DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05526-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38279114

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-26

الدعم الاجتماعي، مرونة الأسرة والمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى غسيل الكلى: دراسة طولية

الملخص

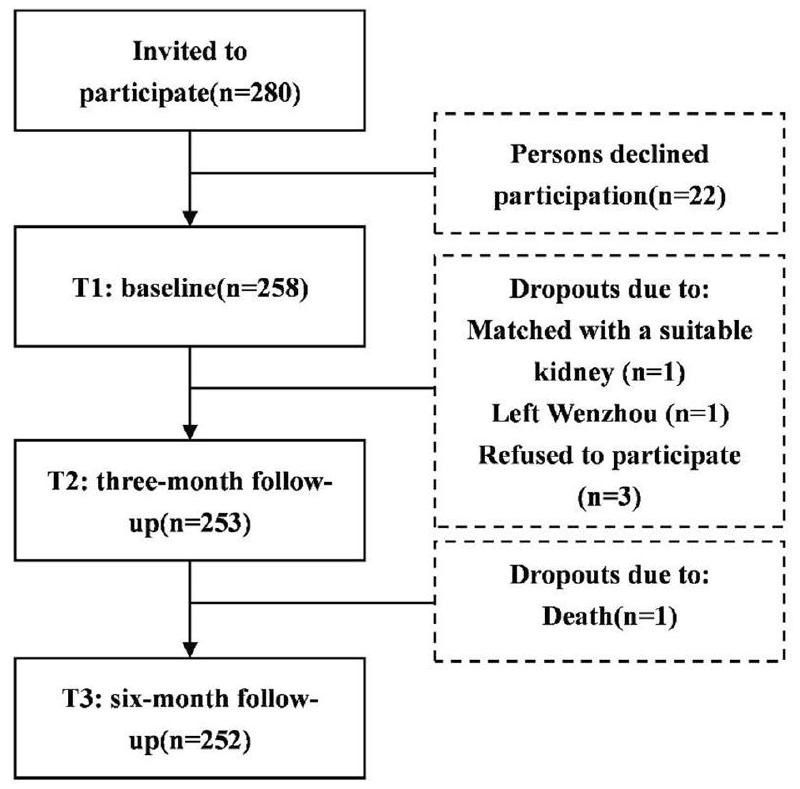

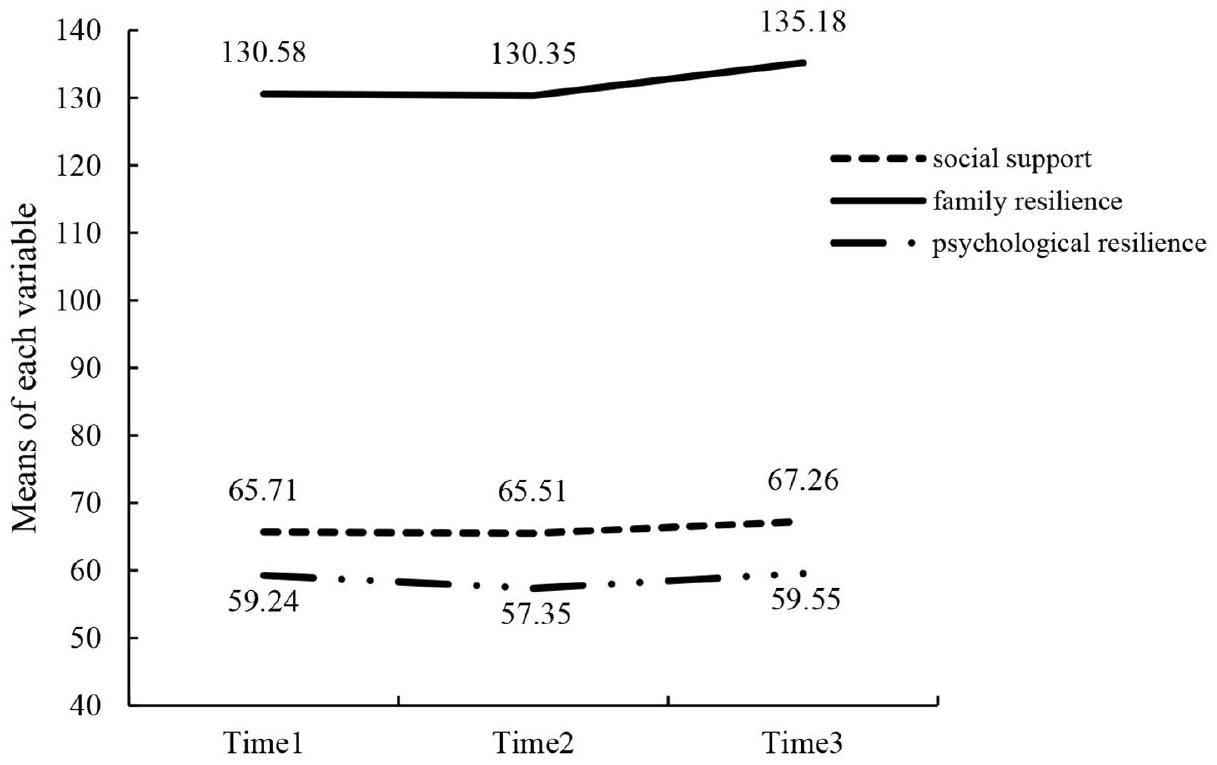

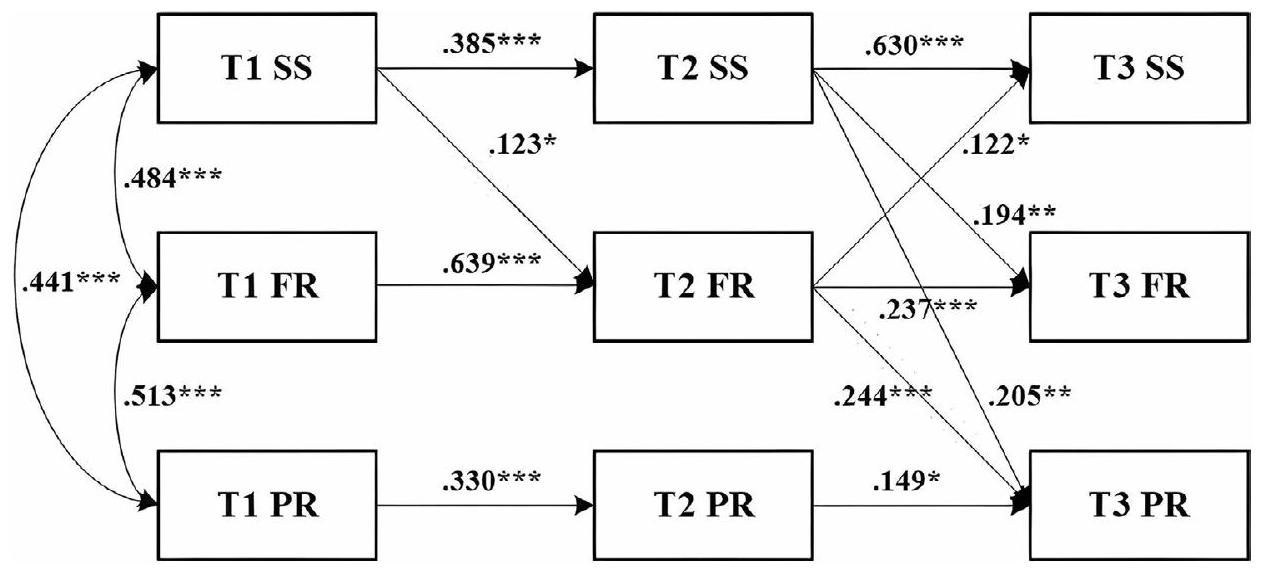

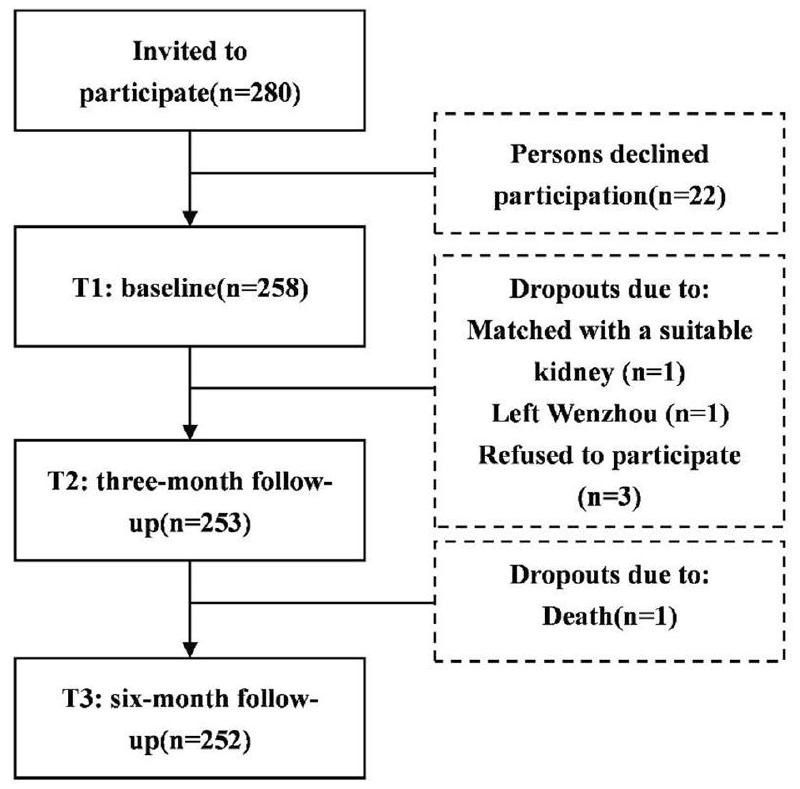

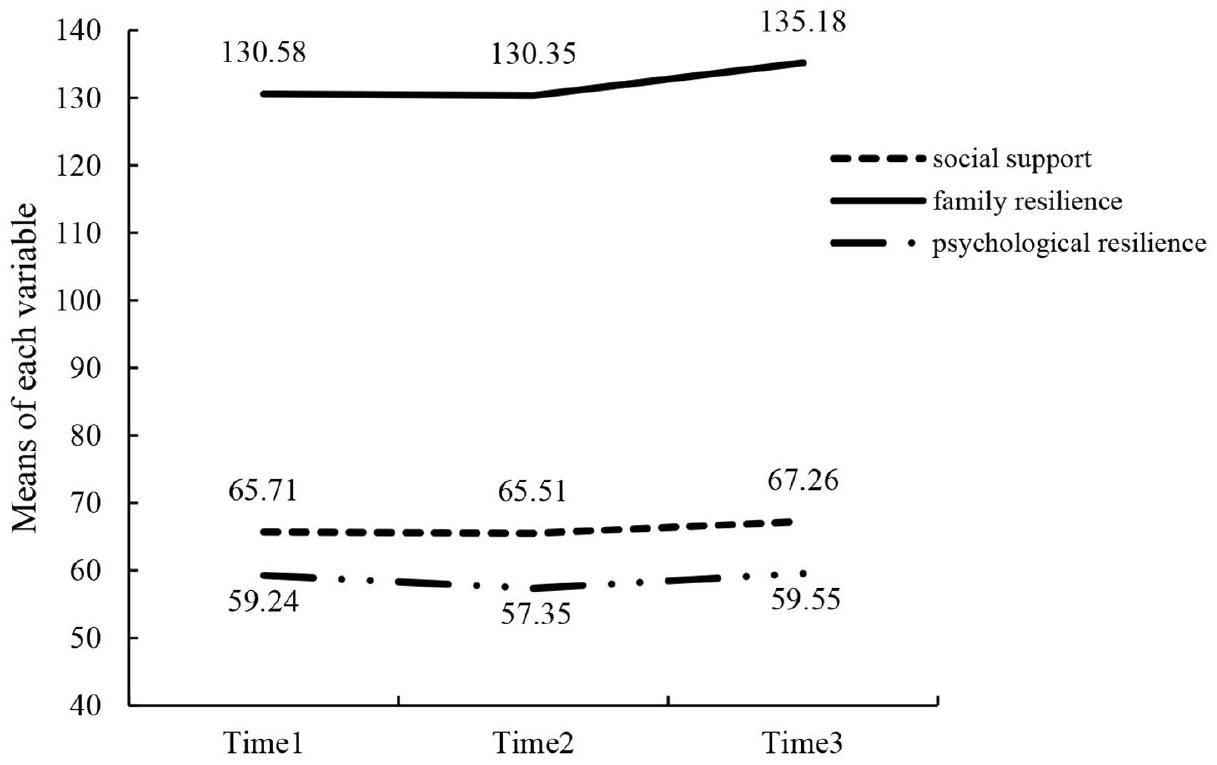

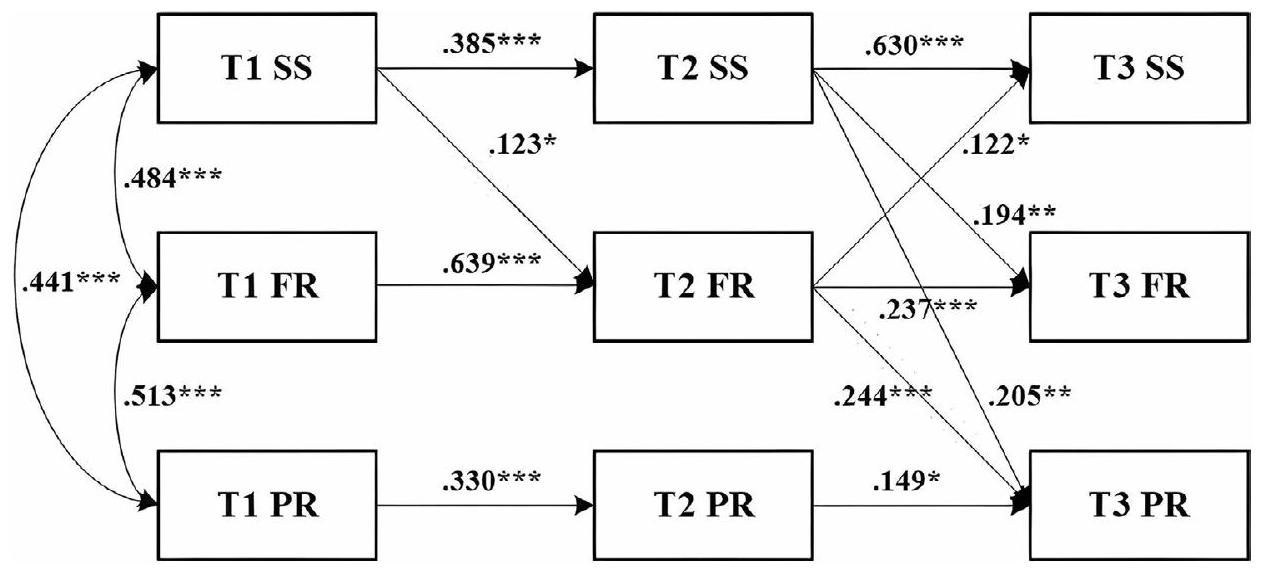

الخلفية: الضغوط النفسية شائعة بين مرضى غسيل الكلى، ويمكن أن تعزز المرونة النفسية العالية الرفاهية النفسية. تركز الأبحاث الحالية على عوامل الحماية للمرونة النفسية مثل مرونة الأسرة والدعم الاجتماعي. ومع ذلك، لم يتم استكشاف مسارات المرونة النفسية ومرونة الأسرة والدعم الاجتماعي بمرور الوقت وعلاقاتها الطولية بين مرضى غسيل الكلى بشكل كامل بعد. لذلك، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استكشاف العلاقة الطولية بين هذه العوامل. الطرق: تم تجنيد المرضى الذين تلقوا علاج غسيل الكلى المنتظم لأكثر من ثلاثة أشهر في مراكز غسيل الكلى في ثلاثة مستشفيات تعليمية في تشجيانغ، الصين، من سبتمبر إلى ديسمبر 2020. أكمل 252 مريضًا استوفوا معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد ثلاثة استبيانات متابعة، بما في ذلك تقييمات الدعم الاجتماعي ومرونة الأسرة والمرونة النفسية. تم استخدام تحليل التباين المقيس المتكرر لاستكشاف الفروق في درجاتهم في نقاط زمنية مختلفة. تم إجراء التحليل المتقاطع المتأخر في AMOS باستخدام طريقة الاحتمالية القصوى لفحص العلاقات التنبؤية المتبادلة بين هذه العوامل. النتائج: ظل الدعم الاجتماعي والمرونة النفسية مستقرين نسبيًا بمرور الوقت، بينما أظهرت مرونة الأسرة اتجاهًا طفيفًا نحو الزيادة. وفقًا للتحليل المتقاطع المتأخر، توقع دعم اجتماعي أعلى في T1 مرونة أسرية أعلى في T2 [

الكلمات الرئيسية: غسيل الكلى المنتظم، الدعم الاجتماعي، مرونة الأسرة، المرونة النفسية، التحليل المتقاطع المتأخر، دراسة طولية

الخلفية

