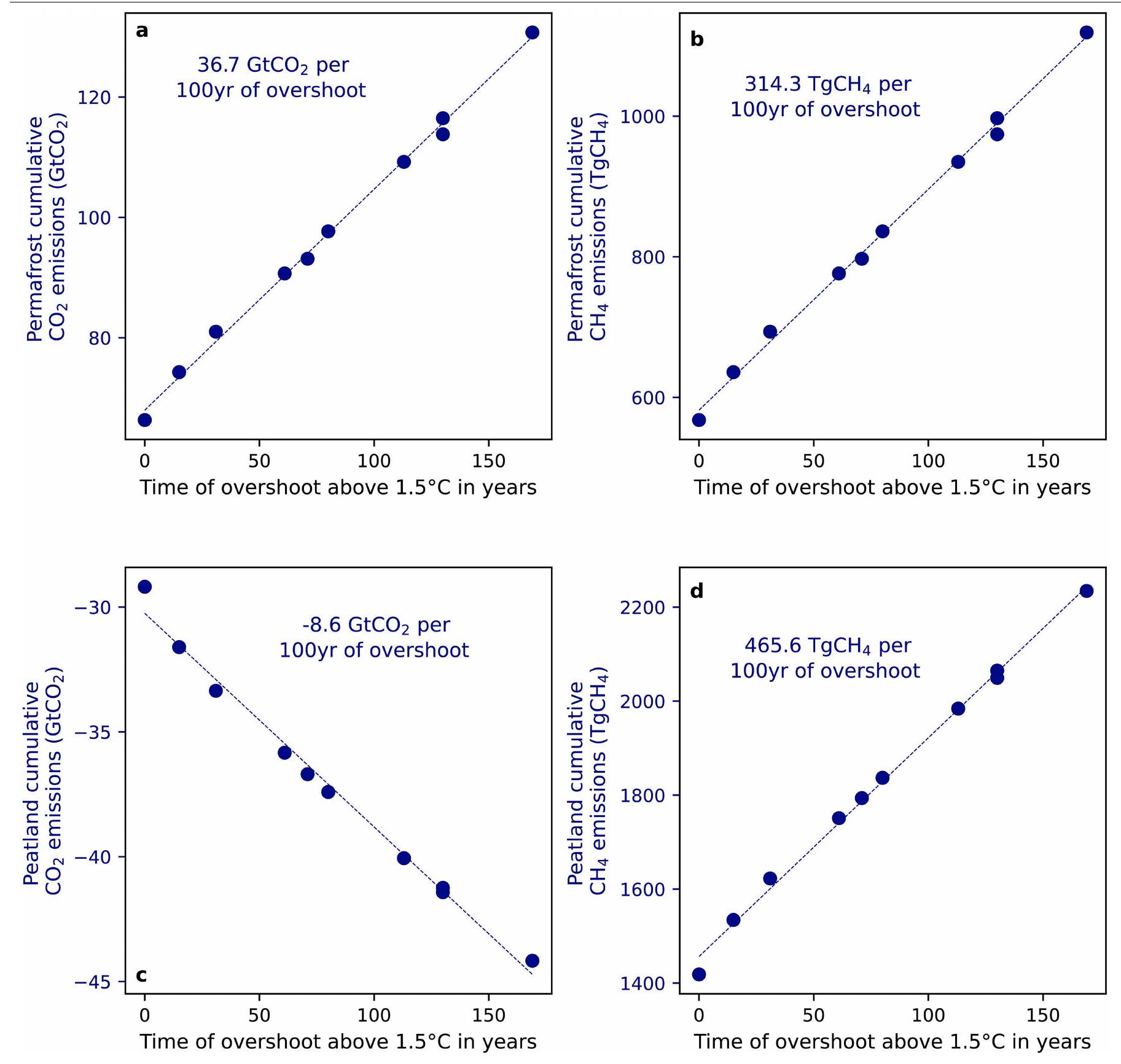

For global sea-level rise, we find that every 100 years of overshoot above

A similar pattern emerges for 2300 permafrost thaw and northern peatland warming leading to increased soil carbon decomposition and

increase by a similar order of magnitude. We warn that the diagnosed linear relationship between overshoot length and impact outcome may depend on the set of pathways that it was derived from. The underlying pathways assume overshoots starting from a period of delay in climate action followed by a steady reduction to net-zero GHG emissions implying a similar rate of long-term temperature decline in all pathways. The relationship could be different for more, or less extreme overshoot outcomes.

