المجلة: Nature Geoscience، المجلد: 18، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822308

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-01

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822308

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-01

الحفاظ على الكربون العضوي في الرواسب البحرية المدعوم بعمليات الامتزاز والتحول

تاريخ الاستلام: 2 مايو 2023

تاريخ القبول: 29 أكتوبر 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 3 يناير 2025

تحقق من التحديثات

تاريخ القبول: 29 أكتوبر 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 3 يناير 2025

تحقق من التحديثات

تظل الضوابط على الحفاظ على الكربون العضوي في الرواسب البحرية مثيرة للجدل ولكنها حاسمة لفهم الديناميات المناخية الماضية والمستقبلية. هنا نطور نموذجًا رياضيًا مفاهيميًا لتحديد العمليات الرئيسية للحفاظ على الكربون العضوي. يأخذ النموذج في الاعتبار العمليات الرئيسية المعنية في تحلل الكربون العضوي، بما في ذلك التحلل المائي للكربون العضوي المذاب، والخلط، وإعادة التمعدن، وامتصاص المعادن، والتحول الجزيئي. وهذا يسمح بإعادة تعريف كفاءة الدفن ككفاءة الحفاظ، والتي تأخذ في الاعتبار كل من الكربون العضوي الجزيئي وكربون المرحلة المعدنية. نوضح أن كفاءة الحفاظ أعلى تقريبًا بثلاث مرات من كفاءة الدفن المعرفة تقليديًا وتتناسب التنبؤات مع بيانات الحقل العالمية. تعتبر الامتصاص الديناميكي والتحول الضوابط السائدة على الحفاظ على الكربون العضوي. نستنتج أن تأثيرًا تآزريًا بين الامتصاص الديناميكي والتحول الجزيئي (الجيوبوليمرization) يخلق ناقلًا معدنيًا حيث يتم حماية كربون المرحلة المعدنية العضوية من إعادة التمعدن في الرواسب السطحية ويتم إطلاقه في العمق. تفسر النتائج لماذا يستمر الكربون العضوي المتحول على مدى فترات زمنية طويلة ويزداد مع العمق.

يعد الحفاظ على الكربون العضوي (OC) في الرواسب البحرية أمرًا حيويًا لدورات الكربون والأكسجين العالمية، وبالتالي، لمناخ الأرض وتركيب الغلاف الجوي

الحفاظ على الكربون

الحفاظ على الكربون

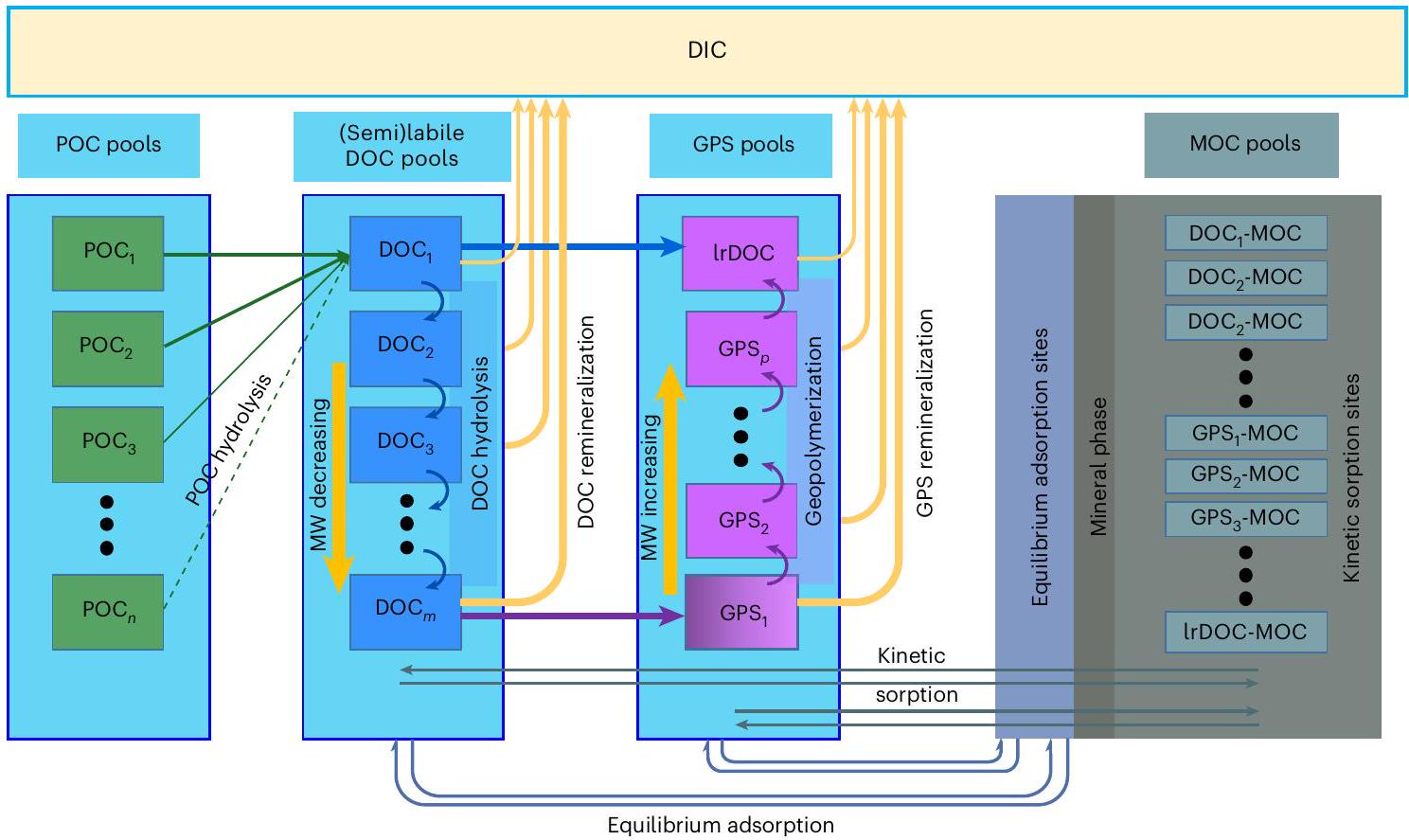

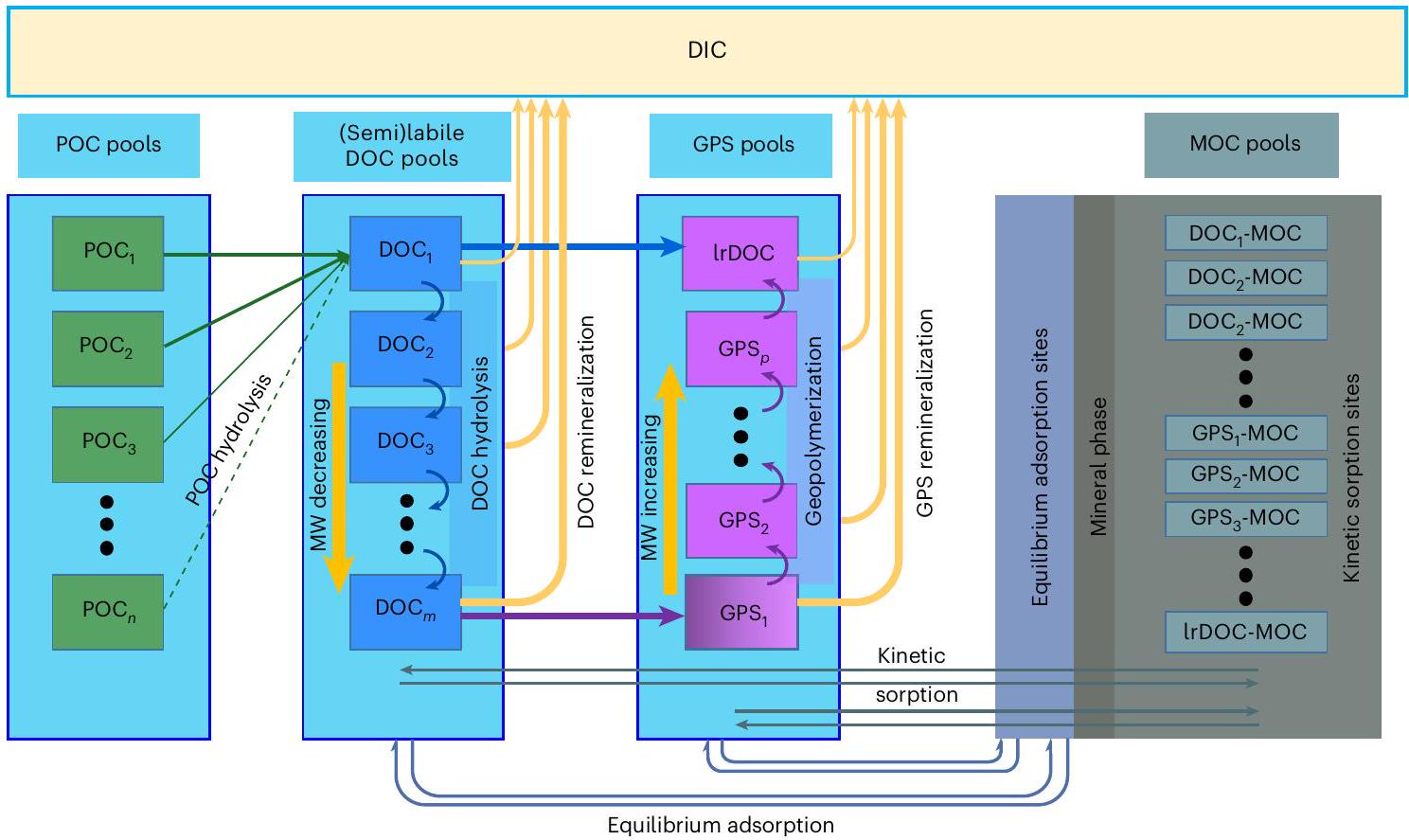

الشكل 1| نموذج مفاهيمي لدورة DOC في الرواسب. يتضمن النموذج المفاهيمي المقترح آليات الجيوبوليمرization، وامتصاص التوازن، والامتصاص الديناميكي ومفهومًا معدلًا للتحلل المائي الذي يتبع دورة DOC في عمود الماء

على أي عمق في الرواسب أو تبقى غير متحللة. يتم نقلها في الرواسب بشكل مشابه للمعادن الصلبة في الرواسب. يتم نقل تجمعات MOC بشكل مشابه للمعادن الصلبة في الرواسب وPOC، ولكنها تنشأ من صافي امتصاص DOC وGPS وIrDOC إلى المعادن ويفترض أنها غير تفاعلية ما لم يتم إزالة الكربون من المعادن. يعتبر جزء من POC، الذي لم يتم تحلله عند عمق معين، وجزء من MOC، الذي لم يتم إزالته عند ذلك العمق، مدفونًا بشكل دائم.