مما يشير إلى أنه من الضروري تحسين المرونة النفسية لمرضى MHD. وبالتالي، هناك حاجة لاستكشاف عوامل الحماية للمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى MHD من أجل تعزيز حالتهم النفسية وجودة حياتهم.

طرق

تصميم الدراسة والمكان

المشاركون

الإجراء

في المستشفى، استخدمت الدراسة نفس النهج لجمع بيانات المتابعة في المستشفى. تم تضمين المرضى الذين أكملوا جميع الموجات الثلاث من الاستطلاع فقط في تحليل البيانات. تلتزم الدراسة بإرشادات تعزيز تقارير الدراسات الرصدية في علم الأوبئة (STROBE) للبحث الرصدي (الملف الإضافي 1).

القياسات

الدعم الاجتماعي

مرونة الأسرة

المرونة النفسية

المتغيرات المشتركة

تحليل البيانات

M1 – نموذج أساسي مع مسارات ذاتية الانحدار وارتباطات عرضية؛

M2 – نموذج يحتوي على مسارات متقاطعة من الدعم الاجتماعي السابق والمرونة النفسية إلى المرونة الأسرية اللاحقة، الذي درس الدعم الاجتماعي والمرونة النفسية كمؤشرات للمرونة الأسرية؛

M3 – نموذج يحتوي على مسارات متقاطعة من المرونة الأسرية السابقة إلى الدعم الاجتماعي والمرونة النفسية اللاحقة، حيث تم فحص المرونة الأسرية كعوامل متنبئة بالدعم الاجتماعي والمرونة النفسية؛

نموذج M 4-A الذي درس العلاقات الثنائية الاتجاه بين الدعم الاجتماعي ومرونة الأسرة،

أو بين مرونة الأسرة والمرونة النفسية.

نموذج M 5-A الكامل الذي يحتوي على جميع المسارات التي افترضناها والتي تفحص العلاقات الثنائية الاتجاه بين الدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، والمرونة النفسية.

الاعتبارات الأخلاقية

النتائج

خصائص المشاركين والاختلافات في الدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، والمرونة النفسية

الدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، ومرونة الصحة النفسية لمرضى الاضطرابات النفسية في ثلاث موجات

العلاقة بين الدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، والمرونة النفسية

تحليلات المسارات المتقاطعة للدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، والمرونة النفسية

| متغير | ن(%) | الدعم الاجتماعي | ت/ف |

|

مرونة الأسرة | ت/ف |

|

المرونة النفسية | ت/ف |

|

| عمر | ||||||||||

| <60 | 129 (51.2%) |

|

|

0.786 |

|

|

0.916 |

|

|

0.063 |

|

|

123(48.8%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| جنس | ||||||||||

| ذكر | 169 (67.2%) |