Socioeconomic impacts

mean temperature increase from warming-induced permafrost and peatland emissions and sea-level rise implied by stabilizing temperatures at peak warming (achieving and maintaining net-zero

Adaptation decision-making and overshoot

Even under the optimistic assumption of nearly full reversibility of a climate impact driver under overshoot, a planning horizon of 50 years or more might be required before prospects of a long-term decline would start to affect adaptation decisions today or in the immediate future (Fig. 5a). Few adaptation plans and policies operate on these timescales: for example, the EU Adaptation Strategy spans three decades, whereas other national adaptation plans have similar or shorter time horizons

The application of cost-benefit approaches in adaptation measures, and the time scale over which these are assessed, requires decisions on intergenerational equity reflected in the choice of the intertemporal discount rate

It therefore seems that long-term impact driver reversibility after overshoot may be of relevance only in specific cases of adaptation

decision-making. A notable exception is adaptation against time-lagged irreversible impacts such as sea-level rise for which overshoots will affect the long-term outlook (Fig. 4). However, as we have shown above, long-term global temperature decline cannot be relied on with certainty. Thus, a resilient adaptation strategy cannot be based on betting on overshoot, and only limiting peak warming can effectively reduce adaptation needs.

Reframing the overshoot discussion

strong assumptions about the applicability, effectiveness and governance of SG interventions. Accounting for uncertainties in the physical climate response, and in the evolution of future emissions after SG is deployed, implies that an SG intervention aimed at peak-shaving an overshoot could result in a multi-century commitment of both SG and CDR deployment

hard-to-abate sectors. This further underscores the importance of very stringent near-term emission reductions to limit long-term risks. Although we argue that the build-up of a preventive CDR capacity is required to hedge against high warming outcomes, this same CDR capacity could, in case high warming outcomes do not materialize, also be deployed to draw down long-term temperatures and thereby reduce climate risks.

Online content

- Rogelj, J. et al. Credibility gap in net-zero climate targets leaves world at high risk. Science 380, 1014-1016 (2023).

- IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) 1-48 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

- Prütz, R., Strefler, J., Rogelj, J. & Fuss, S. Understanding the carbon dioxide removal range in

compatible and high overshoot pathways. Environ. Res. Commun. 5, 041005 (2023). - Schwinger, J., Asaadi, A., Steinert, N. J. & Lee, H. Emit now, mitigate later? Earth system reversibility under overshoots of different magnitudes and durations. Earth Syst. Dyn. 13, 1641-1665 (2022).

- Pfleiderer, P., Schleussner, C.-F. & Sillmann, J. Limited reversal of regional climate signals in overshoot scenarios. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 015005 (2024).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 3-32 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- MacDougall, A. H. et al. Is there warming in the pipeline? A multi-model analysis of the zero emissions commitment from

. Biogeosciences 17, 2987-3016 (2020). - Smith, S. et al. The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal 1st edn (MCC, 2023).

- Deprez, A. et al. Sustainability limits needed for

removal. Science 383, 484-486 (2024). - Schneider, S. H. & Mastrandrea, M. D. Probabilistic assessment of “dangerous” climate change and emissions pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15728-15735 (2005).

- Wigley, T. M. L., Richels, R. & Edmonds, J. A. Economic and environmental choices in the stabilization of atmospheric

concentrations. Nature 379, 240-243 (1996). - Azar, C., Johansson, D. J. A. & Mattsson, N. Meeting global temperature targets-the role of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034004 (2013).

- Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Science and policy characteristics of the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 827-835 (2016).

- Rajamani, L. & Werksman, J. The legal character and operational relevance of the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20160458 (2018).

- Riahi, K. et al. Mitigation pathways compatible with long-term goals. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Shukla, P. R. et al.) 295-408 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

- Rogelj, J. et al. A new scenario logic for the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal. Nature 573, 357-363 (2019).

- Schleussner, C.-F., Ganti, G., Rogelj, J. & Gidden, M. J. An emission pathway classification reflecting the Paris Agreement climate objectives. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 135 (2022).

- Forster, P. et al. The Earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, and climate sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 923-1054 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

- Palazzo Corner, S. et al. The Zero Emissions Commitment and climate stabilization. Front. Sci. 1, 1170744 (2023).

- Grassi, G. et al. Harmonising the land-use flux estimates of global models and national inventories for 2000-2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1093-1114 (2023).

- Meinshausen, M. et al. A perspective on the next generation of Earth system model scenarios: towards representative emission pathways (REPs). Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 4533-4559 (2024).

- Zickfeld, K., Azevedo, D., Mathesius, S. & Matthews, H. D. Asymmetry in the climatecarbon cycle response to positive and negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 613-617 (2021).