على أي عمق في الرواسب أو تبقى غير متحللة. يتم نقلها في الرواسب بشكل مشابه للمعادن الصلبة في الرواسب. يتم نقل تجمعات MOC بشكل مشابه للمعادن الصلبة في الرواسب وPOC، ولكنها تنشأ من صافي امتصاص DOC وGPS وIrDOC إلى المعادن ويفترض أنها غير تفاعلية ما لم يتم إزالة الكربون من المعادن. يعتبر جزء من POC، الذي لم يتم تحلله عند عمق معين، وجزء من MOC، الذي لم يتم إزالته عند ذلك العمق، مدفونًا بشكل دائم.

حتى الآن، لم تحظَ مساهمات هذه العمليات في الحفاظ على OC، وبالتالي، دورة الكربون باهتمام كبير وتظل غير معروفة بشكل سيء. علاوة على ذلك، فإن المفهوم التقليدي لكفاءة دفن OC (BE) في الرواسب – مؤشر على القدرة على الحفاظ على الكربون وقياس الميزانيات العالمية للكربون في الرواسب الحديثة والقديمة

هنا، نطور نموذجًا ميكانيكيًا للتفاعل والنقل (RTM) يأخذ في الاعتبار العمليات الرئيسية للحفاظ على OC في الرواسب البحرية عبر دورة DOC. بعد التحقق الشامل، يتم استخدام النموذج جنبًا إلى جنب مع تحليلات مونت كارلو والشبكات العصبية الاصطناعية (ANN) لتوفير رؤى عالمية حول دور العمليات التي تتحكم في الحفاظ على الكربون في الرواسب البحرية وتظهر أين وكيف يحدث الحفاظ.

تصور دورة الكربون والحفاظ عليها في الرواسب

يبدأ نموذجنا المفاهيمي لدورة الكربون والحفاظ عليها في الرواسب مع التحلل المائي لعدة كسور POC منفصلة (

عبر نقل مباشر لـ

عبر نقل مباشر لـ

نقوم بإدماج نموذجنا المفاهيمي (الشكل 1) في RTM تم حله عموديًا للرواسب البحرية الذي يربط بين عمليات النقل (على سبيل المثال، سرعة دفن الرواسب قبل الضغط، والخلط الناتج عن الكائنات الحية)

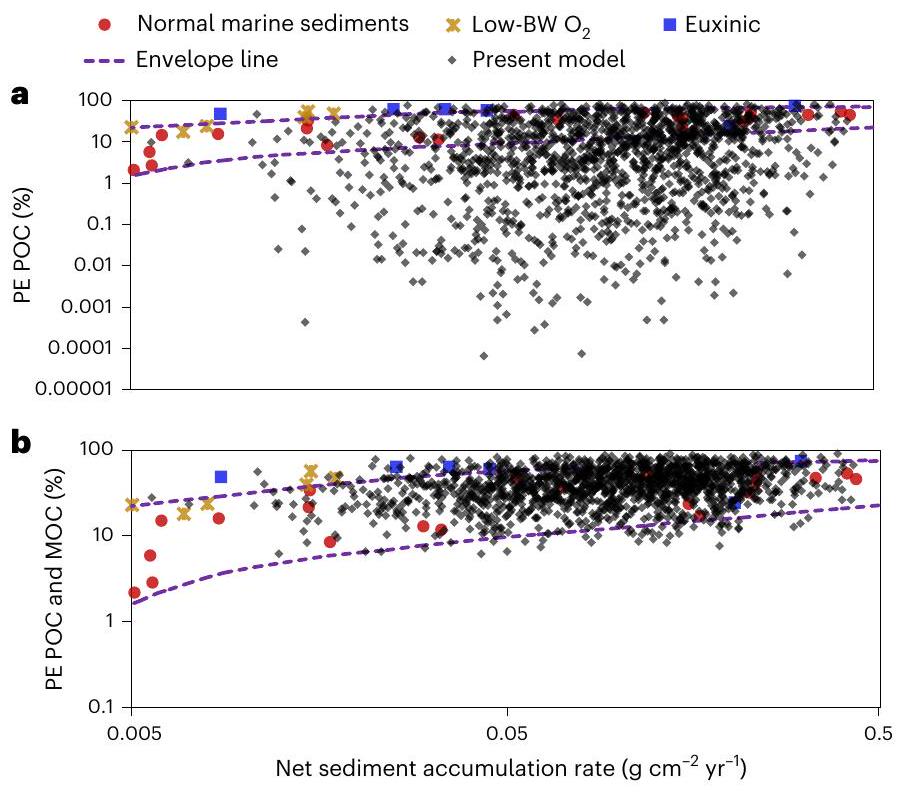

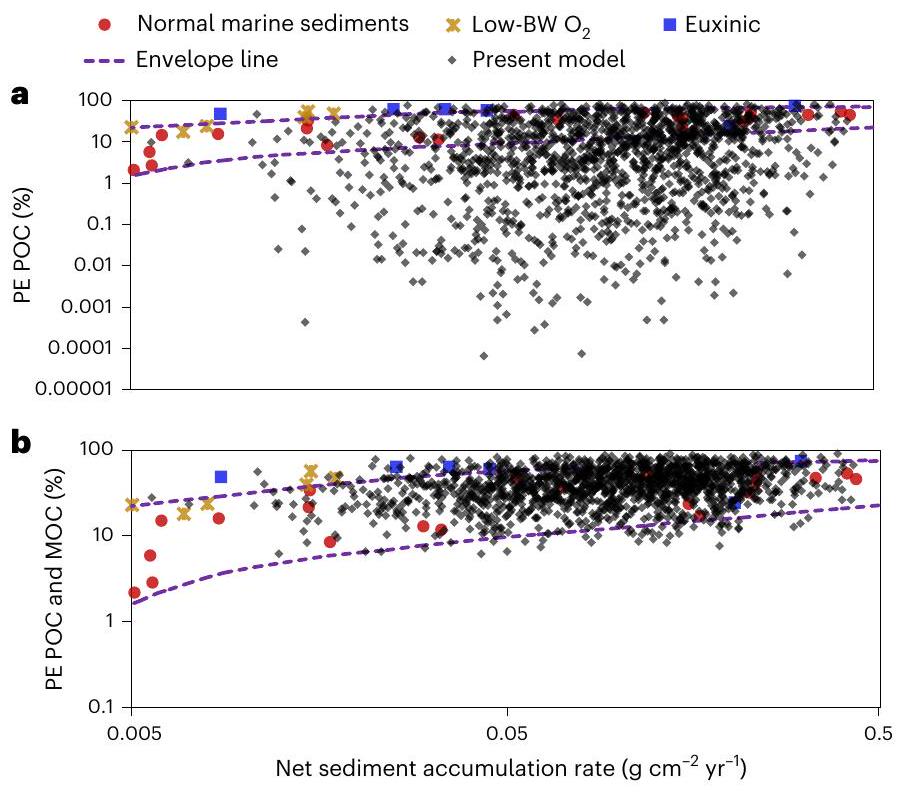

الشكل 2 | مقارنة PE الناتج عن النموذج مع بيانات الأدبيات. أ، ب، البيانات الناتجة عن 1450 تشغيل نموذج في نهج مونت كارلو (نقاط سوداء شفافة) للطريقة التقليدية لحساب PE لـ POC التي تأخذ في الاعتبار فقط POC (أ) ولـ PE المحدد حديثًا الذي يأخذ في الاعتبار كل من POC و MOC (ب). يتم مقارنتها مع بيانات الحقل من دراسات سابقة

ضمن نطاقات ذات صلة عالمياً (الجدول التكميلية 1) بناءً على التوزيعات الإحصائية المأخوذة من ست مجموعات بيانات نمذجة ميدانية (الأشكال التكميلية 1 و 2) وعشر دراسات سابقة (الجدول التكميلية 2) لفحص الدور الأوسع لعمليات الحفاظ على OC المختلفة (الشكل التكميلية 3، المرحلة 1).