|

|

0.348 |

|

|

0.850 |

|

|

0.141 |

| أنثى | 83 (32.9%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| حالة التوظيف | ||||||||||

| موظف | ٤٥ (١٧.٩٪) |

|

|

0.004 |

|

|

0.036 |

|

|

0.000 |

| عاطل عن العمل | 207 (82.1%) |

|

||||||||

| المعتقد الديني | ||||||||||

| لا | ١٢٢ (٤٨.٤٪) |

|

|

0.665 |

|

|

0.428 |

|

|

0.941 |

| نعم | 130 (51.6%) |

|

|

|||||||

| مستوى التعليم | ||||||||||

| المدرسة الابتدائية وما دون | 68(27%) |

|

|

0.001 |

|

|

0.045 |

|

|

0.000 |

| المدرسة المتوسطة | 96 (38.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| المدرسة الثانوية | 57 (22.6%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الكلية أو أعلى | 31 (12.3%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الدخل الشهري للأسرة للفرد | ||||||||||

| <2,000 يوان | ٣٦ (١٤.٣٪) |

|

|

0.006 |

|

|

0.110 |

|

|

0.000 |

| 2,000-4,000 يوان | 91 (36.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 4,001-6,000 يوان | 74 (29.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| أكثر من 6,000 يوان | 51 (20.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الحالة الاجتماعية | ||||||||||

| أعزب/مطلق/أرملة/مفصول | 29(11.5%) |

|

|

0.000 |

|

|

0.378 |

|

t=-2.096 | 0.037 |

| متزوج/يعيش معاً | ٢٢٣(٨٨.٥) |

|

|

|

||||||

| التأمين الطبي | ||||||||||

| لا | 5(2%) |

|

|

0.487 |

|

ت = -1.243 | 0.215 |

|

ت = -1.639 | 0.173 |

| نعم | 247(98%) |

|

|

|||||||

| مدة المرض | ||||||||||

| <1 سنة | 13(5.2%) |

|

|

0.413 |

|

|

0.928 |

|

|

0.611 |

| 1~<5 سنوات | 51(20.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 5~<10 سنوات | 54 (21.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

134 (53.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| مدة غسيل الكلى | ||||||||||

| <1 سنة | 48 (19%) |

|

|

0.029 |

|

|

0.643 |

|

|

0.071 |

| 1~<5 سنوات | 106 (42.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 5~<10 سنوات | 64 (25.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