- Baur, S., Nauels, A., Nicholls, Z., Sanderson, B. M. & Schleussner, C.-F. The deployment length of solar radiation modification: an interplay of mitigation, net-negative emissions and climate uncertainty. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 367-381 (2023).

- Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 673-816 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

- McLaren, D., Willis, R., Szerszynski, B., Tyfield, D. & Markusson, N. Attractions of delay: using deliberative engagement to investigate the political and strategic impacts of greenhouse gas removal technologies. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 6, 578-599 (2023).

- Powis, C. M., Smith, S. M., Minx, J. C. & Gasser, T. Quantifying global carbon dioxide removal deployment. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 024022 (2023).

- Lamb, W. F. et al. The carbon dioxide removal gap. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 644-651 (2024).

- Prütz, R., Fuss, S., Lück, S., Stephan, L. & Rogelj, J. A taxonomy to map evidence on the co-benefits, challenges, and limits of carbon dioxide removal. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 197 (2024).

- Stuart-Smith, R. F., Rajamani, L., Rogelj, J. & Wetzer, T. Legal limits to the use of

removal. Science 382, 772-774 (2023). - King, A. D. et al. Preparing for a post-net-zero world. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 775-777 (2022).

- Bellomo, K., Angeloni, M., Corti, S. & von Hardenberg, J. Future climate change shaped by inter-model differences in Atlantic meridional overturning circulation response. Nat. Commun. 12, 3659 (2021).

- Schwinger, J., Asaadi, A., Goris, N. & Lee, H. Possibility for strong northern hemisphere high-latitude cooling under negative emissions. Nat. Commun. 13, 1095 (2022).

- Möller, T. et al. Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions critical to limit climate tipping risks. Nat. Commun. 15, 6192 (2024).

- Santana-Falcón, Y. et al. Irreversible loss in marine ecosystem habitability after a temperature overshoot. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 343 (2023).

- Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Crop productivity changes in

and worlds under climate sensitivity uncertainty. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 064007 (2018). - Meyer, A. L. S., Bentley, J., Odoulami, R. C., Pigot, A. L. & Trisos, C. H. Risks to biodiversity from temperature overshoot pathways. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 377, 20210394 (2022).

- Mengel, M., Nauels, A., Rogelj, J. & Schleussner, C.-F. Committed sea-level rise under the Paris Agreement and the legacy of delayed mitigation action. Nat. Commun. 9, 601 (2018).

- Andrijevic, M. et al. Towards scenario representation of adaptive capacity for global climate change assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 778-787 (2023).

- Thomas, A. et al. Global evidence of constraints and limits to human adaptation. Reg. Environ. Change 21, 85 (2021).

- Birkmann, J. et al. Poverty, Livelihoods and Sustainable Development. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1171-1274 (IPCC, 2022).

- Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235-239 (2015).

- Parry, M., Lowe, J. & Hanson, C. Overshoot, adapt and recover. Nature 458, 1102-1103 (2009).

- Williams, J. W., Ordonez, A. & Svenning, J.-C. A unifying framework for studying and managing climate-driven rates of ecological change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 17-26 (2021).

- UNFCC. National Adaptation Plans 2021. Progress in the Formulation and Implementation of NAPs (UNFCC, 2022).

- Caney, S. Climate change, intergenerational equity and the social discount rate. Polit. Philos. Econ. 13, 320-342 (2014).

- MacMartin, D. G., Ricke, K. L. & Keith, D. W. Solar geoengineering as part of an overall strategy for meeting the

Paris target. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20160454 (2018). - Biermann, F. et al. Solar geoengineering: the case for an international non-use agreement. WIREs Clim. Change 13, e754 (2022).

- Fyson, C. L., Baur, S., Gidden, M. & Schleussner, C. Fair-share carbon dioxide removal increases major emitter responsibility. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 836-841 (2020).

- Silvy, Y. et al. AERA-MIP: emission pathways, remaining budgets and carbon cycle dynamics compatible with

and global warming stabilization. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-488 (2024). - Hallegatte, S. Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 19, 240-247 (2009).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