ثم نستخدم مجموعة البيانات الناتجة عن RTM لتدريب

تقييم النموذج

تمت مقارنة دمج MOC في نماذج PE مع النهج الكلاسيكي

تم اقتراح العديد من العوامل المختلفة لشرح الحفاظ على OC في الرواسب البحرية

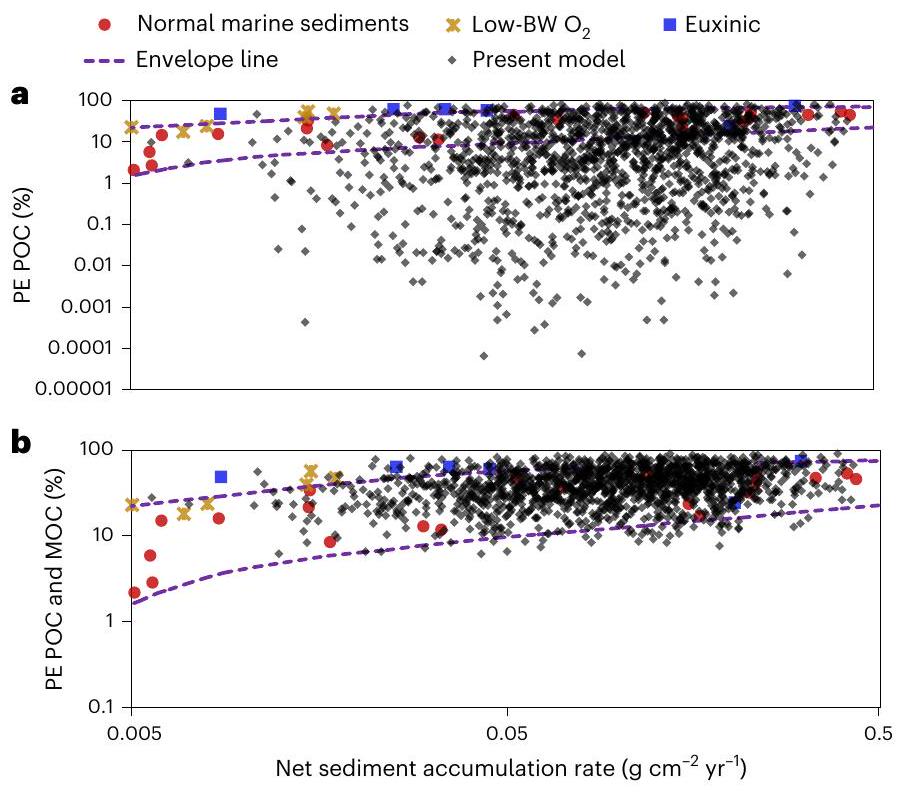

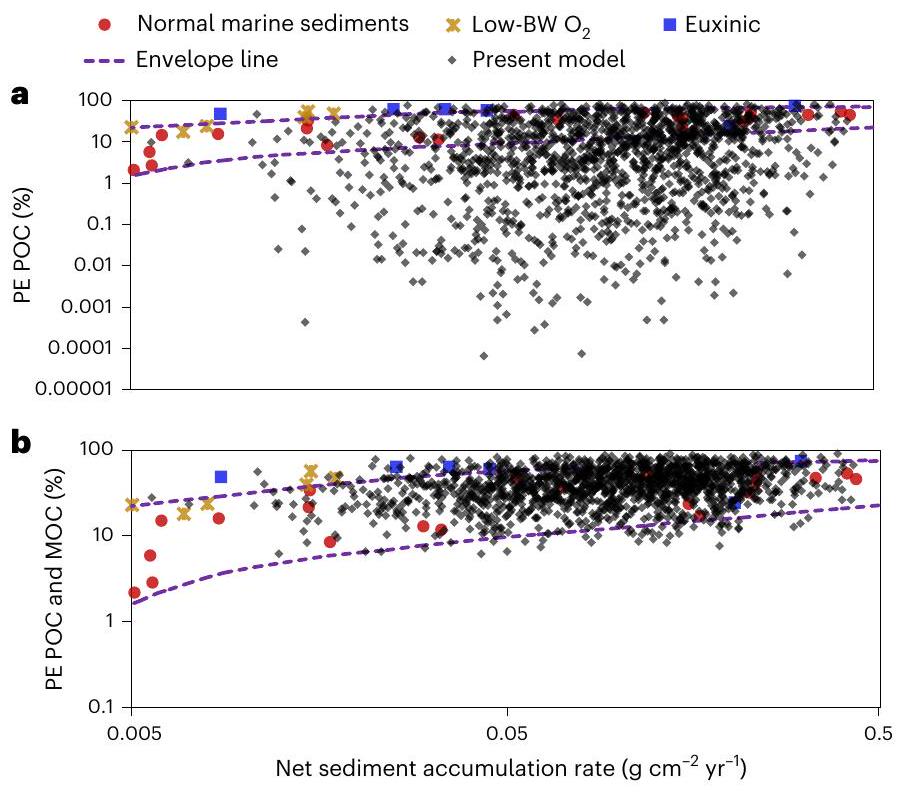

الشكل 3 | الأهمية النسبية لعمليات مختلفة. أ، ب، الأهمية النسبية (%) لست عمليات لـ PE عندما يتم اعتبار MOC بالإضافة إلى POC (أ) ومعدلات الحفاظ على MOC (ب). العمليات الست هي تحلل DOC، إعادة معدنة DOC، الخلط، الامتصاص التوازني، الامتصاص الحركي والجيوبوليمرization. يتم إعطاء PE المحدد حديثًا بواسطة المعادلة (7). يتم عرض معدلات الحفاظ على MOC كمعدل لتشكيل MOC، وهو مجموع معدلات الامتصاص الحركي الصافية المدمجة عند عمق

ديناميات الكربون ليتم ترجمتها إلى فهم عالمي دون الحاجة إلى ضبط النموذج لمواقع محددة قد تقدم عدم اليقين المرتبط بالظروف المحددة للموقع.

تعريف نموذجنا لتحلل POC مشابه لذلك الذي يعتبر إعادة معدنة POC في أماكن أخرى

دور العمليات المختلفة في الحفاظ على الكربون

نحن نقوم بتحديد أهمية ست عمليات نموذجية في التحكم في المؤشرات الرئيسية للحفاظ على الكربون، بما في ذلك PE ومعدلات تشكيل MOC (أو معدلات امتصاص DOC). يُفهم تقليديًا أن ثلاث عمليات مهمة للحفاظ على الكربون

تكشف النتائج أن الامتصاص الحركي هو العملية الأكثر أهمية لـ PE مع أهمية نسبية قدرها