34 (13.5%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الأمراض المصاحبة | ||||||||||

| لا | 75 (29.8%) |

|

|

0.971 |

|

|

0.910 |

|

|

0.839 |

| واحد | 117 (46.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| اثنان أو أكثر | 60 (23.8%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| مقدمو الرعاية الأساسيون | ||||||||||

| زوج | 208 (82.5%) |

|

|

0.031 |

|

|

0.004 |

|

|

0.225 |

| نسل | 6(2.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| الآباء | 23 (9.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| أخ” أو “أخت | 15(6%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| متغير | الوقت 1 | الوقت 2 | الوقت 3 |

| الدعم الاجتماعي | |||

| إجمالي |

|

|

|

| دعم ملموس |

|

|

|

| الدعم المعلوماتي/العاطفي |

|

|

|

| الدعم التفاعلي الاجتماعي |

|

|

|

| دعم حنون |

|

|

|

| مرونة الأسرة | |||

| إجمالي |

|

|

|

| التواصل الأسري وحل المشكلات |

|

|

|

| استخدام الموارد الاجتماعية والاقتصادية |

|

|

|

| الحفاظ على نظرة إيجابية |

|

|

|

| القدرة على فهم المعاناة |

|

|

|

| المرونة النفسية | |||

| إجمالي |

|

|

|

| الإصرار |

|

|

|

| قوة |

|

|

|

| التفاؤل |

|

|

|

أظهرت النتائج أن مستويات أعلى من الدعم الاجتماعي

نقاش

استقرار وتطور الدعم الاجتماعي، ومرونة الأسرة، والمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى الاضطرابات النفسية والعقلية

| متغير | الدعم الاجتماعي T1 | مرونة عائلة T1 | المرونة النفسية T1 | الدعم الاجتماعي T2 | مرونة عائلة T2 | المرونة النفسية T2 | الدعم الاجتماعي T3 | مرونة عائلة T3 |

| الدعم الاجتماعي T1 | 1 | |||||||

| مرونة عائلة T1 | 0.484** | 1 | ||||||

| المرونة النفسية T1 | 0.486** | 0.551** | 1 | |||||

| الدعم الاجتماعي T2 | 0.390** | 0.195** | 0.177** | 1 | ||||

| مرونة عائلة T2 |

|

0.706** | 0.433** | 0.256** | 1 | |||

| المرونة النفسية T2 | 0.278** | 0.244** | 0.390** | 0.520** | 0.225** | 1 | ||

| الدعم الاجتماعي T3 | 0.327** | 0.135* | 0.084 | 0.684** | 0.284** | 0.390** | 1 | |

| مرونة عائلة T3 | 0.169** | 0.156* | 0.064 | 0.273** | 0.294** | 0.181** | 0.446** | 1 |

| المرونة النفسية T3 | 0.263** | 0.203** | 0.169** |

|

0.319** | 0.298** | 0.493** | 0.552** |

| نموذج |

|

df |

|

CFI | تي إل آي | RMSEA | SRMR | مقارنة النماذج |

|

|

| M1 | 63.799 | ٢٥ | ٢.٥٥٢ | 0.957 | 0.888 | 0.079 | 0.081 | – | – | – |

| M2 | ٥٩.٤٥٣ | ٢٤ | ٢.٤٧٧ | 0.961 | 0.893 | 0.077 | 0.075 | M2 مقابل M1 | 4.35(1) | <0.05 |

| M3 | ٥٥.٦٦٣ | 23 | ٢.٤٢٠ | 0.964 | 0.897 | 0.075 | 0.070 | M3 مقابل M2 | 3.79(1) | >0.05 |

| M4 | ٥٥٫٢٤٢ | 23 | 2.402 | 0.965 | 0.899 | 0.075 | 0.068 | M4 مقابل M2 | 4.211(1) | <0.05 |

| M5 | ٤٤.٨٠١ | 19 | 2.358 | 0.972 | 0.902 | 0.074 | 0.065 | M5 مقابل M4 | 10.441(4) | <0.05 |

العلاقة بين الدعم الاجتماعي ومرونة الأسرة والمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى الغسيل الكلوي. العلاقة بين الدعم الاجتماعي ومرونة الأسرة لدى مرضى الغسيل الكلوي.

موارد مهمة قد تؤثر على قدرة الأسر على التحمل والإدارة في ظل وجود أزمة. وبالمثل، وجد وونغ وآخرون أن “استمداد القوة” كان عاملاً رئيسياً في تعزيز مرونة الأسرة لدى مرضى وحدة العناية المركزة. أي أن أسر مرضى العناية المركزة حصلت على الدعم العاطفي والمعلوماتي من أفراد أسرهم وأسر مرضى آخرين في حالة حرجة للتخلص من الضعف العاطفي العالي واستعادة السيطرة، مما زاد من مرونة الأسرة. ومع ذلك، تنص نظرية ضغط الأسرة على أن إدراك الأسرة للحدث المجهد والموارد المتاحة لها سيحدد كيفية تفاعل ضغط الأسرة وقدرة الأسرة. وهذا يعني أنه، بالإضافة إلى الدعم الاجتماعي، تؤثر عوامل أخرى مثل التقييم المعرفي للأسرة للأزمة على العملية الديناميكية لمرونة الأسرة. يمكن أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية بشكل منهجي الآليات التي تؤثر بها عوامل مثل إدراك الأسرة على مرونة الأسرة، نظرًا لأن تأثير هذه الجوانب لم يؤخذ في الاعتبار في هذه الدراسة.

العلاقة بين الدعم الاجتماعي والمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى الاضطرابات النفسية

أشير إلى أن الدعم من الأقران كان موردًا محتملاً يمكن أن يوفر دعمًا عاطفيًا إضافيًا ومساعدة معلوماتية لمرضى غسيل الكلى، بينما يعزز من كفاءتهم الذاتية وإدارة أنفسهم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قلل الدعم الاجتماعي التفاعلي من العبء بين المرضى أثناء غسيل الكلى وأدى إلى نتائج سريرية أفضل وتكيف نفسي اجتماعي [59]، مدعومًا بتعزيز المرونة لتقليل المعاناة.

العلاقة بين مرونة الأسرة والمرونة النفسية لدى مرضى الاضطرابات النفسية

آليات ديناميكية للتأثير على المرونة النفسية لمجموعة متنوعة من العوامل، مثل عوامل المرض والعبء النفسي.

الملاءمة للممارسة السريرية

القيود

الاستنتاجات

| اختصارات | |

| الفشل الكلوي النهائي | مرض الكلى في المرحلة النهائية |

| MHD | غسيل الكلى الصيانة |

| ستروب | تعزيز تقارير الدراسات الرصدية في علم الأوبئة |

| موس-ساس | استطلاع دعم المجتمع في دراسة النتائج الطبية |

| سي-فراس | النسخة الصينية من مقياس تقييم مرونة الأسرة |

| CD-RISC | مقياس مرونة كونر وديفيدسون |

| SD | الانحراف المعياري |

|

|

مربع كاي/درجات الحرية |

| CFI | مؤشر الملاءمة المقارن |

| TLI | مؤشر تاكر-لويس |

| RMSEA | جذر متوسط مربع خطأ التقريب |

| SRMR | المتوسط الجذري التربيعي المتبقي الموحد |

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 26 يناير 2024

References

- Yang C, Yang Z, Wang J, Wang HY, Su Z, Chen R, et al. Estimation of prevalence of kidney disease treated with Dialysis in China: a study of insurance Claims Data. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(6):889-97. https://doi.org/10.1053/j. ajkd.2020.11.021.

- Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M. Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol (Carlton). 2016;21(3):241-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.12586.

- Liu L, Zhou L, Zhang Q, Zhang H. Mediation effect of self-neglect in family resilience and medication adherence in older patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. J Cent South University(Medical Science). 2023;48(07):1066-75. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2023.230045.

- Zhang L, Zhao MH, Zuo L, Wang Y, Yu F, Zhang H et al. China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET) 2016 Annual Data Report. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2020;10(2):e97-e185https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2020.09.001.

- Global regional. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0140-6736(20)30045-3. and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

- Ibelo U, Green T, Thomas B, Reilly S, King-Shier K. Ethnic Differences in Health Literacy, Self-Efficacy, and self-management in patients treated with maintenance hemodialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022;9:20543581221086685. https://doi.org/10.1177/20543581221086685.