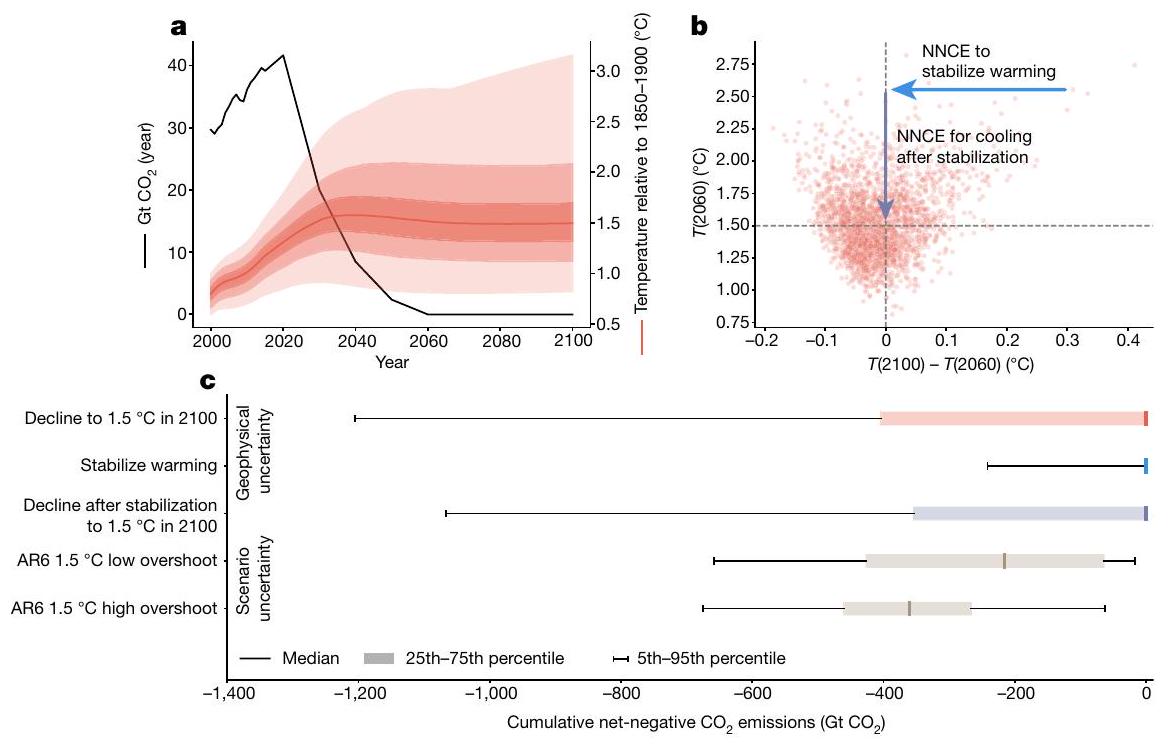

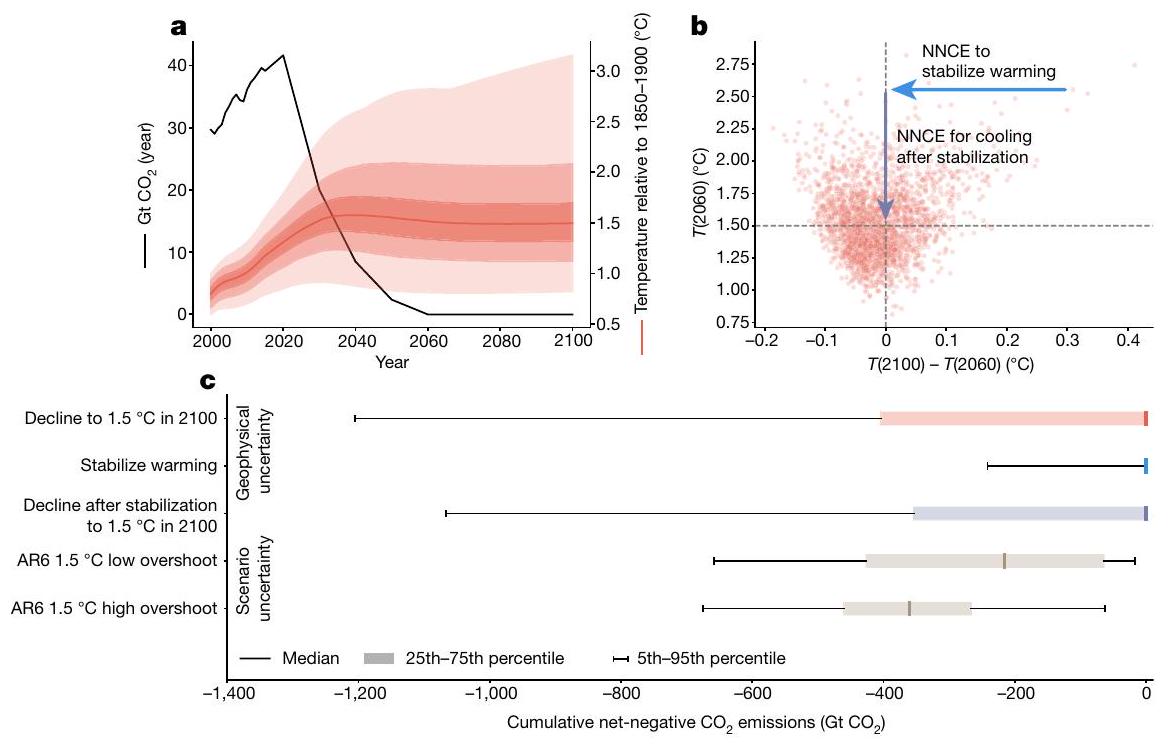

Evaluating net-negative

- The effective transient response to cumulative emissions (up), or eTCREup: this metric captures the expected warming for a given quantity of cumulative emissions until net-zero