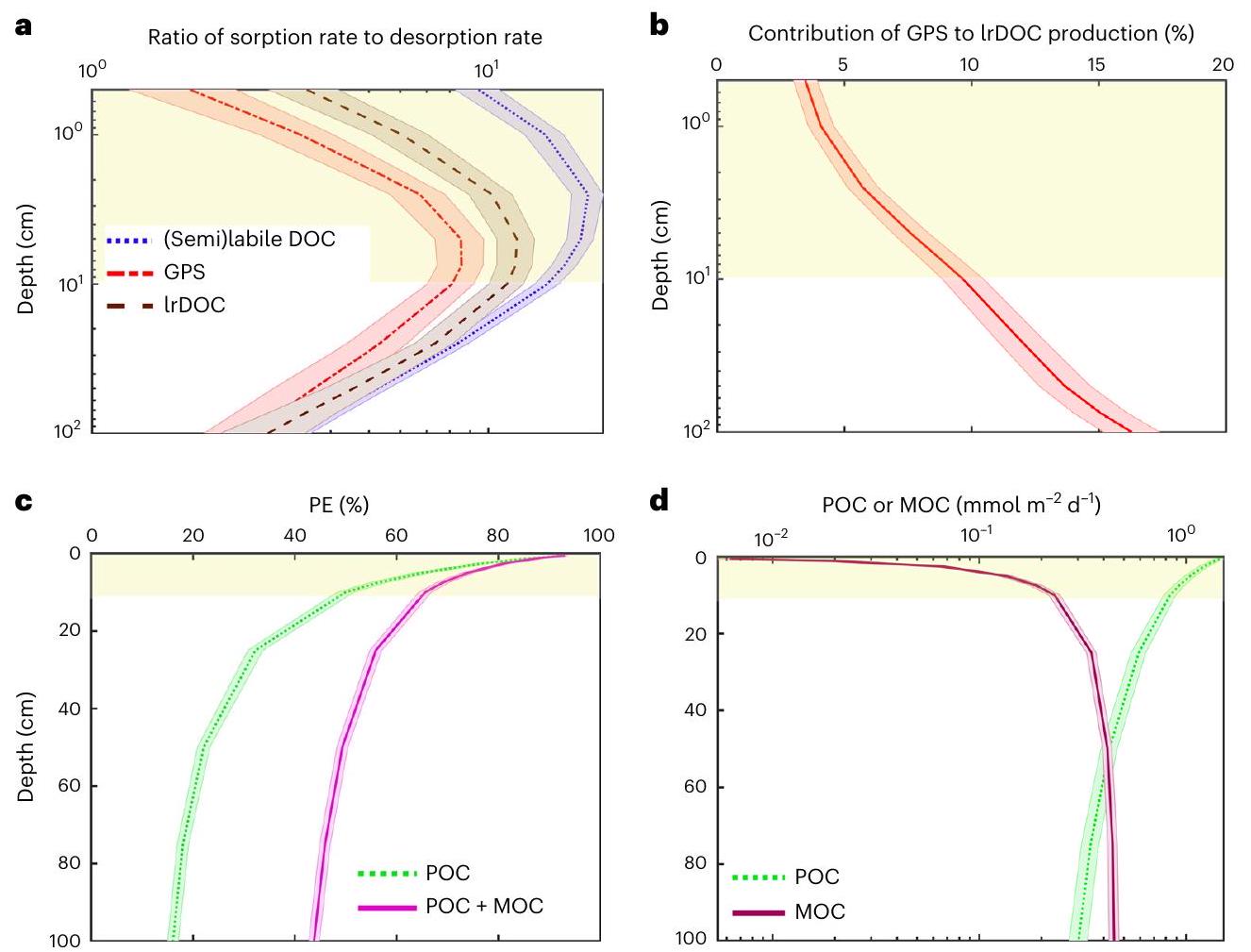

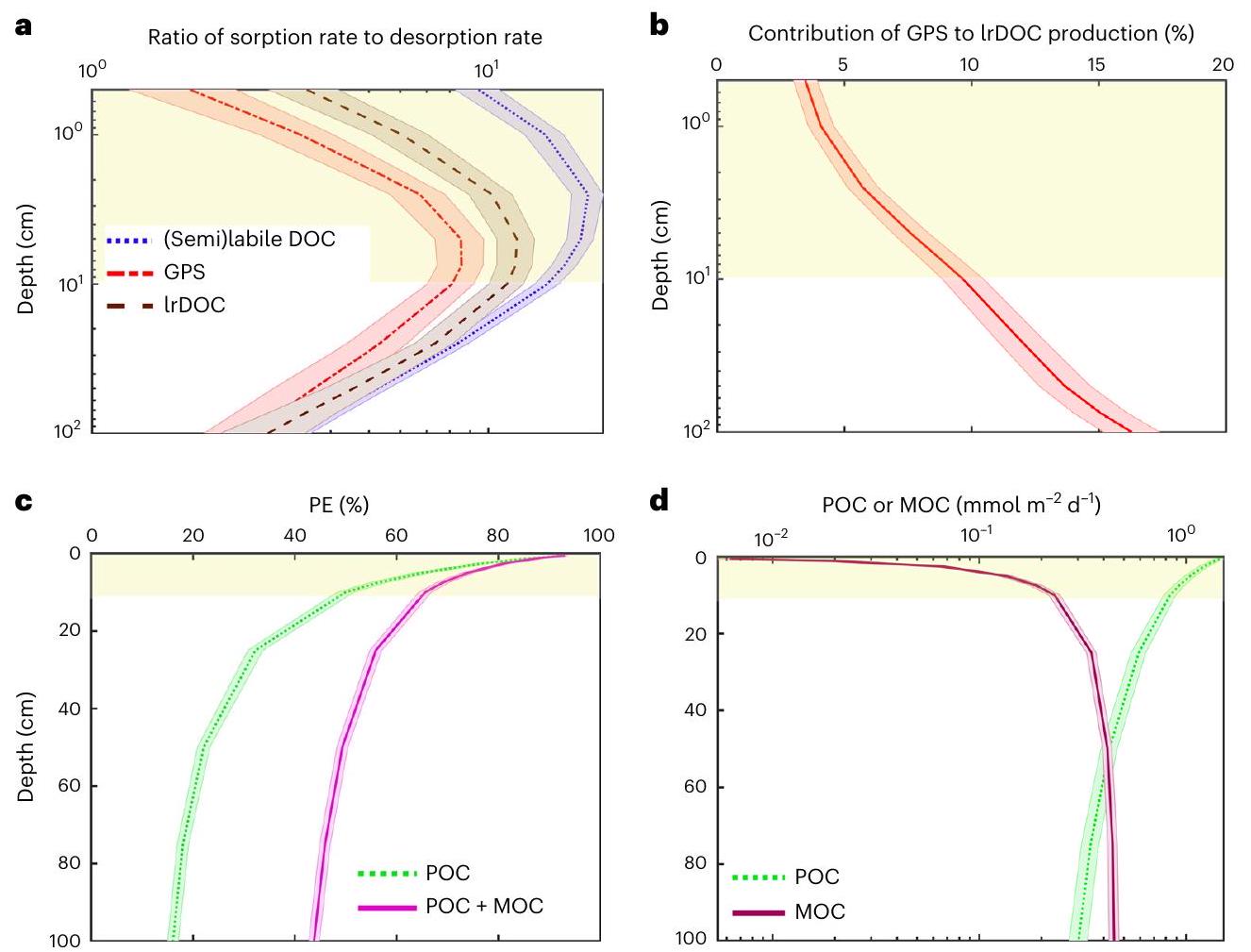

الشكل 4 | ملفات العمق التي تم الحصول عليها من نمذجة مونت كارلو. أ، نسبة معدلات الامتصاص الحركي المتوسطة لـ 1450 تشغيلًا من نمذجة مونت كارلو إلى معدلات الإزالة المتوسطة أيضًا لـ 1450 تشغيلًا نموذجية عند أعماق مختلفة. ب، النسبة المئوية لمساهمة مجموعة GPS النهائية في إجمالي إنتاج IrDOC (الشكل 1) عند أعماق مختلفة. تم متوسط هذه المساهمات لـ 1450 تشغيلًا من نمذجة مونت كارلو. المعادلات الرياضية المستخدمة لإنتاج هذه الرسوم البيانية موضحة في القسم التكميلية 3. ج، PE (%) لـ POC فقط ولـ POC و MOC معًا، مما يوضح أن MOC يزيد

PE المحسوبة بمقدار 2.7 عند عمق 1 متر مقارنة بالطريقة التقليدية التي تأخذ في الاعتبار فقط POC. د، تدفقات POC ومعدل الحفاظ على MOC. يتجاوز محتوى MOC POC عند عمق

كانت الاعتبارات السابقة لامتصاص DOC في الرواسب البحرية محدودة بعملية امتصاص سطح توازني بسيطة معبر عنها باستخدام معامل تقسيم (

مؤخراً، تم إظهار أن الجيوبوليمرية في شكل تفاعل تكثيف من نوع ميلارد من خلال التحفيز بواسطة الحديد والمغنيسيوم المذاب أو الجزيئي هي عملية حاسمة لـ DOC القاعية

دورة

دورة

كيف تتحكم الامتصاص والجيبوليمرية في حفظ OC

نستخدم ملفات عمق الرواسب (الشكل 4 والقسم التكميلي 3) المستمدة من محاكاة مونت كارلو لتوفير رؤية أوسع حول كيفية تحكم العمليات المختلفة في حفظ OC. نلاحظ أن الطبقة المختلطة تعمل كوسيلة نقل لمجموعات DOC المختلفة من خلال حمايتها من التعرض للأكسجين والمواد المغذية والإنزيمات الميكروبية، وبالتالي، تحد من إعادة التمعدن السريع لها في الطبقة المختلطة وتوصيلها إلى أعماق أكبر (الشكل 4أ). كما نحقق في مسارات إنتاج IrDOC، التي تظهر أن الجيوبوليمرية تساهم

نلاحظ أيضاً أن PE يمكن أن يتغير مع أفق عمق الرواسب أو أفق العمر

في الختام، تكشف نتائجنا أنه، بخلاف العمليات المعروفة تقليديًا (التحلل المائي، والخلط وإعادة التمعدن)، فإن الامتصاص الحركي والجيبوليمرية ربما تلعب دورًا رئيسيًا في حفظ OC. يخلق الامتصاص الحركي وسيلة نقل معدنية تزيل DOC بفعالية من الطبقة السطحية النشطة وتطلقه في العمق، بينما تجعل الجيوبوليمرية كعملية تعتمد على العمر OC أقل تفاعلاً. يؤدي الامتصاص الحركي إلى تشكيل جزء مرتبط بالمعادن يصبح أكبر من مجموعة POC تحت

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

أي طرق، مراجع إضافية، ملخصات تقارير Nature Portfolio، بيانات المصدر، بيانات موسعة، معلومات تكملية، شكر وتقدير، معلومات مراجعة الأقران؛ تفاصيل مساهمات المؤلفين والمصالح المتنافسة؛ وبيانات توفر البيانات والرموز متاحة على https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y.

References

- Alcott, L. J., Mills, B. J. W. & Poulton, S. W. Stepwise Earth oxygenation is an inherent property of global biogeochemical cycling. Science 366, 1333-1337 (2019).

- Berner, R. A. Biogeochemical cycles of carbon and sulfur and their effect on atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time. Glob. Planet. Change 1, 97-122 (1989).

- Amon, R. M. W. & Benner, R. Rapid cycling of high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nature 369, 549-552 (1994).

- Li, Z., Zhang, Y. G., Torres, M. & Mills, B. J. W. Neogene burial of organic carbon in the global ocean. Nature 613, 90-95 (2023).

- Abelson, P. H. Organic matter in the Earth’s crust. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 6, 325-351 (1978).

- Hatcher, P. G., Spiker, E. C., Szeverenyi, N. M. & Maciel, G. E. Selective preservation and origin of petroleum-forming aquatic kerogen. Nature 305, 498-501 (1983).

- Smetacek, V. et al. Deep carbon export from a Southern Ocean iron-fertilized diatom bloom. Nature 487, 313-319 (2012).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Potential use of engineered nanoparticles in ocean fertilization for large-scale atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1342-1351 (2022).

- Arndt, S. et al. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: a review and synthesis. Earth Sci. Rev. 123, 53-86 (2013).

- Kleber, M. et al. Dynamic interactions at the mineral-organic matter interface. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 402-421 (2021).

- Burd, A. B. et al. Assessing the apparent imbalance between geochemical and biochemical indicators of meso-and bathypelagic biological activity: what the @$#! is wrong with present calculations of carbon budgets? Deep Sea Res. Part II 57, 1557-1571 (2010).

- Burdige, D. J. Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments: controls, mechanisms, and an imbalance in sediment organic carbon budgets? Chem. Rev. 107, 467-485 (2007).

- Burdige, D. J. & Komada, T. in Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter (eds Hansell, D. A. & Carlson, C. A.) 535-577 (Elsevier, 2015).

- Burdige, D. J., Komada, T., Magen, C. & Chanton, J. P. Modeling studies of dissolved organic matter cycling in Santa Barbara Basin (CA, USA) sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 195, 100-119 (2016).

- Burdige, D. J., Berelson, W. M., Coale, K. H., McManus, J. & Johnson, K. S. Fluxes of dissolved organic carbon from California continental margin sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1507-1515 (1999).

- Keil, R. G., Montluçon, D. B., Prahl, F. G. & Hedges, J. I. Sorptive preservation of labile organic matter in marine sediments. Nature 370, 549-552 (1994).

- Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., Ouellet, A. & Gélinas, Y. Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron. Nature 483, 198-200 (2012).

- Hemingway, J. D. et al. Mineral protection regulates long-term global preservation of natural organic carbon. Nature 570, 228-231 (2019).

- Hedges, J. I. & Keil, R. G. Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis. Mar. Chem. 49, 81-115 (1995).

- Dittmar, T. et al. Enigmatic persistence of dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 570-583 (2021).

- Moore, O. W. et al. Long-term organic carbon preservation enhanced by iron and manganese. Nature 621, 312-317 (2023).