- Gerogianni G, Babatsikou F, Polikandrioti M, Grapsa E. Management of anxiety and depression in haemodialysis patients: the role of non-pharmacological methods. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(1):113-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11255-018-2022-7.

- Liu YM, Chang HJ, Wang RH, Yang LK, Lu KC, Hou YC. Role of resilience and social support in alleviating depression in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:441-51. https://doi.org/10.2147/ tcrm.S152273.

- Lowney AC, Myles HT, Bristowe K, Lowney EL, Shepherd K, Murphy M, et al. Understanding what influences the Health-Related Quality of Life of Hemodialysis patients: a collaborative study in England and Ireland. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):778-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jpainsymman.2015.07.010.

- Ma Y, Yu H, Sun H, Li M, Li L, Qin M. Economic burden of maintenance hemodialysis patients’ families in Nanchong and its influencing factors. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(6):3877-84. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1787.

- Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Farrington K. Depression in end-stage renal disease: current advances and research. Semin Dial. 2010;23(1):74-82. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00628.x.

- Oliveira CM, Costa SP, Costa LC, Pinheiro SM, Lacerda GA, Kubrusly M. Depression in dialysis patients and its association with nutritional markers and quality of life. J Nephrol. 2012;25(6):954-61. https://doi.org/10.5301/jn.5000075.

- Yu X, Zhang J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the ConnorDavidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behav Personality: Int J. 2007;35(1):19-30. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19.

- García-Martínez P, Ballester-Arnal R, Gandhi-Morar K, Castro-Calvo J, GeaCaballero V, Juárez-Vela R, et al. Perceived stress in relation to quality of life and resilience in patients with advanced chronic kidney Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2). https://doi. org/10.3390/ijerph18020536.

- Kumpfer KL. Factors and Processes Contributing to Resilience. Springer US. 2002https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47167-1_9.

- Gebrie MH, Asfaw HM, Bilchut WH, Lindgren H, Wettergren L. Patients’ experience of undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. An interview study from Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(5):e0284422. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone. 0284422.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Encyclopedia of psychology. Volume 3. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 129-33. https://doi.org/10.1037/10518-046.

- Walsh F. Family resilience: a framework for clinical practice. Fam Process. 2003;42(1):1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x.

- Tao L, Zhong T, Hu X, Fu L, Li J. Higher family and individual resilience and lower perceived stress alleviate psychological distress in female breast cancer survivors with fertility intention: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(7):408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07853-w.

- Li Y, Wang K, Yin Y, Li Y, Li S. Relationships between family resilience, breast cancer survivors’ individual resilience, and caregiver burden: a crosssectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;88:79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijnurstu.2018.08.011.

- Dong C, Xu R, Xu L. Relationship of childhood trauma, psychological resilience, and family resilience among undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):852-9. https://doi. org/10.1111/ppc.12626.

- Zhang X, Wang A, Guan T, Zhang Y, Kong YX, Meng J, et al. Caregivers’ caring ability and Disabled Elderly’s Depression:a Chain Mediating Effect Analy-Sis of Family Resilience and Psychological Resilience. Military Nurs. 2023;40(06):437. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2023.06.011.

- Wang H, Wang D, Zhang P. Relationships among Post Traumatic Growth,Resilience and Family Hardiness in Colorectal Cancer patients. Military Nurs. 2018;35(17):33-6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2018.17.008.

- Leve LD, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal transactional models of development and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(3):621-2. https://doi. org/10.1017/s0954579416000201.

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.59.8.676.

- Wilks SE, Croom B. Perceived stress and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: testing moderation and mediation models of social support. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(3):357-65. https://doi. org/10.1080/13607860801933323.

- Costa ALS, Heitkemper MM, Alencar GP, Damiani LP, Silva RMD, Jarrett ME. Social Support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life

and resilience in Brazilian patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(5):352-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc. 0000000000000388. - Sippel LM, Pietrzak RH, Charney DS, Mayes LC, Southwick SM. How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecol Soc. 2015;20:10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07832-200410.

- Ong HL, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Fauziana R, Tan ME, et al. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):27. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1616-z.

- Chen C, Sun X, Liu Z, Jiao M, Wei W, Hu Y. The relationship between resilience and quality of life in advanced cancer survivors: multiple mediating effects of social support and spirituality. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1207097. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1207097.

- Walsh F. A family resilience framework: innovative practice applications. Fam Relat. 2002;51(2):130-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x.

- Zhang Y, Ding Y, Liu C, Li J, Wang Q, Li Y, et al. Relationships among Perceived Social Support, Family Resilience, and Caregiver Burden in Lung Cancer families: a Mediating Model. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2023;39(3):151356. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2022.151356.

- Chen JJ, Wang QL, Li HP, Zhang T, Zhang SS, Zhou MK. Family resilience, perceived social support, and individual resilience in cancer couples: analysis using the actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52:101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101932.

- He Y, Chen SS, Xie GD, Chen LR, Zhang TT, Yuan MY, et al. Bidirectional associations among school bullying, depressive symptoms and sleep problems in adolescents: a cross-lagged longitudinal approach. J Affect Disord. 2022;298(Pt A):590-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.038.

- Galletta M, Vandenberghe C, Portoghese I, Allegrini E, Saiani L, Battistelli A. A cross-lagged analysis of the relationships among workgroup commitment, motivation and proactive work behaviour in nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(6):1148-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12786.

- Martens MP, Haase RF. Advanced Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Counseling Psychology Research. Couns Psychol. 2006;34(6):878-911. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000005283395.

- Boomsma A. The robustness of maximum likelihood estimation in structural equation models. Boomsma A, editor. In: Cuttance P, Ecob R, editors. Structural modeling by example: applications in educational, sociological, and behavioral research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. pp. 160-88.

- Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(2):135-43. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20008.

- Dong C, Gao C, Zhao H. Reliability and validation of Family Resilience Assessment Scale in the families raising children with chronic disease. J Nurs Sci. 2018;33(10):93-7. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2018.10.093.

- Duran S, Avci D, Esim F. Association between spiritual well-being and Resilience among Turkish hemodialysis patients. J Relig Health. 2020;59(6):3097109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01000-z.

- García-Martínez P, Ballester-Arnal R, Gandhi-Morar K, Temprado-Albalat MD, Collado-Boira E, Saus-Ortega C, et al. Factors Associated with Resilience during Long-Term Hemodialysis. Nurs Res. 2023;72(1):58-65. https://doi. org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000627.

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66(4):507-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF02296192.

- Lt H, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Kline P. Handbook of psychological testing. Kline P. editor: Routledge; 2013.

- Norman E. Resiliency enhancement: putting the strength perspective into social work practice. Norman E. editor: Columbia university press; 2000.

- Tian R, Bai Y, Guo Y, Ye P, Luo Y. Association between Sleep Disorders and Cognitive Impairment in Middle Age and older adult hemodialysis patients:

a cross-sectional study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:757453. https://doi. org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.757453. - Pompili M, Venturini P, Montebovi F, Forte A, Palermo M, Lamis DA, et al. Suicide risk in dialysis: review of current literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;46(1):85-108. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.46.1.f.

- Yin Y, Zhou H, Liu M, Liang F, Ru Y, Yang W, et al. Status and influencing factors of social isolation in elderly patients with maintenance hemodialysis. Chin J Nurs. 2023;58(7):822-9. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2023.07.008.

- Costenoble A, Rossi G, Knoop V, Debain A, Smeys C, Bautmans I, et al. Does psychological resilience mediate the relation between daily functioning and prefrailty status? Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s1041610221001058.