. - The effective transient response to cumulative emissions (down), or eTCREdown: this metric captures the expected warming or cooling for a given quantity of cumulative net-negative emissions after net-zero

. This is a purely diagnostic metric and also incorporates the effects of the effective Zero Emissions Commitment (eZEC). - The eZEC: the continued temperature response after net-zero

emissions are achieved and sustained . Here eZEC is evaluated over 40 years (between 2060 and 2100).

We need to take a different approach for estimating the second metric ( eTCRE

(per ensemble member) that is necessary to ensure post-peak cooling to

we cannot rule out high ECS/ZEC ensemble members that drive the tail of our NNCE distribution (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Yet, we find high NNCE outcomes also materialize for moderate-high ECS and ZEC outcomes.

Overshoot reversibility for annual mean temperature and precipitation

corresponds to land grid cells in western central Europe (WCE) and northern Europe (NEU). NAO45 corresponds to ocean grid cells in the North Atlantic region above

We then estimate the global temperature change (

Data availability

Code availability

51. Lamboll, R., Rogelj, J. & Schleussner, C.-F. A guide to scenarios for the PROVIDE project. ESS Open Archive https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar. 10511875.2 (2022).

52. Luderer, G. et al. Impact of declining renewable energy costs on electrification in low-emission scenarios. Nat. Energy 7, 32-42 (2022).

53. Riahi, K. et al. Mitigation pathways compatible with long-term goals. in IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

54. Byers, E. et al. AR6 scenarios database. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5886912 (2022).

55. Smith, C. J. et al. FAIR v1.3: a simple emissions-based impulse response and carbon cycle model. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 2273-2297 (2018).

56. Nicholls, Z. et al. Cross-Chapter Box 7.1: Physical emulation of Earth System Models for scenario classification and knowledge integration in AR6. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

57. IPCC. Annex VII: Glossary. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Matthews, J. B. R. et al.) 2215-2256 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

58. Sherwood, S. et al. An assessment of Earth’s climate sensitivity using multiple lines of evidence. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000678 (2020).

59. Dunne, J. P. et al. GFDL’s ESM2 Global Coupled Climate-Carbon Earth System Models. Part II: carbon system formulation and baseline simulation characteristics. J. Clim. 26, 2247-2267 (2013).

60. Burger, F. A., John, J. G. & Frölicher, T. L. Increase in ocean acidity variability and extremes under increasing atmospheric

61. Terhaar, J., Frölicher, T. L., Aschwanden, M. T., Friedlingstein, P. & Joos, F. Adaptive emission reduction approach to reach any global warming target. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1136-1142 (2022).

62. Frölicher, T. L., Jens, T., Fortunat, J. & Yona, S. Protocol for Adaptive Emission Reduction Approach (AERA) simulations. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 7473133 (2022).

63. Seland,

64. Jones, C. D. et al. The Zero Emissions Commitment Model Intercomparison Project (ZECMIP) contribution to C4MIP: quantifying committed climate changes following zero carbon emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4375-4385 (2019).

65. De Hertog, S. J. et al. The biogeophysical effects of idealized land cover and land management changes in Earth system models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 629-667 (2023).

66. O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 9, 3461-3482 (2016).

67. Quilcaille, Y., Gasser, T., Ciais, P. & Boucher, O. CMIP6 simulations with the compact Earth system model OSCAR v3.1. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 1129-1161 (2023).

68. Qiu, C. et al. A strong mitigation scenario maintains climate neutrality of northern peatlands. One Earth 5, 86-97 (2022).

69. Lamboll, R., Rogelj, J. & Schleussner, C.-F. Scenario emissions and temperature data for PROVIDE project (v.1.1.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6963586 (2022).

70. Lacroix, F., Burger, F., Silvy, Y., Schleussner, C.-F., & Frölicher, T. L. GFDL-ESM2M overshoot data. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11091132 (2024).

71. Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Accompanying scripts for Schleussner et al. Overconfidence in Climate Overshoot. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13208166 (2024).