- Arrieta, J. M. et al. Dilution limits dissolved organic carbon utilization in the deep ocean. Science 348, 331-333 (2015).

- Middelburg, J. J. Escape by dilution. Science 348, 290-290 (2015).

- Hansell, D. A. Recalcitrant dissolved organic carbon fractions. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 421-445 (2013).

- Sexton, P. F. et al. Eocene global warming events driven by ventilation of oceanic dissolved organic carbon. Nature 471, 349-352 (2011).

- Lenton, T. M., Daines, S. J. & Mills, B. J. W. COPSE reloaded: an improved model of biogeochemical cycling over Phanerozoic time. Earth Sci. Rev. 178, 1-28 (2018).

- Katsev, S. & Crowe, S. A. Organic carbon burial efficiencies in sediments: the power law of mineralization revisited. Geology 43, 607-610 (2015).

- Bradley, J. A., Hülse, D., LaRowe, D. E. & Arndt, S. Transfer efficiency of organic carbon in marine sediments. Nat. Commun. 13, 7297 (2022).

- Hedges, J. I. The formation and clay mineral reactions of melanoidins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 69-76 (1978).

- Schrumpf, M. et al. Storage and stability of organic carbon in soils as related to depth, occlusion within aggregates, and attachment to minerals. Biogeosciences 10, 1675-1691 (2013).

- Mayer, L. M. The inertness of being organic. Mar. Chem. 92, 135-140 (2004).

- Henrichs, S. M. & Sugai, S. F. Adsorption of amino acids and glucose by sediments of Resurrection Bay, Alaska, USA: functional group effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 823-835 (1993).

- Henrichs, S. M. Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis-a comment. Mar. Chem. 49, 127-136 (1995).

- Dale, A. W. et al. A revised global estimate of dissolved iron fluxes from marine sediments. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 691-707 (2015).

- Babakhani, P., Bridge, J., Doong, R. A. & Phenrat, T. Parameterization and prediction of nanoparticle transport in porous media: a reanalysis using artificial neural network. Water Resour. Res. 53, 4564-4585 (2017).

- Canfield, D. E. Factors influencing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 114, 315-329 (1994).

- Boudreau, B. P. Diagenetic Models and Their Implementation Vol. 410 (Springer, 1997).

- Berner, R. A. Inclusion of adsorption in the modelling of early diagenesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 29, 333-340 (1976).

- Sohma, A., Sekiguchi, Y. & Nakata, K. Modeling and evaluating the ecosystem of sea-grass beds, shallow waters without sea-grass, and an oxygen-depleted offshore area. J. Mar. Syst. 45, 105-142 (2004).

- Mayer, L. M. Surface area control of organic carbon accumulation in continental shelf sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 1271-1284 (1994).

- Lee, C. Kitty litter for carbon control. Nature 370, 503-504 (1994).

- Mayer, L. M. Relationships between mineral surfaces and organic carbon concentrations in soils and sediments. Chem. Geol. 114, 347-363 (1993).

- Keil, R. G. & Mayer, L. M. in Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn (eds Holland H. D. & Turekian K. K.) 337-359 (Elsevier, 2014).

- Rothman, D. H. & Forney, D. C. Physical model for the decay and preservation of marine organic carbon. Science 316, 1325-1328 (2007).

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/.

(c) The Author(s) 2025

(c) The Author(s) 2025

طرق

المنهجية

نظرة عامة على إجراء النمذجة. تم تطوير RTM للنظر في دورة وحفظ DOC في الرواسب البحرية. ثم يتم محاكاة هذا RTM باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي، الذي يستخدم كأداة لإجراء تحليل قوي لأهمية العمليات. يتم عرض مخطط سير نشر النموذج في الشكل التكميلي 3. التقنية الذكاء الاصطناعي التي نستخدمها في هذه الدراسة هي ANN، ويتم محاكاة RTM باستخدام ANN من خلال نهج مونت كارلو (الشكل التكميلي 3، المرحلة 1)، حيث يتم تنفيذ RTM عدة مرات (على سبيل المثال،

من بين 68 معلمة إدخال غير معروفة للنموذج، نحصل على النطاقات والتوزيعات الإحصائية لـ 6 من معلمات الإدخال، بما في ذلك عمق المياه

صياغة RTM. يأخذ RTM في الاعتبار جميع تفاعلات الدياجينيس المبكرة الشائعة لمركبات مختلفة بما في ذلك الأنواع المذابة (

المعادلات الثلاثة الحاكمة لنموذج RTM للأنواع المذابة، والأنواع الجزيئية، والأنواع الممتصة، على التوالي، هي كما يلي، بينما يتم تقديم التفاصيل الكاملة لتطوير النموذج والتحقق من صحته

في الأقسام التكميلية 1 و 2:

(1) المعادلة الحاكمة للأنواع المذابة:

في الأقسام التكميلية 1 و 2:

(1) المعادلة الحاكمة للأنواع المذابة:

(2) المعادلة الحاكمة للأنواع الجسيمية:

(3) المعادلة الحاكمة لمرحلة المعادن، MOC، الناتجة عن الكمية الممتصة حركياً من الأنواع المذابة:

أين

تعتبر المرحلة الأولى من التحلل المائي مشابهة لنموذج الانحلال التقليدي من الدرجة الأولى متعدد نقاط التحلل المعروف باسم نموذج متعدد الجوانب.

أين

تم وصف المرحلة المتسلسلة من التحلل المائي باستخدام تعبير تفاعل من الدرجة الأولى المتتالي.

أين

نفس المعادلة الرياضية تُستخدم لوصف الجيوبوليمرة

حساب PE. يُعرف PE، المعروف أيضًا باسم BE، تقليديًا بـ

أين

معدل الامتصاص هو معدل الامتصاص الديناميكي الصافي لمادة الكربون العضوي الذائب (معدل الامتصاص ناقص معدل الإزالة أو معدل تكوين المادة العضوية الصافية). تم تقديم مزيد من الشروحات حول المعدلات في الأقسام التكميلية 2.4 و3. على الرغم من أن اعتبار آفاق العمق مقابل العمر في نمذجة التحلل المبكر يمكن أن يكون مهمًا للتنبؤات العالمية، كما تم تسليط الضوء عليه مؤخرًا.

الشبكة العصبية الاصطناعية لتحليل أهمية العمليات. تعتبر الشبكة العصبية الاصطناعية أداة متعددة الاستخدامات وعالمية لمشاكل تقريب الدوال وتتميز بتطبيقها على الأنظمة المعقدة وغير الخطية.

تحقق النموذج. نحن نتحقق من نموذجنا بعدة طرق. نحن نتحقق من المعادلات الحاكمة التي طورناها لنموذج RTM بناءً على نهج تحليلي. في هذا النهج، للحالة التي يُتوقع فيها أن يتصرف الامتصاص التوازني والامتصاص الحركي بشكل مشابه، أي عند معدلات تبادل عالية، نقوم أولاً بتشغيل النموذج بعد إيقاف الامتصاص التوازني ثم نقوم بتشغيل النموذج مرة أخرى بعد إيقاف تعبير الامتصاص الحركي. بعد ذلك، تتم مقارنة مخرجات النموذج لهذين النوعين من المحاكاة. استخدمنا بيانات النمذجة الميدانية الموجودة (بشكل رئيسي من حوض سانتا باربرا، نظرًا للتفاصيل الشاملة)

تتوفر مجموعة البيانات

تتوفر مجموعة البيانات

تظهر نتائج مقارنة مخرجات النموذج بين الحالات التي تكون فيها الامتصاص الحركي فعالاً وتلك التي يكون فيها الامتصاص في حالة توازن عند معدل نقل كتلة مرتفع تطابقاً ممتازاً.

نتائج النموذج الملائم لعدة مجموعات بيانات ميدانية أو نمذجة، بما في ذلك دراسة ميسمان وآخرون.

نموذج الشبكة العصبية الاصطناعية يمكن أن يتناسب مع البيانات في جميع الحالات مع أفضل ملاءمة تنبؤية وفقًا لمعيار كفاءة نموذج ناش-سوتكليف.

تم حساب ميزانيات الكتلة لمقاطع العرض المختلفة للنموذج المفاهيمي المبسط الموضح في الشكل التوضيحي 14 بناءً على النتائج المتوسطة لجميع جولات نموذج مونت كارلو.

يجب ملاحظة أن هناك حدًا في سعة مواقع الامتصاص، على سبيل المثال، امتصاص طبقة أحادية.

ينطبق على إنتاج MOC لدينا. علاوة على ذلك، فإن الامتصاص الحركي أبطأ من الامتصاص في حالة التوازن، المعروف بأنه فوري. وبالتالي، فإن الامتصاص الحركي، الذي يحده تركيزات المياه في المسام التي تتحكم فيها أيضًا التحلل المائي، والتحلل، وما إلى ذلك، من غير المرجح أن يواجه قيدًا ثانيًا من سعة مواقع الامتصاص مقارنةً بالامتصاص الفوري في حالة التوازن، الذي تم تعريف أنواع مختلفة من الإيزوثرم له، مثل الخطية، ولانغموير، وفرويدليتش.

ينطبق على إنتاج MOC لدينا. علاوة على ذلك، فإن الامتصاص الحركي أبطأ من الامتصاص في حالة التوازن، المعروف بأنه فوري. وبالتالي، فإن الامتصاص الحركي، الذي يحده تركيزات المياه في المسام التي تتحكم فيها أيضًا التحلل المائي، والتحلل، وما إلى ذلك، من غير المرجح أن يواجه قيدًا ثانيًا من سعة مواقع الامتصاص مقارنةً بالامتصاص الفوري في حالة التوازن، الذي تم تعريف أنواع مختلفة من الإيزوثرم له، مثل الخطية، ولانغموير، وفرويدليتش.