- Tamura S, Suzuki K, Ito Y, Fukawa A. Factors related to the resilience and mental health of adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(7):3471-86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05943-7.

- Harding SA. The trajectory of positive psychological change in a head and neck cancer population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(5):578-84. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.09.010.

- Chang PY, Chang TH, Yu JM. Perceived stress and social support needs among primary family caregivers of ICU patients in Taiwan. Heart Lung. 2021;50(4):491-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2021.03.001.

- Lee EY, Neil N, Friesen DC. Support needs, coping, and stress among parents and caregivers of people with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;119:104113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104113.

- Tak YR, McCubbin M. Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(2):190-8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02259.x.

- Wong P, Liamputtong P, Koch S, Rawson H. The impact of Social Support Networks on Family Resilience in an Australian Intensive Care Unit: a Constructivist grounded theory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51(1):68-80. https://doi. org/10.1111/jnu.12443.

- Axelson LJ, Mccubbin HI, Cauble AE, Patterson JM. Family stress, coping and Social Support. Fam Relat. 1982;32(3):452.

- Powathil GG, Kr A. The experience of living with a chronic illness: a qualitative study among end-stage renal disease patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2023;19(3):190-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2023.2229034.

- Bennett PN, St Clair Russell J, Atwal J, Brown L, Schiller B. Patient-to-patient peer mentor support in dialysis: improving the patient experience. Semin Dial. 2018;31(5):455-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12703.

- Silva SM, Braido NF, Ottaviani AC, Gesualdo GD, Zazzetta MS, Orlandi Fde S. Social support of adults and elderly with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:e2752. https://doi. org/10.1590/1518-8345.0411.2752.

- Kukihara H, Yamawaki N, Ando M, Nishio M, Kimura H, Tamura Y. The mediating effect of resilience between family functioning and mental well-being in hemodialysis patients in Japan: a cross-sectional design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01486-x.

- Nam B, Kim JY, DeVylder JE, Song A. Family functioning, resilience, and depression among North Korean refugees. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:451-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.063.

- Chen Y, Cui W, Sun L, Wang Y. Survey of psychological resilience level and coping style in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Chin J Blood Purif. 2016;15(1):55-7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-4091.2016.01.015.

- Sihvola S, Kuosmanen L, Kvist T. Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022;56:102079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102079.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم Yuxin Wang وYuan Qiu بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

تشاوقونغ دونغ

dcq1208@163.com

تتوفر القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف في نهاية المقالة

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05526-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38279114

Publication Date: 2024-01-26

Social support, family resilience and psychological resilience among maintenance hemodialysis patients: a longitudinal study

Abstract

Background Psychological distress is common in maintenance hemodialysis patients, and high psychological resilience can promote psychological well-being. The current research focuses on psychological resilience protective factors such as family resilience and social support. However, the trajectories of psychological resilience, family resilience, and social support over time and their longitudinal relationships in maintenance hemodialysis patients have not been fully explored yet. Therefore, this study aims to explore the longitudinal relationship between these factors. Methods Patients who received regular hemodialysis treatment for more than three months at dialysis centers of three tertiary hospitals in Zhejiang, China, were recruited from September to December 2020. A total of 252 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria completed three follow-up surveys, including social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience assessments. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to explore differences in their respective scores at different time points. The cross-lagged analysis was performed in AMOS using the maximum likelihood method to examine the the reciprocal predictive relationships between these factors. Results Social support and psychological resilience remained relatively stable over time, whereas family resilience indicated a little increasing trend. According to the cross-lagged analysis, higher T1 social support predicted higher family resilience at T2 [

Keywords Maintenance hemodialysis, Social support, Family resilience, Psychological resilience, Cross-lagged analysis, Longitudinal study

Background

indicating it is urgent to improve the psychological resilience of MHD patients. Consequently, there is a need to explore the protective factors of psychological resilience in patients with MHD in order to promote their psychological status and quality of life.

Methods

Study design and setting

Participants

Procedure

in the hospital, the study used the same approach to collect follow-up data in the hospital. Only patients who completed all three waves of the survey were included in the data analysis. The study adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline for observational research (Additional file 1).

Measurements

Social support

Family resilience

Psychological resilience

Covariates

Data analysis

M1 – A baseline model with autoregressive paths and cross-sectional correlations;

M2 – A model with cross-lagged paths from prior social support and psychological resilience to later family resilience that examined social support and psychological resilience as predictors of family resilience;

M3 – A model with cross-lagged paths from prior family resilience to later social support and psychological resilience that examined family resilience as predictors of social support and psychological resilience;

M 4-A model that examined bidirectional associations between social support and family resilience,

or between family resilience and psychological resilience.

M 5-A full model containing all the paths we hypothesized that examined bidirectional associations between social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience.

Ethical considerations

Results

Characteristics of participants and differences in social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience

Social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience of MHD patients in three waves

Relationship between social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience

Cross-lagged path analyses of social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience

| Variable | N(%) | Socail Support | t/F |

|

Family resilience | t/F |

|

Psychological Resilience | t/F |

|

| Age | ||||||||||

| <60 | 129(51.2%) |

|

|

0.786 |

|

|

0.916 |

|

|

0.063 |

|

|

123(48.8%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 169(67.2%) |

|

|

0.348 |

|

|

0.850 |

|

|

0.141 |

| Female | 83(32.9%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Employed | 45(17.9%) |

|

|

0.004 |

|

|

0.036 |

|

|

0.000 |

| Unemployed | 207(82.1%) |

|

||||||||

| Religious Belief | ||||||||||

| No | 122(48.4%) |

|

|

0.665 |

|

|

0.428 |

|

|

0.941 |

| Yes | 130(51.6%) |

|

|

|||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||

| Primary school and below | 68(27%) |

|

|

0.001 |

|

|

0.045 |

|

|

0.000 |

| Middle school | 96(38.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| High school/secondary school | 57(22.6%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| College or higher | 31(12.3%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Monthly household income per capita | ||||||||||

| <2,000 RMB | 36(14.3%) |

|

|

0.006 |

|

|

0.110 |

|

|

0.000 |

| 2,000-4,000 RMB | 91 (36.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 4,001-6,000 RMB | 74(29.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| >6,000 RMB | 51 (20.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single/divorced/widow/separated | 29(11.5%) |

|

|

0.000 |

|

|

0.378 |

|

t=-2.096 | 0.037 |

| Married/cohabitating | 223(88.5) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Medical insurance | ||||||||||

| No | 5(2%) |

|

|

0.487 |

|

t=-1.243 | 0.215 |

|

t=-1.639 | 0.173 |

| Yes | 247(98%) |

|

|

|||||||

| Duration of disease | ||||||||||

| <1 year | 13(5.2%) |

|

|

0.413 |

|

|

0.928 |

|

|

0.611 |

| 1~<5 years | 51(20.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 5~<10 years | 54(21.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

134(53.2%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Duration of hemodialysis | ||||||||||

| <1 year | 48(19%) |

|

|

0.029 |

|

|

0.643 |

|

|

0.071 |

| 1~<5 years | 106(42.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| 5~<10 years | 64(25.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