72. Lane, J., Greig, C. & Garnett, A. Uncertain storage prospects create a conundrum for carbon capture and storage ambitions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 925-936 (2021).

73. Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions—part 2: costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

74. Anderegg, W. R. L. et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 368, eaaz7005 (2020).

75. Heikkinen, J., Keskinen, R., Kostensalo, J. & Nuutinen, V. Climate change induces carbon loss of arable mineral soils in boreal conditions. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 3960-3973 (2022).

76. Chiquier, S., Patrizio, P., Bui, M., Sunny, N. & Dowell, N. M. A comparative analysis of the efficiency, timing, and permanence of CO2 removal pathways. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4389-4403 (2022).

77. Mengis, N., Paul, A. & Fernández-Méndez, M. Counting (on) blue carbon-Challenges and ways forward for carbon accounting of ecosystem-based carbon removal in marine environments. PLoS Clim. 2, e0000148 (2023).

78. Jones, C. D. et al. Simulating the Earth system response to negative emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 095012 (2016).

79. Realmonte, G. et al. An inter-model assessment of the role of direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 10, 3277 (2019).

80. Krause, A. et al. Large uncertainty in carbon uptake potential of land-based climatechange mitigation efforts. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 3025-3038 (2018).

81. Minx, J. C. et al. Negative emissions-Part 1: research landscape and synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063001-063001 (2018).

82. Grant, N., Hawkes, A., Mittal, S. & Gambhir, A. Confronting mitigation deterrence in low-carbon scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 64099-64099 (2021).

83. Carton, W., Hougaard, I.-M., Markusson, N. & Lund, J. F. Is carbon removal delaying emission reductions? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 14, e826 (2023).

84. Donnison, C. et al. Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS): finding the winwins for energy, negative emissions and ecosystem services-size matters. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 12, 586-604 (2020).

85. Heck, V., Hoff, H., Wirsenius, S., Meyer, C. & Kreft, H. Land use options for staying within the Planetary Boundaries – Synergies and trade-offs between global and local sustainability goals. Glob. Environ. Change 49, 73-84 (2018).

86. Doelman, J. C. et al. Afforestation for climate change mitigation: potentials, risks and trade-offs. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 1576-1591 (2020).

87. Lee, K., Fyson, C. & Schleussner, C. F. Fair distributions of carbon dioxide removal obligations and implications for effective national net-zero targets. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 094001 (2021).

88. Ganti, G. et al. Uncompensated claims to fair emission space risk putting Paris Agreement goals out of reach. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 024040 (2023).

89. Yuwono, B. et al. Doing burden-sharing right to deliver natural climate solutions for carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Based Solut. 3, 100048 (2023).

developed the pathway classification and designed Fig. 1, Table 1 and Extended Data Table 1 with support by G.G. The global climate response section, including the analysis underlying Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2, was led by G.G. and supported by Z.N., C.J.S., R.L., C.-F.S. and J.R. The section on CDR, including Extended Data Table 2 and Extended Data Fig. 3, was led by R.P. with support from S.F., C.-F.S., M.J.G. and J.R. The section on climate change reversibility, including Fig. 3 and Extended Data Figs. 4-8, was led by P.P. with support from N.J.S., T.L.F., F.L., B.S. and C.-F.S.; F.L. conducted the GFDL ESM2M overshoot and stabilization simulations supported by T.L.F. The analysis underlying the section on time-lagged impacts was led by B.Z. supported by M. Mengel, T.G. and P.C. with inputs from R.W., J.P., F.M. and C.-F.S. The section on adaptation decision-making was led by C.M.K., J.W.M., E.T. and R.M. with inputs from J.S. and C.-F.S.; S.I.S., Y.Q. and M. Meinshausen provided inputs on the conceptualization of the entire Article. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Carl-Friedrich Schleussner.

Peer review information Nature thanks Amy Luers, Nadine Mengis and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

Estimates to the right of the purple line indicate ongoing warming after 2060.c, Diagnosed eTCREup and eTCREdown (estimated from PROVIDEREN_ NZCO2_20), d, Cooling between 2100 and 2060 versus warming in 2060 for PROVIDE REN_NZCO2 and PROVIDE REN_NZCO2_20.

ensemble members. Solid and dashed horizontal (vertical) lines indicate the median and

experiments. a,c show transient 31-year mean

carbon budget difference between the overshoot and stabilisation experiments for the GFDL-ESM2M and NorESM experiments during the upward (orange) and downward (blue) phases also highlighted in a,c.

region (31-year averaged anomalies relative to 1850-1900). e,f regional differences in annual precipitation between overshoot and stabilisation scenarios over hundred years of long-term GMT stabilisation (grey shaded area in panels