توفر البيانات

البيانات المرتبطة بالأشكال 2-4 متاحة عبر figshare علىhttps://doi. org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273006 (مرجع 68). البيانات المتعلقة بالأشكال التكميلية 13 و 15 و 16 ومجموعات البيانات الرئيسية (مثل تلك التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة RTM من خلال عملية مونت كارلو (المرحلة 1) والتي تم استخدامها في تحليل أهمية عملية ANN (المرحلة 2)) متاحة عبر figshare علىhttps://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273030 (مرجع 69).

توفر الشيفرة

رموز الكمبيوتر متاحة من المؤلفين عند الطلب.

References

- Burwicz, E. B., Rüpke, L. H. & Wallmann, K. Estimation of the global amount of submarine gas hydrates formed via microbial methane formation based on numerical reaction-transport modeling and a novel parameterization of Holocene sedimentation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 4562-4576 (2011).

- Restreppo, G. A., Wood, W. T. & Phrampus, B. J. Oceanic sediment accumulation rates predicted via machine learning algorithm: towards sediment characterization on a global scale. Geo-Mar. Lett. 40, 755-763 (2020).

- Lee, T. R., Wood, W. T. & Phrampus, B. J. A machine learning (kNN) approach to predicting global seafloor total organic carbon. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 37-46 (2019).

- WOA18 Data Access (National Centers for Environmental Information, 2018); https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa18/woa18data.html

- Bohlen, L., Dale, A. W. & Wallmann, K. Simple transfer functions for calculating benthic fixed nitrogen losses and C:N:P regeneration ratios in global biogeochemical models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3029 (2012).

- Burdige, D. J., Komada, T., Magen, C. & Chanton, J. P. Methane dynamics in Santa Barbara Basin (USA) sediments as examined with a reaction-transport model. J. Mar. Res. 74, 277-313 (2016).

- Jørgensen, B. B. A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments: I. Measurement with radiotracer techniques. Geomicrobiol. J. 1, 11-27 (1978).

- Bradley, J. A. et al. Widespread energy limitation to life in global subseafloor sediments. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0697 (2020).

- Rogalinski, T., Liu, K., Albrecht, T. & Brunner, G. Hydrolysis kinetics of biopolymers in subcritical water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 46, 335-341 (2008).

- Leong, L. P. & Wedzicha, B. L. A critical appraisal of the kinetic model for the Maillard browning of glucose with glycine. Food Chem. 68, 21-28 (2000).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Comparison of a new mass-concentration, chain-reaction model with the population-balance model for early-and late-stage aggregation of shattered graphene oxide nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A 582, 123862 (2019).

- McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115-133 (1943).

- Yu, H. et al. Prediction of the particle size distribution parameters in a high shear granulation process using a key parameter definition combined artificial neural network model. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 10825-10834 (2015).

- Nourani, V. & Sayyah-Fard, M. Sensitivity analysis of the artificial neural network outputs in simulation of the evaporation process at different climatologic regimes. Adv. Eng. Softw. 47, 127-146 (2012).

- Gevrey, M., Dimopoulos, I. & Lek, S. Two-way interaction of input variables in the sensitivity analysis of neural network models. Ecol. Modell. 195, 43-50 (2006).

- Yerramareddy, S., Lu, S. C. Y. & Arnold, K. F. Developing empirical models from observational data using artificial neural networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 4, 33-41 (1993).

- Gevrey, M., Dimopoulos, I. & Lek, S. Review and comparison of methods to study the contribution of variables in artificial neural network models. Ecol. Modell. 160, 249-264 (2003).

- Meysman, F. J. R., Middelburg, J. J., Herman, P. M. J. & Heip, C. H. R. Reactive transport in surface sediments. II. Media: an object-oriented problem-solving environment for early diagenesis. Comput. Geosci. 29, 301-318 (2003).

- Kraal, P., Slomp, C. P., Reed, D. C., Reichart, G. J. & Poulton, S. W. Sedimentary phosphorus and iron cycling in and below the oxygen minimum zone of the northern Arabian Sea. Biogeosciences 9, 2603-2624 (2012).

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Autom. Control IEEE Trans. 19, 716-723 (1974).

- Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—a discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282-290 (1970).

- Clark, M. M. Transport Modeling for Environmental Engineers and Scientists (Wiley, 2011).

- Langmuir, D. Aqueous Environmental Geochemistry (Prentice Hall, 1997).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Babakhani_etal_main_text_figure_source_ data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273006 (2024).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Babakhani_etal_supplementary_data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273030 (2024).

شكر وتقدير

نحن نشكر D. Burdige على إرسال بيانات الميدان و B. Mills على المناقشة المفيدة ومراجعة النسخة السابقة من ورقتنا. يتم الاعتراف باستخدام مرافق الحوسبة عالية الأداء (ARC) في جامعة ليدز. نحن نشكر التمويل من المجلس الأوروبي للبحث (ERC) بموجب برنامج الأبحاث والابتكار Horizon 2020 التابع للاتحاد الأوروبي (رقم اتفاقية المنحة 725613 MinOrg). C.L.P. تعبر عن امتنانها لجائزة البحث من الجمعية الملكية Wolfson (WRM/FT/170005) وزمالة Leverhulme للبحث (RF-2023-395\4).

مساهمات المؤلفين

تصور: ب.ب، س.ل.ب. و أ.و.د. تنسيق البيانات: ب.ب، س.ل.ب. و أ.و.د. التحليل الرسمي: ب.ب. التحقيق: ب.ب. المنهجية: ب.ب، أ.و.د. و س.ل.ب. التصور: ب.ب. الحصول على التمويل: س.ل.ب. إدارة المشروع: س.ل.ب. الموارد: س.ل.ب. البرمجيات: ب.ب. و أ.و.د. الإشراف: س.ل.ب، أ.و.د. و ج.و. التحقق: ب.ب، أ.و.د، س.ل.ب. و ك.-ك.س. الكتابة – المسودة الأصلية: ب.ب. الكتابة – المراجعة والتحرير: ب.ب، س.ل.ب، أ.و.د، ج.و، أ.و.م، ك.-ك.س. و ل.س.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر مجلة Nature Geoscience المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل. المحرر الرئيسي: شوجيا جيانغ، بالتعاون مع فريق Nature Geoscience.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد إضافية متاحة علىhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى بييمان باباخاني.

مدرسة الأرض والبيئة، جامعة ليدز، ليدز، المملكة المتحدة. قسم الهندسة المدنية والإدارة، جامعة مانشستر، مانشستر، المملكة المتحدة. مركز جيومار هيلمهولتز لأبحاث المحيطات كيل، كيل، ألمانيا. مدرسة الجغرافيا، جامعة ليدز، ليدز، المملكة المتحدة. قسم البيئة والجغرافيا، جامعة يورك، يورك، المملكة المتحدة. مركز أبحاث العلوم البيئية والإيكولوجية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، بكين، الصين. البريد الإلكتروني:peyman.babakhani@manchester.ac.uk

Journal: Nature Geoscience, Volume: 18, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822308

Publication Date: 2025-01-01

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822308

Publication Date: 2025-01-01

Preservation of organic carbon in marine sediments sustained by sorption and transformation processes

Received: 2 May 2023

Accepted: 29 October 2024

Published online: 3 January 2025

Check for updates

Accepted: 29 October 2024

Published online: 3 January 2025

Check for updates

Controls on organic carbon preservation in marine sediments remain controversial but crucial for understanding past and future climate dynamics. Here we develop a conceptual-mathematical model to determine the key processes for the preservation of organic carbon. The model considers the major processes involved in the breakdown of organic carbon, including dissolved organic carbon hydrolysis, mixing, remineralization, mineral sorption and molecular transformation. This allows redefining of burial efficiency as preservation efficiency, which considers both particulate organic carbon and mineral-phase organic carbon. We show that preservation efficiency is almost three times higher than the conventionally defined burial efficiency and reconciles predictions with global field data. Kinetic sorption and transformation are the dominant controls on organic carbon preservation. We conclude that a synergistic effect between kinetic sorption and molecular transformation (geopolymerization) creates a mineral shuttle in which mineral-phase organic carbon is protected from remineralization in the surface sediment and released at depth. The results explain why transformed organic carbon persists over long timescales and increases with depth.

The preservation of organic carbon (OC) in marine sediments is critical to the global carbon and oxygen cycles and, thus, to Earth’s climate and atmospheric composition

carbon preservation

carbon preservation

Fig. 1| Conceptual model for DOC cycling in sediments. The proposed conceptual model incorporates mechanisms of geopolymerization, equilibrium adsorption and kinetic sorption and a modified concept of hydrolysis that follows DOC cycling in the water column

at any depth in the sediment or remain unhydrolysed. Their transport in the sediment is similar to the sediment solid minerals. MOC pools are transported similarly to sediment solid minerals and POC, but they originate from the net sorption of DOC, GPS and IrDOC to minerals and are further assumed to be unreactive unless the carbon is desorbed from minerals. Part of the POC, which is not hydrolysed at a given depth, and part of the MOC, which is not desorbed at that depth, are considered to be permanently buried.

at any depth in the sediment or remain unhydrolysed. Their transport in the sediment is similar to the sediment solid minerals. MOC pools are transported similarly to sediment solid minerals and POC, but they originate from the net sorption of DOC, GPS and IrDOC to minerals and are further assumed to be unreactive unless the carbon is desorbed from minerals. Part of the POC, which is not hydrolysed at a given depth, and part of the MOC, which is not desorbed at that depth, are considered to be permanently buried.

So far, the contributions of these processes to OC preservation and, thus, carbon cycling have received relatively little attention and are poorly known. Moreover, the conventional concept of OC burial efficiency (BE) in sediments-an indicator of the potential to preserve carbon and quantify global budgets of carbon in modern and ancient sediments

Here, we develop a mechanistic reaction-transport model (RTM) that considers the key processes of OC preservation in marine sediments via DOC cycling. After extensive validation, the model is used alongside Monte Carlo and artificial neural network (ANN) analyses to provide global insights into the role of the processes controlling carbon preservation in marine sediments and show where and how preservation occurs.