34(13.5%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| No | 75(29.8%) |

|

|

0.971 |

|

|

0.910 |

|

|

0.839 |

| One | 117(46.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Two or more | 60(23.8%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Primary caregivers | ||||||||||

| Spouse | 208(82.5%) |

|

|

0.031 |

|

|

0.004 |

|

|

0.225 |

| Offspring | 6(2.4%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Parents | 23(9.1%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Sibling | 15(6%) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Variable | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 |

| Social Support | |||

| Total |

|

|

|

| Tangible support |

|

|

|

| Informational/emotional support |

|

|

|

| Social interactive support |

|

|

|

| Affectionate support |

|

|

|

| Family resilience | |||

| Total |

|

|

|

| Family communication and problem solving |

|

|

|

| Utilizing social and economic resources |

|

|

|

| Maintaining a positive outlook |

|

|

|

| Ability to make meaning of adversity |

|

|

|

| Psychological Resilience | |||

| Total |

|

|

|

| Tenacity |

|

|

|

| Strength |

|

|

|

| Optimism |

|

|

|

findings revealed that higher levels of social support

Discussion

Stability and development of social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience in MHD patients

| Variable | T1 social support | T1 family resilience | T1 psychological resilience | T2 social support | T2 family resilience | T2 psychological resilience | T3 social support | T3 family resilience |

| T1 social support | 1 | |||||||

| T1 family resilience | 0.484** | 1 | ||||||

| T1 psychological resilience | 0.486** | 0.551** | 1 | |||||

| T2 social support | 0.390** | 0.195** | 0.177** | 1 | ||||

| T2 family resilience |

|

0.706** | 0.433** | 0.256** | 1 | |||

| T2 psychological resilience | 0.278** | 0.244** | 0.390** | 0.520** | 0.225** | 1 | ||

| T3 social support | 0.327** | 0.135* | 0.084 | 0.684** | 0.284** | 0.390** | 1 | |

| T3 family resilience | 0.169** | 0.156* | 0.064 | 0.273** | 0.294** | 0.181** | 0.446** | 1 |

| T3 psychological resilience | 0.263** | 0.203** | 0.169** |

|

0.319** | 0.298** | 0.493** | 0.552** |

| Model |

|

df |

|

CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Model comparison |

|

|

| M1 | 63.799 | 25 | 2.552 | 0.957 | 0.888 | 0.079 | 0.081 | – | – | – |

| M2 | 59.453 | 24 | 2.477 | 0.961 | 0.893 | 0.077 | 0.075 | M2 vs. M1 | 4.35(1) | <0.05 |

| M3 | 55.663 | 23 | 2.420 | 0.964 | 0.897 | 0.075 | 0.070 | M3 vs. M2 | 3.79(1) | >0.05 |

| M4 | 55.242 | 23 | 2.402 | 0.965 | 0.899 | 0.075 | 0.068 | M4 vs. M2 | 4.211(1) | <0.05 |

| M5 | 44.801 | 19 | 2.358 | 0.972 | 0.902 | 0.074 | 0.065 | M5 vs. M4 | 10.441(4) | <0.05 |

The relationship between social support, family resilience, and psychological resilience in MHD patients The relationship between social support and family resilience in MHD patients

an important resource that might affect families’ ability to endure and manage in the presence of a crisis. Likewise, Wong et al. [55] found that “drawing strength” was a major facilitator of family resilience in ICU patients. That is, ICU families gained emotional and informational support from their family members and other families of critically ill patients to break free from high emotional vulnerability and regain control, thereby increasing family resilience. However, family stress theory [56] states that the family’s perception of the stressful event and its available resources will determine how family stress and family capacity interact. This means that, in addition to social support, other factors such as the family’s cognitive evaluation of the crisis influence the dynamic process of family resilience. Future research could systematically explore the mechanisms by which factors such as family perceptions influence family resilience, given the impact of these aspects was not taken into account in this study.

The relationship between social support and psychological resilience in MHD patients

suggested that peer support was a potential resource that could provide additional emotional support and informational assistance to hemodialysis patients while enhancing their self-efficacy and self-management. Besides, social interactive support reduced the interpersonal burden of patients during hemodialysis and led to better clinical outcomes and psychosocial adjustment [59], aided by the fostering of resilience to reduce suffering.

The relationship between family resilience and psychological resilience in MHD patients

dynamic mechanisms of influence on psychological resilience of a variety of factors, such as disease factors and psychological burden.

Relevance to clinical practice

Limitations

Conclusions

| Abbreviations | |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| MHD | Maintenance hemodialysis |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| MOS-SSS | Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey |

| C-FRAS | Chinese version of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale |

| CD-RISC | Conner and Davidson resilience scale |

| SD | Standard deviation |

|

|

Chi-square/degree of freedom |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 26 January 2024

References

- Yang C, Yang Z, Wang J, Wang HY, Su Z, Chen R, et al. Estimation of prevalence of kidney disease treated with Dialysis in China: a study of insurance Claims Data. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(6):889-97. https://doi.org/10.1053/j. ajkd.2020.11.021.

- Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M. Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol (Carlton). 2016;21(3):241-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.12586.

- Liu L, Zhou L, Zhang Q, Zhang H. Mediation effect of self-neglect in family resilience and medication adherence in older patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. J Cent South University(Medical Science). 2023;48(07):1066-75. https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2023.230045.

- Zhang L, Zhao MH, Zuo L, Wang Y, Yu F, Zhang H et al. China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET) 2016 Annual Data Report. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2020;10(2):e97-e185https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2020.09.001.

- Global regional. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0140-6736(20)30045-3. and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

- Ibelo U, Green T, Thomas B, Reilly S, King-Shier K. Ethnic Differences in Health Literacy, Self-Efficacy, and self-management in patients treated with maintenance hemodialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022;9:20543581221086685. https://doi.org/10.1177/20543581221086685.

- Gerogianni G, Babatsikou F, Polikandrioti M, Grapsa E. Management of anxiety and depression in haemodialysis patients: the role of non-pharmacological methods. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(1):113-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11255-018-2022-7.

- Liu YM, Chang HJ, Wang RH, Yang LK, Lu KC, Hou YC. Role of resilience and social support in alleviating depression in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:441-51. https://doi.org/10.2147/ tcrm.S152273.

- Lowney AC, Myles HT, Bristowe K, Lowney EL, Shepherd K, Murphy M, et al. Understanding what influences the Health-Related Quality of Life of Hemodialysis patients: a collaborative study in England and Ireland. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):778-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jpainsymman.2015.07.010.

- Ma Y, Yu H, Sun H, Li M, Li L, Qin M. Economic burden of maintenance hemodialysis patients’ families in Nanchong and its influencing factors. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(6):3877-84. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1787.

- Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Farrington K. Depression in end-stage renal disease: current advances and research. Semin Dial. 2010;23(1):74-82. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00628.x.

- Oliveira CM, Costa SP, Costa LC, Pinheiro SM, Lacerda GA, Kubrusly M. Depression in dialysis patients and its association with nutritional markers and quality of life. J Nephrol. 2012;25(6):954-61. https://doi.org/10.5301/jn.5000075.

- Yu X, Zhang J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the ConnorDavidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behav Personality: Int J. 2007;35(1):19-30. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19.

- García-Martínez P, Ballester-Arnal R, Gandhi-Morar K, Castro-Calvo J, GeaCaballero V, Juárez-Vela R, et al. Perceived stress in relation to quality of life and resilience in patients with advanced chronic kidney Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2). https://doi. org/10.3390/ijerph18020536.

- Kumpfer KL. Factors and Processes Contributing to Resilience. Springer US. 2002https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47167-1_9.

- Gebrie MH, Asfaw HM, Bilchut WH, Lindgren H, Wettergren L. Patients’ experience of undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. An interview study from Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(5):e0284422. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone. 0284422.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Encyclopedia of psychology. Volume 3. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 129-33. https://doi.org/10.1037/10518-046.

- Walsh F. Family resilience: a framework for clinical practice. Fam Process. 2003;42(1):1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x.

- Tao L, Zhong T, Hu X, Fu L, Li J. Higher family and individual resilience and lower perceived stress alleviate psychological distress in female breast cancer survivors with fertility intention: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(7):408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07853-w.