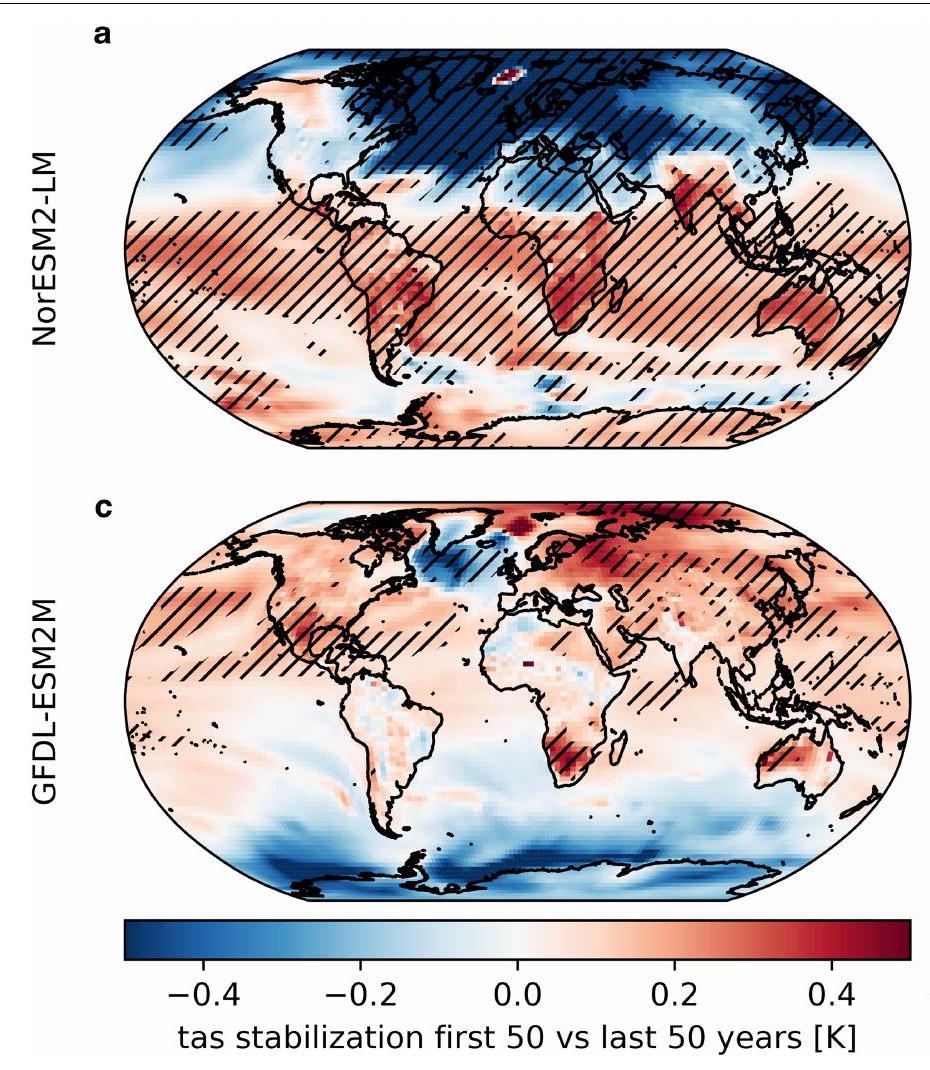

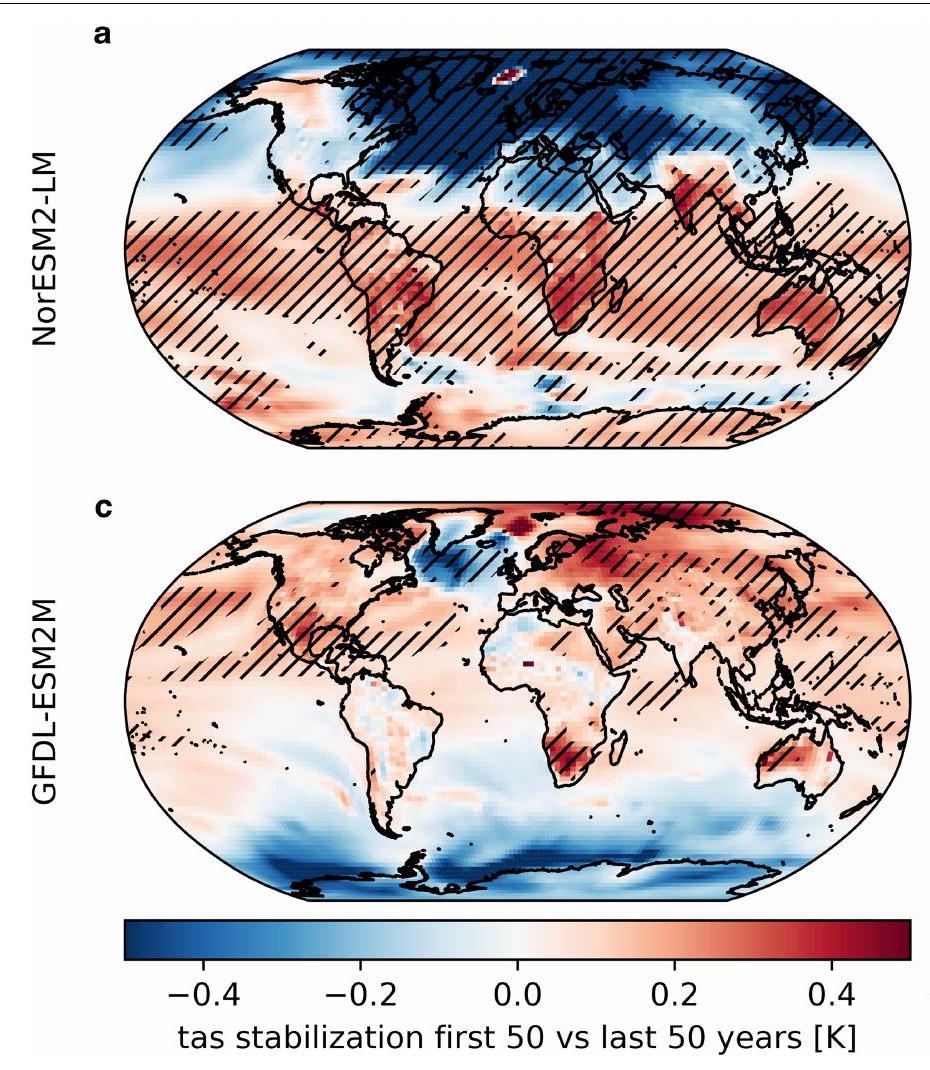

scenario. a,b show results for NorESM, c,d for GFDL-ESM2M, a,c for annual temperature over the first 50 years of GMT stabilisation vs. the last 50 years (compare Fig. 3a). Negative values mean the first period is cooler than the

second.c,d like a,c but for annual precipitation. Hatching highlights grid-cells where the difference exceeds the 95th percentile (is below the 5th percentile) of comparable period differences in piControl simulations (see Methods).

the 95th percentile (is below the 5th percentile) of comparable period differences in piControl simulations (see Methods). For the ensemble median (last panel) stippling indicates a model agreement in the sign of change of at least 66% of the models.

mean temperature from warming-induced permafrost and peatland emissions and sea-level rise increase implied by stabilising temperatures at peak warming by achieving net-zero

| Pathway Category | Temperature Characteristics | Emission Characteristics (Best Estimates) | |||||||

| Pathways that limit warming to

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pathways that return warming to

|

|

|

|||||||

| Paris Agreement compatible pathways

|

|

|

| Description of constraints and potential for overconfidence | |

| Readiness | Current removal capacities are far from what is required to be compatible with the Paris Agreement. In the coming years, removal scales need to go up while costs need to come down both at highly ambitious levels. Implementation gaps already arise, potentially precluding reliance on CDR to steer back from overshoot

|

| Permanence & Resilience | Permanent and secure storage of removed carbon is key. Overconfidence may arise from neglected uncertainty of the geological storage potential

|

| System feedbacks | Mitigation effects of CDR may be offset by weakened and potentially reversed land and ocean carbon sinks, and other undesired system feedbacks

|

| Policy response & Governance | Betting on CDR effectiveness may lead to insufficient emission reductions if CDR underperforms, or physical climate feedbacks are stronger than expected. The outlook of potential future CDR availability could deter mitigation, meaning that required gross emission reductions may be delayed and/or weakened

|

| Sustainability & Acceptability | The extensive land use footprint associated with large-scale CDR may threaten environmental integrity

|

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria. Geography Department and IRITHESys Institute, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Climate

Hamburg, Germany.

Hamburg, Germany.

Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Berlin, Germany. Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment, Imperial College London, London, UK. Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Germany. Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland. Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology, MeteoSwiss, Zürich, Switzerland. Institute of Geography, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, London, UK. Department of Atmospheric and Cryospheric Sciences, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria. School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Climate Resource, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research, Oslo, Norway. Met Office Hadley Centre, Exeter, UK. School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research and School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. Present address: Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research, Oslo, Norway. e-mail: schleussner@iiasa.ac.at