Conceptualizing carbon cycling and preservation in sediments

Our conceptual model for carbon cycling and preservation in sediments begins with the hydrolysis of several discrete POC fractions (

via a direct transfer of

via a direct transfer of

We incorporate our conceptual model (Fig. 1) into a vertically resolved RTM for marine sediments that couples transport processes (for example, sediment burial velocity before compaction, and bioturbation mixing)

Fig. 2 | Comparing model-generated PE with literature data. a,b, Data generated for 1,450 model runs in a Monte Carlo approach (transparent black dots) for the conventional approach to calculate PE of POC that considers only POC (a) and for the newly defined PE that considers both POC and MOC (b). These are compared with field data from previous studies

within globally relevant ranges (Supplementary Table 1) based on statistical distributions taken from six field-modelling datasets (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) and ten previous studies (Supplementary Table 2) to examine the broader role of different OC preservation processes (Supplementary Fig. 3, stage 1).

We then use the RTM-generated dataset to train an

Model evaluation

The incorporation of MOC into models of PE is compared with the classical approach

Many different factors have been proposed to explain OC preservation in marine sediments

Fig. 3 | The relative importance of different processes. a,b, The relative importance (%) of six processes to PE when MOC is considered in addition to POC (a) and to preservation rates for MOC (b). The six processes are DOC hydrolysis, DOC remineralization, mixing, equilibrium adsorption, kinetic sorption and geopolymerization. The newly defined PE is given by equation (7). The preservation rates for MOC are shown as the rate of MOC formation, which is the sum of net kinetic sorption rates integrated at the depth of

carbon dynamics to be translated into global understanding without the necessity for model fitting to specific sites that may introduce uncertainties related to site-specific conditions.

Our model definition of POC hydrolysis is similar to that considered as POC remineralization elsewhere

The role of different processes in carbon preservation

We quantify the importance of six model processes in controlling key indicators of carbon preservation, including PE and MOC formation rates (or DOC sorption rates). Three processes are traditionally understood to be important for carbon preservation

The results reveal that kinetic sorption is the most important process for PE with a relative importance of

Fig. 4 | Depth profiles obtained from Monte Carlo modelling. a, The ratio of the kinetic sorption rates averaged for 1,450 runs of the Monte Carlo modelling to the desorption rates also averaged for 1,450 model runs at different depths. b, The percentage contribution of the final GPS pool to the total IrDOC production (Fig.1) at different depths. These contributions are averaged for 1,450 runs of the Monte Carlo modelling. The mathematical equations used to produce these plots are presented in Supplementary Section 3. c, The PE (%) for only POC and for both POC and MOC together, demonstrating that MOC increases

calculated PE by a factor of 2.7 at 1 m depth compared with the conventional approach considering only POC. d, POC fluxes and MOC preservation rate. MOC content exceeds POC at a depth of

Previous considerations of DOC sorption in marine sediments have been limited to a simple equilibrium surface adsorption process expressed using a partition coefficient (

Recently, it has been shown that geopolymerization in the form of a Maillard-type condensation reaction through catalysis by dissolved or particulate iron and manganese is a crucial process for benthic DOC

cycling

cycling

How sorption and geopolymerization control OC preservation

We use sediment depth profiles (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Section 3) obtained from the Monte Carlo simulations to provide a broader insight into how different processes control OC preservation. We observe that the mixed layer acts as a shuttle for different DOC pools by protecting them from exposure to oxygen, nutrients and microbial enzymes and, consequently, limiting their rapid remineralization in the mixed layer and delivering them to greater depths (Fig. 4a). We also investigate the pathways of IrDOC production, which show that geopolymerization contributes

We further observe that PE can vary with the sediment depth horizon or age horizon

In conclusion, our results reveal that, aside from conventionally known processes (hydrolysis, mixing and remineralization), kinetic sorption and geopolymerization probably play a major role in OC preservation. Kinetic sorption creates a mineral shuttle that effectively removes DOC from the active surface layer and releases it at depth, while geopolymerization as an age-dependent process renders OC less reactive. Kinetic sorption leads to the formation of a mineral-associated fraction that becomes larger than the POC pool below

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y.

References

- Alcott, L. J., Mills, B. J. W. & Poulton, S. W. Stepwise Earth oxygenation is an inherent property of global biogeochemical cycling. Science 366, 1333-1337 (2019).

- Berner, R. A. Biogeochemical cycles of carbon and sulfur and their effect on atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time. Glob. Planet. Change 1, 97-122 (1989).

- Amon, R. M. W. & Benner, R. Rapid cycling of high-molecular-weight dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nature 369, 549-552 (1994).

- Li, Z., Zhang, Y. G., Torres, M. & Mills, B. J. W. Neogene burial of organic carbon in the global ocean. Nature 613, 90-95 (2023).

- Abelson, P. H. Organic matter in the Earth’s crust. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 6, 325-351 (1978).

- Hatcher, P. G., Spiker, E. C., Szeverenyi, N. M. & Maciel, G. E. Selective preservation and origin of petroleum-forming aquatic kerogen. Nature 305, 498-501 (1983).

- Smetacek, V. et al. Deep carbon export from a Southern Ocean iron-fertilized diatom bloom. Nature 487, 313-319 (2012).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Potential use of engineered nanoparticles in ocean fertilization for large-scale atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1342-1351 (2022).

- Arndt, S. et al. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: a review and synthesis. Earth Sci. Rev. 123, 53-86 (2013).

- Kleber, M. et al. Dynamic interactions at the mineral-organic matter interface. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 402-421 (2021).

- Burd, A. B. et al. Assessing the apparent imbalance between geochemical and biochemical indicators of meso-and bathypelagic biological activity: what the @$#! is wrong with present calculations of carbon budgets? Deep Sea Res. Part II 57, 1557-1571 (2010).

- Burdige, D. J. Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments: controls, mechanisms, and an imbalance in sediment organic carbon budgets? Chem. Rev. 107, 467-485 (2007).

- Burdige, D. J. & Komada, T. in Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter (eds Hansell, D. A. & Carlson, C. A.) 535-577 (Elsevier, 2015).

- Burdige, D. J., Komada, T., Magen, C. & Chanton, J. P. Modeling studies of dissolved organic matter cycling in Santa Barbara Basin (CA, USA) sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 195, 100-119 (2016).

- Burdige, D. J., Berelson, W. M., Coale, K. H., McManus, J. & Johnson, K. S. Fluxes of dissolved organic carbon from California continental margin sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 1507-1515 (1999).

- Keil, R. G., Montluçon, D. B., Prahl, F. G. & Hedges, J. I. Sorptive preservation of labile organic matter in marine sediments. Nature 370, 549-552 (1994).

- Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., Ouellet, A. & Gélinas, Y. Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron. Nature 483, 198-200 (2012).

- Hemingway, J. D. et al. Mineral protection regulates long-term global preservation of natural organic carbon. Nature 570, 228-231 (2019).

- Hedges, J. I. & Keil, R. G. Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis. Mar. Chem. 49, 81-115 (1995).

- Dittmar, T. et al. Enigmatic persistence of dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 570-583 (2021).

- Moore, O. W. et al. Long-term organic carbon preservation enhanced by iron and manganese. Nature 621, 312-317 (2023).

- Arrieta, J. M. et al. Dilution limits dissolved organic carbon utilization in the deep ocean. Science 348, 331-333 (2015).

- Middelburg, J. J. Escape by dilution. Science 348, 290-290 (2015).

- Hansell, D. A. Recalcitrant dissolved organic carbon fractions. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 421-445 (2013).

- Sexton, P. F. et al. Eocene global warming events driven by ventilation of oceanic dissolved organic carbon. Nature 471, 349-352 (2011).

- Lenton, T. M., Daines, S. J. & Mills, B. J. W. COPSE reloaded: an improved model of biogeochemical cycling over Phanerozoic time. Earth Sci. Rev. 178, 1-28 (2018).

- Katsev, S. & Crowe, S. A. Organic carbon burial efficiencies in sediments: the power law of mineralization revisited. Geology 43, 607-610 (2015).

- Bradley, J. A., Hülse, D., LaRowe, D. E. & Arndt, S. Transfer efficiency of organic carbon in marine sediments. Nat. Commun. 13, 7297 (2022).

- Hedges, J. I. The formation and clay mineral reactions of melanoidins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 69-76 (1978).

- Schrumpf, M. et al. Storage and stability of organic carbon in soils as related to depth, occlusion within aggregates, and attachment to minerals. Biogeosciences 10, 1675-1691 (2013).

- Mayer, L. M. The inertness of being organic. Mar. Chem. 92, 135-140 (2004).

- Henrichs, S. M. & Sugai, S. F. Adsorption of amino acids and glucose by sediments of Resurrection Bay, Alaska, USA: functional group effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 823-835 (1993).

- Henrichs, S. M. Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis-a comment. Mar. Chem. 49, 127-136 (1995).

- Dale, A. W. et al. A revised global estimate of dissolved iron fluxes from marine sediments. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 691-707 (2015).

- Babakhani, P., Bridge, J., Doong, R. A. & Phenrat, T. Parameterization and prediction of nanoparticle transport in porous media: a reanalysis using artificial neural network. Water Resour. Res. 53, 4564-4585 (2017).

- Canfield, D. E. Factors influencing organic carbon preservation in marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 114, 315-329 (1994).

- Boudreau, B. P. Diagenetic Models and Their Implementation Vol. 410 (Springer, 1997).

- Berner, R. A. Inclusion of adsorption in the modelling of early diagenesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 29, 333-340 (1976).

- Sohma, A., Sekiguchi, Y. & Nakata, K. Modeling and evaluating the ecosystem of sea-grass beds, shallow waters without sea-grass, and an oxygen-depleted offshore area. J. Mar. Syst. 45, 105-142 (2004).

- Mayer, L. M. Surface area control of organic carbon accumulation in continental shelf sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 1271-1284 (1994).