- Li Y, Wang K, Yin Y, Li Y, Li S. Relationships between family resilience, breast cancer survivors’ individual resilience, and caregiver burden: a crosssectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;88:79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijnurstu.2018.08.011.

- Dong C, Xu R, Xu L. Relationship of childhood trauma, psychological resilience, and family resilience among undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):852-9. https://doi. org/10.1111/ppc.12626.

- Zhang X, Wang A, Guan T, Zhang Y, Kong YX, Meng J, et al. Caregivers’ caring ability and Disabled Elderly’s Depression:a Chain Mediating Effect Analy-Sis of Family Resilience and Psychological Resilience. Military Nurs. 2023;40(06):437. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2023.06.011.

- Wang H, Wang D, Zhang P. Relationships among Post Traumatic Growth,Resilience and Family Hardiness in Colorectal Cancer patients. Military Nurs. 2018;35(17):33-6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2018.17.008.

- Leve LD, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal transactional models of development and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(3):621-2. https://doi. org/10.1017/s0954579416000201.

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.59.8.676.

- Wilks SE, Croom B. Perceived stress and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: testing moderation and mediation models of social support. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(3):357-65. https://doi. org/10.1080/13607860801933323.

- Costa ALS, Heitkemper MM, Alencar GP, Damiani LP, Silva RMD, Jarrett ME. Social Support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life

and resilience in Brazilian patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(5):352-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc. 0000000000000388. - Sippel LM, Pietrzak RH, Charney DS, Mayes LC, Southwick SM. How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecol Soc. 2015;20:10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07832-200410.

- Ong HL, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Fauziana R, Tan ME, et al. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):27. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1616-z.

- Chen C, Sun X, Liu Z, Jiao M, Wei W, Hu Y. The relationship between resilience and quality of life in advanced cancer survivors: multiple mediating effects of social support and spirituality. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1207097. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1207097.

- Walsh F. A family resilience framework: innovative practice applications. Fam Relat. 2002;51(2):130-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x.

- Zhang Y, Ding Y, Liu C, Li J, Wang Q, Li Y, et al. Relationships among Perceived Social Support, Family Resilience, and Caregiver Burden in Lung Cancer families: a Mediating Model. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2023;39(3):151356. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2022.151356.

- Chen JJ, Wang QL, Li HP, Zhang T, Zhang SS, Zhou MK. Family resilience, perceived social support, and individual resilience in cancer couples: analysis using the actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52:101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101932.

- He Y, Chen SS, Xie GD, Chen LR, Zhang TT, Yuan MY, et al. Bidirectional associations among school bullying, depressive symptoms and sleep problems in adolescents: a cross-lagged longitudinal approach. J Affect Disord. 2022;298(Pt A):590-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.038.

- Galletta M, Vandenberghe C, Portoghese I, Allegrini E, Saiani L, Battistelli A. A cross-lagged analysis of the relationships among workgroup commitment, motivation and proactive work behaviour in nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(6):1148-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12786.

- Martens MP, Haase RF. Advanced Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Counseling Psychology Research. Couns Psychol. 2006;34(6):878-911. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000005283395.

- Boomsma A. The robustness of maximum likelihood estimation in structural equation models. Boomsma A, editor. In: Cuttance P, Ecob R, editors. Structural modeling by example: applications in educational, sociological, and behavioral research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. pp. 160-88.

- Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(2):135-43. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20008.

- Dong C, Gao C, Zhao H. Reliability and validation of Family Resilience Assessment Scale in the families raising children with chronic disease. J Nurs Sci. 2018;33(10):93-7. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2018.10.093.

- Duran S, Avci D, Esim F. Association between spiritual well-being and Resilience among Turkish hemodialysis patients. J Relig Health. 2020;59(6):3097109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01000-z.

- García-Martínez P, Ballester-Arnal R, Gandhi-Morar K, Temprado-Albalat MD, Collado-Boira E, Saus-Ortega C, et al. Factors Associated with Resilience during Long-Term Hemodialysis. Nurs Res. 2023;72(1):58-65. https://doi. org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000627.

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66(4):507-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF02296192.

- Lt H, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Kline P. Handbook of psychological testing. Kline P. editor: Routledge; 2013.

- Norman E. Resiliency enhancement: putting the strength perspective into social work practice. Norman E. editor: Columbia university press; 2000.

- Tian R, Bai Y, Guo Y, Ye P, Luo Y. Association between Sleep Disorders and Cognitive Impairment in Middle Age and older adult hemodialysis patients:

a cross-sectional study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:757453. https://doi. org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.757453. - Pompili M, Venturini P, Montebovi F, Forte A, Palermo M, Lamis DA, et al. Suicide risk in dialysis: review of current literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;46(1):85-108. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.46.1.f.

- Yin Y, Zhou H, Liu M, Liang F, Ru Y, Yang W, et al. Status and influencing factors of social isolation in elderly patients with maintenance hemodialysis. Chin J Nurs. 2023;58(7):822-9. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2023.07.008.

- Costenoble A, Rossi G, Knoop V, Debain A, Smeys C, Bautmans I, et al. Does psychological resilience mediate the relation between daily functioning and prefrailty status? Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s1041610221001058.

- Tamura S, Suzuki K, Ito Y, Fukawa A. Factors related to the resilience and mental health of adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(7):3471-86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05943-7.

- Harding SA. The trajectory of positive psychological change in a head and neck cancer population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(5):578-84. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.09.010.

- Chang PY, Chang TH, Yu JM. Perceived stress and social support needs among primary family caregivers of ICU patients in Taiwan. Heart Lung. 2021;50(4):491-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2021.03.001.

- Lee EY, Neil N, Friesen DC. Support needs, coping, and stress among parents and caregivers of people with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;119:104113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104113.

- Tak YR, McCubbin M. Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(2):190-8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02259.x.

- Wong P, Liamputtong P, Koch S, Rawson H. The impact of Social Support Networks on Family Resilience in an Australian Intensive Care Unit: a Constructivist grounded theory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51(1):68-80. https://doi. org/10.1111/jnu.12443.

- Axelson LJ, Mccubbin HI, Cauble AE, Patterson JM. Family stress, coping and Social Support. Fam Relat. 1982;32(3):452.

- Powathil GG, Kr A. The experience of living with a chronic illness: a qualitative study among end-stage renal disease patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2023;19(3):190-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2023.2229034.

- Bennett PN, St Clair Russell J, Atwal J, Brown L, Schiller B. Patient-to-patient peer mentor support in dialysis: improving the patient experience. Semin Dial. 2018;31(5):455-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12703.

- Silva SM, Braido NF, Ottaviani AC, Gesualdo GD, Zazzetta MS, Orlandi Fde S. Social support of adults and elderly with chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:e2752. https://doi. org/10.1590/1518-8345.0411.2752.

- Kukihara H, Yamawaki N, Ando M, Nishio M, Kimura H, Tamura Y. The mediating effect of resilience between family functioning and mental well-being in hemodialysis patients in Japan: a cross-sectional design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01486-x.

- Nam B, Kim JY, DeVylder JE, Song A. Family functioning, resilience, and depression among North Korean refugees. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:451-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.063.

- Chen Y, Cui W, Sun L, Wang Y. Survey of psychological resilience level and coping style in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Chin J Blood Purif. 2016;15(1):55-7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-4091.2016.01.015.

- Sihvola S, Kuosmanen L, Kvist T. Resilience and related factors in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2022;56:102079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102079.

Publisher’s Note

Yuxin Wang and Yuan Qiu contributed equally to this work.

*Correspondence:

Chaoqun Dong

dcq1208@163.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article