- Lee, C. Kitty litter for carbon control. Nature 370, 503-504 (1994).

- Mayer, L. M. Relationships between mineral surfaces and organic carbon concentrations in soils and sediments. Chem. Geol. 114, 347-363 (1993).

- Keil, R. G. & Mayer, L. M. in Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn (eds Holland H. D. & Turekian K. K.) 337-359 (Elsevier, 2014).

- Rothman, D. H. & Forney, D. C. Physical model for the decay and preservation of marine organic carbon. Science 316, 1325-1328 (2007).

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/.

(c) The Author(s) 2025

(c) The Author(s) 2025

Methods

Methodology

Overview of the modelling procedure. A RTM is developed to consider the cycling and preservation of DOC in marine sediment. This RTM is then emulated with artificial intelligence, which is used as a tool for conducting a robust process importance analysis. The flowchart of the model deployment is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The artificial intelligence technique we use in this study is an ANN, and the RTM is emulated with ANN through a Monte Carlo approach (Supplementary Fig. 3, stage 1), whereby the RTM is executed multiple times (for example,

Among the 68 unknown input parameters of the model, we obtain the ranges and statistical distributions for 6 of the input parameters, including water depth

Formulation of the RTM. The RTM considers all common early diagenesis reactions for different compounds including dissolved species (

The three governing equations of RTM for dissolved species, particulate species and sorbed species, respectively, are as follows, while the full details of the model development and validation are provided

in Supplementary Sections 1 and 2:

(1) The governing equation for dissolved species:

in Supplementary Sections 1 and 2:

(1) The governing equation for dissolved species:

(2) The governing equation for particulate species:

(3) The governing equation for mineral phase, MOC , resulting from the kinetically sorbed fraction of dissolved species:

where

The first stage of the hydrolysis is considered similar to the conventional first-order multi-POC degradation model known as the multi-G model

where

The sequential stage of the hydrolysis has been described using a consecutive first-order reaction expression

where

The same mathematical formula is used to describe geopolymerization

Calculation of PE. PE, elsewhere known as BE, conventionally considered for

where

The sorption rate is the net DOC kinetic sorption rate (sorption rate minus desorption rate or the net MOC formation rate). Further explanations about the rates are provided in Supplementary Sections 2.4 and 3. Although the consideration of depth-versus-age horizons in early digenesis modelling can be important for global predictions, as was recently highlighted

ANN for process importance analysis. The ANN is a versatile and universal tool for function approximation problems and is notable for its application to complex, nonlinear systems

Model validation. We validate our model in a number of ways. We validate our developed governing equations of the RTM on the basis of an analytical approach. In this approach, for the condition where equilibrium adsorption and kinetic sorption are expected to behave similarly, that is, at high exchange rates, we first run the model after turning off equilibrium adsorption and then run the model again turning off the kinetic sorption expression. Then, the model outputs for these two types of simulation are compared. We used existing field-modelling data (principally from Santa Barbara Basin, given the comprehensive

dataset available)

dataset available)

The results of the model output comparison between the cases when kinetic sorption is operative and when the equilibrium adsorption is operative at a high mass transfer rate show an excellent match (

The results of the model fit to several field or modelling datasets, including Meysman et al.

The ANN model could fit the data in all cases with the best predictive fit Nash-Sutcliffe model efficiency criterion

The mass budgets for different cross-sections of the simplified conceptual model shown in Supplementary Fig. 14 were calculated on the basis of averaged results of all Monte Carlo model runs

It should be noted that limitation in the capacity of sorption sites, for example, monolayer sorption

applicable to our MOC production. Furthermore, kinetic sorption is slower than equilibrium adsorption, which is known to be instantaneous. Thus, kinetic sorption, which is limited by pore water concentrations that are also controlled by hydrolysis, degradation and so on, is less likely to face a second limitation by the capacity of sorption sites compared with instantaneous equilibrium adsorption for which different types of isotherm, such as linear, Langmuir and Freundlich, have been defined

applicable to our MOC production. Furthermore, kinetic sorption is slower than equilibrium adsorption, which is known to be instantaneous. Thus, kinetic sorption, which is limited by pore water concentrations that are also controlled by hydrolysis, degradation and so on, is less likely to face a second limitation by the capacity of sorption sites compared with instantaneous equilibrium adsorption for which different types of isotherm, such as linear, Langmuir and Freundlich, have been defined

Data availability

Data associated with Figs. 2-4 are available via figshare at https://doi. org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273006 (ref. 68). Data related to Supplementary Figs.13,15 and 16 and the main datasets (such as those generated by RTM through the Monte Carlo process (stage1) and used in the ANN process importance analysis (stage 2)) are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273030 (ref. 69).

Code availability

Computer codes are available from the authors upon request.

References

- Burwicz, E. B., Rüpke, L. H. & Wallmann, K. Estimation of the global amount of submarine gas hydrates formed via microbial methane formation based on numerical reaction-transport modeling and a novel parameterization of Holocene sedimentation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 4562-4576 (2011).

- Restreppo, G. A., Wood, W. T. & Phrampus, B. J. Oceanic sediment accumulation rates predicted via machine learning algorithm: towards sediment characterization on a global scale. Geo-Mar. Lett. 40, 755-763 (2020).

- Lee, T. R., Wood, W. T. & Phrampus, B. J. A machine learning (kNN) approach to predicting global seafloor total organic carbon. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 37-46 (2019).

- WOA18 Data Access (National Centers for Environmental Information, 2018); https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa18/woa18data.html

- Bohlen, L., Dale, A. W. & Wallmann, K. Simple transfer functions for calculating benthic fixed nitrogen losses and C:N:P regeneration ratios in global biogeochemical models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3029 (2012).

- Burdige, D. J., Komada, T., Magen, C. & Chanton, J. P. Methane dynamics in Santa Barbara Basin (USA) sediments as examined with a reaction-transport model. J. Mar. Res. 74, 277-313 (2016).

- Jørgensen, B. B. A comparison of methods for the quantification of bacterial sulfate reduction in coastal marine sediments: I. Measurement with radiotracer techniques. Geomicrobiol. J. 1, 11-27 (1978).

- Bradley, J. A. et al. Widespread energy limitation to life in global subseafloor sediments. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0697 (2020).

- Rogalinski, T., Liu, K., Albrecht, T. & Brunner, G. Hydrolysis kinetics of biopolymers in subcritical water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 46, 335-341 (2008).

- Leong, L. P. & Wedzicha, B. L. A critical appraisal of the kinetic model for the Maillard browning of glucose with glycine. Food Chem. 68, 21-28 (2000).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Comparison of a new mass-concentration, chain-reaction model with the population-balance model for early-and late-stage aggregation of shattered graphene oxide nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A 582, 123862 (2019).

- McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115-133 (1943).

- Yu, H. et al. Prediction of the particle size distribution parameters in a high shear granulation process using a key parameter definition combined artificial neural network model. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 10825-10834 (2015).

- Nourani, V. & Sayyah-Fard, M. Sensitivity analysis of the artificial neural network outputs in simulation of the evaporation process at different climatologic regimes. Adv. Eng. Softw. 47, 127-146 (2012).

- Gevrey, M., Dimopoulos, I. & Lek, S. Two-way interaction of input variables in the sensitivity analysis of neural network models. Ecol. Modell. 195, 43-50 (2006).

- Yerramareddy, S., Lu, S. C. Y. & Arnold, K. F. Developing empirical models from observational data using artificial neural networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 4, 33-41 (1993).

- Gevrey, M., Dimopoulos, I. & Lek, S. Review and comparison of methods to study the contribution of variables in artificial neural network models. Ecol. Modell. 160, 249-264 (2003).

- Meysman, F. J. R., Middelburg, J. J., Herman, P. M. J. & Heip, C. H. R. Reactive transport in surface sediments. II. Media: an object-oriented problem-solving environment for early diagenesis. Comput. Geosci. 29, 301-318 (2003).

- Kraal, P., Slomp, C. P., Reed, D. C., Reichart, G. J. & Poulton, S. W. Sedimentary phosphorus and iron cycling in and below the oxygen minimum zone of the northern Arabian Sea. Biogeosciences 9, 2603-2624 (2012).

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Autom. Control IEEE Trans. 19, 716-723 (1974).

- Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—a discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282-290 (1970).

- Clark, M. M. Transport Modeling for Environmental Engineers and Scientists (Wiley, 2011).

- Langmuir, D. Aqueous Environmental Geochemistry (Prentice Hall, 1997).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Babakhani_etal_main_text_figure_source_ data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273006 (2024).

- Babakhani, P. et al. Babakhani_etal_supplementary_data. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 27273030 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge D. Burdige for sending field data and B. Mills for helpful discussion and review of an earlier version of our paper. The use of High-Performance Computing (ARC) facilities at the University of Leeds is acknowledged. We acknowledge funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 725613 MinOrg). C.L.P. gratefully acknowledges the Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award (WRM/FT/170005) and Leverhulme Research Fellowship (RF-2023-3954).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: P.B., C.L.P. and A.W.D. Data curation: P.B., C.L.P. and A.W.D. Formal analysis: P.B. Investigation: P.B. Methodology: P.B., A.W.D. and C.L.P. Visualization: P.B. Funding acquisition: C.L.P. Project administration: C.L.P. Resources: C.L.P. Software: P.B. and A.W.D. Supervision: C.L.P., A.W.D. and C.W. Validation: P.B., A.W.D., C.L.P. and K.-Q.X. Writing—original draft: P.B. Writing—review and editing: P.B., C.L.P., A.W.D., C.W., O.W.M., K.-Q.X. and L.C.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information Nature Geoscience thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Xujia Jiang, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01606-y.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Peyman Babakhani.

School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. Department of Civil Engineering and Management, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Kiel, Germany. School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. Department of Environment and Geography, University of York, York, UK. Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. e-mail: peyman.babakhani@manchester.ac.uk